PROPERTIES FROM CARITAS OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF

PROPERTIES FROM CARITAS OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF

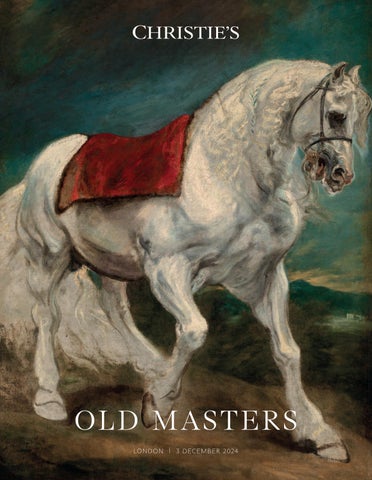

FRONT COVER

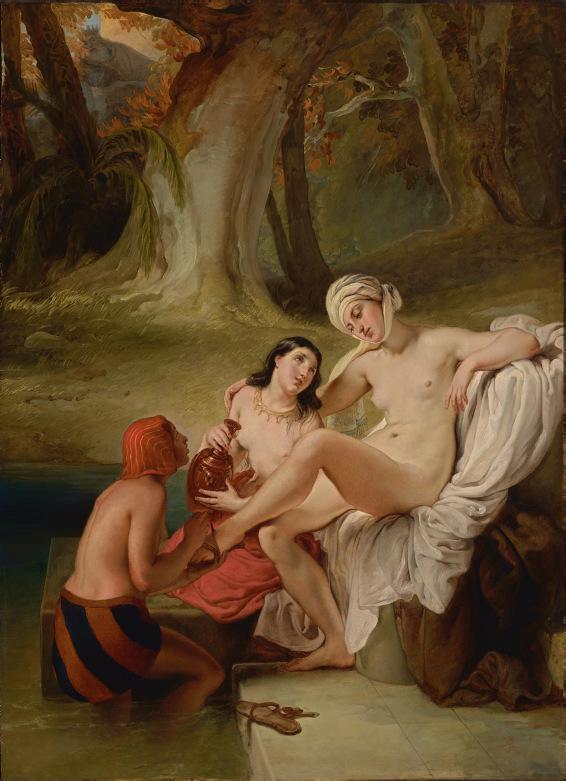

Lot 7 (detail)

INSIDE FRONT COVER

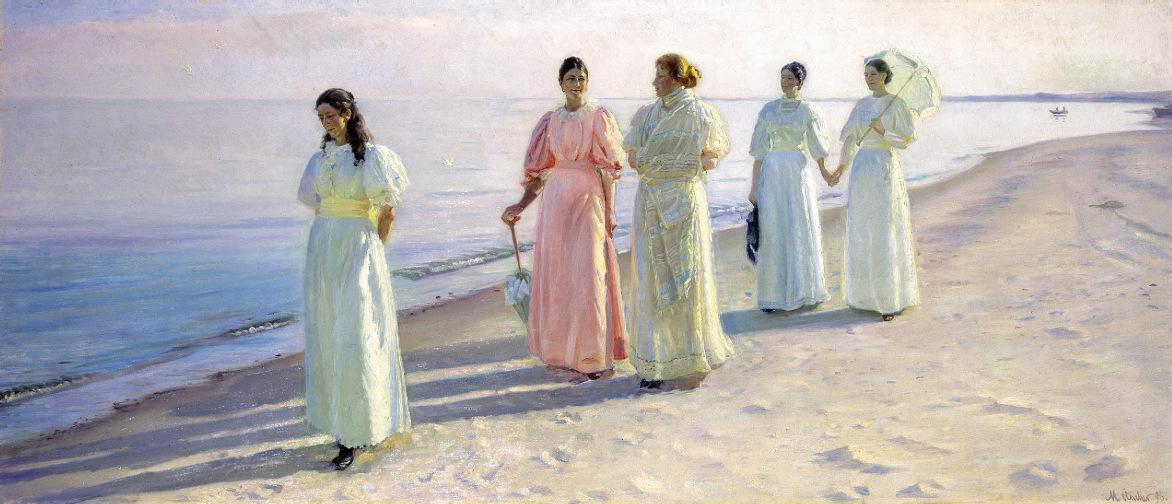

Lot 22 (detail)

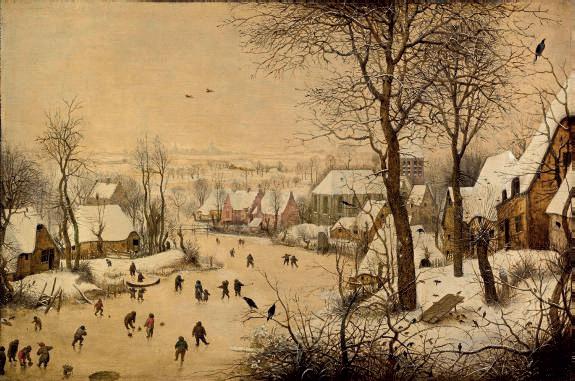

PAGES 2-3

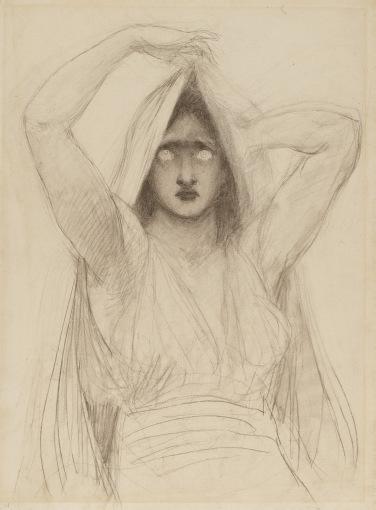

Lot 4 (detail)

OPPOSITE

Lot 25 (detail)

INDEX

Lot 20 (detail)

BACK COVER

Lot 4 (detail)

Tuesday 3 December 2024 at 6.30 pm

8 King Street, St. James’s London SW1Y 6QT

Friday 29 November 9.00 am - 5.00 pm

Saturday 30 November 12.00 pm - 5.00 pm

Sunday 1 December 12.00 pm - 5.00 pm

Monday 2 December 9.00 am - 8.00 pm

Tuesday 3 December 9.00 am - 5.00 pm

Henry Pettifer

In sending absentee bids or making enquiries, this sale should be referred to as SACHA-22691

Admission to the sale is by ticket only. To reserve tickets, please email: ticketinglondon@christies.com. Alternatively, please call Christie’s Client Service on +44 (0)20 7839 9060

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2658 Fax: +44 (0)20 7930 8870

The sale of each lot is subject to the Conditions of Sale, Important Notices and Explanation of Cataloguing Practice, which are set out in this catalogue and on christies.com. Please note that the symbols and cataloguing for some lots may change before the auction. For the most up to date sale information for a lot, please see the full lot description, which can be accessed through the sale landing page on christies.com.

In addition to the hammer price, a Buyer’s Premium (plus VAT) is payable. Other taxes and/or an Artist Resale Royalty fee are also payable if the lot has a tax or λ symbol.

Check Section D of the Conditions of Sale at the back of this catalogue. Estimates in a currency other than pounds sterling are approximate and for illustration purposes only.

GLOBAL HEAD, OLD MASTERS

Andrew Fletcher

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2344

INTERNATIONAL DEPUTY CHAIRMAN

Henry Pettifer

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2084

INTERNATIONAL DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, UK & IRELAND

John Stainton

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2945

INTERNATIONAL DEPUTY CHAIRMAN

François de Poortere

Tel: +1 212 636 2469

GLOBAL HEAD OF RESEARCH & EXPERTISE

Letizia Treves

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 5206

HEAD OF DEPARTMENT, LONDON

Clementine Sinclair

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2306

HEAD OF DEPARTMENT, NEW YORK

Jennifer Wright

Tel: +1 212 636 2384

HEAD OF DEPARTMENT, PARIS

Pierre Etienne

Tel: +33 (0)1 40 76 72 72

DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, UK

Francis Russell

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2075

HONORARY CHAIRMAN

Noël Annesley

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2405

WORLDWIDE SPECIALISTS

AMSTERDAM

Manja Rottink

Tel: +31 (0)20 575 52 83

BRUSSELS

Astrid Centner

Tel: +32 (0)2 512 88 30

HONG KONG

Georgina Hilton

Melody Lin

Tel: +85 22 97 86 850

LONDON

Freddie de Rougemont

John Hawley

Maja Markovic

Flavia Lefebvre D’Ovidio

Lucy Speelman

Isabella Manning

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2210

NEW YORK

Jonquil O’Reilly

Joshua Glazer

Oliver Rordorf

Taylor Alessio

Tel: +1 212 636 2120

MADRID

Adriana Marín Huarte

Tel: +34 915 326 627

PARIS

Olivia Ghosh

Bérénice Verdier

Victoire Terlinden

Tel: +33 (0)1 40 76 85 87

CONSULTANTS

Sandra Romito

Alan Wintermute

GLOBAL MANAGING DIRECTOR

Imogen Giambrone

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2009

PRIVATE SALES

Alexandra Baker

International Business Director

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2521

LONDON

Scarlett Walsh

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2333

CONSULTANTS

Donald Johnston

NEW YORK

William Russell

Tel: +1 212 636 2525

PARIS

Alexandre Mordret-Isambert

Tel: +33 (0)1 40 76 72 63

Aurore Chevillotte Froissart +33 (0)1 40 76 83 71

AUCTION CALENDAR 2024-2025

TO INCLUDE YOUR PROPERTY IN THESE SALES PLEASE CONSIGN TEN WEEKS BEFORE THE SALE DATE. CONTACT THE SPECIALISTS OR REPRESENTATIVE OFFICE FOR FURTHER INFORMATION

21 NOVEMBER

MAÎTRES ANCIENS: PEINTURESDESSINS - SCULPTURES PARIS

5 - 22 NOVEMBER

MAÎTRES ANCIENS: PEINTURESDESSINS – SCULPTURES, ONLINE PARIS

3 DECEMBER

OLD MASTERS PART I

LONDON

4 DECEMBER

OLD MASTERS PART II: PAINTINGS, SCULPTURE, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS

LONDON

5 FEBRUARY 2025

OLD MASTERS

NEW YORK

SENIOR SALE COORDINATOR

Sacha Sabadel

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2210

BUSINESS MANAGER

Lottie Gammie

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 5151

First initial followed by last name@christies.com (e.g. Clementine Sinclair = csinclair@christies.com). For general enquiries about this auction, emails should be addressed to the Sale Coordinator.

ABSENTEE AND TELEPHONE BIDS

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2658

Fax: +44 (0)20 7930 8870

AUCTION RESULTS

Tel: +44 (0)20 7839 9060 christies.com

CLIENT SERVICES

Tel: +44 (0)20 7839 9060

Fax: +44 (0)20 7389 2869

Email: info@christies.com

POST-SALE SERVICES

Nick Meyer

Senior Post-Sale Coordinator

Payment, Shipping, and Collection

Tel: +44 (0)20 7752 3200

Fax: +44 (0)20 7752 3300

Email: PostSaleUK@christies.com

BUYING AT CHRISTIE’S

For an overview of the process, see the Buying at Christie’s section. christies.com

The Crucifixion with the Madonna, Saint John the Evangelist and two angels tempera on gold ground panel, triangular, in a partially integral frame 13¬ x 19º in. (34.6 x 49 cm.)

£100,000-150,000

US$130,000-190,000

€120,000-180,000

PROVENANCE:

Acquired by the grandfather of the present owner, and by inheritance.

Paolo Veneziano was the most prominent artist in Venice during the fourteenth century, running a thriving workshop that arguably laid the foundations of the Venetian school of painting in successive centuries. With his roots in the Byzantine tradition, he created a new idiom that would earn commissions from his native city and beyond.

This panel, to date unknown, is a significant addition to the corpus of the artist, providing further insight into his activity during his late maturity. It almost certainly served as the central pinnacle of a triptych, or polyptych; the triangular shape is unusual in his oeuvre, indeed this may be the only such example. In its overall design, the composition is close to the middle panel in the upper register of the Polyptych of Saint Lucy, given to Veneziano and his workshop, made circa 1325 for the Abbey of St. Lucy in the village of Jurandvor, Croatia. In terms of execution it can be compared most instructively to the Crucifixion in the National Gallery of Art, Melbourne (fig. 1), which is on a larger scale and of a different format, and dates to circa 1350. Both these panels feature a parapet with crenellations behind the lower part of the cross,

a motif that represents the wall of Jerusalem, and occurs more widely in the artist’s work (for example in the Crucifixion in the National Gallery of Art, Washington). It is also used here, in this newly discovered panel, where the surface of the wall itself is embellished with foliate decoration. The parapet acts as an elegant pictorial device that gives the work depth and volume.

The figure of Christ, which is well preserved, is executed with great refinement, with delicate highlights on his face and torso. Dr. Christopher Platts, to whom we are grateful, first proposed that this is a mature work by the artist (on the basis of photographs), datable to circa 1350, noting that the handling of Christ is in fact of higher quality than other comparable figures given to Paolo Veneziano and his workshop around the same time. We are also grateful to Dr. Cristina Guarnieri and Dr. John Witty, who have further endorsed the attribution, also on the basis of photographs. All scholars note that the gold ground – and consequently the figures' haloes – appear to be for the most part new, unfortunately obscuring Paolo Veneziano’s characteristic punch marks that can be helpful in the dating of his paintings.

An Allegory of Transience

indistinctly signed (upper right, on the column) oil on canvas, unframed 48¬ x 38¿ in. (123.6 x 96.8 cm.), with additions to the upper and lower edges of º in. (0.5 cm.)

inscribed 'Defecerun[t] si[cut] fumus dies / mei Psalm 101' (centre right, on the paper held in the book)

£100,000-150,000

US$130,000-190,000

€120,000-180,000

PROVENANCE:

Sir Charles Arthur Turner, K.C.I.E. (1833-1907), London. Michiel Onnes, called Onnes van Nijenrode (1878-1972), Castle Nijenrode, Breukelen; his sale, Frederik Muller & Cie, Amsterdam, 4 July 1933, lot 20, as 'Attributed to Anthony van Dyck, with the suspected collaboration of Daniel Seghers' (unsold). Anonymous sale; Sotheby's, Amsterdam, 12 November 1991, lot 218, as 'Daniel Seghers and Cornelis Schut'.

Anonymous sale; Sotheby's, London, 16 December 1999, lot 59, as 'Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert' and 'an unidentified hand working in the following of Daniel Seghers', where acquired by the present owner.

EXHIBITED:

London, Royal Academy of Arts, Exhibition of Works by Van Dyck 1599-1641, 1 January-10 March 1900, no. 110, as 'Anthony van Dyck', measuring 43Ω x 33Ω in. (lent by Sir Charles Turner).

LITERATURE:

E. Schaeffer, Van Dyck: Des Meisters Gemälde, Klassiker der Kunst, XIII, Stuttgart and Leipzig, 1909, p. 462.

Though the figure of the gesturing putto in this painting has previously been attributed to Sir Anthony van Dyck, Cornelis Schut and Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert, and the still life elements to Daniël Seghers or a close follower, Dr. Bert Schepers has recently proposed instead that it is the work of Erasmus Quellinus II (on the basis of photographs; private communication, 7 June 2024), a talented pupil and collaborator of Sir Peter Paul Rubens in the 1630s. Fred G. Meijer has further suggested that the still-life elements are by one, possibly two, thus far unidentifiable hands (private communication, 4 October 2024).

The early attribution to van Dyck is understandable because, as Schepers has pointed out, the figure derives from the angel seated at the base of van Dyck’s Christ on the cross with Saint Catherine of Siena, Saint Dominic and an angel of circa 1622-7 in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp (fig. 1). Intriguingly, van Dyck’s painting was engraved by Schelte à Bolswert in 1653 from an intermediary drawing by Quellinus. A similar putto also appears at lower centre in Quellinus’s grisaille modello for Paulus Pontius’s engraved double portrait of Rubens and van Dyck, which was recently returned to the Devonshire Collection at Chatsworth House after its theft in 1979.

The Latin inscription on the leaf of paper tucked between the pages of the book emphasises the painting’s vanitas theme, translating to ‘For my days vanish like smoke’, taken from Psalm 101:4. The putto, in turn, further reinforces the idea by pointing over his shoulder to billowing smoke while sitting atop a sarcophagus inscribed with the letters ‘D.M.S.’ for ‘Dis Manibus Sacrum’ (‘for the ghostgods’), a common pagan inscription preceding the name of the deceased on a tombstone. The floral bouquet similarly conveys a sense of transient beauty, for the flowers will wither and die, while the skull, crown, sceptre, richly worked cloth and bag of money all convey the ultimate futility of seeking earthly wealth and power.

The evident superior quality of the present picture has led Dr. Schepers to believe it to be the prime of this composition, of which various inferior versions have appeared on the market in recent years, including one given to Willeboirts Bosschaert at the Dorotheum, Vienna, 17 October 2007, lot 228; another described as by a follower of Jan van den Hoecke, sold at Bukowskis, Stockholm, 14-16 June 2023, lot 709; and one given to the workshop of Quellinus that appeared at Audap & Associés, Paris, 28 March 2024, lot 37.

We are grateful to Dr. Bert Schepers for suggesting the attribution to Erasmus Quellinus on the basis of photographs and for identifying the source for the putto, and to Dr. Fred G. Meijer for his thoughts on the still-life elements.

PROPERTY FROM A PRIVATE EUROPEAN COLLECTION 3 JAN BRUEGHEL I (BRUSSELS 1568-1625 ANTWERP) AND JOOS DE MOMPER II (ANTWERP C.1564-1635)

A winter river landscape with travellers on a path oil on panel 26¿ x 61Ω in. (66.4 x 156.2 cm.)

£100,000-150,000

US$130,000-190,000

€120,000-180,000

PROVENANCE:

Collection of the Barons de Heusch de la Zangrye, and by inheritance in the family to the following, Baroness de Heusch de la Zangrye, s'Hertogenbosch, from whom acquired by, Piet de Boer (1894-1974), Hergiswil, by 1964, by whom very probably sold to, Dr. Andreas Becker, Dortmund, by 1967 and until 1975.

with Galerie Cramer, The Hague, where acquired by the father of the present owner in July 1976.

LITERATURE:

R. Fritz, Sammlung Becker I: Gemälde alter Meister, Dortmund, 1967, no. 73, illustrated. 'Delft Antique Dealers' Fair 1975 - Galerie Cramer Advertisement', Apollo, CII, October 1975, p. 84.

M. L. Flammersfeld, 'Vorschau auf die Delfter Antiekbeurs', Weltkunst, XLV, 1 October 1975, p. 1592, illustrated.

K. Ertz, Jan Brueghel d. A. Die Gemälde mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog, Cologne, 1979, pp. 484-6 and 624, no. 404, fig. 587 and 588 (detail).

T. Gerszi, 'Joos de Momper und die Bruegel-Tradition', Netherlandish Mannerism, Stockholm, 1985, p. 163, fig. 21, as 'Joos de Momper'.

K. Ertz, Josse de Momper der Jüngere (1564-1635): die Gemälde mit kritischem Ouvrekatalog, Freren, 1986, pp. 140 and 577, no. 401, fig. 117.

K. Ertz and C. Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere: die Gemälde, mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog, IV, Lingen, 2008-2010, p. 1583, no. 771, illustrated.

Jan Brueghel the Elder and Joos de Momper the Younger enjoyed a fruitful collaboration over the course of some thirty years beginning in the early 1590s, through to at least 1623, that resulted in no fewer than 200 hundred surviving pictures (see Ertz and Nitze-Ertz, op. cit., nos. 604-810). The vast majority of these paintings saw Brueghel add the figures into the mountainous panoramas for which de Momper was so highly regarded. The present winter landscape is a relatively unusual collaboration between the two artists, with fewer than thirty such examples known. Their joint production of these winter scenes only appears to have begun in the second decade of the seventeenth century.

It is perhaps fitting that Jan the Elder provided the staffage for this landscape, which Klaus Ertz has dated to circa 1615-20 (op. cit.). As Teréz Gerszi has pointed out, the painting is a unique take on the tradition of Jan’s father, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (op. cit.). The painting, which Gerszi described as a ‘very high quality forward-looking’ (‘sehr qualitätvolle vorwärtsweisende’) landscape, displays ‘only a faint reflection’ (‘nur einen schwachen Abglanz’) of the elder Bruegel’s pioneering Winter landscape with skaters and bird trap of 1565 in Brussels (fig. 1). Specifically, de Momper has flipped the structure of the composition so that the most prominent houses anchor the left rather than right-hand portion of the composition while retaining the earlier painting’s striking orthogonally-drawn canal.

The Sermon of St. John the Baptist oil on panel

40¡ x 65¿ in. (102.5 x 165.2 cm.)

£800,000-1,200,000

US$1,100,000-1,600,000

€970,000-1,400,000

PROVENANCE:

J.B. Blommaert; his sale (†), D. Massyn and H. Lecler, Rue Longue des Violettes no. 136, Ghent, 8-9 October 1855, lot 33, as 'Tableau très-curieux du plus beau faire du maître', where acquired by, Baron Ludovicus Le Candèle van Humbeek (d. 1880), and by inheritance to his nephew, son of his late sister, Isabelle (1802-1865), wife of Baron Édouard-Jean Lunden, Baron Théophile Lunden (1834-1908), 's Gravenkasteel, Grimbergen, and by descent to the present owners.

LITERATURE:

G. Marlier, Pierre Brueghel le Jeune, Brussels, 1969, p. 57, no. 16. K. Ertz, Pieter Brueghel der Jüngere, I, Lingen, 1988/2000, p. 377, no. F345, under questionable attributions and catalogued as unseen by the author.

This Sermon of Saint John the Baptist is one of the finest treatments of what was Pieter Brueghel the Younger's most successful and popular large-scale religious composition. Yet, until now, it has remained largely known only through its first and last appearance at auction in 1855, when it was acquired by ancestors of the present owners (see Provenance). It would first be published in 1969 in Georges Marlier’s catalogue raisonné on the artist under Brueghel’s unsigned autograph versions (op. cit.). Decades later, Klaus Ertz would include it in his own catalogue, this time under the artist’s questionable works, having never seen it in the flesh or seemingly from an image, referencing only Marlier’s description of the work in his entry. Its reappearance and constitutes a major addition to our appreciation of Brueghel the Younger's oeuvre remarkable both in terms of the skilfully detailed characterisation of the figures and its wonderful state of preservation.

The inspiration for the subject, as with so many of the younger Brueghel's paintings, was provided by a work of his father Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569), widely acknowledged as the picture dated 1566 in the Széptmûvészeti Museum, Budapest (fig. 1). The quality and number of extant versions by the younger Brueghel suggest that he knew his father's original in spite of the thirty years or more that elapsed between his own production and his father's death. Klaus Ertz recorded thirteen autograph versions, including dated examples from 1601 (Bonn, Rheinisches Landesmuseum), 1604 (St. Petersburg, Hermitage), 1620 (Bern, Ludwig Collection) and 1624 (Lier, Stedelijk Museum Wuyts-Van Campen en Baron Caroly), as well as significant undated examples, such as that formerly in the collection of Baron Evence III Coppée (1882-1945), sold in these Rooms, 7 July 2009, lot 8 (£1,497,250). Like the present picture, many works would also remain on the walls of private collections and unknown to Ertz, like the remarkable example also sold in these Rooms on 8 December 2009 (lot 16, £1,553,250).

Painted in the year of the iconoclastic outbreaks in the Low Countries, scholars have long held the view that Bruegel the Elder's picture offered a coded comment on the religious debates that raged in the region during the 1560s,

interpreted as an allusion to the clandestine sermons that Protestant reformers held in the countryside in response to anti-Protestant Habsburg policies. Yet Bruegel’s Sermon was significant not for its presumed political associations but the ‘transformation of the theme from an earlier landscape tradition into a rationale for portraying the great variety of humanity' (A. Woollett and A. van Suchtelen, eds., Rubens and Brueghel: A Working Friendship exhibition catalogue, Los Angeles, 2006 p. 188).

In the central foreground, as here, the artist (a devout Catholic) depicts a man in black who faces the viewer and reads the palm of his neighbour, which can be seen as thinly veiled defiance against Calvin's prohibition of the reading of palms. The distinctive face of the perpetrator suggests that it may be a portrait, and several candidates have been proposed, including the artist himself, the commissioner of the painting or Thomas Armenteros, the adviser to Margaret of Parma, though all remain supposition. The figure of Christ has often been identified either as the man in grey behind the left arm of the Baptist or the bearded man further to the left with his arms crossed. Inverting the relationship between the religious subject and its setting, the scene is filled with an astonishing assortment of figures and delightful vignettes that emphasise the disassociation from the message of God, with the viewer also placed in the role of a spectator, observing the scattering of diverse figures from behind.

The popularity of the picture a generation later, in the time of Brueghel the Younger, attests to a more general, aesthetic appreciation of the theme, when the subject had not only lost its political implications but ran contrary to the religious current of the time. Jacqueline Folie observed that the composition was enjoyed more for its representation of humanity, with the motley crowd gathered around John the Baptist embodying 'the whole human race in all its diversity of races, social conditions, temperaments and inner dispositions –eager, attentive, curious, sceptical or indifferent listeners’ (translated from the French, in Bruegel: Une dynastie de peintres exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, 1980, p. 143).

Memento mori: Death comes to the table

oil on canvas, unframed

32Ω x 40Ω in. (82.5 x 102.8 cm), including additions, measuring 2 in. (5.1 cm.) along the upper edge, and 1 in. (2.5 cm.) along the left, right and lower edges

£100,000-150,000

US$130,000-190,000

€120,000-180,000

PROVENANCE:

with P. & D. Colnaghi & Co., London, by 1959, as 'Angelo Caroselli'.

Anonymous sale; Sotheby's, London, 29 November 1961, lot 100, as 'Pietro Paolini', sold for £220 to the following, with Arcade Gallery, London.

Anonymous sale; Christie's, London, 5 July 1996, lot 42, where acquired by the present owner.

LITERATURE:

The Illustrated London News, Christmas issue 1959, 235, 6274A, p. 82, as 'Angelo Caroselli'.

B. Nicolson, 'Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions', The Burlington Magazine, CI, no. 674, May 1959, p. 199, as 'attributed with excellent reason to Caroselli'.

B. Nicolson, '"Figures at a Table" at Sarasota', The Burlington Magazine, CII, no. 686, May 1960, p. 226, as 'an artist, probably Flemish, of the type of Finson' (in connection with a related picture).

R. Spear, Caravaggio and His Followers, Cleveland, 1971, pp. 88-9, fig. 19, as 'attributed to Jean Ducamps'.

B. Nicolson, The International Caravaggesque Movement, Oxford, 1979, p. 47, as 'Jean Ducamps'.

B. Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe, ed. L. Vertova, Turin, 1990, I, p. 104; II, fig. 365, as 'Jean Ducamps/Giovanni Martinelli'.

L. Vertova, ‘La Morte Secca’, Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz, XXXVI, 1992, pp. 116 and 117, fig. 11.

F. Baldassari, La Pittura del Seicento a Firenze. Indice degli Artisti e delle loro Opere, Turin, 2009, p. 525, with erroneous ex-Fonteguerri provenance. (Possibly) S. Bellesi, Catalogo dei Pittori Fiorentini del 600 e 700: Biografie e opere, Florence, 2009, p. 194.

G. Cantelli, Repertorio della Pittura Fiorentina del Seicento. Aggiornamento, Pontedera, 2009, p. 141, as a 'replica' and with an incorrect 1996 sale date.

G. Papi, ‘Giovanni Martinelli, fra Artemisia e Vouet’, Giovanni Martinelli, da Montevarchi pittore in Firenze, Florence, 2011, pp. 35-6, 47, footnote 9, fig. 4.

This allegorical painting is a fine work by Giovanni Martinelli, an enigmatic painter active in Tuscany during the first half of the seventeenth century who is mysteriously absent from the Notizie by the Florentine biographer Filippo Baldinucci and has only re-emerged as a significant artistic figure in recent decades. As noted by Gianni Papi in a collection of essays published to coincide with the first monographic exhibition dedicated to the painter in 2011: ‘Giovanni Martinelli is to this day a painter too little known with respect to his true worth and that of contemporary painters who are held in far higher esteem’ (op. cit., p. 33).

Elegantly dressed figures are gathered around a table laid with food and wine – a crusty tart, roasted quail and red grapes are on display in silver (or more likely pewter) plates. The party has been abruptly disturbed, its guests caught by surprise by a skeleton holding out an hour-glass, a symbol of the passage of time and inevitability of death. What moments ago must have been a scene of merriment has taken a sudden turn for the worse: the skeleton has disrupted their meal to remind them that Death can strike anyone, at any time, even in a moment of joyful recreation (‘memento mori’ meaning literally ‘remember you must die’). The impending doom is underlined by the reaction of the youth in the foreground who impulsively unsheathes his sword. The figures’ gestures underscore the sense of unease: the two women whisper conspiratorially as they look towards the intruder, one of them pointing to the young man who looks over his shoulder at the skeleton while grabbing the edge of the table. He seems astonished and draws his other hand to his chest in recognition of the fact that he is the intended recipient of the skeleton’s warning – the young man’s time is, quite literally, up. Eloquently described by Benedict Nicolson, the great twentieth-century scholar of Caravaggesque painting, this ‘group of young lovers [are] tiresomely reminded of the transitory nature of youth and pleasure’ (Nicolson, op. cit., 1959).

This painting’s composition clearly enjoyed considerable success, for it exists in a number of autograph variants and copies (nine are listed in Nicolson, ed. Vertova, op. cit., p. 104). The finest, and the most ambitious, is in the New Orleans Museum of Art (known as The Isaac Delgado Museum of Art prior to 1971) and broadly repeats the composition of the present work though with some differences and including two additional figures at left (fig. 1). The attribution of this interrelated group of paintings has been the subject of much debate among scholars, with various names being attached to one or other of the variants. Over the years, the New Orleans canvas has been ascribed to

Bartolomeo Manfredi, Cecco del Caravaggio, Jean Le Clerc, Nicolas Tournier and Rutilio Manetti, while the names of Pietro Paolini and Angelo Caroselli have been attached to the present variant (the latter ‘with excellent reason’, according to Nicolson, op. cit., 1959). Not only did the identity of the painter baffle scholars, but also his nationality; Nicolson posited that the painter was Flemish and Richard Spear noted that ‘numerous features reveal the northern training of the artist of this picture’, namely the marked care with which the still-life details are described and the vanitas subject matter that was more commonly found in northern Europe than in Italy at this time (Spear, op. cit., 1971, p. 88).

A further clue was provided by the initials ‘DC’ found on two paintings of Gamblers by the same hand as the author of the Memento Mori group. These initials were interpreted as representing the signature of Jean Ducamps, or Giovanni del Campo (1600-1648), a pupil of Abraham Janssens in Antwerp who became a founder member of the Bentvueghels in Rome and died in Spain sometime after 1628. Although the attribution to Ducamps was taken up by Spear and Nicolson, an alternative identification with Domenico Carpinoni, a Bergamasque follower of Palma il Giovane, was put forward by Ruggeri (see a summary of attributions in Nicolson, ed. Vertova, op. cit., p. 104). It was not until the comprehensive study of Florentine paintings in 1980s, by Giuseppe Cantelli and others, that the name of Giovanni Martinelli was associated definitively with the composition, an attribution that subsequently found favour among other scholars of Florentine Seicento painting, namely Sandro Bellesi and Francesca Baldassari (op. cit.). A formal and stylistic comparison between the figures in this painting and those in other recognised works by Martinelli provides compelling evidence for this attribution. In particular, the two women in the centre of this composition are directly comparable in pose and type to the gesturing female and violinist in Martinelli’s Youth with Violin in the High Museum of Art, Atlanta (fig. 2).

The numerous variants of this composition attest to the popularity and demand for pictures of this type in seventeenth-century Italy. Falling somewhere between a genre painting and a still life, the image carries a moralizing message: life is short and not to be frittered away, particularly since Death can strike at any moment. The picture probably dates from the 1630s, by which time Caravaggesque painting was falling largely out of fashion, but the dramatic nature of its subject is all the more vivid owing to the stark lighting and tightly cropped composition, both of which ultimately derive from Caravaggio.

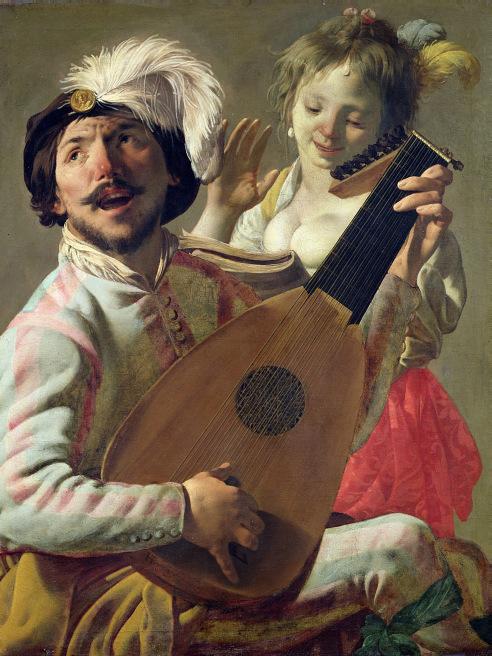

A lady playing a lute and a gentleman with a viola da gamba oil on canvas

19Ω x 15 in. (49.5 x 38.1 cm.)

£80,000-120,000

US$110,000-160,000

€96,000-140,000

PROVENANCE:

(Probably) Hendrik Schut, Rotterdam; his sale, Buurt, Rotterdam, 8 April 1739, lot 1, as 'Adriaen van der Werff' (f 305).

(Possibly) Pieter van Dorp, Leiden; (†) his sale, Luchtmans, Leiden, 16 October 1760, lot 2, as 'Caspar Netscher' (f 260).

Baron Willem Joseph van Brienen van de Groote Lindt (1760-1839), The Hague, and by descent to his son,

Baron Arnoud Willem van Brienen van de Groote Lindt (1783-1854), The Hague, and by descent to his son,

Baron Thierry van Brienen van de Groote Lindt (1814-1863), The Hague; (†) his sale, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 8 May 1865, lot 47 (FF 2600 to Say).

(Probably) Anonymous sale; Christie's, London, 24 November 1900, lot 28, as 'G. Netscher' (26 gns. to Shepherd).

with Colnaghi, London, where acquired by, Emma Ranette Budge (1852-1937), New York and Hamburg; (†) her involuntary sale, Graupe, Berlin, scheduled for 27 September but postponed until 4-6 October 1937, lot 6, as 'Caspar Netscher' (RM 15,000).

Eugene L. Garbáty, Schloss Alt-Doebern, Niederlausitz, and later Shore Haven, CT, until 1946.

with Bree and van Groot, The Hague, 1958. with Leger Galleries, London, 1958, as 'Constantijn Netscher'. with Acquavella Gallery, New York.

Rudolf von Fluegge, New York; his sale, Doyle, New York, 25 January 1984, lot 23, as 'Caspar Netscher'.

with Richard Green, London, 1984, as 'Eglon van der Neer', where acquired by, Private collection, Washington, D.C. with Johnny Van Haeften, London, 1987-1994. with Otto Naumann, New York, by 1997.

Anonymous sale; Sotheby's, New York, 4 June 2009, lot 45 (sold pursuant to a restitution settlement agreement with the heirs of Emma Budge), where acquired by the present owner.

EXHIBITED:

Hamburg, Kunsthalle, Leihausstellung aus Hamburgischem Privatbesitz in der Kunsthalle, 1925, no. 248, as 'Caspar Netscher'.

New York, New School, Loan Exhibition of Paintings from Collections of Associate Members, 3-17 March 1946, no. 10, as 'Casper Netscher'. Rotterdam, Historisch Museum, Rotterdamse Meesters uit de Gouden Eeuw, 15 October 1994-15 January 1995, no. 71, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'. New York, The Chinese Porcelain Company, The Age of Gallantry, Fine and Decorative Arts of the Netherlands 1672-1800, 12 October-4 November 1995, no. 5, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

Greenwich, CT, The Bruce Museum, Pleasures of Collecting: Part I: Renaissance to Impressionist Masterpieces, 21 September 2002-5 January 2003, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

LITERATURE:

G. Hoet, Catalogus of Naamlyst van Schilderyen met derzelver pryzen..., I, The Hague, 1752, p. 572, no. 1, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

J. Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish and French Painters of the Seventeenth Century, IV, London, 1833, p. 211, no. 103, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

(Possibly) C. Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters of the Seventeenth Century, V, London, 1912, p. 189, nos. 120 and 125f, as 'Caspar Netscher'; X, Stuttgart and Paris, 1928, p. 278, no. 164, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

S.J. Gudlaugsson, 'Ten onrechte aan Caspar Netscher toegeschreven schilderijen van Adriaen van der Werff, Renier de la Haye, Thomas van der Wilt, en Johannes van Haensbergen', Oud Holland, LXV, 1950, pp. 242-243, 246, fig. 1, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

B. Gaehtgens, Adriaen van der Werff, 1659-1722, Munich, 1987, pp. 203-5, no. 9, pl. I, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

M.E. Wieseman, Caspar Netscher and late seventeenth century Dutch painting, Ph.D. dissertation, 1991, p. 511, no. C59, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

M.E. Wieseman, Caspar Netscher and Late Seventeenth-Century Dutch Painting, Doornspijk, 2002, no. C66, p. 351, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

W. Franits, Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting, New Haven, 2004, pp. 254-55, fig. 235, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

E. Schavemaker, Eglon van der Neer (1635/36-1703): His Life and His Work, Doornspijk, 2010, pp. 65, 75-6, 484-5, no. 81, pl. XXVI.

S. Avery-Quash, 'The Travel Notebooks of Sir Charles Eastlake: Volume I', The Volume of the Walpole Society, LXXIII, 2011, p. 544, as 'Adriaen van der Werff'.

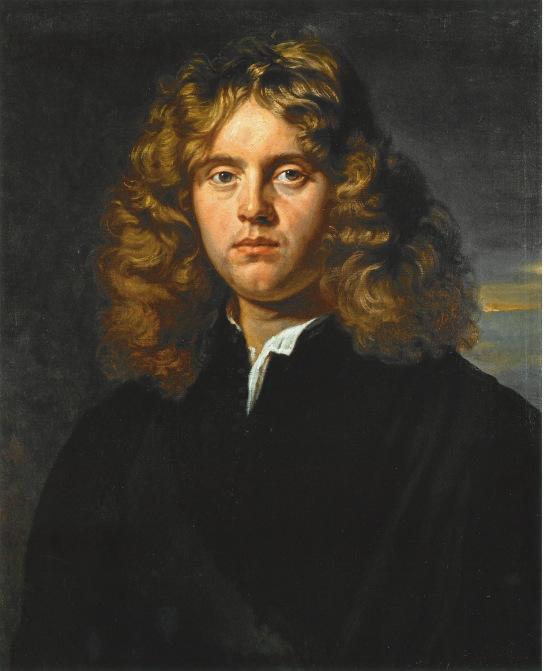

Though attributed solely to Adriaen van der Werff by John Smith (1833), Cornelis Hofstede de Groot (1928), Sturla J. Gudlaugsson (1950), Barbara Gaehtgens (1987), Betsy Wieseman (1991, 2002) and Wayne Franits (2004), this painting has recently and convincingly been recognised as an intriguing example of a collaboration by van der Werff and his master, Eglon van der Neer (see Schavemaker, op. cit., pp. 75-76). Following an eighteen-month apprenticeship with the otherwise unknown Cornelis Picolet around 1669, in or around 1671, the then twelve-year-old van der Werff entered van der Neer’s Rotterdam studio, initially for a one-year period. At the end of this period, the term of study was extended for three additional years and, in 1675, van der Werff signed a new contract to serve as van der Neer’s apprentice for eighteen more months. During his apprenticeship, van der Werff was allowed to split his time equally working for van der Neer and on independent projects. Though van der Werff became a fully independent master before his eighteenth birthday in 1677, he and van der Neer remained close. The younger artist may even have been ‘hired’ as an independent master to complete the elder artist’s paintings in the years before he settled in Brussels in 1680.

As Eddy Schavemaker has suggested, the present painting is one of perhaps only five extant works that suggests the involvement of both artists. In addition to the present painting, the author cited the Woman with a ring and a man of 1678 (fig. 1; St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum), the only example that bears the signature of both painters; the Two boys with a mousetrap and cat in a window of 1676 (Germany, Private collection, on loan to the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), which is signed solely by van der Werff but whose quality exceeds that of the artist's other known paintings in the period; the Portrait of a woman of 1678 (Europe, Private collection), which is signed by van der Werff but largely by van der Neer, with the younger artist putting only the finishing details on the painting; the Man with a pipe and rummer in a window of 1682 (South Carolina, Private collection), which is signed exclusively by van der Neer; and the Sophonisba being Offered the Poisoned Cup (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum), which is signed by van der Werff but which Schavemaker suggests was ‘probably made in collaboration with his teacher van der Neer’ (op. cit., p. 217, no. 3, under Appendix IV). Van der Neer had previously treated this historical subject in a painting dated 1674 (present location unknown).

The hallmarks of each artist are especially clear in the present painting, with the differences particularly evident in the faces of the young woman and man. The woman’s head, viewed in three-quarter profile, is notably skilful in its handling and is highly comparable to a number of similar heads in van der Neer’s oeuvre

The man’s face, viewed more-or-less head-on and with almond-shaped eyes, is instead characteristic of the youthful van der Werff. Van der Werff similarly appears to have been the one responsible for the young man’s beautifully rendered torso and the atmospherically conceived background, while van der Neer likely painted the viola da gamba, chair legs and the woman’s flowing satin gown, all of which are depicted with his usual precision (for further discussion on the two hands, see Schavemaker, op. cit., pp. 75-76).

The man’s face in the present painting is especially close to that of the youthful drummer in van der Werff’s Boy playing a drum (present location unknown; see Gaehtgens, op. cit., pp. 202-3, no. 7, fig. 7). That painting is in turn based on one dated 1676 by van der Neer (United Kingdom, Private collection; see Schavemaker, op. cit., p. 478, no. 66, fig. 66). While Schavemaker did not posit a specific dating for the present painting, in her monograph on van der Werff,

Gaehtgens noted the close similarities between it and van der Neer’s works of 1674-8 and plausibly concluded that it should be dated to circa 1678 (loc. cit.), the year in which – insofar as can be determined – the two artists collaborated most regularly.

The subject of couples making music was a popular one among artists who specialised in the production of high-life genre paintings in the second half of the seventeenth century and carried with it connotations of intimate affections between the participants. Instruction in music and dance was also a standard feature of an upper-class education in the seventeenth century, an idea which is reinforced here by the protagonists’ sumptuous clothing and elegant, slightly languid posture. However, the two artists have cleverly, if subtly, called into question our preconceived perceptions of the situation: the woman holds the theorbo both the wrong way around and upside down; the man holds the bow in his left hand; and both instruments appear with broken strings.

An Andalusian horse (recto); A wooded landscape – a sketch (verso) oil on canvas

52 x 41æ in. (132 x 106 cm.), including a horizontal extension of 2æ in. (7 cm.) along the upper edge

£2,000,000-3,000,000

US$2,600,000-3,900,000

€2,500,000-3,600,000

PROVENANCE:

with R.P. Nicholls, London, from whom acquired in 1859 by the following, Thomas Gambier Parry (1816-1888), Highnam Court, Gloucester, and by descent until, Anonymous sale; Christie’s, London, 13 December 2000, lot 30, where acquired by the present owner.

EXHIBITED:

London, British Institution, 1860, no. 43 (lent by T. Gambier Parry).

Leeds, General Infirmary, National Exhibition of Works of Art, 1868, no. 816 (lent by T. Gambier Parry).

London, Royal Academy, Winter Exhibition, 1888, no. 150 (lent by T. Gambier Parry).

LITERATURE:

T. Gambier Parry, Manuscript catalogue of the pictures at Highnam Court, December 1863, no. 75.

National Exhibition of Works of Art, Leeds: Baines’s Handbook to the Picture Galleries, Leeds, 2nd ed., 1868, p. 38, no. 816.

‘The Royal Academy – Winter Exhibition’, exhibition review, The Athenaeum, no. 3143, 21 January 1888, p. 91.

E. Gambier Parry, Manuscript inventory of pictures at Highnam Court, July 1897, MSS. Courtauld Institute Gallery, London, no. 67, recording the tradition that the horse depicted was given to Van Dyck by Rubens.

A. Blunt, ‘Seventeenth and eighteenth-century pictures in the Gambier-Parry Collection’, The Burlington Magazine, CIX, March 1967, p. 177, questioning the Wilton provenance.

D. Farr, 'Thomas Gambier Parry as a collector', Thomas Gambier Parry (1816-1888) as artist and collector, London, 1993, p. 43, no. 48.

J. Hedley, Van Dyck at The Wallace Collection, London, 1999, p. 143.

O. Millar, ‘Van Dyck: Horses and a Landscape’, The Burlington Magazine, CXLIV, March 2002, pp.161-3, figs. 34 and 35.

O. Millar in S.J. Barnes et al., Van Dyck: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, New Haven and London, 2004, pp. 95-6, no. I.102, figs. I.102R and I.102V.

M. Jonker and E. Bergvelt, Dutch and Flemish paintings: Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 2016, pp. 88-9 and 91, note 54, fig. 12.

Painted shortly before van Dyck left Antwerp for Italy in the autumn of 1621, this striking picture of an Andalusian stallion constitutes the artist’s first independent grand-scale depiction of a horse. It was executed in preparation for the posthumous equestrian portrait of Emperor Charles V now in the Uffizi, Florence (c. 1621; fig. 1), van Dyck's earliest surviving equestrian portrait in a genre that hastened his reputation as one of the most sought-after portraitists in Europe during the first half of the seventeenth century. The canvas, painted with extraordinary fluency and vigour, provides a thrilling demonstration of the young artist’s virtuoso handling of paint and bravura technique. This is equally true of the sketch on the unprimed reverse – discovered after removal of the relining canvas following the 2000 sale – which, remarkably, stands as the artist's only surviving oil landscape study.

Van Dyck’s canvas – a forceful image of equine power – is a masterful performance in economy; using the prepared grey ground to superb effect, the artist has employed rapidly brushed strokes of dark brown paint to articulate the outline before lavishly applying highlights in lead white to capture the modelling and head of the horse. This expressive use of paint is typical of the artist during his formative years in Antwerp when his works are characterised by a richness and variety of texture that are in striking contrast to the restrained, courtly style that brought the artist such success during his final years in England. Van Dyck’s approach here compares closely with other studies of horses painted from this early period, the finest example of which is the Study of a Soldier on Horseback, dated to circa 1617-18, from Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford (present whereabouts unknown; fig. 2).

For the canvas in the Uffizi, van Dyck based his composition on Titian’s celebrated 1548 portrait of Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg, a work that Rubens had previously studied for his equestrian portrait of The Duke of Lerma, painted in 1603 during the Flemish artist’s first visit to Spain (both pictures are in Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado; fig. 3). Although the Uffizi picture's compromised state of preservation has given rise to some attributional debate among scholars in the past, Susan Barnes noted that passages clearly resembled van Dyck's work from circa 1621 (op. cit., 2004, p. 95, no. I.101).

While van Dyck was required to turn to earlier portraits for his likenesses of the sitter, he clearly observed the horse itself from nature. The painter’s fondness for the animal is recounted in the much cited anecdote – described by André Félibien in his 1685 biography of the artist – of Rubens presenting van Dyck with one of the most beautiful horses from his stable before his most gifted pupil departed for Italy. After Thomas Gambier Parry acquired the present picture in 1859, he noted that the horse shown was traditionally thought to be that which van Dyck had received from his master. The horse here invites a comparison to Virgil, evoking lines in his Georgics referring to a foal: 'His neck is high, his head clean-cut, his belly short, his back plump and his gallant chest is rich in muscles... Again should he but hear afar the clash of arms he cannot keep his place; he pricks up his ears, quivers his limbs, and snorting rolls beneath his nostrils the gathered fire’ (H. Rushton Fairclough, Virgil with an English Translation, 1928, I, p.161).

In his 2002 Burlington article on this picture, Sir Oliver Millar left open the possibility that it was in fact an earlier version of the Uffizi commission, cut down at a very early stage before being adapted by the artist to a study of the horse. This theory was prompted by the revelation of an armoured rider in an X-ray carried out in 2000, at the time of the restoration treatment undertaken by Simon Folkes in London. Millar further noted that a later hand had ‘tidied up’ passages in the sky and landscape surrounding the horse (ibid.). A small version of the composition at Dulwich Picture Gallery – executed in oil on paper and laid down on panel – has not been discounted as a possible autograph study for the horse and would therefore stand as the first stage in this sequence of works for the Uffizi commission (Millar, 2004, op. cit., pp. 95-6).

The discovery of the landscape on the reverse of the original canvas, revealed following removal of the later relining, marked an important addition to van Dyck’s oeuvre. Painted with the unprimed canvas turned on its horizontal axis, the artist shows a steep tree-covered bank on the left, sloping down to a lake where a dog can be seen drinking. As with its counterpart on the recto, the handling is dazzlingly free. While it is known that van Dyck painted independent landscapes – five are listed in Antwerp collections in the seventeenth century – this is the only surviving oil in the genre from his entire career.

That the artist delighted in studying nature is evident in the many portraits and subject pictures with landscape backdrops or settings, but it is arguably in the group of surviving drawings where his veneration of the natural world is most eloquently expressed. In the introduction to the catalogue for the 1999 exhibition The Light of Nature: Landscape Drawings and Watercolours by Van Dyck and His Contemporaries, Martin Royalton-Kisch observed of van Dyck’s landscapes: ‘Although the accidents of survival must distort the true picture… these notations are set down with a skill and sensitivity to atmosphere that even the most distinguished landscape specialists active in Europe in his day found hard to equal’ (p. 10). It is telling that many of these works on paper, invariably executed in brown ink with brown wash and watercolour, were owned by later artists, including Jonathan Richardson Senior, Thomas Hudson and Joshua Reynolds, as well as collectors such as Richard Payne Knight, celebrated for his theories of picturesque beauty (see lot 21). Interestingly, Payne Knight also owned a grand-scale picture of a rearing stallion by van Dyck (sold in these Rooms, 25 January 2012, lot 12).

Millar noted that the sloping bank crowned with trees is very close to the landscape backdrop in the portrait, now in the Louvre, showing a father and young boy, possibly Joannes Woverius with his son (op. cit., 2002; fig. 4). That the Paris portrait can be dated to circa 1620 strengthens the argument that both sides of the present canvas were executed before van Dyck left Flanders. While Millar conceded that this landscape sketch does not betray a direct link with anything in Rubens’s work, he observed that some elements – the prominent twisting trees and glimpses of water – may well have been inspired by passages from the older artist’s compositions, such as ‘La Charette Embourbée’ and The Watering Place, pictures that both date to the years van Dyck was working in Rubens’s studio (the former c. 1617; St. Petersburg, Hermitage; and the latter c. 1615-22; London, National Gallery). In van Dyck's own work, there is a link in the treatment of the trees, albeit in general terms, with his drawing in the Louvre of A fallen tree, a work that corresponds very closely to a passage in Rubens’s Landscape with a boar hunt of circa 1618 (Dresden; Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister), which van Dyck is thought likely to have assisted with.

Van Dyck was undoubtedly one of the leading artists in the development of equestrian portraiture; his works in this field not only provide some of the defining images of the seventeenth century but have loomed large in the artistic psyche of subsequent generations. This picture marks his first essay in the genre, one that gained favour with key Genoese patrons such as Anton Giulio Brignole-Sale (1627; Genoa, Galleria di Palazzo Rosso), a commission for which van Dyck also produced a preparatory study of the sitter’s Andalusian horse. The years following van Dyck's return from Italy in the summer of 1627, known as his ‘second Antwerp period’, witnessed a magnificent troop of equestrian portraits, notably those of Albert de Ligne, Prince of Arenberg and Barbançon (1629-32; UK, Private collection), Francisco de Moncada, Marqués de Aytona (1633/4; Paris, Musée du Louvre) and Prince Francis Thomas of SavoyCarignano (1634-5; Turin, Galleria Sabauda), a work aptly described by Julius Held as an ‘icon of power’. It was in England, where he arrived in the spring of 1632, that van Dyck's mastery in this field reached its climax; the celebrated portraits of Charles I on horseback in the Royal Collection and National Gallery of London (1633 and c.1636-7 respectively) stand as two of the outstanding masterpieces from his final years and arguably two of the most famous equestrian portraits in the history of western painting. In 1805, the portraitist John Hoppner observed of the former work, in which the King is shown with his riding master and equerry M. de St Antoine, that ‘a part of one of the hind legs is simply an outline on the bare canvas; yet under the circumstances in which it is seen, it is better, and more truly expressed, then if it had been, in the vulgar sense of the term, finished’ (Oriental Tales, translated into English Verse, 1805, pp. ix-x). Hoppner's words seem equally apposite when confronted with the present study.

Andalusian horses, derived from the original Arab stock, were highly prized by the European nobility from the fifteenth century and have long been associated with the Spanish Hapsburgs. By the sixteenth century, during the reigns of Charles V and Philip II, their status as the finest horses in the world was established, as illustrated through their increasing presence in equestrian portraits of Europe’s princes and monarchs, including that of King Francis I of France (1494-1547). On his wedding to Katherine of Aragon, King Henry VIII of England received Spanish horses from Charles V, Ferdinand II of Aragon and the Duke of Savoy. In 1667, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle, the celebrated horse breeder, wrote of the Andalusian horse: ‘He is the noblest horse in the world... the most beautiful that can be... He is of great spirit and of great courage... and is the lovingest and gentlest horse, and fittest for a King in his day of triumph’.

Thomas Gambier Parry assembled a remarkable collection of early Italian Renaissance pictures for Highnam Court, near Gloucester, the house he acquired in 1838 and subsequently rebuilt. A manuscript inventory of the pictures, compiled by Gambier Parry’s son, Ernest, and dated July 1897, states that the picture had been in the collection of the Earls of Pembroke at Wilton, a house celebrated for its holdings of works by van Dyck. On a visit to Highnam Court in 1863, Lady Herbert recognised it as having been among the pictures that went missing from Wilton during the minority of the 12th Earl of Pembroke (b. 1791). However, the absence of any potential candidates in the Wilton inventories suggest this claim was unfounded. The catalogue also states that Gambier Parry acquired the picture before Sir Charles Eastlake had time to secure it for the National Gallery. Gambier Parry’s collection, which included important works by Bernardo Daddi, Lorenzo Monaco, Fra Angelico and Mariotto Albertinelli, survives substantially intact at the Courtauld Institute of Art. The van Dyck – the outstanding northern picture in his collection – can be seen in Henry Jamyn Brook's Private View of the Old Masters Exhibition, Royal Academy, 1888 (1889; London, National Portrait Gallery; fig. 5), where it is hung next to van Dyck's magnificent 1630 full-length portrait of Philippe Le Roy which in turn flanks, along with the pendant of his wife Marie de Raet (both London, Wallace Collection), Rubens' equestrian portrait of The Duke of Buckingham (c. 1625; formerly Earl of Jersey, Osterley Park, destroyed).

Portrait of Isabella Clara Eugenia (1566-1633), Governess of Southern Netherlands, as a widow, three-quarter-length oil on canvas

50º x 38 in. (127.6 x 96.5 cm.)

£200,000-300,000

US$260,000-390,000

€250,000-360,000

PROVENANCE:

James Jewett Stillman (1850-1918), Paris, and by descent to the following, Isabel Stillman Rockefeller (1876-1935), New York, and by descent to the following, Isabel Rockefeller Lincoln (1902-1980).

Chancey Devereux Stillman (1907-1989).

Lothar Graf zu Dohna (b. 1924).

Acquired by the present owner in 1985.

This picture is an important discovery of one of the most renowned - and most reproduced - portraits in Rubens’s oeuvre. It shows Isabella Clara Eugenia, daughter of Philip II of Spain and Elisabeth of Valois. She married Albert, Archduke of Austria, in 1598, and the couple reigned as independent sovereigns of the Spanish Netherlands from 1599 until Albert’s death in 1621, when the territory reverted to the Spanish crown. On account of their childless marriage, Isabella ruled exclusively as governor on behalf of her nephew, Philip IV. In October 1621, she joined the Third Order of St Francis and as a sign of mourning following her husband’s death, she wore the habit of the Poor Clares, as in this portrait. This became her official state portrait for the remainder of her life.

Rubens had been appointed court painter by Isabella and Albert in September 1609, and maintained a close rapport with the Infanta until her death in 1633. Isabella visited Antwerp in 1625, following the capture of Breda in June, a triumphant trip that was well documented by a number of contemporary sources. During this visit, Rubens is known to have painted her portrait and designed a related engraving (fig. 1), where Isabella is shown precisely as she is here: in three-quarter-length pose, holding her long black veil in her hands while she gazes at the viewer, against a neutral background with an aura, likely symbolising Divine Providence, surrounding her head. It is possible that she sat for the portrait during a recorded visit to Rubens’ house on 10 July 1625. The making of the portrait and the engraving are recounted by writers of the time, including Philippe Chifflet and Hermanus Hugo. Chifflet wrote: ‘1625. Rubens peignit l’Infante à Anvers avec una coronne civique sur laquelle M. Gevart fit les vers qui sont dans sa lettre’; while Hugo related: ‘While Isabella was in Antwerp she was painted by the brush of the eminent artist Rubens and engraved in copper by his etching needle, and saw herself adorned with a civic crown in this truly noble picture. After this glorious triumph [the capture of Breda] she deserved to be depicted thus, and by no other hand than that of the famed Apelles; [in the margin] ‘The famous portrait of the victorious Isabella, painted by Rubens’ (H. Hugo, Obsidio Bredana, Antwerp, 1626, p. 125).

The present, hitherto unpublished, canvas has emerged, after restoration treatment, as one of the most compelling known portraits of this type. There are a number of clear pentiments that are now visible, notably the adjustment of the black veil on her (proper) left, and the repositioning of the fingers on her right hand. Rubens’s typically confident, spontaneous brushwork creates a sense of true volume in the drapery and the modelling of the face lends sharp characterisation to the sitter’s features. Hans Vlieghe discussed the versions previously known in his Corpus volume, including one formerly in the collection of Lord Aldenham, which despite not showing the aura around her head was believed by Burchard to be autograph and the best of the then known versions; this view was however rejected by Vlieghe. Another canvas in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena was also given to Rubens by Burchard, an opinion only accepted ‘with much reserve’ by Vlieghe. Interestingly, the Norton Simon picture is smaller than the present lot (116 x 89.5 cm.), as are all of the three further copies listed in the Corpus, each of similar dimensions (116 x 96 cm.; 115 x 85 cm.; 116 x 92 cm.) (H. Vlieghe, Rubens Portraits of Identified Sitters in Antwerp, Corpus Rubenianum, Ludwig Burchard, XIX, London and New York, 1987, pp. 119-123, nos. 109-112, figs. 128-131).

Such was the success of the portrait that van Dyck based his full-length of the Infanta, made circa 1628 (fig. 2; Turin, Galleria Sabauda) very closely on Rubens’s composition. Van Dyck’s portrait was equally acclaimed: he received

from the Infanta a gold chain valued at 750 guilders following its completion. As with Rubens’s canvas, a number of repetitions and copies are known, including a full-length version now in the collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein, that may be identical with the portrait for which van Dyck was paid £25 on 8 August 1632, and three-quarter-length versions formerly in the collections of King Louis XIV of France and Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in Vienna (see S.J. Barnes, N. De Poorter, O. Millar and H. Vey, Van Dyck: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings, New Haven and London, 2004, p. 319, under no. III.90). Another picture from the studio of van Dyck also recently came to light, formerly in the collection of King Louis-Philippe d’Orléans at Château d’Eu (sold Christie’s, New York, 1 May 2019, lot 245).

This lot was formerly in the collection of James Jewett Stillman (1850-1918), the founder of one of America’s great banking families, the chairman of National City Bank, which later became Citibank. He forged great links with the Rockefellers, with both of his daughters marrying members of the latter family.

We are grateful to Ben van Beneden and Katlijne Van der Stighelen for both endorsing an attribution to Sir Peter Paul Rubens and his studio.

A stack of cheese on a pewter platter, with butter on a plate, a stoneware jug, bread, pretzels, wine in a façon-de-Venise glass and a knife, on a ledge oil on panel 18º x 25Ω in. (46.1 x 64.8 cm.)

£100,000-150,000

US$130,000-190,000

€120,000-180,000

PROVENANCE:

Mrs. Nelson Vandevoort Judah, Los Angeles (according to RKD records). Anonymous sale; Sotheby's, London, 8 May 1974, lot 105. with Thomas Agnew and Sons Ltd, London, 1975. with K. & V. Waterman, Amsterdam, 1981. Private collection, Kiel, and by descent to the following, Private collection, Hamburg.

Anonymous sale; Stahl, Hamburg, 28 April 2018, lot 16, where acquired by the present owner.

EXHIBITED:

Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Austin, University of Texas Art Museum; Pittsburgh, Carnegie Museum of Art; and New York, The Brooklyn Museum, Women Artists 1550-1950, 21 December 1976-27 November 1977, no. 18.

LITERATURE:

A. Sutherland Harris and L. Nochlin, Women Artists 1550-1950, Los Angeles, 1976, p. 133, no. 18, illustrated.

C. Grimm and I. Bergström, et al., Natura in posa: La grande stagione della natura morta in Europa, Milan, 1977, p. 206, illustrated.

N.R.A. Vroom, A Modest Message as intimated by the Painters of the Monochrome Banketje, II, Schiedam, 1980, p. 103, no. 516. 'Waterman Advertisement', Tableau, January-February 1981, p. 492.

P. Hibbs Decoteau, Clara Peeters, 1594-ca. 1640, and the development of still-life painting in northern Europe, Lingen, 1992, pp. 47, 58, fig. 43, as 'Circle of Peeters'. C.C. Barko, 'Rediscovering Female Voice and Authority: The Revival of Female Artists in Wendy Wasserstein's "The Heidi Chronicles"', Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, XXIX, no. 1, pp. 125-6 and 137.

In her Pulitzer Prize-winning play The Heidi Chronicles, Wendy Wasserstein’s protagonist spoke of pictures like the present and how they made Clara Peeters ‘the greatest woman artist of the seventeenth century’: ‘she used more geometry and less detail than her male peers. Notice here the cylindrical silver canister, the disc of the plate, and the triangular cuts in the cheese. Trust me. This is cheese’ (Barko, op. cit. p. 125). Peeters belonged to the first generation of European artists specialising in still-life painting and was one of its most original practitioners in the seventeenth-century Lowlands. Her earliest dated work appeared within six years of the first known food and flower still-life paintings in northern Europe, and she was also in all likelihood the first European artist to paint a fish still-life (1611; Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado), which would become something of her specialty. As one of the first great female artists, she declared her distinctive artistic personality by discreetly including self-portraits in the reflective surfaces of objects in a number of her works.

Despite her central position in the development of the still-life genre in the Netherlands, biographical details remain scarce, with fewer than forty signed works by her known today. Neither her place nor date of birth is documented, though all available evidence suggests she worked chiefly in or around Antwerp, with at least six of her copper and panel supports bearing the maker’s marks of the city. Equally unknown is when (and whether) she joined Antwerp’s painters guild, from which women were not specifically forbidden, though in practice comparatively few did. However, that Peeters’s name does not appear among the extant records should not be taken as an indication that she was not a member. As Pamela Hibbs Decoteau noted when addressing this issue, the guild lists in Antwerp are missing for the critical years between 1607 and 1628, a period that encompasses the entirety of Peeters’s known activity (op. cit. p. 9).

Peeters used the motif of the cheese stack and dish of butter in six further works, all of which share clear geometric patterns and are viewed from a low vantage point. These include the painting from the Carter collection at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Amsterdam, formerly Westermann collection; Amsterdam, Willem Russell collection; The Hague, formerly A. von Welie collection; The Hague, Mauritshuis; and the picture sold in these Rooms, 12 December 2001, lot 6 (£498,750). Knowing the present example only through black and white images, Hibbs Decoteau deemed it a variant of the Russell picture, with compositional differences, and painted by an artist from Peeters’s

circle (op. cit.). Dr. Fred G. Meijer, in concurrence with previous scholarship, most recently reconfirmed Peeters’s authorship (private communication, 2024).

In this still-life genre, which Ingvar Bergström classified as ontbijtes, or ‘breakfast still-lifes’, cheese held a special place, gaining its own particular subgenre. Cheese could be used as a reference to the centrality of dairy products in the agricultural and economic health of the Netherlands, standing as a symbol of national pride and prosperity. It was both a display of gastronomic luxury and a symbol of religious ideas, alluding to overabundance, with a well-known Dutch saying warning: ‘one dairy product upon another is the work of the devil’ (‘zuivel op zuivel is ‘t werk van den duivel’). It was equally regarded as Lenten fare among Protestants, described by the Dutch poet Jacob Westerbaen as ‘a metaphor of the powerful flavour of a simple repast’, particularly when coupled with bread and wine as reminders of the Eucharist.

As here, all of Peeters’s cheese stacks have pride of place in their compositions, and, while each possess their own distinguishing features, they follow a consistent formula. At the base is Gouda, on top of which lies a triangular sheep’s cheese, and in the foreground, a ripe, green, Edam-like cheese, with the shavings of butter always on top. In each cheese can be seen a small carvedout sample suggesting the presence of their taster. Cheeses of this kind, made primarily of cow’s milk, were produced mainly in the province of North Holland and can be recalled in the still-lifes of Haarlem painters like Floris van Dijck (c. 1575-1651), Nicolaes Gillis (c. 1592-c.1632/55) and Floris van Schooten (1585/881656). Peeters seems to have been one of the only painters in the Southern Netherlands to have painted cheese so distinguishably ‘made in Holland’ (see A. Vergara, The Art of Clara Peeters exhibition catalogue, Antwerp and Madrid, 2016, p. 50).

Peeters exchanged the rich colour of her early works for more humble tones, rendering the textures and surfaces of objects with evident relish. Describing the stack of cheese and butter with particular brio, she uses thick impasto in the highlights and extraordinary subtlety in the rendering of the grooves in the surfaces, at once making them tangible and consumable objects. Bright light from the left creates brilliant accents on the glass, jug, butter and pretzels, offset against the earthy brown of the ledge, while the red currants and yellow and white tones of the cheese and bread draw attention to the silver platters and knife, which balances precariously over the edge of the ledge to reinforce the impression of depth. Peeters employed a standard repertoire of objects in her compositions, including the present façon-de-Venise glass, which can be seen in the Westermann and Russell cheese stacks, as well as in the picture sold in these Rooms in 2001, and the stoneware Raeren jug, which also features in the Mauritshuis picture at a different angle (fig. 1) and the Still life with an artichoke (Germany, Private collection; Hibbs Decoteau, op. cit. no. 21).

Absent any definitive documentary information about Peeters’s life, the works themselves provide the clearest evidence for reconstructing her painterly activities. Eleven dated works allow for something of a chronology to be developed, which show general tendencies towards an ever-increasing command over the drawing of objects and an ever-lower vantage point from which they are viewed. While none of Peeters’s ‘cheese stack’ paintings are dated, they have traditionally been placed in the artist’s maturity. Hibbs Decoteau, Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin argued for a dating of the group to the late 1620s and early 1630s, when the artist’s style moved away from the highly finished, vibrant compositions of her earlier pictures towards the ‘monochrome banketje tradition that evolved in Haarlem with Pieter Claesz. (1597-1624) and Willem Claesz. Heda (1593-1680) in the second quarter of the seventeenth century (op. cit.). Recent scholarship, however, has reassessed this dating, placing works in the group to an earlier period, from circa 1612 to 1621, the year that the last document referred to her as an active artist (see Vergara, op. cit., nos. 14 and 15). Yet given the paucity of details regarding Peeters’s life and activities, any dating remains hypothetical.

The Crucifixion

tempera on gold ground panel, in a later engaged frame, arched top 11 x 9¿ in. (28 x 23 cm.)

£80,000-120,000

US$110,000-160,000

€96,000-140,000

PROVENANCE: with Moretti Galleria d'Arte, Florence, by November 2011, where acquired by the present owner.

This is a characteristic work by one of the more productive Sienese masters in the orbit of Duccio di Buoninsegna, who was subsequently influenced by Simone Martini and Ugolino di Nerio. Active in the opening decades of the trecento, the master takes his name from the Maestà in the monastery of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, east of Siena, which G. de Nicola associated with a number of other pictures in 1912. His oeuvre has subsequently been considerably enlarged by Cesare Brandi, to whom his soubriquet is due, and Gertrude CoorAchenbach, James Stubblebine and other scholars. Stubblebine (Duccio di Buoninsegna and his School, Princeton, 1979, I, p. 92) believed his was ‘a oneman operation’ and that there was ‘insufficient evidence’ that he ‘had assistance’. In design, this panel conforms closely with the treatment of the figure in a series of representations of the crucifixion by the master (op. cit., II, figs. 219, 211, 213, 214 and 217), but such details as the diagonal folds of the loincloth distinguish it from these.

PROPERTY OF CARITAS OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF

The Cesarini Venus

bronze; on an integrally cast square plinth and on a square ebonised wood base; the underside of the base with two paper labels, one inscribed 'M / 660', the other '400' 13º in. (33.5 cm.) high; 19Ω in. (49.5 cm.) high, overall

£200,000-300,000

US$260,000-390,000

€250,000-360,000

PROVENANCE:

Private collection, Austria, until 2024, when bequeathed to the present owners.

EXHIBITED:

Very likely the example exhibited in De Triomf van het Maniërisme: een Europese stijl van Michelangelo tot El Greco, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, July - October 1955, p. 162, no. 303.

COMPARATIVE LITERATURE:

J. von Schlosser, Werke der Kleinplastik in der Skulpturensammlung des A. H. Kaiserhauses, Vienna, I, 1910, p. 10.

C. Avery and A. Radcliffe, eds., Giambologna (1529-1608): Sculptor to the Medici, London, 1978, p. 62.

C. Avery, Giambologna: The Complete Sculpture, Frome, Somerset, 1987, pp. 97-107, 254, no. 12.

A. Radcliffe, Giambologna's Cesarini Venus, exhibition catalogue, Washington, D.C., 1993, pp. 15-16.

A. Radcliffe, 'Giambologna's "Venus" For Giangiorgio Cesarini: A Recantation, La Scultura: Studi in Onore Di Andrew S. Ciechanowiecki, A. González-Palacios, II, 1996, p. 64.

S. Sturman, 'A Group of Giambologna Female Nudes: Analysis and Manufacture,' Small Bronzes in the Renaissance, New Haven and London, 1998, pp. 131, 133.

M. Leithe-Jasper and P. Wengraf, European Bronzes from the Quentin Collection, exhibition catalogue, New York, 2004, pp. 146-157, no. 12.

W. Seipel, ed., Giambologna: Triumph des Körpers, exhibition catalogue, Vienna, 2006, no. 21, pp. 15-19, 196-198, 203.

This bronze is an exceptional example of the work of master Renaissance sculptors Giambologna (1529-1608) and his principle assistant Antonio Susini (fl. 1580-1624). Many of Giambologna’s most celebrated compositions are believed to have been executed by Susini, combining the former’s ingenious compositions with the latter’s unparalleled technical ability in bronze production. Their combined talents are exemplified in this cast of the Cesarini Venus which records the overall, mannered, posture of the figure alongside fine details such as the plaits of hair, her elongated fingers and her carefully delineated toenails.

Tabletop bronzes like the present lot were in high demand among wealthy patrons in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries and were often given by the ruling Medici family as diplomatic gifts. To meet this demand, Giambologna trained a series of assistants who assimilated his style and were able to execute bronzes from the master's models. Antonio Susini is known to have trained and worked in Giambologna’s foundry between circa 1580 and 1600, and specialised in preparing moulds of Giambologna’s models for casting and finishing these statuettes when cast (Avery, 1978, op. cit., p. 157). After 1600 he left to work independently, becoming successful in his own right. He continued to cast bronzes from models by his former master in addition to creating his own original compositions. Even after he set up on his own, Susini’s style remained very close to that of Giambologna meaning that it is not always easy to distinguish between the sculptures of the assistant and those of the master as their works are both stylistically and compositionally intertwined.

The composition of the present lot is related to a marble figure carved by Giambologna in Florence in the period 1580-1583, today known as the Cesarini Venus. A letter dated 28 July 1580 records that Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici promised Giangiorgio II Cesarini, Marquis of Civitanova, that he would allow Giambologna - the most brilliant artist of his court - to undertake the carving of a marble statue for the Villa Ludovisi, Cesarini's palace in Rome, as soon as the sculptor had completed all his existing commissions (Wengraf in Seipel, op. cit., p. 118). On 9 April 1583 the Duke of Urbino’s ambassador Simone Fortuna wrote to Duke Francesco Maria II della Rovere, stating that the sculptor had the figure of Venus in hand (‘fra mano’), suggesting that the sculpture was then in the process of being carved (Radcliffe, 1996, op. cit., p. 60). Presumably completed in 1583, it was installed in the Villa Ludovisi. It eventually found its way to another Ludovisi property, the Villa Margherita, today the home of the American embassy, where it stands today.

The dating of this group of bronzes, and their relation to Giambologna’s marble figure, has long been the subject of debate. They come in two distinct sizes: a group of smaller examples including the signed bronze in Vienna which measures 24.8 cm, and a larger size – including the present bronze – which measures between 33 and 34 cm. In 1584, Giambologna's biographer Raffaello Borghini described a diplomatic gift from Cosimo I de’ Medici to Emperor Maximillian II in 1565 of ‘una figurina pur di metallo’ which von Schlosser associated with the bronze model of Venus Drying Herself in Vienna (Schlosser, loc. cit.). This assumption led scholars to conclude that the bronzes had to pre-date the marble Venus and that for Cesarini’s commission Giambologna transformed a small model he made twenty years earlier into a life-size marble. This would be in direct contrast to his usual practice, which involved the creation of small bronzes based on his large-scale marbles (Radcliffe, 1996, loc. cit.). However, as Radcliffe has argued (ibid.), at the time of Cesarini’s commission Giambologna was exceptionally busy and re-working an earlier model would have been a significant time-saving device.

Some scholars have continued to question whether Giambologna would have been content to reproduce an old model for one of his more important

commissions. Previous translations of Borghini’s note of ‘a female figure also of metal’ (Wengraf in Seipel, op. cit., p. 118) may also be misleading, as ‘figurina’ literally translates into English as 'figurine’ and is therefore not gender specific. It should also be noted that the signed Venus in Vienna only appears with certainty in an inventory of 1730, though it may be identifiable with entries in very early seventeenth-century inventories.

Although the early provenance for the present lot is not known there are several descriptions of the composition in sixteenth- and early seventeenthcentury inventories which could describe the present bronze. For example, in 1586 Ferdinando de’ Medici sent Emperor Rudolf 'Una Venere di mano di Giovanni Bologna, simile a quella del S.or Cesarini’ (‘a Venus from the hand of Giambologna similar to that of Signor Cesarini’). By the 1607-1611 inventory of Rudolf’s Kunstkammer, the Emperor had seemingly acquired a second cast. A third cast of this model is also recorded in inventories of the Villa Medici in 1588 and 1671 (Wengraf in Seipel, op. cit., pp. 118-120).

It has been argued that, stylistically, the model for the ‘Cesarini’ Venus fits best into Giambologna’s oeuvre in the 1560s (Leithe-Jasper in Seipel, op. cit., p. 203, and Radcliffe, op. cit.). However, there is a general consensus that the larger group of bronzes of this subject was probably cast by Antonio Susini and the model was therefore created around the time of the carving of the large-scale marble – that is, in the 1580s (ibid., p. 199). Some believe that the larger model represents an evolution of the composition, with its slightly more elongated proportions and greater sense of torsion.

As noted by Avery (op. cit., no. 52, p. 259), this model was among Giambologna’s most popular compositions and there exist many examples from later foundries of the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Wengraf and LeitheJasper have discussed the variant models and divided them into types ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘D’. The present bronze corresponds broadly to type ‘C’, that is, the larger model but on a square plinth. Other examples from this group include the bronze from Anglesey Abbey (National Trust, Fairhaven Collection) and the example in the Quentin Collection (Leithe-Jasper and Wengraf, op. cit., p. 146). Although the authors suggest that most of these bronzes probably date from the second and third quarters of the seventeenth century, there is an important distinction to be noted regarding the present example. As discussed in the entry of the Quentin bronze, the marble example of the Cesarini Venus was originally displayed outdoors and was badly damaged at some point before 1616 (Radcliffe, op. cit., p. 70). During the restoration, which was largely confined to the lower sections but also the top of the head, the area of the hair within the circular section formed by the intertwined plaits was altered from a central parting with hair combed out to both sides, to hair combed directly down from the front of the head to the back. They argue convincingly that the rare number of bronzes with the central parting must pre-date the restoration of the marble, which took place before 1624 (ibid., p. 154). The much more common bronzes with the hair combed from front to back therefore post-date the restoration. This would place the bronze offered here among the rare examples cast in the late sixteenth and very early seventeenth centuries. The relative freedom of details such as the naturalistic curls of hair framing the forehead of this figure would suggest a relatively early dating in Susini’s time with Giambologna – perhaps in the 1580s or 1590s; his later casts seem to become more rigid and goldsmith-like in their finishing.

With its lustrous reddish-gold patina and its exquisite details, the present bronze represents an exciting discovery in the world of late Renaissance bronzes. It is perhaps notable that it has appeared from a collection in Austria, where the Hapsburg dynasty represented one of Giambologna’s greatest and most enduring patrons.

The Crucifixion with the Virgin, Mary Magdalene, John the Evangelist and a Franciscan Saint tempera on gold ground panel, in its original engaged frame 16¿ x 10º in. (40.9 x 26 cm.) with its original painted reverse

£80,000-120,000

US$110,000-160,000

€96,000-140,000

PROVENANCE:

Achillito Chiesa (1881-1951), Milan, by 1926; his sale, American Art Association, New York, 16 April 1926, lot 12, as 'Pietro Lorenzetti', when acquired for $5,600 by the following, with Ercole Canessa, New York and Naples. with Albrighi, Florence, 1946-1950. with Frascione, Florence, 1950. with Wildenstein and Co., New York, by 1974, where acquired by the following, Private collection, New York, from whom acquired by the present owner in circa 2018.

EXHIBITED:

London, Helikon Gallery, Exhibition of Old Masters, June-September 1974, no. 1, as 'Pietro Lorenzetti'.

LITERATURE:

'Chiesa Paintings', Art News, XXIV, 24 April 1926, p. 11, no. 12.

E.T. Dewald, Pietro Lorenzetti, Cambridge Mass., 1930, p. 38.