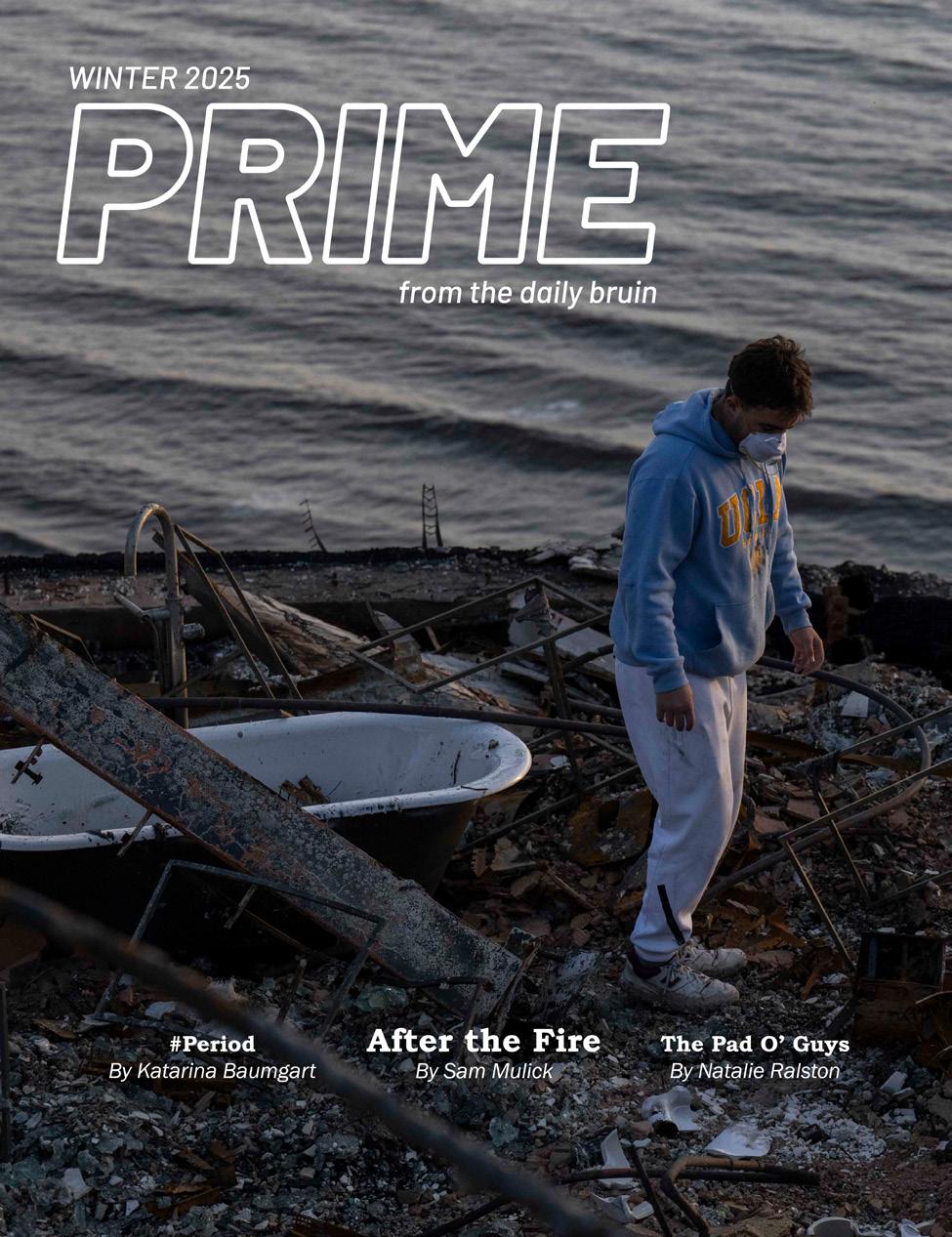

FALL 2025

PRIME

from the daily bruin

COVER

Slipping Between the Aisles

College can symbolize a newfound independence, but what does that look like in practice?

ALSO INSIDE

The Extracurricular Expat - Liberation Left Untold - and more

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Dear reader,

For many, the return to campus represents the epitome of novelty – new clubs, new housing, new style and new friends. Some will find themselves mesmerized with an endless array of tables at the Enormous Activities Fair, while others will face off against the trials and tribulations of adjusting to apartment life. Regardless, there’s plenty of curiosities to catch the eye of passersby and PRIME writers alike – and what better way to satiate this desire than by experiencing it directly?

This issue, PRIME writers took this philosophy to heart – tagging along in grocery stores and hopping around campus extracurriculars to answer their pressing questions. How do students adjust to shopping for themselves? How are they finding community in a disconnected world? Through endeavors in first-person reporting, these writers embody the humanity that lies at the crux of these topics.

For some, the experience came before the reporting.

In a love letter to language, PRIME staff writer Tulin Chang Maltepe recounts her summer studying abroad in Beijing, China, as a Chinese American. Newfound perspectives were also common for those on campus. While they may have grown accustomed to Westwood’s scholastic stomping grounds, writers challenged themselves to inquire about its weathered wonders.

From the legacy intertwined with the LGBTQ Campus Resource Center to the lives of first responders of color, stories explore the deeper histories behind the institutions and figures that color the periphery of student life.

Whether it be through a sit-down with a culinary icon or university-level decision-makers, the season of sleuthing is upon us.

What will you find?

Davis Hoffman PRIME content editor

Leydi Cris Cobo Cordon PRIME director

director

PAST ISSUES @primedailybruin

CONTENTS

8 Liberation Left Untold

written by CAITLIN BROCKENBROW

Decades after helping ignite UCLA’s early LGBTQ+ liberation movement, Donald Kilhefner reflects on the early setbacks and triumphs in the fight for visibility.

30 Behind the Bark: Q&A with Perro Tacos’

Luis Garcia

written by DAVIS HOFFMAN

Food trucks such as Perro Tacos have become a staple among the Hill’s dining options. Through family, food and fans, see what life is like for a cook behind the line.

13

Break Glass in Case of Emergency

written by ALISHA HASSANALI

With the added complexity of identity, first responders must contend with the glass ceiling while balancing the physical and emotional demands of their profession.

35

Connecting Across Characters

written by

TULIN CHANG MALTEPE

PRIME staff writer Tulin Chang Maltepe reminisces on her summer in Beijing through a language-filled and introspective personal narrative.

18

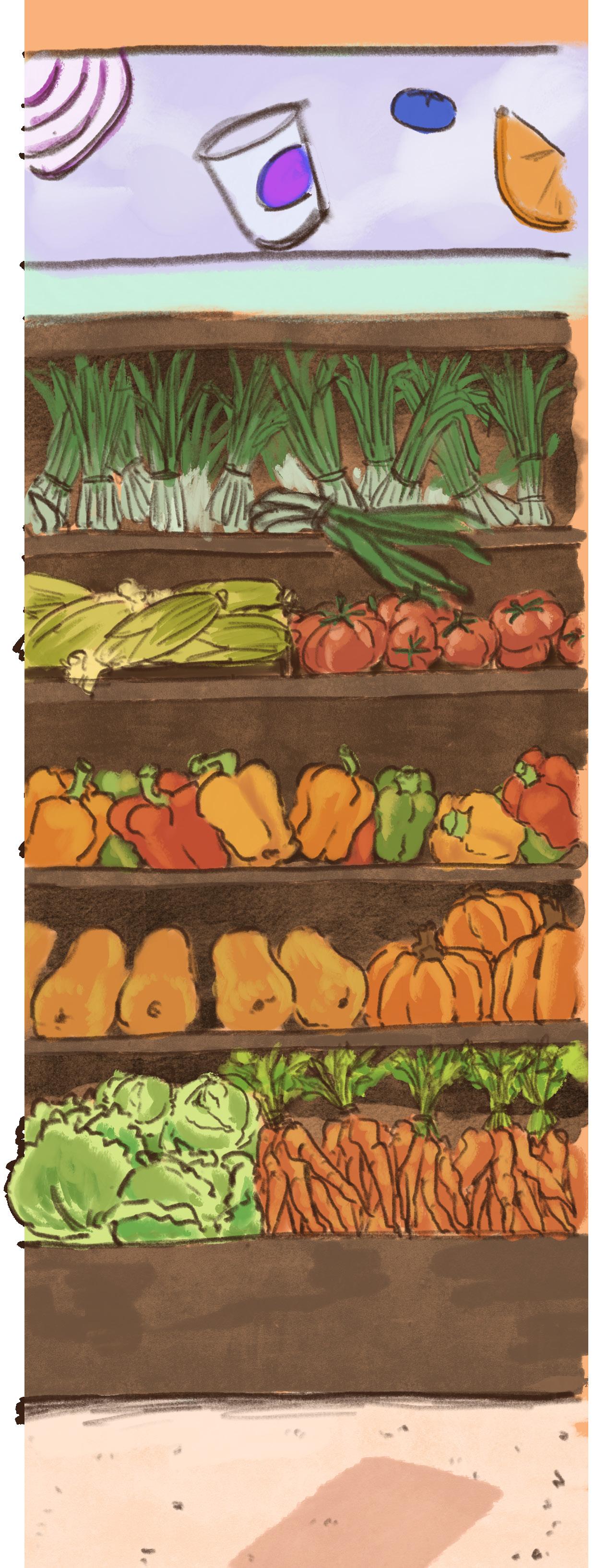

Slipping Between the Aisles

written by KATARINA BAUMGART AND HELEN JUWON PARK

College can symbolize a newfound independence, but what does that look like in practice? Explore a closer look at student grocery runs in Westwood.

24 The Extracurricular Expat

written by PATRICK WOODHAM

Humans are creatures of habit. In a daring feat of extroversion, PRIME writer Patrick Woodham sets forth to explore where others find community.

41

A Seat at the Table

written by SHIV PATEL

Known for meeting in the Meyer and Renee Luskin Center, the UC Regents can feel distant from student life. What does it look like when those are one and the same?

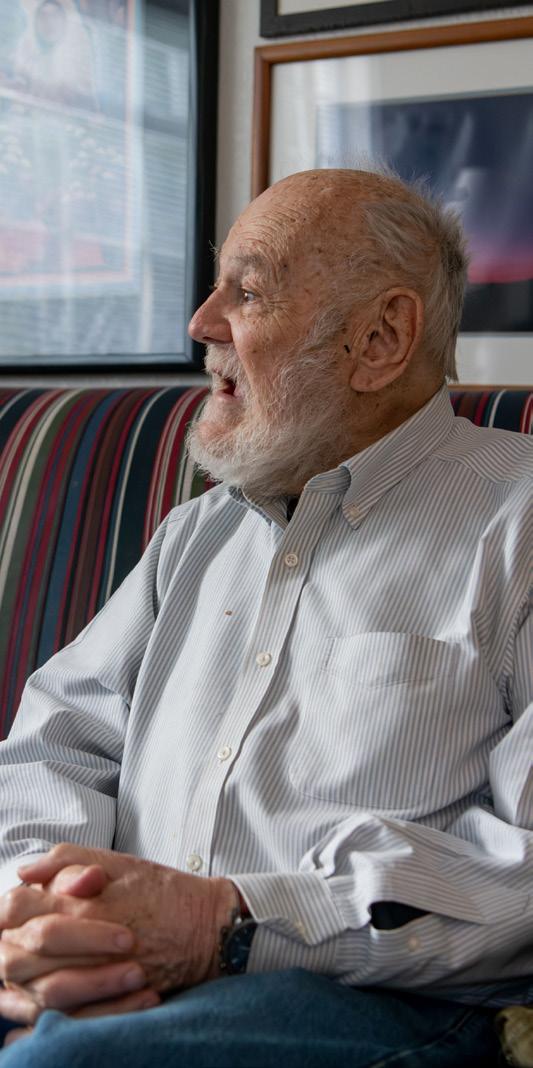

liberation left untold

written by CAITLIN BROCKENBROW

“The definition of bravery is, “you do it even though there’s fear.”

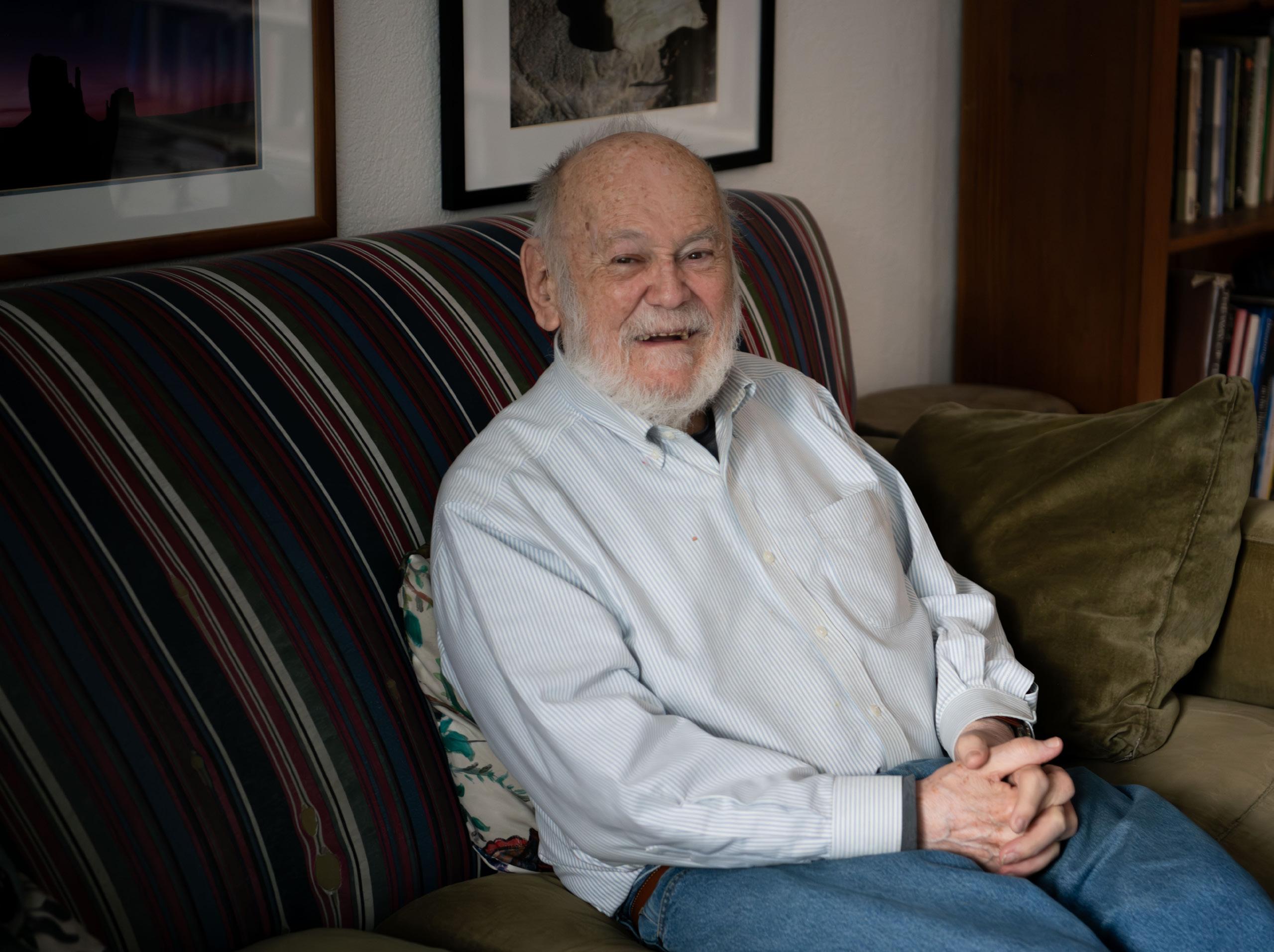

Donald Kilhefner’s voice is calm when he says this, but there’s a weight beneath the words. At 87 years old, he has had a lifetime to measure what bravery really means – the kind that does not come from acceptance or applause but from doing something when no one else dares. His voice is steady, almost amused, like a man who has spent 60 years watching the world try to

photographed by BRIANNA CARLSON

soften what was never meant to be soft.

That steadiness also defined the path he chose when stepping into the earliest waves of organizing queer liberation in Los Angeles. He entered the movement as organizers were laying the groundwork for what would become a broader push for visibility.

Kilhefner’s story traces the origins of a movement and, over time, became that of a lifelong organizer challenging complacency, revealing

designed by CAITLIN BROCKENBROW

how bravery – once born of necessity – continues to evolve in a community still defining what liberation means. Looking back on it all, Kilhefner said he had three pivotal events in his life. The first was joining the Peace Corps and working in Ethiopia from 1962 to 1965, which he said gave him a much larger view of the expansive possibilities available to him. The second was receiving his master’s degree in African studies from Howard University, a historically Black university. He said

“The definition of bravery is, ‘You do it even though there’s fear.’”

he wanted to be taught Black history by Black professors, describing it as one of the best educations he ever had.

The third was going to UCLA.

Kilhefner’s organizing on campus reflected a broader wave of queer activism emerging across the country, as students and community members began linking their struggles to the era’s wider movements for queer liberation.

The Stonewall rebellion erupted in New York in June 1969, sending shockwaves through a country already roiling with protests against the Vietnam War and cries for civil rights and women’s liberation. California had its own battlegrounds, from police raids on gay bars to the newly formed LA Gay Liberation Front, which Kilhefner became deeply involved with.

The then-doctoral student in African and Islamic studies started a chapter of the Gay Liberation Front at UCLA alongside fellow students Rand Schrader and Steve McGrew. They had been inspired by the Columbia and UC Berkeley students organizing gay student unions. After reading the requirements to form a campus organization, Kilhefner said the three thought the process would

be very easy and quickly wrote a mission statement. They were about to finish the process when they ran into a final problem.

It was not widespread student opposition or campus-wide discrimination – it was finding a faculty advisor.

He said the three were certain one of a handful of faculty members would be on board. However, they all declined, saying it was too risky and could cost them their careers. While wondering what to do with all the other pieces in place, a fellow graduate student suggested they talk to a sociology professor – known for being a Marxist, anti-Vietnam War, pro-feminist and supporter of the Civil Rights Movement – who they were inclined to think would be on board. The sociology professor agreed on the one condition – that he never had to attend their meetings or in any way be involved afterward. They just had to keep him informed about what was happening so he would not be caught by surprise.

Kilhefner said he could not

remember the professor’s name because he only talked to him twice. Once to ask if he would be their sponsor and then again when he signed the organization’s official founding document. At the time, Kilhefner said LGBTQ+ people were not seen on campus, and they certainly were not supposed to be heard. But that invisibility did not last long.

In October 1969, the UCLA chapter of the Gay Liberation Front held its first meeting, initially in Campbell Hall, with around 10 people in attendance. By their second meeting, they started planning an LGBTQ+ dance in Ackerman Union for the following quarter. The dance ultimately had 200 attendees, which included about 150 LGBTQ+ students and 50 allies, with the group only growing from there.

The rapid growth of those first gatherings placed the UCLA chapter within a larger lineage of queer activism that took shape in LA over the previous decades, Kilhefner said. The Gay Liberation Front emerged

from a long and complicated lineage of organizing in LA, he added. One of the earliest gay rights organizations in the United States was founded in 1950. The Mattachine Society operated quietly in Los Angeles under a liberal but cautious agenda, seeking gradual social acceptance rather than open confrontation. The group saw a decline in membership only three years later.

“In 1953, that (Mattachine Society) fell apart because Harry Hay, one of the founders, was outed as a former member of the Communist Party,” Kilhefner said. “People fled fearing the Red Scare was happening, fearing that they would be raided.”

What followed, Kilhefner said, was the homophile movement, a starkly different effort that sought respectability and restraint. Led largely by conservatives and moral reformists, he said its leaders urged LGBTQ+ people to behave and not rock the boat in the hope that quiet conformity might lead to acceptance, something more akin to assimilation than revolution.

When the Gay Liberation Front movement rose in 1969, he said it shattered the mold by taking power back through civil disobedience. The goal was not to fit in but to fight back and claim space, voice and power in a society that had long denied their existence. As Kilhefner put it, gay liberation was not a plea for tolerance but a political awakening – a demand to be seen and heard on their own terms. Today, Kilhefner still speaks with the same clarity and conviction that drove him all those decades ago.

“Fuck acceptance, who wants that?” he said.

Unlike the homophile organizations of the 1950s and early ‘60s, which sought quiet acceptance through respectability and assimilation, the Gay Liberation Front embraced confrontation and visibility as tools of liberation. Its members rejected the notion that queer identity needed to be justified or hidden to earn legitimacy.

“We were a political movement.”

“They weren’t going to accept us anyway,” Kilhefner said. “We put the emphasis on gay people developing self-respect, self-acceptance and it worked, and we developed a political

strategy. We were no longer arguing whether we’re sick or not, but we were a political movement.”

By winter 1970, he had taken a leave of absence from UCLA and was working as the Gay Liberation Front of LA’s live-in office manager. He spent his days organizing off campus and his nights sleeping on the office’s sofa in a sleeping bag, having had no place to live. His fellowship had been paused until his return, leaving him without any income.

Schrader and McGrew stayed

primarily involved with the UCLA chapter, focusing on building a visible and sustainable presence for LGBTQ+ students on campus. After its first few meetings, the student organization had been swamped. Kilhefner said it was like the LGBTQ+ student population was ready, just needing someone to open the door. As he shifted focus off campus, he said liberation organizing brought him to life in a way that his doctoral program did not.

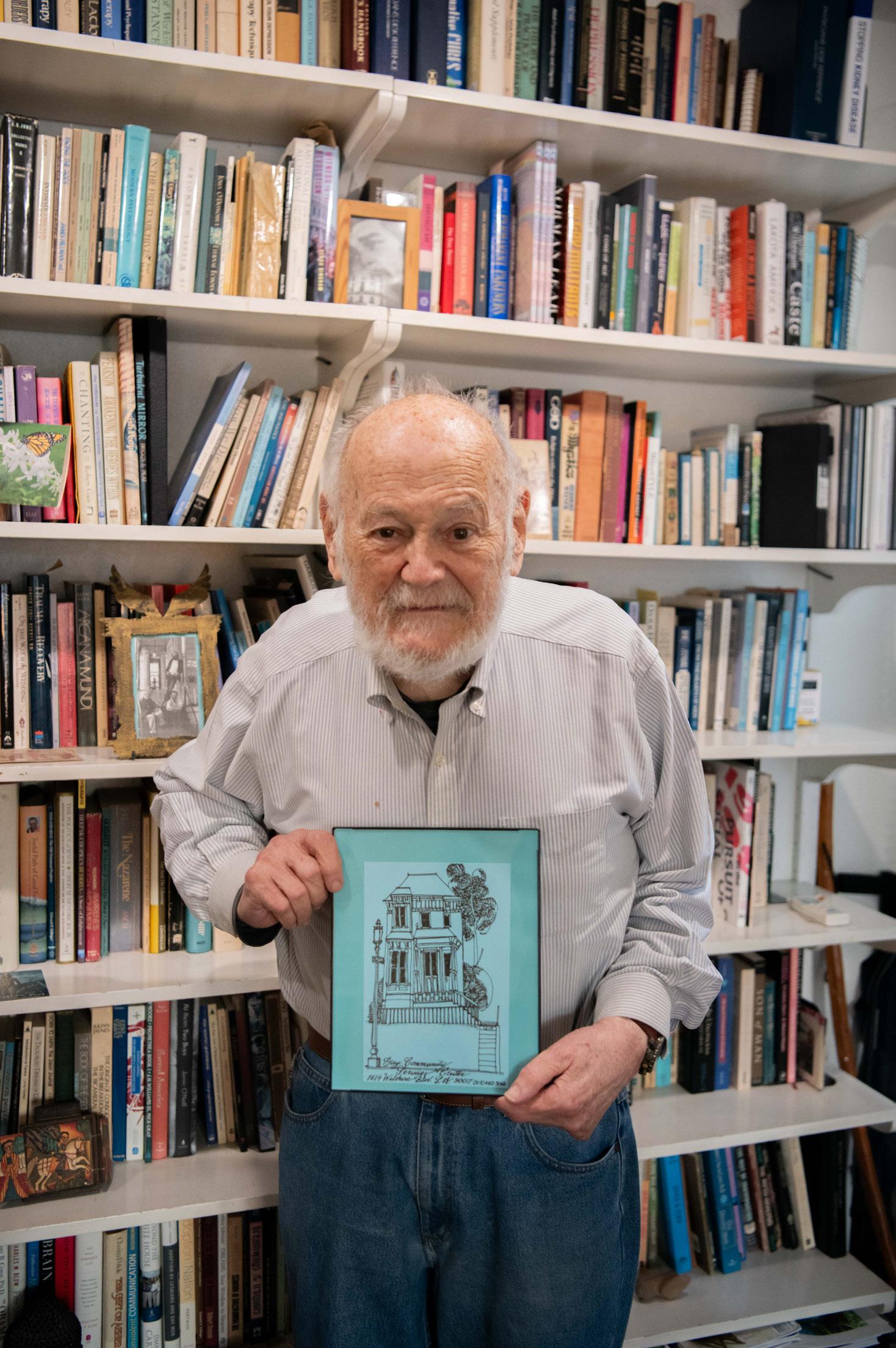

Kilhefner went on to co-found the Gay Community Services Center, now known as the Los Angeles LGBT Center, in 1971 to advocate for and provide health services for the community. In the years that followed, he helped launch and support numerous other organizations and initiatives alongside his work as a psychotherapist. In the present day, Kilhefner still writes and actively engages in LGBTQ+ activism.

As the years went by, the lives of

“Gay, lesbian and trans people have evolved and I don’t expect them to be the same people they were in 1969.”

many times the AIDS diagnosis was a death sentence, and then I stopped hearing from him (McGrew), and my phone calls and emails were not answered,” Kilhefner said. “Those days, we knew what that meant.”

More than half a century later, the movement that began in those early campus meetings continues to ripple through UCLA’s history. The legacy of that early organizing at UCLA

continues to take tangible shape on campus with the UCLA LGBTQ Campus Resource Center, whose foundation draws back to LGBTQ+ activism on campus such as that of the original Gay Liberation Front chapter.

Paul Moore, executive director of the David Bohnett Foundation, said the foundation has been supporting the now-named UCLA LGBTQ

created to ensure

physical space. The foundation also hosts the Judge Rand Schrader Pro Bono Program at the UCLA School of Law, honoring Schrader, Bohnett’s late partner.

The spirit that drove his early organizing still defines him today. To those who know him – like his newsletter collaborator Danny Battista – his dedication has never wavered.

“He has a lot of gravity to what he knows,” Battista said. “He’s seen how much things have changed and evolved and has firsthand experience having lived through and participated and led a lot of the efforts that have led to our present reality.”

But Kilhefner said the world around him has changed, that the power structure in the LGBTQ+ community has been taken over by elite, wealthy people, largely white men. There is a big difference between gay liberation of the 1970s and what is going on today. In his eyes, a gay movement does not exist anymore. Instead, people have become spectators of their own movement. Recent legal challenges to LGBTQ+ rights also

make the present a very dangerous time for the LGBTQ+ community, in which the advancement of the last 60 years could be wiped away, Kilhefner said. However, new challenges are expected. For Kilhefner, what matters most is finding new solutions.

“Gay, lesbian, trans people have evolved, and I don’t expect them to be the same people they were in 1969,” Kilhefner said. “I’m interested in moving it forward. What is the struggle now? What do we need to do now?”

BREAK GLASS IN CASE OF EMERGENCY

written by ALISHA HASSANALI

When James Alcantara first told his parents he wanted to be a firefighter, he was met with concern.

He was “not the right color,” they said. Though he had already decided to pursue the career, as a kid he struggled to imagine becoming a firefighter.

“Growing up, all you see are blonde hair, stacked, jacked, 6’4”, 250 (pound)

firefighters, right?” he said. “That was my existence.”

For communities of color, trust in first responders has never come easily. The creation of the 911 system was a response to the Civil Rights Movement, and over 60 years later, Black and Hispanic Americans still distrust law enforcement, according to a 2023 Gallup Poll. Further, modern-day policing traces its origins to the “slave patrol,” which

used terror and excessive force to control enslaved people in the early 1700s. People of color in the United States also find it harder to access quality health care.

Alcantara is one of 4.6 million first responders in the U.S. – firefighters, police officers, security personnel, EMTs and paramedics, among others – who risk physical danger and emotional trauma while working long hours to ensure public safety.

Though each poses its own unique set of challenges, many first responders of color also find strength in their identities.

As a paramedic at the Culver City Fire Department who works with the UCLA Health Mobile Stroke Unit, Alcantara’s profession is no longer a point of confusion – rather, it has become a source of pride for his family. When Alcantara’s family members meet other firefighters while traveling, they’re always eager to share his story and celebrate his accomplishments. Getting hired as a

firefighter, he said, was like fighting “an uphill battle,” and he credits his family, whose constant support and encouragement made it possible.

“ Growing up, all you see are blonde hair, stacked, jacked, 6’4”, 250-pound firefighters, right?” he said. “That was my existence. “

Gabrielle Dizon, a second-year business economics and psychobiology student, said her cultural background has also been a source of strength in her work as an EMT, as it allows her to connect with other health care workers on a deeper level and forge bonds.

For example, she recalls transporting a patient undergoing chemotherapy who appeared

very weak. Dizon said she was heartbroken overhearing him and his visibly worried wife discussing his treatment and how uncertain they were about his health. His wife told Dizon that she felt comforted by the fact that Dizon is Filipino and could speak Tagalog. This cultural bond gave the patient’s wife a sense of safety.

“She even brought me and my other EMTs food, which they said has never happened before in their career,” she said.

Dizon added that she has also experienced a similar sense of cultural solidarity and mutual care with other Filipino health care workers. She said while Filipinos are known for caring for everyone, there’s also a special bond and mutual care within their own community – a sense of taking care “of our people.” When she meets other Filipino healthcare workers, she immediately feels a sense of connection from their shared identity.

However, many first responders like Dizon struggle to articulate the traumatic and violent aspects of the job. For one, Alcantara struggles to respond to the common question of, “How is work?” from his friends and family. He internally compartmentalizes the traumatic events he witnesses during the day, whether that be the death of an infant or injuries from a deadly car accident.

But when he comes home to his two young daughters, he leaves the pain of the day at the door – the injuries, the deaths, the chaos. Instead, he smiles and tells them about their uncle’s pineapple upsidedown cake. Another day, he tells them his friends are having a baby.

“We take a lot of that home, and we sweep it under the rug,” he said. “It internalizes and it then resurfaces through a lot of mental health.”

Eighty-five percent of first responders report symptoms related to mental health conditions. Now, Alcantara participates in a peer support program to help first responders process depression,

anxiety, PTSD and substance misuse.

James Echols, UCPD’s community services division lieutenant, said many first responders choose not to say anything to their families to protect them from the trauma, but the lingering effects of suffering in silence “sneaks up on you.”

“

“If you work 911, you see the worst of the worst happen,” Dizon said. “You see people get shot. You see people die. People die in your ambulance and after that call, you’re expected to go to another call, clean up your ambulance like nothing ever happened. And that’s hard. That’s really hard.”

She recalled responding to a call to transport a patient – a task that was physically demanding for everyone involved. Her team grew demoralized as the patient repeatedly blamed them for his discomfort, showing little appreciation for their efforts. Despite her own physical and

do about that,” she said.

In addition to the psychological and physical tolls, first responders also have to contend with racism as they try to do their jobs. Echols said people sometimes try to distract law enforcement during arrests through racist comments, especially when they feel intimidated or threatened during encounters with first responders.

If you call and there’s a need and that officer satisfies that need, that should be the focus. “

Dizon adds that the physical demands of the job, such as lifting patients, moving gurneys, transferring people to hospital beds and carrying heavy equipment, cause significant strain on first responders’ bodies – a painful addition to the mental burdens of the field.

emotional exhaustion, she struggled to keep her frustration in check and maintain empathy. She said her job as an EMT requires her to balance her emotions in life-threatening situations.

“Unfortunately, sometimes you will be the last person there with them, and especially if they’re dying in the ambulance, there’s nothing you can

“They don’t know you as a person, so they can’t attack your character,” he said. “They don’t know where you come from or what you’re dealing with, so the only thing they have is what you look like, so they attack that.”

Echols believes that the racist comments he hears stem from anger at law enforcement. He understands that the people aren’t truly angry at him, but rather they’re upset because they were caught or because Echols is enforcing laws that may punish them for their actions.

“I just take it with a grain of salt that no matter what race they are, if they’re saying something that is racist in nature, I know what their intent is, and I have to be above that,” he added.

Despite the many stressors of the job, Alcantara added that he values the selfless, inclusive nature of his

work as a first responder. He said it’s easy to lose sight of the human side of caring for others in such a fast-paced, high-pressure environment.

Echols added that he wishes there could be a move beyond bias or prejudice to judge first responders by their actions and professionalism.

An officer’s race, ethnicity or appearance should not affect how they are treated when they respond to emergencies.

“If you call and there’s a need and that officer satisfies that need, that should be the focus, not what the person looks like when they show up,” he said.

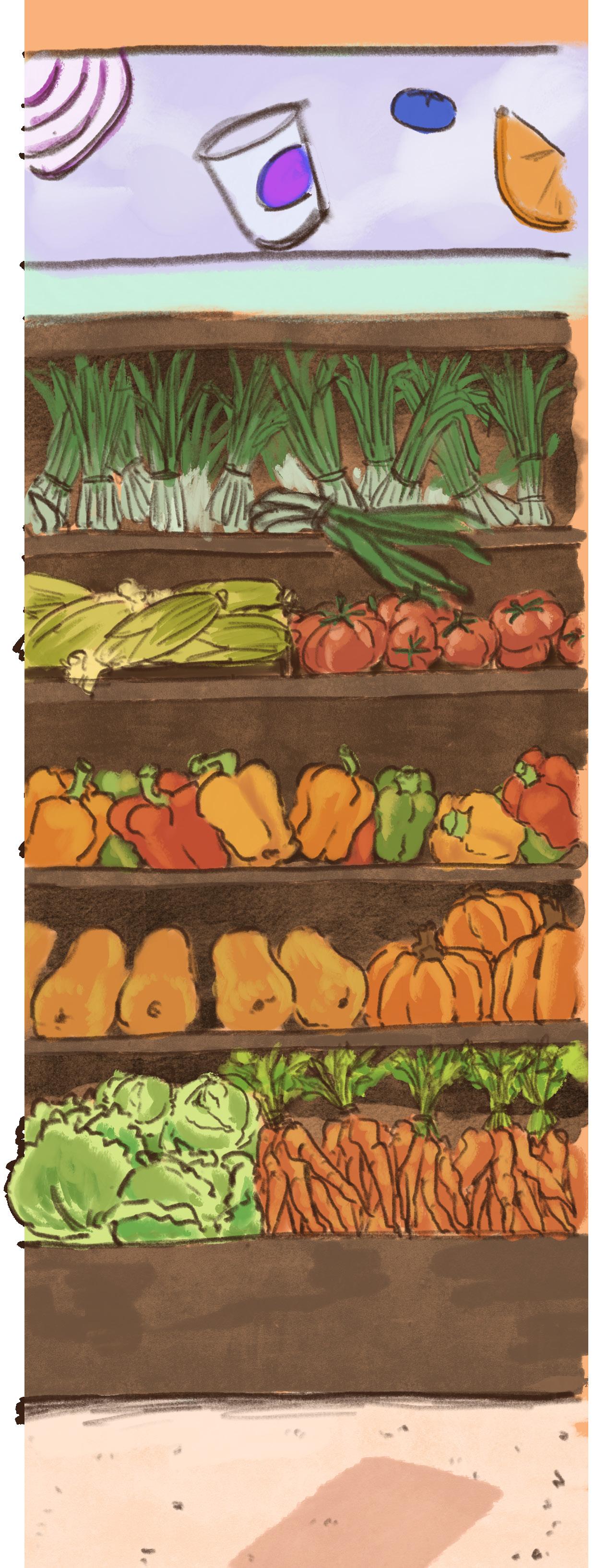

Slipping Between the Aisles

Crossing Trader Joe’s at golden hour, I watch as students take on grocery shopping in pairs, parties and alone. As the clock nears 4 p.m., parents and children start to fill the store. Three women gaze intently into the yogurt aisle as Hawaiian shirt-clad staff bustle around. I smile at the sight of a shopper – basket in one hand, not-so-small dog under the other.

A Trader Joe’s employee recognizes me after my third pass around the store with a different student – I worry at first, but am quickly reassured by his smile and chuckle. Forging ahead, I spark up conversation with the next available basket-laden Bruin.

Armed with grocery bags and coupons, UCLA students learn to bear the added weight of budgeting, meal planning and caring for themselves

away from home. Students from beyond the West Los Angeles region navigate additional changes, such as accessibility and managing finances. Curious about their attitudes and strategies during this transition, we set out to find answers among the aisles of Westwood’s grocery stores.

Amid colorful signs and a cacophony of voices, I spot two students conversing across the Trader Joe’s produce aisle. Preparing for a housewarming charcuterie party, Kalani Emde and Shonan Chiang deliberate goat cheese’s popularity and warmly recount their recipe-creation adventures.

The pair bonded over attempting TikTok recipes in the Saxon Suites. But in their current off-campus

apartment, Trader Joe’s fuels some of their midnight creations. Most recently, Chiang said they fashioned a tower out of pumpkin brioche, pumpkin butter and cream cheese to accompany their late-night show.

The shift from living on the Hill to an off-campus apartment has also come with a need for greater economic awareness, said Emde, a fourth-year molecular, cell and developmental biology student. Among the grocery stores in

“Be grateful to still have B Plate.”

Westwood, she said Trader Joe’s offers the most variety and affordability — not to mention its seasonal treats and produce.

“Be grateful to still have B Plate,” Emde chimed in.

Chiang, a fourth-year human biology and society student, also mitigates costs by purchasing essentials in bulk from Costco – such as Greek yogurt, steak, deli turkey, pretzels and cottage cheese – which her parents pick up during their visits from San Diego. While the bulk portion sizes can mean temporarily repetitive diets as they battle spoilage, the students still opt to shop for essentials there.

Kayla Diep browses Trader Joe’s for its unique snacks and frozen meals when food on the Hill gets repetitive. The second-year biology student added that Trader Joe’s is the most affordable among Westwood’s grocery stores, though it is still marginally more expensive than her hometown’s location in the Inland Empire. While it may not be essential, Diep said she finds joy in grocery shopping.

“It’s a nice escape,” Diep said. “I feel like I’m exiting the simulation of school.”

Diep isn’t the only student who shops for leisure.

Although Stella Lau has finished her grocery shopping for the week, her lackadaisical walk to Whole Foods Market reflects her typical grocery shopping style. A Ralphs frequenter otherwise, the second-year psychology student enters without a grocery list and relaxes while shopping, using the trip as a relaxing break. She and her travel companion, second-year mathematics student Carlos Martin, enter the higher-end store around 9:30 p.m. for a leisurely late-night stroll to browse for snacks. As she scans the wall of assorted carbonated drinks, Lau reminisces on life at home – where grocery shopping was more labor-intensive than relaxing.

“Shopping for a family is a lot,” Lau said. “Someone’s got to help them with the grocery bags. Also, I don’t want my mom to feel lonely. I feel bad, (so) I’ll just be like, ‘I’ll come with you Mom!’”

In the Trader Joe’s flower section, I find Julieanna Li. She meanders around the grocery store she visits as a go-to for snacks. The shift from being fed by parents to feeding oneself can be a challenge, explains

the third-year data theory student from Indiana. Living independently made her better understand her parents’ strong aversion to wasting food. She still prefers, however, apartment living to the dorms

because she has more freedom over everyday choices.

Nearby, in the drink aisle, I spot Amelia Jeffs on the phone deliberating the best lemonade flavor to purchase. Hailing from northern

California, the third-year psychology student said her hometown grocery stores are similar to Westwood’s –making shopping decisions familiar and easy. She said she typically purchases produce from Whole Foods

for its longevity and opts to buy frozen meals from Trader Joe’s. In their off-campus apartment, she and her roommates typically share a few essentials such as milk, condiments and spices, but their differing schedules mean they primarily shop for themselves.

For Li, the lower cost of living informed her choice to live off the Hill. On the Hill, Li recalls several instances where her peers wasted food, either from not eating to-go order leftovers or missing meal periods on a Regular plan. In the off-campus apartments, Li can make all the food she wants and save leftovers for another day. Apartment living also allows for the bartering of responsibilities, such as Li’s roommates occasionally cooking in exchange for her doing the dishes.

Carpooling from their off-campus apartment, roommates Sharon Park and Kendall Gomes shop to accompany each other and split their Trader Joe’s bill. Park, a fourthyear sociology student, said living in the apartment has made her cook more frequently, because eating out every day is unsustainable. On the other hand, leaving the Hill brought money to the forefront of Gomes’ mind.

“Living on the Hill, you get all the food through a swipe, so it doesn’t feel like real money,” the third-year economics student said. “So now it’s like, ‘I have to pay for this.’”

Peering over the pair’s moderately full grocery cart, I ask how they divide the cost of groceries. Since the roommates were close friends prior to living together, Park said they often share common goods such as cream cheese and bread. For instance, she doesn’t mind footing the ketchup bill for the group, since her roommates would do the same.

I emerge from Target’s toilet paper aisle to find another set of roommates discussing canned goods. As an alternative to dining hall breakfasts, Caryn Dea said she opts to make grab-and-go items such as overnight oats in her dorm. The first-year human biology and society student’s decision is a product of having a 14P meal plan and limited

time before early classes. First-year political science student Skyler Dang said Westwood’s Target prices are higher compared to the Foods Co. and Safeway the pair frequent

“I feel like I’m exiting the simulation of school.”

in San Francisco – enough even to merit checking Amazon for cheaper products.

Discussing the feeling of “adulting,” Dea adds that Dang is awaiting the

results of her Electronic Benefits Transfer interview, which she had earlier in the day. Although most students with meal plans do not receive approval, Dang said she is hoping for the additional financial support.

The recent government shutdown led to a temporary loss of benefits for recipients of California’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, CalFresh — including EBT or Food Stamps. While it has since reopened, repercussions for students are expected to continue.

On an emergency grocery run to Whole Foods, Vicky Gao notices price increases and expressed concerns over losing EBT access if she decides to move back home post-graduation.

In the meantime, the fourth-year psychology student utilizes resources such as the Wednesday free grocery distributions at the Tipuana University Apartments.

I encounter Romy Billard and Joshua Coenraads in Ralphs, two second-year business students in UCLA Extension, debating the freshness of the store’s beef. Billard said she feels more reassured going to Trader Joe’s because more students go there, but found herself at Ralphs because of its late hours.

Billard also mentions her fears around getting sick from California’s differently regulated products, such as eggs not vaccinated for salmonella. Billard also said she finds foods significantly sweeter in the United States than in her home country of France, but is embracing the new default sugar content during her year in the U.S. Compared to shopping at home, shopping as independent adults in Westwood made her buy

“It (swipes) doesn’t feel like real money.”

less frequently.

Justin Dixon strategically comes

the cart they received for their birthday instead. While examining vegetables for plastic film, the third-year design media arts student notes the difference in taste between organic and non-organic bell peppers.

Worries about rising prices initially led Kaufman to prioritize how far they could stretch their food, but

speakers cordially informs shoppers to wrap up and leave. As if the announcement fell on deaf ears, there is no visible urgency in the grocery store patrons – but cashiers gain newfound excitement as closing draws near. The metropolis sky darkens with light pollution, marking the young bustling of a college town Saturday night.

Behind a bag-and-skateboardwielding student, I, too, exit the grocery story.

written by PATRICK WOODHAM

The Extracurricular Expat

Iwoke up at 7:30 a.m. Debating whether this was worth it, I got up because I had a friend to hold me accountable, knowing I would try to skip it – but I still went back to bed. Then, I remembered the purpose behind my mission, so I got up and got dressed. I normally wake up early to drink coffee, but my routine was changing. As a New Yorker, birds have been my greatest enemy ever since a pigeon pooped on me in second grade. But this had a purpose.

I was going to join the Bruin Birding Club on a walk.

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, people have yearned for connection but are hindered by a variety of factors. In a study from UC Santa Barbara Gevirtz Graduate School of Education, 40% of adolescents reported a diminished social well-being (connectedness to peers and family, integration with community, etc.) three years after COVID-19 restrictions were put in

I wanted to test this out for myself. I wanted to see if I could attend different social clubs and find a community there. Even if their activities may be unconventional or against the grain, I wanted to experience the ways others may be finding community in an ever-more disconnected world. So I visited four different clubs and joined whatever open events they had available. By the time we arrived, there were about 25 people waiting with a diverse set of ages and majors. We split into two groups after the usual “name, year, major” introductions. From their intros, people seemed excited to see birds, a stark contrast from me, who did not know birds could be interesting. From firstyears to doctoral students studying anything from history to applied math, everyone was there to embark on a hike through North Campus and catalog any birds they found. Bird species were being yelled out every few minutes. However, chirps

“I wanted to experience the ways others may be finding community in an ever-more disconnected world.”

place. A press release from Stanford discussed how Gen Z young adults have lower levels of happiness relative to other age groups. While there is no one reason, it coincides with two other trends: growing economic inequality and negativity-filled media ecosystems.

would silence the group as some birders tried to guess the species. While some were recognizable by their names, others were because of their actions. “Misogyny” and “Misandry” are two birds known to members of this club (Misogyny is notably more of a nuisance).

What made the experience pleasant, more than anything else, was the people. I never felt I was in the wrong place for trying something new. Everyone was open to teaching me their favorite bird fact.

Even though I dreaded the first few minutes, the last few felt like I had found a new friend group.

Video Game Appreciation Club was the next group I visited. I wanted to explore a more stationary activity. Even though I have been playing video games all my life, I was still nervous to go. I prefer my video games in solitude and barely tell anyone when I play because I find comfort in consuming my singleplayer games alone. I opted to go

because I wanted to change my opinion and try experiencing video games with other people.

After a confusing set of twists and turns in the Mathematical Sciences Building, I found the actual meeting room on the building’s fifth floor –which I had originally entered on – for the VGA’s ape-themed game night. In front of me was an old CRT TV that was going to house SEGA’s Super Monkey Ball. On the projector was Nintendo’s Donkey Kong Bananza, released only a few months ago. Behind me was a computer with an emulator for Sony’s Ape Escape.

Similar to the bird walk, the beginning was the usual introductions that every college

student has done a million times –but with a twist – name, year, major and favorite video game. I picked Hades, a popular dungeon crawler from 2020.

Sheffield Hocker, a fourth-year communications student, founded the club in winter 2024 with a few friends. He said he wanted to emulate clubs that watch films together and have a casual space to share a hobby that feels less intimidating in comparison to competitive gaming communities. Hocker added that as a transfer student, he knows the difficulties of trying to acclimate to UCLA.

“I know how stressful it is at the beginning being here and not knowing anybody,” he said. “It’s such a big campus, and there’s a lot of really intimidating stuff, so just to have a place that I’m hoping is very welcoming and fun and light – I’m hoping that’s something people can resonate with.”

As a third-year traditional student, I do not completely understand the struggle of friends at the beginning of one’s collegiate tenure. As opposed to the shared unknown of being a freshman, a transfer student is dropped into the deep end of the pool, where everyone is already friends and knows what they like. If you come in knowing no one or do not live in the transfer living-learning community, housed in De Neve Holly, it’s easy to understand how quickly that can become isolating if you do not have a good idea of how to make friends.

The understanding of that struggle is what brings clubs like VGA and Bruin Birding together.

Adeline Hung, a second-year molecular, cell and developmental biology student and co-marketing and communications director of Bruin Birding, said even though two people may be strangers, both of you knowing about birds or nature is enough to make a connection.

“Sometimes you meet people who you’ve never seen before, but because of birds, you have the same topic about nature, and you get to know them more,” Hung said. “Surprisingly,

they might know the same facts as you know, and you have a common language from the start.”

Emma Hwang, a third-year ecology, behavior and evolution student and co-president of Bruin Birding, said she enjoys seeing people connect with one another while birdwatching. Hwang added that she’s especially happy when she sees people new to bird watching. Through the club, they are able to build their understanding of the activity.

In addition to camaraderie, some also join over their shared love to make others laugh.

Shenanigans Comedy Club at UCLA held a performative male contest. A performative male, according to Book Club Chicago, is a man with “traditionally feminine hobbies with the sole intent of cultivating an inauthentic aesthetic that might appeal to progressive women.” These contests appear to have evolved out of celebrity and pop culture character-lookalike contests cropping up across the country since last year. While I do have some grievances with the internet joke, I set them aside to see the contest for myself. I wanted to find a different way to form a community.

At 4 p.m. on Janss Steps, I found a crowd of people with matchas in hand, unsheathed guitars and tampons in abundance. Some contestants brought books such as “I Am Malala.” One contestant even had a Walkman in their pocket.

guitar. While they all had different ways to perform in front of the crowd, they did share one thing in common – making everyone laugh. Occasionally, someone would

“I never felt I was in the wrong place for trying something new.”

Throughout the show, contestants showed off how performative they could be. One read “A Kids Book About Feminism” from start to finish. Another briefly serenaded the crowd with their

proclaim how much they loved women or shout out female family members and public figures. As each contestant described their outfit,

it slowly escalated from thrifting to making the outfit entirely by hand, defeating the purpose of the sustainability trope they were trying to uphold. But it did not matter what I thought. Everyone in the crowd was enjoying the sight of seeing these contestants try to play up a version of a man whose only goal is to court women –so much so that they make a fool of themselves. After the contest, people took pictures with the winner, and the contestants traded Instagram handles with one another.

Andy Liu, a third-year psychobiology student and president of Shenanigans Comedy Club, said

he has been a member since his first year, and Shenanigans helped him find community. He added that while he wants large and public events like these to advertise the club itself, the overarching goal was to foster community and help people meet. I eventually found myself grabbing lunch in the Court of Sciences for my next stop – The Quiet Club at

“I found a crowd of people with matchas in hand, unsheathed guitars and tampons in abundance.”

UCLA. I waited a bit until I realized I had no idea how to find the club. I was in the right place at the right time, but I assumed asking random tables, “Are you the quiet club?” was a bad idea. I saw one of the board members, confirming that I was thankfully right in my guess. About eight people came to the table with a mix of chicken tenders, sandwiches and

Yoshinoya plates. There was no initial “name, year, major” routine until someone asked. This started a conversation, but it quickly ended in a lull. I was antsy to continue adding to the conversation but stopped myself so as not to ruin the sanctity of the club, which was created as a space for introverts.

However, in spite of the aforementioned club name, people tried to make conversation by divulging their stories of how they got to UCLA or why they chose the school. Even though I had hit my own limit of awkward silence and pauses, others seemed to bask in it and found comfort in a way that I never could.

more content with being alone. Social clubs help to combat this. While some are a bit more overt in their pursuits of connection, others

what way, they all have the same goal in mind of bringing people together in this isolated world. What I learned from visiting all of these clubs is to go out and make friends. I am already normally an extroverted person, but I wanted to make more friends. I wanted to see how it felt to join different communities in their endeavors to carve out their own within the larger UCLA community. So this is where I implore you, reader.

“While I’m no scientist, I think we have become less open to meeting new people and more content with being alone.”

Post-quarantine socializing has changed. While I’m no scientist, I think we have become less open to meeting new people and

do it in alternative ways that feel comfortable to them. No matter

Talk to the person next to you in class. Join the club you have always wanted to join. Do that fun thing with a friend you have been putting off for three months. Who knows?

You might find your new community.

Q&A Q&A

Behind the Bark with Perro Tacos’ Luis Garcia

written by DAVIS HOFFMAN

photographed by ANDREW RAMIRO DIAZ

designed by VIENNA VIPOND

Experiencing Los Angeles’ food scene doesn’t have to be an uphill battle.

Born of the city’s rich street food culture, UCLA introduced food trucks in fall 2021 as a temporary solution to post-pandemic staffing shortages at its dining halls. Although on-campus food truck presence has seen a decline since fall 2023, the trucks still remain a fixture in the UCLA Dining landscape, turning Rieber Court and Sproul Court into rich, culinary stomping grounds.

Similar to the culinary offerings of UCLA Dining restaurants, the food trucks serve a broad array of global cuisine, including Thai, Central American and New Zealandic dishes.

Among the most visited trucks is Perro Tacos, which serves one-pound Sonoran-style tacos.

PRIME’s Davis Hoffman sat down with founder and general manager Luis Garcia to discuss the hilltop connections forged by the UCLA regular.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

PRIME: To begin, could you tell me a bit about yourself in relation to Perro Tacos?

Luis Garcia: I’m the one that started everything. It was just me and my brother. Back in 2020, I was contracting. It was not going very well for us, so it threw me off. And then things started going financially

“We’re known. It feels good. People will ask, ‘Hey, you work for Perro?’ and they get excited to see us.”

bad, so I invested a lot of money, lost it and finished the job. From there, my brother turned 18, so I was like, “Do you want to start a business or get a job?” Since he didn’t want to go to school anymore, he was like, “Start a business.” From there, it was a quick reaction. We went straight to downtown LA to a place where they sell the grills and all the stuff for the taco stands. We bought the grill. We bought a few things from there. That was Jan. 10, 2020.

From there, we practiced (for) about three weeks straight, just making one taco on the menu. We didn’t have any experience cooking – none of that. Feb. 21, 2020 – that’s when we started. That was our first day on the street. COVID-19 hit us, so we got banned from the streets. It took us about four months. That was July 21 – I still remember. I’d seen a taco guy on the street around the corner from my house in LA, and he was selling no problem. I called my brother, and I was like, “Hey, are we going to get back on it? We’re starting this Friday.” Since that day, we haven’t stopped.

PRIME: The company website mentions how TikTok virality played a role in allowing you to purchase your first food truck. What was that moment like? Can you walk me through the exact moment you found out you had gone viral?

LG: It was crazy. I remembered my son had a tournament in Arizona that weekend, so Mr Biggs – he’s a

popular influencer, foodie guy – he came by a week before, took some videos and recorded himself eating the taco. He started mentioning, “One-pound taco – you guys got to try it.” It was Instagram. The video did okay, but then I called him, and I was like, “Hey, why don’t you throw it on TikTok? You just have to charge me.” So he posted it, and then I took off to Arizona that day.

My brother calls me. He was paranoid – “Hey, I don’t know what’s going on, but we have a big line, like (a) crazy line.” And it was a crazy line. It was easily 150 people lined up. We sold out in one hour. That video made everything happen. Everything started from there. The opportunities came. The truck came. (A) close friend got involved with us and partnered up. Since then, it started getting busier. People started to know about us, and, since you can’t get a taco like this anywhere else, it helps a lot.

PRIME: The COVID-19 pandemic hit close to Perro Tacos’ conception. What were those early days like, and how did that compare to the post-TikTok virality era?

LG: I was blessed financially, and even my family got closer to me, so I got closer to my family. I’ve been working since I was a teenager. I started working more than regular hours – I do 60 or 80 hours a week, so I will hardly see my kids. And COVID came in, and it was a blessing for us. All the restaurants were closed, so for

us, it was good starting from a taco stand. If I would have started in a restaurant, I don’t think we would be here today.

PRIME: How does selling on the Hill compare to selling off-campus?

LG: It’s totally different outside. You don’t see those numbers. Let’s say we post a video and it goes viral – we don’t get a line since we have mastered our system, but UCLA is different. It’s a huge number out there, so you can’t compare it to the streets at all.

PRIME: Could you run me through a typical shift at the Perro Tacos truck at UCLA during the dinner period? What is it like?

LG: The prepping time – we have mastered (it). We’re ready for big numbers. We know every time we go there, it’s a hitter. We just get ready for 800 to 1,000 servings. The processes start early morning. The meat gets done around 5 a.m., 6 a.m. The beans is the next step before taking off since we can’t do it out there, so it takes about another two hours. And all the veggies, they get cut. That one’s a little bit faster – I’ll say one hour,

“We went straight to downtown LA to a place where they sell the grills and all the stuff for the taco stands.”

three guys. We get everything done. The guacamole – we smash everything before heading out there, so we have everything ready.

PRIME: What’s the line operation like inside the truck?

LG: We have a guy for veggies. We have a guy for the meat and beans. We have a guy in the grill flipping cheese and tortillas and another guy just giving out orders. Another guy’s taking orders, and the other guy – we have

him as a backup – so he’s running everywhere – refilling waters, ice, passing bags of meat, passing bags of cheese.

PRIME: What’s the dynamic in the truck during that shift?

LG: It’s like everybody’s programmed, so it gets tense. If someone messes up, everybody starts pushing him – ”Hey, you can’t do this. Get it right.” It’s the process that everybody wants to finish right. I guess we’re used to it, but, definitely, it feels good pushing a lot of orders out. That’s satisfying for the guys too.

PRIME: Looking back on your early UCLA days, how has your operation on the Hill changed from when you first started serving there?

LG: It made us better. It made us way better. With the way we have been doing things, we’re fast, but UCLA definitely made us better, faster. That’s like a training camp for speed. We took it like that. It just made everybody sharp and better.

PRIME: What has been the most gratifying part of catering to UCLA students?

LG: Knowing that kids love our food. We’re known. It feels good. People will ask, “Hey, you work for Perro?” and they get excited to see us. Students (are) coming over to our restaurants, supporting us, even though they’re not allowed to get the food since they move up grades. Recently, I sent a quote for someone getting married from UCLA. Three years ago, she had our taco, and she was like, “I had to hire you guys for my catering.” So that feels really, really good.

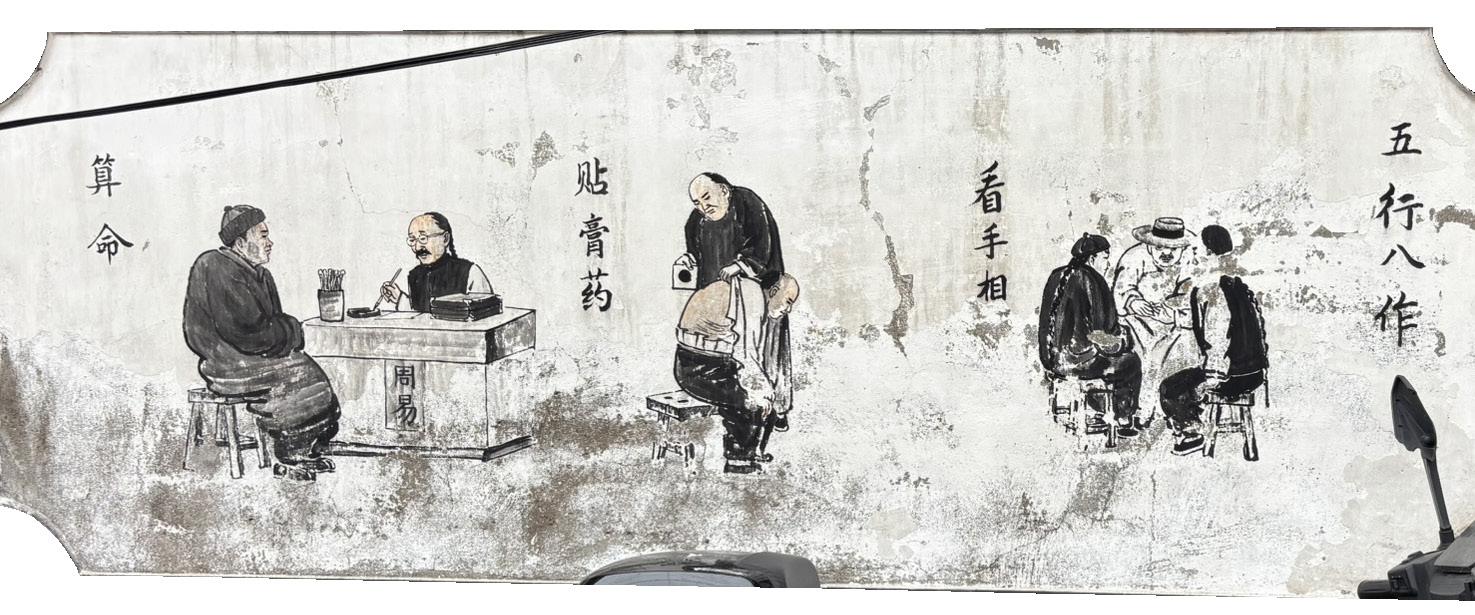

CONNECTING ACROSS

written by TULIN CHANG MALTEPE

photos courtesy of TULIN CHANG MALTEPE AND DAVID DAI

designed by AVA JOHNSON

Ihad never fallen in love with a place in this way.

The city is a mix of old and new. In its center, the Forbidden City is surrounded by both modern malls and singlestory sìhéyuàn-style (四合院) homes that make up the small hútòng (胡 同) alleyway. These sìhéyuàn-style homes are a type of traditional Chinese architecture, designed to respect the five elements and Confucian values – key facets of

Chinese culture. Inside the hútòng is another layer of juxtaposition: Some sìhéyuàn homes have been converted into modern homes and hotels while others remain inhabited by families who have been there for generations.

No matter how busy the main streets were, there was always a moment of stillness strolling through the hútòngs in the summer rain, stumbling upon street art, calligraphy stores and even live-

H A R A C T E R S

music bars.

The crowds were fierce.

On the side of Zhōngguāncūn road – the main road separating my dormitory from Peking University’s campus – cars, mopeds, buses, bicycles and swarms of people zoomed past. Even when I was on my way back from a night of eating meat skewers or noodles, people were always present and in motion. The crowds moved through intersections, down tunnels and through stations. People were moving in every direction but still got where they were going.

My grandfather, who was a civil engineer, had a hand in the infrastructure development that made it possible for me to travel so seamlessly. When the United States established relations with China in 1979, my grandfather, like some of his colleagues who had eventually settled in the U.S., returned to China to build. I got to see the developments that came out of the sacrifices that accompanied those choices.

Compared to the cities I grew up in, I could zip seamlessly through the city streets on a shared bike – accessible through many of the payment apps that are used daily in

China. These bikes are safe to use in a city where protected bike lanes are the norm. Every metro station I walked into was air-conditioned and nearly spotless. The buses connected the areas that weren’t as reachable by train, and, if you needed a car, a driver from DiDi – a rideshare service – would pick you up in minutes.

The convenience of the city mixed with the buzz of possibility felt fresh in a way my life in Los Angeles and San Francisco did not – these infrastructure elements do not exist at the same scale in the cities I call home.

I was at Peking University in Beijing, China, to continue learning hànzì (汉字) – Chinese characters – and the dialect pǔtōnghuà (普通 话) also known as Mandarin. While I’ve spent my entire life learning pǔtōnghuà, in Beijing, I had to use that skill every day to navigate a place filled with people I had never met. What stuck with me the most during my time in China was how – even in the face of language barriers and cultural differences

– the people I met from across the world pushed through them to communicate.

To forge those connections, I often had to break through other peoples’ perceptions of me. I frequently received prolonged stares and double takes from strangers in the security line at metro stations, while strolling through the hútòngs, at art museums and at the Great Wall.

Although I am half Chinese, I stood out from the crowd.

On one occasion, I noticed the little girl I was sitting next to look inquisitively at my friends. Against the hush of the subway, I heard her ask her mother in a whispered voice why one of my friends had blonde hair. Once her mother answered, I leaned over and asked the girl if she could guess where we were from. After we exchanged a few words, her mother whispered to the girl, “Tell the older sister, ‘Welcome to Beijing!’”

Often, my friends and I were praised by strangers on the street for our ability to speak in pǔtōnghuà. Even an off-handed “Excuse me” or “Thank you” was met with a slightly shocked, “Your Chinese is so good.” I always found it mildly amusing that whispering a few words brought so many compliments. I hadn’t experienced it before. Even when I was meeting other Peking University students who were from China, they repeatedly praised my pǔtōnghuà, impressed I could keep up with their discussions about politics and their doctoral research.

After too much praise, I embarrassed myself by saying, “Your Chinese is so good, too!”

One of my professors explained that Chinese people in China praised us not out of politeness but rather out of encouragement. They knew firsthand how difficult learning pǔtōnghuà was, so they encouraged foreigners to learn for the sake of passing down the language, she added. I found this to be true in pockets across the city. Toward the end of my trip, I was strolling the small streets of the 798 Art Zone, a district full of art museums, galleries,

the way language can be used to communicate cultural nuances. Given this encouragement, I was all the more motivated to learn.

“Her mother whispered to the girl, ‘Tell the older sister, welcome to Beijing!’”

thrift stores and artisanal goods. As I shopped for handmade leather goods, the store’s shopkeeper praised me for continuing my language education. He said, “We need more people who can act as bridges between our cultures.”

After returning from Beijing, I developed a greater appreciation for

As someone who has grown up juggling three very different languages at home, learning another language is a matter of trial and error, picking yourself up when you make mistakes and pushing through despite stumbling. Fluency waxes and wanes with your surroundings and the amount of effort you put into practicing. When I don’t have an immersive environment now like I did in Beijing, I find fluency quickly slipping through my fingers.

Understanding pǔtōnghuà and reading, and writing in hànzì all work different skills. Pronunciation is not always obviously tied to the way individual characters are written. Because there are so many heteronyms in pǔtōnghuà, reading, speaking and listening have additional layers of difficulty. Even mastering more than a 1,000 characters ceases to be effective when you’re confronted with more abstract idioms, colloquialisms and lines of poetry – yet these subtleties are central to mastering the language. To my professor, everything that came out of our mouths sounded like dà báihuà ( 大白话), words that are easy to understand but lack depth and meaning. Teachers and parents

often use dà báihuà to critique the overly simplistic language of their students and children.

During this discussion, the issue of using the restroom came up. In pǔtōnghuà, there are multiple ways to announce going to use the restroom. “我去上厕所,” “我去上 洗手间” and “我去上卫生间” are, colloquially, the most common. After a month of using these phrases somewhat interchangeably, our professor informed us that, outside of our close social circles and casual settings, our announcements were too direct. Instead, she said that in some contexts it would be better to use “我要去方便一下,” which directly translates to, “I am going to take a moment to relieve myself.” To my American English ear, this phrase feels just as direct as the others.

That’s the thing

about learning other languages. Translation sometimes fails you. While the bathroom example is a more light-hearted one, English words cannot always concisely

pǔtōnghuà courses, students from all over the world had to communicate with each other despite not always speaking the same language. One of his classmates did not speak English, but, between their limited pǔtōnghuà, translation apps and hand gestures, they were able to understand one another.

While my friends and I struggled to battle the seemingly neverending complexity of pǔtōnghuà, I learned that the struggle worked

“Rehearsing my words before I said them felt more difficult than just saying them.”

the other way too. Over beef noodle soup in the Zhōngguāncūn plaza shopping mall, my language partner told me how she found English difficult to learn. For her, hànzì are strung together feels more

In hànzì, many individual characters are composed of semantic elements that indicate the meaning of the word while the phonetic component provides a hint for the pronunciation of the word. When strung together with another character, words are organized into more explicit categories. For example, words such as liver (肝脏), heart (心脏), kidney (肾脏) and lungs (肺脏) all share the character for organ, zàng (脏). That being said, some characters

“To my professor, everything that came out of our mouths sounded like dà báihuà (大白话).”

also falsely hint at pronunciation – there are not always cut and dry rules in any language, let alone pǔtōnghuà.

At least we were in the confusion together.

It was valuable to push through that common struggle. Otherwise, I would not have been able to share the moments that made this trip stand out to me so much. I would not have spent an afternoon eating Húběi cuisine’s famous lotus root soup while discussing the differences between Chinese and American politics and values. I would not have discovered hole-inthe-wall local restaurants around Niú Jiē, the Muslim quarter of Beijing or spent countless hours overlooking the lakes of Shíchàhǎi exchanging life stories. I would not have spent so many nights watching Chinese indie bands perform in beautiful bars and speakeasies in the Gǔlóu area. I would not have made friends with people from all around the world who I look forward to reconnecting with when I travel next – had all of us not pushed ourselves to genuinely connect.

On the final night of the trip, my friends from the UCEAP program and our new friends from Beijing had one last meal together. Inside a private dining room, around a giant Lazy Susan table, the room was filled with the smell of steamed fish, sauteed vegetables, sizzling meats, fragrant noodles and báijiǔ, a type of liquor made from fermented sorghum typically served with food. Since we could not drink báijiǔ without raising a toast, we each took a turn to say a few

words, thanking each other for the friendship and memories that had shaped the last two months. When it came time for our friends from Beijing to raise a glass, idioms and lines of poetry flowed out of their mouths like running water. Poetry is an essential part of Chinese language and culture, and the nuggets of wisdom offered by Chinese poets are often used regularly in conversation or to toast new friends and old. One of them used a line from a poem by a Tang dynasty poet named Wáng Bó (王勃), which states, “For friends who intimately know your heart, even across long distances, we’ll still feel like neighbors (海内存知己,天涯 若比邻).”

Wáng Bó’s wise words ring true, but I never would have heard them if I let the discomfort and initial awkwardness swallow me into paralysis.

In a world where it feels like we’re more consumed by the information

on our screens instead of our present environments, making new connections feels more daunting than ever – but all we can do is be brave and try. Being in a place I had never been to and surrounded by no one I had ever met pushed me to swim through the minor discomforts of forging new bonds. Braving these waters has shown me just how rewarding doing so can be. Every time I took the small risk of interacting with a stranger on the street or chatting with a DiDi driver or museum docent, I felt fulfilled for at least attempting to connect. For me, one of life’s most beautiful gifts can be our connections with other people, no matter how long or profound –even if stumbling through foreign language is part of the process.

“Idioms and lines of poetry flowed out of their mouths like running water.”

A SEAT AT THE TABLE A SEAT AT THE TABLE

written by SHIV PATEL

Josiah Beharry is a student who supported increasing tuition.

“It was really a data-informed decision,” he said. “It was a necessary decision.”

In November 2024, the UC Board of Regents voted to hike nonresident tuition by $3,402. The increase, recommended by a UC Regents committee Beharry sat on – and later approved by the full board – faced condemnation from student groups. The UCLA Undergraduate Students Association Council and Out of State Student Association both later expressed their opposition to the measure.

Beharry was a member of the UC Board of Regents from 2024-25. The board governs the University; it hires campus chancellors and is responsible for setting UC policies, from systemwide tuition rates for the University’s nearly 300,000 students to guidelines about how the 10 UC campuses can operate.

Beharry was not one of the 18 regents – often high-ranking businesspeople or community leaders – appointed by the governor of California, nor was he a public official serving on the board in an ex officio capacity.

He was the UC student regent.

“I actually didn’t even know about the UC regents or the Board of Regents,” Beharry, a doctoral student at UC Merced, said. “I had no background knowledge of the UC system governance structure, but I got into it because a friend sent it to me.”

The application process begins more than a year before the eventual student regent assumes the role, with the selected student serving as student regent-designate for a year to prepare. Any UC student who will still be student for two years following their application is eligible to apply to be the student regent, and the job isn’t without its perks; the UC waives tuition and mandatory fees for both the student regent and regentdesignate.

The position was established by a 1974 statewide ballot proposition that reformed the board. Of the 51 people who have held the position, at least 15

have been UCLA students, including the current student regent, Sonya Brooks.

For Brooks, the job has also involved building personal connections with her colleagues, something she enjoys. One of these colleagues is Richard Leib, the board’s former chair who is also the president and CEO of the consulting firm Dunleer Strategies.

“I know his family. He knows mine,” she said. “It’s really an interesting dynamic to be put into this position where I’m meeting people who are very well-known in not only their industries but nationally – and even some worldwide – that I would have never had the opportunity to meet had I not been in this position.”

While the doctoral student in

education said she has valued the opportunity to interact with “people that you never thought that you would have the opportunity to meet,” she added that, for her, there’s another side to the coin.

“It’s letting them into my world, not only as a student but as a graduate student, as a mom, as a scholar, as a researcher, as an advocate – as all of these different things and people and intersections that they may not necessarily have had an opportunity to meet before,” Brooks said.

Brooks, who was the 2023-24 vice president for external affairs of the UCLA Graduate Student Association, said someone suggested she apply for the role because she had been involved in UC-level advocacy.

Applying to the position is hardly a guarantee for getting it. In 2019, 113 students applied for the position, according to the Daily Nexus, and only six to eight become finalists for the position each year, with only one student ultimately being selected as student regent-designate.

“I was like, ‘Absolutely not. I’m not applying for that. I’m not going to get it,’” she said. “I don’t like rejection.”

Brooks said she ended up submitting her application just a minute before the deadline. From there, the months-long application process progresses to interviews with members of the UC Student Association and UC Graduate and Professional Council before the regents ultimately nominate and confirm the student regent.

After going through this process, Brooks became the first Black woman to hold the position.

The pathway from student government to the student regent position is not a rare one. Avi Rejwan was the 2013-14 USAC internal vice president. Though he enjoyed working with different groups of people across campus, he said he wanted a change from student government.

“I thought that student government at the time was rewarding, but it was also super political,” Rejwan said.

After a year on the council, the then-thirdyear economics student applied to be the 201516 student regent, hoping to find a less political channel for advocacy. However, Rejwan said he soon discovered that the student regent position was more political – with a controversy from his campaign for student government surfacing over a year after the fact.

After his nomination by a Regents committee, Rejwan, who is Jewish, faced allegations that, when he ran to be USAC IVP, he did not properly disclose a donation from Adam Milstein, a member of and donor to several pro-Israel

“I actually didn’t even know about the UC regents.”

organizations. Hundreds of students signed a petition calling on the board to delay Rejwan’s appointment, and the UC Student Association held an emergency meeting.

Rejwan said he felt the issue at hand was that he had accepted money from a Jewish donor. The situation and controversy left him disappointed, he said.

“It was a devastating time for me,” he said. “I felt very betrayed and misrepresented.”

USAC candidates were not required to disclose donation sources, a student government advisor said at the time, and the regents ultimately confirmed Rejwan.

Rejwan wanted the regents to get even more student input, successfully pushing for a nonvoting adviser to be added.

“They (the regents) just thought that there’s already two students on the board, the board is already big, and they

didn’t really understand a lot of the purpose behind it,” he said. “At that point, that’s when I learned that relationship building was key to this.”

Rejwan said he had conversations with individual regents, eventually convincing them to support the initiative. Though the adviser seat was nixed in 2019, Rejwan said the process of lobbying for the position was informative, though he added that he wished the position hadn’t come with a sunset provision.

Devon Graves, a then-doctoral student in higher education and organizational change at UCLA, was the student regent three years after Rejwan. Graves said it can be easy to get lost in the novelty of the role, but he added that, just like the rest of the board’s members, the student regent has a vote when it comes to making decisions for the University.

There are eight standing committees and two special committees of the Regents, each tasked with strategizing different areas of the University’s operations such as finances and academics.

Graves, the first student to chair any Regents committee, said he was proud that his board voted to reduce tuition for in-state students – the first time

in nearly 20 years the regents had done so.

The board’s actions are not always as popular. It’s far from uncommon to see protesters with banners and megaphones marching outside the board’s meetings, criticizing the regents and the University. During the 2024-25 academic year, when Beharry was student regent and Brooks was regent-designate, students and community members protested against the UC both inside and outside meetings, calling on the University to divest from companies associated with the Israeli military.

“I definitely understand where the students are coming from,” Brooks said. “If I wasn’t in this position, I would be right there with them.”

She added, however, that the decisions made by the regents are complex and must take into consideration the academic, institutional and business needs of the UC. Brooks added she wants to help students better understand why the board makes the decisions it makes.

“It was a difficult time to be there because you’re trying to do right by the students who feel passionate about this,” Beharry said. “You’re trying to do right by the university and the institution. You’re trying to do right by the law. You’re trying to do right by the California taxpayer.”

In addition to the regents’ meetings, pro-Palestine demonstrators also protested outside the Brentwood,

“If I wasn’t in this position, I would be right there with them.”

California, home of UC Regent Jay Sures – who is Jewish – in February, leaving red handprints on his garage door.

Brooks said she was stunned by the protest, which she felt had gone too far. Still – though she disagrees with their actions – she empathizes with where the protesters are coming from.

“I understand that when you feel as if you’ve talked, and you’ve pleaded, and you’ve begged, and nothing is really happening, what more can you do?” Brooks said. “What more can you do to show the level of sincerity and the passion that you have behind these issues?”

Brooks added that being a student regent felt isolating because she had access to information that most students did not.

“I want to say, ‘Hey, y’all, guess what?” Brooks said. “I want to, but I know that it will cause more havoc

than help.”

Amid all of this, the student regent must also be a student.

Graves said it was difficult balancing his commitments as a graduate student – such as being a teaching assistant and working on his dissertation – as well as a regent. Brooks, a parenting student, said the student regent must be “an expert in time management” and “an exquisite planner.” She said, however, that the regents understand she has responsibilities as a student.

Regardless of which campus the student regent hails from, the position comes with travel requirements. In recent years, the regents have generally split their bimonthly meetings between Los Angeles and San Francisco. During one meeting, Rejwan had a final exam for a UCLA economics class while the regents met in San Francisco. After finishing the exam, Rejwan had to

immediately return downstairs where the regents were meeting.

Rejwan added that, during the final, he encountered a confusing question, spending about 20 minutes trying to understand its wording. Since he wasn’t in class, he wasn’t able to simply ask the professor for clarification and instead had to communicate through a proctor.

But Rejwan said the role helped him develop his communication and advocacy skills, something he still uses today as a litigator.

Beharry said, in hindsight, he does not know how he balanced being a graduate student and a regent.

I asked Rejwan, Graves, Beharry and Brooks if they’d do the job again.

“Is there anyone who said ‘no?’” Beharry asked me.

There wasn’t.

STAFF

prime.dailybruin.com

Leydi Cris Cobo Cordon [PRIME director]

Davis Hoffman [PRIME content editor] Vienna Vipond [PRIME art director]

Katarina Baumgart, Caitlin Brockenbrow, Alisha Hassanali, Davis Hoffman, Tulin Chang Maltepe, Helen Juwon Park, Shiv Patel, Patrick Woodham [PRIME writers]

Andrew Ramiro Diaz [photo editor]

Selin Filiz, Michael Gallagher, Aidan Sun [assistant photo editors]

Karla Cardenas-Felipe, Brianna Carlson, Andrew Ramiro Diaz [photojournalists]

Helen Juwon Park [illustrations director]

Yejee Kim [cartoons director]

Britany Andres, Katarina Baumgart, Luna Fukumoto, Helen Juwon Park [illustrators]

Crystal Tompkins [design director]

Karina Aronson, Katie Azuma, Rachel Kristen Lee Yokota [assistant design directors]

Caitlin Brockenbrow, Armaan Dhillon, Ava Johnson, Helen Juwon Park, Crystal Tompkins, Vienna Vipond, Millie Walker [designers]

Lucine Ekizian, Wendy Mapaye [copy chiefs]

Sophie Acker, Rori Anderson, Natalie Canalis, Amelia Chief, Ellie Kim, Barnett Salle-Widelock, Sophie Shi, Lauren Trautenberg, Bettina Wu [slot editors]

Evelyn Cho, Narek Germirlian, Samantha Jiao [online editors]

Richard Yang [PRIME website creator]

Alicia Carhee, Layth Handoush, Gwendolyn Lopez, Tulin Chang Maltepe, Katy Nicholas, Isabel Rubin-Saika [PRIME staff]

Katarina Baumgart, Julian Dohi, Jacqueline Jacobo, Shermaine Lim Sher Min, Eghosa Otokiti, Juliette Regier, Kathryn Sarkissian, Andrew Wang, Danielle Workman [PRIME contributors]

Dylan Winward [editor in chief]

Shiv Patel [managing editor]

Zimo Li [digital managing editor]

Jeremy Wildman [business manager]

Abigail Goldman [editorial advisor]

The Daily Bruin (ISSN 1080-5060) is published and copyrighted by the ASUCLA Communications Board. All rights are reserved. Reprinting of any material in this publication without the written permission of the Communications Board is strictly prohibited. The ASUCLA Communications Board fully supports the University of California’s policy on non-discrimination. The student media reserve the right to reject or modify advertising whose content discriminates on the basis of ancestry, color, national origin, race, religion, disability, age, sex or sexual orientation. The ASUCLA Communications Board has a media grievance procedure for resolving complaints against any of its publications. For a copy of the complete procedure, contact the publications office at 118 Kerckhoff Hall. All inserts that are printed in the Daily Bruin are independently paid publications and do not reflect the views of the Editorial Board or staff.

To request a reprint of any photo appearing in the Daily Bruin, contact the photo desk at 310-825-2828 or email editor@dailybruin.com.