24! Fragen an die Konkrete Gegenwart Questions for the Concrete Present

Banz & Bowinkel

Carsten Beck

Anna-Maria Bogner

Nina Brauhauser

Martim Brion

Sebastian Dannenberg

Lena Ditlmann

Fabian Gatermann

Vladiana Ghiulvessi

Charlotte Giacobbi

Dave Großmann

Toulu Hassani

Erika Hock

Marile Holzner

Silvia Inselvini

Patrizia Kränzlein

Schirin Kretschmann

Sali Muller

Cătălin Pîslaru

Fiene Scharp

Marco Stanke

Virginia Toma

Amalia Valdés Mujica

Jonas Weichsel

Museum für Konkrete Kunst Ingolstadt

Museum im Kulturspeicher Würzburg

Herausgeber / Editors

Henrike Holsing, Mathias Listl, Theres Rohde

24! Fragen an die Konkrete Gegenwart Questions for the Concrete Present

Das Museum für Konkrete Kunst Ingolstadt und das Museum im Kulturspeicher Würzburg danken / The Museum für Konkrete Kunst Ingolstadt and the Museum im Kulturspeicher Würzburg thank

allen an der Ausstellung beteiligten Künstler*innen / all of the artists participating in the exhibition

allen leihgebenden Galerien / all lending galleries

Galerie Anita Beckers, Frankfurt a. M.

Circle Culture Gallery, Berlin, Hamburg

Galerie Kuckei + Kuckei, Berlin

Galerie Isabelle Lesmeister, Regensburg

Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, München / Munich

Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin

und privaten Sammlern / and private collectors

Sammlung Stadler, München / Munich

sowie den Institutionen und Galerien, die das Projekt unterstützt haben / as well as the institutions and galleries that have supported the project Bezirk Unterfranken

Freundeskreis Kulturspeicher e. V. Fundação Gulbenkian, Lissabon / Lisbon

Jecza Gallery, Timişoara

Galerie Petra Rinck, Düsseldorf

Rumänisches Kulturinstitut Berlin

Artists

in Ingolstadt

Carsten Beck

Anna-Maria Bogner

Martim Brion

Lena Ditlmann

Vladiana Ghiulvessi

Dave Großmann

Questions for the Concrete Present ... Are Expressly Welcome!

Artists

Henrike Holsing/ Theres Rohde

Konkrete Kunst. Über Ursprung, Unschärfen und Aktualität eines – circa – 100 Jahre alten

Begriffs

Mathias Listl

In Ingolstadt präsentierte Künstler*innen

Toulu Hassani

Marile Holzner

Silvia Inselvini

Fiene Scharp

Marco Stanke

Jonas Weichsel

Mathias Listl

Fragen an die

Gegenwart … sind

Mariana Aravidou

In Würzburg präsentierte Künstler*innen

Patrizia Kränzlein Schirin Kretschmann

Sali Muller

Cătălin Pîslaru

Virginia Toma

Amalia Valdés Mujica

Mariana Aravidou, Henrike Holsing

Einführung und Vorwort

Konkrete

ausdrücklich erwünscht!

Es ist kompliziert! Zu einem Beziehungsstatus jenseits jeder Perfektion Theres Rohde Introduction and Foreword Concrete Art: On the Origin, Vagueness, and Topicality of a Concept (around) a Hundred Years Old

presented

presented

Banz & Bowinkel

Brauhauser

Dannenberg

Gatermann Charlotte Giacobbi Erika Hock It’s Complicated! On a Relationship Status beyond All Perfection 5 11 25 77 93 143 4 10 25 76 93 142 26 30 34 38 42 46 50 54 58 62 66 70 94 98 102 106 110 114 118 122 126 130 134 138

in Würzburg

Nina

Sebastian

Fabian

One Hundred Years of Concrete Art—and Still Topical?

As precise as Concrete Art may be, there is no correspondingly accurate documentation of the exact hour of its birth. For although the term was first demonstrably introduced to art theory officially in published form with the eponymous manifesto by Theo van Doesburg in 1930, a second, incomparably vaguer birthday circulates: the year 1924. According to tradition, Van Doesburg first applied the term that year to his own works, so it was already being expressed in words at that time. The hundredth anniversary of this unofficial birth year of Concrete Art in 2024 offers a fitting opportunity to ask questions of a very fundamental nature of this long-established art movement, even about its not-entirely-uncontroversial name: Does Concrete Art have its finger on the pulse of our times? How intensely and with what intention do people (still) “live” by its principles today? And how do artists of our day regard the sense of mission of their artistic forebears, who in its early years tried to define this movement as precisely as possible and propagate it, above all in the form of manifestos?

The Museum für Konkrete Kunst (MKK) in Ingolstadt and the Museum im Kulturspeicher (MiK) in Würzburg ask these questions as institutions that are especially committed to Concrete Art. Since its acquisition of Eugen Gomringer’s collection and its founding in 1992, the MKK has concentrated exclusively on this art movement, while the MiK houses the Peter C. Ruppert Collection, one of the most important collections of Concrete Art after 1945 on German soil. In both institutions, one can experience classics of this movement: works by artists such as Josef Albers, Max Bill, Verena Loewensberg, Günter Fruhtrunk, Victor Vasarely, Anton Stankowski, and more. They show how Concrete Art continued to evolve actively from its beginnings in the 1920s and into the second half of the twentieth century as a universal language of an artistic bond across national borders. Many of these works, which were revolutionary and avant-garde in their day, now seem almost classical. Does Concrete Art meanwhile belong to a past epoch? If one looks at current art, one no longer finds, especially among younger artists, many who would call their works Concrete Art. But the ideas and principles of this art movement appear to live on, though much less dogmatically and more open at the edges.

For the exhibition project 24! Questions for the Concrete Present, we set ourselves the task of investigating how Concrete Art lives on in contemporary art today. In keeping with the anniversary year, we chose twenty-four artists, all of whom belong to the generation born after 1980 and hence are similar in age to the pioneers of Concrete Art in the mid-1920s, including Sophie Taeuber-Arp (born 1889), Jean Arp (born 1886), and Theo van Doesburg (born 1883). In order to sound out their understanding of and relation to Concrete Art, we confronted young artists with our questions in the form of a questionnaire to which they responded in the run-up to the exhibition. It included ten questions such as: “Do I see myself as a representative of Concrete Art?” “Have the early days of Concrete Art had a direct influence on my own work as an artist?” “And? Is the term Concrete Art still necessary (at all)?” The answers to the questionnaire provided a picture of their diverse opinions, but none of those asked would describe their work as Concrete without provisos. Yet all of them engage with the principles of Concrete Art in one way or another, clashing with them, expanding them, distinguishing themselves from them. That is clear not only in their written statements but also in their works, in which they let a constructive rigor reign, only to playfully violate it again straightaway, in which they make the exhibition space itself the subject of a work of art. Painting on ping-pong tables, making paintings three-dimensional, covering surfaces with ink from ballpoint pens, and so on and so on. All have in common a formal language that is not committed to representation or to a message primarily about content—as well as the great freedom with materials, space, and the concept of the work that perhaps represents the core of Concrete Art. In that spirit, we believe, the idea of Concrete Art can still be relevant even another hundred years from now.

This project is the first cooperation of the MKK and the MiK—not in the sense of a traveling exhibition but as an exhibition in two places: twelve of the artists selected will be shown in Ingolstadt and twelve in Würzburg. Our guests are invited to visit both institutions over the course of the spring and

4 INTRODUCTION AND FOREWORD

100 Jahre Konkrete Kunst – und noch aktuell?

So präzise sich die Konkrete Kunst auch darstellt – über die genaue Geburtsstunde ihrer Namensgebung gibt es keine entsprechend exakte Überlieferung. Denn während der Begriff mit der Veröffentlichung des gleichnamigen Manifests von Theo van Doesburg 1930 ganz offiziell und in gedruckter Form nachprüfbar in die Kunsttheorie eingeführt wurde, steht mit dem Jahr 1924 ein zweites, ungleich unschärferes Geburtsdatum im Raum. Der Überlieferung nach hat van Doesburg den Begriff bereits in diesem Jahr für eigene Werke verwendet, also bereits zu jenem Zeitpunkt sprachlich ausformuliert. Dieses quasi inoffizielle, sich 2024 zum 100. Mal jährende Geburtsjahr der Konkreten Kunst bildet eine passende Gelegenheit, Fragen ganz grundsätzlicher Art an die längst etablierte Kunstrichtung wie auch an ihren nicht gänzlich unumstrittenen Namen zu stellen: Ist die Konkrete Kunst am Puls unserer Zeit? Wie intensiv und aus welcher Intention heraus werden ihre Prinzipien auch heute (noch) „gelebt“? Und wie sehen Künstler*innen unserer Tage das Sendungsbewusstsein jener künstlerischen Vorläufer*innen, die vor allem in Form von Manifesten diese Kunstrichtung in ihren Anfangsjahren genauestens zu definieren und zu propagieren versuchten?

Das Museum für Konkrete Kunst in Ingolstadt (MKK) und das Museum im Kulturspeicher Würzburg (MiK) stellen sich diesen Fragen als Institutionen, die sich in besonderem Maße der Konkreten Kunst verschrieben haben. Das MKK konzentriert sich seit dem Ankauf der Sammlung Eugen Gomringers und der Gründung des Museums 1992 ausschließlich auf diese Kunstrichtung, während das MiK mit der Sammlung Peter C. Ruppert eine der bedeutendsten Sammlungen Konkreter Kunst nach 1945 auf deutschem Boden beherbergt. In beiden Häusern also kann man Klassiker dieser Kunstrichtung erleben, Werke von Künstler*innen wie Josef Albers, Max Bill, Verena Loewensberg, Günter Fruhtrunk, Victor Vasarely, Anton Stankowski und und und … Sie zeigen, wie lebendig sich die Konkrete Kunst nach ihren Anfängen in den 1920er-Jahren auch in der zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts als universelle Sprache künstlerischer Verbundenheit über alle Landesgrenzen hinweg weiterentwickelt hat. Viele dieser Werke, in ihrer Zeit revolutionär und avantgardistisch, muten heute geradezu klassisch an. Gehört Konkrete Kunst also einer mittlerweile vergangenen Epoche an? Wenn man sich im aktuellen Kunstgeschehen umschaut, findet man gerade unter den jüngeren Künstler*innen nicht mehr viele, die ihre Werke als Konkrete Kunst bezeichnen würden. Ideen und Prinzipien dieser Kunstrichtung scheinen aber weiterhin lebendig zu sein, allerdings viel weniger dogmatisch und zu den Rändern hin offen.

Mit dem Ausstellungsprojekt „24! Fragen an die Konkrete Gegenwart“ haben wir es uns zur Aufgabe gemacht, dem Fortleben des Konkreten in der heutigen Gegenwartskunst nachzuspüren. Passend zum Jubiläumsjahr haben wir 24 Künstler*innen ausgewählt, die sämtlich der Generation der nach 1980 Geborenen angehören und sich somit in einem vergleichbaren Lebensalter befinden wie die Pionier*innen der Konkreten Kunst Mitte der 1920er-Jahre, darunter etwa Sophie TaeuberArp (*1889), Jean Arp (*1886) und Theo van Doesburg (*1883). Um ihr Verständnis und ihr Verhältnis zur Konkreten Kunst auszuloten, haben wir die jungen Kunstschaffenden mit unseren Fragen in Form eines Fragebogens konfrontiert, den sie im Vorfeld der Ausstellung beantwortet haben. Enthalten waren zehn Fragen, etwa: „Verstehe ich mich selbst als Vertreter*in der Konkreten Kunst?“, „Haben die Anfänge der Konkreten Kunst einen direkten Einfluss auf meine eigene künstlerische Arbeit?“, „Und? Braucht es den Begriff Konkrete Kunst (überhaupt) noch?“ Die Antworten ergaben ein vielstimmiges Meinungsbild, auch mit dem Ergebnis, dass keine(r) der Befragten sich ohne Einschränkungen als konkret arbeitend beschreibt. Alle aber setzen sich in irgendeiner Form mit Prinzipien der Konkreten Kunst auseinander, reiben sich an ihnen, erweitern sie, grenzen sich ab. Dies wird nicht nur in ihren schriftlichen Äußerungen deutlich, sondern auch in ihren Werken, in denen sie etwa konstruktive Strenge walten lassen, nur um sie gleich wieder lustvoll aufzubrechen, in denen sie den Ausstellungsraum selbst zum Gegenstand des Kunstwerks machen, Tischtennisplatten als Malfläche verwenden, Gemälde ins Dreidimensionale überführen, Flächen mit Kugelschreibertinte füllen etc. etc. Allen gemeinsam ist dabei eine nicht dem Gegenständlichen oder einer vorrangig inhaltlichen Botschaft verpflichtete Formensprache – und eine große Freiheit im Umgang mit Material, Raum und 5

EINFÜHRUNG UND VORWORT

summer of 2024. The two parts of the exhibition are bracketed by this catalogue. In his text Mathias Listl reviewed the beginnings of Concrete Art in the 1920s and their consequences. Theres Rohde, by contrast, examined the attitudes of artists today by evaluating their responses to our questionnaire. Finally, Mariana Aravidou dedicated herself to the artists’ approaches as such, categorizing them and relating them to Concrete Art. We would like to thank sincerely all of the authors here as well as Harald Pridgar, who was responsible for the innovative graphic design of the catalogue. At the Deutscher Kunstverlag, Luzie Diekmann enthusiastically managed the project; we also thank the copyeditors Michael Konze and Aaron Bogart and the translator Steven Lindberg. Mathias Listl deserves very special thanks for providing the initial idea for the project, being the driving force behind it, and judiciously curating the exhibition in Ingolstadt. Mariana Aravidou took the curatorial reins for Würzburg, for which we thank her sincerely as well! We also thank the museum teams at both institutions: without the committed work in various areas—overseeing loans and organizing transportation, publicity, education and outreach, building technology, and restoration, but also security and ticket sales—this exhibition would not have been possible. For financial support, we in Würzburg are especially grateful to the Freundeskreis Kulturspeicher e. V. and the Unterfränkische Kulturstiftung.

Our biggest thank-you, however, goes to the artists. All twenty-four of them contributed actively to the project, proposing works and in some cases making works especially for the exhibition. Not least, they accepted the arduous task of responding to the questionnaire to offer us informative insights into their specific artistic attitudes. Both in the questionnaire and in their works, they offer no simple answers to the question asked in the title of this foreword: “One Hundred Years of Concrete Art—and Still Topical?” What we—and, we hope our visitors and readers of the catalogue—will take away from it is valuable inspiration to reflect on the essence of Concrete Art in the present day.

Henrike Holsing

Theres Rohde Acting Director of the Museum Director of the Museum im Kulturspeicher in Würzburg für Konkrete Kunst in Ingolstadt

6 INTRODUCTION AND FOREWORD

Werkbegriff, die vielleicht den Kern der Konkreten Kunst ausmacht. In diesem Sinne, so denken wir, könnte die Idee der Konkreten Kunst auch in weiteren 100 Jahren noch Relevanz haben.

Dieses Projekt ist die erste Kooperation von MKK und MiK – nicht im Sinne einer Wanderausstellung, sondern einer Ausstellung an zwei Orten: 12 der ausgewählten künstlerischen Positionen werden in Ingolstadt gezeigt, 12 in Würzburg. So sind unsere Besucher*innen eingeladen, im Laufe des Frühjahrs und Sommers 2024 beide Häuser zu besuchen. Die Klammer der Ausstellungsteile bildet dieser Katalog, in dem die Künstler*innen beider Ausstellungsorte mit kurzen Texten und Werkbeispielen vorgestellt werden. Mathias Listl lässt in seinem Text noch einmal die Anfänge der Konkreten Kunst in den 1920er-Jahren und ihre Folgen Revue passieren, Theres Rohde untersucht dagegen die heutige Haltung der Künstler*innen, indem sie die Antworten auf unseren Fragebogen auswertet. Mariana Aravidou schließlich widmet sich den künstlerischen Ansätzen selbst, ihrer Einordnung und ihrem Bezug zur Konkreten Kunst. Allen Autor*innen danken wir an dieser Stelle sehr herzlich, ebenso wie Harald Pridgar, der für die innovative grafische Gestaltung des Kataloges verantwortlich zeichnet. Im Deutschen Kunstverlag hat Luzie Diekmann das Projekt engagiert betreut, ihr danken wir ebenso wie den Lektoren Michael Konze und Aaron Bogart sowie dem Übersetzer Steven Lindberg.

Ein ganz besonderer Dank gilt Mathias Listl, der die initiale Idee für das Projekt hatte, es als treibende Kraft vorangebracht und die Ausstellung in Ingolstadt umsichtig kuratiert hat. Für Würzburg hat Mariana Aravidou als Kuratorin die Fäden in die Hand genommen, dafür sei ihr ebenfalls sehr herzlich gedankt! Unser Dank gilt außerdem den Museumsteams in beiden Häusern: Ohne die engagierte Mitarbeit in den verschiedenen Bereichen – der Verwaltung mit der Betreuung des Leihverkehrs und der Transportorganisation, der Öffentlichkeitsarbeit, Kunstvermittlung, Haustechnik und Restaurierung, aber auch in der Aufsicht und an der Kasse – hätte die Ausstellung nicht realisiert werden können. Für finanzielle Förderung danken wir in Würzburg besonders dem Freundeskreis Kulturspeicher e.V. und der Unterfränkischen Kulturstiftung.

Unser größter Dank jedoch gilt den Künstlerinnen und Künstlern. Alle 24 haben sich engagiert in das Projekt eingebracht, haben Werkvorschläge gemacht und teilweise Werke extra für die Ausstellung geschaffen. Nicht zuletzt haben sie sich der mühsamen Beantwortung des Fragebogens gestellt und uns so aufschlussreiche Einblicke in ihre jeweilige künstlerische Haltung gewährt. Sowohl im Fragebogen als auch durch ihre künstlerischen Werke geben sie uns auf die im Titel dieses Vorworts formulierte Frage „100 Jahre Konkrete Kunst – und noch aktuell?“ zwar keine einfachen Antworten; was wir – und hoffentlich auch unsere Besucher*innen und Leser*innen des Katalogs –jedoch mitnehmen, sind wertvolle Impulse für das Nachdenken über das Wesen der Konkreten Kunst in der Gegenwart.

Henrike Holsing

Theres Rohde Stellvertretende Direktorin Museum Direktorin Museum im Kulturspeicher Würzburg für Konkrete Kunst Ingolstadt

7 EINFÜHRUNG UND VORWORT

Do I see myself as a representative of Concrete Art?

8

Yes 1

No 13

Unclear 10

UNKLAR

Verstehe ich mich selbst als Vertreter*in der Konkreten Kunst?

13

10

According to the German dictionary Duden, “Begriff ” (concept) means the “entirety of essential features in a unit of thought.”1 As the “mental, abstract content of something,” it thus represents a summary of the essential qualities of a thing, circumstances, or person condensed as accurately as possible in a short linguistic form.

In that spirit, the coinage “Concrete Art” and its introduction into art theory by Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931) ① was in turn the extremely difficult attempt to summarize a current that had been forming in fine art since the beginning of the twentieth century in different centers with distinct intentions, that is to say, to put it in a short linguistic form that was universally understandable. And at the same time that was supposed to make it as easy as possible to apply it to other language regions. In addition to the fact that the art movement concerned was not at first glance clearly outlined or easy to grasp, the neologism of the Dutch painter, architect, and art theorist had to struggle with another central difficulty: it stood—and stands—in competition with other existing and subsequent labels and -isms such as De Stijl, Suprematism, Neoplasticism, Constructivism, and Minimalism, which in some cases overlap vaguely in Doesburg’s names for the movements or are nearly identical to them without referring to precisely the same thing.

If one believes Theo van Doesburg himself, the birth of the concept Concrete Art celebrates its one hundredth anniversary in 2024. As far as we know, he first used the term for his own works in 1924, before he introduced it to art history by using it in the title of a manifesto published in 1930.2 Both the adjective “concrete” and the noun “concretization” turn up earlier in his writings to describe trends that were then still unnamed or that had been given other labels, and used by other artists as well, above all Hans (Jean) Arp, 3 Max Burchartz, 4 and representatives of the Russian avant-garde, sometimes in reference to their own works. 5 In the case of Van Doesburg, the use of the word “concrete” in connection with his own view of art and that of his colleagues in De Stijl circles can be traced back at least to 1916, according to Evert van Straaten. 6 As already mentioned, in 1924 he first applied the term to his own works of that period and also used it in his manifesto on Elementarism in 1926–27.7 Finally, in 1930 he introduced it officially into art theory in his manifesto that defined the dividing line between Abstract and Concrete art in a way that was at once sharp and blurry. For even if Van Doesburg’s discussion clearly outlines generally speaking the difference between the imitation of nature and a purely intellectual form, it also offers enough latitude in detail for different interpretations and exegeses. The text ② reads in English translation:

We declare:

1. Art is universal.

2. The work of art must be entirely conceived and formed by the mind before its execution. It must receive nothing from nature’s given forms, or from sensuality, or sentimentality.

3. The picture must be entirely constructed from purely plastic elements, that is, planes and colors. A pictorial element has no other meaning than “itself” and thus the picture has no other meaning than “itself.”

4. The construction of the picture, as well as its elements, must be simple and visually controllable.

5. Technique must be mechanical, that is, exact, anti-impressionistic.

6. Effort for absolute clarity. 8

As Tobias Hoffmann has noted elsewhere, it must be said that the concept would surely not have been long-lived if artists in Zurich around Max Bill and Richard Paul Lohse had not adopted and refined its theoretical foundation, and used it in the titles of their own exhibitions and texts, not only keeping it alive but taking it further out into the world.9 For already in March 1931, just one year after the official introduction of the concept, Van Doesburg died of heart disease in Davos. And the Concrete Art artists’ group he founded and its eponymous journal, only one issue of which was published, were thus already history.

CONCRETE ART

12

Laut Duden versteht man unter einem Begriff die „Gesamtheit wesentlicher Merkmale in einer gedanklichen Einheit“.1 Als „geistiger, abstrakter Gehalt von etwas“ stellt er also eine möglichst treffende Zusammenfassung der wesentlichen Eigenschaften der jeweils sprachlich zu einer Kurzform zu verdichtenden Sache, Gegebenheit oder Person dar.

In diesem Sinne war die Wortfindung Konkrete Kunst und deren Einführung in die Kunsttheorie durch Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931) ① wiederum der äußerst schwierige Versuch, eine sich seit Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts in verschiedenen Zentren und mit unterschiedlichen Intentionen formierende Strömung innerhalb der Bildenden Kunst auf den Punkt, sprich in eine allgemein verständliche sprachliche Kurzform zu bringen. Und diese sollte sich gleichzeitig auch möglichst leicht auf

① Werner Graeff, Theo van Doesburg (eigentlich Christian Emil Marie Küpper) in der Ciné-Dancing der Aubette (Straßburg) während der Einrichtung, 1927, Gelatinesilberabzug , 11,5 x 8,5 cm / Werner Graeff, Theo van Doesburg (born Christian Emil Marie Küpper) in the cine-dancing of the Aubette (Strasbourg) during the installation, 1927, Paper, gelatin silver print, blackand-white photograph, 11.5 × 8.5 cm

andere Sprachräume übertragen lassen. Neben der Tatsache, dass sich die betreffende Kunstrichtung nur auf einen ersten Blick als klar umrissen und leicht zu fassen gibt, hatte die Wortneuschöpfung des niederländischen Malers, Architekten und Kunsttheoretikers noch mit einer weiteren zentralen Schwierigkeit zu kämpfen: Sie stand – und steht – in Konkurrenz mit anderen bereits existierenden wie nach ihr entstehenden Etiketten und Ismen wie etwa De Stijl, Suprematismus, Neoplastizismus, Konstruktivismus oder Minimalismus, die sich mit van Doesburgs Richtungsnamen teilweise diffus überlappen oder mit diesem nahezu deckungsgleich sind, ohne immer auch auf das genau Gleiche zu verweisen.

Schenkt man Theo van Doesburg selbst Glauben, so jährt sich 2024 die Geburtsstunde des Begriffs Konkrete Kunst zum 100. Mal. Soweit wir wissen, verwendete er diesen 1924 erstmals für eigene Arbeiten, ehe er ihn 1930 als Titel seines gleichnamigen Manifests auch auf publizistischem Wege in die Kunsttheorie einführte.2 Sowohl das Adjektiv „konkret“ wie auch das Substantiv „Konkretisierung“ tauchten bereits zuvor in seinen Schriften zur Beschreibung dieser damals noch namenlosen beziehungsweise auch mit anderweitigen Etiketten versehenen Tendenzen auf, und auch von anderen Künstler*innen, vor allem von Hans (Jean) Arp 3 , Max 13

KONKRETE KUNST MATHIAS LISTL

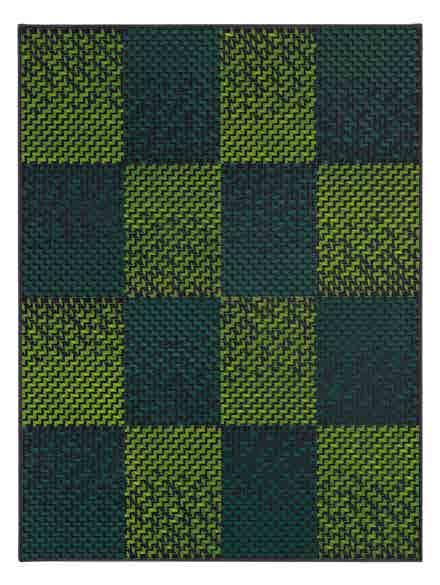

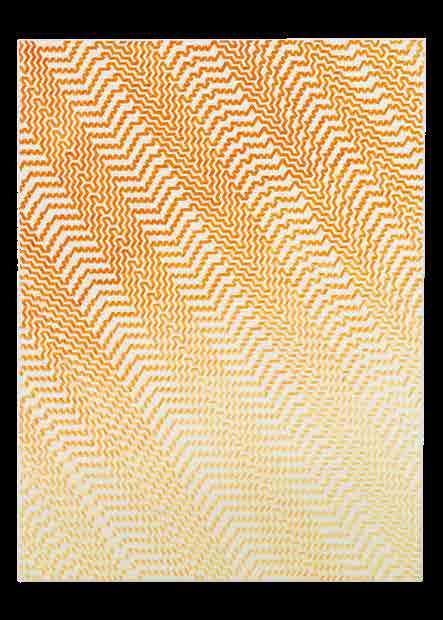

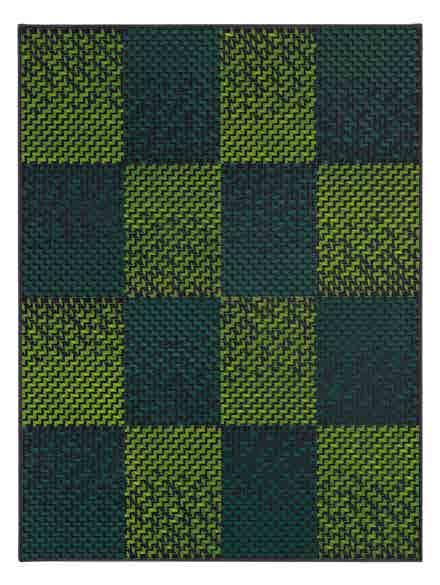

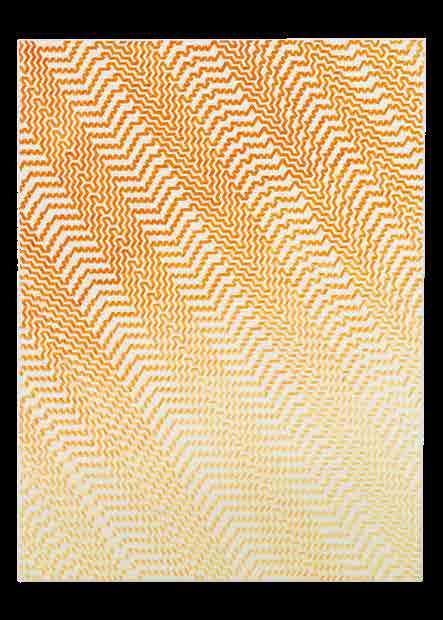

Toulu Hassani

*1984

*1984

Wie für viele klassische Vertreter*innen der Konkreten Kunst bilden oftmals auch für Toulu Hassani Ordnungssysteme aller Art eine entscheidende Grundlage ihrer Grafiken, Gemälde und skulpturalen Bildobjekte. So kombiniert die Künstlerin immer wieder die grafische Darstellung mathematischer oder astrophysikalischer Prinzipien mit kleinteilig angelegten Rastern. Mäanderartig abgetreppt und scheinbar makellos füllen diese Ornamente mitunter ganzflächig ihre Werke aus und ziehen den Blick unwillkürlich tiefer in den Bildraum. Abweichungen von der Norm, die den so entstandenen streng geometrischen Mustern bewusst eingeschrieben sind, erkennt man dagegen meist erst auf den zweiten, genaueren Blick. Risse, Krümmungen, Verzerrungen, Knicke und auch subtil eingesetzte Farbverläufe und Verschiebungen in der nur scheinbar perfekten Struktur sorgen nicht nur für visuelle Irritationen. Diese Unregelmäßigkeiten verleihen Hassanis meist aufwendig in Öl auf Leinwand ausgeführten Arbeiten gleichzeitig auch ihren ganz eigenen, individuellen Charakter, in dem René Zechlin eine Analogie zu einem handgeknüpften Teppich erkennt1, bilden doch erst dessen Abweichungen und Unregelmäßigkeiten – seien es Web- und Knüpffehler oder Variationen in der Stärke und Farbigkeit des Fadens – die spezielle Besonderheit des jeweiligen Einzelstücks.

In anderen malerischen Werkgruppen richtet die Künstlerin ihren Fokus wiederum auf die Materialität und den Objektcharakter von Gemälden, in dem sie etwa den ansonsten verdeckten Bildträger zum eigentlichen Darstellungsmotiv erhebt. Die Suche nach anderen Verschränkungen von zweidimensionaler Malerei und dreidimensionaler Plastik bildet eine weitere Grundkonstante in Hassanis Œuvre.

1. René Zechlin, „Verdichtungen eines Mediums“, in: Ausst.-Kat. Ludwigshafen a. R., René Zechlin, Wilhelm-Hack-Museum (Hrsg.), Toulu Hassani. Iteration, Ludwigshafen a. R. 2017, S. 22–25, hier S. 22.

As they do for many classical exponents of Concrete Art, ordering systems of all kinds often represent a crucial basis for Toulu Hassani’s prints, paintings, and sculptural objects. The artist repeatedly combines graphic representation of mathematical or astrophysical principles with intricately laid out grids. Meanderingly graduated and seemingly flawless, these ornaments sometimes fill her works entirely and draw one’s gaze involuntarily deeper into the pictorial space. Deviations from the norm that are deliberately inscribed into the strictly geometrical patterns that result are usually only spotted on a second, closer inspection. Tears, curves, distortions, bends, and subtly employed courses of colors and shifts in the only seemingly perfect structure provide not only visual vexations. At the same time, these irregularities lend Hassani’s works, which are usually elaborately executed in oil on canvas, their own individual character, in which René Zechlin sees an analogy to a hand-knotted rug1 in that it is these deviations and irregularities—whether weaving and knotting mistakes or variations in the thickness and color of the thread—each individual piece is special.

In other groups of paintings, the artist focuses in turn on the materiality of paintings and their character as objects by elevating the otherwise covered support the real motif of the depiction. The search for other interlockings of two-dimensional painting and three-dimensional sculpture represents a further fundamental constant in Hassani’s oeuvre.

①

Ohne Titel, 2021

Feinminenstift, Ölfarbe auf Leinwand, 60 × 47 cm

Sammlung Stadler, München

②

Ohne Titel, 2023

Feinminenstift, Acryl- und Ölfarbe auf Leinwand, 40 × 30 cm

Privatbesitz

③

Ohne Titel, 2023

Feinminenstift, Acryl- und Ölfarbe auf Leinwand, 40 × 30 cm

Sammlung Stadler, München

Untitled, 2021

Fine-tip mechanical pencil, oil paint on canvas, 60 × 47 cm

Stadler Collection, Munich

Untitled, 2023

Fine-tip mechanical pencil, acrylic and oil paint on canvas, 40 × 30 cm

Private collection

Untitled, 2023

Fine-tip mechanical pencil, acrylic and oil paint on canvas, 40 × 30 cm

Stadler Collection, Munich

in Ahwaz, Iran

und arbeitet in Hannover

lebt

in Ahwaz,

in Hanover

Iran lives and works

50

1. René Zechlin, “Condensations of Medium,” in Toulu Hassani: Iteration, ed. René Zechlin, exh. cat. Wilhelm-Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen am Rhein (Berlin: Revolver, 2017), pp. 26–29, esp. p. 26.

51 ①

②

③ 53

Fabian Gatermann

Von jeher war es ein zentrales Anliegen vieler konkret und konstruktiv arbeitender Künstler*innen, physikalische Phänomene sowie geistige und psychische Energien in ihren Werken erfahrbar zu machen – eine Sensibilität und ein Bewusstsein für das zu schaffen, was unter der Oberfläche ist. Dazu bekennt sich auch Fabian Gatermann, wenn er auf die Frage, ob er sich als Vertreter der Konkreten Kunst verstehe, auf etwas „Universales“ verweist, das „die Physikalität oder die Welt hinter den Dingen als schöpferisches Prinzip oder Transzendenz sichtbar“ mache. Dafür arbeitet er nicht mit traditionellen Werkstoffen und Bildträgern, sondern bedient sich unterschiedlichster Mittel und Materialien: Blumen – Flowers – erwachsen aus auf Papier übertragenen computergenerierten fraktalen Sequenzen, und in den Cyanotypien der Serie LUX/Photon werden an Vögel erinnernde Formen von großer Leichtigkeit und Schönheit durch die Einwirkung des Sonnenlichts auf dem Fotopapier erzeugt.

In anderen Arbeiten dominieren konstruktiv-geometrische Formen; so in den in der Ausstellung gezeigten, ebenfalls das physikalische Phänomen Licht und seine Spektralfarbigkeit thematisierenden Light Edges, in denen Wandskulpturen aus Plexiglas sich durch das Licht ins Malerische aufzulösen scheinen: Körperhaftes wird transparent und zu reiner Farbe, die über die Objektgrenzen hinauswirkt und sich je nach Beleuchtung und Betrachterstandpunkt verändert. Zeit und Bewegung werden so Teil des Werks. Interaktiv sind auch die Werke, die Gatermann mit Mood Poem betitelt hat: In klassischem Gemäldeformat sind hier kleine quadratische Farbflächen in strenger Geometrie angeordnet. Diese Flächen werden mit einer dahinter liegenden LED-Technik unterschiedlich beleuchtet und verändern – durch eine App vom Betrachtenden steuerbar – fließend ihre Farbe. Dem Zauber der sich wandelnden Lichtstimmung und der Schönheit der reinen Farbigkeit kann sich der Betrachtende kaum entziehen. Der Mensch bleibt, wie Gatermann selbst betont, die „Referenzgröße“ – seine Wahrnehmung, seine Sensibilität, seine Emotion. (HH)

It has long been a central concern of many artists working in a Concrete Art and Constructivist manner to make it possible to experience physical phenomena and mental and psychological energies in their works— creating a sensitivity to and awareness of what is under the surface. Fabian Gatermann professes that as well when he responds to the question whether he considers himself an exponent of Concrete Art by referring to something “universal” that “makes the physicality or world behind things visible as a creative principle or transcendence”. To do so, he works not with traditional materials and supports, but rather makes use of highly diverse means and materials: in his Flowers, flowers grow out of computer-generated fractal sequences transferred to paper, and in the cyanotypes of the LUX/Photon series forms of great lightness and beauty that recall birds are produced by the effect of sunlight on photographic paper.

Other works are dominated by constructive-geometric forms, such as his Light Edges, included in the exhibition, which also address the physical phenomenon of light and its spectral colors, and in which Plexiglas wall sculptures seem to dissolve light into the painterly: the corporeal becomes transparent and pure color that has an effect beyond the boundaries of the object and changes according to the lighting and the viewer’s standpoint. Time and movement thus become part of the work. The works for which Gatermann employs the title Mood Poem are also interactive: in the classic format of paintings, small squares of color are arranged in a strict geometry. These squares are lit variously by LEDs behind them and change their color fluidly—which can be controlled by the viewer with an app. The viewer can scarcely resist the transforming mood of the light and the beauty of pure color. As Gatermann himself emphasizes, human beings remain his “point of reference”: their perception, their sensitivity, their emotion. (HH)

① Light Edge, 2020

Dichroitische Beschichtung auf Plexiglas, 15 × 15 × 3,5 cm, Installationsansicht Artionale Nazareth Projekt – Kirche anders als gewohnt!, Nazarethkirche München Bogenhausen, 2019

②/③ Mood Poem, 2018

Einscheibensicherheitsglas, Tinte, APP, Touchpad, rgbWW LED, 106 × 73,5 cm

Dichroitic coating on plexiglas, 15 × 15 × 3,5 cm, View of installation Artionale Nazareth Projekt – Kirche anders als gewohnt!, Nazarethkirche München-Bogenhausen, 2019 Mood Poem, 2018

ESG glass, ink, APP, Touchpad, rgbWW LED, 106 × 73,5 cm

*1984 in München lebt und arbeitet in München *1984 in Munich lives and works in Munich

Light Edge, 2020

106

107 ①

②

109 ③

Color, form, or line? Which fundamental form of artistic expression from Concrete Art is most important to me?

Zusammenspiel aus allen dreien: Interplay of all three:

You can see it coming: here, too, hardly anyone wanted to be pinned down. Rather than simple information, they offered explanatory texts; some named several; and really all of them found everything important …

IT’S COMPLICATED!

7

Form 13 6 160

Farbe, Form oder Linie?

Welches grundlegende künstlerische Ausdrucksmittel der Konkreten Kunst ist mir am wichtigsten?

Farbe Color 10

Ausbrechende Antwort: der Punkt, der Zwischenraum, der Körper, der Raum, das Material, die Zeit Breaking out answer: the point, the space in between, the body, the space, the material, the time

Man ahnt es schon – auch hier wollte sich kaum jemand festlegen. Statt simplen Angaben gab es erklärende Texte, manche setzten Mehrfachnennungen, und eigentlich fanden alle alles wichtig …

ES IST KOMPLIZIERT! THERES ROHDE

Linie Line

12

161