HONORING THE LEGACY

OF THE DIX PARK LAND

The People We Honor - A Park for Everyone

The history of the Dix Park site is layered, complex and important in shaping the future of this public space.

For thousands of years, Indigenous people traversed and drew sustenance from the land. In the late 1700s, the

“The complicated, unspoken, and often uncomfortable histories of slavery, abuse, segregation, and removal that have occurred in this space must be documented. The issues of race, mental health, and communal healing inherent in our space are inseparable from our desires for what this park could become.”

— CITY OF RALEIGH IN ITS APPLICATION TO THE INTERNATIONAL COALITION OF SITES OF CONSCIENCE

INDIGENOUS INHABITANTS

Indigenous people have lived and thrived on this land for thousands of years. Archaeological and historical evidence indicates the lands that comprise present-day North Carolina have been occupied by groups of Indigenous peoples for at least 13,000 years, thousands of years before European colonists arrived causing widespread loss to traditional lifeways. Although the names of these groups remain unknown, the descendants of these communities are reflected today in the more than 130,000 American Indians living throughout North Carolina. The state recognizes these eight tribes, each with its own distinct community, history and tribal government: Coharie, Cherokee, Haliwa-Saponi, Lumbee, Meherrin, Occaneechi, Sappony and Waccamaw Siouan. American Indians have contributed much to our state and nation and today promote a culture and way of life centered on ties to one’s relatives, pride in one’s tribe, nourishment of the land and harmony with nature.

Senora Lynch, a nationally recognized artist from the Haliwa-Saponi Indian Tribe, helps children create clay turtles at the Dix Park Annual Inter-tribal Pow Wow. Photo by Alexandra Williams

PLANTATION DESCENDANTS

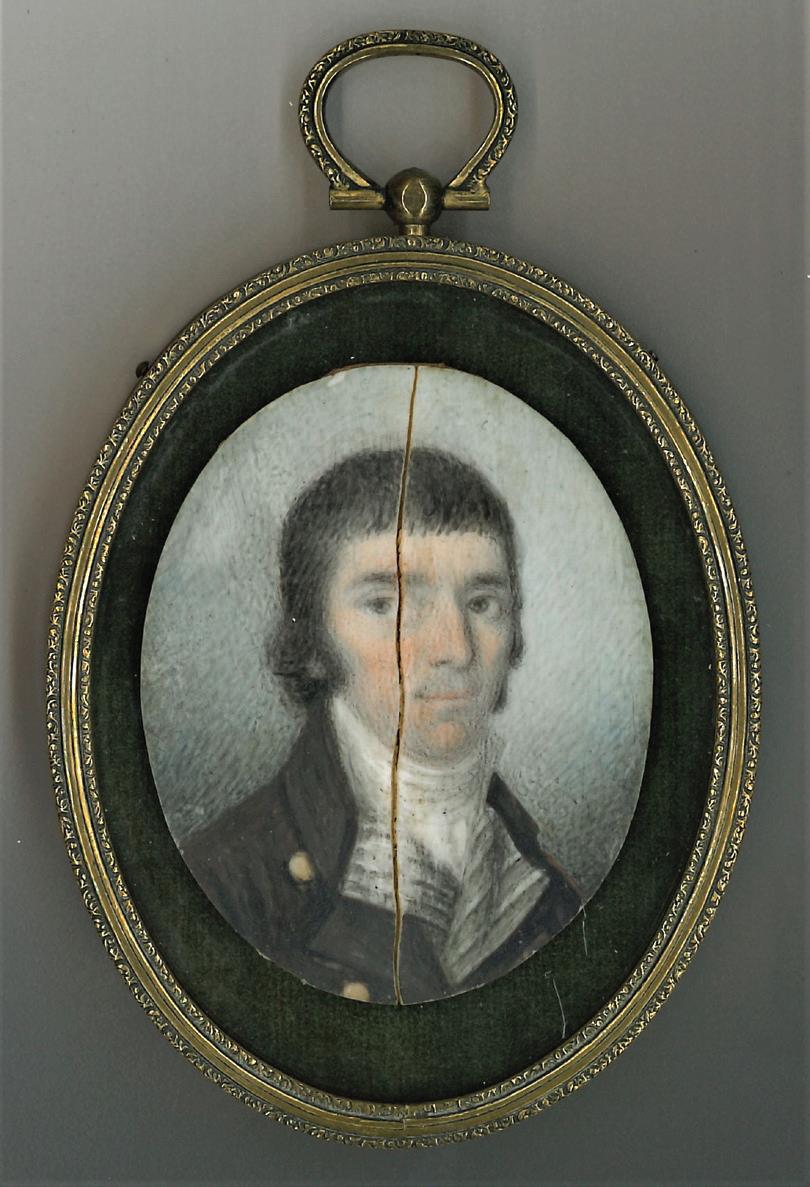

By 1790, the land encompassing Dix Park belonged to Theophilus Hunter Sr., an officer in the North Carolina militia during the American Revolution and a founder of the City of Raleigh. Agricultural operations at the Spring Hill plantation were extensive, and labor was provided by enslaved people who built wealth for the landowner’s family. Following Hunter Senior’s and Junior’s deaths in 1798 and 1839, their estate inventories listed 63 and 64 enslaved persons respectively. Through ongoing genealogy research by local historians and family members, more descendants of the Hunters and those enslaved at Spring Hill are being identified and connected to their family’s history. The Spring Hill house and 128 acres surrounding it were transferred to NC State University in 2001.

The Spring Hill house is a registered historical building, built around 1815 in the Georgian style as the main house of the Spring Hill plantation. The name refers to a spring of water arising at the foot of the hill. The house is now the Japan Center located on NC State’s Centennial Campus directly across from Dix Park.

A portrait of Theophilus Hunter Sr., who owned the land that later became known as Spring Hill plantation. Image courtesy of the

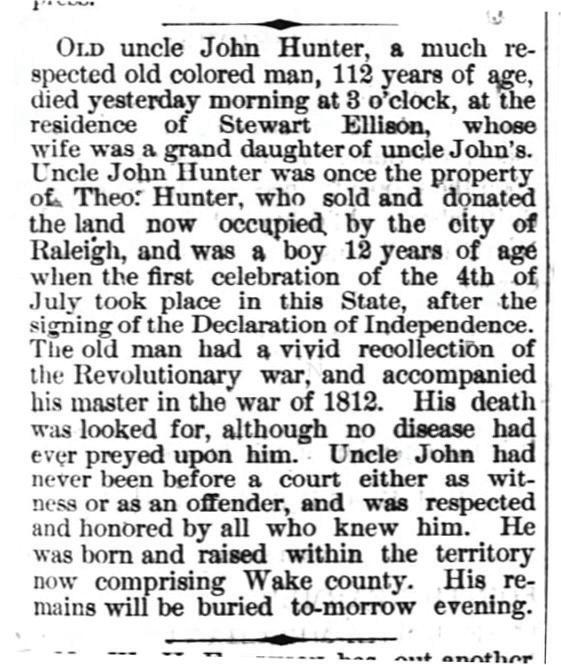

“Uncle” John Hunter was an enslaved person at Spring Hill plantation who was born in the 1760s and lived to be 112 years old. Many of his descendants have recently been identified and connected to their ancestors and other family members previously unknown to them through ongoing genealogical research.

MENTAL HEALTH COMMUNITY

The “Insane Hospital of North Carolina” admitted its first patient in 1856. At its peak, the hospital treated almost 3,000 patients annually and had nearly 1,300 employees on 2,500 acres of land with 282 buildings. The hospital trained providers and nurses for much of its history. Many former employees and patients remember the hospital as a haven on a hill where patients lived and were cared for by dedicated staff and volunteers. Many employees and their families lived on the grounds as well, fostering a close-knit community. Despite good intentions, not all treatments and medications were helpful, and the state’s four hospitals were not integrated until the late 1960s.

In 2012, Dorothea Dix Hospital’s last patients were moved to a new facility in Butner, and the hospital was closed as part of a national trend to provide care for patients in community settings rather than institutions. Mental health care remains an issue of great community importance, and many feel that community-provided mental health services have fallen short of initial promises. The Dix Park Conservancy aims to honor the history of mental health care at this site by remaining engaged in mental health topics and providing admission-free programs related to mental health and wellness.

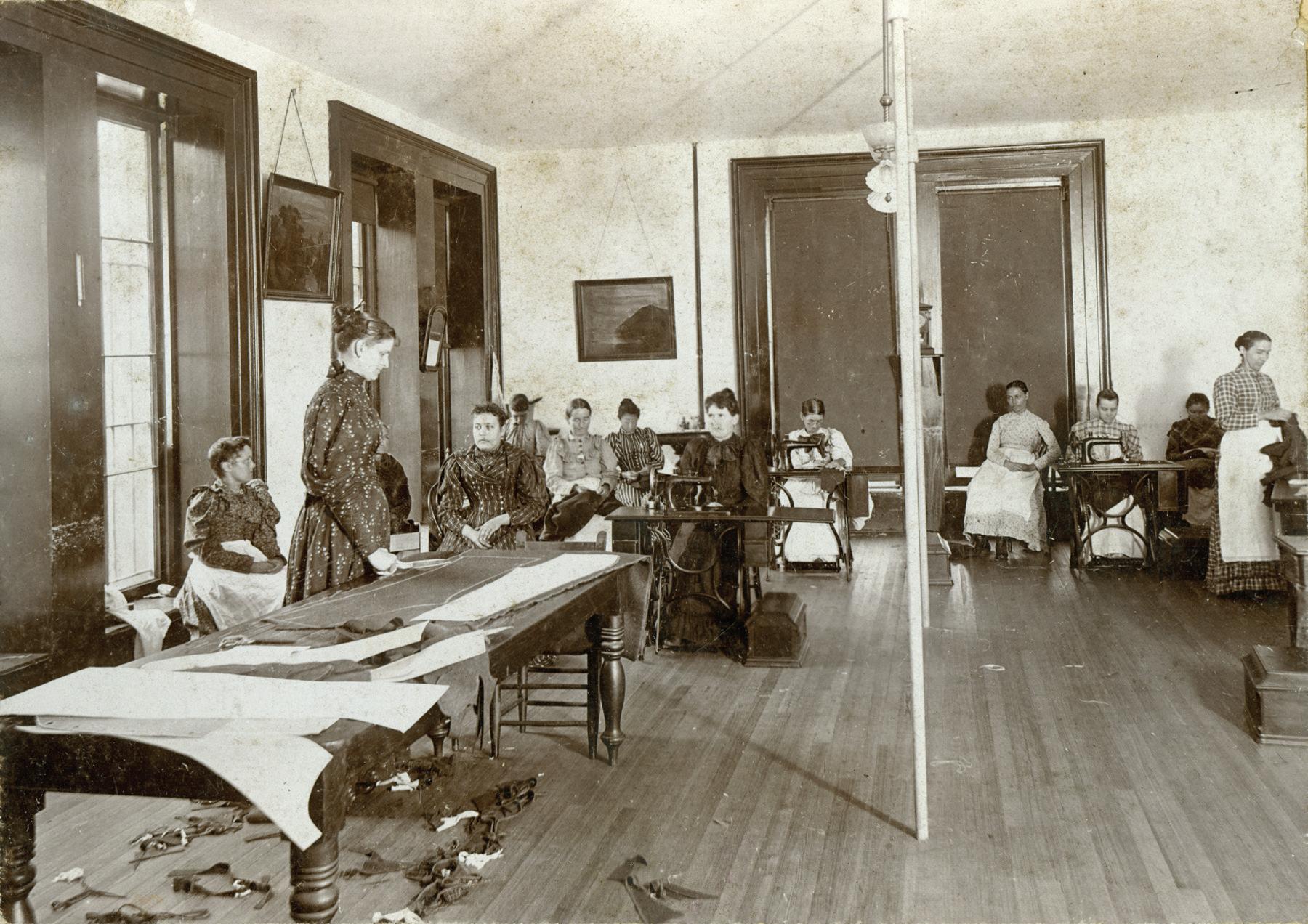

From its start, the hospital used the land for agricultural operations, and patients often provided the labor, which was thought to have therapeutic qualities.

Built in part by enslaved labor, the hospital was constructed on high ground overlooking Raleigh and initially called Dix Hill. It was largely self-sufficient with its own farm, water supply, and power plant. Photo courtesy of NC State Archives

The Dix Park property is home to a 3-acre cemetery that contains more than 900 graves. The cemetery was actively used from the hospital’s opening until the early 1970s. Photo courtesy of City of Raleigh

Photo by Greg Jacobs

Musician at Dix Park’s Juneteenth celebration

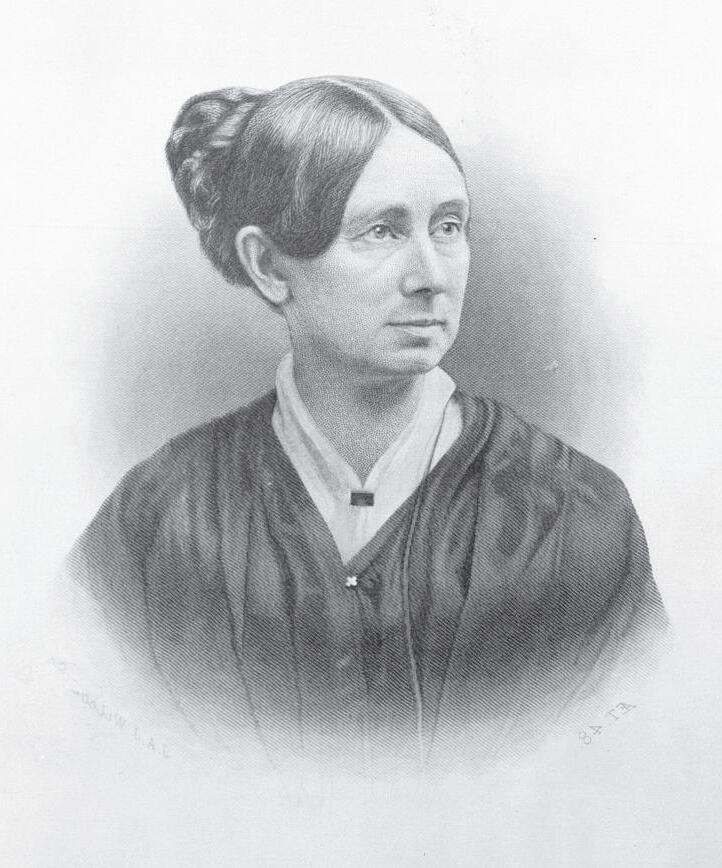

Who was Dorothea Dix?

Dorothea Lynde Dix was a 19th century advocate for the humane treatment of people with mental illnesses. She exposed the deplorable conditions patients often endured and successfully petitioned the NC General Assembly to establish a “State Hospital for the Protection and Cure of the Insane.” When the hospital opened in 1856, Dix requested that it be named in honor of her grandfather who was a physician. In 1959, it was renamed Dorothea Dix Hospital to recognize her pioneering and enduring contributions to reform mental health care in the United States and abroad.

Honoring the Human Legacies of Dix Park

The Dix Park Conservancy established the Legacy Committee in 2015 to recommend ways to honor the legacy of Dorothea Dix in the new park. Its mission was later expanded to include recognizing other legacies including:

• Indigenous people who traversed the region.

• Enslaved people and slaveholders who lived and worked at Spring Hill.

• Patients, their families, providers, staff, volunteers and members of the mental health community associated with Dix Hospital.

• And all who are connected to the park land and their descendants.

The committee seeks concrete ways to honor these legacies. The members are focused on capturing stories about the park’s human legacy, developing programming to inform visitors about the park’s human history and contributing to the development of the park’s Cultural Interpretive Plan. The committee’s work is also focused on the land itself, fostering resilient, sustainable designs and practices, honoring our past and revering our future.

Photo courtesy of Barden Collection, NC State Archives

Front cover images: (top) Photo courtesy of Barden Collection, NC State Archives, (center) Photo is by Alexandra Williams, (bottom) Photo courtesy of NC State Archives. Back cover photo: Dix Hospital Sewing Room, Photo courtesy of NC State Archives