Where the Wild Things Are

GUEST EDITED BY ROMAN AND WILLIAMS

GUEST EDITED BY ROMAN AND WILLIAMS

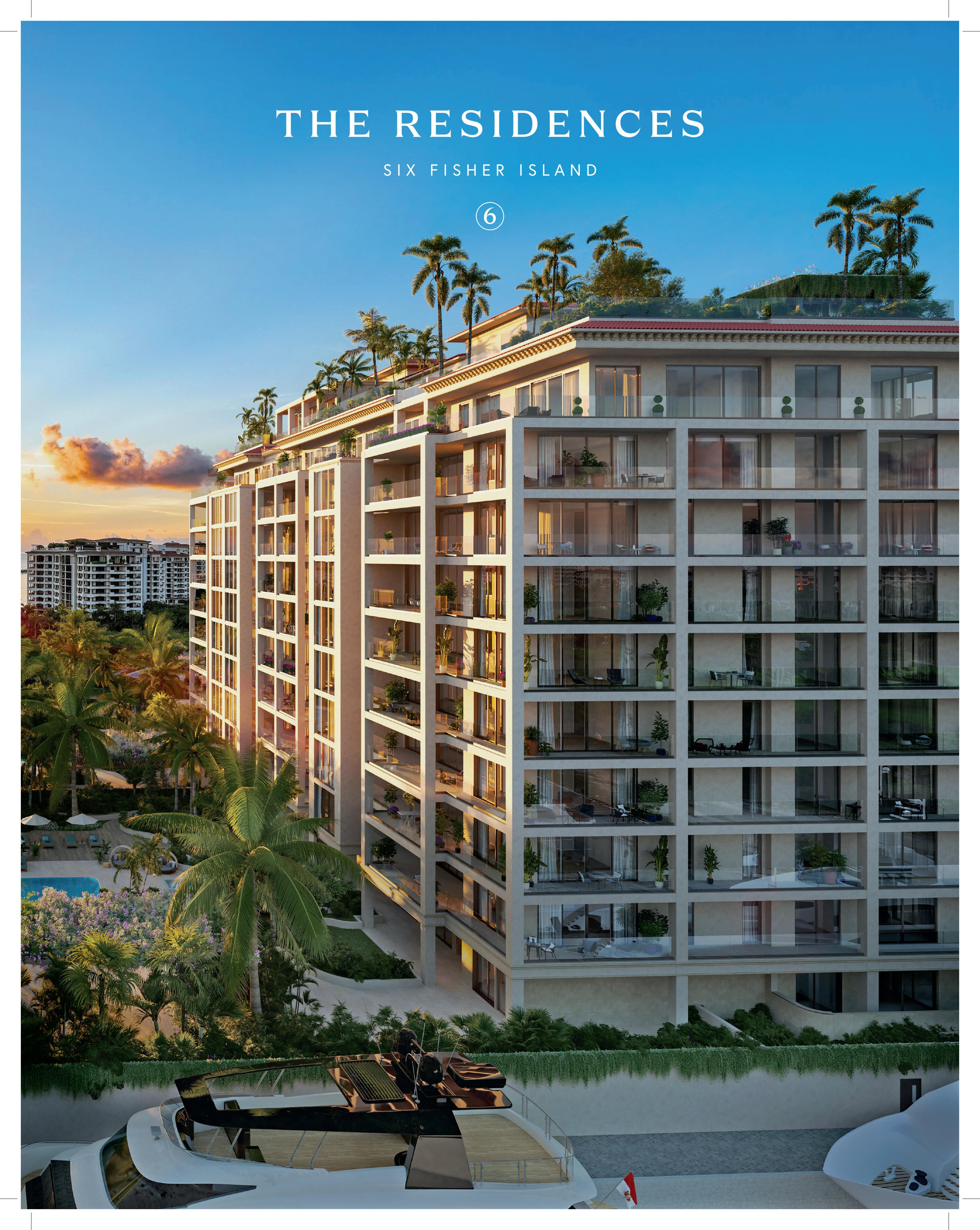

Live on the world’s most private island. Estate-style homes on Fisher Island’s pristine shoreline, steps from the exclusive Fisher Island Club, with its award-winning golf course, tennis facilities, spa, beach club and restaurants. The Residences’ unprecedented amenities and white-glove service set a new standard, with five-star dining, resort-style pools, and a waterfront lounge. It’s the pinnacle of coastal living, minutes from Miami but a world away.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

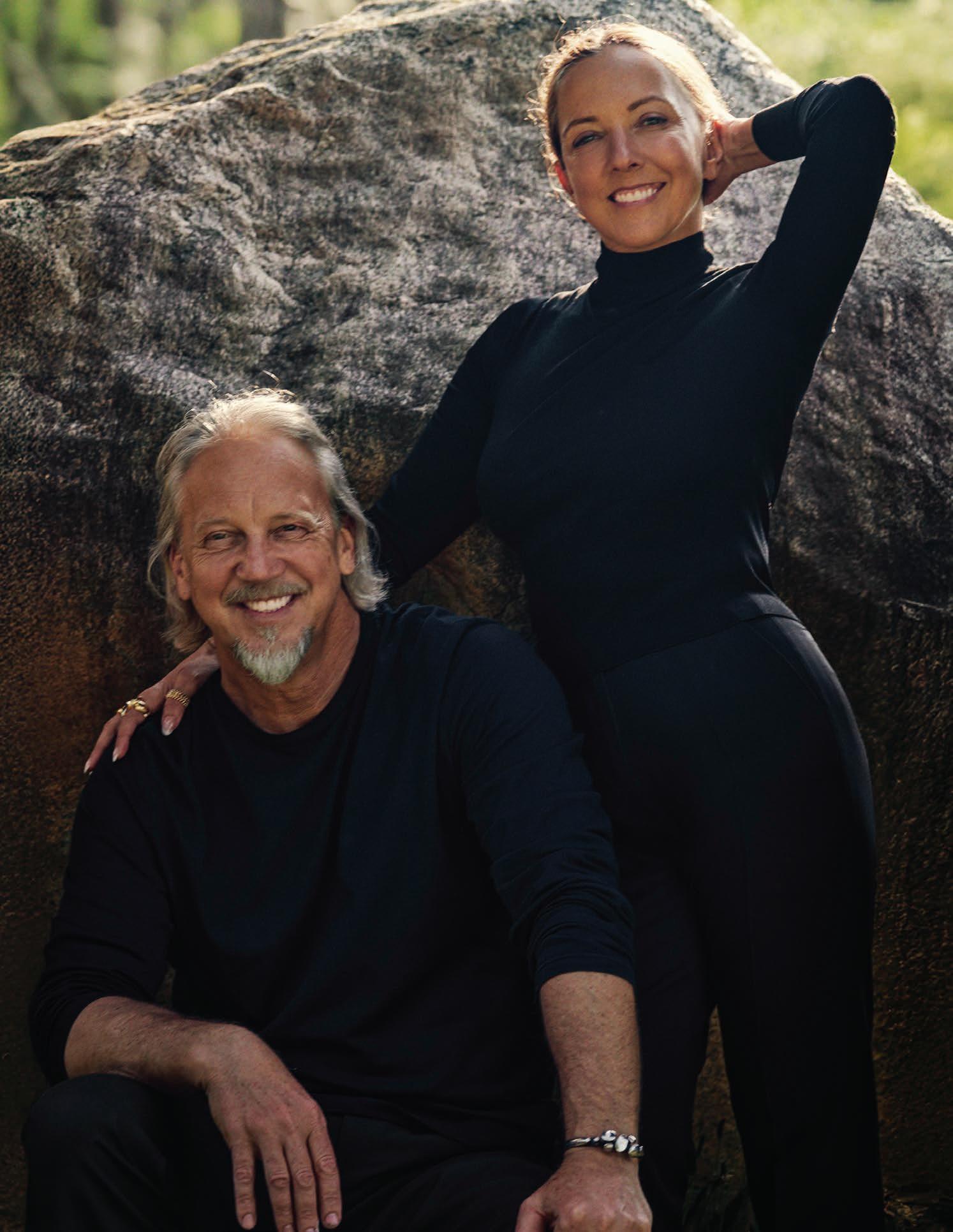

There are no two people better equipped to conjure the East End’s spirit and lore than Robin Standefer and Stephen Alesch. This issue’s guest editors are partners in the purest sense of the word—whether they’re helming their design and architecture firm, Roman and Williams, or cultivating the rich, wild landscape at Sea Ranch, their Montauk retreat. When the time came to begin CULTURED’s late-summer Hamptons edition, they were my first and only call.

—SARAH HARRELSON

Summer out East is poetic—the air, salt, sand, sea. A sticky haze, sunlight filtered through humid air, fireflies buzzing, birds calling, the power of the Atlantic. When Sarah Harrelson asked us to guest edit CULTURED’s Hamptons issue, we knew we wanted to capture the sensations of nature, that ephemeral soul—to spotlight the magic, the bohemian spirit that has all but become an endangered species in the Hamptons.

Our world is in Montauk—the end. The last stop. A wild enclave of raw cliffs and windblown fescue at the outer tip of the eastern seaboard, it stirs the soul and requires fortitude to survive. It remains naturally wild and is a magnet for seekers of an untamed edge. Montauk has been home for the intrepid, from surfers to musicians, from artists to fishermen, for over a century.

At the heart of this issue is Sea Ranch, our artistic compound of 20 years—a sprawl of studios, gardens, and meadows that fuels our work with our design company, Roman and Williams. It’s where ideas take seed, art is made, and friends let loose.

In this issue, we meet kindred spirits: Charlie Marder, whose nursery supplies the grandest gardens but whose hidden passion lies in his astonishing rock

collection, mined by artists like Lee Ufan; and Galerie Sardine, where Valentina Akerman and Joe Bradley cultivate a creative community in an Amagansett farmhouse. Elsewhere in these pages, the actor Liev Schreiber—one of the issue’s cover stars—takes a moment’s pause from his busy production schedule to reveal a few of his favorite Montauk haunts to CULTURED’s readers, and our old friend David Salle throws open the doors of his East End home and studio.

Friends share their go-to spots, far from the madding crowd. We trace a century of creative legacy on the East End through historic artist studios. We look at the distinctive rooflines of Hamptons architecture—particularly the beguiling barns that define the landscape. And we share glimpses of our own work— Stephen’s drawings of our orchard, which feeds both our art and our cooking, from Montauk to our restaurant La Mercerie, as well as Robin’s collections of natural ephemera.

This issue is a love letter to a place where nature, history, and art converge. We hope it helps carry forward the integrity and wild beauty that make the East End so vital.

—ROBIN STANDEFER AND STEPHEN ALESCH

CHRISTINE MACK COLLECTS FOR THE FUTURE The arts patron deploys collecting as a tool for community building and talent cultivation. 20 22

24 26 28 30

7 LATE-SUMMER SHOWS TO CATCH IN THE HAMPTONS

The late-summer slate is jam-packed. Here’s what you can’t miss.

YOUR GUIDE TO HIDING OUT IN THE HAMPTONS

We’re revealing the hushhush playbook for a lush summer.

THE UNSCENE EAST END

A handful of locals share a glimpse of their low-key haunts out East.

SUN, SEA, AND SARDINE Galerie Sardine rings in a second season in Amagansett.

REQUIRED READING: ISAAC MIZRAHI The designer and performer has a bookshelf as far-ranging as his output.

AN ALTAR TO BLACK LIFE OUT EAST Storm Ascher renews her commitment to platforming the artistic legacy of her community. 32

STUDIO FREQUENCIES: ARCMANORO NILES

The painter invites CULTURED inside his East Hampton atelier, where time melts away. 34

KEITH MCNALLY AIRS HIS DIRTY DISHES

The legendary New York restaurateur tells us what he thinks of himself.

A HIGHER CALLING What is it that, for nearly two centuries, has drawn artists to the East End?

A TASTE OF PARADISE Stephen Alesch is never without a sketchbook.

Liev Schreiber has had a nonstop year. It’s about time the actor got back to the East End. 36 38 42 44

THE KING OF MONTAUK

46

A BARN IS A BARN IS A BARN Historic barns throughout the Hamptons have become havens for art, architecture, and history.

THAT WAS THEN, THIS IS NOW The 72-year-old artist David Salle still has the same mantra: Do your work, and stay clear of the nonsense.

58

ROCK STARS Across the road from Charlie Marder’s renowned East End nursery, the beloved arboristaesthete pays tribute to another passion: rocks.

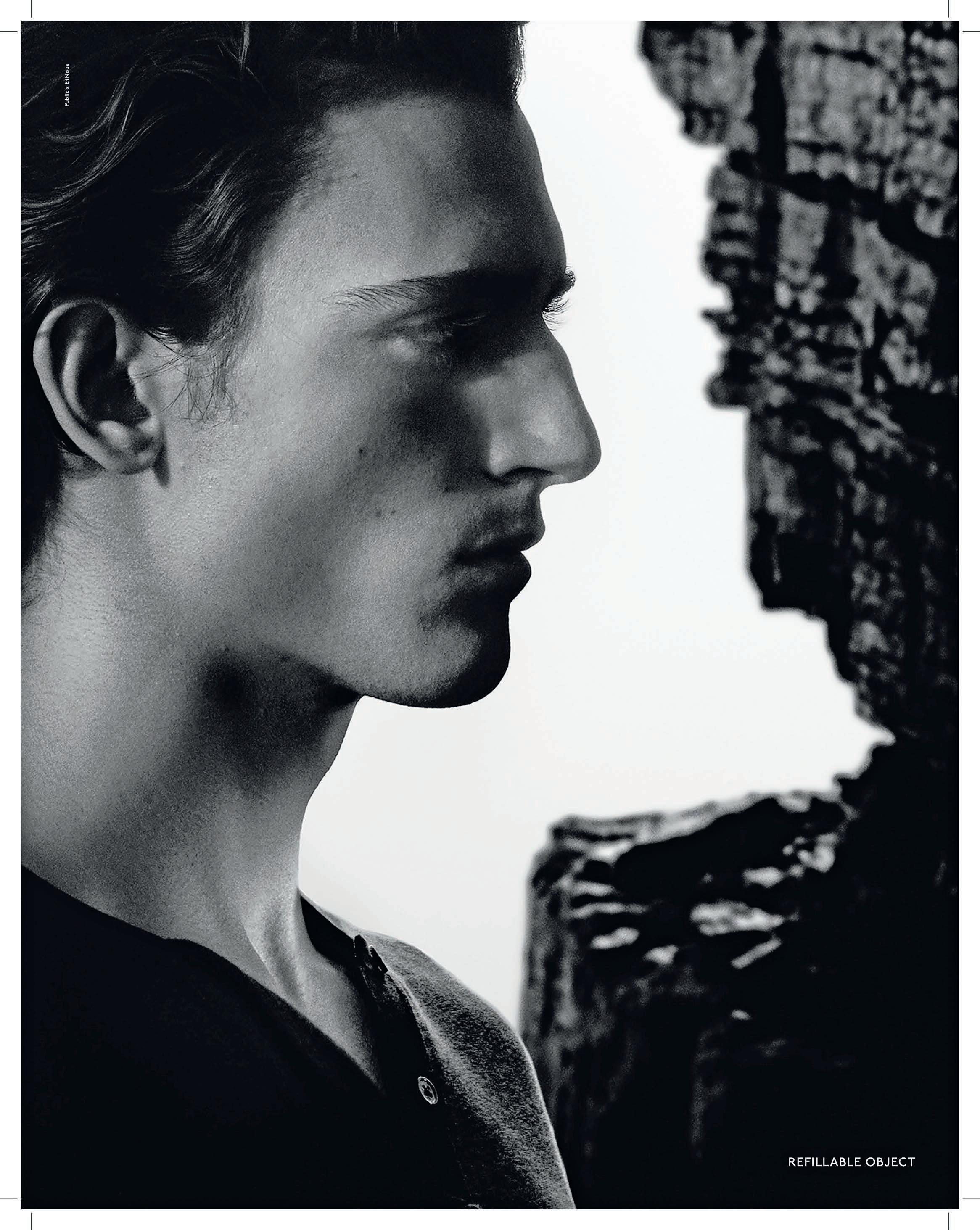

AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD Husband-and-wife design duo Robin Standefer and Stephen Alesch let their creativity run wild in a refurbished oasis in Montauk.

“[Sea Ranch is] where ideas take seed, art is made, and friends let loose.”

—ROBIN STANDEFER AND STEPHEN ALESCH

THE LATE-SUMMER SLATE IS JAM-PACKED.

HERE’S WHAT YOU CAN’T MISS.

“MARY

Where: Guild Hall, East Hampton

When: Aug. 3–Oct. 26

Why It’s Worth a Look: A high diver in San Francisco as a teenager, abstract painter Mary Heilmann has always been interested in the geometry of water. From the crests of her Long Line installation (which was recently expanded into a resting space inside the Whitney Museum) to the techniques of her painted forms, her nuanced work evokes the ephemeral sluices of the beach.

Know Before You Go: Although the 85-yearold artist has split her time between New York City and Bridgehampton for decades, this is her first solo show on the East End.

“SEAN SCULLY: THE ALBEE BARN, MONTAUK”

Where: Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill

When: Through Sept. 21

Why It’s Worth a Look: In 1982, a 37-yearold Sean Scully took up residence in the Albee Barn, a white wood, gambrel-roofed artist’s retreat nestled on a secluded knoll in Montauk. The residency proved pivotal for Scully, both creatively and personally. It was the first time the Minimalist artist had truly lived amidst nature, and it was there that he began painting on small multipanel scraps of wood, a technique that has been central to his practice ever since.

Know Before You Go: Bringing together over 70 works from four decades of the renowned Minimalist’s career, the show features 15 pieces from Scully’s original fellowship at the Barn.

FRANCESCO

Where: Tripoli Gallery, Wainscott

When: July 18–Aug. 18

Why It’s Worth a Look: Art-world mainstays (Katherine Bernhardt, Julian Schnabel, and Robert Nava) and rising stars propose their perspectives on the notions of rest and escape, in a gathering of works that touch on leisure, memory, and spiritual reflection—an instant dose of meditative balance for passing viewers.

Know Before You Go: Katherine Bradford’s hazy paintings depict sun-soaked swimmers in between peace and play, while Robert Nava’s Zombie Star Angel confronts the religious dimension of Sunday through depictions of angels in Abrahamic faith.

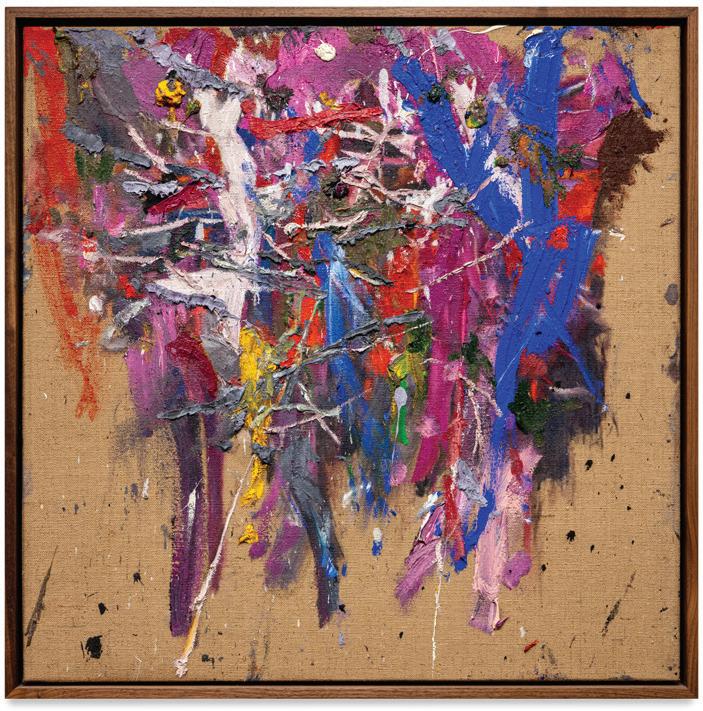

Where: Harper’s, East Hampton

When: Aug. 16–Sept. 17

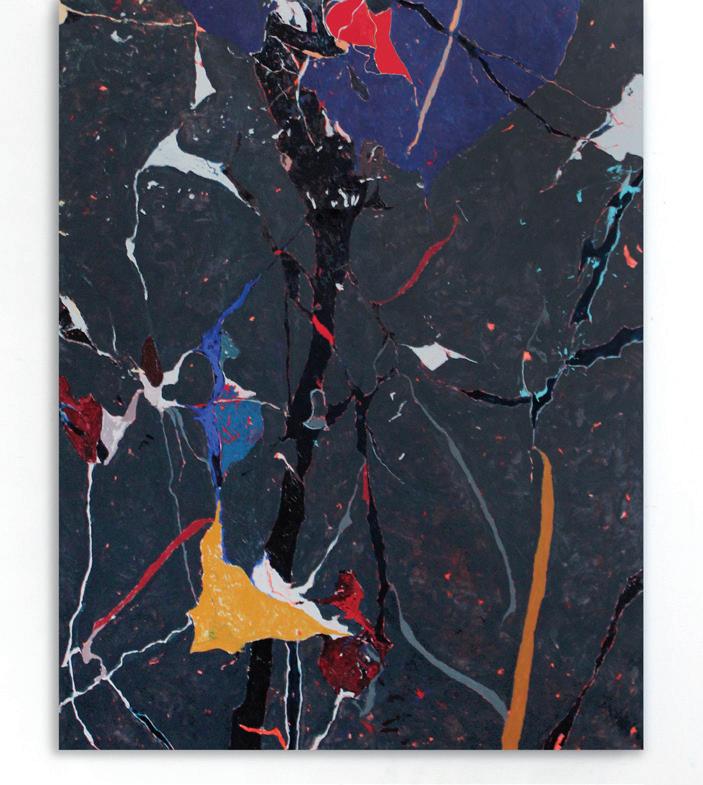

Why It’s Worth a Look: For his second show in East Hampton, Spencer Lewis departs from his typical hulking abstractions on raw jute for smaller fare.

Know Before You Go: Lewis spent his childhood tracing copies of Hans Hoffmann and Willem de Kooning works, but his freehand paintings (combining oil, acrylic, and spray paint) have just as much in common with the improvisational gestures of graffiti.

“JOSEPH

Where: Halsey McKay, East Hampton

When: Aug. 2–25

Why It’s Worth a Look: Abstract painter Joseph Hart explores the clash and confluence of discrete things in his everyday visual life—from the many overlapping cultures and subcultures of New York, to the panels of his childhood comic books, to the voluminous foliage of the Catalpa tree that grows outside his apartment window.

Know Before You Go: Whether they’re marbled surfaces, hairline fractures, or deep volcanic fissures, Hart’s works contain both a sturdiness and a volatility.

“THE

Where: The Ranch, Montauk

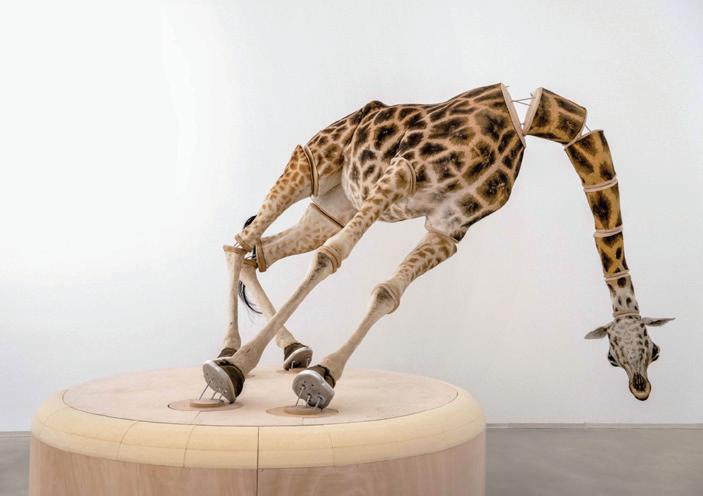

When: Aug. 7–Sept. 27

Why It’s Worth a Look: Von Bismarck’s Whipping Willow transforms a living tree into a kinetic sculpture. Towering at 30 feet and permanently rooted at the Ranch, the work offers a rare chance to witness the artist’s blend of ecological spectacle and conceptual provocation come alive.

Know Before You Go: Von Bismarck is also presenting his “Fire With Fire” series, which explores the catastrophic forces of nature, and his landscape series, which uses photographic and painterly techniques to render vistas ranging from a Mexican jungle to a slum in Nairobi to a Spanish quarry to a Russian forest.

When: Through Sept. 30

Why It’s Worth a Look: Where there’s great art, there’s great design—and the Hamptons are no exception. At his eponymous gallery, Jeff Lincoln brings together work from prominent contemporary artists with rare mid-century furniture and fixtures.

Know Before You Go: This summer, the gallery is highlighting outdoor sculptural design by artists from every corner of the globe. Basalt, concrete, travertine, and bronze gleam in the sunlight, courtesy of a United Nations of creatives: American designer Wendell Castle, Lebanese-French artist Najla El Zein, South Korea–based artist Byung Hoon Choi, and English designer Faye Toogood.

BY SAM FALB

Christine Mack has a knack for transforming art from private passion to public catalyst. Born in the Philippines and raised in Sweden, she has made it her mission to bring artists to her adopted hometown of New York so that they can benefit from the frenetic creative energy the city has to offer.

This summer, Mack’s collection will touch down in a considerably slower-paced environment: the Southampton Arts Center. The exhibition of her holdings, “Beyond the Present: Collecting for the Future,” opens July 26 and presents work by 71 artists ranging from blue-chip stalwarts Rashid Johnson and Cindy Sherman to rising stars like Ana Benaroya and Woody De Othello.

The show also includes works by the 12 artists who have participated in a residency at the Mack Art Foundation’s Greenpoint space. Mack, who also has a home in the Hamptons, trained her eye as a designer and serves on various councils for the Studio Museum and the Guggenheim, among other institutions. It’s all proof that, for her, collecting is as much about giving as it is about acquiring.

As you prepare to unveil the show at the Southampton Arts Center, what excites you most about sharing your collection in this way?

It’s a great opportunity for me to talk about what I do and how important it is to support artists. When the Center gave me the chance to show my collection, I started thinking, You know what? This is amazing. It’s such a special platform for me to highlight the artists I care about, especially my residency artists and other

young talents, who I feel are incredibly gifted.

What projects are capturing your imagination in the Hamptons right now?

I’ve been going to the Hamptons since I was a teenager. I love the Church in Sag Harbor, and, of course, the Parrish Art Museum. I’m always interested in what happens in the off-season: the community projects, the fundraising, the way they engage different groups. That’s what’s so interesting to me, the layers of the community itself.

I’m also really eager to start a residency in the Hamptons. There’s something special about Montauk in particular.

I’d love to bring artists here, especially those who aren’t from the United States, so they can discover the incredible light that artists have been drawn to for so many years.

You’ve poured a great deal of energy into building community in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, alongside your work in the Hamptons. What do you envision as the next step for you in this journey?

I just want to give people opportunities. I came to New York when I was 18 and I fulfilled my dream. It’s so amazing to have a residency in New York. As an artist, it’s the best place in the world to be—the people, the exhibitions, the museum shows, the curators, the galleries. I had no idea what I was doing when I set out to start a foundation. I don’t even come from the art world, but you can figure it out! You can get the information, ask people questions, and create something impactful.

Your wealth. Your mission. Your investments.

Let’s talk.

Whether you’re an institutional or individual investor, important decisions start with important conversations. At Glenmede, you receive sophisticated wealth and investment management solutions combined with the personalized service you deserve.

When Amber Waves runs out of fresh grapes, or a Pilates class with your neighbors feels too claustrophobic, East Enders know there’s only one cure for the creeping malaise: bringing it all inhouse—literally.

From Southampton to Montauk, the Hamptons have perfected the art of nesting in style. Here, we’re revealing the hush-hush playbook for a summer so lush, you might forget there’s a world beyond your front yard. That includes bespoke facials in the sunroom, Pilates taught by trainers who sweat with A-listers, and floral deliveries so fresh they still smell of petrichor. Consider this the ultimate game plan for avoiding, well, everything—because why wait in line when that time could be well spent in the sun?

CELEBRITY ESTHETICIAN, FOUNDER OF EPONYMOUS SKIN CARE LINE, CHANEL BEAUTY PARTNER

She’s a red-carpet skin savior whose hands have been in Vogue, T Magazine, and on a bevy of famous names too long to share in print. Each summer, she pops up out East for house calls with private clients and appointments at the Chanel Hamptons Summer Salon, leaving behind a trail of glowy complexions in her wake.

PILATES INSTRUCTOR

If the idea of a sweaty group reformer class makes you want to flee to a faroff (Shelter) island, fear not: Shakayle

Covington hosts private Pilates in fully equipped studios, and can make house calls to any perfectly manicured doorstep for movement therapy. Slip into a world that’s sprinkled with crystals, floral garnishes, and, of course, the applicable weights and blocks. From East Hampton to Sag Harbor, Covington’s sessions sculpt the body and soothe the soul.

If your pores are shouting for help after a few seasons in dusty city air, call Pietro. His clinic in East Hampton is the ideal spot to shop, lounge, and glow. The facialist—also the guru behind the firstever Goop facial room in Sag Harbor— lifts faces, tightens jawlines, and generally makes guests feel poreless and bouncy all summer long. Simone is the out-of-home outlier on our list (but not for nothing). Treatment that even Gwyneth Paltrow co-signs is worth the travel.

He also runs a foundation supporting youth in his native Cameroon, offering a special opportunity to give back in every workout.

Erika Halweil is the Hamptons’s wellness secret weapon. With nearly 30 years of teaching under her belt—and a toolkit that fuses ancient Vedic wisdom with modern biohacking—she helps clients reclaim their health, calm the nervous system, and remember that joy isn’t optional, it’s essential (especially in the summer months).

Halweil delivers private, home-based wellness experiences that are personal, potent, and anything but conventional. Think bespoke breathwork, sound healing, lymphatic practices, and rituals that keep the body lit from within.

If you want to hit your surf session or poolside tanning hour with extra tone this summer, call David Nso. This NASMcertified powerhouse trains Fortune 500 executives, pro athletes, A-listers, and anyone else who refuses to sit idle at home (even when hiding behind the hedges).

From corrective exercises to performance enhancement, Nso sculpts and strengthens clients across New York and the Hamptons with all the discipline of a Marine—and a gentleman’s charm. Bonus:

Your homebound hibernation deserves the best florals. Enter Missi Flowers, which serves the Hamptons and New York with blooms that belong in a glossy spread but live gracefully on your dining room table instead.

Specializing in private homes, weddings, and parties, with a range that stretches from wild garden flourishes to minimalist arrangements, Missi Flowers adds a touch of artful style that’s hard to come by.

Who says you have to leave your house to experience the party of the season? Enter Mayday, the events and catering outfit helmed by chef Chris Kronner and events planner Josh Hamlet. Based in New York and LA but perfectly at home behind any private gate, the company specializes in transforming environments (your backyard or high-ceilinged living room included) into Michelin-level affairs—minus the prying eyes and club valet line.

This is the team that once designed an entire event to mimic the scent notes of a French perfume. Whether it’s sustainably sourced small-boat seafood or farmfresh produce from the field over, every ingredient is carried over the doorstep with style and discretion.

Some Hamptonites’s favorite mode of transport (and others’ most loathed), Blade is a seaplane service so fast, you’ll be poolside before the Jitney has even made headway. The service operates from Memorial Day through Labor Day, with options such as the $4,450 Summer Pass, which locks in flights at $795 each way.

The transport is known for spacious cabins and baggage flexibility, accommodating vital carry-on items (like golf clubs) upon request. Whether heading out for a weekend getaway or a quick day trip, Blade ensures a swift and comfortable journey.

ROBIN STANDEFER AND STEPHEN ALESCH TASKED A HANDFUL OF THEIR LOCAL FRIENDS AND NEIGHBORS WITH SHARING A GLIMPSE OF THEIR LOW-KEY HAUNTS OUT EAST—LESSER-KNOWN HIDEAWAYS WHERE THEY SHOP, HIKE, AND EVEN GET HAIRCUTS.

FOUNDER

“If you have tweens, teens, or any kidsat-heart who are into mysterious tales à la Stranger Things, you must hike around Camp Hero, a decommissioned military base in Montauk. It’s one of a kind in its eeriness, and full of government conspiracy lore that makes it feel like you’re walking through a sci-fi set. I also love strolling Shadmoor, up along the cliffs west of Ditch Plains—breathtaking! And for a perfect family hike, the Amsterdam Beach trail is a favorite. You’ll even catch a glimpse of the Warhol estate along the way. Total Montauk magic.”

HOTELIER, THE CROW’S NEST INN, THE CHELSEA HOTEL, THE BOWERY HOTEL

“When the Ditch Plains beaches get too crowded, I often head to Culloden Point for a respite. Named for the British warship HMS Culloden, which ran aground in 1781, Culloden Point is also where the illegally enslaved men on the Amistad overthrew their captors and came ashore in 1839. Today, it offers pristine secluded beaches, spectacular sunsets, and treasure-hunt diving for remnants of the Culloden shipwreck.”

“The first is Galerie Sardine, the curatorial space situated in an old farmhouse on Main Street, Amagansett.”

FASHION DESIGNER

“The first is Galerie Sardine, the curatorial space situated in an old farmhouse on Main Street, Amagansett. It is wonderful and feels unexpected. Second, bonfires with friends who are family, as well as our families, on Navy Beach.”

FOUNDER, FREEBIRD PRODUCTIONS

“One of my favorite summer rituals out East starts early when the air is still cool. We paddle our kayaks across Three Mile Harbor through the salt marshes by Sammy’s Beach and treat ourselves to coffee and pastries on the other side at Buongiorno. Those calm moments on the water, especially with our daughters along for the ride, are some of the best of summer.”

“Those calm moments on the water, especially with our daughters along for the ride, are some of the best of summer.”

Valentina Akerman and Joe Bradley have curated an exceptionally beautiful rotating collection of art and design, overflowing with the soul of the wonderful community of artists behind it. We also take advantage of our favorite hair stylist, local icon Danny Dimauro. His men’s cut is unrivaled. You can only book through friends and word of mouth—or, if you’re lucky, by Instagram. You can check @deepcutsbydanny for last-minute openings.”

LANDSCAPE DESIGNER

“Naturally, all of my recs are nature-based. The Walking Dunes are crazy beautiful— they’re a unique ecosystem of sand dunes that end in wet bogs with native cranberries and (some carnivorous!) orchids. Now, the secret: If you keep walking, turn to the north a bit and loop back around to the west through the woods, you’ll be rewarded

with great views of big and little ponds. It is not easy to find the trail, but it doesn’t matter; it’s a fun place to wander and discover amazing, old, contorted oak trees. A little local gem is the South Fork Natural History Museum in Bridgehampton. Good for children and adults—their staff is so engaging and enthusiastic.”

“The Walking Dunes are crazy beautiful—they’re a unique ecosystem of sand dunes that end in wet bogs with native cranberries and (some carnivorous!) orchids.”

“Our favorite spot these days in Amagansett is Galerie Sardine, quietly tucked away just off Main Street in a beautiful historic house.

“The soul of the wonderful community of artists behind it.”

LONGTIME OWNER OF THE BELOVED AMAGANSETT STAPLE TIINA THE STORE

“Cedar Point is an exquisite sliver of land with views of Gardiner’s Bay and a historic lighthouse. A perfect, peaceful hike at any time of the year. On the North Fork, 8 Hands Farm is my absolute favorite place to buy organic produce. It’s a family-run farm with pasture-raised sheep, pigs, and chickens, and there’s a great selection of eggs, meats, vegetables, and prepared foods. The little drive and the ferries are a way to experience a more authentic side of eastern Long Island.”

BY EMMA LEIGH MACDONALD PHOTOGRAPHY BY WESTON WELLS

As a child, Valentina Akerman remembers overhearing her mother tell a friend, “The problem with Valentina is that she likes everything.” Memorable at the time for its tongue-in-cheek candor, the quip has taken on a prescient quality in the years since—today, the curator sees her mother’s observation as an early sign of a powerful desire to do it all.

The latest manifestation of this urge is Galerie Sardine, the Amagansett art space Akerman founded with her husband, artist Joe Bradley, just last summer. While spending time out East getting the program running, the pair decided to move into the building—a rustic 18th-century farmhouse—as

well. Despite the whirlwind speed of the gallery’s rise to recognition (the outfit counts Larry Gagosian as a fan and patron), the experience has unfolded quite naturally for Akerman and Bradley. For one thing, location was a no-brainer: Amagansett holds a special place in the couple’s story (the beach town was an impulse destination for one of their first dates, in the dead of winter). It’s also a font of creative inspiration: “The Hamptons has layers to its history—a refuge from the city for artists, for weirdos,” says Akerman. Galerie Sardine channels this haven-for-weirdos spirit with a program that feels insistently attuned to its location. This makes sense, given that the couple lives alongside the work—a

choice that also felt natural. “There is an intimacy to being in this old, unassuming, 1700s farmhouse. The texture is a bit more domestic.”

The gallery’s summer program has kicked off—first with a residency for jewelry designer Jean Prounis in June and concurrent shows with painter Julian Kent and artist Joline Kwakkenbos. Up next is an exhibition with painter Tenki Hiramatsu and a series of light sculptures by Nate Lowman, an artist and friend, opening July 18. The pair will be hosting a few more personal happenings at the house on the side—including a Beni Rugs summer residency featuring designs by Colin King, and two dinners

in the garden helmed by Mina Stone and Elijah Tarlow.

“The great thing about summer programming is that you can be a little bit more unbuttoned,” Akerman observes. If the pair are taking a leisurely approach to the season, you wouldn’t know it—alongside the exhibitions in-situ, a Sardine program curated by Akerman is on view at Le Consortium Museum in Dijon, France, through Sep. 7, and Bradley is showing a new body of work at David Zwirner London until Aug. 1. This geographic and conceptual spread is a sign of more far-flung Sardine programming to come, and a strong vote in favor of doing it all.

‘I

AND PERFORMER ISAAC MIZRAHI HAS A BOOKSHELF AS VARIED AS HIS OUTPUT.

Isaac Mizrahi has been described as “a founding father of a genre that fuses performance art, music, and stand-up comedy.” Is it any surprise, then, that his bookshelf is as eclectic as his resume?

The Brooklyn-born designer will take his onstage talents to the Hamptons this summer with a one-night-only cabaret performance at Guild Hall in East Hampton on Aug. 10. Blending personal anecdotes, biting cultural commentary, and a songbook that ranges from Stephen Sondheim to Madonna, Mizrahi’s distinctive style—on display earlier this season at his annual Café Carlyle residency back in New York—has earned him a devoted following off the runway. Like any performer worth his salt, he knows the value of good source material. So ahead of his turn as a headliner out East, where he lives part time, CULTURED asked Mizrahi about the books that made him.

Where’s your favorite place to read?

Favorite time to read?

My favorite place to read is in the bathtub just before dinner. I like bathing before dinner because I feel thin! And I love reading in the bathtub.

Describe the type of reader you are in three words.

Completist, faithful, and easily bored. Oh, and one more thing: skeptic of books on tape!

How do you find your next book?

I find books through authors I adore, whether it’s Leo Tolstoy, Henry James, Truman Capote, Philip Roth, Jonathan Franzen, etc. I read complete works. Also, I listen to smart people. I will not be left out if people are talking about a book—I must read it. As in: Graydon Carter’s and Keith McNally’s memoirs.

An artist, actor, or designer you feel deserves a biography but doesn’t have one yet?

I’d love to read a biography about the great director David Lynch.

One book you recommend to anyone who spends time in the East End?

A book I’ve been recommending recently

is Moby Dick, which I only just read last year and was dazzled by. I would recommend it to anyone in an East Coast beach town only for the way Herman Melville captures Nantucket and Cape Cod, which, because I live on the East End, feels a lot like Montauk. Also, the subtle, beautiful homoeroticism. Also, the insanely beautiful language, dialogue, and descriptive passages.

One book your childhood self loved?

When I was too young, my mother was obsessed with Colette and got me to start reading her books. Way too early, in my preteen age, I became Francophile through reading Colette. If I think about it, based on that early exposure I then went on to invest in French literature: Zola, Flaubert, Stendhal, Baudelaire, Proust, Hugo…

“Darling, please edit me. This is ridiculous. You have too many books.”

One book that ruined you, in the best possible way?

I was ruined in the best possible way by Marcel Proust. I read all of In Search of Lost Time about 10 years ago and I’m rereading it now. I think it might be the most beautiful, satisfying thing I have ever or will ever read. I don’t know if I will find anything to replace it with, except to continue rereading it forever.

One book you stopped reading in the middle and never finished?

I tried a few times with various Kurt Vonnegut books and could never quite make it. Same with Philip K. Dick.

One trashy book to wedge in your vacation bag?

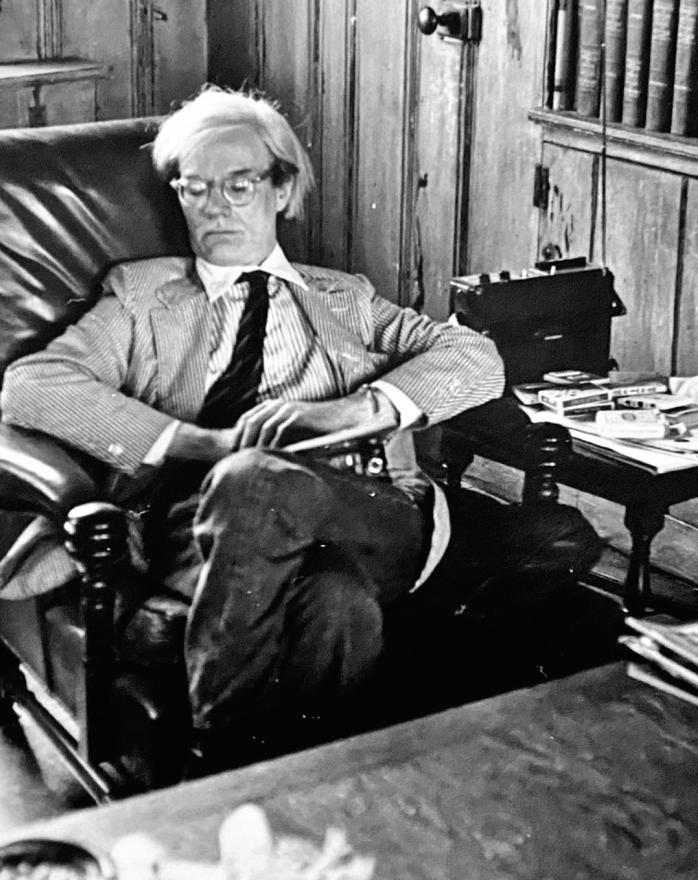

I don’t really define books in that way. There’s literature, there’s biography, there’s nonfiction, and then gossipy things like The Andy Warhol Diaries or Great Demon Kings by John Giorno—things I reread which I think are great but lighter, and which I keep by my bedside to take breaks from things like Anna Karenina

If your bookshelf could wake up and talk to you, what would it say? “Darling, please edit me. This is ridiculous. You have too many books.”

“My favorite place to read is in the bathtub just before dinner. I like bathing before dinner because I feel thin! And I love reading in the bathtub.”

elevated ta e,

& n e of e alc

NONPROFIT, THE HAMPTONS BLACK ARTS COUNCIL, STORM ASCHER RENEWS HER COMMITMENT TO PLATFORMING THE ARTISTIC LEGACY OF HER COMMUNITY—ONE CONVERSATION AT A TIME.

“All these years in the Hamptons, I’d paint on the beach by myself, having these moments where I was thinking, There’s something else here for me,” reflects Storm Ascher. The artist and curator, who has spent summers and winters on the East End since 2013, wasn’t referring to white parties or sceney Gurney’s: “There’s something else that I’m connecting to spiritually,” she recalls telling herself.

Ascher started Superposition Gallery, her nomadic platform for artists, in 2018. The inspiration for the Hamptons Black Arts Council—a nonprofit with a mission to support public programming for Black artists and arts organizations—came just two years later. Ascher credits its inception to a variety of influences, including the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement. “I was living in Sag Harbor during George Floyd,” she says, describing a period of population shift and strained resources. The contrast between those working every day in stores throughout lockdown and those ensconced in their second homes struck her. “There was a lot of backlash about people escaping the city for these beautiful, lush areas that were more populated during Covid—people who didn’t have to deal with normal societal issues.”

She also also attributes her success to figures such as Dr. Georgette Grier-Key, without whom the Hamptons Black Arts Council may not have come to fruition. “She’s the one who connected me with the rest of the Black community in the Hamptons,” Ascher says of the Eastville Community Historical Society of Sag Harbor’s inaugural executive director and chief curator. “Eastville is a treasure trove of archival materials of Black history in the Hamptons.”

This month, the council reaches several milestones. One of them is “Mami Wata,” the Eastville Community Historical Society’s benefit exhibition (on view through Nov. 30), which is deeply personal for Ascher. “This show is all about the goddess of water—how she brings greatness and destruction,”

BY JACOBA URIST

she explains. “The idea [behind the exhibition] is that there were these powerful women who bought up property on the beach and really founded parts of Sag Harbor.” For example, she points to the Black queer architect Amaza Lee Meredith, who shaped the area into a safe summer haven for Black people in an era of segregation and racial violence. But, as Ascher shared on Instagram, “Mami Wata” is also “an altar” for healing after a personal neardeath medical experience, “one that too many Black women carry in silence…

“We want more artists to feel like they have history in the Hamptons, not just a place to bus out to for the day.”

—STORM ASCHER

screaming into the void of a health care system that has never taken our pain seriously.”

In addition, the Hamptons Black Arts Council is spearheading the establishment of a permanent contemporary art collection at Eastville. So far, donations include works by Sanford Biggers, Derrick Adams, Alisa Sikelianos-Carter, and a Queen Nanny portrait by Renee Cox. Ultimately, Ascher says, “We want more artists to feel like they have history in the Hamptons, not just a place to bus out to for the day.”

THE PAINTER INVITES CULTURED INSIDE HIS EAST HAMPTON ATELIER, WHERE TIME MELTS AWAY.

BY JULIA HALPERIN

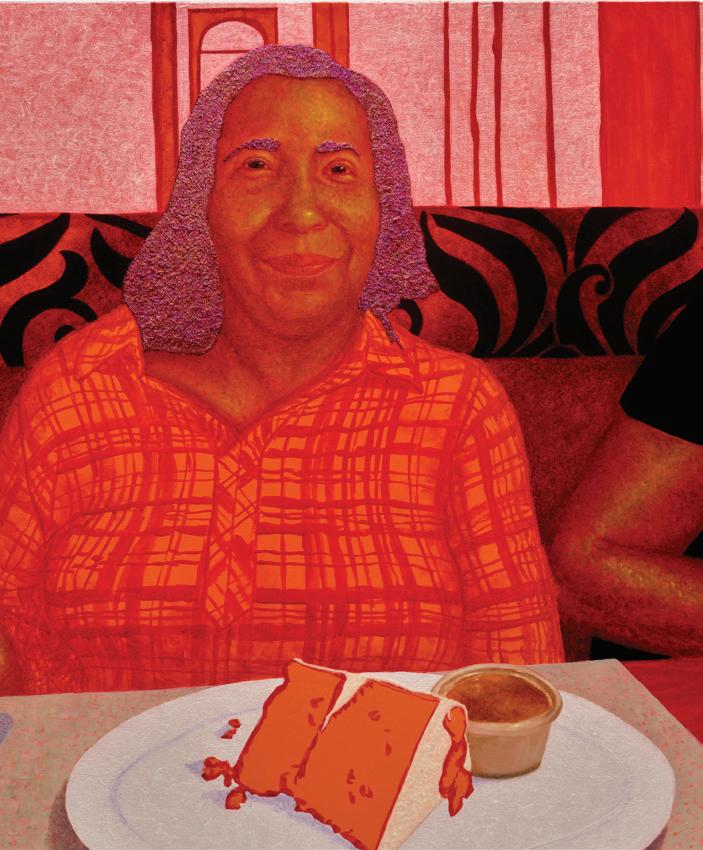

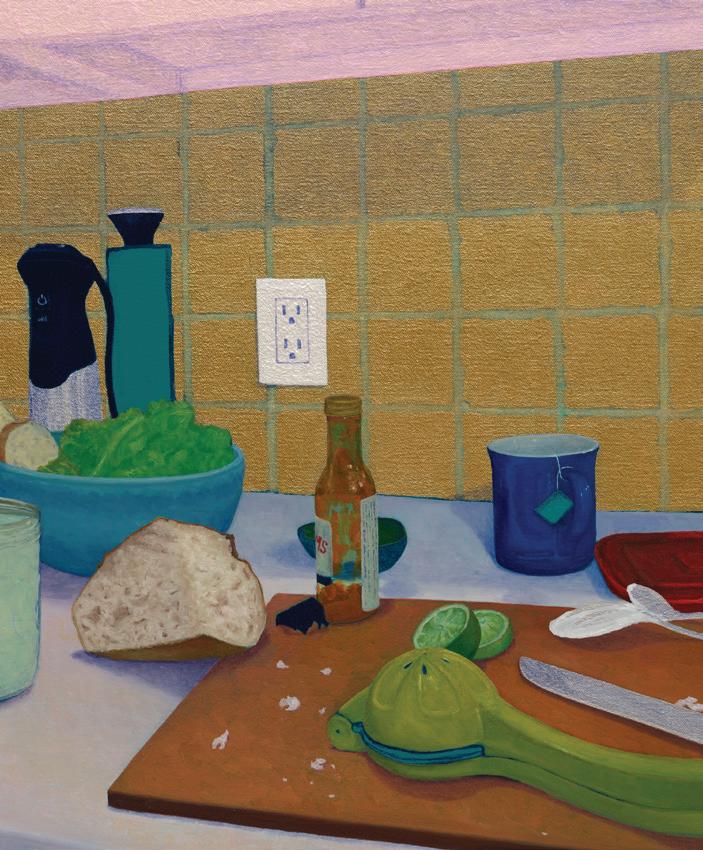

You’d be forgiven for thinking that a painting by Arcmanoro Niles could keep you warm on a chilly night. The artist made his name creating domestic scenes and portraits in a palette of teals, reds, pinks, and oranges so deeply saturated that each canvas seems to glow from within, radiating heat. As the critic Seph Rodney writes, Niles makes “oil and acrylic paintings that do something unconventional under the cloak of conventionality.”

The painter’s latest quotidian scenes— including a rare self-portrait—are on view at Lehmann Maupin in Chelsea through Aug. 15. The Washington, DC, native created them at his home in East Hampton, where he has been based since 2022. The New York presentation doubles as a preview for Niles’s forthcoming solo exhibition at Guild Hall next summer. CULTURED caught up with the artist about his strangest studio must-have, his ability to time travel while making art, and why he doesn’t throw anything away.

What’s the first thing you do when you enter your studio?

I take some time to just sit, look, and be with the paintings in progress.

If you could have a studio visit with one artist, dead or alive, who would it be? Either Norman Lewis or Mark Rothko.

What’s the weirdest tool you can’t live without?

There’s one tool that I use all the time that I didn’t realize was odd, but that I always get a lot of questions about when someone comes to my studio—Q-tips. The floor is usually covered with them.

When do you do your best work?

I’m a night owl. I do my best work in the late evenings into the nighttime.

Do you work with any assistants or do you work alone?

I work alone, which can be a bit isolating because painting can take so much time. But I really love getting lost in my thoughts and process. There is some -

thing a bit freeing and peaceful when, for a moment, two or three hours into painting, you can let everything go.

What’s your studio uniform?

I haven’t thought about this before, but funny enough, my studio uniform is partially my old work uniform. I typically wear old T-shirts from past jobs—so a lot of Ben & Jerry’s and Utrecht shirts, plus sweatpants or shorts and some Crocs with socks. The socks are very important.

There are a lot of costs that come with being an artist. Where do you splurge and where do you save?

Materials are very important for me and they always have been—from the ones that go into the construction of the canvas, to the brushes, to the paint. These are things I have always splurged on, because I believe the materials make a big difference, especially when working with vibrant colors. As for saving—I enjoy working from home, so for most of my life, my studio has always been in the house. I think I probably save a lot there.

What was the last time you completely lost track of time while working?

Somehow, I always lose track of time, and at the same time, I’m always surprised when it happens. It’s been this way since I was a kid. I would sit down to draw something in the morning and then next thing I knew, I’d look up and it’d be dinnertime, or even bedtime. I think that’s why I’ve always been drawn to making art—I can do it continuously, all day. I remember as a child, it always felt like time traveling.

Have you ever destroyed a work to make something new?

Never, except for maybe some things I did for class. Honestly, I’ve kept almost everything, even things I drew in elementary school. When I look back at old work, I remember what it felt like to make and what I achieved. Even if I fall short of what I set out to do, I’m grateful for each painting and drawing.

“I think that’s why I’ve always been drawn to making art—I can do it continuously, all day. I remember as a child, it always felt like time traveling.”

—ARCMANORO NILES

EVERYONE

AND THEIR MOTHER HAS AN OPINION ABOUT KEITH MCNALLY. RIDING HIGH OFF THE RELEASE OF HIS CANDID NEW MEMOIR THIS MAY, THE LEGENDARY NEW YORK RESTAURATEUR TELLS US WHAT HE THINKS OF HIMSELF.

BY JULIA HALPERIN PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS BLACK

Keith McNally opens his new memoir with a quote from George Orwell that reads, “Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful.” Rest assured, the scandal-prone restaurateur’s book passes the test.

I Regret Almost Everything takes readers back to the East End of London, where the founder of beloved downtown Manhattan eateries like the Odeon, Balthazar, and Minetta Tavern had a hardscrabble upbringing. After a stint as a child actor, he set out at 19 to travel through India and Nepal, then ended up in New York. McNally chronicles the many strokes of good fortune (including getting taken under the wing of Anna Wintour, his customer at One Fifth in the ’70s) that led him to go from oyster shucker to one of the city’s most successful restaurant proprietors. But despite its rags-to-riches arc, the book is far from a victory lap.

The now-73-year-old is unsparing in his account of the flaws, feuds, and challenges—both professional and personal—that accompanied his success. In 2016, he suffered a stroke—the effects of which he still experiences today—and, two years later, a dangerous bout of depression that landed him in a psychiatric hospital.

On the heels of the publication of his clear-eyed and disarming memoir, CULTURED asked McNally about his worst customer, the art he surrounds himself with, and what he expects from his staff.

You wrote the first line of your memoir “in a loony bin in Massachusetts in August 2018.” What compelled you to put pen to paper?

A close friend of mine—playwright Alan Bennett—knew about my depression

and suicide attempt and suggested I “jot things down.” For once, I took someone’s advice and wrote most of the first chapter in two days. The rest took six years.

Best and worst parts of New York restaurant culture?

The best part is the number of young, interesting people who are part of that culture. The worst part—besides the absurdly high rents—is that the culture also attracts an increasing number of vain, self-important restaurateurs.

Your restaurants are legendary for their ambiance. How do you keep the magic alive across multiple venues without losing the individuality that makes each spot feel special?

To have any chance of making a restaurant special, you must be there night and day for at least the first three years. You, as owner, must lay down the unalterable tracks of behavior. Behavior toward the customers is of course important, but the way you treat your staff is more important.

Do you have any non-negotiables for your staff?

Bullying. I’m a big believer in second chances. I’ve given employees a second chance for lying, stealing, and fornicating in the locker room, but never for bullying.

If you had to describe your culinary journey in one dish, what would it be— and more importantly, would you eat it again?

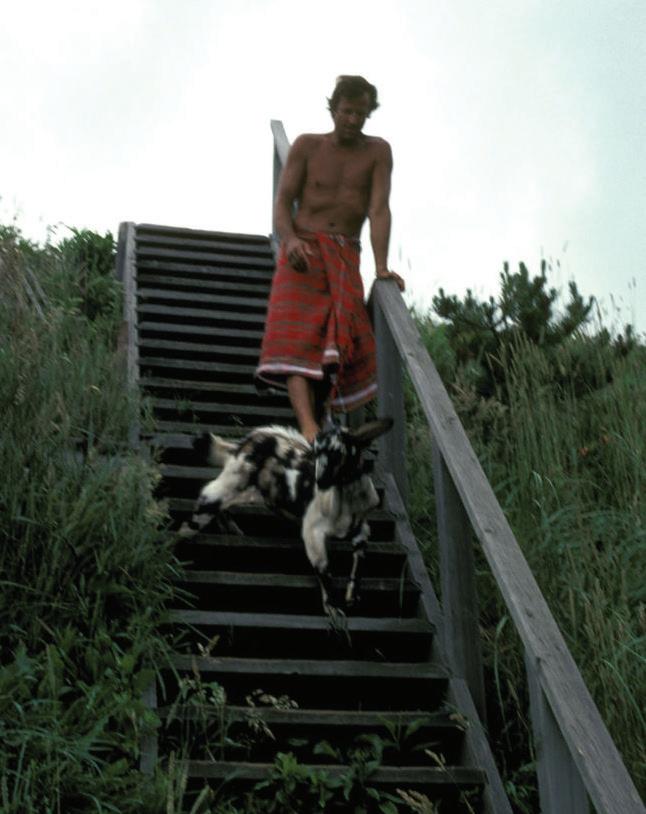

I didn’t fully understand food until I started growing it. In 2007, I owned and operated a farm with pigs, sheep, goats, chickens, and a huge vegetable garden. I used to milk my goats by hand and make goat cheese.

“Never take advice from an older person. They know a lot less than you do.”

In your time as a restaurateur, who has been your favorite guest?

My favorite guests are often single diners. In 1996, I built a Russian vodka bar, Pravda, and not long after we opened, the actor Jim Carrey came in completely alone at 6 p.m. and stayed in the same small booth until 2 a.m. He was wonderful to my staff and never asked for anything special.

Your least favorite?

Bill Cosby was the worst. I can’t mention the reason why without risking a lawsuit.

You’ve been collecting art for 40 years. How would you describe your taste in art?

I very much like German Expressionism, Modernism, and Cubism. I also like the Bloomsbury Group, especially Vanessa Bell’s and Roger Fry’s paintings. Although the paintings I buy come from different genres, they’re exclusively 20th century, and most tend to have somber images and muted tones.

Did you ever want to give up on the restaurant business? What changed your mind?

In the past, I regularly wanted to give up restaurants and make films. I considered filmmaking to be a more dignified profession than operating restaurants. Eventually, I realized that it’s not the job

that gives a man dignity, it’s the man doing the job.

If you could time-travel back to the Keith McNally who was just starting out, what one piece of kitchen wisdom (or life wisdom) would you pass along—and would that younger version of you even listen? Never take advice from an older person. They know a lot less than you do.

Time for rapid-fire questions. How many beverages do you start your day with? I start the day with a double espresso.

What’s the most expensive meal you’ve ever had?

Balthazar’s Chicken for Two.

Was it worth it?

Definitely not!

If Balthazar were a work of art, what would it be?

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

If you could have a director adapt your memoir into a film, who would it be? Orson Welles.

And who would play you? Joseph Cotten.

SATURDAY, AUGUST 2 | 5:00 PM

An evening program of enchanting music including selections from Ravel, Bach, Chopin, Gershwin, Louis Moreau Gottschalk and Meredith Monk

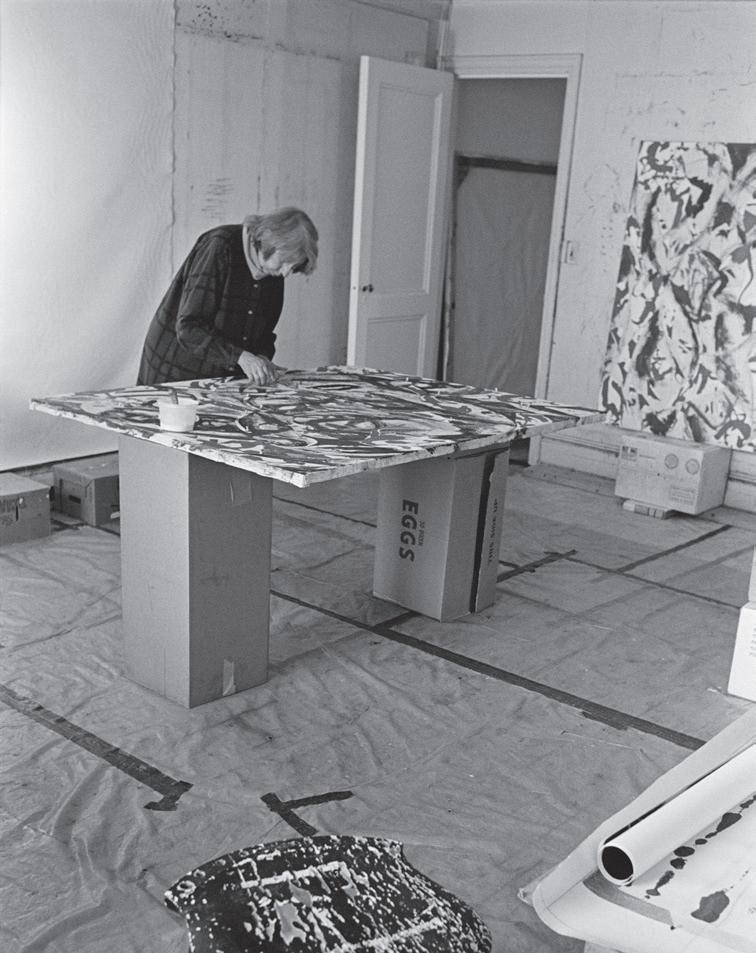

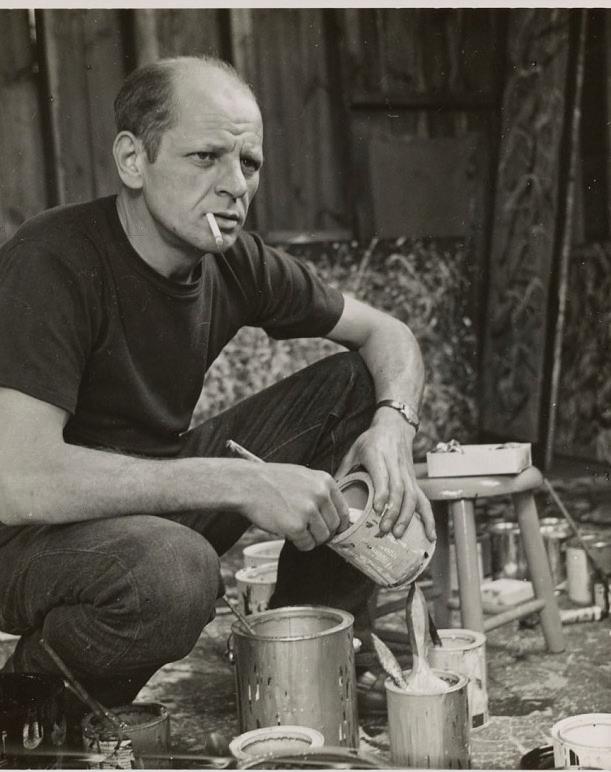

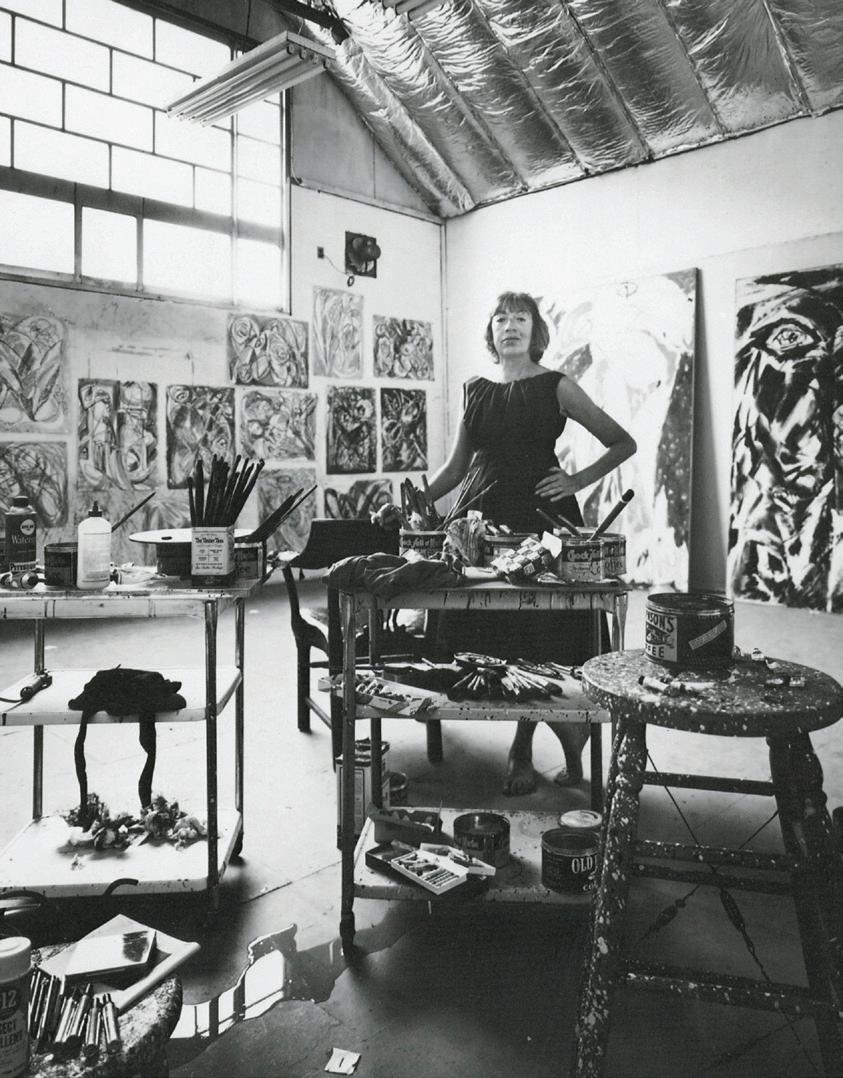

WHAT IS IT THAT, FOR NEARLY TWO CENTURIES, HAS DRAWN ARTISTS TO THE EAST END? HERE, ROBIN AND STEPHEN ASSEMBLE A RICH ARCHIVAL COMPENDIUM OF EAST END STUDIOS AND HOMES OF ARTISTS PAST—SITES OF COUNTLESS GATHERINGS, TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS, AND EPIPHANIC MOMENTS.

STEPHEN ALESCH IS NEVER WITHOUT A SKETCHBOOK. HE HANDDRAFTS ALL OF THE PLANS FOR ROMAN AND WILLIAMS’S BUILDING PROJECTS, AS WELL AS THEIR FURNITURE AND LIGHTING DESIGNS.

For this issue, he shares his drawings of the Sea Ranch orchard, which he and Robin Standefer affectionately call “the fruit loop.” Its rings of peach, plum, apple, and pear trees echo the sacred geometry of the classical labyrinth garden, which featured a resplendent assemblage of fruit trees with hyssop, artichokes, radicchio, artemisia, and other medicinal herbs. He also presents a 21st-century interpretation of a historic botanical drawing that diagrams two types of apples. The forbidden fruit, cultivated on Long Island since the 17th century, has long captivated Robin and Stephen’s imaginations—in art and in food. The variation on tarte tatin on the menu of La Mercerie, the French restaurant at the heart of SoHo’s RW Guild, is just one of their tributes to the fruit’s timeless tang.

“The layout was inspired by traditional labyrinth gardens; classical places like the Alhambra in Granada, Spain; and the culinary gardens of Versailles— albeit a rougher, wilder seaside interpretation.”

“The formal garden, for us, serves as a counterbalance to the rambling, mostly native meadows and thickets in the area.”

“Day after day, long into late August, we cruise along the ‘fruit loop,’ collecting armfuls of things to make into other things— completing the circle.”

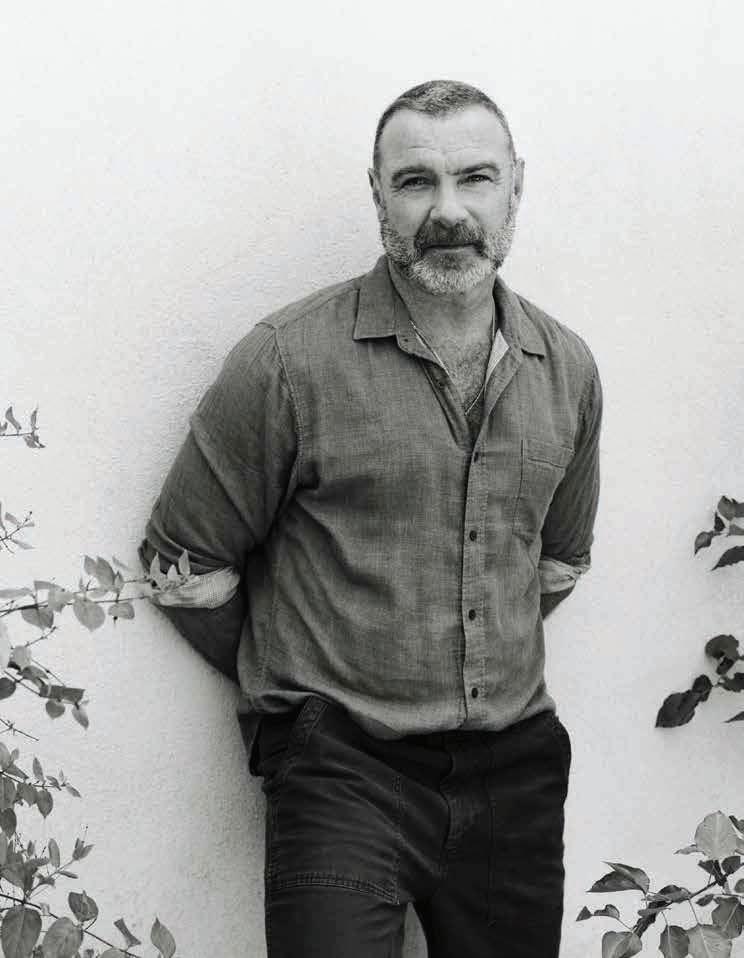

LIEV SCHREIBER HAS HAD A NONSTOP YEAR—FROM HIS APPEARANCE OFF-BROADWAY THIS SPRING TO HIS LATEST TURN IN THE WILD RIDE THAT IS DARREN ARONOFSKY’S CAUGHT STEALING . IT’S ABOUT TIME THE ACTOR GOT BACK TO THE EAST END.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEFF HENRIKSON BY

MARA VEITCH

Although Liev Schreiber has grown increasingly synonymous with Montauk, the actor is not currently in Montauk. When we speak, he’s between New York and Pittsburgh—neither of which has much in common with the small fishing town on the easternmost tip of Long Island that has been Schreiber’s treasured respite for years.

The actor is back and forth to the Rust Belt hub to shoot the forthcoming Apple TV+ series Lazarus, a bone-chilling cop thriller about an ex-soldier who moves to a small town looking for a more peaceful life. The show is the latest in a wave of

projects that have occupied Schreiber over the last year, including a Critics Choice Award–winning appearance in Netflix’s The Perfect Couple, a lead role in the off-Broadway play Creditors this spring, and the wild ride that is Darren Aronofsky’s Caught Stealing (out on Aug. 29).

For the actor, Montauk is an escape from the crush of city life and shooting on location. It’s no surprise, then, that he’s currently missing it. “The thing is, I never realize how much I need to be there until I arrive,” he says. “When I get out of the car or the bus and smell the air, it’s like a trigger. Something in me relaxes.” So

CULTURED brought the Hamptons to the actor with a questionnaire guaranteed to summon the environs’ singular feel.

Tell us about what you’re shooting at the moment You’re in Montauk’s sister city, Pittsburgh.

I am. Lazarus is an adaptation of a book [series] by a Swedish writer called “The Sandman,” about a serial killer thriller.

We’re so ready for that. You are? Okay, good. I’m doing my best. It’s Stephen Graham and an actress named Zazie Beetz. Some really good actors, so I’m excited for people to see it.

When you’ve finished a long, demanding project and you finally get back to Montauk, what is the first thing you do? What’s the Liev Schreiber self-care regimen?

Oh, the first thing I do is clean. Typically, finishing a big project means I haven’t been in the house for a while. There are all sorts of things you’ve got to deal with out there, like ants and moths and other creatures that find their way in when you’re out. Then, I jump in the ocean. If you want an instant reset, that’s all you need to do.

So spend the day cleaning, then walk into the sea.

That’s pretty much it. Gets all the dirt off.

What does a perfect day look like out East?

I get up with [my daughter] Hazel. We go for a walk—if it’s early enough, maybe we’ll see some deer and lots of bunnies. Then we’ll walk to Anthony’s and get pancakes for Hazel. Then we come back and have a swim before Hazel has her nap. That’s usually when I start to work— reading scripts, that sort of thing. When she wakes up, we’ll go down to the beach, spend a couple of hours there, maybe get some ice cream. Hazel loves the red swing behind the church—she tells me about it pretty much all day. “Red swing, red swing.” At the end of the day, we have bath time, do books, and go to sleep.

We’ve heard that you’re obsessed with ice cream.

It’s my superfood. It’s my desert island food. It’s my weakness.

What’s your top choice?

I hate to admit this, but I like soft serve. If I’m buying it from the store, I’ll get Ben & Jerry’s Americone Dream or Phish Food.

What are the hot spots for ice cream?

There’s not an ice cream shop I haven’t hit out there, so this is going to be a long list. Number one is John’s for me. I have also been known to frequent Ralph’s and Carvel—

“I NEVER REALIZE HOW MUCH I NEED TO BE IN MONTAUK UNTIL I ARRIVE. WHEN I GET OUT OF THE CAR OR THE BUS AND SMELL THE AIR, IT’S LIKE A TRIGGER. SOMETHING IN ME RELAXES.”

Are you talking about Carvel, like the chain? That’s number three?

Yeah, don’t mess with me on this.

What are your favorite hidden gems out East?

This is a catch-22 situation. I don’t want anyone to know about the places I like, but I’ll share. Crow’s Nest is always good. Air + Speed has the best surf gear. They make great pizzas at Dive Bar Pizza. Wasabi Beach has great sushi.

What is your sign that you’ve stayed too long in the city and that it’s time to go out East?

The thing is, I never realize how much I need to be there until I arrive. When I get out of the car or the bus and smell the air, it’s like a trigger. Something in me relaxes.

Do you ever hit a point where you’re like, “Time for me to get back to the city”? No. I’d be perfectly happy staying out there all the time.

Describe your fashion sense. How does it change when you’re in the Hamptons? My fashion sense typically is whatever I had on yesterday. Out there, it’s the same, just less sleeve and less pant leg.

What’s the biggest myth about Montauk? Oh, that it’s full of rich people. Montauk’s a real community; it’s hanging on to that. It used to have a really thriving commercial fishing industry, which has fallen apart. Now the locals are living off the seasonal stuff that comes with all of the tourism. But there’s also this community of people who, like anywhere else, call this place home year-round. That feels good. That’s why we drive the extra distance to be there.

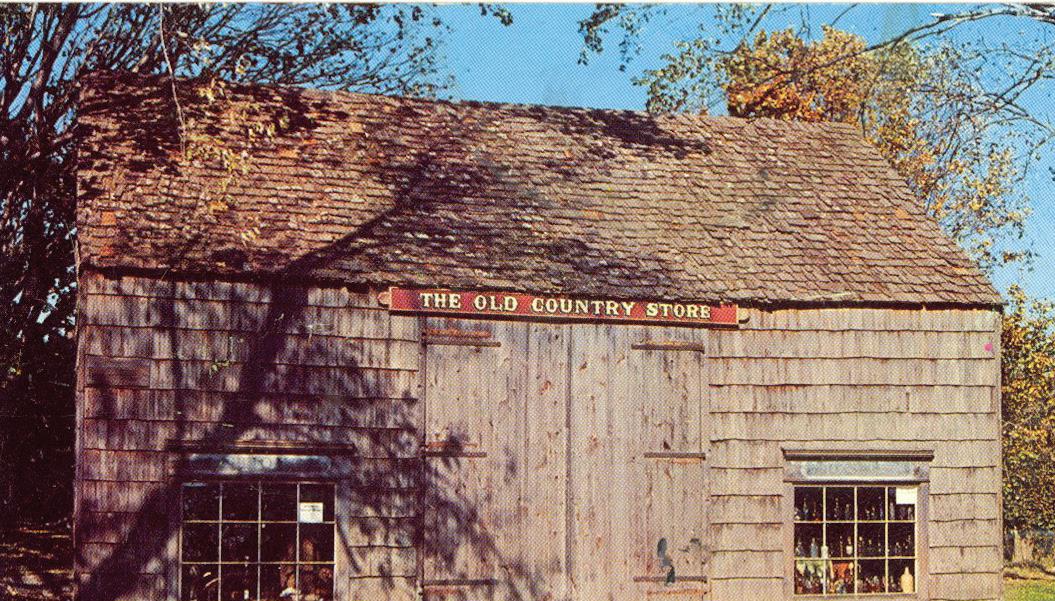

ONCE HUMBLE SHELTERS FOR LIVESTOCK AND HAY, HISTORIC BARNS THROUGHOUT THE HAMPTONS HAVE BECOME HAVENS FOR ART, ARCHITECTURE, AND HISTORY—REVEALING HOW A SIMPLE GABLED SILHOUETTE CAN EVOKE CENTURIES OF CULTURAL MEMORY AND MATERIAL REINVENTION.

Few buildings are immortalized in literature quite like the barn. One beloved contribution to the genre is Charlotte’s Web. In the 1952 children’s book, E.B. White chronicled the unexpected friendship that blossoms between a spider and a pig as the arachnid’s life cycle comes to an end, forever epitomizing the barnyard’s function as a space of nostalgia. Off the page, the barn’s unpretentious aesthetic codes have been consistently co-opted in restaurants, retail spaces, and museums as a shortcut to making people feel at home.

How did we get there? The barn typology as we know it emerged during the Middle Ages, with a central passageway for wagons typically flanked by two aisles of bays. These purpose-built structures evolved to house livestock, farming

equipment, and crops. Barns developed to include ingenious features like pitched gable roofs that mitigated snow and rain runoff while creating loft space for additional storage. Others were partially subterranean, allowing storage of potatoes and ice at a consistent temperature year-round.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, English- and Dutch-style barns were farmstead mainstays across the state of New York, from the wooded regions upstate down to the tip of Long Island. Before it was the summer destination it is today, the East End’s thousands of acres of farmland were dedicated to the cultivation of corn, potatoes, and cauliflower. That began to change in 1870, when the Long Island Railroad added a Sag Harbor station, ushering in a new

BY KAREN WONG

wave of development that would transform the region. Over the last 150 years, farming has maintained a modest foothold in the Hamptons, alongside a burgeoning number of vineyards that have sprung up since the ’70s.

Given this rich agrarian history, it’s no surprise that the Hamptons have adopted the barn silhouette as the mascot of their architectural offerings. In many regional riffs on the humble structure, one recognizes a sense of reverence. The Parrish Art Museum, founded in 1898, was originally located in Southampton in a stately Italian Renaissance Revival–style building designed by Grosvenor Atterbury. In 2005, the institution purchased a 14-acre site in Water Mill, commissioning the Swiss architecture firm Herzog & de Meuron to design a structure with

a twin-gabled roof, extruding the barnlike facade to a length of 615 feet. The minimalist shed—with its airy ceilings and luminous gallery spaces—acknowledges the Hamptons’s pastoral beginnings as well as the vital role artists have played in shaping the region’s culture. (There’s also a sense of irony in the barn’s architectural legacy out East—last year, The New York Post ran a story with the headline “Historic Bridgehampton potato barn transformed into artists’ sanctuary lists for $4.45M.”)

As the barn typology is adapted to unexpected ends in the Hamptons, one question persists: To paraphrase Gertrude Stein, when is a barn is a barn is a barn? Here, CULTURED’s contributing architecture editor spotlights four local case studies that have withstood the test of time.

This colonial barn was built in 1739 and purchased in 1826 by Isaac Sayre, a hotshot whaling captain whose family owned the farm for over a century.

Situated at the intersection of ancient trade routes that remained active until the first half of the 1900s, the barn’s

exterior was often covered in flyers for traveling circuses, missing criminals, trade store sales, and community events, earning it the nickname Billboard Barn. By the 1930s, ownership transferred to the Dimon family, who added two display windows and converted the barn into an antique store that they dubbed “the most attractive shop on the Atlantic Seaboard.” In 1954, the family donated the Sayre Barn to the Southampton Historical Museum, located down the road on Meeting House Lane. The barn’s

Few buildings are immortalized in literature quite like the barn.

transfer was made possible by laborers who wedged rounded logs underneath the building and literally rolled the structure to its new address, where it took on a new name to reflect its new role: the Old Country Store. In 2008, the deteriorating barn was deemed a hazard and closed to the public. A fundraising campaign ensued, and in 2014, the Sayre Barn was meticulously restored using as many of its original materials as possible. Today, it holds a place of pride among the 14 restored historic buildings owned or leased by the museum.

Given this rich agrarian history, it’s no surprise that the Hamptons have adopted the barn silhouette as the mascot of their architectural offerings.

The Mulford Farm remained in the family that gave it its name for 10 generations before finally changing hands in 1949. This 1721 building is a powerful example of an early Englishplan barn. In 1990, it was recognized as

the second most important 18th-century barn in New York State by the State Department of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. The rectangular form, with its gable roof and lean-to addition, is clad in wooden shingles and

was constructed using a typical postand-beam oak frame with mortise and tenon joints (an ancient interlocking method in which a protrusion from one piece of the wood fits into the socket of another). The Mulford Barn hosted

several seasons of performances from the Mulford Repertory Theatre in the early 2010s and is now open to the public as a museum.

Established in 1658 and billed as the oldest cattle ranch in the United States—not to mention the birthplace of the American cowboy—Deep Hollow Ranch boasts a series of working barns that support a long-standing tradition of cattle and sheep grazing. The property is surrounded by 3,000 acres of coastal parkland that creates organic boundaries for roaming livestock. Deep Hollow Ranch is open to the public and offers a number of trail rides, including one along the ocean.

Across the Montauk Highway is a private property simply dubbed “the Ranch.”

Purchased by art dealer Max Levai in 2021, the property features two barns built in the late 1920s by industrialist Carl Fisher, who had grand plans to transform Montauk into the Miami of the North. Ultimately, Fisher’s vision was thwarted when he ran out of money, and the property fell into disrepair. Levai currently maintains one barn as a stable to breed competitive quarter horses. He refurbished the second barn using only natural materials found on the property, leaving the exterior untouched. Levai has used the 2,500-square-foot galleries to exhibit work by contemporary artists, including Daniel Lind-Ramos, Donna Dennis, and Jamian Juliano-Villani.

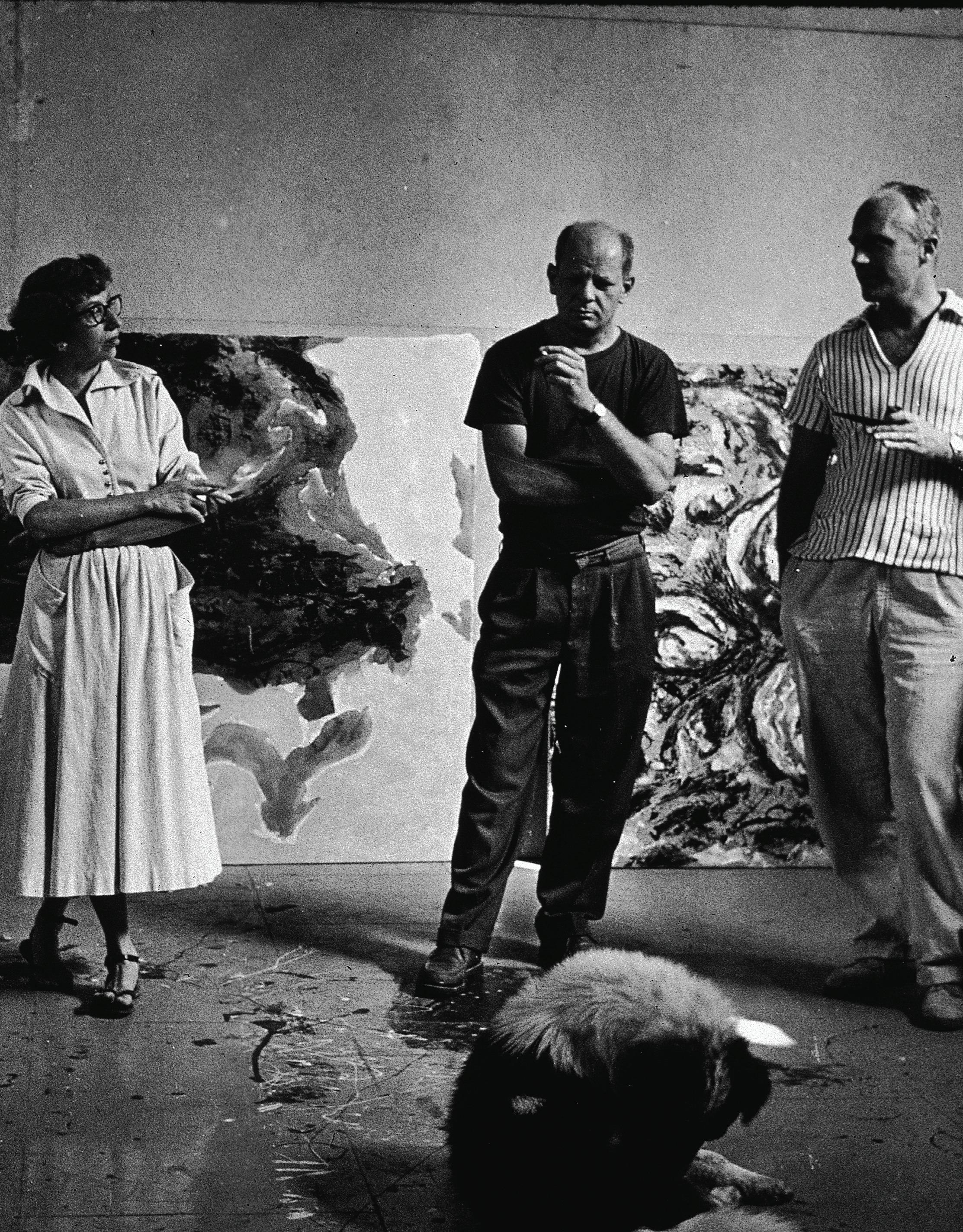

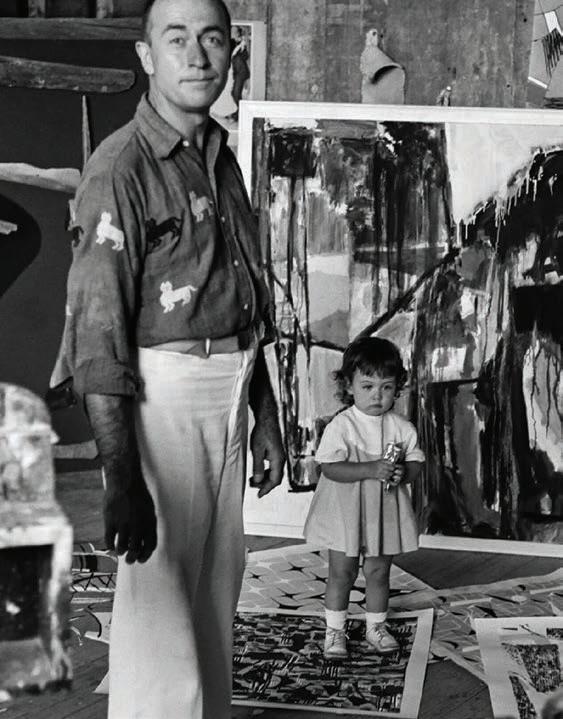

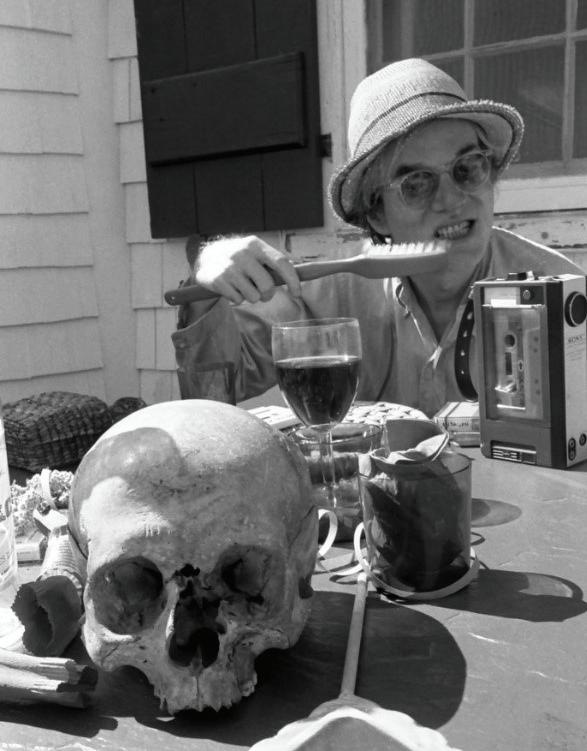

DAVID SALLE FIRST VISITED THE HAMPTONS IN 1976 AND FELL SO IN LOVE WITH THE RICH LAYERS OF ART LORE HE ENCOUNTERED THAT HE LATER SET UP A HOME AND STUDIO THERE. A LOT HAS CHANGED IN THE REGION, BUT THE 72-YEAR-OLD ARTIST—WHO WELCOMED CULTURED INSIDE HIS EAST HAMPTON HOME—STILL HAS THE SAME MANTRA: DO YOUR WORK, AND STAY CLEAR OF THE NONSENSE.

THERE ARE Hamptons artists, and then there is David Salle. The renowned Neo-Expressionist’s presence on the East End affirms the region’s place on today’s art history map, much like the titans of Abstract Expressionism did in the last century. For 40-plus years, Salle has been known for richly collaged mash-ups of high-low imagery that interweave pop culture references, cartoons, interior decor, print media, television iconography, and art masterpieces to capture the essence of Postmodernism and the contemporary. Recently, Salle added another element to this mélange, using machine learning to reinterpret his own canvases. This summer, as part of the

BY JACOBA URIST

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JESSICA DALENE

ongoing exhibition “David Salle: Under One Roof” at Seoul’s Storage by Hyundai Card space, the artist debuts “Windows,” a new series of paintings, as well as a survey of older works from the ’90s and early aughts.

For decades, Salle has split studio time between New York and the South Fork. Last month, CULTURED’s Hamptons editor sat down with the luminary to discuss his exhibition in Korea, the East End art scene, and the 18th- and 19th-century barns that make up his quietly eclectic East Hampton lifestyle.

What is the relationship between your

new “Windows” series, on view until Sept. 7 in Seoul, and your “Tree of Life” series?

The “Windows” paintings are based on an idea I originally had for a digital game, in which characters that originated in my “Tree of Life” paintings migrated into apartment building windows. The idea is simple: You’re walking down the street and look up at an apartment building. You notice someone in the window—on the phone, or smoking a cigarette, or having a private thought. We’ve all had that fleeting, voyeuristic glimpse into another life. It’s a hallmark of the urban experience. I took it one step further and placed the “Tree of Life” characters

in front of imagistic backgrounds, as if the character is standing in front of a painting—that painting being a detail from a work of mine. I went through 40 years of my paintings and selected details that could function in this compressed way.

When did you discover the Hamptons? I visited for the first time in the summer of 1976. I came because Paul Brach— who had been the dean at CalArts, where I went to school—owned a modest 19thcentury carriage house right on Montauk Highway, not far from where I am now. The grand house to which the carriage house had originally belonged was called

“When I first started coming out here, it was, of course, much less developed … I still have a lot of artist friends here; we do our work and try to steer clear of the obvious nonsense.”

“The Creeks.” In the ’50s, it was owned by the assemblage-ist, surrealist painter Alfonso Ossorio, who was the heir to a sugarcane fortune. He was also a great collector, the biggest collector of Jackson Pollock’s work at that time. To put this in context, Pollock was on his way to Ossorio’s house when he had his fatal

car crash. That first weekend I came to the Hamptons, Paul took me to the Green River Cemetery in Springs to visit Pollock’s grave. From the beginning, I was inculcated with the history of this place as it had developed during the first and second generations of Abstract Expressionist painters.

How do you describe the style of your home?

I think many artists have a strong sense of the things in a room—what they signify, what vibrations they give off, how they work together. This house has evolved with time. There’s pleasure in exercising a sense of juxtaposition

and counterpoint. It’s like composing a picture: If done successfully, the composite gives off a little charge every time you look at it.

Which of the artworks in your home holds the most meaning for you? I have several works by my teacher,

“This house has evolved with time. There’s pleasure in exercising a sense of juxtaposition and counterpoint. It’s like composing a picture: If done successfully, the composite gives off a little charge every time you look at it.”

William Dickerson, from when I was growing up in Kansas. I started working with him when I was 9 years old. He was part of a generation of American realists and regional artists who flourished in the 1930s and ’40s. As a watercolorist, I think he’s as good as Edward Hopper. I love living with Bill’s work; it’s a concrete

reminder of the aesthetic principles that I absorbed early on. I also have paintings by Charlene von Heyl, Joe Bradley, Ross Bleckner, and Alex Katz, all of whom are good friends of mine. The art I live with is quite diverse. To use a musical analogy, everything strikes a particular note, and the notes together form a chord.

What is life in the Hamptons like now compared to your early days here? When I first started coming out here, it was, of course, much less developed. Even though it’s changed a lot, those early impressions inform how I feel about it now. I still have a lot of artist friends here; we do our work and try to steer

clear of the obvious nonsense. It’s still a beautiful place. I don’t feel a gravitational pull to be anywhere else during the summer.

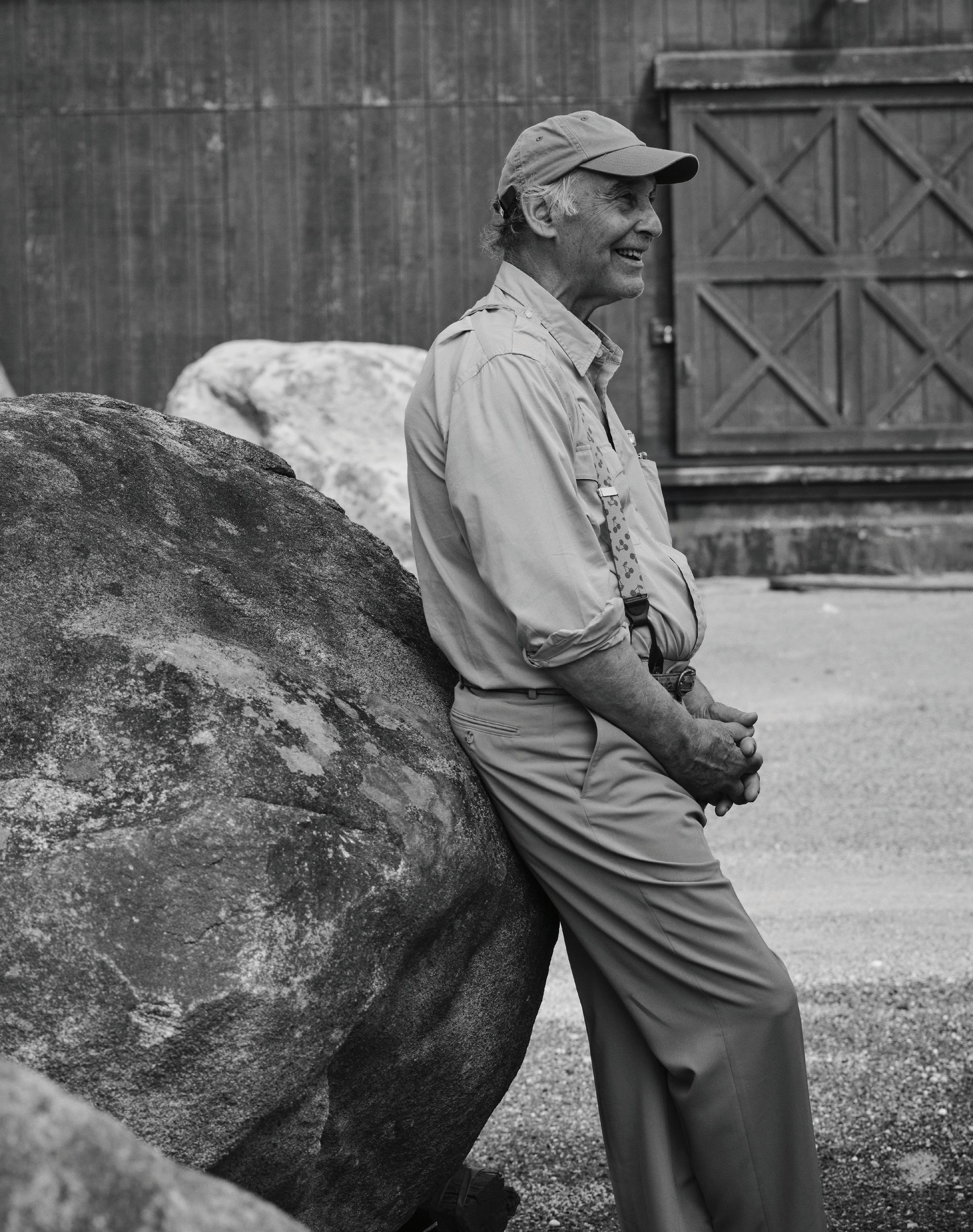

THE ROAD FROM CHARLIE MARDER’S RENOWNED EAST END NURSERY, THE REGION’S BELOVED ARBORIST-AESTHETE PAYS TRIBUTE TO ANOTHER ARDENT PASSION: GIGANTIC ROCKS.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DITTE ISAGER

ON THE EAST END, Charlie Marder is known as the “tree whisperer.” The Hamptons-based horticulturalist has collaborated with all manner of notable locals, from Peter Marino and Maya Lin to Julian Schnabel and Helmut Lang, who trust in his reverence for art and its intersection with nature.

Marder and his wife, Kathleen, founded their eponymous Bridgehampton nursery, legendary for its towering redwoods and copper beeches with 30-inch trunks. The New York Times dubbed the place “a horticultural MoMA.”

Across the road from all this botanical grandeur lies Marder’s true passion: rocks. In an open field bisected by a dirt driveway, Marder has assembled

a sprawling constellation of geological specimens: 10-ton boulders relocated through feats of machinery (according to local lore, Marder holds the record for the Shelter Island South Ferry’s widest-ever load), pebbled slabs of cliff, stones pocked with primordial patterns.

Salvaged from development sites, quarries, and roadside demolitions, Marder’s sanctuary feels part Jane Goodall sanctuary, part Noguchi sculpture garden: The hulking forms scattered across the field like a herd of sleeping bison.

For this issue, Robin Standefer—who purchased a rock from Marder’s collection for her birthday one year—spoke with the horticulturalist about time on the geological scale, the ethics of placement, and

the human urge to give new life to some of the world’s oldest matter—all while perched against a particularly compelling specimen.

Robin Standefer: I came to visit you one rainy day in February, and you said, “I want to show you something.” Suddenly, I was wandering your stone sanctuary, cradled by all this mass and mineral. While the design world chases lightness, [my husband] Stephen and I were getting into heavier objects. I’ve been figuring out how to work with heavier pieces and pure materials: massive stones, solid wood, and bronze. But what you’re doing is on a whole other level.

Charlie Marder: “Heavy” just makes me excited. I’ve always been obsessed

with rocks—even before I was obsessed with plants. I remember, as a kid, selling rocks on the side of the road. I gave one to my wife before we got married. It was a nice rock. I found it. Almost everyone has a rock they remember, whether it’s a childhood stone, a marker by the porch, or something that lives in a pocket.

Standefer: I’ve collected rocks for years, but only the ones I could carry. When my birthday came around, I told Stephen, “I’m getting older. I want something older than me.” He said, “We should buy one of [Charlie’s] rocks.” When we came to choose one, I spent hours with the boulders. I wasn’t just looking for a rock, I was looking for the one I will live with forever. I was meeting all these different characters. It was as much about

“Some stones might seem smart, others feel lazy. Some are gentle, others are a little edgy. Some like to be alone; some like to be social. They all have something to say.”

—CHARLIE MARDER

compatibility as composition.

Striations read like geological and emotional biographies, each revealing a rock’s distinct personality and way of being.

Marder: Some stones might seem smart, others feel lazy. Some are gentle, others are a little edgy. Some like to be alone; some like to be social. They all have something to say.

Of course, some are simply rock stars. They make you pay attention. They tell you where and how they want to be— turned just so. They don’t whisper.

Standefer: When I was there with you, looking at the rocks and experiencing their color and stillness, I left with a profoundly heavier heart. What can I say?

Marder: Ten tons heavier. [Laughs] To believe in a rock is to see its potential. When you move them, or shift their context, they reveal themselves. A wild animal in the woods just looks like its generic species. Bring that same animal into a new environment, however, and you start to notice how it reacts and adapts. Rocks do the same thing. Their unique character emerges when they’re placed somewhere new.

Standefer: There’s something primal about collecting and placing rocks. They feel like talismans. Time is the ultimate expression of slow design, and what’s more stable than a billion-year-old stone?

Marder: The tension is that a rock is always evolving depending on where it’s placed: the way the sun hits it, what happens when water collects, when insects move into its cracks. The rock we placed together in Montauk had a slight depression in it. I thought, This is going to form a little dish for water

Standefer: Sure enough, the birds come.

Marder: Really, though, we’re so unsophisticated about this. The Chinese and Japanese have centuries-old terminology for how water collects on rocks, how moss or lichen grows. Their devotion to nature is so culturally embedded.

Standefer: When you’re constantly moving, you miss the gesture. Most of us only keep the ones that we can pick up, but you’re working on another scale entirely.

Marder: My ability to carry things is exponential, thanks to the crews and machines I have access to. Lifting a giant rock is spiritual.

Standefer: Tell me about what drives your rock rescues.

Marder: I rescue them to protect them. Otherwise, they get buried, smashed, forgotten. Once a rock leaves its resting place, where it’s been since the glaciers, it can’t go back. It needs a new home worthy of it.

Standefer: When did you start collecting rocks, the ones too big to carry?

Marder: Maybe 25 or 30 years ago.

Sandefer: Rock collecting is like discov -

ering an unknown artist, right? Believing in something you think is beautiful and daring to say: “I’m going to invest in this, even though I don’t totally know what’s next.” I know you’ve been Arne Glimcher’s horticultural accomplice for decades. And you’ve also done some work with the artist Lee Ufan.

Marder: I worked with Pace Gallery and the team that helps Lee produce shows, as well as commissions and installations. I brought Lee here, and we spent a couple of days scouting rocks. It’s nice to work with somebody who’s better than you are. Lee sees rocks as partners in composi -

tion. Sometimes it takes days to find the right position. Once it’s set, it’s no longer just a rock.

Standefer: It’s about the relationship the object creates between people.

Marder: Exactly. I often place rocks in threes. The negative space between them becomes part of the composition. As you move around them, the perspective shifts, like in a Japanese garden. It’s kinetic, though nothing moves. There’s something ancient about it. I remember one boulder we moved completely shifted how my crew saw the work they do. They

“There’s something primal about collecting and placing rocks. They feel like talismans. Time is the ultimate expression of slow design, and what’s more stable than a billionyear-old stone?”

—ROBIN STANDEFER

treated that rock like architecture. The act of moving it transformed all of us.

Standefer: It’s a kind of reverse obsolescence. In a world obsessed with speed and disposability, rocks are forms of resistance, in a way.

Marder: A rock is like the opposite of a trend. It holds the memory of a place or a time, but is never truly mastered. You can design an entire landscape around it, or you can sit beside it and let it ground you.

HUSBAND-AND-WIFE DESIGN DUO ROBIN STANDEFER AND STEPHEN ALESCH, OF ROMAN AND WILLIAMS, LET THEIR CREATIVITY RUN WILD IN A REFURBISHED OASIS IN MONTAUK.

BY JACOBA URIST

PHOTOGRAPHY

BY

DITTE ISAGER

and Williams wouldn’t be Roman and Williams. The influence of the Hamptons getaway is something Robin Standefer, who co-founded the ne plus ultra architecture and design studio alongside her husband Stephen Alesch, is only beginning to grasp, two decades after they bought the ramshackle mid-Atlantic Colonial cottage they call Sea Ranch in 2006.

Pulled east by Alesch’s love of surfing and their shared affection for the ocean, the home “started off as a creative respite and place to restore,” Standefer says. “But it has really evolved to be the center of our artistic life.” Alesch, raised in the hills above Malibu, likens the dynamic to pottery: “New York is our kiln where we just crank up the heat and manifest,” he explains. “Montauk is where we shape and form. Then we go back and fire it up.”

The couple met on the set of the 1994 film The New Age and have worked on more than 20 movies over the years. They’ve brought their imaginative sensibility—research-heavy, theatrical, and inviting—to restaurants, hotels, and

gathering spaces around the world, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s British Galleries to London’s private club Maison Estelle. They have also developed their own nature-infused furnishings collection, Roman and Williams Original Designs, which specializes in artisanal tables, chairs, and chandeliers, while building residences for aesthete celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow. Their SoHo shop, Roman and Williams Guild Original Designs, sells their original designs alongside tableware handmade by like-minded artists from around the world. Along the way, their hybrid home-workshop in Montauk has become the laboratory for everything they do. It’s where Alesch makes furniture prototypes and Standefer, a New York native, experiments with assemblage and ceramics. “These things just wouldn’t happen in the city because of the intensity there,” she says. Alesch adds, “We never have a conversation about the cost of things or margins in Montauk. That’s city talk.”

On the edge of the 99-acre Shadmoor State Park, Sea Ranch is spread over three modest mid-century structures, set amid a wild wonderland of mature trees, indige -

nous flowers, and medicinal plants. The result: a sliver of French countryside meets Scandinavian-SoCal bohemia, elements of which wind through some of the couple’s most high-profile projects. “We tested tambour cladding in Montauk,” says Standefer. “We were inspired by its flexibility. Let’s start using this all over the walls.” The historical, timeless technique is reimagined in the Boom Boom Room and 18th-century Estelle Manor.

Standefer describes the process of converting Montauk’s cookie-cutter spaces into kunstkammer-like coves as an excavation. “We took all the drywall off, leaving the ceilings open. From a philosophical perspective, it’s always unfinished,” she says. She points to Roman and Williams Guild’s popular Oscar pendant hanging from a block of wood affixed to the raw, vintage beams overhead.

Underfoot in the kitchen–sitting room, a fantastically worn Moroccan rug—the product of “12 hours of negotiating in Marrakesh in a room with a lot of mint tea”— embodies the pair’s unfussy, plein air living. “We love nomadic rugs because they were originally meant to be used outside,”

Standefer explains. Large, screenless doors let butterflies—as well as the odd bug—in and out, “which we kind of love,” says Alesch. As Standefer puts it, “The doors and windows are the eyes of the house, and we like them on a huge scale.” (Just don’t ask them to install a large wall of glass: “We believe in muntins,” she notes, referring to the strips of wood separating smaller window panes.)

Given the couple’s award-winning French eatery La Mercerie in the SoHo Guild shop, it’s no surprise that eating sumptuously—garden-to-table—is a big part of their Montauk routine. This winter, they will unveil a new restaurant in partnership with Sotheby’s at the Brutalist Breuer building on the Upper East Side.

The duo brings the same intense connoisseurship to dining as they do to design. “We might have a discussion for 45 minutes about whether cucumbers and yogurt work in an Indian meal as well as in a Middle Eastern meal,” Standefer says. “It’s all about trade routes and the country of origin and how you express that.” Their meals—like the surroundings they enjoy them in—“have a tremendous artistic

“New York is our kiln where we just crank up the heat and manifest. Montauk is where we shape and form. Then we go back and fire it up.”

—STEPHEN ALESCH

“[What] started off as a creative respite and place to restore … has really evolved to be the center of our artistic life.”

—ROBIN STANDEFER