APPALACHIAN DOWNTOWN DEVELOPERS

Planning Summary, Strategic Recommendations, and Implementation Road Map >> SPRING 2025

Planning Summary, Strategic Recommendations, and Implementation Road Map >> SPRING 2025

Downtowns are the beating heart of small cities, towns, and rural communities. Downtowns are what gives a place character, where residents come together, and where local ownership, small businesses, and quality jobs anchor a local economy. Decades of disinvestment from Central Appalachia and across Rural America has hollowed out many downtowns, to the great detriment of community well-being and local economic vitality. Fortunately, there has been a shift in recent years of recognizing the pivotal roles that downtowns play in our social fabric and in the shape our local economies take.

Downtowns - especially in small cities, towns, and villages - are once again a place where people want to live, work, shop, play, pray, meet, and interact with neighbors and strangers alike. While there has been a resurgence of interest in supporting the growth of downtowns across America, Central Appalachia has struggled to meet the opportunity of this moment because of a critical barrier: a lack of public, private, and non-profit developers with the capacity, experience, commitment and resources to redevelop the historic built environment of Downtown Appalachia.

The Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative is a collaborative effort of 40+ organizations and 60+ individuals across eastern Kentucky, western North Carolina, southwest Virginia, and all of West Virginia who have come together to tackle a persistent barrier to downtown revitalization in our region: the need for a sustained, resourced and strategically integrated support system to launch the next generation of Appalachia’s developers.

It is well documented that sustained locally-driven economic development has had the most success in places where it works in tandem with community development. At the same time, the work to revitalize and rebuild vibrant local economies is increasingly centered on a place-based strategy of redeveloping downtowns. Central Appalachia has witnessed some of this successful downtown-based development, particularly in places where multiple diverse stakeholders partner together to drive downtown revitalization and redevelopment through strategies that center community needs and local economic activity. This work often starts with organizing, planning, and engagement of residents,

local businesses, and other stakeholders. To achieve transformative community progress, this work must be complemented by the tangible and tactical work of mission-aligned real estate development and revitalization.

Real estate serves as the critical foundation of downtown revitalization and - in several important ways - of community development and civic health. Yet, even in places where there is sustained collaboration and creative strategies for downtown revitalization that are right-sized for each individual community, sustained and systemic challenges to achieving downtown revitalization remain. In particular, these challenges relate to the built environment in communities that are lowincome and have a significant portion of real estate that are historic, dilapidated and with limited space for new development.

Real estate links critical issues and challenges of downtown development, including: ownership and control, access and belonging, wealth-building and entrepreneurship, resilience and longevity, and culture and local identity. As we pursue downtown revitalization strategies through real estate development, key questions must be grappled with, including: Who owns downtown real estate and redevelopment projects? Who develops it? What is its purpose? Who does it benefit?

As various initiatives across Central Appalachia have pursued aspects of downtown revitalization and real estate development, partners across the region have identified patterns: what is working, what the gaps are, and what it will take to capture the massive opportunity that communityoriented downtown development presents.

In the midst of this planning process, Tropical Storm Helene brought unprecedented wind and rain to southern Appalachia leading to the worst disaster in our region’s history. As a native and resident of WNC, I witnessed firsthand the storm’s devastation of homes, businesses, buildings, infrastructure, and entire landscapes. Neighborhoods and downtowns were devastated that anchor entire economies and countless livelihoods. But I also saw how rural downtowns served as the epicenters of locally-rooted recovery efforts. Volunteers, residents, and recovery agencies worked side by side to restore their beloved downtowns. Much redevelopment, renovations, and new construction will be necessary. The need for community-oriented downtown developer capacity, support networks, technical assistance, flexible financing, training, and collaboration is more apparent and acute than ever. We must do what we can to keep our downtowns rooted by local ownership and geared towards community benefit, in WNC and across Appalachia.

- Andrew Crosson, Asheville, NC

The Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative was born out of a desire to pull these lessons and this progress together to catalyze a new phase of downtown development across multiple states in Central Appalachia. But as the name of this initiative indicates, the key to unlocking the opportunity in Appalachia’s downtowns is in the developers themselves - the entities (organizations, businesses, agencies) that can actually do the real estate projects in a way that advances community interests, and which become the permanent capacity for place-based development when they achieve success. If we want to see deep and lasting benefits from downtown development work, these entities should be locally rooted and motivated by community benefit to the greatest extent possible.

The vision guiding this initiative is of an Appalachian region full of thriving communities and economies centered on vibrant downtowns. Realizing that vision will take a whole ecosystem of support and resources centered around Appalachian downtown developers. We have seen powerful engagement, excitement and belief in the value of this initiative from the partners in this planning process, demonstrating to us that we are in a unique moment to make something new together. The region is ready to build a comprehensive initiative that weaves together multiple strategies into a new integrated approach to downtown development that is created by and for Appalachians. Through this report we hope to demonstrate the need in the region, the opportunity of the moment, and a clear vision of how to put a suite of strategies into action.

There has never been a greater time to invest in rebuilding the downtowns of Central Appalachia. We believe that by investing directly in the developers that are central to these rebuilding efforts, we will cultivate a generation of growth, development and economic opportunity for our region.

We thank the many leaders from across the region that committed time, expertise and guidance to the development of this project and analysis. The enthusiasm for this initiative demonstrates the energy and commitment of Central Appalachia, as well as the demand for a comprehensive strategy to catalyze downtown revitalization by building on the strength of our built environment and our many local leaders.

Beka Burton, Economic Development Specialist – Community and Economic Development Initiative of Kentucky

Dave Clark, Executive Director – Woodlands Development and Lending

Andrew Crosson, CEO – Invest Appalachia

Kim Davis, Executive Director – Friends of Southwest Virginia

Mae Humiston, Director of Grants and Operations – Invest Appalachia

Nicole Intagliata, Vice President of Programs – Fahe

Christine Laucher, Strategic Partnership Manager – Mountain BizWorks

Ray Moeller, Economic Redevelopment Specialist – Northern Brownfields Assistance Center at West Virginia University

Bryan Phillips, Project Manager Consultant – West Virginia Community Development

Billie Rogers, Project Manager Consultant –Friends of Southwest Virginia

Caroline Stahlschmidt, Senior Project Manager – Destination by Design

Stephanie Tyree, Executive Director – WV Community Development Hub

Hannah Vargason, Senior Project Manager – Center for Impact Finance, UNH Carsey School of Public Policy

Paul Wright, Business Coach – Wright Venture Services

This work was made possible through support from the following organizations:

The Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative (ADDI) is a plan for a comprehensive, coordinated, and ecosystem-based approach to supporting new and emerging community-based real estate developers. ADDI will invest in building a generation of place-based developers that have increased individual, organizational, and financial capacity to lead downtown development across Central Appalachia. In addition, ADDI will support the physical redevelopment of hundreds of downtown real estate projects and will ultimately launch a new era of investment into downtown revitalization in communities across Central Appalachia. ADDI will accomplish this by linking local public, private, and non-profit local developers to the technical and financial resources and support they need at each step of the downtown real estate development process.

Appalachia’s downtowns are the linchpin of our local economies. They have assets to build on - historic buildings, walkable streets, beautiful landscapes. There is new energy and economic opportunity across the region - main street businesses seeking space, tourists seeking lodging and activities, and residents and newcomers seeking housing. Yet successful community-centered downtown development remains a challenging endeavorexpensive, slow, and fraught with complications.

The system that provides investment and support for downtown revitalization in rural Appalachia is not meeting the opportunities that communities are creating. Across the region, investment in Main Streets have been inequitably distributed as small towns - and entire regions - with high redevelopment potential struggle to implement community revitalization plans and major real estate projects that can drive business development, access to affordable housing, and local economic growth. At the same time, a forward-looking and

coordinated approach to downtown redevelopment is necessary as the Appalachian region confronts the future implications of population change, economic revitalization, and resilience for our downtowns.

The primary barriers to rural downtown development in Appalachia have been clearly identified and include (1) insufficient local developer capacity (or lack of local developers) in most parts of the region, (2) a lack of peer networks and support for developers, (3) disjointed and inconsistent technical assistance resources and training for local developers, and (4) limited access to flexible investment capital for communityoriented projects.

To address these disparities and opportunities, the Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative conducted a state-level landscape analysis across four contiguous states, and developed a multi-

pronged implementation plan. This plan is grounded in a robust analysis of the history of downtown development in the region (See Chapter 2.1-2.2), and of existing strategies and programs relevant to this topic (See Chapter 2.3-2.4). The planning process involved over 60 individuals from 40+ different organizations who are working on some aspect of downtown development. Their collective input and analysis, through focused working groups and an in-person convening, validated a focus on strengthening the local developers themselves as the key to transformative downtown development across the region. This focus on downtown developers involves five key pillars: training programs, technical assistance services, peer-to-peer developer support, flexible investment capital, and a comprehensive regional infrastructure to coordinate programs and foster connections.

The result of this planning process is a proposal for an integrated, comprehensive approach to downtown development that links emerging and established developers to the resources and support they need at each step of the development process. These four strategically coordinated programs are:

1. A training program that will include a virtual self-paced course for prospective developers as well as a hands-on cohort model for developers working on a specific project.

2. A technical assistance program providing matching funds and vetted TA providers for eligible projects (building on the Opportunity Appalachia model).

3. A flexible fund of capital products providing grant-funded financial assistance to help secure investment for downtown development projects.

4. A developer peer support network, including a “mentorship” program matching experienced and emerging developers and a “co-developer” model to provide hands-on support to emerging developers taking on projects.

Wherever a developer is in their maturity, and whatever stage their project is, there will be a way for them to plug into the ADDI network for critical support and resources.

The implementation project will also explore structures and operating models for ongoing coordination and resource provision, potentially transitioning to a permanent “Appalachian Downtown Developers Association” entity by the end of the grant period.

Appalachia’s economic revitalization will require transformative investment in the physical assets of our downtowns if it is to be lasting, inclusive, or resilient. And we need locally-rooted and community-oriented developers to take on projects and guide them from concept to reality.

A project-by-project, town-by-town approach to revitalization will not meet this moment. Therefore, the ADDI leadership council and project partners are excited to propose a bold, comprehensive, and coordinated regional strategy for developerfocused downtown revitalization in Appalachia.

Chapter 1: Background and Purpose

Chapter 2: Discovery and Analysis

Chapter 3: State Assessments

The Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative (ADDI) Implementation Plan serves as the chief planning document to guide Invest Appalachia and its partners in the anticipated implementation of the Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative. This chapter summarizes the foundation and intent of this important work and provides insight on the plan purpose, goals, process, and overall organization.

IN THIS CHAPTER:

1.1 Project Background

1.2 Project Goals

1.3 Planning Process

1.4 Plan Organization

Led by Invest Appalachia and the WV Community Development Hub (The Hub), the Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative is a regional project supported by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) through the Appalachian Regional Initiative for Stronger Economies (ARISE) program. The initiative convened over 60 organizational partners and subject matter experts from Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia to research and design an implementation plan for increasing the capacity of place-based developers to revitalize downtowns and economic hubs across the Central Appalachian region.

The need for locally-driven downtown development in Central Appalachian communities has been identified by several organizations, including Main Street America in their “Small Deal” survey, the Downtown Appalachia Working Group (DAWG) in West Virginia, and in the Downtown Revitalization Playbook, published in 2021.

According to the “Small Deal” survey by Main Street America, a major obstacle to economic growth in Appalachian downtowns is the difficulty of rehabilitating small buildings and advancing infill development. Seventy percent of local leaders in Main Street America communities identified a lack of built-out space as a key barrier to growth. This shortage of functional infrastructure limits the ability to launch new businesses or expand existing ones.

The Downtown Appalachia Working Group of West Virginia identified the need for more locally-based developers as a key barrier to

economic development and local revitalization in a strategic planning assessment in 2019. The group recognized that “Downtowns represent a third space for West Virginia’s future. In places where downtown development is working, these places are building the local economy, improving quality of life, and showing that this can be done. We have seen again and again that major national franchises and chains are not working at the scale of our downtowns. So instead, we must look at how to construct something more localized or regional that meets those same needs.” Starting in 2021, the analysis of this group focused particularly on the need for more mission-driven developers who are regionally focused and deeply embedded in local communities, using community priorities to drive real estate development strategies. More detail on DAWG and its analysis of West Virginia’s downtown redevelopment needs are included in the full WV State Assessment

The Downtown Revitalization Playbook makes the case that downtowns in Central Appalachia are primed for redevelopment and includes multiple case studies of successful downtown redevelopment strategies across the region, including highlighting individual, organizational and collaboratively developed real estate development projects that have succeeded across the region. The Playbook provides an analysis for how to determine if a community is ready for a downtown redevelopment strategy, and provides detailed guidance for multiple stakeholders on how to move forward downtown redevelopment within the context of the region.

These external analyses all identified the primary barriers to rural downtown development in Appalachia as including (1) insufficient local developer capacity, (2) a lack of peer networks and support, (3) disjointed and inconsistent technical assistance resources and training for local developers, and (4) limited access to flexible predevelopment financing and investment capital for community-oriented projects.

To address these disparities, the Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative conducted a state-level landscape analysis across four contiguous states, and developed a multipronged implementation plan. This plan focuses on five key pillars: training programs, technical assistance services, peer-to-peer development support, flexible financing, and a comprehensive regional infrastructure to manage and drive the project.

Conduct an assessment of the downtown development landscape for each state, including an analysis of existing assets, unmet needs, potential partners, and developmentready communities.

Engage community leaders from each state, regional partners, and subject matter experts to conduct thorough research, collaboratively develop innovative designs, and strategically plan an implementation process.

Identify strengths within the region to leverage, pinpoint gaps that need to be addressed, and explore opportunities for collaboration with stakeholders to promote economic growth and foster revitalization in rural downtown areas.

Address the unique needs of each state while ensuring the fair distribution of resources and opportunities across the region.

Develop a collaborative regional implementation process with a multi-faceted strategy focused on increasing local developer capacity, supporting peer networks, and expanding investment capital.

The ADDI Implementation Plan represents the culmination of nearly a year of analysis, collaboration, and planning. The planning process involved more than 60 partners and subject matter experts across the region and five major phases, including:

LAUNCH MARCH 2024 - MAY 2024

Established a Leadership Council composed of the project management team and the state and working group leads. Facilitated a directionsetting meeting with the Council to establish the vision and goals for the planning process and to identify key project partners.

APRIL 2024 - SEPTEMBER 2024

Conducted interviews, surveys, and demographic research to understand the current landscape and needs of downtown development in Central Appalachian communities.

JUNE 2024 - SEPTEMBER 2024

State and Working Group leads conducted a series of group meetings and interviews to assess the gaps, barriers, and opportunities within each state and the region. Groups collectively compiled a report reflecting their findings and recommendations.

JULY 2024 - SEPTEMBER 2024

The Leadership Council compiled draft findings and reports, and prepared presentations on their findings to present to all project partners at the Partner Summit. All project partners were invited to convene at the in-person ADDI Partner Summit in Bristol, Virginia to review and refine the recommendations.

OCTOBER 2024 - FEBRUARY 2025

Developed the comprehensive implementation plan that incorporates the state-specific reports and the implementation recommendations provided by the five working groups as identified during the planning process.

The ADDI Implementation Plan is organized into nine (9) major chapters as outlined below.

The current chapter, which outlines the plan’s purpose, goals, process, and organization.

A snapshot of the regional context, regional and state demographics, related programs, and strategically aligned programs are presented here.

The assessment of the downtown development landscape in Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia are summarized in this chapter.

This chapter outlines the results of the Training Program Working Group including the analysis methodology, training assessment and gaps, and recommended training and education products.

All aspects of the Technical Assistance recommendations are outlined here including analysis methodology, regional challenges, recommended programs, eligibility criteria and cost share, and types of TA providers.

The Co-Developer Model chapter includes analysis methodology, types of developers in the region, challenges for developers, the role of housing, and the co-developer and mentorship models.

This chapter outlines the recommendations for Capital Products including analysis methodology, existing capital products, systemic gaps, financing challenges, and proposed capital products.

All aspects of the Regional Association recommendations are outlined here including analysis methodology, existing regional development associations, relevant organizations, and proposed structures for the ADDI Regional Organization.

This chapter outlines implementation guidelines, including general recommendations and a proposed organizational chart.

This chapter explores the regional context and demographics as they relate to downtown development and economic growth. It also offers a high-level overview of the current challenges facing downtown development, as well as related and strategically aligned programs in Central Appalachian communities. The chapter is organized into the following sections:

IN THIS CHAPTER:

2.1 Regional Context

2.2 State of the Downtown Development Field

2.3 Related Programs

2.4 Strategically-Aligned Programs

The Appalachian Downtown Developers Initiative (ADDI) is focused on the region in Central Appalachia composed of the 165 counties in Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia that are part of the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) region. (See Map 01: ADDI Region, page 28)

The ADDI service area encompasses diverse communities deeply rooted in regional and local cultural traditions, characterized by rugged terrain, rolling hills, and dense forests that define its scenic beauty. While the four states share common economic challenges, each maintains a distinct identity shaped by its unique landscape and history.

For decades, industries like coal mining, timber, and manufacturing drove local economies, providing jobs and fueling community growth. However, market shifts and resource depletion have led to significant economic stagnation, with many communities experiencing population loss and disinvested downtown commercial districts marked by vacant storefronts and deteriorating infrastructure.

The region is home to over 300 small cities and towns, many featuring historic main streets and buildings rich with potential for rehabilitation. These communities now stand at a critical turning point, with aging

structures at risk of decay and demolition without strategic intervention. Supporting local, community-based developers in revitalizing downtown districts can preserve historic spaces, stimulate economic activity, create employment opportunities, and attract new populations.

The macro economic and social context in the U.S. today supports a renewed focus on downtowns in rural communities and small towns. There is a wave of economically and geographically mobile population that is seeking authentic places with walkable main streets, nearby recreational assets and unique, locally owned business offerings that are more original than many of the suburban communities and commercial centers built in the last half of the 20th century. Coupled with demographic shifts and larger trends around urban affordability, lifestyle choice, and the expanded ability to work remotely, these factors make this a moment in time where small towns and cities have an unprecedented opportunity to reinvent themselves physically and economically.

Main Street programs play a crucial role in downtown preservation for the ADDI region, with 63 designated communities across the 4 states that have access to training,

technical assistance, grant programs, and other resources. Main Street programs served as critical partners in each of the four state working groups in the ADDI planning project and brought significant guidance and expertise to the project’s analysis. That said, programs vary greatly from state to state and the number of designated communities and the capacity/level of support Main Street programs provide is inconsistent across the four states. The majority of communities analyzed through the ADDI program were not in Main Street programs and many communities currently lack capacity and resources to participate in the program. The ADDI Leadership Council anticipates that the program implementation will work in close coordination and collaboration with state and national Main Street partners and ideally will serve as a capacity building mechanism to prime more communities in the region to participate in the critical services of the Main Street programs.

The project’s focus on downtown redevelopment aligns with the Appalachian Regional Commission’s investment key priorities of promoting local businesses and supporting regional culture and tourism. By transforming historic downtowns into entrepreneurial hubs, these efforts not only support home-grown businesses but also showcase the region’s rich cultural heritage and potential for economic diversification

Downtowns are the epicenters of rural communities and small towns across Appalachia and beyond. They house business, provide housing, and maintain critical infrastructure and community resources. Downtowns also have a major role to play in determining a community’s level of resilience. Streetscapes and green spaces, water and sewer systems, electrical grids, building materials, roadways and bridges, building siting and design - these are all aspects of downtown development that can help reduce negative impacts while also preparing communities for the predictable effects of natural disasters. As we witnessed in the 2022 flooding in E. Kentucky, 2016 floods in West Virginia, and the catastrophic impacts of 2024’s Hurricane Helene on Western NC and parts of Tennessee and Virginia, our downtowns are where natural disasters can hit hardest and where response, recovery, and long-term resilience are rooted. In small towns and rural communities, disaster preparedness and recovery relies more heavily on local capacity and community networks than urban centers that larger government programs are designed well for. Downtown development and revitalization can and should be aligned with the goal of resilience and adaptation, to give Appalachian communities the best possible chance to thrive in a changed future.

L e g e n d

S t a t e B o u n d a r i e s

A R C C o un t i e s

K e n t u c k y

N o r t h C a r o l i n a

V i r g i n i a

We s t V i r g i n i a

I n d i a n a

L e w i s

G r ee n u p

N i c h o l a s

B a t h R o w a n

C l a r k

M a d i s o n

G a rr a r d

E d m o n s o n

H a r t

M e n i f e e

P o w e l l

J a c k s o n

R oc k c a s t l e

L a u r e l

K n o x

M o r g a n

Wo l f e Magoffin

B r e a t h i t t

P e rr y

H a r l a n

L a w r e n c e

J o h n s o n

F l o yd

K n o t t

L e t c h e r

W h i t l e y

P i k e

B u c h a n a n

D i c k e n s o n

W i s e

B e l l

R u ss e l l

Wa s h i n g t o n

M i t c h e l l

Ya n c e y

H a y w oo d B u n co m b e

M c D o w e l l

S w a i n

G

C h e r o k e e

M a co n

J a c k s o n

H e n d e r s o n

Tr a n s y l v a n i a

R

Ta z e w e l l

B u r k e

A s h e

M o n

P u l a s k i

W i l k e s

TOTAL POPULATION

5,653,350

TOTAL # OF HOUSEHOLDS

2,342,326

MEDIAN AGE (compared to 39.3 in the US)

43.4

TOTAL BUSINESSES

193,509

TOTAL # OF MAIN STREET COMMUNITIES

63 MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME

$56,237 (compared to $79,068 in the US)

COLLEGE DEGREE

HOUSEHOLDS WITH DISABILITIES

POPULATION 65+

26%

13.6% (compared to 9.63% in the US)

WORKING AGE POPULATION (18-64)

21.9% (compared to 18.1% in the US)

HOUSEHOLDS BELOW THE POVERTY LEVEL

58.6% (compared to 60.8% in the US)

17% (compared to 12% in the US)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2018–2022.

As discussed above, multiple initiatives have identified the opportunity for downtown redevelopment in Central Appalachia as a critical component and driver of local economic development. Significant resources have been invested in the region over the past decade to increase local community capacity, build local leadership, and increase access to private and public resources for economic development. Despite these opportunities, persistent barriers to downtown revitalization have stymied real estate development projects across Appalachia. Without targeted interventions, development will continue to drive towards economically vibrant areas of the region and leave high-need and high-potential communities behind, increasing the disparity across the region.

Critical challenges that continue to create barriers to downtown real estate development in Central Appalachia were analyzed by the Co-Developer Working Group, led by Dave Clark, Executive Director of Woodlands Development and Lending, who has decades of experience in community and housing development, real estate financing, and small business support in West Virginia. The sustained challenges impacting downtown development in the ADDI region that this group identified serve as a useful grounding landscape analysis of the field, and include:

Several initiatives in recent years have worked with communities in Central Appalachia to identify vacant, dilapidated, or underutilized buildings, and plan for redevelopment. Those include Opportunity Appalachia, West Virginia University Brownfields Assistance Center’s Blighted and Dilapidated Buildings Program, the Downtown Appalachia Working Group in West Virginia, Invest Appalachia’s Framers Training (in partnership with the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond) and others. Additionally, regional partners including community development financial institutions (CDFIs), the Central Appalachian Network (CAN) and the Appalachian Funders Network (AFN) have all documented the persistent and growing need for services to support real estate development projects in rural, distressed communities in Appalachia. Through these efforts, communities have identified hundreds of assets in their downtowns that need to be addressed, and have consistently found that demand for services, financing and support outstrips available resources in the region.

THE NUMBER OF COMMUNITY-BASED DEVELOPERS SERVING CENTRAL APPALACHIA HAS DECLINED over the last 20 years due to leadership attrition, relative decrease in federal grant programs, the decline of support for Community Development Corporations (CDCs), and long-term impacts of the 2008-2010 housing crisis. This has resulted in decreased capacity for downtown redevelopment, along with decreased capacity for housing development that responds to local priorities. Significant geographies across the region have limited or no access to communitybased developers. Multiple communities have attempted to tackle real estate development through initiatives led by community volunteers or municipal programs, which often lack the capacity, expertise or sustained resources to complete complex projects.

SUBSIDIES AVAILABLE FOR DOWNTOWN AND HOUSING DEVELOPMENT INCREASINGLY RELY ON MARKET-DRIVEN APPROACHES. Funding for federal grant programs, like the US Housing and Urban Development (HUD) HOME Investment Partnerships and Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) programs, has been reduced or remained flat for over 20 years. Subsidy programs for real estate development that have grown significantly over this time rely largely on incentivizing market-based investments, such as New Markets Tax Credits, Opportunity Zone Investments, Community Reinvestment Act, etc. These market-driven programs heavily favor large, urban projects and are often inaccessible or overly complex for the size and scope of downtown redevelopment projects in Central Appalachia.

2. PROJECT FINANCING HAS GROWN SIGNIFICANTLY MORE COMPLEX as a result. As funding/financing resources have decreased and construction and project development costs have increased nationally, redevelopment in rural areas often needs to rely on multiple smaller sources of financing for individual projects. Individual funding programs typically have specific requirements and prioritized outcomes, so layering these programs together on any given project can mean juggling multiple performance criteria and reporting requirements. Small projects may require dozens of layered financial resources, each with their own requirements and timelines. This leads to projects whose capitalization is unreplicable, requiring a custom funding approach each time and consuming time that could be better spent actually delivering finished projects.

3. ACCESSING AND MANAGING THESE RESOURCES REQUIRES SIGNIFICANT CAPACITY AND TECHNICAL EXPERTISE BY LOCAL DEVELOPERS, INCENTIVIZING DEVELOPERS TO CONCENTRATE ON LARGER PROJECTS OR COMMUNITIES THAT HAVE MORE RESOURCES FOR REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT. Projects that may be community priorities can fail because of a lack of local technical expertise to successfully manage the financial complexity of rural real estate development projects.

4. THE REAL ESTATE MARKET IN RURAL AREAS HAS BEEN DISPROPORTIONATELY IMPACTED BY COVID AND RECENT MARKET SHIFTS. Mirroring national trends, construction costs have increased substantially without a corresponding increase in either rental rates or incomes – making real estate development more difficult to pencil out.

5. REAL ESTATE DEVELOPMENT AS AN INDUSTRY IS INCREASINGLY MOVING AWAY FROM SMALLER PLACES AND BESPOKE PROJECTS, IN SEARCH OF MORE FORMULAIC MODELS IN HIGH VELOCITY MARKETS. This means capital, purpose, expertise and construction capacity are moving further and further from the communities that need it the most.

This historical context is important to understand the current moment for downtown development work. While the opportunity and need is greater than ever, systemic challenges and project complexity have raised the barriers to effective community-based development. The ADDI implementation plan aims to provide a clear-eyed assessment and strategic framework identifying what it will take to empower a network of community-minded developers to build thriving downtowns across the region.

Despite these challenges, there is energy and optimism in the region, as demonstrated by the sustained engagement of dozens of partners committed to building a new system to achieve locally-driven real estate development in Central Appalachia. There is a shared sense that we must build something new that works for our region, learning from others across the country and taking advantage of the unique strengths and opportunities of Appalachian communities.

We have defined the following categories of developers in order to match ADDI support to developers based on their stage of maturity, in an effort to build long-term capacity. ADDI will include non-profit and for-profit communitybased developers, including individuals, across all categories. Additionally, developers may be real estate owners or fee-for-service developers, though eligibility criteria will include clear and full commitment to the project and community.

Potential developers with relevant skills and interest in leading a real estate project, for whom support is focused on understanding the development process and their personal capacity.

Developers identifying their first project, for whom support is focused on testing project viability and their fit as a developer.

Developers who are actively working on their first several projects, for whom support is focused on advancing and managing the risk of projects.

Developers who have completed several projects, for whom support is focused on managing the risk and complexity of scaling.

Developers who have a strong portfolio of projects, for whom support is focused on managing the risk of taking on new partners and/or riskier projects.

The Appalachian Downtown Developer Initiative (ADDI) draws insights from several regional programs targeting similar economic development objectives. These existing initiatives are providing critical services to specific areas of downtown redevelopment in the region and provide various valuable frameworks. At the same time, they have various limitations that prevent them from taking a multi-state approach to addressing downtown development challenges in rural areas. Limitations that have limited these programs from taking this multi-state approach include: geographic limitations (restrictions to certain counties, states or regions); participation constraints (time-bound programs with limitations on the number of participants each year); and discordant timelines that may not align with other programs. As part of the planning process, we identified key functions or resources they provide, lessons learned from each of these programs, and how ADDI can complement their results or ongoing efforts. Key comparative programs include:

Created by Invest Appalachia and implemented in partnership with local or regional partners (currently with the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond), this investment program uses a cohort model to increase the skills, knowledge, tools, and connections of place-based individuals seeking to advance community projects towards investment readiness. Training from this program provides fundamentals necessary to activate investment-worthy projects related to small business, social enterprises, housing, community facilities, and downtown real estate development. The Community Investment Framer curriculum designers and instructors participated in the ADDI working group focused on training to help guide the training recommendations. Status: Founded 2021, ongoing annual cycles.

The West Virginia University Brownfields Assistance Center coordinates the Downtown Appalachia Redevelopment Initiative in partnership with Partner Community Capital (PCAP). The program provides multiple layers of targeted assistance for downtown redevelopment projects throughout West Virginia, including individual project technical assistance, a property redevelopment handbook including templates and a resource guide, and access to grants or loans to reduce project development expenses. Services are limited to projects in commercial business districts in West Virginia towns that have demonstrated market opportunity and existing community capacity to support redevelopment. The lead of this program, Ray Moeller, also led the ADDI Technical Service Working Group, and provided valuable recommendations based on his multiple years of experience running this state-based downtown real estate development technical services program. He has also served as the West Virginia state liaison to the Opportunity Appalachia program, described below. Status: Ongoing

Main Street America is a national movement dedicated to reenergizing and strengthening older and historic downtowns and neighborhood commercial districts through place-based economic development and community preservation. In collaboration with partners, Main Street America provides grants and technical services to support thriving local economies and resilient Main Streets. The guiding principles of Main Street America helped inform the ADDI implementation plan and leaders from the organization have been actively involved in the design of the implementation plan. Status: Ongoing.

State Main Street Programs provide downtown strategic economic development planning and project-specific technical assistance to help successful and enduring community revitalization. Training, framework, and educational opportunities are provided to support and promote healthy, vibrant, and sustaining downtowns and business districts for economic growth and community pride. Representatives from the four Main Street programs (Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia) participated in the planning process and helped inform the ADDI implementation plan. Status: Ongoing, varies across states.

Opportunity Appalachia (OA), coordinated by Appalachian Community Capital, provides coaching and financial assistance for predevelopment of real estate development projects. Investment priorities include downtown development, housing manufacturing, IT, healthcare, education, food systems, clean energy, and heritage tourism and recreation with a primary focus in rural communities. OA has a limited number of projects and is not exclusively focused on downtown redevelopment but many aspects of the program have inspired the recommended implementation strategy for ADDI. Status: Ongoing, 2-year cycles (grant dependent).

The Mon Forest Towns (MFT) partnership cultivates relations across the Monongahela National Forest gateway communities in order to enhance the economy and quality of life for residents and visitors while sustaining the quality of the environment. Twelve towns participate in the Mon Forest partnership and draw visitors to festivals, lodging, local dining, and outdoor recreation. Aspects of this program have inspired the ADDI, especially for cities and towns that are gateway communities to public lands. Status: Ongoing

The Appalachian Downtown Developer Initiative (ADDI) aligns with key regional and national programs focused on rural economic revitalization. These initiatives share core goals but offer unique strategies, creating a collaborative ecosystem. As ADDI is implemented, the leadership team will continue to collaborate with these organizations and partners. Key programs include:

The ARC POWER Initiative targets federal resources to help communities and regions that have been affected by job losses, coal mining, coal power plant operations, and coal-related supply chain industries due to changes in energy production. Investments aim to strengthen a variety of industries, bolster re-employment opportunities, create jobs in existing and new industries, and attract new sources of private investment in coal-impacted communities. Significant economic development capacity building and project development across the four states within the ADDI project have received ARC POWER funding.

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund aims to mobilize funding for greenhouse gas and air pollution reducing projects in communities across the country, with a subset of funding dedicated to low-income and disadvantaged communities. Small businesses, non-profit organizations, state, territorial, local and Tribal governments are eligible to receive funding through financial intermediaries.

See Opportunity Appalachia program description in Section 2.3. Chapter 5: Technical Assistance outlines how the ADDI program will align with Opportunity Appalachia’s approach and resources.

Green Bank for Rural America, started by Appalachian Community Capital, provides public and private capital that enables rural areas to gain the most benefit from the new energy economy, with prioritization investments in Appalachia, rural communities of color, and Native communities. Funding will be used by community lenders to create jobs, preserve the quality of life in rural communities, and reduce harmful pollution. Eligible projects relevant to ADDI include green building construction, energy efficiency improvements, renewable energy, and other physical improvements to real estate that move buildings towards net zero emissions. Available funding includes Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

Emerging from Main Street America’s “Small Deal Initiative”, this emerging fund will focus on downtown revitalization and construction projects that are aligned with Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund eligibility criteria. Their target project types and impact goals are in line with ADDI’s focus on downtown development projects in small towns and rural communities.

Building Small is a grass roots initiative with national reach. The program has evolved over thirteen years to build a community of Small Scale Developers across the US, focusing on all asset classes and at all stages of experience.

Now hosting two Small Scale Developer Forums (SSDF) per year, the program reaches over 1,000 individuals who are actively developing smaller scale projects in communities across the rural to urban transect. In 2017, the projects, sponsor stories and challenges encountered inspired the research and publication of Building Small: A Toolkit for Real Estate Entrepreneurs, Civic Leaders and Great Communities by Urban Land Institute in 2021. The need for continuous learning and desire to maintain the professional networks led to an open source, online social community and resource sharing network open to all small developers, policy makers, lenders and citizen activists interested in small-scale incremental development as a tool for rebuilding downtowns, neighborhoods and communities.

This chapter summarizes the shared needs across the states in the ADDI region related to developer support, economic development gaps, and opportunities. It also provides state-level snapshots for Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. These state profiles include a state map highlighting developmentready communities, state-specific demographics, and identified place-based developers. Each state group contributed a detailed report of its findings, which are included in full in the appendix. The chapter is organized into the following sections: IN THIS CHAPTER: 3.1 Regional Themes and Key Findings 3.2 Kentucky 3.3 North Carolina 3.4 Virginia 3.5 West Virginia

While each state has a unique landscape for downtown development, developers across the region share many common needs to enhance their long-term capacity and their success with individual projects.. Below is a summary of developer needs identified through the planning process, along with an assessment of these needs for each state.

development for the construction trades

on sustainable development practices and building materials

Streamlined permitting process and updated zoning regulations

or mentor to provide guidance and support on projects

Enhanced understanding of historic preservation

Flexible capital with streamlined and accessible funding mechanisms

for projects in floodplains

and affordable bridge loans to finance the early stages of a project

Credit enhancements to de-risk investment on larger projects

Improved access to state historic tax credits for smaller developers

Several common themes emerged related to economic development gaps and needs. Below is a summary of the gaps and needs identified by two or more states.

REGION-WIDE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Limited availability of prepared sites and buildings

Lack of connectivity between building owners/landlords and potential tenant businesses looking for space

Inadequate infrastructure in some areas, including transportation networks, broadband, utilities, and water supply shortages

Limited collaboration among stakeholders, including public, private, and nonprofit entities

Connectivity and coordination between resources, such as federal, state, philanthropic, and private sector support

Lack of accessible investment for small scale development and emerging developers

Inadequate incentives compared to neighboring states

REGION-WIDE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT NEEDS

Regional collaboration/coordination mechanisms

Incentives for small and medium-sized businesses

More technical assistance and business support for real estate development

Support for small businesses and entrepreneurs

Better coordination and resource alignment among capital providers, including expertise in real estate finance and tax credit navigation

Zoning and permitting reforms

Comprehensive infrastructure investment including utility improvements

Strategic economic diversification initiatives, such as tourism, advanced manufacturing, and local agriculture

Workforce retention strategies

Public-private partnerships

Sustainable development strategies including renewable energy and conservation

Within Eastern Kentucky, there are 54 counties and approximately 80 cities and towns in the Appalachian Regional Commission’s region. The Kentucky State Group consisted of 12 members, with representatives from seven organizations, and was led by the CEDIK at the University of Kentucky and Beka Burton.

While findings reflect available information and insights from group members, the data and analysis should not be considered definitive due to the ambiguous and evolving nature of the “downtown development space”.

For the detailed Kentucky state report, please see Appendix A3. Kentucky State Report, page 132.

Beka Burton, Group Lead – CEDIK at University of Kentucky

Jessica Bledsoe – Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky

Kitty Dougoud – Kentucky Main Street

LaTasha Friend – SOAR

Robin Gabbard – Mountain Association

Colby Hall – SOAR

Peter Hille – Mountain Association

Nicole Intagliata – Fahe

Madilyn Jarman – SOAR

Colby Kirk – OneEast

Les Roll – Mountain Association

Ruby Smith – Fahe

“By focusing on regenerative development, fostering collaboration among stakeholders, and providing clear guidance on available resources, Eastern Kentucky can advance toward a more resilient economic future.”

~

Kentucky State Group

Total Population: 1,162,206

Number of Households: 465,047

Median Age: 42.1

Median Household Income: $48,959

College Degree: 19%

Households with Disability: 16.2%

Population 65+: 19.8%

Working Age Population (18-64): 58.8%

Households Below the Poverty Level: 24%

Total Businesses: 37,489

Main Street Communities: 10

* Source: U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2018–2022.

Western North Carolina’s Appalachian Regional Commission region includes 31 counties and approximately 70 cities and towns. The North Carolina State Group, led by Christine Laucher of Mountain BizWorks, comprised 11 members representing nine organizations, including local and state government leaders, mission-driven developers, and nonprofit organizations.

While findings reflect available information and insights from group members, the data and analysis should not be considered definitive due to the ambiguous and evolving nature of the “downtown development space”.

For the detailed North Carolina state report, please see Appendix A4. North Carolina State Report, page 154.

Christine Laucher, Group Lead – Mountain BizWorks

Ann Bass – NC Department of Commerce

Beverly Carlton – Olive Hill Community Economic Development Corporation

Kyle Case – Western Piedmont COG

Andrew Crosson – Invest Appalachia

Ingrid Johnson – PODER Emma

Bernadette Peters – Town of Sylva Main Street

Matt Raker – Mountain BizWorks

Russ Seagle – Sequoyah Fund

Stephanie Swepson-Twitty – Eagle Market Streets Development Corporation

Anthony Thomas – Eagle Market Streets Development Corporation

“Western North Carolina (WNC) has a more robust and diversified economy than most of Central Appalachia, including many downtowns in advanced phases of revitalization and redevelopment. This is thanks in part to a robust state Main Street program, the third largest in the country. However, there is a shortage of local community focused and non-profit real estate developers. Most large downtown development projects are owned and managed by developers from other states or large cities, which are less likely to serve community interests and build local wealth.”

~ North Carolina State Group

Total Population: 2,067,146

Number of Households: 865,576

Median Age: 43.9

Median Household Income: $61,803

College Degree: 31%

Households with Disability: 11.6%

Population 65+: 22.8%

Working Age Population (18-64): 58.2%

Households Below the Poverty Level: 14%

Total Businesses: 79,763

Main Street Communities: 10

* Source: U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2018–2022.

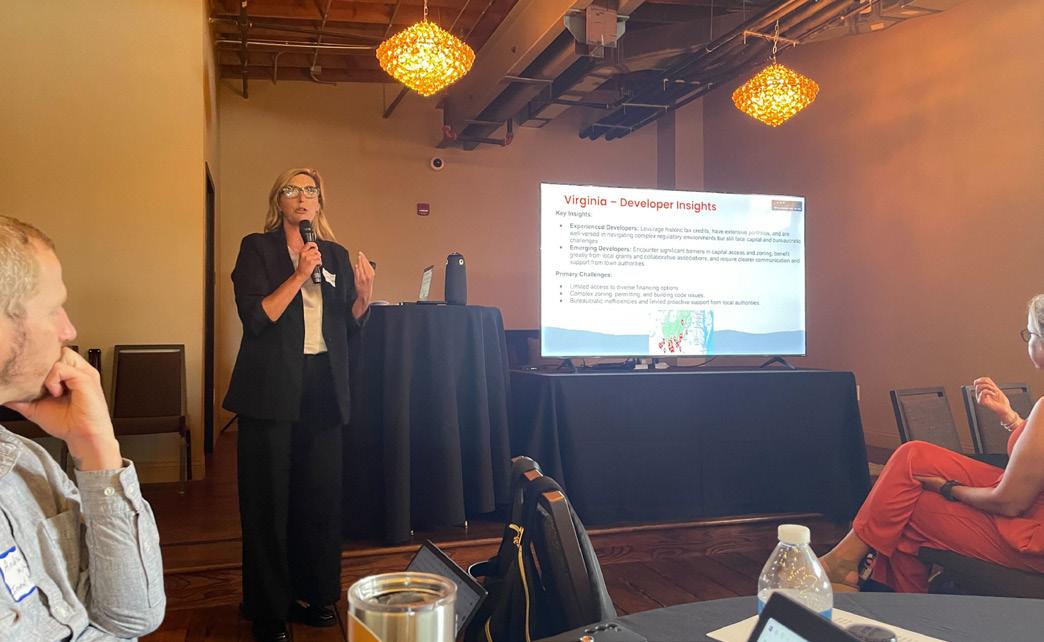

Southwest Virginia includes 25 counties and over 55 cities and towns within the Appalachian Regional Commission’s region. The Virginia State Group, made up of 13 members from eight organizations, was led by Kim Davis and Billie Roberts from the Friends of Southwest Virginia.

While findings reflect available information and insights from group members, the data and analysis should not be considered definitive due to the ambiguous and evolving nature of the “downtown development space”.

For the detailed Virginia state report, please see Appendix A5. Virginia State Report, page 168.

Kim Davis, Group Lead – Friends of Southwest Virginia

Billie Roberts, Group Lead – Friends of Southwest Virginia (contractor)

Alicia Bynum – Friends of Southwest Virginia

Cindy Green – Locus Impact Investing

Jessica Hartness – Virginia Dept of Housing and Community Development

Stephanie Lillard – People Incorporated

Taylor Lindsay – TYL Properties, LLC

Ellie Dudding-McFadden – Virginia Main Street

Chris McNamara – Virginia Housing

Courtney Mailey – Virginia Dept of Housing and Community Development

Chris Thompson – Virginia Housing

Rebecca Rowe – Virginia Dept of Housing and Community Development

Kelli Smith – People Incorporated

Emma Wyatt – The Innovate Fund

“Overall, Southwest Virginia presents a mixed landscape of developer activity and capacity. Large mainstream developers are active in the interstate corridor of I-81 and the larger towns (e.g. Roanoke, Bristol, Christiansburg), while most towns struggle to attract developer attention for smaller or boutique projects (with success stories like St. Paul). Like other states, Southwest Virginia is challenged by the “missing middle” of local developers with the interest and capacity to take on multiple small to medium sized development projects.”

~ Virginia State Group

Total Population: 650,185

Numbers of Households: 273,411

Median Age: 44.5

Median Household Income: $52,600

College Degree: 23%

Households with Disability: 14.2%

Population 65+: 23.3%

Working Age Population (18-64): 59%

Households Below the Poverty Level: 17%

Total Businesses: 20,205

Main Street Communities: 30

* Source: U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2018–2022.

The Appalachian Regional Commission’s jurisdiction encompasses all 55 counties and over 100 cities and towns in West Virginia. The West Virginia State Group, composed of 18 members from 10 organizations, was led by the WV Community Development Hub under the leadership of Stephanie Tyree, Bryan Phillips, and Beth Thompson.

While findings reflect available information and insights from group members, the data and analysis should not be considered definitive due to the ambiguous and evolving nature of the “downtown development space”.

For the detailed West Virginia state report, please see Appendix A6. West Virginia State Report, page 186.

Stephanie Tyree, Group Lead – WV Community Development Hub

Bryan Phillips, Group Lead – WV Community Development Hub (contractor)

Beth Thompson, Group Lead – WV Community Development Hub

Jennifer Brennan – West Virginia Main Street

Brian Chenoweth – Coalfield Development Corporation

Dave Clark – Woodlands Development and Lending

Maddie Coffman – Partner Community Capital

Carla Ferguson – Coalfield Development Corporation

Jennifer Hudson – Greater Williamson Community Development Corporation

Marten Jenkins – Partner Community Capital

Lauren Kemp – RenewALL

Kayleigh Kyle – USDA Rural Development

Marlo Long – Truist

Monica Miller – M. Miller Development Services

Ray Moeller – Northern Brownfields Assistance Center at West Virginia University

Carrie Staton – Northern Brownfields Assistance Center at West Virginia University

Emily Wilson-Hauger – Woodlands Development and Lending

Bill Woodrum – Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation

“At the start of this planning process, the WV State Group expected that one of the key challenges facing the state was the lack of developers serving West Virginia. Surprisingly, we were able to identify a significant number of developers serving the state, though the capacity of those developers varied widely. The number of emerging and growing developers identified in West Virginia indicates the opportunity for growth in the state, and the direct value that capacity building for emerging developers will bring to muchneeded downtown development projects throughout West Virginia.”

~ West Virginia State Group

Total Population: 1,773,813

Number of Households: 738,292

Median Age: 43.4

Median Household Income: $56,394

College Degree: 26%

Households with Disability: 14.2%

Population 65+: 21.9%

Working Age Population (18-64): 58.8%

Households Below the Poverty Level: 17%

Total Businesses: 56,052

Main Street Communities: 11

* Source: U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2018–2022.

Chapter 4: Training Program

Chapter 5: Technical Assistance

Chapter 6: Co-Developer Model

Chapter 7: Capital Products

Chapter 8: Regional Association

Chapter 9: Overall Implementation

The shortage of community-based developers serving rural Appalachia, limited capacity of current local developers, and limited access to flexible capital have been identified as critical barriers to economic growth in communities throughout Central Appalachia. At the same time, a forwardlooking and coordinated approach to downtown redevelopment is necessary as we confront economic shifts and consider the implications for the region’s infrastructure, downtowns, housing, and more. This project brings together key partners from across the region who are working on downtown redevelopment and proposes a coordinating strategy that links technical assistance services, peersupported developer models, and financing.

The recommended implementation phase of ADDI will include 4 strategic programs that have been collaboratively designed and will complement and align with existing programs:

A training program that will include a virtual self-paced course for prospective developers as well as a hands-on cohort model for developers working on a specific project.

A technical assistance program providing matching funds and vetted TA providers for eligible projects (building on the Opportunity Appalachia model).

A flexible fund of capital products providing grant-funded financial assistance to help secure investment for downtown development projects.

A developer peer support network, including a “mentorship” or coaching program that matches experienced and emerging developers, and a “co-developer” model to provide hands-on support to emerging developers taking on projects.

The implementation project will also explore structures and operating models for ongoing coordination and resource provision, potentially transitioning to a permanent “association” entity by the end of the grant period.

The following chapters summarize the analysis, design considerations, and ultimate recommendation from the working group tasked with developing the plan for each of these strategic interventions.

State + Local groups and partners

Ecosystem PartnersCAN, AFN, Fahe, etc.

Potential Developers

Policy / program best practices

Individual Coaching

Early stage TA

Emerging Developers

Predev. Services

Peer Network

Self-led education

Main Street programs

Perm. Financing

Instructorled training

Mentorship by Developers

Mature ("Serial") Developers

Bridge Financing

Training

Technical Assistance

Mentorship & Partnership

Capital Products

Developers

Stakeholders

Perm. Financing

Communitycentered, Downtown

Revitalization Projects

CoDeveloping

The Training Program Working Group was tasked with developing a framework for a comprehensive training curriculum aimed at building the capacity of emerging and prospective downtown developers. The Training Group is composed of eight members and led by Hannah Vargason from the UNH Carsey Center for Impact Finance. This chapter includes:

IN THIS CHAPTER:

4.1 Analysis Methodology

4.2 Training Assessment and Gaps

4.3 Recommend Training and Education Products

Hannah Vargason, Group Lead – UNH Carsey School Center for Impact Finance

Beka Burton – CEDIK at University of Kentucky

Andrew Crosson – Invest Appalachia

Kaleigh Kyle – USDA Rural Development

Rebecca Rowe – Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development

Anthony Thomas – Eagle Street Markets

Beth Thompson – WV Community Development Hub

Paul Wright – Wright Venture Services

The Training Program Working Group conducted the following research and analysis to inform its recommendations:

• Reviewed historical and current communitybased real estate development initiatives and training programs, including the Appalachian Investment Framer Action Cohort.

• Researched external training programs with relevant content or components to inform the ADDI curriculum.

• Identified target participant characteristics and needs.

• Identified subject matter experts (SMEs) to support curriculum development.

The following recommendations are informed by lessons learned from programs with a successful, long-term track record of capacity building for mission lenders and project developers, including the Center for Impact Finance training. Notably, the Working Group also consulted with Grow America (formerly National Development Council), the Incremental Development Alliance, Community Preservation Corporation (CPC), and Capital Impact Partners which, with CPC, also represents a national collaborative of CDFIs that run developer support programs. Key insights from these experts and research literature include:

• A mix of in person, live-remote, and self-guided training should be used to address the various stages/steps of the development process and development finance

• Novice tier participants quickly realize whether they want to advance on their development journey

• Emerging developers don’t know what they don’t know, require “hand holding,” and for whom 1:1 coaching is essential

• Emerging developers need a blend of training, mentorship, and flexible financing

• Blended cohorts of individuals with 0 –3 years’ experience are most effective and participants value networking opportunities

• Access to resources to sustain developer growth is essential; incubation could take a few years to a decade

• Most community-based developers are focused on housing; and housing carries mixed-used projects and builds demand for commercial products/services

• Key topic areas include entrepreneurship, team building, practical market analysis, project due diligence, good design (i.e. how buildings need to work), and risk mitigation

To meet the needs of developers with varying degrees of expertise and interest, the recommended curriculum includes three components: open-access resources, self-paced courses, and accelerator training.

Criteria: Objectives:

Outputs:

Criteria: application & registration fee

promote program and support ecosystem development understand real estate development process, personal capacity, and professional development pathway

Outputs: completed activities and passed quizzes

Objectives:

Criteria: self-paced course, risk assessment, and references

Outputs: development plan package

instructor led, cohort based training paired with targeted technical assistance for emerging developers

Objectives:

master the real estate development process by doing - take a project through exploration & discovery

The self-paced course will be targeted to start-up and nascent developers and will serve as a gateway to the full suite of ADDI products/services. The learning objectives for developers in the self-paced course are to understand the real estate development process, their personal capacity, and next steps on their professional development pathway. Developers will be required to successfully complete the self-paced course to access other program offerings, unless they can demonstrate equivalent relevant experience, effectively “testing out.”

The self-paced course will be virtual and completely asynchronous, i.e., developers will start and complete the course on their own. The course curriculum will include:

• Readings

• Recorded presentations and conversations

• Self-guided activities

• Automatically graded quizzes

Ideally, the course will be housed and accessed through a learning management system (LMS), which will help guide the student through the curriculum and allow for interaction with program managers and other participants. The curriculum will be built on existing products and resources, customized for rural markets.

Successful completion of the course for the purpose of accessing additional ADDI

products/services amounts to passing all quizzes, with no limit on the number of attempts (in addition to any other criteria for additional products/services).

The targeted estimated time to complete the course is approximately 8 hours, consistent with the level of effort for a micro-credential from a higher education institution. To receive a micro-credential, participants would have to submit the course activities for review and certification by an instructor. The program will fully explore micro-credentialing as part of the curriculum development process.

Prospective participants will have to apply and pay a registration fee to access the course. The primary purpose of both the application and fee is to demonstrate value and, thus, generate interest in the ADDI program. The application also serves as a mechanism to capture baseline data and market information.

The registration fee will be $150, with discounts for nonprofit/municipal personnel (i.e., repeat customers) and scholarships for individuals from disadvantaged communities (e.g., rural residents, veterans, individuals in recovery, women and people of color). Participants will also receive access to office hours and a Network Directory of all program participants. (See Exhibit 06: ADDI Training & Education Products, page 62)

In addition, program managers will consider making some information and resources open access online, as a means of promoting the ADDI program and supporting ecosystem development. For example: this may include basic information about the real estate development process that provides insight into the self-paced course and accelerator training curriculum; or terms/definitions and recordings of short talks that would help a broad range of stakeholders understand the investment ecosystem.

The ADDI Accelerator will consist of cohortbased training and targeted technical assistance for emerging developers, i.e., those with some experience (1-3 completed projects) or high potential for success based on relevant experience. In the accelerator training, participants will “learn by doing,” taking a real project through the exploration and discovery phase of the real estate development process.

There will be no cost for the training and support from co-instructors; there may be a cost-share requirement for targeted technical assistance, including coaching.

Program managers will determine what information/resources should be open-access based on frequently asked questions and other feedback from program participants – this will be an on-going process. (See Exhibit 06: ADDI Training & Education Products, page 62)

The training will include self-guided work as well as regular virtual classes/group meetings and periodic in-person workshops, led by 2 co-instructors with real estate development expertise and guest presenters with specific subject matter expertise.

Ideally, successful participants will earn a certificate/credential from a recognized leader in community development training/education. ADDI will select a qualified training partner as part of the curriculum development process described below, who may be able to offer credentialing.

The timeline for a cohort will span 6 months, including an early-stage sprint and flexible virtual content to accommodate different project timelines, on-going meetings, and 2-3 in-person intensive workshops. The targeted total level of effort is 70+ hours, consistent with certificate/ credential programs at a higher education institution. Cohorts will include up to 20 people.

As part of the training work, participants will complete the following:

• Project development plan

• Team roster

• Market analysis

• Pro forma financial projections

• Construction/rehabilitation budget

• Pitch deck

Successful completion of the accelerator will serve as eligibility criteria for additional ADDI products/services and a seal of approval to lenders/investors, indicating developer capacity (i.e., risk mitigation for lenders/investors). These materials will represent an important baseline for project refinement and advancement, while recognizing that some materials will eventually need to be professionally prepared in order to meet investment/underwriting requirements.

To apply for the Accelerator Training, applicants must:

• Complete the self-paced course (or “test out”)

• Commit fully to the training schedule

• Identify a potentially viable project to work on during the training course

• Draft a business model canvas and basic risk assessment

• Provide a letter of recommendation from a community-based stakeholder demonstrating community buy-in on the project

• Submit character references

The application will be reviewed by a real estate development expert, who will provide a recommendation to program managers as to whether the applicant is ready for the Accelerator Training and/or what technical assistance they may need. Program managers may choose to provide targeted technical assistance to applicants in advance of the training to address critical risk areas as part of assessing project viability. (See Exhibit 06: ADDI Training & Education Products, page 62)

The Technical Assistance Working Group was charged with identifying a range of technical assistance products and services designed to support community-based developers. The group was composed of 13 members and led by Ray Moeller from Northern Brownfields Assistance Center at West Virginia University. This chapter includes:

IN THIS CHAPTER:

5.1 Analysis Methodology

5.2 Regional Challenges

5.3 Proposed Structure for Technical Assistance Services

5.4 Types of TA Providers & Solicitation

5.5 Eligibility Criteria & Cost Share

Ray Moeller, Group Lead – Northern Brownfields Assistance Center at West Virginia University

Ann Bass – North Carolina Commerce

Lacey Bacchus – Retail Strategies

Jennifer Brennan – West Virginia Main Street, WV Department of Economic Development

Brian Chenoweth – Coalfield Development Corporation

Maddie Coffman – Partner Community Capital

Kitty Dougoud – State Main Street Coordinator, Kentucky Heritage Council

Christine Laucher – Mountain BizWorks

Courtney Mailey – Virginia Dept of Housing and Community Development

Chris McNamara – Virginia Housing

Bernadette Peters – Sylva Main Street

Kathryn Coulter Rhodes – Rural Support Partners

Stephanie Tyree – West Virginia Community Development Hub

The Technical Assistance Working Group conducted the following research and analysis to inform its recommendations:

• Compiled a list of current and past TA service programs for rural downtown development projects within the ADDI region.

• Analyzed the successes, limitations, and gaps of existing programs and services in the region.

• Researched external TA programs that could serve as models or inspiration for ADDI’s implementation.

• Identified qualified subject matter experts at the local, state, regional, and national levels, with the capacity to provide TA services to emerging community-based lenders.

Technical Assistance programs within the ADDI region vary significantly based on local government and regional agency support, nonprofit resources, and state programs. While a suite of technical assistance programs have arisen in the region over the past 5-10 years (most notably the Opportunity Appalachia program managed by Appalachian Community Capital), the sustained impact of these programs has demonstrated multiple barriers and areas of persistent challenge that were identified by the Working Group. In particular, current robust technical assistance services in the downtown development space are largely project-focused and not integrated with developer capacity building services.

Common gaps and barriers in Technical Assistance offerings across the region include:

• Match Requirements: Some programs require local matching funds, which can be a barrier for communities and projects with limited financial resources.

• “Main Street” Community Participation: Certain services are only available to designated or active “Main Street” communities, excluding other communities that might benefit but do not hold this designation.

• Local Engagement: The success of many projects hinges on their ability to connect with viable local government and community leadership that can actively engage in support of the redevelopment process. Local capacity varies significantly throughout communities across the region, and can often hinge on a single person or small group of leaders. Generational turnover, staff changes, and limitations on the capacity of local electeds creates persistent barriers to sustained local engagement. Technical assistance without community engagement is usually not sufficient for a successful project.

• Program/Staff Capacity: Many initiatives face limitations due to constrained organizational capacity, reducing their awareness of as well as ability to access and deploy the impactful technical assistance that may be available. Consistently programs were operating with staffs of 1-4 people, serving dozens of communities and in some cases multiple states. This limited the ability of program staff to provide the depth or breadth of services that were needed in the region. These staffing challenges were often a result of funding limitations.

• Designated Geography: Many programs have geographic restrictions, offering services only to specific regions or designated areas, which limits broader access.

• Program Timing: Most programs operated on a structured timeline with a single point of entry to the program at the beginning of the program start. This limited when new and emerging projects and developers could access the program, particularly if the project came to fruition at a time that was not before the start of a technical assistance program.

• Limited Funding: A common challenge across programs is restricted funding, which can limit the scale or duration of support offered to communities/projects.

• Cost of Pre-development Technical Assistance: Grant funding for predevelopment support at a scale of more than a few projects is high and often the most risky of development project costs.

• Applicability to Redevelopment: Certain programs may have limited relevance to on-the-ground redevelopment efforts, focusing instead on community planning, local capacity building, or conceptual guidance without sufficient support for project implementation.

• Awareness of technical program availability: Potential clients may not have visibility/insight into the existing technical assistance programs within each ADDI participating State. Awareness of programs depended largely on networks that local project developers were connected into and how well connected the state service providers were with each other and with local communities.