JOANNE CARSON

Interview w ith David Rimanelli

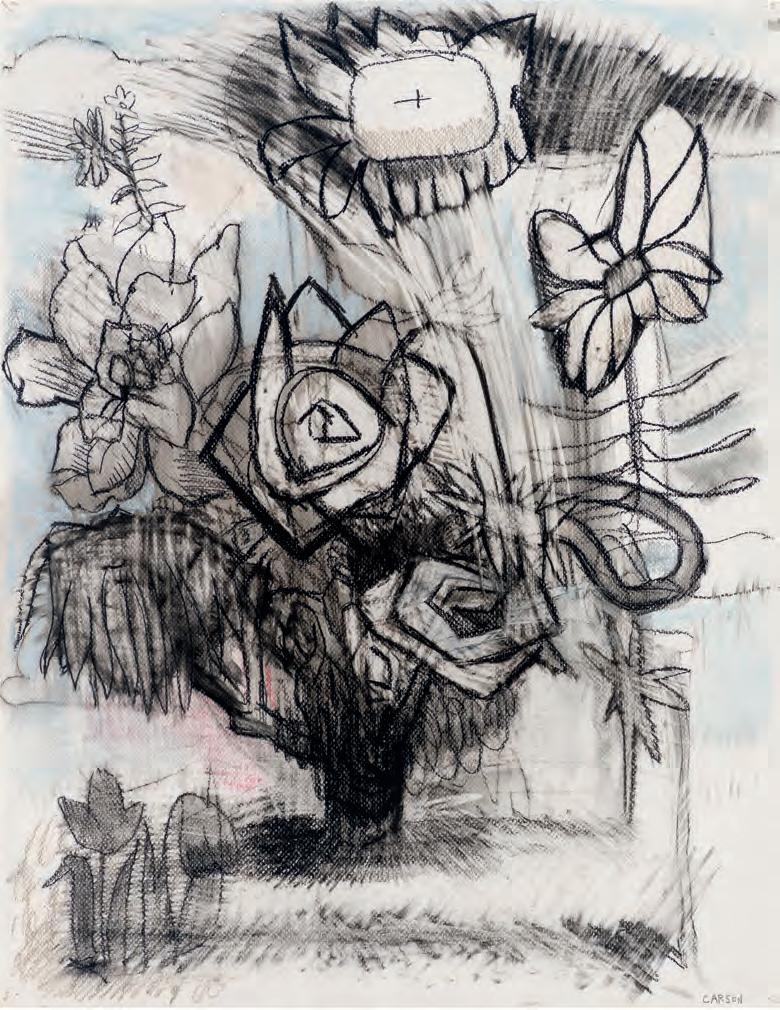

In her recent series of paintings, JoAnne Carson continues her journeys into the real, surreal, and mythopoeic arboreal realm. Trees. Carson thinks of each tree as a character, a personage. Or maybe she also feels that each one has character, a character, with multifarious characteristics. Their branches might sway, but their trunks are unmoving, obdurate even: the trunk’s a statement, a prolegomenon, a position. A written life story. And that non-acting quality is taken often as their strength: impassive and unmoving like an oak, a maple, a sequoia.

David Rimanelli: Tell me about your background and where you’re from, and what kind of art you liked at first.

JoAnne Carson: All right, starting at the very beginning! I grew up in suburban Maryland in a house on a river. The foliage was dense and overgrown, and we would go crabbing and sail in a small homemade boat. It was a very idyllic setting. My father was an aeronautics engineer and my mother was an artist. As you know, she was married to Mark Rothko in the 30s and early 40s and we had several of his early paintings hanging in our house. That was a huge influence on me as a child as you can imagine.

Interview W ith David Rimanelli

JoAnne Carso n’s Garden

DR : They’re so different from what one expects from mature Rothko.

JC : They’re surreal. I remember how spooky they seemed to me, because they had fragments of figures hands, heads, eyes all arranged together and a very quiet color palette. Years later I saw some of those same elements emerge in my own work; it was an unconscious influence. The thing about influences is you don’t necessarily see them at the time. But they are out there waiting for you.

So that was my very early years, and then I went to school for undergrad and graduate work in Chicago and spent several years there. I felt very grateful for that

DR : Why were you grateful for it ?

JC : Because it was the early 1980s, and it was a big social scene in Chicago, but without the intense edifice of New York City. I had a loft on Hubbard Street, which is right downtown. And the art world was very loose. There was no such thing as a studio visit people would come over for dinner or a drink, and then look at your work. When I got to New York in 1985, it just seemed so professionalized and serious by comparison.

DR : And then you were very successful early in your career. How was that? How did it feel to be like this young star?

JC : When you’re young, you don’t know what the future will be, so you assume that things will just keep going forward in the same way, right? You just think this is it. So at the time I thought, wow, being an artist is great! I graduated from University of Chicago, and then pretty immediately, I was in a Whitney Biennial. And I got important prizes like the Prix de Rome and the Awards in the Visual Arts and even had a couple of museum shows.

So I was very lucky.

DR : Oh, not just luck.

JC : Well, I was fortunate to have such a powerful model as my mother who had lived the life of an artist and that showed me a lot. And I’ve always worked hard, and because I came up in the early 80s, when there was no established orthodoxy, that was kind of freeing. I just wanted to make big, crazy, improbable, funny and serious things, and I was able to do that. I’ve never been intimidated by things I don’t know how to do. I just thought, I’m not a good carpenter, but just drill a hole and get a piece of wire and tie it together!

DR : That’s the real art spirit, right?

JC : It is, yes.

DR : Can you tell me about the work that first gave you a profile in the art world? Would that be the kind of work that was in between painting and sculpture, or does that come later?

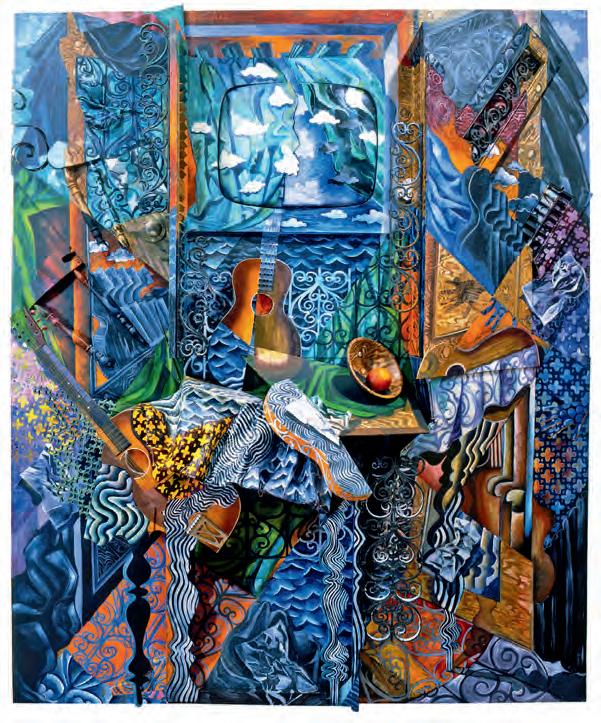

JC : They were the constructed wall assemblages I love a puzzle and a collage, and how I put together paintings is so improbable. I got objects and combined them in some sort of interesting whirlwind way, that I then painted over, or camouflaged with paintings by Cezanne and Cubist painters. They seemed unified when viewed from the front but as the viewer approached, suddenly a TV set would pop out, or a broken chair. They changed as you moved around them and only operated as a still painting from one vantage point.

DR : I want to talk about the mood of that period. You told me that you felt like your work had a kind of feminist angle. Is that something that you felt from the beginning, or that you grew into?

JC : No, I felt it at the time, because I went to school when Feminist

w, 2025. Acrylic on canvas, 42 x 50 inches

Curtain Cal I, 1983. Oil on wood and objects, 96 x 78 x 25 inches

Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, A gift in loving memory of Ted and Iva Hochstim by Ethan, Michelle, and David, U-6913.2019

art was much more visible and applicable to young women artists like myself, and there didn’t seem to be any real rules. It was very pluralistic. The art world was recovering, in a way, from strict formalism. I’ve always had a very strong decorative impulse, which at the time was a sort of declared feminism like Judy Chicago’s work and strategy.

DR : What about more formalist female artists that you mentioned being close to when you first came to New York, like Judy Pfaff ?

JC : In addition to Judy Pfaff, Elizabeth Murray was very influential with her shaped canvases and cartoon-inflected painting. But the person who I loved more than anybody was Lee Bontecou. I still remember the first time I ever saw her work, and it can still operate this way when I look at it. Because what are you looking at? You’re looking into a hole. And yet it feels like it’s a picture, because it’s black, so it seems like this flat shape, yet it’s projecting off the wall with such a force that there’s this impact between the flat and the sculpture, and it happens immediately. They were made with pieces of stained canvas that are just punctured with wire and then twisted together. She was a model for me of making powerful forms but very DIY and simply made. You know, when you’re trying to make some-

thing, and you see another artist who is maverick, it gives you permission to go for broke.

DR : Are you still doing sculpture, or are you mostly working on painting now?

JC : Right now I’m working on paintings. But when I have time I will go back to sculpture, because I love making physical things. Meanwhile, my Vermont garden is a kind of fill in for sculpture. It’s very elaborate with topiaries, fruit trees and perennials on a steep slope. It’s hardscaped with rocks and little tumbled together handmade walls so building it was absolutely like making sculpture.

DR : That’s a kind of sculpture that’s immersive, yeah?

JC : It is. I sometimes feel like I’m walking around in one of my paintings. Someone called it a Dr. Seuss garden because it is so zany.

DR : Do you feel, in some ways, that the garden is a laboratory of subject matter and material, or is it something in and of itself ?

JC : It’s both. It has greatly influenced my paintings and sculptures but also the garden has been modeled on my studio work. I was

moving away from sculpture and trying to create a world that had a fully inhabited space to it.

My husband and I bought the house and property in 2011, and that’s when my painting started to become the paintings they are today. They have been very influenced by the garden by watching the plants grow, thrive or die. The garden took me to a place where I could practice and envision how to make a painting. The energy was infectious and invaded my paintings. Because when you put a tree in the ground and put something next to it, you’re making a composition. I was only gardening in the area that I could see through the window. So when I look through the frame, which is the window, it looks like a painting.

DR : Something that you talk about is how your work gives you the sense of this incredible aliveness. For instance, this comes from another interview, “my work is hot and malleable like a lava lamp. It celebrates the wild female spirit of a burgeoning life force, outsized, opulent, decorative, humorous and erotic.” And somewhere else, you said something about how you felt that the duty of the artist was to speak to their time, which seems to suggest a kind of a political or socially conscious art. But I don’t think you meant

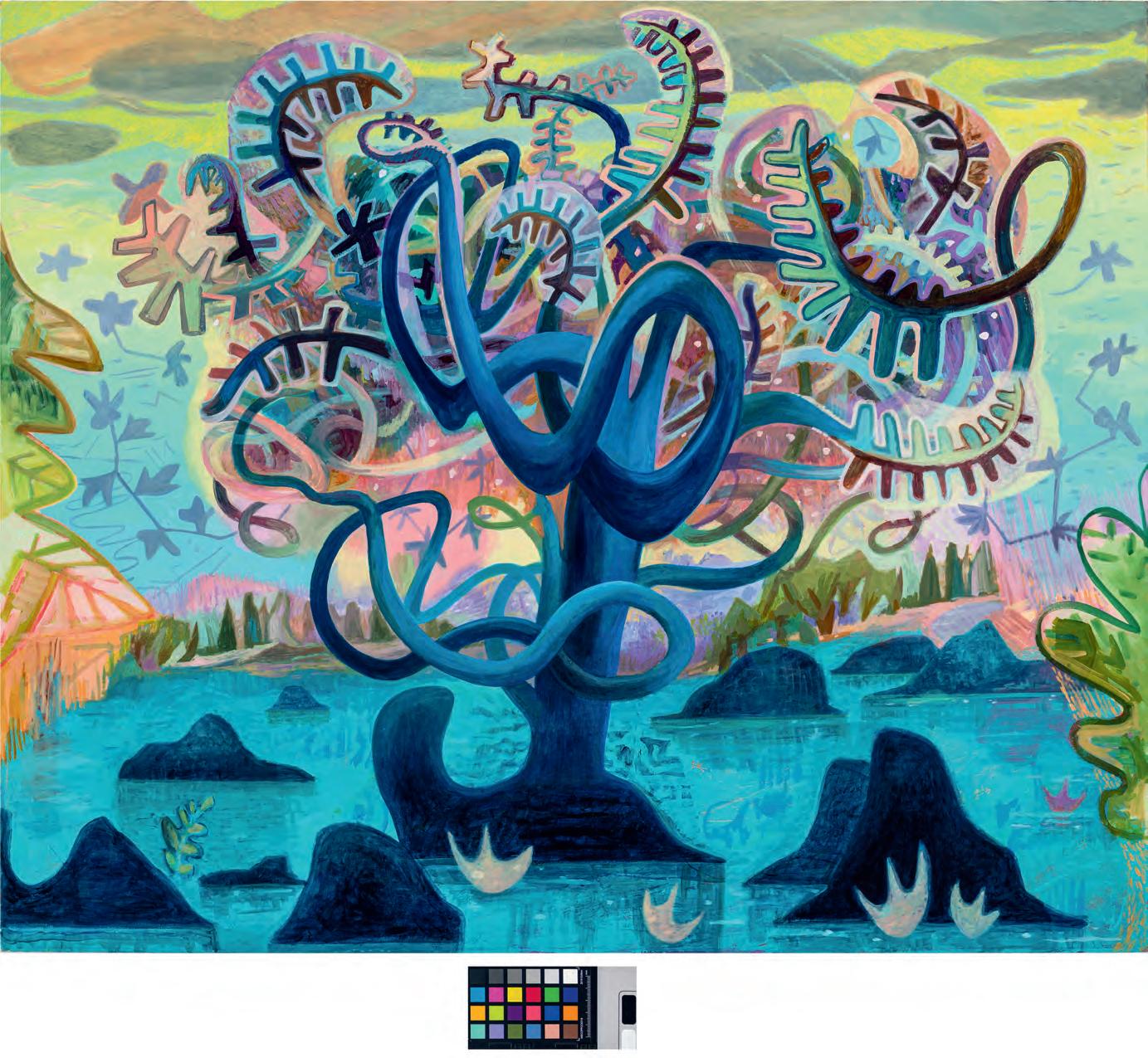

Switchback , 2025. Acrylic on canva s, 48 x 58 inches

that, because that isn’t what your work seems to be about. How do you feel you want to speak about our time and how does your work now want to speak to it?

JC : As a point of comparison, think of landscape painting of another period but particularly American landscape painting of the Hudson River School. Those artists were working in a way that was a celebration of the unknown frontier and Western expansion. It was a grandiose and theatrical depiction that valued the concept of wildness. I love those paintings and have elements in my work that mirror that theatricality. However, we don’t believe that wildness and “untouched” nature exists anymore. We feel that we’ve destroyed nature and we’re living with trepidation and guilt about what has happened.

So my work is, in a way, reflecting on the synthetic quality of nature, the way that anything could, or feels like almost anything can be produced in a laboratory. The fact that I have a hybridity between a plant, an animal, and a creature mirrors the kind of new nature that we live with.

DR : So you are saying that your work is actually part of the reality of our time?

JC : Yes, I think so.

DR : I think so too.

DR : I mean your painting is very happy and excited and cheerful in a way, but then sometimes it seems a bit teetering, a little bit almost frenzied. There is this sense of the trees as being hybrid creatures, between the plant world and the animal world, or between the zoological world and the anthropological world. They’re personages, very much thriving. I feel also like your paintings seem almost to come out of the canvas, like the trees are almost bouncing out and many of them have that kind of quality of something that’s barely contained about to explode with powerful energy.

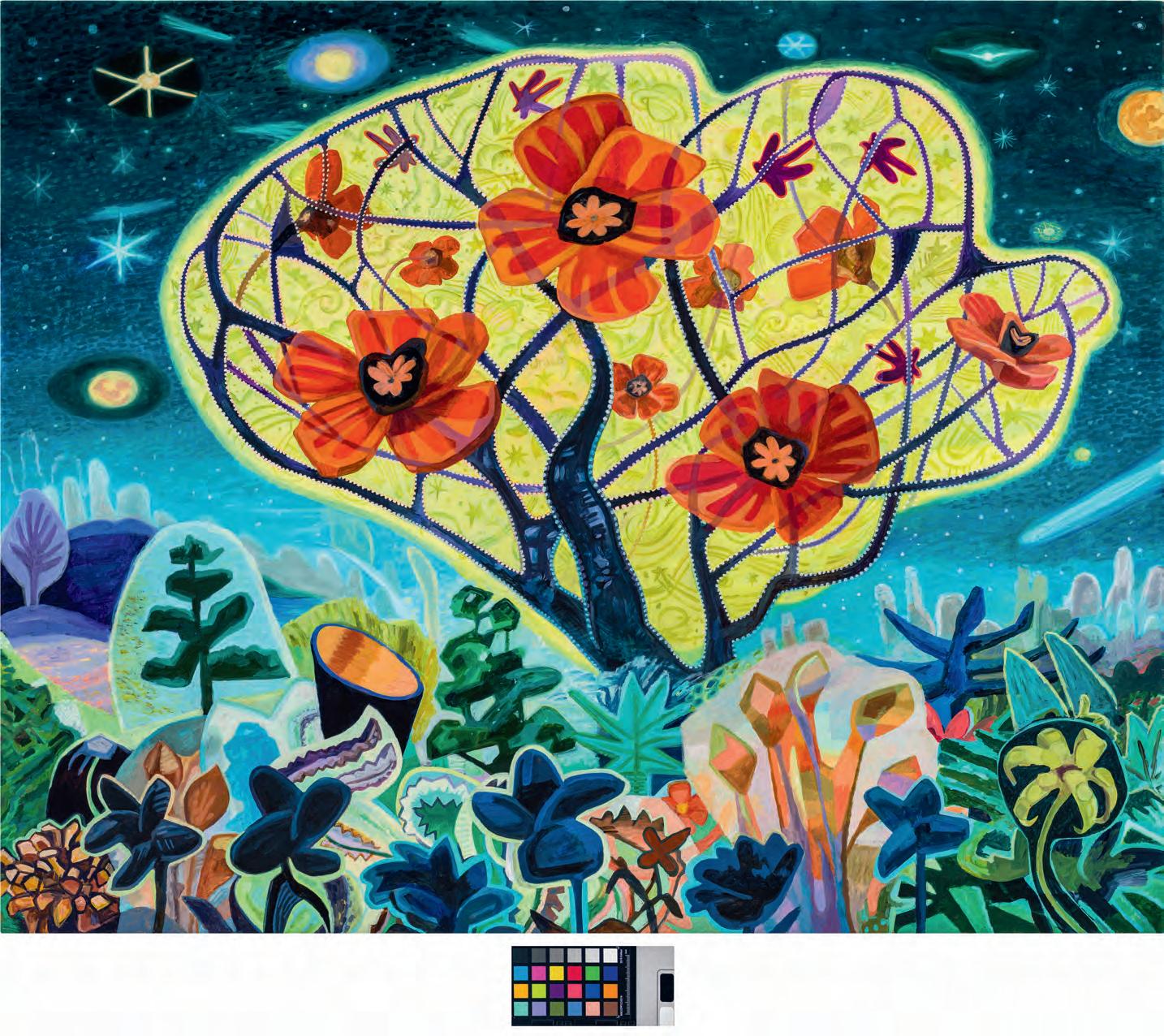

JC : The tree characters in each painting operate differently and have different personalities. But I think that all of them yearn for something. You know, that’s the part that’s not cheerful, is this excessive quality of desire for freedom or escape. For example, in Hothouse (p. 19), the tree is its own light source and represents a sort of interiority while the sky around it is zooming with stars and comets. The tree character is soothing itself for being separate and solitary in the universe.

I think that all my work has an element of exuberance, but I think

Misericordia , 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 60 inches

of it as the kind that puppies have when they play with each other, where they’re so excited that the play can turn into a fight. There’s something aggressive about them, like aggressively joyful or aggressively full of emotion.

DR : Full of a powerful and clarion kind of feeling, emotion that, yes, is a great thing it’s so vivid and so powerful. Where does that power come from? If we talk about the landscape, an idealized landscape, being what the culture wishes for itself, refracted through different artists. What is this telling us about the moment?

JC : To some degree, I feel that my work reflects the nervous energy of contemporary life. For example, a painting in the show, Ghost of a Chance (p. 11), the title refers to the frenzy that the character seems to be in trying to make something happen but it is all corkscrewed up. Whatever it wants, it has a ghost of a chance of getting it but not from lack of trying.

Also, when I’m working on a painting, it has to feel like it has a quality of magic, which is really subjective, but I feel it. I can say a painting’s okay, but if it doesn’t feel like it transports me to another place, it isn’t finished. This body of work is increasingly, I want to say magical.

DR : I was about to say visionary. You are having visions, and you’re translating them into like pictures.

JC : And that has happened increasingly. So this body of work is more visionary and even perhaps spiritual something that’s beyond this world. I feel that the paintings show something that’s beyond this life.

DR : Well, that’s what’s so cool. I think beyond this world is on a lot of people’s minds, when they think about mortality. But also, just in a day-to-day way, like the everyday world that we live in is fascinating, it’s brilliant, it’s glittery, it’s very dramatic and very frightening. And then there’s the desire for something that’s beside all of that.

JC : And in that regard, I feel that there’s something both animated and soothing about my worlds, where everything has its own presence, its own agency, its own sense of operating in this constructed world that I’ve made for it.

I think of it all the time when I’m making a painting, like this tree is ignoring this little flower who trying to get its attention it’s like a negligent mother. Or the painting that’s called Misericordia (p. 15), which is an art historical subject where Mary wears a cloak that is

sheltering and protecting all these little human souls. And so that reflects the idea of protection and aggression, and the whole range of things that my characters enact, that comes out of a sort of hyped up quality of aliveness.

DR : Also there’s a quality of a kind of happy aggression. I mean, so they don’t seem like angry paintings, but they seem in a context of what gave rise to them. Our relationship to the natural world has shifted because it’s kind of touch and go now.

JC : Our relationship to nature operates on different levels and reflects what we fear the climate change, people dying from flooding, from earthquakes, from fires. But then you go out and you look at the night sky, and it still has this ethereal power of wonderment.

David Rimanelli is a writer and poet. From 1993 to 1999, he was a regular contributor to Th e New Yorker ; since 1997 he has been a contributing editor at Artforum , writing also for Bookforum , Intervie w, Texte zur Kunst , Vogue Paris , frieze , The New York Times , and Flash Art .

Jo Anne Carson’s exuberant paintings of unruly, hybrid trees pull together allusions to Cubism, pop culture, mid-century animation, and changes in the natural environment.

Throughout her career, she has oscillated between two and three dimensions, beginning with constructed paintings with found objects, to free standing sculptures, to paintings on canvas and garden cultivation. She currently works in in all these media with the ambition to create a sense of enchanted, other-worldliness.

Born in New York City, JoAnne Carson splits her time between Brooklyn, New York, and Shoreham, Vermont. She received her MFA from the University of Chicago and completed her undergraduate studies at the University of Illinois.

Her sculptures, paintings, and drawings have been shown in numerous solo and two-person exhibitions including The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas; The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Illinois; and the Zillman Art Museum, Bangor, Maine. She has participated in notable group exhibitions at institutions such as the Whitney Biennial Exhibition, New York; the New Orleans

Museum, Louisiana; the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, New York; the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; and the Sheldon Art Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska.

Carson is the recipient of many awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome, the Louise Bourgeois Residency from Yaddo, and an individual artist grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. She is Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University at Albany, SUNY.

Her work is in the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum, New York; Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois; Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, Nebraska; Smart Museum of Art, Chicago, Illinois; and Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles, California, among others.

535 West 22 Street New York , New York 10011

21 2 . 24 7 . 2 111 dcmooregallery.com

This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition

J oAnne Carso n , Cosmic Ch a t t er

DC Moore Gallery

Septembe r 4 – October 1 1, 2025

Catalogue © DC Moore Gallery , 2025

Interview © David Rimanelli , 2025

isbn : 9 78 -1- 96503 7- 00 - 3

design : Joseph Guglietti

photography : © Steven Bates

printing : Brilliant

cover:

Fireball , 2025 ( detail ). Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 144 inches

opposite and inside front cover:

Chlorophyllia ( A World Without Color ), 20 17

Thermoplastic, apoxie clay, and paper pul p, 96 x 72 inches