PLA Y CE ( )

RE-IMAGINING PLACE THROUGH PLAY AND STORYTELLING

Acknowledgment

Thank you to my thesis professors, Julia Kowalski-Perkins and Claudia Bernasconi for your continuous support, insightful feedback, and encouragement throughout this process.

A special thank you to my external advisor, Claire Antrassian, for your expertise and for offering a new perspective that has helped shape this work.

To my family and friends – special thanks to Bushra for your unwavering support and willingness to accompany me on endless coffee runs kept me motivated every step of the way.

Thank you all for being a large part of this journey.

Thesis Studio Advisor: Julia Kowalski-Perkins

Thesis External Advisor: Claire Anstrassian

Thesis Research Methods Advisor: Claudia Bernasconi

Thesis Studio ARCH 5100-5110

Thesis Research Methods ARCH 5200-5210

Fall 2024/Winter 2025 School of Architecture and Community Development SACD

University of Detroit Mercy

I, Danica Bogdanovic certify that I have not used Generative Al in any way to write this Thesis Book.

Follow me along through this thesis. Hi,

I'm Buddy!

Synopsis

Play is a powerful tool for shaping the built environment, fostering emotional attachment, and strengthening community connections. By examining how people develop bonds with a place and applying these insights to design, this research highlights the role of placemaking in creating spaces that cultivate belonging. Play serves as both a design tool and an engagement method, encouraging interactions that deepen attachment. Through play, designers move beyond rigid problem-solving methods, embracing iterative processes that tie together narratives, memory, and the layered histories of a place. Using participatory methods, this approach amplifies community voices to explore how play and storytelling shape perceptions of place. In doing so, it cultivates empathy, and ensures that urban spaces remain personal, adaptive, and deeply connected to the communities they serve.

Play

Play is often overlooked as an urban design tool, yet it serves as a powerful engagement method for activating spaces. Play allows for interaction between people, not only creating opportunities for social bonding but creating attachments though engagement.

Henri Lefebvre’s Production of Space offers a framework for understanding how play can be woven into the urban fabric. Lefebvre identifies three interrelated types of space, perceived space, conceived space, and lived space, all of which can be applied to activate an environment. Perceived space is the physical layout and design features of a place. The physical environment influences how people engage within space and each other. If designed for flexible and adaptive use there is opportunity for creativity, spontaneous play and interactions to occur naturally. Conceived space is the way designers and planners shape the space intentionally. By introducing elements like installations or sculptures, urban spaces become more inviting for play. Lived space is experienced by individuals as they engage with the environment. Play can become a key aspect of lived space as it creates the opportunity for personal and shared memories. As Lefebvre suggests, play engages the physical and sensory aspects of our environment, transforming space into,

interactive place. The act of playing can deepen a participant's physical relationship with the environment as it becomes an embodied experience, people create a more intimate connection to the place.

Play can also serve as a connection for building relationships and creating a sense of identity. As Rojas and Kamp (2022) notes in Dream Play Build, play fosters social interaction that builds communal bonds, transforming spaces into places of shared experience. When communities engage in playful activities together, they create new forms of social cohesion and belonging, enabling them to connect not just with one another but the place itself. In this context, play can be a form of narrative placemaking, where the stories people create through interaction contribute to its identity. By integrating storytelling into public space, people can engage not only with the physical environment but with its history and memories (Kerrison, 2024, pg. 10-13) this process helps create places with a strong identity and sense of belonging, as participants shape the place through their collective stories and experiences.

Despite knowing the benefits of play, it is often neglected in urban planning and overlooked in public space. The idea that

play is a luxury, something only available to those with leisure time George Bernard Shaw said, “we don't stop playing because we grow old; we grow old because we stop playing.” the Hello Lamp Post Project in Bristol, England, provides an example of how play can be integrated seamlessly into urban environments. This Project allowed people to have playful conversations with pre-existing infrastructure, such as lamp post, mailboxes and trash bins. Participants would text numbers attached to these objects, and the objects would “respond,” sparking spontaneous moments of creative interaction. This simple intervention encouraged people to explore their surroundings and create moments of connection.

The integration of play into spaces is not about recreation it is focused on the emotional connections, social bonds, and relationship with place. Play transforms passive environments into lived space where lasting attachments through interaction and engagement can be formed. This thesis explores how place attachment is shaped by how individuals experience their surroundings, and play offers a means to actively shape and reinvent these spaces.

"This space [conceived space] is the dominated — and hence passively experienced — space which the imagination seeks to change and appropriate. It overlays physical space, making symbolic use of its objects."

- The Production of Space: Lefebvre, pg 39

Play and Pause Interaction and Play

Play can change the routines of urban space, encouraging people to move differently, pause, explore, and interact in new ways.

Play can transform planned, designed spaces by introducing elements of spontaneity and interaction, making them more dynamic and engaging.

Re-imagining Place

Play is an act of exploration and transformation, allowing people to reshape their surroundings and create new meanings within a space.

Space to Place

The Place

Placemaking Place Identity Place Attachment

The Person

Placemaking is the process of transforming a physical space into a meaningful place through community participation, cultural expression, and the integration of social and historical contexts. By emphasizing collaboration and local identity, placemaking empowers people to shape their public spaces in ways that reflect their collective needs and aspirations. It is not about designing spaces for people but with people to allow for a sense of connection between people and the places they inhabit. When individuals engage in the placemaking process they begin to see themselves reflected in their surroundings. This transformation marks the shift from space as a neutral setting to place as a site of meaning and belonging.

As a space takes on meaning, it contributes to an individual or community’s place identity— the way people define themselves in relation to their environment. Place identity is shaped by both personal experiences and cultural narratives, evolving over time. As people interact with and internalize aspects of their surroundings, a place becomes an extension of self-identity and a reflection of collective community values

Over time, this evolving relationship between people and place leads to place attachment—an emotional bond that ties individuals to a location. Place attachment appears from repeated interactions, sensory experiences, and shared memories within a place, deepening as both personal and

collective histories accumulate. It is not static but grows and evolves, reflecting changes in the environment and the individual. As people continue to interact with a place, this attachment creates stewardship, and long-term engagement, reinforcing the cycle of placemaking as individuals and communities continue to shape their surroundings.

PLACEMAKING

Physical To Social Meaning

Transforming physical spaces into places of meaning through community involvement and interaction fostering a sense of ownership.

PLACE IDENTITY

Internalized Meaning

Personal experiences and cultural narratives shape how people internalize their surroundings, forming a sense of self in relation to place. As spaces gain meaning, they influence and refine this self-definition, deepening the connection between identity and environment.

PLACE ATTACHMENT

Emotional Connection

Place attachment is an evolving bond between people and place, shaped by repeated interactions, sensory experiences, and shared memories. As both personal and collective histories accumulate, this connection deepens, growing alongside environmental and individual changes.

How can interactions between people and public spaces contribute to place attachment?

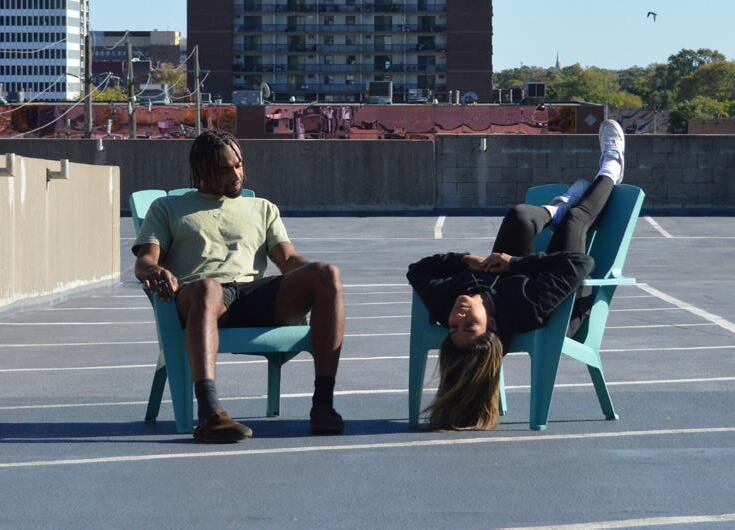

Where Would You Have a Conversation?

This study revealed the potential for overlooked and unconventional spaces to become sites of meaningful human connection. By prompting participants to consider “Where can you have a conversation?” and encouraging them to place chairs in unexpected locations, the project challenged conventional notions of public space and its uses. The results demonstrated how movement and placement in different environments can influence comfort levels, proximity, and the nature of social interactions, shedding light on the dynamic relationship between space and connection.

One key outcome was the participants’ ability to re-imagine chaotic or unstructured spaces as places for conversation, revealing the adaptability of human connection.

Method:

Co-constructed Participatory Observation

Intent:

To study unconventional or unexpected places where conversations can occur. It highlights that connection isn’t confined to traditional settings.

Despite environmental factors like noise or crowding, participants noted that the locations often sparked new topics or memories, adding depth to their interactions. The act of placing chairs in unconventional areas forced participants to reconsider their assumptions about public space, illustrating that the quality of a connection is less about the physical environment and more about the interaction itself.

Participants remarked that revisiting these sites would likely evoke memories of the conversations they had, suggesting that attachment to a space can be built through shared experiences. This underscores the idea that even ephemeral or spontaneous uses of space can leave lasting impressions, fostering emotional connections to place.

Ultimately, this exploration challenged the traditional definition of public space, showing that connection is not confined to predefined settings like parks or cafes. Instead, public space becomes defined by its capacity to foster interaction and connection, regardless of its physical attributes.

By studying these interactions, the project highlighted the transformative potential of noticing and re imagining spaces, contributing to a broader understanding of how creative placemaking can inspire emotional attachment and redefine our relationships with the built environment.

How do the memories embedded in a place shape emotional connections and strengthen place attachment?

Study Narratives of Detroit

To explore the relationship between personal memory and collective narrative, stories from Detroit residents were gathered, revealing personal connections to the city’s places. These narratives were paired with photographs and quotes to create a visual and textual representation of how individuals’ recollections contribute to the narrative. The layering of media symbolizes the intersection of personal and communal experiences, emphasizing how these connections form a mosaic of spirit, belonging and identity. This approach frames the shared impact of place on both individuals and communities.

The process of making the installation became a form of research that involved collecting, analyzing and visually interpreting the personal stories and memories shared by Detroit residents. By creating posters that combined narratives and photography, it engaged a qualitative exploration of the interconnection between memory and place. Layering the media to represent these stories offered insights into the significance of places, recognizing patterns, themes, and contrasts within individual and collective experiences. This process of storytelling and documentation not only communicated an aspect of Detroit’s narrative but also provided insight into how a personal memory can evolve into shared narratives.

full of murals, reflecting the resilience of the community. This duality demonstrates how memories transform the feeling of a location over time. Similarly, stories surrounding the Russell Industrial Center revealed its contrasting identities. Some describe it as a thriving creative hub for artists, while others saw it as an underutilized industrial space, marked by its gritty, unpolished character. These contrasts exemplify how a single place can embody both opportunity and neglect, depending on one’s perspective. These patterns show how personal experiences shape collective understandings. These findings inform the boarder thesis topic by reinforcing the importance of recognizing the emotional attachments and a sense of belonging that people form with places through the interaction of individual and shared memory. This understanding provides a framework for exploring how design and placemaking can celebrate these connections, emphasizing the role of storytelling in uncovering and amplifying the relationships between people and the spaces they inhabit.

This isn’t a place i would normally stumble into. But when you start to explore it you find a very creative artist community

The sketch problem revealed a new understanding of the connection between memory and place, emphasizing how spaces are not just physical locations but hold personal and communal stories. Narratives shared by Detroit residents highlighted themes and contrasts that illustrate how personal recollections both shape and are shaped by the significance of space. For example, the Birwood Wall stands as both a historical divider and a reclaimed place

Based on the feedback, the next steps will focus on deepening community engagement through storytelling by gathering more narratives from Detroit residents about their connections to places within the city. This expanded approach aims to capture a broader spectrum of perspectives throughout the city, gathering stories from residents across different neighborhoods to highlight the unique connections that shape each community’s relationship with place.

Playing in front of people during open mic nights is what got our name out there. Back then this place was the place to be, to see those that were holding it down

Instead of tearing it down it is now covered in murals that tell the stories of people that grew up in this community. Birwood Wall, separated Black and white residents in Detroit’s Eight Mile-Wyoming neighborhood during the 20th century.

themselves that performed there. From the outside you might have thought they were

gems within the city that mirror the

Study

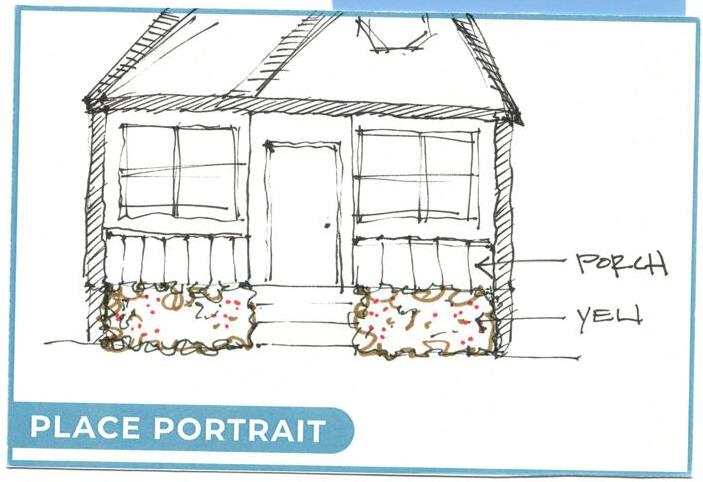

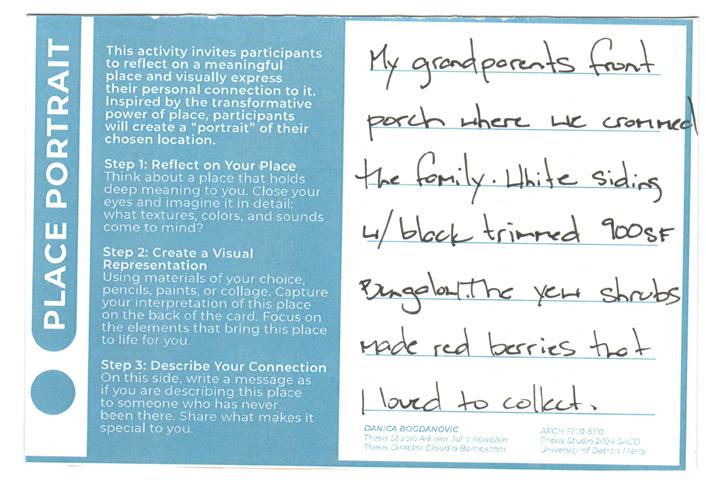

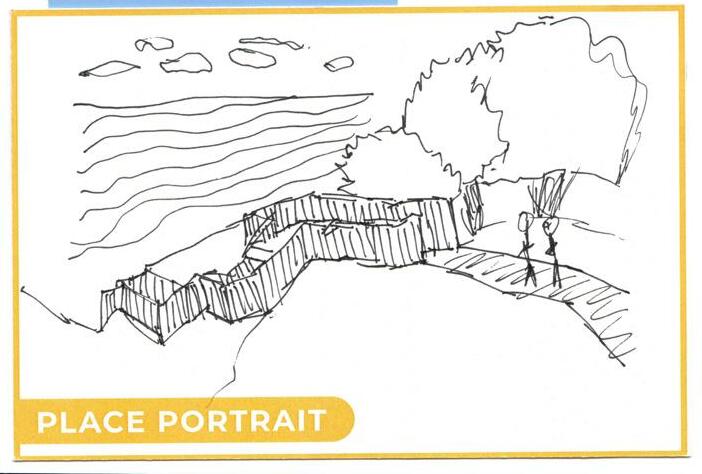

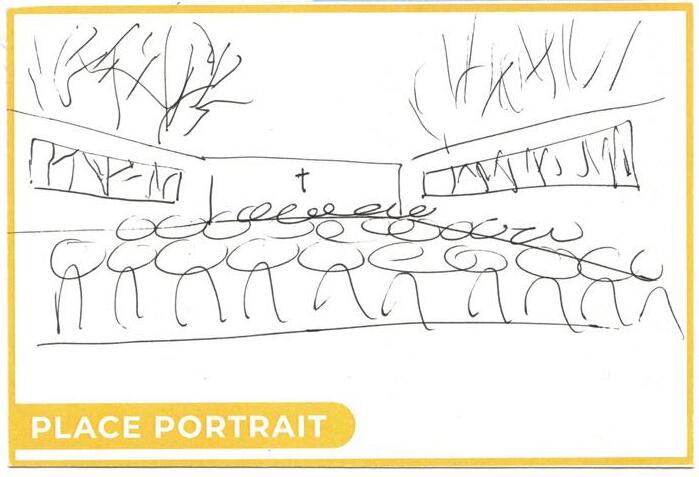

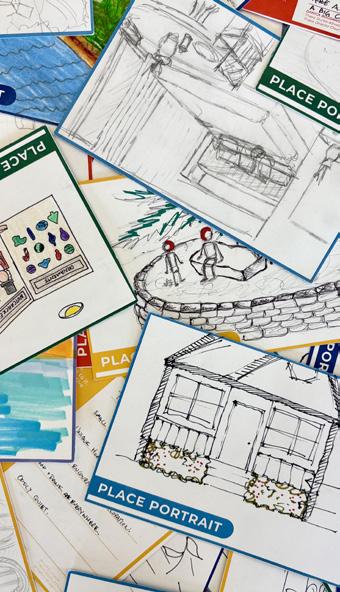

Place Portraits

Place Attachment

Person

Individual Personal connection to place (Experience, Self Definition)

Group

Shared experience of all inhabitants

Affective "Love of Place" positive or negative; an emotional bond

Process Place

Behavioral Actions to maintain historical and cultural heritage elements

Cognition Memories, Knowledge, beliefs or a sense of belonging associated with place.

Triparted Organized Framework of Place Attachment (Scannell & Gifford 2010) Re-Visualized

Social Social ties, belongingness to the place, and familiarity

Physical Specific to a built place

The intent of this study is to investigate the nuanced connections people form with specific places, using the tripartite framework of place attachment as defined by Scannell and Gifford (2010). By analyzing participants’ responses, the study aims to explore how the Person, Process, and Place dimensions of place attachment manifest in individuals’ experiences. Through this study,

it was revealed that place attachment exists in layers. It is shaped by who is attached, a group or individual (Person), why they are attached to the place (Process), and what they are attached to (Place). Together, these dimensions create a sense of connection, however the way in which these connections are created vary. Some attachments are deeply personal, tied to private spaces that

hold intimate memories, while others are collective, shaped by shared experiences in public spaces. The results from this study also brought to light that place attachment is not static but evolves over time. Repeated interactions strengthen emotional bonds, while shifts in social or physical environments can transform or dispute attachment.

Person: Individual Process: Cognition Place: Social

Person: Process: Place: Group Affective Physical

Person: Individual Process: Affective Place: Physical

Person: Group Process: Cognition Place: Social

Person: Individual Process: Affective Place: Social

Person: Individual Process: Cognition Place: Social

Person: Individual Process: Cognition Place: Social

How can play be used both as a design tool and engagement method to create connections?

How to Include

Play in the Design Process?

In design, play has been identified as a powerful tool for engaging communities, allowing individuals to express their stories and envision the places they inhabit. Building on the thesis research, this framework draws from James Rojas' Place It method and Henri Lefebvre's concepts of conceived and lived spaces. It explores how playful placemaking creates connections and actively engages individuals in designing and caring for the places within their communities. (Defined by Author)

Place Keeping

Encouraging community stewardship ensures that spaces remain dynamic, evolving to meet the needs of those who use them.

Co-Creation

Communities shape their environments by working together, fostering a sense of ownership and agency in the design process.

Imagining Our Places

Hands-on building and drawing allows people to share their visions, making the design process accessible and inclusive.

Gathering the Stories

Using play and storytelling, participants uncover core values, reconnect with meaningful places, and engage with space on an emotional level.

Multi-Sensory Engagement

Engaging touch, sound, movement, and sight deepens emotional connections and strengthens place attachment. This method can be used implemented in all engagement methods

Play in the Place

Engage with the space through spontaneous play and a child’s perspective to reveal new possibilities for connection and interaction.

The Place

Implementing Framework

The site at the viaduct and corner behind Michigan Central Station Park was chosen for its location at the intersection of multiple communities—Southwest Detroit, Hubbard Richard, and Corktown. Each neighborhood carries its own unique history, culture, and identity, contributing to the layered narrative of the area. Southwest Detroit are deeply rooted in storytelling traditions, reflected in their vibrant murals and cultural festivals that showcase the community’s pride. Corktown, Detroit’s oldest neighborhood, holds generations of memories, with residents sharing nostalgic stories of their childhoods

at Roosevelt Park and the old Tiger Stadium. Hubbard Richard, while facing challenges such as industrial encroachment from the Ambassador Bridge, remains resilient, with its tight-knit community fighting to preserve its identity. This site was selected to honor and build upon these diverse histories, creating a space that reflects and celebrates the stories and cultural identities embedded in the area.

“It isn’t just where I’m from—it’s the foundation of everything I do. From the colorful murals on local viaducts to the mom-and-pop shops that thrive against all odds, this community taught me lessons that shape how I approach my work...”

Detroit’s oldest neighborhood

“We lived three-quarters of a mile from Tiger Stadium, I remember on game days, people would park up and down the street, and you could even hear the roar of the crowd sometimes, when somebody hit a home run, or did something good. So, it was pretty nice, and you know, like I said, the neighborhoods were vibrant” -Detroit Historical Society

.He attended Most Holy Trinity and was a batboy for the Detroit Tigers for three years in the early ’70s as the great Al Kaline was winding up his playing career.

SOUTHWEST

THE PLACE

“growing up in a community so rich with history taught me the importance of storytelling. The murals on the walls, the festivals in Clark Park, the recipes passed down through generations— Southwest Detroit doesn’t hide where it comes from; it celebrates it.”

“you don’t know about Detroit until you experience southwest. Theirs a lot happening here. All the roots are here.”

“Diverse and United”

Hubbard Richard faces the unique challenge of both gentrification and industrial encroachment while striving to preserve its identity as a diverse and united community.

Gathering the Stories

Residents of Hubbard Richard, Southwest, and Corktown shared personal stories and memories that define their connection to these neighborhoods. Through a community- driven survey and engagement at local businesses and community centers, participants were invited to reflect on their experiences, responding to questions such as “what’s a memory you have of your neighborhood?” and “where is your place? Where do you spend most of your time, and what makes it special to you?” The responses highlighted a rich tapestry of personal and collective stories. Some are rooted in family stories and histories. Others talked about public spaces such as Clark Park and community traditions such as Cinco de Mayo, Blessing of the Lowriders and Die de los Muertos. These narratives

demonstrate that a neighborhood is more than just a physical space; it's shaped by the relationships and shared experiences of those that live here.

This study served as part of the site analysis for the viaduct at the corner of Newark and Vernor behind Michigan Central Station. By gathering these narratives, the research looked to uncover emotional and cultural connections that link Southwest, Corktown, and Hubbard Richard. Rather than focusing solely on the physical aspects of the place, this study aims to reflect the lived experience and identity of the communities. This intervention will highlight the enduring connections between these neighborhoods, creating a place that acknowledges their stories.

Collection of stories were gathered through

• Interviews

• Surveys

• Informal conversations in cafes and rec. centers

“My great grandparents lived in Southwest Detroit after immigrating from Mexico. They were involved and loved their community. There is a mass celebrating them twice a year at Holy Redeemer Church to this day.”

- Past Southwest Resident, Interview

DISCOVERING ROOTS

This neighborhood is where my great grandfather decided to make his home when he immigrated from Switzerland.

My grandmother was then born here, then mother and all of my siblings. I learned this when I moved back to Southwest

SOUTHWEST

COMMUNITY & IMMIGRATION

“My great grandparents lived in Southwest Detroit after immigrating from Mexico. They were involved with the community. There is a mass celebrating them twice a year at Holy Redeemer Church to this day.”

PLACES TO COME TOGETHER

“Clark Park — a park central to the neighborhood that can accommodate gatherings and activities for people of all ages, ethnicities and cultures.”

THE PLACE

CORKTOWN

ROBERTO CLEMENTE RECREATION CENTER

RESILIENCE & RENEWAL

RESILIENCE & RENEWAL

Corktown—In college, my friends and I crawled into the basement of the abandoned train station, It felt like a forgotten piece of the past. Now, seeing the station restored and full of life again is something I never imagined happening so soon.

PLACES TO COME TOGETHER

“Batch Brewery has become a local watering hole for friends. It’s more than just a bar—it has supported the community by opening its kitchen to local businesses, like Taqueria El Rey, after their building was lost to a fire.”

CARING FOR OUR PLACES

“I spend the most time tending to my front garden, restoring the natural habitat around my home. Caring for this space connects me to nature and gives me a sense of accomplishment.”

PLACES TO COME TOGETHER

“Stanton Park, a community garden and playground at the heart of Hubbard Richard, serves as a gathering space where families, friends, and neighbors come together. It was a space for everyone to connect during COVID.”

CELEBRATING HERITAGE & CULTURE

“Celebrations in Southwest Detroit are like none other in the city. Blessing of the Lowriders/ Cinco de Mayo, Die de los Muertos, Southwest Fest to name a few.”

HUBBARD RICHARD

GENERATIONAL HOME

“My grandparents lived in Hubbard Richard and because of the memories i had growing up here I decided to purchase a home in this neighborhood.”

HONEY BEE MARKET

Playing in the Place

The act of playing in place became a method of embodied research for this area. This is an exploratory process guided by movement, intuition, and sensory engagement. Rather than relying solely on formal surveys or visual analysis, playing in place meant moving through the neighborhoods with a sense of openness, allowing the built environment to speak through its textures, rhythms, and histories. This method paralleled a previous engagement exercise, where the simple act of placing two chairs in unconventional public spaces invited strangers to engage and co-create momentary sites of connection. In both cases, play operated as a tool for discovering the deeper meanings and overlooked narratives and shifting the designer’s role from outside observer to active participant in the social life of place.

Walking the corridor between Corktown, Hubbard Richard, and Southwest Detroit became a recurring practice. These walks weren’t about arriving somewhere, but about exploring the environment through pausing, noticing, photographing, and exchanging words with residents. Through these playful yet intentional acts, these motifs began to emerge not just in architecture, but in how memory and cultural identity were embedded into everyday infrastructure. In Southwest Detroit, wrought iron gates stood out as recurring expressions of culture. These weren’t just functional objects they were canvases of ornamentation, marked by swirling, floral, and geometric motifs. Their forms had a resemblance to traditional Mexican ironwork, or rejería, a craft passed down through generations and rooted in Spanish and Indigenous design traditions. Historically used to protect homes while still allowing for openness and visibility, rejería reflects a deep cultural ethos of hospitality, resilience, and beauty in everyday life. The gates served as both barrier and invitation. Creating thresholds where personal identity meets public space.

In Corktown, architectural details revealed influences tied to Irish heritage. Celtic motifs were visible in the form of knots and clovers. Some were etched into the entrances of churches or echoed in the patterned metal of grates and windows. Even the geometry of Michigan Central Station’s windows seemed to carry this lineage of design.

By engaging with the built environment through walking, observing, and documenting, these subtle visual languages became symbolic of migration, rootedness, and memory. The motifs uncovered through this process did not emerge from a studio or sketchbook, but from time spent in place. These discoveries became the foundation for the installation’s design.

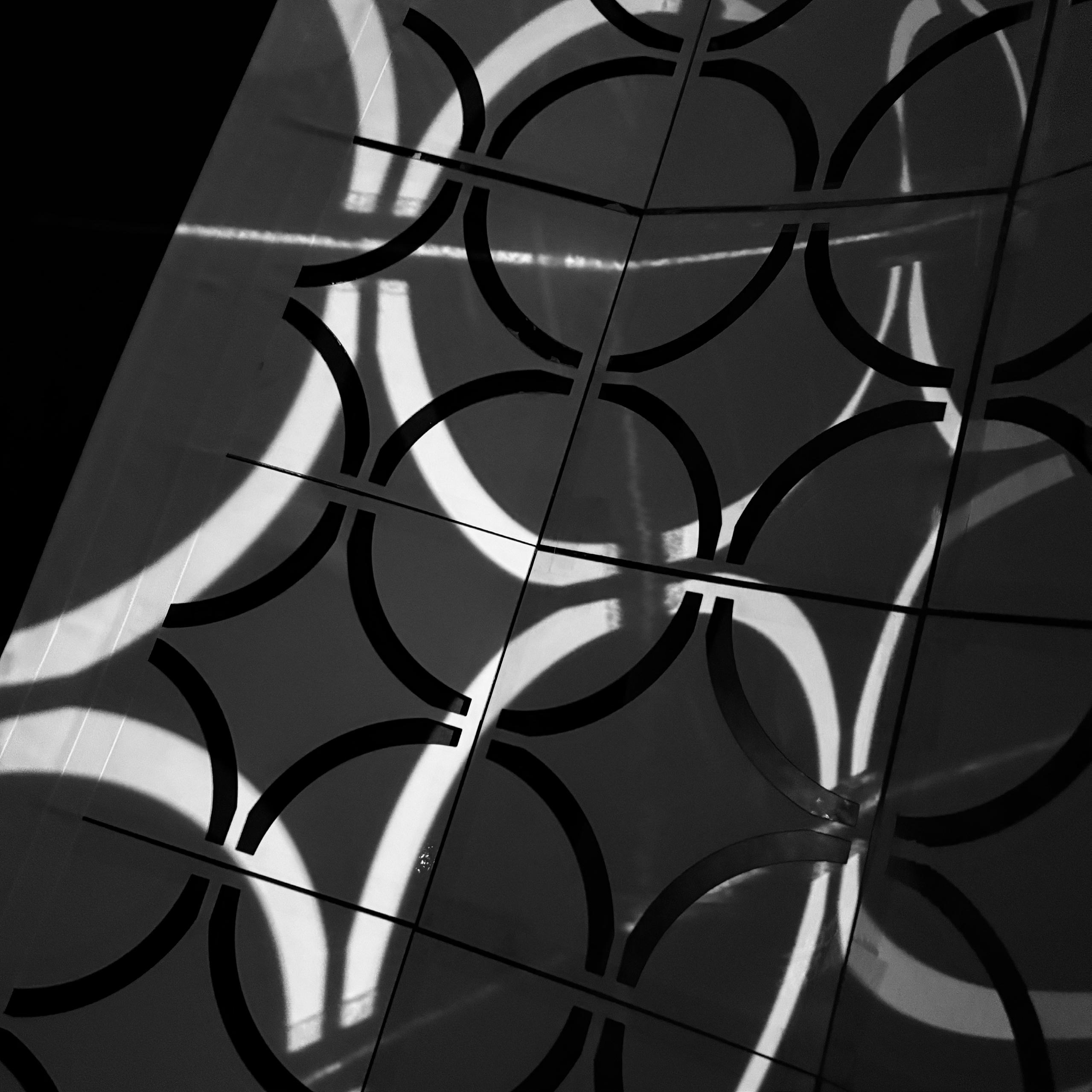

The Viaduct, positioned as a threshold between neighborhoods, was transformed into a space for reflection and gathering. The installation features a series of reflective panels, referencing the decorative ironwork seen throughout the neighborhoods. During the day, the panels cast intricate shadows across the sidewalk and street; at night, lights placed below illuminate the structure, allowing it to shift and shimmer with passing movement. The reflective surfaces speak to the transitional yet lasting nature of migration; people passing through, leaving impressions, and building community across generations.

In this way, the installation doesn’t impose a new narrative onto the site—it reflects the existing ones. The design invites viewers to slow down, look closer, and consider the many layered identities that make up this shared urban landscape.

Swirls found on thresholds of businesses and homes in southwest

Entrance to famous Tamaleria Nuevo Leon

Decorative wrought iron gates around houses

Pattern found on art and pottery in Southwest

Michigan Central Station drains

Breeze blocks at entrances found in Southwest

Celtic patterns found on murals in Corktown

Michigan Central Station windows

Clover pattern on entrance

St. Paul’s German Evangelical Lutheran Church in Corktown

Discussion

This project explores the transformation of urban spaces through the lens of placemaking and play, emphasizing how sensory experiences, memory and interaction shape emotional connections to place. Grounded in the belief that play fosters agency, interaction and belonging, the work investigates how community narratives and embodies experiences can inform more inclusive and responsive design practice. By positioning play as a method for participatory design, the project challenges conventional top-down processes and proposes an alternative mode of engagement, rooted in acknowledgment and co-creation.

The strategies proposed for integrating play into the design process such as playing in place, imagining our places and multisensory engagement; are not intended as a definitive guide. Rather than functioning as a checklist or step by step methods, they represent entry points into a design approach that centers playfulness, improvisation, and interaction. What unites these strategies is their emphasis on active interaction with both the environment and individuals. In each tool, play becomes a means of building understanding and connection.

Effective placemaking and co-creation require time, sustained presence and deep engagement with those who inhabit a place. These processes unfold slowly, through trust and shared experiences. Within the

constraints of the academic year, these relationships can only begin to take shape. This project represents an early gesture to this process, a beginning then a conclusion. While the intention was to develop an inductive design process through play, the timeline inevitably limited the depth and duration of engagement.

Another limitation of the project lies in the nature of the intervention itself. As a temporary installation, the work primarily focuses on the visual and atmospheric qualities of the space, rather than the ground plane or physical infrastructure. It offers a sensory re-imagining intended to evoke memory and identity but does not propose specific functional or longterm changes. The context in which the installation was placed further underscores these limitations. While the design process emphasized responsiveness and flexibility, the initial selection of the site did not emerge through community co-creation. Instead, it was chosen for its role as a connective threshold between neighborhoods and its proximity to future development sites, such as those led by Ford and the Detroit City FC soccer club. As development continues in this area, there is both a challenge and an opportunity: to ensure that future design decisions reflect not only the aspirations of those who may arrive, but also honor the needs and memories of those already present.

Often, place attachment and place identity are internalized long before any visible transformation occurs. Even when spaces appear empty or overlooked by outsiders, individuals and communities may have developed deep relationships with them through everyday use and lived memory. Placemaking should therefore begin with an acknowledgment of these existing meanings. It is not simply a process of adding value to a space, but one of recognizing and nurturing the value that is already present. This work does not claim to resolve the complex dynamics of placemaking, memory, and development. Instead, it opens space for further inquiry: How can play be more deeply integrated into the design process? What does it mean to honor emotional attachments in spaces marked for change? How can design reflect the iterative—and often invisible—labor of co-creation?

In asking these questions, this thesis affirms the importance of designing not just for communities, but with them. It embraces play as a powerful method for building connection, listening deeply, and making space for stories that already exist. Ultimately, it suggests that meaningful transformation happens not only through physical change, but through the relational, emotional, and participatory processes that give places their meaning.

How can interactions between people and public spaces contribute to place attachment?

How can play be used both as a design tool and engagement method to create connections?

PLACELESSNESS TO PLACE

How do the memories embedded in a place shape emotional connections and strengthen place attachment?