MAVERICKS

THREE MASTERS OF JAPANESE CERAMI CS

KOINUMA MICHIO KAWAMOTO GORO

TSUBOSHIMA DOHEI

MAVERICKS: THREE MASTERS OF JAPANESE CERAMICS

EXHIBITION CATALOG | ASIA WEEK NEW YORK 2025

ON VIEW: SEPTEMBER 11 – 19, 2025

18 EAST 64TH STREET, STE 1F NEW YORK, NY, 10065, USA WWW DAIICHIARTS COM

FOREWORD

BEATRICE CHANG

FOUNDER & DIRECTOR, DAI ICHI ARTS

The word “maverick” refers to an independentminded person One who defies convention and follows their own path, regardless of trends or expectations The term traces its roots to Samuel Maverick, a 19th-century Texas rancher who refused to brand his cattle In time, his name became synonymous with those who don’t conform, those who leave a unique mark simply by being true to themselves.

In the world of Japanese ceramics, long shaped by centuries of tradition and functional aesthetics from the wabi-sabi spirit of tea wares to the wholesome philosophy of mingei being a maverick is no small feat To diverge from the well-worn path without losing touch with clay’s deep cultural gravity takes courage, vision, and above all, sincerity

This exhibition brings together three such figures: Koinuma Michio, Kawamoto Gorō, and Tsuboshima Dōhei While vastly different in approach, temperament, and trajectory, they each embody the maverick spirit They question norms, forging new languages in clay, and remaining fiercely devoted to their own ideals

Koinuma Michio (1936-2020) entered ceramics not through formal training but through a selfdriven, almost irreverent impulse. He says: “There’s nothing interesting, so why not make it yourself?” His brief but formative time at both Osaka and Waseda Universities cemented his own path as a potter-thinker. Koinuma’s work emerges not from instinctive emotion, but from intellectual rigor, archaeological research and a deep respect for clay, fire and form He treats firing as an arena of discovery, where true

emotion resides Artistic expression is generative, and for Koinuma, it is created not in the moment of making, but in what fire reveals in the end Contrary to asymmetric aesthetics, he resists romanticizing accidents: if a form warps, it is not necessarily beauty He does not follow the traditional qualities of Japanese aesthetics of wabi-sabi, where imperfections are embraced and considered a part of an artwork.

To Koinuma, intention is everything. A perfectionist at heart, Koinuma envisions each work with clarity and follows it to the end, yielding solemn, geometric forms that invoke spiritual and efficacious objects like roadside Jizō Bosatsu or weathered shrines that embody an archaeological consciousness and accumulated history despite their contemporaneous make In this way, his ceramics are rooted in archaeology and historical inquiry, drawing from the idea that material objects can hold temporal depth

Ash fired surfaces mimic the appearance of weathered Sue-ware from the Kofun period; it seems almost a necessary trait in Koinuma’s works, that his ceramic surfaces bear the impression of time passing Echoing Walter Benjamin’s reflections in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Koinuma’s works resist replication; instead, they bear an aura and an irreproducible presence shaped by time, experience and transformation. His ceramics are not decorative objects, but vestiges of human presence and mystery and an ongoing battle between mind and matter

Kawamoto Gorō (1919-1986) was a quiet radical He eschewed fame and steered clear of trends His work cannot be neatly categorized Neither traditional nor avant-garde, his ceramics exists in their own category, poetic in form and defiant in abstraction and surface Gorō once said, “If it [an object] is separated from the era it should be in, it is nothing more than a style supported by a simple and sentimental nostalgia.” He believed that ceramics must speak to the time in which they are made, but that beauty must be real, rooted in truthful, life experiences His hand-built pieces reject the potter’s wheel; his modeling is bold, melodic, and calculated In the kiln, his forms come alive, scorched by fire and reborn in romantic colors and striking shapes His later devotion to blueand-white porcelain led him to transcend its historical limitations, arriving at an entirely new expression: a fresh vision built on tradition, not trapped by it

Tsuboshima Dohei (1929-2013) is an artist who never aimed to copy the past, but to carry its spirit forward Trained by the multifaceted Kawakita Handeishi (1878–1963), he was taught never to constrain himself Kawakita’s affinity for calligraphy, poetry, and philosophy resonates deeply in Tsuboshima’s own work. With a background in classical painting and calligraphy, Tsuboshima approached the glazed surface as a space for contemplation; it was a field to linger upon, and relish. What makes Dōhei’s pottery so compelling is that each piece asserts a distinct presence, differing from Handeishi’s more intuitive style of “following the flow of the heart ” Tsuboshima mastered nearly every major style of Japanese ceramics Shino, Oribe, Iga,

Karatsu, Akae, and more not to imitate, but to internalize and reimagine them His Shino pieces are infused with the bold soul of the Momoyama era, yet unmistakably contemporary His gestural, painterly surfaces are not merely decorative; they are statements His red-glazed jars, expressive iron underglaze brushwork, and more all culminate to a transcendence of tradition, setting a new standard rooted in personal freedom and technical mastery. His pieces stand apart: strong, lyrical, and courageous

I came into this field without formal training in ceramics Instead, I chose to develop my connoisseurship through time spent meeting artists, working in developing their formal directions, researching, curating alongside scholars of the field, and honing my eye by looking and looking Perhaps that’s what allowed me to wander freely, to follow instinct over instruction In this way, I feel a deep kinship with the artists in this show I, too, have attempted to follow my intuition and heart in making unconventional curatorial matches In discovering, presenting, and celebrating ceramic artists who may not always fit neatly into categories, I have become drawn to those who challenge expectations and surprise us with their vision. To me, these three artists are not only mavericks: their fearless spirit are beacons that inspire. Their work reminds us that tradition is not a cage, but a foundation. And from it, one can reach infinite potential

THREE MAVERICKS OF CONTEMPORARY JAPANESE CERAMICS

KOINUMA MICHIO, TSUBOSHIMA DOHEI, AND KAWAMOTO GORO

TODATE KAZUKO

PROFESSOR, TAMA ART UNIVERSITY

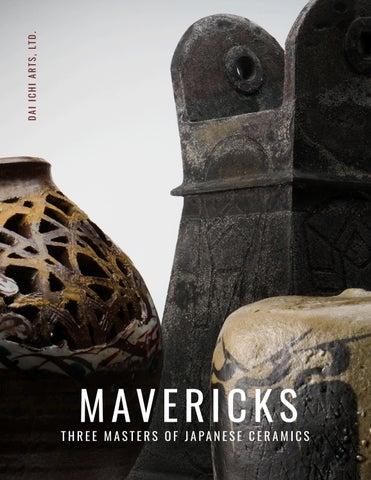

Seiichi Tanaka, “Portrait of Koinuma Michio working,” undated, photograph, in Toh 陶 (Vol 10), Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄, (Japan: Kyotoshoin, 2009)

INTRODUCTION

In the world of Japanese ceramics, individual ceramic artists began to emerge in the early 20th century. Until the 19th century, ceramic production was primarily the result of a division of labor among craftsmen and kiln leaders. However, at the beginning of the 20th century, a new type of ceramic artist appeared: those who created their own original forms and patterns using their personal ideas and skills.

Beyond ceramics made solely for practical use, there are three main directions in the expressive work of individual ceramic artists One is the creation of figurative forms, such as people and animals Another is the development of abstract or semi-abstract forms (objects), which emerged in the late 1940s A third area in which Japanese ceramic artists have excelled is the use of vessel forms as a means of expressing individuality and originality, as exemplified by the three artists discussed in this exhibition essay

Beginning in the 1910s, pioneering individual ceramic artists such as Tomimoto Kenkichi 富本 憲吉 (1886–1963), Hamada Shoji 濱田 庄司 (1894–1978), and Kusube Yaichi 楠部 彌弌 (1897–1984) demonstrated originality in their vessels. They were followed in the postwar period by artists like Kamoda Shoji 加守田 章二 (1933–1983), among others.

The three ceramic artists featured in this essay

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄 (1936–2020), Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平 (1929–2013), and Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎 (1919–1986) are positioned in the lineage of such ceramic artists of vessel expression, and each artist has established their own world with their different and unique styles of vessels.

KOINUMA MICHIO 肥沼美智雄 (1936-2020): ROBUST & POWERFUL FORMS

Koinuma Michio was born in Tokyo and majored in economics at university. He became a ceramic artist in Mashiko, Tochigi Prefecture, due to his admiration for Kamoda Shoji, a ceramic artist active in the Mashiko area. In Japan, where there are many centers of ceramic production and potters, Koinuma Michio’s decision to pursue ceramics, despite not coming from a pottery family, represented a new path to becoming a ceramic artist in the modern era

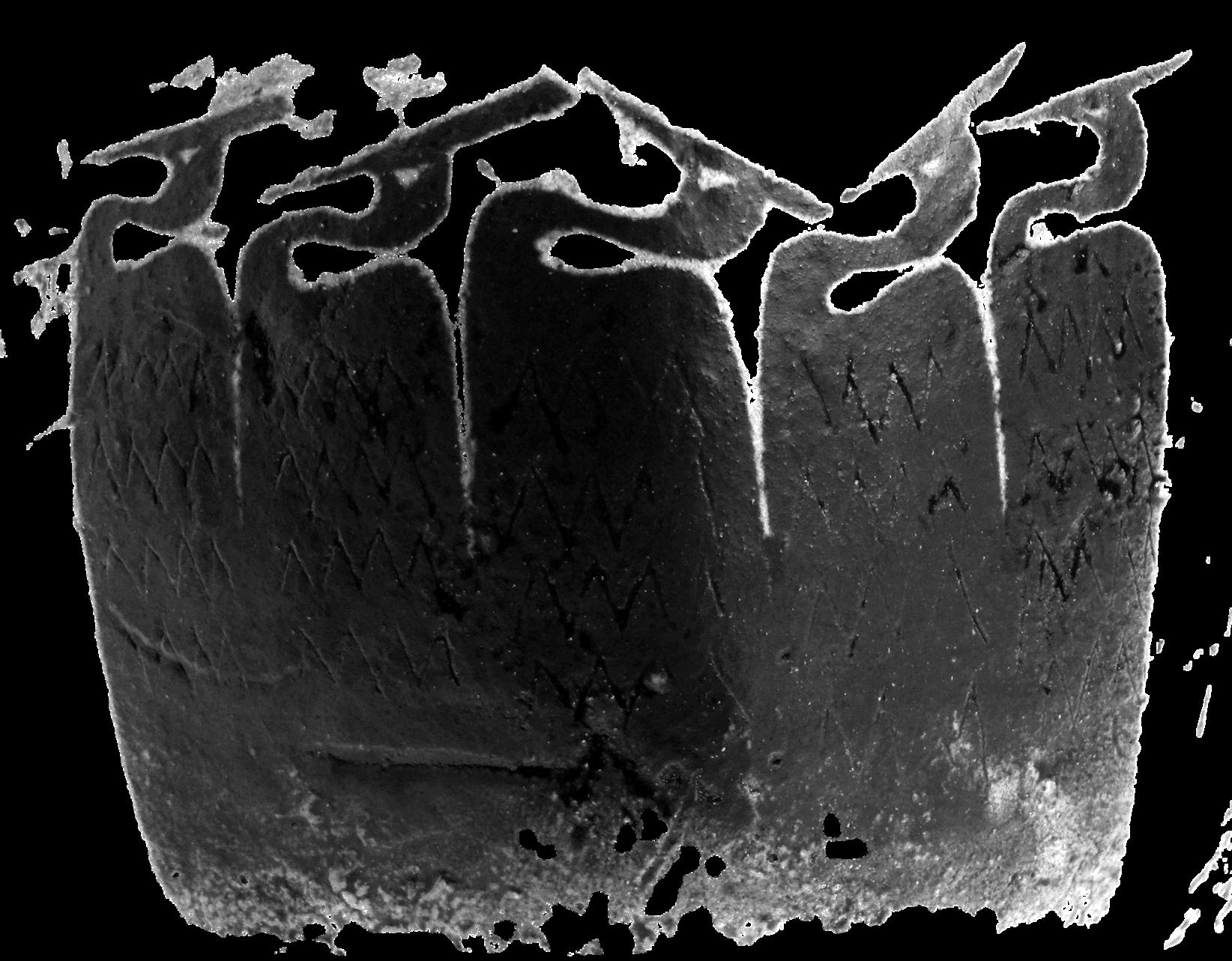

Koinuma Michio's works are created through hand-building and coil-building techniques, without the use of a potter’s wheel The surface of his vessels reveals the character of dark clay, and they appear robust and strong His pieces exhibit a toughness that sometimes evokes the look of aged stone or metal Even when glazed, Koinuma Michio's vessels retain a bold and

(Above) Group of works by Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄, Kawamoto Goro

河本 五郎, and Tsuboshima Dohei 坪

島 圡平

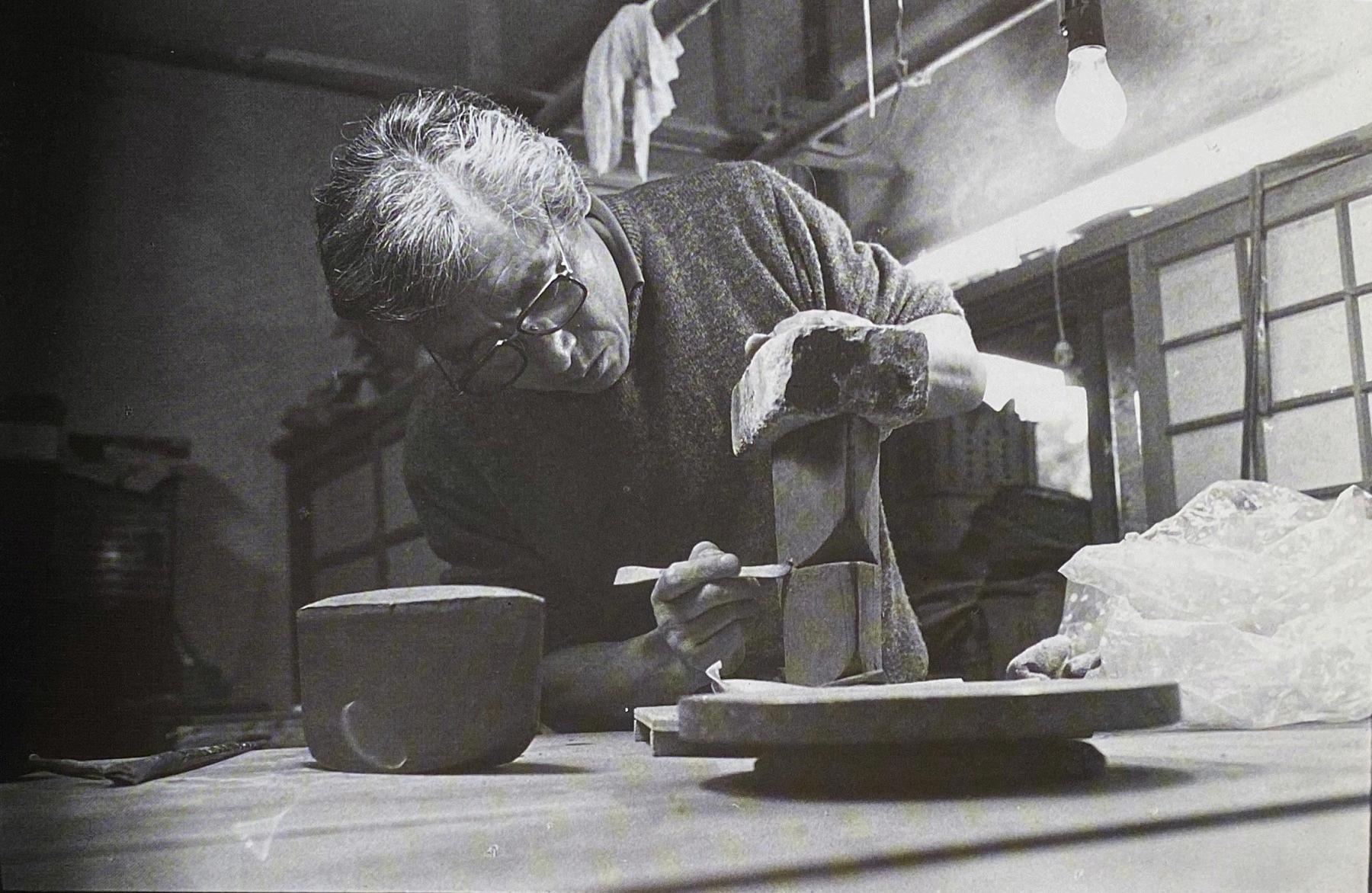

Unknown, “Portrait of Tsuboshima Dohei.” Image courtesy of Gallery Senkaku, Japan.

imposing presence, allowing the viewer to fully experience their solid and grounded nature.

In 2022, the exhibition “Koinuma Michio and His Age” was held at the Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art in Tochigi Prefecture and was widely acclaimed by a broad audience, including enthusiasts of ceramic artists associated with Mashiko.

TSUBOSHIMA DOHEI 坪島 圡平 (1929-2013): RHYTHMIC AND EXPANSIVE SURFACES

Among the lineage of ceramists who borrowed the style of all tableware to build their own world, Tsuboshima Dohei is one who mainly worked with tableware and vessels. In contrast to Western culture, the Japanese custom of holding and appreciating tableware directly in the hands fosters interactive tactility, akin to the experience of handling and drinking from tea bowls in the Japanese tea ceremony

Tsuboshima's teacher was Kawakita Handeishi 川 喜田半泥子 (1878–1963), a former businessman and well-known tea ceramic artist Kawakita Handeishi began making pottery as a hobby and is now known as "the Kitaoji Rosanjin 北大路魯山 人 (1883–1959) of the East and the Kawakita Handeishi of the West in Japan " Kawakita Handeishi and Kitaoji Rosanjin were both ceramic artists and culturally well-educated individuals.

Tsuboshima was born in Osaka and met Kawakita Handeishi in Tsu City, Mie Prefecture, the city where Tsuboshima's mother had evacuated to from the war. In 1946, at the age of 17, he began studying under Handeishi, from whom he inherited a free-spirited approach to form in his vessels.

However, while his teacher Kawakita Handeishi focused almost exclusively on tea ceremony vessels such as tea bowls, Tsuboshima worked not only in tea ceramics but also in a wide range of painted tableware, flower vases, and occasionally, large works such as stoneware lanterns His painting style is free, gestural, and vigorous His work is rhythmic and expansive even when portraying traditional Japanese motifs such as flowers and birds Both in surface and form, his expression remains unmistakably free-spirited

At first glance, Tsuboshima’s works may seem quite different from those of his teacher, Kawakita Handeishi, yet he clearly inherits Handeishi’s refined potter’s sensibility and generous spirit.

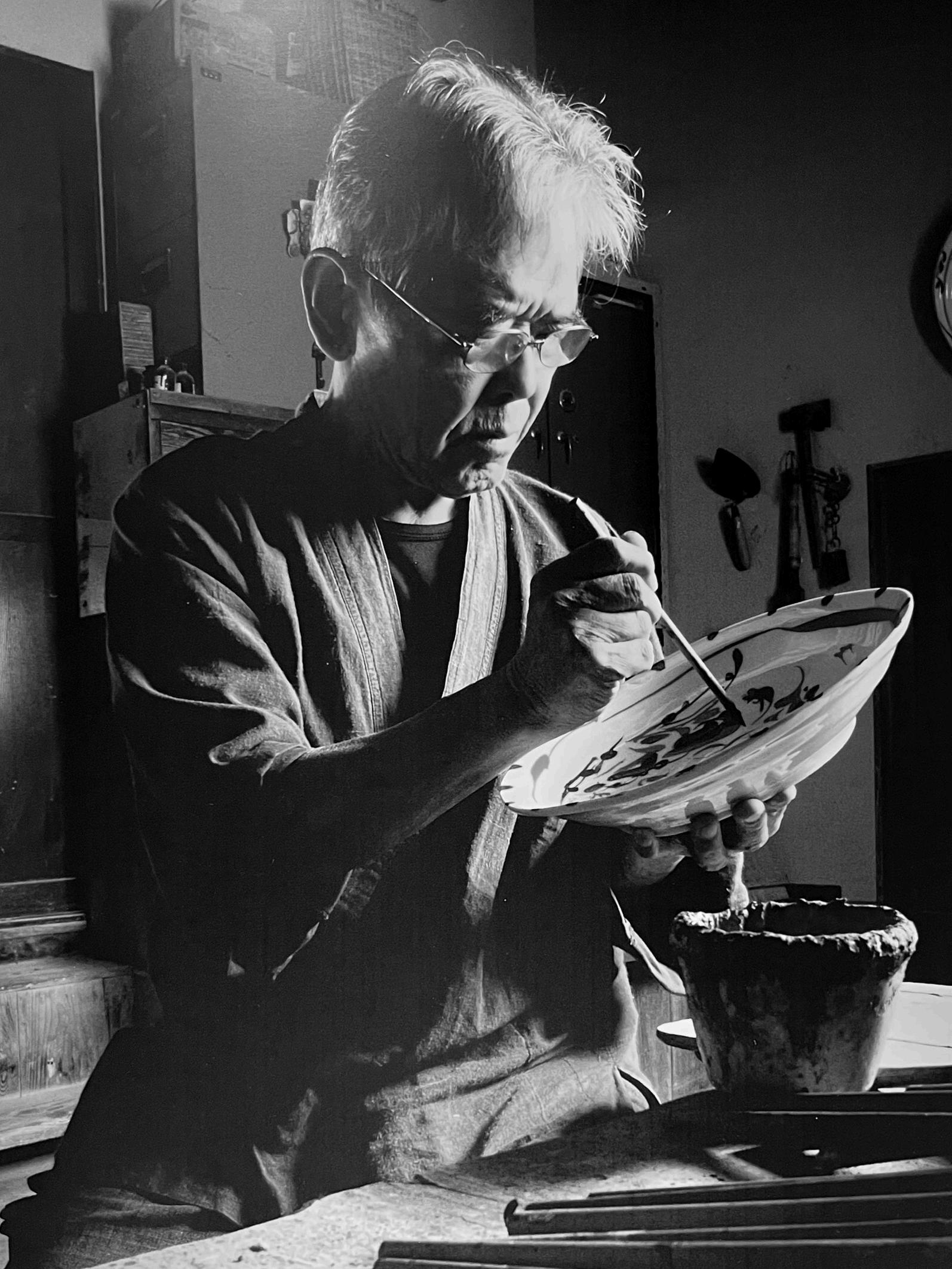

(Left) Unknown, “Portrait of Kawamoto Goro,” c 1960s, photographic print, Aichi

Prefectural

Ceramic Museums Special Exhibition- Kwamoto Goro- a Retrospective / 生誕90年河本五郎

展 (Japan: Aichi Prefectural Ceramics Museum, 2009)

(Below) Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Sometsuke jar with drawings of a banquet of the hungry ghosts, c. 1980, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 19.0 × (w) 20.3 cm

KAWAMOTO GORO 河本 五郎 (1919-1986): FREE-FORM PORCELAIN CRAFTED THROUGH SLAB CONSTRUCTION

Kawamoto Goro is the only one of the three artists in this essay who was born in one of Japan's most famous ceramic production areas Although he inherited his family's pottery business, he developed a new form of ceramic expression as an individual ceramic artist with an artistic expression based in free-form slab construction

Kawamoto Goro was born in Seto City, Aichi Prefecture, in 1919. Seto has a pottery history of approximately 1,000 years and is one of the oldest pottery-producing areas in Japan, known as one of the Rokkoyō (the Six Old Kilns). He studied ceramic design at the Design Department of the National Ceramics Institute in Kyoto, and after his experience as a prisoner of war, he became the adopted son of Kawamoto Rekitei (1894–1975) in 1950 at the age of 31 Rekitei was the third generation of the Kawamoto family of potters, known for their underglaze blue porcelain called SetoSōmetsuke

Although Kawamoto Goro, as a member of the Kawamoto family, produced Seto-Sometsuke porcelain with painted surface decorations in cobalt underglaze expressing motifs based on his family's elegant bunjinga (traditional Chinese painting) style However, he also developed his own distinctive designs. In addition to motifs such as dragons and various birds, he created works covered with numerous scattered human figures, spirits, as well as scenes depicting various relationships between men and women. His painted decorations, often humorous or satirical, differed significantly from conventional porcelain designs.

Furthermore, while Japanese potters up to that time modeled their work on the refined, wheelthrown porcelain of China, Kawamoto Goro went against the grain and chose to work with slabs of porcelain clay rather than using the potter’s wheel, producing vessels composed of flat planes Slab-formed porcelain tends to distort during firing, but Kawamoto Goro challenged conventional expectations by incorporating even slight warping or irregularities into the final form of his works

In 2023, the exhibition “Kawamoto Goro: Rebellious Ceramics” was held at the Kikuchi Tomo Museum of Art in Tokyo and was well received by a wide audience.

CONCLUSION: CREATION AND EXPANSION OF VESSEL ART

As described above, the three artists Koinuma Michio, Tsuboshima Dohei, and Kawamoto Goro each created their own distinctive worlds of “vessels as unique expressions” by bringing a sense of modernity to traditional vessel forms

Their works are not simply utilitarian containers but can be regarded as creative expressions of ceramic vessel art They are objects to be displayed, used, appreciated, and cherished

This exhibition, held in September 2025 at Dai Ichi Arts in New York, offers a rare opportunity to view the works of Koinuma Michio, Tsuboshima Dohei, and Kawamoto Goro together in one setting. The inventive and compelling vessels of these three artists are certain to resonate with and be appreciated by audiences from around the world.

河 本

KAWAMOTO GORO

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Ash glazed flower vase with bird motifs, c. 1960's, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 21 × (w) 26 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Flower vessel with sometsuke (cobalt) bird motif drawings, c 1980’s, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h)

Kawamoto Goro 河本

Ash glazed flower vase with deer and bird motifs, c 1970's, with signed wood box, ash glazed stoneware (h) 21 5 × (diameter) 10 1 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎, Sometsuke flower vase with Ox motifs, 1980’s, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 23 5 × (w) 10 cm × (d) 10 cm

Three works by Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

(Left) Tea bowl with ash glaze, 1970’s, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 8 2 × (w) 14 × (d) 13 1 cm

(Middle) Sometsuke water jar with Ox motifs, 1980’s, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 18 5 × (w) 19 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Ash glazed tea bowl, c. 1970's, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 8.2 × (w) 14 × (d) 13.1 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Flower vessel, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 28.5 × (d) 9.3 × (w) 6.5 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Sometsuke flower vase showing a banquet of the hungry ghosts in "Utagaki" design, c 1980, with signed wood box, porcelain with blue underglaze, (h) 25 4 × (w) 11 4 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Flower vase with figurative aka-e designs, 1980's, with signed wood box, Porcelain with overglaze enamels, (h) 30.4 × (w) 12.7 cm

Two ash glazed vases by Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

(Left) Ash glazed vase, 1980, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 21 3 × (w) 9 4 × (d) 9 4 cm

(Right) Ash glazed jar, c 1960, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 22 6 × (w) 16 5 × (d) 11 4 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Sometsuke jar with drawings of a banquet of the hungry ghosts, c. 1980, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 19.0 × (w) 20.3 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Sometsuke flower jar with plant motifs, c 1980, with signed wood box, glazed stoneware, (h) 18 × (w) 19 4 × (d) 19 7 cm

Kawamoto Goro 河本 五郎

Sometsuke flower vase with with designs depicting a banquet of the hungry ghosts, c 1975-80, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 25 4 × (w) 13 2 × (d) 12 7 cm

坪

島 圡 平

TSUBOSHIMA DOHEI

Two works by Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平

(Left) Oribe square dish, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 8 9 × (w) 24 6 × (d) 26 2 cm

(Right) Oribe glazed rectangle-shaped bowl, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 4 × (w) 28 × (d) 17 cm

Large jar with Aka-e phoenix motifs, c 2003, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 31 × (w) 39 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平, Polychrome enamel jar with scalloped cloud designs, 1990's, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 19.1 × (w) 19.6 cm

(Left) Large jar with aka-e and inlaid gold and silver designs, c 1993, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 30 5 × (w) 33 × (d) 32 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平

Basket with inlaid gold and silver designs, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 18.5 × (w) 30.5 × (d) 28 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 土平

Lidded box with inlaid gold and silver bird motifs, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 10.5 × (w) 29 cm

Two works by Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平

(Left) Ko-Seto style ash-glazed flower vase with lugs, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 29.2 × (w) 18 cm

(Right) Iga flower vase, 1990's, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 22 × (w) 14 × (d) 11.5 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平

Large ash-glazed jar, c 1990's, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 29 2 × (w) 30 4 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平 Bowl with cloud and bird design in red painting, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 10.3 × (diameter) 17.7 cm

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平

(Left) Incense container with fish motifs, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 2 5 × (diameter) 6 5 cm

(Right) Sometsuke water jar with mountain and river landscape, c 2005, with signed wood box, porcelain, (h) 16 0 × (w) 15 2 cm

Two dishes by Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平

(Left) Decorated dish showing Musashino motif in gold glaze, c 1989, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 4 5 × (w) 24 5 × (d) 19 cm

(Right) Ash-glazed dish with Japanese arrowroot motif, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 4 2 x (w) 27 4 cm

MAVERICKS OR INDIVIDUALISTS?

DANIEL McOWAN

JAPANESE ART CURATOR & SPECIALIST

Entrance to Kawakita Handeishi’s kiln estate, the Hironaga Kiln, a space that Tsuboshima Dohei shared and ultimately helmed after his teacher Kawakita’s passing. The kiln was renamed “Senkaku Kiln” in the 2020's. Image courtesy of Gallery Senkaku, a museum in Mie prefecture that now oversees the display of Tsuboshima Dohei and Kawakita Handeishi’s legacy.

There is little doubt that Japanese ceramics of the twentieth century will go down in history as one of the great traditions of ceramic making

There seems to be an endless number of ceramicists who have their own style and who produce work at an astounding level of skill A number of factors have fed into this development: long and respected traditions, a commitment to both artistic and technical excellence, an almost monastic training regime, and a marketplace that appreciates skill and innovation and partakes in the promotion of these. Nowhere are these causes so obvious as in the three ceramicists in this exhibition.

All born well before the start of the Second World War, these three ‘mavericks’ shared the same societal background but varied considerably in their training.

Kawamoto Goro (1919–1986), born the second son of Seto potter Shigegoro Shibata (n d ), graduated from the Aichi Ceramics School in 1936, after which he attended the Kyoto City Ceramics Research Institute In 1940, he joined the military, and following this, joined the Seto Ceramics Association In 1950, at the age of 31, he was adopted by the famous Seto potter Kawamoto Rekitei (1894–1975), and, inheriting his surname, he became Kawamoto Goro He eschewed the potter’s wheel, seeing this as being for routine production, not artist’s ceramics, and devoted his efforts to handbuilding the forms and adopting various forms of hand decoration or glazing.

Tsuboshima Dohei (1929–2013), at the age of seventeen, became the apprentice to amateur potter, banker, and ceramics patron Kawakita Handeishi (1878–1963). He worked with Handeishi

for the next seventeen years and, at the age of thirty-four, succeeded him as head of Handeishi’s Hironaga kiln in 1963 Tsuboshima’s work reflects his scholarly background and results from a clear awareness and reinterpretation of very early Japanese ceramic traditions He is not the first to do this, but the breadth of what he draws upon distinguishes him

Koinuma Michio (1936–2020) graduated in economics from Osaka University and then moved to Waseda University for postgraduate work. Inspired by the work of Hamada Shoji, he decided at the age of thirty-three to change direction and moved to Mashiko. He opened his own kiln in 1970 and began exhibiting at major galleries in 1978.

Japan is often portrayed as a conformist society, but at the same time, there has always been respect for the outlier In painting, this is clearly seen in the work of Soga Shohaku (1730–1781) and Ito Jakuchu (1713–1800), the “Individualists,” who are so classified because they fall into none of the defined groupings art historians have imposed The same phenomenon occurs with ceramicists, with the true outliers being Otagaki Rengetsu (1791–1875) and Rosanjin (Kitaoji Fusajiro, 1883–1959) masters in their own domains with few equals So, our “mavericks” are in good company in pursuing their own directions. All three possess strong artistic integrity, which has led to a definable, consistent body of technically superb work from each of them.

Three works by Tsuboshima Dohei, Koinuma MIchio, and Kawamoto Goro.

NOTES ON STYLE, SURFACE, HISTORY

Koinuma Michio’s pieces reflect a similar awareness of historic styles, but this time looking back to the early history of ceramics in Japan It is from Yayoi ceramics (100 BCE–100 CE) that the horizontal flanges derive, but the frontality and the projection of “ presence ” in so many of the works derive from the later Haniwa pottery of the 6th century To these ziggurat and other forms, Koinuma has added a matte ash surface that gives his work a brooding quality, while at the same time imbuing it with a somewhat mystical power that evokes a sense of reverence for the object While functional as these pieces are, they have a sculptural presence that almost forbids their practical use. They are like altars to which one must pay obeisance.

Koinuma, like Tsuboshima, has a second style that demonstrates the same mastery as his ashsurfaced works. The forms in this style are far

more organic, and the decoration relies on surface impressions This is often suggestive of Korean or Mishima-inspired work, but Koinuma’s manner of linking these impressions to create a running decoration around the pot places them in a class of their own. Jōmon wares of the 3rd–4th millennium BCE possibly offer the inspiration, and this is consistent with the approach he has used previously.

Few Japanese ceramicists have utilized these early historic ceramic styles as inspiration, and Koinuma’s exploitation of them is exemplary. Hamada may have been his initial inspiration to become a potter, but this work is a long way removed from the concepts of Mingei and the Mashiko tradition yet he remains an undisputed master of his own style

Three works with carved motifs by Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄 (1936-2020)

Images of Tsuboshima Dohei’s kiln and study workspaces in Mie Prefecture, Japan Image courtesy of Gallery Senkaku

Three vessels by Tsuboshima Dohei

(Above) Tsuboshima Dohei, Bowl with overglaze decoration in red and green enamels, porcelain, S2010 30, Hironaga kiln, Tsu, Mie prefecture, Japan

Permanent collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art Image courtesy of the museum

Tsuboshima Dohei’s work draws on a number of threads and a comfortable movement between the porcelain and stoneware traditions His porcelain work draws upon the dominance of Chinese styles of decoration Chinese landscapes in underglaze blue appear on his mizusashi (water jar), but in this exhibition, the more prominent style derives from late-Ming porcelain, with on-glaze red and green decoration A piece by Tsuboshima with this decoration is in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art. Both styles tie in with literati tastes and the popularization of SinoJapanese wares, which took their impetus from sencha drinking in the 19th century.

The larger part of Tsuboshima’s work is stoneware, and some of these reflect historic Japanese styles such as Oribe ware, Karatsu

ware, Ko-Seto ware, and Iga ware Others celebrate the traditional richness of Kyoto-style ceramics by using silver and gold to highlight the details of nature-based imagery The potential of all these styles is both exploited and reinterpreted to create the impressive body of work in this exhibition

In both his forms and decoration, Kawamoto Goro is in his own world There are distant echoes of historical works in the decorative techniques he uses, but that is where the resemblance ends. His slightly zany motifs his hungry ghosts, for example are entirely from his own imagination. His cows, birds, and dancing figures are again wholly his own creations.

Image of Tsuboshima Dohei & Kawakita Handeishi at their kiln. Image courtesy of Gallery Senkaku.

Tsuboshima Dohei 坪島 圡平, Shino octagonal dish with heron painting, 2007, with signed wood box, shino stoneware, (h) 9.9 × (w) 33.5 cm

Underglaze cobalt decoration features in many of his works, reflecting its use by both his mentor Kawamoto Rekitei and, more broadly, Seto ceramics in general His hand-built forms range from geometric structures sometimes of considerable complexity to fully organic shapes resulting from coiling or pinching Between his forms and his decorative schemes, one cannot help but continually respond to his originality and creativity

Like Tsuboshima, Goro moves comfortably between porcelain and stoneware, selecting the medium to complement his form or decorative technique His stoneware often exploits ash glazes, which he either uses thickly to envelop his forms or applies lightly to suggest archaeological remnants. At other times, he uses ash glazes as an overall coloring to provide a canvas for his whimsical figures of birds and beasts. He continually demonstrates his mastery of a vocabulary of forms and decoration that are entirely his own.

So, yes, we have three “mavericks” but also absolute masters of their craft, each working within the confines of their own influences and styles All three deserve high profiles as part of the great 20th-century Japanese ceramic movement They all respect tradition, work with originality, and maintain a high level of proficiency Each deserves a place in the world’s great private and public collections

Three works by Kawamoto Goro in sometsuke and ash glaze

肥

KOINUMA MICHIO

Single spouted geometric flower vase, c 1985

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 19 × (w) 8 8 × (d) 8 8 cm

(Left) Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄

Vessel, stoneware, (h) 29.2 × (w) 17.7 × (d) 19 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄 Jar, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 25.9 × (w) 13.9 × (d) 12.7 cm

(Left) Jar with carved motifs, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 23 3 × (w) 20 3 × (d) 13 9 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄

(Middle) Large Jar, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h)

(Right) Jar, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h)

Koinuma Michio 肥沼

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄

Object, signed at the base, stoneware, (h) 30 × (w) 33 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄 Jar, 1989, signed KOI 肥 at the base, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 46.5 × (w) 22 × (d) 22 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄

Vessel, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 35 5 × (w) 33 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄, flower vase in the shape of a snake's belly, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 15 × (w) 13.2 × (d) 7.2 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄 (Left) Kabuto 兜, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 34 × (w) 19 × (d) 16 5 cm

Jar, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 16 4 × (w) 13 6 × (d) 9 4 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄

Sculpture: Pug, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 13 2 × (w) 19 0 × (d) 8 8 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼

(Left) Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄

Jar, with signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 22 8 × (w) 22 8 × (d) 17 7 cm

Koinuma Michio 肥沼 美智雄

(Middle) Vessel, c 1985, stoneware, (h) 26 4 × (w) 16 5 × (d) 10 9 cm

(Right) Flower vessel, stoneware, (h) 19 5 × (w) 11 4 cm

MAVERICKS: KOINUMA MICHIO, KAWAMOTO GORO & TSUBOSHIMA DOHEI | THREE MASTERS OF JAPANESE CERAMICS

EXHIBITION CATALOG | ASIA WEEK NEW YORK 2025 ON VIEW: SEPTEMBER 11 – 19, 2025

ISBN: 979-8-9985525-1-9

CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: BEATRICE CHANG, KAZUKO TODATE, DANIEL MCOWAN CATALOG PRODUCTION: KRISTIE LUI, HARUKA MIYAZAKI PHOTOGRAPHY: NAOMI SAITO, YORIKO KUZUMI

IMAGES CREDITS AND COURTESY OF CITED INSTITUTIONS.

PUBLISHED BY DAI ICHI ARTS, LTD. 2025 © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.