CELEBRATING OUR

CELEBRATING 60 YEARS OF SERVICE TO THE VETERINARY PROFESSION IN 2025 Follow Tom Hungerford’s ‘goanna track to success’…

NEXT LEVEL PROTECTION for dogs

The most complete parasite protection, all in one tasty, monthly chew

C&T

Issue 321 | December 2025

Control & Therapy Series

PUBLISHER

Centre for Veterinary Education

Veterinary Science Conference Centre

Regimental Drive

The University of Sydney NSW 2006 + 61 2 9351 7979 cve.marketing@sydney.edu.au cve.edu.au

Print Post Approval No. 10005007

CVE Director

Associate Professor Kate Patterson kate.patterson@sydney.edu.au

EDITOR

Lis Churchward elisabeth.churchward@sydney.edu.au

VETERINARY EDITOR

Dr Richard Malik

VETERINARY SUB-EDITOR

Dr Jo Krockenberger joanne.krockenberger@sydney.edu.au

DESIGNER

Samin Mirgheshmi

ADVERTISING

Lis Churchward elisabeth.churchward@sydney.edu.au

To integrate your brand with C&T in print and digital and to discuss new business opportunities, please contact: MARKETING & SALES MANAGER

Ines Borovic ines.borovic@sydney.edu.au

DISCLAIMER

All content made available in the Control & Therapy (including articles and videos) may be used by readers (You or Your) for educational purposes only.

Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broadens our knowledge, changes in practice, treatment and drug therapy may become necessary or appropriate. You are advised to check the most current information provided (1) on procedures featured or (2) by the manufacturer of each product to be administered, to verify the recommended dose or formula, the method and duration of administration, and contraindications.

To the extent permitted by law You acknowledge and agree that:

I. Except for any non-excludable obligations, We give no warranty (express or implied) or guarantee that the content is current, or fit for any use whatsoever. All such information, services and materials are provided ‘as is’ and ‘as available’ without warranty of any kind.

II. All conditions, warranties, guarantees, rights, remedies, liabilities or other terms that may be implied or conferred by statute, custom or the general law that impose any liability or obligation on the University (We) in relation to the educational services We provide to You are expressly excluded; and

III. We have no liability to You or anyone else (including in negligence) for any type of loss, however incurred, in connection with Your use or reliance on the content, including (without limitation) loss of profits, loss of revenue, loss of goodwill, loss of customers, loss of or damage to reputation, loss of capital, downtime costs, loss under or in relation to any other contract, loss of data, loss of use of data or any direct, indirect, economic, special or consequential loss, harm, damage, cost or expense (including

PerSPective no. 167

Engage With Your Profession

The Control & Therapy Series was established in 1969 by Director Dr Tom Hungerford. His aim was to publish uncensored and unedited material contributed by vets writing about:

...not what he/she should have done, BUT WHAT HE/SHE DID, right or wrong, the full details, revealing the actual “blood and dung and guts” of real practice as it happened, when tired, at night, in the rain in the paddock, poor lighting, no other vet to help.

The C&T forum gives a ‘voice’ to the profession and everyone interested in animal welfare. You don’t have to be a CVE Member to contribute an article or reply to a 'What's YOUR Diagnosis?'. We welcome contributions from Vets, Techs, Nurses, allied professionals and anyone interested in animal welfare—Non CVE Members included.

Submit your C&T article

A template and information about uploading high resolution images for print can be found here cve.edu.au/submit-article

Questions?

Please contact cve.marketing@sydney.edu.au

Join In!

The C&T is not a peer-reviewed journal. Rather, it is a unique forum allowing veterinary professionals to share their cases and experiences with their colleagues. We are keen on publishing short, pithy, practical articles (a simple paragraph is fine) that our members/readers can immediately relate to and utilise. Our editors will assist with English and grammar if required.

I enjoy reading the C&T more than any other veterinary publication.

-Terry King, Veterinary Specialist Services, QLD

Thank You to All Contributors & Advertisers

The C&T Series thrives due to your generosity.

Major Winners

Prize: A CVE$500 voucher

—Moira van Dorsselaer page 3

—Christopher Simpson page 8

Winners

Prize: A CVE$300 voucher

Sandra Hodgins page 11

Madison Newton page 25

Q&A Best Answer

Prize: A CVE$300 voucher

Nurazlin Binti Che Mat ariffin page 35

Best Visuals

Prize: A CVE$300 voucher

Robert Johnson page 38

Centre for Veterinary Education Est. 1965

One of the great privileges of this role is seeing what happens when members of our community choose to step forward to share what they know. It’s not just information; it’s lived experience and practical wisdom that you can only learn from someone who has been there with their sleeves rolled up. Every contribution helps someone else take the next step with a little more clarity and confidence.

In that spirit, I want to acknowledge three remarkable colleagues: Drs Zoe Lenard (Diagnostic Imaging), Jane Yu (Feline Medicine) and Mark Newman (Surgery).

Next year they will be pursuing new opportunities and stepping back from teaching our Distance Education programs. Their impact is hard to capture in a sentence; they have taught with a generosity and depth that has helped to shape the practice and confidence of so many veterinarians in our community. They will be missed, and I thank them for their important contributions over the years with CVE.

I’m delighted to share some wonderful news. In our milestone 60th anniversary year, Dr Kim Kendall (longtime CVE member and contributor to C&T and with another article in this issue on P30) has made a generous gift that will fund a project dedicated to making C&T more accessible, searchable and properly archived. Thank you Kim – this is an incredible investment in preserving our shared knowledge and ensuring it remains useful for decades to come. This ambitious project will launch in 2026 and we are looking forward to sharing the progress with you.

This issue also features Dr Robert Johnson’s goanna article, a timely reminder of our founding Director Dr Tom Hungerford’s message: follow the goanna track to success. Robert’s piece captures exactly what that phrase has always meant; 'Veterinarians need to identify an area of interest and devote time to it, listening, learning, and building what he called a "tree of knowledge". Climbing that tree offered a unique vantage point from which other opportunities for growth and development could be identified.'

As we close out another year, I hope you can take pride in the progress made, the challenges met, and the learning shared. And as we look toward 2026, there is genuine excitement ahead.

Associate Professor Kate Patterson Director

Small animal

MAJOR Winner

The prize is a CVE$500 voucher

Herpesvirus Keratitis

Moira

van Dorsselaer BVSc

The Cat Clinic Hobart

150 New Town Rd

New Town TAS 7008

e. moira@catvethobart.com.au

t. +613 6227 8000

C&T No. 6097

Moira van Dorsselaer is the Principal Veterinarian and proud owner of The Cat Clinic Hobart, which she founded in 2013 to give cats the calm, purpose-built environment they deserve. After graduating from the University of Queensland in 1998, she worked as a small animal clinician before following her heart into a feline-only practice — the best career decision she’s ever made. Moira is unashamedly passionate about cats and the people who love them, and she enjoys the mix of complex medical cases, surgery, and everyday care that comes with this unique role. Outside the clinic, she’s happiest when spending time with her family, watching her daughter play field hockey, and loving life in Australia’s most liveable city. Cats may rule her workday, but they’ve also shaped her life.

Gizmo, an 800g kitten, was presented to our clinic by a local rescue with severe flea infestation, alopecia (suspected ringworm), scabbing, and diarrhoea. Fur samples were collected for fungal culture, and she was started on Pro-Kolin by the rescue.

Two weeks later, she returned with minimal weight gain (200g; BCS 3/9), poor appetite, and severe upper respiratory infection consistent with feline herpesvirus. She had been started on doxycycline paste by another clinic. Clinical signs included bilateral ocular discharge with lids adhered shut, marked chemosis, fullthickness positive fluorescein staining, and pyrexia. We recommended hospitalisation for IVFT, analgesia, and serum eye drops, but the rescue opted for outpatient care with doxycycline (10 mg/kg SID PO), famciclovir (90 mg/kg TID PO), and lubricating eye drops (chloropt) TID.

One week later, Gizmo re-presented in respiratory distress with severe bilateral ocular pathology, including chemosis, bulging conjunctiva, corneal clouding, and extensive fluorescein uptake. She was tachypnoeic, tachycardic, normothermic, and still BCS 3/9. She was admitted for supportive care, analgesia, and accurate administration of ophthalmic and systemic medications.

In-hospital treatment included:

i. Doxycycline (10 mg/kg SID PO)

ii. Famciclovir (90 mg/kg TID PO)

iii. Buprenorphine (0.015 mg SC BID)

iv. Meloxicam (0.05 mg/kg SID PO)

v. Ocular therapy every 2 hours: Hyloforte, chloropt, Systane

vi. Twice-daily steam therapy to relieve nasal congestion

vii. Cidofovir ophthalmic drops 1 drop/eye TID

She showed rapid clinical improvement, with increased appetite, comfort, and activity. Cidofovir ophthalmic drops were initiated upon arrival (1 drop/eye TID), alternated with Hyloforte and chloropt at night. Due to the rescue’s capacity limitations, Gizmo stayed with me for continuous care. She gained 400g in 4 days.

After two weeks, all medications were tapered and discontinued. At one month, she received her first vaccination and remained active, with improved ocular signs. Persistent corneal scarring and possible adhesions were noted, but she retained functional vision.

Over subsequent months, Gizmo was desexed, completed her vaccination course, and was adopted alongside her companion kitten, Slipper. She now lives comfortably with minor residual corneal opacities, near normal vision and no ongoing ocular concerns.

Reflections and Lessons Learned:

– Persistence pays off: With appropriate medications and supportive care, even severely affected kittens can recover remarkably.

– Analgesia is critical: Pain management transformed Gizmo’s demeanour and initiated her clinical improvement. See video.

– Cidofovir is invaluable: Treat early and often; I feel antiviral ocular therapy was key to preserving her vision.

– Multimodal therapy matters: Combining doxycycline, famciclovir, and cidofovir was essential in managing infection and preventing enucleation.

Special thanks to Dr Richard Malik for his guidance and encouragement throughout Gizmo’s care and ensuring I did not give up.

Video: Gizmo 24 hours after hospitalization and pain relief etc started—you can see despite how horrible her eyes look she is so happy cve.edu.au/gizmo

Figures 1 A,B & C. Eyes on presentation

2. Cidofovir 0.5% eye drops

3. Gizmo March 2024

4. Gizmo May 2024

EDITOR’S NOTES

1. I think starting early is critical—vets who see shelter cases should always have a bottle in the fridge— YOU CANNOT AFFORD THE 3 days wait to have it delivered.

2. BOVA make 0.5% Cidofovir. At time of writing the price is $102.

3. The dose of Famvir listed in Plumbs is 40-90mg/ kg per os every 8-12 hours; however, I never give more than 40 mg/kg BID or TID. The Davis group recommend 90 mg/kg BID to get decent levels in tears, but the levels are never all that good—even at that dose, it’s expensive and the tablets are BIG and not that easy to give.

4. The Famvir treats the whole cat including the respiratory system—and blood levels of 40 mg/ kg are not that different to 90 mg/kg because the cat's liver has a ceiling rate of conversion of famciclovir to the active drug penciclovir.

5. Cidofovir is a STRONGER antiviral, but it’s too toxic to give systemically; however, it works a treat TOPICALLY.

6. Doxycycline has benefits in relation to healing, and adding eye drops with hyaluronic acid is helpful as herpes wipes out the Goblet cells in the conjunctiva.

BOTTOM LINE

When severe ocular herpetic disease is present—it’s more cost effective to give Famvir at 40 mg/kg BID to TID and cidofovir eye drops BID, than giving massive doses of famciclovir systemically to get decent levels in tears.

Patient care is important from the moment they come

into the clinic to the time they leave. When drawing up a medication, we check the drug, double check the dose and label the syringe with the appropriate sticker to indicate who the drug is for and what is in the syringe.

So why would we not want the same safety check with our infusion lines?

Enhancing Safety and Efficiency in Veterinary Infusion Therapy: Introducing Colour-Coded Minimum Volume Tubes

Our patients rely on us to give them the best care possible. They, and their owners, trust that what we use to deliver their treatments will not cause them any harm. In the fast-paced environment of veterinary hospitals, clarity and precision in drug administration are essential—not just for outcomes, but for peace of mind. The introduction of colour-coded minimum volume IV tubing marks a meaningful step forward in infusion therapy—designed to support clinicians in delivering safe, efficient, and error-reduced care.

Veterinary teams often manage multiple high-potency drugs simultaneously. Colour-coded tubing enables clear drug assignment and rapid identification at a glance, helping reduce the risk of medication errors and enhancing workflow efficiency during critical procedures.

In addition to offering three vibrant colours (BLUE MAGENTA, and GREEN), Perfusor™ tubing retains these vital, yet sometimes overlooked characteristics:

1. Low priming volume (≤1.27 mLs) minimizes drug waste and ensures rapid therapy initiation.

2. Pressure resistance up to 2 bar supports reliable performance with syringe drivers, even in demanding clinical scenarios.

3. Luer-Lock fittings ensure secure connections across all standard syringe driver systems.

Safe Materials for Sensitive Patients

Made from polyethylene (PE), the Perfusor™ Line is free from PVC, DEHP, and latex, making it a safer choice for sensitive animal patients. Its low sorbing properties and kink-resistant design further support consistent drug delivery—because every patient deserves the best we can offer.

Optimized for Veterinary Workflow

Available in two lengths (150 cm and 200 cm), the Perfusor™ Line adapts to varied clinical setups. Whether managing anaesthesia, critical care, or post-operative recovery, veterinary professionals can rely on its excellent start-up characteristics and minimal residual volume to maintain therapeutic precision.

What Materials Are Your Current Infusion Lines Made From?

DEHP-Free Infusion Therapy: A Safer Standard for Veterinary Hospitals

In veterinary medicine, where precision and patient safety are paramount, the materials used in infusion therapy can have a profound impact—especially in high-risk procedures involving neonates, critical care, and long-duration infusions. One such material under global scrutiny is DEHP (Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate), a plasticiser commonly used in PVC-based medical devices.

Why DEHP-Free Matters

DEHP has been classified by the European Union as a Substance of Very High Concern, specifically toxic to reproduction. Studies have shown that DEHP can leach from PVC tubing during medical procedures, potentially affecting the testes, liver, and kidneys in animal models, and is suspected to impair fertility in humans—particularly in critically ill male neonates, unborn children of pregnant women, and nursing infants exposed to high levels of DEHP. [DEHP-Free A4]

Global health authorities have responded decisively:

– EU: Banned DEHP in toys and baby articles since 2007; mandatory labelling for medical devices since 2010. [DEHP-Free A4]

USA (FDA): Issued public health notifications and precautionary guidelines to reduce DEHP exposure. [DEHPFree A4]

– Australia: Declared products with >1% DEHP unsafe for children; DEHP in medical devices can reach up to 40%. [DEHP-Free A4]

– Canada: Requires manufacturers to disclose DEHP content exceeding 0.1%. [DEHP-Free A4]

B. Braun’s Commitment to Safety

Although not mandated in Australia, B. Braun has proactively converted its entire infusion therapy portfolio to DEHP-free materials—with no change in part numbers or pricing. This reflects a deep commitment to patient safety, environmental responsibility, and the professionals who care for animals every day. [DEHP-Free A4]

References:

1. EU directive 67/548/EEC

2. Directive 93/42/EEC and its amendment 2007/47/EG

3. FDA Public Health Notification 12/07/2002

4. The Commonwealth of Australia Consumer protection Notice No. 11 of 2011

5. NICNAS - Existing chemicals information sheet 01-2010

6. Health Canada notice 08-111801-312, May 2008

7. Safety Assessment of DEHP, released from PVC Medical Devices FDA, 2001

8. SCENIHR - “Opinion on the safety of medical devices containing DEHP-plasticised PVC or other plasticisers on neonates and other groups possibly at risk”, Feb 2008

9. Umwelt bundesamt (Germany) “Phthalates - Useful plasticisers with undesired properties”, Feb 2007

10. K. Ruzidckova, M. Cobbing, M. Rossi, T. Belazzi, “Preventing Harm from Phthalates, Avoiding PVC in Hospitals”, Health Care without Harm, June 2004

MAJOR Winner

The prize is a CVE$500 voucher

Colonic FIP in a Cat

Christopher Simpson BVSc MANZCVSc

Victoria Veterinary Clinics

Hong Kong

e. simpson_christo@icloud.com

C&T No. 6098

Dr Christopher Simpson is a graduate of The University of Melbourne, but has practiced in Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra, the US, the UK, and even the South Pacific island of Vanuatu! Since 2015, however, he has found his spiritual home in Hong Kong, where he is attracted to the thrilling pace of life, Cantonese food, language, trail-running, and of course the fascinating caseload that only tropical Asia can offer! He is a member of the Australian & New Zealand College of Veterinary Scientists, has completed a Residency in Small Animal Internal Medicine at Melbourne University, and contributed scientific papers to the Australian Veterinary Journal, the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, and several veterinary textbook chapters. He is also a regular contributor to the Control & Therapy series and enjoys sharing the rich and varied experiences of practicing in Hong Kong.

Cha Cha is a 9-month-old male neutered Domestic Shorthair cat. He was initially seen by another clinic for straining to defecate and blood in the stool. He was otherwise very bright, active, eating well and in good body condition.

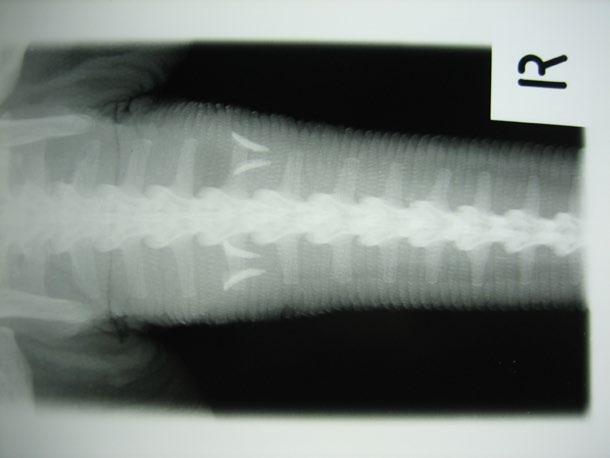

An ultrasound at the other clinic identified marked thickening of the descending colon.

The owners were advised that this was most likely to be neoplastic and were advised to undertake a subtotal colectomy.

The owners came to us for a second opinion. Our ultrasound confirmed the findings of the previous clinic. There was a marked focal thickening of the descending colon:

Figure 2. Ultrasound image of the caudal abdomen showing marked thickening (10.9 mm) of the descending colon

Although neoplasia was indeed considered in the differential diagnosis, a recent publication (Müller et al JFMS 2023—Abdominal ultrasonographic findings of cats with feline infectious peritonitis—an update) had also indicated that this was amongst the increasingly varied recognised presentations for FIP. Indeed, historically it was referred to as ‘focal FIP’.

We considered the lesion to be accessible to colonoscopic biopsy, and so this was conducted, in an attempt to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

The lesion was readily accessible to endoscopic biopsy but unfortunately the results were inconclusive. Lymphoma was considered unlikely, and there was no indication of any other neoplasia.

Several years ago, we would have recommended exploratory laparotomy at this point.

Without a definitive diagnosis, and with FIP still considered a fatal disease, excision biopsy would have been the most appropriate clinical recommendation.

However, over the last few years, the treatment of FIP has been revolutionised by highly effective antiviral medications with excellent safety profiles. After a difficult period in which these medications were only available from the black market and of dubious quality, these drugs have now become safe and readily available in most jurisdictions.

We discussed with Cha Cha’s owner the option of a therapeutic trial with the antiviral nucleoside analogue GS-441524, now known affectionately all over Hong Kong simply as ‘四四一’ (Cantonese for ‘four four one’). Keen to avoid invasive surgery at all costs, the owners readily consented.

The results were nothing less than stunning.

After weeks of relentlessly worsening dyschezia, Cha Cha’s symptoms disappeared within 2 days.

A repeat ultrasound after 10 days of treatment indicated early evidence of a reduction of the colonic lesion.

The treatment was extended.

Treatment protocols for FIP have been rapidly refined in a short space of time due to the sudden widespread availability of effective antivirals, such as GS-441524.

After an initial recommendation for 84 days of treatment, a recent study showed 42 days to be equally effective (Zuzzi-Krebitz et al Viruses 2024—Short Treatment of 42 Days with Oral GS-441524). Worthy of note is the fact that cases in this study were predominantly ‘wet’, and there is some evidence to suggest that longer courses may still be required for successful and definitive treatment of other forms (e.g. ‘dry’, focal, CNS, and/or ocular disease).

We planned to provide 42 days of treatment and serially assess the lesion by ultrasound to determine the effect of the treatment.

There were no side effects from the medications at any time.

Here are the sequential images:

At the time of writing, 1 month after completion of a 42 day course of medication, Cha Cha is asymptomatic, with no clinical, clinical pathological, or sonographically detectable signs of disease. This response is very difficult to attribute to anything other than highly effective treatment of focal, colonic ‘dry’ FIP with GS-441524.

We have set up a schedule of serial repeat scans in the event that there is disease recurrence, and further treatment is required. We tentatively intend to re-scan at 1 month, 3 months, and then 6 months, or sooner at any time if clinical signs recur.

Despite inconclusive histopathology, we elected to use ‘441’ in this case due to accumulating evidence that this is a highly safe and effective medication, to the point that a therapeutic trial with the drug represents an absolutely

valid diagnostic test in itself, especially when other available options are expensive, invasive, or hazardous.

We submit that the landscape for managing FIP has undergone almost unrecognisable change in the last short few years, and as a profession, we should adjust our approaches accordingly…

Certainly in Hong Kong at least, the word on the street is that ‘四四一’ is close to a magical drug…

Perhaps we should allow ourselves to enjoy the remarkable power we have been given to treat this once brutal and incurable disease.

Have You Seen Any Cases Like This?

Melissa Barbuto

Tropical Queensland Cat Clinic e. info@tqcatclinic.com

C&T No.6099

I own a feline-only clinic in North QLD Australia and we run a foster kitten program. We have seen a number of orphan kittens aged between 3-5 weeks (around weaning) demonstrating acute onset (minutes to 2 hours) neurological symptoms not consistent with fading kitten syndrome.

Read here for more information and description of the cases cve.edu.au/any-cases-like-this

We would love to hear from any other vets who have seen similar cases.

Please email me at info@tqcatclinic.com and copy in cve.marketing@sydney.edu.au so that we can share your case with C&T readers.

Filgrastim in Feline Panleukopenia

A Case Series from General Practice

Sandra Hodgins

Summer Hill Village Vet (NSW)

29 Grosvenor Crescent

Summer Hill NSW 2130

e. contact@summerhillvillagevet.com

t. (02) 9797 2555

C&T No. 6100

Panleukopenia in rescue kittens remains one of the most heartbreaking presentations we see in general practice. The disease can devastate entire litters, and while we often do our best with fluids, antibiotics, antiemetics, and nursing care, survival is far from guaranteed— particularly in the underweight, under-vaccinated kittens that typically arrive via rescue.

This case series describes the use of filgrastim—a recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), a drug discovered in Australia by Don Metcalf at the Walter and Elisa Hall Institute—in three littermates with confirmed feline panleukopenia, treated in general practice with limited diagnostic resources but a high level of commitment from a rescue group. It’s not a magic bullet, but in this instance, it may have tipped the scales.

Case Summary

Three 14-week-old kittens arrived at Maggie’s Rescue care on 4 May 2025, with no known vaccination or parasite history. They were wormed and given an inactivated F3 vaccine on arrival by the cat co-ordinator. One kitten—’Professor Fuzzball’—presented to us within 24 hours with vomiting, diarrhoea, pale mucous membranes, and hypothermia. His body weight was 1.3 kg. A SNAP Parvo test was strongly positive, but given the recent vaccination, we also proceeded with a complete blood count (CBC) which revealed profound panleukopenia. See all the kittens CBC results here cve.edu.au/kittens-cbcs

Based on clinical presentation, the positive test, and his likely exposure during the impounding process, we diagnosed feline panleukopenia virus (FPV). Having previously used filgrastim in a dog with chemotherapyinduced neutropenia (accidental CCNU overdose), and with a recent Romanian paper [ Animals. 2024;14(24)] citing its successful use in FPV-infected cats (6 µg/kg SC for three days), we elected to treat.

Treatment Protocol

All three kittens were treated with:

– Filgrastim: 6 µg/kg SC SID

– IV fluids: 2 mL/kg/hr

– Piperacillin–tazobactam: 50 mg/kg IV BID

– Maropitant: 1 mg/kg IV SID

Vomiting in the two littermates (‘Zoomie’ and ‘Turbo’) was more severe. They also received:

– Ondansetron: 1 mg/kg IV BID

– Buprenorphine: 0.01 mg/kg IV TID

Zoomies developed worsening diarrhoea but improved rapidly on oral metronidazole (10 mg/kg BID). Turbo—just 0.9 kg—also required metronidazole after Day 6 due to persistent soft stools and perineal dermatitis.

Turbo’s recovery was complicated by persistent ataxia, possibly due to cerebellar hypoplasia or post-viral cerebellitis. A video consult with Prof. Richard Malik suggested the likely FPV-associated neuropathy was due to destruction of granule cells in the cerebellum. Turbo remains otherwise well and will be rehomed as a special needs kitten.

Outcome & Reflections

All three kittens survived and were recently desexed and are ready to be rehomed.

We were fortunate to have filgrastim on hand and a rescue willing to fund its use. As a GP vet working with rescue groups who work hard for every dollar they fundraise, I can’t always justify the use of PCR panels or referral, but clinical judgment, patient history, and a good CBC can still guide us to effective interventions.

A question I have for the cat specialists: Would earlier CBCs on the asymptomatic littermates and pre-emptive filgrastim have changed their course? We might need more data on that.

For now, this experience has given me one more tool to consider in treating a disease that too often ends in despair. The cost for treatment of each kitten with filgrastim in this case was approximately $25 and, if access can be managed, it may be a worthwhile adjunct for rescue kittens with confirmed or high-risk panleukopenia—especially when the will to try is there.

Editor’s Note

Filgrastim (a recombinant human granulocyte colonystimulating factor, (G-CSF) shows promising efficacy in treating parvoviral infections in both kittens and puppies, particularly for managing severe leukopenia/ neutropenia.

Below is a synthesis of evidence from peer-reviewed studies:

Use in Kittens with Feline Panleukopenia Virus (FPV)

Dosage and Protocol

Administered subcutaneously at 5–6 µg/kg for 3 consecutive days, with hematological evaluation on day 5.1 2

A break day (Day 4) is typically included before reassessment.1 2

Efficacy

100% survival rate observed in a study of 22 FPV-infected cats treated with Zarzio® (filgrastim).1 2

Significant improvement in WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes (p < 0.01).1 2 3

Leukocytosis noted in 31.8% of cats, resolving without intervention.1 2

Side Effects

Transient reduction in RBC, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelets (p < 0.01).1 2

No long-term adverse effects reported.1 3

Use in Puppies with Canine Parvoviral Enteritis (CPE)

Dosage and Protocol

10 µg/kg subcutaneously for 3 days alongside standard supportive care (fluids, antibiotics).4

Efficacy

84.2% recovery rate (16/19 dogs) vs. lower rates in standard treatment alone.4

Significant increase in WBC, neutrophils, and lymphocytes by day 5 ( p < 0.001).4

Faster resolution of fever and clinical symptoms.4

Mechanism

Counters virally induced bone marrow suppression, accelerating neutrophil recovery.4

Key Considerations

– Off-Label Use: Filgrastim is not FDA-approved for veterinary use but is clinically adopted.1 ,3,4

– Timing: Early intervention is critical; administer at diagnosis of severe leukopenia. 1 3,4

– Species-Specific Responses: Cats show higher survival rates than dogs in current studies, possibly due to protocol differences or disease progression. 1,3

Filgrastim is a promising adjunct therapy for parvoviral infections, significantly improving survival and hematological recovery in both species when combined with standard supportive care. Further large-scale trials could optimize dosing and long-term safety.

References

1. Dascalu MA, Daraban Bocaneti F, Soreanu O, Tutu P, Cozma A, Morosan S, Tanase O. Filgrastim Efficiency in Cats Naturally Infected with Feline Panleukopenia Virus. Animals (Basel). 2024 Dec 11;14(24):3582. doi: 10.3390/ani14243582. PMID: 39765486; PMCID: PMC11672453.

2. Loya, K., Muhee, A., & Hussain, S. A. (2025). Effects of filgrastim on severe leucopenia associated with feline panleucopenia in cats Applied Veterinary Research , 3(2), 2024009. doi.org/10.31893/ avr.2024009

3. Ekinci, G., Tüfekçi, E., Abozaid, A.M.A., Kökkaya, S., Sayar, E., Onmaz, A.C., Çitil, M., Güneş, V., Gençay Göksu, A. and Keleş, İ., 2024. Efficacy of filgrastim in canine parvoviral enteritis accompanied by severe leukopenia. Kafkas Üniversitesi Veteriner Fakültesi Dergisi 30(4), pp.433-443. DOI: 10.9775/kvfd.2023.31456.

4. Punia, S., Kumar, T., Agnihotri, D., and Sharma, M. (2021). A study on effect of filgrastim in severe leucopenia associated with hemorrhagic gastroenteritis in dogs. The Pharma Innovation Journal , SP-10(11), pp.868-870. Available at: thepharmajournal.com [Accessed 15 Oct. 2021].

AIM, NSAID Nephrotoxicity & Genetic Susceptibility in Cats

—A hypothesis that can be readily tested! Matthew Wun, Andrea Harvey & Richard Malik

e. m.wun@hotmail.com

e. richard.malik@sydney.edu.au

e. andrea.harvey@sydney.edu.au

C&T No.6101

What is AIM?

AIM stands for Apoptosis Inhibitor of Macrophage (also known as CD5L). It is a circulating glycoprotein produced mainly by tissue macrophages. Under normal physiological conditions, AIM binds to the IgM pentamer in serum, which stabilizes the glycoprotein and prevents its rapid renal clearance. During acute kidney injury (AKI) in most mammals, AIM dissociates from IgM, appears in the urine, and plays a critical role in renal repair.

Normal Physiology of AIM

In health, AIM contributes to homeostasis by supporting macrophage survival and regulating lipid metabolism. In the context of kidney injury, AIM is particularly important. When tubular epithelial cells undergo necrosis, intraluminal debris accumulates within the nephron. AIM facilitates the clearance of this debris by enhancing macrophage activity and promoting its excretion via the urine. This process prevents tubular obstruction, supports tubular regeneration, and helps limit the transition from AKI to chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Species Differences: Cats vs Humans

Cats are unusually susceptible to chronic kidney disease, and AIM biology might provide a possible explanation. In humans and most other mammals, AIM has relatively low affinity for IgM, allowing it to dissociate efficiently during AKI and reach the renal tubules. In cats, however, AIM binds IgM with much higher affinity, preventing its release into the urine. As a result, cats cannot clear tubular debris as efficiently, leaving them predisposed to ongoing nephron loss and progression to CKD after renal insults.

The fAIM Exon 3 Variant

Recent work from Washington State University (WSU) (Evangelista, Court, Mealey, Villarino et al., 2025) has demonstrated that many cats carry duplication(s) of exon

Renal Hypoperfusion + Tubular Epithelial Injury

Wild-type AIM (2 copies exon 3)

AIM released from IgM Debris cleared from tubules

Tubular Patency Restored Renal Function Recovers

3 in the feline AIM (fAIM) gene. This leads to production of a 4-domain AIM protein. Cats with 4 copies of exon 3 were shown to have significantly higher odds of CKD progression compared to cats with only 2 copies. This suggests that the exon 3 duplication further compromises AIM function and debris clearance.

NSAID Nephrotoxicity in Cats

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as meloxicam, are widely used analgesics. In cats, however, high doses (0.1-0.3mg/kg SCI) or repeated administration have been associated with AKI (The association between injectable non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acute kidney injury in dogs and cats, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia (https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S1467298725002223). The conventional explanation has been that prostaglandin inhibition when combined with hypotension (e.g. due to low cardiac output under anaesthesia or dehydration) results in reduced renal perfusion (failure of autoregulation). Yet not all cats are equally affected, not all cases have been associated with anesthesia or clinically apparent dehydration, and some develop catastrophic AKI while others are unaffected or get mild reversible AKI and readily recover.

Linking AIM Genetics and NSAID Susceptibility

The new understanding of fAIM variants provides a potential unifying explanation for this variability. Cats with wild-type AIM (2 copies of exon 3) may experience transient renal ischemia in association with NSAID use but can readily release AIM into the tubules to clear debris and recover renal function. In contrast, cats with exon 3 duplications (3 or 4 copies) have defective AIM activity: so, in theory, if they are exposed to NSAID-induced ischemia, they may not efficiently clear necrotic tubular debris, leading to persistent obstruction, nephron loss, and progression from AKI, leading to CKD.

Clinical and Research Implications

AIM remains bound to IgM Debris not cleared

Persistent Tubular Obstruction Progression to AKI CKD

framework for understanding why some cats develop AKI after receiving meloxicam, while most cats do not.

If you have had a cat with reversible or irreversible acute kidney injury after meloxicam or another NSAID—please write to one of the authors by e-mail so we can arrange a blood specimen or cheek swab from affected cats in order to conduct genomic testing.

We propose collecting blood samples or cheek swabs from cats with documented episodes of AKI associated in time with meloxicam administration. While our primary focus is on AKI following injectable meloxicam, cases occurring after other injectable NSAIDs (e.g. robenacoxib) and oral therapy would also be highly relevant.

Once an adequate cohort is assembled, these samples could be batch-tested at WSU for the fAIM exon 3 variant. Approximately 20% of the general cat population in the Pacific Northwest of the USA is homozygous for this variant in the WSU DNA bank.

If a substantially higher proportion is identified among a cohort of cats with NSAID-associated AKI, this would provide strong support for our hypothesis. We would then get a random population of 100 cats from Australia to see what the prevalence of the variant was in the Australian feline population.

If our hypothesis proves to be the case, it could become prudent for veterinarians to determine a cat’s AIM genotype before procedures where high doses of meloxicam are planned as part of postoperative analgesia, or for ongoing management of osteoarthritis.

Conclusion

AIM biology provides a powerful lens to understand why cats are uniquely vulnerable to CKD and NSAID nephrotoxicity. The discovery of exon 3 duplication variants might provide a cogent explanation as to why some cats are particularly prone to irreversible AKI following meloxicam exposure. These insights open the door to genetic risk stratification, more judicious use of NSAIDs, and potentially transformative new therapeutics based on recombinant AIM or AIM modulators. Such work is ongoing in Japan. NSAID Exposure (High-dose meloxicam)

This combined model—NSAID administration as the environmental trigger and AIM genetic status as the determinant of recovery—provides a compelling

The Mind of a Surgeon: Beyond the Scalpel

Bronwyn Fullagar & Chris Tan

CVE Surgery Distance Education Tutors

Follow on IG @drbronfullagar

C&T No. 6102

When most people picture a great surgeon, the image is of steady hands, perfect sutures and a complicationfree caseload. Technical skill matters, of course. But after years in theatre, we’ve learned that the scalpel is only part of the story.

What really defines a good surgeon is mindset: the way we approach uncertainty, complications, and the very human side of operating.

As neurosurgeon Henry Marsh once wrote: ‘Operating is the easy part. The hard part is the decision-making.’

The growth mindset: ‘I can’t do it… yet’

Surgery isn’t about being born with gifted hands. It’s about recognising that skill evolves with time and practice. Students often say, ‘I’ll never be a surgeon—I’m terrible with my hands.’ The truth is, everyone starts that way; driving a car feels impossible at first too, yet with practice, nearly everyone can do it.

The difference lies in how you frame the learning curve. A growth mindset turns ‘I can’t do this’ into ‘I can’t do this yet.’ That shift gives permission to make mistakes, reflect, and constantly improve.

This mindset doesn’t just shape careers—it protects mental health. Early on, many surgeons are devastated when things don’t go perfectly and a complication can feel like personal failure. With experience, we learn to care just as much about outcomes, but to ruminate less. Reflection becomes constructive: What could I have done differently? rather than, I’m not cut out for this

Are surgeons born or made?

Ask around, and you’ll hear the stereotype of the surgeon as confident, arrogant, maybe even a little ruthless. Historically, those personalities often thrived but outcomes tell a different story. The ‘cowboy’ surgeon, willing to try anything and operating completely independently, generally produces worse results than the thoughtful, reflective surgeon who works within a team.

Modern surgery is moving towards the pilot-in-a-cockpit model: confident enough to take control, but humble enough to listen to their crew. Decision-making improves when the whole team feels empowered to speak up.

That’s why surgery isn’t reserved for a narrow personality type. The real requirements are enjoying incremental improvement, being comfortable with learning in public, and holding yourself accountable to the highest standard—even when no one else is watching.

Complications, confidence, and perspective

Every surgeon remembers the sting of early complications. For some, it’s enough to avoid surgery altogether—the mental burden outweighs the enjoyment. But confidence grows when you’ve built enough skill to know that a complication doesn’t mean you’re incompetent. As we progress through our surgery careers, we become better at avoiding complications in straightforward cases, and better at managing the inevitable complications that come with taking on more advanced or unusual procedures.

Surgeons also learn to strike a balance between selfcriticism and self-compassion. We want to hold high standards—there’s always something to improve—but endless rumination isn’t helpful. The sweet spot is reflection and introspection that feeds growth without paralysing us for the next case. One helpful strategy used by professional athletes is to focus on ‘winning the next point’. When faced with an acute moment of stress or an unexpected complication during a day of surgery, being able to recover quickly and focus fully on the next step of the procedure (or the next case of the day) is a key skill to ensure we stay present in the moment. Later, it can be helpful to debrief the case with a trusted coach or mentor, when there is time to reflect on opportunities for improvement.

The art of ‘chunking’

One of the most useful mental strategies for tackling difficult or unfamiliar cases is ‘chunking.’ Rather than seeing a daunting procedure as one giant hurdle, break it down into familiar steps.

Take a splenectomy. If you can open and close an abdomen, ligate vessels, and maintain sterility, the only

new step is the specific anatomy of the spleen. Suddenly it’s not a terrifying new frontier, but a set of skills you’ve already practised with one or two new crux points.

This approach works at every level. Recently, one of us tackled a case where a six-month-old puppy had swallowed a stick that lodged in its stomach, burrowed up through the oesophagus, pierced a lung lobe, and ended up sitting beside the aorta. At first glance, it was overwhelming, but broken into chunks—gastrotomy, lung lobectomy, thoracic exploration—it became a sequence of known procedures with only a couple of truly ‘unknown’ moments to manage.

The skill of breaking a new or challenging procedure into more manageable, familiar steps helps experienced surgeons to walk into new territory without panicking.

Speed versus efficiency

New surgeons often equate speed with competence. Practices sometimes reinforce that view, measuring surgical proficiency by time taken to complete a procedure, or number of procedures completed in a given day. In reality, surgeons who have achieved mastery are efficient and effortless, not ‘fast’. Every movement is purposeful. Every instrument is the right one. They don’t flap, backtrack, or redo steps.

‘Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.’

True mastery comes from thousands of hours of deliberate practice and there are few shortcuts. To become efficient over time, first practice the fundamentals: thorough preoperatively planning, gentle tissue handling, precise instrument selection, and avoiding wasted motion.

Feedback from an experienced surgical coach can help new surgeons to identify opportunities to improve efficiency. Speed will come naturally with experience. If speed is the primary focus too early, technical skills will plateau and surgical outcomes will be suboptimal.

Fundamentals and equipment

Great surgeons don’t neglect the basics. Instrument and tissue handling, preservation of anatomy and precise surgical planning directly affect patient outcomes.

Equipment matters. Too many vets fight their way through surgery with blunt scissors, worn-out needle drivers, or drapes the size of a tea towel. Small drapes limit movement and compromise sterility. Cheap instruments force clumsy tissue handling. The difference in cost between poor and good quality instruments is minor compared to the cost of inefficiency, tissue damage, and surgeon stress.

Create a clear visual field: position the patient on the surgical table to allow the best visualisation, clip wide, drape wide, set the table to a comfortable height, and ensure adequate lighting. This isn’t ‘demanding behaviour’—it’s about making surgery more efficient and safer for patients, and more enjoyable for the surgeon and team.

Checklists and culture

– One of the simplest but most powerful tools in surgery is the surgical safety checklist. The WHO surgical safety checklist has saved countless lives in human medicine, and veterinary adaptations are just as valuable. Cray et al (Vet Surg, 2018) found that using a checklist in a veterinary teaching hospital significantly reduced total perioperative and postoperative complications from 40.9% to 29.3%.

– An effective surgical safety checklist helps to improve patient safety by preventing medical errors that are clearly identifiable, preventable and serious in their consequences—for example, operating on the wrong limb, or unintentionally leaving a surgical gauze inside a patient.

– Checklists foster a culture of teamwork and communication and a shift towards shared accountability for ensuring patient safety. Importantly, checklists need ‘stop points’, where the team member in charge of the checklist—usually a nurse—feels empowered to pause proceedings at key steps to ensure that the list is completed. Introducing checklists isn’t always smooth. Some clinics resist them as ‘extra paperwork’ or a time-waster. The truth is, they save time by preventing errors and inefficiencies.

They also send a clear message: we’re all human, and we are all responsible for each patient’s safety.

Mentorship and culture shift

Surgeons and surgical training are undergoing a gradual cultural shift. Along with a shift towards more diversity in surgeon demographics and backgrounds, there is now an increased awareness of the importance of mental health, resilience and emotional regulation. Modern surgical training values introspection, constructive feedback and emotional as well as technical debriefs following each case. Younger surgeons and students are pushing for supportive mentorship, open conversations about complications, and kinder workplaces.

The goal is a safe space where surgeons can say, ‘This didn’t go well—what could I have done differently?’ without fear of judgment.

That cultural shift matters. Surgery is stressful enough without adding unnecessary shame or competition. If we can normalise debriefing, support, and shared reflection, we’ll not only produce better surgeons—we’ll keep them in the profession longer.

Take-home message

Being a great surgeon involves more than just advanced technical skills. A growth mindset, seeking constructive feedback, working efficiently with a team, and a commitment to lifelong learning are just as important to the development of true expertise.

The knot tying is just the beginning.

Surgery Distance Education now includes free access to A Cut Above podcast

Mastering surgery takes time, repetition, and reflection — both in and out of the theatre.

In 2026, participants in the CVE Surgery Distance Education course (cve.edu.au/surgery) will all receive free access to A Cut Above, a podcast from Dr Hubert Hiemstra and The Vet Vault team featuring A/Prof Chris Tan, Drs Bronwyn Fullagar, Mark Newman, and Justin Ward, bringing perspectives from specialists, examiners, and successful Membership candidates.

The podcast episodes have been carefully integrated to complement the learning in every Surgery DE module, helping you strengthen key concepts, reinforce understanding, and apply knowledge with confidence.

Designed for veterinarians preparing for Surgery Membership examinations, residents, and anyone eager to take their surgical skills to the next level, A Cut Above offers rich, conversational insights into the why behind surgical principles—not just the how.

Not “Naughty”, Not “Normal” Behaviour Conference + Masterclass

9 - 13 February 2026 | Early Bird rate expires 31 Dec 2025

This dynamic 5-day program covers a range of important topics that integrate behaviour as a multidisciplinary and holistic discipline.

cve.edu.au/a-cut-above

International keynote speakers Gonçalo da Graça Pereira (Portugal) and Shana Gilbert-Gregory (USA) are supported by an impressive line-up of local experts: Rachel Basa, Gabby Carter, Isabelle Resch, Jacqui Ley, Sally Nixon, Kersti Seksel, Rich Seymour & Bronwen Bollaert.

CVE Members enrol at discounted rates

Combine your members savings: Professional 20%, Part-Time Professional, Recent Graduates & Nurses 40% with the EB rate. Better in your wallet!

cve.edu.au/behaviour

Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (NCL)

Elliot Wynne 5th year vet student Harper & Keele Veterinary School United Kingdom

e. x4p20@students.hkvets.ac.uk

C&T No. 6103

Meet the Patients

Sometimes, a case just doesn’t sit right.

When Storm and Talon, two 9-month-old littermates, both of whom were rescued as kittens, presented to practice with bizarre neurological signs including marked ataxia, intermittent seizures, tremors, ‘rearing up like meerkats’ and falling over backwards, their vet knew something was seriously amiss. Symptoms began in the siblings a mere two days apart and were progressive, prompting their owners to get them checked out.

Neurological cases presenting to practice can be challenging at the best of times for clinicians to work up; add in a set of odd presenting signs and the sibling relation, and this case proved a diagnostic challenge for all involved.

Diagnostic Workup & Differentials

History taking from the owners revealed the cats to be ‘fit and healthy’ prior to the onset of symptoms. When probed about access to potential environmental toxins this seemed unlikely. Routine haematology and biochemistry panels came back unremarkable, and the cats remained afebrile, muddying the picture further!

Given the progressive nature of the condition and lack of systemic abnormalities, an initial differential diagnoses list consisted of:

– Metabolic disorders (e.g. thiamine deficiency, hepatic encephalopathy)

– Structural abnormalities (e.g. cerebellar hypoplasia, hydrocephalus)

– Infection (e.g. toxoplasmosis, FIP, viral encephalitis)

– Toxicity (e.g. heavy metals)

– Neurodegenerative/Storage Diseases

It was at this point that the attending vet opted to trial treatment for a few of the treatable common differential diagnoses.

– Thiamine supplementation—no response

– Clindamycin for potential toxoplasmosis—no response

– Keppra (levetiracetam) for a primary seizure disorder— minimal response

Biochemistry including fasting ammonia and pre-prandial bile acids, serology (FeLV, FIV, feline coronavirus, toxoplasma), CSF analysis and MRI may be helpful to narrow differentials in similar cases.

However, with progressive neurological decline in the cats and no clear diagnosis, it was at this stage decided that euthanasia was the kindest option.

Post-Mortem Findings

Samples of both cats’ brains were submitted to Finns Pathologists with the hopes of finding a cause for the cats’ condition.

No gross changes were visible on initial assessment, and it was only at a histological level that clues started to show.

Throughout the brain, particularly the cerebellum and hippocampus, neurones were found to be filled with deeply eosinophilic-glassy material that formed circular bodies within the cytoplasm (Figure 2) Purkinje cell loss and white matter degeneration throughout the cerebellum was also noted.

It was at this stage that the pathologists began to strongly suspect some form of storage disease. Storage diseases are a group of inherited metabolic disorders, with the central idea being that affected animals are deficient in certain enzymes (often the result of a genetic mutation) leading to accumulation of metabolic products within cells of the body. The predominant two types of storage disease in animals can be split into lysosomal storage diseases and glycogen storage diseases, the associated conditions of which are detailed in Figure 3. Given the wide variety of these diseases documented in veterinary medicine, further testing was required to identify the specific type seen in Storm and Talon’s case.

Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis

Lipopigments (lipofuscin, ceroid) Dogs, cats, sheep, cattle, exotic spp.

Progressive neurological decline, seizures, blindness

GM1 Gangliosidosis GM1 Ganglioside Dogs, cats, sheep, cattle Progressive neurological decline, ataxia, dysmetria

GM2 Gangliosidosis

Fucosidosis

Mucopolysaccharidoses (I-VII)

GM2 Ganglioside Dogs, cats, pigs, exotic spp.

Fucose containing substances Dogs & cats

Mannosidosis Oligosaccharides

cats, cattle, goats

Progressive neurological decline, tremors, stiff gait, dysphagia

Progressive neurological decline, behaviour changes, ataxia, dysphagia

Stunted growth, skeletal deformities, facial dysmorphia, corneal opacity

neurological decline, ataxia, paralysis

GSD Type 1-a (Von Gierkes Disease)

GSD Type 3 (Cori’s

GSD Type 4 (Andersen’s Disease)

(Norwegian forest cats)

Depression, failure to thrive, death

Muscle tremors, gait abnormalities, death Stillbirth, flexural limb deformities, seizures GSD Type 5 (McArdle’s Disease)

a GSD and lysosomal storage disease

seizures, vision loss, ataxia, cognitive decline

Table 1. Tables highlighting the different categories and presentations of storage disorders currently documented in veterinary

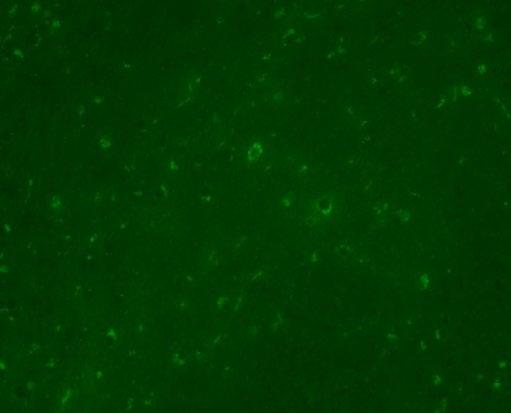

Figure 2. Histopathology of neuronal tissue showing eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions in neurones (green arrows)

A Light in the Dark

Special stains were the next step needed to crack this case.

– Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS)—Negative for glycogen (ruled out glycogen type storage diseases)

– Luxol Fast Blue—Negative for myelin breakdown (ruled out leukodystrophies or other primary myelin disorders)

It was under fluorescence microscopy at the RVC that the light bulb moment (literally!) happened for pathologists working on the case. Green autofluorescence was detected, indicating accumulated lipofuscin within affected neurones (Figure 4). This last result led to the diagnosis of NCL, a hereditary storage disease in both cats.

What is NCL?

NCLs are autosomal recessively inherited neurological disorders that have so far been diagnosed in a wide array

Figure 4. Autofluorescent inclusions consistent with NCL

of veterinary species including dogs, goats, a Vietnamese pot-bellied pig, a mallard duck and a cynomolgus monkey to name but a few! Little is known about the disease in cats with only a handful of cases documented in the literature. The disease causes mutations in genes involved with lysosomal function. This leads to dysfunctional lysosomes that cannot break down certain cell waste products efficiently. As a result, lipopigments start to build up inside neurones, eventually becoming toxic and leading to progressive neurological signs. The mutation leading to the disorder has been documented to vary between cats, with a defect in the CLN6 and MFSD8 genes both noted in case reports.

Clinical signs in cats can be unusual but tend to have a neurological focus. The following have been noted by clinicians in the few documented feline cases:

– disorientation

– partial and generalised seizures

– auditory +/- tactile hyperesthesia

– visual defi cits (blindness, absent menace response)

– compulsive pacing

– sporadic myoclonus

– cataplexy

– progressive weight loss

– abnormal posture

– altered behaviour

It is interesting to note that although not seen in Storm and Talon’s case, gross changes of an affected feline brain may be seen in some cases post-mortem with a study by M.D Chalkley et al (2014) noting findings in three affected cats of ‘mild to moderate, diffuse, symmetrical cerebral and cerebellar atrophy’ as well as ‘extensively flattened and narrow cortical gyri and cerebellar folia’ and ‘a dull brown discoloration of the entire cerebral

Diagnosis of feline NCL as seen in Storm and Talon’s case remains a challenge. With no known gold standard antemortem test for the condition, a definitive diagnosis is only possible postmortem. With that being said, by following a comprehensive differential diagnosis list and ruling out common things in turn, clinicians may gain confidence to suspect a presumptive diagnosis of a storage disease earlier in these cases.

A recent study at Liverpool University Small Animal Teaching Hospital exploring MRI findings of a feline NCL case has bought to light the use of MRI as a possible part of ante-mortem testing. The study did fi nd identifiable MRI changes in an affected patient and so the use of MRI may be benefi cial to support a diagnosis of NCL where there is already strong clinical suspicion. Although it should be noted that lack of MRI fi ndings would not completely rule out the condition (mutation type, early stages etc).

The future of NCL prevalence in cats is unknown, and it is only through documentation of cases and molecular investigation of the different forms and causative gene defects that pathologists will be able to build a bank of knowledge about the condition. As more mutations are identified and any trends recorded, it is pathologists’ upmost hope that targeted breeding and treatment protocols may be explored.

To any vet in practice who stumbles across this article, I would urge you to encourage owners to submit any similar case for pathological analysis. It is only by knowing about these bizarre cases that we can try and understand more about lesser-known conditions like NCL.

With special thanks to Storm and Talon’s owners, M elanie Dobromylskyj of Dobropath dobropath.com/about-1, and Pete Coleshaw from Jaffa Vets for information regarding the case

Neurological abnormalities in a South Australian Huyacaya Alpaca

Read the full article and watch the video here: cve.edu.au/alpaca and cerebellar cortices’. White C, et al (2018) also documented ‘moderate atrophy with widening of sulci’ in a feline NCL patient (Figure 5)

Figure 5. NCL affected cat brain showing macroscopic changes, White C, et al (2018)

References are available here: cve.edu.au/6103

Zoe J K Adams BVSc BHSc MaVBM MRCVS

Meadows Veterinary Centre e. meadowsvetcentre@gmail.com

Jessica Scriven DVM

Kate Werfel DVM

Zoe Hamilton e. zham6032@gmail.com

C&T No. 6104

A 3-year-old female Huacaya alpaca presented with progressive ataxia, stiffness, and proprioceptive deficits, unresponsive to initial thiamine supplementation.

This case highlights the value of clinical reasoning in neurological disease, as well as the importance of remaining vigilant to potential biosecurity risks posed by expanding feral deer populations.

Congratulations to the Distance Education Class of 2025!

For your dedication and commitment, especially when juggling study commitments with work and family, to complete this vigorous but rewarding continuing education. —CVE Tutors & Staf f

Anaesthesia & Analgesia

Tutors: Christina Dart & Eduardo Uquillas

—Fundamentals

Sandra Borg-Ryan, Australia

Callie Burnett, Australia

Kaiser Dawood, Australia

Nigel Dougherty, Australia

Christopher Godfrey, Australia

Nicole Hawken, Australia

Caroline Houston, Australia

Kate Jackson, Australia

Tuovi Joona, Australia

Derek Keeper, Australia

Craig Kelly, Australia

Phil Kowalski, Australia

Kayoko Kuroda, Australia

Alice Liaw, Singapore

Chloe McGillivray, Australia

Panida Nasongkhla, Thailand

Madeleine Nicholls, Australia

Luana Nieman, Australia

Finn Parker, Australia

Claire Phillips, Australia

Tim Portas, Australia

Siwachaya Sattapanyo, Thailand

Nuntarat Varatorn, Thailand

Thanaphan Vimooktanon, Thailand

Martine Visser, Australia

Stephanie Wong, Australia

—Compromised Patients

Jodi Bailey, South Africa

Timothy Choi, Hong Kong

Craig Kelly, Australia

Eleanor Lam, Australia

Kwei-Farn Liu, Australia

Panida Nasongkhla, Thailand

Alexandra Sharp, Australia

Philippa Simms, Australia

Olivia Thiris, Australia

Nuntarat Varatorn, Thailand

Thanaphan Vimooktanon, Thailand

—Unusual Pets

Sandra Borg-Ryan, Australia

Brett Fong, Australia

Craig Kelly, Australia

Jessica Kenworthy, Australia

Anna Muffert, Australia

Pradyumna Sathishkumaar, Australia

Jade Wastell-Stevens, Australia

Beef Production Medicine

Tutor: Paul Cusack

Katie Benson, Australia

Alan Forte, Australia

Ian Hodge, New Zealand

Chris Nel, Australia

Renee Nesser, Australia

Daniel Reiner, Australia

Josh Robinson, Australia

Rory Speirs, Australia

Behavioural Medicine

Tutors: Kersti Seksel, Jacqui Ley, Barbara Lindsay, Sally Nixon & Isabelle Resch

Emily Balch, Australia

Fauve Buckley, Australia

Ting-Yu Chen, Taiwan

Ying Cheung Andy Chiu, Hong Kong

Michelle Clinch, Australia

Lesley Hawson, Australia

Johnny He, Taiwan

Melissa Holmes, Australia

Yun Sun Hong, Hong Kong

Nathanon Hooncharoen, Thailand

Kai-Lin Huang, Taiwan

Phattanan Korjaranjit, Thailand

Fei Kuo, Taiwan

Ping Kwan, Australia

Nadia Lau, Australia

Sally Pegrum, Australia

Damien Rixon, Australia

Timothy Ruschena, Australia

Outi Tulenheimo, Finland

Brittany Ward, Australia

Cardiorespiratory Medicine

Tutor: Niek Beijerink & Mariko Yato

Alexandra Blayden, Australia

Kayniga Chodsudsaneh, Thailand

Samantha Christian, New Zealand

Pichaya Chumpholanomakhun, Thailand

Kate Johnson, Australia

Jansen Ng, Singapore

Nualsakul Noipheng, Thailand

Yanisa Pakdeenit, Thailand

Victor Poon, Hong Kong

Krorakan Thongsombat, Thailand

Jacqueline Tong, Hong Kong

Clinical Neurology

Tutors: Laurent Garosi & Simon Platt

Madeleine Baird, Australia

Manita Benyasut, Thailand

Bishal Bhattarai, Russia

Sirikanda Boonsaeng, Thailand

Yu-An Chang, Taiwan

YI AN Chen, Taiwan

Nuanrat Nateetaweesak, Thailand

Carol O’Donoghue, Australia

Preeyavart Rattanakom, Thailand

Tanakon Ruangklad, Thailand

Gentiana Seicaru, Romania

Benjamin Stewart, Australia

Clinical Pathology

Tutor: Sandra Forsyth & Karen Jackson

Carmen Chu, Australia

Heather D’Mello, Australia

Chun Ki Ho, Hong Kong

Sarah Hopf, Australia

Dermatology

Tutors: Ralf Mueller, Sonya Bettenay,

Stefan Hobi & Callum Bennie

—Advanced

Patsara Aryatawong, Thailand

Suchaya Bua-u-rai, Thailand

Tawanwad Leelaporn, Thailand

Pranpariya Lertponrat, Thailand

Phrut Phlapsawat, Thailand

Rinyarat Punpattrapong, Thailand

Maneekarn Singharat, Thailand

Eleanor Street, Australia

Namida Techamathuchartnan, Thailand

Waritha Thosaksith, Thailand

—Infectious Skin Disease

Patsara Aryatawong, Thailand

Suchaya Bua-u-rai, Thailand

Bongkoch Chonglomkrod, Thailand

Alisha Gilmore, Australia

Tawanwad Leelaporn, Thailand

Siew Nee Lim, Australia

Phrut Phlapsawat, Thailand

Rinyarat Punpattrapong, Thailand

Sasakorn Sakulpolwat, Thailand

Maneekarn Singharat, Thailand

Margaret Sung, Australia

Namida Techamathuchartnan, Thailand

—Pruritic Skin Disease

Patsara Aryatawong, Thailand

Suchaya Bua-u-rai, Thailand

Bongkoch Chonglomkrod, Thailand

Ellen James, Australia

Tawanwad Leelaporn, Thailand

Pranpariya Lertponrat, Thailand

Deborah Phillips, Australia

Phrut Phlapsawat, Thailand

Rinyarat Punpattrapong, Thailand

Rebecca Quam, United States

Nicole Rooke, Australia

Sasakorn Sakulpolwat, Thailand

Margaret Sung, Australia

Tiffany Tagros, Philippines

Qiao Yoke Tan, Australia

Namida Techamathuchartnan, Thailand

Waritha Thosaksith, Thailand

Michel Tomlinson, Australia

Diagnostic Imaging

—Abdominal

Tutor: Zoe Lenard

Jordana Capriotti, Australia

Tammy Chan, Australia

Kathryn Elliott, Australia

Rebecca Fusaro, New Zealand

Connell Healy, Australia

Chun Ki Ho, Hong Kong

Rasmeet kaur, Australia

Veronica Law, Hong Kong

Kaytlyn Playford, Australia

Isabelle Seah, Australia

Carla Werrin, Australia

—Musculoskeletal

Tutor: Xander Huizing

Emma Burpee, Australia

Jordana Capriotti, Australia

Tammy Chan, Australia

Doris Cho, Hong Kong

Rianna Dinon, Australia

Rebecca Fusaro, New Zealand

Connell Healy, Australia

Chun Ki Ho, Hong Kong

Samantha Leaver, New Zealand

Gunilla McPherson, Australia

Isabelle Seah, Australia

Johan Steyn, Australia

Maithreyi Sundaresan, Australia

Lyddy van Gyen, Australia

—Thoracic

Tutor: Belinda Hopper

Zoe Allison, Australia

Belinda Bertram, Australia

Tegan Boyd, Australia

Jordana Capriotti, Australia

Giulia Cerone, Australia

Tammy Chan, Australia

Tsz Ching Cheung, Australia

Jess Divall, Australia

Kathryn Elliott, Australia

Ameerunnisa Esmail, Singapore

Daniel Gerrard, Australia

Vanessa Grose, Australia

Chun Ki Ho, Hong Kong

Alex Hockton, Australia

Bruce Krumm, Australia

Yin Wai Leung, Australia

Rebecca Lewis, Australia

Jamie Liu, Australia

Eva Lorenz, Australia

Michelle Pacey, Australia

Carla Pendini, Australia

Cathy Pheiffer, Australia

Gabriella Robinson, Australia

Lily Simpson-Kennedy, Australia

Michael Stern, Australia

Johan Steyn, Australia

Valencia Jia Xuan Tan, New Zealand

Helen Tanzer, Australia

Amy Underwood, Australia

Katherine Wells, Australia

Emergency Medicine

Tutors: Yenny Indrawirawan & Sophia Morse

Nikita Besseling, Australia

Amy Brown, Australia

Sharlet John, Australia

Prach Maihasap, Thailand

ANIL MURARI, United States

Ngar Ting Denise Ying, Hong Kong

Feline Medicine

Tutors: Rachel Korman, Katherine

Briscoe, Michael Linton, Katie McCallum, Kerry Rolph, Ashlie Saffire, Samantha

Taylor, Jane Yu, Alison Jukes, Petra

Cerna, Sally Coggins, Ellie Mardell & Christina Maunder

Vanessa Aird, Australia

Tuva Akerjord, Norway

Michael Auld, Australia

Maria Azevedo, Portugal

Tabitha Baibos-Reyes, United States

Manuel Bajo Marijuan, Spain

Alae Bhoola, South Africa

Roberta Bocedi, UK

Jessica Brown, United States

Darren Burgess, Australia

Ester Caires, Ireland

Alexandra Carleton, Australia

Kongpop Choijinda, Thailand

Hannah Colley, United Kingdom

Fiona Coutts, United Kingdom

Steven Crowe, Ireland

Lalida Damrongchonlatee, Thailand

Joyce Doornhein, Netherlands

April Fegredo, Australia

Ines Fernandez Zapata, United Kingdom

Elise Fookes, Australia

Revathi G, Australia

Michael Garner, Germany

Kristin Gjerde, Norway

Helena Gomes, Portugal

Julie Hermansen, United States

Lindsay Hodgson, UK

Rachel Johnson, Canada

Anja Kiessler, New Zealand

Erja Knuth, Finland

Michelle Korhonen, Finland

Inga Kozlovaite, United Kingdom

Joanna Kwok, Australia

Vanessa Lambert, United Kingdom

Fiona Le Surf, Australia

Sam Leaney, UK

Waranpat Lengvilas, Thailand

Siri Linde, Sweden

Hailey MacDonald, Canada

Sarah Mitchell, Australia

M Belen Montoya Jiménez, Spain

Bastian Ness, Australia

Tiina Nikupeteri, Finland

Sofia Nóbrega, Portugal

Kathryn Orr, New Zealand

Peerakarn Pongleardrit, Thailand

Kasamyra Sainsbury, Australia

Roelie Schrijnders, Australia

Shannen Schultz, Australia

Pornkamol Siriphattarasophon, Thailand

Angie Smith, United States

Nally Tan, Singapore

Jutamas Udomkiattikul, Thailand

Charlotte Wells, Australia

Anneleen Wröbel, Belgium

Internal Medicine: A Problem Solving Approach

Tutors: Jill Maddison, Sue Bennett & Susan Carr

Alexandra Carey, Australia

Tori Carroll, Australia

Alice Chen, Australia

Alicia Cheong, Australia

Chak Hei Justin Cheung, Hong Kong

Yan Kiu Damien Cho, Hong Kong

Meagan Coolahan, Australia

Jaclyn Fung, Hong Kong

Natalia Gomez, Australia

Julien Grosmaire, Australia

Guen Hodgkiss, Australia

Lachlan Indian Manning, Australia

Melinda Khong, Australia

Ting En Khor, Singapore

Anastasia Kusumo, Australia

Yan Kei Lai, Hong Kong

Alice Lawson, Australia

Samantha Lo, Australia

Emily Sandow, Australia

Sarah Schultz, Australia

Eugenia See, Singapore

Olga Sjatkovskaja, Estonia

Yanling Tan, Singapore

Marcel Walsh, Australia

Margot Walton, Australia

Danlei Wang, Australia

Kin Yee Wong, Hong Kong

Internal Medicine: Keys to Understanding

Tutors: Darren Merrett, Steve Holloway & Jen Brown

Vanesa Bai, Australia

Emma Croser, Australia

Paige Cross, Australia

Natsuko Druery, Australia

Michele Goh, Australia

Matilda Hunter, Australia

Madhuka Nishany Kola Baddage, Australia

Santiago Neumann, Australia

Liesel Park, Australia

Jonathan Pratt, Australia

Katherine Simpson, UK

Melanee Suksamranthaweerat, Thailand

Laura Wood, Australia

Frank Yuen, Australia

Ophthalmology

Tutors: Robin Stanley & Matthew Sanders

Chanida Assawamachai, Thailand

Charlotte Cavanagh, Australia

Nadzariah Cheng-Abdullah, Malaysia

Arunluck Darunsawat, Thailand

Rachel Greenhill, Australia

Kathleen Ho, Australia

Weejarin Paphussaro Ittarat, Thailand

Ueakarn Luckkate, Thailand

Sarah Monaghan, Australia

Tanakanok Ngampongsai, Thailand

Pareeyaporn Pomjucksin, Thailand

Natchapol Preedarat, Thailand

John Rigley, Australia

Saranya Srisawat, Thailand

Sutawee Suksin, Thailand

Chayapa Udomthanakij, Thailand

Patidta Veerasai, Thailand

Kwun Yuet Wong, Hong Kong

Surgery

Tutors: Chris Tan, Mark Newman & Wendy Archipow

Celia Alman, Australia

Chris Andersen, Australia

Eloise Bartlett, Australia

Kitanjali Batliwalla, Australia

Hiu Chung Cheryl Chan, Hong Kong

Anthony Wing Chung Chow, Australia

Nicci Da silva, Australia

Charlotte Dilnutt, Australia

Amanda Dunn, Australia

Tom Harsant, New Zealand

Prabkirat Kaur, Singapore

Eleanor Lewis, New Zealand

May Lyn Lim, Malaysia

Janae Lo, Australia

Harrison Mackenzie, Australia

Chelsea Manley, Australia

Amos Nichols, Australia

Sarah Orpin, Australia

Kathleen Rebgetz, Australia

Madeleine Richard, Australia

Kristin St. John, Australia

Marena Stols, Australia

Sabrina Ying, Australia

VPOCUS: Practical Applications for GPs Distance Education

Tutors: Soren Boysen & Serge Chalhoub

Sanchi Aggarwal, Australia

Olivia Allen, Australia

Camille Armstrong, Australia

Clementine Barton, New Zealand

Elizabeth Bayne, Singapore

Cheryl (Li Wen) Cheah, Australia

Ashley Cheang, Australia

Jonathan Chee, Australia

Jessica Chen, Australia

Shirley Chow, Australia

Coty Chum, Hong Kong

Louise Clohesy, Australia

Melissa Closter, Australia

Eliza D’Arcy-Moskwa, Australia

Nina De Goede, Australia

Alisdair Eddie, Australia

Alannah Fitzgerald, Australia

Tiffany Fitzpatrick, Australia

Rebecca Fusaro, New Zealand

Kathy Gillies, Australia

Eleanor Gomersall, Australia

Tegan Hadley, Australia

Bronwen Harper, Australia

Nathan Harris, Australia

Melissa Hayde, Australia

Sarah Heineman, United States

Yan Wing Ho, Australia

Chun Ki Ho, Hong Kong

Kara Holt, Australia

Hui Ku, Australia

Crystal Mak, Australia

Kamila Osiak, Australia

John Pascall, Australia

Christine Powell, Australia

Ying Pung, Australia

Anne Quain, Australia

Natalia Ramos Reyes, Australia

Simon Roberts, Australia

Emma Shepherd, Australia

Kellie Steven, Australia

Ruby Thorn, Australia

Kanako Toda, Australia

Fumie Tokonami, Australia

Christiane Weingart, Germany

Nina Zhang, Australia

2026 Distance Education enrolments still open!

Anaesthesia & Analgesia

University of Sydney Micro-credentials

Tutors: Christina Dart & Eduardo

Uquillas

Fundamentals

Compromised Patients

Unusual Pets

Behaviour Medicine

Tutors: Kersti Seksel, Jacqui Ley, Barbara Lindsay, Sally Nixon & Isabelle Resch

Clinical Neurology

Tutors: Laurent Garosi & Simon Platt

Clinical Pathology

Tutors: Sandra Forsyth & Karen Jackson

Cardiorespiratory Medicine

Tutors: Niek Beijerink & Mariko Yata

Dermatology

Tutors: Sonya Bettenay, Stefan

Hobi, Ralf Mueller & Callum Bennie

Infectious Skin Disease

Pruritic Skin Disease

Advanced Dermatology

Diagnostic Imaging

Abdominal Imaging

Tutor: To be announced

Musculoskeletal Imaging

Tutor: Xander Huizing

Thoracic Imaging

Tutor: Belinda Hopper

Emergency Medicine

Tutors: Yenny Indrawirawan & Sophia Morse

Feline Medicine

Tutors: Katherine Briscoe, Petra Cerna, Sally Coggins, Alison Jukes, Rachel Korman, Michael Linton, Ellie Mardell, Christina Maunder, Katie McCallum, Kerry Rolph, Ashlie Saffire & Sam Taylor

Internal Medicine: Keys to Understanding

Tutors: Jen Brown, Steven Holloway & Darren Merrett

Internal Medicine: A Problem Solving Approach

Tutors: Jill Maddison, Sue Bennett & Susan Carr

Ophthalmology

Tutor: Robin Stanley & Matthew Sanders

Ruminant Nutrition

Tutor: Paul Cusack

Surgery

Tutors: Chris Tan, Wendy Archipow, Bronwyn Fullagar & James Crowley

Practical Oncology

Tutor: Katrina Cheng

VPOCUS: Practical Applications for GPs

Tutors: Soren Boysen & Serge

Chalhoub

cve.edu.au/distance-education

Winner

Entitled to a CVE$300 voucher

Unusual Fungal Infection in a Cat

Madison Newton

Tropical Vets

184 Queen Street, Ayr QLD 4807

e. Ayr@TropicalVets.com.au

t. 07 4783 2055

C&T No. 6105

‘The Big Boy’ is a 5-year-old male neutered Ragdoll cat who presented to me as a second opinion after a 6-month history of pigmented skin lesions which appeared and then grew, never resolving. They were originally thought to be cat fight wounds by another vet clinic and were treated with meloxicam and Amoxyclav.

The lesions then progressed to being multifocal over most of the body, including pinna edges, nares, trunk and abdomen, down the tail, on the paw pads …etc.

On presentation the nasal lesions had been affecting his upper respiratory tract for about a month with the owners noticing noisy breathing and sneezing. He did not open mouth breathe, was still eating well and had no nasal discharge. He was FIV / FeLV negative and had a relatively unremarkable CBC / Biochem / UA / T4.

The lesions were biopsied with a disposable skin biopsy punch and submitted for histopathological examination and mycological culture.

Diagnosis: Severe Chronic nodular pyogranulomatous dermatitis with intralesional pigmented fungi

Cutaneous infection with fungal organisms is often opportunistic and usually the result of traumatic implantation or wound contamination.

Disseminated infection is uncommon and when seen is often associated with immune dysfunction. In animals developing this condition while receiving immunosuppressive therapy, tapering and discontinuing these medications is often necessary for successful treatment of the fungal infection. In some cases, complete excision of solitary or multifocal cutaneous lesions may be curative; however, recurrence at the same or new sites is fairly common, sometimes months or even years following initial excision.

In this instance, the disseminated nature of lesions is most likely the result of a fight in which there were

1A

1B

1C

numerous bites and scratch injuries, which enabled impregnated fungal elements to ‘set up shop’ and develop into pigmented lesions. The melanised nature of the lesions was a big tip off for the presence of a dematiaceous (pigmented) fungal pathogen, with melanin elaborated by the fungus giving rise to the pigmented nature of the lesions.

PCR testing