2025 Number 55

Clinical Effectiveness Bulletin

Clinical Governance Directorate of the British Orthodontic Society

FREE Core CPD Online courses

FREE Core CPD Online Courses

Free registration with ProDental CPD in mandatory topics is a BOS members benefit. ProDental CPD includes courses in a range of GDC recommended topics including:

Free registration with ProDental CPD in mandatory topics is a BOS member benefit. ProDental CPD includes courses in a range of GDC recommended topics including:

Medical Emergencies

Medical Emergencies

Radiography/Radiation Protection

Radiography/Radiation Protection

Decontamination/Disinfection

Decontamination/Disinfection

To register, please email executivesec@bos.org.uk and enter BOS CPD in the subject line. Please provide your name and GDC number and you will be sent an invitation to access the FREE core CPD available to BOS members It really is that easy!

To register, please email ann.wright@bos.org.uk and enter BOS CPD in the subject line. Please provide your name and GDC number and you will be sent an invitation to access the FREE core CPD available to BOS members.

It really is that easy!

Thank you for the opportunity to update the Society on the work of the Governance team in this latest issue of the Clinical Effectiveness Bulletin (CEB). As I enter my last year as Chair of Governance and the advert for my successor has been published, it does seem an opportunity to reflect. I would like to thank Robert for his fantastic stewardship of the CEB. Robert has published an excellent series of Bulletins and has organised their contents so that all the Bulletins are searchable via the BOS website. This was an enormous task that has proved very successful and will be a lasting legacy. I would like to thank Robert on behalf of the Governance team and the BOS. The Bulletin remains an effective way for audits and service evaluations to be shared by members of the BOS and is a resource developed by our members for our members.

We continue to offer the opportunity to ask members of the Society their views on a wide range of topics through Dr Mariyah Nazir, Chair of Audit. These surveys can be very powerful and often form part of the research component of training for our specialist trainees or come directly from the Society in order to ensure our executive keeps in touch with the views of the membership. Either way, I would encourage everyone to make the effort to have your voice heard. I know we all face a daily blizzard of email requests for our attention and our opinions, but your views are crucial for the successful running of our Society, or represent the research aspirations of one of our young colleagues. They need your help so please do complete these surveys do not let them down.

Dr Sameer Patel, Chair of Publications has continued to publish and update our written information for patients and our advice sheets.

These advice sheets are not prescriptive or restrictive but represent the research and opinions of their authors who have often faced the challenges which the advice sheets might help you to avoid. I am very grateful to Sameer who has pioneered the regular publication of a selection of these documents, as too often our members would only read the advice sheet after problems had occurred. As a Society we are very fortunate we have so many members who are willing to give up their time and publish their opinions in this format and I know many members have found the information, useful and well-constructed.

I am sure we have all seen the scope of practice guidance from the General Dental Council. Our Chair of Ethics, Dr Nicky Stanford, has worked with the regulator to produce the orthodontic aspect of this scope of practice guidance. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Nicky for his dedication and steadfast support.

Finally, I would like to thank all our British Orthodontic Society team, now based at the Royal College of Surgeons of England, for their help for me as Chair of Governance. I am grateful for their patience, their wisdom and their dedication to our wonderful specialty.

Stephen Chadwick Director of Clinical Governance of the British Orthodontic Society

Aims and Scope

The British Orthodontic Society Clinical Effectivness Bulletin is an official bi-annual publication of the British Orthodontic Society Clinical Governance Directorate. The primary focus of articles in the Bulletin is the reporting of the quality of orthodontic care and ways to improve it via both clinical audit and effectiveness. The British Orthodontic Society Clinical Effectiveness Bulletin welcomes submissions reporting both these aspects of clinical governance. Clinical audits (in particular multi-cycle audits) and service evaluations would be considered for publication.

All submitted articles undergo peer-review. Acceptance of articles will be based on the recommendations of the reviewers with the final decision made by the Editor. In addition, submissions will be judged against the following criteria:

1. Does this article add anything new to the existing literature?

2. Does the subject content reflect any relevant national topics?

3. Have the authors implemented a change in clinical practice and assessed the effects? i.e. re-audits

submitted to the Editor

Articles sent to regional Sub-editors

Articles sent to peer -reviewers (Post-CSST trainees) via Sub-editors

Peer-reviewed articles returned to Editor from Sub-editors with comments/decisions Final decision made by Editor

Provisional article acceptance

Articles returned to authors including:

• Amended article

• Peer-reviewers checklist with comments/ feedback

Amended articles returned to Editor with 8 weeks for final editorial changes

Final acceptance email sent to authors prior to publication

Article rejected

Articles returned to authors including:

• Amended article

• Peer-reviewers checklist with comments/ feedback

Editor's Remarks

Welcome to the Autumn edition of the Clinical Effectiveness Bulletin.

As I come to the end of my three-year tenure as Editor of the British Orthodontic Society Clinical Effectiveness Bulletin, I’ve taken a moment to reflect on my time in the role. It has been a privilege to help shape the direction of the Bulletin and to work alongside such a dedicated editorial team, contributors, and readers.

One of the highlights of this period was overseeing the publication of our 50th issue — a significant milestone that speaks to the enduring relevance and quality of the Bulletin. Reaching this landmark was not just a celebration of longevity, but a testament to the collective efforts of all those who have contributed over the years.

Another achievement I’m particularly proud of is the development of a searchable digital archive of past articles, available on the Society’s website. This resource opens up decades of insight, discussion and scholarship to a wider audience, and I hope it will continue to support both clinical practice and academic inquiry for years to come.

Adverse Incident Reports

Since the last edition report (Spring 2025) there have been 2 incidents reported to the Society through our confidential reporting system.

A transpalatal arch fractured at the solder point whilst a patient was eating, and was subsequently swallowed. The patient was referred to A&E, following radiographic examination they were advised to allow the appliance to pass, no surgical treatment was required. Subsequent to which, a review of materials of the laboratory as well as the addition of a warning on the statement of conformity regarding safe use of intra-oral devices and risk of fracture. It was thought the appliance fatigued over time.

Congratulations to the CEB Prize winners who were announced at the conference, Ailidh Carney, Sean Daley and Joseph Bell – very well done. The quality of submissions remains high for the Bulletin, which really does make choosing the winners difficult for the Editorial team!

Throughout my time as Editor, I’ve been continually inspired by the breadth of perspectives and the spirit of collaboration that defines our community. Thank you to all who have submitted articles, offered feedback, and supported the Bulletin in countless ways. I would like to extend specific thanks to Dr Stephen Chadwick, Mr Chris Baker and the team for their support in producing this issue of the Bulletin. Finally, I would like to wish Dr Madeleine Storey all the best as she takes on the role of Editor. I leave the role with a deep sense of gratitude and confidence in the future of the publication.

Robert Smyth Editor, BOS Clinical Effectiveness Bulletin

Following the fitting of fixed anterior bite turbos on the upper central incisors, external resorption on palatal aspect of UL1 was noticed. The bite turbo was subsequently removed and the patient referred for investigation regarding root canal treatment. The bite turbo was constructed chairside using a mould and filled composite. Possible increase in occlusal forces may have contributed to the resorption.

Farooq Ahmed

Adverse Incidents Officer British Orthodontic Society

Assessment of orthodontic case complexity for NHS hospital treatment: A multicentre audit.

V Ravindra, L Cockerham, K Patel, L Davenport-Jones, R Stephens, G Mack

Are we checking orthodontic new patients for oral cancer abnormalities? A local two-cycle audit at the Queen Victoria Hospital.

L Brooks, L Rennie

A two-cycle audit assessing the orthodontic attendances at the Royal Surrey Hospital.

J Watt, S K Kassam, N Taylor, G Minhas

A service evaluation of virtual orthodontic education clinics at the Birmingham Dental Hospital.

N Caratela, A Bains, S Higgins, S Kotecha

A multi-centre two-cycle audit into the use of Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) for investigation of ectopic canines.

B Gill, F Jones, C Casey

A two-cycle audit to assess orthodontic treatment outcomes at Liverpool University Dental Hospital.

YM Lin, S Turner, J Harrison

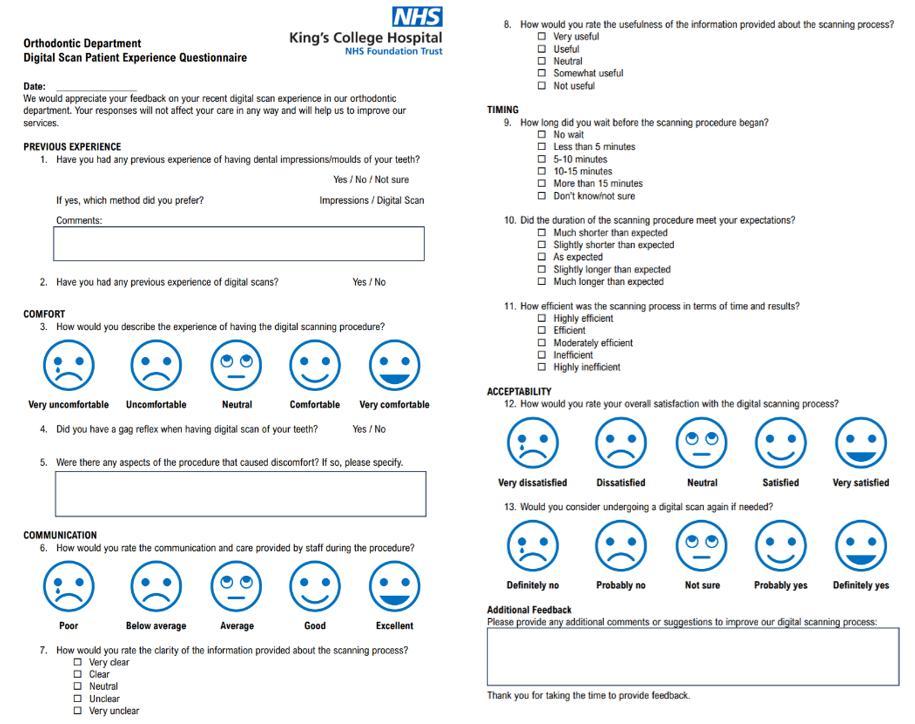

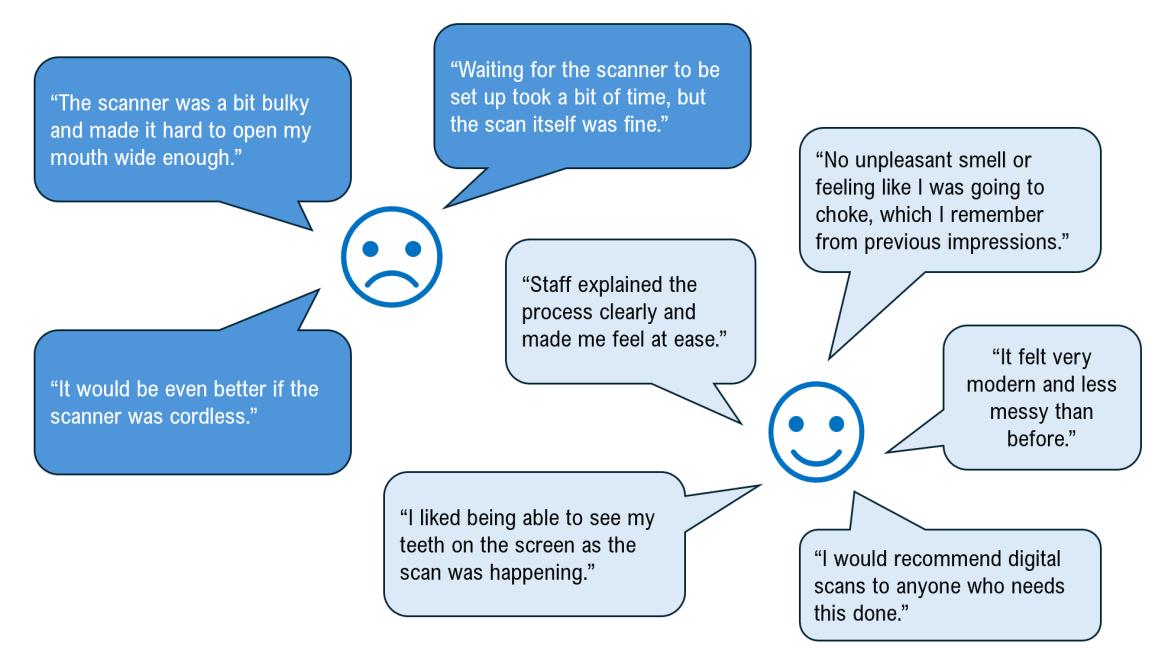

Patient experience of digital scans in the orthodontic department at King’s Dental Institute: A service evaluation.

B McGuckin, J Watt, M Shahid Noorani

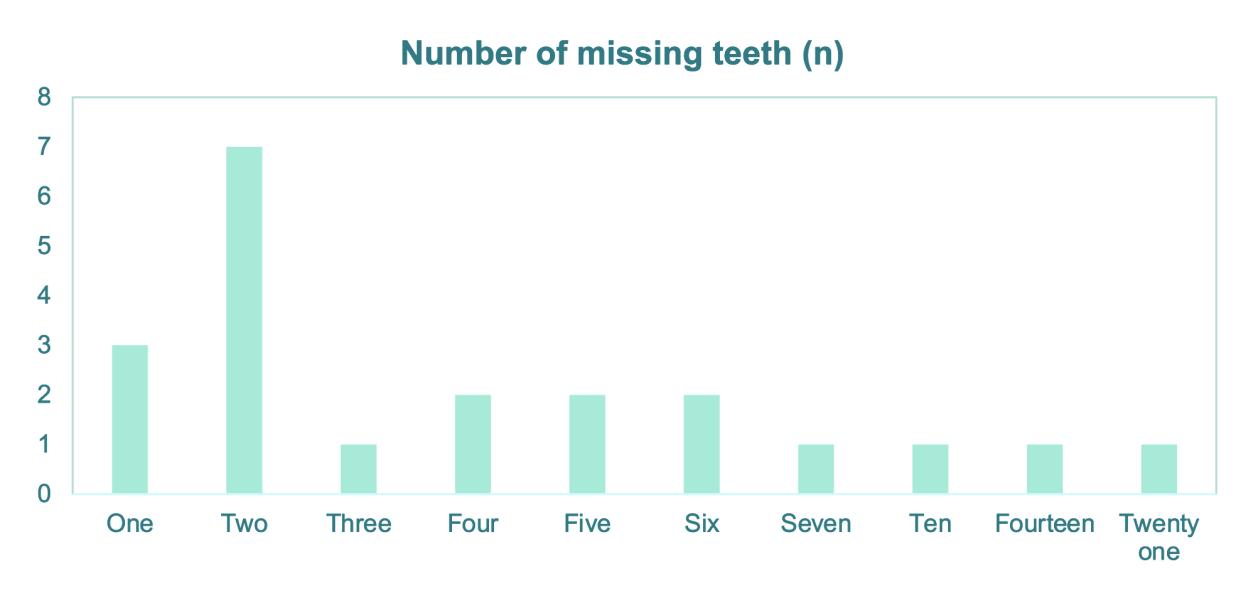

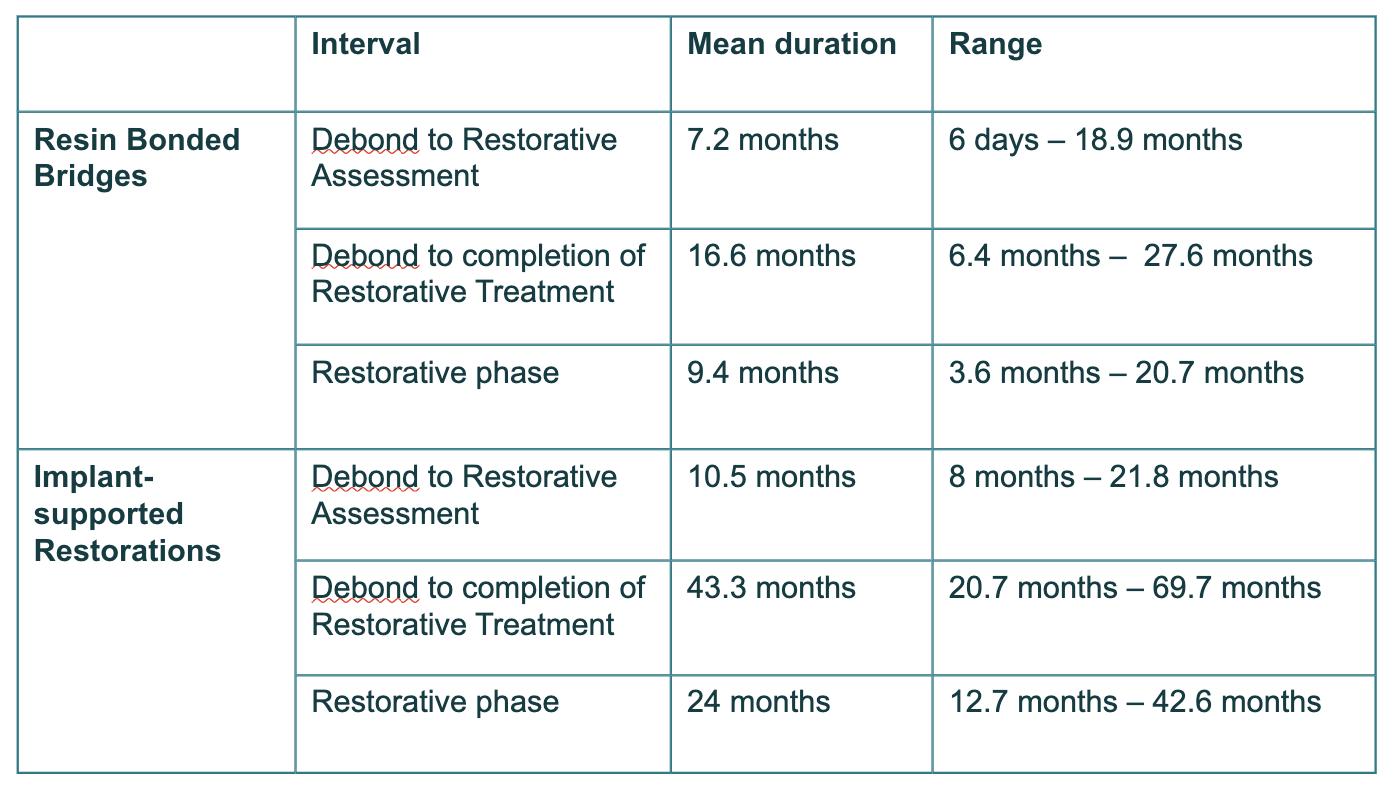

Managing the gap: a local service evaluation of the multidisciplinary management of hypodontia.

SL Tan, M Aldihani, R Jennings, H Moseley, FS Ryan

Ectopic maxillary canine referrals: A two-cycle audit.

A Carter, R O’Brien

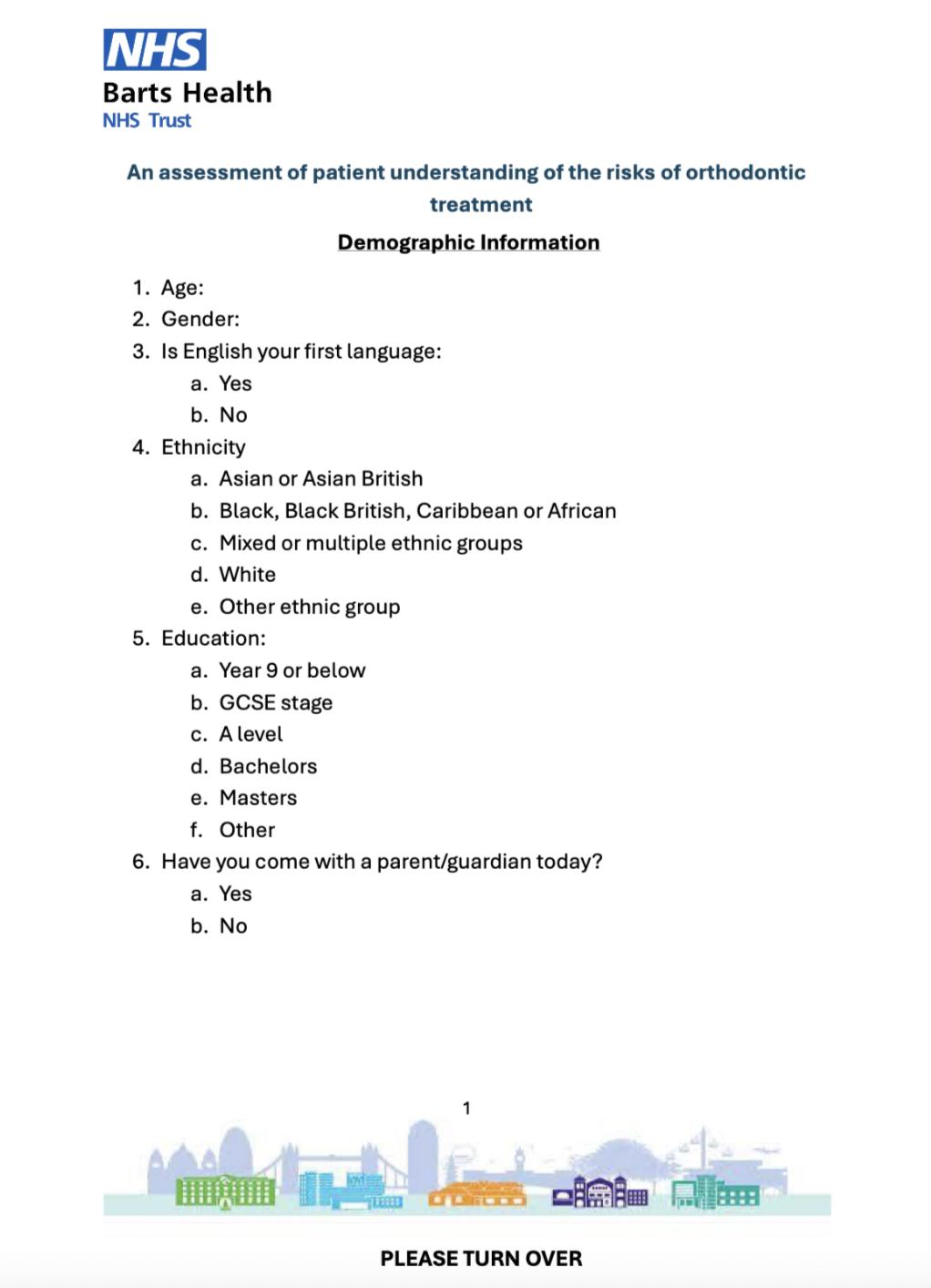

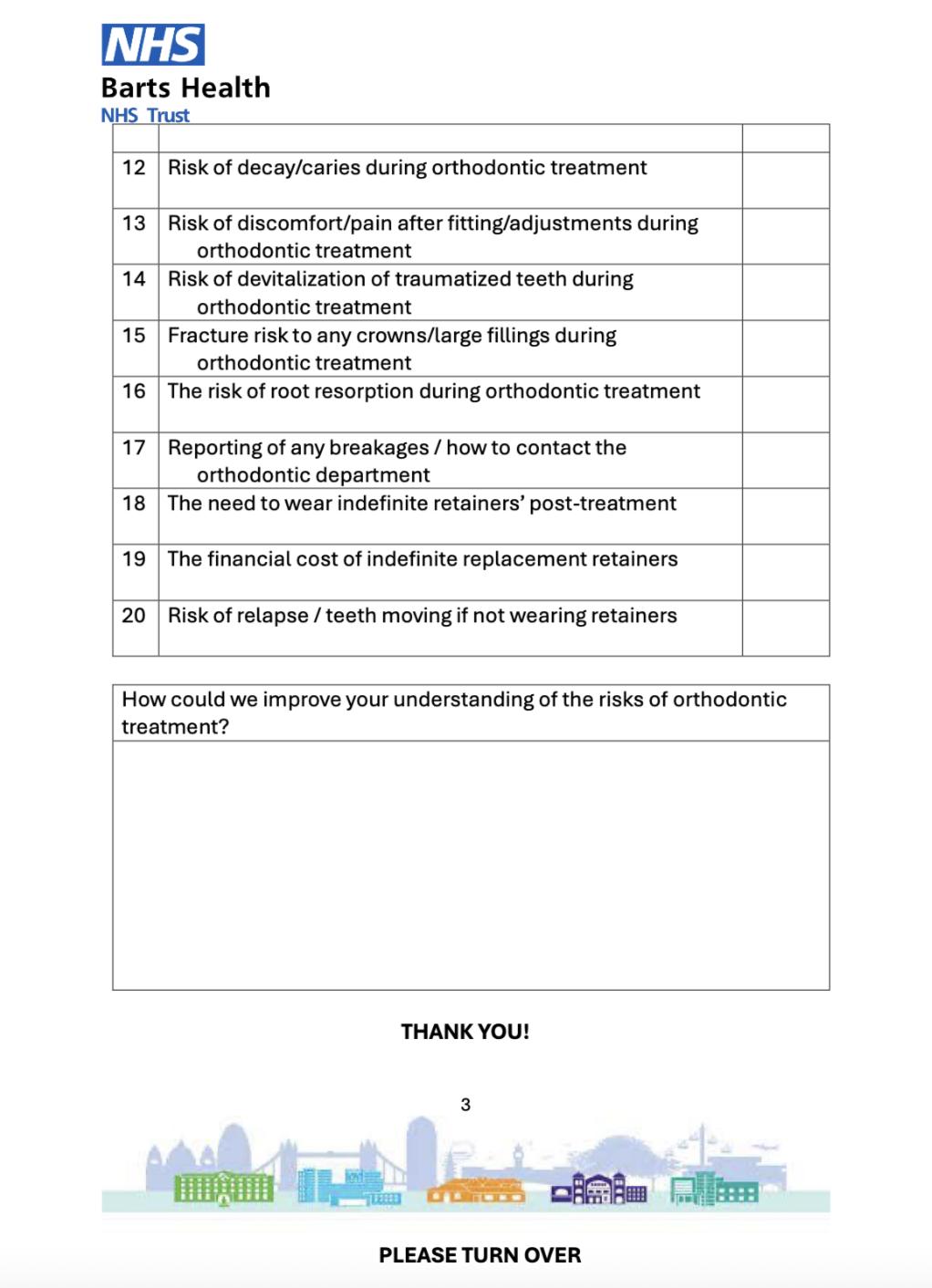

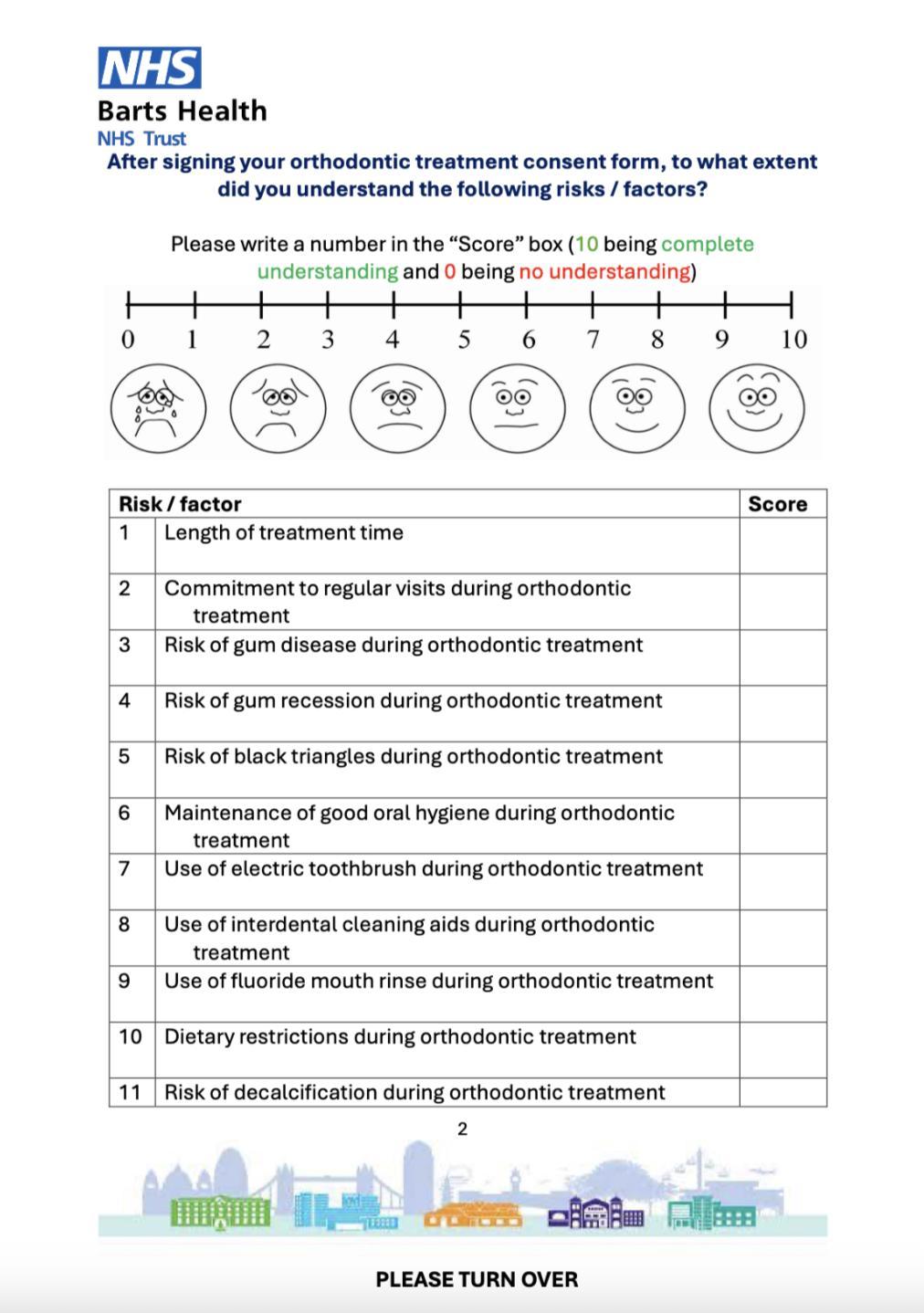

An assessment of patient understanding of the risks of orthodontic treatment at The Royal London Hospital.

E Johnson, P Jauhar

Complexity of hospital orthodontic new patient referrals accepted for treatment: A two-cycle audit.

MB Javed, R McDowall

Canine assessment at the optimal age: A three-centre retrospective audit.

O Thompson, E O’Sullivan

Assessment of orthodontic case complexity for NHS hospital treatment: a multicentre audit

Vinya Ravindra (ST), Laura Cockerham (Orthodontic Therapist), Kishan Patel (Post CCST), Lucy Davenport-Jones (Consultant), Rachel Stephens (Consultant) and Gavin Mack (Consultant) King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

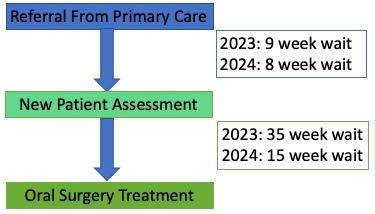

Background/Rationale NHS England produced guides for commissioning dental specialities in 2015 and subsequently produced the clinical standard for orthodontics in 2023 to reflect the need and complexity of patient care and clinician competency required to undertake treatment1,2. The framework describes the patient journey from primary care to specialist care and aims to generate consistency at a national level, ensuring effective utilisation of NHS resources by rationing service commissioning in orthodontics. The guide categorises the provision of treatment based on tier complexity levels (level 1, 2, 3a and 3b) with referrals to secondary care for consultant specialist services fulfilling level 3b criteria based on treatment complexity, multidisciplinary (MDT) input, medical and/or social history.

Specialty registrars (StRs) and specialists undertaking higher training after their Certificate of Completion of Specialist Training (post-CCST) should have an adequate case mix (level 3a and/or 3b respectively) to fulfil training requirements stated in the Orthodontics Specialty Training Curriculum produced by the Special Advisory Committee (SAC) and quality assured by the General Dental Council (GDC)3,⁴. Patients accepted for treatment must demonstrate excellent oral hygiene, absence or stabilisation of oral disease and commitment to the overall treatment, including their willingness to attend frequent appointments and motivation towards wearing appliances.

Aims and Objectives

This multicentre audit aims to assess the complexity of orthodontic referrals received and case acceptance to demonstrate compliance with the NHS England commissioning guide as well as the ability to fulfil postgraduate training requirements for training orthodontic specialists and post-CCST.

The objectives were to assess the complexity of orthodontic referrals by means of the complexity descriptors defined in the NHS England commissioning guide and assess the criteria for case acceptance for orthodontic treatment based on complexity, training provision and dental health status at 3 postgraduate orthodontic training units in South London - King’s College Hospital (KCH), St George’s Hospital (SGH) and Queen Mary's Hospital (QMH).

Standards/guidelines/evidence base

The regionally agreed standards between the units were based on previously published audits⁵,⁶. The first standard was that 80% cases accepted for orthodontic treatment should be IOTN 4/5 and/or complexity level 3b1,3,⁴. The second standard was 100% of accepted cases should be deemed

suitable for orthodontic treatment (i.e. excellent oral hygiene and no active dental disease)2.

Standards for this project were adopted as follows: 100% of referrals for ectopic canines should be received for orthodontic assessment between the ages of 10-12 years of age. 100% of referrals for ectopic canines should have the appropriate accompanying radiographs of good diagnostic quality.

Sample and data source

All patients who attended new patient clinics over a 4 consecutive week period (8th January 2024 – 2nd February 2024) at all 3 sites were included in this audit cycle. Patients were identified through electronic case note review using the relevant consultant-led new patient clinic codes with consultant-led triaging of the referrals to populate the face-to-face assessments. All patients who attended the new patient clinics were included in the sample with no restriction on age and gender.

Audit type

Retrospective

Methodology

A data collection tool was developed and piloted amongst all relevant orthodontic departments to ensure homogenous data collection. The data collection forms were completed using the electronic clinical notes from the new patient assessments and then collated onto a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Cases were excluded in the presence of insufficient data.

Patient demographics were captured, and each patient allocated a local audit patient identification number. Medical and social history was also noted to justify case acceptance owing to patient management in secondary care. The referring practitioner and details about the presenting malocclusion including IOTN and tier

complexity were included as well as MDT requirements and clinic outcome.

Findings

Within the 4-week period, 76 patients were identified at KCH, 35 patients at SGH and 43 patients at QMH. At KCH, 27 (36%) patients were accepted for treatment, 9 (26%) at SGH and 35 (81%) at QMH. 11 (15%) patients were planned for consultant-led review and 2 for other treatment including debond and retainers only at KCH. 1 patient was referred to another specialty at SGH and 1 patient planned for consultant-led review at QMH (Figure 1). Table 1 describes the IOTN, tier complexity levels, dental health status, clinic outcome and reasons for discharge across all units.

Table 1 IOTN, tier complexity level, outcome and dental health status of accepted and discharged patients

Table : IOTN, tier complexity level, outcome and dental health status of accepted and discharged patients

1: Outcome of new patient clinic assessment

The results from this audit cycle show that the set standard of 80% for cases accepted with IOTN 4 or 5 and/or tier complexity level 3b was only met at SGH with 100% IOTN 4/5 and 90% complexity 3b. At KCH and QMH, 85% and 89% were IOTN 4/5 respectively, however, 74% complexity 3b at both sites. Furthermore, the set standard of ‘100% cases accepted for treatment should be dentally fit’ was not met at any of the sites with 11% accepted patients deemed not dentally fit at KCH and QMH. 22% accepted patients at SGH were not dentally fit.

Primary reasons for discharge were patients not meeting the criteria for hospital orthodontic treatment, cases suitable for treatment in specialist practice and being deemed too early for treatment.

Figure 2 summarises the main reasons for discharge collectively.

Observations

This audit demonstrated that the included orthodontic units were not appropriately accepting cases for orthodontic treatment with regards to tier complexity, case mix and dental health status.

This may be attributed to a shortage of patients for trainees at KCH with the absence of an active waiting list to allocate from during the set audit period. Thus, the threshold for case acceptance is likely to have been lower to ensure training requirements are met and trainees have an adequate number of patients to treat with a varied case mix. KCH and QMH are also part of the same trust and accommodate more trainees in comparison to SGH resulting in a greater demand for training cases.

Figure 2: Primary reason for discharge following new patient clinic assessment

Dental trauma and development defects (e.g. amelogenesis imperfecta) may also justify case acceptance below the level 3b complexity tier.

Although several patients were accepted with inadequate dental health (poor oral hygiene and/or active caries), they were appropriately informed that orthodontic treatment would only commence on establishment of a dentally fit status with demonstration of excellent oral hygiene. Furthermore, a significant number of patients were referred to a multidisciplinary clinic of which the outcome is unknown and not within the remit of this audit. Patients with active dental disease may have been referred to the clinic for extraction based treatment only and therefore it is unclear whether these patients were accepted for orthodontic treatment following the multidisciplinary assessment.

A previous similar audit undertaken by Sedgwick et al. (2021) used the same standard for case complexity, which was successfully met in their audit6. In this audit, only IOTN was used as a measure of treatment need but the Index of Functional Treatment Need (IOFTN) should have also been included in the audit standards for patients referred for orthognathic surgery, similar to the previous audit. This may have resulted in case acceptance with a lower IOTN for orthognathic patients with a greater functional treatment need, thus deviating from the set standard.

The limitations of the audit include insufficient documentation and subsequent bias as data was collected retrospectively.

Recommendations

1. Findings will be disseminated to the wider team as well as referring practitioners to encourage more referrals to the department of dentally fit patients.

2. Electronic new patient clinic documentation templates to be amended to include all data required in this audit to minimise bias in a 2nd audit cycle when data can be collected prospectively ensuring that appropriate measures including IOFTN can be included.

3. Assessment of incoming referrals during the triaging stage to evaluate the appropriateness of orthodontic referrals to secondary care at the point of acceptance for face-to-face assessment.

4. Distribution of the complexity of allocated cases can be assessed using individual trainee logbooks.

5. Establishing clear referral guidelines with consistency at a national level would facilitate meeting the agreed standards and ensure effective utilisation of NHS resources as well as optimising the quality of clinical care that can be provided.

Project involvement

Dr Vinya Ravindra (Project lead)

Ms Laura Cockerham (Data collection assistant)

Dr Kishan Patel (Reviewer)

Miss Lucy Davenport-Jones (Supervisor)

Miss Rachel Stephens (Supervisor)

Mr Gavin Mack (Supervisor)

References

1. NHS England (2015b) Guides for commissioning dental specialties: orthodontics. Available at: https://www.england. nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/ sites/12/2015/09/guid-comms-orthodontics.pdf

2. NHS England. (2023). Clinical standard to dental specialties – orthodontics. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/ publication/clinical-standards-for-dentalspecialties-orthodontics/

3. The Joint Committee for Postgraduate Training in Dentistry and The Specialist Advisory Committee in Orthodontics. Curriculum and Specialist Training Programme in Orthodontics. 2010. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/docs/ default-source/specialist-lists/ orthodonticcurriculum.pdf?sfvrsn=76eecfed_2

4. Joint Committee for Postgraduate Training in Dentistry (2012) Guidelines for UK post-CCST training appointments in orthodontics. Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/-/media/files/rcs/ fds/careers/jcptd/guidelines-for-postccsttraining-Orthodontics-july-2012.pdf

5. Giles, E., Rizvi, Z., Gray, J. A., Barker, C. S., & Spencer, R. J. (2019). To accept, or not to accept? A service evaluation to appraise complexity assessment of orthodontic patients referred into a secondary care setting. British dental journal, 226(12), 963–966. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0384-6

6. Sedgwick, M., Nirmal, H. and Bhamrah, G. (2021) ‘Assessment of referral complexity and case acceptance for NHS Hospital Orthodontic Treatment’, Faculty Dental Journal, 12(3), pp. 138–143. doi:10.1308/rcsfdj.2021.33.

Are we checking orthodontic new patients for oral cancer abnormalities? A local two-cycle audit at the Queen Victoria Hospital

Laura Brooks (ST) and Lisa Rennie (Consultant)

Orthodontic Department, Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, East Grinstead, UK

Background/Rationale An extra and intra-oral examination to screen for soft and hard tissue abnormalities is an essential part of orthodontic and dental care, along with asking patients about their smoking/vaping status and alcohol intake1. The incidence of oral cancer has increased in the UK by 34% in the last decade, with a significant increase of 19% and 22% in overall cancer rates in patients aged 0-24 and 25-49 years respectively2. The majority of secondary care orthodontic patients are in this age group, therefore a thorough history and examination is essential to detect any abnormalities. Risk factors for oral cancer include: smoking and alcohol (synergistic effect), chewing tobacco/betal nut, poor diet with <5 portions of fruit and vegetable/day, HPV (human papillomavirus) and social deprivation3, ⁴. Screening is important as early detection can boost the chances of survival from 50-90%3. In the orthodontic clinical notes, a full extra-oral and soft tissue examination was not often documented and few clinicians recorded patient’s smoking/vaping status and alcohol intake. This audit was essential to improve record keeping and standards of care delivered to patients.

Aims and Objectives

This audit aimed to assess the documentation of extra-oral and intra-oral soft tissue assessment of all new patients in the orthodontic department along with the smoking/vaping and alcohol status of adult patients. The audit also aimed to raise awareness of the importance of screening for oral abnormalities and to make recommendations to improve record keeping.

Standards/guidelines/evidence base

100% of new patient clinical notes to document the following details as part of a new patient assessment as stated by the Faculty of General Dental Practice 2016 Good Practice Guidelines - Clinical Examination and Record Keeping1.

Criteria: (1) An extra-oral examination including the TMJ, lymph nodes and asymmetries. (2) An intra-oral soft tissue examination. (3) Smoking status, vaping status and alcohol intake in patients over 18 years of age as this is the legal age to smoke/vape and drink alcohol in the UK⁵-⁷. Although 40% of 11-15 year olds have had an alcoholic drink and 9% are e-cigarette users, 43% were secret smokers and their family did not know⁸. It was felt as the vast majority of under 18 year olds are accompanied by their parents/legal

guardian to their appointment, they would not be entirely truthful regarding their smoking/vaping and alcohol status when asked in front of caregivers.

Sample and data source

Data was collected from the clinical notes of 50 consecutive new patients attending orthodontic new-patient clinics at the Queen Victoria Hospital, in October 2023 (cycle 1) and May 2024 (cycle 2). All patients were included regardless of age or if they were referred for orthodontic treatment or a mandibular advancement splint for obstructive sleep apnoea. No exclusion criteria was used. The clinical notes were accessed via the Trust electronic notes system.

Audit type

Retrospective.

Methodology

Data was collected from new patient notes and entered into a proforma. The following data was collected: age of the patient, date of the new patient clinic, type of patient (<18 yrs, >18 yrs or referred for a mandibular advancement splint), grade of the clinician that examined the patient, extra-oral examination: asymmetry, lymph nodes, TMJ; intra-oral soft tissue examination; smoking/ vaping and alcohol status.

Patients attending the new patient clinic ranged from 7 to 66 years old. The majority (60%) were under 18 years of age, 22% were over 18 and a further 18% were referred for the construction of mandibular advancement splints for managing obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) (Figure 1: Types of patients in new patient clinic). Most patients were examined by a consultant (72%), 18% by a post CCST, 6% by an associate specialist and 4% by a specialist registrar. There was no difference

between the level of documentation and the grade of the clinician. Clinical entries correctly recording the required information in the 1st cycle (October 2023) were as follows: TMJ 52%, asymmetry 52%, lymph nodes 2%, soft tissues 14%, smoking/ vaping status 10% and alcohol status 25% (Figure 2: Documentation results-extra-oral and intra-oral assessment, Figure 3: Documentation results- alcohol and smoking/vaping status). None of the clinical entries recorded all three parts of the extra-oral examination required, which included the TMJ, the presence of asymmetry and examination of the lymph nodes.

Types of patients in new patient clinic

2: Documentation results - extra-oral and intra-oral assessment

status

Intervention

The results were presented at the Orthodontic Department Audit Meeting in March 2024 to raise clinicians’ awareness of the importance of recording a full extra-oral and soft tissue examination along with the alcohol and smoking/vaping status of patients. Clinicians were also encouraged to update their new patient proformas. A teaching session was given to the orthodontic department on oral cancer including trends, signs and symptoms and risk factors and a re-audit was planned for May 2024.

Cycle 2

In cycle 2 (May 2024), the patients seen ranged from 9-75 years old. Most (84%) were under 18 years old, 8% were over 18 and 8% were referred for mandibular advancement splints to manage obstructive sleep apnoea. (Figure 1: Types of patients in new patient clinic). The majority of patients in this cycle were also examined by a consultant (66%), 2% post CCST, 18% by an associate specialist and 14% by a specialist registrar. Again in cycle 2, there was no difference between the level of documentation and the grade of the clinician. The percentage of clinical entries correctly recording the required information had each increased as follows: TMJ 78%, asymmetry 92%, lymph nodes 70%, soft tissues 78%,

smoking/vaping status 43% and alcohol status 43% (Figure 3: Documentation results - alcohol and smoking/vaping status). In 56% of patients all three aspects of the extra-oral examination were recorded (Figure 2: Documentation results-extra-oral and intra-oral assessment).

Observations

The gold standard was not met in either cycle but significant improvements were made after changes were implemented, which included presenting the audit results to the Orthodontic Department Audit Meeting, changing new patient clinic proformas and providing an oral cancer teaching session. Examination of the lymph nodes increased by 68% (cycle 1: 2%, cycle 2: 70%) and the soft tissues by 64% (cycle 1: 14%, cycle 2: 78%). These two aspects of a full patient examination are particularly important in detecting oral cancer, however, they were less commonly recorded possibly because they do not influence orthodontic treatment planning and are therefore more easily forgotten. Although less relevant in detecting oral cancer, the examination of the TMJ increased by 26% (cycle 1: 52%, cycle 2: 78%) and asymmetry increased by 40% (cycle 1: 52%, cycle 2: 92%). They were recorded more in both cycles than other factors as they are more relevant to treatment planning.

The alcohol and smoking/vaping status of patients were less commonly recorded and the results from cycle two showed that this was only noted in 43% of adults. It was observed that the department’s medical history form does not include a section where smoking/vaping and alcohol status can be documented, most likely because the vast majority of our patients are under 18 years of age. Importantly, age does not preclude those patients from smoking/vaping and drinking and it is important to know a patient’s smoking/vaping status as it can increase the risk of infection following dentoalveolar or orthognathic surgery⁹. If patients are smoking/vaping and drinking heavily, it is our duty of care as clinicians to signpost them to smoking/vaping cessation and alcohol support services for their general health and well being. Following cycle 2, the department has approved a new medical history form that includes smoking/vaping and alcohol status.

The OSA patients seen in the department are generally of an older age cohort than the orthodontic patients (age 56-75 years). These patients are referred by the secondary care respiratory sleep services, rather than primary care, and during the audit it was observed that a significant number of the OSA patients had not accessed dental care for many years. Patients reported that difficulties accessing a NHS dentist, especially since COVID-19, have increased this trend. This patient cohort is therefore potentially at a higher risk of undetected hard and soft tissue abnormalities due to their age, especially as OSA and oral cancer patients can share common risk factors10. It is essential that a thorough extra and intraoral examination is carried out and clinicians should be mindful that some groups of patients may not have regular screening with a GDP.

Recommendations

1. Update the department’s medical history form to include smoking, vaping and alcohol status. This was introduced in December 2024.

2. Present the results of both cycles at the next Orthododontic Department Audit Meeting.

3. Ensure all clinician new patient proformas include the required information to ensure 100% compliance in the re-audit.

4. Re-audit in 12 months and as an improvement of the audit to ask patients under 18 years old their alcohol and smoking/vaping status, as previously mentioned NHS England surveys show young people in this age group regularly drink and smoke/vape.

Project involvement

Laura Brooks (Project lead, project design, data collection, analysis, presentation, manuscript preparation).

Lisa Rennie (Project supervision, project design and manuscript review).

References

1. Hadden AM. Clinical Examination and Record Keeping: Good Practice Guidelines. 3rd ed. London: Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK); 2016.

2. Cancer Rearch UK. Cancer incidence by age [Internet]. London: Cancer Research UK; 2024 [Accessed 23rd April 2025]. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/healthprofessional/cancer-statistics/incidence/age#heading-Three.

3. Oral Health Foundation. The State of Mouth Cancer UK Report 2024 [Internet]. Rugby: Oral Health Foundation; 2024 [Accessed 23rd April 2025]. Available from: https://www.dentalhealth. org/thestateofmouthcancer.

4. Ravaghi V, Durkan C, Jones K, Girdler R, Mair-Jenkins J, Davies G, et al. Area-level deprivation and oral cancer in England 2012–2016. Cancer epidemiology. 2020;69:101840.

5. GOV.UK. Alcohol and young people [Internet]. UK: GOV.UK; 2025 [Accessed 24th April 2025]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/ alcohol-young-people-law#:~:text=If%20 you're%20under%2018%2C%20it's%20 against%20the%20law%3A,to%20buy%20 alcohol%20for%20you.

6. GOV.UK. Youth Vaping: call for evidence. [Internet]. UK: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities; 2023 [Accessed 24th April 2025]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/ calls-for-evidence/youth-vaping-call-forevidence/youth-vaping-call-for-evidence#:~: text=call%2Dfor%2Devidence-,Introduction, substantially%20less%20harmful%20than%20 smoking.

7. Legislation.GOV.UK. Children and Families Act 2014: Tobacco, nicotine products and smoking [Internet]. UK: legistation.gov.uk; 2021[Accessed 24th April 2025].

Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ ukpga/2014/6/part/5/crossheading/tobacconicotine-products-and-smoking#:~:text=92 Prohibition%20of%20sale%20of,to%20 persons%20aged%20under%2018.

8. NHS England. Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use among Young People in England, 2021 [Internet]. England: NHS England; 2022 [Accessed 24th April 2025]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/ data-and-information/publications/statistical/ smoking-drinking-and-drug-use-among-youngpeople-in-england/2021/part-5-alcohol-drinking-prevalence-and-consumption#pupils-whohad-an-alcoholic-drink-in-the-last-week.

9. Kuhlefelt M, Laine P, Suominen AL, Lindqvist C, Thorén H. Smoking as a significant risk factor for infections after orthognathic surgery. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2012;70(7):1643-7.

10. Mitra AK, Bhuiyan AR, Jones EA. Association and Risk Factors for Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review. Diseases. 2021;9(4):88.

A two-cycle audit assessing the orthodontic attendances at the Royal Surrey Hospital

John Watt (ST), Shaira Karim Kassam (Post CCST), Nigel Taylor (Consultant Orthodontist) and Gursharan Minhas (Consultant Orthodontist)

Royal Surrey County Hospital, Surrey, London, UK

Background/Rationale

Unsupervised orthodontic treatment following missed appointments can be detrimental to patients’ dental health, compromise treatment outcomes and have financial impacts on limited NHS resources creating further pressures on waiting lists. Many orthodontic patients are dependent on their parents/guardians to attend appointments, therefore the ‘was not brought’ (WNB) initiative was developed to recognise that children (0-17 year-olds) are not responsible for their missed appointments¹. Non attendance for this cohort of patients should be recorded in the clinical notes as ‘WNB’, instead of ‘Did not Attend’ (DNA). To ensure appropriate outcomes regarding missed appointments, both WNB and DNA should be documented and followed-up. Correct documentation allows clinical staff to monitor potential safeguarding concerns and to identify when to discharge patients with poor attendance to improve best use of resources.

Aims and Objectives

The aims of this audit include:

i) Reviewing attendance (WNB and DNA) of all orthodontic appointments, including new patient clinics, treatment clinics and multidisciplinary clinics specifically in line with the set standard.

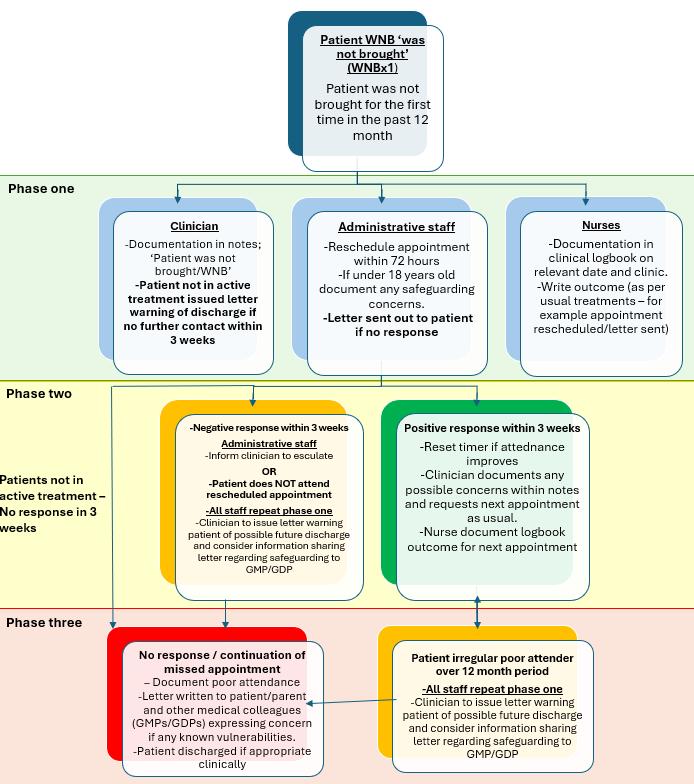

ii) Developing a new departmental protocol to ensure appropriate follow up and management occur, following missed appointments.

The objective is to ensure all missed appointments are appropriately recorded, including the safeguarding management for 0–17 year-old vulnerable patients at the Royal Surrey Hospital.

Standards/guidelines/evidence base

All WNB appointments must be followed-up; either discharged with letter sharing information to General Dental practitioners/General Medical practitioners (GDP/GMP), or a further appointment arranged as per WNB guidance1.

Sample and data source

The data sample included all orthodontic patients attending orthodontic appointments at Royal Surrey Hospital, including new patient assessments and attendance on multidisciplinary clinics with

allied specialities. Period of data collection included between October 2023-January 2024 (n= 2877) and after allowing for a period of change, May 2024 – July 2024 (n=1297). Data was collected from trust computer systems and confirmed from paper clinical diary logbooks to assess patient attendance and outcomes when patients failed to attend. Data was separated between 0-17 years old (WNB) and those 18 and over (DNA).

Audit type

Retrospective audit for the first cycle and prospective audit for second cycle, following the action plan and implementation of the protocol.

Methodology

Electronic patient records (Cerner) and clinical paper logbooks within the orthodontic department at the Royal Surrey Hospital were reviewed during select dates for each cycle of this audit. The first cycle was retrospective to align with the start date of new orthodontic trainees within the department (October 2023). The second cycle was prospective following local and regional presentation of results. Data collection included all orthodontic appointments including multidisciplinary clinics with allied specialities, new patient clinics and all clinicians’ treatment sessions within the orthodontic department. Orthodontic clinicians within the department included three

orthodontic consultants, one speciality doctor, five orthodontist registrars and one orthodontic therapist. Specific information collected for analysis included patient attendance at appointment, patients age at appointment, type of clinic (i.e. treatment, new patient, multidisciplinary), type of treatment if applicable (i.e. fixed adjust, retainer review etc.), day of the week, documentation of DNA/WNB evidenced in clinical notes, and outcome if the patient missed the appointment (i.e. appointment rescheduled, patient discharged, telephone follow-up etc.).

Results from the initial audit cycle were discussed at a local audit meeting with implementation of a new protocol (diagram 1), followed by a regional orthodontic audit discussion. The second cycle of data collection used the same method and commenced after a 3-month period, to allow change. There was no exclusion of patients who repeatedly failed to attend their appointments.

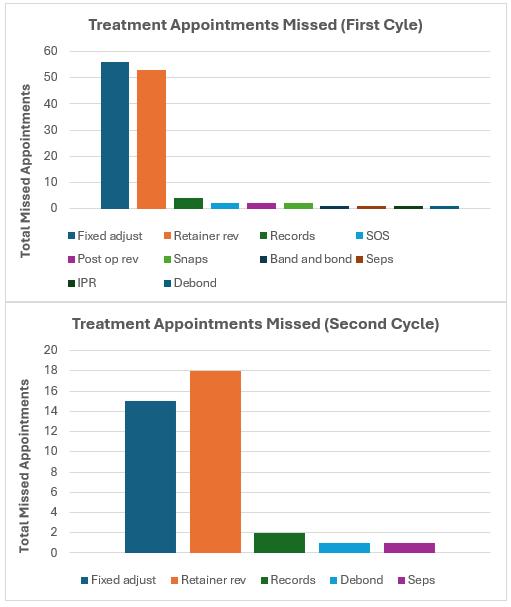

Findings

Between the first and second cycles, there was an overall improvement in attendance rate, record keeping and appropriate follow up (Table 1).

Table 1: Summary of results ducation Delivered

From this audit, orthodontic missed appointment rate decreased from 5.67% (163/2877) to 3.79% (49/1294). Documentation in clinical notes, recording appropriately whether a patient failed to attend their appointment, dramatically improved between cycles from 36.81% (60/163) to 75.51% (37/49).

Appropriate follow up for WNB appointments had improved from 58/60 (96.67%) to 14/14 (100%), meeting our standard that all patients 0-17 years of age, who miss their appointment should be appropriately followed up. The rate of WNB missed appointments had decreased between cycles from 60/163 (36.81%) in the first cycle to 14/49 (28.57%) in the second cycle.

From types of appointments missed in the first cycle, 123/163 (75.46%) of appointments were treatment sessions vs 40/163 (24.54%) joint clinic assessments. The second cycle is 37/49 (75.51%) vs 12/49 (24.49%) joint clinics. The significance is that MDT appointments may have greater financial implications to the trust or greater impact on overall to treatment if the patients are mid-treatment and have to be placed on a waiting list to be seen again.

Table 2: Comparison of missed treatment appointments, between cycles

The majority were unsurprisingly fixed adjust appointments 56/123 (45.53%) followed by retainer reviews 53/123 (43.09%). Both of these make up large portions of appointment types in orthodontic patients. Other missed appointments included records 4/123 (3.25%), emergency ‘SOS’ appointments/post operative reviews and snap reviews which has 2/123 patients missing their appointment for each category (1.63%). Placement of separators, interproximal reduction (IPR), band and bond and debond each made up 1/123 (0.81%) patient for each category.

In the second cycle there was less variation in the type of appointments which were missed, likely due to smaller sample size. Retainer reviews and fixed adjust appointments made up the majority of missed appointments 18/37 (48.65%) and 15/37 (40.54%) retrospectively. Other missed appointments included orthodontic records 2/37 (5.41%) and a single patient missed an appointment for placement for separators and a debond 1/37 (2.70%)

Observations

The first cycle failed to achieve the standard criteria with 96% of WNB patients appropriately followed up. However, the standard criteria of 100% was met in the second cycle. A local protocol was developed to minimise missed appointments and to ensure appropriate safeguarding outcomes were followed. The protocol, based on the published BDA flowchart 2 was shared with all staff and suggests patients are contacted within 72 hours of not attending, with different stages of outcomes depending on treatment type (Diagram 1).

Despite most patients being appropriately followed up, there was a lack of documentation of patients missing appointments within the Trust’s electronic paper record (EPR) system. Failure of documentation makes it difficult for staff to identify trends in poor attendance and potential safeguarding concerns. Following the implementation of the protocol (Diagram 1) there was a dramatic increase in documentation of missed appointments within the EPR (36.81% vs 75.51%).

Between cycles, there is a decrease in the department's missed appointments rate from 5.67% to 3.79%. This is lower than the national average of all NHS specialities of 6.43% from the 2022/23 publication3. The overall percentage of 0-17 year-olds not attending their appointments had decreased, potentially due to an increase in letters warning of safeguarding concerns (36.81% vs 28.57%).

The majority of appointments patients failed to attend in both cycles were ‘active treatment sessions’ (75.46% and 75.51%) (figure 2). Both cycles had similar representation of ‘fixed adjust’ and ‘retention’ appointments which were missed, that made up most of the overall missed appointments.

In the first audit cycle, fixed adjust accounted for 56/123 (45.53%) of missed appointments, followed by retention reviews 52/123 (43.09%). In the second cycle fixed adjust represented 15/37 (40.54%) of missed appointments, followed by retainer reviews 18/37 (48.65%) (table 2).

Friday was the least likely day for patients to miss appointments making up 14% vs 10% in the first and second audit cycle, respectively. Whereas missed appointments appear to most likely occur on a Wednesday (first cycle – 34%) or Tuesday (second cycle – 26%). This would correlate with the two days of the week where new patient clinics were scheduled. Further explanation would require further analysis, which is outside the scope of this audit.

In conclusion, to ensure continuation and improvement of results, all new staff will be informed about the missed appointment and WNB

safeguarding protocol. Copies of the protocol have been distributed in folders on clinic for reference. Similar audits have been undertaken at other institutions i.e. Eastman Dental Hospital⁴. Population demographics do vary, and additional Trust information could be useful for a general database for the NHS for orthodontics. This audit demonstrates how it is possible to improve DNA/ WNB rate by putting a protocol in place.

Recommendations

1. All staff need to be aware of the DNA/WNB protocol, including existing clinical and administrative staff and new staff and document on EPR as this indicates to clinician previous WNB and DNA.

2. Protocol can be disseminated to other departments wishing to improve attendance rate and safeguarding measures.

3. Re-audit in 12 months.

Project involvement

John Watt (Audit and protocol design, data collection, audit lead, presenter)

Shaira Karim Kassam (Audit design, data collection)

Nigel Taylor (Audit and protocol design, audit supervisor)

Gursharan Minhas( Protocol design)

References

1. Kirby J, Harris J C. Development and evaluation of a 'was not brought' pathway: a team approach to managing children's missed dental appointments. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 291-297.

2. British Dental Association (BDA). Implementation ‘Was Not Brought’ In your practice, 5 (2000). Available from: wnb-implementation-guide-2024_v3.pdf (Accessed: 04/11/2024).

3. NHS Digital. Summary Report – Attendances. September 2023 cited July 2024. Available from https://digital.nhs.uk. (Accessed: 04/11/2024).

4. Murphy, I, Johnson, A, Sheriteh, Z. Was Not Brought: A three cycle audit of missed children’s appointments in the orthodontic department. BOS Clinical Effectiveness Bulletin. 2023; 50: 44-47

A Service Evaluation of Virtual Orthodontic Education Clinics at the Birmingham Dental Hospital

Nabeela Caratela (DCT), Amandeep Bains (ST) and Shane Higgins (Consultant Orthodontist) and Sheena Kotecha (Consultant

Orthodontist) Birmingham Dental Hospital, UK

Background/Rationale Patients on the orthodontic treatment waiting list at Birmingham Dental Hospital are invited to attend a 45-minute virtual education clinic with an oral health education trained orthodontic nurse. This takes place prior to their initial orthodontic records appointment. The consultation includes a PowerPoint presentation and discussion focussing on:

1. The risks of orthodontic treatment including dental caries and decalcification.

2. Tailored oral hygiene (OH) and dietary advice. Patients are given plaque disclosing tablets and are asked to use them 10-15 minutes before the session to demonstrate their tooth brushing technique.

3. The standard of compliance required for successful orthodontic treatment and details of the hospital attendance policy.

4. What to expect at their first clinical appointment and throughout their treatment journey.

The remote consultation clinics have been operational within the department since the COVID-19 pandemic. Lockdown measures during the pandemic forced healthcare systems to reduce face-to-face clinical contact. To minimise aerosol generating procedures (AGPs), it was no longer deemed acceptable for patients to brush their teeth on clinic. Whilst the virtual delivery of oral health education poses some challenges, it confers many benefits regarding opportunities to enhance and update the delivery of patient education1, 2 .

Aims and Objectives

• To assess patient experience of the remote consultations, including suitability for intended purpose, accessibility, clinical value and effectiveness.

• To explore the limitations of online remote consultation clinics for patients.

• To ensure continuous evaluation of remote clinic provision to facilitate improvements for patients using this service.

Standards/guidelines/evidence base

This was a service evaluation with no published guidelines.

Locally set standards were agreed by the department:

• 100% of patients should rate their understanding of the orthodontic treatment process and oral health level expected as “well understood or very well understood” following the remote consultation.

• 100% of patients should agree that safety and confidentiality is not compromised by the remote consultation process.

• 100% of patients should report no technical issues/concerns.

Sample and data source

All patients who completed the virtual clinic were invited to complete a survey directly following the remote consultation. The ‘Smart Survey’ platform was used for the questionnaire. There were no exclusion criteria.

In cycle 1 (October 2022 - June 2023), 36 responses were obtained, and for cycle 2 (July 2023 – January 2024), there were 31 responses.

Audit type

Prospective patient questionnaire-based service evaluation.

Methodology

The service evaluation was registered and approved by the Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Clinical Governance Team. The questionnaire was developed within the orthodontic department at the Birmingham Dental Hospital and was piloted with 5 patients via a face-to-face consultation. The final questionnaire was agreed with the Orthodontic Department Lead and Clinical Governance Team.

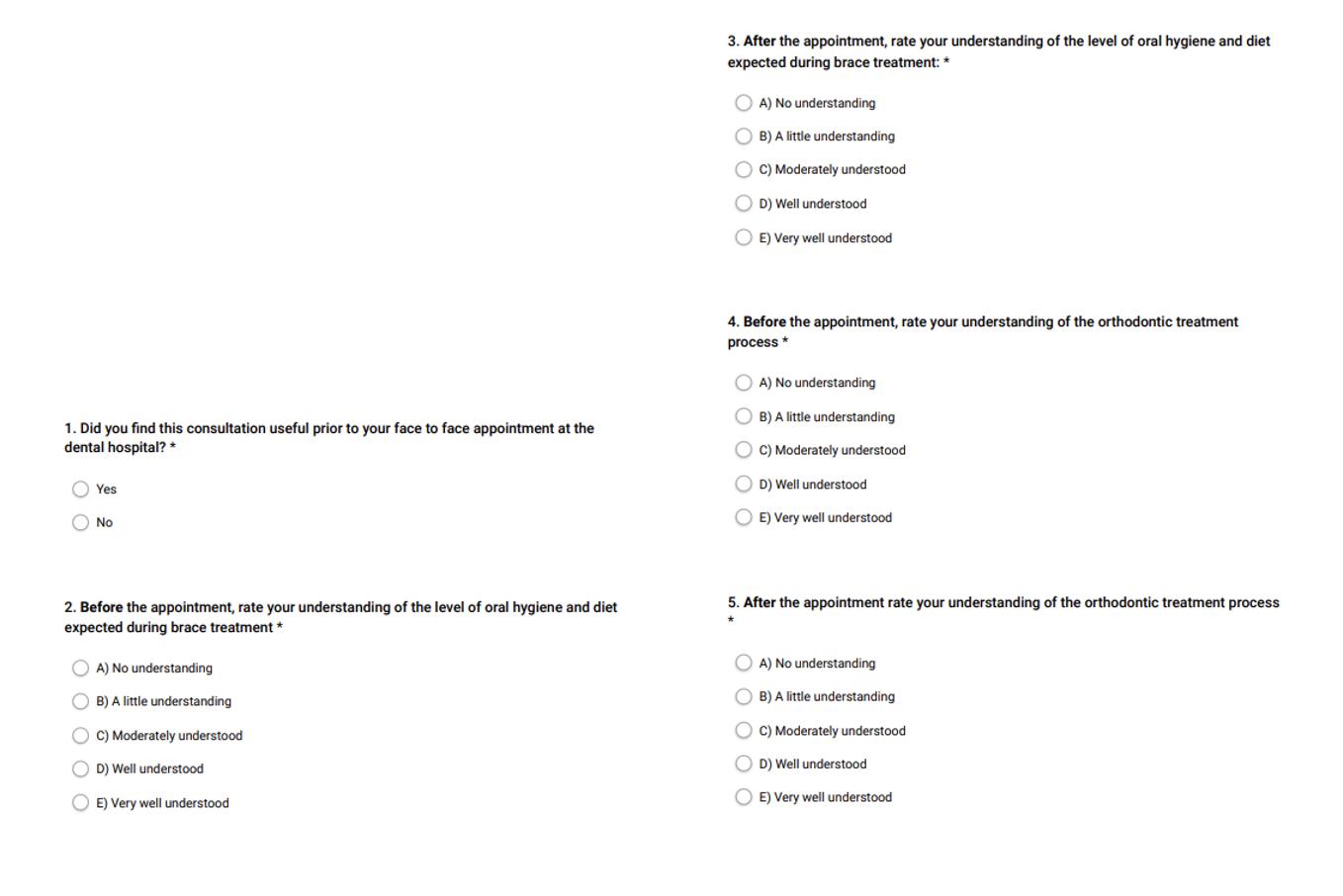

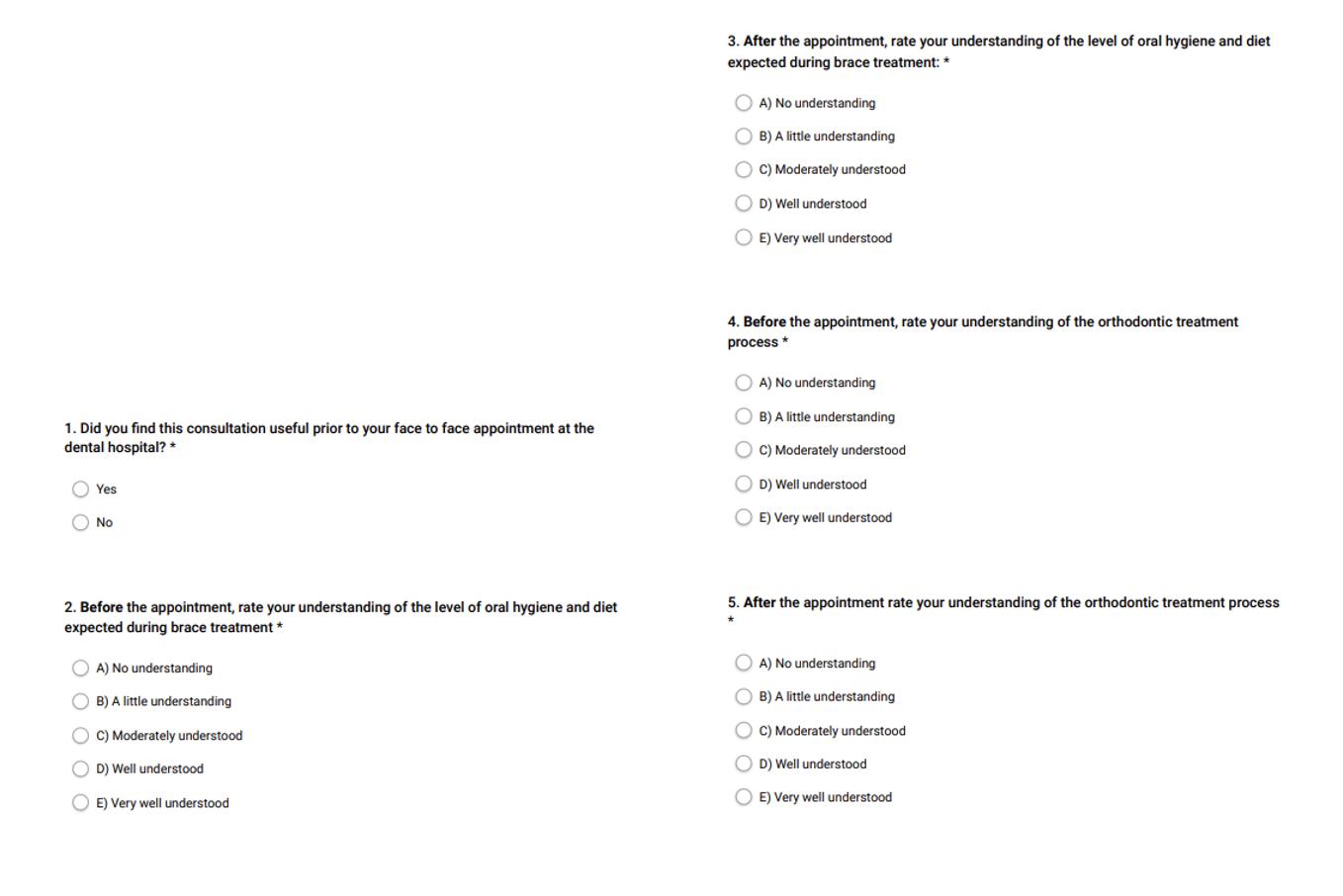

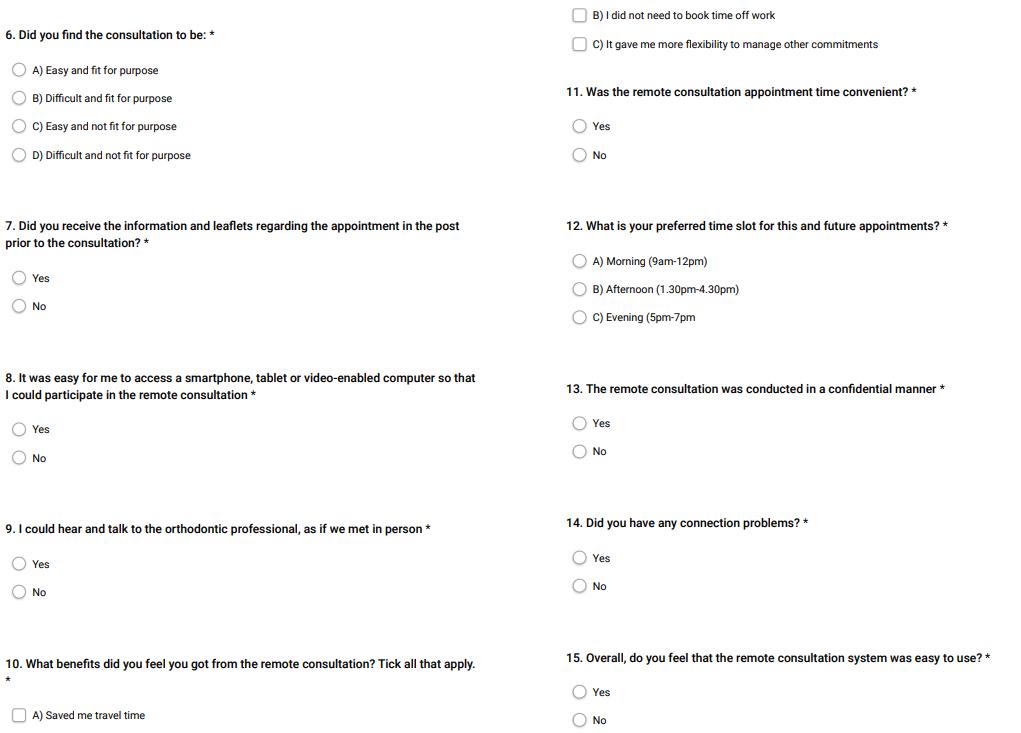

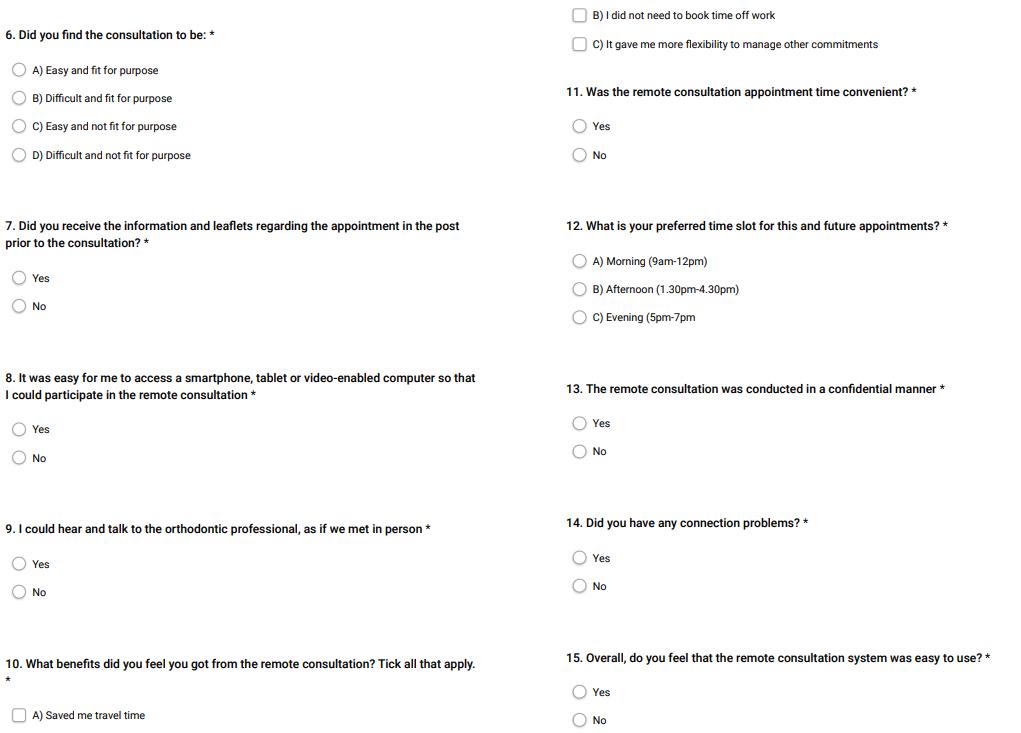

The questionnaire consisted of 15 questions developed to assess patients’ understanding of the orthodontic treatment process, the level of compliance required, ease of access to remote consultations, technical issues encountered and overall patient opinions on the remote clinics.

Anonymous questionnaires were distributed to patients via the online ‘Smart Survey’ platform

(Figure 1) following the virtual clinic for both cycles. For children, the survey was completed by their parents or individual with parental responsibility.

Baseline data were collected in cycle 1 (June 2023). The action plan following this cycle consisted of a revision of the PowerPoint presentation to improve the explanation of patients’ journey throughout

Cycle 2 (January 2024) assessed the impact of this change to the remote clinics.

The data from the questionnaires were analysed using Microsoft® Excel™.

Findings

Across cycles 1 and 2, 100% of participants agreed that their confidentiality was maintained, 100% understood the level of OH expected during treatment and 100% of respondents found the consultation easy to navigate, fit for purpose and useful prior to the face-to-face appointment.

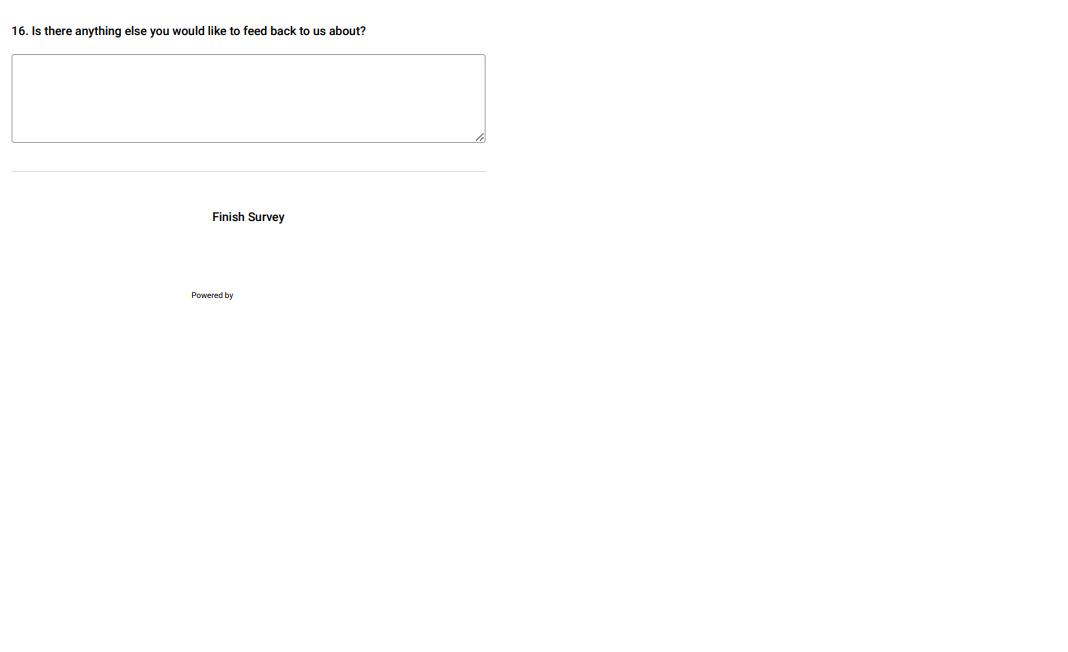

Figure 2: Cycle 1 and 2 results for levels of understanding of the orthodontic treatment process pre and post remote consultation.

The findings in cycle 1 showed that 89% understood the treatment process at the level of ‘well understood or very well understood’ and the remaining 11% reported a ‘moderate’ understanding of process. In cycle 2, 91% understood the treatment process at level of ‘well understood or very well understood’ and the remaining 9% reported a ‘moderate’ understanding post consultation.

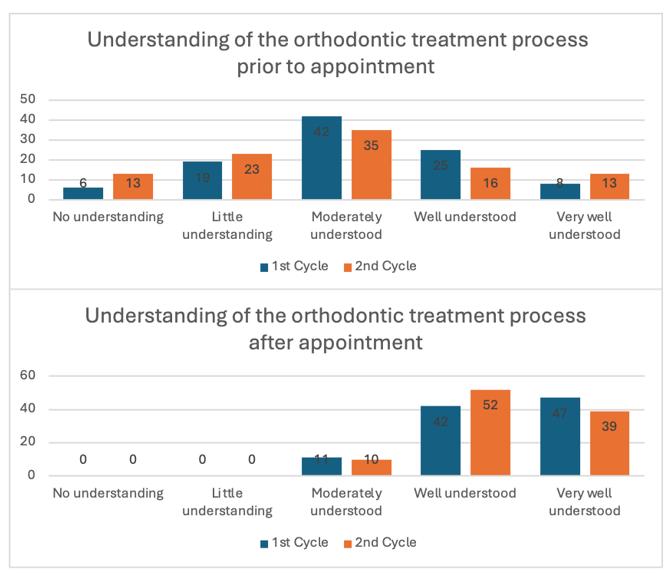

Figure 3: Cycle 1 and 2 results for levels of understanding of compliance required for orthodontic treatment pre and post remote consultation.

During cycle 1, 100% reported it was easy to access a smartphone, tablet or computer for the consultation, but this reduced to 93% in cycle 2. In cycle 1, 100% reported they could hear and talk to the nurses as if they were in person and in cycle 2 this was 97%. Fourteen percent of participants reported connection issues in cycle 1, and this increased to 17% in cycle 2. In cycle 1, 94% agreed the consultation was booked at a convenient time for them, however this reduced to 84% in cycle 2.

There were 3 additional comments left by the respondents in cycle 2 stating “very helpful”, “easy to talk to” and “easy to access”.

Observations

Suitability

In both cycles, 100% of patients found the remote consultations suitable for the intended purpose and all patients felt their confidentiality was maintained throughout, encouraging patients’ confidence in the system. All patients are given an anonymised identification number according to their IP address, therefore patient identifiable information is not shared.

Accessibility

Overall, the remote consultations were accessible for patients. However, accessibility was reduced in

the second cycle due to issues with access to devices and internet connection problems. This could likely be due to the optimisation of internet connection and access to devices immediately following the COVID-19 pandemic which could be reflected in cycle 1 findings. Whilst the gradual return to face-to-face work and education activities over time could have resulted in difficulties in accessing the appointments in cycle 2.

Furthermore, 6% of patients reported not receiving the pre-consultation information letter; this could be explained by the postal industrial action during the cycle 2 data collection period. The preferred appointment times in cycle 1 were afternoon and evening, however in cycle 2 the preferred timing of appointments was the morning. Timing preferences vary between patients; differences in appointment time preferences could be due to work/education commitments and appointments corresponding with school holidays. Flexibility with appointment times would help address the differences in patient preference.

Clinical value

All respondents reported the appointment was useful and found it increased their understanding of the standard of oral hygiene and diet required during treatment. The respondents’ understanding of the orthodontic treatment process, sequence of appointments and attendance requirements was also improved. This highlights the benefit of the virtual clinic in making patients aware of their responsibilities in terms of oral hygiene, diet and attendance during their orthodontic treatment.

Benefits to patients

Most patients found the remote clinic saved them travel time. In cycle 2, 84% found the allocated time convenient. Approximately one third of respondents did not need to take leave from work to attend the appointments.

The potential limitations identified in this project were the small sample size and the short length of time between cycles. Additionally, in cases where the patients were children, responses provided by parents may not fully reflect the child’s own understanding or perspective.

Overall, patient attendance at a virtual orthodontic education clinic prior to commencement of orthodontic treatment appeared to be an effective

intervention. Clinicians feel that the levels of understanding regarding treatment and compliance have shown improvement due to the remote clinics. Patient confidentiality is being maintained in the process. Challenges highlighted in this service evaluation include connectivity issues and suitability of appointment times.

Recommendations

1. To review the appointment timing allocation to facilitate patient flexibility and reduce the need to take leave from work for appointments.

2. To consider the implementation of virtual clinics in other areas of orthodontic treatment, for example, retainer review clinics.

3. To complete a further service evaluation to measure the impact of the interventions in 12 months.

4. Aim to increase the response rate of the questionnaire to ensure accuracy of results for the next cycle of the service evaluation.

Project involvement

Nabeela Caratela (Manuscript and project write-up) Amandeep Bains (Project lead, data collection and analysis, presentation of results)

Shane Higgins (Project Supervisor) Sheena Kotecha (Project Supervisor)

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Ms. Sheena Kotecha and Mr. Shane Higgins for supervising this project, and the Orthodontic Nursing Team at the Birmingham Dental Hospital for operating the remote clinics and supporting the data collection for this project.

References

1. Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC public health. 2020 Dec;20:1-9.

2. British Orthodontic Society. Guidance on teledentistry and remote interactions in orthodontic care [Internet]. London: BOS; 2022. Available from: https://www.bos.org.uk/ wp-content/uploads/2022/02/BritishOrthodontic-Society-Guidance-onteledentistry-and-remote-interactions-inorthodontic-careFinal-v5awamended.pdf (Accessed: 01 October 2024).

A multi-centre two-cycle audit into the use of Cone-Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) for investigation of ectopic canines

Balraj Gill (ST), Francine Jones (Post-CCST) and Christine Casey (Consultant)

The Royal London Dental Hospital, London, UK

Background/Rationale CBCT investigations have many uses within orthodontics and are commonly used for localised examination of the anterior maxillary region to assess the position of ectopic unerupted canine teeth and to exclude root resorption of adjacent incisors1. Plain film radiographs are still considered sufficient for diagnosis in most ectopic canine cases and can be supplemented with use of parallax. CBCT imaging needs to be sufficiently justified to ensure there is ‘net benefit’ to the patient. The principle of optimisation should be taken into account given the effective dose for CBCT is greater than that of conventional radiographic techniques2. Generally, the effective dose of panoramic radiographs falls within 2.7−38 μSv and 0.3−21.6 μSv for periapical radiographs3. This can vary widely for CBCT imaging with a range of 11 - 674 μSv for dentoalveolar CBCTs, with exposure settings even more pertinent since our cohort of patients are predominantly children and young adults. With this in mind, an audit into justification and referral criteria for CBCTs within a large secondary care orthodontic service at The Royal London Dental Hospital and Whipps Cross Hospital was performed.

Aims and Objectives

The primary aims were to measure compliance of orthodontic CBCT justification and referral criteria against nationally published guidelines and compare results against a previous local CBCT clinical audit completed in 2022-3. Furthermore, a concurrent service evaluation was performed to investigate CBCT use, looking at factors including patient demographics, number and type of plain films taken and wait times for CBCT.

Standards/guidelines/evidence base

Currently, there are no published guidelines which can be used as a gold standard for CBCT justification and referral criteria in orthodontics. Local standards were set, based upon European guidelines from SEDENTEXCT1, orthodontic radiograph guidelines from the British Orthodontic Society (BOS)2 and guidelines from the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) in 20224. The aims were agreed upon following discussion and consensus decision within a departmental meeting with Senior Consultants. This led to creation of four clinical standards in relation to CBCT requests, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1: Agreed local standards and target compliance

For standard 4, there should be no CBCT canine cases where sufficient information had already been obtained through plain film imaging. This was developed specific to ectopic canines as it was derived from selection criteria published by RCS ‘Management of the palatally ectopic maxillary canine’ and BOS ‘Orthodontic Radiographs Guidelines’ (pg. 22)2, ⁴. Additionally, a previous local service evaluation in 2022 highlighted that the majority of CBCT requests were related to ectopic canines and so by developing this local standard it would be more representative of the department.

Sample and data source

The sample comprised of 256 child and adult orthodontic CBCT requests in total. In the second cycle, this included additional requests (n = 34) from Whipps Cross Hospital. CBCT cases were identified by the local clinical effectiveness unit from a radiographic logbook and relevant

electronic case notes were analysed for the following data sets: Patient age and gender; number and type of plain film imaging prior to CBCT requests (only imaging relating to the tooth/teeth in question on CBCT request were included); CBCT justification given by clinician and date from CBCT referral to exposure.

Exclusion criteria included any requests that were made by another specialty because the primary aim of this audit related to orthodontic CBCT requests. Further, any duplicates, specifically patients that had CBCT of maxilla and mandible (n=43) were counted as one request as it was not the number of requests being evaluated through this audit, but the justification given.

Audit type

A two cycle, multi-centre audit undertaken between July-December 2023 and July-December 2024. The first cycle single-centre and retrospective, the second cycle multi-centre and prospective).

Methodology

The project arose from a previous audit carried out between February 2022 – June 2023, which sampled 60 patients attending a joint canine MDT clinic and underwent subsequent CBCT. This formed the basis to expand further to include all cases referred for CBCT regardless of which clinic they attended. The project was registered with the local clinical effectiveness unit (ID: 13826 and reaudit 14369). Data was collected during two separate timepoints: Cycle 1 July-December 2023 and Cycle 2 July-December 2024.

Records were analysed according to the data sets as described above and collated into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Specifically, electronic casenotes were reviewed to determine the justifications given by clinicians when requesting CBCT and compared against the agreed standards. Standards 1-3 were carried over from the previous audit, whilst standard four was added for this current two-cycle audit following review at a departmental meeting. Both cycles were presented locally, with overall recommendations discussed in January 2025. Figure 1 highlights the timeline of events.

Figure 1: Audit timeline

Findings

There was an almost equal proportion of male:female patients that underwent CBCT examinations between 2023-24, with a mean age of 16-years-old and age range from 11-58 years old. For standard 1, 2 and 3, the compliance rate was maintained at 100% between cycles. In over half of the cases referred for CBCT, it related to ectopic canines (n=78), which was then followed by impacted teeth (excluding canines – predominantly second molars and premolars) and supernumerary teeth (see figure 2). All cases had some form of plain imaging taken prior to CBCT, with the vast majority being DPT (n=92%) whereas peri-apical and upper standard occlusal radiographs were not taken as frequently (n=35).

CBCT Justification Canine

Supernumerary

Impacted tooth (other than canine)

Odontome

Surgical planning

Cystic changes

Pulp canal anatomy

Cleft planning

Resorption

For standard 4, The first cycle data revealed one canine case in which plain imaging confirmed severe resorption of adjacent teeth and correct localisation of the tooth, which would typically be sufficient for treatment planning purposes. However, a subsequent CBCT was requested with the same reasoning given as plain film imaging and there was no change in the clinicians’ treatment plan pre-or-post CBCT. This highlights how plain films were likely to be sufficient for orthodontic purposes for this specific case. Following the second cycle, there was improvement in compliance to 100% as all cases were referred for CBCT because there was insufficient information provided by plain imaging.

Observations

A total of 256 CBCT cases have been analysed as part of this two-cycle audit, which has demonstrated that ectopic canines remain the most common justification for CBCT requests within orthodontics, which has also been found in similar audit projects⁵. However, the concurrent service evaluation revealed variation between cases in terms of plain imaging taken prior to CBCT, as evidenced in a drop of 25% in the number of canine cases that have parallax done prior to CBCT, highlighting the need for national standards. Wider agreement in the orthodontic community on what is deemed insufficient information obtained from plain films would aid in planning. Although CBCT has been shown to be more accurate than conventional radiographs in localisation of ectopic canines⁶, clinicians should avoid requesting CBCT for every case due radiographic exposure risk. It is also important to note that standards cannot be entirely prescriptive and there should be a balance with clinical findings informing decision-making.

Comparing first and second cycle data, there has been a drop of roughly 40% in the number of canine cases that have parallax done (vertical or horizontal) prior to CBCT and mean wait times for CBCT from request increased from 35 to 59 days. Further exploration would be required to definitively determine reasoning for both of these points and if this trend continues with a subsequent audit cycle planned in 12 months’ time.

Recommendations

1. To re-audit in 12-months to assess if compliance continues with sufficient justification prior to CBCT requests. Local standards should be based on BOS, SEDENTEXCT and RCS Guidelines in terms of CBCT requests1,2, ⁴.

2. To disseminate specific guidance to the orthodontic team from the RCS on management of ectopic canines, which highlight the need for CBCT if plain film imaging is not sufficient for treatment planning purposes. Whether clinicians opt to carry out CBCT should take these guidelines into consideration in order to avoid unnecessary radiographic exposures.

3. Future local CBCT audits should always ensure a sufficient sample size, as opposed to the previous audit carried out in 2022-2023, considering over 300 orthodontic requests for CBCT are typically carried out per year.

4. These recommendations will be shared with staff during clinical governance meetings and through email. The audit will be repeated in 18 months using the updated data collection form.

Project involvement

Balraj Gill (Project lead, project design, data collection and analysi)

Francine Jones (Project design, project supervision, manuscript revision)

Christine Casey (Project design, project supervision, manuscript revision)

Acknowledgements

Mr Edward Spirling and Mr Nicholas Ogunlaga, Clinical Effectiveness Unit, Barts Health NHS Trust, for compiling relevant CBCT requests from electronic casenotes.

References

1. SEDENTEXCT. Radiation protection 172. Cone beam CT for dental and maxillofacial radiology: Evidence based guidelines. Luxembourg: European Commission; 2012.

2. Isaacson K, Thom A, et al. Guidelines for the use of radiographs in clinical orthodontics. 4th ed. British Orthodontic Society; 2015.

3. Horner K, Eaton KA. Selection Criteria for Dental Radiography 3rd edn. Faculty of General Dental Practice (UK), 2013.

4. Hussain J, Burden D, McSherry P, Hania M.

Management of the palatally ectopic maxillary canine. The Royal College of Surgeons of England, Faculty of Dental Surgery Clinical Guidelines, 2022.

5. Lin Y, Hamilton S. Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT): Are we scanning appropriately? A service evaluation. Clinical Effectiveness Bulletin, British Orthodontic Society, May 2023.

6. Serrant, P.S, McIntyre, G.T., & Thomson, D. J.

Localization of ectopic maxillary canines – is CBCT more accurate than conventional horizontal or vertical parallax? Journal of Orthodontics. (2014). 41(1):13-18

A two-cycle audit to assess orthodontic treatment outcomes at Liverpool University Dental Hospital

Yen Ming Lin (ST), Sarah Turner (Consultant Orthodontist) and Jayne Harrison (Consultant Orthodontist)

Liverpool University Dental Hospital, Liverpool, UK

Background/Rationale The Orthodontic Commissioning Guide (2015) offers direction to specialist dental services to promote consistent, high-quality care1. All primary care orthodontic providers in England and Wales are contractually obliged to submit PAR score changes as one of five key performance indicators of annual activity. All cases must be scored if the contractor completes <20 cases/year however, if completing >20 cases/year, then 20 cases plus 10% of the remaining cases, need to be scored. The PAR index is a form of outcome measure, although overall outcome measures should also include PROMs and PREMs.

To provide good care for patients and to ensure efficient use of NHS resources, we aim to provide treatment in a timely manner in line with locally recommended treatment times2. This is important for patient compliance and informed consent, as patients should be aware of realistic timescales involved before commencing treatment, as some may find it difficult to commit to the duration of orthodontic treatment 3 .

Assessment of treatment outcomes at Liverpool University Dental Hospital (LUDH) has not been undertaken since 1993, so this audit was long overdue.

Aims and Objectives

Primary Aim: To determine whether orthodontic PAR score outcomes at LUDH fell within NHS Commissioning guidelines.

Secondary Aims: To assess compliance with locally set standards that for 80% of patients: treatment was carried out within ≤30 months, patients were treated by ≤2 clinicians for continuity of care and PAR scores were recorded at debond.

Standards/guidelines/evidence base

Standard 1 and 2: As outlined by NHS England (2015) in ‘Guides for Commissioning Dental Specialities – Orthodontics’1: ≥75% of completed cases should exhibit a reduction in PAR score of ≥70% and ≤3% of completed cases should have a PAR score reduction of <30%.

Standard 3: The NHS advises that orthodontic treatment usually lasts from 12 months to 2 and a half years so we set the standard that ≥80% of patients should have a treatment time of ≤30 months.

Standard 4: There is evidence to suggest that transfer of care to other clinicians increases treatment time⁴ so we set a standard that ≥80% of patients should be treated by ≤2 clinicians

Standard 5: To ensure that we have a representative sum of cases, we set a standard that ≥80% of pre- and post-treatment PAR scores should be recorded at debond.

Sample and data source

A retrospective convenience sample of 50 patients who attended for orthodontic debonding of their fixed appliance, starting from 30th September 2023 for cycle 1 and 31st January 2025 for cycle 2 was identified. Cases were identified using the departmental debond diary. Clinical case notes and letters from Medical Records were retrieved and reviewed.

One of the two dental technicians, trained and calibrated in PAR scoring study models, should have scored plaster study models, taken at initial record collection and at debond and recorded the PAR scores in the Laboratory database as per the department protocol.

Exclusion criteria were patients with cleft and/or craniofacial deformities, moderate or severe hypodontia, receiving orthognathic treatment, treatment with limited objectives, removable appliance treatment only or who discontinued treatment.

Any cases with missing pre- or post-treatment study models or incomplete medical records were recorded and excluded. Only patients treated by orthodontic therapists, ST1-ST5 trainees and postgraduate students at any point throughout their course of treatment, were included. Patients treated by consultants were excluded as their caseload was comprised of predominantly patients with moderate/severe hypodontia and/or receiving orthognathic treatment.

Audit type

Local retrospective cross-sectional audit.

Methodology

Data were collected retrospectively for 50 patients per audit cycle between March and September 2023 for cycle 1 and September 2024 and January 2025 for cycle 2. Information was extracted from patient notes including dates of bond-up and debond to determine treatment duration and the number of clinicians who had treated the patient over their course of orthodontic treatment.

Study models (SMs) were expected to have been scored in both cycles. This had not occurred prior to cycle 1, so the SMs were retrieved and scored by one of two dental technicians. To facilitate SM scoring, time was identified for the technicians for PAR scoring to be completed, and a new lab card was designed and implemented prior to cycle 2.

Findings

PAR Score

Standard 1: >75% have PAR reduction of >70% (Figure 1)

Cycle 1: 86% of cases had a PAR score reduction ≥70% whereas the remaining 14% had a PAR score reduction between 30–69%.

Cycle 2: 78% of cases had a PAR score reduction of ≥70%, 16% of cases had a PAR score reduction between 30-69%.

The standard was met in both cycles.

Standard 2: ≤3% have PAR reduction <30% (Figure 1)

Cycle 1: No cases had a PAR reduction of <30%. Standard met.

Cycle 2: 6% of cases had a PAR score reduction of <30%. Standard not met.

Standard 3: ≥80% have treatment time of ≤30 months (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Comparison of LUDH treatment duration in cycle 1 (2024) versus cycle 2 (2025)

Cycle 1: 56% of cases had a treatment time of ≤30 months.

Cycle 2: 60% of cases had a treatment time of ≤30 months.

Mean treatment time was 33 months (95%CI=29-37 months) in cycle 1 compared to 30 months (95%CI=26-35) in cycle 2. The standard was not met in both cycles.

Standard 4: Continuity of Care – ≥80% treated by ≤2 clinicians (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Comparison of LUDH number of clinicians in cycle 1 (2024) versus cycle 2 (2025)

Cycle 1: 84% of cases were treated by ≤2 clinicians.

Cycle 2: 90% of cases were treated by ≤2 clinicians.

The mode number of clinicians per patient was 1 in both cycles. The standard was met in both cycles.

Standard 5: ≥80% of PAR scores done

Cycle 1: None of the cases had PAR scores completed by technicians, at the start of data collection. Standard not met.

Cycle 2: 98% of cases had been PAR scored at the start of data collection. Standard met.

Observations

This audit demonstrated that PAR score changes complied with the agreed standards in cycle 1 but not cycle 2 with 6% of patients having <30% reduction in PAR score. Despite this, they still objectively show that the standard of treatment was high.

The same technician did not PAR score all cases, however both technicians were trained and calibrated, therefore scores should be reliable⁵. However, the audit could have been improved by assessing the inter-rater reliability. All treatment was planned and supervised by a Consultant Orthodontist and the overall results suggests this system works well⁶. This enables trainees to treat complex cases with an IOTN of 4 and 5, under supervision of a Consultant Orthodontist, to obtain good treatment outcomes⁷.

Patients with moderate or severe hypodontia were not included in the audit as changes in tooth position and occlusion when opening or closing space are reflected poorly by PAR, despite the increased complexity and greater technical skill required⁸. Orthognathic cases were not included as PAR only assesses dental occlusion and has no quantitative measure for skeletal changes⁹. PAR should not be used in isolation to determine treatment complexity and the Index of Complexity Outcome and Need (ICON) has been developed for this purpose. Treatment results should be viewed together with other performance indicators such as qualitative patient satisfaction questionnaires⁶,10

Unmet Standards

Treatment time for 44% and 40% of cases was >30 months in Cycles 1 and 2 respectively. The wide variation in treatment times is potentially due to a combination of biological variation, treatment complexity, patient compliance, operator type and skill 2. As this audit was undertaken in a teachinghospital, increased treatment time may be attributed to levels of operator experience as most patientwere treated by clinicians in training. Change of operators has also been linked to increased treatment duration⁴ therefore, the number of operators should be limited to reduce the likelihood of extended treatment duration. In this audit most patients were treated by 1 clinician.

It was disappointing that none of the cases had PAR scores completed prior to cycle 1. This was fed back to the Laboratory team who acknowledged that PAR scoring models at debond had not become embedded into their routine. In addition, key information regarding e.g. impactions, missing or extracted teeth was rarely supplied by clinicians on the lab card at debond. Following implementation of the new lab debond card, 98% of cases were PAR scored prior to cycle 2.

This audit was performed retrospectively which may have limitations due to its reliance on cases having been entered correctly in the departmental debond diary. Two technicians carried out the PAR scoring and this could have potentially affected the inter-rater reliability of the scores

Recommendations

1. Continue using the new debond laboratory card (available at https://archive.bos.org.uk/ Portals/0/Public/docs/Research%20and%20 Audit/PARSCORINGSHEET.pdf) to facilitate recording of PAR scores by technicians as this improved PAR scoring significantly by cycle 2.

2. Provide opportunities for training and recalibration of laboratory technicians to provide consistently accurate PAR scores.

3. Implement locally agreed departmental policy regarding transfer cases to ensure that each course of treatment is provided by a maximum of 2 clinicians, unless unavoidable, to improve continuity of care and reduce treatment times.

4. Re-audit in 12 months to reassess the impact of the transfer of care policy.

5. Extend audit regionally to allow comparison of outcomes and share good practice between units.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the dental technicians for all their help in PAR scoring the study models.

Project involvement

Yen Ming Lin (Project lead, project design, data collection and analysis, manuscript drafting and submission)

Sarah Turner (Project supervision, project design, manuscript editing and approval)

Jayne Harrison (Project supervision, project design, manuscript editing and approval)

References

1. NHS England and NHS Improvement. Guide for Commissioning Orthodontics. 2015.