UNIVERSITY DECLARATION

8. UJ A NTI-PLAGIARISM DECLARATION FORM (COVER PAGE)

FADA

Assignments cover page/Anti-plagiarism declaration

This serves to confirm that I (Full Name[s] and Surname ):

Courtney James Morton

Student number :

220119446

… enrolled for the qualification:

Master of Architecture

Graduate School of Architecture

in the Department ………………………………………………… ……………… at the Faculty of Art Design and Architecture, herewith declare that my academic work is in line with the UJ Policy: Student plagiarism and the UJ Student Guide to Avoiding Plagiarism, with which I am familiar.

I further declare that the work pre sented in the module: for the unit: and assessment:

Design Portfolio

5 Final Portfolio Review

… is authentic and original unless clearly indicated otherwise and in such instances full reference to the source is acknowledged and I do not pretend to receive any credit for such acknowledged quot ations, and that there is no copyright infringement in my work. I declare that no unethical research practices were used or material gained through dishonesty. I understand that plagiarism is a serious offence and that should I contravene the Plagiarism Po licy notwithstanding signing this affidavit, I may be found guilty of a serious criminal offence (perjury) that would amongst other consequences compel the UJ to inform all other tertiary institutions of the offence and to issue a corresponding certificate of reprehensible academic conduct to whomever request such a certificate from the institution.

Signed at (the place) : on this day of 2019

Signature

Linden, Johannesburg the 16th of October 2025

STAMP COMMISSIONER OF OATHS (Masters and Doctoral candidates)

Affidavit certified by a Commis sioner of Oaths

This affidavit conforms to the requirements of the JUSTICES OF THE PEACE AND COMMISSIONERS OF OATHS ACT 16 OF 1963 and the applicable Regulations published in the GG GNR 1258 of 21 July 1972; GN 903 of 10 July 1998; GN 109 of 2 February 20 01 as amended.

The format of this declaration is adapted from the University of Johannesburg’s Policy: Plagiarism, Appendix D (2013:19) to accommodate undergraduate and Honours submissions.

DESIGN

Urban Fabric Mapping

Ecological Evolution

Invasive Species

Invasive Growth

Ecological Sections

Microbiology of the Mosquito

Heat Mapping

Precedent Studies

Colour Studies

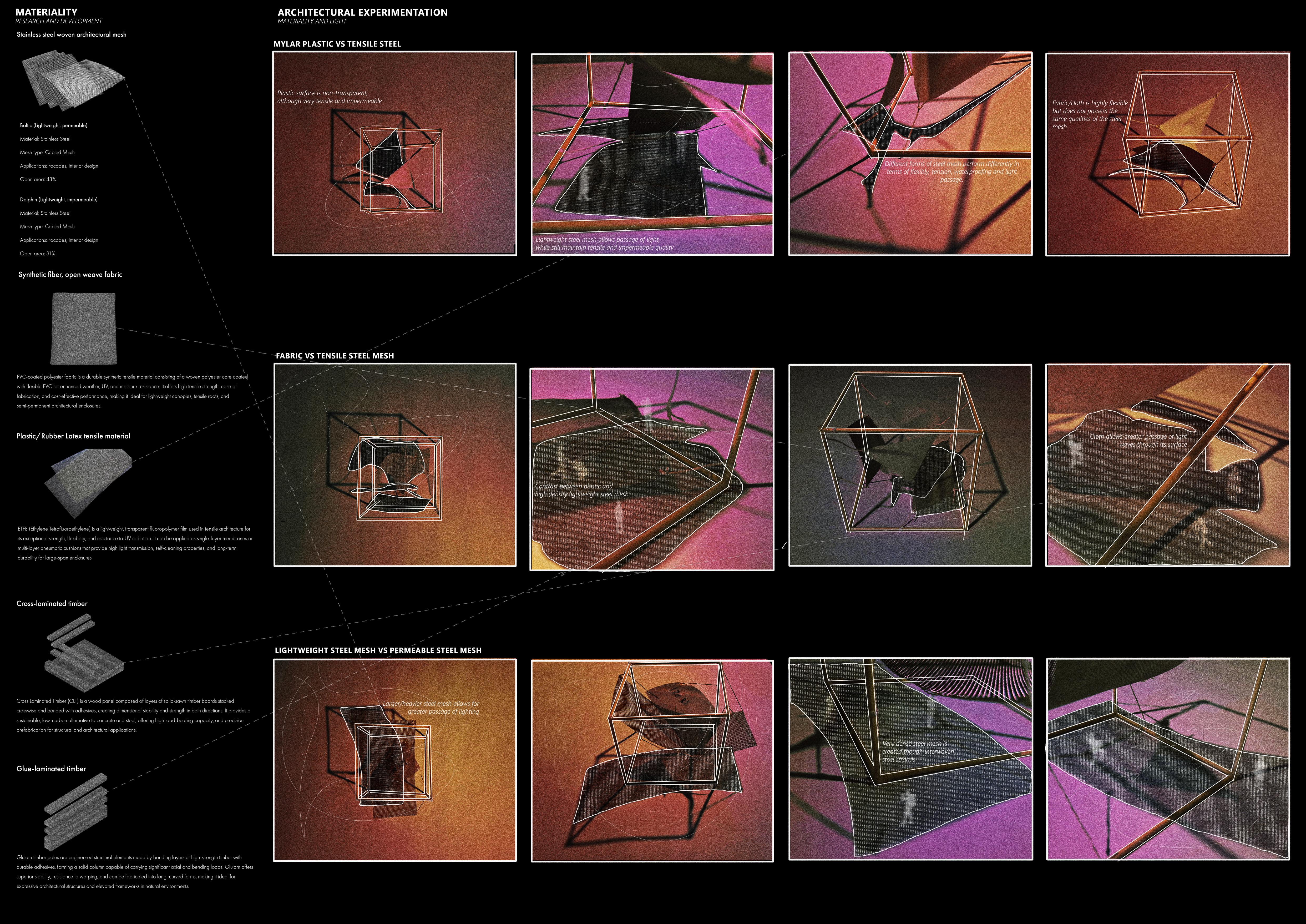

Materiality Experimentation

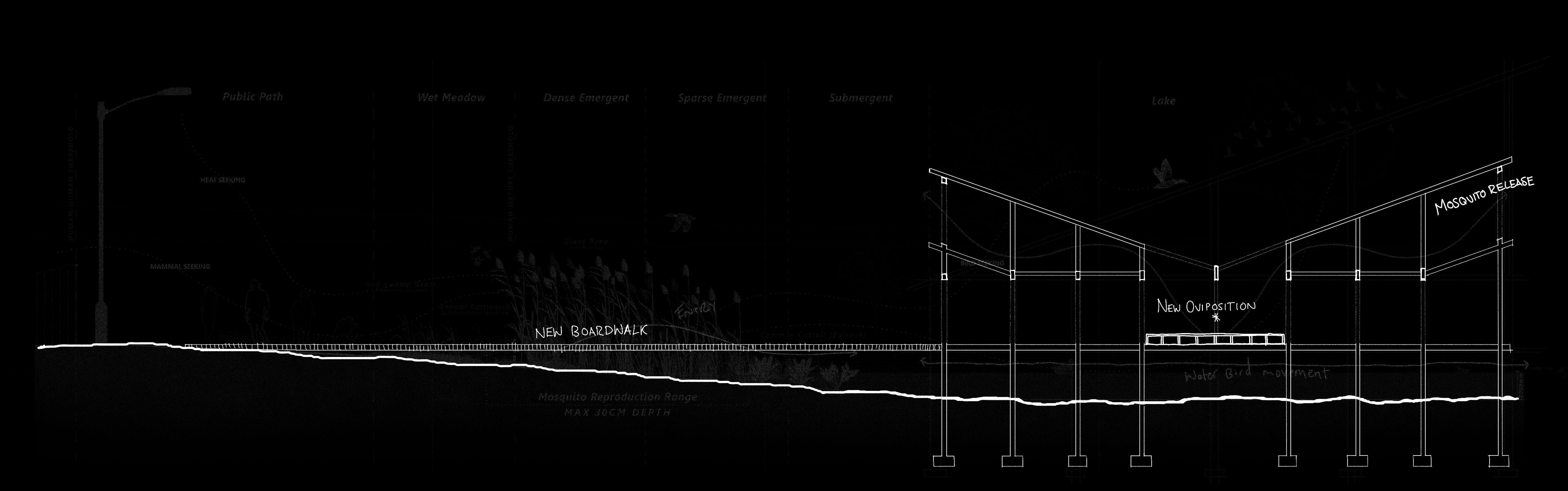

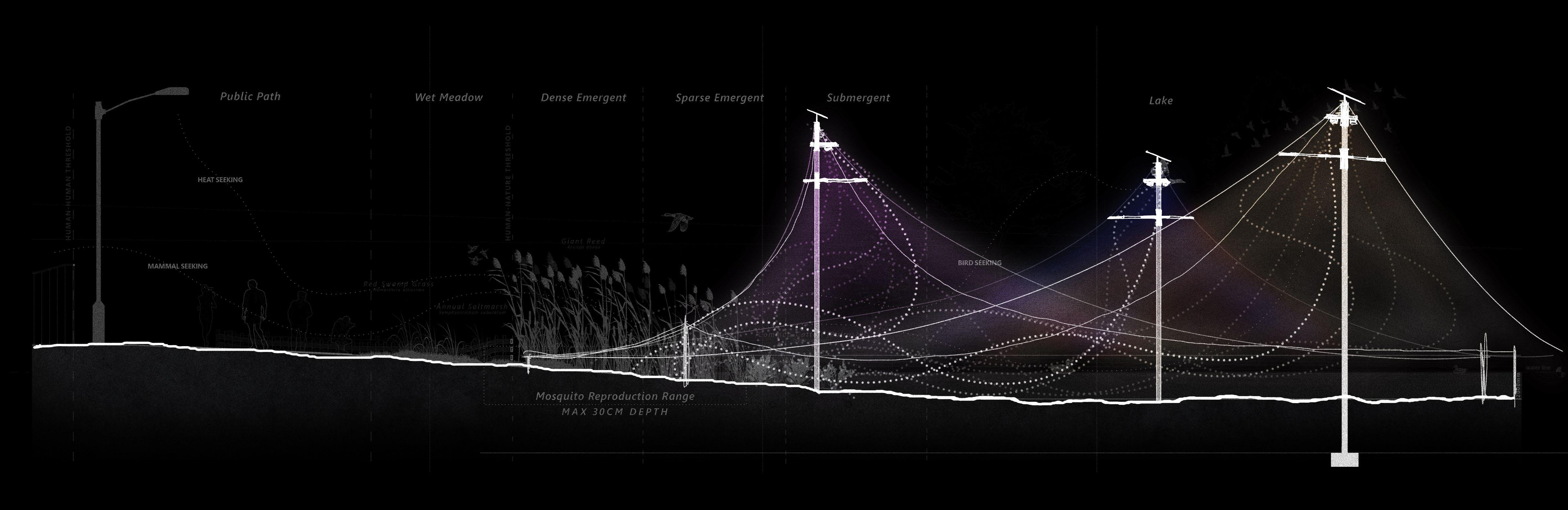

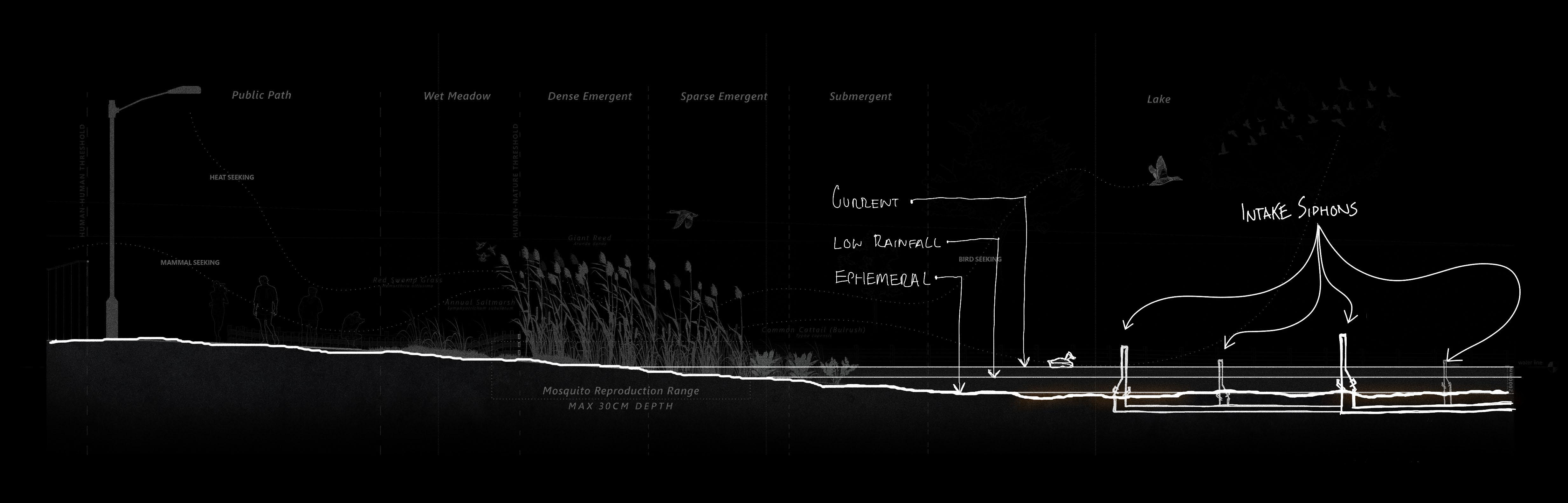

Sectional Concepts

Concept Development

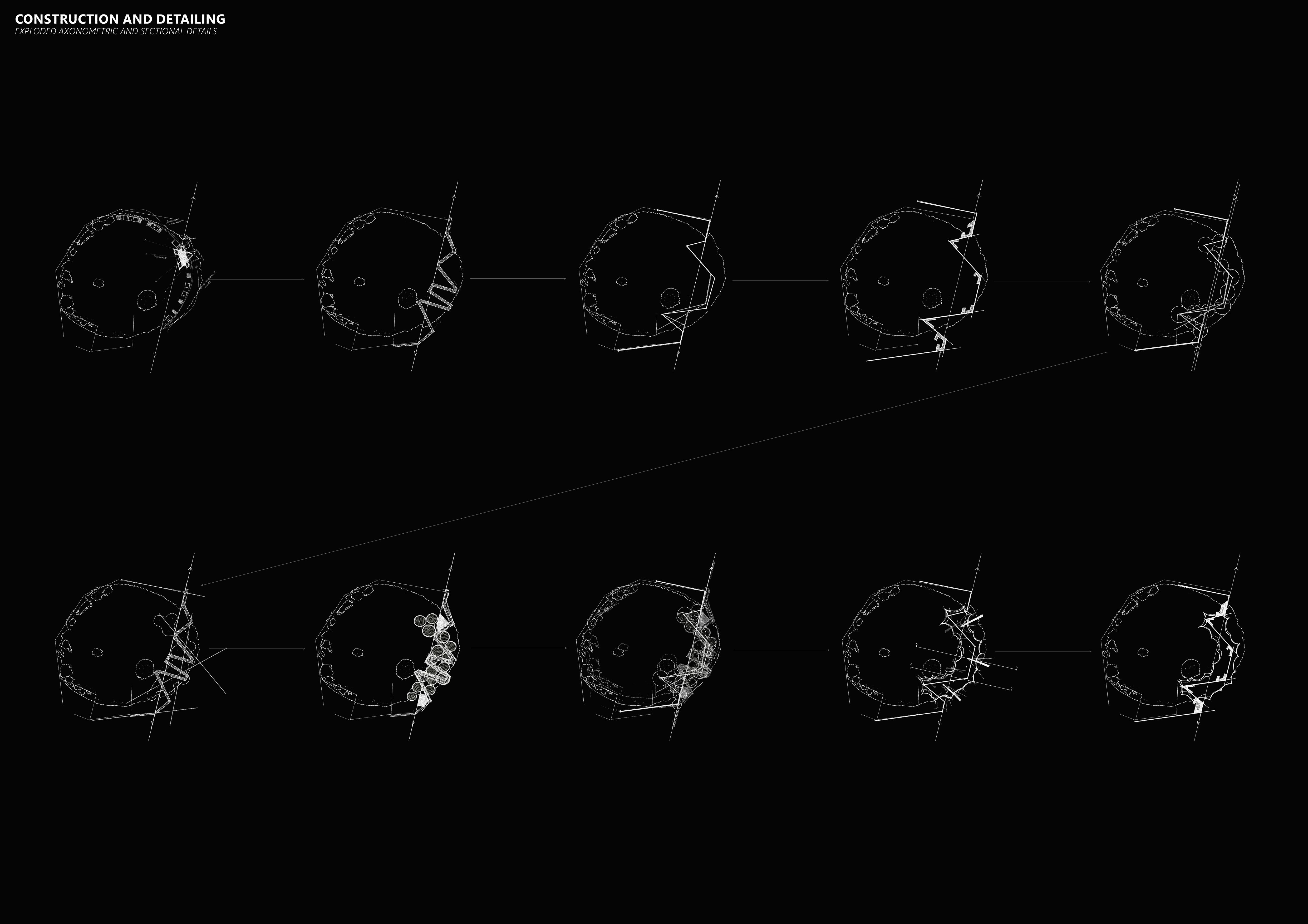

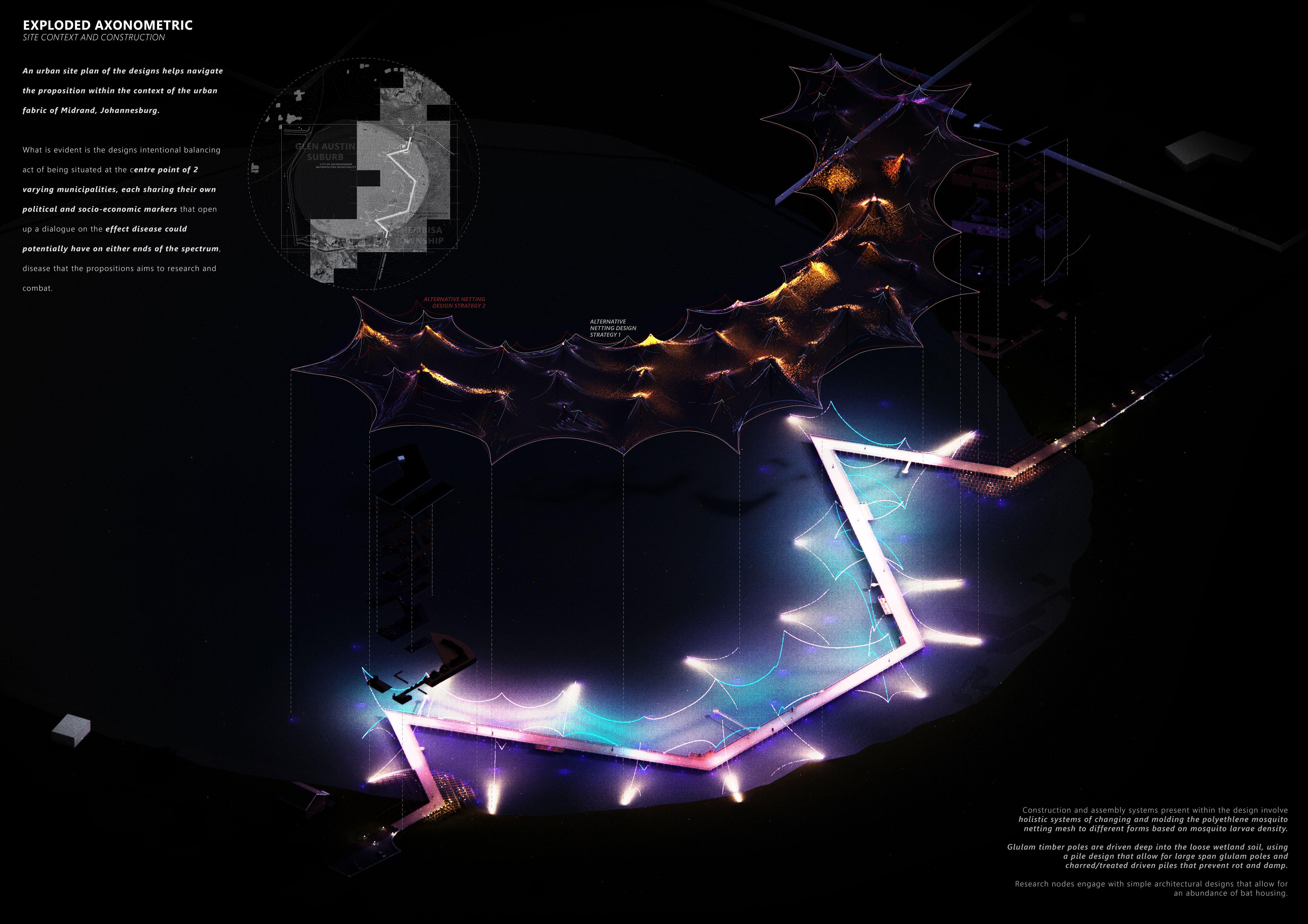

Exploded Axonometric

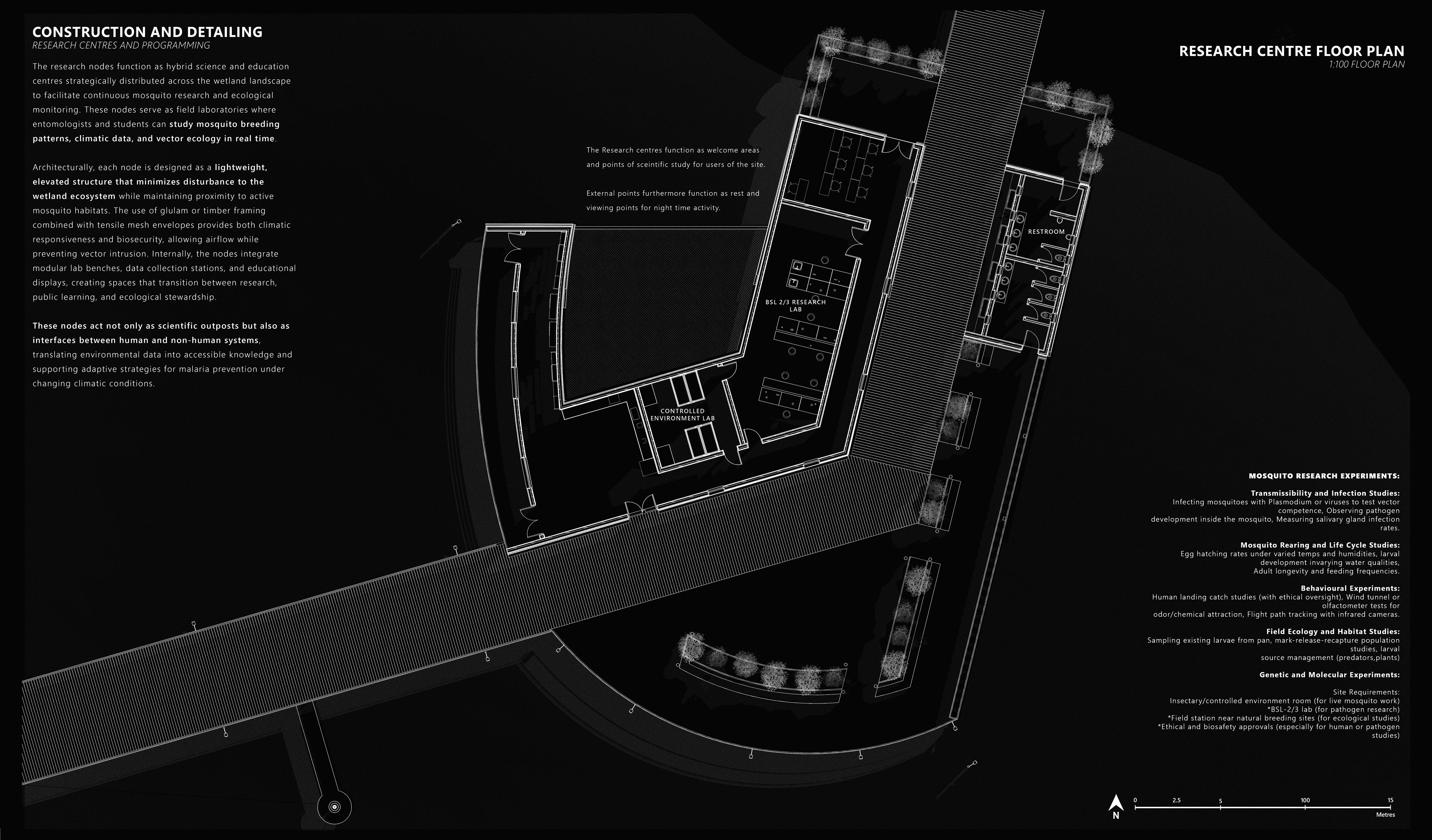

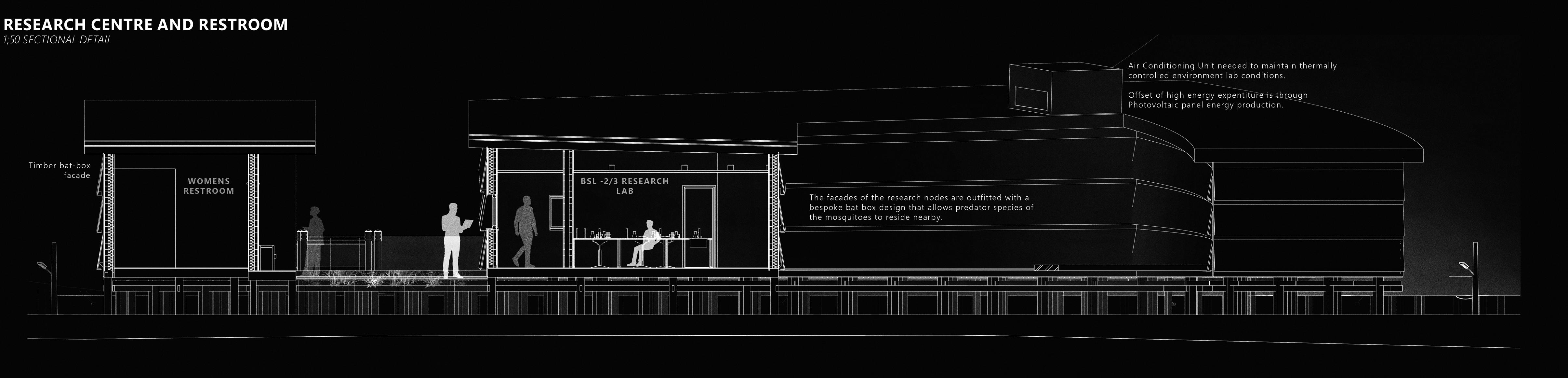

Research Nodes

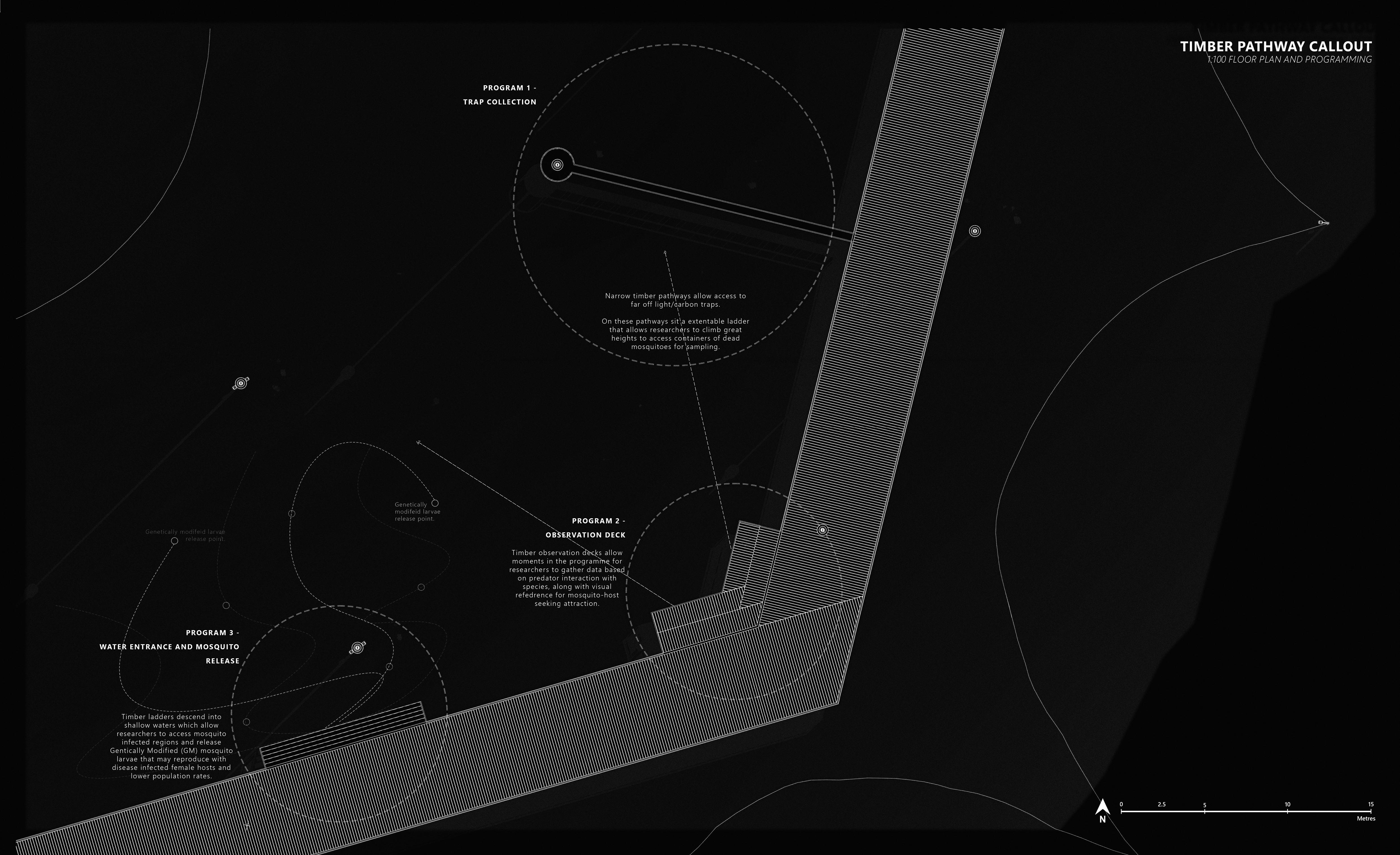

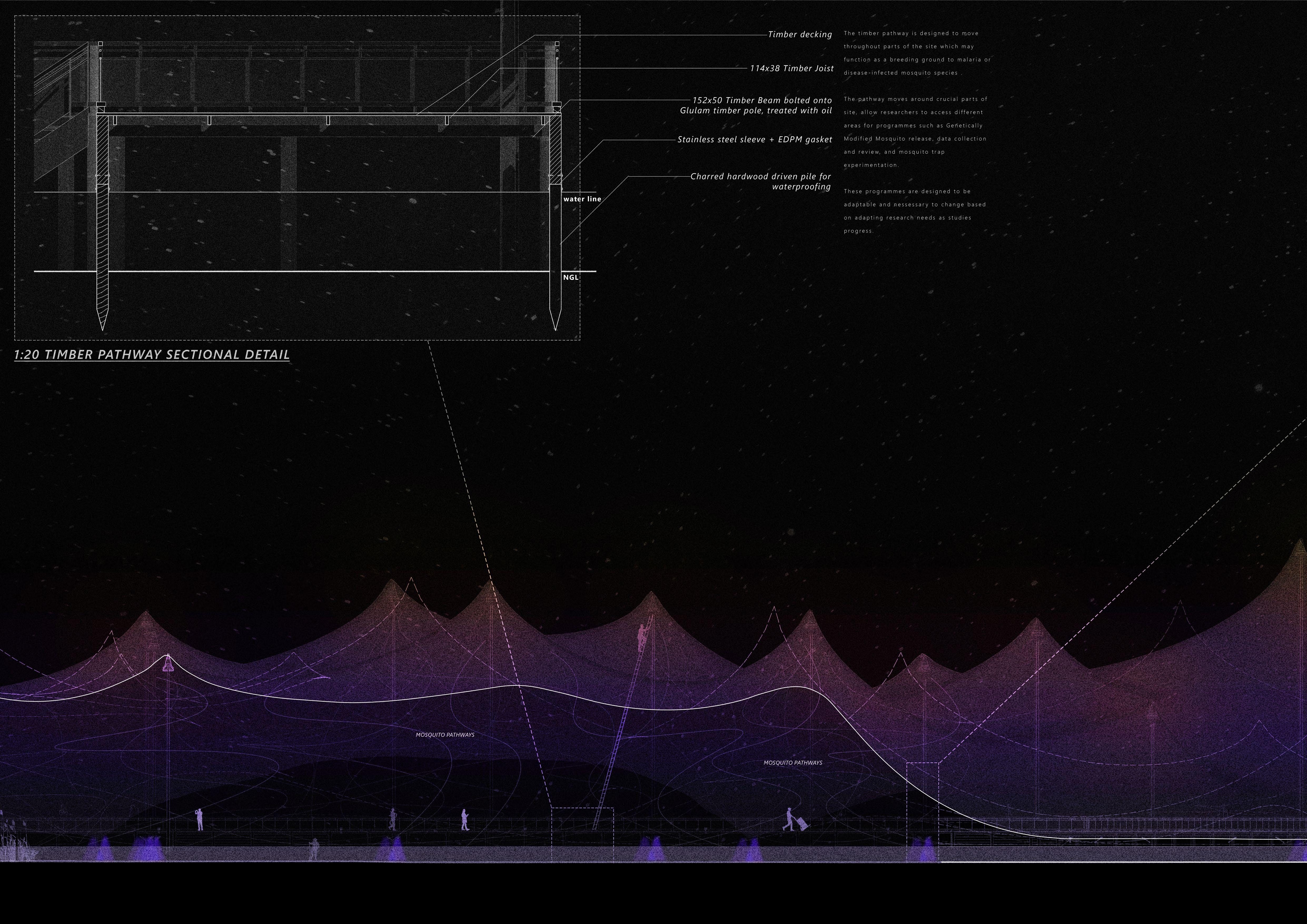

Pathway Programming

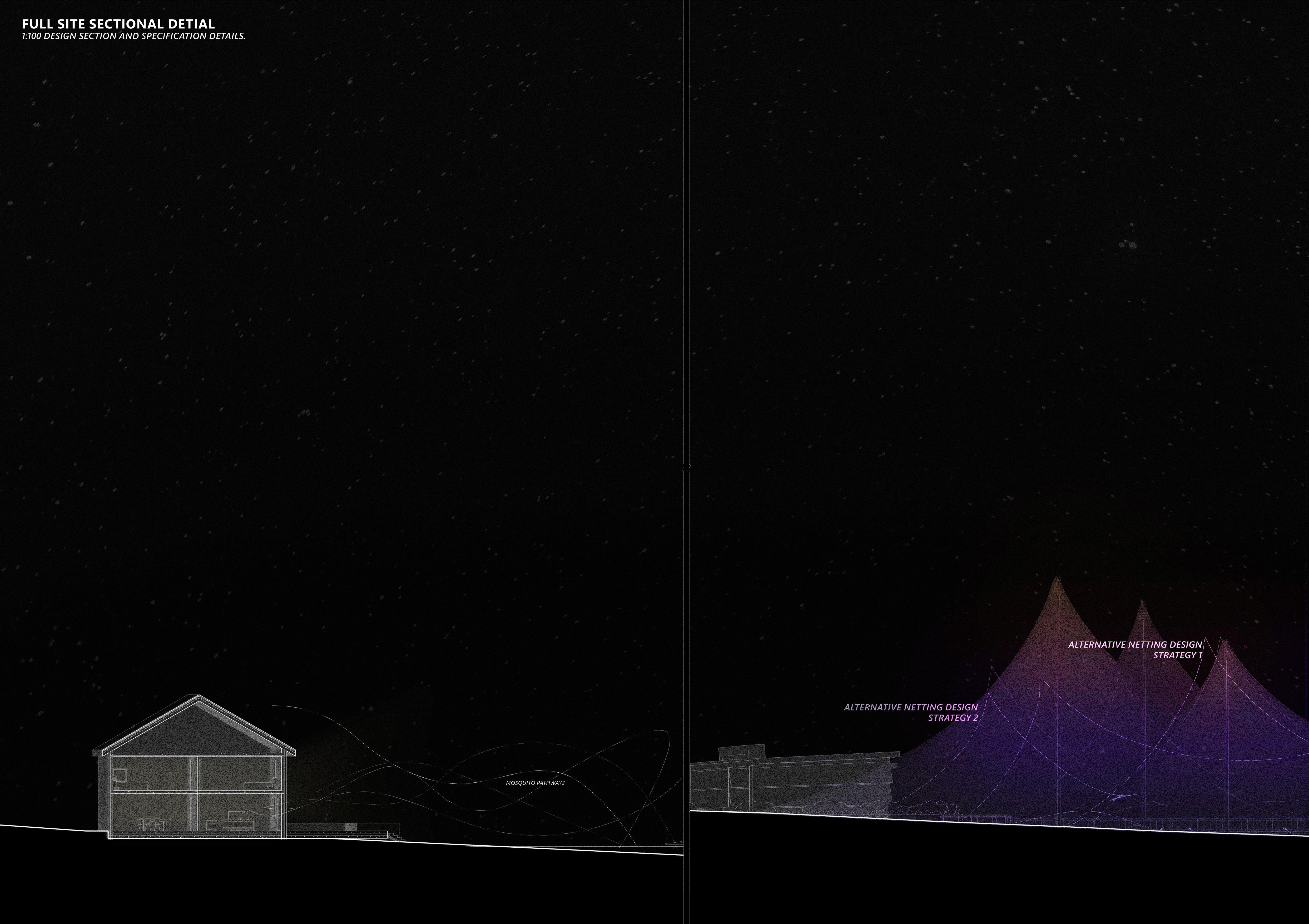

Full Site Section

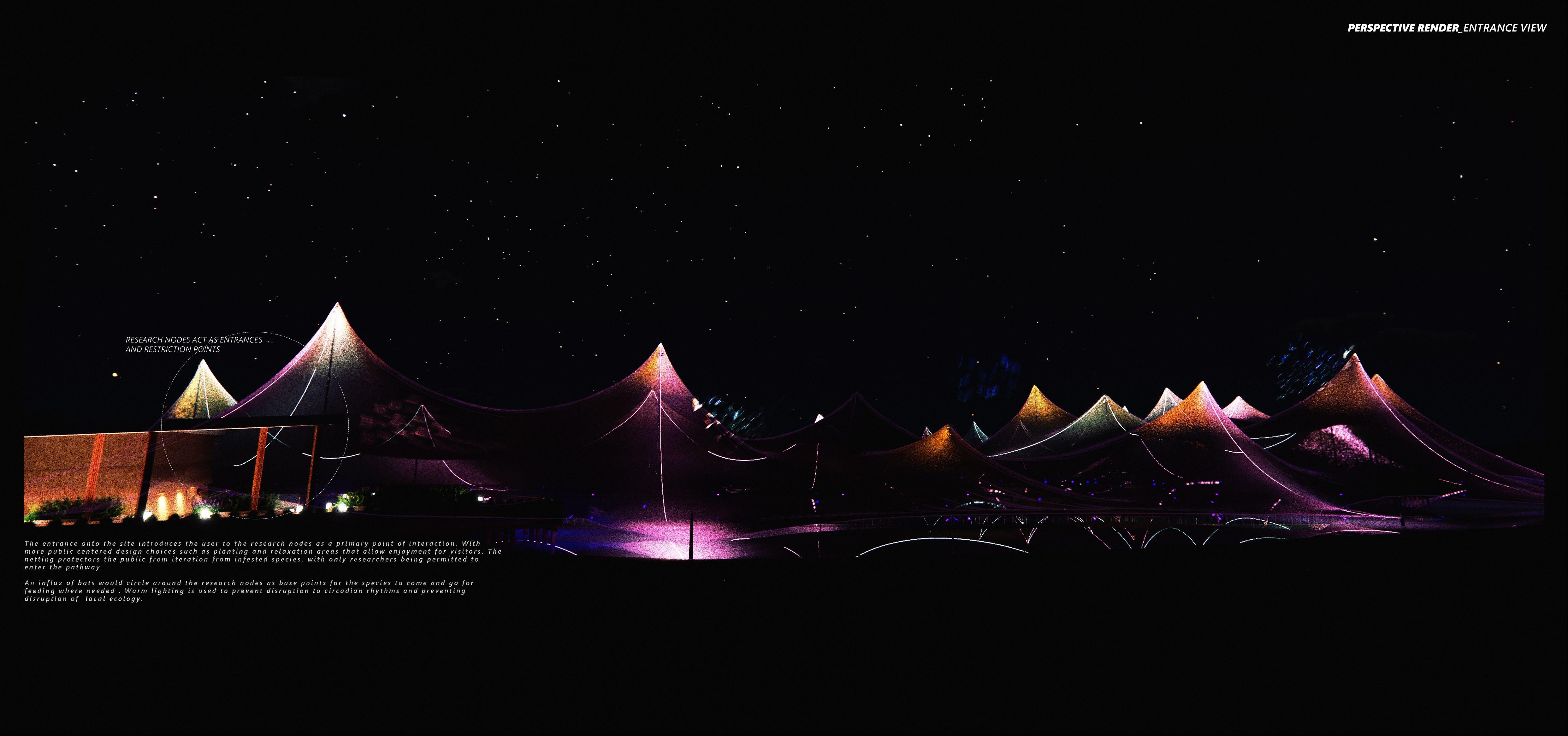

Perspective Renders

Fig

Fig 4.6 Focus on the netting and bamboo supports of the original design, and their connections.......19

Fig 4.7 Reconfiguring the net by flipping it horizontally, changing the utility of the mechanism..........19

Fig 4.8 Reapplication of understood mechanisms and materiality into an on site application...........19

Fig 4.9 Experimental huts (Carrasco-Tenezaca et al. 2021),.....................................20

Fig 4.10 Mean mosquito house entry in huts at different heights (Carrasco-Tenezaca et al. 2021)......20

Fig 4.11 Mean indoor and outdoor temperatures (Carrasco-Tenezaca et al. 2021)..................20

Fig 4.12

Mean carbon dioxide concentration (Carrasco-Tenezaca et al. 2021) ....................20

Fig 4.13 Raised and two-storey constructions in sub-Saharan Africa (Carrasco-Tenezaca et al. 2021)..20

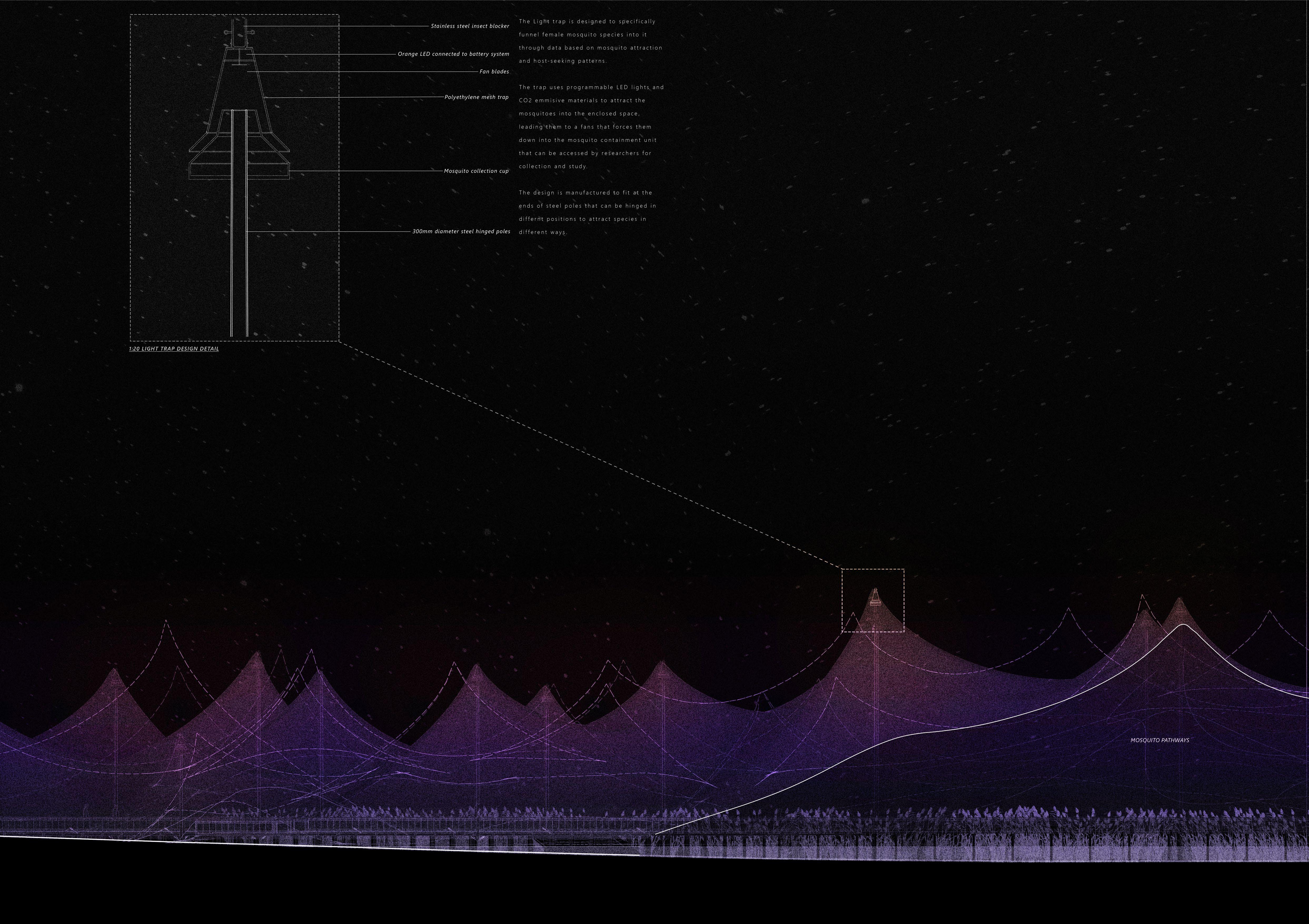

Fig 5.1 Light wavelength analysis, how they affect species found within the pan.....................21

Fig 5.2 Material analysis; tensile and shading experimentation..................................22

Fig 6.1 Initial conceptual ketch, research node...............................................23

UNIT 5_INTERSPECIES DESIGN

SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURAL PRACTICE

CONTEXT OF THE RESEARCH

This research project aims to understand the microbiology and life cycle of the mosquito to inform an architectural design that will prevent the spread of mosquito-borne disease on the ecologically threatened Glen Austin Bullfrog highveld pan in Midrand, Johannesburg.

By the year 2030, the world climate is expected to warm by >1.5-degrees Celsius ( Lindsey & Dahlman , 2024). This change is set to be succeeded by a drastic increase in climate related disasters, and the extinction of numerous species, permanently affecting and disrupting ecosystems around the planet ( IPCC, 2021). This change in climate not only effects the natural systems of the planet but will also affect the people living within it, presenting problems such as food and water insecurity, overpopulation, destructive weather conditions, and an increase of vector-borne diseases ( Wickremasinghe et al , 2024).

With rising temperatures and shifting climates, a dramatic rise in disease-infected species reproduction in stagnant water bodies, such as pans, lakes, swamps etc. is increasing in likeliness. Africa has historically been significantly affected by multiple vector-borne diseases. ( World Bank Group , 2013). This research project is anticipating this future climatic shift and using it as a lens to engage with how architecture could be implemented to combat or dissipate the potential ecosystem disservices that Johannesburg is set to face due to climate change.

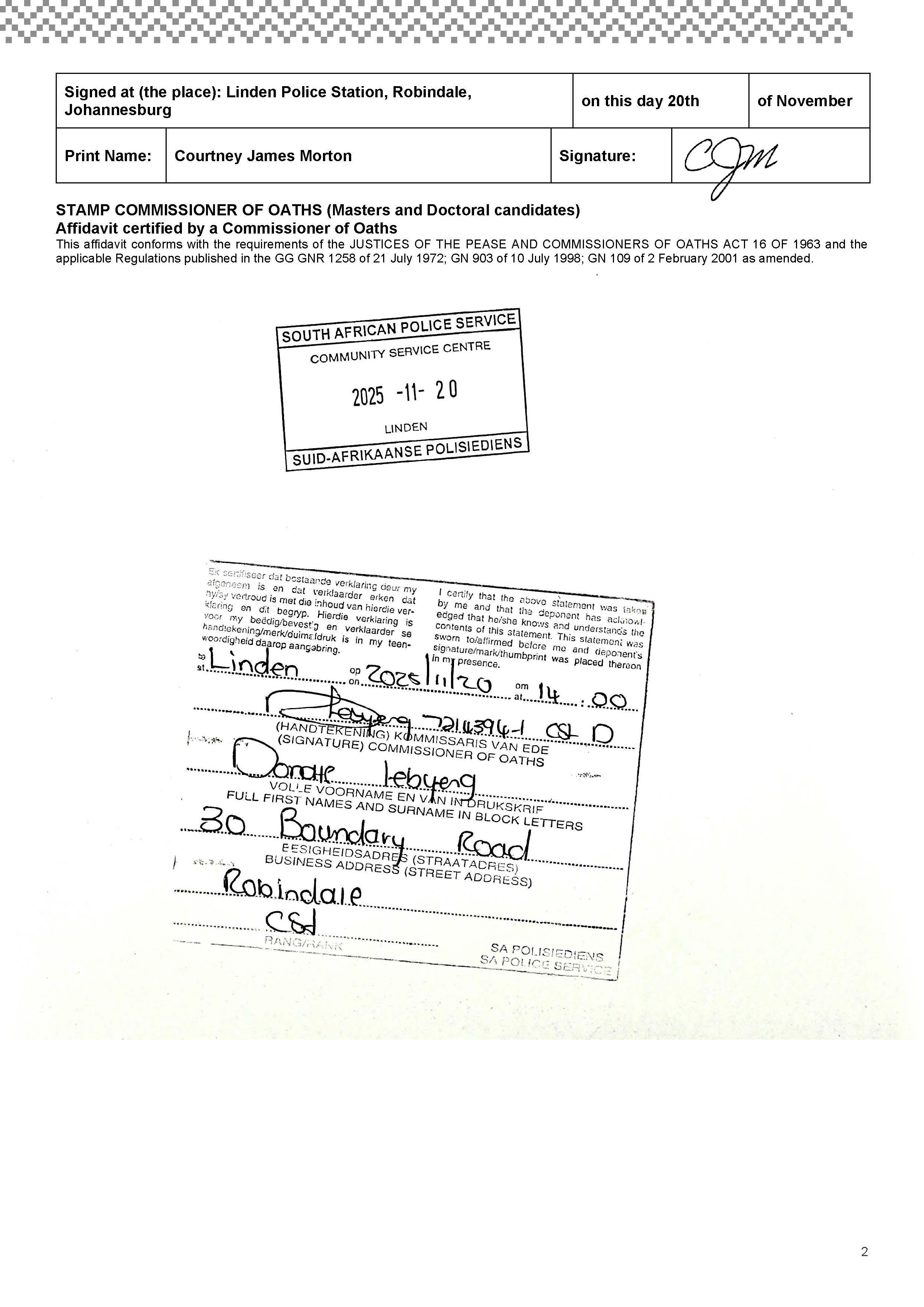

This master’s dissertation is focused on the increasing risk of dissemination of mosquito-borne illness as a direct correlation to climate change. Using the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA) Unit 5’s guidelines, workshops and briefs, this proposal’s intention is to use the speculative potential of architecture to create an adaptive, sustainable and disease preventative proposition. Initial academic and material prompts of my study introduce the exploration of the Glen Austin Bullfrog pan, extensively tracking, exploring and analysing the site in its various ecological intricacies in relation to its both endemic and invasive flora and fauna. The Glen Austin depressional wetland functions as a compelling point of study due to its classification as a conservation site, while simultaneously functioning as a publicly available and accessible site that finds a large influx of public usage through multiple and varied programmes. As the inhabitants of the site include the endangered African Giant Bullfrog ( Pyxicephalus adspersus ) and a variety of bird species that visit throughout the year. My research process incorporates microscopic analysis as an observational method to access the micro-ecology of the site. Initial studies of water and soil samples discovered the mosquito as a species of engagement that will be further investigated.

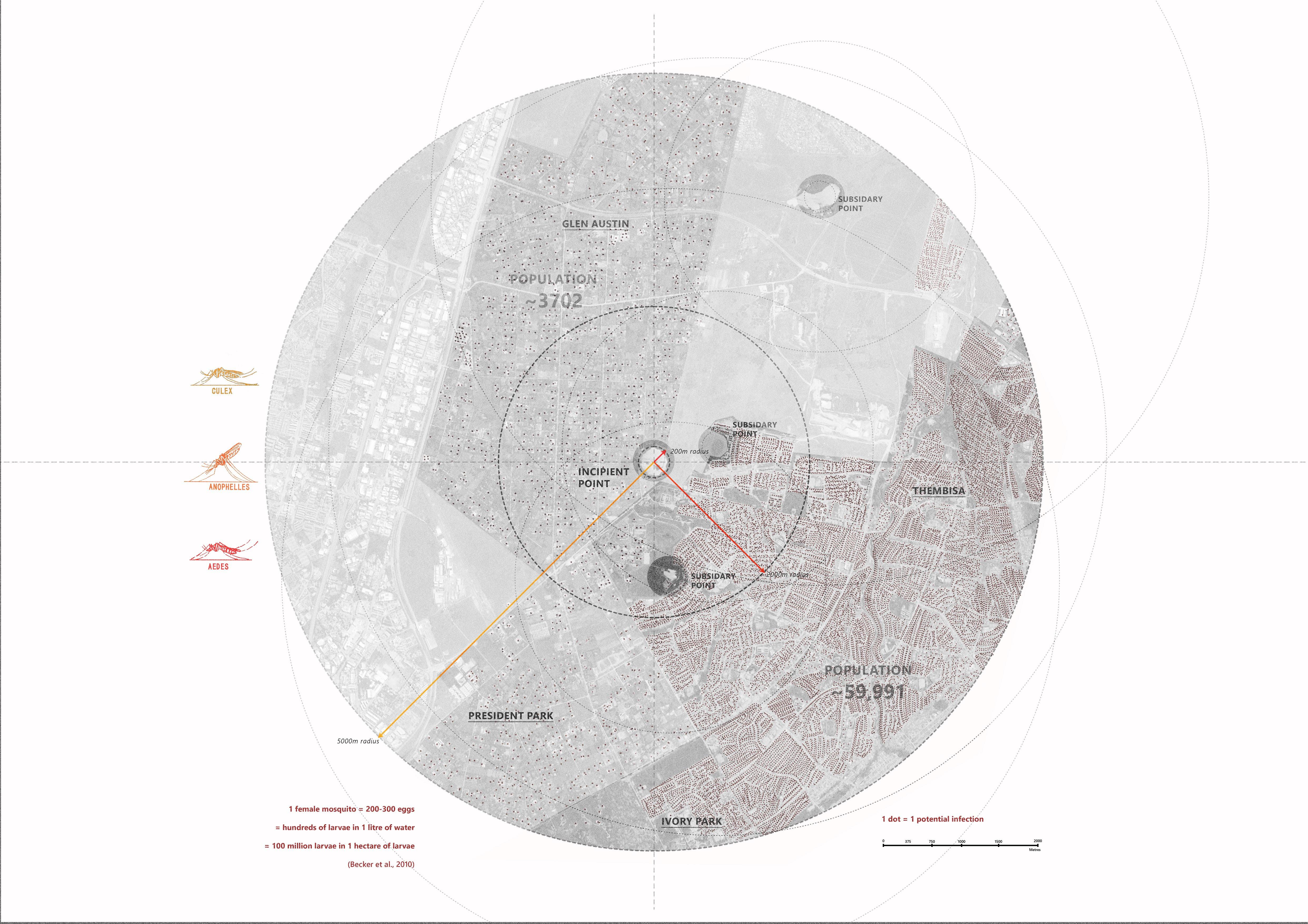

Mosquitoes ( Culicidae ) are a family of ectoparasitic flies, with the Aedes, Culex and Anopheles species most well known as carriers of multiple diseases across the world. Vector-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, zika virus etc. (Spielman, A. & D’Antonio, M, 2001) are highly infectious and potentially lethal, and result in approximately 700 000 death per year according to the World Health Organisation (2024). The classification of this species as a distributor of disease prompts research into the species biology, its role within ecosystems and understanding its cultural, and spiritual perceptions globally. Specifically, my research will focus on the microbiology of mosquito larva, its physiological system and how it functions as a semi-aquatic species from the earliest stages of its life cycle. The research questions and potential answers that arise from studying its

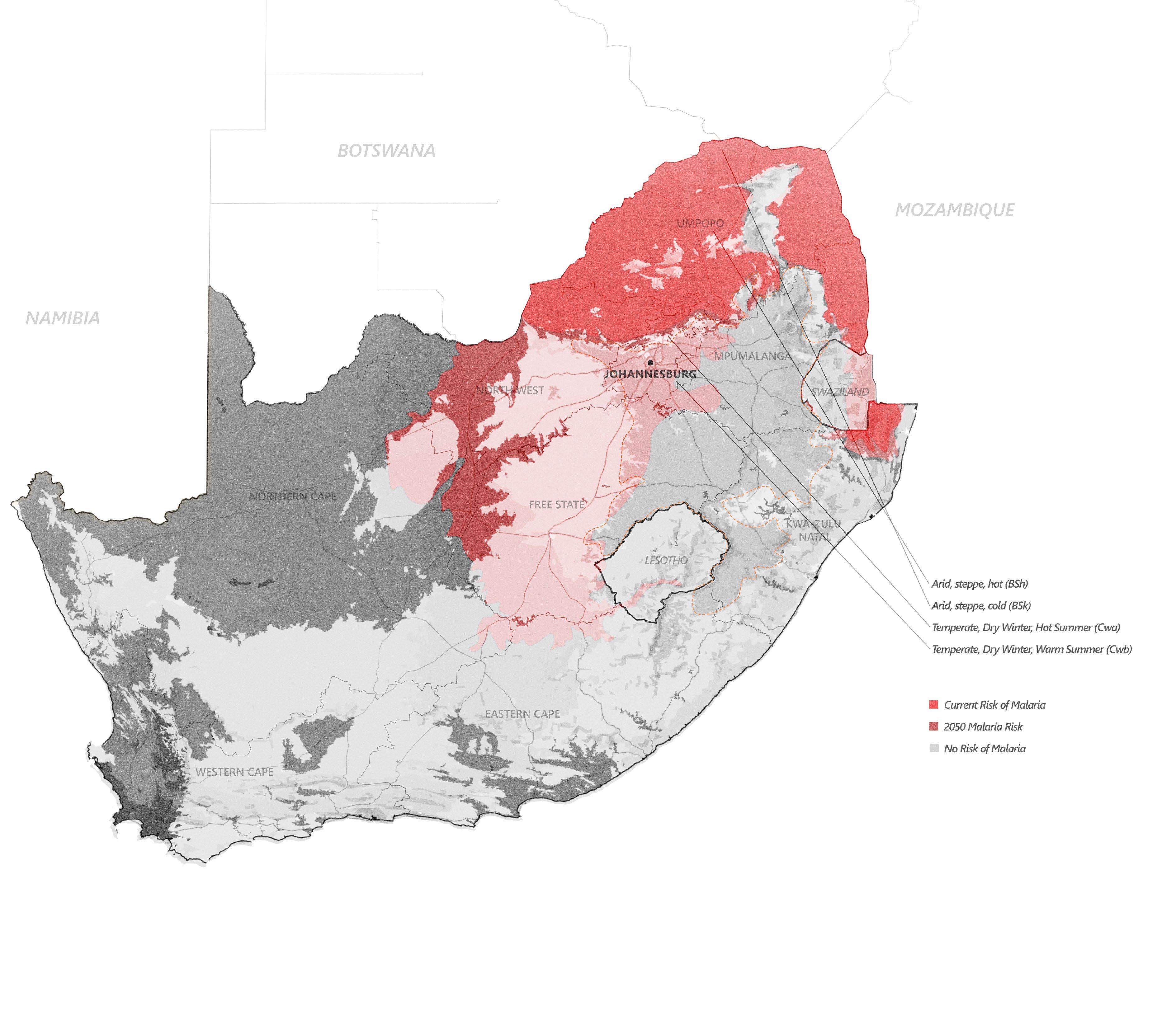

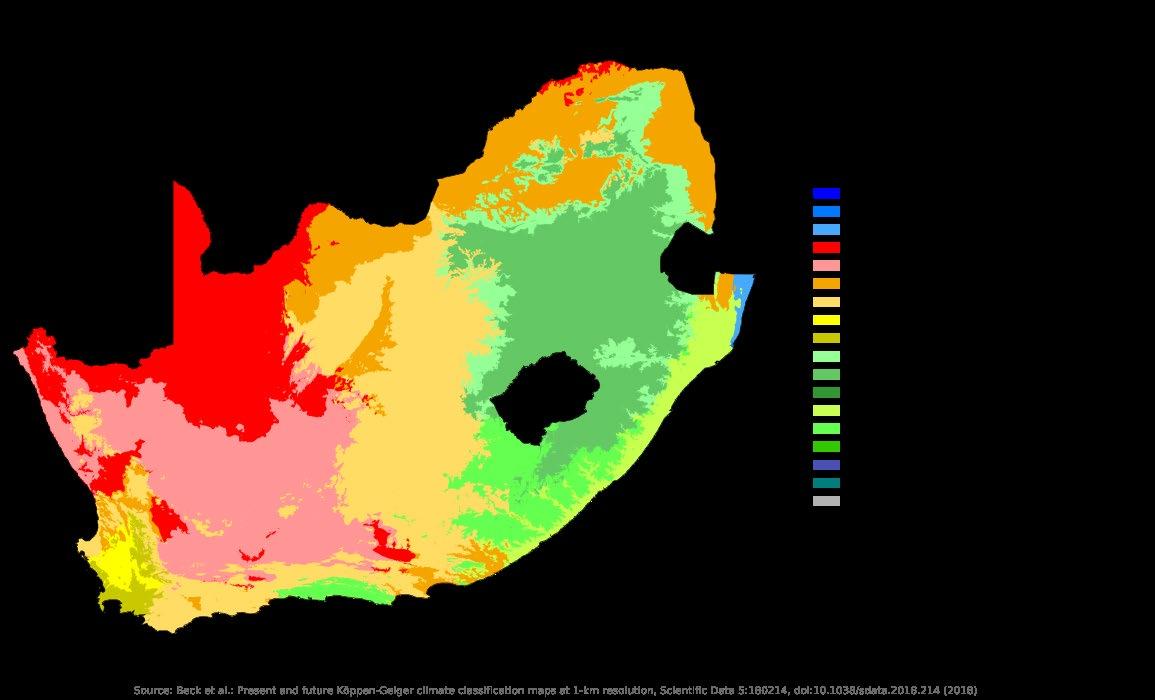

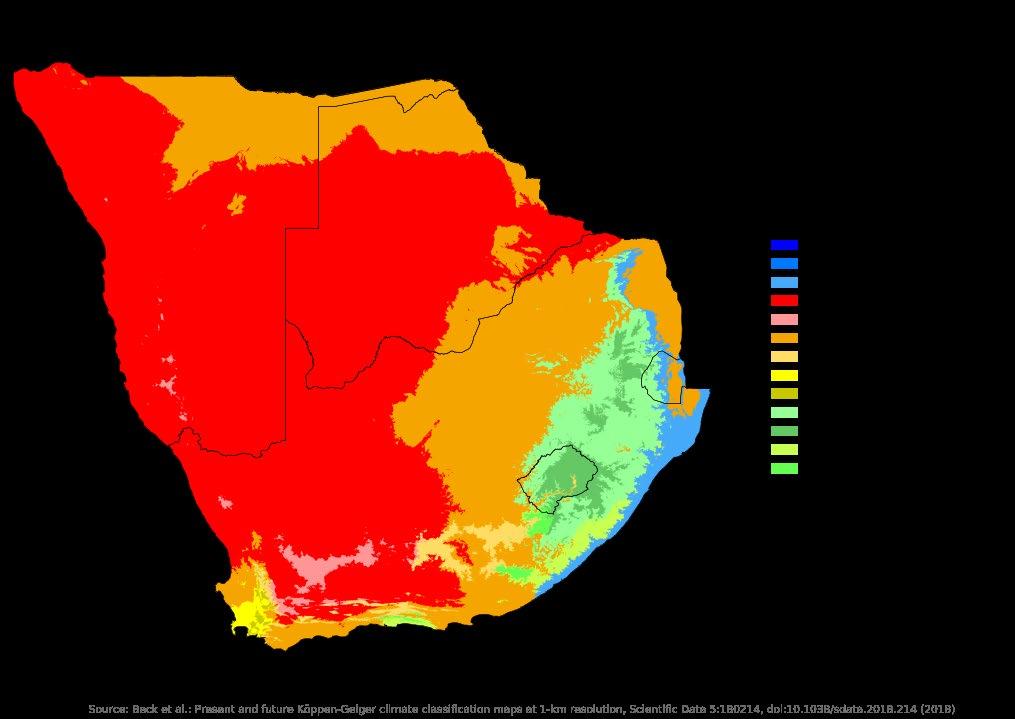

complex physiological system will provide me conceptual and practical inspiration that can be translated into an architectural intervention, helping people engage with the complex ecological systems of the site found in air and water. This mosquito species reproduces in hot and humid climates, a possible future climate for Johannesburg. Climate change could increase the probability of mosquito-borne diseases that have as of now been contained due to the city’s cooler, dryer climate. This assumption will be tested by a review of academic literature on the subject. The outcomes of this review will be used as an inspiration point to explore architectural interventions centered on the Glen Austin bullfrog pan that aim to engage with future mosquito breeding grounds in urban environments, and how it may be possible to utilize depressional wetlands (pans) as points of programmatic engagement.

This year, Unit 5 is exploring the intersection between the built environment (with emphasis on sustainable design) and the natural world. Looking at the endemic species of South Africa and Gauteng and how they may be affected by climate change and future industrialization. The programme’s goal is to explore how architecture can be used as a tool to explore and research lost cultural rituals, identity and spirituality and use these findings within the city, allowing us to revive Johannesburg’s threatened landscapes and wildlife. As the city grapples with climate change, rapid growth, and ecological collapse, architects hold the power to transform conflict, creating spaces where both people and nature can thrive. Various tools and ideologies will be used in both a conceptual and pragmatic way, using industry standards, advanced performance modeling, fieldwork, and critical engagement with green building rating systems to further enhance academic proposals into technically engaged projects that can have material and practical applications. These systems and programmes include engaging with the Net Zero Carbon, Water, Waste and Ecology certifications, that provide a guideline for future-focused sustainable architectural designs. With our site this year being a focused look through the lens of the Glen Austin Bullfrog Pan—one of Johannesburg’s most endangered landscapes—Unit 5 will delve into the intricate connections between land, wildlife and community and how our architectural propositions can further explore the fragile ecosystem present within Johannesburg’s botanically rich landscapes.

This proposals chosen topic relates to the units theme due to its acknowledgment into the potential effects of climate change in the urban landscape of Johannesburg and how an increase in temperature could correlate towards the reproduction of migrating mosquito species, particularly those that may carry certain strains of diseases, proving to be a cause of concern for the residents of urbanised Johannesburg, especially to those situated in landscapes with ecological systems such as depressional wetlands or similar water systems, providing breeding grounds for the aforementioned mosquito species. By deeply researching not only scientific and technical aspects of the mosquito, but furthermore its relevance to culture in the context of South Africa and Johannesburg, gaps in literature and research may be found that allow potential architectural solutions to problems brought about by climate change.

REFLECTIVE ESSAY

INTRODUCTION

My research project this year has been a deeply reflective and exploratory journey for myself, with my aims to understand the microbiology and life cycle of the mosquito to inform an architectural design that will prevent the spread of mosquito-borne disease on the ecologically threatened Glen Austin Bullfrog highveld pan in Midrand, Johannesburg.

By the year 2030, the world climate is expected to warm by >1.5-degrees. This change is set to be succeeded by a drastic increase in climate related disasters, and the extinction of numerous species, permanently affecting and disrupting ecosystems around the planet. This change in climate not only effects the natural systems of the planet but will also affect the people living within it, presenting problems such as food and water insecurity, overpopulation, destructive weather conditions, and an increase of vector-borne diseases. With rising temperatures and shifting climates, a dramatic rise in disease-infected species reproduction in stagnant water bodies, such as pans, lakes, swamps etc. is increasing in likeliness. Africa has historically been significantly affected by multiple vector-borne diseases. This research project is anticipating this future climatic shift and using it as a lens to engage with how architecture could be implemented to combat or dissipate the potential ecosystem disservices that Johannesburg is set to face due to climate change.

From beginning of the year, I had a few apprehensions and uncertainties that I hoped to unpack and address as the year continued; I was uncertain about which species would allow me to create a strong architectural proposition. I also carried worries about how to integrate the “Making” aspect of the brief; an area I struggled with in my honours year. I was further worried that my architectural skill-set would let me translate deep architectural concepts into tangible and realistic construction outcomes.

This reflection essay unpacks how my uncertainties gradually evolved into a coherent architectural response throughout the four quarters of this year through the application of iterative research, making, and design.

Q1 EARLY PHWASE

The year began with an open-ended brief, asking us to ground our research by focusing on a specific animal/species that either had strong cultural connections to us, or a species which give us a specific emotional response. Through which we were expected to create a few posters that engaged with the species through literature and then work on a physical model/artefact that abstracted these ideas/connections into the Making aspect of our Brief. I began to unpack unit 5’s exploration of how architecture can weave lost cultural rituals, identity, and spirituality into the city, reviving Johannesburg’s threatened landscapes and wildlife. Most effectively through a fruitful site visit to the Glen Austin bullfrog pan, collecting data, samples and immersing myself within the site, understanding its deep ecological importance as an endangered site of Egoli Granite Grassland that responds to its rapidly changing yet extremely rich ecological system that inhabit it. Through this site visit I retrieved a sample within the water that after microscopic analysis was confirmed to be mosquito larvae, providing a strong basis in which to begin focusing my research on the effect a pool of water such as the Glen Austin pan could have on its surrounding communities regarding an infestation of mosquitoes. With this lens to view the unit themes, I began the process of researching mosquito biology, cultural and societal impact and more importantly how its role as a proliferator of vector-borne disease currently affects communities around the world, and furthermore into the future concurrently with risks associated to climate change. It became increasingly important to understand the site’s role in functioning as an infestation point, and so I began to document the change in the pan

throughout the years, looking deeply into the change in water depth, flora growth and fauna development (Figure 1). Through a series of posters, I researched and analysed these aspects of the site in depth which allowed me to understand the ecological aspects of the site and potentially speculate how it may change in the future due to climate change. My findings through this analysis found that the site was in a state of constant flux, with changing water levels, plant variety and density and new fauna engaging and using the land in differing ways. It also found that a great number of invasive species of flora, most noticeably the giant reed, was overtaking the natural Egoli granite grassland of the site, which invited new species onto the wetland, and ultimately intrinsically changes the way in which the ecosystem functioned over time. I felt that although my research had depth and was well sourced which came across through my posters and graphic language, I fell flat in my attempts to create a physical artefact. I found it difficult to translate cultural perceptions of the mosquito into a physical model, which ultimately meant my progress regarding the Making requirement of the brief were not being met. From my Q1 Review, I was told to use making as a way to more deeply explore the physiological aspects of the mosquito larvae through my physical model design, which would prove to be a far more pragmatic approach to the artefact exploration. I then went into Quarter 2 with this goal.

Reflecting on this phase, Quarter 1 was a period of exploration and missteps that were necessary to sharpen my focus. I felt extremely privileged to find such a powerful species to study through my microscopic analysis, and while my posters effectively communicated the ecological and cultural depth of the mosquito, my artefact lacked clarity. Yet the process of failure became productive: it forced me to confront my discomfort with making and set the stage for a more experimental and physiological approach in Quarter 2.

Q2 DEVELOPMENT

Quarter 2 marked a shift from foundational research towards development and experimentation. Guided by my Q1 feedback, I reoriented my approach to Making, using it as a lens to dissect the mosquito’s physiology. This re-framing allowed me to break down complex biological systems into architectural possibilities, deepening my knowledge into my topic and using guidelines to employ my knowledge of my species in the context of climate change by the end of the year. I began looking deeper into historical and cultural engagement between human and mosquitoes, how disease may spread and current systems in place to reduce and/or prevent the spread of deadly disease (in my case a specialised look into malaria within the African context). Developing diagrams and sketches that linked important information of mosquito behaviour, rhythms, physiological responses etc. I combined them into a poster that could provide a case for intervention within my site based upon it being a potential infestation point within the urban context of Midrand. My mapping of the site became important within Q2 as it reflected the impact the mosquito could have in Glen Austin looking through the lens of multiple differing scales, looking at urban scale all the way down to microscopic scale.

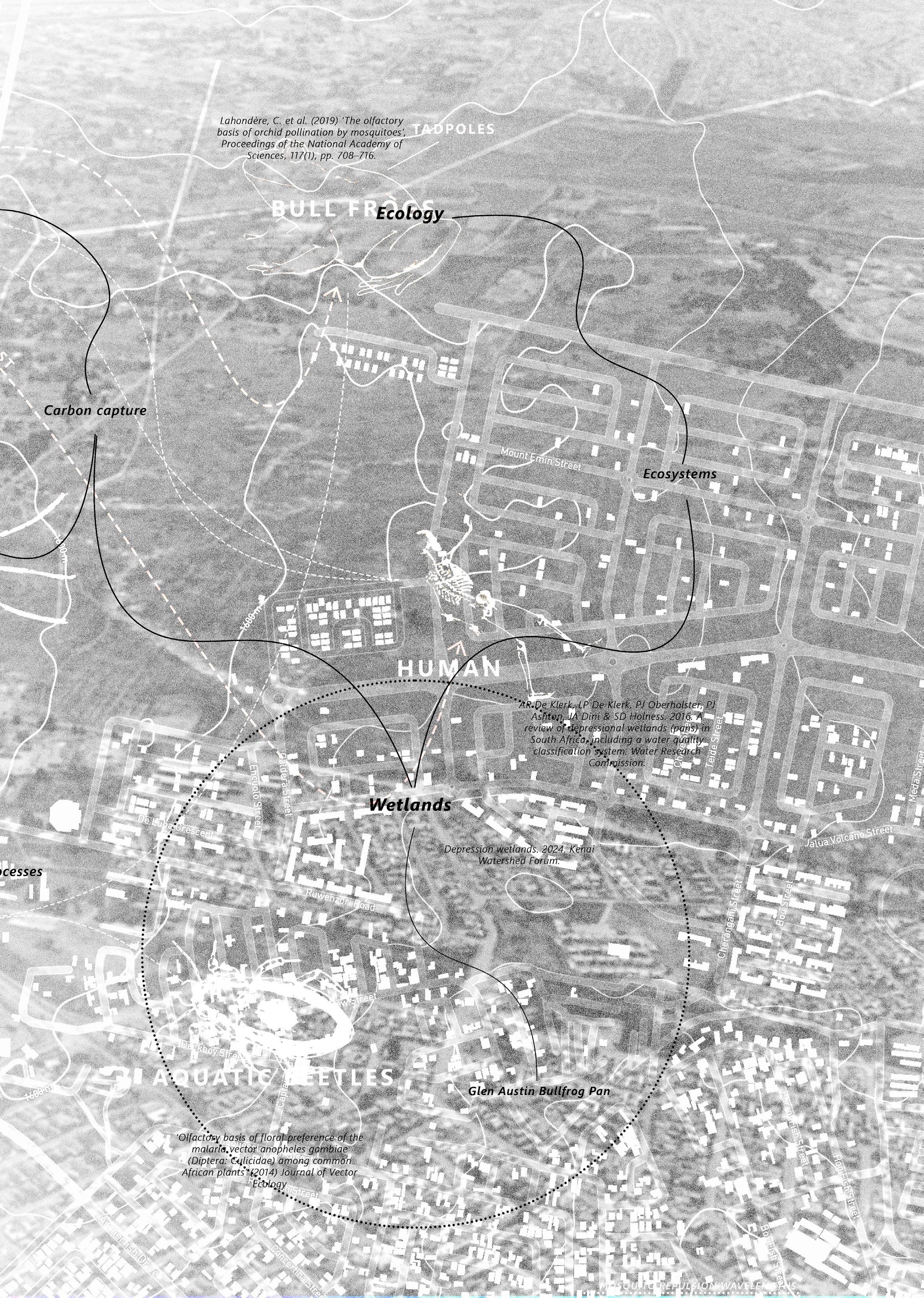

For integration into Making, I took the guidance given from the previous quarter and began experimenting with physical models that helps me break down and potentially integrate systems within the mosquito larvae physiology that helps it breathe while underwater through a siphoning system that travels throughout its body. Through a series of iterative models, I explored the structure of the siphon, translated it into a potential architectural frame, and finally emerged with a model that used a vacuum system to allow passage of air into it, while remaining waterproof through the use of a hydrophobic steel mesh that functions similarly to the larva’s

own siphon closure nodes. This model helped me develop insight into the species, bringing up new ideas that could relate to my project regarding siphon systems in the water that disrupt the natural stagnation of the water, it furthermore introduced me to instances of materiality that could be potentially used in my project as I refine an architectural design.

By the end of Quarter 2, my research allowed me to begin speculation on potential spatial programs that could benefit my site. It became clear to me through the research that using the site as a point of study and monitoring of vector-borne disease for specialized individuals became an important aspect of the design. The design then needed to span along the water, for multiple moments of sample collection to be brought towards spaces for analysis. Despite progress, I remained dissatisfied with how Making was integrated into the project. While the siphon-inspired model was conceptually productive, my physical models lagged behind my research sophistication. Models often served as proofs of concept rather than explorations of materiality or spatial experience. Moving into Quarter 3, I planned to better integrate making as a driver of design, not as an afterthought.

Q3 REFINEMENT

Quarter 3 was a turning point in refining both the conceptual depth and architectural clarity of my project. Feedback from my Q2 review emphasized the importance of situating mosquitoes within broader ecological systems, examining not only the insect itself but also its relationships with predators, humans, and the landscape. This ecological lens expanded my focus beyond the mosquito, positioning architecture as an orchestrator of multi-species interactions. Moreover, I was told to begin engaging with various precedents that may help me better understand how existing architecture has been utilized to combat outbreaks of malaria in other affected countries, and how my research and literature can be used to fill in gaps I may find within the research.

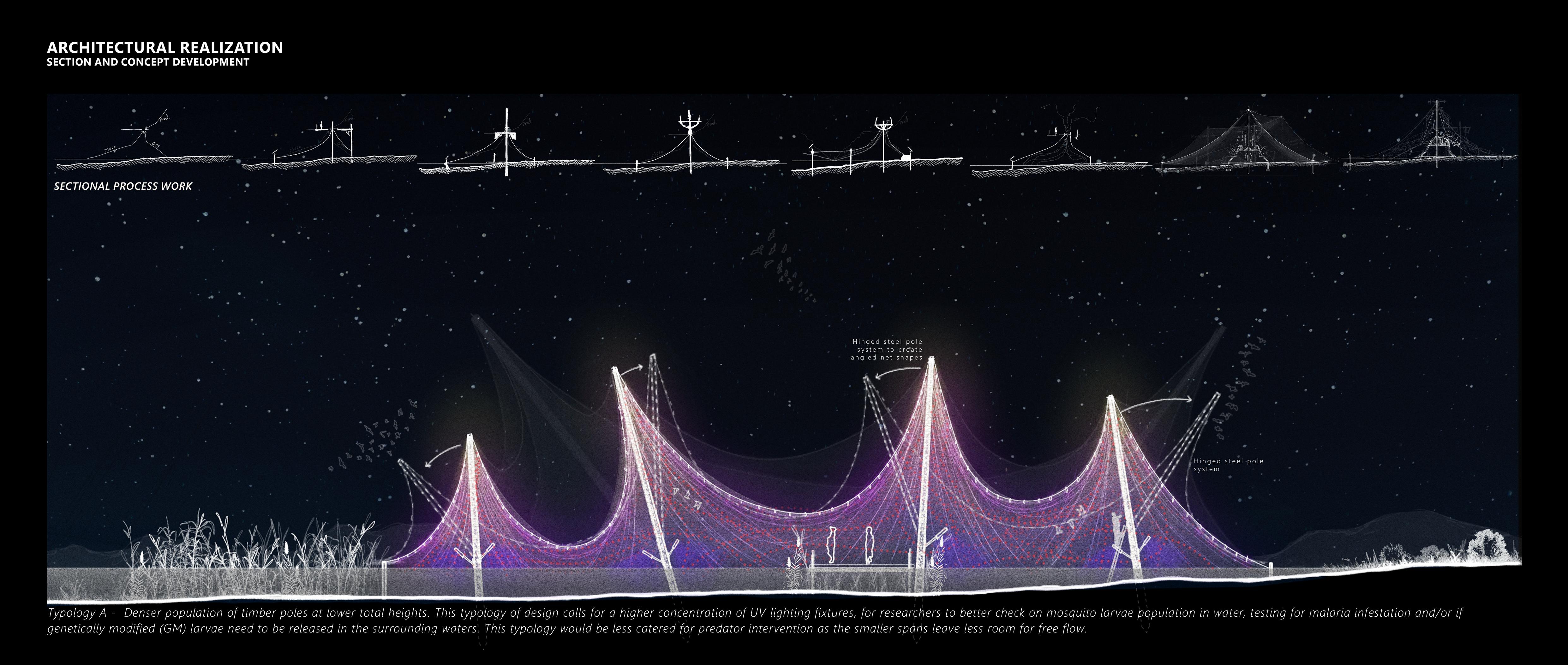

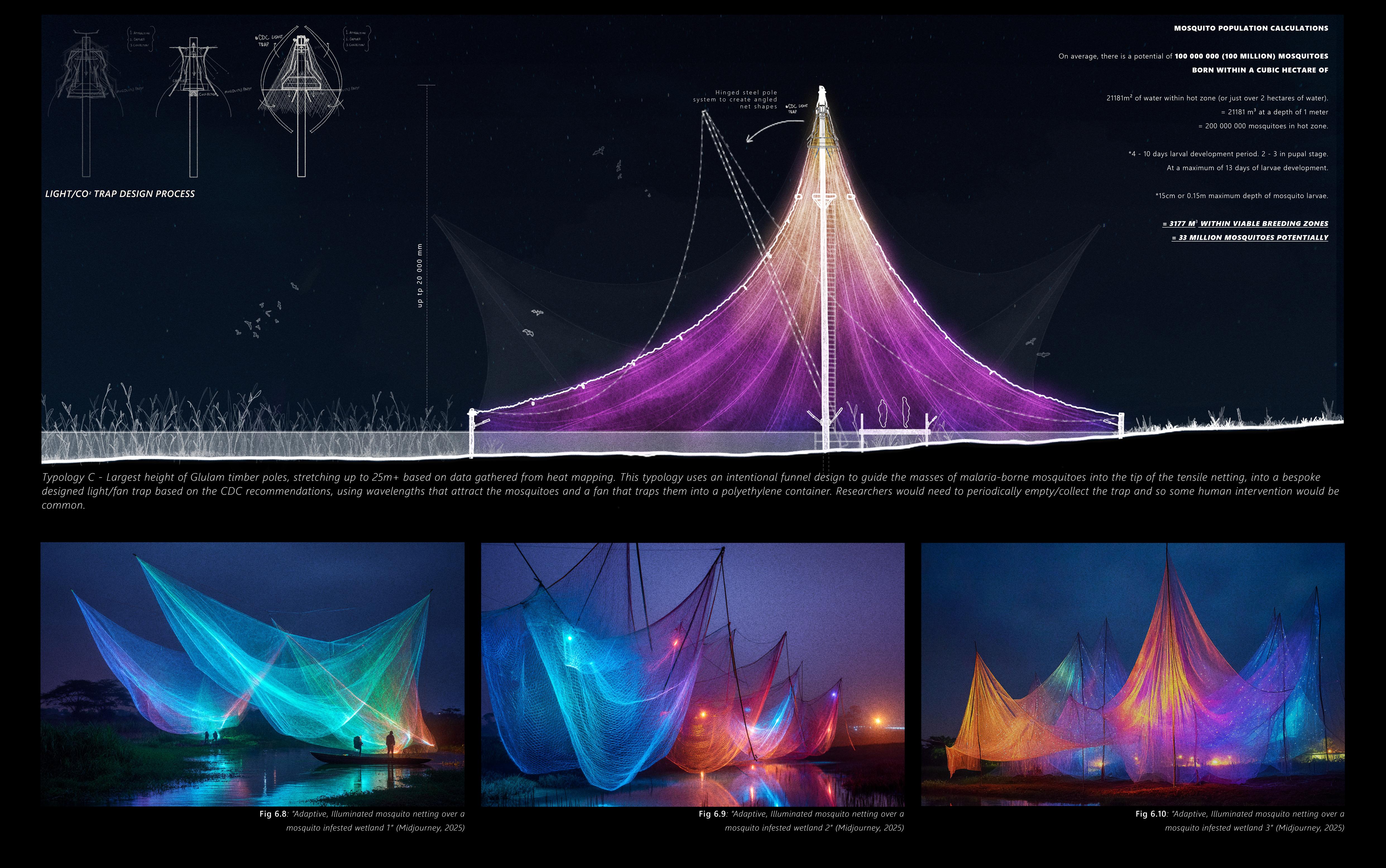

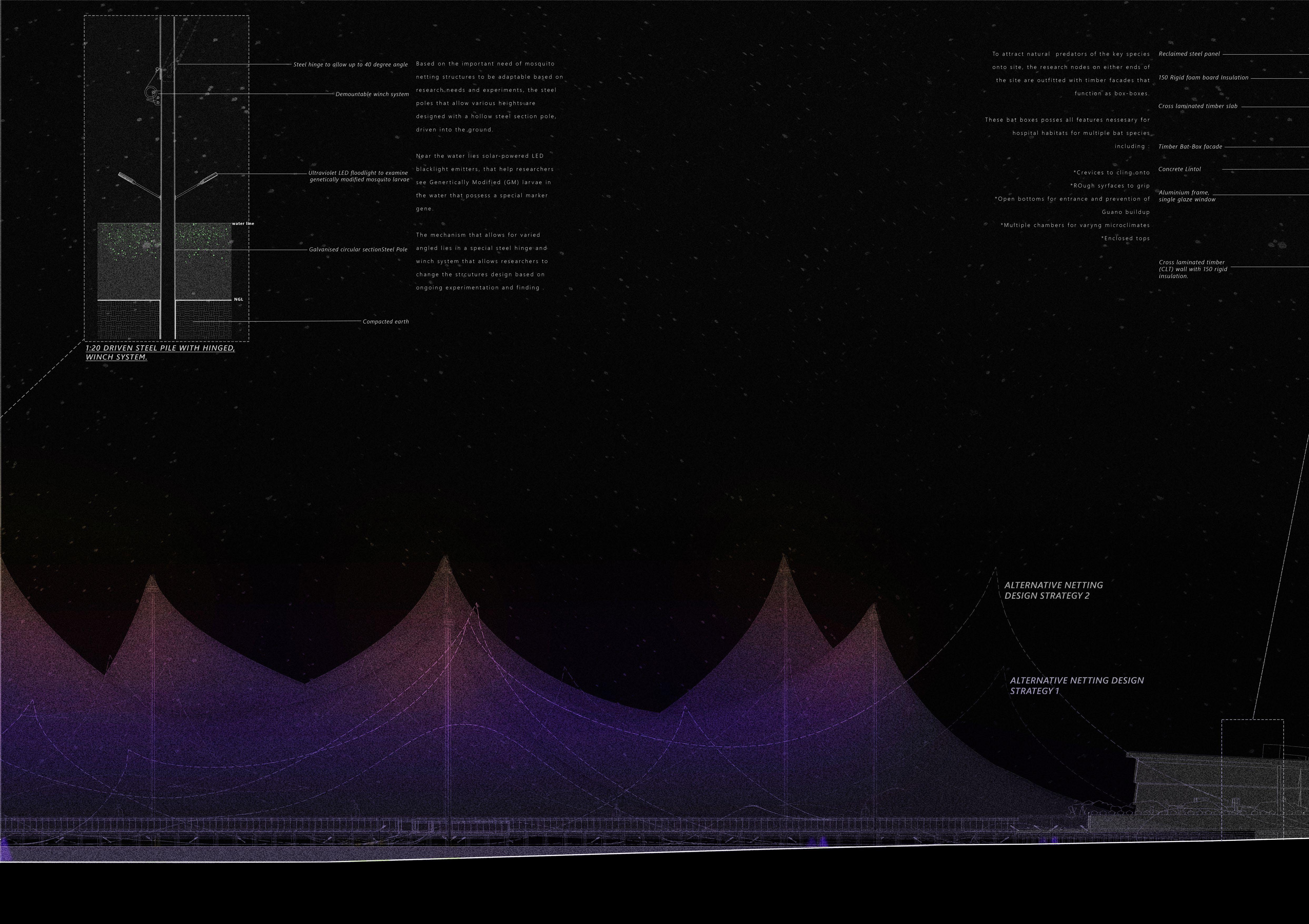

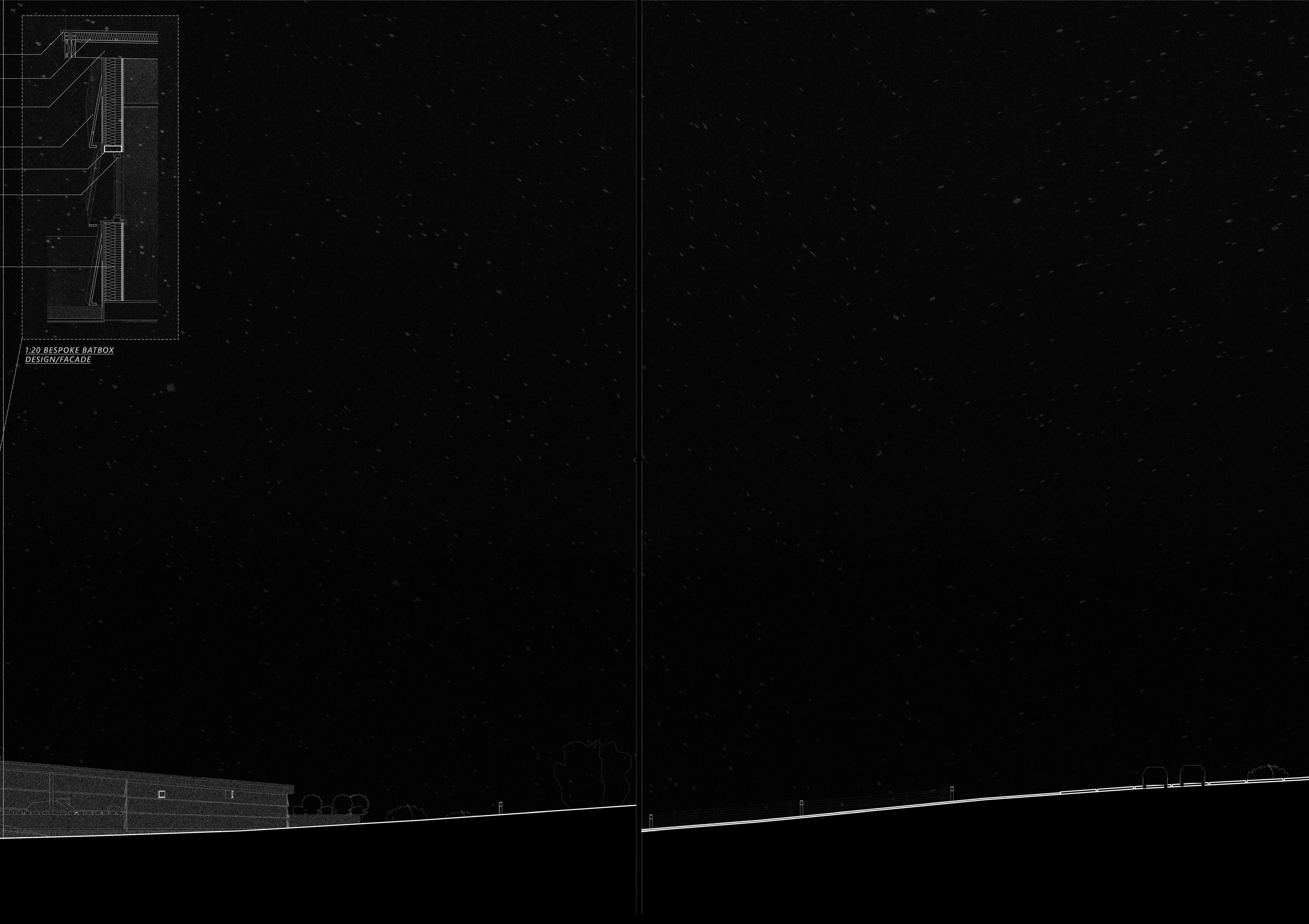

In Quarter 3 I began to use more plan and section scale drawings to engage with the site differently and explore how I could experiment with space and form to better control and guide mosquitoes born within the water to designated spots. The form of my design needed to be carefully designed to cover areas at which were most likely to house disease-bore mosquitoes. Through a series of 3-dimensional heat maps that analyzed the site through the lens of water depth, flora and artificial light, I began to understand how an architectural design could better adapt to the surrounding context. Through taking sections of the heat maps, and understanding the density of heat at certain points, I was further able to extract height data from the diagrams that provided a strong reference point for my potential intervention for the tensile structure. Throughout the rest of Quarter 3 I continued to refine my design, understanding what architectural routes I could take to most effectively control mosquitoes born within ‘heat zones’, along with this, I used my analysis of the sites existing ecological systems to help adapt designs that could promote the use of natural predators into my design, most prevalently birds and bats. Along with the design of my research centers to be used by students/researchers, I used these nodes as an opportunity to design bat housing units that could fit onto the walls of the structure, functioning as a façade that could invite the species into the area.

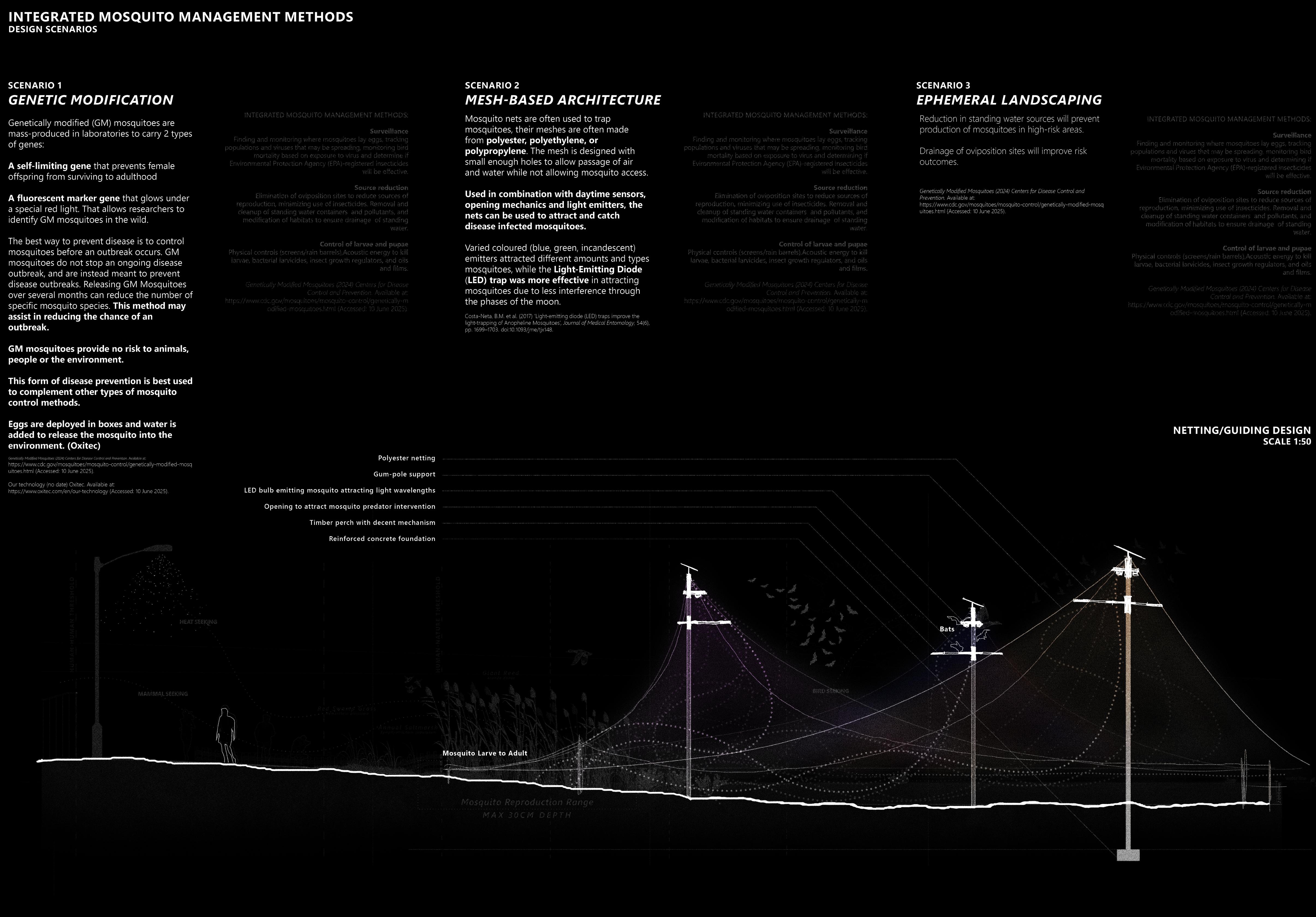

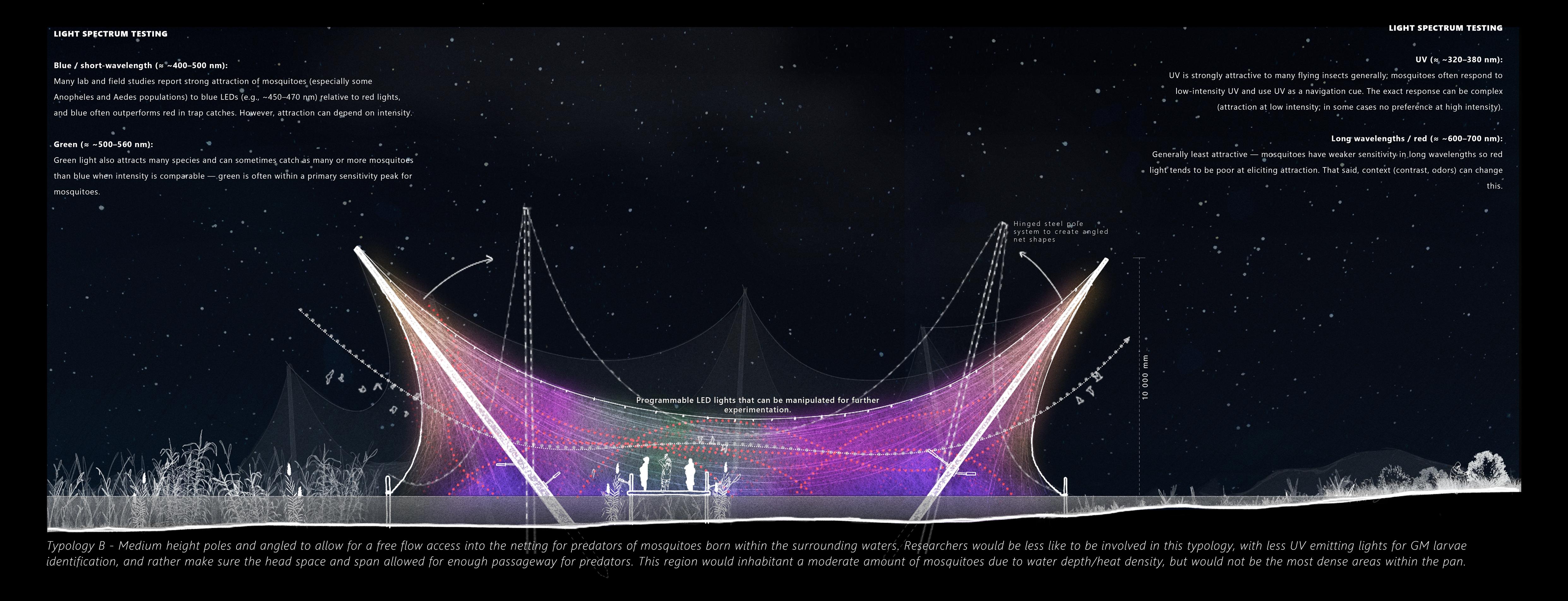

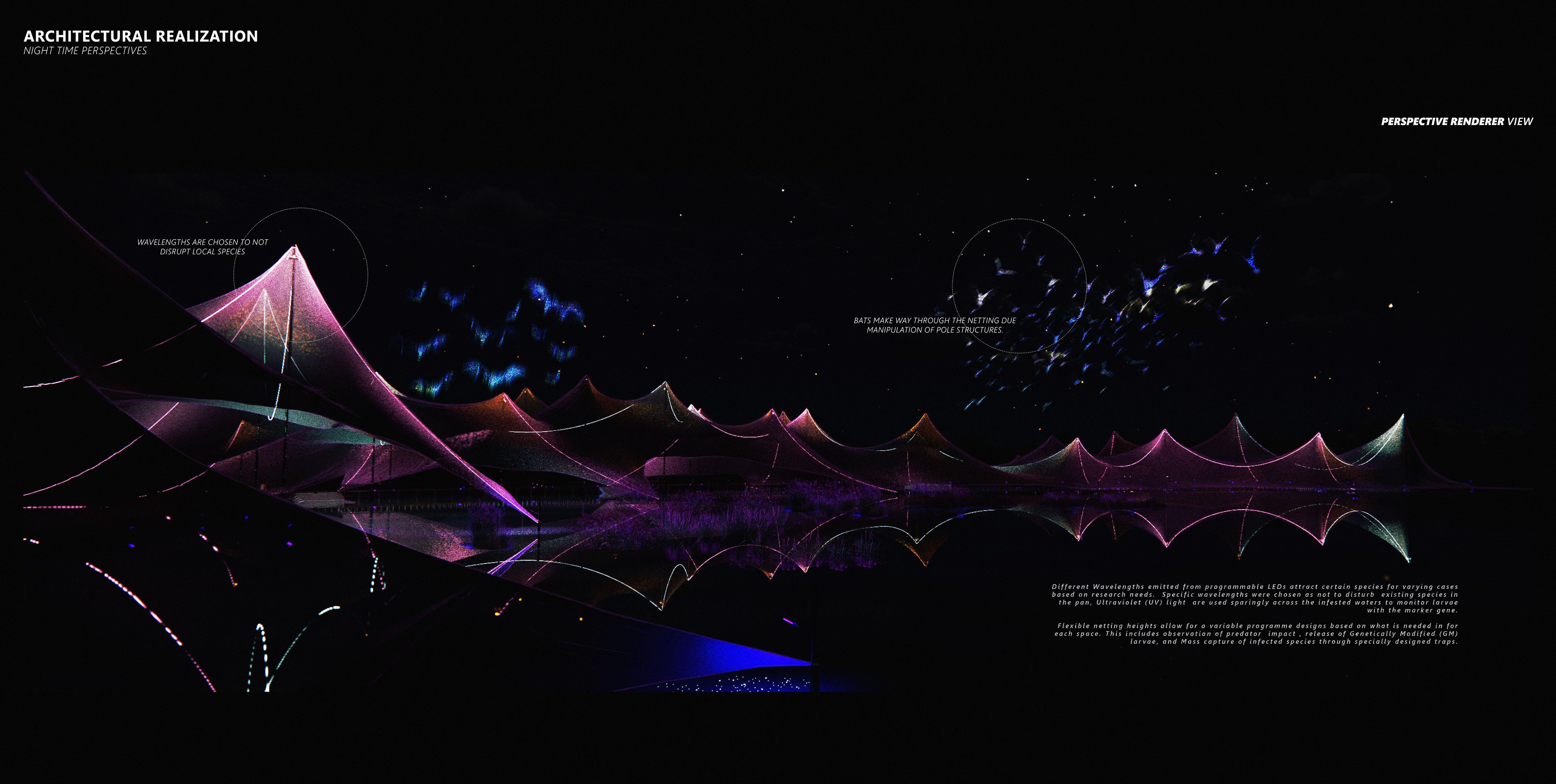

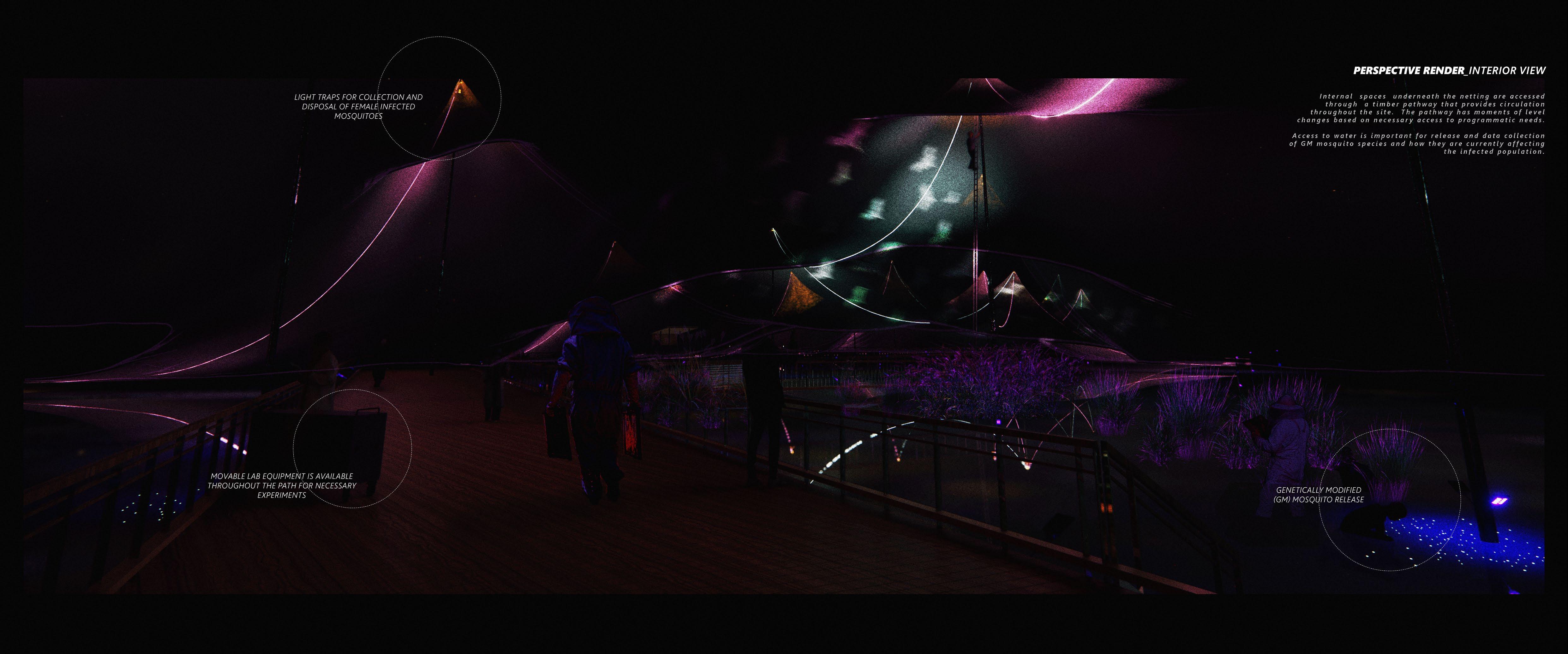

For the Making aspect of Q3, I began looking into the interaction between tensile materiality and light waves of different spectrum lengths, and which combination I could use to best attract mosquitoes while reducing light pollution into the surrounding context that could potentially affect the ecosystem around it. These experiments were guided through my research into mosquitoes and similar species behaviour in the presence of artificial lighting. Towards the end of the Quarter, I continued to work on the realization of my design, landing upon a large tensile structure, made from polyester netting and spanning across high breeding areas within the pan. Running along the netting would be small LED lights that emit various colours depending on how I wanted mosquitoes to react within each specific section.

Reflecting on Quarter 3, I felt my project matured significantly. The integration of ecological systems, technical mapping, and spatial design generated a more holistic proposal. Yet I felt many challenges remained; balancing technical precision with conceptual clarity and ensuring the tensile structure did not dominate or overwhelm the delicate pan environment. These tensions became focal points to resolve in Quarter 4.

Q4 CONSOLIDATION

The final quarter required consolidation: synthesizing a year’s worth of research, experimentation, and feedback into a coherent architectural proposition. Entering Q4, I had a strong conceptual foundation but needed to refine clarity, scale, and technical resolution. I went into Quarter 4 with a good idea of the outcomes I would like to achieve by the end of the year. Comments made after my reviews explained that I needed to work on the clarity of my posters to help examiners better understand the thought/design process of my work and the reasoning for my design choices. It was also explained how I needed to experiment more with my tensile roofing structure, as the moderators found it to be too static, obtrusive and great in scale; with an emphasis on my drawings not displaying the materiality and experiential elements of my design being properly conveyed. Making feedback for my presentation explained how I needed to position the proposition in such a way that the structure advocates for awareness and more exploration of materials that can provide such advocacy and lean towards a more tailored specification of details that talk to the awareness aspect. It was also suggested that I could use a white bedding sheet that could be overlayed on top of coloured lighting at night, as a physical test that could represent and experiment with which light wave spectrum’s could influence movement of mosquitoes most effectively. I found these comments to be helpful, particularly with how I try to convey information and how to improve clarity of my drawings to help others better understand my process.

For the rest of the 4th Quarter, I continued to focus on my architectural proposition, consolidating the years’ worth of research into a carefully considered and implemented design. Using the data gathered from my site analysis, my design became much lighter and smaller in scale, growing and shrinking in different places depending on where the population of mosquitoes increased. I engaged with several different typologies that functioned differently based on how I wanted the mosquitoes to be controlled, managed or extracted. This includes spaces that allowed for bat movement, spaces where human interaction is most important, and spaces that are used to collect and remove masses of mosquitoes from specific regions. I found this process to be especially challenging in both technical and conceptual aspects, as I feel the design needs to be carefully considered due to the highrisk environment. Moreover, it was recommended that I think of my project in ways that could be implemented at varied scale in different parts of the world as an effective combatant to the spread of vector-borne disease, which I would still like to potentially consider.

CONCLUSION (250 WORDS)

Reflecting on this year, my research project has been transformative, reshaping how I understand architecture’s role in the world, providing a new lens in which to research and consider architecture from a non-anthropocentric viewpoint, allowing me to engage with fields of study outside the normal of traditional architectural practice which only allowed me to strengthen my existing knowledge foundations. Key finding from this year of study include an acute understanding of the role and responsibility of architects to design and understand various species, how they inhabit space and how designing with multiple species in mind can only strengthen architectural design which will become an important factor in design as we move towards a world responding to the dangers and outcomes of climate change. This unit also helped me gain a better understanding on the impact climate change will have in a very tangible sense on the world around us, be that the change in South Africa’s own climatic conditions, the species that will be affect, disease that will likely spread throughout the planet more regularly etc.

This perspective has allowed me to think more deeply into the way I would like to practice Architecture into the future, and what steps I can take to begin making an impact in this relation to the field. I plan to use these skills and learning experiences and take them into my plans for future practice, drawing inspiration and knowledge from multiple unconventional avenues to assist in inspiration and knowledge-based research to strengthen architectural proposal. I would like to use this knowledge and design psychology in the future to utilize architecture as a tool to inspire and educate the existing architectural landscape through transformative sustainable methods to engage with existing ecological and anthropological connections within urban landscapes across the world.

“Where we left ourselves”

MALARIA ACROSS SOUTH AFRICA

Fig 2.1: Projected climate comparison in South Africa

Fig 2.2: Koppen-Geiger climate classification map, for1980-2016. (Beck et al. 2018)

Fig 2.3: Koppen-Geiger climate classification map, for 2071-2100. (Beck et al. 2018)

URBAN FABRIC MAPPING

Fig

Fig 3.1: Ecological Evolution of Glen Austin Pan

Fig 3.2: Invasive Species present in the Glen Austin Pan

Fig 3.6: Diagrammatic sketches of Mosquito life cycles

Fig 3.5: Microscopic pictures taken of the Mosquito Larva

Fig 3.7: Heat map of flora density and

Fig 3.9: Heat map of light pollution and height projections

Fig 5.2: Material analysis; tensile and shading experimentation

Fig 6.1: Initial conceptual sketch, research node

Fig 6.2: Initial conceptual sketch, netting traps with lighting

Fig 6.3: Initial conceptual sketch, water siphoning systems

Fig 6.5: Sectional sketch, typology a

Fig 6.6: Sectional sketch, typology b

Fig 6.7: Sectional sketch, typology c

Fig

Fig 7.1: Exploded axonometric of proposal

Fig 7.4: Floor plan of

Fig 9.1: Night-time perspective render, adjacent view

Fig 9.2: Night-time perspective render, interior view

Fig 9.3: Night-time perspective render, external view

A day-time perspective of the design shows how the net and poles can be manipulated to allow public access to both endemic species and humans. Opening up a plethora of new programmes that could take place within the site. The existing poles are kept to act as perches for the multiple bird species in the pan, while the pathway itself allows for viewing of the pan, birdwatching, exercise etc.

Fig 9.4: Day-time perspective render, interior view

s.

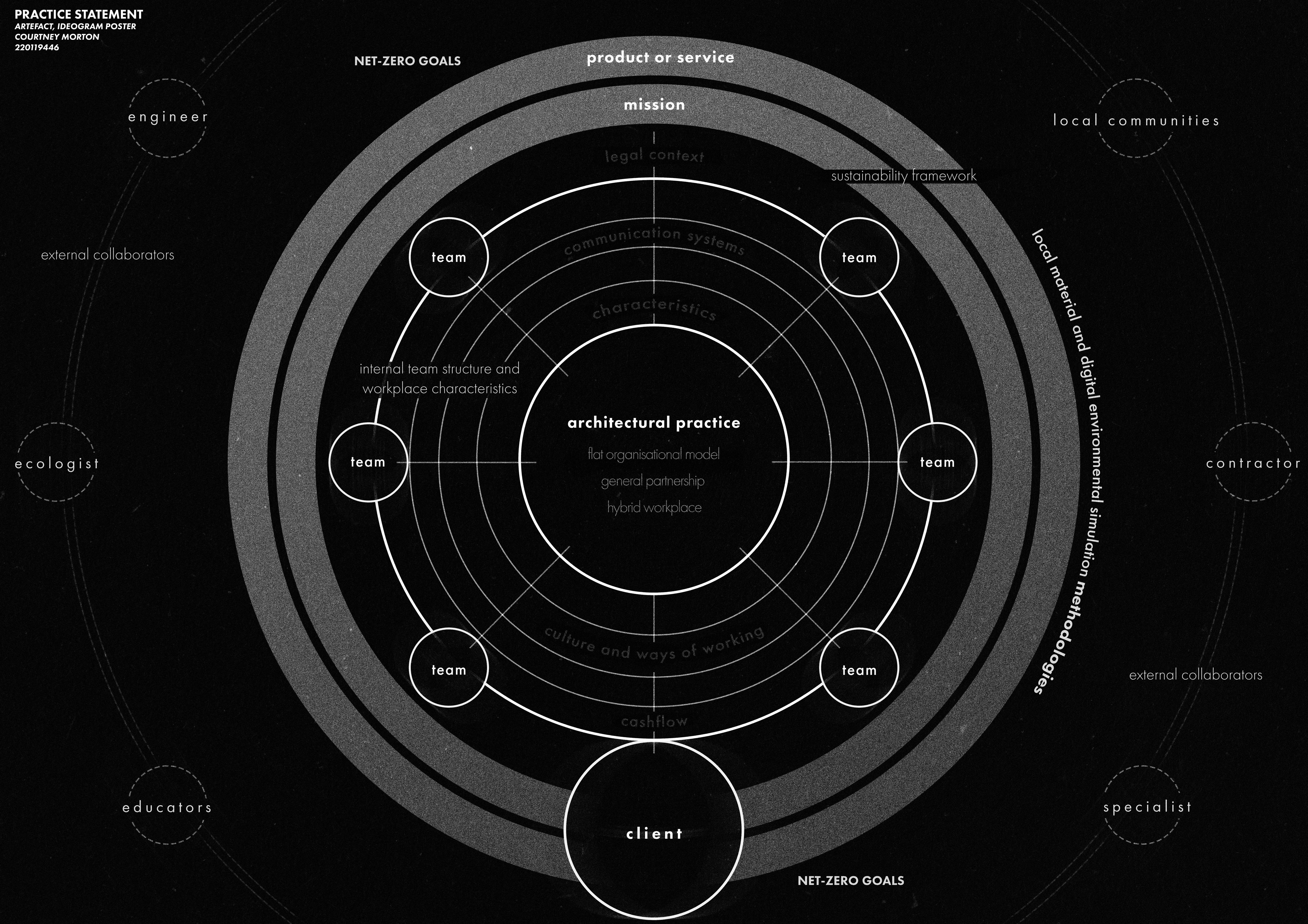

PRACTICE STATEMENT

A1 PRACTICE ARTEFACT AND THEMES EXPLORED

DEFINING YOUR PRACTICE:

The type of architectural practice I aim to pursue will be a small ecologically focused creative design studio based out of Johannesburg, South Africa, with a goal to prioritize sustainable future-forward buildings, as well as creatively adapting Net-Zero guidelines and systems into existing building around the country, in according to the global 2030 Net-Zero goals. The practice’s goal will be to bridge and restore the relationship between architecture and the living systems they occupy, within the context of South Africa’s rapidly urbanising ecological zones. The studio will aim to integrate architectural data, material life-cycle analysis and community-based repair.

PRACTICE STRUCTURE:

The studio will follow a Partnership structure consisting of a core team of 3-5+ members functioning as principal architects, with flexible collaborations across multiple disciplines including experts such as ecologists, engineers, artisans and data scientists. The studio will follow a flat organisational model, which decentralises authority and will give employees more involvement in company decisions, creating a cooperative workspace where decision-making is transparent and each employee can contribute to design direction, research and client engagement. Ideally, each project will become a prototype/learning opportunity to ensure continuous ecological and technical refinement through lessons learned.

PRACTICE MISSION:

The mission of my practice will aim to address climate change through implemented design strategies and ideologies that can be idealised in measurable but still poetic ways. The practice’s research interests will align with multiple sustainable practices, understanding passive design, local and sustainable material choice and empowering local communities. The practice’s success will not only be defined by its adaptation od carbon reductions strategies, but furthermore through the continued education of clients and communities towards ecological literacy.

UNIQUE CHARACTERISTICS:

What will differentiate my practice to other South African architectural practices will be its dual action approach to design and technology: designing new and innovative ecological architecture while still maintaining a goal of adaptive reuse in existing buildings across the country to align with the global sustainable goals brought about towards a Net-Zero architectural design philosophy. Many buildings within South Africa are extremely energy intensive but nevertheless built to last with high embodied carbon materials such as concrete. The practice therefore will seek to transform these buildings into low energy, low carbon passive systems. Our methodologies will combine digital environmental simulation with on-site and local material testing, which will aim to bridge the gap between technological and vernacular architectural systems within South Africa.

CULTURE AND WAYS OF WORKING:

The culture my practice will aim to create within the studio will be open, collaborative and encourage critical dialogue between team members with an intent to foster a transparent, open and non-hierarchical structure overall. Collaboration will not end within the studio, and we will aim to work often with environmental and community organisations, local universities and researchers etc. The working environment will prioritize mental and physical well being for all team members with flexible working hours, a hybrid workplace model, shared lunches and open, outdoor workplace environments.

PRACTICE LEGAL CONTEXT:

The studio will operate as General Partnership, registered under the South African Council for the Architectural Profession (SACAP) as a Professional Architectural Practice. And will comply with SANS 10400, National Building Regulations, and local municipal laws. The studio will aim to collaborate with environmental consultants to meet Green Star and Net-Zero certification standards as often as possible.

Practice Communication Systems:

All internal communication within the practice will be maintained through a cloud-based design management platform that could allow flexibility of staff while still having key in-person studio reviews as often as a project needs. Externally, there will need to be frequent and transparent client communication supported by illustrated proposals and ecological data that will reinforce trust and education towards the clients.

PRACTICE COMMUNICATION SYSTEMS:

All internal communication within the practice will be maintained through a cloud-based design management platform that could allow flexibility of staff while still having key in-person studio reviews as often as a project needs. Externally, there will need to be frequent and transparent client communication supported by illustrated proposals and ecological data that will reinforce trust and education towards the clients.

PRACTICE CASH FLOW MANAGEMENT:

The practice will be a medium sized Architectural firm, and financially, the practice will follow a lean model: small-scale commissions, research collaborations, and retrofit projects forming the revenue base. A percentage of profits will fund ongoing environmental research. Staff will receive fair salaries, along with creative autonomy, and shared profits allow for both financial and creative sustainability for all involved.

A quality product or service that would come out of the practice would be one that could balance aesthetic clarity and environmental intelligence. This system would require a combination of contemporary parametric environmental and form modelling with analog and tactile material exploration/craftsmanship. Each project should document drawings with intense ecological performance metrics, clearly understanding how buildings performed through energy and material analysi

DESIGN REFERENCES:

Respiration in aquatic insects (2015) 2015 ENT 425General Entomology. Available at: https://genent.cals. ncsu.edu/bug-bytes/aquatic-respiration/ (Accessed: 04 April 2025).

Dr. Biology. “Mosquito Anatomy”. ASU - Ask A Biologist. 17 Jun 2024. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. Available at: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/mosquitoanatomy.

Depression wetlands. 2024. Kenai Watershed Forum Available at: https://www.kenaiwatershed.org/cookinlet-wetlands/wetland-types/depression-wetlands/ (Accessed: 04 April 2025).

AR De Klerk, LP De Klerk, PJ Oberholster, PJ Ashton, JA Dini & SD Holness. 2016. A review of depressional wetlands (pans) in South Africa, including a water quality classification system. Water Research Commission.

Schneider, B.S. et al. (2004) ‘aedes aegypti salivary gland extracts modulate anti-viral and Th1/Th2 cytokine responses to sindbis virus infection’, Viral Immunology, 17(4), pp. 565–573.

Rossignol, P.A. and Lueders, A.M. (1986) ‘Bacteriolytic factor in the salivary glands of Aedes aegypti’, Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry, 83(4), pp. 819–822. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(86)90153-7.

Lahondère, C. et al. (2019) ‘The olfactory basis of orchid pollination by mosquitoes’, P roceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 117(1), pp. 708–716.

Lee, S.C., Kim, J.H. and Lee, S.J. (2017) ‘Floating of the lobes of mosquito (aedes togoi) larva for respiration’, Scientific Reports , 7(1).

‘Olfactory basis of floral preference of the malaria vector anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) among common African plants’ (2014) Journal of Vector Ecology , 39(2), pp. 372–383.

Chisumbe, S. et al. (2024) ‘Effectiveness of housing design features in malaria prevention: Architects’ perspective’, Frontiers in Built Environment, 10.

Wickremasinghe, R., Wickremasinghe, A.R. and Fernando, S.D. (2012) ‘Climate change and malaria a complex relationship’ , UN Chronicle, 47(2), pp. 21–25.

Lindsey, R. and Dahlman, L. (2024) Climate change: Global temperature, NOAA Climate.gov. Available at: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/ understanding-climate/climate-change-globaltemperature (Accessed: 29 April 2025).

IPCC 2021, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, the Working Group I contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Spielman, A. & D’Antonio, M. (2001). Mosquito: A Natural History of Our Most Persistent and Deadly Foe Hyperion.

Obame-Nkoghe, J. et al. (2024) Climate-influenced vector-borne diseases in Africa: A call to empower the next generation of African Researchers for Sustainable Solutions - Infectious Diseases of poverty, BioMed Central . (Accessed: 06 May 2025).

World Bank Group (2013) The global burden of disease: Main findings for Sub-Saharan Africa, World Bank . (Accessed: 06 May 2025).

Worrall, E., Basu, S. and Hanson, K. (2005) ‘Is malaria a disease of poverty? A review of the literature’, Tropical Medicine & International Health, 10(10), pp. 1047–1059. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01476.x.

Nolan Oswald Dennis. (2018) No compensation is possible (working diagram).

Em’kal Eyongakpa. (2013-2016) rustle 2.0.

Jan van Ijken. (2022) Microscopic Plankton.

MAKING REFERENCES:

Jatta, E. et al. (2018) ‘How house design affects malaria mosquito density, temperature, and relative humidity: An experimental study in Rural Gambia’, The Lancet Planetary Health , 2(11).

Carrasco-Tenezaca, M. et al. (2021) ‘The relationship between house height and Mosquito House entry: An experimental study in rural gambia’, Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 18(178), p. 20210256. doi:10.1098/ rsif.2021.0256.

jr., S.P. (2021) Green building elements from Giant Reed – the houses of the future, Arundo BioEnergy. Available at: https://arundobioenergy.com/green-buildingelements-from-giant-reed-the-houses-of-the-future/ (Accessed: 25 May 2025).

Flores and Prats (2023) Drawing without Erasing and Other Essays w