How can participatory architecture methods contribute to creating more inclusive and ‘complete’ streets in Sheffield for residents and

stakeholders?

Darcy Fearn

Undergraduate BSc (Hons) Architecture

CONTENTS

Introduction................................................................1

> Background Area

> Academic Context

> Methodologies

Inclusivity and Urban Architecture ..............2

Urban Street Priorities......................................................3

> Traffic 1950s-1960s

> Pedestrian Safety 1970s....................................................4

> People 1990s....................................................................5

> Covid-19 Pandemic and Community Revival 2020............6

> Community Inclusivity Today..............................................7

Complete Streets Concept................................8

> Background

> Context within the UK........................................................9

Participatory Architecture..................................10

> Introduction of Participation

> Political Movement.............................................................11

> Conflictual Participation

> Issues with Participation.....................................................12

Sheffield Community Land Trust.....................13

> Community led project at planning stage

> Methodologies

>Member groups and Limitations...........................................14

Case Study: Division Street.................................15

> Community led project at planning and use stage

> Trial closure 19th-20th October

> Methodologies.....................................................................16

>Timeline of Division Street Pedestrianisation .........................17

Questionnaire.............................................................18

> Results.............................................................................18-19

> Limitations..........................................................................19

Conclusion....................................................................20

Appendix A....................................................................21

> Questionnaire Participant Information Sheet

Appendix B.....................................................................22

> Questionnaire Data Answers

References and Figures......................................23-24

> Reference List > Figure List

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND AREA

The aim of my study is to explore how participation can improve inclusivity of city streets by utilising community input to understand what street user’s need. I will research the history of city streets and how historical context has altered their priorities, to conclude what the street priorities of today are. The ideas for street improvements by social activists and urban planners such Jacobs and Gehl will be explored to gain understanding of methods to tackle issues that city streets have previously faced. Whilst completing my literature review, my attention was drawn towards the Complete Streets concept, which I will further explore as an example of modern frameworks that could inspire methods of achieving inclusivity. Participation is a widely recognised method of achieving inclusivity in the 21st century, however uses of it dates to the 1950s. Prominent architects in the field, Jones and Turner, have completed initial community-led projects. One example that is discussed is the self-housing project in Peru (Turner, J.F. (1972). Later works from Miessen show the political movement of participation over decades leading up to today, with proposed forms of participation such as Crossbenching urging communities to challenge failed government policies (Miessen, M. (2016). To relate my research to my study question, community projects in Sheffield will be explored at the planning stage through the attendance of a community-led project meeting with Sheffield Community Land Trust. In addition to this, I will explore a recent community-led project through a case study on Division Street at the use stage, and evaluate methodologies utilised. My findings should conclude how modern methods of participation and the attempt to define ‘completeness’ can contribute to achieving inclusivity in city streets.

ACADEMIC CONTEXT

Academic context of my study includes similar studies that have been completed. Government schemes that have been created in response to the Covid-19 Pandemic effects on UK high streets, such as Build Back Better (GOV, 2021) have been challenged by Shakespeare Martineau, a UK law firm, with their report More than Stores (Martineau, S. (2023) in response. The report argues that shops are no longer a city priority, and community input is required to understand what new priorities are. One study (Hui et al., 2018) already challenges the grey area of the Complete Street concept being unclear, with the definition of ‘complete’ being unmeasurable without qualitative data. From this, I intend to explore the levels of success of recently completed community led projects, and how ‘complete’ can be defined by stakeholders closer to the heart of the city. The recent report on Crossbenching (Miessen, 2016) presents a new form of participation, thus showing that the aims of participatory methods today are unclear; I will attempt to gain an understanding of possible ways of unblurring the lines between community and architect relationships during planning stages of projects.

METHODOLOGIES

Methodologies used are a literature review, case study and questionnaire. My literature review explores the background area of urban street priorities and main sources for my study. The case study on Division Street in Sheffield has been chosen due to the location’s popularity, implying a wide range of sources being available. Furthermore, the cases study location is in Sheffield, which supports my hypothesis. The questionnaire will be inspired by any issues or questions that arise from my study.

1

INCLUSIVITY AND URBAN ARCHITECTURE

Inclusivity in cities is vital for residents to feel connected to the place they reside in, and the community they live around. Inclusivity should be accounted for during all stages of architectural works; most importantly, the planning phase. The 21st century has introduced the diminishing of inclusivity through ignorant governing policies that have been curated by distant shareholders in society who act blind to the needs of those outside of their profession. Modern barriers to inclusivity are argued as lack of leadership and awareness from policy makers, who restrict themselves to urban development that is driven solely by demand (Smith, E. (2020). For a city to be defined as inclusive, it must cater for all people regardless of personal factors; represent a mixture of communities (Planner, T. (2017).

In my literature review, I collated a range of sources to gain an understanding of how priorities of urban streets have been considered in relation to their historical context, with the belief that the most valuable priorities are the needs of the people who reside within them.

2

URBAN STREET PRIORITES

TRAFFIC 1950s-1960s

Over time, the perception city streets in the western world and how they are used by residents has evolved. During the mid-20th century, the rise of mass car ownership presented a significant change for city streets, with a seemingly beneficial means of transport due to it’s perceived efficiency. Cities in the UK that were never designed for motor transport, such as Glasgow and Birmingham, were forced to respond to traffic issues by implementing a major phase of motorway building (Gunn, S. (2011). Whilst this could be perceived as a successful method of mitigating traffic issues, opposing views argued more roads resulted in more car users (Mann, A. (2014). Similar sources agreed that fewer roads would mean fewer traffic (Gehl, J. (2010). See Figure 1 for car parks that dominate space in Sheffield City Centre today. The concept of induced demand emerged in the 1970s in response to government policies that fueled a cycle of a growth in road users (Blumgart, J. (2022). A controversial report Traffic in Towns (1963) was produced by a British architect and town planner in response to traffic issues caused by the rise in motor transport in the 1950s. Whilst the report proposed solutions for the traffic increase in cities, such as multi-level decks that provide separate routes for different modes of transport, it is argued that the agenda focuses on streets and not roads (Gunn, S. (2011). This implies that for many, the priorities of streets for the decade following post-war Britain were solely focused on making streets more accommodating for road users rather than active transport users.

B9 BUILDING ROAD CAR PARK 3

1

Figure

WHERES’S THE PEOPLE? “ ”

(Jacobs, J. (1961)

Urban planners quickly recognised that the increase in car ownership was detrimental to the future of cities: priorities of city streets started to shift from traffic, to people and safety. Danish Architect, Gehl, recognises in Cities for People (Gehl, 2010) that Jacobs was the catalyst spokeswoman that urged for change in city design. Jacobs’s ideas are widely respected by architects and city planners. She is regarded to as “the lady who saved the neighbourhood” (Saunders, D. (1997). Like the ideology of induced demand, Jacobs proposed that due to changes made by government planned development in an attempt to mitigate traffic issues, positive feedback is caused. Motor transport is described to have eroded the cities, with governing bodies producing traffic arteries such as car parks and petrol stations that accommodates traffic rather than diminish it (Jacobs, J. (1961). Jacobs presents an interesting observation, that a district should offer several functions to facilitate the use of a street at different times of the day, where occupants are there for different purposes whilst sharing common facilities (Jacobs, J. (1961). The vitality of cities were beginning to be recognised as the abundance of street life, with the need to counteract motor dominance by providing cities with streets that were protected by their user’s own eyes. Market forces made this difficult, by shifting focus onto individual buildings. Important elements such as crime and safety were considered, with a solution of buildings overlooking the streets to provide pedestrians with eyes to watch over one another (Gans, H. (1962). Rudofsky, an Austrian-American architect, explores historic means of pedestrian facilitation in cities such as floating architecture and canopied streets (Rudofsky, B (1982). Canopied streets and bridges provide pedestrians with a segregated means of access through a city which, whilst useful, could be seen as granting pedestrians with an alternative route within cities, thus withholding a post modern solution that brings communities together.

PEDESTRIAN SAFETY 1970s

4

PEOPLE 1990s NECESSARY

In later studies by social activists, planners were urged to adapt to other ways of claiming city streets back for pedestrian use. Whilst many blamed road users for the decline in street life, it is crucial to acknowledge that cities should offer choice. All users must be accommodated for, to ensure inclusivity (Jacobs, J. (1961). The human dimension was intended by Gehl as a planning framework to inject inclusivity into cities. Elements of this dimension include transport, congestion charges and urban renewal. Optional and necessary activities are perceived as a way of understanding how street users behave, and are required for street vitality (Gehl, J. (2010). Relevant to Jacob’s analysis of car parks facilitating the increase of motor use in cities, from 1962 various car parks in Copenhagen were transformed into squares to encourage optional activities. Gehl’s methods are predominantly regarding the concern for cyclists and pedestrians, with the belief that more space in cities invites more people. Thus, priorities of streets remained with people, safety, and transport for decades. (Gehl, J. (2010).

FUNCTIONAL STREET 5 Figure 2

OPTIONAL SOCIAL

COVID-19 PANDEMIC and COMMUNITY REVIVAL 2020

Rise in car ownership post-war Britain posed a significant challenge for urban planners striving to revive city streets. The Covid-19 pandemic, which resulted in a national lockdown of the UK 23rd March 2020, was arguably the next major event affecting city streets to overcome (Government, U. (2024). The national lockdown saw all non-essential shops close, leading to the shift of online retail. Furthermore, new technological ways of working such as remote and hybrid working were required for businesses to thrive through the pandemic, drawing dwellers away from city living and reducing the need for housing in cities (Martineau, S. (2023). The primary effects of the pandemic had critical secondary effects for cities: reduced levels of footfall, decline in retail shops and community interaction (Smith, A. (2023). The depletion of these components are detrimental for a city’s ability to thrive and facilitate an inclusive environment for a healthy community (Jacobs, J. (1961).

On the contrary, this accommodated urban possibilities for city planners to transform disused spaces into new innovative ideas. The UK government attempted to revive their high streets with schemes such as a new permitted development right that allows Class E structures, such as the disused spaces, to be replaced with homes. Their policy paper Build Back Better High Streets (GOV, 2021) proposes plans for government funds to be used on community renewal: predominantly focused on introducing new shops. However, it is recently argued that replacing unsuccessful shops with new shops is a short term solution (Smith, A. (2023). A study was collated by Harris Group that concluded that 72% of millennials aged 24-38 would prefer to invest in an experience rather than shopping, therefore counteracting the government’s response to the pandemic (Grimsey, B. (2020). Priorities of streets in the 21st century have evidently shifted from safety and people to reconnecting communities.

6 Figure 3

4

Figure

COMMUNITY INCLUSIVITY - TODAY

To conclude, the secondary effects of the Covid-19 pandemic has led to community engagement decline in cities. The UK government has attempted to revive high streets in the UK with the proposed solution of replenishing shops. The proposed government funding to support the scheme is argued to be unjust, since the total funding of £9.9 billion would match the cost of three King’s Cross Stations, showing that cities in the UK aren’t treated equally (Martineau, S. (2023). Current policies are curated by distant members of society in a position of political power, who cannot advocate for needs of every street in the UK with contextual sensitivity due to residing elsewhere (Zehngebot et al., 2014). I conclude that community input is required to support the design process of streets by gaining an understanding of individual street user’s needs. This leads me to ask the question “would people want to be involved?”.

MASS CAR OWNERSHIP 1960 1980 1990 2020 PRESENT COVID-19 PANDEMIC

PARTICIPATION METHODS CONSIDERED PEOPLE INCLUSIVITY OUTDOOR

FAILURES OF GOVERNMENT POLICIES INCREASE IN MOTORWAYS STREET IMPROVENT CONCEPTS DEVELOPED 7 Figure 5

TRAFFIC SAFETY

SPACES

COMPLETE STREETS CONCEPT

BACKGROUND

The Complete Streets concept is a strategy I am interested in exploring in my study, with the opinion that it was one of many catalysts for priorities of urban streets shifting from safety to community needs. A research proposal (Greenberg et al., (2003) argues that “pedestrian safety was not taken into consideration before the idea of complete streets was developed”. On the contrary, previously explored city street design activists, such as Jacobs, have shown many aspects of consideration for people’s needs which inherently involve safety that date back to the 20th century (Jacobs, J. (1961). However, the Complete Street concept focuses specifically on safety in relation to transportation modes and air quality.

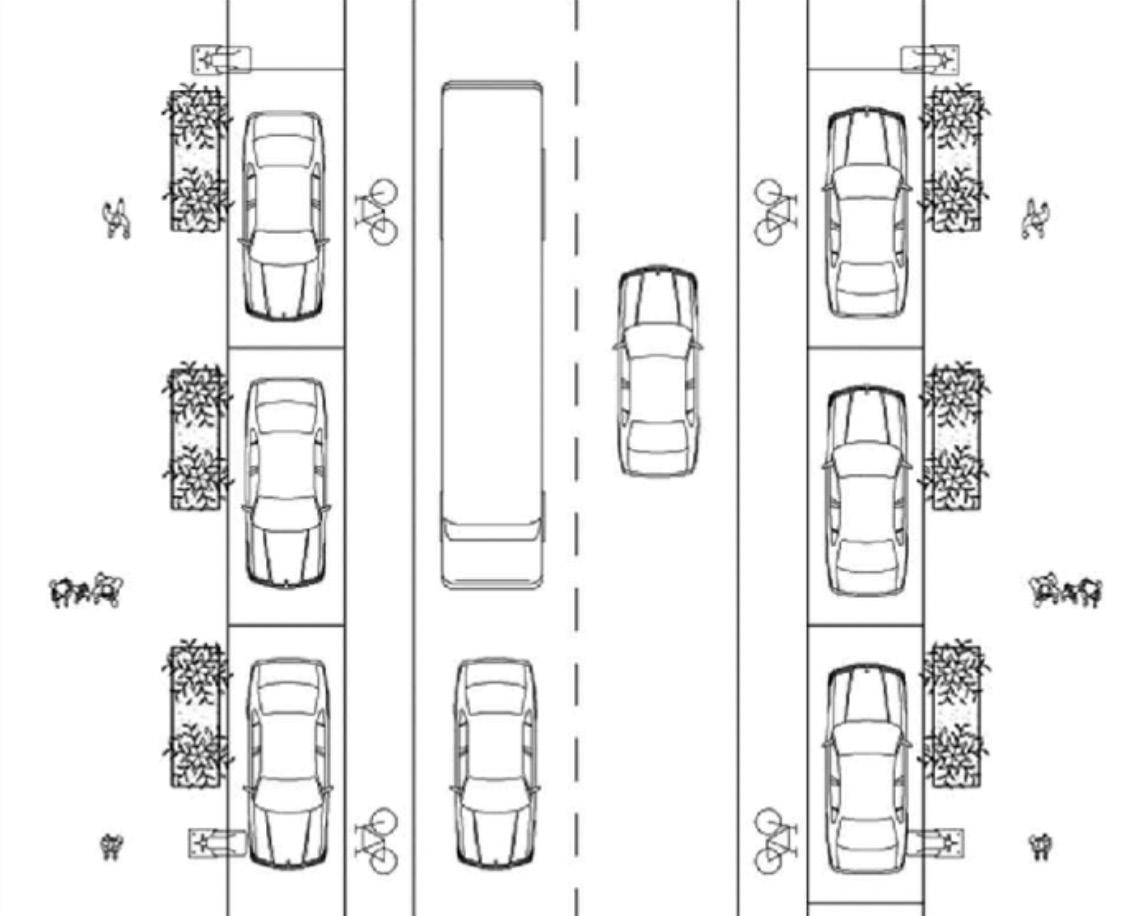

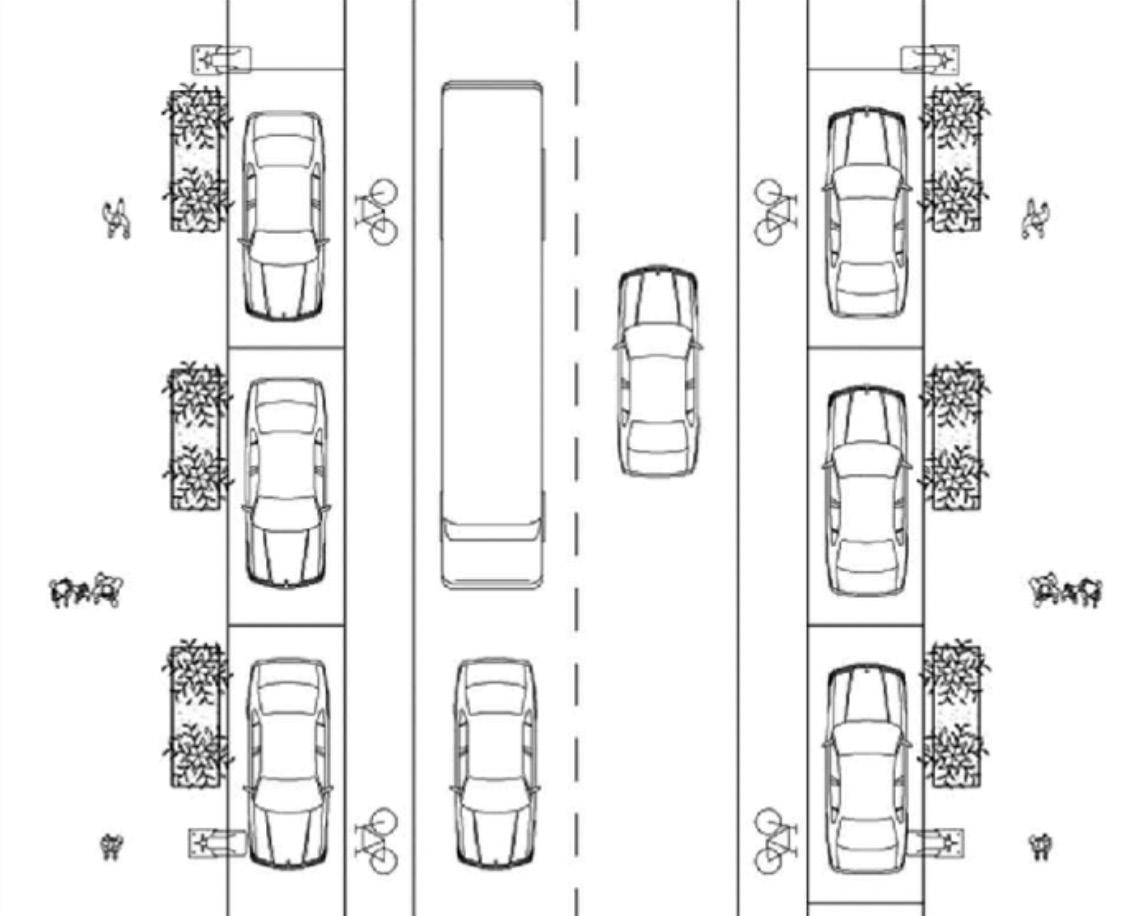

It is evident that streets in the UK are disconnected to communities. The recent American derived concept, “Complete Streets” was introduced in 2003, in response to North America’s traffic congestion issues (Calloway et al., (2020). The framework was intended on inspiring urban planners to consider certain elements of streets that can improve safety for it’s users, regardless of mode of transport (Keippel et al., (2017). Planning processes that influence the Complete Street strategy are exemplified to be age, mode of transport, and mobility (Winters et al., (2015). Active transportation modes, such as cycling and walking, are encouraged with motives to decrease road area. Thus, wider areas for active transport modes can be facilitated (Kahn, R.C, (2016).

Whilst the Complete Streets initiative portrays as a highly beneficial method of street improvement, it sparks debates on how ‘complete’ is defined, and who by. In conjunction to this, it is argued that the term ‘complete’ implies that streets would require specific characteristics, therefore not flexible in accommodating specific user’s needs (Grimsey, B. (2020). My research has so far collated that government planning does not consider the user’s needs, leading to dissatisfaction from communities and a disconnection to the city. How can governing bodies be trusted to understand what makes a street ‘complete’ if they do not reside around the user?

8

Figure 6

CONTEXT WITHIN THE UK

The UK government has recently attempted to implement a similar concept to that of Complete Streets, in the form of a policy paper: Build Back Better High Streets (GOV, D. (2021). With economical motives, the paper argues that for city streets in the UK to be revived, lost businesses must be replaced to encourage footfall in cities. Successful examples in Sheffield are voiced, such as the opening of Peace Gardens in 1938. These public space improvements were said to increase shopping visits by 35%, therefore increasing spending in the area (GOV, D. (2021).

Nevertheless, relying on historic evidence is an unreliable method of implementing change: if government’s considered community views and broadened their business orientated motives, they would realise that with the rise of online retail, shops in city centres will not encourage modern citizens to walk the streets (Smith, A. (2023). Presently, there is a greater preference for experiences that unite communities, compared to the expenditure on shop items, implying that communities may be interested in participating in community projects (Grimsey, B. (2020).

Limitations to the Complete Street concept are not directly related to the elements considered for safer streets, but for the lack of consideration for specific user needs, and the clarity around the phrase ‘complete’. One study (Winters et al., 2015) infers that street improvement initiatives will vary depending on specific community wants. Similarly, (Hui et al., 2018) urges for contextual sensitivity to be considered when designing a street.

To conclude, if urban planners consider using an open strategy when measuring completeness of a street, in comparison to abiding by government policies and therefore avoiding the opportunity of change, urban street renewal could go beyond the creation of safer spaces (Grimsey, B. (2020). Participation may be the answer to an open strategy.

9

Figure 7

PARTICIPATORY ARCHITECTURE

INTRODUCTION OF PARTICIPATION

The late 20th century saw the pivotal moment for architects to utilise participatory processes during the design stages of architectural works, in line with community based design movements in response to urban planning showing little regard for community needs (Blundell-Jones et al., 2005). Whilst the works of Jacobs date back to the 1950s that urge for community input, the community led design movement spread across nations decades later (Blundell-Jones et al., (2005).

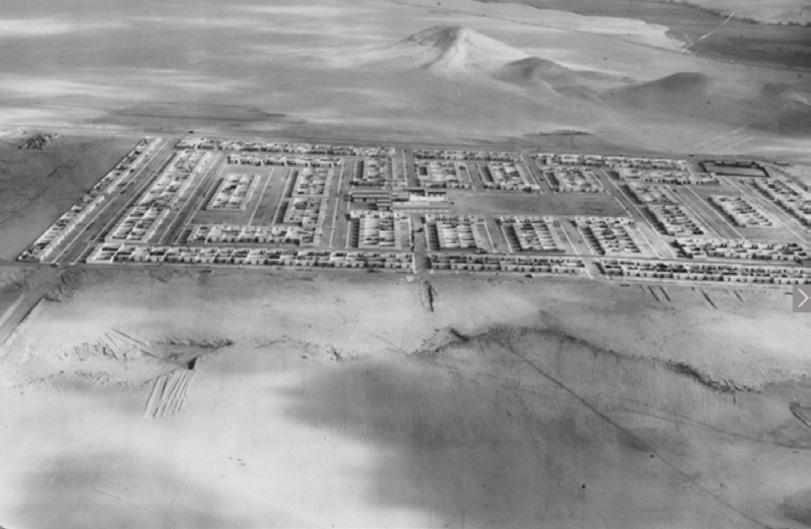

American architect, John F Turner, introduced a framework for architects to widen their resources for urban planning by involving the community in design processes and providing them with opportunities to be artistic (Turner, J.F. (1972). Turner worked on many community projects, one being the development of self-help housing in Peru; The Lima Project. This project was in response to the housing crisis that struck Peru in the 1950s, where the government failed Lima residents by attempting to supply the demand of housing however proving inadequate for low income families (Harris, R. (2003). Methods of community inclusivity were utilised by Turner such as workshops, meetings with residents, education on construction processes and formations of a community committee (Turner, J. F. (1972). Within his research, Miessen (2016) argues that participation facilitates the “withdrawal” of politicians taking responsibility of urban issues that city user’s rely on them to resolve, however Turner’s methodologies for bringing communities together created a sense of ownership within the community, which is recently recognised as an innovative method of achieving inclusivity within urban spaces within the 21st century (Grimsey, B. (2020).

WORKSHOPS COMMUNITY MEETING EDUCATION COMMUNITY COMMITTEE

10

Figure 8

Figure 9

POLITICAL MOVEMENT

Turner’s response to government failures is an example of a catalyst for future urban planners to recognise that architectural planning and politics correlate. It is evident that relying on governing bodies to tackle urban issues is detrimental to the vitality and inclusivity of cities, with their prominent priority being economic gain; not street user’s needs (Miessen, M. (2016). Communities have become disconnected from their cities, and public participation facilitates the outcome of architectural works to remain permanently open. The quality of planning can be defined by designers to understand the difference between “planning for and planning with users” (Blundell-Jones et al., (2005).

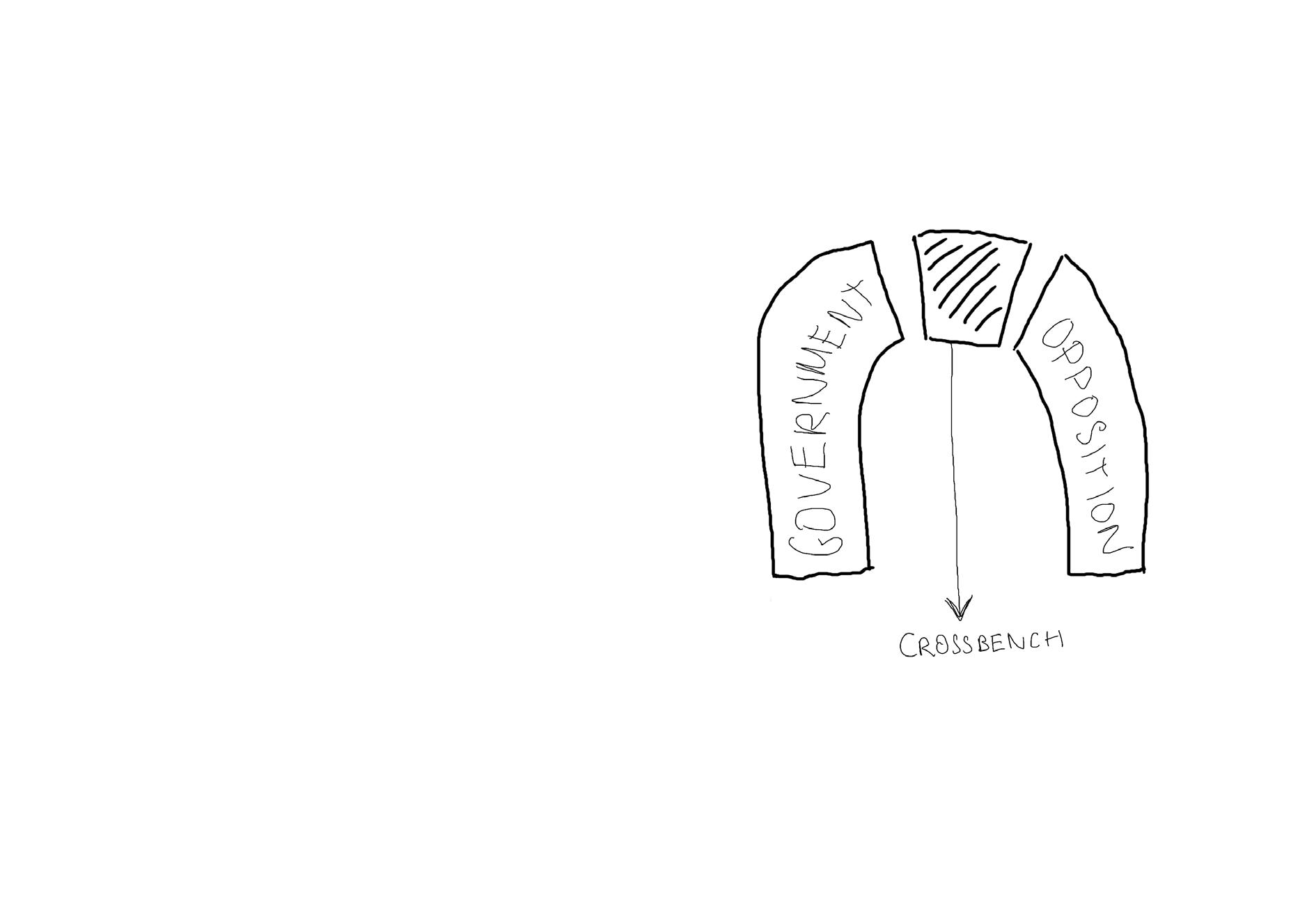

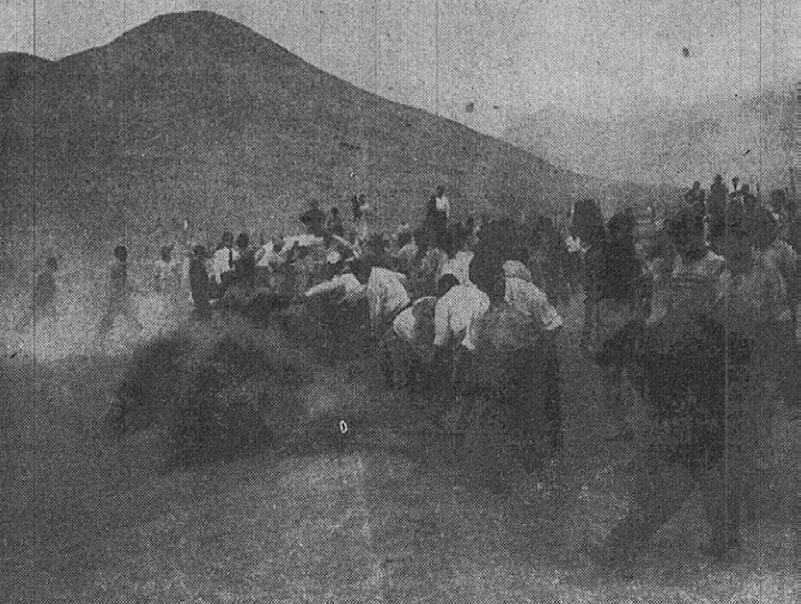

CONFLICTUAL PARTICIPATION

Miessen’s work prominently highlights the urge for communities to challenge government policies (Miessen, M. (2016). Critical spatial practice is seen as a political movement within architecture; a constant war between architects and the government. Developers and businessmen have become more prominent in planning and economic processes within cities, who are driven by representative architecture and restrictive regulations.(Grimsey, B. (2020). Miessen supports the idea of participation, however argues that the definition of participation is an issue in itself. In my opinion, participation is working together with others to come to a solution. In his research, Miessen (2016) exemplifies a definition as “sharing something in common with others”. An alternative outlook, conflictual participation, is proposed: collaboration between the architect and community member should spark debate, maximise friction that reflect true user’s opinions and complicate design process stages (Miessen, M. (2016). Crossbenching is proposed as a new form of participation, with the idea of attempting to engage people that desire change over following governing policies (Sterling, B. (2010).

MARCUS MIESSEN

11

Figure 10

Figure 11

ISSUES WITH PARTICIPATION

Architects may perceive participation as a potential threat, presenting a barrier they must overcome. Participation expands the opportunity for residents to share their desires and exposes architects to issues that they may have preferred to delay solving (Blundell-Jones et al., (2005). Architects must overcome this outlook by understanding that whilst their design role is vital, implementation of communication between themselves and any nonexpert in the field will benefit both parties (Blundell-Jones et al., (2005).

A secondary barrier relating to community members, is that members of society that show interest in change may lack relevant skills and knowledge on issues surrounding city streets, hindering their ability to provide quality input that would be effective in improving street designs. For community needs to be considered at planning level, planners should educate residents on community development (Kennedy, M. (1997). It is argued that community involvement is essential for the improvement of city life, but current guidance on methods of achieving these aims are minimal (Blundell-Jones et al., (2005).

To conclude, methods of participation must be continually explored by architects to gain understanding on effectiveness and areas to improve. Furthermore, architects need to use participation to understand what level of input stakeholders should be based at.

12

SHEFFIELD COMMUNITY LAND TRUST MEETING 2024

COMMUNITY-LED PROJECT AT PLANNING STAGE

To support my research study, on 3rd January 2024 I attended a 2 hour meeting with Sheffield Community Land Trust (SCLT): an non-profit organisation that advocate for affordable housing through community projects. The meeting was arranged to recruit community members for participation in upcoming projects, facilitate an open dialogue regarding brownfield areas in Sheffield, and discuss any opportunities that they could present. There was an option to pay £2 for a membership, which was an easy exchange of interest from community members to the trust that allows members to vote on key decisions in upcoming projects. The meeting was held as Union St Café, which is managed by a community interest company whose profits go towards amenities that Sheffield city needs (Street, U. (2024).

METHODOLIGIES

I had a predominantly positive experience during the meeting. I was approached by various volunteers from the trust, who asked questions, allowed me to feedback and be curious in exchange. To challenge ideologies related to my findings on Miessen (2016) on how to involve the wider community and cause friction, I asked “what do members of interest achieve from participating?”. Their response was that members of interest gain a sense of ownership, and a feeling of being heard. Relating to statements from a study (Miessen, 2016) the organisation being non-profit requires the community to be actively engaged and encouraged to share their needs, which should be socially beneficial, rather than facilitating government methods for economic gain.

Pin boards were used to display brownfield areas of interest to SCLT, with sticky notes provided to encourage comments and queries to be shared by meeting attenders. The option of these brownfield areas were made possible by the SCLT being granted funding from the South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority (Community, L.T, S. (2023).

PROCESS OUNDS EOPLE LACES

13

MEMBER GROUPS AND LIMITATIONS

The main aim of the meeting was to recruit members for specified member groups: people, process, pounds, places. Each member group has a different role; volunteers of SCLT guided interested members to the group that would match their existing skillset. I see this as a participatory method of creating a community committee for decision making (Miessen, M. (2016). The choice of plosive consonance placement combined with alliteration strikes the reader’s attention through an plosive ‘P’ sound being used for the member group names. See Figure 12 for tasks required by each group, taken from notes made during the meeting I attended.

Whilst various stakeholders within the community attended, I found that a limitation to the SCLT’s methodologies was that it didn’t engage the wider community. Their recruitment interests were limited to designers and experienced persons in the field, therefore project outputs may not necessarily reflect a true representation of Sheffield’s wider community needs, thus restricting inclusivity. This is a difficult topic to overcome, as it is not yet clear how to spark interest in members outside of traditional norms, and may require support and coverage from council members who have a public platform for facilitating change and education.

14

Figure 12

CASE STUDY / DIVISION STREET, SHEFFIELD 2019

COMMUNITY-LED PROJECT AT PLANNING AND USE STAGE

To support my research, I am exploring a case study of a community-led project to help my understanding of modern participation by providing an example of how a community project can be implemented, which methods are used, and gaining feedback on the outcome. Community feedback is a vital step in community led projects to understand if levels of desired inclusivity have been met and provide community members with a final step in the process (ClementsCroome, D. (2019). My chosen case study is a local community project on Division Street in Sheffield. 2019 saw the start of Division Street’s pedestrianisation, to prioritise pedestrians and cyclists. Division street is one of the busiest areas in Sheffield City Centre, and therefore is a good choice of street to study (FinneganSmith, T. (2023). In their trial, CycleSheffield reflect the ideologies of creating conflict with Sheffield City Council, their local authority, to gather community input and feedback on the needs for change in the city (Miessen, M. (2016).

TRIAL CLOSURE 19TH-2OTH OCTOBER

In conjunction with the newly introduced Sheffield Transport Strategy, a trial pedestrianisation assessment was carried out by CycleSheffield to consider how a car free space would work and facilitate community input from businesses, residents and visitors (Johnstone, D. (2019). Motor vehicles were prohibited between Westfield Terrace to Trafalgar Road, to provide a section of Division Street with pedestrian and cycle access only. Positive results from the trial closure led to a public consultation urging the council to implement a daytime pedestrianised area that covers Division Street and Devonshire Street to a maximal amount possible (Finnegan-Smith, T. (2023).

As the Covid-19 Pandemic arrived, the demand for open space and wider pavements in cities were dominant. For social distancing measures to be followed, people would be forced to walk on the road, thus creating a conflict between motor vehicles and pedestrians. Conveniently, the trial closure was admired by local authorities, granting a Temporary Traffic Regulation Order on Division Street that supported reintroduction of pedestrianisation to resolve these conflicts in August 2020 (Johnstone, D. (2019).

The changes were extended in January 2022, with an Experimental Traffic Order (ETO), which enabled the public to feedback on the outcome of the scheme. Feedback was mandatory for the ETO to be made permanent, as the council must consider any objections to the scheme prior to authorising change (Finnegan-Smith, T. (2023).

By June 2023, the ETO scheme was huge success, with mostly positive responses through a local letter drop supporting the council’s decision to permanently prohibit motor transport on a section of Division Street (Information Centre, S. (2023). This proves that challenging government policies as a community can lead to permanent change.

15

13

Figure

METHODOLOGIES

SOCIAL MEDIA

Online platforms allow users to share their opinions through written communication. Prior to implementation of the trial closure, a GIF was shared to Twitter by interaction designer, Sam Wakeling (Wakeling, S. (2019). See Figure14 which presents possibilities of future street improvements.

This is way of reaching widespread audiences efficiently, and helping users to feel comfortable expressing their needs who may not otherwise do so in verbal communication. On the contrary, it poses threats such as inaccurate proposals being displayed which may not be reflected in the final product. Furthermore, due to the rise in social media use in the last decade, it is difficult to distinguish reliability of posts online, therefore providing minimal reassurance to community members on whether post interaction would be beneficial to them.

SOCIAL MEDIA

PUBLIC CONSULTATION

FEEDBACK

Feedback received was mostly positive, thus showing that the scheme was successful, such as “this should happen more often” (Johnstone, D. (2023).

Whilst many of the responses were predominantly of a similar nature, conflicting issues were raised by others such as the negative economic impact the closure could have on businesses due to lack of parking (Johnstone, D. (2019). Similar feedback was given in response to a prototype methodology used to showcase a better street design in Rotterdam, stating that drivers were reluctant to want to give up their road space (TEDxTALKS, (2015). Previously discussed, it is vital to educate community members on the benefits of active transport to eradicate selfish views (Kennedy, M. (1997). In despite of this, conflict between the client and designer should be seen as a step in the right direction to achieve true inclusivity as conflict creates spatial opportunities and allows the community to set boundaries (Miessen, M. (2016). This is a process that architects and designers must put their problem-solving skills towards to achieve inclusivity in streets.

To conclude, the permanent pedestrianisation of a section of Division Street exemplifies the power that communities can have in achieving inclusivity on city streets by challenging local authorities. Practising community-led processes allows designers to constantly improve through feedback and analysis of results.

16

LOCAL LETTER DROP FOR ETO

Figure 14

Sheffield Transport Strategy 19th-20th OCtober 2019 May 2020 Augsut 2020 January 2022 June 2023 Trial Closure Temporary Projects Fund Temporary Traffic Regulation Order PERMANEMT

ZONE Experimental Traffic Order Sheffield City Council urged to implement pedestrian area on Division street Temporary changes sustained Feedback encouraged through local letter drop 17 Figure 15

TIMELINE OF DIVISION STREET PEDESTRIANISIATION (Finnegan-Smith, T. (2023)

PEDESTRIAN

QUESTIONNAIRE

I conducted a questionnaire aimed at residents in Sheffield relating to use of and opinions on Division Street, levels of interest in expression of city street needs, and open dialogue for respondents’ ideas for change. Furthermore, the aims of my questionnaire were inspired by areas that arose from my study. 34 respondents took part, with Figure 16 showing age group and gender of respondents.

RESULTS

Firstly, I gave respondents the opportunity to be open with their expression of needs (Blundell-Jones et al., (2005). I did this by utilising a qualitative question “Is there anything you would change about streets in your central Sheffield area?” followed by “if you answered yes, what would you change?”. This shows contextual sensitivity to a city street user’s needs. (Zehngebot et al., (2014). From the results, I have produced a visual representation of what a city street could look like based on responses.

The Street Designed by Sheffield Users in Figure 18 could exemplify a way for planning proposals to be presented, in comparison with Wakeling’s Twitter post that was designed by planners (Wakeling, S. (2019). The methodology of social media by Wakeling was a way of allowing expression of community member needs who may not want to verbally communicate said needs. 20.6% of respondents answered no to feeling comfortable expressing their needs for a street in Sheffield. This supports the idea that whilst participation is voluntary, support and alternative upcoming platforms such as social media may be required for wider input.

Secondly, respondents were asked if they would be interested in helping with the design of their city streets, with 92% of respondents within the 18-25 age group answering yes. This could be argued as a need for change within current design processes, since young people are rarely included in them (Grimsey, B. (2020). One respondent within the 18-25 age group answered no because “other people could think of smarter ways to design them”. This shows that community members could benefit from education on the benefits of community input, to make their views feel valued (Kennedy, M. (1997).

Age Group Number of Participants 18-25 25 26-45 5 46-49 2 60+ 2 Male Female 5 29 18

16

Figure

Figure 17

Thirdly, respondents were asked if there are any community events that Division Street could benefit from hosting. 77% of answers from respondents within the 18-25 age group were experience based, in comparison to shopping. These results are similar to the study by Harris Group mentioned in an article (Grimsey, 2020) showing that 72% of millennials within the 24-38 age group would prefer to spend money on an experience rather than shopping. Thus, further proving that the governments response to the pandemic was not considerate of user’s needs (GOV, D. (2020).

LIMITATIONS

One limitation to my methodology is that it participation could only be completed via an online link, possibly excluding non technological device users and wider community of Sheffield. A way to overcome this could have been to offer paper questionnaires to people face to face in the City Centre.

A second limitation is that qualitative questions rely on openly answered feedback. Not all feedback is reliable, as some respondents may be reluctant to sensitive topics, or drive the outcome of the questionnaire in their favour. To overcome this, I reassured participants in my participation form that all answers are data protected and anonymous.

A third limitation, which has been shown in questionnaire results, is the ignoring of questions. This could be due to questions being unclear, or too difficult for respondents to understand. With some questions in my questionnaire being ignored, I could have avoided this by narrowing down the questions.

19

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, participation is vital for communities to be revived after the social effects in cities that the Covid-19 pandemic caused. Participation enables a positive conflictual relationship between the architect and street user. However, my research has shown that the aims and efficient methods of participatory work are yet to be solidified. Consistent participatory processes with feedback from all parties with open communication can assist us and communities to solve this issue of the unknown, which can cause frustrations tempt architects to shy away from any possible threats of unwanted issues to solve. Whilst the Complete Street concept lacks the ability to show consideration for individual user’s needs, it has sparked my interest in finding ways to measure and define completeness with contextual sensitivity and qualitative data. Furthermore, a step in the right direction could be to combine Miessen’s conflictual participatory methods to challenge eachother, with community-led projects such as Division Street that proved permanent change can be implemented with public action, whilst considering the idea of making streets “complete” for users.

Ways of engaging the wider community are still required, with current community participatory projects presenting the desire for experts in the field. This must be actioned to widen satisfaction gained by community members from design processes in cities, with a positive outlook on participation and the exchange of knowledge and skills to better cities for all.

20

APPENDIX A

INFORMATION SHEET

Participant Information Sheet for questionnaire

1. How can participatory architecture contribute to creating more inclusive and ‘complete’ streets in Sheffield for residents and stakeholders?

Legal basis for research for studies

The University undertakes research as part of its function for the community under its legal status. Data protection allows us to use personal data for research with appropriate safeguards in place under the legal basis of public tasks that are in the public interest. A full statement of your rights can be found at : www.shu.ac.uk/about-this-website/privacypolicy/privacy-notices/privacy-notice-for-research However, all University research is reviewed to ensure that participants are treated appropriately and their rights respected. This study was approved by UREC with Converis number ERxxxxxxx. Further information at: www.shu.ac.uk/research/excellence/ethics-and-integrity

2. Opening statement: Please will you take part in my study about streets in Sheffield? This is because in order to answer my question on how participatory architecture (community involvement) can support my study, answers to my questionnaire are needed to gather data on public opinion.

3. Why have you asked me to take part? You have been asked to take part as you have been interacting with a chosen area in Sheffield for my study in the period that I had chosen to complete my questionnaire.

4. Do I have to take part? It is up to you to decide if you want to take part. A copy of the information provided here is yours to keep , along with the consent form if you do decide to take part. You can still decide to withdraw at any time without giving a reason , or you can decide not to answer a particular question.

5. What will I be required to do? You will be asked several questions regarding your interactions on the street that you have been approached on. Most questions will be multiple choice, with a few others asking for your opinion.

6. Where will this take place? This questionnaire will take place online via scanning a QR code or link using a device such as phone or computer.

7. How often will I have to take part, and for how long? The questionnaire should only take approximately 5 -10 minutes. Once the questionnaire is completed you will not have to take part again.

8. If deception is involved in the study No deception is involved in the study.

9. Are there any possible risks or disadvantages in taking part. There are no possible risks or disadvantages in taking part.

10. What are the possible benefits of taking part? Thinking about how you interact with this space in Sheffield and experiencing the feeling of community involvement in the design process of a space you use.

11. When will I have the opportunity to discuss my participation? You will have the opportunity at the end of the questionnaire to feedback on your experience of participating.

Participant Information Sheet 1 V1

21

APPENDIX B - Questionnaire Results

Timestamp What is your age? What is your gender? On average how many days a week do you visit Sheffield City Centre? If you answered never, please explain why below Division Street in Sheffield City Centre was recently pedestrianised, meaning cars are prohibited to drive through a certain section. Do you ever visit or pass through Division Street? If you answer was rarely, sometimes or often, what reason would you visit or pass through Division Street? Are there any community events in Sheffield that you think Division Street could benefit from hosting, and if so, what? If you could describe Division Street in three words what would they be? Would you be interested in helping with the design of your city streets? If you answered no, why? Would you feel comfortable expressing your needs for a street in your city? Which central area of Sheffield do you live in? Is there anything you would change If 24/03/2024 19:27:42 18-25 Female 7 Sometimes Recreational Food festival Developing Yes Yes Broomhall Yes need 24/03/2024 19:33:40 18-25 Female 3-5 Sometimes Recreational Active Unique Social Yes No moor street No 24/03/2024 19:45:13 18-25 Female 7 Often Recreational, Cycle Walk-RouteWeekend market Potential, bustling, cool. Yes Yes Highfield Yes Investment 24/03/2024 19:48:54 18-25 Female Never Unless I’m travelling through, or getting train don’t really have a reason to do so Never maybe a charity fundraiser Similar, safe, social Yes Yes Ecclesall No 24/03/2024 19:54:34 18-25 Female 1 Sometimes Recreational, Cycle WalkNotRoutesure Busy, vibrant, unique Yes No Ecclesall No 24/03/2024 19:57:07 18-25 Female 1 Rarely Recreational Ruff Yes Yes Yes Be 24/03/2024 20:01:20 18-25 Female 1 Often Recreational Yes Yes Ecclesall No 24/03/2024 20:01:44 18-25 Male 1 Sometimes Recreational No Yes Ecclesall No 24/03/2024 20:05:32 18-25 Male 3-5 Rarely Recreational No Other people could think of smarter ways to design them No Attercliffe No 24/03/2024 20:10:18 18-25 Female 3-5 Often Recreational, Cycle WalkNotRoutethat can think of Uninviting, boring, inconvenient Yes Yes Sharrow Yes You 24/03/2024 20:14:29 18-25 Male 3-5 Often Recreational Good places for pints Yes Yes Ecclesall Yes Greggs 24/03/2024 20:15:50 18-25 Female 1 Sometimes Recreational Could set up a street food market with all the local independent small businesses - similar to Rex market in Kelham Island Independent, Diverse and Social Yes Yes Kelham Yes think 24/03/2024 20:18:29 18-25 Female 1 Sometimes Recreational Charity shop market / Local Bars opening Cool trendy / Yes Yes Ecclesall Yes Cleaning 24/03/2024 20:20:30 18-25 Female 3-5 Sometimes Recreational, Before or after university sometimes Markets or a parade or independent Sheffield seller Vintage. Trendy. Sociable Yes Yes Ecclesall Yes would 24/03/2024 20:21:07 18-25 Female 3-5 Sometimes Recreational Maybe a street party or markets for summertime Vintage, quaint and trendyYes No Ecclesall Yes Add 24/03/2024 20:57:14 18-25 Female 3-5 Often Recreational Safe, busy, nice Yes Yes Ecclesall Yes Have 24/03/2024 21:40:02 18-25 Female 1 Often Recreational Beer festivals Indi, vibey, students Yes Yes Highfield Yes Fill 24/03/2024 21:47:53 18-25 Female 3-5 Often Recreational Food markets, outdoor thrift/vintage markets Edgy, buzzing, people focused Yes Yes Ecclesall Yes Making 24/03/2024 21:51:09 18-25 Female 1 Rarely Recreational Food stalls or vintage markets Lively, student focused, has everything u want on it Yes Yes Ecclesall Yes Lack 24/03/2024 21:58:29 18-25 Female 3-5 Sometimes Work Street markets Varied inclusive and friendlyYes Yes Heart of the City Yes Street 24/03/2024 23:18:45 18-25 Female 3-5 Sometimes Recreational, Cycle Walk Route Popular, eclectic, cosmopolitan Yes Yes Heart of the City No 25/03/2024 07:33:14 18-25 Male 3-5 You’ve not put a 2 day a week answer ya silly Sometimes Cycle Walk Route Music events Beer Yes Yes Broomhall Yes More 25/03/2024 09:37:19 18-25 Female 3-5 Sometimes Recreational, Cycle Walk Route convenient, accessible, quirky Yes Yes Ecclesall Yes Pedestrianise 25/03/2024 16:07:11 18-25 Female 3-5 Sometimes Recreational Yes Yes Ecclesall No 26/03/2024 11:42:41 18-25 Female 3-5 Often Recreational, Work Vibrant, loud, whimsical Yes Yes Ecclesall No 24/03/2024 19:36:38 26-45 Male 1 Sometimes Recreational Beer festivals Hip, Diverse and Fun Yes No Devonshire Yes Make 24/03/2024 20:02:29 26-45 Female 3-5 Often Recreational, Work A local market, division Street is full of independent businesses, and as it is already pedestrianised it would be a good place for a local independent/craft market Independent, local, interesting Yes Yes Manor Top Yes Easier 25/03/2024 17:52:33 26-45 Female 3-5 Rarely Cycle Walk Route Job fairs Good accessible clean Yes Yes Gleedless No 25/03/2024 17:58:06 26-45 Female 3-5 Sometimes Recreational, Work, Cycle Walk Route Walkable, alive, hub Yes Yes Heart of the City No 25/03/2024 21:45:26 26-45 Female 1 Never No No Woodseats No 25/03/2024 17:43:14 46-59 Female 3-5 Sometimes Recreational Maybe a food event in the summer Quirky unique vintage Yes Yes Gleadless No 26/03/2024 21:23:58 46-59 Female 1 Sometimes Work None Upbeat, busy, Student basedYes No No 25/03/2024 22:36:58

Female

Often

Walk Route

Make

25/03/2024 22:41:06 60+ Female

Recreational

22

60+

1

Cycle

A street market.like nether edge market or sharrow vale areas of sheffield type market in the street and local artist, artisan market .food markets local produce. For all the family to go too ,not just burger van type food.. Family activities on devonshire green would be good which is all part of division street. Popular, trendy,ageless. Yes Yes S12.not central. Yes Make

Take

3-5 Rarely

Quirky, cosmopolitan, livelyNo Maybe if I was younger would take a bigger interest. Yes Western Park Yes find

REFERENCES

BBC. (2014, February 3). Crossbench peers and their influence. BBC Democracy Live. https://www.bbc. co.uk/democracylive/26020448 Blumgart, J. (2022, March 8). Why the concept of induced demand is a hard sell. Governing. https://www.governing.com/now/why-the-concept-of-induced-demand-is-a-hard-sell

Bromley, R. (2003). Peru 1957–1977: How time and place influenced John Turner’s ideas on housing policy. Habitat International, 27(2), 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-3975(02)00049-8

Buchanan, C., & Crowther, G. (1963). Traffic in towns : a study of the long term problems of traffic in urban areas. H.M.S.O.

Calloway, D. M., & Faghri, A. (2020). Complete Streets and Implementation in Small Towns. Current Urban Studies, 08(03), 484–508. https://doi.org/10.4236/cus.2020.83027

Car Free, A. (2017). Typical complete street layout. Researcah Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Typical-complete-street-layout-that-include-provisions-for-public-transportation_fig2_329967422

City Council, S. (2019, March). Transport strategy, March 2019. Transport Strategy. https://www.sheffield.gov. uk/sites/default/files/docs/travel-and-transport/transport strategy/Sheffield Transport Strategy (March 2019) web version.pdf]

Clements-Croome, D. (2019). The role of feedback in building design 1980–2018 and onwards. Building Services Engineering Research and Technology, 40(1), 5-12.

Community Land Trust, S. (2023, July 20). Funding! Sheffield Community Land Trust. https://sheffieldclt. uk/2023/07/20/funding/

Finnegan-Smith, T. (2023). Report to Policy Committee. Sheffield City Council. https://democracy.sheffield.gov. uk/documents/s60274/Division%20Street%20ETRO%20objection%20report%20V5.pdf

Gans, H. (1962, February 1). The Death & Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs. Commentary Magazine. https://www.commentary.org/articles/herbert-gans/the-death-life-of-great-american-cities-by-janejacobs/#:~:text=Anyone%20who%20has%20ever%20wandered

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for people. Island Press.

Grimsey, B., Trevalyn, R., Perrior, K., Hood, N., & Sadek, J. (2020, June). Build Back Better: COVID-19 Supplement for Town Centres. Vanishing High Stret. http://www.vanishinghighstreet.com/wp-content/ uploads/2020/06/Grimsey-Covid-19-Supplement-June-2020.pdf

GOV, D. for L. U., Housing &. Communities. (2021, July 15). Build back better - gov.uk. Build Back Better High Streets. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60f935638fa8f50435634947/Build_Back_Better_ High_Streets.pdf

Government, U. (2024, January 24). The impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on crime demand and charge volumes in England and Wales. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-impact-of-covid19-lockdowns-on-crime-demand-and-charge-volumes/the-impact-of-covid-19-lockdowns-on-crime-demandand-charge-volumes-in-england-and-wales#:~:text=23%2F03%2F2020

Gregory, S. (2019, May 8). Division street redesigned: A future without traffic. Now Then Sheffield. https://nowthenmagazine.com/articles/division-street-redesigned-a-future-withouttraffic

Gregory, S. (2019, November 17). Traffic-free Division Street: Trial closure deemed “wonderful.” Now Then Sheffield. https://nowthenmagazine.com/articles/traffic-free-divisionstreet-trial-closure-deemed-wonderful

Gunn, S. (2011). The Buchanan Report, Environment and the Problem of Traffic in 1960s Britain. Twentieth Century British History, 22(4), 521–542. https://doi.org/10.1093/TCBH/ HWQ063

Harris, R. (2003). A double irony: the originality and influence of John FC Turner. Habitat International, 27(2), 245-269.

Hobbs, C. (1938). St Pauls Church Sheffield 1720 - 1938. Chrishobbs.com. https:// chrishobbs.com/sheffield/stpaulschurchsheffield.htm

Information Centre, S. (June, 2023 15) Sheffield City Council Transport, Regeneration and Climate Policy Committee 14 June 2023 [Video]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/_VIIWpso_ bw?si=XF6wFiHv94rkm0ru

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. https://www.petkovstudio.com/bg/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/The-Deathand-Life-of-Great-American-Cities_Jane-Jacobs-Complete-book.pdf

Johnstone, D. (2019, November 17). Division street and Devonshire Street pedestrianisation – cyclesheffield assessment. Cycle Sheffield. https://www.cyclesheffield.org.uk/2019/11/17/ division-street-and-devonshire-street-pedestrianisation-cyclesheffield-assessment/

Keippel, A. E., Henderson, M. A., Golbeck, A. L., Gallup, T., Duin, D. K., Hayes, S., Alexander, S., & Ciemins, E. L. (2017). Healthy by Design: Using a Gender Focus to Influence Complete Streets Policy. Women’s Health Issues, 27, S22–S28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. whi.2017.09.005

Kennedy, M. (1997). Transformative community planning: empowerment through community development. NEW SOLUTIONS: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 6(4), 93-100.

Maidment, C. (2021). Timber Beds, Protests and Publics: Conflicting Meanings of the Public Interest on Devonshire Street, Sheffield. https://doi.org/10.3828

Mann, A. (2014, June 17). What’s up with that: Building bigger roads actually makes traffic worse. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2014/06/wuwt-traffic-induced-demand/

Martineau, S., & Design, Planning and Development Consultant, M. (2023). More than stores report. Event Management. https://shma.microsoftcrmportals. com/more-than-stores/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_

23

Parkes, S., Gore, T., Weston, R., & Lawler, M. (2021). Room to Move: Impacts of roadspace reallocation.

Peirson, E. (2021, January 11). John FC Turner (1927- ). Architectural Review. https://www. architectural-review.com/essays/reputations/john-fc-turner-1927

Pere, P. P. (2017). The effect of pedestrianisation and bicycles on local business. Case studies for the Tallinn High Street Project. https://futureplaceleadership.com/wp-content/ uploads/2017/05/Tallinn-High-Street-Case-studies-Future-Place-Leadership.pdf

Planner, T. (2017, June 17). Cities for all: Why inclusivity matters to planners. The Planner. https://www.theplanner.co.uk/2017/06/14/cities-all-why-inclusivity-mattersplanners#:~:text=An%20inclusive%20place%20ensures%20that,to%2C%20and%20 their%20rights%20respected.

Richman, R. S.-C., Gareth. (2020, July 4). Incredible aerial photos capture eerily empty London on lockdown. Evening Standard. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/londonlockdown-empty-streets-photographs-birdseyeview-a4488591.html

Rudofsky, B. (1982). Streets for people: a primer for Americans (p. 351).

Saunders, D. (1997, October 11). Citizen Jane. Doug Saunders. https://www. dougsaunders.net/1997/10/jane-jacobs-interview-doug-saunders/

Smith, A. (2023, October 30). Reshaping generation – thinking “more than stores” for UK high streets. Anthropy. https://anthropy.uk/blog/anthropy-reshaping-generation-thinkingmore-than-stores-for-uk-

Smith, E. (2020, February 20). Q&A: Why we need to measure inclusion in cities. Devex. https://www.devex.com/news/q-a-why-we-need-to-measure-inclusion-in-cities-96601

Sterling, B. (2010, October 26). The Nightmare of Participation. Wired. https://www.wired. com/2010/10/the-nightmare-of-participation/

Street, U. (2024). Coworking Space Sheffield | Union St | United Kingdom. Union St. https:// www.union-st.org/

TEDxTalks (2015).

Architect’sHands:HowCanWeDesignBetterStreets|EvelinaOzola|TEDxRiga[Video]. YouTube.

Turner, J. F., & Fichter, R. (1972). Freedom to build: dweller control of the housing process. (No Title).

Wakeling, S. [@samwake]. (2019, April 30). Sheffield Folk… how do you feel about Division Street like this? [Tweet]. Twitter.

https://x.com/samwake/status/1123253619200012289?s=20

Zehngebot, C., & Peiser, R. (2014). Complete streets come of age. Planning, 80(5), 26-32.

FIGURES

Figure 1 - Mapping of Sheffield showing where car parks are integrated into the city centre (Author)

Figure 2 - Venn diagram showing how providing necessary, social and optional activities, ensures a street is functioning (Gehl, J. (2010).

Figure 3 - Satellite image of London during national lockdown (Richman, R. (2020)

Figure 4 - Satellite image of empty park during national lockdown (Richman, R. (2020)

Figure 5 - Timeline showing priorities of urban streets have changed since post-war Britain (Author)

Figure 6 - Plan of typical complete street proposal (Car Free, A. (2017)

Figure 7 - Peace Gardens, Sheffield, in 1938 after demolition (Hobbs, C. (1938)

Figure 8 - Image of community led project in Peru (Peirson, E. (2021)

Figure 9 - Image of residents helping one another build self housing homes in Peru. (Peirson, E. (2021)

Figure 10 - Line drawing showing plan layout of crossbench in parliament (Author)

Figure 11 - Image of parliament (BBC, (2014)

Figure 12 - Digital scans of notes and cards retrieved from SCLT meeting (Author)

Figure 13 - Image of message on pavement of Division Street during trial closure (Gregory, S. (2019)

Figure 14 - Proposed layout of Division Street posted on twitter platform (Wakeling, S. (2019)

Figure 15 - Timeline of Division Street steps towards permanenet pedestrianisation (Author)

Figure 16 - Table with data retrieved from questionnaire, showing how many respondents are from each age group (Author)

Figure 17 - Table with data retrieved from questionnaire, showing number of female and male respondants (Author)

24