issn 1757-4625

volume 11 issue 4 november 2018 issn 1757-4625 the journal of the dental technologists association

issn 1757-4625

volume 11 issue 4 november 2018 issn 1757-4625 the journal of the dental technologists association

In this issue:

Ensuring quality and safety in dental practice

Technicians’ scope of practice

Occlusion and implants

HOURS OF VERIFIED CPD

● are individually registered with the GDC to be able to use the titles that relate to our role in the UK

● maintain our own lifelong learning through relevant continuous professional development (as provided free to the Dental Technologists Association [DTA] members)

● ensure that we are covered by specific indemnity insurance related to our dental laboratory custom-made dental device manufacturing work, and if necessary, related clinical work and/or extended roles

● work within the GDC Scope of Practice for our registered role, along with other extended areas as confirmed by further additional training

● are, as a current GDC registered dental technologist, able to sign-off custom-made dental devices under MHRA/MDR regulations, indicating that such appliances are fit for purpose as stated on the Statement of Manufacture

● maintain and develop our dental team networks to enhance patient care

Editor: Derek Pearson

t: 07866 121597

Advertising: Rebecca Kinahan

t: 01242 461 931

e: info@dta-uk.org

DTA administration: Rebecca Kinahan Operations Coordinator

Address: PO Box 1318, Cheltenham GL50 9EA

Telephone: 01242 461 931

Email: info@dta-uk.org Web: www.dta-uk.org

Stay connected: @DentalTechnologists Association

@The_DTA @dentaltechnologists association

Dental Technologists Association (DTA)

DTA Council:

Joanne Stevenson President Chris Fielding

Deputy President

Tony Griffin Treasurer Delroy Reeves DTA Liaison Delegate

Joanne Clark, James Green, Raya Karaganeva, Robert Leggett, Patricia MacRory and Jade Ritch.

Editorial panel: Tony Griffin Joanne Stevenson

Editorial assistant: Dr Keith Winwood

DTA Column

A Poppy Dunton: A dental therapist’s unexpected journey A Another Dental Tip: Occlusion and implants – Chris Turner

A Raising Concerns – Kevin Lewis

A Stress – Part II – Management Strategies – Tracey O’Keeffe

A The AI in Dentistry Debate

A From Molars to Manes – Meet the dental therapist who treats lions in South Africa

A Who should I report unregulated dental technology to? – Anthony Griffin A Scope of Practice for Dental Technicians: Knowledge, Attitudes and Future Views: Part One – Ella Cook

Corus Byrnes’ “digital leap” with Carbon 3D Printing – Ashley Byrne

ISSN: 1757-4625 Views and opinions expressed in

The DTA Council is set to convene on Saturday, 8th November 2025, at 09:30. This meeting will be an important event where our key focuses for 2026 will be discussed and set.

The agenda includes several significant items for discussion and decision. Among the highlights are the Treasurer’s Finance Report for 2024/25, and the 2025/26 budget proposal. These financial discussions will be led by Tony Griffin, the Treasurer.

Stay tuned for more updates following the meeting.

A If you would like to get more involved with your association and gain a better understanding about how it is run, please register your interest in taking up a Council position.

The DTA annual member survey is now open. Your feedback shapes our products and services for Dental Technologists.

Complete the online survey by January 30, 2026, for a chance to win a £100 Amazon voucher—just scan the QR code on the front cover or on this page. If you can’t access the online version, use the paper copy inserted in this issue and return it in the pre-paid envelope.

The DTA management team has decided to keep the 2026 subscription fee at £125 for a 12-month membership.

We are deeply concerned about the University of Aberdeen’s proposal to suspend student intake for the Diploma in Dental Technology (DT) programme for the 2025/26 and 2026/27 academic years. The decision is based on economic planning and low student numbers. Although we are worried about the impact such a move might have on both dental technology education and the availability of qualified dental technicians in Scotland, we are also encouraged by the University’s commitment to support its current students and its proactive approach towards developing new education and training pathways for dental technicians.

At the Dental Technologists Association (DTA) we are deeply concerned by the growing number of dental technology training programmes across the UK that are facing closure or suspension.

In recent months, announcements of closure have emerged regarding three separate institutions – although we have been informed that, as yet, no final decisions have been formally confirmed.

The DTA has made strong representations to educational bodies and Dental Officers regarding the plight and difficulties that some dental technology training establishments are undergoing if they are to remain financially viable. In the current financial and political climate, we have not seen any major support for the profession. With numbers of registered dental technicians steadily decreasing we have to ask where the next generation of these oral healthcare team members will come from?

Are we going to see colleagues working in a closed in-surgery shop where the Dentist keeps their own good dental technicians to themselves and strive to not share the vital skills of those dental technicians with others in the profession?

The government has updated the Skilled Worker visa which tightens the restrictions around eligibility.

As of 22 July 2025, certain dental roles, including dental technicians, dental hygienists and dental nurses are no longer eligible for the Skilled Worker or Health and

Recently, we have been made aware of the significant pressures facing other education centres. For instance, in Northern Ireland, Pearson has announced the withdrawal of the BTEC Level 3 Dental Technology programme, which until now they had continued to offer. Furthermore, it has come to our notice that another Dental Technology programme in England is now under serious review. We have already mentioned the University of Aberdeen’s potential suspension of its Dental Technology provision for one or two years due to insufficient student numbers.

The DTA warns that these developments represent a critical threat to the future of our dental technology workforce and is sure to impact oral healthcare throughout the UK. Dental technicians are an essential part of the oral healthcare team, working behind the scenes to provide patients with essential custom-made dental devices such as dentures, crowns, bridges and orthodontic appliances.

Without a sustainable escalator of training opportunities, the UK risks a shortage of skilled professionals who are able to support patient care. There is no formal advertising of the professional role of dental technicians, and the public are almost totally unaware of the essential role these

members of the Oral Health Care team carry out. DTA President Joanne Stevenson said: “The closure or suspension of three training pathways in such a short space of time is an alarming signal that dental technology education is in crisis. Dental technicians play a vital role in maintaining oral health for the public, yet there is insufficient national recognition or support towards sustaining the workforce. Without urgent intervention, patient care will suffer.” The DTA is calling on government, regulators, senior Oral Healthcare managers and education providers to:

A Safeguard existing training programmes and ensure stability for students and staff.

A Develop new, nationally supported pathways into the profession to both widen access to education facilities and improve the attraction of dental technology as a career option.

A Recognise dental technology as a critical part of oral healthcare planning, not an afterthought.

A The Dental Technologist Association stresses that the future of the dental technology profession – and, by extension, safe and timely quality patient care – is at risk. It requires immediate action at a national level, and it requires it urgently. The time to act is now!

Care Worker visas. These roles no longer meet the updated skill threshold (now RQF Level 6, equivalent to a degree). They are

also not included on either the Immigration Salary List or the Temporary Shortage List.

At the DTA we understand the importance of maintaining both physical and mental health. That’s why we’re excited to introduce our Health and Wellbeing Hub, which has been designed to support our members across every aspect of their wellbeing.

Our Health and Wellbeing Hub covers a range of essential topics, including stress awareness, financial health, staying motivated, and happiness at work. Each month, we provide updates and new content to keep you informed and engaged. Whether you’re looking for tips on managing stress, advice on financial planning, or ways to stay motivated in your professional life, our hub has something for you. In addition to valuable articles and resources, our

members have access to 24/7 wellbeing support, including a free confidential counselling helpline. This service is here to provide you with the support you need, whenever you need it.

Join us in prioritising your health and wellbeing. Explore the Health and Wellbeing Hub today and take the first step towards a healthier, happier you.

Lifestyle vouchers can be redeemed online, in-store or both depending on the retailer. This gives you the full flexibility you need to choose your redemption method while also maximising your savings. Vouchers can be split and spent across multiple big brand names. Lifestyle gives you the most choice of retailers, all in one place.

A Prof. Grant McIntyre Defends Fluoride Safety – Professor Grant McIntyre – The Technologist February 2025

As a valued member of the DTA, we encourage you to raise awareness of dental technology (DT) as a profession at careers fairs for school leavers. By sharing your passion and knowledge about DT, you can inspire the next generation to consider this rewarding career path. If you need any resources, please don’t hesitate to contact the DTA for presentations or flyers to help promote DT to school leavers. Your efforts can make a significant difference in shaping the future of our profession.

We are calling on all dental technicians who have qualified in the past three years to share their inspiring stories! We want to hear about what sparked your interest in a career in dental technology, the courses you took, how you gained valuable experience, and the job situation you are currently involved with. Your career journey can motivate and guide aspiring dental technicians. If you are interested in sharing your story, please email us to info@dtauk.org. And if you’re feeling particularly creative, consider creating a ‘Day in the Life’ reel. Your experiences will prove invaluable in promoting and advancing the cause of our profession.

Are You Bullied at

- Pamela A.

– The Technologist February 2025 A Living and working with change Part 2: Generational change - Kevin Lewis –The Technologist February 2025

A Octopus Sucker Denture Fix – Dr Eda Dzinovic – The Technologist February 2025

The DTA office will be closed over the festive period from Friday 19th December at 1.00pm and will reopen on Monday 5th January 2026 at 9.00am.

If your membership renewal is due during this time and you need to make any changes, please send an email to info@dtauk.org prior to 5th December 2025 in order to provide our team with sufficient time to deal with your request.

We send monthly newsletters and Rewards emails – if you’re not receiving them, check your spam folder to ensure you don’t miss any discounts or important updates.

A North of England Dentistry Show Manchester Central Convention Complex | 7 March 2026

A BDIA Dental Showcase

ExCeL London | Friday, March 13, 2026Saturday, March 14, 2026

A Dental Technology Showcase (DTS) 2026 NEC Birmingham | Friday 15thSaturday 16th May 2026

As part of The Technologist’s ongoing introduction to key figures in the dental profession, we meet Poppy Dunton, the newly appointed Chair of the College of General Dentistry’s Faculty of Dental Hygiene and Dental Therapy. Here she reflects on her career in dentistry and how her mantra that “every day is a school day” has supported her development.

Never would I have expected to have the career that I have had out of dentistry. I was a disgruntled 15-year-old being told my graphic design two-week work placement had pulled out. With everyone else having picked their placements, I was left with the unexpected choice of a dental practice.

“A dental practice! You’ve got to be joking?” I initially thought. Yet, as I made cups of tea and filed blue forms, the hustle and bustle of the place felt surprisingly comfortable. To say I enjoyed it was an understatement.

As the two-week period ended, the principal dentist offered me a part-time after-school job – making tea and cleaning the old impression trays (pre-single use era), and earning £3.15 per hour. I jumped at the chance, feeling like I was made of money. Every day after school, I would walk and do my 4pm–6.30pm shift.

When a trial day at Northampton College for photography didn’t sit right with me, I informed the principal dentist that evening. My father was called in for a meeting, and that’s when the principal dentist said, “I’ll only give her a job here, Graham, if she makes something of her life.” That evening became the catalyst for my passion in dentistry.

The evolution of my career is intricately tied to a commitment to education. I embarked on an evening college course, alongside my apprenticeship, to train to become a dental nurse. Tuesday evenings in Milton Keynes led to passing the NEBDN Certificate in Dental Nursing. Once I had this, I spent the following months learning as much as possible – four-handed dentistry, impression taking, and implant nursing. The practice grew, and another was bought over the road, giving me the chance to set up an oral hygiene programme.

A Age UK Advice for an ageing dental technologist workforce – DTA/Caroline Abrahams – The Technologist February 2025

A Alternatives – Dr Chris Turner –The Technologist February 2025

A Healthwatch England Priorities for Patient Access - Rebecca Curtayne –The Technologist February 2025

Following my return from Cardiff University, where I completed a Diploma in Dental Hygiene and Dental Therapy, I was privileged enough to be offered my job back in the practice where I had started. The first week was a week to remember; I ran an hour late, fell down the stairs, and stuck two teeth together. I had the most patient mentors, and working in an NHS practice was fantastic, allowing me to complete my full scope of practice, including paediatrics. Was it hard? Yes. Did it teach me speed and resilience? Absolutely.

After graduating in 2012, there were limited postgraduate options. Notable pursuits included constantly upskilling and working in a team supportive of therapists.

Composite courses with GC in Belgium, a Level 6 qualification in employment law, and being promoted to operations manager of two NHS practices – eventually managing a team of 64 staff – led to me being offered a practice manager position four years into my career. This opened learning about people psychology, leadership and planning team meetings alongside my clinical career.

I was privileged enough to then open a squat practice alongside my principal, with a business plan for two surgeries over two years which resulted in 10 surgeries being opened over five years, including a vaccination clinic. Three CQC inspections later, and the role of CQC manager was also added to my repertoire. The most rewarding part of project managing the development of this new practice was recruiting a group of individual dental professionals and watching them grow into a wonderful team.

Upon completing the Perio School Diploma in Periodontics for Hygienists and Therapists and the Smile Dental Academy Diploma in Restorative and Aesthetic Dentistry for Dental Therapists, I was introduced to the College of General Dentistry and was eager to explore the recognition I could gain as a dental therapist. Unfortunately, the course credits were not enough per course to

contribute towards Fellowship, so I joined the College’s Certified Membership Scheme (CMS) to gain guidance on how to continue advancing my career and choose the best postgraduate training to reflect my aspirations. As part of the scheme, I have regular contact with a facilitator who consistently ensures that my investment in courses leads me in the correct direction.

Ongoing self-reflection allows me to constantly critique myself, and the leadership module fits well with my management of staff, completing practice meetings and public speaking. Being part of the CMS has supported me to complete a City & Guilds Diploma / ILM Level 5 Diploma in Leadership and Management by enabling me to choose an appropriate course and help develop leadership qualities.

The College’s Professional Framework, which underpins the CMS, maps 22 key capabilities, many of which have played a crucial role in my journey. Emphasising the value of postgraduate education, I would encourage new graduates to embrace opportunities for further learning and to constantly be self-critical of their work. Recording self-reflection, taking photographs, and analysing what went well in each case, shadowing peers, or approaching colleagues for their opinions are essential. Don’t fear failure; it’s what makes you better.

In my experience, this profession can be challenging and, at times, isolating. There are days when running late, neglecting notes, skipping meals and even necessities like restroom breaks become the norm. The toll on one’s body—back pain, eye strain, and hand fatigue—can be significant. Looking after your long-term career is vital. Record-keeping has been one of the largest changes I’ve seen, starting in my early career with very short notes. Now, ensuring my conversations with patients are highlights in notes, and my nurses help and scribe during appointments. This has proved invaluable when a complaint arises. Protecting yourself is vital.

The most unexpected rewards in my dental therapy role often come during these challenging moments. Patient gratitude and the joy of assisting anxious individuals through treatment illuminate the darker days.

This career has allowed me ongoing dedication to continuous learning, reflecting on my mentor’s ethos of “every day is a school day”. My commitment to education and mentorship is rooted in a desire to guide new professionals in navigating complexities while maintaining their wellbeing. In 2023, I was privileged to join the Board of the Faculty of Dental Hygiene & Dental Therapy for the College, and I am even more privileged to have now been appointed Chair.

Recently I have relocated due to family illness, and this marks the end of a significant chapter in my career, prompting reflection on the unconventional path that led me to the field of dentistry, the intricacies of managing a bustling practice, combined with the personal growth and educational pursuits that defined my journey. Alongside all early career dental professionals, I continue to embrace new challenges and aspirations, remaining steadfast in my commitment to contributing positively to the ever-evolving world of dental therapy.

A Further details of Poppy’s career to date, and of the role of the Chair of the Board of the Faculty of Dental Hygiene and Dental Therapy, are available at https://cgdent.uk/news

Chris Turner, MSc, BDS, MDS, FDSRCS, FCGDent, QDR Specialist in Restorative Dentistry (Rtd)

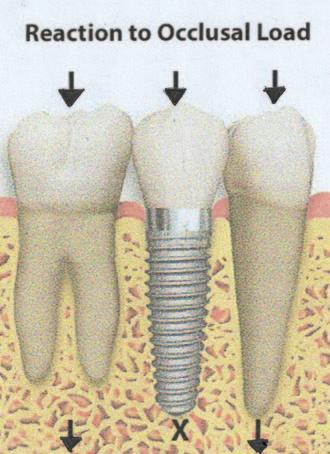

In respect of implants, it is essential to have a stable occlusion either before the placement of implants as is the case when restoring occasional spaces in the dentition, or when more extensive restorations are required and to have planned the expected occlusal outcome.

The requirement is always to achieve ‘the physiological position for the reconstruction of the occlusion is when both condyles are in the highest point in the glenoid fossa when the head is upright and when the vertical dimension is correct’ (Gerber, 1966). In other words, to achieve centric occlusion at centric jaw relation.

We know that implants function best when occlusal loads are applied in the long axis of the tooth, and that for dentate patients,’ mandibular velocity is greater with group function than a canine protected occlusion’ (Jemt et al, 2004). This suggests that greater

loads are placed on these teeth. Manging occlusal forces is critical to the longevity of dental implants. Looking at dentate patients further we need to understand how normal occlusion works.

When chewing, the first contact of natural teeth is a gentle touch followed by further contraction of the muscles of mastication into centric occlusion, maximum intercuspation.

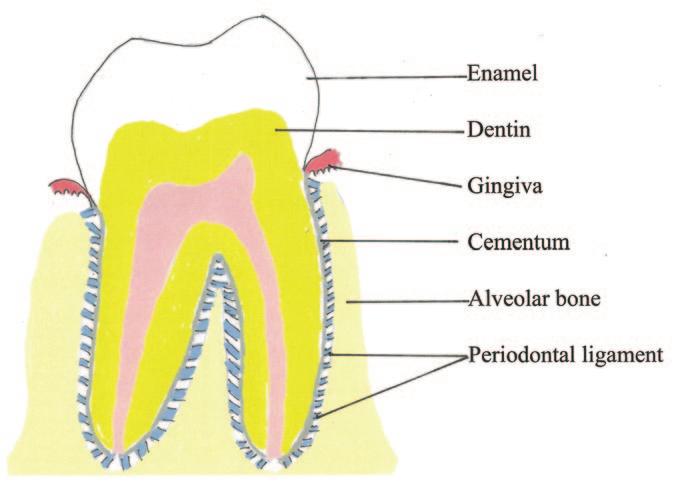

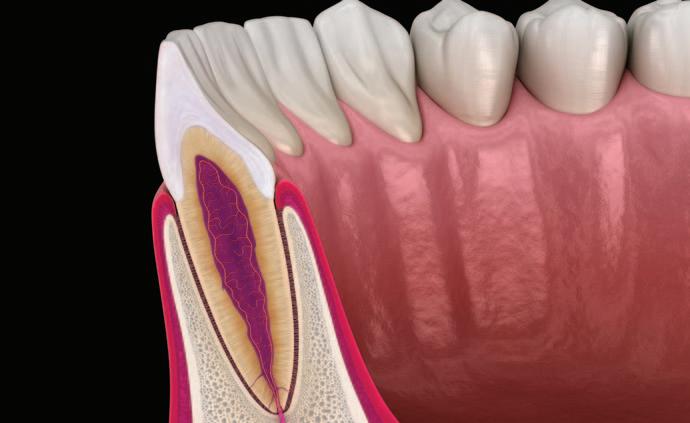

This is dependent upon the elasticity of the periodontal ligament and as such means that the natural teeth intrude into the alveolar bone by a small amount and then rebound. However, implants are osseointegrated into the alveolar bone and have no rebound capacity and therefore can be in a traumatic occlusion leading to bone loss and the increased risk of developing peri-implantitis as the anatomy of the gingival cuff changes.

Aims:

■

■

1 Is a specialised connective tissue principally made up of collagenous fibroblasts, 45-55 nm in diameter, whose vitality and completeness is critical in a healthy functioning tooth. Its average width is from 0.15 to 0.38mm.

2 PDL fibres are arranged in directions that reflect their functional properties that vary in different parts of the root depending on whether the tooth is single or multirooted.

3 Fibre directions have been described as horizontal, oblique, alveolar crestal and trans-septal.

4 It functions to transmit and absorb mechanical stresses acting as a natural shock absorber between bone and cementum.

5 Provides a vascular supply to itself, cementum and alveolar bone.

6 Is attached into cementum by Sharpey’s fibres.

7 Has proprioceptive nerve endings to provide biofeedback as teeth touch in occlusion.

8 Osteoblasts and osteoclasts reside in the PDL on the surface of the lamina dura and in endosteal surfaces of the alveolar bone and are also responsive to mechanical stress.

9 The PDL width is not uniform varying along the length of the root and decreases with age.

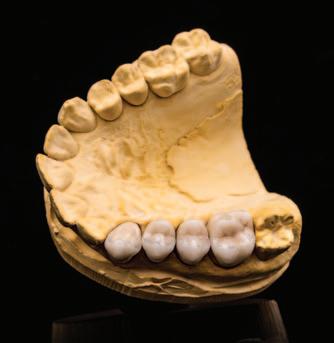

It follows that if implant crowns are made in the laboratory in the usual way with contacts between crowns and opposing teeth, they can be in traumatic occlusion when placed in the mouth and screwed or cemented into position using the normal techniques with articulating paper and asking patients to bite together, followed, if necessary, by occlusal adjustments by selective grinding. But, articulating paper varies in thickness depending on the manufacturer from 20 to 200 microns. This is far too thick for accuracy when reviewing implant occlusal interferences.

Is this traditional, unrefined approach a factor in implant failure or the loosening of implant screw retainers?

In my experience and opinion, we have to think again about how the occlusion is checked for implants placed in dentate patients and take cognisance of the importance of the PDL in normal chewing patterns and its elasticity and rebound, without which natural teeth themselves would fracture.

I ask my technician to place a thin layer of foil, well burnished down on any opposing tooth or teeth on working models made from full mouth impressions taken with great care in metal trays by either rubbing

alginate into the occlusal surfaces before placing the rest of the impression material, or by syringing elastomeric impression material into these surfaces before placing the tray in order to achieve working models with no blows on their surfaces and therefore, causing an inbuilt inaccuracy. It is essential that the foil does not increase the occlusal vertical dimension. Technicians will have to learn this new approach.

I suggest that these cases as a routine should be mounted on semi-adjustable articulators having taken facebow records and created customised incisal guidance tables.

In this way, the crown, when it is returned for fitting, may not be in traumatic occlusion

Additional requirements

You need to have available a supply of shimstock that is 8 to 13 microns thick, Kerr’s occlusal indicator wax and a pair of fine straight 6” mosquito forceps, to hold the shimstock, and a pair of fine straight scissors for example 5” iris scissors to cut the shimstock to the width of each implant crown without overlap on natural teeth.

The next are in the surgery at the chairside. Dentists have to follow these steps. Remove the temporary crowns especially if there are more than one. All must go as they are usually made of a polymeric resin that has some elasticity and may be influencing the occlusion.

Try in the crown for fit, shape, aesthetics and contact points, looking especially at the emergence angle. Is the crown too bulky? Will it be difficult for your patient to control their plaque around it?

If the crown passes the above four tests move on to checking the occlusion. Centric occlusion at centric jaw relation is the first place to test. Place a trimmed piece of shimstock in the mosquito forceps, place it on the tooth and hand the instrument to your nurse.

As you are sitting behind the patient place your hands gently under the mandible, as if you are going to carry out a Dawson manoeuvre, a manoeuvre more accurately called Dawson’s Bimanual Manipulation. This is a dental technique developed by Dr Peter Dawson to help register the jaw’s centric relation (CR) position – the jaw’s most posterior and superior position against the maxilla.

Sit behind the patient. Then, using all eight fingers, four on each side placed under the mandible, a dentist gently manipulates the

mandible while the patient relaxes, allowing the condyles to move into their correct physiologic position within the joint. This accurate CR registration is essential for the precise construction of prosthetic devices and for diagnosing and treating complex occlusal problems.

Then ask your patient to close their teeth very gently until they just touch. If the spacing is correct your nurse should then be able to slowly pull out the shimstock. Then replace the shimstock.

This time ask your patient to close to the just touching position and then close further until the teeth are touching with the PDL therefore in function. The shimstock should then be held in place and not removeable.

I must stress the need to hold the mandible as above. You can then feel under your

fingertips if your patient is following instructions. It does take practice and a gentle touch.

The next step for this tooth is to test with green occlusal indicator wax. This material:

1 verifies occlusal clearance.

2 Identifies premature contacts.

3 Ensures balance occlusion.

Place a piece over the crown in question and ask your patient to close their teeth together as though they were biting into a small piece of food. Again, feel what they are doing. When you remove the occlusal indicator wax and hold it up to the light you should see either a very thin area of just a small area of perforation. This means that there is just contact in centric occlusion and that opposing teeth are unlikely to over-erupt which will upset the occlusal balance. If you can, take a photograph for your records.

Next, for group function occlusions check border movements. I prefer indicator wax for this too, and adjust according to the BULL rule, which stands for “Buccal Upper, Lingual Lower” and is a guideline for correcting premature contacts during the working side movements of the jaw. When you are fully satisfied that the occlusion is correct, either cement the crown in place (and this can disrupt the occlusion you have so carefully checked) or torque down the

retaining screw to the manufacturer’s recommended pressure.

I usually than complete that restoration by sealing the screw access hole with composite resin, then check the occlusion again, just in case I have placed an excessive amount.

Now you can move on to the next crown and repeat the process if necessary. The rule is quite simple, one tooth at a time. Then, when the case is completed, go back and check the other crowns too.

I know this can be time consuming. You want to make sure that you have taken every precaution to establish the best occlusion possible on your implant crowns

and have proof that you have done so, just in case there is a complaint. Check, check, and check again and recall patients and check again etc. If periimplantitis starts to develop then both oral hygiene and occlusion could be a factor.

To complete your CPD, store your records and print a certificate, please visit www.dta-uk.org and log in using your member details.

Q1 According to the author, when do implants function best?

A Within the first three years of placement

B When occlusion loads in the long axis of the teeth

C When osseointegration is completed

D When an effective hygiene regime is followed after placement

Q2 When chewing, the first contact of natural teeth is described as what?

A Lingual upper to buccal lower

B A grinding side-to-side motion

C A light touch

D Occlusal force based on food being chewed

Q3 What is the average width of a periodontal ligament?

A 0.15 to 0.38mm B 0.20 to 0.42mm

C 0.12 to 0.23mm D 0.22 to 0.37mm

Q4 What is described as the periodontal ligament’s function?

A Avoiding friction between tooth and alveolar bone

B Acts as a cushion for the tooth in the socket

C As a natural shock-absorber between bone and cementum

D To provide blood to the cementum

Q5 Where would Dr Turner ask his dental technician to place a thin layer of foil on working models made from full mouth impressions?

A At the tooth’s margins for greater precision

B In the sockets to make disassembly easier

C At the centre line to make measurements easier

D On any opposing tooth or teeth

Q6 What thickness of shimstock do you need to check occlusion?

A 6 to 11 microns B 8 to 13 microns

C 9 to 16 microns D 11 to 18 microns

Q7 How many stages/tests must be completed before moving on to the occlusion?

A Two B Three C Four

D None, the occlusion should be checked throughout the procedure

Q8 What is the purpose of the Dawson manoeuvre?

A It helps calm nervous patients

B It keeps the patient’s jaw steady while taking an impression

C It helps the clinician judge the patient’s temporomandibular position

D It helps register the jaw’s centric relation position

Q9 What does the BULL rule stand for?

A Bite Under Load Labially

B Buccal Upper, Lingual Lower

C Bite Under Lateral Load

D Buccal Upper Laminal Layer

Q10 If peri-implantitis develops what might be a factor?

A Patient’s oral hygiene B Existing bruxism

C Occlusion D a) and c) only

In memory of Kevin Lewis, a great friend to the DTA and valued contributor to The Technologist over many years, over the next two issues we are republishing an article he wrote about raising concerns – but with new CPD questions.

Kevin was a true gentleman who passed away on the 30th July 2025 at the age of 76 after a long battle with liver cancer. He will be missed.

Kevin Lewis, BDS (Lond) LDSRCS

This article is being split across two consecutive issues. In this issue the first part will consider the principles of when and how to raise concerns (especially when they relate to other healthcare professionals), and in the next issue the second part will turn to the question of ‘safeguarding’ vulnerable individuals

■ to identify the types of concern that might need to be raised

■ to improve understanding of the principles of raising concerns

■ to understand the process of raising concerns

■ to understand the additional responsibilities of employers and managers

■ to effectively communicate with patients, the dental team and others across dentistry, including when obtaining consent, dealing with complaints, and raising concerns when patients are at risk

■ to effectively manage one’s self and effective management of others or effective work with others in the dental team, in the interests of patients; providing constructive leadership where appropriate

■ to maintain skills, behaviours and attitudes that maintain patient confidence in you and the dental profession and put patients’ interests first [professional behaviours]

As healthcare professionals there is a higher expectation placed upon us, compared to most other members of the population, that we will apply our extra knowledge and experience to protect members of the public both collectively and individually. In this respect we are accountable to our professional regulator, the General Dental Council (GDC).

In Standards for the Dental Team¹, the GDC sets out its expectations at Principle 8, ‘Raise concerns if patients are at risk’. The GDC explains that in circumstances which give rise to any concerns about the health, performance or behaviour of a dental professional or the environment where treatment is provided, patients have a right to expect that dental health professionals (and team members with whom they work) will act promptly to protect their safety and will also raise any relevant concerns about the welfare of vulnerable patients.

The phrase ‘raising concerns’ means different things to different people, of course, and the threshold of what qualifies as a legitimate ‘concern’ and/or what

‘raising’ actually means in practical terms, similarly varies from one person to another. It is also true that dental technicians and CDTs have a different perspective to, say, a dental nurse, hygienist or dentist –sometimes because of where they work and sometimes because of what they do and what they see.

Each group of GDC registrants therefore has a slightly different perspective and CDTs and dental technicians are no exception. But it is important to appreciate that Standards for the Dental Team applies, as the name suggests, to all dental registrants equally. When reading and reflecting upon this guidance, you need to think about and interpret each paragraph in the context of your own work environment, the work you do and the contact you have with others (whether directly or indirectly).

A laboratory-based dental technician will receive work from a variety of dentists –some they know well and some they have never met. One might form a view about the quality of the clinical work in an individual case, or a pattern of work over a number of cases, over a period of time. That

view might be coloured by considerations such as the quality of the impressions, or tooth preparations, or even the information provided in the laboratory prescription/ instructions and communications in relation to that. Other interactions with the dentist (for example, in person, or over the phone) may similarly shape your perceptions. Any of this could lead you to have concerns about a dentist’s health and wellbeing, or his/her behaviour, or their professional performance. You might receive impressions that appear not to have been disinfected, and/or see things if you ever visit the practice that might make you question other aspects of their infection control or working environment.

You may have concerns about issues ranging from a person’s mental or physical health to the abuse of alcohol and other substances that are affecting (or might be affecting) the care provided to patients. Over time, in a longstanding relationship, you may notice deterioration in standards, the possible explanation(s) for which you may or may not be aware.

On the other hand you may have similar concerns about colleagues in your own (laboratory) working environment. The GDC makes it clear that in these situations you

must speak up and raise a concern even if you are not the owner or manager, or otherwise in a position to control or influence that working environment. This can obviously be quite difficult and perhaps even an uncomfortable or intimidating prospect.

Most of us are either worried about the possible consequences of being the person who challenges or speaks out against a colleague (or manager/owner), or we feel disloyal. In an ideal world it might be possible to speak directly to the person you have concerns about, in the first instance, and to gain an insight into their point of view – but this is not likely to be possible in many situations.

Not everyone would react favourably to feedback such as this, however well intentioned. But the GDC emphasises the fact that you must not allow any personal or professional loyalties to deter you from raising legitimate concerns, when necessary, putting patient safety and the quality of their care above all other considerations.

It is natural to feel that you are in some way betraying the trust of a colleague – perhaps one that you have worked with for many years – but your first duty must be to patients, and their safety. Sometimes it is the timely intervention of a concerned and well-intentioned colleague that avoids the worsening of a situation, allows the cause to be addressed and is much more beneficial to that work colleague in the long run.

The most difficult assessment to make is often that of whether or not your concerns are genuine and justified, and sufficient in scale to merit the involvement of other bodies. The whole point of ‘raising concerns’ is that it is not your role to investigate the concern but simply to alert an appropriate party so that they can do so, if they feel it appropriate.

Very often they will have a lot more experience than you in making that assessment, and crucially, they are independent and sufficiently removed from the situation to be able to view it fairly and objectively. One should, however, be cautious about acting upon rumour and uncorroborated ‘hearsay’ and place greater weight upon things that are within your personal first-hand knowledge and experience.

You must not raise spurious concerns as a means of settling scores or gaining a personal advantage (such as gaining leverage over the other party in a dispute over money or the non-payment of a bill). Nor should concerns be raised vexatiously i.e. brought in bad faith without sufficient grounds, purely or primarily to cause the other party embarrassment, hurt, stress, damage or annoyance.

The GDC reminds us that the fact that you raise a concern that later proves to be unfounded will not be held against you –provided that you had a reasonable justification for raising the concern. But, on the other hand, your own registration may be placed at risk if you knowingly fail to act to protect patients by not raising concerns when you should have done so.

It is often a good idea to discuss your concerns informally with a colleague who can ‘sense check’ your perceptions through a different pair of eyes, but this may not always be possible. It is obviously easier if they are a colleague you trust and respect that can understand and relate to the situation you face, but is also independent from it (perhaps because they work elsewhere). The next port of call might be your manager or employer, but this can be equally impracticable, especially if they happen to be the subject of your concern or have a longstanding relationship (or friendship) with the person you are concerned about.

Other sources of advice and guidance include:

A your professional association

A your indemnity provider/insurer

A the care and facilities inspectorate in the country where you work – the Care Quality Commission in England (CQC), Healthcare Improvement Scotland (HIS), Healthcare Inspectorate Wales (HIW) or the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA) in Northern Ireland

Ultimately you may need to involve the GDC itself if other avenues are impractical or have not resolved your concerns, or where the concerns are so obviously serious that the situation may present a clear and immediate risk to patients.

Graduated in London 1971. He spent 20 years in full time general dental practice and 10 further years practising part time. He became involved in the medico-legal field in 1989, firstly as a member of the Board of Directors of Dental Protection Limited (part of the Medical Protection Society group of companies). He became a dento-legal adviser in 1992 and from 1998 was the Dental Director of Dental Protection for 18 years and also an Executive member of the Council (Board of Directors) and Executive management team of the Medical Protection Society, roles from which he stepped down in 2016. Since 2018 he has been a Special Consultant to the British Dental Association, in relation to BDA Indemnity.

He was a Founder and Ambassador for the College of General Dentistry, and was a Trustee Board member 2017-22

Kevin has been writing a regular column in the UK dental press since 1981 –originally as the Associate Editor of Dental Practice and since 2006 as the Consultant Editor of Dentistry magazine. He wrote and lectured regularly in the UK and internationally, and had been awarded honorary membership of the British, Irish and New Zealand Dental Associations. Kevin also became an Honorary Member of the British Society for Restorative Dentistry.

You should have a written policy in your workplace and ensure that all members of your staff are aware of it and follow it consistently. This policy should set out the process to be followed in the event of concerns being raised and you should keep a record of the concerns raised, what action you took, and what the outcome was.

The ‘culture’ of any organisation is shaped by the people at the top, and it is healthy if people feel able to raise concerns constructively, without fear of the consequences. It also reflects well on your leadership and the example you set if they feel able to raise concerns or make suggestions for improvements in a business that you run or the work that you do.

It doesn’t make it feel any better or more welcome at the time but giving wellintentioned, blame-free feedback is ultimately brave and admirable, constructive and valuable – especially if it’s justified and acted upon.

If, on the other hand, you have concerns about the health, behaviour or performance of someone that you employ, you must have systems in place to flag up those concerns, discuss them with the person in question, make further enquiries to satisfy yourself as to the nature and scale of the issues, and then decide whether the issues lend themselves to being managed and monitored in-house, or whether they are so serious that you need to take advice from others and/or raise concerns formally to an external body (including, where necessary, the GDC). You must not allow personal or commercial interests (such as adverse publicity for your business) to deter you from doing what is necessary in the interest of patients and the public.

The issue of ‘raising concerns’ is quite emotive. People who are younger and/or in the early years of their career in and around healthcare, generally find the principle

much easier to understand and accept because they have grown up in that milieu and it is the only professional working environment they have known. Older colleagues, who remember the days when it was considered unethical to criticise or ‘point the finger’ at a colleague, let alone report them to the GDC, tend to be much more uncomfortable.

But the situation was changed for ever by a succession of medical scandals from the horrific case of Harold Shipman and his exploits through the 1970s–1990s, to the Bristol paediatric cardiology cases in the 1980s and 1990s and the ensuing recommendations in the 2001 Kennedy Report², to the catalogue of hospital failings at Mid-Staffs identified in the Francis Report³ in 2013. More recently the case of the surgeon Ian Paterson4 who carried out hundreds of unnecessary breast surgery procedures both within the NHS and privately in the Spire Hospital group.

A recurring theme was that people and organisations in healthcare (and beyond) knew things or suspected things but did nothing about it. They had concerns but didn’t feel able to voice them. They didn’t want to be the person who put their head above the parapet.

The intention of the modern arrangements is to put patients and their safety and welfare first, being fair and supportive to colleagues in need, but also proactive in identifying and hopefully remedying issues at a low level before they escalate to something more serious.

Unfortunately there is some truth in the proposition that ‘whistleblowing’ has increasingly become used by a small minority as a convenient ‘cover’ to legitimise actions being taken against a colleague (or former colleague) with whom there has been a dispute, competing interests, professional friction or jealousy.

Such unworthy actions and the selfcentred motives driving them become glaringly obvious once any investigation takes place and paradoxically they can end up softening the impact of the allegations while raising separate concerns about the perpetrator of the criticisms. Organisations such as the GDC get plenty of opportunity to distinguish the genuine from the malicious – and they also have the power to take appropriate action against people who are abusing the process of ‘raising concerns’.

The second of these two linked articles will appear in the next issue, and will look at ‘Safeguarding’ i.e. raising concerns about the health, safety and welfare of vulnerable patients and other individuals.

Notes

1 Standards for the Dental Team. General Dental Council: www.gdc-uk.org

2 Learning from Bristol. The Report of the Public Inquiry into Children’s Heart Surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995: http://www.uhbristol.nhs.uk %2Fmedia%2F2930210%2Fthe_report_o f_the_independent_review_of_childrens _cardiac_services_in_bristol.pdf

3 Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: executive summary. February 2013. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk% 2Fgovernment%2Fuploads%2Fsystem% 2Fuploads%2Fattachment_data%2Ffile% 2F279124%2F0947.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0yP rVKPTpXyhZdbctMdjeB

4 Independent Inquiry into the Issues Raised by Paterson: www.paterson inquiry.org.uk/terms-of-reference

To complete your CPD, store your records and print a certificate, please visit www.dta-uk.org and log in using your member details.

Q1 In the GDC Standards for the Dental Team, under which Principal does it advise “Raise concerns if patients are at risk”?

A Principal 5

B Principal 8

C Principal 11

D Principal 3

Q2 According to the author, which of the following examples might cause a dental technician to have concerns about a client dentist’s health and well-being?

A They seem to have a persistent cough

B They are often angry and bad tempered

C They voice opinions the dental technician does not agree with

D They provide a dental impression that appears not to have been disinfected

Q3 Who should raise concerns about the behaviour of colleagues in the working environment?

A Any member of the team who has valid concerns

B Only the owner

C Only the manager

D Only those in a position of control or influence

Q4 What does the GDC insist must be put above all other considerations?

A Honesty, transparency, and candour

B Respect for others and professional standards

C Patient safety and the quality of their care

D Only working with properly registered colleagues

Q5 What is listed as the “point” of raising a concern?

A To put the guilty party in the spotlight

B To comply with GDC registration requirements

C To alert an appropriate party

D To calm the reporter’s concerns

Q6 When raising a concern, on what should you place the “greater weight”?

A Personal first-hand knowledge and experience

B What you have heard others discussing

C When it is common knowledge that you’ve heard

D You’re not sure but the gossip worries you

Q7 When must you not raise “spurious concerns”

A For settling scores

B To gain leverage in a dispute over money

C Vexatiously without sufficient grounds

D To cause the other party hurt and stress – and all of the above

Q8 What happens if you raise concerns that later prove unfounded?

A You can appear before a fitness to practice procedure

B You can be prosecuted for defamation

C You can receive a written warning and be put on probation for up to a year

D Nothing if you had reasonable justification

Q9 What might happen if you knowingly fail to act to protect patients by raising concerns?

A Your own registration might be put at risk

B It is unlikely to be noticed if you keep quiet

C You are not the guilty party, so nothing

D It will be acceptable if you add your concerns after the event to those raised by others

Q10 When might you need to involve the GDC itself regarding your concerns?

A Immediately, no matter how slight the case

B Where the concerns are so serious there is a clear and immediate risk to patients

C When you have written or photographic evidence

D When the person causing concerns has threatened you personally

Tracey O’Keeffe, Coach Practitioner and Mindfulness Teacher MA (Education), BSc (Critical Care), RN, MAFHP, MCFHP

This is the second follow-up paper exploring stress. Having examined how the body and mind reacts in stressful situations, this article now moves into understanding how we can help to manage those experiences in a healthier way. Stress exists for everyone as it is just a reaction enabling a move away from a current state or as a means to recreate balance. That trigger may be something positive or negative, acute or chronic, but the mechanism that follows is non-specific (Seyle 1065). Essentially, recognising when the effect is becoming overwhelming or damaging means we can then initiate management strategies to promote positive well-being.

Bautista et al. (2023, p.1) describe the complexity of well-being highlighting the variances in the way it is seen and portrayed. However, they suggest it is often reflected by a state of “wellness, health, happiness, and satisfaction”. However, definitions will change depending on the context and focus, with physical well-being feeling different to psychological, social or economic well-being. This reflects the World Health Organization (2023) definition of health as “a complete state of mental, physical and social well-being; not merely

the absence of disease”. Therefore, wellbeing could be seen holistically, mirroring the Biopsychosocial Model of health (Engel 1977). Stress has the power to influence any of these areas, occurring within the biological, social or psychological dimensions of the individual, and affecting any or all of those areas. Whilst this adds layers of potential difficulty, it also creates opportunity to approach coping and positive management of the stress response through a variety of lenses tailored to the person and the situation. Consideration here can be both reactive (dealing with the stress once it arrives) but also more “upstream” and proactive (creating habits that promote well-being). Essentially, this means working towards a healthier lifestyle that allows us to respond rather than react to stress.

Although there is overlap into social and psychological elements, this section predominantly focuses on factors of selfcare and health promotion from a physical perspective. It will explore three key areas: sleep, diet and exercise (movement).

Sleep disturbance is relatively common with over one third of people stating they have some issue with sleep (Kerkhof 2017; Ohayon 2011). There are clear links between stress and sleep and this seems to be a bidirectional relationship reflecting that of physical and mental health (Clew 2016); not sleeping can create stress, but stress can also create problems with sleep. Either way, the impact can affect the whole person, exacerbating physical symptoms but also impacting emotional regulation (Scott et al.

2021) (see Figure 1). Yu et al. (2025) discuss the complex nature of stress and sleep, suggesting that stressor intensity and duration can in fact cause limited and disrupted sleep or indeed promote sleep. This is related to a concept called sleep reactivity (Drake et al. 2013) which can be considered a human trait which influences the person’s response to stress. Kalmbach et al. (2018) explain that those with a higher sleep reactivity notice more deterioration in sleep when stressed. However, conversely, those with low sleep reactivity sleep well when stressed. Stress-induced sleep (perhaps that innate need to block out the stress), has also been shown to have some benefits including increased resilience, improved processing of emotional events and alleviation of anxiety. As humans, particularly with higher sleep reactivity, this can be difficult due to over-thinking, intrusive thoughts and worry related to the original stressor ( Yu et al. 2025).

Targeting the right amount of sleep can be difficult as it does vary from person to person. However, Suni and Singh (2023) advocate a full 7 hours for most adults. Working through sleep problems can be supported by what the NHS (2023a) call sleep hygiene. The concept here focuses on routine and an appropriate sleep space. Regular timings for sleep (bedtime and rise time), plus a technology free slot prior to bed, can help to facilitate sleep.

Furthermore, limited caffeine and alcohol can prevent wakefulness or reduced sleep quality respectively. A cool room, plus proper darkness can also support positive sleep cycles which result in waking more refreshed and rested.

Bremner et al. (2020) suggest that links between diet and stress are evident but still in infancy in terms of proven research. The overall picture is quite complex, but there once again appears to be a bi-directional link between diet and stress. Furthermore, diet can be seen as a modifiable risk factor which may be helpful with relative low risk (Wildgust et al. 2010) and the benefits of

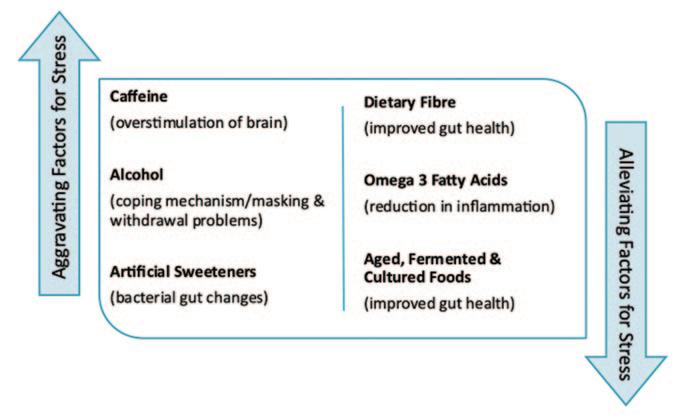

change could reach both physical and mental health (Mental Health Foundation 2017). Some dietary approaches (such as a Mediterranean diet) can positively influence overall health as well as gut microbiome and the immune system (Firth et al. 2020). Probiotic foods and foods high in fibre support digestion and can help avoid erratic blood sugar which can result in lethargy, depression and irritability (Mind 2023), thereby stabilising mood. Naidoo (2020) suggests three main aggravating groups and three main alleviating groups in terms of diet and stress (see Figure 2) and these could be areas addressed relatively easily for most people.

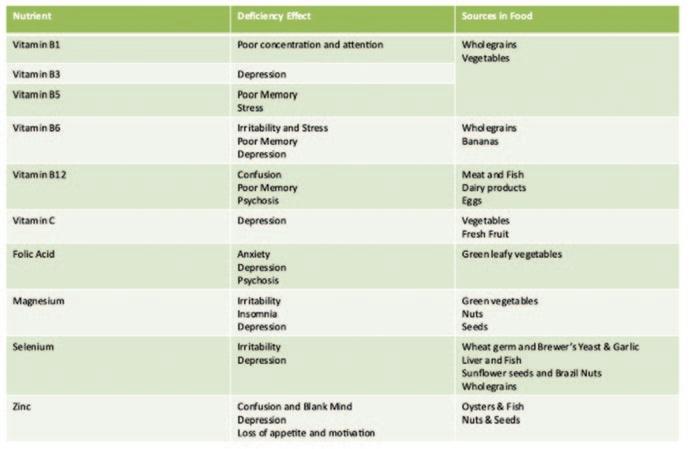

As well as considering specifics like this, it is worth noting that a good diet consists of two elements: balance and nutrition (Mental Health Foundation 2017). This means eating a variety of foods in appropriate proportions. Eating habits like timings, patterns, and motivation, can be explored alongside calorie intake and quality of food, including heavy processing or over-use of pesticides. By using a sensible approach, all the main food groups can be included with some (like protein and healthy fats) being instrumental in brain function (Mind 2023). Furthermore, a varied and balanced diet will ensure inclusion of the micro elements which influence mood and mental health (Holford 2003) (see Figure 3 overleaf).

As well as being a physical and mental distraction from stress (Peluso and Andrade 2005), exercise can also improve the efficiency and connectivity of the brain neural pathways. Smith and Mervin (2021) suggest that the involvement of increased dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin results in changes to the neurotransmitter pathways. They also highlight the ability of the brain to grow and change through neuroplasticity, with exercise providing a meaningful and rewarding activity.

The result is that there may be increased emotional regulation when facing future challenges. Intensity may also be important, with aerobic exercise improving blood circulation to the brain (Guskowska 2004), and the increased intensity may actually mimic anxiety and stress. With exercise being undertaken in a safe, non-threatening environment, the individual can learn to develop coping mechanisms which can be used when experiencing similar feelings due to psychological pressures (Smith and Mervin 2021). Communication channels between different cerebral areas develop adjustments in these situations too, and this includes the stress response centre (amygdala) as well as mood, motivation and memory areas (hippocampus and limbic system).

The recommended amount to undertake is 30 minutes of moderate intensity exercise 3 times a week (Sharma et al. 2006), but this will be dependant on individual ability and opportunity.

It is important to note that any movement away from a sedentary lifestyle is beneficial and this can also be incorporated in to daily activities or social experiences.

Psychological and emotional wellbeing can be considered by exploring positive psychology and the utilisation of coping strategies.

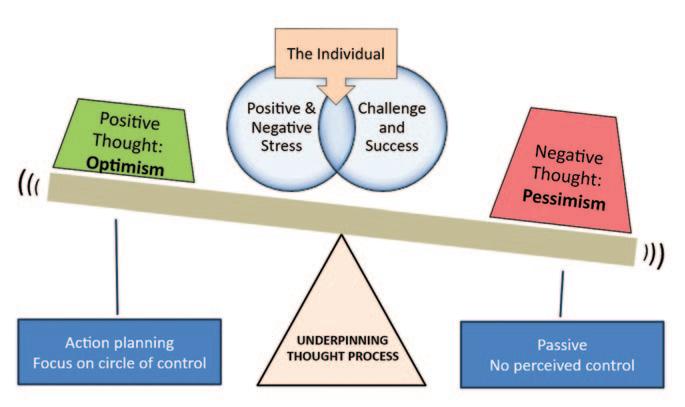

The focus of positive psychology is the recognition of strengths which foster positive thoughts providing purpose and meaning to life. It was originally introduced by Martin Seligman who highlighted the importance of emotions such as hope, courage and perseverance (Psychology Today 2023). Underpinning this is the concept of optimism and pessimism, and the way these can affect the perception of life events with associated adaptation (Das et al. 2020). With positivity can come increased resilience in the face of stress (Cherry 2020) and this is supported by an inner sense of control and empowerment held by the individual to influence and action plan accordingly. Ultimately, this can tip the balance towards proactivity in stressful circumstances (see Figure 4).

Although personality traits like optimism, extraversion, high self-esteem and selfefficacy can help to alleviate negative thought processes and experiences (Soto 2015; Strobel et al. 2011; Khan and Husain

2010), skills can be developed to nurture these attitudes (Beiranvand et al. 2019). Understanding and working through worry can lessen intensity or over-reaction, with an ability to detach more (Eagleson et al. 2015). Cognitive reframing is another methodology which can help individuals to see alternative perspectives on a situation, thereby moving to a more solution-focused approach (Scott 2020).

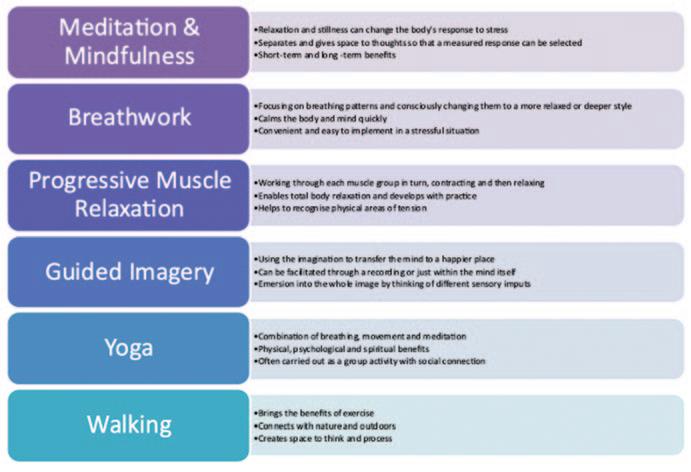

Numerous practical strategies exist to support psychological wellbeing (see Figure 5) and they can work in combination with each other. The aim of these is to provide an outlet for stress when it occurs, but perhaps more importantly to build a reservoir of calm and resilience proactively in between high intensity times. Embedding them as a routine is not always easy at the start, but even a more haphazard approach can bring benefits for some. Another cathartic release to stress can be journaling. It has been shown to reduce anxiety (Sohal et al. 2021), with best results coming again from some regularity and commitment (Hayman et al. 2012).

More formal approaches to problems or stress (often with professional guidance) can be those of emotion-focused or problem-focused coping. Schoenmakers et al. (2015) describe emotion-focused as working through and understanding the emotional fall-out from problems by changing perception. Problem-focused

Figure 5: Coping Strategies (based on Psychology Today, 2023)

coping involves unpicking the problem itself and finding possible solutions, thereby removing or adjusting the underpinning cause of the stress. This can result in forward movement in a positive way (Theeboom et al. 2016), albeit with a risk of over-ambition and failure (Oettingen 2012). One avenue of professional support is coaching which can help facilitate exploration in a safe environment.

The final aspect to discuss is the social element of tackling stress. With some overlap from above, the two elements

examined here are connectedness, and joy and interest.

Social support can have a positive impact for individuals during stressful situations (Das et al. 2020). It can act as a prophylactic layer buffering feelings of distress or anxiety (Cohen 2004; Kawachi and Berkman 2001).

Loneliness itself can induce stress (NHS 2023b; Mental Health Foundation 2023), so forming connections through clubs, family, work, and cultural groups can help to prevent escalation of emotions as well as creating happiness. Griffin (2010) suggests that although online and remote connections add value, face-to-face provide the maximum benefit. In that face-to-face space, hugging and other physical contact has positive impact (Cohen et al. 2015) and can also show a reduction in conflict (Murphy et al. 2018). Although still a relatively new research area, it is thought that the reduced pressure of not having to verbalise support alongside the physical demonstration of comfort, acts as a safe mechanism for connectedness when carried out in an appropriate situation and relationship (Cohen et al. 2015; Jukubiak and Feeney 2014).

Joy and interest stimulate play and exploration respectively (Frederickson 2004) and this creates a platform of new life experiences and the development of personal resources, to support the biopsychosocial being. Creating this as a priority in life can be based around balancing free time with work and commitment. Stress can become overwhelming without space for joy and interest, and creating leisure time can help an individual move towards a feeling of positive well-being (see Figure 6).

Linked with this concept is also the notion of gratitude. Waters (2011) describes how journaling can be used in this way with a reflective and analytical attitude bringing into focus positive life areas and experiences. Working with gratitude can be a means of distraction away from the stressful event or enable reframing of the stressor against a backdrop of appreciation of the wider context of life and the world (Sansone and Sansone 2010). Focusing on others and reaching out with appreciation can also create a sense of connectedness, joy and interest.

Stress is a normal part of human existence stemming from both positive and negative experiences. A sustained exposure to stress can create health problems affecting the whole person. Rather than desperately trying to avoid stress, (which is arguably impossible), individuals can proactively develop a reservoir of resilience and coping mechanisms. Inherent in this is the ability to recognise the stress response and detect when it is becoming overwhelming and unhealthy. Strategies can then be implemented to mitigate against subsequent compounding damage or escalation. Finding options that suit the individual is key so personal well-being can be nurtured in a comfortable and enjoyable way.

– Bautista, T.G., Roman, G., Khan, M., et al. 2023. What is well-being? A scoping review of the conceptual and operational definitions of occupational well-being. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science. 7(1):e227. Available at: doi: 10.1017/cts.2023.648.

– Bremner, J.D., Moazzami, K., Wittbrodt, M.T., et al. 2020. Diet, Stress and Mental Health. Nutrients. 13;12(8):2428. Available at: doi: 10.3390/nu12082428.

– Clew, S. 2016. Closing the gap between physical and mental health training. British Journal of General Practice. 66 (651). 506-507

– Cohen, S. 2004. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist. 59: 676–684

– Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., Turner, R.B., Doyle, W.J. 2015. Does hugging provide stress-buffering social support? A study of susceptibility to upper respiratory infection and illness. Psychol Sci. 26(2):135-47. Available at: doi: 10.1177/0956797614559284.

– Das, K.V., Jones-Harrell, C., Fan, Y. et al. 2020. Understanding subjective wellbeing: perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Rev. 41 (25). Available at: doi.org/10.1186/ s40985-020-00142-5

– Drake, C.L., Pillai, V., & Roth, T. 2013. Stress and sleep reactivity: A prospective investigation of the stress-diathesis model of insomnia. Sleep. 37, 1295–1304.

– Eagleson, C., Hayes, S., Mathews, A., Perman, G., Hirsch, C.R. 2016. The power of positive thinking: Pathological worry is reduced by thought replacement in Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Behav Res Ther. Mar;78:13-8. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.017.

– Engel, G. L. 1977. “The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine”. Science. 196 (4286): 129–136. Available at: doi:10.1126/ science.847460

– Firth, J., Gangwisch, J. E. Borsini, A., Wootteon, R. E. and Mayer, E. A. 2020. Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? BMJ. Available at: doi:10.1136/bmj.m2382

– Fredrickson, B.L. 2004. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions.

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences. 359(1449):1367–77.

– Griffin, J. 2010. The Lonely Society. [online] [viewed 30.5.23]. Available at: www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/fi les/the_lonely_society_ report.pdf [Accessed on 23/02/16]

– Guszkowska, M.2004. Effects of exercise on anxiety, depression and mood Psychiatr Pol. 38:611–620

– Hayman, B., Wilkes, L., Jackson, D. 2012. Journaling: identification of challenges and reflection on strategies. Nurse Res. 19:27–31.

10.7748/nr2012.04.19.3.27.c9056

– Holford, P.2003. Optimum Nutrition for the Mind. London: Piatkus

– Jakubiak, B., Feeney, B. 2014. Keep in touch: The effects of imagined touch support on exploration and pain. Unpublished manuscript

– Kalmbach, D.A., Anderson, J.R., Drake, C.L. 2018. The impact of stress on sleep: Pathogenic sleep reactivity as a vulnerability to insomnia and circadian disorders. J Sleep Res. 27(6):e12710. Available at: doi: 10.1111/jsr.12710.

– Kawachi, I., Berkman, L.F. 2001. Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health. 78:458–467.

– Kerkhof, G.A. 2017. Epidemiology of sleep and sleep disorders in The Netherlands. Sleep Med. 30:229–239.

– Khan, A., Husain, A.. 2010. Social support as a moderator of positive psychological strengths and subjective well-being. Psychological Reports. 106(2):534–8 – Mental Health Foundation. 2023. Relationships in the 21st century: the forgotten foundation of mental health and well-being. [online] [viewed 28.5.23]. Available at: Relationships in the 21st century: the forgotten foundation of mental health and well-being | Mental Health Foundation

–

Mental Health Foundation. 2017. Food for Thought: mental health and nutrition briefing. [online] [accessed 28.4.23]. Available from: food-for-thought-mentalhealth-nutrition-briefing-march-2017.pdf (mentalhealth.org.uk)

– MIND. 2023. Food and Mental Health. [online] [accessed 27.5.23]. Available from: Food and mental health - Mind

– Naidoo U. 2020. Eat to Beat Stress. Am J Lifestyle Med. 8;15(1):39-42. Available at: doi: 10.1177/1559827620973936.

– NHS. 2023a. Sleep Problems. [online] [viewed 22.5.23]. Available at: Sleep problems - Every Mind Matters - NHS (www.nhs.uk)

– NHS. 2023b. Maintaining health relationships and mental wellbeing. [online] [viewed 29.5.23]. Available at: Maintaining healthy relationships and mental wellbeing - NHS (www.nhs.uk)

– Oettingen, G. 2012. Future thought and behaviour change. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 23, 1–63. Available at : doi: 10.1080/ 10463283.2011.643698

– Ohayon, M.M. 2011. Epidemiological overview of sleep disorders in the general population. Sleep Med Res. 2(1):1–9

– O’Keeffe, T. 2023. Mental Health. Part IV –Health Coping Strategies and Healthy Lifestyles. The Journal of Podiatric Medicine for the Private Practitioner. 88 (2). 22-34

– Peluso, M.A., Andrade, L.H. 2005. Physical activity and mental health: the association between exercise and mood. Clinics. 60:61–70

– Sansone, R.A., Sansone, L.A. 2010. Gratitude and well being: the benefits of appreciation. Psychiatry (Edgmont). Nov;7(11):18-22.

– Schoenmakers, E.C., van Tilburg, T.G., Fokkema, T. 2015. Problem-focused and emotion-focused coping options and loneliness: how are they related? Eur J Ageing. Feb 11;12(2):153-161. Available at: doi: 10.1007/s10433-015-0336-1.

– Scott, E. 2020. How to Reframe Situations So They Create Less Stress. [online] [viewed 18.5.23]. Available at: www.verywellmind.com

– Scott, A.J., Webb, T.L., Martyn-St James, M., Rowse, G, Weich, S. 2021. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. Dec; 60:101556. Available at: doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101556.

– Seyle, H. 1965. The stress syndrome. The American Journal of Nursing. 65 (3). 97-99

– Sharma, A., Madaan, V., Petty, F.D. 2006. Exercise for mental health. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 8(2):106. Available at: doi: 10.4088/pcc.v08n0208a.

– Sohal, M., Singh, P., Dhillon, B.S., Gill, H.S. 2022. Efficacy of journaling in the management of mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Med Community Health. Mar;10(1):e001154. doi: 10.1136/ fmch-2021-001154

– Soto, C.J. 2015. Is happiness good for your personality? Concurrent and prospective relations of the big five with subjective well-being. Journal of Personality. 83(1):45–55

– Strobel, M., Tumasjan, A., Spörrle, M. 2011. Be yourself, believe in yourself, and be happy: self-efficacy as a mediator between personality factors and subjective well-being. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 52(1):43–8

– Takiguchi, Y., Matsui, M., Kikutani, M., Ebina, K. 2022. The relationship between leisure activities and mental health: The impact of resilience and COVID-19. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. Feb; 15(1):133-151. Available at: doi: 10.1111/ aphw.12394.

– Theeboom, T., Beersma, B., and van Vianen, A. E. 2014. Does coaching work? A meta-analysis onthe effects of coaching on individual level outcomes in an organizational context. J. Posit. Psychol. 9, 1–18. Available at: doi: 10.1080/17439760.2013. 837499

– Waters, L. A. 2011. Review of schoolbased positive psychology interventions. Aust Educ Dev Psychol. 28 (2). 75-90. Available at: doi: 10.1375/aedp.28.2.75

– Wildgust, H.J., Beary, M. 2010. Are there modifiable risk factors which will reduce the excess mortality in schizophrenia? Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 24(4_supplement Supplement editor: Professor TG Dinan):37-50. Available at: doi:10.1177/1359786810384639

– World Health Organisation. 2023. Health and Well-being. [online] [viewed 17.5.23]. Available at: Health and Well-Being (who.int)

– Yu, X. Nollet, M., Franks, N. P. and Wisden, W. 2025. Sleep and the recovery from stress. Neuron. 113 (18). 2910-2926. Available at: doi.org/10/1016/ j.neuron.2025.04.028

To complete your CPD, store your records and print a certificate, please visit www.dta-uk.org and log in using your member details.

Q1 How might the ‘trigger’ for stress be described?

A Acute or chronic B Positive or negative

C Sudden sharp pain D a) and b) only

Q2 According to Kerkhof (2017) and Ohayon (2011) what percentage of people have some issue with sleep?

A Nearly a quarter B Over a third C 50% D 73%

Q3 Suni and Singh advocate how many hours of sleep for most adults?

A 8 to 9 hours B At least 6 hours C A full 7 hours

D There is no fixed amount, it depends on the individual

Q4 According the charity Mind, erratic blood sugars due to diet can cause what?

A Lethargy B Obesity C Irritability D a) and c) only

Q5 What kind of foods can help avoid erratic blood sugars?

A Foods rich in protein B Foods rich in Omega 3

C Probiotic foods and foods high in fibre

D Foods containing natural sweeteners

Q6 What can result from a vitamin B5 deficiency?

A Poor bone quality B Type 2 Diabetes

C Lethargy D Poor memory and stress

Q7 What is listed as a source of vitamin B5?

A Wholegrains and vegetables

B Eggs and cheese C Citrus fruits

D Lean protein such as chicken

Q8 What is the amygdala?

A The part of the brain that stores memories

B The stress response centre for the brain

C The part of the brain involved with dreams and sleep

D The part of the brain that drives the body’s response to exercise

Q9 What is the recommended level of moderate intensity exercise according to Sharma et al. (2006)?

A 3000 steps a day B A gentle walk every day

C 30 minutes three time a week

D 10 minutes every day before breakfast

Q10 Which of the following is NOT one of the important emotions highlighted by Martin Seligmann?

A Hope B Contemplative thought

C Perseverance D Courage

The Technologist dips into the profound lake of dental opinion regarding the future of AI...

“I know you’re not supposed to talk about AI in a positive light because it’s the dark robot overlord that will kill us all, but I’m slightly excited about some of the opportunities that are going to come.”

Jurassic World Rebirth director Gareth Edwards in an interview with Empire magazine.

Gareth Edwards was talking about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) technology in movie making, but The Technologist is more interested in exploring and reporting the developments that are impacting the dental profession from surgery to dental laboratory.

In August 2025 the GDC published ‘Artificial Intelligence in Dental Service Provision: A Rapid Evidence Assessment’. What follows is what the regulator said in its precis of its findings.

The REA focused on identifying and synthesising international evidence from 2020 onwards to understand:

Aims:

■ To gain an insight into how AI has become integrated into modern dentistry

■ To discuss those areas in which AI is not yet suitable for dental treatments and why

CPD Outcomes:

■ Maintenance and development of knowledge and skill within your professional scope

■ Clinical and technical areas of study

Development Outcome: C

In September 2024, the GDC commissioned a Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) to explore how AI is currently being used in dental service provision and to consider its potential implications for dental professionals, patients and the wider sector.

The research was carried out by a team from Peninsula Dental School at the University of Plymouth, supported by subject specialists in AI and robotics. It followed an established rapid review methodology and forms part of the GDC’s wider horizon scanning work on emerging technologies and their potential impact on dental regulation and practice.

A The current use of AI in live dental service delivery.

A Its benefits, risks, and challenges, including implications for equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) and data protection.

A Areas of future development in AI applications.

A Methods used to evaluate the role and impact of AI.

A Gaps in the evidence base and priorities for future research.

The review screened over 3,800 studies, with 114 assessed at full-text stage. A total of 45 studies met the inclusion criteria, all

involving real-world use of AI in patient care. These included:

A 18 case reports or series (mainly small-scale)

A 13 clinical trials (including pilot and RCTs)

A 6 cohort studies

A 4 cross-sectional studies

A and a small number of surveys, observational and experimental studies.

Most research originated from China (18 studies) and the USA (13), with smaller contributions from India, Italy and several other countries. No UK-based studies were identified.

On usage, the review found that most of the current applications of AI in dentistry fall into three categories:

A Robotics, particularly in implant surgery, where systems such as the Yomi robot are being used to assist with precision placement.

A Deep learning, used for remote monitoring and caries detection through smartphone apps that analyse intraoral images.

A Supervised machine learning, with applications in paediatric dentistry, such as predicting and identifying early childhood caries.

While the research indicates promising benefits of AI, including improved accuracy, enhanced patient outcomes, and opportunities for remote care, it also highlights some challenges and risks.

These include the risk of using robotics in implant surgery for patients with poor bone quality, training needs for professionals, and potential patient concerns such as anxiety during robot-assisted procedures or difficulties using AI tools effectively at home.

The review shows that, despite growing interest and technological advancements, real-world implementation of AI in dental services remains limited.

Significant gaps exist in the evidence relating to best practice guidelines, largescale trials, UK-specific applications, ethical considerations, data protection, and the impact on equality, diversity and inclusion.

AI has seen a rapid surge in popularity and is becoming more accessible to the dental profession and other healthcare professionals with AI tools becoming increasingly integrated into clinical workflows. In 2024 it was reported that –globally – more than half of healthcare organisations are using some form of AI and its overall adoption is expanding rapidly within the dental arena.

But much as with the statement by Gareth Edwards, there is still some uncertainty and widespread misconceptions about the technology’s implementation and limitations. Although AI’s potential is widely recognised, we find dental professionals reluctant to jump too eagerly onto the AI bandwagon.