END-TO-END DIGITAL WORKFLOWS ACROSS THE MINING VALUE CHAIN, FROM EXPLORATION TO PROCESSING

END-TO-END DIGITAL WORKFLOWS ACROSS THE MINING VALUE CHAIN, FROM EXPLORATION TO PROCESSING

32 The challenge of mineral discovery under cover by Nick Lisowiec, Exploration Manager (Eastern Australia) at Gold Road Resources

36 Bringing back the romance of exploration by Steve Beresford, Co-Founder of Altai Resources

Sanja Prvulovic Managing Director of Reflex Drilling, Serbia

Diyana Chunga Business Development Representative at Cipembele Exploration & Mining Services

Nick Lisowiec Exploration Manager (Eastern Australia) at Gold Road Resources

June 2025

Cover photo MDH

Issue 31

ISSN 2367-847X

Not for resale. Subscribe: coringmagazine.com/subscribe

Contact Us

Coring Media Ltd.

57A Okolovrasten pat street, r.d. Manastirski Livadi, Triaditsa region, 1404 Sofia, Bulgaria

Phone +359 87 811 5710

Email editorial@coringmagazine.com Website coringmagazine.com

Andrew Bailey CEO of MinEx CRC

Dr Scott Halley Director of Mineral Mapping

Steve Beresford Co-Founder of Altai Resources

Peter Leckie Head of Product— Axis, Orica Digital Solutions

Publisher Coring Media

Executive Officer & Editor in Chief

Martina Samarova

Editor Maksim M. Mayer

Section Editor – Exploration & Mining Geology

Dr Brett Davis

Digital Marketing Manager

Elena Dorfman

Assistant Editor Adelina Fendrina

Graphic Design Cog Graphics

Want to contribute to Coring Magazine? Get in touch with us at: editorial@coringmagazine.com

Coring Magazine is an international quarterly title covering the exploration core drilling industry. Published in print and digital formats, Coring has a rapidly growing readership that includes diamond drilling contractors, drilling manufacturers and suppliers, service companies, mineral exploration companies and departments, geologists, and many others involved in exploration core drilling.

Launched in late 2015, Coring aims to provide a fresh perspective on the sector by sourcing authentic, informed and quality commentary direct from those working in the field.

With regular interviews, insightful company profiles, detailed product reviews, field-practice tips and illustrated case studies of the world’s most unique diamond drilling and mineral exploration projects, Coring provides a platform for learning about the industry’s exciting developments.

Despite coming from a mining town in Eastern Serbia, Sanja got her start in the industry in an unusual way. With the connections from the restaurant she worked at, she found a low-bed truck for some drillers and a new job in the process.

In 2006, Sanja began working with IDS. Later, she joined MRS Morocco and moved to Ghana to become a General Manager. In 2014, Sanja took the position of a Mud Engineer and Sales Manager for Eastern Europe and Central Asia for IMDEX.

Since starting Reflex Drilling Serbia with her business partner in 2017, the company has grown steadily, and they have achieved many milestones in the country, including designing their own customized drill rig. Sanja emphasizes taking the most positive aspects of all these experiences, spanning nearly 20 years and several continents.

Grigor Topev: It’s a pleasure to have you as our guest interviewee at Coring Magazine! I like to start every interview with the same question: how did you first get into the drilling industry, and what drew you to it?

Sanja Prvulovic: I am from a mining town in Eastern Serbia, but it’s not that I knew what drilling was at that time. I finished a Business Academy, specializing in Customs and Taxes, but getting a job in a profession was always hard in Serbia, so I worked in a restaurant, and my English was passable—just enough to get by. One day, a guest asked if I knew someone with a low-bed truck for rig transport. The only one in town had broken down, and they had been searching for days without success. Working in a restaurant meant getting to know a lot of people, so within 12 hours, I found a replacement for them. That simple connection changed everything—a job offer followed, and that’s how my journey in drilling began.

GT: Could you please tell us more about your professional journey and the companies you have worked for?

SP: In 2006, I started working for IDS, an Australian-owned company. It was a real challenge to be working with people from different countries and different cultures. Being the only woman on site didn’t make things easier. I constantly needed to prove myself and work twice as hard to gain the trust of my colleagues. In the end, I was rewarded.

In 2008, the company and projects were sold to Capital Drilling, one of the biggest companies in the industry. This transition was a great opportunity to see firsthand how one of the most successful drilling companies at that time operated, organized people, and trained them. We met many skilled people and had a good exchange of experience.

One long year after the Global Financial Crisis, I got an offer to work in Morocco with MRS Morocco, which I gladly accepted, and was with them until we moved to Ghana. We were the same company but under a different name: Reflex Drilling Ghana. I was there until the market slowed down in 2013.

As with every crisis, new opportunities are born, so that’s how I became

part of the IMDEX. After a very good training session in Western Australia, I started working as a Mud Engineer and Sales Manager for Eastern Europe and Central Asia for the next three years.

GT: You mentioned working in Ghana for several years. What made an impression on you there and what lessons did you learn from this experience?

SP: Working in Ghana as a General Manager was very exciting and challenging at the same time. The culture was different, but the people were very friendly, kind, and easy to work with. What stood out to me were the opportunities available there. The country is rich in different minerals, but at the same time, very poor in everything else like infrastructure, health services, etc. I was used to living in Europe and having everything at hand, and Ghana was totally the opposite.

GT: You are the Managing Director of Reflex Drilling, Serbia. Tell us more about the company and how you started it.

SP: Reflex Drilling began with an idea from my former boss, James. In 2013, when many projects had come to a halt, he decided to step away from the drilling industry. At the time, I was working as a Mud Engineer, and through my experience, I had built strong connections in the drilling field. Some of them expressed interest in renting rigs from James, but he was hesitant to lease equipment to people he didn’t personally know. Instead, he suggested that I take on the responsibility, and that’s how my business partner, Taner Tahir, and I started a company.

After a period of renting equipment, we decided to buy the company, and I want to take this moment to once again thank James for the trust and opportunity he gave us. Since starting Reflex Drilling in 2017, we have grown steadily, becoming busier each year, and today our company is the preferred partner for our clients.

GT: What makes clients choose Reflex over other companies offering similar services?

Reflex way from the start ensures consistency, and clients appreciate seeing familiar, trusted faces on every project.

As for attracting new talent, we’ve observed a decline in interest in drilling careers. Many seek easy and relaxed jobs, and we find that fewer people possess the drive and determination needed for this demanding industry. The energy, spirit, and ambition to excel in drilling are becoming harder to find.

GT: What was the most challenging project you’ve tackled? Tell us about it.

SP: I would say a project we are currently working on – the famous Čoka Rakita Project by DPM. When we started 2017, holes were shallow—up to 500 m (1640 ft) in depth, and I can freely say, easy to drill.

But these days, you cannot find a project with shallow holes; they are all beyond 1000 m (3281 ft), and in very challenging ground conditions. Doing a lot of directional drilling and passing through many fault zones. Lucky for us, a satisfied client with a lot of great results is what makes us proud.

‘Our team is truly our own - most of them have been with us from the very beginning. We take pride in training our people from offsiders into drillers and supervisors, and they are loyal; once they join us, they stay.’

SP: I would say a professional approach and flexibility while maintaining high-quality drilling services, close and friendly communication, and connections with our clients. We pride ourselves on making quick, informed decisions and providing effective solutions to keep operations running smoothly on our well-maintained equipment, continual investment in new technology and rigs, and development.

GT: Tell us more about your team. Is it difficult to attract new talent into the drilling industry?

SP: Our team is truly our own—most of them have been with us from the very beginning. We take pride in training our people from offsiders into drillers and supervisors, and they are loyal; once they join us, they stay. On some occasions, when workload demands increase, we bring in external drillers, though we prefer to train our own. Learning the

GT: What are your short- and longterm goals for the company?

SP: Would it be bold to say that we are going with the wind? As a small drilling company, we started with just one rig in 2017, and now, with two new deep-hole rigs arriving by the end of June, we will have a total of seven. Our initial dream was to operate two or three rigs, keeping things small and close-knit. However, demand doesn’t always align perfectly with dreams.

Beyond drilling, one of our greatest ambitions has been designing drill rigs. With the support of our friends and business partners at Gemsa General Makine in Turkiye, we successfully designed our own customized drill rig with a capacity of up to 2000 m (6562 ft) in N-size, the Gemcor RD15. Its capacity and capability exceed expectations, and since its arrival in March 2024, it has been drilling nonstop without issues. The satisfaction of having a rig that performs flawlessly, with no maintenance concerns beyond regular service, is unmatched. We have just built two more rigs, and they are on their way.

GT: Tell our international readers about the drilling landscape in Serbia. Which are the main players, and what are the big projects?

SP: Serbia may be small, but its mining and drilling sector is home to several major international players. Companies like Dundee Precious Metals, Zijin Mining, Rio Tinto, and Strickland Metals, are actively involved in exploration and drilling, contributing significantly to the industry.

One of the most important mining projects in Serbia is the Čukaru Peki copper and gold deposit, near Bor, operated by Zijin Mining. This site is considered one of the richest copper and gold deposits globally and plays a crucial role in Serbia’s mining landscape. Additionally,

the Timok Magmatic Complex and the Čoka Rakita Deposit are both key areas for copper-gold exploration.

Serbia has also attracted foreign investment in mining, with companies exploring resources, such as lithium, boron, and metallic raw materials. The Jadar lithium-borate project, led by Rio Tinto, is particularly noteworthy, as it has the potential to become one of the largest lithium deposits in the world.

GT: What unique advantages or challenges does Serbia offer compared to other markets in the region?

SP: One of Serbia’s biggest advantages is its rich mineral potential, particularly in copper, gold, and lithium. The country’s geology has led to significant discoveries, attracting

major international players eager to tap into these resources. Serbia’s strategic location in the Balkans also makes it well-positioned for investment.

GT: You mentioned the government, how supportive is it of mining and drilling?

SP: The government is very supportive. We can see this from the extensive exploration and drilling undertaken in the last 20 years, as well as the many exploration licenses that have been issued. The government’s support for the mining sector, through favorable policies, permitting processes, and infrastructure development, has encouraged both domestic and foreign companies to invest.

GT: Last year, there was a major anti-mining project in Serbia that made international news. What is the people’s attitude towards drilling in the country? Is there anything that could change it?

SP: In Serbia, there are active groups against mining and exploration, primarily due to environmental concerns. This is not unique to Serbia—it’s a global trend where communities push for stronger ecological protections. However, attitudes toward drilling vary. In regions with active or historic mining operations, communities tend to be more familiar with the industry and its benefits, leading to a more balanced perspective. Where mining is new, skepticism is stronger. Mining companies can build trust by demonstrating their commitment to environmental responsibility, investing in sustainable practices, and engaging with local communities.

GT: Is there enough collaboration between companies, universities, and the government to support the next generation of drilling professionals in Serbia?

SP: Not really, it is significantly below what is required. The industry would benefit from stronger partnerships, especially in education, training programs, and talent development.

Currently, there are limited structured initiatives to equip students with hands-on drilling experience. While some companies invest in internal training, there’s no widespread effort to encourage young professionals to pursue careers in drilling. Given the declining interest in the sector, internships and technical workshops could be a key step forward.

If approached strategically, improved collaboration could lead to a more skilled workforce. It’s something worth looking into for the future.

GT: Do you see the Serbian drilling market expanding? Why or why not?

SP: I can’t really say, but what we saw in the past few years is that many key mining companies are continually discovering new deposits.

GT: Has the entry of international drilling companies into Serbia affected the drilling business there?

SP: I wouldn’t say so, they are always a refreshing challenge. Healthy competition will only make you fight more and do better.

GT: What regulatory or logistical improvements would you like to see in Serbia to better support companies like Reflex Drilling?

SP: I would say higher availability of on-site drilling equipment in the country. Other than that, Serbia is pretty much well-positioned in Europe.

GT: Going a bit further, what would you change in the global drilling industry?

SP: Everyone is talking about digitalization, artificial intelligence, and new drilling technologies, but honestly, drilling techniques have not changed much in the last 30-40 years or maybe even more. You still need to pull rods out for a bit change. Maybe this is something I would want to see changed. A major shift could come from automation and smart drilling systems that eliminate repetitive manual tasks like rod pulling, reducing downtime and improving efficiency.

GT: What do you do to relax?

Do you have any hobbies?

SP: This is a tough one—I work a lot, so there’s not much time for hobbies. But if I had to choose, gardening would be my goto. I love growing flowers and vegetables, and I always make time in the morning before work to tend to the garden. There’s something deeply satisfying about nurturing plants, watching them thrive, and caring for them—it’s a simple joy that brings a sense of peace before the day begins.

GT: Thank you for taking the time to answer our questions! Do you have any parting words for our readers?

SP: Looking back at the companies I have

worked for, I have always been left with a positive impression everywhere, and I believe that I have always taken the most positive aspects from my entire career. Everything was wonderful and good. And this is who I am today.

After so much experience and time in the sector, the moment came for me to start my own company. From here, I want to thank everyone I have worked with. It was truly great to work with each and every one of them, to learn something from every person, and I hope that others have also learned something from me.

MDH was founded in Peru in 1966 as a mining contractor and specialist in diamond drilling. Hernán Villafuerte, the current general manager, shares the history and achievements of the company.

The history of Peruvian mining is deeply intertwined with the history of exploration and MDH has marked a steady path in that terrain for almost six decades. Founded in 1966 by the visionary engineer Guido del Castillo Echegaray, MDH was born with a clear mission: to professionalize mining drilling in Peru, bringing technology, safety and vision to a sector in full transformation. Today, his legacy is more alive than ever, driving a new generation of professionals who understand mining as an ecosystem of precision, efficiency and positive impact.

One of the main drivers of this new stage is Hernán Villafuerte, MDH’s current general manager. A mining engineer from Arequipa, Villafuerte has more than 20 years of experience in the drilling sector, during which he has led highly complex operations in various regions of the country. His technical knowledge of Peruvian geology, together with his strategic vision and leadership, make him the ideal person to

lead this new generation of drillers.

‘MDH is much more than a drilling company,’ he says from the company’s Lima headquarters. ‘It is an organization that has been able to evolve with the mining sector, and that today is committed to a different way of doing things: with innovation, agility, and an unwavering commitment to safety and sustainable development.’

MDH’s history dates back to 1966, when its founder Guido del Castillo identified the need to provide more technical, reliable and longterm drilling services. At a time when mining was still lacking in local,

high-level specialized services, his proposal was revolutionary: to bring the international standard in diamond drilling to Peru.

During the early years, the company operated mainly in exploration projects in the Central Highlands. As the country advanced in the development of its modern mining industry, MDH grew with it.

In 1994, it consolidated a strategic alliance with the Canadian Bradley Group, giving birth to Bradley-MDH. This stage represented a fusion of local experience with international technologies and methodologies, which further professionalized the processes, increased operational safety and strengthened the organizational culture.

‘That partnership was key to our maturity as a company,’ Villafuerte recalls. ‘We incorporated processes, technology and also a new way of looking at the business: oriented toward quality, risk prevention and operational sustainability.’

In its nearly six decades of existence, MDH has drilled more than five million meters in projects throughout Peru. From the Andes to tropical and desert areas, the company has demonstrated outstanding technical and logistical capabilities.

Currently, it provides services in the main mining units in the country, working with companies such as Compañia Minera Antapaccay, Ares, Minsur, Nexa Resources, Volcan. Beyond the names, what stands out is the sustained trust that clients place in MDH, reflected in obtaining long-term contracts—a great recent strategic achievement.

‘A long-term contract is not earned with low prices,’ Villafuerte clarifies. ‘It is earned with performance, with consistent compliance and with a relationship of trust based on data, reportability, security and sustained results.’

In line with this vision, MDH has succeeded in obtaining and maintaining ISO 9001 (Quality management), ISO 14001 (Environmental management), ISO 45001 (Occupational health and safety) and ISO 37001 (Anti-bribery management systems) certifications, supporting its comprehensive commitment to excellence and ethics.

MDH’s portfolio of services has evolved into a comprehensive technical proposal. Although diamond drilling remains the main service, the company also develops reverse circulation (RC) operations, geotechnical and hydrogeological drilling, installation of piezometers, inclinometers, and carries out tests such as SPT, Lugeon and Lefranc.

In addition, it has developed specialized capabilities in water well drilling, with high-pressure compressor technology and maneuverability. This service has become strategic in projects requiring sustainable water infrastructure in remote areas.

A service that was recently developed is the logging, cutting and sampling of cores, which allows the company to offer a comprehensive range of exploration services.

‘Our vision is to be the client’s technical partner, not just a contractor. We want them to see us as an extension of their geology or geotechnical team. That is the new way to add value,’ explains Villafuerte.

MDH operates a fleet of more than 70 drilling rigs, many of them adapted or designed specifically for Peruvian terrain conditions. Among its main units are:

• HTM-2500 with a rod handler for safe rod handling, which is capable of drilling more than 3000 m (9843 ft);

• LF-230, ideal for deep, high-precision drilling;

• STM-1500, especially useful for in-mine drilling, with capacities up to 2000 meters (6562 ft) in NQ;

• Schramm T685WS, used in water wells, with compressors from 1150 cfm to 500 psi.

This investment in first-class equipment is accompanied by a strategy of preventive maintenance, telemetry and continuous improvement.

‘Drilling well is not just about getting to depth, it’s about getting to depth with recovery, without deviation, safely and on schedule. That can only be achieved if the equipment, the technology and the operator are aligned,’ he says.

Among MDH’s most important technical achievements is the execution of a diamond drill hole at a depth of over 2500 m (8202 ft), with a more than 95% recovery, without significant deviations and in adverse geological conditions. This technical milestone was possible thanks to a meticulous drilling design, the use of directional tools, and specialized equipment in continuous operation.

In another project, the team executed a geotechnical drilling campaign in an environmentally sensitive area, using clean techniques, biodegradable muds and zero-impact waste management systems.

‘The client chose us because of our technical capacity, but they hired us again because of how we did things. That’s the difference,’ says the general manager.

Behind every successful operation, there are people. MDH has more than 600 employees in operations and technical support, all of them constantly trained under internal training programs and international standards. The company has implemented labor inclusion programs which promote the participation of women in the field as drillers, assistants and geotechnical technicians.

It also develops a local employability model: it hires unskilled labor from communities near its operations, who are then trained and professionalized. In several operations, up to 100% of the local unskilled labor comes directly from these areas.

‘We don’t just drill into the ground. We also open roads for people. That’s the mining we believe is worth doing,’ says Villafuerte.

MDH also collaborates with technical institutions such as TECSUP, promoting the training of young people in careers related to mining and maintenance, encouraging the labor insertion of new generations of technical professionals.

‘We don’t just drill into the ground. We also open roads for people. That’s the mining we believe is worth doing.’

Working at MDH is not just about filling a position: it is about being part of a culture of excellence, safety and continuous improvement. With internal evaluation and promotion processes, as well as a per manent training system and benefits oriented towards the well-being of workers and their families, MDH has built a solid reputation as an employer of reference in the mining services sector.

‘We are committed to the growth of internal talent. There are many cases of people who started as assistants and today they lead crews or projects. That is also part of our essence: to develop people,’ Villa fuerte points out.

• B20 Drill Heads “H” & “P”

• 12HH Chuck Assy’s

• “H” & “P” Hydraulic Clamps

• Quality Repair Parts

• Jaw Sets

- Boyles 12HH, 35PH

- LY Nitro Chuck

- Christensen

- MiRoW “P” Clamp

MDH is ready for the challenges of the future. And it is open to work ing with new customers looking for efficiency, safety, technology and real social commitment. But it is also welcoming towards new talent who share its passion for doing things right, with pride and responsi bility.

‘We want customers to give us the opportunity to show what we can do. And we want the best professionals to see us as their home. Here is a place to grow, to innovate, and to make a mark.’

MDH’s motto, ‘Drilling into the future with the agility of a new generation’, summarizes its current identity. They are a company with 59 years of history, founded by a visionary like Guido del Castillo. Today they are led by professionals like Hernán Villafuerte, who understand that technical success must be accompanied by responsibility, respect for people and a real contribution to the country.

And so, with every drill hole, MDH continues to write a deep, technical and human history. A history that honors its past, leads the present and drills, with agility, the future.

For more information Visit: mdh.com.pe

by Andrew Bailey, CEO of MinEx CRC

MinEx CRC, the world’s largest mineral exploration research collaboration, and its sponsor organizations are investing in novel sensing technologies to be deployed in the borehole during drilling operations, aiming to deliver near-realtime exploration data for more efficient drilling and timely decision-making.

Combined with downhole steering and multilateral drilling techniques currently under development in their CT drilling project, these technologies will enable explorers to modify drill targets and alter the drilling trajectory ‘on the fly’. This will decrease the cost of drilling (fewer holes and fewer meters drilled) and increase the chances of intercepting target mineralization.

Following advice from end-user mining companies and mining, equipment, technology, and service providers (METS), MinEx CRC have focused their downhole sensing research on electromagnetic (EM) and geochemical logging tools aimed at developing functionality not available in the current market.

Borehole EM sensors have been part of the mineral exploration toolkit for decades; however, they are only used in a small percentage of drill holes, typically deployed by wireline (requiring a separate deployment by a specialist logging crew) and have functionality limited by the single, or sometimes dual, frequency settings of the source EM field. The MinEx CRC research team, based at Curtin University (Western Australia), has developed a unique downhole ‘Swept Frequency’

EM sensor system which cycles through hundreds of source frequencies at each measurement location. The tool has been designed for small-diameter mineral exploration drill holes and can be deployed by wireline or as part of the drilling bottom-hole assembly. The latter is a critical aspect of MinEx CRC’s approach as it enables the options of logging-while-tripping or logging-while-drilling, thus removing the requirement for a separate logging deployment and significantly reducing the risk of hole collapse between drilling and logging.

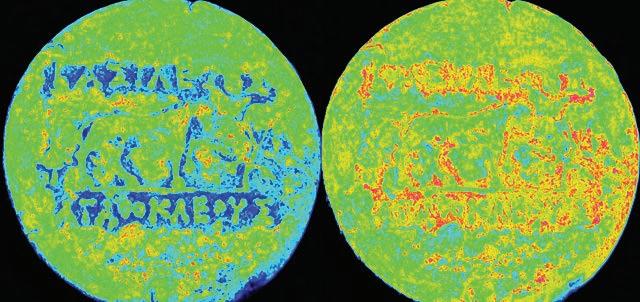

The frequency-dependent response from the surrounding geological formation delivers an exceptionally rich data stream, which is ripe, can be used to derive multiple physical properties (conductivity, induced polarization, magnetic susceptibility) and characterize the geophysical response meters from the drill hole.

Over the past year, MinEx CRC have progressed their downhole Swept Frequency EM tool from a laboratory prototype (TRL4) to a field-tested prototype (TRL6), with the successful acquisition of data from a 900 m (2953 ft) drill hole at Curtin University. In parallel, researchers have been conducting controlled experiments in environments with high but well-constrained conductivity contrast (designed to understand the temperature-dependent response of the tool). The data will help create calibration procedures for collecting reliable, high-quality data. MinEx CRC plans to progress the Swept Frequency EM tool to TRL7 this year.

At the same time, the petrophysical logging research team will step up their efforts to develop a novel downhole Time Domain EM (TDEM) tool. A downhole equivalent to conventional surface TDEM methods, with similar waveforms that can be integrated with surface measurements for improving resolution and confidence in subsurface modeling, it will deliver greater depth penetration (tens of meters) than the swept frequency tool. This offers the potential to locate and model off-hole conductors and inform drilling decisions (including trajectory control or kickoff for multilateral drilling from the same drill hole).

If achievable, in situ geochemical logging of the drill hole has the potential to change dramatically the approach to mineral exploration in three ways. Firstly, by reducing reliance on high-quality sample recovery (thus permitting more cost-efficient drilling techniques), secondly, by generating an objective, multidimensional data stream for automated multiparameter geological logging, and thirdly, by bringing real-time decision making to the drill site.

LIBS has several advantages over alternate downhole geochemical techniques. Among these are:

• It can measure the entire periodic table at relevant detection limits (<10 ppm);

• Pulses of the high-energy laser source can be used to dry or clean the drill hole wall pre-analysis;

• Each analysis is very rapid, so a time-efficient logging strategy can deliver hundreds of analyses per meter. These can be integrated to provide a bulk-rock composition at user-defined intervals or used as input into geochemical and spatial analytics software. The data are conducive to clustering and domaining techniques for automated drill hole logging;

• Each analysis covers a tens of microns in diameter area with the ability to resolve single mineral grains (and simple mixtures of mineral grains). This enables data processing techniques that can be used to determine quantitative mineralogy, mineral chemistry and proxies for mineral texture (e.g. grain size distribution).

If the design, deployment, and data processing challenges for a downhole LIBS system can be solved, MinEx CRC will be able to deliver an extremely rich dataset for rapid, objective, quantitative geological logging of drill holes.

After consultation with end-user and service provider participants, MinEx CRC have focused on delivering a market-ready tool for airfilled drill holes. The LIBS research team based at CSIRO, Melbourne/ Perth, and UniSA, South Australia, has progressed the downhole LIBS tool from a concept to a field-deployable prototype (TRL5). Laboratory testing was focused on key technical challenges, including:

• Optics and spectrometer design to fit within the constrained space of a borehole;

• Ruggedized housing to survive drill hole conditions;

• The requirement to collect analyses while the tool is in motion;

• The likelihood that the drill hole wall will be uneven at the millimeter to centimeter scale;

• The likelihood that the drill hole wall will be wet or dirty.

Additionally, researchers are developing novel calibration and data processing algorithms to achieve high-quality, repeatable data with partial detection limits per million range for multiple elements from the same LIBS spectra. Using the data, researchers are working on algorithms to generate user-defined derived data, such as data clustering, automated boundary detection, integrated bulk-rock analyses, quantitative mineralogy, mineral chemistry and proxies for texture.

In October 2023, MinEx CRC filed a provisional patent based on their prototype downhole LIBS system, which incorporates a high-powered, variable-focus laser and optics and spectrometers capable of detecting all elements on the periodic table to part per million levels.

The tool has a ruggedized chassis with a diameter of 75 mm (3 in), which fits within most mineral exploration drill holes (all drill holes larger than or equal to NQ diameter). In-hole stabilizers protect the tool from being damaged by the drill hole wall and position the laser at an optimum distance from the wall during analysis. The prototype tool is deployed by wireline (although future versions are intended to be driller-deployable) with a winch system controlled by bespoke software that allows user-controlled logging of velocity and sampling rates. The system also includes an in-field calibration module and additional sensors for monitoring instrument performance.

With the support of MinEx CRC Participant IMDEX Limited, June 2024 saw the first within-hole trials of the prototype tool collecting over 220 logging meters (722 ft) in shallow drill holes at the Australian Automation and Robotics Precinct (AARP), Western Australia. Multiple logging runs were conducted in the same drill hole with varying parameters (wet vs dry walls, with and without autofocus mechanism, with and without air jets for cleaning). Specific intervals were doped with elevated concentrations of target elements Cu and Li. The tool returned geologically sensible data under various operating parameters and could detect and measure Cu and Li concentrations

in the doped intervals. The results are used to refine the tool design, including a redesign of the optical front end and deployment process. MinEx CRC plans to progress the downhole LIBS tool to TRL7 by 2027, working in parallel with potential industry partners to ensure that the final product is technically sound (robust and delivering high-quality data) and commercially viable (delivering valid data within an affordable and profitable business model).

The MinEx CRC downhole EM tools and downhole LIBS geochemical tool are enabling technologies that can contribute to an overarching stretch target of MinEx CRC that spans multiple research projects and exemplifies the portfolio nature of its research—to deliver logging-while-drilling and real-time trajectory control within a safe, environmentally-friendly, and cost-effective CT drilling platform.

Several technical hurdles remain. Tools intended to operate during active drilling must withstand the extreme conditions—high pressures, abrasion (both from drilling fluids and cuttings and from physical contact with the drill hole wall) and severe vibrations caused by the drilling process. These challenges will be easier to overcome for the EM tools (designed to operate underwater and with a relatively high tolerance for physical stress) than for the downhole LIBS tool (currently designed for use above the water table and relying on finely-tuned mirrors and lasers that are prone to disruption by physical stress). The downhole tools have been designed to offer commercialization potential as standalone products, with the option of being deployed by wireline or as logging-while-tripping tools. The latter allows the driller to collect end-of-shift or end-of-hole data for within-program decision-making without a separate wireline deployment.

Equally important to the vision of real-time trajectory control is the ability to accurately locate and steer the drill bit while drilling. This is the subject of ongoing research for CT drilling engineers working in collaboration

with UK-based drilling technology provider AnTech Limited. MinEx CRC’s strategy is to miniaturize a bottom-hole steering assembly, whose larger version is proven to occur during Phase 3. Additional resources were provided by MinEx CRC Participants to build a field prototype in 2024, with a series of field trials planned for late 2025.

If steering while drilling proves not to be viable, MinEx CRC will revert to their fallback strategy to deliver multiparameter drill hole logging combined with accurate location of the drill bit and the ability to drill multiple deviations from the same drill hole. During 2024, UniSA-based drilling engineers conducted successful trials of hardware and operating procedures to ‘kickoff’ from an existing drill hole, creating the potential for multiple deviations from the same collar location. The trials were conducted in soft formations (at UniSA Mawson Lakes Campus) and hard formations (at Kapunda in collaboration with MinEx CRC Affiliate EnviroCopper). The procedure involves setting a casing wedge at the required depth and drilling a pilot hole using a full-face bit and reamer developed in collaboration with Hardcore Diamond Products. To demonstrate the viability of the ‘kickoff’, the drill hole was re-entered with a diamond coring bottom-hole assembly and 3 m (9.84 ft) of drill core were collected from the new trajectory. This is a passive approach to achieving an outcome comparable to steering while drilling, namely that the driller can control the drilling trajectory in response to geological and geophysical data while the hole is being drilled. The component technologies to enable this vision have now been designed and built by MinEx CRC and are at various stages of field testing. Each has a standalone commercialization potential, and in combination they have the potential to deliver a profound improvement in drilling functionality, cost, and success, measured by meters drilled per discovery.

For more information Visit: minexcrc.com.au

Stringent marking guides on the face and side of the core ensure consistently sharp and quality marks every time.

Every orientation is validated, supporting the classification of drill run confidence ratings.

Digital QA/QC data supports geologists with core reassembling and logging, improving overall productivity in the core shed.

Featuring a no-break comms workflow, core is orientated without rotation of the core tube.

by Peter Leckie, Head of Product—Axis, Orica Digital Solutions

Since October 2022, Orica Digital Solutions’ Axis Mining Technology has seen a steady stream of product improvements and is now releasing a slew of new technology, setting a new industry standard for surveying workflows.

Building on Axis Mining Technology’s history of bringing industry-leading hardware innovations to market—notably the Champ™ Gyro and Champ™ Ori—the past two years have seen a bolstered product development and an engineering team who are seeking to set a new industry standard, not only with Axis’ renowned hardware, but in tightly integrated software workflows for drillers and geologists alike.

In early 2024, software developments were released to support new, customer-requested workflows from office to field. Following soon after was the introduction of Champ™ Navigator 2, offering highspeed vertical continuous surveying and incorporating incremental increases in measurement precision that have since been applied to the whole Champ™ Navigator suite.

Significant advancements continued in late 2024 with the launch of

AXIS Connect™—a new ground-up cloud application that seeks to offer industry-leading survey management via simplified workflows and modern integration points, enabling seamless interoperability with other industry-standard software platforms such as Seequent, CorePlan and Blackfox (AcQuire).

Less than six months later, in early 2025, another major announcement came with the introduction of the AXIS Aligner™. Launching at the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) conference, AXIS Aligner™ features a three-minute start-up time, ergonomic one-arm lift, and innovative push-button clamping mechanism, representing a significant advancement in the safe, easy and precise alignment of a drill rig.

Joshua Brink, Project Manager for Timberline Drilling—an early trial partner of the AXIS Aligner™—says, ‘I’ve had the opportunity to use the new AXIS Aligner on multiple drills, and it is great. The calibration time is incredible, and with the new lightweight design and magnetic clamping system, it’s going to be hard to beat.’

Also on display at PDAC was the soon-tobe-released AXIS All-Gyro™, which is the first downhole tool on the market to offer true all-angle, north-seeking surveying—a game-changer to now support measurements across all angles and modes from a single device. Housed in a significantly smaller enclosure and suited to application in both exploration and production applications, the AXIS All-Gyro™ looks to combine with the full stack of other Axis hardware and software, taking surveying into the future.

Peter Leckie, Head of Product for Axis at Orica Digital Solutions, gave insight into what is next for Axis: ‘Axis’ proposition is simple to describe, but requires close customer relationships and cutting-edge hardware and software to execute. We want to be the driller’s choice by making it as easy as possible for them to collect the measurements they need to as part of their campaign, and to be best in industry for support when things don’t go to plan. We want to be the geologists’ choice because our software enables them to execute their survey plans and make decisions effectively, and to lead the market in interoperability so their data goes where it needs to go. Happy geologists mean drillers can just drill, and happy drillers mean geologists get great execution of their plans.’

‘I’ve had the opportunity to use the new AXIS Aligner on multiple drills, and it is great. The calibration time is incredible, and with the new lightweight design and magnetic clamping system, it’s going to be hard to beat.’

by Diyana Chunga, Business Development Representative at Cipembele Exploration & Mining Services

In Zambia’s dynamic mining sector, a wholly Zambian-owned drilling company is making significant strides. ATL Drilling Ltd is transitioning to Cipembele Exploration & Mining Services - a rebranding that better reflects its expanding footprint and ambitious vision. Founded in 2013 and led by CEO Leroy Schultz, the company is demonstrating how local expertise can thrive in a space traditionally dominated by international players.

Cipembele Exploration & Mining Services Ltd is currently spearheading two mineral exploration projects under the ZCCM-IH portfolio. The first, located in Serenje in the Central Province, is known as the Kabundi Project, and is targeting copper and manganese deposits. This project is set to last about two months, ending in June 2025. The second project in Rufunsa, Eastern Province, focuses on gold exploration. It is set to last about three months and is now projected to end in June 2025.

Together, these projects cover over 5000 m (16 404 ft) of combined drilling and employ a total of 46 employees. These employees include site managers, drill supervisors, drillers, offsiders, core markers, drivers, chefs, camp attendants, boiler makers, mechanics, paramedics, safety officers, and local community helpers. In Serenje, Cipembele Exploration & Mining Services Ltd is drilling to depths of up to 700 m (2296 ft), while the Rufunsa project includes boreholes ranging from 40 to 200 m (131–656 ft). Both are currently in the exploration stages, and progress is well underway.

Zambia’s geology poses unique challenges, among which are variations in ground formations. In their explorations, Cipembele

have encountered hard rock, broken formation, soft formation, clay, and sand. Both sites share similarly broken geological formations, making drilling unpredictable, with the team averaging between 9 to 45 m (30–148 ft) per shift, depending on how the ground holds. Common challenges include fractured rock, cavity zones, and water loss, all of which complicate core recovery and borehole stability.

To overcome these, Cipembele employs a combination of advanced rigs, all of which are transportable by land. At Kabundi, a multipurpose Sandvik UDR 650 is deployed, while the Rufunsa site uses a Lane Christensen CS 3001 diamond rig. The latter boasts impressive drilling depths, up to 2360 m (7743 ft) for BQ-sized core, with a pullback capacity of 15 tons. The team is also looking to add to these Hanjin D&B 30 HDD Drilling Rigs that are manufactured in the Republic of Korea. With the current equipment, the company is set to complete 2100 m (6890 ft) in Serenje and 3000 m (9843 ft) in Rufunsa.

Cipembele Exploration & Mining Services Ltd adapts drilling strategies based on ground conditions, switching between triple tube core

barrels in fractured zones to standard barrels when formations stabilize. While they have not had to customize equipment locally, their operational flexibility ensures they stay efficient even in the toughest terrain. What sets Cipembele Exploration & Mining Services Ltd apart is its deep understanding of Zambia’s terrain and its ability to respond quickly thanks to strong regional relationships across the DRC, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Botswana. This enables them to source parts, expertise, and support rapidly, often within a day.

Technology is becoming a cornerstone of Cipembele’s workflow. The company has begun implementing CorePlan, a digital system for core logging and operational tracking. Looking ahead, they are keen to invest in modern telemetric systems to enable real-time borehole monitoring, which will vastly improve directional drilling accuracy and decision-making. Currently, directional drilling decisions rely on the driller’s expertise and ground feedback, but the goal is to transition to engine draw rigs equipped with full telemetry. Operating in remote areas brings logistical hurdles, including long travel times (up to eight hours) to the nearest support town. Cipembele mitigates this by stationing essential spare parts on site and maintaining a standby team to quickly respond to breakdowns.

Reliable communication is crucial, and thanks to Starlink connectivity, real-time collaboration with client geologists and technicians has improved drastically. Safety is also non-negotiable. Dedicated safety officers conduct daily inspections, and the company enforces rigorous protocols, including alcohol testing and fatigue checks. Environmentally, they manage water loss by increasing the supply to compensate for losses in fractured zones and work to minimize surface disturbance

through precise drilling techniques.

Cipembele’s workforce combines local talent and experienced international personnel. While retaining staff is a challenge in the competitive mining sector, the company maintains a core management team while engaging contract crews as needed. And despite the difficulty of long-term skills development in such a fluid labor market, it remains committed to growing Zambian capacity.

One of Cipembele’s proudest achievements is its success in winning contracts with international heavyweights and also some of Zambia’s largest mining companies with a specific focus on copper and cobalt. Winning a contract with international mining companies is a testament to the quality and competitiveness of a local company in a global market. ‘We are the only wholly Zambian-owned exploration drilling company operating at this level,’ Schultz notes. Cipembele has won contracts with other international companies such as FQM, Midnight Sun, Moxico Resources, Arc Minerals.

As the company completes its rebrand, it remains focused on pushing boundaries in both geology and business. With proven experience in complex terrain, an adaptive mindset, and a commitment to innovation, Cipembele Exploration & Mining Services Ltd is redefining what it means to be a local leader in Africa’s mineral exploration landscape.

FEXMIN - Exploration and Mining Convention, organized by the Chilean Association of Geologists, is Chile’s foremost event exclusively focused on mineral exploration. This year’s 7th edition will take place from August 26-28 at the Espacio Riesco Convention Center, the largest event center in Santiago, and will coincide with Chile’s National Mining Month.

FEXMIN is a vital platform for connecting investors, mining companies, exploration projects, service providers, and technology innovators from across the Americas and beyond. It is the only fair in Chile dedicated solely to exploration and continues to grow in strategic importance every year. Over 200 mining and exploration projects were presented throughout the convention’s six previous editions, fostering knowledge exchange and industry growth in the region.

In 2024, FEXMIN welcomed over 1250 participants and featured more than 30 exploration projects, attracting geologists, executives, investors, and mining professionals. The 2025 edition promises an even greater reach and impact.

This year’s event was preceded by the ‘Road to FEXMIN 2025’ monthly talk program, launched in April. The program consists of exhibitions of diverse exploration projects and talks by leading geologists and industry professionals on topics of interest for mining exploration, such as metallogenesis. Both of these are transmitted over the internet through Netmin’s virtual platform.

FEXMIN aims to grow and consolidate itself as the premier meeting place for the community of Chilean and foreign explorers, while attracting a wide participation of investors from all latitudes. This year’s convention will provide ample space for presenting mining projects, prospects and concessions, as well as promoting service companies and suppliers of geological tools and exploration services.

• An exhibition area with around 65 booths, hosting mining companies, service providers, and technological innovators;

• Presentations of exploration projects from Chile and Peru, with Argentinian participation expected;

• All projects are open to various forms of negotiation, including partnerships, investments, joint ventures, and acquisitions;

• A robust schedule of plenary conferences led by top-level specialists, addressing key themes in geoscience and

exploration;

• Showcases of the latest technological advancements in mineral exploration, from AI-based tools and geophysical systems to sustainable and remote exploration methods.

All presentations will be recorded and made available to attendees. The organizers will also provide simultaneous translation between English and Spanish throughout the event. The fair visit will be live streamed in both languages as well, allowing for remote participation worldwide.

The preliminary program of the event will soon be available on FEXMIN’s website. Whether you are looking to present a project, explore new partnerships, or stay informed on the latest in mineral exploration technology, FEXMIN 2025 is the place to be. The organizing committee looks forward to welcoming participants this August in Santiago, Chile.

For more information

Visit the website: fexmin.cl

Contact the organizers: contacto@fexmin.cl

In this Issue:

Q&A from the experts

In conversation with Dr Scott Halley, Director of Mineral Mapping

Being a ‘first wave’ female underground mining engineer by Alex Atkins, ASX Non-executive Director and Corporate Advisor

The challenge of mineral discovery under cover by Nick Lisowiec, Exploration Manager (Eastern Australia) at Gold Road Resources

Bringing back the romance of exploration by Steve Beresford, Co-Founder of Altai Resources

Dr Scott Halley Director of Mineral Mapping

Brett Davis: Firstly, thanks for giving Coring the opportunity to interview you, Scott. Please take this as a compliment when I say it seems like you have been a geological heavyweight of the mining and exploration industry for a very long time. You have gained enormous respect in the geological community while you’ve been doing it, especially with the way you’ve almost single-handedly revolutionized how we deal with geochemical information. Can you tell us what interested you in a career in geology?

Scott Halley: Way back, at primary school age, I spent weekends with my grandmother fossicking old mine dumps for minerals, digging for agates to cut and polish, sieving and panning in local creeks in North West Tassie for big red zircon crystals, sapphires and spinel. I was hooked from an early age.

BD: Do you get many opportunities to revisit some of your old geological stomping grounds, e.g. the Kalgoorlie region? And have you seen any of your ideas come to major fruition or change radically?

SH: I moved from Perth back to Tasmania at the beginning of 2018. I have not had a lot of trips back to Kalgoorlie since then. I am con-

After graduating with a B.Sc. from the University of Tasmania (1982) and a PhD from the Australian National University (1987), Scott worked as an exploration geologist with RGC, Goldfields, AurionGold, and Placer Dome, before establishing his own consultancy, Mineral Mapping, in 2005. For the last 20 years, he has worked as an independent consultant, specializing in Exploration Geochemistry, particularly in the use of multi-element ICP geochemistry and SWIR analysis to map far-field expressions and alteration mineral zonation patterns around hydrothermal systems.

Since 2018, he has been a part-time collaborator on research projects and a regular presenter in the M.Sc. (Econ Geol) at the Centre for Ore Deposit and Earth Sciences (CODES) at the University of Tasmania.

stantly amazed at how many new deposits are being found in and around Kalgoorlie, where geologists have been exploring for 150 years. Whenever I hear of some new find, I go back into the data and try to figure out how and why I/we missed it in the past. It is very humbling. One thing I have been doing for fun in my spare time is pasting together all the geochemical analyses I have ever worked on in the Kalgoorlie region to make mega maps of the whole greenstone. That is a real eye-opener.

BD: Is there a particular mineralization style or deposit type that interests you, and why? I know you have a passion for porphyry- and orogenic gold-style deposits, but it seems like you have worked on almost every style of mineralization.

SH: The principles of chemistry are the same regardless of deposit type, so many of the ideas and skills are transferable across deposit styles. Anthony Harris described porphyries as ‘big dumb deposits’, with predictable zoning patterns and massive footprints.

BD: This is a question I like to ask because the diversity of answers is really interesting. So, leading on from the previous question—

everyone has a handful of deposits that have left a mark on them, be it because of the amazing geology, the hideous conditions, the people they worked with, etc. Which deposits do you hold dear, and which ones really were difficult to work on?

SH: The two deposits, or camps, that I spent the most time working on were Henty and Kundana. My hypotheses around the origins of the Henty system were totally wrong (another humbling experience). Still, we found significant extensions to the system just by geological mapping, drilling, and drawing serial cross sections, and understanding the alteration patterns (no geophysics, no geochemistry). The Kundana camp was the gift that kept on giving. Our mistake at the time was being too conservative with the drilling programs. Haverion is one of the most interesting deposits I have seen. On the bell curve of weirdness, it is two standard deviations from normal.

BD: Do you think that there are any mineral exploration strategies or technologies that are under-employed but could make a big difference to an exploration campaign if people used them more? I’m really keen to see if you can say something outside

of the sphere of geochemistry.

SH: Quite the opposite; we do a bunch of things that are over-employed and not worth doing. Much of the data collected goes into a database and is never looked at again. There are lots of new technologies out there being promoted by snake-oil merchants. When you look at case histories of new discoveries and the techniques used to find them, most of the deposits look bleedingly obvious in multiple data layers—you can pick them from the map patterns, or geochem footprint, geophysical footprint. Greg Hall says, ‘When you start in the right place, everything works. When you start in the wrong place, nothing works.’ We need to do the basic, effective methods, but do them properly. The alteration haloes surrounding orebodies are usually two orders of magnitude larger than the orebody itself. It is hard to find an orebody, but it is relatively easy to detect the footprint of the system. Choose a suitable technique to find the system, then make a robust 2D geology map and 3D model to find the drill target.

BD: Piggybacking on the previous question, how well do you think the different geological disciplines manage to integrate? I’m particularly keen to know what could be done to employ combined structural geological and geochemical approaches because there seems to be a wide gap in our industry. Many of us are captive to what we are good at, and it seems that client companies too rarely employ the services of geochemists and structural geologists at the same time on the same jobs.

SH: When Mike Christie started at First Quantum, he used to run campaigns at the mine sites and advanced projects. The campaigns would include a structural geologist, 3D modeler, geophysicist, and geochemist, as well as all the site geologists. These were the most fun and productive jobs I ever worked on. It doesn’t happen often enough. As a geochemist, I can also say that we need to collect data that can be used to inform metallurgists and engineers about mineralogy and rock properties. When we work alone, we get part of the story, but not the bit that matters to other people.

BD: You have a consultancy called Mineral Mapping, and client companies stand in a long queue to engage your services. What is the most maddeningly common and frustrating

thing that you encounter when you visit a client site and are asked to perform your geochemical wizardry?

SH: Two technical issues: data quality and data management. Think of an analogy from geophysics. In the 1980s, we flew airmag surveys in fixed-wing aircraft with a 400 m (1312 ft) line spacing and 200 m (656 ft) ground clearance. By the 1990s, we used helicopters, 100 m (328 ft) line spacing and 50 m (194 ft) clearance. Now we use drones. Why, oh why do companies still use 1980s-style digests and analytical methods for geochem data? Also, it is not unusual to spend a massive chunk of time fixing data exported directly from a company database. When I have to do that, it is a pretty clear indication that if the company people had looked at the data themselves, they would have seen the errors.

‘It is hard to find an orebody, but it is relatively easy to detect the footprint of the system.’

BD: What projects are you working on now? And what is your level of involvement? Given the current multi-commodity mineral boom, are you doing a lot of work outside of the commodities and deposit styles you have traditionally worked on?

SH: Well, I am actually semi-retired (LOL). Just for fun, I am returning to the hundreds of databases I have worked on to teach myself about magma chemistry. This is quite fundamental to mineral deposits, and there are not many people out there who know much about it. I am also working on a modal mineralogy calculation so that you can take an assay table with ppm of elements, apply a mass balance calculation, and convert it to weight percent of minerals. I think this will be a game changer in ‘orebody knowledge’. The other thing I am really interested in is building a new spectral (SWIR) interpretation system. We have had a massive explosion in new spectral gadgets, but nobody has

done the basic calibrations to properly pick mineral chemistry in the important minerals, particularly white mica and chlorite. We should be able to look at those squiggly lines from a spectrometer and interpret mica and chlorite compositions in terms of K, Al, Si, Mg, Fe2+, and Fe3+ atoms per formula unit. That would totally change the way we look at zoning patterns in mineral systems.

BD: Apart from me, who have been some of the people who have positively influenced your career?

SH: Simon Gatehouse, my most influential mentor.

Greg Hall encouraged a generation of geologists to apply science to exploration.

John Walshe realizes the limitation in our knowledge of ore-forming systems and calls it out.

John Dilles and Gerard Tripp—the best communicators of geological ideas.

Mike Christie and Jamie Rogers—best exploration ‘team-builders’.

Anthony Harris and Ned Howard—applying some serious science while still being pragmatic explorers.

Markus Staubmann is my tip for an emerging geology superstar.

BD: Has there been any single satisfying moment in your career that rates above all the others?

SH: At about 6 p.m. one Friday afternoon in Queenstown, Tasmania, 1991, the drill core from hole HP096 landed on the logging table. Everyone else had left for beer o’clock. That hole returned about 12 m (39.37 ft) at 107 g/t Au.

BD: I’ll always ask this question on the flip side of the previous one, typically getting very diplomatic responses. Many of us have interfaced with lessthan-savory individuals or experienced toxic workplaces. Have there been any incidents that really disappointed you?

SH: It is difficult to answer this diplomatically. I don’t like working with people who are primarily motivated by a desire to demonstrate how clever they are at the expense of others around them.

BD: One of the things you are held in high regard for is your capacity to make seemingly complex geochemical relationships and datasets easily understandable to people who aren’t experts in your specialty field. What are the secrets

to conveying this information?

SH: The most important part of being a consultant is the ability to communicate ideas, but it took me a long time to work that out. I like to demonstrate processes by giving real-world examples. The best way to teach something is to give people the tools to work it out for themselves. I still write shit reports.

BD: Time to massage your ego a bit. How many deposits do you think you have looked at? And, just for giggles, give us an idea of how many hyperspectral plots you think you have examined.

SH: I have a hard drive with about 20 million TerraSpec files. Last time I counted the number of companies I had worked for, it was more than 150, but that was a few years ago.

BD: One topic we commonly talk about but rarely put into print is the health hazards of working in different countries and environments. Has your health ever been particularly challenged, and if so, what happened?

SH: One memorable trip, I did a back-to-back from Mauritania at +45°C (113°F) to Romania at -10°C (14°F). After finishing Stage 1 in Mauritania, I was sitting in a plane on the runway in Morocco, and I could start to feel

my guts rumbling. I survived the flight to Dubai but then spent the six-hour stopover sitting on the dunny, overdosing on Imodium as fast as I could. It worked, just in time. Landed in Romania, and my luggage arrived two days later. Luckily, I had the foresight to put my down jacket in my carry-on luggage.

BD: This is a standard question of mine because it never fails to elicit really interesting and important answers. If you had abundant financial funding, is there a fundamentally annoying geology question you’d like to solve or a topic you’d like to work on?

SH: You shouldn’t have asked this question, Brett. I could fill an entire issue of this magazine, giving my suggestions about what we need to do in research space to help make new discoveries.

Researchers, government bodies and companies need to collaborate on themes that will lead to an increased rate of new discoveries. I have a very long wish list. Lots of researchers do academically interesting stuff that will never contribute to a new discovery, but companies support them, looking for the next silver bullet. I am not interested in the isotopic ratios of unobtainium in minerals that are rarely found in nature, but 40 years

after the first PIMA was sold, we still do not have the ability to estimate complete white mica and chlorite compositions from those squiggly lines. This is just a basic calibration exercise that nobody has bothered to do properly.

BD: Let me ask a question about the roles of vehicles that distribute your knowledge. Do you find that media platforms such as LinkedIn have helped in the promotion and understanding of geochemistry? And do you think that societies such as the Society of Economic Geologists (SEG) have moved with the times in terms of interfacing your work with the huge population of industry geologists?

SH: I have been presenting short courses for CODES as part of its M.Sc. (Econ Geol) program for 13 years. I put a lot of work into those, and I rarely present the same material twice. After a while, I started putting some of those on my website and giving them away. The other thing that happened to me some time ago was that I had prostate cancer. My experience with the medical system in Australia was quite traumatic, so I was keen to contribute to a nonprofit organization that voluntarily tries to make life easier. I ran a

series of professional development courses sponsored by companies as fundraisers for the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia. I advertised these events on LinkedIn and was amazed by the responses.

Most of the SEG members are industry geologists, but their journal is written by academics, for academics. You won’t find a single paper that shows pathfinder element patterns around a mineral deposit with actual company ICP-MS data, but you will find 100 papers on cerium anomalies in detrital zircons. It is good science, but who does it help?

BD: You are incredibly altruistic with your knowledge, as evidenced by freely disseminating conference presentations, papers and tutorials on your Mineral Mapping website. What is your opinion about people ‘giving back’ to the industry and how they should go about it?

SH: If Simon Gatehouse had not taught me about chemistry in the 1990s, I would not

and industry, and our geology departments are rapidly shrinking. Graduate geologists will not find out about the skills they need in the real world until they start an industry job. I feel like I have an opportunity to pass on some knowledge and help prepare them to contribute to the industry (that is a nice way of saying that I am passing on my cognitive bias).

BD: Now, to some personal questions. Does Scott Halley get any time away from work? If so, what does he do in his downtime? For example, I heard a rumor you are an accomplished flamenco dancer and biscuit maker, but I rarely believe scuttlebutt!

SH: I moved back to Tasmania because I like the great outdoors. I am spoilt for choice between hiking trails, sea-kayaking, rafting down the rivers, or cycling around country roads that are almost free of traffic.

BD: I know Scott Halley is trying to retire and has a small plot of land. So, a

because you commonly mention goats!).

SH: Memoirs… I have often thought about the need to write a new geochemistry textbook, but that thought never lasts for more than a nanosecond. It is easier to publish more tutorials online.

Favorite animals: I am not into farm animals, but we have an abundance of native fauna here. We have heaps of wallabies, Tasmanian native turbo chooks, possums, and echidnas in the backyard, sea eagles, Australia’s biggest penguin rookery 2 km (1.2 mi) away along the coast, and migrating whales and dolphins just offshore.

BD: Finally, any concluding comments or words of wisdom from an industry veteran?

SH: I am learning new things faster now than I ever did before. It has just come around decades too late.

WE ARE SWICK.

Hard rock mining’s heavyweight - innovating, manufacturing and delivering end-to-end excellence in drilling and underground diamond coring. A partnership with us is an investment in safety and versatility improvements in diamond drilling like no other.

INDUSTRY-LEADING DIAMOND DRILL RIGS MATCHED BY A TEAM DETERMINED TO ALWAYS PERFORM BETTER THAN THE DAY BEFORE? THAT’S EXCELLENCE UNEARTHED. THAT’S SWICK.

DRILL INTO THE POSSIBILITIES.

by Alex Atkins, ASX Non-executive Director and Corporate Advisor

Just before Christmas last year I headed into the Western Australia mine safety regulator (known as DEMIRS) and sat two exams to keep my First Class Mine Manager’s Certificate (FCMM) current and obtain a Site Senior Executive Certificate (SSE) under the new Workplace Health & Safety (WHS) Act 2020 and WHS (Mines) Regulations 2022. At the age of 56, you might wonder why.

Because I was in what I call ‘the first wave’ of female underground mining engineers to earn an FCMM Certificate in Western Australia (1998), in Queensland (2000), and in Tasmania (1999; though they repealed the legislation on the day I went in to pick it up). These tickets are a treasured and hard-won part of my unique value proposition— part of my mining ‘street cred’.

I didn’t know women ‘weren’t meant to be’ underground mining engineers when I decided that would be my career. When I tried to take the mining engineering stream after completing common first-year

engineering at the WA School of Mines, I was instead encouraged to study for a BE (Mineral Exploration & Mining Geology with a major in Structural Geology). After a couple of years of working in Queensland gold mines and exploration as a geologist, I was accepted into the University of Queensland’s BE (Mining), majoring in Rock Mechanics. I then focused on obtaining my minimum five years of post-graduate operations experience all over QLD, Tasmania, Papua New Guinea and WA to get my ‘tickets’. This experience was in addition to over a year as a miner, rotating through drill and blast (which, incredibly for me,

included time as an airleg miner with a fabulous air-legging crew), load and haul, and services. This ‘underground time’ was, and still is, a regulatory prerequisite for statutory mine management tickets. How can you give directions to miners, and appreciate the safety implications and time and resources required if you haven’t done the job?

When I completed high school in 1985, it was straight after the Equal Opportunity Act of 1984 was enacted. Girls in high school were told, ‘Girls can do what boys can!’ I was keen to pioneer!

I earned two engineering degrees, qualifying me as a mining engineer, geologist and geotechnical engineer. I worked across siloes performing various tasks that enabled me to understand cause-and-effect relationships and to see—through operational experience—how to holistically and commercially optimize the mine as a complex system of interdependencies. This was a valuable foundation for my work today overseeing safe mine management, technical and operational due diligence, and transitions to new technologies (like Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning and Automation).

Over my more than 30 years in mining, I’ve seen both enormous and very little change. The enormous change is the number of women in the industry and how amazing they are, thanks to the development opportunities they now receive, making them next-level awesome.

They were always wonderful because they joined the industry for a challenge, wanting to do a good job. But spirits were often broken, often making women give up. Those with the mental grit to persevere have mostly done so because of purpose—making the industry better, and self-belief—knowing they earned their seat at the table. Those female seats at the table almost weren’t there. In Australia’s mining states, it only became legally permissible for women to work in underground mines in 1987. It’s still not legal in Papua New Guinea and was only recently made legal in India.

Great contributions women have made over the last 30 years in mining include: improving safety performance/risk management; fostering innovation and encouraging the collaboration required for the transition to digitalization and automation; as well as improving social performance. I believe women and their collectivistic qualities can bring out the best in people and thus projects.

Get in touch with Alex on LinkedIn

by Nick Lisowiec, Exploration Manager (Eastern Australia) at Gold Road Resources

According to the CSIRO, approximately 80% of the Australian landmass is under post-mineralization cover and regolith, but most mineral discoveries to date have occurred where mineralization is located at or near the surface. Exploration through un-mineralized cover is substantially more difficult and costly, especially as the depth of cover increases. This is reflected in the discovery rate, where new discoveries, concealed under more than 50 m (164 ft) of cover, are rare.

This pattern is not unique to Australia and is relevant globally because the easy, outcropping discoveries have mostly been made. A significant quantity of future mineral supply will come from extensions/ expansions and/or mining lower-grade ore within existing deposits, but the shortfall must come from new or ‘greenfield’ discoveries.

Exploring under cover represents an opportunity to test new areas that haven’t previously been prospected or assessed. This article aims to break down some of the challenges associated with it and present some possible ways the industry can improve.

Cover refers to either consolidated or unconsolidated rocks, gravels, or sands that have been deposited over the top of a mineral deposit after the mineralization event occurred (e.g. Figure 1). This could be thousands, millions, or billions of years after the deposit formed. The nature of the cover material can be extremely variable and can include any rock type deposited or formed at the surface (sediments, volcanic rocks, etc.). In geologically complex settings, there could be multiple phases of cover rocks overlying a deposit.

Regolith is a type of cover associated with the weathering of rocks at or near the surface and includes soil, alluvium, saprolite (weathered bedrock), duricrusts, etc. Regolith can be either in situ (in place) or transported from its source, usually via gravity, glacial or aeolian processes. This article focusses on material deposited on top of and subsequent to the bedrock mineralization and not on in situ weathering.

Cover rocks effectively reduce the exploration toolkit for geologists. In areas of outcrop or in situ regolith, traditional exploration methods, such as geological mapping and surface sampling (soils, rocks, stream sediments, etc.), can be used to assess the prospectivity of an

area. Whilst economic mineralization may not occur at the surface, geologists may detect evidence of veining or alteration, related to the distal expression of a hydrothermal system. With increasing data, the geologists can then focus their efforts and vector towards the deposit. Without the surface bedrock exposure, geologists are effectively blindfolded and critical geological information can only be inferred through geophysics or obtained via drilling. Geophysics such as magnetics, gravity, seismic and electromagnetics (EM) can be used to extrapolate areas of known geology (from outcrop or previous drilling) into the unknown areas under cover. However, the degree of confi-

↑ Figure 1 - Schematic cross section of the Oak Dam Cu-Au deposit showing the relationship of mineralization to the overlying (and unmineralized) cover sequence.

Source: BHP Operation Review for year ended 30 June 2023.

dence will depend on the geological terrain and the distance from the known geological reference points.

The style of mineralization sought will also impact the type of geophysics used. Many mineral systems can be directly detected or inferred by geophysical techniques, due to sulfides, magnetic susceptibility, density contrasts, etc., which may be associated with the mineralization itself or altered host rocks. Other mineralization styles are more cryptic and have a subtle response that is much harder to confidently detect, or they have no geophysical response at all.

Whilst geophysical techniques are essential to exploration undercover, many methods are impacted by the physical characteristics and/or depth of the cover. For example, saline groundwater and high porosity within the cover sequence can impact electrical geophysical methods and mask the bedrock response. The depth of the cover can also weaken the response/signal, making subtle anomalies more difficult to distinguish above the background noise.

When a target or anomaly has been identified via geophysics, the only way to test is to drill holes and recover samples. Cover rocks can often be difficult to drill, especially in poorly consolidated ground. Unconsolidated ground may be more likely to collapse, resulting in more time conditioning holes or trying to free stuck drill rods, etc. Porous formations may contain significant aquifer(s), which need to be controlled or contained. The depth and physical characteristics of the cover will influence the type of drilling required (e.g. Aircore vs RC vs Mud Rotary vs Diamond), as well as site preparation and cost. Due to the lack of geological information available prior to drilling, exploration for concealed mineralization may require multiple drill campaigns to understand and/or test the target prior to reaching a decision point. There are also the economic costs associated with mining and converting a potential discovery into an orebody. Many factors are involved, such as grade, geometry, geotechnical, metallurgy, etc., but in general, the deeper the deposit, the more likely it is that it will be mined from underground. Whilst mining methods shouldn’t impact