B R E A T H I N G V E S S E L S

Dai Ichi Arts, Ltd is a fine art gallery exclusively dedicated to celebrating modern and contemporary works of ceramic art from Japan

Since our inception in 1989, we have focused on placing important Japanese ceramics at the center of New York's contemporary art scene. The gallery has introduced pieces to the permanent collections of several major museums, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the Princeton University Art Museum, and many more

We are committed to providing authoritative expertise to collectors, liaising with artists, and showcasing inspiring exhibitions and artworks We welcome you to contact us for more information

Breathing Vessels: Contemporary Ceramics by Yanagihara Mutsuo

Exhibition catalog

On view: May 15 - 30, 2025

18 East 64th Street, Ste. 1F

New York, NY, 10065, USA

www daiichiarts com

F O R E W O R D

BEATRICE CHANG

DIRECTOR, DAI ICHI ARTS, LTD

My first encounter with Yanagihara Mutsuo-sensei’s work was over twenty years ago, when I was co-authoring Fired with Passion with the late Samuel J Lurie Among the works we chose to write about was a remarkable work from the National Craft Museum: a sculptural work with a system of rounded forms clothed in a shimmering silver with white dots bursting against a navy blue glazed surface That piece so alive, so daring made a lasting impression

The second unforgettable encounter came when I found his work in a book featuring contemporary artists responding to Japan’s ancient ceramic traditions Once again, Yanagihara sensei’s piece stood out The work was a study in tension: a dark, wide, silver cylindrical form with a raised back, as if inhaling filling its lungs with air Fleshy in volume and outlined in black, it felt both anthropomorphic and primal yet also futuristic and geometric Rooted in tradition, it came alive with its own energy

Fifteen years later, I finally had the privilege of visiting him at his home and studio, thanks to an introduction by Umeda Mitsuko of Utsuwakan in Kyoto It was the summer of 2022 When I arrived, he was deep in conversation not with me, but with Mitsuko-san speaking calmly about his burial plans Since he was not the eldest son, he explained, he was not obligated to be interred in his family plot in Ehime Instead, he was considering one of the sub-temples of Daitoku-ji (⼤徳寺), a place he deeply revered Though there was no rush, he said, with a serene smile

Even in that moment contemplating death in the quiet dignity of age there was clarity. He remained fully present, fully himself That same clarity and vision runs through his work

To him, creativity must remain free: He spoke critically of institutions, which he felt constrained artistic imagination Once an artist aligns with such groups, he said, their work begins to serve the institution rather than their inner voice It was this belief that kept him independent and institutionally unaffiliated, devoted only to his own practice and rhythm. He wanted to be understood by his own country. He wanted his legacy to take root in the soil that had shaped him.

Amid the waves of topics we explored Ikebana and its avant-garde practitioners like the late Nakagawa Yukio, and

the quiet companionship between botany and ceramics I also pressed him gently about having an exhibition at Dai Ichi Arts “It’s about sharing your truth across oceans and generations It’s about listening,” I said We spoke at length about our work at the gallery: our research into Shikōkai (四耕会), our commitment to artists such as Murata Gen and Yasuhara Kimei, and many more whose contributions might otherwise be overlooked in the west.

“Let us honor your life’s work,” I said “Let your breath be felt while you are still with us ”

He smiled

Then, quietly, he invited me to see his newest creations: a group of works in the drying room, still awaiting glaze. When I returned two years later, those same forms had come alive, having matured into beings of their own. It is no wonder that artists so often speak of their works as their children now I understand the truth of it These pieces are not born in months, but over years, through care, contemplation, and presence Each form, each thought, each conviction it is as intimate as one ’ s breath made visible in clay

This exhibition is not just a presentation of his works, it is also a living conversation between solitude and vitality, oscillating between memory and presence. It traces not only the arc of an artist’s career but the course of a human life Yanagihara-sensei’s works have lived in museums, studios, and private homes Now, we welcome them into our gallery not as static objects, but as living witnesses These vessels come alive They create dialogues among themselves: some bulge and swell, while others reach skyward They breathe through form, glaze, and energy alive in their presence, and transforming the spaces they inhabit in different ways

There has been a quiet, humanistic, and sacred devotion in bringing Yanagihara Mutsuo’s work to this moment. More than a retrospective, this exhibition is also a rite of passage an act of breathing life and energy to the world through clay

At Dai Ichi Arts, I am grateful to Kristie Lui and Haruka Miyazaki, who breathed youthful energy into this exhibition catalog’s design and organization I am also grateful to Yoriko Kuzumi, who has brought her mature understanding of depth, energy and presence into the photographs of his work From Kyoto, Minoru and Mitsuko brought their vision and connection, infusing this project with fresh perspective and care We are also deeply grateful to Dr Andreas Marks of the Minneapolis Institute of Art, whose extensive research and in-depth interviews with the artist culminated in a beautifully written essay for this exhibition one that offers rich insights and brings these storied objects vividly to life.

As for myself after thirty-five years in this field I’ve come to see that every artist I’ve chosen to work with, every object I’ve curated, forms part of a larger story I’m telling There is something profoundly human in the act of bringing an artist’s work into view Each curatorial project still takes my breath away in its own way It is an honor to be able to tell the story of a life through art.

We are humbled to be part of Yanagihara-sensei’s journey breathing new life into his ideas, reflecting his spirit, and bringing his gift forward into the world

Y A N A G I H A R A M U T S U O :

A L I F E F O R P L A Y A N D F O R M

DR. ANDREAS MARKS

MARY GRIGGS BURKE CURATOR OF JAPANESE AND KOREAN ART AND DIRECTOR OF THE CLARK CENTER AT THE MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART

The artist pictured in his studio with images of Ikebana designs by artist Nakagawa Yukio in a group of Yanagihara’s own vessels, 2022, Kyoto, Japan Image courtesy of Dai Ichi Arts

In 2024, a legend turned 90: Yanagihara Mutsuo. For nearly 60 years, Yanagihara has been at the forefront of ceramics in Japan, pursuing a distinctive and instantly recognizable style. Deeply committed to originality in both concept and form, he develops decorative, flowing themes and crafts complex, organic shapes by intricately weaving together a sophisticated system of curves His ceramics seamlessly blend surface pattern with form, showcasing a harmonious union

I had the honor of visiting the retired Osaka University of Arts professor at his home on the outskirts of Kyoto. Sitting in his living room, surrounded by dozens of his colorful vessels, he casually introduced himself “I’m Mutsuo” and apologized that his English was not as strong as it had been decades ago, when he lived in the United States However, the lengthy monologue that followed demonstrated that his command of the English language remained undiminished

Between 1966 and 1982, Yanagihara received grants and appointments that allowed him to live in the U S three times, each for nearly two years. In 1966, a Fulbright grant enabled him to teach ceramics at the University of Washington in Seattle. He returned in 1972 as an Assistant Professor at Alfred University in New York State, and later taught at Scripps College in Claremont, California His third “tour” began in 1980 with a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, which supported his lecturing and teaching of ceramics at various institutions

Yanagihara Mutsuo, 柳原睦夫, Flower vessel with gold and silver luster overglaze (Kon’yū kingin-sai kabin 紺釉⾦銀彩

花瓶), 1971, glazed stoneware, 32 8 × 24 9 × 25 cm © Kure Municipal Museum of Art 呉市⽴美術館 所蔵 Image courtesy of the museum

Tomimoto Kenkichi 富本憲吉 (pictured to the right) and Kondō Yūzō 近藤悠三 (pictured to the left) photographed in Kyoto, 1956 Image courtesy Tomimoto Kenkichi Public Domain Archives and the Tsujimoto Isamu Collection

Few Japanese artists or educators have had such extensive first-hand experience in the United States While Yanagihara was influenced by the American Pop Art movement he encountered there, he also developed a distinctive style of his own, independent of those influences.

Yanagihara was born in 1934 in the city of Uwajima, Ehime Prefecture, on the scenic island of Shikoku, into a family of medical doctors His grandfather was an internist, and his father an otolaryngologist When Yanagihara was three years old, his parents moved 80 miles (130 km) east to Kōchi City His upbringing on the Pacific coast of Shikoku the smallest of Japan’s major islands, known for its rich vegetation and in a well-educated family fostered in Yanagihara an early appreciation for both botany and the human body, themes that are later expressed in his ceramics.

In 1954, he moved to Kyoto and entered the Department of Crafts at Kyoto City University of Arts to study ceramics Coincidentally, this was a watershed moment in the long history of Japanese ceramics, marked by the emergence of an avant-garde movement Yanagihara’s teachers were three important figures in modern ceramics: Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886–1963), Kondō Yūzō (1902–1985), and Fujimoto Yoshimichi (1919–1992) Tomimoto, the founder of the department, is now regarded as Japan’s most influential ceramic artist of the 20th century. Kondō, who later became the university’s president, is known for his modernist approach to classic blue-and-white porcelain (sometsuke). Fujimoto, renowned for depicting natural motifs in overglaze enamels, also joined the avant-garde group Sōdeisha (literally translated as the "Crawling through Mud Association") in 1957, remaining a member for several years

(Pictured left and above) Yanagihara Mutsuo, 柳原睦夫, Vase, 1967, stoneware, 18 4 × 27 9 × 27 9 cm © Seattle Art Museum, Gift in honor of Millard B Rogers (93 14) Image courtesy of the museum

Tomimoto in particular, for whom Yanagihara served as a teaching assistant after graduating in 1960, had a significant impact on Yanagihara In 1959, before graduating, the young Yanagihara achieved his first success as an artist when he received the Association Prize at the ninth annual exhibition of the Modern Art Association The exhibition was displayed at four prestigious venues: Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art (then the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art), Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, and Kochi Daimaru. This was only the second time Yanagihara had participated in the exhibition, and he was not admitted into the association as a member until 1962

The winning artwork was an abstract sculpture in vessel form, standing two feet (62 cm) tall, titled Appearance (Bō 貌, 1959), which is now in the collection of The Museum of Art, Kōchi Already apparent in this piece and in other works from the late 1950s and early 1960s is Yanagihara’s enjoyment of experimenting with form. He clearly strove to create shapes that no one had made before him. These early works were initially monochromatic mostly in brown and green and worlds apart from the bright palette that would later become his signature His surface treatments are asymmetrical, often divided between smooth planes and rough edges

Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫 Pigeon Nest (Hato no su 鳩の巣), 1963 glazed stoneware, 37 6 × 46 8 × 22 4 cm © Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama 和歌⼭県⽴近代美術館 所蔵 Image courtesy of the museum

Yanagihara Mutsuo, 柳原睦夫, Vase, 1971, glazed stoneware, 27 × 31 × 28 cm, Awarded the prize of 29th International Competition of Contemporary Ceramic Art, Faenza, 1971 © International Museum of Ceramics, Faenza & The Japan Cultural Institute, Rome, Italy

While his forms from the first half of the 1960s are scu theory This is demonstrated in two works titled Pigeon of Modern Art, Wakayama Absorbing Green I (Kyūchaku suru midori I 吸着する緑Ⅰ), housed in the Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum, could even function as a flower vase

Once Yanagihara reached the United States in 1966, he expanded his range of shape and decoration to tubular forms that have an organic feel, while adding striped decoration in brightly colored glazes to the otherwise muted surface. During his time, as visiting professor of ceramics at the University of Washington, Yanagihara was accepted to local group exhibitions and even won an award At the Northwest Craftsmen’s Exhibition in 1967 (Nov 21–Dec 24) held at the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture (then called the Cheney Cowles Memorial Museum) in Spokane, WA, he was one of twelve winners from a pool of 245 participants In 1968, Museum West in San Diego, CA, organized a twoperson exhibition (May 17–Jun. 23) that juxtaposed the complex textile weavings of Colombian artist Olga de Amaral (born 1932) with Yanagihara’s much more minimal ceramics.

After returning to Japan in 1968, Yanagihara became an assistant professor of ceramics at Osaka University of the Arts In 1970, Yanagihara began creating many series of sculptures that shared distinctive forms and patterns that he would pursue for a few years before moving onto the next This cycle would continue for the next 50 years The first series comprises dark blue glazed vessels with a white dot pattern accented with gold and silver luster overglaze (kon’yū kingin-sai 紺釉⾦銀彩). The vessels are mostly flower vases, the most acclaimed of which resemble a flower bud Yanagihara submitted one of the vases from this series to the prestigious 29th International Competition of Contemporary Art Ceramics in Faenza, Italy in 1971 and was awarded the Ravenna City Chamber of Commerce Prize

Yanagihara Mutsuo, 柳原睦夫, Sign of the Sky (Sora no hyōshiki 空の標識), 1978, glazed stoneware, 32 1 × 28 9 × 28 9 cm Collection of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz

tes, he attained something of a celebrity status within cripps College in California in the autumn of 1973 was can Craft Council (vol. 33, no. 5, p. 7). When he pendent rather than join any association. Although t, patronage, and encouragement from other ilosophy Remaining independent was more important to Yanagihara, as it allowed for greater imagination and freedom in his art

Perhaps the most radical interlude of his career was the Sky (Sora 空) series which he developed in 1977 and pursued until 1981. With this series, Yanagihara further removes the seriousness from the medium ceramics and turns towards playfulness He pursued the contradiction to make atmospheric-themed works out of heavy, solid material Cube, disc, and balloon-like forms balance on undulating platforms, each dominated by elements colored in shades of blue and decorated with white clouds One type of form comprises cubes that balance on a single point, and therefore emulate lightness––like clouds

Westerlies (Henseifū 偏西⾵) is made up of a square panel pierced with a round hole, through which a twisting cloud seems to float The object is today in the collection of the Museum of Modern Ceramic Art, Gifu Like Westerlies, Yanagihara bestowed the unique objects with titles referencing wind and sky like Dynamics of the Sky (Sora no rikigaku 空の⼒学) or Memories of the Sky (Sora no kioku 空の記憶)

Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Smiling Pot, 1985, stoneware decorated with gold over blue and yellow glazes, 48 8 × 32 7 × 28 cm © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, United Kingdom. Image courtesy of the musuem

In 1984, Yanaghira became a professor a his first year at the university, he began w g p y pp g , sometimes embellished with gold and silver, harkening back to the innovative style of his teacher Tomimoto and his mantra “Don’t make pattern out of pattern” (Moyō kara moyō o tsukuru na ⽂様から⽂様をつくるな) Yanagihara continued this new pop and funk series until 1991, concentrating primarily on three types of vessels that he developed and named: cylindrical vases (tō kabin 筒花瓶), boot-shaped vases (kutsu kabin 沓花瓶), and smiling pots (shōkō-ko 笑 ⼝壺). The so-called boot-shaped vases have a cylindrical body that is attached to a round foot which protrudes to one side. The smiling pots are of inverted cone shape with an opening that is thicker on one side and hangs down like the fleshy lower lip A vivid yellow and blue are the dominant colors in this series and are applied in patterns that reflect flowing water

Works from this series were featured in the exhibition Four Aspects of Contemporary Japanese Ceramics, organized by the Newcastle Region Art Gallery and held in nine different Australian cities from 1987 to 1989 (In this exhibition, the “smiling pots” were called “vessels with cosmic patterns”) The objects in this series were coil-built by Yanagihara from fine stoneware clay and then fired with a transparent glaze at 1260 degrees Celsius Finally, he applied color and luster glazes and low-fired each object several times at 670 degrees Celsius

In parallel, Yanagihara began working on another series that he identified as Oribe, referring to the type of ware that developed around 1600 in the vicinity of Kyoto, where his studio was located Typical of Oribe ware are asymmetrical or distorted shapes and a combination of stylized drawings and copper-green glaze, as well as black or red tones Most of his new Oribe works are a combination of yellow, black, and silver, with the occasional addition of orange From around 1992, he sometimes substituted yellow with blue, eventually abandoning yellow entirely after 1997 The patterns achieved after this are more geometric and less fluid than in the previous series, with clear boundaries achieved through the use of masking tape when applying the color.

Yanagihara remained true to his emphasis on “play,” and in 1992 he conceived a new shape of vessel that he described as Flower-eating (kashoku 花喰) Positioned on a thin, triangular-shaped foot is a turnip-shaped form with a swollen belly and a round opening resembling a mouth Since the tops are flat and closed, the “mouth” is where the flowers would need to be placed. Around 1994–1995, he introduced another form that he called the Retroflex Vessel (kōkutsuhei 後屈瓶): an elevated upper section in the shape of a cylinder with an opening for flowers is lifted by a flexed leg, lending the vessel a dynamic presence In 1997 came the celebrated Licking-up Vessel (perotto-hei ペロット瓶), which resembles an insect with a long snout

Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫 Flower vessel with gold and silver luster overglaze (Kon’yū kingin-sai kabin 紺釉⾦銀彩花 瓶), 1971, glazed stoneware, 62 × 49 8 × 21 cm © The National Crafts Museum 国⽴⼯芸美術館 所蔵 Photo by Hatakeyama Takashi

Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Vessel with Jomon Decoration and Yayoi Form (縄⽂式弥⽣形壺), 2002, glazed stoneware, 52 × 50 × 41 cm © The Museum of Oriental Ceramics Osaka (Gift of Mr Sugiyama Michio) ⼤阪市⽴東洋陶磁美術館 所蔵(杉⼭道夫⽒寄贈)

Image courtesy of the museum 写真:⿆⽣⽥兵吾. Photo: Mugyuda Hyogo.

urned to utilizing silver but employed a dull, orks Set against black tones, the silver color ars tarnished, as if aged In 2000, he used o evoke the decorativeness of Jōmoniod (3rd century BC–3rd century CE) pottery. The expansive curved edges, coupled with spiraling motifs, alongside meticulously crafted interior designs, lead the viewer’s eye into the vessels’ interior

In his mid-60s, Yanagihara received accolade after accolade for his achievements He was awarded the Kyoto City Art Contribution Prize in 1998, the Kyoto Prefecture Prize for Cultural Contribution in 2000, the Japan Ceramic Society Prize in 2003, and the Kyoto Art Culture Prize in 2005. After retiring from Osaka University of Arts in 2006, Yanagihara remains active and full of vigor, and has embarked up on multiple new series, such as Anti-Vessel (han-ki 反器) in 2004, Well (ido 井戸) in 2007, Topological Standing Pots (toporo-ritsu tsubo トポロ⽴壷) in the second half of the 2010s, and Exhalation and Inhalation (Koki kyūki 呼気・吸気) in the 2020s

In his 80s–– and now in his 90s–– Yanagihara has concentrated on creating single-footed creature-like objects with round, swollen bodies and organic, uneven openings He remained true to his idea of creating unique shapes and achieving a symbiosis of an abstract sculpture and functional vessel against the dichotomy of their natures. Throughout his artistic life, Yanagihara has been devoted to playfulness and stayed true to the fusion of form and decoration

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baekeland, Frederick, and Robert Moes 1993 Modern Japanese Ceramics in American Collections New York: Japan Society

Fujioka, Mamoru, ed 1992 Yanagihara Mutsuo Toh: The best selections of contemporary ceramics in Japan 55 Kyoto: Kyōto Shoin

Inui Yoshiaki 1990 Tōgei no genzai, Kyōto kara: Jū-nin no tōgeikaga enshutsu suru kūkan no dorama Tokyo: Takashimaya Bijutsubu

Karasawa, Masahiro, Masanori Moroyama, and Narita, Nodoka, Nomiyama, Sakura, eds 2016 Craft Arts: Innovation of "Tradition and Avant-Garde," and the Present Day Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Kōchi Kenritsu Bijutsukan, ed 2003 Yanagihara Mutsuo to gendai tōgei: TOSA-TOSA 2003 Yanagihara Mutsuo to gendai tōgei no sen'eitachi. Kōchi-shi: Kōchi Kenritsu Bijutsukan.

Marks, Andreas, ed. 2008. Generosity in Clay: Modern Japanese Ceramics from the Natalie Fitz-Gerald Collection. With the assistance of A Marks, C Meyet and K Tanaka Clark Center Exhibition Series 3 Hanford: Clark Center for Japanese Art and Culture.

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, ed. 2007. Kōgeikan meihinshū: Tōgei. Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Newcastle Region Art Gallery 1987 Four Aspects of Contemporary Japanese Ceramics Newcastle [N S W ]: Newcastle Region Art Gallery

Norment, Kate, ed 1995 Messages in Clay and Fire from Kyoto: Hiroaki Taimei Morino and Mutsuo Yanagihara New York: Takashimaya

Tankōsha, ed 1989 Kinki I: Kyōto Gendai no nihon tōgei Tokyo: Tankōsha

B R E A T H I N G

V E S S E L S

CERAMIC WORKS

L I S T O F W O R K S

Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Yellow Oribe tea bowl ⻩織部茶碗, 1989

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 76 × (diameter) 128 cm

2 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Red Oribe tea bowl 紅オリベ茶碗, 1991

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 8.7 × (diameter) 14 cm

3 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫 Tea bowl with gold and silver glaze ⾦銀彩彩⽂茶碗, 1997

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 85 × (diameter) 119 cm

4 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Irabo glazed flower vase イラボ釉鉄絵花瓶, 1966

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 22 × (w) 241 × (d) 241 cm

With signed wood plate, stoneware (h) 72 × (w) 33 × (d) 364 cm

With signed wood box, stoneware (h) 31 × (w) 20 × (d) 19.5 cm

5 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Silver Oribe vessel with Jōmon decoration and Yayoi form 縄 ⽂式弥⽣形壺 (銀オリベ), 2000

6 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Cloud vase 雲ノ絵花瓶 1976

With signed wood box, stoneware (h) 348 × (w) 333 × (d) 227 cm

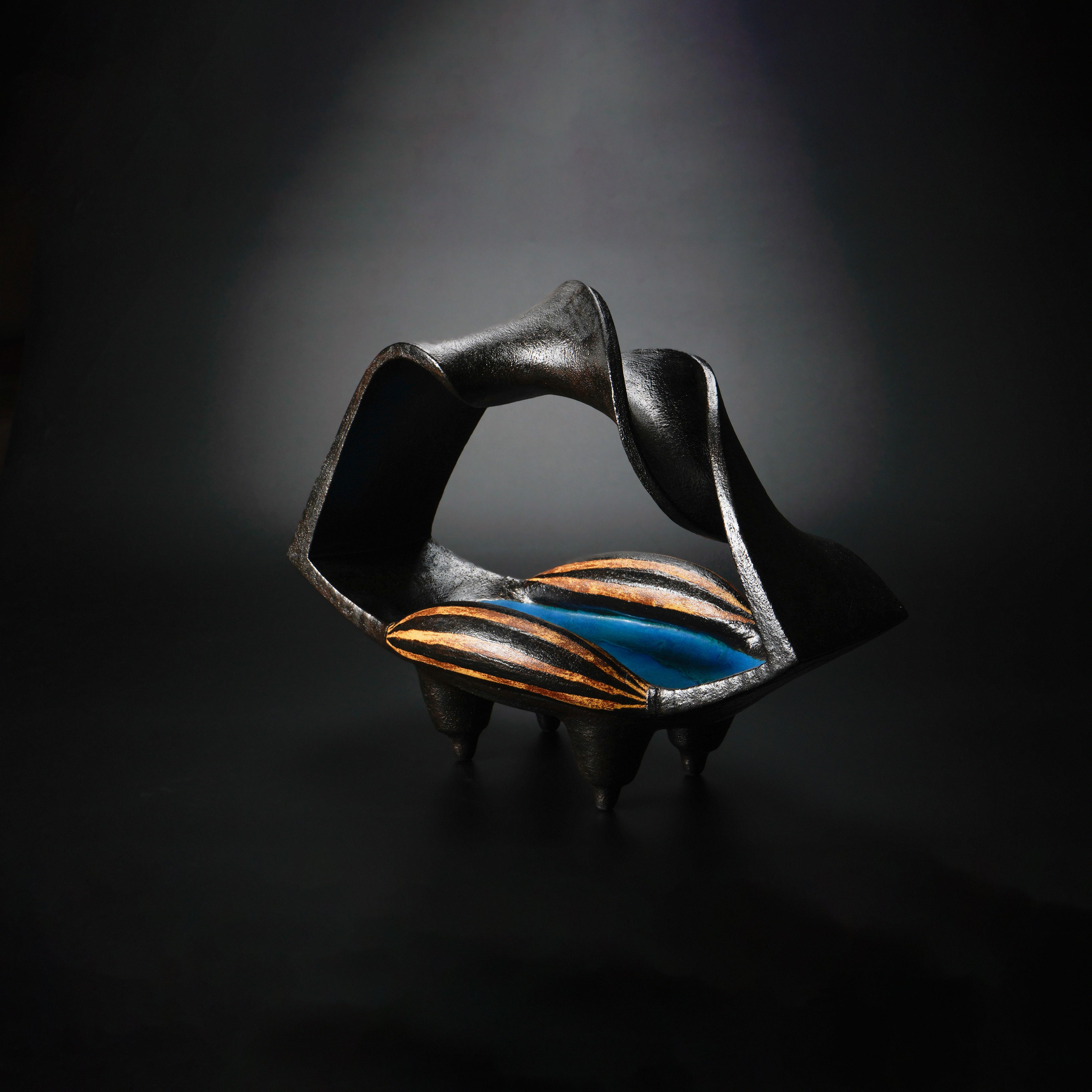

7 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Anti-vessel (Basket form) 捻り⼤⼿付反器, 2004

With signed wood plate, stoneware, (h) 394 × (w) 382 × (d) 403 cm

8 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Flower-eating Vessel (flared vessel with white glaze) ⽩釉開く形, 2012

9 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Anthropomorphic three-legged vessel with black glaze 黒彩三脚壺 2007

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 318 × (w) 439 × (d) 218 cm

10 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫 , Silver Oribe flower vase with lugs 銀オリベ⽿付筒花⼊, 2020

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 21.8 × (w) 13 × (d) 10.6 cm

11 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫 Flower-eating Vessel (cylindrical flower vase with yellow Oribe glaze) キオリベ⻑筒花瓶, 1992

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 368 × (w) 172 × (d) 142 cm

12 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Topological Vessel: The Sound of a Pulse (standing vase with azure glaze) 碧釉トポロ⽴壺⿎動を聴く, 2020

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 305 × (w) 17 × (d) 208 cm

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 23 × (w) 136 × (d) 139 cm

13 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Tubular flower vase with white glaze ⽩釉筒花⼊, 2013

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 176 × (w) 97 × (d) 109 cm

14 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫

Topological Vessel (tubular flower vase with azure glaze) 碧釉トポロ筒花⼊ 2020

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 203 × (w) 164 × (d) 169 cm

15 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Tubular flower vase with azure glaze 碧釉筒花⼊, 2015

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 364 × (w) 249 × (d) 173 cm

16 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Flower-eating Vessel (flared vase with azure glaze) 碧釉開く 形, 2009

17 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Topological Vessel: The Sound of a Pulse (standing vase with azure glaze) 碧釉トポロ⽴壺"⿎動を聴く, 2020

With signed wood plate stoneware, (h) 461 × (w) 257 × (d) 242 cm

18 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫 Topological Vessel: The Sound of a Pulse (standing vase with azure glaze) 碧釉トポロ⽴壺'"⿎動を聴く" , 2017

With signed wood plate stoneware, (h) 50 × (w) 255 × (d) 23 cm

19 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Form of an eroding wind ⾵蝕の形, 2018

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 224 × (w) 212 × (D) 242 cm

20 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Tubular flower vase with white glaze ⽩釉筒花⼊, 2010

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 22 × (w) 241 × (d) 241 cm

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 254 × (w) 115 × (d) 175 cm

21 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Tubular flower vase with white glaze ⽩釉筒花⼊, 2010

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 34.5 × (w) 32 × (d) 33 cm

22 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Flower-eating

Vessel (wide-mouthed vessel with a swollen belly) ⼤⼝⿎腹花喰ふくら壺, 2023

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 26 × (w) 27 × (d) 265 cm

23 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Flower-eating Vessel (wide-mouthed vessel with a swollen belly) ⼤⼝⿎腹花喰ふくら壺, 2023

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 445 × (w) 34 × (d) 33 cm

24 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Flower-eating Vessel (wide-mouthed vessel with a swollen belly) ⼤⼝捻袋花喰ふくら壺, 2024

agihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫 Flower-eating wide-mouthed vessel with a swollen ⼤⼝⿎腹花喰ふくら壺 2024

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 475 × (w) 338 × (d) 335 cm

agihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Chrysalis ng flower vessel) まゆとたまかひの形 2015

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 25.1 × (w) 21.8 × (d) 16.7 cm

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 72 × (w) 63 × (d) 77 cm

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 78 × (w) 78 × (d) 7 cm

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 74 × (w) 68 × (d) 88 cm

29 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Eggplant tea caddy with white glaze ⽩釉蓋器, 2010-2013

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 8.7 × (w) 8.7 × (d) 7.5 cm

30 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Eggplant tea caddy with white glaze ⽩釉蓋器, 2010-2013

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 88 × (w) 64 × (d) 7 cm

31 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Eggplant tea caddy with white glaze ⽩釉蓋器, 2010-2013

With signed wood box, stoneware, (h) 17 × (w) 124 × (d) 127 cm

32 Yanagihara Mutsuo 柳原睦夫, Topological Vessel (standing vase with azure glaze) 碧釉トポロ⽴壺, 2018

AUTHORS

Andreas Marks is the Mary Griggs Burke Curator of Japanese and Korean Art and Director of the Clark Center at the Minneapolis Institute of Art

Beatrice Chang is the founder & director of Dai Ichi Arts, LTD and author of Fired with Passion

EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION

Kristie Lui

Haruka Miyazaki 宮崎晴⾹

Mitsuko Umeda 梅⽥美津⼦

Minori Umeda 梅⽥稔

PHOTOGRAPHY

Yoriko Kuzumi 久住依⼦

B R E A T H I N G V E S S E L S

Contemporary Ceramics by Yanagihara Mutsuo

Exhibition catalog

On view: May 15 - 30, 2025

ISBN 979-8-9985525-0-2

Published by Dai Ichi Arts, LTD © All rights reserved