Tour; Church

P.A.; Mixing The Lumineers Live;

Sound at Montreux

*

FOLLOW US twitter.com/Mix_Magazine facebook/MixMagazine instagram/mixonlineig

CONTENT

Content Directors Tom Kenny, thomas.kenny@futurenet.com

Clive Young, clive.young@futurenet.com

Senior Content Producer Steve Harvey, sharvey.prosound@gmail.com

Technology Editor, Studio Mike Levine, techeditormike@gmail.com

Technology Editor, Live Steve La Cerra, stevelacerra@verizon.net

Contributors: Craig Anderton, Barbara Schultz, Barry Rudolph, Robyn Flans, Rob Tavaglione, Jennifer Walden, Tamara Starr

Production Manager Nicole Schilling

Design Directors Will Shum and Lisa McIntosh

ADVERTISING SALES

Managing Vice President of Sales, B2B Tech

Adam Goldstein, adam.goldstein@futurenet.com, 212-378-0465

Janis Crowley, janis.crowley@futurenet.com

Debbie Rosenthal, debbie.rosenthal@futurenet.com

Zahra Majma, zahra.majma@futurenet.com

SUBSCRIBER CUSTOMER SERVICE

To subscribe, change your address, or check on your current account status, go to mixonline.com and click on About Us, email futureplc@computerfulfillment.com, call 888-266-5828, or write P.O. Box 8518, Lowell, MA 01853.

LICENSING/REPRINTS/PERMISSIONS

Mix is available for licensing.

Contact the Licensing team to discuss partnership opportunities. Head of Print Licensing: Rachel Shaw, licensing@futurenet.com

MANAGEMENT

SVP, MD, B2B Amanda Darman-Allen VP, Global Head of Content, B2B Carmel King MD, Content, AV Anthony Savona

Global Head of Sales, Future B2B Tom Sikes

Managing VP of Sales, B2B Tech Adam Goldstein VP, Global Head of Strategy & Ops, B2B Allison Markert VP, Product & Marketing, B2B Andrew Buchholz

Head of Production US & UK Mark Constance

Head of Design, B2B Nicole Cobban FUTURE US, INC.

I’m sure that more than a few readers will skip right past this month’s feature story on the making of Woody At Home—Volumes 1 & 2, asking themselves why in the world, with all the new music coming out today, Mix would take the time and space to talk about a man who died nearly 60 years ago. Well… I could go on for hours if we were sitting in a pub, believe me, all while putting aside the fact that one day history will judge him to be one of the most important figures in 20th century America. And not just for his music.

As for why we asked senior writer Steve Harvey to dig into the story behind the making of a two-volume set of previously unreleased recordings, from a simple one-mic-and-a-recorder setup at his New Jersey home in 1951 and 1952, there are a few compelling reasons. The first, and most important, is that he wrote thousands and thousands of great songs—many of them still being covered and recorded in 2025. And now, thanks to technology and a bit of passion, as Steve tells us in his excellent feature article, we get a chance to go back to the raw originals and hear them in an entirely new light.

“It all starts with the song.” In my 35-plus years at Mix, I can’t tell you how many times a producer or engineer has prefaced their answer to a question by saying that no matter what they might do—EQ moves, adding effects, employing every mix trick or technique they might dream up— none of it matters if there isn’t a great song to start with. Strip everything else away, and it’s pretty simple: A great artist with a great band and a great song make for a great record.

Woody Guthrie wrote more than 3,000 songs in his lifetime, many of them for publishers, many for album recordings, many just lyrics on paper that are still being discovered. My own children grew up to Woody’s 20 Grow Big Songs; he wrote hundreds of songs for kids. He wrote Dust Bowl Ballads based on his own experience. He wrote “This Land Is Your Land,” for goodness sakes. In an alternate universe, it could be our National Anthem. And yet, he never considered his masterwork finished—as he says on the disc in “Howie, I’d Like to Talk to Yuh”:

“I have never yet put a song on tape or a record, or wrote it down or printed it down or typed it up, or anything else that I really thought was a through and a finished and a done song, and it couldn’t be improved on, couldn’t be changed around, couldn’t be made better.”

That made me think of all the mix engineers I’ve interviewed over the years who say some kind of variation on the same theme: “A mix is never really finished; at some point, it’s just abandoned.”

Which brings me to the second reason there’s a story about Woody in this month’s issue: technology. These recordings were made on a consumer

tape deck in 1951 and 1952, his first time recording to tape. TRO Music set him up with a mic and a Revere T-100 Crescent recorder, and now, 73 years later, as Grammy-winning Woody At Home producer Steve Rosenthal says in the story, “One of my favorite things is that Woody’s going to get All Music and Discogs credits as a recording engineer. Isn’t that amazing?”

From that point on, there’s a great story of meticulous tape transfers by Sean McClowry at The Attic Studio in New Jersey, then the use of demixing and source separation software by mix/mastering engineer Jessica Thompson, in order to separate the guitar and vocal from the mono recording, then remix them so that it would sound like Woody “was sitting right next to you on the couch.” Audio technology in 2025 is an amazing thing, and it can bring us treasures like they were meant to be heard. Woody was a pioneer. No question.

And the final reason that we are writing about Woody: his humanity.

There’s a long history of musicians coming together to unite the world, or regions of the world, in times of crisis. Live Aid, Farm Aid, We Are the World, Playing for Change. Music unites people, and Woody knew of its power. Woody was the original. He represented the downtrodden and the forgotten, the hobos and the poor, the refugees and the laborers. It’s no coincidence that the first single from the project, released by his family on July 14, his birthday, was his only known recording of one of his greatest works, “Deportee.”

I’ve read about Woody since I first discovered Bob Dylan long ago, and in doing some background research this month, I came across the following Woody quote on Wikipedia, from a December 1944 radio show. It’s as good a summary of a good man as you’ll find, and it’s in his own words:

“I hate a song that makes you think that you are not any good. I hate a song that makes you think that you are just born to lose. Bound to lose. No good to nobody. No good for nothing. Because you are too old or too young or too fat or too slim, too ugly or too this or too that. Songs that run you down or poke fun at you on account of your bad luck or hard traveling. I am out to fight those songs to my very last breath of air and my last drop of blood. I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world and that if it’s hit you pretty hard and knocked you for a dozen loops, no matter what color, what size you are, how you are built, I am out to sing the songs that make you take pride in yourself and in your work.”

Tom Kenny, Co-Editor

By Clive Young

When Fritz Sennheiser founded his eponymous company in 1945, the first product out the door was a voltmeter, but a year later, the German manufacturer produced a broadcast microphone—its first step toward becoming one of the best-known proaudio brands in the world. Eighty years later, that journey continues and third-generation co-CEOs Andreas and Daniel Sennheiser see a bright future ahead for the industry mainstay.

These days, Sennheiser is involved in many spaces—pro-audio, content creation, immersive sound and even in-car audio—but the CEOs say the company’s approach to every market has always been to focus on customer needs.

Andreas notes, “We have two or three examples which really transformed the industry. One was in 1957, bringing out the first wireless microphone— that was the first of its kind and allowed everybody on stage or in front of a TV camera to roam freely without a cord attached, unleashing the creative potential of whoever was on stage there. The second example is a shotgun microphone in the 1970s—close-miking was no longer needed, so the whole film world could record scenes from a distance and get close-up audio…. [Now,] with Spectera, it was it was time to think differently.”

Spectera, introduced last year, is Sennheiser’s bidirectional wideband solution for wireless products like mics and IEMs, based around the WMAS (Wireless Multichannel Audio Systems) protocol. Approved by the FCC in early 2024, WMAS is a more spectrally efficient process than previous RF methods but was only given the green light after years of campaigning by major players in the audio industry—which means Sennheiser began Spectera development long before 2024.

Characterizing it as “a bet,” Daniel notes Spectera was under development for more than a decade: “In

Co-CEOs since 2013, Daniel (standing) and Andreas Sennheiser are the third generation of their family to lead the pro-audio industry cornerstone.

parallel, you create the regulatory environment for it to be legal. We believe that WMAS is a better solution, and the authorities understood that this is a very efficient system. It uses more or less half the spectrum that a system would use in a traditional way, and it’s actually a transceiver, so it goes both ways. It’s the start of an ecosystem. Sennheiser has been pushing the limits of what’s physically possible since 1945, and we continue to do so.”

While Sennheiser has grown over the years, it has also acquired brands such as Neumann and Merging Technologies, and invested in startups like SoundBase, but the strategy isn’t based on financial results. “We have a very clear principle that we don’t acquire for growth, but we acquire for better solutions for the customer,” says Andreas. “Our

focus is limited to where it makes an addition to what our customers want to do and not necessarily whether it gives us more revenue or not.”

Customers have an ever-broadening range of things they want to do, however, and the rise of the content creator in recent times has blurred the lines between entry-level and professional audio gear. Sennheiser has leapt into that creator space with offerings like its Profile Wireless microphones. Daniel notes, “For the ambitious content creator…we believe that we can make a difference [not only with products] like with Profile Wireless, but also with professional headphones like the HD 25, which is still the DJ headphone of choice after 37 years. That’s not a consumer product…I think that is really a

production tool that people understand the value [of]. We have a very clear understanding of what that customer wants from us—tools and almost an instrument rather than a consumer product.”

Nonetheless, having products for everyone from amateurs to pros creates familiarity, as the company is well aware. “We see the customer journey through different stages of professionalism very often,” says Andreas. “[Our products are] on stage when somebody starts with an €89 wired microphone, then upgrades to a wireless, gets into Evolution Wireless and eventually tours with Spectera and Clair Global around the world.”

Sennheiser’s R&D efforts can be found far beyond studios and stages, however. Results of its spatial audio research can be heard in homes—Netflix’s spatial audio feature is powered by Sennheiser Ambeo 2-Channel Spatial Audio technology—and vehicles, as Sennheiser in-car systems can be found in certain premium car models.

That spatial audio research has been going on for upwards of 40 years now. “We did try out some things like our surround listening device called the Surrounder,” says Andreas. Released in 1999, the device provided 4.1 sound via five speakers in a giant, neck-worn Styrofoam travel pillow. “That was kind of an innovation, but not a commercial success; let’s leave it there,” he says with a wry smile. If the product was questionable, the spatial audio technology behind it was solid and paved the way for the company’s Ambeo VR 3D microphone and its adoption among software developers for Meta’s Quest VR platform. “Suddenly we saw where our research [could find] a home,” he continues. “It was immediately adopted by the Facebook Developer Conference as ‘This is the new standard.’”

Ambeo’s inroads didn’t end there; Netflix was initially reluctant to adopt the technology, but tested it anyway, discovering that attachment rates—the number of viewers who stick with a show—were higher on programs imbued with Ambeo algorithms. “There was real user proof that it did do something to Netflix consumers, hence they pivoted toward it and it’s been used in a lot of productions ever since,” says Andreas.

Eighty years into its existence, Sennheiser continues to develop microphones, headphones meeting and conference systems, in-car audio, Ambeo and more, and the company’s leaders

remain as ambitious as ever about the future.

Asked how they make being co-CEOs—and siblings—work, Andreas quips, “Boxing gloves every morning,” before Daniel adds, “We are very different—we have different backgrounds, different knowledge, different views on the world. At the same time, we have the same value system and a lot of respect for each other for

the work that the other can do. It’s actually a great privilege to look at every problem from two sides and be able to discuss it…. We believe that connecting all the dots from two different sides creates what the brand ultimately stands for—reliability, a really sustainable edge on innovation and of course, the remarkable audio experience that Sennheiser stands for.” ■

By Robyn Flans

The song “Creep” may never have been recorded if Sean Slade and Paul Kolderie hadn’t overheard Radiohead messing around with it one day after they had been hired to produce and engineer two other songs for the band. While on the phone with both of them, they detailed the fortuitous evolution.

The two songs they were assigned—“Inside of My Head” and “Million Dollar Question”— were not the band’s best material, says Kolderie (“no offense to Radiohead”), though both were eventually released in Japan and later came out in the Pablo Honey box set. Thankfully, the producer/engineer duo knew how to work with

the other challenge ahead: how to work with an inexperienced group of musicians.

Slade and Kolderie had met at Yale, played in bands together and opened a grungy studio in the Boston area where they produced and engineered plenty of bands that had never recorded before. They estimate having spent an accumulated 50,000 hours in their little studio as a team, defining and developing their working dynamic as having no real delineated roles. They seem to have the philosophy that two smart heads are better than one, and they are quite simply equal partners who perform all functions together.

The fact that they had previously worked on projects with American bands like the Pixies and Dinosaur Jr., who were very well received in England, fit management’s bill for Slade and Kolderie to produce this new band Radiohead, as they had hopes of bringing them to the American music marketplace. The band was also keen on the producers’ resumes.

Slade says they did the best they could with the original two songs, but one day before going into the studio, while still at a rehearsal space Slade describes as an old shed in an apple orchard in

Oxford, the band started playing “this other song.”

“We looked at each other, and as they finished the song, Thom mumbled something about ‘That’s our Scott Walker song,’ but we thought he said, ‘That’s a Scott Walker song.’” Kolderie recalls. “You know, Scott Walker has a lot of obscure songs, so Paul turned to me when we left the rehearsal and said, ‘Too bad the best song is a cover.’”

About a week later, while they were having an off day in the studio, Kolderie thought he’d try to get them in a better mood by suggesting they “play that Scott Walker song.” They pushed Record and off they went.

“They only played it once, and that was it,” Kolderie says of the basic track, cut on Chipping Norton’s Trident TSM console. “That was the magic thing that happened. They just played it, and they were so happy to be playing something else that they wanted to play, that it just came out. That song just wanted to be born, and it just blasted itself out of the ether. That was ‘Creep,’ one take.”

“The reason we didn’t do a second take was twofold—we knew we had captured lightning in a bottle,” Slade adds. “It was a magic moment and everybody knew it—the band knew it, we knew it—but the other reason was that we were getting paid by the song. I realized instantly that if we added the third song, the A&R guy would assume that we were just doing it to make more money. Which is exactly what he thought.”

Kolderie finishes the story, explaining that after working on the song for a short while after lunch, at the end of the day, he called Keith Wozencroft, the A&R person at the time. “I said, ‘We’re working on these songs, but we have another song that I think you should hear.’ And he was like, ‘Hmm, well, hmm, I don’t know.’ He thought that was maybe a little bit of a squeeze play we were putting on him, you know. He said, ‘I’ll drive out to Oxford from London after work.’

“So he got there around 7 and we played it for him, and then he said to play it again, and we played it again,” he continues. “It was still in a rough form. It wasn’t really finished, but you could tell what was going on. And he said, famously, ‘Well, you can finish it, but it’s not a hit; it’s not a single.’ And I said, ‘Respectfully, I think it is a single, and I think we should finish it.’ And he said, “All right, go ahead.’”

In the studio with Thom Yorke (vocals, guitar, piano, keyboards); brothers Jonny Greenwood (guitar, keyboards, other instruments) and Colin Greenwood (bass); Ed O’Brien (guitar, backing vocals); and Philip Selaway (drums, percussion),

the goal was to make the band comfortable, as if they were in a rehearsal room—no click and “have them play live.” Even with three guitars, they could record live because, as Slade explains: “They had already clearly delineated what each person did.”

“A lot of bands would have the three guys playing the same thing,” Kolderie asserts. “That’s not good, but they were smart. They understood that each guy needed to have a part and that each part should work together. We didn’t have to figure that stuff out with them too much. Everybody seemed to know what his part was going to be.”

“Ed would play rhythm guitar and create more textures and parts that added to the overall arrangements.” Slade adds. “Thom would play very traditional rhythm section guitar, which was very tight with the bass and drums, and Jonny was just the wild card—the X factor who created wild bursts of sound and great solos and quirky parts on top of that.”

They spent a week at Chipping Norton, a residential rehearsal/studio facility in Chipping Norton, England, on the original two-song “audition,” and when they were officially hired for the project, they booked the studio for a month where they recorded and mixed “Creep” entirely, as well as pieces of other songs on Pablo Honey. They later decamped to Courtyard Studios for a change of pace to work on some of the other tracks.

There were really only three overdubs on “Creep”—Yorke’s vocals with a Telefunken U47, a piano part played by Jonny Greenwood, and an additional track of the big guitar noise that prefaces the lead guitar parts going into the choruses, which Kolderie describes as an electric guitar through a pedal through an amp.

The band had already worked out a version of that big sound when they had played it down originally, but Slade and Kolderie wanted it on its own track in case they needed to make it louder in the mix later on, so they re-recorded it with a Fet 47 in the drum room.

“The drum room was very live, so we put the amp in there,” Kolderie explains. “I remember thinking, ‘I’d better get the first take because it’s going to be the best one,’ and sure enough, he killed the first one, and the second one took us about 20 tries.”

Slade points out other interesting sonic properties about the drum room: “It was made with actual rocks dug up out of the ground around Chipping Norton, so the fact that all the rocks were different acted like some weird diffusion. The room was very reflective in a unique way. One thing I had never seen before and have never seen since was there were two Sennheiser 441 mics embedded in the ceiling, which are dynamic mics—completely against the Hollywood paradigm where you have to use condenser mics to get the cymbals. I thought, ‘They must know something.’ And it sounded great; that became part of the drum sound on ‘Creep,’ too.”

Kolderie recalls a happy accident in the mix on “Creep.” “To keep the noise down, we were starting with most of the faders down and as we got about two minutes into it, I looked at my fingers and said, ‘Damn, I forgot to put the piano in,’” he says. “I didn’t stop the mix because we had finished the bridge and we were heading into the chorus at the end that is not loud, and I said, ‘Let’s put it in here,’ so right on the 1, I put the piano in just for that part, which made it kind of a coda. It was a brilliant move, but it was a mistake.” ■

New all-digital chain features an Avid S6 console, iPhone/iPad comms and BSS BLU control.

By Tom Kenny

Back in 2014, with the installation of a then-new Dolby Atmos/Auro-3D/ DTS:X monitoring and control system in the William Holden Theater, Sony Pictures Studios quietly launched a long-term plan to update and modernize the technology backbone of its world-class, multi-theater, multi-studio, multi-stage post-production facilities.

The Cary Grant, Kim Novak, Burt Lancaster, Anthony Quinn and Holden (again) theaters were all upgraded to immersive playback. Sound design suites were created, IMAX capability was added, TV mix stages were updated to Atmos, and now, the final step: Converting the three ADR (Automatic Dialog Replacement) stages, the last of the analog holdouts, to an all-digital audio chain, starting with the storied ADR 3.

“Typically, ADR stages don’t change over as often,” says Lane Burch, executive director of engineering postsound services. “It’s all about vocal recording, and there’s a comfort level with the systems that are in place. ADR 3 still looked something like a Colorado recording studio from the 1970s, right down to the wood paneling and Yamaha console, but it was very popular and was booked all the time. Then, last year, the mixer who had worked in the room for a long time retired, so we took the opportunity to go in and do a complete overhaul.”

The renovation started with a complete gutting of the two rooms down to the studs, which enabled for a slight expansion and reconfiguration. All the copper wiring and old cabling (“tons of it,” Burch says) was removed, a window was covered up, and new walls, insulation and acoustic treatments were put in place. Then the new gear arrived.

“Terry Bradshaw, one of our engineers, had put together a proof-of-concept plan for converting the ADR stages to digital,” Burch

explains. “We brought in a small 24-fader Avid S6 with MTRX II I/O, Pro Tools HDX, a Tascam DA6400 recorder and BSS BLU for routing and switching. There’s a completely modern cue system, Klang headphone amps, Shure wireless, iPhone and iPad comms, new system for streamers, new camera system...it was a total refresh.”

The new ADR 3, which opened in March and is now the home of ADR mixer Marilyn Morris, can comfortably host small ensembles of six to ten for group sessions and has already proven a favorite among voice actors. It is located adjacent to the world-famous Barbra Streisand Scoring Stage on the Sony Pictures Studios lot, and a handful of those actors might recall that, prior to its conversion to ADR in 1989, it was once a room that handled a very different type of recording.

The spacious ADR 3 live room, which has been expanded both physically and technically, can host up to 10 performers comfortably and features an updated, unobtrusive video recording and playback system,

is now ADR 3, where he ran Sheffield Labs with a four-lathe, direct-to-disc setup. That window which was covered up, but not replaced, during the recent renovation? It provides a direct view of the Streisand Stage, where Sax would watch the orchestra perform as he cut direct-to-vinyl.

In the late 1970s, Doug Sax, one of the alltime great mastering engineers, occupied what

Sax, who also owned and operated The Mastering Lab in Los Angeles, later moving it to Ojai, Calif., passed away in 2015. ■

Music takes centerstage at the 12th annual Mix Presents Sound for Film & Television event this year as award-winning film, television and videogame composer Harry Gregson-Williams and A-list engineer/producer/mixer Alan Meyerson will sit down to talk about the creative Renaissance underway across film and television music in a special Keynote Conversation.

The eye-opening discussion will open the event, to be held Saturday, September 27, at the world-renowned sound editing and re-recording facilities of Host Partner Sony Pictures Studios, Culver City, Calif.

“We’re in the middle of a creative explosion right now in film and TV music, a generational change,” says Tom Kenny, co-editor of Mix. “Harry Gregson-Williams perfectly represents that change. He’s so versatile, he writes for film, TV and videogames. Meanwhile, Alan is a true pioneer— one of the top scoring mixers in the world, yes, but he also played a huge

part in creating the sound of the modern film soundtrack.”

British composer, conductor, orchestrator and music producer Harry Gregson-Williams is one of the world’s top composers, with credits as wide-ranging as Shrek, Spy Game, The Equalizer, The Martian, Chicken Run, Gladiator II and dozens of others, as well as the Metal Gear videogame franchise and, along with his brother and fellow composer, Rupert, every season of the hit HBO series The Gilded Age Engineer, producer and mixer Alan Meyerson began his score recording and mixing career in the mid-1990s as one of the early members of Hans Zimmer’s legendary Remote Control Productions. He has since built a lengthy list of credits as either score mixer, score recordist or both, including Speed, The Thin Red Line, Black Hawk Down, Pirates of the Caribbean, Dunkirk, Dune: Part Two, Bob Marley: One Love, and Gladiator II. He has collaborated with Gregson-Williams on the majority of the composer’s work over the years. ■

By Clive Young

Nearly 50 years into his career, country legend Vince Gill is as busy as ever, recording, touring, producing and even playing places like Sphere as a member of the Eagles. Then there’s also his considerable live schedule, which includes jaunts like his recent 30-plus date tour that ranged all over the U.S., closing out in August with a five-night residency at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. They weren’t quick, phone-it-in shows either—a Vince Gill concert runs over three hours, peppered with arch storytelling, familiar favorite songs and impressive musical repartee between the star and his nine-member band.

Onstage, Gill is backed by a trusted team of Nashville session aces cultivated over time, like guitarists Tom Bukovac and Jedd Hughes, but the audio pros that bring those musicians to the crowd have also been part of his camp for years—like monitor engineer Matt Rausch, who has worked with him since 2008. “This is my only live gig,” said Rausch. “I kind of got thrown into it from being a studio engineer at Vince’s home studio—and he’s stretching the words ‘home studio’ because it started in 2008 as, ‘We’re gonna put it in to do guitars and vocals,’ and it turned into, ‘Oh, we could do whole records here.’ We’ve done the last three

or four records at his house—full tracking, Nashville-style. One day, he goes, ‘Hey, would you come on the road?’ This is probably 2015, 2016, and I said, ‘I’ve never done that.’ He goes, ‘Aw, you’ll be fine’—and that’s how I ended up on the bus.”

FOH engineer/production manager Josh Isenberg has been on that bus for years, too, having first come aboard as a 19-year-old production assistant back in 2011, fresh out of SAE Nashville. “They knew I was coming in to learn and that audio was what I planned on doing, so I was like a pseudo audio guy,” he recalled. “I’d get all my production stuff done

early, then head to the stage to help patch; that folded me into doing a monitor tech job and then eventually monitor engineering. I basically did two years at each job and worked my way up to production managing and front of house. This is where I’ve always wanted to be from the beginning—before I was doing anything else, I enjoyed mixing out front.”

These days, that mixing is done on a Yamaha Rivage PM5 console, part of a control package provided by Clair Global. Isenberg knew his way around Yamaha desks—he uses a CL5 to mix the veteran western swing band The Time Jumpers at Nashville’s 3rd and Lindsley every Monday night—but he hadn’t tried a Rivage until Gill’s 2025 tour.

“The idea was to find a console on a digital platform that felt analog,” he said. “I’m a younger cat that got raised in a house full of seasoned cats, so I was raised with an analog mentality in a digital world. Having that and then switching to this console really made sense. When I say ‘analog mentality,’ for instance, I use everything on the channel. I don’t have anything external, anything crazy, any weird routing; I want it as analog as it can possibly be without being analog, just to keep everything as simple as we can get it. I did that to prove to myself that I don’t have to have four plug-ins stacked onto a channel strip to make it work, a $10,000 server with external plug-ins, and everything else. You don’t need all that stuff to provide the sonic quality of a guy who has 22 Grammys.”

Isenberg applied the desk’s onboard Rupert Neve Designs Portico 5045 to the main and

backing vocals, while its Bricasti Design reverb was put to use elsewhere: “I’ve got one reverb—a Bricasti with a live hall preset—that’s doubled, and I stack it on the snare, and I have it on the vocals; the only difference in them is a little bit of time changes of decay. On other consoles over the years, I never got the reverb to sound the way I wanted; it always had a little bit of artifact or artificialness. I had to trim the top end and the bottom end, and try to form the tone with EQ and post effects. With this, I didn’t have to do anything besides send the vocal to the ’verb and return it back on a channel; I found the preset I wanted, and we were off to the races.”

That house mix was heard over a variety of P.A. systems as Gill and Company played through rigs from L-Acoustics, JBL Professional and, for the first time, the Holoplot system installed inside New York City’s Beacon Theatre. “A lot of this tour has been d&b audiotechnik,” said Isenberg. “Some of the best shows I’ve had have been on their J rigs.”

Beneath those P.A. hangs, the musicians heard themselves through a phalanx of Cohesion CM14 stage monitors, with Gill and monitor engineer Rausch listening through stereo pairs. “This gig is about 90% wedges,” said monitor tech Anderson Hall. “The only guys using in-ears are the guitar techs off-stage. There’s also not a single guitar wireless transmitter. Normally, I have to coordinate upwards of 100 frequencies a day, but on this gig, I calculate three, and realistically, I’ll only use one of them.”

Key to a Vince Gill show is a vocal mic

that can handle energetic singing and quiet storytelling with equal aplomb. “Vince is a dynamic performer, and when we’re talking about vocals and his wedge, it’s got to be bright and loud and clear with as much potential gain as possible,” said Rausch. “These days, we’re on the sE V7.”

Much like Isenberg, Rausch mixed on a Rivage PM5, using onboard effects and features. “I run consoles pretty simple, and if they pass signal, I’m usually happy,” he laughed. The band’s mixes were fairly typical, though Gill’s went easy on the guitar: “I don’t feed him any of his amps. He’s got plenty right behind him—big old things—and then maybe a smattering of acoustic. He loves Seymour Duncan D-Tar pickups; they are really good on acoustic for DI stuff.”

The tour’s focus on simplicity and an analog mentality dovetailed well with the straightforward way that all involved approached their jobs. “I’m very thankful to work with people like Matt and Anderson who care deeply about doing the best work they can,” said Isenberg. “Matt and I have been working side-by-side for several years now, and the trust I have in his ear and ability over in monitorworld gives me confidence to do my job out front every night; I really mean that.

“This tour has been cultivated over the years, and when I can be a part of that, lending a hand and helping make it as good as it can be, then I show Vince respect by continuing to do the best I can, and he shows me respect by continuing to call me—and I like to keep it that way.” ■

New York, N.Y.—American singer-songwriter Teddy Swims has been touring the world this year, bringing his mix of country, pop and R&B around the globe, and along for the ride is FOH engineer Drew Thornton, bringing his experience mixing the alt pop of Billie Eilish to the effort. “My history is mixing pop elements, attuned to mixing like a record, whereas Teddy’s tour is a nice hybrid,” explains Thornton. “This is a unique camp where they use a lot of my board feeds for Teddy’s social media. I’ll add a little bit of ambience and then sidechain it to timecode, so it dips it when the song’s happening. I’m basically building a broadcast mix.”

Thornton is riding the faders on an Allen & Heath dLive S5000: “I love how much I can get out of this desk,” he continues. “I don’t like going out of the console for anything that’s very show pertinent, such as effects or input processing.” Adjacent to it are a pair of Waves Extreme SoundGrid Servers. “There’s a lot of options with Waves, such as the SuperRack LiveBox VST3 plug-ins, but I also do enjoy the redundancy and the safety of it.”

Bringing the house mix to the masses is a sizable d&b audiotechnik KSL rig, chosen by Thornton: “To me, there’s so many things happening in this show—a lot of people on stage needing attention—and I want everyone to sound big across the whole room.”

Main hangs are a mixture of KSL8s and KSL12s and KSL side hangs. A decision to fly SL-Subs came as audience demand grew in the U.K., and the

audio team then opened the rig to 270-degrees, adding a rear hang of d&b V Series. Ground subs are more SL-Subs & Y10Ps for front fills.

In monitor world and by special request after the tour visited Australia, monitor tech Lara Smith was drafted in from the JPJ Audio offices in Sydney to support Swims’ monitor engineer, Justin Walker. Smith sets up the stage and has been using the brand-new Shure Axient Digital PSM IEM system, powered by WMAS.

“We were one of the first tours in the world to take out the new system and it’s been fantastic,” she says. “They sound amazing; they’re incredible to work with, visually everything is at your fingertips, and we’ve been able to solve any wireless monitoring issues quickly and easily.” ■

Corpus Christi, Texas—Church Unlimited’s Corpus Christi worship facility works hard to bring its message to parishioners, but in recent years, that effort was hindered by a 20-year-old P.A. that was ready for its last rites. In need of a system that would meet the facility’s changing needs and expectations, the church brought in Georgia-based integrator Messenger AVL, which specializes in worship spaces.

“Church Unlimited wanted to create a feeling of width and immersion,” says Parker Gann, senior systems engineer at Messenger AVL. They were working with a fixed budget and specific sonic goals—chief among them, a desire to get even coverage throughout the room while ideally using a short, visually unobtrusive array. The match for all those parameters, Gann found, was to recommend an Eastern Acoustic Works ADAPTive sound system.

Messenger AVL designed a left-center-right configuration centered around four Anna loudspeakers as mains, four Anya loudspeakers providing out fill and two AC6 column loudspeakers adding additional horizontal coverage. Bolstering that on the low end, the system included a dozen SBX218 subwoofers—six flown and six on the ground—to meet the church pastor’s request for musical, full-range bass throughout the room.

Once the hangs were in place, Messenger AVL used EAW’s ADAPTive technology to fine-tune the coverage throughout the room, focusing on providing intelligibility and balance. The result was a low-profile,

unobtrusive system that covered the congregation.

“I was floored at what the AC6s can do and the amount of space they can cover,” says Gann. “The system has so much headroom and power while barely touching the boxes. It’s incredible how the P.A. just disappears above the trim height of the production lighting; the church loves the clean aesthetic.” ■

New York, N.Y.—The Lumineers are on the road, hitting ballparks, arenas and amphitheaters across the U.S. with the group’s tried-and-true brand of folk music. At front of house is the band’s longtime FOH engineer, Josh Osmond, overseeing an Avid Venue S6L-32D console that uses modern-day technology to recreate the group’s old-school folk sound. “On the surface, they’re a folk-rock band,” he says, “but the reality is far more intricate.”

Osmond’s prep for the tour began early, as he stayed in touch with the group’s studio team during the recording of Automatic, allowing him to determine early on how its sounds could be recreated on stage in order to align the technical setup with the emotional tone of the record.

With that in mind, Osmond turned to his S6L. With more than 165 inputs routed through two Stage 64s and one Stage 32 on stage, plus another Stage 32 and Local 16 for outboard effects at front of house, the scale of the show demanded an upgrade to Avid’s new Venue | E6LX-256 Engine. Now he has detailed user layouts and more than 100 control events to automate everything from input changes to mic swaps. The system includes custom fader banks per song and instant access to essential layers.

Given the desk’s Pro Tools integration, Osmond typically records each show, capturing up to 216 channels over a Cat cable using AVB-HD. His

mix includes ambient mics, utility routing and a suite of analog outboard processors, but he notably doesn’t use a single plug-in on input channels: “All my inputs are using built-in compression, gates, or Heat. Any plug-ins I use are either for effects or on group buses—and even then, they’re there mainly in case of analog outboard gear failure.”

While The Lumineers are in many ways a folk band, the band’s shows have all the necessities of a big rock concert—stage thrusts, multiple vocal mic positions, rolling drum kits and more. In any show, there’s up to 20 vocal mics and various instruments being moved or swapped throughout the set, keeping Osmond on his toes throughout. “They trust me pretty heavily to put together a mix that’s going to be the best sound we can put forth,” he says. “My relationship with them ends up being sort of like a producer role in the live setting,” he adds, noting that it’s all in service of one goal: “It’s a group effort…and they just want to put the best product out to the audience.” ■

Montreux, Switzerland—A lot can happen to a festival in six decades; just ask the organizers of the Montreux Jazz Festival, which celebrated its 59th edition in July. The famed fest has long presented far more than just jazz, as this year’s lineup proved, offering Latin music, R&B, pop, rock, EDM and hip hop just for starters. While every edition features a mix of icons and fresh faces, however, some things stay the same, such as the organization’s longstanding partnership with Meyer Sound

This year, that meant Meyer provided more than 400 loudspeakers used across 15 stages, ensuring that the 250,000 music fans who attended the festival over the course of two weeks heard every note from acts like Samara Joy, Max Richter, Raye, Benson Boone, Shaboozey and Brandi Carlile.

All audio, lighting and video equipment was supplied once again by Swiss rental company and integrator Skynight, with audio systems designed by Meyer Sound’s application architect José Gaudin.

At the festival’s Lake Stage—its last year before a planned move back

to the Auditorium Stravinski in 2026—Meyer Sound deployed a system powered entirely by Class D amplification. Panther large-format linear line array loudspeakers anchored the system, supported by Leopard, Lina and Ultra-X40 loudspeakers and 2100-LFC low frequency control elements.

“People love it; the detail is so crazy, you can hear things you’ve never heard on another system,” says Martin Reich, the festival’s sound coordinator and Lake Stage engineer. “The system is so well-behaved and precise, we can keep the energy focused on the audience without shaking the neighbors’ windows—even with a five-story apartment building right beside us. The festival sits in the middle of town, so control is critical.”

Beyond the Lake Stage, Meyer Sound systems enabled immersive and experimental performances across Montreux. At Ipanema—the festival’s premier DJ venue—two Ultra-X80 point source loudspeakers served as the main P.A., with support from Ultra-X40 and Ultra-X20 compact point source loudspeakers. Spacemap Go, Meyer Sound’s spatial sound design and mixing tool, allowed DJs to move sound throughout the room even when working from simple stereo sources. “At first, I didn’t expect it to work as well as it did with just a left/right signal, but it makes the room feel more alive,” says Sebastian Hefti, Ipanema’s front of house engineer. “It keeps the energy moving without distracting the artist.”

Elsewhere, the Memphis venue, centered around late-night jam sessions, used Ultra-X80 loudspeakers as the main left/right system, complemented by other Ultra family loudspeakers for immersive effects. The space’s Spacemap Go system supported both traditional mixes for visiting engineers and more spatial soundscapes, including real-time sound panning. ■

Rising producer/engineer, a self-described ‘imperfect perfectionist,’ has turned her L.A. home into a recording musician’s workshop.

By Lily Moayeri • Photos by

Suzy Shinn’s Los Angeles home studio, perched like a haunted house on a hill, inspires instant intimidation. The metal gate buzzes open after a few firm pushes; then begins the climb to the multi-storied structure. Stepping into the foyer, all intimidation falls away. This space is a music creator’s dream.

The first floor houses an elaborate control room and isolation booth, plus a second room that is a storage space for guitars and synths—but could quickly become another functioning studio. Next door is a guest room and a bathroom. Upstairs, the entire living area is an open-plan studio with a pitched roof featuring five skylights, lots of arched windows pouring in natural light, a spacious kitchen, and a couple of rooms that are living spaces for Shinn and her partner, Fidlar’s Zac Carper.

“I live where I work,” Shinn states, tucking into one of the couches with her dog, Jack. “I combined the two so that essentially the house is a recording studio, and music encompasses our lives.”

This setup is what Shinn has been working toward for most of her life. A native of Wichita, Kansas, she began writing songs as a child, attended Berklee College of Music for a couple of years, and interned in a Los Angeles studio while working as a server at a strip club. She connected with Crush Music, one of the studio’s clients, who snatched her up and put her with producer Jake Sinclair (Panic! at the Disco, Weezer). Serving, literally, as Sinclair’s right hand while he recovered from an injury, Shinn honed her studio skills, becoming a triple threat as an inventive producer, intuitive engineer and natural songwriter.

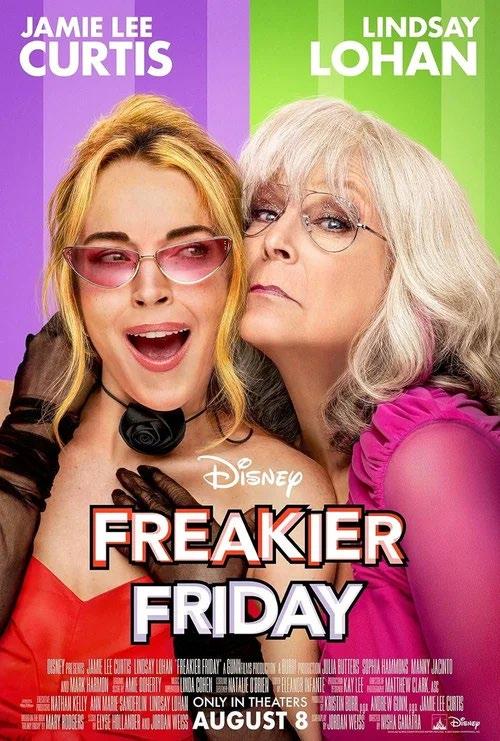

She produced Weezer’s Van Weezer, engineered Panic! at the Disco’s Pray for the Wicked and vocal produced Dua Lipa’s “Begging” and Sophie’s “Reason Why,” plus she co-wrote Bethany Cosentino’s “Natural Disaster,” to mention just a handful of credits. August saw the release of the Freakier Friday soundtrack and stripped back versions of select songs from Jack’s Mannequin’s debut album, Everything in Transit, marking its 20th anniversary, all produced by Shinn. A Modest Mouse EP is soon to be announced, and she’s working on songs with Kid Sistr, a Los Angeles-based trio at the cusp of its career, and a passion project for Shinn.

Many of these upcoming releases were worked on in Shinn’s home, where the laid-back atmosphere is welcoming and low-pressure. “I always start the session off with some conversation,” she says. “We’re in a beautiful space. I’m very good at reading the room. I try to match the level and meet people

where they are. I have a mental list of what I want to get done each day, and I aim for that.”

Organization is a cornerstone of Shinn’s workflow. For example, she has a Pro Tools template that lists every instrument in the home studio with the correct inputs. In the comments section, she has the signal chain. This assists in smooth and speedy capture of performances, from anywhere in the house, which is entirely connected by tielines to Shinn’s rig downstairs, making every room a live room or an iso booth as needed.

The iso booth downstairs holds an array of amps as well as a Wunder CM7 microphone, which sometimes functions as a guitar mic, or she’ll use a Royer R-121, Shure SM57 or Sennheiser MD 421. A couple of Apogee Symphony Mk IIs (32/32 and 16/16 combined) serve as the audio interface, and the studio is laptop-based so anyone who installs the driver can plug into the system. A Starsound Dynamix 3000 console

with Dave Gallo mods is the centerpiece with 48 inputs, all of which are used. Shinn purchased the board from Phil Feinman, one of the owners of Los Angeles’ defunct music mecca Bedrock. Upstairs is what Shinn refers to as “the drum room,” as there’s a full olive badge Ludwig kit miked up, ready to go. Shinn sees this room as Studio B, which she says is “relaxed, for when I don’t want the darker, serious vibe.”

“It’s very complicated and intricate setting this place up and getting stuff to work,” she continues. “A lot of the time, I don’t have an engineer. Everything stays up, ready to record. When inspiration hits, you don’t want to then be like, ‘Okay, well, I need an hour to set up.’”

The drum room has AKG 414s about 20 feet across and six to seven feet in the air. A Yamaha U3 piano has a pair of AKG N8s, and a Monheim microphone is a faraway stairwell overhead for any of the instruments upstairs to provide what Shinn calls “that really far weird sound.” Behringer Powerplay 16 headphone systems are everywhere upstairs and downstairs, and anyone who uses them can control their own levels, from wherever they are in the house.

“I can get all the same sounds that I could at most other studios that I would usually have rented out in L.A.,” says Shinn, who prefers creating sounds by playing or tapping on instruments, as opposed to using soft synths, although she admits she loves those, too.

“I can get really lost in soft synths,” she says. “I can spend a lot of time looking for the perfect sound instead of trying to make something that is musical....It’s interesting how quickly a song gets made and sounds full [with a band] rather than me going through samples or synth sounds. At the end of the day, music isn’t about having a piece of gear. I feel that giving people limitations, in a way, goes back to the song.”

Shinn has a knack for vocal production which became apparent early on in her career. At the home studio, she leans either on a CM7 or SM7. That goes through a TG2 or BAE, depending on how clean the vocal needs to be, then into a Purple 1176.

“There’s a bypass button on it so I can check my gain structure,” she says. “If I’m using the SM7, I’m generally using a Cloudlifter. I try not to compress too hard—three to five dB when I’m hitting.”

She has two approaches based on the song

comps later, which is dependent on the artist, the first take, how the song is broken down for recording, and if the artist knows the lyrics.

“If I’m comping as I go along, I go into freak mode,” she explains. “I hate the talkback button. A hundred percent of the time, in every session, you are not going to press the talkback button when someone’s talking; you’re going to miss it, and then you’re going, ‘Sorry, can you say that again?’ I also hate dead silence. I’m so fast because I hate the awkward silences. I have my SM7 on my desk as my talkback mic. It’s in input the entire time. I have a plug-in called Muteomatic—every time the music is playing, the mic is stopped, so as soon as the song stops, I can talk and be like, ‘That sounds sick. You want to do another?’ In that time, I’ve made a new playlist, and I’m ready to press Record.”

Once she has the take she likes, she’ll make a verbal and written note of the number, then do two more. She pulls the one she likes best to a new track labeled, for example, as verse box one, verse box two, chorus box one. Once she has the lead, she doubles that until it sounds right, then triples it until she has her rough comp. In addition, she has two or three “security takes” in case she needs to pull a word or do more tweaking. She makes cuts in the takes as markers

to help her remember which she preferred.

“I’ll usually have some kind of rough chain on it,” she says. “I’ll use iZotope RX to get all the mouth clicks out of the way. I’ll make sure the breaths sound good. Maybe it needs a little Autotune. Sometimes it needs nothing at all, like Modest Mouse, but most likely, I put it into Melodyne and I tune it by hand.

“If you think about it, only vowels are sung. Consonants shouldn’t be tuned. They should be untouched. The breath should be untouched. I cut every vowel, and I tune the vowels that need to be tuned. That’s the long process, but I’m the imperfect perfectionist. There’s still an art form there for me, and I take pride in knowing I can get a million-dollar vocal.”

Shinn’s vocal producing experience came in handy when she was tapped to produce the on-screen songs for Freakier Friday by producer Andrew Gunn, who also produced Freaky Friday (2003). The song “Take Me Away” from the 2003 film is reimagined for the new film, produced by Shinn, as are two original songs: “One Fine Day” written by Jason Evigan and Natania Lalwani, and “Baby” written by Sarah Aaron.

There are multiple versions of the latter in the

rock version and an indie/acoustic version.

“We have one version that I whipped up so fast,” says Shinn. “Nisha [Ganatra], the director, was like, ‘I want to put “Baby” in the scene where Lindsay’s surfing. Can you slow it down like this Billie Eilish song.’ It was 40 bpm slower. And I was like, ‘No, I can’t. It’s going to sound insane.’

Before the next day when she went back in to keep editing the movie, I made something where I sang it and did a very ballad-y version.

“Two weeks later, they’re doing strings for the whole score. The composer, Amie Doherty, is at the lot with a massive orchestra, and they’re putting strings on the song that I whipped up in one night. There’s an orchestra playing this piece of music I made with my voice. That was a very surreal moment.”

Modest Mouse’s Isaac Brock came to Shinn’s studio for a few days, but mostly she worked with him in Portland, Oregon. From December 2024 to April 2025, every few weeks, Shinn would travel to his Ice Cream Party Studio for a week.

Prior to working with Shinn, Brock had jammed with his band and done some writing with Jacknife Lee (U2) and Justin Raisen (Kim Gordon, Magdalena Bay), resulting in an array of material—jams, interludes, 40-second songs and six-minute songs. Shinn had to keep things moving, comping as they were doing the tracking live. She would bring the recordings back to her home studio in between Portland visits and make bounces to determine the next steps.

On “Impossible Somedays,” there is a guitar that sounds like a talkbox—a Korg Miku Stomp pedal which emulates Hatsune Miku singing. “She says different phrases based on what you play into it, like an anime pedal,” Shinn explains, “and he’s playing it in time. There’s a big latency, so it’s crazy how you have to play to get it to lock into time. That part of the song was supposed to be gone at one point, and I was like, ‘I don’t know, it’s pretty cool and weird and sad and different.’”

Shinn had worked with Andrew McMahon of Jack’s Mannequin on “New Year’s Song,” released on January 1, 2021. He came back to her with the idea of re-creating Jack’s Mannequin’s seminal Everything in Transit, for its 20th anniversary. The original was produced by Jim Wirt and McMahon. It features Tommy Lee on drums and was mixed by Chris Lord-Alge.

Shinn knew the album by heart—sometimes recalling the lyrics quicker than McMahon. The concept for the new version was to play everything on a miked instrument. If any synths were used, they had to have a speaker and be battery-powered. No DI and nothing plugged into electricity—with the exception of a Mellotron cello sound on a few of the songs. They didn’t rework every song from Everything in Transit, but in a two-week period, they did enough for a five-song EP.

“We used the piano upstairs,” Shinn says. “I got poster tack. I got blue masking tape. I got eraser heads. We had all kinds of things and treated the piano to make it sound different, including running it through guitar pedals. I had my friend Allie Stamler, who’s an amazing violinist, come in with no parts written, with me and Andrew singing what we wanted her to do. We would build a little section, then pitch the violin down an octave to make it sound like a cello. We used a Mellotron cello sound, building, doubling it, quadrupling it.

“I recorded the room for every piano part, every vocal part,” she continues. “If we didn’t record the room, then I would re-send the vocal back up through a speaker, and then re-amp the room. We had Drew Tachine come in and play drums with chopsticks on one song—literal chopsticks.”

With all the demands on her time and for her skills, Shinn still fits in projects that touch her musically and personally, like Kid Sistr, for which there is no budget, but there is endless enthusiasm, plus talent and genuine friendship. She treats it with the same level of attention as her high-profile projects.

“I don’t put anyone on a pedestal,” she says. “You’re just a human who did some cool human things that humans are capable of doing. We’re hanging. I don’t do anything special, but I don’t do anything crazy. I stand my ground, though. If you go off on me, I’m not going to go off back. But I’ll be like, ‘I think we’re good for today, but we can pick it up tomorrow.’” ■

A treasure trove of unreleased material, recorded by Woody himself, is resurrected through the use of source separation technologies and old-fashioned manual labor, syllable by syllable.

By Steve Harvey

Iconic American folk singer, songwriter and activist Woody Guthrie posthumously added a new title—recording engineer—to his long list of accomplishments in August with the release of Woody at Home—Volumes 1 & 2. The new collection features 22 unreleased recordings, 13 of them previously known only from the published lyrics, that were drawn from approximately 140 songs that Guthrie recorded at home in Brooklyn in 1951 and 1952.

In 1951, TRO Music, Guthrie’s longtime publisher, gave him a Revere T-100 Crescent tape recorder—a mono consumer machine that ran at 3-¾ inches per second to capture material that could be released as sheet music and pitched to other artists. He went on to fill 32 reels of Scotch 111, marking the first time he had ever worked with tape, having previously only recorded to wire or lacquer disc, common formats at the time. These tapes, archived by Guthrie’s publisher (now TRO Essex Music Group), are likely his final recordings, although there is a rumored studio session that may yet be unearthed.

“The point of this project is to show Woody as a working songwriter; we’re sharing his process here,” says Steve Rosenthal, a multi-Grammy Award-winner, former owner of New York’s Magic Shop recording studio, and co-producer of this latest release. Woody at Home is his sixth project with the Guthrie family. “I’ve known about these tapes for over 20 years,” he says, but it was only with the recent emergence of commercial demixing tools allowing the

separation of the guitar and vocal that their release became feasible.

The first step was to transfer the selected songs. Rosenthal worked with New Jersey-based Attic Studio owner Sean McClowry, a restoration and transfer specialist, to find the machine best suited to the character of the tapes, experimenting with combinations of decks, headstacks and electronics.

“We did a shootout with five or six different tape machines and landed on the Ampex 350,” McClowry reports. An all-tube machine, like Woody’s, the 350 is period-accurate, adds McClowry, who settled on a half-track headstack. The tapes were transferred to Pro Tools at 192 kHz using a Mytek Audio Brooklyn converter. Because of the Revere machine’s limitations, there was very little audio above 8 kHz. Also, Guthrie’s aging splices frequently separated and had to be repaired.

“We had to be delicate with these tapes,” McClowry says. “When we needed to fastforward, we would just play the tape at sevenand-a-half inches per second.”

“Woody only had the one microphone, and where he placed it would vary, so Sean would tweak the playback level song by song,” Rosenthal adds, along with an aside: “One of my favorite things is that Woody’s going to get All Music and Discogs credits as a recording engineer. Isn’t that amazing?”

The original tapes and this new release may be mono, but don’t think for a second that the mix process was easy or quick. For one thing, the balance between the guitar and vocal can

change within a song, but a bigger issue is the 60 Hz hum that varies in intensity depending on where Guthrie placed the mic relative to the tape machine.

“The process took a massive amount of trial and error and then refinement,” notes Jessica Thompson, who mixed and mastered the recordings at her facility in San Francisco. To rebalance the voice and guitar, Thompson initially ran the songs through RipX DAW demixing software.

“That’s when I discovered, serendipitously, that the RipX tool put the hum on the bass track,” she laughs. “So that was hilarious and magical and wonderful all at once.” That said, “There was still plenty of hum between sung syllables at the very beginning and end of phrases, because these are not perfect, precise tools. The only way to address that properly, elegantly and invisibly was straight-up hard labor.” Pulling each song into iZotope RX, she says, “I literally went millisecond by millisecond, drew lines around the residual hum, then hit the gain reduction.”

As for the mix, “I’m really trying to make the listener feel like they’re sitting next to Woody on the couch,” Thompson explains. “I have the good fortune of being married to a guitar player, so I know what that sounds like. I just tried to find a balance that felt real, and sometimes that was done phrase by phrase.”

However, with the “bass track”—the 60 Hz hum—removed, there were artifacts in the room ambience, she says, which were addressed by bringing the track into the mix and rolling it off below 3 kHz. “I let the algorithm add back in the ambience from the bass track with the guitar and vocal tracks, and that mathematically resolved, so you hear the original ambience of the recording without the artifacts left over from demixing.”

Whatever the historical project, Rosenthal likes to retain what he calls the “timestamp”— audible aspects such as a limited frequency response or background noise that reflects the recording’s origin.

“It’s important to be true to when the recording was made,” he says with conviction. “It’s important that the frequency response of the recording is not manipulated.” For Woody at Home, that also meant not editing out the sounds of Guthrie’s three kids talking and running around the small apartment.

“That makes you feel close to him and his

creative process,” Thompson observes. On the other hand, Guthrie clearing his throat, as another example, was edited out. “Those are decisions that I made based on whether it feels part of the experience or it pulls you out of it.”

The songs for the new release were chosen by Rosenthal and his co-producers, Woody’s daughter Nora Guthrie (who can be heard as a youngster on the tapes) and her daughter, Anna Canoni, president of Woody Guthrie Publications.

Guthrie witnessed the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, World War II and the Korean War, and the timeless, universal themes of his lyrics— racism, corruption, inequality, fighting fascism and war—resonate to this day. The first song released to streaming, on Guthrie’s birthday, July 14, was “Deportee,” about migrant farm labor. (The song was popularized by Pete Seeger and has been covered by Dolly Parton, Joni Mitchell, the Byrds, Billy Bragg and others.)

Today, an artist typically goes into the studio to record the definitive version of a song, but Guthrie was constantly tinkering with his material. Indeed, “This Land Is Your Land,” arguably his best-known song, appears on this collection with new words added.

“I think it’s important for people to know that his songs were never fixed; they were never finished,” Rosenthal stresses. “That is a very different way of thinking about songwriting and opens up the chance for young songwriters to go at these 22 songs and say, ‘Here’s the way I think these songs should be presented.’”

As Guthrie himself explains in a recorded message to his publisher included in the new collection, “I have never yet put a song on tape or a record, or wrote it down or printed it down or typed it up, or anything else that I really thought was a thorough and a finished and a done song, and it couldn’t be improved on, couldn’t be changed around, couldn’t be made better.” ■

By Barry Rudolph

UAD’s A-Type Multiband Dynamic Enhancer plug-in emulates the long-obsolete Dolby A-Type noise reduction system, which was invented to take care of the deficiencies and flaws of analog tape recording. In the 1960s, multitrack tape recorders came into wider use, and with it came a corresponding buildup of tape hiss, buzzes, hum, high-frequency noise, and layer-to-layer print-through.

The buildup of tape hiss became unacceptable, especially when recording and mixing large orchestras, with the many tape tracks each contributing to the tape hiss. The Dolby A-Type stereo A301 (1966) and single-channel A361 (1970) units achieved about 8 dB to 10 dB of noise reduction. UAD’s A-Type plug-in addresses the most egregious flaw: tape hiss.

Dolby A-Type uses a multiband, two-part compression/expansion (companding) technique. Part One encodes input audio by splitting it into four overlapping frequency bands that were determined to be the most effective in reducing audible noise. These four bands are each inversely compressed with quiet, low-level sounds compressed more, and louder sounds less, or not at all.

Principally, the lower-level mid- and high-frequency bands are emphasized and recorded at a higher level on the tape. The same four filter bands are also used in Part Two to decode the recorded audio using an expander. If the system is carefully aligned, the original recording’s amplitudes, phase and spectral makeup are restored, but with less high-frequency noise.

In those days, studios had racks of Dolby A-Type units connected to and from the multitrack tape recorder and mixing/recording console. Studio techs aligned both the Dolby units and tape recorders before every session. Likely first discovered by accident, somebody played a Dolby-encoded tape without the decoder and a whole new studio effect was born.

In 1975, I tried this trick intentionally to chase the sound of a lead vocal I had heard on a hit album recorded in England. What I heard was amazing! On the lead vocal track, it sounded like a super-bright EQ but also had a unique, compressed clarity and crystalline quality. But I also heard subtle nuances and annoying pops and clicks and the extreme sibilance in the recording. The Dolby units were used as a send/return effect like reverb or delay, but not designed to be a special effect.

Eventually, hardware “hacks” were developed to customize the effect for particular sources. One was to remove low-frequency Band 1 and 2 cards from an A301 unit, leaving only a high-frequency “gloss.” The newer A361 units had all four bands on a single, removable Cat-22 cartridge in which certain parts were bypassed or removed to produce a desired effect. A few producers had collections of modified Cat-22 cartridges, each labeled for specific uses—vocals, drums, acoustic guitars etc.

The UAD-A Type plug-in provides control over many internal parameters not available in the original hardware units, transforming this vintage

noise-reduction system into a fully adjustable, multichannel, dynamic effect. Included are presets that duplicate circuit modifications used by a “who’s who” of hitmaking record producers and engineers at the time.

A-Type’s GUI starts with a center-mounted, edgewise VU meter for reading Gain reduction from 0 to -40 dB, also setting Input level from -60 dB to +12 dB. You will be surprised to see huge gain reductions with most of the presets.

The Side Chain Filter has flat, a 12 dB/octave 150 Hz highpass filter and Tilt positions. Tilt is a linear 3 dB/octave boost. The main controls on the GUI are the large Amount (threshold) and Wet/Dry knobs. Practically speaking, I was constantly tweaking these two controls and the three-position Sidechain switch.

Two of the five processor modes, Excite and Expand, produce the encode and decode functions of the original Dolby A-Type noisereduction units. The other three are for special effects not possible with the vintage units.

Excite uses a variable, infinite:1 compression ratio and is the basis for the “A-Type EXCITE Stock HW Encode” preset. An Excite-based preset called “Acoustic Guitar Clarity and Detail” worked great for acoustic guitars, along with the Side Chain Filter. Expand is the decode mode analogous to the green “Play” button on the A361 units. Expand is used in the “A-Type EXPAND Stock Decode” preset for playing back encoded recordings correctly.

Air mode sounds like how I remember playing back Dolby-stretched tapes. It adds a classic glassy, airy sound. In honor of the recently departed producer, I called up a preset called “Roy Thomas Royalty.” It sounded fantastic on backing vocals. The manual says that with Air mode, “a little goes a long way.” It will definitely reveal and make audible fast attacks, ticks and crackles just like un-decoded audio back in the day.

The Dolby A-Type hardware used a variable

ratio from 4:1 to infinity:1 that provided the most transparent sound. Crush and Gated are singleband processors with a fixed 4:1 ratio that adds A-Type’s utility. The Crush-based “A-Type Multiband Enhancer 3” preset was killer for a flabby kick drum at 50% wet. The Amount control works like the input control on a UA 1176LN, making Crush a good-sounding, FET-based compressor. The Straight Gate preset (with some tweaks) chopped up an acoustic guitar track into techno hamburger. The Amount control now sets the threshold.

Clicking on a small arrow under the GR/Input meter opens up the Circuit Mods window. Circuit Mods includes many of the hardware mods done on the original units with all the controls to modify processing. This window shows a small four-band parametric dynamic equalizer display with the active bands enabled for a particular Mode.

You may alter frequency centers, band crossovers and gain of each band. I got in the habit of leaving this window always open to check on these parameter changes when switching Modes. I also kept the Auto Cal switch disabled to lock in my customized parameters to retain them when switching through modes, but you can revert to the preset values. This is a great feature.

Using a 4:1 ratio along with an adjustable soft/hard Knee control and slow/fast Release

COMPANY: Universal Audio

PRODUCT: A-Type Multiband Dynamic Enhancer Plug-in

WEBSITE: www.uaudio.com

PRICE: $199 USD

PROS: A whole new dynamic processor with unique Dolby A-Type effects. CONS: Clunky Preset functionality

time settings opens up A-Type to be a dynamic compression processor adaptable for any source. Attack time is nonlinear, with an initial fast attack that slows down as threshold is reached. A useful Output level fader and the adjustable HR Headroom control are for reducing or increasing dynamic range. Higher HR I for more subtle processing, and lower settings for extreme processing effects.

A noted mastering engineer sent me a stereo .wav (at 192 kHz) copy of a Dolby-encoded stereo master tape from the mid-1970s, including its 100 Hz, 1 kHz and 10 kHz alignment tones. He also sent the same master tape (.wav file) decoded using a Dolby A361 system. Both the encoding and decoding processes were carefully set up using the same alignment tones and tape recorder. On the encoded track, I inserted the A-Type plug-in with “A-Type EXPAND Stock HW Decode” preset.

I used Trident Audio’s TriMeter plug-in to measure the -18 dBfs, 1 kHz alignment tone split into two mono channels and fed to separate L/R faders going to the input of A-Type. It read -1.5 dB below 0 VU, and less than 0 dB on A-Type’s input meter. However, a second TriMeter placed on A-Type’s output read 0 dB. To set 0 dB on A-Type’s input meter required turning up the Amount control a little above the grease pencil mark—the output remained at 0 dB. The Wet/Dry Mix control was at maximum in this preset, and the Side Chain Filter was off. It all works! When played through A-Type, the encoded copy matched the decoded tape copy.

I think Universal Audio is on to something here with A-Type. What started as an emulation of a vintage noise reduction system has expanded the capabilities to become a new multiband effect—one that was discovered by accident a long time ago but has withstood the test of time. ■

By Michael Cooper

If you’ve ever wished to be able to use a synthesizerstyled ADSR on previously recorded audio tracks, now you can. Newfangled Audio’s recently introduced Articulate plug-in shapes your vocal and instrument tracks’ envelopes in ways that even transient designers can’t, providing independent control over their attack, decay, sustain and release (room tone) stages—what Newfangled calls Smack, Punch, Body and Air, respectively.

If ADSRs are alien to you, think of Articulate as a processor that splits the signal into time bands rather than frequency bands. (The plug-in does not use a transient detector.) The four bands overlap somewhat but are roughly centered at 0 ms, 10 ms, 250 ms, and 500 ms and longer.

Each processing stage/time band is independently controlled by a corresponding “channel” fader, which you can adjust to provide up to 12 dB of gain or as much as -∞ cut (muted). You can also mute, solo or bypass (turn off) each channel using switches; in the latter two states, the envelope stage’s audio signal is passed through at 0 dB (producing no processing).

That’s a quite useful construct: Soloing lets you identify, in isolation, what slice of your audio track’s envelope will be processed before you start messing with it, whereas toggling a channel on and off lets you A/B its wet and dry signals in combination with the other three (processed or dry) channels.

A Separation slider in the UI’s bottom-center area controls the speed of the transitions between ADSR channels, analogous in a way to how a slope control works in a filter bank. Moving the slider fully to the left (Smooth setting) avoids pumping but can introduce considerable bleed between channels—even to the

point where the fourth and final stage (release) might pass attack transients treated in the first stage. When the slider is moved fully to the right (Focused setting), there is no bleed between channels, but there could be pumping artifacts introduced. Use your ears to find the optimal setting; as you’ll soon see, the most artifact-free is not always the best!

When the Sidechain button in the UI’s bottom-left area is activated, Articulate reacts to audio signals routed in your DAW to the plug-in’s sidechain input, but the ADSR channel settings get applied instead to the track on which Articulate is instantiated. For example, say you want to duck the attack of your bass guitar track every time a kick drum hit occurs. Simply instantiate Articulate on the bass guitar track, route the kick drum to Articulate’s sidechain input and lower the plug-in’s Attack fader. The bass guitar’s attack

will duck in level only when a kick drum hit occurs.

When you activate the Limiter button (bottom-right area of the UI), a combination of clipping and limiting—similar to that used by Newfangled’s Saturate and Invigorate plug-ins— is applied at the plug-in’s output. Unfortunately, there is no threshold control; the limiter is basically an insurance policy against digital “overs.” But you can always follow Articulate with a full-featured limiter plug-in if you want to slam and destroy.

The vertical, high-resolution, left- and rightchannel I/O meters simultaneously show peak, RMS and peak-hold levels, with corresponding numeric readouts. Click and drag the I/O readouts to adjust input and output levels for the plug-in. To hear the delta signal (the output of the plug-in minus the input signal), click on the triangle (∆) icon. A Mix control lets you blend the wet and dry signals to the degree you wish, facilitating parallel processing.

In the navigation bar at the top of the plugin are controls that enable sequential prompts of undo or redo, toggling between A and B workspaces, and recalling both factory and previously saved user presets (all organized according to their suggested instrument or vocal applications and individually tag-able as favorites). You can even add your name and website URL to custom presets you’ve created and share them online, thereby directing your followers on social media to your website.

In one of the Settings menus, you can hide certain elements in the UI to simplify its look. The GUI’s size is also fully adjustable. Hovering your mouse over a control reveals helpful tips on how to use it.

Using Articulate on a variety of tracks, I could create sounds ranging from the outrageous to the sublime.

On a hard-rock production’s top-miked snare drum, cranking the plug-in’s Attack, Sustain and Release faders and lowering the Decay fader— with the Limiter button activated—transformed the track from an okay acoustic backbeat to an aggressive hammer (see Fig. 1).

The cranked Attack fader sharpened the stick strikes, while 12 dB each of added sustain and release boosted the sizzle, as if the drum

was also bottom-miked, and increased the room reverberation four-fold. I initially set the Separation slider to 72% for the song’s barebones drum intro to avoid excess pumping, but once the electric guitars and bass kicked in on a driving vamp, I floored the slider to make the snare pump like it was having an anxiety attack. To say the track was transformed would be a severe understatement.

Using similar settings on room mics for trap drums gave me the best of all worlds. By plunging the Decay fader all the way, I could separate the hyper-accentuated kick and snare hits from the extended room ambience, creating a sonic hole in the middle that let the close-miked traps dominate in my mix. Setting the Separation slider to 58% produced just enough pumping for the room mics that they didn’t overwhelm and

COMPANY: Newfangled Audio

PRODUCT: Articulate

WEBSITE: www.newfangledaudio.com

PRICE: $69

PROS: Sounds incredible. Versatile. Simple, intuitive interface. Included sidechain. Extremely affordable.

CONS: No threshold control for the included limiter.

blur the manic snare drum track.

On electric bass guitar, boosting the Attack and Sustain faders produced results similar to using a transient designer, accentuating pick strikes and extending note durations. Also, cranking the Decay slider made the bass fuller and rounder in a way that would be difficult or impossible to achieve with a transient designer or EQ. Nose-diving the Release fader tightened up the steady stream of eighth-notes played. The overall result was a punchy and round sound, yet tight.

For an oneiric ballad, I instantiated Articulate on an aux track following a reverb plug-in with a 3.6-second RT60, to which the lead vocal was routed via a send. I muted Articulate’s Attack and Decay channels, boosted the Sustain fader 5.7 dB and cranked the Release fader to the max. The final touch, adjusting the Separation slider to 78%, created a fascinating, pulsing reverb that defies precise description—sort of like a reverse reverb with a super-long predelay, but with a faster ramp-up and stronger peaks. Strangely beautiful as it was, I challenge the uninformed listener to figure out how that sound was created.

These are but a few examples of the sounds you can create with Articulate. And especially considering it sells for only $69, every mix engineer should own this extraordinary plug-in. ■

By Craig Anderton

“Thekeytosuccessissincerity.Ifyoucanfakethat,you’ve got it made.”

—George Burns (though I’m guessing that the phrase pre-dated him)

My previous column, “Strip-Mining the Emotion from Music,” covered how the misuse of technological tools can remove emotion from music. But I didn’t see the full scope of the problem—the erosion of emotion. If I hear the following argument one more time, I will reluctantly conclude that while there may be intelligent life on Earth, it may not have a soul: