3 It Makes No Never Mind

James Nalley

5 Preserving Hancock County’s Cultural Tapestry

The Ramassoc Chapter, NSDAR and the Old Jail

Betsy Arntzen

8 Sir Francis Bernard

Royal Governor helped survey Southwest Harbor

Brian Swartz

13 Pembroke’s Charles Herbert Best

Noteworthy scientist helped discover life-saving insulin

Wanda Curtis

18 The Angler’s Prize

Ellsworth’s Hollis Grindle catches a 31-pound togue

John Murray

21 Bar Harbor Becomes Fall Destination

Summerfolk stay for the autumn red

Phil Thibeau & Brian Swartz

26 Cherryfield’s Carlton Willey

From downeast Maine to the major leagues

Charles Francis

30 Albert Gallatin, A Swiss Founding Father

Bored in Boston and amused in Maine

Tom Reeves

36 Millinocket - The Magic City

The melting pot of Maine

Charles Francis

41 Bradford’s Parker Lumber Company

New owners carry on the legacy

Brian Swartz

44 Bangor’s Charles Peddle.... And the personal computer industry

James Nalley

49 Newport Celebrates Its Centennial A vision for the future of business

Charles Francis

52 Lily Bay’s Edward B. Jackson

The Santa Claus of Moosehead

Sean & Johanna S. Billings

57 John James Audubon

Bird illustrator inspired by downeast Maine

Kathy Claerr

61 Frederic Henry Hedge

Spreading transcendentalism in Maine

James Nalley

Publisher Jim Burch

Editor Dennis Burch

Design & Layout

Liana Merdan

Field Representative Don Plante

Contributing Writers

Betsy Arntzen

Sean & Johanna S. Billings

Kathy Claerr

Wanda Curtis

Charles Francis

John Murray

James Nalley

Tom Reeves

Brian Swartz

Phil Thibeau

info@discovermainemagazine.com www.discovermainemagazine.com

by James Nalley

t the time of this publication, it will be the midst of summer and tourists and Mainers will be enjoying the outdoors, which typically includes visiting the beach, exploring the mountains, or attending a local food/ music festival. However, for something a bit different, a new Maine tradition has emerged: touring wild blueberry farms. Now, before embarking on this blueberry quest, it is important to be armed with some knowledge about these blue fruits.

According to the British Columbia (BC) Blueberry Council, the blueberry (genus Vaccinum) is the one of the only commercially available fruits native to North America and the only food that is naturally blue in color. In this regard, the pigment (anthocyanin) is the same compound that ranks them number one in antioxidant health benefits (out of 40 fruits/vegetables). Blueberries were also called “star fruits” by North American indigenous peoples because of the five-pointed star shape formed at the blossom end of the berry. As for their consumption, they have been linked to reduced risk of cancer, increased insulin response, and reversed age-related memory loss. Surprisingly, a single bush can produce as many as 6,000 blueberries per year. Finally, the silvery sheen on the blueberry skins is a natural compound that protects the fruit.

As stated by the BC Blueberry Council, “This is why you should only wash blueberries right before you eat them. The berries should also be stored in the refrigerator, which will keep them fresh for up to 10 days.”

For those interested in nibbling on these small but mighty “superfoods,” there is the 5th Annual Wild Blueberry Weekend (August 2–3, 2025). In this month’s region, there are numerous farms offering tours, family-friendly activities, and of course, delicious wild blueberries. The following are just a few, in no particular order of importance. First, there is Blue Barrens Farm on 11 High Street in Cherryfield, the “Blueberry Capital of the World.” This multigenerational family farm dates back 34 years and offers a blueberry processing tour, with a complimentary slice of organic blueberry piece afterwards. Of course, fresh/frozen blueberries are for sale.

Second, for those interested in the science behind blueberries, there is the University of Maine’s Blueberry Hill Research Farm on US-1 in Jonesboro, the only university-based wild blueberry research facility in the country. There, researchers/students will provide tours about how blueberries are grown and harvested, including nutrition, water retention, and pest management.

Third, there is the Blue Hill Berry Company at 104 Front Ridge Road in Penobscot. Owned and operated by Ruth Fiske and Nicolas Lindholm for more than 26 years, they harvest up to 30,000 pounds of blueberries across five towns on the Blue Hill peninsula. They will be on hand to show a small wild blueberry field in production and provide tours of their new building, with the opportunity to purchase fresh/ frozen wild blueberries.

Finally, other participating farms in the region include Burke Hill Farm in Cherryfield; Copeland Hill Wild Blueberries in Holden; Lakeview Farms in Columbia Falls; Lynch Hill Farms in Harrington; Smithereen Farm in Pembroke; Welch Farm in Roque Bluffs; Wescogus Wild Blueberries in Addison; and the Wild Blueberry Heritage Center/Museum in Columbia Falls.

At this point, let me close with the following jest: An old man is dying, with his young grandson by his bedside. He asks his grandson to lean over and whispers, “Johnny, I smell your grandma’s blueberry pie, which just came out of the oven. Go to the kitchen and bring me a piece.” Johnny gets up. Two minutes later, he comes back empty handed and says, “Sorry grandpa. Grandma says its for after the funeral.”

by Betsy Arntzen

In the heart of coastal Maine, where currents of history converge, lies a testament to the enduring legacy of America’s past. The Ramassoc Chapter of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) stands as a guardian of this heritage, weaving together the threads of patriotism, education, and historic preservation.

Established in 1890, the NSDAR has been a stalwart defender of America’s narrative, inviting women with Revolutionary War lineage to join its ranks. Among its chapters, Maine State Organization Daughters of the Amer-

ican Revolution’s Ramassoc Chapter stands out for its unwavering commitment to preserving Hancock County’s rich historical landscape.

The Ramassoc Chapter, NSDAR based in Bucksport, epitomizes the convergence of history and community. Its establishment in 1976 coincided with a resurgence of interest in historical preservation across the state and the nation, marking the beginning of a new era of reverence for America’s Revolutionary War ancestors.

At the heart of the NSDAR’s Historic Preservation Grant mission lies the

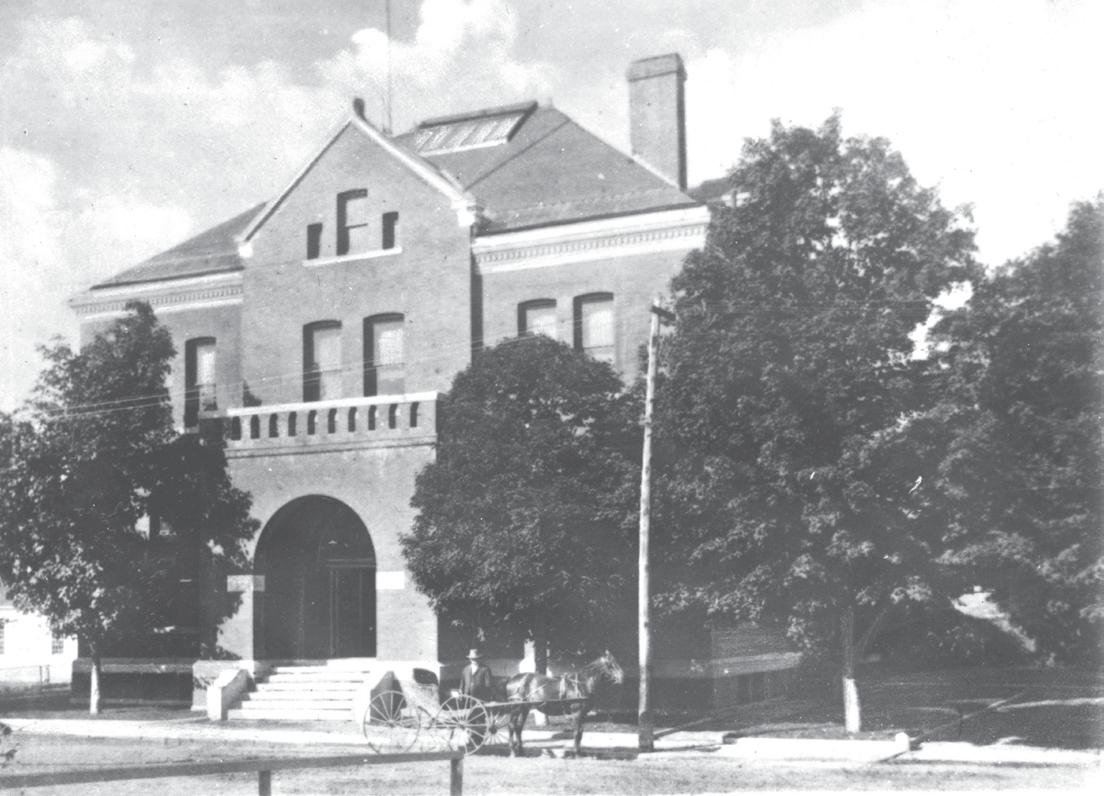

preservation of tangible remnants of the past, such as the Old Hancock County Sheriff’s Home and Jail (Old Jail), in the Hancock county seat of Ellsworth. Built in 1886 by notable Maine architect Frances Fassett, it is an architecturally significant building in Hancock County history. It is located in Ellsworth’s Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and located at a Southern entry to the federally designated Downeast Maine National Heritage Area. The building itself is an artifact. The sheriff’s home — finished in a style elegant for the (cont. on page 6)

(cont. from page 5)

19th century — is in the front half of the building, and the prison cells are in the rear half of the building. The sheriff with law enforcement staff was responsible for the legal details, and the sheriff’s wife was responsible for cooking and feeding those in the jail — passing food through a slot in the kitchen wall. This dual-function government structure is rare both in Maine and in the U.S. because it is unchanged and is being rehabilitated by the Ellsworth Historical Society (EHS) to reopen to the public as a museum. When the current jail was constructed, Hancock County Commissioners turned over the Old Jail to the EHS, its current owners.

Maine was under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts during the American Revolution, and Hancock County was incorporated in 1790, seven years after the 1783 Treaty of Paris and thirty years before statehood. The Ellsworth Historical Society has researched (pri-

marily from secondary sources) all of Hancock County’s jails and sheriffs from 1790 and forward. The first sheriff of Hancock County was Major Richard Hunnewell of Castine in 1790, serving for nine years, and the sheriff of the new 1886 Hancock County Jail was Civil War veteran Dorephus L. Fields of Ellsworth, who served for five years.

Today, the Old Jail faces the challenges of time, with aging materials and exposure to the elements threatening its integrity. Yet, thanks to the dedicated efforts of the Ramassoc Chapter, NSDAR this historic landmark is beginning its rehabilitation. Through initiatives like the NSDAR Historic Preservation Grant, the chapter can help to sponsor crucial support for local restoration projects, ensuring that future generations can connect with their shared history.

The impact of the Ramassoc Chapter NSDAR’s preservation efforts extend

beyond Hancock County’s Old Jail. Through community involvement and engagement, the chapter fosters a sense of pride and ownership in a shared heritage among residents, ensuring that the Old Jail as well as other historic preservation projects remain cherished symbols of Maine’s past.

For 48 years, the Ramassoc Chapter of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution has been dedicated to fostering education and citizenship among area high school students throughout Maine. Through various contests, honors, and awards, the chapter encourages students to excel academically and demonstrate good citizenship. One notable high school program and scholarship contest is the NSDAR Good Citizens Program, which recognizes a Senior student who exhibits outstanding qualities of leadership, patriotism, service, and dependability within their schools and communities.

Additionally, the chapter acknowledges exceptional work in American History through various NSDAR competitions and awards, one of which is the 11th Grade Excellence in American History Book medal and certificate, inspiring students to deepen their understanding of the nation’s past. Moreover, the Ramassoc Chapter also extends its rec-

ognition to elementary age students by presenting the NSDAR Youth Citizenship Medal Award to an eighth-grade student, exhibiting the values of Honor, Service, Courage, Leadership & Patriotism, rewarding the values of responsible citizenship from a young age. The chapter also awards an eighth-grade Excellence in American History Award Certificate, book and medal. Through these initiatives, the chapter empowers students across Maine to strive for academic excellence and make meaningful contributions to society.

The NSDAR’s mission focuses on preserving America’s heritage, with chapters like Ramassoc playing a vital role. Through dedication and stewardship, these chapters ensure historical continuity. Their efforts inspire future generations to cherish and protect Maine’s legacy.

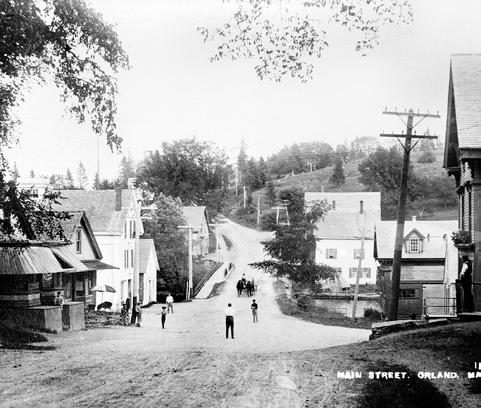

by Brian Swartz

Taking a breather from thoroughly irritating his subjects, Royal Governor Sir Francis Bernard sailed to Mount Desert Island in autumn 1762 to survey the countryside around future Southwest Harbor.

Named governor of Massachusetts Bay province in late 1759, Bernard was a hardliner, focused on enforcing Parliament’s egregious anti-colonial laws. Amidst the political bickering with the province’s general assembly, he decided to join surveyors sent to map a township or two on MDI.

At 5 p.m. on Tuesday, September 28, 1762, Bernard boarded the sloop Massachusetts off Castle William in Boston Harbor. The crew immediate-

ly weighed the anchor. “A thick fog arose” on Wednesday morning as the sloop “passed Cape Ann by [dead] reckoning” and steered for Portsmouth, the governor noted. Sailors avoided ship-killing Boon Island Ledge, and the “weather cleared up” around 2 p.m. Suddenly “a fresh gale arose” and sent the Massachusetts hurrying into the Piscataqua River’s estuary through “a narrow channel between frightful rocks.” Dropping anchor in Portsmouth Harbor at 4 p.m., the crew waited out the “great storm at sea” that swept the eastern New England coast that night.

After easing out to sea on Thursday morning, the crew steered east northeast as a west wind filled the sails. Ber-

nard watched as sailors “put out lines & caught some cod & haddock.” Passing the Wood Islands, Cape Elizabeth and Seguin Island to port, the sloop aimed for Monhegan Island and entered Penobscot Bay as the eastern sky brightened on Friday, October 1.

As the ship passed the Fox Islands, Bernard gazed eastward at the Mount Desert Island peaks, “at near 30 miles distance.” The Massachusetts dropped anchor above Fort Pownall (in modern Stockton Springs) at 11 a.m.; as the ship sailed past the fort, Bernard watched as the garrison “saluted us with 11 guns,” and the sloop “returned 7 guns.”

On Saturday the ship sailed at 7 a.m. and reached Naskeag Point at 11 a.m.

There Bernard noticed several ships, including the “Schooner with my surveyors on board.” They transferred to the Massachusetts, which took on a pilot and steered across Blue Hill Bay for Mount Desert Island. Rounding Bass Harbor Head, “we came into a spacious bay formed by land of the great Island on the left & one of the Cranberry Islands on the right,” Bernard noticed. The MDI peaks rose dramatically to port; then the ship’s bow swung that direction as “we turned into a smaller bay which is called South West Harbour. “This last is about a mile long & three-fourths of a mile wide,” Bernard observed. “On the North Side of it is a narrow opening to a River or sound [Somes Sound] which runs into the Island 8 miles.” With the sound visible, the ship dropped anchor “about the middle of South West Harbour” around 5 p.m. Bernard and the surveyors went ashore after breakfast on Sunday, October 3, took a compass reading, and

“went into the Woods” about half a mile. They found and followed a path leading past salt marshes to Southwest Harbor, then reboarded the Massachusetts

On Monday “we formed two sets of Surveyors,” went ashore, and selected “a point at the head of the S. West Harbour,” Bernard noted. Taking “different courses,” the two teams “surveyed that whole harbour except some part on the south side [future Manset].”

On Tuesday Bernard “surveyed a [Norwood] Cove in the North River [Somes Sound],” and on Wednesday he “& Lt. Miller surveyed the remainder of the S. W. harbour & a considerable part of the great harbor [Eastern Way].” The other surveyors “traced & measured the path to the Bass Bay creek.”

On October 7 sailors and a ship’s boat took Bernard and the surveyors up Somes Sound, “a fine channel having several openings & Bays,” the governor said. “We passed thro’ several hills

covered with woods of different sorts; in some places the rocks were almost perpendicular to a great height,” a scene found today at Valley Cove north of Southwest Harbor.

Eight miles above the sound’s entrance, “we turned into a bay [Somes Harbor] & there saw a settlement in a lesser bay,” Bernard noted. Going ashore with his companions, he walked to the log cabin built by Abraham Somes, the first white settler on Mount Desert Island.

The visitors found the cabin “neat & convenient, tho’ not quite furnished; & in it a notable woman with 4 pretty girls clean & orderly.” Near the cabin “were many fish drying,” and past the cabin the visitors walked to a beaver pond (apparently Somes Pond) and studied at least two beaver dams and the beavers’ “manner of cutting trees to make them.”

On Friday Lt. Miller “surveyed the [Greening] Island on the East side” of (cont. on page 10)

(cont. from page 9)

the Somes Sound entrance, noted Bernard, going ashore himself with a surveyor who “ran the base line of the intended Township.”

His mission accomplished, the governor had the sloop’s crew weigh anchor at 8:30 a.m., Saturday, October 9. Sailing for Boston, the Massachusetts reached Falmouth (later Portland) on Sunday, and Bernard “went about the Town” on Monday. “A very growing place” with “some fine houses there building,” Bernard noticed.

After reaching Portsmouth on Tuesday, October 12, he went ashore for good, his wife traveled up from Boston by coach, and the Bernards departed Portsmouth for Boston on the same coach on October 15.

by Wanda Curtis

One of Maine’s noteworthy medical scientists was Charles Herbert Best. His research helped to save millions of lives worldwide. He and Canadian physician/pharmacologist Frederick Banting co-discovered insulin, which soon became the drug of choice for treating diabetes. Charles also discovered the enzyme histamine and the vitamin choline. He was one of the first to suggest using the anticoagulant heparin to treat blood clots. He developed a purified form of heparin which was used to prevent blood clots during open heart and transplant surgeries.

Charles Best was the son of Herbert Huestis Best (a medical doctor from

Nova Scotia) and Luella May Fisher Best (a soprano singer, pianist, and organist). He was born in the small, rural town of West Pembroke (near Machias), where the economy was built upon sardine canning. Charles was raised and received his early education there. His father practiced medicine in West Pembroke while Charles was growing up.

According to Profiles, Before and After Insulin: Charles Herbert Best (1899-1978), Charles became involved in his father’s medical practice when he was only 12 years old. He would travel with his father to make house calls and help drive their horse-drawn carriage on winter roads and frozen lakes.

During emergencies, he would reportedly administer anesthesia while his father performed surgery on kitchen tables.

After graduating from high school, Charles enrolled in a general arts program at the University of Toronto but later switched to a physiology and biochemistry program. Students began to hear rumors of fighting in France, as World War I was raging at that time. Many, including Charles, enlisted in the Canadian military. He sailed for England to begin training for the frontlines in France.

The authors of the Profiles: Before and After Insulin article noted that, about the same time that Charles set (cont. on page 14)

(cont. from page 13)

sail for England, the Great Flu Epidemic was sweeping across the world. They reported that many on the ship contracted the virus and were buried at sea. However, Charles managed to escape the virus because, as he later explained, he was on mast duty each day keeping watch for other ships. That meant he slept on the top deck, apart from many of the other passengers. By the time that the ship arrived in England, 28 passengers had succumbed to the virus, but Charles survived. His life was spared, a second time, when World War I ended, shortly after he arrived in England. That was fortunate not only for him, but also for the millions whose lives were spared because of his medical research.

After he returned home, Charles resumed his studies at the University of Toronto. He was employed as a research assistant for Professor J.J. Macleod while completing his degree.

In 1971, Macleod shared Charles’ services with Dr. Frederick Banting, who was working on a project to develop a pure form of insulin to treat diabetes. Charles had a special interest in diabetes because his father’s sister (who was a nurse) developed adult-onset diabetes and died several years later.

According to the Diabetes Center of Excellence at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Charles and Banting were the first to isolate the insulin molecule. They conducted their research in a small University of Toronto lab where they removed the pancreas of dogs to induce a diabetic state in the dogs. They used the pancreases they had removed to produce insulin, which they injected into diabetic dogs. After several weeks they were producing insulin that was able to lower the blood sugar of diabetic dogs.

In January 1922, the pair began testing insulin on humans. The first patient

was 14-year-old Leonard Thompson (a Canadian boy who had severe diabetes). He was injected with insulin created from the pancreas of dogs, at Toronto General Hospital. The boy had an allergic reaction to the insulin. So, the researchers headed back to the lab to work on purifying the insulin. They succeeded in creating a more purified form of insulin from the pancreas of cattle. That insulin lowered the boy’s blood sugar to almost normal. Later that year, Charles followed in his father’s footsteps when he entered medical school. He graduated in 1925.

For their work with insulin, Banting and Macleod received a Nobel Prize. Charles wasn’t a recipient of the prize, reportedly because he hadn’t completed his medical degree yet. However, Banting volunteered to share half of his prize money with Charles. Likewise, Macleod shared half of his prize money with biochemist James Collip who

assisted the team with the purification of

As a dedicated researcher, Charles didn’t allow the lack of recognition to deter him from more lifesaving discoveries. Instead, he formed a second research team to continue working with insulin. He also created a more purified form of heparin. By 1935, heparin was used successfully to prevent clotting during open heart surgeries and was later used for transplant surgeries as well.

Though Charles was born and raised in a small, relatively obscure Maine town, he achieved worldwide fame by conducting some of the most important medical research in history. His work has helped to extend the lives of multitudes of diabetics and others with medical issues during the last century. Stonington High School girls basketball

by John Murray

The Algonquian and French Canadians called this great forkedtailed fish a togue. In Maine, this name is still affectionately used today for the cold water fish known as a lake trout. In retrospect, perhaps the name “togue” better suits this revered gamefish that inhabits the deepest lakes in Maine because, despite its appearance, the lake trout isn’t really a trout at all. In reality, this ancient fish is not an actual member of the trout family but is in the same family group as the arctic char. Togue are very choosey about the water they live in. For a togue to survive, the water must be clean and very deep and cold. The state of Maine has multiple lakes that have water depths in

excess of one hundred feet. This is directly linked to the Laurentide Glacier that carved out the basins for many deep lakes in Maine more than ten thousand years ago. As the thick mass of glacial ice pushed in a southeast direction the landscape was roughly scoured to the bedrock. When the ice melted, fresh water filled the deep depressions and formed giant lakes. This long-lasting glacial event was cataclysmic to the previous landscape and was linked to the extinction of many species of animals including the wooly mammoth, saber-toothed tiger, and dire wolf. Yet in the aftermath togue flourished and are numerous today throughout a large portion of Maine.

Residing in cold water aids in the longevity of the togue. Biologists are certain that the togue can live a life span that exceeds thirty years. When the ability to live for many years is combined with a voracious appetite the end result is a fish that can achieve truly huge body sizes. Understandably, big gamefish develop a loyal fan club of diehard anglers, and many anglers fish the deep lakes of Maine with the hope of hooking onto a large togue.

Among these anglers was a man named Hollis Grindle, and during the third day of August in 1958, Hollis Grindle would catch the biggest togue ever caught in Maine. A record that still remains unbroken to this day, near-

ly six decades later.

A native resident of Maine, Hollis Grindle lived in Ellsworth in Hancock County. In the 1950s fishing was a popular pastime with Mainers and those who visited here. Yet for Grindle, fishing wasn’t just an occasional venture. Grindle fished often and enjoyed it immensely. When Grindle wasn’t actually fishing he was thinking of fishing, and those thoughts occupied his mind often while he was at his highway maintenance job. In the time leading up to the day when he would capture the record fish, Grindle already had spent many days at his favorite fishing spot which was Beech Hill Pond in Otis. As soon as the departing winter ice left, Grindle was in a boat and regularly prowling the water for togue.

Grindle shared his passion for fishing with his good friend Bernard Lynch, and they were both experienced fishermen who knew the secrets of catching togue. In 1958 Grindle and Lynch were already having a superb fishing season

on Beech Hill Pond. That particular season they had already brought thirty large togue to the net. Their key to success was constantly adjusting tactics to follow the moving fish as the weather of the season changed. In early spring the togue would be feeding near the cold surface of the water but as the summer heat warmed the water the togue would spend all their time in the deepest depths.

To reach the togue in the deep water the anglers would use a lead core fishing line that was heavy and sank rapidly into the depths. 30 feet of strong monofilament was attached to the end of this lead core line and the baited hook was connected to the business end of the rig. The bait of choice was a shiner minnow or smelt and both of these items were relished by the togue. Trolling was the most efficient way to cover the most water and was the preferred tactic of Grindle and Lynch. The angler’s outboard motor was run at a low idle to move the boat slowly along (cont. on page 20)

(cont. from page 19)

the surface of the water as the baited hook was pulled along underneath the water behind the boat.

On Sunday August 3rd Grindle and Lynch arrived at Beech Hill Pond early in the morning and discussed their fishing plan as they launched their boat from the dock. The term ‘Pond’ is a misleading word in regards to the size of a body of water in Maine. This particular pond — Beech Hill Pond — is quite large at half a mile wide, 4.5 miles in length, and 104 feet deep. By 6 a.m., fishing lines were in the water and they were starting to probe the depths. Summer fishing is considerably more challenging because the elusive togue may be anywhere in the deep water of the lake. It wouldn’t be until 3 hours later that Lynch’s rod bent with the weight of a fish and a 9½ pound togue was brought to the net.

Afterward, Grindle decided to get his bait to a depth of sixty feet and they

brought the boat through a promising section with cliff banks that was known as “the ledges.” Nearly at the end of the run where the anglers would turn the boat for another pass through the area, Grindle’s line went tight. Initially thinking that he may have snagged the bottom of the pond, he was shocked when the fishing line began to rapidly strip the line from his reel.

What ensued next was the fishing battle of a lifetime. The big togue bulldogged downward and shook its head then changed tactics and decided to swim for parts unknown. Unable to stop the forward progression of the togue, the fishermen turned off the outboard motor and the big togue actually towed the heavy boat for a considerable time. Grindle was able to keep his wits and after a nearly 30-minute battle with the beast, the togue finally began to tire. At last the big togue came to the surface near the boat where Lynch was able to

scoop him up inside a long-handled aluminum net. Upon lifting the heavy togue into the boat the weight of the togue even bent the handle of the net. The big togue was brought into town where it was officially weighed and measured. Shockingly, the togue weighed 31 pounds, 8 ounces, and had a girth of 24 inches — with an incredible length of 41 inches. With that weight, the togue was officially confirmed by Maine fishery biologists the new state record. That record remains unbroken to this day.

Hollis Grindle always thought there was bigger togue in Beech Hill Pond and continued to fish with the hope of catching a larger togue. Alas, that prize usually occurs just once in the lifetime of a lucky angler and Grindle was never to top his own record. Today, other anglers have the same hope of catching the largest togue in Maine.

by Phil Thibeau & Brian Swartz

Several million people annually visit Mount Desert Island, Bar Harbor, and Acadia National Park today. There was one particular summer before the park existed that summerfolk also packed MDI.

“It has been a rather odd season,” a Bar Harbor Record journalist opined in late summer 1902. “Seldom have we seen so large a colony of summer visitors as this year.”

People visiting MDI that summer either arrived by ship — various steamers called at the island’s ports — or by riding the Maine Central Railroad to Washington Junction in Hancock. From there a special train took well-heeled passengers and their servants and bag-

gage to a Hancock dock to board a ferry crossing Frenchman Bay to Bar Harbor. Seeking to escape urban heat and summer diseases in America’s large East Coast cities, wealthy families relocated to MDI each summer. Palatial cottages dotted the island, especially in Bar, Northeast, and Seal harbors, and many island residents worked at the different estates.

Summerfolk transferred their lifestyles to MDI. Gentlemen played golf at the Kebo Valley Club, which “never justified itself more convincingly than it did this season,” the journalist observed. From elsewhere in the United States came reports “that golf had lost its hold,” but not at Kebo, where “from

the official figures there has been no falling off in the number of players.”

More than golf took place at Kebo. Tennis had regained its popularity and had the swimming pool been “finished in time … there is no doubt” it “would have been a most popular spot for morning sessions.” At Kebo, “the dinner dances were a positive boon,” the journalist thought. “The crowds that came in to dance after dinner overflowed the limits of the main room in the club.” Perhaps the club’s directors could add a ballroom in 1903 “to accommodate several hundred guests” at a time?

Summerfolk spent time at sea, yet “the yachting season, while filled with (cont. on page 22)

(cont. from page 21)

events, lacked interest” that summer when larger private yachts “completely outmatched” most “boats in the 30-footer class.” That did not deter the social elite from holding sailing parties on their private yachts. Summerfolk also entertained at home, but “there has seldom been so few affairs of note,” the journalist said. Despite that lack (which likely referred to social events attracting the glitterati), “in a general way there was a great deal of entertaining … as usual it centered mostly about food. Dinners have been the hostess’ mainstay,” keeping private chefs and kitchen staffs busy.

Summer residents could rent saddle horses or horse-drawn conveyances (including buckboards) at a Spring Street stable in Bar Harbor. Not far away in a Main Street gallery, the well-heeled could shop for “rare antique ceramics,” “enameled cabinet curios,” and “artistic inlaid furniture.” Caterers, mil-

liners, and plumbers advertised their services. Whatever the wealthy summerfolk needed, Bar Harbor businesses could provide. Even the Maine Central Railroad got into the act by offering “a delightful sail across the bay to Sorrento,” where passengers could enjoy “a delightful six-mile drive, known as the Circuit drive,” around the town.

June passed into July, which folded into August. Late that month the journalist reported, “The hotel registers continue a good list of arrivals, and it can hardly be said that the tide has set” for summer’s end, since “practically none of the cottage people have yet begun to contemplate a return to the cities.”

In late August, Seal Harbor’s two hotels reported no “serious decline” in arriving guests. People flocked to Seal Harbor for the August 30-31 ceremonies to dedicate the new Congregational church, “a very pretty little structure

of stone and wood.”

September arrived, “but the social army shows no disposition to strike camp and move cityward,” the journalist reported. The “most perfect” weather had convinced many summerfolk to stay “who would have gone a fortnight ago.” In fact, “the breakup of the summer colony” would not be decisive until “well towards October. “The autumn days that seem more beautiful and invigorating here than anywhere else are gradually winning over many converts to a long stay, and the cottage element” — a delightful term — “generally have their establishments until November.”

Then in early September the journalist noticed that “far up through the deep green arches of the Gorge” separating Cadillac and Dorr mountains that “the Red God has come again.

“One scarlet tree amidst the forest people flings wide its open arms against the deep leafy green,” wrote the

Come experience a timeless railroad journey on board the Downeast Scenic Railroad. Enjoy a ride on restored passenger cars, pulled by a vintage locomotive, on a rail line completed in 1884. Learn about the history of rail travel from a time gone by. Trains depart Saturdays and Sundays from Washington Junction for this excursion of approximately one hour and thirty minutes.

by Charles Francis

When I was a kid growing up in the 1950s, major league baseball was a lot different than it is today. There were no instant millionaires or players getting in trouble with the law over everything ranging from beating up a girlfriend to drug abuse. The idea of a player strike was something that no one believed possible. The players then were ‘the boys of summer’ who went out to do their best, improving their team’s standing and possibly making it to the playoffs. At least that was the way it seemed. It was a nice simple black-and-white scenario. If you lived in Maine you were a Red Sox fan and hated the Yankees. That was the rivalry that invoked the

deepest passions and the one that made baseball fun. Then, things changed. Old established teams began to move and it became necessary to adjust to strange names like the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Francisco Giants. Baseball was suddenly big business. There were even expansion teams. Looking back on those years now, it seems like the last time major league baseball was fun was when the Mets came along.

In their first years, the Mets gave some old players that otherwise would have been out of the game another season or two in the sun. They also gave some young players, who were nothing more than journeymen minor leaguers, a shot at the big time. The antics of

some of them on the field were fun to watch. Then, there were the few bright stars like Tom Seaver, Ed Kranepool, and Bud Harrelson who began to show promise around 1963. Backing them up was a pitcher by the name of Carlton Willey.

Carlton Willey was a downeaster from Cherryfield. In 1958 he was Rookie of the Year with another of those teams that moved, the Milwaukee Braves. With the 1963 Mets, Willey pitched four shutouts and had an amazing 3.10 E.R.A. Part of what made Willey’s E.R.A. so amazing was the fact that the Mets fielding was just beginning to show signs of jelling. Maine has produced a few players

who made it in the big leagues. In recent years, these include Billy Swift and Mike Bordick. In the distant past, there was Freddy Parent of the 1903 World Series-winning Red Sox, and Jack Coombs, who won twenty-four games in 1906 and pitched thirteen shutouts overall.

As a Maine baseball player who made it in the big leagues, Carlton Willey seems sort of a bridge between the players of the past who were real heroes and played for the love of the game and the ones today who are sports businessmen. Part of the reason Willey seems more real than the players of today is that his baseball career was interrupted by a tour of duty in the military, The fact that Willey was drafted somehow makes him more of a real person, subject to the vagaries of life even if he also did a really good job entertaining us when the Braves and the Mets were on television.

How does one make it to the major

leagues from Cherryfield? The answer is – you try out. No big league scout is going to watch a high school team in eastern Maine, especially when it has a graduating class of twelve.

Carlton Willey was nineteen when he tried out for the Braves in 1949. At the time, the Braves were still in Boston and routinely sent a scout to the Bangor area. The scout asked Willey to come to Boston for a closer look. Willey must have impressed the Braves there as they signed him. According to the records, he had a fastball that routinely zinged along at over ninety miles an hour.

Willey played a couple of years in the minors before being drafted into the military in 1953. After two years in Europe, he returned to the Braves who were now in Milwaukee. In 1958, in his first game in the big leagues, he pitched a shutout. It was against the Giants who had batters like Willie Mays and Orlando Cepeda. Unfortunately for Willey,

the Braves had a solid pitching staff at this time. The rotation was Warren Spahn, Bob Buhl, and Lew Burdette. Willey didn’t break into the rotation. Nevertheless, he was named Braves’ Rookie of the Year. He also pitched one inning in the 1958 World Series against the Yankees, putting down the side. Willey spent five seasons playing with the Braves before being traded to the Mets in 1962. Playing with the Mets, Willey displayed his usual hustle and dedication to the game. That hustle resulted in his being hit with line drives on innumerable occasions. One broke his jaw. All told, Willey played three years with the Mets. 1963 was his best year. After that, he won just one more game. Today, however, he is regarded as one of the team’s first true All-Stars. Willey’s last stint in baseball was as a scout for the Phillies. He was with them for nine years. After that, he returned to Cherryfield where he worked as a painter. At some point, a sign went (cont. on page 28)

(cont. from page 27)

up at Willey’s home reading “Ridge Road Old Men’s Club.” One can but wonder if baseball is ever a subject of discussion among club members, especially around World Series time or when the Braves or Mets are driving for the pennant.

Today, Carlton Willey baseball cards draw respectable prices with collectors. Some have gone for as much as twenty dollars. Recently one of Willey’s cards had the dubious distinction of being placed in the top five of ‘Baseball’s Ugliest Players.’ The group also includes Warren Spahn and Honus Wagner. Much more noteworthy, however, is the fact that Sports Illustrated has recognized Carlton Willey as one of Maine’s fifty greatest all-time athletes.

by Tom Reeves

Albert Gallatin was born on January 29, 1761 to a wealthy Swiss merchant family. The city he grew up in, Geneva, had a population of about 25,000 and was part of the Swiss Confederacy.

Upon graduating from the Academy of Geneva in 1779, where he finished first in his class in Latin translation, mathematics, and natural philosophy, Gallatin and another classmate, Henri Serre, contemplated where they might find a life of adventure and make a fortune. From a nineteen year old perspective, what better place to realize this

dream than going to a vast, uncharted, emerging nation across the Atlantic.

On May 27th they set sail for America. Their bold aspirations were not without some protective buffer. Prior to leaving, Gallatin had secured through family intermediaries letters of introduction from Benjamin Franklin who at the time was the American minister in Paris. He also had used some family funds to purchase tea which he planned to sell for a profit in the colonies to gain additional start-up capital for his commercial ventures.

After a month and a half journey

they reached Boston on July 15th. It did not take long for the pair to realize that they had miscalculated. With the ongoing war the economy of Boston was at a standstill and they were unable to sell their tea. Their travel plans to venture south to Philadelphia were also stymied by the war. Gallatin describes Boston as a city having about 18,000 inhabitants occupying an area larger than Geneva for “there are gardens, meadows, and orchards in the middle of the town, and each family generally has its own house…” He was thoroughly disenchanted with the social conditions. He

wrote: “We’re very bored in Boston. There are no public amusements…” and “the inhabitants are neither refined, nor honorable nor educated; they are quite full of themselves…”

At the tavern where they were staying they meet another Swiss couple who were planning to go north to the last settlement in the colonies reachable only by sea. Having few other options, and the appeal of living in one of the most remote frontiers in colonial America, they decided to join them. Before leaving Boston they bartered their tea for rum, sugar, and tobacco believing these goods would be more merchantable. Their destination was a township incorporated by the Massachusetts General Court just 10 years earlier. In its grant the General Court cautioned that “As the township is remote from the center of the Province, and at a great distance from his Majesty’s surveyor of wood and timber, the Petitioners were required to take special care not to de-

stroy or cut any of his Majesty’s timber on or about said township.”

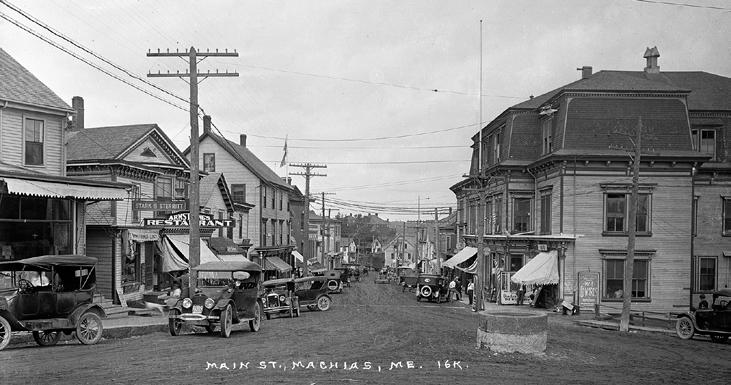

They set sail on October 1st and they found that that journey was even more perilous than their Atlantic crossing. After two weeks of travel they reached their destination of Machias on October 15th. It was a tiny settlement consisting of a core of 20 houses, a small garrison, Fort Gates, and 150 families spread over ten square miles. The region’s economy was based on subsistence and barter as the inhabitants possessed no currency and therefore the supplies Gallatin and Serre brought had no market value. As a last resort they gave their goods to the men at the garrison in exchange for a promissory note for $400 from the state of Massachusetts. When they attempted to redeem it, the treasury of the state was so insolvent it provided only $100 for the note.

Despite these hardships they sought to engage in their new home. They attempted to settle a lot of land in what is

today nearby Perry as “a beginning of a homestead” and cut hay in a meadow for that purpose. They survived by being woodcutters. They also acted the role of young adventurers, having a good time and invited friends to visit them in Maine. In what is one of the earliest promotion of Maine as a place to vacation, Henri Serre wrote in one of his letters:

We dwell in the middle of a forest on the edge of a river; we can hunt, fish, bathe, go skating when we like. At present we warm ourselves merrily before a good fire, and what is better is that it is we ourselves who go to cut the wood in the forest. You know how we amused ourselves in Geneva. Well, I still amuse myself here by sailing in the canoes of the Indians. They are constructed of the birch bark and are charming…

They explore Passamaquoddy Bay in the wintertime “with a kind of ma(cont. on page 32)

(cont. from page 31)

chine which is attached to one’s feet, called snowshoes…”

After a year of living in Machias they decided to return to Boston, for as one biographer of Gallatin observes that “despite the Rousseauesque attractions of the wild, Gallatin had no desire to spend another winter in the place.” They set sail back to Boston in October 1781, the same month that the Battle of Yorktown was fought, the last major military operation of the War of Independence.

It is out of this inauspicious beginning that a foundation was laid for a legendary career. Twenty years after leaving Machias, Gallatin in 1801 was nominated by President Jefferson to serve as Secretary of the Treasury. He served both Presidents Jefferson and Monroe in this post until 1814. No person ever held this post longer. He reduced the U.S. debt which allowed the

federal government to finance the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 through a favorable bond issue. It is an ironic twist, that as a perspective settler in Machias Gallatin was unable to secure a single lot, and as Treasury Secretary facilitated the doubling the size of the country.

In 1808 he issued a report, Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the Subject of Public Roads and Canals, which envisioned linking the country together by a system of canals and roads. His report called for “a great turnpike extending from Maine to Georgia in the general direction of the seacoast and main post road, and passing through all the principal seaports.”

To keep the costs manageable, Gallatin proposed that the 1,600 mile long road be built for passengers rather than for the transport of heavy articles so that “the expense cannot exceed the rate of 3,000 dollars a mile.”

After a long public service career Gallatin moved to New York City and took a leading role in the founding of New York University in 1831 for the purpose of providing “a system pf rational and practical education fitting for all and graciously open to all.” In 1832 the university opened with a student body of 158 and a faculty of 14 including the artist Samuel Morse. Within a few years after opening, the university established an Arts in Design department, the first one in the United States. Morse would use his faculty appointment to pursue other interests in communications which would significantly impact the history of the United States, Maine, and Washington County. Today New York University is one of the leading research universities in the country. With a faculty of over 3,100, and a student body of nearly 40,000, larger than the entire popula-

tion of Washington County, the scale of the university would be unrecognizable to Gallatin.

Over the years, Gallatin received numerous honors and place names. New York University has a school named after him, and one of the buildings at Harvard’s Business School honors his name. In Montana there is the Gallatin Mountain Range as well as the Gallatin River. Outside the Treasury Building on Pennsylvania Avenue, adjacent to the White House, there is an eight-foot-high statute commemorating his achievements. In Down East he is virtually unknown, and his presence is as tangible as its coastal fog.

As for Down East today: it endures as a rural idyll, timeless, an outlier retaining many traits which Albert Gallatin himself would recognize.

Moosehead Cedar Log Homes, Maine's largest "home-grown" cedar log home, cabin, and garage manufacturer is ready to assist with your new structure planning for 2025 or beyond!

MCLH offers "One-Stop Shopping" with in-house sales & design services - available by appointment, at (2) local Sales Offices, in Dover-Foxcroft and Houlton - call or email today to schedule a visit. MCLH features custom "to your desires" pre-cut log materials packages, In-Stock "Readyto-Ship today" camp/cabin and garage kits, multiple log sizes & profiles, and as part of the Pleasant River Lumber family of companies, access to a variety of State of Maine produced products, such as framing lumber (PRL), metal roofing (Crescent Metals), custom cabinetry (Woodsmith's Mfg.), and many more new home construction related products (Ware-Butler Bldg. Supply).

Check us out on Facebook and visit our website - www.mclh.net - for exciting new updates and additional information on other available cedar products - T&G paneling, log siding, decking, etc.

Plus, stay

by Charles Francis

The sounds of happy laughter filled the schoolyard of Millinocket’s new grade school. Children ran and played. “Look at me,” six-year-old Andreas called to Helvi as he hung upside down from the front step railing. Immediately he was joined by Levi and Gino who called out to their friends to see what they were doing. The children had only been in Millinocket a short time but already they had established friendships and connections as if they had always been together. That Helvi’s parents came from Finland, that Andreas was Hungarian and Gino Italian made absolutely no difference to them nor did it to Levi, who had recently moved to town from Cherryfield. They

were simply kids more alike than dissimilar regardless of where they came from or what language their parents spoke at home. They were a part of the melting pot that was Millinocket at the turn of the century.

Workers and their families came from almost everywhere, drawn to the “miracle city” of the north in Maine. There were mill and construction workers from as far away as Eastern Europe. There were shopkeepers and businessmen from the Maritime Provinces of Canada. There were chemists and engineers from the elite colleges and universities of the east, and there were executives from the leading industrial centers of the country. They came to

be a part of something new, the birth of the first paper company to be built at its source of supply, the Great Northern Paper Company.

Plant production was scheduled to start September 1, 1900. Yet, in January of that year nothing had been done to even clear the land where Great Northern’s mills and the future town of Millinocket would stand. In February the company sent construction boss John Merrill to Boston. Here he recruited Italians, Poles, Finns, and Hungarians as workers. These were joined by Downeasters from Hancock and Washington counties fresh off railroad construction. They were all brought in on the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad.

By May over 500 construction workers were hard at work along Millinocket Stream. A month later there were more than 1,000. 400 Italians settled what came to be called “Little Italy” on one of the public school lots belonging to the town on the east bank of Millinocket Stream. First they lived in hastily thrown up shacks — they had no time to build more — then the shacks were replaced by modest homes — Great Northern’s land agent allowed no house to be erected for under $750. The Finns, Poles, and other ethnic groups settled in similar little communities.

In 1899 there had been a single farm on the bank of Millinocket Stream. Then Great Northern purchased some 500,000 acres of virgin timberland in the region. Suddenly a town materialized as if out of thin air. By June of 1900 there were over 100 houses. When the mill opened in the fall there were forty more and Millinocket had a population of just over 2000. The first

church in town, a Catholic church, had been built. The Windsor House was accommodating visitors, and it would soon be followed by the Great Northern Hotel. A school was under construction. Millinocket had jobs to offer and workers came to fill them and they stayed. Laborers earned $1.50 a day, skilled workers, $2.00 to $2.50, and machine men, $3.00 to $5.00. There was no reason for men to leave good paying jobs like these and so the most culturally diverse town in Maine was born.

Historians tell us the United States is a “melting pot.” At least it was around the turn of the century. Immigrants came from all over Europe to build a life in America’s land of opportunity. At first they settled in ethnic enclaves. Then as time passed they, or more likely their children, mingled with peoples of different backgrounds, cultural distinctions blurred. This is what happened in Millinocket, for the town was a microcosm of the country.

In those early years Millinocket was a boom town. A boom town, if it is to endure, needs professional men, businesses, and stores. It needs organization, leadership, and dedication to a better future. Millinocket attracted men and women who were all these things and more.

The first doctor in Millinocket was Charles Bryant, who came from Plainfield, New Jersey. Bryant was just the sort of man to help build this new community. He was twenty-six when he arrived in town in 1900, fresh out of Harvard Medical School. Not only did Bryant provide excellent medical attention to his patients, but in 1920 he opened his own hospital. Millinocket was a magnet for men like Charles Bryant, people who were prepared to serve and build in their new hometown. The first general merchandise store was opened in 1900 by Gilbert Moran. Moran had been born in Forest City, New Brunswick and had established (cont. on page 38)

(cont. from page 37)

a clothing store in Island Falls. When news of the new town being hewn out of the wilderness reached him, he decided to get in on the ground floor. By the 1920s Moran’s store was the largest in town, and Moran was one of the many prominent civic leaders in the community.

Another of Millinocket’s settlers of 1900 who typified the town’s ethic of community service, was Frederick Gates. Gates came from Old Town, where he had served as city marshal and chief of police. He was Millinocket’s first police chief and in 1906 he also became fire chief. In addition, he served as chairman of the Board of Health and as road commissioner.

It was, however, the people who came to work for Great Northern who were the most committed to the development of a strong and stable community. One of these was George Stearns, Great Northern’s real estate agent who

was responsible for selling building lots on company land. Stearns, in addition to being chairman of the Board of Selectmen, was superintendent of schools. Under his direction the first schoolhouse was built in 1901. The two and one-half story clapboard structure cost $20,000, a huge sum for the time. It had seven classrooms, a library, and administration offices. In addition, Stearns saw to it that only the best teachers were hired.

By 1910 another schoolhouse had been built and nearly 500 children were attending classes. All of Millinocket’s teachers were experienced, perhaps because the town paid them $10 to $15 a month above the state median salary.

Mililinocket was a community of young families. The enrollment ages of school children in 1910 clearly show this. The high school, grades ten, eleven and twelve, had twelve boys and twenty girls. This was a class A high

school — one of the few in the state — offering classical courses as well as general.

It was in the primary grades where the great numbers of Millinocket school children were to be found. First grade had 174 students, second, 84, third, 66, fourth, 59, fifth, 52, sixth, 39, seventh, 36, eighth, 21, and ninth, 24. It was in the elementary grades where the children of European, Canadian and American backgrounds met and mingled to form Millinocket’s melting pot. While their parents were busy creating their own social institutions, the children were breaking down barriers and creating their own society.

By 1904 Millinocket had fourteen secret societies, including the Masons, several Independent Orders of Foresters, the Knights of Columbus, the Knights of Pythias, the Red Men, and two Loyal Orange Institutes. In addition, the town had several church-

es — Catholic, Episcopal, Baptist, and Congregational. This is not to imply, however, that the adults isolated themselves along cultural lines.

It is said that music breaks down barriers. This definitely was true in Millinocket. In 1903 the Millinocket Band, a brass band, was organized. It quickly became recognized as one of the best in Aroostook and Penobscot counties. Later the Philharmonic Club was formed to promote musical culture. The group had nearly fifty members. There were also a number of music teachers in town, including Mary Campbell, who taught violin, and Mae Weeks, who taught piano.

The story of the birth of Millinocket and Great Northern is a single story. Before any paper was produced at its mills the company invested some $3,000,000 in its plant and the community. That Great Northern was willing to invest in the town is one reason why

people of such divergent origins chose to stay. Today the traditions of Great Northern’s founders and the town’s first settlers live on. Nowhere is this clearer than in the support the townspeople give to the athletic teams of Stearns

the school

for the town’s first superintendent of schools. When the basketball team won the New England championship, it was to the applause of all the town’s residents.

by Brian Swartz

After growing up in New Jersey, brothers Jeff and Don Parker moved to Maine in the late 1970s. They purchased a two-person sawmill and set it up in 1980 at 511 Middle Road in Bradford.

That was the first mill on the site, said Brian Parker, Jeff’s son. Parker Lumber Company initially sawed “hardwood, softwood, a little bit of everything, but for the last 30 years it’s been predominantly eastern hemlock with lesser amounts of spruce and eastern white pine.”

An automatic mill replaced the two-person sawmill in 1983. Jeff and Don “built a brand-new mill” in 1987 that “improved efficiency” at what “has always been known as a timber saw-

mill,” Brian said.

He “grew up right next door to the mill.” At age 3 Brian stacked “stickers,” which are “narrow pieces of wood that you put between each layer” of airdried lumber. On his seventh birthday, “before the mill fired up for the day, I sawed my first log. My uncle stood over me and showed me what to do.”

The sawmill burned in 1997. Jeff and Don immediately built a new sawmill. Selling its products “all along the Atlantic Seaboard,” Parker Lumber Company employed around 24-25 people, Brian said. He joined the company full time in 2009.

Brian purchased Parker Lumber from Jeff and Don in 2012. “A big challenge was keeping a sufficient labor

force. Operating in a rural area and in this type of business, you need people who are physically strong and mentally sharp to perform” the work, Brian said. “We have to constantly find markets, which are ever changing,” he said. “What sells well one year may not sell well the next year.”

Brian called Jonathan Davis one day in 2015 and offered him the position of operations manager at Parker Lumber. Growing up in North Carolina, Jonathan worked in a family-run truss-manufacturing plant at age 17. Becoming a structural systems designer at age 19, he later worked for other companies. Jonathan’s wife, Kristy, is from Maine, primarily from Corinth with “family roots in Bradford. Both sides (cont. on page 42)

(cont. from page 41)

of my family are from Bradford.” She was working as a pediatric occupational therapist when the Davises decided to move to Maine with their two children, Ellie and Alexander, to be closer to Kristy’s family.

Jonathan worked at Mainely Trusses in Fairfield. “Parker Lumber Company was one of our customers,” and he corresponded with Brian Parker only by phone. Then one day “Brian made a call to me and asked if I would be interested in helping to run his company.” Jonathan drove up and visited the sawmill.

After discussing the job offer and praying about it, “we took a leap of faith,” he said. As operations manager, Jonathan learned the production process, met the employees, and became familiar with Bradford and the surrounding areas, where most employees lived. “Being a family-run company, you work closely with the guys; you

get to know them well,” Jonathan said.

Deciding to sell Parker Lumber in 2023, Brian asked Jonathan and Kristy if they would buy it. “Jonathan knew the business inside and out, better than any other potential buyer,” Brian said. “I trusted him to carry the torch.”

After carefully studying the proposal and praying about it, the Davises bought the company on June 28, 2024, and renamed it Timber Ridge Sawmill & Lumber. The “specialty timber mill” buys all its logs in Maine, from within a 100-mile radius of Bradford, Jonathan said. Annually producing 9 million to 11 million board feet, the mill converts every bit of a log into various products, including timber, siding, dimensional lumber, v-match, and shiplap.

Timber Ridge recently introduced a double-lap clapboard called Ridge Clap; although the same shape as 1-by8-inch clapboard, it goes up much faster. Eastern white pine V-match “is very

popular,” Jonathan said. The company ships wholesale “all over the United States and into Canada.” and retail sales extend throughout Maine and New England.

Kristy works together with Jonathan to help “make this a great place for our employees and customers” and to support the community, Jonathan said. The Davises are proud to carry on the Parkers’ legacy. They are honored to work alongside their amazing staff of more than 20 employees, many of whom have been with the company for more than 20 years. Jonathan and Kristy have immense respect for what the Parker family built and will strive to keep Timber Ridge Sawmill & Lumber one of Maine’s strongest forest-product businesses.

More information about Timber Ridge Sawmill is available at timberridgesawmillandlumber.com.

by James Nalley

When discussing personal computer (PC) systems and microprocessors, the names Bill Gates (Microsoft) and Steve Jobs (Apple) come to the forefront, since they revolutionized the PC experience and laid the foundation for the so-called Information Age. Although not one of the better-known names in the world of PCs and microprocessors, a Bangor-born man named Charles Peddle was equally important. In this regard, technology journalist Phil Lemmons in 1982 wrote, “More than any other person, Peddle deserves to be called the ‘founder of the personal computer industry.’ He made the personal computer possible.”

Charles (“Chuck”) Ingerham Peddle was born in Bangor on November 25, 1937. Regarding his upbringing, his father was a successful farm machinery

salesman immediately after World War II. However, according to Peddle in a 2014 interview with Douglas Fairbairn and Stephen Diamond of the Computer History Museum, “And then he was ill. Right after the war, all the doctors had come back believing penicillin was a wonder drug. And they almost killed him because by that time, they discovered that maybe it was good for about 90% of the people. For other people, it was literally a poison. So, my father never really recovered from that, and we grew up poor.”

The day after he graduated from high school, his mother urged him to find a job based on one reason: “Because we can’t afford you.” In this case,

Peddle stated, “So, I went out and got a job doing pick and shovel on the road. I was really good at it because I worked hard. And they treated me nice because I was good at it. But 12 hours a day at the dumb end of a shovel is hard work. Working on a computer for 24 hours a day is not.” After a summer working on the road gang, he decided to attend the University of Maine, where he graduated with a degree in engineering in 1959.

Peddle began his career at General Electric, where he had a wide range of engineering duties in defense and commercial systems during his 11 years with the company. According to him, “For the first nine months, I was working for missile and space vehicles and working on Gatling guns and re-entry nose cones.” During that time, he started a company, Intelligent Terminal Systems, to design a point of sale (POS) system. However, it failed to get off the ground. In 1973, he worked at Motoro-

la, developing the 6800 processor. This was when he recognized a market for a low-price processor, after which he began to champion a design to complement the $300 Motorola 6800.

Not surprisingly, Motorola management advised Peddle to drop the project. He then left for MOS Technology in Pennsylvania, where he headed the design of the 650x family of processors, which were the $25 answer to the Motorola 6800. This was a major breakthrough for him. At that time, the most famous member of the 650x series was the 6502 (developed in 1975), which was priced at 15% of the cost of an Intel 8080. It was subsequently used in numerous microcomputer devices, with five well-known products being the Apple I, the Commodore VIC-20, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), the ATARI 8-bit computers, and the BBC Micro from Acorn Computers. Interestingly, despite Peddle’s knowledge and skills in computer de-

sign, he was incredibly down-to-earth and straightforward about his opinions of the people that he met. For instance, when discussing Apple co-founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak (Woz), he stated, “Anyhow, the point is that Woz was a technician, and Jobs was a promoter. If you look at Jobs’s background, he’d gone from being whatever he was doing over in India to coming back and being a great promoter. He had a great artistic sense when it came to packaging and things like that, which you see in Apple.” He continued, “His ability to know the difference between something that people like and don’t like was one of his talents. But he didn’t know anything about the computers and everything. He totally depended on Woz for that.”

In 1980, Peddle left MOS Technology, together with Commodore Business Machines (CBM) financer Chris Fish, to found Sirius Systems Technology. In late 1982, Sirius acquired Victor Busi(cont. on page 46)

(cont. from page 45)

ness Systems (known for its calculators and cash registers) and later changed its name to Victor Technologies, where the Victor 9000 was developed. As for this device, advertisements cited its graphics, multiple operating systems, 128 KB of RAM, and high-quality audio. While unsuccessful in North America, the Victor 9000 became the most popular 16-bit business computer in Europe, especially in Great Britain and Germany. Although the company made a public stock offering in the first half of 1983, it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection by the end of 1984.

Despite the ups and downs of the market, it was the 6502 that Peddle was most proud of. According to him, “I tell everybody that the 6502 is the best single project I ever worked on. As a team, we went there, we did it in the time that we said we would do it, and we got the results we expected it to do.” In one of his last interviews, he

also ensured that the proper people received due credit. For instance, he stated, “I just want to make sure that I’ve given credit to Bill Davidow. He’s the one that made the 8088, the real basis for MS DOS. Bill Mensch, of course, has already been getting credit because he did the 6502, and made a fortune off of it. Then, there’s Terry Holt, who is still in the PC business. John Paivinen, I can’t say enough about John, a major

character in his own right.”

On December 15, 2019, Peddle died at his home in Santa Cruz, California. He was 82 years of age. In April of that year, the University of Maine (UMaine) honored Peddle with its Edward T. Bryand Engineering Award, on the 60th anniversary of his graduation from UMaine. In the same month, the UMaine Alumni Association awarded him its Career Award. As stated by UMaine President Joan Ferrini-Mundy, “His Maine roots and UMaine engineering education were the foundation for his truly inspirational career. His legendary vision, talent, and entrepreneurial spirit changed our world.” In this regard, The New York Times also wrote, “His $25 Chip Helped Start the PC Age.” Aside from these accolades, his career might be best summed up in his own words: “You take a dream and you build the dream. Then, you keep building on it. You don’t let anyone stop you.”

Creative Options is looking for Shared Living Providers for our Adult Foster Care program: We need Shared Living Providers in Penobscot, Piscataquis and Hancock county to provide a home and support to an adult with intellectual disabilities. Shared Living is similar to adult foster care, wherein, you would provide someone with an opportunity to become part of your home and your family while providing them with care and support for their everyday needs. In turn, you will receive a generous, daily, tax-free stipend, paid out bi-weekly, plus training, respite, and room & board from the individual, which covers their rent and food while living with you in your home. Call us today if you are interested in making a difference in someone’s life, as well as your own!

by Charles Francis

Newport celebrated its 100th birthday in June of 1914. The celebration was a two-day event. The Newport Board of Trade was the driving force behind much of the festivities’ organization. In fact, it was the Board of Trade that came up with the idea for the reenactment of Sleeping Beauty, featuring Miss Newport. The tableau symbolized Newport’s entry into its second hundred years.

The Sleeping Beauty reenactment featured Prince Charming waking Sleeping Beauty with his traditional kiss. The play was presented on the first day of the centennial celebration. Prince Charming symbolized Newport businesses, and Miss Newport’s awak-

ening symbolized the beginning of a new era of prosperity for the town. The production was appropriately named Kiss of Business.

The Board of Trade’s involvement in Newport’s centennial celebration came about because of the leadership of one of its most influential members, Charles Clark. At the time of the centennial, Clark was serving in the Maine Senate. He was also a member of the Board of Trade and had served as its president several times. For Clark, whose Newport business interests included building the town’s electric plant, the centennial offered a chance for the town to showcase its current prosperity, as well as its future potential.

The highlight of the second day of the centennial was a parade of boats around Lake Sebasticook. The boat parade route centered on the tower cove not far from Newport Village, and wound around Sebasticook to give cottage owners at shore locations, such as Breezy Point, full view of the spectacle. The decision to include the boat parade as part of the centennial was by no means happenstance. Lake Sebasticook has long played an important role in the history of Newport and the surrounding region.

Maine’s Native American population frequented Sebasticook in prehistoric times. Remnants of ancient fish weirs dating to before the time of Christ (cont. on page 50)

(cont. from page 49)

show this, as do other artifacts that have been found there. The lake was also on one of the major Indian trails that connected the coast with the highlands that separated Maine from Quebec. Because of this, Benedict Arnold visited the area and the shores of Sebasticook when he was looking for a route to attack British forces at Quebec City. Early freight, stage, and rail lines connecting Bangor to towns like Dexter and Skowhegan followed these same Indian trails. Undoubtedly, the lake also played a part in attracting the first settlers to Newport, or as it was first designated, Township No. 4, 3rd Range. Early selectmen certainly saw the lake’s value, and they sold salmon fishing rights in the early 1800s.

John Hubbard of Readfield was the first owner of Township No. 4, 3rd Range. He acquired it in 1796, but sold it to David Greene of Boston for the sum of $5,635 in 1800. But Greene

never visited his newly acquired holdings. The first permanent settlers began arriving shortly after 1800, and established East Pond Plantation. On June 14, 1814 the Massachusetts General Court recognized the incorporation of the plantation as the town of Newport.

At the time of the centennial, the leading industries of Newport included lumber, wool, canning, veneer, and wooden novelties. Cooper Brothers manufactured the veneer, and the Portland Packing Company, owned by the Baxter family, canned corn there. The Borden Company also had a factory that produced condensed milk. The reason why larger companies such as Portland Packing and Borden had come to Newport was, in part, because of Charles Smith’s electric plant. Business was obviously thriving in 1914, but that had not always been the case. That may explain why the Board of Trade wanted to highlight Newport’s future with its

production of Kiss of Business

In 1866 Newport voters approved an article that completely abated property taxes on businesses with startup capital of $40,000 or more, and established a grace period of ten years. The reason that the article passed so easily was simple. In previous years, fire had destroyed many of Newport’s businesses. In 1847 Fisher and Southwick, the largest tannery in the state, burned to the ground. One of the tannery’s kilns exploded, destroying many of the town’s other businesses with the resulting conflagration. In 1862 fire consumed more businesses. When fire again wreaked havoc in 1866, the town responded with its tax break incentive. It also responded with an appropriation that created a fire department and the purchase of firefighting equipment. By the time of the centennial, the Newport Volunteer Fire Department was one of the most modern in the state. It boasted

some thirty-five firefighters and a powerful, state-of-the-art water pump.

While the Newport centennial celebration was geared to highlight the town’s business potential, it also had a flavor of small-town celebrations of earlier times, the kind that one can still find in many towns in Maine. The Centennial took place on Saturday and Sunday and was actually broken up into three sections. On Saturday there were speeches in the morning, baseball, a track meet, and a giant picnic in the afternoon, complete with a band concert in the evening. Sunday morning was the time for religious observations. The great boat parade was in the afternoon, but it wasn’t the only parade of the celebration. All told, there were four parades, the other three in the streets of the town.

by Sean & Johanna S. Billings

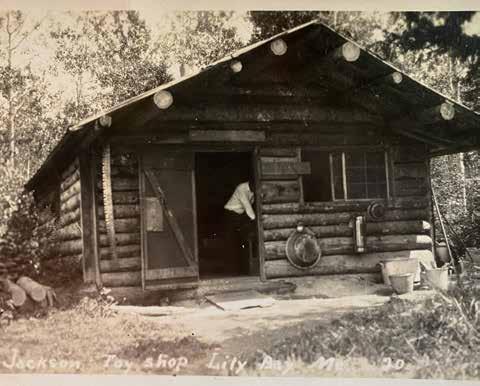

If you left Greenville and ventured down Lily Bay Road toward Kokadjo in the late 1920s and 1930s, you would have seen a log cabin with a sign above the door that said, “Toy Shop” or “Home of Santa Claus.” The cabin, which had no water or electricity, served as a home and shop for toymaker Edward Bundberry Jackson. He used the cabin, which was what remained of a lumberman’s camp near Lily Bay, with the permission of the owners, according to a newspaper interview Edward gave in 1941.

Edward made all sorts of playthings, including toy dogs and cats, automobiles, fire engines, trucks, dolls

and wagons. A 1936 newspaper article claimed his toys were shipped all over the world.

Edward liked living in the woods, according to the article. “Coming to the woods has prolonged my life and I expect to stay here until I die,” he is quoted as saying. “The city is no place for any normal being unless he has barrels of money to buy all of the best comforts of life.”

Another newspaper article called Jackson “one of Maine’s veteran hermits.” Although he had spent 30 years living in the North Woods by that time, he was born May 15, 1872, in Providence, R.I., the son of Walter M. and

Blair Hill and Highlands on Moosehead Lake:

Autographed copies are available at our shop, Lily Cat Antiques. It is also available at area bookstores and gift shops.

Most people are familiar with the Blair Hill Inn. But the rest of the hill has a fascinating history, too, including a former resident who was a Titanic survivor and a landscape painter who was Greenville’s �irst preacher — and who died after being accidentally poisoned by his wife. This book covers the history of the hill overlooking Moosehead Lake from the original settlers to the present.

Amelia Gosley Jackson. His grandfather, Charles, was a manufacturer of cotton goods in the city. According to the 1880 census, Edward, who was 8, was living on Greenwich Street in Providence with his father, Walter, 38, who was a physician; his mother, Amelia, 30; and his sister, Isabel, 10.

On April 17, 1883, Edward’s sister died of typhoid fever. Shortly thereafter, Edward’s father took him to the North Woods for a while, possibly to get away from typhoid in the city. Later, Edward attended the University of New York and became a successful florist. The 1900 census says Edward, who was 27, lived on Oliver Street in

Stamford, Conn., with his parents. Edward’s father died Nov. 15, 1908, in Stamford. Sometime between 1908 and 1910, Edward and his mother moved to Second Avenue in Mount Vernon, N.Y., a suburb of New York City.

It’s not clear when Edward moved to Maine. The 1936 newspaper article says that he came to the North Woods at age 30 after being stricken with a serious illness. Although he was 30 in 1902, the 1910 census indicates he was still living in Mt. Vernon at that time. It’s possible he was summering in Maine rather than living here year round.

The 1910 census also indicates Edward was living with his mother, who was 60, and her 8-year-old grandson, Richard S. Jackson. Edward was the only surviving child of Walter and Amelia, so Richard S. must have been Edward’s son. In fact, his obituary lists Richard Stonewall Jackson of New (cont. on page 54)

(cont. from page 53)

York as a survivor. Richard married in 1928, and the marriage license indicates his mother was Florence Jenkins. It does not appear Edward and Florence married; Edward is listed as single in the 1910 census.

Whenever Edward moved to Maine, he started out making a living as a trapper and collector of spruce gum. In 1920, at age 47, Edward continued to earn a living as a trapper, according to census data for Lily Bay Township. The 1920 census lists him as being married but does not include his spouse’s name. The 1930 census lists the 58-year-old Edward’s occupation as “none.” He was also divorced at this point, according to the census. On Feb. 4, 1934, Edward’s mother, Amelia, died.

Sometime between 1941 and 1947, Edward moved into the Willowcrest Rest Home in Pittston, Maine, where he died Aug. 17, 1947. He was buried in the Plaisted Cemetery in Gardiner in unmarked grave 100 of the 265 unmarked graves in that cemetery.

Edward was quoted in the 1941 newspaper article as saying, “I wasn’t born to achieve greatness.” Maybe he wasn’t a great man, but he was good enough to have postcards made of his toy store and newspaper articles written about him.

by Kathy Claerr