Ice Wine & Cider Hacks Verdejo: Spanish For Refreshing Clearing Up Your Wines WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022- JANUARY 2023 VOL.25, NO.6 • TOP 100 WINE KITS RANKED • DESSERT KIT TWEAKS & TIPS

CHEMISTRY MADE PRACTICAL

& COLD

WINE

KIT WINES WORTH THEIR HEAT

STABILIZATION MEDALS

COLLECTION © 2022 RJS Craft Winemaking Learn more at rjscraftwinemaking.com or bsghandcraft.com Charismatically Crafted. Expressively Enjoyed. Five charismatic Australian & South African stars ready to set your winemaking soul on fire.

•Full Day of Live Online Seminars and Q&A Panels

•Access to Video Recordings of All Sessions

•3 Learning Tracks: Business/Sales, Winery Operations, and Start-Ups

•Get your Questions Answered Live by Industry Experts

•Interact with Other Small Wineries and Wineries in Planning

•Q&A Sessions with Leading Small Winery Industry Suppliers Register

Now

WineMakerMag.com/GaragisteCon

WINERIES FEBRUARY 17, 2023

And Save $100

BIG IDEAS FOR SMALL-SCALE

features

32 26 PROTECTION FROM THE ELEMENTS

Heat (protein) and cold (bitartrate) stability issues in wine cause off-putting aesthetic defects that are often brought to light after the wine is in the bottle and undergoes a temperature swing if not taken care of during bulk aging. Learn how (and if) you should take these heat and cold stabilization precautions at home.

by Dwayne Bershaw

by Dwayne Bershaw

32 TOP 100 WINE KITS OF 2022

More than 400 wines made from kits were judged at the 2022 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition. Many received recognition; and here we share the 100 kit wines that performed best, according to the judging results.

36 MEDAL- WINNING DESSERT KIT TIPS

Following the directions that come with your wine kit will result in very good wine, but sometimes experimenting is part of the fun. Three award-winning winemakers share how they go about making adjustments to dessert wine kits — a category of wine that works well with fortification and other tweaks.

by Dawson Raspuzzi

by Dawson Raspuzzi

42 THE SCIENCE OF WINEMAKING

There is a lot of chemistry involved in winemaking — the better you understand it, the better chance you have of consistently making quality wine. Learn the role science plays and how to use it to your advantage when it comes to Brix, pH, titratable acidity, and more.

by Clark Smith

by Clark Smith

2 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER contents December 2022-January 2023, VOL. 25 NO. 6 WineMaker (ISSN 1098-7320) is published bimonthly for $29.99 per year by Battenkill Communications, 5515 Main Street, Manchester Center, VT 05255. Tel: (802) 362-3981. Fax: (802) 3622377. E-mail address: wm@winemakermag.com. Periodicals postage rates paid at Manchester Center, VT, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to WineMaker, P.O. Box 469118, Escondido, CA 92046. Customer Service: For subscription orders, inquiries or address changes, write WineMaker, P.O. Box 469118, Escondido, CA 92046. Fax: (760) 738-4805. Foreign and Canadian orders must be payable in U.S. dollars. The airmail subscription rate to Canada and Mexico is $34.99; for all other countries the airmail subscription rate is $49.99.

26 36 42

Explore

HOW DOES IT WORK?

+ Choose the Frequency

+ Kits Shipped Right to Your Door

+ Never Run Out of Wine Again

+ Cancel Anytime

Save

WHAT’S INCLUDED?

+ Quality Ingredients to Make 6 Gallons of Wine

+ Curated Kits from Around the World

+ Classic & New Styles

ON ORDERS OVER $49 FREE SHIPPING

+ 100% Free Shipping a New Wine Every Month

Time. Save Money. DRINK WINE. TO SHOP NOW SCAN QR CODE

WINE CELLAR SUBSCRIPTION

departments

8 MAIL

A pro winemaker shares why he continues reading WineMaker long after exchanging his amateur status for commercial production. We also update readers on where they can find us on social media.

10 CELLAR DWELLERS

A time for friends and family to gather and celebrate, the holiday season is best paired with good food and wine. Be sure you plan ahead to match the main course with the vino. Also, learn about the latest wine-related news, new products, and upcoming events.

14 WINE WIZARD

As a winemaker evolves, learning how to evaluate their wine during different stages of maturation can be key. The Wine Wizard has some thoughts on what to expect when tasting wines at various young ages as well as kegging homemade wine.

18 VARIETAL FOCUS

Spain’s fifth most planted white wine grape, Verdejo, enjoys warm climates while being able to retain some acidity. Learn the merits of this grape from the Iberian Peninsula and how to make the best wines with it.

46 TECHNIQUES

Commercial producers of ice wines and ice ciders are highly regulated in their production, but hobby wine and cidermakers don’t need to abide by those rules. Learn some creative ways to produce these coveted, sweet sippers.

49 ADVANCED WINEMAKING

While haze can sometimes just be aesthetically off-putting and not a true flaw, it’s something many winemakers like to avoid. Get the scoop on reducing haze and other benefits, as well as drawbacks, that come with the use of fining agents.

56 DRY FINISH

This past October, a team of four super wine-tasting women (who are also amateur winemakers) traveled to Champagne, France, along with their coach to compete against over 30 teams from various countries in order to find out who the best wine tasters are.

4 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

52 2022 STORY INDEX 53 SUPPLIER DIRECTORY 55 READER SERVICE where to find it ® 18 Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.com

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 5 www.lallemandbrewing.com/wine FULL RANGE OF PREMIUM WINE YEAST K1 ™ (V1116) FRESH AND FRUITY STYLES EC1118 ™ THE ORIGINAL “PRISE DE MOUSE” 71B ™ FRUITY AND “NOUVEAU” STYLES D47 ™ FOR COMPLEX CHARDONNAY QA23 ™ FOR COMPLEX SAUVIGNON BLANCS RC212 ™ FOR PINOT NOIR STYLES Looking for Bottles, Caps and Closures? 888-539-3922 • waterloocontainer.com Like us on Facebook! • Extensive inventory of ready-to-ship bottles, caps and closures • No MOQ on most items – we serve all sizes of customers • Industry expertise to guide you through the packaging process • Quality products and customization to create or enhance your brand You Can Rely on Us

EDITOR

Dawson Raspuzzi

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Dave Green

DESIGN

Open Look

TECHNICAL EDITOR

Bob Peak

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Dwayne Bershaw, Chik Brenneman, Alison Crowe, Wes Hagen, Maureen Macdonald, Bob Peak, Phil Plummer, Dominick Profaci

CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS

Jim Woodward, Chris Champine

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Charles A. Parker, Les Jörgensen

EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Steve Bader Bader Beer and Wine Supply

Chik Brenneman Baker Family Wines

John Buechsenstein Wine Education & Consultation

Mark Chandler Chandler & Company

Wine Consultancy

Kevin Donato Cultured Solutions

Pat Henderson About Wine Consulting

Ed Kraus EC Kraus

Maureen Macdonald Hawk Ridge Winery

Christina Musto-Quick Musto Wine

Grape Co.

Phil Plummer Montezuma Winery

Gene Spaziani American Wine Society

Jef Stebben Stebben Wine Co.

Gail Tufford Global Vintners Inc.

Anne Whyte Vermont Homebrew Supply

EDITORIAL & ADVERTISING OFFICE

WineMaker

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Tel: (802) 362-3981 Fax: (802) 362-2377

Email: wm@winemakermag.com

ADVERTISING CONTACT:

Kiev Rattee (kiev@winemakermag.com)

EDITORIAL CONTACT:

Dawson Raspuzzi (dawson@winemakermag.com)

SUBSCRIPTIONS ONLY

WineMaker

P.O. Box 469118

Escondido, CA 92046

Tel: (800) 900-7594

M-F 8:30-5:00 PST

E-mail: winemaker@pcspublink.com

Fax: (760) 738-4805

Special Subscription Offer

6 issues for $29.99

Cover Photo: Charles A. Parker/Images Plus

PUBLISHER

Brad Ring

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Aging Wine Kits

Do

you have a favorite holiday meal and what type of wine do you pair it with?

We usually do a turkey for family holiday dinners. I find that Pinot Noir is a great wine to pair with the bird; plus, its earthy, tart cherry flavors also play well with all of the yummy side dishes.

At Christmas or New Year’s we love a traditional Englishstyle roast prime rib or standing rib roast with Yorkshire pudding, Brussels sprouts, and all the trimmings. For the main meal, we go for ‘big reds’ like Napa Valley or Alexander Valley Cabernet Sauvignon (usually of my own making) and always include a Zinfandel, often from California’s Sierra Foothills, for the in-laws. I do tend to include one of my Pinot Noirs from the Russian River or Carneros, for those who don’t want something so tannic and potentially heavy. The most important part of any celebration is the people — surround yourselves with friends and family and, no matter what you serve, love makes everything taste its best!

For a holiday meal of ham, turkey, stuffing, and the rest of the fixings, my go-to wine would be Viognier. They tend to be full-bodied and very floral and flavorful — even a touch of sweetness from their fruit notes. They are a great match that can stand up to the heavier foods and the spices like nutmeg and clove.

Kiev Rattee

ADVERTISING SALES COORDINATOR

Dave Green

EVENTS MANAGER

Jannell Kristiansen

BOOKKEEPER

Faith Alberti

SUBSCRIPTION CUSTOMER SERVICE MANAGER

Anita Draper

Kit wines are often consumed fairly young, but great things can happen if you allow the bottles to age longer. Two supply shop owners give guidance and teach the basics of patience and best practices for aging kit wines. https:// winemakermag.com/technique/agingwine-kits-tips-from-the-pros

MEMBERS ONLY

Dessert Wines

Perfect for afterdinner treats, dessert wines are some of the most complex beverages in the world. Get tips for making your own icewine, Sherrystyle, and Port-style wines at home. https://winemakermag.com/article/ dessert-wines

Tannin Chemistry

All contents of WineMaker are Copyright © 2022 by Battenkill Communications, unless otherwise noted. WineMaker is a registered trademark owned by Battenkill Communications, a Vermont corporation. Unsolicited manuscripts will not be returned, and no responsibility can be assumed for such material. All “Letters to the Editor” should be sent to the editor at the Vermont office address. All rights in letters sent to WineMaker will be treated as unconditionally assigned for publication and copyright purposes and subject to WineMaker’s unrestricted right to edit. Although all reasonable attempts are made to ensure accuracy, the publisher does not assume any liability for errors or omissions anywhere in the publication. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or in whole without written permission is strictly prohibited. Printed in the United States of America. Volume 25, Number 6: December 2022-January 2023.

Soft, silky, velvety, youthful, puckery, aggressive, harsh, bitter, astringent: These are all adjectives used in winespeak to describe the many taste sensations from tannins in red wines. Learn about the science behind them. https:// winemakermag.com/technique/1045tannin-chemistry-techniques

MEMBERS ONLY

Mastering Wine Acid Balance

Sometimes the acidity of your grapes, juice, or wine will need to be adjusted. Learn some of the finer details surrounding how, and when, to make those acid adjustments to your wine. https://winemakermag.com/ technique/mastering-wine-acid-balance

MEMBERS ONLY

* For full access to members’ only content and hundreds of pages of winemaking articles, techniques and troubleshooting, sign up for a 14-day free trial membership at winemakermag.com

6 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER WINEMAKERMAG.COM suggested pairings at ®

WineMakerMagazine @WineMakerMag @winemakermag

Q

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 7

FOR HOBBYISTS AND PROS ALIKE

I have been producing wines in a small-scale winery for eight years. I started in a friend’s winery in 2014 as a hobby and then opened Blue Mule Wines (Fayetteville, Texas) in late 2017. I continue to subscribe to WineMaker because of the articles that are relevant to both hobby and commercial winemakers.

Mike Gamble • Fayetteville, Texas

Mike Gamble • Fayetteville, Texas

We always love to hear from former home winemakers turned pro winemakers who still read the magazine. While we have always had a focus on the hobby winemaker, we strongly feel that much of the content in every issue is just as applicable to those who make wine on larger scales at a commercial level. In fact, according to our annual survey results, about 5% of our subscribers are pro winemakers, and another 15% have aspirations of turning pro. These numbers (as well as a lot of other feedback we’ve received over the years) is why we launched GaragisteCon Online earlier this year with a focus on small-scale commercial wineries. Our second annual GaragisteCon Online event, which has three learning tracks (Business/Sales, Winery Operations, and Start-Ups), will be held February 17, 2023 and we’re looking forward to connecting with more commercial winemakers and those aspiring to turn their hobbies into professions. In case others may want to learn more about what it takes to become a professional winemaker or open a small-scale winery, we also offer the quarterly Garagiste e-newsletter — with content geared specifically to those in the industry — which anyone who is signed up to receive WineMaker’s weekly e-newsletter also receives.

NEW FACEBOOK ACCOUNT

Does WineMaker still have a Facebook page? I used to follow the magazine because I loved seeing the stories that were posted as well as photos and updates from the wine competition and events, but it doesn’t look like the page is still active.

Jen Smith • via email

Why, yes, we do still have a Facebook page (as well as Twitter and Instagram pages) that our readers can follow along on! We did have to change our Facebook handle after the previous page was hacked . . . but you can continue to follow us on Facebook at “WineMakerMagazine,” and stay in touch on Instagram @winemakermag and on Twitter @WineMakerMag for the latest happenings and home winemaking content! We hope to see you there!

Dwayne Bershaw began making wine in his garage in 2006 while working as an engineer in Silicon Valley. The passion grew and in 2010 he received a master’s degree in viticulture and enology from UC-Davis. He has four years of experience in a variety of temporary positions in Sonoma and Napa County wineries, and served four years as the Associate Director of the Southern Oregon Wine Institute at Umpqua Community College where he taught all of the enology coursework. There he was also responsible to schedule and manage production of 300–700 cases of wine per year with student participation at the school’s commercial winery. Since 2015 he has held a lecturer position in the food science department at Cornell University.

Starting on page 26, Dwayne describes the purpose and process for putting your wines through heat and cold stabilization to avoid visual defects.

Dawson Raspuzzi has been with WineMaker magazine since 2013 and became the Editor of WineMaker, as well as its sister publication Brew Your Own magazine, in 2017. He is a 2007 graduate of the journalism program at Castleton University in Castleton, Vermont. Out of college he was a reporter for a couple of Vermont newspapers. He can say without a doubt that wine and beer are much more enjoyable subjects to write about than school board meetings. When he isn’t working he’s chasing his three kids around, playing with his hound dog, and enjoying the nature that surrounds him in southern Vermont.

Beginning on 36, Dawson puts his journalism background to good use by interviewing three award-winning kit winemakers about the adjustments they’ve made to dessert wine kits.

Clark Smith is one of California’s most widely respected winemakers. In addition to his own WineSmith wines, he has built many successful brands and consults for hundreds of wineries on five continents. His popular course, Fun-damentals of Winemaking Made Easy, has graduated over 4,500 winemakers to rave reviews. Winemaker, inventor, author, musician, and teacher, Smith was named the Innovator of the Year at the 2016 Innovation + Quality conference (presented by Wine Business Monthly), was named among Wine Business Monthly’s 2018 list of the 48 Most Influential People, and is considered among the world’s foremost experts on pairing wine and music. His revolutionary Postmodern Winemaking was Wine and Spirits magazine’s 2013 Book of the Year.

Beginning on page 42, Clark explains the fundamental chemistry that is critical for winemakers to understand in order to make consistent, high-quality wine.

8 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER contributors MAIL

Balazs Hungarian

Oak Barrels

Balazs is a long-trusted brand of Hungarian oak barrels coopered by the famous Balazs Nagy. These barrels are equal to or better in quality than French Oak barrels but are available at a competitive price. Known for respecting fruit, Balazs Hungarian Oak barrels offer winemakers a great option to impact the mouthfeel, structure, and flavor of wine without stepping on the terroir of your grapes. They contribute a ton of complexity like a French barrel and have always been known for emphasizing fruit.

MOREWINE.COM

5 to 225 Gallon Sizes Available

Shipping Over 9000 Products From Two Distribution Centers!

NEW TABLE WINES

Winexpert™ Winery Series kits are perfect for small to medium-sized wineries. This unique series of craft winemaking kits allows you to make high quality table wines in a variety of popular flavors.

Aseptic packaging

Available Flavors:

CALIFORNIA CHARDONNAY

CALIFORNIA MOSCATO

CHILEAN CABERNET SAUVIGNON

CHILEAN DIABLO ROJO

Sold exclusively through LD Carlson. Contact us today for more info!

No messy crushing or pressing

No acid or pH adjustments

Ready in 4 weeks

Yields 12.2 gallons (46.2 L)

www.ldcarlson.com

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 9

Kent, OH 44240 | 800-321-0315

RECENT NEWS

Rethinking Vertical Shoot Position Trellis Systems

A new study out from UC-Davis has shown that the popular vertical shoot position (VSP) trellis system is likely not the best trellising for warmer, sunnier sites like those found in California. The study looked at six different trellis systems, each at three different irrigation levels for two consecutive seasons. They tested a standard VSP trellis, two variations of the VSP system, a single high-wire cordon system, a high quadrilateral system, and Guyot-pruned VSP system. The irrigation levels were at 25%, 50%, and 100% of the crop’s evapotranspiration level.

The researchers concluded that the single high-wire cordon system had higher yields and accumulated anthocyanins at harvest. They found that the VSP trellis had reduced anthocyanins and that the leaf arrangement with this style of trellising was overexposing the fruit to sun. Their conclusions were clear for those vineyards in a hot and sunny climate: It’s time to replace your VSP trellises. The irrigation aspect of the study was less surprising with higher irrigation leading to larger berry size and yields, but lower anthocyanin and flavonol levels. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.1015574/abstract

New Products:

Winexpert Winery Series The World Of Natural Wine

A new line of kits from Winexpert is aimed at smallto mediumsized wineries. This unique series of craft winemaking kits allows you to make table wines in a variety of flavors. The Winery Series kits come in 3.7-gal. (14-L) concentrates and yield 12.2 gal. (46.2 L) of finished wine. They are releasing a California Chardonnay, California Moscato, Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon, and a Chilean Diablo Rojo. As with many of the kits, ease of use and dependability are key features. Sold in the U.S. exclusively through LD Carlson. https://www.ldcarlson.com/

FRIDAY, JANUARY 20, 2023, 1 TO 5 PM (EASTERN)

Backyard Grape Growing Online Workshop with Wes Hagen. Former professional vineyard manager and WineMaker’s longtime “Backyard Vines” columnist Wes Hagen will lead you online for four hours through all the steps a small-scale grape grower needs to know: Site selection, vine choice, planting, trellising, pruning, watering, pest control, harvest decisions, plus more strategies to successfully grow your own great wine grapes. All attendees will also receive a free download of Wes’ Guide to Growing Grapes and have access to the video recording.

https://winemakermag.com/product/2023-backyard-grape-growing

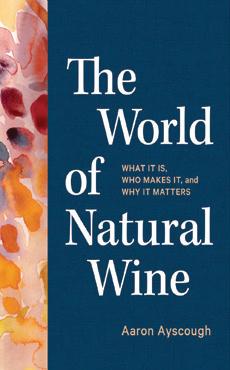

While the world of natural wines can be fairly polarizing in some wine circles, there is no denying that it can produce some interesting wines. Made from grapes alone — organically farmed, fermented, aged, and bottled without additives — they’re a winemaker’s expression of linking wine directly to nature. Author Aaron Ayscough looks to navigate this movement in The World of Natural Wine. Meet the obsessive, often outspoken, winemakers; learn about the regions of France where natural wine culture first appeared and continues to flourish today; and explore natural wine in Spain, Italy, Georgia, and beyond. https:// www.workman.com/products/the-world-ofnatural-wine/hardback

TUESDAY JANUARY 31, 2023

Early Bird Registration Deadline for Feb. 17, 2023 GaragisteCon

Online. A full day of live online seminars and Q&A panels for smallscale wineries and aspiring wineries. All attendees will have access to video recordings of all sessions. There are three learning tracks: Business/Sales, Winery Operations, and Start-Ups as well as Q&A sessions with leading small winery industry suppliers. Get your questions answered live by industry experts. Also attendees get to interact with other small wineries and wineries-in-planning to compare notes. Register by January 31, 2023 to save $100.

https://winemakermag.com/garagistecon

News

10 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER UPCOMING EVENTS

Photo by Ed Kwiek

AWARD-WINNING KITS

Here is a list of medal-winning kits for the Port Style category chosen by a blind-tasting judging panel at the 2022 WineMaker International Amateur Wine Competition in West Dover, Vermont:

Port Style

GOLD

RJS Craft Winemaking Cru Specialty

Black Forest Dessert Wine

RJS Craft Winemaking Cru Specialty

Crème Brûlée Dessert Wine

RJS Craft Winemaking Cru Specialty

Raspberry Mocha Dessert Wine

RJS Craft Winemaking Cru Specialty

Toasted Caramel Dessert Wine

RJS Craft Winemaking Cru Specialty

Vanilla Fig Dessert Wine

RJS Craft Winemaking Cru Specialty

Limited Release Coffee Dessert

Wine

Winexpert Après Chocolate

Raspberry Dessert Wine

Winexpert Speciale Peppermint

Mocha Dessert Wine

SILVER

RJS Craft Winemaking Cru Specialty

White Chocolate Dessert Wine

Winexpert Après Chocolate Salted

Caramel Dessert Wine

Winexpert Après Toasted

Marshmallow Dessert Wine

BRONZE

Winexpert Blackberry Port Style

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 11

BY DAVE GREEN

BEGINNER’S BLOCK WINE PAIRING FOR THE HOLIDAYS

As the days grow shorter and shorter here in the Northern Hemisphere, it’s no wonder many of our ancestors chose this time of year for celebrations. The fall harvest has been stored away for the winter and to prevent from going stir crazy, they decided a party would be in order instead. So as we plan this year’s holiday seasons’ menus, what wine you plan to pair with the food should also be on that planning agenda. While the food menu may be diverse from house-to-house depending on family traditions, there are some good general rules of thumb to follow based on the main course.

TURKEY PAIRINGS

Here in the U.S. turkey has practically become synonymous with holiday feasts, mainly focused around Thanksgiving, Christmas, Passover, and Easter celebrations. Being such a staple in so many homes during holidays means that it should be one that most people should be able to pair wine with. Luckily there is a wide range of wine styles that pair well with turkey: White, rosé, lighter-bodied reds, and sparkling wines.

When it comes to pairing whites with turkey, it’s nice to find one with a moderate to high acid level with some minerality that can really brighten the flavors found in the bird. Alsace-style white wines are where my tastes head to first. Early-picked Chardonnay (fermented and aged clean), Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Albariño, or Chenin Blanc are a few varietals that spring to mind. Dry rosé with a nice acid profile can also enhance the flavors.

If going for a red to pour, a lowtannin, lighter-bodied, and higher acidity wine would best pair with turkey . . . Pinot Noir, Gamay, or Grenache are three that may fit that bill. Finally, drier brut-style sparkling wines pair excellently when turkey is at the center of your holiday table. You know your cellar best though and may find other

wines that fill the role well.

HAM PAIRINGS

Many homes will find ham on their table for either Christmas or Easter. Often salty and sweet, pairing ham with a medium-bodied red wine that can lean towards jammy is one direction to take the pairing. Varietal wines like Zinfandel or Syrah should foot that bill. A blend such as a Grenache-Syrah-Mourvèdre (GSM) could work very well here. If the ham you are cooking is not to be sweetened with a glaze, I would lean to a more austere medium-bodied red. Grenache or maybe a lighter Merlot or Sangiovese might work well in this wine-food pairing.

If you’re looking to put some white wines on the table as well, look to full-bodied whites to pair well with a ham. A little oak-barrel aging on that Chardonnay may play well with the roastiness of the ham. Chenin Blanc, Riesling, Sémillon, or Viognier may also play well on your palate to match that sweet and savoriness of the ham. Don’t overlook the possibility of pairing rosé as well, particularly a darker, more full-bodied rosé.

Also, don’t forget about the possibility of a slightly sweeter white or even rosé sparkling wine. Think a Prosecco style of sparkling wine.

ROASTED BEEF PAIRINGS

There are several cuts of beef that different cultures will serve for the holidays like a prime rib or brisket. Here is where bigger red wines are going to shine at the dinner table. Any full-bodied Bordeaux-style blends or their varietals such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, or Malbec; bigger Syrah, Tempranillo, Nebbiolo, or Sangiovese wines; or even lesser-known varietals like Aglianico or Graciano, will play nicely with a beef main course. Just like with a steak, the fat will cut the larger tannin load found in these styles of

wines and proteins found in the roast, providing a smooth, fruity, and delicious pairing.

If you do want to try to pair a white wine with a roasted beef I would say that you would try best to match the richness of the beef. A white that has been aged sur lie would be a good start, but a California-style Chardonnay may also fit the bill with malolactic fermentation and some time on oak providing a buttery richness.

SEAFOOD DISH PAIRINGS

Growing up, my family always had seafood lasagna on Christmas Eve as the Feast of the Seven Fishes was a popular Italian tradition. What type of seafood and how it is prepared are going to be the driving forces behind what kind of wine you would want to pair it with. Is it going to be creamy-based northern Italian-style preparation or will there be more a southern, tomato-based sauce or even citrus? There is a large array of possible pairings here, but the main focus will often be white, rosé, or sparkling styles of wine. Lighter reds like those mentioned in the turkey section could also be utilized if you would like a red to sit on the table too. For example, salmon and a light, fruity Pinot Noir are a great match.

MEATLESS PAIRINGS

If your household doesn’t serve meat, well then there is no way to tell exactly where you may want to go with your pairing. The sky is the limit considering all the meatless options that we find out there today. You have to go on science and gut. Luckily for us, Bob Peak’s “Techniques” column from the AprilMay 2022 issue (or found at https:// winemakermag.com/technique/ delicious-endeavors-the-scienceof-food-wine-pairings) digs into the science behind making those decisions.

Happy holidays no matter what you are celebrating or wine you are drinking!

12 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 13

BY ALISON CROWE

WINE WIZARD TASTING WINE IN STAGES

Also: Bottling blues

QI’M SUPER EXCITED TO BE HEADING TO BORDEAUX, FRANCE, THIS COMING SPRING ( COVID REVENGE TRAVEL, HERE WE COME!) AND OF COURSE WE’RE PLANNING ON HITTING A NUMBER OF WINERIES. ONE OF THE EVENTS WE’LL BE ATTENDING ( AND MAYBE MORE ) HAS AN OPPORTUNITY TO DO BARREL TASTINGS OF SOME OF THE CHATEAU’S NEWEST WINES. I’M SOMEWHAT EXPERIENCED WITH TASTING MY OWN YOUNG WINES ( I MOSTLY MAKE FRUIT- BASED WINES IN MISSOURI ) SO I WOULD LOVE SOME ADVICE ON HOW TO APPROACH THESE KINDS OF VERY SERIOUS WINES AT SUCH A YOUNG STAGE IN THEIR LIVES. MY HUSBAND AND I ARE PRETTY EXPERIENCED BORDEAUX DRINKERS; BUT WHAT SHOULD WE FOCUS ON: FRUIT STRUCTURE, ACIDITY, LENGTH, ETC.? ALSO, WHAT ARE THE THINGS THAT MIGHT BE DIFFERENT TASTING WINE LESS THAN A YEAR OLD IN BARREL VS. SOMETHING LIKE WHICH WE TYPICALLY WOULD DRINK IN A BORDEAUX, NAMELY SOMETHING THAT’S “FINISHED WINE” WITH AT LEAST FOUR OR FIVE YEARS OF AGE.

EMILY CATTON JEFFERSON CITY, MISSOURI

EMILY CATTON JEFFERSON CITY, MISSOURI

AI apologize in advance for the lengthy response, but this is a fantastic question and I really wanted to flesh out my answer for you. You’re absolutely right to realize that tasting new and developing wines is vastly different than tasting the finished and bottled wines we are all accustomed to. As wines gain bottle age they change even further, developing secondary and tertiary “bottle bouquet” aromas. Before bottling, wine is in a whole different world. In general, over time, new wines, both red and white, increase in clarity as sediment falls out. They generally decrease in acidity and harshness as malolactic fermentation occurs and dissolved carbon dioxide evolves out of the wine. Wines become rounder and more “together” in the mouth as tannins condense and fall to the bottom of the aging vessel. Aromas develop from very primary fruity and funky during fermentation to become the mature and seamless aromas one associates with finished, bottled wine.

The length and finish of a new wine tend to be shorter and will lengthen with age.

Below are some details about what to look for at various stages of a wine’s life — depending on which barrels they show you (and when you visit), the new wine probably will be about five months old. The below will help you (and fellow readers) assess young wine at any stage. Whether tasting after a pumpover during harvest in Chile or barrel tasting at En Primeur in France (or after a racking of raspberry wine in Missouri), hopefully the below information can give you an idea of what to expect and how the wine will differ from something that’s “finished” and in the bottle.

COLOR

Fermenting wine: Newly crushed wines have the highest level of turbidity and sediment they ever will due to all those bits of grape pulp and skin floating around. As a result, the true color of the wine-to-be is quite masked. Due to the turbidity and sediment, this is not

14 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

If the wine is going through MLF it will still taste sour and gassy at this stage, which will make the tannins appear even rougher.

Most wines that are presented to us will be properly matured, but being able to judge an immature wine can be a handy skill for a winemaker.

a very pretty stage for any wine and, therefore, it’s difficult to judge what the pressed-off and settled color will be. Experience working with the same grapes over many harvest seasons will give you the experience needed to be able to predict final color.

1–6-month-old wine: Once a wine is dry and reds have been pressed off and settled, it’s easier to get a look at the color. Very young whites will still be very turbid, so samples need to be centrifuged in order to really get a good look. Be aware that, in red wine, suspended lees are almost a kind of whitening agent; the real wine behind the lees will always settle out darker than a leesy sample might suggest.

6–12-month-old wine: Color is very stable at this point and most reds exhibit the kind of color they’ll carry through the next five years or so. Well-settled whites will exhibit the color they’ll have for about the next two to three years; white wines oxidize and become more brown-hued after about five years in the bottle. White wines on a lees-stirring program will still be turbid, making color difficult to judge.

CLARITY

Fermenting wine: As mentioned earlier, fermentation is the most turbid a wine will be. Grape skin, pulp particles, and yeast cells all contribute to a juice or must that is impossible to see through. Don’t worry, time and gravity will take care of most if not all of this. Experienced tasters and winemakers will know but general consumers will often be very turned off by cloudy wine.

1–6-month-old wine: The wine will still be very turbid, especially if malolactic fermentation (MLF) happens and the weather is cold; suspended bacterial cells in a prolonged MLF will continue to make the wine appear cloudy or hazy.

6–12-month-old wine: Wine should be “falling bright” as gravity causes particulate matter to fall to the bottom of the barrel. It’s still unlikely the wine will be completely clear at this point, especially if lees are kicked up due to purposeful lees stirring or even during routine monthly sulfur dioxide additions and topping.

AROMA

Fermenting wine: This is a fun stage to experience as many types of smells from fabulous (think loads of ripe fruit percolating out of the fermenter) to funky (think of a microbial house party with wildly reproducing yeast and bacteria). The finished wine smells almost nothing like a wine during active fermentation.

1–6-month-old wine: Experienced tasters and winemakers know what to look for but general consumers are often very put off by wines at this stage. MLF can confuse and obfuscate positive and typical finished wine aromas. Compounds like hydrogen sulfide (rotten eggs) or other sulfur-containing compounds can contribute to a reduced (slight hydrogen sulfide) aroma during the early stages of a wine’s life. The wine can smell leesy and microbial; this is a classic stage for malolactic aromas like hamster-cage and mouse-pee that, though they will go away, are temporarily alarming. Though you can certainly smell some great, bright primary fruit aromas at this stage it is usually a very awkward time for most wines.

6–12-month-old wine: The wine will only now begin to take on more of the character of a finished product. The longer MLF goes on, the younger and more unfinished the wine will seem because the dissolved carbon dioxide and reproducing bacteria will keep it in a fermentative and unsettled state. In later months, the wine is “growing up” and turning slowly into what it will be in the bottle. Aromas go from fresh and very fruity to more complex and integrated, especially if oak extraction is involved. In barrel-aged red wines look for spice, vanilla, clove, leather, and black tea beginning to make an appearance.

TASTE, MOUTHFEEL, AND FINISH

Fermenting wine: As in the aroma category, this is an adventurous stage to taste! You’ll get sweet, sour, and everything in between as the yeast turn the grape sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide. As you might expect, wine during primary and secondary (malolactic fermentation) can carry a large amount of dissolved carbon dioxide gas, such that it will feel harsh on the palate and not smooth at all. Tannin content will be minimal at this stage because in red wines the grape skins are just beginning to extract into the aqueous, then increasingly alcoholic, solution.

1–6-month-old wine: The wine is now pressed so all of the tannins that come from the grape (some will come from the barrel, later) are in the wine. The tannins in reds will taste harsh, rough, and aggressive at this stage, unless the grape is a low-tannin variety like Pinot Noir. If the wine is going through MLF it will still taste sour and gassy at this stage, which will make the tannins appear even rougher. Alcohol + tannin + carbon dioxide + acidity all enhance/increase the sensation of the other, which is one of the reasons young wine is so unpleasant to taste.

The wine will taste disjointed, as if the parts have not really begun to hang together yet. It takes a lot of mental gymnastics to try to get a sense of what a wine will become at this time. At six months in the barrel, if new wood, the oak will have begun to make its presence felt. Approaching six months, tannins in red wines will begin to condense into larger molecules, appearing smoother on the palate. The largest tannin molecules may even fall out of solution and accumulate as lees and sediment in the bottom of tanks and barrels.

6–12 month old wine: By now the elements that will make the final wine have begun to really come together, and because so much has “settled down” (carbon dioxide levels have subsided, MLF is over, etc.) it’s easier to pick out the taste elements that will stay with the wine as it ages further and as it’s bottled and bottle-aged. The wine will feel smoother in the mouth as tannins condense and mature. The small amounts of oxygen released into a barrel or in a tank through micro-oxygenation will help keep the wine on a forward-moving trajectory towards aging and will prevent (hopefully!) a return to a reductive state. The finish will start to lengthen though it’s nowhere near what it will be at 18 months to two years in barrel.

It’s important to realize that when barrel tasting, you may only be tasting one barrel out of many that may make its way into a final blend. Each barrel is like its own mini tank— even

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 15

WINE WIZARD

if you put the same wine into it, in six months it can be very different from its siblings, especially if different coopers and toast levels are used. Be sure to ask what the situation is; you may be tasting wine from a barrel that has recently been homogenized and put back down to barrel in a group or you may be tasting a barrel in which the wine has been residing for six months or more. If the latter is the case, it can be very interesting to compare the same original wine across different kinds of barrels. Do be a cautious consumer — it’s unlikely that

any winery will just randomly let the public in and wander around tapping any old barrel. They will probably present some of the best stuff to you, and the “barrel sample” may be a very carefully composed blend!

I hope the above has been helpful to you for your travels as well as your own winemaking. I wish you the best of luck on your travels and I’m sure that you will find plenty of tasting joys that will give you a wealth of new information about how wines develop!

QI REALLY HATE BOTTLING. I PRETTY MUCH DETEST ALMOST EVERYTHING ABOUT IT, FROM THE HASSLE OF CLEANING TO ASSEMBLING ALL OF THE PARTS AND PIECES OF GEAR AND SUPPLIES. THE ONLY THING I LIKE ABOUT IT IS HAVING MY FRIENDS OVER WHILE I FEED THEM PIZZA AND BEER ( NO WINE ALLOWED ON BOTTLING DAY ) AND PRESS GANG THEM INTO GIVING ME A BUNCH OF FREE LABOR. THEN THERE ARE THE TIMES WHEN I HAVE A CORKED BOTTLE TURN UP AFTER ALL THAT HARD WORK . . . I COULD GO ON! SORRY TO COMPLAIN. I’VE BEEN CONTEMPLATING KEGGING MY WINE I KNOW IT’S MAYBE A LITTLE WEIRD AND IT DOES FEEL LIKE UNKNOWN TERRITORY. I’VE NEVER HOMEBREWED BEER BUT SOME OF MY BUDDIES HAVE, SO I FEEL LIKE I COULD GIVE IT A TRY. WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT KEGGED WINE YAY OR NAY?

AHey, I’ve been there . . . a couple of years ago I also entered into unknown territory. After years of bottling one of my commercial Pinot Noirs in Stelvin screwcaps, I embarked on an adventure into the land of wine kegs, or “wine-on-tap.” I kept hearing from sommeliers and restaurant staff how by-the-glass programs were exploding for them and wine-on-tap was leading the way. Consumers liked the environmentally friendly message, they liked the often higher-end choices of wine on offer, and, ultimately, they liked the quality they were tasting in the glass.

The restaurant owners and staff loved the fact that they didn’t have to toss half-used bottles of open wine that hadn’t sold, didn’t have empty glass bottles to recycle, and that their staff was more efficient now that the “cork popping” tableside ceremony was happening less and less often.

But, as a home winemaker, what if you’re not planning on selling your wine like I do and therefore the above reasons to keg your wine don’t really apply to you? Rest assured there are still plenty of reasons for home winemakers to take their wine for a spin in the stainless container. So, if you’re not going to be selling your wine like I do and still want to know why you should have yourself a wine kegger, check out these compelling reasons:

A glass of fresh wine every time, from first glass to last.

• Ever been to a restaurant, ordered a wine by the glass with which you are familiar, only to have it come to the table tasting tired, oxidized, and ho-hum? Chances are you were served from a bottle that had been open since yesterday, or worse, for longer! When you buy (or serve at home) wine from a keg, pushed out with an inert gas, you know the last glass will be as nice as the first.

No oxidation and no cork taint.

• Since there is no cork involved here there is no chance of

cork taint from that source. Since you don’t have to worry about the integrity of a plug of tree bark, there’s less chance of air coming in from that source. Every glass tastes like you meant it to taste.

Less “bottle shock”

• Think about it this way . . . kegging up wine is more like bottling in “large format” (3- to 5-L) big bottles than your standard 750-mL model. The smaller the vessel, the larger the ratio of oxygen-to-wine. I believe that bottle shock is very much about big slugs of oxygen getting into your wine and then chewing its way through it as it “figures itself out” (I know, that’s a touchy feely way of putting it, but forgive me). By packaging in bigger vessels, you lower that oxygen-to-wine ratio and therefore the oxygen-equilibrating blowback of bottle shock.

It’s the “green” choice — massive reduction in carbon footprint compared to bottles

• This is a reason that everyone can get behind!

• Reusable kegs can be used for 30+ years.

• No waste to the landfill: Each reusable steel keg saves over 2,340 lbs. (1,060 kg) of trash from the landfill over its lifetime (source: www.freeflowwines.com).

To get you up to speed on the (limited, I promise!) gear, I really recommend you check out Tim Vandergrift’s excellent piece “Kegging Your Wine” at our website, (https://winemakermag. com/technique/1408-wine-on-tap). He really breaks down the details for you and walks you through the process. Probably the easiest way to get started is to use a Cornelius keg, a.k.a., “Corny keg,” as Tim suggests. If you can borrow some of the set-up bits and bobs from one of your brewing friends, that makes it even easier and more affordable. Kegging wine can have a ton of benefits . . . and you don’t need to invite a gang of friends over to help, though you can still certainly have a pizza and beer night (with some tastes from your keg) afterwards!

16 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

ARNOLD ALEXANDER BEND, OREGON

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 17 WINEMAG 10 % OFF ENTER DISCOUNT CODE AT CHECKOUT mail@catalyst-manufacturing.com CONTACT US www.catalyst-manufacturing.com The Carboy Killer A complete system for fermenting, aging and transferring wine IntelliTank Italian Wine Equipment in Stock! Store Location: 575 3rd St. Building. A, Napa CA 94559 - Inside the Napa Expo Fairgrounds www.NapaFermentation.com QUALITY, FRESH PRESSED GRAPE JUICE VINIFERA - FRENCH HYBRID NATIVE AMERICAN 2860 N.Y. Route 39 • Forestville, N.Y. 14062 716-679-1292 (FAX 716-679-9113) OVER 20 VARIETIES OF GRAPE JUICE... PLUS Apricot, Blackberry, Blueberry, Cherry, Cranberry, Peach, Pear, Plum, Pomegranate, Red Raspberry, Rhubarb and Strawberry We Ship Juice in Quantities from 5 to 5000 gallons WALKER’S... GROWING SINCE 1955, SUPPLYING AWARD WINNING JUICE TO OVER 800 WINERIES IN 37 STATES Walkers Qrtr-pg Ad.qxp_Layout 1 12/3/18 9:33 AM Page 1 www.walkerswinejuice.com (For inquiries email jim@walkerswinejuice.com)

VARIETAL FOCUS

BY CHIK BRENNEMAN

A warm-climate white wine grape VERDANT VERDEJO

Writer’s block is something every writer experiences from time to time, and sometimes the blockade is removed under some of the most bizarre situations. We were shopping in the local Carrefour Express Market in Cullera, Spain, over the summer and I had a bottle of wine in each hand trying to decide which one to buy. I called over to my wife, Polly, and asked which one she “liked,” the one in my right hand or the left, without knowing either variety. Something was lost in the translation because she interpreted it as which one I should write about. Typical married couple of 33+ years, the Venus and Mars syndrome, I assumed she referred to the one in my right hand, which is the one that we purchased. We were walking back to our apartment and she asked me what made me decide on that variety. I responded it was the one in my right hand, just like she requested. Confusing looks on both of our faces told us we had no clue what had just happened, but in the end we enjoyed that bottle of Verdejo that evening over a good laugh! It was the “right” variety and as it turns out after all these years of writing this column, we have never covered it in detail.

Verdejo is named for the green color of its berries. It is truly an Old-World variety having been introduced to the Rueda region of Spain long before Moorish rule, around the 5th century. Verdejo is sometimes confused with the variety Godello, grown to the northwest in the Galicia region. Verdejo is also confused with the varieties Verdelho and Gouveio, which are both synonyms for Godello in nearby Portugal. However, DNA parentage analysis suggests Godello is a sibling of Verdejo.

The clusters are compact, small- to

medium-sized, thin-skinned berries. They are early- to mid-budding, making it somewhat prone to spring frost. As the season progresses the berries take on a distinctive blue-green bloom, a coating on the berries themselves. Its vines are generally of low vigor and do best in warm to hot regions in low-fertility clay soils. It is highly susceptible to powdery mildew and tradition holds it is best cane pruned.

The Rueda is a warm climate region in the north central part of the country and Verdejo has been described as its pride and joy. It is Spain’s fifth most planted white wine variety with 44,333 acres (17,931 ha) reported in 2016, with an upward trend in vineyard area planted to it. It was mostly known for its fortified styles, but it has been a rising star in the dry whites it is being made into. Despite its popularity as a dry white varietal wine, the regulations of the Rueda DO allow for blending with another up and coming grape of the region, that being Sauvignon Blanc. The DO regulations do allow for white wines to be predominantly made from or solely from Sauvignon Blanc. A fairly progressive DO, you will also find Verdejo in sparkling wines and fortified Sherry-like wines.

The wines are very aromatic, medium to high acidity, and full bodied with notes of laurel and bitter almonds. They become nuttier with age and respond well to barrel fermentations and oak aging. Of course that all depends on how the fruit behaves in any given season and how the grapes and juice present themselves to the winemaker.

There are two main contributing factors to making Verdejo wine in the style I prefer; yeast and acid. We’ll tackle the latter first. While I mentioned that the grape retains its acidity, that is relatively speaking. In warmer climates, some acid

18 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

Photo

Shutterstock.com

The wines are very aromatic, medium to high acidity, and full bodied with notes of laurel and bitter almonds.

courtesy of

VERDEJO Yield 5 gallons (19 L)

INGREDIENTS

100 lbs. Verdejo fruit or 6 gallons (23 L) juice

Distilled water

10% potassium metabisulfite (KMBS) solution (Weigh 10 g of KMBS, dissolve into about 75 mL of distilled water. When completely dissolved, make up to 100 mL total with distilled water.)

5 g Lalvin QA23 yeast

5 g Diammonium phosphate (DAP)

5 g Fermaid K (or equivalent yeast nutrient)

EQUIPMENT

5-gallon (19-L) carboy

6-gallon (23-L) carboy

6-gallon (23-L) plastic bucket

Racking hoses

Inert gas (nitrogen, argon, or carbon dioxide will do)

Refrigerator (~45 °F/7 °C) to cold settle the juice (remove the shelves so that the bucket will fit)

Ability to maintain a fermentation temperature of 55 °F (13 °C)

Thermometer capable of measuring between 40–110 °F (4–45 °C) in one degree increments

Pipettes with the ability to add in increments of 1 mL

Tartaric acid (addition rate is based on acid testing results)

STEP BY STEP

1. If starting with juice, begin at step

7. Crush and press the grapes. Do not delay between crushing and pressing. Move the must directly to the press and press lightly to avoid extended contact with the skins and seeds.

2. Transfer the juice to the 6-gallon (23-L) bucket. During the transfer, add 2.5 mL per gallon (0.66 mL per L) of 10% KMBS solution. (This addition is the equivalent of about 35 ppm SO2.)

3. Move the juice to a refrigerator at 45 °F (7 °C). Let the juice settle at least overnight. Layer the headspace with inert gas and keep covered.

4. When sufficiently settled, rack the juice off of the solids into the 6-gallon (23-L) carboy.

5. Mix up the Fermaid K in about 50 mL of previously boiled water (to sterilize it so you can add it to the juice) then add to juice.

6. Prepare yeast. Heat the 50 mL water to 104 °F (40 °C). Do not exceed this temperature as you will kill the yeast. If you overshoot the temperature, start over, or add some cooler water to get the temperature just right. Sprinkle the yeast on the surface and gently mix so that no clumps exist. Let sit for 15 minutes undisturbed. Measure the temperature of the yeast suspension. Measure the temperature of the juice. You do not want to add the yeast to your cool juice if the temperature difference exceeds 15 °F (8 °C). Acclimate your yeast by taking about 10 mL of the cold juice and adding it to the yeast suspension. Wait 15 minutes and measure the temperature again. Do this until you are within the specified temperature range.

7. When the yeast is ready, add it to the carboy and move the carboy to an area where the ambient temperature can be maintained at 55 °F (13 °C).

8. You should see signs of fermentation within about two to three days. This will appear as some foaming on the surface and the airlock will have bubbles moving through it. If the fermentation has not started by day four, you might consider warming the juice to 60–65 °F (16–18 °C) temporarily to stimulate the yeast. Once the fermentation starts, move back to the lower temperature. If that does not work, consider re-pitching the yeast as described above.

9. Dissolve the DAP in as little distilled water required to dissolve completely (usually ~20 mL). Add to the fermenting juice after the fermentation has started and is progressing noticeably.

10. Normally you would monitor the progress of the fermentation by measuring Brix. One of the biggest problems with making white wine at home is maintaining a clean fermentation. Entering the carboy to measure the sugar is a prime way to infect the fermentation with undesirable microbes. So at this point, the presence of noticeable fermentation is good enough. Leave well enough alone for about two weeks.

11. If your airlock becomes dirty by foaming over, remove it, clean it, and replace as quickly and cleanly as pos-

sible. Sanitize anything that will come in contact with the juice.

12. Assuming the fermentation has progressed, then after about two weeks, it is time to start measuring the sugar. Sanitize your thief; remove just enough liquid to for your hydrometer. Record your results. If greater than 7 °Brix, then wait another week before measuring. If less than 7 °Brix, begin measuring every other day.

13. Continue to measure the Brix every other day until you have two readings in a row that are negative and about the same.

14. Taste the wine, if there is no perception of sweetness, consider it dry and add 3 mL of 10% KMBS per gallon (0.8 mL per L). If there are any sulfide like (rotten egg) odors, rack the wine off the lees. If the wine smells good, then let the lees settle for about two weeks and stir them up (bâttonage). Repeat this every two weeks for eight weeks. This will be a total of four stirs. 15. After the second stir, check the SO2 and adjust to 30–35 ppm free.

16. After eight weeks, let the lees settle. At this point, the wine is going to be crystal clear or a little cloudy. If the wine is crystal clear, then that is great! If the wine is cloudy, then presumably, (if you have kept up with the SO2 additions and adjustments, temperature control, kept a sanitary environment, and there are no visible signs of a re-fermentation) this is most likely a protein haze and you have two options: Do nothing – it’s just aesthetics or clarify with bentonite.

17. While aging, test for SO2 and keep maintained at 30–35 ppm.

18. Once the wine is cleared, it is time to move it to the bottle. This would be about six months after the onset of fermentation. Keep in mind this wine has had the malolactic fermentation inhibited. If all has gone well to this point, given the quantity made, it can probably be bottled without filtration. Your losses during filtration could be significant. That said, maintain sanitary conditions while bottling, and you should have a fine example of a clean, crisp Verdejo that pairs well with lemon-based chicken or seafood dishes. Enjoy with friends!

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 19

Other winemaking considerations to ponder are the use of sur lie aging with bâttonage and the use of oak or oak products.

supplement may be necessary. The grapes generally come in at a pH around 3.8 and an acid of 0.55 g/L. The acidity and pH at harvest is very much influenced by soil type and rootstock. So for me, I always have an open mind when evaluating these parameters of the must. In my climate, other white grapes will come in with much higher pH values and lower acids, thus requiring a considerable acid supplement. With respect to Verdejo, a cursory glance tells us that the numbers are not bad and would probably be a nice wine if left alone. But I like a little crispness so I target to taste my whites with an acid level around 0.65 g/L and a general comfortability in driving the pH down a little bit. Therefore, I generally supplement with about a 1 g/L addition of tartaric acid at the crusher. I follow up after primary fermentation to make decisions on further acid supplement, if any is required. I tend to inhibit the malolactic fermentation (MLF) to preserve the acidity. I have toyed with MLF in the past on Verdejo grown in a vineyard

FILL YOUR PASSION.

BOTTLE FILLING MADE EASY!

block at UC-Davis, however I prefer the crisper version with grapes grown in California. That might be different in Virginia or Spain.

Now let’s consider the yeast. Hopefully you have read about some of the designer yeasts available because with respect to this variety, this can make a difference. I have done yeast trials with Verdejo and have found that the yeast QA23 (Lallemand) is the choice for me. Independent of the product literature, I found that this yeast fermented the most aromatic, clean, citrus-based flavors. I found that CY3079 (Lallemand) also produces wonderful aromatics, but I struggled at the end of the fermentation with some sulfide issues. That wasn’t the fault of the yeast; that was the winemaker. We all have our challenges. The take-home lesson on your yeast choice is to do your homework on them. They have to be happy to stay happy. It is your job as the winemaker to give them a reasonable juice to live in. Good sugar, good temperature control,

Scan

XF460 VOLUMETRIC

drew horton , Enology Specialist, University of Minnesota Grape Breeding & Enology Project

6x9” | illustrated | 614 pages

ISBN: 978-1-55065-563-6 $24.95 (trade paper)

ISBN: 978-1-55065-593-3 $59.95 (cloth)

Distributed by Independent Publishers Group

20 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

BOTTLE

CAN FILLERS are handcrafted and custommade to order in the USA. We offer five types of fillers: Volumetric Filler,

Filler, Carbonated Beverage,

Filler, and a Hot

Filler. With ten models to choose from, there is an XpressFill that will fit your needs. Order yours today!

VARIETAL FOCUS XPRESSFILL

AND

Level

Counter Pressure

Fill Level

FILL

844.361.2750 (toll free) sales@xpressfill.com XPRESSFILL.COM this code to view all of our products!

–

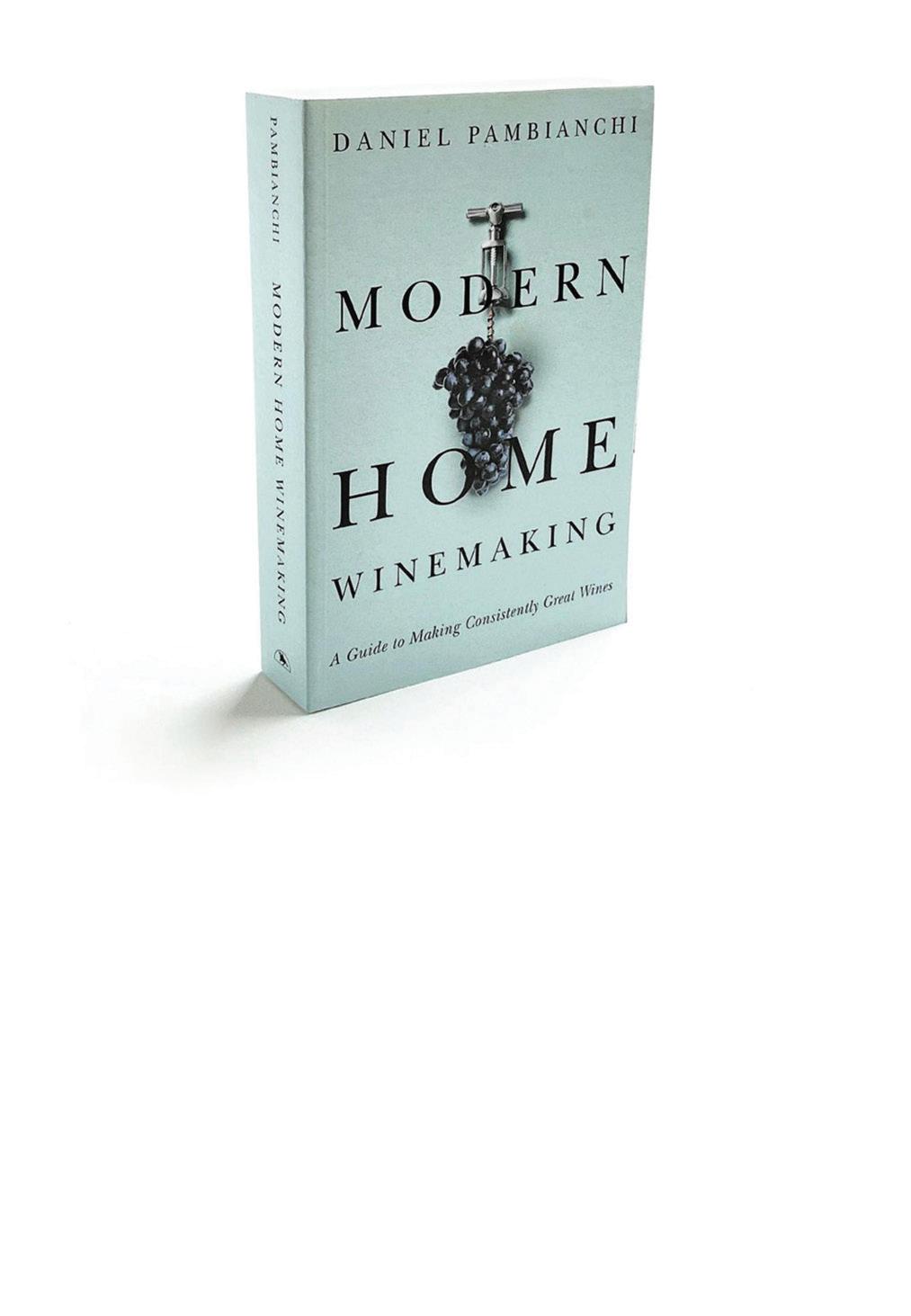

“This book contains techniques and methods for the home winemaker but would also be helpful to winemakers of any experience level from beginner to advanced commercial winemakers. It is thorough, complete, incredibly well researched, and contains the latest research on wine testing and analytical methods…this book leaves nothing out.”

and the equivalent of three square meals a day.

Over the years since I first worked with Verdejo I have done some practice on aromatic whites and how winemakers work to enhance those aromatics through some skin contact; with or without the use of enzymes. Personally, I tend to shy away from any enzymatic intervention in that while these products are well studied by the manufacturers and their technical support specialists are very willing to help out, it goes against my belief of “minimal intervention winemaking.” Verdejo is a delicate grape with thin skins so it should not require a lot of intervention. Rather than using the word “press,” I like to call it de-juicing the must, using rice hulls as a pressing aid to improve juice yields in a series of small, light cycles of the press. Squeeze until the juice flow slows down, back off, and massage it again. When I see the pH of this juice fraction climbing it implies your job is done! Elevations in pH during pressing tell me that I am fracturing the skins too much, releasing potassium. Remember that in dry white wines it is very easy to notice some of the phenolic components from the skins, so in my world it’s best to go easy.

Other winemaking considerations to ponder are the use of sur lie aging with bâttonage and the use of oak or oak products. It’s something to consider but it’s good to weigh your options having successfully moved on from the fruit processing and fermentation stage. Sur lie with bâttonage can help improve your mouthfeel, but also consider some enhancements of vanilla and butterscotch flavors with oak products, which can also lead to improved mouthfeel. Maybe a combination of the two. Whatever I decide to do, it is always keeping the preservation of the aromatics in mind. Low temperatures (less than 55 °F/13 °C) go a long way in preserving aromatics.

So whatever happened to the Spanish Carrefour Express shopping trip that was reminiscent of the comic strip characters Pickles and Earl (A couple that love each other dearly, but sometimes go about their daily lives in their own world, connecting most of the time, but periods of disconnection exist and become laughable at a later

time)? Verdejo became our “go-to” white wine while we were visiting friends. We tried many styles — and it was fun. Our hosts, Jose and Edu, were not real big wine drinkers, but discovered something new and learned a lot about what is happening in the wine world nearby. They might as well have been living down the street from Disneyland having never visited their local Rueda wine country. For Polly and me, it was

a great experience to focus on after a month in France. The vineyard block at UC-Davis where the Verdejo was grown is now gone. Succumbing to a changing staff, environment, disease, and growing priorities for something that matures somewhat later in the fall season when class starts. If I could ever get my hands on some of these delicious wine grapes without having to move to Spain, I’d be all over it.

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 21

AND MALOLACTIC CULTURES

PIONEERING PREMIUM YEAST

ENTER YOUR BEST HOMEMADE WINES IN THE WORLD’S LARGEST COMPETITION FOR HOBBY WINEMAKERS!

DON’T WAIT — SEND YOUR ENTRIES NOW! ENTRY DEADLINE: MARCH 17, 2023

Enter your wines and compete for gold, silver and bronze medals in 50 categories awarded by a panel of experienced wine judges. You can gain international recognition for your winemaking skills and get valuable feedback on your wines from the competition’s judging panel.

Entry Deadline: March 17, 2023

5515 Main Street • Manchester Center, VT 05255 ph: (802) 362-3981 ext. 106 • fax: (802) 362-2377

email: competition@winemakermag.com

You can also enter online at: www.winemakercompetition.com

22 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

SPECIAL BEST OF SHOW MEDALS

Gene Spaziani Grand Champion Wine

WineMaker of the Year

will be awarded thanks to our award sponsors:

Best of Show Red

Retailer of the Year

Best of Show White

U-Vint of the Year

Best of Show Dessert

Club of the Year

LALLEMAND BREWING

Best of Show Mead

Best of Show Country Fruit

Best of Show Sparkling

Best of Show Estate Grown

Best of Show Kit/Concentrate

Category Medals (gold, silver, and bronze) will be awarded thanks to our category sponsors:

19.

34. Red Table Wine Blend (Any Grape Varieties)

35. Blush Table Wine Blend (Any Grape Varieties)

36. Grape & Non-Grape Table Wine Blend

37. Apple or Pear Varietals or Blends

38. Hard Cider or Perry

39. Stone Fruit (Peach, Cherry, Blends, etc.)

GLCC Co.

40. Berry Fruit (Strawberry, Raspberry, Blends, etc.)

GLCC Co.

41. Other Fruits

GLCC Co.

42. Traditional Mead

43. Fruit Mead

Moonlight Meadery

44. Herb and Spice Mead

45. Flower or Vegetable

46. Port Style

47. Sherry Style

48. Other Fortified

49. Sparkling Grape, Dry/Semi-Dry or Sweet

50. Sparkling Non-Grape

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 23

1. White Native American Varietal

2. White Native American Blend

3. Red Native American Varietal

4. Red Native American Blend

5. Blush/Rosé Native American

6. Red or White Native American Late Harvest and Ice Wine

7. White French-American Hybrid Varietal

8. White French-American Hybrid Blend 9. Red French-American Hybrid Varietal 10. Red French-American Hybrid Blend 11. Blush/Rosé French-American Hybrid

12.

Red or White French-American Late Harvest and Ice Wine

13.Chardonnay UWinemaker 14.

Pinot Grigio/Pinot Gris

15.Gewürztraminer 16.Riesling 17.

Sauvignon Blanc

18. Other White Vinifera Varietals

White Vinifera Bordeaux

Style Blends

23. Merlot Vinmetrica 24. Shiraz/Syrah 25. Pinot Noir 26. Sangiovese 27. Zinfandel MoreWine!

Other Red Vinifera Varietals

Red Vinifera Bordeaux Style Blends Tin Lizzie Wineworks

Red Vinifera Blends Label Peelers Beer & Winemaking Supply

Blush/Rosé Red Vinifera

Red

20.

Other White Vinifera Blends

21. Cabernet

Franc

Five Star Chemicals & Supply, Inc. 22. Cabernet Sauvignon All in One Wine Pump Company

28.

29.

30. Other

31.

32.

or White Vinifera Late Harvest and Ice Wine

33. White Table Wine Blend (Any Grape Varieties)

RULES & REGULATIONS

1. Entry deadline for wines to arrive is March 17, 2023

Wines are to be delivered to: Battenkill Communications

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255 Ph: (802) 362-3981

2. Send ONE (1) BOTTLE per entry. Still wines must be submitted in standard 750 ml wine bottles. Ice wines or late harvest wines can be submitted in 375 ml bottles. Meads and Hard Ciders can be submitted in 12 oz. or 22 oz. beer bottles. Sparkling wines must be in champagne bottles with proper closure and wire or crown cap. All bottles must be free of wax, decorative labels and capsules. However, an identification label will be required on the bottle as detailed in rule #5.

3. Entry fee is $30 U.S. dollars (or $30 Canadian dollars) for each wine entered. Each individual person is allowed up to a total of 15 entries. You may enter in as many categories as you wish. Make checks payable to WineMaker Only U.S. or Canadian funds will be accepted. On your check write the number of entries (no more than 15 total) and the name of the entrant if different from the name on the check. Entry fees are non-refundable.

4. All shipments should be packaged to withstand considerable handling and must be shipped freight pre-paid. Line the inside of the box with a plastic trash bag and use plenty of packaging material, such as bubble wrap, around the bottles. Bottles shipped in preformed styrofoam cartons have proven reliable in the past. Every reasonable effort will be made to contact entrants whose bottles have broken to make arrangements for sending replacement bottles. Please note it is illegal to ship alcoholic beverages via the U.S. Postal Service. FedEx Air and FedEx Ground will destroy all amateur wine shipments so do not use either of these services. Private shipping companies such as UPS with company policies against individuals shipping alcohol may refuse your shipment if they are informed your package contains alcoholic beverages. Entries mailed internationally are often required by customs to provide proper documentation. It is the entrant’s responsibility to follow all applicable laws and regulations. Packages with postage due or C.O.D. charges will be rejected.

5 Each bottle must be labeled with the following information: Your name, category number, wine ingredients, vintage.

Example: K. Jones, 9, 75% Baco Noir, 25% Foch, 2020. If you are using a wine kit for ingredients please list the brand and product name as the wine ingredients. Example: K.Jones, 22, Winexpert Selection International French Cabernet Sauvignon, 2021. A copy of the entry form, listing each of your wines entered, must accompany entry and payment.

6. It is entirely up to you to decide which of the 50 categories you should enter. You should enter each wine in the category in which you feel it will perform best. Wines must contain a minimum of 75% of designated type if entered as a varietal. Varietals of less than 75% must be entered as blends. To make sure all entries are judged fairly, the WineMaker staff may re-classify an entry that is obviously in the wrong category or has over 75% percentage of a specific varietal but is entered as a blend.

7. Wine kits and concentrate-based wines will compete side-by-side with fresh fruit and juice-based wines in all listed categories.

8. The origin of many Native American grapes is unknown due to spontaneous cross-breeding. For the purposes of this competition, however, the Native American varietal category will include, but is not limited to, the following grape families: Aestivalis, Labrusca, Riparia and Rotundifolia (muscadine).

9. For sparkling wine categories, dry/semidry is defined as <3% residual sugar and sweet as >3% residual sugar.

10. Contest is open to any amateur home winemaker. Your wine must not have been made by a professional commercial winemaker or at any commercial winery. No employee of WineMaker magazine may enter. Persons under freelance contract with Battenkill Communications are eligible. No person employed by a manufacturer of wine kits may enter. Winemaking supply retail store owners and their employees are eligible. Judges may not judge a category they have entered. Applicable entry fees and limitations shall apply.

11. All wines will be judged according to their relative merits within the category. Gold, silver and bronze medals within each category will be awarded on point totals and will not be restricted to the top three wines only (for example, a number of wines may earn enough points to win gold). The Best of Show awards will be those wines clearly superior within those stated catego-

KEY DATES

Entry deadline for wines to arrive in Vermont: March 17, 2023

Wines judged: April 21-23, 2023

Results first announced at the WineMaker Magazine Conference in Eugene, Oregon June 3, 2023

(Results posted June 4, 2023 on winemakermag.com)

ries. The Grand Champion award is given to the top overall wine in the entire competition.

12. The Winemaker of the Year award will be given to the individual whose top 5 scoring wine entries have the highest average judging score among all entrants.

13. The Club of the Year, Retailer of the Year and U-Vint of the Year awards will be based on the following point scale: Gold Medal (or any Best of Show medal): 3 points

Silver Medal: 2 points

Bronze Medal: 1 point

The amateur club that accumulates the most overall points from its members’ wine entries will win Club of the Year. The home winemaking retail store that accumulates the most overall points from its customers’ wine entries will win Retailer of the Year. The U-Vint or On-Premise winemaking facility that accumulates the most overall points from its customer’s wine entries will win U-Vint of the Year.

14. The Best of Show Estate Grown award will be given to the top overall scoring wine made with at least 75% fruit grown by the entrant. Both grape and country fruit wines are eligible.

15. All entrants will receive a copy of the judging notes for their wines. Medalists will be listed by category online.

16. All wine will become the property of WineMaker magazine and will not be released after the competition.

17. All decisions by competition organizers and judges are final.

24 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

Deadline: March 17, 2023

Entry Fee: $30 (U.S.) or $30 (Canadian) per wine entered

Number of entries _____ x $30 (US) or $30 (CD) = $________Total (limit of 15 entries per person)

q Enclosed is a check made out to “WineMaker” in the amount of $_________.

Name___________________________________________________________________________

Address_________________________________________________________________________

City________________________State/Prov______Zip/Postal Code____________________

Telephone___________________________________________________________

E-Mail____________________________________________________________________________

Winemaking Club:________________________________________________________________

Winemaking Retailer:_____________________________________________________________

U-Vint / On-Premise Store:________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage: Please list fruit varieties and percentages used in each wine. Example: “75% Baco Noir, 25% Foch.” If you are using a wine kit for ingredients, please list the brand and product name as the wine ingredients.

Example: “Winexpert Selection International French Cabernet Sauvignon.”

Wine 1 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ____________________________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 2 Entered:

Category Number___________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 3 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

ENTRY FORM

Please note that you can also enter online at:

winemakercompetition.com

Remember that each winemaker can enter up to 15 wines. If entering more than eight wines, please photocopy this entry form. Entry shipment includes ONE BOTTLE of wine per entry. 750 ml bottle required for still wines. Ice or late harvest wines can ship in 375 ml bottles. Still meads can ship in 12 oz. or 22 oz. beer bottles. Sparkling wines must ship in champagne bottles with proper closure and wire or crown cap.

Send entry form and wine to:

Battenkill Communications

5515 Main Street

Manchester Center, VT 05255

Ph: 802-362-3981 • Fax: 802-362-2377

E-mail: competition@winemakermag.com

If entered online at winemakercompetition. com, please print a copy of your entry form and send it along with your wine.

Wine 5 Entered:

Category Number_________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 6 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 7 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 4 Entered:

Category Number___________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Enter online at: winemakercompetition.com

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

Wine 8 Entered:

Category Number__________________________________________________________

Category Name____________________________________________________________

Wine Ingredients and Percentage

Vintage ______________________________________________________

Are at least 75% of the ingredients grown by you? q yes q no q I feel it necessary to decant this wine_______hours before serving.

WINEMAKERMAG.COM DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 25

DON’T WAIT — ENTER NOW!

Putting your wine through cold and heat stabilization

by Dwayne Bershaw

by Dwayne Bershaw

e’ve all heard that great wines are made in the vineyard, and there is a lot of truth to that saying. It’s impossible to make high-quality wine if you’re starting with damaged or unripe fruit. Grape growing, harvesting, and fermentation are sort of the sexy part of wine production and thus these activities often come to mind first when we consider what winemaking is all about. Still, there are a group of activities that occur once the wine has been fermented that are also critical to quality wine production, especially for white wines. These processes and checks involve the chemical and microbial stability of wine. Once primary and malolactic fermentation are completed, chemical and microbial stability are the main concerns of the winemaker prior to final clarification, filtration, and packaging. I covered microbial stability in depth in the October-November 2022 issue, so this go-round we’re going to focus our discussion on heat and cold stability.

26 DECEMBER 2022 - JANUARY 2023 WINEMAKER

Photo by Charles A. Parker/Images Plus