3 It Makes No Never Mind

James Nalley

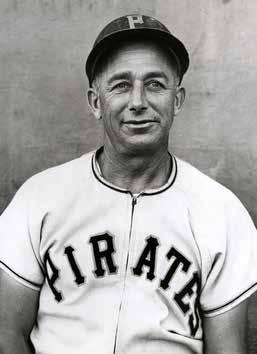

4 Washington’s Clyde Leroy Sukeforth

The emergence of Jackie Robinson

James M. Lilley

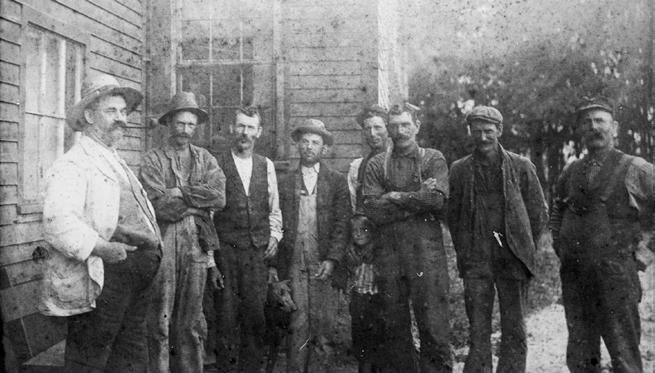

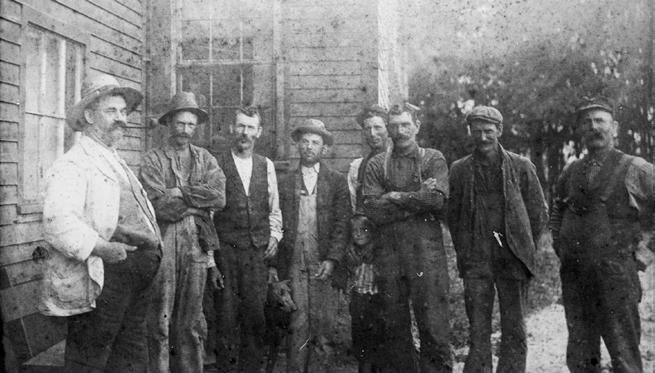

11 Woodsmen In The Woods Of Maine

A window into America’s Depression-era history

Helen Anderson

14 The Battle Of Cape Porpoise

Arundel Patriots spank the British

Brian Swartz

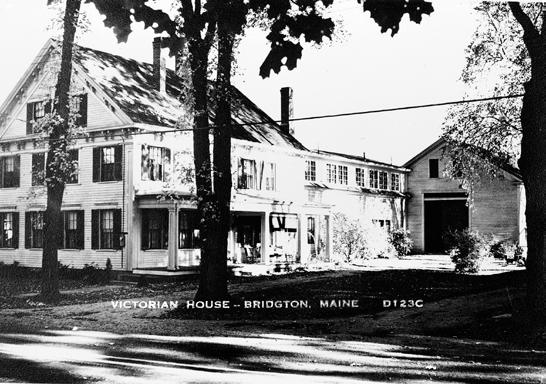

19 The Cleaves Brothers Of Bridgton

A “Maine at War” exclusive

Brian Swartz

24 Senator William Pitt Fessenden

Voting your conscience

James Nalley

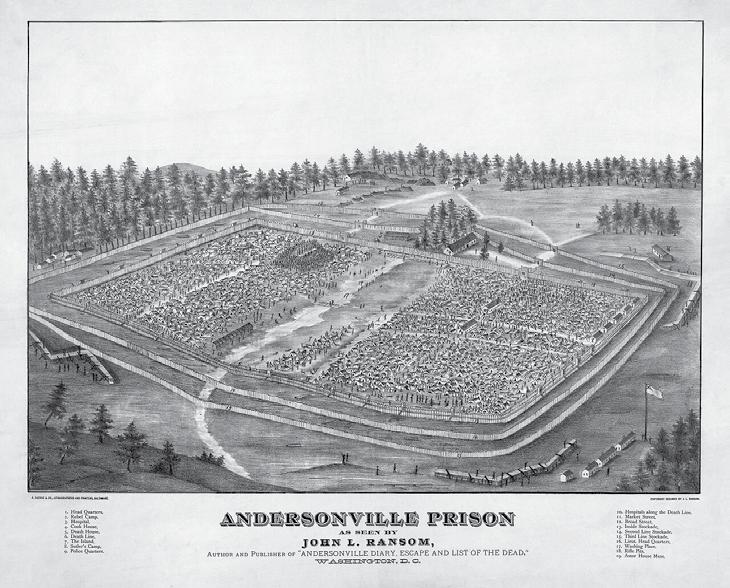

29 Camp Sumter And After

The disturbing lithograph at Casco Bay’s Memorial Hall

Jeffrey Bradley

34 Topsham’s Holman Melcher

The Little Round Top incident

James Nalley

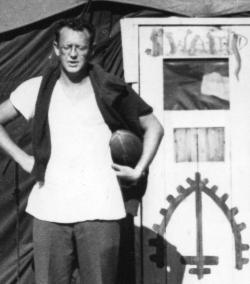

41 Bremen’s H. Richard Hornberger

The real Hawkeye Pierce

Charles Francis

46 Rockland’s Maxine Elliott

The troubled Maine starlet

James Nalley

50 Boothbay Deepwater Fishermen

Dories were filled with codfish

Charles Francis

52 The 1870 Rockland Bank Robbery

Burglars bungle the break-in

Brian Swartz

54 Warren’s Norman Wallace Lermond

Naturalist and socialist

James Nalley

56 Southern Maine’s Ocean Park

A living Chautauqua community

Valerie Kazarian

Publisher Jim Burch

Editor

Dennis Burch

Design & Layout

Liana Merdan

Field Representative

Don Plante

Contributing Writers

Helen Anderson

Jeffrey Bradley

Charles Francis

Valerie Kazarian

James M. Lilley

James Nalley

Brian Swartz

by CreMark, Inc. 10 Exchange Street, Suite 208 Portland, Maine 04101

by James Nalley

t the time of this publication, temperatures will have dropped, the summer crowds will have disappeared, and the fall foliage will be vibrant. It will also be peak pumpkin season in Maine, which typically runs from late September to October. However, before running out to grab your orange orb, here are some interesting facts to keep in mind.

First, pumpkins are native to Central America and Mexico, but they now grow on all continents (except Antarctica). Originally small and somewhat bitter, these fruits (yes, fruits!) were selectively bred by Native Americans to be bigger, fleshier, and sweeter. Additionally, every part of the pumpkin is edible, including the skin, leaves, flowers, and stem. During World War II, many Americans grew “Victory Gardens” to supplement their grocery rations. According to Pennsylvania’s The Victory Garden Handbook (1944), “Growing and eating pumpkins is highly recommended, due to their nutritional value.”

Second, there are more than 45 different types of pumpkins, with each containing approximately 500 seeds. In Maine, some farms boast more than 30 varieties. They also come in all sizes, with the heaviest pumpkin to date coming in at 2,749 pounds! In this regard, Atlantic Giants are the largest species,

which can grow as much as 50 pounds per day.

Third, when it comes to Thanksgiving pies, many people are still staunch traditionalists. Based on a 2017 national survey by Delta Dental, 36% would choose pumpkin pie, compared to pecan and apple pie, at 17% and 14%, respectively. Meanwhile, the world record for the largest pumpkin pie is currently 3,699 pounds. Made in New Bremen, Ohio, the diameter was 20 feet, while the crust consisted of 440 sheets of dough. To accomplish this feat, the bakers used 1,212 pounds of canned pumpkin, 2,796 eggs, 109 gallons of evaporated milk, 525 pounds of sugar, seven pounds of salt, and 14.5 pounds of cinnamon.

Fourth, there is the annual Damariscotta Pumpkinfest & Regatta. This festival includes a pumpkin weigh-off in which the largest pumpkins in Maine are showcased as well as a pumpkin regatta where participants race on the river in hollowed-out giant pumpkins. There are also art displays, a parade, a 5K Road/ Trail Race (the Tour de Gourd), a pumpkin derby, a pumpkin pie-eating contest, a pumpkin drop, and a pumpkin dessert contest. For more information, go to www.mainepumpkinfest.com

Finally, for a more hands-on experience, many farms offer pumpkin picking. As for this region of Maine, there is

Pineland Farms in New Gloucester. Visitors can purchase a two-hour farm pass, which includes access to the pumpkin patch and corn maze (www.pinelandfarms.org/pumpkins-pineland-farms). There is also Spiller Farm in Wells (www.spillerfarm.com), the Snell Family Farm in Buxton (www.snellfamilyfarm.com), and Pumpkin Valley Farm in Dayton, which hosts a Fall Festival every October (www.pumpkinvalleyfarm. com).

In light of this month’s theme, let me close with the following jest: A truck driver working over Thanksgiving stopped at a roadside diner for lunch and ordered a cheeseburger, a Coke, and a slice of pumpkin pie. As he was about to eat, three tough-looking bikers walked in. After staring the trucker down, one grabbed his cheeseburger and took a huge bite, while the second drank his Coke. Then, the third biker gobbled his pumpkin pie, only leaving the crust. Meanwhile, the trucker didn’t say a word but simply paid the bill and left. As the waitress walked up, one of the bikers growled, “Well, he ain’t much of a man, is he?” She replied, “Well, he ain’t much of a driver, either…He just backed his 18-wheeler over those three motorcycles!”

by James M. Lilley

According to Baseball Almanac, only 77 players from the state of Maine have ever played major league baseball. Surprisingly, one of the most accomplished of those players was a back-up catcher named Clyde Leroy Sukeforth. Clyde’s career in baseball spanned over 40 years. He played for the Cincinnati Reds and Brooklyn Dodgers, and later became a coach, manager, and scout for the Dodgers and the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Clyde became famous not for his accomplishments on the field, but rather for his role in signing the first African-American to play major league baseball in over 60 years. Thanks in

part to Clyde, the great Jackie Robinson became a Dodger and went on to break baseball’s long-standing color barrier.

Clyde was born in Washington, Maine on November 30, 1901, to Perl and Sarah Sukeforth. Perl worked in several different trades throughout his life to support his family. Sarah, better known as Sadie, was a homemaker. Sadie spent her waking hours raising her children and tending to their home and family farm.

As a young boy, Clyde fell in love with the game of baseball. When not working around the farm or out fishing for bass, Clyde would be found ei-

ther playing baseball with his friends, or following his favorite major league team, the Boston Red Sox. Long before the days of radio and television, the only way to follow baseball was to read the box scores in the daily newspaper. Clyde faithfully walked to the newsstand every day to wait for the stagecoach that delivered the Boston Post. Upon arrival, he would turn to the sports section and read about the previous day’s game. Clyde became the envy of his friends, when in 1918 he traveled to Boston to watch Babe Ruth pitch in the World Series. Whether Clyde was on the field or off the field, nothing meant more to him than baseball.

Clyde was an excellent student and took immense pride in his schooling. As a child he attended a one-room schoolhouse where he walked three and a half miles each way. In 1916, Clyde transferred to the Coburn Classical Institute, a college preparatory school in Water-

ville. Upon graduation, Clyde enrolled at Georgetown University in Washington DC. His athletic ability earned him a spot on the varsity baseball team.

Clyde went on to play several years in minor league baseball with both the Nashau Millionaires and the Manchester Blue Sox. Both teams were based in New Hampshire. In 1926, the Cincinnati Reds of the National League were in search of a back-up catcher for their starter Bubbles Hargrave. Clyde caught the eye of a Cincinnati scout and was offered a contract to play for the Reds organization. For Clyde, this was the fulfillment of a lifelong dream, Clyde Leroy Sukeforth was now a professional baseball player. At the time, no one would ever believe that 20 years later, he would play a significant role in changing the makeup of major league baseball forever.

Clyde began to play so well it appeared he would soon take over as the

Reds starting catcher. Unfortunately for Clyde, that would never happen. While hunting with friends, Clyde was hit in the eye by a stray shotgun pellet. His doctor informed him there was a chance he might lose his eye. If he did, his career would be over after just two years as a professional. Thankfully, doctors were able to save Clyde’s eye, but the injury was so severe it hampered his playing ability for the rest of his career.

In 1932 the Reds traded Clyde to the Brooklyn Dodgers where he played for the next three seasons. At the beginning of his fourth season, he was informed he would be sent down to the minor leagues. Rather than report to the minors, Clyde retired as a player and returned home to Maine. With baseball in his blood, Clyde could not stay away from the game for long. In 1936, he accepted a position as Player-Manager for one of Brooklyn’s minor league teams based in North Carolina. This was the (cont. on page 6)

beginning of Clyde’s 30-year tenure as a coach, manager, and scout.

Ten years after Clyde had played his last game and thought his playing days were behind him, he was called upon once again to be the Dodgers back-up catcher. The year was 1945 and America was still engaged in World War II. At the time, over 500 major league players and approximately 2,000 minor league players had joined the armed forces to fight for our country. Since teams were desperately looking for players, Clyde agreed to a dual role as both a back-up catcher and a scout. Clyde was now playing in the major leagues at the age of 43.

As a scout, Clyde reported directly to Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Dodgers. Rickey was a true baseball legend with a career that spanned 50 years. He was a player, manager, and general manager for various teams from 1905 to 1955. Rickey was (cont. from page 5)

a longtime proponent of allowing African-Americans to play in the major leagues. He believed if African-Americans fought and died for their country, Major League Baseball should welcome them with open arms.

Clyde and Rickey became exceptionally good friends and worked very well together. Rickey considered Clyde to be the only person he could confide in when tough decisions had to be made. Surely, the most monumental of those decisions was whether he should continue with his plan to break the color barrier. Rickey believed that if he did, most major league players, executives and fans would bitterly oppose him. To his dismay, it became clear that he was correct in that assumption.

For Rickey, no amount of pressure would stop him from moving forward. On the advice of a scout named Tom Greenwade, Rickey and Clyde decided that Jackie Robinson was the play-

er they needed. Rickey directed Clyde to meet with Robinson in Chicago and persuade him to travel back to Brooklyn to discuss his future in baseball. On the train ride back to New York, Clyde had to pay a surcharge to allow Jackie to sit with him in the “all white” section of the train.

Robinson signed with the Dodgers and went on to become the first African-American to play major league baseball since 1884. His first game as a Dodger was on April 15, 1947. Due to the suspension of manager Leo Durocher, Robinson’s manager on that historic day was none other than Clyde Sukeforth. Clyde had agreed to be the interim manager when Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler suspended Durocher for associating with known gamblers.

Jackie went on to play for the Dodgers for 10 years. He produced an impressive list of awards that included

Rookie of the Year in 1947 and Most Valuable Player in 1949. Jackie received the ultimate honor when he was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1962.

After retiring from baseball, Clyde went home to Maine and lived in Waldoboro, just 13 miles from Washington where his life had begun almost a century before. Clyde spent his final years enjoying the things he always loved as a child, working around the house, fishing for bass, and following his beloved Boston Red Sox. On September 3, 2000, Clyde passed away at the age of 98. Along with Jackie Robinson, Branch Rickey, and Tom Greenwade, Clyde will always be remembered for his contribution to breaking baseball’s long-standing color barrier.

October 12, 2025 • November 9, 2025

December 14, 2025 • January 11, 2026

February 8, 2026 • March 8, 2026 April 12, 2026

6

by Helen Anderson

Waldo Peirce’s mural Woodsmen In The Woods of Maine, once displayed on the wall of the Westbrook Post Office and now at the Portland Museum of Art, provides a window into Maine’s Depression-era history. Lasting from 1929 to the onset of World War II, Maine did not initially see the effects of the Great Depression to the extent of other regions, but the state still faced high unemployment and devastation in the farming and tourism industries. Maine received aid from government agencies in various ways to boost the economy, which included providing work relief for artists and dis-

pensing nationalist morale through art, evident in Peirce’s 1937 mural.

The stock market crash of 1929 is considered the primary instigator of the economic failure that followed. According to Alan Nasser in Overripe Economy: American Capitalism and the Crisis of Democracy, in the three years after the crash, over 32,000 businesses across the United States went bankrupt and unemployment reached 24.9 percent in 1933. Maine did not immediately see the effects of the Depression that the rest of the country was facing. Yichen Jiang’s Waterville’s Jewish Retailers during the Great De-

pression explores how the state was protected in its rural nature: farmers were not exposed to the same devastating conditions as those in the Midwest, and in turn, they were able to continue to produce goods. This allowed them to be both self-sufficient and continue to profit. That said, with the majority of the country facing economic downturn, Maine’s unique prosperity was not sustainable. By 1933, unemployment had reached 15 percent, with 20 percent of the state’s manufacturing workers out of work. In Jennifer Munson’s Publicity and Tourism: The Maine State Government’s Response to the Great

(cont. on page 12)

(cont. from page 11)

Depression, she shares how tourism, a staple of Maine’s economy, was in decline across the state, while Jiang further explores how farmers were unable to pay their taxes and mortgages because prices of their goods dropped.

To combat the rate of unemployment, the United States government under President Franklin D. Roosevelt instigated programs to provide jobs for Americans under the New Deal and the Second New Deal. These programs included government funded work relief for artists, creating opportunities to convey nationalist messaging through art, according to Josep Armengol in Gendering the Great Depression: rethinking the male body in 1930s American culture and literature. Across New Deal artwork, there is a theme of labor, which was used at the time to boost morale; in a time of economic depression, the art showed Americans prospering. New Deal works were also largely dis-

played in federal buildings, like post offices, so the messaging could be communicated to anyone passing by.

The Treasury Section of Fine Arts, in place from 1934 to 1943, was one of the New Deal art programs. The Section was created by Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., and directed by Edward Bruce, a lawyer and painter. While many New Deal programs, including art-focused programs, were instituted to provide jobs for unemployed artists, the Treasury Section of Fine Arts prioritized quality art. Instead of unemployed individuals applying for work, anyone — artist by trade or not — could enter into the competitive application process and be chosen not based on need for aid, but instead artistic ability. The Treasury Section of Fine Arts also took into account the applicant’s familiarity with the region, as they wanted the artwork to reflect the area. If the applicant was not from the

community, they were encouraged to visit and immerse themselves to best understand who and what they were depicting. Like other New Deal artwork, the work was largely displayed in federal buildings, and many took the form of murals. While differing from other New Deal programs’ emphasis on jobs, the Section’s focus on making the messaging pertinent to the region and in federal buildings aligned with the overall goal of boosting the public’s morale through artwork.

Peirce’s Woodsmen In The Woods of Maine characterizes New Deal art, and more specifically the Treasury Section of Fine Arts precisely. Once found in the Westbrook post office, and now held at the Portland Museum of Art, Peirce was commissioned to paint the 9.5’ x 10’ mural on the wall surrounding the postmaster’s door. The painting depicts four men at work in the woods. In turn, in both location and content, the

work reflects New Deal principles: the art was painted and displayed in mural form in a federal building. Peirce’s portrayal of four strapping men working a typical Maine job also aligns with the themes of the period.

Peirce himself reflects the ideals of the Treasury Section of Fine Arts. He was born in Bangor on December 17th, 1884, to the son of lumber barons. In a Harvard Magazine piece, William Gallagher depicted Peirce’s life, sharing that he attended Phillips Academy, Harvard University, and then studied art in New York City, Spain and France. Amidst his studies and work, he also drove ambulances in World War I, where he befriended Ernest Hemingway. In the 1930s, Peirce returned to Maine, and in that time, he produced “Woodsmen In The Woods of Maine” in the Westbrook post office. He was an ideal candidate to the Treasury of Section of Fine Arts, as he was a skilled

painter, familiar with Maine and with the lumber industry, a staple for the Maine economy.

The Westbrook post office was moved from Beckett Street to Main

Street in 1978, but Peirce’s mural was not moved with the building. His work was installed at the Portland Museum of Art in 1991, where it is now in storage today.

by Brian Swartz

“Crazy” Samuel Wildes his Arundel neighbors likely called him, and perhaps he did defy British on August 8, 1782 and take a musket ball in his knee for his efforts.

Or, perhaps he did not paddle a canoe out to two British warships moored in Cape Porpoise Harbor that Thursday and order their crews to “cease and desist” their capturing of two American merchant vessels.

Whatever Wildes’ role preceding or during the Battle of Cape Porpoise, history confirms that Mainers hustled off the British vessels and exacted a bloody toll on their crews.

Two British warships sailed into

Cape Porpoise Harbor sometime after dawn on August 8, 1782. The anthologies, from Charles Bradbury in his 1937 History of Kennebunkport to recent Web sites delving into contemporary 1782 newspaper accounts, differ slightly in the details. Sources concur, however, that a brig mounting 16 “guns” (cannon) and a top-sail schooner outfitted with 12 cannon sailed into Cape Porpoise Harbor from “eastward.”

Bradbury describes the enemy as “English.” Subsequent events would suggest that the English sailors actually were Loyalist privateers, including Captain Richard Pomroy aboard the 16-gun brig Meriam. The top-sail

schooner was likely the Hammond, skippered by a “Penobscot Loyalist” named Doty.

From the British brig departed the ship’s boat carrying “about 36 to 38 men” armed to the teeth to capture the American sloop, whose crew opened fire with a cannon. Oars likely flailing, the British sailors spun away from the sloop and, hauling “two cannons” with them, landed on Goat Island. Meanwhile, the British warships edged into the harbor and fired on the American sloop. Recognizing the martial reality, the American boys abandoned their ship and rowed ashore. Piling into their longboat, the British

sailors departed Goat Island to capture the sloop and schooner.

Splitting their numbers, the Brits manned both vessels and quickly got them under way. Into this moment in history paddled Samuel Wildes, viewed by his Arundel neighbors as “partially deranged,” to quote Bradbury.

Wildes might be considered crazy simply for climbing into “a small canoe” and paddling across Cape Porpoise Harbor to where the British sailors hurriedly loosened sails and tugged at lines aboard the captured vessels. According to Bradbury, Wildes actually approached the Meriam and, challenging the Crown’s authority, peremptorily “ordered” the British sailors “to give the vessels up and leave the port.”

A British sailor ordered Wildes aboard the brig. When he declined the offer “and turned to pull ashore,” sailors opened fire with muskets.

At least one musket ball struck him

and essentially shattered his knee.

Unfortunately for Wildes, the Boston press ignored his involvement while subsequently reporting the Battle of Cape Porpoise. Wildes did exist, however, and local eyewitness accounts solidly maintained that the “crazy” guy took a bullet for his country.

Sometime during the morninglikely not long after the first cannon fired - British sailors departed the harbor aboard the captured schooner. The sloop evidently sailed later; a southerly breeze drove this vessel ashore on Goat Island. The outgoing tide stranded the ship and assorted British sailors.

Meanwhile, approximately 40 Arundel militiamen poured into Cape Porpoise and crossed to Trott Island, separated from Goat Island by a channel then fordable at ebb tide. The Arundel boys ferried with them two cannon; espying these, British sailors hurriedly calculated the time until next high tide

and decided that they could not wait to float the captured sloop. They set the ship afire.

Seeing smoke starting to billow and British sailors frantically scrambling about Goat Island, the Arundel boys forded the channel. The Maine men plowed through the swirling sea as sailors aboard the Hammond continuously fired across the channel.

Scrambling onto Goat Island, the Arundel boys apparently did not hesitate; they ran south as British sailors leaped into a longboat and hauled toward the British brig. The anthologies, both Bradbury’s and contemporary accounts, suggest a close encounter, with the British tars only a short distance offshore as the Arundel boys “poured in their fire with a brisk and lavish hand.”

All accounts agree that the British brig opened fire, her gunners hurling cannon balls and grape shot across Goat Island. The southerly wind and (cont. on page 16)

(cont. from page 15)

ebbing tide now conspired against the British sailors, especially those fleeing Goat Island.

The brig had evidently moored only 70 yards off Goat Island, and for the next few hours, both sides poured on the lead. In fact, the brig’s crew took to their boats to tow and warp the vessel away from Goat Island. This activity required several hours; the Meriam would not escape until sunset.

American eyewitnesses (as described by a Boston newspaper) claimed that the Arundel boys inflicted heavy casualties on the British. Gunfire killed 14 sailors and wounded 20 (six mortally) aboard the longboat ferrying the British prize crew from Goat Island to the Meriam. American gunfire also left “four or five [sailors] killed in a boat carrying out the anchors to warp out the brig,” the Boston newspaper claimed.

“The Americans kept sheltered behind the [Goat Island] rocks and discharged their muskets at the brig ... when they could it without exposing themselves,” Bradbury reported. A Captain James Burnham, a local militia officer, died late in the fight when struck in his chest by a British musket ball; he was the only American fatality.

On Monday, September 18, 1782, American Navy Captain George Little sailed his sloop Winthrop into Boston Harbor while escorting four (perhaps five) captured British vessels. In a daring raid against Castine, Little and his crew captured the Meriam, the Hammond, the Loyalist schooner Ceres, and “an unnamed wood schooner that was a recent prize of the Brig Meriam,” a Boston newspaper reported. These were the ships that Little escorted into Boston Harbor in mid-September.

by Brian Swartz

One Bridgton brother went to war, the other did not, but not even death kept them from bestowing a promised gift on their hometown.

People started pouring into Bridgton early on Thursday, July 21, 1910, “and long before noon the streets were filled with a throng,” observed a Lewiston Evening Journal reporter. Up from Portland steamed a train packed to capacity; sixty members of the Westbrook-based Cleaves Rifles (a National Guard unit) poured from their car, and from another stepped some 50 aging veterans belonging to Bosworth Post No. 2, Grand Army of the Republic.

“Many distinguished guests” from

elsewhere arrived throughout the morning, and soon after lunch “more than 3,000 people” drifted up Main Street to its intersection with High Street, the reporter noted. The crowd encircled a 36-foot monument, “not completely veiled.”

Almost within the monument’s shadow stood 70-year-old attorney Henry Bradstreet Cleaves, wishing that one more person was present: his older brother, Nathan. Years ago, the two brothers had repeatedly discussed giving a Civil War “monument to their native town of Bridgton.” Nathan had died in his Portland home on September 5, 1892, “and the whole matter for the time being was dropped,” the re-

porter learned.

With time nipping at his heels, Henry Cleaves decided to keep that promise. Representing himself and Nathan, he “notified the town authorities of his intention” in 1909. “The gift was to the town,” Henry insisted, and with “the members of the Grand Army … fast passing away,” he wanted to erect a monument immediately.

Given the esteem with which they held the Cleaves brothers, Bridgton residents welcomed the gift.

The second oldest of five children, Nathan Cleaves was born in Bridgton to Thomas and Sophia (Bradstreet) Cleaves on January 9, 1835 in a house that still stood in 1910. After attending (cont. on page 20)

Portland Academy, he graduated from Bowdoin College in 1858 “with high honors” and studied for the law in Portland.

Admitted to the Maine bar in April 1861, he initially practiced in Bowdoinham before relocating to Portland, which offered more lucrative cases for aspiring attorneys.

Politically a Democrat, Nathan Cleaves registered for the draft in 1863 but did not serve during the Civil War. He married Caroline Howard on May 10, 1865, but she died in Augusta in February 1875 while Nathan served his second term as a Portland state representative.

Five years younger than his brother, Henry Cleaves was born in Bridgton on February 6, 1840. Educated “at the old Lewiston Falls Academy” and then at Bridgton Academy, “of him it may well be said that his education has been ongoing thru (sic) all the succeeding (cont. from page 19)

years,” the reporter commented.

Henry mustered as a private with Company B, 23rd Maine Infantry Regiment in Portland on September 29, 1862. A nine-month regiment, the 23rd Maine garrisoned Washington, D.C. forts and saw no combat. Orderly Sergeant Henry Cleaves mustered out with the regiment in mid-July 1863.

Arriving home, he promptly enlisted in the 30th Maine Infantry Regiment. Appointed the first lieutenant of Company F, he “was noted among his comrades as a fearless and dashing officer.” Henry fought in Louisiana and Virginia and emerged from the war as a combat veteran who never forgot the men with whom he had served.

Now “without any employment or profession,” Henry worked at “stacking boards … in the old sash and blind factory” in Bridgton. “Even there he displayed intellectual ability and force of character that made him marked among

his fellow workers,” the LEJ reporter commented.

Perhaps at Nathan’s suggestion, Henry then studied law; admitted to the Maine bar in 1868, he partnered with Nathan in a Portland-based law firm. The Cleaves saw their careers expand considerably afterwards.

Elected the Cumberland County judge of probate in 1876, Nathan was elevated to the Maine Supreme Court by Governor Harris Plaisted (another war veteran) in 1880. Although “a strong partisan in politics,” Nathan “held the unstinted respect of all his opponents.”

A life-long Republican, Henry Cleaves “represented Portland in the legislature and … also served two terms” as Maine attorney general, according to the Lewiston Evening Journal. Elected governor in 1892, he won his second term in 1894 with an “unprecedented majority of 40,000 votes.” (cont. on page 22)

(cont. from page 20)

A member of Bosworth Post 2, Henry convinced Nathan to help fund a monument dedicated to that esteemed GAR group. But time intervened; Nathan Cleaves died in his Portland home in 1892. He lies in Evergreen Cemetery in Portland.

Forging ahead, Henry paid for the Bosworth Post monument dedicated at Evergreen Cemetery on Memorial Day 1895. Holding in his left the staff from which an American flag hung, a bronze soldier stood atop a granite base provided by Hallowell Granite Works.

The monument was “Erected and Presented by Nathan Cleaves & Henry B. Cleaves,” an inscription read.

Prior to Nathan’s unexpected death, the Cleaves had discussed giving a similar monument to Bridgton. Henry commissioned with Hallowell Granite Works “a costly contract” to sculpt an ornate granite base, atop which would stand a bronze flagbearer similar to the one at Evergreen Cemetery.

asssociation.

Shortly before 2 p.m., July 21, 1910, the Bosworth Post members and the Cleaves Rifles formed a hollow square by the monument. “Fine music” and a Congregational minister’s prayer opened the ceremonies, and Henry Cleaves stepped forward to speak. He “was received with unstinted applause and it was several moments before he could make himself heard,”

the LEJ reporter noted. Cleaves “was deeply touched by the kindly reception. He “very modestly and generously … gave the larger share of the credit to the brother he loved so well.”

With the monument’s unveiling, a local band struck up The Star-Spangled Banner. Onlookers noticed that on the monument’s front, a granite worker had inscribed, “To Bridgton’s Sons Who

The th ing about eye disease is, you may n o t know you have it. Some conditions are asymptomatic, and by the time symptoms do present we’re left with fewer options. An annual examination at GFVC can ensure that we diagnose any latent disease with cutting-edge technology. We’ll also check your vision and adjust your prescription. And while you’re here, you can check out the latest designer frames.

Defended the Union. Presented by Nathan and Henry B. Cleaves. 18611865.” The promise made to Bridgton had been kept.

by James Nalley

Prior to the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865), the country was in political turmoil, due to the widening rift between the North and South regarding slavery and the federal government’s rights over the southern states. Among the many strong political voices at the time, there was a Bowdoin-educated, anti-slavery Whig and lawyer who not only became the architect of many of the nation’s wartime revenue policies but was also influential in founding the Republican Party in 1854. Moreover, due to his keen political skills in the U.S. Senate and his knowledge about the nation’s financial needs, President Abraham Lincoln nominated him as Secretary of the Treasury, a po-

sition he held from July 1864 to March 1865.

Fessenden was born in Boscawen, New Hampshire, on October 16, 1806. He was the son of Samuel Fessenden, a prominent attorney, abolitionist, and politician, who served in both houses of the Massachusetts state legislature. In 1823, Fessenden graduated from Bowdoin College and went on to study law. He was admitted to the bar in 1827 and practiced in Bridgton, Bangor, and Portland. In 1832, he was elected to the Maine House of Representatives and became its leading debater. Despite calls for him to take his skills to the U.S. Congress, he chose to continue his work in Maine. In fact, he refused

nominations to U.S. Congress in 1831 and 1838. However, he was eventually elected for one term as a Whig in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1840. After serving his term, Fessenden returned to Maine to solely focus on his law business. Yet, by 1845, he was again serving in the Maine state legislature.

By 1854, Fessenden’s staunch anti-slavery principles resulted in his election to the U.S. Senate, based on the support of Whigs and Anti-Slavery Democrats. Upon taking office, he spoke against the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which stoked national tensions regarding slavery and contributed to a series of armed and bloody conflicts in

both states. It is important to note that such tensions over slavery eventually led to the U.S. Civil War.

Meanwhile, his impassioned speeches on the Senate floor garnered the highest praise among his peers. For example, his criticism of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case, in which the Court held that the U.S. Constitution was not meant to include American citizenship for black people (enslaved or free), was considered one of the best speeches on the topic. As stated earlier, he was also influential in the founding of the Republican Party in 1854. In fact, after serving for many years as a Whig, he was re-elected to the U.S. Senate as a Republican in 1860.

In 1861, after the outbreak of the Civil War, the Republicans acquired control of the Senate, after which Fessenden became the Chairman of the Finance Committee. According to the

U.S. Senate Historical Office, Fessenden designed many of the country’s wartime revenue policies. For instance, “When the Revenue Act of 1861 failed to generate necessary funds, he revised a House revenue bill in 1862. After consultation with members, lobbyists, and the Lincoln administration, Fessenden introduced ‘this infernal tax bill’ in May. The Senate finally approved the bill with more than 300 amendments on June 6, 1862, with only one dissenting vote — an indication of Fessenden’s adroit political skills.” Such results prompted President Lincoln to nominate Fessenden as Secretary of the Treasury.

At that time, the finances of the nation were in shambles, since the former Secretary of the Treasury (Salmon P. Chase) had just withdrawn a $32 million loan from the market, thus exhausting the country’s capacity to lend. Meanwhile, the paper dollar was only

worth 34 cents. After reluctantly taking his position on July 5, 1864, Fessenden declared that no more currency should be issued. As stated in the book Fessenden of Maine, Civil War Senator by Charles Jellison, he prepared the 7-30 loan, which proved to be a tremendous success. This loan was “in the form of bonds bearing interest at a rate of 7.30%, which were issued in denominations as low as $50 so that people of ‘moderate means’ could take them.” It is important to note that, from August 1862 to February 1876, fractional currency was introduced by the U.S. government in 3-, 5-, 10-, 15-, 25-, and 50-cent denominations. As stated in the article Pastimes: Numismatics by The New York Times, the Civil War economy “catalyzed a shortage of U.S. coinage. Gold and silver coins were hoarded, given their intrinsic bullion value relative to irredeemable paper currency at the time.” Due to Fessenden’s noto(cont. on page 26)

(cont. from page 25)

riety, he was depicted on the 25-cent note, which made him one of only three people included on U.S. fractional currency during their lifetimes.

With the country’s financial situation improving, Fessenden resigned as Secretary of the Treasury on March 3, 1865, after which he returned to the Senate and became Chairman of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction. This committee was responsible for overseeing the re-admission of the former Confederate states into the Union. It also provided safeguards to prevent “the rebellious states” from initiating similar actions in the future. At that point, Fessenden became the acknowledged leader of the Republicans in the Senate.

However, history has shown that politics can be fickle. For example, in 1868, during President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial, Fessenden broke party ranks (along with six other Republican senators) and voted for ac-

quittal. His decision was based on his notion that the proceedings had been manipulated and that the evidence was one-sided. As a result, a 53-19 vote in favor of removing the President failed by a single vote of reaching a two-thirds majority. According to Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy by David Stewart, “Congressman Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts conducted hearings on the widespread reports that Republican senators had been bribed to vote for Johnson’s acquittal. In his hearings, there was increasing evidence that some acquittal votes were acquired by promises of jobs and cash cards.” Although Fessenden was not formally implicated in such actions, he was alienated from his fellow Republicans and the Republican Party itself, which he had practically founded.

On September 8, 1869, Fessenden died while serving in the U.S. Senate. He was buried at the Evergreen Cem-

etery in Portland. This particular city was special to him, since he frequently returned to it between his various posi tions in Washington, D.C. Likewise, he is the only person to have three streets in Portland named after him: William, Pitt, and Fessenden streets in the city’s Oakdale neighborhood.

Do

Do

If

by Jeffrey Bradley

Peaks Island knows a little something about secession. A bid for independence from the city of Portland having recently failed, this historic artsy little island seems about as resigned to its current status as to the inevitable influx of summer tourists.

But just down the road in the Fifth Maine Museum hangs an impressive 4½ x 9-foot lithograph entitled Andersonville Prison. Camp Sumter, Ga. As It Appeared August 1ST 1864, When It Contained 35,000 Prisoners Of War that shows in exacting detail what secession can lead to. A captive Union soldier’s firsthand account of life in that “Hell on Earth” most commonly called

Andersonville, the sprawling panorama features a backdrop of marching Confederate soldiers against a looming log stockade filled with hundreds of tiny writhing Federal figures the artist himself calls “a scene of indescribable confusion in every imaginable position, standing, walking, running, arguing, gambling… lying down, dying, praying, giving water or food to the sick, crawling on hands and knees… the sick being assisted by friends, others skirmishing for graybacks [picking nits]… trading in dead bodies, fighting, snaring, shouting…”

It’s bedlam, in other words.

Synonymous with Civil War-era

atrocity, Andersonville hardly stands alone. North and South alike kept thousands of captive soldiers within appalling conditions but, after all, they were just prisoners, the dregs of war and deserving of nothing less. With hygiene barely a concept, these bug-ridden unfortunates were piled into noxious hovels, starving, and beset by rampant diseases, left to subsist on swill and die in their droves. In fact, these squalid sinks in many ways early foreshadowed the infamous concentration camps. Still, in its own time Andersonville was considered a rank pesthole far even beyond the fact that the South could barely sustain its own as the war dragged (cont. on page 30)

(cont. from page 29)

on, let alone the hated Yankees. Camp commander Major Henry Wirz proved himself a sadist and (as any prisoner would be quick to tell you) a “d-mned Switzer” to boot. Under his supervision the prisoners turned on each other until the strong very nearly came to literally devouring the weak.

Such brutal conditions caused many to simply lose their will to live.

Located far from the frontlines, this 6½ acre rectangular wooden stockade was built in 1864 by slave labor and meant to hold a population of 10,000; that doubled after prisoner exchanges ended, and by August 33,000 men were crammed inside.

Statistics tell the tale: in just 15 months of operation fully forty percent of all the Union prisoners that had died in captivity perished here.

All was captured in ghastly detail by Union prisoner Thomas O’Dea. A 16-year-old Irish immigrant that enlist-

ed with Company E of the 16th Regiment Maine Infantry Volunteers in 1863, he was captured during the Wilderness Campaign and landed in Andersonville the following summer. He was lucky; he survived. The harrowing ordeal and some erroneous sketches spurred him into action: [They] “induced me to try my hand at producing one… to supply the deficiencies, correct the misrepresentations… and give the public a truer description of the suffering in the prison”, he later explained. To anyone questioning such precise recall, he would simply remind that no “Guest of the Confederacy” — the prisoners — could ever forget those awful “scenes of southern hell.” Drawn from memory and without formal training, O’Dea resolved the sketch be as accurate as possible minus rancor or bias. Unveiled in 1885, his opus reaped such wide acclaim that he was able to turn successful businessman, marry, and raise five children.

And it still helps to inform our image of Andersonville.

Three borders contain lurid vignettes. One, for instance, shows a heaped wagonload of corpses being carted away, while scarecrowish figures in another hunt a fetid swamp for roots along the margins of a sluggish stream that served for drinking water and a la-

trine. Another portrays a prisoner being shot dead for approaching too near the Dead Line — a rope barrier set some distance back from the walls to keep prisoners away — and simply assess salvaging some scrap blown just inside that forbidden area. (Guards actually took bets on how many “Yanks” they’d have to shoot each day for the attempt.) Still another shows Captain Wirz’s vicious “pets”, the ravening hounds kept on hand for setting upon any wretch desperate enough to try and escape. Other lethalities were recorded. With no shelter provided, some prisoners are pictured pillaging weaker comrades for anything useable to cover their miserable living pits. And where a mere scratch could spell death from infection many are shown avoiding the camp “hospital,” for from that infernal place no one returned. Even the fate of the marauding “raiders” that preyed on their fellow inmates, especially those newly-arrived and disoriented prison-

(cont. on page 32)

(cont. from page 31)

ers known as “fresh fish,” was noted in the hunting down and execution of the ringleaders.

Following the war, the odious Captain Wirz stood trial. Excoriated for permitting “such nameless blasphemy” and “savage orgies” he was denounced, found guilty and promptly hanged. Lew Wallace, the future author of Ben Hur, presided over his trial.

At the bottom of the sketch is the fitting inscription — flanked by the emblem of the National Association of Ex-Prisoners of War and the badge of the Grand Army of the Republic:

TO THE PARENTS, WIDOWS, ORPHANS, AND FRIENDS, OF THOSE WHO PERISHED IN THIS PRISON AND TO THE REMAINING SURVIVORS, IS THIS PICTURE RESPECTFULLY AND FRATERNALLY DEDICATED.

by James Nalley

On July 2, 1863, a Topsham-born man played a major role in the bayonet charge at Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg, which helped repulse the Confederate attack. On the second day of the battle, military forces moved to Little Round Top, where Colonel Joshua Chamberlain began preparing strategic options. The defense of this important hill, with the bayonet charge by the 20th Maine Infantry (the 20th Maine), has become one of the most fabled episodes in the U.S. Civil War. However, although Chamberlain went on to some fame after winning the Medal of Honor for his actions, there has been some controversy among

historians regarding who exactly led the charge.

Holman Staples Melcher was born in Topsham on June 30, 1841. As a young boy, he worked on his family farm and attended public school in Topsham. A gifted student, he graduated from high school and enrolled at Bates College in Lewiston (then Maine State Seminary) at the age of 15. During the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War in 1861, Melcher was completing his studies at Bates College and holding a teaching job in Harpswell. Upon concluding his studies, he immediately quit his job and enlisted in the 20th Maine on August 29, 1862. A week after enlisting, Melcher

was mustered into the Union Army at the rank of Corporal. He would serve with the 20th Maine for the duration of the war.

Melcher and the 20th Maine first engaged in combat at the Battle of Shepherdstown Ford, also known as the Battle of Boteler’s Ford, in September 1862. In this case, elements of the Union Army dueled with Confederate forces, after which the Union Army was forced back across the Potomac. During the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 1862), Melcher was promoted to Sergeant-Major for “meritorious conduct,” by Colonel Adelbert Ames. Subsequently, Melcher’s actions

and natural leadership skills earned him a promotion to First Lieutenant of Company F on April 20, 1863.

As company commander, Melcher had a heavy responsibility at the Battle of Gettysburg. As fighting raged in the Wheatfield and Devil’s Den, brigade commander Colonel Strong Vincent had a precarious hold on Little Round Top, an important hill at the extreme left of the Union line. As stated earlier, Joshua Chamberlain was ultimately awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on Little Round Top, especially regarding leading the famed bayonet charge. However, a certain faction of historians argue that Melcher physically engaged first.

This was later confirmed by Brigadier General Ellis Spear, who stated that Melcher initiated the charge “by ordering the remains of his company to move forward a few steps to cover and protect fallen comrades in front of

them on top of the hill.” Spear concluded that, prior to the order of Chamberlain to fix bayonets, Melcher “led the impulsive charge, responding to the cries of wounded comrades between the lines.” However, it should be not-

ed that the key source for this conclusion was from an 1882 book written by a private in the regiment who was not present at the battle. Specifically, Private Theodore Gerrish wrote, “With a cheer and a flash of his sword (cont. on page 36)

(cont. from page 35)

that sent an inspiration along the line, full ten paces to the front he sprang –more than half the distance between the hostile lines…’Come on! Come on!’ [Melcher] shouts. The color sergeant and the brave color guard follow, and with one wild yell of anguish wrung from its tortured heart, the regiment charged.”

Meanwhile, according to a July 2017 article on Historynet.com by Tom Desjardin, Chamberlain stated the following: “I went for the Color then at the angle in our center and the Color bearer was beside me advancing when Lieutenant Melcher came dashing in and right up to my side. I was then in front of the commanding officer of the advancing front line of rebels. He fired one shot of his pistol at me and I raised my saber to give him the point when he handed me his sword and pistol both at once and called out ‘we surrender.’”

Despite Chamberlain referring to

this controversy as “The Melcher Incident,” he was always complimentary of Melcher’s role in the charge. Although he credited him with saving his life, he did not mention him leading the charge. For example, according to paper “Chamberlain to Theodor Gerrish” (1882) in the Bowdoin College Archives, “I think it was the sight of Melcher and his squad coming down like Tigers that both made him quit firing on me and surrender. Had not Melcher come on, I think this officer would have shot me (four barrels were loaded when I took his pistol) and very likely his men would have got such headway that might have swept us all back.”

At this point, it is important to note that Melcher’s position was in the center of the regiment on top of a large rock formation (where the unit’s monument currently stands). By every account of the battle written by men on both sides,

the 20th Maine’s charge began on the far left of the regimental line, several dozen yards from Melcher’s position. Thus, the well-known “right wheel” of the regiment could not have started at its center. In addition, for Melcher to have initiated the charge of the left wing of the regiment, he would have had to lead his men over a 15-foot drop from the rock formation directly in front of them without breaking the regimental line, which would have been physically impossible.

During the Battle of the Wilderness (May 1864) near Richmond, Virginia, Melcher led a company of 17 men through a forest in order to align with the adjoining company. Due to the heavy fog, they failed to notice Confederate soldiers moving up to their left flank and surrounding them. He then ordered his men to lay on the ground and start shooting, capturing 30 Confederates while sustaining mi-

nor injuries. Approximately three days later, Melcher was shot in the right leg during the Battle of Laurel Hill in Spotsylvania, Virginia. He was immediately rushed to a makeshift hospital. Due to the seriousness of the injury, he was sent to Armory Square Hospital in Washington, D.C., and then to Maine for recuperation. He returned to active duty in the fall of 1864.

Despite his heroic actions, the war did have an emotional effect on this former schoolteacher. According to Melcher himself: Our whole division of over 10,000 strong is camped in a beautiful green field…The thousands of white tents dotting this green surface, and the many wagons, which go with the marching column makes a really grand sight. And the bands have been playing all evening, making music sweet and soul-stirring…But I am moved when I think that before another evening, this beautiful scene will be

stained in

By the end of the war, Melcher was brevetted to the rank of Major, and he was mustered out on July 16, 1865. In his post-war years, he founded and

operated the H.S. Melcher Company, a wholesale produce business on Fore Street in Portland. After many years, Melcher sold the company for a profit to what would become the A&P grocery chain. Although his business and

(cont. from page 37)

wartime service earned him wide respect in the community, it was Joshua Chamberlain who remained steadfast in his support. For instance, Chamberlain wrote the following to the advertisement board of the city:

I want to propose a name for the Republican nomination for mayor – a name that needs no recommendation; a man with a record of splendid courage and endurance in the late war. From the beginning to the end, he has been an honorable, high-minded citizen and energetic businessman, enjoying the confidence and respect of his fellow citizens in both parties. From this man, no pledges need or will be asked. All these years of his well-regarded life are pledges for his good conduct in any situation. And his name is Holman S. Melcher.

Melcher was elected as Mayor of Portland on January 1, 1889, and elected to a second term ending in 1895. As mayor, he was committed to Veterans

Affairs and founded the 20th Maine Regiment Association (1876-1905). Later in his life, he suffered from poor health due to the pain from his old war wounds. He eventually died after a long battle with Bright’s Disease (inflammation of the kidneys) on June 25, 1905. He was 64 years of age. Melcher was buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Portland, Maine.

As for his legacy, many Melcher’s papers are currently stored at the Maine Historical Society, Bates College, and Bowdoin College. Melcher’s writings, along with his correspondence with members of the 20th Maine were published in With a Flash of His Sword: The Writings of Maj. Holman S. Melcher, 20th Maine Infantry (1994), edited by William Styple. Melcher’s house survives at 84 Pine Street in Portland.

by Charles Francis

Hawkeye Pierce is one of the most famous fictional people born in Maine. In the book

M*A*S*H: A Novel About Three Army Doctors, Hawkeye is a tall, rangy character with nerves of steel who is a natural athlete. He plays football at Androscoggin College, a thinly-veiled version of the real Bowdoin College, and in a game between Androscoggin and Dartmouth, Hawkeye intercepts a Hail Mary pass thrown by Dartmouth quarterback John McIntire. Hawkeye is from Crabapple Cove, near the town of Spruce Harbor. The book was written by H. Richard Hornberger, a thoracic surgeon who lived in Bremen and performed surgery in Waterville. The book is now considered a humorous classic,

and many believe it’s better than the TV series, which ran for eleven years, or the movie.

Dr. Hornberger was a Captain, and practiced medicine with the 8055th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in Korea during the war. His experiences inspired him to write the novel and invent characters like Hawkeye. After the war he wrote part of the book during his offtime in his Bremen office. While Hornberger had nerves of steel to practice thoracic surgery in the midst of combat, he wasn’t much of an athlete.

In 1980 I saw him play in a doubles tennis tournament, with his wife as his partner. I saw this while at a summer job working for the Long Cove Point Association. It was a social organiza-

tion which centered its activities on its clay tennis court, and the Hornbergers were members. My responsibilities included managing hours of court usage, and making sure that members were on time for tournament matches. Often I had to call Dr. and Mrs. Hornberger regarding a change in their schedule. She was very nice about it because she wanted to play in tournaments, while he was indifferent.

H. Richard Hornberger came to Bremen via Cornell Medical School and Korea. He was born in Trenton, New Jersey, and attended the elite Peddie School prior to college. He wrote M*A*S*H, published in 1968, using the pen name of Richard Hooker. Film rights were bought by Ingo Preminger (cont. on page 42)

(cont. from page 41)

for a reputed one hundred thousand dollars. Hornberger didn’t write the script for either the movie or the TV series. He did write two sequel novels, M*A*S*H Goes to Maine and M*A*S*H Mania. There were other M*A*S*H books written, but not by him. His sequels, in my opinion, are funny, but not as humorous as the original.

When the Hornbergers were playing tennis at the Long Cove Point Association, M*A*S*H was a mega TV hit, and he became an instant celebrity. He had a degree of notoriety in the Bremen area because of his driving habits. Local police granted him some leeway when he exceeded the speed limit. Thoracic surgery is one of the most difficult surgeries to perform, and he had to deal with losing patients. A psychologist might say that he used speeding, like the humor of his writing, as a means of dealing with the stresses of his demanding profession.

Dr. Hornberger was a revered figure in the central Maine and mid-coast areas. People tended to be protective of him. I saw evidence of this among members of the Long Cove Point Asso-

ciation, and heard others speak of it. It’s comparable to the protectiveness some Mainers have today for Stephen King. In the case of Hornberger, I believe it had to do with the fact that he saved lives, as well as for his fame as a writer. There was also the question of the success of the M*A*S*H movie and TV show. A good many felt that Hornberger was taken advantage of by Hollywood fast-talkers and flimflam artists. They felt he should have profited more from the movie and TV series. H. Richard Hornberger, the thoracic surgeon who created one of Maine’s most famous native-born fictional figures, passed away in 1997 and is buried in Bremen.

by James Nalley

In New York City in the 1910s, a Rockland-born stage and film actress was both the owner and manager of a theater near Broadway. At that time, she was the only woman in the United States running her own theater. However, her personal life was equally (if not more) interesting, between her tempestuous romances, mental health challenges, interpersonal dramas, and social activism.

Maxine Elliott (birth name Jessie Dermott) was born in Rockland on February 5, 1868. The daughter of Thomas Dermott, a sea captain, and Adelaide Hill Dermot, she had three siblings: a younger sister, Gertude Elliott (who became a well-known stage

actress as well), and two brothers, one of whom became a sailor and was lost at sea in the Indian Ocean. Foreshadowing the drama to come in her life, at the age of 15, Elliott was seduced by a 25-year-old man and became pregnant. According to her biographer Diana Forbes-Robertson, “She lost the baby, leaving a psychological wound for the rest of her life.”

When she was 18, she developed a secret relationship with Arthur Hall, who was from a wealthy local family. However, when suspicions of her pregnancy emerged and her relationship was publicly exposed, her father took her away to South America for an undisclosed time. As stated by Mary Lovell

in the book The Riviera Set (2016), “In her later years, she would make bitter remarks about the separation between her and Hall.”

In 1889, at the age of 21, she adopted her stage name, Maxine. In the following year, she made her first stage appearance on Broadway in New York in The Middleman, a four-act play by Henry Arthur Jones. Subsequently, she was noticed by renowned manager, playwright, and stage director Augustin Daly. In 1895, he hired her as a supporting actress for his star, Ada Rehan, which launched her stage career. Three years later, Elliott married comedian Nat Goodwin (known for his performances in musical theater and light opera), after which the two starred at home and abroad in several hits such as Nathan Hale and The Cowboy and the Lady, both by Clyde Fitch. By 1903, Elliott had become widely popular, earning her some of the high-

est fees in the business. For example, for her appearance in The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare, she negotiated a contract for $200 ($7,000 today) and one-half of the profits over $20,000. In the same year, she was billed alone in the Broadway production of Her Own Way by Clyde Fitch.

(cont. on page 48)

(cont. from page 47)

At that point, it was clear that she had become a star.

Meanwhile, she had a wild lifestyle. For instance, in 1905, when the production moved to London, England, King Edward VII asked that she be presented to him. Despite her marriage to Goodwin, they were rumored to have had an affair. In 1908, Goodwin and Elliott divorced, after which she became acquainted with wealthy financier J. P. Morgan. Although it was rumored they had an affair as well, Morgan also gave her sound financial advice, which helped her become a wealthy woman. Subsequently, Elliott returned to New York City, where she opened her own theater, The Maxine Elliott Theater, located on 39th street near Broadway. As stated earlier, she was the only woman in the United States managing her own theater.

In 1913, Elliott began acting in silent films, including Slim Driscoll, Sa-

maritan, When the West Was Young, and A Doll for the Baby. Meanwhile, she began dating New Zealand tennis star Anthony Welding, who was 15 years younger. According to The Seattle Star, “Elliott had planned to marry Wilding, but he was killed on May 9, 1915, at the Battle of Aubers Ridge in World War I.” Traumatized by his loss, she had become obsessed with the war and moved to Belgium, where she volunteered both her time and income to the Belgian relief efforts. In fact, she had become so involved that she was eventually awarded the Belgian Order of the Crown, one of the country’s highest honors.

After Elliott returned home in 1917, she signed with the newly formed Goldwyn Pictures to make the films Fighting Odds (1917) and The Eternal Magdalene (1919). Meanwhile, Elliott was frequently seen with Charlie Chaplin, again sparking rumors of an

affair. In 1920, she made her last stage appearance in Trimmed in Scarlett, after which she retired at the age of 52. In this regard, she publicly announced that she “wished to grow middle-aged gracefully.” According to her biographer Robertson, when summing up her career, “critics were divided on whether it was her beauty or her acting ability that attracted such attention.”

At the time of her retirement, Elliott had owned homes both in the United States and abroad. However, she settled down in England at Hartsbourne Manor. In fact, there is a photograph of Winston Churchill (accompanied by his wife, Clementine) working on an oil painting on the grounds of this estate. In 1932, Elliott moved to Cannes, France, where she built le Chateau de l’Horizon. There, she continued to entertain guests, including David Lloyd George (the Prime Minister of England from 1916 to 1922) and James Vincent

Sheean (American journalist and novelist). This white deco villa featured multiple rooms, complete with a large terrace and a swimming pool overlooking the Mediterranean Sea.

Interestingly, in her old age, diarist Sir Henry Channon described Elliott as “an immense bulk of a woman with dark eyes, probably the most amazing eyes one has ever seen.” She was also “lovable, fat, oh so fat, witty and gracious. He also wrote that “he watched her eat pat after pat of butter without any bread.”

On March 5, 1940, Elliott died at her chateau from a heart ailment. She was 72 years of age. She was subsequently buried at the Protestant Cemetery in Cannes, far from her humble Rockland beginnings. Her estate currently belongs to the Saudi royal family.

by Charles Francis

Boothbay lies on a peninsula on one of the most jagged coastlines in the world. In fact, looking at it on a map, it appears that it barely escaped being an island. To the east one finds the Damariscotta River, to the west the Sheepscot. The immediate shoreline is indented with countless coves and inlets. Moreover, Boothbay Harbor is the second-largest harbor on the Maine coast.

No rail lines lead to Boothbay. For this reason, in the nineteenth century, the community’s commercial interests continued to look to the sea as the rest of Maine began linking to the outside world with bands of iron. And, for Boothbay and neighboring Southport, the sea meant the Georges or Grand Banks with their seeming limitless schools of cod.

For much of the nineteenth century Lincoln County furnished the United States with some of the ablest seamen in the world. Lincoln County men, especially men from Boothbay, were almost as much at home on the far reaches of the seven seas as they were on their own Gulf of Maine. The chief reason for this is that at some point in their lives most Boothbay men made

their living for some eight months of every year as deepwater fishermen on the Grand Banks.

The Grand Banks are shallow places in the North Atlantic where plant and animal plankton thrive and feed huge schools of codfish. In fact, early accounts of the region have the schools of fish so thick that they actually impeded a ship’s passing through them. The Cabots, father and son, reported there was no need for a net or hook and line to fish. All that was necessary was to drop a bucket over the side. While these accounts may have been exaggerations, they were only mild ones, for the Grand Banks made many men extremely wealthy and provided countless others with substantial livelihoods. Unfortunately, the “Banks” also cost a good many lives.

Almost every old Boothbay family can point to an ancestor or a relative who made his living as a deepwater fisherman. And, all too many can come up with the name of a family member who lost his life at sea. In 1872 Reuben Pierce was lost from the Annie Linwood. In 1876 the D.E. Woodbury lost two men, David Corson and Captain Franklin D. Pinkham. In 1890 the Isaac

A. Chapman lost Captain Ozro Fritch. Southport was the same. In 1866 Captain Richard Rose was lost from the J.H. Huntress, and in 1869 William Gardner from the Sophronia. Fritch left behind a wife and four children. Rose left a wife and five children.

Most Boothbay deepwater fishermen were dorymen. What they did was ship their own handmade dory on a Grand Banks schooner in early spring until late fall. Most schooners could take a dozen or so dories. They would then sail out to the Banks and drop off the dories at spaced intervals much like a bus dropping off passengers at regular stops.

The dory was the deepwater fisherman’s pride and joy. He carefully chose the wood for it, seasoned it for a year or more, and then fashioned his craft, usually the exact same way his father had done before him. What he produced was one of the most stable small crafts known to man. Some dories have been known to ride out hurricanes.

Most dorymen were long-line fishermen. They would drop off a line with a float at either end. At six-foot intervals there was a baited hook. Sometimes the fish were so plentiful that all that was

necessary was to set out a single line. Other times the dorymen would set out several long-lines.

Dories usually had a crew of two, the dory owner and a stern man. One man would haul the line in as the other unhooked the fish. Some long-line fishermen simply dumped the line in the bottom of the dory and then returned to the schooner to unload their fish and rebait their hooks. Others, however, kept a tub in the bottom of their boat. As the long-line was hauled in, the line was coiled in the tub with the hooks placed on the lip of the tub. They would then rebait their hooks without returning to the schooner. This was known as “tub-trawling,” and was by far the most efficient way to fish. The only drawback was that some dorymen tended to overload their boats.

For much of the nineteenth century the waterfront wharves and fish houses of Boothbay and neighboring Southport bustled with activity. Then, around 1870 the fish firms of both towns began to experience a slow decline. Part of the reason for this was that more and more vessels from countries like Portugal and Sweden were frequenting the Grand Banks. In addition, the centers of the fishing industry were moving southward to towns like Gloucester, Fall River, and Provincetown.

For the deepwater fisherman of Boothbay a new day was dawning. Young people did not stay in town, but began moving away to greener

pastures. By the turn of the twentieth century the few remaining deep water fishermen were turning to lobstering. Dories which had been propelled for so long by a man standing amidships with his hand-fashioned ash oars were now setting out with one-lungers, as the single piston engines were called.

Today it is hard to visualize Boothbay Harbor, with its myriad of pleasure

craft, as a working harbor. Yet there was a day when two hundred or more Grand Banks schooners and an almost countless number of dories could be seen there. It was the day of the deepwater fishermen, who gave their name to Fishermen’s Passage and Fisherman Island.

by Brian Swartz

Peace and quiet spread like a blanket over downtown Rockland in the wee hours of Wednesday, May 4, 1870. Deputy City Marshal E.S. McAllister patrolled the streets, a few human owls swooped hither and yon, but darkness shrouded the Knox County shiretown, and people slept soundly. “Ka-boom!”

A muffled explosion rumbled across the Limerock Street vicinity around 3:30 a.m. Believing the detonation occurred near Lime Rock Bank, McAllister ran toward that prominent institution and saw four men bounding down the bank’s exterior steps. They vanished around the building’s corner onto Limerock Street; for some reason McAllister ran to alert City Marshal Carver rather than chase the suspects. A man saw them clear the corner, and Gilman Lovejoy watched them pass his home at the intersection of Limerock and Union streets. One suspect tossed a bag beneath a building known locally as the “Old Schoolhouse.” A few minutes later people heard two wagons rattling and clattering really fast out on Limerock Street.

The wagons rolled past someone on the Meadow Road and vanished toward Beech Woods and Waldoboro.

Carver and Deputy Sheriff Torrey rushed to Lime Rock Bank, which shared a building with the Western Union Telegraph Company office. The law officers determined the burglars had muscled into the telegraph office and pulled down the window blinds and secured them, so no light escaped around their edges.

After breaking through the brick wall between the office and bank, the burglars huddled around the bank’s safe. With a hammer they pounded

steel wedges into the safe’s top and side. Then the burglars poured blasting powder into the wedge-created crevices and set and lit the fuse. “Ka-boom!”

The explosion blew off the safe’s door, cracked and bent the safe’s walls, blew out telegraph-office windows, dropped ceiling plaster on the floor, and injured one burglar. Grabbing what they could, the burglars fled, their wounded comrade spraying blood drops down the stairs and into Lime Rock Street.

Bank personnel arrived to assess the damage. The perps stole $1,100 in cash and bonds and securities owned by specific bank customers. Worth around $22,500, these papers could not be cashed by the burglars, nor could the $2,500 in stolen bank-owned securities.

The stolen loot totaled around $26,000. For reasons unclear, the burglars overlooked a box containing $12,000 in gold and a tin box stuffed with bank bills, equivalent to cash. Carver and Torrey went after the burglars and met a witness who saw Addison F. Keiser, a former Rockland cop, hightailing it out of town on a wagon soon after the break-in. Keiser happened to roll his wagon back into Rockland sometime after sunrise; police officers swiftly arrested him and hustled him to jail.

He sang like a canary during the resulting interrogation. Law officers hauled Rockland businessman Alden Litchfield to jail around noon. Then, while searching Litchfield’s house, they discovered New York City safe cracker Joshua Adams lying in a bed. Claiming he was sick did no good. Kicked out of bed and told to dress pronto, Adams went to jail, too.

Meanwhile, authorities learned another suspect, E.E. Rand, had hired

South Thomaston resident John Graves Jr. to take him in a horse-drawn wagon to Belfast. Cops nailed Graves there, but Rand had boarded the Portland-bound steamer City of Richmond.

A descriptive telegram sent to Portland saw cops meet him at the dock, but Rand blustered his way past them and caught the Boston train. Keiser said “two New York professionals” had hired him and Rockland resident Asa Black to transport them by wagon to a specific spot several miles outside the city. Keiser was supposed to meet them at 8 p.m., Wednesday and drive them farther away from Rockland.

Escorted by police officers, deputies, and a large posse, Keiser drove his team out to the designated meeting spot. Just short of it, the law officers quietly spread around the site. Keiser hailed the New Yorkers, and the law nabbed them without incident.

Initially identified by baggage tags as Charles H. Brooks and John Stevens, the men went to jail. They were named Charles Hight and Langdon W. Moore, well-known criminals. Hight was the burglar who, while firing a fuse, got caught in the resulting explosion that left his face not a pretty sight.

Also arrested elsewhere were Black and McAllister, the latter suspected of complicity. Joshua Adams turned out to be Joshua Daniels, a crook allegedly dying from tuberculosis.

All in-custody suspects were arraigned in police court. Judge Hall presided over the arraignment proceedings that started inside Rockland City Hall on Saturday afternoon, May 7. A literal standing-room-only crowd packed the room. Hall ran a tight ship, Keizer and McAllister and others testified, and ultimately McAllister was charged

only with being an accessory. Daniels, Hight, Moore, and John W. Rand were charged with the bank robbery and Litchfield “with being an accessory before the fact.” All held without bail.

Maine Supreme Court Justice William G. Barrows opened the trial on Tuesday, September 27, 1870. Hight

immediately pleaded guilty, the others pleaded not guilty, and the 12 jury members took their seats. Testimony ran late in the day, so Hall continued the trial on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday.

Testimony revealed that Litchfield organized much of the heist, even to

bringing in the professional New York criminals. The jury found him, Hight, and Moore guilty; the last two were sentenced to seven years’ hard labor at the Maine State Prison in Thomaston. Litchfield ultimately got a similar sentence.

by James Nalley

In the late 19th century, a Warren-born man completed high school in Boston, Massachusetts, and found work as an accountant for a regional railroad company. However, behind this somewhat typical situation was an intriguing character with deep knowledge of bivalve shellfish. In fact, although he claimed to be an amateur naturalist, a 2004 article in Northeastern Naturalist by Scott Martin stated that “He was not only the foremost naturalist in New England, but he also labored tirelessly to organize both professionals and amateurs alike to study the natural history of Maine.” Meanwhile, what made him even more colorful was that he greatly admired the idea of a utopian society and became a full-fledged Socialist who co-founded the Socialist Party of Maine.

Norman Wallace Lermond was born in Warren on July 27, 1861. The son of Omar and Rebecca Lermond, his family moved to Boston, Massachusetts, when he was 11 years old. He was then sent to a religious boarding school in Hartford, Connecticut, after which he graduated from the English High School in Boston (one of the first public high schools in the United States, founded in 1821).

Like many of his fellow graduates, he either worked or continued to college. In this case, he chose the former and first worked as a staff member for the trade journal The Boston Telegram and then as an accountant for the New York and New England Railroad.

Meanwhile, Lermond was a self-

taught amateur naturalist who studied the natural history of New England, especially Maine and the Boston area. According to Martin, “He also studied flora and fauna of the Pacific Coast, the states of Arkansas and Tennessee, and dredged for shells off the coast of Florida.” With an ever growing need to expand his collection and knowledge, he studied nature in the Bahamas and Cuba, and even camped in the Everglades with a party of eminent researchers. Despite lacking a college education, his knowledge earned him an assistant position at Harvard. Although he continued to amass an extensive collection of mollusks, his life changed in 1890, when a visitor brought Edward Bellamy’s best-selling 1887 novel, Looking Backward. As stated in a 2019 biographical article of Lermond in the Courier-Gazette, “This book about utopian society appealed greatly to Americans after the 1883 Depression and post-war social upheaval.” Regarding this book, Lermond wrote, “Bellamy’s blueprint of a new and very different economic, social, and political system opened up to me a whole new world: a world without poverty, crime, or disease. After reading Bellamy’s

book, I became a full-fledged Bellamy Socialist. And I am still a Socialist, a stronger Socialist than ever.”

Within the year, Lermond became active in the region’s populist organizations. In 1891, he co-founded the Socialist Party of Maine and envisioned “local unions” (communities) with several of his like-minded colleagues. At this point, it should be noted that Lermond ran for U.S. Congress in 1892, as a Populist, but finished in a distant third with 3.6% of the vote. However, disregarding the lack of public interest on a wider scale, Lermond and his colleagues established the Brotherhood of the Cooperative Commonwealth, which was a system of cooperatives/ collectives that would supply one another with various goods and services. According to the Courier-Gazette, “This plan gained some local interest. In fact, a local union of the Brotherhood was formed in Warren in 1895, and in Damariscotta and Camden in 1896.”

After these unions were established, Lermond proposed that “Socialist pioneers should invest $100 to buy land, natural resources, and equipment, and turn them into buildings, tools, factories, etc.” Each community would then focus on a specific industry such as clothing, farm equipment, and textiles. Such products would be exchanged according to an equitable unit of labor.

In 1898, Lermond helped create the Equality Colony in the state of Washington. Consisting of approximately 300 people on 640 acres, it was meant to serve as a model that would eventually convert the state and then the country to Socialism. However, as stated in the Courier-Gazette, the colony was a failure. Specifically, “Internal jealousy and organizational disputes quickly divided the colony and Lermond returned to Maine in poor health in August 1898.”

Lermond remained active in both his scientific endeavors and Socialist politics. As for the latter, he wrote, “Our Socialist county organization hired rooms on Main Street in Rockland, bought a piano, and held regular meetings every

Miss Rogers played the piano and sang, while the Rogers boys promoted plays. The Rogers, La Follett the blacksmith, the cigar makers Sobel and Morier, and the baker all took part in fascinating debates.” With greater plans for society, in 1900, Lermond ran for Governor of Maine, becoming the first Socialist candidate for governor in Maine history. However, Republican businessman John Fremont Hill easily won, with 62.33% of the vote, whereas Lermond was last, with only 0.55% of the vote.