#Period

By Katarina Baumgart

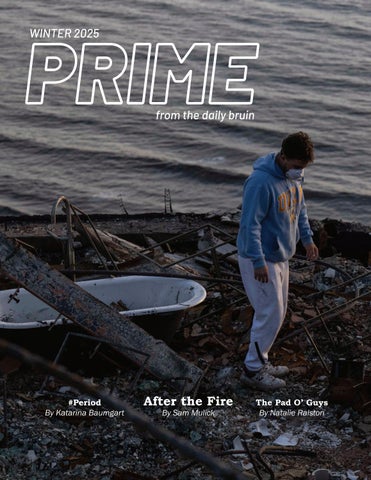

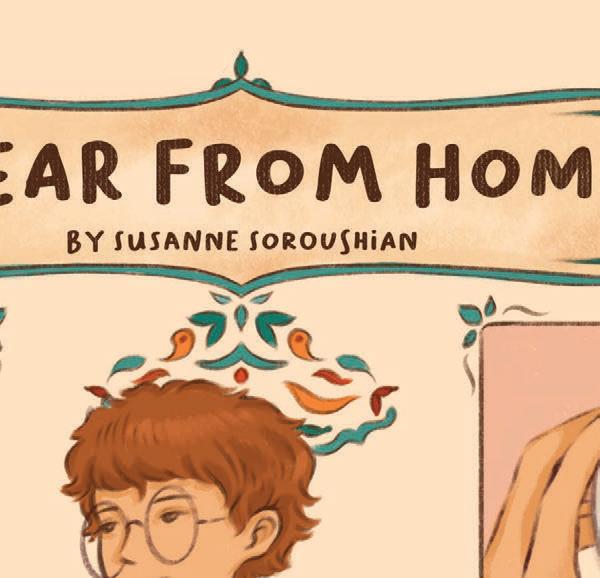

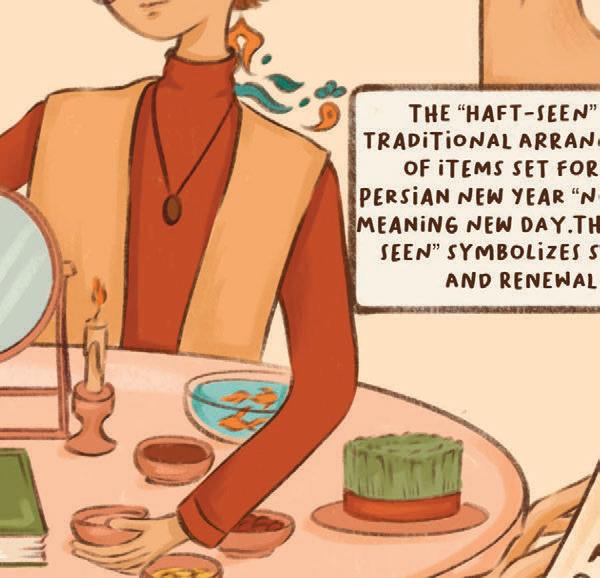

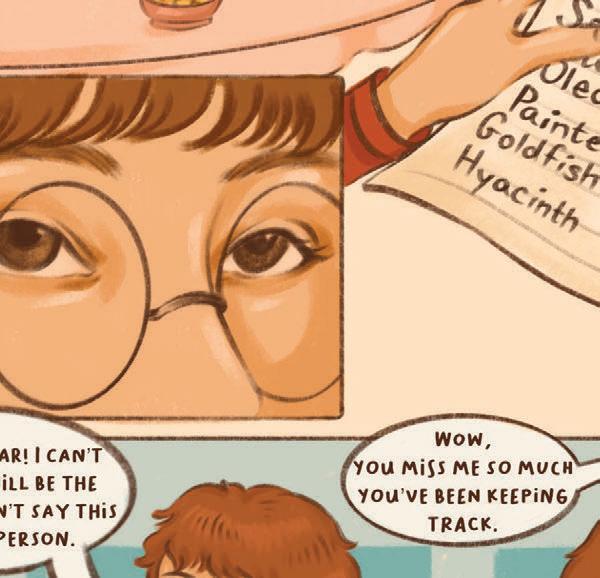

After the Fire

By Sam Mulick

By Natalie Ralston

#Period

By Katarina Baumgart

By Sam Mulick

By Natalie Ralston

Dear reader,

Winter quarter is typically a time of routine. New students have their feet on the ground, and seniors march through their penultimate quarter en route to graduation.

This quarter broke that routine. The school year began with wildfires across Los Angeles, impacting every Angeleno as tens of thousands of acres burned. UCLA students and faculty were compelled to evacuate as air quality worsened and the fires spread. For some Bruins, the impact was far more than a temporary shift to online school, with lives completely upended after the costliest natural disaster in California’s history.

Leo Rochman is one such Bruin. Our cover story, “After the Fire,” focuses on his experience losing his home in the Palisades fire and his efforts to support his family and community in the aftermath. PRIME staff writer Sam Mulick committed himself completely to this piece – he spent hours in interviews with Leo, drove out to see the Rochmans’ properties firsthand and even captured our cover photo for this magazine. We are grateful to Leo’s openness and Sam’s dedication to crafting the best possible profile, and we cannot wait for you to read Leo’s story.

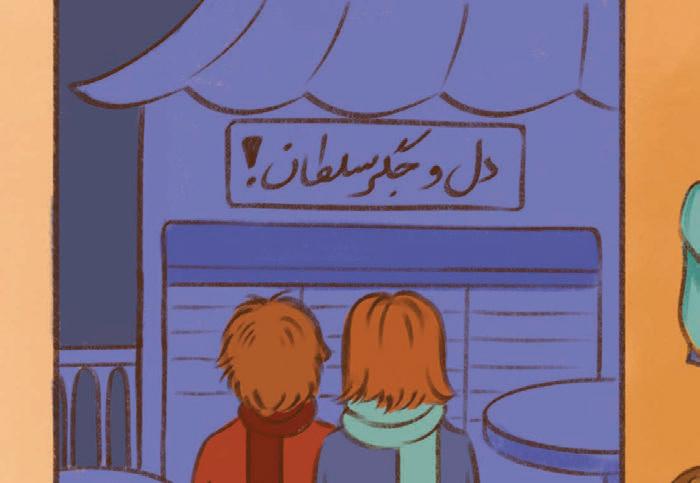

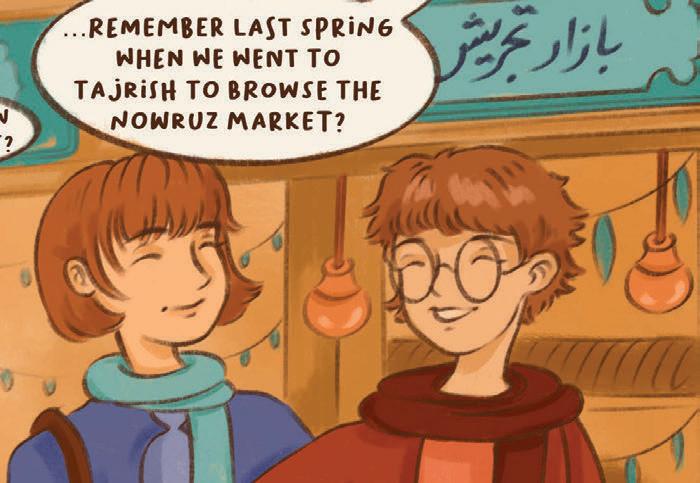

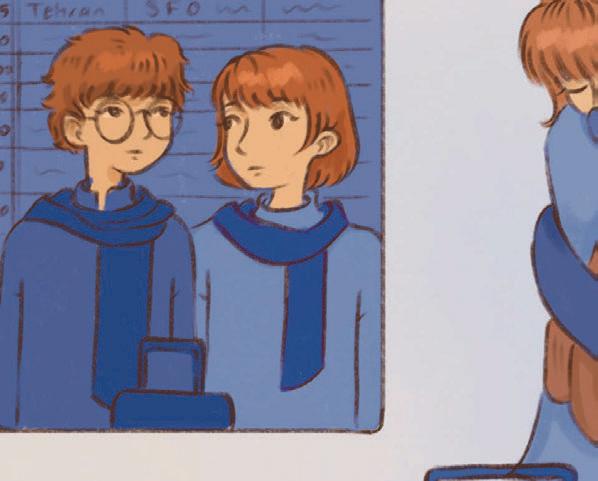

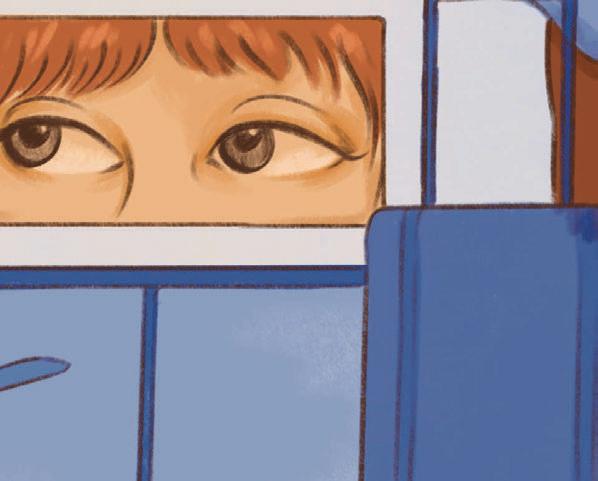

Beyond our cover story, this magazine also captures other paradigm shifts – for example, PRIME contributor Sasha Zimet explores the students and professors embracing generative AI in the classroom setting. Other articles capture those changes on a personal level, such as PRIME staff writer Katy Nicholas’ shifting worldview studying abroad in Nepal or Susanne Soroushian’s first year from home in Iran – captured in graphic novel form.

No matter which story you read first, we hope it reveals a new experience or perspective from across our UCLA community. Thank you for picking up our magazine, and we hope you enjoy.

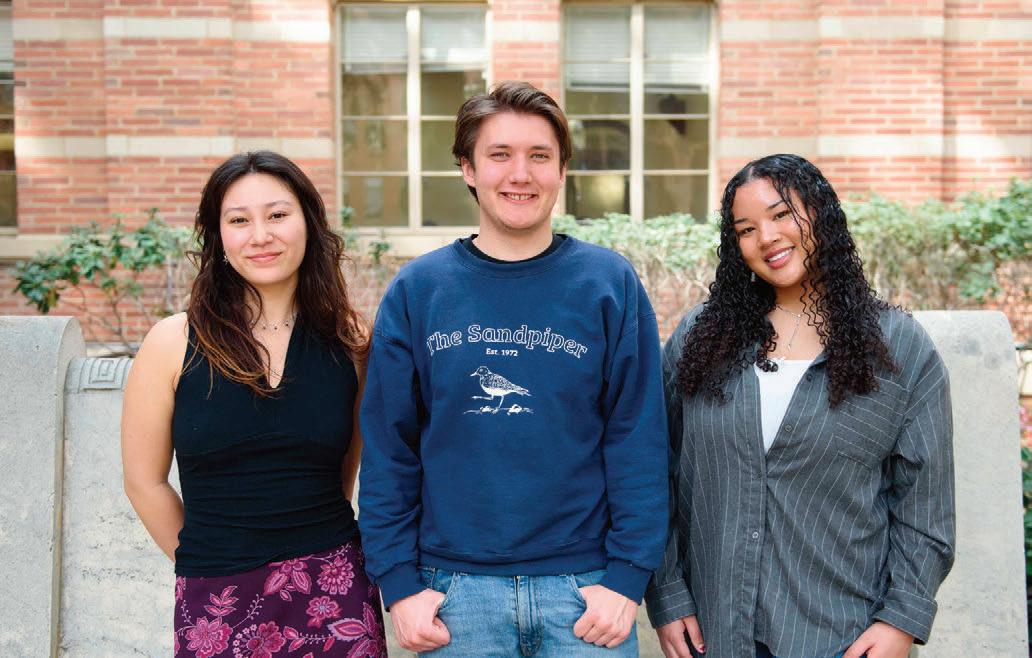

Isabel Rubin-Saika PRIMEart director

Martin Sevcik PRIME director

Alicia Carhee PRIMEcontent editor

CAMPUS

6

CONTENTS WINTER 2025

Generative AI, the New Teacher’s Pet?

written by SASHA ZIMET

LIFESTYLE

11

Beyond the Bargain

written by DANIELLE WORKMAN

16

written by ANDREW WANG CULTURE

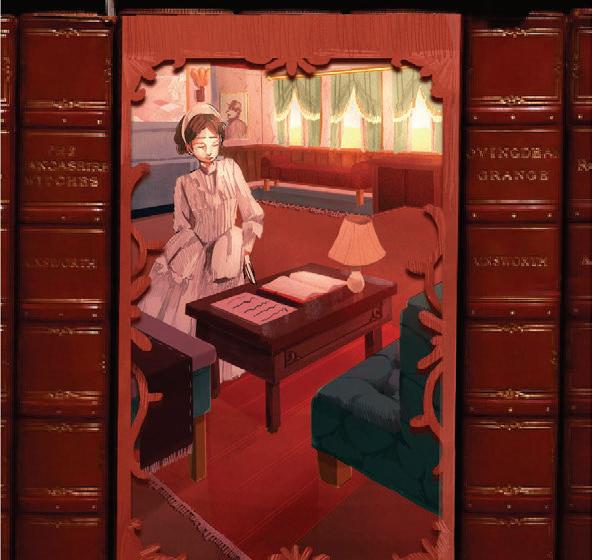

Stewarding the 19th Century

FEATURE

20 The Pad O’ Guys

written by NATALIE RALSTON

After the Fire written by SAM MULICK

33 PERSONAL CHRONICLE

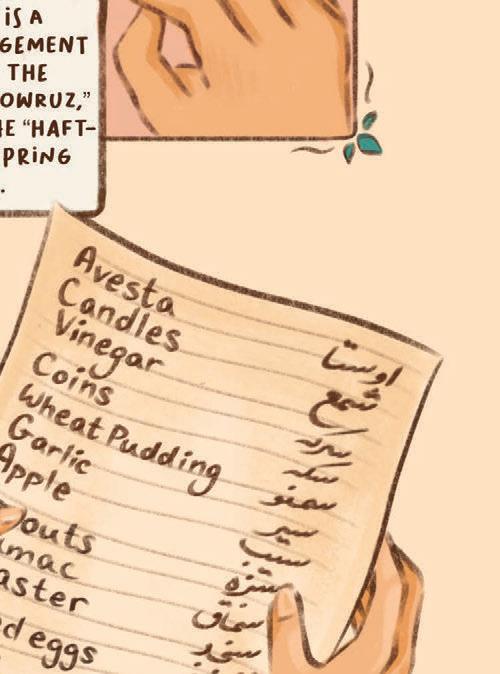

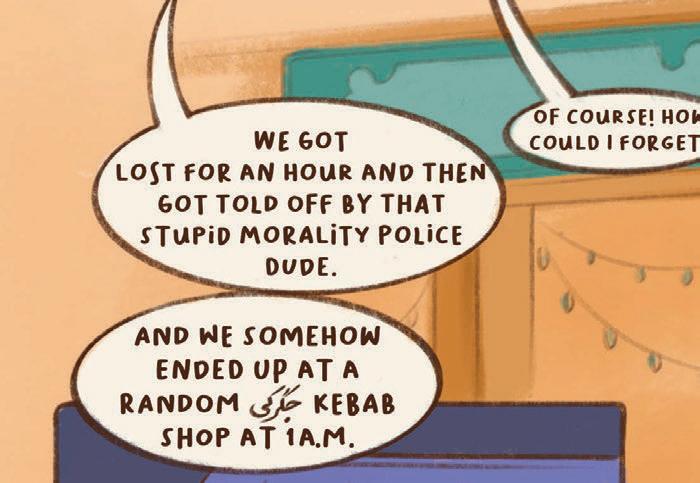

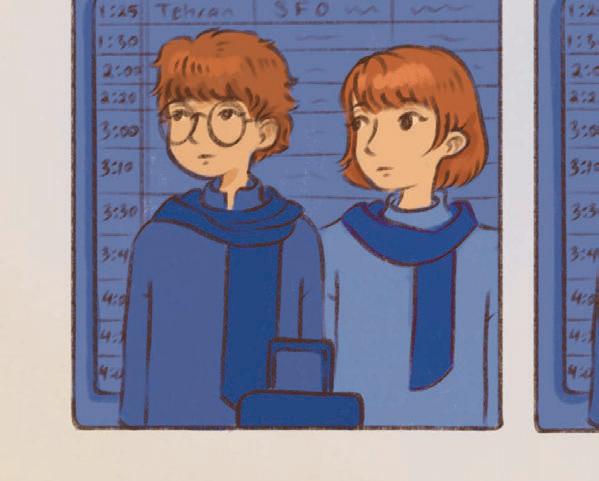

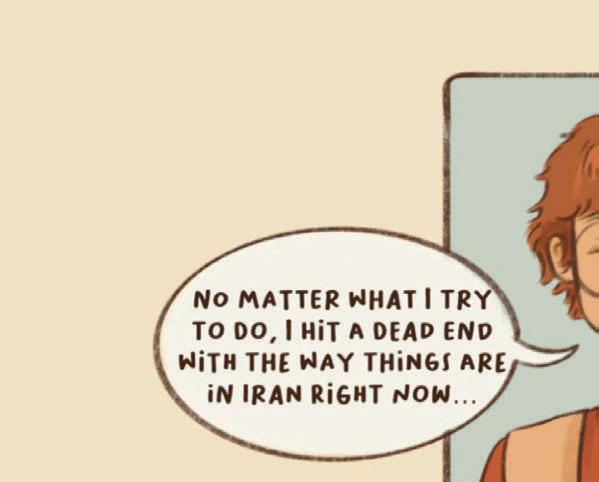

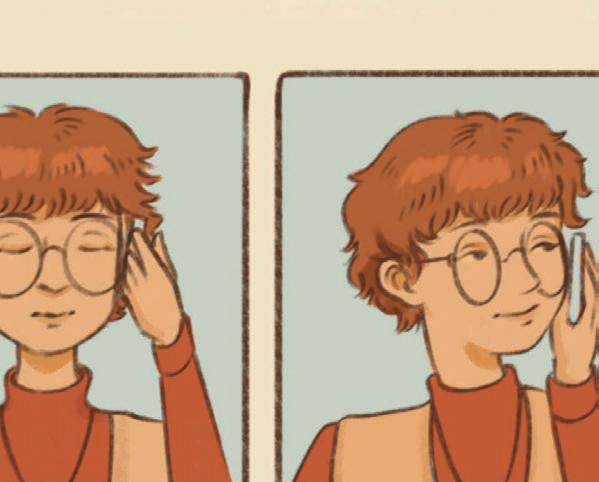

A Year From Home

written by SUSANNE SOROUSHIAN

37 #Period

written by KATARINA BAUMGART

TRAVEL DIARY

42 In the Mountains of Nepal

written by KATY NICHOLAS

written by SASHA ZIMET

illustrated by SHIMI GOLDBERGER

designed by PACO BACALSKI

I’m not afraid of many things. Heights are just glorified elevations; spiders, just misunderstood creatures; public speaking, just multifaceted conversation. So it came as a surprise to learn I was afraid of something that existed within the pixelated confines of my computer screen: generative artificial intelligence. And at UCLA, I’ve been forced to come face-to-face with it more than I ever expected.

Generative AI came into my life as quickly as it can generate text. I sat in my high school English class –daydreaming about everything but the assigned “Pride and Prejudice” analysis – when my teacher interrupted my churning imagination with a brute, disappointed tone. She claimed my neighboring classmate had copied and pasted her prompt into ChatGPT’s text box.

She challenged his integrity and forewarned the rest of us students about using this new tool. Perplexed, I turned to my classmate charged with the offense and asked him what ChatGPT was. His eyes widened, sparkling with ambition as he introduced me to this technological Narnia.

Now, ChatGPT is what appears in all my peers’ search engines when they type a “c” into the Google search bar. For me, however, it has remained an enigma. Don’t touch it, don’t talk about it – but use it coyly with a dimmed browser to ask whether your email is professional or not. At least, those were my guidelines until coming to UCLA, where I found generative AI being embraced by professors and students alike.

I set out to explore how generative AI is being used in the classroom, shaping the ways professors teach and students learn. Since its rise to the mainstream in the early 2020s, some have praised its ability to personalize learning and streamline lesson preparation, while others warn of its social biases and unwarranted use in the classroom. With AI cementing a place in academia, some UCLA professors and students are learning how to adapt –and embrace – this technology for the classroom.

Despite its recent rise, generative AI first appeared in the 1960s as chatbots. The tool has since slowly meandered its way into active use. In 2022, however, there was a drastic surge in its popularity after the introduction of GPT-3.5 – which was uniquely able to generate an answer to almost any postulate at any time, often within seconds. As soon as students learned how to use the software, it began proliferating in classrooms, leaving teachers with the difficult question of how to manage its use.

Ashita Singh, a third-year computer science student and president of Bruin AI, said AI is at the forefront of innovation. She is excited to keep using the evolving tool in several capacities throughout her work.

“It’s already getting everywhere, and it’s probably going to be more widespread as times go and as more

technology is developed,” Singh said.

UCLA in particular is open to the use of this evergrowing device. UCLA was the first California university to implement ChatGPT use in its academic, administrative and research operations. ChatGPT Enterprise can be accessed by UCLA students, staff and faculty alike, instituting an AI-friendly ambiance on campus, according to a UCLA press release.

Other universities are embracing this technological change as well. The California State University system recently announced an initiative to become the nation’s first and largest AI-empowered university system. In this deal, CSU said it planned to provide cutting-edge tools to faculty and students, which would create a hub of learning opportunities.

Many professors were initially hesitant to embrace these tools. Leslie Bruce, a lecturer in the English, comparative

“ChatGPT, just like any other tool, is not in itself bad or good.”

literature and linguistics department at CSU Fullerton, teaches faculty how to adapt to AI. She described how she had banned the use of ChatGPT in her class in 2023, much like my own high school teachers. Even with this ban, she experienced a deluge of unoriginal essays turned in by students, all interlaced with AI-generated errors.

“I’m going to probably know that you used AI where you weren’t supposed to be using it – but more importantly, that reflects on your credibility as a writer,” Bruce said.

UCLA professors also experienced a wave of unoriginal essays, with students caught AI-handed left and right.

Elizabeth Landers, a UCLA doctoral candidate in history, said she experienced an influx of AI-generated essays as a teaching assistant. This challenged her mode of assessment, as she and other instructors navigated possible solutions to reducing the amount of AI-generated assignments.

But rather than banning the use of ChatGPT in her classroom, Zrinka Stahuljak – a professor of comparative literature and French – collaborated with Landers to see how they could teach students to use the tool to improve their writing.

“ChatGPT, just like any other tool, is not in itself bad or good,” Stahuljak said. “It is what we do with it.”

They worked together to design a lesson that would teach students the flaws of an entirely ChatGPT-written essay, demonstrating how to use the tool rather than ignore it. Landers said a lesson plan might start with asking ChatGPT to write an essay based on a given prompt and then critiquing the essay to demonstrate the technology’s strengths and weaknesses.

“Right now, it’s about figuring out how to use it to make a better experience for the students, for the TAs and for the faculty,” Landers said.

Before my conversation with Landers and Stahuljak, I had primarily considered generative AI a tool for crafting complete written works – writing entire blog posts or stories at the press of a button. But Landers’ suggestion to use AI as a helping hand began to creep its way into my own writing. If I had an essay, an email or anything else I wanted to proofread, I began to ask ChatGPT instead of a friend.

“We feel like AI will unlock the power of humans in the courses and actually get more human interaction time.”

Landers said they wanted to incorporate AI tools in ways that enhanced learning about the material as well as the tools themselves.

After about a year of banning generative AI, Bruce also came around to using it as a helping hand. In 2024, she lifted the ban on ChatGPT in her classroom and encountered a stark improvement in student performance. She found that not only did the number of blatant errors diminish, but also, students were able to express themselves better, enhancing their writing skills. She began to encourage students to use generative AI chatbots as starting points for their work, as well as potentially experimenting with

them as proofreading tools.

Students like Singh are also identifying generative AI’s role as a helper, not a doer.

“It should be used as a learning tool,” Singh said. “It should not be used as an escape from learning.”

adapt to students’ different preferred ways of learning. Whether it be a podcast for a student who learns better through hearing rather than reading or a chatbot waiting to answer a student’s question, the textbook molds to entice active learning from students.

“My point has been that this is not about replacing but about enhancing,” Stahuljak said. “I couldn’t do a whole number of things with the students that I can do now.”

And also for students like Singh, generative AI can be used beyond academics. Singh said Bruin AI uses generative AI to better prepare Bruins for the professional world, especially as companies continue to adopt this technology. Bruin AI has worked with tech companies on projects but has also worked on projects related to human resources startups, insurance firms and other companies without a direct connection to AI.

For burgeoning generative AI companies, UCLA can create opportunities for AI experimentation in syllabi and course curricula. This quarter, Stahuljak and Landers designed a course that uses an entirely AI-generated textbook made by educational company Kudu. The move generated some controversy within the academic world, with one professor specifically criticizing the textbook for coming at the expense of teachers as well as those who genuinely care about learning.

Landers and Stahuljak have more positive things to say about the textbook’s implementation. Stahuljak said generative AI was not the sole source of knowledge but instead a stepping stone in creating the textbook, expanding her capabilities as a teacher.

She and Landers added that there was a significant increase in student participation in lectures with the use of this textbook. Landers also said the AI textbook can

Warren Essey – one of Kudu’s founders – added that in Stahuljak’s textbook, generative AI was used to further incorporate the professor’s “wishlist” of items in a time- and cost-efficient manner. AI wasn’t the scribe, just the pen, and humans were heavily involved in the process, he said.

“Ironically, we feel like AI will unlock the power of humans in the courses and actually get more human interaction time,” Essey said.

Bruce added that in her experience, students’ confidence can be uplifted through the use of generative AI. The technology can help students learn at their own pace, such as by distilling texts to simpler reading levels to make them more approachable.

“You can take a really complex text that you want students to read, and you can show students how to translate parts of it into, say, a 10th-grade reading level – so that the first time they read it, it’s not so intimidating,” Bruce said.

It was this example in particular that made me reconsider my reluctance toward generative AI. I can think of numerous instances in which I’ve procrastinated assignments because of frustration with

“You do have to know that this is your own risk.”

about the world’s elections, got one in five responses wrong.

But other students aware of this issue do not view generative AI with such pessimistic optics. Kevin Lu, Bruin AI’s financial director, asserted that generative AI is not perfect – but as long as students and professors view it with this informed lens, he said it can still be used to enhance one’s learning.

“You do have to know that this is your own risk,” he said. “It’s just unfortunately a tool at this point – and whether you use it correctly is up to you.”

Landers added that controlled and specific use of AI tools can minimize bias and inaccuracies. In the case of her AI-generated textbook, she knew the exact inputs it was using and therefore trusted its ability to produce accurate material in line with her teaching goals.

“The AI is not going out and searching Wikipedia and random websites to come up with information. It’s only basing itself and all of the content on that which we have given it,” Landers said.

Bmy comprehension. Letting the verbiage of the United States Constitution best me, daydreaming instead of close-reading “Pride and Prejudice” – these are all things that might have been prevented if my fear of the artificial unknown did not consume me.

Even with these benefits, professors still identified flaws with the technology in a classroom setting.

For example, AI exhibits gender and cultural biases. Bruce described an incident in which a professor asked AI to generate information about two artifacts: one from a Western culture and one from a non-Western one. The program generated lines and lines of information about the artifact from the Western culture and just a few sentences on the non-Western one.

“It was much more effusive about the Western artifact –as if it were more important,” she said.

Bruce also identified a gender bias in generative AI, which has been observed by her academic peers and AI investigators alike.

In a study published by UNESCO and its International Research Centre on Artificial Intelligence, researchers found that when various large language models were asked to construct narratives about both men and women, they were much more detailed and rich in their accounts of the men’s stories. Men were described with adjectives such as “adventurous,” whereas women were “gentle” and consistently had husbands in each scenario. This gender bias, according to the study, is woven into the core of generative AI.

In tandem with these social biases, it has been largely reported that AI is frequently wrong. According to Bloomberg, even the most polished generative AI models, when tested with questions as simple as information

In the face of these concerns, Stahuljak said the proliferation of AI mirrors technological advancements in writing from the past – and it is but a new component of the forever-evolving writing timeline. Stahuljak said scribes were once laid off during the growth of print workshops, fueled by the printing press. Those scribes soon adapted to printers and carried writing in a new direction.

To her, generative AI is just another example of this innovative progression, acting as the printing press of an evolving technological landscape.

But we are still in the early days. ChatGPT took the world by storm less than three years ago. My classmates then – and my classmates now – are coming to terms with this auspicious tool, sharing questions and knowledge to further shape and sharpen it. In my reporting, my understanding of generative AI as taboo was challenged. Rather, professors and students have found it tentatively helpful as a learning tool – and I’ve begun to see it the same way.

Bruce said the technology is not only here to stay but to grow. She said its use will infiltrate the lives of all –students, professors, anyone – including by enhancing expression for those without strong writing skills.

She described a future where my peers will no longer have to type the laborious “c” into their search engine, because generative AI will be the search engine itself – drastic change bubbling to the surface and altering schools such as UCLA forever.

written by DANIELLE WORKMAN

designed by MIA TAVARES

photographed by VIVIAN LE

Iam no longer allowed to buy jackets.

As a chronic shopper since I was 4 years old, my closet was stuffed with an endless supply of jackets, vests, belts and other pieces of clothing that still ha had tags on them. Waste was an important topic in my household, but growing up, I had only considered it in the context of clearing my plate – finishing every bite of food to avoid being wasteful. It never occurred to me that waste could also mean an overflowing closet, full of clothes I barely wore – consuming resources just to sit untouched. So when my mom instated my “no jackets” rule, I simply thought she wanted me to freeze at school.

Savers. After hours of sifting through bins, I left the thrift store empty-handed and frustrated. When I complained to my mom, she just shrugged. She told me that once I found something I liked amid all the clothes I didn’t, I would love and appreciate it that much more.

At the time, I rolled my eyes. But later, as I stared at the untouched jackets in my closet – tags still dangling – I started to understand what she meant. Now, after years of rifling through racks and scouting for Pasadena’s best thrift stores, I have found unique clothes I will cherish forever – from a vintage Burberry coat I took on my senior trip to Italy to a checkered sweater I wore for my first day at UCLA.

Following my jacket ban, I tried slipping various sweatshirts, cardigans or any jacket alternative into shopping carts while out with my mom. Sensing my desperation for a loophole, she gave me one way out: The only jacket I could ever buy had to be thrifted. My mom thought she had me beat, knowing my distaste for secondhand shopping and its negative reputation at the time.

However, a TikTok video of a girl thrifting a “The Birds Work for the Bourgeoisie” sweatshirt, a 2019 trend I found absolutely hilarious, motivated me to trek to my local

Young people across the United States are becoming conscious of the waste in their closets and shopping habits. Generation Z has turned away from overconsumption, flooding “For You” pages with thrift hauls and warnings about the fast fashion industry. But thrifting isn’t just a phenomenon on social media. At UCLA, students, professors and organizations are using thrifting and secondhand fashion as tools to cultivate stronger, more connected communities built on shared values of creativity and sustainability.

Thrift culture’s popularity fast fashion, a relatively recent development in American fashion consumption.

in response to the trends, at the expense of wear – leading unworn some

Felipe Caro, a professor of decisions, operations and technology management at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, explained that the fashion industry used to be based mostly on collections – seasonal groups of clothing and accessories based on a specific style or idea –lasting up to six months. The development of fast fashion producers such as Zara and H&M flipped the script, introducing new products in as quickly as a few weeks and aiming to capitalize on consumers’ desires for current trends, often at the expense of quality. The fad-based business model of fast fashion incentivizes frequent purchases, even if consumers don’t use or wear them to closets full of unworn jackets, like my own.

Caro added that some companies, such as Shein or Temu, produce at rates exponentially than with inferior quality, leading waste overall than the seasonal

around sustainability, said

Sam Trezona, a fourth-year ecology, behavior and evolution student. Initially introduced to thrifting through social media, Trezona has since expanded their personal commitment to sustainability

introduced to style.

“Thrifting was my entry point into sustainable fashion, much like many people,” Trezona said. “I saw it on TikTok at some point and was like, ‘OK, I’m going to do this.’”

“I’ve heard of people that buy them, and if they don’t like them, they immediately throw them away,”

Caro said. “They don’t even bother returning them because they’re so cheap.”

These issues of overconsumption in fashion are frequent topics of online discussion among youth today. Thrifting is one response that has gained traction and serves as a sustainable and mindful alternative to fast fashion.

Thrifting initially was primarily a practical choice driven by necessity in its early history, but it has

journalism she and fashion of RefineLA, to much more model. always been centered a sustainable fashion club on campus. “I try to thrift

new I am are

Lauren Kim, a second-year public affairs and sociology student, said she began to thrift after social media highlighted it as an eco-friendly way to score individual, one-of-a-kind pieces. Since coming to UCLA, she has become the director of FAST at UCLA, which university’s first organization, and a member the vast majority of my clothes,” Kim said. “Nowadays, the majority of the clothes that secondhand, through some kind source, whether that’s thrifting

of source, that’s or vintage.”

content as a surge in with

Kim and Trezona credit social media for the boom of thrifting. They both identified thrifting creators as surge in popularity, with influencers like Ashley Rous –and

Emma Chamberlain piquing the interest of them and their

Influencer Alena Yuan, a fourth-year communication and economics student, is one of the creators contributing to the thrifting craze, promoting secondhand fashion in her videos. Since her first exposure in secondhand fashion from the handme-downs gifted to her by her mom, Yuan has thrifted since high school as a way to get clothes for cheap. Yuan began to collect her tips and tricks on building one’s style affordably a decided to make videos to share them with others.

She started her TikTok page this past summer, sharing aimed at helping followers explore their fashion style and discover beauty products on a budget. Now surpassing 700,000 followers across social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram and YouTube, Yuan has been able to reach her

aimed at followers explore fashion

“Thrifting is a lot more mainstream now, so a lot more people go thrifting, even if they don’t necessarily need it,” Y said. “A lot of college students at UCLA are very sustainable, eco-friendly kind of people, so it also helps build a more

Not only does thrifting help young people take on overconsumption and sustainability issues, but it also serves as a catalyst for community – from online spaces like Yuan’s to networks of fashion enthusiasts and buzzing flea market

Once a month in Westwood, locals can thrift at the Bruin Flea, an outdoor market bringing local businesses and brands together to support small vendors and build community. Luis Lopez, founder and creative director of the Bruin Flea, created this market on the front yard of a UCLA fraternity house in 2022 and is now hosting vendors all the way down at Broxton

Lopez got his start in flea markets as a kid, helping his mom sell fragrances and makeup at their local swap meet. Eager to join in on the fun, Lopez started selling small toys – sparking growing interest in sustainable entrepreneurship, he added. His focus soon turned to thrifting, be it clothes, furniture pieces even a UCLA lamp he found and later gifted to a friend.

“Repurposing, rebuying, recycling, reusing clothing – all the ‘re-’s – that is 100% what you’re advocating for when you’re

Lopez hopes to use the Bruin Flea to help fashion-forward students and vendors create a community centered around

For many vendors, that community is growing. Nestled among her dozens of racks and bins of vintage clothing, Laura Wences – a San Jose State University alumnus and owner of the secondhand fashion business With Laura Co – can be found selling at the Bruin Flea market. Inspired by a flea market booth selling handmade earrings, Wences initially started out in the sustainable fashion scene by making bucket hats by hand. At the Bruin Flea, she now sells vintage and upcycled clothing, such as a Free People-inspired jacket she made out of

with the help thrifting. scenes. Avenue. a or thrifting,” Lopez said. sustainable, secondhand clothing. thrifted baby blankets.

“Now, I can give back to students who want sweaters, who need jackets, who need affordable clothing. Any offers I get (to sell at the Bruin Flea), I try to just say yes to,” Wences said

Wences met Nicole Chrisney, a UCLA alumnus from the class of 2019 and owner of the fashion brand REBELFLOW, at a past Bruin Flea. Their friendship started when Wences offered to look after Chrisney’s booth as Chrisney was packing up. At the January Flea, Wences and Chrisney’s booths were positioned next to each other, allowing them to make small talk between sales.

“We’re all in this together, and we’re all one person,” Wences said. “I always tell all my vendor friends, ‘Look, markets don’t happen unless we’re there. It’s vendors, markets and then the customers. If it’s all strong and working well, it’s going to be a good market.’”

At its core, Lopez said the relationships between every participant at the market, be they customers or vendors,, is what the Bruin Flea is all about.

“It’s about the vendors, and it’s about the people who get to go shop there and that interaction,” Lopez said. “It’s about the people who are coming to shop and connect and learn from one another.”

Other members of the Westwood thrift community are bringing similar attention to creating community through a shared love for fashion.

Now the president of Unravel at UCLA – a fashion club centered on sustainability and social justice – Trezona leads club members through events ranging from smaller-scale thrift trips to largerscale runways, exhibitions and community engagement workshops.

“Being around so many people who are so creative and so passionate about what they do is just really exciting,” Trezona said.

preparing for their winter quarter exhibition, titled “Thrifting: A Critical History,” Unravel at UCLA and Trezona have prioritized highlighting thrifting’s deep relationship with sustainability and equity. Throughout the first week of March, Unravel at UCLA presented five different sections in its exhibition in Kerckhoff Art Gallery, taking viewers through the history of thrifting with various art installations. The exhibition emphasized the origins of thrifting in minority and low-income communities and its current challenges to rising prices and fast fashion, its history outside its current appeal.

In preparing due to prices highlighting its mainstream

“This art gallery about the history of thrifting is mainly a reflection,” Trezona said. “Everybody loves to thrift. You walk around campus, you talk to people about Unravel, they hear ‘sustainable fashion,’ and they immediately go, ‘Well, I love thrifting.’ And while that’s great, there is a part of thrifting culture that has become a trend.”

While thrifting has created hubs for community and sustainable efforts, it also raises a bigger question: Does it actually address the unsustainability of the fast fashion industry, or does it simply offer an alternative within the same cycle of consumption?

Students like Kim and Trezona wondered if the thrifting trend is really rooted in sustainable efforts. Trezona explained that while thrifting is a great practice, thrifting just to film a haul, score a deal and never wear the clothes you bought doesn’t solve the problem.

“This was always meant to be community-building, and I think focusing on that – and not focusing on, ‘What steals can I get?’, ‘How much can I get for how little?’ – that’s ultimately what we want to see shift,” Trezona said.

Kim added that individual habits affect thrifting’s overall impact on the fashion industry.

“I think sustainability is – at least among our generation – kept in mind a lot more. Whether or not that actually informs our choices, I think that depends on the individual more so than the industry as a whole,” Kim said. “In an ideal world, thrifting would be making every clothing brand in the world more green, but there’s definitely a spectrum of how much change is happening.”

Lopez said. By emphasizing intention over impulse, thrifting challenges a culture of waste and redefines the way Generation Z shops for clothes.

Additionally, with the growing popularity of thrifting, those who thrift out of necessity are losing out on buying affordable clothes, with some thrift and vintage stores driving prices up with the increase in demand.

“It’s our job as UCLA students to be cognizant of the communities that we’re entering who rely on thrift stores for access to clothes,” Trezona added.

While it currently takes up less than 10% of the apparel market share, thrifting as a market is expected to continue growing, Caro said. He explained that this growth in thrifting will slow the issues caused by overconsumption, but efforts at the policy level must still be made to resolve them.

who slow the

Although limited in scale, thrifting plays a meaningful role in reshaping consumption habits. Beyond just an alternative to fast fashion, it encourages a shift in mindset – one that values sustainability, appreciation for craftsmanship and the love behind each piece of clothing,

As thrifting continues to grow, Caro explained that is one practice that helps slow down downsides of fast fashion, with other possibilities including renting or recycling one’s clothes.

thrifting is one the downsides

Trezona reflected Caro’s sentiments, saying that upcycling can provide more benefits than thrifting when reducing waste. Trezona said they actively upcycle their clothing, frequenting the Pasadenabased arts and crafts thrift store Remainders Creative Reuse.

“It (thrifting) can’t be the end-all, be-all. It has to be the first step,” Trezona said.

Thrifting has become more than just a way to shop – it’s a way to rethink value, community and responsibility. While my jacket ban started as a restriction, it ended up shifting how I see clothing and consumption altogether. Now, every thrifted piece of clothing isn’t just another addition to my closet – it’s a reminder that clothing carries stories. My mom’s war on jackets wasn’t just about buying secondhand or making me cold at school – it was about breaking the cycle of waste and choosing to be part of something bigger.

written by ANDREW WANG

designed

by

FELICIA KELLER

Above and beyond publishing journal articles, credentialing young people and producing spectacles on the court, the field and the gridiron, the job of a university is to keep the books.

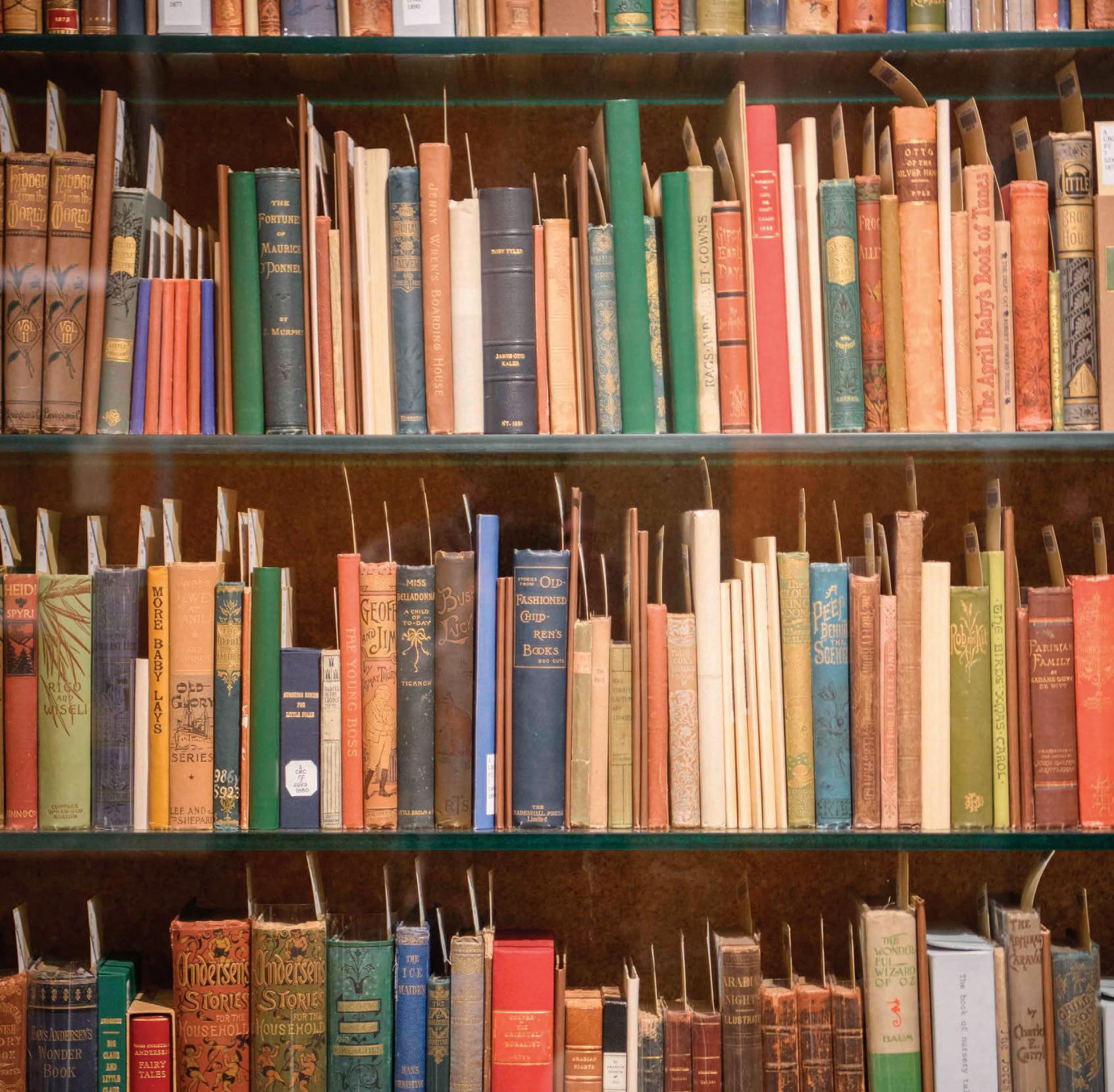

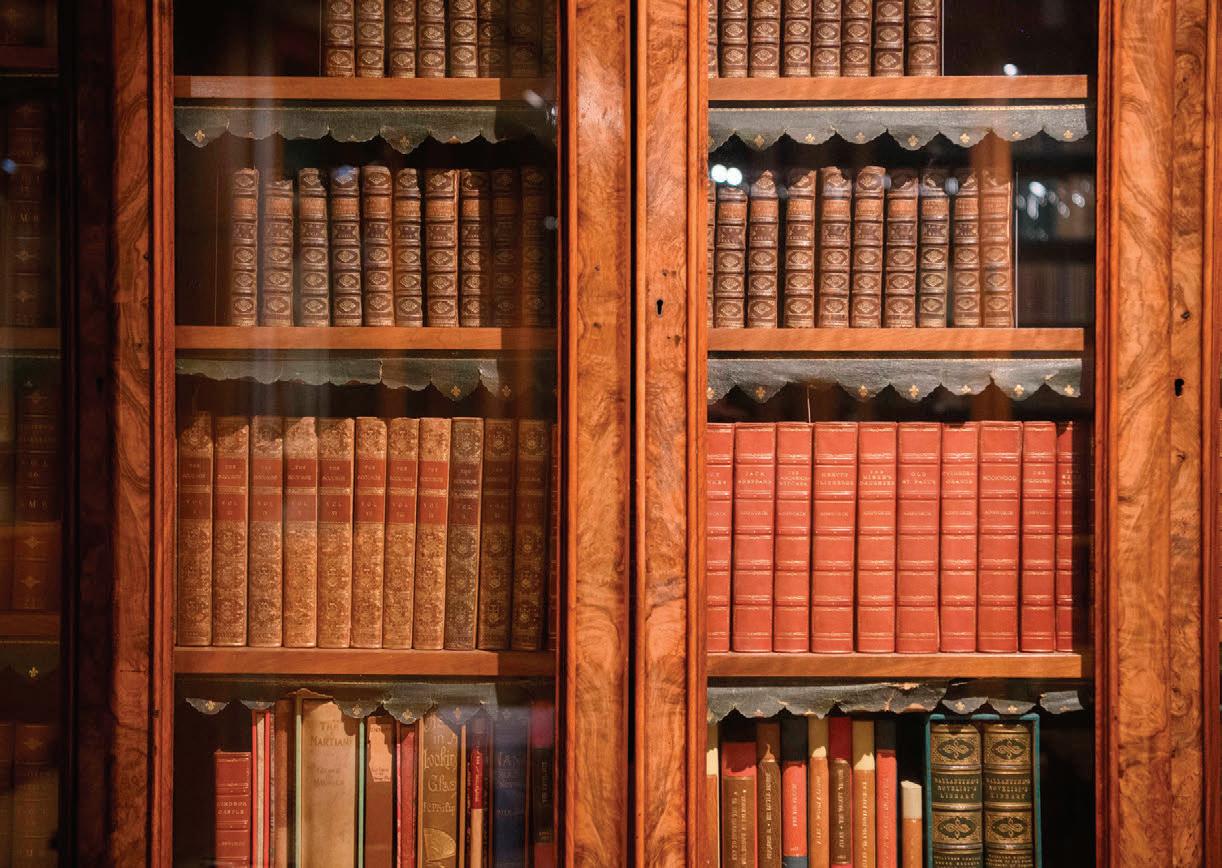

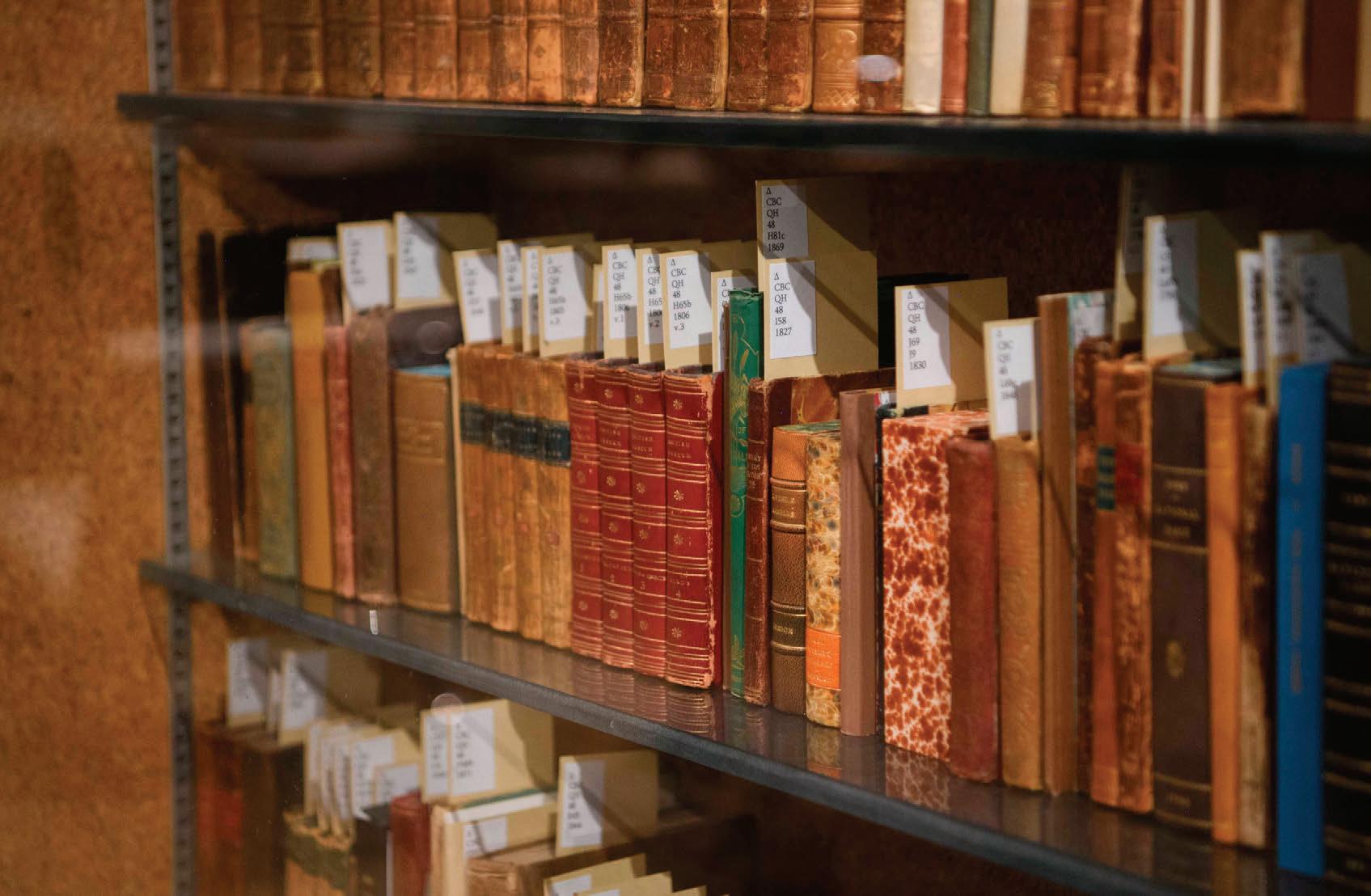

Less visible than some of the university’s more prominent architectural symbols, the Michael Sadleir Collection of Nineteenth-Century British Fiction is deeply tied to the history, and the purpose, of UCLA. The whole organism of the university is seen in action around the collection: Administrators allocate budgets for expansion and acquisitions, archivists preserve the physical copies of

novels, researchers produce new knowledge based on the contents of the collection, and instructors communicate that knowledge to a new generation of students.

In 1948, university librarian Lawrence Clark Powell purchased 1,925 volumes of minor Victorian novelists on the recommendation of Bradford Booth, the thenchairman of the English department.

“He (Powell) was interested in advancing our status as a relatively newer institution, as compared to the Ivies,” said Courtney Jacobs, head of public services, outreach and community engagement at UCLA Library Special Collections. “They had significant holdings in their

collection that made them unique and desirable for certain areas of research, and Lawrence Clark Powell was looking for a way to put us on the map.”

Powell’s acquisitions were only the beginning of UCLA’s famous Victorian collection, and a significant advancement soon followed. In 1950, Michael Sadleir, an English literary historian and self-described “bibliomaniac,” was selling his valuable collection of British novels to fund business ventures after the financially disruptive WWII. Initially reluctant to pay the $65,000 asking price, the UC Board of Regents eventually approved the acquisition after serious interest from a competitor – the English department of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Adjusted for inflation, the original $65,000 would be worth around $850,000 today.

The purchase was finalized in December 1951. Fortythree separate boxes containing almost 2,000 volumes arrived four months later. It took another year for everything to be moved, unpacked, examined and shelved at the College Library. The collection would later be moved one last time to a specially built room in the University Research Library, now called the Young Research Library.

Before UCLA attained R1 status, indicative of the highest research merit, the university had sought to acquire diverse texts – not only to boost intellectual output but to elevate its standing among institutional peers. The collection has since produced dissertations and academic conferences and served as a teaching aid for undergraduate and graduate courses alike. Buying the collection would, in Powell’s words, “make UCLA one of the great USA centers for research in this field.”

Today, the Michael Sadleir Collection is firmly integrated into the UCLA library system, the second largest collection by titles held in the nation. Preserving the works of both celebrated and forgotten writers, the collection serves as an intellectual hub for researchers, literature enthusiasts and wandering undergraduates alike –offering a window into the literary tastes and ambitions of Victorian novelists. In fact, anyone can request to see its materials – with supervision – at Library Special Collections.

The books themselves are kept in a well-lit and humidity-controlled room at the A level, one floor below the entrance of the Young Research Library. A single wooden door leads into a tall room dominated by floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. Rows of display lights hang from the ceiling like CCTV

cameras, their concentrated beams illuminating rows and rows of book spines behind glass panes. There are few paperbacks in this room. Nearly every item is bound with leather and cloth of green, black, chestnut brown or mahogany.

A request must be made to see an item. Once the reader arrives, a staff member retrieves the material from its corresponding bookshelf. The collection is ordered with the Library of Congress system alongside Sadleir’s original single numerical system – he counted them, beginning at “1.” Hardcover volumes are stored with protective sleeves of plastic and must be examined not on a lectern but on a reading cradle, a specialized cushion for easily damaged books. Gloves are not required.

Sadleir’s collection, broadly speaking, contains many novels in the realist tradition – fiction that mimics the language and rhythms of daily life, whose plots are plausible and settings recognizable. According to Megan Stephan, a continuing lecturer in the English department, the goal of these novels was to depict the entire social environment as accurately as possible.

“Those authors believed ... that reading novels actually made you a better person because it enabled you to have empathy for people whose lives were not exactly like yours.”

While many of the canonical writers were of higher class, their works represented various characters from a spectrum of socioeconomic backgrounds.

The novelists writing these stories also emphasized the inner lives of their characters and their interrelations. In one of Charles Dickens’ better-known novels, a young woman interacts with a stranger whom the novelist delays in revealing as her biological mother for hundreds of pages.

“Those authors believed … that reading novels actually made you a better person because it enabled you to have empathy for people whose lives were not exactly like yours,” Stephan said.

Those same writers also hoped their popular appeal would energize the public into social reforms. A variety of true-to-life characters exposed readers to a diverse society they would not otherwise be able to meet.

Stephan became an expert in Marie Corelli, a forgotten novelist of the occult and the pen name of English writer Mary Mackay, for her dissertation work. Stephan was interested not only in the writers whose work was considered of the highest caliber, those whose fictions have been validated by scholarship, but also in the pulpy and popular. Gaining an insight into the broad reading palette of past readers is also insight into the lives of

people not exactly like our own – a kind of sociology of literature.

Not all of the thousands of books are entertaining or instructive. Only a fraction will make it to readers outside the English department in the form of “classics.”

”He (Sadleir) was very interested in representing women writers who we don’t necessarily talk about anymore,” Stephan said. “They’re not household names anymore – we don’t come across them in the same way. But they were household names during the time period when the books were published.”

This fading recognition, Stephan noted, underscores the need for a sustained readership to ensure a novelist’s works endure. Some of these writers were so forgotten by the 21st century that no popular bibliographies existed of them except within the Sadleir collection. In fact, important works are frequently neglected during their own time. For books like these, rediscovery depends on motivated collectors and motivated scholars. The collection even has such a novel, one “Moby-Dick.” A household name now, the work was virtually forgotten between the author’s death and its revival by literary scholars in the 1920s.

Before then, it stood, perhaps like other obscure classics soon to be rediscovered, in collections like Michael Sadleir’s.

“He had a huge capacity for thinking about books that people thought were ephemera or garbage at the time, and he saved us that history of those books,” said Jonathan Grossman, a professor in the English department.

Usually, acquired research items are simply absorbed into a greater archive, and many are simply inaccessible without special permission, or do not have standalone exhibition rooms. But as Grossman explained, the Sadleir collection has the uncommon privilege of being stored together in one room – mostly. A set of Sadleir’s Gothic novels was bought by another collector and is now owned by the University of Virginia.

Besides its main appeal – the novels of 19th-century writers – the collection room has other interesting memorabilia. On the side of each bookshelf hang Vanity Fair cartoons of famed writers – color-pencil drawings of bearded, bespectacled men with too-large heads and too-thin bodies. Arranged artfully throughout are dark, elegant tables and chairs from mid-century America.

“He had a huge capacity for thinking about books that people thought were ephemera or garbage at the time, and he saved us that history of those books.”

“He was interested in the condition of the books. He really wanted the most special, the fanciest looking.”

wanted the most special, the fanciest looking.”

Described by Powell in a letter as “unassuming, witty, urbane, and of course, bookish,” Sadleir began his eclectic journey of collection at age 18. It began with his undergraduate textbooks, soon expanding – first to the poetry of French avant-gardists, then to London press pamphlets and periodicals, followed by Gothic romances. He collected Silver Fork novels, fiction about the English aristocracy and yellow-backs, cheap, short, sensational stories. By the time of the sale, Sadleir’s collection counted 8,625 rare books in total.

“Predominantly, he was a bibliographer, … somebody who’s interested in amassing an intellectual understanding of all the things that were published around a specific time period,” Jacobs said.

In his autobiography, Sadleir writes, “As my interest in moderns began to wane, I became possessed by childish memories.” Turning to the novels of his childhood, he began collecting the authors who populated his childhood home – Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope.

Material composition-wise, little has changed about novels. We are still using paper; we are still using ink. But while most commercial fiction flies off the printing press today as a single volume, many 19th-century novels were published in three separate parts, Jacobs said. That’s why catalogs of this period frequently distinguish between “titles” and “volumes.”

“The explosion (of publications) after steam printing and paper making and automated typesetting, which is the 1880s – when all that happens, it’s just so much more

class person in Victorian England, and it would have been an entire monthly wage for … the working class. So you start to get these private libraries – not libraries like you think of today,” Jacobs said.

As it turns out, the public library is a recent invention. Michael Sadleir didn’t just preserve the books of the 19th century, he also preserved the Victorian model for how books – the durable, expensive editions capable of repeat reading – were circulated among wealthier readers. A private collector, after amassing a useful number of volumes, could lease their books for a subscription fee.

Such collections were called circulating libraries, and the economics of lending encouraged multi-volume novels.

“If you’re a private library and you have this huge collection of books, you can charge somebody more money to loan the first volume while you’re loaning the second volume to somebody else, while somebody else has the third volume,” Jacobs said.

It still works much in the same way – the lending part, not the paying part. Under the stewardship of UCLA, the Sadleir Collection, once the passion and profession of one man, has been preserved as a source of knowledge and intellectual community. As long as the inquisitive visitor has a UCLA catalog account, anything in the collection may be called up.

“I always want to be able to show 21st-century students, physically, practically, what does it mean that the 19th century had a thriving print culture?” Stephan said. “A collection like the Sadleir is a way to point to that and say, ‘See here.’”

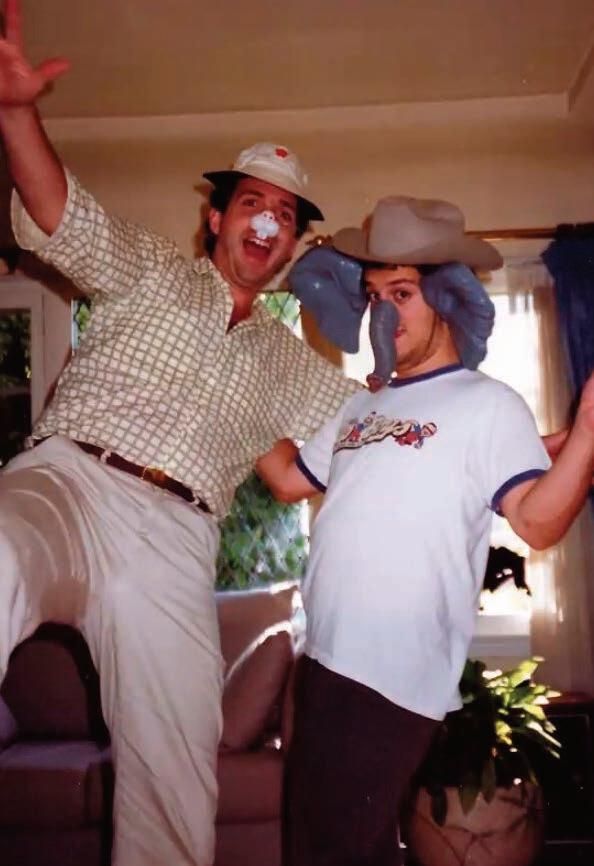

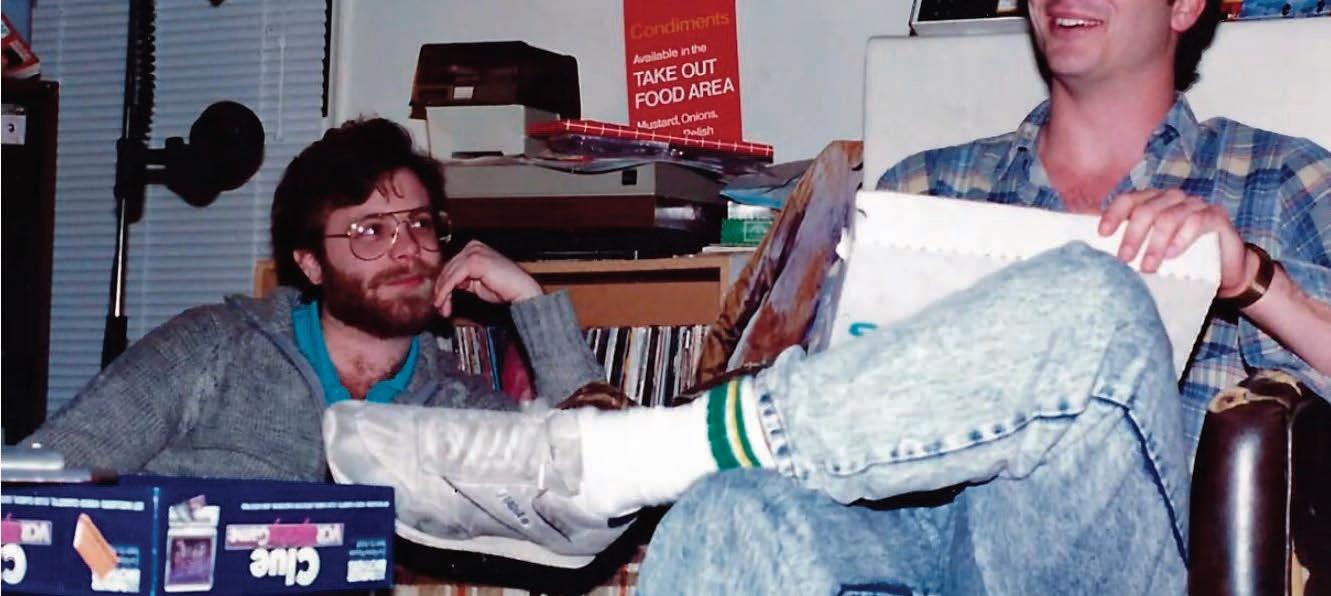

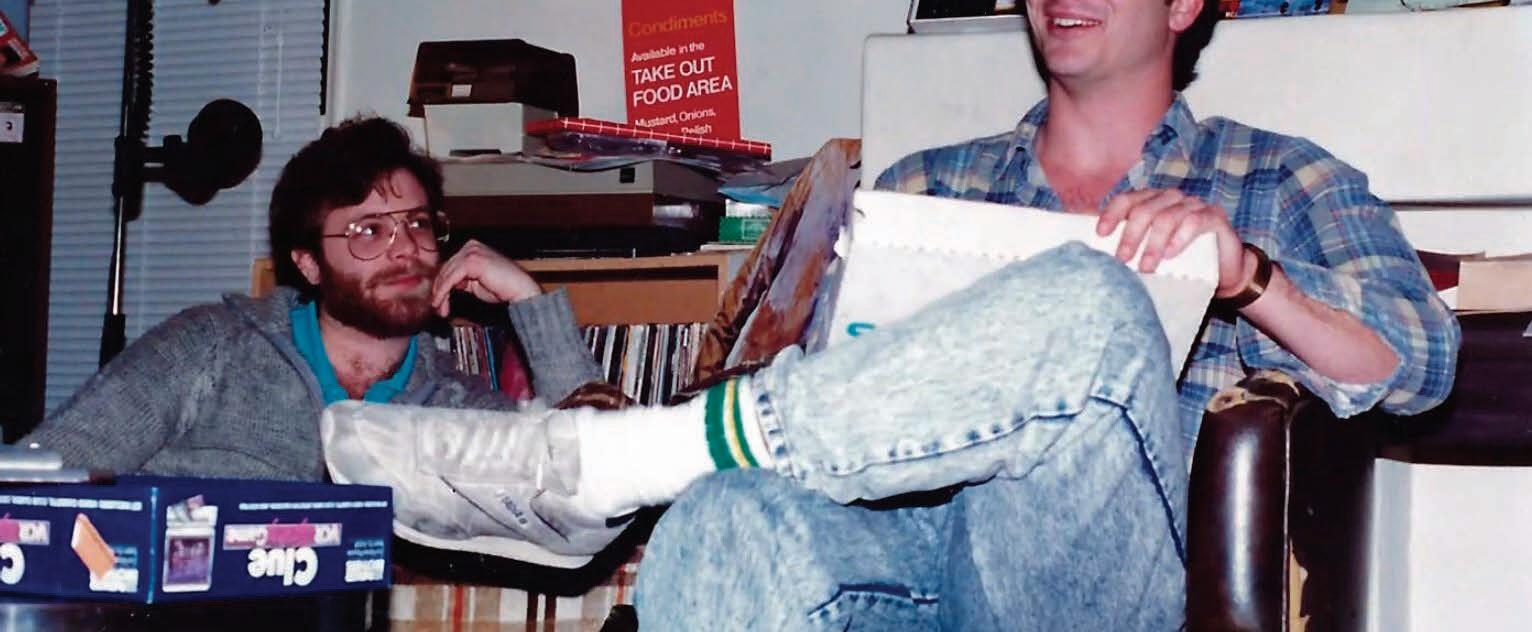

written by NATALIE RALSTON designed by KARINA ARONSON

“Frankly, I’m puzzled at you wanting to do a story about a 40-year-old, brief spate of screenwriting sales – a sort of temporary uptick or phenomenon – which had a bunch of nerds sitting around in a building.”

I sat on a call with Shane Black, the creator of “Lethal

Weapon” – and one of the best-paid screenwriters in Hollywood. I had tracked him down as part of my fascination with the “Pad O’ Guys,” an innocuous West Los Angeles bachelor pad that was allegedly once home to Hollywood’s greatest screenwriting talents. There were a few things wrong with what he just said.

For one, the inhabitants were far more than random film nerds. Among them were David Silverman, the original lead animator and director of “The Simpsons”; Fred Dekker, writer of “Night of the Creeps”; and Jim Herzfeld, writer of the billion-dollar “Meet The Parents” franchise. Throw in Dave Arnott, co-writer of “Last Action Hero,” and together, they’re responsible for franchises that have collectively ranked billions in box office sales, redefining the Hollywood landscape.

They had a few things in common beyond film clout. For one, they were all UCLA alumni, besides “The Adventures of Ford Fairlane” co-writer and USC stowaway James Cappe. In fact, they rented a Westwood bungalow and lived together after graduating – just as their careers were blossoming. As they began to write, they quickly turned into some of Hollywood’s most credited screenwriters. Their shared spec scripts became acclaimed films, and the antics from their lives would seep into the filmmaking culture around them. But the formative years they spent shaping their friendship at UCLA never left them. In fact, they still meet every Friday over Zoom. I had to know more. And before I knew it, I was on a Zoom call – questions burning.

A sizable “Jaws” movie poster leaned against the corner of Dekker’s porcelain-toned bedroom. “Demolition Man” writer Robert Reneau twirled a pen in his mouth and adjusted his black-rimmed glasses as a “Murder on the Orient Express” poster loomed behind him. Ryan Rowe, co-writer of “Charlie’s Angels,” donned a gray UCLA crewneck while Cappe flaunted a flamboyant pink button-up.

They wasted no time diving into private jokes I was 40 years too late to be in on, riffing off each other like musical visionaries composing an improvised melody. The self-proclaimed “old farts” enthusiastically shared memories from their UCLA days, and after our two-hour

conversation, I realized this seemingly quotidian group was much more influential than they let on.

“I had five agencies that wanted to sign just because I was with the Pad O’ Guys,” Cappe said. “This was the height of crazy spec script sales. People wanted to know, ‘Are there more like you at home?’ And we all lived together, so yeah – we were the ones back at home.”

It all started when Dekker and Cappe, former high school best friends, decided to move in together after attending separate colleges. Future members of the Pad performed weekly stand-up in cramped dorm rooms, bonding over their material at the UCLA Comedy Club. Others met through the UCLA film and theater departments, where they wrote student productions and produced one-act plays.

They graduated from UCLA with degrees in film, theater or English –except for Ed Solomon, the writer of the “Now You See Me” franchise and “Men In Black,” who was ridiculed for being

an economics student. They bonded over their love of movies, spending nights feeding a rotation of action films into the VHS player. After so much time together, Rowe said they knew it was time to rent an apartment.

Dekker, Cappe, Reneau and Rowe were the original 1982 inhabitants of the first pad in Westwood – a cramped two-bedroom apartment that could barely contain them and their steady stream of guests. Black and Arnott lived just down the street, and other friends, like Solomon, would visit occasionally, transforming the Pad into a central hub for the group’s earliest work and ideas. In 1984, they and a few apartment regulars moved into a modest, beige Spanish-style home in West LA, which they turned into a film nerd’s paradise.

Some nights were spent playing “Pad O’ Jeopardy” – a hot-blooded, hourslong game of trivia they invented entirely about themselves and their inside jokes. Other nights, when the filmmaking bug struck, they would write scripts for spontaneous short films and shoot on a swanky camera Cappe managed to secure – which was no easy feat in the ‘80s.

“That camera was our entertainment for like eight years. We made videos before videos were a thing,” Cappe said. “I was always behind the camera because I’m not as flamboyant as some of the people in our group – but with the actor friends, it was amazing.”

There was always someone sleeping in the living room, scouring the fridge or reviewing someone else’s spec scripts. And when neighbors grew annoyed with the rowdy troupe next door, Silverman and Dekker would spin the interaction into a column they called “Pad O’ Guys Comix” – another piece of self-serving entertainment. Silverman used the comics he sketched in the Pad’s garage as practice for a budding career in adult animation, animating for “The Tracey Ullman Show” during this time and becoming one of the original lead animators and directors of “The Simpsons.”

“I didn’t have any peers at the time who were working in animation,” Silverman said. “A lot of them were pretty serious about making serious films or seriously funny comedy films, but I was the animation guy.”

With a packed, rowdy bunch of bachelors all under one roof, “Criminal Minds” actor and fellow UCLA alumnus Don O. Knowlton declared the house was a “Pad O’ Guys” –and the name just stuck.

Amid the chaos, Dekker said those in the group spent their free time reaching out to agents and placing polished scripts on directors’ desks until they landed unexpected work. Solomon said members of the Pad feverishly wrote and rewrote screenplays, and he himself would ask the others to trade scripts, knowing he could count on them for their candid feedback.

I had five agencies that wanted to sign just because I was with the Pad O’ Guys.”

In those early years, the Pad never anticipated its eventual success. Solomon said he almost gave up on film entirely after an agent dropped him, convinced that his shared script – which would eventually become “Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure” – had no potential. But they seized whatever opportunities came their way, whether it was Cappe working as an animator on the Pillsbury Doughboy or Rowe collaborating on UCLA theater productions like “Doggy Tom.”

After a few years of constant writing and rewriting, the screenwriters started landing big breaks. At 22, Black

sold “Lethal Weapon” for $250,000, and at 28, he sold “The Last Boy Scout” for $1.75 million to Warner Bros – the highest price ever paid for a screenplay at that time. Dekker sold “Night of the Creeps” at 27, serving as both writer and director. As for Reneau, he noted that much of the attention he received back then came simply from living at the Pad.

“When I was living there, the world just came to me,” Arnott said. “I never had to think, ‘What am I doing tonight?’ because my social life would just show up.”

Their success was also a uniquely collaborative effort. Solomon and fellow UCLA alumnus Chris Matheson cowrote a script together based on a routine they performed at the UCLA comedy club, which would eventually become “Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure.” Black and Dekker created “The Monster Squad,” with Dekker doubling as the director. Cappe and Arnott joined forces as screenwriters on “The Adventures of Ford Fairlane,” and Black and Arnott co-wrote “The Last Action Hero.” And whenever one guy climbed up the ladder, he would roll it back down, referring friends to agents until they all reached the top together, Rowe added. The credits kept rolling, with the Pad’s fingerprints all over some of Hollywood’s biggest franchises.

“I think show business is really lonely for a lot of people – they feel like they’re in it on their own,” Rowe said. “There was this feeling of we were kind of all in it together.”

Before long, the Pad became a cultural touchpoint for the industry around it. David Fincher was introduced to the Pad during a summer LA film program in the ‘80s. During the press tour for his film “The Social Network,” he said his time with the group – observing their heated film discussions and late-night lifestyle – provided the framework for Mark Zuckerberg’s fiery debates in the movie. But instead of computer programming, it was movies.

And Seth Kurland, producer on “Friends” and a fellow UCLA film school alumnus, occasionally visited the Pad as well. Cappe said Kurland convinced the “Friends” team to include a trivia game in an episode inspired entirely

by the “Pad O’ Jeopardy.” And there was also Joel Silver, producer of “Die Hard” and “Project X,” who helped launch the careers of several Pad members. The “Pad O’ Guys” was becoming a household name among Hollywood insiders.

“When you’re living it, you don’t think it’s anything special,” Herzfeld said. “It was so uncommon to find yourself in this situation. I wish I would have realized that and enjoyed it more.”

But by 1991, only a few members of the Pad remained. They officially moved out, breaking up the group for the time being. Some settled into sumptuous mansions, their summer parties following massively successful Hollywood careers. Others spread across LA, building new lives with their families. Meanwhile some, like Reneau, took unexpected paths in the industry, with him eventually becoming the film program coordinator at the Academy Museum. Actors became writers, writers became directors and vice versa.

While some kept in touch, most moved on with their lives, leaving the Pad as a construct of the past.

“There was no big fight or argument or whatever – we just geographically separated. We moved from the hub,” Arnott said. “Jay said that one time to me, ‘Well, now we’re going to find out (who is really friends with who)’ –and we did find out. I mean, at the time, I remember

“

Life is harder when you’ve been through a lot of it, and I think you realize how important friends are.

thinking that was cynical of him, but he was completely correct.”

The formative years they had spent tirelessly crafting their futures together suddenly came to an end. All that remained were the memories that shaped them – and their unwavering love of film.

That was until 2020, at least.

During the height of the pandemic, Cappe suggested a Zoom meeting with the members of the Pad. The decades apart had seemingly done little to affect their friendship. Since then, the group has continued to meet online every Friday night from their homes across LA – with the exception of Solomon, who occasionally joins from his home in London. Their conversations range from impassioned games of “What the Dub?!” to reflections on life’s inevitable – but never less challenging – tragedies and triumphs over the past 40-something years.

“Back then, everyone had a future and not much of a past. Now, most of our life is in the past, and so even trivia games have the weight of a lifetime of being an adult,” Solomon said. “Life is harder when you’ve been through a lot of it, and I think you realize how important friends and how important laughing with friends is

are – and how with friends is – and how important sharing a past can be.”

Even Black, one of the most successful of the group, made time for these Zoom calls. As I sat with him for our interview in a bustling LA coffee shop, he recalled

spending most of his childhood as a “scared kid who lived inside books and movies.” He studied theater and film history with a devotion that only the Pad could truly understand, he added.

I asked him about his contribution to redefining the action genre – optimizing the buddy-cop dynamic and infusing characters with witty dialogue, which wasn’t common in the action-comedy formula at the time. He hesitated before admitting he views his success as a “minor miracle” and refused to take credit for his influence. And when asked about the group’s evolution over time, Black took a deep breath and paused for a moment before answering.

“We had lives – some of us did. I never did. I kept doing what I was doing, and I never had a house in Sherman Oaks, or a wife and divorce or children. So it’s been different for me. I just sort of pace around and haunt my own house,” Black said. “We would all get together on Friday nights and reconnect, and that’s been fun, but it’s equal parts joyful and bittersweet.”

My months of research and perfectly crafted opinions seemed to crumble at my feet. A successful screenwriter and key member of one of the most influential groups of film bros was so seemingly unaware of his genrebending influence. He grasped desperately at the looming ideas he never accomplished – dwelling on the past that had shaped his fate. Or maybe reaching that level of intangible success wasn’t as glamorous as it seemed.

I finally began to realize the essence of a “Pad O’ Guy.” They were precisely the group Black first described when talking about the Pad – scrawny nerds with nothing better to do than rolling tape.

“It (the Pad O’ Guys) brought me through some of the worst times in my life – like when I’ve had clinical depression or when I had a devastating breakup, I would

end up over there. And, invariably, we’d pick up a video camera and do something,” Black said. “I don’t know that the was

any good, but we were walking around all night shooting a video, when otherwise I’d be sitting at home just absolutely torn apart.”

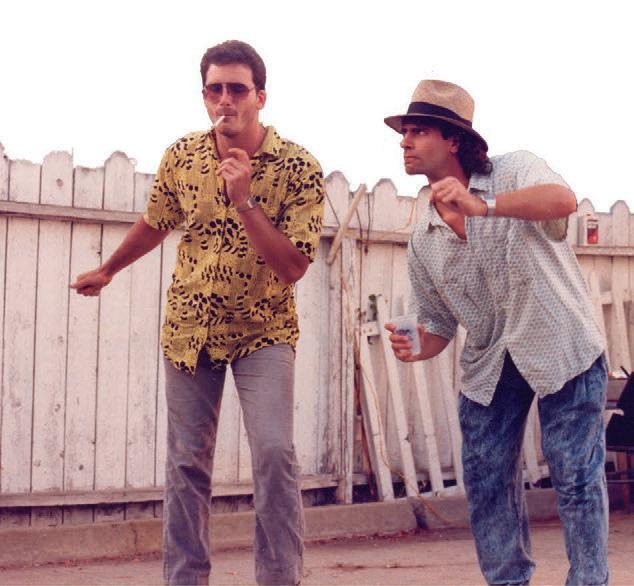

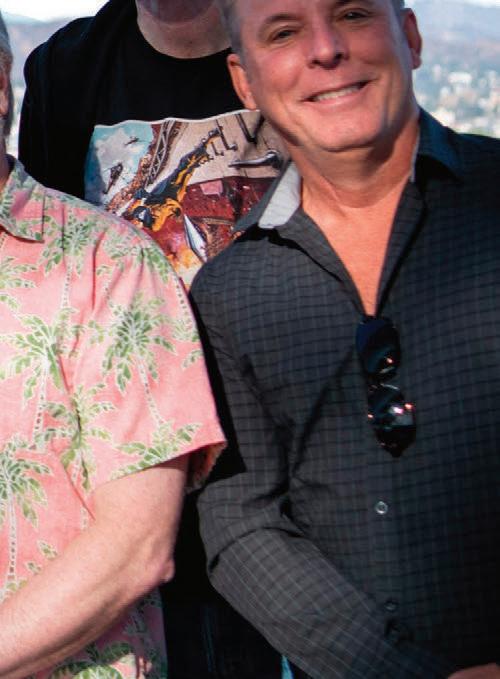

Forty years later, the guys were still willing to gather around a camera – this time with a Daily Bruin photographer. After much deliberation, we settled on a date, and Reneau secured us VIP tickets to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures for a private shoot.

After arriving at the museum’s parking lot, I scanned the premises for an animated bunch of white-bearded men. No luck. The concrete landscape was desolate. I fiddled with the ringer on my phone, staying alert for any sign of their arrival, my head turning at every distant conversation. Had I already missed them? I began to lose hope.

the 40-year-old comedy specs I met through my computer screen. Cappe thanked me for my persistence in scheduling a meet-up and mentioned that this many group members hadn’t met in person for several years. Realizing they were just as excited as I was to be there,

It (the Pad O’ Guys) brought me through some of the worst times in my life. “ life.

Then, I heard the sound of laughter. My head snapped toward the towering grey parking garage, where I slowly made out a clump of fedora-clad men emerging from the shadows. Their infectious laughter grew louder as their figures began to separate, moving as if in slow motion. Squinting, I carefully pieced together the mysterious group’s features while absently fiddling with my sleeve, standing nearly half a mile away. I could almost hear “The Weapon” playing in the background, a dramatic explosion fizzling out behind them as they advanced –still in slow motion, of course.

The Pad spotted my crimson sweater and hurried in my direction. Cheerfully, they extended their hands in unison, greeting me as if I were a potential employer.

Cappe, Dekker, Herzfeld, Silverman, Rowe, Reneau and Knowlton had come to life from

I unhooked my sweater, leveled my shoulders and felt my anxieties begin to ease. I closed my eyes and tried to channel the dynamic director the group insisted I become – if only for the day.

“Tell us where you want us to go – it’s your vision,” Dekker told me.

Despite being some of the pioneering visionaries in the film industry, the Pad insisted I position them according to my own creative intuition. They included me in conversations filled with memories of their boundless past and wished me luck on my own work, seemingly forgetting their own stature.

As they posed for a photo overlooking the LA landscape, I saw the same group of friends who made swanky short films and performed zany comedy sets in dorm rooms 40 years ago – as if no time had passed.

“Iwas born in the greatest place on Earth.”

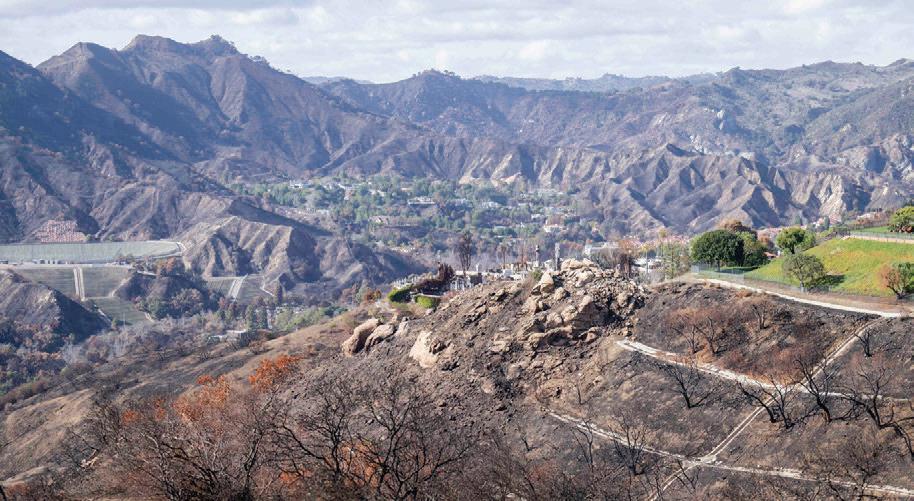

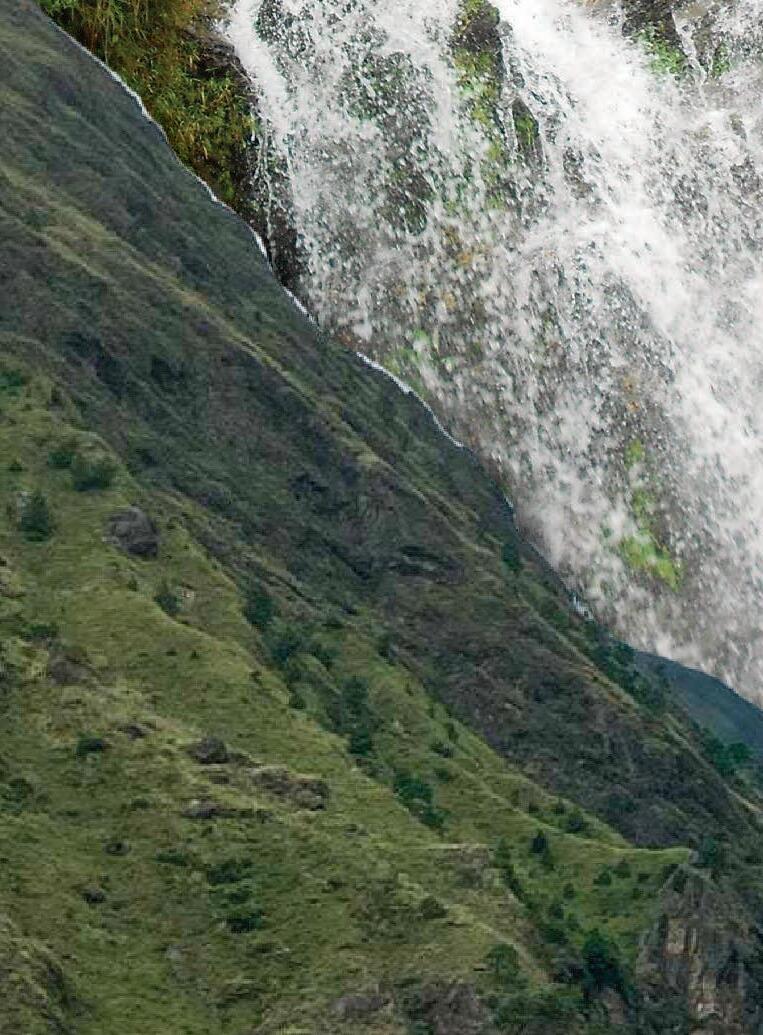

Pacific Palisades is filled with spots to view the ocean sunset, but Leo Rochman’s favorite is a cul-de-sac at the bottom of the hill in the bluffs overlooking the coast.

Leo talks about his childhood home in the Palisades with as much pride as someone can have in their hometown. Down the block from Will Rogers State Beach and off the Pacific Coast Highway, Leo spent his childhood playing in the street and biking around one of the most scenic neighborhoods in the country. When he got older, he would walk down the street and spend summer nights listening to music with friends. But one of the best days of the year, Leo said, is the Palisades’ annual Fourth of July parade – a day when the community comes out to see a 5K run, skydiving show and fireworks.

“Everyone knew each other,” he said. “I was best friends with my next-door neighbor – I could scream to him from our side yard, where we would grow vegetables, and then we would just play on the street and go bike around.”

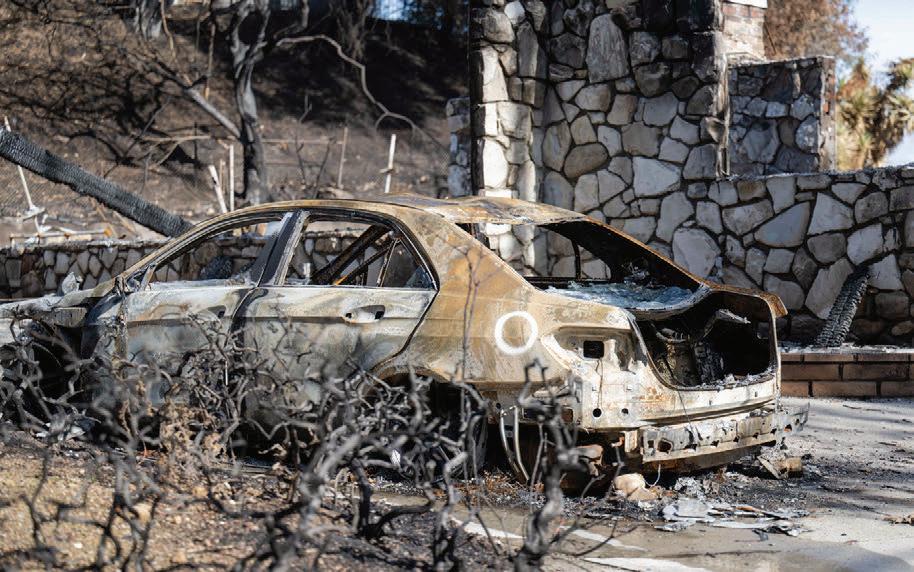

But there’s no one around in the neighborhood today. As Leo climbs through the white ash, broken walls and ceilings that once made up his house, he bends down and picks up a mug – one of the few items he can salvage.

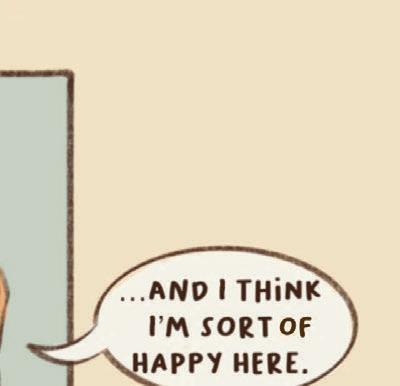

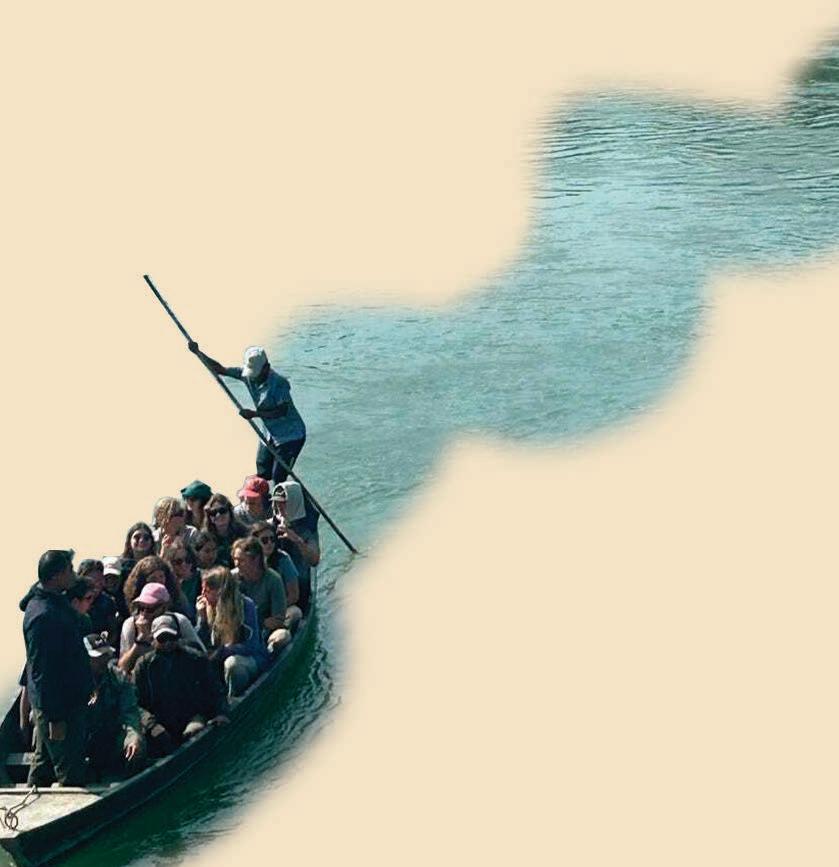

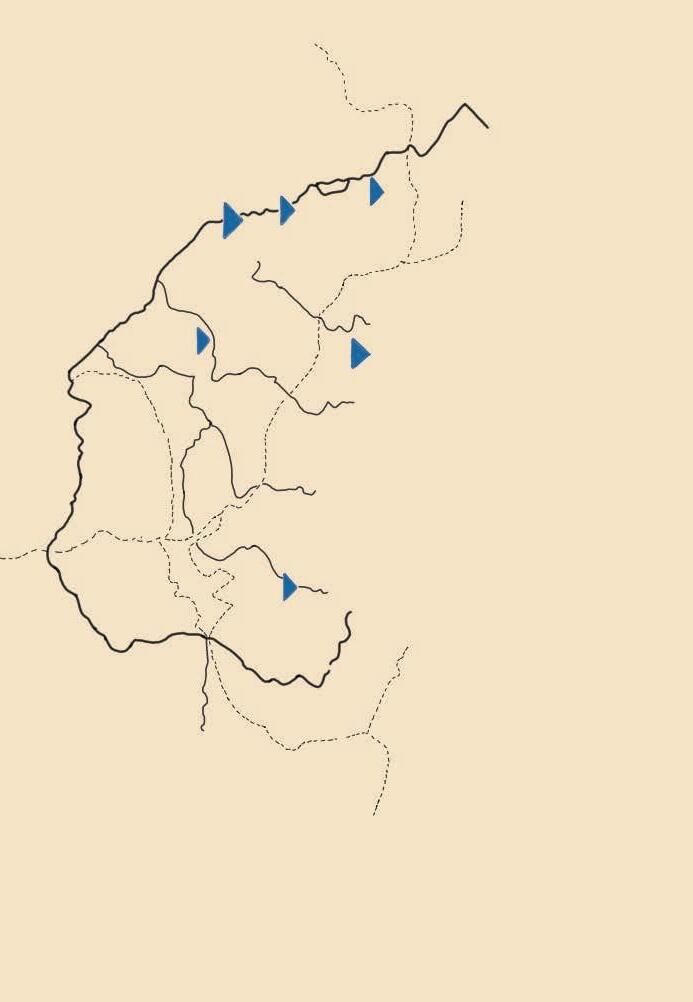

Leo and his family lost two homes in the Palisades fire – a wildfire that burned more than 23,707 acres, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. After the fires, Leo, a fourth-year philosophy student, has chosen to do what he can to rebuild his family along with the community he loves.

written by SAM MULICK

photographed

by

SAM MULICK

photos courtesy of LEO ROCHMAN

designed by MILLIE WALKER

Leo’s family’s roots in the Palisades go back generations. His grandfather Jerry built his own house in 1994 in Castellammare, a neighborhood right next to the Getty Villa Museum, while Leo grew up down the street at house No. 286 – a number now tattooed on his bicep. His family later moved to a neighborhood near Palisades Charter High School, or “Pali High,” when he was 13 years old.

His white house with green shutters, a black iron gate and a canopy roof over the front porch became a haven

for Leo’s family and friends. His family always opened their doors – whether it be to Zac Udy from New Zealand, who lived with Leo for months when he had nowhere else to stay, or his friend Matt Fischer, who moved to Los Angeles at 20 years old and didn’t know anyone.

“Leo took me in. His family took me in, and right off the bat, it was just love, and they treated me as his family,” Matt said.

Wyatt Standish, Leo’s childhood best friend who also lost his home in the Palisades fire, said Leo’s household was like his second family while growing up, as the two spent afternoons playing baseball together at the Palisades Recreation Center.

While Wyatt was a timid freshman in high school, he said Leo was the opposite – naturally charismatic and able to talk to anyone. In turn, Leo often helped Wyatt get out of his comfort zone, creating countless memories together.

“I had all my firsts at Leo’s house,” Wyatt said.

“Like my first party – I remember I was in high school, was in Leo’s backyard, and he had to drag me down from his room.”

During his time in high school at Crossroads School for Arts & Sciences in Santa Monica, Leo decided he wanted to pursue college baseball, ultimately achieving his dream by playing at

Oberlin College in Ohio – where he pitched for one year.

“He set his mind that he wanted to play college baseball, and I’ve never seen someone work as hard as he did to get to where he wanted to be,” Wyatt said.

Leo eventually left Oberlin in search of a better education, following in his dad and aunt’s footsteps by transferring to UCLA in fall 2023. He chose to study philosophy – like his dad and cousin – drawn to writing over test-taking.

Inspired by his love for baseball and streaming video

“I’ve never seen someone work as hard as he did to get to where he wanted to be.”

games on Twitch, Leo co-launched a media brand called Enjoy The Show in 2022 and collaborated on a channel called DSARM to produce sports-related content. Together with his friends, Leo went on to attract millions of views on YouTube through the brands, posting videos of the group covering international baseball in the Bahamas and batting with retired MLB pitcher Jeremy Guthrie – all while balancing his coursework at UCLA.

Leo moved into a house with his content collaborators in September 2024 so they could more fully devote themselves to their work, eventually filming on the field at Yankee Stadium when the LA Dodgers won the 2024 World Series. The house is decked out with everything baseball – cleats, bats and jerseys, all branded with the groups’ last names – to commemorate different chapters of their journey as a content brand. Leo was splitting his time between the content house and his home in the Palisades when winter quarter started.

On Jan. 7, Leo drove to school for his first day of classes for winter quarter. As he made his way to school, he started to get notifications on his phone about a fire near his family’s neighborhood in the Palisades.

“Fires aren’t a foreign thing to us,” he said. “I’ve grown up always being aware of them.”

Leo kept checking in with his mother on the way to school, calling her once he reached his first class of the day. While waiting to speak with a professor in the hopes of getting off the class waitlist, he saw his neighborhood move from an evacuation warning to a mandatory order.

With his dad and sister out of the house and his mom stuck in traffic, Leo left campus to get his two cats, Ollie and Jonathan.

“My mom’s freaking out because she has her purse and nothing else, and she can’t get back to our house,” he said. “So at that point, I’m running to my car, going past Royce Hall. Any second counts here – I need to get there now.”

In retelling the story, Leo spoke matter-of-factly –knowing he would do everything he could to protect his house.

Flooring it on the PCH, he watched smoke pour from his

neighborhood. Leo reached a police blockade at Temescal Canyon Road, where an officer would not let him through in his car – but told him that if he chose to go on foot, he would look the other way. Leo immediately started the two-mile journey to his house.

He looked up the hill toward home. Dark smoke filled the sky. He knew this was a bad sign – dark smoke meant the fire was still burning strong. People were fleeing the Palisades in cars, later abandoning them on the PCH because of traffic. Leo watched as people fled on foot –including a gardener who gave his mask to Leo, who was seemingly the only one running toward the fire.

There’s no way the fire can jump Sunset Boulevard, he kept thinking.

“My town is not going to burn,” he said. “They’re going to protect us at all costs. They have air tankers. They have trucks. They have everything fighting this fire.”

As he ran into his home, he was confident he would be able to return the next day. But with the smoke getting worse, Leo knew his time that day was limited. He tried to retrieve his cats, only to find them visibly scared and refusing to go into their carrier.

The cats ran upstairs, and as he followed, it occurred to him to grab two family photo albums to bring back for his parents to flip through while waiting for the evacuation to lift. He then walked out onto the street and called for help. A neighbor he had never met before came in and held the carrier open while Leo got the cats in.

Not knowing what else to do, Leo started walking back to his car two miles away with his cats, the photo albums

“I replay walking on my street and deciding to leave every single day.”

and medicine his mom had asked for –which ended up as the only belongings saved from the fire.

I have nothing that is from my life that I can pass on to my kids that is before I was 18 or 20. “

“I replay walking on my street and deciding to leave every single day,” he said. “There’s guilt that comes from it, even though I know I’m not responsible and there wasn’t a ton I could have done.”

The wind picked up so much that palm trees started falling. Embers jumped around, igniting entire trees on fire. Police drove down the street with bullhorns, ordering every person to evacuate. A line of cars waited to leave the Palisades as the smoke grew worse and worse.

Leo made it to his car right as police extended the PCH closure to Santa Monica, much further away from his house. If Leo hadn’t left campus to go to his house when he did, he never would have made it, he said.

When he arrived at his godfather’s house, he found his sister crying and his parents watching the news in shock. Leo stayed up until the early morning, watching online as his hometown burned – his elementary school, his favorite restaurant Beech Street Cafe, apartments, houses, nursing homes. Once he saw Pali High catch fire, he knew his house was in serious danger. But as long as it stayed standing until the morning, he thought things would be OK.

“I’m going to wake up, my house is going to be there in the morning, and I’m going to go and protect it,” he said.

The next morning, Leo – along with his dad, his godfather, Matt and Wyatt – began a four-mile trek from Santa Monica to their homes in an effort to protect them. With road closures blocking cars, they walked – passing active fires burning on the beach and neighbors’ houses reduced to ash, fallen trees and power lines.

They made it to the bottom of Leo’s hill around noon, as the smoke darkened. They watched as houses, cars and propane tanks along the street caught fire. Together, Leo and his dad climbed the hill and reached their street 20 minutes later. Finally, they caught a glimpse of their house. There was smoke in the backyard. The neighboring house on one side was completely burnt to the ground, and the house on the other side was on fire.

He knew it was too late. As a final hope to save their house, their street and their neighborhood, they called the fire department.

“I’m calling 911 – I’m like, ‘Please come to my neighborhood. I see 10 houses. Maybe you can save them,’” Leo said. “They said, ‘They’re where they need to be, sir.’”

They left. It was too dangerous to stay and watch.

The house where he hosted Matt for Thanksgiving. The house where he made Wyatt walk down to his first party in high school. Where he played shuffleboard and table tennis in the backyard. Everything he hoped to pass on to his future children. His and his sister’s childhood boxes, autographed baseballs, his high school baseball

jersey, his childhood photos, artwork from when he was in preschool, years’ worth of birthday cards, his father’s cleats from when he ran high school track at Windward School, a signed note from grandfather – who had recently died – that said, “Leo, success is written all over the way you carry yourself.”

All gone.

“I have nothing that is from my life that I can pass on to my kids that is before I was 18 or 20,” he said. “The place where I found the most peace – I’d wake up every morning and walk down the street, look at the ocean, look at dolphins, talk to my neighbors. That’s all gone.”

The Palisades is barely recognizable now. Driving through his town with Leo and his friends, we see a massive military vehicle where the National Guard is stationed before we enter the downtown business district. Only the brick frames of buildings – once home to businesses such as Café Vida and Casa Nostra Trattoria –now stand. People wait in line at World Central Kitchen tents, while recovery workers in all-white hazmat suits examine rubble. As we turn onto a street, I can see the entire horizon. Houses that once blocked the view are no longer there.

As soon as he was allowed back into the Palisades, Leo attempted to return almost every day to his family’s properties. With the help of Fire Station 15, specifically a firefighter named Chris, Leo was able to find remnants of china, some of his parents’ artwork and the dishwasher –which still contained plates covered in sauce.

His first goal was to find his mother’s engagement ring and wedding bands, which she had put in the family’s fireproof safe while gardening before the fires broke out. On Jan. 25, the firefighters came to help while off shift before the rain would potentially wash items away. After finding the safe, the firefighters used a gas-powered saw to open it up, only to reveal that almost everything in the safe had melted. Determined to bring something back to his mother, Leo sifted through the ash and the melted objects himself. He pulled out the engagement ring, along with her wedding bands and other jewelry –18 days after the fire started.

“That was the first real win that we had,” he said. “Fire Station 15 – they’re the greatest people ever.”

One of the firefighters recognized the bumper sticker on Leo’s truck that said “Enjoy The Show” and realized he knew Leo from his content creation. As thanks for helping them, Leo sent the firefighters some batting gloves for their kids who play baseball.

When Leo enters his family’s properties, he puts on a mask, gloves and work boots – prepared to be covered in sticky white ash and debris by the time he’s done going through the day’s rubble. Rummaging through the wreckage only to find a few items began to take a physical and emotional toll, he said. But everything he was able to salvage – the plates, mugs, salsa bowls, a

coin from his father’s collection – he put in a box for his future kids to one day show them the place that was home to so many people who needed it.

“The five or so days that I spent at the property, digging and trying to do stuff – it was stuff that was necessary,” he said. “Because it was just part of me saying goodbye and coming to terms with everything that happened.”

In the aftermath, Matt set up a GoFundMe for both Leo and Wyatt’s families – something Leo said he was initially uncomfortable with and only wanted if half the proceeds went to community organizations and businesses. They ended up donating to Beech Street Cafe, Café Vida and to Louvenia Jenkins – a 96-year-old woman who was one of the first Black female homeowners in Pacific Palisades.

“I know how much of a struggle people are in – and they’re in worse places than we are,” Leo said.

Whenever Leo saw neighbors arrive to search through their own properties, he lent a helping hand by offering protective masks and showing them how to safely search through the rubble. He helped one man search for a Jesus necklace that had been in his family for over 40 years. While they were not able to find the necklace, Leo helped him recover some of the family’s plates and ceramics.

He soon realized that many of his neighbors were not prepared for what they were coming home to – that there was little to recover from the rubble. One neighbor returned by himself to see his property for the first time since the fire. Leo stayed by his side so he wouldn’t have to face it alone.

“You just want to talk to them because you want to feel this connection and feel like it’s kind of normal, even though you don’t really know them,” he said.

Leo feels a stronger bond with the people of the

I still hopefully want to one day raise my family in the Palisades.

Palisades now more than ever, he added. On one of Leo’s drives through the town, a sign outside a neighbor’s property said, “Thank you to all our wonderful neighbors. We can rebuild this beautiful town together.”

Before stopping at his house, Leo took me to a vista point near Marquez Knolls overlooking the Santa Ynez Canyon on the left and the Santa Monica mountains ahead in the distance. Standing with Leo before another stunning view ravaged by the fires, I started to understand the scale of the disaster. The Palisades fire burned everywhere from the Palisades Highlands to Will Rogers State Beach, from the PCH in Malibu to Sunset Boulevard in the Palisades. Looking at the Palisades from the bottom of the hill, what once showed a row of houses is now an array of black soot and ash.

“That’s why I wanted to bring you here,” he later told me.

Leo recently helped his parents move into a new rental. Rent hikes immediately after the fires made it difficult for them to find a place, he said. Leo, who was set to graduate in June, met with counselors at UCLA and decided to become a part-time student going forward so he can help his family rebuild and focus on his content creation while finishing his degree.

He added that his friends and content crew have been his strongest support system, showing him love either through listening, finding practical solutions or

distracting him with a laugh – something his friends were not short of at all on the day I spent with them. He added that Matt especially has been with him since everything started – staying with him on the phone when he retrieved his cats and visiting the rubble with him many times after. The fire has only affirmed Leo’s love for his hometown, and Wyatt agrees.

“There’s no doubt in my mind, and I’m sure Leo would say the same thing, that I still hopefully want to one day raise my family in the Palisades,” Wyatt said. “I don’t think either of us would ever let a fire stop us from doing that.”

When Leo drove me through Castellammare, the neighborhood where his grandfather’s house burned down, I got out of the car and almost couldn’t believe my eyes. Standing in front of the rubble, the house gave way to a view of the never-ending ocean with the sun setting – the type of view that is impossible not to get lost in.

As I stood there watching the sunset, Leo walked past a completely melted car in what was once the garage and noticed a few plates left untouched in the ash. He started digging with his hands. After a minute, he found a ceramic pot, a tin mug, a couple of teacups and a few smaller plates – some of the only physical memories of the house his grandfather built. He walked the items back to his truck, one by one.

We watched as the sky became increasingly orange, the waves continuing to fall on the shore.

“The sunset’s still beautiful,” Leo said. “The view is still there, and that gives you hope for a lot of things. Gives you hope that our land is still good, but it also gives you hope like, ‘Let’s rebuild.’”

warma is the correct font. Please keep the body text as Karma. You can change the font of other

The correct font size is 10 pt. The correct

Do not change the page numbers, do not change the position of the page numbers. leading is pt.

do not change the position of the

written

by

KATARINA BAUMGART

illustrated byCHRISTINE RODRIGUEZ

written KATARINA by RODRIGUEZ CHRISTINE

designed byJAYANTI

SINGLA

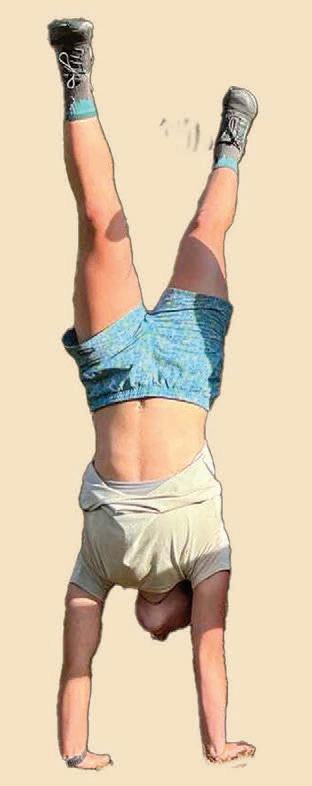

Social media led Annie Wong into an unexpected world of crimson-tinged activism.