Auction | Melbourne | 26 November 2025

Auction | Melbourne | 26 November 2025

Lots 1 – 59

Auction | Melbourne | 26 November 2025

Lots 1 – 59

Wednesday 26 November 7:00 pm

105 Commercial Road South Yarra, VIC telephone: 03 9865 6333

Tuesday 11 – Sunday 16 November 11:00 am – 6:00 pm 36 Gosbell Street Paddington, NSW telephone: 02 9287 0600

Thursday 20 – Tuesday 25 November 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

105 Commercial Road South Yarra, VIC telephone: 03 9865 6333

email bids to: info@deutscherandhackett.com telephone: 03 9865 6333 fax: 03 9865 6344 telephone bid form – p. 158 absentee bid form – p. 159

www.deutscherandhackett.com/watch-live-auction

www.deutscherandhackett.com | info@deutscherandhackett.com

Chris Deutscher

Executive Director — Melbourne

Chris is a graduate of Melbourne University and has over 40 years art dealing, auction and valuation experience as Director of Deutscher Fine Art and subsequently as co-founder and Executive Director of Deutscher~Menzies. He has extensively advised private, corporate and museum art collections and been responsible for numerous Australian art publications and landmark exhibitions. He is also an approved valuer under the Cultural Gifts Program.

Fiona Hayward

Senior Art Specialist

After completing a Bachelor of Arts at Monash University, Fiona worked at Niagara Galleries in Melbourne, leaving to join the newly established Melbourne auction rooms of Christie’s in 1990, rising to become an Associate Director. In 2006, Fiona joined Sotheby’s International as a Senior Paintings Specialist and later Deputy Director. In 2009, Sotheby’s International left the Australian auction market and established a franchise agreement with Sotheby’s Australia, where Fiona remained until the end of 2019 as a Senior Specialist in Australian Art. At the end of the franchise agreement with Sotheby’s Australia, Smith & Singer was established where Fiona worked until the end of 2020.

Crispin Gutteridge

Head of Indigenous Art and Senior Art Specialist

Crispin holds a Bachelor of Arts (Visual Arts and History) from Monash University. In 1995, he began working for Sotheby’s Australia, where he became the representative for Aboriginal art in Melbourne. In 2006 Crispin joined Joel Fine Art as head of Aboriginal and Contemporary Art and later was appointed head of the Sydney office. He possesses extensive knowledge of Aboriginal art and has over 30 years’ experience in the Australian fine art auction market.

Alex Creswick

Managing Director / Head of Finance

With a Bachelor of Business Accounting at RMIT, Alex has almost 30 years’ experience within financial management roles. He has spent much of his early years within the corporate sector with companies such as IBM, Macquarie Bank and ANZ. With a strong passion for the arts Alex became the Financial Controller for Ross Mollison Group, a leading provider of marketing services to the performing arts, before joining D+H in 2011.

Jennifer Terace

Front of House Manager – Melbourne

Jennifer holds a Bachelor of Visual Arts from Edith Cowan University and has experience across event management, retail operations, and community arts program coordination. She has worked as a practicing artist, artist’s assistant, and gallery assistant, gaining valuable insight into both the creative and logistical aspects of the visual arts sector.

Danny Kneebone

Design and Photography Manager

With over 25 years in the art auction industry as both photographer and designer. Danny was Art Director at Christie’s from 2000–2007, Bonham’s and Sotheby’s 2007–2009 and then Sotheby’s Australia from 2009–2020. Specialist in design, photography, colour management and print production from fine art to fine jewellery. Danny has won over 50 national and international awards for his photography work and art practice.

Damian Hackett

Executive Director — Sydney

Damian has over 30 years’ experience in public and commercial galleries and the fine art auction market. After completing a BA (Visual Arts) at the University of New England, he was Assistant Director of the Gold Coast City Art Gallery and in 1993 joined Rex Irwin Art Dealer, a leading commercial gallery in Sydney. In 2001, Damian moved into the fine art auction market as Head of Australian and International art for Phillips de Pury and Luxembourg, and from 2002 – 2006 was National Director of Deutscher~Menzies.

Henry Mulholland

Senior Art Specialist

Henry Mulholland is a graduate of the National Art School in Sydney, and has had a successful career as an exhibiting artist. Since 2000, Henry has also been a regular art critic on ABC Radio 702. He was artistic advisor to the Sydney Cricket Ground Trust Basil Sellers Sculpture Project, and since 2007 a regular feature of Sculpture by the Sea, leading tours for corporate stakeholders and conducting artist talks in Sydney, Tasmania and New Zealand. Prior to joining Deutscher and Hackett in 2013, Henry’s fine art consultancy provided a range of services, with a particular focus on collection management and acquiring artworks for clients on the secondary market.

Veronica Angelatos

Art Specialist and Senior Researcher

Veronica has a Master of Arts (Art Curatorship and Museum Management), together with a Bachelor of Arts/Law (Honours) and Diploma of Modern Languages from the University of Melbourne. She has strong curatorial and research expertise, having worked at various art museums including the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice and National Gallery of Victoria, and more recently, in the commercial sphere as Senior Art Specialist at Deutscher~Menzies. She is also the author of numerous articles and publications on Australian and International Art.

Ella Perrottet

Senior Registrar

Ella has a Masters of Arts and Cultural Management (Collections and Curatorship) from Deakin University together with a Bachelor of Fine Art (Visual Art) from Monash University, and studied in both Melbourne and Italy. From 2014, Ella worked at Leonard Joel, Melbourne as an Art Assistant, researcher, writer and auctioneer, where she developed a particular interest in Australian women artists.

Eliza Burton

Registrar

Eliza has a Bachelor of Arts (English and Cultural Studies and History of Art) from the University of Western Australia and a Master of Art Curatorship from the University of Melbourne. She has experience in exhibition management, commercial sales, and arts writing through her work for Sculpture by the Sea and The Sheila Foundation.

Poppy Thomson Gallery Manager, Sydney

Poppy holds a Bachelor of Art History and Curatorship (Honours) from the Australian National University and has professional experience as a curator and research assistant. Prior to this role, she spent time in Paris after winning the 2023 Eloquence Art Prize, and now sits on the board of Culture Plus.

Chris Deutscher

Damian Hackett 0411 350 150 0422 811 034

Henry Mulholland

Fiona Hayward 0424 487 738 0417 957 590

Crispin Gutteridge Veronica Angelatos 0411 883 052 0409 963 094

Administration and Accounts

Megan Mac Sweeney Poppy Thomson (Melbourne) (Sydney) 03 9865 6333 02 9287 0600

Absentee and Telephone Bids

Jennifer Terace 03 9865 6333

Shipping

Ella Perrottet 03 9865 6333

Roger McIlroy Head Auctioneer

Roger was the Chairman, Managing Director and auctioneer for Christie’s Australia and Asia from 1989 to 2006, having joined the firm in London in 1977. He presided over many significant auctions, including Alan Bond’s Dallhold Collection (1992) and The Harold E. Mertz Collection of Australian Art (2000). Since 2006, Roger has built a highly distinguished art consultancy in Australian and International works of art. Roger will continue to independently operate his privately-owned art dealing and consultancy business alongside his role at Deutscher and Hackett.

Scott Livesey Auctioneer

Scott Livesey began his career in fine art with Leonard Joel Auctions from 1988 to 1994 before moving to Sotheby’s Australia in 1994, as auctioneer and specialist in Australian Art. Scott founded his eponymous gallery in 2000, which represents both emerging and established contemporary Australian artists, and includes a regular exhibition program of indigenous Art. Along with running his contemporary art gallery, Scott has been an auctioneer for Deutscher and Hackett since 2010.

Lot 2

Lots 1 – 59 page 12

Prospective buyers and sellers guide page 154

Conditions of auction and sale page 156

Telephone bid form page 158

Absentee bid form page 159

Attendee pre-registration form page 160

Index page 175

oil on canvas

19.5 x 35.5 cm

signed and inscribed lower left: A. Schramm / Adelaide 1851

Estimate: $60,000 – 80,000

Provenance

Private collection

Adrian Mibus and Louise Whitford, Whitford Fine Art, London and Brussels

Private collection, Adelaide, acquired from the above c.1980s

Of all Australia’s colonial artists who took on the challenge of por traying A boriginal people, whether sympathetically or not, one stands out as particularly difficult to categorise. Arriving in Adelaide from Hamburg aboard the Prinzessin Victoria Luise on 7 August 1849, Carl Friedrich Alexander Schramm was aged 36. The son of a Berlin book dealer, Schramm had studied art in that city and had painted in Italy and Poland. His Boating Party at Treptow, 1838 conforms to a particular variant of Biedermeier art, with ‘theatrical staging, narrow prosceniumlike foregrounds and flat patterning that often suggest scenic decoration.’ 1 Enough survives of Schramm’s German output to indicate that he had begun producing artworks with a sharpened critique of the false ‘idyll’ which Biedermeier art often portrayed. Indeed, his work may well have attracted the attention of German authorities, perhaps accounting for his presence on the Prinzessin Victoria Luise whose passenger list included sympathisers with the 1848 uprisings.

Those hints of Schramm’s attitude become more evident when we turn to his Australian output. His first Australian painting, perhaps the most ambitious of his career, was a large and detailed portrayal of an encampment of Murray River Aboriginal people on the northern bank of the River Torrens – Adelaide: A Tribe of Natives on the Banks of the Torrens, 1850 (National Gallery of Australia). These people had been attracted to the city by the government ration distribution but had outlived their welcome; the camp housing more than 80 people was soon regarded as a public nuisance. Schramm’s picture presented an alternative view of a complex and ebullient sociality. In its crowded but clear delineation it was not so far removed from the Boating Party at Treptow.

That benchmark oil painting established Schramm’s reputation, a nd he was to paint similar tableaux of multiple Aboriginal figures and scenes within scenes, as if the colonial world had been pushed back and made irrelevant. These sold well, won prizes at the Society for Arts annual shows, and lithographs followed. As these large encampments fragmented, Schramm might well have turned to more lucrative society portraiture, yet he persisted. He did not completely abandon his Biedermeier style –his Bush Visitors series, 1858 – 1860 conveys the same theatrical impression with bright colouring and distinct figuring, but he had also found another way to approach his subject, applying an acid, sardonic critique to the unfolding predicament of a colonised people dealing with their own displacement and emasculation.

In 1851, barely a year after Adelaide: A Tribe of Natives on the Banks of the Torrens, Schramm produced the work under consideration here. A straggling trail of partly clothed Aborigines with their dogs enters the field of view, arriving at the edge of settlement at sunset. One figure gestures towards a small cottage on a riverbank, overlooked by ragged eucalypts. Individual features are blurred by the sun’s glare, shifting the painting’s register from descriptive to allegorical. The group has arrived at the edge of the colony, and we are all familiar with the consequences.

[Aboriginal group on the tramp, towards evening], 1851 is perhaps the first colonial painting to steer a course past the literal, the ethnographic, the scenic, into the core of the colonial impasse. Using variants on this theme in sketches, lithographs and oil paintings, Schramm would confront this impasse repeatedly over the following decade until his death in 1864, aged 51.

1. Boime, A., ‘Biedermeier culture and the revolutions of 1848’ in Art in an age of civil struggle 1848 – 1871. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2007, p. 471

Philip Jones

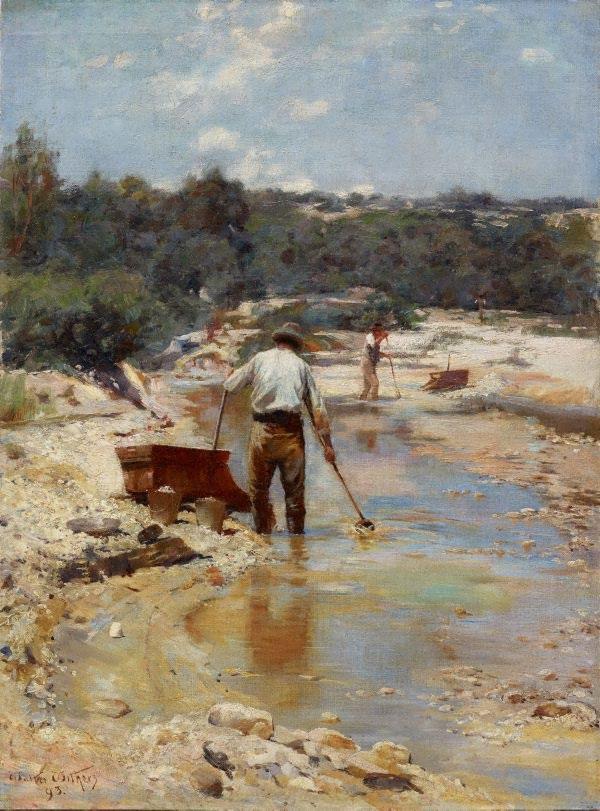

oil on board

55.5 x 40.5 cm

signed and dated lower left: J Miller Marshall / 1892 bears inscription verso: Prospecting for Gold / on the Gold Creek nr Creswick + Ballarat

Estimate: $60,000 – 80,000

Provenance

Private collection

Sotheby’s, Chester, England, February 1986

Private collection

Deutscher Fine Art, Melbourne Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in April 1986

Exhibited

Australian Art: Colonial to Modern, Deutscher Fine Art, Melbourne, 9 – 25 April 1986, cat. 52 (as ‘Gold Prospecting, near Creswick, Ballarat’)

Literature

Ingram, T., ‘Even in Chester they holler for a Marshall’, The Australian Financial Review, 27 March 1986, p. 38 (as ‘Gold Prospecting, near Creswick, Ballarat’)

Topliss, H., The Artist Camps: ‘Plein Air’ Painting in Australia, Hedley Australia Publications, Melbourne, 1992, pl. 17, pp. 20 (illus. as ‘Gold Prospecting, near Creswick, Ballarat’), 186

Related works

Fossicking for Gold, 1893, oil on canvas laid down on board, 44.0 x 33.0 cm, private collection, Victoria Walter Withers, Seeking for gold – cradling, 1893, oil on canvas on hardboard, 67.0 x 49.6 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Percy Lindsay Fossicking for gold, 1894 oil on canvas

29.5 x 21.8 cm

Private collection

Australian art history is replete with evocative stories of artists living and working together in the landscape. Think, for example, of the camaraderie of Australian Impressionists Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton and Louis Abrahams at the plein air painting camp at Box Hill in the summer of 1885, or of Curlew Camp on Sydney’s North Shore, where in the early 1890s Roberts and Streeton found creative inspiration in their rustic but picturesque ocean-side accommodation. Painting outdoors, these artists captured the effects of light and colour at different times of the day and in different seasons, communicating both the appearance and the experience of their landscape subjects.

Walter Withers met Roberts, Abrahams and Frederick McCubbin as a student at Melbourne’s National Gallery school and he too was an artist ‘who went out [in]to nature, and made successful attempts to represent her varying moods.’ 1 In 1893, he and his friend James Miller Marshall were invited to Creswick, a town not far north of Ballarat, to teach a summer school. ‘[They] spent several weeks… holding an out-of-door class during the month of January. Creswick, with its Italian colouring of blue and gold, made an ideal painting ground, and the students were

Walter Withers Seeking for gold - cradling , 1893 oil on canvas on hardboard

67.0 x 49.6 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

enthusiastic workers. Amongst those who took advantage of this opportunity were Percy Lindsay (then a promising young landscape painter), and, at the evening drawing class held in the [Ballarat] School of Mines, his young brother, now the wellknown Norman Lindsay – a schoolboy then, whose remarkable facility in drawing aroused Withers’ wonder and delight.’ 2

English born, Marshall was the son of a painter who ‘received his early training as an artist at the South Kensington school, but as soon as he had acquired a sufficient grounding in the technical knowledge of drawing and painting… followed the example of the great French and English artists of the new school, painting and studying direct from nature.’ 3 He exhibited a series of landscapes at the Royal Academy of Art in London during the 1880s before travelling to Australia in 1890. While he primarily painted in and around Melbourne, Sydney Harbour from the Domain, 1893, a watercolour in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, suggests that he also ventured further north during his years in Australia. Another Lindsay brother, Lionel, who also undertook art classes with Marshall in Creswick described him fondly as a ‘big, bearded simple soul who asked from life a

full day’s painting and a pot of beer at eve on an ale-house bench’, and recalled his advice, ‘Plenty of water. Plenty of water and a full brush: that’s the secret of watercolour.’4

One of the notable outcomes of this summer in Creswick was a series of paintings by Marshall, Withers and Percy Lindsay which depict miners fossicking for gold. Among them, a trio of closely related paintings includes this work by Marshall, Withers’ Panning for gold, 1893 and Lindsay’s Fossicking for gold, 1894 (both private collection). Withers and Lindsay depict a lone prospector kneeling beside a shallow creek panning for gold with a cradle – a wooden sieve used to separate alluvial gold from washed soil – and other tools of the trade nearby. Both artists use the familiar blue and gold palette of the Impressionist landscape and emphasise space and distance, describing the long meandering path of the creek towards faraway hills. Marshall’s painting is the largest of the three and depicts two prospectors at work. His colouring is more sombre, with a moody sky above the creek and rocky ground, which is painted in rich shades of burgundy, brown and blue. The pictorial space of Marshall’s picture is also more condensed and perhaps, as a visitor to the country who was unfamiliar with the native flora, he pays particular attention to the depiction of the reedy growth along the creek edge and the gum trees, carefully describing the distinctive drooping habit of their foliage. Fossicking for gold, 1893, now in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, is one of at least two other related works that Marshall painted at the time.

The discovery of gold in the 1850s transformed the Australian colonies, drawing huge numbers of migrants from across the world who travelled to the goldfields eager to find their fortune. The settler population more than quadrupled in the decades between 1851 and 1871, with many arriving in Victoria where, in the first decade of the gold rush, more than a third of the world’s gold was found. Although the peak of the Victorian gold rush was over by the 1890s, as these paintings demonstrate the subject of miners at work in the landscape continued to be one that interested contemporary painters.

Walter Withers Panning for Gold, 1893 oil on canvas

46.0 x 30.4 cm

Private collection

1. ‘Art of Walter Withers’, The Argus, Melbourne, 29 July 1919, p. 6

2. McCubbin, A., The Life and Art of Walter Withers, Alexander McCubbin, Melbourne, 1919, p. 19

3. Table Talk, 24 June 1898, cited in Ingram, T., ‘Even in Chester they holler for a Marshall’, The Australian Financial Review, 27 March 1986, p. 38

4. Lionel Lindsay, cited in Clifford-Smith, S., biography of J. Miller Marshall, Design & Art Australia Online, at: https://www.daao.org.au/bio/version_history/j-miller-marshall-1/ biography/ (accessed 23 September 2025)

Kirsty Grant

oil on canvas

36.0 x 54.0 cm

signed lower left: Walter Withers inscribed on old label verso: Phillip Island

Estimate: $25,000 – 35,000

Provenance

John May, Melbourne, by 1920

Leonard Joel, Melbourne, 24 May 1973, lot 31 (as ‘Phillip Island’)

Sir Leon and Lady Trout, Brisbane Private collection

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 22 April 1996, lot 61 Private collection, Melbourne

Exhibited

Master Works from the Collection of Sir Leon and Lady Trout, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 21 September – 14 December 1977, cat. 61 (label attached verso and illus. in exhibition catalogue, as ‘Phillip Island’)

Literature

Withers, F., The Life and Art of Walter Withers, Australian Art Books, Melbourne, 1920, pp. 24, 25 (illus.)

‘Melbourne’s private art galleries. Mr John May’s collection. The art of Walter Withers.’, The Age, Melbourne, 12 April 1930, p. 5

Mackenzie, A., Walter Withers: The Forgotten Manuscripts, Mannagum Press, Victoria, 1987, p. 129

Related work

Morning Mist, Eltham, oil on canvas, 62.0 x 73.5 cm, private collection

In a photograph of early Heidelberg, the family home of Walter Withers sits on a rise above the railway line. Titled ‘Withers Court’, the handsome double-fronted cottage is located opposite that of John May, a collector more fairly described ‘as a specialiser, for in the pictures which cover the walls of his Heidelberg home, certainly three-fourths are the work of one painter, the late Walter Withers… probably the most representative group of his works collected under one roof.’ 1 Indeed, Withers’ wife Fanny noted that this painting The morning ride, c.1894 – 1902, was one which took ‘pride of place’ in May’s home2, and it was also one of the small selection of images which she reproduced in 1920 in a small book dedicated to her late husband’s career. In a newspaper article on May’s collection published in 1930, the writer also singled out the painting for praise as ‘another landscape which gives pleasure… A morning ride, charming in composition, and while couched in a low key, is luminous and full of colour movement.’ 3

Withers rarely travelled far for his subjects and found most around his various homes in Creswick, Heidelberg and Eltham. According to Mrs Withers, The morning ride dates from ‘these Heidelberg years’4, that is, 1894 to 1902, noting also that these small works, usually painted en plein air, captured much that is fresh and appealing in her husband’s best work. Although Withers had painted alongside, and maintained strong friendships with, the artists of the Heidelberg school, his paintings rarely shared the intense light and high key colour seen in those by Streeton and Roberts. Although a strong colourist, Withers’ paintings maintain rather a lower key more akin to David Davies, as seen in The morning ride where the lowering sky casts shadows across the land apart from a small burst of sun on the horizon line. A number of the artist’s paintings, such as Nearing the township, 1901 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), feature travellers returning home and this illuminated patch may easily be interpreted as an optimistic indication of journey’s end. Rather than grand narratives, Withers was drawn to the momentary and commonplace, what art historian Bernard Smith described as ‘an endeavour to capture the ‘spirit’ of the landscape… not to record its anatomy but to portray its soul.’ 5

In 1897, Withers was awarded the first Wynne Prize – which he won a second time in 1900 – establishing him as a firm favourite among audiences and collectors. Following a major commission to paint a series of murals for the Manifold family at their grand western-districts mansion ‘Purrumbete’, Withers left ‘sleepy Heidelberg… with its winding roads, its wooded hills, and quiet village life’ 6 and moved to Eltham in 1902, with his subsequent paintings all based around that location. He was highly respected amongst his peers, serving briefly as President for the Victorian Artists’ Society before co-founding the Australian Art Association in 1912. Plagued by ill-health, Withers died at Eltham in 1914 leaving a collection of paintings that were exhibited to appreciative audiences the following year at Collins House, Melbourne.

1. ‘Melbourne’s private art galleries. Mr John May’s collection. The art of Walter Withers.’, The Age, Melbourne, 12 April 1930, p. 5, at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/ page/18959684 (accessed 4 September 2025)

2. Withers, F., The life and art of Walter Withers, Alexander McCubbin, Melbourne, 1920, p. 24

3. ‘Melbourne’s private art galleries’, op. cit.

4. Withers, op. cit.

5. Smith, B., Place, Taste and Tradition: a study of Australian art since 1788, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1945, p. 121

6. Withers, F., A short biography of Walter Withers, reprinted in Andrew Mackenzie, Walter Withers: the forgotten manuscripts, Mannagum Press, Victoria, 1987, p. 103

Andrew Gaynor

oil on canvas on board

30.5 x 41.0 cm

signed lower right: GRUNER

Estimate: $25,000 – 35,000

Provenance

Arthur Hancock, Melbourne

Thence by descent

Private collection, Melbourne

Thence by descent

Private collection, Melbourne

Related work

Beach idyll, 1934, oil on canvas on board, 46.5 x 44.0 cm, New England Regional Art Museum, New South Wales, gift of Howard Hinton

We are grateful to Steven Miller for his assistance with this catalogue entry.

As a teenager, Elioth Gruner was forced to take on family responsibility early due to the death of his father when he was very young, followed by that of his eldest brother when Gruner was sixteen. Such tragedies led to him working twelve-hour days as a draper’s assistant to support his mother whilst informally attending Julian Ashston’s art classes in the evening. This left little time for him to indulge in recreation – of which swimming and body surfing with close friends was a favoured pastime. The resultant paintings of these rare, hedonist moments are amongst the earliest sustained images depicting Australia’s love affair with the beach. Following World War One, Gruner’s focus turned inland, and it wasn’t until the 1930s that he returned to painting beaches and headlands, by which time he had perfected his mature, softly modernist style. Whilst these latter images were mostly de-populated, Figures by the shore, 1934, adds narrative intrigue with its two bathers looking back to the viewer whilst a third sits contemplating the ocean beyond.

Gruner’s early beach paintings coincided with a loosening of society’s rules regarding beach bathing; indeed, it was not until 1903 that bathers were officially allowed in the water during daylight hours. Gruner’s paintings between 1912 and 1918 are therefore additionally fascinating as his bathers are already within their environment, totally at home in the sand or water. In works such as Bondi Beach, c.1912 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), the clustered sunbathers have become ‘vibrant

and economical studies in colour and tone (demonstrating) a new interest and facility in the simple arrangements of figures in patterns.1 This fascination with formalised design carries over into Figures by the shore with its classicist structure of the two main characters bracketed by trees; however, by placing these figures off centre, Gruner imparts a pleasing informality to the scene. The freshness of the brush marks also indicates that it was painted en plein air, in front of the motif.

Gruner suffered from depression and thus was not prolific, often destroying works he felt were not up to his exacting standards. In 1934, by contrast, he was buoyed by the previous year’s successes which included the magazine Art and Australia devoting an issue to his recent work, an act of public support which they had previously done to great acclaim in 1929. This positive affirmation continued when Gruner was awarded his fifth Wynne Prize in 1934 for Murrumbidgee Ranges, Canberra (National Gallery of Australia). In light of such events, it is tempting to detect a joyous purity within Figures by the shore, and in its companion work Beach idyll, 1934 (New England Regional Art Gallery). Whilst both are a welcome return to the figure-beach interaction, Gruner’s overall subject remains ‘the fine and subtle emotional quality of light (combined with a) feeling for design and form which (he) so courageously imposed on his work.’ 2

1. Clark, D., Elioth Gruner: Texture of light, Canberra Museum and Gallery, Australian Capital Territory, 2014, p. 17

2. Burdett, B., ‘The art of Daryl Lindsay’, Art in Australia, series 3, no. 39, August 1931, p. 23 Andrew Gaynor

Elioth Gruner (1882 – 1939)

Landscape, Bacchus Marsh, 1930

oil on plywood

30.0 x 40.0 cm

signed and dated lower right: GRUNER / 1930 bears inscription verso: LANDSCAPE / BACCHUS MARSH (W. BUCKLE)

Estimate: $30,000 – 40,000

Provenance

The artist, Sydney (probably ledger no. 370, as ‘Road with poplar’)

W. G. Buckle, by 1933

Arthur Hancock, Melbourne

Thence by descent

Private collection, Melbourne

Thence by descent

Private collection, Melbourne

Exhibited

Exhibition of Pictures from Southern States, Queensland National Art Gallery, Brisbane, 22 July – 16 August 1930, cat. 8a (as ‘A road near Bacchus Marsh’)

Loan Exhibition of the Works of Elioth Gruner, National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 21 December 1932 – 21 February 1933, cat. 43

Elioth Gruner Memorial Loan Exhibition, National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 17 April – 31 May 1940, cat. 39, lent by Mr W.G. Buckle (label attached verso)

Literature

Art in Australia, Sydney Ure Smith, Sydney, 3rd Series, no. 50, June 1933, p. 37 (illus., as ‘Landscape, Bacchus Marsh, Victoria’)

Related works

Morning, Bacchus Marsh, Victoria, 1930, oil on canvas, 50.5 x 61.0 cm, private collection, sold Deutscher and Hackett, Sydney, 22 November 2023, lot 27

Werribee Gorge, 1930, oil on canvas on cardboard, 30.0 x 40.7 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

We are grateful to Steven Miller for his assistance with this catalogue entry.

Landscape, Bacchus Marsh, 1930, dates from a pivotal period in the career of Elioth Gruner when the many personal painting challenges he had undertaken over the previous seven years coalesced into his instantly recognisable mature technique. It was executed in the same year as two other significant works: Morning, Bacchus Marsh, Victoria, 1930 (Deutscher and Hackett, Sydney, 22 November 2023, lot 27), and the widely reproduced Mitchell River, Victoria (aka Gippsland lakes), 1930 (Deutscher and Hackett, Sydney, 14 September 2022, lot 24). These painting challenges had been triggered by an encounter with the British artist Sir William Orpen in 1923, who criticised Gruner’s technique and design, encouraging him to change to smaller canvases and to utilise a thinner, more pastel-like application of paint.

Gruner subsequently travelled to Europe looking closely at post-impressionists such as Paul Gauguin and absorbing their lessons on the flattening of space. Although some colleagues in Australia – most famously Norman Lindsay – were appalled by his subsequent, mildly modernist approach, audiences responded strongly to the new works, and between 1929 and 1937, Gruner added four more Wynne Prize awards for landscape painting to the three he already possessed.1 These included the nowiconic On the Murrumbidgee, 1929 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) shown in the competition in early 1930, a ‘high point of his progression towards creating modern landscape from a plein air practice of direct observation before the subject.’ 2

Buoyed by his success, Gruner undertook an extended drive through the south coast of New South Wales and on to the Gippsland region of Victoria where he painted Mitchell River, Victoria (aka Gippsland lakes), 1930. Following this, he travelled back to Melbourne and by May, was in regional Bacchus Marsh on Woiwurrung and Wathaurong country. Notably, he was in the company of two significant artist-educators – namely, George Bell, who would open his renowned modernist school two years later, and Daryl Lindsay, member of the famed artistic family and future Director of the National Gallery of Victoria. 3 This was a working holiday charged with much intellectual discussion and analysis, and contemporaneous paintings by each bear witness to shifts in emphasis and technique. It is interesting to compare Lindsay’s and Gruner’s paintings in particular. Although both exhibit a marked flattening of space, in works such as Lindsay’s Landscape at Myrniong, c.1930, and Landscape at Bacchus Marsh, c.1930 (both in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria), the brushwork comprises stipples of impasto strokes whilst the skies are filled with highly mannered clouds. By comparison, Gruner’s paintings from Bacchus Marsh demonstrate the continuing strength of his vision. In the lot on offer here, the majestic poplar and companion oak provide a central focus, whilst the forked roads lead the eye back to the foreground, bracketed by the boundary fence to the right and two small cottages at the left. However, it is the sensual pleasure that Gruner expresses with his sky and clouds that truly completes the image. Taking cues from other modernist contemporaries such as Grace Cossington Smith (see Gum Blossom, c.1928 – 32, Deutscher and Hackett, Melbourne, 28 August 2024, lot 49), the blue brushstrokes radiate to the heavens, while the clouds on the horizon impart a true sense of reality. Indeed, Gruner himself was also impressed, writing to the critic Basil Burdett that he had ‘painted a sky at last.’4

1. Gruner was awarded the Wynne Prize in 1916, 1919, 1921, 1929, 1934, 1936, and 1937.

2. Clark, D., Elioth Gruner: Texture of light, Canberra Museum and Gallery, Australian Capital Territory, 2014, p. 12

3. Lindsay and his wife were temporarily renting a cottage at Bacchus Marsh, see: Lindsay, D., The leafy tree: my family, F.W. Cheshire, Melbourne, 1965, p. 153

4. Elioth Gruner, Letter to Basil Burdett, 29 May 1930 in Art Gallery of New South Wales archives, MS1995.9, 1/17/10.

Andrew Gaynor

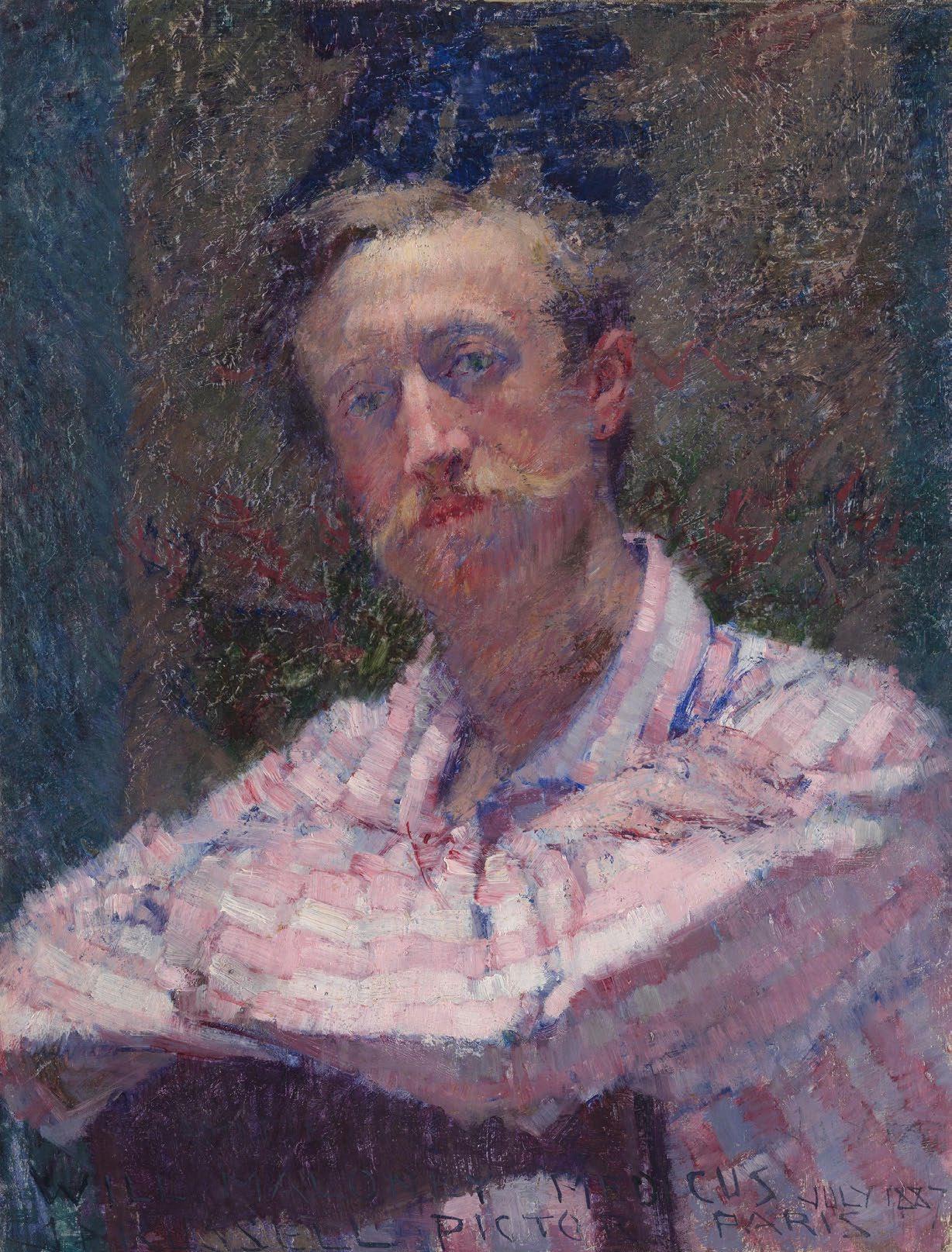

oil on canvas

55.5 x 47.5 cm

signed lower right: JP RUSSELL

Estimate: $1,000,000 – 1,500,000

Provenance

Bequeathed by Dodge Macknight to his sister–in–law, Elise Queyrel, Massachusetts, USA

Thence by descent

Mrs George W. Bruce, Massachusetts, USA

Thence by descent

Private collection, Delaware, USA

Deutscher and Hackett, Melbourne, 29 August 2007, lot 48

Private collection, Melbourne

Exhibited

An Impressionist in Sandwich: The Paintings of Dodge Macknight, Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, Massachusetts, 15 November –21 December 1980, cat. 68 (illus. in exhibition catalogue, p. 4)

Australian Impressionists in France, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 15 June – 6 October 2013 (label attached verso)

John Peter Russell: Australia’s French Impressionist, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 21 July – 11 November 2018

Literature

Letter from Vincent van Gogh to John Peter Russell, Arles, 19 April 1888

Salter, E., The Lost Impressionist: a biography of John Peter Russell, Angus and Robertson, London, 1976, pp. 75, 95

Galbally, A., The Art of John Peter Russell, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1977, p. 34

Pickvance, R., Van Gogh in Arles, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1984, p. 253

Bailey, M., ‘A Friend of Van Gogh, Dodge Macknight and the Post–Impressionists’, Apollo Magazine, London, July 2007, pl. 4 (illus.), pp. 30, 31 (illus.)

Fish, P., ‘Spring bidding budding’, The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 25 August 2007

Jansen, L (ed.) et. al., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, 2009, vol. 4, p. 60 (illus.)

Taylor, E., Australian Impressionists in France, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2013, frontispiece (illus.), pp. 56, 57 (illus.)

Tunnicliffe, W. (ed.), John Peter Russell: Australia’s French Impressionist, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2018, pp. 39, 41 (illus., dated 1887 – 88), 203

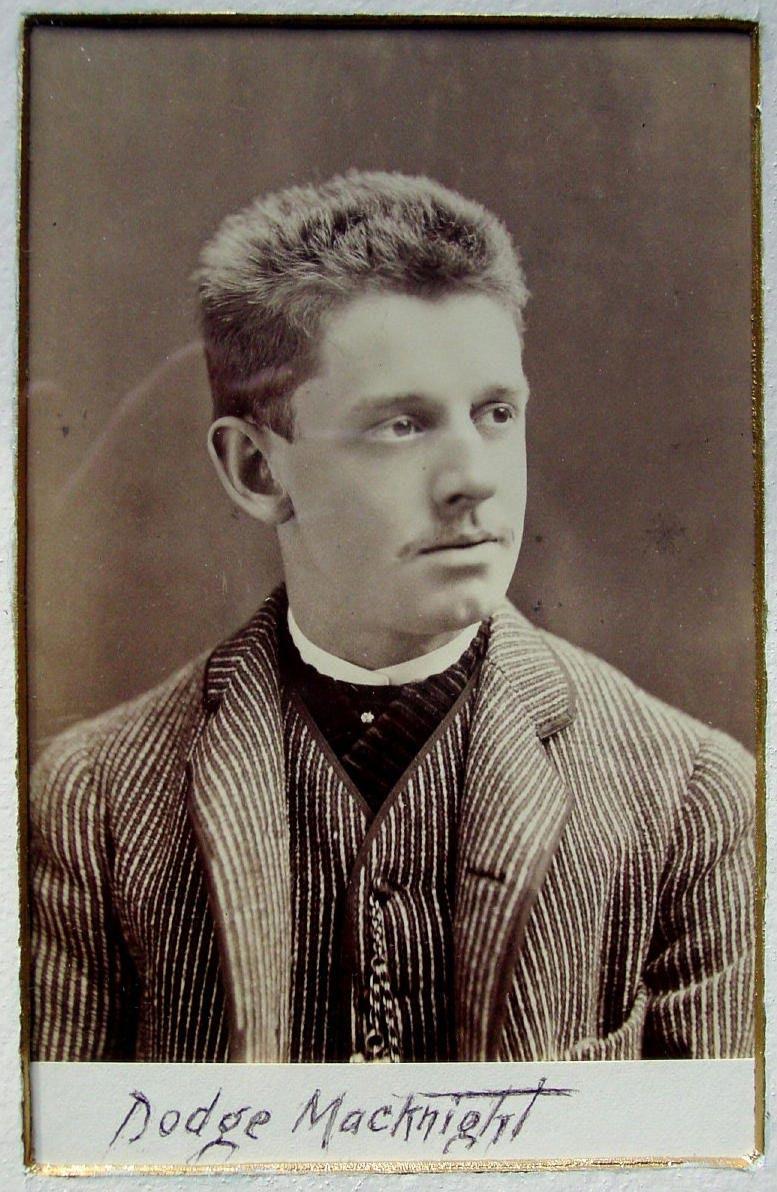

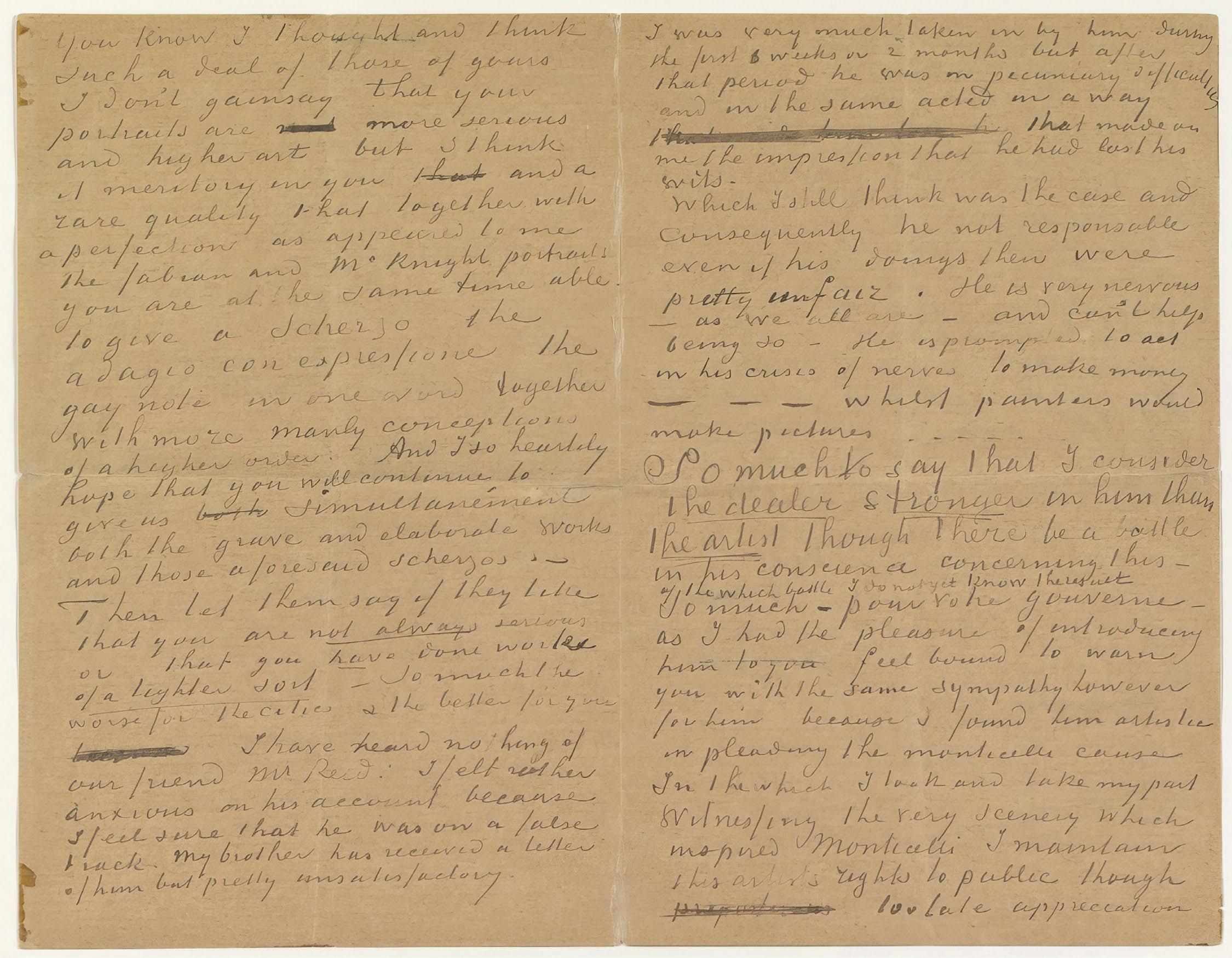

When one of the greatest exponents of modern painting, Dutch master Vincent van Gogh, wrote admiringly of John Peter Russell’s portraits as ‘more serious and higher art’, praising in particular ‘such perfection as appeared to me in the Fabian and Macknight portraits’ 1, he articulated a keen appreciation for the work of Australia’s ‘lost impressionist’ that continues to resonate more than a century later. Occupying an esteemed position within Russell’s oeuvre, indeed the present Portrait of Dodge Macknight, c.1888 not only encapsulates superbly the artist’s technical brilliance and emotional breadth but, as the only known portrait of the American post-impressionist, the painting bears invaluable historical significance as well. With its whereabouts unknown until 2007, the work’s recent rediscovery has been a particularly exciting one for art critics and collectors alike; as acknowledged by the late Ursula Prunster, curator of the major Belle-Île exhibition held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2001 which featured the work of Russell, Monet, and Matisse, ‘I have been looking for this painting for a while...’ 2

John Peter Russell Dr Will Maloney, 1887 oil on canvas

48.5 x 37.0 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Although not as widely appreciated today, during his lifetime Dodge Macknight was highly regarded by his contemporaries as America’s first modernist and certainly, one of the world’s four greatest watercolourists. 3 Discussing his legacy, a critic for The New Bedford Standard suggested, ‘In contemplating an exhibit of Macknight’s work, one should bear in mind that he is an extremist in an extreme school. His work should not be judged merely in the light of one’s own taste, but as an exposition of the artist’s conceptions. Some people call his paintings mere daubs of colour, others designate them as recorded thoughts transmitted through the eyes.’4

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Macknight began his career in the art world as an apprentice to a theatrical scene designer before entering the firm of Taber Art in New Bedford, Massachusetts, a company that manufactured reproductions of paintings and photographs. In December 1883, at the age of 23, he migrated to Paris where he enrolled at the studio of academic

John Peter Russell

Fabián de Castro, c.1888

oil on canvas

65.5 x 65.2 cm

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, USA

painter Fernand Cormon, studying alongside Toulouse-Lautrec, Émile Bernard and Louis Anquetin, together with the two artists who would play a key role in introducing Macknight to the Parisian avant-garde, Eugène Boch and John Peter Russell.

As Martin Bailey elucidates, Macknight and van Gogh first met through Russell in March 1886, the month that van Gogh joined Cormon’s studio, having arrived in Paris from Antwerp on 28 February 1886. Shortly thereafter, Macknight left Paris, heading first for the south of France and later that year for the Algerian coast, while van Gogh remained in Paris for another two years, during which he frequently met with Russell. 5 Connected through their mutual status as outsiders in an intensely competitive Parisian art scene, Russell and van Gogh soon forged a close friendship – one that would endure through well-documented letters and exchanges of artwork right up until the latter’s tragic death in 1890. And indeed, it was most probably during these Paris years that the Dutchman posed for his celebrated portrait by Russell which, now housed in the van Gogh Museum,

Amsterdam, he clearly cherished; as he would subsequently write to his brother Theo in one of his final letters, ‘Take good care of my portrait by Russell which I hold so dear.’ 6

On 20 February 1888, van Gogh arrived in Arles and several weeks later, Macknight came to Provence, staying in the nearby village of Fontvielle, north-east of Arles.7 Writing to his friend Eugène Boch, Macknight noted that he had ‘unearthed a couple of artists at Arles – a Dane [Christian Mourier-Petersen]’ and Vincent whom I had already met at Russell’s – a stark, staring crank, but a good fellow.’ 8 Van Gogh too would recount the meeting in a subsequent letter to Russell: ‘Last Sunday, I have met Macknight and a Danish painter, and I intend to go to see him at Fontvielle next Monday. I feel sure I shall prefer him as an artist to what he is as an art critic, his views as such being so narrow they make me smile.’ 9 And again, in his correspondence with Theo, ‘I must go and see him and his work, of which I have seen nothing so far. He is a Yankee, and probably paints better than most Yankees do. But a Yankee all the same. Is that saying

Macknight (1860 – 1950)

The Bay, Belle-Île, 1890 watercolour on paper

38.0 x 38.0 cm

Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

enough? When I’ve seen his paintings or drawings I’ll concede about the work. But about the man, still the same...’ 10 Ironically perhaps, van Gogh’s brusque assessment reflects more of his own notoriously volatile personality than any real dissatisfaction with Macknight, for only days later he would mention to his brother that he had invited the American to move into the Yellow House in Arles: ‘…it’s not impossible that he may come to stay with me here for a while. Then we would benefit, I think, on both sides.’ 11

Upon sighting Macknight’s work for the first time, van Gogh was typically gruff, recalling to Theo that ‘…He’s at the stage when the new colour theories are tormenting him, and while they prevent him from doing things according to the old system, he hasn’t sufficiently mastered his new palette to be able to succeed this way.’ 12 Yet, despite his criticism, the Dutchman was obviously impressed for less than one month later, after having seen various still-lifes that Macknight had just finished featuring ‘a yellow jug on purple foreground, red jug on green, orange jug on blue’ 13, he executed one of his famous

Sunflower canvases with orange flowers in a yellow pot, set against a turquoise background.14 Thus, contrary to the popular assumption of van Gogh as an artistic recluse in Arles, it would seem rather, that he and Macknight were exploring in tandem the theory of disparate colour complementaries.15

At the same time, working with Monet on the remote, storm-tossed island of Belle-Île off the coast of Brittany, interestingly Russell was embracing very similar techniques; as he elucidates in a letter to Heidelberg school artist Tom Roberts back in Melbourne: ‘…No vehicle colour only on absorbed canvas or better on stiff canvas prepared only with glue. Simple colours but strong keep pure as long as possible.’ 16 Thus, in stark contrast to the darker tonalities of Russell’s 1886 portrait of van Gogh, the present offers a luminous demonstration of the French impressionist technique with the brushstrokes open and relaxed, and the coarse texture weave of the canvas soaking up the paint upon application to reveal the artist’s hand visibly at work. Cropped asymmetrically in a manner reminiscent of Japanese woodcut prints, the vivid white,

red and blue-purple palette – shading through a toned white, pink and grey – is at once arresting and harmonious, contributing to create a portrait of great sensitivity and beauty. Closely related to Russell’s highly acclaimed Portrait of Dr Will Maloney, 1887 (National Gallery of Victoria) executed around the same time, the portrait moreover betrays that powerful quality of immediacy and informality so essential to the vision of the European avant-garde.

Following in the footsteps of Russell and Monet, in November 1888 Macknight made the first of many visits to Belle-Île where, pursuing a passion for colour shared and encouraged by the Australian, he would produce some of the finest watercolours of his career. In 1892, he married the governess of Russell’s children, Louise Queyrel, and in 1897 the couple and their young son returned to the United States, settling in East Sandwich where Macknight would remain for the rest of his life. Although initially condemned as ‘grotesque and uncouth’ 17 – barbs not unfamiliar to impressionist artists internationally at that time – his work was soon eagerly sought-after and acquired by public and private collectors alike, including eminent art patron Isabella Stewart Gardner, who had a dedicated ‘Macknight Room’ in her

Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890) Self-Portrait with Straw Hat, 1887 oil on artist board, mounted to wood panel 34.9 x 26.7 cm Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit

house at Fenway (now the Gardner Museum) and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts which purchased its first watercolour by Macknight in 1907 (five years before the first Sargent acquisition).

Returning to America with Macknight and subsequently passed down through the artist’s family before its first appearance on the market in 2007, thus the present work not only offers a rare glimpse into one of the most fascinating yet often forgotten members of impressionism, but notably, is accompanied by an impeccable provenance. In addition to its historical significance, Portrait of Dodge Macknight also embodies the radical avant-garde theories and experiments which, gleaned by Russell through his personal connection with the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, so distinguish him from the local movement pioneered by the Heidelberg school. As celebrated French sculptor Auguste Rodin astutely prophesised of Russell’s artistic legacy, ‘Your works will live on, I am certain. One day you will be placed on the same level as our friends Monet, Renoir and Van Gogh.’ 18

Letter from Vincent van Gogh to John Peter Russell, Arles, 19 April 1888, with reference to Russell’s Portrait of Dodge Macknight Thannhauser Collection, Guggenheim Museum, New York

1. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to John Peter Russell, Arles, 19 April 1888, letter 598, at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let598/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

2. Ursula Prunster, in conversation with Deutscher and Hackett art specialists (August 2007)

3. Hind, C. L., Art and I, The Bodley Head, New York, 1921, pp. 98, 100 – 101 & 176. The other three were Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent and Hercules Brabazon.

4. The New Bedford Standard, January 1902, cited in An Impressionist in Sandwich: The Paintings of Dodge Macknight, Trustees of the Heritage Plantation of Sandwich, Massachusetts, 1980, p. 6

5. Bailey, M., ‘A Friend of Van Gogh: Dodge Macknight and the Post-Impressionists’, Apollo, July 2007, p. 30

6. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, 5 and 6 September 1889, letter 800, at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let800/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

7. Bailey, op. cit.

8. Dodge Macknight, Letter to Eugène Boch, Fontvielle, 19 April 1888

9. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to John Peter Russell, 19 April 1888, op. cit.

10. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh, Arles, c.25 April 1888, letter 601, at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let601/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

11. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh, Arles, c.4 May 1888, letter 603 at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let603/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

12. ibid.

13. Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Theo van Gogh, Arles, 29 July 1888, letter 650 at https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let650/letter.html (accessed October 2025)

14. Bailey, op. cit., p. 32

15. ibid.

16. John Peter Russell, Letter to Tom Roberts, Paris, 26 December 1887, reproduced in Galbally, A., The Art of John Peter Russell, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1977, p. 90

17. An Impressionist in Sandwich, op. cit., p. 6

18. Auguste Rodin , Letter to John Peter Russell, cited in ‘The Art of John Peter Russell’, Women’s Weekly, 3 May 1967, p. 34 at https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/4832171 (accessed October 2025)

Veronica Angelatos

Vase in the window, 1945

oil on compressed card

58.0 x 46.0 cm

signed and dated lower left: G. Cossington Smith 45. signed and inscribed with title on artist’s label verso: Vase in The Window / Grace Cossington Smith inscribed verso: Hydrangeas in the Window bears inscription verso: PROPERTY OF MARY TURNER

Estimate: $60,000 – 80,000

Provenance

Macquarie Galleries, Sydney (label attached verso) Mary Turner, Sydney Private collection, Sydney, acquired directly from the above

Exhibited

Grace Cossington Smith, Exhibition of paintings, Macquarie Galleries, Sydney, 17 – 29 September 1947, cat. 4

Private Treasure – Public Pleasure, Orange Regional Gallery, New South Wales, 5 February – 5 March 1998 (label attached verso)

Literature

‘Grace C. Smith Exhibition’, The Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 17 September 1947, p. 9

As was the case for many female painters of the late 19th and early 20th century, the domestic interior became the centre of Grace Cossington Smith’s artistic production, the crucible of her modernist experience. While flower pieces and still-life compositions were mainstays of Smith’s creative practice, by the 1940s, these were evolving from tightly cropped, rhythmic compositions to expanded views of still-life arrangements by the window, presented within the rooms of the house where she had lived for almost 50 years. Vase in the window, 1945, sets a spindly hydrangea cut straight from the garden against the corner of a windowsill, its blue flowerheads shimmering against an array of golden hues. Finding wonder in familiar surroundings, Smith has transformed this ordinary scene into a subtle expression of the genius loci of the home that bore her name.1

The death of the family’s patriarch, Ernest Augustus Smith, in September 1938, was a major event in the artist’s otherwise stable and quiet life – ‘rooms were purged, lives reorganised and relationships re-negotiated’ 2, the family home seen anew. Alongside her two unmarried sisters, Madge and Diddy, Grace gained full autonomy of the house, formally relocating her studio from the shed at the bottom of the garden. Although a few examples of imagined narrative subjects exist from the wartime period – for example, Dawn landing, 1944 and Signing, 1945 – the

majority of Smith’s regular output at this time was focused on the home front, retreating indoors and producing confident still lives marked by ‘a milky consistency of touch, verging on the tonal.’ 3

With a stately vertical composition, Vase in the window is an early example of the artist’s celebrated paintings of a still life in the window, which reached their high-pitched apogee in the mid1950s. The painting is vertically divided between yellow drapery on the left and, on the right, an amorphous, misty landscape seen through the windowpane, each painted with the artist’s textured square pointillism. Set against a complex geometry of diagonal and perpendicular lines from the tilted plane of the table and sill, the contours of Smith’s singular subject, alternately titled Hydrangeas in the window, shimmer with fractured brushstrokes, risking dissolution into the broader mosaic of the picture plane. Painted from the inside looking out, Smith’s interiors and still lives harness the vitality of the natural world, from ordinary cut garden blooms to the rare shafts of natural light that reached the house’s Quaker interior. More specific than the bouquets of wildflowers that proliferate around this time in Smith’s oeuvre, the common hydrangea, with its striking puffed heads and broad leaves, is elevated into a ‘flamboyant emblem of the lifeforce.’4

Vase in the window was first owned by Mary Turner, founder of Orange Regional Gallery and co-director of Macquarie Galleries, where Grace Cossington Smith faithfully exhibited her work for over forty years. The unwavering support and friendship Smith received from Turner and Macquarie Galleries was foundational to her significant artistic achievement and can be considered one of the greatest artist-patron associations in Australian art. 5

1. Her mother’s childhood home, ‘Cossington Hall’, in Leicestershire, was adopted c.1920 as a both a name for the new family home in Turramurra, and Grace Smith’s artistic nom de plume.

2. James, B., Grace Cossington Smith, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1990, p. 110

3. ibid, p. 116

4. ibid, p. 147

5. Proudfoot, A., ‘Not (just) the charm school: contemporary art at the Macquarie Galleries 1938 – 1963’, The art world came to us: the Macquarie Galleries, 1938 – 1963, Ngununggula, New South Wales, 2024, p. 36

Lucie Reeves-Smith

hand-coloured woodcut

18.5 x 24.5 cm (image)

26.5 x 29.0 cm (sheet)

edition: 3/50

signed with initials in image lower left: MP. signed, numbered and inscribed with title below image: Sturt’s desert pea / 3rd proof / Margaret Preston

Estimate: $12,000 – 15,000

Provenance

James R. Lawson, Sydney, c.1960s

Private collection, Sydney

Thence by descent

Private collection, Sydney

Exhibited

Thea Proctor and Margaret Preston Exhibition, Grosvenor Galleries, Sydney, 18 November – 2 December 1925, cat. 20 (another example) Exhibition of Woodcuts by Margaret Preston, Dunster Galleries, Adelaide, September 1926, cat. 66 (another example)

Literature

Woman’s World, Sydney, vol. 6, no. 1, January 1926, p. 64 (illus., another example, as ‘N.S.W. Wild Flowers’)

The Home, Sydney, vol. 8, no. 8, August 1927, p. 26 (illus., another example)

Art in Australia, Sydney, 3rd Series, no. 22 (Margaret Preston Number), December 1927, pl. 41, p. 76 (illus., another example, as ‘Australian Wild Flowers’)

Art in Australia, Sydney, no. 57, 15 November 1934, p. 90 (illus., another example)

Butler, R., The Prints of Margaret Preston, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1987, cat. 88, p. 109 (illus., another example)

Related work

Other examples of this print are held in the collections of the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide and the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Preston (1875 – 1963)

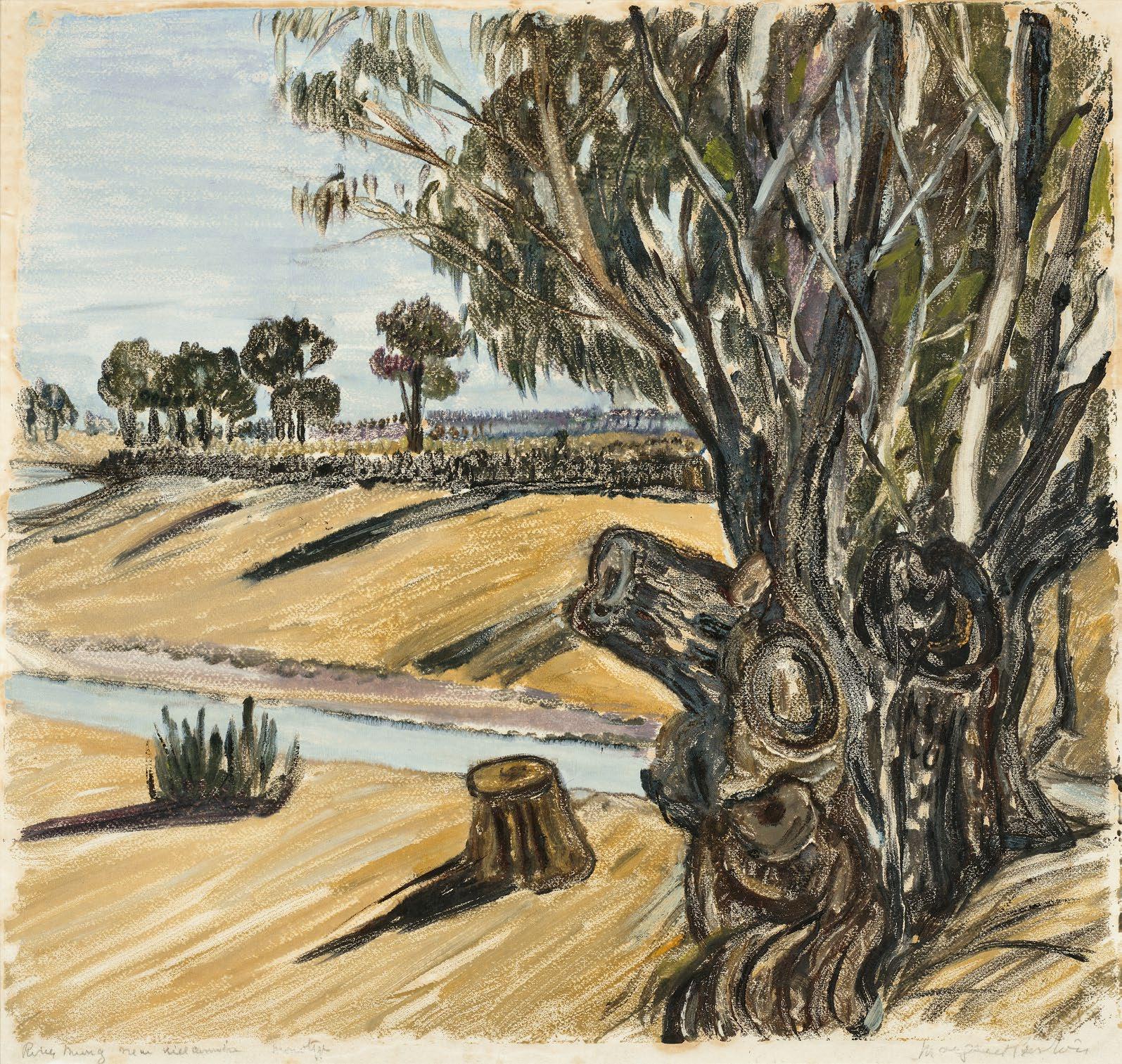

The River Murray near Wilcannia, 1946

colour monotype

36.0 x 38.0 cm (sight)

signed and inscribed with title below image: River Murray near Wilcannia monotype Margaret Preston

Estimate: $15,000 – 20,000

Provenance

H. A. McClure Smith C.V.O., Sydney, by 1949

James R. Lawson, Sydney, 14 December 1964

Private collection, Sydney

Thence by descent

Private collection, Sydney

Literature

Ure Smith, S., Margaret Preston’s Monotypes, Ure Smith, Sydney, 1949, p. 67

Butler, R., The Prints of Margaret Preston, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1987, cat. 304, p. 246

colour stencil on black paper

31.5 x 23.0 cm

from an edition of 3 (plus 2 proofs) signed with initials in image lower right: M.P.

Estimate: $25,000 – 35,000

Provenance

Henry Castle, New South Wales, acquired directly from the artist Thence by descent Private collection, New South Wales

Exhibited

probably Gouache Stencils by Margaret Preston, Grosvenor Galleries, Sydney, September 1949

Margaret Preston: The Art of Constant Rearrangement, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 27 December 1985 – 9 February 1986 (another example)

Cutting Through Time–Cressida Campbell, Margaret Preston, and the Japanese Print, Geelong Gallery, Victoria, 17 May – 28 July 2024 (another example)

Literature

Your Garden: Australia’s down-to-earth gardening magazine, The Argus and Australasian Ltd, Melbourne, April 1954 (illus. front cover, another example)

Butel, E., Margaret Preston: The Art of Constant Rearrangement, Penguin Books & Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1985, cat. P.59, pp. 68 (illus., another example), 92 Butler, R., The Prints of Margaret Preston: A Catalogue Raisonné, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 1987, cat. 361, pp. 279 (illus., another example), 336

Related works

Other examples of this work are in the collections of the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney and the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

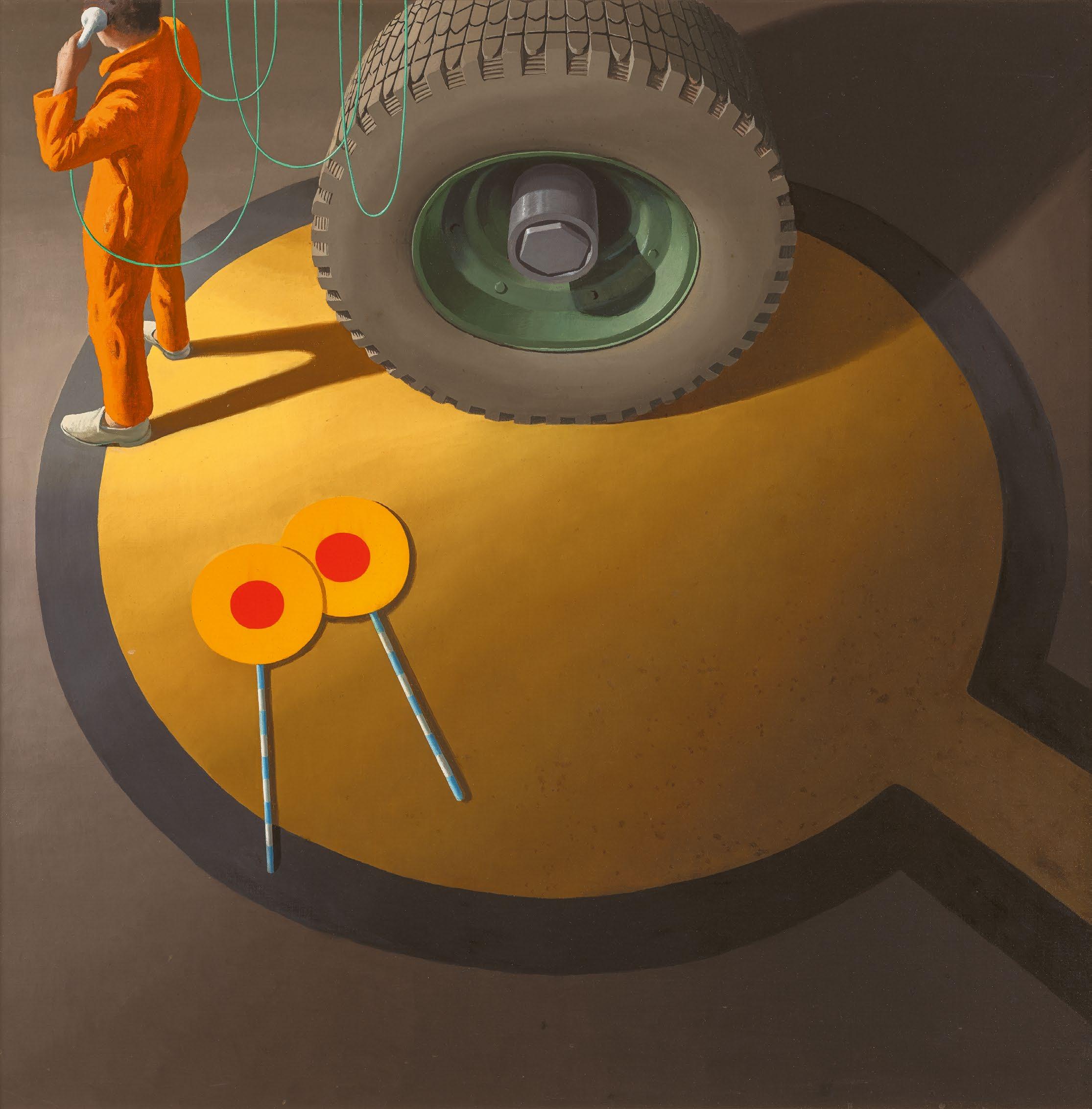

The windmill, c.1959

oil on composition board

25.5 x 35.5 cm

signed lower right: Arthur Boyd

Estimate: $45,000 – 65,000

Provenance

Australian Galleries, Melbourne

Mrs R. J. Anderson, Beaumont, Texas, USA, acquired from the above

Thence by descent

Ross Anderson, Texas, USA, 1977

Thence by descent

Mary Anderson, Texas, USA, 1980

Rago Auctions, Lambertville, New Jersey, USA, 11 June 2025, lot 168

Private collection, Melbourne

Literature

Philipp, F., Arthur Boyd, Thames and Hudson, London, 1967, cat. 8.59, p. 256

Arthur Boyd’s paintings of the Victorian countryside, produced in the late 1950s before he departed for England in 1959, comprise the artist’s most exhaustive exploration of the genre since his highly acclaimed Berwick and Wimmera series from 1948 to 1951. Displaying an intimate and subjective response to rural living, The windmill, c.1959, recalls the ‘landscapes of love’ produced during Boyd’s time at Berwick with his young family.1 This small pastoral scene is a window into quotidian life, presenting a tender view of a mother and child exploring the home paddock, safely enclosed by a fence line and a tangled spinney.

Arthur Boyd’s dry, straw-toned landscapes of his home state are paintings of his childhood, youth and early adulthood, infused with truthful feeling and sharp observation. In contrast to the Shoalhaven riverine landscapes painted throughout the last decades of his life, these early Victorian works depict an inhabited landscape, humanised and cultivated. During this time, Boyd painted the landscape wherever possible, ‘showing Australians where they lived, mapping it, writing it home with his brush.’ 2 Although traces of the primeval and untamed forests of The Hunter series from the early 1940s remain in the claw-like white trees of these paintings, the landscape is no longer presented as a threat. The pair of figures comfortably embedded in this landscape possibly depicts the artist’s wife, Yvonne, and their third child, Lucy, born in 1958. Though small, they constitute the focal point of this landscape, the baby gesturing to the towering presence of the windmill. Incidentally employing the sky-blue hues traditionally associated with the Virgin Mary, Boyd’s figure group of a Madonna and child reinforces the dominant goldand-blue chord of brilliant Australian sunshine in the bush.

This pastoral idyll, seen through a veil of tall thistles, rushes and weeds in the foreground, presents a rural Australian version of the hortus conclusus, the full and enclosed garden. While Boyd’s sparse Wimmera landscapes expressed the vastness and remoteness of inland Australia with a distant and shimmering horizon, here the horizon is obscured by a dense thicket of trees. The faithful windmill, an iconic silhouette of rural Australia, stands tall against the smooth blue sky, poking just above the textured line of vegetation. Alongside the small dam and grazing cow, the windmill is what Franz Philipp has called ‘motifs of habitation’, familiarising the wild bush into a warm and tranquil scene. 3

Prior to leaving for England, where he would stay for twelve years, Boyd’s paintings of the Australian landscape received significant critical acclaim. Where previously Boyd’s interpretations of the landscape had been modelled on European landscapes, his approach during this period became more personal and specifically Antipodean. When a number of these landscapes were exhibited for the first time at Australian Galleries, Melbourne in 1959, an enthusiastic Alan McCulloch exclaimed: ‘in these landscapes [Boyd] has come to an ‘old master’ phase, probably the best, if not his last.’4 The significance of Arthur Boyd’s reinterpretation of the traditional pastoral scene was further acknowledged in 1958, when his work was chosen to be presented alongside that of Arthur Streeton, together representing Australia at the Venice Biennale.

1. Margaret Plant, cited in Philipp, F., Arthur Boyd, Thames & Hudson, London, 1967, p. 64

2. Bungey, D., Arthur Boyd: a life, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2007, p. 248

3. Philipp, F., op cit., p. 60

4. McCulloch, A., Herald, Melbourne, 14 April 1959

Lucie Reeves-Smith

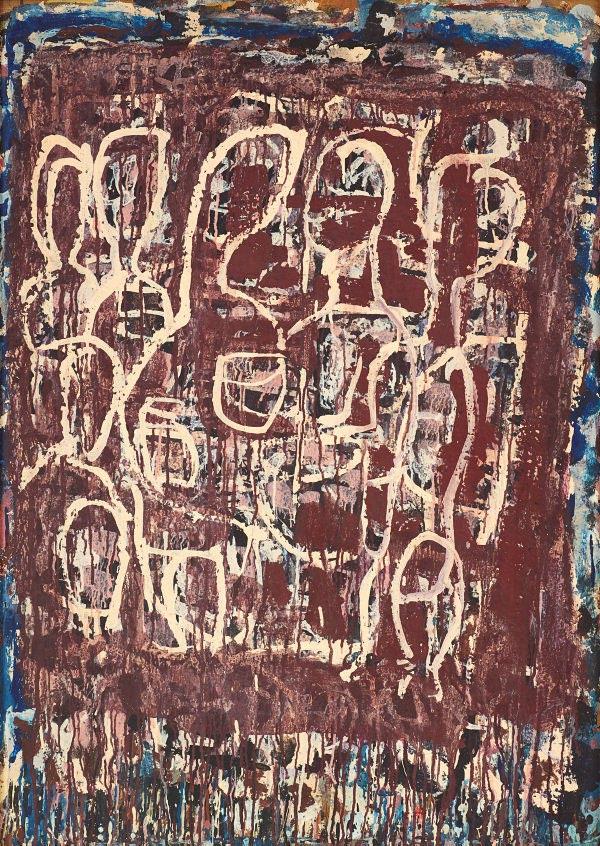

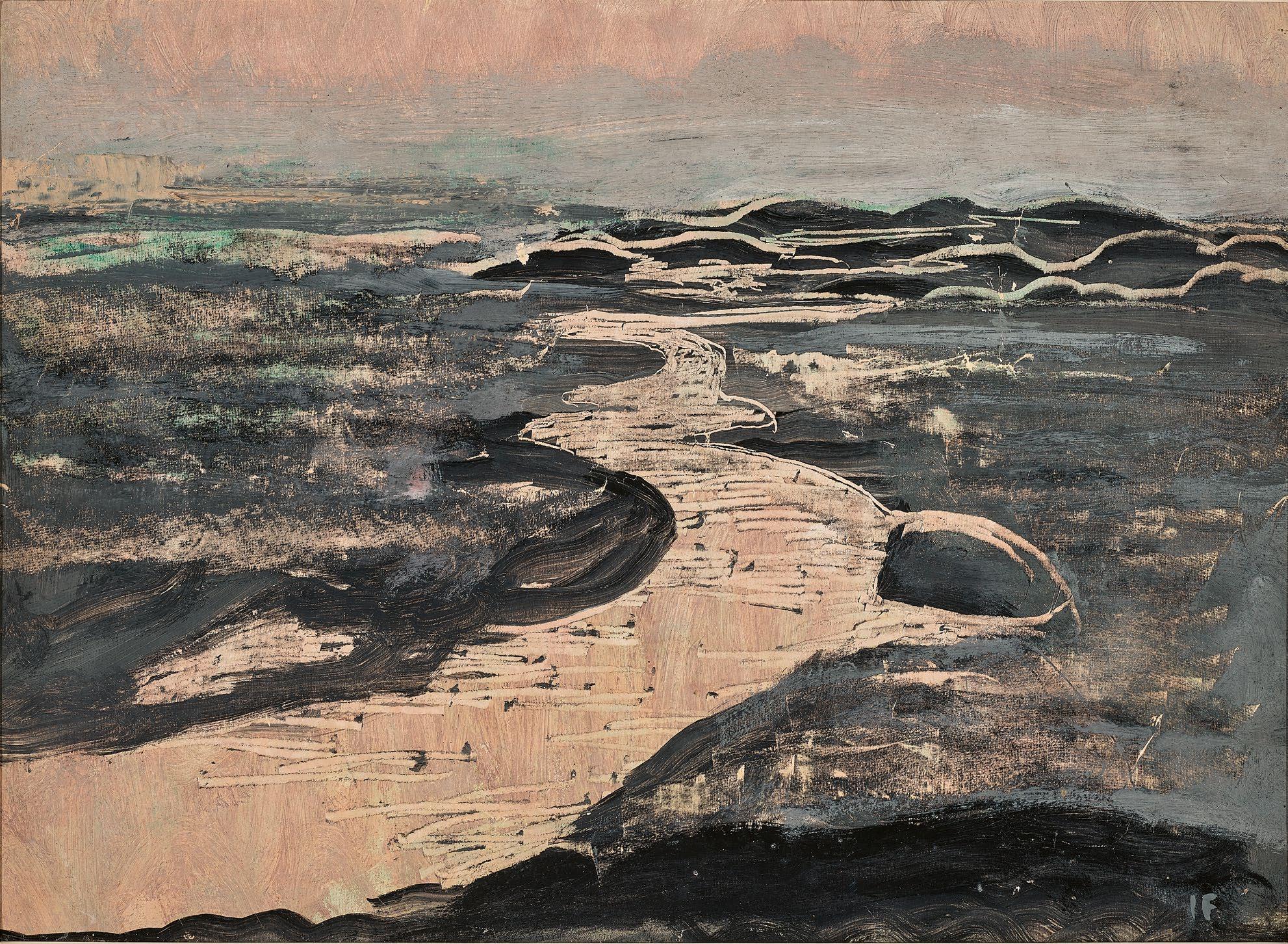

Figure group I, 1969

synthetic polymer paint and gouache on cardboard on composition board

76.0 x 104.0 cm

bears inscription verso: FIGURE GROUP I (1969) / NO 10.

Estimate: $250,000 – 350,000

Provenance

Estate of the artist, Queensland Macquarie Galleries, Sydney Christie’s, Melbourne, 28 April 1976, lot 500 Private collection, Melbourne and Victoria

Exhibited

Recent Paintings by Ian Fairweather, Macquarie Galleries, Sydney, 28 October – 9 November 1970, cat. 10 (label attached verso)

Ian Fairweather, A Posthumous Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings, Macquarie Galleries, Sydney, 3 – 15 September 1975, cat. 1 (label attached verso, signed by Mary Turner)

Literature

Bail, M., Ian Fairweather, Bay Books, Sydney, 1981, cat. 225, pp. 230 (illus.), 260

Ian Fairweather

Composition with figures, 1969 synthetic polymer paint and gouache on cardboard on hardboard, 105.0 x 74.6 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney © Ian Fairweather/DACS. Copyright Agency 2025

Ian Fairweather Barbecue, 1963

synthetic polymer paint and gouache on cardboard on composition board (4 sheets), 134.0 x 181.5 cm

Private collection

Sold Deutscher and Hackett for $1,708,000 (inc. BP), 10 April 2019, Sydney © Ian Fairweather/DACS. Copyright Agency 2025

Ian Fairweather has been described as ‘the least parochial of Australian painters, an artist of exceptional force and originality’ 1 and he is undoubtedly one of the most singular artists to have worked in Australia during the twentieth century. Although he is claimed as an Australian and spent many years living here, he had a restless spirit, and the story of his life reads like something borrowed from the pages of an adventure book. Born in Scotland in 1891, Fairweather undertook his formal art education at London’s Slade School of Fine Art, studying under the formidable Henry Tonks and in 1922, being awarded second prize for figure drawing. As a prisoner of war in Germany during the First World War he had access to books about Japanese and Chinese art, and later, studied these languages at night. In 1929, he sailed to Shanghai where he lived for several years – the unique art, culture and philosophy of China exerting a lasting influence on his art. Peripatetic by nature, or perhaps reluctant to establish roots and commit to ongoing relationships, Fairweather travelled extensively – from London, to Canada, Bali, Australia, the Philippines, India and beyond – ‘always the outsider, the nostalgic nomad with a dreamlike memory of distant places and experience.’ 2

In the early 1950s, Fairweather settled on Bribie Island, off the coast of Queensland, where, for the rest of his life, he famously lived and worked in a pair of huts built with materials salvaged

from the surrounding bush. Conditions were primitive – no running water, sewerage or electricity – and Fairweather’s handmade bed and chairs were reportedly upholstered with fern fronds. 3 Black and white photographs show him working in the dedicated studio hut – often with a pipe in one hand and a paintbrush in the other – where paintings in progress are tacked up on rudimentary, handmade easels. Nearby, tins of paint stand open with brushes ready and waiting to be used. Surfaces are covered with random spatters and dribbles of paint, colours layered one on top of the other creating a visual trace of the pictures that were made there. In these images we see the artist once described as someone who ‘needed to paint like one needs to breathe’ and understand the spontaneity and energy with which he worked.4 Despite the rudimentary nature of his surrounds however – or perhaps because of it – the next two decades witnessed the production of many of Fairweather’s finest paintings and the 1960s saw his art acknowledged in significant ways, with works being included in the landmark exhibition Recent Australian Painting at the Whitechapel Gallery, London (1961), the European tour of Australian Painting Today (1964 – 65), acquisitions for important public and private collections, and in 1965, a major travelling retrospective of his work being mounted by the Queensland Art Gallery.

Ian Fairweather in his studio hut, Bribie Island, Queensland, 1968 photographer: David Beal

Being interviewed in 1965, Fairweather described painting as ‘something of a tightrope act’, saying it was ’difficult to keep one’s balance.’ He went on to explain that for him, painting sat ‘between representation and the other thing – whatever it is.’ 5 The ‘other thing’ was abstraction and while he made his first foray into purely non-representational art in the late 1950s, this tension in his art is evident in much of the work that followed including the largescale masterworks Monastery, 1960 (National Gallery of Australia) and Monsoon, 1961 – 62 (Art Gallery of Western Australia). Figure group I, 1969 is one of a series of paintings made between the late 1960s and early 1970s in which the outline of human forms and other recognisable subjects emerges from a complex and elaborate ground, here a combination of brushstrokes and dribbles of paint in a muted palette of black, brown, grey and white with touches of pink and purple. If it was not for the title of the painting itself, it would be easy to miss the figures within the dynamic tracery of Fairweather’s mark-making which Murray Bail identifies as a reinvention of a mid-1950s image of boys playing with a ball.6

Returning to pictures again and again over an extended period of ti me, Fairweather developed painted surfaces which vibrate and shimmer with movement, directing our view from top to bottom and side to side. As the final layer to be applied however, it is the figurative element of this painting that prevails, introducing structure and stability to the rhythmic energy of the layers below.

Driven by a need to paint and charting his own unique path, Fairweather produced paintings that made a profound contribution to the development of Australian art. Combining varied influences and balancing figuration and abstraction, he created some of the most distinctive and important works of the twentieth century.

1. Bail, M., Ian Fairweather, Bay Books, Sydney, 1981, p. 220

2. Bail, M., ‘The Nostalgic Nomad’, Hemisphere, Canberra, vol. 27, no. 1, 1982, p. 54

3. Bail, M., Fairweather, Murdoch Books, Millers Point, 2000, p. 119

4. Ryckmans, P., ‘An Amateur Artist’ in Bail, M., Fairweather, Art and Australia Books in association with the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 1994, p. 18

5. Ian Fairweather, cited in Bail, ibid., p. 139

6. Bail, 1981, op. cit., p. 224 Kirsty Grant

Colin McCahon (New Zealand, 1919 – 1987) Fish Rock, c.1959

oil, tempera and ink on unstretched canvas

180.0 x 90.0 cm

signed and inscribed with title and medium on timber hanging rod verso: McCAHON FISH ROCK TEMPERA N.F.S

Estimate: $200,000 – 300,000

Provenance

Molly Ryburn, Auckland, New Zealand, a gift from the artist Martin Browne Fine Art, Sydney Private collection, Sydney, acquired in 1993

Exhibited

The Group Show, Canterbury Society of Arts Durham Street Art Gallery, Christchurch, New Zealand, 8 – 23 October 1960, cat. 29 (nfs)

The Group Loan Show, Robert McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch, New Zealand, 27 October – 6 November 1960, cat.8 (In 1960 The Group held its usual annual exhibition at the C.S.A and a selection of paintings from it was shown four days later at the Robert McDougall Art Gallery.)

Literature

Bloem, M., and Browne, M., Colin McCahon: A Question of Faith, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam & Craig Potton Publishing, New Zealand, 2002, pp. 193, 253 Simpson, P., Colin McCahon: There is Only One Direction, vol. 1 1919 – 1959, Auckland University Press, New Zealand, 2019, pp. 290, 350 Colin McCahon Online Catalogue, cat. CM000127: https://www.mccahon.co.nz

A strong and vibrant painting not seen in public since 1960, Fish Rock, c.1959 belongs to a small group of works by Colin McCahon painted during late 1959 which share a common medium, a common reference to a particular landscape (French Bay in the Manukau Harbour, Auckland), and a roughly similar size (although with variable widths). Other titles in the group include Rocks at French Bay (two versions, Auckland Art Gallery and private collection) and French Bay with Fish Rock and Headland (Gow Langsford Gallery, previously known as French Bay ). In size, materials and medium this group is also related to two major slightly earlier series – the monumental, 16-panel The Wake, 1958 (Hocken Collections) and 8-panel Northland panels, 1968 (Te Papa Tongarewa) – which McCahon made soon after his watershed visit to the United States in March-August 1958.

Although the primary focus of McCahon’s visit to America was to study museum practices (he was deputy director of Auckland Art Gallery), he also relished the opportunity to explore major

institutions and dealer galleries all across America. It was his first extensive exposure to international art since visiting the National Gallery of Victoria in 1951. Among the artists mentioned as highlights in his letters from the States were Mondrian, Diebenkorn and Tomioka Tessai in San Francisco; El Greco, Tintoretto and Renoir in Washington; Cézanne and Picasso in Philadelphia; Rothko and Hofmann in Baltimore; Juan Gris, Pollock, de Kooning and Kline in New York; and Gauguin in Boston. Much of his prodigious output in the year after his return from America (with the exception of The Wake) made up a major exhibition at Gallery 91 in Christchurch in October 1959: Colin McCahon: Recent Paintings November 1958 – August 1959. Notably, the show included the Northland panels, Northland triptych, 1958; the innovative Elias series, 1959 (various private collections and Auckland Art Gallery), and many other important individual works such as Cross, 1959 (Auckland Art Gallery) and Tomorrow will be the same but not as this is, 1958 – 59 (Christchurch Art Gallery). In the final weeks of 1959, after his big Christchurch show, McCahon returned for the last time to the land-and-seascapes of Titirangi and French Bay to make the

Colin McCahon, 1961

The New Zealand Woman’s Weekly, 27 March 1961

Image courtesy: Bernie Hill

small, tight group that includes Fish Rock. He subsequently moved to central Auckland early in 1960, a transition which initiated a new phase of his work – the geometric abstraction of the Gate series.

Many of the changes in McCahon’s practice from the prolific year after his return from America are evident in Fish Rock and related works. Such modifications include abandoning frames for strips of unstretched canvas hung from wooden rods; a significant increase in size to near two metres in height, and discarding conventional oil paints for other pigments including ink and diluted commercial house paints. There was a significant shift in imagery too away from the dense networks of small lozenges of paint almost pointillist in methodology of the period prior to his travel abroad (seen, for example, in Flounder fishing, night, French Bay, 1957), towards freer and more gestural methods of paint application, and constructing paintings with larger, more open, quasi-geometrical units – a development anticipated in Rocks are for building with, 1958 (Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth). Significantly, Fish Rock was gifted by McCahon to Molly Ryburn, a friend and colleague at Auckland Art Gallery,

Colin McCahon Rocks at French Bay, 1959 ink and oil on unstretched canvas 196.0 x 192.5 cm

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Auckland Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

who already owned Flounder Fishing, night, French Bay – a stylistic predecessor of F ish Rock. And indeed, it was in letters to Ryburn from San Francisco, New York and Cleveland that McCahon mentioned some of the highlights listed earlier.

French Bay is a small tree-fringed bay on the Manukau Harbour close to where the McCahon family lived in the bush suburb of Titirangi from 1953 to 1959. The bay (and bush) were frequent subjects of McCahon’s painting throughout those seven years, and there is a distinct French Bay series for each year from 1954 to 1959. Initially his focus was on boats and islands, then on the pohutukawa-fringed margins of the bay and the prismatic play of light on water, later on banded (and abstracted) strips of sky, land and water, and finally, upon the structure of rock formations at the water’s edge (evident in the 1959 group in particular). The French Bay paintings range from near realism at one end

of the spectrum to complete abstraction at the other. Fish Rock, com posed of strongly abstracted land and water references, is located around midway between these two polarities.

Fish Rock depicts irregularly shaped rectangular forms intruding from all four sides into the picture space, sometimes overlapping each other or seen through water. The colours include various shades of ochre from pale to dark, strongly outlined, but the dominant hue is a startling patch of bright blue towards the bottom of the picture which inevitably – because of the marine associations of the title – suggests water, though the absence of regular perspective means that the elements don’t easily resolve themselves into a sea-shore ‘scene’. The jostling quasi-geometrical shapes create a dynamic energy that strongly anticipates the more purely abstract arrangements in McCahon’s next major series, the Gate paintings of 1961 – 62. Fish Rock is distinctively located between past and future. Peter Simpson

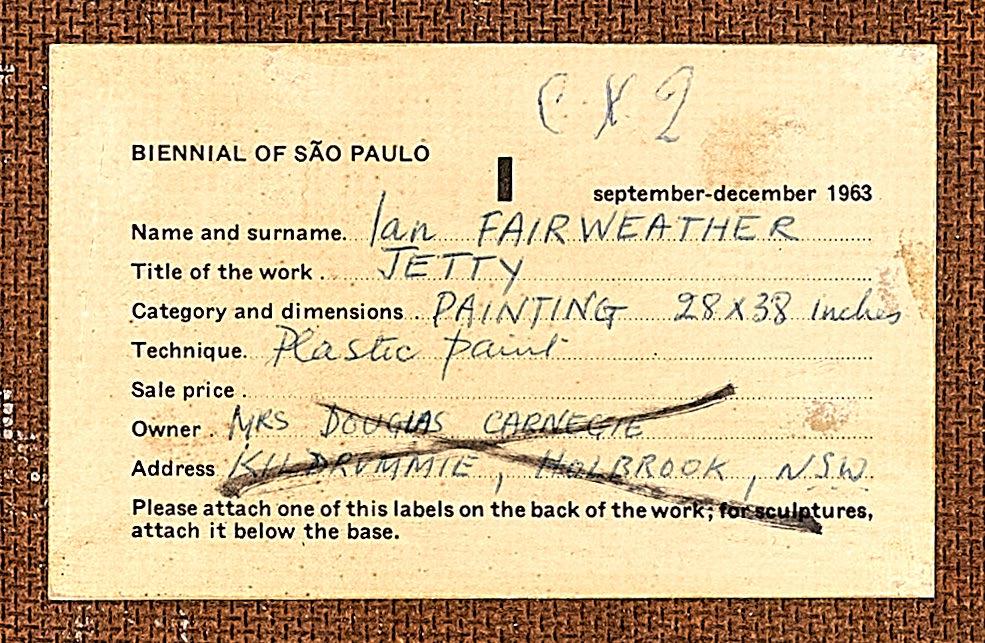

synthetic polymer paint on cardboard on composition board

70.0 x 98.0 cm

bears inscription verso: “JETTY” / BY IAN FAIRWEATHER

bears inscription verso: JETTY / Res for Mrs D Carnegie

Estimate: $200,000 – 300,000

Provenance

Perth Galleries, Western Australia

Douglas and Margaret Carnegie, New South Wales, by 1963

Private collection

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 30 April 1995, lot 68

Private collection

Niagara Galleries, Melbourne (label attached verso)

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in March 2008

Exhibited

7th São Paulo Art Biennial, Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, Ibirapuera Park, São Paulo, Brazil, 28 September – 22 December 1963, cat. 11 (label attached verso)

Blue Chip X: The Collectors’ Exhibition, Niagara Galleries, Melbourne, 4 March – 5 April 2008, cat. 8

Literature

Bail, M., Fairweather, Murdoch Books, Sydney, 2009, p. 243 Roberts, C. & Thompson, J. (eds.), Ian Fairweather: A Life in Letters, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2019, p. 326

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Ian Fairweather/DACS. Copyright Agency 2025

In mid-1953 at the age of sixty-two, Ian Fairweather settled on Bribie Island, off the coast of Queensland, where he lived in a pair of self-built huts for the rest of his life. Despite the lack of creature comforts which most people take for granted, the relative contentment that Fairweather found in this environment was reflected in his artistic output which, over the following two decades, witnessed the production of many of his finest paintings. In 1962, a solo exhibition at the Macquarie Galleries in Sydney saw buyers camp out overnight in order to secure one of his recent works. The Sydney Morning Herald headline hailed Fairweather as ‘Our Greatest Painter’ and more than half of the sixteen paintings in the show were acquired for public collections, including Epiphany, 1961 – 62 (Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art); Mangrove, 1961 – 62 (Art Gallery of South Australia); and Shalimar, 1961 – 62 (National Gallery of Australia) which was purchased for the then-developing national collection. Among the determined collectors who waited outside the gallery in driving rain was the art critic, Robert Hughes, who bought Monsoon, 1961 – 62 – later acquired by the Art Gallery of Western Australia – describing it as ‘a pure example of ecstatic motion.’ 1

The critical and commercial success of this exhibition built on the momentum that had been growing for some years, and the ensuing decade saw Fairweather’s art acknowledged in significant ways. Although he was geographically isolated from the contemporary artworld, his work was well known – primarily through commercial exhibitions at Macquarie Galleries, as well as occasional visitors to the island – and highly regarded by critics, collectors and curators alike. During these years his paintings were included in the landmark exhibition Recent Australian Painting, curated by Bryan Robertson at the Whitechapel Gallery, London (1961); the European tour of Australian Painting Today (1964 – 65); and in 1965, a major travelling retrospective of his work was mounted by the Queensland Art Gallery.

In 1963, Fairweather was one of seven artists including John Perceval, Albert Tucker and Leonard Hessing selected to represent Australia at the VII Bienal de São Paulo. Although he was more than twenty years older than all his fellow Australian exhibitors – and the only one who was born in the nineteenth century – his work was utterly contemporary and very at home

Fairweather

, 1962 synthetic polymer paint on four sheets of cardboard on composition board 139.6 x 203.2 cm

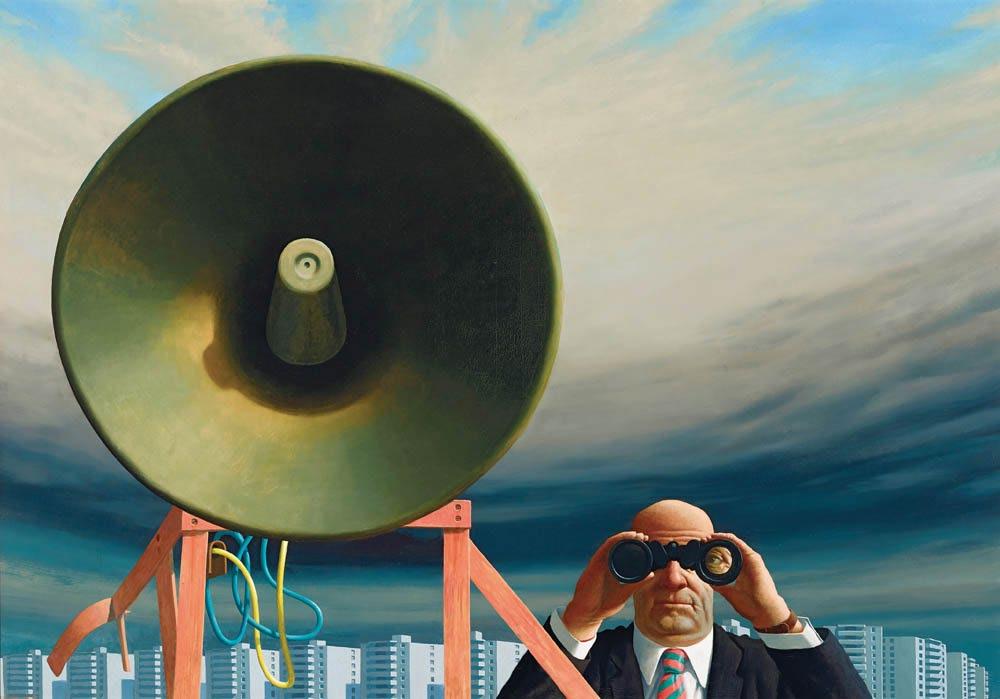

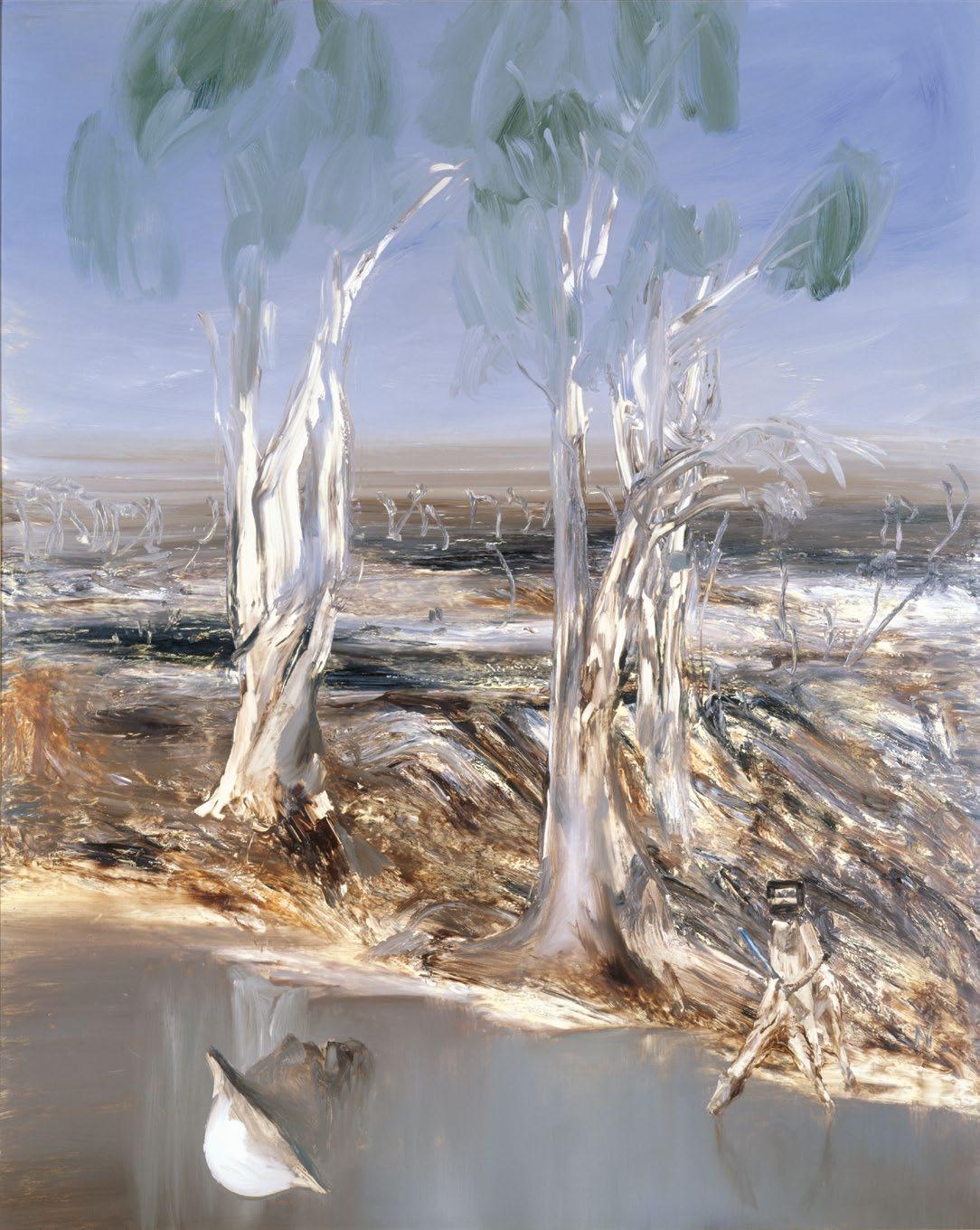

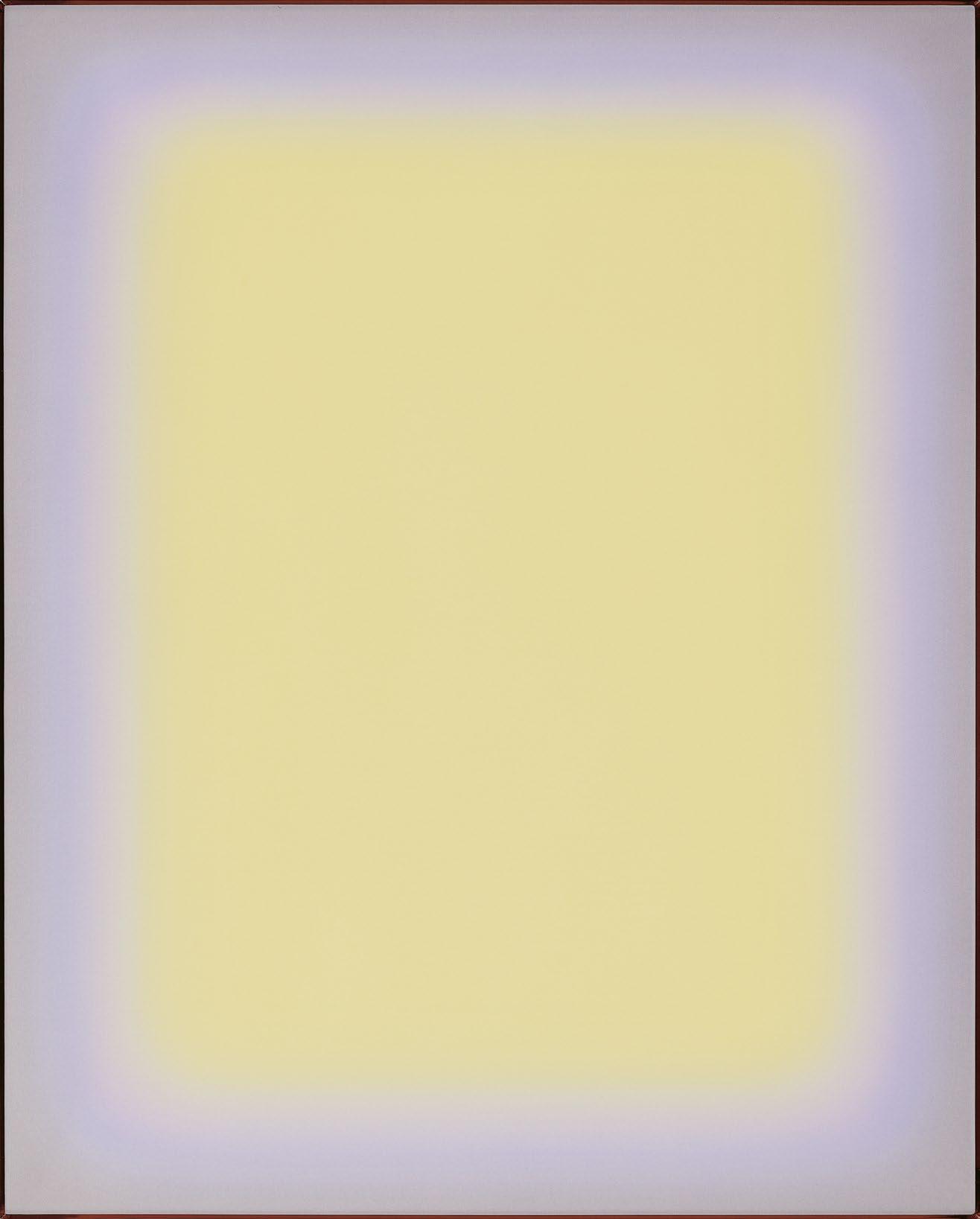

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane © Ian Fairweather/DACS. Copyright Agency 2025