By Danielle Nauman danielle.n@dairystar.com

South Africa — On the gently sloping foothills of the Magaliesberg Mountains, in the northern South African province of Gauteng, is a unique dairy farm.

The Donkey Dairy PTY LTD, is exactly what it sounds like: a one-of-a-kind farm home to 146 donkeys,

including a milking herd that uctuates between 30 to 40 jennies.

Jesse Christelis established the farm in 2012 in Magaliesberg after his passion for natural remedies led him to discover the naturopathic value of donkey milk.

“The benets of donkey milk are rooted in ancient healing traditions, yet backed by modern science,” Christelis said. “Donkey milk offers unparalleled nutritional and medicinal properties.”

Donkey milk is the closest milk type to human breast milk. According to Christelis this makes it an ideal substitute for infants with milk and formula allergies. He said besides being rich in vitamins

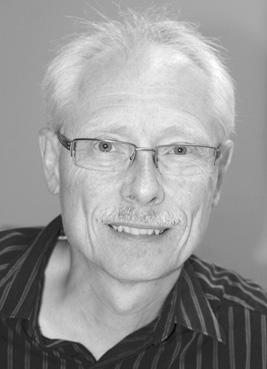

Jesse Christelis takes a moment with a spo ed donkey in 2023 at The

aliesberg, South Africa. The 75-acre farm is home to 146 donkeys,

30-40 jennies.

and minerals, it is also loaded with antioxidants and enzymes that strengthen the immune system and combat autoimmune issues. It also has natural antihistamine properties, making it effective in alleviating respiratory issues like asthma and bronchitis.

“Donkey milk is a true

superfood for overall health and well-being,” Christelis said. The nearly 75-acre donkey farm consists of both grazing areas and rugged mountainous terrain in a moderate climate with warm summers and mild winters — a combination Christelis said

is perfect for donkeys that are browsers and grazers by nature. The farm also has access to a natural spring to provide mineral-rich water he says is vital for producing high-quality donkey milk.

Turn to SOUTH AFRICA | Page 4

Volume production is not the goal in donkey dairying, Christelis said, with average production being just over 8 ounces per day, per jenny. The jennies at The Donkey Dairy produce just over 50 gallons of milk per month, collectively. The jennies are milked by hand.

“The limited production makes donkey milk an exceptionally rare and valuable product,” Christelis said. “You would need 160 donkeys to match the output of one dairy cow.”

Foals must remain at their mother’s sides for donkeys to lactate, Christelis said. Milk production is linked to an oxytocin release created by the presence of the foal.

“Our milking process is a delicate balance,” Christelis said. “We share the milk with the foal while ensuring minimal stress for mother and baby.”

While Christelis said donkey milk is delicious with a light, slightly sweet taste, it is not consumed in the same manner or volume as cow or goat milk.

“Donkey milk is sought for its health benets,” Christelis said. “It’s an excellent alternative for individuals with dairy allergies or skin conditions. Historical records even suggest that Cleopatra bathed in donkey milk for its rejuvenating effects.”

To ensure the long-term sustainability of the farm, Christelis has focused on harnessing those qualities of donkey milk, creating a line of natural skincare products.

Milk, and all-natural skincare products are sold directly to consumers at the farm, through an online store and at select retailers.

Christelis also looks towards agritourism and ecotourism to help diversify the farm’s business model.

“This area is a popular tourism destination and brings visitors interested in ethical farming and animal interactions,” Christelis said. “The Donkey Dairy is more than just a farm — it’s a mission to promote ethical, sustainable farming while fostering a deeper connection between people, animals and nature. These additional revenue streams help sustain our operations while allowing us to share the beauty of our farm with others.”

Like other areas of the world, the South African dairy industry is dominated by cow milk and goat milk. Christelis believes The Donkey Dairy is the only one of its kind in the country and that only one other donkey dairy operates in the region in Botswana.

“(This) gives us a unique market position but also means we bear the responsibility of educating the public of the benets of donkey milk,” Christelis said. “Consumer education is a major challenge we face. A signicant part of our efforts goes into informing potential customers of the benets of donkey milk.”

Working with the donkeys on a daily basis brings its own reward, Christelis said, added to the knowledge of the positive impacts donkey milk can have to help people.

“Knowing what we are doing can help a child with allergies to dairy or a person suffering from skin conditions is fullling,” Christelis said.

With over a decade of milking donkeys under his belt, Christelis continues to look towards the future, with goals to increase production efciency, expand tourism efforts and develop new donkey milk-based products. Christelis hopes to enter the global market with his products.

“Long-term we envision The Donkey Dairy becoming a globally

recognized name in donkey milk production and ecotourism while maintaining our commitment to ethical farming,” Christelis said.

With those goals in mind, Christelis is excited to continue to share the benets of donkey milk alongside the story of The Donkey Dairy.

“We are proud to be pioneers in this industry,” Christelis said. “We started The Donkey Dairy out of a love for these gentle animals and a belief in the untapped potential of donkey milk in South Africa. Our goal is to continue expanding our ethical and sustainable approach to donkey milk production while increasing awareness of its incredible health benets.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture again lowered its 2025 milk production forecast from last month in its latest World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report, citing lower expected cow inventories. Milk supply and use estimates for 2024 were adjusted to reect December domestic and trade data.

2024 production and marketings were projected at 225.9 and 224.9 billion pounds respectively, up 100 million pounds on both from last month’s estimate. If realized, both would be down 500 million pounds or 0.2% from 2023.

2025 production and marketings were projected at 226.9 and 225.9 billion pounds respectively, down 300 million on both from a month ago. If realized, both would be up 1 billion pounds or 0.4% from 2024.

Milk and dairy product price forecasts reected updated price formulas of the Federal Milk Marketing Order, as published in the Federal Register Jan. 17 by the Agricultural Marketing Service. Butter, nonfat dry milk and whey prices were lowered based on recent prices. The cheese price was raised on recent prices and tight inventories from 2024 that are expected to carry into 2025.

Cheese was projected to average $1.88 per pound in 2025, up 1.50 cents from last month’s estimate, and it compares to $1.8634 in 2024 and $1.7593 in 2023.

Butter was projected at $2.6450 per pound, down a nickel from a month ago, and it compares to a $2.8870 average in 2024 and $2.6170 in 2023.

Nonfat dry milk was projected with a $1.2950 average, down 4.50 cents from last month’s estimate, and it compares to $1.2420 in 2024 and $1.1856 in 2023.

Dry whey is expected to average 60.50 cents per pound in 2025, down 3.5 cents from last month’s estimate, and it compares to a 49.13 cent average in 2024 and 36.18 cents per pound in 2023.

Class III and Class IV milk price forecasts for 2025 were lowered. Look for the Class III to average $19.10 per hundredweight in 2025, down 60 cents from last month’s projection; this compares to $18.89 in 2024 and $17.02 in 2023. The Class IV price is expected to average $19.70, down $1.10 from last month’s estimate, which compares to $20.75 in 2024 and $19.12 in 2023.

This month’s corn outlook was unchanged. The projected season-average price was raised 10 cents to $4.35 per bushel. Global coarse grain production was forecasted at 1.492 billion tons, which is 1.8 million lower.

This month’s outlook is for reduced production and trade, as well as ending stocks. Foreign corn production was forecasted down, with declines in Argentina and Brazil.

Soybean supply and use projections were also unchanged. The season-average soybean price was projected at $10.10 per bushel, down 10 cents from last month. Soybean meal and oil prices were unchanged at $310 per short ton and 43 cents per pound, respectively. Global soybean supply and use forecasts included lower production, higher use and lower ending stocks.

Production was reduced for Argentina and Paraguay due to persistent heat and dryness in January. Brazilian soybean production was unchanged at 169.0 million tons. Benecial weather in the Center-West is boosting soybean prospects, but drier weather in the South accelerated soybean development at the expense of yields, according to the WASDE.

U.S. dairy culling continues to lag. The USDA reported 57,500 dairy cows were sent to slaughter the week ending Feb. 1, 6,000 more than the previous week but 2,500 or 4.2% below a year ago. Year to date, 275,700 cows had retired from the dairy business, down 9,200 head or 3.3% from a year ago.

Cash dairy prices in Chicago were a bit skittish with the “T” word (tariffs) being bandied about again the week leading up to Valentine’s Day. However, the Cheddar blocks closed Friday at $1.92 per pound, up 6 cents on the week and 44 cents above a year ago. The barrels crept to $1.83 by Thursday but closed Friday at $1.8175, 3.75 cents higher, 21 cents above a year ago and a higher-than-normal 10.25 cents below the blocks. There were eight CME sales of each on the week.

StoneX stated in its Feb. 12 Early Morning Update, “It’s important to remember that the 10-year spot block price average in February is $1.7020. $1.90 block cheese today is appropriately reective of a tighter-than-normal cheese market.”

Meanwhile, Midwest cheesemakers reported mixed demand, according to Dairy Market News. Italian-style cheesemakers, particularly hard Italian styles, said sales are strong. Cheddar makers say demand varies plant to plant, with some being oversold. Milk availability also varies. Plant downtime continues to impact milk prices. Some cheesemakers had a lot of offers this week, while others said milk was short and they were looking for more but having no luck.

Demand for Class III milk from western cheese manufacturers is generally at or above expectations, DMN said. Class I milk demand is seasonally strong, and bottlers were pulling heavily on milk volumes as well as cheese manufacturers. Cheese output was steady to stronger. Inventories are reportedly tight on certain varieties, while others are generally far from short. Demand is mostly steady from retail and steady or lighter from food service, according to DMN.

Results of this year’s Super Bowl were a win-win for the dairy industry as well as for the Eagles. The Daily Dairy Report pointed out that National Pizza Day fell on the same day, which is the biggest pizzaeating day of the year. The DDR stated, “The Washington Post notes that Americans eat 3 billion pizzas annually, the equivalent of 46 slices per person. Assuming a 14-inch pizza is topped with 9 ounces of cheese, consumers eat nearly 1.7 billion pounds of cheese on pizzas each year, or about 35% of U.S. Mozzarella production.”

The DDR added that the playoffs and Super Bowl may have been part of the reason USDA’s December Dairy Products report showed record high Mozzarella production. Americans love cheese, and that’s great news for U.S. dairy farmers.

Butter jumped to $2.43 per pound Wednesday but

closed Friday at $2.3775, down a quarter-cent on the week, lowest since June 26, 2023, and 37.25 cents below a year ago. There were 51 sales on the week, 31 on Wednesday alone.

Midwest butter makers relay that demand has yet to move out of its seasonal hiatus despite a slight pickup from January in retail. Outside of some planned and unplanned plant downtime this week, churning was unquestionably in one of its busiest runs of the year, DMN said. Cream is markedly abundant in the region and moving in from the West at “undeniably affordable rates.”

Cream is plentiful in the West, and multiples were again below the prior week. In some cases, offers for distressed loads were at much lower multiples. Churns are busy while butter demand is moderate to steady, according to DMN.

While powder prices were higher in last week’s Global Dairy Trade, Chicago Mercantile Exchange Grade A nonfat dry milk saw its Friday close at $1.28 per pound, down a nickel on the week, the lowest CME price since Aug. 22, 2024, but still 11 cents above a year ago on 15 sales.

The Daily Dairy Report points out that Mexico did not include nonfat dry milk in its list of potential targets for retaliatory tariffs; however, “Trade tensions have chilled cross-border commerce. Dairy Market News describes Mexican demand for U.S. milk powder as ‘subdued,’ and exporters expressed concerns about committing today to buy milk powder that could face tariffs if the trade spat heats up.” It also reported that domestic buyers have taken a step back “to avoid catching the proverbial falling knife.”

Dry whey closed Friday at 55.50 cents per pound, down 3.25 cents on the week, the lowest since Aug. 28, 2024, but 3.50 cents above a year ago, with 4 CME sales.

Fluid milk sales headed back up in December after falling 1.5% in November, and 2024 sales topped the 2023 level, ending decades of decline. Consumers do not appear to be overly concerned about bird u and may be turning away from plant-based beverages and returning to natural cow’s milk, particularly organic.

Conrmation continues to mount on the health benets of milk. The Jan. 27 Daily Dairy Report detailed a recent study showing that drinking an 8-ounce glass of milk daily could cut the risk of colorectal cancer by nearly a fth.

USDA’s December data shows packaged sales climbed to 3.75 billion pounds, up 2.6% from December 2023. Conventional product sales totaled 3.5 billion for the month, up 2.0% from a year ago. Organic products hit 270 million pounds, up an impressive 10.1% from a year ago, and represented 7.2% of total milk sales in the month, up from 6.8% in November. December whole milk sales totaled just under 1.4 billion pounds, up 2.9% from a year ago and up 2.0% year to date. Whole milk represented 36.1% of total milk sales for the month and 35.5% for the year. Skim milk sales came in at 153 million pounds, down 8.0% from a year ago and down 10.2% year to date.

Packaged uid sales for all of 2024 totaled 43.0 billion pounds, up 0.8% from 2023. Conventional product sales amounted to 39.9 billion pounds, up 0.4% from a year ago. Organic products, at 3.0 billion pounds, were up 7.2% and represented 7.1% of total milk sales in the year. The gures represent consumption in federal market orders, which account for about 92% of total uid sales in the United States.

Dairy Market News reported that “Bottlers, nationwide, continue to take on steady amounts of milk. Demand from Class I has remained strong well into February while demand from other Classes is somewhat mixed.” Milk is “cool” again.

However, cheese utilization fell in December, down 1.7% from December 2023, primarily due to poor domestic usage, down 3.3%. Exports were up 21.2%. Domestic demand accounts for about 92% of total use, according to HighGround Dairy, and totaled 1.1 billion pounds. Exports amounted to 96.7 million pounds.

After hitting an all-time high in November, December butter consumption plunged to 199 million pounds, down 7.0% from a year ago, the largest monthover-month fall since April 2021, HGD said, but it was still historically very strong through the second half of 2024, driving annual volume up 5.5% from 2023. At 6.3 million pounds, Butter exports were up 43.2% and up 6.7% year to date.

Nonfat dry milk and skim milk powder utilization fell to 161 million pounds, down 22.6%, the lowest monthly volume since November 2018, HGD said; they also reported, “Poor international shipments and dismal domestic demand left 2024 to post the smallest annual disappearance (2.1 million pounds) since 2012.”

Dry whey use rebounded in December from November, up 9.6%, but fell short of a year ago by 7.4%.

“The signicant loss in domestic consumption observed throughout the second half of 2024 offset marginal gains in exports resulting in both categories declining annually from 2023,” HGD said.

In politics, Robert Kennedy was conrmed as secretary of health and human services this week, and Brooke Rollins was conrmed as agriculture secretary. The House Committee on Education and the Workforce passed the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act this week, 24 to 10, which would allow for whole (3.25%) and reduced-fat (2%) milk to once again be served in school cafeterias.

Michael Dykes, president and CEO of the International Dairy Foods Association, praised the move, stating, “(The passage) Demonstrates the widespread support the bill enjoys in Congress and among parents, nutritionists and school meals professionals alike. After more than a decade of waiting, it’s time to lift the ban on whole and 2% milk and give children more nutritious choices in school cafeterias.” He also urged passage of the bill by the full House and Senate.

Tuesday’s GDT Pulse saw 4.3 million pounds of product sold, same as the Jan. 28 Pulse and 96.9% of what was offered. The price on skim milk powder was slightly lower. Whole milk powder was up from the last Pulse.

Tariffs were back in the news this week after President Trump postponed them on Canada and Mexico last week. China was hit with 10% tariffs last week, though items $800 and less were paused, according to HighGround Dairy. China in turn imposed a 15% tariff on U.S. coal and liqueed natural gas and 10% on crude oil, agricultural machinery and large-engine vehicles. Trump also announced new tariffs this week of 25% on all imports of steel and aluminum as well as reciprocal tariffs on any country trading with the U.S.

Tariffs and bird u were two main topics at this week’s World Ag Expo in Tulare, California, according to HGD’s Curtis Bosma in the Feb. 17 “Dairy Radio Now” broadcast. He said the expo is the world’s biggest farm equipment show and covers just about every aspect of agriculture; Tulare has a population of 60,000 people, and the expo draws about 100,000 per day, according to Bosma.

Dairy farmers there had a lot of optimism coming out of 2024 with higher milk prices and lower feed costs, which resulted in a better margin opportunity, Bosma said. Bird u has certainly taken a toll on the state especially, but dairy revenue protection payouts and USDA assistance have farmers in “a pretty good spot.”

The tariffs came up a lot in conversations, according to Bosma.

“We’re going to see a much different tone when it comes to foreign relations and how this administration navigates these things,” he said. “With that comes some enhanced volatility in the commodity markets, so it’s a good time to be talking to folks like us because these are the times when things get a little crazy, but we have some opportunities to mitigate some of that risk.”

This herd has a 74-pound tank average, 4.5 fat, 3.4 protein and our somatic cell count is 150,000. This is young and promising herd of cows. There are 45 first lactation and 40 second lactation animals on this sale. The Keranen’s milk their cows twice a day and test with DHIA. The cows are housed in a freestall barn and fed a high forage TMR. For many years, the Keranens used a mixture of AI breeding and bull breeding. In the last three years all the cows have been AI by the likes of Tahiti, Alphabet, Barclay and Milky and the heifers have been bull bred. Darren said he has been careful in bull selection and likes to choose bulls that come from good cows and good cow families. They vaccinate at dry off with Ultrabac and Vira shield.

“I first started milking with 10 cows with my brother, I slowly grew my herd for a few years then it worked out for me to buy the home farm where I grew up. After a lot of updating my wife and I had our own farm. To this day my brother and I still work together putting in and harvesting crops together. Over the years of building up my herd I have purchased most of my cows from two local herds. They have always sold me good cows for a fair price. There were a few herd dispersals over the years that I bought a few cows from. Overall my herd of cows have treated me very good. It has been a very difficult decision to make to sell the cows but when your heart is not into

it is

very

A look at how the dairy industry’s most popular feeding style took shape

By Dan Wacker dan.w@dairystar.com

Editor’s note: Information for the article was provided by Jenna Neuheisel, a consultant with Ag Consultants Team Inc. in Sparta, Wisconsin, Steve Gerke, a territory manager at Roto-Mix Inc., and Chuck Friedley, a retired salesman from KUHN North America Inc., along with independent research.

One of the great revolutions of the dairy industry is the introduction of the total

mixed ration. Although commonplace in today’s enterprise, TMR faced skepticism when it was rst introduced. The concept — every nutrient a cow needs in a single bite — evolved and is now regarded as one of the most efcient ways to feed cattle.

When TMR was launched, component feeding, still utilized today by some dairies, was the most popular form of feeding. It individualized diets by cow but brought about a different set of challenges with inconsistency in ration and consumption.

Component feeding features more estimation per cow. Without the use of scales to accurately measure the amount of ingredients given to each cow, the ration can vary depending on the feeder.

Turn to TMR | Page 12

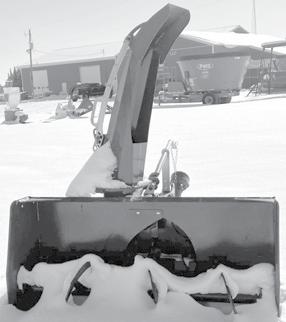

WACKER/DAIRY STAR

Mike Wacker feeds his pre-fresh cows a batch of feed from his Jaylor ver cal total mixed ra on mixer Feb. 14 on his farm near Sparta, Wisconsin. Ver cal mixers evolved from reel mixers while horizontal auger mixers gained popularity in the mid-1990s.

Total mixed rations were a practice that began in the beef cattle industry in the 1950s. The dairy industry adopted this feeding strategy later, becoming more popular in the 1970s.

Total mixed ration feeding creates a cattle feeding system that ensures each mouthful is a balanced diet. Because of eating a variety of ingredients at once, TMR mix also helps improve rumen health.

2,755

A KUHN/Knight horizontal mixer sits Feb. 13 on the lot at Steinhart’s Farm Service Inc. in Pla eville, Wisconsin. Horizontal mixers were one of the rst evoluons of mixers, shortening the amount of me it took to mix batches of feed.

TMR eliminates that estimation and is more concise, ensuring each mouthful is balanced. It also helps dairy producers better use lower-quality forages because they are blended with better forages in a way cows cannot sort. Nutritionists have also found that a TMR mix can help improve a cow’s rumen health.

“We’ve seen increases in components and a more level rumen pH with a TMR feed source because it’s not just all grain being eaten at one time,” Jenna Neuheisel said.

Neuheisel is a consultant with Ag Consulting Team Inc., working with herds in western Wisconsin.

When TMR was rst introduced in the 1950s, dairy producers doubted its value. The beef industry had already started implementing TMR strategies early and had seen improvements in their cattle. However, promoting a single ration for the majority of a dairy herd was not commonplace.

With TMR mixed for the top 75% of the herd, it gave cows the ability to eat more. Higher producers consumed more of the ration, leading to an increase in production. With production increasing with the new style of feeding, farmers began attempting to implement it how they could.

Implementation was difcult during early years because dairy farms were not set up to allow TMR mixers to feed directly. Some smaller farms began to utilize tumble mixers because of their ability to maximize feed that was housed in silos. Expanding beyond stationary mixers often required feeding systems to be restructured.

As these barns were phased out on some farms in favor of freestall barns, the transition to full TMR feeding was underway in the dairy industry. In these new setups, component feeding was impractical. Barns were constructed with drive-through feed areas to help improve the speed of feeding and to incorporate the new TMR style.

The evolution of trailer mixers and truck mixers made feeding more efcient in the new barns. Nutrition-

A benefit of total mixed ration is that mixing feed for the top 75% of the herd enables higher-producing cows to consume more of the ration, leading to an increase in production.

ists played a vital role in the growth of TMRs too as they helped producers determine which mixer was best for their farm.

“In those early years, we’d hold meetings where we’d have specialists come in and teach producers how the TMR would work for them,” said Chuck Friedley, a retired salesman with 43 years of experience in implement sales. “We’d discuss the right mixer for each farm and give them a trial to use the new mixer.”

Friedley sold TMR mixers of multiple kinds across his career. He retired in 2022. He spent the last 20 years of his professional career working with KUHN as the salesman for a territory that included North and South Dakota, western Minnesota, northwest Iowa and northeast Nebraska.

Friedley said TMR mixer trials lasted six months. This was long enough for the farm to work through the initial challenges and see what the TMR mix could add to the herd.

“If the mixer didn’t work out in that trial period, we’d take it back,” Friedley said. “There were only a handful that we needed to take back. Most people who started using them learned how to make it work for their herd.”

As TMR mixers began to take hold in the Midwest, the variation of styles became even more important. Deciding whether a farm should use a reel mixer, an auger mixer, or a tumble mixer was dependent on each farm, their goals, forages and even the terrain.

“We always had to nd out what the farmer was feeding,” Friedley said. “That helped us determine what would work best for them.”

Early adaptations of TMR mixers saw reel mixers being more heavily used. This evolved to horizontal mix-

Turn to TMR | Page 13

Early total mixed rations were mixed with a reel mixer. The reel mixer was more forgiving for overprocessing for users with less experience. As farms continued to evolve their feeding approach, this led to the introduction of horizontal and vertical mixers, which are more prominent in today’s market.

ers in the 1980s to the eventual vertical mixers gaining popularity in the mid to late 1990s.

A major issue when adapting to TMR feeding was overmixing and decreasing particle size. Reel mixers were initially the most popular style of mixer, especially in the early days because it was more forgiving in terms of overprocessing, using fewer blades to mix feed.

Horizontal mixers owned most of the market during the 1980s because of their quicker mixing times. A drawback to that quicker mix was that it made it easier to overprocess the mix. Horizontal mixers also struggled with hay processing, which led to the evolution of the vertical mixer.

Vertical mixers took hold of the market during the 1990s and still hold most of the market today. The new development is the most efcient way to process hay, allowing nutritionists to continue to add dry hay to the ration.

Hay processing has been a challenge for TMR mixers and has factored heavily in the evolution of machine design.

Friedley said farmers learned more about each mixer over time, and which style suited their farm best.

“Those six-month trials were knocked down to three or four days when farmers were looking for their second mixer,” Friedley said. “Those trials were as important because it would prove what would work and help them dial in what kind of mixer they wanted.”

Testing new styles of mixers became an important element in the evolution of the machine. Actual performance played a key role in determining which mixer would work best.

“We’d try to think of everything with mixer design, but we really started to gure things out when we tested the mixers on the farms,” Friedley said. “We tried to account for everything, but without fail, we’d nd new challenges when the mixers got on the farm.”

Continuing to develop new methods and strategies to create better feed for livestock remains at the forefront of the feed industry. With the introduction of robotic milking units, some elements of component feeding have found their way back into the metaphorical mix.

Adding TMR to dairy herds increased production and changed the way barns were built. It reshaped the dairy industry, increasing protability through more efcient feeding. As feeding evolves, TMR mixers continue to help farmers produce more product with less time and feed waste.

Total mixed ration feeding faced obstacles with barn structures early on.

Because TMR was proven to increase production, producers constructing new barns built them to accommodate the drive-through feeding requirements of TMR mixers.

Harner shares tips for mixing faster, reducing waste

By Dan Wacker dan.w@dairystar.com

The way cows are fed is a building block that sets a foundation for a dairy’s success. Recently, the Professional Dairy Producers of Wisconsin hosted Dr. Joe Harner, an engineer with 40 years of experience with livestock and grain facilities at Kansas State University, as part of its Dairy Signal program for a presentation about feed center management.

Harner detailed feeding strategies that drive feeding efciency: improving the timing of feeding, preventing feed waste, regular maintenance of equipment, and effective communication with dairy managers and feeders.

To improve efciency, Harner said producers should think about feed centers as having four zones. In zone one, the only equipment is the loader used to ll a stationery or mobile feed mixer.

Zone two features space for ingredient delivery trucks and commodity bays. This should be set up in a way that trucks do not hinder the total mixed ration loader from accessing ingredients.

The third zone is primarily for the TMR mixer or feed

delivery trucks. This allows for nonstop travel from the feed center to the feed bunks.

The nal zone is the exterior access to the feed center. This area gives the ingredient delivery trucks the ability to move from scale to feed center without compromising biosecurity protocols.

With this setup, Harner has discovered that dairies can mix feed 25% faster on the weekends than Monday through Friday. This is due to the congestion that zones 1, 2 and 4 can have during the week because of heavier trafc from visitors and deliveries to the farm during the week compared to the weekend.

With a goal to average 12 tons of feed mixed per hour per employee, these zones create a more efcient feeding pattern. This equates to mixing a batch of feed every 30 minutes.

This would be based on an approximate timing of 10 minutes to load forages and grains, ve minutes for liquids, ve minutes for mixing and 10 minutes for delivery. This formula was for a batch with 4-6 ingredients per load, using pre- or batch-mixes to help with small inclusion ingredients.

The timing of his 30-minute goal is also predicated on having a limited amount of stops for the TMR mixer. All ingredients are located near the TMR with a maximum of 2-3 stops per load. If needing to move the TMR mixer, one stop should be near the commodity bays and another at

forage locations to aid in efciency.

Trafc patterns play a role in the efciency of mixing as well. When possible, there should not be interference from other unloading trucks or equipment. Limiting the number of gates that need to be opened and closed and ensuring there is no cattle trafc can help improve the efciency of feeding too.

Preventing feed shrinkage is a critical aspect of de-

creasing waste and improving efciency. Harner said identifying the cost of the top 3-5 ingredients and setting a goal to reduce that ingredient’s purchase by 2-3% can cut costs signicantly. He also detailed the importance of identifying feeder problems versus facility problems.

Feeder problems consist of the time to perform a task, unloading of trucks, potential carelessness of employees and

records utilization.

Facility problems were specied as rain, wind and solar radiation, excess purchases, co-mingling of ingredients, storage issues and mixer calibration.

Harner said most challenges are the result of having inadequate facilities to handle the volume of product moving through a feed center.

Harner discussed practices to limit co-mingling and waste. Recently, the construction of commodity bays has seen a normally 12- by 16-foot building nearly double in size, with most construction moving to a 24- by 30-foot design.

In the larger buildings, or when applicable to current commodity bays, deeper bays with higher walls have seen a decrease in wasted feed due to co-mingling. Commodity bays that are 40- by 50-feet deep with a wall height of 1216 feet minimize overow in adjacent bays.

The size and height of new commodity bay construction can vary by region. In some regions, ingredients are delivered with different style trucks, which plays a role in the construction of space. The specic delivery truck style can also limit availability and timeliness of delivery, or be an extra cost incurred by the dairy.

Harner said a simple way to reduce waste is with regular maintenance on equipment. In a 22-farm study by the Vita

By Emily Breth emily.b@star-pub.com

ST. CLOUD, Minn. — Animal health is one of the top priorities on dairy farms. Kari Ripley-Boysen and Lindsey Zemanek, members of the Wifery Livestock Skills Consortium, shared some of their knowledge about animal care at the 2025 Minnesota Organic Conference Jan. 9-10 at the St. Cloud River’s Edge Convention Center.

Ripley-Boysen has a degree in veterinary medicine and worked as a veterinary technician for a small animal vet. Zemanek also attended college for veterinary medicine before switching majors.

Ripley-Boysen has a hobby farm in southern Minnesota. She has Hohenberg goats, chickens and ducks. Zemanek also has a small hobby farm with mainly sheep but also horses, meat birds and rabbits.

Both women have shared and grown their knowledge for animal health through the Wifery Livestock Skills Consortium.

“We want to provide the skills at our workshops and the tools to give people the (option) to use their own skills,” Ripley-Boysen said.

Six women with vet skills and knowledge established the organization. Ripley-Boysen said the group was launched because many vets in their area were retiring, switching to small animals or no longer doing farm visits. Through the group, they share knowledge in the veterinary eld with producers around Minnesota.

Their goal is to alleviate the stress of vets getting overwhelming calls by educating producers about what to look for and how to care for minor illnesses and parasites. Although the pair knows the most about small ruminant animals, many of their strategies can be utilized across other types of animals.

“I think some people have the mindset, if you have knowledge, you should kind of guard it because it gives you power. (It’s the) exact opposite for us.”

KARI RIPLEY BOYSEN

The pair is a part of the

Consor um and shared informa on on how to check for anemia.

“I think some people have the mindset, if you have knowledge, you should kind of guard it because it gives you power,” Ripley-Boysen said. “(It’s the) exact opposite for us.”

In their presentation, the duo focused on anemia in livestock, what it is and how to check for it.

One way to check for anemia is with the FAMACHA system developed at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, to gauge anemia caused by the barber’s pole worm.

The FAMACHA chart has ve different levels membrane color ranging from blood red to cream white. The deepest red is a sign of a healthy animal while white is severely anemic.

“If you’re looking at a three, particularly in goats you might think about what else is going on with that animal … (and) if you want to (address) it or not,” Ripley-Boysen said. “Four and ve is where I would think about medicating with some sort of de-wormer.”

Even though FAMACHA originated in goat herds it works for most mammals they said.

A method to check on the color for anemia on the membranes around the eyes is the push, pull, pop method. It requires two hands. The rst step is to push the eye of the animal in slightly, pull the lower lid down and the mucus membrane will partly pop out.

“Your rst judgment call on what you see is

what you’re going to gauge it on,” Ripley-Boysen said.

On animals not handled regularly or who do not like being touched, Zemanek said they found it easier to quickly pull down the eyelid and then look at the color of their gums or another indicator.

“If something’s wrong with that, you need to (know) what’s going on,” Zemanek said. “If you can get a look at the membranes, it tells you if you’re dealing with something that’s causing anemia. If it’s causing anemia, it can go fast.”

Many things can cause anemia, including feed rations, iron deciency or parasites.

Each animal reacts differently to the different levels of anemia the pair said. Zemanek said they had a draft horse that was acting off and when checked, it was in the middle range. But with some of her sheep that were acting just a little strange, their membranes were white.

“I have some really thrifty sheep,” Zemanek said.

Even with the shared knowledge between the group, they all know they are still in need of vets in their area.

“We love our vets; we’re not trying to take the place of vets,” Ripley-Boysen said. “We want to be able to do as much as we can in the situations that we need to and (utilize) all of our tools in our tool belt.”

Plus Corporation, 50% of mixer scales were found to be inaccurate. The equipment was never calibrated and binding or load cells were not working properly.

Harner recommended consistent TMR system checks. The study revealed regular problems included TMR frames covered in debris, like mud and feed, support arms that were rusted or broken, shifts in frame mounts, or the mixer itself riding on the frame and not allowing load cells to work properly.

Harner said before setting sights on a new feed center to make sure the current one is running to its highest potential. This is a more cost-efcient way to improve feeding than investing in a new one. Harner said to start by taking care of equipment, ensuring load scales are accurate, cleaning areas and making sure everything works

properly. All this can improve the current feed center.

Another solution Harner presented was focusing on people. Discussing with the feeders their importance to the operation, the importance of each ingredient and explaining which ingredients cost the most each day can help create a better understanding of the importance of efciency.

Harner said understanding how feed affects milk production and herd health is a simple, yet effective strategy to improve feeding efciency. Harner said he recommends dairy managers mix feed on the farm at least once a month. This lets the manager see what the feeders are experiencing. Then, the two can work cooperatively to identify where there is a lack of efciency and discuss ways to improve.

• No rust or corrosion, minimal sweating on the inside of the tank

10:00 a.m. • Cattle 11:00 a.m.

(9) Holstein Tie stall cows. 12 to 65 days in milk. 53 to 74lbs. Reputation set!

PENDING: COMPLETE DISPERSAL:83 Holstein cows. All AI breeding, 68 lb. tank average. Milked in tie stalls, housed in sand bedded free stalls. (8) Angus cross strs 5 to 600 lbs. 2 rounds of shots. (7) Holstein strs 1x vacc. 450 to 600lbs. We accept unadvertised drive-in cattle on

and Bulls VERY COMPETITIVE MARKET PRICES Call 712-432-5500 for daily market report SALE CONDUCTED BY: Oberholtzer Dairy Cattle & Auction Co. Auctioneer: Mark Oberholtzer, WI license #2882-052 Mark Oberholtzer 715-773-2240 Irvin Martin 715-626-0002 • Office 715-255-9600 www.oberholtzerauctions.com

Sale Location: W1461 State Hwy 98, Loyal, WI 54446 From Spencer, WI take Hwy 98

By Stacey Smart stacey.s@dairystar.com

MADISON, Wis. —

When it comes to carbon footprints, milk processors are putting the needs of their dairy farmers above the needs of their customers who sometimes demand a lot of data.

During a milk processor panel at Carbon Conference 3.0 hosted by Professional Dairy Producers Jan. 28 in Madison, four representatives from three processing plants shared thoughts on carbon markets. Those present included Jeff Montsma, U.S. operations milk procurement manager at Agropur; Hansel New, assistant vice president of sustainability strategy and programs at Dairy Farmers of America; and Dr. Paul Rapnicki, veterinarian and director of producer services at Grande Cheese Company. Jacqueline Stroud, sustainability project manager at Agropur, joined virtually.

“Our job as a farmerowned cooperative is to represent farmers and ensure farmer data is protected,” Hansel said. “We want to ensure it is being used in a way that in the end is going to benet farms.”

Hansel said a lot of evolution has taken place in carbon markets, sustainability and the quest for data in the seven years he has been with DFA.

“We’re doing business with all the large internal (consumer packaged goods) companies, and the data requests are not slowing,” he said. “Part of our job is to help determine the boundaries of what information the co-op is willing to share from the farms to do business and what information should be a value-add.”

Stroud said most, if not all, of Agropur’s carbon projects are driven by the customer.

“Four to ve years ago, they started coming to us with requests that turned into demands,” she said. “To build a credible program in the carbon space, it comes down to data, and we need to take this at a collaborative level. It’s important for us to work with every single member of the value chain.”

One of the data pieces is a farm’s carbon intensity score, derived from a tool such as the Farmers Assuring Responsible Management Environmental Stewardship Program. This program gives a customized carbon footprint to farms. From this baseline, a farmer can learn how they compare to other farms in their area and the U.S.

When looking at carbon intensity of farms, all three processors tend to examine the

aggregate data for a milkshed versus an individual score.

to individual farm data, that’s up to the farm.”

Hansel New of Dairy Farmers of America (from le�), Dr. Paul Rapnicki of Grande Cheese Company and Jeff Montsma of Agropur share their thoughts on carbon markets Jan. 28 at Carbon Conference 3.0 hosted by Professional Dairy Producers in Madison, Wisconsin. Not pictured is Jacqueline Stroud of Agropur who joined the conference virtually. Turn to CARBON

“We’re particularly concerned with the milk pool and how that number can be brought down over time through projects or incentivebased programs,” Hansel said. “Customers are all for that and want to support with cost-share opportunities. When it comes

Grande has 65 producer dairies and has done FARM ES on over 90% of its milk.

“CI scoring is only part of what we need to understand about our milk supply,” Rapnicki said. “How our farms treat their employees and animals still matters. Fifteen years

ago, the questions were mainly around animal welfare. Since carbon has taken off, our welfare questions have dropped to nearly zero. Assuring animal welfare is still critically important to our farms and for us in running our business.”

Stroud said there are opportunities in other markets for producers to gain incentives based on CI scores. Individual farms are asking what type of incentive they can receive if they make adjustments to lower their score.

“When you start implementing programs, you’re trying to bring down that number as much as possible so you go after the producers who might not be at the forefront of some of these initiatives,” Stroud said.

Some DFA customers are asking if they can get milk from farms with low CI scores.

“We certainly wouldn’t give away those low-carbon farms for free,” Hansel said. “How much is that worth to the customer? And more importantly, how much is it worth to the farmers who are already leaders in this space? It’s interesting to see where that goes down the road and if there will be customers willing to pay.”

Historically, and up to today, Stroud said incentives have been project-based at Agropur. If a producer wants to implement a new practice or activity, Agropur offers grants or supply chain funding to incentivize.

For example, Agropur has been using Nestlé and U.S. Department of Agriculture grants as a project-based incentive on the front end in its central milk region where product for Nestlé is sourced.

Stroud said they keep tabs on what the leaders are up to. Through a performance gap analysis, they see where the market is heading and determine action items.

“Customers are taking a step back and saying they don’t want to manage these projects anymore for the farms; they just want to see the results,” Stroud said. “They want to see a line item with the cost of the product they are buying and the carbon footprint of that product, but it’s not widespread in the market.”

For farms with generations of low CI scores, Stroud said it is their turn to get some of these dollars.

At DFA, incentives are outcomebased through existing carbon markets. The downstream customer agrees to take a certain number of credits for the year or for the next ve years at a specied price.

“The last couple of years, we’ve seen a shift from upfront, incentivebased payments to outcome-based programs,” Hansel said.

Grande Cheese Company currently does not participate in any incentivebased programs.

“We have not seen any impact on our ability to do business based off the CI score,” Rapnicki said. “We’re not a consumer-facing brand. We go to restaurant operators, and they’re not ask-

ing us about CI scores. Five years down the road, the CI score of the milk might be more important.”

Rapnicki said in some areas however, reporting carbon might become a cost of doing business.

“We don’t make cheese in California, but we certainly want to sell into California,” he said. “In that case, we’re being regulated to do it for market access.”

Hansel said DFA continues to champion that farmers should be able to choose between an inset market where available. If unavailable, a farm should be able to enter an offset market without penalty.

“It’s their carbon and it’s their reductions that they should be able to monetize,” Hansel said. “It’s the carbon rules globally that need to evolve to be able to adequately recognize that.”

Hansel said carbon market rules were not written for agriculture and forestry.

“They were written for the emitters, not an industry like ag that can be both an emitter and a sequester,” he said. “The rules have to change.”

Rapnicki said producers can be the ones to drive discussion of changes in rules.

“There is no expert with all the answers, so we need to gure this out because no one can tell us exactly what the answer is,” he said. “We need our producers’ help to gure out where this needs to go.”

Hansel said demonstrating sustainability is necessary to maintain milk markets.

“We maintain that data has value, and we’re more than willing to give them the compliance data they need to maintain open milk markets and be a supplier of choice,” Hansel said. “There does come a point where we’re going to push back on the amount of data requested and use that as a negotiating point.”

Stroud said the processor is in a unique position.

“We’re going to be asked everything,” she said. “It’s our job to lter out what is actually required for this relationship and what’s a nice-to-have. Customers probably use 2% of the data.”

Rapnicki said quality is what moves products off shelves for processer and customer.

“We’re committed to supporting the U.S. dairy industry, which is the most efcient across the world at producing a pound of energy-corrected milk,” he said. “We’ve seen a lot of hot topics come and go. This is a hot topic, and it will be interesting to see where it goes next. What’s real is going to stick.”

From the kitchen of Deb Cota, Tomah, Wisconsin

1 1/2 cups mayonnaise

3/4 cup sour cream

1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

1/2 tablespoon dry mustard 1/2 tablespoon garlic powder

3 ounces blue cheese crumbles

Mix all ingredients in a bowl; store chilled.

From the kitchen of Deb Cota, Tomah, Wisconsin

1 box spice cake mix

1 can pumpkin puree

1 cup water

3 eggs

1/2 cup vegetable oil

Mix cake mix, pumpkin, water, eggs and oil in a bowl. Pour into a pan. Bake 30-33 minutes at 350 degrees until toothpick comes out clean. Pull out of the oven, poke holes all over the cake and spread 1/2 cup of caramel sauce over the top. Set aside to cool. While cake is cooling, prepare cream cheese frosting. Mix cream cheese, powdered sugar and milk until smooth. Fold in whipped topping and then frost cake. Drizzle the rest of the caramel sauce over the top.

The best quality feed needs the best quality mix. Penta TMR Mixers are designed, tested and farm proven to deliver the best mix on the market. Our Hurricane Auger allows forage to circulate faster through the mix for quicker processing and mixing times.

www.pentaequipment.com

‘17 Gehl RT250, ISO/Dual H-Ctrls, Dsl, Camso Tracks HXD 450x86x58, Both Standard and Hi-Flow Hyd, 2 Spd, Hydra Glide, 295 hrs, Warranty

till 6-30-26 or 1000 hrs ................................$48,500

‘18 Gehl R220, JS Ctrls, Dsl, 2200 Lift Cap, SS, 4,854 hrs ...............................................$17,500

‘17 Gehl R220, H-Ctrl, Dsl, 2500 Lift Cap, C&H, 2 Spd, 4635 hrs..................................$28,500 Gehl V400, T-Bar Ctrls, Dsl, 4000 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, 2,570 hrs ..............................$37,750

‘21 Gehl V330, JS Ctrls, Dsl, 3300 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, Hydra Glide, 1224 hrs ..........$53,900

‘19 Gehl V270, JS Ctrls, 73HP Dsl, 2700 Lift Cap, C&H, 2 Spd, 250 hrs ...........................$57,500

‘19 Gehl R260, T-Bar Ctrls, Dsl, 2600 Lift Cap, C/H, 2 Spd, 1,400 hrs .........................$39,500

Gehl RT135, ISO Ctrls, 46HP Dsl, 1350 Lift Cap, C/H/A, SS, 107 hrs. .....................................$46,500

‘21 Gehl RT165, T-Bar Ctrls, Dsl, 15” All Season Tracks, 2150 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, 2,015 hrs......................................................$36,000

‘20 Gehl RT165, T-Bar H-Ctrls, 70HP Dsl, 15.5” All Season Tracks, 2100 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 1,875 hrs......................................................$36,800

‘21 Gehl R190, T-Bar Ctrls, 69HP Dsl, 2000 Lift Cap, C&H, 2 Spd, 1,184 hrs.

Gehl 4835, T-Bar Ctrls, Deutz, C & H, SS, 4,600 hrs..................................................... $15,500

‘23 Manitou 3200VT, ISO Hyd Pilot Ctrls, 3.6L Dsl, 114HP, 4572 LBS At 50%, 3200 LBS At 35%, Machine Weight 11,800, Standard and Hi-Flow (38GPM) Hydraulics, C/H/A, 2 Spd, Fold Up Door, Camera, All Season Tracks, Warranty Until 8-23-2025............................................$77,900

‘23 Manitou 1900R, H/F JS Ctrls, Dsl, 2100 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, 185 hrs .................................$48,500

‘22 Manitou 1650RT, H/Ft Ctrls, Dsl, 12” Tracks, 1650 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, 169 hrs .........$56,500

‘21 Mustang 1650R, H/F Ctrls, Dsl, C/H/A, SS, 3,640 hrs ...............................................$32,900

‘18 Mustang 1650RT, H/F Ctrls, Dsl, 2350 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, 975 hrs ..................$48,500

‘20 Mustang 1650RT, H/F Ctrls, 68HP Dsl, 2350 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, 1,517 hrs ......$38,700 ‘19 Mustang 2150RT, Hyd Pilot- H Ctrls, 72HP Dsl, 18” All Season Tracks, 3000 LBS At 50% Tip Load, C/H/A, 2 Spd, 660 hrs .................................$44,900

‘19 Mustang 2700V, ISO Ctrls, 72HP Dsl, 2700 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, Hydra Glide, 14 Pin, Back Up Camera, 261 hrs. ............. $58,900 ‘16 Mustang 2200R, ISO/Hyd JS Ctrls, 72HP Dsl, 2200 Lift Cap, C/H/A, 2 Spd, 3,375 hrs ......$35,500 Bobcat 7753, H/Ft Ctrls, Dsl, 1700 Lift Cap, SS, 6,300 hrs

manitou.com