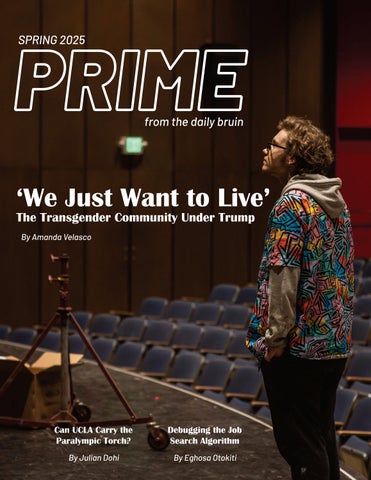

‘We Just Want to Live’

The Transgender Community Under Trump

By Amanda Velasco

Can UCLA Carry the Paralympic Torch?

By Julian Dohi

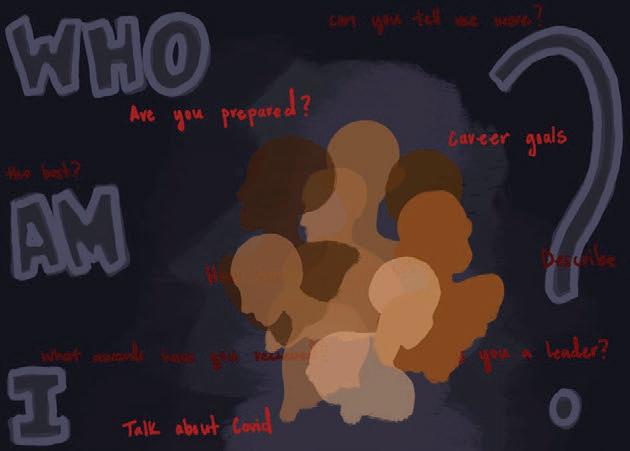

Debugging the Job Search Algorithm

By Eghosa Otokiti

By Amanda Velasco

Can UCLA Carry the Paralympic Torch?

By Julian Dohi

Debugging the Job Search Algorithm

By Eghosa Otokiti

Dear reader,

For UCLA students, spring quarter is the culmination of a year of hard work. Between research showcases, year-end celebrations and internship offers, rightful recognition for accomplishments is seemingly around every corner. For graduating students, that excitement is only amplified as they walk across the stage toward their futures.

I am one such senior – and this is my final magazine. In my first quarter at UCLA, I joined the Daily Bruin specifically to write for PRIME. In my final quarter, I am fortunate enough to spend my final weeks preparing this very special spring edition – the longest magazine PRIME has produced since the pandemic.

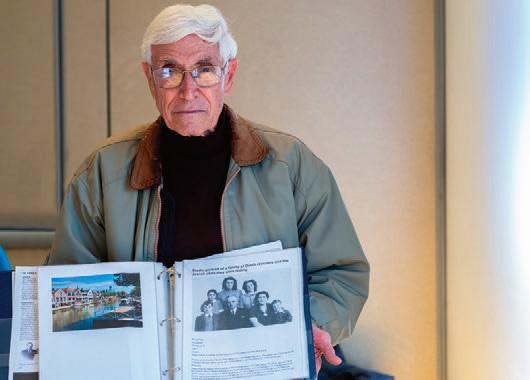

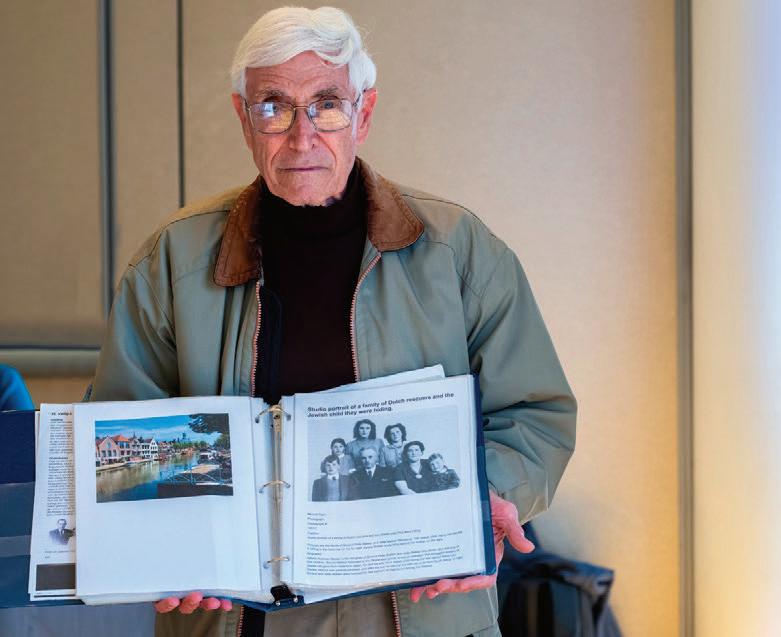

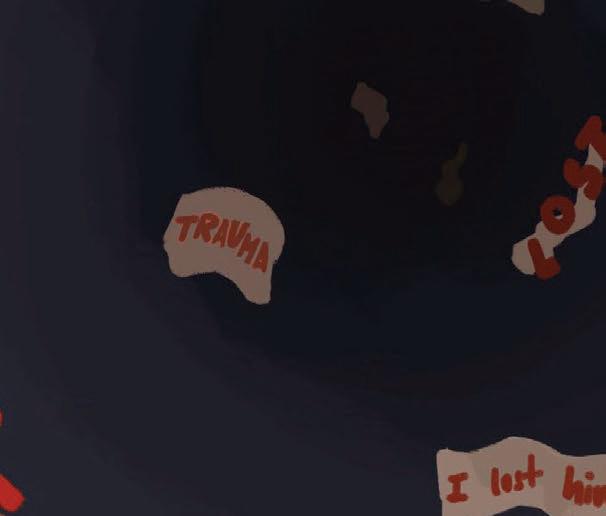

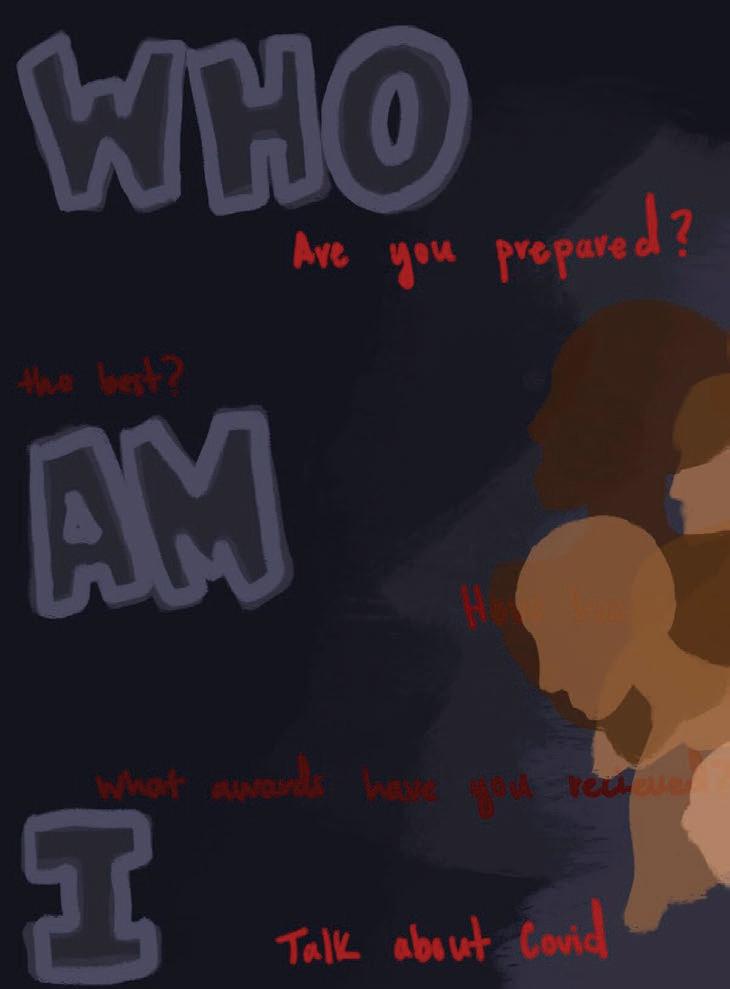

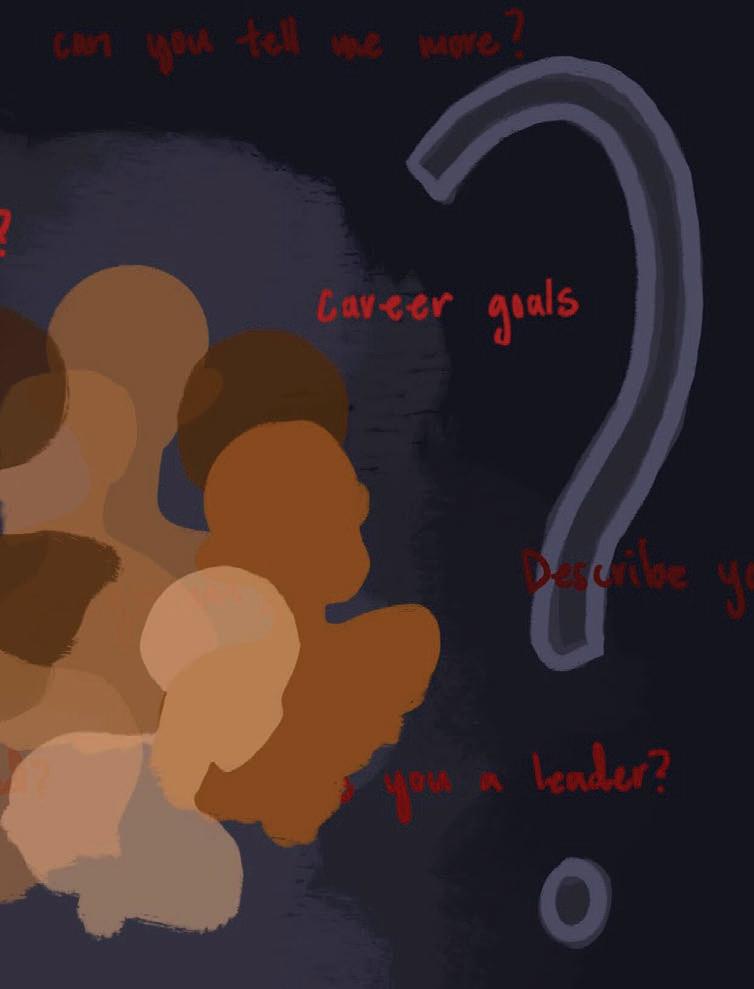

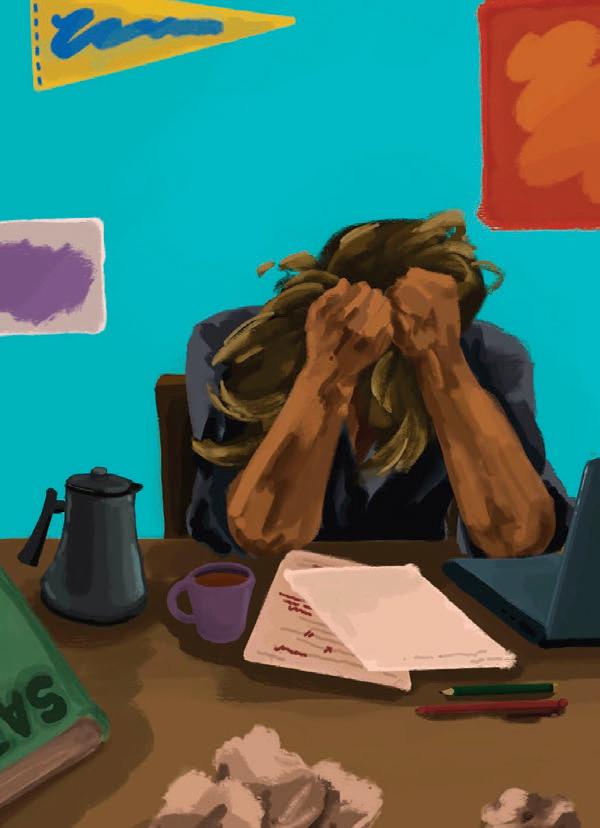

These 64 pages are filled with 13 amazing stories, many of which come from fellow soon-to-be graduates reflecting on their time at UCLA. Looking back on her applications, Aisosa Onaghise explores traumadumping culture in college admissions. Reflecting on her time in the Bearing Witness program, Rachel Rothschild explores how Holocaust remembrance is evolving on campus and beyond. And a year after the police sweep of UCLA’s Palestine Solidarity Encampment, Anna Dai-Liu explores the mental health consequences for student journalists who report on violence.

PRIME’s writers define the magazine, and this issue is a celebration of their hard work this quarter and beyond. But none of this would be possible without Alicia Carhee and Isabel Rubin-Saika, the dream team content editor and art director duo that made every single page possible. This magazine is nothing without them – our writers could not have asked for better mentors, collaborators and friends this year. This is our final magazine, and they deserve nothing less than this extraordinary issue as their farewell.

So read on for stories about students who stream, Los Angeles’ murals and UCLA’s Paralympic Village preparedness. Thank you for picking up PRIME magazine – we hope you enjoy it!

Isabel Rubin-Saika PRIMEart director

Martin Sevcik PRIME director

Alicia Carhee PRIMEcontent editor

Collectives Over Capitalism: The Impact of LA’s Mutual Aid

written

by

LAYTH HANDOUSH

‘We Just Want to Live’: The Transgender Community Under Trump

written

by

AMANDA VELASCO

The Future of UCLA’s Wastewater

written

by

TULIN CHANG MALTEPE

A City of Murals

written

by MYKA

FROMM

Can UCLA Carry the Paralympic Torch?

written

by

JULIAN DOHI

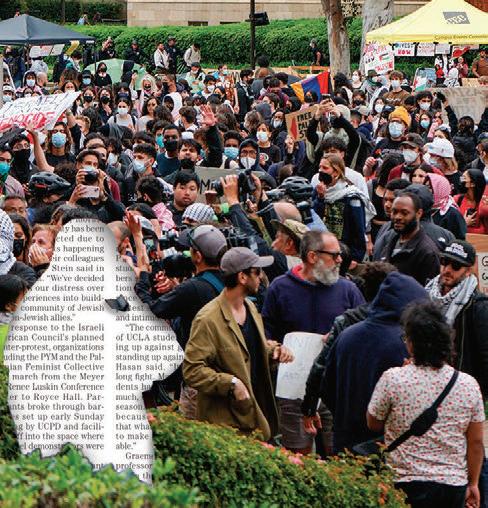

Violence, Trauma, Burnout: What Student Journalists Learned From the Encampments

written by ANNA DAI-LIU

Oversharing the College Dream written by AISOSA ONAGHISE

From the College Dorm written by PACO BACALSKI

Eileen Strempel’s Swan Song written by REID SPERISEN

Art of Game-Making

HOFFMAN

LOPEZ

written by LAYTH HANDOUSH

courtesy of

photo illustrations by AVA

The Los Angeles County fires left many residents with nothing but each other. Fortunately, people power is a force to be reckoned with.

When government initiatives were unequipped to contain the fires raging across the county in January, community mutual aid became the people’s champion.

Groups such as Westwood Mutual Aid and SELAH Neighborhood Homeless Coalition rallied to supply affected community members with provisions to carry on – not just food and clothing but spaces to rest, mourn and combat the alienation together.

“We had so many people who reached out because they wanted to immediately help,” said Maebe Pudlo, the operations manager for SELAH. “The silver lining of a tragedy is people want to come together and help.”

Organizations like these, started by and for community members, have sustained LA neighborhoods for decades – working year-round to help those in need when the administration falls short.

As LA holds the largest unsheltered population of any city in the United States, residents have developed a robust mutual aid network to support often-overlooked communities. Founded in response to larger community crises and discriminatory government practices, these groups inform their actions with firsthand experience, tailoring resources to locals’ immediate needs. By offering free critical services to community members – unhoused or otherwise – they combat LA’s high living costs and insufficient government resources.

The Mutual Aid LA Network is made up of over 100 grassroots organizations across Southern California, addressing community needs such as food, clothing and political advocacy. They are typically independently funded, not for profit and operate primarily on a volunteer basis.

Many of these mutual aid services go beyond material supplies. Concerned for homeless populations in and around Silver Lake, a neighborhood in LA, SELAH grew from a small band of neighbors in 2017 to an organization of over 600 volunteers today, Pudlo said. In addition to distributing food and hygiene products, it advocates for fair housing laws and holds educational workshops to teach volunteers how to best support their unhoused neighbors.

Pudlo said SELAH serves as an educational tool for the community, empowering its members to apply their work to their everyday lives and their own neighborhoods.

“People have become so desensitized to seeing abject poverty on our streets that it’s easy to forget that that’s a human being,” Pudlo said. “You should be offended at the circumstances in our society that allow that to happen.”

While SELAH assists those who are housing insecure, its mission is to change the discriminatory narrative around people experiencing homelessness – making its work resonate with all members of the community.

These inclusive efforts are a trademark of mutual aid groups. While they are often made synonymous with charity organizations, mutual aid is more accurately a practice of reciprocity, said UCLA doctoral student in

sociology Sam Lutzker. It disrupts the unilateral movement of charity that goes from higher-income to lower-income individuals, instead emphasizing the importance of sharing resources between all people.

“Mutual aid is survival for poor populations, especially, but also for middle class folks,” Lutzker said. “The classic example of going to borrow flour or sugar from your neighbor.”

With this understanding, the practice of mutual aid can be traced throughout the history of communal living. It represents a legitimate, alternative approach to modern capitalism, predating the genesis of LA’s high rent costs and No. 1 cause of homelessness in the city, said Theo Henderson, the host of iHeartRadio’s “We the Unhoused” podcast. For more than 70,000 people in LA County who can’t make ends meet, mutual aid has become critical for survival.

Henderson learned the importance of community-based assistance firsthand after eight years of living in various degrees of houselessness. Unable to continue work as a teacher because of a medical emergency, Henderson couch surfed, stayed in shelters and slept on neighborhood streets – all while pursuing unsustainable government aid such as Section 8 housing, which places applicants on a sometimes 10-year-long waiting list for rent assistance.

“It’s a very difficult thing when people say there are services out there,” Henderson said. “Yes, there are, but you have to understand houselessness is not one person where you can go and get these services, and magically, things are going to be fixed.”

Misinterpreting government aid as easily obtainable to those without shelter, many homeowners become desensitized to the inequity that comes with living on the streets, Lutzker said. Henderson added that the Supreme Court’s ruling in City of Grants Pass, Oregon v. Johnson – which allowed cities to prohibit public camping – and local laws across Southern California criminalize the existence of people experiencing homelessness and reinforce the apathy that permeates society’s view of them.

“If you can dehumanize an individual, you can then criminalize them,” Henderson said.

Indifference toward people experiencing homelessness – or any marginalized group – by the larger population allows the government to impose harmful practices on said groups. This is

evident in what Lutzker refers to as the government’s “sweep” approach to homelessness. These large-scale evictions of homeless camps act as an aesthetic BandAid, Lutzker said, removing unhoused communities from view under the guise of dismantling the systemic barriers that prevent them from accessing long-term assistance.

Lutzker added that within the current capitalist framework, equitable and humanitarian solutions by mutual aid groups are often dismissed by the government, whose work is more influenced by voters in higher tax brackets.

“It can be adversarial to what the state does, because the state is – yes, sometimes concerned with care – but also concerned with all these other things, including displacing and dispossessing poor unhoused people, because it becomes a problem for them, for their favorite constituents,” Lutzker said.

empowering them to pursue sustainability in other aspects of their lives.

“It’s a place to enrich and fulfill your values and your needs socially as well – not just your basic needs,” Jaschke said.

While government agencies provide some tangible needs to their communities, such as temporary shelters and food stamps, mutual aids such as SELAH believe that building strong community bonds is just as important. It is in this way that these groups facilitate holistic support for their communities and support their mental and emotional well-being, Pudlo said.

Shift Our Ways Collective follows this model of service in addressing the nutritional needs of LA County residents. The Arleta, California-based mutual aid prides itself on “eco hubs,” where local families can harvest two pounds of free produce per week directly from stem and soil. Madison Jaschke, co-founder and executive director of SOW, said that in an urban food desert where high-quality meals are largely unaffordable, the mutual aid gives its community greater access to green space and fresh foods, as well as

Through SOW’s Youth & Community Harvest Internship, teens and young adults are encouraged to apply their career skills to sustainability projects that foster the collective’s growth. Jaschke shared that these projects take endless forms – from making solar-powered produce refrigerators to programming educational events for urban planners – and their creators exercise their own innovation for positive community change.

Lutzker said it is this type of creative problem solving that characterizes the work of mutual aid groups and should garner interest by government bodies. These ideas are motivated by a desire for comprehensive social betterment rather than the desires of specific interest groups.

“They have some of those really radical anarcho-socialist ideas – not just big-state socialism but also other ideas of care that I think are intriguing, worth discussing, worth also bringing into the halls of power,” Lutzker said.

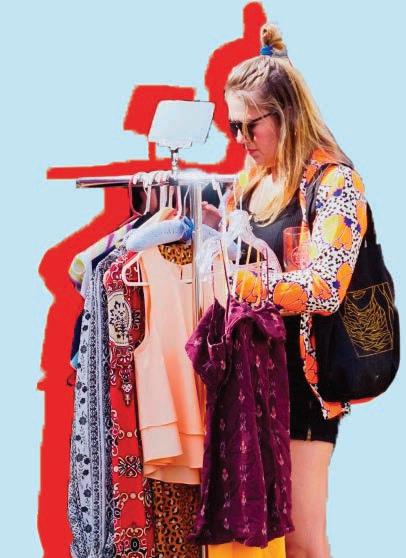

Nicole Macias and Enriquetta Navarro, the respective cofounder and co-director of Radical Clothes Swap, said they believe mutual aids are necessary for diluting capitalism’s potent control of people’s livelihoods. By holding free clothing swap meets across LA, Radical Clothes Swap helps offset levels of material overproduction by large fashion manufacturers – in turn supporting a circular economy that is environmentally sustainable.

‘‘‘‘ If you can DEHUMANIZE an individual, you can then CRIMINALIZE them.

With the rate of global material production tripling over the last 50 years, according to the United Nations Environment Programme, Macias said it’s not only unnecessary for manufacturers to continue making and selling clothes but detrimental to the health of our natural world.

“We’re literally killing the planet with all of these things that we’re consuming on the daily,” Macias said.

Navarro said Radical Clothes Swap decentralizes modern consumer culture and educates people about the ways in which overconsumption causes harm to the environment and each other. Lutzker said the coexistence of overproduction and poverty

is a direct outcome of a capitalist society; the hazardous abundance produced is only accessible to those able to pay the highest price.

Though industries and elected officials hold the whips that spur overproduction into rampancy, Navarro said that in order for the work of Radical Clothes Swap to be commonplace, mutual aids must be backed by government policy.

“It cannot just be our responsibility to combat this,” Navarro said. “There has to be something bigger that’s happening.”

The issue isn’t a lack of government programs. The 1980 Superfund Act was an attempt to clean up toxic waste sites across the country, and LA Mayor Karen Bass’ Inside Safe program was designed to provide people experiencing homelessness with indoor living facilities. The problem is that programs like these fail to provide sustainable solutions for impacted groups and often cite budget deficits as a considerable reason for this.

However, whether or not the relevant government departments are in need of cost-cutting measures is up for debate. Westwood Neighborhood Council President Lisa Chapman said LA County has billions of budget dollars that, rather than being put toward productive welfare initiatives, are primarily used to cushion the salaries of those involved with the current ineffectual programs.

“All of those entities, they are so bureaucratic in themselves that when you take an astounding problem like this, they don’t deal with it well,” Chapman said.

She added that lawmakers must push for legislation that holds the current bureaucracy accountable for how it spends its budgets. Though its influences on capitalism are severe, Lutzker recognized that a complete overhaul of government operations isn’t necessary to meet people’s needs. Rather, he advocated for greater government regulations and an increase in welfare assistance.

“Capitalism also doesn’t have to look this bad,” Lutzker said. “There are different ways to rein in some of the worst

products of that system. The U.S. is just not doing it.”

While the efforts of mutual aids and the government can appear adversarial, there is wide acknowledgement that they must all work together to correct the missteps taken toward marginalized communities. Lutzker and Chapman argue that, in proper cooperation, it is the responsibility of mutual aids to challenge government practices and for the government to inform its legislation with community perspectives in mind.

Chapman said comprehensive services – not piecemeal fixes for individual issues – would better the chance of providing people with sustainable care, rather than temporary fixes that ultimately leave their situations unchanged.

“It seems like this vicious cycle that we just can’t get out of, and it’s because we don’t have the resources set up so that we can succeed,” she said.

As the federal administration continues along a divisive course – with limited progress on these issues at the local level and looming threats against marginalized communities and the environment at the national level –mutual aids such as SOW and Radical Clothes Swap believe their work is more important than ever. Their work goes beyond meeting the needs of their neighbors, stretching to unite communities in demanding more collaboration between them and the government.

By weaving mutual aid practices into everyday life, a new cycle can replace that which is outdated and commonplace – one where capitalistic pursuits are made secondary to community knowledge and reciprocity.

“Doing something good for the community, showing up and then inspiring others to also do that,” Jaschke said. “Because who’s going to do the work if it’s not us?”

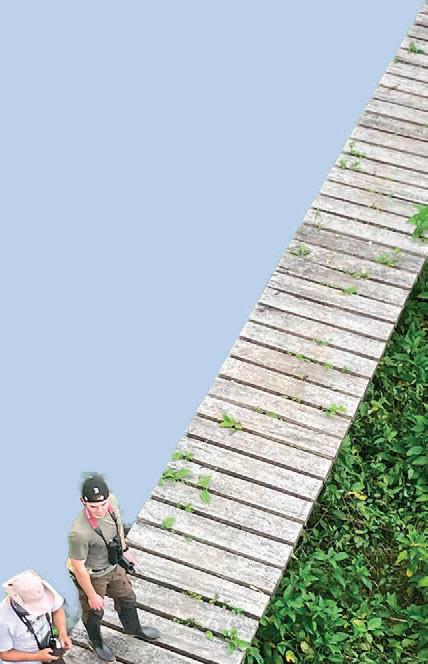

written by AMANDA VELASCO

photographed by SELIN FILIZ AND RUBY GALBRAITH

designed by LINDSEY MURTO

Editor’s note: This article contains discussions of suicide that may be disturbing to some readers.

Sgt. 1st Class Kate Cole rarely says no to service. Her list of deployments is seemingly endless.

She enlisted at 17 years old, spent one year in Afghanistan as a designated marksman and later served several rotations in the Baltic states during the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea. Cole was also stationed in Colorado and Germany, later going to Korea for a 12-month deployment where she led 36 soldiers as a platoon sergeant.

Seventeen years later, Cole works as a UCLA Army ROTC military science instructor from an office in the Student Activities Center – guiding students to become skilled leaders.

To her students, she is a model for service. But to the Trump administration, she’s a target.

Eight years into Cole’s service, she came out as a transgender woman, receiving nothing but support from fellow soldiers. Yet her identity came under scrutiny when President Donald Trump signed executive orders attempting to bar her and other transgender personnel from service.

“I just want to continue to do my job that I’ve been doing

for 17 years,” she said. “That’s all I’m asking for, and that’s all most people are asking for. We just want to continue to do our job.”

Transgender individuals make up less than 1% of adults in the United States. But as legislation shifts at the national level, transgender members of the UCLA community fear erasure and the long-term repercussions Trump’s executive orders might bring. With medical care, careers and safety at risk, they are determined to continue living their lives.

Trump has attempted to roll back transgender people’s rights in his second term through several executive orders, some of which include a ban on openly transgender service members and moves to limit transgender people’s access to health care and federal documentation. Implementing anti-transgender legislation is also a priority to a currently Republican-controlled Congress.

Will Tentindo – a staff attorney at the Williams Institute at the UCLA School of Law – said the executive orders may have limited impacts on federal law because of additional rulemaking procedures, constitutional nondiscrimination laws and potential lawsuits from advocacy organizations.

But even just the threat of legislation can dehumanize transgender people and push some into hiding.

“Some of the impacts are going to be felt immediately, but others might take a while to go into place,” Tentindo said.

Just eight days into his second term, Trump issued an executive order to revoke federal funding for gender-affirming care for people under 19. If implemented, the order would impact people covered by statefunded insurance plans,

while directing federal agencies to cut research and education funding of federally funded medical institutions that provide genderaffirming care. Some medical providers have already halted care before they were legally required to.

For people such as fourth-year theater student Tyler Neufeld, gender-affirming care is lifesaving and essential to mental health.

Experiencing gender dysphoria, Neufeld had suicidal

“Some of the impacts are going to be felt immediately, but others might take a while to go into place.”

thoughts and attempted suicide at 8 years old. He was pulled out of public school and enrolled into a Christian homeschool program, limiting his interactions with friends until he returned to public school in his junior year. For two years, his parents refrained from calling him any name at all. Since he began attending UCLA, his family has come to terms with his identity.

“I was trying to ignore my dysphoria for as long as I could – and as much as I could – just to survive until age 18,” Neufeld said.

Once he came to college, Neufeld gained the newfound freedom to be himself. After accessing UCLA’s genderaffirming care services through the UC Student Health Insurance Plan scholarship, his mental health improved, and his life changed for the better, he said.

But that autonomy might be taken away. He questioned if transgender people will have the same opportunities and degree of visibility in politics and health care as everyone else.

“Health care should be a basic human right, and trans health care

is health care,” Neufeld said.

Michael Hunter, a lecturer in LGBTQ studies and urban studies, said the vilification of gender-affirming care in conservative media contributes to widespread misconceptions that doctors perform unsafe surgeries on minors.

However, decades of research by organizations such as the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and the Endocrine Society support the treatment and describe it as a process guided by patient and guardian consent. Empirical evidence indicates gender-affirming care results in lower rates of suicidal tendencies among transgender people – with leading medical groups such as the American Medical Association, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American Academy of Pediatrics opposing government interference in doctor-patient relationships, including gender-affirming care.

The issue of transgender access to health care reflects a larger question of medical autonomy that affects all human beings, Hunter added.

“The threat to policing trans bodies is a threat to policing all of our bodies,” he said.

Neufeld added that criminalizing gender-affirming services will not stop the practice. Another student, a fourth-year STEM student who was granted anonymity due to fear of retaliation, said that in the wake of these orders, people wasted no time stockpiling medical supplies and creating backup plans to move to other countries more accepting of transgender people.

For Tentindo, he believes the gender-affirming care executive order will not have an immediate effect across California health care providers but may be visible down the line. The executive orders do not override all state protections – such as California Senate Bill 923, which aims

“Health care should be a basic human right, and trans health care is health care.”

to increase access to gender-affirming care services in California.

“The Trump executive order can only go so far,” he said. “However, the Trump administration has already tried to revoke funding from certain community health care centers that provide care for transgender people.”

Tentindo added that the national impact of antitransgender legislation will depend on the outcomes of the Supreme Court case United States v. Skrmetti, a lawsuit challenging Tennessee’s ban on gender-affirming care for people under 19.

Although Bruins may still be able to access care at UCLA and in California, they may not have those same protections elsewhere.

The fourth-year STEM student, a transgender man, knows this firsthand. As an aspiring paleontologist, he travels to the Midwest for fieldwork, living the life he always dreamed of as a “dinosaur kid.” Now, he is researching how climate affects the ecology of the California coast. Throughout his lab work, he earned the opportunity to choose official names for undefined specimens in the fossil record and assign them to species.

But as he travels across the country for field visits, fear for his safety hangs over his head.

“If I have an accident on a field site, will I be able to be treated by a doctor because my gender marker on my medical records doesn’t match my lived gender?” the fourth-year asked.

He added that he is afraid of being assaulted while traveling to a field site, such as stopping to use a gas station bathroom. This fear reflects broader trends, according to a 2021 study by the Williams Institute. Transgender people are over four times more likely to experience rape, sexual assault, and aggravated or simple assault than cisgender people. The data comes from results of the 2017 and 2018 National Crime Victimization Survey.

“We’re just people at the end of the day, you know,” the fourth-year student said. “We’re not big, scary monsters like how the government is trying to paint us. We’re just trying to live life.”

The student prepared to update all his documents to reflect his gender. But one day before his appointments,

Trump issued an executive order directing the departments of State and Homeland Security and the Office of Personnel Management to ensure government-issued identification documents – including passports, visas and global entry cards – reflect a person’s sex assigned at birth. This order is in line with the directive to redefine sex as a biological difference between men and women.

Tentindo said if people apply to get a gender marker different from their sex assigned at birth, the request would be denied – subsequently exposing transgender people to an increased risk of discrimination. He added that mismatched documents put transgender people at risk for increased security screenings when trying to cross the border into a different country – making them vulnerable to invasive questioning.

The executive order feels like much more than just a denial of his existence as a transgender man, the fourthyear student said.

“It basically outs us to federal workers who see our documentation, and it lets people be open bigots to us because they know who we are,” he added.

The fourth-year said he is tired of being afraid. Sylvan Oswald is, too.

Oswald, the head of playwriting at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television, will see his sex assigned at birth on his passport, ID and global entry card upon their renewal for the first time in 14 years, he said.

Now, he has to think twice at every turn. He will be anxious when flying to see his partner, who lives outside California. He will fear the simple task of driving his car across the country, just because it means crossing states with anti-transgender policies, he said.

“It just returns me to a time when I didn’t pass as well as I do now, and I was much more nervous all the time,” he said.

The order has already limited transgender people’s access to professional opportunities. The fourth-year sought to attend a professional conference hosted by the Geological Society of America – a milestone significant

We’re not big, scary monsters like how the government is trying to paint us. We’re just trying to live life to his graduate school applications. However, the student said he opted not to attend the conference because he feared traveling to states with anti-transgender legislation.

While the fourth-year is restricted in his ability to pursue his passions, other transgender community members fear the orders could have large impacts on their careers.

When Cole retires, she plans to become a climbing guide in Colorado. But today, the question is no longer “when” –it’s “if.”

Military service members are eligible for retirement benefits after 20 years, and Cole is just three years away.

However, with Trump’s executive order barring openly transgender service members from the army, her career might be put to an end, she said.

Despite the uncertainty, Cole remains deeply committed to her work. Her favorite part about serving the army is being able to teach ROTC students at UCLA, she said. Students often consult her on “con-ops,” or a concept of operation slide, and Cole would spend hours talking through their products, labs and field training.

“I just want to make good leaders,” she said. “I want these cadets to be awesome officers whenever they commission.”

This same passion in service stemmed from her peers in the military. For half of her life, she spent 18 to 24 hours a day with her troop members on holidays and in combat zones. In every new deployment in a faraway country or state, Cole started over with her fellow soldiers. The army is her “forever family,” she said.

A love for her found family is the reason why Cole, alongside five other transgender service members, is suing the Trump administration for its transgender military ban. The National Center for Lesbian Rights and GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders filed the lawsuit just one day after the executive order was announced – the order based on troop “readiness” and “integrity.” While officials at the Defense Department say there are 4,240 active duty personnel diagnosed with gender dysphoria, some transgender rights activists say there are as many as 15,500 transgender individuals in active service – all at risk of being pulled from the armed forces for a single aspect of their identity.

“Right now, there are trans people who are deployed to combat zones,” she said. “There are trans people who are working in hospitals. There are trans people who are lawyers, and we’re all on active duty, and we all just want to continue to serve.”

As Cole fights for her career through legal means, other transgender community members are reclaiming their rights in their own ways.

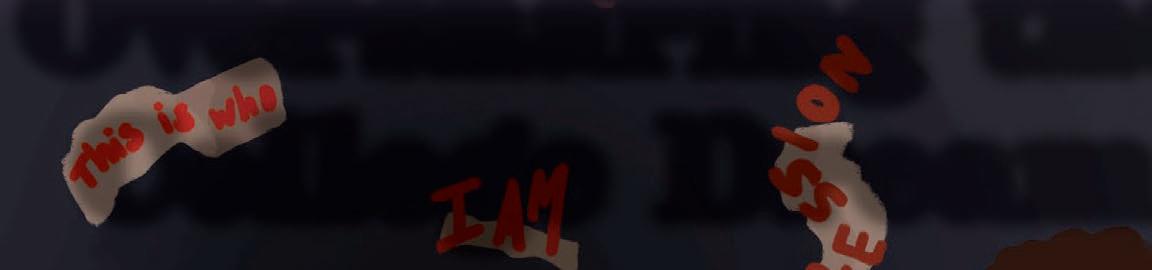

As a kid, Neufeld naturally turned to art to find solace. He often made backyard productions, performed jukebox musicals with Vacation Bible School

CDs and wrote original songs from piano compositions. Now, in his last year of college, he is harnessing scenic design and playwriting to make a statement. Since entering UCLA, Neufeld has been featured in the Los Angeles Times for transforming a Courtside dorm into an immersive escape room with recycled cardboard and blankets.

His latest production to premiere at the Hollywood Fringe Festival is “Escape! The Great Specific Garbage Catch.” Through interactive puzzles and themes of climate activism, it aims to make people think twice about the waste they produce, he said. Neufeld also delves into traditional theater, as he produced a comedic play to raise awareness on everyday issues transgender people face. With an increasing amount of attacks against transgender people, he said the comedic play aims to bring more joy within the LGBTQ+ community. He wanted to show them they aren’t alone, he said.

“Creating art about something is just a way to try to bring a little bit more peace and connectedness to the world,” Neufeld said.

Despite Trump’s executive orders limiting rights and access for transgender people, these UCLA community members continue with their work and daily lives.

Neufeld is focused on making interactive art that sparks social change, and the STEM double-major is on track to pursue graduate school. While Cole’s lawsuit is still underway, she continues to hold onto her plan to retire in Colorado.

For Oswald, he described his role as a professor creating a bigger impact than his gender identity. In higher education institutions, students need to see that every kind of person is represented – because his students are every kind of person too, he said.

As a guest speaker in a lecture on “High Winds” – a play he wrote inspired by his experiences with insomnia, gender transition and moving to LA – he recalled a tearful student telling him he was the first trangender adult they had ever met.

“They need to see that I’m here,” Oswald said. “I’m doing it. This is happening. I’m living life. I’m fine and well adjusted and mature – and they will be, too.”

Cranks, clangs and beeps echo off the walls of buildings covered in multicolored, winding pipes. In the distance, Pacific waves crash against the shore as palm trees frame the background of this otherwise industrial landscape. The faint odor of sewage comes and goes with the wind.

written by TULIN CHANG MALTEPE

designed by ISABEL RUBIN-SAIKA

Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant sits just next to the Pacific Ocean, right along the Santa Monica Bay. As the largest plant in Los Angeles’ wastewater system, it handles nearly 100 billion gallons of wastewater every year – including all of UCLA’s sewage. This volume includes sewage from LA as well as 29 other cities that send wastewater to Hyperion, where it is treated and sent back into the ocean.

But in the next 10 years, instead of being sent back into the ocean, that wastewater will be recycled and used throughout LA. As the city plans to make massive changes to its sewage infrastructure, Hyperion’s role in wastewater recycling will only grow.

To meet this need, the LA Department of Water and Power and LA Sanitation & Environment have initiated a project called Pure Water LA, which aims to prepare LA for a more sustainable and self-reliant future by helping the city reach its goal of recycling 100% of Hyperion’s wastewater by 2035 and increase local water sources. As the largest wastewater treatment plant in LA, the project will lean on Hyperion to make this large-scale reclamation feasible.

These changes raise questions – such as: Who bears the brunt of industrial expansion and waste processing infrastructure? The program’s effects will be felt across the city, helping determine the future of UCLA’s wastewater programs and potentially creating new environmental considerations for the plant’s neighboring community in El Segundo. With Hyperion’s presence in a historically white enclave, its environmental hazards do not fit squarely into typical environmental justice narratives and reveal a hidden history of LA.

Currently, Southern California heavily relies on water imported from the Colorado River and the northern and eastern Sierra Nevada for its drinking water supply, bringing 1.5 billion gallons of water into the region every day. However, as climate change dries up external water sources, LA is considering other collection solutions, such as increasing the amount of wastewater treated and recycled locally. If properly filtered, the wastewater can be used in almost every way groundwater can.

Eric Hoek, a professor in the UCLA Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and a member of Pure Water LA’s technical advisory board, said Hyperion plans to expand its current wastewater treatment to include infrastructure that supports indirect potable reuse – or the process of making wastewater drinkable. Currently, Hyperion has a small advanced water purification facility that can produce 1.5 million gallons of recycled water daily.

Sanjay Mohanty, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at UCLA, said recycling wastewater for broader use would require building new processing facilities such as reverse osmosis infrastructure. Reverse osmosis is a process that removes all pollutants, including sewage particulates, from water through high-pressure straining.

“They do it so that they can take all that water and inject it back in the ground – so that that water becomes available for the LA community,” Mohanty said.

Mohanty said the existing process of sending wastewater into the ocean is wasteful. He instead believes treatment facilities such as Hyperion should recycle wastewater to be used for a wide range of purposes, such as drinking

“

water.

Through Hyperion’s advanced water purification facility, it has slowly begun recycling wastewater using these technologies. Wastewater treated using reverse osmosis and other purifying measures only accounts for less than 1% of Hyperion’s daily sewage output. By expanding this capacity, Hyperion may be able to accommodate LA’s wastewater recycling goals.

But progress toward that expansion is still in its early stages.

They can take all that water and inject it back in the ground – so that that water becomes available for the LA community.

“Hyperion hasn’t done any of this yet, but this is all in the works,” Hoek said. “This is over the next 10 to 20 years. They’re going to be implementing in different phases.”

As that transition occurs, UCLA’s wastewater will add to Hyperion’s increased recycling load – but the university may soon pursue a recycling plant of its own, Hoek said.

One of the primary reasons UCLA has considered building its own wastewater recycling plant comes down to infrastructure: There are currently no pipes that can carry Hyperion’s recycled wastewater back to campus.

In turn, this facility would primarily recycle wastewater to cool down UCLA’s power plant. Since the UC Office of the President mandated a 36% reduction of drinking water usage per campus by 2025, Hoek said the only way to reach that goal would be by reducing the amount

of water used for the power plant, such as by using recycled wastewater from the dorms. Another benefit of a new recycling plant would be that the facility could house a research laboratory used to test new wastewater treatment technologies and run training programs.

Despite positive feedback on the project over the last 10 years, executing the plan has been challenging.

“LADWP and Sanitation have always supported this project. They’ve always thought it was a great idea, and they want the research facility there and all that,” Hoek said. “They’ve been really wonderful in support – but there has been a movement of, ‘Well, who’s going to own it? Who’s going to pay for it? Who’s going to operate it?’”

Another reason for the delay, Hoek added, is the Pure Water LA initiative, which includes building pipes that send recycled wastewater throughout the city –potentially making a UCLA-specific plant unnecessary.

While the city plans to expand its wastewater recycling efforts, the impact on the surrounding community remains to be seen. If UCLA does continue to rely on Hyperion, it will become one small contributor to this impact.

The El Segundo neighborhood sits directly east of

the Hyperion treatment plant. When things go wrong – such as sewage spills and sludge overflows – it is the community that bears the brunt of the environmental fallout. In 2021, Hyperion unintentionally discharged millions of gallons of untreated sewage into the Pacific Ocean, releasing high levels of hydrogen sulfide into the air. Residents felt the effects immediately, with waves of odor pollution sweeping through the community. While the treatment facility has worked to address the spill and reduce odor levels, pockets of El Segundo still reported persistent odors three years later.

country, housing policies in the 1930s segregated people of color – particularly Black Americans – to neighborhoods the government deemed less than desirable – areas often exposed to environmental hazards such as pollution. Through redlining, people of color were systematically denied access to better-quality housing, including housing away from hazardous waste sites and other heavy polluters such as oil wells – which has had lasting effects.

While there are oil and gas wells across the county, the majority of toxic release inventory sites are in neighborhoods with predominantly Black and Latino residents, such as Huntington Park, Bell Gardens and Compton. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, these sites can release toxic chemicals into the air, water or land.

But El Segundo does not fit squarely with these trends. Of the more than 17,000 residents in El Segundo, almost 70% of them identify as white, according to 2021 U.S. Census Bureau estimates. Black people make up less than 5% of the population.

Besides Hyperion, El Segundo is surrounded by potential polluters. North of El Segundo is LAX, where particulate matter from aircraft exhaust heavily pollutes neighborhoods within 10 miles of the airport. South of El Segundo is a Chevron oil refinery, which was named by a 2023 study as the worst emitter of several water pollutants among United States refineries. The eastern side of the city borders Interstate 405 – which, because of rampant vehicle traffic, is a source of pollution from vehicle exhaust.

“In LA, marginalization and the presence of environmental harm are linked. Across the

Since before Sanitation & Environment and the Department of Water and Power even existed, El Segundo has been a dumping ground. The 200 acres Hyperion currently sits on were initially purchased by the City of LA in 1892 to create the city’s first outfall sewer. Shortly after, workers for what was then known as the Standard Oil Company of California began settling in the city of El Segundo. In 1950, the sewer transformed into a secondary treatment facility, which it still is today.

Because of El Segundo’s close proximity to a sewage waste facility, it would have fit the requirements to be a redlined district. Instead, it only got a yellow grade.

It was white-owned companies looking out for white workers and ensuring they were going to – oftentimes explicitly – only hire white men.

Daniel Cumming – an environmental history postdoctoral fellow at Queens College, City University of New York – said this could be attributed to El Segundo’s historic racial demographics. Much like the rest of the LA Basin, Chevron had racially selective hiring practices.

“Oftentimes, it was white-owned companies looking out for white workers and ensuring they were going to – oftentimes explicitly – only hire white men,” Cumming said. “That’s not to say that Black workers were not also being hired, but … the opportunity was incredibly scarce. It (oil) was almost an entirely white industry.”

Despite this history of segregation, El Segundo stands in contrast to a common pattern across the country of marginalized communities, not white neighborhoods, tending to be surrounded by environmental hazards. Hyperion has since implemented technologies and practices to limit the impact of wastewater processing on the surrounding community – with multiple contingency plans for heavier sewage flows and any system failures. Besides crisis management, it works to limit the impact of day-to-day operations on El Segundo with odor prevention methods. Even the plant itself does

not have an incredibly strong sewage smell.

Not every community impacted by treatment plants has these benefits, however.

Shakira Hobbs, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at UC Irvine, said her family in Dundalk, Maryland, does not benefit from extensive odor management infrastructure – which causes the community to persistently smell like sewage.

It’s surrounded by waste factories. It’s not a great place to live, environmentally.

“We always know when we’re in Dundalk because of the smell,” Hobbs said. “It smells awful, especially during the summer.”

According to Hyperion’s website, direct community input has led to operational changes. At nearly every treatment point, large white pipes capture foul air, which is then treated in biotrickling filters using microorganisms and carbon polishers to remove pollutants and odors.

These technologies are expensive, with Hyperion’s biotrickling filter infrastructure costing over $21 million to build. As a result, a community’s access to this technology is often dependent on its members’ economic and political power. Hobbs said a community like Dundalk, which is a relatively low-income area, does not have the same odor management technology as El Segundo.

“One of the big questions I’ve always had when I was there is, ‘Why are the houses here so expensive?’” Taylor said. “That’s really something that’s always blown my mind. And it’s surrounded by waste factories. It’s not a great place to live, environmentally.”

In the four years that Taylor and her family lived in El Segundo, she said she saw its housing prices rise dramatically. Between February 2020 and February 2024, the median sale price of houses in El Segundo jumped from $1.1 million to $1.65 million, according to Redfin. Taylor said she believes the city’s largely white demographic may factor into the high cost of housing.

Comparatively, Hawthorne – which is directly east of El Segundo – typically has a median home sale price less than $1 million, according to Redfin, despite being further from environmental hazards. The city is predominantly Black and Latino.

“I don’t believe that technology exists in Dundalk. Dundalk is known to be a smelly town,” Hobbs said. “Maybe that’s where economics or socioeconomics may be playing a role in that (Hyperion’s) infrastructure and preventing how big of a plume that smell may be.”

In this way, Hyperion’s proactive approach to the community differs from other waste-impacted communities across the country and LA.

Despite being so close to many environmental hazards, El Segundo’s property values remain higher than those of some other surrounding communities. In addition to the city having a high-ranking school district and being right on the coast, it is possible that efforts by Hyperion and other facilities to mitigate risk keep prices high.

Tanya Taylor, the founder and executive director of the arts education program Black in Mayberry and a previous resident of El Segundo, said she always marveled at how expensive the city was despite its close proximity to environmental harms.

“I’m certain that if it (El Segundo) had been a predominantly Black, Latino, (or) Asian community, the house prices would never have reached that high – not with those issues that it’s surrounded by,” Taylor said.

From the ground at Hyperion, El Segundo is nowhere in sight. Tucked behind a low hill, the city sits just beyond the 144-acre treatment plant. The machinery clanks on, and the freeway hums without pause – and beyond the ridge, people go about their lives, sharing space with LA’s largest wastewater facility. Though the city may be out of view, the plant’s environmental impacts still linger with the wind.

As Hyperion prepares to expand operations to meet LA’s growing water recycling goals, its impact on the surrounding community may increase as well. The shift from sprawling clarifier pools to advanced treatment systems marks a turning point – one that will likely demand greater investment in odor management and community-first planning. And if UCLA plans to go through with building a treatment plant, it’ll have to consider how to invest in both the infrastructure and the neighborhoods that stand beside it.

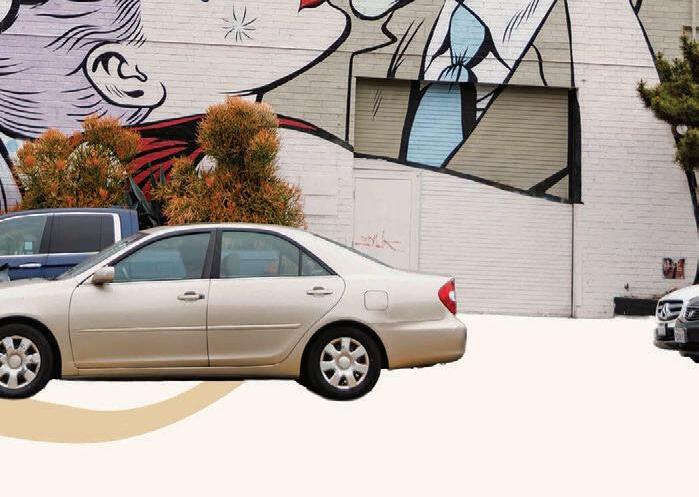

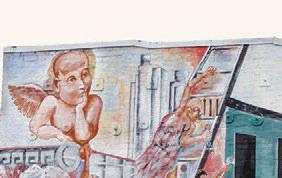

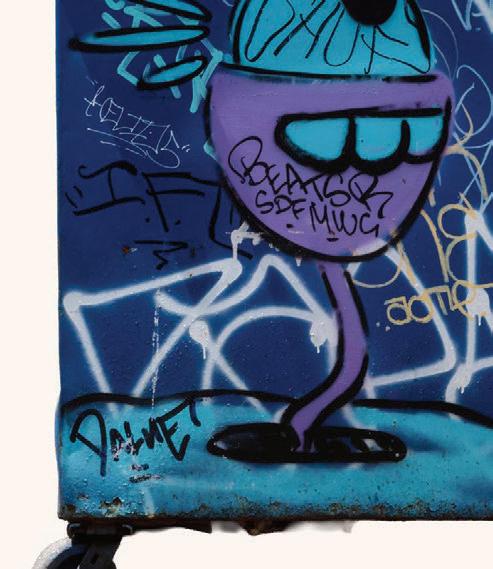

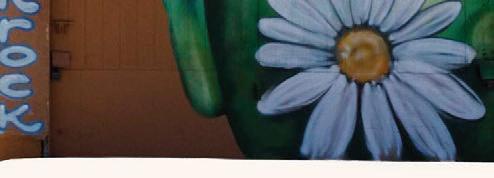

TVenice. Just off the main road, a quiet, shaded street offers some reprieve. A shiplap fence stands mightily with two spraypainted rabbits sprawled across it. Next to the rabbits, in the same bright white spray paint, a thought bubble reads, “Muck Rock.”

he April sun shines down on an afternoon in

neighborhood, where dozens of her murals cover everything from storefronts to garages to back-alley walls.

This is the home studio belonging to Jules Muck, a muralist known as Muckrock. Her sister and a droopy-eyed bloodhound met me at the gate as Muck trailed behind a few steps, the paint stains on her worn jeans illuminated in the sun. The studio itself takes up about half of the house – a large

room with bright windows, a

A mural is public art, so it’s always a collaboration between me and the environment that I’m in.

“ ”

“I will do everything and anything for Venice,” Muck said. Muck is far from the only person creating these artistic forms of community expression in LA. Countless professional and amateur artists apply their unique sense of style to the city’s public areas. To these artists and communities, a mural is so much more than paint on a wall – it is a form of storytelling between an artist and the viewer.

vaulted ceiling and bright, eccentric paintings lining the walls – but the building otherwise disguises itself amongst the rest of the residential

As Muck escorted me through the space, I recognized on her canvases many of the same motifs that appear in her street art throughout Los Angeles – cigarettes, body parts, cartoon characters and fantasy-like distortions of humans. These images have begun to define

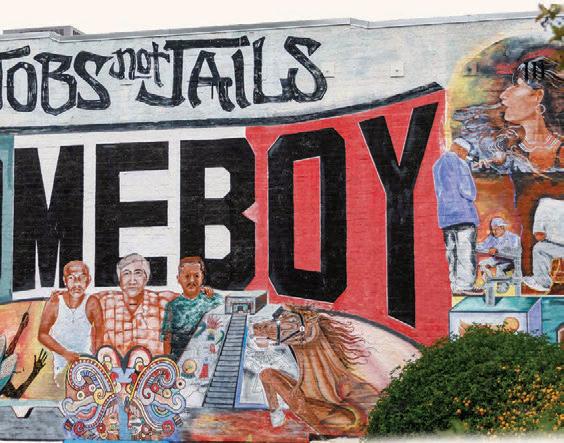

Thought of as the oldest form of human-made visual art, murals can serve a variety of purposes: advertising, beautifying a space, conveying a political message or celebrating a moment in history. LA’s murals have, for decades, conveyed the struggles of equal rights movements, particularly the Chicano Movement of the 1960s, and told the stories of major contemporary events such as the 1984 LA Olympics. These art pieces have been tools

of advocacy, commentary and self-expression.

“A mural is public art, so it’s always a collaboration between me and the environment that I’m in,” Muck

Despite a robust history of mural culture, LA has not always promoted artistic freedom on its streets. In an effort to limit the number of obtrusive advertisements dominating walls across the region, the city voted in 2002 to ban all new murals. Even with consistent protests from art activists, the ban stayed in place until 2013, becoming an 11-year-long period coined the “dark ages.”

This era can still be felt from the ban’s irreversible damage. Out of the 2,500 murals throughout LA when the ban took effect, the city had painted over several hundred by the end of the moratorium. Since the LA City Council lifted the ban, however, street artists have been resurrected in full force, now allowed to flourish their artwork in a way they had not since the start of the new millennium.

“By really dealing with the

connect with their community through the piece they create.

“Hopefully there is some sort of thought toward how that piece, if it is a community mural, is in direct conversation or reflection with the community that will be right outside of its doors,” Persaud said.

A community might not be just a neighborhood or a group of people. One common site for a mural is a school campus, including UCLA.

language around public artwork in the city of LA, that moratorium eventually ended,” said Davida Persaud, a lecturer in the UCLA Department of World Arts and Cultures/Dance. “We’re in this kind of exciting moment in Los Angeles right now where we’re seeing the production of more murals.”

A community mural does more than just beautify a space: It speaks for the people, whether it reflects those who live nearby or those represented within the art itself. Persaud, who is also the chief operating officer of sustainable art materials company MuralColors, said community muralism means the community is actively engaged in creating the artwork, not just consuming it.

“The role of murals is to communicate directly with the community outside of the usual spaces like a gallery or a museum, and it takes art directly into the community,” said Douglas Miles, a San Carlos Apache-Akimel O’odham artist and activist. “It’s so community driven, and its impact is more immediate.”

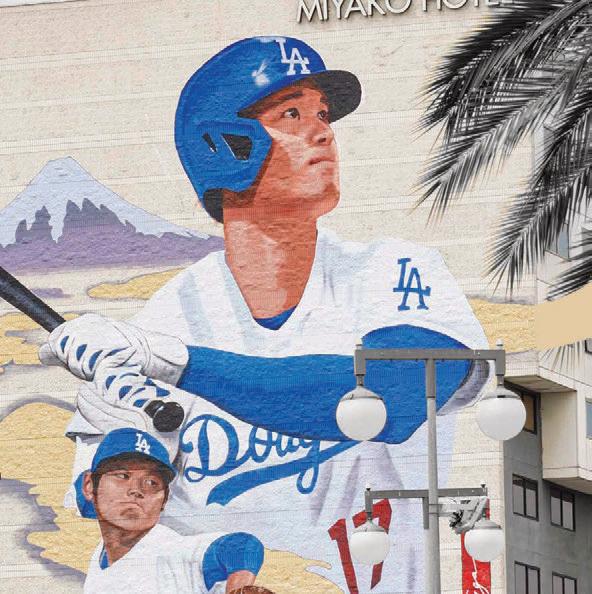

On a drive through Little Tokyo, I see a mural of Shohei Ohtani standing prominently against the city skyline, a depiction of the star Dodgers player gazing upward after a hit. As I weave through the alleyways in Echo Park, I see colors bursting off of murals on every block. The quiet streets of Boyle Heights celebrate Mexican American culture on their walls, many of the murals chipping and fading with age. In North Hollywood, I stroll down the half-mile-long Great Wall of LA, taking in the city’s political and cultural history captured in the expansive work – everything from prehistoric California landscapes to the birth of rock and roll. Each of these small communities creates the fabric of the vast, diverse landscape of LA’s culture.

But regardless of the content of the artwork, Persaud explained, most community muralists have one goal: to

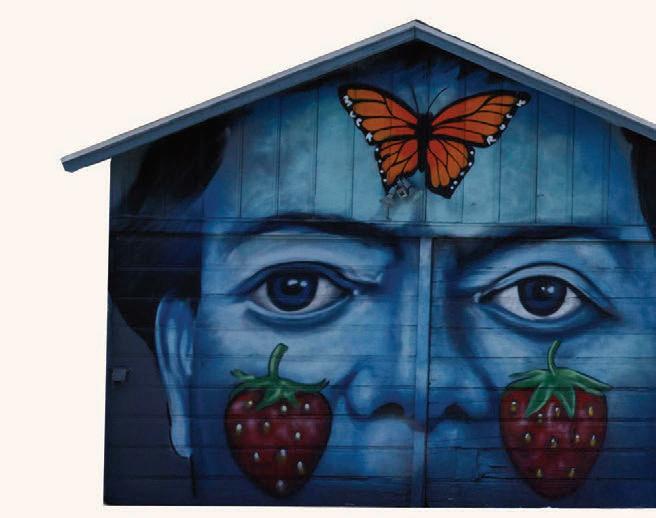

The Black Bruin Resource Center sits nestled into a back hallway of Kerckhoff Hall’s first floor, offering programs, guidance and a space for Black and African diasporic members of the UCLA community. When you walk in, your eye is immediately drawn to a mural spanning the entire back wall. The image depicts Black historical figures – smiling, singing, engaged in sports – positioned around a table in conversation with one another.

In 2021, UCLA opened a contest for anyone to submit a design for the mural focused on the theme of Black history at UCLA.

After talking through ideas with her family, UCLA alumnus Maia Hadaway, then a student, designed “A Seat at the Table,” an 18-by-7-foot mural that celebrated both current and

The role of murals is to communicate directly with the community outside of the usual spaces like a gallery or a museum.

historical figures with accomplishments in science, athletics, the arts and various other fields. One of Hadaway’s priorities was to emphasize that the present is part of a living history and that today’s generation has the opportunity to shape it. She described people’s tendency to separate themselves from the past’s significant figures without recognizing their own potential to make an impact.

“It’s so hard to fathom someone of our age doing something that MLK did,” she said. “No, he was at that place before, too. And I just wanted to instill that drive in people now, and especially for a college setting where people are growing, people are transitioning into adulthood.”

Much of her feedback since creating the mural has been positive, but several UCLA students reached out to her indicating their frustration that she did not include them in the mural. For Hadaway, a community mural represents so much more than just the specific individuals portrayed on the wall.

“My whole thing was that this whole mural was to incorporate you,” she said. “It was for you to see yourself in it. And I think that’s something I’m actually working on now in my art practice – to show people that, again, you can relate to someone who does not look just like you.”

This idea of building

connection through art in academic spaces extends beyond universities. Miles has painted murals at several K-12 schools in his Apache community in Arizona. These murals create lasting legacies for students, shaping how they see themselves and their community.

“It’s very rare when we see this type of Apache representation in this kind of art,” Miles recalled a student saying after he completed a mural at their school.

Similarly, even though Persaud’s classes do not focus exclusively on murals, she often shares examples of murals in her lectures. She noted how impactful it is for students – even those outside of the arts – to resonate with a work of public art, especially when the artwork responds to the world around them or traces back to a collective experience.

Despite that desire for personal connection, Persaud noted that this connection does not require directly seeing oneself represented in the mural.

“Even artworks that are really, really specific to a unique lived experience can still have this appeal to students from diverse backgrounds because it’s beginning to pull upon a real, relatable human experience or a struggle that we’ve seen across communities,” Persaud said.

Even though physical community is a central aspect of many murals, artists often move between cities or travel internationally to create new public art. Muck, for example, has commissioned murals across the United States, as well as in parts of Mexico, Europe and Asia. And although Miles paints primarily within his Apache community, he too has journeyed up to LA to

collaborate with other muralists and make his mark on a new place.

But no matter where Miles is, his community is always top of mind.

“I’m just going to paint an Apache character and write Apache on it as … a nod to history,’” he said.

An artist’s motivation to create a mural, however, might not always be centered around artistic expression or representing a community. Often, it’s financial.

Hadaway said the primary reason she will choose to paint a mural instead of a traditional canvas painting is if a company reaches out to her directly and provides her a commission. But because of its large number of aspiring artists, LA is not always the most

lucrative space for muralists.

“In LA, I mean, it’s not a great place to make money as an artist because there’s so many freaking artists,” Muck said. “If you don’t have a name, they don’t know that you’re charging money because you can do better.”

Otherwise, Hadaway tends to produce more of her works on canvas, due in part to the unique finished feel of paintings.

Sometimes these mediums overlap. The mural project she is currently working on for a reparations-focused organization in Chicago consists of three large paintings that will be hung side by side.

Hadaway described this as the best of both worlds for her art style –she can create on a larger scale while still capturing the feeling of her paintings.

While making a living as a

muralist is not always easily attainable, the LA art scene offers a unique environment for such a diversity of artists to gain inspiration from each other and from their surroundings.

It’s not a great place to make money as an artist because there’s so many freaking artists. “

Hadaway discussed how much LA-specific pride is clear in Angeleno artists. Ultimately, these murals capture something underlying about the human experience – something that bridges beyond one neighborhood, one city or one group of people. Art can resonate with us no matter our backgrounds and, as a result, broaden existing communities.

“I really do commend LA for making this space, making this community feel special,” she said. “Their pride is beautiful.”

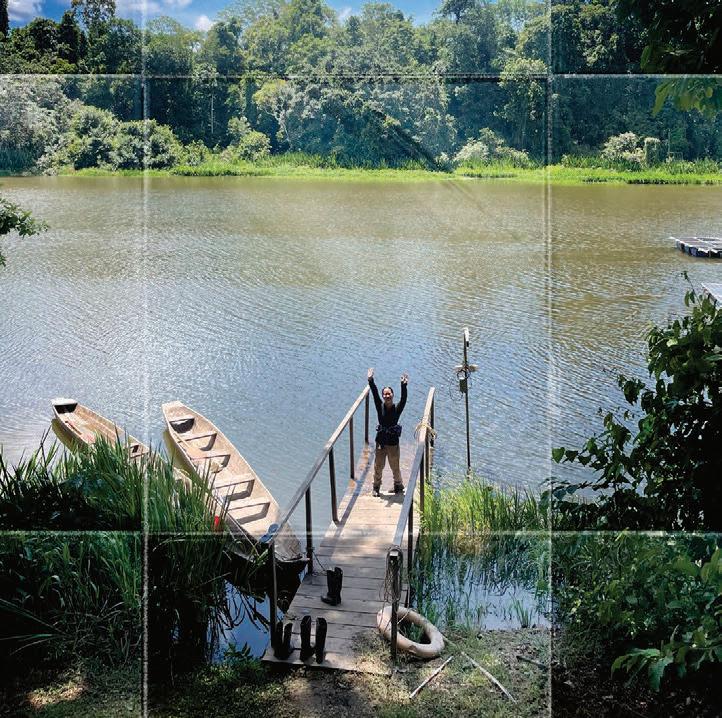

written by JULIAN DOHI

designed by FELICIA KELLER

photographed by ANNA DAI-LIU

illustrated by ISABEL RUBIN-SAIKA

Allen Daniels Jr. leveraged the holding bar, twisted his torso and pushed his arm forward, propelling the cast iron ball into the air. It landed on the soft turf of the field. A young volunteer ran after it and called out the distance. Daniels, sitting on the throwing frame – a tall metal seat strapped to the ground –nodded and stretched his arm. He was still warming up.

On this chilly March afternoon, Daniels was competing at a track meet held by Angel City Sports, an adaptive sports nonprofit, on Harvard-Westlake Upper School’s campus. On the track next to Daniels’ shot-put zone zipped three wheelchair racers. Their hands alternated between thrusting their wheels forward and adjusting the compensator, which helps them turn and propel at the same time. Coaches pumped the tires of a few bright blue racing wheelchairs, while a handful of volunteers carried around water bottles and rubber javelins.

Angel City Sports intersperses smaller events such as

these with larger competitions and fairs across Los Angeles to promote adaptive sports, athletic activities modified to accommodate people with disabilities. The organization hopes to expand access to adaptive sport opportunities and equipment to Angelenos, which is something the city has historically lacked. Their work is more important than ever because in three years, LA will become the center of the para-athletic world.

With the 2028 Paralympic Games coming to LA, para-athletes, activists and officials are rushing to meet the moment. UCLA, which will host the Paralympic Village and accommodate thousands of athletes with varying mobility and visual disabilities, often struggles to support the needs of its disabled student community. Three years out from the opening ceremony, LA’s accessibility and adaptive sports landscape reveals not just what to expect in 2028 but also how prepared our city and campus really are to support athletes and communities with disabilities.

LA has previously hosted the 1984 Olympic Games, during

which UCLA hosted the Olympic Village, but 2028 will be the first time both the city and the school host Paralympians. The 1984 Paralympics were split between New York City and Stoke Mandeville in the United Kingdom.

LA may now be hosting the 2028 Paralympics, but 10 years ago, Team USA said it had given up looking for Paralympic talent in Southern California, said Clayton Frech, Angel City Sports’ CEO and a UCLA alumnus.

He said one of main obstacles to providing adaptive athletic infrastructure in LA is a lack of public awareness. It is hard to convince many corporations, big donors and foundations – the major sources of funding for many nonprofits – that adaptive sports are a worthwhile pursuit, he said. Additionally, he said schools, parks and recreation programs, and other organizations such as the YMCA or the Boys and Girls Club of America generally don’t do this work at scale.

Much of

the work is left to small regional nonprofits, said Frech, which is particularly challenging in LA.

“This is one of the best talent pipelines in the world for professional sports,” Frech said. “And yet we’re in the dark ages when it comes to Paralympics.”

Alvin Malave, the program manager for Angel City Sports, said it is a little frustrating that building adaptive sports infrastructure can be so slow in a city with so many resources.

As I spoke with Malave over Zoom, he was driv- ing around a car loaded with adaptive athletic equipment to prepare for the Abilities Expo 2025 – an adaptive sports expo. He occasionally stopped to direct others where to unload their equipment.

“The work that we do is truly life-changing work,” Malave said. “We give kids and adults and veterans a space where they could come and con- nect with their peers and have all this social emotional learning – along with moving and doing exercise and getting fit and living a more active, healthy life.”

that in the past decade, awareness and programs for adaptive athletics have increased – particularly because of social media and the internet – but more work needs to be done.

In 2015, he co-organized the first Angel City Games, held at UCLA, to meet the significant demand for adaptive sports in LA. Now, Angel City Sports facilitates more than 25 sports and 250 clinics per year, according to its website. It has a loaner program to connect people with equipment and three annual competitive games.

But people still have to drive multiple hours on weekends to go to adaptive athletics events, Frech said.

“We’ve got this incredible need. No one’s filling it, except for nonprofits,” Frech said. “The business model of the nonprofits is a real challenge, and so what we have is really inconsistent quality and quantity of programming around the country.”

In the past decade, organizations such as Angel City Sports and Triumph Foundation, which specializes in assisting people with spinal cord injuries or disorders, have improved the landscape of adaptive athletics in Southern California. A $160 million investment from the LA Organizing Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Games 2028 and the International Olympic Committee led to the creation of the PlayLA Youth & Adaptive Youth Sports Program, which aims to increase sport accessibility ahead of the 2028 Games. The city is no longer the “black hole for Paralympic sport” it was 10 years ago, Frech said.

“We’re in the dark ages when it comes to Paralympics.”

Despite over one in five adults living with a disability in California, Frech said adaptive athletics programs are uncommon and limited in scope across the state. Malave said

As LA’s adaptive athletics organizations expand their reach, concerns have emerged over whether the city has the infrastructure to support the 2028 Paralympics. Many of the buildings in LA are compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act, but that just means they have the bare minimum accommodations, said Celina Shirazipour, a research consultant with Invictus Games and an assistant professor at the David Gef- fen School of Medicine. She said many facilities in LA and on UCLA’s campus may be unable to accommodate the thousands of visitors the Olympics and Paralympics will bring – even if they are technically compliant.

That influx of visitors may impact other aspects of the city’s infrastructure. Christopher Ikonomou, UCLA alumnus

and disability rights activist, expressed concerns about the capacities of LA’s metro ahead of the influx of visitors over the summer, even though bus ramps and elevators of LA’s metro were generally accessible in his personal experience.

Although LA has not announced the construction of any new facilities for the Olympic and Paralympic competitions, it has received nearly $900 million in federal funding to increase subway and bus transportation throughout the city. One such improvement is a metro line connecting UCLA to downtown, which is expected to be completed by 2027. LA has stated it is aiming to add 2,700 buses to its fleet for the 2028 Games.

“We have an opportunity to be a huge success. We also have an opportunity to be a bit of an embarrassment.”

Many of the training facilities at UCLA are topographically far below where the Paralympians would be living, Malave said. It is very difficult for a wheelchair user to go up the Hill, he said, even if they’re a trained athlete. He and Ikonomou said there is a particularly steep section of Bruin Walk that is circumvented by the elevator by the tennis courts. Ikonomou said it was frequently broken.

With this spotlight and attention on LA for the upcoming games, there is the potential to demonstrate strong support for athletes with disabilities.

“We have an opportunity to be a huge success. We also have an opportunity to be a bit of an embarrassment,” said Sam Silverman, the interim track coach for Angel City Sports.

Those concerns extend to UCLA’s campus. UCLA announced in 2016 that it will host the Paralympic and Olympic villages, essentially providing housing and facilities for all the athletes and any care partners. There is, however, concern about the accessibility of UCLA’s campus among those familiar with the school.

Frech shared he did not anticipate his son Ezra, a Paralympic gold medalist who competes in track and field, would explore much of Westwood or the campus if he competed in the 2028 Paralympics because of the valuable energy it expends to navigate UCLA’s steep terrain.

“That is not an easy campus to get around,” Frech said.

“Their ability to be on a podium or to medal is fractions and fractions of a second, ... where every little ounce of energy is important. I think this campus is actually going to be a real challenge.”

A recent Daily Bruin investigation found that a majority of elevators on the Hill have expired permits, and elevators are frequently out of order. Jennifer Miyaki, a coordinator for the Disabled Student Union who will graduate with her BA and MA in linguistics, said out-of-service elevators are a regular problem.

“I know that the Kerckhoff one is going to go under maintenance. Kerckhoff only has one elevator,” Miyaki said. “They (the administration) had said you can email us if you need accommodations, but I’m thinking, ‘Well, what accommodations could you provide?’”

Ikonomou described UCLA’s campus as notoriously inaccessible. It was not the first time the word “notorious” had come up in my interviews.

Other, more administrative, issues came up. Ikonomou said that when he went to UCLA, the BruinAccess vans were unreliable, and the drivers were not properly trained to support students with disabilities. Another Daily Bruin investigation found that the Bruin Access vans were frequently delayed and unreliable.

Two sources alleged that the UCLA administration has violated the ADA on multiple occasions. In 2021, several student organizations performed a 16-day sit-in at Murphy Hall in the longest continuous protest action since the pandemic and demanded changes such as the hiring of an ADA compliance officer. In April, two students filed a lawsuit alleging that UCLA had violated the ADA through inaccessible campus navigation and incomplete staff training.

Miyaki said it is hard to connect with disability specialists because they are so overworked. There are 11 disability specialists on the staff registry at the Center for Accessible Education, serving approximately 4,000 students with disabilities – with sometimes as few as three specialists on staff during the

past three years, according to a Daily Bruin investigation.

Despite these reservations and concerns for UCLA’s readiness, the arrival of the Paralympics could change the status quo. The money and public pressure the Olympics and Paralympics bring to LA and UCLA could fund the changes that disability activists have been fighting for, Ikonomou said, expressing disappointment that it might take until 2028.

“UCLA talks a lot about being No. 1,” Ikonomou said. “How about we become No. 1 in accessibility for students and letting people excel because we’re giving them all that they need to succeed?”

and the U.S. – what the disabled community can do, Frech said. He said it is important to spread awareness for the Paralympics because 90% of Paralympic tickets are bought by locals.

“They compete in silence with nobody in the stands all year long. Let’s give them one moment where we actually pack the stands and show up for them,” Frech said.

“Let’s give them one moment where we actually pack the stands and show up for them.”

Additionally, many people are excited about UCLA hosting the Paralympic village because of its welcoming community and state-of-the-art athletic facilities, Frech said. UCLA’s Adaptive Recreation Program is a valuable resource for students interested in adaptive sports, Malave said, offering programs like wheelchair basketball. The program partners with other organizations in LA, such as Angel City Sports and the Triumph Foundation.

The 2028 Paralympics could also increase the public’s awareness of adaptive sports and disability activism. Frech said

At the Angel City Sports track meet, Mayra Lopez watched as her 12-yearold son dashed around the track in a racing wheelchair. She said he enjoys Angel City events and keeps asking her when the next one is.

Malave was right behind him, shouting words of encouragement.

Silverman doesn’t get many days off, but when they do, they said they spend them with Angel City Sports. She said working with Angel City was the ideal intersection of her health care career and her love of sports – all while doing fulfilling community work.

“This is my life and my work-life balance,” Silverman said. “I recommend to anyone and everyone – if you’re needing some time to build your faith in humanity, if you want to get out in the community, if you want to volunteer – this is a great opportunity.”

the U.S. is behind other countries when it comes to understanding the event, and he hopes hosting will help it catch up. The broadcast of the 2012 London Paralympics marked a shift in people’s awareness of para-athletics, Shirazipour said. Since then, the U.S. viewership gap between the Olympics and Paralympics has shrunk, all while participation in the Paralympics has grown.

The 2028 Paralympics is a big chance to show the world –

Daniels, the shot put thrower, said he hopes to compete in the 2028 Paralympics. Until then, he said he was going to stay involved with Angel City Sports for the foreseeable future because it was the closest adaptive athletics organization to him.

He said goodbye and headed toward his car. He was facing an hour-and-a-half drive home. But he said it was worth it – and he’s going to keep coming back.

“I’m motivated to work out, meet other people, hear their stories, get the conversations, converse with other people that are in similar situations,” Daniels said. “It’s definitely a blessing.”

E

ditor’s note: This article includes a mention of a rape threat.

Iget asked every once in a while, by peers or supervisors or curious reporters new to the Daily Bruin, what spring 2024 was like. The answer is: There isn’t much I can remember at all.

Spring, this year, is the end of my career at The Bruin –and full-time journalism, for now. But just over one year ago was the weeklong Palestine solidarity encampment at UCLA. I remember the encampment in concepts: a 24-hour watch and constantly following rallies with press pass and camera in tow; hearing people yell obscenities and chase my coworkers around. I remember April 30, 2024 – fireworks, tear gas and colleagues assaulted. And May 1 to 2, 2024 – law enforcement officers with less-thanlethal munitions and hundreds of people arrested.

I am a student journalist. I reported on all of these things – even in the moments I could barely breathe –in articles whose details I memorized by heart, down to the exact times at which police arrived or ambulances

left. That was the responsibility I had then and the responsibility I still carry now.

Since then, I have never talked in any real public-facing manner about what happened in those seven days. It seems like an irony in a profession where the job is to keep a record. We run to tell the stories of others but never our own. We cover others’ trauma – but we were there, too.

I am not the first student journalist to experience something traumatic, and I most likely will not be the last. I am also certainly not the only person – between protesters, security and more – who witnessed violence those nights.

But I came to realize, through speaking to other student journalists who covered pro-Palestine encampments across the nation, that almost none of us got to talk about it. We didn’t – and still don’t – have formal spaces to talk through those experiences that range from sun poisoning to burnout and even arrest. Some of us have difficulties

covering protests or hard news at all, while others found more meaning in their work. But all of us are irrevocably different people because of it in ways that we lack the space to acknowledge.

At the end of the day, we were students thrown into the same protests national outlets sent their most seasoned journalists to.

“This isn’t our full-time job. Nor should it be, I think, expected to be. But I did find myself prioritizing this coverage over classwork and probably health,” said Sam Parker, former managing editor at the Daily Wildcat at the University of Arizona. “In the moment, it feels like this is the most important thing. And I’m proud of the coverage we did, and I’m glad I was there for it – and I don’t regret it.”

ones who could report these stories. After an attempted encampment at the University of Southern California on April 24, 2024, that resulted in 93 arrests, the campus was closed to visitors, said Nicholas Corral, an associate managing editor and then-assistant news editor at the Daily Trojan. That meant only reporters from the university’s two student media outlets – one of which was the Daily Trojan – could report what was going on inside the gates, Corral said.

“In the moment, it feels like this is the most important thing. And I’m proud of the coverage we did, and I’m glad I was there for it – and I don’t regret it”

All the student journalists I spoke to shared that mindset – that covering the encampments was some of the most important work they could ever do. Many journalists pursue the career out of a sense of moral obligation, said Lea Didion, a psychologist who is part of the Journalist Trauma Support Network.

For some, the obligation came from the desire to counter a common narrative. Taylor Parise, an alumnus of Santa Monica College who reported at its newspaper, the Corsair, covered the police sweep of the Palestine solidarity encampment at UCLA from the inside – her first time ever covering a major protest. Parise said she wanted to combat misconceptions from mass media outlets that were primarily covering the events from outside the barricades.

Particularly as a then-editor in chief, Mercy Sosa – a rising seventh-year journalism student of California State University, Sacramento –said she felt she had the responsibility to keep going with coverage, despite the pressure of final exams looming.

These obligations, however, had their physical and mental drawbacks.

“When we’re caught up in one of the most important events on campus’s history, it’s hard to take that in when you’ve never done that before and evaluate your mental health,” said Andrew Miller, a managing editor last spring at the Indiana Daily Student at Indiana University Bloomington.

At other schools, student journalists were the only

This intense work and stress across days and sometimes months – in Miller’s case, 100 days – led to issues of newsroom burnout. Burnout occurs when the body’s resources are depleted, which can lead to mental consequences such as fatigue and poor concentration but also physical effects including chronic tension and pain, Didion said.

Significant protest activity took place during Miller’s finals week, but the rising fourth-year history and

journalism student at IU Bloomington recalled putting a 30-page paper on the back burner for reporting shifts through the night. Daily Trojan reporters – who were also taking finals throughout the height of the protests – had trouble limiting themselves to assigned shifts and schedules, often showing up unscheduled because they wanted to help, said Corral, a rising third-year journalism student at USC. For then-news editor Parker, being the main reporter covering the protests meant she was on alert for a full month – adrenaline so high that it made it difficult to fall asleep.

But burnout is one thing; trauma is another. Witnessing violence – even without directly experiencing physical harm – can lead to trauma, Didion said. Therapist Heather Herz, another member of the Journalist Trauma Support Network, added that journalists, who may be unaware of what a situation might bring, often do not have a choice in witnessing it.

Ninety-five percent of last year’s pro-Palestine encampments did not involve any protester violence, according to a report from Princeton University’s Bridging Divides Initiative. But violence on the part of police did occur. Law enforcement was involved in around 260 demonstrations and detained more than 3,000 people, employing less-than-lethal force in at least 24 schools –including UCLA – and allegedly deploying snipers at five, according to the same report.

However, such “less-than-lethal” force, which according to the United States Department of Justice can include batons and tasers, has far from negligible effects – and can potentially be lethal if improperly deployed, medical experts said.