This issue, Carla’s 40th, is a biggie: It marks our ten-year anniversary. It represents a significant milestone for the publication, and also a personal one for me, Carla’s founder and editor-in-chief all these years; during the span of this issue’s circulation, I too will turn 40—an auspicious coincidence.

Carla has evolved beyond what I ever could have imagined when I founded the publication in 2015, working out of a shared live-work space in DTLA while scraping various art jobs together—art handling here, gallery assisting there. The organization has grown since those early days of cold-calling galleries to introduce the magazine in hopes of an ad sale. In the beginning, as an unpaid staff of one, I used to stuff my Honda Civic to the brim with still-off-gassing magazines, driving them around to art spaces across the city. We’ve since grown, covered thousands of artists, worked with hundreds of writers and art spaces, gained nonprofit status, and fostered a lively membership community.

And yet, much about the original vision for Carla—its scope, tone, and mission (our north star, as it were)—has remained unchanged. I wrote in my very first letter from the editor about my desire to pair rigor with community: “Community and criticality should exist in tandem, balancing and challenging each other.”

Ten straight years of quarterly publishing signals that Carla has the active support of that community, too. By reading, becoming a member,

hosting a launch party, or publishing your words with us, you are insisting on the importance of accessible yet rigorous writing about our region’s art and artists. I offer my profoundly sincere thanks to everyone who has been a part of our work over these years.

To the writers whose ideas fill our pages, who have engaged in our intimate editing process. To the unsung grammar heroes who examine every comma. To the designers and color correctors who diligently visualize Carla to communicate our ethos. To our dedicated board members who offer advice, feedback, and time to build sustainability for Carla’s future.

To the advertisers who have worked with us for years. To our membership community, who support us with essential participation. To our small but very mighty staff that keeps Carla on track and operating smoothly. And, to the dedicated readers who have collected every single issue of the magazine, discussing its contents over dinner with friends.

In celebration of a decade of community-minded impact, Carla is hosting an anniversary soirée and art auction on June 14, 2025. The auction will feature accessibly-priced works by an impressive roster of (drumroll!)

101 L.A.-based artists. The event will be a night of community, celebration, and art, and we look forward to seeing you there (see p. 6–7 for the artist list and more details about the event).

I signed off that first editor’s letter, hopefully, “cheers to many more,” not knowing how many more were really in store. Looking back on the last decade of Carla—and the community we’ve been a part of—I can’t wait to see what the next ten will bring.

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Cheers to many more,

Lindsay Preston Zappas Founder, Editor-in-Chief, & Executive Director

Investing in Black Art

Evan Nicole Brown

On Scientist Ed Wortz’s Relationship with Artists

Catherine G. Wagley

Four Artists on Octavia E. Butler

Jessica Simmons-Reid

Rebuilding Art Practices in the Wake of Wildfires

Featuring: Beatriz Cortez, Kari Reardon, Margaret Griffith, and Jamison Carter

Photos: Monica Orozco

Kati Kirsch at Cheremoya —Zoey Greenwald

Kenneth Webb at Huma Gallery —Steven Vargas jinseok choi at Peter and Merle Mullin Gallery —Hande Sever

Sasha Fishman at Murmurs

—Qingyuan Deng

Charlie Engelman at Château Shatto —Ashlyn Ashbaugh

June 14, 2025, 7-10pm

Preview: 5-7pm

About the event

Founded in 2015 by artist and writer Lindsay Preston Zappas, Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla) is an essential voice made in and for Los Angeles.

Carla remains committed to building entry-points into the arts for the greater L.A. community, and in celebration of ten years of being an impactful presence in the landscape, we are hosting an anniversary soirée and art auction. The soirée will coincide with the release of the milestone 40th issue of our quarterly print magazine. The event will also feature our first-ever art auction of accessibly-priced works on paper by an impressive roster of L.A.-based artists, many of whom have been featured in our pages over the last decade —the artists included will mirror Carla’s dynamic and inclusive coverage.

Join us for a lively evening of art, music, and drinks, plus a special performance (to be announced). Come soirée with us and help keep art and cultural production in L.A. thriving.

Host Committee

Alex K. Scull

Analia Saban

Dominique Clayton Echelon

Hannah Sloan Curatorial & Advisory

Jenn Pablo & Paco De Leon

Jennifer Ferro

Jobert Poblete

Nazarian / Curcio

Neil and Anjelica Sarkar

Solid Art Services

Tim Disney

West of West Architecture + Design

This project is supported by Critical Minded, an initiative to invest in cultural critics of color cofounded by The Nathan Cummings Foundation and The Ford Foundation.

If you are interested in learning more about participating in the host committee, please email lindsay@contemporaryartreview.la.

Adam Beris

Adam de Boer

Aimee Goguen

Alex Anderson

Alex Olson

Alicia Piller

Alika Cooper

Alison Blickle

Amanda Ross-Ho

Amia Yokoyama

Amy Bessone

Andrea Castillo

Antonia Pinter

April Street

Ariel Herwitz

Ava McDonough

Ben Sanders

Benjamin Weissman

Cammie Staros

Canyon Castator

Carrie Cook

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer

Chase Biado

Cissi Efraimsson

Clifford Prince King

Dani Tull

Daniel Wheeler

David Horvitz

Devin Farrand

Devon Tsuno

Dhiren Dasu

Dianna Molzan

Ed Fella

Elise Vazelakis

Elliott Hundley

Erik Frydenborg

Francesca Gabbiani & Eddie Ruscha

Georgianna Chiang

Heather Rasmussen

Henrik Munk Soerensen

iris yirei hu

Isabel Yellin

Jemima Wyman

Jonathan Casella

Jules Garder

Julia Haft-Candell

Justin Olerud

Karl Haendel

Kayla Tange

Kour Pour

Kyungmi Shin

Lani Trock

Lindsay Preston Zappas

Liv Aanrud

Liz Walsh

Luka Fisher

Maria Maea

Marty Schnapf

Max Maslansky

Meghan DeRoma

Michael Rey

Michelle Jane Lee

Mike Swaney

Mikki Yamashiro

Molly Haynes

Molly Larkey

Mungo Thomson

Naotaka Hiro

Nasim Hantehzadeh

Nick Aguayo

Nick McPhail

Patrick Jackson

Pau S. Pescador

Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Penny Slinger

Public Sculpture Archive

rafa esparza

Rakeem Cunningham

Rema Ghuloum

Rodrigo Valenzuela

Roksana Pirouzmand

Rosha Yaghmai

Ross Callahan

Sarah Ippolito

Sarah Miska

Sarah Rosalena

Seffa Klein

Senon Williams

SHAGHA

Sharif Farrag

Sophie Roessler

Steven Wolkoff

Sylvie Lake

Tanya Brodsky

Todd Gray

Trulee Hall

Vincent Pocsik

Wayne Atkins

Widline Cadet

Zane Zappas

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles is an essential voice made in and for Los Angeles. Founded in 2015 by artist and writer Lindsay Preston Zappas, Carla is a nonprofit organization and publishing platform that is dedicated to providing critical, thoughtful, and inclusive perspectives on contemporary art. Our quarterly print magazine is an active source of dialogue on Los Angeles’ art community and is available for free in over 160 galleries and art spaces in L.A. and beyond.

Editor-in-Chief & Executive Director

Lindsay Preston Zappas

Managing Editor

Evan Nicole Brown

Contributing Editor Allison Noelle Conner

Graphic Designer Satoru Nihei

Copy Editor Rachel Paprocki

Administrative Assistant Aaron Boehmer

Color Separations

Echelon, Los Angeles

Printer Solisco Printed in Canada

Submissions

For submission guidelines, please visit contemporaryartreview.la/submissions, and direct all submissions to submit@contemporaryartreview.la.

Inquiries

For general inquiries, contact office@contemporaryartreview.la.

Advertising

For ad inquiries and rates, contact ads@contemporaryartreview.la.

W.A.G.E.

Carla pays writers’ fees in accordance with the payment guidelines established by W.A.G.E. in its certification program.

Copyright All content © the writers and Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles.

Social Media

Instagram: @contemporaryartreview.la

Cover Image

Widline Cadet, Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis] Appearance #1) (2019). Image courtesy of the artist, LACMA, and Nazarian / Curcio Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: © Widline Cadet, digital image © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Contributors

Lindsay Preston Zappas is an L.A.-based artist, writer, and the founder of Carla. She received her MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art and attended Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2013. Her writing has appeared in Track Changes: A Handbook for Art Criticism, KCRW, Carla, ArtReview, Flash Art, SFAQ, Artsy, LACanvas, and Art21 Recent solo exhibitions include those at the Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art (Buffalo, NY), OCHI (Los Angeles), and City Limits (Oakland).

Evan Nicole Brown is a Los Angeles-born writer, editor, and journalist who covers the arts and culture. Her work has been featured in Architectural Digest, ARTnews, CULTURED, Dwell, The Hollywood Reporter, The New York Times, T Magazine, and elsewhere. She is also the founder and host of Group Chat, a conversation series in L.A.

Allison Noelle Conner is an arts and culture writer based in Los Angeles.

Satoru Nihei is a graphic designer.

Rachel Paprocki is an editor and librarian who lives and bikes in Los Angeles.

Aaron Boehmer is a writer and photographer from Texas. He is interested in writing and research related to the intersection between politics and art and has written for publications such as The Nation, The Drift, and Texas Monthly

Lindsay Preston Zappas, Executive Director Melissa Lo, Board Chair MJ Brown Trulee Hall

Membership

Carla is a free, grassroots, and artist-led publication. Club Carla members help us keep it that way. Become a member to support our work and gain access to special events and programming across Los Angeles.

Carla is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization; all donations are tax-deductible. To learn more, visit join.contemporaryartreview.la.

Thank you to all of our Club Carla members for supporting our work. A special thank you to our La Brea and Western members:

Anjelica Triola, Anthony Cran, Chad Karty, Charles James, Heather Mingst, Ian Stanton, Jennifer Michaela Byrne, Jobert Poblete, Laurie & Rick Raskin, Michael Zappas, Michal Hall Bravo Ramirez, Melissa Lo, Philippe Browning, Raskin Foundation, Sarah Ippolito, Solid Art Services, Tim Disney, Tiffiny Lendrum, and West of West Architecture + Design.

Los Angeles Distribution

Central

1301 PE

7811 Gallery

Anat Ebgi (Wilshire)

Arcana Books

Artbook @ Hauser & Wirth

as-is.la

Babst Gallery

Baert Gallery

Bel Ami

Billis Williams Gallery

BLUM

Canary Test

Central Server Works Press

Charlie James Gallery

Château Shatto

Cheremoya

Chris Sharp Gallery

Cirrus Gallery

Clay ca

Commonwealth and Council

Craft Contemporary

D2 Art (Inglewood)

D2 Art (Westwood)

David Kordansky Gallery

David Zwirner

Diane Rosenstein

dublab

FOYER–LA

François Ghebaly

Gana Art Los Angeles

Giovanni’s Room

Hannah Hoffman Gallery

Harkawik

Harper’s Gallery

Hashimoto Contemporary

Heavy Manners Library

Helen J Gallery

Human Resources

ICA LA

JOAN

KARMA

LACA

Lisson Gallery

Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery

Louis Stern Fine Arts

Lowell Ryan Projects

Luis De Jesus Los Angeles

M+B

MAK Center for Art and Architecture

Make Room

Matter Studio Gallery

Michael Werner Gallery

MOCA Grand Avenue

Monte Vista Projects

Morán Morán

Moskowitz Bayse

Murmurs

Nazarian / Curcio

Night Gallery

Nonaka-Hill

NOON Projects

O-Town House

OCHI

One Trick Pony

Pace

Paradise Framing

Park View / Paul Soto

Patricia Sweetow Gallery

REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney

CalArts Theater)

Regen Projects

Reparations Club

Roberts Projects

Royale Projects

Sean Kelly

Sebastian Gladstone

Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Smart Objects

SOLDES

Sprüth Magers

Steve Turner

Stroll Garden

Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

The Box

The Fulcrum

The Hole

The Landing

The Poetic Research Bureau

The Wende Museum

Thinkspace Projects

Tierra del Sol Gallery

Tiger Strikes Asteroid

Tomorrow Today

TORUS

Track 16

Tyler Park Presents

USC Fisher Museum of Art

Various Small Fires

Village Well Books & Coffee

Webber

Wönzimer East

BOZOMAG

Feminist Center for Creative Work

Gattopardo

GGLA

Junior High

la BEAST gallery

Marta

Nicodim Gallery

OXY ARTS

Parrasch Heijnen Gallery

Philip Martin Gallery

Rusha & Co.

Sea View

South Gate Museum and Art Gallery

The Armory Center for the Arts

The Pit Los Angeles

Umico Printing and Framing

Vielmetter Los Angeles

Vincent Price Art Museum

Wilding Cran Gallery

North

albertz benda

ArtCenter College of Design

ArtCenter College of Design, Graduate Art Complex

The Aster LA

South

Angels Gate Cultural Center

Long Beach City College

Space Ten

The Den

Torrance Art Museum

West

18th Steet Arts

Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center

Dorado 806 Projects

L.A. Louver

Laband Art Gallery at LMU

Marshall Gallery

ROSEGALLERY

Von Lintel

Zodiac Pictures

Bortolami Gallery (New York, NY)

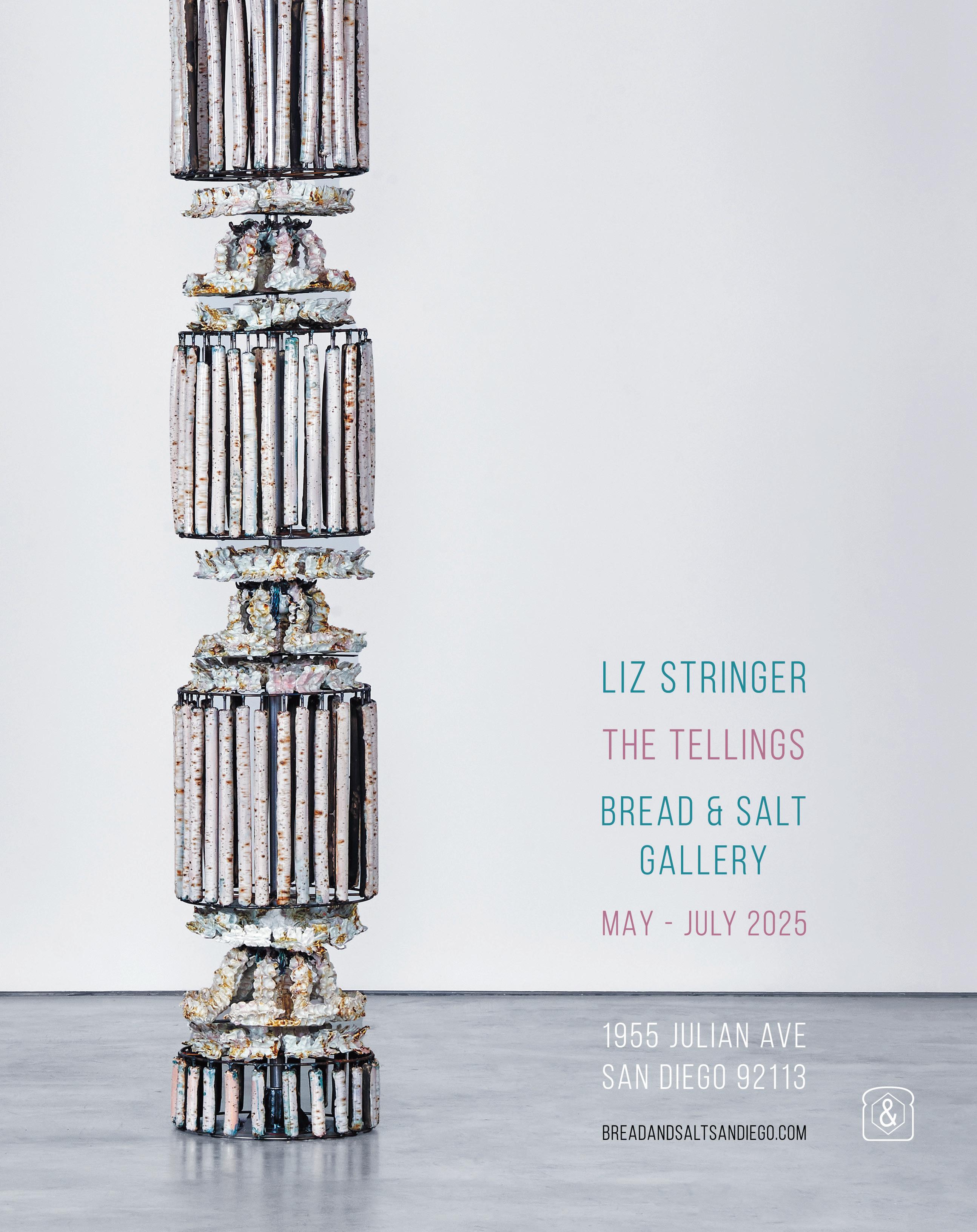

Bread & Salt (San Diego, CA)

Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art (Buffalo, NY)

Chess Club (Portland, OR)

DOCUMENT (Chicago, IL)

Et al. (San Francisco, CA)

Fresno City College (Fresno, CA)

High Desert Test Sites (Joshua Tree, CA)

Left Field (Los Osos, CA)

Level of Service Not Required (La Jolla, CA)

Los Angeles Valley College (Valley Glen, CA)

Mandeville Art Gallery, UC San Diego (San Diego, CA)

Mrs. (Queens, NY)

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (La Jolla, CA)

OCHI (Ketchum, ID)

Oolong Gallery (Encinitas, CA)

Pitzer College Art Galleries (Claremont, CA)

Libraries/Collections

Baltimore Museum of Art (Baltimore, MD)

Bard College, CCS Library (Annandale-on-Hudson, NY)

Charlotte Street Foundation (Kansas City, MO)

Cranbrook Academy of Art (Bloomfield Hills, MI)

Getty Research Institute (Los Angeles, CA)

Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (Los Angeles, CA)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Los Angeles, CA)

Maryland Institute College of Art (Baltimore, MD)

Midway Contemporary Art (Minneapolis, MN)

Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, CA)

Pepperdine University (Malibu, CA)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, CA)

School of the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY)

University of California Irvine, Langston IMCA (Irvine, CA)

University of Minnesota Duluth, Tweed Museum of Art (Deluth, MN)

University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA)

University of South Florida St. Petersburg (St. Petersburg, FL)

University of Washington (Seattle, WA)

Walker Art Center (Minneapolis, MN)

Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY)

Yale University Library (New Haven, CT)

Scan to access a map of Carla’s L.A. distribution locations.

When the late Dr. Samella Lewis, an award-winning artist, author, and art historian, joined the staff at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 1968 as education coordinator, the spirit of the institution was in a different place than it is today.1 Frustrated by the exclusion of Black artists from the museum’s exhibitions and the absence of adequate Black art representation in the permanent collection, the arts educator (who would later establish L.A.’s Museum of African American Art and the scholarly International Review of African American Art in 1976) resigned the following year, saying, “We were not included in the art museum here.”2

Dr. Lewis’ statement was supported —emboldened, even—by months of ensuing protests agitating for LACMA to expand its worldview by deepening the institution’s awareness of Black artists and outreach to Black audiences.3

The museum course-corrected shortly thereafter with a string of subsequent exhibitions that brought Black artists into the fold, such as Three Graphic Artists: Charles White, David Hammons, Timothy Washington (1971); Los Angeles 1972: A Panorama of Black Artists (1972); and the museum’s first comprehensive survey of AfricanAmerican art, Two Centuries of Black American Art (1976).4 The last show retroactively acknowledged the contributions of Black artists between 1750 and 1950 and featured more than 63 artists and 200 works across painting, sculpture, drawing, graphic design, craft, and decorative arts. The Black

Arts Council (BAC), founded in 1968 by LACMA art preparators Claude Booker and Cecil Ferguson, was the organizing force behind collective public pressure calling for the development of African-American programming at the museum, which would eventually lead to these three seminal exhibitions in the institution’s history.5 BAC was comprised of both museum employees and, beyond LACMA’s white walls, members of L.A.’s art community. The organization proposed events for the public (including a three-part lecture series and the one-time, day-long Black Culture Festival), planned field trips for students, and staged small protests to call attention to the lack of exhibition opportunities for Black artists.

In the decades since this era of pivotal advocacy and organizing on behalf of Black artists, their work, and its essential place in the art historical canon, LACMA—as with many institutions, in the art world and beyond—has evolved to a place of greater and more consistent inclusion, though the work of making up for centuries of exclusion (and worse, erasure) is long. Generally, there are trends toward museum exhibitions and collections expanding to prioritize a more nuanced view of the robust work coming directly from, or aesthetically inspired by, the continent. In an effort to guard against these efforts as merely symbolic gestures (performed for a “woke” and watching public that is rightly critical of the integrity behind institutional promotions of “diversity” and “inclusion”), some art spaces are taking predictable virtue signaling a step further by considering what tangible, meaningful investment in these narratives looks like in practice. But the reality of underrepresentation in museum holdings is still damning: A 2022 Burns-Halperin Report found that only 2.2 percent of acquisitions and 6.3 percent of exhibitions at 31 U.S. art museums between 2008 and 2020 were of work by Black American artists; unsurprisingly, the biggest spike (by approximately 200 percent)

Evan Nicole Brown

in acquisitions took place following the founding of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013.6 And though statistics regarding international interest in acquiring contemporary African art—via auctions, art fairs, and gallery sales into private collections— demonstrate solid financial investment, they are still on the decline. In 2022, the global total sales value of art by African-born artists at auction peaked at $197 million, and by 2024 these sales dipped to $77.2 million.7

LACMA’s current Pan-African exhibition of contemporary art, Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics, helps redefine what it means to invest not only in showcasing Black art from an ethical standpoint, but also in supporting Black artists from an economic one (over half of the works in the show were acquired by LACMA). The exhibition, on view through August 3, translates the intangible power of the universal albeit varied Black experience into an aesthetic exploration of time, place, and approaches to record-keeping. The root of this show, which gathers different explorations of remembering (and how we preserve those cultural memories through artmaking as storytelling), reflected in the institutional choice to invest in collecting many of these works for preservation in the larger archive, rather than to temporarily borrow the bulk of the offering from private collectors or other art institutions. Curated by Dhyandra Lawson, the Andy Song Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art at LACMA, the show brings together 60 contemporary artists working across Africa, Europe, and the Americas. Of the 70 works spanning the mediums of painting, sculpture, photography, works on paper, and time-based media, 42 are new acquisitions into LACMA’s permanent collection, exemplifying how institutions can expand their Pan-African holdings in a way that also sustains the livelihoods and creative practices of Black artists.

“This was an intentional strategy in terms of my curatorial methodology from the get-go,” Lawson told me.

“I was considering the history of LACMA and the history of how contemporary Black art from outside the U.S. has been exhibited in California and on the West Coast. LACMA is the largest encyclopedic museum in the western United States and we have done great work growing our collections of Black American art, [but] it seemed to me that we had a lot more work to do in looking at Black art internationally.” This decision to invest in art that reflects the creative multiplicity of the global Black diaspora for the museum’s permanent collection highlights an effort to address the gaps and erasures within most public collections. And by prioritizing the acquisition of the majority of the show’s works (as not only a symbolic effort toward greater representation but also a form of meaningful curatorial ethics), Lawson offers a progressive view of what it means to support Black artists across the diaspora. She is interested in exploring diaspora not only as an aesthetic concept, but also as a way to think about how broadly and dynamically curators and collectors should be seeking out and investing in contemporary Black art—across generations, locations, styles, and experiences. Lawson’s efforts also emphasize public collections as living monuments to record-keeping, a cultural responsibility that preserves history and also establishes the sanctity of its contents for audiences and scholars to come.

Walking through Imagining Black Diasporas is a practice in presence; the show, organized into conceptual categories that each highlight an aspect of the Black experience—speech and silence, movement and transformation, imagination, and representation— requests an embodied, reflective approach to witnessing the myriad artworks, which are as varied and beautiful as the African diaspora itself. Los Angeles native Sanford Biggers’ silhouetted images of afro-crowned Black Power figures stretch high up

on a white gallery wall, towering over the intricate, small-scale work of Senegalese artist Abdoulaye Ndoye: a book of invented script drawn on henna-washed pages that he describes as poesie graphique, 8 or visual poetry. Chelsea Odufu’s eight-channel video installation Moved by Spirit (2021), which was previously exhibited at the Dakar Biennale as part of the U.S. Embassy’s programming in 2024,9 is a faith-based investigation of water as a material for cleansing and its movement, a vessel for migration. The film explores the syncretic roots of Senegalese Sufism and includes footage of spiritual rituals and worship, vignettes of figures in Afrofuturist costumes engaging in traditional dance sequences, and pictures “the Door of No Return,” a passage in the stone wall of Elmina Castle on Ghana’s coast, which was a prominent hub of the transatlantic slave trade. Elsewhere, Ibrahim Mahama’s repurposed jute coal sack, a mixed-media assemblage dyed and adorned with cloth embellishments, puts a spotlight on the troubled, interconnected legacies of labor, colonialism, and capitalism in his native Ghana. Mahama refers to his practice as a form of “time travel”10—a nod to the material journey his objects take from manufacture, utilitarian use, and eventual acquisition and reimagination by himself, the artist.

There are several prominent American museums focused specifically on the preservation and pedestalling of Black art and material culture as an act of memory-keeping and selfdetermination (L.A.’s California African American Museum, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C., among others). But the impact of an investment in more diverse holdings has different implications when carried out by a general-focus institution like LACMA. Instead of this gesture being at the center of the institution’s purpose and therefore part of a long history of collecting and archiving the work of Black artists (as is the case with the aforementioned museums), this

move by LACMA shows a fairly new commitment to supporting and preserving contemporary Black art in ways that go beyond the superficial: It signals a reconsideration of the museum’s own collection practices writ large.

In essence, Imagining Black Diasporas is a show that is not solely concerned with the present context of diasporic works being mounted for audiences to view for a fixed amount of time, it is also simultaneously focused on correcting a long history of underinvestment in Black art. By acquiring more pieces for the permanent collection from a diasporic group of Black artists, the museum is actively making steps toward manifesting a future where generations of audiences may have access to works like these as a default rather than as an anomaly. And while this curatorial approach does model a new path toward more consistently diverse collecting practices, LACMA (whose encyclopedic collection boasts more than 150,000 objects) still has broad improvements to make; a 2019 study showed that at the time, almost none of the museum’s collection was dedicated to Black artists.11 Part of Lawson’s motivation for prioritizing permanent investments came when reflecting on the curatorial strategies behind many Pan-African exhibitions throughout time, which “tend to compile loans,” she says. “I think the impulse has been to show as many works as possible and to gather a large grouping of works, but here it felt really important to think through what it would mean to actually make investments in artists by making purchases, and receiving gift offers from generous donors.”

While the show includes generational American greats like Glenn Ligon, Lorna Simpson, Kara Walker, and others, it is also a celebration of emerging and mid-career artists working outside of the United States, representing both the Pacific Rim and the Black Atlantic. This offers an expanded, contemporary understanding of Pan-African art—a movement that encompasses various artistic expressions that reflect Africa’s rich cultural

history and diverse creativity while promoting a unified sense of shared identity. This is a crucial reframing of “diaspora” as more than just a shorthand for shared ancestral homeland, as it is most commonly deployed—an application that oversimplifies the myriad shades and sensibilities of Blackness globally into a universal origin story that belies the abundance of languages, customs, and aesthetic choices that exist within it.

Awash in hues of blue and lavender so delicate they’re almost surreal, Widline Cadet’s photograph, Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis] Appearance #1) (2019), is at once a very personal self-portrait and also a broader reflection on memory-keeping and migration—particularly for immigrants like the Los Angeles-based Haitian artist herself, whose proximity to home has shifted at various points throughout her life. In the image, Cadet stands in the water, looking on at a collection of smaller images showing the artist during her childhood in Haiti superimposed on a larger print of palm trees, hanging on a backdrop stand in the ocean before her. Sheets of corrugated metal attached with spring clamps to the stand almost wink with iridescence, under a quality of natural light that looks like it belongs to the morning. The backdrop stand is more practical than beautiful—a contrast to the femininity of her sea-soaked silhouette—but sturdy enough to ensure that her memories won’t be washed away.

The photograph, Cadet told me, is her way of “imaging that absence, that lack of access” to her home island, and is additionally an exploration of her relationship to photography as a medium. “I barely had any exposure to [it].… My first interaction with photography was getting my passport [photo] taken as a kid.” The image is, in some ways, a fantasy of the artist’s subconscious: a dream-like photomontage where time and space are collapsed and she is at once both girl and woman, home and away. The resonant impact of Cadet’s work entering into LACMA’s permanent holdings

is not lost on her: “The way I see my work functioning in the world is as an archive, so I really enjoy the prospect of it becoming a part of a public collection at LACMA.… The idea that my work will exist in its collection for years and years to come and be accessible to people in the future means a lot, and I think it adds another layer to my work,” Cadet said.

Over the course of curating the show, Lawson told me she was thinking through the ethics (and historically problematic nature) of collecting African art—particularly Indigenous objects—in museums. By focusing on contemporary artists and their work, she was able to facilitate transactions that prioritized the curator-artist relationship and the transparent communication that blooms as a result. “We are having open and frank conversations about how much things cost and it is super important that we can do that now,” she said. “It is a way to acknowledge the looting that has happened historically and to, in a contemporary moment, choose a different path.”

Imagining Black Diasporas —the exhibition itself and the curatorial and collecting practices surrounding it—reminds us that honoring the diversity of diaspora involves an active process of remembering and recordkeeping, and that to advocate for a nuanced collecting practice is also to advocate for the necessity of permanent collections that reflect the breadth of contemporary Black art. Museum holdings act as living archives, with a responsibility to accurately represent the reality of art that exists but also has existed. And if there’s a gulf in that presence historically, it is important to seek out opportunities to close the gap. “We can bring this diasporic memory into our holdings for the first time with this show,” Lawson mused. “Once an artwork is in a collection, it is [available] for a lifetime of new interpretations.”

Evan Nicole Brown is a Los Angeles-born writer, editor, and journalist who covers the arts and culture. Her work has been featured in Architectural Digest, ARTnews, CULTURED, Dwell, The Hollywood Reporter, The New York Times, T Magazine, and elsewhere. She is also the founder and host of Group Chat, a conversation series in L.A.

1. Marcos Ribero, “Dr. Samella Lewis,” Samella Lewis, February 5, 2024, https://samellalewis.com/bio/.

2. Samella Lewis, interview by Richard Cándida Smith, Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities (J. Paul Getty Trust, 1999), https://archive.org/ details/imagebeliefsamel00lewi/mode/2up%20/%20 https://www.thepomonan.com/exhibitionsopenings/2022/6/1/celebrating-the-life-andachievements-of-dr-samella-lewis.

3. “In Memoriam: Samella Lewis (1923–2022),” June 9, 2022, Unframed, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, https://unframed.lacma.org/2022/06/08/memoriamsamella-lewis-1923%E2%80%932022.

4. LACMA, “Two Centuries of Black American Art,” January 13, 2022, https://www.lacma.org/art/exhibition/ two-centuries-black-american-art.

5. LACMA, “Two Centuries of Black American Art at LACMA: Who’s Who,” January 13, 2022, https://www. lacma.org/two-centuries-black-american-art-lacmawhos-who.

6. Julia Halperin and Charlotte Burns, “Exactly How Underrepresented Are Women and Black American Artists in the Art World? Read the Full Data Rundown Here,” December 13, 2022, ArtNet, https://news.artnet. com/art-world/full-data-rundown-burns-halperinreport-2227460.

7. Margaret Carrigan, “ Temperature Check: Is Africa’s Art Market Cooling?” February 15, 2025, ArtNet, https://news. artnet.com/market/temperature-check-is-africas-artmarket-cooling-2609191#:~:text=Global%20total%20 sales%20value%20of,decline%20year%2Don%2Dyear.

8. Christa Clarke, “Abdoulaye Ndoye, Ahmed Baba,” Smarthistory, April 10, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/ abdoulaye- ndoye-ahmed-baba/.

9. Nicolò Lucarelli, “Dakar Biennale 2024: A Mirror of Lights and Shadows of Contemporary Africa,” Contemporary Lynx, December 9, 2024, https:// contemporarylynx.co.uk/dakar-biennale-2024-amirror-of-lights-and-shadows-of-contemporary-africa.

10. “Ibrahim Mahama,” White Cube, April 8, 2025. https:// www.whitecube.com/artists/ibrahim-mahama.

11. Hakim Bishara, “Artists in 18 Major US Museums Are 85% White and 87% Male, Study Says,” Hyperallergic, August 15, 2022, https://hyperallergic.com/501999/ artists-in-18-major-us-museums-are-85-white-and-87male-study-says/.

In the summer of 1969, the scientist Edward Wortz began organizing the first National Symposium on Habitability, at NASA’s bequest. The goal was to determine how to make foreign environments habitable enough to allow long term space missions. He likely would have taken a different approach before he met the artist Robert Irwin.

But Wortz, a physiological psychologist researching space travel, had spent the last few months collaborating with Irwin and James Turrell as part of LACMA’s Art & Technology project. He had been annoyed when his employers at the Garrett Corporation let him know that two artists were on their way to his laboratory. Then he met them. “It was like love at first sight,” Wortz recalled in 1977.1 He had already been pushing the boundaries of “acceptable procedures and acceptable perception”2 within his own field, and here were two people who were also doing that, if from a different vantage. They worked together for two years, using an anechoic chamber at UCLA to explore the effects of sensory deprivation on perception, using an electroencephalogram (EEG) machine to try to measure the consciousness reached when in a meditative state, and developing a number of exercises in meditation. The three of them never produced an actual artwork. As Wortz put it, making any finished product “got more and more irrelevant.”3

The inaugural National Symposium on Habitability was held in Robert Irwin’s Los Angeles studio in

May 1970. The scientists, city planners, physicians, engineers, and other experts in attendance stayed at the International Hotel by the airport and took a bus to the Venice Beach studio. The schedule, made up of lectures and panels, resembled a typical conference. But the environment did not. Irwin had knocked a hole into a brick wall in his space, which participants had to step through before emerging into a pristine room lit ambiently by colored skylights, with pillows on the floor. The red canvas chairs for panelists were set up to face each other, so that the experts would speak directly to one another. During the first day of the symposium, a line of white cardboard columns covered a far wall. The next day, the columns were gone, exposing a window covered in multi-colored translucent film. The third day, the window itself was gone. Irwin’s interventions into the space made participants uncomfortable at first, but so did the diversity of the people in the room—many of the scientists and scholars in attendance weren’t used to thinking alongside people from dramatically different fields. “The first day of the symposium was a very intense situation,” Wortz recalled.4 There was no second National Symposium on Habitability,5 and Wortz soon left aerospace altogether. “My exploration led me to change my career as well as changing my colleagues, my lifestyle, my family, everything,” Wortz said in a 1986 interview.6

I first learned about Wortz in the early 2010s, when I started researching the Art & Technology program, which paired artists with technological corporations to give artists unprecedented resources for artmaking. Within these pairings, conflicts abounded as artists’ sensibilities and politics clashed with corporate culture. Few corporate figures engaged as fully with the artists as Wortz did. I continued to see his name pop up as I did research for my forthcoming book about women-run art galleries in Los Angeles. In his oral history, the artist Tom Wudl mentions the time Wortz handed him a translated copy of the Avatamsaka Sutra, a

Catherine G. Wagley

canonical Buddhist text. When Wudl started reading, he thought, “This is it. This is what I've been looking for all my life.”7 The book helped him stop comparing his career to others, and he started making ornate, methodical drawings based on lotus flowers.

The collaboration with Irwin and Turrell, two of the most famous artists to emerge from Los Angeles’s 1960s ferment, was sensational, but Wortz’s quieter, constant presence in the local art scene—which began in the 1970s and continued until his death in 2004—compelled me more. His persistent presence in the lives of artists underscored for me the way that art, in its most beautiful and inspiring forms, requires experimental approaches to thinking and living. These approaches are difficult to sustain. Because of this, there is inevitably a tapestry-like support network surrounding artists, and Wortz’s own interests and affections led to his unique role in this network. While the Turrell and Irwin collaboration has been cited in multiple art histories, little in the canonical written history of art in Los Angeles traces Wortz’s role after that. But when stories like Wortz’s fall by the wayside, their absence impoverishes the story of art, reducing it to a myth that props up cults of the individual and glorifies art objects over the energies and possibilities that allowed them to exist.

Wortz was born in 1930 and grew up near San Antonio, Texas. He spent three years serving on the USS Rochester in Korea before finishing his PhD research at the University of Texas, Austin in 1957. Since he had begun working in aerospace in graduate school, he continued. He took contract work for NASA and eventually landed at the Garrett Corporation in Los Angeles, where he lived with his wife Sue Nelson and his twin daughters. By the time he met Irwin and Turrell, Wortz was the director of the Life Sciences Department at Garrett. He met the critic and art historian Melinda

Wortz (née Farris) through Turrell and Irwin, artists associated with the L.A. Light and Space movement about which Melinda wrote avidly. She and Wortz married in the early 1970s, after both of their first marriages ended (Melinda had three daughters with her first husband, former Pasadena Museum of Art director Thomas Terbell). Wortz’s encounter with art coincided with other shifts: Before he left the Garrett Corporation, he began working with the Buddhist monk Ven. Dr. Thich Thien-An, who would eventually ordain Wortz. Together, they founded the International Buddhist Meditation Center in Koreatown, an exceptionally interdisciplinary and interfaith center. It opened in 1970, shortly before Wortz enrolled at the newly-founded Gestalt Therapy Institute of Los Angeles. He enrolled hoping to become a better scientist. In his research, he had been using EEG biofeedback, a technique meant to increase mind-body awareness by connecting electric pads to a person’s body. The pads read brain waves and emit a sound to indicate increased anxiety or increased heart rate. This way, someone can learn to better regulate their own energy, a skill essential for astronauts in alien environments. “The people I was working with…were having profound experiences and having some difficulty integrating those experiences into their lives,” he explained in 1986.8 He felt a responsibility to help his subjects navigate the effects of his research. He didn’t intend to become a therapist, but by 1973 he was licensed and practicing the process-based Gestalt method, which privileges presence and awareness in the moment over mining the past.

This was an unusual trajectory for a scientist, but for Wortz, it all felt connected. He had already been looking at the relationship among physiology, emotions, and intellect, and he had used meditation techniques to help train astronauts to cope with the environment of space shuttles; therapy involved using the same strategies, but with different applications. He left

the corporate world gradually, staying on at Garrett until 1976, dropping his workload to four days a week, then three, and then one.

In Melinda and Ed’s Pasadena home, the boundaries between art, spirituality, and exploration were fluid. While Ed practiced Buddhism, Melinda was on the vestry at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena. The artist Barbara T. Smith, who attended weekly group Gestalt therapy meetings at the Wortzes’ home, used to babysit their daughters. Smith had met Wortz through Irwin and she would visit him to talk about her ideas and he “would walk me right over to a laboratory where the people working would listen and begin to fantasize a solution.”9 She felt validated by the access Wortz gave her as a scientist, and then as a therapist—he embraced as serious ideas that others in the art world treated as outlandish. When she was unhappy, separated from her children following her divorce, Wortz asked her, “Barbara, why don’t you do just one thing to make yourself happier?”10 So, she took a lover. For his therapy sessions, Wortz practiced out of a home office. He had a “greeter cat,” as the artist Scott Grieger recalled, who would walk clients back to meet him. His approach to therapy was practical, problem-oriented. “He was interested in your sad story,” Grieger said, “but his take on things was ‘let’s not dwell on it.’”11 Or as Wortz himself put it in the Buddhist publication he edited, Dharma Family Journal, “I like to train my clients to construct and deconstruct the experiences that are causing them difficulty.”12 Many of his clients were artists, writers, or filmmakers. At one point, he was seeing so many Los Angeles artists that it was a running joke. “Why haven’t you come to see me yet?” Wortz shouted across the yard to the artist and critic Peter Plagens, at a party.13 Sometimes Wortz accepted art in lieu of payment, though he referred to his own visual sensibility as “clumsy”: “I usually appreciate [the artists] far more than I do the things that they make,” he said.14 Visual acuity did not matter much to him—it mattered more that

he understood and shared the impulse to push the limits of perception and to experiment with materials and ideas. “It’s really exciting to have one foot on a banana peel and the other hanging over an abyss,” Wortz said in 1977, when asked about Robert Irwin’s penchant for repeatedly reinventing his approach to art making.15 As a therapist attuned to the peculiarities of artists, and also deeply embedded in the city’s nascent, evolving art scene, he offered something unique—emotional and psychological support—to a class of people whose work required emotional intelligence. “I think he helped a lot of people keep going with their art,” Karen ComegysWortz, who was married to Wortz when he passed in 2004, told me of her late husband’s influence on artists.

As Wortz made his transition from scientist to therapist, the L.A. art scene was itself changing. A robust feminist art movement was emerging alongside a surge in experimental, conceptual, and performance art practices. Wortz’s interdisciplinary, exploratory approach to his own life and work felt right on time. Perhaps he knew this when, in 1973, right as he was becoming a therapist, he made his second attempt at a convening around habitability, but this time without the concerns of the space race hanging over them. One of his takeaways from the NASA-sponsored symposium had been that “largely people weren’t aware of how environments affected their behavior.”16 Once again, he pulled in artists alongside city planners, policymakers and aerospace engineers for a conference held in Monterey and sponsored by the California Council of the American Institute of Architects.

Sheila Levrant de Bretteville— the artist and designer who helped found the Woman’s Building, which opened in 1973 in downtown Los Angeles—gave a talk at the symposium. She argued that before they could address strategies for improving “life quality” or executing “good design,” those very terms required interrogation. Whose quality of life? Good for whom? For de Bretteville, generalized

assumptions about “good” design and its effects on people became a form of control, one which “inevitably operates through oversimplification, enforcing a single reading or use.”17 This was exactly what Wortz invited by bringing a designer like de Bretteville into this conversation: to push the boundaries of how he and others understood the “habitability” of our world, still an urgent question best answered by the kind of interdisciplinary collaboration that remains elusive today.

In the years that followed, as Wortz’s involvement in the arts also continued through his friendships and his therapy practice, he also intermittently collaborated with artists. In 1976, he helped plan a public sculpture project along the Northern Waterfront area of San Francisco. In 1991, he co-curated an exhibition called and about Addictions at the

Santa Barbara Contemporary Arts Forum (now Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara), with the artist Walter Gabrielson. Gabrielson explained in the catalogue for the show that he wanted the benefit of Wortz’s wideranging expertise as someone who understood Buddhism, artists, substance abuse, and biofeedback.

When he became ill with prostate cancer in the early 2000s, Wortz had already spent over a decade caring for Melinda, who had received an Alzheimer's diagnosis right before she turned 50 and passed in 2002. He stayed in constant conversation with his friends and his doctors about his experience with his illness. Irwin believed Wortz kept cancer at bay through his curiosity. “He researched it and got into the whole process,” Irwin told the writer Lawrence Weschler. “The doctors…loved him because

he was the best feedback candidate they ever could have had.”18 Wortz would get tired in the afternoons and have to lie down. Sometimes, during visits, Irwin would lay beside him. “We’d actually hold hands,” Irwin recalled, “and he would talk about this whole process of dying.”19

Irwin said that Wortz had given him a lesson in how to die. But they had both already been teaching each other how to live for decades. Wortz had developed, through the time he spent with artists, an inclusive theory of art’s value that pivoted away from capital: “The profession of art provides the individual with a lot of options. It’s a very wealthy profession,” he said, acknowledging that this “wealth” was not typically monetary. “The options have to do with behavior, lifestyles, dress, environment, and all sorts of things society lets the artist get away with. This makes the artist very rich.”20 Others have recognized this potential richness, but Wortz found a way to keep helping the people around him access the possibilities that living experimentally and open-mindedly invited. I stumbled recently upon an exuberant 1980 painting by the L.A. artist Caron Colvin, a portrait of Ed and Melinda Wortz. They both smile warmly. Ed holds a plant in his right hand and a finger growing out of his head reaches out to touch a plant growing out of Melinda’s head. Red block letters next to him read, “being as existence manifests only through relationship,” a precept Ed likely articulated, and the painting itself —with the plants, the words, the kind eyes of both subjects, Colvin’s gestural vivacity—makes this statement resonate.

Catherine G. Wagley is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. Her book She Wanted Adventure, about supporting each other while living through and around art, is forthcoming from FSG.

1. Oral history interview of Ed Wortz, 1977, “Robert Irwin Project Interviews,” UCLA Center for Oral History Research.

2. Oral history interview of Ed Wortz.

3. Oral history interview of Ed Wortz.

4. Oral history interview of Ed Wortz.

5. Not officially, nor with NASA’s involvement. The Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota did host an experimental online habitability symposium in 2020.

6. Ed Wortz, interview by Saibra Vickland, March 22, 1986.

7. Oral history interview with Tom Wudl, July 17, 2020, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

8. Wortz, interview by Vickland.

9. Barbara T. Smith, The Way to Be: A Memoir (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2023), 39.

10. Smith, The Way to Be, 140.

11. Scott Grieger, interview with the author, March 17, 2025.

12. Ed Wortz, “Relationships, Dependency and Dukkha,” Dharma Family Journal 1 (no. 2), March 2000.

13. Peter Plagens, interview with the author, March 14, 2025.

14. Oral history interview of Ed Wortz.

15. Oral history interview of Ed Wortz.

16. Oral history interview with Ed Wortz.

17. Sheila de Bretteville, “Habitability from a Feminist Point of View,” in Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the CCAIA: Habitability (Monterey, CA: California Conference of American Institute of Architects/ CCAIA, 1973). This is quoted in James Merle Thomas’s 2014 Stanford University dissertation, “The Aesthetics of Habitability: Edward C. Wortz, NASA, and the Art of Light and Space, 1966–1973,” a rare in-depth consideration of Wortz’s contributions to art.

18. Lawrence Weschler, Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008).

19. Weschler, Seeing is Forgetting, 289–90.

20. Wortz, interview by Vickland.

Last year, I spent some time rereading several novels by Octavia E. Butler. Perhaps subconsciously, I started with Parable of the Sower, which begins in July 2024 on the outskirts of a ruined and lawless Los Angeles, the city an “oozing sore.”1 Distressed by the carnage of our own world, the primal terrors of Butler’s post-apocalyptic world offered a bleak yet welcome distraction. I’m not the only one to think so: Parable of the Sower, published in 1993, debuted on The New York Times bestseller list in 2020 at the height of the pandemic (and 14 years after Butler’s death), attesting to its relevance as a narrative of calamity and survival. In the years since, Butler, a foremother of Afrofuturism and a 1995 MacArthur Fellow, has continued to exert posthumous cultural influence, with numerous publications issuing renewed considerations of her novels and with multiple film and TV adaptations currently in the works.2 Additionally, numerous artists—including Firelei Báez, Connie Samaras, Alicia Piller, and American Artist3—have made work inspired by her words. The discourse around her writing reached a crescendo in January in the aftermath of the firestorms that ravaged the Pacific Palisades and Altadena, where Butler once lived and is now buried, with many noting that Parable of the Sower envisions a similar catastrophe (in the novel, recurring fires create an “orgy of burning”).4

While her fiction may seem to eerily prophesize our current moment, Butler’s science fiction stories (mostly written in the 1980s and ’90s) grew from her acute observation of the very

real crises brewing around her (racism, inequity, climate change), allowing her to anticipate how our unchecked societal malignancies could metastasize over time. Butler poured these observations into fantastical realms inhabited by non-heteronormative beings, creatures she wielded to subversively challenge the hierarchical norms endemic to our own world. As a dystopian tale marked by the threat of fascism and the extreme ramifications of climate change—scarcity, destitution, fanaticism, slavery, tyranny, violence— Parable of the Sower and its sequel, Parable of the Talents (1998), offer some of Butler’s keenest insights into the perils of life in the contemporary United States. Their relevance persists because, out of all of her imagined realities, the Parable novels’ fractious future is the one that most incisively incriminates our present, and not only because the novels’ fictional timeline now coincides with our current moment. Butler ultimately viewed both novels as warnings, yet the crises she forewarned are already here: To quote her protagonist, “things are unraveling, disintegrating bit by bit.”5 Eventually, disintegration yields to collapse.

The two novels, often referred to as the Earthseed series, span the years 2024–2027 and 2032–2035, respectively, conjuring a speculative future marred by environmental and societal collapse. Protagonist Lauren Oya Olamina, the teenage Black daughter of a preacher, lives with her family behind the fortified walls of a close-knit, working-class community. Due to an unspecified apocalypse, the world beyond the walls is dangerously brutal, with violence and savagery running amok. The structures of government and society have remained intact just enough to allow for a villainous fascist to reign, one who ominously talks of “making America great again.”6 In response to the tumult around her, Lauren develops a personal religious philosophy called Earthseed, which posits that there is no God in the traditional monotheistic sense—God is simply the force of change. She approaches her belief system as a kind

Jessica Simmons-Reid

of found object: not a thing that she concocts from the depths of her imagination, but rather a fundamental truth that she observes in the world around her. She eventually codifies this theology into a network of cooperative Earthseed communities that collectively espouse environmental stewardship and mutual care—radical prospects for a world splintered by brutality and deceit. Parable’s most frequently cited quotation, etched on Butler’s tombstone, posits this notion of change as a type of personal and collective reciprocity: “All that you touch, you change. All that you change, changes you. The only lasting truth is change.”7

In one of the novel’s more imaginative elements, Lauren secretly suffers from a sensory disorder called Hyperempathy that causes her to palpably experience any bodily wound she witnesses as if it were inflicted upon her own flesh. This pernicious condition ultimately offers the potential for radical social transformation: “if everyone could feel everyone else’s pain…who would cause anyone unnecessary pain?”8 The subtext is that change can be simultaneously somatic and systemic, and that gestures of reciprocal care can stanch the bleed of collective suffering.

Many of the artists inspired by Butler’s work have seized upon this tenet of transformation, examining how our bodies, environments, and societal milieus can alternatively wound or nurture one another, highlighting their intrinsic entanglements. Firelei Báez’s large-scale painting, On rest and resistance, Because we love you (to all those stolen from among us) (2020), which was part of New York’s Public Art Fund Art on the Grid installation project in 2020 and on view at the Bronx Museum in 2021, allegorizes this sentiment.9 Melding abstract, figurative, and surrealist sensibilities, the work depicts a tightly cropped Black female figure at rest in a field of grass, her face nearly obscured by lush blooms that disperse into thick, shiny coils of rich brown hair. A single eye, almost cloaked, meets the viewer’s gaze. The subject,

bedecked in a diaphanous dress beautifully rendered by Báez’s gleaming brushstrokes, has a copy of Parable of the Sower laying open in her lap. This idyllic vision of a Black woman symbiotically communing with an abundant green earth—eschewing the toils of capitalism in favor of leisure and literature—represents a moment of pleasure, agency, and bodily sovereignty that nonetheless eulogizes the toils of the past (and present), as the title suggests. It also establishes a dialectical tension with the unseen viewer, who hovers from a voyeuristic vantage point of power. The figure’s lack of vigilance subverts this hierarchical dynamic, supposing instead a reciprocal exchange of vulnerability and trust. By framing Butler so prominently, the painting ultimately positions Parable of the Sower as both an emblem and an omen: This Edenic tableau, like the novel’s hellish dystopia, functions as a speculative social reality that is contingent on our collective behavior toward one another.

Connie Samaras’ conceptual photographs based on Parable of the Sower similarly employ the book as a symbolic object within a verdant composition. Her images depict vignettes of cacti and other flora from the Huntington Desert Garden in Pasadena, which she photographed through enlarged transparencies made from Butler’s handwritten notes about the book (Butler’s archives are currently housed at the Huntington Library). In Huntington Desert Garden (agave) and OEB 1723, novel fragment from Parable of the Sower, 1989 (2016), the sinuous limbs of a large, variegated agave occupy the entire image frame in a tangled and semi-abstract composition. Superimposed over the plant are snippets of Butler’s handwriting; her notational marks disappear and re-materialize like guarded murmurs. Though it’s nearly illegible, the word “changing” functions as one of the image’s most visually prominent elements. This reference to Earthseed’s central belief system simultaneously implicates our ongoing detrimental

alteration of the environment and identifies perpetual metamorphosis as the natural world’s native state, in which survival necessitates interspecies symbiosis. Samaras’ title for this series, The Past is Another Planet, positions the work as a botanical study of an existentially threatened ecosystem—an eventual vestige of Earth’s fertile past.

Together, both Báez and Samaras offer intimate, microcosmic glances at hyper-specific moments or environments, one ecological and one interpersonal, suggesting that sustained care for a single being bolsters the integrity of the entire living system. In both Parable novels, Samaras’ notion of the past as another planet emerges quite literally. Butler details how climate change has obliterated Earth’s fragile ecology—a brittle Southern California wilts without rainfall for years—making edible plants, fruits, and seeds precious and laborintensive commodities. While Lauren’s Earthseed community nurtures the land as if it were a living body, tending to it so that it may sustain its inhabitants in return, the movement’s ultimate (and somewhat contradictory) goal lies in abandoning this synergistic relationship altogether and eloping to other planetary worlds: “The Destiny of Earthseed is to take root among the stars.”10 Humans, Lauren asserts, can function as seeds for propagating life beyond the bounds of this planet, just as a windborne plant embryo takes root in the soil of a distant island. Alicia Piller’s immersive sculpture, Mission Control. Earthseed (2024), included in The Brick’s PST exhibition, Life on Earth: Art and Ecofeminism, specifically interprets this element of the narrative. Like Samaras, Piller culled from Butler’s archives at the Huntington, embedding images of the author’s handwritten notes within the work. The sculpture recalls the crew module of a spaceship, represented as a pliable, tent-like structure that stretches down from the ceiling and encompasses three large chairs, which seem to have the potential to grasp

onto a body (viewers are encouraged to sit). Composed of pliant, salvaged materials including vinyl, paper, and fabric, the sculpture has the supple elasticity of skin, perhaps a nod to the living, womb-like spaceship central to Butler’s Dawn (the first novel in her Lilith’s Brood trilogy). Emerald green with trailing, snake-like limbs, the back of each chair exhibits ornate patterning reminiscent of the reproductive organs of a flower or a human vulva: elliptical orifices, looping folds, embedded seed pods, tiny hairs. With the inclusion of these symbolic fruiting bodies, this futuristic craft seems poised to sow its organic cargo, perhaps with the aim of attracting unknown pollinators as it traverses extrasolar worlds. Piller employs Butler’s narrative as a fulcrum for a speculative sculptural abstraction, creating a hybrid automotive being that conceptually intertwines the processes of change and creation. Whereas Piller contextualizes Butler’s work in an abstract visual lexicon, American Artist hones in on its wider philosophical and cosmological implications. Their years-long, multi-venue exhibition project, Shaper of God, connects the novels’ science fiction themes to the real-world development of rocket technology, the history of which has deeply shaped Southern California’s social, economic, and natural landscapes. (Like Butler, American Artist hails from Altadena). The Monophobic Response (2024), exhibited at LACMA in 2024 and recently on view at Brooklyn’s Pioneer Works, takes its title from Butler’s eponymous 1995 essay that explores the human instincts of fear and longing. In a video performance, the artist deploys a fully functional rocket engine in the Mojave Desert, a reenactment of a 1936 launch test. The video imagines a multiracial cohort of Earthseed adherents gathering in barren terrain to ignite their engine prototype, proposing an alternative reality wherein cooperative communities, rather than neocolonial oligarchs, revolutionize space exploration for the existential

and spiritual betterment of all humans. Together, these artworks merge the premises of Butler’s literature with the predicaments of our own imperiled reality, using the theses of her fiction—change, attentiveness, care, reciprocity—as relational propositions for shaping the contours of our own future, however speculative. Artists, with their unique attunement to material fallibility, share a kinship with Butler’s protagonist, whose condition of hyperempathy is a metaphor for the role of the artist at the end of the world: to absorb the pains and pleasures of their environs and translate them into something new. Harnessing this ethos, the artists discussed here propose dictums of change through tenets of care that mitigate collective pain and trauma: How do we relate to vulnerable bodies and ecosystems, now and in the future? This question dissects power’s inevitable abuse: Who gets to dictate the terms of our mutual survival? Báez’s incandescent painting, Samaras’ enigmatic photograph, Piller’s anthropomorphic spaceship, and American Artist’s Afrofuturistic vision will not, on their own, obliterate fascism or stall our extinction; collectively, however, they underscore the notion—crystalized by Butler herself— that kernels of radical thought and subtle shifts in perspective can, over time, ripple outward to elicit seismic sociocultural changes. Perhaps, then, we can one day implement the antidote to our own self-induced apocalypse. In the meantime, as large catastrophes overwhelm, small poetic gestures sustain. If we lose those, what remains?

Jessica Simmons-Reid is an artist, writer, and critic based in Los Angeles and Joshua Tree, CA. Her writing has appeared in Artforum, Carla, frieze, Momus, and The New York Times. She is a 2024 recipient of AICA’s Young Critic Prize.

1. Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (New York City: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993), 109.

2. The New York Times, The New Yorker, Artforum, and The Paris Review, among others, have published commentary. Ava DuVernay is developing Dawn (1987), the first novel in Butler’s Xenogenesis/Lilith’s Brood series, for television; Amazon Studios is developing a drama series based on the Patternist series; and Garrett Bradley is directing a feature film based on Parable of the Sower.

3. Kara Walker’s new commission at SFMOMA, Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine) (2024), counts Parable of the Sower as one of its many references. Toshi Reagon and Bernice Johnson Reagon’s opera based on the novel opened at New York’s Lincoln Center in 2023.

4. Butler, Sower, 144.

5. Butler, Sower, 123.

6. Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Talents (New York City: Seven Stories Press, 1998), 21.

7. Butler, Sower, 3.

8. Butler, Sower, 115.

9. Underscoring the social commentary of this painting, Báez has written that "this work is in reference to the 70,000 black women and girls in the United States currently missing,” and that the figure in the piece is modeled on a circa-1961 photograph of sleeping Freedom Riders. Firelei Báez for the Public Art Fund: Art on the Grid, James Cohan, accessed April 9, 2025, https://www.jamescohan.com/public-exhibitions/ firelei-baez-for-the-public-art-fund?view=slider.

10. Butler, Sower, 84.

As Carla celebrates our 10-year anniversary, we wanted to look back over each year of the magazine, tracing our growth along with the major exhibitions and events that have shaped the L.A. art community and world at large. Museums and galleries have opened and closed, unions have rallied, and striking shows have animated the city. We asked a group of 10 writers, staff, and board members to reflect on Carla’s archive, prompting each contributor to reflect on one Carla article from each of our 10 years. Alongside this, the writers highlight notable cultural moments that have impacted both L.A.’s art scene and their own personal engagement with the city.

Carla, issue 2

Layers of Leimert Park

—Catherine G. Wagley

Catherine G. Wagley captures a nuanced, complex, contextual, and above all local picture of a neighborhood in Los Angeles with both rich historical weight and an unclear future. Wagley deftly unspools the intertwining realities of power, history, real estate, and the public good that the contemporary art world has a hand in shaping, for better or for worse.

L.A. exhibition

Vengeance, film noir tics, Cronenberg-ian assemblages, and flashing lights comprised John Bock’s installation Three Sisters. The 40-minute film centerpiece both chews and is chewed by the film’s scenery, which filled up Regen Projects’ main room as if flung out by the film’s intensity. Drama of my favorite sort.

Carla, issue 8

Interview with Penny Slinger

—Eliza Swann

Eliza Swann, whose own work as an artist and teacher I deeply admire, spoke to artist Penny Slinger at the Goddess Temple where Slinger then lived, a home in the redwoods specifically built to honor the divine feminine. She spoke to Swann about the difficulty of doing sincerely spiritual, sexual work in the contemporary art world.

Art world news

Protests against galleries in Boyle Heights began in earnest in September 2016, as certain mid-size galleries that had opened during L.A.’s gallery boom from 2013–15 were already losing their spaces thanks to greedy landlords who had only rented to them while waiting for Soho House or Google to arrive in the neighborhood.

Carla, issue 10

She Wanted Adventure: Dwan, Butler, Mizuno, Copley

—Catherine G. Wagley

Drawing on archival sources and interviews, Wagley documents the historical importance and innovative practices of four female gallerists, positing that their absence from the official story may have been in part a result of their subversive strategies that were at odds with both their male counterparts and conventional efforts of historicization.

Standout artist

I first encountered Lauren Halsey’s work in black is a color, a summer 2017 group show curated by Essence Harden at Charlie James Gallery. Into a grid of whiteon-white carved gypsum panels she monumentalized images of Black identity: from jazz musicians and the P-Funk mothership, to Afrofuturist pyramids, and phrases like “Black owned beauty supply”and “here nobody surrenders.”

Carla, issue 12

Interior States of the Art —Travis Diehl

“An artwork may or may not be what it says it is,” Diehl writes in an article that examines artworks that exist in the ether—their materials, only discernible to the viewer via wall didactics. These works are a profound trust exercise in which a viewer must believe an artist at their word.

L.A. exhibition

Nina Chanel Abney’s colorful, dense, graphic compositions in her dual shows at CAAM and ICA LA exploded with an array of references, some political, others pop-cultural, others merely playful. Not wanting to be boxed into any one discourse, Abney has fervently pursued a painterly language that fuses synchronal subject matter, stacked and tangled.

Carla, issue 18

Putting Aesthetics to Hope

—Catherine G. Wagley

Wagley’s examination of work by Carmen Winant in relation to the womyn’s land movements of the 1970s and ’80s coalesced around questions crucial to both photography and feminism —invoking gaze, authorship, intimacy, and agency—while also suggesting the limitations of a feminism that isn’t wholly intersectional.

Art world news

Local art world events —the successful unionization of MOCA employees and the attempted unionization of Marciano Foundation employees (which spurred the Marcianos to abruptly shutter the museum)— reflected larger national debates, highlighting deepening divisions over workers’ rights as well as echoing growing calls for institutional transparency and accountability.

Honey Lee Cottrell. Image courtesy of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Carla, issue 22

The Glitch Strikes Back: Legacy Russell’s Feminist Manifesto

—Allison Noelle Conner

Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism, dissected by Conner, reclaims tech glitches as feminist rebellion, shattering gender and race binaries. Glitches disrupt norms, empowering “messy,” non-binary identities online. It’s a bold lens on how cyberspace can liberate when it breaks, urging marginalized voices to hack oppressive systems.

World event

The world was collectively traumatized as the pandemic locked most of us at home to exist primarily in digital realms. Work, education, social life, and yes—the art world too—all went virtual. Black Lives Matter protests shined a spotlight on widespread racial injustice, and U.S. political divisions were amplified.

Carla Podcast, episode 29

Interview with Patrick Martinez

My brother and I used to play this game when I visited L.A.: You abruptly shout out the large text you pass while driving across the city— storefront signage, banners, billboards. Patrick Martinez spoke about his penchant for these surfaces: “not the anti-advertising, but the flip side of a community advertising or aesthetic.” His work translates the experience of landscape rather than representing landscape.

Former U.S. President Joe Biden’s words, “America is back,” linger in my memory of 2021—they remain fractured, untrue, and nostalgic for an imaginary America that acted in accordance with the values it espoused. I leaned heavily on Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights that year as these realities and non-realities surrounded us.

Carla, issue 29

From Both Sides of the Lens: Ulysses Jenkins’ Self Reflexive Video Practice —Neyat Yohannes

One of the joys of Yohannes’ feature lies in her ability to sketch out a loose image of the Black art scenes in the 1970s and ’80s. She deftly explores Jenkins’ prescience in turning the camera into a self-reflexive tool, where the artist played dual roles as “both witness and subject.”

Organized as an extension of Simone Leigh’s exhibition at the U.S. Pavilion, the Loophole of Retreat at the 59th Venice Biennale was a three-day conference at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini that gathered scholars, artists, and activists. Through performances, film screenings, and dialogues, the symposium celebrated the breadth and rigor of Black women’s theory and imagination, outlining the many expressions of sovereignty and liberation.

Carla, issue 34

Tuning In and Dropping Out: Spiritual Frontiers in Recent Art and Curation

—Isabella Miller

Miller's piece explores the American West as a spiritual frontier, and the shared “distrust of modernity [and] interest in the occult” that guided the work of a community of artists. She examines the tenuous yet fertile relationship between mysticism and the art market.

L.A. exhibition

Some of my most powerful and cherished childhood memories revolve around Faith Ringgold’s Tar Beach, the book (1991) and the story quilt (1988). Her survey at Jeffrey Deitch reminded me of the whimsical magic her artworks hold, which inspired me to dream as a young girl. Now, just one year after Ringgold’s death, I am struck by how profoundly alive her vivid narratives have always been.

Emil Bisttram, Oversoul (c. 1941). Oil on masonite, 35.5 × 26.5 inches. Private collection. Image courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York.

Carla, issue 37

The Connective Role of Art in UCLA’s Pro-Palestine Encampment

—Aidann Gruwell, Alex Bushnell, Alex Yang, Katherin Sanchez, and Ricky Shi

Last spring, students and community members established Gaza Solidarity Encampments on campuses across the country, demanding their universities divest from companies profiting from and facilitating the genocide in—and occupation of—Palestine. The authors wrote as participants in the UCLA encampment, where students used visual art as a tool “to agitate, to criticize, and to unify.”

Standout artist

Ironically, I first heard of Evan Apodaca after his art was censored by the San Diego International Airport in 2023 for being too critical of the city’s hyper-militarism. The following year, he plastered rocks with cyanotype reprints to confront eviction and displacement brought on by L.A.’s Dodger Stadium.

UCLA encampment occupying Royce Quad shortly before law enforcement began forcibly removing the demonstration and arresting more than 200 protesters, May 1, 2024. Photo: Keegan Holden.

and her answers unfolded into a love letter to the L.A. region. Our conversation opened up into a larger continuum of histories: collectively understood, spoken, carried—and intimately interconnected.

CJ Salapare: How did your personal relationship with L.A. come to be?

I first met curator Erin Christovale in 2020 during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time, I was a Getty Marrow intern at the Hammer Museum working with Erin on her 2022 exhibition Ulysses Jenkins: Without Your Interpretation. In the months that followed, the power and prescience of Jenkins’ work was undeniable amid Zoom calls and Black Lives Matter protests. I admired his radical sensibility homegrown in Los Angeles, and I soon realized that Erin also embodied this very spirit.

The ensuing years that I’ve known Erin have only confirmed this belief. Los Angeles, with all of its enigmas and edges (including Long Beach, where we were both raised), is inextricable from her ways of working and being. Her curatorial work—from the 2018 edition of Made in L.A., to Jenkins’ longoverdue survey, to the 2022 Sylvia Wynter-inspired exhibition No Humans Involved—is grounded in the intergenerational practices of Black radical imagination, archival preservation, and local experimentalism.

Alice Coltrane, Monument Eternal (February 9–May 4, 2025), which Erin recently curated at the Hammer with Nyah Ginwright, is her latest imagining brought to fruition. The multimedia exhibition brings together the visionary musician and spiritual guru’s music and archives alongside works by 19 multi-generational artists. What emerges is a dual portrait of a dynamic life and legacy.

For this interview (which took place on Valentine’s Day), I asked Erin to reflect on her sense of place,

Erin Christovale: I've lived in L.A. County for practically my entire life. I grew up in Long Beach and the city has always been a cornerstone to my existence, to the way that I think, the way that I move, the way that I navigate spaces. […] I always think of L.A. as, like, this sort of B [or] C-list actress who had that one breakout role and her career didn’t really take off after that. She’s a glamour girl, but she's also very raw and gritty and seedy. [L.A. is] ruled by the entertainment industry. […] It's also a city that has very deep political and racial underpinnings. I think about the LAPD being one of the most militarized police departments in the country. I think about a history of uprisings from Watts to South Central. I think about a city that’s always sunny…. To say that imbues some positivity or beauty, but actually what it means is the city [rarely] gets rain. What does it mean if the city is never sort of replenished in that way? There’s so many layers to this incredible city. I love just being in the thick of all of that… and also incorporating that into what I do as a curator.

CJS: Can you expand on this dissonance between the region’s associations with Hollywood’s glitz and glamour and these more visceral layers of meaning that inform your curatorial work?

EC: I’ve always been interested in the study of film. […] I remember so clearly one of the classes at USC that really had an impact on me was a class taught by Professor Kara Keeling on the history of African-American cinema, and one of the first films that she showed was The Birth of a Nation.