3 It Makes No Never Mind

James Nalley

4 Shenanigans At The Lewiston Fairgrounds Be careful who you rent from Brian Swartz

8 Windham’s Jean Marie “Jeff” Donnell Recurring character actress James Nalley

12 Fryeburg’s James Ripley Osgood Publisher of numerous literary figures James Nalley

18 Railroading Over Crawford Notch Celebrating 150 years

Brian Solomon

26 Auburn’s Payson Smith And W.W. Stetson Maine’s great education reformers

Charles Francis

30 Golf Pro Arthur H. Fenn He left his mark at the Poland Spring Resort

Brian Swartz

36 Cornish Dinner Parties Good conversation and good pie Jennie Pike (1851-1922)

38 Rufus Porter Finds A Home Bridgton honors a restless genius Toni Seger

44 Bethel’s Marshall Stedman Versatile actor of stage and screen

James Nalley

48 William Lloyd Garrison’s Visit To Waterville Sparks the anti-slavery movement

Charles Francis

52 Farmington’s First Congregational Church Stained glass windows tell a story

Greg Davis

57 The Genealogy Corner Internet use — some pros and cons

Charles Francis

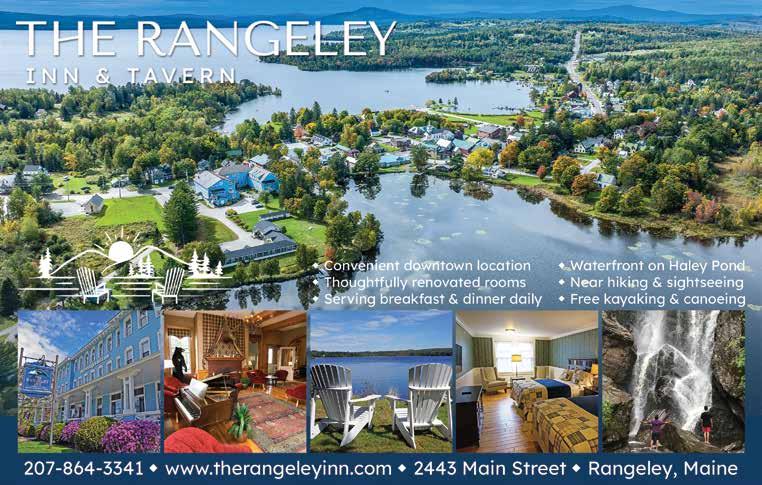

61 Maine’s Rangeley Lakes Region A haven of fishing and birding

Brian Swartz

64 The White Nose Pete Fly Fishing Festival The perfect event for all fly-fishing enthusiasts

Sue Damm

69 Skowhegan High School Baseball It was all the rage in 1911

Brian Swartz

74 Strong’s Elizabeth Dyar Participant in the Boston Tea Party

Barbara Adams

77 Moosehead’s First Sporting Camps From public domain to a way of life

Charles Francis

79 1909 Fire Scorches Downtown Skowhegan “Box 34” alarmed residents to danger

Brian Swartz

80 General Russell B. Shepherd Skowhegan’s reluctant hero Rosemary K. Poulson

Publisher Jim Burch

Editor Dennis Burch

Design & Layout

Liana Merdan

Field Representative

Don Plante

Contributing Writers

Barbara Adams

Sue Damm

Greg Davis

Charles Francis

James Nalley

Rosemary K. Poulson

Jennie Pike

Toni Seger

Brian Solomon

Brian Swartz

Exchange Street, Suite 208 Portland, Maine 04101 Ph (207) 874-7720 info@discovermainemagazine.com www.discovermainemagazine.com

Discover Maine Magazine is distributed to town offices, chambers of commerce, financial institutions, fraternal organizations, barber shops, beauty salons, hospitals and medical offices, newsstands, grocery and convenience stores, hardware stores, lumber companies, motels, restaurants and other locations throughout this part of Maine.

Front Cover Photo: Main Street in Fryeburg. Item # LB2007.1.100879 from the Eastern Illustrating & Publishing Co. Collection and www.PenobscotMarineMuseum.org NO PART of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from CreMark, Inc. | Copyright © 2025, CreMark, Inc.

SUBSCRIPTION FORM ON PAGES 37 & 82

All photos in Discover Maine’s Western Maine issue show Maine as it used to be, and many are from local citizens who love this part of Maine.

by James Nalley

y the time of this publication, Western Mainers will have survived yet another winter and are probably ready to get out and do something (or at least see something that is actually green). The following are just a few suggestions in this region of the state. However, remember to bring your trusty pair of Muck Boots (for the mud) and note the roads posted with red “Heavy Load Limited” signs.

First, there is the Heart of Poland Trails, which are a wooded network of easy hiking trails from Tripp Lake Road to the public library that takes visitors to a vernal pool (or spring pool), a quarry, rare white oak trees, and a small cave formed millions of years ago. Specifically, it includes the Cave Trail (0.3 miles), the Huntress Trail (1.2 miles), the Quarry Spur (0.1 miles), the Ricker Trail (0.3 miles), and the White Oak Trail (0.7 miles). As for the latter, due to a unique cellular structure that makes their timber water- and rot-resistant, they were once highly valuable for shipbuilding in the colonial days. Interestingly, Poland includes the only white oak hill in Maine.

Second, for those who want a bit more, there is the Maine Wildlife Park, which reopens in mid-April. Located

in Gray, it is home to approximately 30 species that cannot be returned to their natural habitats. Some are there because they were injured or orphaned, while others were raised (sometimes illegally) in human captivity. In other words, they are entirely human dependent. As the park states, “You are guaranteed to see moose and more animals in a day than you could ever spot in the wild!” Season or day passes are available online.

Third, there is Nezinscot Farm in Turner. As the first organic dairy farm in Maine, it has evolved into a one-stop shop that offers farm-raised beef, pork, chicken, dairy, eggs, fruits, and vegetables. They are particularly known for their bread (oatmeal, seven-grain, wheat, cinnamon swirl, etc.), cheese (made without synthetic hormones, antibiotics, etc.), and pastries (doughnuts, muffins, cookies, cinnamon rolls, croissants, etc.). There is even an herbal apothecary (with medicinal herbs grown on the farm), headed by resident herbalist Gloria Varney.

Finally, for something a bit different, there is the Western Maine Beer Trail. This is a self-guided tour of the local craft brew scene in western Maine. When launched in 2009, it in-

cluded around 25 breweries. However, there are currently more than 100. To participate, visit beertrail.me to create an account. When visiting a Maine brewery, look for the poster titled, “Visit Breweries, Get Rewarded.” Enter the four-digit code within the Maine Beer Trail online web-app to “stamp” your beer trail. In this case, 25 visits earn you a Maine Brewers’ Guild hat and 50 visits earn you a short-sleeved shirt, with a prize pack for visiting all the breweries.

At this point, let me close with the following jest. A lawyer comes home after a long trial in which it was decided that his client, John Wright, would be hanged that night. He is greeted at the door by his wife. “You’re home late and tracking mud all over the place… please take your shoes off!” He replied, “Look, I’ve had a hard day…I’m gonna take a bath.” Later, her husband’s boss calls and tells her that they are not going to hang Mr. Wright. She immediately runs upstairs and opens the bathroom door to see her husband bending over drying off his naked body. She proclaims, “They’re not hanging Wright!” He scowls, “Geeze woman! Can you just stop criticizing me for one minute!”

by Brian Swartz

Did the Lewiston fairgrounds owner set a trap for a local attorney on May 5, 1935?

Bespectacled lawyer Harold Redding resembled a banker, but after serving as the Androscoggin County district attorney, he had returned to private practice and had professionally represented his clients, no matter their legal woes.

For Lewiston residents Isaac Cripps and his wife, that woe was Frank W. Winter, an Auburn resident who owned the Maine State Fairgrounds on Main Street. The Cripps owned Cottage 19

on the fairgrounds, but Winter owned the land beneath their home.

Other cottage owners had similar arrangements with Winter, but he wanted everybody out, not just the Cripps. In fact, Winter had issued 30-day notices to all his tenants “more than two years ago,” according to a local paper.

The Cripps did not leave, so early on Friday, May 5, 1935, “Winter ordered me out,” Mrs. Cripps told a newspaper reporter. Winter had already turned off the water to Cottage 19 and begun ripping up the water line, an altogether unfriendly act.

On top of that, the Cripps had paid for the water line’s installation.

That morning, Winter’s hired hands “started piling boulders, tree stumps,” and dirt “in front of my cottage,” Mrs. Cripps said. “I can’t open my front door as the dirt and boulders are piled up to a height of three or four feet.”

She telephoned Redding, a lawyer who defended the underdog. He “told me to keep count of each load they brought” and dumped outside the front door, as well as “the time each load was dumped here.

“That is all I have done all day

long,” Mrs. Cripps sighed.

The elderly Crippses had returned to Lewiston in April after wintering in Florida. Imagine their surprise when they arrived at their cottage and found “horse dressing” (a euphemism for what was removed daily from the horse barns) stacked 6 feet high between their cottage and its next-door neighbor.

The horse dressing, which included manure, covered the side door of Cottage 19.

Soon after the Crippses arrived home, Winter told them to move their house elsewhere. When they failed to respond quickly, he apparently decided to block access to the cottage to deliver a message: Get out or you won’t get in.

And if the rough barrier blocking the front door proved ineffective, Winter had his men drop “a huge stump” outside the next-door cottage.

“They intend to put that in front of my side door,” Mrs. Cripps told the press.

So, she called Harold Redding on May 5, and he promptly drove to the fairgrounds. According to Winter, “Redding entered despite the three large signs which warn against trespassing. Those gates had been closed for six months.

“When he (Redding) went into the grounds, he slipped in behind another car which had a right to be there,” Winter said.

“I went there to see a client,” said Redding, referring to the Crippses. He looked over the debris piled outside their cottage, took notes, and slipped into his car to head home.

Frank Winter knew that Redding was visiting the Cripps. The fairgrounds had three gates, and Redding had entered the grounds via the Cottage Street gate. While the attorney spoke with his clients, Winter ordered that gate closed and his own car parked to block the exit.

“A man was locking the gate” as

Redding drove up after leaving the Crippses. “I asked him to move his car and open the gate, and he refused.” Redding checked the other locked gates. Had Winter deliberately trapped him? Not wanting to spend the night inside the fairgrounds, Redding apparently returned to Cottage 19 and asked to use the telephone.

He contacted Benjamin L. Berman, a well-known local attorney, explained the situation, and essentially asked, “What should I do?” “Wait til I get there,” Berman responded.

Hopping into his car, Berman drove to the Cottage Street gate and, after arriving around 9 p.m. and chuckling about his friend’s predicament, figured out that a locked gate was not necessarily a secured gate.

“Ben and I lifted the gate off the hinges, drove my car through, and then replaced the gate,” Redding explained. Still steaming about being trapped, he drove to his office to cool off and de(cont. on page 6)

(cont. from page 5)

cide if additional action was warranted against Winter.

“Redding got caught trespassing,” said Winter, wanting to press charges against the attorney.

Dubbed the “Fair Ground Trapping,” the incident stirred conversation in Lewiston for days to come. Redding and Winter each had their supporters, but many people found the tale humorous.

The Crippses did not, because on Monday, May 8, “several rugged timbers similar to timbers used to move buildings” were placed outside Cottage 19, a newspaper noted.

Then news broke that Isaac Cripps, 72, had allegedly assaulted Winter on April 26. Arrested on a charge of “threatened assault,” Cripps was arraigned at Lewiston municipal court on May 15.

Harold Redding represented Cripps,

accused of throwing a rock at Winter and then approaching him while carrying a straight razor. Two training-stable operators, brothers William J. McManemon and J.W. McManemon, testified about seeing Cripps “throw a rock” at Winter while holding a razor in his hand.

Denying he had threatened Winter, Cripps said, “I called him names.”

Unfortunately, other neighbors testified to seeing Cripps throw the rock, and Redding did not help his client’s case by persistently asking Winter questions that the judge “deemed irrelevant.” Ultimately Redding was threatened with fines for contempt of court if he continued with those questions; Cripps signed a $500 bond promising that he would keep the peace.

In the end, the Crippses moved elsewhere as Winters removed Cottage 19.

of the Civil War, as

and

who

and preserve the United States. Maine At War Volume 1 draws on diaries, letters, regimental histories, newspaper articles, eyewitness accounts, and the Official Records to bring the war to life in a storytelling manner that captures the time and period.

by James Nalley

In the 1940s, a Maine-born actress became a fixture at Columbia Pictures, one of the so-called Big Five production studios in the country. Under their contract, she steadily worked in everything from comedies and mysteries to Westerns and musicals. Despite her versatility, she typically played the house tomboy, the comic sidekick, or the plain-speaking confidante to a glamorous or dramatic lead. Although Columbia did give her the glamour treatment in the late 1940s, she never managed to move past the sidekick image in films or the recurring supporting character roles in her numerous television appearances. Jean Marie Donnell was born on July 10, 1921, in South Windham. As a child, she self-appointed her nickname

“Jeff ” Donnell in the 1940s

of “Jeff,” based on her obsession with Mutt and Jeff, the long-running and widely popular American comic strip created by Bud Fisher in 1907. Later in her career, to avoid gender confusion, she was sometimes billed as “Miss Jeff Donnell.” In 1938, she graduated from Towson High School in Towson, Maryland, and attended the Leland Powers School of Drama in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Yale School of Drama in New Haven, Connecticut. Subsequently, she was active with the Farragut Playhouse in New Hampshire, which was founded by her first husband, whom she married at the age of 19.

In 1941, she was noticed by a talent agent from Columbia Pictures, after which she signed a multi-year contract

with the studio and was immediately whisked off to Los Angeles, California. Interestingly, despite her dramatic training and stage experience, she made her film debut as Helen Loomis in My Sister Eileen (1942). According to Turner Classic Movies, this “screwball comedy starred Rosalind Russell, Brian Aherne, and Janet Blair. It even had an appearance by The Three Stooges.” As stated earlier, although the studio gave Donnell the glamour treatment, especially after playing the troubled heiress in The Phantom Thief (1946), she never shed the sidekick/supporting character image.

When her contract with Columbia Pictures ended, she freelanced at other studios, with most of her appearances in low-budget action films. However, in 1948, Donnell met Lucille Ball on the set of the RKO Radio Pictures production Easy Living. In 1950, Ball remembered Donnell and recruited her to play her sidekick in the Columbia Pictures (cont. on page 10)

(cont. from page 9)

slapstick comedy The Fuller Brush Girl (1950). Meanwhile, as stated by Turner Classic Movies, although “she stepped it up a notch to play a larger role in the 1950 noir In a Lonely Place, as the best friend to the tormented Gloria Grahame,” Donnell still found her way playing smaller character roles in various films and television series.

According to Quinlan’s Illustrated Dictionary of Film Character Actors (1993) by David Quinlan, “Jeff Donnell was a happy-looking, red-haired American actress who played bobby-soxers, kid sisters, prairie flowers, best friends, secretaries, shop-girls, and other second-leads for 15 years, only graduating to mothers when she turned 40.” Such roles included: George Gobel’s wife, Alice, in The George Gobel Show (1954-1957) on NBC-TV; the needy secretary in Sweet Smell of Success (1957); and Gidget’s mother, Dorothy Lawrence, in the films Gidget Goes

Hawaiian (1961) and Gidget Goes to Rome (1963).

In the mid-to-late 1960s, Donnell moved more squarely into guest spots on television series, including five appearances as Evelyn Driscoll on Dr. Kildare (1966), with only a few more film roles, including a part as a flight instructor in the drama of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). Her final Columbia feature was as Ruth in the 1972 women’s lib-themed comedy Stand Up and Be Counted, starring Jacqueline Bisset, Stella Stevens, and Steve Lawrence.

As for her personal life, Donnell’s first marriage was in 1940 to William Anderson, who was her teacher at the Leland Powers School of Drama. She had her only children with him, Michael (b. 1942) and Sarah Jane (b. 1948), before they divorced in 1953. She would eventually get married three more times, with all the unions short-

lived. For example, there was American television and film actor Aldo Ray (married 1954, divorced 1956), John Bricker (married 1958, divorced 1963), and Radcliffe Bealey (married 1974, divorced 1975).

In 1979, Donnell began a recurring role as Stella Fields (the wealthy Quartermaine family housekeeper) on the soap opera General Hospital. According to the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), on April 11, 1988, “Dogged by ill health, including a serious bout with Addison’s disease (a rare disorder of the adrenal glands), Donnell died of a heart attack at her home in Hollywood.” She was 66 years of age. As per her wishes, she was cremated, and her ashes were scattered at sea in the Pacific Ocean. Meanwhile, her sudden absence from General Hospital was simply explained away by the writers as her character having won the lottery and quitting her job.

by James Nalley

In 1881, Walt Whitman, one of the most influential poets in American literature, finalized a 10-year contract with a successful publishing company in Boston, led by James Osgood, a Fryeburg-born, Bowdoin College graduate. In October of that year, they agreed to publish Leaves of Grass, which was highly controversial during its time for its explicit sexual imagery. However, Osgood agreed to let Whitman “retain all the ‘beastliness’ of the earlier editions,” after which the 7th edition was to be sold to the public at two dollars a copy. However, Boston District Attorney Oliver Stevens classified Leaves of Grass as “obscene literature,”

James Ripley Osgood

ordering Osgood to remove several offending poems/passages or cease publication altogether. Although Whitman was willing to make some changes, he refused to completely change his manuscript, resulting in a settlement in which both men parted ways. This was one of Osgood’s many well-known clients, which included William Howells, Harriet Beecher-Stowe, Bret Harte, Thomas Hardy, and Mark Twain.

James Ripley Osgood was born in Fryeburg on February 22, 1836. A child prodigy, Osgood understood Latin by the age of three and entered Bowdoin College at the age of 12. He graduated in 1854 at the age of 18 and briefly

read law in Portland, Maine. However, his career path changed when he was introduced to the publishing world in the following year. Specifically, he started working as a clerk for Ticknor and Fields, a prominent Boston publishing company. According to his biographical article in The Vault at Pfaff’s by Lehigh University, “In 1868, he attained the status of partner, along with James T. Fields. Then, the pair established Fields, Osgood, and Company.” In 1869, the newly formed company published American author and abolitionist writer Harriet Beecher-Stowe’s comedy-drama novel, Oldtown Folks. By that time, she had written the immensely popular Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). The firm also inherited The Atlantic Monthly, which focused (and still features) articles on politics, foreign affairs, business, and the economy. As a publisher, Osgood’s reputation continued to rise with the successful

publication of American short story writer and poet Bret Harte’s The Luck of Roaring Camp and Other Stories (1870), followed by a volume of poems and another “condensed novel.” Although Osgood advanced Harte $10,000 for future work, Harte did not write another story for him. In 1875, Osgood published American writer Blanche Willis Howard’s One Summer, which became a best-selling novel. In this case, Osgood became the most important publishing contact for most of her career.

Interestingly, the publishing world changed names as quickly as they started, with some attempting to avoid bankruptcy and others attempting to expand. For instance, The Walt Whitman Archive states, “By 1871, the firm had become R. Osgood and Company, with Osgood and Benjamin Ticknor as partners. In 1878, the firm merged with H.O. Houghton to form Houghton, Os-

good, and Company, which only lasted until 1880, when Osgood left to form James R. Osgood and Company. In 1881, Osgood offered to publish Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass As stated earlier, Whitman finalized a 10-year contract, with the 7th edition of his collection of poems to be published at two dollars a copy. However, Osgood had to give into the criticism of the work as “obscene literature.” The settlement in which the two men parted ways included a payment of $100 to Whitman in cash and 225 copies of the book (along with the stereotype plates).

Meanwhile, Osgood had befriended Samuel L. Clemens, also known as “Mark Twain.” In 1882, Osgood’s company published Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper and The Stolen White Elephant. The same year, Osgood accompanied Twain on a riverboat trip collecting material for Life on the Mississippi, which was published the fol(cont. on page 14)

(cont. from page 13)

lowing year. The book was simultaneously sold in the United States and the United Kingdom.

According to The Walt Whitman Archives, “After the Boston ‘suppression,’ Richard Maurice Bucke (biographer of Whitman), John Burroughs (American naturalist), and William O’Connor (American author) rallied around Whitman and used the event to promote the poet as a victim of prudishness and comstockery.” Moreover, “Using the plates from the Osgood edition, Rees Welsh and Company of Philadelphia sold approximately 6,000 copies of Leaves of Grass. Although not a direct result of the Whitman fiasco, Osgood and Company went out of business in May 1885.”

After the company’s bankruptcy, Osgood’s young partners, Thomas and Benjamin Ticknor, found a third partner and started a new firm. Meanwhile, Os-

good went to work for Harper’s Magazine, which was (and still is) a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. However, Osgood returned to the publishing business in 1891. In partnership with Clarence McIlvaine in London, England, they formed James R. Osgood, McIlvaine, and Company.

This new firm had its greatest success with English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles (1891). Osgood personally saw its initial three-volume publication that year. However, on May 18, 1892, Osgood died in London, before its publication as a single volume. According to the New York Tribune (May 20, 1892), “For some time, he had been suffering from bronchitis, with the transatlantic voyage and the subsequent London climate aggravating the disease. His death was unexpected to his friends, since let-

ters received the first of the week stated that he had been feeling much better.” He was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery in Kensington, England. He was 56 years of age.

As for his legacy, one can consider that his life was not necessarily successful, based on his constant shifting from one company to another, his relatively early death, and the fact that his definitive biography titled, The Rise and Fall of James Ripley Osgood, was published in 1959 by Carl Jefferson Weber. However, like any business venture, there are many factors to consider. In Osgood’s case, the benefits of publishing the renowned works of the some of the greatest authors in the field outweighed the business risks.

by Brian Solomon

The opening of the railroad to the Gateway at Crawford Notch on August 7, 1875 was a momentous event. At 12:24pm, Portland & Ogdensburg Railroad’s president General Samuel Anderson drove the final spike in place. A cannon, brought by train from Portland, fired ten cacophonous salutes and a brass band played The Star Spangled Banner. The history of this railroad line is a story of unintended consequences while the mystique of running trains and the allure of its rugged scenery, has captivated visitors for a century and a half.

In the 1830s, farsighted entrepreneurs and industrialists began construction of numerous independent and largely disconnected railroads in the eastern United States. Some projects emulated the success of the Erie Canal by aiming to connect port cities with the interior of the country. By comparison, Northern New England was slower to build than the more industrialized areas. Where the bulk of American railroad traffic was focused on an east-west axis, railroads in northern New England focused on connecting cities in Quebec with New England ports while developing local traffic. After the American

This

is looking east from the

Civil War, American railroads entered a dynamic phase characterized by consolidation and rapid evolution of larger regional railroad systems.

In 1867, the Maine legislature granted a charter to the Portland & Ogdensburg Railroad to build west from Portland. P&O would follow the course of the Saco River to its headwaters at New Hampshire’s Crawford Notch, and then to a point on the Connecticut River as the eastern portion of a through trunk

route to Ogdensburg New York. This developing port on the St. Lawrence River had been identified as a suitable point to tap Great Lakes freight traffic for forwarding via Portland.

Portland was a major investor in the P&O. In September 1869, westward construction of the line quietly began in the city and by that time New Hampshire had authorized P&O construction to the Vermont border. Tracks reached Steep Falls, Maine by Novem(cont. on page 20)

(cont. from page 18)

ber 1870, and North Conway, New Hampshire. on August 10, 1871, where the railroad built a temporary western terminus. This included a small roundhouse to service locomotives, complete with turntable to turn them, along with freight and passenger stations. These facilities were located off Depot Street, and today vestiges of the turntable pit survive in the trees near the modern day North-South road. Less than a year later a second railroad was completed to North Conway. This was the Conway Branch built by the Portsmouth, Great Falls & Conway (a component of the Massachusetts-based Eastern Railroad, an erstwhile competitor to the Boston & Maine). By 1874, P&O and Conway Branch had both extended their lines to Intervale where a connection between them was built that included interchange tracks and a small station. P&O continued to Bartlett, New Hampshire, where it constructed a small yard and

terminal facilities.

Building west of Bartlett presented P&O’s builders with a huge engineering challenge. This involved conquering the rugged, and comparatively steep

eastward ascent to Crawford

(On the P&O, the directions regardless of the compass were always considered ‘east’ toward Portland, and ‘west’ toward Ogdensburg). West of Bartlett, at

Call 207-582-1960 or

Bemis (now known as Notchland) the gradient reached 2.2 percent (a rise of 2.2 feet for every 100 feet traveled), which had been previously established as the recommended maximum gradient for many railroads built in the American West. P&O’s line required several large bridges, including a spindly tower-support curved iron trestle over the gorge near the Frankenstein cliffs (almost 80 miles west of Portland) and another high bridge over the Willey Brook gorge near the top of the Notch. Shelves were cut out of stone in many places to provide the rightof-way for the line and combined with high fills constructed from stone debris. At the so-called ‘Gateway’ at the top of the Notch, a 300-foot long cutting was blasted out of the stone that in places was 75 feet deep. Beyond was a natural plateau, where the railroad located its Crawford Station.

On June 29, 1875, an excursion train operated from Portland to Fran-

kenstein. More famous was the previously described trip on August 7, 1875, to celebrate the opening of the line at Crawford Notch. Excursions were different than the railroad’s regularly scheduled passenger trains operated for general transportation. Where regularly scheduled trains made stops along the way to board and discharge passengers and collect and distribute the US Mail, these excursions were strictly aimed at bringing passenger out and back to view the scenery and marvel at the achievement of the railroad.

The eastward assent of Crawford Notch was immediately acclaimed for its outstanding views. Early on, P&O recognized that passengers would travel over the line simply for the thrill of taking in the scenery and to reach one of the many grand hotels in the White Mountains. The railroad capitalize on this traffic by advertising the stunning scenery, while cooperating with connecting lines, notably the Eastern

Railroad via the Conway Branch, in the operation of through trains to bring passengers from Boston directly to the White Mountains without needing to change trains. Significantly, P&O pioneered covered, open-air observation cars with swiveling seats to allow its passengers to better enjoy the scenery. Passenger traffic was a supplemental business, and the railroad hoped to earn its greatest revenue by hauling local and through freight traffic. Opening of the P&O route had helped develop the Mount Washington Valley’s timber trade, and several purpose-built logging railroads were constructed to feed traffic to P&O’s mainline. The most significant, and by far the longest lived of the these, was The Sawyer River Railroad (1877-1937). This connected with the P&O route four miles west of Bartlett at its namesake and climbed into the mountains to serve the company logging settlement of Livermore (now a ghost town).

(cont. on page 22)

(cont. from page 21)

The railroad’s original vision of moving great volumes of through freight via Ogdensburg never materialized. While most of the projected route was built, it was never coordinated under unified ownership. Complicating matters was that in the 1880s the middle and western portions of the Ogdensburg route came under the control of established railroads that were focused on Boston and New London, which competed with Portland for traffic. During that time the vision of a Portland-Ogdensburg trunk faded, and the P&O subsisted largely on local freight and passenger business.

Meanwhile, in the 1870s the Eastern took controlling interest in the Maine Central. And then Boston & Maine leased the Eastern in 1884 and melded this one-time competitor into its growing network. In 1888, the struggling P&O was leased by the Maine Central, which continued to operate the line

as its Mountain Division. The P&O route offered Maine Central alternative western connections via St. Johnsbury (principally with Canadian Pacific), while the railroad also built a secondary route compass northward into the province of Quebec. The former remained an important freight route for many years, while the latter adventure proved short-lived and was scaled back to the US border during the 1920s. Maine Central continued to invest in its Mountain Division, significantly upgrading bridges and track to accommodate heavier modern locomotives and cars, and much longer freight trains.

During the Golden Age of railroad passenger service—before the proliferation of the automobile and modern paved highways — some Mountain Division passenger trains carried through cars between Portland and Montreal, and for a short time carried through sleeping cars between Portland and

Chicago (via Montreal). In the 1930s, B&M and Maine Central assigned their jointly-owned state-of-the-art Buddbuilt stainless steel diesel streamliner to service as Mountaineer. This train operated for the benefit of summer tourists between Boston and Littleton, New Hampshire, running by way of the Conway Branch to Intervale, over the Crawford Notch to Whitefield, and then via B&M’s line to Littleton. This distinctive train had been purchased in 1935 for Boston-Portland-Bangor Flying Yankee service for which it is still remembered today. (In 2024, the historic Budd train was relocated to Conway Scenic Railroad’s Conway, N.H yard for eventual restoration by its new owner, the non-profit Flying Yankee Association.)

With the rise of automobile ownership, Maine Central’s regularly scheduled intercity passenger services ceased operating profitably, and the Crawford (cont. on page 24)

(cont. from page 22

Notch service ended in 1958. Through freight service continued until 1983, at which time the melding of B&M and Maine Central operations under the recently formed Guilford Transportation Industries resulted in the railroad’s through freight being routed west over B&M’s lines instead of via Maine Central through St Johnsbury. After a decade of dormancy in the mid-1990s, Maine and New Hampshire acquired significant portions of this historic route in their respective states. New Hampshire assigned Conway Scenic Railroad as the designated operator of the route over Crawford Notch, and CSRR invested in rebuilding and reopening this scenic route, and developed it into a significant tourist line that has entertained tens of thousands of passengers annually. In 2025, Conway Scenic plans to expand its Crawford schedule and run special event trains to celebrate the line’s 150 years

of rail service. CSRR is also actively exploring opportunities to work with Maine to reopen the Mountain Division to Portland to redevelop and revitalize this historic railroad as a passenger and freight corridor.

Brian Solomon is the manager of marketing at Conway Scenic Railroad. He has authored more than 70 books on railroads, and writes a monthly column for Trains Magazine.

by Charles Francis

At the end of the nineteenth century, public school education in Maine was in a state of chaos. The primary reason for this was fragmentation. Except for a few school unions, school management resided at the town level. For much of their history, most Maine towns had partitioned themselves into school districts that had their own governing boards. For example, the town of Perham in Aroostook County, which had a population of just under six hundred and fifty, had six oneroom schools, each governed by its own school committee that was responsible

for hiring a teacher, purchasing supplies, and keeping the building in an appropriate state of repair. Then, in 1894 the legislature abolished this system requiring each town to have a single superintendent to oversee a town’s schools. Towns then chose a school superintendent by popular vote, and this individual, in many cases, was not qualified for the position. In other words, the state of public education in much of Maine around 1900 was much as it had been in colonial times. The man who did more than anyone else to modernize public school education in Maine was Payson

Smith, who built upon a foundation of reform initiated by W.W. Stetson. Smith and Stetson were both from Auburn. Payson Smith was Maine State Superintendent of Schools from 1907 to 1916. His immediate predecessor was W.W. Stetson, who served from 1895 to 1907. Payson Smith and W.W. Stetson were well acquainted with public education in Maine. Besides having served in various positions in the Auburn educational system, both had taught in a variety of Maine schools ranging from the one-room schoolhouse to large city schools.

When W.W. Stetson became state superintendent, the position was little more than ceremonial and demanded next to nothing. State superintendents had an annual salary of fifteen hundred dollars and a five hundred dollar expense account. By statute, the state superintendent was charged with preserving “all school reports of the State and other States that may be sent to his office... and other articles of interest to school officials and teachers as may be procured without expense to the state.” Obviously most state officials were content with the existing status of Maine public education. Stetson and Smith were to change this, most notably in the area of industrial education and in teacher training.

In 1895 W.W. Stetson visited two hundred schools in rural Maine. Forty-one percent of them he graded as “poor” or “very poor.” Many schoolrooms were even decorated with ad-

vertisements for tobacco. In forty-three percent of the schools Stetson visited, the teaching of arithmetic was nothing more than a memorization of rules, and reading was the recitation of unintelligible words.

Stetson also sent out a questionnaire to town superintendents. He presented the results of his findings at a meeting of the Maine Pedagogical Society in Lewiston in December of 1896. Some of the statistics Stetson revealed are as follows: Four percent of superintendents had never attended school, Thirty-five percent had never taught. Sixty-eight percent had never read a book on teaching methodology. Thirty-five percent of Maine’s teachers had not even attempted the certification test required by state law.

At the close of Stetson’s presentation, President Hyde of Bowdoin College commended him by saying, “The State superintendent has done an au-

dacious thing. He has had the courage to tell the plain and awful truth about these schools of ours.”

In the next few years, W.W. Stetson lobbied the state legislature for new laws to improve public school education in Maine. Among other things, he received funding for summer schools for teachers and a law saying that teachers who held state certification were not to be examined by local school boards or superintendents. He also made recommendations regarding teacher training, especially in the areas of science, mathematics, and industrial or manual training. In addition, he called for the amalgamation of small towns into school unions.

Payson Smith’s educational philosophy centered around his belief that “The common schools are for the common people.” For this reason, he fought for state support of and state mandates for vocational and industrial training. (cont. on page 28)

(cont. from page 27)

In 1909 Smith persuaded the legislature to pass a resolution authorizing him to conduct “an investigation of systems of industrial education in other states and countries and to make a report thereon.” Smith even secured a small appropriation from the legislature to carry out the endeavor. In other words, Payson Smith had now directly involved state government in the future direction of education in Maine.

Smith then got some of the most influential individuals in the state to serve as a committee to make the investigation and report. Included on that committee were George Fellows, President of the University of Maine, Francis North, Principal of Portland High School, W.E. Sargent, Headmaster of Hebron Academy, C.S. Stetson, Grand Master of the Maine State Grange, E.M. Blanding, Secretary of the Maine State Board of Trade and Charles O.

Beals, President of the Maine Federation of Labor.

Payson Smith’s committee represented a broad range of talents, interests, and resources. By the time it produced its report the committee had visited various industries in Maine, collected similar investigative reports from across the United Satiates, most notably from Massachusetts and New Jersey, the two most highly industrialized states of the period, and the American Federation of Labor. In addition, it collected data on industrial education in England and Germany, where it was much more advanced than in America. The results of the committee’s efforts were more than even Payson Smith could have hoped for.

In 1911 the legislature passed a law to encourage the development of industrial education in Maine public schools. Under the law, the state provided two-

thirds of the salary paid each teacher in those schools that established manual training or domestic science programs. It gave approval authority to the State superintendent for courses of study, equipment, and qualifications for manual training and domestic science instruction. Aid was also given to those high schools and academies giving instruction in agriculture and the mechanical and domestic arts. Included in the latter were carpentry, such business subjects as typewriting and stenography, and such home economic subjects as sewing.

Payson Smith left Maine in 1916 to become the Massachusetts Commissioner of Education. Before he left, however, he successfully lobbied the legislature for Maine’s first teacher pension system.

Payson Smith was succeeded by Dr. Augustus O. Thomas, who had been

Commissioner of Education in Nebraska. In 1928 Thomas reported that “Considerable progress has been made in vocational education, consisting of all-day schools, part-time schools, and evening schools and classes. The work covers industrial forms, home economics, and agriculture.” He also reported that the eighteen agricultural high schools in the state were turning out between three and four hundred graduates a year. In addition, Thomas reported that eighty percent of Maine teachers had normal school training and that by 1930, it would no longer be necessary for Maine schools to employ any teacher who was not “technically prepared for the service they are to render.”

Payson Smith and before him, W.W. Stetson, both sons of Auburn, almost single-handedly moved Maine public school education into the modern age of industry and technology.

Counselors and campers posed outside Methodist Camp in Winthrop. Item # LB2010.9.118723 from the Eastern Illustrating & Publishing Co. Collection and www.PenobscotMarineMuseum.org

by Brian Swartz

Hired to design a nine-hole golf course at Poland Spring Resort in the 1890s, Arthur H. Fenn left his mark on golfing in Maine and New England.

Born in Waterbury, Connecticut in 1857, Fenn “was obliged to make his own way in the world,” a Maine newspaper later reported. A self-starter, he skillfully played baseball in Waterbury. Offered the opportunity to play for the New York Nationals in the nascent National League, he declined and went into the hospitality industry, managing hotels in South Carolina and New Hampshire.

Along the way Fenn met Almon C. Judd, a New England hotel manager, and later married his sister, Mary E. Judd. They would have a son, Harris Fenn, and a daughter, Bessie Fenn, who would become famous in her own right. Arthur Fenn started playing golf; a newspaper claimed, “he was one of the first men in this country to take up golf seriously and is said to be one of the first homebred professionals.” Poland Spring Resort historians claim that Fenn was America’s first native-born golf pro.

While managing the Poland Spring House in 1895, Almon Judd spoke with

the Ricker family about hiring Fenn to design a golf course at Poland Spring Resort. Fenn and the Rickers negotiated a scenario by which he would design a nine-hole course while working as the resort’s pool-room manager as “the course was being built.” Fenn was “anxious to keep his standing as an amateur,” essentially because he was pursuing the Lenox Golf Cup in the annual tournament played in Lenox, Massachusetts. Fenn won the Lenox Golf Cup in 1895, 1896, and 1897. He turned professional afterwards. He designed Poland Spring Resort’s nine-hole course and played it imme-

diately. After establishing a course record with a blistering 47 strokes, Fenn returned the next day and blitzed the course with just 45 strokes!

His design placed the ninth hole near the Maine State Building, which the state constructed for the 1894 Chicago World’s Fair. The Ricker family later purchased the building and had it dismantled and moved to the resort.

After the Poland Spring golf course opened, Fenn stayed on as the resident pro, living in a cottage across the road (modern Route 26) from the resort’s road entrance. The renovated cottage opened in 2015 as Fenn Ice Cream Shop.

In May 1897 Fenn competed for the prestigious Worthington Whitehouse Silver Cup at the Knollwood Country Club in Westchester County New York. Facing stiff competition from American and European golfers, he won the cup with his masterful 85 strokes, nine

strokes ahead of the second-place golfer.

Fenn returned to Westchester County that October to compete in a St. Andrew’s Gulf Club tournament featuring a “who’s who” of professional golfers. William H. Sands, the club’s amateur champion, offered a silver cup to the tournament’s winner.

Golfers and fans remembered how “the strong wind which swept over the course with the force at times of a small gale made low scoring … more difficult” that day. Hitting “a beautiful long drive” that landed four feet shy of the hole on the difficult fifth green, Fenn sank a putt on his third stroke. He won the silver cup with his 76 strokes. While competing against top golfers, Fenn talked about the Poland Spring Resort course. Recognizing Fenn’s skill, top golfers from the United States, England, and Scotland played golf at the resort. The golf course closed

in the fall, and each winter Fenn traveled to Palm Beach, Florida to work as a golf pro until warm weather returned to Maine. He was the Palm Beach Golf Club’s pro for 27 years.

Fenn designed other New England golf courses. In 1895 he established the Fall River Country Club in Massachusetts in 1895 and designed its first ninehole course. Early in the 20th century he designed a nine-hole golf course for the Country Club of Farmington in Connecticut. His course replaced a nine-hole course laid out east of the Waterville Road in 1895. Fenn left seven greens to the road’s east side and placed two greens west of the road. His course was later replaced by an 18-hole course.

At age 61 Fenn captured the title in the first Maine Open golf tournament, played at the Waterville Country Club in 1918. Now located at Poland Spring Resort, the Maine Golf Hall of Fame (cont. on page 32)

(cont. from page 31)

inducted him in 1993.

Arthur Fenn died in Lewiston on May 21, 1925; his funeral took place at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Waterbury, Connecticut on May 23. Bessie Fenn took his place as Poland Spring Resort’s golf pro that summer, and later that year she applied to replace her father at the Palm Beach Golf Club, now known as The Breakers’ Ocean Course. Competing against 399 male applicants, Bessie got the job and held it for 34 years. She was a nurse by education and profession, but her father instilled in her a love for golf.

The th ing about eye disease is, you may n o t know you have it. Some conditions are asymptomatic, and by the time symptoms do present we’re left with fewer options. An annual examination at GFVC can ensure that we diagnose any latent disease with cutting-edge technology. We’ll also check your vision and adjust your prescription. And while you’re here, you can check out the latest designer frames.

by Jennie Pike (1851-1922)

About this time of year the old folks gave parties, and as interesting as the young people’s gatherings were, I really think that the older folks’ dinner parties were more so. We called them “the old folks” even then, and as I think back, the ones who made up our visiting list were no doubt all somewhere between twenty-five and forty years of age — just the right age to begin to be sensible.

There was the McKusick family, Stone and Bracken families, all with many children. There were two Clark families in one house with a maiden sister who was a most congenial neighbor. Three Guptill families there were,

and to distinguish them, the heads of these households were always spoken of by their first names, thus Mr. Frost, Mr. True, and Mr. Wilson, many of us not knowing for years that they owned any other names. An Eastman household, a Parker, Pease, and a Merrifield family made up the immediate circle that I remember.

Oh, yes, and the Crowleys, Jerry and Betsy as they were always called, who lived over behind Hoosac Mountain in a little bird’s nest pocket of a farm, their only way out being up over the back of the mountain and into our valley neighborhood. Jerry had only one hand, and the lack of it appeared to

have strengthened his brain, for he read and thought so much in solitude that when he got out among his neighbors he could argue and expound mightily. Theology in all its branches was ABC to Jerry. Betsy was as big, fat, and jolly as Jerry was lean, lank, and serious, yet they were a happy pair, seemingly well content with each other.

So when mother spoke up lively some morning thus; “Come, girls, you must fly around and help me now, for we are going to have company for dinner.” We knew our parts — to put the downstairs bedroom in perfect order, for here the lady guests were to lay aside their things, to brighten the parlor

andirons, to sweep, dust, and wash up the red brick hearth, and to stay out in the kitchen after the company arrived, for “children are to be seen…” Oh, how I hated that saying, forever dinned into our ears. I hated it and disregarded it, for after my father, Jerry, and Mr. Frost settled into a deep religious or Civil War controversy, I would always slip in unnoticed with my little cricket and listened to my heart’s content.

Mrs. Jerry and Mrs. Frost knitted and gossiped aside by themselves, the wonder being how they could knit without looking at their work.

As the dinner hour approached, the odor of fresh-roasted spare ribs, mince pie, coffee, cake, and homemade cheese grew stronger until the door was thrown open. “Come, lay aside your work,” was the call to dinner, each guest expressing surprise that dinner was ready notwithstanding that they were there for the express purpose

of dining. Each one did ample justice to the eatables for the better part of an hour, while the children waited hungrily in hopes that there would be some pie left.

Sometimes the minister came, sometimes the doctor’s family, and sometimes the schoolmaster, which sent me into a seventh heaven of quivery delight, for a schoolmaster was a small god in those days.

And all the afternoon long, whoever the guest chanced to be, I recall their conversations were always learned, argumentative, courteous, and everything else that was delightful to remember. God bless the memories of the old days. We are forgetting them too fast.

DiscoverMaineMagazineispublished eighttimeseachyearinregionalissuesthat spantheentireStateofMaine.Eachissueis distributedforpickup,freeofcharge,onlyin theregionforwhichitispublished. ItispossibletoenjoyDiscoverMaineyear 'roundbyhavingalleightissuesmaileddirectlytoyourhomeoroffice.Mailingsare donefourtimeseachyear. Subscription Rates:

by Toni Seger

ufus Porter, (1792-1884) artist, musician, educator, cultural promoter, inventor, and founder of Scientific American magazine, led a nomadic life that took him from his birthplace in West Boxford, Massachusetts, across the country and as far away as Hawaii. During the course of his almost constant journeying, Porter frequently supported himself by painting the residential wall murals depicting idyllic landscapes that collectors have come to prize. In this manner, Porter created a style and a school of folk art painting that has left its mark, especially around New England.

Though Porter is finally being laud-

ed for his major contribution to and influence on period folk and primitive art, it’s been all too easy to lose touch with this extraordinary man. Decades of wallpaper have obscured many of his murals. Fire and neglect have taken many of the homes in which he painted.

Now, for the first time, Porter’s life is being celebrated with a museum dedicated to his work and legacy.

The Rufus Porter Museum and Cultural Heritage Center at 67 North High Street (Route 302) in Bridgton, gives this “Yankee DaVinci,” as he was described by Time Magazine (September 7, 1970), a home at last.

The museum is believed to be the

original residence of Nathan Church, Bridgton’s first Congregational minister. It contains authentic Porter murals exposed after removing wallpaper. In the Bridgton area alone, between 1825 and 1835, Porter painted wall murals in a dozen area homes. Unfortunately, all but three are gone.

Rufus Porter’s family arrived in Massachusetts in the early 1600s from Dorset, England. They moved to Flintstown, later called Sebago, in 1802, and to Pleasant Mountain Gore, in 1804. Rufus Porter’s uncle, Nathaniel, was one of the founders of Fryeburg Academy, at that time a one-room schoolhouse young Rufus attended for six

months. It was all the formal schooling he ever received.

Throughout his long, peripatetic life, Porter taught, painted, and invented. He taught music in New Haven, Connecticut where, in 1816, he briefly opened a dance school. He built wind-driven gristmills in Portland and developed his first ‘camera obscura’ in 1820 while walking to Virginia. Between 1824 and 1844, he painted murals.

Despite all of his traveling, Porter married twice, fathering ten children with his first wife and five with his second, though only one of these survived infancy. Wherever he went, Porter’s murals contain reminders of the favorite views from his youth such as Portland Harbor and the Observatory on Munjoy Hill overlooking Casco Bay. Fryeburg’s surrounding scenic mountains figure frequently in his work, especially Jockey Cap.

Porter took out more than a hundred

patents in his life, a testament to his ever-curious mind. In 1936 a Boston Globe article stated that Porter knew “more about aerial dynamics than any other man of his time.” In addition to founding Scientific American magazine, Ported invented a hot air balloon and successfully demonstrated an airship in New York City, making it circle the rotunda at the Merchant’s Exchange eleven times.

Resourceful and brilliant, Porter’s restless intelligence was always moving to something new. Focused on the act of invention, he didn’t bother to associate his name with any of the extraordinary devices he created. Instead, his wandering intellect moved rapidly to his next idea, as when he sold all rights in his revolving rifle to Samuel Colt for one hundred dollars. Indeed, his intelligence was described as “grasshopperish” because his attention leaped from topic to topic.

Porter’s lack of business sense left him in a constant struggle for money. Sometimes he sold his rights to an invention just to be able to buy food. His never-ending travels meant his name was never associated with any single location. In the years after his death, no center ever formed around his work and little was written about him until he was rediscovered in the mid-20th century.

In 2004, when the two-acre parcel on North High Street containing two period buildings became available, a group of community advocates in Bridgton formed to support the development of a museum that would honor and bring attention to an extraordinary native son. This unique museum also contains a seasonal exhibit with work by Maine artist John Mead, born in the Stone House on Burnham Road in South Bridgton. Known primarily for his fish paintings, Mead painted the ex(cont. on page 42)

(cont. from page 39) hibited oil-on-board of his family farmstead in 1883.

Also displayed at the museum are four John Brewster portraits painted in Bridgton in 1825, early watercolor portraits by Rufus Porter, and other period paintings of Porter’s day, plus two small landscapes by Vivien Akers of Norway, painted in the 1940s.

Fifteen Porter murals removed from the home of Dr. Francis Howe of Westwood, Massachusetts are another part of the museum’s seasonal exhibit. Considered his best work, they are the only ones both signed and dated by the artist.

The Rufus Porter Museum and Cultural Center operates seasonally with plans of being open year-round. For more information visit www.rufusportermuseum.org

Iby James Nalley

n 1892, a Bethel-born man graduated from high school, and like many of his classmates, was considering a possible career path. His father was a decorated U.S. naval officer, and, at the time of his death in 1939, was the oldest surviving graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and one of only three retired officers who saw service in the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865). Naturally, as his only son, this young man seemed destined for service in the navy. However, breaking from tradition, he went on to college in Colorado and began a decades-long career in stage and film. Edward Marshall Stedman, Jr. was born on August 16, 1874. He was one of two children of Edward Sr. and Eliza

Nestled on 60 acres in beautiful Stoneham, Maine, our unique treehouses and cabins offer a perfect blend of adventure and relaxation. Ascend our 50ft mountaintop tower for panoramic views of the White Mountains, explore scenic trails, and challenge yourself on our one-of-a-kind 18-hole mountain disc golf course. For more details or to book your stay, visit: www.inthetreesmaine.com

Putnam. He received his early education in the public school system of Chicago, Illinois, and eventually graduated from South Division High School. As stated earlier, it was assumed that he would continue and attend the U.S. Naval Academy, following his father’s footsteps. Nevertheless, Stedman attended Colorado College in Colorado Springs and joined William Morris’s stock company, as a fledgling actor. At the time, Morris was a star on the Broadway stage, usually playing “gruff fathers or bad guys,” according to The New York Times. Due to Stedman’s natural ability on stage, he quickly earned leading roles in Morris’s productions, playing, for

example, Bob Appleton in Ludwig Fulda’s three-act drama The Lost Paradise, and Ned Annesley in Sowing the Wind, a four-act play by renowned English dramatist Sydney Grundy. As stated in the book Who’s Who in the Film World (1914) by Fred Justice, “Stedman later joined E.H. Sothern for two seasons and went on to star in several one-act plays. He was also versatile enough to land prominent roles in Shakespearean repertoire productions.”

Around 1899, Stedman’s family, including his father, sister, grandmother, and uncle, moved to Gilpin County, Colorado. According to The Weekly Register (December 1, 1899), the Stedman family (like many other families in the region) “became involved in a promising mining venture near America City, called the Charlemagne Lode.”

Yet again, after a relatively short stint, Stedman left his family and ventured back into acting and coaching.

In January 1900, Stedman married

Myrtle Lincoln, a young silent film actress who he had worked with in Chicago. Ironically, their only child, Lincoln Stedman, would go on to follow in his father’s footsteps and have an active career in Hollywood. In fact, between 1917 and 1934, he appeared in more than 80 films. Unfortunately, he died of a heart ailment at the age of 40.

By 1906, Stedman’s experience in teaching helped him earn a position as the Head of the Drama School at Chicago Musical College. However, after holding this position for roughly four years, Stedman again followed his passion and spent a season in vaudeville before heading into the film industry as a director with Essanay Studios. This motion picture studio, founded in Chicago in 1907 (with a film lot in California) included a roster of renowned stars such as Gloria Swanson and Charlie Chaplin. Then, Stedman signed with the Selig Polyscope Company, as an actor, director, and producer. As a direc-

tor, he became known for three works in particular: Between Love and the Law (1912), A Motorcycle Adventure (1912), and The Suffragette (1913).

Around 1915, Stedman returned to teaching as a drama instructor at the Eagan School of Drama and Music in Los Angeles. Meanwhile, during his tenure, he remained active on stage, this time as a villain in several films by director Hobart Bosworth, who was known for producing the Jack London melodramas for Paramount Studios.

Always one to venture into new, but related areas of acting, Stedman started writing. Conveniently, his first works were one-act plays in community theater productions performed by his students. In the late 1920s, Stedman founded the Marshall Stedman School of Drama and Elocution in Culver City, California. There, he served as an administrator and instructor, and honed his skills writing more plays and acting-related books. From 1925 to 1946, (cont. on page 46)

(cont. from page 45)

he wrote more than 25 works, including one-act plays and collections of monologues (both drama and comedy). Regarding the latter, they had interesting but straightforward titles such as Distinctive and Different Monologues (1927), Clever Monologues (1928), Sure-Fire Monologues (1928), and Amusing Monologues (1940). For the rest of his career, he maintained this balance of writing and teaching.

On December 16, 1943, Stedman died at his home in Laguna Beach, California. He was 69 years of age. He was buried at Melrose Abbey Memorial Park in Anaheim, California. As stated earlier, his son, Lincoln, would die just five years later at the age of 40. Aside from his impact on stage, drama teaching, and early silent films, Stedman is another example of one who has chosen to live his life not by a predestined path, but by his passion.

by Charles Francis

It is often said that the people of the State of Maine were largely unaffected by the antislavery and abolition movements which swept the North prior to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States. One reason for this is that by and large the Maine men who rushed to volunteer for the regiments that went off to fight in the War Between the States like the famous Twentieth Maine did so not because they were opposed to the institution of slavery but rather because they were determined to preserve the Union.

However, this fact does not mean that the issue of slavery went ignored in the state. In fact, Maine boasted two vigorous and well-organized associations that were affiliated with national movements opposed to the South’s “peculiar institution.” They were the Maine branches of the American Colonization Society and the American Antislavery Society, societies that, while they both agreed slavery had to be abolished, differed dramatically in the methods for accomplishing this end. It was this difference which brought the great ab-

olitionist William Lloyd Garrison to Maine, where his visit to Waterville sparked the formation of the first antislavery society in the state and where he had his most notable confrontation with supporters of the American Colonization Society.

Few Maine residents ever had slaves. The few that did had slaves prior to 1780. That year the new constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, of which Maine was a part, forbade the keeping of other human beings as chattels. However, when Maine became a state in 1820 with the passage of the Missouri Compromise that was inexorably linked to slavery, some Mainers began coming out in opposition to the continued practice of keeping people in bondage. One of the first to do so was a young Congregational minister by the name of Asa Cummings.

Asa Cummings began his crusade against slavery the same year that Maine became a state. At the time he

was a tutor at Bowdoin. Cummings, however, was not a radical abolitionist. Cummings called for the gradual elimination of slavery. However, he believed that it was impossible for freed slaves and whites to exist side by side in the United States. Cummings’ ideas were those of the American Colonization Society, which advocated a gradual freeing of slaves and their orderly deportation or expatriation to Africa. In the early 1820s Cummings became editor of the Christian Mirror, a Congregational newspaper published in Portland which was in actuality the chief voice of the American Colonization Society in Maine. There were, however, any number of influential Maine figures who called for the immediate abolition of slavery, the most notable being General Samuel Fessenden.

Samuel Fessenden was something of a Maine hero, having been a militia general in the War of 1812. In addition, he was an able lawyer as well as

a Christian. Therefore, when he heard William Lloyd Garrison give one of his impassioned speeches coached in Biblical terminology calling for the immediate abolition of slavery, he became Maine’s most ardent antislavery proponent.

William Lloyd Garrison had begun his attack on the gradualism of the American Colonization Society in the pages of The Liberator in Boston in 1831. The next year he made Maine, where Asa Cummings and the Christian Mirror had been enjoying remarkable success with the plan to send freed slaves to Africa, his chief battleground. One reason Garrison chose Maine for the site of his first battle with the American Colonization Society was that he had Maine ties. His parents had spent the early part of their marriage in Eastport.

Garrison arrived in Maine in September of 1832. His first stop was Portland where he spoke before a large (cont. on page 50)

(cont. from page 49)

audience which included Samuel Fessenden. When Garrison finished, Fessenden took him aside and the two spent most of the night discussing the evils of slavery in general and the American Colonization Society in particular. Fessenden went on to be a driving force in the foundation of the Maine Antislavery Society as well as its vice president. He and Garrison also formed a friendship that was to last the rest of their lives. From Portland, Garrison went on to Hallowell, Bangor, Waterville, and Augusta.

Garrison’s Waterville host was Jeremiah Chapin, the president of Waterville College, which today is Colby College. Garrison’s message was so well received among the students of Waterville College that they formed the first antislavery society in the state. Garrison would later point to his sojourn to Waterville as a turning point in

Maine. After his visit, the state became serious about taking up the cause of abolition, and the state’s branch of the American Colonization Society began a steady decline.

Garrison’s last stop in Maine was Augusta. Here he had a face-to-face confrontation with the Reverend Cyril Pearl of the American Colonization Society who had come to Maine with the specific purpose of diffusing Garrison’s campaign in the state. According to individuals who witnessed the meeting, it was a clear victory for Garrison.

The Maine Antislavery Society was founded in 1834 when local societies like the one formed at Waterville College met to coordinate their efforts. The first line of the society’s constitution reads as follows:

“The fundamental principles of this society are that slave-holding is a heinous sin against God, and therefore that

immediate emancipation without the condition of expatriation is the duty of the master and the right of the slave.”

In the 1840s members of the Maine Antislavery Society formed the Maine Liberty Party with the abolition of slavery as its single issue. Samuel Fessenden was a four-time Liberty Party candidate for governor. However, as with most single issue political parties, it was markedly unsuccessful. Eventually it merged with the Free Soil Party, which in turn helped form the Republican party and elect Abraham Lincoln and Maine’s Hannibal Hamlin as the first Republicans to hold the nation’s highest offices. This whole sequence of events could be said to have happened because the first antislavery society in Maine was founded by a group of Waterville college students who were captivated by William Lloyd Garrison’s message in the fall of 1832.

by Greg Davis

hurch members don’t really know the origin of the “Old South Church” label applied to the First Congregational Church in Farmington, according to Pastor Richard Waddell. He said one possibility is that the name was brought by the first preachers visiting from the Old South Church in Hallowell whose founders had, in turn, come from the Old South Church in Boston, Massachusetts. The Farmington church was organized in 1814 with a parish forming in 1822. The first pastor and the one of the longest

duration was Isaac Rogers who served the church from 1825 until 1858.

The first building was constructed on the site in 1836 but was a casualty of the great fire of 1886, which also leveled the nearby Methodist and Baptist churches as well as the entire end of downtown Farmington. When the loss occurred, contributions came from as far away as California, and a new brick building was rededicated in 1888. The architect was George Coombs of Lewiston and the building was constructed by Libby and Green-

leaf of Auburn. Waterville contractor Levi Bushy & Son did the foundation. Fresco work was created by L. Habberstrom & Son of Boston, with most of the church’s impressive stained glass windows created by Redding & Baird of Boston. The present organ, by M.P. Moller, Inc. of Hagerstown, Maryland, was installed in 1956 at a cost of twenty thousand dollars. Renovation work has continued over the years with some of the most recent performed only several years ago by Tony Castro.

All of the stained glass windows are

memorials to people who were central to the life of the church. One window memorializes Hiram Belcher, the son of Supply and Margaret Belcher, born in 1790, and who moved to Farmington with his family in 1791. He died in 1857. Hiram was admitted to the state bar in 1812 and was described as “honest, with a dry wit, a good lawyer, over six feet tall, (a rarity in those days), and thin and gangly.” Mr. Belcher served as town clerk from 1814 to 1819, served in the state legislature for three years and in the Senate for two years as a Federalist in a Democratic town. He was a U.S. Representative for two years during the Polk administration, and the only Whig in the Maine delegation. His office was located where the present office of attorneys Joyce, Dumas, David, and Hanstein now sits.

The Thomas Wendall (1790-1862) window remembers the first clerk of the church and one of the original twelve

who organized the church in 1814. An anchor motif in the window apparently refers to when, at age ten, an orphaned Thomas Wendall served as a cabin boy on a privateer during the Revolutionary War. At age ninety he could recite most Psalms and the four gospels from memory. He helped to establish Farmington Academy. The Frederick Stewart (1806-1887) window remembers a man whose family helped in the construction of the new church building. He saw the plans but died a year before the building was completed. The plans are now in the possession of the Portland Historical Society.

The Martha Norton Blake (17861875) window was presented by her son who also donated the three thousand pound bell that sits in the bell tower. The bell tolls in E-flat and was originally designed to harmonize with the nearby F-key Methodist and A-key Baptist bells.

Much information is known about Robert and Mary Goodenow for whom another window is dedicated. Goodenow was the last Whig U.S. Representative from District 2, from 1850 to 1852. As a Congressman, Goodenow once dined with Daniel Webster. Their daughter, Ellen, married Ambrose Kelsey, the preceptor/principal of Farmington Academy, and later Farmington Normal School. The Goodenows lived at 80 Main Street, and Robert founded the Franklin Savings Bank in 1868. Many letters between Robert and Mary survive. In one, Mrs. Goodenow writes of her son Nathan, “I am sorry to say that he smokes a good deal and also chews tobacco. One of those habits I think is quite sufficient.” Nathan went on to be a colonel in the Civil War and later a successful Chicago lawyer.

The Good Shepard Window above the altar remembers Rev. Isaac Rogers, pastor of the church for thirty-two (cont. on page 54)

(cont. from page 53)

years until 1858. He was known for his “long prayers which served all of the purposes of a local newspaper. From them, members of the congregation learned of those who during the preceding week had been married, who were sick, who had died, gone on a journey, to college or back from college. No names were given, so it was a guessing game,” according to the writings of Lyman Abbott. After retiring in 1858, Rev. Rogers was allowed to live in the parsonage rent-free until his wife, Eliza, died in 1867. He died in 1872 at the home of Frederick Stewart. Rev. Isaac and Eliza were popularly called “Father and Mother Rogers” during his time as pastor.

A rose window remembers Reuben Cutler who joined the church in 1858 and was a deacon until the time of his death. It recalls the celebration of the Lord’s Supper. Cutler was part of the committee charged with selling the par-

sonage. Just three years later, the church bought it back to house its pastor.

A bronze plaque memorializes Mary S. Morrill who worshiped at Old South and graduated from Farmington School in 1884. She was active in the Sunday School class, and in 1889 went to China as a missionary in response to a Chinese student’s wish “that my mother in China could be told about Christ and his religion.” She was caught up in the Boxer rebellion in 1900 and murdered, and today is considered to be a martyr of the church.

Another plaque and baptismal front remembers Francis Gould Butler, given by his son-in-law, Dr. Charles Thwing, who was president of Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Mrs. Julia Butler was Thomas Wendall’s daughter.

by Charles Francis

Almost everyone who has taken up researching their family history and building a family tree has dipped into the internet at one time or another. Some have come to rely on this modern marvel almost exclusively. Others have given up on it as simply too daunting to navigate. As a general statement, neither reaction is appropriate.

The recent growth spurt in researching family history and the rapid expansion of the internet have gone hand in hand. According to various marketing surveys, genealogy sites rank either number two or number three of all sites.

Internet genealogy and family history sites range from those requiring a user fee to free ones. Some of the sites

are massive and require one to hop from one subsite or link to another. A major portion of the 1880 United States census, as well as that of the 1881 census for Canada and Great Britain, is there.

At the opposite extreme, one can find family history or genealogy sites put up by a single individual interested in collecting data about his or her family or in letting others know what informa-

tion they have. There is an interesting example of a site in the latter category involving the Clough family and Androscoggin and surrounding counties.

Androscoggin County genealogy and family history is well represented on the internet. There are sites devoted to local historical societies, cemetery records, and well-known or once well-known individuals. The internet site for the branch of the Clough family mentioned above is not an example of individual first-hand research but instead comes from several other internet sources. These in turn were taken from books on the Clough family, and therein lies the problem with the site. It is a third-hand or even fourth-hand (cont. on page 58)

With digital banking we don’t need to be close by or even open to provide you with account access.

There are over 170 credit unions in Maine and 5,000 in the USA where you can make transactions just like you do with us.

From youth savings to making retirement plans, we are here every step of the way to help you grow.

You will always speak to a real person right here at Oxford FCU who will do all they can to help.

(cont. from page 57)

account.

The first thing to realize about anything on the internet is that it is second-hand information. Historians refer to this sort of information as a secondary resource. Unlike primary resources, secondary resources are always suspect. They are the same as hearsay. Simply put, anything on the internet was put there by someone who had control over what went up. Information can be altered either intentionally or by error. This alteration can take the form of a misspelling or incorrectly sited date to a totally falsified story. Therefore, it is necessary to cross-reference any data one sees popping up on their computer screen with another source to be sure of its accuracy.

The above comments do not mean that the internet does not have uses, however. It is a wonderful way to see what others with the same interests as you are doing and of discovering what

is out there in the way of resources. In addition, for those who can’t get out and research, it provides easy access to secondary resources as well as books that can be acquired through interlibrary loan. There are a number of caveats to keep in mind when accessing family history and genealogy sites on the internet, especially those that charge fees.

One thing to remember is that the information genealogy sites offer for a price can almost always be found elsewhere for free. Census data, birth, death, and marriage records and the like are a matter of public record. You don’t even have to contact the particular government agency responsible for them to access them. They can be found in big libraries which in turn can be accessed by smaller libraries through interlibrary loan. Whoever put the data you want on the internet for a fee did so by copying something for free.

As far as accessing the internet for family history research is concerned, there are a number of “how-to” sites. Look for ones that were put up by reputable sources, though. One of the best belongs to the University of Toronto in Canada. While a bit heavy on Canadian genealogy, it does cover the best American and European internet sites. It is Using the Internet for Genealogy. Make sure you go to the University of Toronto internet site.

The National Genealogical Society has a page devoted to internet use. It is Genealogical Standards & Guidelines: Standards For Use of Technology in Genealogical Research. The Society also sets out other standards which serve as a guideline for the beginning family history researcher to evaluate material he or she runs across.

The most comprehensive source for genealogy research is the Family History Library of the Mormon Church in