Los Angeles

Letter from the Editor

The adage “no man is an island,” penned by English poet John Donne in the seventeenth century, has been recycled across culture so many times that it hardly feels revelatory. In the movie adaptation of the Nick Hornby book, About a Boy, the protagonist, played by Hugh Grant, hears the Donne quote and scoffs, opining that these days “all men are islands.”

He rants on about how we are living in an “island age.” “100 years ago,” he explains, “you had to depend on other people. No one had… DVDs or videos or espresso makers… whereas now… you can make yourself a little island paradise.”

The character, privileging his independence over community, later realizes (spoiler!) that we are all connected, and do, in fact, need other people.

While Grant’s lone-wolf character feels unrelatable, his techfueled isolation is certainly familiar. Mired on our own islands and ungratified by the connection that our phones claim to offer us, many of us still seek the kind of soul-fulfillment that being in connection with others can bring. Particularly as we face the rise of bigotry and fascism in our country, as well as direct harm being done to members of our community, we are searching for grassroots support networks and interconnectedness. Across this issue, we see stories of connection. Sean Koa Seu writes on Judy Baca’s decades-long Great Wall project and the ways she is tangibly rewriting history to more accurately include the diverse stories of our

communities, building relationships with students and volunteers along the way. As Seu describes, the project was “never a mere wall, the mural was mutual aid.” Echoing this notion, Sarah Plummer’s article on California’s printmaking history shines a light on many local outfits that have reworked the printmaker’s historical role (read: anonymous) into one that visualizes and celebrates the process of producing an editioned work— namely, the intimate collaboration between artist and printer. Here, too, relationships are more important than product.

Aaron Boehmer’s article looks at artists who utilize political typography, reconfiguring their artwork from a gallery context and repurposing it to be used in protest settings. These artists call upon the visual language of past movements, celebrating history by activating it in the present. Maya Livio speaks to a different kind of community relationship: the one between an artistin-residence and her environment, arguing that it is vital for visiting residents to attune with local ecology. Later, writer Andrea Gyorody explores Gregg Bordowitz’s intersecting identities and how congregating with others has become central to his worldview.

In L.A. and globally, we are seeing how mutual aid efforts are essential in combating threats to the well-being of our communities in real time. Donne’s original quote continues, “Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind.” This 41st issue points to the ways our communal existence is more important than ever, proposing some of the different shapes that communal support can take.

Lindsay Preston Zappas Founder, Editor-in-Chief, & Executive Director

L.A.’s History of Collaborative Printmaking

Sarah Plummer

Judy Baca and the Great Wash of Los Angeles

Sean Koa Seu

On Preserving Dissenting Letterforms

Aaron Boehmer

Maya Livio

Andrea Gyorody

The Dealers

Carlye Packer Bets Big

Photos and text: Claire Preston

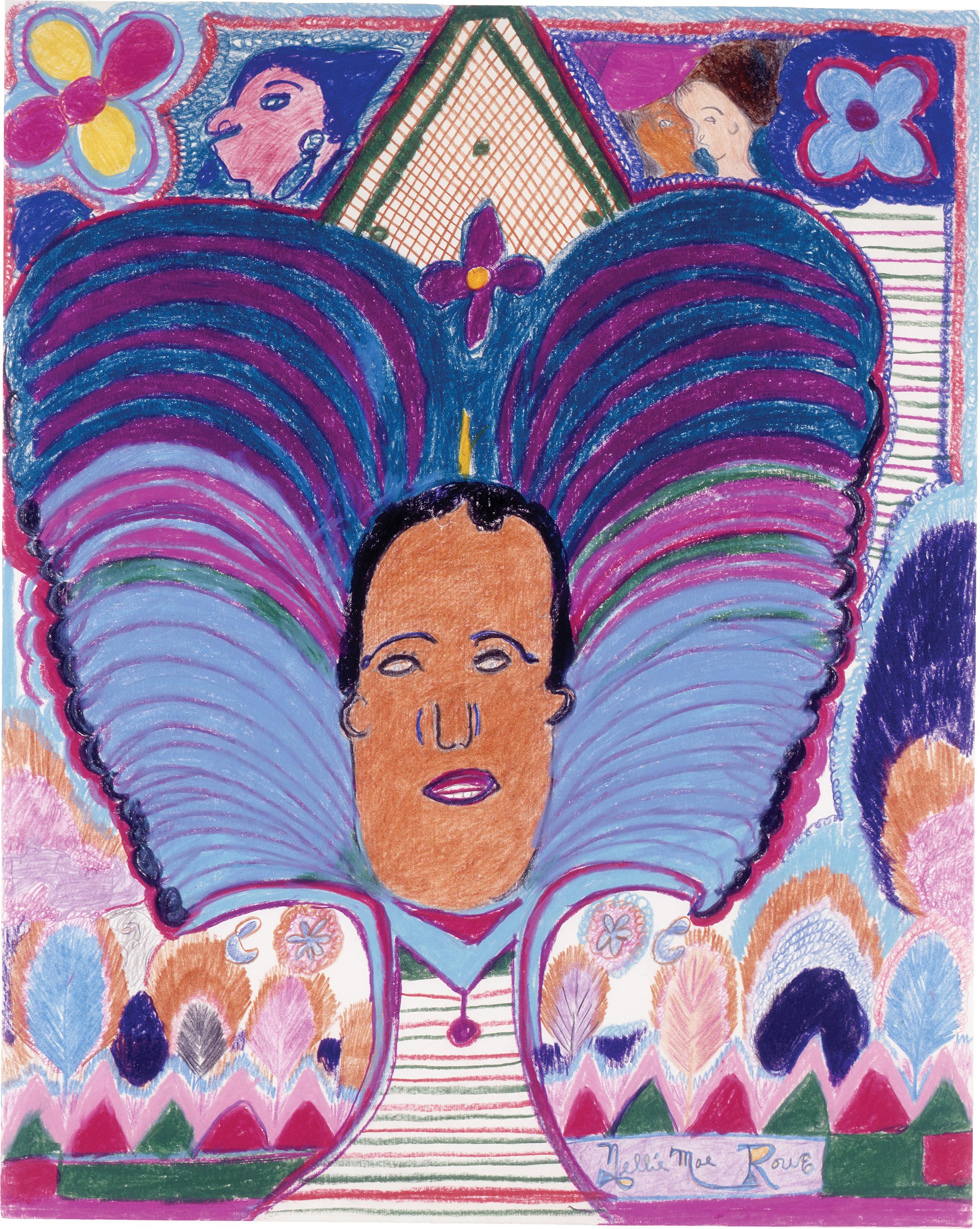

Nellie Mae Rowe at California African American Museum

—Hannah Tishkoff

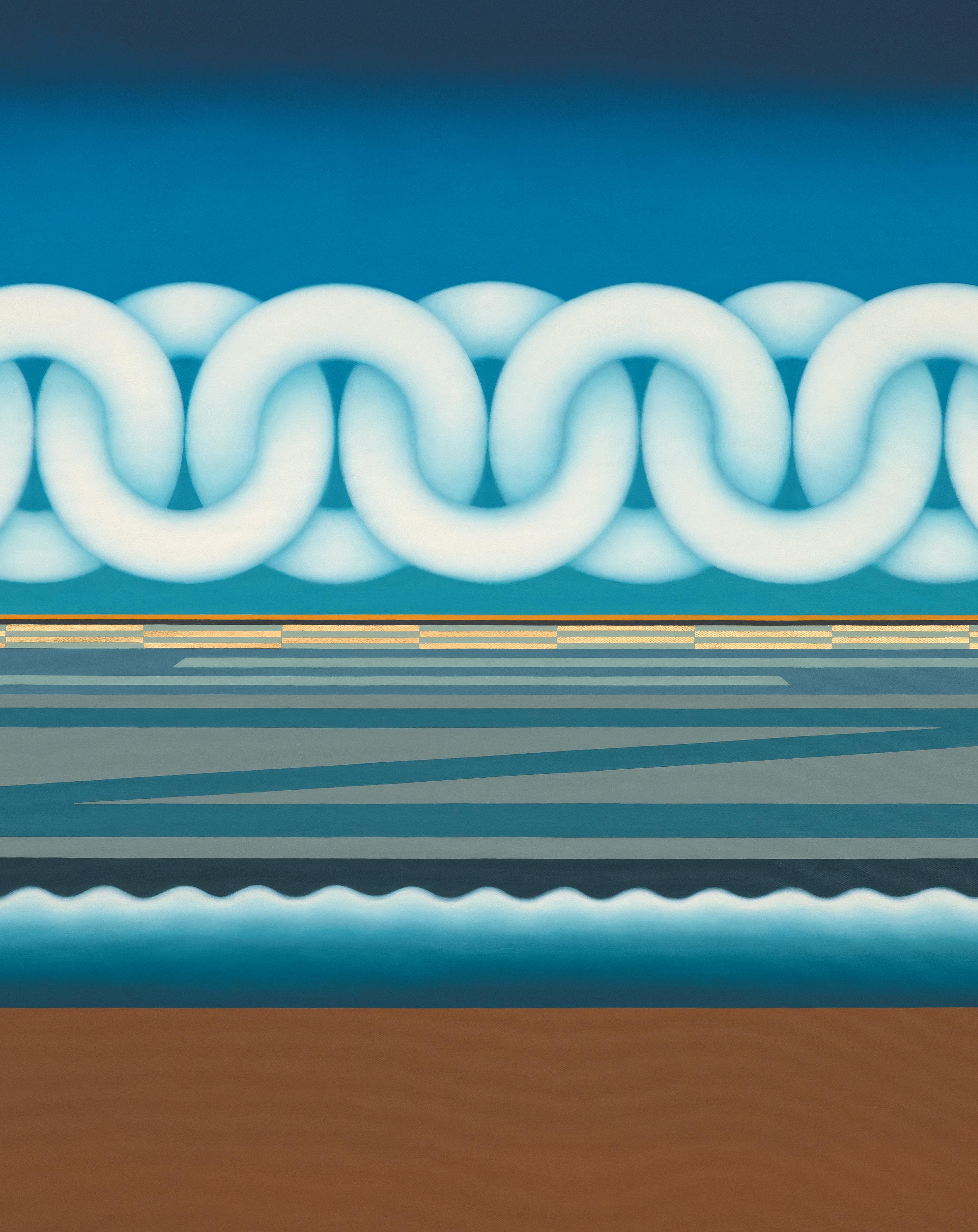

Earthshaker at Del Vaz Projects

—Teresa Fleming

Counter/Surveillance at Wende Museum

—Alexander Schneider

Carolee Schneemann at Lisson Gallery

—Olivia Gauthier

Tony Cokes at Hannah Hoffman Gallery —Shani Strand

Image: Gay Activists at First Gay Pride Parade, Christopher Street, New York (detail), 1970, printed 2021, Arthur Tress. Gelatin silver print. Getty Museum, Gift of David Knaus.

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles is an essential voice made in and for Los Angeles. Founded in 2015 by artist and writer Lindsay Preston Zappas, Carla is a nonprofit organization and publishing platform that is dedicated to providing critical, thoughtful, and inclusive perspectives on contemporary art. Our quarterly print magazine is an active source of dialogue on Los Angeles’ art community and is available for free in over 160 galleries and art spaces in L.A. and beyond.

Editor-in-Chief & Executive Director

Lindsay Preston Zappas

Managing Editor Evan Nicole Brown

Contributing Editor Allison Noelle Conner

Graphic Designer Satoru Nihei

Copy Editor Rachel Paprocki

Administrative Assistant Aaron Boehmer

Getty Marrow Publications Intern Talia Tepper

Color Separations Echelon, Los Angeles

Printer Solisco Printed in Canada

Submissions

For submission guidelines, please visit contemporaryartreview.la/submissions, and direct all submissions to submit@contemporaryartreview.la.

Inquiries

For general inquiries, contact office@contemporaryartreview.la.

Advertising

For ad inquiries and rates, contact ads@contemporaryartreview.la.

W.A.G.E.

Carla pays writers’ fees in accordance with the payment guidelines established by W.A.G.E. in its certification program.

Copyright All content © the writers and Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles

Social Media

Instagram: @contemporaryartreview.la

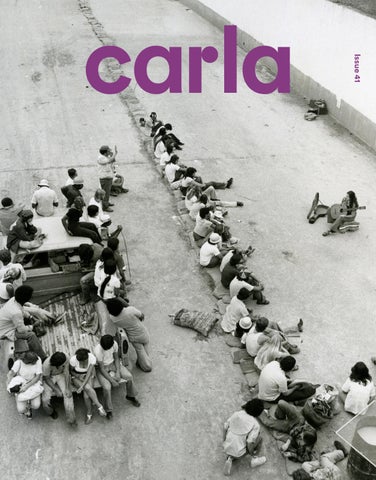

Cover Image

Aerial view of a music performance at The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1981). © SPARC. Image courtesy of the SPARC archives and LACMA. Photo: Linda Eber.

Contributors

Lindsay Preston Zappas is an L.A.-based artist, writer, and the founder of Carla. She received her MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art and attended Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2013. Her writing has appeared in Track Changes: A Handbook for Art Criticism, KCRW, Carla, ArtReview, Flash Art, SFAQ, Artsy, LACanvas, and Art21 Recent solo exhibitions include those at the Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art (Buffalo, NY), OCHI (Los Angeles), and City Limits (Oakland).

Evan Nicole Brown is a Los Angeles-born writer, editor, and journalist who covers the arts and culture. Her work has been featured in Architectural Digest, Dwell, Getty Magazine, The Hollywood Reporter, L.A. Times Image, The New York Times, T Magazine, and elsewhere. She is also the founder and host of Group Chat, a conversation series in L.A.

Allison Noelle Conner is an arts and culture writer based in Los Angeles.

Satoru Nihei is a graphic designer with an MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art. His work has been featured in The Tokyo TDC Design Annual, METROPOLIS, Graphic Design: The New Basics, and other publications, and has been showcased internationally at exhibitions including the Golden Bee Global Biennale of Graphic Design, Peru Design Biennial, Graphic Matters, Trnava Poster Triennial, Shenzhen International Poster Festival, and others. He judged the 2019 PRINT Magazine Regional Design Awards and received the Golden Bee Award in both 2022 and 2024.

Rachel Paprocki is an editor and librarian who lives and bikes in Los Angeles.

Aaron Boehmer is a writer based in New York City. He covers the arts, culture, and politics and has written for The Nation, Texas Monthly, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Drift, and others.

Talia Tepper is from Los Angeles and studies international literature, visual studies, and philosophy at Tufts University. She works on Currents Magazine, Tufts Observer, and loves Joan Didion.

Board of Directors

Lindsay Preston Zappas, Executive Director

MJ Brown Trulee Hall

Joseph Daniel Valencia

Membership

Carla is a free, grassroots, and artist-led publication. Club Carla members help us keep it that way. Become a member to support our work and gain access to special events and programming across Los Angeles.

Carla is a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization; all donations are tax-deductible. To learn more, visit join.contemporaryartreview.la.

Thank you to all of our Club Carla members for supporting our work. A special thank you to our La Brea and Western members:

Philippe Browning, Anthony Cran, Tim Disney, Sarah Ippolito, Tiffiny Lendrum, Rebecca Morris, Jobert Poblete, Michal Hall Bravo Ramirez & Octavio Bravo Ramirez, Laurie & Rick Raskin, Anjelica & Neil Sarkar, Ian Stanton, Michael Zappas, Critical Minded, Solid Art Services, and West of West Architecture + Design.

Los Angeles Distribution

Central

1301 PE

7811 Gallery

Anat Ebgi (Wilshire)

Arcana Books

Artbook @ Hauser & Wirth

as-is.la

Babst Gallery

Baert Gallery

Bel Ami

Billis Williams Gallery

BLUM

Canary Test

Central Server Works Press

Charlie James Gallery

Château Shatto

Cheremoya

Chris Sharp Gallery

Cirrus Gallery

Clay ca

Commonwealth and Council

Craft Contemporary

D2 Art (Westwood)

David Kordansky Gallery

David Zwirner

Diane Rosenstein

dublab

FOYER–LA

François Ghebaly

Gana Art Los Angeles

Giovanni’s Room

Hannah Hoffman Gallery

Harkawik

Harper’s Gallery

Heavy Manners Library

Helen J Gallery

Human Resources

ICA LA

JOAN

KARMA

LACA

Lisson Gallery

Los Angeles Municipal

Art Gallery

Louis Stern Fine Arts

Lowell Ryan Projects

Luis De Jesus Los Angeles

M+B

MAK Center for Art and Architecture

Make Room

Matter Studio Gallery

Michael Werner Gallery

MOCA Grand Avenue

Monte Vista Projects

Morán Morán

Moskowitz Bayse

Murmurs

Nazarian / Curcio

Night Gallery

Nonaka-Hill

NOON Projects

O-Town House

OCHI

Official Welcome

One Trick Pony

Pace

Paradise Framing

Patricia Sweetow Gallery

REDCAT (Roy and Edna Disney CalArts Theater)

Regen Projects

Reparations Club

Roberts Projects

Royale Projects

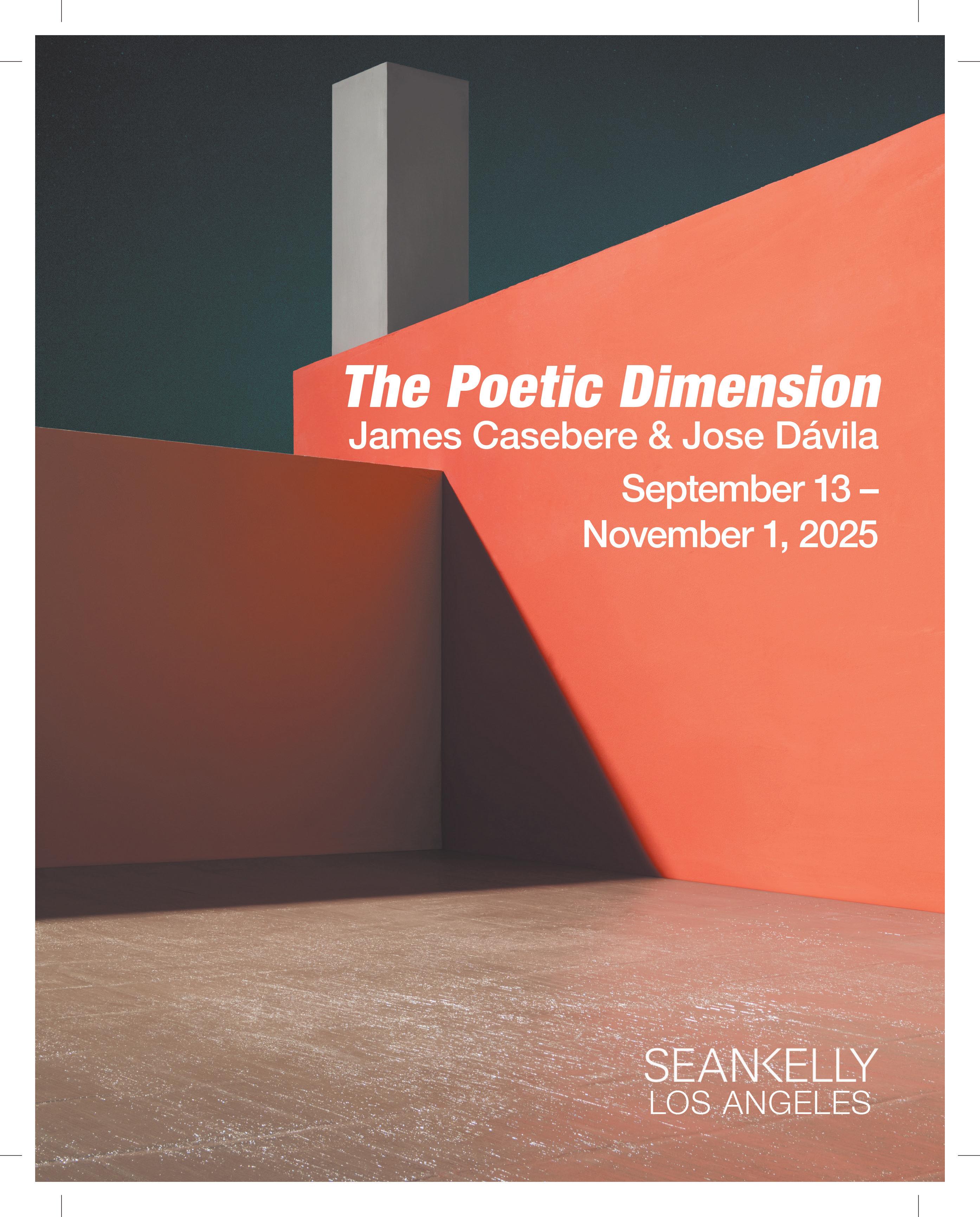

Sean Kelly

Sebastian Gladstone

Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Smart Objects

SOLDES

Sprüth Magers

Steve Turner

Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

The Box

The Fulcrum

The Hole

The Journal Gallery

The Landing

The Poetic Research Bureau

The Wende Museum

Thinkspace Projects

Tierra del Sol Gallery

Tiger Strikes Asteroid

TORUS

Track 16

Tyler Park Presents

USC Fisher Museum of Art

Various Small Fires

Village Well Books & Coffee

Webber

Wönzimer

East

BOZOMAG

Feminist Center for Creative Work

Gattopardo

GGLA

Junior High la BEAST gallery

Marta

Nicodim Gallery

OXY ARTS

Parrasch Heijnen Gallery

Philip Martin Gallery

Rusha & Co.

Sea View

South Gate Museum and Art Gallery

The Armory Center for the Arts

The Pit Los Angeles

Umico Printing and Framing

Vielmetter Los Angeles

Vincent Price Art Museum

Wilding Cran Gallery

North

albertz benda

ArtCenter College of Design

ArtCenter College of Design, Graduate Art Complex

The Aster LA

South

Angels Gate Cultural Center

D2 Art (Inglewood)

Long Beach City College

The Den

Torrance Art Museum

West

18th Steet Arts

Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center

Dorado 806 Projects

L.A. Louver

Laband Art Gallery at LMU

Marshall Gallery

ROSEGALLERY

Von Lintel

Zodiac Pictures

Outside L.A.

Bortolami Gallery (New York, NY)

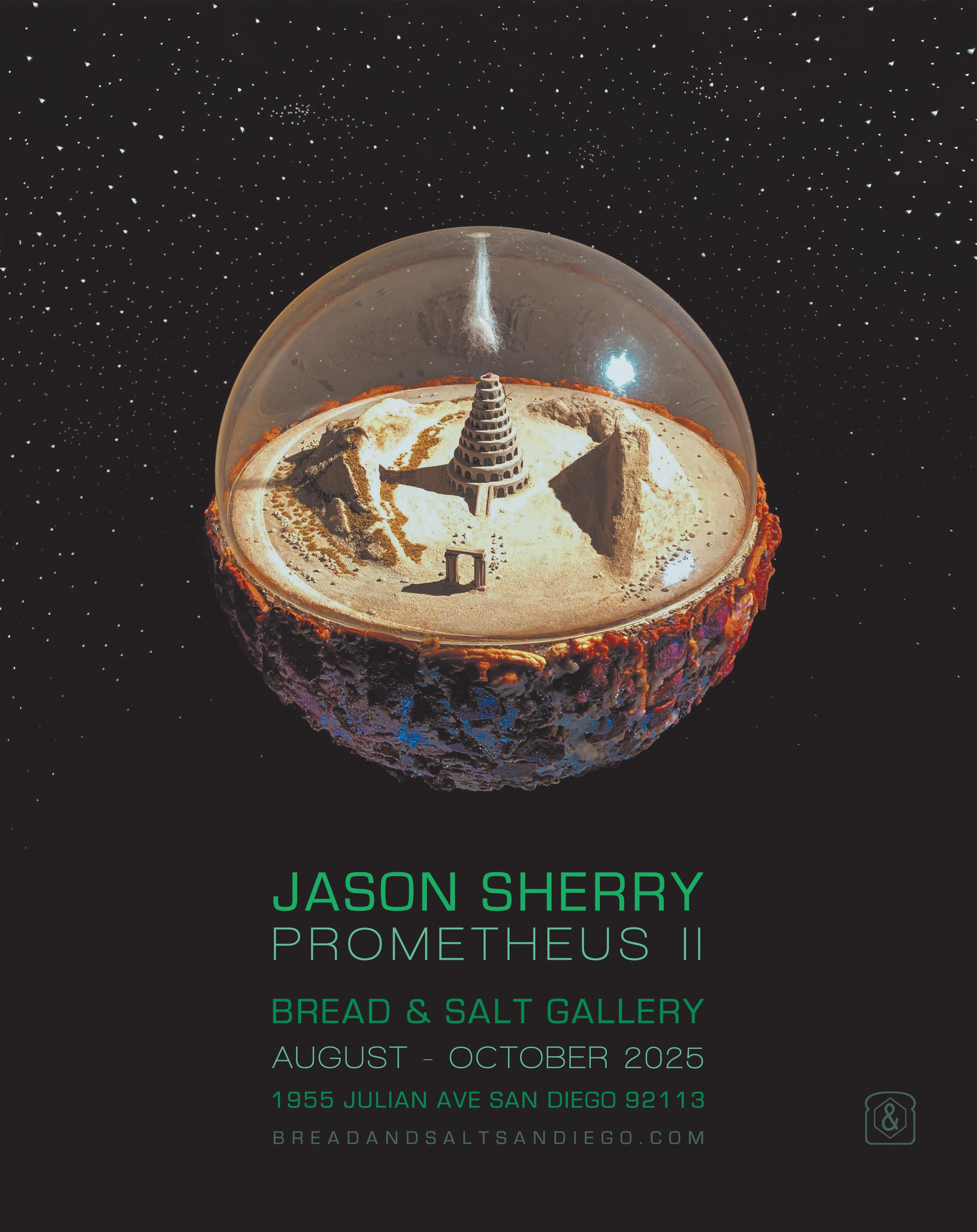

Bread & Salt (San Diego, CA)

Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art (Buffalo, NY)

Chess Club (Portland, OR)

DOCUMENT (Chicago, IL)

Et al. (San Francisco, CA)

Fresno City College (Fresno, CA)

High Desert Test Sites (Joshua Tree, CA)

Left Field (Los Osos, CA)

Level of Service Not Required (La Jolla, CA)

Los Angeles Valley College (Valley Glen, CA)

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (La Jolla, CA)

OCHI (Ketchum, ID)

Libraries/Collections

Baltimore Museum of Art (Baltimore, MD)

Bard College, CCS Library (Annandale-on-Hudson, NY)

Charlotte Street Foundation (Kansas City, MO)

Cranbrook Academy of Art (Bloomfield Hills, MI)

Getty Research Institute (Los Angeles, CA)

Los Angeles Contemporary Archive (Los Angeles, CA)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Los Angeles, CA)

Maryland Institute College of Art (Baltimore, MD)

Midway Contemporary Art (Minneapolis, MN)

Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, CA)

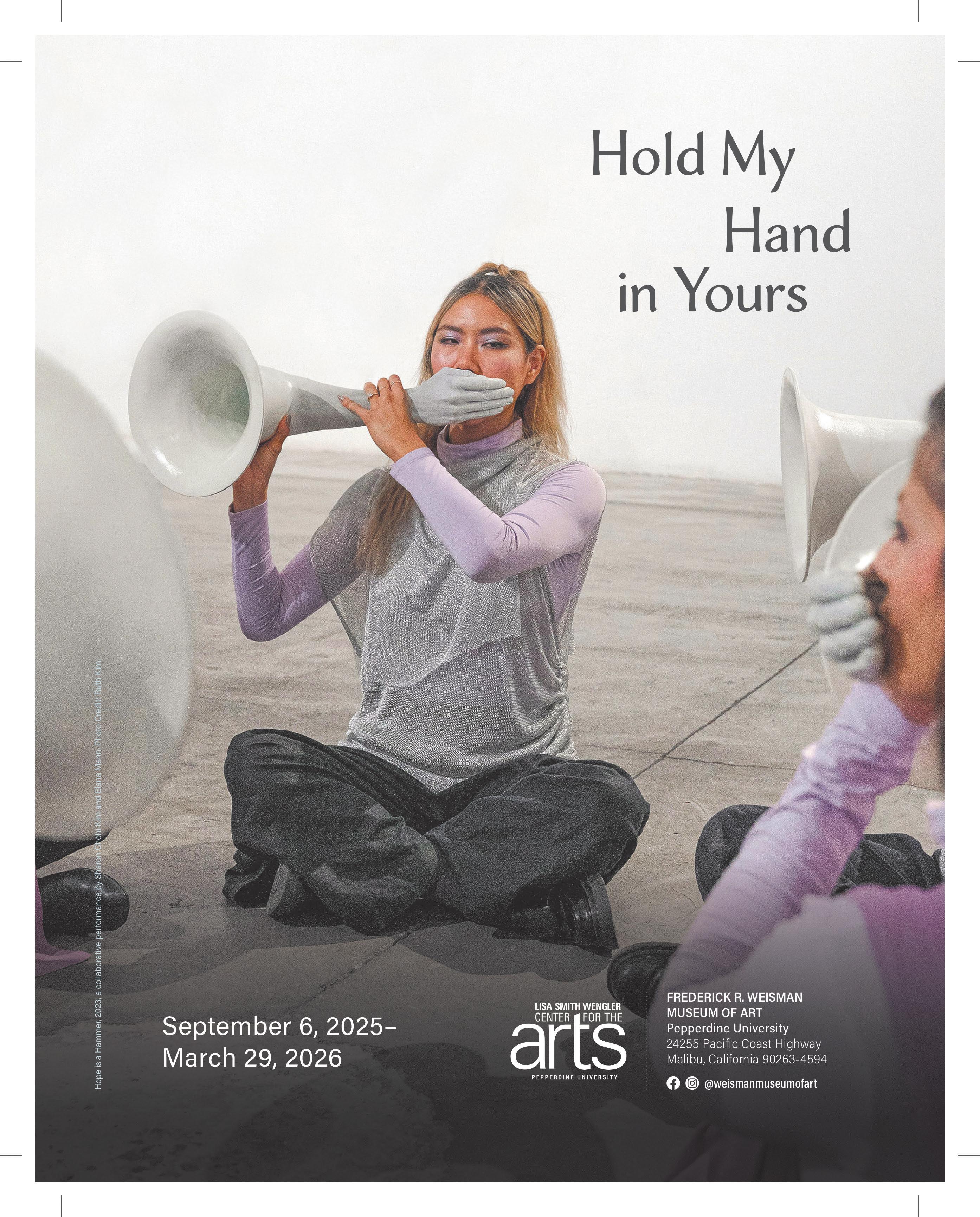

Pepperdine University (Malibu, CA)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (San Francisco, CA)

School of the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY)

University of California Irvine, Langston IMCA (Irvine, CA)

University of Minnesota Duluth, Tweed Museum of Art (Deluth, MN)

University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA)

University of South Florida St. Petersburg (St. Petersburg, FL)

University of Washington (Seattle, WA)

Walker Art Center (Minneapolis, MN)

Whitney Museum of American Art (New York, NY)

Yale University Library (New Haven, CT)

Scan to access a map of Carla’s L.A. distribution locations.

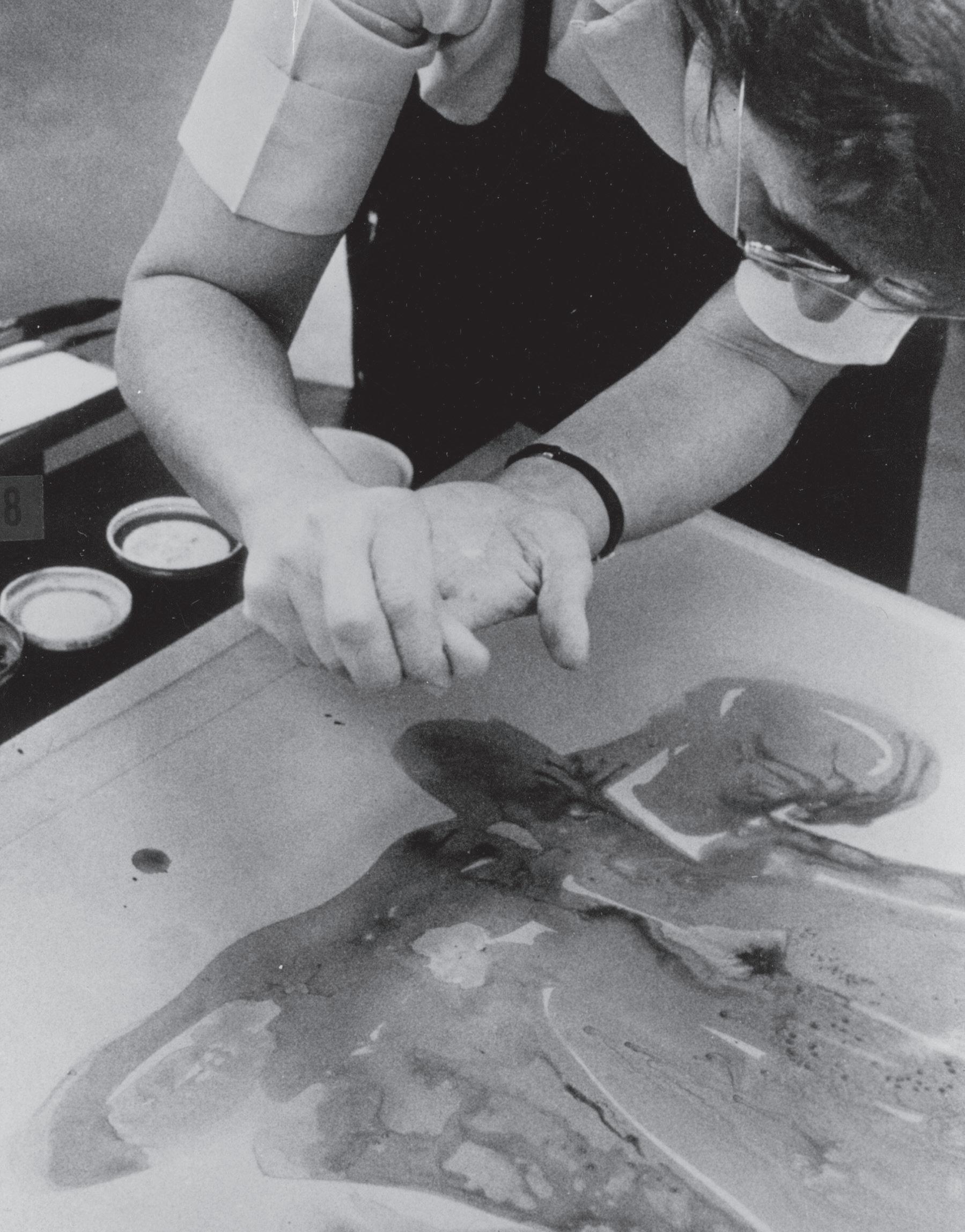

June Wayne working on a stone at Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Los Angeles (c. 1960).

Image courtesy of Tamarind Institute and the Center for Southwest Research, The University of New Mexico.

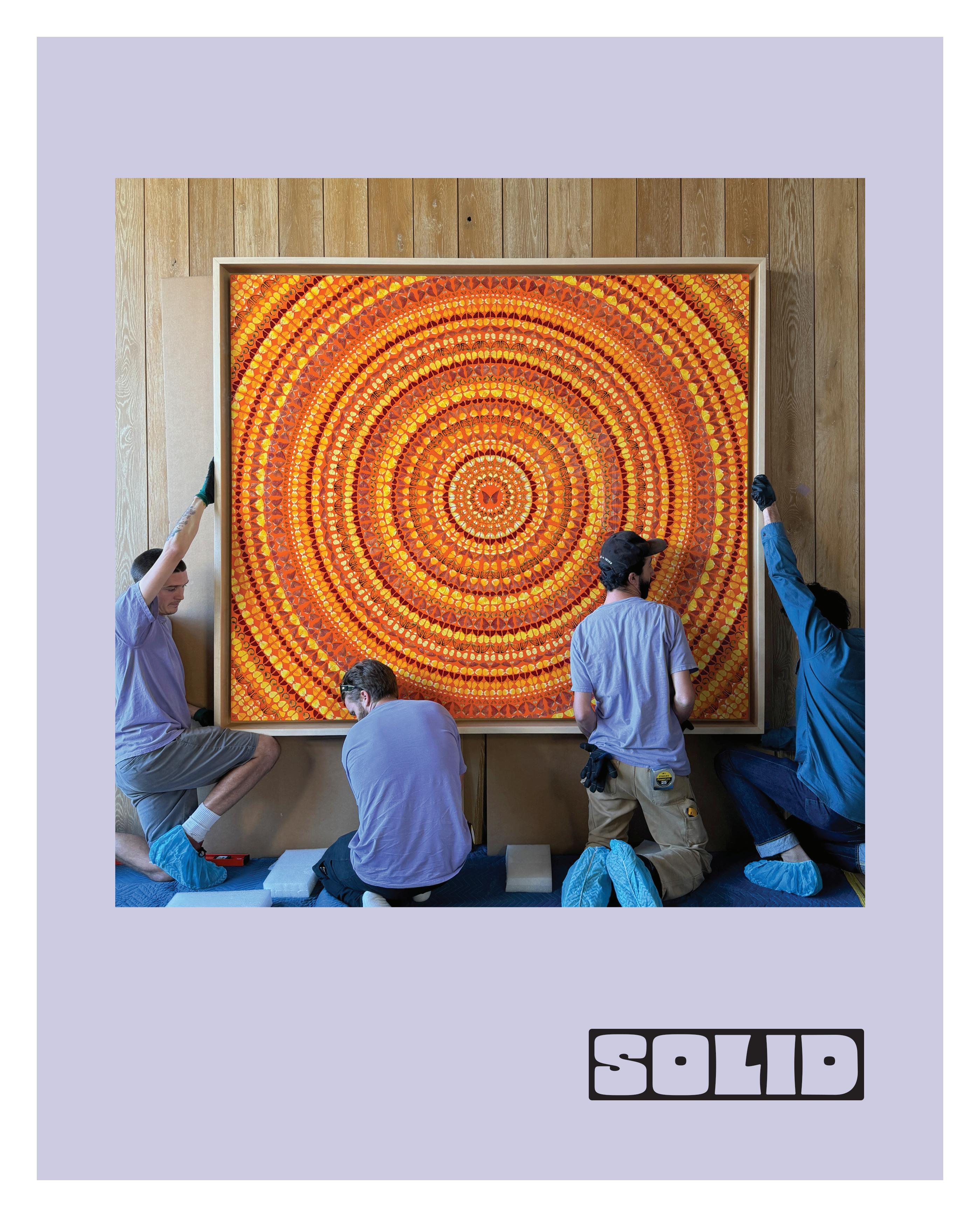

Working Hand-in-Hand

On L.A.’s History of Collaborative Printmaking

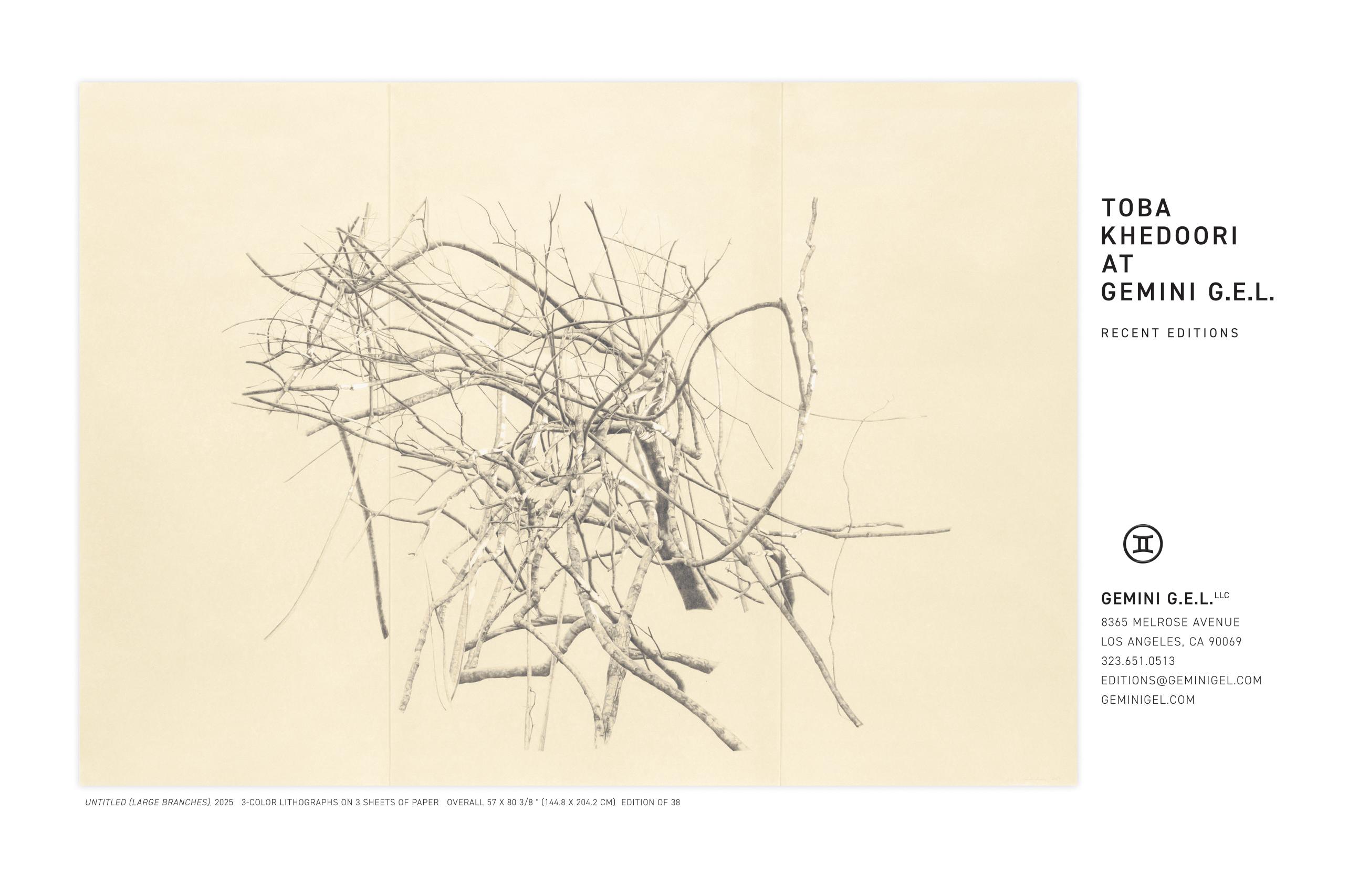

The first time I sat in Gemini G.E.L. co-founder Sidney Felsen’s office— nestled modestly within the striking Frank Gehry structure on Melrose Avenue—he gave me a gold star. Surrounded by wall-to-wall photographs of artists at work and the most colored pencils I’d seen in one place, Sidney held out his hand, offering me a jumbo-sized cardboard star, and with it, a job. “I think you might be the fourth member of the lithography team at Gemini,” he said. I had recently completed my training at Tamarind Institute—a long-term dream that remains one of the best things I’ve ever done. As I stood in that surreal moment amidst a salon hang of Sidney’s photographs —capturing countless collaborative moments at Gemini—and holding my jumbo star, I felt the intersection of vertices, as if I had entered one corner of a vast web, the silk threads of history unfolding around me.

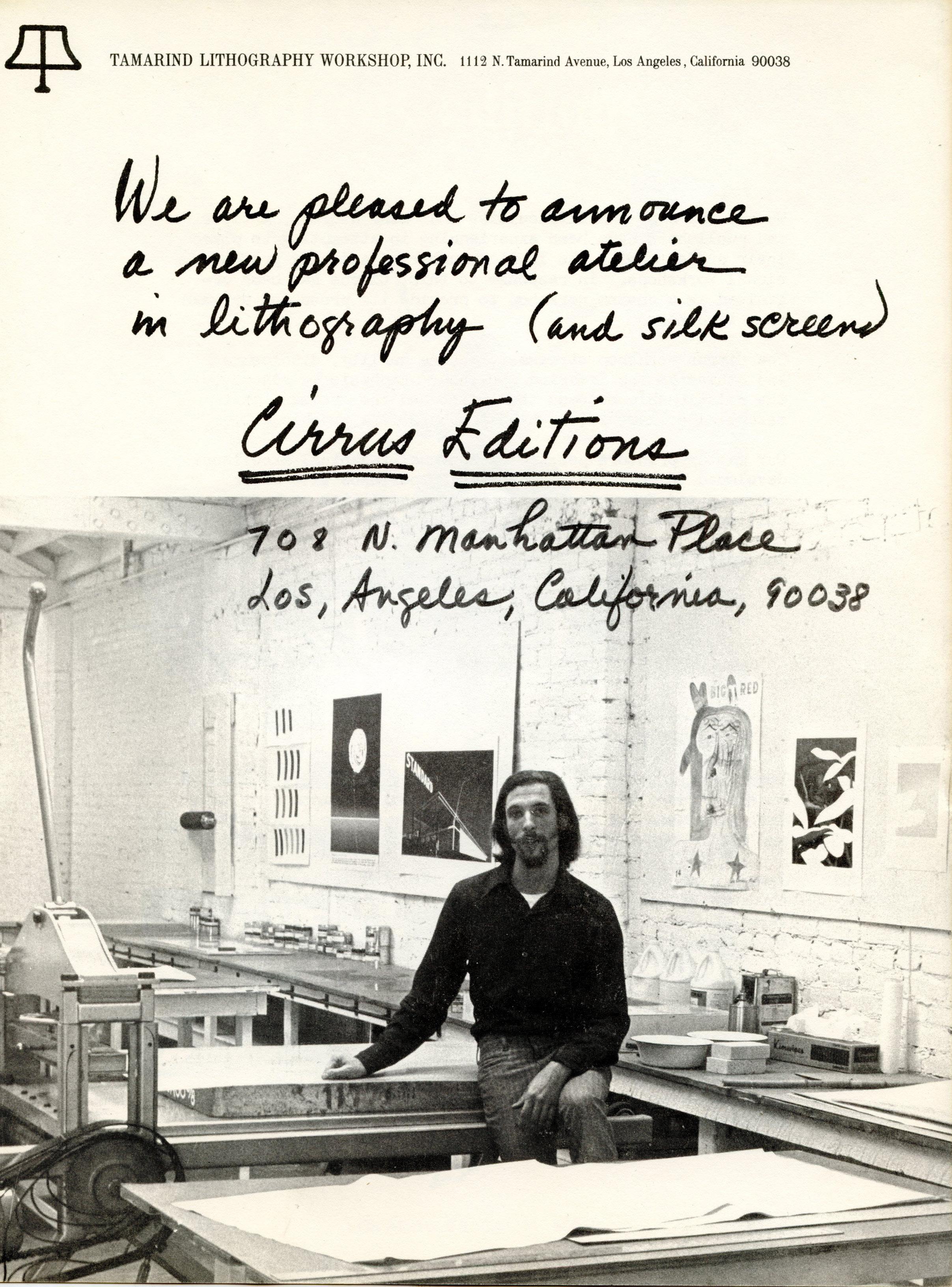

Over the last 12 months, the fine-art print world has mourned the deaths of three of California’s most distinguished print publishers, Felsen among them. In addition to Felsen, Jean Milant, Master Printer and founder of Cirrus Editions, Los Angeles and Kathan Brown, Master Printer and founder of Crown Point Press, San Francisco have recently passed. This succession of losses constitutes a historic moment within the annals of American graphic arts. The post-war Print Renaissance1 (within which each of the aforementioned studios were of great consequence) engendered a lasting culture of collaboration

in California and brought a newfound visibility to the role of the printer. Nevertheless, the medium of print continues to be siloed within a broader arts discourse—having been left out of predominant narratives of Western art history in the past—while the visibility of labor is modulated by an art world shaped by capital. Today, these legacy workshops endure alongside younger print initiatives, having paved the way for a new type of artist /printer relationship: one that recognizes and celebrates the printer as a critical participant in the realization of an artist’s vision, within a highly relational collaborative process.

In 1957, dissatisfied with a local printshop’s inability to meet her creative demands, artist and printmaker June Wayne travelled to France to execute a series of lithographs with artist Joan Miro’s printer, Marcel Durassier.2 Here, she was inspired by the ubiquity of the European print atelier—in comparison, skilled technicians in the United States were scarce. Upon her return, Wayne envisioned an American workshop whose principal goal was the training of Master Printers, and soon enough, Tamarind was formed. Tamarind Institute (formerly Tamarind Lithography Workshop) was founded in Los Angeles in 1960 and quickly became one of the foremost exponents of the Print Renaissance on the West Coast. At a time when fine-art print publishing was nascent on the cultural map of America, the convergence of a boom economy with advances in technology gave rise to a broadening middle class and an artistic climate characterized by a spirit of possibility. “Hollywood is a giant craft preserve where every sort of creator, technician, and supplier lives and works,” Wayne articulated. “Dreaming, making, and hoping are a way of life here… Collaboration is so normal in Hollywood that it goes unnoticed.”3

Although printers had been working in collaboration with artists for centuries in both Europe and the US, the role of the printer had historically remained invisible.4 It was workshops such as Tamarind, followed shortly

Sarah Plummer

after by Crown Point Press (founded in 1962), Gemini G.E.L. (founded in 1966), and Cirrus Editions (founded in 1970), that subverted the insular guildship model inherited from Europe, whose criterion for artistry was for the printer to be traceless—a quality that was, in turn, conflated with insignificance. Forming a new, distinctly American paradigm, these Californian workshops saw printer-cum-publishers placing identifying printer marks (or chops)5 on the editions they printed, thus distinguishing their unique work as craftspeople.6 Kenneth Tyler, Gemini G.E.L.’s first Master Printer, was known for his dynamic personality to the extent that it shaped the workshop’s image in its early years. Clinton Adams, director of Tamarind Institute for over a decade, set Ken Tyler in the canon with his statement that “no other printer has so directly affected the work that has come from his studio.”7 Similarly, in a conversation with now-retired curator Ruth Fine 1984 Gemini G.E.L. attested to Tyler’s influence, sharing that “everything pretty much depended on his personal wizardry.”8 Like so, the identity of these key American workshops became inextricably linked to the printers and the people who led them, and the relationships built therein. Attuned to this, Gemini co-founder Sidney Felsen took photographs documenting the printshop’s projects, creating a vast archive that observes artists, printers, and historic moments of process-based innovation. The archive, amounting to over 70,000 photographs, is a collection whose impact on the understanding of—and respect for—collaborative printmaking cannot be underestimated. Felsen’s photographs encourage the viewer to consider print in ways that move beyond its replicative function, focusing instead on the processes of making and the human relationships that form around that process. In his book of photographs, The Artist Observed, Felsen writes, “The spirit of Gemini is best captured by the word ‘collaboration.’ It’s about artists and printers working hand-in-hand to create works of art.”9

One contemporary artist whose work is both complemented and amplified by the poetics of the print process is Analia Saban, an artist who has a longstanding collaborative relationship with Gemini G.E.L. While the vehement material inquiry that preoccupies much of Saban’s work well predates her indoctrination into the cult of print, the resonance she discovered there propelled the artist into collaboration with some of Los Angeles’s most renowned printshops, including Mixografia and El Nopal Press. Saban’s practice of deconstructing and reconstructing art materials afforded her a natural affinity with the language of printmaking, since the conception of any print begins with deconstruction into layers and into a sequence of processes. Her experimental print-projects have worked to reimagine the bounds of the printing process itself, taking router bits directly to printing plates or using dried and bonded cotton paper fibers to create sculptural, high-relief replicas of domestic hand towels, all the while working with Master Printers to help push against established technical boundaries. Regarding his experience collaborating with Saban, Gemini Master Printer Case Hudson shared, “When Analia first showed up, all she wanted to do was watch us work… She was looking at the materials we were using, the equipment, the way we were physically moving—all these things. It was a satisfying way of building a relationship with an artist.”10 While the intermedial practice of an artist like Analia Saban lends itself perfectly to print collaboration, it remains the printer’s duty to bring well-honored, innovative approaches to any artist’s work in a material language that can often feel foreign to them. This posture is typified by Master Printer and publisher Jacob Samuel, yet another West Coast print luminary who, alongside Kathan Brown of Crown Point, can be thanked for the revival of etching as a medium of serious art-making in America.11 In an interview discussing his 48-year career, Samuel reflected on his

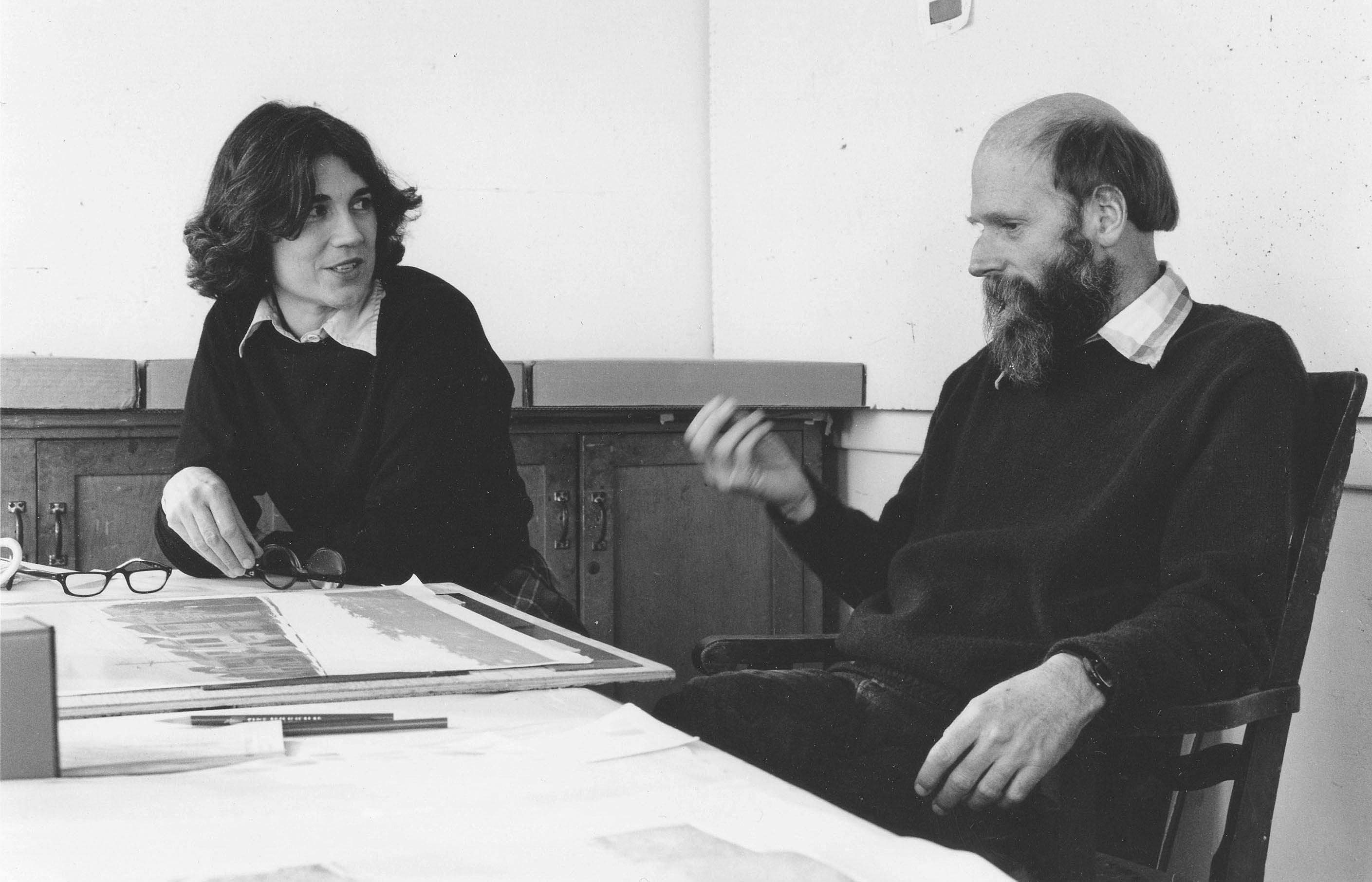

Top: Robert Bechtle with Kathan Brown in the Crown Point studio (1983).

Image courtesy of Crown Point Press.

Photo: Colin McRae.

Bottom: Judy Pfaff in the Crown Point studio (1987). Image courtesy of Crown Point Press.

Jean Milant at Cirrus Gallery (c. 1970). Image courtesy of Cirrus Editions.

philosophy: “My goal is to leave no fingerprints,” he says. “All you see is the artist’s work…to do that and be completely spontaneous, I trust the materials.”12 This radical invisibility of the human hand can be traced all the way back in time to relics such as Claude Mellan’s The Sudarium of Saint Veronica (1649). Engraved with a single unbroken line, this portrait of Christ is considered acheiropoietic —translating literally to “made without hands.”13 The implications of this belief are profound, as they acknowledge the transfer of human perception to their materials with such finesse that human involvement is deemed impossible. While the invisibility of fingerprints may be something that many printers strive for, it is vital that the makers behind the process are visible, credited for their hand in realizing the artist’s work in print. A contemporary example of such sublime conception is Susan York’s Achromatopsia 1 (yellow) (orange) (red), published by Tamarind Institute in 2015. As an artist working primarily in values of grey and black, York is greatly interested in the experience of people affected by achromatopsia (a condition of total color blindness). Working with several monochromats, York had the individuals match colored ink samples with shades of grey in which they saw no discernable difference. These greys were then printed on the face of the print, with the corresponding color printed on the back. Floated against their bright white matting, a subtle glow from the edges of each float-mounted print offers a suggestion of their color-printed backs. Through a mastery of materials, Master Printer Bill Lagattuta’s translation of ideas illustrates a deep imbrication of the technical within the conceptual, allowing the duality of perception that so interested York to manifest within a single artwork. This tension between visibility and invisibility within printmaking exists on multiple planes and is difficult to reconcile. Over the last few years, several galleries including David Zwirner,

François Ghebaly, and most recently Marta L.A. have established in-house publishing programs for fine-art prints. By investing in production, these galleries support the tradition of collaborative printmaking and the Master Printers behind the work. Since independent printers are often dependent on contract work to sustain their own ventures, this kind of alliance is essential. Having said this, these gigs hold the potential to create an awkward double-bind where printers functioning in both capacities (as contract printers and print publishers) become own competitors, producing prints for galleries whose reach is much broader than their own. It is here that the matter of credit becomes essential in order to prevent a relapse into the kind of invisibility that the California print movement has been so instrumental in upending. One place where this standard is being set is Problems Printing, a fine-art silkscreen studio and print publisher located in South El Monte, Los Angeles. Founded just last year, Problems works with both emerging and established artists to produce and publish editions in collaboration with Lead Printmaker Tom Kracauer, a former printer at Cirrus Editions. Since each project requires many hands, Kracauer makes a point of crediting every person involved intentionally, and conspicuously. This kind of visibility is one of the privileges inherited by the current generation of fine art printers, the observance of which remains vital to our livelihood. Sidney Felsen, Jean Milant, and Kathan Brown (alongside other allies such as June Wayne, Ken Tyler, and the Remba family of Mixografia) understood that fine art print publishing—and the collaboration with artists that ensues— is a performance sport. The dynamism of these individuals was, without a doubt, essential to the growth and recognition of printmaking in California, and to the disruption of hidden labor trends that dominate the trade’s history. They established a degree of attention on prints and their makers, affording us the chance to clarify the collective role of printmakers as so much more

than skilled fabricators: We are listeners, mediators, counselors, technicians —the artist’s envoy—out of sight, and utterly essential.

Sarah Plummer is a collaborative lithographer, maker, and writer, lately of Australia and more recently of California. She has produced fine-art prints at Wingate Studio, Tamarind Institute, Gemini G.E.L., and for The Met. Sarah is captivated by the alchemic expanse of lithography and loves things that seem impossible. Her work leads an investigation into land, memory, material, grief, and love.

1. The Print Renaissance refers to a period from the mid-1940s to the late-1980s that saw a rapid revitalization of fine-art printmaking traditions in the United States. Several California-based print publishers are cited for their significance to the movement: “from Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) to Tamarind, from Crown Point Press to Gemini G.E.L. A veritable print renaissance, American artists gathered at these shops to create prints much like their European counterparts had done with verve since the nineteenth century.” Samantha Rippner, “The Postwar Print Renaissance in America,” October 1, 2004, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www. metmuseum.org/essays/the-postwar-print-renaissancein-america.

2. June Wayne, “Broken Stones and Whooping Cranes: Thoughts of a Willful Artist,” Tamarind Papers 13, no. 1 (1990): 16–27.

3. Wayne, “Broken Stones,” 17.

4. How often do we hear about Roger Lacourière or Fernand Mourlot, two vital collaborative printers of Pablo Picasso’s work?

5. A printer’s chop is a symbol that is either embossed or stamped on each print of an edition as a way of identifying the printer or publisher.

6. Rosemary Miles, “Reviewed Work: Making Prints, Doing Art: 35 Years at Crown Point Press, by Karin Breuer, Ruth E. Fine, and Steven A. Nash,” Print Quarterly 15, no. 3 (1998): 330–333, http://www.jstor. org/stable/41825115.

7. Clinton Adams, review of Ken Tyler, Master Printer, and the American Print Renaissance, by Pat Gilmour, Print Collector’s Newsletter 17 (1986): 108.

8. Timothy Isham, conversation with author, 7 April 1983, as cited by Ruth Fine in Gemini G.E.L.: Art and Collaboration (Abbeville Press, 1984), 20.

9. Sidney B. Felsen and Constance W. Glenn, The Artist Observed: Photographs by Sidney B. Felsen (Los Angeles: Twin Palms Publishers, 2002).

10. Case Hudson, “Analia Saban and Printmaking in L.A,” Hammer Channel video, 1:24:17, May 6, 2025, https:// channel.hammer.ucla.edu/video/1947/analia-sabanand-printmaking-in-la.

11. Susan Tallman, The Contemporary Print: From Pre-pop to Postmodern (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1999).

12. Jacob Samuel, “A master printer makes his last print,” interview by Sarah Cowan, Museum of Modern Art, 2023, audio-visual, 3:21, https://www.moma.org/magazine/ articles/976.

13. Jennifer L. Roberts, Contact: Art and the Pull of the Print (Princeton University Press, 2024), 3.

Top: Robert Rauschenberg with Sidney B. Felsen and Stanley Grinstein at Gemini G.E.L. during Rauschenberg’s Tibetan Keys and Locks project (1986). Image courtesy of Gemini G.E.L.

Bottom: Serge Lozingot and Anthony Zepeda at Gemini G.E.L. working on a woodblock for Roy Lichtenstein’s Head from the Expressionist Woodcuts series (c. 1980). © 1980 Sidney B. Felsen. Image courtesy of Gemini G.E.L.

Photo: Sidney B. Felsen.

Judy Baca on a scissor lift (1983). © SPARC. Image courtesy of Judith F. Baca, the SPARC archives, and LACMA. Photo: Linda Eber.

History is a River

Judy Baca and the Great Wash of Los Angeles

The Tujunga Wash is a 13-mile stream that flows through the San Fernando Valley. It is a major tributary to the Los Angeles River, which, in the dry season, is not saying much, since both the Wash and the River become mere trickles. There is an old myth about the Tujunga, which translates to “place of the old woman” in Tongva. In this myth, a matriarch, whose daughter has been killed in a water dispute, retreats to the mountains and turns to stone.1

The stream itself has also turned to stone, concretized over decades of urban development, and it is within one of these concrete flood channels that artist Dr. Judith F. Baca painted

The Great Wall of Los Angeles. Commissioned in 1974 by the Army Corp of Engineers, Baca’s mural was meant to beautify the drab infrastructure. She and a team of local adolescents painted the half-milelong history directly onto the concrete, a timeline of Los Angeles’s development beginning with the mammoths in 20,000 BC and culminating in a tribute to the 1984 Olympic Games. After a nearly decade-long process of research, organizing, and painting, the wall was finally complete.2

The first time I saw the mural in 2023, it was a particularly hot July afternoon. The wash had all but dried up. The wall was dusty, monumental, as if it had been there forever. Despite all its color, the wall and its environment was not the dynamic Los Angeles I had come to recognize. Baking in the summer heat, I gazed at a relic from a lost century. A past set in stone.

That fall, as the Tujunga began to flow again, Judy Baca began to paint. In Painting in the River of Angels: Judy Baca and The Great Wall, an exhibition that ran from October 2023 to July 2024 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Baca transformed a gallery into a temporary studio. She and her team from the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC) had started the years-long process of creating additions to the painting in the Tujunga Wash, an expansion that will eventually extend the piece by another half-mile. The goal: to update the wall’s historical timeline, adding vignettes from the 1960s through the 2010s.

I visited LACMA that winter and had the chance to observe Baca’s team painting. As I entered the gallery, I was greeted by the sounds of laughter, of conversation, of shoes on polished floors. To my left, a scissor lift buzzed as it raised an artist high into the air. She was coloring a new panel labeled “East L.A. Walkouts,” the 1968 protests lead by Chicano students. One of their demands: a rectification of LAUSD’s white-washed historical curriculum. The right-most portion of the panel was still only ink. In blue outline, students gathered in front of an old school building, carrying signs reading: “SCHOOLS NOT PRISON,” and “NO MORE RACIST TEACHINGS,” among other things. The left-most portion of the panel was slowly being filled in—three women’s hats had been painted a dull rust, emblematic of the Chicano paramilitary organization the Brown Berets. And the panel itself, I noted, was far from concrete—in fact, it seemed to be made of a flexible material, spooled on either end, continuously unfurling as the painters worked from left to right.

This was far from the dusty monument I had visited in the summer. It was fluid, dynamic: more of a performance than an object. I had a feeling that this performance was the entire point of the piece, wherein the process of not only art-making, but historymaking, was on full display.

Sean Koa Seu

Top: Active worksite of The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1976). © SPARC.

Image courtesy of Judith F. Baca, the SPARC archives, and LACMA.

Photo: Linda Eber.

Bottom: Digging in the river during the production of The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1976).

© SPARC. Image courtesy of Judith F. Baca, the SPARC archives, and LACMA.

Photo: Linda Eber.

It goes without saying, but the Tujunga flood channel is designed to, well, flood. In fact, in 1983, just as The Great Wall was nearing completion, flooding wiped away the painters’ scaffolding.3 Additional funds were raised to offset this loss and complete the painting.4 But this has not prevented the wash from flooding in the decades since—nor has it prevented the wall from baking in the California sun, or shaking through its frequent earthquakes. This is no white box; it is precarious urban ecology.

As such, the mural undergoes continuous, though minor, restorations during the dry season—especially since 2011, when SPARC finally initiated The Wall’s first major restoration.5 The painting is a rather unstable object; it is not fixed, but instead undergoes minor replacements and revisions. The paint on the wall, like the river that washes it, is never the same.

The history depicted in The Great Wall was not an established one. In the 1970s, according to Baca, there were no shelves in “the library” devoted to Chicano history, to Black history, to a history of L.A.’s working poor.6 Instead, Baca proposed the creation of “an alternative form of history.”7 This was a history largely unacknowledged in the Valley, which had been redlined for decades and whose teachers once specialized in “Americanization,” a grim euphemism for the assimilation of Mexican children into “American” culture.8 Baca’s new history would be written by “ethnic groups—including women in the various groups—in a manner not taught in public schools.”9 This history—of Mexican farmers, of Jewish refugees, of Black students, of women laborers, of gays and lesbians—she dubbed a history of the People.10

In order to recover this history, Baca had to research not decades, but millennia. This was not a onewoman job. At first, Baca attempted to secure support from the Department of Recreation and Parks but had to

pivot due to censorship.11 To evade city interference, Baca—alongside artists Christina Schlesinger and Donna Deitch—founded SPARC and hired teams of artists and local historians who would conduct research alongside schoolchildren.12 These youth and educators worked together to excavate the under-told stories of the region’s most forgotten people. Many of these histories had never been—and sometimes are still not—officially recognized. But by taking the most scoffed-at historical claims seriously, the researchers did not just study history. They created it.

Take the panel featuring Thomas Alva Edison. He faces us, backgrounded by an illuminated cityscape, Los Angeles at night. In his left hand, a lightbulb; in his right, a piece of film. And then, floating above the city like an ancient UFO: an Aztec pyramid. A woman made of corn whispers something into Edison’s ear—the secret of electric light? This is alternative history in a mythic form, an allusion to a Mexican legend in which Edison was descended from Aztec kings.13

Another panel—this one a part of the new addition—depicts the Cooper Do-nuts Riot, a pre-Stonewall queer uprising on Main Street. Men on the roof of a shop hurl a slew of pink-frosted donuts at two cops. A trans woman raises a donut in defiance. Two men kiss in the foreground. Yet, the reality of these events is contested. The uprising left behind no articles in the L.A. Times, no police reports, no verifiable eyewitness accounts; if queer people did throw coffee at cops, it left no official record.14 Although it is now largely accepted as part of L.A.’s queer history, the story springs from John Rechy’s 1963 novel City of Night; it is a fiction, a fabulation, or perhaps an exaggeration of a real event.

The inclusion of these panels puzzled me. The anecdotes are somewhat ahistorical—not verifiable by the archive. They seem out of place next to much more “concrete” historical panels, such as the East L.A. Walkouts, Japanese Internment, or The Red Scare—events which are clearly rooted

in archival evidence. At first, I thought Baca might be distorting history and taking artistic liberties. I now realize it is precisely this artistic liberty that frees history from the prison of empiricism. If history is only what can be evidenced, then what are we to do when the evidence is burned, sold to the highest bidder, or painted over in white? Baca critiques this kind of history-making. Instead, she responds to archival erasure by opening up the historical record to speculation. She allows fiction to fill in the gaps, and in some cases to account for the unfathomable, for historical catastrophes. For example, on The Great Wall, colonization is explained by the legend of Queen Califia, who seduced the Spanish into seeking gold and silver on California’s shores. Today, Aztec Edison reclaims the advancement of technology from the so-called genius of a white man and dares to locate that genius in an Indigenous lineage. Cooper Do-nuts gives retrospective voice to queer and trans people, canonizing them in history despite official attempts to erase them. Whether these stories are strictly factual is irrelevant; the designation of history lends power to myth. From her place in the present, Baca changes the definition of history itself. History is not set. It can always be retold, revised, flooded over, repainted.

Today the Tujunga is a shallow but steady stream, like the blacktop under a carwash. As I write this, the students at Flintridge Preparatory School, near Altadena, are presenting The Great Wall of Los Angeles, an exhibit curated by the seventh grade class. A friend of mine attended the presentation and sent me a video: Two students read shyly from their notecards, discussing a panel called “Immigrant and Indigenous People Build California.” The poster behind them analyzes images of Chinese immigrants, fishing boats, oranges, the railroads. This exhibit—now a tradition at this small middle school—is just

one of many ways students across the Southland continue to engage with Baca’s wall as curriculum. These are not the first students to be enraptured by The Wall. The painters were students as well, many from starved corners of the city. SPARC had to “find homes for those who had to be runaways”15 from abuse and gang activity. Never a mere wall, the mural was mutual aid. Its legacy has never been just the painting or the history that it illustrates, but always the process in which the painting came to be, a process of care and ongoing education. The Wall asks not “What is the history?” but “How does our history help us live together—right here, right now?”

As another fire season returns and the wash runs dry, I can’t help but dwell on Los Angeles’s horrific present: neighborhoods up in flames, ICE ripping parents from their children, the denial of life-saving healthcare to working people and to our trans friends. Funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, once crucial to projects like Baca’s, rescinded. Histories foreclosed. And I feel stuck, as if the great march of time will abruptly end in total apocalypse. I am reminded of Tujunga, that old Tongva woman paralyzed by grief, and I wonder if we, too, will turn to stone forever.

But then I remember the first time I saw the wall, how wrong I was in calling it a monument, how The Wall’s apparent fixity was only an illusion. The Wall continues onward, a testament to the resilience of those people whom the wall historicizes, a people who have long managed to survive despite abandonment, denial, redlining, brutality. The Wall is already unfurling, incomplete, changing. History is not fate, but a practice. Not concrete, but a river.

Sean Koa Seu is a writer, dramaturg, and critic. He writes about representations of the Southland in art, film, and literature. His work has appeared in The Rebis and in zine form at the L.A. Art Book Fair. He is currently pursuing an MA in Aesthetics and Politics at CalArts.

Top: Judy Baca painting The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1983). Image courtesy of Judith F. Baca, the SPARC archives, and LACMA.

Bottom: Judy Baca working on Painting in the River of Angels: Judy Baca and The Great Wall (installation view) (2024). © Judith F. Baca. Image courtesy of the artist and LACMA.

Photo: Museum Associates/LACMA.

Judith F. Baca, Painting in the River of Angels: Judy Baca and The Great Wall (installation views) (2024). © Judith F. Baca. Images courtesy of the artist and LACMA. Photos: Museum Associates/LACMA.

1. Chester King, Overview of the History of American Indians in the Santa Monica Mountains (Topanga, CA: Topanga Anthropological Consultants, 2011), prepared for the National Park Service Pacific West Region Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, 388—393.

2. Social and Public Art Resource Center, “History & Description,” Great Wall Institute, accessed July 3, 2025. https://sparcinla.org/programs/greatwallinstitute/ history-description/.

3. Greg Risling, “Mural Restoration Paints Bright Future,” Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2000, accessed July 3, 2025, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000oct-30-me-44271-story.html. latimes.com

4. Risling, “Mural Restoration Paints Bright Future.”

5. Social and Public Art Resource Center, “Great Wall Restoration,” Mural Rescue, accessed July 3, 2025, https://sparcinla.org/programs/mural-rescue/greatwall-restoration/.

6. Judy Baca, interview by A Martínez, Morning Edition, NPR, July 4, 2024. https://www.npr.org/transcripts/ nx-s1-4914135.

7. Judith Francisca Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles (Master's thesis, California State University, Northridge, 1980), https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/ rn301472m, viii.

8. Kevin Roderick, The San Fernando Valley: America’s Suburb (Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times Books, 2001), 139.

9. Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles, viii.

10. Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles, iv.

11. Judith F. Baca, “Birth of a Movement,” in Community, Culture and Globalization, ed. Don Adams and Arlene Goldbard (New York: Rockefeller Foundation, Creativity & Culture Division, 2002), 36.

12. Alejandra Vasquez and Sam Osborn, Baca, Los Angeles Times Short Docs, March 18, 2024, https://www. latimes.com/shortdocs/0000018e-528f-dfc2-a1ce7eafcbdf0000-123.

13. “Links Edison Line to Old Aztec Kings: Mexican Woman Says Inventor’s Features Prove Descent—Sees Signs in His Face,” New York Times, March 13, 1923. https://www. nytimes.com/1923/03/13/archives/links-edison-line-toold-aztec-kings-mexican-woman-says-inventors.html.

14. There is some speculation as to whether the LAPD had an interest in destroying extant police reports on this incident. However, as Los Angeles historian Nathan Marsak points out, even if the LAPD had destroyed its records, an incident like this “would have made the papers.” See “We Need to Talk About Cooper Do-Nuts,” Bunker Hill, Los Angeles, June 15, 2021, https:// bunkerhilllosangeles.com/2021/06/15/we-need-totalk-about-cooper-do-nuts/.

15. Baca quoted in Vasquez and Osborn, Baca, 3:52.

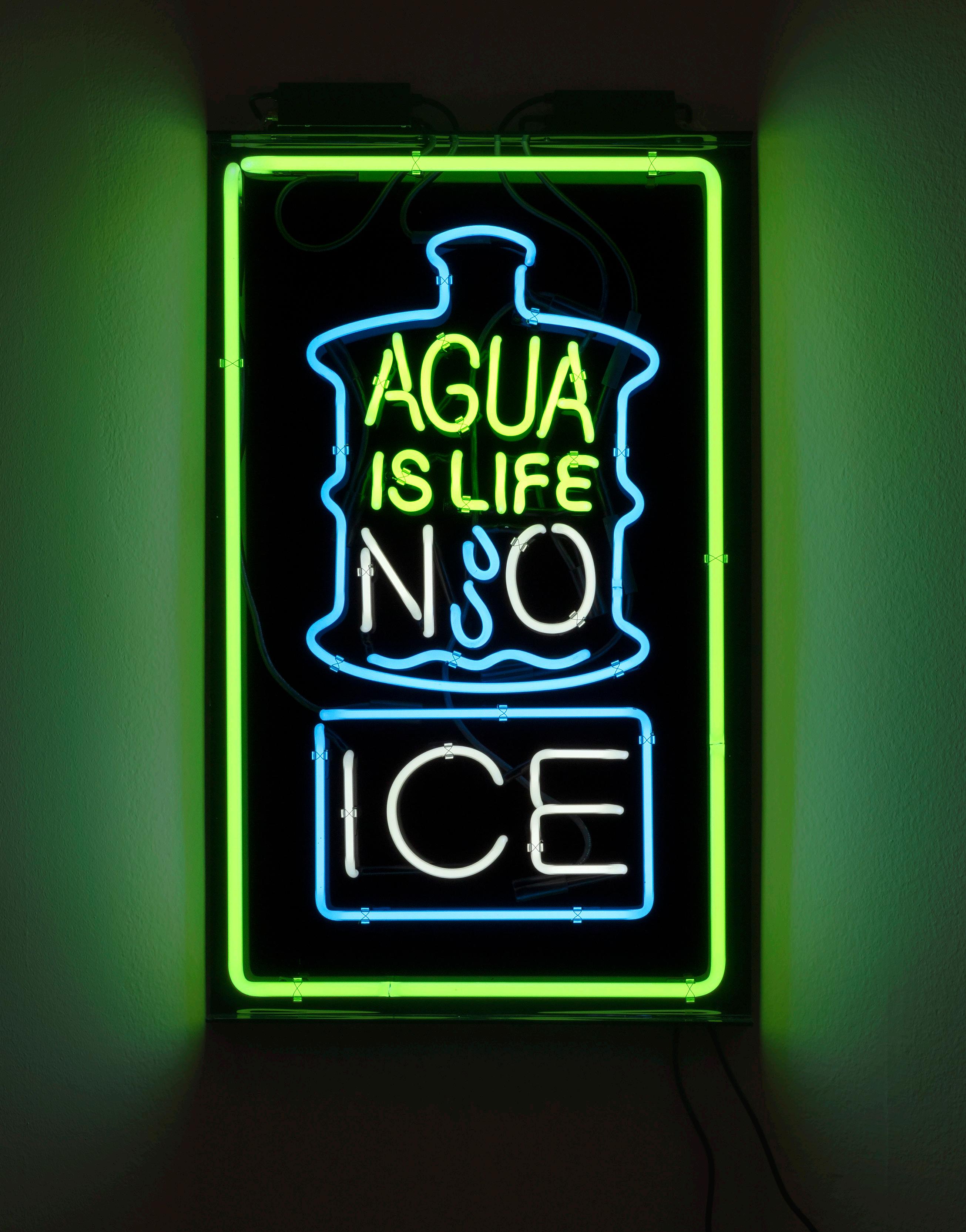

Patrick Martinez, Hold the Ice (2020). Neon on plexiglass, 36 × 22 inches; edition of 3. Image courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery. Photo: Kevin Todora.

The Aesthetics of Protest Typography

On Preserving Dissenting Letterforms

In 1968, photojournalist Ernest C. Withers captured an image of the Memphis sanitation strike. The blackand-white photograph depicts a group of Black male workers holding up copies of the same sign: in a vertically elongated black typeface set on a stark white background, the signs read, “I AM a Man,” with “AM” bolded and underlined. Derived from the line “I am an invisible man” in Ralph Ellison’s National Book Award-winning novel Invisible Man, the posters edit out the word “invisible.” In doing so, they reinforce the Black worker’s presence in the workplace while simultaneously referencing Ellison’s expression of alienation brought on by the Jim Crow era.1 The “I AM a Man” signs would initiate an iconic protest phrase of the movement.

With knowledge of this history, typographer Tré Seals created Vocal Type, a type foundry for creatives of color, in 2016.2 “I had already known about the ‘I AM a Man’ signs since fourth grade,” Seals said.2 “That’s why Martin was the first [typeface] I made.” The Martin typeface takes from the original posters’ use of uneven bold lettering, mixed capitalization, and underlining, infusing a sense of urgency into the written text. Seals’s typefaces, many inspired by Black liberatory movements and figures, focus not only on the overall messaging of a letter, phrase, or sentence used in protest signage, but also the typography—the letter

shape, arrangement, and aesthetic— and how those elements convey, assert, or obscure meaning.

The need for dissenting typography is as abundant today as it was in 2016 or in 1968. In June of this year, ICE and law enforcement agencies at the federal, state, and local level conspired to facilitate mass raids across L.A., abducting people, tearing communities apart, and attacking those protesting against them. Thousands of people mobilized in response, taking to the streets to demand that ICE get out of Southern California. Some protesters in downtown L.A. held up 18 x 24-inch posters designed by L.A.-based artist Patrick Martinez with an image of a neon sign reading “DEPORT ICE,” glowing in a cold, arctic blue, a color that cheekily resembles an ice cube.3 (“ICE melts in the summer heat” is a common refrain at protests across the country.) Martinez’s neon works and accompanying protest signs appropriate a typographic form ubiquitous across L.A. His neon signs, hallmarks of consumerism, also signal the neighborhood momand-pop shop. As a result, he embeds protest language into the everyday, using commercial typeface design in ways that disrupt the consumerist status quo while pointing to the very fabric of L.A.’s diverse population and workforce.

A month earlier in New York City, demonstrators with Writers Against the War on Gaza held posters that utilized the plain serif font of The New York Times in all caps as though it were a breaking news headline on the front page of the paper. The text was placed above yet another image of Palestine on fire at the hands of the West. This sign, held up by a demonstrator standing in front of The New York Times offices, read: “NYT IGNORES GENOCIDE IN PALESTINE.”4 Through this typographic subversion, there’s no way the message could be more legible.

If typography is a study of and practice in legibility, then in reference to the language of protest, it is also a site of power, access, utility, and archival

Aaron Boehmer

history. The text and fonts printed on protest signs have the potential to remix the everyday in ways that provide powerfully layered meaning, rooting out contradictions, confronting power imbalances, and making clear our most intimate, innate demands: autonomy, freedom, love. The protest sign functions as the medium through which a movement speaks—to the world and to participants en masse. It’s the most direct screen onto which a protestor can cast demands if only because it is the protestor, the author of those demands, who controls what is written, how it is written, and the forms and shapes it takes.

What happens when these protest letterforms, originally created for an object meant for use at a demonstration (flag, banner, sign), are recycled into an artwork? On one hand, by bringing the language of protest into the gallery, there is potential for the lifespan of the referenced protest and its cause to be extended, brought into an art historical canon, and thereby preserved in the archive. Unavoidably, though, bringing protest language into a white-walled space also risks removing the protest ephemera and its letterforms from its vital context and, most importantly, from its utility. Though, if an artist is mindful of this dynamic, perhaps it creates an opportunity. An artist can bring a protest’s typography into an art space or institution, not to sterilize it or water it down, but to keep it from getting lost to a materialistic news cycle that is only focused on what’s next. The typography remains long after crowds are dispersed from a demonstration, slowing the protest so as to sustain its message over time. After all, substantive change is urgent, but that change is also a long-term project. Change takes time, care, and attention. Still, artists like Martinez are finding ways to strike a balance with their use of dissenting text, creating protest letterforms that introduce urgent messages to the archive (within institutions or galleries) while also offering utilitarian and community access to their typography,

so it might continue to do its work outside of the institution. The language of dissent, then, is at once preserved and usable.

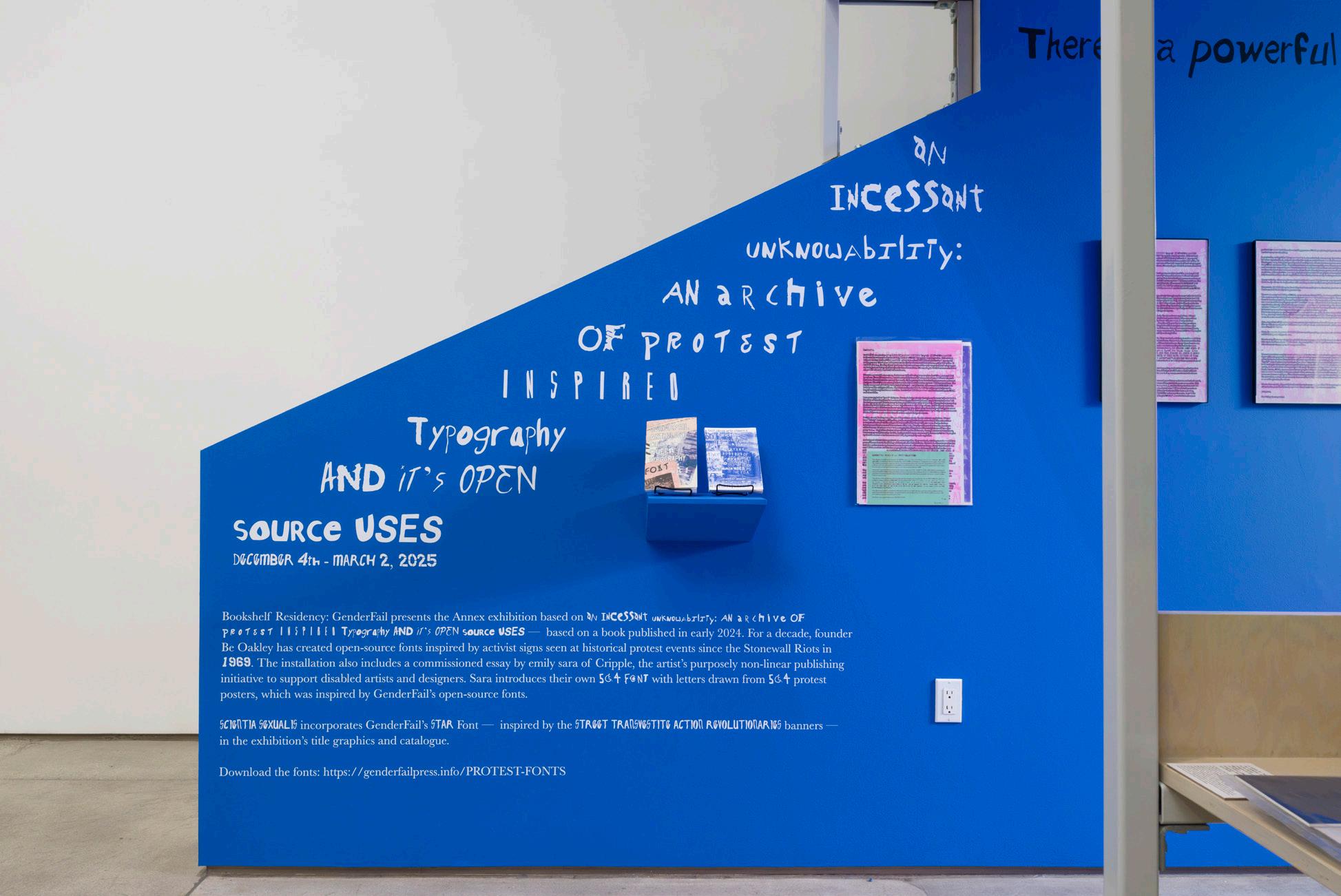

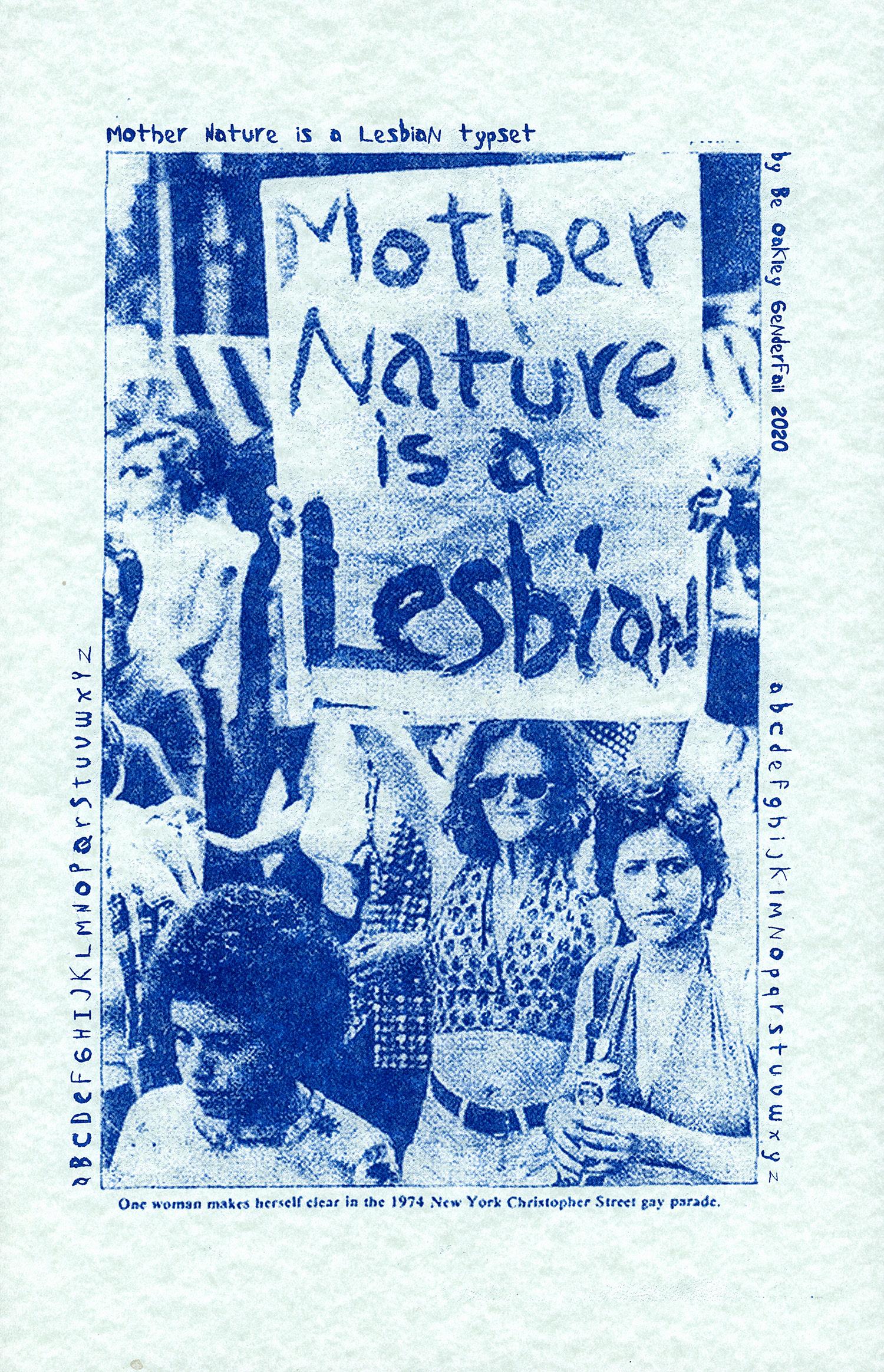

In 1970, during a Gay Liberation Day march in New York City, photographer Donna Gottschalk took to Christopher Street with a sign that read in imperfect, uppercase handwriting “I AM YOUR WORST FEAR I AM YOUR BEST FANTASY.”5 Nine years later in 1979, at the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, a group of demonstrators held up a banner that read in all-caps akin to Gottschalk’s sign from nearly a decade earlier that read “FIRST GAY AMERICANS” in a bold, confronting, and messy hand drawn scrawl.6 Through their publishing platform GenderFail, the artist Be Oakley coalesced these individual moments, both from the Gay Liberation Movement, to create a single, downloadable typeface called “I am your worst fear; I am your best fantasy / FIRST GAY AMERICANS.”7 This typeface and nine others produced since 2018 were the subject of Oakley’s 2024–25 exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Each of Oakley’s fonts are derived from distinct but intrinsically interconnected socio-political movements—from the Stonewall Riots in 1969 and ACT UP in the 1980s and ’90s, to the resurgent calls for Black liberation in 2020, and the student uprisings for Palestine in 2023–25. The fonts are symbolically meaningful, wherein the “uppercase letters [do not have] any hierarchical importance over lowercase letters.”8 But they are also meant primarily to be useful, readily downloadable for queer, trans and non-binary folks, and queer people of color to use for protest signs, fundraising and mutual aid purposes, personal projects, and more.

In this way, an archive of past protest typography is transformed into a tool for the present and future. Oakley engages with the archive of protest not

An

GenderFail,

Incessant Unknowability: An Archive of Protest Inspired Typography and Its Open Source Uses (installation views) (2024–25).

Images courtesy of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photos: Jeff McLane/ICA LA.

Be Oakley / GenderFail, Mother Nature is a Lesbian Font (2020). Image courtesy of the artist and GenderFail.

as a fixed or nostalgic look at the past, but as a dynamic and living resource —a place from which a movement can be both catalogued and continually reimagined. The “I am your worst fear” typeface is not merely a symbol of queer history, but an instrument for queer futurity, allowing generational knowledge from a movement that has been decades in the making to be passed down, active and defiant.

Oakley certainly isn’t the only contemporary artist to reference the histories of socio-political and economic upheaval in their work, nor is Oakley the only artist to employ a typographic means to do so, especially in Los Angeles. From Dr. Judith F. Baca’s Great Wall of Los Angeles and Mary-Linn Hughes and Reginald Zachary’s Love is for Everyone mural, to Elana Mann’s collaborative banners and sculptural protest rattles, to print projects by L.A.-based organizations such as the Feminist Center for Creative Work and the Center for the Study of Political Graphics, artists and collectives across the city continue to reference and, like Oakley, reinvigorate protest movements by way of typography.

Last summer, while visiting the Dallas Contemporary, I found the landscape of L.A. staring back at me. Patrick Martinez’s immersive Histories exhibition, which ran from April 2024 until January of this year, recalled the visual language of East Los Angeles through large-scale installations of brick walls adorned with vibrant murals that depicted an array of references: flowering bougainvillea and Sitting Bull, Mayan warriors and Emiliano Zapata, Larry Itliong and feathered serpents. The bricks in the sculptural mural were also collapsing, signifying rich and vital histories of place that are being disappeared by racialized eviction and gentrification.

Installed throughout the gallery were Martinez’s signature neon signs. These works reference street-level commercial marketing and its diverse

history within L.A., while also subverting it, swapping marketing copy for a more dissident kind. Among a tightly-packed line of neons, the border of a rectangular sign—the sign itself a little bigger in size than a storefront’s “open” display— glowed a bright purple, the inside reading “TIERRA Y LIBERTAD” in an uppercase type. Another, bigger sign nearby critiqued the city’s housing crisis (“NOTHING IS UP BUT THE RENT”) while others envisioned new and greater forms of collectivism (“MUTUAL GIVING CREATES COMMUNITY”) and demanded an end to racialized violence (“STOP ASIAN HATE”).

Subversively, Martinez also reworks his own neon artworks, which are purchased by institutions and collectors, into lawn signs. Partnering with Mixed Media Editions, Martinez brings objects that are otherwise secluded behind gallery walls into real neighborhoods and onto the city’s streets to be used at actual demonstrations and protests.9 While these lawn signs are for sale at $80 a piece (perhaps a bit expensive when compared to the few dollars one might spend to make their own), a portion of every sale goes to the Coalition for Humane Immigration Rights (CHIRLA), one of California’s largest immigrant rights organizations. In particularly urgent moments, Martinez distributes the signs for free, such as during the Solidarity L.A. March & Rally on March 15 at City Hall,10 or donates all of the proceeds to CHIRLA. The gesture, however complex, is meaningful. While the actual neon signs are displayed in privatized spaces, his lawn signs offer another way to engage with the work—an engagement that is accessible to a broader public and that enacts his typographic slogans in real spaces of dissent, working to actualize their impact.

Martinez and Oakley’s works are the most generative when they step outside of the art gallery and into the streets, as a lawn sign available at a demonstration or a free typeface that protestors can download and utilize. These works then operate on two levels. First, as art projects, they preserve

histories of protest inside institutions. Rather than maintaining the institution as an exclusionary boundary, the artists use the institution as just another tool at their disposal—one that allows for expansive record-keeping, maintenance, and exposure. These artists’ letterforms also operate in a second way: By turning their typographic artworks into tools to be used by protesters, they are creating accessible ways of disseminating history, aesthetic power, and knowledge to the public. This intentional use of letterforms becomes a means by which to continually dissent with every word, every consonant, every vowel—a living archive, and a slow (but steady) protest.

Aaron Boehmer is a writer based in New York City. He covers the arts, culture, and politics and has written for The Nation, Texas Monthly, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Drift, and others.

1. Tré Seals, “Martin,” Vocal Type, June 5, 2023. https:// www.vocaltype.co/history-of/martin.

2. Kaleena Sales, Centered: People + Ideas Diversifying Design, Princeton Architectural Press, 2023, 164-167.

3. Patrick Martinez, “Abolish Ice.” Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, 2018. https://crystalbridges.emuseum.com/ objects/11356/abolish-ice.

4. PYM NYC (@nycpym), May 28, 2025, https://www. instagram.com/p/DKLjetBtx3y/?utm_source=ig_web_ copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==.

5. Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Donna Gottschalk holds poster ...” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/ items/510d47e3-5f6e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

6. Joel Rinne and Earl Colvin, “FIRST GAY AMERIANS,” National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, October 14, 1979.

7. Be Oakley, “i am your worst fear i am your best fantasy / FIRST GAY AMERICANS Bold Italic Version 2.000; hotconv 1.0.109; makeotfexe 2.5.65596. Open Type Font. Be Oakley, 2020. https://drive.google.com/file/d/ 1q3YCeH9-gsjFMJCL5P5wKb-v7NFnwRkv/view

8. Be Oakley, “GenderFail Open Sourced Protest-Inspired Fonts.”

9. Patrick Martinez (@patrick_martinez_studio), March 17, 2025, https://www.instagram.com/p/DHUtdCzPLs7/ ?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh= MzRlODBiNWFlZA==.

10. Patrick Martinez (@patrick_martinez_studio), “Abolish Ice” lawn signs / protest signs are now available...“ (Instagram), March 11, 2025, https://www.instagram. com/p/DHEVpn6v1Of/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_ link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==.

Patrick Martinez, Ceasefire (2024). Image courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

Photo: Patrick Martinez.

Modeling Home

A Call for New Approaches to Art and Research Residencies

“These ants made their way inside again?!” I exclaim to myself, exasperated, wiping out lives with a damp rag while in residence at the FitzpatrickLeland House. I’m here for a project on cohabitation, mapping the connections and compromises necessary for human and more-than-human livability in Los Angeles. Naturally, my attention is drawn to the living in this living space, and the invasive ants represent only a few of my housemates. The title of my residency project is Hospes, the Latin root for multiple English words including, paradoxically, both ‘host’ and ‘guest’. Carrying dual meaning, hospes is a linguistic trick, a reminder that hosting and guesting are never binary. Those who are guests must on other occasions serve as hosts, and vice versa. The word hospes makes visible the fluid dynamics of reciprocal responsibility, all are active participants in creating conditions of home and well-being. My residency, itself hosted by the MAK Center and SOM Foundation, is grounded in questions such as: “What is required of good guests and hosts in order to cultivate just habitability?”

So far, I have shared this space with centipedes, a house spider who lives in the original jade green bathtub, a giant silverfish, and several daddy long-legs who lounge in tall corners. At least three crane flies have made themselves at home upstairs. Out of the house’s swimming pool, I scoop three or four honeybees a day. Most are still alive, hanging on in some energy-saving mode, but at least five

have died, not counting those who surely float into the pool filter unnoticed. Other survivors have included the iridescent jewel that is the native ultragreen sweat bee, butterflies, moths, and beetles. What does it mean to be in residence alongside so many others who already reside?

“Residence” is a sticky orienting principle in this proto-white box of glass and concrete which was never intended to be inhabited at all. Built in 1936, in the biodiversity hotspot that is Laurel Canyon, the Fitzpatrick-Leland House was commissioned by developer Clifton Fitzpatrick as a speculative home. It was then designed by R.M. Schindler, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, as a gleaming lure with which to entice speculators and spectators to these Hollywood Hills.1 Eventually, what began as a model went through cycles of remodeling, inhabitation, and de-modeling through the mechanism of exponentially appreciating real estate. In the 1990s, it was restored to its original condition by architectural designer Russ Leland, who donated it to the MAK Center, and it has since served as an exhibition and residency space for artists such as Florian Hecker and Kim Gordon.

In predictable Wright protégé fashion, the house consistently negotiates the boundaries of inside and outside. Large windows open directly into tall beds of ferns that collapse indoors. Leaf litter and eucalyptus bark blow in from the west along the ocean breeze, as does smog from Mulholland Drive and Laurel Canyon Boulevard just below. The shower opens out to the surrounding hills, where every night in June a pack of baby coyotes can be heard rehearsing their serenades. Often, they sing in the round with passing sirens, a territorial call-and-response. As the weeks go by, a Dark-eyed junco and Western fence lizard have each made home visits through the windows. Though I’m intimately familiar with L.A.’s living landscapes, the act of “guesting” in this specific architecture, where the built and unbuilt environment have been made deliberately permeable, offers emergent perspectives. The

Ava DeCapri during a Work-Trade Residency at A–Z West / High Desert Test Sites.

Image courtesy of High Desert Test Sites.

Photo: Anne Müchler and Nico Schmitz.

frequent multispecies encounters of the porous house bring the concept of residency itself, with all its questions of shared stewardship, into focus. With origins as a speculative home, perhaps the Fitzpatrick-Leland House is now poised to function as a space for imagining what new models of residence could look like.

Art and research residencies in the U.S. today are rooted in longstanding lineages, from the informal artist colonies of New Mexico in the 1880s to Black Mountain College in the 1930s. But as cultural producer Irmeli Kokko reminds us, the structure and priorities of residencies have shifted over time, often in response to fluctuations in creative practices.2 Residencies of the 1970s and ’80s, for example, figured the studio as a private workspace, a protected isolation zone shielding artists and researchers from the outside world. According to curator Miwon Kwon, creative practitioners increasingly centered their work on travel during the broader turn towards globalization of the 1990s, and the number of residencies worldwide subsequently multiplied.3 Those residencies became more outwardfacing, no longer intended to insulate artists but instead to entwine them with peers, communities, and publics. Illustrating this development is the Guide of Host Facilities for Artists on Short-Term Stay in the World, the first international residency catalogue, published in 1995. To be eligible for inclusion, residencies were not only required to provide artists and researchers with workspace but also to embed them in place and to network them with “new contacts.”4 The creative works made in residence during this period became more thoroughly bound together with the locations and communities of their making. As a result, site-specificity was cemented as a residency priority, one which often continues today. In recent years,

that site-specificity has noticeably extended further, beyond the walls of the studio and into the land, with an increasing number of residencies asking visitors to connect with environmental place in their work. Potential residents are commonly asked to identify what draws them to the residency site in particular, or which of the residency’s spaces, tools, or communities would be useful to their practice. Today, land itself may also be offered up as potential “resource.”

This shift, from the residency as isolated and private to site- and land-specific, raises critical and ongoing questions about the colonial logics through which artists may “[parachute] in to suck up place:”5 If a resident has not spent time on this land or with this community before, are they capable of making meaningful interventions there? Is it possible for residents to make adequately responsive work without sustained and embodied relationbuilding? Site-specific residencies risk treating land and its inhabitants as mineable for cultural value. This extractive mode places host and guest in a hierarchical and antagonistic relationship, illustrating how nuanced and complicated the host/ guest coupling can be.

It also makes explicit the need for alternative models. For example, centering relations within a residency’s ecosystemic neighborhoods has become more pressing alongside accelerating environmental change. In Southern California in particular, which sits at the edge of the climate crisis and is built atop layered histories of extraction, residencies have become more environmentally vulnerable. This was brought into sharp relief during the January 2025 wildfires, when multiple residency spaces around the city were threatened or damaged, leaving institutions and residents from near and far to navigate increased volatility. The Villa Aurora residency, which houses artists and journalists from Germany, was damaged by the Palisades Fire,6 a warning regarding the changing tensions of welcoming

Top: The Fitzpatrick-Leland House (2022). Image courtesy of MAK Center for Art and Architecture. Photo: Tag Christof / MAK Center for Art and Architecture.

Bottom: Interior of the Fitzpatrick-Leland House during a research residency (2024–25).

Photo: Maya Livio.

Top: Nora Rolf and Wendy Roberts in the A–Z West weaving studio at High Desert Test Sites.

Image courtesy of High Desert Test Sites.

Photo: Anne Müchler and Nico Schmitz.

Bottom: Earthbag terrace construction at ExtraTerraceTrill residency in Los Angeles (2025). Photo: Huntrezz Janos.

international guests to the coastal sage and chaparral. The Residency Project, which supports visiting artists with housing in Pasadena, was similarly near enough to the Eaton fire to sustain ash, smoke, and wind damage.7 As environmental catastrophe continues to threaten both residents and treasured cultural institutions, what could new and adaptive residency models look like, ones that co-support human and nonhuman thriving in the face of rapid change?

Residencies are already wellequipped to evolve in response to mutating needs, as they have always been in flux alongside shifting creative practices. Much like host/guest relations, residencies flourish when they allow for continual transformation in response to internal and external environments.

off studio lights by 9 pm to reduce light pollution. The gleaming silver water tank of the main house is located directly outside of the shower window, where it seems to sit as a reminder of scarcity. Sparkling in the desert sun, it focuses host and guest attention on water usage. The majority of residents at A-Z West come in through the work-trade program, which offers lodging and studio access in exchange for the labor of maintaining the site of residence—tending compost, cleaning, feeding rescue tortoises, and crafting A-Z West Works Containers in the ceramics studio.

These trade-based and sustainable practices blur the boundaries of host and guest, making residents an active part of the residency structure and engaging them in what is already ongoing.

By July, the Fitzpatrick-Leland’s pool edges are dotted with dead insects. I now scoop four or five lifeless bodies a day, including a native yellow-faced bumblebee. Many still survive but enough die to make it uncomfortable. One morning, I find a mouse swimming laps. Thirst is presumably what drives these risky behaviors, everyone is a little more parched. The small patch of undeveloped canyon land across the street has dried up too and I occasionally see volunteers managing dry vegetation there for fire mitigation. It is an intervention that hints at opportunities for Southern California residencies to lead a new wave of residency adaptation, particularly given their situatedness at the front lines of environmental vulnerability. Several local residencies are already experimenting with methods and infrastructures that resonate with hospes. For example, A-Z West in Joshua Tree, founded by artist Andrea Zittel and now stewarded by High Desert Test Sites, has embedded environmentality into its processes and systems. The site relies on solar power and residents are asked to turn

In Los Angeles, the emerging residency project Extraterracetrill offers another salient example of how residency protocols can be refigured. Currently in development by artist Huntrezz Janos, the site already welcomes Janos’ own artist community as guests when visiting from elsewhere or seeking a gathering place. Once fully operational, it will also host programming. Extraterracetrill functions off-grid and features regenerative agricultural practices and water reclamation. It is partially built of earthbags, a sustainable building material. Moreover, Janos’ vision includes a novel approach that treats residency spaces as “public-private gradient,” allowing unhoused locals to use portions of the area in addition to visiting artists. In this way, the hierarchy of host and guest is destabilized, signaling the changing dynamics (and expanding the types of support) a residency can offer to local communities, especially those who are most vulnerable. If residencies were once conceived of as protecting artists and researchers from the outside world, then as encouraging engagement with that world as visitors, they now necessitate more reciprocal, responsible, and humble co-participation in place,

with local expertise as guide. While residents from afar are always at risk of perpetuating exploitative logics, their position as guests also offers an oblique perspective for noticing details and kinships anew. Residencies have an opportunity, then, to demonstrate the potential for hospes as a guiding principle, one that can function not as a restrictive framework but as generative provocation towards less extractive modes of relation.

1. The Fitzpatrick-Leland was not Fitzpatrick’s only speculation. He later developed the mythically imaginative Valhalla Memorial Park Cemetery in Burbank. After he and his development partner were caught reselling cemetery plots, some as many as 16 times, he was indicted by a federal grand jury. Like many in L.A., Fitzpatrick was in the business of peddling—though not necessarily delivering on—dreams, fabricating idyllic places in which to reside in life and in death. See Stephen G. Bloom, “Valhalla Cemetery Records History of Famous, Forgotten,” Los Angeles Times, Sept. 2, 1985.

2. Irmeli Kokko, “A Brief History of Artist Residencies,” in Bringing Worlds Together: A Rethinking Residencies Reader, eds. Kari Conte and Susan Hapgood (New York: Rethinking Residencies, 2023).

3. Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004).

As I close out my time at the Fitzpatrick-Leland House, I assemble a list of recommendations for more convivial forms of residence there, which my hosts warmly welcome: A resident communication channel for distributing leftover food and supplies to reduce waste, for instance, and a bee fountain and small ramp to help drowning animals. The coyotes have quieted down and blue dasher dragonflies have started to keep me company in the pool. Sometimes they dive over me to kiss the water.

Maya Livio works at the interfaces of ecosystems and technological systems. An assistant professor of environmental media at American University, she holds a PhD from the University of Colorado and MA from the University of Amsterdam. She is a resident of the California coastal sage & chaparral and Chesapeake rolling coastal plain ecoregions.

4. As cited in Kokko, “A Brief History of Artist Residencies,” 18.

5. Lucy Lipaprd, “Then and Now,” Canadian Art, October 9, 2018, https://canadianart.ca/essays/lucy-lippardthen-and-now/

6. “News,” Villa Aurora and Thomas Mann House, May 26, 2025, https://www.vatmh.org/en/newsreader-en/ on-the-current-situation-of-the-wildfires-in-los-angeles. html

7. Sarah Umles, “After the Eaton Fire,” The Residency Project, https://www.theresidencyproject.org/updates.

Aerial view of A-Z West, Joshua Tree, California. Image courtesy of High Desert Test Sites.

Photo: Josh Cho.

Interview with Gregg Bordowitz

In Exodus 3:14, G-d reveals his personal name to Moses, a name typically translated as “I will be what I will be” or “I am what I am.”1 In Hebrew, the name is composed of the four letters yod, he, vav, and he, spelling a word observant Jews consider too sacred to pronounce aloud and therefore simply refer to as the “Tetragrammaton.”

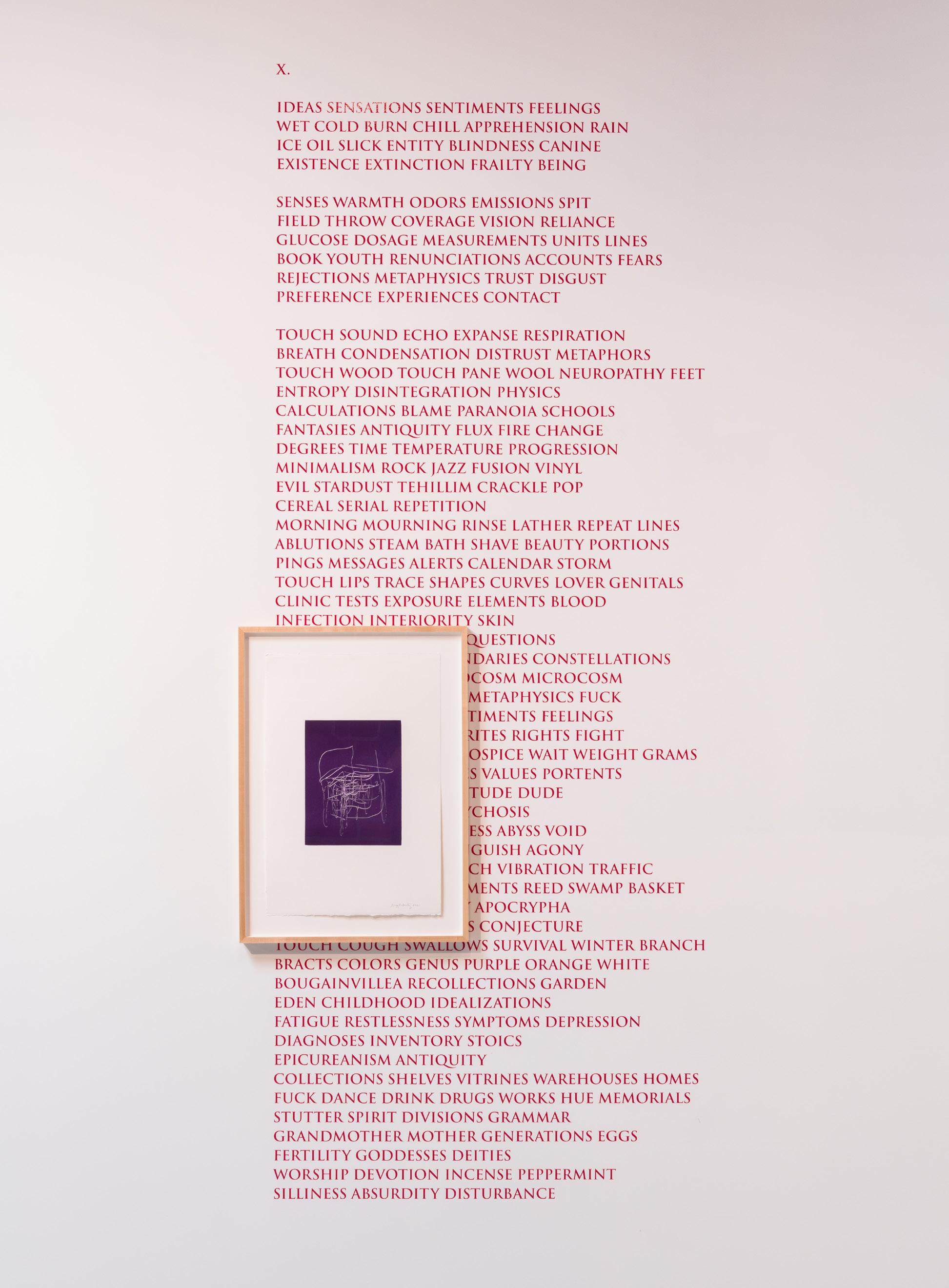

The letters of the Tetragrammaton appeared over and over in Gregg Bordowitz’s recent exhibition This is Not a Love Song, in calligraphic scrawls captured in a series of monotypes that encircled The Brick’s main gallery. The prints were shown alongside (and in some cases physically on top of) an epic associative poem in a funerary typeface; wooden structures that recalled tree protectors on the sidewalks of New York; a video of Bordowitz reading a poem by the light of a headlamp; and cartoonish plaster sculptures of clouds drawn from a Baroque monument to the plague. In an adjacent space played a feature-length video compilation of the artist’s deadpan stand-up routines, poetry readings, and a Yom Kippur sermon, interspersed with jarring cell phone footage of a man on his deathbed.

Altogether, the many individual components of the exhibition set a tone that alternated between holy and playful, heavy and buoyant— descriptors that could easily apply to Bordowitz’s relationship to Jewishness, a facet of his identity that has been an explicit part of his work from the beginning. His breakthrough video Fast Trip, Long Drop (1993), for example, is an autobiographical documentary

in which he contends with the complexities of living with HIV, with straight-to-camera narration and found footage set rather pointedly to stirring music by The Klezmatics. The video, much like This is Not a Love Song, transforms contradiction into life-affirming duality, centering identity in order to destabilize the self.

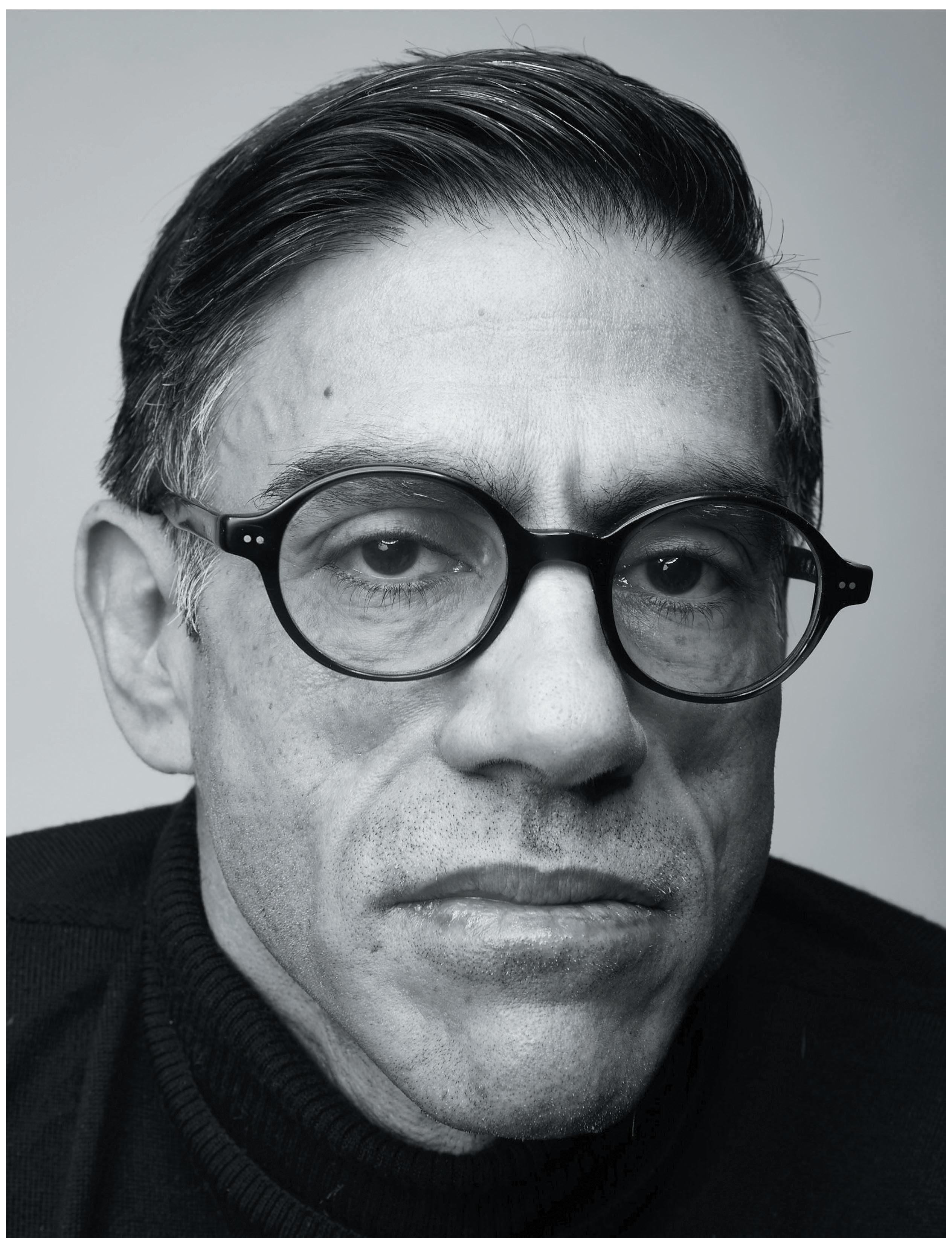

Over three hours of conversation at a café in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, Bordowitz graciously answered my questions, often with a dizzying array of references to pop culture and erudite Jewish scholarship, much of which did not make it into this condensed transcript. More importantly, he shared how experiences marked by pain, loss, joy, and hope have informed his evolving artistic practice, which continues to reach for the universal—and the political—through the personal.

Andrea Gyorody: I felt like the crux of your exhibition at The Brick was articulated in the compilation video, where you say that Jewishness is the key to understanding all the other identities that make up who you are. What is the Venn diagram for you between Jewishness and queerness, and how has that changed over time?

Gregg Bordowitz: The names and categories that we use to identify ourselves are impoverished in relationship to the lived complexity of our lives. I came up at a formative moment as an artist, as a young person within the framework of identity politics, and identity politics came to mean various things. For me it meant allowing identities and names and labels to attach to me and to embrace them in their contradictions and complexity so that the combined weight of all of the identities would actually lead to the collapse of the self. So ultimately, my definition of identity politics is about defeating identity structures.

At the same time—and I don’t think it’s a contradiction, it’s a conundrum that we live—identity politics or identitarian claims are extremely

Andrea Gyorody

Image courtesy of the artist.

Photo: Justin Bettman.

important politically. In my experience, they can mean survival. It’s the way we form communities. It’s also the way we open ourselves up to the world.

AG: Was that the Jewish community for you, as a kid growing up in Queens?

GB: My family had a very complicated relationship to Jewish life. My parents were Jewish hippies. My grandfather was Orthodox. In my family it was all very culturally Jewish. And the older people, by that I mean my grandparents and their generation, my aunts, my uncles, they were all Yiddish speaking, they were all either from Europe or were the firstborn children to European immigrants. My family was huge when I was a child, and every Sunday we got together, at least 20 people at my Aunt Gertie’s house in Long Island. It’s Yiddish, Jewish food, but a varying level of commitment [to observance] based on various trajectories of complexity, of lived lives. […]

I went to heder [Hebrew school] as a young child. I was often used in the classroom as an example of the assimilated Jew, because I had really long hair, and it was clear that I wasn’t observant, or as observant as many of my fellow students. But I was well embraced and smart and had an amazing attachment to some of my teachers there. I fell in love with Jewish study, with Torah study, Talmud, and it shaped my intellectual aspirations.

AG: A lot of kids are repelled by Hebrew school, but it seems like you were drawn deeply to Torah study.

GB: In some ways it’s like any object attraction. It comes unbidden. My mom taught me how to read before I got into school. […] My mom was a reader. She loved reading. My grandfather was a reader. My grandfather was studious. These are not collegeeducated people, but they are really super smart. And yeah, I just fell for it. I kind of went queer for it in a certain way. […] There was something that