DTA Rewards save on everyday spending

MHRA Regulation: The Facts In this issue:

We are not immune, plague and vaccination

Digital Dental Technology & Dental Technologists

Joanne Stevenson: DTA President Interview

HOURS OF VERIFIED CPD

MHRA Regulation: The Facts In this issue:

We are not immune, plague and vaccination

Digital Dental Technology & Dental Technologists

Joanne Stevenson: DTA President Interview

HOURS OF VERIFIED CPD

● are individually registered with the GDC to be able to use the titles that relate to our role in the UK

● maintain our own lifelong learning through relevant continuous professional development (as provided free to the Dental Technologists Association [DTA] members)

● ensure that we are covered by specific indemnity insurance related to our dental laboratory custom-made dental device manufacturing work, and if necessary, related clinical work and/or extended roles

● work within the GDC Scope of Practice for our registered role, along with other extended areas as confirmed by further additional training

● are, as a current GDC registered dental technologist, able to sign-off custom-made dental devices under MHRA/MDR regulations, indicating that such appliances are fit for purpose as stated on the Statement of Manufacture

● maintain and develop our dental team networks to enhance patient care

Editor: Derek Pearson t: 07866 121597

Advertising: Rebecca Kinahan

t: 01242 461 931

e: info@dta-uk.org

DTA administration: Rebecca Kinahan

Operations Coordinator

Address: PO Box 1318, Cheltenham GL50 9EA

Telephone: 01242 461 931

Email: info@dta-uk.org Web: www.dta-uk.org

Stay connected: @DentalTechnologists Association

@The_DTA @dentaltechnologists association

Dental Technologists Association (DTA)

DTA Council:

Joanne Stevenson President Chris Fielding

Deputy President Tony Griffin Treasurer

Delroy Reeves DTA Liaison Delegate

Joanne Clark, James Green, Raya Karaganeva, Robert Leggett, Patricia MacRory and Jade Ritch.

Editorial panel: Tony Griffin Joanne Stevenson

Editorial assistant: Dr Keith Winwood

The Dental Technologist Association (DTA) is delighted to announce the appointment of new Council members, Raya Karaganeva and Joanne Clark, as well as the return of James Green, following the successful elections in May 2025.

On behalf of the team, DTA President Joanne Stevenson warmly welcomes you to the management team. We extend our heartfelt congratulations on your new roles and express our sincere gratitude for your voluntary contributions to the profession, all while continuing your dedicated work as registered dental technicians.

Raya Karaganeva

Raya is a Lecturer in Dental Technology at the Queens Dental Sciences Centre, University of Greater Manchester. She qualified as a dental technician in 2015 at Manchester Metropolitan University, where she went on to complete a PhD in 2019. Her doctoral research focused on the effects of custom-made mouthguards on retention, comfort, and physiological responses during exercise. Since then, she has had a primary interest in Sports Dentistry and has worked closely with Dental Trauma UK and the DTA to disseminate knowledge and raise awareness of custom-made mouthguards. Raya has previously delivered CPD seminars for Health Education England and has

presented as an invited speaker at national and international conferences. Currently, she is involved in research projects which aim to investigate contemporary developments in dental materials and is open for collaboration.

James Green is a Maxillofacial and Dental Laboratory Manager for Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) in London and Broomfield Hospital in Chelmsford, Essex.

James trained at Barts and the London, Queen Mary’s School of Medicine and Dentistry, and Lambeth College, London, and qualified as a dental technician in 2001. This was followed by a vocational training year at the Royal London Hospital and two years based at the Eastman Dental Hospital, University College London Hospitals NHS Trust, before transferring to GOSH in 2004.

He developed the auricular splint, a custommade medical device that maintains projection and dimensions following auricular reconstruction (which was published in the Annals of Plastic Surgery)

and an obturator prosthesis for children with teeth that cannot accommodate clasps due to insufficient eruption (published in the Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry).

James has delivered more than 50 invited lectures, both nationally and internationally, and authored or co-authored more than 25 peer-reviewed journal articles. His awards include the British Orthodontic Society Technicians Award (2002) and the British Orthodontic Society Award to an Orthodontic Technician for Distinguished Service (2024). James first joined the DTA council in 2008 and served as Deputy President from 2014 to 2016 and President 2016 to 2018. He is also a council member for the Orthodontic Technicians Association, where he served as Treasurer between 2007 and 2016 and Secretary since 2018.

Joanne is a prosthetics technician working in and running her family-owned dental lab in east London, alongside her brother. Joanne initially joined her family in the lab in 2003 in an admin role before studying to become a dental technician herself, completing a BTEC in dental technology at Lambeth college in 2017. Joanne now splits her time between hands-on prosthetic work and overseeing the smooth running of the lab as a whole.

Lifestyle vouchers offer DTA members a choice of everyday treats from the high-street, online, your weekly food shop, leisure and travel sectors – with access to over 300 of the UK’s biggest brand names. Save 6% at M&S, Argos, Boots, Currys, ASOS, Costa, John Lewis, Nandos, Tui, Sainsbury’s and hundreds more!

How to make the most of this saving?

Lifestyle vouchers can be redeemed online, in-store, or both depending on the retailer. This gives you the full flexibility you want to choose your redemption method while also maximising your savings. Vouchers can be split and spent across multiple big brand names. Lifestyle gives you the biggest choice of leading retailers, all in one place.

Starting a new year of CPD for 2025-2026

Your 2024-2025 CPD cycle has ended, and the GDC requires you to submit a statement by 28 August 2024, if you haven’t already done so.

You don’t need to submit your records now, but it’s essential to keep them safe in case the GDC requests them.

A If you have any concerns, reach out to the GDC promptly by calling the helpline, 0207 167 6000 or emailing renewal@gdc-uk.org

Important CPD dates:

CPD year runs from 1 August to 31 July

Then you have four weeks to make a CPD statement by 28 August.

Any CPD completed on or after 1 August counts towards the following year.

Here are some simple steps to help you when starting your new year of CPD:

1 Make sure you download your files from your 2023/2024 logbook.

2 Save your CPD certificates to your computer.

3 Add to and update your personal development plan for the year ahead.

4 You can now start taking CPD for your new 2024/2025 cycle year. Remember, on average dental technicians should complete around 10 hours per year and the GDC state that you must complete at least 10 hours over a two-year period.

5 For those that have now reached the end of your 5-year cycle and this means you should have completed 50 hours (or 75 for CDTs). You therefore might want to think about setting new goals for the new 5-year cycle ahead.

The first dental technician in the UK to achieve a fully digital Immediate load using Nobel’s latest system

Visitors were captivated by Davide Accetto’s presentation at the Dental Technicians Hub on Saturday, 17 May during DTS. As the first dental technician in the UK to achieve a fully digital Immediate load using Nobel’s latest system, Davide shared his groundbreaking experience and insights during the session and discussed the use of photogrammetry FastMap X-guide together with an IOS making it possible to CAD design and 3D print full arches on surgery day, to be screwed directly on MUAs with extreme accuracy without conventional methods. If you missed his talk during DTS, we will be sharing a filming of the session as a webinar soon. ‘Experience the future with digitally designed 3D printed immediate load.’ Don’t miss this opportunity to learn from a pioneer in the field and explore the cutting-edge advancements in dental technology.

The DTS Prize Draw

Thank you to everyone who visited our stand at the Dental Technology Showcase. Congratulations to Chris Ellis the winner of the prize draw and recipient of 12 months’ free membership!

may result from their work. Membership with the DTA offers exclusive discounted indemnity insurance in partnership with UK Special Risks.

A From the Crib to the Archwire –Orthodontic Wire – Articulate, September 2024

A Regulating Honesty and Integrity –Articulate, September 2024

Apprenticeships and routes to registration

To be a General Dental Council (GDC) registered dental technician trainees must complete an approved dental technology programme. This can be achieved through various routes, including university courses, college courses, apprenticeships, or a combination of practical training and part-time education in a commercial dental laboratory or dental hospital. The GDC maintains a list of approved qualifications and course providers on their website. We plan future interviews with education providers.

As a newly qualified dental technologist, do you understand your obligations? Once their educational requirements have been met, the dental technician must apply for registration with the GDC. This involves completing an application form and providing evidence of their qualifications and training. The GDC also requires dental technicians to have appropriate indemnity or insurance in place to cover their professional practice in order to ensure that they are protected against any claims that

In addition to these requirements, dental technicians must adhere to the GDC’s Standards for the Dental Team. These standards set out the principles, standards, and guidance that govern the conduct, performance, and ethics of dental professionals. They include putting patients’ interests first, communicating effectively with patients, obtaining valid consent, maintaining and protecting patients’ information, and working within their professional knowledge and skills. Dental technicians must also engage in continuing professional development (CPD) to maintain their registration. This involves completing a minimum of 50 hours of verifiable CPD every five years.

By meeting these requirements, dental technicians can ensure they are providing safe and effective care to their patients while also maintaining their professional standing with the GDC.

The DTA offers invaluable support to newly qualified dental technicians in meeting their professional obligations. As a member, dental technicians gain access to a wealth of resources, including comprehensive guidance on regulatory updates, technical FAQs, and business management templates. The DTA also provides a range of CPD opportunities, over 20 hours annually, ensuring that members can easily meet their CPD requirements. With the introduction of a wellbeing helpline, a comprehensive resource hub, and the DTA’s new membership benefits scheme, ‘DTA Rewards,’ (mentioned above) designed to help members save on everyday expenses – your personal interests are well-supported too.

A Flexible Dentures A Case Study –Jo Stevenson – The Technologist, November 2024

A Audit Again: Crown and Bridgework –Dr Chris Turner – The Technologist, November 2024

A Living and Working with Change Part 1: Technological Change – Kevin Lewis –The Technologist, November 2024

Show organisers celebrated the success of Dental Technology Showcase 2025, exhibitors and visitors alike found much to discover and enjoy. The DTA stand was a focus of attention keeping DTA Operations Coordinator Rebecca Kinahan and DTA Liaison Delegate Delroy Reeves busy dealing with enquiries, members dropping in, and friendly visitors. A spokesperson for the show offers more details.

DTS, co-located with The British Dental Conference & Dentistry Show (BDCDS), concluded following another year of resounding success. Held at Birmingham NEC on the 16 and 17 May, the show brought together thousands of industry professionals to explore the latest advances in dental technology and explore game-changing innovations, with countless business connections made. A highlight for many in the dental calendar, the show surpassed all expectations and received outstanding feedback from delegates and exhibitors alike. Rebbeca Peltier from DB Orthodontics said, “We love doing DTS. There are some fantastic customers, regular customers, yearly, that come to see us, and new customers too. It’s always nice to see some new faces, but we find DTS a great opportunity to showcase our products to new customers. We love all our face-to-face interactions.”

Over 80 exhibitors, including the biggest names in dental technology, showcased their latest innovations and the floor was

abuzz with excitement and inspiration. From state-of-the-art equipment to the latest in digital tools, there was something for everyone, proving DTS is the ultimate place to discover solutions that can revolutionise your lab.

The innovative Digital Dentistry Theatre, in collaboration with the IDDA, proved a must-attend destination. Live demonstrations and sessions on cuttingedge topics – from AI in diagnostics to 3D printing and digital workflows – offered attendees a hands-on glimpse into the future of dentistry. Delegates walked away with practical knowledge and inspiration to enhance their digital capabilities.

Portfolio Director, Alex Harden said: “It’s been another exceptional year, and truly inspiring to see the dental community come together to push boundaries and elevate the profession. From world-class speakers and valuable networking opportunities to the energy across the aisles, stands, and theatres – it’s been a privilege to host it all under one roof and provide a vibrant platform for professional growth and development.”

Over 50 world class speakers took to the stage across three dynamic show theatres. Covering the latest trends and topics of interest, the packed agenda included

insights into the latest trends, discoveries, and best practices in dental technology. Delegates were able to gain up to 12 free eCPD hours, a fantastic way to boost their knowledge while meeting professional development goals.

The show also proved it is more than a conference and provided multiple networking opportunities bringing together thousands of key decision-makers, thought leaders, and innovators in the dental technology sector for meaningful conversations and career-building connections. Jo Bentley from Ivoclar said: “It’s great to attend Dental Technology Showcase because we love meeting new and existing customers, and it’s a great way to showcase what we’re all about. It was a fantastic couple of days.”

A The Dental Technology Showcase 2026 will take place on 15 and 16 May, at the NEC in Birmingham. For more information on show updates visit https://the-dts.co.uk

New DTA President Joanne Stevenson looks back over her career and forward to the association’s future.

Let me introduce myself. I am a prosthetic dental technician originally from Manchester, currently residing and working in Belfast. My career as a technologist really began during my school years, guided by my careers officer. I had a strong aptitude for sciences and was keen on working in a laboratory setting but couldn’t decide on a clear career pathway. I attended interviews at microbiology labs at Christie Hospital and Scottish and Newcastle Brewery before I was eventually introduced to a dental laboratory. I was

immediately captivated by possibilities of the field, I felt it perfectly combined my passion for hands-on work with my interest in science.

Iwas able to connect with a group of dentists offering scholarships to aspiring dental students and it was they who enabled my placement in a prosthetics lab. I subsequently enrolled at Manchester Metropolitan University to pursue a BTEC National in Dental Technology, where for four years, I balanced my time between working in the lab four days a week and attending classes one day a week.

I qualified in 1995 and relocated to Belfast, where my family originated. Currently, I work in the prosthetics department at one

of the largest laboratories in Northern Ireland and my duties encompass all aspects of prosthetics, including implantretained overdentures and hybrid bridges.

I first joined the DTA council during the lockdown period after submitting an article for The Technologist publication, which led to an invitation to join the management team. After three years working as part of the team, I was elected deputy President alongside then President Delroy Reeves. My two years as deputy garnered invaluable insights and experience under Delroy’s leadership, until this year (2025) when I had the honour of being elected as the first female President of the DTA. I feel it to be both a tremendous privilege and a great responsibility to be entrusted with this role by my fellow council members, and I am

committed to leading the association with dedication and integrity.

The DTA has always been a strong advocate for our members, providing them with advice and guidance throughout their careers. I see an important part of my responsibility is to promote effective education and training, offering lifelong learning opportunities and advocating for the highest standards of practice. The management team is always looking for ways to improve the benefits for our members and provide them with as much information as possible. Just thinking about what we can do fills me with energy, we have an exciting year ahead.

Our new benefits package, ‘DTA Rewards’, designed to save our members money on day-to-day spending, can actually save them more than the cost of their membership!

We are also developing a series of free CPD digital education videos, with a focus on digital dental technology for 2025 and more to come in 2026. We are also committed to offering comprehensive Wellbeing support and have invested in a resource hub to provide our members with valuable tools and information to support their professional and personal growth, and we hope to continue adding valuable resources for our members as the profession evolves.

The field of dental technology is advancing at a remarkable pace, and I believe we will one day see dental technicians transitioning from traditional bench work to a more digital-based workflow. We have a comprehensive look at digital developments for technologists in this issue (pages 9-15) but I know that an understanding of dental anatomy and time working in an analogue format strengthens my work ethic, and the ability to work with one’s hands remains essential. While many of the labour-intensive and messy aspects of the job are being replaced by digital processes, the final finishing touches and the creation of high-end cases still require the skill and creativity of a technician.

I want to remind members of the DTA Fellowship programme which recognises dental technicians for their high-quality work in manufacturing custom-made dental device. This award is only presented to experienced DTA members who have demonstrated excellence in their field, showcasing their skill and dedication through their creations. The DTA Fellowship programme not only acknowledges these people’s contributions to the field but also inspires others in the profession to strive for the highest standards of quality and innovation.

Digital technology will continue to broaden the horizons for dental technicians, including digitally designing restorations for laboratories worldwide; it is such an exciting time to be part of the dental technology family and seeing these new career opportunities open up. We should be sharing this message with schools to incentivise the next generation and bring them to the modern, cleaner streamlined dental laboratory. The integration of AI and innovative techniques will transform the way dental devices are manufactured –while, handmade custom-made, porcelain

dental appliances may become rarer but will remain highly sought after.

I mentioned our need to reach out to the next generation, it is vital. The decline in dental technician numbers is a real concern, and while there are still several colleges offering training courses the situation is becoming particularly challenging in Northern Ireland, where training opportunities are more limited when compared to the UK mainland and too many students have had to resort to distance learning to pursue their education. The DTA is committed to supporting students throughout their studies by providing copies of The Technologist publication and offering reduced-price student memberships.

In trying to maintain a level playing field, we are committed to educating our members and raising awareness of regulations to all professional bodies ensuring compliance with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and Medical Device Regulations (MDR) for custom-made dental devices.

We have a very informative article in this

issue of The Technologist (pages 16 to19) that explains the DTA stance in much more detail, but in summary, the laws state:

A Manufacturers of custom-made dental devices must register with the MHRA and provide each patient with a statement of manufacture for each device.

A This requirement applies to both the manufacture of dental devices in the UK and the importation of dental appliances from overseas.

A In-clinic fabrication of dental devices must also be regulated by the MHRA and the MDR.

A The GDC emphasises that compliance with the MHRA is essential for custommade dental devices in the UK, as outlined in the Standards for the Dental Team 2013.

A Registrants who sub-contract or use dental laboratories outside the UK must ensure that the manufacturer complies with the UK MDR and are liable for this responsibility.

The DTA continues to advocate for compliance with these regulations and

highlights the essential role of dental laboratories in oral healthcare. We regularly meet with regulators to discuss these important topics.

The way I see my role as President of the DTA is as a colleague and supporter of our profession, our members, and the whole dental team.

We have great relationships with all our fellow associations and work with the GDC, Chief Dental Officers and industry influencers and leaders to ensure our members are informed about technological developments, regulatory changes, and trends in the dental landscape. We see technologists as key members of the whole dental team, not just artisans working in the background but very often in the vanguard of dental developments.

Above all we members of the DTA council want to continue the excellent work and support that the DTA has always provided to our members. We are a cohesive team, each of us brings a unique vision to the association, and, working together we bring

a powerful collaboration of insight and experience to our members. We are working to enhance educational resources and training opportunities for dental technologists, we are constantly advocating for regulatory compliance and high standards in dental technology, wiping away any confusion about who should or should not be regulated and by whom, and we are striving to promote the tremendous opportunities in our profession to help attract new talent and address the decline in the number of dental technicians.

Coming into my position as President after Delroy Reeves was a humbling prospect, he left some big shoes to fill, but he is still with us as the DTA liaison delegate and we all value his contribution. We have welcomed our new council members Raya Karaganeva and Joanne Clark, as well as James Green returning to the fold, and Chris Fielding takes my place as deputy President. It is very much the DTA fielding its strongest, world class team. All I can hope is that, with their support, when my tenure as President comes to an end, the association will remain as strong as it is now and, under my leadership, will have moved on to even greater achievements.

I hope together we can continue to have a significant impact by advancing the standards of dental technology, supporting the professional growth of dental technologists, and ensuring the highest quality of care for patients as invaluable members of the dental team.

My aim is to leave a legacy of innovation, collaboration, and excellence. I am deeply grateful for this opportunity to serve as the President of the DTA and I am genuinely excited about the future of dental technology.

I look forward to working with my fellow DTA members and our entire dental community to help establish a pathway that will lead technicians to the future they rightfully deserve.

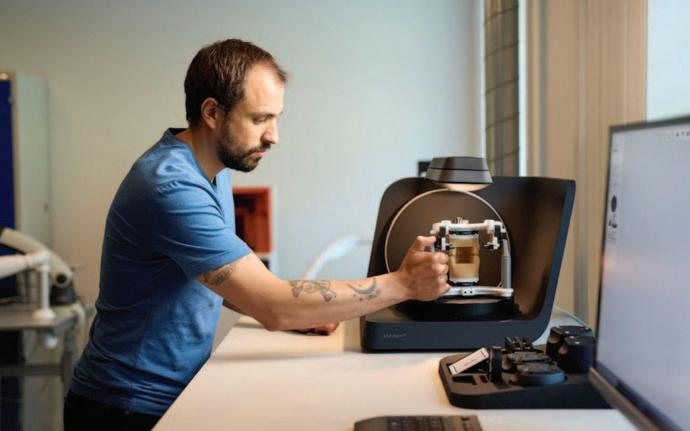

DTA Student Representative Dan Bant introduces our digital feature with an overview of what you need to consider when converting from analogue to digital in the dental laboratory.

The advice from every side is that if you don’t invest in digital you are going to be left on the platform when the train to the future pulls away and heads off towards tomorrow. Can you afford not to? the pundits ask. Perhaps not, but first and foremost, you need to take a cold and clinical look at the finances.

Step one, know your budget; there are various different routes into digital but the most important is knowing your budget before you get started. How much is your initial outlay and what is your predicted ROI (return on investment)? And, realistically, how long that might take to break even.

Step two, is your computer up to the job?

Can it handle the download portals (more of which later) and various other CAD software, such as exocad or 3Shape etc., Believe me, there’s nothing more frustrating than depending on a slow computer when controlling the efficiency of your workflow.

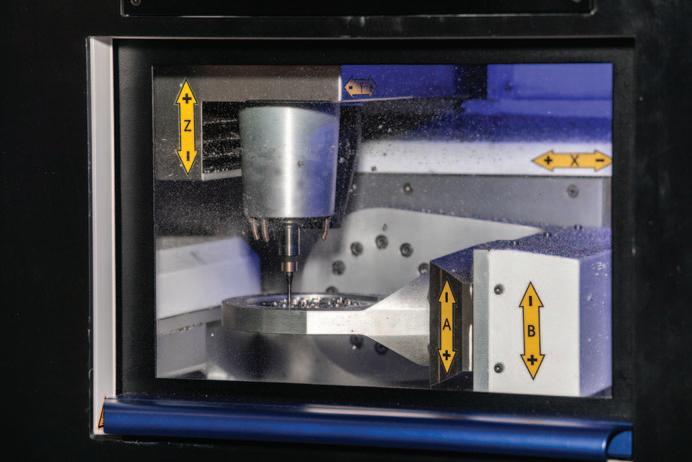

Step three, before raiding the kids’ piggy banks to jump on the CAD-CAM express, take time to research your choices for equipment and software. Dental shows have many examples on offer, but I think it’s best to also ask those who have already invested in certain products and get their honest opinion regarding their true value. Ask for advice as to where you might best begin your digital workflow. There will be a learning curve so it might be best to start simple and expand from there. You’ll need a little flexibility in your workplace – you must be prepared to adapt to new technologies and any new workflow systems will come with fresh problems –but there are always others who have been in the same position and have dealt with the same issues who may be able to help. Ask whether your technology provider can offer a training programme, a mentor on demand who can guide you through your first steps on your digital journey. You are lucky in the fact that you already have analogue experience at the workbench, you

understand dental anatomy in a way that cannot be replicated by AI. The digital tools you choose are simply an adjunct to skills you already possess, being aware of that might help level-out that learning curve you’re facing.

Or you can outsource your work to others. All you need to start the digital process is to download the online portals I mentioned previously to transmit your CAD cases to labs already equipped with CAM systems such as 3shape, iTero, Medit, DS core etc., and then you can outsource for all areas of work without any need to personally invest in such equipment. This can help to ease you into a full digital workflow while also allowing you to research your next move and take your time to invest in chosen areas along the way.

So, what next? Training! Let’s say you are now the proud owner of your carefully selected digital technology and it is fully integrated into your laboratory workflow. If

you have staff working with you, you must also ensure that they are trained and up to speed with the use of your selected design software, 3D printers, scanners, milling machines etc., to ensure they can get the best out your investment. I can’t stress enough that digital technology is a tool that will help make your workflow faster and more productive, but only if you understand how to use it. The most important element in any digital workflow is the human interface between the dentist’s prescription, the manufacturing process, and the device that ends up in the patient’s mouth. That human interface is you and your team.

And finally, communicate! Advise your dentists of your intention to move to a digital workflow. You might want to switch to a fully digital workflow and at that point prefer to no longer accept analogue impressions, but stop and think. First, is your clinician already working with an intraoral scanner? If not, are they ready to invest the thousands that these scanners cost? A small modern laboratory scanner could be the answer, it can read an analogue impression

both buccally and lingually in the most detailed way, ready for the CAD stage of manufacture, so that your analogue dentist can still work with you, at least until they too see the digital light.

Have the courage to make the change, but first get your digital ducks in a row. It may seem daunting at first but this is the only way the industry is moving and nobody wants to see you get left behind while that train to the future fades away into the distance.

Over the last ten years, more and more dental professionals in the UK have started to adopt digital tools. In a growing number of laboratories, technologies like intraoral scanners, CAD/CAM software, and 3D imaging systems are now used to support everyday work for more precise results and a more efficient workflow and patient outcome. However, while some laboratories have already started the digital journey, many others still rely on traditional methods. Overall, there is a long way to go to fully adopt and integrate digital tools across the sector.

Digitalisation offers a valuable opportunity for dental laboratories: It has the potential to simplify work, reduce the time taken to complete cases and thus increases

Aims:

■ To explore the latest updates in digital developments

■ Keeping up-to-date with the digital workflow

■ Digital communication

CPD Outcomes:

■ Maintenance and development of knowledge and skill within your professional scope

■ Technical areas of study

■ Emerging technologies

■ Communication with the dental team

Development Outcomes: A&C

efficiency, improve communication between laboratories and clinics as well as with patients, and provide more accurate and consistent results. That is why, “the vast majority of UK labs have adopted – or are considering adopting – digital tools to a greater or lesser extent, whether it is a 3D printer used simply for model printing or a full digital workflow.,” says Jason Longden, National Sales Manager Laboratory, Henry Schein Dental UK.

This article looks at how dental laboratories in the UK are working nowadays, how digital tools are starting to transform the way they work, and what the future might look like. It also shares thoughts from industry professionals about what they believe digital workflows can offer for both dental laboratories and patients.

Digitalisation in dentistry is evolving rapidly. New and more sophisticated equipment and tools are appearing every year, contributing to the advancement of oral health and helping to improve patient care. The dental laboratory sector in the UK is no exception to this evolution and is also undergoing change. However, digitalisation in its broadest sense is still in the early stages for many laboratories.

There are over 1,000 dental laboratories registered with the Dental Laboratories Association (DLA) in the United Kingdom,1 with an estimated total of around 1,500 laboratories across the country in 2024.2 This number has decreased over the past decade, partly due to many laboratory owners reaching retirement age. Some of these businesses have closed, while others have been taken over by larger lab groups. As a result, the number of independent laboratories has

decreased, and a few larger players are becoming more visible in the market.

At the same time, expectations from dental practices are changing. Dentists and patients are in need for faster services, reliable results, and an overall improved experience. This is encouraging more laboratories to consider investment in digital tools. However, laboratories that fully benefit from complete digital workflows are still relatively uncommon.

There is also a difference between NHSfocused laboratories and private

laboratories in terms of digital adoption. Outside of some of the large volume or milling centre dedicated laboratories, a high number of NHS laboratory workflows remain analogue to one extent or another.

“Small labs that serve NHS practices often work with tight budgets. For them, moving to fully digital workflows needs to be done in steps, with a clear plan for how to use each tool and platform effectively.” Jason Longden.

In addition, a broad number of dental laboratories in the UK that have already started to incorporate digital tools still use a

mix of traditional and digital techniques. As a result, technicians often move back and forth between manual and digital steps to complete a single case.

One of the main drivers of digital adoption among dental laboratories appears to have been the increasing use of intraoral scanners (IOS) in dental practices. As more practices are moving away from traditional impressions and adopting digital scanning, laboratories are receiving more digital files, compelling them to adapt their processes accordingly.

Along with the rise of IOS, the increased availability of CAD/CAM technology and 3D printers has also encouraged this shift. The COVID-19 pandemic seemed to be an accelerator for the adoption of digital tools in the past years, as both clinics and laboratories looked for more efficient ways to treat cases with less physical contact.

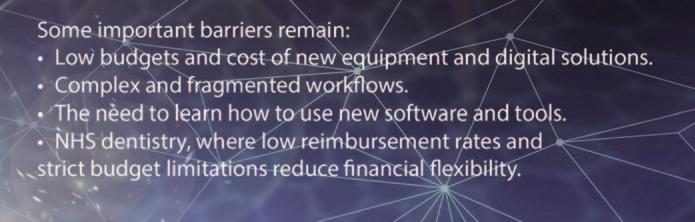

However, several barriers to digitalisation still remain.3 On the one hand, there are laboratories working primarily with the National Health Service (NHS), which need to focus more on high volumes and lower-

cost solutions, providing most of their services on an emergency basis. On the other hand, there are smaller laboratories with limited budgets and greater difficulty in incorporating new technologies – which ultimately impacts their ability to adapt and embrace digital transformation. In addition, there is a clear need for more innovation in certain workflows, such as the production of complete digital prostheses – a growing need among the older population.

Another challenge to overcome to drive the digitalisation of laboratories is the fragmentation and complexity of most current digital workflows. In addition, dental laboratory professionals need to stay up to date with the innovation and the use of new equipment and digital solutions which requires continuous education:

“Many dental practices and laboratories that have begun their transition often use multiple devices – frequently from different manufacturers – that are not seamlessly integrated. This makes it harder for dental professionals to work efficiently and fully benefit from these tools from a clinical perspective”., says Davide Fazioni, Vice

President, Global Dental Equipment & Service and Digital Workflow, Henry Schein.

Overall, the solution lies in developing both the technical and financial capacity to invest in new systems and training, given the current landscape of the sector in the country.

With an ageing population, the need for dental restorations – such as crowns, bridges, and full dentures – is expected to increase. This highlights the growing need for laboratories to deliver work quickly and accurately, and at an affordable cost. In response, digitalisation is increasingly seen as a way to meet these needs. As more laboratories explore and expand their use of digital tools, new opportunities are emerging that could reshape the profession.

These technologies and materials can support laboratories in improving the quality of treatments, meeting deadlines more easily, and reducing costs. An additional advantage of going digital is that practices and laboratories can work more closely together. A dentist can send a scan directly to the laboratory, where a technician can start designing the case straight away. If both sides use compatible systems, the entire process – from scan to final restoration – can remain digital.

Digital workflows can also contribute to improving the patient experience, reducing the number of appointments by providing more predictable results compared to traditional analogue processes. This can also help enhance laboratory efficiency, increase chair utilisation at the practice, and reduce the environmental footprint by minimising transport needs and material waste. However, buying a machine is not enough. Even with these benefits, laboratories still need to plan digitalisation carefully, with the support of a knowledgeable and trusted partner who fully understands their needs and goals, as well as the opportunities available in the market and how to make the most of them to increase efficiency and improve results

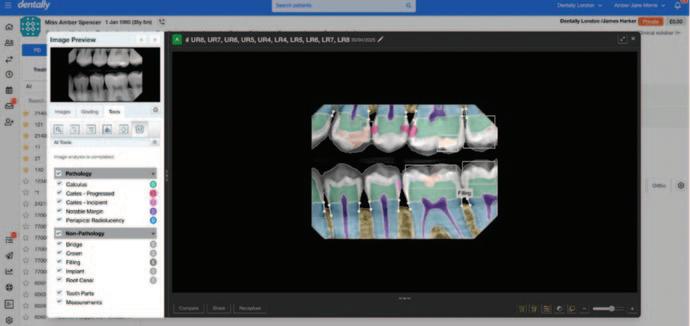

When it comes to software, teams also must understand how to work with digital files, manage changes to workflow, and keep learning as the tools evolve. As an example, artificial intelligence (AI) is already starting to play an important role, and its impact is expected to grow over time. AI might help detect margins, suggest crown shapes, or check occlusion during the design process for dental experts. This could help save time and allow technicians to focus more on customising each case. To make that happen, dental professionals need to embrace continuous learning and collaboration.

“It’s not simply a matter of adopting the software. Practices and labs must consider how they collaborate, communicate, and adapt their workflows. Practice management software plays a critical role in this by connecting the entire practice team, streamlining processes, and ensuring information flows smoothly. That’s the key to making a digital workflow truly efficient and to delivering exceptional patient care,” states Ben Flewett, Vice President and Managing Director Henry Schein One International.

With the right elements in place – such as training, planning, and equipment – more dental laboratories in the UK could start benefiting from these advancements now and in the years ahead.

Looking ahead: What digitalisation can bring to laboratories and patients

Digital tools are gradually becoming part of the day-to-day work in dental laboratories. While most are not yet fully digital, many are taking significant steps toward adopting the technologies available in the market. Professionals need to identify the laboratory aims and thus the fitting tools that can support their workflows in an optimal way. In addition, it is crucial for the whole team to learn how to best use them in ways that improve efficiency and enhance patient care. This continuous effort is accumulative and, at the pace digitalisation in dentistry is evolving worldwide, many laboratories might be working mainly with digital equipment and tools.

Looking ahead, 3D printing and other advanced manufacturing solutions will continue to play an important role in the next phase of digital transformationespecially for crown and bridge fabrication, as well as for full digital denture workflows. These technologies could further streamline production, reduce material waste, and improve accuracy across more types of restorations.

Additionally, a key area shaping the future of digitalisation is the simplification and integration of systems. Many laboratories and practices today face the challenge of using multiple devices and software platforms that are not always compatible. This lack of integration often complicates workflows and limits the full potential of digital tools, but this will change in the near future.

“In order for customers to really use what they already purchased – or to invest in what they want to purchase – simplification is absolutely critical. We know that and we are working on the simplification of all the various software platforms dental professionals have to work with to be successful from a clinical perspective,” says Mackenzie Richter, Vice President, Global Commercial Digital Workflow Solutions at Henry Schein.

Simplification is about reducing complexity, but also about unifying fragmented digital processes into more connected, intuitive workflows. Integration across systems can help make everyday operations smoother, reduce the number of steps required, and ultimately benefit both laboratories and the practices and patients they support.

In the coming years, dental practices and laboratories will be able to access every element of the workflow – from the first appointment to the final step of treatment – through a single platform, thanks to greater connectivity between systems and equipment, regardless of brand or manufacturer.

This vision for the future includes seamless, centralised systems that digitally connect every stage of the workflow, tying together all aspects of a dental practice and laboratory. Such integration will offer laboratories the opportunity to work more efficiently, reduce turnaround times, and increase precision - ultimately improving operational efficiency and enhancing patient care.

However, achieving this will require more than just new tools and solutions, it will also depend on changes in how teams work, communicate, and adapt to new processes.

“We foresee a world in which the clinical team opens up practice management at the beginning of the day – and that is the one platform that you have to open.”

Mackenzie

Richter,

There may also be more opportunities for remote collaboration. As an example, a technician in one city could design a restoration that is then produced in another location. This increased flexibility could help laboratories expand their capabilities and support broader access to dental care, especially in communities or areas with less access to dental resources.

Dental laboratories in the UK are currently at a turning point. With continued investment in training, planning, and equipment – together with the

simplification and fully seamless integration of digital systems in the near future – the transition to full digital workflows could help laboratories evolve and thrive. This digital transition is about integrating new technologies, as well as about redefining the role laboratories will play in the dental industry.

As digital integration grows, laboratories might take on more strategic roles in treatment planning and patient care. Those who embrace it with a wellthought-out plan will be better suited to stay competitive, enhance collaboration with clinics, and provide high-quality service to patients. Ultimately, those who take the right first steps today will lead the way and help shape the future of laboratories as key contributors to improved oral health tomorrow.

1 https://dentallaboratory.org.uk/dentures/dentallaboratories-association/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

2 https://rentechdigital.com/smartscraper/businessreport-details/list-of-dental-laboratories-in-unitedkingdom

3 Committee of Public Accounts – “Fixing NHS Dentistry” report. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/ 47347/documents/245396/default/

Development Outcomes A&C – 60 minutes

To complete your CPD, store your records and print a certificate, please visit www.dta-uk.org and log in using your member details.

Q1 How many dental laboratories are estimated to be in the UK?

A 1800 B 2300 C 1500 D At least 1000

Q2 What is said to be causing a decrease in the number of dental laboratories?

A Owners reaching retirement age

B More clinics with in-house CAD/CAM

C Some businesses taken over by larger groups

D a) and c) only

Q3 In the article, what is said to be different about NHS focused laboratories?

A They remain analogue to one extent or another

B They are largely single person businesses

C They are often based in a hospital or practice

D They use cheaper materials

Q4 Name one of the main drivers of digital adoption.

A More digital equipment coming onto the second-hand market

B The increased use of intraoral scanners in dental practices

C Computer-savvy students coming into the profession

D Better financial planning

Q5 Why was the COVID-19 pandemic considered an ‘accelerator’ for the adoption of digital tools?

A More people were working from home

B Technicians had more time to study the new technology

C Training was more accessible online

D Clinics and laboratories looked for more efficient ways to treat cases with reduced physical contact

Q6 What is specifically described as a growing need among the older generation?

A Faster treatments with less chair time

B A more aesthetic treatment outcome

C Complete digital prosthesis

D More affordable dental devices

Q7 ‘Fragmentation’ and what is recognised as a challenge to be overcome in most current digital workflows?

A Complexity

B Incompatible technology

C Fake materials

D Poorly translated user manuals

Q8 How can the digital workflow reduce dentistry’s environmental footprint?

A Minimise transport needs

B Reduce material waste

C Reduce the power needs of the laboratory

D a) and b) only

Q9 Which of the following is NOT cited as an impact of AI in the dental laboratory?

A Predict the development of dental caries

B Detect margins

C Suggest crown shapes

D Check occlusion

Q10 What did Mackenzie Richter describe as ‘absolutely critical’ for customers to use what they already purchased, or invest in what they want to purchase?

A Training

B Ongoing provider support

C Simplification

D A fully integrated digital dental workflow

by AD Griffin, MBE. DTA Treasurer

Aims:

■ To better understand the legal and registration requirements for manufacturing custom-made dental devices in the UK

■ Keeping up-to-date with GDC and MHRA law

■ Effective business management

CPD Outcomes:

■ Maintenance and development of knowledge and skill within your professional scope

■ Ethical and legal issues and developments

Development Outcome: B,C&D

Many members of the Dental Technologists’ Association (DTA) are concerned about what appears to be in-clinic manufacturing of custom-made dental devices which does not abide by current regulatory requirements. In trying to maintain a level playing field with regard to regulatory compliance, the DTA – as a professional body – continues to provide guidance to its members and raise awareness of regulations to all professional bodies responsible for the UK manufacturer of these custom-made dental devices.

According to current regulations, in order for manufacturers of custom-made dental devices to legally comply – from the inclinic manufacture of anything from a bruxism splint to a crown – by law, requires registration with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and also requires the manufacturer to provide each patient with a statement of manufacture for each device. This relates not only to the manufacture of dental

devices in the UK but also to the importation of dental appliances from overseas, more of which later.

This statement of manufacture provides details about the device, including the manufacturer’s address, their MHRA reg number, that it’s intended use is for a specific patient, and a confirmation that it conforms to relevant standards and a registrant clinician’s prescription. It also details the materials used. The clinician who prescribed the appliance is responsible for making the patient aware of this statement and must provide it upon request.

But who should comply with the MHRA registration requirements, and are there any exceptions? Some have suggested that clinicians are exempt from registration with MHRA, as they hold the view that their own in-clinic milling is not manufacturing but rather, as per the previous MDD regulation, ‘...adapt(ing) devices already on the market to their intended purpose for an individual patient’.

Put simply, by law, this cannot be the case. The manufacturer is not exempt just because the manufacturing occurs in the dental clinic. The DTA has consistently lobbied the GDC, governments and other professional bodies with regard to this issue saying that, as it is for dental laboratories, such in-clinic fabrication should always be regulated by the MHRA. If MHRA registration is necessary for registered dental technicians, then surely it must be the same for dentists manufacturing in their clinics.

The GDC has also presented papers to indicate that compliance with the MHRA is an essential requirement for custom-made dental devices in the UK. These requirements are made very clear in the Standards for the Dental Team 2013. GDC publication. Standard 1.9.1

It states that: If you make a dental appliance, whether you are a dental technician, dentist, or any other registrant, you must understand and comply with your legal responsibilities as “manufacturer” under the Medical Device Regulations (MDR). (ref GDC published ‘Guidance on Commissioning and manufacturing dental appliances’.) This includes the legal requirement to register with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

If you prescribe a dental appliance to be made by a person in the UK who is not a registered dental technician, you may put your registration at risk. Equally, you may put your registration at risk if you receive a dental appliance made in the UK by a person who is not a registered dental

technician. The signing off of an appliance as fit for the market by a registered dental technician assumes that they can trace by audit the manufacturing processes and that the materials used within that process are appropriate for oral cavity use.

If you decide to either sub-contract the manufacture of a dental appliance or use a dental laboratory or agent which sources dental appliances from outside the UK you take on additional responsibilities. These include a responsibility to ensure that the manufacturer or their authorised representative has complied with all relevant obligations in the UK Medical Device Regulations (MDR).

So, every GDC registrant that manufactures custom-made dental devices is required to register with the MHRA and provide the patient with the statement of manufacture, and the DTA will continue to indicate that this should continue to be seen as an oral healthcare team opportunity to work within

the law and showcase the dental laboratories’ essential role in oral healthcare.

For those who are still sceptical, then maybe the extracts from the NHS Business Authority2 will make interesting reading. See Figure 1 below

A further interesting requirement of the NHS appears later in this page,3 providing direct clinician advice on their in-house milling of custom-made dental devices (see Figure 2 overleaf ). There cannot be one requirement for NHS appliances from dental laboratories and a legal case for non-compliance for private/independent dentistry in-clinic manufacturing. It’s all manufacturing of custom-made dental devices and requires the manufacturer to register with the MHRA.

Further guidance is also provided by the government to clinicians needing to register with the MHRA because they are manufacturers of custom-made dental devices by milling in-clinic or other such manufacturing methods.4 The link provided is to GOV.UK advice on how to Register medical devices to place on the market.

It states: You must register5 if you or your company sells, leases, lends or gifts:

A Class I, IIa, IIb or III devices you have manufactured

A Class I, IIa, IIb or III devices you have refurbished or re-labelled with your own name

A Any system or procedure pack containing at least one medical device

A Custom-made devices

A IVDs you have manufactured

A IVDs undergoing performance evaluation

It is quite plain manufacturing of Custommade dental devices requires MHRA registration. It is the law, and registrants need to know that this “affect(s) your work and they need to follow the requirements...” (Standard 1.9).

Within the GDC document on custommade dental devices that require registration, the Council clearly defines a range of dental appliances that they describe as manufactured, ‘mainly outside of the mouth’. The GDC then provides a range of examples, including fixed bridges, bleaching trays, crowns, splints, retainers, etc., that they regard as custom-made dental device manufacturing, thus requiring by law for the manufacturer to register with the MHRA.

Likewise, the GDC indicates that a clinician who accepts dental appliances made in the UK by an unregistered dental technician or a dental laboratory not registered with MHRA may also put their registration at risk. The Standards for the Dental Team, standard 1.9 clearly states that as a registrant ‘You must find out about laws and regulations affecting your work and follow them’.

And finally, with regard to registrants signing off on overseas manufactured custom-made dental devices it can be impossible to verify the materials used in manufacture and the UK registrant – dental

technician or dentist – is legally liable for any problems that might result from say, an allergic reaction to alloys used in the device once placed in the patient’s mouth.

It is best to source from trusted suppliers with reputable and traceable manufactures sources. Cheap probably means suspect materials from which you could be manufacturing and then signing off custom made dental devices and for which you will be taking responsibility. This is also something that GDC registrants should be indemnified or insured to carry out.

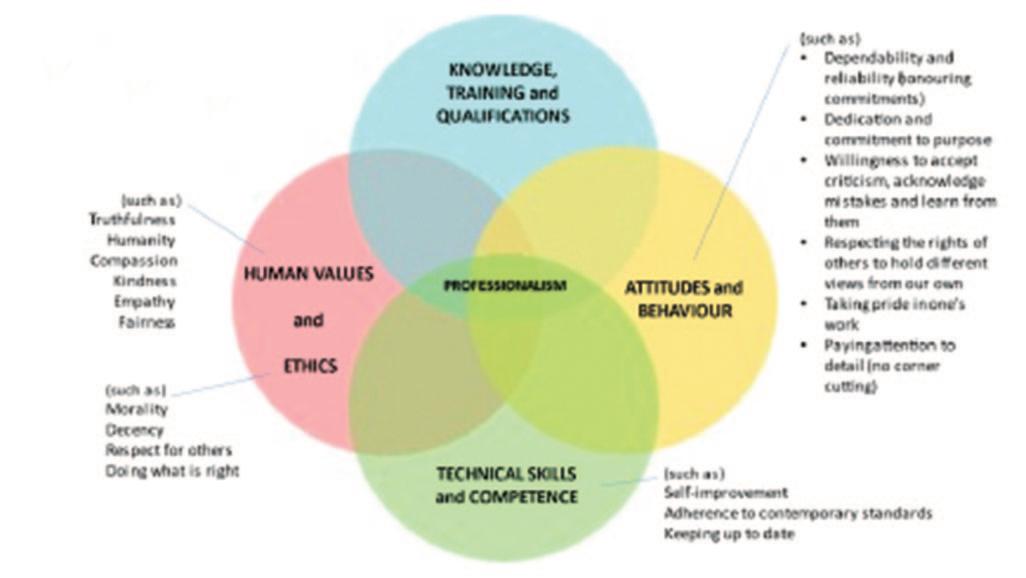

Keeping up-to-date with such MHRA regulations is something we all as registered professionals need to do, while those wider attributes of professionalism includes displaying honesty and ethical behaviour. Within the education sector of Oral Healthcare team of professionals an updated requirement has been introduced from 2025 by the GDC called ‘Safe Practitioner – Framework’ 6 This outlines for students a range of attributes that professionals should show such as P1.12 ‘Describe the responsibility that dental practices and individual practitioners have in compliance with legal and regulatory framework’ therefore all team members are expected to know about the legal requirements and in particular for dental technicians the manufacturing of custommade dental devices under MHRA (UK MDR).

Regarding Medical Devices Regulations (MDR) which came into force 26 May 2020. Since 26 May 2021, the EU Medical Devices Regulation (Regulation 2017/745) (EU MDR) has applied in EU Member States and Northern Ireland. As these EU regulations did not take effect during the transition period, they were not EU law automatically retained by the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 and therefore do not apply in Great Britain. Therefore, refer

to the UK MHRA MDR regulations for custom-made dental devices.

A Please get in touch if you have any queries relating to this article, email info@dta-uk.org

1 Standards for the Dental Team 2013. GDC publication. Standard 1.9 https://www.gdc-uk.org/docs/defaultsource/information-standards-and-guidance/guidancedocuments/guidance-on-commissioning-andmanufacturing-dental-appliances79b4ee91c3a64f 12b5772a26dec28601.pdf?sfvrsn=9463dd00_10#:~:t ext=From%2026%20May%202020%20the,comply%2 0is%20a%20criminal%20offence Accessed June 2025.

2,3 NHS Business Authority. https://faq.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/ knowledgebase/article/KA-01757/en-us Accessed June 2025

4 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/register-medical-devicesto-place-on-the-market

5 https://www.gov.uk/guidance/register-medical-devicesto-place-on-the-market#who-must-register

6 The Safe Practitioner: A framework of behaviours and outcomes for dental professional education - Dental Technician https://www.gdc-uk.org/docs/defaultsource/education-and-cpd/safe-practitoner/spf-dentaltechnician.pdf?sfvrsn=75edb41e_3

To complete your CPD, store your records and print a certificate, please visit www.dta-uk.org and log in using your member details.

Q1 What is the MHRA?

A Manufacturers and Healthcare Regulation Agency

B Manufacturing for Healthcare Registration Agency

C Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

D Medicine and Healthcare providers Regulation Agency

Q2 What does the Statement of Manufacture include?

A MHRA registration number

B The materials used

C Manufacturer’s address

D All of the above

Q3 Are clinicians exempt from registration with MHRA?

A Yes, they are adapting devices already on the market

B Yes, they are providing devices for a specific patient, not the general market

C No, by law this cannot be the case

D It is not clear, the regulation requires clarification

Q4 In the GDC Standards for the Dental Team, where is it made clear that a manufacturer has a legal requirement to register with the MHRA?

A Standard 1.9

B Standard 1.5

C Standard 1.7

D Standard 1.6

Q5 The signing off of an appliance assumes that the manufacturer can trace by audit the manufacturing processes, and what?

A That the device was manufactured by a GDC registrant

B The materials used are appropriate for oral cavity use

C That the device will be placed into the named patient

D That the device was manufactured to a registrant’s prescription, and all of the above

Q6 Are dental devices manufactured outside the UK exempt from regulation?

A Yes if they are made in the EU

B Yes if the manufacturer resides in one of six specific countries

C No, the sub-contractor must ensure the appliance complies with UK MDR requirements

D If the UK registrant is happy with the appliance they can sign it off.

Q7 What direct requirement regarding inclinic milling is demanded by the NHS?

A Practices producing such restorations must register with MHRA

B The manufacture of such restorations requires at least six-months training

C Such restorations can be manufactured by any member of the dental team under proper supervision

D Such restorations require a Statement of Manufacture

Q8 Does the in-house milling requirement by the NHS impact private/independent practices?

A No, the NHS has its own rules

B Yes, there cannot be one rule for the NHS and another for private practice

C No, independent practices are under separate requirements

D No, not if the device has specifically been made for an existing patient

Q9 The Government states that manufacturers must register with MHRA if they provide, what?

A Class I, IIa or III devices they have manufactured

B Any system or procedure pack containing at least one medical device

C Custom-made devices

D All of the above

Q10 Is not knowing about the MHRA regulatory requirements a valid excuse for not registering, as some clinicians think?

A Yes, they have enough to think about

B Clinicians are amongst the most regulated professions in healthcare, they can be trusted to act ethically at all times

C Yes, it is the regulator’s job to inform them

D No, all team members are expected to know about their legal requirements

■ Stress Part I – What is it and how does it affect us?

Tracey O’Keeffe, Coach Practitioner and Mindfulness Teacher MA (Education), BSc (Critical Care), RN, MAFHP, MCFHP

This paper, and a second one to follow, will explore stress and how we can mitigate against the damaging effects it can have on our minds and bodies. Stress is something most people can relate to and will have experienced in their lives. Indeed, Ghasemi et al. (2024, p.1) state it is “an inevitable aspect of human existence”. The world today operates as a fast-paced and pressured environment for many, and the levels of stress are rising and becoming more evident throughout the population (Candeias et al. 2024). Understanding what stress is, what can trigger it, and how we can respond rather than react may be instrumental in preventing some of the long-lasting and potentially damaging effects it can have on an well-being (Yaribeygi et al. 2017).

A seminal piece of work about stress is that of Selye (1956) who explained it as a physiological response to both physical and psychological stimuli. Charmandari et al. (2005) suggest that those stimuli may be exposure to pathogens, physical harm or chemical imbalances, although it is also acknowledged that stress can be triggered by any sort of tension, worry, or a difficult situation (World Health Organisation 2025). Essentially, anything that poses a threat or disrupts the equilibrium of the body manifests as stress and a need for the body to return to stability and balance (Ghasemi et al. 2024).

The word “stress” often brings to the mind negativity, and from the definitions and explanations above, it would seem that it predominantly brings problems. However, Seyle (1965) described it as a non-specific response from the body in order to create

change from an existing state. The Stress Curve is a well-known model based on the work Yerkes and Dodson (1908) which considers when stress moves through a positive motivating force to a negative influence (see Figure 1). What the curve shows is how positive stress, or “eustress”,

enables us to reach our optimum performance levels. Becoming “distressed” however, with an overload of stress, tips us over the brow of the curve and into possible burnout. In essence, rather than always detrimental, some degree of stress can be a stimulus for action, results and necessary

adjustment. Stress stems from the need to respond to a situation with the body activating the sympathetic nervous system into “fight or flight” mode.

Neurotransmitters and hormones (such as adrenaline and cortisol) are released which transforms the body into a state of alertness. The body senses the stress stimulus as something which needs challenging (“fight”) or something to flee from and run (“flight”). The analogy often used here is the concept of a caveman fighting a sabretooth tiger. If the body needs this physical capability, the changes within the body are useful and productive. However, if the reaction is due to a perceived but non-life threatening situation, the stress response can continue to elevate and create on-going issues (Harvard Health 2025), which will be discussed in more detail later. Stress triggers or determinants may be short-term, discrete situations or they may more long-standing historical events and experiences (Harvard Health 2025; Schneiderman et al. 2005) (see Figure 2). The variety and scope is vast, and it is worth noting that positive events such as marriage, promotion, childbirth, although not included in Figure 2, can also create stress for an individual as they adjust to change and altered personal perception and responsibility.

As shown in Figure 2, stress may be shortlived, transitory and necessary or it can remain with someone for a longer sustained period. Acute stress is usually not damaging and can in fact be beneficial. Mifsud and Reul (2018) suggest that enables further damage to the body to be prevented such as in the case of trauma or surgery. Similarly, if preparing for a particular event (such as an exam or interview) a small amount of stress can actually help with performance and alertness (as in Figure 1) (World Health Organisation 2025). However, if the acute stressor is repetitive or if it is a chronic

situation, then the health burden can increase resulting in physical and psychological problems, depending on the person’s individual situation (Schneiderman et al. 2005). If the “fight or flight” continues without moving into a recovery phase, an exhaustion stage can result leading to burnout, anxiety, and reduced stress tolerance (Seyle 1950) as well as physical health problems (Yaribeygi et al. 2017; Hasin et al. 2023; Ghasemi et al. 2024). Sometimes this can be considered as the “freeze” response where there is a level of disengagement and incapacity to act, almost as a protective factor. This is

ultimately related to physical changes within the body and the subsequent maladaptive response.

The way the body reacts to a stressful stimulus is a complex series of changes and processes involving many body systems (Carrasco and Van de Kar 2003) instigated by the autonomic nervous system (Tortora and Derrickson 2017). As well as this, there are behavioural modifications. Initially, the cardiovascular system prepares for an

emergency situation, increasing heart rate and increasing vasoconstriction in certain areas of the body. This enables oxygenated blood flow to be directed to the cardiac and skeletal muscles (for action) and the brain (for alertness). The respiratory rate also increases to match the perceived demand for oxygen (Harvard Health 2025). This activation of the sympathetic nervous system is effective when needed and it can be felt in the body with the heart racing, the breath quickening and a state of heightened arousal. Usually it is then followed by the parasympathetic nervous system coming into play once the stressor has resolved (Ulrich-Lai and Herman 2009). This reversal or “rest and digest” phase sees the slowing of the heart rate and respiratory rate with a reducing blood pressure. The circulation returns to areas such as the gut so that body can renew stores of energy. Equilibrium overall is restored.

Longer term and unrelenting stress responses in the body can result in health conditions relating to many body systems, both physical and mental, as well as behavioural adaptations or manifestations (see Figure 3). Schneiderman et al. (2005) also suggest that the more intense and severe the stressor, the greater response. This is also matched with a sense of control; the less control a person feels they have, the greater the effect of the stress on them.

As well as potential changes and risks noted in Figure 3, people may experience musculoskeletal problems like neck and back pain caused by tension (Umann et al. 2019). This can often be work-related, exacerbated by manual work or from poor posture and sedentary challenges. Psychological changes also often manifest as anxiety and depression which may be short-term or enduring (Ghasemi et al. 2024).

As a final discussion point, it is worth reenforcing that stress cannot be seen as an

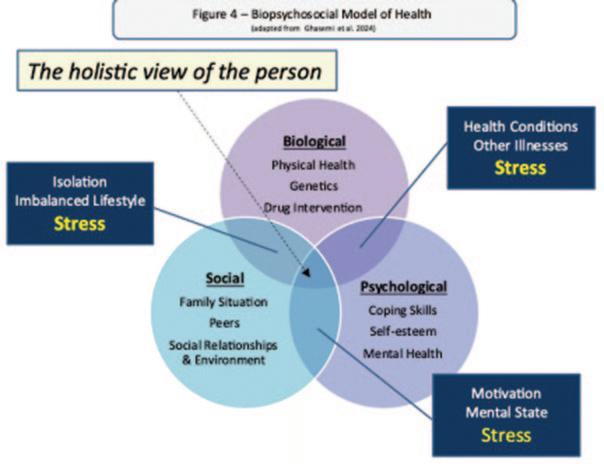

isolated phenomenon. It interacts with the individual from a biopsychosocial perspective both in terms of its origin and its solution. The biopsychosocial model of health is well-documented and utilised through healthcare, and Figure 4 demonstrates how stress as a concept sits within it. Stressors can come from biological, psychological and/or social contexts. Similarly, the way they are managed or mitigated against, can come from those three stances and each approach will vary in effectiveness for each individual situation. Indeed, Robinson (2018) notes the complexity of stimulus, appraisal and response. Stress is multidimensional and cannot be examined or solved away from the context of the situation.

Stress is inherent in life and it can be difficult to navigate through. Although our body is designed to respond in an appropriate way, the stressors we experience in day-to-day life may not warrant that response. Repetitive acute stress or long-term chronic stress can result in potentially damaging physical changes as well as maladaptive thought processes and behavioural approaches. Understanding possible management strategies is key to coping and they can be developed through self-awareness and a variety of different mechanisms which will be discussed in the next paper.

Candeias, A. A., Galindo, E., Reschke, K., Bidzan, M. and Stueck, M. 2024. Editorial: The interplay of stress, health, and well-being: unravelling the psychological and physiological processes. Frontiers in Psychology. 15. 1-4. DOI=10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1471084

Carrasco, G. A. and Van de Kar, L. D. 2003. Neuroendocrine pharmacology of stress. European Journal of Pharmacology. 463. 1. 235-272

Charmandari, E., Tsigos, C., and Chrousos, G. 2005. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annual Review of Physiology. 67. 259-284

Ghasemi, F., Beversdorf, D. Q., and Herman, K. C. 2024. Stress and stress responses: A narrative literature review from physiological mechanisms to intervention approaches. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. 18. 120. DOI: 10.1177/18344909241289222

Harvard Health. 2025. Stress. [online] [accessed 27.6.25]. Available at: Identifying and relieving stress - Harvard Health

Hasin, H., Johari, Y. C., Jamil, A., Nordin, E., and Hussein, W. S. 2023. The Harmful Impact of Job Stress on Mental and Physical Health. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences. 13. 4. 961-975

Mifsud, K. R. and Reul, J. M. H. M. 2018. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor-mediated control of genomic responses to stress the brain. Stress. 21. 5. 389-402

Nickerson, C. 2023. The Yerkes-Dodson Law of Arousal and Performance. [online] [accessed 28.6.25]. Available at: The Yerkes-Dodson Law of Arousal and Performance

Robinson, A. M. 2018. Let’s talk about stress: History of stress research. Review of General Psychology. 22. 3. 334-342. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000137

Scheiderman, N., Ironson, G., and Siegel, S. D. 2005. Stress and Health: Psychological, Behavioural, and Biological Determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 1. 607-628.

doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141

Seyle. H. 1950. Stress and the general adaptation syndrome. British Medical Journal. 1. 4667. 13831392

Seyle, H. 1956. The stress of life. New York; McGraw-Hill

Seyle, H. 1965. The stress syndrome. The American Journal of nursing. 65 (3). 97-99

Tortora, G. and Derrickson, B. 2017. Tortora’s principles of anatomy and physiology. 15th edn. Singapore; John Wiley & Sons

Ulrich-Lai, Y. M., and Herman, J. P. 2009. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10. 6. 397–409. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nrn2647

Umann, T., Jager, M. and Lutticke, J. 2019. Job stress as a risk factor for musculoskeletal disorders in healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 14. 6. e0216857

World Health Organisation. 2025. Stress. [online] [accessed 28.6.25]. Available at: Stress

Yaribeygi, H., Panahi, Y., Sahraei, H., Johnston, T. P., and Sahebkar, A. 2017. The impact of stress on body function: a review. EXCLI Journal. 16. 1057-1072. http://dx.doi.org/10.17179/excli2017-480

Yerkes, R. M. and Dodson, J. D. 1908. The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Punishment: Issues and experiments. 27-41.

Kevin Lewis

■ To explain the nature of choice and how/why we make decisions in different circumstances

■ To explain how we are predisposed to make certain choices, without realising this

■ To provide practical illustrations of the consequences of the choices we make and how instinctive choices can have serious implications

CPD Outcomes:

■ Effective communication with patients, the dental team and others across dentistry, including when obtaining consent, dealing with complaints, and raising concerns when patients are at risk

■ Effective management of self and effective management of others or effective work with others in the dental team, in the interests of patients; providing constructive leadership where appropriate;

[Effective practice and business management]

■ Maintenance and development of knowledge and skill within your field of practice; Clinical and technical areas of study: Emerging technologies and treatments

■ Maintenance of skills, behaviours and attitudes which maintain patient confidence in you and the dental profession and put patients’ interests first.

[Professional behaviours]

This article looks at some of the many choices we face in our personal and professional lives, and illustrates that most or all of the choices we make have a legal and/or ethical dimension, and often, professional and human consequences. Many of these consequences are not immediately apparent, nor uppermost in our mind, at the moment when we are faced with these choices.

Choices are not always binary, ie selecting one of two possible options. In many cases there are several choices. Sometimes one option is doing nothing or taking no active step to take a different course; infact that is still a choice. Some choices have to made in a split second, while others allow more time

to weigh up the options and perhaps explore new options that you weren’t previously aware of.

Three years ago, in an earlier article in this series on Legal and Ethical issues,1 we looked at the essential ingredients of professionalism. For the benefit of those who didn’t see or read that article (and for the convenience of those who did), a key section of that text is reproduced below :-

If you were to ask different people to describe a professional person, you are likely to get a range of answers (depending on who you ask). But the descriptions would probably include things like

A They are members of an acknowledged profession (accepting that the scope of this definition has widened over the years)

A They have a special level of training, knowledge and skill in their particular field

A They have achieved some kind of recognised professional qualifications

A They are good at what they do in their chosen professional field

A They enjoy an above-average level of status, respect, confidence and trust within society

But if you were then to ask those same people what was meant by ‘behaving professionally’, the focus of the description might shift away from proficiency, knowledge and practical skill levels , towards things such as

A They are principled and ethical

A They act with integrity

A They have respectable human values and maintain appropriate standards of behaviour

A They show respect for others, and their rights and dignity

A They honour the commitments they make, and take a pride in what they do

A They respect and follow the law

A They take responsibility for their actions

A They continually seek to develop, learn and improve themselves

A They demonstrate their understanding of, and their respect for, professional boundaries, ie attitudes and behaviours that are unacceptable in the context of their professional life – even if they might be acceptable in their private/personal life

There is an inherent perspective bias surrounding professionalism: those within a given profession might have a different understanding to those on the receiving

end of their professional services. Those who (perhaps by virtue of not having completed the necessary training and/or obtained the relevant qualifications) sit outside the ‘inner circle’ of the profession and/or are resentful at being excluded from it, might become disaffected or even motivated to question or undermine that exclusivity or chip away at its edges. Third parties like regulatory bodies (eg the GDC)

might have different views again and apply and enforce incongruous expectations that coincide neither with those of the providers nor the recipients of the professional service being regulated. Meanwhile funders and commissioners of services, are likely to have a very specific agenda – perhaps in the hope of securing the delivery of a service with a semblance of professionalism and all its potential benefits, without actually having to pay a premium for them.

The wisdom of hindsight will be familiar to all of us. Reflecting after the event upon whether we, or someone else, has made a sensible choice, is informed by knowing what happened as a result of that choice –and whether there might have been a different outcome, had a different choice been made. Any and every party comes to this discussion with a personal viewpoint and perhaps bias, which reflects their own individual value system. There may be subjective skews and conflicts in arriving at that view, which the individual may or may not be aware of.

All this in turn is a product of all the experiences of their lifetime from their early childhood, through all stages of their education, into their adult and working life. By that stage it has been influenced by family, teachers, peers and third parties of many different kinds (and in many cases a mix of both positive and negative influences) and there is a fascinating debate to be had regarding whether these values and

Figure 1: The text reproduced below is extracted from the GDC’s Guidance Standards for the Dental Team, these extracts having been chosen for the specific purpose of this article. To place this statement in its correct, original context you should refer to the full text of the Guidance.7

Standard 1.7: You must put patients’ interests before your own or those of any colleague, business or organisation

Principle 9 – Make sure your personal behaviour maintains patients’ confidence in you and the dental profession

Patients expect: -

– That all members of the dental team will maintain appropriate personal and professional behaviour

– That they can trust and have confidence in you as a dental professional

– That they can trust and have confidence in the dental profession