PROPERTIES FROM

THE HEIRS OF DANIËL GEORGE VAN BEUNINGEN (1877-1955)

THE COLLECTION OF MICKEY CARTIN

THE ESTATE OF SANFORD R. ROBERTSON

THE COLLECTION OF THE VISCOUNT WIMBORNE

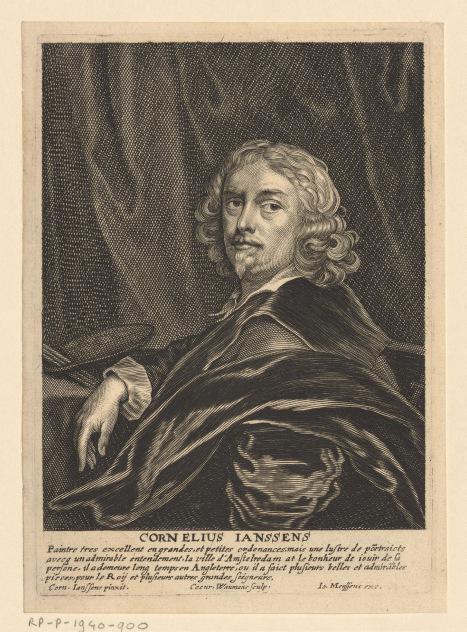

FRONT COVER Lot 8 (detail)

INSIDE FRONT COVER

Lot 42 (detail)

PAGE 2

Lot 6 (detail)

OPPOSITE

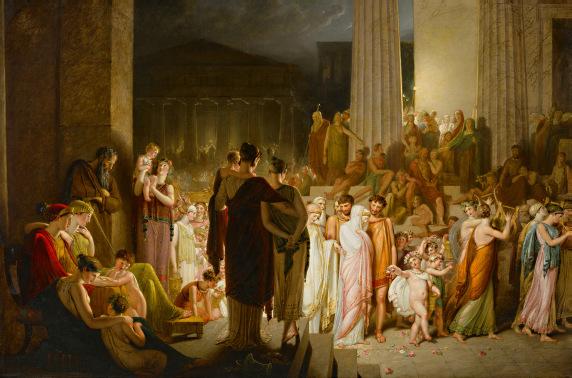

Lot 22 (detail)

INDEX

Lot 7 (detail)

BACK COVER

Lot 4 (detail)

Tuesday 1 July 2025 at 6.30 pm

8 King Street, St. James’s London SW1Y 6QT

VIEWING

Thursday 26 June 10.00 am - 5.00 pm

Friday 27 June 9.00 am - 5.00 pm

Saturday 28 June 12.00 pm - 5.00 pm

Sunday 29 June 12.00 pm - 5.00 pm

Monday 30 June 9.00 am - 5.00 pm

Tuesday 1 July 9.00 am - 3.00 pm

Henry Pettifer

In sending absentee bids or making enquiries, this sale should be referred to as ISABELLA-23859

Admission to the Evening Sale is by ticket only. To reserve tickets, please email: ticketinglondon@christies.com. Alternatively, please call Christie’s Client Service on +44 (0)20 7839 9060

ABSENTEE AND TELEPHONE BIDS

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2658

Fax: +44 (0)20 7930 8870

The sale of each lot is subject to the Conditions of Sale, Important Notices and Explanation of Cataloguing Practice, which are set out in this catalogue and on christies.com. Please note that the symbols and cataloguing for some lots may change before the auction. For the most up to date sale information for a lot, please see the full lot description, which can be accessed through the sale landing page on christies.com.

In addition to the hammer price, a Buyer’s Premium (plus VAT) is payable. Other taxes and/or an Artist Resale Royalty fee are also payable if the lot has a tax or λ symbol.

Check Section D of the Conditions of Sale at the back of this catalogue.

Estimates in a currency other than pounds sterling are approximate and for illustration purposes only.

GLOBAL HEAD, OLD MASTERS

Andrew Fletcher

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2344

INTERNATIONAL DEPUTY CHAIRMAN

Henry Pettifer

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2084

INTERNATIONAL DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, UK & IRELAND

John Stainton

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2945

INTERNATIONAL DEPUTY CHAIRMAN

François de Poortere

Tel: +1 212 636 2469

GLOBAL HEAD OF RESEARCH & EXPERTISE

Letizia Treves

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 5206

HEAD OF DEPARTMENT, LONDON

Clementine Sinclair

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2306

HEAD OF DEPARTMENT,

NEW YORK

Jennifer Wright

Tel: +1 212 636 2384

HEAD OF DEPARTMENT, DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, PARIS

Pierre Etienne

Tel: +33 (0)1 40 76 72 72

DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, UK

Francis Russell

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2075

HONORARY CHAIRMAN

Noël Annesley

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2405

WORLDWIDE SPECIALISTS

AMSTERDAM

Manja Rottink

Tel: +31 (0)20 575 52 83

BRUSSELS

Astrid Centner

Tel: +32 (0)2 512 88 30

HONG KONG

Georgina Hilton

Melody Lin

Tel: +85 22 97 86 850

LONDON

Freddie de Rougemont

John Hawley

Maja Markovic

Flavia Lefebvre D’Ovidio

Lucy Speelman

Isabella Manning

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2210

GLOBAL MANAGING DIRECTOR

Imogen Giambrone

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2009

PRIVATE SALES

Alexandra Baker

International Business Director

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2521

AUCTION CALENDAR 2025

TO INCLUDE YOUR PROPERTY IN THESE SALES PLEASE CONSIGN TEN WEEKS BEFORE THE SALE DATE. CONTACT THE SPECIALISTS OR REPRESENTATIVE OFFICE FOR FURTHER INFORMATION

18 NOVEMBER

MAÎTRES ANCIENS: PEINTURESDESSINS - SCULPTURES

PARIS

6 - 20 NOVEMBER

MAÎTRES ANCIENS: PEINTURESDESSINS – SCULPTURES, ONLINE PARIS

2 DECEMBER

OLD MASTERS EVENING SALE LONDON

3 DECEMBER

OLD MASTERS TO MODERN DAY SALE: PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS, SCULPTURE LONDON

NEW YORK

Jonquil O’Reilly

Joshua Glazer

Oliver Rordorf

Taylor Alessio

Kyra Cseh

Tel: +1 212 636 2120

MADRID

Adriana Marín Huarte

Tel: +34 915 326 627

PARIS

Olivia Ghosh

Bérénice Verdier

Victoire Terlinden

Tel: +33 (0)1 40 76 85 87

CONSULTANTS

Sandra Romito

Alan Wintermute

SENIOR SALE COORDINATOR

Sacha Sabadel

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2210

BUSINESS MANAGER

Lottie Gammie

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 5151

First initial followed by last name@christies.com (e.g. Clementine Sinclair = csinclair@christies.com). For general enquiries about this auction, emails should be addressed to the Sale Coordinator.

ABSENTEE AND TELEPHONE BIDS

Tel: +44 (0)20 7389 2658

Fax: +44 (0)20 7930 8870

AUCTION RESULTS

Tel: +44 (0)20 7839 9060 christies.com

CLIENT SERVICES

Tel: +44 (0)20 7839 9060

Fax: +44 (0)20 7389 2869

Email: info@christies.com

POST-SALE SERVICES

Miranda Achille

Post-Sale Coordinator

Payment, Shipping, and Collection

Tel: +44 (0)20 7752 3200

Fax: +44 (0)20 7752 3300

Email: PostSaleUK@christies.com

BUYING AT CHRISTIE’S

For an overview of the process, see the Buying at Christie’s section. christies.com

The Harrowing of Hell oil on panel

12 x 11√ in. (30.5 x 30.3 cm.)

with a later inscription ‘1584’ (lower left)

£50,000-70,000

US$68,000-94,000

€60,000-83,000

PROVENANCE:

Anonymous sale; Hugo Helbing, Munich, 25 April 1904, lot 9, as 'Hieronymus Bosch'.

Anonymous sale [Auswärtige Privat-Galerie]; Rudolph Lepke, Berlin, 8 May 1906, lot 44, as 'Hieronymus Bosch'.

Anonymous sale; Rudolph Lepke, Berlin, 5 March 1907, lot 133, as 'Hieronymus Bosch'.

Anonymous sale; Paul Brandt B.V., Amsterdam, 24 May 1977 (=1st day), lot 93, as 'Gillis Mostaert'.

Acquired by the father of the present owner before 1988.

This intriguing panel, which in the early twentieth century was believed to be by Hieronymus Bosch himself, belongs to a small group of Boschian images painted within the master's lifetime. Bosch's influence would come to have a lasting and widely felt impact on the visual arts throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Perhaps the most inventive and individual painter working in the Netherlands during the late Middle Ages, Bosch’s unique imaginative powers and vivid pictorial vocabulary proved a source of constant inspiration for painters seeking to imagine and visualise the otherworldly.

The Harrowing of Hell seems first to have appeared in the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, written in the mid-fourth century, and was later adapted and disseminated by popular theological texts, like the Legenda Aurea of Jacobus de Voragine. While no depictions of this subject by Bosch are known today, four apparently different pictures of this, or closely related subjects, are recorded in early sources. In 1574, a painting by Bosch showing ‘the Descent of Christ our Lord to Limbo’ was given by Philip II of Spain to the Escorial outside Madrid, with a further painting by the artist of ‘Christ after the Resurrection in Limbo, with many figures’ owned by the king upon his death. Another depiction of the same subject was listed in the 1595 inventory of Archduke Ernest of Austria (1553-1595) at Brussels, and a final one recorded by Karel van Mander in his famous Het Schilder-boeck (1604), which described a ‘Hell […] in which patriarchs are released’ (see L. Campbell, The Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen: The Early Flemish Pictures, Cambridge, 1985, p. 11, under no. 7).

It is likely that the present painting was derived from one of these lost works by an artist who was working in Bosch’s orbit within his lifetime. Dendrochronological analysis of the oak panel provides the earliest felling date of 1483, with a possible date of creation from 1485 onwards (report by Dr. Peter Klein, 29 October 2024, available upon request). Infrared reflectography reveals a combination of planned underdrawing and more spontaneously executed elements, with Christ and the figures before him partially underdrawn and the landscape and surrounding staffage rendered with greater freedom (fig. 1; analysis by Tager Stonor Richardson, 26 April 2025, available upon request). The painting's composition, conceived within a unique square format, also suggests that it may have been intended for a specific form of display, attested to by the barb of its painted edges.

Bosch’s diabolic landscapes created an artistic phenomenon so revered in his lifetime and beyond that they gained a life of their own, with his designs disseminated by draughtsmen, painters and printmakers through an intense exchange of models. Artists would reinterpret Boschian themes through motifs derived from drawings, often assembled in sketchbooks and modelbooks, and while most such books are now lost or dismembered, one can imagine that such an invaluable workshop tool may have helped the present artist build a visual repertoire as a means of developing this composition.

Christ’s Descent into Limbo was, like many Christian iconographies that were popularised during the Middle Ages, not based on the Biblical account of his life. As told in de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea, following his Crucifixion, Christ descended into Hell in triumph, bringing salvation to the righteous who had died since the beginning of the world. Arriving at the entrance of Hell, he called out in a voice ‘as of thunder… Lift up your gates…and the King of Glory shall come in’ (Gospel of Nicodemus, 16:1). The figure of Christ, dressed in a red mantle and carrying a banner of victory, is shown smashing down the gates of Hell at centre of this work. Surrounding him is a disturbing account of the tumultuous mass of sinners and demons that were to fascinate and horrify Bosch’s contemporaries, retaining even today their enduring force.

Three head studies of a bearded man oil on panel

18æ x 25 in. (47.7 x 63.5 cm.)

£100,000-150,000

US$140,000-200,000

€120,000-180,000

PROVENANCE:

Peter Michallat, Lower Failand, Bristol; his sale (†), Christie's, London, 23 January 2011, lot 36, as 'Manner of Sir Peter Paul Rubens', where acquired after sale by the present owner.

This rediscovered panel is a vigorously worked and psychologically penetrating study of the head of a bearded man viewed from three vantage points, providing an insight into the reproduction and diffusion of figure types by the most significant Flemish painter of the seventeenth century: Sir Peter Paul Rubens.

When the painting was offered in 2011, the head studies were only faintly perceptible beneath dark, obscuring layers of historic dirt and discoloured varnish, which left it largely overlooked at the sale, after which it was acquired by the present owner. Subsequent conservation was transformative, revealing the original paint surface beneath.

Rubens’s prolific use of head studies for his larger multi-figural compositions is well documented. Spontaneous, rapidly painted studies from a model in the studio provided Rubens with an essential cast of real-life characters to draw from. Recorded often from a variety of angles, they were never intended as finished paintings for display, but kept as working tools to add variety and a sense of human veracity to his history paintings, communicating the master’s ideas to his assistants. Along with his compositional modelli, these head studies were amongst his most important possessions, which he relied on as part of his working practice for his whole life. Indeed, a work of this type was referenced in the so-called Specificatie – an inventory of works compiled for auction following Rubens’s death in 1640 – testifying to their importance for the artist: 'Une quantit des visages au vif, sur toile, & fonds de bois, tant de Rubens, que de Mons. Van Dyck' ('A parcel of faces made after the life, vppon bord and Cloth as well by Sir Peter Paul Rubens as van Dyck'; see J. Müller, Rubens: The Artist as Collector, Princeton, 1989, p. 145).

The present heads were evidently painted by at least one talented hand, and perhaps multiple, working in Rubens’s orbit at the end of the 1610s, which included the young Anthony van Dyck and Jacob Jordaens. They leave a fascinating record of study heads that may have been based on now-lost individual prototypes by Rubens. The majority of Rubens’s large projects were executed with the assistance of pupils and collaborators working under the master’s supervision. The present head studies can be associated, with slight divergences, to figures found in works by the artist from around 1617, during one of the busiest phases of his career: the upturned head at left, the first of the three to have been rendered on the panel, bears semblance to the shepherd raising his hat in Rubens’s Adoration of the Shepherds of circa 1617 (Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts); the head in the centre, painted second, closely resembles that of Saint Peter in Rubens’s Saint Peter Finding the Tribute Money of circa 1617 (Dublin, National Gallery of Ireland; fig. 1), which Rubens sold to Sir Dudley Carlton in 1618 as part of an exchange of goods agreed between the two; and the last, painted in the lower right, can be associated with the figure holding the shroud in the upper right of Rubens’s Descent from the Cross, again of circa 1617 (Lille, Musée des Beaux-Arts). Dendrochronological analysis of the present panel supports a similar time of execution, providing a felling date to after circa 1594 and usage before circa 1630 (dendrochronological report by Ian Tyers, June 2024, available upon request).

SELECTIONS FROM THE COLLECTION OF MICKEY CARTIN (LOTS 3, 20, 21 AND 22)

°*3

Portrait of Margret Halseber of Basel, also known as 'The Lady with the two beards', bust-length oil on panel 12Ω x 10º in. (31.7 x 26 cm.)

£300,000-500,000

US$410,000-670,000

€360,000-590,000

PROVENANCE:

(Possibly) Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle (1517-1586), Besançon, as 'Tête de femme portant barbe, de la main de Guillaume Chayez' (Jonckheere, op. cit., p. 133). (Possibly) Joseph van Huerne, Ghent (d. 1844); his sale (†), Dullaert-Vandervin, Ghent, 21 October 1844, lot 22, as 'Holbein' (210 FF).

Private collection, England, as 'Hans Holbein the Younger'.

Gustave Becker, London (according to a note on the reverse of a photograph in the RKD Research Files).

Miss B. Campe-Becker; Christie's, London, 13 July 1951, lot 39, as 'Sir Antonio Mor', where unsold. with Colnaghi, London, circa 1957, as 'Antonio Moro' (according to labels on the reverse and Koopstra, op. cit.), where acquired by, Benjamin Sonnenberg (1901-1978), 19 Gramercy Park South, New York; his sale (†), Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, 5 June 1979 (=1st day), lot 75, as 'Willem Key'. Dr. Samuel Schaefler (1929-1991), New York.

Anonymous sale; Arteprimitivo, online, 23 April 2007, lot 67, as 'Anthonis Mor'.

Anonymous sale [The Property of a Lady]; Sotheby's, Amsterdam, 7 May 2008, lot 7. with French & Company, New York, where acquired in 2011 by the present owner.

EXHIBITED:

New York, David Zwirner Gallery, Seen in the Mirror: Things from the Cartin Collection, 4 November-18 December 2021, unpaginated.

LITERATURE:

(Possibly) A. Castan, Monographie du Palais Granvelle à Besançon, Paris, 1867, p. 332. (Possibly) T. von Frimmel, Geschichte der Wiener Gemäldesammlungen, I, Lepizig, 1899, p. 480.

A. Koopstra, Schattengalerie: die verlorenen Werke der Gemäldesammlung, exhibition catalogue, Munich, 2008, pp. 140-4, no. 60.

K. Jonckheere, Willem Key (1516-1568): Portrait of a Humanist Painter, Turnhout, 2011, pp. 132-135, no. A68, illustrated.

E. Gordon and S. Holmes, ed., Seen in the Mirror: Things from the Cartin Collection, London, 2023, pp. 35 and 40.

ENGRAVED:

P. de Vlaminck, 1836.

This highly unusual and wonderfully preserved portrait depicts Margret Halseber (Halscher), as testified through an inscription on an autograph replica (formerly Aachen, Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, stolen in 1972), about whom nothing is known. She may have had hirsutism, a condition caused by an imbalance in hormones, namely testosterone, that results in the growth of coarse hair on the face, chest and back. This unusual medical condition must have been a source of curiosity – and perhaps ridicule – in the early modern era. Some eighty years later, in 1631, Jusepe de Ribera would paint a woman with the same condition in his well-known Magdalena Ventura with her husband and son (fig. 1; Toledo, Fundación Casa Ducal de Medinaceli, on long-term loan to the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid).

A label on the reverse of the present panel identifies the sitter as being a resident of Basel and the artist as Hans Holbein the Younger. While this was previously taken as evidence that the present painting was probably the panel attributed to Holbein that featured in both the 1819 sale of the Chevalier François Xavier de Burtin and that of the Van Huerne collection in 1844, in each of which it was said that the panel in question lacked the inscription that appears on the ex-Aachen example (see, for example, the entry to the 2008 Sotheby’s sale, op. cit.), it can now be shown for the first time that the present panel was definitively not the version in the collection of de Burtin. The second volume of his Traité des connaissances nécessaires aux amateurs de tableaux (Brussels, 1808) mentions how ‘Margret Halseber’s name is spelled out in full’ (‘le nom de Margret Halseber se lit en toutes lettres’) in the painting in his collection (p. 217), referring to the inscription on the Aachen picture, which must therefore have instead been the one in his possession.

For much of the twentieth century, the painting was frequently attributed to Antonis Mor, though in 1931 Louis Dimier correctly gave the composition to Willem Key on account of contemporary documentary evidence relating to one of the versions in the collection of Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle (1517-1586) in Besançon (op. cit.). There, the panel is described as the work of one ‘Guillaume Chayez,’ whom Dimier correctly identified as Willem Key. As Koenraad Jonckheere has surmised, the present painting was probably the version in Granvelle’s collection as the inventory fails to make mention of the inscription that appears on the ex-Aachen version (op. cit., pp. 133-134). Granvelle apparently maintained a particular fascination with portraits of distinctive individuals. In addition to commissioning this portrait from Key, he ordered from Mor a portrait of a person with dwarfism in his household (Paris, Musée du Louvre). That Granvelle was equally familiar with Key is confirmed by his having sat for a portrait by the artist (see Jonckheere, op. cit., no. A41).

Despite the uncharacteristically vivacious, virtuoso and carefree execution of this painting within Key’s oeuvre, from a technical point of view, Jonckheere has stressed how ‘several features fit in seamlessly with Willem Key’s manner of painting’ (op. cit., p. 134). These include the rapid, summary underdrawing in black chalk, visible in places where the paint has been fairly thinly applied; its comparatively coarse finish (especially when compared with paintings by Mor); and the ochre-pink tonality of the woman’s flesh tones, which can likewise be found in other portraits by Key.

While the ex-Aachen example has not resurfaced since its theft and consequently has not benefited from technical examination, several factors point to the present painting being the prime version of this composition. While the two versions correspond in almost every detail, the treatment of the beard in the two paintings is different and it appears the Aachen portrait lacks the underdrawing so evident in our example.

In addition to the second version formerly in Aachen, this portrait is known through a copy in the collection of the Alte Pinakothek, Munich (see Jonckheere, op. cit., no. E3).

A pie on a pewter plate, a partially peeled lemon and overturned silver spoon on a pewter plate, crayfish and shrimp in a Wanli bowl, fruit, a walnut and an oyster on a pewter plate, a basket of fruit, a fluted glass, a silver-gilt cup, a roemer, an overturned silver tazza on a strong box, a silver ewer and a bread roll all on a partially draped table with a curtain beyond signed and dated ‘J. De Heem f. A° 1649’ (lower left, on the table) oil on canvas

29¡ x 44¡ in. (75.3 x 112.7 cm.)

£3,000,000-5,000,000

PROVENANCE:

(Possibly) Jacques Meijers (d. 1721), Rotterdam; his sale (†), Willis, Rotterdam, 9 September 1722, lot 118 (f 225).

US$4,100,000-6,700,000

€3,600,000-6,000,000

E.H. Davenport, Davenport House, Bridgnorth, Shropshire, by 1881, and by inheritance to his daughter, Mrs. Leicester-Warren; Christie’s, London, 12 June 1931, lot 74 (740 gns. to Collings).

Alexander Jergen, Cincinnati, presumably by 1931 and until 1984. with French & Co., New York, 1984.

Linda and Gerald Guterman; their sale, Sotheby’s, New York, 14 January 1988, lot 19, where acquired by the following, with Thomas Brod, London. Private collection, Germany.

Anonymous sale [The Property of a Gentleman]; Christie’s, London, 3 December 1997, lot 22, where acquired.

EXHIBITED:

Whitechapel, London, Saint Jude’s School House, Annual Fine Art Loan Exhibition, 1886, no. 138.

Cincinnati, Cincinnati Museum of Art, until 1984, on loan. Delft, Stedelijk Museum het Prinsenhof; Cambridge, MA, Fogg Art Museum and Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum, De Rijkdom Verbeeld / A Prosperous Past: The Sumptuous Still Life in the Netherlands, 1600-1700, 1988, no. 40 (cat. by S. Segal). Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Jan Davidsz de Heem und sein Kreis, 1991, no. 7A (cat. by S. Segal).

LITERATURE:

G. Hoet, Catalogus of naamlyst van schilderyen met derzelver pryzen…, I, The Hague, 1752, p. 277, no. 118.

G. Keyes, in Dutch and Flemish Masters – Paintings from the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, exhibition catalogue, Minneapolis, Houston and San Diego, 1985, p. 52, under no. 17.

‘Auction: Sotheby’s: Thursday January 14,’ Tableau, X, December 1987, p. 83, illustrated. F. Fox Hofrichter, ‘Review of the exhibition A Prosperous Past: The Sumptuous Still Life in the Netherlands 1600-1700,’ The Burlington Magazine, CXXX, no. 1029, December 1988, pp. 962-963, fig. 109.

C. Hergenröder, ‘Gesunder Markt mit Hochpreistendenzen. Altmeistergemälde in den vergangenen Jahren,’ Kunst und Antiquitäten, 5/88, 1988, pp. 16-17, illustrated.

S. Segal, ‘De Heem and his Circle,’ in A Prosperous Past, exhibition catalogue, Delft, Cambridge, MA and Fort Worth, 1988, pp. 151-153, plate 40, as ‘[a] magnificent work’.

S. Segal, ‘De rijkdom verbeeld,’ Tableau, X, no. 6, 1988, pp. 67 and 69, illustrated.

I. de Wavren, ‘Le Triomphe de l’Éphémère,’ L’objet d’art, III, June 1988, pp. 102-103, illustrated in reverse.

F.G. Meijer, ‘Book review of Exh. Cat. A Prosperous Past: The Sumptuous Still Life in the Netherlands 1600-1700,’ Simiolus, XX, 1990/1, no. 1, p. 96.

S. Segal, in Jan Davidsz de Heem en zijn kring, exhibition catalogue, Utrecht and Braunschweig, 1991, p. 214, note 1.

J. Briels, Vlaamse schilders en de dageraad van Hollands Gouden Eeuw, 1585-1630. Met biografieën als bijlage, Antwerp, 1997, p. 281, illustrated.

‘Adjugé,’ L’Estampille, March 1998, p. 19, illustrated.

C. Fritzsche, Der Betrachter im Stilleben. Raumerfahrung und Erzählstrukturen in der niederländischen Stillebenmalerei des 17. Jahrhunderts, Weimar, 2010, pp. 55, 62-63, 92-93, 104, 175 and 284, fig. 16.

F.G. Meijer, Jan Davidsz. de Heem 1606-1684, I, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Amsterdam, 2016, pp. 105, 157-158, 160-161, 192, 209, 358, illustrated; II, pp. 141-142 and 308, no. A 121.

F.G. Meijer, Jan Davidsz. de Heem, 1606-1684, I, Zwolle, 2024, pp. 210-211, fig. 253, illustrated (detail), as ‘[t]he core work for the year 1649’; II, pp. 588-589, no. 126, illustrated.

F.G. Meijer, Opulence Distilled: The Still Lifes by Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Antwerp, 2024, p. 53, fig. 54, as ‘[t]he core work for the year 1649’.

This luxurious and immaculately preserved still life is among the finest paintings by the artist to have appeared on the market in recent decades. On account of its exceptional quality, the two most important scholars of northern still-life painting in recent times, Fred G. Meijer and Sam Segal, have praised it variously as ‘the core work for the year 1649’ (see Meijer, op. cit. 2024, p. 210) and ‘a magnificent work’ (see Segal, op. cit., 1988, p. 152).

The painting reprises themes from an extraordinary group of four large-scale paintings that de Heem executed earlier in the decade. Two of these paintings are today at the Louvre (inv. no. 1321; fig. 1) and the Musée de la Ville de Bruxelles (inv. no. K.1878.5). A third is in a private collection, and the fourth was sold for a world auction record at Christie’s in London on 15 December 2020. Much like the present painting, the variety of textures and sheer number of expensive foods and objects the artist managed to compose within a relatively tight pictorial space offers the viewer an example of virtually everything de Heem was capable of and perhaps served as a calling card to display the range of his abilities.

De Heem’s meticulous, refined handling of paint in the present painting contrasts strikingly with his more broadly brushed works of 1647. A number of the still-life elements can, however, be found in other of de Heem’s paintings or associated with surviving examples, including the silver-gilt cup and cover, silver tazza and silk-covered box. An identical tazza, for example, reappears in a painting from the 1650s in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (fig. 2), while, as Segal has noted (op. cit.), the cup and cover is similar to one made by Friedrich Hirschvogel in Nuremberg around 1638. Similar pies with different crust designs likewise appear sporadically in de Heem’s still lifes of the 1640s and early 1650s, including in the aforementioned work sold in 2020. Other details, like the elaborate silver ewer at right, are unique to this painting. No similar ewer with swan-head spout surmounted by a seated putto, repoussé and chased neck with a grotesque mask and scroll handle with applied motif

of Hercules and the Nemean Lion is known today, suggesting it may be de Heem’s own invention or, as Meijer has proposed (op. cit., p. 210), added at the behest of a patron.

De Heem’s refined approach and the painting’s exceptional state of preservation enable the appreciation of a number of small details cleverly reflected in the metal and glassware. The central boss of the silver-gilt cup shows the reverse of a painting on an easel, while certain still-life elements, a candlestick and books on a table can be made out in the mirror-like vacant cartouche of the ewer. Claudia Fritzsche perceptively pointed out that the artist himself can be seen in this cartouche (fig. 3; op. cit.). Additionally, though it has never before been pointed out in the literature, the windows reflected in the roemer also include a church spire (fig. 4), presumably that of the Cathedral in Antwerp where de Heem was then working.

This painting may be identical with the de Heem still life described simply as ‘Een Tafel vervult met Fruyten, en andere eetwaare’ in the 1722 posthumous sale of the leading Rotterdam collector and art dealer Jacques Meijers. Despite the generic description in the sale catalogue, it is the only known painting by de Heem whose size comports so closely with the dimensions provided in the catalogue: ‘h: 2 v: 5: duym, b: 3:v:6½ duym.’ Meijers was a Catholic collector who privileged quality over a focus on a specific school of painting. In addition to the Dutch and Flemish paintings one would expect from a Dutch collector of his generation, Meijers included sterling examples by a number of the best French and Italian artists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Among the Italian works that appeared in the sale were paintings attributed to Caravaggio, Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese. Meijers also owned no fewer than nine paintings given to Nicolas Poussin, including his Camillus and the Schoolmaster of Falerii (Pasadena, CA, Norton Simon Museum) and Venus and Mercury (Dulwich Picture Gallery), and Claude’s The Sermon on the Mount (New York, The Frick Collection). Highlights of the Dutch and Flemish paintings include a pair by Gerrit Dou depicting women bathing (both St. Petersburg, The State Hermitage Museum), ten paintings attributed to Peter Paul Rubens – the finest of which was the artist’s large-scale masterpiece depicting The Meeting of David and Abigail (fig. 5; Detroit Institute of Arts), which was previously in the collection of the Duke of Richelieu and Roger de Piles – and five works given to Anthony van Dyck.

Two somewhat reduced painted copies of this still life are known, one of which by Anthony Oberman (17811845). A seventeenth-century drawing, previously attributed to de Heem but recently rejected by Meijer (op. cit., p. 671, no. D R 07), was offered Sotheby’s, London, 4 July 2012, lot 115.

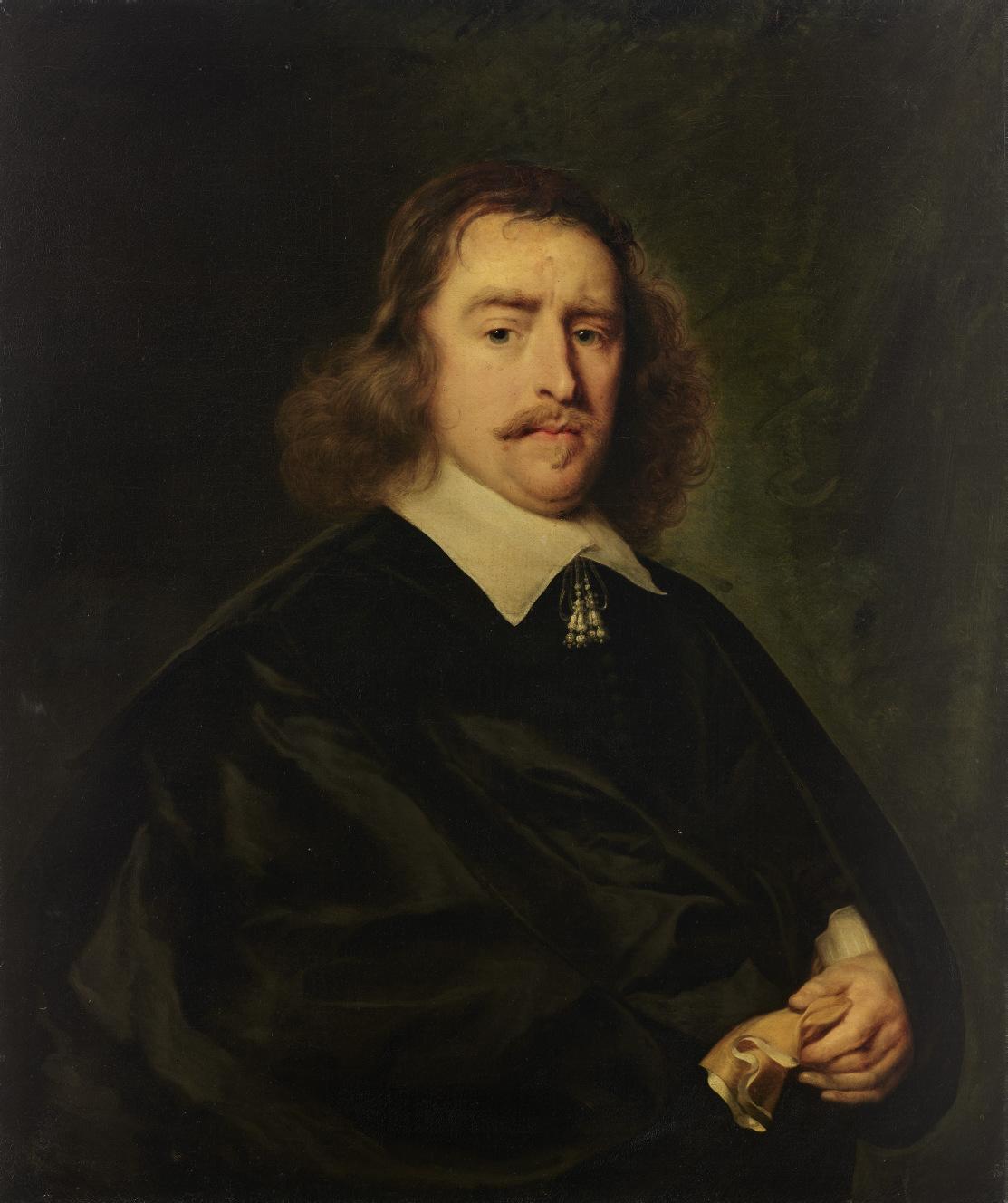

Portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck (1617-1666), half-length, in black dress, holding a book oil on panel

12¿ x 9æ in. (30.8 x 24.7 cm.)

£600,000-800,000

US$810,000-1,100,000

€720,000-950,000

PROVENANCE:

Sir James Stuart (Sir John James Stuart of Allanbank, 5th Bt.?); his sale, Christie's, London, 23 May 1835, lot 64, as 'Frank Hals [sic]', where acquired for 15 gns. by, Andrew James, Harewood Square, London, and by inheritance to his daughter, Miss Sarah Ann James (d. 1890), Norfolk Square, London; (†) Christie's, London, 20 June 1891 (=1st day), lot 31, as 'F. Hals' (230 gns. to M. Colnaghi).

Mrs. Joseph, London, from whom acquired by, with P. D. Colnaghi & Co., London, from whom a quarter share was acquired on 29 May 1911 by the following, with Knoedler & Co., Lippmann, Sulley & Co., from whom acquired on 28 June 1911 by the following, with Roebel and Reinhardt Galleries, Milwaukee. Emory Leyden Ford (1876-1942), Detroit, and by descent.

EXHIBITED:

London, Royal Academy, Exhibition of the works of the Old Masters, associated with works of deceased Masters of the British School, 1871, no. 250, as 'Frans Hals' (lent by Miss James).

Detroit, Museum of Art, Exhibition of Paintings loaned by E.L. Ford, Esq. of Detroit, Michigan, October 1915, no. 2, as 'Frans Hals' (illustrated on the front cover).

Detroit, Institute of Arts, Fifty Paintings by Frans Hals, 10 January-28 February 1935, no. 42.

LITERATURE:

E.W. Moes, Frans Hals: sa vie et son oeuvre, Brussels, 1909, p. 102, no. 49, as 'Frans Hals'.

C. Hofstede de Groot, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century, III, London, 1910, p. 60, no. 194, as a 'replica', with incorrect dimensions.

W. von Bode and M.J. Binder, Frans Hals: Sein Leben und Seine Werke, II, Berlin, 1914, pp. 63, 73 and 83, no. 225, pl. 143a, as 'Frans Hals', with incorrect dimensions.

W.R. Valentiner, Frans Hals: Des Meisters Gemälde (Klassiker der Kunst), 1st ed., Stuttgart and Berlin, 1921, p. 209; 2nd ed., 1923, p. 222, as 'Frans Hals'.

W.R. Valentiner, Frans Hals Paintings in America, Westport, 1936, p. 78, as 'Frans Hals'.

S. Slive, Frans Hals, III, London and New York, 1974, p. 85, no. 165.1, fig. 42, as 'a reduced copy by another hand after the Brussels painting'.

S. Slive, Frans Hals, exhibition catalogue, London, 1989, pp. 300 and 302, fig. 60c, as 'Unknown artist, copy after Hals'.

ENGRAVED:

Jonas Suyderhoef (1613-1686), 1651. Jan Brouwer (c. 1626-after 1688).

The re-emergence of this small-scale portrait of Johannes Hoornbeeck after more than a century offers an opportunity to look afresh at an important part of Frans Hals’s oeuvre: the small-scale portrait. Hals’s small-scale portraits on panel or copper, nearly forty of which are known or documented today, occupied a critical place in his artistic production and count among the artist’s liveliest and most spontaneous works. This relatively small group of paintings amounting to little more than fifteen percent of Hals’s known output would come to be especially prized by generations of collectors and commentators in ensuing centuries.

Théophile Thoré, the driving force behind the resurgence of interest in the artist and his work in the middle of the nineteenth century, first gave voice to the particular appeal of these intimately scaled works when, in 1860, he enthused about the artist’s 1634 portrait of the Haarlem historian Pieter Christiaansz. Bor: ‘What a jewel this little Frans Hals is!...Here in Rotterdam, Frans Hals enclosed his man in an oval medallion 22 centimetres high; only the bust, but with one hand…All of this is of such skill, such knowledge, such freedom, such spirit!’ The painting was sadly destroyed when a fire broke out four years later at the Museum Boymans in Rotterdam, but its appearance is known today through a print executed in the same year by Adriaen Matham.

The identities of a surprising number of Hals’s sitters for his small-scale portraits have come down to us, in large part due to the fact that – as with his portrait of Bor and the present picture – they often served as models for engravings in which the sitter’s name is inscribed in the print. Nearly one-third of the surviving or documented small-scale panels by Hals were copied in prints, generally appearing in reverse on account of the printing process and

of identical scale, suggesting they were traced by the printmaker. In addition to the lost Bor portrait, evidence exists for at least three further modellos – the portraits of Arnold Möller (Slive, op. cit., no. L9), Caspar Sibelius (Slive, op. cit., no. L11) and Theodor Wickenburg (Slive, op. cit., no. L17) – for which only a print is known today. The panel portrait depicting the Deventer preacher Sibelius, sadly destroyed by fire in 1956 when in the collection of Billy Rose, was regarded by Cornelis Hofstede de Groot (1910), Wilhelm von Bode (1914), Wilhelm Valentiner (1921) and, most recently, Justine Rinnooy Kan (2023) as Hals’s modello for a print of similar scale by Jonas Suyderhoef (for an image of the painting, see W.R. Valentiner, op. cit., 1923, p. 150). Seymour Slive, who knew the portrait of Sibelius solely from a poor black-and-white photograph, described it instead as ‘either very badly abraded and clumsily restored or…a copy by another hand after one of Suyderhoef’s prints’ (op. cit., III, under no. L12). That the ex-Rose painting was executed in reverse of Suyderhoef’s print confirms that it is not a copy after the print but most likely the lost prototype by Hals.

Hals enjoyed particularly friendly relations with the select group of contemporary printmakers who made engravings after his painted portraits. No fewer than twenty-six of Hals’s portraits were engraved in his lifetime, though by only nine engravers, three of whom hailed from the Matham family. As Rinnooy Kan has pointed out (‘Portrait Prints’, Frans Hals, exhibition catalogue, London and Amsterdam, 2023, p. 143), both Jacob Matham – who was perhaps the first to engrave a portrait by Hals when, in 1618, he produced a scaled print after the portrait of Theodorus Schrevelius – and Hals were members of the local chamber of rhetoric, De Wijngaertrancken (Vine Tendrils). Hals similarly knew Jacob’s son, Adriaen, whom he painted at far left in a civic guard portrait around 1627. Adriaen, who made three prints after Hals’s portraits in the mid1630s, also witnessed the baptism of Hals’s daughter, Susanna, in 1634. Jan van de Velde II, who produced a further six prints after Hals’s portraits, similarly served as a witness to the baptisms of Hals’s niece, Hester, in 1624 and his son, Reynier, in 1627. But it was Jonas Suyderhoef, a precociously talented Haarlem engraver nearly thirty years his junior, who enjoyed the strongest binding ties with the elder artist and, perhaps unsurprisingly, produced the largest number of reproductive prints after his portraits. Archival records reveal that Jonas’s brother, Adriaen, appeared in 1641 as a witness in a court case alongside Hals’s second wife. A decade later the engraver would become a member of Hals’s extended family through Adriaen’s marriage to the painter’s niece, Maria.

Suyderhoef produced thirteen prints after portraits by Hals between about 1638, when he engraved Hals’s extraordinary portrait of Jean de la Chambre, and at least 1651, the year in which he engraved both the present portrait (fig. 1) and Hals’s lost depiction of Willem van der Cramer (collaboration between the two artists may have continued several years thereafter with the portrait of Theodor Wickenburg, which was probably painted in the first half of the 1650s). The close working relationship between these two artists can be inferred not only through the sheer number of collaborations but their consistent approach to working together. Of the nine instances in which Hals’s painting survives, smallscale portraits to aid the engraver are known for all but one – the Conradus Viëtor of 1644 (New York, The Leiden Collection). This stands in stark contrast to Hals’s collaborations with the other eight printmakers, where in nearly twothirds of cases where Hals’s portrait survives, small-scale portraits are unknown. This striking dichotomy between Hals’s collaboration with Suyderhoef on the one hand and that of other printmakers on the other apparently bespeaks a particular preference on Suyderhoef’s behalf to work directly from a modello at scale rather than be compelled to personally reduce a large-scale portrait.

The present example is exceptional within the Hals/Suyderhoef collaboration in that it is the only instance in which both a life-size portrait (fig. 2) and small-scale modello by Hals have survived. However, evidence exists for several further instances in which Hals painted both life-size and small modello portraits that functioned as an aid to the printmaker. Archival documents, for example, suggest that the surviving small-scale portrait of the Haarlem minister Hendrick Swalmius was probably once accompanied by a life-size example. The 1662 estate inventory compiled following the death of his wife, Yda Willems, mentions two portraits of the sitter: ‘A portrait of Henricus Swalmius’ (‘Een conterfeytsel van Henricus Swalmius’) and ‘Another small portrait of Henricus Swalmius’ (‘Noch een cleijn conterfeytsel van Henricus Swalmius’) (Haarlem, NHA, acc. no. 1617, ONA, inv. no. 388, notary Jacob van de Camer, fols. 76-80, 12 September 1662). While Frans Grijzenhout, who has recently studied Hals’s portraits of Protestant ministers, interpreted this as ‘the painted version,

probably in a somewhat bigger frame, and the print, either in smaller frame or unframed’ (‘The Religion(s) of Frans Hals', Frans Hals: Iconography – Technique – Reputation, N.E. Middelkoop and R.E.O. Ekkart, eds., Amsterdam, 2024, p. 25), this likely more straightforwardly references two paintings, one small and one large.

Similarly, Hals’s portrait of René Descartes, the artist’s most famous sitter, is known today through a small, compromised modello (Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptothek) and no fewer than eight copies (the best of which is in the Louvre Museum in Paris). Five of these paintings measure ± 76 x 65 cm., a format Hals frequently employed in the mid-1640s, including for his life-size portrait of Hoornbeeck in Brussels. There is a strong likelihood, therefore, that each of these copies is modelled after a now-lost life-size portrait by Hals. As Slive himself has previously concluded, ‘the possibility that an original life-size painting based on the Copenhagen sketch [of Descartes] may turn up one day cannot be excluded’ (op. cit., p. 90).

Nor was Hals opposed to making autograph replicas of his portraits. In the mid1630s, he executed the first of two informal portraits of Willem van Heythuysen (fig. 3). Following the sitter’s death in 1650, the artist painted a replica for the regents' room of the Van Heythuysen hofje in Haarlem, which is now thought to be the version in Brussels (fig. 4; P. Biesboer, ‘Willem van Heythuysen en zijn twee portretten’, Hart voor Haarlem: Liber amicorum voor Jaap Temminck, H. Brokken et al., eds., Haarlem, 1996, pp. 113-126).

Johannes Hoornbeeck was precisely the type of man who would have valued having his visage painted by Hals and engraved by Suyderhoef. He belonged to a group of at least fifteen clergymen to have been painted by Haarlem’s leading portraitist. Most, including Hoornbeeck, who was born in Haarlem in 1617, had connections to the city in which Hals lived and worked. However, unlike many of the other prelates who sat for Haarlem’s greatest portraitist, Hoornbeeck was less orthodox in his Calvinist sensibilities, preferring moderation and unity over dogma and conflict.

Hoornbeeck, whose eponymous grandfather had immigrated from Flanders to Haarlem in 1548, left Haarlem to begin his university studies in Leiden in 1633. Two years later, an outbreak of the plague in the city compelled him to transfer to Utrecht. He would stay there until September 1636, by which point the plague subsided and he returned to Leiden. The death of his father, the merchant Tobias Hoornbeeck, in April 1637 necessitated a return to his hometown, where he would remain until early 1639. On 1 March of that year, he became a minister at Mülheim near Cologne and remained there through late 1642, when he again returned to Haarlem. On 2 December 1643, he was promoted to Doctor of Theology in the Utrecht academy. Several months later, he was named minister in Maastricht on 19 February 1644 and on 3 March he accepted the same position in Graft in Noord-Holland. In May of 1644, he took up the position of professor of theology at Utrecht University, giving his inaugural lecture in July, as well as the Illustre School in Harderwijk. It was these appointments

that may well have induced him to commission the life-size portrait from Hals in Brussels. On 20 April 1650, he married Anna Bernard of Amsterdam, whose grandfather was the famous geographer Jodocus Hondius. After nearly a decade at Utrecht University, Hoornbeeck – who spoke thirteen languages – left for Leiden University, where he gave his inaugural address on 9 June 1654. He remained in the position until he passed away, aged 48, on 1 September 1666.

Described as ‘a scholar of no ordinary stamp’ (‘een geleerde van niet alledaagschen stempel’; J.P. de Bie and J. Loosjes, Biographisch Woordenboek van Protestantsche Godgeleerden in Nederland, IV, The Hague, 1931, p. 278), Hoornbeeck was a notably prolific writer. Between 1644 and 1674, more than forty treatises were published (and at least four texts appeared posthumously) dealing with topics as diverse as euthanasia (1651; 2nd ed. 1660) and the origins of Arminianism (1662), many going through multiple editions.

Hals presents his sitter in a manner befitting his role as both a preacher and academic. As Grijzenhout has pointed out (op. cit., pp. 21-2), all but two of Hals’s portraits of Protestant ministers depict their sitter wearing a skullcap. Moreover, these religious men frequently hold a book, a finger placed between the pages. It is as if their reading has been momentarily interrupted, either by the painter or viewer.

Since it first came to light nearly 200 years ago, this small portrait has generally, if not universally, been given to Hals. Hals’s production of small-scale portraits on panel reached their apogee between about 1645 and 1660, with around fifteen surviving examples dating to this decade-and-a-half period. As Dr. Norbert E. Middelkoop has recently pointed out following first-hand inspection of the present picture (private communication, 9 May 2025), this portrait of

Hoornbeeck anticipates a number of similar works painted in the second half of the 1650s or shortly thereafter. These include the Portrait of a preacher of circa 1657-60 (fig. 5); the Portrait of a man of circa 1660 (The Hague, Mauritshuis) and the Portrait of a preacher of circa 1660 (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts).

In the course of the twentieth century, all major scholars of Hals and his work attributed the painting to Hals without reservation, the only exception being Seymour Slive (op. cit., 1974; 1989). These include Ernst Wilhelm Moes (op. cit., 1909), Cornelis Hofstede de Groot (op. cit., 1910), Wilhelm von Bode (op. cit., 1914) and Wilhelm Valentiner (op. cit., 1923; 1936). In a letter dated 7 September 1911 that was transcribed in full and included in the catalogue of the 1915 exhibition at the Detroit Museum of Art (now Detroit Institute of Arts), von Bode not only praised the painting’s quality but was the first to point out the relationship between it and the print:

‘the free, spiritful and broad way in which it is handled, proves absolutely that it is an original direct from nature…Taking Snyderhoef’s [sic] engraving into consideration, one can positively conclude that this engraving was copied from that little portrait of Franz Hals, as it is exactly of the same size’ (op. cit.).

The attributional history of this painting is, therefore, comparable to the aforementioned portrait of Heythuysen, now regarded as Hals’s prime. Slive only appears to have had the opportunity to study the small portrait of Hoornbeeck on one occasion, at the Detroit Institute of Arts on 26 January 1974, just as the third volume of his catalogue raisonné was about to go to press (private communication between Frederick J. Cummings and the painting’s then-owner). In published opinions, Slive would come to regard the painting as ‘a reduced copy by another hand after the Brussels painting’ (op. cit.,1974) and a ‘copy after Hals’ (op. cit., 1989), much as he had with the portrait of Heythuysen. The unpublished letter from Cummings, then the director of the Detroit

museum, relayed Slive’s further belief that this and other known copies of Hoornbeeck ‘were probably produced for members of the sitter’s family or for his friends’. At no point does Slive appear to have recognised the function of this small portrait of Hoornbeeck as the modello for Suyderhoef’s print.

Recent dendrochronological examination of the present panel undertaken by Ian Tyers demonstrates that the portrait was all but assuredly produced in advance of Suyderhoef’s print (report dated April 2025, available upon request). The latest heartwood ring present in the board dates from 1633 and no sapwood was present, suggesting the panel dates from after circa 1639 if one is to allow for a minimum number of sapwood rings. To this can be added the fact that the painting and print overlay with almost no discrepancies, save a millimetre or two in the fingers.

Middelkoop has also presciently noted that certain details, including the unusually long baby finger in the painting in Brussels, have been corrected in the modello, a detail Suyderhoef adopted in his print. He further noted that the sitter’s face in the present painting is slightly thinner than that of his visage in the picture in Brussels. Unlike so many of us, Hoornbeeck appears to have lost a bit of weight in the years that had elapsed since the Brussels portrait. Middelkoop noted a similar phenomenon in the two versions of Heythuysen, whose appearance is that of a man more advanced in age in the portrait in Brussels when compared with the one that appeared on the market in 2008.

With the purpose of this small painting firmly established, its authorship should be on equally firm ground. It is instructive that the attribution of none of the other seven known modellos for prints by Suyderhoef has been credibly questioned. Only Claus Grimm has regarded the majority of these works – with the notable exception of the portrait of Jean de la Chambre in London – as workshop productions, often, as in the case of the

extraordinarily penetrating portrait of Samuel Ampzing on copper in The Leiden Collection, as the product of a workshop assistant ‘working from a no longer extant model by Hals’ (Frans Hals and His Workshop: RKD Studies, online, under 1.15, 'A presumably more expensive commission'). Among the other modello portraits that Grimm consigns to a studio hand are the portraits of Petrus Scriverius (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art), Swalmius (fig. 6) and Theodorus Schrevelius (Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum; for further information on the relationship between modello and print, see M. Bijl, ‘The Portrait of Theodorus Schevelius', The Learned Eye: Regarding Art, Theory, and the Artist’s Reputation: Essays for Ernst van de Wetering, M. van den Doel et al., eds., Amsterdam, 2005, pp. 47-55). The notion that, in each instance, Hals’s prototype has been lost while a workshop variant survives strains credulity.

Martin Bijl (private communication, 8 May 2025) and the late Pieter Biesboer (private communication, 14 May 2025), both on the basis of photographs, have proposed that the present painting is a joint venture between Frans Hals and his son, Frans II. Few, if any, pictures have generally been given to Frans II with certitude, making this suggestion difficult to prove. In light of the close collaboration between Hals and Suyderhoef, the lack of evidence for two distinct hands, the painting's small scale and, not least, its evident quality, the notion that Hals might have uniquely entrusted the production of a modello for one of Holland’s leading academics and theologians in part to his son is not a wholly satisfactory one. If nothing else, Bijl and Biesboer raise interesting questions about the degree to which others would come to participate in Hals’s portrait production in the final two decades of his career.

The attribution has been endorsed by Dr. Norbert E. Middelkoop and others upon first-hand inspection of the portrait. We are further grateful to Dr. Middelkoop for his insightful thoughts on this entry and to Martin Bijl and Pieter Biesboer for their comments on the basis of photographs.

The Birdtrap signed 'P·BREVGHEL·' (lower right)

oil on panel

15º x 22¿ in. (38.6 x 56.2 cm.)

£1,000,000-1,500,000

US$1,400,000-2,000,000

€1,200,000-1,800,000

PROVENANCE:

François-Michel Ghesquière, seigneur de Stradin (1717-1792), and by descent. with Galerie Finck, Brussels, 1970.

Anonymous sale; Ader Tajan, Paris, 18 December 1991, lot 37, as 'Attribué à Pieter Brueghel II'. with Galerie de Jonckheere, Paris, from whom acquired by the present owner in October 1997.

LITERATURE:

K. Ertz, Pieter Brueghel der Jüngere (1564-1637/38): Die Gemälde mit kritischem Oeuvrekatalog, II, Lingen, 1998/2000, pp. 580-1 and 619, no. E715, fig. 484.

This Birdtrap is a finely preserved example of what is arguably the Brueghel dynasty’s most iconic invention and one of the most enduringly popular compositions of the Netherlandish landscape tradition. Although no fewer than 127 versions have survived from the family’s studio and followers, only 45 are now believed to be autograph works by Pieter Brueghel the Younger himself, with the remainder being largely workshop copies of varying degrees of quality (K. Ertz, op. cit., pp. 605-30, nos. E682 to A805a).

The original prototype for the composition appears to be the panel, signed and dated 1565, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, now in the Musées Royaux des Beaux Arts in Brussels. This work has been almost universally accepted as the prime, though authors like Gustav Glück have doubted its attribution, with another version dated 1564, formerly in the A. Hassid collection in London, complicating the debate. Whatever the prototype, the composition derives ultimately from Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s celebrated masterpiece The Hunters in the Snow of 1565 (fig. 1; Vienna, Kunsthistoriches Museum) in which the basic formal components were established in subtly modulated tones of white, blue, brown and black. As was the case for many of his compositions and designs, Brueghel the Younger adapted and reused various themes and subjects that had originated in his father’s workshop. In the case of The Birdtrap, it is perhaps his work, and that of his studio, that truly established the composition as one of perennial popularity from the seventeenth century onwards.

The Birdtrap is one of the earliest and certainly most significant winter landscapes of the Netherlandish tradition. In contrast to The Hunters in the Snow where the figures trudge through a stark, still countryside, the present work shows villagers enjoying the pleasures of winter in a more convivial atmosphere, offering a vivid evocation of the various diversions of wintertime. In the middle ground, blanketed by snow, a group of villagers are shown skating, curling and playing games of hockey and skittles on a frozen river. The cold winter air, conveyed with remarkable observation through the artist’s muted palette, is carefully interrupted by the lively red clothes of figures peppered across the ice.

Yet beneath the seemingly anecdotal, light-hearted subject lies a moral commentary on the precariousness of life: as the birds crowd around the eponymous trap at the right of the composition, they mirror the skaters on the frozen river, both unaware of the danger each poses. Elsewhere, villagers rush onto the ice without apparent consideration of its fragility, reminding the viewer of the dangers lurking beneath the innocent pleasures of the Flemish winter countryside. The ephemeral nature of life was a message commonly associated with ice and winter in the early modern Netherlands, with a print of Skating before the Saint George’s Gate, Antwerp by Hieronymous Cock, after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, underlying the poignant theme in its inscription: ‘Oh learn from this scene how we pass through the world, Slithering as we go, one foolish, the other wise, on this impermanence, far brittler than ice’ (N.M. Ortsein, Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Drawings and Prints, exhibition catalogue, New York, 2001, p. 176).

Cloud Study, possibly over Harnham Ridge oil on paper, laid down on panel 4Ω x 9º in. (11.3 x 23.5 cm.)

£150,000-250,000

US$210,000-340,000

€180,000-300,000

PROVENANCE:

(Possibly) by descent from the artist to his daughter, Isabel Constable (1823-1888); her sale (†), Christie's, London, 17 June 1892, lot 140, 'Constable's Palette, together with several oil sketches by him', where acquired for 4 gns. by the following, with Thomas McLean, London (his post-1866 label on the reverse). Private collection, France; Deauville Enchères, Deauville, 7 June 2024, lot 51, as 'Workshop of Constable', where acquired by the present owner.

It is testament to John Constable’s genius that he was able to capture on a slender sheet of paper the immensity of the heavens. In swift, sure strokes he captures dark rain clouds massing on the horizon, airy cirrus clouds scudding high across still blue skies, and heavy cumulous clouds resting on the far ridge. In all paintings, the sky, omnipresent and ever-changing, was for Constable ‘the “key note” – the “standard of scale” – and the chief “Organ of Sentiment”’ (J. Constable, letter dated 23 October 1821), but it is in studies such as the present work that this idea is distilled down to its purest form.

It is likely that this sketch depicts Harnham Ridge. Situated to the west of Salisbury, it was an area that Constable explored with his great friend Archdeacon John Fisher (himself a keen amateur artist), producing numerous paintings of the gentle landscape. John’s uncle, Bishop Fisher, had first invited Constable to stay in Salisbury in 1811. The artist returned for extended periods on a number of occasions over the following decades, with his final two visits being in 1829 after the death of his wife, Maria, when he turned to his friend for support. Harnham was then for the artist a place of both artistic possibility and personal importance. The elevated viewpoint of the present composition implies that it may have been executed looking out from an upper window of Fisher’s house, rather than from a vantage point in the garden, as is the case in works such as Harnham Ridge from Leadenhall Gardens (Private collection, UK), in which he is clearly looking up at - rather than down on - the scene.

Constable’s interest in the changing appearance of the sky dates to his very first forays into artistic creation. At twenty-two, newly enrolled as a student at the Royal Academy, he described the London sky as being how ‘a pearl must look through a burnt glass’ (quoted by J.E. Thornes, ‘Constable’s Meteorological Understanding and his Painting of Skies’, Constable's Clouds, exhibition catalogue, Edinburgh, 2000, p. 155). It is not, however, until 1805 that we find his first dated weather notes on the back of a sketch, when he wrote ‘Nov. 4 1805 – Noon very fine day on the Stour’. As he developed as an artist, the notes on his sketches became more and more detailed. Perhaps the most famous group of pure cloud studies dates from the period 1821-22, when Constable was living in Hampstead. On these he made comments such as ‘Septr. 13th – One o’clock. Slight wind at North West, which became tempestuous in the afternoon, with rain all the night following’ (Study of Altocumulus Clouds, Yale Centre For British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, PA-F01129-0065).

While it might be tempting to see Constable’s plein air oil sketches, so different from the pencil and chalk studies of his contemporaries, as a form of nascent Impressionism, this type of very careful note marks a clear difference in both their aim and their conception. Whilst Monet’s Impression, Sunrise spoke of the search for spontaneous expression and presented a (debatably utopian) notion of the present, Constable’s commentary shows that he was trying to capture a sense of time and place that was much more closely linked to a lived experience that by necessity incorporated the passage of time. His altocumulus clouds were intended to tell the viewer not only of the prevailing weather, but also of previous and future weather, the night of rain that was to come. Similarly, in the present study, the gold highlights in the grass speak of hot summer sun, that in the preceding weeks has bleached the dark green grass, and the grey clouds to the left tell of rain to come. With great agility, Constable thus situates his viewer at a point that stretches both forwards and backwards in time.

We are grateful to Anne Lyles for endorsing the attribution after first-hand inspection.

Venice, the Return of the Bucintoro on Ascension Day oil on canvas

33√ x 54¡ in. (86 x 138.1 cm.)

Estimate on Request

PROVENANCE:

Sir Robert Walpole (1676–1745), created 1st Earl of Orford in 1742, 10 Downing Street, London, by 1736 and until his resignation as Prime Minister in 1742, when removed to another of his London residences, and by descent to his son, Robert Walpole, 2nd Earl of Orford (1701–1751), and by descent to his son, George Walpole, 3rd Earl of Orford (1730–1791); his sale, Langford’s, London, 13 June 1751 (=1st day), lot 65 as ‘Ditto [Cannaletti]. The Marriage of the Sea by the Doge, it’s Companion’, where acquired for £34-13 by ‘Raymond’ for the following, Samson Gideon (1699–1762), Belvedere, near Erith, Kent, and by descent to his son, Sir Sampson Gideon, 1st Bt. (1745–1824), created Baron Eardley in 1789, Belvedere, near Erith, Kent, and by descent to his daughter, Maria Marow Gideon (1767–1834), wife of Gregory William Twistleton (from 1825 Eardley-Twistleton-Fiennes), 14th Baron Saye and Sele (1769–1844), Belvedere, near Erith, Kent, and by descent to their son, William Thomas Eardley-Twistleton-Fiennes, 15th Baron Saye and Sele (1798–1847), Belvedere, near Erith, Kent, Sir Culling Smith, 2nd Bt. (1768–1829), widower of Lord Eardley’s second daughter Charlotte Elizabeth (d. 1826), Belvedere, near Erith, Kent, and by descent to their son, Sir Culling (Eardley-) Smith, 3rd Bt. (1805–1863), who assumed the name of Eardley, Belvedere, near Erith, Kent, from which removed in 1860 to Bedwell Park, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, and by descent to his eldest daughter, Frances Selena, who married in 1865 Robert Hanbury M.P., who added the name of Culling to his surname, Bedwell Park, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, and by inheritance to her sister, Isabella (d. 1901), wife of the Very Rev. the Hon. William Henry Fremantle, M.D., Dean of Ripon (1831–1916), Bedwell Park, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, and by descent to their son, Lt.-Col. Sir Francis Edward Fremantle, O.B.E. (1872–1943), Bedwell Park, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, from whom acquired on 3 July 1930 (with its pendant Venice: The Grand Canal looking North-East from Palazzo Balbi to the Rialto Bridge) by the following, with Thos. Agnew & Sons Ltd., London, where acquired on 4 April 1940 (with its pendant) for £4,400 by, with Giuseppe Bellesi (1873-1955), Florence and London. Senator Mario Crespi (1879-1962), Milan, by 1954 (with its pendant; according to Moschini, under Literature).

Presumably acquired with its pendant in Paris in the 1960s, and by descent until sold at the following, Anonymous sale, Ader Tajan, Paris, 15 December 1993, lot 13, where acquired.

EXHIBITED:

London, British Institution, 1844, no. 89, as ‘Marriage of the Doge of Venice’ (lent by Lord Saye and Sele).

London, British Institution, 1861, no. 68, as ‘Doge marrying the Adriatic’ (lent by Sir Culling Eardley).

Lausanne, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Les Trésors de l’Art Vénitien, 1 April - 31 July 1947, no. 125 D (ex-catalogue).

LITERATURE:

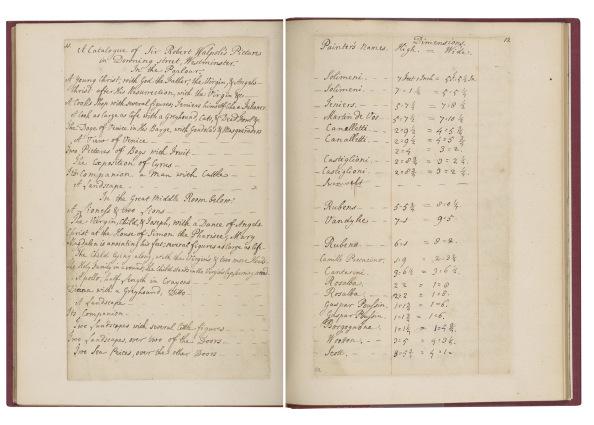

Anon. [Horace Walpole?], A Catalogue of Sir Robert Walpole’s Pictures in Downing Street, Westminster, Ms. 1736 (part of a complete catalogue of Sir Robert Walpole’s collection of pictures bound into Horace Walpole’s personal copy of the Aedes Walpolianae.., 2nd ed. of 1752, Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, PML 7586), no. 125, as ‘The Doge of Venice in His Barge, with Gondola’s & Masqueraders. Canaletti. 2-9½ 4-5¾’ and as hanging in the Parlour (with its pendant).

R. and J. Dodsley, London and its Environs described, containing An Account of whatever is most remarkable for Grandeur, Elegance, Curiosity or use, In the City and in the Country Twenty Miles round it, London, 1761, I, p. 272, as ‘Ditto, with the Doge marrying the sea. Its companion’ Height 2 feet 9 inc. Breadth 4 Feet 6 inc. [Painted by] Canaletti’.

T. Martyn, The English Connoisseur: containing an Account of Whatever is Curious in Painting, Sculpture, & c. In the Palaces and Seats of the Nobility and Principal Gentry of England, both in Town and Country, London, 1766, I, p. 12 (repeating Dodsley).

E.W. Brayley, The Beauties of England and Wales…, VII, London, 1808, p. 546, as ‘the collection of pictures evince a very judicious choice: among them is a view of Venice, and its companion, with the ceremony of the Doge marrying the Sea, by Canaletti’. Exhibition review in The Atlas, 947, XIX, 6 July 1844, p. 456, as ‘one of the unrivalled artist’s masterpieces’.

Pictures at Belvedere, 1856, p. 3, as hanging in the Dining Room with its pendant, this one to the right of the chimneypiece [This document is known from a typescript in the library of the National Gallery, London, entitled Pictures at Belvedere 1856. Copy of a Manuscript Catalogue. The paintings by Canaletto are recorded on p. 2 of the typescript.]

G.F. Waagen, Galleries an Cabinets of Art in Great Britain, London, 1857, p. 282, as hanging in the Dining Room and described (with its pendant) as ‘Good specimens of the master’.

E.J. Climenson, Passages from the Diaries of Mrs Philip Lybbe Powys of Hardwick House, Oxon. A.D. 1756 to 1808, London, 1899, p. 150, noting that she recorded in her diary in 1771 having seen ‘two views of Venice by Canaletti’ shortly before the remodelling of Belvedere.

A. Graves, A Century of Loan Exhibitions 1813-1912, London, 1913, I, pp. 143 and 144. V. Moschini, Canaletto, London and Milan, 1954, p. 22-26, illus. fig. 114 and pl. 16 (colour detail), as datable to circa 1730 and in the collection of Mario Crespi, Milan. W.G. Constable, Canaletto: Giovanni Antonio Canal 1697-1768, Oxford, 1962, I, illus. pl. 64; II, p. 336, no. 340.

L. Puppi, L’opera completa del Canaletto, Milan, 1968, p. 100, no. 109 A, as datable to 1731-32.

L. Puppi, Tout l’oeuvre peint de Canaletto, Paris 1975, p. 100, no. 109 A, as datable to 1731-32 and location unknown.

W.G. Constable, ed. J.G. Links, Canaletto: Giovanni Antonio Canal 1697-1768, Oxford, 1976, I, illus. pl. 64; II, p. 361, no. 340, as location unknown and without its earliest provenance (the painting’s connections with Sir Robert Walpole being then unknown).

J.G. Links, The Complete Paintings, St Albans, 1981, pp. 36, 44, no. 115, illus. p. 40.

A. Corboz, Canaletto, una Venezia immaginaria, Milan, 1985, p. 627, no. P205, illus. J.G. Links, A Supplement to W.G. Constable’s Canaletto, Giovanni Antonio Canal 16971768, London, 1998, pp. 22-23, under no. 216(a), and p. 34, no. 340, illus. pl. 271, fig. 340. L. Dukelskaya and A. Moore, A Capital Collection. Houghton Hall and The Hermitage, New Haven and London, 2002, pp. 23, 24, 35, 52, note 133, and Appendix VII, p. 458. A. Bradley, in C. Beddington, Venice. Canaletto and His Rivals, exhibition catalogue, London, 2010, pp. 169-170, illus. on p. 169, fig. 72, as datable to c. 1731-32; C. Beddington, in Canaletto: Painting Venice. The Woburn Series, exhibition catalogue, London, 2021, pp. 90-91, note 10, and pp. 181, 183, note 12.

This breathtaking view of the Feast of Ascension Day has been largely inaccessible to scholars, having appeared at auction only twice in its 300-year history, in 1751 and 1993. It is in a remarkable state of preservation – the surface of the painting is beautifully textured and the impasto on many of the figures intact – and this is in large part due to its relatively few passages in ownership. The painting is first recorded at 10 Downing Street, in the collection of Britain’s first Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole (1676–1745). This distinguished early eighteenth-century provenance has only recently come to light and was not known at the time of the painting’s sale in 1993. Canaletto painted the view at the beginning of the 1730s, a highpoint in the artist’s career and a time during which his views were in great demand, particularly among British collectors. Exceedingly ambitious in both scale and conception, this is Canaletto’s earliest known representation of the Bucintoro returning to the Molo on Ascension Day; a subject to which he would return repeatedly throughout the ensuing two decades.

Falling on the fortieth day after Easter Sunday, the Feast of the Ascension of Christ was the most spectacular of all Venetian festivals and was frequently commented upon by visitors and travellers who witnessed it. It was on this day exclusively that the Bucintoro, the official galley of the Doge of Venice and a symbol of the Serenissima, was used. The model depicted here, the last to be made at the Arsenale, was designed by Stefano Conti and decorated by the sculptor Antonio Corradini, identifiable by the lion – symbol of the city of Venice – on the prow and the figure of Justice. Accompanied by the city’s officials, the doge would sail out to the Lido on the Bucintoro and cast a ring into the water, a symbolic act representing the marriage of Venice to the sea. It was a ceremony that brought the entire city together and remained a key date in the Venetian calendar until the fall of the Republic in 1797. Given the popularity of Ascension Day among tourists in Venice, views of the occasion by Canaletto were in particular demand and several different treatments of the celebrations by the artist are known, though these vary in viewpoint, scale and staffage.

The Bacino di San Marco, where the scene is set, was the usual – and certainly the most thrilling – point of arrival for visitors coming to Venice by sea. This oblique panoramic view looks west towards the entrance to the Grand Canal and the composition is framed by the Punta della Dogana at left and the Molo, in sharply angled perspective, at right. In the centre is the Bucintoro, decorated in red and gold, moored between gondolas and other boats alongside the Piazzetta. The impressive buildings lining the waterfront provide the perfect backdrop to the pomp and spectacle of Ascension Day, with the principal landmarks forming a theatrical backdrop to the lively boats and staffage. Particularly prominent are the Palazzo Ducale, with its unique Gothic forms and distinctive pink Verona marble patterned façade, and the towering Campanile behind. The picture is imbued with the warm tonality of an early summer’s day. The lagoon is populated with elegantly-dressed figures reclining in gondolas, the moored Bucintoro stands majestically beyond, and a crowd of onlookers gathers on the Molo in the distance.

Canaletto’s technique is supremely confident: controlled flicks of the brush evoke feathered parasols and trailing ribbons. Vivid accents of colour guide the viewer’s eye around the composition, with touches of vibrant red punctuating the entire composition. As noted by Viola Pemberton-Pigott, ‘despite the impression of colour and brightness in so many of Canaletto’s paintings, his range of pigments is remarkably limited’ (V. Pemberton-Pigott, ‘The Development of Canaletto’s Painting Technique’, in K. Baetjer and J. G. Links eds., Canaletto, exhibition catalogue, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1989, p. 58). Canaletto seems to have already mastered the formula for creating the effect of rippled water, as pale arcs skip across the surface of the lagoon. He demonstrates an assured touch in describing figures in movement, even those in different planes. The elegant protagonists in the gondolas are painted as individual characters whilst the throng gathered on the Molo pulsates with life despite being painted in abbreviated form as ‘calligraphic squiggles’ (Pemberton-Pigott, op. cit., p. 57). The foreground figures are given an almost three-dimensional structure through the application and manipulation of the paint itself, with Canaletto’s vivid use of impasto – so characteristic of his paintings in the 1730s – beautifully preserved. The artist demonstrates complete mastery of his medium and technique: as Pemberton-Pigott observes, Canaletto ‘has learned to control the viscosity of the binding medium so that the paint retains its shape and assumes the form it represents’, such as the folds and creases of voluminous skirts and shawls or the gilded ornamentation of the Bucintoro, which stands out in relief (op. cit., p. 54). The scene as a whole has an airy, spontaneous quality and yet Canaletto’s technique is very precise. His architecture is meticulously constructed, with every building outlined and detailed with rigorous precision. Canaletto used a ruler and incising instrument ‘sometimes for laying in his design into the ground layers and sometimes for outlining or incising architectural details into the upper paint layers’ (ibid., p. 54): this is clearly evident on the ground-floor arcade of the Palazzo Ducale and Palazzo delle Prigioni at far right.

Canaletto planned his painted compositions carefully and this is confirmed by the existence of the Cagnola Sketchbook, a book of 138 pages of architectural drawings, now in the Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice. In that sketchbook there are drawings for the whole panoramic view of the Bacino di San Marco –spanning from the church of San Giorgio Maggiore at left to the Palazzo delle Prigioni at right (fig. 1). Although dating from the 1730s, and thus placed in relation to the series of paintings for the Duke of Bedford at Woburn Abbey,

we can safely assume that Canaletto would have made similar use of drawings when composing the present view slightly earlier in the decade. The drawings that survive vary in finish from rapidly sketched building outlines drawn by eye or from memory, called ‘scaraboti’ (‘scribbles’) by Canaletto, to more careful drawings of buildings in red or black pencil, worked over in black or brown ink. The latter are frequently annotated with the names of shops and colours, while building materials and numbers of windows, arches or columns are also noted. Canaletto also made use of a camera obscura (pinhole camera) in the elaborate process of planning his compositions. With it, he was able to sketch out individual buildings or record partial detailed views, assembling them later into a visually more coherent whole. Canaletto was singled out by the eighteenth-century art historian Antonio Maria Zanetti the Younger (1706–1778) for his ability in ‘correcting’ the distortions of the projected image to ensure that his compositions aligned more closely with what the eye perceived. Though Canaletto ‘frequently shows a disregard for topographical precision’, he went to ‘considerable lengths to disguise his use of [the camera obscura], notably by giving the impression that viewpoints had been used which were, in fact, unattainable’ (Beddington, op. cit, 2021, p. 28).

Canaletto demonstrates a great sensitivity to changing weather conditions, intersecting a fluffy white cloud at centre with a bold horizontal brushstroke, painted wet-in-wet, and applying a streaky haze on the horizon. A gentle breeze can be felt through the water ripples in the Bacino and the movement of the gondoliers’ feathered caps.

This view dates from about 1732, with the 1730s being considered ‘the great decade of Canaletto’s production of Venetian views’ (Beddington, op. cit., 2010, p. 24). It was during these years that he received some of his most distinguished commissions from British patrons, notably the series of views for the Duke of Bedford, still at Woburn Abbey. In the 1720s Canaletto had rapidly cornered the market in painting Venetian views and the merchant and banker, Joseph Smith (c.1674-1770), British Consul in Venice from 1744 to 1760, took the painter under his wing. Acting as his principal agent and dealer, Smith did a great deal to promote the artist among the British clientele in addition to commissioning works from Canaletto himself. This particular view would prove to be extremely popular and Canaletto would adopt a similar viewpoint for notable paintings of the same subject later in the 1730s; a large canvas commissioned by the Duke of Bedford and still at Woburn Abbey (1732-36; fig. 2); another painted for the

Duke of Leeds, today in the National Gallery, London (c. 1738); and a third on loan from the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona (c. 1739). The view under examination here is the earliest and marks the starting point for Canaletto painting festivals; a genre which, by the fifth decade of the eighteenth century, the painter and his studio had turned into a specialty.

The Return of the Bucintoro on Ascension Day was formerly accompanied by a pendant showing The Grand Canal, looking North-East from Palazzo Balbi to the Rialto Bridge (private collection; fig. 3). The two paintings share a remarkable early history, having been owned by Britain’s first Prime Minister, the great patron and collector Sir Robert Walpole. Their presence in Walpole’s collection was first noticed by Sir Oliver Millar, who found them referenced in the 1736 manuscript catalogue of paintings at 10 Downing Street and in the 1751 sale (see Links, op. cit., 1998). The Return of the Bucintoro on Ascension Day is to be identified with the first of the ‘Canalletti’ hanging ‘In the Parlour’, described as no. 125, ‘The Doge of Venice in His Barge, with Gondola’s & Masqueraders’ (fig. 4). This reference is particularly significant for it is the earliest record of a Canaletto painting hanging in a house in England, predating George III’s purchase of Consul Joseph Smith’s Canalettos by a quarter of a century.

The Downing Street residence was offered to Sir Robert Walpole by King George II in 1732. The British architect William Kent gutted the interiors of two adjacent properties and united them to create a new complex of sixty rooms. Sir Robert and his wife took up residence in 1735, remaining there until Walpole left office in 1742, whereupon he took his collection of pictures to Houghton Hall in Norfolk. Sir Robert had begun collecting in the 1720s and his 1736 inventory lists 154 paintings at 10 Downing Street, 120 at Houghton, 78 at Orford House in the grounds of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, and 66 in his five-bay terrace house at 16 Grosvenor Street, Mayfair, with its first-floor Great Room where pictures were displayed. It is not known how or when Sir Robert acquired this magnificent view and its pendant. It may have been through his son Edward, who was dispatched to Venice charged with acquiring works of art between January 1730 and March 1731, though both views are datable on stylistic grounds to circa 1731-32 and, as such, slightly postdate Edward’s Venetian sojourn. Whilst no doubt facilitated by Edward’s connections in Venice, the purchase of the pictures must have been instigated by the refurbishment of the Downing Street residence in 1732-35.

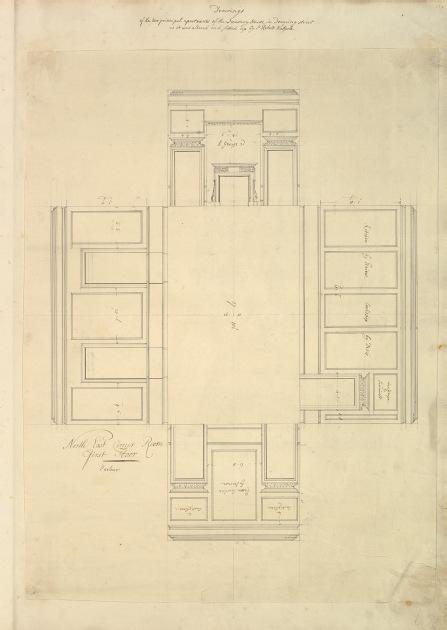

Fig. 4 ‘A

The original picture-hanging plans for ‘Treasury House’, 10 Downing Street, by Isaac Ware survive in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Taken together with the 1736 inventory, they allow for an accurate reconstruction of the arrangement of pictures. The Return of the Bucintoro on Ascension Day and its pendant hung on either side of the fireplace in the first-floor Parlour, also known as the ‘North East Corner Room’ (figs. 5 and 6). A number of old masters were on display in this room, including a pair of pictures by Francesco Solimena, two described as by Castiglione (now attributed to Antonio Maria Vassallo), and a painting by David Teniers the Younger which was paired with a kitchen scene by Paul de Vos. As noted by Andrew Moore, ‘the effect of these paintings in the rooms at Downing Street was quite stunning and it was here that the collection acquired its early reputation’ (L. Dukelskaya and A. Moore, op. cit., 2002, p. 24).

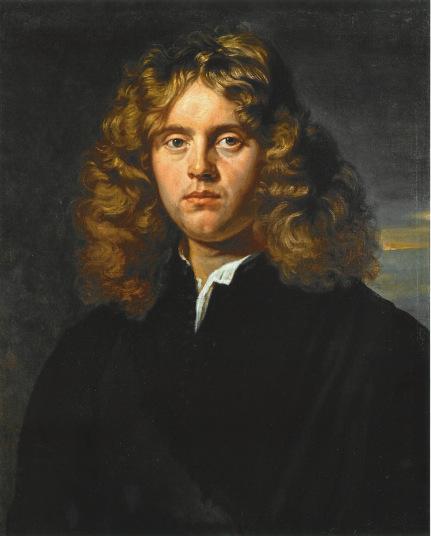

Sir Robert Walpole (fig. 7) was a collector and patron of the highest order, making full use of the financial opportunities of his long period in power as First Lord of the Treasury and Prime Minister for his own sake and that of members of his family. He formed a collection of old master pictures which outshone even that of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough and stimulated three architects in succession to create at Houghton what was effectively his own masterpiece and remains one of the great achievements of European architecture. Of pictures he was a connoisseur rather than a patron, and this majestic view and its former pendant were unquestionably the greatest works by a contemporary painter that he acquired.