CLAIRE SHERMAN

T he H our o f L a n d

Ter r y Te m pest W illiams

20 June 2013

My Dearest Carl:

It is raining and my heart is with you. I pray your health is steady. In the desert, when the winds pick up and clouds roll in, a sweet, pungent aroma arrives, sharp and fresh. There is a word for this smell: petrichor.

Lightning strikes. Nitrogen and oxygen molecules split and separate into atoms. Some of these recombine into nitric oxide, and dance in the atmosphere, sometimes producing a molecule made up of three oxygen atoms 03 ozone. I love the science of this pleasure. The scent of ozone heralds a storm because in the frenzy of a thunderstorm, call it a downdraft, winds carry 03 from higher altitudes to nose level.

So when the desert smells like rain it is ozone. Petrichor. There is another level to petrichor and it has to do with oils exuded by certain plants especially, in times of drought. When it rains, these oils that have been absorbed into the dry soil and rocks are released into the air with another compound known as geosmin.

This phenomenon added to the flash of lightning that creates ozone creates the sweet smell of rain when it is needed most.

Scientists believe this aroma has a purpose beyond pleasure. As the smell follows rain into the desert, turning arroyos into creeks that run into rivers, certain fish may receive aromatic cues that alert them that this a good time to spawn. Other information supports this smell as a messenger. Camels will follow their nose to water.

Paying attention to what appears to be peripheral This is what interests me. This is what I want to write about. What is peripheral eventually moves to the center. What rabbits know. What pronghorn know.

What we have forgotten with our predatory eyes facing forward.

What is peripheral is petrichor, the unmistakable scent of rain before it falls.

We are warned by side knowledge of what is to come and too often, we discount it.

the whispering of “the still small voice” that when ignored comes in on a storm: sheet lightning, thunderbolts deluge derecho

When we hear someone say, “It is the calm before the storm,” we feel it. We ignore it. Sometimes we act. Most often, we move on. But the directives that save us are the subtle exchanges with our soul. It’s what mountaineers know, if one person in the group has an instinct to stop and continue no further on: the designated route, the whole group turns back, no questions asked.

Instinct. Intuition. Peripheral vision.

I feel this storm coming.

We are evolving faster than Darwin could have imagined. I can imagine that children in the future will be born with wider-set eyes becoming closer to a prey species, pray species, either way it is to our species’ advantage to develop peripheral vision, including prayer. I can also imagine our own eyes slowly migrating toward our ears as we choose to listen more fully beyond words. A child once drew me a picture of an owl flying at night whose wings were ears. The world is changing and so are we.

What is being asked of us?

What am I asking of myself?

My beloved Carl, this desert, these Canyonlands, are becoming sites of disturbance. I think back to the day last fall when we were standing at the overlook at Island in the Sky and could see the Needles and into the Maze all the way to the bitten horizon, and you said, this was your peace.

I wish I was at peace now, but the desert has become my heartbreak. Perhaps that is the nature of deserts to break us open, wear us down to bedrock. Castle Valley has been reconfigured by flood, a flash in the night that came with such force, such ferocity, I heard it before I saw it, the thunderous roar.

That night, that roar, lives inside of me.

I opened the front door the desert was a vast and shining sea, a mirror reflecting stars. I didn’t know where I was. The turbulence didn’t register, only the strangeness of water in the desert. The only thing separating the water from me was a dike built in anticipation of a deluge such as this. I walked up to the dike and witnessed the water moving sideways with such velocity that rolling boulders became a parade passing by with uprooted junipers and cottonwood trees, hundreds of years old, being flushed down the valley, through every widening arroyo parallel to our house.

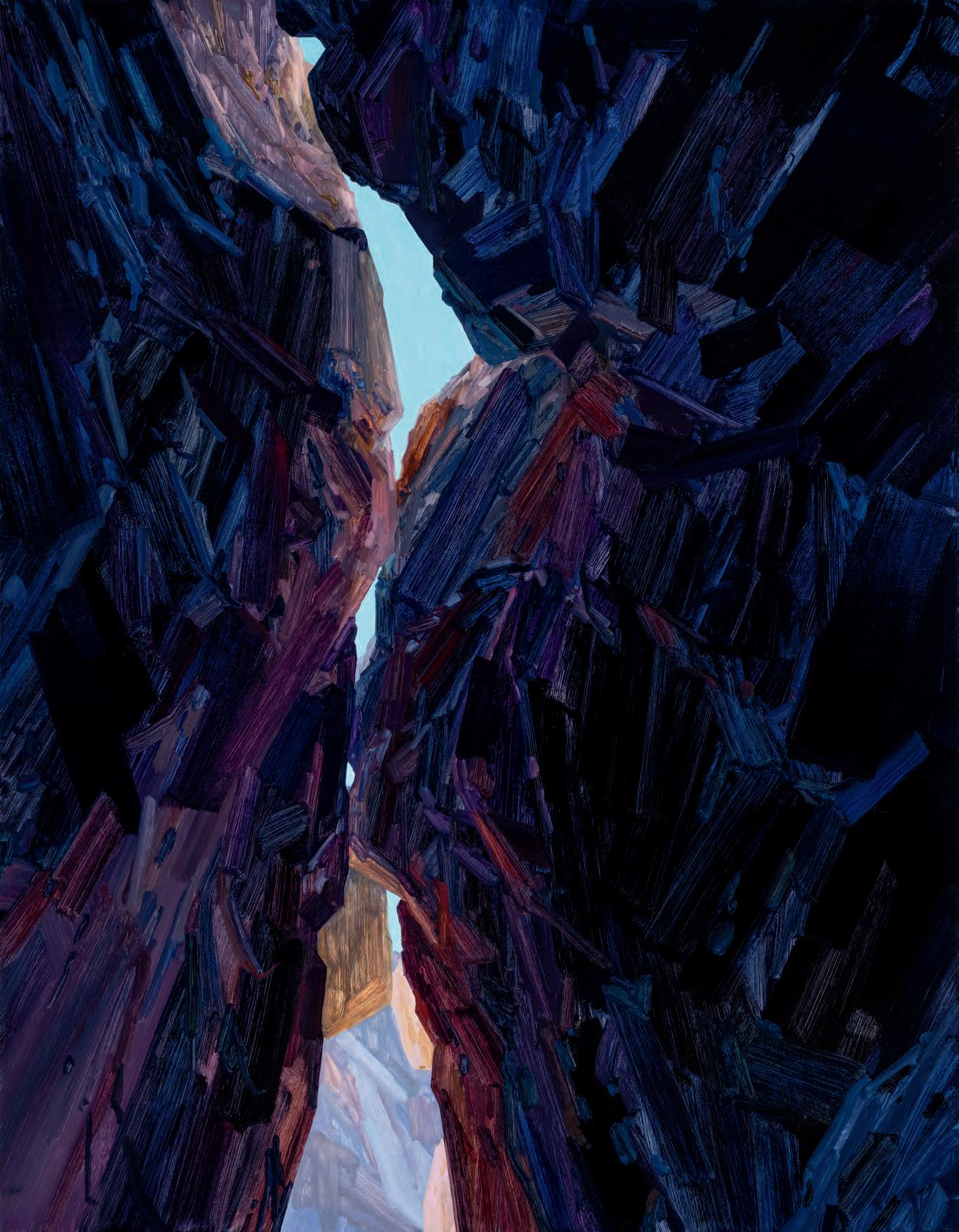

I stood on the dike alone and watched my known world being washed away. There was nothing I could do. T ree and Vines , 20 2 4 Oil on canva s, 84 x 66 inches

And then, as quickly as the flash flood came, it was gone

In the morning, the desert was returned dry. I walked to the place of my midnight dreaming and knelt down to touch the red sand. It was damp, that was all. By the end of the day, that same sand was running through my fingers like sand in an overturned hourglass. I walked back to the house and picked up a rake. I returned to the site of disturbance and began raking sand.

I am at home in the desert raking sand.

Sixty miles north on the banks of the Green River is the site of a proposed nuclear plant. East of Green River, plans are being made for the first tar sands development in the United States to be placed in the heart of the Book Cliffs, one of the wildest areas in Utah, where mountain lions stalk the tops of mesas and wild horses are commonplace. And now, when you traverse the plateau that leads you to Dead Horse Point, where the curvature of the Earth can be viewed, you see more oil rigs and gas flares than ravens rising from branches of junipers. These are the changes I cannot abide. Canyonlands and Arches National Parks are becoming annexes for oil fields. America’s red rock wilderness is under siege.

Just like the rest of the world.

What do we do?

My friend Trent Alvey makes art. A wedding dress she fashioned from plastic bubble wrap hangs from a whitewashed branch of a disembodied tree. It is a fourteen-foot shimmering cascade of fossil fuel dreams where the bubbles of our own illusions are about to pop. “The Very Large Wedding Dress” dares to ask the questions, “What are we married to?” and “What is the nature of our commitments?”

If Alvey allows us to witness marriage as a prison that ties us to a ball and chain of our own making, be it to a person or an ideology that tethers us to

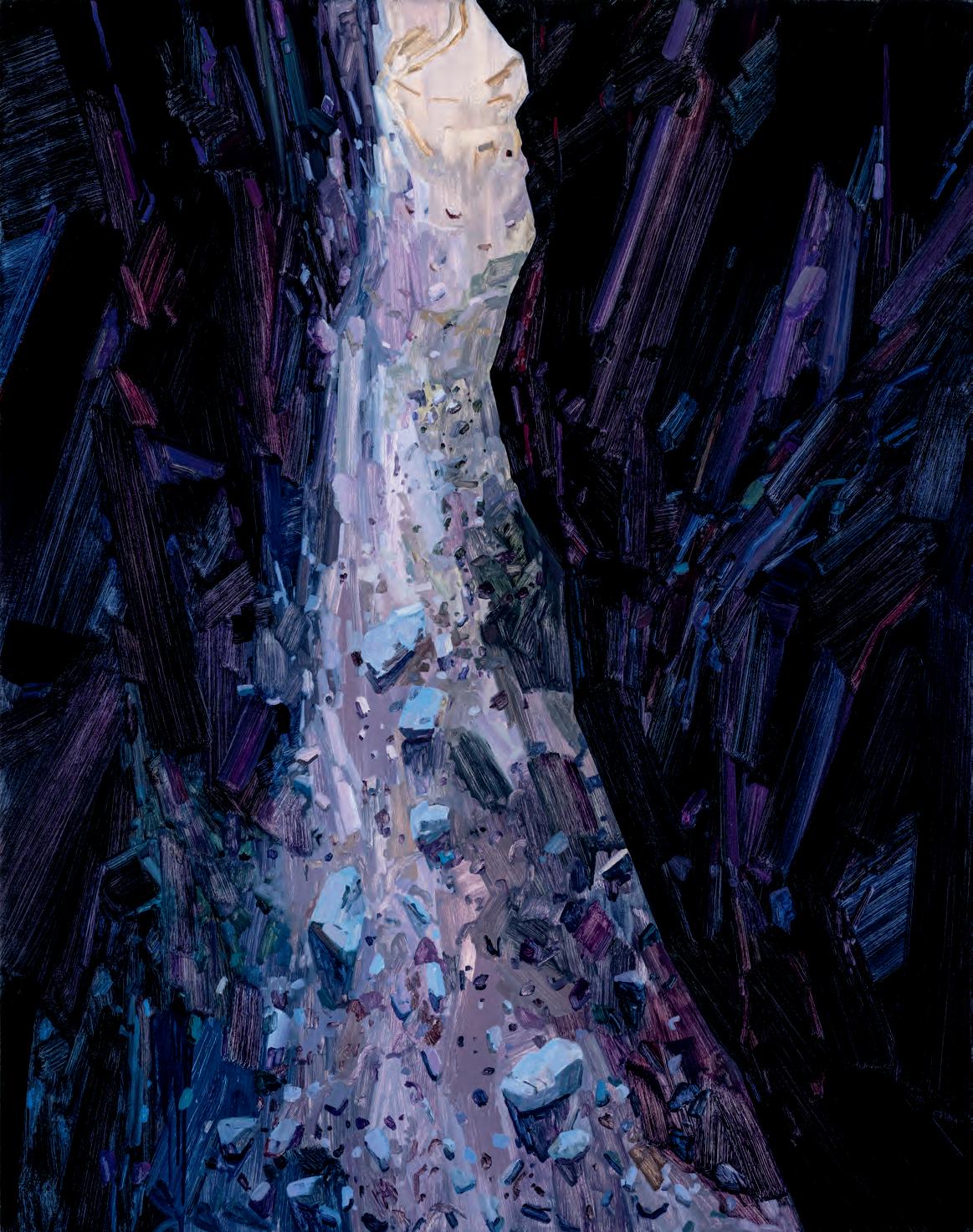

Underb rus h, 20 2 5 Oil on canva s, 42 x 36 inches

our own oppression, how are we then to change and move forward toward a sustainable life? Or are we left hanging like a perversity from a dead limb of our own family trees.

We must divest from our current future. We must slip the bubble-wrap dress off the branch and make something of it.

We have never been here before.

Climate change. Will we change?

You and I may disagree on our capacity as human beings to change.

Your first gift to me, after all, was Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. It is your belief that it is in our nature to destroy.

I believe it is in our nature to change if we are to survive the disturbances we have created.

And then, there was the day we read Genesis out loud in the Garden of Eden in Arches. You asked me to write you a story that is needed now. I am searching for that story.

So for now, dear Carl, I stand on our dike in the desert, this beloved desert of red rocks and ravens that bears a history of erosion, be it wind or water or my own human presence. It is over 112 degrees with a hot, dry breeze blowing through our valley. There is no contentment here, only the truth and terror of more disturbances to come.

For now I will continue to rake sand in the desert.

Love, Terry

Terry Tempest Williams, The Hour of Land: A Personal Topograph y of America’s National Park s, New York: Farra r, Straus and Giroux , 2 016, pp 2 81– 85

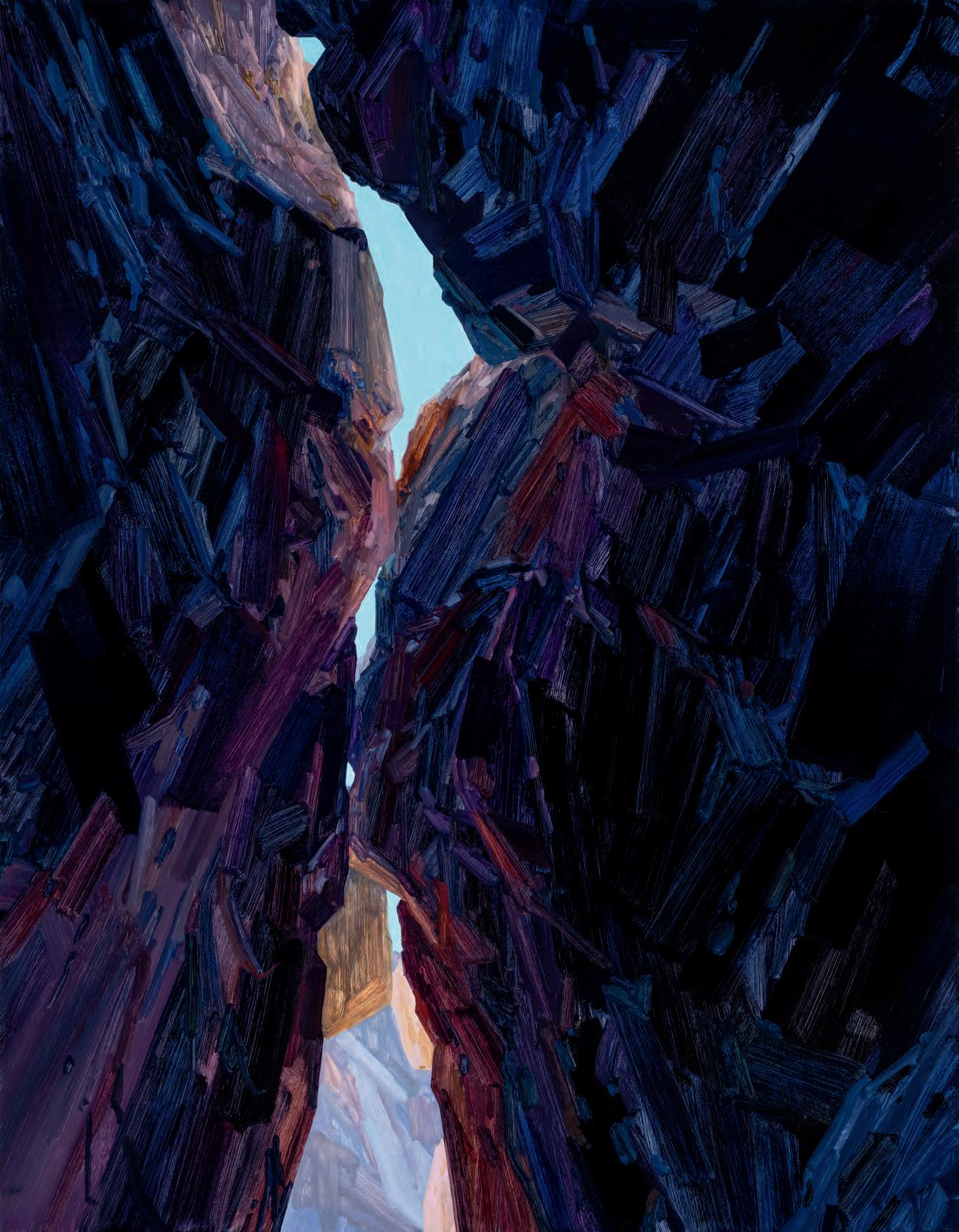

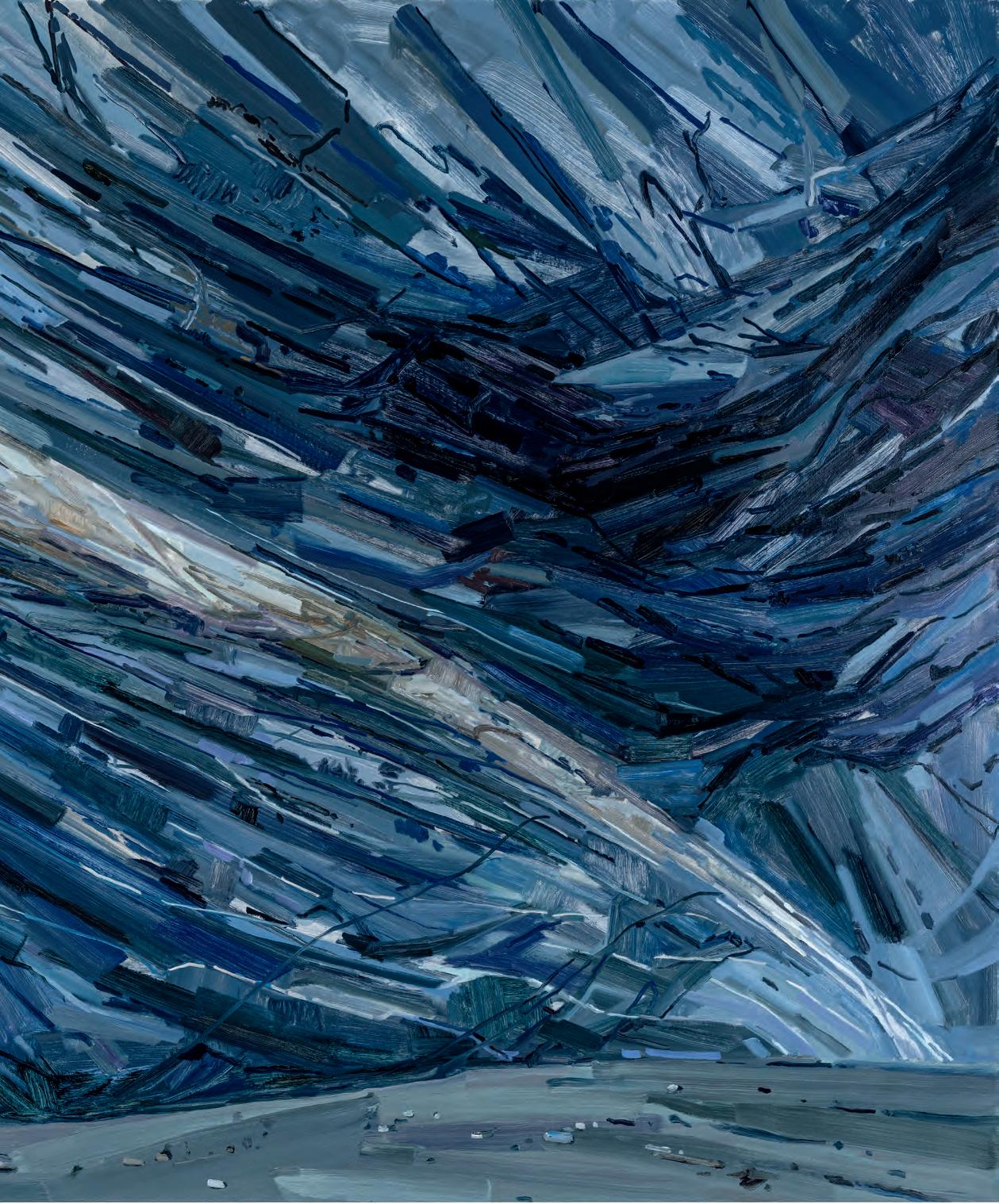

Claire Sherman engages the tradition of landscape painting and the sublime, subverting genre to address our current relationship to the environment and contemporary media. Creating paintings that are seductive yet ambiguous, she disrupts expectations of idealistic imagery, depicting undulating and disintegrating forms. Sherman’s landscapes close in and unravel around the viewer, immersing them in an unstable world that shifts between abstraction and representation. At once particular and ubiquitous, the locations might be anywhere or any environment: tropical, arctic, lunar, or mundane. In defying specificity, they open into psychological spaces.

Sherman travels extensively to inform her paintings, returning with photographs which trigger memories in the studio. To research this exhibition, she hiked through several deserts in the American West. These direct, personal experiences within the landscape charge the paintings with their physicality and sense of mystery.

Claire Sherman has exhibited widely throughout the United States and in Amsterdam, Leipzig, London, Seoul, and Turin. She has completed residencies at the Terra Foundation for American Art in Giverny, the MacDowell Colony, the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council ’s Workspace program, the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program, Yaddo, and the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. Sherman earned her BA from The University of Pennsylvania in 2003 and her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2005

535 West 22 Street Ne w Yor k , Ne w York 1 0 0 11

212 24 7. 2 111 dcmooregaller y.com

This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition

Cl aire Sherma n : Petrichor

DC Moore Gallery

February 27 – March 29, 2025

Catalogue © D C Moore Galler y, 2025

The Hour of Land © Terry Tempes t William s, 2 016

isbn : 978 -1-736772 3-8-6

Design: Joseph Guglietti

Photography © Jonathan Cancro

Printing: Brilliant