CLASSICS 2025/26

TCHAIKOVSKY SYMPHONY NO. 4

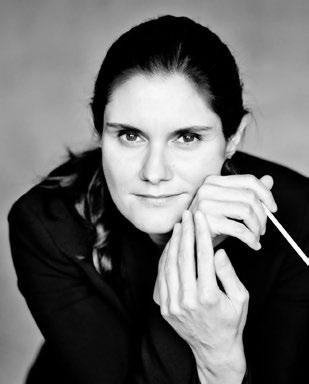

DELYANA LAZAROVA, conductor

MARTIN HELMCHEN, piano

Friday, October 3, 2025 at 7:30pm

Saturday, October 4, 2025 at 7:30pm

Sunday, October 5, 2025 at 1:00pm

Boettcher Concert Hall

UNSUK CHIN

MOZART

subito con forza

Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. 491

I. Allegro

II. Larghetto

III. Allegretto

— INTERMISSION —

TCHAIKOVSKY

Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36

I. Andante sostenuto

II. Andantino in modo di canzona

III. Scherzo: Pizzicato ostinato

IV. Finale: Allegro con fuoco

CONCERT RUN TIME IS APPROXIMATELY 1 HOUR AND 45 MINUTES INCLUDING A 20 MINUTE INTERMISSION.

Friday’s concert is sponsored by nancy and tony accetta saturday’s concert is in memory oF charles

PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY

DELYANA LAZAROVA, conductor

As a conductor, Delyana Lazarova thinks of herself as a musician among musicians. Collaboration, openness, and sensitivity to the specific sound and character of every orchestra are the foundation of her work; all in service to the music. Orchestras worldwide appreciate her ability to communicate sound and create an environment in which music can simply unfold.

News of Lazarova’s remarkable talent has spread far and wide, leading to her appointments as Principal Guest Conductor of Utah Symphony and BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra both starting from the 2025-26 season. This season, she makes her debut with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, hr-Sinfonieorchester, Minnesota Orchestra, Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne, the Malmö Symphony, Orquesta Sinfónica de Tenerife, and Orquestra Sinfonica do Estado de Sao Paolo. She will also work with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg and the Royal Northern Sinfonia for the first time. Furthermore, following her debut at the Enescu Festival last season, she opened the George Enescu International Competition in autumn 2024.

Delyana Lazarova’s international musical education influences her wide-ranging repertoire. Born in Bulgaria, she has a natural affinity to Eastern European and Russian repertoire (Dvořák, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky, Bartók), but feels equally at home in the Viennese Classical period, influenced by her studies in Switzerland. Lazarova is passionate about music of the 20th and 21st centuries. This season, 2024-25, she begins her role as Artistic Partner of ROCO in Houston, a chamber orchestra specialising in contemporary music, with whom she will premiere Clarice Assad’s piano concerto ‘Total Eclipse’, among others. Lazarova’s first CD, recorded with the Hallé, with works by Bulgarian composer Dobrinka Tabakova, was released in October 2023.

After winning the inaugural Siemens Hallé International Conductors Competition, Lazarova served as Assistant Conductor to Sir Mark Elder at the Hallé Orchestra and Music Director of the Hallé Youth Orchestra from 2020-2023. She also assisted Cristian Măcelaru at the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln and the Orchestre National de France. In 2020, she won the James Conlon Conductor Prize at the prestigious Aspen Music Festival. Earlier successes include the NRTA Conducting Competition in 2019, and the Bruno Walter Conducting Scholarship at the Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music in California in 2017 and 2018.

Lazarova studied conducting at the Zürcher Hochschule der Künste (ZHdK) with Professor Johannes Schlaefli. She has attended numerous master classes with Bernard Haitink, Paavo Järvi, Leonard Slatkin, Mark Stringer, Robert Spano, and Matthias Pintscher among others. In addition to her master’s degree in conducting, she is an accomplished violinist with a master’s degree and performance diploma from the Jacobs School of Music in Indiana, where she studied under Mauricio Fuks and received a scholarship for artistic excellence.

BIOGRAPHIES

MARTIN HELMCHEN, piano

“… Martin Helmchen formed melodic phrases as clear and elegant as the columns of a Greek temple…his playing made sparks fly …“

– The New York Times

German pianist Martin Helmchen has been performing on the world’s most prestigious stages for two decades and is one of the most soughtafter pianists of today. His originality and intensity of interpretation, which he presents with impressive tonal sensitivity and technical finesse, sets him apart as a musician. In 2020 he was honored with the prestigious Gramophone Classical Music Award.

Martin Helmchen has performed with numerous renowned international orchestras, including the Vienna and Berlin Philharmonic, the Concertgebouworkest, the Gewandhaus Orchestra Leipzig, the Staatskapelle Dresden, the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich, the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, the Orchestre de Paris, the Vienna Symphony, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, and The Cleveland Orchestra. He regularly collaborates with conductors such as Herbert Blomstedt, Christoph von Dohnányi, Alan Gilbert, Bernard Haitink (†), Manfred Honeck, Jakub Hrůša, Paavo Järvi, Vladimir Jurowski, Fabio Luisi, Andrew Manze, Klaus Mäkelä, Andris Nelsons, Sakari Oramo, Tarmo Peltokoski, and Kazuki Yamada.

Chamber music holds a special place for him – a passion for which Boris Pergamenschikow provided significant inspiration. His close chamber music partners include Marie-Elisabeth Hecker, Frank Peter Zimmermann, Julian Prégardien, Augustin Hadelich, and Antje Weithaas.

He is a guest at renowned festivals such as the BBC Proms, Tanglewood, Schubertiade, Lockenhaus and Lucerne Festival, as well as the Marlboro and Aspen Music Festivals. He is additionally the co-founder and co-artistic director of the Fliessen International Chambermusic Festival alongside Marie-Elisabeth Hecker.

Martin Helmchen records for the label Alpha Classics. His most recent release, in May 2024, was a recording of the Six Partitas by Johann Sebastian Bach, for which he received a Critic’s Choice from Gramophone Magazine. In March 2022, his highly praised album “Novelletten and Gesänge der Frühe” featuring piano works by Robert Schumann was released. His previous recordings include, among others, Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations, Messiaen’s “Vingt regards sur l’EnfantJésus,” and albums with Marie-Elisabeth Hecker featuring works by Schubert and Brahms.

Born in Berlin in 1982, he initially studied with Galina Iwanzowa at the Hochschule für Musik “Hanns Eisler” Berlin before moving to study with Arie Vardi at the Hochschule für Musik Hannover. Other mentors include William Grant Naboré and Alfred Brendel. His career was significantly shaped by winning the “Concours Clara Haskil” in 2001 and the Credit Suisse Young Artist Award in 2006. Since 2010, Martin Helmchen has been an Associate Professor of Chamber Music at the Kronberg Academy. He lives in Germany with his wife, cellist Marie-Elisabeth Hecker and their four daughters.

BIOGRAPHIES

UNSUK CHIN (born in

1961)

subito con forza (“Suddenly, with Power”)

COMPOSITION & PREMIERE OF WORK:

subito con forza was composed in 2020, and premiered on September 24, 2020 in Amsterdam by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, conducted by Klaus Mäkelä.

CSA LAST PERFORMANCE:

Colorado Symphony Premiere

INSTRUMENTATION:

Two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, percussion and strings

DURATION:

About 5 minutes.

Unsuk Chin, born in 1961 into the family of a Presbyterian minister in Seoul, South Korea, had little formal musical instruction when she was young, but taught herself piano by playing in her father’s church and composing by copying scores of well-known composers. Chin was admitted as a composition student to Seoul National University on her third try, and there became familiar with the leading contemporary European composers. A piece of hers was played at the 1984 ISCM World Music Days in Canada, the following year she won an award from the Gaudeamus Foundation in Amsterdam, and in 1985 she received a German government grant to study in Hamburg with György Ligeti, whose influence proved decisive in forming her creative personality. Chin moved to Berlin in 1988 to compose and work at the Electronic Music Studio of the Technical University, and has since made that city her home. She began to build her international reputation when Die Troerinnen (“The Trojan Women”) for orchestra and women’s voices was premiered in Bergen in 1990, and she was soon having her works performed and commissioned by leading orchestras, ensembles and soloists around the world; her growing acclaim was validated when she received the prestigious Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition from the University of Louisville in 2004 for her Violin Concerto. Chin’s many other honors include the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize, Arnold Schoenberg Prize, Prince Pierre Foundation Music Award, Wihuri Sibelius Prize, Hamburg Bach Prize, Kravis Prize and Leonie Sonning Music Prize; her Alice in Wonderland was named “World Premiere of the Year” by the German publication Opernwelt (“Opera World”) following its first production, in Munich in 2007. In 2022, Chin started a five-year tenure as Artistic Director of the Tongyeong International Festival in South Korea and Artistic Directorship of the Weiwuying International Music Festival in Taiwan.

Chin composed subito con forza (“Suddenly, with Power”) in 2020 “on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth,” as she inscribed in the score. The five-minute subito con forza has several references to Beethoven’s music, mostly immediately the stern chords borrowed from the Coriolan Overture that open the work, but British critic Simon Cummings wrote that “the piece is less about quotation than celebrating, and mirroring, the indomitable attitude of one of music’s truly great innovators. Chin has sought to embody one of the key defining characteristics of Beethoven’s music: the restless, relentless fire and energy that propels his music with seemingly unstoppable force. This is articulated, as the title implies, via a connected sequence of sudden shifts.” Chin confirmed Cummings’ description: “What particularly appeals to me are the enormous contrasts: from volcanic eruptions to extreme serenity.”

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791)

Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. 491

COMPOSITION & PREMIERE OF WORK:

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed the C minor Concerto in 1786, and was soloist at its premiere on April 7th of that year at the Burgtheater in Vienna.

CSA LAST PERFORMANCE:

March 11-13, 2022. Jose Luis Gomez, conductor.

Joyce Yang, piano

INSTRUMENTATION:

Flute, pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets, timpani and strings.

DURATION:

About 31 minutes.

As Mozart reached his full maturity in the years after arriving in Vienna in 1781, his most emotional manner of writing, whose chief evidences are the use of minor modes, chromaticism, rich counterpoint and thorough thematic development, appeared in his compositions with increasing frequency. This style had regularly been evident in the slow movements of his piano concertos, but in 1785, he actually dared to cast an entire work (the Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 466) in a minor key, though he did relieve its austerity somewhat by concluding it with a third-movement coda in a bright, major tonality. “An experiment, just an aberration,” thought the Viennese public, who recognized Mozart’s talent, if not its full range and power. They assumed he would return to the more popular and accepted means of expression the following season, and subscribed to his 1786 concerts in large numbers. In March, he presented his patrons with the beautiful and deeply felt A major Concerto (K. 488), with a passionate middle movement in the key of F-sharp minor. A month later he introduced the Concerto in C minor (K. 491), which, unlike the earlier D minor Concerto, maintains its tragic mood throughout. “It is hard to imagine the expression on the faces of the Viennese public when on April 7, 1786, Mozart played this work at his subscription concert,” wrote Alfred Einstein. Having thus stirred the doubts of Viennese audiences about the artistic path he was following, it is little wonder that Figaro received only small applause when it was premiered at the Burgtheater on May 1st. The following year his concert subscription list was returned almost blank. The year 1786, which had begun with hope for great success, ended with frustration. The noble C major Concerto (K. 503) of December was the last such work he was to play at one of his own concerts, after which he was never again able to secure enough patrons to sponsor another similar venture.

The extravagant chromaticism and wide leaps of the main theme of the C minor Concerto’s opening Allegro recall the music of Bach, which Mozart had studied with great profit. The mood of what Hermann Abert called “titanic defiance” continues undiminished throughout the movement, balanced in its intensity by the cool perfection of the form. The tranquil serenity of the Larghetto is heightened by the music’s placement between two large movements of tragic grandeur. The finale, a set of variations on a dolorous theme of sighing intervals, ends with a coda whose jaunty meter seems almost an ironic taunt to its solemn melodic and harmonic content.

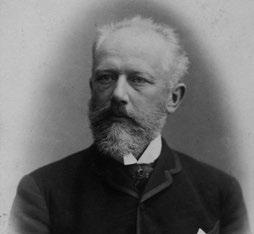

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893)

Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36

COMPOSITION & PREMIERE OF WORK:

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed the Fourth Symphony between April 1877 and January 7, 1878. Nikolai Rubinstein conducted the premiere, in Moscow on February 22, 1878.

CSA LAST PERFORMANCE:

October 14-16, 2022, Aram Demirjian, conductor.

INSTRUMENTATION:

Pairs of woodwinds plus piccolo, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion and strings.

DURATION:

About 44 minutes.

The Fourth Symphony was a product of the most crucial and turbulent time of Tchaikovsky’s life — 1877, when he met two women who forced him into a period of intense introspection. The first was the sensitive, music-loving widow of a wealthy Russian railroad baron, Nadezhda von Meck. Mme. von Meck had been enthralled by Tchaikovsky’s music, and she first contacted him at the end of 1876 to commission a work. She paid him extravagantly, and soon an almost constant stream of notes and letters passed between them: hers contained money and effusive praise; his, thanks and an increasingly greater revelation of his thoughts and feelings. She became not only the financial backer who allowed him to quit his irksome teaching job at the Moscow Conservatory to devote himself to composition, but also the sympathetic soundingboard for reports on the whole range of his activities — emotional, musical, personal. Though they never met, her place in Tchaikovsky’s life was enormous and beneficial.

The second woman to enter Tchaikovsky’s life in 1877 was Antonina Miliukov, an unnoticed student in one of his large lecture classes at the Conservatory who had worked herself into a passion over her young professor. Tchaikovsky paid her no special attention, and he had quite forgotten her when he received an ardent love letter professing her unquenchable desire to meet with him. Tchaikovsky (age 37), who should have burned the thing, answered the letter of the 28-year-old Antonina in a polite, cool fashion, but did not include an outright rejection of her advances. He had been considering marriage for almost a year in the hope that it would give him both the stable home life that he had not enjoyed in the twenty years since his mother died, as well as to help dispel the all-too-true rumors of his homosexuality. He believed he might achieve both those goals with Antonina. He could not see the situation clearly enough to realize that what he hoped for was impossible — a pure, platonic marriage without its physical and emotional realities. Further letters from Antonina implored Tchaikovsky to meet her, and threatened suicide out of desperation if he refused. What a welter of emotions must have gripped his heart when, just a few weeks later, he proposed marriage to her. Inevitably, the marriage crumbled within days of the wedding amid Tchaikovsky’s searing self-deprecation.

It was during May and June that Tchaikovsky sketched the Fourth Symphony, finishing the first three movements before Antonina began her siege. The finale was completed by the time he proposed. Because of this chronology, the program of the Symphony was not a direct result of his marital disaster. All that — the July wedding, the mere eighteen days of bitter conjugal farce,

the two separations — postdated the actual composition of the Symphony by a few months, though the orchestration took place during the painful time from September to January when he was seeking respite in a half dozen European cities from St. Petersburg to San Remo. What Tchaikovsky found in his relationship with this woman (who by 1877 already showed signs of approaching the door of the mental ward in which, still legally married to him, she died in 1917) was a confirmation of his belief in the inexorable workings of Fate in human destiny. He later wrote to Mme. von Meck, “We cannot escape our Fate, and there was something fatalistic about my meeting with this girl.” The relationships with the two women of 1877, Mme. von Meck and Antonina, occupy important places in the composition of the Fourth Symphony: one made it possible, the other made it inevitable, but the vision and its fulfillment were Tchaikovsky’s alone.

After the premiere, Tchaikovsky explained to Mme. von Meck the Symphony’s emotional content: “The introduction [stentorian brasses heard immediately in a motto theme that recurs throughout the work] is the kernel of the whole Symphony. This is Fate, which hinders one in the pursuit of happiness. There is nothing to do but to submit and vainly complain [the melancholy, syncopated shadow-waltz of the main theme, heard in the strings]. Would it not be better to turn away from reality and lull one’s self in dreams? [The second theme is begun by the clarinet.] But no — these are but dreams: roughly we are awakened by Fate. [The brass fanfare over a wave of timpani begins the development section.] Thus we see that life is only an everlasting alternation of somber reality and fugitive dreams of happiness. The second movement shows another phase of sadness. How sad it is that so much has already been and gone! And yet it is a pleasure to think of the early years. It is sad, yet sweet, to lose one’s self in the past. In the third movement are capricious arabesques, vague figures which slip into the imagination when one has taken wine and is slightly intoxicated. Military music is heard in the distance. As to the finale, if you find no pleasure in yourself, go to the people. The picture of a folk holiday. [The finale is based on the Russian folk song A Birch Stood in the Meadow.] Hardly have we had time to forget ourselves in the happiness of others when indefatigable Fate reminds us once more of its presence. Yet there still is happiness, simple, naive happiness. Rejoice in the happiness of others — and you can still live.”

©2025 Dr. Richard E. Rodda

Mahler Symphony No. 9 with Andrew Litton OCT 17-19 FRI-SAT 7:30 | SUN 1:00