In 1925, the Leica I made history. Compact, fast, and revolutionary, it opened the door to a new visual language. It made photography portable. It made history visible. And it became a legend. It all began with one bold decision.

We’re honoring the Leica I, the camera that changed the world of photography, and commemorating 100 years of innovation, craftsmanship, and timeless moments that continue to inspire.

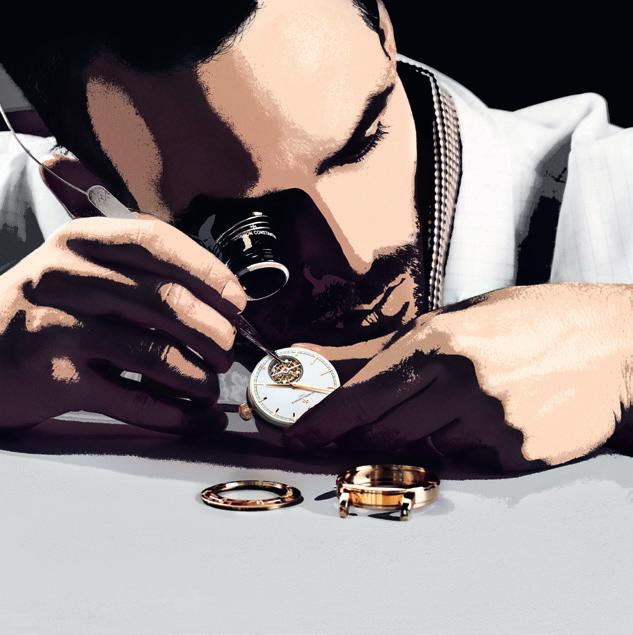

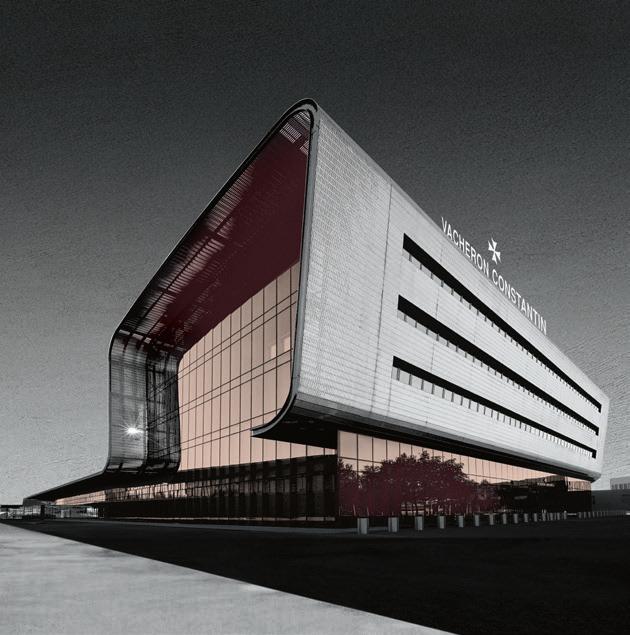

270 YEARS OF DOING BETTER IF POSSIBLE

IN 1755, IN GENEVA, A QUEST BEGINS. A QUEST FOR EXCELLENCE IN HIGH WATCHMAKING.

A QUEST OF PASSION, PERSEVERANCE AND MASTERY. A QUEST TO « DO BETTER IF POSSIBLE, AND THAT IS ALWAYS POSSIBLE ».

A QUEST THAT NEVER ENDS.

VACHERON CONSTANTIN CELEBRATES SEEKING EXCELLENCE FOR 270 YEARS.

ANNIVERSARY

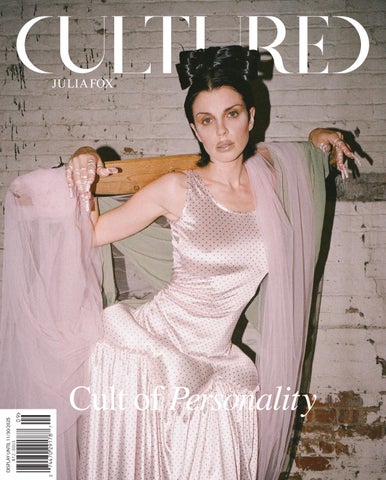

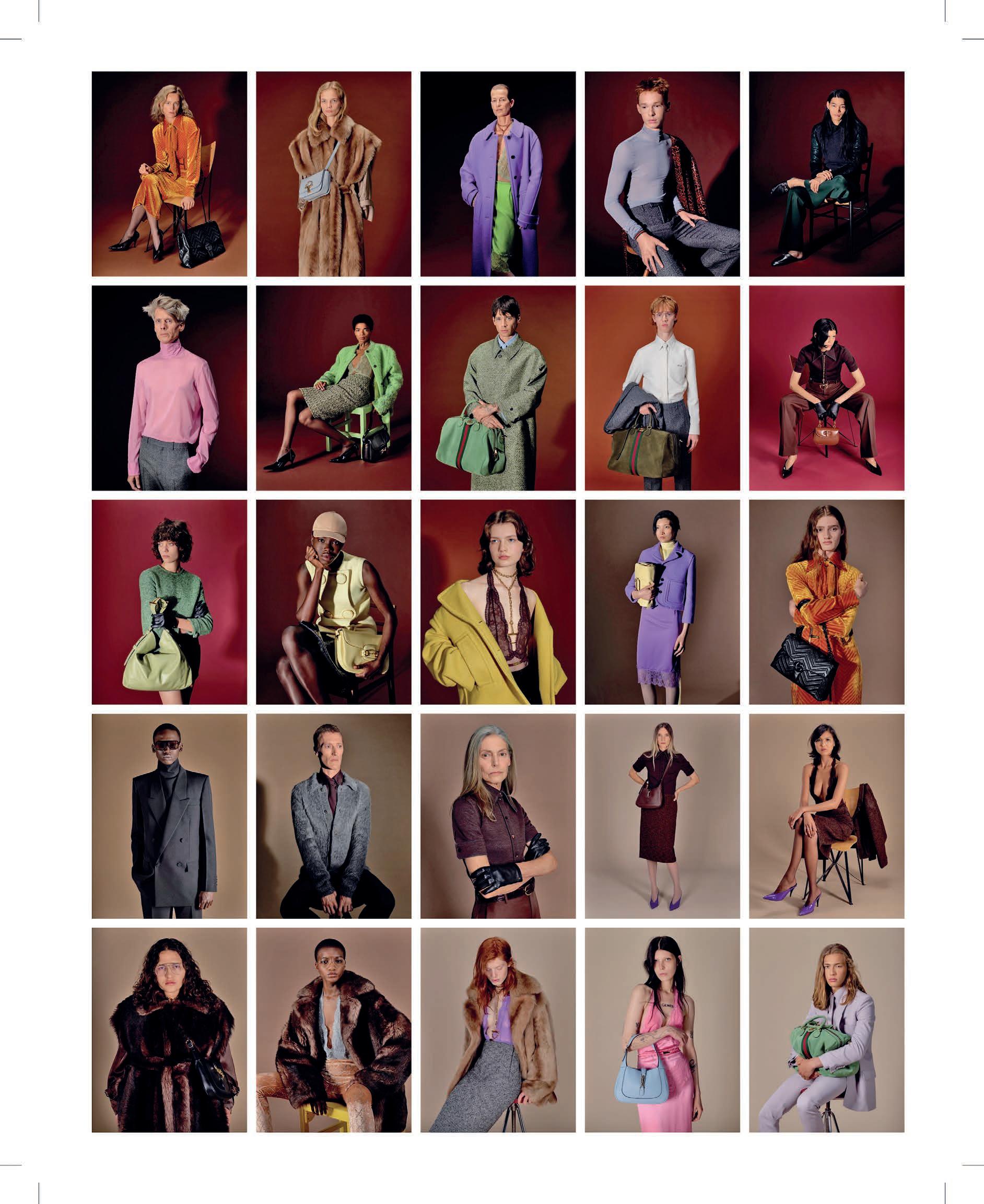

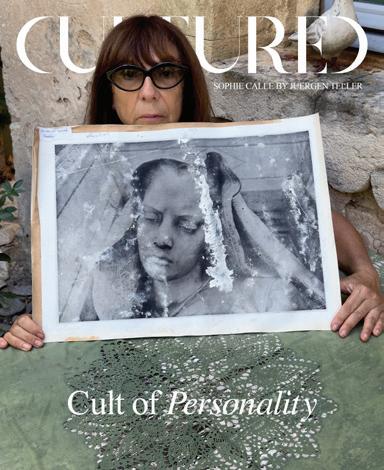

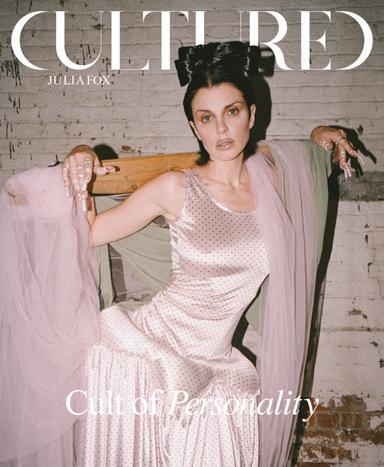

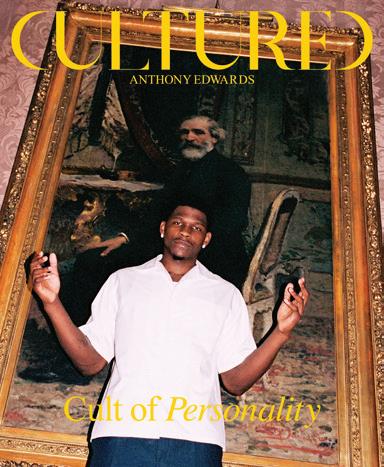

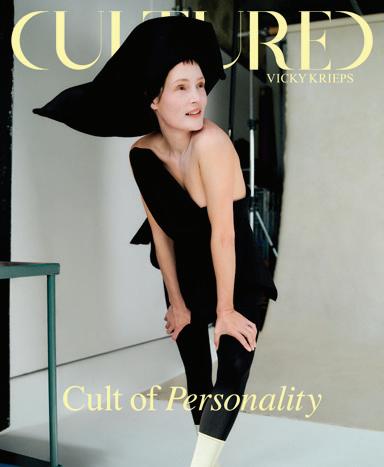

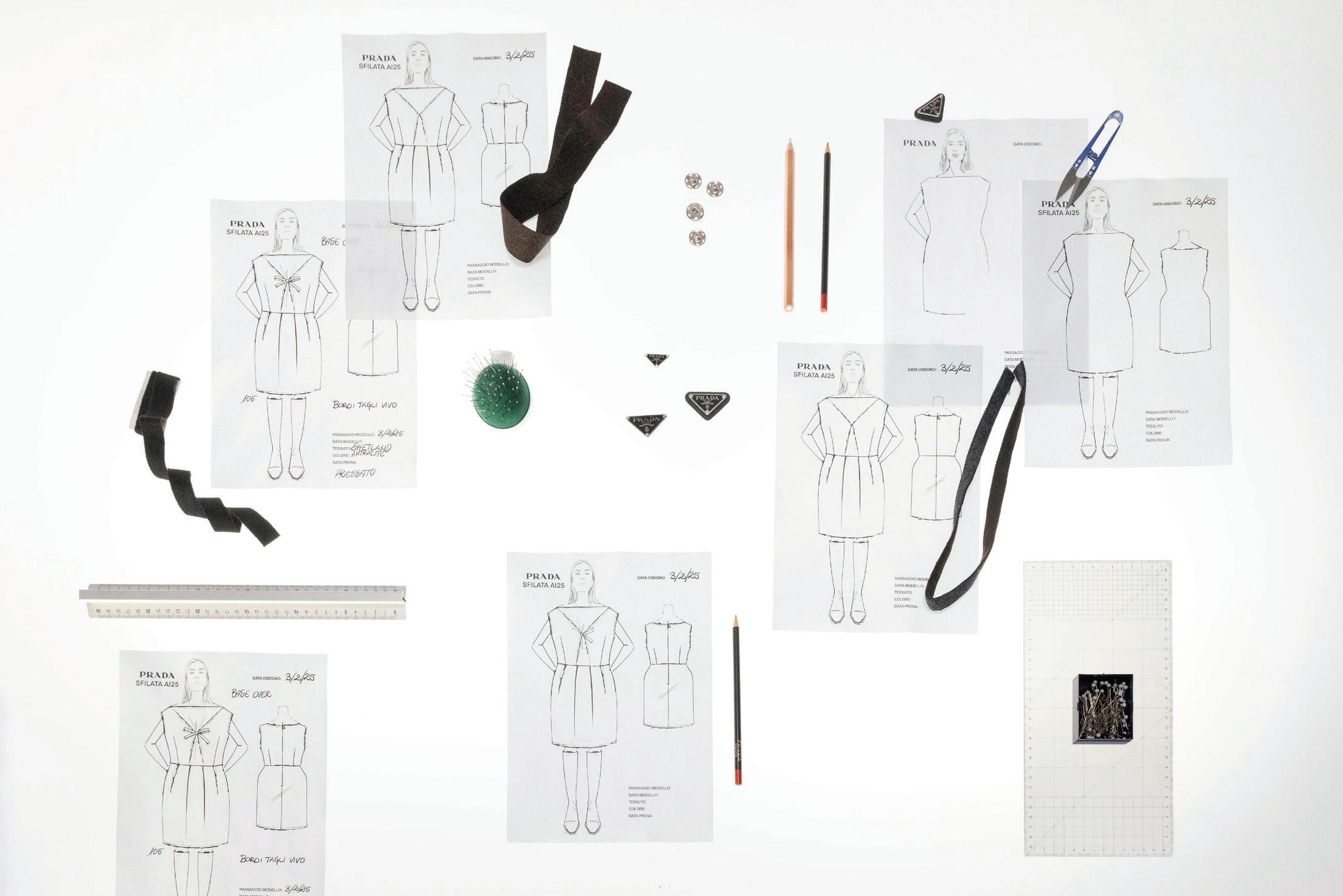

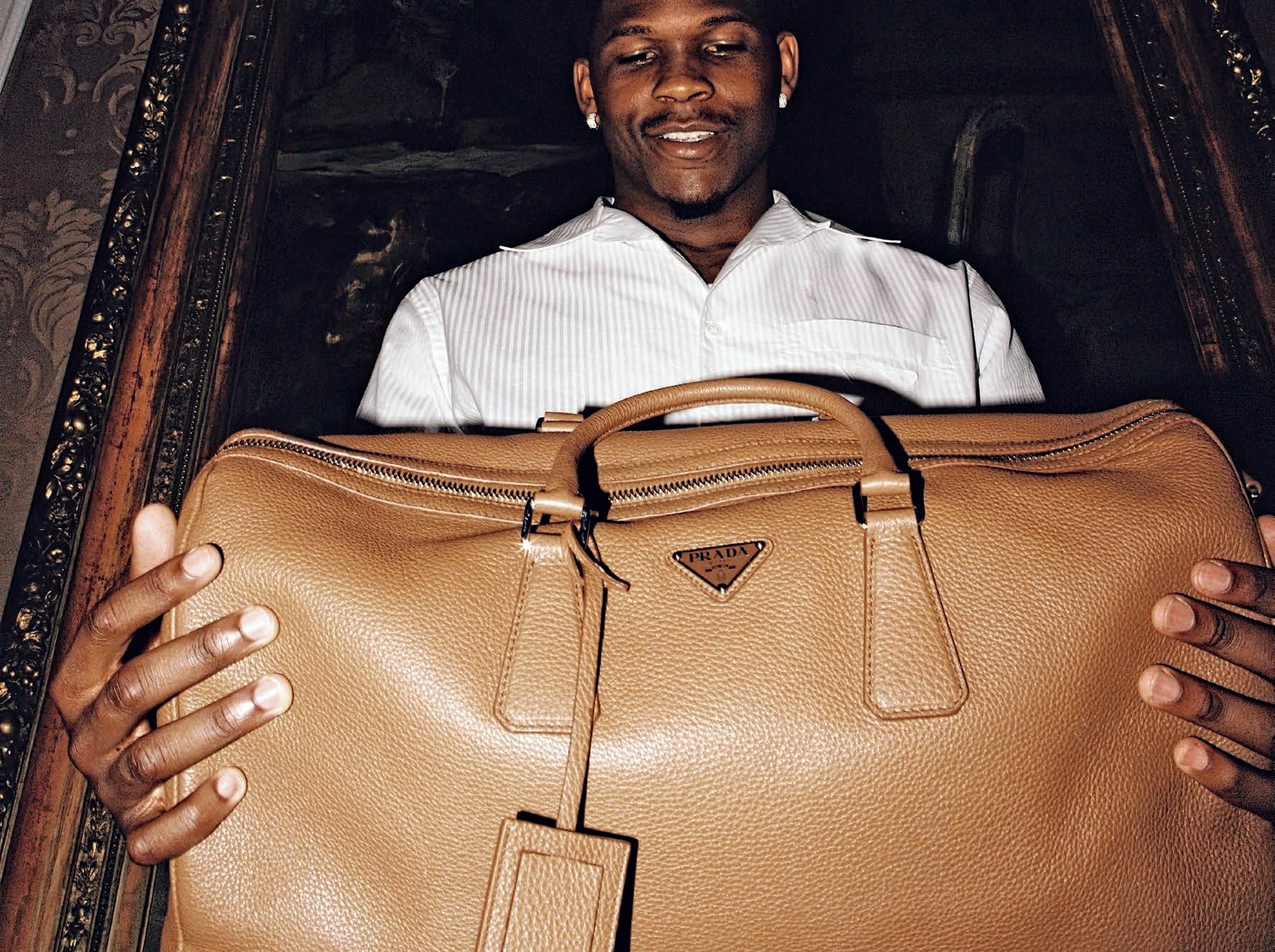

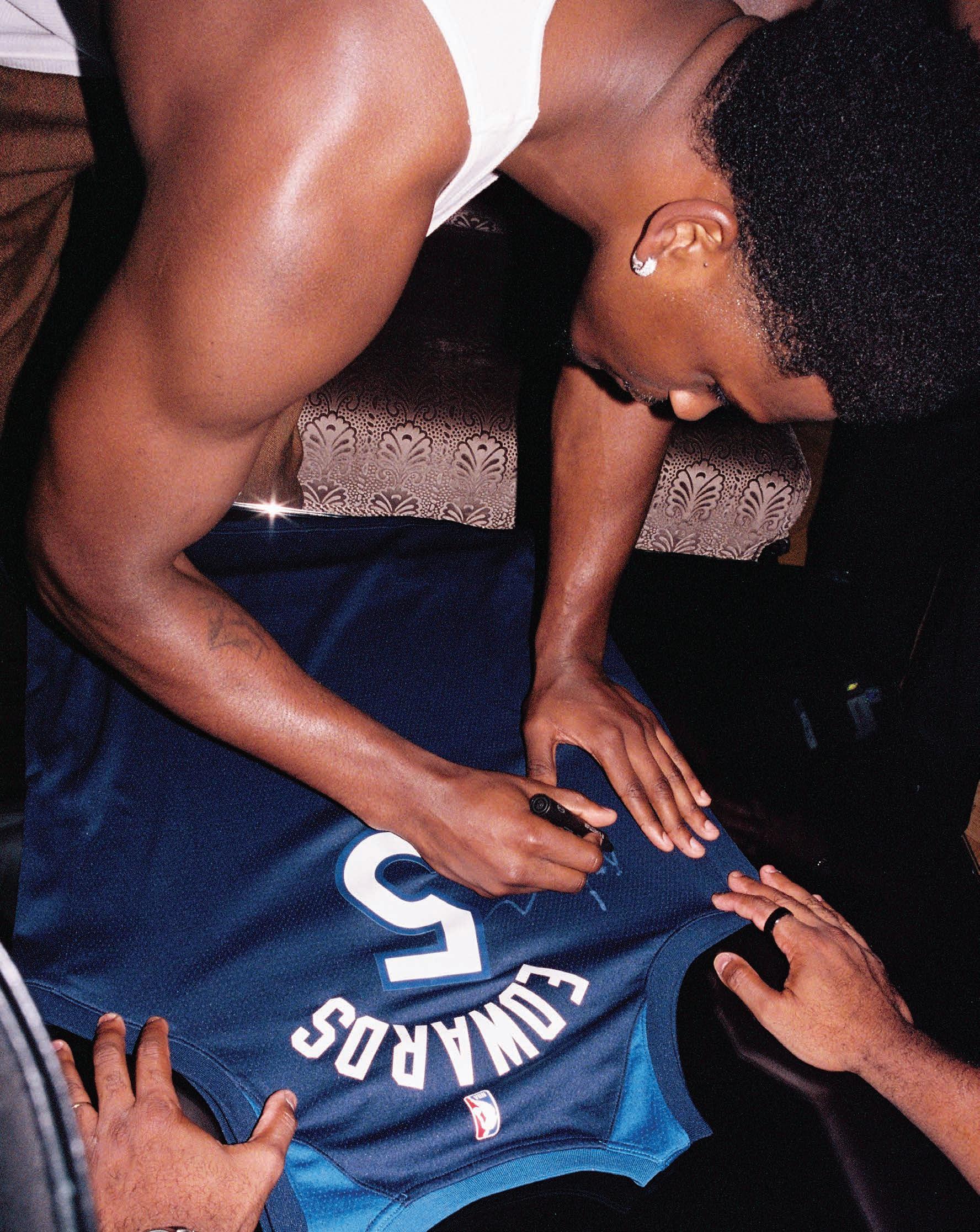

Fashion is everywhere. Style, that intangible sense of personal texture, is much more elusive. When we put together our September Art + Fashion issue each year, we look to people who have unearthed and cultivated their style through their crafts and on their bodies. This time, we’ve dedicated the issue to the cult of personality—a mix of instinct, idiosyncracy, and conviction that proves irresistible. In a culture preoccupied with influence, these figures, four of whom are this issue’s cover stars, seem surprisingly rare. That’s because a cult figure is, by design, not for everyone. Artist Sophie Calle—shot for this issue by the legendary Juergen Teller—has dedicated her career to exposing the private eccentricities that make us interesting. The actor and writer Julia Fox is consistently outrageous—flouting dogma and traipsing among the fashion, film, and literary worlds, leaving a trail of bemused and adoring audiences in her wake. The 24-year-old basketball star Anthony Edwards has turned the NBA’s established hierarchies on their heads, promising to restore the game’s old glory with his ebullient trash talk and flamboyance on the court. Actor Vicky Krieps has earned a devoted following for performances that thrum with emotion, refusing to participate in the fame machine that defines her industry along the way.

In these pages, you’ll find dozens of other people who, like our cover stars, have earned niche, devoted fan bases because of the raw and honest ways they present themselves to the world. Vaginal Davis, the interdisciplinary artist and countercultural icon, is preparing a major exhibition at MoMA PS1; prolific 98-year-old artist Alex Katz refuses to rest on any laurels and is preparing for a suite of exhibitions this season; Apple’s visionary vice president of human interface design, Alan Dye, introduces CULTURED and a cadre of artists to Liquid Glass, his team’s latest technological innovation, in Aspen; and a swath of debut novelists assembled and interviewed by Books Editor Emmeline Clein are proudly writing for “if you know, you know” audiences, even as they step onto a bigger stage.

What draws us to cults of personality is the winking self-awareness it requires. It’s the people who understand and trust themselves who are best equipped to summon what hasn’t existed before into the world. At a moment when we desperately need alternatives to the way things have always been done, I hope you find the unconventional visions in this issue as galvanizing as I do.

What draws us to cults of personality is the winking self-awareness it requires. It’s the people who understand and trust themselves who are best equipped to summon what hasn’t existed before into the world.

Photographer

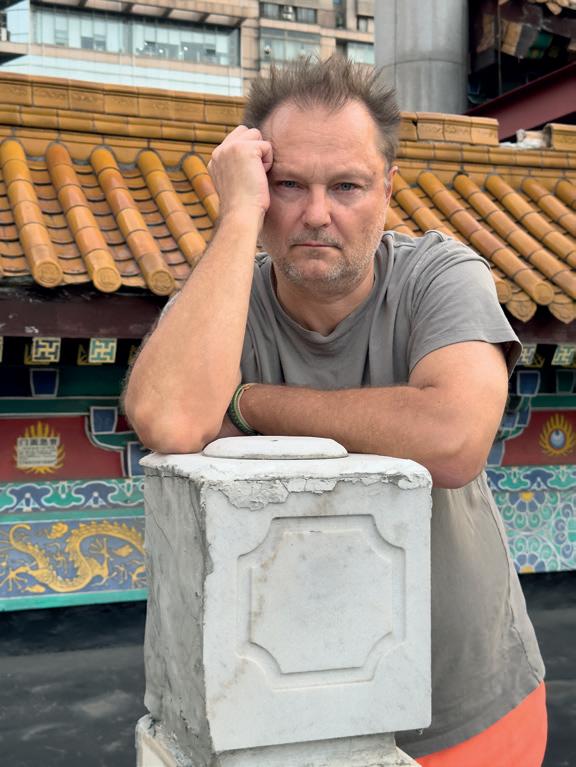

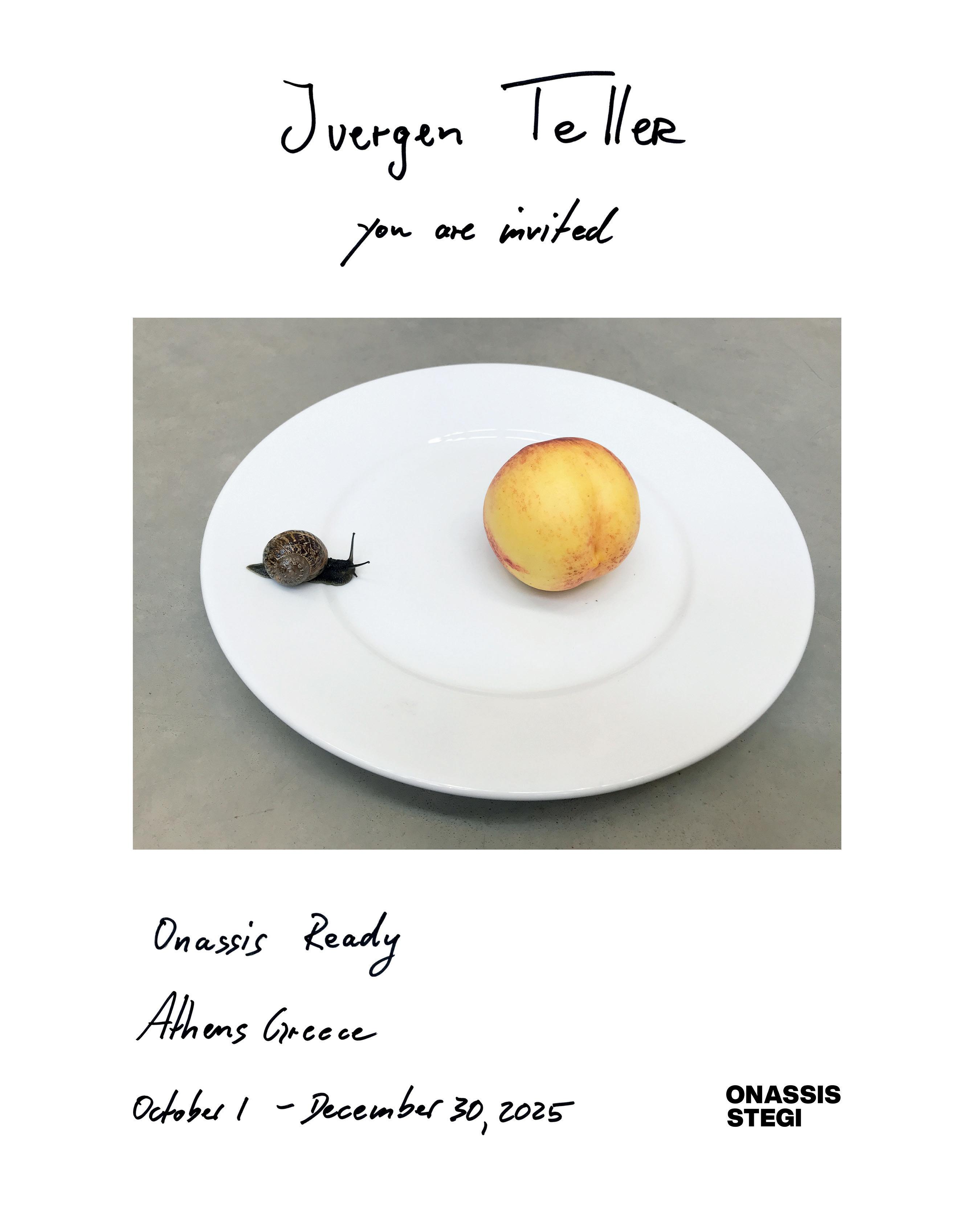

You can spot a Juergen Teller photograph anywhere—they’re unmistakably posed and stripped of all pretension. The image-maker is uniquely adept at catching subjects unguarded, a skill that was put to the test when he traveled to Arles, France, to meet up with artist Sophie Calle for her cover shoot. “I have known Sophie for a long time and it was a pleasure to collaborate again,” says the photographer. “I arrived to her house in the South of France to be greeted by her and a large number of her stuffed animals. Sophie moves between the mischief of a child and confident intelligence.” Calle joins an illustrious list of Teller subjects that includes Kate Moss, Cindy Sherman, George Clooney, and fellow CULTURED cover star Julia Fox. The breadth of the photographer’s reach is dwarfed only by the number of institutions holding his work in their collections: the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in Zurich, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and countless more.

“SOPHIE MOVES BETWEEN THE MISCHIEF OF A CHILD AND CONFIDENT INTELLIGENCE.”

KATE ZAMBRENO Writer

“While I was interviewing Sophie Calle, I kept thinking how young she was when she made her early ’80s pieces, and how her style and voice

was already so fully formed,” says Kate Zambreno, who traversed the span of the French artist’s career for this issue. Zambreno is the author of books including The Light Room, a meditation on art and care, and Animal Stories, a book on zoos and Kafka, both newly out from Transit Books. They are also a Ph.D. student in Performance Studies at NYU. Two novels, Foam and Performance Art, will be published by Semiotext(e) in fall 2026 and spring 2027. A match for Calle in both rigorous inquiry and style, in the cover story Zambreno pushes the bounds of what an interview can, or should, be.

“I KEPT THINKING HOW YOUNG SOPHIE CALLE WAS WHEN SHE MADE HER EARLY ’80S PIECES, AND HOW HER STYLE AND VOICE WAS ALREADY SO FULLY

FORMED.”

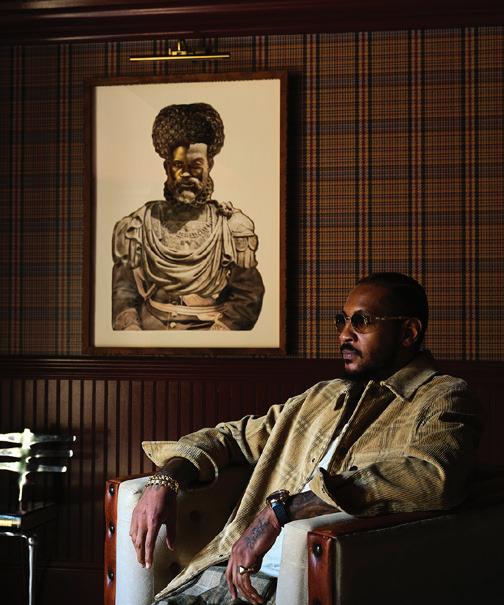

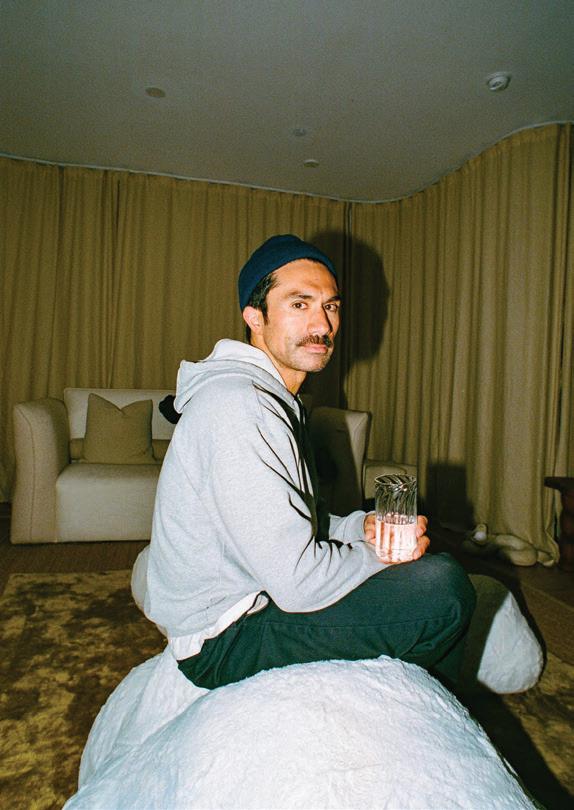

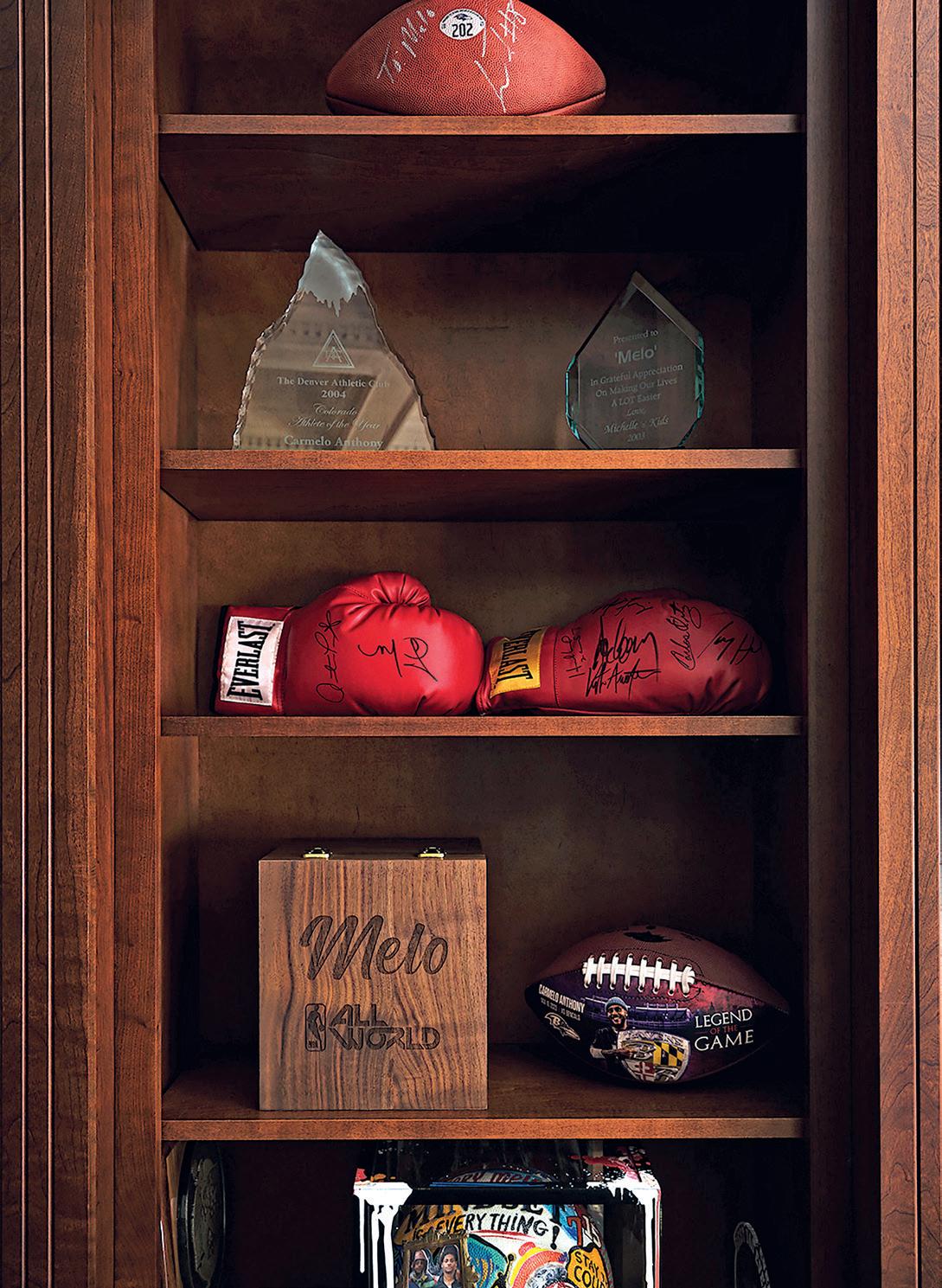

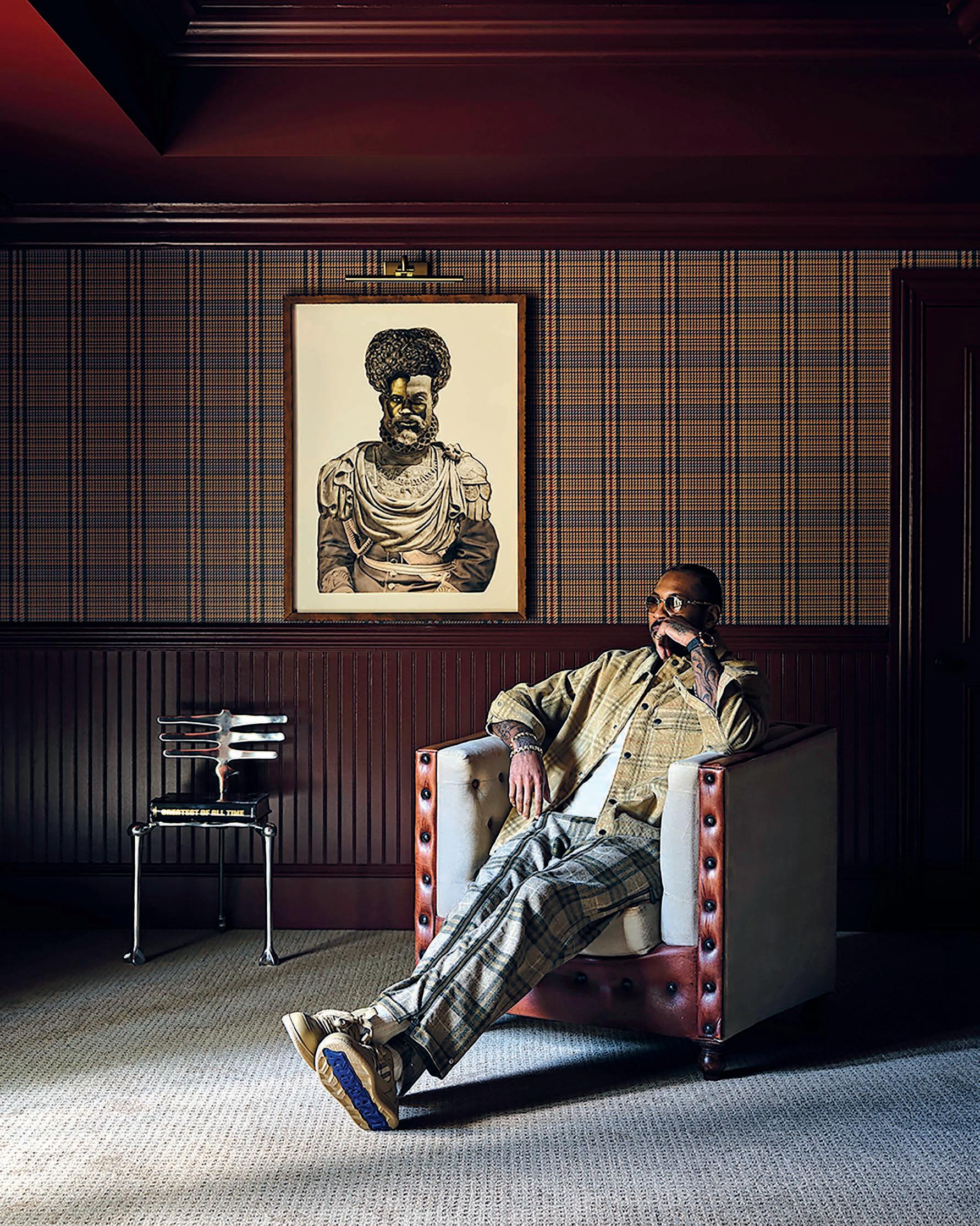

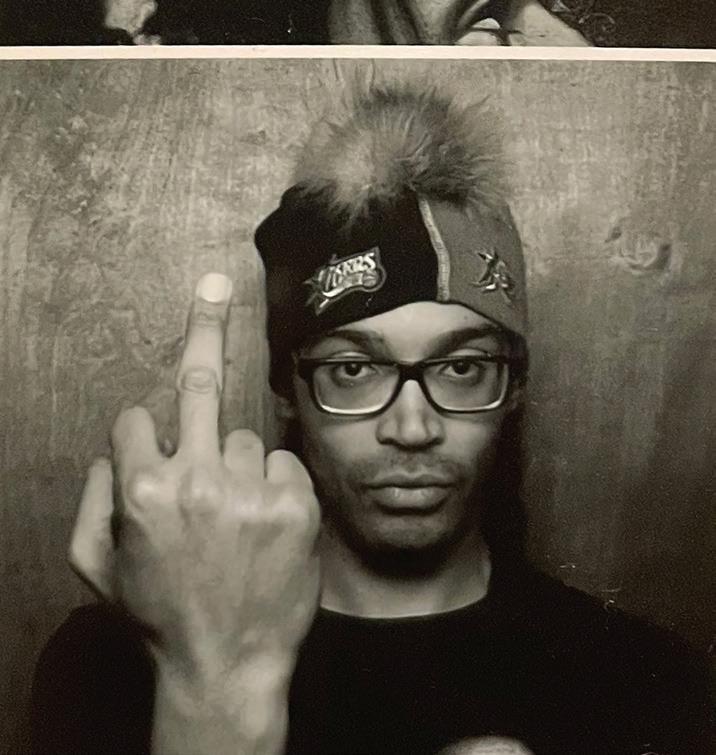

Max Berlinger is interested in the crosshairs of culture. For this issue, he narrowed in on the intersection between sports and art, specifically as former NBA player Carmelo Anthony sees it.

“Carmelo was a really thoughtful guy, and I loved hearing his approach to collecting,” Berlinger shares. “I felt like this was really a passion for him, and a practice that he developed over the years. He really emphasized how this is a personal endeavor and how a person’s collection should be a reflection of their tastes, not about the market or what’s cool and trendy. I thought that was a really thoughtful, beautiful sentiment.” Elsewhere, Berlinger has explored these niches for The New York Times, GQ, The Wall Street Journal, and more.

“CARMELO EMPHASIZED HOW THIS IS A PERSONAL ENDEAVOR AND HOW A PERSON’S COLLECTION SHOULD BE A REFLECTION OF THEIR TASTES, NOT ABOUT THE MARKET OR WHAT’S COOL AND TRENDY.”

Writer

Minnesota Timberwolves player Anthony Edwards’s career is transforming at the speed of light. To match his momentum, we needed someone who’s been there from the start. “I have known Ant for six years now and have had countless basketball conversations with him over the years. But I have always wanted a chance to broaden the horizons of our conversations,” says writer Jon Krawczynski, who has covered sports in Minnesota—first for The Associated Press and now for The Athletic—for more than two decades. “This conversation allowed me to delve into a different side of his persona, to look beyond the athlete to see how he is opening up to an entire world that is becoming accessible to him.” In this issue, Krawczynski sits down with Edwards to explore his journey to becoming one of the league’s most charismatic stars.

“I HAVE KNOWN ANT FOR SIX YEARS NOW AND HAVE HAD COUNTLESS BASKETBALL CONVERSATIONS WITH HIM… THIS CONVERSATION ALLOWED ME TO DELVE INTO A DIFFERENT SIDE OF HIS PERSONA, TO LOOK BEYOND THE ATHLETE.”

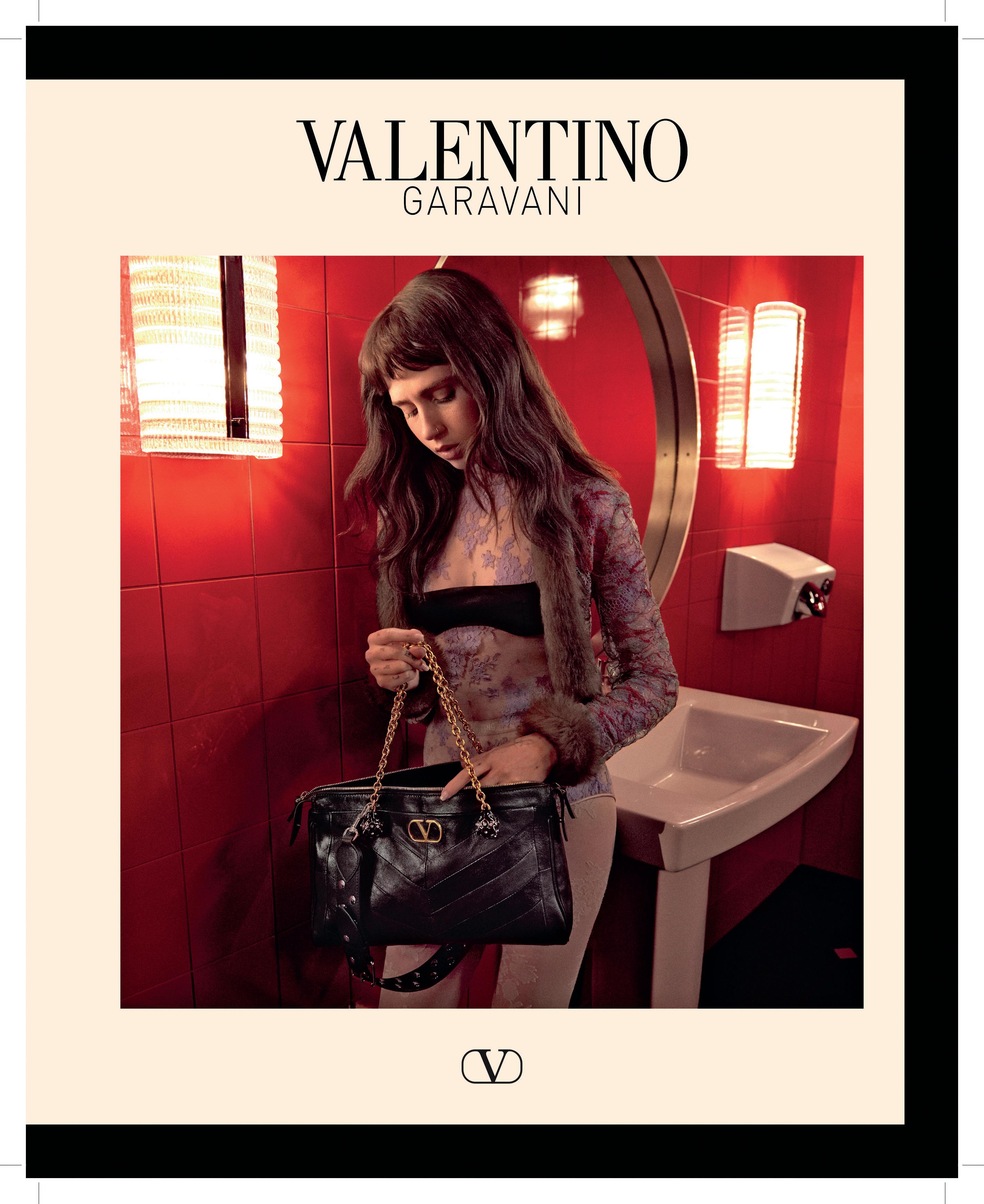

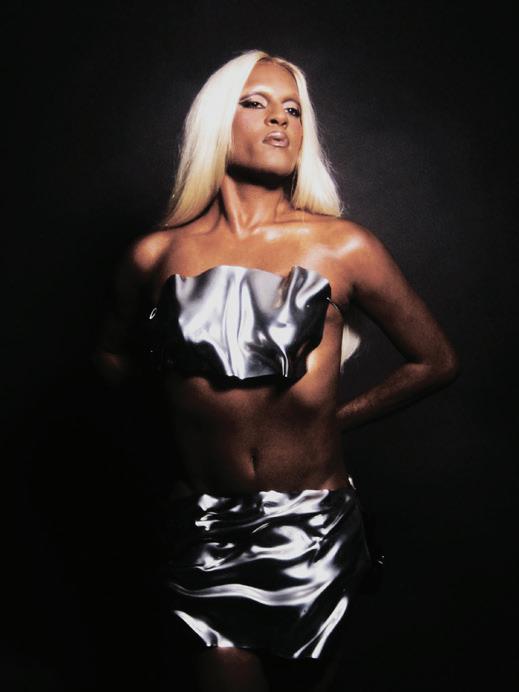

haunting, refusing to let go.” She knows those characters well, as the pair have been close friends since their teenage years, rising together into New York’s creative echelon. Shazam now works across disciplines as a photographer, model, and filmmaker who has lensed Chappell Roan, Doechii, and Charli XCX for Valentino Beauty, Interview, The Cut, and more. For this issue, she set Fox in a whimsical theater, complete with tomato throwing. “She moved through the space with this electric presence, breaking the fourth wall like it was second nature,” says Shazam. “It wasn’t just a shoot; it was a layered performance, raw and unapologetically her.”

“IT WASN’T JUST A SHOOT; IT WAS A LAYERED PERFORMANCE, RAW AND UNAPOLOGETICALLY HER.”

FRANK FRANCES Photographer

“Before photographing Melo, I made it a point to drive through the Red Hook Houses to better understand where he came from,” says Frank Frances, who took us inside former NBA player Carmelo Anthony’s Westchester, New York, home for this issue. For Frances, photography is as much about the memories that give way to the current moment as it is about what currently lies in front of the camera. “As an artist documenting his story, I felt it was important to connect with his roots firsthand. Being in his home, surrounded by his collection, revealed a profound sense of resilience and determination that was deeply embedded in the space.” Elsewhere, Frances’s work has been shown at the Studio Museum in Harlem and in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and other publications.

“Shooting Julia was like watching all her inner characters come to life,” says Richie Shazam of photographing Julia Fox, “each one vivid,

“BEING IN CARMELO’S HOME, SURROUNDED BY HIS COLLECTION, REVEALED A PROFOUND SENSE OF RESILIENCE AND DETERMINATION THAT WAS DEEPLY EMBEDDED IN THE SPACE.”

TAYLOR DAFOE Writer/Photographer

Taylor Dafoe is the only contributor in this issue with a double byline. Ahead of Raúl de Nieves’s new showing, Dafoe profiled and shot the artist in his Brooklyn workspace. The Upstate New York creative has also contributed to the likes of Frieze, Interview, and ArtNews, and written on everything from gallery overhauls to the rise of “ick art” for CULTURED. “De Nieves’s studio was every bit as colorful as he is,” Dafoe recalls. “His work lined the walls and windows, while rogue beads, rhinestones, and other materials overflowed onto the floor. During my visit, de Nieves’s dog, Penguini, never left his side— especially as I photographed him.”

“DE NIEVES’S STUDIO WAS EVERY BIT AS COLORFUL AS HE IS.”

ISABELLE WENZEL Photographer

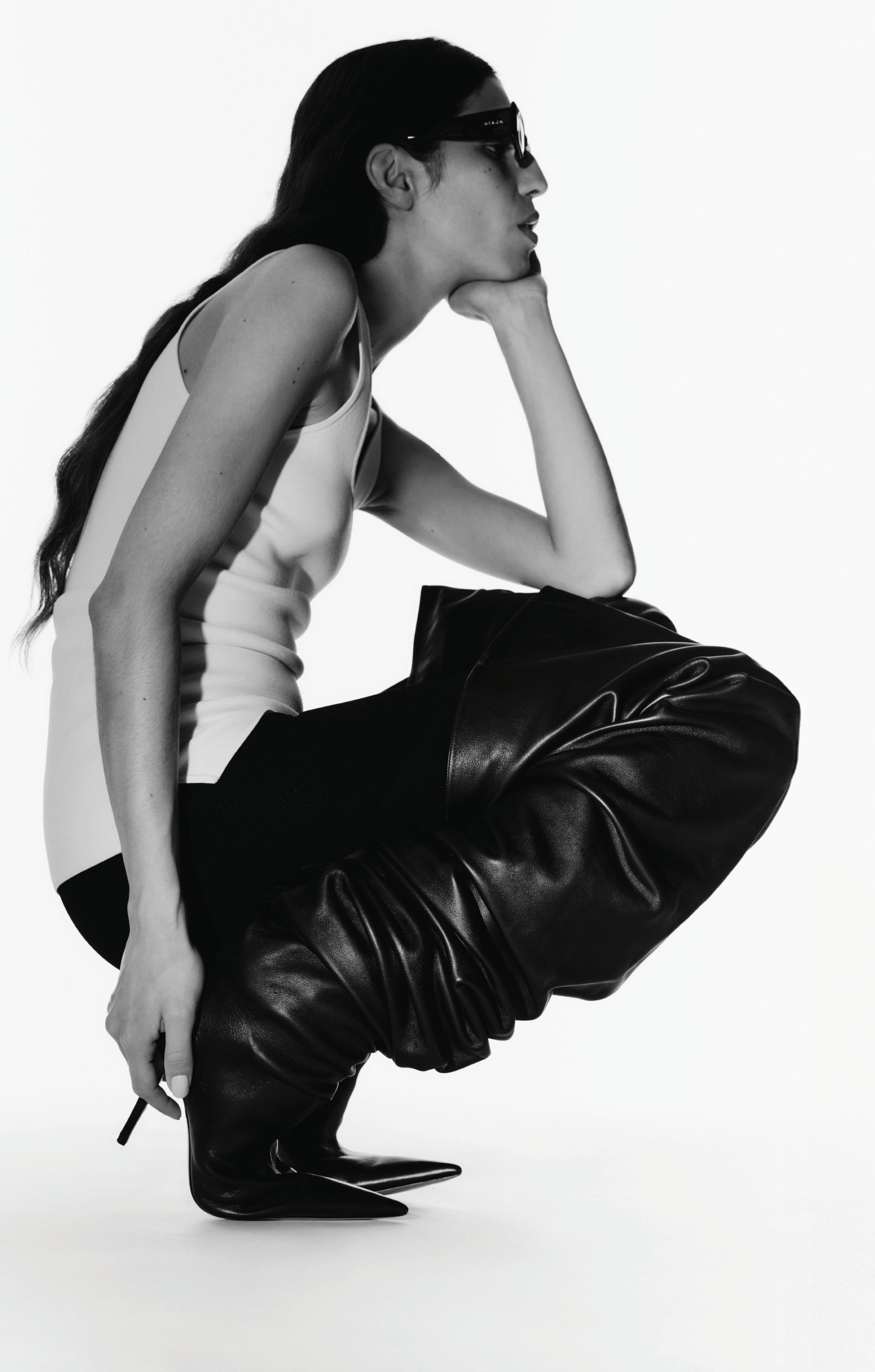

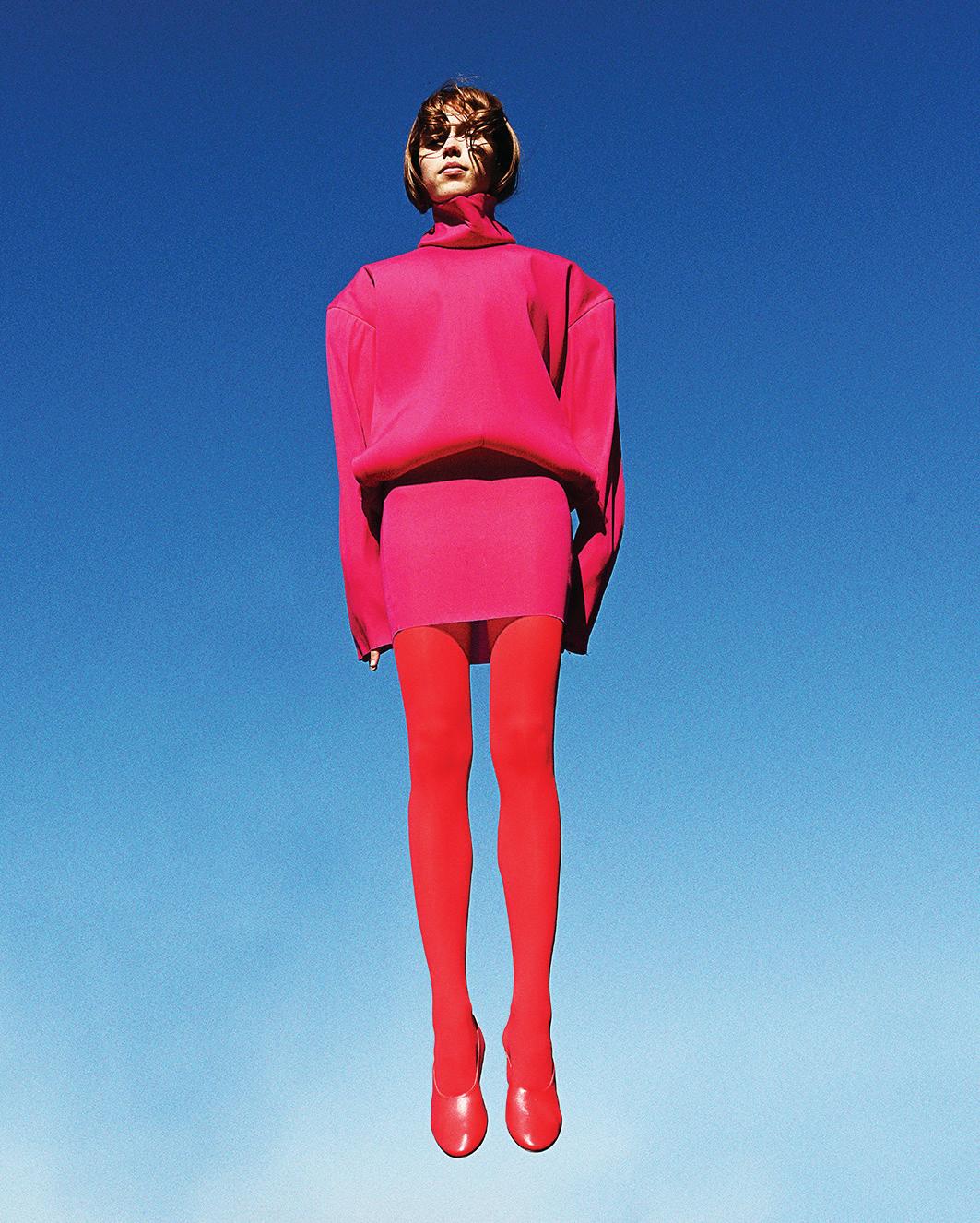

Wuppertal, Germany–based Isabelle Wenzel is one of fashion’s least predictable image-makers. An acrobat by trade, the photographer is as comfortable capturing models in motion as in repose. “It’s more like a study of physical expression paired with beauty. I often feel more like a movement director who happens to press the shutter at just the right moment,” she says. Her work has been exhibited everywhere from Copenhagen to Miami, but for this issue, she traveled to the countryside outside London to shoot the latest

from houses including Prada, Balenciaga, and Loewe. “[We played] with the idea of overcoming gravity, which, of course, is an absurd endeavor on planet Earth. Yet the struggle against it gave rise to images full of power and fluidity.”

“WE PLAYED WITH THE IDEA OF OVERCOMING GRAVITY, WHICH, OF COURSE, IS AN ABSURD ENDEAVOR ON PLANET EARTH. YET THE STRUGGLE AGAINST IT GAVE RISE TO IMAGES FULL OF POWER AND FLUIDITY.”

ZITO MADU

Writer

“As a writer and former athlete, I believe that on an existential level, athletes are chasing the same goal as writers and artists,” says Zito Madu, “the possibility of creating a masterpiece that captures and embodies one’s full self.” For this issue, the Nigerian-American writer explores the continuity of his own career—how the drive of one pursuit carried into the next. Madu is the author of the surrealist memoir The Minotaur at Calle Lanza, a finalist of the National Book Critics Circle award for Autobiography in 2024, and a regular contributor to CULTURED’s Critics’ Table, where he traverses New York in search of the next great show.

“AS A WRITER AND FORMER ATHLETE, I BELIEVE THAT ON AN EXISTENTIAL LEVEL, ATHLETES ARE CHASING THE SAME GOAL AS WRITERS AND ARTISTS.”

MARA VEITCH Executive Editor

JOHN VINCLER Co-Chief Art Critic and Consulting Editor

ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT Senior Editor

SOPHIA COHEN Arts Editor-at-Large

JACOBA URIST New York Arts Editor

KAREN WONG Contributing Architecture Editor

SAM FALB Design Editor-at-Large

ALEXANDRA CRONAN

KATE FOLEY Fashion Directors-at-Large

GEORGINA COHEN European Contributor

KRISTIN CORPUZ Social Media Editor

PALOMA BAYGUAL Digital and Marketing Coordinator

CAT DAWSON

DEVAN DÍAZ

ADAM ELI

ARTHUR LUBOW

HARMONY HOLIDAY

LAURA MAY TODD

EMMA LEIGH MACDONALD

LIANA SATENSTEIN Writers-at-Large

DOMINIQUE CLAYTON

JOHN ORTVED

YASHUA SIMMONS Contributing Editors

SARAH G. HARRELSON Founder, Editor-in-Chief

JULIA HALPERIN Editor-at-Large

JOHANNA FATEMAN Co-Chief Art Critic and Commissioning Editor

ALI PEW Fashion Editor-at-Large

EMILY DOUGHERTY Beauty Editor

MINA STONE Food Editor

JASON BOLDEN Style Editor-at-Large

SOPHIE LEE Assistant Editor

TOM SEYMOUR London Correspondent

EMMELINE CLEIN Books Editor

EVELINE CHAO Senior Copy Editor

ROXY SORKIN Lifestyle Columnist

SIMON RENGGLI CHAD POWELL Art Directors

HANNAH TACHER Junior Art Director

ORIANA REN Junior Designer

CAROL SMITH Strategic Advisor

AHIMSA LLAMADO

LAYLA HUSSEIN

NATALIA BADGER Social Interns

CARL KIESEL

Vice President, Chief Revenue Officer

LORI WARRINER

Vice President of Sales, Art + Fashion

DESMOND SMALLEY Director of Brand Partnerships

HAILEY POWERS Marketing and Sales Associate

SAMAH DADA Culinary Columnist

ETHAN ELKINS

DADA GOLDBERG Public Relations

PRIYA NAT Sales Consultant, Home + Travel

PETE JACATY & ASSOCIATES Prepress/Print Production

BERT MOO-YOUNG Senior Photo Retoucher

JOSÉ A. ALVARADO JR.

SEAN DAVIDSON

SOPHIE ELGORT

ADAM FRIEDLANDER

JULIE GOLDSTONE

WILLIAM JESS LAIRD

GILLIAN LAUB

JEREMY LIEBMAN

YOSHIHIRO MAKINO

LEE MARY MANNING

BJÖRN WALLANDER

BRAD TORCHIA

Contributing Photographers

EVA BIANCHINI

GIULIANA BRIDA

KARLY QUADROS

MARK MANKARIOUS

SAVANNA CHADA

Editorial Interns

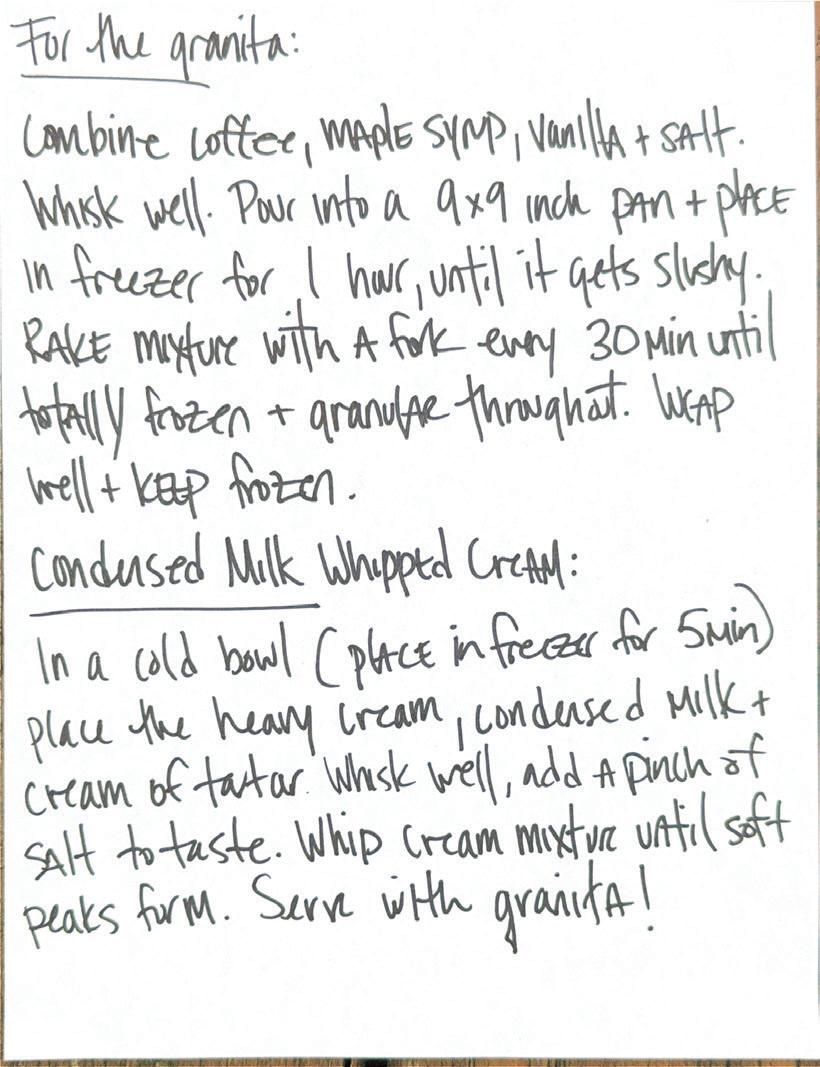

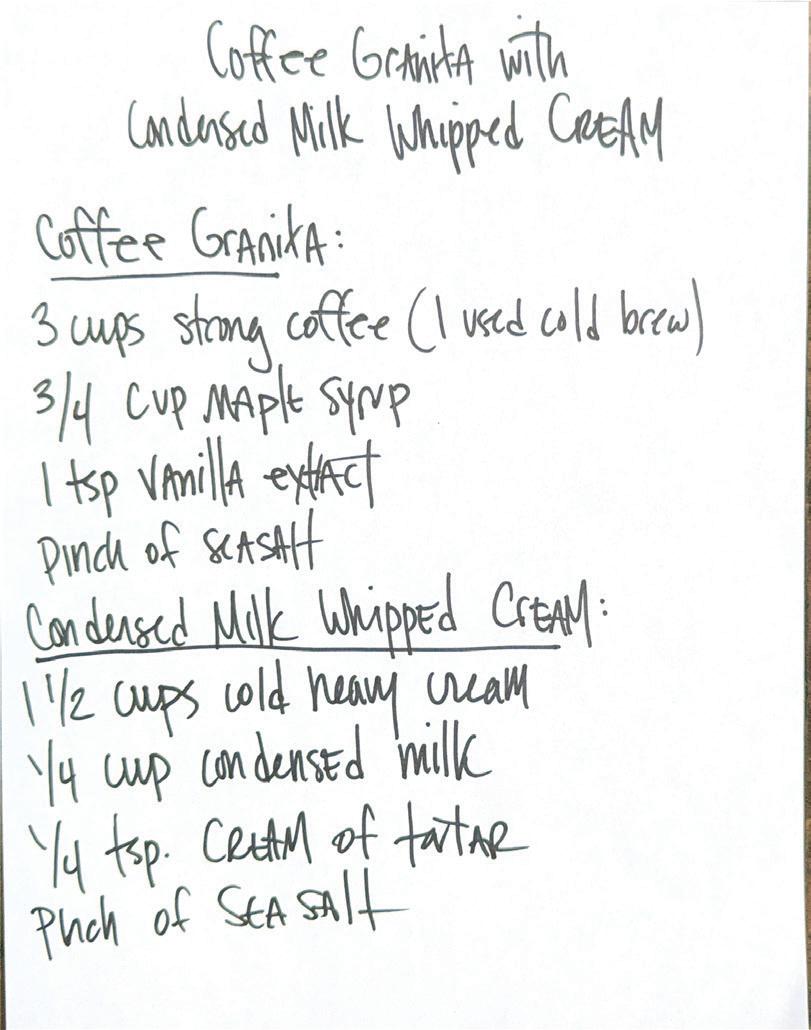

This celebratory twist on iced coffee is the perfect accompaniment to a frenzied September afternoon.

Inspired by the back-to-school spirit of September in New York, this granita is a riff on the iced coffee that keeps most of us going throughout the day. The recipe is as simple as it gets: Freeze a mix of coffee, maple syrup, and vanilla; scrape it into a slushy consistency; and top it with condensed milk whipped cream, a nod to Vietnamese coffee that lends the dish a cloud-like creaminess. When our schedules kick into high gear, what’s better than an energizing treat you can enjoy for both breakfast and dessert? —Mina Stone

Unpredictable

By ADAM ELI

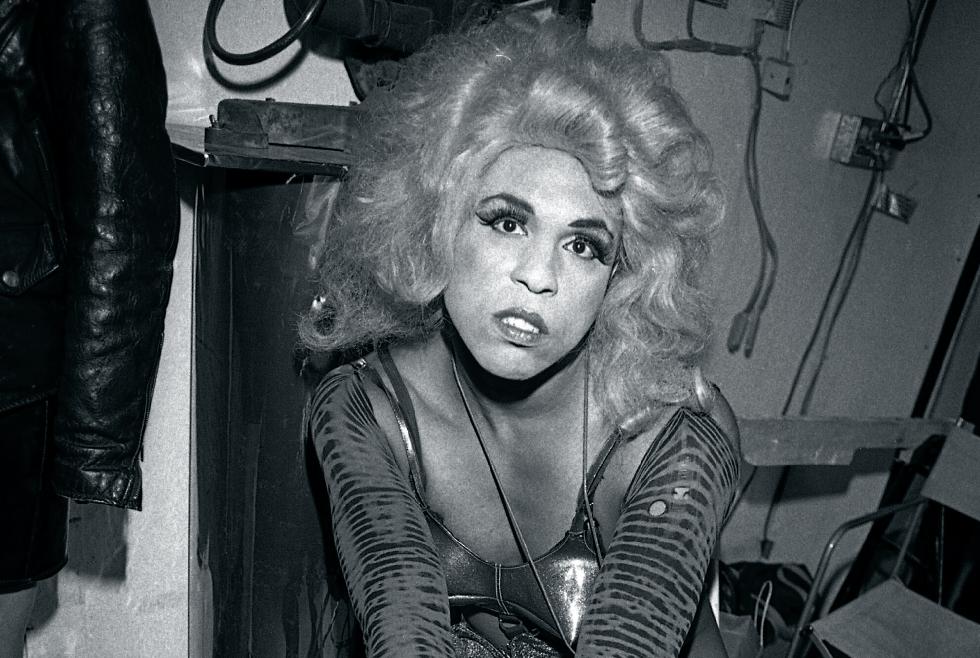

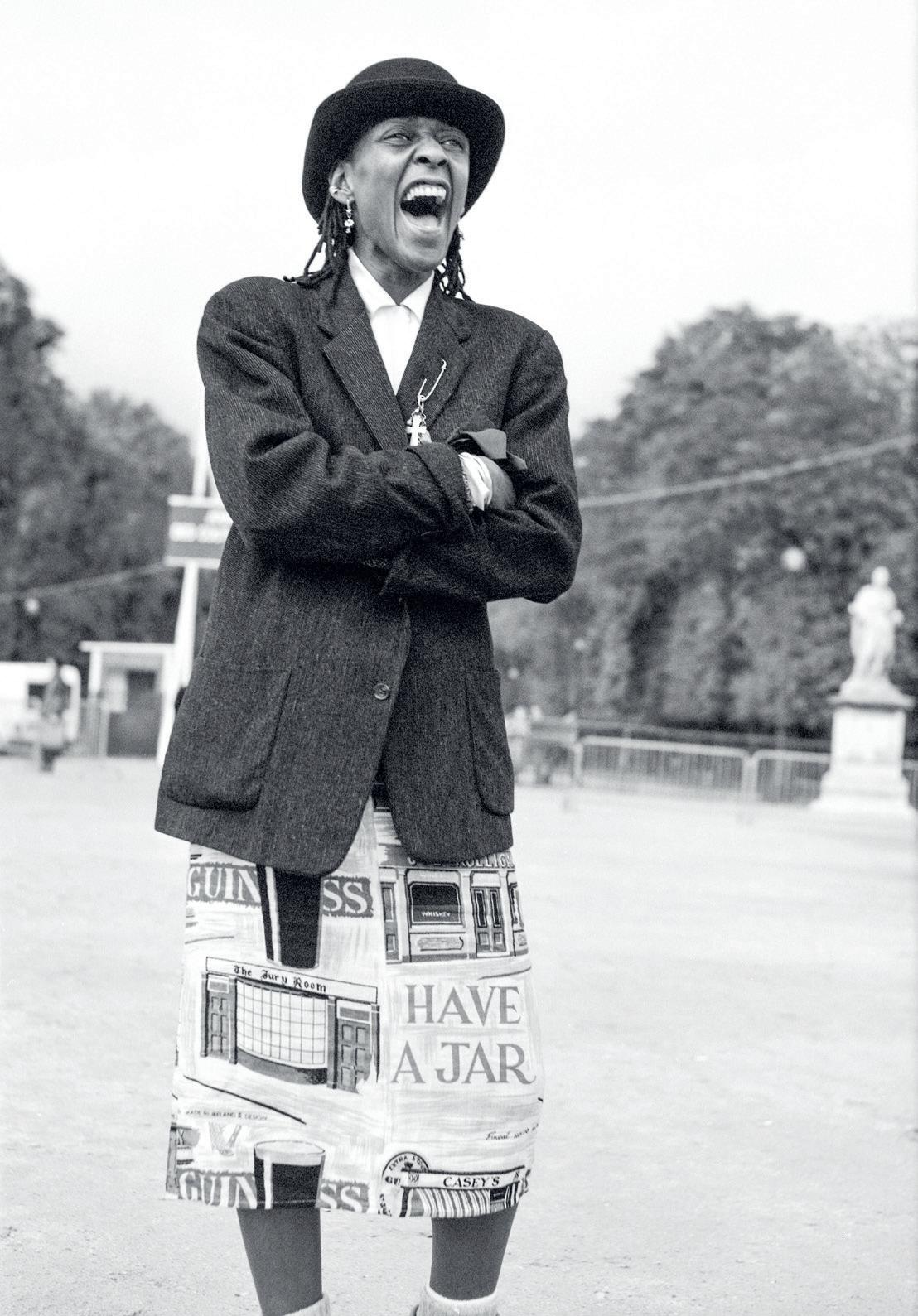

A godmother to the worlds of drag, queercore, zine publishing, house galleries—what hasn’t Vaginal Davis touched? A new show at MoMA PS1 traces her extraordinary life in art.

A muse to Pina Bausch, a confidante to Rick Owens, a case study for José Esteban Muñoz: Vaginal Davis is the blueprint. The categoryallergic artist and musician’s taste for the stage was jumpstarted by the rendition of Mozart’s The Magic Flute she saw in South Central LA when she was only 7; she has reigned as the Queen of the Night over an abundance of scenes—drag, queercore, experimental film, and fine art among them—ever since. This fall, a survey spanning five decades of Davis’s contributions to these fields and beyond is landing at MoMA PS1 in New York. Ahead of its opening Oct. 9, I called up the artist, who currently lives in Berlin, to talk legacy, therapy, and mortality.

Were you born a performer, or did you become one?

I’ve been performing since I was a child, and I think I turned myself into a performer because

being shy and reserved just wasn’t going to fly. People think performers are extroverts, but I’m an introvert. I have to turn into this other thing to get almost anything done. If you peel back all the layers—if there is a “real me,” because after so many years you just become a construct—the real me is shy and sort of dorky.

What is the construct of Vaginal Davis?

It’s hard to articulate because there’s no clear line between the private person and the public persona. That happens with a lot of performers, writers, artists, especially people in entertainment. Everything gets blurred. That’s why I’m in therapy—once a week, sometimes twice. I’m a mess-tacle, a big mess plus a spectacle. When you’re a mess-tacle, you need someone outside your realm to bounce things off of. Reflecting on my life, I see mortality differently. I never thought I’d live to be 64,

“I think I turned myself into a performer because being shy and reserved just wasn’t going to fly.”

especially with the AIDS pandemic that took so many from my generation. The goddesses laid out a path for me, and you accept your lot in life and move on.

Based on the extraordinary nature and scope of this show, which spans so many mediums and so much time, what do you hope the legacy of Vaginal Davis is?

People were always accusing me of being artsyfartsy, even as a child. I was just doing what felt organic to me, not thinking of it as a body of work. I’d do something, move on, never look back. I wasn’t a good archivist. Luckily, other people saw value in what I did because I rarely kept copies. Growing up poor, in a non-academic family—I was the only one who went to college—there wasn’t a careerist mindset. Today, most artists come from generational wealth or privilege; it’s rare for someone from my background to be recognized at all.

Jeff Briggs, a high school student back in the ’80s, kept a lot of things I produced that I didn’t. Through him, Moderna Museet was able to gather much of what became this exhibition. With all the moves, floods, and damaged apartments, it’s a miracle any of it survived. When Moderna first staged the show, I never thought it would travel. It was a shock to hear it would come to New York. If you’d told me this eight or nine years ago, I’d have laughed in your face. Things like this don’t happen to people like me. I guess that’s my legacy—it’s a patchwork that others saw value in, even when I didn’t.

Something I’ve heard you say many times before is, “You can’t change institutions from the inside; they always wind up changing you.” How have you approached these institutional collaborations?

I really believe that they’ll always change you. You have to make your “yes” mean yes and your “no” mean no. I follow the advice of the legendary Diana Vreeland: “There is elegance in refusal.” If something doesn’t feel right, I don’t do it.

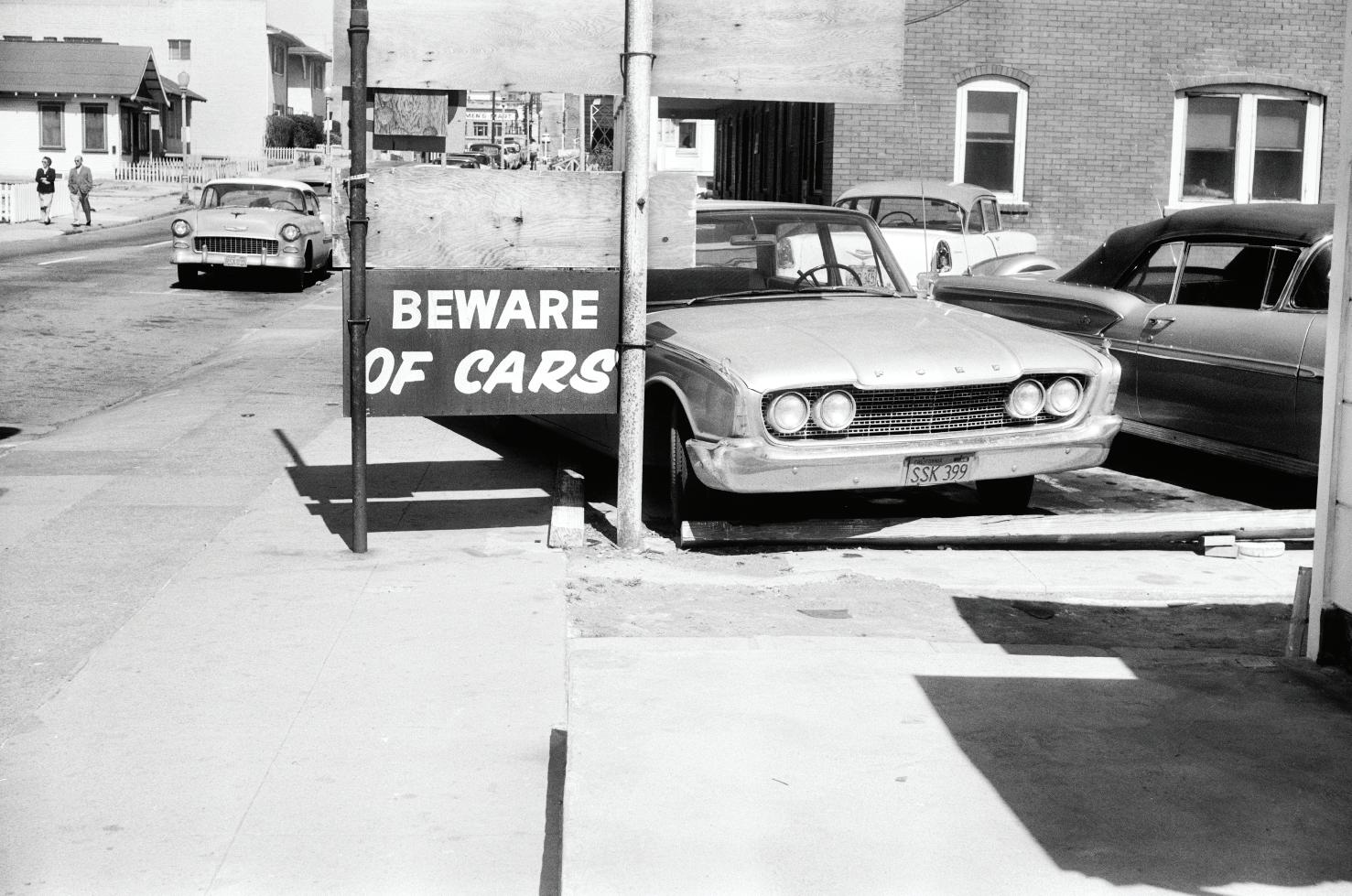

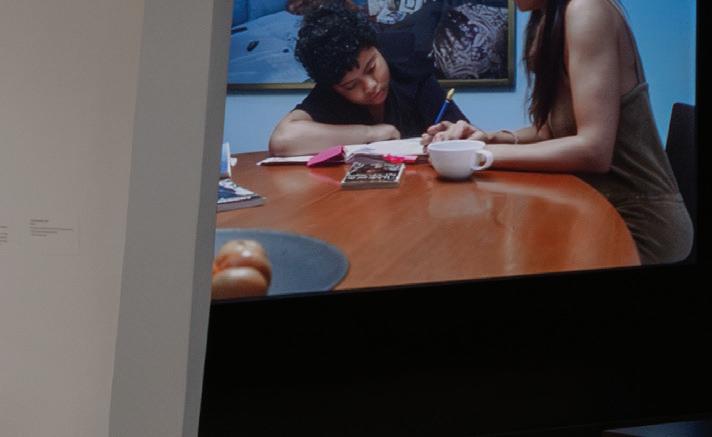

By JANELLE ZARA

For the seventh edition of “Made in L.A.,” the Hammer Museum’s biannual survey of art in the city, curators Essence Harden and Paulina Pobocha began with a list of more than 1,000 artists and what they fondly describe as “no ideas.” Foregoing a predetermined theme “was a way of not creating a limit before we started,” says Harden, an independent curator who cut her teeth at the California African American Museum. Then, the duo set out to “visit as many studios as possible.”

Over roughly half a year, Harden and Pobocha, a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago and former senior curator of the Hammer, arrived at a slim list of 28 artists whose thematic connections emerged after the fact. The lineup includes people who fall outside the traditional

definition of an artist, like Hood Century’s Jerald Cooper, an online archivist of South LA’s modernist architecture, and Black House Radio’s Michael Donte, who will be programming DJs inside his installation at the museum. Fitting for America’s entertainment capital, there will be plenty of experimental filmmakers (among them Bruce Yonemoto, Na Mira, and Mike Stoltz), as well as four episodes of Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff’s 2024 metafictional documentary series THEATER. The show will also include choreography by Will Rawls, ceramics by Alake Shilling and Brian Rochefort, and installations by Gabriela Ruiz and Patrick Martinez.

Throughout the development of the show, as Los Angeles weathered the ongoing turbulence

of wildfire and military invasion, Harden and Pobocha realized that any attempt to respond to these rapidly evolving conditions would always feel incomplete. “Real life—material, physical, psychic reality—is changing every day,” says Harden. Instead, she and Pobocha ultimately focused on LA as a discursive site that has shaped the work of a wide range of artists. There is car culture’s influence on Pat O’Neill and Carl Cheng’s sculptures and the unmistakable Southern California light gracing Greg Breda’s portraits. Spanning generations and media, the connective thread among this eclectic group is their enduring engagement with the constantly evolving history, economy, and landscape of LA.

‘What

By EVA BIANCHINI

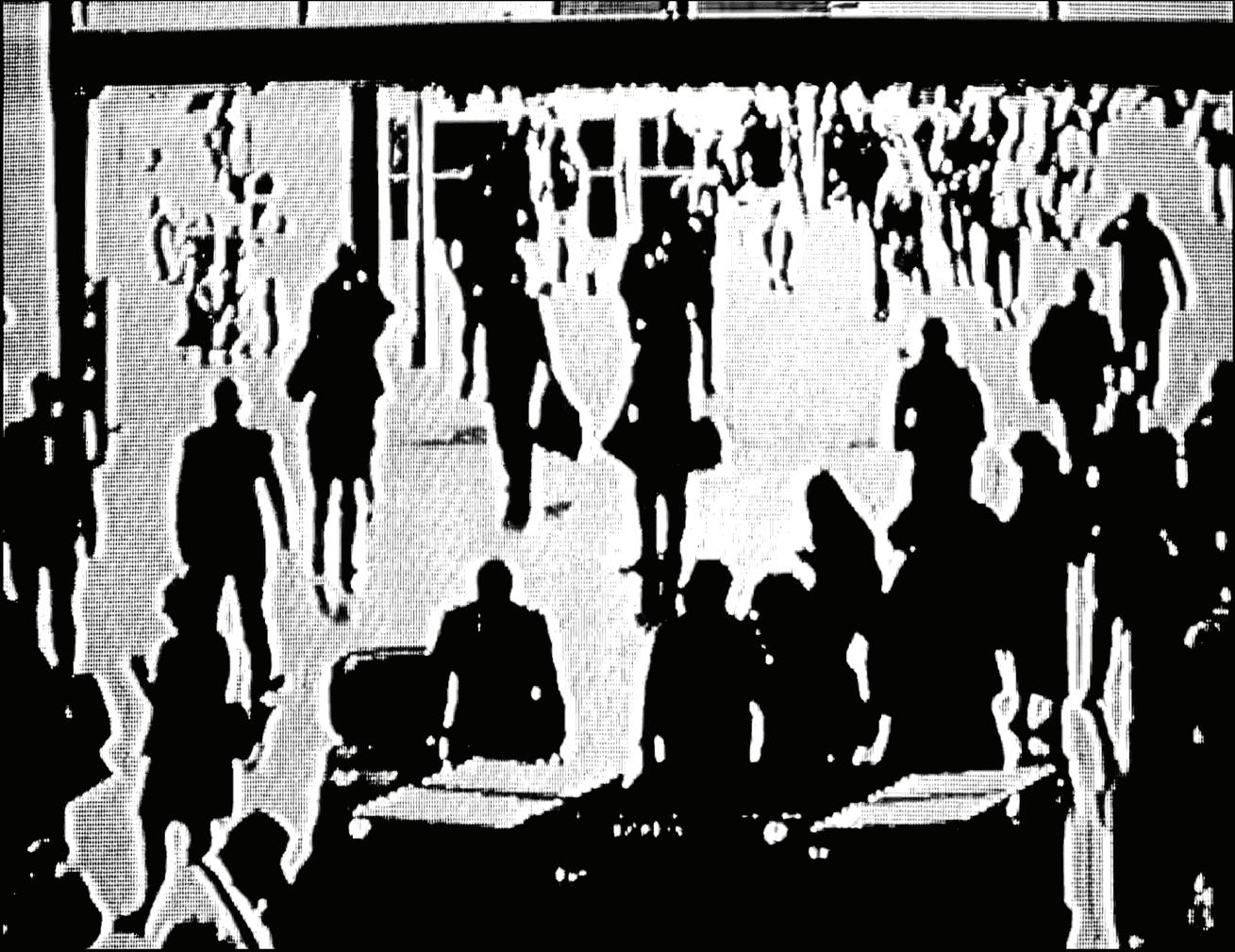

What we deem authentic or true has never been more in flux. For its 15th anniversary, the Istanbul International Arts and Culture Festival returns with a referendum on the question.

Since 2010, curator Demet Müftüoğlu-Eşeli and filmmaker Alphan Eşeli—cofounders of the Istanbul International Arts and Culture Festival—have sparked rich multidisciplinary dialogues focused on the intersections among the arts. For three days in October, the festival convenes creative minds from the film, technology, photography, literary, and art worlds for a series of panels, screenings, workshops, and exhibitions. This year’s theme, “What Is Really Real?” explores the most pressing subject of our time: the slippery premise of reality in our digitally mediated world. Müftüoğlu-Eşeli and Eşeli sat down with artist José Parlá, a festival board member and frequent collaborator of the organization, to reflect on the weight of truth today.

The theme of this year’s festival is “What Is Really Real?” Why is it so critical to interrogate

the fault lines between the authentic and the artificial?

Alphan Eşeli: The subjectivity of reality has always been with us; it’s woven into human nature. We’re moving quickly toward a moment when “artificial” will no longer be synonymous with “inauthentic.” Immediacy, convenience, and the promise of precision are seductive. Our job is to track where things come from and keep our judgment intact as this integration deepens.

Demet Müftüoğlu-Eşeli: The theme is an invitation to pause, question, and reconnect with a sense of wonder, that feeling of being grounded in the world and invited to see it differently.

José Parlá: It has always been important to question what we consider reality, and authenticity. We must examine not only the

obvious fabrications but also the subtler energies and intentions in the people, environments, and information we surround ourselves with.

José, have these questions of reality versus illusion impacted your artistic practice?

Alphan, your filmmaking?

Parlá: Everything I experience finds its way into my paintings and my creative work, and this became especially true after waking from a four-month coma during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. The dreams I had in that state registered as real memories, leaving me to navigate the blurred line between those dreams and the shared reality of this dimension. My “CICLOS” series delved into this period of recovery—exploring memory, dreams as reality, and the translation of physicality and movement through painting.

Eşeli: It has always had a huge impact on my work. In every film, my characters encounter events through their own subjectivity; what happens matters less than what it means to them. I’m drawn to ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, because pressure clarifies; the more extreme the situation, the deeper the search for what’s real.

What has the festival meant to you over these past 15 years?

Eşeli: It’s taught me to trust audiences, listen harder, and meet different views with curiosity. For me, it has always been a renewal.

Müftüoğlu-Eşeli: It’s been a love letter to Istanbul and a cultural bridge to the world. The festival has been described as turning the city of Istanbul into a “living laboratory.”

What does this phrase mean to you?

Müftüoğlu-Eşeli: The city becomes our playground. For three days, Istanbul transforms into an open, ever-evolving space where boundaries between disciplines dissolve—where a filmmaker might find themselves in dialogue with a fashion designer, or a world-renowned musician might collaborate with an up-and-coming talent. We experiment not only with artistic formats but with how people encounter and interact with art and with each other. That’s why we choose to realize our main exhibition in a neighborhood setting, integrating it into the city’s daily rhythms.

By ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

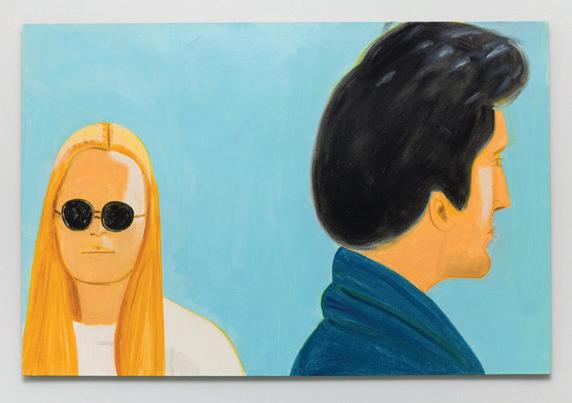

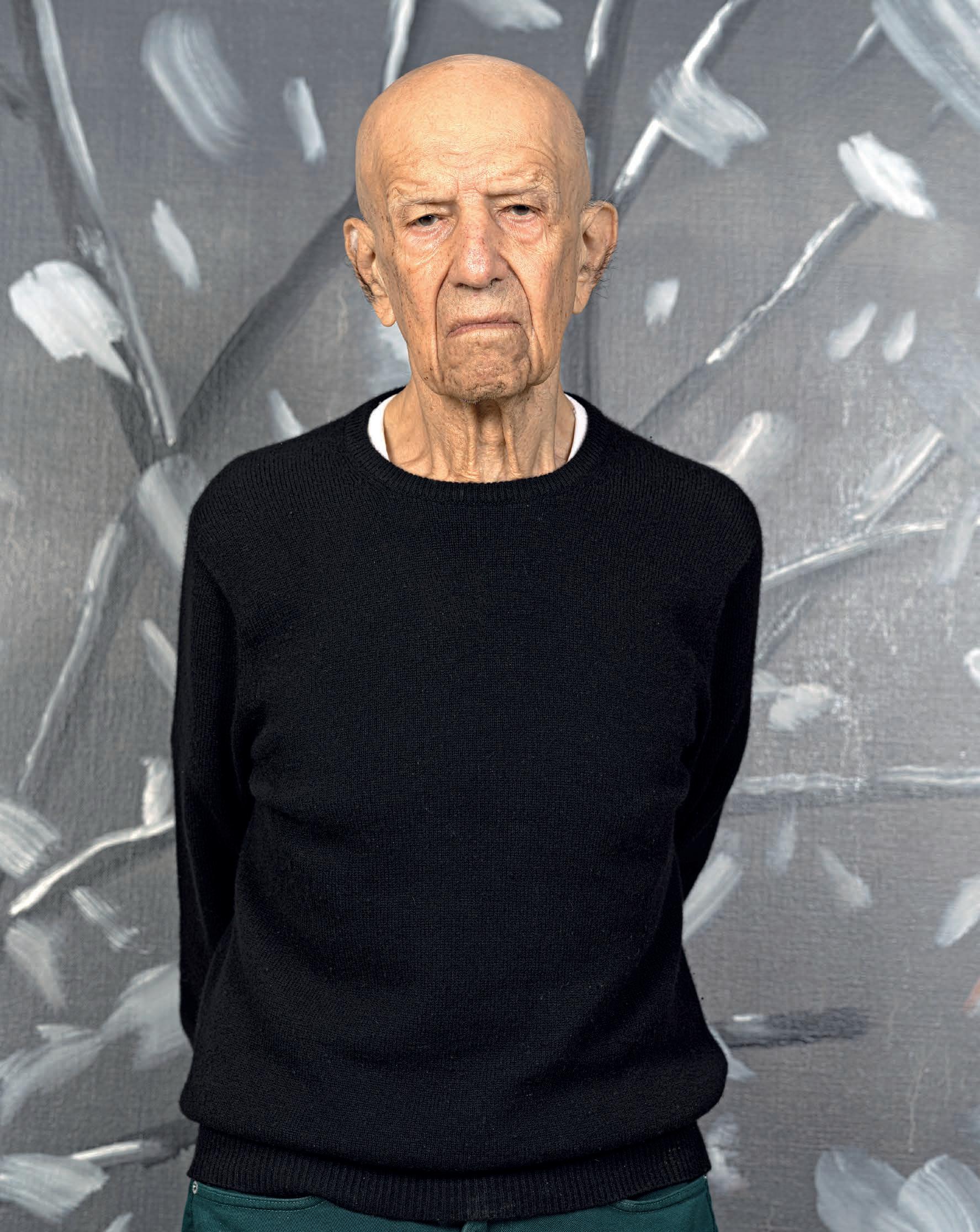

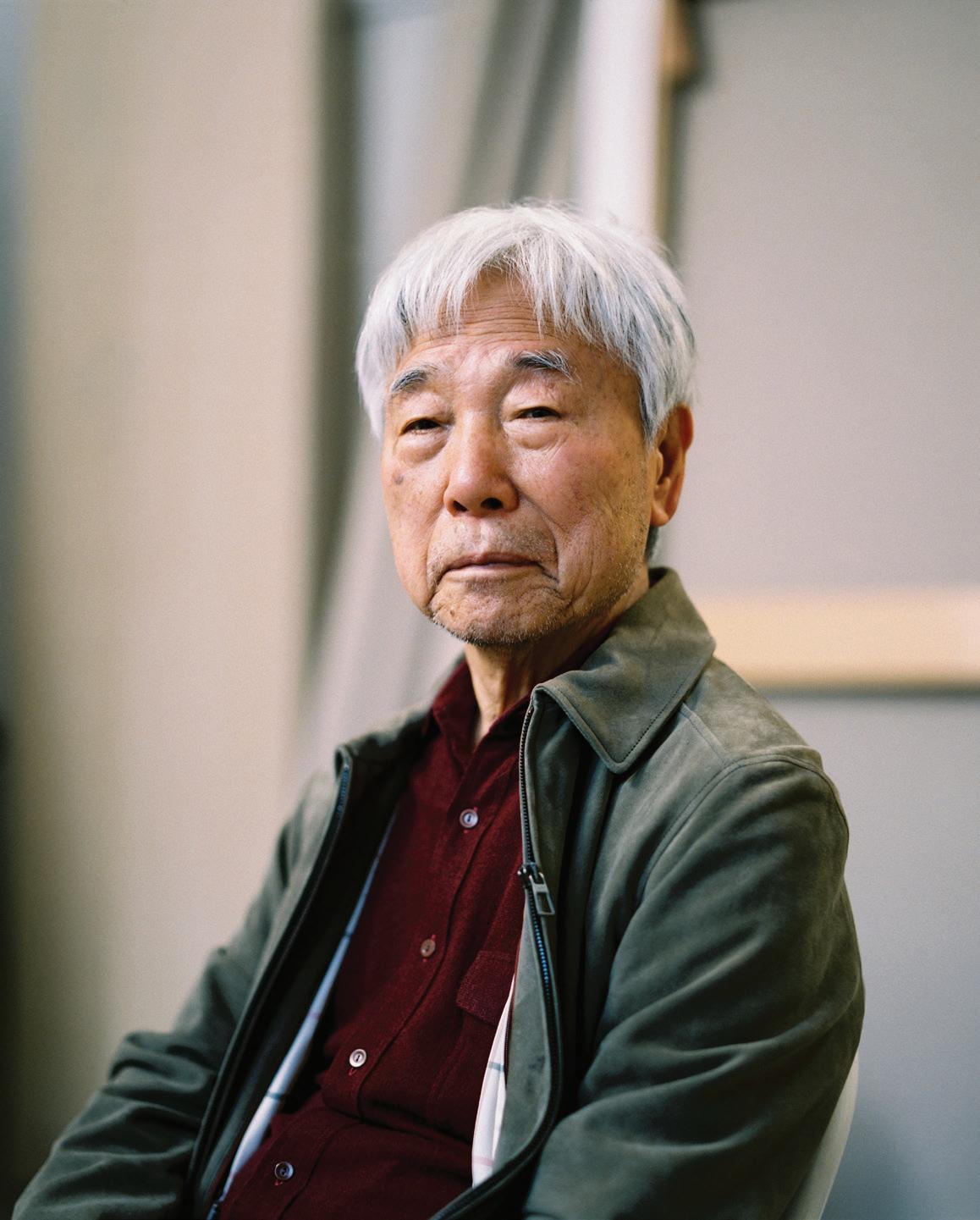

Seven decades into his practice, Alex Katz is proving that 98 is as good a time as any to be prolific.

Alex Katz has never been one to assign narrative to his work. The artist has committed a wide range of characters to the canvas over his seven-decade career: his wife of 67 years, New York’s beau monde, modern dancers, even idling vacationers. But he’s always opted for style over story, preferring to dwell on the crease of a garment or glare of sunglasses rather than the portent of an expression or the personal life of a subject.

It is perhaps this interest in the surfaces of existence that drew him to The White Lotus (at least for part of an episode), the television series that lends its name to his latest show. On view at Gray Chicago through Sept. 20, the body of work has indeed only a superficial connection to Mike White’s biting anthology; its blown-up faces and cool glances originated on a beach in Maine, where Katz has had a home since 1954, by way of Antonioni’s L’Avventura. Other cinematic paintings of the artist’s are on view at SCAI Piramide in Tokyo and San Diego’s Museum of Contemporary Art, and Gladstone Gallery will dedicate an exhibition to a suite of his orange abstractions, the first of which were shown in a duo show with Matthew Barney at O’Flaherty’s in 2024, this fall. In the midst of it all, CULTURED checked in with the towering figure in American art to see what his studio practice looks like these days.

You’ve made a career out of portraying people and landscapes associated with leisure and contemplation. In a world that feels increasingly hostile, stratified, and dispiriting, have you ever considered turning to other subject matter? I paint for my temperament. I couldn’t paint from Pollock’s or de Kooning’s temperament. You relate to different things, and they relate to you. When I saw a Veronese at the Louvre, I could relate to the power and the proficiency of the painting, and the solidity, which Pollock and de Kooning don’t have. The

Goya in the Louvre has a tenderness I could relate to that they also lack.

What’s the first thing you do when you enter your studio? Look at what I’ve done.

What’s on your studio playlist? I like jazz, Miles Davis, and Bach’s St. Matthew Passion . I’ve been listening to Sonny Rollins’s The Complete Prestige Recordings this summer.

If you could have a studio visit with one artist, dead or alive, who would it be? Fra Angelico. He seems so sophisticated.

What’s the biggest studio mishap you’ve experienced? I was painting on a 12-by-30-foot painting, and I used the wrong jar of paint on the face! The face turned out pretty good with the wrong paint, so I continued to paint the painting.

Have you ever destroyed a work to make something new? I destroyed 1,000 paintings. I destroyed a painting once and much later I got a reproduction of it and repainted it. It turned out a little better than the original.

When was the last time you felt jealous of another artist? I don’t think I’ve ever felt jealous of another artist. At certain times, other artists seem better than I am, but I’ve never felt jealous.

Have you ever wanted to give up on being an artist? Why didn’t you? When I was around 30, I hit bottom. My mother told me, “You’re either an artist or a phony. Your personal life doesn’t matter.”

What’s the most exciting thing about being an artist today? I have proven that I was right. And the people who disliked me or wouldn’t talk to me or gave me bad reviews were wrong.

“When I was around 30, I hit bottom. My mother told me, ‘You’re either an artist or a phony. Your personal life doesn’t matter.’”

“I paint for my temperament. I couldn’t paint from Pollock’s or de Kooning’s temperament.”

By SOPHIE LEE

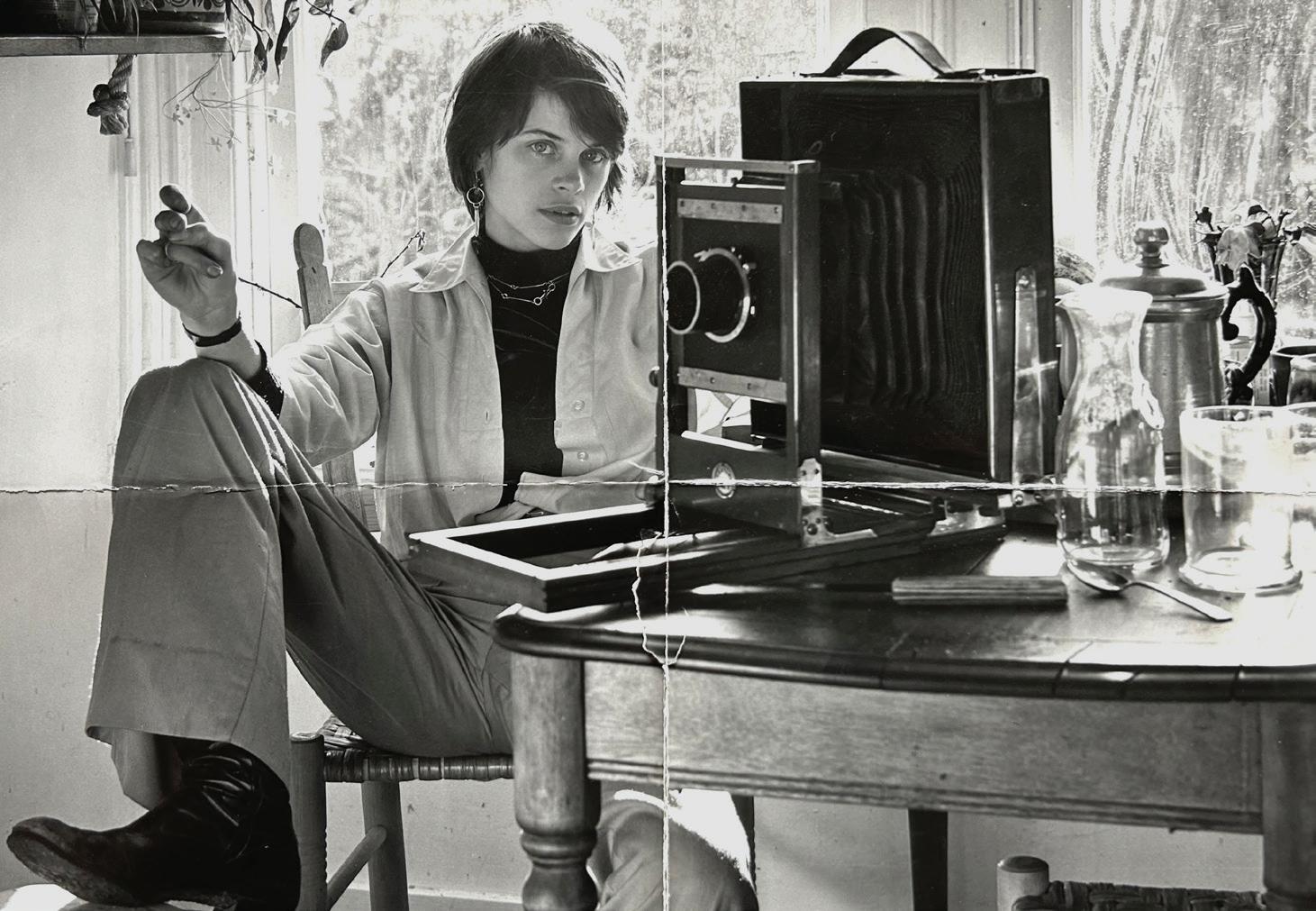

Countless artists have committed their practice to paper with memoirs, but we guarantee that few are keeping it as real as the 74-year-old photographer.

The title of photographer Sally Mann’s new book is revealing on two fronts. Art Work is, of course, what the celebrated creative produces. In 2001, she was named “America’s Best Photographer” by Time, and her intimate, unflinching images are held everywhere from the Met to the Victoria and Albert Museum. But, as Mann, 74, clearly outlines in this follow-up to her National Book Award finalist, the memoir Hold Still, making art is also a lot of work. Between scans of journal entries and outtakes, Mann parses through her career highs and lows, offering lessons learned along the way. Here, she shares what she hopes the next generation will read into her unsparing account.

You’re reflecting on a career and sharing advice that you’ve picked up over the years. What does it feel like to reach that period?

“You

You mean what does it feel like to be an old woman?

Accomplished and introspective!

It’s one of those double-edged swords. You only get to be accomplished and successful at the end of your career. So you spend your whole life desperate for this moment, and then it’s vanishingly short. Once you’re there, all you have left to do is die, really. Just statistically—I’m in the peak of health. I’m probably in better shape now than I’ve ever been in my life. I feel pretty confident now.

There’s a line in the book about having this urge to make a career of shattering norms. Is there an art-world norm you’re interested in shattering?

only get to be accomplished and successful at the end of your career. So you spend your whole life desperate for this moment, and then it’s vanishingly short.”

I still subscribe to the idea of the purity of the art world. I always think of art as somehow above commercialism. Art and commerce are now inextricably melded, so I’m just adjusting to that. I’ve never done commercial work because of that whole rarefied, Olympian idea of art. I guess the celebrity aspect of the art world has never been exactly my ambition. It’s not something I particularly enjoy. I’ve seen it ’cause I’m with Gagosian, so you can’t miss the art-world celebrities who keep the door open. But I’m just a natural recluse.

Is there something that you think up-andcoming creatives get wrong about what it’s like to be an artist?

I do think there’s a hazard in instant success, and that happens a lot these days. There’s so many people who had this shockingly fast rise into whatever their field is who then just fizzle out. You never hear from ’em again.

Is it an uncomfortable period, that middle stage of your career where you’re not on the way up but you’re also not doing retrospectives?

It is uncomfortable ’cause when you’re young, you’re full of hope and ambition and confidence. Then you get to a certain level, let’s just call it a plateau. You just have to grind it out and look for the next little moment of ascendancy where you can move to the next level. If you don’t move to the next level, you’re fucked. At my stage in a career, there’s a risk there too, because if you have a reputation and you’ve done well and you’re successful, people are more likely to forgive mediocre work because you’re famous.

Cy Twombly, he did all that really exciting work. And then there was a plateau. America didn’t cotton to his work. They rejected it. He got really humiliating reviews. People don’t write about it now, but my father saved them, and I have a little folder of terrible reviews of Cy Twombly’s work. Then he has this burst of great work at the very end. He’s breaking new ground. It’s full of energy and exciting. If I can be like Cy when I’m in my 80s, I’ll feel like I’ve lived my life correctly as an artist should. That’s his story, and I’m trying to follow in his gigantic footsteps.

Gagosian

456 North Camden Drive, Beverly Hills September 25 – November 1, 2025

By JULIA HALPERIN

Photography by JEFF FUSCO

Calder Gardens, a new cultural institution in Philadelphia dedicated to its native son

Alexander Calder, is not your typical single-artist museum. In

fact, it’s not a museum at all.

The first thing to know about Calder Gardens is that it is not a museum. The new $90 million Philadelphia cultural institution doesn’t have a collection, thematic exhibitions, or even wall labels. It consists of an 18,000-square-foot building designed by Herzog & de Meuron; a carefully landscaped-to-look-wild garden by High Line designer Piet Oudolf; and a rotating display of sculptures by Alexander Calder, a Philly native famous for creating the mobile.

Developed in partnership with local philanthropists including Joseph Neubauer and the nearby Barnes Foundation, which is offering operational support, Calder Gardens aims to create an art space that is not for learning or doing, but rather for thinking and feeling. Ahead of its Sept. 21 opening, CULTURED caught up with Alexander S.C. Rower, the Calder Foundation’s president (and grandson of the artist), and Juana Berrío, Calder Gardens’s senior director of programs, about what it takes to build a new kind of cultural experience from the ground up.

Where did the idea for Calder Gardens come from?

Alexander

up and said, “I want to do a Calder Museum in Philadelphia, in his hometown.” I said, “I’m not interested in doing a museum, but I would do something else.” Calder Gardens is an experiment.

What does that look like in practice? What parts of the conventional museum world did you move away from?

Juana Berrío: We’re prioritizing storytelling rather than scholarship. I’m thinking about these meditation, mindfulness, and contemplation practices that we’re going to include. We’re commissioning artists to do audio walks.

Rower: There isn’t a biography available. There aren’t titles and dates available. We don’t know how agitated people will be to not have wall labels. But it’s not about the artist’s experience. It’s about what could be your experience.

Berrío: It speaks so much about the present moment—how we are conditioned by elements in our culture that tell us you cannot do things on your own. You cannot go from point A to point B without Google Maps. You cannot learn something if someone is not teaching you. We want to make sure that people feel

that they can find their own tools within themselves.

Berrío: I’m from Colombia, and more than 20 years ago, I had the chance to live in the forest on the Pacific Coast for several months. I noticed things about my body and my brain, like how you get attuned to particular sounds, how you isolate different things, how you respond to light. So that’s why I trust that we all have those tools.

Nature plays a key role in Calder Gardens. How does the landscape relate to Calder’s work?

Berrío: Every element—the works by Calder, the garden, the building—they’re all constantly moving and changing.

Rower: Calder was an ecologist. In the ’70s, when I was a little kid, I had these big discussions with my grandfather about the future of water, how water was a resource that we were losing track of. Piet Oudolf’s gardens are really specific in that they don’t just make an annual four-season revolution. They continue to evolve and step up, which is exactly what your experience with Calder’s art is [like].

“We don’t know how agitated people will be to not have wall labels. It’s not about the artist’s experience. It’s about what could be your experience.”

—Alexander S.C. Rower

By ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

After almost five decades spent examining the extraordinary lives of ordinary people, the writer takes a magnifying glass to her own existence with her first memoir.

“Writing is a really interesting mix of magic and routine, and you need the routine to be able to conjure the magic.”

“I had to really convince myself that there was any reason anyone would want to read this,” Susan Orlean says across the screen. “To suddenly be looking at myself, I felt like, Yeah, but so what? ”

The veteran journalist is speaking to me for the first in what will inevitably be a marathon of interviews ahead of the publication of her first memoir, Joyride , in October. You might accuse someone who’s been a New Yorker staff writer since 1992, seen two of her stories become cult films (Adaptation and Blue Crush , with Meryl Streep playing a fictionalized version of Orlean in the former), and witnessed many of her other contributions to the field of journalism cemented in the canon, of a little bit of false humility. But she’s also right: Many writers who dedicate their lives to documenting interesting people don’t have time to have interesting lives themselves, so why bother with memoir? Orlean, however, has grabbed life by the metaphorical horns, and Joyride revels as willfully in her personal ups and downs (be they romantic or professional) as the stories she spent the rest of her time reporting. Expect a frank account of someone watching her marriage disintegrate as her career takes off, rebounding in Bhutan of all places, and being won over with an exotic (as in exotic animal) Valentine’s Day surprise. Beyond these adventures of the heart and no shortage of reporting capers chronicled, I must say I felt the most engrossed when I read Orlean write about writing. She relates the agony and ecstasy of the perpetually new task with the pep of someone who committed to this path for life, not just a living, and knows she chose right. Her boundless enthusiasm, in a world that’s tired and cynical, is no small balm.

The logline of sorts for your new memoir Joyride is this quote: “The story of my life is the story of my stories.” Which of your stories feels particularly evocative to you at this moment?

“The American Man at Age Ten,” because in so many ways it embodies my interests and my principles as a writer. I was asked to do a celebrity profile of Macaulay Culkin [for Esquire], and I said, “I don’t think a profile of a 10-year-old actor is go be very meaningful.” I

asked to do this story of this ordinary boy. I wrote that story a million years ago [1992], but it resurfaced in the last year with the show Adolescence. There is new interest in the question of what exactly is happening to men. The boy I wrote about was not toxically masculine in any way, but the attention on young boys has become a preoccupation because of these issues of toxic masculinity and incel mentality as embodied by the Trump administration—a certain kind of exaggerated, bullying masculinity. Where does this sense of bravado and dominance emerge? Ten happens to be an age that’s extremely formative.

Your reporting has taken you into pretty extreme situations over the years. What does your everyday as a writer look like?

My office is a hundred feet from my house and where I do all of my work. Writing is a really interesting mix of magic and routine, and you need the routine to be able to conjure the magic. My writing metabolism is pretty consistent. I usually start at about 11 a.m., and I try to write a 1,000 words a day. When I was a runner, I would say, “I’m gonna run five miles.” I did not run four and a half miles or four and three-quarters miles. Same with 1,000 words.

What’s your relationship to showing people your work, or reading other people’s work while you’re writing?

I rely very much on my husband [to read my work]. I can tell if he’s saying it’s not quite there. And if he says to me, “I love it,” I trust that as well. It used to be that I’d only show things to my editor when I thought they were literally ready to print. In the case of this memoir, because it’s a new form for me, I showed it to him when I was maybe a third or a quarter of the way done. I just needed to hear him say, “I get it. You’re doing it right. Don’t worry.” Depending on what I’m working on, besides what I’m reading for research, I do look at work that is analogous. That shows me how it’s done well. I have a couple of books that I keep at my left hand all the time, the same few books that, when I get stuck, I flip through.

One is Calvin Trillin’s book Killings . One is Ian Frazier’s book Great Plains The White Album by Joan Didion, of course. Then there are a

couple of journalism collections that have a bunch of really great stories—The Literary Journalists and Literary Journalism . I go back to the same books all the time. I practically don’t need to even open them anymore because these have been my guides for so long, but they’re always helpful.

The way that we write has changed so much since you came onto the scene—from the inescapability of email to the rise of Substack to how much we write about ourselves now.

It’s true that when I look back at the great writers that inspired me, they were present in their writing, but it was rarely about them. I have a Substack; I use it to write these little first-person essays. I never reject life moving forward. I’m not somebody who goes, “It used to be real journalism.” People’s appetites change—I’ve never found that frightening. But my commitment to the kinds of stories I want to do hasn’t changed. I feel like there is still an appetite to learn about the world and other people and other subcultures and circumstances and slices of forgotten history. It’s just not being practiced as much. And frankly, the number of magazines running those kinds of stories has shrunk enormously, as I’m sure the opportunity to publish those kinds of things has diminished.

In many ways, I am the transitional generation. When I came to The New Yorker, they barely had bylines. Nobody knew what a single writer at The New Yorker looked like. The bylines on the huge features were at the end of the story in tiny type. There was no index. There were no contributors’ notes. The New Yorker went out of its way more than any other magazine to shield the writers from any sort of public persona. I came to the magazine as that was slightly changing. In the beginning, I felt that there were people there that thought I must not be a good writer because I’m a little too public. I do think that kind of false backgrounding of the writer is a little exaggerated and pointless. Like, why shouldn’t you know who wrote the story? But now we’ve gone a bit overboard. I’m not that interested in seeing Writer X in a video talk about the thing that Writer X just wrote. I can just go read it.

By KARLY QUADROS

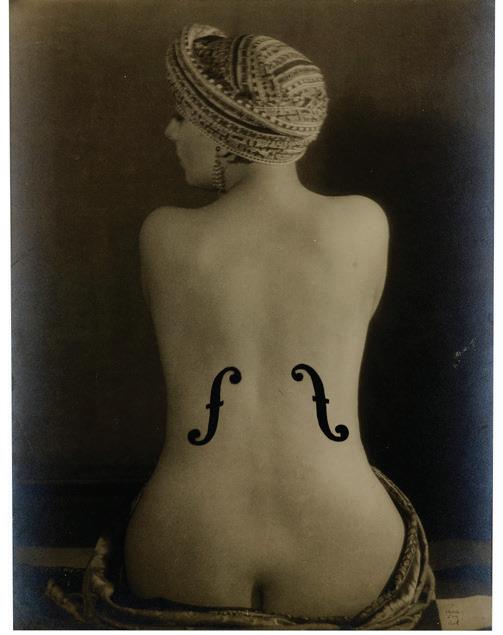

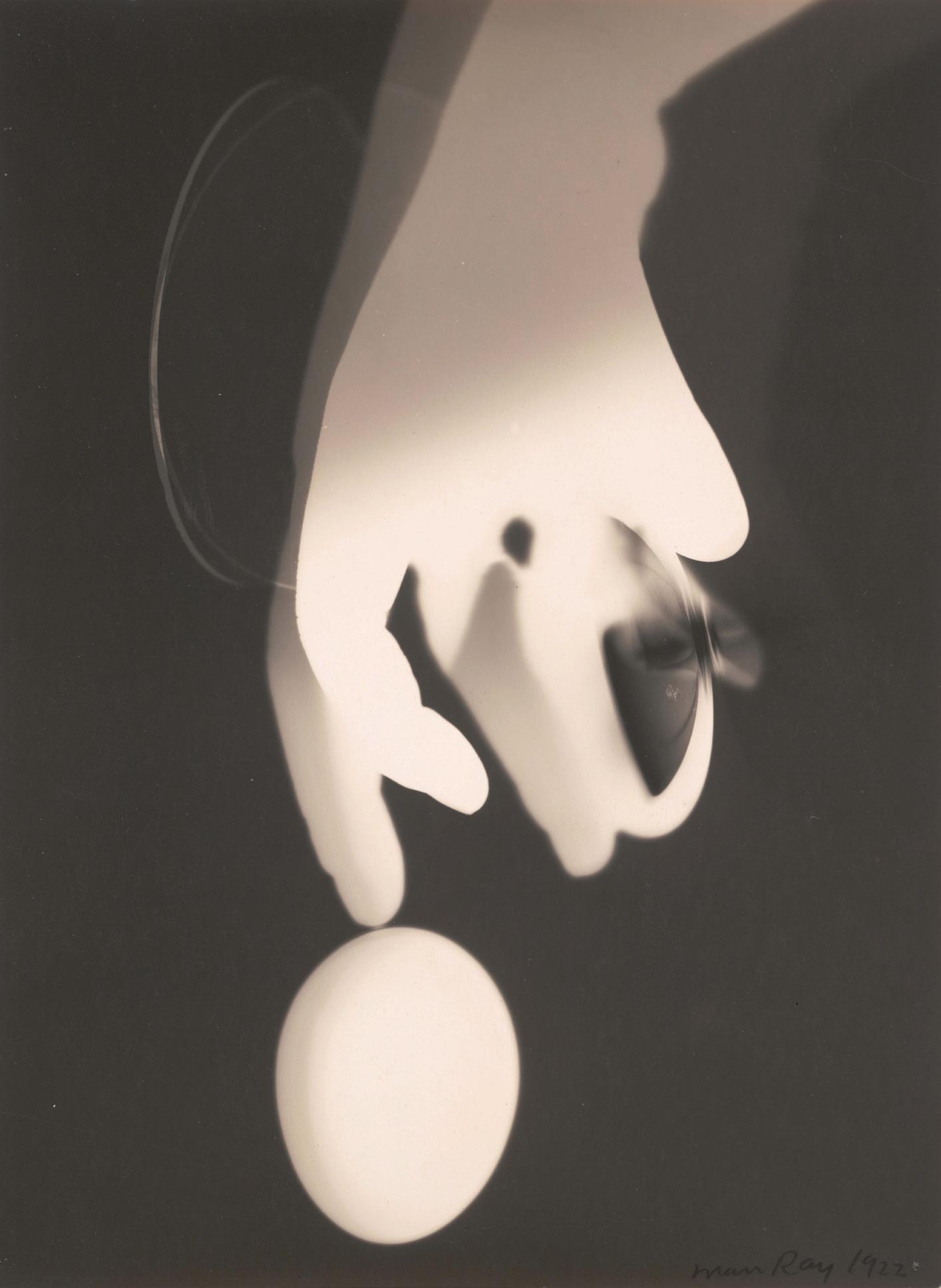

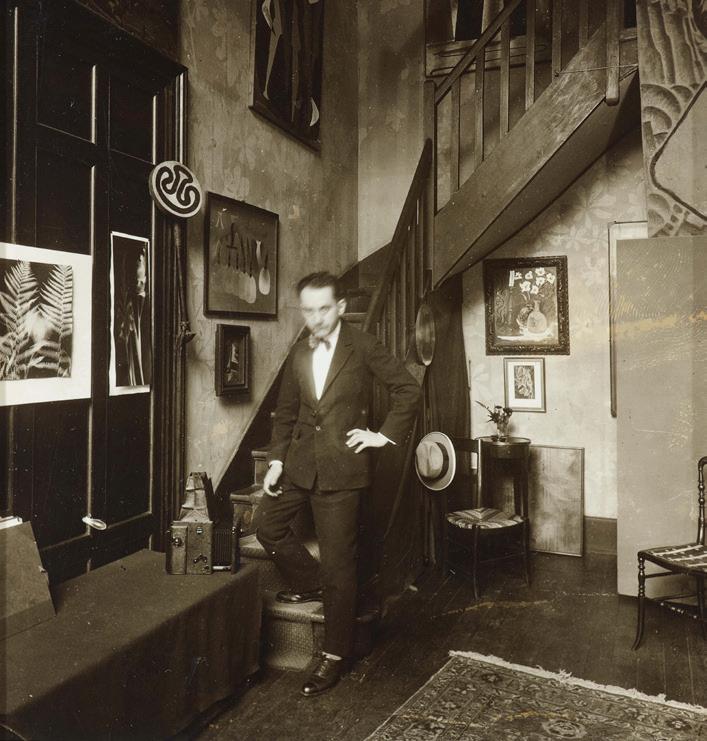

A late-night darkroom mishap by a young Man Ray—and the aesthetic revolution it provoked— is the focus of a new exhibition at the Met this fall.

In 1921, a young photographer in Paris accidentally created something new.

Working late in the darkroom one evening, Man Ray absentmindedly placed three glass tools— a thermometer, a cylinder, and a funnel—on top of an unexposed sheet of photo paper. Before his eyes, silhouettes began to form. The resulting image was sharp and spectral; the poet Tristan Tzara described it as capturing the moment “when objects dream.” Ray named his cameraless creation after himself, and with that, “rayographs” were born.

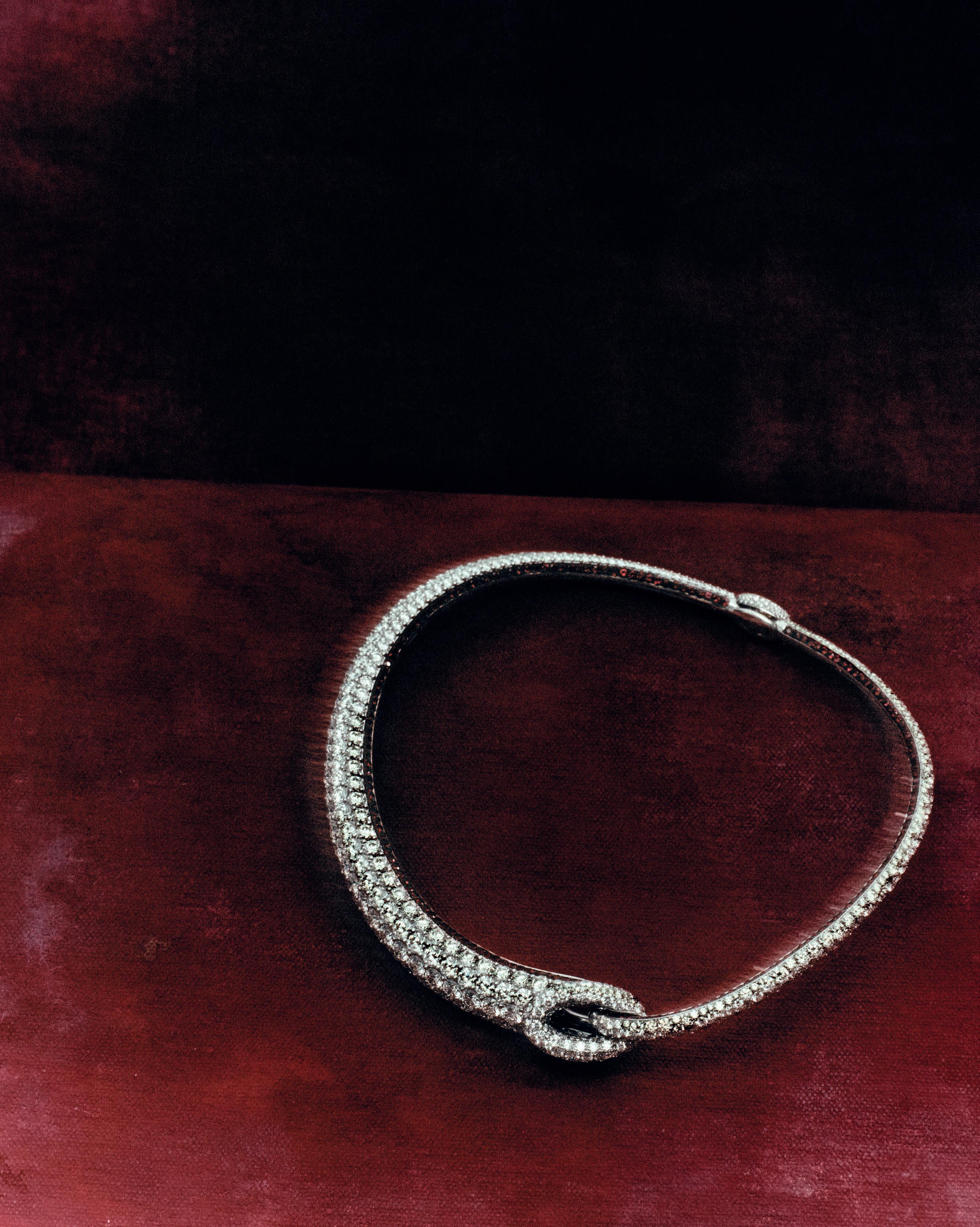

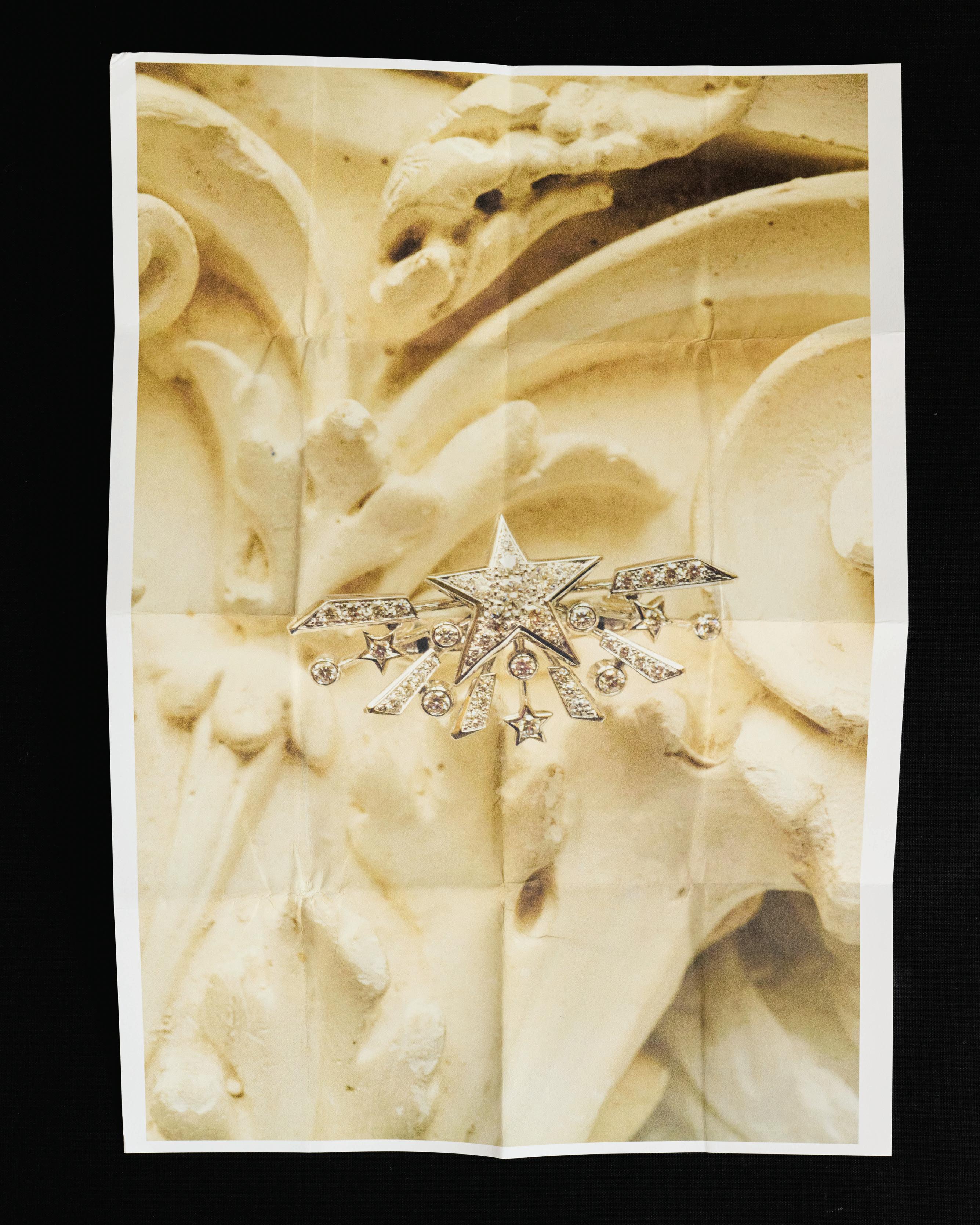

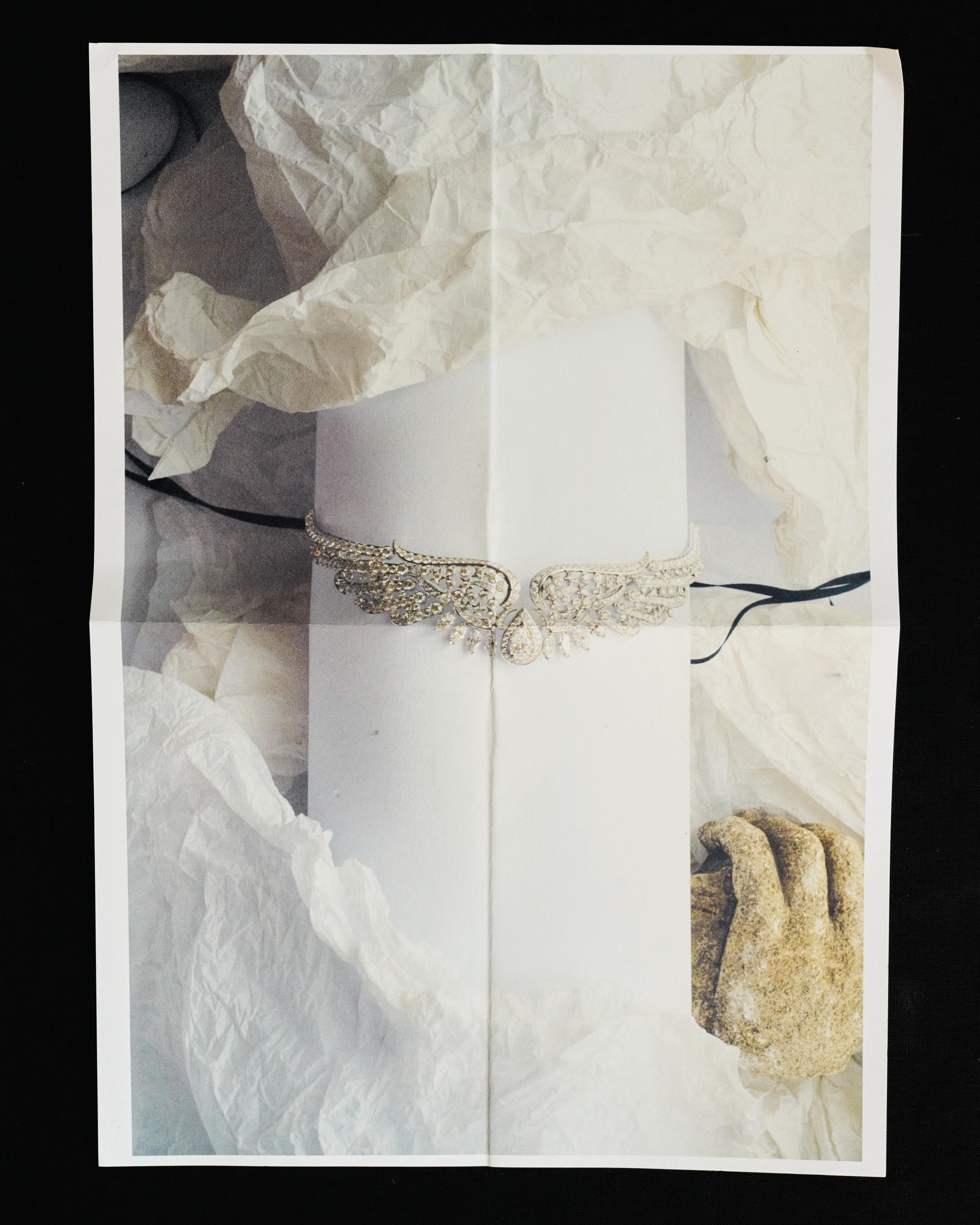

More than a century later, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is opening “When Objects Dream,” the first exhibition to examine the late experimental artist’s rayographs in the context of his broader oeuvre. The show, on view until Feb. 1, 2026, brings together more than 60 of these specimens alongside 100 paintings, objects, drawings, and films spanning Ray’s career. Its supporters include the haute couture house Schiaparelli, whose founder and namesake, Elsa Schiaparelli, was a close friend and collaborator of Ray’s, at the heart of the 1920s avant-garde in Paris.

Both Schiaparelli and Ray were preoccupied with the ways that people present themselves to the world—and how they are often driven by unconscious desires lurking just beneath the surface. Born to a tailor father and designer mother, Ray was exposed to the tools of the fashion trade from the start. One of his earliest and best-known pieces, Gift, 1921, which will appear in the Met show, is an iron studded with spikes—a domestic tool transformed into something lurid and fantastical. Schiaparelli executed similar transformations through her Surrealist designs, like a lobster dress created in collaboration with Salvador Dalí and a pair of hypnotic golden spectacles designed alongside Ray.

“I’ve always had a special feeling for Man Ray— like me, he was an American … [and] an outsider in Paris, a voyeur of a scene who later became synonymous with it,” says Daniel Roseberry, Schiaparelli’s current creative director. “And like Elsa Schiaparelli, he blurred the lines between fashion and art: Before fashion became a commercial enterprise, it was an artistic one, and that’s in no small part thanks to them.”

By KARLY QUADROS

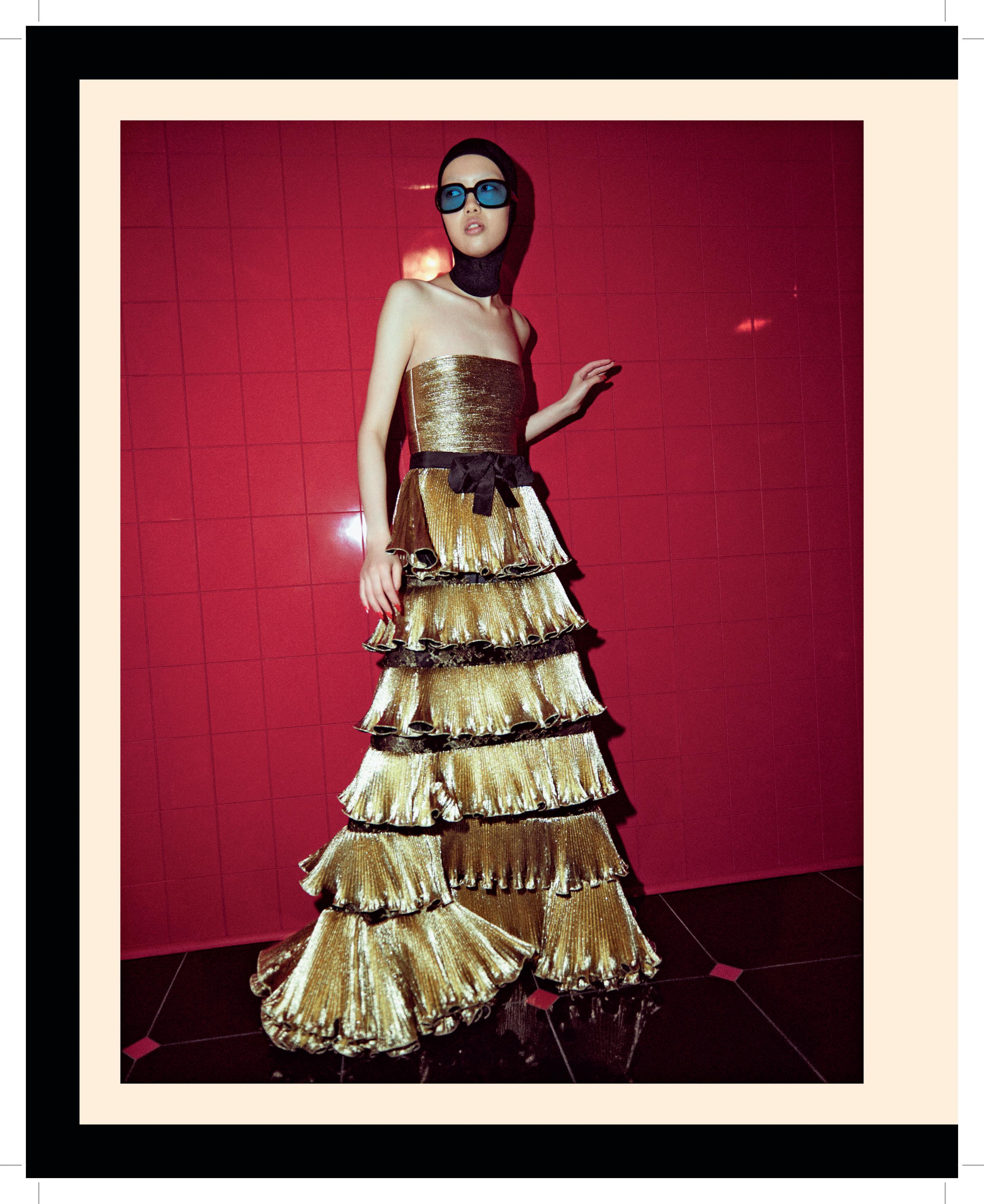

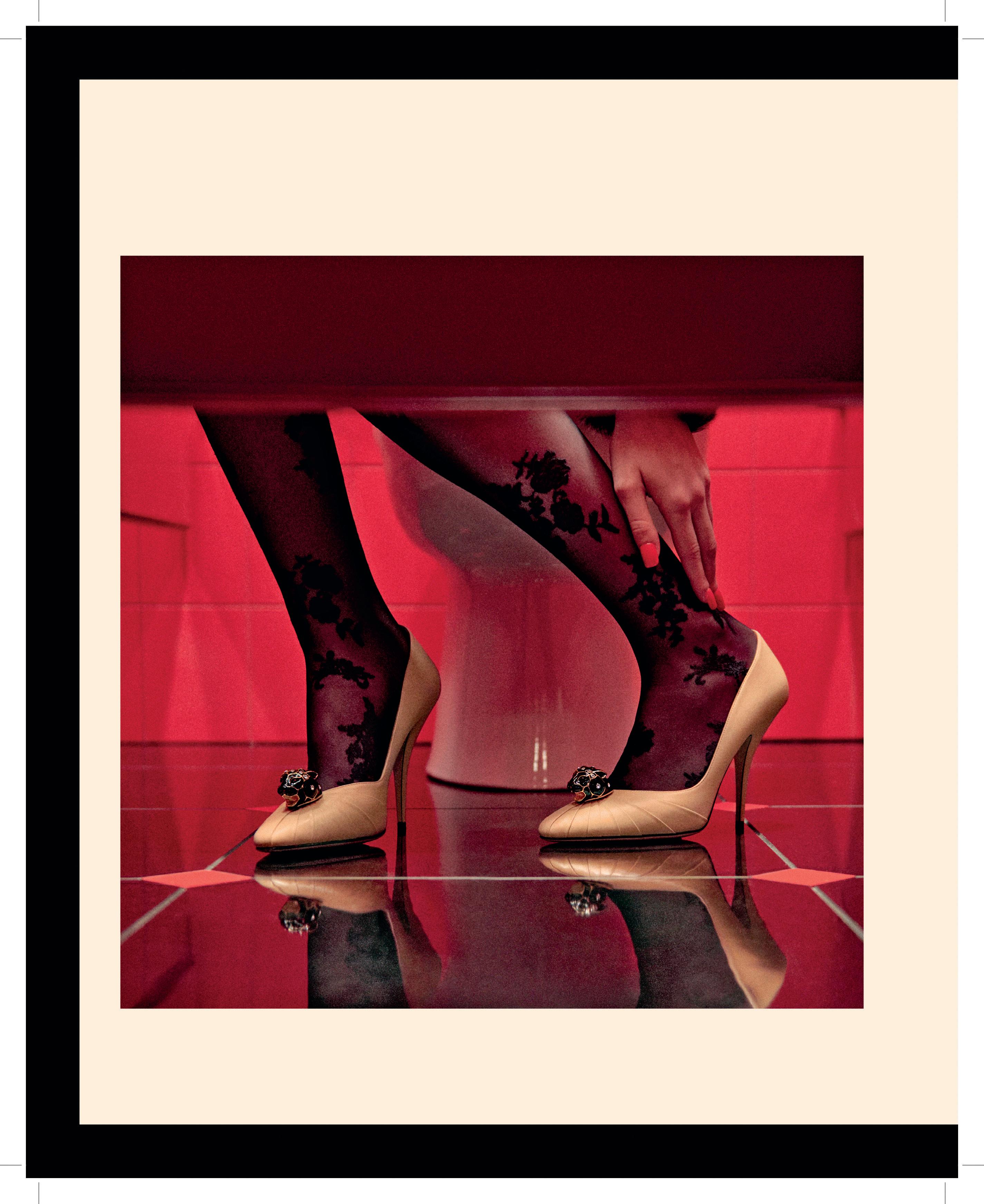

From frayed jeans to rusted gowns, a new exhibition at the Barbican looks to the rebellious past and sustainable potential of fashion’s filthy side.

In 1993, Hussein Chalayan, then a fashion student at Central Saint Martins, buried a pile of flutter-sleeve dresses, vests, and maxi skirts under a heap of iron filings and soil in his friend’s London garden. Six weeks later, he exhumed them. Stained with rich shades of rust and ochre, the collection was soon scooped up in its entirety by luxury department store Browns. The decaying garments were an instant hit, a (not so) subtle nod to the ephemeral nature of every fashion cycle.

It was a high-fashion statement on a simple truth: Sometimes, it’s fun to get dirty.

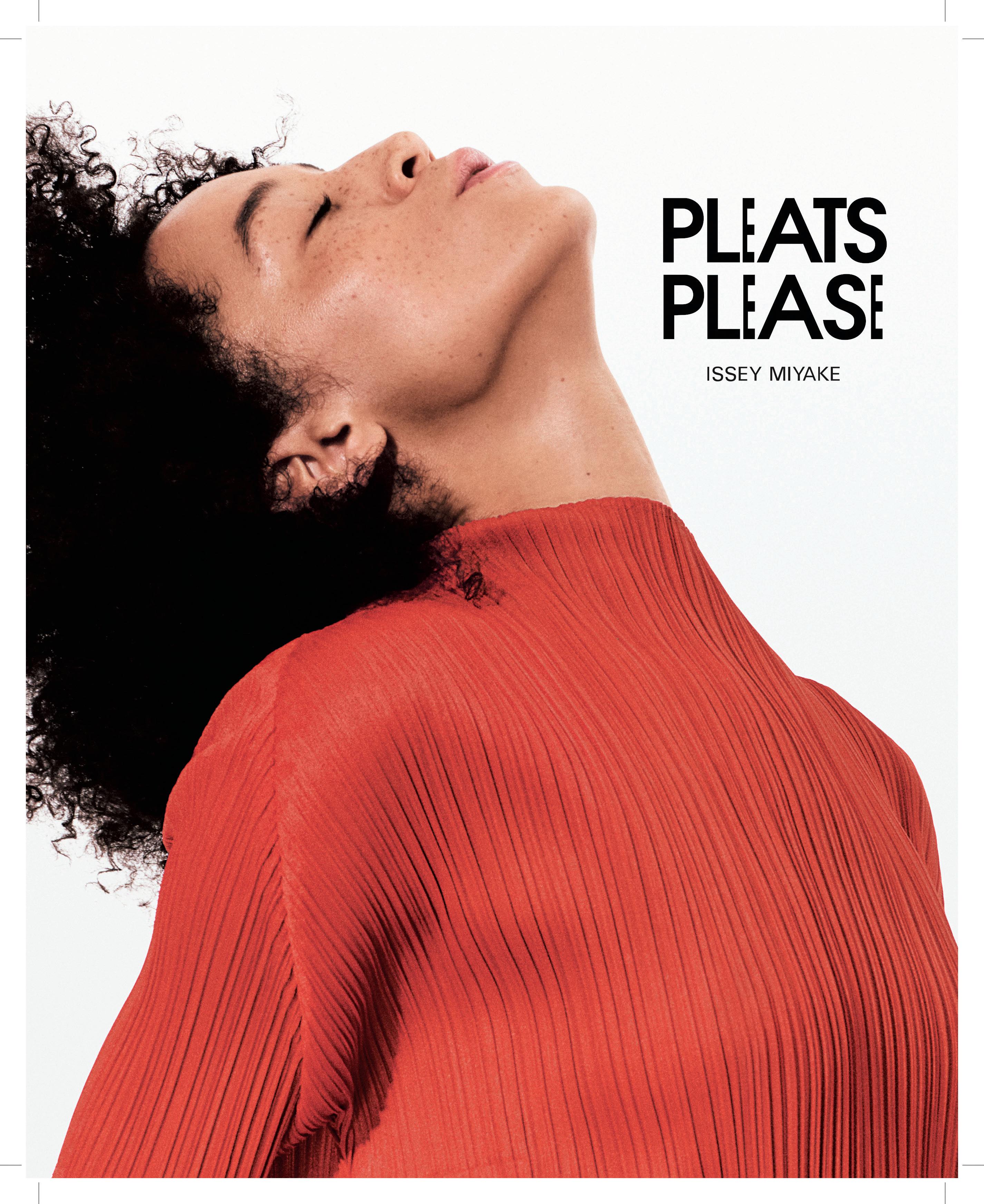

A new show opening Sept. 25 at the Barbican, “Dirty Looks: Desire and Decay in Fashion,” unearths the manifold ways the industry has harnessed rot and rebirth, from the transgressive tears of Vivienne Westwood to the moth-bitten knits of Maison Martin Margiela. The first fashion-centric exhibition at the London institution in nearly a decade, “Dirty Looks” recenters the museum’s commitment to fashion as a visual medium and features garments from over 60 disruptive houses, including gunpowder-speckled pleats from Issey Miyake, crumpled denim from Calvin Klein, and wine-stained couture gowns from Robert Wun.

“They are not necessarily anti-fashion, but they expand the horizon of what we call ‘beautiful’ or ‘fashionable,’ and what fashion can be,” says Barbican curator Karen Van Godtsenhoven, who cut her teeth at MoMu, Antwerp’s fashion museum, and the Met’s Costume Institute.

The exhibition also sees five young designers, including Elena Velez and Michaela Stark, explore dirty fashion’s regenerative potential in the face of the industry’s rampant waste. “The saying goes ‘cleanliness is next to godliness’ ... That still holds for the glossy surfaces of fashion, even though a new generation of designers are breaking up with those ideas,” Van Godtsenhoven concludes. “Embracing our dirty side might be just what’s needed for fashion to get our creative juices flowing again, in a way that doesn’t kill people or the planet.”

By SAM FALB

HER LIBRARY: TONI MORRISON AND JOAN DIDION. IN HER DAYDREAMS: BJÖRK’S UNWRITTEN MEMOIR. HERE, ONE OF THE INDUSTRY’S HARDESTWORKING MODELS INVITES US ON A TOUR OF WHAT SHE READS.

Famously discovered by none other than Pat McGrath, in just a decade Paloma Elsesser has become one of the most visible and iconic working models, walking for Coperni, Ferragamo, Fendi, and Marni, and featuring in campaigns for the likes of Balenciaga and Willy Chavarria. Though image is her art form, it’s a book—or Kindle—that’s always at arm’s reach. She reads to punctuate a day’s casual cadence or to ease the marathon travel that comes with bookings across the world’s fashion capitals. At home in Brooklyn, her bookshelf is as eclectic as her CV, with everything from bell hooks’s Talking Back to Miranda July’s All Fours, and tomes like A Wrinkle in Time or The Year of Magical Thinking adding a touch of the melancholy Elsesser admits she’s drawn to. Also on the shelf is TREASURE , the vulnerable surgery documentation project Elsesser wrote, paired with photography by Zora Sicher, in 2023. Ahead of what promises to be another busy fashion month, she shares the literary discoveries that will keep her going from the airport to backstage, and fittings to flashing lights.

Where is your favorite place and time to read?

I love to read at night in bed or on a plane, but a book or my Kindle is always in arm’s reach. It comes with me on a visit to the doctor’s office, a pedicure, or a quiet Sunday afternoon when I’m stretched out and lazy. I read wherever there’s time to fill, or time to savor.

Describe the type of reader you are in three words.

Voracious, tolerant, curious.

How do you find your next great read?

Word of mouth, frequenting big bookstores and niche ones, or doing research.

Name one public figure you feel deserves a biography, but doesn’t have one yet.

Björk. All of the existing ones are too focused on the production, mixing, et cetera, and not on the extensive details of her life. I’d love for her to write a memoir.

Which book has taught you something new about your industry?

The Chiffon Trenches by André Leon Talley.

Was there a particular work that your childhood self loved?

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle.

What book has helped you understand the world we live in right now?

The Mushroom at the End of the World by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing.

Which book has made you want to live your life in a certain way?

Talking Back by bell hooks.

Which book ruined you, in the best possible way?

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion.

Where do you turn when you’re starved for inspiration?

Beloved by Toni Morrison.

Can you share one trashy book to wedge in your vacation bag?

All Fours by Miranda July. Not trashy but quite naughty, and a fast read.

If your bookshelf could wake up and talk to you, what would it say?

“Don’t be so sad.”

“I READ WHEREVER THERE’S TIME TO FILL, OR TIME TO SAVOR.”

“You cannot decide you’re an It girl. Someone has to bestow it upon you.”

—Marisa Meltzer

By Karly Quadros

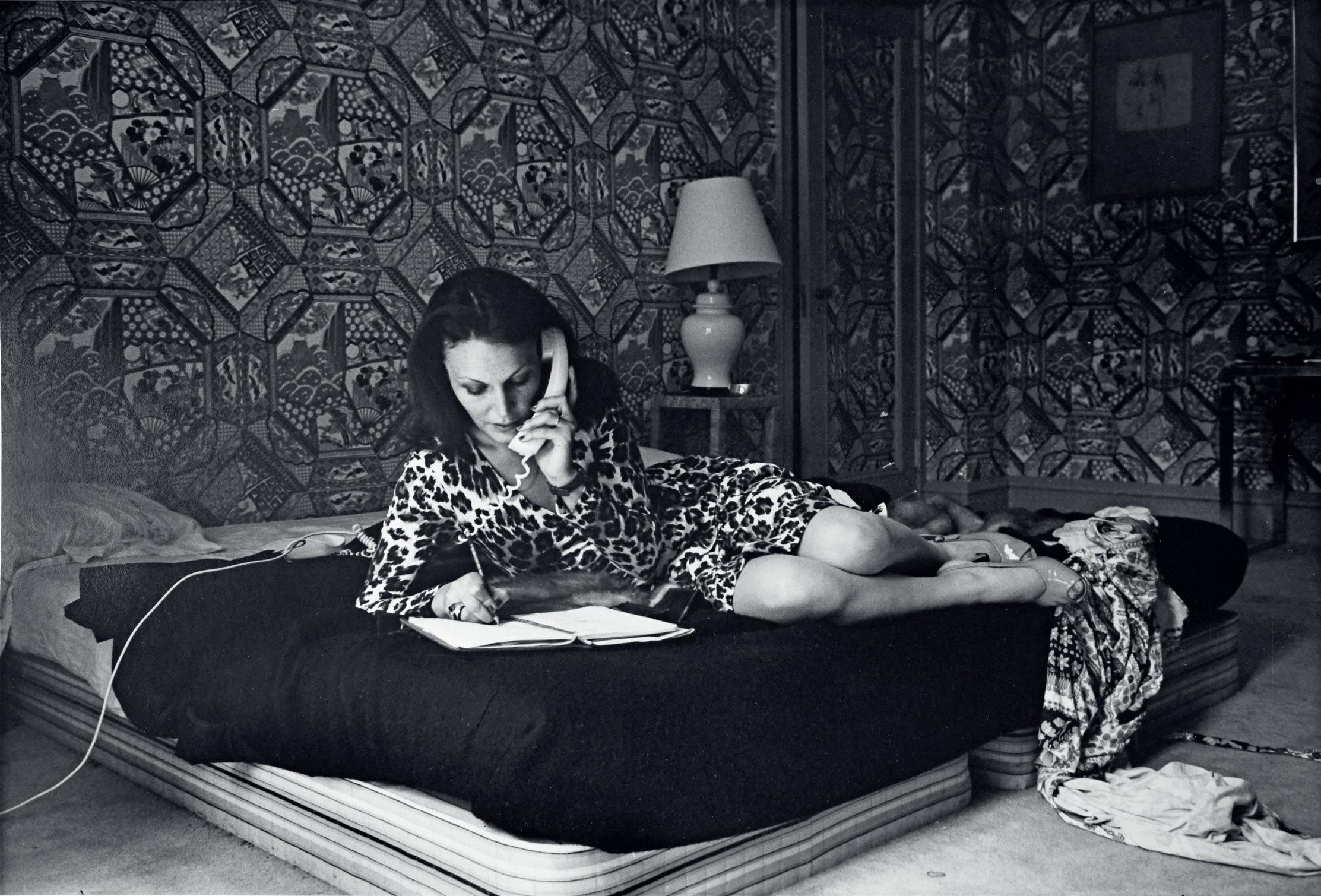

Bangs mussed to a T, a penchant for the mini (of the dress or shorts variety), and a bag that’s harder to get your hands on than the nuclear launch codes: Jane Birkin’s name has become virtually synonymous with cool. From her swingin’ young adult years, spent cavorting with the Beatles in London, to the ’70s in the heart of Paris, where she was embroiled in a tempestuous love affair with the louche songwriter Serge Gainsbourg, Birkin surfed the changing societal and sartorial tides with a witches’ brew of sincerity and insouciance. There was only one way to describe her: It girl.

That’s the term Marisa Meltzer has taken as the title of her new biography of the singer, out Oct. 7. Known for her 2023 bestseller Glossy: Ambition,

THE SINGER AND ACTOR DID WHAT FEW DID WHAT FEW IT GIRLS MANAGE TO DO: SHE GREW UP.

Beauty, and the Inside Story of Emily Weiss’s Glossier, the journalist looked for the woman behind the late muse in the archives of French Vogue, Hermès workshops, and the black-velvetlined townhouse that Birkin shared with Gainsbourg, complete with old cigarette butts and the songwriter’s beloved Lolita poster. Here, she gives CULTURED a peek at her process.

It Girl’s epigraph is from The Importance of Being Earnest: “To be natural is such a very difficult pose to keep up.”

I thought it really got to the heart of what Jane Birkin was all about, which was seeming like everything was easy. The challenge of this book was showing the truth behind it. There’s this real difference between how she thought of herself, what preoccupied her, and how the world thinks of her. There was jealousy over actors that were taken more seriously. There were things that she’s known for, like the Birkin bag, that did not seem to really preoccupy her at all.

What do you think it means to be an It girl, and what made Jane Birkin one?

You cannot decide you’re an It girl. Someone has to bestow it upon you. An It girl is somehow representative of the moment, usually in style and in personality, what she’s doing, who she’s hanging out with. She really reflected but also anticipated the way that women wanted to dress for her entire life. Few people can do that. The ultimate French girl is alluring, but someone who went and infiltrated the French world is even more exciting. If you look at the history of French It girls, there’s a lot of foreign-born ones: Josephine Baker, Marie Antoinette, Jane Birkin.

What was Jane’s relationship with designers of the time?

She definitely embraced the younger designers. You didn’t see her in Dior or Chanel. She loved Paco Rabanne and Thea Porter. She was a great friend of Yves Saint Laurent. You’d also see her in a lot of stuff that she picked up on vacations, like the basket bag she bought at a market in London. She went to a steak dinner in the early ’90s that Princess Di was at. If you look at the footage, Diana is wearing this heavy, intense gown, and she looks melancholy, like she often does. Meanwhile, Jane Birkin is at the same dinner, wearing a custom slinky silk shirt and tuxedo jacket, looking so comfortable.

By JACOBA URIST

What is the legacy of Land art in a time of climate catastrophe? Eighty-year-old artist Meg Webster, whose ever-urgent work is on view in New York and Paris this season, shares some thoughts.

When I met artist Meg Webster on a muggy Manhattan afternoon in July, I’d just returned from a Land-art pilgrimage to Michael Heizer’s magnum opus City. The more-than-mile-long concrete behemoth in the remote Southern Nevada desert took 50 years and an estimated $40 million to build. Webster, now 80, worked as Heizer’s studio assistant in her late 30s. But she has made her own career as a land artist in a very different kind of terrain: the concrete and chrome of downtown Manhattan.

Since moving to New York in 1979, Webster has created potent sculptures out of moss, beeswax, and salt that use smell, scale, and texture to invite city dwellers and country folk alike to consider their relationship to the natural world anew. This spring, nine of her sculptures went on long-term view at Dia Beacon, a temple to minimalism, conceptual practice, and Land art in Upstate New York.

“PEOPLE ARE NOT TAUGHT ABOUT ECOLOGY IN SCHOOLS. THEY DON’T KNOW THAT THEY NEED BUGS.”

For decades, Land art has been considered an especially macho form, as much about mastering the unruly earth as communing with it. Touchstones of the movement include Robert Smithson’s black basalt rock coiling 1,500 feet into the Great Salt Lake and Walter De Maria’s 400 steel rods conjuring lightning in New Mexico’s high desert. With few exceptions, female land artists like Webster have been given short shrift. In recent years, however, several exhibitions have attempted to right the imbalance. At the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, curator Leigh Arnold mounted “Groundswell: Women of Land Art” in 2023, featuring work by Webster and contemporaries like Agnes Denes, Alice Aycock, and Nancy Holt.

The Nasher show also upended the myth that Land art is made only in wide-open, remote landscapes. “Increasingly, the attitude of scholarship [is] that a lot of Land art occurred within very dense urban contexts,” Arnold says. “Getting away from this idea of a pilgrimage to a place to have this once-in-a-lifetime experience, Land art could occur just outside the artist’s studio if they were living in Manhattan.”

Webster’s story—and the place it occupies in art history—will receive yet another overdue revision in October, when she features prominently in a group exhibition dedicated to Minimal art at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris. Alongside Donald Judd and Carl Andre—and Lynda Benglis, Eva Hesse, and Anne Truitt—Minimalism is another movement where Webster is a pioneer. Her use of natural materials like salt and beeswax infuses Minimalism’s geometric forms and sharp angles with a warmth and aliveness not found in the fluorescent bulbs of Dan Flavin or the plywood sheets of Judd. (She also belongs in surveys of performance art: Her pared-down stainless steel Bench for Two Backs Leaning, in

which two people sit back-to-back to activate the sculpture, evokes Marina Abramović.)

Since she received her MFA at Yale in 1983, Webster has sculpted mud, sand, and sticks as a

tal, beautiful, and inspiring.” Among my favorites is her “Moss Bed” series: large, spongy-verdant cushions that smell like a dank forest (Moss Bed, King is currently at Dia, as is Webster’s Wall of Wax, a globby, 24-foot-long curved beeswax wall

tender and primal response to the environment. “I’ve done some pieces that are biggish,” she says. “But I’ve been dragging soil and forming it inside as well. It’s not about the monumental, although this [Dia] work is definitely monumen-

that looks like an organic take on Richard Serra, and Cono di Sale (Salt Cone), a 92-inch-high crystalline tower, first shown at the 1988 Venice Biennale.) Webster’s interest in Land art began in the early ’80s, when the survival of the planet

felt exceedingly fragile. “My professor David Von Schlegell, a wonderful man, read an important text in The New Yorker about nuclear war and that was shocking,” she recalls. “We were right at the edge of having a serious Earth

the end of the Earth” after nuclear winter, she says.

Just a short walk from Judd’s studio, Walter De Maria’s Earth Room, a loft packed with 250 cubic

problem. So that started why I was making earth forms.” In 1984, Donald Judd invited Webster to show her work on the ground floor of his Spring Street studio. “I ended up putting a giant mound of salt on the floor to symbolize

yards of dirt in the heart of SoHo’s bustle, continues to inspire Webster. (“I have definitely been reacting to his work,” she emails several hours after our interview. “I strived to add plants and ecology, wanting to bring people to

the joys of the planet and its creatures.”) In 2016, Webster brought similar magic to Chelsea when she bathed Paula Cooper Gallery in a futuristic pink glow for the installation Solar Grow Room. The four raised wooden flower and vegetable planters, powered by an off-grid solar electrical system, felt both ominous and beautiful.

This is not to say that Webster foregoes the great outdoors. That same year, Webster constructed Concave Room for Bees at Socrates Sculpture Park, a visceral living sculpture of flowers and herbs designed to attract the pollinators. Webster’s installation felt like a breathing, botanical take on Donald Judd’s first outdoor artwork in concrete, the 1971 circle at Philip Johnson’s Glass House. I remember walking my young son through the pungent air—he was captivated by the buzzing—looking out at the East River and the skyline. “People are not taught about ecology in schools,” Webster reflects on the piece. “They don’t know that they need bugs.”

“THERE’S A HOPEFULNESS TO IT, BUT ALSO AN URGENCY— LOOK AT THIS AND THINK FOR A MINUTE.”

This is truer now than ever. In an era of extreme weather (Webster and I meet three days after the catastrophic floods in Texas), climate policy rollbacks, and cuts to scientific research, I fear the Land art I’ve treasured hasn’t achieved what its makers had hoped. Here in the U.S., we have yet to train our collective gaze on the majesty of the natural world, nor shift our attention to the toll we’ve taken on our fragile ecosystem. If anything, a half-century after the Land art movement began, we’ve resoundingly turned our back on both.

Against this backdrop, what exactly can Land art do today? “We’ve got many major problems,” Webster responds. “There’s a giant political crisis. Trump is just horrible. And there’s an environmental crisis, thanks to him partly. We’re in meltdown. And you can’t just get back from that.” At the same time, she explains, “it doesn’t work to just scream and yell and create awful feelings.” The works at Dia are meant to register, but at a delicate frequency. Indeed, Webster is the rare legacy artist who vibrates with a soulfulness of unbridled optimism.

“Certainly, people are calmed by the Dia show,” says Webster. “There’s a hopefulness to it, but also an urgency: Look at this and think for a minute.”

“IT DOESN’T WORK TO JUST SCREAM AND YELL AND CREATE AWFUL FEELINGS.”

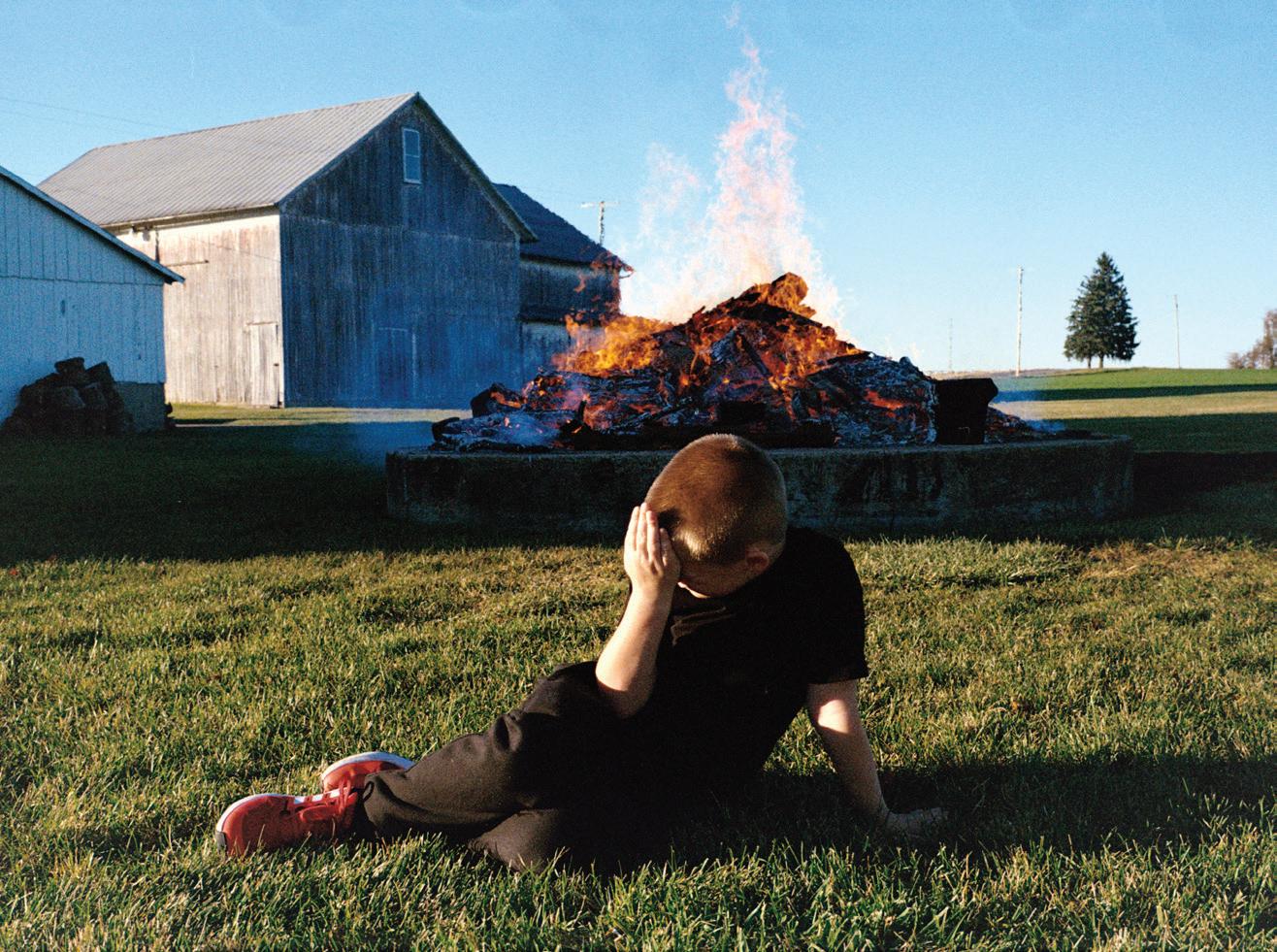

A LOT HAS CHANGED SINCE 2011. ZORA SICHER TURNED 16 THAT YEAR; SHE’D TRADED BROOKLYN’S TWEEN PUNK-BAND CIRCUIT FOR THE DARKROOM AND WAS ALREADY WELL ON HER WAY TO BECOMING ONE OF HER GENERATION’S FOREMOST DOCUMENTERS OF INTIMACY, WHETHER BODILY OR EMOTIONAL. A YEAR LATER, SHE WOULD GET HER FIRST TATTOO WITH A FRIEND, EDEN. THAT IMAGE, SHARED EXCLUSIVELY WITH CULTURED BELOW, CLOSES SICHER’S FIRST MONOGRAPH, GEOGRAPHY, OUT THIS MONTH WITH DASHWOOD BOOKS. THE TOME SEES THE IMAGE-MAKER, WHO HAS WORKED WITH EVERYONE FROM PALOMA ELSESSER TO MARNI, SIFT THROUGH THE ARCHIVE SHE’S ACCUMULATED SINCE 2011—AN EXERCISE THAT REVELS AS MUCH IN THE PEAKS AND VALLEYS OF GROWING UP AS IN THE ACT OF MAKING SOMETHING TOGETHER, WHETHER THAT’S A FRIENDSHIP, LOVE, OR A PHOTOGRAPH.

—ELLA MARTIN-GACHOT

“This image is of myself and a dear friend that I grew up with. We were both born in the year 1995, and it was my first tattoo we got together at 17 years old. She opens the book as well with another image of a tattoo, which initially wasn’t an intentional decision...

but something that subconsciously came together through laying out the images. I think the fragmented nature of these ‘portraits’ establishes the notion of mapping the body— a theme I began to explore during the collecting of these images throughout an extended period of time.”

By SOPHIA COHEN

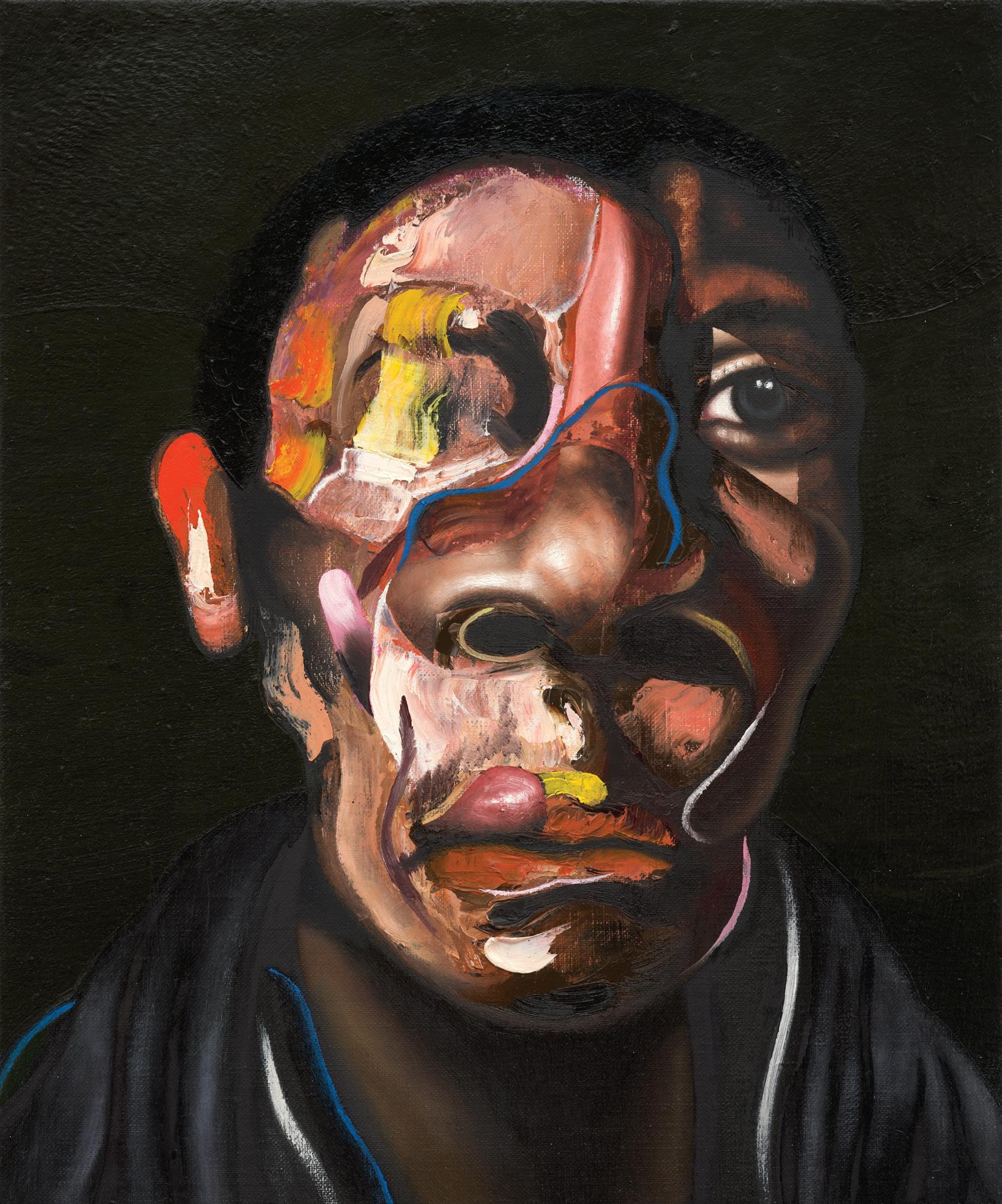

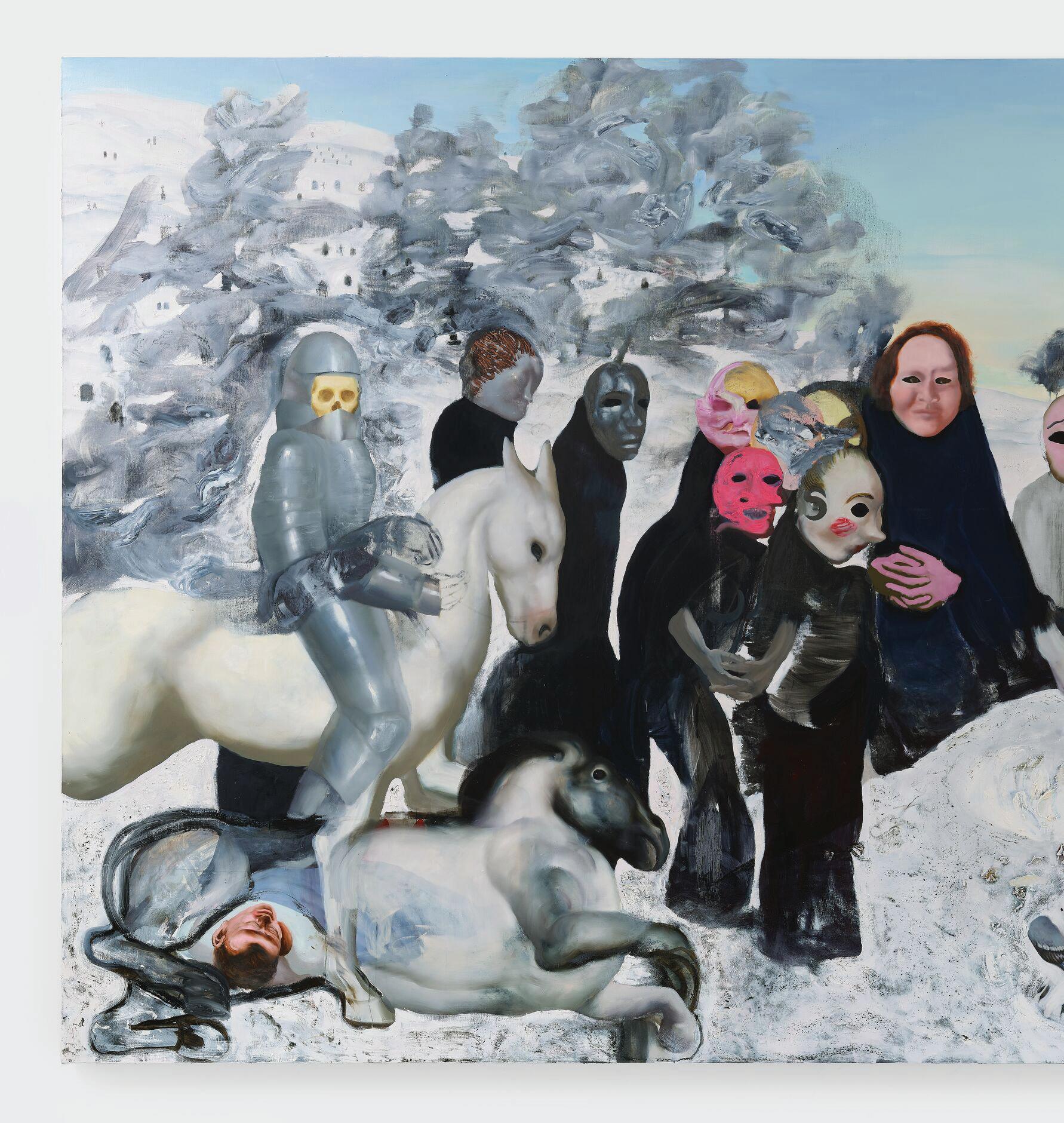

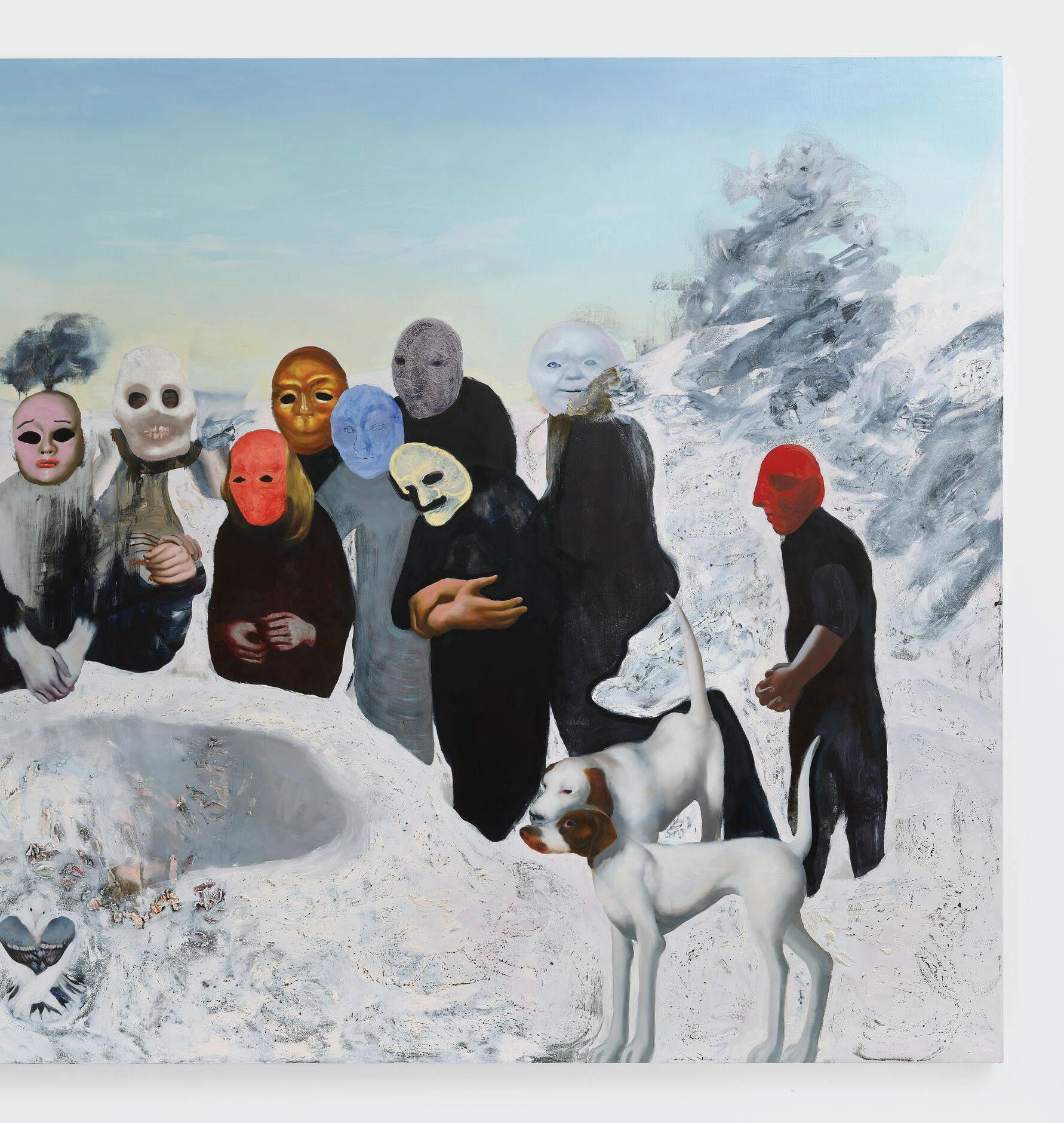

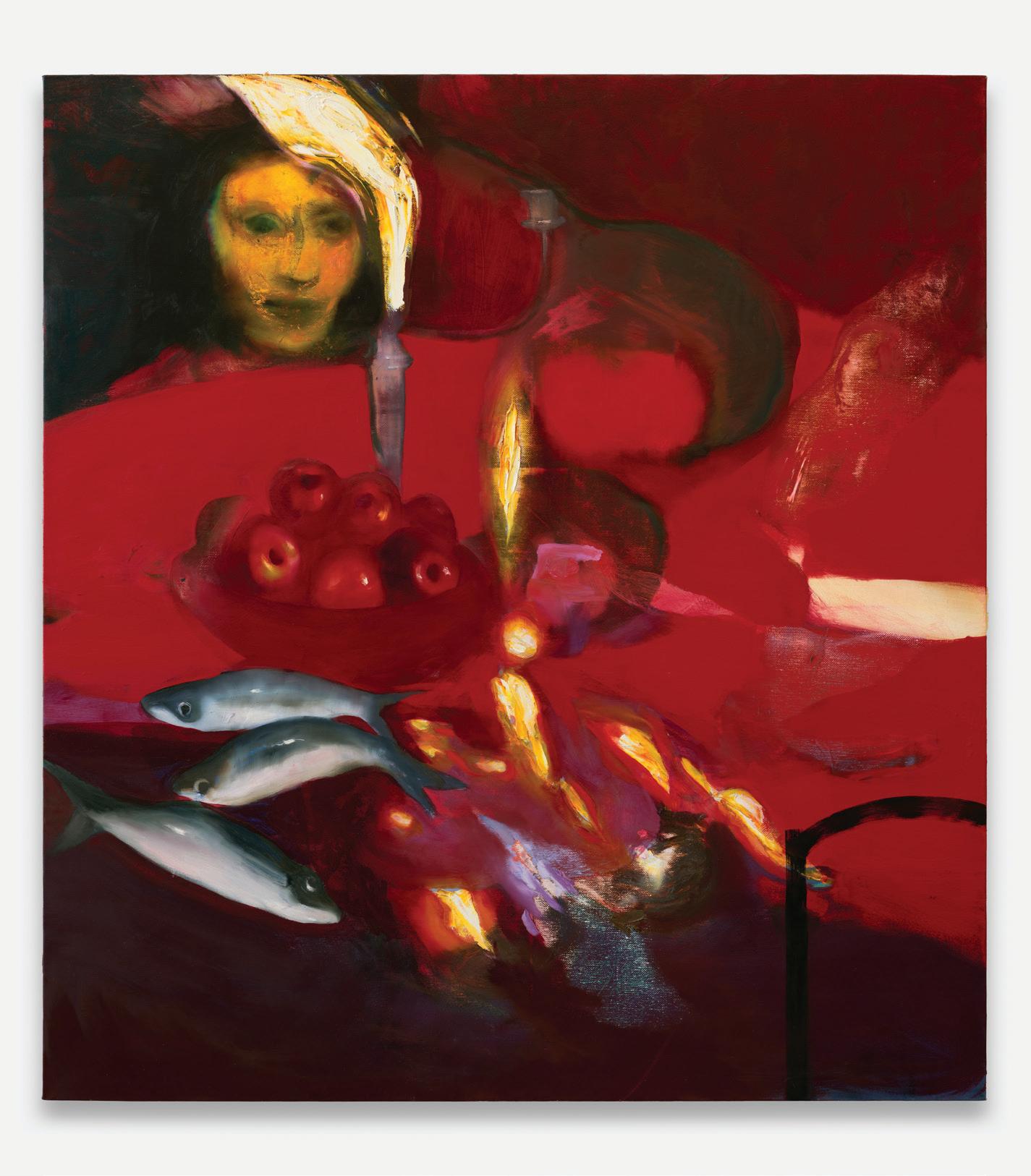

An Alice Walker novel about three generations of Black American life in the South has helped Nathaniel Mary Quinn fill in the gaps of a family history that’s informed every step of his practice—including a new show at Gagosian.

“I work for hours on end to come face-to-face with my own fragility, fears, insecurities, and doubts.”

Every Nathaniel Mary Quinn work is an exercise in excavation.

The Chicago-born artist is a material alchemist—manipulating oils, pastels, and charcoal into haunting portraits—and a memory worker. Many of the moments in time Quinn evokes come from his own singular upbringing: At 15, his mother passed away, and he was left to take care of himself following the sudden desertion of his other family members. Fragmented recollections of these years were spun into evocative compositions that have landed in the collections of the Whitney, LACMA, the Art Institute of Chicago, and more.

This fall, Quinn is opening his fifth solo with Gagosian, “ECHOES FROM COPELAND,” which filters touchpoints of his life through a 1970 novel by Alice Walker, The Third Life of Grange Copeland , about three generations of Black Americans living in the South. Ahead of the opening on Sept. 10, he sat down with CULTURED ’s arts editor-at-large, Sophia Cohen, to parse through his novel inspirations.

courageous turn. I wanted to find a way to blend these disparate parts without the strict, strong stock demarcation of lines, which led to the discovery of a process I’d like to call paint-drawing: a combination of the two.

You’ve been talking about the layering of ourselves and creating a structure within that. What role is your biography playing in this story, if any?

In this body of work, there is a strong departure from my biography, no doubt about it. But this book [by Alice Walker, The Third Life of Grange Copeland ,] offered me another pathway into something about my family that I never knew about. I have no working knowledge of my mother’s upbringing, of her childhood, or what life was like for her when she was a teenager. My mom passed away when I was 15, so I couldn’t ask her these questions that I imagine children ask their parents when they become adults. I do know that my mom was from the South. I do know she was born in Mississippi during a particular era in American history. The book offers a glimpse into what might have been her lived experiences.

I know that you added your mother’s name, Mary, to your own, so that you’ll carry her name with you as you build on the life that she started for you.

I’m never bored of talking about this because, of course, she’s my mom, and I love her with all my heart. Seeing my name on any institution’s wall—at museums and galleries or in a book, even the monograph [of my work] that Gagosian did [last year]—that beautiful monograph has my name on the cover, and my mother’s name, too. Now, I’m entering spaces and having experiences that my mother could never fathom—they would seem like science fiction to her. This woman was poor. She had no education. She did not have material accomplishments, but she was a lovely woman. She’s the best mother I could ever imagine.

The visual language of my work is inextricably tied to my biography. In the way I construct my figures, there’s always this rippage, this cut and slice and blending back together. All of that is a reflection of my childhood experiences of being abandoned by my family and finding a way to resolve those feelings. My mother had two strokes; she was crippled. All my figures are a reflection of that body that I first came to know intimately, within the context of a mother and a child.

“The visual language of my work is inextricably tied to my biography. In the way I construct my figures, there’s always this rippage, this cut and slice and blending back together.”

Those who are less familiar with your work often mistake it for collage, but it’s not. Why is that distinction important to you?

In the process of making my works, I don’t think about collage at all. I am thinking about how to create harmony with parts that don’t seem to fit together, because that’s the way I imagine identity is constructed—from many different experiences that don’t have a seamless fit. You must contend with them; you must face them. In this body of work, I’ve taken another

Even if you’re exploring different themes, there’s always a piece of you in there. That piece of you is something that people feel connected to.

I can’t imagine doing anything else with my life. Like any artist, I work for hours on end to come face-to-face with my own fragility, fears, insecurities, and doubts. I would argue that those things are as much artistic tools as oil paint is.

By SOPHIE LEE

Photography by MAEGAN GINDI

At home in Pound Ridge, James Frey is surrounded by work that fuels his passionately written prose, like this year’s Next to Heaven.

“I buy art because I want to feel what art makes me feel—joy, inspiration, awe, curiosity, respect—as much as I can in my everyday life,” says James Frey, whose collection at home in Pound Ridge includes pieces by Rashid Johnson, Robert Colescott, and Nate Lowman. As an author, Frey trades in the full spectrum of emotion across A Million Little Pieces, Bright Shiny Morning, and this year’s novelistic exploration of the darkness underlying a charming American town, Next To Heaven

In the mid-aughts, Frey was lambasted in the press for greatly exaggerating the facts in his bestselling memoirs about addiction and rehab. In 2025, an era of “emotional truths” and with scant capacity for shock, Frey’s writing style reads as ahead of its time—though he’s taken a turn toward fiction, where his imagination can run free. He collects art with the same unbridled enthusiasm, offering as little regard for market trends as he does critiques from the literary establishment (“I just sit in my castle and giggle,” he recently told The New York Times). These works of art are pieces he wants to gaze up at over dinner, and here, Frey gives us a seat at the table.

Who do you think is tougher: art critics or book critics?

I think it’s probably the same. Critics are critics in every medium. The fundamental difference is that the art world is much smaller than the book world. The audience is vastly smaller. How many people see the most well-attended art shows in New York, versus how many read the bestselling books in the world? It’s the tens of thousands versus many millions. So when you get savaged by a book critic, as opposed to an art critic, it tends to be seen by many more people.

Where does the story of your personal art collection begin?

I have been art obsessed since I was a kid. I always dreamed of having cool pictures on the wall, and whenever I have had money in my life, I spend it on art. When I was 24, I had a job that paid in cash and required great discretion. I had to do something with the cash. In 1994, laws related to money were very different than they are now, and large cash purchases could be made without government knowledge or interference. The first piece I bought was a Picasso drawing in blue crayon from 1908, and the second was a Matisse drawing of a woman from 1918, both from a well-known gallery that was, at the time, happy to sell art to me for cash. I was six months out of jail and rehab, and carrying a backpack with $50,000 in it. It took a

while to convince the gallerist I wasn’t a cop or a thief.

Which work in your home provokes the most conversation from visitors?

A large, early Rashid Johnson mirror painting called Soul on Ice. It’s white spray paint on a large mirror. It is the only piece hanging in my kitchen and dining area, and it dominates the room. It’s both raw and gorgeous, and many people who see it, especially those not interested in art, aren’t sure what it is or why I have it in my house or what it means. It’s a piece that does what I believe art should do, which is create an emotional reaction in everyone who sees it. That leads to a great conversation or inspiring someone else to look at Rashid’s work, or art in general.

If you could snap your fingers and instantly own the art collection of anyone else, who would it be and why?

A Manet. I don’t need someone’s entire collection. I would love something made by the hand of Manet, preferably a painting, but a drawing would be a delight. Just seeing a Manet every day would make me smile for just about forever.

“I was six months out of jail and rehab, and carrying a backpack with 50,000 in it. It took awhile to convince the gallerist I wasn’t a cop or a thief.”

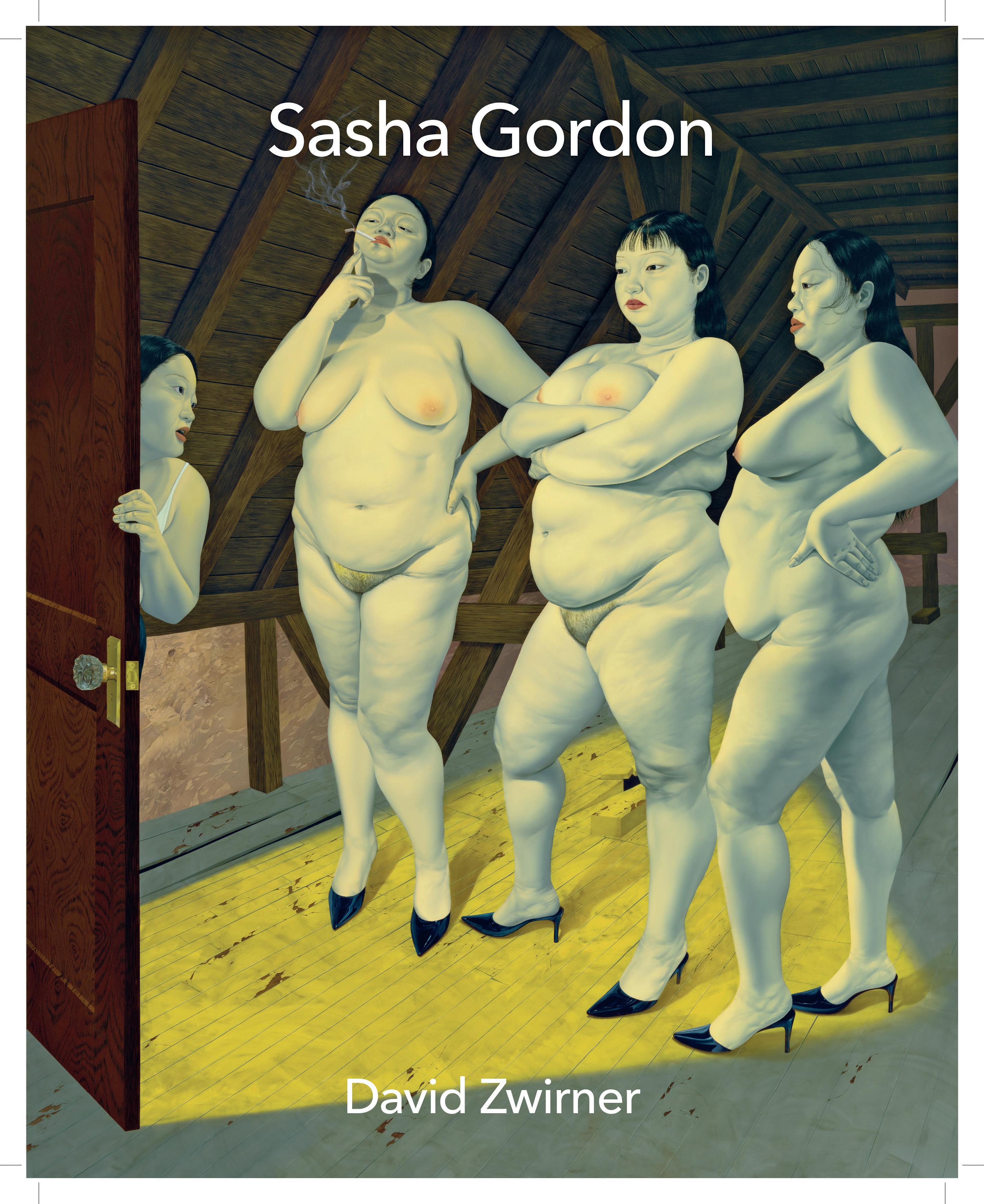

Raúl de Nieves has filtered everything from drag culture to Catholic iconography into his more-is-more sculptures. At Pioneer Works this fall, he’s leaving excess behind—for good.

It’s late in the day and the sun is pouring into Raúl de Nieves’s spacious Williamsburg studio. Through the windows, the Manhattan skyline is framed like a poster one might find in an Airbnb—an apt, if somewhat ironic, symbol of the ascent that this queer, Mexico-born artist has experienced in recent years. But it’s not success that is on his mind these days. What he’s thinking about is failure.

“I’ve seen so much growth,” de Nieves says of his practice of more than two decades. “I’ve also seen so much failure.” The 42-year-old, who arrived in San Diego with his family at the age of 9 and has exhibited at august institutions such as the ICA Boston, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and the Cleveland Museum of Art, is sitting on a threadbare couch in the back of his studio. The floor is covered with stray beads, strips of plastic, and pools of hardened resin— vestiges of the bedazzled, mixed-media sculptures and collages for which he’s become known. His small dog, Penguini (“like little penguin pasta”), is velcroed to his side. “The more that I see that I need to work on something, the more it allows me to know myself better,” he says.

De Nieves is speaking ahead of “In Light of Innocence,” his latest institutional show opening Sept. 12 at Pioneer Works in Red Hook. It’s a

“In a way, this show has really allowed me the opportunity to think about the next chapter of my life.”

venue with which the artist has a long history— his band Haribo was among the nonprofit’s first musical artists in residence—and one that offers the kind of supple exhibition space suited to his fantastical, more-is-more sculptures. The show has all the makings of a victory lap. Instead, it will arrive like a valediction.

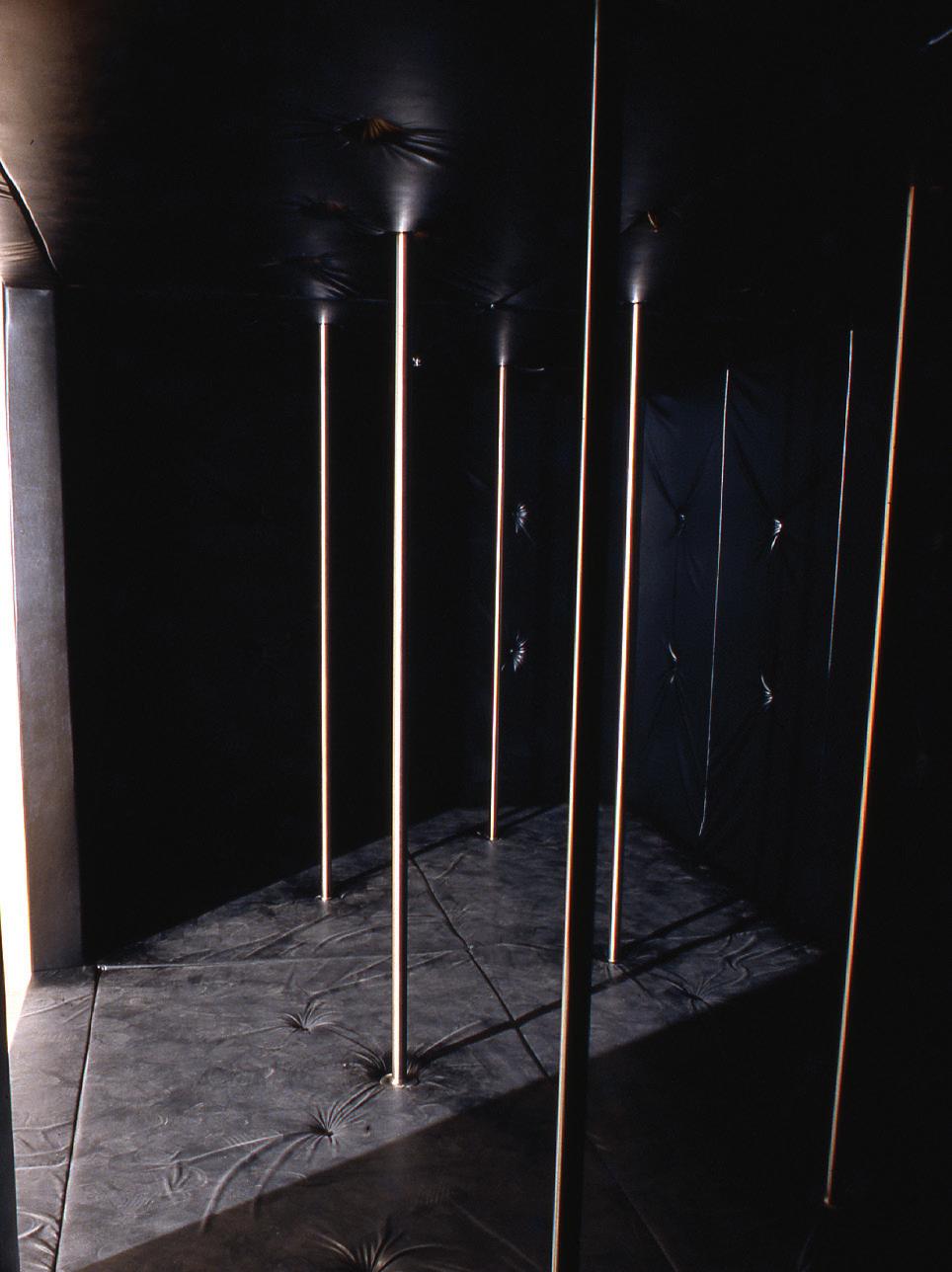

“This is the last time I want to do this kind of work,” de Nieves says of his signature “stained glass” assemblages, 50 new versions of which will line Pioneer Works’s windows. Made from tape, acetate, and other inexpensive (he hates the word “cheap”) materials, these pieces have been a staple of the artist’s oeuvre since his breakthrough turn in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. In past shows, they’ve cast a glittering glow over his sculptures nearby, but for “In Light of Innocence,” they’ll be installed above a gallery inhabited by just one modest, floor-bound work.

This is a form of restraint not typically associated with de Nieves, a big personality in life and

art. But the new stained glass pieces brim with enough symbols and suggestions to offset the emptiness below. Along with the nods to Mexican craft, Catholic iconography, and drag culture that appear in so much of de Nieves’s art, they feature names, phrases, and images from the Tarot. De Nieves is not much of a practitioner himself, but he appreciates how the cards offer audiences a flexible framework through which to examine their own lives. It’s about “finding these things that can open up a portal,” he says.

“The more that I see that I need to work on something, the more it allows me to know myself better.”

That’s what de Nieves is after with “In Light of Innocence.” He sees the show’s negative space as a kind of invitation, a portal through which we might find the guidance we’re seeking. The departure comes with risk, but he’s willing to make that trade. “In a way, this show has really allowed me the opportunity to think about the next chapter of my life,” he says. Then the artist points to a new stained glass work, embedded with a phrase that has become a mantra of late: “Growth arrives cloaked in failure’s grace.”

By KAT HERRIMAN Photography by JUSTINE KURLAND

Chicago-born fashion designer Colleen Allen’s distinctly offline cult following signals a quiet rebellion by a generation exhausted with algorithmic femininity.

The girls roast pigs, comb each other’s hair, hang boys by their feet, bathe in the stream. They hunt and kiss and band together into large troops that could bring the world down.

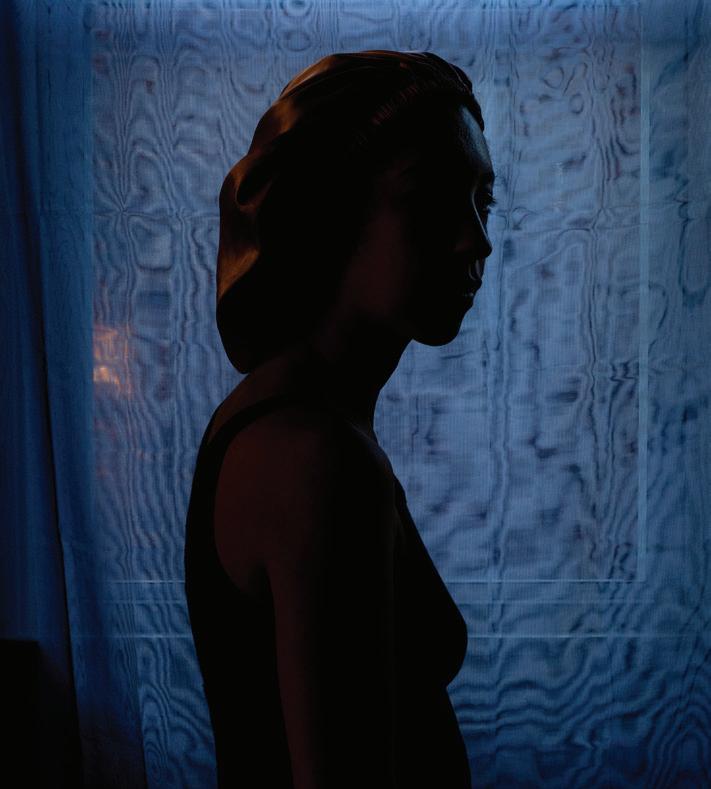

These are all scenes from Justine Kurland’s “Girl Pictures.” The artist started making the 1997–2002 series to stage images of youthful defiance over the course of long road trips. What she made, while zigzagging across America, were photographs that captured the sense of communion young women feel when they are given the space to make believe with one another. Reflecting on this seminal body of work, Kurland wrote, “I intended for them to play act a state of communal bliss. As it turned out, the girls didn’t have to pretend.”

On a Monday morning in July, Kurland once again opened the portal to her radical female imaginary, this time for fashion designer Colleen Allen, who—shot alongside a handful of like-minded friends and muses, including legendary executive Judy Collinson, jeweler Alice Waese, and models Charlotte O’Donell and Irina Shnitman—stepped through the looking glass in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

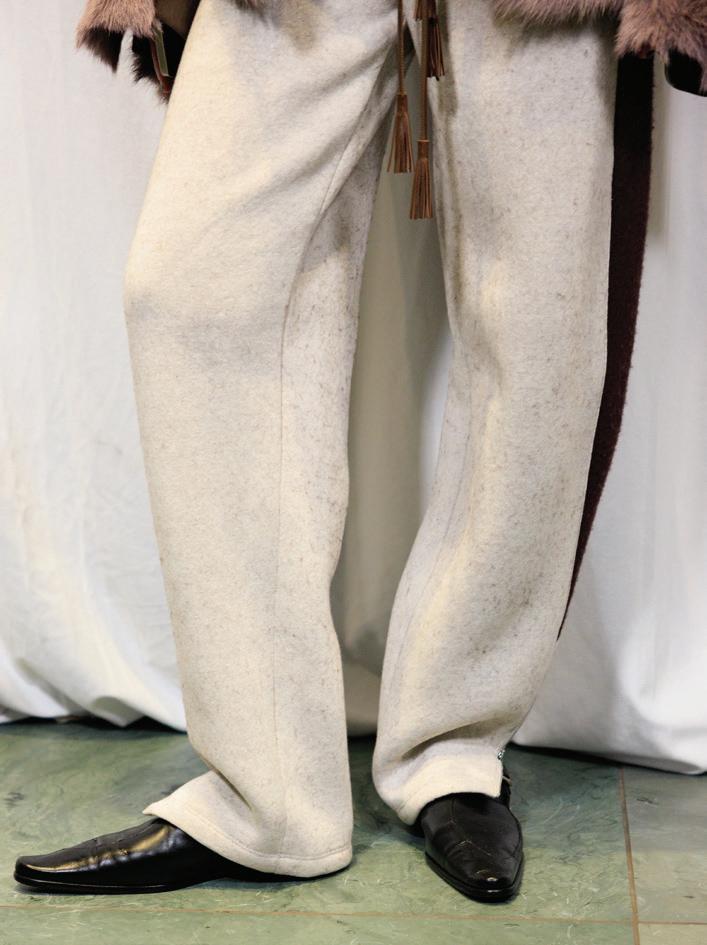

It was a dream come true for Allen, 29, who has seen herself time and again in Kurland’s images of teenagers stripped down to their realness. The photographs remain a touchstone for her namesake line which, in the past year or so, has amassed a substantial girl gang all its own. What Allen’s clothes share with Kurland’s “Girl Pictures” is an otherworldliness—a vision of girlhood unhooked from a The Wing–like commodification of gender and instead infused with a deep reverence for art history and the contributions of women whose convictions once rendered them hysterical, ostracized, or worse.

Muses for past seasons have included witches real and imagined, including surrealists like Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning. For her upcoming spring collection, Allen found her spark in something slightly more contemporary: Red Comet, Heather Clark’s recent biography of Sylvia Plath. Listening to the audiobook in her studio, Allen was struck by parallels to her own life: For one thing, both American women crossed the Atlantic for their education. Allen attended Central Saint Martins in London (before returning to New York to intern under Raf Simons at Calvin Klein, and later at the Row), while Plath made the pilgrimage to the University of Cambridge from Boston. Allen was particularly intrigued to learn that Plath had once been a fashion intern in New York—and loathed it. She fixated on an anecdote in which Plath and her fellow interns defiantly tossed their mandatory girdles off a rooftop, an episode that made its way, in an altered form, into Plath’s best-known work, The Bell Jar. This small act of rebellion became the seed for Allen’s new collection, a suite of lingerie-infused house clothes that reclaim the domestic wardrobe while nodding to histories of care, control, and the women institutionalized on account of both.

As with past collections, there is specificity to the colors and plushness of Allen’s latest garments, which she repeatedly trials on herself before sharing with a small circle of confidantes. “That’s the specialness of being really small—I get to have that quiet space to work through things on my own,” Allen confesses. “I am trying to take advantage of this time while I can.”

This intimate methodology ensures feel comes first, which explains why silk lines many of Allen’s signature fleece coats. As we talk, Allen constructs an image of herself groping her way

through racks of fabrics and vintage clothing like a chef shopping for the right melon.