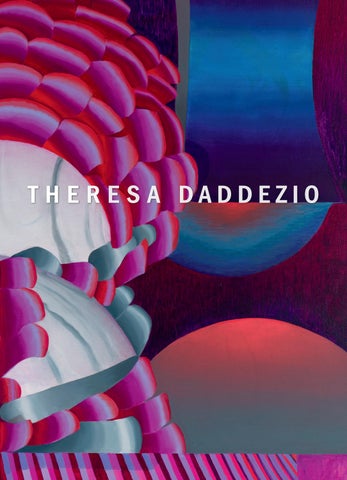

the r esa daddezio

theresa da d d ezio

B l o o m

D C MOOR E GALLE R Y

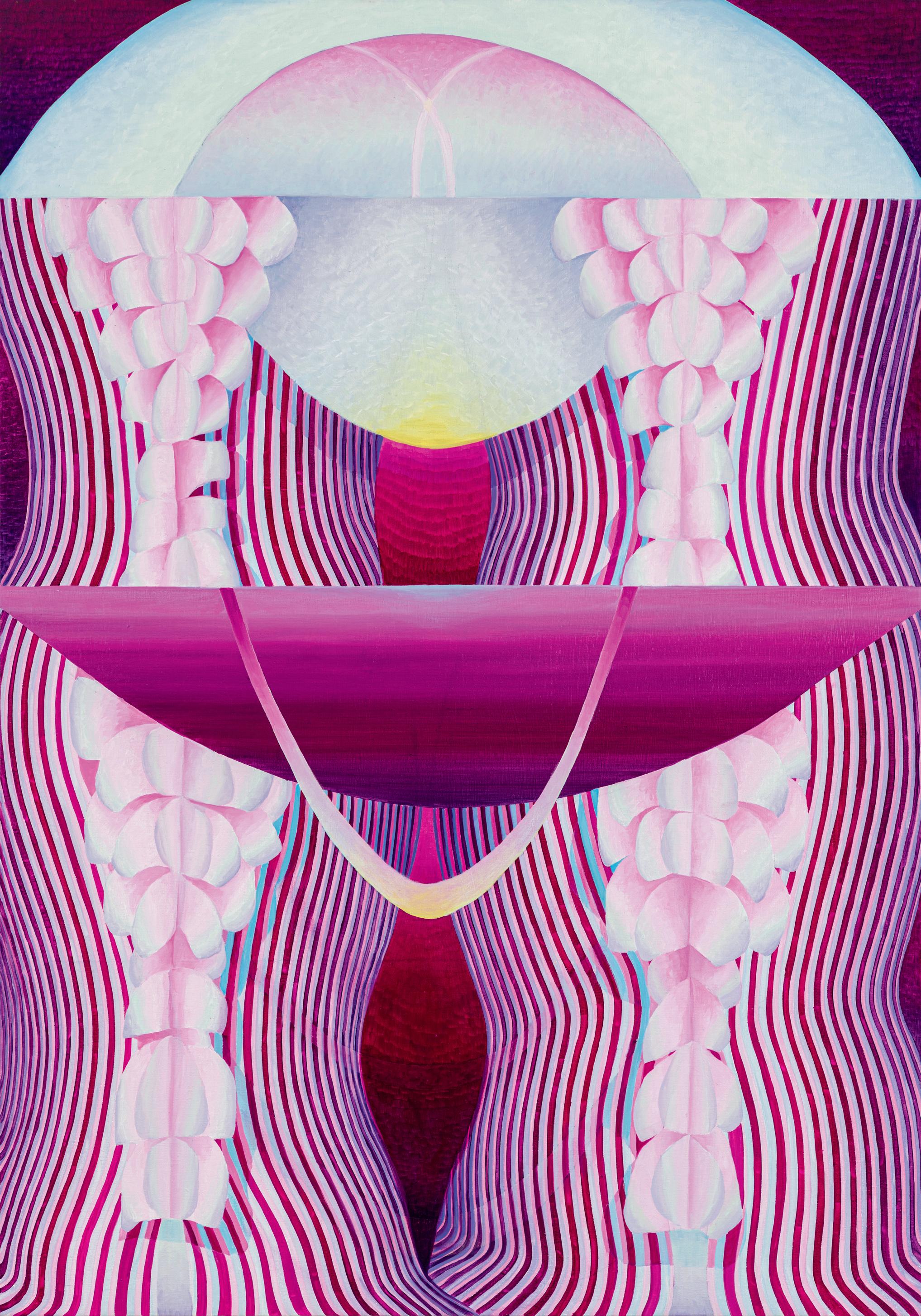

AWAKENIN G , 2024 Oil on linen , 68 x 78 inches

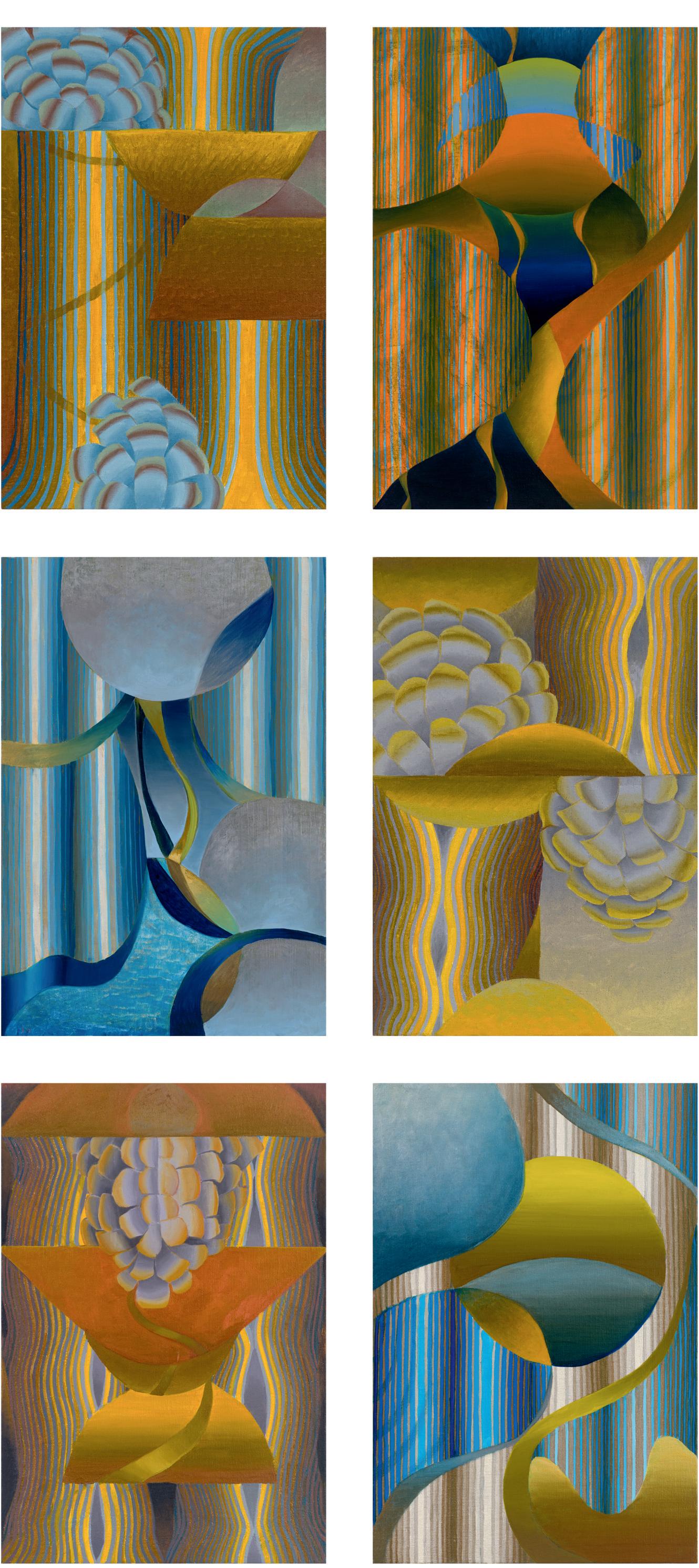

TIME CHAMBE R , 2024 Oil on linen, 50 x 35 inches

a l ossles s b loo m

O n the wo rk of T heresa D a d d ezio

WE CAN FEEL OUR LANDSCAPE FADING ; fazed by the ways that it matches the speed of our approach to it to keep its distance, like the border of a vir tual world that hasn’t yet built itself beyond its edge. We sense that it is withdrawing, readying itself to survive yet another mass extinction event; preparing to whisper new form s new survival tactics encoded in the spores of growth and sprawl. Each new design is already rendering at an imperceptible frame rate; a cloud erasing itself within another cloud.

The ophrys apifera evolved the shape of its petals to attract a species of bee that died out long ago. This orchid is now a relic of this love, a statue of longing, grasping for something that is no longer there. How will the landscape remember that we were once here? It is trying out new lines of code, clone-stamping a dense and haunted undergrowth. Each unfurling bloom reveals a deeper register of time; a tendrilled knowledge that gradually loosens its memory’s hold on us. It’s almost too much to bear; all of the finality in its desire, and all of the images of dead things that are reflected and contained within its form.

Theresa Daddezio captures an image of naturalism as it recedes, rendering a portrait of this post-humanist garden out of a deeper need to better understand what may be approaching. She is tracking the inexhaustible knowledge that the landscape is searching for. Her paintings depict a lossless biome, where plant forms become both bodies and scalar fields; shimmering petals and writhing patterns. Pinnules replicate themselves into systems, neither fully a code of DNA or of algorithm. Their invisible subroutines generate plumes that are bountiful and vital, self-replicating to be a mesmerizing warren. Each is a mass of growth without shed, enveloping and circulating like a Delta Maidenhair fern built of channels

and layer masks. As they unwind and gather into swarms, the lascivious desires of crowds in primavera come to mind, of Rubens’ decadent paintings of kermis, but in Daddezi o’s case they are made up of petals, spur, and vine instead of body and bone. They are so captivating that we wonder if they contain a threat.

Daddezi o’s world is distinct and parallel to our own. Its sense of time is its own. Are these forms a precursor to a world developed entirely on a screen? Are they the last things to be left alive? The plumes may hold some ecological account, of their own flourishing survival and persistence through everything we have done to annihilate them. Are these paintings capturing them in high fidelity, so we can see their rebirth in every exquisite detail? Or are they ghost images, haunting us with what we feel we are losing and may have already lost?

And then there is their scale. Are they towering and impossible, like ominous biotic obelisks on the horizon, or small and enclosed, hiding within the waves of cybernetic tall grass? As we look for a way to anchor ourselves, Daddezio leaves a pearl on the wave. More than just a formal repous soir , it reveals that in fact the scale is barely magnified. Each form within each painting is close to the width and height of the body from the waist up, mimicking our silhouettes, reflecting us within the surface of the mirror. This suggests a kind of mimicry, or an empathy that we are meant to feel. We are left gazing straight into these technomystic figures, seeing forms that mimic our own scale and presence within this pastoral virtua, that have something to reveal within their slow and chambered movements.

But this could also be too literal. They just as easily deny all narrative interpretation and remain distan t faint with recognition, announcements of pure abstraction. We can just as easily believe that Daddezio uses abstraction in a way that still holds the weight of representation’s physics. There is a real sense of gravity to them, and a sense that pattern is affected by the horizon beyond it. If we resist personifying the forms, we can instead encounter them as formalist actions or affect-forms. Rather, they may be the psychic verbs of the inside of growing things, or the aura

SHADOW WITHIN A SHADO W, 2024 Oil on line n , 50 x 35 inches

; DAWN ; MAGMA MOON II ; THE CLEARIN G , 2024 Oil on linen, 18 x 12 inches each

of what unyielding and infinite landscapes feel like through simulations. Maybe they are meant to be encountered purely as formal attributes. The form is the content. The gradient bends are achieved through dialectical colo r chromatic shifts of colors whose undertones generate complex neutrals that are difficult to classify, but ultimately result in harmony.

It is an interesting split. Daddezi o’s work is multivalent, and can be perceived as depictions of post-humanist worlds or as pure abstraction. At Hunter College, she committed to the structure of a painting, and took on the responsibilities of a lineage of painting that has been maintained and preserved by women oracles. She was mentored by Gabriele Evertz and Carrie Moyer, who each challenge the position of pattern and collage within aesthetics, and insisted on what they could offer as critique to patriarchal ideologies of painting. Daddezio responded to their teaching with a kind of Orphic system paintin g infusing the priorities of the Hunter Color School of the last century with mystic curiosity. This position understands the generosity that system painting has to offer; how its poetics of subtle difference could amplify microcosms into magnitudes while also remaining open to the esoteric charge of visionary painting.

In the last year, Daddezio has become increasingly interested in Medieval painting, searching for the moments where the space of a painting was prioritized not as an illusion but sought its own inner system. You can see faint traces of the patterns of Hildegard of Bingen blended in with Franti s ˇek Kupka and Sonia Delaunay. There is the impulse in Daddezi o’s paintings to generate the time required to look at hermetic designs; but there is also the remoteness of Kay Sage’s landscapes, populated perhaps with the light of Wenzel Hablik’s mirrored cities. Light pours out when paint mimics the effects of stained glass, but it is not natural light. It is the spiritual light of Neo-Tantric painting or Annie Besant’s Thought Forms but, just as easily, it is the conceptual non-natural exploration of color that extends the lineage of Miyoko Ito and Deborah Remington. For every move of Daddezi o’s that suggests a painting to be a mystic site of meditation, there is another that wants to better understand how color can drop out, fold back, and form its own gravitational pull.

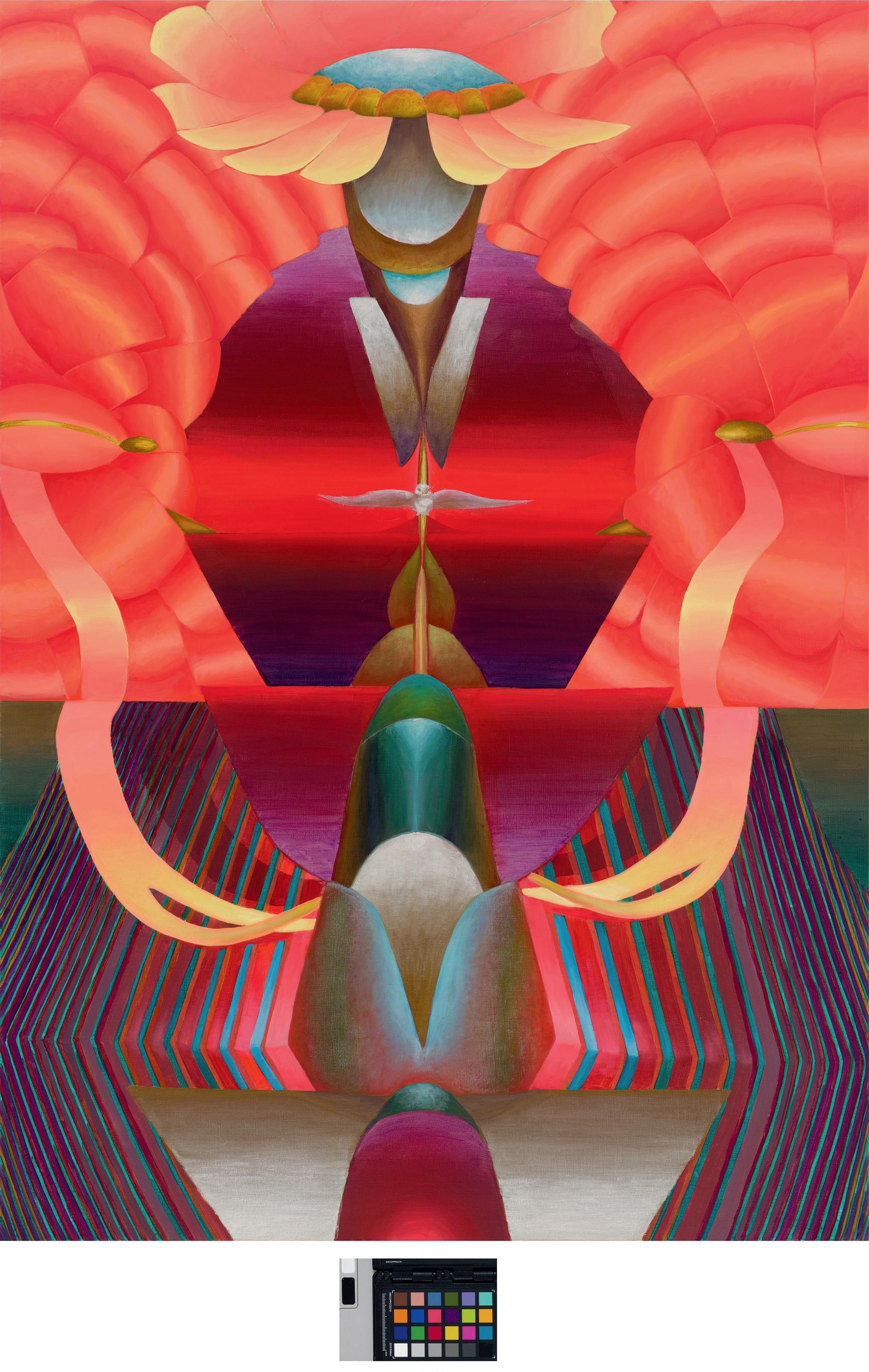

So what then are the properties of Daddezi o’s paintings? What are their criteria, and what do their priorities reveal? At the center of Daddezi o’s cosmology is the plume, which functions as both a figure, but also an important compositional cruciform that breaks up flat things. The plume can be a frond, a ribbon jumble, or a moire of ruffles. Are they hydrangea made of a jpeg cascade, mignonettes made of RGB channels, a gradient bump map of rhododendron, or all and none of these? But then there’s clearly a dove in the painting of the same name. Maybe it’s more a symbol of a dove than an actual one. Daddezio took it from a postcard she collected in Prague and inserts it into a horizon or a static bend, an important clue that this is not just abstract. Daddezio describes it as a way for “the representation to protect the non-objective.” It’s an important acknowledgment that reveals how important it is for Daddezio to make a painting that keeps some uncertainty to i t that representation can preserve abstraction by complicating its interpretation.

Difficulty is a constant throughout the work. She begins each painting with a set of issues to overcome. Repetition is significant, and also the insistence on paintings’ frontality. She suggests symmetry, but then develops divisional fallacies. She begins with a flat composition that turns the painting into an object, and then sets out to slowly layer back in its depth.There is a coyness at wor k a formal feint or a bluff. The initial expectation that Daddezio is adherent to system painting, or to painting that declares itself as an object, is then circumvented. She changes strategy. She upends the mirrored surface of symmetry, and the surface deriving a relationship to flatness after Frank Stella, and goes towards a different criteria.

Another misdirection in Daddezi o’s work is in its suggestion of painting as a kind of marquetry. While on first glance it may appear that the paintings are made of hard, inflexible outlines that suggest the cutouts of collage or inlay, closer inspection reveals the work to be deeply insistent on its own humanity, on preserving the hand. The line wavers. The silhouette is achieved over the errant textures of earlier layers, ghost markings that Daddezio allows to pulse through the surface. We can appreciate the moments where something is done in one-go versus when the artist decides an area

SPARROW

requires multiple attempts. Daddezio looks for ways to catch forms off guard, searching for ways to allow their misalignment to subtly announce themselves. As much as she is interested in the smooth gradient and decisive color mixing, she is also interested in when the double-loaded brush falters, then gets it right, then moves on. It is integral that the painting has different levels of finish. It is a significant priority that reveals the clarity of Daddezi o’s subjectivity; that whether a mark is applied as a flourish or whether it is developed through layers of pentimento, they are left as evidence of the artist’s deep conviction and intent.

Daddezi o’s worldbuild has to come from its own internal parameters . A forma l logic is set up by the chosen color palette in the first step. She settles on a color and begins mixing it to see its flexibility: how many temperatures and hues can be generated from it to form a committed adherence to itself. If there is a theory to her painting, it may be Spinozian paintin g a world made entirely of “a single substance having an infinity of attributes. ” They’re getting dense. They’ve gone from two layers to four. They build up the unreal through repetition, taken to a degree that makes the forms almost exceed themselve s to create a density that keeps the eye endlessly looping through them. This extensive copy-paste seems loamy with wifi or data, or the presence of image bends. Whatever they are, they are anything but verdant. In fact, green is possibly the most underrepresented color in Daddezi o’s palette. They are argent and azure, even hot with gules and vermillion red, but rarely green. The color dazzles but also cloaks. Ferrari red next to celadon generates a vibration that is almost impossible to see, confusing cones and rods to build a camouflage of complements made up of the difficult neutrals between them.

But the surprising answer to what makes system painting, formalism, frontality, and symmetry all insufficient on their own for Daddezio is what she acknowledges as spirit. The spiritual is her acknowledgment “that nothing ceases.” It is a concept of spirit that is bound up in ecological dread and death, a kind of post-humanist spiritualism. The early philosophers differentiated between physis and techn e that which produces on its own and that which is manufactured. Daddezi o’s forms blurs and

THE DOVE , 2024 Oil on linen, 50 x 35 inches

blends this distinction, allowing the words to define themselves. They are often half submerged, or split by alien horizon s as beams of light with dazzling patterns. Unfathomable space develops and spreads out from them. Their abstraction invites the long and calibrated looking that only mystic images can achieve, not towards a new religious structure, but towards the quasi-futures that they imply are indissolubl e set in permanent flow. We have time to consider a plant that never was, may never be, that Daddezio keeps and preserves somewhere else. But just as easily, the intensity of our focus may remind us of our own garden, and of all the natural miracles they sustain, to maintain and care for in the here and now and make it infinite to cherish.

– ANDREW PAUL WOOLBRIGHT

ANDREW PAUL WOOLBRIGHT is an artist, writer, and curator living and working in Brooklyn, NY. He is an Editor-at-Large at the Brooklyn Rail

THERESA DADDEZIO lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. She received her MFA in Visual Art from Hunter College (2018). She participated in Brookly n’s Sharpe Walentas Studio Program (2021– 22) as well as the Wassaic Residency Project in upstate New York (2018). Daddezio has exhibited work at Nathalie Karg Gallery, Hesse Flatow, DC Moore Gallery, and New York Stu dio School (New York City); Transmitter Gallery (Brooklyn); Pentimenti Gallery (Philadelphia); the University of Hawai ‘ i at M a ¯noa ; and Studio Kura (Itoshima, Japan). Daddezi o’s work was also featured in New American Paintings (2021).

BLUE THUNDER, 2024 . Oil on linen, 74 x 60 inches

D C MOOR E GALLE R Y

535 West 22 Street New York, New York 10 011

212 . 2 4 7. 2111 dcmooregallery.com

This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition

THERESA DADDEZIO: BLOOM

DC Moore Gallery

January 23 – February 22, 2 0 25

Catalogue © DC Moore Galler y, 2025

ISBN : 9 78 - 1- 736 7 723 -7- 9

A Lossless Bloom © Andrew Paul Woolbright, 2025

Design: Joseph Guglietti

Photography © Steven Bates

Printing: Brilliant

D C M O OR E GALLE R Y