JOY JENNINGS

Feeling-into One Another; Exploring Empathy, Meaning and collective experience, facilitated by artistic expression

May 2025

Art & Philosophy BA (Hons)

DOI 10.20933/100001379

Except where otherwise noted, the text in this dissertation is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license.

All images, figures, and other third-party materials included in this dissertation are the copyright of their respective rights holders, unless otherwise stated. Reuse of these materials may require separate permission.

Feeling-Into One Another; Exploring Empathy, Meaning and Collective Experience, Facilitated by Artistic Expression

Joy Jennings 2464100

Included alongside the physical copy is a bronze figurative sculpture called a ‘Formable’, which is there to offer a physical vessel to engage with while contemplating the act of ‘feeling-into’ which is outlined in this dissertation

Art and Philosophy BA (Hons)

Word count: 8211

*Excluding abstract, contents, footnotes, bibliography, indented quotes, and image captions

Dissertation submitted as partial fulfilment of the requirements of a Bachelor of Arts (Hons) Degree in Art and Philosophy

Duncan and Jordanstone Collage of Art and Design

University of Dundee

2025

Abstract

This paper approaches the topic of empathy through the lens of phenomenology, specifically engaging with the work of Edith Stein, in her thesis On the Problem of Empathy, which offers a comprehensive analysis of the underlying conditions and process of empathic experiences that distinguishes it from the similar social concepts compassion and sympathy. Empathy originated in 19th century Germany in the sphere of aesthetics as the word ‘Einfühlung’ which directly translates as ‘feeling-into’, this concept was then later applied in the fields of psychology and neuroscience. While a single definition of empathy has not been agreed, its significance is without doubt. I therefor aim to explore the nuanced and complex nature of ‘feeling-into’ the lived experiences of others while honouring the origin of the concept in aesthetics and art

I will discuss Steins phenomenological approach to empathy and apply it to how visual arts can evoke empathy and deepen empathetic understanding. Looking at works by artist such as Deborah Padfield and Jaakko Autoi who’s practice centres on the concepts of radical empathy, otherness and lived experience, to explore how artistic expression and the phenomenological method work together and consider art as a conduit for lived experience that allows us to transcend our isolated subjectivity, by feeling- into (Einfühlung) Others, not through imagining or inferring but experiencing their subjectivity through direct participation facilitated by art. Solidifying empathy as a radical act that deepens our understanding our own nature and the nature of others, while maintaining self-other differentiation.

Keywords; Empathy, Einfühlung, feeling-into, experience, Self, Other, understanding, transcendence, intuition, meaning

Preface

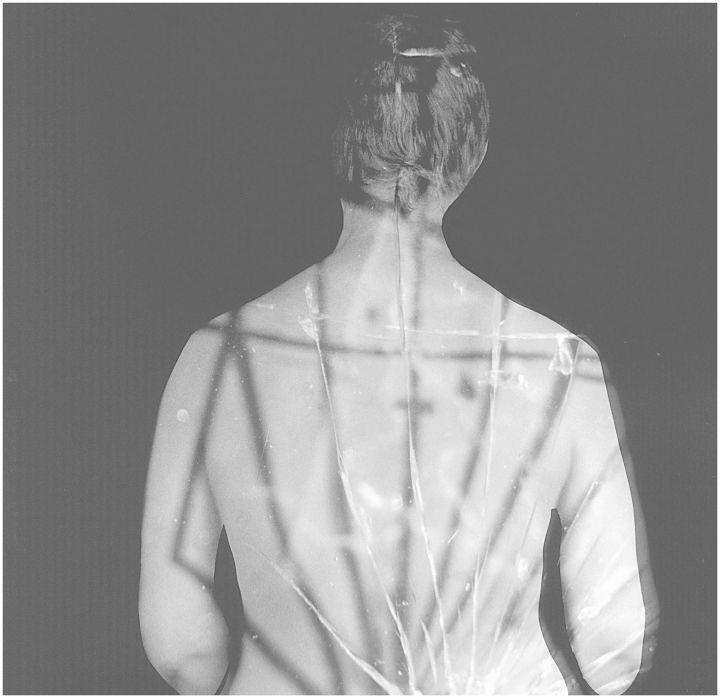

This paper is a reconciliation of various methods in which I attempted to communicate my lived experience with chronic pain. I became interested in the subject of creating a visual language for pain, specifically physical pain. I am often asked to describe my perpetual experience with chronic pain in the physical body through descriptive language, whether that’s by medical personnel or personal intrigue. The more often I was asked to describe my internal experience of pain, words such as ache, sharp, dull, stabbing did not accurately aline with my perpetual lived experience, yet those were the words available in which I could attempt to communicate. I therefore became fascinated with the exploration of a visual language of pain, where words were not able to offer a whole understanding of my experience, a more sensory receiving of my experience through visual or physical expression would be more effective.

Through artistic practice I tried to articulate the multifaceted nature of chronic pain and its symptoms through visual mediums such as painting, sculpture and most successfully performance, while trying to engage intentionally with the sensations I usually try to dull and distract from in daily life While some were able to grasp elements of my lived experience, in particular the fatigue, frustration, and joint movement restrictions through the performance, I found the reception of the piece still could not fully encapsulate my experience from those whose own experience differs greatly. Then occurred to me an issue in the receiving of the work rather than the work itself, a dissonance in the “feeling-into’ of lived experience. Communication requires both the communicator and the receiver, someone desperate to be understood and another willing to understand. What is a daily experience for me is incomprehensible to others, who may not have been prepared to comprehend the content of the performance. I became interested in exploring this relationship, especially regarding the output of an artist to create work based on experience and the output that is required of the audience to engage with the work in the way it was intended. Unable to reach a satisfactory conclusion through artist practice alone, I wanted to expand the exploration with a dualistic approach of artist research and philosophical investigation through the lens of phenomenology ( the study of experience). During my research I came across the work of Edith Stein which prompted me to root my exploration of communication within the phenomenon of Empathy. As my research progressed, I became less interested in the intention of the artist and became interested in how we instinctively experience artwork as viewers, leading to my exploration of ‘feeling-into’ art as a intersubjective experience.

Figure 1 –Visulaising chronic pain, Image from proformance piece, Joy Jennings, 2022 Photographed by Lois Christe https://youtu.be/u6Sg3zQpILw

Title

Abstract

Preface

Introduction

Einfühlung, Empathy and Feeling-Into p7

The history Einfühlung p7

Edith Stein and Einfühlung ….. p8

Scientific explorations of phenomenon .p11

Where words fail p13

Art facilitation of ‘feeling-into’ p13

Going beyond empathy p17

Transcendence, meaning and value ……………………….p17 I, You and We

Postlude

Introduction

Empathy, as a phenomenon explores understanding the nature of human experience, by disclosing subjectivity between Self and Other1 . Empathy derives from the German word ‘Einfühlung’ directly translated to “feeling-into’, originally used in the sphere of aesthetics to describe the experience of ‘feeling-into’ a work of art, however Edith Stein’s phenomenological approach in her thesis ‘On the problem of empathy’ (Stein, 1964) elevates Einfühlung as a way of ‘feeling-into’ another consciousness, rather than objects. Despite the seemingly complex aspects, Stein simplifies ‘Einfühlung’ to the ‘experience of foreign consciousness’, therefore, to empathise is to experience another (foreign) experiencing (consciousness). Empathy has typically been understood to be an ‘imagining’ of another person’s circumstances that you respond emotionally to, (putting on someone else’s shoes) however Stein’s work challenges this idea and establishes empathy as a form of ‘radical otherness’. This paper will explore the history of Einfühlung across aesthetics, psychology, and phenomenology, as well as its translation into English as empathy. Distinguishing empathy from the likes of sympathy and compassion and establishing it as a complex act of consciousness, that can help us further understanding of Self and Other I will explore how Stein’s phenomenological act of ‘feeling-into’ can be reapplied to its origin in art and aesthetics and offer an application of empathy that can operate in contexts without interpersonal interaction, where the ‘Other’ is absent To do this I will connect Stein’s “feeling-into” consciousness, with Henry Bergson’s method of intuition, to reconcile ‘feelinginto’ art as an object Laying the foundation for a collaborative exploration of ‘feeling-into’ and arts ability to point beyond the material world, and gives realisation to the abstract realms of consciousness within Self, such as value and meaning, which cannot be naturally perceived.

While Stein intentionally diverted Einfühlung (empathy) away from aesthetics and the ‘feelinginto’ of objects, I believe there is scope for the phenomenological and artistic framework to intersect to uncover how art can serve as a conduit for empathic experience and understanding. Within the context of art, empathy can expand beyond interpersonal relationships and offer the ability to engage with creative works at a profoundly intersubjective level I aim to explore this possibility by engaging with artist such as Freida Kahlo and Deborah Padfield who’s work could serve as a compelling application of Stein’s concepts and conditions of Einfühlung (empathy), as both artists engage with themes of empathy, vulnerability, and communicating lived experience through artistic expression. I will then expand the potential of ‘feeling-into’ with the inclusion of Bergson’s Intuition to propose, that what can be grasped while experiencing art extends beyond the boundaries of empathy and into a transcendent realm of meaning and value. Using examples from Mark Rothko and Jaakko Autio I will propose that what we grasp within Self, through ‘feeling-into’, by intuition, opens the potential for art to be both a vehicle for personal and communal understanding, as we acknowledge what we grasp in common, through our subjective experiences.

I also acknowledge that there are many various forms of expression that could be serve as a conduit for empathetic experience such as theatre, literature, music ect however, I will be containing this paper to expression through visual arts. I also do not aim to clarify a singular definition of empathy, rather explore its potential through the perspectives of Stein and Bergson As well as identify the limitations of ‘feeling-into’, where the Self is not open and willing to grasp the essence that artistic expression has realised, and therefore remains in the subjective isolation, unable to participate in intersubjective communal experiences I will conclude by summarising my exploration of ‘feeling-into’ as it relates to Self, Other and communal understanding, through

1 Capitalised to reflect Stein’s use of Self and Other as it relates to consciousness, rather than self and other as the object of discussion.

the vessel of artistic expression. I will conclude by stating, that as we acquire new values and understanding of Self through empathetic (feeling-into) engagement with the Other, so too can we acquire new meanings, value and understanding through ‘feeling-into’ works of artworks by intuition and grasping that which is being offered (realised) within Self. This opens the potential for a radical form of empathy that allow for the abstract realms of meaning and value to be subjectively grasped, communally experienced, collectively understood and applied to how we engage with each other and the world.

Einfühlung, Empathy and Feeling-into – Section 1

Brief History of Einfühlung

The concept of empathy originates in German philosophy in the study of aesthetics, philosopher Robert Vischer introduced the term ‘Einfühlung’ in his1873 paper, ‘on the optical sense of form: a contribution to aesthetics’ (Vischer, 1994) . He used the term to describe how we might project into a work of art, referring to the way a viewer can imaginatively ‘enter into’ the work and immersivly experience its content, in this way Einfühlung became an act that relates to aesthetic appreciation of artworks. The idea of Einfühlung was further developed by Theodor Lipps who expanded the scope of Einfühlung into psychology to not only describe our engagement with aesthetics objects, but also as a process for understanding Other’s emotions and experiences. However similarly to Vischer, Lipp’s defined Einfühlung (empathy) as a type of ‘imagining’ that allows individuals to resonate with the internal states of Others through imagining their experience in order to resonate with them, which he named imitation theory. During Lipp’s writing in 1909 the philosophical field of phenomenology was developing with Edmund Husserl, one of Husserl’s students Edith Stein deeply explored Einfühlung in her 1916 dissertation ‘On the problem of empathy’ (Stein, 1964) (Zum Problem der Einfühlung) which heavily cited and critiqued Lipp’s work2 as she further expanded the concept of Einfühlung and its applications to engage with lived experience.

Stein takes Einfühlung out of the grasp of psychology and elevates the concept through the phenomenological method of lived experience, bringing Einfühlung into the philosophical discourse regarding the nature of human experience, in relation to subjectivity and intersubjectivity. She argues that Einfühlung as it relates to the nature of human experience must be defined and explored through a philosophical phenomenological study as,“Psychology is entirely bound to the results of phenomenology. Phenomenology investigates the essence of empathy, and wherever empathy is realised this general essence must be maintained” (Stein, 1964, p. 21). While Stein’s phenomenological approach to Einfühlung is closely tied to Vischer and Lipp’s theory that a viewer could ‘feel into’ an object or subject3, Stein moves Einfühlung away from objects4 and towards subjectivity (consciousness). This is possible through phenomenology as, imitation theory, “simulation theory and the theory-theory […] both deny that it is possible to experience other minds […]. It is precisely because of the alleged absence of an experiential access to the minds of others that we need to rely on and employ either theoretical inferences or internal simulations.” (Zahavi, 2010, p. 286), phenomenology does not have this issue as its based in experience as knowledge. Stein is therefore able to redefine Einfühlung as a process of ‘perceiving’ consciousness through direct experience rather than ‘imagining’ as the previous thinkers proposed. Steins distinct approach highlights the importance of Einfühlung (empathy) and the possibilities of its unfolding nature within the framework of the

2 Stein and Lipps agree that Einfühlung is an “ ‘inner participation’ in foreign experiences. Stein is critiquing Lipp’s work and correcting his approach to be more inline with a phenomenological method, but not entirely refuting it.

3 Person as subject

4‘object’ referring to physical spacial materials, opposed to becoming the ‘object’ of empathetic experience

phenomenological method, as her writing investigates Einfühlung in relation to lived experience (“I”), Self and Other, social cognition and, in her later works, collective experience.5

Empathy was translated into English in 1909 (same time as Lipps writing) by British phycologist Edward Titchener as a direct translation of Einfühlung as ‘feeling into’, a combination of the Greek rooted “em” (in) and “pathos” (feeling) resulting in ‘empathy’ that we use today. The similarity of the Greek roots of Empathy and sympathy, coupled with the timing in which empathy arrived into English vocabulary6; before the fleshing out of the concept of ‘feeling-into’ by Husserl, Stein and other thinkers, may be the reason these two words are still used so interchangeably, especially when describing social interactions with others and engaging with their emotional states and physical circumstances. The concepts of empathy, sympathy and compassions are often misconstrued as interchangeable, as all are frequently in relation to interpersonal relationships, emotional intelligence and a response to negative emotional states or circumstances of others. Its important that before exploring conditions of Einfühlung (empathy), it must be defined what it is not, which is neither sympathy nor compassion. Sympathy has various definitions,7 the most frequently used presently is to have emotional response for someone else's misfortune and circumstance, that we understand through imagining ourselves in their position, resulting in feelings of care, sorrow, or pity towards them. However, other than an acknowledgement of their situation, sympathy in isolation doesn’t result in practical action to change that circumstance. Sympathy remains in emotion which is distinctly different from Stein’s definition of empathy (Einfühlung) as a direct experiencing of Other’s experience, which extends beyond our imagination and emotions.8 While sympathy is an internal response to another9, compassion is often seen as a more practical response, leading to an attempt relieve the suffering or circumstance of another. A call to action, as a consequence of emotionally responding and acknowledging another’s pain or suffering, leading to a practical intervention to attempt to alleviate it. Both sympathy and empathy can lead to compassion, however compassion in conjunction with empathy could be argued to be more effective, as the practical response would stem from true empathetic understanding, which should therefore produce a practical action that is informed by direct experiencing of the Other, rather than a sympathetic imaginative understanding. These important distinctions between empathy (Einfühlung), sympathy and compassion, lay the groundwork for Stein’s definition of empathy as a form of ‘radical otherness’, that is set apart from sympathy and compassion.10

Edith Stein and Einfühlung

“An experience grasped in reflection has no sides” (Stein,1964, p32)

5 Edith Stein’s 1922 treatise psychology, philosophy and humanities

6 Empathy was translated and used in English 7 years before Edith Steins thesis in German and therefore before Einfühlung had been explored in depth in the sphere of phenomenology. As Stein states ‘Psychology is entirely bound to the results of phenomenology.’

7 Another definition of sympathy is an understanding between people often a shared feeling, sentiment or agreement on a subject matter. However this definition does not apply to this context

8 Stein would define this type of response as ‘relection’

9 Using lower case other and another to differentiate between typical use from Steins use of capitalised Self and Other in relation to consciousness

10 Its important to acknowledge that later in this paper I will discuss philosopher Henry Bergson and his method of intuition in which he uses sympathy, in relation to an act by we can grasp the essence of things, to avoid confusions and also in keeping with my proposed method, I will refer to Bergson’s sympathy as a form of ‘feeling-into’

Whilst Stein writes within the complex structures of experience, she is able to summarise empathy in an accessible manner, defining Einfühlung (empathy) as simply the ‘experience of foreign consciousness’, therefore to empathise is to experience another (foreign) experiencing (consciousness).11 While empathy is often used in regards to negative situations of the Other, Stein encapsulates all experiencing of another’s consciousness as empathetic experience, regardless of content, whether you are ‘feeling-into’ their joy or pain, the act of Einfühlung is occurring, “ while I am living in the other’s joy, I do not feel primordial joy, it does not issue live from my I (self)” (Stein, 1964, p. 9). In her thesis she not only aims to identify the essence of acts of ‘Einfühlung’ (empathy) but also distinguishes it from the similar acts of ‘memory, expectation and fantasy’ outlining the difference between primordial and non-primordial content. All experience is experienced primordially but not every experience contains primordial content. Memory, is an act experienced primordially while containing non-primordial content, as its content is being recalled (re-presented)12 from a past primordial experience but presently experienced as non-primordial, as the experience of remembering is not the same as you experiencing an experience on the day it happened. Stein also outlines expectation and fantasy as acts that contains non-primordial content, however unlike memory the content does not have to stem from a previous primordial experience, but rather imagining or envisioning an experience that has not happened or possibly will happen, however we experience these imagined experiences primordially, as previously stated all experiencing is primordial whether the content is imagined or re-presented.13 Stein uses these distinctions to set Einfühlung apart, despite the same structural form of the other acts, the non-primordial content of memory, expectation and fantasy originates in Self (my own primordial experiences), while the content of empathy originates in the Other (another person’s primordial experience). The primordial experiences of another is not primordial to me even if I grasp it empathetically it is still not my experience, therefore empathy is too an act that is primordial while containing non-primordial content, however that content originates outside of Self.

Einfühlung doesn’t necessary bridge the gap between Self and Other, there is no blurring of the line between two persons but rather a ‘disclosure’ that makes the Self aware of the Other’s subjectivity (as an embodied consciousness) outside of Self. 14 Rather than just seeing the body of another and inferring that they must therefore be a person, I am experiencing their subjectivity directly as something I am receiving by ‘feeling-into’ their subjective experience, therefore I am primordially experiencing their experience as it is given to me through empathy. By ‘feeling-into’ the Other we are not temporarily loosing Self, on the contrary, by engaging with the Other empathetically while maintaining the subjective nature of Self, it is possible to deepen our own understanding of Self and our individuality in reference to the Other. One of Stein’s condition for Einfühlung is there be a maintained distinct boundary between Self and Other, in doing so Stein emphasises the impact Other can have on Self, when Self is open and willing to engage by ‘feeling-into’ subjectivity outside of Self and apply it to their own understanding.

“By empathy with differently composed personal structures we become clear on what we are not, what we are more or less than others. Thus,together with self knowledge, we also have an important aid to self evaluation. Since experience of value is basic to our own value, at the same time as new values are acquired by empathy, our own unfamiliar values become visible.” (Stein, 1964, p. 105)

11 Stein uses the term ‘foreign consciousness’ to describe a conscious Being outside of ourselves, however I find the term produces negative connotations that alienate rather that bring together consciousness’, I will therefore exchange the term with the ‘Other’ as a descriptor for consciousness outside of Self.

12 Similar to Husserl’s “Vergegenwartigung” which outlines “presentive” and “re-presentive” acts

13 Lipps imitation theory

14 Which alines with the phenomenological stance on the body, that there is no body/mind dualism.

Our ability to fully understand and experience the Self is therefore linked to our openness to experience the Other. The dialog between Self and Other facilitated by empathetic experience enriches our understanding of Self and makes us aware of uniqueness of a singular consciousness, which can lead to the acquisition of new values and understanding as we become conscious of unique consciousness’ (Others) outside of Self and make applications in consequence of this new knowledge (social cognition). To understand the Self is to understand the Other, and to understand the Other is to understand the Self, one cannot be without the other.

Scientific explorations of phenomenon

In Stein’s application of empathy, it is implied by context that the ‘Other’ be present for the experience of empathy to occur, however she does not address in relation to art within her phenomenological definition, leaving space for exploration of how empathy can operate in contexts without interpersonal interaction, where the ‘Other’ is physically absent, such as interactions with visual art. As outlined previously Stein’s method is concerned with how Einfühlung (empathy) allows Self to understand Other and vise versa, and how empathetic interaction shapes our engagement with the world, this would therefore include artworks. When Robert Vischer first discussed Einfühlung, he placed it within the boundaries of aesthetics and art. He discussed Einfühlung as a phenomena that can allow a person to ‘feel-into’ art, as an external object, to the extent that we may ‘become one’ with the art, as Vischer states, “We move in and with the forms” (Vischer, 1994 p.101). He specifies a physiological basis for his theory, ‘muscular empathy’ which attempts to link aesthetic appreciation with rhythmic physiological responses in the body (external) (Mallgrave and Ikonomou, 1994).

His theories were later adopted by psychologists (Theodor Lipps and Edward Titchener) and more modernly, expanded into neuroscience, his theories became the foundation of the study of ‘Mirror neurons’ which aims to explain the neural processes underlying empathic responses, including responses to art.15 This research implicates empathy (Einfühlung/feeling-into) back into imitation and simulation, which Stein has already refuted in relation the Lipp’s writing, in fact it reduces empathy to a cognitive ‘corporeal sensation’ that proposes while empathising we physiological respond in direct relation to ‘bodily received’ visual stimulus, whether that is a physical person we are perceiving or an artwork, under this theory both are perceived as object, to which the response can be measured and defined. A specific example would be David Freedberg and Vittorio Gallese’s paper where they state that empathetic responses to art ought to have ‘a precise and definable material basis in the brain.’ (Freedberg and Gallese, 2007.)

Like Vischer, Stein also discusses the physiological side of empathy, however she writes of the body as a ‘living body’, and it is within the context on the’ living body’ the she explores emotion, feeling, and expression as they relate to empathetic experience. “living body belonging to “I”, an “I” that senses, thinks, feels and wills. The living body of this “I” not only fits into my phenomenal world. It faces this world and communicates with me” (Stein, 1964, p. 6)16 As Stein previously concluded in response to Lipp’s, any theory that contradicts lived experience (phenomenology) to try and conclude something as quantifiable disregards the nature of

15In this dissertation I cannot provide a full explanation and evidence for the neurological perspective of empathy within the study of ‘mirror neurons’. I am acknowledging ‘mirror neurons’ to give further historical and academic context to how Steins phenomenological method of empathy differs from other explorations, and have different implications to the empathetic experience, in this case in relation to artworks. Read Freedberg, D., & Gallese, V. (2007). Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience. Trends in cognitive sciences, 11(5), 197–203.

16 Steins phyco-physical approach aligns with the phenomenological stance that there is no body/mind dualism.

empathy as a phenomenon. While theories of mirror neurons were not presented till well after Stein's writing she actively argues against any theory that removes a phenomenon from its status.

Psychologists….usually reduce it to “mere association”. This “mere” indicates phycology’s tendency to look at explanation as an explaining away, so that the explained phenomenon becomes a “subjective creation” without “objective meaning”. We cannot accept this interpretation. Phenomenon remains phenomenon. (Stein, 1964, p. 42)

This is a similar perspective to that of French philosopher Henry Bergson17, who also believed that science had its place, but isn’t necessarily the right mode of knowledge to investigate phenomenon, “the scientific intelligence asks itself therefore what will have to be done in order that a certain desired result be attained, or more generally, what conditions should obtain in order that a certain phenomenon take place.” (Bergson, 2002, p 245) while Stein and Bergson philosophical writings are distinctly different, there are some intersections in which methods and perspectives are similar in relations to their respective conclusions. One such similarity is they both believed that scientific methods aren’t appropriate in the investigations of fundamental truths of being, concluding that lived experience cannot be measured or explained through scientific and binary exploration. When Stein elevated Einfühlung from the cognitive and psychological to the realm of ‘feeling-into’ consciousness and an intersubjective dialog between Self and Other, she redirected focus of the conversation away from art and aesthetics. However, this doesn’t mean that Stein’s definitions of empathy cannot be practically applied to reinclude empathetic engagement within the sphere of art and aesthetics.

Stein’s critique of Vischer “feeling-into’ art as an object, seemingly brings up issues regarding applying Einfühlung as a ‘feeling-through’ art, and “feeling into” the consciousness (Other) beyond the physical ‘object’, as the art is still perceived spatially as an object. To reconcile this, we can again apply similarities with Bergson, who uses the terms relative and absolute knowledge to describe objects are known to us through experience. ‘Relative knowledge’ refers to how we perceive objects in matter, it is given to us through descriptions, which may be linguistic analysis, dialect description, scientific analysis, or maths all of which Bergson defines as forms of symbols.18Bergson counters this way of knowing (knowledge) with his method of intuition19 which he describes as a form of direct, immediate knowledge. Intuition is a way of grasping by “feeling into”20 the essence of things which cannot be captured through scientific ordering. Through intuition Bergson outlines this second form of knowledge as ‘absolute knowledge’, ‘feeling-into’ the inner being of object to grasp its uniqueness, getting back to knowing the thing itself, its essence. This grasping of uniqueness is comparable to Stein’s outlining of ‘feeling-into’ the uniqueness of subjective consciousness, which is fully grasped through ‘feeling-into’, just as what is grasped by intuition is always grasped fully (absolute), in the sense that is fully what it is, when grasped. This distinction between relative and absolute knowledge contributes to Stein’s critique of Vischer, for when he sumises a “feeling-into” of art, he remained at surface level, as he proposed an engagement with art through imagination (relative knowledge), rather than intuition (absolute knowledge) and therefore it could not be grasped through ‘feeling-into’. What is grasped through intuition is not perceived physiologically (in the mind) but is grasped within Self (“I”). Intuition is an immediate direct knowledge, as is Einfühlung an immediate experience,

17 I will expand on Bergson philosophies later in this paper.

18 This gives further insight to Stein and Bergson’s critics of scientific analysis, as by its structures is not able to grasp fluid lived experience.

19 Not to be confused with a Kantian application of intuition

20 Im acknowledge the term Bergson uses ‘sympathy’ but for the sake of clarity in relation to Steins definition I will be using “feeling into’, and due to the nature it is applied in this paper Bergson’s ‘sympathy’ is a form of ‘feeling-into’

which is both directly and indirectly perceived, just as intuition is both an intellect and instinct, “Intuition, connected to both instinct and intellect, goes beyond each to the extent that it seeks out the whole, the entirety of life undivided from its necessary connections with matter.” (Bergson, 2022, iv). Therefore ‘feeling-into’ art it is both what we perceive naturally (living body) and what can only be perceived through intuition (“I”), it is both mind and the thing. 21

How can one ask the eyes of the body, or those of the mind, to see more than they see? Our attention can increase precision clarity and intensify it cannot bring forth in the field of perception what was not there in the first place. That's the objection - it is refuted in my opinion by experience. For hundreds of years in fact, there have been men whose function has been precisely to see and to make us see what we do not naturally perceive. They are the artists.

(Bergson, 2002, p.251)

Not only does Bergson help reconcile the “feeling-into’ of objects, but also outlines the significance of an artist’s role, as the work they create not only expresses the naturally perceivable (matter), but to also expresses (brings into realisation) that which is only perceivable by “I” through communication with ‘living body’ through feeling-into by intuition.

Scientific explorations of phenomenon

In Stein’s application of empathy, it is implied by context that the ‘Other’ be present for the experience of empathy to occur, however she does not address in relation to art within her phenomenological definition, leaving space for exploration of how empathy can operate in contexts without interpersonal interaction, where the ‘Other’ is physically absent, such as interactions with visual art. As outlined previously Stein’s method is concerned with how Einfühlung (empathy) allows Self to understand Other and vise versa, and how empathetic interaction shapes our engagement with the world, this would therefore include artworks When Robert Vischer first discussed Einfühlung, he placed it within the boundaries of aesthetics and art He discussed Einfühlung as a phenomena that can allow a person to ‘feel-into’ art, as an external object, to the extent that we may ‘become one’ with the art, as Vischer states, “We move in and with the forms” (Vischer, 1994 p.101). He specifies a physiological basis for his theory, ‘muscular empathy’ which attempts to link aesthetic appreciation with rhythmic physiological responses in the body (external) (Mallgrave and Ikonomou, 1994).

His theories were later adopted by psychologists (Theodor Lipps and Edward Titchener) and more modernly, expanded into neuroscience, his theories became the foundation of the study of ‘Mirror neurons’ which aims to explain the neural processes underlying empathic responses, including responses to art.22 This research implicates empathy (Einfühlung/feeling-into) back into imitation and simulation, which Stein has already refuted in relation the Lipp’s writing, in fact it reduces empathy to a cognitive ‘corporeal sensation’ that proposes while empathising we physiological respond in direct relation to ‘bodily received’ visual stimulus, whether that is a physical person we are perceiving or an artwork, under this theory both are perceived as object, to which the response can be measured and defined. A specific example would be David

21 Husserl’s phenomenology, it is both mind and the thing. getting back to knowing the thing itself

22In this dissertation I cannot provide a full explanation and evidence for the neurological perspective of empathy within the study of ‘mirror neurons’ I am acknowledging ‘mirror neurons’ to give further historical and academic context to how Steins phenomenological method of empathy differs from other explorations, and have different implications to the empathetic experience, in this case in relation to artworks. Read Freedberg, D., & Gallese, V. (2007). Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience. Trends in cognitive sciences, 11(5), 197–203.

Freedberg and Vittorio Gallese’s paper where they state that empathetic responses to art ought to have ‘a precise and definable material basis in the brain.’ (Freedberg and Gallese, 2007 )

Like Vischer, Stein also discusses the physiological side of empathy, however she writes of the body as a ‘living body’, and it is within the context on the’ living body’ the she explores emotion, feeling, and expression as they relate to empathetic experience. “living body belonging to “I”, an “I” that senses, thinks, feels and wills. The living body of this “I” not only fits into my phenomenal world. It faces this world and communicates with me” (Stein, 1964, p. 6)23 As Stein previously concluded in response to Lipp’s, any theory that contradicts lived experience (phenomenology) to try and conclude something as quantifiable disregards the nature of empathy as a phenomenon. While theories of mirror neurons were not presented till well after Stein's writing she actively argues against any theory that removes a phenomenon from its status.

Psychologists….usually reduce it to “mere association”. This “mere” indicates phycology’s tendency to look at explanation as an explaining away, so that the explained phenomenon becomes a “subjective creation” without “objective meaning”. We cannot accept this interpretation. Phenomenon remains phenomenon (Stein, 1964, p. 42)

This is a similar perspective to that of French philosopher Henry Bergson24, who also believed that science had its place, but isn’t necessarily the right mode of knowledge to investigate phenomenon, “the scientific intelligence asks itself therefore what will have to be done in order that a certain desired result be attained, or more generally, what conditions should obtain in order that a certain phenomenon take place.” (Bergson, 2002, p 245) while Stein and Bergson philosophical writings are distinctly different, there are some intersections in which methods and perspectives are similar in relations to their respective conclusions. One such similarity is they both believed that scientific methods aren’t appropriate in the investigations of fundamental truths of being, concluding that lived experience cannot be measured or explained through scientific and binary exploration When Stein elevated Einfühlung from the cognitive and psychological to the realm of ‘feeling-into’ consciousness and an intersubjective dialog between Self and Other, she redirected focus of the conversation away from art and aesthetics. However, this doesn’t mean that Stein’s definitions of empathy cannot be practically applied to reinclude empathetic engagement within the sphere of art and aesthetics.

Stein’s critique of Vischer “feeling-into’ art as an object, seemingly brings up issues regarding applying Einfühlung as a ‘feeling-through’ art, and “feeling into” the consciousness (Other) beyond the physical ‘object’, as the art is still perceived spatially as an object. To reconcile this, we can again apply similarities with Bergson, who uses the terms relative and absolute knowledge to describe objects are known to us through experience. ‘Relative knowledge’ refers to how we perceive objects in matter, it is given to us through descriptions, which may be linguistic analysis, dialect description, scientific analysis, or maths all of which Bergson defines as forms of symbols.25Bergson counters this way of knowing (knowledge) with his method of intuition26 which he describes as a form of direct, immediate knowledge. Intuition is a way of grasping by “feeling into”27 the essence of things which cannot be captured through scientific ordering.

23 Steins phyco-physical approach aligns with the phenomenological stance that there is no body/mind dualism.

24 I will expand on Bergson philosophies later in this paper.

25 This gives further insight to Stein and Bergson’s critics of scientific analysis, as by its structures is not able to grasp fluid lived experience.

26 Not to be confused with a Kantian application of intuition

27 Im acknowledge the term Bergson uses ‘sympathy’ but for the sake of clarity in relation to Steins definition I will be using “feeling into’, and due to the nature it is applied in this paper Bergson’s ‘sympathy’ is a form of ‘feeling-into’

Through intuition Bergson outlines this second form of knowledge as ‘absolute knowledge’, ‘feeling-into’ the inner being of object to grasp its uniqueness, getting back to knowing the thing itself, its essence. This grasping of uniqueness is comparable to Stein’s outlining of ‘feeling-into’ the uniqueness of subjective consciousness, which is fully grasped through ‘feeling-into’, just as what is grasped by intuition is always grasped fully (absolute), in the sense that is fully what it is, when grasped. This distinction between relative and absolute knowledge contributes to Stein’s critique of Vischer, for when he sumises a “feeling-into” of art, he remained at surface level, as he proposed an engagement with art through imagination (relative knowledge), rather than intuition (absolute knowledge) and therefore it could not be grasped through ‘feeling-into’ . What is grasped through intuition is not perceived physiologically (in the mind) but is grasped within Self (“I”). Intuition is an immediate direct knowledge, as is Einfühlung an immediate experience, which is both directly and indirectly perceived, just as intuition is both an intellect and instinct, “Intuition, connected to both instinct and intellect, goes beyond each to the extent that it seeks out the whole, the entirety of life undivided from its necessary connections with matter.”

(Bergson, 2022, iv). Therefore ‘feeling-into’ art it is both what we perceive naturally (living body) and what can only be perceived through intuition (“I”), it is both mind and the thing. 28

How can one ask the eyes of the body, or those of the mind, to see more than they see? Our attention can increase precision clarity and intensify it cannot bring forth in the field of perception what was not there in the first place. That's the objection - it is refuted in my opinion by experience. For hundreds of years in fact, there have been men whose function has been precisely to see and to make us see what we do not naturally perceive. They are the artists.

(Bergson, 2002, p.251)

Not only does Bergson help reconcile the “feeling-into’ of objects, but also outlines the significance of an artist’s role, as the work they create not only expresses the naturally perceivable (matter), but to also expresses (brings into realisation) that which is only perceivable by “I” through communication with ‘living body’ through feeling-into by intuition.

Where words fail – Section 2

Arts facilitation of ‘feeling-into’

“I don’t paint dreams or nightmares, I paint my own reality.” – Freida Kahlo

Art is recognised for its transcendent nature, its ability to evoke emotional and cognitive responses from viewers and is often used as a visual translator for fantasy, memory (history) and emotion As Stein is concerned with lived experience, art, in the phenomenological sense, may be more accurately described as, an embodiment and expression of subjective experience. The ‘living body’ is how we sensorily and externally perceive the artwork yet the ‘feeling-into’ of the work is perceived by Self (“I”) The artist experiences subjectively, the artist in turn through living body (physically) visually expresses and communicates through their artwork, then I (the viewer) engages with the art as its presented to me, and my living body communicates the visual stimuli and physiological response with “I” so that “I” can grasp the given content of the work to decode and experience the experience of the artist empathetically. The fusion between living body and “I” allows art to act as a conduit, an embodiment and expression of subjective experience of the artist.

28 Husserl’s phenomenology, it is both mind and the thing. getting back to knowing the thing itself

For example Frida Kahlo was an artist who intentionally aimed to visually communicate her individual lived experience. Figure 2 was painted by Freida after being forced fed at the direction of her doctor, as part of treatment for various chronic illness a depiction of the physical and emotional suffering she endured at the time, the visual elements of the painting are so specific to her suffering, illness, culture, her subjective reality. Many of her other paintings throughout her life also depict specific moment of her lived experienced translated through visual media. It is easy as a viewer to try and imagine yourself in Kahlo’s situation, imagine what is like to be force fed or bedbound, and/or associate it with a remembered experience of your own of being trapped, choking or having something forced upon you, and conclude that through that association, you therefore know, at least partially, what she must be experiencing in her depiction, as Stein states “it is easily possible for another’s expression to remind me of one of my own, so that I ascribe to his expression its usual meaning for me” (Stein, 1964, p. 26) I (myself) as someone who suffers from chronic pain and has been bedbound for a period of time, associate my own remembered experience when I perceive this painting, as I ascribe my own lived experience with the subject of the painting, very aware that it is an object (artwork not a person), yet cannot help but feel as though I can connect with Kahlo’s very real lived experience through the painting expression of it I am aware that she is separate from me and her experience distinctly subjective, as are mine, however in the understanding I can grasp through the lens of my own experience, I become aware of that which I am grasping through the givenness of the painting itself As I ‘feeling-into’ the painting I feel past the shapes, colours and medium and feel

Figure 2 ‘Without Hope’. Oil painting, 1945, By Frida Kahlo

through to the embodied subjective experience of Kahlo herself despite the painting being merely an expression of it.

Figure 3 The patient’s back with shattered glass. Photograph co-created by Deborah Padfield with Nell Keddie from the series Perceptions of Pain (Padfield, 2003)

A Contemporary example of this is artist Deborah Padfield, who collaborates with patients to use photography, as a visual conduit of their lived experience, intentionally aiming to evoke empathy to transcend verbal and audible language as a descriptor to encourage understanding, and awareness of patient’s subjective pain, which Padfield collated into a series, ‘Perceptions of pain’(Padfield, 2003) Both Kahlo and Padfield’s work depicts pain specifically in the context of being a patient suffering from persisting pain and treatment However there are many difference in their work, the distinct one being the intentions29 of the work Kahlo exclusively expressed her own lived experience, whereas Padfield depicts another’s, while she is in collaboration with the

29 This may be further explored through exploration of Aesthetic empathy, as it relation to intentional understand the intention of an artist from a viewer perspective. However there is not the scope for this concept within this paper

person with the lived experience, she places herself in the role of facilitator, “Pain is subjective and very difficult to communicate or share. Feeling misunderstood and not believed is a frequent sentiment expressed by those who live with pain” (Padfield, 2019) Padfield as a chronic pain sufferer herself is acutely aware of the challenges of communicating lived experience, and is clearly aware of its subjective nature, therefore she explicitly uses art in conjuncture with empathy to produce these photographic works. Because the experience is outside of herself, Padfield must therefore empathise with her collaborator to effectively create work that express their lived experience, and visually produce it in a way so that it can be empathetical grasped by a viewer. Rather than being the subject ‘empathised with’ Padfield instead empathises and brings awareness to the patient, so that they become the subject empathised with. Unlike Kahlo’s work the subjects of Padfield’s pieces are often not figurative, expressing the sensations the patients experience, abstracting the painful experience from the identity (Self) of the patients. But the ability to empathise despite the lack of whole depicted embodied person remains, as the expressed subjective experience is still given. just as perceiving figure 2 I could feel through the visual elements of the piece to grasp Kahlo’s experience empathetically, I can therefore also grasp the givenness of figure 3 empathetically as an expression of a lived experience belonging to Other.

It can be argued that both Kahlo and Padfield are examples of practical applications of Steins understanding of Einfühlung within the context of art, due to the work being able to be grasped by the viewers through ‘feeling-into’, and “feeling-into” also being present in the creative process itself This application of the act of ‘feeling-into’ in these examples allows the viewer to feel-into the consciousness of the artist or subject (Other) through the expression of their lived experience captured in artwork However, this example of ‘feeling-into’ art is not possible in all artworks, as an artist’s lived experience informs their work, 30not all artists intentionally create works that are expression of ‘Other’ (consciousness) For this proposed form of ‘feeling-into’ to occur there must be a sense of Self and Other, therefore if a sense of Other is not present in an artwork “feeling-into’ in this way is not possible. However, many artworks without an expression of an Other, for example abstract works that viewers experience as profound and impactful, despite their apparent lack of particular content. The question then arises what are we grasping within those works? Are we still ‘feeling-into’ the artist on the other side? Maybe we are grasping something that is not of the artist at all but is something they have brought into realisation in their work, something that like consciousness, transcends what we can naturally perceive, but we can grasp by ‘feeling-into’. Art has generally been known to possess transcended qualities, some believe it to be transcendent in nature, as Bergson suggests artists are able “to make us see what we do not naturally perceive” (Bergson, 2002, p.251) and in this way art in transcendent by the nature it which is reveals to us something can only be perceived by intuition through feeling-into. While artistic expression can evoke empathy (feeling-into) and is often present within the creative process, it is not productive to keep art within the bounds of empathy as it expands beyond that, therefore we must explore artistic expression and how we subjectively experience it, in relation to Self (“I”) and the transcendent nature of art, as Stein does not explicitly write on art we must expand some of her writings and the concept ‘feeling-into’ further and include other thinkers such as Bergson to continue our exploration.

30 Their subjective view of the world

Going beyond empathy – Section 3

Transcendence, meaning and value

“The Eyes See Only What The Mind Is Prepared To Comprehend.” (Bergson, 2002)

It is imperative to acknowledge Stein’s Christian theological perspective that informs her philosophy of art. The concept of ex nihilo31 plays a role throughout Stein’s writing32, however not explicitly in relation to art, we can use this concept to understand its influence on her views on creation, art and the role of an artist in relation to the dimensions of meaning and transcendence Stein comes from the Christian perspective on creation and the human creative process, that God can create ex nihilo (out of nothing) however human beings cannot Beings create from that which already exists, which includes material matter such as clay, wood, paint etc, however this also relates to that which is not perceived naturally (through the senses) such as ideas and values that you’ve received through lived experience as consciousness. Through this perspective Stein gently corrects the idea that we have infinite creative abilities, we do not ‘invent’ but rather we ‘realise’ and bring into view which had been previously unrealised, beings create from something, whether that is material or not, “No man creates ex nihilo, but out of the materials supplied to him by his predecessors, his contemporaries, and his own experience.”

33(M. Beer, 1919, p277)

Once again there are similarities to this perspective of human creativity and Bergson’s philosophy34 Unlike Stein, Bergson’s theories are deeply interlinked with art especially the creative process which he adopts in relation to his theory of intuition. For Bergson intuition35 is a form of direct, immediate knowledge. Intuition is a way of grasping the essence of things which cannot be captured through scientific ordering, a fluidity akin to that of artistic expression. “Intuition is the capacity to connect, from within oneself, through a kind of [feeling-into]36, with the inner orientations of things, of species, of life itself, and of the whole from which life constitutes itself.” (Bergson, 2022, p xiv ). Both Stein and Bergson see art not just as an aesthetic pursuit but as a way to reveal deeper, often transcendent meanings that go beyond the material and what is naturally perceivable. This does bring question as to the origin of that meaning, Is the meaning something I am putting into it? Does the experiencing of the Art create meaning? did the artist make the meaning? And were they aware of it? Some of these are answered by through the concept of ex nihilo which affirms that artist cannot make meaning, however these other question seemly stems from the false dichotomy that art is either subjective or objective, art is neither, and to try and define otherwise keeps the transcendent nature of art limited, Art is not a subjective creation with objective meaning nor is it an objective creation with subjective meaning. Rather is something the artist’s bring into realisation and make that which exists, but is not yet know to us, into a dimension that is perceivable (material) opens the opportunity to grasp, that which has been realised.

31 Latin word that translates to ‘out of nothing’ had been used since the late 1500’s, and gained further momentum since the 1920’s, often used in discussions about creation, philosophy, and theology to explain the concept of creating something without pre-existing materials

32 Appears in her book finite and eternal

33 This quote is in the context of british socialism politics however the use on ‘ex nihilo’ remains relevant to this context also

34 Important to acknowledge Bergson’s Jewish heritage, and therefore holds this understanding of creation

35 Not to be confused with a Kantian application of intuition

36 Bergson uses the word ‘sympathy’ in is writing, however for clarity through this paper I will be using ‘feeling-into’

[T]he poet and the novelist to express a mood certainly do not create it out of nothing; they would not be understood by us if we did not observe within ourselves, up to a certain point, what they say about others. As they speak, shades of emotion and thought appear to us which might long since have been brought out in us but which remained invisible; just like the photographic image which has not yet been plunged into the bath where it will be revealed. The poet is this revealing agent. But nowhere is the function of the artist shown as clearly as in the art which gives the most important to imitation, I mean painting. The great painters are men who possessed a certain vision of things which has or will become the vision of all men.... Shall it be said that they have not seen but created, that they have given us products of their imagination, that we adopt their inventions because we like them? (Bergson, 2002, p251)

Therefore, it is the artists role to capture essence so that it may be realised, and it is the role of the viewer to grasp that essence by intuition through ‘feeling-into’ it. Through this lens, art points beyond the material world, highlighting arts transcendent nature that gives realisation to the abstract realms of consciousness within Self, such as value and meaning. This is especially apparent when experiencing an abstract artwork which often doesn’t contain the naturally perceived forms that we recognise and recall from memory to associate with our own lived experience such as figures, objects, locations ect Without this association it is simpler to attain that you are ‘feeling-into’ an artwork, grasped its essence through intuition, rather than intellectually assessed and described the piece through ‘relative knowledge’ This distinction is apparent in the later work of Mark Rothko, who’s abstract37paintings are expressions of human emotion, “And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate those basic human emotions….If you…are moved only by their colour relationships, then you miss the point.” (MoMA, 2004, p196) While there is clearly an emotional response to Rothko’s work, I believe the impact of his work goes beyond feelings that can be grasped within the realm of consciousness (“I”), “in every literal act of empathy, ie., in every comprehension of an act of feeling, we have already penetrated into the realm of the spirit, so a new object realm is constituted in feeling. This is the world of values.’ (Stein, 1964, p83) Rothko’s own philosophy of art echoes this when he says, "art to me is an anecdote of the spirit” (National Gallery of Art, 2016). In application, Rothko removes any indication or association of what his work may or may not relate to, anything which might influence or inhibit the ‘feeling-into’ of the works expression (essence). He rebelled against the limitations of description, to the degree in which he eventually disregarded the use of conventional titles, naming them only by colours, numbers or often left ‘untitled’.

37 I’m using abstract as a description for the word as it is typically acknowledged as, however Rothko himself had critique of ‘abstract’ as defined in his time, as he stood again that defining of his work and the possibility of an objective narrative and therefore made distinction to his specific form of abstract art.

Figure 4 Untitled, oil on canvas 1952 by Mark Rothko

Another intentional element of his work is the scale, the large-scale of these canvases tower over its viewer, enveloping them, as if to contain them within its bounds. Rothko intended that this create an intimacy, so that the experience of the work, at least firstly, may be ‘within the picture’, indicating a kind of physical feeling-into of the work (as object), in tandem with the ‘feeling-into’ of the work by intuition, this further alines Rothko’s practices with our exploration of art as a facilitation of ‘feeling-into’ and echoes Bergson’s merging of instinct and intellect through intuition As Rothko doesn’t necessary categorise his work, it seemingly sits between the abstraction of forms that are known and representation of that which is not,38 emphasising the transcendent nature of his work, not solely due to the transcendent nature of art, but rather the work containing transcended content (value and meaning). “In this regard, "unknown" pictorial space describes a realm that somehow surpasses two dimensions while avoiding the illusive threedimensional space of conventional representation.” (National Gallery of Art, 2016). In line with Stein and Bergson, Rothko’s work accesses the abstract realm of meaning and value that can only be grasped through intuition by ‘feeling-into’.

While we experience Rothko’s work, we grasp its givenness distinct to Self (“I”), as we grasp the givenness of anything distinct to ourselves (Self). Just as there must be a sense of Self for ‘feelinginto’ (Einfühlung) to occur, as it is an act rooted39 in Self (Stein), so too must ‘feeling-into’ by intuition, as to grasp by intuition is to grasp ‘from within oneself’(Bergson). When we feel-into an artwork (in this case Rothko’s) we gain new understanding of Self as the essence of the work is grasped from ‘within Self’. Just as we acquire new values and understanding of Self through empathetic (feeling-into) engagement with the Other, so too can we acquire new meanings and understanding through ‘feeling-into’ works of art by intuition and grasping that which is being offered (realised) within Self. In the same way that we (Self) subjectively experience these works, as does the Other40 In relation to Rothko, many have conveyed experiencing his works similarly, implying there is an essence within the paintings that they are responding to in common, through their own subjective experiencing There is a quality of Rothko’s work that elicits a realisation of a transcendent dimension, noting that his, “concentration on pure pictorial properties such as colo[u]r, surface, proportion, and scale, accompanied by the conviction that those elements could disclose the presence of a high philosophical truth.” (National Gallery of Art, 2016). This collective41 acknowledgement that Rothko’s work has revealed something transcendent, something ‘absolute’, opens the potential for art to be both vehicle for both personal transformation and communal understanding, as it opens us up to the dimensions of meaning and value that we can communally experience. What is known by ‘absolute knowledge’ grasped from within Self when we experience artworks by intuition, implies that what it revealed is something in common ‘within’ Self and Other that we subjectively grasp and intersubjectively collectively acknowledge, Bergson highlights this when he stated that the ‘vision’ (essence) that artist capture “has or will become the vision of all men” . (Bergson, 2002, p251)

38 Rothko makes reference to ‘spirit’ as a dimension in the making of his work

39 This will be further expanded later in this paper

40 Another person subjectively experiencing the same work

41 A large enough quantity of people who view his work and experience it in a common way

I, You and We – Section 4

Radical empathy

“Basic security is essential for the experience of participation and the assimilation of new understanding” –Jaakka Autio

This proposed fusion between Stein’s “feeling-into’ and Bergson’s method of intuition, facilitated by artistic expression, produces a radical form of empathy, that allows for the abstract realms of spirit, meaning and value to be realised and subjectively grasped, while intersubjectively shared. This moves our exploration away from ‘feeling-into’ Self (I), and Self and Other (I and You) and expands our scope to communal experience and collective understanding (We). Stein proposed ‘feeling-into’(Einfühlung) as a form of ‘radical Otherness’, however this new application through artistic expression proposes a radical form empathy, to which that implies a ‘radical’ application of ‘radical otherness’ Finnish sound artist Jaakko Autio uses the phrase ‘radical empathy’ as a descriptor artistic practice His work directly engages with empathy, experience, otherness, communal experience, and interpersonal understanding, through his immersive soundscapes that intend to “shake assumptions of otherness in a gentle way and aim to dismantle invisible boundaries between us” (Autio, 2024). His work brings together much of what has been established through our exploration of “feeling-into”, and aids in our framework for a radical form empathy

Figure 5 – Illustration of ‘radical’ change to Self through empathic understanding with Other

The use of ‘radical’ across both philosophy and art leads to a further exploration of the significance of “radical” itself. Etymologically, ‘radical’ comes from the Latin ‘Radix’ which directly translates to ‘root’, we typically use radical in relation to something extreme and very different from anything that has come before it, to create a radical change is to affect the fundamental nature of the thing. For radical change to occur there must be a ‘root’, an essence from which that change can be oriented from. A condition of Einfühlung (empathy) is that there is a sense of Self, if there isn’t a sense of self there cannot be a sense of Other, radical is similar, as is must maintain a ‘rooted’ locus or it cannot be radically changed, it would simply be changed to something entirely outside of itself (unrooted). Within this context Einfühlung is an act rooted in Self but is radically impacted by the Other, (Fig 5) Self remains Self, Einfühlung cannot transcend it, however it can allow Self to ‘feel into’ the Other, which in turn changes Self as “new values are acquired by empathy’ (Stein, 1964, p. 105), Hence Steins defining of Einfühlung as a “radical Otherness”. Autio interestingly uses the term “radical empathy’ to describe his art practice, in relation to Stein’s definition of empathy and our outline for definition of ‘radical’ in relation to that, by defining empathy as a radical act of change, therefore Autio in this context implies a radical implementation of empathy itself. “My artistic practice is guided by the philosophy of radical empathy. I aim to create safe and inclusive spaces where the individual is always approached with a gentle gaze. Basic security is essential for the experience of participation and the assimilation of new understanding” (Autio, 2024), he also acknowledges open and willing participation of experience a necessary aspect of acquiring new understanding, which again echoes Steins conditions of ‘radical otherness’ (feeling-into). This is however, where the similarities between the two ends, as Stein remains in the theoretical scope of philosophy and Autio offers practical applications through artistic expression that envelops ‘radical otherness’ and produce a form of ‘radical empathy’ that explores how Self and Other participate in a communal experience, with shared meaning and values, that each Self have acquired in common.

42

42 In Stein’s later works, she discussed collective intentionality, social acts, and the nature of social groups. In her 1922 treatise ‘individual and community’, however this is beyond what can be discussed in this paper

Though Autio’s work is not overtly visual art is the typical sense, the curation of his instillations play a vital role in aiding his soundscapes, I also believe tocontinue our exploration of‘feelinginto’ through visual stimuli alone, would limit the potential for the intersubjective sharing of experience we are proposing. As living body communicates with “I”, it does so in entirety through all the senses, therefore artistic expression the takes form through engaging with other senses is a logical direction to expand our exploration. Autio often uses water as a visual element of his soundscapes including figure 6, which consist of 16 speakers in a circular composition round a central pool of water. The resulting experience consists of being emersed in the sounds of a Nordic vocal choir (Nomad), that can be seen resonating across the water, creating visual and audible ‘sound bath’, as the voices of the choir layer together they resonate both internally (within viewer) and externally (water) with the viewer. This experience is compounded through physical engagement with the water, both visually and by touch, by reaching out and touching to water, you become an active participant of the experience, not just as you grasp the work by intuition, but the works creation as if you were a member of the choir resonating on the water. In this way the water becomes a physical containment for what is being realised in the work, by ‘feeling-into’ the work you subjectively grasp from within Self what is realised and simultaneously become aware of a collective aspect to the experience, “infused with a connection to other people and to nature within”(Autio, 2021). Autio believes that water allows us to see “the world as something fluid” (Autio, 2021) in a way that echo’s the fluidity of experience By ‘feeling-into’ this form of artistic expression it opens us up to the dimensions of meaning and value that we can communally experience as we grasp from ‘within us’ subjectively “community becomes conscious of itself… in us” (Stein, 2000, p. 139).

Figure 6 – ‘EROS’, Image from instillation, 2021, Jakko Autio, (Autio, 2021)

Through his artist expression Autio creates an intimate space that living body wants to dwell in, while we grasp the transcendent content of the work through immediate and direct experiencing through ‘feeling-into by intuition, what is grasped in that realisation can lead to internal reflections as we gain new understanding of Self in relation to Other’s and acknowledge that “at [Our] core is the simultaneity of diverse and shared humanity.” (Autio, 2024), and it is within that space of communal understanding in which we wish to dwell. In conclusion Autio demonstrates the potential for a form a ‘radical empthay’ through arts facilitation of interpersonal sharing of subjective experience, through a grasping in common of the abstract realms of meaning and value brought into realisation through artistic expression, within the framework of ‘feeling-into’ and grasping it by intuition.

To summarise this exploration, which proposed a form of ‘radical empathy’ facilitated by artistic expression. Which began by outline the framework of Stein’s act of ‘feeling-into’ as a form of ‘radical Otherness’ that defines a way in which we can engage in intersubjective dialog between consciousness, through a direct experiencing of Self and Other, that expands our understanding of Self in relation to Other. Then fusing ‘feeling-into’ with Bergson’s method of intuition, through which we may grasp the essence of an objects and the “inner orientations of things, of species, of life itself” (Bergson, 2022, p xiv ), through a combination of both instinct and intellect, that can be grasped from ‘within’ us (Self). Combining both these theoretical application of philosophies within the physical application within the context of artistic expression. Proposing art as a conduit for communicating lived experience that allows us to transcend our isolated subjectivity, by feeling- into (Einfühlung) Others, not through imagining or inferring but experiencing their subjectivity through direct participation facilitated by art. This exploration expanded beyond grasping only consciousness through artistic expression and outlined transcendent content that reveals itself through artist bringing realisation of it into the material world through their artworks. Which allows us to grasp by intuition through “feelinginto’ allowing us to grasp the realm of meaning and value through its realisation in art, which uncovered a ‘grasping in common’ that we can communally experience. This acknowledgement opens the potential for art not only gain understanding of Self but also a vessel of communal understanding, in which we can better understanding of Self in relation to community and the world. The exploration concluded with the work of Jakko Autio as an example of how the proposed theoretical outline of ‘radical empathy’ may come to realisation through contemporary artistic expression. In conclusion the framework of artist expression offers a unique vessel in which artist bring what is not naturally perceivable into realisation in material form, which we can grasp through the phenomenological framework of ‘feeling-into’ by intuition. This intersection between artistic expression and philosophy helps us to further understand Self and what we collectively share with Other’s, leaving our subjective isolation and enter into community and grasp within us an understanding of Self as one of a collective group of subjective consciousness in the world

Postlude

This dissertation reconciled the theoretical aspects of my exploration of communicating lived experience, and expanded the scope from subjective experience to communal experience. Highlighting the powerful impact potential of communication through ‘feeling-into’ experience as a way to gain new understand of Self, Other and Community, with practical applications through artistic expression Just as this dissertation stems from my personal intrigue as an artist, that I realise through my own artistic practice, the completion of this paper mirrors the new direction my practice has taken. My previous work, which I referred to in the preface, aimed to communicate my own lived experience to gain empathetic understanding from others, that echoed Stein’s original application of ‘feeling-into’ as it relates to the communication of lived experience between Self and Other. While this work is of personal significance and served well as exploration of its subject matter, in relation to this further research it serves as a beginning point.

The shift from subjective experience to communal experience through my research, while theoretically explored this paper, has also been the subject of my artistic exploration. Which has produced a collection of sculptural figures named the ‘Formables’ that explores understanding of Self through physical engagement and subjective experience. While individually they are experienced subjectively by the viewer they sit in relation to multiples, eluding to Self’s relation to wider community . using varying materials, colours, and forms to highlight the multifaceted nature of community. This work continues to develop and come to realisation, and reflects the acts, aspects and themes that have been outline throughout this dissertation.

Included with the physical copy of this dissertation, I have paired a Formable, as a physical representation of my realisation of ‘Feeling-into’ throughout my explorations of the topic

Figure 7 –‘The Formables’, bronze, jesmonite and ceramics, 2024, Joy Jennings, photographed by Lois Christie

Bibliography

Autio, J. (2021) EROS. Soundscape instillation, [online] Avalible at: https://jaakkoautio.com/2021/06/12/aanen-aika-ii-iii-m_ita-nykytaiteen-biennaali-mikkelintaidehalli-12-6-2021/

Autio, J. (2024). Bio & CV. [online] Jaakko Autio - Sound Artist. Available at: https://jaakkoautio.com/2024/02/21/bio-cv/ [Accessed 6 Jan. 2025].

Bain, D., Brady, M. and Corns, J. (2018). Philosophy of Pain. Routledge.

Beer, M. (Ed.). (1919). A History of British Socialism: Volume 2 (1st ed.). Routledge.

Benjamin, W., Eiland, H. and Michael William Jennings (2006). Walter Benjamin : selected writings. Vol. 3, 1935-1938. Cambridge, Mass. ; London: Belknap.

Bergson, H. (2002). Henri Bergson: key writings. A&C Black

Bergson, H. (2022). Creative evolution. Translated by D. Landes. Routledge.

Burns, T. A. (2016). The curious case of collective experience: Edith Stein’s phenomenology of communal experience and a Spanish fire-walking ritual. The Humanistic Psychologist, 44(4), pp 366–380.

Burns, T.A. (eds.) (2017). Empathy, Sociality, and Personhood : Essays on Edith Stein’s Phenomenological Investigations. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp.128–142.

Coplan, A. (2014). Empathy : philosophical and psychological perspectives. New York: Oxford

Freedberg, D., & Gallese, V. (2007). Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience. Trends in cognitive sciences, 11(5), 197–203. d University Press, , Cop.

G. D. Schott. (2015). Pictures of pain: their contribution to the neuroscience of empathy. Brain, Volume 138, Issue 3, Pages 812–820

Havi Carel (2016). Illness : the cry of the flesh. London: Routledge.

Havi Carel (2018). Phenomenology of illness. Oxford, United Kingdom ;Anew York, Ny: Oxford University Press.

Iacoboni, M. (2009). Mirroring people : the science of empathy and how we connect with others. New York, N.Y.: Picador.

Lanzoni, S. (2018). Empathy A History. Yale University Press.

Mallgrave, Harry Francis, and Eleftherios Ikonomou, eds (1994). Empathy, Form, and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873-1893. Santa Monica: Getty Center, 1994. Print.

National Gallery of Art (2016). Mark Rothko: Classic Paintings. [online] Nga.gov. Available at: https://www.nga.gov/features/mark-rothko/mark-rothko-classic-paintings.html.

Padfield, D. (2003). Perceptions of pain. Stockport: Dewi Lewis Publishing.

Padfield, D. (2019). Visualising Pain - Deborah Padfield. [online] Available at: https://deborahpadfield.com/Visualising-Pain [Accessed 28 Dec. 2024].

Petraschka, T. and Werner, C. (2023). Empathy’s Role in Understanding Persons, Literature, and Art. Taylor & Francis, pp.251–271.

Stein, E. (1964). On the problem of empathy. The Hague: M. Nijhoff.

Stein, E. (2000). The collected works. 7 Philosophy of Psychology and the Humanities. Washington, Dc Ics Publ.

The Museum of Modern Art. (2004) MoMA Highlights (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999) Pp 196.

Vischer, R. (1994). On the Optical Sense of Form: a Contribution to Aesthetics In Empathy, Form, and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873-1893. Santa Monica: Getty Center, 1994. Print. Pp 89123

Zahavi, D. (2010).” Empathy, Embodiment and Interpersonal Understanding: From Lipps to Schutz.” Inquiry 53 (3). Pp 285-306