ambassadors without diplomatic passport

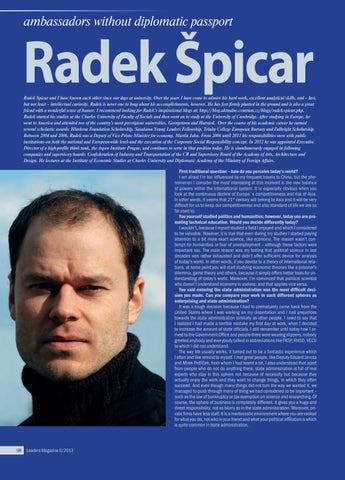

Radek Špicar Radek Spicar and I have known each other since our days at university. Over the years I have come to admire his hard work, excellent analytical skills, and – last, but not least – intellectual curiosity. Radek is never one to brag about his accomplishments, however. He has feet firmly planted in the ground and is also a great friend with a wonderful sense of humor. I recommend looking for Radek’s inspirational blogs at: http://blog.aktualne.centrum.cz/blogy/radek-spicar.php. Radek started his studies at the Charles University of Faculty of Socials and then went on to study at the University of Cambridge. After studying in Europe, he went to America and attended two of the country’s most prestigious universities, Georgetown and Harvard. Over the course of his academic career he earned several scholastic awards: Hlavkova Foundation Scholarship, Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship, Trinity College European Bursary and Fulbright Scholarship. Between 2004 and 2006, Radek was a Deputy of Vice-Prime Minister for economy, Martin Jahn. From 2006 until 2011 his responsibilities were with public institutions--on both the national and European-wide level--and the execution of the Corporate Social Responsibility concept. In 2012 he was appointed Executive Director of a high-profile think tank, the Aspen Institute Prague, and continues to serve in that position today. He is simultaneously engaged in following companies and supervisory boards: Confederation of Industry and Transportation of the CR and Supervisory Board of the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design. He lectures at the Institute of Economic Studies at Charles University and Diplomatic Academy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. First traditional question – how do you perceive today’s world? I am afraid I’m too influenced by my frequent travels to China, but the phenomenon I consider the most interesting at this moment is the new balance of powers within the international system. It is especially obvious when you look at the continuous decline of Europe´s competitiveness and rise of Asia. In other words, it seems that 21st century will belong to Asia and it will be very difficult for us to keep our competitiveness and also standard of life we are so far used to. You yourself studied politics and humanities; however, today you are promoting technical education. Would you decide differently today? I wouldn’t, because I myself studied a field I enjoyed and which I considered to be valuable. However, it is true that even during my studies I started paying attention to a bit more exact science, like economy. The reason wasn’t contempt for humanities or fear of unemployment – although these factors were important too. The main reason was my feeling that political science in last decades was rather exhausted and didn’t offer sufficient device for analysis of today’s world. In other words, if you devote to a theory of international relations, at some point you will start studying economic theories like a prisoner’s dilemma, game theory and others, because it simply offers better tools for understanding of today’s world. Moreover, I’m convinced that political scientist who doesn’t understand economy is useless; and that applies vice versa. You said entering the state administration was the most difficult decision you made. Can you compare your work in such different spheres as enterprising and state administration? It was a tough decision because I had to prematurely come back from the United States where I was working on my dissertation and I had prejudices towards the state administration similarly as other people. I need to say that I realized I had made a terrible mistake my first day at work, when I decided to increase the amount of state officials. I still remember until today how I arrived to the Government Office and people there were wearing slippers, nobody greeted anybody and everybody talked in abbreviations like FKSP, RHSD, VECU to which I did not understand. The way life usually works, it turned out to be a fantastic experience which I often and like remind to myself. I met great people, like Deputy Eduard Janota and Mirek Petříček, from whom I had learnt a lot. I also understood that apart from people who do not do anything there, state administration is full of real experts who stay in this sphere not because of necessity but because they actually enjoy the work and they want to change things, in which they often succeed. And even though many things did not turn the way we wanted it, we managed to push through many of thing we had considered to be important – such as the law of bankruptcy or tax exemption on science and researching. Of course, the sphere of business is completely different. It gives you a huge and direct responsibility, not as blurry as in the state administration. Moreover, private firms have less staff. It is a meritocratic environment where you are ranked for what you do, not who is your friend and what your political affiliation is which is quite common in state administration.

98

Leaders Magazine II/2013