Auction | Melbourne | 27 August 2025

Auction | Melbourne | 27 August 2025

Lots 1 – 52

Auction | Melbourne | 27 August 2025

Lots 1 – 52

Wednesday 27 August 7:00 pm

105 Commercial Road South Yarra, VIC telephone: 03 9865 6333

Tuesday 12 – Sunday 17 August 11:00 am – 6:00 pm 36 Gosbell Street Paddington, NSW telephone: 02 9287 0600

Thursday 21 – Tuesday 26 August 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

105 Commercial Road South Yarra, VIC telephone: 03 9865 6333

email bids to: info@deutscherandhackett.com telephone: 03 9865 6333 fax: 03 9865 6344 telephone bid form – p. 168 absentee bid form – p. 169

www.deutscherandhackett.com/watch-live-auction

www.deutscherandhackett.com | info@deutscherandhackett.com

Chris Deutscher

Executive Director — Melbourne

Chris is a graduate of Melbourne University and has over 40 years art dealing, auction and valuation experience as Director of Deutscher Fine Art and subsequently as co-founder and Executive Director of Deutscher~Menzies. He has extensively advised private, corporate and museum art collections and been responsible for numerous Australian art publications and landmark exhibitions. He is also an approved valuer under the Cultural Gifts Program.

Fiona Hayward

Senior Art Specialist

After completing a Bachelor of Arts at Monash University, Fiona worked at Niagara Galleries in Melbourne, leaving to join the newly established Melbourne auction rooms of Christie’s in 1990, rising to become an Associate Director. In 2006, Fiona joined Sotheby’s International as a Senior Paintings Specialist and later Deputy Director. In 2009, Sotheby’s International left the Australian auction market and established a franchise agreement with Sotheby’s Australia, where Fiona remained until the end of 2019 as a Senior Specialist in Australian Art. At the end of the franchise agreement with Sotheby’s Australia, Smith & Singer was established where Fiona worked until the end of 2020.

Crispin Gutteridge

Head of Indigenous Art and Senior Art Specialist

Crispin holds a Bachelor of Arts (Visual Arts and History) from Monash University. In 1995, he began working for Sotheby’s Australia, where he became the representative for Aboriginal art in Melbourne. In 2006 Crispin joined Joel Fine Art as head of Aboriginal and Contemporary Art and later was appointed head of the Sydney office. He possesses extensive knowledge of Aboriginal art and has over 30 years’ experience in the Australian fine art auction market.

Alex Creswick

Managing Director / Head of Finance

With a Bachelor of Business Accounting at RMIT, Alex has almost 30 years’ experience within financial management roles. He has spent much of his early years within the corporate sector with companies such as IBM, Macquarie Bank and ANZ. With a strong passion for the arts Alex became the Financial Controller for Ross Mollison Group, a leading provider of marketing services to the performing arts, before joining D+H in 2011.

Jennifer Terace

Front of House Manager – Melbourne

Jennifer holds a Bachelor of Visual Arts from Edith Cowan University and has experience across event management, retail operations, and community arts program coordination. She has worked as a practicing artist, artist’s assistant, and gallery assistant, gaining valuable insight into both the creative and logistical aspects of the visual arts sector.

Danny Kneebone

Design and Photography Manager

With over 25 years in the art auction industry as both photographer and designer. Danny was Art Director at Christie’s from 2000–2007, Bonham’s and Sotheby’s 2007–2009 and then Sotheby’s Australia from 2009–2020. Specialist in design, photography, colour management and print production from fine art to fine jewellery. Danny has won over 50 national and international awards for his photography work.

Damian Hackett

Executive Director — Sydney

Damian has over 30 years’ experience in public and commercial galleries and the fine art auction market. After completing a BA (Visual Arts) at the University of New England, he was Assistant Director of the Gold Coast City Art Gallery and in 1993 joined Rex Irwin Art Dealer, a leading commercial gallery in Sydney. In 2001, Damian moved into the fine art auction market as Head of Australian and International art for Phillips de Pury and Luxembourg, and from 2002 – 2006 was National Director of Deutscher~Menzies.

Henry Mulholland

Senior Art Specialist

Henry Mulholland is a graduate of the National Art School in Sydney, and has had a successful career as an exhibiting artist. Since 2000, Henry has also been a regular art critic on ABC Radio 702. He was artistic advisor to the Sydney Cricket Ground Trust Basil Sellers Sculpture Project, and since 2007 a regular feature of Sculpture by the Sea, leading tours for corporate stakeholders and conducting artist talks in Sydney, Tasmania and New Zealand. Prior to joining Deutscher and Hackett in 2013, Henry’s fine art consultancy provided a range of services, with a particular focus on collection management and acquiring artworks for clients on the secondary market.

Veronica Angelatos

Art Specialist and Senior Researcher

Veronica has a Master of Arts (Art Curatorship and Museum Management), together with a Bachelor of Arts/Law (Honours) and Diploma of Modern Languages from the University of Melbourne. She has strong curatorial and research expertise, having worked at various art museums including the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice and National Gallery of Victoria, and more recently, in the commercial sphere as Senior Art Specialist at Deutscher~Menzies. She is also the author of numerous articles and publications on Australian and International Art.

Ella Perrottet

Senior Registrar

Ella has a Masters of Arts and Cultural Management (Collections and Curatorship) from Deakin University together with a Bachelor of Fine Art (Visual Art) from Monash University, and studied in both Melbourne and Italy. From 2014, Ella worked at Leonard Joel, Melbourne as an Art Assistant, researcher, writer and auctioneer, where she developed a particular interest in Australian women artists.

Eliza Burton

Registrar

Eliza has a Bachelor of Arts (English and Cultural Studies and History of Art) from the University of Western Australia and a Master of Art Curatorship from the University of Melbourne. She has experience in exhibition management, commercial sales, and arts writing through her work for Sculpture by the Sea and The Sheila Foundation.

Poppy Thomson Gallery Manager, Sydney

Poppy holds a Bachelor of Art History and Curatorship (Honours) from the Australian National University and has professional experience as a curator and research assistant. Prior to this role, she spent time in Paris after winning the 2023 Eloquence Art Prize, and now sits on the board of Culture Plus.

Chris Deutscher

Damian Hackett 0411 350 150 0422 811 034

Henry Mulholland

Fiona Hayward 0424 487 738 0417 957 590

Crispin Gutteridge

Veronica Angelatos 0411 883 052 0409 963 094

Administration and Accounts

Megan Mac Sweeney Poppy Thomson (Melbourne) (Sydney) 03 9865 6333 02 9287 0600

Absentee and Telephone Bids

Jennifer Terace 03 9865 6333

Shipping

Ella Perrottet 03 9865 6333

Roger McIlroy Head Auctioneer

Roger was the Chairman, Managing Director and auctioneer for Christie’s Australia and Asia from 1989 to 2006, having joined the firm in London in 1977. He presided over many significant auctions, including Alan Bond’s Dallhold Collection (1992) and The Harold E. Mertz Collection of Australian Art (2000). Since 2006, Roger has built a highly distinguished art consultancy in Australian and International works of art. Roger will continue to independently operate his privately-owned art dealing and consultancy business alongside his role at Deutscher and Hackett.

Scott Livesey Auctioneer

Scott Livesey began his career in fine art with Leonard Joel Auctions from 1988 to 1994 before moving to Sotheby’s Australia in 1994, as auctioneer and specialist in Australian Art. Scott founded his eponymous gallery in 2000, which represents both emerging and established contemporary Australian artists, and includes a regular exhibition program of indigenous Art. Along with running his contemporary art gallery, Scott has been an auctioneer for Deutscher and Hackett since 2010.

Lots 1 – 52 page 12

Prospective buyers and sellers guide page 164

Conditions of auction and sale page 166

Telephone bid form page 168

Absentee bid form page 169

Attendee pre-registration form page 170

Index page 183

Lots 1 – 2

Bessie Davidson’s 1928 solo exhibition at Galerie Ecalle in Paris prompted the art critic Pierre Müller to ask, ‘Does art have a nationality?’ 1 Aware of Davidson’s antipodean origins, as well as the fact that Paris (and France more broadly) was home to a significant number of expatriate women artists from all over the world, he concluded, ‘I do not think so. Bessie Davidson, like Mary Cassat, like Beatrice How, is as much one of us as of elsewhere, she is from any land where there is a taste for beauty, grace and refinement.’ 2

Part of a group of trailblazing Australian women artists who travelled to Europe during the first decades of the twentieth century, Davidson went to Paris primarily seeking to expand her artistic education. The City of Light offered a pluralist and progressive approach to art with private academies that provided tuition to women, as well as opportunities for them to exhibit alongside their male counterparts. In the words of Australian writer Edith Fry, Paris was ‘the only truly cosmopolitan city of the world for artists, whose work stands a better chance there than in any other art centre of being judged on its merits.’ 3 Being away from home also had the added advantage of freeing these artists from family expectations and gendered social conventions of marriage and motherhood. While many of these women returned home after their study and travels, sharing what they had learned of international modernism both informally and in organised classes, Davidson and a small number of others – including Agnes Goodsir, Anne Dangar and Stella Bowen – remained, establishing successful careers and living overseas for the rest of their lives, part of a transnational group of artists whose experiences and work radically extend traditional narratives and definitions of Australian art.4

Davidson was born in Adelaide in 1879, the second of five children and the eldest daughter. It is likely that she undertook private lessons or studied at the Adelaide School of Design like many of her South Australian peers, however her first documented experience of formal art education was in 1899 when she attended classes with Rose McPherson. Later and better known as Margaret Preston, McPherson had recently returned to Adelaide after studying at the National Gallery School in Melbourne and during the years that she was Davidson’s

teacher, the two women established a strong friendship. In 1904 they sailed together to Europe, initially studying in Munich as a concession to Davidson’s father who requested that they did not go to Paris ‘because Frenchmen are so immoral.’ 5 The modern art they saw there shocked and disturbed them however, prompting McPherson to declare with characteristic directness that ‘half German art is mad and vicious and a good deal of it is dull’ 6, and by the end of the year they had left for Paris. It is possible that they attended classes run by fellow Australian artist Rupert Bunny, and in 1906 Davidson (and possibly also McPherson) enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in the heart of Montparnasse.7 Both artists achieved some success with paintings being accepted for display in the Salon des Artistes Françaises and as they sailed home to Australia at the end of 1906, they were already dreaming of their return.

With an allowance that supported income from painting sales, Davidson returned to Paris in 1910. She reconnected with friends including the artist René-Xavier Prinet, who had taught her at la Grande Chaumière – probably also taking classes with him – and in 1912 moved to Montparnasse, where there was a large community of expatriate artists, into a studio apartment on Rue Boissonade. Located on the second floor of a late nineteenthcentury building, the apartment had high ceilings and large windows that looked out over a central courtyard. Recorded in contemporary photographs and many of Davidson’s own paintings, the interior incorporated a ‘round mahogany Empire dining table and… distinctive curved-back chairs, the small octagonal sewing table, the little bergère chair with its loose cover of sprigged cretonne and the Louis XV fauteuil (armchair) upholstered in petit-point. There are Persian rugs on the polished floorboards and heavy purplish curtains… the whole studio heated by a pot-bellied stove in the middle of the room.’ 8

Apart from visits to Australia in 1914 and again in 1950, Davidson remained in France, a resident of Rue Boissonade, for the rest of her life. As well as speaking fluent French, she developed a wide network of friends, was well-connected within the artistic community and established a successful career, exhibiting regularly at the Salons and gaining much critical attention for

her work. In 1920, she was elected as an associate member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, only the fourth Australian to receive this acknowledgement – following George Lambert, Rupert Bunny and George Coates – and the first Australian woman ever to do so. Two years later, she was the first Australian artist to receive full membership. Davidson was a founding member of the Salon des Tuileries (1923) and the Société des Femmes Artistes Modernes (1930), serving as vice-president for its first decade of operation. Arguably the greatest accolade, however, came in 1931 when Davidson was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur for services to the arts, the only Australian woman to have received this honour at the time. 9

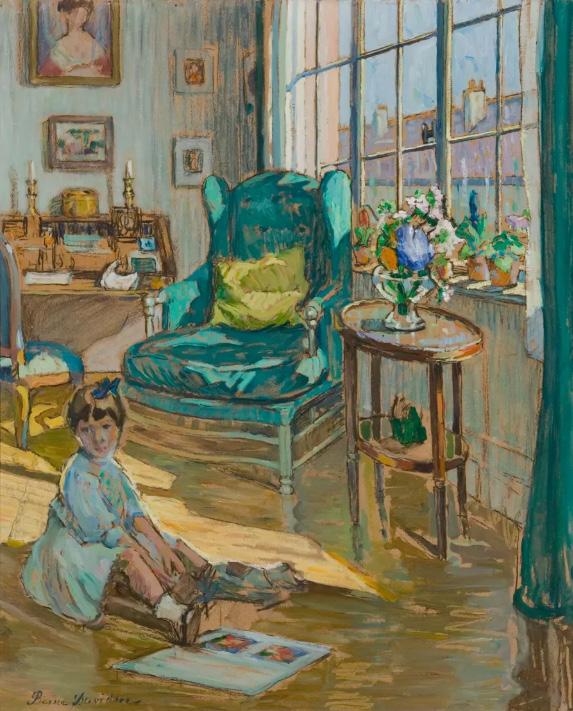

Primarily painted in tempera and oil, Davidson’s oeuvre includes the images of women and children in domestic settings for which she is best known, including Jeune fille au mirroir (Young girl with mirror), 1914 (National Gallery of Victoria) and An interior, c.1920 (Art Gallery of South Australia), as well as portraits and still lifes. From the mid-1920s she also increasingly painted the landscape, often recording quick gouache impressions of views seen during her extensive travels through country France and further afield. The Art Gallery of South Australia acquired a portrait of her friend, the artist-potter Gladys Reynell, in

An interior, c.1920 oil and charcoal on board

73.1 x 59.7 cm

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

1908, but Davidson’s absence from the local art scene meant that it is only in relatively recent times that her art has been collected by most Australian State galleries.10 Reflecting the sentiment that ‘Bessie Davidson [was] the most Parisian of them all’ 11, her work was acquired by the French State during her lifetime however and is represented in several French collections including the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris.

1. Pierre Müller, cited in Little, P., A Studio in Montparnasse: Bessie Davidson: An Australian Artist in Paris, Craftsman House, Melbourne, 2003, p. 100

2. ibid.

3. Edith Fry, cited in Speck, C., ‘Paris Calls’ in Bessie Davidson: An Australian Impressionist in Paris, exhibition catalogue, Bendigo Art Gallery, Bendigo, 2020, p. 17

4. See Rex Butler and A.D. S. Donaldson, ‘French, Floral and Female: A History of UnAustralian Art 1900 – 1930 (part 1), Emaj, issue 5, 2010, at: https://www.index-journal. org/media/pages/emaj/issue-5/french-floral-and-female-by-rex-butler-and-adsdonaldson/010624421e-1727496756/butler-and-donaldson-french-floral-female.pdf (accessed July 2025) and Freak, E., Lock, T., and Tunnicliffe, W., ‘Dangerously Modern’ in Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890 – 1940, Art Gallery of New South Wales and Art Gallery of South Australia, Sydney and Adelaide, 2025, pp. 13 – 19

5. Little, op. cit., p. 25

6. ibid., p. 29

7. See Taylor, E., ‘Modern Women: Margaret Preston and Bessie Davidson’ in Australian Impressionists in France, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2013, pp. 97 – 101

8. Little, op. cit., p. 56

9. All biographical information is drawn from Little, op. cit.

10. For example, the Queensland Art Gallery I Gallery of Modern Art first acquired Davidson’s work in 1977; the National Gallery of Victoria’s first acquisitions were in 2020; and the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ first acquisition occurred in 2023.

11. Edouard Sarradin, cited in Little, op. cit., p. 108

Kirsty Grant

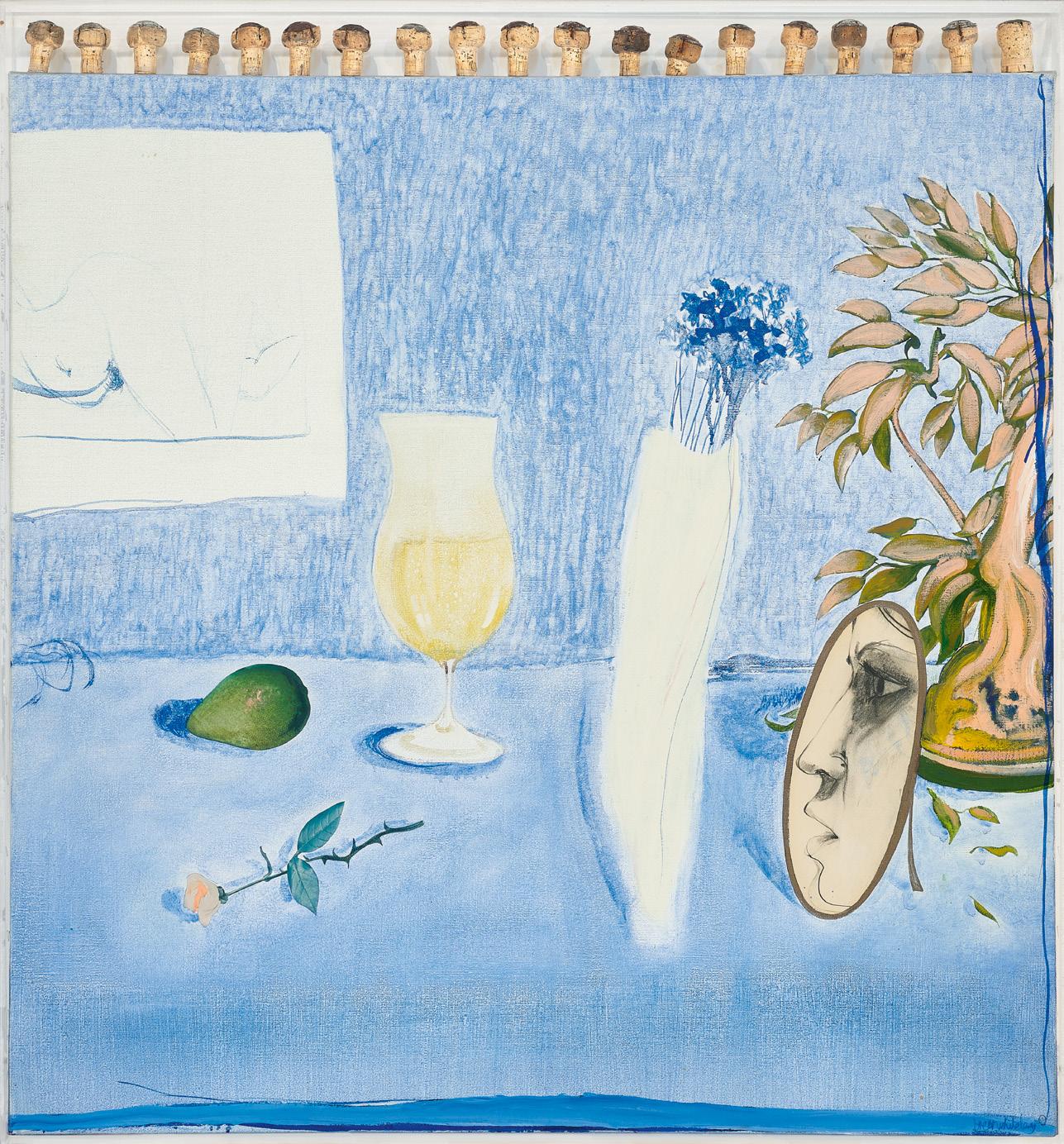

tempera on compressed card

73.0 x 60.5 cm

signed lower left: Bessie Davidson

Estimate: $150,000 – 200,000

Provenance

Salon des Tuileries, Palais de Bois, Porte Maillot, Paris, 1924 Mr & Mrs James P. Cordill, New Orleans, USA, acquired in Paris c.1924 Miss Shirley Cordill, New Orleans, USA, a gift from the above Thence by descent Private collection, New Orleans, USA

Exhibited

Possibly: Salon des Tuileries, Palais de Bois, Porte Maillot, Paris, 1924, cat. 411-bis (as ‘Intérieur’)

Related work

An interior, c.1920, oil, charcoal on composition board, 73.1 x 59.7 cm, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

‘The artist is there, you can feel her presence, yet she doesn’t throw herself at you nor leap upon you proclaiming her genius. There is nothing overwhelming in the welcome extended by these interiors, these landscapes. They make no effort to catch your eye or provoke astonishment. These are well-mannered paintings. But the more carefully you look at them, contemplate them, the more they will give up the secret of their discreet charm’.1

This is how Pierre Müller, art critic for Le Courier, characterised the paintings in Bessie Davidson’s first solo exhibition at Galerie Ecalle, Paris, which opened on New Years Eve in 1928. In addition to receiving a positive critical response, the exhibition marked a significant milestone in her career. Almost twenty years after the South Australian-born artist had returned to Paris, settling there permanently, this presentation of sixty works proclaimed her creative self-confidence and boldly staked a place among the ranks of contemporary artists working in France at the time.

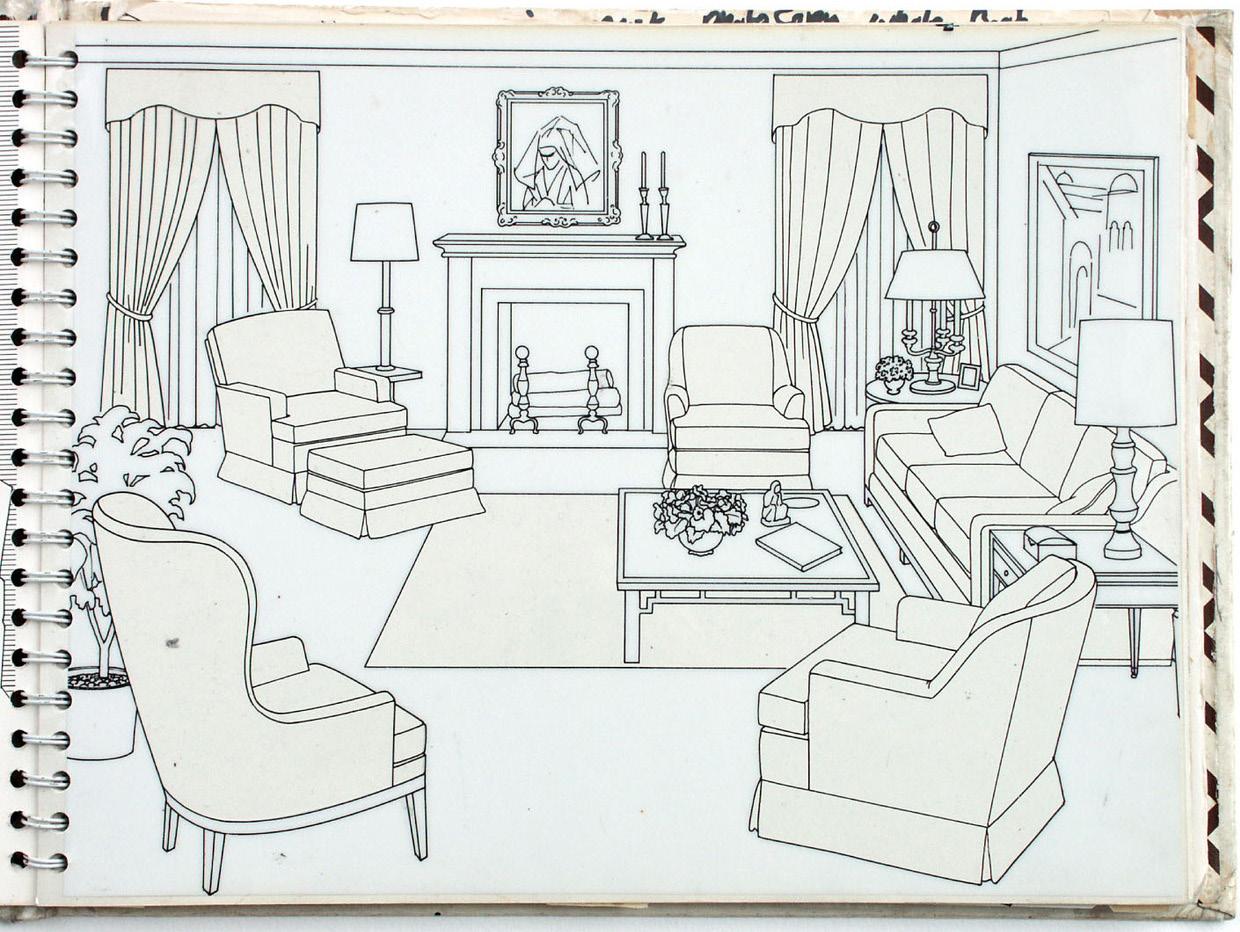

Interior with girl reading, c.1924 is typical of the interiors for which Davidson is best known – painterly celebrations of relaxed feminine domestic spaces that often include a portrait of a female friend or child. The shuttered building visible through the open window locates the scene in Paris, most likely the artist’s second-floor studio apartment on the Rue Boissonade in Montparnasse which had ‘a vast high window composed of tall and slender panes overlooking the courtyard.’ 2 The furniture and style of decoration also is consistent with contemporary photographs and other paintings of Davidson’s residence. The distinctive green armchair on the left appears to be the same chair that features in the Art Gallery

of South Australia’s painting, An interior, c.1920 and indeed, the child in both works might also be the same subject. As much as this painting delights in the depiction of the patterns, shapes and textures of the elegantly homely furniture and furnishings, it is also a skilful exercise in the pictorial representation of light and shade. Davidson had been praised for the ability to ‘bathe her airy interiors with a luminous transparency’3 and this painting is no exception, capturing the bright shaft of sunlight shining through the windows in a diagonal sequence of brilliant highlights that enliven the scene.

This work is painted in tempera, a medium which the New York Herald reported, ‘Miss Davidson prefers to apply… to cardboard… You can be more spontaneous than with [oils], more solid than with [watercolour]’4, noting that ‘[she] accommodates it with an ease so felicitous that it seems not so much a tool as a toy.’ 5 Revealing something of Davidson’s process, traces of preliminary underdrawing are visible throughout the image, as are sections of the cardboard support that remain unpainted (seen here most clearly in the shutters on the building opposite). A technique that was also used by artists including Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, incorporating the exposed board into the final composition of works in both tempera and in oil gives Davidson’s paintings an energy that speaks to the passion with which they were made.

1. Pierre Müller, cited in Little, P., A Studio in Montparnasse: Bessie Davidson: An Australian Artist in Paris, Craftsman House, Melbourne, 2003, pp. 99 – 100

2. ibid., p. 55

3. ibid, p. 90

4. See Little, ibid., p. 89

5. ibid.

Kirsty Grant

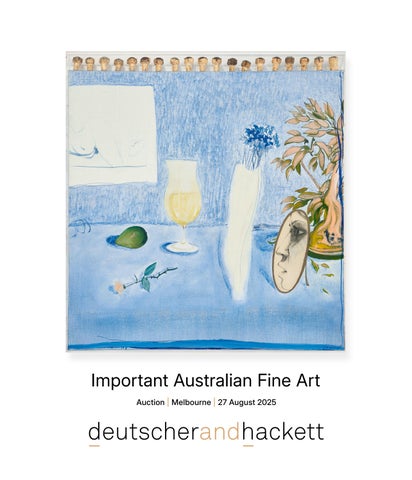

Intérieur, c.1924

oil on board

60.5 x 73.0 cm

signed lower right: Bessie Davidson

Estimate: $250,000 – 350,000

Provenance

Salon des Tuileries, Palais de Bois, Porte Maillot, Paris, 1924 Mr & Mrs James P. Cordill, New Orleans, USA, acquired from the above in 1924 Miss Shirley Cordill, New Orleans, USA, a gift from the above Thence by descent

Private collection, New Orleans, USA

Exhibited

Salon des Tuileries, Palais de Bois, Porte Maillot, Paris, 1924, cat. 409 or 410 (label attached verso)

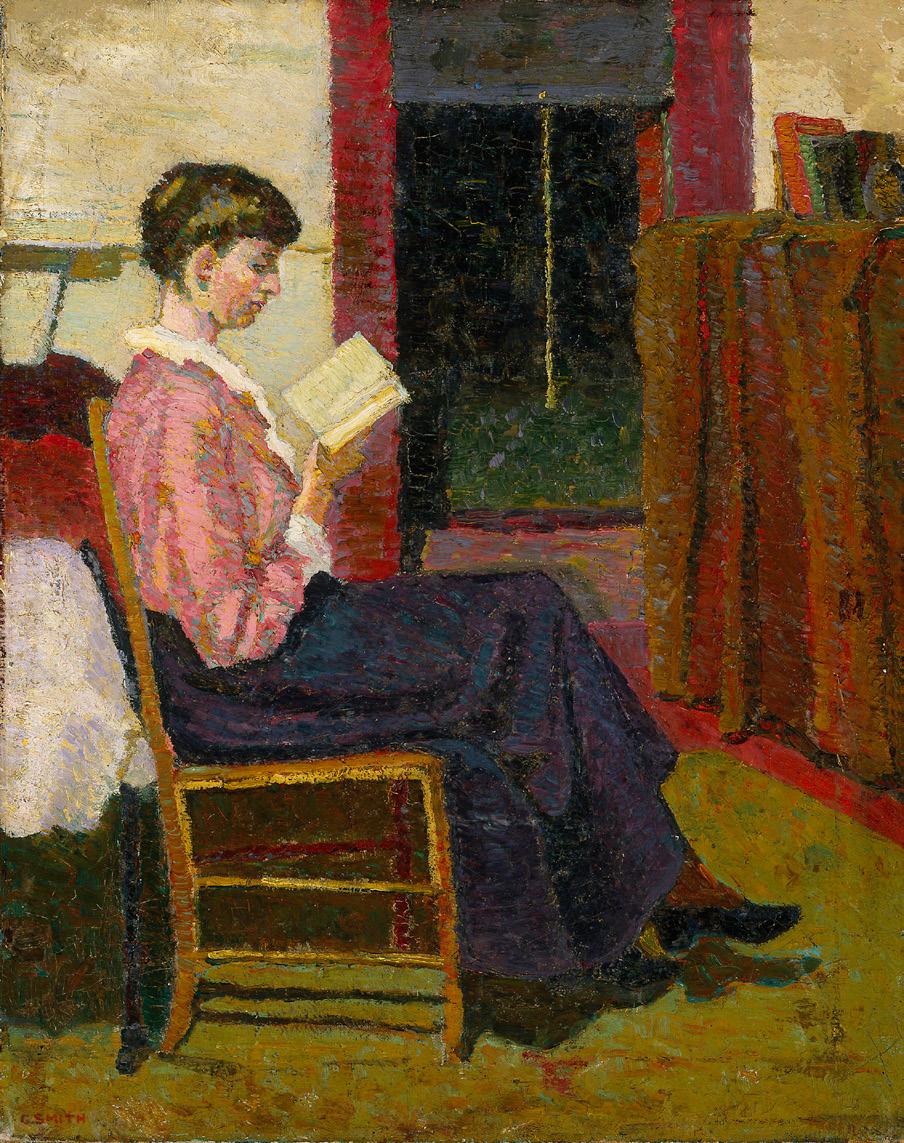

Intimate portraits of her female friends and their children in domestic interiors make up a significant and arguably the best-known part of Bessie Davidson’s oeuvre. They reflect the influence of Édouard Vuillard (1868 – 1940) and the American, Richard Miller (1875 – 1943), who taught her at Académie de la Grande Chaumière, and perhaps even the art of fellow Australian artist Rupert Bunny (1864 – 1947). Also, and more importantly however, they reflect the fabric and rich detail of her own life and experience as an expatriate in Paris from 1910 until her death in 1965. The settings of these paintings were always familiar to the artist, her own studio apartment in Montparnasse often featured in her work, as did the country homes of friends in rural France with whom she would holiday. As Davidson’s biographer, Penelope Little, has written, ‘The interiors… reveal an ambience of bourgeois refinement, not grand but testifying to lives full of interest and occupation. Furniture is elegant but comfortable, shelves are filled with books and ornaments and walls hung generously with paintings. The many different interiors… reveal something of the lives and personalities of their owners… Bessie’s work celebrated the quiet joys of friendship and domestic activity. Her paintings… are filled not only with her women friends but also with their children, their dogs and cats, their sewing, musical instruments, books and paint-boxes.’ 1

Painted around 1924, here Davidson depicts a woman focussed on an unidentified task – sewing or perhaps reading – who is seated in the corner of a room. French doors in front of her open onto a balcony and a view to buildings opposite and tree-tops

beyond, suggesting it is probably Davidson’s own apartment on Rue Boissonade. It is an informal scene, the figure is simply dressed, a shawl draped casually on the table beside her, and the sparsely filled plate of fruit indicates we are being presented with a glimpse of the everyday rather than a carefully staged view. Using lively brushstrokes Davidson takes pleasure describing the details of the interior, from the striped clothing of the figure to the criss-crossed geometry of the cane chair and the patterned wallpaper. She also grapples with the pictorial challenges of portraying the play of light and shade, skilfully depicting the effects of sunlight shining through the delicate curtains and reflections in the highly polished surface of the table which are recorded in a luscious and painterly application of her medium.

Davidson was active and well-connected within the Parisian artworld and in 1923, alongside Lucien Simon, René-Xavier Prinet and other friends, she was a founding member of the Salon des Tuileries. Formed as an alternative to the existing Salons in an effort to raise the overall quality of exhibited works, entry was by invitation only. Davidson exhibited in the inaugural Salon which, as the name indicates, was held in temporary pavilions next to the Jardin des Tuileries, and she continued to participate in following years.2 This painting was purchased from the 1924 Salon des Tuileries, one of three interiors Davidson showed that year, and has remained in the possession of the same American family ever since.

1. Little, P., A Studio in Montparnasse: Bessie Davidson: An Australian Artist in Paris, Craftsman House, Melbourne, 2003, pp. 64 – 65

2. See ibid., p. 94

Kirsty Grant

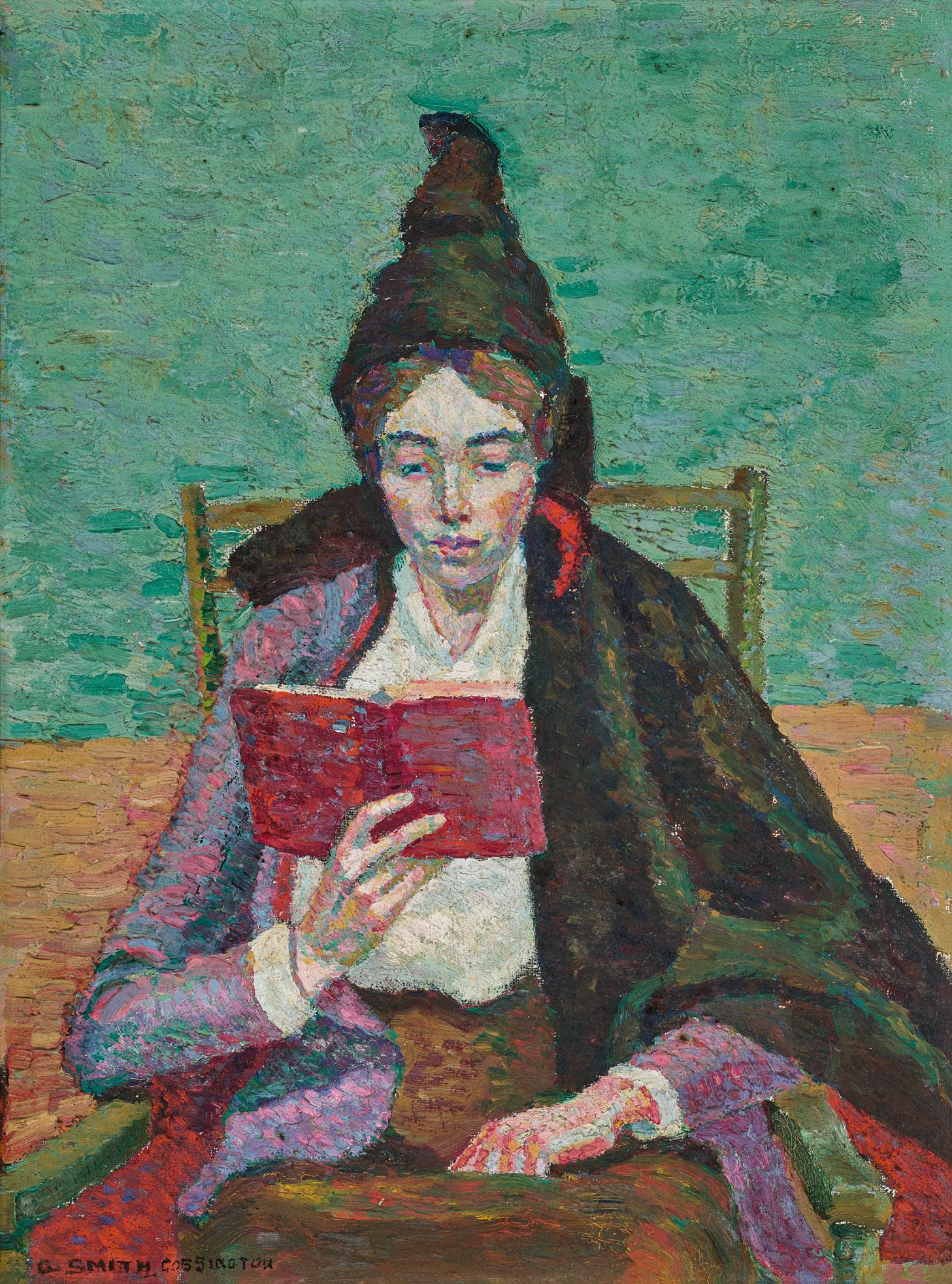

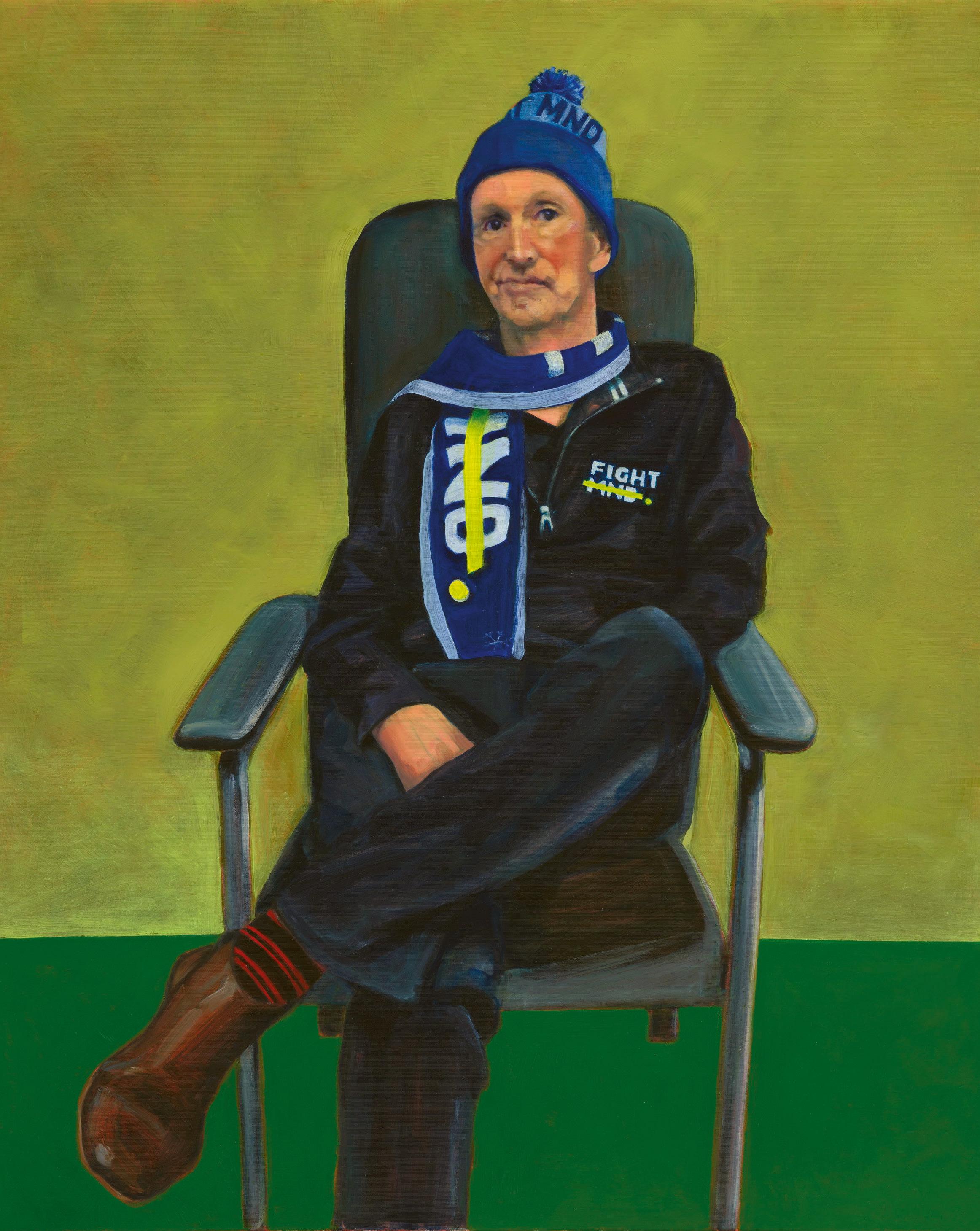

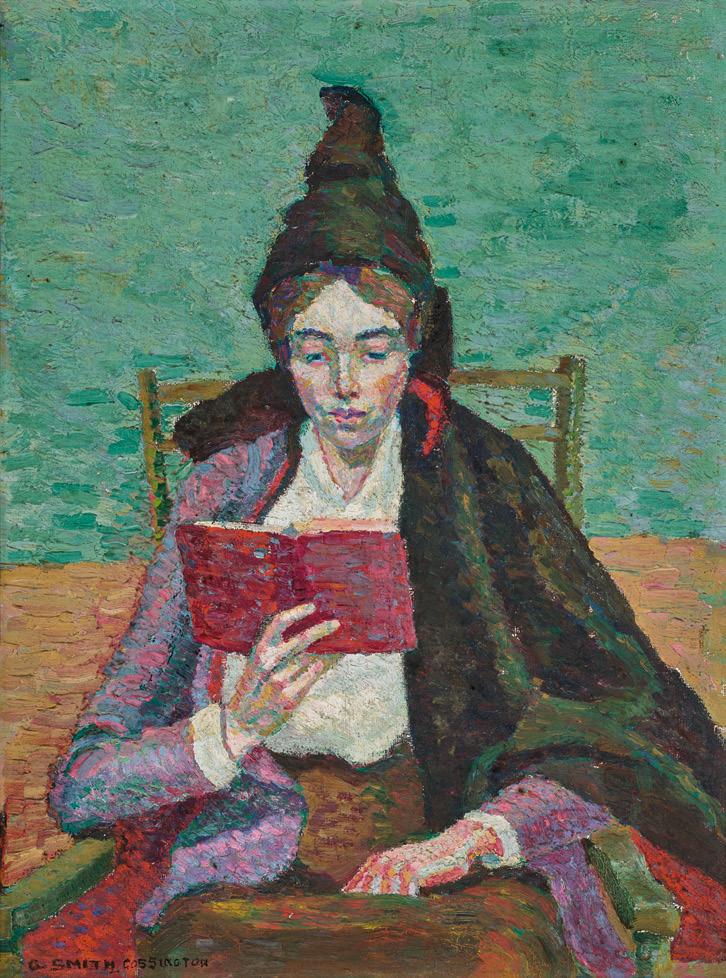

reader (the school cape), c.1916

oil on canvas on pulpboard

32.0 x 24.0 cm

signed lower left: G SMITH. COSSINGTON

Estimate: $400,000 – 600,000

Provenance

Professor Bernard Smith, Sydney, acquired directly from the artist, c.1960

Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 17 April 1989, lot 454 (as ‘The School Cape’) Private collection, Melbourne

Exhibited

Grace Cossington Smith Retrospective, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 15 June – 15 July 1973, then touring to: Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 6 September – 4 October 1973, Western Australian Art Gallery, Perth, 6 December 1973 – 2 January 1974, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 11 January – 10 February 1974, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 26 March – 28 April 1974, cat. 3 (label attached verso)

A century of Australian Women Artists 1840s – 1940s, Deutscher Fine Art, Melbourne, 4 June – 3 July 1993, cat. 90 (illus. in exhibition catalogue, p. 22)

Literature

Thomas, D., Grace Cossington Smith, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1973, pl. 3, pp. 9, 15 (illus., as ‘The School Cape’) James, B., Grace Cossington Smith, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1990, pl. 6, pp. 37 (illus.)

Related work

The reader, 1916, oil on canvas, 51.2 x 40.6 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

51.2 x 40.6 cm

Grace Cossington Smith’s The reader (the school cape), c.1916 is a jewel of a painting which dates from the dawn of modernism in Australia. It is also one of the very few from that time still in private hands. Although it was not until 1940 that a work by the artist entered a state gallery collection1, there is no institution now that does not proudly own at least one example. Such is her importance that the National Gallery of Australia currently lists 1,721 paintings, drawings, watercolours and sketchbooks by Cossington Smith in their collection – a remarkable number that underscores this opinion (by comparison, there are only 469 by Sidney Nolan). Also remarkable is that she had only been painting for one year when she created The sock knitter, 1915, recognised as this country’s first truly modernist piece of art. The reader (the school cape) was painted the following year and displays an even richer celebration of colour – that one true passion lying at the heart of her extensive oeuvre spanning sixty-one years.

Cossington Smith was part of a closely entwined family, and her early portraits were of her parents and siblings. Younger sister Madge was the model for The sock knitter and also for The reader (the school cape), in which she wears ‘a hooded cape which had

been part of Grace’s school uniform at Abbotsleigh, Wahroonga’ 2 –a progressive girls’ school where she received basic training from the artists Albert Collins (who would soon become a director at renowned advertising firm Smith and Julius), and Alfred Coffey (a winner of numerous awards over previous decades when exhibiting with the Royal Art Society of New South Wales). On leaving Abbotsleigh, the headmistress Marion Clarke gave Cossington Smith a farewell gift of art books, and the next year she enrolled in drawing classes run by the flamboyant Neapolitan, Antonio Datilo-Rubbo, at his Sydney atelier in Pitt Street. In 1912, she travelled to Europe with her elder sister Mabel where, in England, she attended drawing classes at the Winchester School of Art before travelling to Stettin, Germany (now Szczecin, Poland) staying with relatives of their mother. Here, Cossington Smith attended ‘a dozen outdoor sketching classes’3 at the town of Speck, even though it was over 100 kilometres from Stettin; the reasons for this choice are unknown. The sisters returned to Sydney in 1914 and Cossington Smith re-enrolled in painting classes with her former teacher, now based in Rowe Street. Unbeknownst to her, Rubbo had experienced a revelation in her absence. A former

student Norah Simpson had returned to his classes the previous year following study in London under the noted British postimpressionists Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore. Significantly, she brought with her a collection of colour reproductions featuring a range of artists’ paintings, including those by Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh. By the time Simpson left Sydney again in May 1915, Rubbo was fired with enthusiasm for these new ways of seeing.

Also inspired was Cossington Smith and her fellow students Roy de Maistre, Roland Wakelin and Constance Tempe Manning. They were, however, now considered ‘wild animals’ ( fauves) as far as the arbiters of local art were concerned and numerous of their more ambitious entries were rejected from RAS exhibitions (the fiery Rubbo even threatened to duel one RAS judge over an excluded submission by Wakelin). The four students began exploring emotive, high-pitched colour, using divided paint marks within a flattened plane. Although The sock knitter is relatively subdued in this regard, the model’s face and hands are coloured with blues, pinks, greens and caramel, and even the large passages of violet in her cardigan are not ‘flat crude colour, (instead, there is) colour within colour, it has to shine; light must be in it, it is no good making

The sock knitter, 1915 oil on canvas

61.8 x 51.2 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

heavy, dead colour.’4 A similar work, also titled The reader, 1916 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) features younger sister Charlotte (also known as Diddy) sitting in a chair in Grace’s bedroom, and here, the ‘shining’ light and colour is even more evocative.

The reader (the school cape), by comparison, almost explodes with pigment intensity. Set within two distinct planes, one in shades of aquamarine, the other of orange-brown, Madge reads a book (itself executed in horizontal brushstrokes of red, blue and violet) whilst wearing the same cardigan as in The sock knitter, only this time the colouration contains pinks, blues and ultramarine. Her hands and face pulsate with at least five distinctly different colours, but are offset in places against an olivegreen ground, which indicates the artist’s knowledge of similar techniques used by Renaissance painters when depicting flesh. The composition too is startling despite the relative simplicity of the pose, as the ruched hood of the Abbotsleigh cape creates a dynamic and unusual apex, the visual ‘weight’ of which is countered by a flash of red near the sitter’s neck. Though small, The reader (the school cape) rewards any repeat viewing.

Grace Cossington Smith

Study of a head: self-portrait, 1916 oil on canvas on board

28.6 x 23.4 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

A final point involves the signature. ‘Cossington’ was the name given to two houses occupied by the family and ‘came from the ancestral home of the artist’s mother: Cossington Hall in Leicestershire, Great Britain.’ 5 The first, where the artist was born, was built by her father in c.1888 in Neutral Bay, Sydney.6 The second, in Turramurra, was initially named ‘Sylvan Falls’ when rented by the family from 1914, before its purchase and re-titling to ‘Cossington’ in 1920. From about 1919, at her mother’s suggestion, the artist began using ‘Cossington’ within her signature ‘as part of her identity as an artist.’ 7 This transition is shown in The reader (the school cape). The first part of the signature ‘G. Smith’ dates from c.1916, but its addendum ‘Cossington’ was clearly painted at a different stage. It may have been added during the process of the painting’s sale to the noted art historian Dr Bernard Smith8, but with this one small detail, Cossington Smith marks her own strategic progress from extraordinarily talented student to mistress of her own artistic identity.

1. In 1940, a group of twenty subscribers bought a still life by the artist and presented it to the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

2. Thomas, D. R., Grace Cossington Smith, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1973, p. 9

3. ibid., p. 69

4. Grace Cossington Smith, interviewed by Hazel de Berg, 16 August 1965, in Hazel de Berg collection, National Library of Australia, DeB 122

5. Hart, D. (ed.), Grace Cossington Smith, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2005, p. 1

6. This property originally opened on to Wycombe Road but has since been sub-divided. The main house now fronts 70 Shellgrove Road.

7. Hart, op. cit., p. 1

8. On the verso of this painting The reader (The school cape) is an extended text written in 1974 by Dr Bernard Smith claiming this version was exhibited with the Royal Art Society of NSW (RAS) in 1916 as ‘The reader’, as opposed to the painting of the same title now in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. As the latter painting was formerly owned by Antonio Dattilo Rubbo, it is accepted that it is the original RAS exhibit, as catalogued by Daniel Thomas in the 1973 AGNSW retrospective.

Andrew Gaynor

– 1984)

House with golden trees (Pink house), 1937

oil on board

75.5 x 90.5 cm

signed and dated lower left: G. Cossington Smith 37 dated lower right: 1937

signed, dated and inscribed with title on label verso: House with Golden Trees / Grace Cossington Smith / 1937

signed and inscribed with title verso: House with Golden Trees / G. Cossington Smith

Estimate: $300,000 – 500,000

Provenance

Macquarie Galleries, Sydney (label attached verso)

Private collection

Deutscher Fine Art, Melbourne (label attached verso, as ‘House with Golden Trees (5 Boomerang Street, Turramurra)’)

Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in December 1983

Exhibited

Grace Cossington Smith, Macquarie Galleries, Sydney, 21 June – 10 July 1972, cat. 14

Related works

House with Trees, 1935 – 39, oil on pulpboard, 54.3 x 64.0 cm, private collection, illus. in James, B., Grace Cossington Smith, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1990, pl. 61

The pink house, c.1935, colour pencil and pencil on paper, 35.0 x 44.4 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Grace Cossington Smith House with trees, c.1935 also known as The pink house oil on pulpboard

54.3 x 64.0 cm

Private collection

Grace Cossington Smith never learned how to drive and until her friends started purchasing vehicles and taking her on painting excursions, it was the streets around her home that provided the bulk of inspiration for her art. She lived her entire adult life in the family house ‘Cossington’ located in Turramurra, a leafy suburb in Sydney’s northern suburbs, and her walks would take her some kilometres in all directions. This focused observation, augmented by forensic examination as she sketched her initial studies, resulted in a range of utterly distinctive paintings that cemented her position as one of Australia’s most original artists of the period. In the 1920s, this included works inspired by the local hilly terrain such as Eastern Road, Turramurra, c.1926 (National Gallery of Australia), and Landscape at Pentecost, 1929 (Art Gallery of South Australia), as well as views from ‘Cossington’ of the tangled bush beyond, best observed in The gully, 1928 (Kerry Stokes Collection, Perth). In the 1930s, the interplay of architectural forms set within local bush gardens increasingly attracted her attention as seen in The winter tree, 1935 (private collection), with the present work, House with golden trees (Pink house), 1937, being a prime example.

Cossington Smith was constantly inventive which is one reason why her images continue to resonate through contemporary eyes. Her particular quest was the depiction of light’s emotional and physical effect on a person, thoughts magnified by her reading (and transcription) of Beatrice Irwin’s pivotal text New science of colour (1915), which ‘expressed the view that the study of colour would lead to more subtle emotions, profound ideas and more quickened spiritual perceptions on a universal level.’ 1 She was also well aware of the colour-music harmonics practiced by her art-school colleague Roy de Maistre and Roland Wakelin, and of the innovative colour wheels devised by de Maistre and by Margaret Preston in the 1920s.2 These understandings underpin the dissolving forms that Cossington Smith has employed in House with golden trees (Pink house) where the house transitions into the foliage of the bordering trees. With the reduction of their canopies into individual forms, Cossington Smith provides a design counterpoint to the open panes within the fence where each ‘view’ within is treated slightly differently from its companions. Close inspection also reveals her use of pencil not only as underdrawing, but also in the emphatic lines indicating the upright

Grace Cossington Smith Eastern Road, Turramurra, 1926 watercolour over pencil on paperboard

40.6 x 33.0 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

palings of the front gate. Technically, her use of divided brushstrokes points to her reverence of Paul Cézanne rather than the gestural flourishes of van Gogh, with whom she is often considered to be aligned. These ‘firm, separate notes of clear, unworried paint’3 are quintessential to Cossington Smith, who was renowned for ‘never revising her brushstrokes, creat(ing) a matt, almost scumbled effect in (her paintings) which, notwithstanding the impasto, gives in parts the impression of paint having partially sunk into the ground.’4

This residence, ‘Didsbury’ at 5 Boomerang Street, Turramurra, is still notably extant, located about 250 metres from Cossington. Built by the architect Augustus Aley in 1929, ‘Didsbury’ features an ‘entrance porch with a circular drum used to link two wings of the building, approached via a circular forecourt’ opening onto the gate at the corner of Fairlawn Avenue and Boomerang Street.5 Cossington Smith’s initial sketch, The pink house, c.1935, which became the painting House with Trees, c.1935 (both National Gallery of Australia) focussed on the façade facing Boomerang Street; however, in House with golden trees (Pink house), she has moved

down to the entrance corner, a tactic which reveals the artist’s continuing re-examination and progressive analysis of her subjects.

1. Hart, D. (ed.), Grace Cossington Smith, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2005, p. 28

2. Grace Cossington Smith, interviewed by Hazel de Berg, 16 August 1965, in the Hazel de Berg collection, National Library of Australia, Canberra, DeB 122

3. Grace Cossington Smith, cited in Thomas, D. R., Grace Cossington Smith, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1973, p. 6

4. Edwards, D., Australian Collection Focus: The Lacquer Room, 1935 – 36. Grace Cossington Smith, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1999, non-paginated

5. Ku-ring-gai Council, ‘PLANNING PROPOSAL: To amend the Ku-ring-gai Local Environmental Plan 2015 to list additional Heritage Items and additional Heritage Conservation Area (PP_2015_KURIN_003_00)’, Ku-ring-gai Council (online), p. 162, see: https://www.krg.nsw.gov.au/files/assets/public/v/1/hptrim/information-managementpublications-public-website-ku-ring-gai-council-website-urban-planning-and-policies/ planning-proposal-to-list-additional-heritage-items-and-hca.pdf (accessed 11 July 2025)

Andrew Gaynor

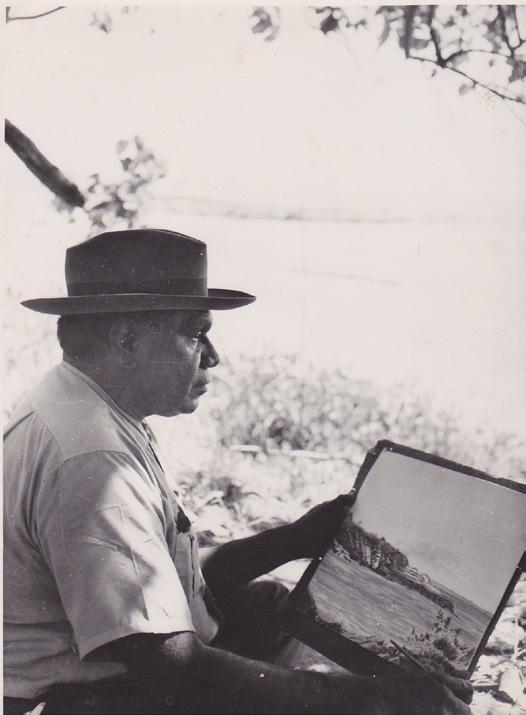

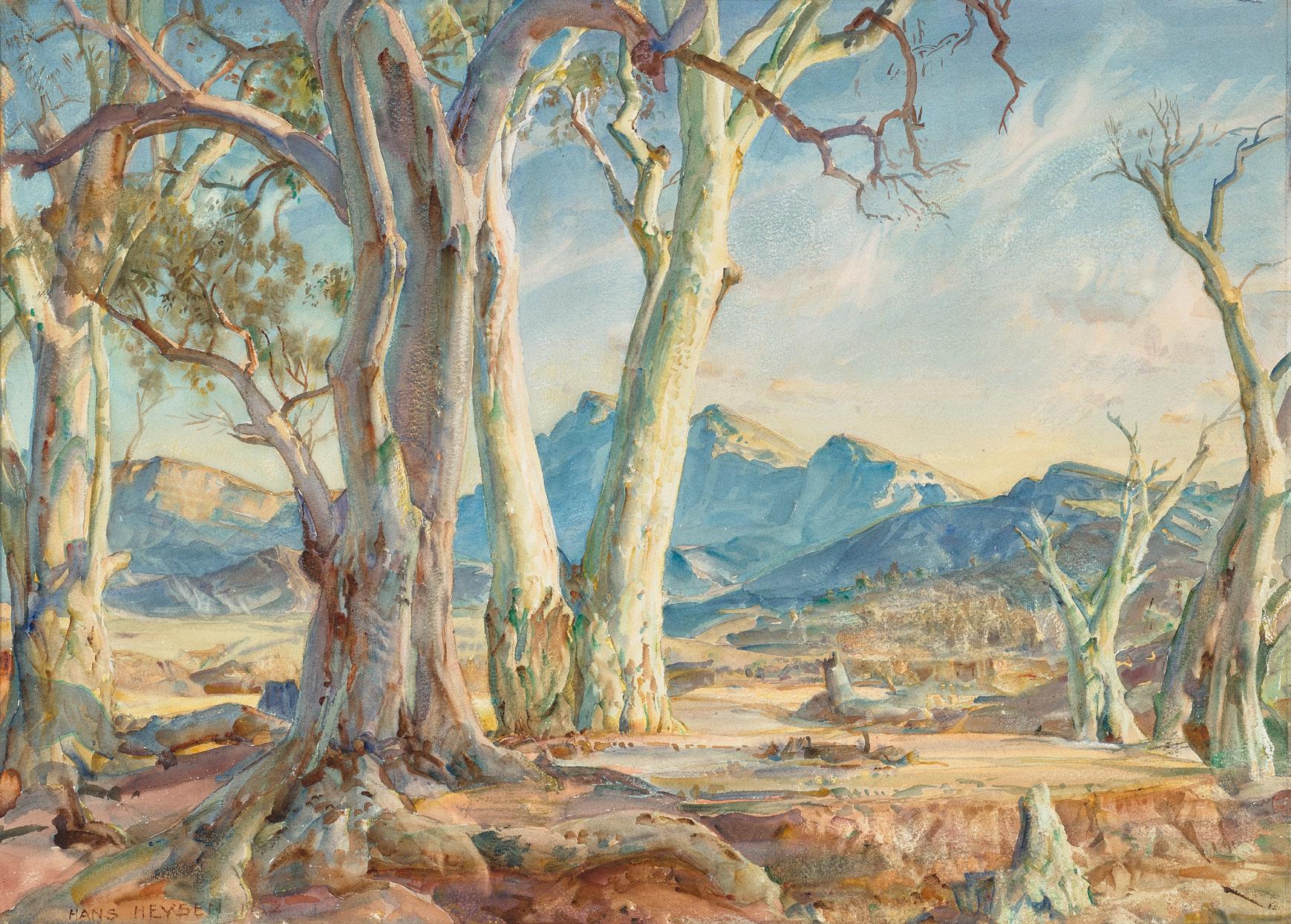

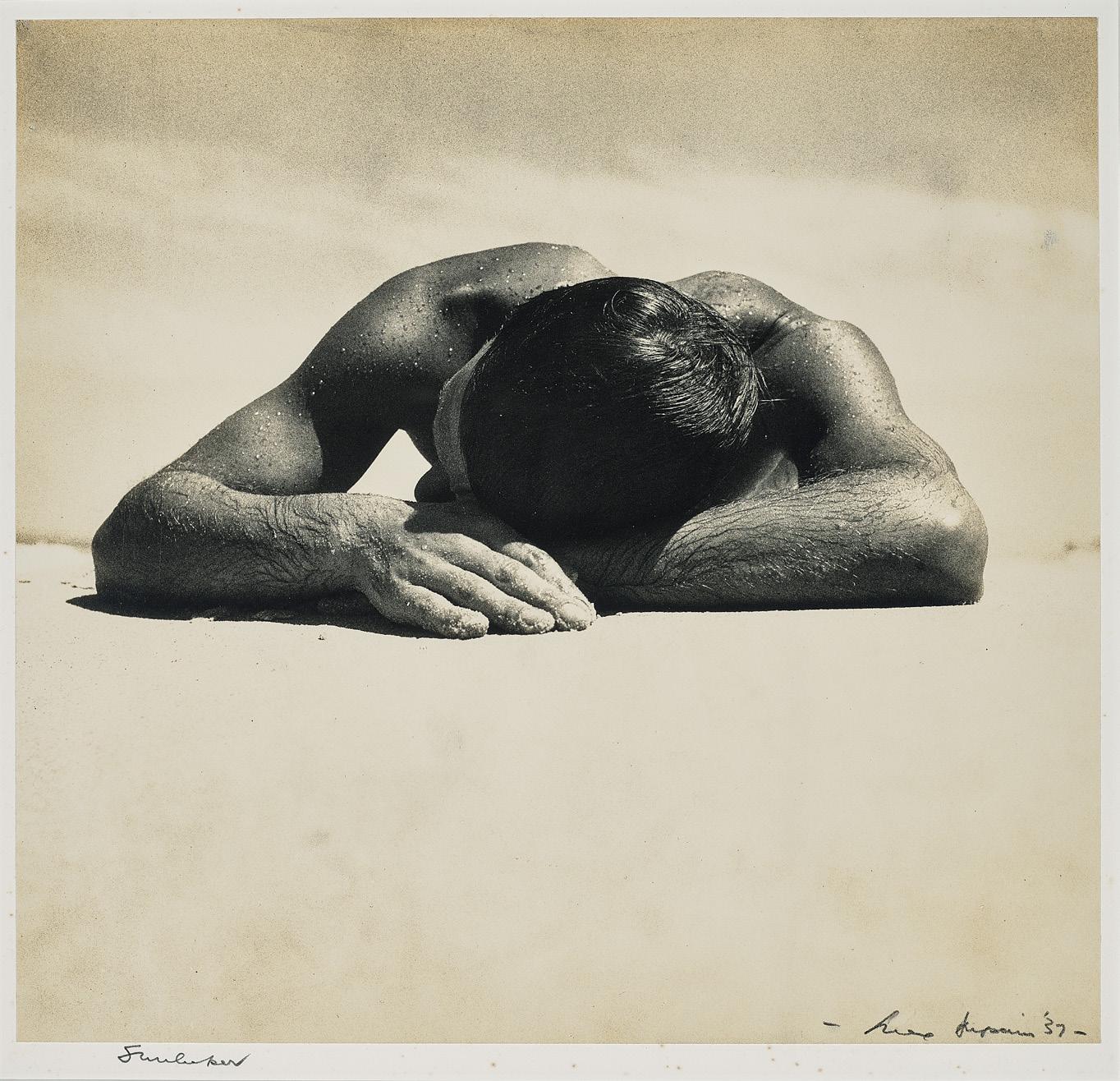

(1911 – 2003)

Flinders Street Station, 1944

oil on canvas on plywood

48.0 x 61.0 cm

signed lower left: Nora Heysen inscribed on label verso: MELBOURNE STREET SCENE / NORA HEYSEN

Estimate: $20,000 – 30,000

Provenance

Private collection, Adelaide

Private collection, Melbourne, a gift from the above, c.1992

Exhibited

Nora Heysen, S.H. Ervin Gallery, Sydney, 8 September – 15 October 1989, cat. 56

Nora Heysen, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 25 October 2000 – 28 January 2001

Literature

Klepac, L., Nora Heysen, Beagle Press, Sydney, 1989, cat. 56, pp. 56 (illus.), 79

Klepac, L., Nora Heysen, National Library of Australia, ACT, 2000, p. 51

Related work

Flinders Street Station no. 2, 1943 – 44 (dated 1946) , oil on canvas on cardboard, 46.0 x 60.9 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

When Nora Heysen was awarded the 1938 Archibald Prize for her striking portrait Madame Elink Schuurman, she set a cat amongst the pigeons, that is, the local scions of the male-dominated art world who complained vociferously. Max Meldrum for one who wrote scathingly that an art career was ‘unnatural and impossible for a

woman’ 1; whilst others claimed she was only treated favourably due to her father, the celebrated Hans Heysen. Of course, nothing was further than the truth and she triumphed again in 1943 when she became the first woman to accept an invitation from the Australian War Memorial to become an official war artist. She was eventually sent to New Guinea but in the interim, she spent some months in Melbourne from October 1943 to April 1944, where Flinders Street Station, 1944 (originally titled Melbourne Street Scene), was painted.

Heysen – or to give her official title, VFX 940085 Captain Heysen, N. AIF – was accommodated at the Menzies Hotel. Her first studio was with other war artists based at the Military History Headquarters on St Kilda Road, then in early 1944 she moved into a new space at 138 Flinders St, a building which had ‘lately been the morgue’,2 from which, she wrote in a letter, ‘the outlook is quite fascinating and I’ve started a canvas of the railway lines and trains.’3 She eventually did two versions of differing views from her window comprising this lot and its companion, the smaller and currently mis-dated Flinders Street Station no. 2, 1943 – 44 (dated 1946) (National Gallery of Victoria) which was also given its current title by the artist prior to its exhibition at the S.H. Ervin Gallery, Sydney, in 1989. However, the artist’s studio was a good 250 metres from the Station and the paintings look to the opposite direction, following the curving rail lines towards Richmond. Visible on the skyline in each is the prominent spire of St Ignatius Church on Richmond Hill, a view which has been obliterated over time by skyscrapers and overgrown vegetation, as well as infrastructure such as the Batman Ave Bridge which now obscures the rail lines.

Initially studying at the North Adelaide School of Fine Art (with generous, low-key input from her father), Heysen was noted first for her extraordinarily precise portraits which presented an accuracy that recalled Vermeer. From 1934 to 1937, she studied in London where she befriended artist Lucien Pissarro’s daughter Orovida, who encouraged her to be livelier with her paint. Indeed, Flinders Street Station could be a magnified incident from a painting by Camille Pissarro, Orovida’s grandfather, whose bustling Boulevard Montmartre, morning, cloudy weather, 1897, was a star of the

Nora Heysen

Flinders Street Station no. 2, 1943 – 44 oil on canvas on cardboard

46.0 x 60.9 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

National Gallery of Victoria’s collection. Following Orovida’s suggestion, Heysen adopted a more painterly technique, as seen in her Archibald winning portrait and in the two Flinders Street views. In the work on offer here, the artist scrutinises the humble scene below her and features three modes of transport set against the vertical pattern made by the palings of the rail-concealing fencing, long since replaced by rusting cyclone wire and now cloaked in ivy.

1. ‘Art Prize to Woman. Marriage before career. Advice by artist’, The Herald, Melbourne, 21 January 1939, p. 8

2. See Nora Heysen, Letter to her parents 19 September 1944, transcribed in Speck, C. (ed.), Heysen to Heysen: selected letters of Nora Heysen and Hans Heysen, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 2011, p. 139. Notably, 138 Flinders Street is still standing, now absorbed within the neighbouring Duke of Wellington hotel redevelopment.

3. Nora Heysen, Letter to her parents, February/March 1944, see ibid. p. 140 Andrew Gaynor

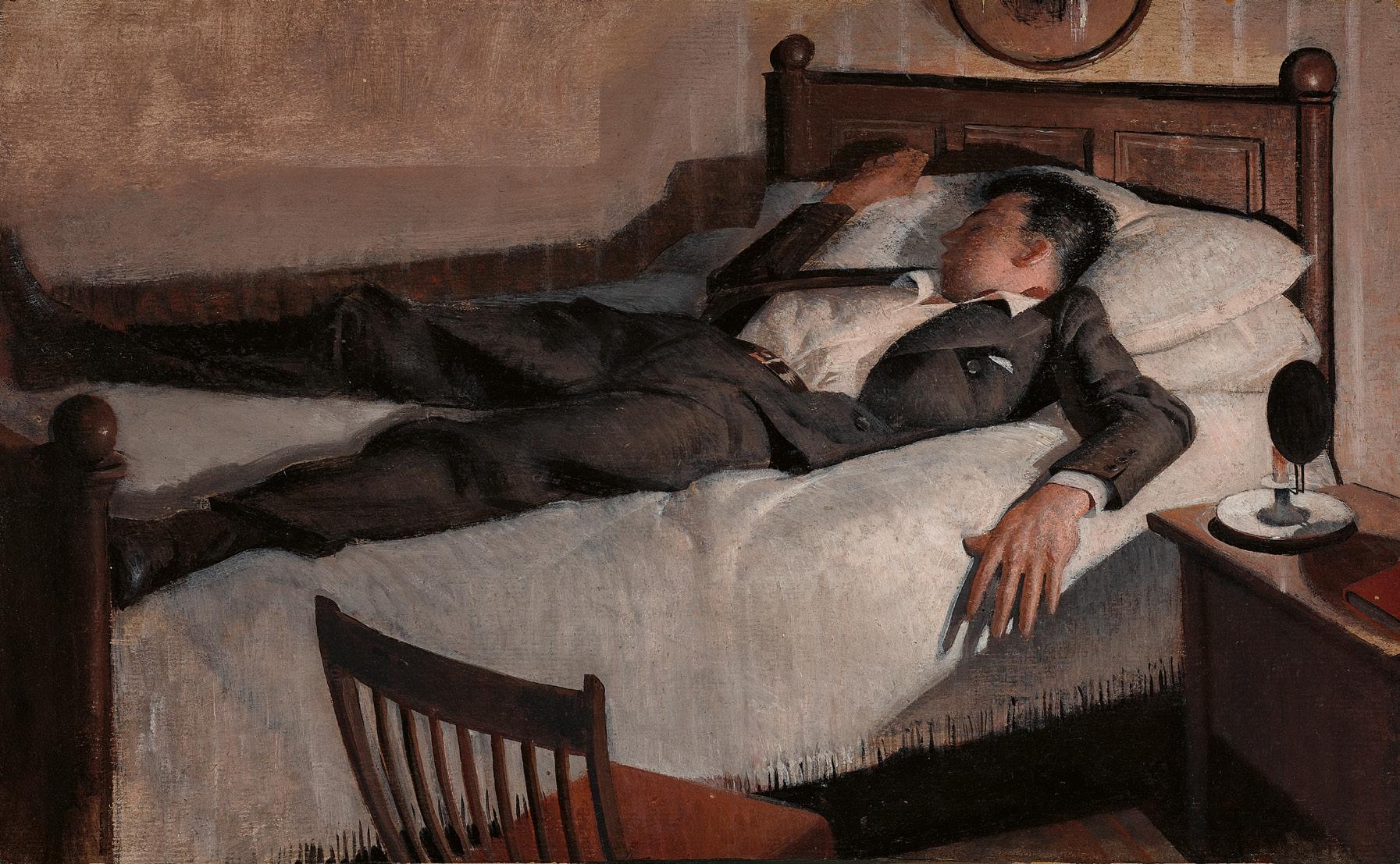

oil on board

27.0 x 44.5 cm

Estimate: $180,000 – 280,000

Provenance

Estate of the artist, New South Wales

Thence by descent

Private collection, the artist’s nephew Sotheby’s, Melbourne, 22 August 1994, lot 76 Private collection, Melbourne

Exhibited

William Dobell: The Painter’s Progress, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 14 February – 27 April 1997, Newcastle Region Art Gallery, Newcastle, 7 May – 6 July 1997, Museum of Modern Art at Heide, Melbourne, 29 July – 21 September 1997, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 25 October – 7 December 1997, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, 8 January – 1 March 1998 (label attached verso)

Literature

Pearce, B., William Dobell: The Painter’s Progress, The Beagle Press, Sydney, 1997, cat. 11b, pp. 34, 49 (illus.)

Related work

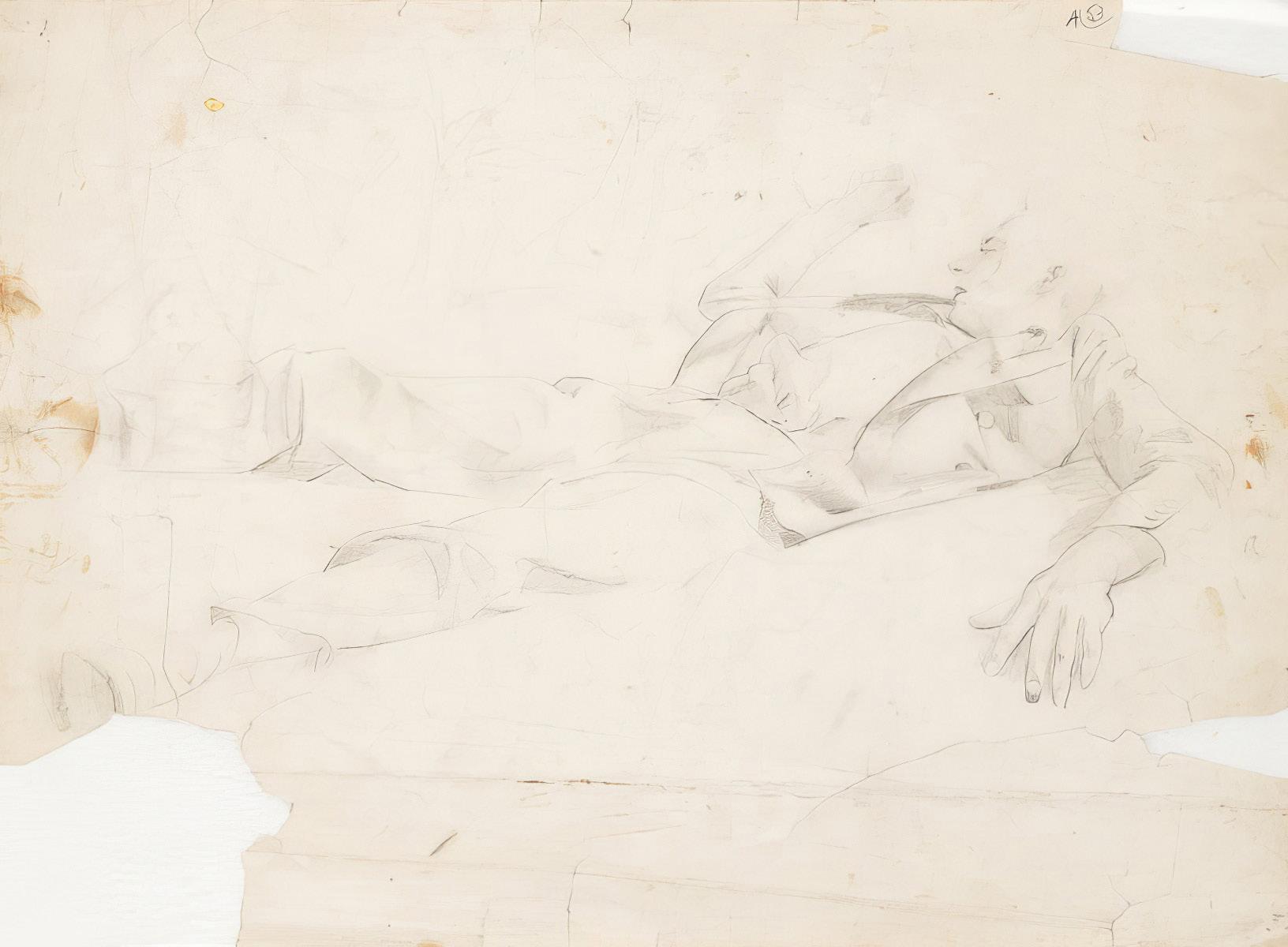

Study for Young Man Sleeping, c.1936, pencil on paper, 26.0 x 35.7 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

William Dobell

(Male figure sleeping) (Student studies), c.1936 pencil on paper 24.0 x 35.7 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney © Courtesy Sir William Dobell Art Foundation / Copyright Agency, 2025

In 1929, William Dobell was awarded the Society of Artists’ twoyear travelling scholarship following an extended period of study at Julian’s Ashton’s art school in Sydney. The award came with a stipend of £250 per year for two years, augmented by funds from the committee for the Artists’ Ball and from Wunderlich Ltd., for whom he worked. He travelled to England where he enrolled at London’s Slade School of Fine Art but even with the scholarship’s financial support, living in the city was expensive and Dobell spent most of his time in conditions close to poverty. At first, he lived in ‘squalid little bed-sitting rooms in Bayswater and Pimlico.’ 1

One room he shared with a burglar named ‘Stiffy’ who used the bed in the daytime whilst his flatmate was at Art School.2

It was during these London years that Dobell truly became an important painter, able to capture the inner life of his subjects, a ‘humanity that is a little sombre in tone, a little uneasy... brilliant, but somehow disturbing.’3 The Slade recognised his talent and in 1930, awarded him first prize for figure painting with his Slade

nude (Newcastle Art Gallery) and shared second prize for drawing. At the National Gallery, he avidly studied the works of Rembrandt, Goya, Soutine, Corot and El Greco, before visiting Holland, France and Belgium, where he found the artists of the Northern Renaissance, particularly Vermeer and Rogier van der Weyden, to be an inspiration. By the time of his return, the scholarship money had run out, but in late 1932 he was fortunate to be given the use of the studio of his New Zealand colleague, Fred Coventry, on the ‘top floor of a trace house in Westbourne Grove, Bayswater.’4 Before Coventry left to take up a commission, Dobell painted his portrait – arms folded, looking askance at the viewer, hair upswept and unruly – an early example of the artist’s finely intuitive portraits. More importantly, Dobell also painted his first masterwork here, The boy at the basin, 1932 (Art Gallery of New South Wales), which had started as a sketch for an unfinished image for the Slade from the previous year. Now transposed to Coventry’s studio, the rumpled, bare-chested figure in striped pyjama pants undertakes his morning ablutions, using a bowl of water set on a counter while the kettle boils

William Dobell

The boy at the basin, 1932 oil on wood panel

41.0 x 33.2 cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney © Courtesy Sir William Dobell Art Foundation / Copyright Agency, 2025

on the flat’s single electric burner, a half bottle of milk and opened box of sugar to one side. It is a ‘a frozen moment in time, with the muted stillness of a Flemish interior’ 5 but has the attention to detail of straightened circumstance that would later be celebrated by the ‘Kitchen Sink’ movement which emerged in Britain in the late 1950s.

Besides Coventry, other Australian artists Dobell mixed with in London included Godfrey Miller, John Passmore and Arthur Murch. All (apart from the independently wealthy Miller) lived on low incomes and often supported each other; indeed, Young man sleeping was painted at a time where Dobell’s frugal living forced him to miss occasional meals whilst using ‘shoe polish on his legs to cover holes in socks.’6 In Young man sleeping, Dobell does not sensationalise such austerity; rather, he imbues the scene with the same refined sensibility as The boy at the basin Technically, the sleeping figure is set at a diagonal which divides the picture plane, an angle emphasised further by the contrasting grey used for his suit and the shirt illuminated by white, scumbled

brushstrokes. The overall design comprises a series of devices that cause the eye to roam across every detail, from the vertical stripes of the wallpaper carried through to the details on the headboard, and on to the irregular fringe of the bedspread. The figure’s left hand dangles by his side, the attenuated fingers mirrored in the upright struts at the back of the chair, and all is illuminated by the bedside lamp, the top of which has been adjusted to blaze solely on the model. This lighting is theatrical, likely informed by Dobell’s experiences as an extra in several London films in 1934. A comparison between Young man sleeping and The boy at the basin clearly illustrates the subdued tenor and masterly technique found in the very best of Dobell’s London paintings.

1. ‘William Dobell: an Australian genius’, People, Sydney, 21 June 1950, p. 42

2. ibid.

3. ibid., p. 44

4. Gleeson, J., William Dobell, Thames and Hudson, London, 1964, p. 33

5. Adams, B., Portrait of an art: a biography of William Dobell, Hutchison, Victoria, 1983, p. 66

6. Gleeson, 1964, op. cit., p. 39 Andrew Gaynor

1968)

Two women in a boat, c.1935

oil on board

64.0 x 52.5 cm

signed lower left: R de Maistre

Estimate: $50,000 – 70,000

Provenance

Miss Doris de Mestre Fisher, United Kingdom, acquired directly from the artist

Thence by descent

Caroline de Mestre Walker, United Kingdom

Related work

Two Women in a Boat, oil on board, 59.0 x 49.5 cm, private collection, illus. in Johnson, H., Roy de Maistre: The English Years 1930 – 1968, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995, pl. 15, p. 38

Caroline de Mestre Walker has been co-copyright holder on de Maistre’s work since 1975 and has generously donated her Roy de Maistre archive and papers to the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

An attractive and sophisticated painting, Two women in a boat, c.1935 exemplifies well de Maistre’s approach to his art, demonstrating his interest in colour and abstracted design. Notably, the painting is a stylised version of a more realistic work, Two Women, 1934 (private collection) and although the subjects here are not named, the composition almost certainly depicts Lady Ashbourne and a companion boating on the river in Compiègne, France. Previously it has been suggested that the second figure is Violet Gibson, Lady Ashbourne’s sister-in-law who achieved notoriety by attempting to shoot Mussolini in 1926, however there is no evidence to support this supposition. Indeed, Violet Gibson was visiting the Ashbournes in 1924 and de Maistre could conceivably have met her, but by 1934, she was housed in a mental institution. Moreover, the painted image bears no resemblance to photographs or descriptions of Violet made at this time.1

After gaining a reputation as an early ‘modern’ painter, de Maistre left Sydney in May 1923 to take up the informal overseas study awarded by the Society of Artists Travelling Scholarship, spending the next two years in Europe, mainly France. A photograph sent to

Roy de Maistre with Lord and Lady Ashbourne photographer unknown

his sister in Sydney during this trip shows the artist seated at the gate of the home of Lord and Lady Ashbourne in Compiègne, France.2 It is not known how de Maistre met the Ashbournes, but Lord Ashbourne (William Gibson) and his wife Marianne (née Marianne de Monbrison) became close friends and the subjects of many of de Maistre’s works which feature the couple relaxing at home or enjoying activities on the nearby river. While Lord Ashbourne, an extremely colourful figure – philosopher, religious scholar and linguist who gave his maiden speech in the House of Lords in Gaelic and commonly dressed in a saffron kilt and espadrilles – has been depicted enthusiastically rowing or actively writing, depictions of Lady Ashbourne typically reveal her engaged in quieter pursuits such as reading, painting or knitting. In the more realistic version of this work, the figures are static – enclosed in a not easily readable but intimate space. They are simultaneously engaged by their proximity and confinement and disengaged by their self-absorption and posture – looking in opposite directions and individually reading.

De Maistre regularly made several versions of his works, often stylising a more realistic version. In the present Two women in a

Roy De Maistre

Two women in a boat, 1934 oil on plywood panel

40.5 x 31.8 cm

Private collection

© Courtesy of the artist’s estate

boat, de Maistre has converted the women’s surroundings to be more obviously a boat, yet at the same time he has flattened and abstracted the scene, emphasising the separation between the figures by framing them in pale triangles and adding decorative elements, particularly related to shape. The lightly depicted decorative pattern on Lady Ashbourne’s shawl has been hardened to geometric motifs, while the ‘pages’ of the second figure’s reading or drawing material have been changed to panels reminiscent of the colour stripes of de Maistre’s later colour music paintings, and Lady Ashbourne’s hair bun and hat have been turned into concentric circles echoed in her companion’s hat. The space surrounding the figures is similarly sharpened by rectangles and

triangles, mostly to the right and left of the foremost figure. De Maistre’s colour expertise is subdued in this work. His dominant use of shades of blue is contrasted by the touches of yellow in the hats and the reddish skin tones of the subjects, thus adding balance and stability to the scene. Although the figures are seated in a rowing boat, there is no movement – only the serenity of a closely shared, yet at the same time, individual, experience.

1. See Stoner Saunders, F., The Woman Who Shot Mussolini, Faber and Faber, London, 2010, Chapter XI

2. Reproduced in Johnson, H, Roy de Maistre. The Australian Years, Craftsman House, 1988, p. 43

Dr Heather Johnson

oil on canvas

41.0 x 35.5 cm

signed lower right: R de Maistre

Estimate: $25,000 – 35,000

Provenance

Miss Doris de Mestre Fisher, United Kingdom, acquired directly from the artist

Thence by descent

Caroline de Mestre Walker, United Kingdom

Caroline de Mestre Walker has been co-copyright holder on de Maistre’s work since 1975 and has generously donated her Roy de Maistre archive and papers to the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Although de Maistre would make his mark in Australian art through the development of an individual style of modernism which related colour and music to create a form of stylised, decorative cubism, the present composition, with its framed view of Fort Denison, is reminiscent of the German Romantic device of Rückenfigur (but in this instance, without the figure). The viewer is firmly placed on the verandah looking towards the harbour which notably features no hint of the active construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge that had inspired fellow modernists such as Grace Cossington Smith and was potentially visible with a short turn to the right. Bereft of any harbour activity at all, the scene has instead been presented as quiet and timeless.

After returning to Australia in 1926 following two years in Europe, de Maistre’s work followed a more realistic style than his earlier adventurous experiments. He supported his practice by cultivating patrons, exhibiting and selling works through solo exhibitions (namely at Macquarie Galleries, Sydney in 1926 and 1928), engaging in decorative work, and giving occasional talks.

Enthusiastic among his patrons were English-born Sir Dudley de Chair, a former naval admiral and governor of New South Wales from 1924 to 1930, and his wife, Lady Enid de Chair who was a very active supporter of the arts during her time in Australia – not only in her official capacity, but also from personal interest. Accordingly, de Maistre painted several works of Government House and garden, and a portrait of Sir Dudley de Chair which he entered in the Archibald Prize in 1929 (presently hanging in Government House, Sydney). It is assumed that it was through the connection with the de Chairs that the artist gained entry to Admiralty House which, in 1929, was subject to some controversy. In June, the Sydney Morning Herald reported a visit of the Attorney General, Mr Latham, on behalf of the Commonwealth Government ‘to enquire into the

ownership of Admiralty House, the Sydney home of the Governor General (Lord Stonehaven)’ which, the report continued, ‘was being claimed by New South Wales following a similar successful claim to Garden Island’.1 One year later, in 1930, due to the depression, Admiralty House was closed and its contents sold at auction, with the Governor General transferring his residence to Yarralumla in Canberra. Admiralty House passed to the Commonwealth and was reopened and redesignated as an official residence in 1948.

By contrast to an earlier undated painting, Government House (private collection), where the building is presented almost as a medieval castle shrouded by trees2, and his other depictions of friends’ homes (largely around Palm Beach) undertaken at this time, the present composition is intimate and homely, defying the building’s colonial grandeur. The patches of pale sky and sea, and the faint gold of the light are enhanced by both the dark green of the plants and verandah, and the contrasting reddish-pink tones of Fort Denison and the background buildings. The scene evokes a reflected Australian sunset. Significantly, de Maistre himself departed the country in 1930, never to return, and thus, the painting may encapsulate a final glimpse of Sydney Harbour – perhaps emphasising the artist’s departure for a more desirable future in England.

Accompanying him upon his departure abroad and signed sometime later (de Maistre used the spelling ‘de Mestre’ until 1930), View of Sydney Harbour from Admiralty House to Fort Denison has never, as far as can be ascertained, been exhibited before and importantly represents a unique subject in the artist’s oeuvre.

1. Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, 29 June 1929, p. 14

2. See Bonham’s, Australian Art, Sydney, 22 August 2024, lot 13

Dr Heather Johnson

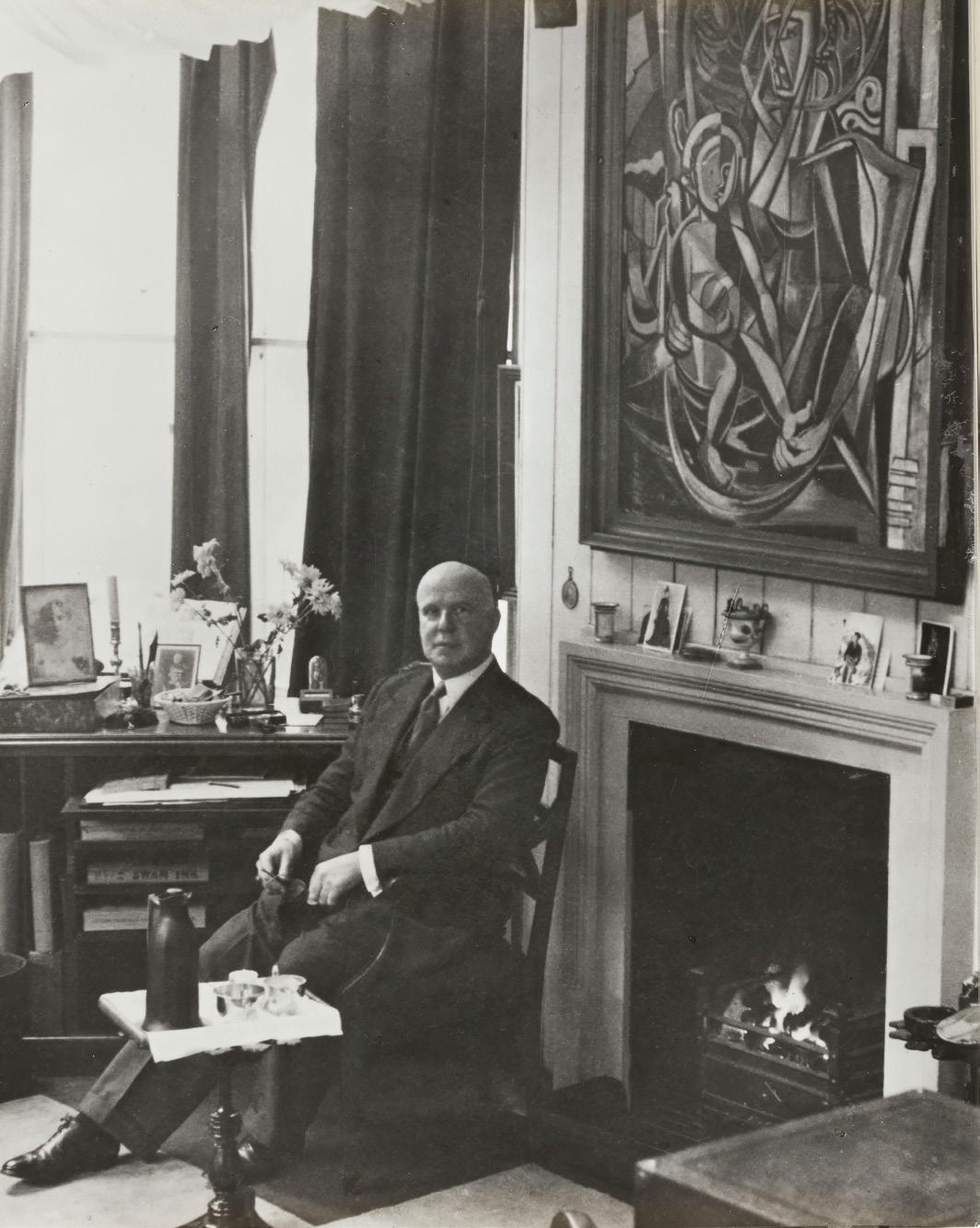

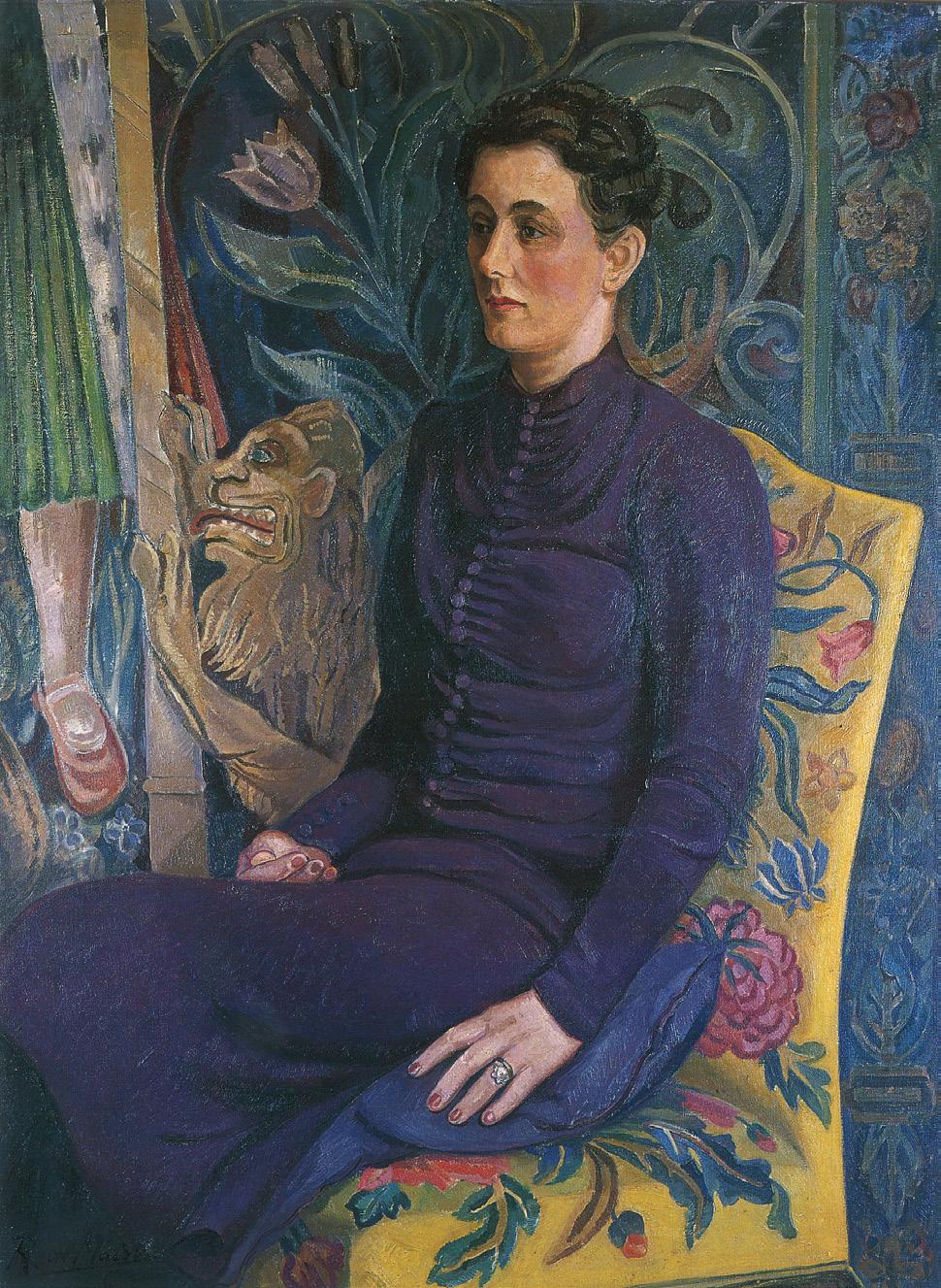

Roy de Maistre (1894 – 1968)

oil on canvas

122.5 x 91.5 cm

signed lower left: R. de Maistre

Estimate: $120,000 – 180,000

Provenance

Lord Ashbourne (William Gibson), London Thence by descent

Christina Gibson (later Mrs J.J. Byam Shaw), London, 1960

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, a gift from the above in 1969

Deutscher~Menzies, Sydney, 15 June 2005, lot 31

Private collection, Melbourne

Exhibited

Roy de Maistre: A Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings 1917 – 1960, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, May – June 1960, cat. 56

Literature

Johnson, H., Roy de Maistre: The English Years 1930 – 1968, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995, pl. 46 (illus.), pp. 109, 111 Rothenstein, J., ‘Roy de Maistre’, Art and Australia, Ure Smith, Sydney, vol. 4, no. 4, March 1967, p. 298 (illus., as ‘Seated Figure (1944)’)

Related works

Portrait of Mrs Florence Bevan, 1937 or 1939, oil on canvas, 116.5 x 89.0 cm, private collection, illus. in Johnson, H., Roy de Maistre: The English Years 1930 – 1968, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995, pl. 45, p. 110 Madonna and Child, c.1947, oil on canvas, 120.0 x 91.0 cm, private collection

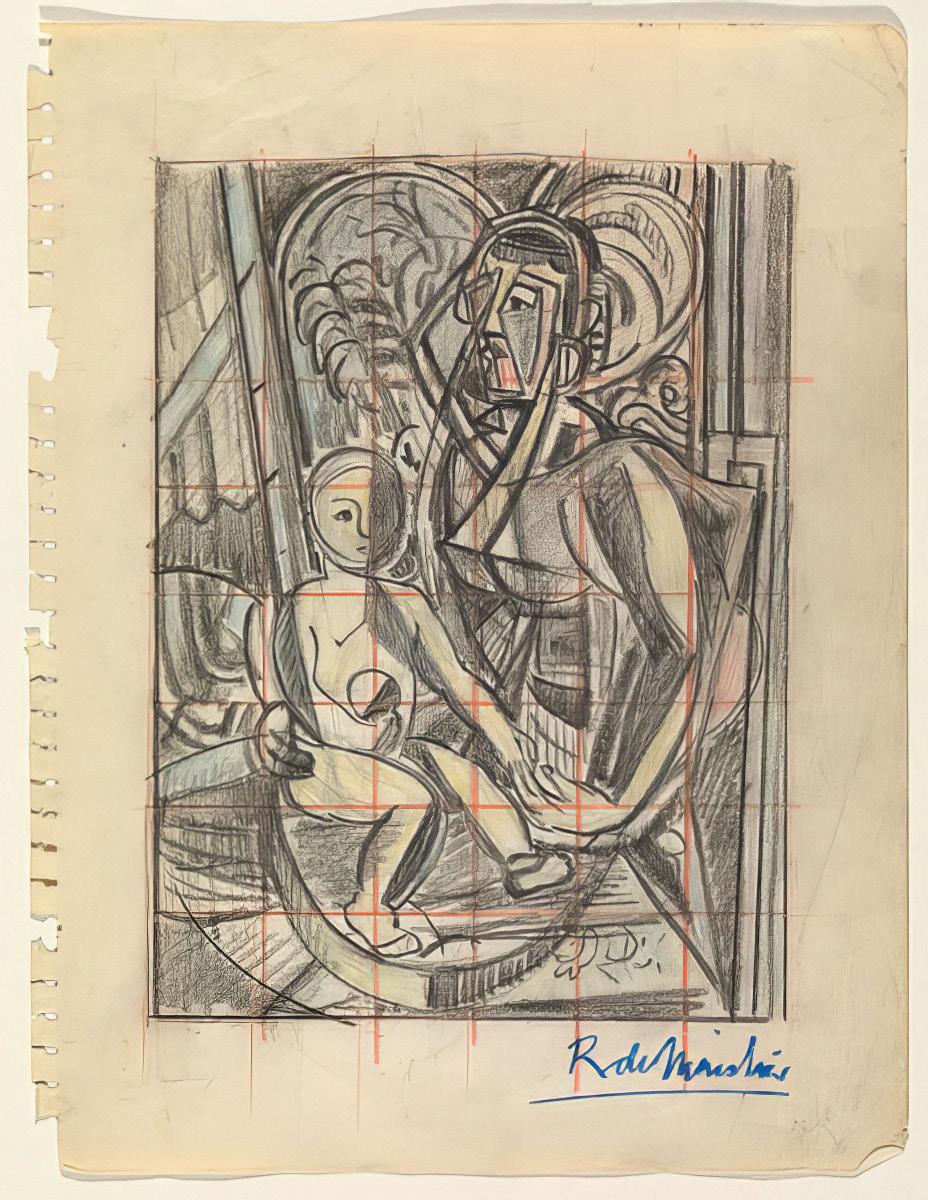

Roy de Maistre [Mother and child], c.1946 drawing in conté crayon, colour pencil 20.4 x 14.9 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Roy de Maistre, c.1950

Madonna and Child, c.1947, pictured

National Art Archive

Art Gallery of New South Wales Institutional Archive

By the late 1930s, Roy de Maistre was living in London and coming to the end of his close association with younger colleague Francis Bacon, whom he had mentored since meeting shortly after his arrival from Australia in 1930. In that time, Bacon’s enthusiasm for Picasso had also passed to de Maistre who began to increasingly explore the possibilities of abstraction to extend initial paintings into more psychic explorations of personality and mood. One of the earliest sequences was based on Bacon’s studio and resulted in the major canvas, New Atlantis, 1933 (National Gallery of Australia). Others reworked scenes painted at Compiègne, France, involving his friends, the Irish peer William Gibson, 2nd Baron Ashbourne, and his French-born wife Marianne (see lot 7). In 1937, he painted Portrait of Mrs Florence Bevan (private collection), a naturalistic image of another close friend and seven years later, this too underwent a sequence of abstractions, starting with this powerful rendition, Woman in a chair, c.1944.

Bevan was ‘the sister of Captain Richard Briscoe, a wealthy businessman, member of parliament and, from 1943 until his death

in 1957, Lord Lieutenant of Cambridge.’ 1 Bevan looked after her brother whose dismissive treatment of his sister angered de Maistre, and in this otherwise affectionate study, she sits slightly slumped as if resigned to her fate, tightly sequestered in a violet dress that buttons firmly up to the neck. A strange lion rampant (possibly a statue?) emerges near her right arm and a truncated portrait of a women brackets the lion’s paw. The contrast between the richly patterned chair and equally florid screen behind her harks back to the society photographs de Maistre styled with Harold Cazneaux for Home magazine in 1928, where wealthy local personalities were set against imported French fabrics. On revisiting Bevan’s portrait for Woman in a chair here, he reimagines the original pose and complex entwining patterns into his personalised form of decorative cubism.

De Maistre lived an impoverished existence yet was a considered a witty and well-read man, a charming companion despite minor eccentricities such as a conviction that he was related to the Royal Family (since discredited). Many people helped support him with baskets of food or invitations to stay at their houses for extended

periods, and this was the same for the Briscoe household whose relationship with de Maistre ‘was one of friendship more than that of artist and patron.’ 2 At the end of 1937, he moved into a three-story building at 13 Ecclestone St, Belgravia, and set up a vast studio. Over time, this became the centre of his world, ‘a veritable Aladdin’s Cave, an enormous space dominated by a winged sofa designed by Francis Bacon in 1930.’3 With the advent of war, de Maistre retreated further into this fastidiously organised environment, and intensely personal abstractions began to dominate his output. The BriscoeBevan friendship continued and he stayed with them on occasion during the war years, which further deepened de Maistre’s friendship with Florence Bevan, informing the psychological intensity found in Woman in a chair, and a subsequent variant, Woman and child (also known as Madonna and child ), c.1947 (private collection).

In Woman in a chair, the sitter’s pose remains as before but is now fragmented into an interlinked sequence of angled facets running from the face to her lap which makes Bevan appear more alert and

Roy de Maistre

Portrait of Mrs Florence Bevan, 1937 or 1939 oil on canvas

116.2 x 88.7 cm

Private collection

© Courtesy of the artist’s estate

aware. The looped stems which formed part of the floral pattern on the screen behind her now continue into a pointed arched line running from jaw to breast on one side and from the peak of her head to the left shoulder on the other: ‘De Maistre explained [the] placing of a cage-like structure around the head of the figure by the feeling her soul was in a cage.’4 This is then echoed by a curved sweep that encloses the hand on her lap, whilst the lion now looks like a Mayan carving. De Maistre has also shifted the palette and Woman in a chair instead brings autumnal orange, oche and brown to the fore, simultaneously reducing the intensity of the blue background seen in the original portrait of Bevan.

1. Johnson, H., Roy de Maistre: The English Years 1930 – 1968, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1995, p. 109. The title Lord Lieutenant is given to the British monarch’s personal representative in the counties of the United Kingdom.

2. ibid.

3. Daniel Thomas, conversation with the author, 17 October 2018. Thomas visited de Maistre in 1966.

4. Mrs Iris Portal, 1988, cited in Johnston, op. cit., p. 109 Andrew Gaynor

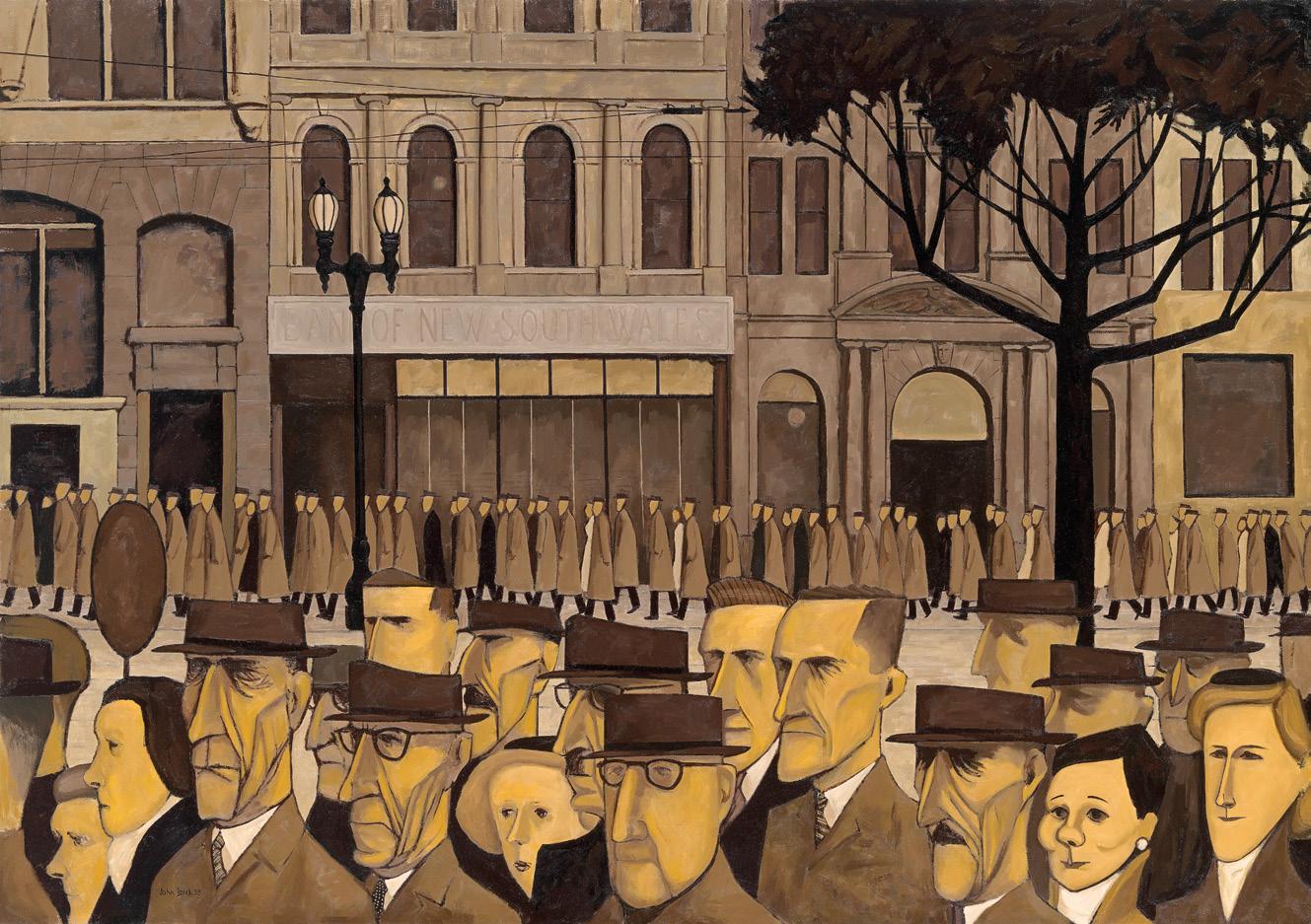

oil on canvas

76.0 x 101.5 cm

signed and dated lower right: John Brack 55

Estimate: $600,000 – 800,000

Provenance

Peter Bray Gallery, Melbourne Australian Galleries, Melbourne (label attached verso)

Miss D Rachor, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1958

Private collection

The Melbourne Art Exchange, Melbourne Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above March 1988

Exhibited

John Brack, Peter Bray Gallery, Melbourne, 19 – 29 March 1956, cat. 2

Contemporary Australian Painting, Auckland City Art Gallery, Auckland, 16 February – 24 March 1957, cat. 3

Helena Rubinstein Travelling Art Scholarship Exhibition, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 5 – 17 August 1958

A Critic’s Choice – selected by Alan McCulloch, Australian Galleries, Melbourne, opened 6 March 1958, cat. 10

John Brack Retrospective, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 24 April – 9 August 2009; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2 October 2009 – 31 January 2010 (label attached verso)

John Brack | Melbourne | 1950s, Sotheby’s Australia, Melbourne, 11 February – 2 March 2019 (label attached verso)

Literature

‘Art Notes: Painter shows originality’, The Age, Melbourne, 20 March 1956, p. 2

Shore, A., ‘Modern Art on Show’, The Argus, Melbourne, 1 December 1956, p. 44

McCulloch, A., ‘Co–ordination and a satirist’, Herald, Melbourne, 21 March 1956, p. 18

Brack on Brack, Discussion Group Art Notes, Council of Adult Education, Melbourne, 1957, p. 5

Millar, R., John Brack, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1971, p. 106

Lindsay, R., John Brack: A Retrospective Exhibition, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1987, pp. 13, 18, 117

Grishin, S., The Art of John Brack, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990, vol. I, pp. 51, 88, 186, 189, vol. II, cat. o43, pp. 7, 93 (illus.)

Delaney, M., Engberg, J. & Plant, S., Melbourne, Modernity and the XVI Olympiad, Museum of Modern Art at Heide, Melbourne, 1996, p. 18

Grant, K., et. al., John Brack, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2009, pp. 42, 43 (illus.), 215

Related works

Still Life with Slicing Machine, 1955, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 76.5 cm, private collection, sold Deutscher and Hackett, Melbourne, 13 June 2018, lot 4

Study for The slicing machine shop, c.1955, black crayon and pencil, 38.5 x 51.2 cm (sheet), National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

John Brack

(Study for The slicing machine shop), 1955 fibre-tipped pen and pencil, squared up in orange pencil 23.3 × 30.2 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © Helen Brack

As a painter of modern life, John Brack found subjects in his immediate surroundings, the suburbs and the city of Melbourne. His best-known paintings of 1950s Australia, such as The new house, 1953 (Art Gallery of New South Wales) and Collins St, 5pm, 1955 (National Gallery of Victoria), are full of acute observations of contemporary living, seemingly humorous and ironic – and from an early twenty-first century perspective, also nostalgic. Such images were primarily motivated however, by Brack’s intense interest in people and the human condition. His early resolution to produce an essentially humanist art that engaged directly with the present was supported by his reading of authors including Rainer Maria Rilke, who advised to ‘seek those [themes] which your own everyday life offers you’ and Henry James, who found inspiration for his stories in random events and snippets of overheard conversations.1 Determined to make art that was relevant to contemporary life, Brack explained, ‘I believe that if there ever is a real Australian Painting, it will be done from the truthful reflection of the life we see about us... I have always found people more interesting than landscape. There are still many things to say about people, in paint. A large number of them work in the town and sleep in the suburbs. Machinery and chromium plating are a part of their lives.’ 2

While Brack strove to create art which engaged with universal themes, his method of identifying subject matter that was close at hand inevitably resulted in images with a distinctly local flavour – recognisable to anyone who grew up in mid-twentieth century Australia, and especially in Melbourne – and unavoidable elements of autobiography appear throughout his oeuvre. The artist’s family inevitably features; his wife Helen was the model for The sewing machine, 1955, for example, and their daughters provided both the visual and thematic inspiration for paintings like The chase, 1959 (both Art Gallery of Ballarat). Similarly, The bar, 1954 (National Gallery of Victoria) – an homage of sorts, which transposes the elegant Parisian setting of Edouard Manet’s famous painting, A bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, to austere 1950s Melbourne – was based on Brack’s experience of the six o’clock swill in city pubs on his way home from work. Critics typically found his work funny and often characterised Brack’s approach as satirical, missing the deliberate irony and layers of allusion and symbolism that are embedded within his compositions. As the artist later said, his paintings were ‘part of a metaphorical system… intended to operate on numerous levels of meaning [and]… to have some reference to the complexity of life.’3

John Brack

Still life with slicing machine, 1955 oil on canvas

63.5 x 76.5 cm

Private collection © Helen Brack

sold Deutscher and Hackett, Melbourne, 13 June 2018, lot 4

Shop window displays provided inspiration for Brack throughout his career and indeed, the experience of seeing reproductions of paintings by Van Gogh in a Little Collins Street shopfront in the late 1930s was a motivating factor in his decision to pursue a career as a professional artist. He later recalled that this vision had a powerful, physical effect, it was ‘a sort of shuddering… overwhelmingly, totally unexpected moment.’4 The most concentrated series of shop window subjects was painted in the early 1960s and the windows which featured in paintings such as Still life with self portrait, 1963 (Art Gallery of South Australia) and The happy boy, 1964 (National Gallery of Australia) displayed surgical instruments, prosthetic limbs and other medical aids. Incorporating obvious associations with the human body, these objects enabled Brack to comment about life without depicting the figure. He often found his subjects walking the city streets and would record the details of what he saw in quick sketches that were later used as aides-memoire in the studio. Additional detail was sometimes provided by photographs taken by his friend Laurence Course, an art historian and keen photographer.

The slicing machine shop, 1955 was the first painting based on a shop window display and it depicts an arrangement of commercial kitchen equipment Brack had seen at the top of Bourke Street in Melbourne He recalled that he made a series of preliminary sketches on site as well as using photographs to record the details of the subject, paring them back in the final composition in the interest of clarity of design.5 Painted in a subdued palette of colours, gleaming meat slicers, measuring scales and giant mixers assume ominous, anthropomorphic qualities belying their inanimate status. Seen through Brack’s eyes, a familiar everyday scene is transformed into something disturbing and uncanny.6 Painted a year earlier, The block, 1954 (National Gallery of Victoria), shares a similar atmosphere of portent as the chopping block, cleaver, meat hooks and other accoutrements of the empty butcher shop assume a quietly unsettling character. In a lecture given at the Council of Adult Education in 1957 the artist explained something of his motivation: ‘I have said we must avoid cliché at all costs. That is one reason for dealing with subjects generally thought to be ‘inartistic’. But I have also suggested that we must come to terms

John Brack

Collins St, 5p.m., 1955

114.8 x 162.8 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne © Helen Brack

with the machine, and perhaps this painting is a tentative move in that direction… [The slicing machine shop] is a still life which uses weighing machines, scales, etc instead of apples and bottles. The colour scheme is cold and sombre, simply because I thought of the machines as steely, hard and sharp. Impersonal objects with personal uses. Blades and handles. Is there a parallel in our lives?’ 7

The slicing machine shop was first exhibited in Brack’s solo show at Peter Bray Gallery, Melbourne in 1956, where it was one of two major paintings alongside Collins St., 5pm, 1955. The latter was acquired from the exhibition along with The car, 1955, by the National Gallery of Victoria and both works, frequently on display, have since developed iconic status. The exhibition was also well received in the press. Alan McCulloch wrote that Brack’s paintings and drawings were ‘distinguished for their elegant finish and their concise summations of character’8, while the unnamed Age art critic insightfully observed that ‘although [John Brack’s] subject matter is drawn from everyday life, it is transcribed in an austere formal style. Consequently, his symbols speak, not of the individual, but of humanity.’ 9 Both critics singled out The slicing

machine shop for comment, noting that in addition to reflecting the artist’s powers of observation it presented a semi-abstract design ‘without losing touch with the appearance of the subject.’ 10

An important example of Brack’s work from a key period in his career, it reflects his distinctive visual aesthetic – as well as the aesthetic of the times – and speaks to major themes that preoccupied his oeuvre.

1. See Grant, K., ‘Human Nature: The Art of John Brack’ in Grant, K., John Brack, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2009, p. 92

2. Brack, J., ‘Brack on Brack’, Council of Adult Education, Discussion Group Art Notes, Melbourne, ref. no. A401, 1957, p. 2

3. John Brack interview, Australian Contemporary Art Archive, no. 1, Deakin University Media Production, 1980, transcript, p. 3

4. John Brack, cited in Grishin, S., The Art of John Brack, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1990, p. 7

5. Brack, 1957, op. cit., p. 5

6. Grishin, op. cit., p. 51

7. Brack, 1957, op. cit.

8. McCulloch, A., ‘Co-ordination and a satirist’, Herald, Melbourne, 21 March 1956

9. ‘Painter shows originality’, Age, Melbourne, 20 March 1956

10. ibid.

Kirsty Grant

oil on composition board

61.0 x 136.0 cm

signed and dated lower left: Tucker Noli 52 dated and inscribed verso: BETRAYAL / 1952 dated verso: 1952

Estimate: $400,000 – 600,000

Provenance

Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne

Michael and Miriam Lasky, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1985

William Mora Galleries, Melbourne Private collection, Melbourne, acquired from the above in 1999

Exhibited

Albert Tucker, Galleria ai Quattro Venti, Rome, 2 April – 2 May 1953

Mostra dei Pittori Australiani: Albert Tucker e Sidney Nolan, Associazione della Stampa Estera, Rome, 20 – 31 May 1954, cat. 1 (as ‘Tradimento’)

Albert Tucker, Bonython Art Gallery, Sydney, 28 October – 19 November 1969, cat. 93

Albert Tucker Paintings 1945 – 1960, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, 1982, cat. 15 (illus. in exhibition catalogue)

Albert Tucker: A Retrospective, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 21 June – 12 August 1990 (label attached verso)

A Link and a Trust: Albert Tucker and Sidney Nolan’s Rome Exhibition, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 18 November 2006 - 20 May 2007, cat. 1 (illus. in exhibition catalogue, n.p.)

Albert Tucker: Marking the Past, Albert & Barbara Tucker Gallery, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, 29 February – 16 August 2020

Literature

Uhl, C., Albert Tucker, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1969, cat. 8.3, pl. K, pp. 52, 56 (illus.), 98

Mollison, J. & Minchin, J., Albert Tucker: A Retrospective, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1990, p. 101 (illus.)

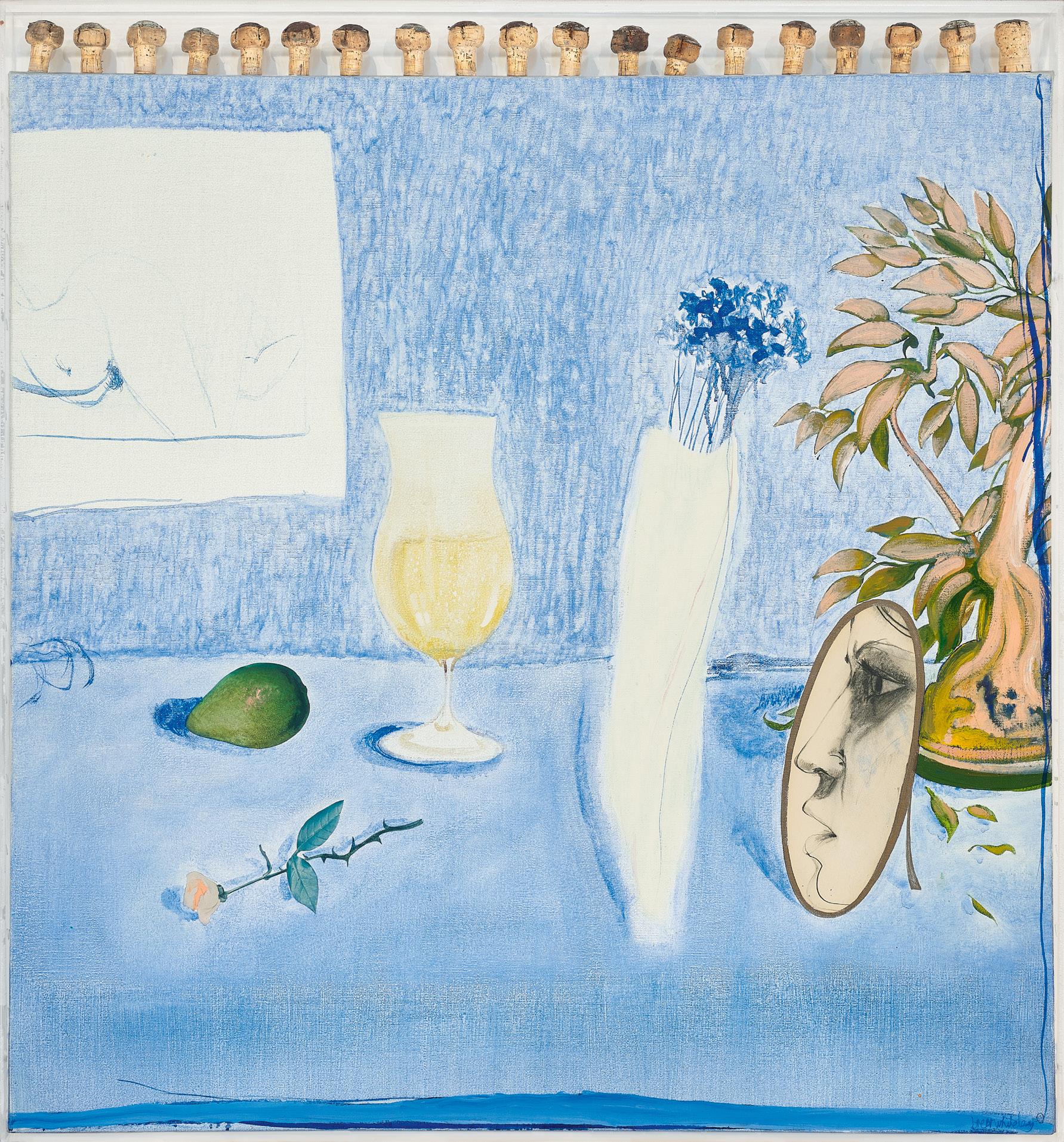

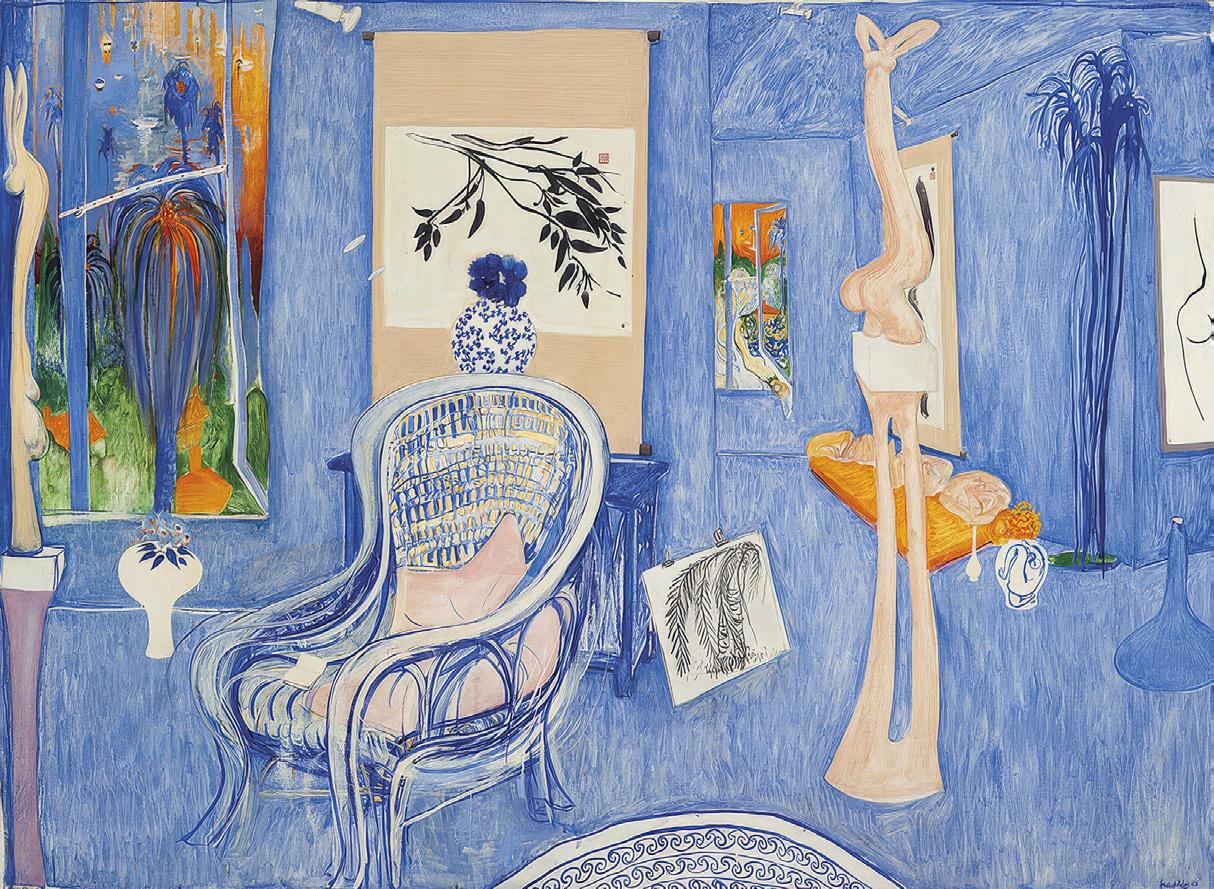

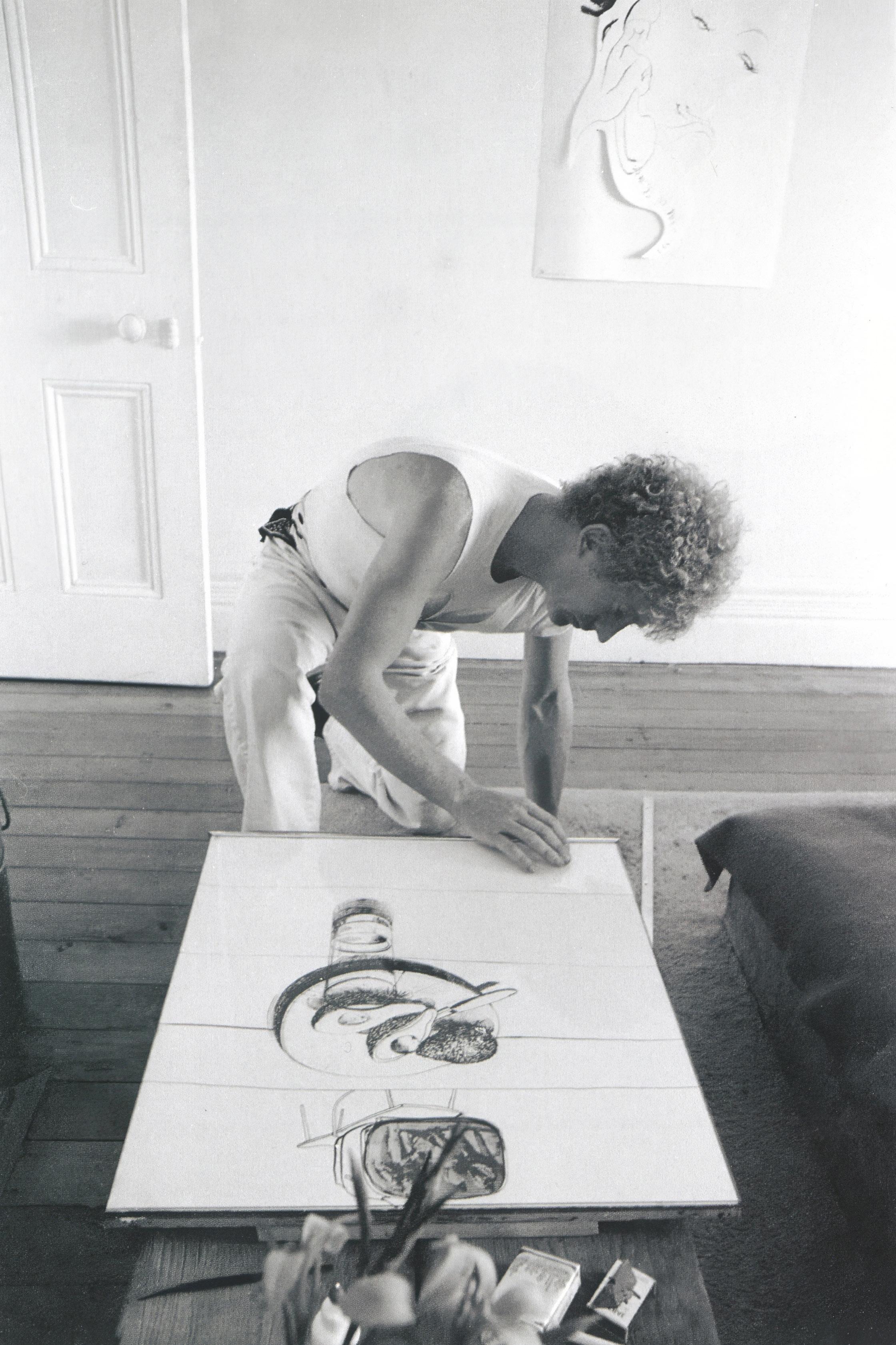

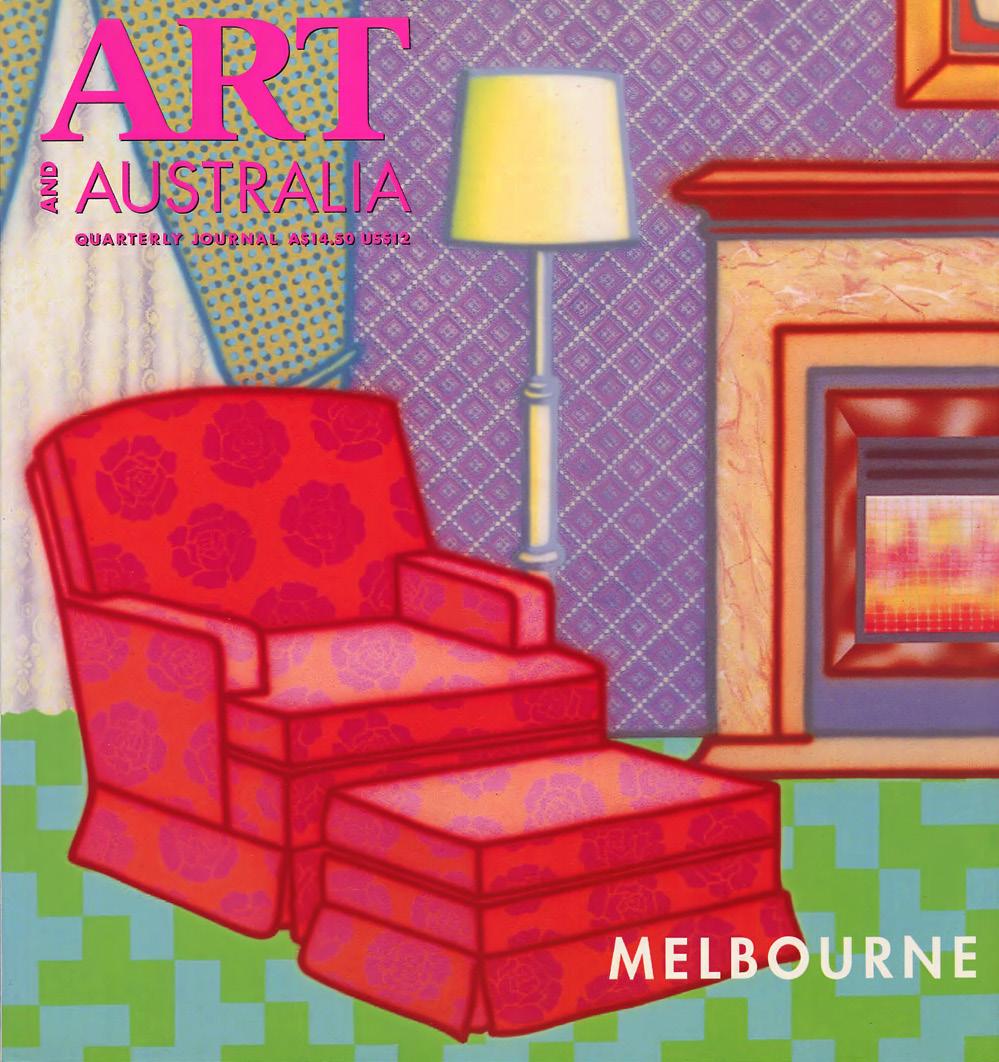

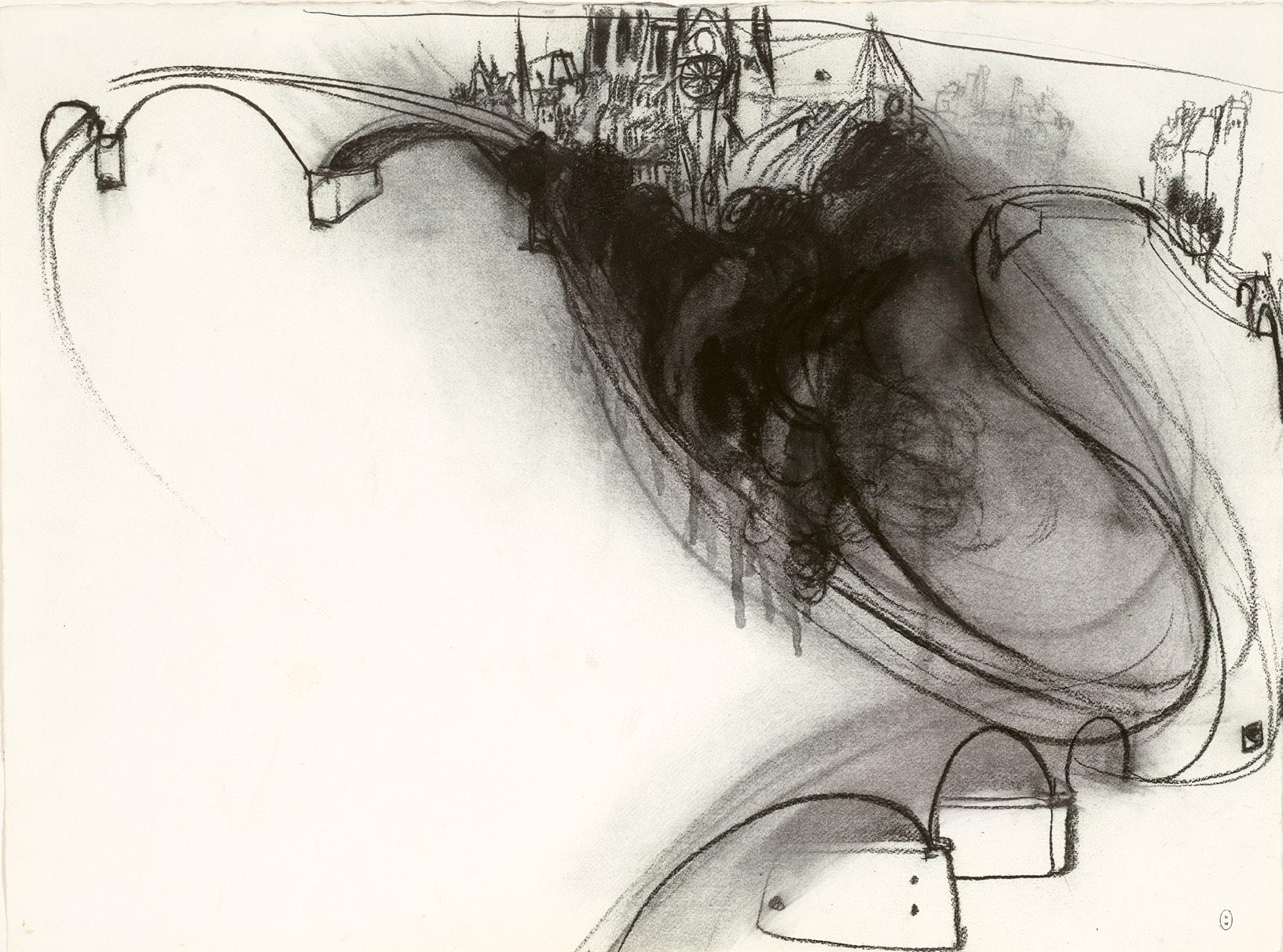

Fry, G., Albert Tucker, Beagle Press, Sydney, 2005, pp. 98 (illus.), 124, 239 (illus.)