Usually striking without warning and spreading rapidly, the effects of Salmonella are devastating.

Protect your herd and family from Salmonella.

Salmonella can pass from your stock to the ones you care about most.

Vaccinate today to reduce the destructive impact of an outbreak*.

14 Strategy to Suit

As Kikuyu creeps more into the Bay of Plenty, farmers Andre and Natalie Meier have decided to embrace the summer grass. We go onfarm with them to find out how switching up their strategy is helping improve their performance.

24 Ginger’s Gene Edit Against BVD

An American calf bred with a gene-edited genome to be BVD resistant is due to have her first calf.

27 Blueprint for a Gene Technology Regulator

The Australian Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (OGTR) will be used as the blueprint for New Zealand’s gene regulator. How does it work?

30 Slick Gene Editing

LIC is dipping its toe in the water with gene editing, using their Slick gene offshore.

33 Glossary

34 Becoming Literate – The Language of Finance

37 No Taxing Surprises

38 What Good Financial Management Looks Like

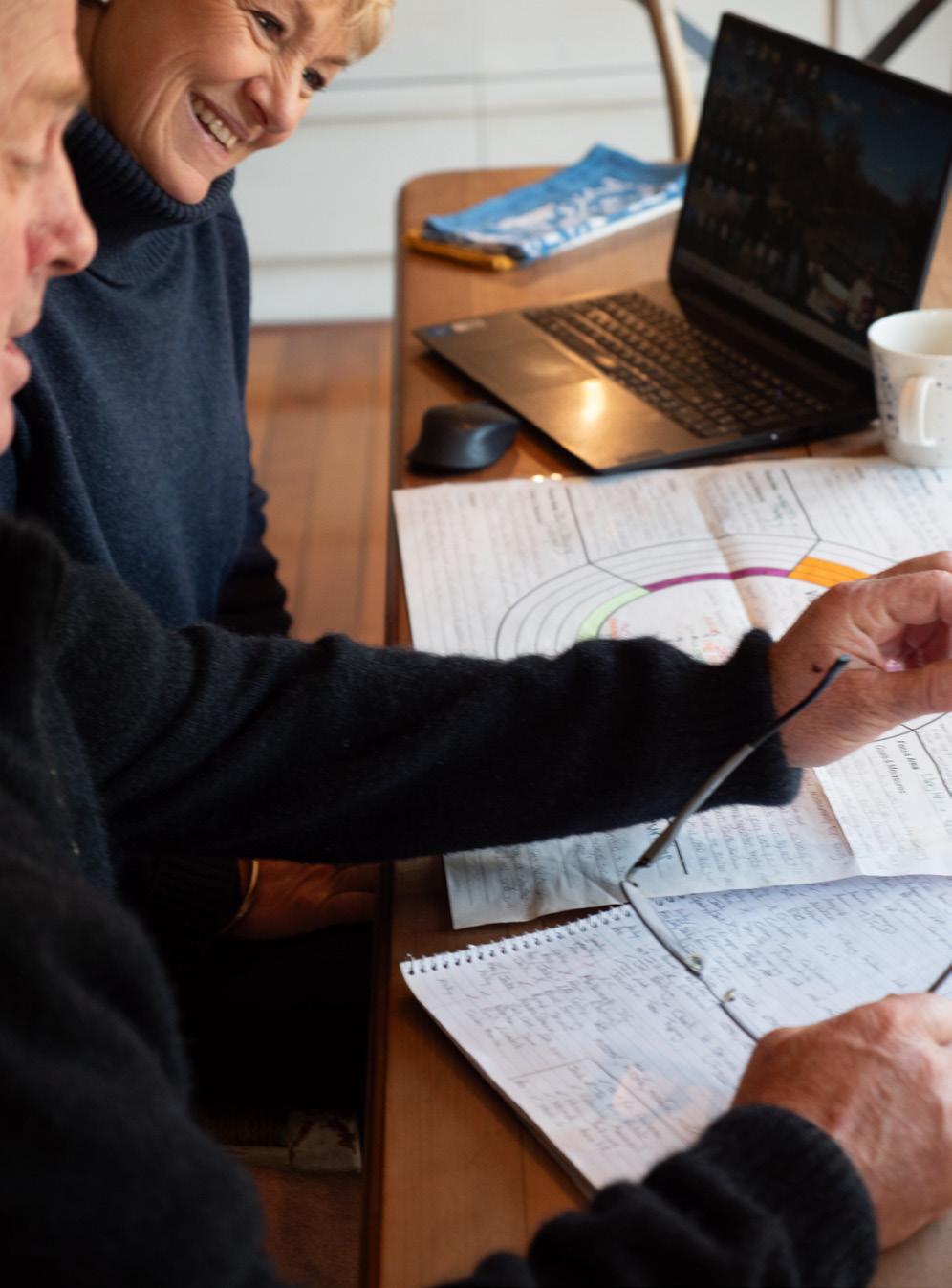

40 In the Driving Seat

Anne Lee goes onfarm with the Andersons to dig into how they manage finances and track their progress.

47 Control

Financial literacy may not be the sexiest topic, but at the end of the day you read NZ Dairy Exporter because dairy is your business, and it’s our job to support you in this, so sexy or not, we have it covered (see page 32).

There is enormous wealth creation available in the dairy industry. From whatever walk of life you come from, a pathway is available for those who wish to do the mahi. But we still need to have the right doors open to us. Whether it’s an employer who encourages you to do more education to step up and be a manager, somebody to take the gamble and give you your first contract milking position, or a family that is ready to open the pathway to farm succession. Whatever your next step is on the dairy ladder, what underpins it all is sound financial literacy: knowing how to make a budget, stick to it, the discipline to spend wisely, knowing where to invest the surplus and how to make your money work for you.

Getting the timing right and a strong structural support around you is vital for that step up to the next rung so you don’t slip and crash to the ground.

In the same breath, we’ve tackled an update on insurance (page 52), what’s happening with premiums and what the future insurance space could look like. While it may not be one of the biggest expenses on your annual budget, it’s creeping up there, and the importance of having the right insurance is only truly obvious when you actually need it.

The other big topic we take a bite out of this issue is drench resistance (page 68) and what the danger is in store for the dairy industry. Lots of our calves are being grazed on calf paddocks or calf blocks which could be cultivating a worm factory. While there isn’t a lot of data known about how widespread drench resistance is in the cattle industry, the first step is testing more to ensure your drenching programme is working for you.

Testing our cows or calves and making sure they have a regular health programme is pretty standard for most farmers. But trying to get a farmer to a regular GP appointment for an annual – or “gasp” six-monthly – check-up can be as frustrating as untangling a reel quickly.

Why are farmers notoriously bad at going to the doctor? You’re happy to pay a costly life insurance or medical insurance invoice, but not so keen to go and do a maintenance check on your most important asset.

Make sure you prioritise your own health this summer. Book an appointment with your GP before you enjoy the Christmas break with the knowledge that the milk price forecast is strong and Santa should be bringing a lucrative 2025.

Meri Kirihimete

SHERYL HAITANA EDITOR sheryl@countrywidemedia.co.nz

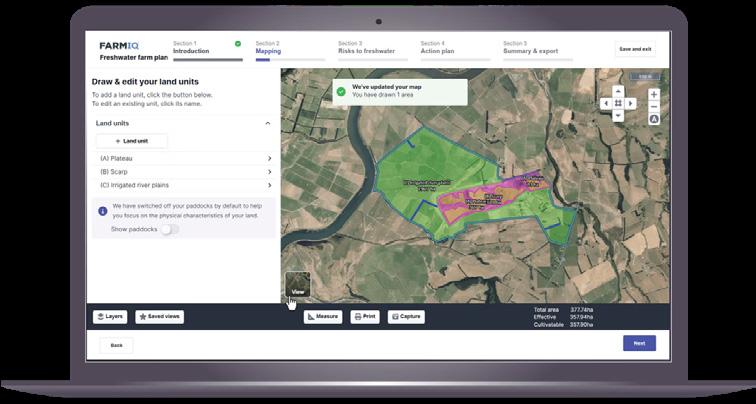

What I’ve been doing

The working mum juggle. Between onfarm interviews, fun work events, being the referee to Miss Four and Miss Two, swimming lessons, pony lessons, planting the vege garden and getting on top of spring growth, I’ve managed to prioritise my exercise. My new midlife crisis has been to sign up for several half-marathon walks and wrangle some friends along with me. Maybe it’s just an excuse for a girls’ weekend, but so far it’s ensuring I get out most days for a walk which is great for the body and the mind. Shout out to my friend Tammy Deans who had the idea to sign up to the first one at Kinloch in August. Check out her article about what you need in your farm environment plan on page 98-99.

PUBLISHED BY

CountryWide Media

0800 224 782

PO Box 167, Tai Tapu 7645 country-wide.co.nz

MANAGING DIRECTOR

Sarah Perriam-Lampp

MANAGING EDITOR

Lucinda Diack

EDITOR

Sheryl Haitana

DEPUTY EDITOR

Anne Lee

ART DIRECTOR

Klaudia Krupa

SENIOR DESIGNER

Jo Hannam

CONTRIBUTORS

Dr Alice Armstrong, Trudi Ballantyne, Philippa Cameron, Heather Chalmers, Rosalind Crickett, Dawn Dalley, Kara Dawson, Tammy Deans, Andrea Dixon, Ginny Dodunski, Esther Donkersloot, Louise Gibson, Michelle Good, Rebecca Greaves, Holly Lee, Tony Leggett, Kylie Leonard, Chris Lewis, Winston Mason, Emma McCarthy, Dr Anneline Padayachee, Trish Rankin, Richard Reynolds, Kathryn Wright

ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES

Viv Montgomerie 027 370 6922 viv@countrywidemedia.co.nz

Donna Hirst 027 520 0466 donna@countrywidemedia.co.nz

David Paterson 027 289 2326 david@countrywidemedia.co.nz

SUBSCRIPTIONS

dairyexporter.co.nz/shop 0800 224 782 subs@countrywidemedia.co.nz

PRINTER Blue Star

Dairy Exporter is published quarterly ISSN 2230-2697 (Print) ISSN 2230-3057 (Online)

There is nothing quite like hearing from a country’s farmers on the way they are governed, financed (i.e. subsidies) and perceived by their population, to understand our own opportunities deeper.

I was excited to spend 10 days in Switzerland as part of the International Federation of Agricultural Journalists Congress as it’s the home of our largest supplier of New Zealand milk, Nestlé, who have been making loud signals on their expectations of our small, unsubsidised island nation to continue to supply them. As a critical journalist I used every opportunity for conversation to grasp an understanding of their thoughts on our proposed gene-editing regulation changes, and their definition of regenerative agriculture to better inform the discussion here at home.

The prequel to the story began in a trendy bar in London as young (under 40) expat Kiwis, working in multinational agriculture and food companies, came together to meet me for a drink and discuss how they are seeing the major trends from abroad. Quotes like “New Zealand has missed the regenerative boat,” and “NZ’s current political narrative of undoing environmental regulations is having a negative taint in our markets,” had me worried and intrigued but not surprised.

give high priority to free choice and mass demands for liberalisation. This becomes increasingly costly and detrimental to economic effectiveness, of which Switzerland is a classic case in point.

Our tour guide, Alex, was the communications director for the Swiss Farmers’ Union who shared the hot topic among farmers that Switzerland’s traditional exercises of direct democracy in action called their initiative rights. It’s a public petition system where 100,000 signed petitions can enact a national referendum on a topic. The current referendum was on increased protected area for biodiversity which its opponents say was an “extreme and inefficient” way to protect biodiversity calling for farmers to lock up 30% of their land for protected habitats. Those in favour of the initiative, such as BirdLife who we heard from at the congress, said the open pastures policy of the government paying farmers subsidies to keep farmland in the Alps clear from encroaching forests was a way for their food marketers and tourism operators to maintain the Heidi-like scene in the mountains. This is the third referendum they have had in 12 months, stopping the nation every quarter. The next one in line is to ban animal agriculture from Switzerland.

This publication uses vegetable-based inks and environmentally responsible paper produced from Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified, Mixed Source pulp from Responsible Sources.

We touched down in the cosmopolitan city of Geneva, home to the United Nations but also a transit population, where half the workers live in France, as it is cheaper to travel across the border to work each day. This was my first glimpse of the desire to earn and invest in Swiss francs, the most stable currency in the world and a safe haven of international investment. In the academic literature of “social licence” they explain how higher levels of economic security and an increase in standards of living from a post-industrial knowledge society such as Switzerland leads to a growing emphasis on the values of its people who

So it’s no surprise they have the Agricultural Information Service, funded by 80 organisations from the agriculture and food industry, whose sole job is to educate schools and the general public about farming. Our trip to Agroscope (the NZ equivalent of AgResearch) was an informative tour of how the environment they farm in is forcing their agriculture research and development. They research management solutions for a future of reduced chemical use and greenhouse gas emissions. I asked one of the principal scientists if they were preparing for any changes to their restriction of gene-editing technologies. He said that would be a long way off for the EU as their sole focus for carbon removal and less chemicals

is on soil health – remember there aren’t incentives to plant out their hill country in trees! We visited Nestlé’s Research and Development in Lausanne to meet with Jeroen Dijkman, the founding head of the Nestlé Institute of Agricultural Sciences. They explained how dairy is 31% of their carbon footprint and that is why they are coming up with their own agronomic solutions to put the science behind defining regenerative agriculture to underpin achieving their procurement targets of sourcing 50% regenerative milk by 2030 and 100% by 2050. They are validating solutions on their test farms such as the Nestlé-funded trial in Taranaki. We were shown through their newly opened laboratory where they had gas chambers to mimic the anaerobic fermentation of rumen microbiomes with different feeds and the enteric methane produced – no GMO or gene-edited feeds are being trialled. We were shown their educational regenerative area about the importance of hedgerows for beneficial insects and the significance of soil cover and porosity for moisture retention. I asked Jeroen about the current discussion on NZ’s gene-editing regulation and received a careful reply: “There will always be a market for New Zealand dairy.” Read into that what you will.

In June 2024, Nestlé was a foundational member of AgroImpact where they provide participating farms with climate premiums calculated based on their level of carbon reduction. We visited a farmer who was a part of the

project and through translation I was able to discover that his carbon storage capacity was measured by a ruler and he didn’t need to pay the premium back when he released carbon into the atmosphere when he lifted the “lowcarbon” sugar beet for Nestlé. They looked at me sideways as to why it would be an individual farmer’s responsibility when you are helping Switzerland “inset” its carbon from the airlines in their soil. Then I got to ask my question to former Nestlé CEO, Mark Schneider:

“I represent New Zealand dairy farmers here and Nestlé is one of our largest suppliers. You talk a lot about the transition (to regenerative) and with New Zealand being in the bottom three in the world for agriculture subsidies, and it doesn’t look like that will change, what is the role of Nestlé to fund that transition [such as through premium payments] or would you see that as an expectation on our government to fund this through subsidies?”

He replied, “What you will see in other countries is a healthy mix. We are not shying away from carbon initiatives or taking the lead, but it’s a systemic problem across the value chain and we share responsibility. Especially in countries where agriculture is large, the government has invested interest like here with dairy in Switzerland you see us step up, but also the government, so everyone has skin in the game.” Switzerland is in the top three countries in the world for agriculture subsidies

to the tune of over $3 billion per year. According to OECD data, subsidies in the EU account for less than 20% of farm income. In Switzerland, the average is 62.7% with 543,000 dairy cows. Even though this is the home of our largest supplier’s global headquarters, they are sourcing, producing and selling Nestlé consumer goods within their “gene-editing” friendly markets such as the United States. So Fonterra’s new strategy to strengthen their ingredients business model of a commodity product tells me that gene editing and regenerative are now the ticket to remain in the commodity game.

SARAH PERRIAM-LAMPP CEO & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF sarah@countrywidemedia.co.nz

Charity Golf Events

October 2024 – February 2025

Play a round and raise money for your local Rural Support Trust.

• November 15 – Whakatāne

• February 21 – Morrinsville rural-support.org.nz

Milking It Live Webinar

November 6 2024

Get to know the stars of the Milking It project, Addie and Kip Nolan, and hear how they’ve learned to take control of their farm’s profitability with the help of CMK Chartered Accountants, Figured and Dairy Women’s Network through their podcast series on Rural Exchange. dwn.org.nz

Owl Farm November Focus Day

November 21 2024

A range of seasonally relevant topics. owlfarm.nz

Managing Risk in Sharefarming

November 2024

Federated Farmers events are being held throughout the country. Learn how to navigate business and individual risks for both sharefarmers and farm owners. A guide through contractual changes, farm assessments, and how to build and maintain strong, enduring working relationships. fedfarm.org.nz

Pasture Summit Fieldays

November 2024

Hosted by farmers for farmers, with input from dairy sector specialists, sharing ideas and developments on achieving profitable food production from grass.

• Waikato – November 13

Dan and Gina Duncan onfarm in Te Awamutu

• Canterbury – November 27

Leighton and Hayley Parker onfarm in Ashburton pasturesummit.co.nz

Primary ITO Courses November–December 2024

Primary ITO courses on Milk Harvesting, Livestock Feed Supply and Demand, Operating Dairy Effluent Management Systems. primaryito.ac.nz

Lameness Management Workshops November 2024 – January 2025

The workshops are designed to give students an overview of issues relating to lameness management and introduce them to the 5-step trimming process according to the 5-Step Method. dairyhoofcareinstitute.ac.nz

NZ Dairy Expo

February 11–12 2025

The Dairy Expo at Matamata will feature more than 100 businesses from across the dairy industry, to showcase the latest innovations in technology, equipment, and services tailored to dairy farming only. nzdairyexpo.co.nz

AGMARDT’s The Common Ground

Interested in industry leadership into the future with the challenges we face? You’ll enjoy The Common Ground podcast hosted by Sarah Perriam-Lampp in conjunction with AGMARDT and KPMG’s report Are industry good bodies good for industry? The podcast series goes deep into the concept of The Common Ground with farmers and industry leaders past and present.

AgResearch’s What’s Next?

AgResearch is tasked with helping our pastoral agriculture sector face its challenges headon so in their podcast series, What’s Next? they explore the big questions facing New Zealand agriculture. Hosted by veteran radio broadcaster Eryn Breading, she talks to experts about greenhouse gas mitigation, water quality, land-use change and its impacts, biosecurity, and the opportunities that new technologies offer for food and fibre producers. All working towards growing our economy and becoming more sustainable.

Farm Source’s Seasonal Focus

With practical onfarm advice from Farm Source’s suppliers and On-Farm Excellence team delivered to your headphones, Seasonal Focus includes episode interviews, as well as highly recommended on-demand webinars ensuring you have all the information you need at your fingertips, when you need it. Whether it’s understanding how to read your Farm Insights Report or calf rearing tips, it’s a great podcast series to get your farm team to start listening to.

The NZ Dairy Exporter is celebrating its centenary in 2025. The NZ Dairy Exporter was the bible to dairy farmers across the country as the dairy industry formed and grew. As we count down to this celebration, enjoy some excerpts from one of our earliest editions.

Properly cleaned udders, thorough sterilisation of milk and cream cans, and adequate cooking are three things essential to a high-quality milk or cream. In the course of an interesting address at the National Dairy Association’s conference, Mr. P.O. Veale, scientist at Hawera laboratory, dealt fully with these three important factors. “In the past, too much attention has been paid to quantity, and insufficient to the more important question of quality.”

Our last review indicated the board’s intention to make a further payment in the second butter pool when the last butter within that pool had been shipped. This having been done, a payment aggregating £350,000 was made on July 31. This payment brings the advances on the second pool to the following figures:

• Finest grade … 1s. 2.16d

• First grade … 1s 1.66d

• Second grade …1s 0.66d

The total quantity of butter handled in this pool amounted to 1,575,920 boxes.

“I have just received a bit of information from a friend of mine in Walsall, England, concerning New Zealand butter which I think will come as a surprise to a large number of dairy farmers. My friend says ‘I am surprised at the treatment meted out to the New Zealand producers by the British butter merchants by giving such a low price to the New Zealand farmers, yet charging a high price to the consumer’... But until that day comes we will have to spank old ‘Daisy’ a little harder, drink the skim-milk, and give the butter-fat to others.” Yours L.M. Nicklin.

nue identi fying your best genetics w i t h G e ne Ma rk

You’ve always tried to breed from your best, and you already know the power of genomics. Through our new GeneMark® Genomic service you can continue to identify superior genetics with increased reliability at a younger age.

GeneMark Genomics takes the guesswork out of matching calves to parents while accessing genomic data, adding precision to your animals’ breeding values at a more cost-effective price.

All of which helps you fast-track your herd’s genetic gain.

So continue breeding from your best and building your confidence with GeneMark Genomics.

Talk to your Agri Manager today or visit lic.co.nz/genemark

There's always room for improvement

As the creeping Kikuyu plant smothers more pastoral land in the North Island, the decision for farmers is to either fight the Kikuyu or embrace it. Bay of Plenty dairy farmers Andre and Natalie Meier have embraced the summer grass, altered their system to once-a-day and are enjoying the productivity wins.

Words SHERYL HAITANA Photos EMMA MCCARTHY

Embracing Kikuyu and switching to once-a-day (OAD) has led to better results for Andre and Natalie.

The couple are equity partners in Natalie’s family business, which includes two dairy platforms, a significant kiwifruit block and a quarry. Four generations of Camerons have farmed at Ōtamarākau since 1930, with land use swaying between sheep and beef, dairy and horticulture.

The farm Andre and Natalie are currently living on had been sold by Natalie’s grandparents Matt and Ethel Cameron and purchased again by Natalie’s parents, Bruce and Gill Cameron, 12 years ago.

The 118ha effective dairy farm is located in the valley, five minutes from the beach, with 90% of the milking platform on flats next to the Waitahanui stream, 70ha of which is irrigated.

Drains weave through the very low lying paddocks, which do have a tendency to flood in winter.

There is another 10ha of grazing across the road on steep country with 42ha retired and planted out in pine trees.

When Natalie and Andre bought into the family business five years ago, it was struggling to fight off Kikuyu on a large proportion of the dairy platform. The business was spending thousands of dollars on spraying paddocks out annually, sowing ryegrass, only to see the Kikuyu take back hold within two years, Natalie says.

The herd was also struggling with the system, producing just 280kg MS/cow with a poor reproductive performance of 55% six-week in-calf rate and an almost 30% not-in-calf rate.

“That was for consecutive seasons; we were pouring in a heap of feed, mainly because of the wet weather events,” Andre says. “We were having to sell cows for low margins as an empty cow then having to go out and buy in-calf cows to replace them.”

It wasn’t great on the cashflow or for the future of their herd.

The company purchased another dairy farm at Otakiri one year after Andre and Natalie had bought in as equity partners. After a couple of tough wet seasons, there was poor reproductive performance and production across both herds. It was evident that things needed to change.

Andre and Natalie did their research and got some experts in to see if running a Northland-style system to embrace the Kikuyu at the Ōtamarākau farm was a good idea.

There is benefit to fighting the Kikuyu when it is minimal and is at a manageable state, but they were just pouring money down the drain trying to fight it on this farm, Natalie says.

“It is so costly to try and get rid of it, and frustrating for it to just grow back.”

On the family’s drystock platform land there were paddocks which had been grown in maize grain for years and had been constantly sprayed with glyphosate.

“We put them back into ryegrass and in just two years the Kikuyu was dominant,” Andre says.

They now run the Northland Dairy Development Trust system with an eightweek regrassing programme over the whole farm.

Kim Robinson from AgFirst has been extremely helpful to the couple and has guided them through it.

“She’s jumped on Zoom calls with us and is on the other end of the phone to answer our questions,” Andre says. “Running this system has definitely turned the farm around; the mulching has been the main thing. We used to undersow every year, but since we’ve brought the mulching in, it resets the whole paddock and takes away any of the competition from that Kikuyu to the new grass.”

Every paddock on the flats gets mulched with a Y-Flail mulcher trying to disturb the Kikuyu stolon as much as possible.

“We’ve modified it a bit ourselves and we drill extra holes to allow us to get it mulching at ground level to disturb the Kikuyu. The first season was slow, it was very wet, but this year the tractor was about 5km/h faster through the paddocks. We try to do everything in-house, and use our own cultivation gear. I used to be an agricultural contractor before I went dairy farming.”

They follow straight in behind the mulcher with the undersow drill to sow Italian ryegrass.

“We buy non treated, the cheapest seed we can buy.”

They plant 15ha of chicory every year which the cows rotate on a 21-day round

in summer. The chicory paddocks are then sowed with a hybrid ryegrass which lasts about three years.

“We don’t put perennials in because after three years the Kikuyu smothers it anyway. You’re just throwing money down the drain so you’re better off having the hybrids which grow faster and have a better ME,” he says.

The family always grew maize on the runoff block as in around November the farm would reach a feed deficit so the maize would supplement this, however, they wouldn’t see much production change in the cows.

“This is where Kim educated us that maize and Kikuyu are both high in carbohydrate, therefore, take the maize out and introduce chicory for protein and you will see results … which we have,” Andre continues.

LEFT Andre, Lindsay and Jamie checking out the pasture. BELOW The ryegrass hybrid is what gets them through winter until the Kikuyu takes over again.

“Kikuyu is very efficient at using water so if the pasture cover gets too high we turn the irrigation off. But if we do get into a tight spot you can turn the irrigation on and within half a week you’re away again.

“We realised we were turning our irrigation on too early some years after drilling new seed and this would encourage the Kikuyu to bolt, smothering the new seed we had planted. If they start running at a surplus they will either shut up the former chicory paddocks which are mostly ryegrass for silage, or mulch the Kikuyu paddocks down to 1400 residual to reset them.

“Irrigation is an extremely cheap way of growing feed. When you can grow your grass it’s a hell of a lot cheaper. We try and use that to as much benefit as we can. Running the irrigation for a month is equivalent to about 4t of palm kernel.”

The Ōtamarākau farm has 22ha on a pivot, with the rest on laterals. Grieve Road has 76ha of the platform irrigated by pivot and laterals. That farm also has 35ha that gets whey from Fonterra’s Edgecumbe factory.

“With that plus the effluent area it’s almost 100% irrigated.”

‘Maize and Kikuyu are both high in carbohydrate, therefore, take the maize out and introduce chicory for protein and you will see results … which we have.’

The next part of the new strategy for the dairy units was looking at going OAD full-time.

“When pulling the farms apart, the thing we kept coming back to was the poor repro results; we knew if we could improve this area then everything else will positively follow in the same direction – which kept bringing us back to OAD,” Natalie says.

With well-fed cows who are under less stress, they have better condition, leading to better reproduction results and a tighter calving spread would lead to more milk in the vat.

“We knew it wouldn’t change overnight, but it was a long-term goal for future benefits to the cows and business.”

Vets and industry professionals had told the couple the only farms in the area that rode the really wet season through were the OAD farms or the really high input farms – and it cost the high input farms a lot.

“The OAD farms had a bit of decrease, but the cows didn’t lose weight and it didn’t impact their following season.”

Andre had experience of switching a farm from twicea-day (TAD) to OAD milking when he was farm manager for Ao Marama Farms further up the road at Pongakawa.

“I knew the benefits of going OAD. We went to OAD on my last farm because we had a staff injury and two junior staff left, and so we were left with me and one other milking 800 cows. We made the call to go OAD and we made it through the season just the two of us.

“We saw the results instantly, we had better mating results, we had surplus in-calf cows which gave us the opportunity to cull the poorer cows. That farm has stuck to OAD and they’ve smashed my TAD record, they are doing nearly 360kg MS/cow on all grass and steep country.”

Going OAD can be viewed negatively by banks, but the couple were surprised at the positive comments and support they’ve had from the banking sector.

It can be a really good option for poor-performing farms on less-productive land, Andre says.

While the Otakiri farm doesn’t have Kikuyu, the poor reproductive performance was reason to go OAD there as well.

They are now in their second season of milking OAD across the two farms. The cows’ production went up in the first season of milking OAD from 280kg MS/cow to 326kg MS/cow and their mating results improved dramatically.

“This last season, our mating results were a 67% six-week in-calf rate, 91% three-week submission rate – with no intervention – and a 13% not-in-calf rate.”

• Equity shareholders Bruce and Gill Cameron, Anna and Rikki James, Natalie and Andre Meier

• Location Ōtamarākau

Two Dairy Units, 118ha and 144ha effective

• Drystock/support block 170ha

• Kiwifruit 70ha (50% green, 50% gold) 100ha pine trees

• Cameron Quarry

ŌTAMARĀKAU VALLEY FARM

• Area 160ha, 118ha effective

• Irrigation 70ha

• Farm Dairy 41-aside herringbone, half ACRs, CowManager

• Cows 340 Friesians

• 2024–25 Target production 326kg MS/cow

• System DairyNZ System 3, OAD, feedpad

• Pasture and crop harvested onfarm 8t DM/ha

• Total feed eaten 15t DM/ha

• Crops 15ha chicory

• Supplement 170kg DM kiwifruit, 150kg DM PKE

• Assistant manager Lindsay Williams

• Herd manager Jamie Fryer

Mating Results from going OAD TAD OAD

• Six-week in-calf rate 55% 67%

• Not-in-calf rate 26% 13%

GRIEVE ROAD, OTAKIRI

• Area 148ha, 144ha effective

• Irrigation 90ha

• Farm Dairy 20-aside double-up, protract, ACRs, CowManager

• Cows 440, 60% Friesians, 40% Jerseys

• System DairyNZ System 2, OAD, 500-cow Herd Home

• Pasture harvested 12.5t DM

• Supplement 76t DM of kiwifruit

• Assistant manager Rāhoroi Tutua Bennett,

• Herd manager Toby Hall Te Kiri

Mating Results from going OAD TAD OAD

• Six-week in-calf rate 55% 76%

• Not-in-calf rate 28% 11%

Cost savings from going OAD

• Farm Dairy Electricity – $10,000

• Breeding/Herd – $12,000

Animal Health – $30,000

At Grieve Road, they had a 76% sixweek in-calf rate and 11% not-in-calf rate.

“We simplified things, we took out a lot of feed, we decreased our stocking rate. We did the opposite to a lot of other people who go OAD. A lot of people increase their herds to try and soften the production loss.

“But with taking the chicory out we were stocked at 3.8 cows/ha and it was putting too much pressure on the system and pouring way too much imported feed. Our stocking rate is 2.8 cows/ha now.”

“I had some industry professionals tell me this Friesian herd would have a lot of blown-out udders, and all sorts of health issues. This season we haven’t had any health issues from going OAD, it’s been all positive. We have saved $40,000 on animal health across both farms.”

The change in system has resulted in some other major savings, including less electricity in the farm dairy and a lower fertiliser bill.

‘This season we haven’t had any health issues from going OAD, it’s been all positive. We have saved $40,000 on animal health across both farms.’

The cows still lose the weight in the spring, but they put it on better over the summer months, Andre says.

“They’re drying off in a better condition so the work is already half done. I find they put the weight on a lot easier.”

Before they made the call they did get independent advice on whether the herd’s udder conformation would handle the change to OAD.

“We have also earnt $60,000 more in milk just from having more cows calved earlier.”

In 2022 they installed CowManager on both farms and the level of information they have captured has been crucial in the strategy change.

“The nutrition tool showed us at Grieve Road our rumination was low – therefore a change in diet was made,” Andre adds.

Rumination has improved across both farms and highlighted the importance

in the dry period and transitioning cows while calving down has helped with milk production, but also getting them cycling quickly again post calving.

“During mating it has simplified our system, we can run a pre-mating report and see if we require any intervention, and during mating each morning we have a list of cycling with some of these having no visual signs we would have previously missed.”

It has also helped reduce animal health costs with identifying sick cows earlier which means they spend less time out of the milking herd.

“Throughout the tough seasons and with inflation we looked for opportunities to cut costs where possible. CowManager was a cost that we saw adding a lot of value to the operation and decided to continue with it and we’re really happy with the results we’ve been gaining with it.”

Another giant win from switching to OAD has been team morale and staff retention. Andre has always prided himself on looking after staff. His manager Lindsay Williams has worked alongside him for the last 11 years.

“One thing I’ve been told is you can’t roll out a good strategy without good team culture. It will never succeed. With this in mind we took our staff along this journey with us, they have been involved in the Zoom calls with Kim, CowManager tutorials, farm consults, etc.

“We have shared our strategy with our staff and the reasons behind it. We have our monthly production targets on the wall in the dairy office and at our weekly meetings we measure how we are tracking towards these, and ensure we are all working together to achieve these.”

This has led to great team culture, executing their strategy and their staff feel empowered.

“The last two seasons we have really worked on this and this season it’s really showing. Nat and I can slip away without any dramas. We can do it because everyone knows their jobs and there is a good culture.”

All the staff on the dairy units choose to still milk the cows at 5.30am and on the weekends they can be finished by 8.30am and take the family out for the day. Or finish early in the afternoon during the week to take the kids to their sport or drive the five minutes down the road to the beach.

“We make it very clear, we still pay our staff the same as on a TAD farm, we don’t sacrifice on that wage. They do similar hours, but more hours are out of the shed benefiting the farm maintenance, etc. and it allows us to be more family orientated.”

The Cameron family business owns a trailer with a barbecue and longline, surfcaster rods and whitebait nets for staff to use and enjoy the beach on their time off.

Through their struggles and poor farm results before doing their strategy change it was becoming very hard to show up each day, Natalie says.

“When you and your staff put in 110% effort, but get back poor results it really does affect you all. We love this industry and that’s why giving up wasn’t an option, even though sometimes that seemed the easier way out. Instead we used all the industry help we could, our family, and did a lot of research.”

The couple were asked to host field days about their journey and at the start it was daunting to open up their business to judgement of others.

“However, we were told that there are so many other farmers in the last couple of years in the same situation and that we need farmers to speak up to support each other and know we aren’t alone; then it made the decision easier,” she says.

“Just like this article, the more people we can connect with and make feel less alone in hard times means a lot to us, but to also share the learnings we’ve had along the way during our research is awesome too.”

For drier, cleaner loafing areas & superior pasture management

Could gene editing animals spell the end to costly, painful diseases? US scientists have used CRISPR and cloning to create an animal resistant to BVD.

Words ANNE LEE

n the heart of Nebraska, United States, a three-year-old cow named Ginger is about to produce her first calf. It is a big moment for scientists in the US and worldwide because Ginger is no ordinary cow.

She is a clone, with one important exception to her genetic make-up when compared with her mother – she has the world’s first gene-edited genome for resistance to Bovine Viral Diarrhoea (BVD).

While the disease does cause diarrhoea, it is also a respiratory disorder as well as a disease that can have severe impacts on reproductive performance, reduce milk production and cause mastitis.

DairyNZ estimates the disease costs about $127 million per year to the dairy sector in New Zealand.

Dr Aspen Workman is the lead researcher responsible for Ginger’s existence, heading up a team of scientists from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), US Meat Animal Research Center, the University

of Nebraska-Lincoln, the University of Kentucky, and industry partners, genetics company Recombinetics and its subsidiary Acceligen.

She says one of the difficulties with BVD is that animals can be continuously shedding the virus although they’re showing no signs of it themselves.

“Another problem is BVD can cross the placenta and infect the developing foetus. There’s a critical time frame between about days 45 and 125 of gestation. If the virus infects [the foetus during that time], it can establish a lifelong, persistent infection (PI). When the (PI) calf is born, it sheds huge amounts of the virus into the environment and because it won’t ever clear that infection, it will go on to potentially infect countless other animals.”

Previous studies have identified the mode of attack of the virus and how it “comes on board” its host at a specific site of the cattle genome known as the bovine CD46 receptor.

“We wanted to target that very first interaction between the virus and the receptor at a cellular level, but we know that receptor is also involved in immune regulation for other diseases, reproduction and other important functions for the animal, so removing CD46 altogether wasn’t a viable option. Instead, we wanted to make the smallest change possible to disrupt the ability of the virus to bind on without affecting other functions.”

Work by other scientists had identified which amino acids are responsible for BVD’s ability to bind, but it was Aspen’s team that took the research to the next stage, using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to alter just six amino acids on CD46. For context, it has about 418 amino acids in total.

Although we’re risking a bit of “alphabet bamboozlement” in the explanation of

‘We wanted to make the smallest change possible to disrupt the ability of the virus to bind on without affecting other functions.’

DR ASPEN WORKMAN Lead researcher

the science, the simplified version is that the work involved removing the amino acid sequence GQVLAL, responsible for allowing BVD to bind to CD46, and replacing it with ALPTFS, a sequence identified on a pig CD46 receptor which doesn’t allow BVD to bind.

Aspen explains that doesn’t mean the work is transgenic in the traditional use of the term because typically that would mean inserting a gene from another organism. Instead, this work involved making a small substitution within a gene that already exists in the cattle genome.

The team carried out numerous tests to ensure the edit reduced BVD virus susceptibility, which it did for every cell type tested. They also checked for any

off-target modifications using whole genome sequencing and found none.

Aspen and her team then took the work a giant leap further – to produce a live calf with that gene edit. That process involved replacing the nuclei of bovine egg cells with the edited material, enabling Aspen and her team to create cloned cattle with the desired edit.

They created 16 embryos, eight with the edit and eight without. Each was placed in separate recipient cows to gestate.

Knowing that days 45–125 of gestation are critical to infection, they took one edited foetus and one unedited foetus at 100 days, exposed cells from those animals to BVD virus and tested their levels of infection.

“We saw a huge reduction in virus in the cells of every tissue type from the edited foetus,” Aspen says.

While it offers numerous benefits in experimentation, one of the big downsides of using cloning technology is the lower survival rate of embryos to full term, Aspen says.

Ginger was the only edited calf to make it to full term. She was born in July 2021. None of the unedited animals made it that far – suggesting it wasn’t the editing process itself that caused the low survival rate.

The next challenge for the scientists and Ginger, was to see if she showed the

same level of resistance to BVD as the cells of the foetus had.

Ginger and the other embryos which started out in the experiment are a GIR breed, but because none of the unedited clones survived, she was compared with a female Holstein Friesian calf born on the same day that had been fed the same colostrum replacement as the edited calf.

At 10 months of age both were exposed to the same PI animal.

“That’s the main route of virus transmission in nature, so we wanted to replicate that as closely as we could.”

The unedited calf showed typical clinical signs of infection and blood tests revealed signs of the virus in her bloodstream for 12 days after exposure.

“Our edited calf, though, did not show any signs of an upper respiratory tract infection and we could never detect the presence of the infectious virus in her blood.”

Aspen says the next steps for Ginger have been to see that she can carry on and do all the things a normal cow

would be able to do such as get in calf, produce milk and remain within normal parameters for other health aspects.

LEFT Aspen Workman and Ginger, the gene-edited cloned calf born in 2021. Ginger is soon to have her own calf which may also carry BVD resistance.

“We’ll be able to test her calf to see if being heterozygous for the edit confers any resistance to BVD.”

Aspen says the next steps may be to look at other breeds, although she doesn’t expect there would be a breed difference in the edit’s success in providing BVD resistance.

She says that in theory existing elite genetics could be edited – both males and females – with the resulting offspring, that include the BVD resistance, then able to be bred from in the usual ways.

Ginger is a proof-of-concept animal and there’s still some work to be done before we are likely to see

‘Our edited calf, though, did not show any signs of an upper respiratory tract infection and we could never detect the presence of the infectious virus in her blood.’

DR ASPEN WORKMAN Lead researcher

She’s been inseminated with semen from an unedited animal and successfully carried a pregnancy so far. She’s due to calve in December.

Ginger is homozygous for the edit which means every cell in her body including both of her sex chromosomes carry the edit.

The bull had no edit so Ginger’s offspring will be heterozygous for BVD resistance – they will have one copy of genes from Ginger with the edit and one copy from the bull without.

commercialisation of the technology, says Aspen

But Ginger is a significant marker on the gene-editing route in agriculture.

Dr Aspen Workman –gene editing for BVD resistance and cloning a world first.

The Australian Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (OGTR) will be used as the blueprint for New Zealand’s gene regulator, likely to be proposed in the bill to be introduced to Parliament later this year. Anne Lee looks across the Tasman at what the OGTR is and how it works.

The Australian Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (OGTR) has been in existence for almost 24 years as an independent, statutory decision maker for activities with genetically modified organisms (GMO).

The office is headed by the gene technology regulator, which is an appointed role. Dr Raj Bhula has been in the role for eight years and has been reappointed through to 2026.

She explains that anyone wanting to work with a GMO must have an approval or apply for a licence and, under the current system, the type of licence is dependent on whether the organism is to be released into the wider environment or not.

Work with a GMO within a laboratory for research for instance requires a “dealing not involving an intentional release (DNIR) licence”.

But a “dealing involving an intentional release (DIR) licence” is required if a crop that has any genetic modification, for instance, is to be trialled or sold commercially.

As of June 2023, there were 56 current DIR and 157 DNIR licences.

Genetically modified (GM) canola, cotton, safflower, carnations, banana and

Indian mustard have all been licensed and are grown commercially in Australia.

Almost 100% of the cotton grown in Australia is GM with various insectresistant and herbicide-tolerant traits. During 2022–23 there were also 932 notifiable low-risk dealings (NLRD) notifications received which were predominantly for research work being carried out in certified facilities.

There are changes afoot to the process though that will likely also see the introduction of a permit-style system for lower-risk research work such as medical studies and clinical trials operating under standardised, compliance-monitored conditions in a laboratory or hospital setting.

Some application processes may be streamlined too, such as instances where field-trial licences are being sought for crops with the same traits as those trialled under licence for many years.

Herbicide-tolerant cotton field trials of a new cultivar that contains the same genetic trait as others already grown commercially could be an example, Raj says.

“The two categories that were put in place at the beginning of the scheme don’t quite fit neatly with everything that’s coming to the office now.”

The OGTR includes two branches.

One is the evaluation branch which carries out the evaluation of licence applications and prepares risk assessment and risk management plans.

The other is the regulatory practice and compliance branch which includes the monitoring of licences to ensure any dealings with GMOs are being carried out in accordance with legislation and licence conditions. The team monitors and audits facilities and field-trial sites. It also inspects field-trial releases to ensure they are carried out so they meet licence requirements.

Raj’s advice for NZ is to have that compliance team in-house.

“It helps that there’s good communication between the risk assessors and the people going out doing the inspections and compliance monitoring.”

When it comes to assessing risk and evaluating licence applications, she also has words of wisdom.

“Make sure you have a very good technical advisory committee. I know NZ has very good expertise and it’s important the expert panel has a range of expertise. Seeking advice from experts elsewhere is also important if the risk assessment team feels they need to.”

The first step in a typical DIR application is to make a public notification informing the public, interest groups, government agencies and expert organisations that an application has been received and what it is for.

The next step is for the staff at the OGTR to carry out a risk assessment and draw up a risk assessment and risk management plan.

Raj says staff at the OGTR carry out extensive reviews of known research on the GMO and can seek advice from experts both in Australia or overseas. While the OGTR sits under the Department of Health and Aged Care, advice is also sought from experts in environmental risk assessment with a close working relationship with the Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water.

The OGTR works with a range of other regulatory organisations too, such as Food Standards Australia New Zealand, the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority and state and federal authorities so advice and consultation can be carried out with the relevant authorities to the application.

These organisations often also have roles to play in regulating effects of the GMOs or the GMOs themselves.

A critical part of the OGTR’s structure and the licensing process is consultation with the 14-member gene technology technical advisory committee.

For a DIR, that consultation with the committee happens twice – once in drawing up the assessment and risk management plan and then again when the assessment and plan are completed. The technical committee is appointed and includes experts with a range of technical knowledge across a number of fields. They look for any gaps, ask a lot of questions and provide feedback for the regulator, Raj says.

The role of the technical expert committee is purely advisory. It does not make decisions on licence applications –that is up to the regulator.

The panel must include a member of another expert group – the gene technology ethics and community consultative committee which has nine members.

In determining risk, a wide range of factors will be taken into account such as

allergenicity, toxicity, potential effects on human and environmental health.

The OGTR operates using a published risk analysis framework.

All submissions including those from the public and interest groups received through the consultation phase are considered when finalising the risk assessment and risk management plan and before the regulator makes a decision on whether or not to issue a licence.

Over the years few applications have been turned down but Raj says in many cases where the application was unlikely

to gain a licence, the applicant would withdraw their application prior to the decision being made.

A crop that has been grown for a long period under licence and has shown no deleterious impacts on human health or the environment, may be placed on the GMO register which could mean anyone is then able to grow it without a licence.

Up until August, carnations – genetically modified for their colour – were the only organisms listed on the register but the OGTR has recently added GM canola –tolerant to the herbicide glyphosate.

In 2019 the OGTR proposed not regulating any genetic modifications made using gene editing where no new genetic material is added.

Known as SDN1 gene editing, it often involves CRISPR-Cas9 technology and results in a break in the genome that may cause a deletion or a modification where a gene is silenced or knocked out. It can also lead to a modification through spontaneous repair of the break that creates a mutation. It’s argued that the end result could theoretically be no different to a natural mutation.

In the risk assessment and risk management plan it was noted that any risks associated with increased use of glyphosate on the crop were outside the scope of the OGTR’s assessments, with its focus on the crop and any effects associated with the GMO itself.

The OGTR releases a number of reports each year on its activities and documents relating to gene technology.

Transparency and public engagement are important for the success of the OGTR, Raj says.

The annual report is detailed and quarterly updates from the OGTR as well as communiques from the technical advisory committee meetings are all posted on the OGTR’s website along with licence conditions.

Community attitude surveys are also regularly carried out and posted on the website.

In the latest survey, published in June, support for genetic modification was reportedly stable with 38% of the Australian community in support of its use in general and 20% against it. There remains a large proportion of the community sitting on the fence at 37% and 6% say they don’t know how they feel.

Support for food crops rose from 38% in 2019 to 44% in 2021 and has settled back to 42% in 2024.

The survey found that for farmers whose income mostly comes from primary production, support for genetic modification and gene technology was greater than for people who do not generate any income from primary production (64% compared to 32%). Similarly, farmers showed greater support for uses in food and crops (63% to 31%), and believe it is a safe way to produce food (43% compared to 16%).

It is often impossible for an SDN1 modification to be detected as a “manufactured modification” as opposed to a naturally occurring variation.

Raj says there was plenty of debate at the time with organic and anti-GMO groups opposed to it. Some states set up moratoria on GMOs but she says they have largely fallen away now with just Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Kangaroo Island remaining GMO-free.

“In the end the debate narrowed to market access rather than risks to health and environment. But when it comes to market access – there are then issues because you can’t detect that GM technology has been used.

“So, traceability is another issue and that’s something that was discussed a lot. If SDN1 had been used in a plant breeding programme, do we want to know about that if the final organism is the same as a conventionally bred plant?

“That’s something NZ will have to work out for itself. But here we don’t regulate organisms developed using SDN1.”

LIC is dipping its toe in the water with gene editing, collaborating offshore with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and gene technology company Acceligen in the United States to produce animals with gene edits that improve outcomes for cattle in Africa. Why, and what could this mean for New Zealand?

Words ANNE LEE

LIC’s involvement in a global partnership that could see a world-first, large-scale breeding programme using semen from geneedited bulls will allow the NZ farmerowned co-operative to build experience in the new technology ahead of regulation changes in NZ.

LIC chief executive David Chin announced plans in September for LIC to supply high breeding worth (BW), low-methane embryos as part of a collaborative project with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The foundation is meeting the $8.3 million cost.

Stem cells from the embryos will be gene edited in the US by Acceligen, a subsidiary of genetic company Recombinetics.

LIC international dairy development manager Jason Schrier is the project lead for LIC and says the project aims to develop gene-edited animals for the Sub-Saharan African environment for smallholder dairy farmers.

The gene edits will include the Slick gene which causes animals to have a shorter, finer coat and confers other heat-tolerance benefits. LIC discovered the Slick variant and holds the intellectual property rights on Slick testing.

Jason says three other gene edits will be carried out – one will be the Bovine Viral Diarrhoea (BVD) resistance edit (see page 24 for more). Another edit will create resistance to trypanosomiasis (Tryp), transmitted by the tsetse fly, which causes anaemia, weight loss and fever in cattle. Humans can be infected by bites

from infected tsetse fly too and catch African sleeping sickness.

The fourth edit is yet to be decided but may be resistance to East Coast Fever, a tick-borne disease that causes anaemia in cattle, or it could be an edit that confers resistance to Bovine tuberculosis (TB).

The gene-edited, male-sexed embryos will be transplanted into recipient cows in the US with the aim to produce 20 gene-edited bull calves that will then be transported to Brazil to be reared as elite sires.

The target is for one million semen straws to be collected from the bulls with straws then sold and distributed in Sub-Saharan Africa through a developed distributor network.

All the edits involve dominant homozygous traits so all calves sired by the edited bull semen will display the traits even though the mothers’ genetics don’t carry those genes.

LIC has been working with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in Africa since 2017.

“They initially approached us to design a livestock information system for Ethiopia with the Ministry of Agriculture there,” Jason says. He’s spent time in Africa throughout that project and has made subsequent trips to progress this new project.

LIC is in the process of breeding the Slick gene into animals using conventional breeding programmes here in NZ, but Jason says the project to edit it into the cattle genome using CRISPR is giving LIC the opportunity to learn more about the process ahead of the legislation changes

the NZ Government has signalled for this country for next year.

“Gene editing also enables us to get the Slick variant into animals far quicker than natural breeding programmes,” Jason says.

Speed is important if NZ and LIC want to play a part in meeting future global food demands, with predictions the world could face a food supply crisis by 2050 due to increasing demand but lower production because of impacts caused by climate change, he says.

LIC general manager commercial Dr Emma Blott says CRISPR technology allows scientists to make a very precise cut in the receptor protein prolactin to truncate that protein and bring about the Slick, short-haired coat phenotype.

The work does not involve transgenics –bringing genes from other species.

She says LIC’s role in the project is multifactorial including having an impact on sustaining and growing dairy production globally. The project will enable LIC to help create improved economic, animal welfare and human welfare outcomes for tropical countries and will also help build knowledge and experience in gene-editing technology.

“Any learnings we have from this over the longer term could be applied to our home market or other international markets in the future, depending on legislation and stakeholder support which of course would include our farmers, dairy customers and the general public,” she says.

Farmer feedback on the project has included questioning the role of the Bill

“The questions have been more around what this technology could provide for their farm in the future. Do we have any intention of bringing that back?

“Some are excited, I’d say some are interested and some are nervous.”

Emma hopes that by sharing information about the project as it progresses, LIC will be able to educate, collect data and myth-bust.

More than 18 months ago LIC carried out surveys of its stakeholders, including a subset of its shareholders to gauge feedback on gene-editing technologies to help develop its stance and determine if it should be involved in such projects.

with the sustainability challenges we have in NZ and globally.

“But it’s really important we don’t introduce any changes into our very valuable food value chain here in NZ without the consensus and understanding of everyone involved along that chain. Because ultimately, what we do upstream here with the animals actually impacts the milk and the meat that ends up with our consumers overseas and in NZ. It’s very important that this is done with learnings, education and very broad consultation.”

Like many others, LIC will be extremely interested to see more detail of the proposed gene technologies bill to be introduced to parliament later this year.

L earning to read starts early in life. It’s a critical skill. Financial literacy and being able to read the language of money and finance is a skill often neglected but one that’s also hugely important.

The terms and jargon can be daunting if they’re not familiar to you, so in this special report we’re stepping you through some of those terms with our glossary.

We’re also making sure you understand the wondrous power of compounding and providing some advice from rural professionals, as well as giving you some insight into how one family farming business always has their numbers at their fingertips.

Words ANNE LEE

A balance sheet is a snapshot of your financial position at a specific time. It shows:

• Assets: What you own

• Liabilities: What you owe

• Equity: What’s left after subtracting what you owe from what you own.

For example, if you want to borrow money, the bank will look at your balance sheet to understand your financial situation. Sometimes it is referred to as your statement of financial position.

These are the things you own. Even if you still owe money on them, they count as assets.

Example: If you have a tractor worth $50,000 but still owe $20,000, the tractor is listed as an asset at its full value of $50,000.

Liabilities are your debts – what you owe to others. This could include:

• Bank loans

• Money you owe for equipment

• Debts to family or other lenders.

Equity is the part of your assets that you actually own outright. It’s calculated like this: Assets - Liabilities = Equity

Example: If your assets are worth $500,000 and you owe $300,000, your equity is $200,000.

This ratio shows how much of your business (total asset value) is funded by debt. Banks use this to measure risk. Debt/Asset x 100

Example: If you owe $100,000 and have $200,000 in assets:

$100,000

$200,000 x 100 = 50%

This measures how much profit you’re making from your assets. It’s useful for assessing the efficiency of your assets to generate a return and is a good way to compare investments. Return (or operating profit)/asset value x 100

Example: If you have an operating profit of $800,000 and assets worth $9 million:

$800,000

$9,000,000 x 100 = 8.8%

Similar to ROA but also includes any gain or loss in the value of your assets over the year.

Example: If your operating profit is $800,000 and your assets increased in value from $9 million to $9.35 million:

$800,000 + $350,000

$9,000,000 x 100 = 12.7%

ROE shows how much profit you’re making from the money you’ve invested, not just the total assets, after accounting for loan interest.

(Return - Interest Cost) / Equity x 100

Example: If your operating profit is $800,000, interest costs are $394,200, and equity is $4.5 million:

$800,000 - $394,200

$4,500,000 x 100 = 9.02%

A budget is your financial plan for the year. It lists all your income (like milk and stock sales) and your expenses (like farm running costs).

A cashflow report shows when money comes in to your business account and goes out each month. It helps you see when you’ll need extra funds, like an overdraft, to cover expenses during low-income or high-expense months.

This report compares your actual budget or cashflow with what you expected, showing whether you’re on track or not.

EBIT is your income after all farm operating costs are paid, but before interest and tax are taken out.

Operating profit includes all your income and expenses, as well as changes in the value of things like livestock, feed inventory, and depreciation. Unpaid family labour and support adjustments are also made. These adjustments ensure that operating profit is the best way to compare farms on a likefor-like basis. It can be expressed on a per hectare, per kg milksolids (MS) or per cow basis when making comparisons.

Depreciation is the gradual loss in value of equipment, buildings and infrastructure over time due to wear and tear. While it doesn’t directly affect your cash balance in the short term, over longer periods of time it should approximate the capital expenditure required to replace these items.

Learning to read the numbers and decipher what they’re telling you is a skill that can be learned. Anne Lee talks to long-time financial educator Paul Bird about the process and discovers the wonder of compounding.

Becoming proficient in any language takes time and practice. The language of finance is no different.

DairyNZ’s Paul Bird has been coaching farmers in the money side of their farming business for more than 20 years.

“Managing budgets and cashflows, doing the accounts – that’s not usually what draws people into farming. But when you understand what those things are telling you, when you can look at the numbers and see the story clearly, that’s when you can be in control of the narrative,” he says.

Paul cites renowned investor Warren Buffett when he says, “Accounting is the language of business.

“There are key accounting terms and financial KPIs (key performance indicators) that tell you where you’re at and if you’re heading in the right direction. They help you see what’s working well and to pinpoint where you need to improve. They also help you make decisions about what to do next, to analyse a venture proposition and see an opportunity.

“If you don’t understand those terms and KPIs, it would be like living in a foreign country and not being able to speak the language. Everything would be so much more difficult.”

Just as it takes time to become fluent in a language, it takes time to become fluent in the language of money.

“If you were moving to France and didn’t speak French, you wouldn’t expect to just turn up and be able to converse. You’d buy the CD and put it in your car or download the app on your phone and start by learning how to say the basics.”

The dairy sector provides numerous opportunities to learn financial skills whether that’s through courses such as those offered by Dairy Training (a subsidiary of DairyNZ) or Primary ITO, online webinars run by farming groups,

accountants or accounting software companies.

“For those starting out, it might mean asking your farm owner or the sharemilker you’re working for, “Hey, when you do your budgets do you mind if I’m involved so I can see what you do and how you do it? Can I sit in when you’re doing your cashflows?”

Paul warns people not to get discouraged if they don’t understand every concept straight away.

“Persevere and practise and don’t be afraid to ask.”

Building financial skills isn’t just for those starting out. Those who have

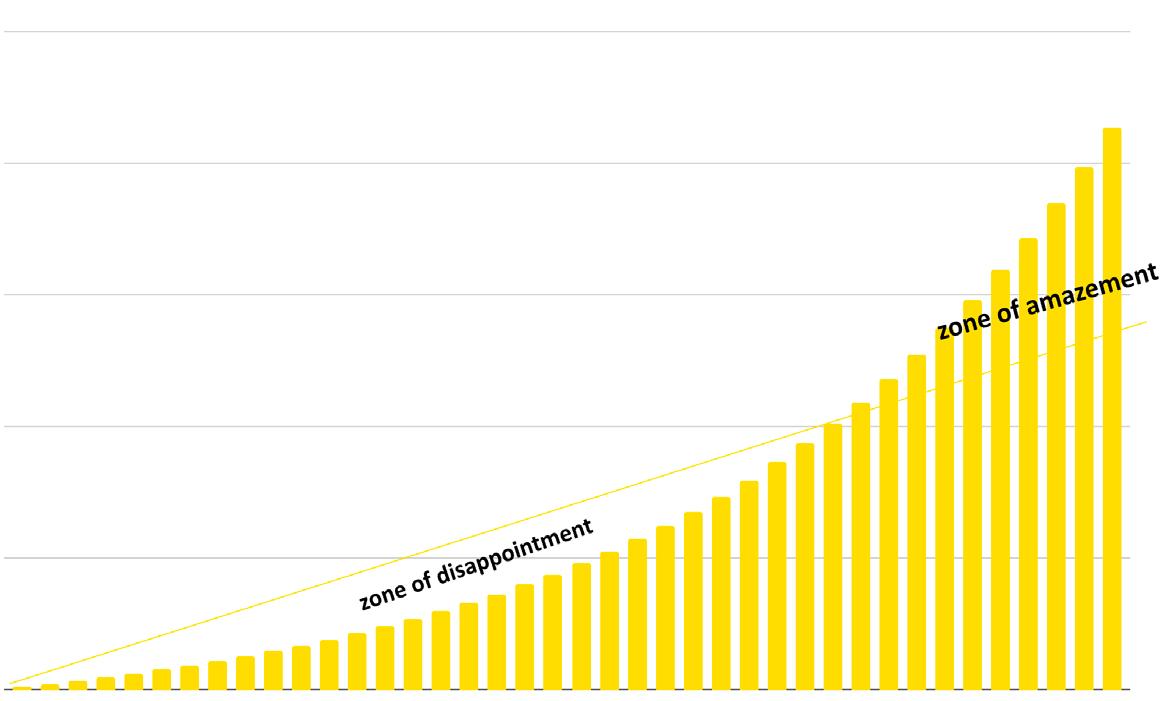

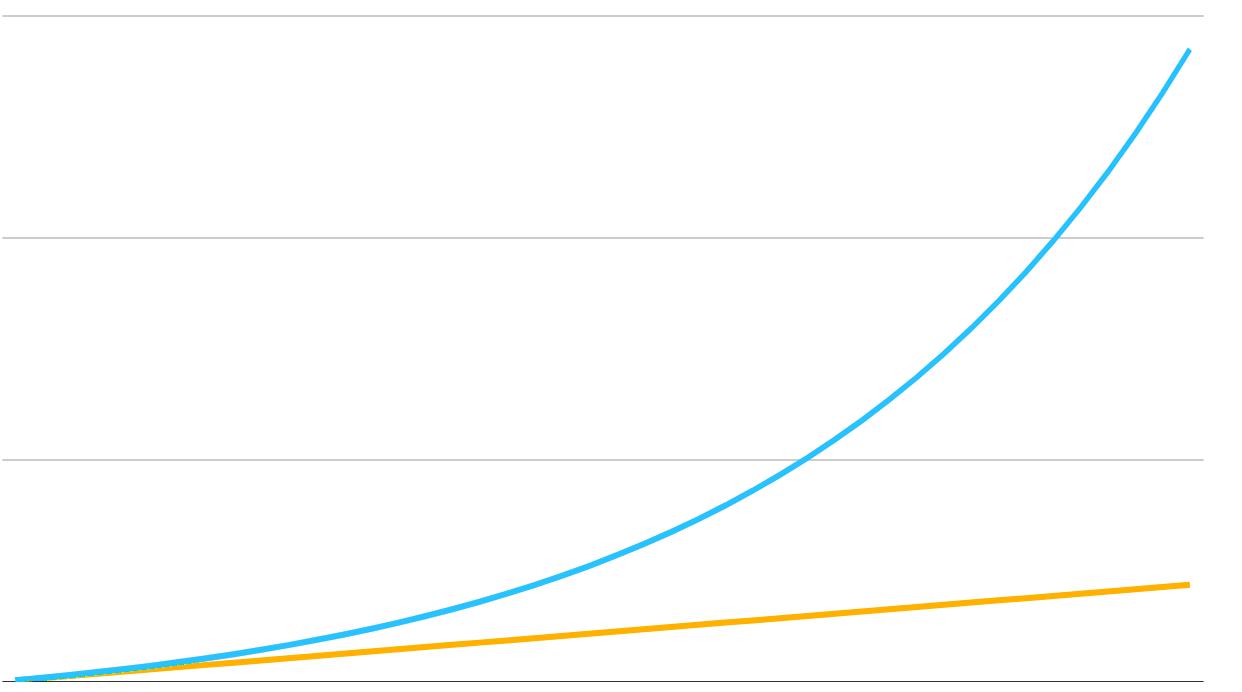

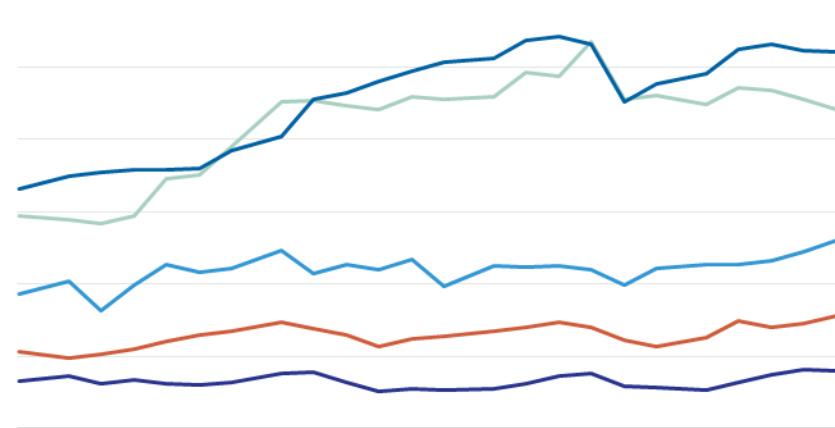

SAVING $20,000 PER YEAR AT 7% RETURN FOR 40 YEARS

been in business for longer can lean on their advisers and shouldn’t be afraid to ask for deeper explanations so they can better understand the advice, ask probing questions and be in control of where the business is going.

“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t … pays it.” Albert Einstein.

Grasping the concept of compounding can be a pivotal “aha” moment for people in business, savers and investors alike, Paul says.

The magic happens when people see that by reinvesting the interest or the returns they have made on an investment each year, they then have a greater amount to earn interest on the next year.

Although the percentage return on the investment or the interest rate remains the same year-over-year, the amount earned grows exponentially as the savings and amount reinvested back grows.

For example:

$100 invested at a 10% interest rate will return $10.

If that’s added back to the original investment, it becomes $110 so a 10% return on that at the end of the next year gives $11, so the original amount is now $121.

At the end of the third year, at the same 10% return, the payment will be $12.10 so you will have $133.10. The total is growing by a larger amount each year. Fast-forward 20 years and the annual increase has gone from $10 to $61.16 and you have $672.75 from that initial $100 even though you’ve done nothing more than returning the interest back into the account each year.

Using your calculator to work out the final compounded value. In this example we use a $20,000 investment with a 10% or 8% return over 10 years.

‘By returning that interest and sticking with the $20,000 annual savings you will have put in $820,000 (in the $20,000 increments), but thanks to the power of compounding you will have $4.5m and be earning $300,453 a year in interest.’

Now look what happens when you do more than just put in a one-off amount at the beginning and each year you consistently save a more significant amount.

The power of compounding really comes into its own.

A $20,000/year saving plan at a 7% return (10% adjusted for inflation) will be returning you an extra $22,097/year. By year 10 you will effectively be doubling what you put in that year.

Step one

Step two

Enter the original amount. Multiply the original amount by 1 plus the interest rate (if

Step three

Press the equals button on the calculator for the number of years you want to calculate the return over (for 10 years press the equals button 10 times). $20,000

Your total savings will have ballooned up to $315,672 – an extra $95,000 over what you have put in of your own money.

If you stick with it for 21 years you will have just over a $1 million savings and each year you will be earning $68,608.

By the end of 40 years, by returning that interest and sticking with the $20,000 annual savings you will have put in $820,000 (in the $20,000 increments) but thanks to the power of compounding you will have $4.5m and be earning $300,453/ year in interest.

In the early years, when saving $20,000/ year may be taking big sacrifices, people can feel disappointed that the savings aren’t going up as fast as they’d like.

“The magic happens when they persevere and those numbers start rising exponentially – they enter the zone of amazement,” says Paul. “Those who truly understand compounding connect daily decisions with long-term wealth creation.”

For instance, if better pasture management leads to an additional 1 tonne of drymatter (DM) per year, that’s an extra $350/ha/year added income. For an average 140ha farm, that’s an extra $49,000/year.

But on a compounding basis, at a 7%/year return, over 30 years that’s equivalent to $5m or $3.6m after tax of additional income.

If you have this mindset, you’ll look at your purchasing decisions a bit differently too.

A one-off capital saving of say $25,000 by purchasing a reliable second-hand vehicle over a brand-new, flash, shiny farm vehicle would be $190,000 if that

one-off saving was invested at a 7% return for 30 years.

“You’ve got to think about making your money work for you over the longer term.”

Paul says he uses 10% per year as a standard return because historically global sharemarkets have returned that amount over longer periods of 25-plus years.

When he takes into account inflation, that long-term return figure becomes 7% per year.

“What we often see is people in their thirties feeling like it’s all just not happening fast enough for them, but there’s a point where the exponential nature of compounding means you start seeing those numbers going up significantly every year.

“Hang in there – if you’re disciplined the rewards are really worth it.”

DairyNZ has several online tools such as:

• Budget templates for farms supplying each of the major processors.

• Cashflow budgets.

• A partial budget to help analyse options.

• Calculators to assess returns from contract milking and variable order sharemilking contracts which include budgets.

• A stock reconciliation calculator to help work out the change in livestock values from year to year and to calculate livestock income.

• A guide for calculating return on assets and return on equity.

$6,000,000

$4,000,000

Forecasting your season ahead and picking the right tax payment system may help to avoid that unexpected eye-watering tax bill.

Words TRUDI BALLANTYNE

One of the pet hates a rural bank manager has is the phone call from a farmer asking for an overdraft extension to pay an unexpected tax bill.

The volatility of farming incomes can often lead to tax surprises – where you are suddenly asked to pay a large amount of tax or where you receive a large tax refund because you shouldn’t have had to pay the tax in the first place.

The traditional provisional tax system means tax payments for the current season are based on what your farm earned in the previous season – or if your financial statements are prepared late – on what happened the season before that. As we know, milk prices, onfarm costs and changing interest rates cause farm profitability to drastically change from year to year – meaning the tax being paid may not be based on upto-date information.

To avoid this, farmers need to “know their numbers”. They need to prepare a forecast to understand what the year ahead looks like. There are some excellent software providers out there that, in conjunction with your accountant, can make this a pain-free process. Once you have a draft budget, ask your accountant to look it over and add in the likely tax flowing from those numbers. By doing this, you are highlighting to your accountant that your profitability is going to vary from the previous year, and you can start a discussion about the best way to handle the tax volatility.

If your profit is going to increase, you may want to consider making a voluntary payment to IRD to avoid hefty interest charges. Alternatively, if your profit is dropping, consideration should be given to filing an estimate with IRD.

There is an alternative to the traditional provisional tax system – AIM – Accounting Income Method. This system allows you to pay your provisional tax every two months alongside your GST. The payment is calculated based on your actual profit for the two-month period. This means you are only paying tax in the periods you make a profit. This may mean that for the first half of the dairy season, provisional

tax payments are minimal with higher payments later in the season as cash starts to flow.

AIM returns do need to be filed in conjunction with your accountant. They need to check over the coding in your accounting software and make sure things like asset purchases and depreciation are calculated correctly every two months – but this is stuff they have to do at the end of the year anyway. By getting an accurate profit result every two months, you get to the end of the financial year with some certainty that your provisional tax payments made via AIM are reasonably accurate and the money left in the bank at the end of the financial year is all yours.

‘By getting an accurate profit result every two months, you get to the end of the financial year with some certainty that your provisional tax payments made via AIM are reasonably accurate and the money left in the bank at the end of the financial year is all yours.’

Whether you use the traditional provisional tax system or the newer AIM system, being proactive with your financial forecasts means you can avoid nasty tax surprises.

Successful farming hinges on more than just good soil and weather; it relies on disciplined financial management, from tidy records to strategic budgeting and clear communication.

Words CHRIS LEWIS

Atop farmer once told me, “A drive around the tanker track will tell you a lot about a farm.” They were right. A tidy, well-organised, well-run farm can be picked out inside the first 200 metres of the farmgate.

In the same fashion, you can pick a business with good financial management by a glance at the farm office desk. Is it tidy and organised, paper records filed, not loosely stacked?

Then you flick open the computer. The cashbook is up to date and reconciling. The budget is being utilised and has an accurate livestock tally.

When you ask a good farming family about their business they can talk to key financial numbers without a flurry of paperwork. They can comfortably answer questions like:

• What is your cost structure per kilogram of milksolids (kg MS)?

• What is your breakeven milk price?

• Which months are tight for cashflow?

• What trading result is expected this season?

• How strong is the balance sheet?

It would be remiss if this article did not pause and reflect on communication of the business plan and financial aspirations. The most important place being at the dinner table. Are spouses

talking the same language? Do they work as a team and commit to the same plan? Are the sacrifices needed to progress being shared?

The successful family business will regularly talk about what they are trying to achieve. They know how far away they are from achieving it and agree on what needs to be done to get there.

With the shared dream, good business systems and a clear plan, the successful farming family will communicate well with their advisers and mentors. Business goals are well articulated and progress towards achievement is being monitored.

Then with a clear understanding of what needs to be achieved, direction can be given to the farm team on implementation. Expectations for physical performance are clear. There will be a few simple monitoring points and if the direction of travel is not as planned, an alert will sound.

Milk production falling below target. Farm expenses tracking ahead of the budget. Feed purchases up or inventory building. Unexpected repairs and maintenance costs. All of these will raise flags in a well-managed dairy farm business and bring about prompt and appropriate management responses.

Timeliness of well-informed decisions are core to good business management.

Your accountant, bank manager and farm consultant will be quick to recognise the above. The accountant recognises the clients that are prompt with their annual records and compliance (PAYE, GST, operating consents) reporting. The informed farming client doesn’t just have tidy records. They are asking questions of their accountant about insights into financial performance, tax management, and seek their expertise.

The bank manager will see budgets that are connected to reality. There will be searching questions from the client about margins, debt structure and interest rate decisions. Funding requests will come with a clear, well-presented plan of what’s required, why and how it will be funded.

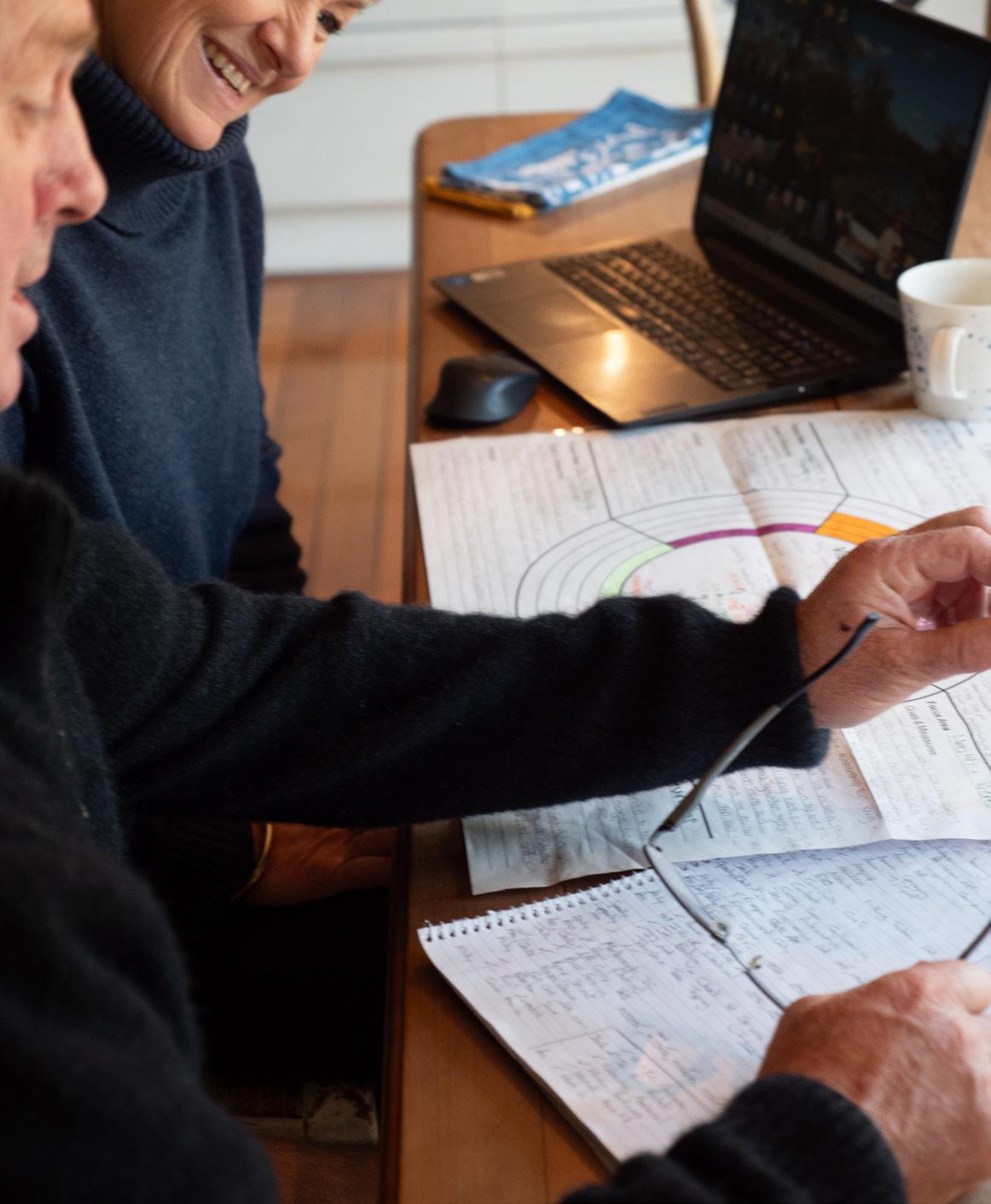

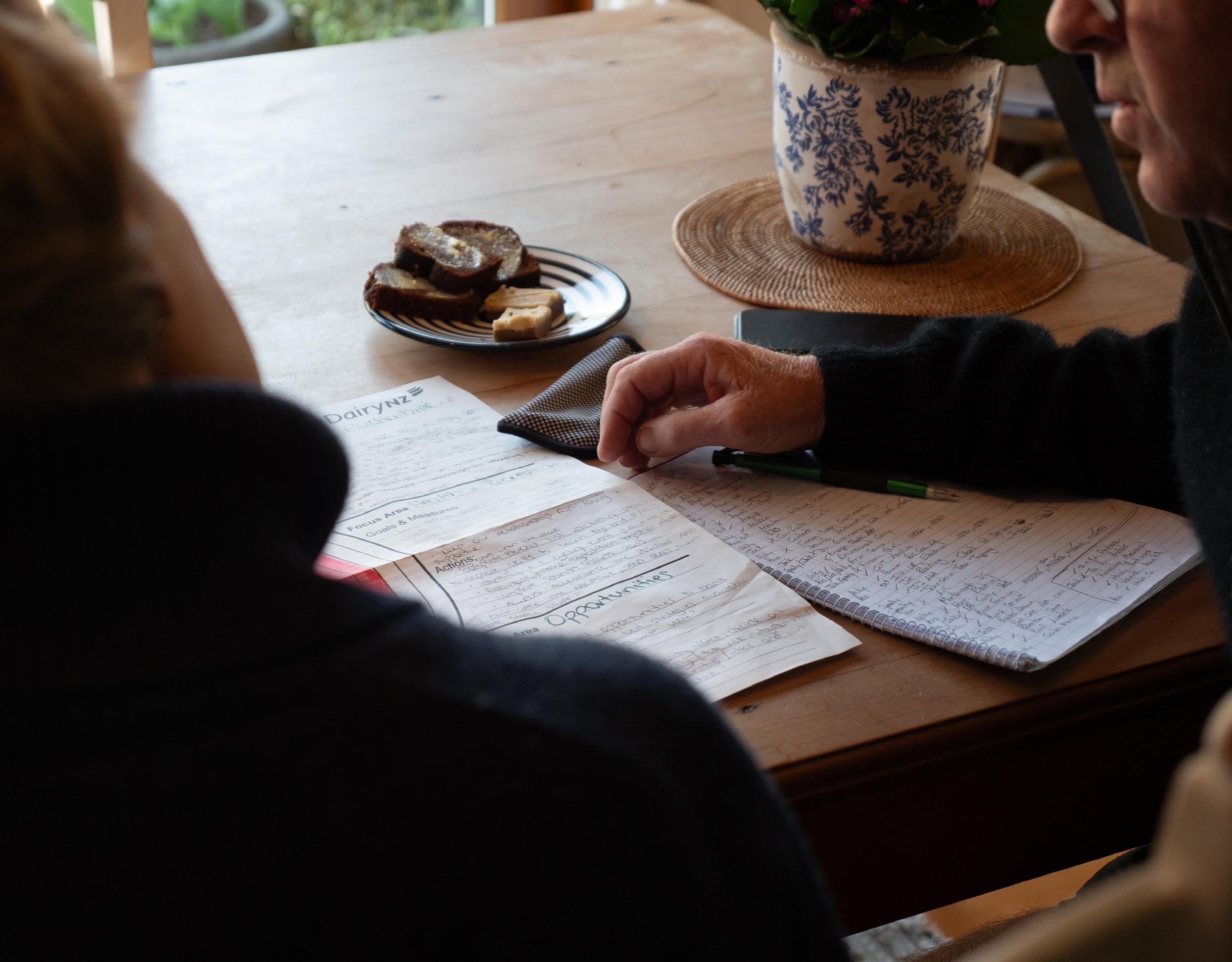

For farm consultants, working with clients on business planning, goal setting, budgeting and monitoring is the “day job”. But the clients who really lead in business, the top 10%, will have pre-prepared the core information. On farm visit day the cashbook is updated

and reconciled ready to view. They will have the financial statements and current physical performance written out and ready on the kitchen table. They know what you need before you ask and there will be a written list of questions, essentially an agenda on what they want addressed during the meeting.