For the last 13 years, CULTURED has dedicated its pages to unearthing and honoring the inner lives of artists.

It’s only fitting, then, that the inaugural issue of CULTURED at Home, the magazine’s first design edition, be helmed by one of its first contributors, Alexandra Cunningham Cameron.

Just as she has in her work as a critic, scholar, and curator of contemporary design at the Cooper Hewitt, Alexandra has approached her role as guest editor of this issue with a reverence for how artists live—departing from cookie-cutter design discourse to offer something unfiltered, personal, and fresh.

Maybe you’re wondering why we wanted to launch another print magazine now. The answer, I believe, is that there’s never been a more urgent moment for it.

When I started CULTURED, I felt there was a void in the cultural conversation—a need for a more intimate, artist-driven lens, more crosscultural exchange, and more space dedicated to supporting emerging talent.

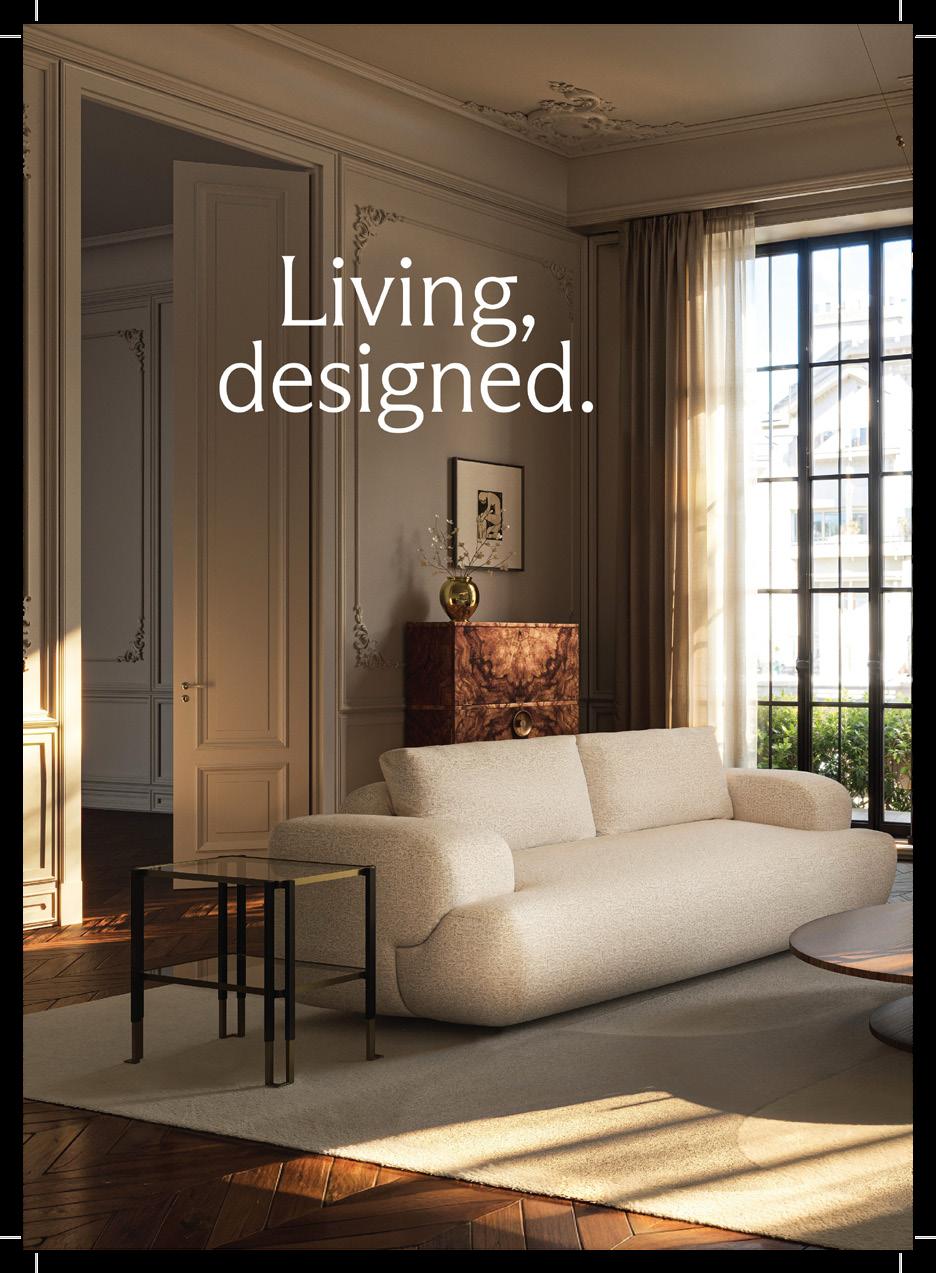

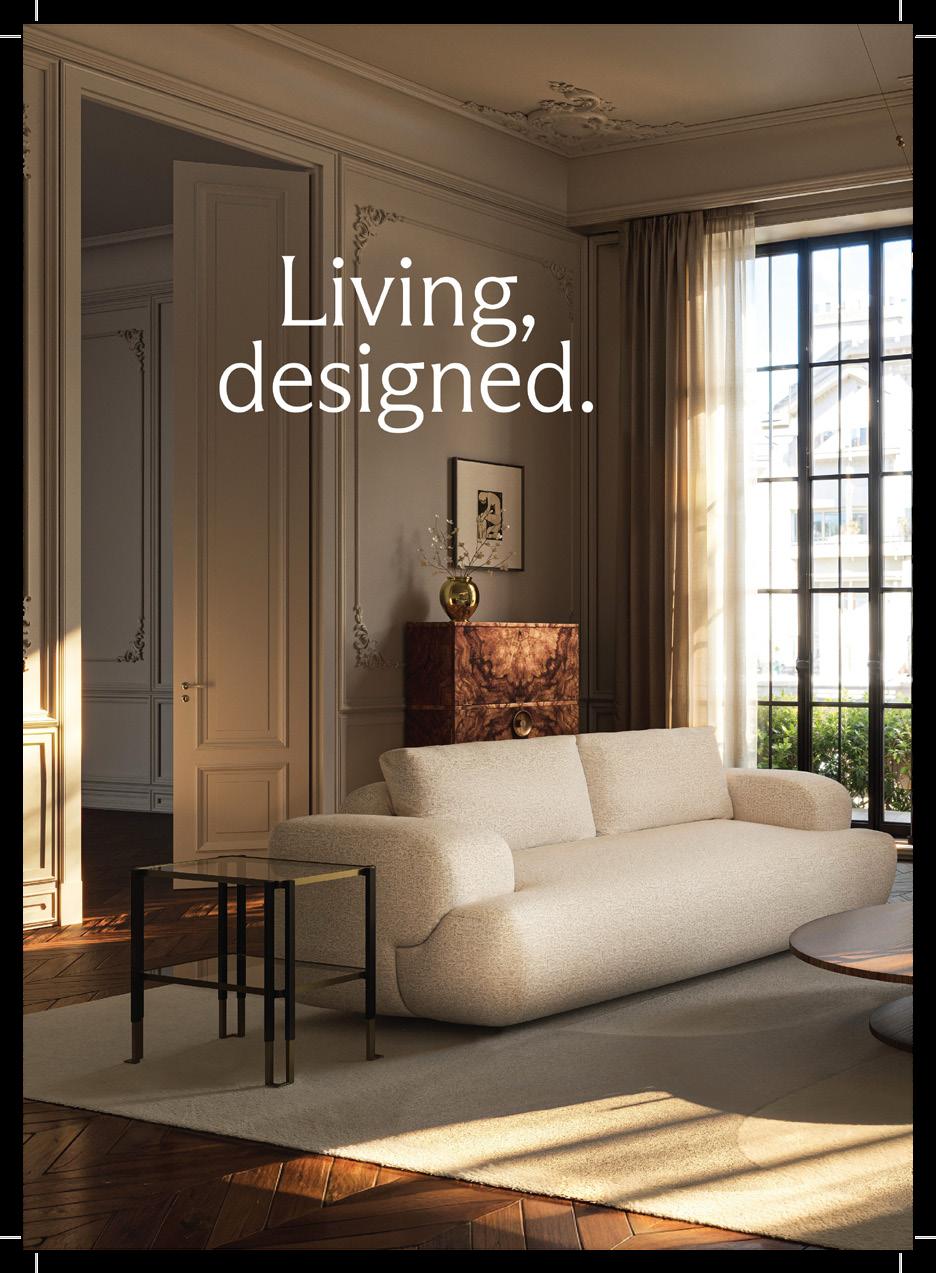

With CULTURED at Home, that instinct returns. People are craving something real. They want to understand how creative people truly live—their habits, their spaces, their stories. Less polish, more presence.

While the digital landscape has expanded in remarkable ways, there is still something irreplaceable about print—its physicality, its authority, its ability to slow things down. CULTURED at Home isn’t just another magazine; it’s an object to be treasured and lived with, a resource to return to. Above all, it’s a reminder that how we live is its own form of art.

Congratulations, ACC!

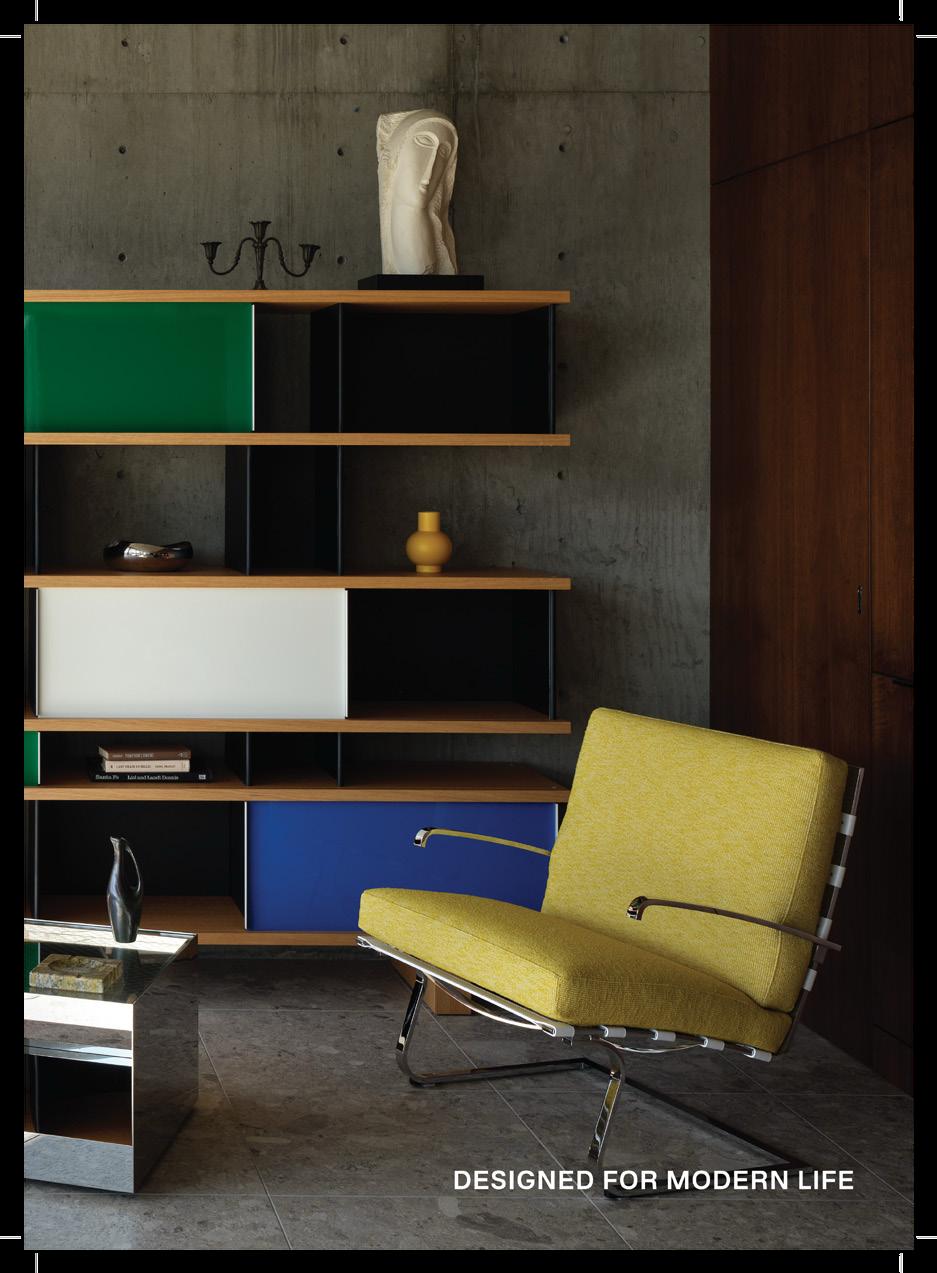

An Italian Design Story moltenigroup.com shop.molteni.it

An Italian Design Story moltenigroup.com shop.molteni.it

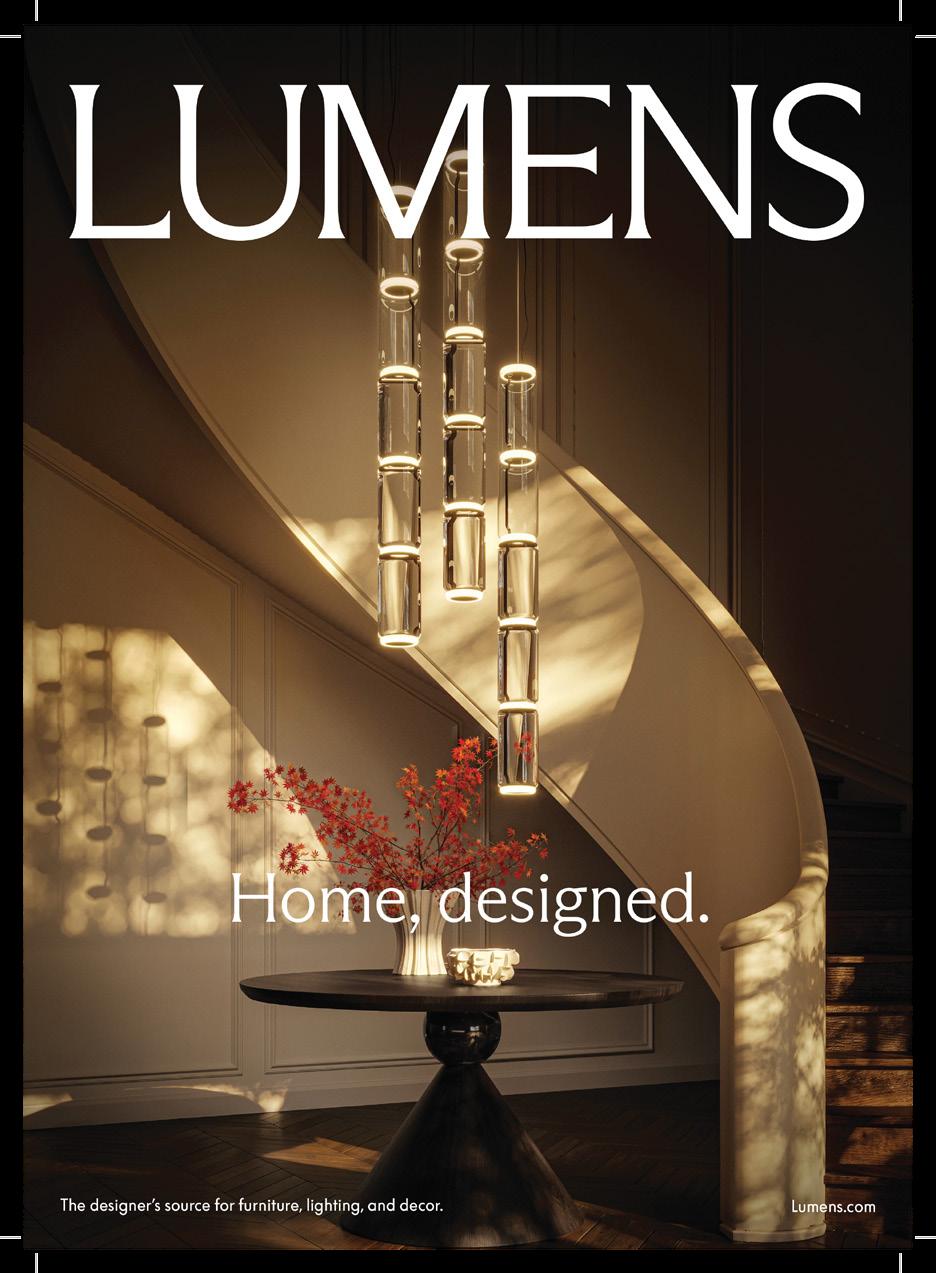

This striking LED light sculpture was hand-cast by contemporary artist and designer Markus Haase. Inlaid with black marble and bronze, the carved white onyx inset filters the LED light.

Haase is one of the only artists working today in lighting design who is capable of this level of stone and metal work by his own hand.

80 Lafayette Street, New York, NY 10013

www.toddmerrillstudio.com

@toddmerrillstudio

Markus Haase, Medusa, DE, 2024

Markus Haase, Medusa, DE, 2024

Resource 84 Design Institutions

Our editors’ favorite places to explore design culture

86 Design Galleries

Our editors’ favorite places to explore design commerce

88 Design Events of the Season

The exhibitions and openings influencing design discourse

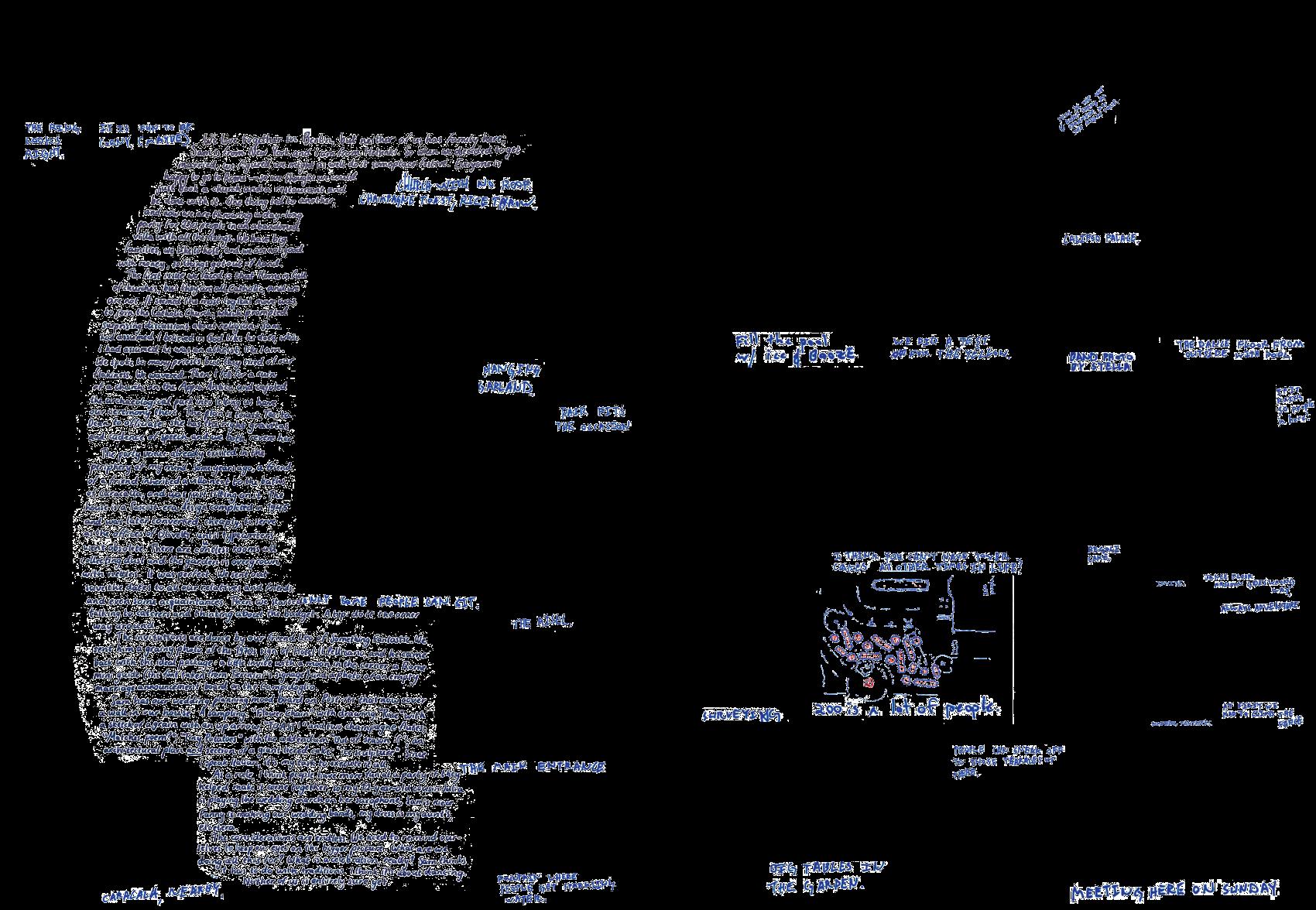

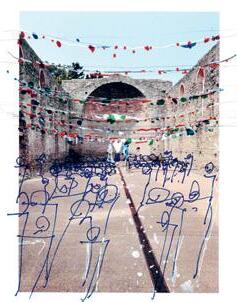

Hosting 96 Sam and Stella Host a Wedding in Rome

Design-world darlings’ planning hijinks

98 Ruba and Lawrence Host Music

After Dark

A home full of the sounds—and people—collected along the way

Tabletop

100 Petal-Shaped, Pendulous

Helle Mardahl offers an array of hand-blown delicacies

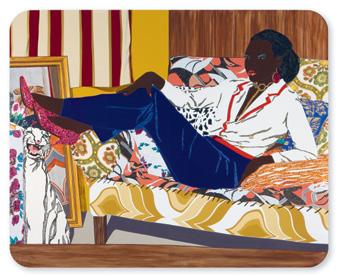

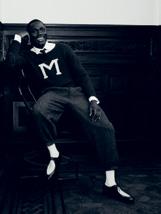

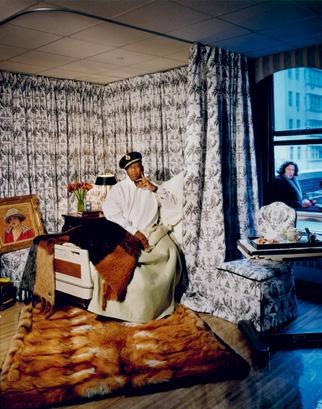

Salon 102 Respectability and Liberation

Black bourgeois aesthetics on stage, screen, and runway

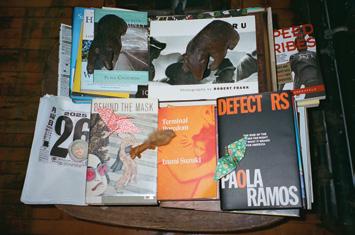

Library 104 Fake News, True Reads

Ten essential design books of 2025

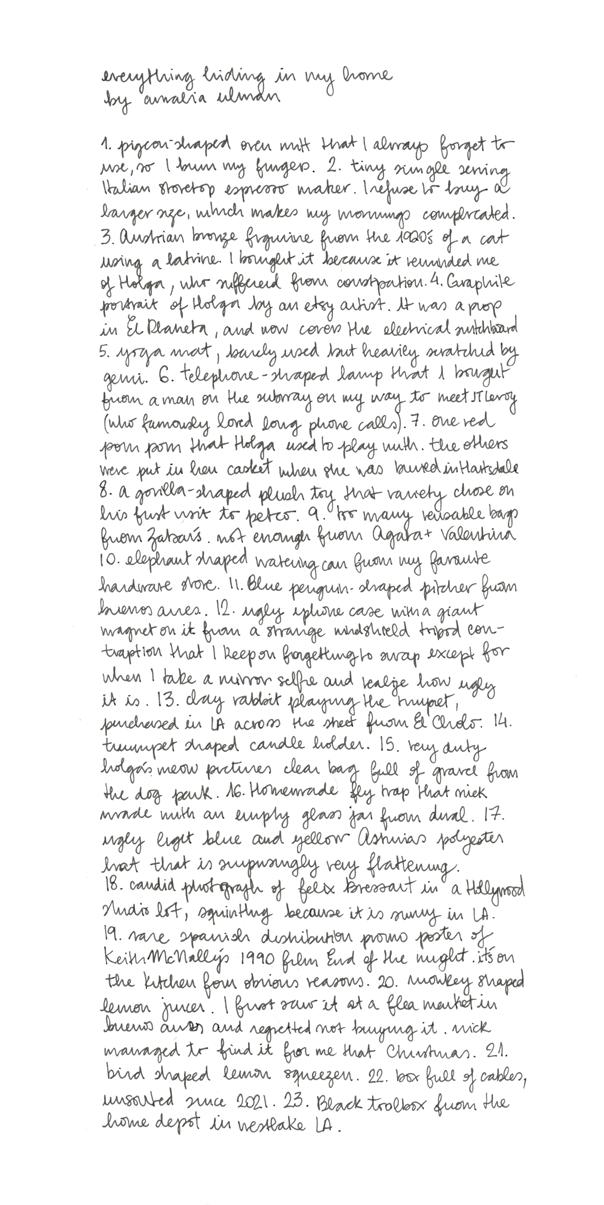

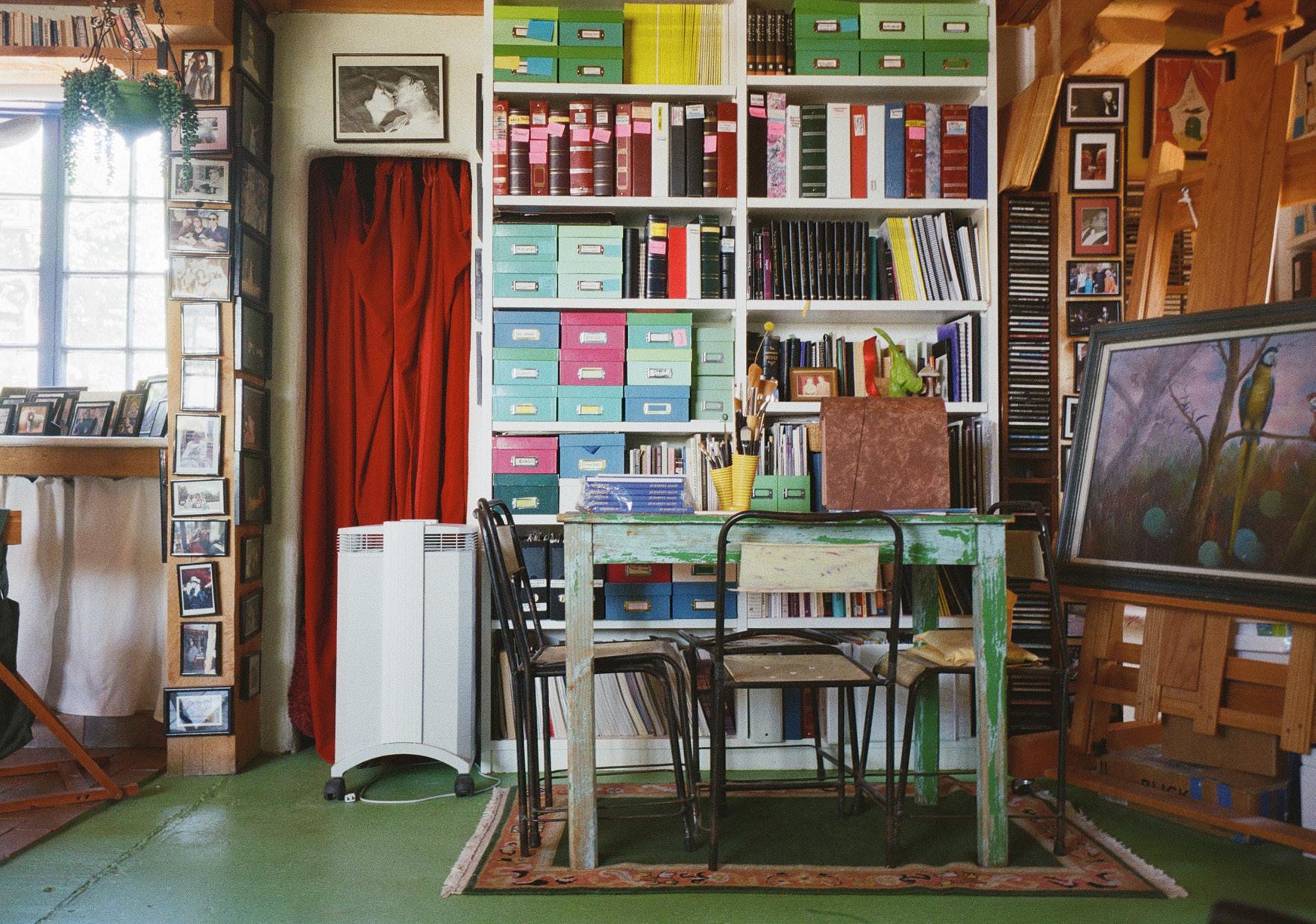

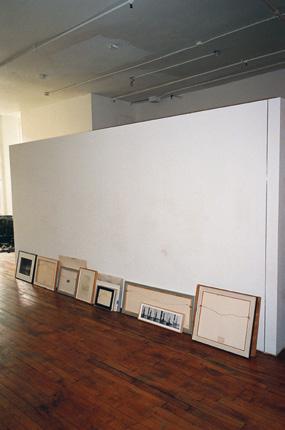

Storage 105 Everything Hiding in My Home

One artist conducts an ambitious inventory

Toys 110 On Toys at Home

A writer and filmmaker surveys objects of play

Bedroom 113 Beside the Window the Bed

Coital encounters offer access to bedroom art across New York

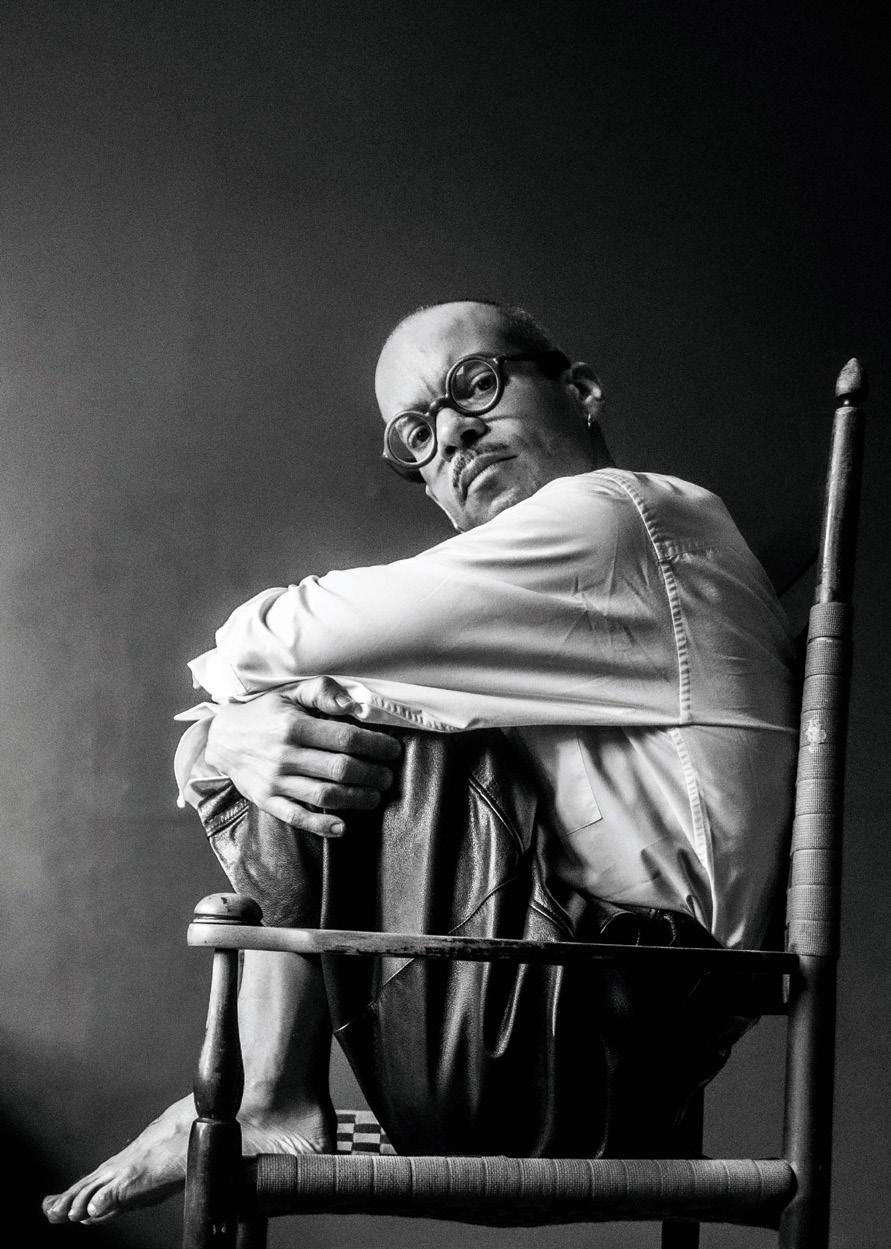

Portrait 118 High-Wire Act

Designer Carlos Soto builds worlds onstage and off

124 Sally Quinn’s Nerves of Steel

Five decades of legendary house parties

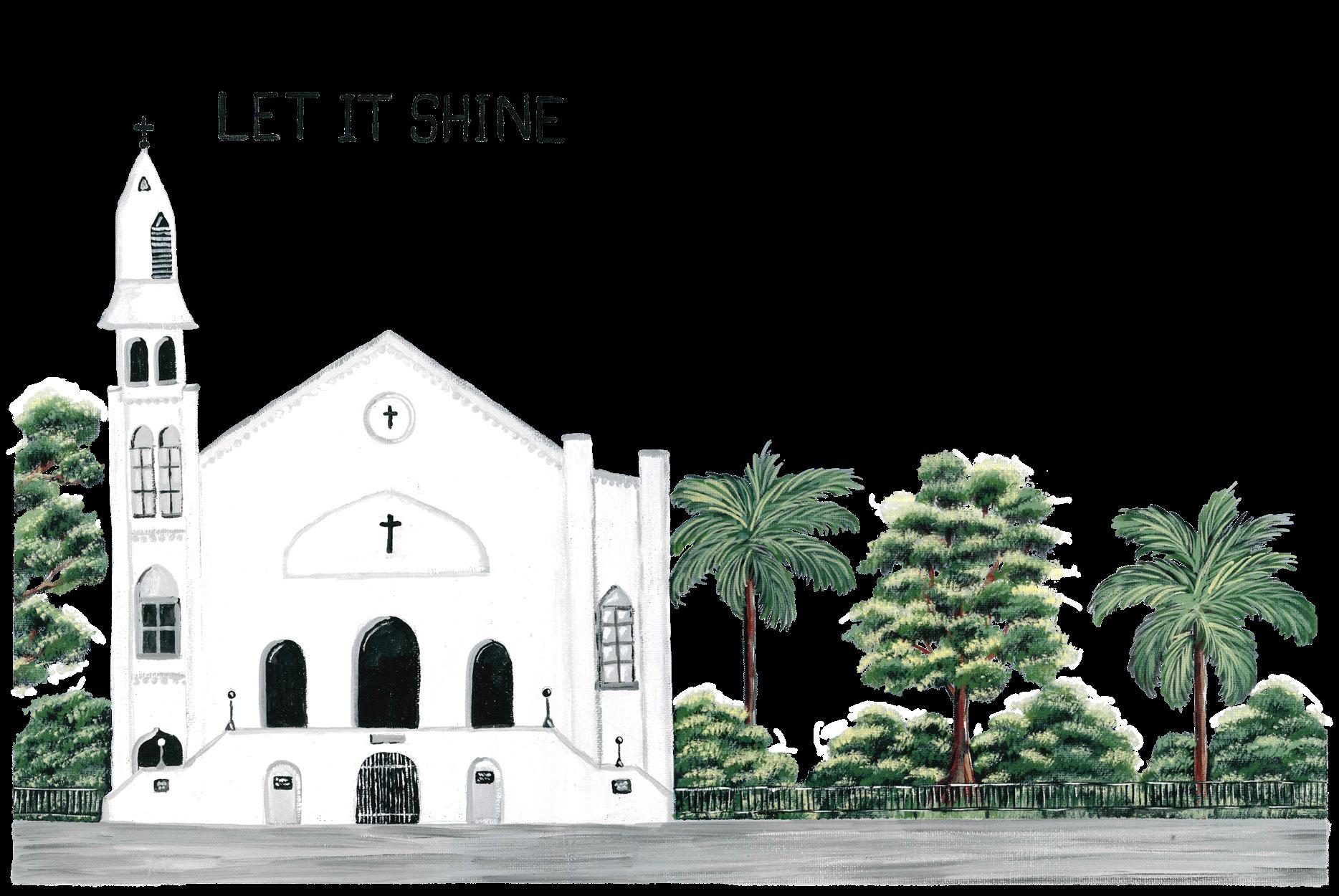

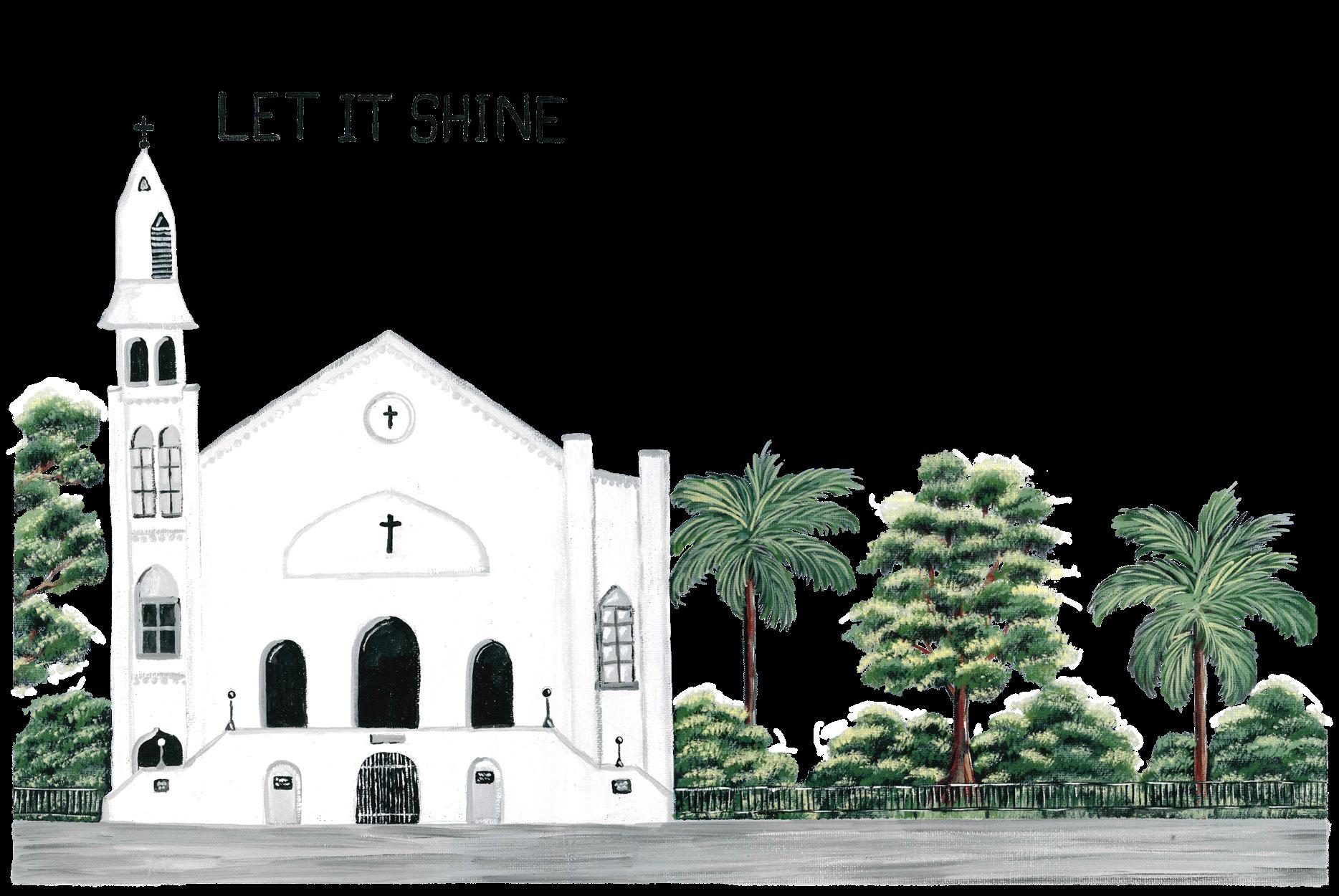

128 Let It Shine

At home in Mother Emanuel AME Church

131 The RISD Effect

How a cohort took design aesthetics by storm

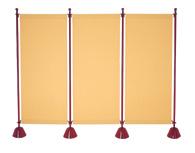

134 Purple Stain

One man revives the color of kings

Bath 135 Game of Thrones

What is a bathroom if not a place of existential vulnerability

Hardware 141 Hardware

Your guide to essential products from global hardware stores

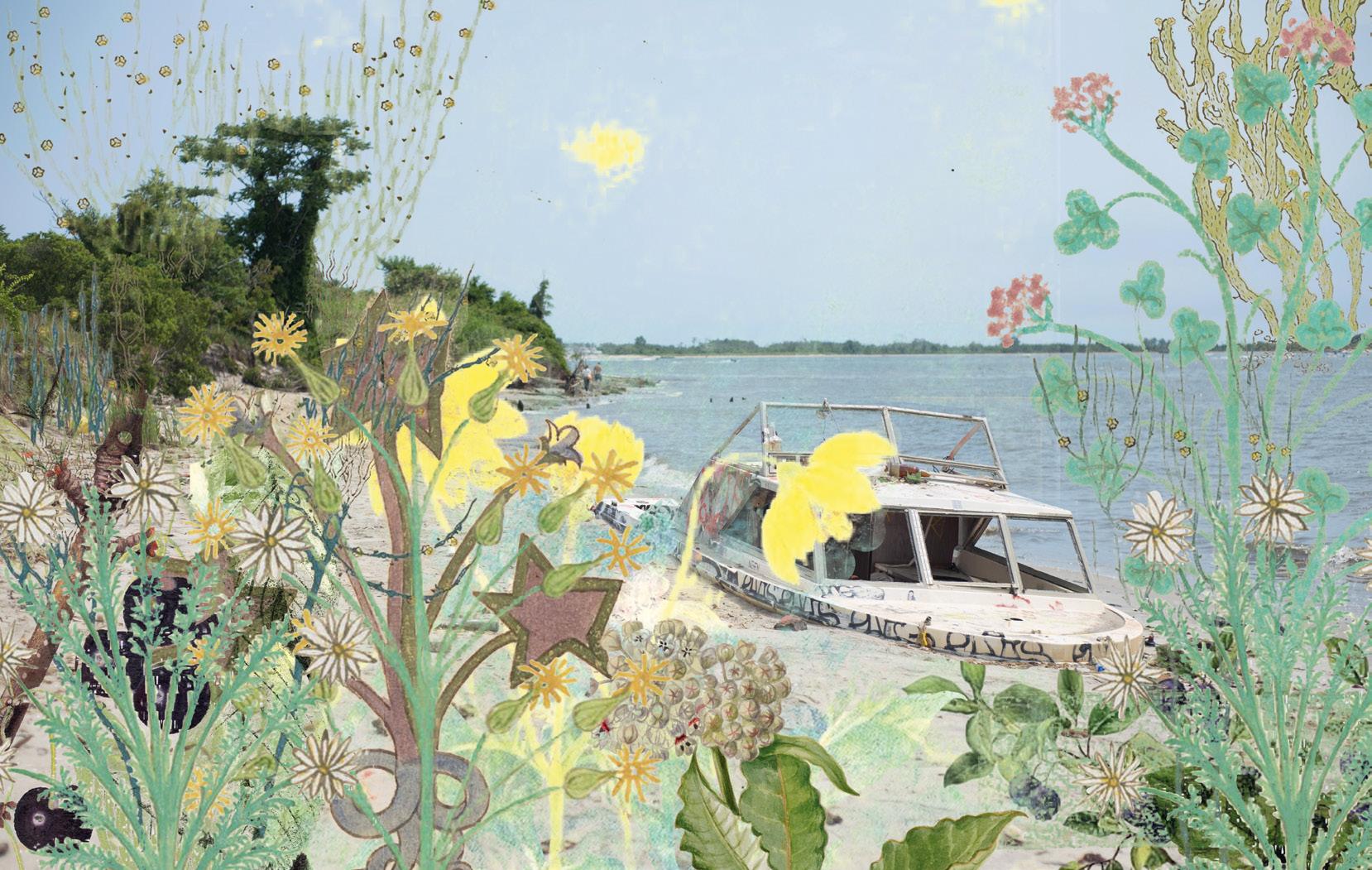

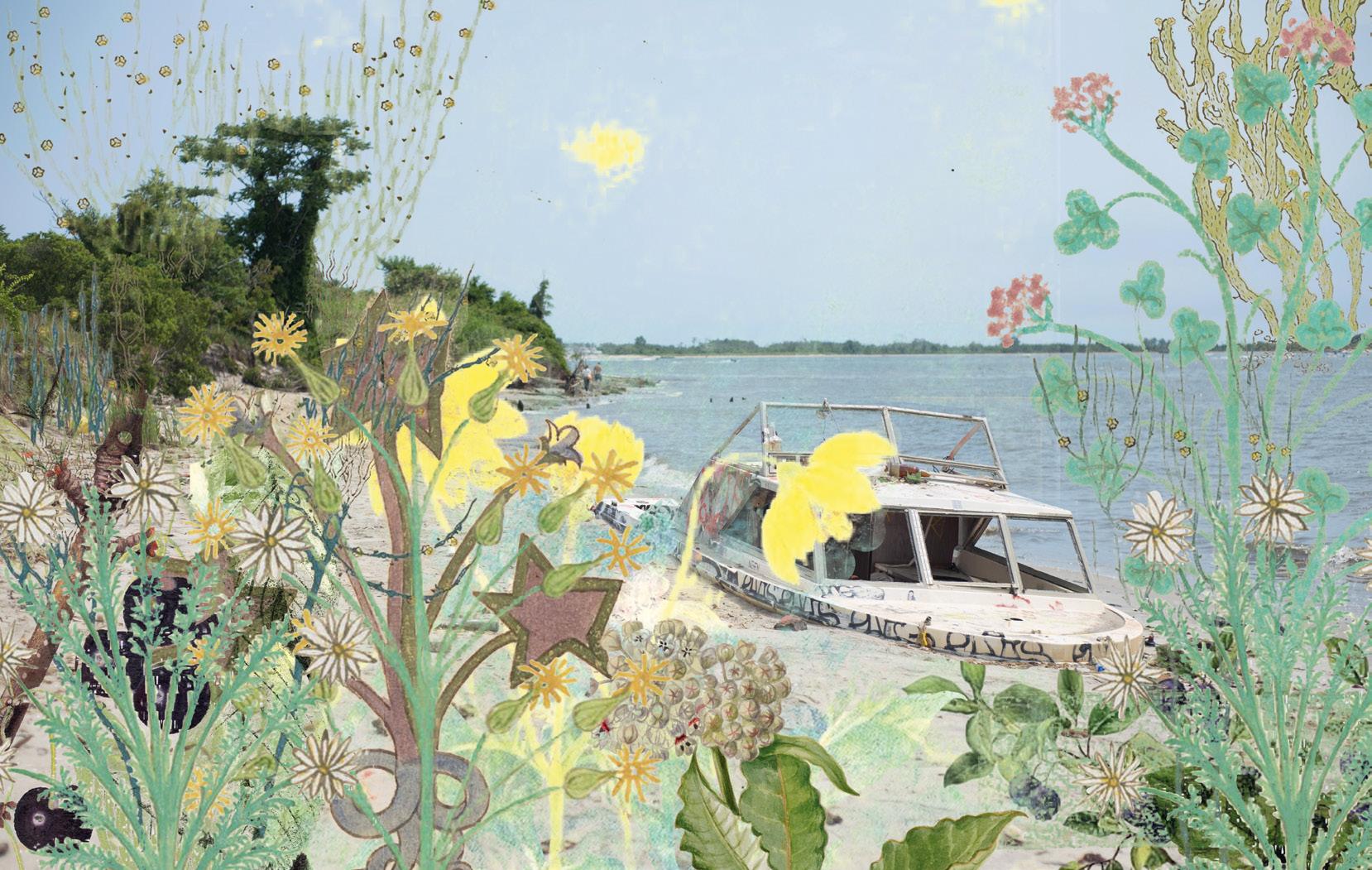

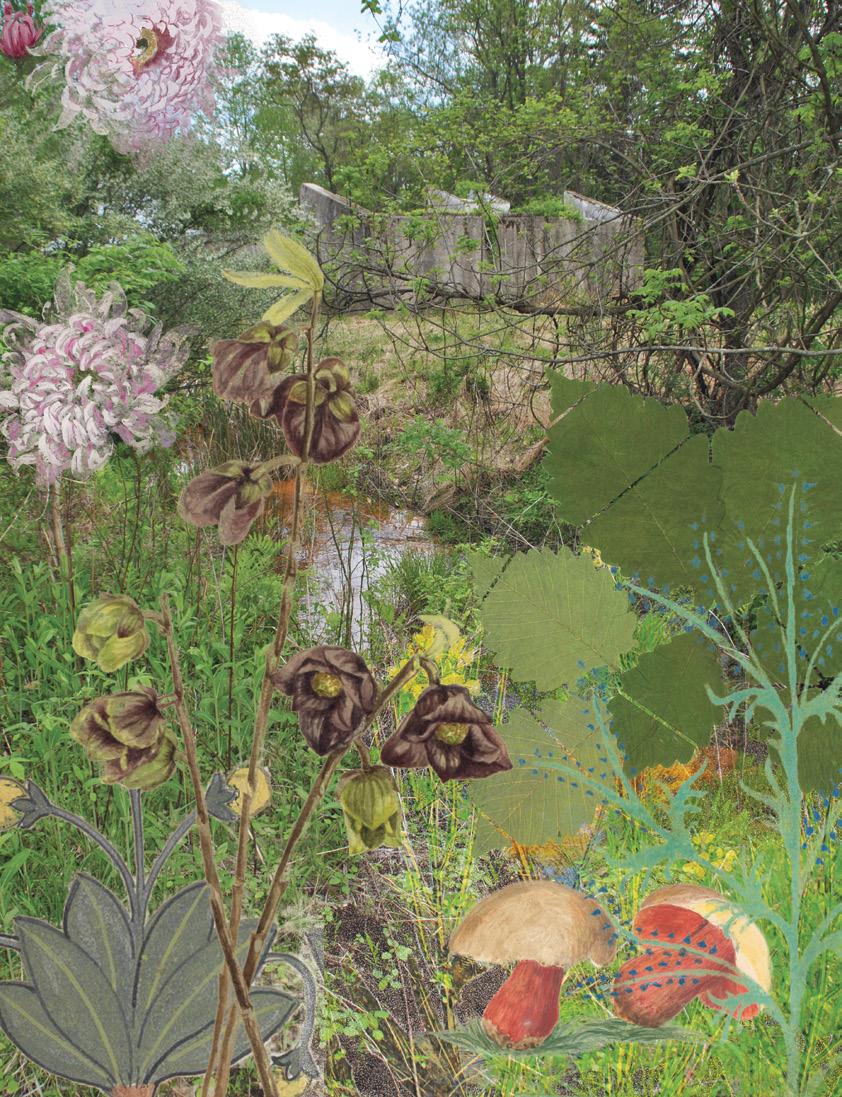

Garden 157 Gardens of Resistance

Five landscapes that defy their circumstances

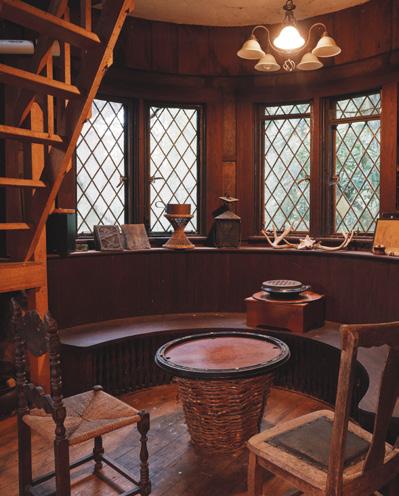

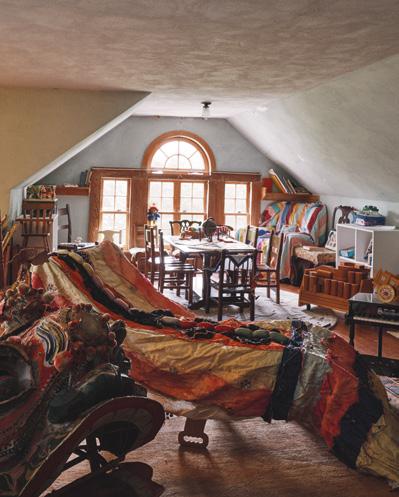

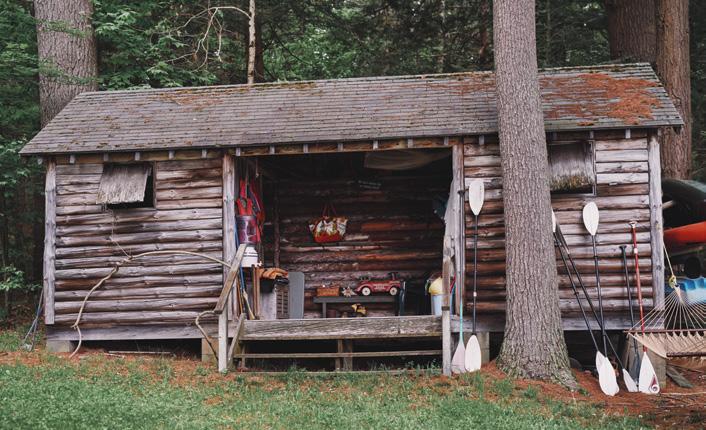

Home 164 Norfolk and Other Stories

A family compound serves generations and imaginations

180 A Canal House in Kyoto Johnston Marklee’s homage to waterway vernacular

196 A Lifelong Duet

Terry and Jo Harvey Allen make work and home in Santa Fe

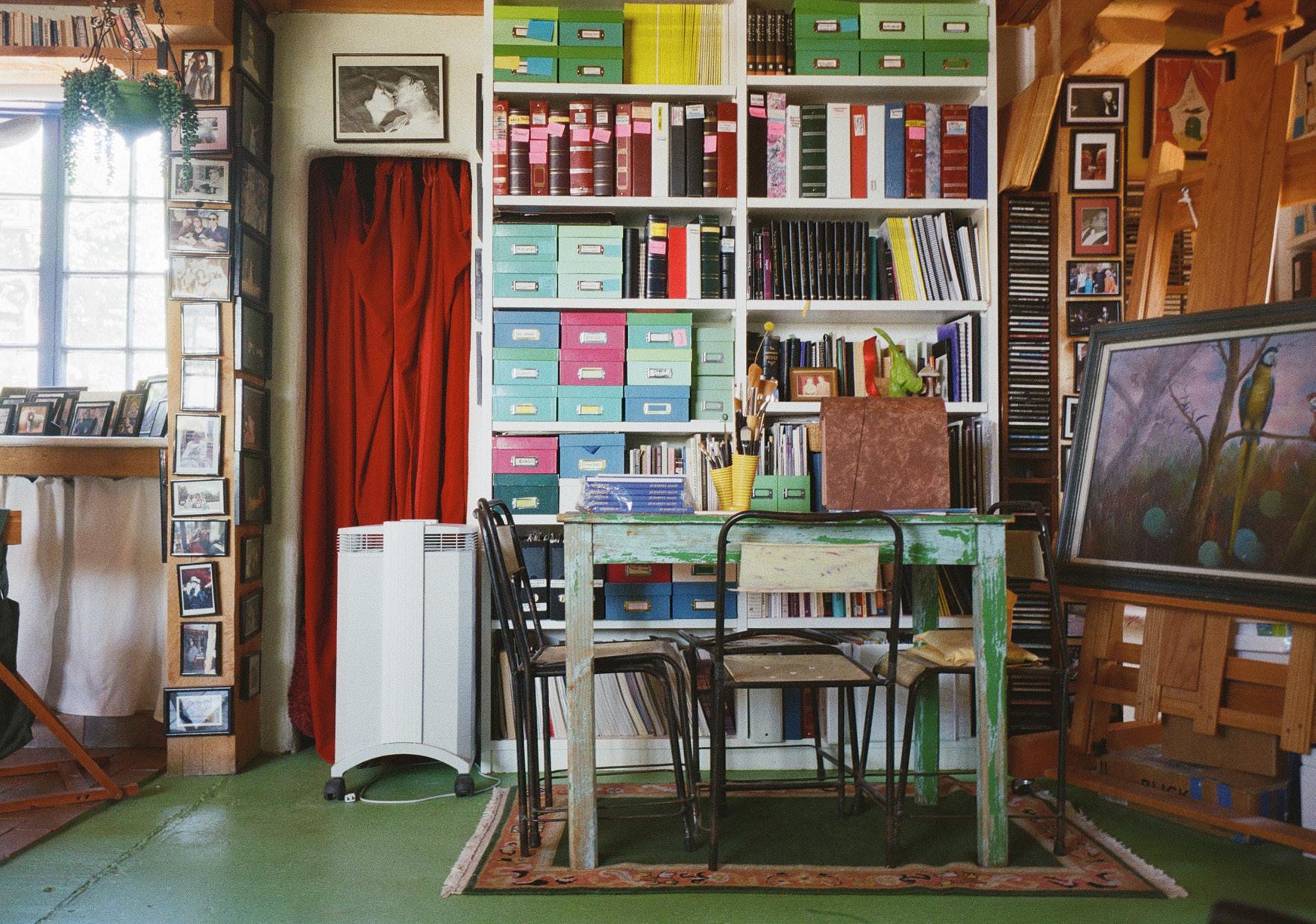

214 Stella Ishii Hasn’t Changed

The designer’s North Star has always been her SoHo loft

222 Everything, Down to the Soap Countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo adopts a High-Tech gem

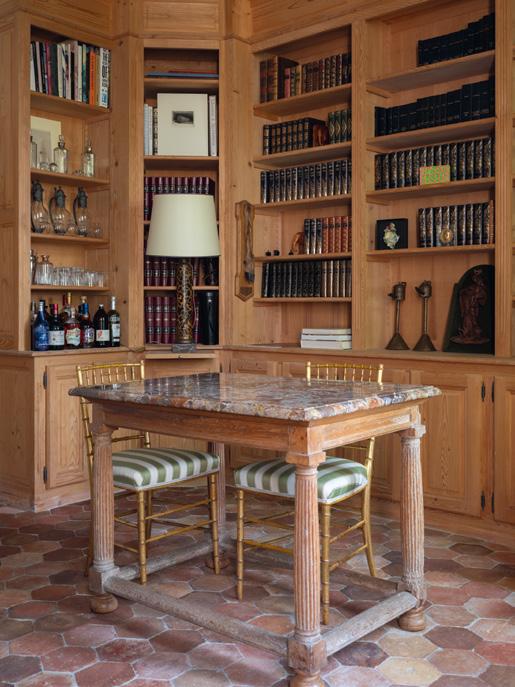

232 Burgundy Belle Époque

Axelle de Buffévent fills an 18thcentury home

Real Estate 244 The Nine Circles of Artist Housing Hell

What does it take for an artist to live and make work

Remodeling

250 Dear Designer, Your trusted source for home improvements, major and minor

What will you dream of next?

In early 2011, Sarah entrusted me to track down the elusive designer Ricky Clifton for CULTURED, her new magazine at the intersection of art and design. Ricky was phoneless, but I knew enough of his friends to find him, eventually, in Williamsburg at model Agyness Deyn’s apartment. He wanted to show me the ceilings he was lacquering and some shapely egg crates he’d rescued from a Trader Joe’s loading dock.

What is it about a designer like Ricky who makes worlds out of sidewalk pickings and paint? Stanley Tigerman has argued that architecture brings “paradise down to earth,” formalizing our existential conditions with its symbolisms; “To be named an architect,” muses John Hejduk, “at least one of your works must have an aura.” Although these distinguished avant-gardists both meant Architecture and Aura with capital A’s, I’d advocate for bringing those atmospheric terms back into the frame of everyday improvisational magic. Less to do with academics, or god, or taste, and more to do with human impulse and the vibration (literally) of light and sound into patterns of energy that move us and, over time, embroider our experience of the world. To place a rose in a vase on the table just so is an opus. It reveals intelligence gained from a lifetime of sensory experience. Only you can do it like that.

More than a decade after those first issues of CULTURED, the inaugural edition of CULTURED at Home chases that impulse for abundant experience across ruined gardens, calamitous interiors, midnight music, and sancta sanctorum, capturing how artists and designers resist neutrality, inventing new forms of expression; how people act out at home, making spaces, families, and ideas their own; and how the things we stare at, touch, taste, and hear form the foundation of imagination—and beauty—itself. This issue of CULTURED at Home is part resource—mapping landscapes of contemporary design culture— and part reverie—protecting the dreamer in all of us with intimate explorations of domestic space from a cross-spectrum of critics, novelists, filmmakers, performers, and designers themselves. The perspectives in these pages make a case for living life to its edges, and with each other.

Alexandra Cunningham Cameron

Juliette Agnel

Juliette Agnel is a multidisciplinary artist exploring the intersection of photography, memory, and space. Her work blends dreamlike landscapes with deeply ingrained cultural narratives, offering immersive visual experiences.

Michael Avedon

Michael Avedon is a photographer based in New York. He collaborates with brands including Tom Ford, Dior, Piaget, Bulgari, Louis Vuitton, and many others. Michael’s 2018 New York magazine cover story, “72 Years of School Shootings,” was awarded Best Cover Photography of the Year by the Society of Publication Designers.

Alissa Bennett is a writer whose essays and short fiction have appeared in The Paris Review, The New York Times, Texte Zur Kunst, and Vogue. Bennett is currently completing work on a script about the life of Edith Wharton. She teaches at the Yale School of Art and at Sarah Lawrence College.

Adraint Khadafhi Bereal is a photographer and author based in New York. Bereal is the author of The Black Yearbook, published by Penguin Random House.

Anne-France Berthelon is a design critic, curator, and journalist based between Paris and Marseille. Her passion for design and its global ecosystem has made her a regular contributor to publications such as IDEAT, Libération, AD China, and DAMN Being curious is her ultimate luxury.

Carson Chan

Carson Chan is an architecture writer and curator. He recently served as the inaugural director of the Ambasz Institute at MoMA, where he was also curator of architecture and design. His writing often appears in journals such as Frieze, Texte zur Kunst, and 032c, where he was formerly editor-at-large.

Adam Charlap Hyman

Adam Charlap Hyman is the co-founder of Charlap Hyman & Herrero, an architecture and design practice out of New York and Los Angeles, working across an array of projects from set design to residential interiors, freestanding buildings to store and exhibition design. His projects have been on the covers of Architectural Digest and Elle Decor, among others.

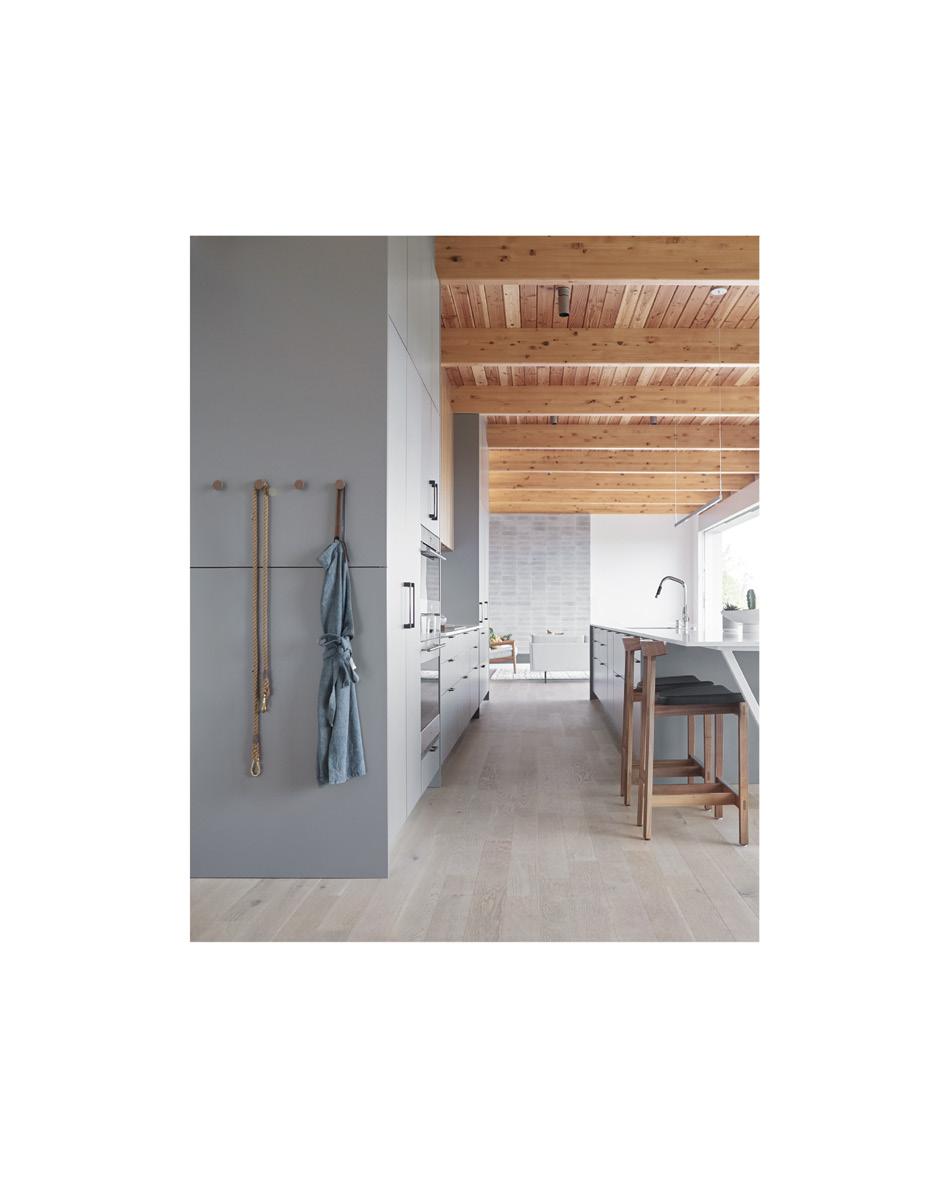

Sam Chermayeff

Sam Chermayeff is an architect, designer, and academic. Trained in architecture at the University of Texas at Austin and the Architectural Association, London, Sam is a founding partner of Sam Chermayeff Office. The studio’s work ranges from large residential towers to community centers to kitchens and furniture. He is currently a professor at Angewandte, Wien.

Durga Chew-Bose is a writer and filmmaker living in Montreal. She is the author of Too Much and Not the Mood. Her work has appeared in Vanity Fair, The New York Times Magazine, The Globe and Mail, and Harper’s Bazaar. Her directorial debut, Bonjour Tristesse, was released this year.

Esther M. Choi is an artist, photographer, and writer based in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in T: The New York Times Style Magazine, Dazed, The New York Times Magazine, and AnOther Magazine, among other publications.

Clarissa Dalrymple is an independent curator living in New York. She is the co-founder of Cable Gallery and an early curatorial champion of Matthew Barney, Ashley Bickerton, Nayland Blake, Sarah Lucas, and other artists.

Fiona Alison Duncan is a CanadianAmerican writer and curator. She is the author of Ex-Best Friends (F. Publications, 2025) and Exquisite Mariposa (Soft Skull, 2019). She lives between New York and Los Angeles.

Jarrett Earnest is a writer and curator living in New York, and the only things he talks about are art, sex, and books.

Akari Endo-Gaut is a New York–based style director and creative and curatorial consultant, celebrated for her ability to transform the ordinary into the extraordinary. Her expertise spans fashion, design, hospitality, and art. She embraces irregularity, finding harmony in the unexpected, and inspiring a deeper appreciation for life’s unevenness.

Rob Franklin is the author of Great Black Hope, which was published in June 2025. A national bestseller, it has been longlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize and named a “Best Book of the Year (so far)” by Vogue, Amazon Books, and Spotify. He lives in Brooklyn.

Born in Portland, Oregon, Adrian Gaut initially pursued painting before falling in love with large-format architectural photography. After relocating to New York, his work has been widely exhibited and published worldwide, with a notable book on Los Angeles architecture, Wilshire Boulevard. He is working on his second book.

Oliver Helbig

Oliver Helbig is a Berlin-based photographer. His depictions of nature, architecture, and portraits have made him a valued editorial contributor to magazines such as 032c, Architectural Digest, Zeitmagazin, PIN-UP, Vanity Fair, and AnOther Magazine. His collaboration with Sam Chermayeff spans more than 10 years.

Takashi Homma is a Japanese photographer born and based in Tokyo. Homma has published myriad books throughout his career. In 1999, he was awarded a Kimura Ihei Commemorative Photography Award for his project “Tokyo Suburbia,” 1998, his formative work now considered a classic.

Ruba Katrib is the chief curator and director of curatorial affairs at MoMA PS1. From 2012–18 she was the curator at SculptureCenter in New York. In 2018, Katrib co-curated SITE Santa Fe’s biennial, Casa Tomada, alongside José Luis Blondet and Candice Hopkins. In 2021, she led the curatorial team for MoMA PS1’s quinquennial survey, Greater New York.

Lawrence Kumpf is the founder and artistic director of Blank Forms, a nonprofit supporting experimental and creative music. He has organized international exhibitions; published widely on artists including Don Cherry, Catherine Christer Hennix, and Éliane Radigue; co-directs the Maryanne Amacher Foundation; and serves on the boards of FourOneOne and the Emily Harvey Foundation.

Thessaly La Force is a writer based in New York. She is a frequent contributor to The New York Times, The New Yorker, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, World of Interiors, Architectural Digest, and elsewhere.

Photographer Jeremy Liebman was born in Berkeley, California, and raised in Texas before moving to New York. He has photographed figures ranging from Bill Gates to John Waters for clients that include Interview, Apartamento, Purple, and The New Yorker. His work has been commissioned by the Met Museum, Apple, and Bottega Veneta.

Camille Okhio is a New York–based writer, curator, and historian. Her work has appeared in Apartamento, W, Architectural Digest, The New York Times, Art in America, Wallpaper*, PIN–UP, and Vogue. Her practice centers on fine and decorative arts and their narrative potential.

Stella Roos is a Finnish writer focusing on the built environment. She is the design correspondent for Monocle and Konfekt magazine, an editor at Berlin Review, and a contributor to various publications. She is currently a Fulbright scholar at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism in New York.

Self

Jack Self is an architect and writer based in London. He is director of the REAL Foundation and editor-in-chief of the Real Review. In 2016, Jack curated the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale. Jack’s architectural design focuses on alternative models of ownership, contemporary forms of labor, and the formation of socioeconomic power relationships in space.

Sina Sohrab is an industrial designer based in Madrid. His office engages with contemporary life through design work and cultural-historical research, parallel practices that yield outcomes ranging from furniture and products to exhibitions and publications. His work has been internationally exhibited and awarded, and in 2024 Phaidon named him among 100 leading designers.

Peter Sutherland lives and works in Salida, Colorado. His select solo exhibitions have been held at Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis; White Cube Gallery, London; Galerie Rodolph Janssen; and Bill Brady KC Gallery. Group exhibitions include the Journal Gallery, Museum DhondtDhaenens, and Nahmad Contemporary.

Amalia Ulman is an artist based in New York. Her multidisciplinary work uses fictional narratives to explore the tensions between globalization, consumerism, public image, and private desires. Her second film, Magic Farm, premiered in 2025 at the Sundance Film Festival and the Berlinale.

Editor-in-Chief

Guest Editor

Creative Director

Executive Editor

Market Editor

Garden Editor

Kitchen and Bath Editor

Books Editor

Contributing Editors

Sarah Harrelson

Alexandra Cunningham Cameron

Erin Knutson

Mara Veitch

Adam Charlap Hyman

Precious Okoyomon

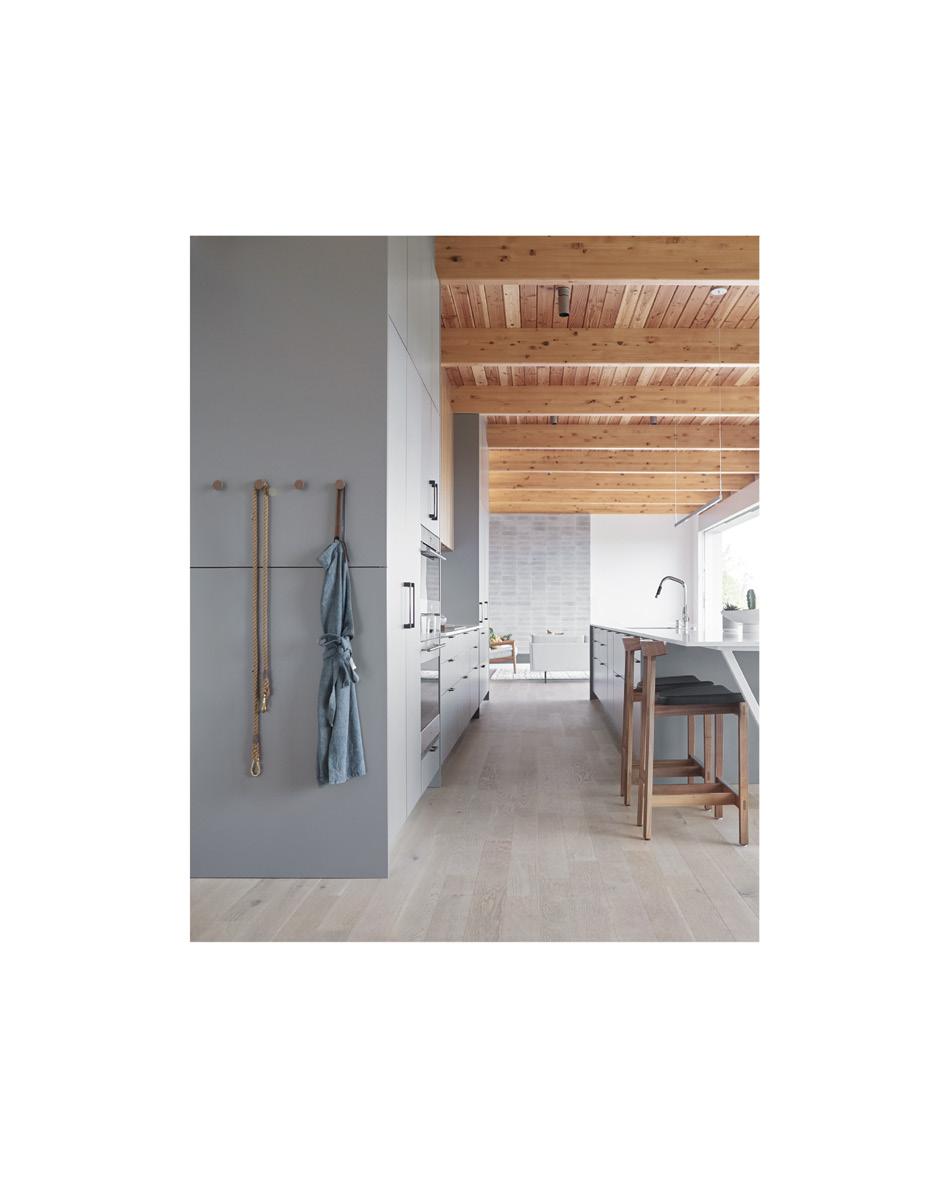

Sam Chermayeff

Carson Chan

Ruba Katrib

Cynthia Leung

Stella Roos

Jason Wigginton

Vice President, Carl Kiesel

Chief Revenue Officer

Vice President Of Sales, Lori Warriner

Art + Fashion

Director Of Desmond Smalley

Brand Partnerships

Marketing Hailey Powers and Sales Associate

Public Relations

Ethan Elkins

Dada Goldberg

Sales Consultant, Priya Nat

Home + Travel

Strategic Advisor

Carol Smith

Creative Producers

Research Editors

Copyeditor

Junior Designers

Printer

Retoucher

Julia Bronheim

Jacob Gaines

Tatum Dodd

Sunena Maju

Karly Quadros

Eveline Chao

Paul Bille

Katie Ehrlich

Printer Trento, IT

Alta Image New York, NY

Our editors’ favorite places to explore design culture.

Cairo, EG Cape Town, ZA Dakar, SN Dakar, SN Kampala, UG Rabat, MA Abu Dhabi, UAE Ahmedabad, IN

Beijing, CN Beirut, LB Doha, QA Higashiyama, JP Hong Kong, CN Seoul, KR Tokyo, JP

Melbourne, AU Amsterdam, NL Barcelona, ES Berlin, DE

Copenhagen, DK Gent, BE

København, DK Köln, DE Lisbon, PT London, GB

Lyon, FR Mérida, SP Milan, IT Munich, DE Paris, FR

Pompeii, IT Riggisberg, CH Rome, IT Rotterdam, NL Stockholm, SE Tilburg, NL Vienna, AT Weil am Rhein, DE Wroclaw, PL Zürich, CH Atlanta, U.S. Bloomfield Hills, U.S. Boston, U.S. Brooklyn, U.S. Charlotte, U.S. Chatham, U.S. Chicago, U.S. Cleveland, U.S. Dallas, U.S. Detroit, U.S. Honolulu, U.S. Houston, U.S. Indianapolis, U.S. Los Angeles, U.S. Mexico City, MX

Minneapolis, U.S. Montréal, CA München, DE

New Baltimore, U.S. New Haven, U.S. New York, U.S.

Philadelphia, U.S. Pittsburgh, U.S. Providence, U.S. San Francisco, U.S. Washington DC, U.S.

Winterthur, U.S. Belém, BR Bogotá, CO Buenos Aires, AR São Paulo, BR

Egyptian Museum

Zeitz MOCAA

Musée des Civilisations Noires

Musée Théodore Monod d’Art Africain

Uganda Museum

Mohammed VI Museum

Louvre Abu Dhabi

Calico Museum of Textiles

National Institute of Design Museum

National Museum of China

Sursock Museum

Museum of Islamic Art

Kanazawa Yasue Gold Leaf Museum

M+ Museum

Modern Design Museum

National Museum of Modern Art

21_21 Design Sight

Japan Folk Crafts Museum

National Gallery of Victoria

Rijksmuseum

Barcelona Design Museum

Bauhaus-Archiv

Tchoban Foundation

Danish Architecture Center

Design Museum Gent Designmuseo

Design Museum Denmark

MAKK

Museum of Art, Architecture & Technology

V&A Storehouse

the Design Museum

Sir John Soane’s Museum

British Museum

Musée des Tissus

Museo Nacional de Arte Romano

Triennale di Milano

Architekturmuseum der TUM

Musee des Arts Décoratifs

Musée du Louvre

Mobilier National

Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine

Pompeii Antiquarium

Abegg-Stiftung

MAXXI

Het Nieuwe Instituut

ArkDes

Textiel Museum

MAK Wien

Vitra Design Museum

Museum of Architecture

Museum für Gestaltung

High Museum of Art

Cranbrook Art Museum

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Brooklyn Museum

Mint Museum

Shaker Museum

The Art Institute of Chicago

Cleveland Museum of Art

Dallas Museum of Art

The Detroit Institute of Arts

Bishop Museum

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Indianapolis Museum of Art

LACMA

Museo Nacional de Antropología

Museo del Arte Popular

Minneapolis Institute of Arts

CCA

Die Neue Sammlung

Cold War Museum

Yale University Art Gallery

Cooper Hewitt

Museum of Modern Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

American Folk Art Museum

The Hispanic Society

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Carnegie Museum of Art

RISD Museum

SFMOMA

NMAAHC

National Building Museum

Winterthur Museum

Museu de Arte de Belém

Museo del Oro

MALBA Museo

Museo de Arte

Moderno

Egyptian material culture

Contemporary African design

Pan-African art & design

Traditional & contemporary African crafts

Ugandan material culture

Moroccan visual culture

Cross cultural & Islamic decorative arts

Indian court textiles

Modern & contemporary Indian design innovation

Chinese decorative arts & design

Islamic & late Ottoman decorative arts

Islamic decorative arts, manuscripts, & textiles

Japanese gold leaf craft & technique

Hong Kong design culture

Korean decorative arts

Modern Japanese design & crafts

Contemporary Japanese design

Japanese ceramics & textiles

Design 1960 to present

Dutch Golden Age design

Spanish decorative arts

Bauhaus & contemporary design

Architectural drawings

Danish architecture

Social impact design

Finnish industrial design

Danish & international design

Jewelry, porcelain & furniture

Art, architecture & tech in dialogue

Open storage design

Product, graphic & fashion design

Neoclassical drawings & models

International decorative arts traditions

Silk, European & global textiles from antiquity

Roman sculptures, mosaics & archaeological display

Italian architecture & design

Architectural drawings, models, & archives

French decorative arts & design

French royal decorative arts

National collection of design

French architecture models & archives

Roman artifacts & casts from Pompeii

Historic textiles from Europe, Middle East, & Asia

20th–21st century architecture

Dutch national design collection

Swedish architecture & design

Historic & contemporary textile design

Austrian & European modernism

Industrial design & architecture

20th-21st century architecture

Industrial & graphic design

American decorative arts

Cranbrook design legacy

Design & decorative arts

Design & decorative arts

North Carolina pottery & design

Shaker design traditions

Architecture & design

Design & decorative arts

Design, decorative arts & jewelry

European decorative arts

Hawaiian design & culture

Design & decorative arts

Campus for art & design

Historic to contemporary design

Pre-Columbian culture & decorative arts

Mexican folk art, textiles, ceramics, & masks

Period rooms, decorative arts & design

International architecture

20th–21st decorative arts

Cold War design & history

American colonial design

U.S. national design collection

Modern design & architecture

Architecture, design & antiquities

Folk & vernacular design

Spanish & Latin American material culture

European decorative arts

Decorative arts & architecture

European design & decorative arts

Design & architecture

National collection of African-American design

Architecture, urban design, & engineering

1640–1860 interiors & material culture

Amazonian, colonial & Brazilian decorative arts

Pre-Columbian goldwork & jewelry

Latin American modern design

Latin American design & craft

egyptianmuseumcairo.eg zeitzmocaa.museum mcn.sn musee-monod.sn ugandamuseums.ug fnm.ma louvreabudhabi.ae calicomuseum.org nid.edu en.chnmuseum.cn sursock.museum mia.org.qa kanazawa-museum.jp mplus.org.hk designmuseum.or.kr momat.go.jp/en 2121designsight.jp mingeikan.or.jp ngv.vic.gov.au rijksmuseum.nl dissenyhub.barcelona bauhaus.de tchoban-foundation.de dac.dk designmuseumgent.be designmuseumgent.be designmuseum.dk makk.de maat.pt/en vam.ac.uk/east designmuseum.org soane.org britishmuseum.org museedestissus.fr museoarteromano.mcu.es triennale.org architekturmuseum.de madparis.fr louvre.fr mobiliernational.culture.gouv.fr citedelarchitecture.fr pompeiisites.org abegg-stiftung.ch maxxi.art nieuweinstituut.nl arkdes.se textielmuseum.nl mak.at design-museum.de ma.wroc.pl museum-gestaltung.ch high.org cranbrookartmuseum.org mfa.org brooklynmuseum.orgg mintmuseum.org shakermuseum.us artic.edu clevelandart.org dma.org dia.org bishopmuseum.org mfah.org discovernewfields.org lacma.org mna.inah.gob.mx map.cdmx.gob.mx new.artsmia.org cca.qc.ca die-neue-sammlung.de coldwar.org artgallery.yale.edu cooperhewitt.org moma.org metmuseum.org folkartmuseum.org hispanicsociety.org philamuseum.org cmoa.org risdmuseum.org sfmoma.org nmaahc.si.edu nbm.org winterthur.org mabe.belem.pa.gov.br banrepcultural.org/bogota malba.org.ar mam.org.br

Our editors’ favorite places to explore design commerce.

Cape Town, ZA Lagos, NG Tunis, TN Bengaluru, IN Mumbai, IN Shanghai, CN Tokyo, JP Antwerp, BE Athens, GR Barcelona, ES Berlin, DE Brussels, BE Copenhagen, DK Leith, U.K. London, U.K.

Milan, IT

Moscow, RU Oslo, NO Paris, FR

Piraeus, GR Prague, CZ Rome, IT Rotterdam, NL Stockholm, SE Venice, IT

Amagansett, U.S. Brooklyn, U.S. Chicago, U.S. Los Angeles, U.S. Mexico City, MX

Miami, U.S. Minneapolis, U.S. New York, U.S.

Southern Guild

Tiwani Contemporary

Musk and Amber Gallery

General Items

AEQUO

Gallery ALL

Ippodo Gallery

Uppercut Space

COUR

The Breeder

Side Gallery

Ulrich Fiedler

Architektur Galerie Berlin

OWN (Objects with Narratives)

Maniera

Etage Projects

Dansk Møbelkunst

Bard

Abel Sloane 1934

Gallery Fumi

Sarah Myerscough Gallery

Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Rose Uniacke

Nilufar Gallery

Galleria Rossella Colombari

Galleria Rossana Orlandi

Erastudio

Booroom Gallery

Galleri Format

Galerie Patrick Seguin

Galerie kreo

Galerie Jacques Lacoste

Galerie Chastel Maréchal

Galerie Yves Gastou

Jousse Entreprise

Laffanour Galerie Downtown

Project Room / India Mahdavi

Anne Sophie Duval

A1043

Galerie Marcilhac

Carwan Gallery

Galerie VI PER

Galleria Giustini/Stagetti

Galerie VIVID

Modernity

Jackson Design

Giorgio Mastinu

Caterina Tognon

Galerie Sardine

Of the Cloth

Volume Gallery

Marta

Edward Cella Art + Architecture

AGO Projects

Masa Galería

Nina Johnson

Idea House 3

R & Company

STUDIOTWENTYSEVEN

Salon 94

Jacqueline Sullivan Gallery

Demisch Danant

Les Ateliers Courbet

The Future Perfect

Superhouse

Hello Human House

TIWA Select

Galerie Was

Friedman Benda

Hostler Burrows

Emma Scully Gallery

Magen H Gallery

a83

Galerie Gabriel

Donzella Ltd.

Cristina Grajales

Galerie56

Gallery Folly

Todd Merrill

Paula Rubenstein

Creative Growth

Oakland, U.S. Philadelphia, U.S.

Point Reyes Station, U.S. South Salem, NY, U.S. Vancouver, U.S. Rio de Janeiro, BR São Paulo, BR

African & diasporic contemporary design

African & diasporic design

Tunisian craft & contemporary design

Ritual-inspired contemporary design

Indian craft & contemporary design

Contemporary Chinese design

Contemporary Japanese craft

Contemporary design

Contemporary design

Contemporary design

Latin American modern & contemporary design

Bauhaus & early 20th-century design

Contemporary architecture

Contemporary design

Contemporary architecture & design

Contemporary design

Modern Danish design

Scottish craft

Early 20th-century design

Contemporary design

Contemporary craft

Modern & contemporary design

Contemporary antiques & design

Italian postwar & contemporary design

Postwar Italian design

Contemporary design

Italian postmodern architecture & design

Contemporary design

Norwegian craft & design

French modern design

Contemporary design

French decorative arts & design

French decorative arts & design

Postmodern design

Modern & postwar French design

French postwar & contemporary design

Contemporary design

Art Deco

20th-century & contemporary lighting

Art Deco

Contemporary design

Architecture & urban design

Italian postwar & contemporary design

Dutch 20th-century & contemporary design

Scandinavian 20th-century design

Scandinavian 20th-century design

Postmodern design & books

Studio glass

Contemporary design

Contemporary craft & design

Contemporary design

Contemporary design

Architectural drawing

Contemporary architecture & design

Contemporary design

Contemporary design

Contemporary design

Contemporary design

Brazilian & Italian modern design

Contemporary design

Postmodern & contemporary design

Postwar French design

Artisanal furniture & lighting

Contemporary objects

Postmodern & contemporary design

Contemporary design

Contemporary craft & design

Contemporary antiques & design

Contemporary design

Nordic & American ceramics & design

Contemporary design

Postwar French sculptural design

Architectural prints

Postmodern & contemporary design

Postwar design

Contemporary design

Modern & contemporary design

European modern design

Contemporary design

20th-century design

Contemporary craft

Moderne Gallery

Dudd House

Fleisher/Ollman

Blunk Space

John Keith Russell Antiques

Douglas Reynolds Gallery

Mercado Moderno

BRAZIL MODERNIST

American studio furniture

Contemporary design

Self-taught & institutional design

Contemporary craft & design

Shaker design

Pacific Northwest Indigenous art

Modern Brazilian design

Modern Brazilian design

southernguild.com tiwani.co.uk musk_and_amber generalitems.in aequo.in galleryall.com ippodogallery.com uppercut.space courgallery.com thebreedersystem.com side-gallery.com ulrichfiedler.com architekturgalerieberlin.de objectswithnarratives.com maniera.be etageprojects.com dmk.dk bard-scotland.com abelsloane1934.com galleryfumi.com sarahmyerscough.com carpentersworkshopgallery.com roseuniacke.com nilufar.com galleriarossellacolombari.com rossanaorlandi.com erastudio.it booroomgallery.com format.no patrickseguin.com galeriekreo.com jacqueslacoste.com chastel-marechal.com galerieyvesgastou.com jousse-entreprise.com galeriedowntown.com india-mahdavi.com annesophieduval.com shop.a1043.com marcilhacgalerie.com carwangallery.com vipergallery.org giustinistagetti.com galerievivid.com modernity.se jacksons.se giorgiomastinu caterinatognon.com galeriesardine.com ofthecloth wvvolumes.com marta.la edwardcella.com ago-projects.com mmaassaa.com ninajohnson.com shop.walkerart.org r-and-company.com studiotwentyseven.com salon94.com jacquelinesullivangallery.com demischdanant.com ateliercourbet.com thefutureperfect.com superhouse.us hellohuman.us tiwa-select.com galeriewas.com friedmanbenda.com hostlerburrows.com emmascullygallery.com magenxxcentury.com a83.site galeriegabriel.com donzella.com cristinagrajales.com galerie56.com galleryfolly.com toddmerrillstudio.com paularubenstein.com creativegrowth.org modernegallery.com jonalddudd.com fleisher-ollmangallery.com blunkspace.com jkrantiques.com douglasreynoldsgallery.com memobrasil.com brazilmodernist.com

The 20 exhibitions, from Kazakhstan to Los Angeles, that are shaping discourse around architecture and design.

Asif Khan’s Tselinny Center Opens Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, Almaty, Kazakhstan Sept. 5, 2025

Chiharu Shiota: Two Home Countries Japan Society, New York, USA Sept. 12, 2025–Jan. 11, 2026

Kazakhstan’s first independent cultural institution opens in a transformed Soviet-era cinema redesigned by British architect Asif Khan. The new cultural hub launches with exhibitions, performances, and lectures, including Barsakelmes, a multidisciplinary program rooted in Kazakh culture, alongside a narrative exhibition of Khan’s renovation and archival explorations of Central Asian art.

Known for her immersive, site-specific installations in which webs of yarn envelop entire spaces, suspending fragments of memory within their threads, Chiharu Shiota creates poignant meditations on war, identity, and the human condition. The artist’s first New York solo museum exhibition commemorates the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II by interlacing collective history with the artist’s personal memory.

Donald Judd’s Architecture Office Reopens Judd Foundation, Marfa, TX, USA Opened September 2025

Dream Rooms: Environments by Women Artists 1950s–Now M+ Museum, Hong Kong Sept. 20, 2025–Jan. 18, 2026

Vacant Futures

VI PER, Prague, Czechia Sept. 24, 2025–Nov. 15, 2025

Four Five Six by OFFICE KGDVS A83, SoHo, New York, USA Sept. 25, 2025–Late November 2025

Built in 1907 as a boarding house and grocery, the building that became Donald Judd’s Architecture Office was restored in 1990 with characteristic precision and restraint. “The only thing different was that it has unusual furniture inside,” he said, referring to his own designs. After his death in 1994, the building’s condition declined. Restoration began in 2018 and was nearly undone by a 2021 fire, which destroyed much of the interior and roof. The reopening, after years of careful reconstruction, is a meditation on how architectural legacy can be both preserved and adapted. The restored facade and new sustainable additions embody Judd’s belief that architecture is a living discipline, impacted as much by history and memory as by material and function.

Donald Judd’s architecture office in Marfa, Texas, will finally reopen after seven years and a nearly devastating fire.

Photography by Matthew Milman. Courtesy of the Judd Foundation, John Chamberlain Art, Fairweather & Fairweather LTD / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Before “installation art” had a name, there were Environments— immersive works from the 1950s and ’60s that blended art, architecture, and design. Dream Rooms features the groundbreaking work of Lygia Clark, Judy Chicago, Nanda Vigo, Tania Mouraud, Marta Minujín, Yamazaki Tsuruko, Pinaree Sanpitak, and Kimsooja.

Through film and visual research, the exhibition examines the uncanny landscapes and unintended habitats that emerge in the wake of stalled developments and unfulfilled promises.

Coinciding with the release of OFFICE KGDVS’s three-part publication, Four Five Six reflects on a decade of the firm’s conceptual, academic, and professional work. Through 96 new limited-edition silkscreen prints produced by A83’s historic print shop, large-scale architectural models by OFFICE, photographs by Bas Princen and Stefano Graziani, and sculptures by artist Rita McBride, the exhibition invites a closer look at how ideas move between page, model, and built form.

The Living Temple: The World of Moki Cherry

The Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia, USA

Sept. 25, 2025–April 12, 2026

Denilson Baniwa Facade Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York, USA

Opened September 2025

Form by Formula

Mass Modern Design, Roosendaal, The Netherlands Oct. 17, 2025–Dec. 17, 2025

Moki Cherry dissolved the boundaries between art and life, creating an ever-expanding universe of tapestries, paintings, ceramics, clothing, music, and performance with her musician husband Don Cherry. Guided by the mantra, “home as stage, stage as home,” she transformed everyday spaces into sites of exchange, whether through vividly patterned textiles, wearable art, or immersive stage environments.

Storefront for Art and Architecture’s historic facade designed by Steven Holl and Vito Acconci in 1993 is reimagined by Indigenous Amazonian artist Denilson Baniwa. Na floresta à noite (In the Forest of the Night) merges ancestral cosmologies with contemporary imagery to create a shifting forest of light and myth.

Form by Formula is the first exhibition devoted to the history of religious furniture shaped by the Plastic Number, a proportional system devised by monk and architect Dom Hans van der Laan. Long obscured by misattribution, with many pieces credited to Van der Laan himself, curator Etienne Feijns reveals the true makers and contexts of these objects. Highlights include a newly discovered 1968 furniture set by Van der Laan, works by his pupil Jan de Jong, Bossche School furniture, and rare architectural drawings and prints.

MONUMENTS

The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and The Brick, Los Angeles, USA Oct. 23, 2025–April 12, 2026

Material Affirmations: Oríkì Acts I–III Tiwani Contemporary, Lagos, Nigeria Nov. 6, 2025–Jan. 11, 2026

French Popular Furniture

Vague Kobe, Hyogo, Japan Nov. 8, 2025–Dec. 31, 2025

How Modern: Biographies of Architecture in China 1949–1979

The Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, Canada Nov. 20, 2025–April 12, 2026

FUNGI: Anarchist Designers

Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, The Netherlands Nov. 20, 2025–Aug. 8, 2026

MONUMENTS confronts the charged legacy of Confederate statues by relocating decommissioned monuments from public spaces into gallery settings. Organizers Hamza Walker, artist Kara Walker and MoCA curators have commissioned and paired these objects with work from artists such as Karon Davis, Abigail Deville, Stan Douglas, Torkwase Dyson, Nona Faustine, Martin Puryear, Hank Willis Thomas, and Davóne Tines to provoke critical reflection on how public memory shapes national identity.

Lagos-based designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello explores locally rooted, community-driven craft traditions, overlooked production networks, and everyday making cultures in Nigeria. Material Affirmations: Oríkì Acts I–III marks the first full presentation of the series on African soil, inviting reflection on tradition, innovation, and the politics of craft.

Curated by Nicolas Trembley, this exhibition places French folk traditions in conversation with Japanese mingei (short for minzoku teki kōgei, meaning folk crafts), revealing how craftsmanship holds cultural memory, identity, and sustainability in its hands. From rural furniture to woven objects, these countryside works invite us to rethink modernity, not as a break from tradition, but as a continuation of it.

Organized by the Canadian Centre for Architecture in collaboration with M+ Museum in Hong Kong, How Modern: Biographies of Architecture in China 1949–1979 reframes the prevailing view of architecture in Mao’s China as monolithic and creatively stifled.

Curated by anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing and design studio terriStories (Feifei Zhou), FUNGI: Anarchist Designers presents fungi as ingenious builders and relentless dismantlers operating at the intersection of science, art, and design. Featuring Ivette Perfecto and Filipp Groubnov’s mapping of the spread of coffee rust benefiting from Latin America’s monoculture industrial coffee plantation to Bettina Stoetzer, Berkveldt, and Åsa Sonjasdotter’s installation on the spread of radioactivity through wild boars’ consumption of radioactive mushrooms.

Made in America: The Industrial Photography of Christopher Payne Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, USA Nov. 21, 2025–Spring 2026

Robert Therrien: This Is a Story The Broad, Los Angeles, USA Nov. 22, 2025–April 5, 2026

Design Miami

Miami Beach Convention Center, Miami, USA Dec. 3–7, 2025

Westwood | Kawakubo

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia Dec. 7, 2025–April 19, 2026

Bruce Goff: Material Worlds Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA Dec. 21, 2025–March 29, 2026

ADFF: STIR Mumbai

National Center for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, India Jan. 9–11, 2026

Cooper Hewitt’s first large-scale photography exhibition, Made in America, brings the object, the machine, and the human hand into sharp focus. Christopher Payne has documented the artistry and precision of American manufacturing—from marshmallow Peeps and colored pencils to tractors and jumbo jets—capturing each at the most compelling moment of production.

Robert Therrien: This Is a Story unfolds five decades of work by an artist who saw the extraordinary hidden in the ordinary. Therrien’s monumental reimaginings of domestic objects transform tables, chairs, and kitchenware into vast landscapes of memory and perception. By enlarging the everyday to dramatic, almost theatrical proportions, he asks us to consider how scale can challenge and distort space and the stories we tell about it.

Design Miami celebrates its 20th anniversary with Make. Believe., an exhibition that honors contemporary and historic creators whose ideas have shaped the future. Maison Perrier-Jouët’s special award presentation adds extra sparkle to this landmark event.

Emerging independently in the 1970s from Britain and Japan, Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo introduced a radical spirit grounded in personal freedom and social critique. The exhibition reveals how these fearless designers questioned fashion’s core assumptions about identity, power, and beauty, inviting viewers to rethink the meaning of style and self-expression in a shifting world.

Known for dramatic geometries and an improbable palette—coal, goose feathers, astroturf, cellophane, sequins—Goff resisted any singular style, creating work that cheerfully defied modernism’s minimalist orthodoxies. Dubbed the “Michelangelo of kitsch” by critic Charles Jencks, Goff’s buildings emerged from a conviction that architecture should be felt as much as seen. Art Institute of Chicago pulls from its dense archive of Goff’s work and belongings, creating a rare opportunity to enter the restless imagination that reshaped the Midwest’s midcentury landscape.

Celebrating the many worlds of architecture and design and their intersections with cinema, ADFF: STIR Mumbai returns with an expanded, multifaceted program building on its 2025 South Asia debut. Its Pavilion Park—curated by Aric Chen, director of the Zaha Hadid Foundation—creates a dynamic space where film, architecture, design, and art converge.

November 6–10 at Park Avenue Armory in New York City

Text and Photography

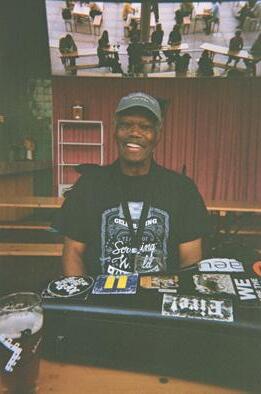

by Ruba Katrib and Lawrence Kumpf

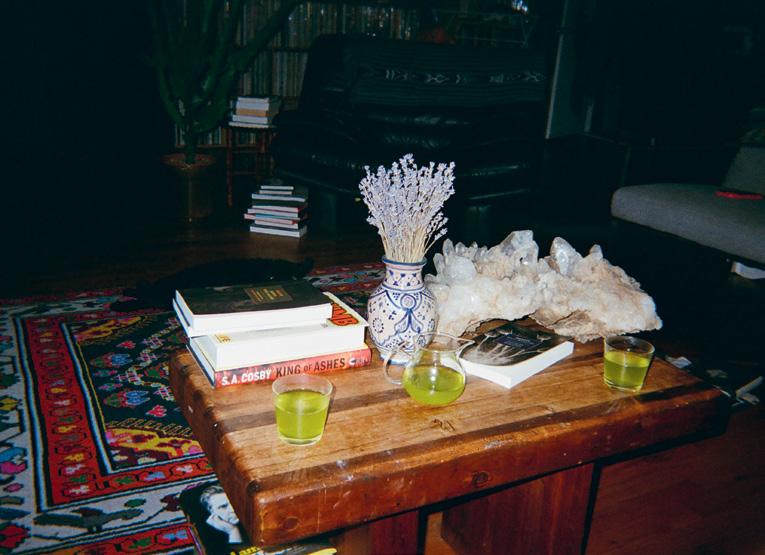

We have a lot of events in our lives, between Lawrence’s work at Blank Forms, Ruba’s at MoMA PS1, and everything else. Since Blank Forms is close to home, we often end up in our apartment with artists, musicians, and other friends late into the evening. Our house is crammed with thousands of books and records—and counting. The real stars of the apartment are the cats, Maki and Doji, named after the Japanese singers Maki Asakawa and Doji Morita. They regularly join us on the table and otherwise lounge around. We’ve always liked to cook for each other and friends, and the Park Slope Food Coop’s amazing produce and affordable prices make it easy. (The Burgundy cuvées that we like to serve with dinner are another issue). Last summer, we experimented with making ice cream: Cilantro, kaffir lime, and Aleppo pepper is a new favorite flavor.

Our life at home revolves around music and is populated with things that we’ve collected along the way. The sound system features Klipsch La Scala speakers powered by a Marantz 8B tube amplifier, with a VPI turntable equipped with a Hana cartridge running through an Isonoe ISO420 mixer. The system includes other components that we update continuously to fine-tune the quality. We found our 1980s Azeri rug on a research trip Ruba took to the Caucasus when we first moved in. It’s become the tapestry that knits everything in our place together. The giant quartz crystal on the coffee table was bought at an estate sale run by a bunch of hippies on the side of the road in New Mexico in 2018, when Ruba was working on the SITE Santa Fe biennial. We live with some art—mostly works from friends and artists we have some connection to: a print by Victoria Mamnguqsualuk from the SITE show, a stuffed creature from a performance Cosima von Bonin did for an exhibition Ruba organized at SculptureCenter, a gift from Yuji Agematsu, a few Tori Kudo ceramics from a show Lawrence did at Blank Forms, a wedding present from Helen Marten, and a Curtis Cuffie.

Blank Forms celebrated its ninth anniversary with performances by Dez Andrés, Douglas Sherman, and 7038634357 at the Ukrainian National Home in the East Village—our wedding venue almost eight years ago and our favorite place for parties.

After a launch for Lawrence’s new book, Alien Roots: Éliane Radigue, and listening session at Blank Forms, a few friends came up to our place, where we made lemon tofu and broccoli for dinner, cherry stracciatella ice cream from scratch, drank French wine, and listened to records with cellist Charles Curtis, musician Lary 7, sculptor Yuji Agematsu, curator Robert Snowden, Artists Space Assistant Curator Stella Cilman, writer Eva Cilman, and artists Oto Gillen, Elizabeth Erlanger, and Jeffrey Perkins.

The legendary Asha Puthli came to New York to play SummerStage and we hung out with her throughout the week, culminating in a dinner hosted by our friends Satya Pemmaraju and Vyjayanthi Rao—whose place we seem to be at whenever we aren’t at ours—with our friend artist Christian Nyampeta, Sweety Kapoor visiting from London, and Satya and Vyjayanthi’s son, Sunder. Vyjayanthi is an incredible cook; they also love fine wine and Caffè Panna ice cream.

----BLANK FORMS ANNIVERSARY PARTY---EYE CONTACT - 7038634357

PERFECT NIGHT - 7038634357

FLIPWOOD MAC - ANDRÉS REALITY - ANDRÉS

WHAT WOULD YOU DO? (TWO SOUL FUSION REMIX)DAMES BROWN FEAT. ANDRÉS & AMP FIDDLER HOUSE PARTY - FRED WESLEY WATER (VANCO EDIT) - TYLA

-JOE MCPHEE AND TCHESER HOLMES AT BLANK FORMSNATION TIME - JOE MCPHEE COLORS IN CRYSTAL - JOE MCPHEE & JOHN SNYDER

------HOME HANG------

SPECIAL REQUEST TO ALL NOTCH - JUNIOR KAHDAFFIE BAFFLIN SMOKE SIGNAL - LEE PERRY

ADDIS ABABA DUB - BULLWACKIES ALL STARS ZIMBABWE - MILES DAVIS MAGGOT BRAIN - FUNKADELIC STOP THE CLOCK - JACKS ECLIPSE - ERIC DOLPHY

ODE TO CHARLIE PARKER - ERIC DOLPHY WITH BOOKER LITTLE

GOD MUST BE A BOOGIE MAN - JONI MITCHELL CARAVAN - THE ENSEMBLE OF SEVEN SLEEP - CHARLES CURTIS MAY 99 - CURTIS, LICHT, ROBERTS

BOKUTO KANKŌ BUS NI NOTTE MIMASENKADŌJI MORITA MY MAN - MAKI ASAKAWA

----GRAHAM LAMBKIN AND LAURA ORTMAN---POEM (FOR VOICE & TAPE) - GRAHAM LAMBKIN LIMP TEST - GRAHAM LAMBKIN

Our neighbors Ari Marcopolous and Kara Walker came for dinner, this time with Charles Curtis. The homemade ice cream failed :( Then, a couple weeks later, musician and artist Graham Lambkin was in town and performed with Laura Ortman in an experimental improv set that packed Blank Forms. Afterwards, we mingled in the street before making a run to Mr. Kiwi for some Amy’s frozen pizzas and to Leon & Son for some bottles to serve.

GROUND CONTORTIONS ROOTED SINGS GREEN - LAURA ORTMAN

PUT THE MUSIC IN ITS COFFIN - THE SHADOW RING

------ASHA PUTHLI------

WHAT REASON COULD I GIVE - ORNETTE COLEMAN

AIN’T THAT PECULIAR - PETER IVERS GROUP MY ROCK - HENRY THREADGILL SEXTETT

FLYING FISH - ASHA PUTHLI

FALL-OUT DUST - ASHA PUTHLI

LATIN LOVER - ASHA PUTHLI

RUBA’S CILANTRO ICE CREAM

INGREDIENTS:

1⅔ cups milk, 1⅔ cups cream, 1 tbsp date syrup, ¾ cup sugar, ¼ cup milk powder, ¼ tsp salt, 1 cup cilantro, ½ tsp kaffir lime powder, ½ tsp Aleppo, 2 tbsp olive oil

STEPS:

[1] Heat milk, cream, syrup to 180°F.

[2] Whisk sugar,milk powder, salt –> add to milk.

[3] Stir in cilantro, lime, Aleppo, oil.

[4] Blend –> strain –> chill –> churn.

Danish glass artist Helle Mardahl presents an array of hand-blown delicacies.

Text by Karly Quadros

Since opening her hand-blown glass studio in 2017, Copenhagen-based designer Helle Mardahl has garnered international attention for her juicy contours. Her latest collection for DWR is an ode to the beauty of contrasts, drawing from her heritage and the design sensibilities of her father, an architect, to distill a confectioner’s fantasy into something more elemental: “I often bring in bold colors and organic, imperfect shapes,” she says, “But this collection gave me the chance to explore a more minimalistic language.”

Mardahl’s array of elliptical barware, petal-shaped serving dishes, vases, and pendulous lamps evoke a languid, late-summer dinner party. The collection’s palette, developed exclusively for DWR, recalls a similar sweetness with shades of rhubarb, plum, coconut, and creamy melon. “We were drawn to tones with warmth and depth—colors that feel timeless, soft, and quietly sophisticated,” says Mardahl. The result is a delectable convergence of Scandinavian and American design traditions.

Recently, I went to see the play Purpose with a friend. This friend, another Black writer, had asked me along because he sensed I might have something to say about the play—its subject a Black political family contending with its legacy after the eldest son returns from a white-collar prison. Before it even began, as we took our seats in the dimming theater, I looked up at the set and knew it was going to be good. The set was not elaborate. Rather, it was the specifcity of the details—vaguely West African masks and tapestries hanging on the warm walls, portraits of Martin and Barack shaking hands with the play’s fctional patriarch—that made me feel instantly, eerily, at home.

My mom had a penchant for African prints. Our barkcloth-inspired couch was topped with Bogolan blankets, and everywhere was evidence of my parents’ travels to the continent: rugs from Moroccan souks, beaded Baluba masks, and paintings of women holding jugs atop their heads. But when my dad became president of Morehouse College in 2007 and my mom oversaw a redesign of the president’s residence, these proclivities were pared back: The West African prints were limited to throws atop neutral-colored couches, and the walls were hung with various photographs of my father, shaking hands with civil rights icons and Black power brokers, along with stoic portraits of each of my parents, much like the ones in Purpose. These design choices communicated a notion of “taste” that was distinctly Black—evincing pride in African American history yet muted enough to be palatable to the celebrities and donors (of all races) who passed through. Throughout my high school years, that house seemed strange to me: sterile and alien, set dressing to a life where my parents wore a public face, uneasy symbols of what is sometimes called “Black excellence.”

In popular culture, I have rarely seen the world of the “Black bourgeoisie” rendered with nuance. I’ve felt fashes of recognition, though few, here and there: reading a well-observed anecdote about a Jack and Jill meeting in Margo Jeferson’s Negroland, or cackling at a cutting joke in the “Juneteenth” episode of Donald Glover’s Atlanta. But in the last year, I’ve noticed a surge in depictions of that milieu. From the Met Gala and accompanying exhibition “Superfne: Tailoring Black Style” to Ralph Lauren’s Oak Blufs capsule collection, there seems to be a renewed interest in defning an aesthetic of Black wealth and glamour. I’m not sure what this reveals about the zeitgeist—perhaps nostalgia for the Obama-era image of Black excellence, or simply that age-old interest in ogling the elite, made more palatable when fltered through the language of “representation”—but I often fnd myself parsing these images for meaning.

Novelist ROB FRANKLIN surveys the interior design language of his youth, tracing its evolution, impact and contemporary resurgency commanding attention across media culture.

by the show’s plans for the Todd Wexleys, a Black couple in the York-Goldenblatt cinematic universe. Given that this latest iteration of the Sex and the City franchise relies so heavily on the popcorn pleasure of designer clothes and elegant interiors, its interest in forging a visual language of Black glamour strikes me as no small thing. Lisa Todd Wexley’s personal style is characterized by bright collisions of maximalist prints and jewel tones, sometimes supplied by young Black designers like

As an eager (if often-disappointed) viewer of HBO’s And Just Like That…, I’ve been intrigued from the frst season

Charles Harbison and Christopher John Rogers. But perhaps the most lived-in aspect of the entire show is the Todd Wexley apartment: an otherwise generic penthouse adorned with works from the Black contemporary canon. Early on, art consultant Racquel Chevremont and the writers decided that the husband, Herbert, would collect photographs, while “LTW’s” focus would be fgurative paintings of Black women. Observing the resultant collection, I notice a tension—the somber respectability of an iconic Gordon Parks photograph from the ’50s jux-

taposed with the audacious, Swarovski glamour of a portrait by Mickalene Thomas—that echoes the family’s dynamics. Indeed, some of the show’s most striking scenes involve Herbert’s mother, Eunice, swanning in wearing her AKA colors, shading LTW’s taste while ofering some old-school lessons in Black respectability (“We never surrender our dignity!”). The family’s interiors hold a mirror to its interiority: an ever-present push-pull between humility and extravagance, respectability and liberation.

Wandering the Met’s “Superfne” exhibition a few months ago, I had a similar thought. The exhibition not only documents a history of Black American style, it probes it for political meaning. Clothing and consumerism, the exhibition catalog notes, indicate “wealth, distinction, and taste”—a performance that

can be

as in

But can it also be a prison? Looming over the exhibition is the larger-than-life specter of André Leon Talley, a man known not only for his dandyish dress but for his perch at the top of high fashion’s precarious ladder—a position defned by its solitude and instability, or as Hilton Als put it in his 1994 profle of Talley for The New Yorker, “the only one.” Style cost Talley, as did solitude. In attempting to “live up to the grand amalgamation of his three names,” Talley died in debt, leaving behind heaps of silken scarves, gold brocade caftans, and six Prada crocodile coats. Even in an exhibition that venerates his contributions to American style, I found it hard not to see Talley’s as a cautionary tale—the compulsion to perform himself, and to embody an ideal of Black glamour and excellence, as his undoing. In defning the aesthetics of Black glamour, certain anxieties—around presentation and afect, and how these impact one’s position in the world—slip into frame. Onstage, the “Jasper family” (whom critics have been quick to note closely resembles Jesse Jackson’s) struggles to reconcile its public face with the complexities of its human interior: the criminality, mental illness, and queerness of the sons. Their home—with its self-conscious mix of signifers of “good taste” recognizable to the white world and prideful nods to Black culture and history—bears the strain of that struggle. And in that strain, I saw myself. Late last summer, I received an invitation to celebrate the Ralph Lauren Oak Blufs collection, part of the brand’s ongoing collaboration with Spelman and Morehouse Colleges, and named for a historically Black section of Martha’s Vineyard where I sometimes vacationed growing up. Curious what this brand, synonymous with Americana, had to say about Black style, I scrolled through the collection online, pausing when I spotted a familiar phrase on one of the shirts. It said “The Five Wells,” a reference to an idea conceived by my father during his tenure as Morehouse’s president: a Morehouse man, or a Black man in general, should strive to be “Well Dressed, Well Spoken, Well Read, Well Traveled, and Well Balanced.” Briefy, I considered what it would mean to purchase the shirt, wearing on my exterior a mantra that, throughout my awkward adolescence, was repeated in my household daily—a paean of Black excellence, an ideal to strive endlessly towards, that I often found oppressive. Would it be a reclamation, or an ironic gesture, to wear this on my skin? I hovered over the purchase button for a while, wondering.

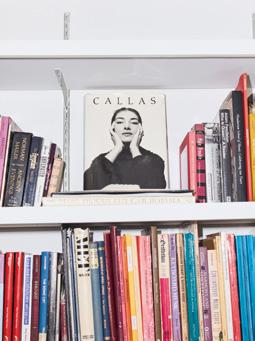

Berlin-based architecture writer and curator Carson Chan picks the essential design books of 2025.

We are living in a time when so much of what we see online is fake, and so much of what is real is terrifying. Within these books, you’ll find companions in thought—people who make sense of the past, offer paths forward, find wonder in fugitive moments, and embrace small pleasures. They remind us that to create, design, and imagine is among the most meaningful work we do as human beings.

Text by Carson Chan

Campania: Recipes & Wandering Across Italy’s Polychromatic Coast

Edited by Belmond Apartamento

Synthesis

Mari Katayama Self Publish, Be Happy Editions

Cooking Up Dinner Speeches: Ise Gropius in Japan

Edited by Almut Grunewald gta Verlag ETH Zürich

Draw

Kenya Hara

Lars Müller Publishers

Furnishing Fascism: Modernist Design and Politics in Italy

Ignacio G. Galán

University of Minnesota Press

Inside the New Shopping Bag: Susan Bijl 25 Years of Thoughtful Design

Susan Bijl

NAi010 Publishers

Monumental: How a New Generation of Artists is Shaping the Memorial Landscape

Cat Dawson MIT Press

A Moratorium on New Construction

Charlotte Malterre-Barthes

Sternberg Press

Visiting: Inken Baller & Hinrich Baller, Berlin 1966–89

Edited by Urban Fragment Observatory Park Books

Walking Sticks

Edited by Keiji Takeuchi and Marco Sammicheli

Lars Müller Publishers

It’s probably because Berlin, where I’ve been spending summers, has been rainy all season, but poring through Apartamento’s new book filled with recipes from the Caruso hotel on the Amalfi Coast and luscious photos by Lea Colombo is a great way to spend a drizzly afternoon on the couch.

This spellbinding collection showcases recent photographs by Mari Katayama, whose multimedia practice continues to explore identity as something selffashioned and constructed. In these images, Katayama poses among the carefully arranged chaos of objects on the verge of coherence, accompanied by her sewn sculptures and handcrafted prosthetic limbs, which draw deeply from her experience as an amputee.

In the spring of 1954, Ise Gropius went to Japan with her husband, Walter, the famous architect. This book is her travelogue, detailing their private and professional meetings and the places they visited as they worked to establish and intertwine their legacy together with that of modern architecture.

Taken from more than four decades of sketches, this book collects drawings from one of the world’s most beloved living designers (most of us know him for his work as art director of Muji). Here, the illustrated thoughts of a designer are offered up for our contemplation.

The rise of fascism in Italy between the two world wars also saw the expansion of the country’s interior design and furnishing industries. Featuring protagonists like Gio Ponti, this prescient and incisive book takes a scholarly look at how we can read the evolution of political ideology in everyday objects.

Twenty-five years ago, Dutch designer Susan Bijl aimed to design the single-use plastic bag out of existence. This didn’t happen, but we do have her iconic twotoned bag that has become a design staple. This book traces the community that has emerged around the bag, detailing the lives of people from Rotterdam to Kyoto who have embraced Bijl’s design.

Monuments have been toppling as the world slowly and painfully decolonizes. Academic Cat Dawson examines how the role of monuments in the USA has shifted through a deep dive into recent art practices that have redefined what a monument is. Featured artists include Kara Walker, Lauren Halsey, and Marc Bradford.

The building sector accounts for 40 percent of the world’s yearly greenhouse gas emissions. Architect and educator Charlotte Malterre-Barthes points out the obvious—let’s stop building. The book spells out what she thinks we should do instead.

Anyone who has spent time in Berlin will have come across one of Inken and Hinrich Baller’s idiosyncratic buildings. From amidst the Neoclassical, the Postwar, and the Industrial, the Ballers present whimsy, fantasy, and ornament in some of the most thought-out, considered, and spatially sophisticated German buildings of the last century.

The catalog to Milan-based Japanese designer Keiji Takeuchi’s exhibition in the Milan Triennial presents the newly commissioned designs of a loaded personal object. Through the walking stick, designers like Maddalena Casadei, Pierre Charpin, Ville Kokkonen, Jasper Morrison, and Jun Yasumoto grapple with issues like aging, personal space, fashion, and ceremony.

Text by Durga Chew-Bose

Another world exists alongside the one full of meetings and deadlines. It’s alive with tiny totems and miraculous discoveries. It’s ruled by a de!ance of time and need. The writer and !lmmaker Durga Chew-Bose ventures in.

, 1904.

to bottom: Illustration from R. Shugg & Co. New York, Mister Fox , 1879; Illustration by Charles Copeland from Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of

!gurine propped against the fruit bowl. I remember watching the wooden nose of a Pinocchio doll (we have a collection) grow before my very eyes as the sun slipped behind a cloud. Cartoon eyes proliferate, googly and abundant; a u y tail pokes out from beneath a cushion; a lone puzzle piece drifts aimlessly, free of context.

have grown accustomed to my son’s little testimonies of play and chaos, like his “bad guys” (Cruella, Scar, Gaston), his sculptures (two rocks and a Lego brick balanced on a Brio train), or his “caves” (anything inside of anything else). I’ve found myself, as time passes, prone to how they slow my day, easing o the edges. How their fanciful scale—the smallness of a doll’s brush or a cluster of colorful dice sitting on our bookshelf—reorders my urgencies. Imagine being late for something, only to !nd a Moomintroll in your shoe. Imagine lifting the lid of a saucepan and discovering that it’s already occupied by an ear of plastic corn and a plush watermelon. Imagine arriving home after a long day and encountering a barricade: three toilet paper rolls taped to a broom handle and balanced across your hallway. “Climb under! Quick! Or else they’ll get you!”

They who? It doesn’t matter. ost of all, my son’s trail of things has created a secondary world that lives alongside mine. If my preoccupations seem pressing, his are sprawling—well beyond the practical, plumbing depths I’m not meant to understand. These are his altars: his love of stones, his pile of Paw Pa trol, his baskets !lled with “soup.”

That’s his shoehorn (which he of ten sleeps with), his crown (anything he puts on his head).

There are phases when he carries his metal harmonica with him for hours, toasty in his palm. When he is at daycare, I catch myself placing it near our front door so he can grab it !rst thing. The harmonica feels a little lifeless, cool to the touch, anticipating his return.

That’s what I love most about my son’s stu . It waits around for him.

Text and Photography by Jarrett Earnest

One writer’s coital encounters have offered him privileged access to bedrooms across New York. The writer considers the intimacies and implications of the art he’s seen hung on their walls.

One of the best things about being a slut, aside from the obvious, is the excuse to go into strangers’ homes. I have friends in New York—very dear ones I’ve known for years and years—whose apartments I’ve never seen. I guess there’s just a culture of meeting out, at events in the world. Or maybe their place is small or messy or uncomfortable to host in, or doesn’t align with their persona, or they are secretly a pet hoarder, or they actually live in Hoboken… the possibilities are endless.

In contrast, over the past 15 years I have inspected at close range many anonymous bedrooms (and living rooms, bathrooms, and hallways) across the city, thanks to a horniness that transcends both boroughs and social milieu. Upon arriving, I’m mostly oblivious to the fner points of decor, beyond making sure there are no visible signs of sociopathy—you know, like overhead lighting (I’ve always said, “If you go into a fag’s apartment and they have overhead lighting—don’t fuck ’em!”). After getting off, I start looking around. The stuff that’s there and how it’s all arranged shapes a little narrative about who this person I just fucked is. I enjoy this part almost as much as the sex, getting privileged access to another’s reality. At points it’s felt like the kind of observational work you might do if you were a novelist, which I am not. Instead, I write about art.

Most people don’t have the kind of art found in a gallery or museum that you’d get to write about for a magazine. But you can tell a lot from what people hang on their walls, whether it’s a Juliana Huxtable poster (hot!—designer furniture salesman) or one for an animated Miyazaki movie (fun!—kindergarten teacher) or a wooden plaque engraved with “A Cowboy’s Prayer”: Two things I love most / good horses and beautiful women / and when I die I hope they tan this old hide of mine / and make it into a ladies riding saddle / so I can rest in peace between the two things I love most (hot and fun!—hair colorist). Three recent examples, all encountered in bedrooms fanking the southeastern edge of Prospect Park last spring.

There was one daddy in a tiny East Village bedroom with blood-red walls; over the bed was a real Warhol, a nude male seen from neck to mid-thigh. He said he bought it for a song at auction in the late 1980s when there was no market for Warhol and nobody wanted work with a big prominent dick in it. How times have changed. (Turns out he’s a famous theatrical costume designer.) I remember fucking another guy in Crown Heights who had a wonky 1970s batik-ish wall hanging over his bed—not bad but also not particularly striking. Looking up in a postcoital haze, I asked, “Did your mom make that?” He looked

freaked out and asked me how I knew. I brushed it off nonchalantly, saying I just guessed, but the real answer is that it was totally incongruous with the room’s grayed-out modernist “good taste.” The place was everything this amateur textile creation was not, which meant it was probably there for sentimental reasons. (For the record, he is a therapist.)

Over my own bed lately is a knitted textile on 20-inch square stretcher bars. When the sun comes through the window, the material is just sheer enough to make out the silhouette of the bars beneath. It was made by the writer and artist Patrick Carroll, who creates everything from shift dresses and thongs to wall works with a knitting machine, materializing cryptic bits of found text into tactile form. Against a reddish ground, this one reads “BESIDE THE WINDOW THE BED” in pale pink thread. Centered over the text is a narrow rectangle of pale blue, with a smaller, thicker, bluer rectangle at the bottom, so that the shape can be read as signifying both the window and the bed.

The line comes from one of my favorite poems by the gay Alexandrian poet C.P. Cavafy called “The Afternoon Sun” (1919). The narrator returns to a room that had once been the site of a passionate affair; now it’s empty, for rent as an offce. He describes what used to be there: The couch was here, near the door, / a Turkish carpet in front of it. / Close by, the shelf with two yellow vases. / On the right—no, opposite—a wardrobe with a mirror. It’s something we recognize immediately and do all the time, recalling the interior of rooms where important things happened to us, as though the precise arrangement of domestic objects was not only a witness, but a participant, as if its perfect reconstitution might arrest if not reverse time. They must still be around somewhere, those old things, the poet says in a daze.

Art in bedrooms is a special subset of art in domestic spaces. It accommodates a different kind of looking—the frst and last thing you see on either side of sleep, in the periphery when fucking, talking late into the night, cuddling. By the nature of its placement, art that goes over the bed always somehow

relates to the unconscious, to desire, to fantasy, and to dreams. My spouse and I painted the walls of our bedroom a shade of soft purple called “Violetta.” At different times of day it appears lilac, then tawny, then gray. All kinds of exceedingly specific stuff is stashed about—books in piles along the foor that don’t ft in the bookcases that cover two of the walls, a couple plastic Sonny Angels (one with a tomato head and the other cherry blossom), a little plaster fgurine of Mary Magdalene covered with hair, a Thornton bentwood chair with a broken seat, a handmade chart of every shade of Crayola crayon pinned to the wall over the desk. On the steel cube bedside tables are a pair of thick clay bricks glazed like Delftware (to be used as a weapon in the event of a home invasion), a sage dreamcatcher, bottles of French perfume, and silicone lube. Try and fgure that out, I think, imagining an outsider attempting their own interpretation of our stuff. Who are these people? (One answer: a writer and a poet. Also: a married couple. Also correct: sensitive weirdos.)

The art hanging over our bed reminds me how much we exist in that space between: the world of beyond the window, the public self; the inner space of the bed, the physical body; the mind roaming between both. I think about the importance of the interiors we create to stage that life, and how the furniture, paintings, photographs, and rugs are a part of it—not only saying something about us, but in real ways making up who we are. I wonder what our various lovers, strangers and otherwise, make of “BESIDE THE WINDOW THE BED,” if they recognize the reference or gather their own meaning from the straightforward but enigmatic phrase—to date, none have ever mentioned it. Maybe they assume it’s something my mom made and leave it at that.

The people featured here— from DC power brokers to Tunisian craftspeople—are designers at grand and intimate scales. Whether through their mastery of social architectures or ancient dyeing techniques, their practices shift how we move through the world and what we see in it.

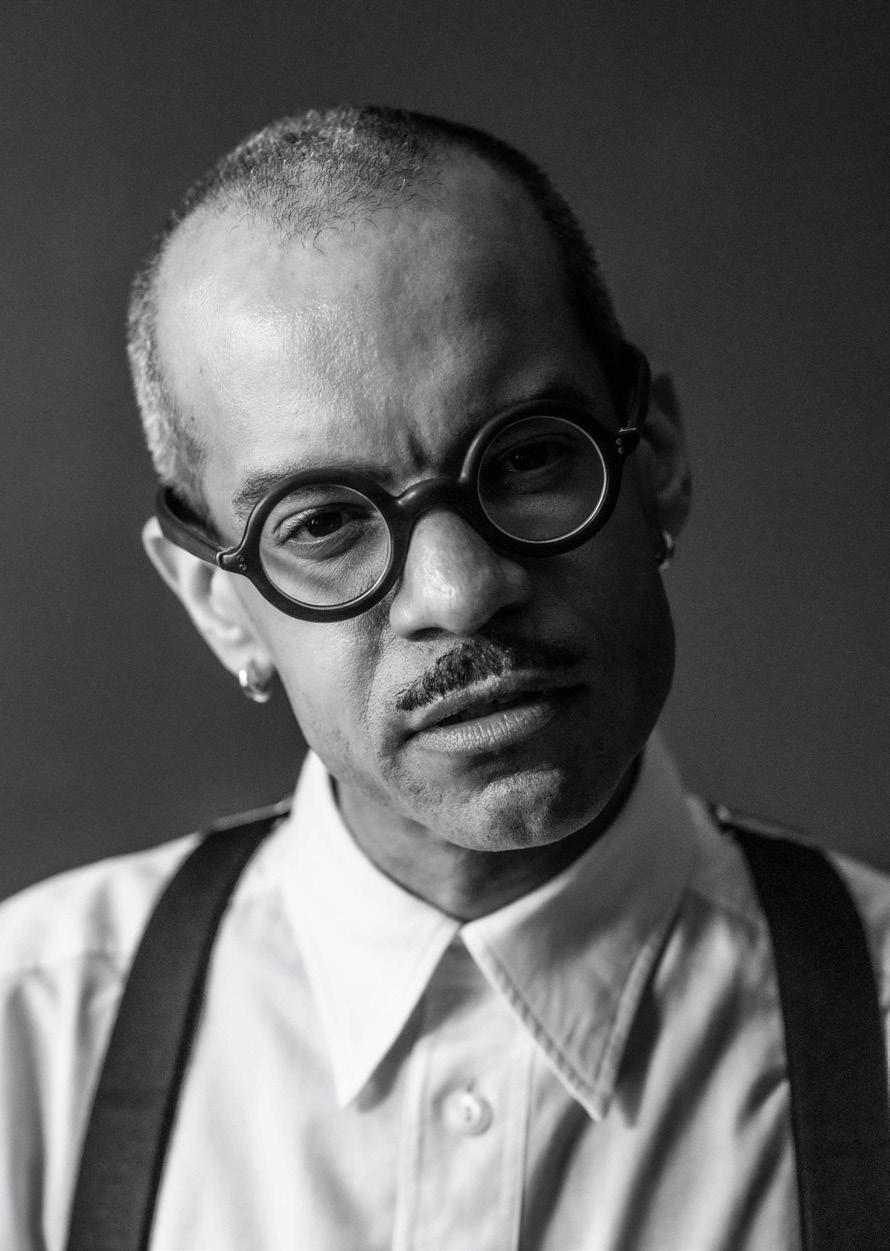

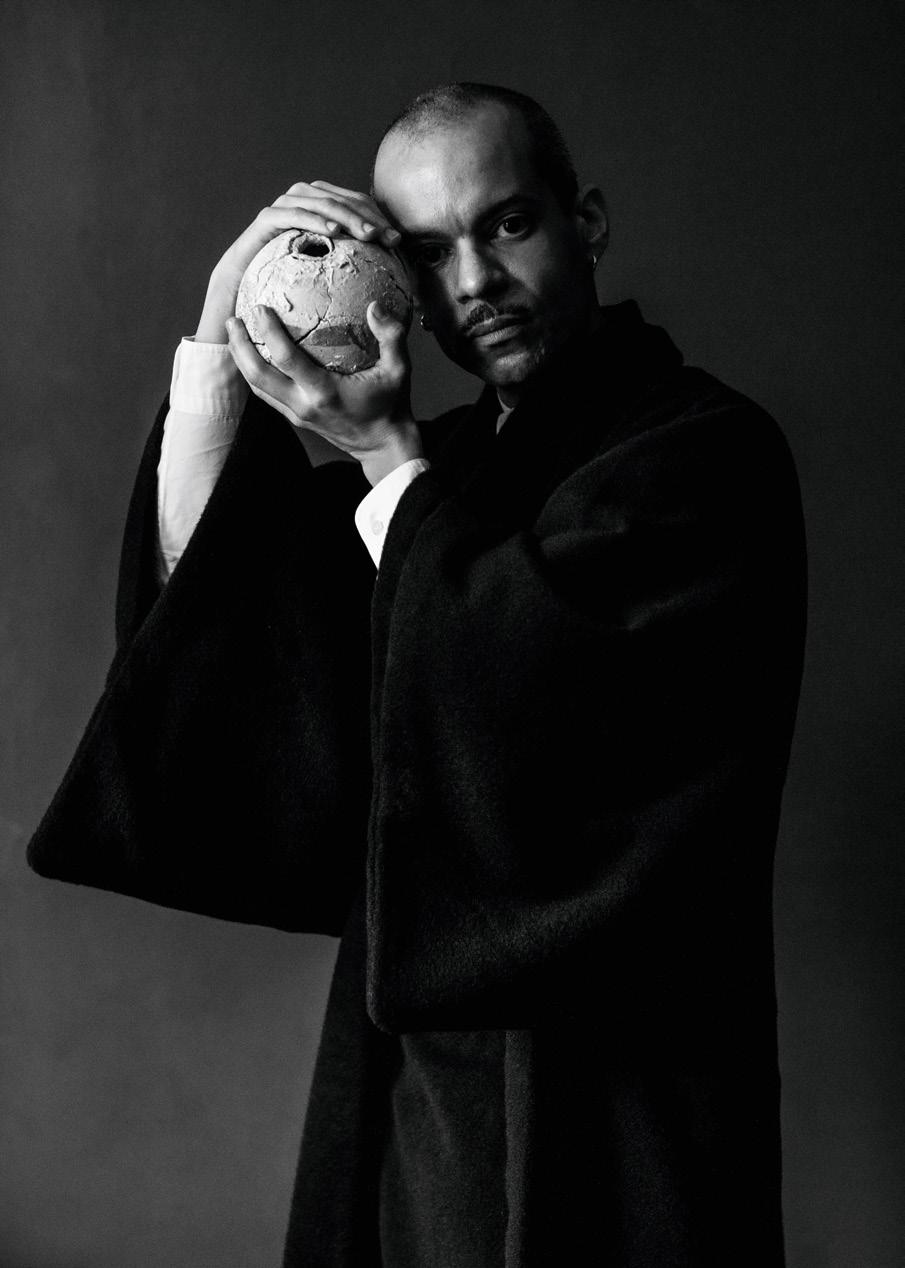

Designer Carlos Soto leads a new wave of agile auteurs reprogramming cultural experience.

“I either want an object to tell me a story or to disappear.”

—Carlos Soto

“I don’t understand how people can be so casual about theater,” says Carlos Soto. His eyes tear up as we speak, emotion thrumming through his limber frame. Today, he’s draped in a handwoven kimono; other days, it’s Margiela-era Hermès or early Lemaire (“It was more romantic then,” he says). We lean toward each other over our table, surrounded by rowdy West Villagers at the vaguely Shaker Commerce Inn. “Theater is the closest I’ll ever come to a religious experience,” Soto says. He is an extreme person—“blunt,” as he puts it— whose essentialist approach to set and costume design has resulted in some of the most refined and emotive visual expressions on the contemporary stage, having crossed from opera to pop to comedy, creative directing and designing with the likes of Solange, Shikeith, David Lang, and the late Robert Wilson. “He can be uncompromising in his belief and his designs,” Wilson said before his passing in July of this year. “He is not afraid to do the wrong thing.” The “wrong thing” is always unexpected, and Soto’s comfort in that territory has refreshed centuries-old narratives in desperate need of reinterpretation.

When we meet, Soto has just returned from Zurich, where he wrapped a production of Robin Hood at the Schauspielhaus directed by artist Wu Tsang, and is spent. In Soto’s Sherwood Forest, righteous thieves fuse with the woodland creatures around them: Robin Hood is a fox, squirrels make up his choir, and Little John is a grizzly bear. His costumes were inspired by animal memes and extensive research into Japanese Noh theater masks, which depict the stages of transformation from human to beast, triggered by intense emotions like rage or jealousy.

Drawing connections between ancient Japanese theater traditions, parasocial meme circles, and a British 14th-century legend demands a singular talent. Soto’s wildly inventive approach springs from a lifetime of venturing down rabbit holes. “He is extremely sophisticated, highly educated and intelligent, well read, and creative,” Wilson told me admiringly. Born in Harlem, Soto spent the earliest years of his life in his parents’ native Puerto Rico. When the family returned to New York, they lived in the Bronx, where Soto still resides. In his adolescence, he began consuming films by Derek Jarman, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Federico Fellini, while spending hours in his prep school’s drama club. “Performing is a strange form of therapy for a painfully shy, anxious person like myself,” says Soto.

At 15, he met Wilson. By 17, he was the youngest person among the group of artists that the legendary theater director and playwright invited into his laboratory for performance in Water Mill, New York. At 18, Soto apprenticed under the costume designer Frida Parmeggiani on Wilson’s production of Lohengrin at the Met, before enrolling briefly at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. It took less than a semester (and an offer to work with Umberto Eco and Ryuichi Sakamoto) to recognize he would learn more outside the confines of academia than within them. He dropped out.

“In Carlos’s portfolio of works, you see a style, a language, a voice that is so uniquely him at the highest level of taste, but also so vastly different from project to project.”

—SOLANGE

More than 20 years later, Soto’s sets, costumes, and creative direction boast a perplexing mixture of ease and precision while confronting a richly varied array of material. He has presented work at Performa, outfitted Terence Koh for his monthlong performance at Mary Boone Gallery in 2011,

designed costumes for Marina Abramović, worked with Philip Glass, and even led production design for comedian Jenny Slate’s 2024 run at BAM. He deftly handled Robert Mapplethorpe’s flagrant fetishism in a presentation supporting an oratorio by Bryce Dessner of the National in 2019. Solange’s triumphant When I Get Home album from the same year is indebted to Soto’s costume design and direction. “In Carlos’s portfolio of works, you see a style, a language, a voice that is so uniquely him at the highest level of taste, but also so vastly different from project to project,” says Solange. “Carlos is an enormous part of my process in prompting me to consider things like the cues in a performance, how instruments enter and exit the stage, how we implement transitions… These might sound like small details, but his ability to charge energy in even the quiet moments is light-years ahead of anyone I have worked with.”

“My home is an experiment in curation,” Soto says. “I move things around, even if just to put them back where they were; creating new tensions between things, new connections, even if they’ve lived in the same room for years.” This ritualistic process of trial and error carves out new avenues between objects as disparate as Bauhaus furniture, Dutch cactus pots, thousand-year-old Ecuadorian figures, and vibrant Amazonian featherwork. An unexpected thread could be drawn, for example, between his Shaker candlestand and Taíno pestle—their simple lines and surfaces warm and inviting. An industrial lamp by Tommaso Cimini juts into space like a visitor from the future, with the beautiful stone head of an Aztec youth perched nearby. A Sudanese ivory bangle carries a similar hue to a white patchwork Joseon pojagi cloth: one valued for its milky purity and implied violence, one for its signs of perpetual repair. Both have felt the touch of countless hands. “I either want an object to tell me a story or to disappear,” Soto says with characteristic directness. “My objects act as aidememoires. They remind me to live.”

Drawing connections between ancient Japanese theater traditions, parasocial meme circles, and a British 14th-century legend demands a singular talent.

It’s not that he is a theater person per se. It’s more that, like most polymaths, he had to choose a lane. “I chose theater because it was the only means for me to make the installations I wanted to make,” Soto says. His two-bedroom apartment in the Bronx, a repository for artifacts as priceless and idiosyncratic as the artist himself, offers another avenue for worldbuilding. Soto arranges his objects, which run the gamut in terms of era and medium, in a way that shocks his eye into attention. None of his objects are coddled for their fragility or covetability: Soto eats off Shigaraki and Iga ware plates. He uses pottery in winter and glassware in summer. He serves his tea in all manner of rare vessels, usually Japanese, and often dependent on the type of tea leaf.

Such a reminder might seem unnecessary, but living, for Soto, is a more demanding endeavor than one might think. His days are structured by creation in its most unfettered form: referencing rare texts collected over decades, peering quietly out the window as a wisp of an idea takes shape, and putting pen to paper, turning those wisps into one clean, powerful gesture. His work is like a wellaimed punch: boiling narratives down to their most essential ingredients and striking the truth with fiction. In this state of constant invention, Soto triumphs where so many have failed, collecting the references of the past and transforming them into the new.

“My objects act as aidememoires. They remind me to live.” —Carlos Soto

This legendary DC hostess knows the art of the party is the art of the deal. Her fabled homes, from Grey Gardens to a haunted Georgetown mansion, have set the stage.

Text by Alissa Bennett Portrait by Adele Makulova

“You have to have nerves of steel to be a hostess in DC,” Sally Quinn tells me, recalling the decades of bipartisan fêtes she and her late husband, Ben Bradlee, threw in the notoriously fraught epicenter of American politics. It’s a sentiment that feels increasingly weighty in a climate contoured by divide and disagreement, in a world where the political and the personal are no longer distinguishable, and in a context in which most of us fnd ourselves capable of arching toward enmity with lovers and strangers alike. Icy blonde, sharp as a tack, and still in command of the volumetric Dallas-esque glamour evident in Warhol’s immortalizations