Beyond “Discovery”: Uncovering the Motives and Consequences of Columbus’ Voyages

Cristina Benedetti, Ph.D., Joshua Lapp

Cristina Benedetti, Ph.D., Joshua Lapp

Funded by the Spanish Crown, Christopher Columbus sought a westerly route to Asia, believing such a route would bypass other European powers and offer quicker, more profitable trade with the East. He was also motivated by personal gain, hoping to find gold and other riches and establish himself as a successful explorer and governor. From his first voyage, Columbus planned to establish a colony on behalf of Spain. He mistakenly believed he had reached Asia when he landed in the Caribbean, setting in motion a disastrous series of interactions with the Taíno people inhabiting the region. Columbus thought the Taíno viewed him as a god and would therefore be easily conquered. He subsequently captured and forced more than 1,500 Taíno into physical labor, marking the beginning of European enslavement in the Caribbean.

The arrival of the Spanish brought violence, disease, and enslavement to the Taíno people. Despite their ongoing resistance to colonization, the Taíno population dwindled. Upon reports of his brutality and mismanagement of the colony, the Spanish Crown ultimately tried Columbus and stripped him and his heirs of future governorship rights in the Caribbean. At the time of Columbus’ death in 1506, he had fallen out of favor with the Spanish Crown. His descendants fought for the reinstatement of governorship rights over the next several decades. Although they never regained the hereditary title of Governor General of the Indies, in 1563 Columbus’ heirs were granted lesser titles in Jamaica and Central America, land rights on La Española, and annual payments from the Spanish Crown.

This paper is intended to build a foundation of historical knowledge for the Reimagining Columbus1 project that is grounded in facts and ongoing scholarly research.2 It discusses the historical context that led to the Genoa, Italy–born Christopher Columbus’ voyages, including the international race to find new trade routes, advancements in navigation, and the Spanish Reconquista. It further covers his motivations, the perspectives of those he interacted with— particularly the native inhabitants of the Caribbean, Central, and South America3 and, to the extent possible, the impact of his actions. The goal is to understand Columbus’ attitudes and actions within the context of his time, and to illuminate how they connect to present-day American life.

Prolonged interactions between the American continents and the rest of the world shaped American society as it exists today—beginning when a group of Indigenous Taíno people first sighted a small ship drifting towards their island in October 1492. When Columbus landed among the Taíno, he believed he discovered, on behalf of Spain, a new trade route to India, China, and Japan that would allow Spain to usurp Portugal’s dominance in overseas trade.

Instead, he had cleverly utilized wind patterns to establish a new route of exchange between continents and peoples that had never been connected before.4 By opening this route, Columbus unleashed a series of consequences that profoundly affected the course of global economics, politics, and human relations in the centuries to come. Sustained contact between the peoples of the Atlantic world may have been inevitable in the long term, but the earliest decisions by Columbus, his family members, the Spanish Crown, and the colonial governors who immediately followed Columbus set the course for the European conquest in the Americas, which was only made possible through the subjugation, genocide, and land theft of the Indigenous people of the western hemisphere.

Over centuries, Christopher Columbus and his accomplishments have become mythologized in ways that erase the complexities of what he wrought in the Americas. Newly uncovered research about the horrors inflicted on the Taíno people by Columbus and his men suggests a need to reexamine the man’s legacy with a more nuanced, modern lens.

1 Reimagining Columbus is a 2-year initiative to engage the Columbus, Ohio community on themes of inclusion, belonging, and cultural heritage; to develop a recommendation for the future disposition of the city's Christopher Columbus statue; and to create a plan to install new art at City Hall. This city-led, community-driven project is funded by the Mellon Foundation’s Monuments Project, which is aimed at transforming the nation’s commemorative landscape to ensure our collective histories are more completely and accurately represented.

2 Quotes from primary source documents, translated into English by various authors, are included throughout this text. While these sources are essential sources of historical information, they contain their own biases, exaggerations, and omissions. When separate accounts of similar events exist, they often contain contradictions. In addition, the historic record of early colonization of the Americas reflects the European perspective, since most available accounts of European and Indigenous American lives and encounters yield from European sources.

3 The terms Americas, America, and American are used throughout this paper to refer to the continents of the Western Hemisphere. However, the term was not used in Columbus' lifetime; it was propagated by map makers in the 1500s taking inspiration from the name of Amerigo Vespucci, a navigator who conducted exploratory voyages for Spain and Portugal during the time of Columbus.

4 U.S. Naval Institute. “The Christopher Columbus Navigation Lesson Nobody Taught Us.” Accessed October 18, 2023.

The story of humans in the Americas begins with the movement of people across the Bering Strait, which separates Russia and Alaska today. In the distant past, sea levels were much lower than they are now. As a result, a land bridge there supported the migration of people and animals from northern Asia to the Americas. Modern archaeological and DNA evidence dates the movement of people and their dispersion throughout the two continents to at least 14,000 years ago, with some evidence suggesting an even earlier human presence.5

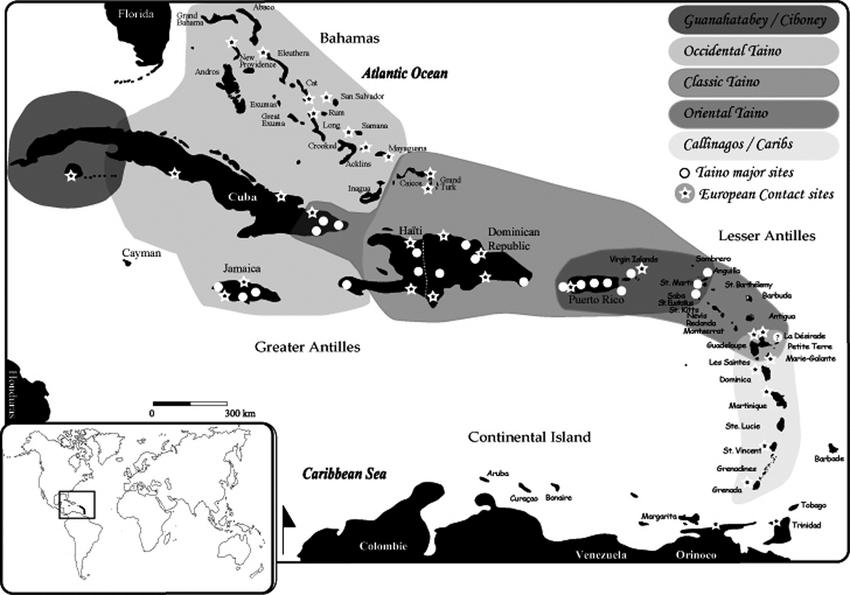

The Islands of the Caribbean were among the last of the lands in the Americas to be

populated. Migration to the islands occurred in successive waves beginning around 6000 BCE. Initial migration occurred from Central America into Cuba and Hispaniola; 2,000 years later, migrants originating in South America began to populate the Lesser Antilles and Puerto Rico. Over thousands of years, additional groups migrated to the islands and either integrated with or displaced the existing inhabitants. Later migrants were part of what is known as the Arawak language group, a name sometimes used to describe the native peoples of both the Caribbean and northern South America, since they shared a common root language.

5 Pringle, Heather. “What Happens When an Archaeologist Challenges Mainstream Scientific Thinking?” Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed April 7, 2024.

The Taíno culture began to develop and disseminate throughout La Española, Cuba, Jamaica, and the Bahamas from about 600 to 1200 CE. In the few hundred years directly before Columbus’ initial voyage, the Taíno developed a complex society that included kings or chieftains called caciques; large towns and ceremonial plazas; sophisticated artwork, religion, and cosmology; and large sea-faring canoes. Their beliefs were passed down through an oral tradition that revolved around the Areito, a ritual ceremony where individuals drank, danced, and repeated the stories of their culture, including their creation myth and their first cacique’s canoe trip, as well as other mythical and historical events.6

The Lesser Antilles were populated by a group most commonly called the Caribe in the historic record. The name Caribe originated with the Taíno, who often referred to them this way to Europeans; however the Caribe referred to themselves as the Kalinago, and Kalinago is the preferred term for the people, language, and territory in the present day. The Kalinago were a population of mixed origin. All historic accounts—including those of their own oral traditions—appear to point to the same general story. Male warriors originating from northern South America traveled to the alreadypopulated Lesser Antillean islands, killing the men and enslaving the Arawak-speaking women there. These warriors ultimately adopted the Arawak language of their enslaved wives while retaining their militaristic culture. Though their society was less organized than

the Taíno, they still had a well-developed mythology and ritualistic practice. Akin to the Areito, the Kalinago had a celebratory ceremony known as Caouynage, which could be called for a variety of reasons—from the birth of a child to the launch of a new canoe.

Culturally, the Kalinago were differentiated from the Taíno in both their militarism and their reported practice of ritualistic cannibalism. Within the context of Kalinago society, this was a tradition thought to be practiced against captured enemies who were of age, after an ornate ceremony. The Kalinago maintained a militaristic culture that included yearly war and raiding campaigns against the Taíno and, later, colonial settlements, during which they would capture and enslave the women and children.

There is no conclusive archeological evidence to support claims of Kalinago cannibalism. Contemporary scholars note that by casting the Caribe/Kalinago as cannibals, the Spanish created a justification for enslaving them. A study in January 2020 sought to revive this theory of the historic Kalinago as cannibalistic, but it was rebutted by a group of scholars who found the study’s methods faulty to a fatal degree.7 Regardless, the Taíno’s fear of the Kalinago is evident from their earliest interactions with the Columbus expedition. The Taíno first described the Caribe/Kalinago’s cannibalism to Europeans, who would inevitably use this purported practice as an excuse to enslave anyone deemed by them a ‘Caribe,’ whether accurate or not.

6 The current understanding of Taíno culture is influenced by accounts of individuals involved in early colonial efforts, most importantly Ramón Pané, who learned some of the native language on Hispaniola and transcribed various accounts of Taíno myths and customs. While Pané’s account is extensive and thorough, his contemporary Bartolomé de Las Casas and current scholars caution against taking his account as pure fact (Deagan & Cruxent p. 39)

7 Christie, Tim. "Researchers denounce revived theory of Caribbean cannibalism." Accessed March 28, 2024.

Humans have navigated the Mediterranean Sea since at least 6000 BCE, as evidenced by the spread of common pottery practices along sea routes.8 For millennia, the Mediterranean Sea served as a superhighway, connecting the cultures of Western Asia, Northern Africa, and Southern Europe through trade, political alliances, and conquest.9 City-states contemporaneous with Columbus—Rome, Florence, Venice, Genoa, Seville, Lisbon, Constantinople, Alexandria, and Tunis, for example—were the networked epicenters of economic, political, and cultural activity in the Mediterranean before the existence of modern nation-states.10 Additionally, since the first century BCE, cultures of both the Mediterranean and Central and East Asia were in contact through what came to be called the Silk Road, a network of trade routes that began with the Han Dynasty’s expansion into Central Asia in 114 BCE.11

By the time Venetian merchant Marco Polo traveled to Central and East Asia in the late 13th century, these trade routes had been established for more than a millennium. People from the Mediterranean and Northern Europe, including Polo’s own family members,

8 “Ancient Maritime History.” Wikipedia. Accessed April 1, 2024.

9 “History of the Mediterranean Region.” Wikipedia. Accessed January 26, 2024.

had been traveling these trade routes for centuries;12 Polo’s unique contribution was his prolific writings about these journeys. He provided extensive and captivating accounts of the cultures, customs, and geographies of the places he traveled, worked, and lived for more than 20 years.13

Columbus carried a heavily annotated copy of Polo’s book, The Travels of Marco Polo, on his own journeys.14 He thought he would encounter the Mongol Empire and Kubilai Khan’s court described vividly by Polo, as evidenced by frequent references in his log and letters to places that Polo described.15 When the Caribbean societies he encountered did not match his expectations, he continued searching for the Mongol Empire throughout his subsequent journeys.

Polo’s father Niccolò and his uncle Maffeo were Venetian merchants. Before Marco Polo’s birth in 1254, Niccolò and Maffeo traveled from Constantinople to Crimea, and then some additional 5,000 miles east to the court of Chinggis (Genghis) Khan’s grandson, Kubilai (Kublai) Khan, in what was likely in the Mongol capital of Khanbaliq, the site of modern-day

10 “The Mediterranean World — 1492: An Ongoing Voyage | Exhibitions — Library of Congress.” Webpage, August 13, 1992.

11 “Silk Road.” Wikipedia. Accessed April 6, 2024.

12 In his account, Polo mentions mercantile quarters for Germans, Lombards, and French in Cembalú (Thubron, p. xi).

13 Robin Brown (2008). "Marco Polo: Journey to the End of the Earth." Sutton.

Beijing. In 1260, Pope Alexander IV issued a papal bull (an official papal letter that can enact religious laws) condemning the Mongol Empire and portraying Mongols as lawless, violent, and sinful. In it he describes, “a terrible trumpet of dire forewarning, which, corroborated by the evidence of events, proclaims with unmistakable sound the wars of universal destruction wherewith the scourge of Heaven’s wrath in the hands of the inhuman Tartars, erupting as it were from the secret confines of Hell, oppresses and crushes the earth.”16

Niccolò and Maffeo were thus surprised to find Kubilai Khan to be courteous, welcoming, and curious about Italy and Christianity.

Kubilai Khan decided that Niccolò and Maffeo Polo would become his ambassadors to the Mediterranean—and, in particular, to the Pope Kubilai Khan dispatched the Polo brothers to the Mediterranean with a message for the Pope and instructions to send Christian scholars and holy relics from Jerusalem to the Mongol Empire. Niccoló and Maffeo made it back to Venice in 1269 after 16 years away, when Marco Polo was 15. Two years later, the Polo brothers brought Marco with them on their journey back to Khanbaliq. The journey took three and a half years, and Marco stayed in China for another 16 or 17 years. During that time, he claimed to have served as an ambassador and confidant of Kubilai Khan, and in his chronicle he provided a portrait of the Kubilai Khan’s world with great detail, intimacy,

and reverence. Polo was drawn to the luxuries of the court, and described in great detail the feasts, ceremonies, costumes, marble palaces, imperial pavilions, hunting, and falconry.17

Marco Polo’s journey only came to be recorded through his unfortunate capture by the Republic of Genoa. Three years after returning to Venice from China, he purchased his own war ship and commanded it against Genoa, Venice’s longstanding sea rival, in the 1298 Battle of Curzola. Venice was defeated, and Polo was held in a palace-prison in Genoa for one year. There, he told his story to Rustichello, a fellow prisoner, who transcribed his story in French. Within a few years, the story had been translated into Latin and vernacular Italian, and began circulating. The world that Polo so vividly described vanished shortly after his first visit to the Mongol Empire: Kubilai Khan died in 1294 and, soon after, the dynasty he founded crumbled. By the time Polo’s story reached Christopher Columbus in the late 1400s—more than 100 years after it had been recorded—central Asia had broken into warring states, and China’s Ming Dynasty had erected the Great Wall against the Silk Road.18

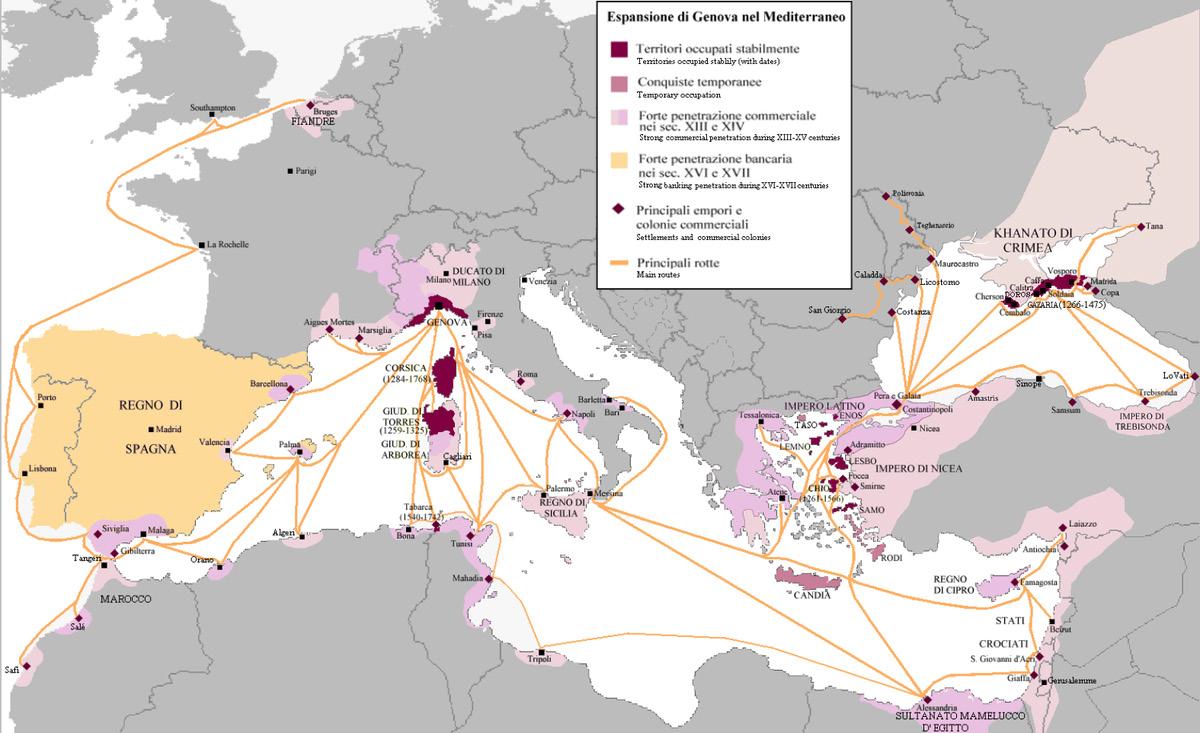

As referenced in Polo’s life story, both Venice and Genoa competed for trade in the Mediterranean and beyond throughout the Middle Ages. A mountainous region with little agricultural land, Genoa thrived by focusing on trade, leveraging its strategic

14 Thubron, p. xvii.

15 Like many historic accounts, Polo's work contains exaggerations, misunderstandings, and outright lies. In his lifetime, Polo's accounts were understood more as fantastical, embellished stories than as accurate, truthful description of Asian cultures. Scholarship over the subsequent centuries has corroborated many aspects of Polo's accounts, while acknowledging their inaccuracies, biases, and misrepresentations.

16 Bergreen, p. 27.

17 Thubron, pp. ix–xi.

18 Thubron, pp. xv–xvii.

location to connect the trade routes of the Mediterranean Sea to overland routes through the mountains of what is now Northern Italy, Central Europe, and France. Merchants from Genoa traded throughout the Mediterranean, from the northern coast of Africa to the Holy Land, the Black Sea, Britain, and what is now the Netherlands.19 Their settlements and commercial colonies in distant lands created the infrastructure to facilitate the flow of commerce, and this approach was later replicated by Portuguese in trading ventures in Africa.

The conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by the Ottoman Empire dealt a major blow to established trade routes in the Mediterranean. Constantinople had been Western Europe’s main source for luxury goods, such as spices and silk produced in the Middle East and Asia. The trading powers of the Mediterranean

19 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 5.

sought new routes that avoided hostility in the Ottoman-controlled regions of the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. This drove Portuguese traders toward overseas expansion, and they developed new technologies to support these profitable ventures.20 Portuguese shipbuilders created the nao and the caravel, two types of ships that could better navigate oceans, and started using other technologies like astrolabes and cross staffs to better understand their location at sea, relative to the angle of the sun. They voyaged south along the coast of Africa, making territorial conquests in Morocco and establishing a port in Ghana. They eventually rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487 or 1488, opening a sea route between Europe and India and reestablishing trade with Asia that had been cut off by the Ottoman conquest.21

20 Wise, Carl and David Wheat. “African Laborers for a New Empire: Iberia, Slavery, and the Atlantic World.” Lowcountry Digital History Initiative. Accessed April 7, 2024.

21 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 7–8.

An outcome of this increased Atlantic trade was a dramatic increase in Portuguese access to sub-Saharan trade networks, which played a major role in the later Atlantic Slave Trade. In the early modern era, enslaved people were usually captives of opposing religious or political factions; Muslim and Christian slaves existed throughout the Mediterranean. Enslaved people could customarily be freed by the payment of a ransom by their families, religious orders, or political powers; becoming enslaved was considered a result of misfortune, and could be temporary.22 However, with Portugal’s expansion into western Africa, merchants began to recognize the enormous economic potential of a large-scale human trafficking enterprise. Legal traditions at that time already regulated the treatment of Jewish, Muslim, and Christian slaves, but the trafficking of Africans raised new legal and philosophical questions. Pope Nicolas V issued a series of papal bulls in 1452 and 1455 that granted Portugal the right to enslave sub-Saharan Africans, which was justified as a Christianizing influence to counter “barbarous” behavior and pagan religions. The papal bull instructed Portuguese King Alfonso V to “Invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans whatsoever… [and] to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to apply and appropriate himself and his successors the kingdoms, dukedoms, counties, principalities, dominions, possessions, and goods, and to convert them to his use and their use and profit...”23

While the powers of the Iberian Peninsula— Portugal and Spain—were launching these new ventures in the Atlantic, the centurieslong Reconquista was coming to an end. The Reconquista describes the era from 722 to 1492 in which Christian forces on the Iberian Peninsula fought to regain territory from the Muslim Moors, who had conquered the region in the early 700s.24 During the Reconquista, the Spanish Crown developed the strategy of using privately-funded captain-governors to battle for Muslim-held territories on the Iberian Peninsula. In exchange for self-funding these campaigns of conquest, these captaingovernors, or adelantados, often received hereditary family governorship of these territories, as well as the right to exploit the labor of Muslim peasants who lived on them. This institution was known as repartimiento, and it both punished the conquered with servitude and rewarded the victors with their labor. Spanish Christian settlers could gain rights to land in newly Christian-held territories through squatters’ rights laws, but since the Spanish military did not have the resources to protect settlers in these frontier areas, a feudal system developed where hidalgos—minor nobility—demanded labor and tribute from settlers and conquered peoples in exchange for military protection. This system, known as the behetría, would later be transported to the Americas and become the encomienda, where European settlers were given similar rights to exploit Indigenous populations if they demonstrated that they were instructing them in Christianity.25

22 Wise & Wheat, “Slavery in Ibera before the Trans-Atlantic Trade.”

23 Wise & Wheat, “Pope Nicolas V and the Portuguese Slave Trade.”

24 “Reconquista — World History Encyclopedia.” Accessed April 7, 2024.

The desire for gold, ivory, pepper, and humans to traffic also pushed the Portuguese and the Spanish westward to the Atlantic islands of The Azores, Madeira, and the Canary Islands.26 The colonization of the Canary Islands from the beginning of the 1400s provided another model that the Spanish Crown would later draw upon in their colonization of the Americas—one marked by private entrepreneurship and forced conversion to Christianity, all encouraged and controlled by the Crown.27 Between 1402 and 1477, several Franco-Norman entrepreneurs established settlements on the islands, in alliance with the Crown of Castille. Initially these entrepreneurs made treaties with the Indigenous Guanche people of the islands, but later a system of fiefdoms owned by European families developed on the islands, which produced and exported sugar, wine, wheat, leather, dyes, and enslaved peoples to Europe. In 1475, disputes between the Portuguese and Castillians over the islands were settled, with Portugal ceding all claims to the Canary Islands in exchange for uncontested rights in the Madeira Islands. Spain launched a formal military conquest of the Canaries led by Crown-appointed (but largely self-supported) captain-governors (adelantados) who were rewarded for their conquests with allocations of land and the right to exploit the Guanche people in their region (repartimientos). Guanche individuals were supposedly granted privileges as Castilian subjects if they converted to Christianity and pledged their loyalty to Spain. Those who resisted were punished with enslavement.

Establishing factorías was another way the Portuguese gained footholds in the lands where they sought to expand their mercantile reach (West Africa and Madeira, for example). Similar to Genoa’s trading posts throughout the Mediterranean, Portuguese factorías on the island of Madeira were trading and agricultural fiefdoms owned by individual families backed by private capital, but licensed by the Crown of Portugal. They generally did not seek political control in the territories where they were built, and often employed immigrant European artisans, craftsmen, and laborers. This model would also influence Spain’s attempts to establish economic footholds in the Americas; however, the more brutal repartimiento model is what eventually took hold.28

With the marriage of King Ferdinand II of Aragón and Isabella I of Castile, the two kingdoms of Spain became politically united, and the Crown sought to enforce a new cultural and religious unity. They increased attacks on minority populations of Jews and Muslims who had lived on the Iberian Peninsula for centuries, and the Inquisition began punishing Jewish converts to Christianity who continued to practice Judaism. Granada, the last Muslim kingdom on the Iberian peninsula, fell in 1492 after a decade-long campaign.

25 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 11.

26 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 7.

27 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 9–11.

28 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 8.

Christopher Columbus was born Cristoforo Colombo in the city-state of Genoa on the Italian Peninsula in 1451, according to archival documents. Columbus came from a workingclass family that had moved to Genoa from the countryside in recent generations. His father worked as a weaver, a tavern owner, and a farmer. Columbus attended a grammar school managed by his father’s guild, but early in his adolescence he went to sea as a merchant’s apprentice, and then as a sailor aboard Genoese ships in the Mediterranean.29

Columbus would not have identified as an Italian national since Italy did not become a country until 1861, but he did identify with his roots as a citizen of the Republic of Genoa all his life, despite spending most of his years living in Spain and Portugal, aside from his time at sea. Though adopting Castilian citizenship would have been advantageous, he maintained his loyalty to Genoa, writing in 1502 to Genoa’s state bank, “Though my body is here, my heart is always with you.”30 In estate documents from 1498, Columbus called upon his heirs to “always work for the honor, welfare and increase of the city of Genoa.”31 Columbus’ identity as a merchant and a navigator was deeply rooted in the industries of his home

29 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 3–5.

30 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 5.

31 "Early Life in Genoa." Accessed April 7, 2024.

32 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 6.

33 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 9–10.

city, embodying the proverb Januensis ergo mercator: “Genoese, and therefore a merchant.”32 Columbus was highly motivated by family ties and legacy—his brothers, cousins, and son accompanied him on voyages, and he was driven by a lifelong determination to elevate and secure his family’s status through commerce and royal patronage.

At the age of 25, Columbus was shipwrecked in Portugal, where he remained for the next 10 years. Operating in Portugal during this time of intense technological advancement benefited Columbus’ skills in navigation. During this time he also worked as a map dealer with his brother Bartolomé in Lisbon. Lisbon was the epicenter of Atlantic exploration at the time, so Columbus had access to the most current maps and centuries of scholarship about cosmography and geography. Using these resources, he calculated that the earth must be no more than 18,000 miles in circumference (rather than the actual 24,830 miles). He became absorbed in Marco Polo’s account of East Asia and its riches, and sought to chart a presumably short western sea route to China and its vast trading opportunities. He proposed his plan to Portugal’s King João II in the early 1480s but it was rejected, in part because Columbus wanted to keep so much of the voyage’s profits.33

Columbus spent most of the 1480s trying to convince various European monarchs to finance an exploratory voyage west to attempt to reach Asia and its commercial wealth.34 Columbus and his brother Bartolomé returned to Spain from Portugal in 1485, by which point their proposal had been rejected by Spain, Portugal, England, and France. Only when Granada fell in 1492 did the Spanish Crown consider funding Columbus’ venture—at that point it was a low-risk opportunity for Spain’s King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I in their quest to overtake Portugal as a state power.35 In the tradition of the adelantados, Columbus was granted the title of governor over any lands that he might find, but he was also an official representative of the Catholic monarchs. This meant that any land he and his family governed was ultimately under the Spanish Crown. His contract with the Crown is known as the Capitulations of Santa Fe, and in it the monarchs named Columbus, “now and henceforth, the Admiral in all islands and mainlands that shall be discovered by his effort and diligence in the said Ocean Seas, for the duration of his life, and after his death, his heirs and successors in perpetuity, with all rights and privileges belonging to that office.” The terms set forth in the Capitulations indicate that the goal of the voyage was to establish Crowncontrolled trading posts in east Asia more easily reachable by sea, along the lines of the

34 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 12.

35 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 12–13.

36 Ibid.

37 Cohen, p. 51.

Portuguese factoría model, that Columbus and his family would administer and control.36

In the summer of 1492, Columbus assembled ships, a crew, funds, and supplies in the port of Palos, Spain. The town helped fund the voyage by providing the caravels Niña and Pinta, and Columbus chartered the Santa María with the additional financial support of some merchants from Genoa and Florence, who acted as partners in the venture. For the most part, local men comprised the 85-person crew. They launched from Palos on August 3 and reached the Canary Islands on September 9, from which they charted a southwesterly course. The favorable winds at that latitude helped propel this and subsequent voyages across the Atlantic to the islands of the Caribbean.

On October 10, one month into their sea journey with no land in sight, Columbus recorded in his log, “Here the men could bear no more; they complained of the length of the voyage.” Columbus’ log reveals that he was intentionally misleading the crew about how far they had traveled, under-reporting how many leagues they made each day in order to hide his miscalculations of how long the journey was expected to be.37 But as the crew was contemplating mutiny, land was sighted over the night of October 11–12. Columbus and some of his crew came ashore on the Taíno

island of Guanahaní, which Columbus renamed San Salvador.38

Columbus’ account describes the first encounter between the Taíno people and the Europeans on Guanahaní as a peaceful interaction, though his own diaries and letters are the only sources available. Columbus declared possession of the island for the Spanish Crown, and was later greeted by Taíno villagers. The two groups reportedly bartered, despite not sharing a common language. Columbus made note of their differing senses of value when it came to exchanging goods, seemingly already considering how to profit monetarily from having an upper hand in these relations, writing:

These people are very gentle, and because of their desire to have some of our things, and believing that nothing is to be given to them unless they give something, but because they do not have anything, they take what they can and then jump into the water and swim away. Moreover, everything that they have, they give for anything that may be given them, for they traded even for pieces of ceramic bowls and broken glass cups, to the point that I even saw them give sixteen balls of spun cotton for three Portuguese ceutís, which are worth one Castilian blanca,39 and the balls there would be more than

an arroba40 of spun cotton. I should have prohibited this and not let anyone take any of it, except that I had commanded that all of it be taken for Your Highness, if it existed in quantity.41

Columbus and his crew left Guanahaní and sailed a course through the Bahamas. Columbus captured Taíno people and made them work as guides and interpreters—a similar tactic employed by the Portuguese on their commercial ventures in Africa.42 His log entries show that Columbus believed that the Taíno individuals he encountered saw him and his crew as deities. On October 14 he wrote of Taíno people watching their ships from the shoreline:

We understood them to be asking of us if we came from the sky . . . men and women alike shouted, ‘Come and see the men who have come from the skies; and bring them food and drink.’ Many men and women came, each bringing something and offering thanks to God; they threw themselves on the ground and raised their hands to the sky and then called out to us, asking us to land.43

Columbus often wrote confidently about his understanding of Taíno communications with him and his men; his ignorance of their

38 Modern scholars have not conclusively determined which Caribbean island is the original Guanahanì. Watling’s Island was renamed San Salvador in 1925 when historians identified it as Guanahanì by interpreting Columbus’ writings; it is believed to be the most likely candidate, but several other islands have been proposed by other scholars (“San Salvador Island”. Encyclopedia Britannica, September 18, 2023).

39 A blanca was a small copper coin. Symcox & Sullivan, p. 71.

40 A unit of weight equal to 11.5 kilograms, or more than 25 pounds. Symcox & Sullivan, p. 71.

41 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 70–71.

42 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 15.

43 Cohen, p. 58.

language and customs should invite some skepticism about his certainty of these understandings.

Columbus believed that the Taíno would readily convert to Christianity. He also thought the peacefulness and hospitality they displayed could be easily exploited:

They should be good servants and very intelligent, for I have observed that they soon repeat anything that is said to them, and I believe that they would easily be made Christians, for they appeared to me to have no religion. God willing, when I make my departure I will bring half a dozen of them back to their Majesties, so that they can learn to speak.44

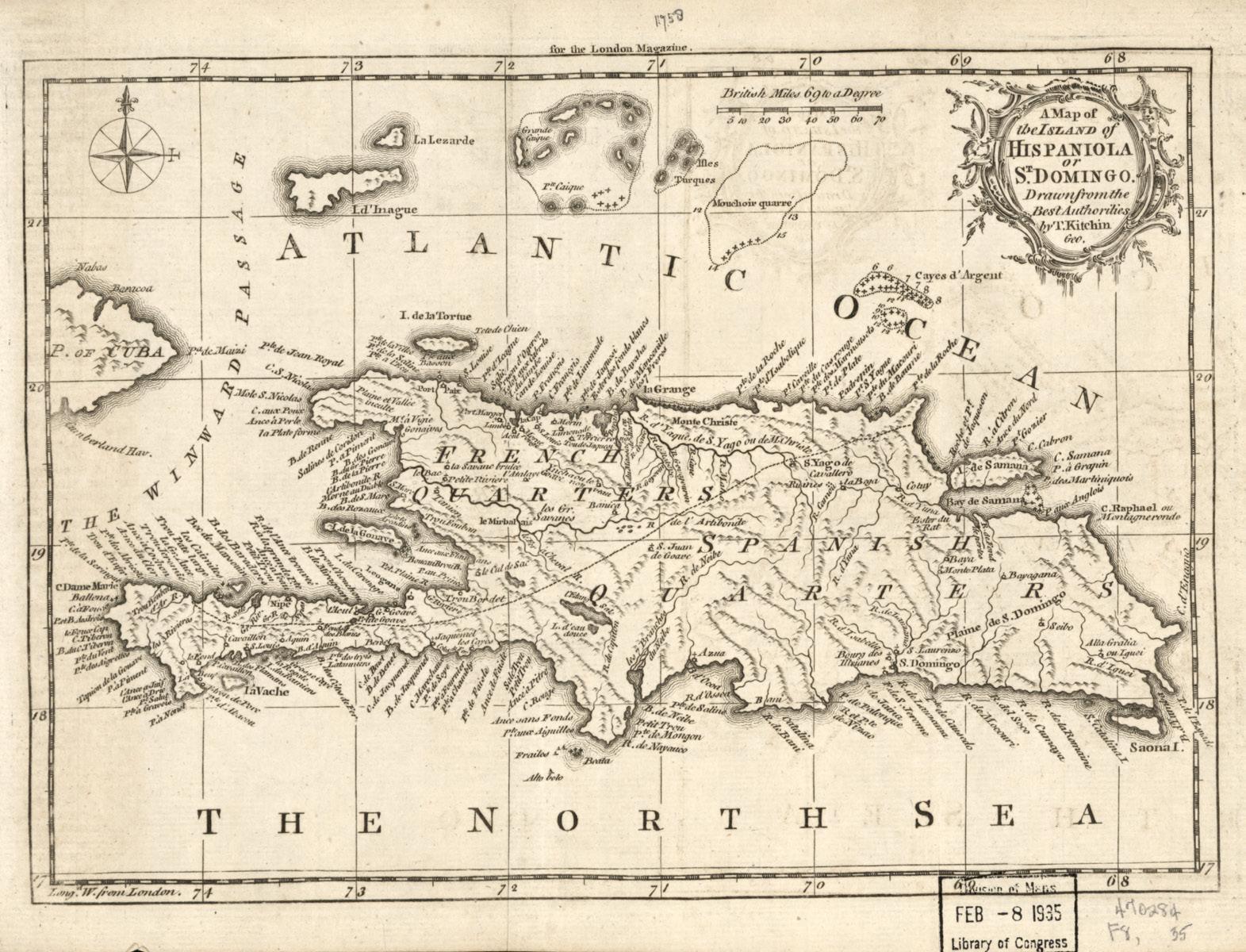

When the fleet reached Cuba (which he renamed Juana), Columbus believed that they had found the Asian mainland. Columbus had brought an interpreter on the voyage who spoke Arabic and Chaldean, languages that would be understood in the court of the Grand Khan of the Mongol Empire, to translate. The translator was sent with the rest of the envoy to seek the court of the Grand Khan.45 They did not find it, of course, but they noticed people wearing gold ornaments, fueling Columbus’ drive to find sources of gold on the islands. They continued to the large island that is now Haiti and the Dominican Republic—which he named La Española, or Hispaniola in English.

From the first days of landfall, Columbus planned to establish a colony. On October 14, he described his intentions while sailing around Guanahanì:

I went to view all this this morning, in order to give an account to your Majesties and to decide where a fort could be built. I saw a piece of land which is much like an island, though it is not one, on which there were six huts. It could be made into an island in two days, though I see no necessity to do so since these people are very unskilled in arms, as your Majesties will discover from the seven whom I caused to be taken and brought aboard so that they may learn our language and return. However, should your Highnesses command it all the inhabitants could be taken away to Castile or held as slaves on the island, for with fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we wish. Moreover, near the small island I have described there are groves of the loveliest trees I have seen, all green with leaves like our trees in Castile in April and May, and much water.46

On December 25, the Santa María was shipwrecked on a reef off La Española. The Taíno chieftain (cacique) Guacanagarí and his people helped Columbus’ crew salvage the ship’s cargo, and Columbus wrote glowingly about them:

44 Cohen, p. 56.

45 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 15.

46 Cohen, p. 58–59.

47 Columbus’ original log in his own handwriting has been lost, but a copy in the handwriting of Bartolomé de Las Casas exists, and is quoted here. Las Casas sometimes refers to Columbus/the Admiral in the third person when he is quoting or paraphrasing Columbus, as he does here (Symcox & Sullivan. p. 65).

As soon as [Guacanagarí] heard the news they say that he wept, and he sent all his people from the town with many very large canoes to offload the ship. This was done and everything was offloaded from the holds in a very short space of time, so great was the expeditiousness and diligence that the king displayed. He in person, with his brothers and family, worked diligently both on the ship and on safeguarding what was taken off so that everything would be fully secure. From time to time he sent one of his relatives weeping to the Admiral [Columbus]47 to console him, saying that they should not be upset or distressed because he would give him everything he had. The Admiral assures the Monarchs that nowhere in Castile would such good care have been taken about everything that not a lace was missing. He ordered everything to be put next to the houses while some which he wanted to make available were emptied and everything could be put there and safeguarded. He ordered armed men to be placed around everything and to guard it all night. He and all his people were crying; they are (says the Admiral) so loving a people and so lacking in cupidity and so willing to do anything, that I assure Your Highnesses that I believe that there are no better people in the world, and no better land. They love their neighbors as themselves, and have the softest speech in the world, and are docile and always laughing. They go naked, men and women, as their mothers bore them. But Your Highnesses may believe that their dealings with each other are very good, and the king has a most

marvelous bearing and such a sober manner that it is a pleasure to see it all, and their memory, and they want to see everything and ask what it is and what it is for.48

Columbus decided to build his first fort at that location out of the ship’s timbers. He named the fort La Navidad (Christmas) after the day of the shipwreck, which he interpreted as divine providence—a sign from God that the first European settlement in the Americas should be built there: “In truth it was no disaster, but rather great good fortune, for it is certain that had I not run aground there, I should have kept out to sea without anchoring at that place.”49 The exact location of the site is debated among present day scholars, but it is believed to be in northwest Haiti.50 Columbus left 39 men at the fort with instructions to trade with Taíno people for gold, and was confident in the outpost’s success, writing:

I have established warm friendship with the king of that land, so much so, indeed, that he was proud to call me and treat me as a brother. But even should he change his attitude and attack the men of La Navidad, he and his people know nothing about arms and go naked, as I have already said; they are the most timorous people in the world. In fact, the men that I have left there would be enough to destroy the whole land, and the island holds no dangers for them so long as they maintain discipline.51

48 Symcox & Sullivan p. 76.

49 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 14.

50 Wilford, John Noble. “COLUMBUS’S LOST TOWN: NEW EVIDENCE IS FOUND." The New York Times, August 27, 1985. Accessed April 7, 2024.

51 Cohen, p. 120.

Columbus charted a northerly return course to Europe with the Niña and the Pinta. He brought Taíno people with him on the journey back to Europe; a later Spanish court chronicler said that ten Taíno arrived in Spain. Of them, seven lived to make the return journey to the Caribbean the following year, though only two of those seven survived that voyage.52

While sailing back to Europe, Columbus wrote an account of his voyage that sought to demonstrate how valuable this and future journeys could be to the Spanish Crown, a document known as “Columbus’s Letter on His First Voyage.” In this letter, and for the rest of his life, Columbus maintained that he had reached Asia, and he called the Taíno “Indians” and their islands the “Indies”—terms that persisted, some to the present day. He described islands with abundant resources and many friendly populations, as well as an encounter with a supposedly cannibalistic population—the so-called Caribe.

Shortly before returning home to Spain, the Niña (Columbus’ ship) was separated from the Pinta during a storm. The Pinta made it to northern Spain, but the Niña made landfall in Lisbon on March 4, 1493. King João questioned Columbus and decided that he had sailed into Portuguese waters—a serious violation perpetrated by the Spanish monarchs. Portugal’s challenges to Spain on the matter brought the two countries to the brink of war in the following months. When he made it home, the Spanish monarchs published Columbus’ account of his voyage in Castilian and Latin to establish their claim to the lands Columbus visited. But this account also circulated biased narratives about the Americas and the people who lived there—people who were either trusting and welcoming (i.e., easy to conquer) or brutal and inhumane (i.e., righteous to conquer).

52 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 15.

Columbus returned to Spain from Portugal and gave his account of his voyage and his encounters with the Taíno people. King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I gave orders to begin preparations for another, larger voyage, with the intent of establishing a frontier trading settlement (a factoría) at La Navidad comparable to those the Portuguese had developed in West Africa,53 but with monopolistic control over commerce held by the Spanish Crown.54 They provided for a fleet of 17 ships, which were assembled at Cádiz. Somewhere between 1,200 and 1,300 colonists enlisted for the voyage. All but about 200 of them were paid a salary by the monarchy, and the documents made in preparation for the voyage suggest that Spain intended for the voyagers to establish and work on the factoría. However, based on the events that would unfold during the second voyage, it seems that many of the voyagers were influenced to enlist because of Columbus’ account published by the Spanish Crown, which suggested to them the possibility of building wealth and social advancement in the Americas. Those hidalgos who enlisted had the institutions of the Reconquista in mind, seeking to establish themselves as landed minor nobility in the new colony.55

The crown sent one notary for each ship, two royal scribes, and three royal treasury officials. About 30 soldiers, armed horsemen and war dogs were sent as well, and several priests of various orders. Representatives of all the trades were present, as were at least two physicians. The fleet carried ample provisions, tools, seeds, and farm animals in the hopes of successfully transplanting and imposing familiar aspects of European life in the Americas.56 They also brought goods intended for trade with the Taíno to help establish relationships to benefit international trade and conversion to Christianity.57

King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I sought the support of Pope Alexander VI (a Borgia, and Spanish by birth) in their conflict with Portugal over claims that the lands Columbus had reached belonged to Portugal. The Pope ruled heavily in favor of Spain, and used the opportunity to impose a religious mission on the “Enterprise of the Indies.” He issued papal bulls that granted Spain sovereignty over “all islands and mainlands found or yet to be found, discovered and yet to be discovered towards the south and west” in perpetuity. This unilateral power was granted with the understanding that Christian conversion of the Indigenous peoples of these lands would be

53 Deagan & Cruxent p. 1.

54 Deagan & Cruxent p. 17.

55 Deagan & Cruxent p. 18.

57 Ibid.

58 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 20.

of the highest priority, and “that the Catholic faith and Christian religion should especially be exalted in our times and be expanded and spread everywhere, and that the salvation of souls should be secured and barbarous nations should be subdued and led to the faith.”58 In a later bull issued in 1501, the church codified the right to levy tithes from Indigenous people to support the local religious infrastructure and livelihoods of those who were attempting to convert them. This further sanctioned and encouraged the encomienda system in which the Taíno were forced to tithe with their labor, effectively enslaving them.59

In the instructions given to Columbus by King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I ahead of his second voyage, they expressed their concern over the conversion of the Taíno people who had been brought to Spain, and those who Columbus was returning to:

The Admiral is to see that the Indians who have come to Spain are carefully taught the principles of Our Holy Faith, for they must already know and understand much of our language; and he is to provide for their instruction as best he can; and that this object may be better attained, the Admiral, after the safe arrival of his fleet there, is to compel all those who sail therein as well as all others who are to go out from here later, to treat the said Indians very well and lovingly, and to abstain from doing them any harm, arranging

59 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 140.

60 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 153–54.

61 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 16.

62 Cohen, p. 133.

63 Cohen, p. 135.

that both peoples hold much conversation and intimacy, each serving the others to the best of their ability.60

The second voyage left Cádiz on September 25, 1493 and reached the Lesser Antilles, the island chain to the southeast of La Española, on November 3. Dr. Diego Álvarez Chanca was one of the physicians on the second voyage, and he chronicled the first months of the voyage in a letter written to the leaders of Seville, a significant source regarding this part of the expedition. During the first voyage, the Taíno told Columbus and his crew that the islands to the southeast were home to the Kalinago (who the Taíno and Europeans called Caribe), who were known for raiding other islands and taking women and young people as prisoners. The Taíno also told them that the Caribe practiced cannibalism, and in his letter Dr. Chanca recounted discovering human bones in the homes of Caribe people who had fled when they saw Columbus and his men coming:

The captain went ashore in the boat and visited the houses, whose inhabitants fled as soon as they saw him. He went into the houses and saw their possessions, for they had taken nothing with them. He took two parrots, which were very large and very different from any previously seen. He saw much cotton, spun and ready for spinning, and some of their food. He took a little of everything, and in particular he took away four or five human

arm and leg bones. When we saw these, we suspected that these were the Caribe Islands, whose inhabitants eat human flesh. Following the indications of their position given him by the Indians of the islands discovered in his previous voyage, the Admiral had set his course to discover them, since they were nearer to Spain and lay on the direct route to the island of Hispaniola, where he had left his men on the previous voyage.61

Chanca also wrote of observing “human bones and skulls hanging in the houses as vessels to hold things.”62, 63

Columbus and his crew engaged in several small-scale violent confrontations as they made their way up the Lesser Antilles. When they encountered Taíno captives of the Kalinago they took them aboard, as well as several Kalinago men and women they defeated in battle. Michele da Cuneo, who accompanied Columbus on the second voyage, described his treatment of a captured woman [CONTENT WARNING]:

While I was in the boat, I captured a very beautiful Caribe woman, whom the said Lord Admiral gave to me. When I had taken her to my cabin she was naked—as was their custom. I was filled with a desire to take my pleasure with her and attempted to satisfy my desire. She was unwilling, and so treated me with her nails that I wished I had never begun. But—to

cut a long story short—I then took a piece of rope and whipped her soundly, and she let forth such incredible screams that you would not have believed your ears. Eventually we came to such terms, I assure you, that you would have thought she had been brought up in a school for whores.64

Columbus reached La Navidad on La Española on November 27 to find the fort completely destroyed, and the colonists dead. Before making landfall Columbus had been visited by Gucanagarí’s cousin and others, who informed them that some of the Europeans had died from disease and infighting. Chanca wrote:

Next morning we were waiting for Guacamari [sic] to come, and in the meantime several men landed, on the Admiral’s orders, and went to the place where they had often been in the past. They found the palisaded blockhouse in which the Christians had been left, burnt, and the village demolished by fire, and some clothes and rags that the Indians had brought to throw into the house [to set fire to the straw roofs].65

The chieftain Guacanagarí recounted that the colonists had been killed by the men of another chieftain named Caonabó. Guacanagarí and Columbus visited each other on land and on Columbus’ ship for several days; they traded and spoke through the two Taíno interpreters who had survived the voyage back from Spain.

62 Cohen, p. 133.

63 Cohen, p. 135.

64 It should be remembered that there is no conclusive archaeological evidence to support the claims of Carib cannibalism, and there were strong motivations for the Spanish to depict the Caribe as cannibalistic in order to justify enslaving them.

65 Cohen, p. 139.

66 Cohen, p. 146.

Though many in Columbus’ circle suspected Guacanagarí and his people of taking part in the killing of the colonists, Columbus decided not to pursue these suspicions, wanting to maintain his alliance with Guacanagarí.

During one of these visits, Chanca wrote, Guacanagarí’s brother advised the ten Taíno women (who had been captured from the Kalinago—Chanca uses the term “rescued”) to jump overboard during the first watch and swim ashore. They did, and Chanca recounted:

By the time they were missed they had swum so far that only four were taken by the boats and not until they were just coming out of the water. They had swum a good half league. Next morning the Admiral went to Guacamari [sic] demanding that he should return the women who escaped during the night, and sent to look for them immediately. When his messengers arrived they found the village deserted—not a person remained in it. Many people then reaffirmed their suspicions; others said that Guacamari [sic] had merely moved on to another village, as was their custom.66

Rather than resettle at La Navidad, Columbus chose to continue sailing to find a suitable location for the next settlement. They left the ruins of La Navidad on December 7, but encountered unfavorable winds, such that it took them 25 days to travel just 100 miles eastward. When they finally spotted a hospitable bay on the northern coast of the present-day Dominican Republic, Columbus decided it was time to end their search. They

named their new settlement La Isabella after their monarch, and by several accounts the location they chose seemed promising. Chroniclers described its large river, green and fertile river banks, abundant fish, and stone quarries.67

However, the problems that would plague La Isabella for its entire existence began almost as soon as the ships landed. Food that had been brought on the voyage was largely spoiled, and within a few days of their arrival most of the men fell sick, and several died. New parasites to the colonists in the local water may have caused widespread dysentery and gastrointestinal ailments among the Europeans, and some historians suggest that both colonists and later Taíno may have contracted influenza from pigs and horses that were brought on the ships.68

Despite the poor health of most of the Europeans, Columbus insisted that they immediately start constructing the town and searching for gold. He dispatched an expedition to the interior of the island, and they returned with tales of abundant gold. In February 1494, Columbus sent news of this gold to King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I in letter on a fleet of 12 ships back to Spain, requesting more provisions to pursue the promise of gold reserves on the island. Several hundred crew members would have left with those 12 ships, leaving only around 800–1,200 people at the settlement.

Bartolomé De las Casas provides most of our historical descriptions of La Isabella. Of the

67 Cohen, p. 152.

68 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 51–52.

construction of the town by the colonists, he wrote, “everyone had to pitch in, hidalgos and courtiers alike, all of them miserable and hungry, people for whom having to work with their hands was equivalent to death, especially on an empty stomach.” Columbus also commandeered the hidalgos’ horses for agriculture and construction, to which they were strongly opposed. The first open rebellion among the colonists against Columbus took place that same February, organized by royal accountant Bernal de Pisa and supported by clergyman Fray Buil. Columbus jailed Pisa and hanged several colonists, which further outraged the hidalgos, and fueled his later discredit in Spain.69

In March, after the first rebellion had been squashed and the colonists’ health had begun to improve, Columbus organized an expedition into the region of La Española they called the Cibao to establish forts and search for gold. In reality, Cibao was the Taíno name for the entire island, but the Spanish used the word to refer to the northern inland mountainous region of the present day Dominican Republic (which remains the name of the region today). Columbus set out for the Cibao with 500 colonists and several Taíno guides on March 12. After a 100-mile march, the group built Santo Tomás, a small fort at a bend in the Jánico River. They did not find gold, other than what they traded for with the Taíno, but Columbus left around 50 men at the fort to maintain

69 Deagan & Cruxent p. 53–54.

70 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 55–56.

71 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 56.

their presence in the region, and returned with the rest to La Isabella.70

They arrived at La Isabella on March 29 to find that illness had struck again, killing many settlers, and that a fire had destroyed twothirds of the settlement. Columbus determined that they must build mills to grind the wheat they brought from Spain since other provisions were running low, but he had to use threats and punishments to force the sick colonists to work. Additionally, just a few days after returning from the expedition, Columbus received word from Santo Tomás that the Taíno were fleeing the nearby villages and that the chieftain (cacique) Caonabó was preparing to attack the new fort.71

Columbus decided to make a show of force against Caonabó and the Taíno. He sent almost 500 men to the Santo Tomás, many of whom were soldiers. Pedro de Margarit, the commander of the fort, was ordered to take 350 of the men and march them through the heavily populated Vega Real, the central plain of the Cibao. Fernando Colón, Columbus’ son and chronicler, wrote:

He decided to send everyone who was fit except the master craftsmen and workers to march through the Vega Real in order to pacify and strike fear into the Indians and also gradually to accustom his men to the local food, because the stores they had

72 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 56–57.

73 Cohen, p. 166.

74 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 57–58.

75 Cohen, p. 169–70.

76 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 58.

77 Cohen, p. 187–88.

brought from Castille were diminishing every day.72

Violent confrontations between the Europeans and the Taíno escalated with the incursion of Columbus’ forces in the Vega Real.73

Although the conditions at both La Isabella and in the Vega Real were far from stable, Columbus decided the time had come to continue exploring the region by sea in hopes of finding the Asian mainland. On April 25, Columbus and around 100 men took two caravels and one nao and departed from La Isabella to Cuba. Columbus was still clinging to the belief that this would lead him to the Asian mainland, despite what he had been told by the Taíno and his own explorations of the island during the first visit.74 He left his brother, Diego Colón, behind as the head of a council to govern La Isabella. Columbus would not return to La Isabella until September 29, five months later.75

Documentary accounts of life in La Isabella and the Vega Real while Columbus was away are limited, but Fernando Colón described the sources of ongoing conflict on the island in his later life history of his father. He wrote:

On departing for Cuba, he had left [Pedro de Margarit] in command of the island and reduced it to the service of the Catholic sovereigns and obedience to the Christians, especially in the province of Cibao, from which the Admiral expected the greatest profit and found just the opposite. No sooner had he departed than Pedro Margarit left with

all his people for the Vega Real, ten leagues from Isabella, making no efforts to control and pacify the island. On the contrary, by his fault, quarrels and factions arose in Isabella. He tried to persuade the council, which the Admiral had formed there, to obey him, and most shamelessly sent them his orders.

On finding that he could not make himself supreme commander, he decided not to wait for the Admiral, to whom he would have to give a complete account of his office, and with his men boarded one of the ships to come from Castile, in which he returned home without giving account of himself or reducing the population to order according to his instructions. As a result every Spaniard went out among the Indians robbing and seizing their women wherever they pleased, and doing them such injuries that the Indians decided to take vengeance on any Spaniards they found isolated or unarmed.76

While this was happening on La Española, Columbus was exploring the coastlines of Cuba and Jamaica. His ships reached the easternmost tip of Cuba and sailed along its southern coast (having visited the northern coast on the first voyage). According to Michele da Cuneo, who was on the voyage, when they reached a populous harbor (likely what Fernando Colón identified as Puerto Grande in his chronicle77), they announced themselves by discharging their cannons (likely with blank shots78)

and sent their interpreters to convince the Taíno people there that they were friendly. Both da Cuneo and Colón remarked on the large amounts of fish that the villagers were preparing, and shared with the Europeans, who reciprocated with gifts like brass beads and small bells. Da Cuneo wrote, “We gave them some of our things, and asked them if there was gold in those parts. They answered no, but that it was certainly true that there was much of it on an island called Jamaica, which was south by southwest from there.”79 They had similar interactions with villagers as they sailed along the coast, and on May 3 Columbus decided to make the crossing to Jamaica.

They made the crossing in two days, and as soon as they drew close to land many Taíno approached their boats in canoes. Colón wrote,

78 Cohen, p. 170.

79 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 93.

80 Cohen, p. 171; Symcox & Sullivan, p. 92–93.

81 Cohen, p. 172.

82 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 93.

83 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 93.

Next day, wishing to examine the harbors, the Admiral went down the coast and, when the boats went to sound the harbor entrances, so many canoes came with armed warriors to defend the land that they were obliged to put back to the ships, not so much out of fear of the Indians as from reluctance to break friendly relations. But on reflecting that if they seemed afraid they would increase the pride and confidence of the natives, they turned to another harbor on the island, which the Admiral called Puerto Bueno. And when the Indians came out from there also, and hurled their spears, the crews of the boats fired with such a volley from their crossbows that the natives were compelled to retire with six or seven wounded.80

Da Cuneo’s account of the skirmish suggests that more Taíno were killed. Of their decision to fight the defending Taíno, he wrote, “We then equipped the boats with shields, crossbows, and cannons and headed in the direction of land. They greeted us as before, and at that point we immediately killed sixteen or eighteen of them with the crossbows and five or six with the cannons.”81 Both Da Cuneo and Colón wrote that, by the next day, the Taíno approached them to share food and trade. When the sailors asked about gold, according to Da Cuneo, they said they had neither heard of nor seen it.82

Columbus’ crew remained in the harbor for four days to repair the ship, departing at last on May 8. They sailed for a few more days along the coast of Jamaica, but unfavorable winds prompted their return to the Cuban coast, from which they continued to sail west. Colón wrote that Columbus “was resolved not to turn back until he had sailed five or six hundred leagues and made certain whether it was an island or the mainland.”83

Columbus’ health deteriorated as he navigated among the many islands along Cuba’s coast— the food on board was poor, he barely slept, and despite his constant efforts the ships ran aground frequently in the shallow waters.84 A Taíno man aboard the ship, who had been seized during the voyage, convinced Columbus that

Cuba was in fact an island.85 Finally registering that the island stretched far to the west, and accounting for the challenges of sailing among the smaller islands, Columbus decided to turn back toward La Española on June 13.86

Travel was difficult as they continued eastward—they encountered bad weather, their rations were reduced to “a pound of rotten biscuit and a pint of wine,” according to Colón, and Columbus’ ship was taking on more water than they could pump out. In Cabo de la Cruz, a cape named by Columbus, the crew were saved by the Taíno, who gave them cassava bread, fish, and fruit to eat. Not finding any favorable winds to return to La Española, Columbus decided to return to Jamaica, where they were again saved from starvation by the Taíno.87 Colón wrote that Columbus wanted to stay in Jamaica, but with their food shortage and deteriorating ship, he decided instead to wait for more favorable weather and continue on to La Española.88

84 Cohen, p. 172.

85 Cohen, p. 175–76.

86 Cohen, p. 177.

87 Cohen, p. 179.

88 Cohen, p. 181.

89 Cohen, p. 182.

90 Cohen, p. 182–185.

When the weather improved, the three ships headed eastward. They lost sight of Jamaica on August 19 and reached La Española a few days later. At Cabo de San Miguel they were hailed by a cacique they had never met, but who knew them by name, so they felt confident that they had returned to La Española. Around the midpoint of the island they encountered Taínos, who told them they had been visited by other Christians and they were faring well. Columbus decided to send men to cross the island heading north to inform the settlers of his return. Columbus and the three ships continued along the southern coast, and when they reached the easternmost tip of the island, they decided to abandon plans to further explore the

Lesser Antilles and return to La Isabella, due to Columbus’ increasingly poor health. They reached La Isabella on September 29, 1494.89

The men Columbus had left in charge of La Isabella and the Vega Real had fled La Española with the ships that had brought Columbus’ brother Bartolomé and other provisions in the spring of 1494. Columbus remained bedridden until January of 1495, and during that time appointed Bartolomé adelantado (captain-governor) of the Indies, with much of the responsibility of governance falling to him as Columbus recuperated. A relief fleet arrived at La Isabella in the winter of 1495 with food, wine, medicine, cloth, livestock, and hardware, though far less than Columbus had requested—possibly in response to reports of the settlement’s mismanagement and depleted population.90

Colón described the state of relations between the settlers and the Taíno when Columbus returned from Cuba and Jamaica:

He found the Island in a bad state: the Christians were committing innumerable outrages for which they were mortally hated by the Indians, and the Indians were refusing to return to obedience. All the caciques and kings had agreed not to resume obedience, and this agreement had not been difficult to obtain. For, as we have said, there were only four principle rulers under whose sovereignty all the rest lived.91

91 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 59–60.

92 Cohen, p. 187–88.

93 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 60.

94 Cohen, p. 187.

Columbus decided to build more fortifications along the route to the Cibao to help control the region: the Magdalena fortress on the Yaque River in the province of the chieftain Guatiguará, and the fortress of Concepción on the Rio Verde, near the capital of the cacique Guarionex. Guatiguará was quick to attack the fort in his province;92 Colón wrote, “The cacique of Magdalena, whose name was Guatigana [sic], killed ten Christians and secretly ordered the firing of a house in which forty men lay sick.”93

Columbus escalated these conflicts when he decided to create a show of force against the rebelling Taíno. He launched an expedition against Guatiguará, and while his men were unable to capture him, they seized more than 1,500 Taíno and marched them to La Isabella—an act which initiated the European enslavement of Indigenous Caribbean people. Some were trafficked back to Spain, while others remained indentured at La Isabella. Da Cuneo, who returned to Spain in February 1494, described the fate of the captured Taínos:

When our caravels were ready to depart for Spain, aboard which I intended to return home, we gathered at our settlement 1,600 Indians, male and female; we loaded 550 of the best—both men and women—aboard those caravels on 17 February 1495. Regarding the rest, it was declared that whoever wanted some of them could take them as he wished, and so it was so. When everyone was supplied, approximately 400 still remained who were

permitted to go wherever they liked. Among those were many females with nursing infants, who, so as to better escape from us, fearing that we would return to take them, abandoned their children to their fate, leaving them on the ground and fleeing like desperate persons. They fled so far that they distanced themselves seven or eight days from Isabella, our settlement, beyond mountains and great rivers, so that it will be nearly impossible to take them in the future.94

More than a third of the 550 Taíno people taken to Spain died before the ship landed. Da Cuneo wrote:

By the time we had reached Spanish waters, approximately 200 of the Indians had died—I believe it was because they were unaccustomed to the air which is colder than theirs—and we cast them into the sea. The first land we sighted was Cape Spartel and very soon after we reached Cádiz, where we unloaded all of the slaves, half of whom were sick. For your information, they are not men made for work, and they fear greatly the cold and do not live long.95

In late February on La Española, the chieftain Caonabó and his army marched against the fortresses of Magdalena and Santo Tomás, which they held under siege for a month. Shortly after Caonabó’s retreat, he was captured and taken to La Isabella. The other caciques of the island allegedly planned an insurrection in the Vega Real to march on La

Isabella in retaliation, but Columbus organized a preemptive strike against them, and on March 24, 1495 he left La Isabella with at least 200 soldiers, 20 horsemen, and 20 war dogs. Columbus’ ally Guacanagarí and his forces accompanied them against the other Taíno caciques and their people. Colón described the battle:

When the infantry squadrons… had attacked the mass of Indians, and they had begun to break under the fire of muskets and crossbows, the cavalry and hunting dogs charged wildly upon them to prevent them from re-forming. The Indians fled like cowards in all directions, and our men pursued them, killing so many and wreaking such havoc among them that, to be brief, by God’s will victory was achieved, many Indians being killed and many others captured and executed.”96

Columbus sent Caonabó and his brother to Spain for trial because of their high ranks. According to Colón, Columbus “contented himself with sentencing many of the most guilty.”97 The Taíno alliance had been severely weakened by the battle, and Columbus took the opportunity to impose a forced tribute system on the Taíno to benefit the colonists. Colón described the system:

In the province of Cibao, where the goldfields lay, every person over the age of fourteen would pay a large bell-full of gold dust, and everywhere else twenty-five pounds of cotton. And in order that the Spaniards should

95 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 95–96.

96 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 96.

97 Cohen, p. 189.

98 Cohen, p. 190.

know what person owed tribute, orders were given for the manufacture of discs of brass or copper, to be given to each every time he made payment, and to be worn around the neck. Consequently if any man was found without a disc, it would be known that he had not paid and he would be punished.

In his account, Colón celebrated that “the Christians’ fortunes became extremely prosperous,” and said that “Hispaniola was reduced to such peace and obedience that all promised to pay tribute to the Catholic sovereigns every three months.”98 The tribute system was organized in the remaining caciques, and reinforced by Columbus and his brothers as they made expeditions throughout the island.99

The years of 1495–1496 were devastating for the Taínos of La Española. Diseases brought by the Europeans continued killing them, and the labor required to maintain the tribute system decreased their own subsistence food production (which was also being cut into by the colonists). In addition, the accounts of Las Casas and Peter Martyr D’Anghiera suggest that Taínos exercised an organized resistance to the colonists’ theft by burning their fields and destroying crops, rather than give them to the Spanish.100

In October of 1495, a fleet of four ships from Spain arrived, led by Juan De Aguado. The ships carried supplies and reinforcements, but also instructions from the Spanish Crown to investigate the administration of the colony in

response to reports from the colony’s former leaders. The monarchs had also sent Maestro Paolo, a master miner, and four assistants to focus efforts on finding profitable sources of gold. Aguado found many extremely dissatisfied, sick, and disabled colonists at La Isabella, and collected their stories for the monarchs. Columbus decided he must return to Spain to plead his own case to the Crown, but all voyages out of La Española were delayed when hurricanes destroyed Aguado’s fleet (Columbus’ own anchored fleet had been destroyed by a hurricane in June 1495).

While the destroyed fleets were repaired and rebuilt, Columbus sent Bartolomé, soldiers, and Maestro Paolo and his miners to explore the southern part of the island around Río Haína, which was thought to contain gold mines. The region did prove more productive in mining, and was named San Cristóbal. Columbus was able to take news of the gold mines back to Spain, and his last orders for Bartolomé before departing in March of 1496 were to build and fortify a settlement in the region, which would become the city of Santo Domingo. Columbus appointed Bartolomé the governor and captain general of the island in his absence. Two hundred twenty Spaniards and 30 Taíno prisoners, including Caonabó and his brother, made the return trip to Spain, according to Colón’s account.101

99 Cohen, p. 190.

100 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 62–63.

101 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 62.

102 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 64–65.

When Columbus arrived in Spain, he was apathetically welcomed—news of the disastrous settlement on La Española was circulating in the court, and the monarchs were occupied with their war with France for control of the southern Italian Peninsula. In the summer of 1496, the monarchs sent a fleet to La Española with supplies and royal orders to abandon La Isabella and establish a new settlement in Santo Domingo. Additionally, they gave instructions to enslave the Taíno caciques and any of their subjects who had used armed resistance against the Europeans. When those ships returned to Spain on September 29, 1496, they carried 300 Taíno prisoners. Many died during the journey, and several others died soon after arriving in Spain.102

It took a full year for the crown to give orders for a third voyage led by Columbus. King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I sent only 330 colonists with him, but this time it was more difficult to recruit a crew, and they resorted to commuting prisoners’ sentences to persuade them to make the journey. They also sent six women artisans, more soldiers and priests, and a group of government officials in an attempt to establish a sense of order on La Española on behalf of the Crown.103 All of these new colonists would be salaried by the monarchy, and Columbus was permitted to grant land to the settlers, with the intention

103 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 66–67

104 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 23–24.

105 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 202.

106 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 24.

for them to establish households, work, and live on the land. Any minerals or brazilwood they found would belong to the Crown, though they did have opportunities to share in the profits.104

The third voyage left Spain on May 30, 1498, more than two years after Columbus last left La Española. Three of the ships headed straight for La Española with the colonists and provisions, while Columbus led the other three on a southwesterly course to try to find the “mainland” he was so doggedly seeking. On July 31, his fleet sighted land—an island off the coast of South America that Columbus named Trinidad (as it is still called today). They explored the island and the coast of what is today Venezuela on the South American continent, and according to various accounts, traded peacefully with the people they met. He had finally reached the mainland, not of Asia, but of South America.105

Columbus had begun to take on a mystic religiosity, and he believed that he may be God’s instrument in spreading Christianity over the world and hastening the second coming of Christ. He believed the riches that must be forthcoming in the Americas could be used to reconquer the Holy Land from the Muslims.106 Las Casas described Columbus’ theories about the phenomena he encountered off the coast of Venezuela:

The Admiral could not get out of his mind the amount of fresh water that he had found and seen in the Golfo de la Ballena between the mainland and the island of Trinidad. And after thinking a great deal about it sifting through his arguments, he came to believe that the earthly paradise must be in that region. One of the reasons that convinced him was the great temperateness that he observed in the land and sea where he was sailing, even though it was so close to the equator, which so many authors had judged to be inhabitable or habitable only with difficulty. Instead, during the mornings there, with the sun in the sign of Leo, it was so cool that he had to wrap himself in a cloak. Another reason was that after traveling one hundred leagues from the Azores, from north to south in that region he found that the compass needles moved more than one quarter to the northwest. As they went to the west the mild weather grew more calm and moderate, and he felt that the sea was rising and the ships were being lifted up gently to heaven. And he says the cause of this increase in altitude is the variability of the circle that the north star describes with the Guards. The farther the ships go west, the more they are lifted, and they will rise higher and there will be more of a change in the stars and in the circles that they describe, he says. From this he arrived at the idea, against all the common knowledge of astrologers and philosophers, that the world was not round. That is, although the hemisphere that Ptolemy and the others knew about was round, this one, that they did not know about,

107 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 25.

108 Symcox & Sullivan, p. 112.

109 Deagan & Cruxent, p. 68–69.

was not round at all. Instead, he imagined it to be like half of a pear with a tall stem, or like a woman’s nipple on a round ball, with this part of the stem higher in the air and closer to heaven and below the equator. And it appeared to him that the earthly paradise could be situated on that stem, even though it might be very far from where he currently was.

De las Casas went on to state that another reason Columbus thought that he might be nearing the earthly paradise was that “he found the people to be whiter, or less black, with long straight hair; they were more astute with greater intelligence, and were not cowardly.”107

On August 15, Columbus left his exploration of the South American continent and sailed back to La Española. It had been almost two and a half years since he left the island to return to Spain, and in that time the tribute system that the Columbus brothers had forced upon the Taíno had a disastrous effect on the population. Colonists also continued to die of disease and starvation, and Francisco Roldán, who Columbus had appointed as the mayor of La Isabella on his departure, organized a rebellion against Bartolomé and Diego Colón in May of 1497. Roldán and the allied colonists rejected the deplorable conditions of life in La Isabella, and instead formed a new polity in the province of Xaraguá.108 The livelihoods they established there looked very different from those attempted in La Isabella, which unsuccessfully replicated European lifeways. These colonists

lived among Taíno communities and forged exploitative alliances with them, including taking Taíno wives and creating mestizo families. They survived by learning Indigenous lifeways while ultimately maintaining their social power over the Taíno.109