Scholars’ Journal 2024

A selection of articles written by our Scholars

The Scholars' Journal has been printed on carbon balanced paper and has offset 0.036 tonnes of CO2 through Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) reduction projects thereby offsetting carbon emissions and helping to prevent climate change.

Scholars’ Journal 2024 Introduction

Following my recent Enlightenment Lecture on the history of ostracism and cancel culture, I am delighted to write the foreword for Cokethorpe’s 2024 Scholars' Journal. As the Cokethorpe Scholars’ Journal articles show, good scholarship allows us to make the most of our individual talents in the service of knowledge and creativity. Cultivating good scholarly habits at school enhances all aspects of life further down the line: it shapes how we communicate, equips us with independence of thought, and makes us more curious about the world. As a PhD candidate, I still implement the critical thinking and essay writing skills I developed while at school.

Whilst doing research is a collaborative activity which contributes to a shared bank of knowledge, it also reflects each scholar’s individuality. The wonderful range of the Scholars’ Journal articles is a testament to the independence and originality of the pupils at Cokethorpe. Nancy Christensen (Lower Sixth, Swift) applied the economic and social theories of Adam Smith and Malcolm Gladwell to argue for investment into the African fashion industry, showing impressively wide reading. Another fascinating article which blended aesthetics with pragmatic economic research was Harry Adams’ (Lower Sixth, Harcourt)analysis of biomimicry in architectural design. Emmeline Black (Fourth Form, Feilden) asked a more abstract question: ‘At what point does a cult become a religion?’, drawing from a remarkable range of examples of cult leaders throughout history and challenging the usefulness of a term as broad as ‘cult’. Oscar Luckett (Lower Sixth, Vanbrugh) also took on an ambitious question: ‘Is the perfect lie truly possible?’ He discussed FBI spy-catching as well as his own experiences playing poker, which was a fantastic use of practical research to address a perennial question.

Caellum Sharp (Lower Sixth, Vanbrugh) confronted one of the most existential questions there is: ‘What is consciousness?’ After disentangling several highly complex theories of consciousness from reductionism to panpsychism, he evoked a topical comparison between human consciousness and AI. Alex May’s (Fourth Form, Vanbrugh) deep dive into the ethical and practical questions surrounding AI in the workplace reminds us that AI is a tool which should facilitate creativity rather than replace it. Some pupils researched the ancient world: Finn Van Landeghem (Lower Sixth, Vanbrugh) combined breadth and depth in his study of literary criticism in Ancient Greek and Roman texts from Pindar’s Odes to Virgil’s Eclogues to Ovid’s Amores. Others asked contemporary scientific questions: Lottie Graves (Second Form, Gascoigne) addressed common misconceptions about coeliac disease and investigated how the rise of veganism can encourage the food industry to expand their accommodations to those with coeliac.

It was a joy to read the Scholars’ Journal articles. I wish the very best to the scholars in their future endeavours, which I am sure will make the School proud.

Jane Cooper MA (Oxon) Fellow, All Souls College, Oxford

Curiosity might drive a person to enquire, but it requires intellectual ambition to get to that point in the first place. Determination can energise a scholar to learn, but it requires wise study habits to adapt to changing situations when goals are not easily attained.

Should you be a scholar now, aspiring to be one in the future, or looking back on your past achievements as you read this many years hence, we hope this journal demonstrates the wisdom of Immanuel Kant: 'Dare to be curious.'

Miss Hutchinson and Mr Elkin-Jones Heads of Scholars

Contents

The Scholars’ Journal is a collection of articles created by pupils from First Form to Lower Sixth. The articles represent a selection of work across a wide range of disciplines.

The Arts and Philosophy

What is Art?

Amelie Boyle - Fourth Form

Should We Invest in the African Fashion Industry?

Nancy Christensen - Lower Sixth

How Does the 2017 Lowery Film A Ghost Story Give Answers to the Ontological Question of Legacy?

Sam Farr - Lower Sixth

How Have Cats Become Domesticated Throughout History?

Alex Hancox - Fourth Form

Beyond the Pastoral: How Did the Greeks and Romans do Literary Criticism?

Finn Van Landeghem - Lower Sixth

What is a Genius?

Evie Walker - Fourth Form

To What Extent Was the Political State of Argentina the Reason They Set Out to Take the Falkland Islands in 1982?

Sam Weldon - Fourth Form

Social Sciences

At What Point Does a Cult Become a Religion?

Emmeline Black - Fourth Form

How Did Harold Shipman Murder an Estimated 250 People Before He Was Caught?

Will Chandler - First Form

To What Extent Can We Trust Our Episodic Memory?

Eva Graves - Third Form

What Motivates Serial Murderers?

Luella Hickey - Third Form

Reality Versus Rhetoric in Sport: Are Women Being Presented as Being Something They are Not?

Ella Hogeboom - Fourth Form

From Farm to Fork: Can We Trust the Food We Eat?

George Keates - Lower Sixth

6-27

28-59

Truth, Deception, and the Human Mind: Is the Perfect Lie Truly Possible?

Oscar Luckett - Lower Sixth

Post Darwinism, are Science and Religion Able to Coexist?

Ellie Lunn - Fourth Form

What is Consciousness?

Caellum Sharp - Lower Sixth

How Well Do Our Prisons Meet Their Objectives?

Katy Stiger - Third Form

STEM

Is the Harnessing of Nature's Wisdom Through Biomimicry a Valuable Pursuit?

Harry Adams - Lower Sixth

Free to Choose: What Can the Coeliac Community Learn from the Rise of Veganism?

Lottie Graves - Second Form

What Will the Implications be of Using AI in the Workplace?

Alex May - Fourth Form

mRNA Vaccines: Will This New Technology be a Game Changer?

Simran Panesar - Lower Sixth

60-77

Could we Build a Bridge an Atom Thin? A Thought Experiment in Quantum Physics

Freya Vincent - Second Form

Appendix 78-79

Additional references

What is Art?

Amelie Boyle, Fourth Form, Harcourt House. Trevis Scholar - Supervised by Mr Elkin-Jones.

There is no one way to determine the definition of art. Art, like true beauty, is defined by the eye of the beholder. If one person feels a connection to a piece, feels emotion, feels it speaks to them, they might consider that to be a piece of art. The piece may conjure up different emotions, or none at all, for another person. The emotion a person feels towards a piece need not be positive. It can evoke anger or conjure up emotions that may not have surfaced if they were expressed aloud. Art could even question and challenge the meaning of art itself. An example of this is Duchamp’s Urinal (Fountain, 1917) which, a hundred years ago, changed art forever. This controversial piece, signed by the mysterious ‘R. Mutt’, made people rethink what art meant, and asked the difficult question, ‘What is art?’ The urinal proved that a piece of art need not have been made by the creator; ‘everyday’ objects could be art and displayed in a gallery. In so doing, elevating them to something more than their original intended purpose (Grovier, 2017). Art can be chosen.

I have been interested in art from an early age. I study Art at GCSE and am an Art Award holder. I have pondered this question for many years and my views are constantly evolving. Art is such a vast topic. It surrounds us in our daily lives in many different forms and yet we do not necessarily realise the meaning behind it, not just from the artist’s point of view but our own view as well. How, though, do we determine what art is? The Oxford English Dictionary defines art as ‘the expression or application of creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form

such as painting, drawing or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power’. I found this definition both interesting and useful. It was useful in that it helped me to put boundaries to the question, narrowing my focus to specific types of media, painting, drawing and sculpture, but then taking a broad approach to the use of these materials – from cave paintings to Tracy Emin’s My Bed (1998). The latter really redefined what art is and how we as a viewing public saw art, although I struggle to convince my parents that the

state of my bedroom has artistic value! Perhaps that reinforces the point that, personally, I believe art can be whatever the individual sees as artistically beautiful or emotional for them. It can broaden our horizons, enable us to travel into the past, can encompass yearnings, dreams, or the meaning of life but it can just come out of the blue, when you least expect it (Fondation Beyeler, 2012). I chose Bice Curiger’s quote to include with this journal article; his perception of the power of art really resonates with me as, I believe, it enhances our everyday lives.

Throughout the ages art has changed and evolved in a number of different ways. In the past, artworks were made out of certain materials, such as oil paint, marble, and bronze; however, now art is made from a vast array of materials including digital and internet art. Art is no longer defined by the material used. The reasons for making art differ greatly from artist to artist. We have come to realise, after many years of debate that there is no one way to define what art looks like. In his book, Playing to the Gallery (2016), Grayson Perry explains how a ‘test for art’ was proposed by one of his tutors. He called it the rubbish dump test. ‘You should place the artwork being tested on to a rubbish dump and it only qualified if a passerby spotted it and wondered why an artwork had been thrown away’ (Perry, 2016, p.68). Later, Grayson makes a really valid point that now the rubbish dump could be art! This demonstrates how quickly art evolves and new ideas about what art can be come to light.

So, at what point does something become art and how can we ‘test’ whether something is art? Whilst there is no firm definition or guidelines, it has much to do with how it is appreciated. The material used does not necessarily determine when something has become art, so does art lie in the way in which things are made? Or is it to do with the artist? Artists can create extremely diverse works, but whether those works are recognised, appreciated, and accepted and bought as art is beyond their control. Is it still a piece of art if the viewing public draws meaning from the painting unintended by the artist, or has the art in some way ‘failed’ because it has not been interpreted as the artist had hoped (Fondation Beyeler, 2012)? I would argue that the viewers judgement has more weight than the artist’s intention. If a viewer finds a piece artistic, then it is. Every age redefines what art is. For instance, Van Gogh only became celebrated as an artist after his death.

Attempting to apply science to define a mechanism for testing whether something is art feels to me like it misses the very powerful point about art itself. Art, to me, is not meant to be constrained by conforming to a formula from which ‘success’ as an artform can be determined. My research would suggest that I am

‘Art opens up new ways of seeing the world. Art liberates us from being imprisoned by conventions and habits of perception and thinking. Art liberates us from mundane functioning in day-to-day life.’

Bice Curiger, curator, Kunsthaus Zurich (Fondation Beyeler, 2012, p.121)

not alone in that view. Nonetheless, there are some common themes which can be applied to a piece that help to shape whether it can truly be called ‘art’. This issue is that like the art itself, our perception of what is artistic changes from generation to generation as it does from person to person. If one was pressed to define a test for ‘art’, one could focus around four themes; the making of the work, the artist and their intention, the perception of the viewing public, and the longevity of a piece as deemed artful – in essence, does it stand the test of time (Fondation Beyeler, 2012). Such tests cannot be applied strictly. Art is not an objective matter.

It is fascinating to attempt to apply these theories to a range of works in order to assess relative value. The cave paintings at Lascaux caves, in France, have been studied by archaeologists and art historians since their discovery in 1940. It is widely agreed that the images adorning the cave walls were created as pieces of art to entertain and delight their audience, as opposed to being a series of images depicting what the local population had recently hunted. The paintings still attract audiences from across the world today who are mesmerised by them, which 17,000 years on from their creation is testament to their longevity. Will Damien Hirst’s shark still be deemed to be art 17,000 years from now? Created in 1991, this piece titled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living questions, as Fountain did in 1917, whether an artwork had to be created by the artist and what constituted ‘art’. Today, it is seen as iconic and has come to symbolise Brit Art. I believe it qualifies as art as it creates feeling, whether positive or negative. For most viewers this will be the closest they will ever come to a shark and so they are able to see this creature in a completely different light, which is what the artist intended.

The graphic style of the Bayeux Tapestry could not be a more different art form to the medium used for the shark, yet it is renowned and has inspired popular culture since its conception. It is often referred to as one of the first comic strips and the storytelling

adopted by its embroiders is echoed in animations and films to this day. In contrast to the tapestry’s storytelling technique, Constable’s Hay Wain (1821) tells a whole story in just one image due to the wonderful use of paint and colours. There is real movement in the water trees and sky. You can almost imagine the conversation between the two figures in the painting. This last piece is considered to be one of Britain’s most loved paintings but differs greatly to the Bayeaux Tapestry, Hirst’s shark, and the cave paintings, which are all celebrated as art in their own right, each made from very different mediums and exhibiting very different skills in their creation. This suggests that art is in the eye of the beholder.

Given that the subject ‘what is art’ is based so much upon individual opinion, the scholars’ presentation evening gave me a wonderful opportunity to ask questions, as well as answer them. I was extremely interested in the perspective of others, so created an informal opinion poll selecting six artworks I thought

might provoke a response. The choice of pieces also attempted to show the evolution of artistic style of ‘what art is’, in much the same way as I journeyed across London and through the evolution of artistic styles when conducting my research. The pieces included Girl with a Pearl Earring by Vermeer (1665), Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888), Girl with Balloon by Banksy (2018), Number 31 by Jackson Pollock (1950), Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan (2019) and the Lascaux Cave paintings, circa 17,000 years old. The results were interesting, with Van Gogh’s Sunflowers coming in first place, followed by Girl with a Pearl Earring, so it seems that the more traditional pieces still evoke the greatest feeling that art is being observed. When discussing this I was told some of the reasons why visitors chose each piece. Viewers explained what art meant to them and I was able to see there were quite a few different points of view. Some chose the more traditional artworks because they seemed most familiar due to their fame or to them represented more of an expression of artistic talent and skill. Others chose pieces because they recalled drawing them in primary school. Equally interesting was that some based their view purely on the emotional response they got from each piece of art. Interestingly, although perhaps unsurprisingly the piece considered to be the least worthy of the title ‘art’ was Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan, which shows a banana taped to a wall. The poll was an intriguing insight into people’s opinion of what art actually is,

but a common theme seemed to be that people like to appreciate the skill an artist has shown in creating their work, and work that was deemed to have less artistic skill shown in its creation was less popular.

What I have learnt from this project is that art has different meanings for different people. Art is not defined by material, nor how it was made, necessarily. Art is defined by the onlooker. If the piece gives meaning or makes the viewer feel positive or negative about the subject or the piece, if it encourages an emotional response or draws the onlooker in, if the onlooker is connected to it, then that is art to them, and it has achieved its purpose. Art encourages us to voice our opinion in a way words cannot. Art will continue to evolve, new artistic styles will be developed, and, with that, new opinions will arise about what constitutes art. We will continue to learn from it, and art can be a powerful means of learning about our society and each other. The definition of art will not remain static, it will evolve just as art itself will continue to evolve. That is the power of art. It seems reasonable to say though that whilst art may change, the four constants of how art it made, the intention of the artist, the response of the viewer and the longevity of the piece form a sound and enduring basis on which works can be tested for artistic value. For me though, most importantly it is the response that a viewer has to a piece. The response of the audience truly defines something as art. As Leo Tolstoy said, ‘Art is about communication, a communication of feeling, just as speech is a communication of thought’ (Persson, 2009, p.2).

References:

Afzal, I. (2023) What is Art? Why is Art Important? [Online]. Available at: https://www. theartist.me/art/what-is-art/ (Accessed 1 October 2023).

Artist Editorial (2022) Why We Make Art? [Online]. Available at: https://www.theartist. me/art/why-we-make-art/ (Accessed 1 October 2023).

Bayeaux Museum (No date) A Never-Ending Source of Inspiration [Online]. Available at: https://www.bayeuxmuseum.com/en/the-bayeux-tapestry/over-the-centuries/ endless-source-of-inspiration/. (Accessed 31 January 2024).

Berger, J. (1990) Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books Ltd.

Burgon, R. (2012) A Line Made by Walking [Online]. Available at: https://www.tate.org. uk/art/artworks/long-a-line-made-by-walking-ar00142 (Accessed 5 October 2023).

Cook, W. (2018) I walk the line: How Richard Long turns epic journeys into art [Online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/1lwlwQLyGK4FR0lTPTklBh9/ i-walk-the-line-how-richard-long-turns-epic-journeys-into-art (Accessed 5 October 2023).

Douglas, K. (2023) The first artists. New Scientist. Issue No. 3465, 18 November 2023, p32-35.

Everypicture.org (No date) Every Picture Tells a Story – Different Ways of Seeing: 'The Hay Wain' by John Constable, 1821 [Online]. Available at: https://www.everypicture. org/the-hay-wain-by-constable#:~:text=The%20Hay%20Wain%2C%20by%20 John,painter%20(after%20his%20death). (Accessed 31 January 2024).

Fondation Beyeler (2012) What is Art? - 27 Questions 27 Answers. Berlin: Hatje Cantz. Fondation Beyeler (No date) What is Art? [Online]. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=yMiK7dj33S8 (Accessed 7 October 2023).

GCFLearnFree (2018) What is Art? [Online]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=QZQyV9BB50E&t=16s (Accessed 1 October 2023).

Grovier, K. (2017) The urinal that changed how we think [Online]. Available at: https:// www.bbc.com/culture/article/20170410-the-urinal-that-changed-how-we-think (Accessed 5 October 2023).

Gur, T (No date) Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it- Bertolt Brecht. What's the meaning of this quote? [Online]. Available at: https:// elevatesociety.com/art-is-not-a-mirror/ (Accessed 1 October 2023).

Marder, L. (2019) Ways of Defining Art [Online]. Available at: https://www.thoughtco. com/what-is-the-definition-of-art-182707 (Accessed 1 October 2023).

Meyer, I. (2021) Why is Art important? – The value of Creative Expression [Online]. Available at: https://artincontext.org/why-is-art-important/ (Accessed 5 October 2023).

Oxford English Dictionary (No date) Art [Online]. Available at: https://www.oed.com/ search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=art (Accessed 7 October 2023).

Penguin Books UK (2014) Grayson Perry: ‘What is Art?’ [Online]. Available at: https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=xClNKXM1pao (Accessed 7 October 2024).

Perry, G. (2016) Playing to the Gallery, 2nd edn. London: Penguin Random House UK. Persson, U. (2009) What is Art?: L. Tolstoy [Online]. Available at: http://www.math. chalmers.se/~ulfp/Review/whatart.pdf#:~:text=To%20Tolstoy%20Art%20is%20 simply%20the%20transmission%20of,just%20as%20speech%20is%20a%20 communication%20of%20thought (Accessed 7 October 2023)

Peterson, C. (2023) David Shrigley: Artist pulps 6,000 copies of 'The Da Vinci Code' and turns them into '1984' [Online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/ entertainment-arts-67218454 (Accessed 26 October 2023).

Stonard, J. P. (2018) Opinion: When does Art become Art? [Online]. Available at: https:// www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-44-autumn-2018/opinion-john-paul-stonard-artmakes-artists (Accessed 1 October 2023).

Wei-Haas, M. (2021) This 45,500-year-old pig painting is the world’s oldest art animal [Online]. Available at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/45500year-old-pig-painting-worlds-oldest-animal-art (Accessed 1 October 2023).

White, L. (2013) The Art of the Sublime - Damien Hirst’s Shark: Nature, Capitalism and the Sublime. Tate Research Publication [Online]. Available at: https://www.tate.org. uk/art/research-publications/the-sublime/luke-white-damien-hirsts-shark-naturecapitalism-and-the-sublime-r1136828 (Accessed 31 January 2024).

Images:

Anon (No date) The Great Black Cow. Lascaux Cave: Ministère de la Culture. Azam, U (2019) Photo of Cattelan's The Comedian. Unsplash.com.

Kotov, M (2020) Photo of person viewing Banksy's Girl with Balloon. Unsplash.com. Van Gough. V (1889) Sunflowers. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Arts and Philosophy

Should We Invest in the African Fashion Industry?

Nancy Christensen, Lower Sixth, Swift House. Supervised by Miss Hutchinson.Clothing is a necessity, not a want. But it can also be a form of art, self-expression and culture. The textile industry can bring together communities and allow individuals to display their creativity and ideas. My research project looks at why companies are hesitant to invest in the African Fashion Industry and why considering these investments may be beneficial, not only for Africa’s economy but also for their community. However, the challenge lies within the issue of whether we are willing to pay the extra cost for the people and the planet to be sure that what we consume is produced ethically.

When we consider major global fashion industries, instantly thoughts of Paris, New York and London all come to mind; Africa is less obvious. It is therefore evident that their reputation is something that is holding investors back. African countries need to create more exposure to their ideas and designs, for example, running fashion shows. An easier solution for designers would be to use social media to create a positive image for their brand and to advertise their designs which would allow them to quickly reach more people. In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s short story The Danger of a Single Story, she explores how perceptions of Africa largely stem from issues they have seen on the news and how a misunderstanding can cause us to create our own ideas of what a place or person is like. This becomes our 'single story'. African countries could combat misjudgement by narrating their own stories far from the perspectives that outsiders may have.

Global fashion retailers commonly host fashion weeks which not only promote their brands and inspire creativity but also bring buyers and educators into the country from all over the world. By improving the image of Africa through buzzing international events, this will hugely impact tourism, ultimately increasing the number of visitors spending in the area. This will be beneficial for other areas of their economy too; employment is focused around industries such as agriculture in Africa – yet there are so many opportunities for employment in the fashion industry. One job created in the textile process leads to the creation of five other jobs, at least, in packaging, advertising and transportation. If there is an increase in tourism, it is likely we will see an increase in employment as the demand of goods will be higher.

Another obstacle that must be identified is the lack of infrastructure. The lack of productive capacity is currently hindering companies from scaling up their brand and rate of production. With limited transport links and factories, the investments are essential for the industry growth. Without the correct working environment, it is difficult to produce high quality goods. Investors are commonly put off investing because of the poor standard of garments produced as a result of insufficient education. The unemployment rate in African countries is growing; in 2022, South Africa had the largest unemployment rate of 32.6%. If the quality of training, wages and working lifestyle can improve then this could have an impact on reducing the high unemployment rate in Africa. It’s also likely that improving the quality of their working environment and training will improve productivity and standards of goods. As the quality and quantity of produce starts to increase, Africa will gradually become more worthy of consideration by other countries when trading and manufacturing. Is it worth considering how South Africa may suffer in the future if investment and efforts aren’t made now? They risk the rates of unemployment increasing in young people entering the fashion industry.

The final reason that should be discussed as to why these companies are unsure of investing is because of the lack of local demand. Locals are favouring internationally imported goods over their local produce because goods produced within the area are charged at a higher price than their disposable income allows. Why would international companies bother investing if even the African community are going to opt for purchasing imports from western countries instead of their own garments? Many African countries take pride in their culture and community so it is important for them to be able to afford to purchase their local designs.

It is clear that Africa is not optimising their local resources because, according to the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), nearly 60% of textile imports sold in South Africa come from China. For possible investors, this will make them realise that there are no benefits to investing in Africa when competitors such as China are such an obvious choice, providing cheap garments at a fast rate and on a large scale. Africa however, could offer something unique to global retailers and the key is focusing on promoting ethical sustainability. There has a been a huge shift in purchasing from brands and high street shops to shopping second hand, with increased awareness on the environmental impacts of fast fashion (mass production of clothes) and disposal into landfill. This is particularly notable in the younger generation. This shift in consumer behaviour is something that will hugely weaken the big brands; they will find it difficult to change so quickly as fast response to trends is their USP. Because of the scale of Africa’s textile industry, they are much more able to adapt to these changes in consumer demand and they should use this to their advantage. For example, if South Africa make using sustainable resources their USP then Western investors will start to consider how this may positively impact their brand loyalty. For consumers, especially younger members of the population, the importance of protecting the environment is becoming increasingly relevant. For international textile retailers, they will want to avoid having a reputation of suppliers that are known for their low labour rates or unsustainable materials.

It is difficult to measure how much a person is willing to pay in order to be sure that what they are consuming is positive for the people and the planet. This is an obstacle that faces all kinds of industries. A simple example of this would be, when entering a supermarket, consumers make claims that what they purchase will be locally produced or 'Red Tractor' goods. However, when faced with the decision it is likely they will opt for the cheapest option of a particular item, even when knowing that perhaps it has been imported from overseas. This is due to the

'Rational Choice Theory'; created by Adam Smith which suggests that an individual always makes a choice that is most beneficial to them and matches their preferences. No matter how much an individual is educated on the negative impacts of making a particular choice, it is likely they will still choose the easiest option. A higher quality good that is produced ethically can only be supplied at a higher price than alternatives. The way we can target this issue is by considering how other people’s opinions can cause us to change our own view. Recently, philosophers from Science online journal have made adaptions to Malcolm Gladwell’s concept The Tipping Point by suggesting that once 25% of the population follow a certain trend or view, then this causes a tipping point in society and other members of the public will follow. If the younger generation can be educated on the importance of understanding where and how your clothes are supplied, then it is more likely that society could reach the tipping point and the habits of consumption will change almost permanently.

The USP is an essential part in building the foundation of a business and separating yourself from competition within the industry. For Africa, the opportunity to promote ethical production will set them apart. Working with investors will help African countries to improve their brand image and fashion reputation. Improvements in infrastructure and education are necessary if Africa want to expand their production and quality of goods. Africa could bring a new element to the industry with their focus on embracing culture and community, an opportunity that investors shouldn’t miss as the population and demand grows.

References:

Africa Strictly Business (2013) Africa’s Fashion Industry: Challenges, Opportunities [Online]. Available at: https://www.africastrictlybusiness.com/africas-fashion-industry-challengesopportunities/ Date accessed: 20/10/2023

BBC News (2018) Reality Check: What are the tariffs on trade with Africa? [Online] Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-45342607 Date accessed: 20/10/2023

Compass Online Library (2021) Africa Fashion Futures: Creative economies, global networks and local development [Online]. Available at: https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ full/10.1111/gec3.12589 Date accessed: 12/11/2023

BBC News (2018) The story behind Africa's free trade dream [Online]. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-43458294 Date accessed: 7/11/2023

BBC News (2020) Global fashion industry facing a 'nightmare' [Online]. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-51500682 Date accessed: 19/09/23

Fashion United (2016) Fashion statistics China. Available at: https://fashionunited.com/ statistics/china Date accessed: 17/09/2023

Annan, R. (2022) The Future of Fashion in Africa [Online]. Available at: https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=JQRT-8Xjd4w Date accessed: 17/09/2023

Britannica (2024) Resources and Power [Online]. Available at: https://www.britannica. com/place/South-Africa/Transportation-and-telecommunications Date accessed: 21/11/2023

Science (2018) Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention [Online]. Available at: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aas8827 Date accessed: 22/01/2024

Image:

Boafo, D. (2021) Runway models. Unsplash.com

Arts and Philosophy

AHow Does the 2017 Lowery Film A Ghost Story Give Answers to the Ontological Question of Legacy?

Sam Farr, Lower Sixth, Swift House. Supervised by Mr Elkin-JonesGhost Story (2017), the third film by director David Lowery, is about a married couple –known only as C and M – who live out a banal existence in rural suburbian America. Lowery began as an indie sensation with his film Ain’t Them Bodies Saints (2013), and after helming the Disney reimagining of Pete’s Dragon (2016), used his subsequent ‘blank cheque’ to fund the production of A Ghost Story.

Arguably, there were few identifiable thematic patterns to be seen in his body of work until the production of A Ghost Story. This was a passion project of his. It attempted to explore Lowery’s philosophical perspective about legacy, an interest that was explored in greater depth through his later film adaption of the great medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

In A Ghost Story, Lowery considers questions surrounding what makes a valuable legacy, the meaning of life, and the irrevocable ephemerality of existence. To help with understanding when I reference the film, I have provided a brief plot summary below.

A Ghost Story: a plot summary

When C dies from a car accident, instead of passing on to the next life, he remains. Covered in a sheet with two eyeholes, C returns to the house he shared with his wife as a ghost and haunts it for years that pass by in moments, picking at a crack in a wall that holds a note his wife left behind. Millenia pass, and for C, time becomes something relative. He retrieves the note, and upon reading it he disappears, passing on to whatever comes next.

Happiness, quiet, joy and esoteric dialogue

The British philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) said ‘A happy life must be to a great extent a quiet life’ (The Conquest of Happiness, 1930) and Lowery explores the importance of the couple’s quiet life through emphasis on the intimacy they share, as if to reflect the rest of Russell’s famous quotation: ‘for it is only in an atmosphere of quiet that true joy can live.’ The use of a 1:33 aspect ratio in A Ghost Story makes the shot squared, with vignetted edges that present an inherent closeness to the couple. To be shown such a personal view of such an ordinary life feels improper, as this life of two people is one that appears so unremarkable you would never hear of it, let alone literally see it unfold. In the brief snatches of conversation we see between the couple, they are full of inside jokes and spontaneity. This is done to make

it difficult for the spectator to understand what is going on, as they know little of the context or couple’s meaning. This natural, intimate dialogue reflects the ordinary existence of the couple; there is no conventional use of exposition written into the script’s ‘narrative’ to make processing their conversations any easier. The seemingly idiosyncratic dialogue therefore creates more a sense of their regular, daily intimacy, as opposed to serving narrative purpose to serve the viewer.

Deliberate lighting

Despite there being so little dialogue, its absence is deeply felt after C’s death. This natural atmosphere is imitated by the minimal use of artificial light. The films’ cinematographer, Andrew Droz Palermo, said ‘[his] lighting package and [his] camera package were extremely small’ (Filmmaker Magazine, 2017). The film relies mainly on natural lighting conditions to maintain this intimacy, as nothing has been altered or changed for the viewer. The sparse lighting – outside of the hazy dawns and smoky urban wastelands – sustains the minimalist, possibly vapid nature to the life of C and M. Yet it is this apparent normality that C later realises is most important for his legacy.

Editing: long takes

Since its first showing at the Sundance Film Festival, A Ghost Story has gained some notoriety for its ‘pie-eating’ scene. In it, the bereaved M devours a chocolate pie in a single five-minute-long take, as C, now in his ghostly form, lingers in the corner of the frame. Lowery, a man who can barely stand to watch the films he creates, says it’s ‘the best thing [he’s] ever done.’ Rooney Mara, the actress playing C, was not so fond of it. ‘Oh, God.’ She said ‘It was some disgusting sugar-free, gluten-free, vegan chocolate pie. It was really gross’ (Indiewire, 2017). Despite – or maybe because - of the difficulty filming it for the actress, the scene is a pitiful breakdown captured in its entirety. Here we can see Lowery exploring the painful process of grief. The breakdown of M is reminiscent of lines Shakespeare gave to in Act Four to the eponymous character in Macbeth: ‘Give sorrow words; the grief

that does not speak knits up the o’er wrought heart and bids it break.’ Here we see M – someone who has withheld her grief and remained unemotional thus far – break and ‘give sorrow words,’ so that she can begin the process of acceptance, something C cannot do.

Distorting time

Furthermore, the static take that refuses to cut denies the person watching respite from the intensity of such a moment, and it denies M the privacy someone deserves in such a moment. Here, Lowery is trying to communicate that in the maelstrom of loss, acceptance, legacy, and grief, the extensive shots provide a comfort for the viewer. In the slow, empty spaces little happens, but that does not make them unimportant. From a technical perspective, the decision to shoot the world of the ghost in thirtythree frames per second with the world of the living at twenty-four frames per second confirms the spatial disconnect between the grieving couple. Backed by a minimal score and fuelled by the ambient soundscape of birds and wind, they are vital in capturing the beauty in the banal. It is in these shots that the subtlety of Lowery’s approach reveals the delicacy of legacy as something not always tangible but qualitative, as the director says:

‘And sure enough, we do what we can to endure. We build our legacy piece by piece, and maybe the whole world will remember you, or maybe just a couple of people, but you do what you can to make sure you’re still around after you’re gone.’

The prognosticator appears

During the latter half of the film, in a house party full of adults, there appears a man, known only as ‘The Prognosticator.’ A prognosticator is a person who foretells or prophesises a future event. This character sits around a dining table littered with plastic cups and monologues for five-minutes to the people around him. His monologue is depressingly nihilistic, predicting a future for humanity that, no matter the resilience, will fundamentally end with everything being forgotten. Deliberately with this reference in mind or not, it aligns with comments made by the twentieth century Romanian philosopher, Emil Cioran says: ‘There is no other world. Nor even this one. What, then, is there?’ (The Trouble with Being Born, 1973). It is this inherent meaningless The Prognosticator tries to communicate; that, when nothing matters, there is ‘the inner smile provoked by the patent nonexistence of both.’ And this is what the ghost learns: the apparent lack of substantial existence and meaning forces a person to find meaning and amusement through internal experience, to find inner peace in the recognition of the illusory nature of reality:

'You can write a play and hope that folks will remember it… keep performing it. You can build your dream house… but ultimately none of that matters any more than digging your fingers into the ground to bury a fence post.'

These words from The Prognosticator should not be taken as an objective truth, more as Lowery representing the fears that develop from the ephemerality of life and legacy. He is pretentious, and I would say that his title – ‘prognosticator’ – is a mocking term, because whilst he cannot see the ghost watching him throughout the monologue, there is a deep irony in complaining about the permanence of death and the futility in forming worthwhile connections and a legacy when in the presence of a ghost. I would argue the value of the prognosticator’s presence is only in communicating what Lowery is trying not to do, as C’s entire journey is about disputing this type of unproductive nihilism:

‘Whatever hour you woke there was a door shutting.’

So begins the Virginia Woolf short story A Haunted House, as does A Ghost Story

The intertextual references

Hovering over a black screen, these words seem confusing until you read the story they reference.

Lowery, in an Indiewire interview spoke of how crucial Woolf is to the text, as her writing ‘corresponds perfectly to my difficult-to-grasp perspectives on ghosts and spectres and their relationship to life and time.’ (Indiewire, 2017) Set in a house where the narrator, assumed to be female, believes there are ghosts haunting the house, is how A Haunted House begins. This ghostly couple reminisce about the house – one they used to live in:

‘Here we left it,’ she said. And he added, ‘Oh, but here too!’

‘It’s upstairs,’ she murmured. ‘And in the garden,’ he whispered.

They are recollecting something, a ‘treasure’ they are attached to; something non-existent in the realm the ghostly couple reside in. Their presence holds no physical impression on the existing couple, as seen through the emptiness where they supposedly reside:

'Not that one could ever see them. The window panes reflected apples, reflected roses; all the leaves were green in the glass.'

Despite this physical disconnect, there appears to be a spiritual connection between the woman and the ghostly couple found in her semi-conscious state:

'Stooping, holding their silver lamp above us, long they look and deeply. Long they pause.'

It is this connection that permits the women to realise the ‘treasure’ the ghostly couple are talking about. And so, the women, waking from her sleep, discovers the ‘it’ they are referring to:

‘Oh, is this your buried treasure? The light in the heart.’

In other words, the love existing between the living couple, the ‘burning’ warmth within them. The ghostly couple were only ever looking to remind themselves of the love they shared. After spending years wondering about his legacy, C, like the woman, realises the ‘treasure’ he seeks is not something concrete. The lack of legacy he has spent millennia trying to make sense of was not something physical. It was the love he shared with M. It did not have to be something he could touch for it to have been valuable, he realises. It only had to have value. Where physical

aspects of legacy may transcend a couple generation (think back to The Prognosticator’s monologue about the ephemerality of even the most impactful pieces of physical legacy), his love with M will always be attached to the house. Whether it be rubble or a patch of grass, their love will always transcend the physical, and can be found in every loving couple that will come to be:

M: What is it you like about this house so much?

C: Seriously?... History.

M: What does that mean?

C: We’ve got history.

M: Not as much as you think.

Lowery explores how C realises the value of legacy and accepts his position as a ghost through creating a narrative that shifts frequently. This experimentation with narrative structure becomes disorienting for the viewer, as they are tossed between a distant dystopia, a 19th century frontier, and even C haunting his living self. This idea presented in a Sight and Sound review of the film, which describes this shift in time as ‘a kind of infinite reverb that shows reality to be no longer sustainable’ (Sight & Sound, 2017). It is as if the state of limbo C occupies is attempting to flush his presence out. He is put into a position in which he is able to access what he has been searching for: the note left by M. He is locating the treasure in the same way the woman was in Woolf’s short story. By watching the moments he and M made their legacy, he comes to realise what the legacy of the ghostly couple is: the unquantifiable love they had together, and not their quantifiable contributions to the world; so much so that when he watches himself die and become a ghost again, he goes to the crack in the wall, and retrieves the note he has spent all this time searching for:

M: When I was little, we used to move all the time, I’d write these notes, and I would fold them up really small… and I would hide them in different place, so that if I ever wanted to go back, there’d be a piece of me there waiting.

C: Did you ever go back?

M: No.

C: See? That’s what I’m saying. M: ‘Cause I did not need to.

This shared moment between C and M at the beginning of the film is one that he obsesses over in death, spending most of his time as a ghost scratching at a crack where M had left her note, thinking it may give him what he needs in accepting his death and passing on to whatever is next. It was Mark Twain that wrote that ‘the fear of death follows the fear of life. A man who lives fully is prepared to die at any time.’ (Autobiography of Mark Twain, 2010) This idea of C feeling chagrin about his death is frequently alluded

to by Lowery, and he conveys this concept through C’s seemingly unending quest for meaning in the afterlife, even if the answer to the question resided with the living. Part of the acceptance for C is, to echo Mark Twain once more, realising he did live fully, even if he was unsure of it. When he retrieves the note, C disappears, realising what he has been searching for all this time resides in a presence he is no longer fully attached to. He can no longer touch or regain what he is after. He has found his ‘treasure’ and can now pass on because of this realisation. Whether it be rubble or a patch of grass, the love between him and M will always transcend the physical and can be found in every loving couple that will come to be.

A lesson in letting go

A Ghost Story is a lesson in letting go; an admission to the ephemerality of existence, and that whilst the physical legacy we leave behind will eventually be forgotten, pure human connection will not. Through the understanding of Woolf’s short story, alongside the various stylistic techniques chosen, C comes to terms with this fact. Lowery explores the concept of quantifiable legacy as something that should not be a requirement for a fulfilled life, rather that sometimes devoting yourself to another creates a legacy that will linger longer than any symphony or novel.

References:

Cioran, E. (1973) The Trouble with Being Born. London: Penguin Books Limited. Filmmaker Magazine (2017) DP Andrew Droz Palermo on 'A Ghost Story', Shooting 1.33 and That Pie Shot [Online]. Available at: https://filmmakermagazine.com/103086-dpandrew-droz-palermo-on-a-ghost-story-shooting-1-33-and-that-pie-shot/ Indiewire (2017) 'A Ghost Story': David Lowery Interview — Making Of, Rooney Mara, Casey Affleck [Online]. Available at: https://www.indiewire.com/features/general/aghost-story-david-lowery-interview-making-of-rooney-mara-casey-afflecksundance-2017-1201774735/

Russell, B. (1930) The Conquest of Happiness. London: Routledge Press. Sight & Sound | BFI (2017) 'A Ghost Story' review: David Lowery explores the delirium of grief [Online]. Available at: https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-soundmagazine/reviews-recommendations/ghost-story-david-lowery-grief-delirium-review Twain, M. (2010) The Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 1. California: University of California Press.

Woolf, V. (n.d.) A Haunted House [Online]. Available at: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/ english/documents/innervate/12-13/06-sophia-achillea-hughes,-q33354-virgina-woolfpp-46-49.pdf

Woolf, V. (n.d.) 'A Haunted House' by Virginia Woolf: What It Means to Feel and to Flow [Online]. Available at: https://medium.com/the-afterglow/ahaunted-house-by-virginia-woolf-what-it-means-to-feel-and-to-flow-e8 d495a8b136%23:~:text=A%2520Haunted%2520House%2520both%2520 is,seem%2520to%2520clearly%2520see%2520them.

Woolf, V. (1921) A Haunted House. London: Hogarth Press.

Images:

Escate, K. (2020) Ghost Photoshoot. Unsplash.com.

Naništa, J. (2016) Psychiatrická nemocnice Bohnice. Prague: Unsplash.com.

How Have Cats Become Domesticated Throughout History?

Alex Hancox, Fourth Form, Harcourt House. Supervised by Mr Elkin-Jones.Picture this: you are in your home on a cold winter’s day sitting reading a book; you are engrossed. And then your cat jumps up onto your lap and starts settles down to sleep. In the peace of the moment, you find yourself wondering 'Why do cats like us? Why do we like them? And why did they come to live with us from the wild anyway?' In short, where do our cats come from?

Arts

Cats: the origins of domestication

It is true that a wild cat is a coldblooded killer. Their claws are like daggers ready to rip into its prey; their teeth as sharp as their claws. In fact, it is estimated that in the USA alone 'free-ranging domesticated cats kill between 1.3-4.0 billion birds and 6.3-22.3 billions mammals annually' (Loss, Will & Marra, 2013). This demonstrates that they truly are the silent killers that stalk the night. These statistics would suggest that cats would not make good pets but research, and our lived experience, suggests otherwise.

It is true that the first animals to be domesticated were wolves that eventually became dogs. According to current experts the early stages of our relationship between the two species 'were ones of increasing co-existence, observation and learning' and 'this may have persisted for 20,000 years or longer'. Gradually 'in other parts of the world, for example, southern Asia, humans began to shape wolves into clearly domestic forms: animals phenotypically distinct from wolves, especially in body size' (Pierotti & Fogg, 2017). However, one of the next animals to be domesticated were the wild cats. The earliest example of the start of the domestication was when wild cats lived alongside people of Mesopotamia over 100,000 years ago, leading to cats probably becoming domesticated for farming purposes (Mark, 2012). It is true that the people of Mesopotamia created and lived their lives around bodies of water due to its scarcity in that dry region. This crop growth in such an climate area led to the rise of many pests, especially rodents. This led to the farmers needing something to protect their crops. The answer was simple, willing and right in front of them. Cats. The relationship equation was simple: the cats caught the rodent pests; we gave shelter and tolerated the presence of the cats. Thus started the period of domestication.

Formalising the relationship between ritual and worship

The evidence for this synergetic relationship is numerous, and for a long time the accepted wisdom that the process began in Egypt around 2,000 BCE. Yet recent research has challenged this position. A human burial site in Cyprus, dating from 7,500-7,000 BCE in the neolithic period, illustrates the first steps in the domestication process:

'The cat buried with the human was approximately eight months old and had almost reached its adult size. The morphology of the skeleton suggests that it was a big cat, similar to wild cats found in the Near East today. The morphological modifications of the skeleton associated with domestication are not yet visible, justifying the use of the term 'tamed', rather than 'domesticated'.'

The human grave contained 'a variety of polished stones, tools, jewellery and other items believed to be offerings. A small pit with 24 complete seashells lay nearby. The offerings were relatively rich for time and region, however, implying that he or she enjoyed some degree of social status'. Given the deliberate nature if this burial, it seems this is now the oldest burial of a domesticated animal with its owner (The Archaeologist, 2021).

With the Ancient Egyptians, from about 2,000 BCE, we find the first firm evidence of the mutual co-existence of cat and human, but by this time the relationship was moving from ‘tamed’ towards ‘guest’ and even ‘god’. In Ancient Egypt, the cat was seen as a vessel for gods, given their mannerisms and characteristics. The first evidence of actual cat worshipped comes from the Middle Kingdom, in the reign of Mentuhotep III. In fact, the Egyptians cared for their cats so much that they started mummifying the cats due to a superstition of the vessel being destroyed after death. The Ancient Egyptians even had law forbidding any person from taking a cat out of the country with the punishment for this crime being

death. It is believed though that the goddess that the cats were a vessel for was called Bastet.

Superstitions and Misconceptions

After the Ancient Egyptians, cats seem to have become embedded and accepted in a very wide range of ways, depending on the society involved. Some societies accepted cats to be used strictly for work, keeping rodents away from food stores; in others, they were worshipped. However, there were also societies where cats were regarded with suspicion, especially if they became linked with those on the extremities of those societies. One type of cat stood out: the black cat. Nowadays, the black cat is something of a cliché, used as a trope in horror fiction and films, associated with bad luck, and all things evil. But where did this cultural meme come from? And why do we as humans now best associate the black cat with Halloween? The earliest example of mistrust towards black cats was during the Middle Ages when black cats became intertwined with black magic. Black cats were thought to be witches' familiars. They were described as animal-shaped demons that had been sent by the witches to spy on humans. And this could have been where the relationship between black cats and Halloween came from. Later in history in the black cat would crop up again in 16th-century Italy where it was believed that death was imminent if a black cat lay on someone's sickbed. (Syufy 2023)

The persecution of cats

Cats have also been persecuted. The first time on a significant scale was directly related to Christianity and the Pope, specifically Pope Gregory IX. The event was termed The War on Cats. During his reign, the Pope held antagonistic views about cats but his strongest belief was that cats were Satan in a fur coat. Reinforced by the backing of his loyal advisors, during the years 1233 to 1234, loyal Christians around Europe exterminated mass numbers of cats and drove the remaining cats out their cities and towns. Some historians believe that this event started the traction for later human witch trials. Yet historians believe it was society that suffered as a result, for when the Black Death hit Europe more than one hundred years later there was a significantly smaller number of cats to manage the rat population that cats traditionally kept at bay. Consequently, the Black Death spread faster due to the vermin having a lessened number of predators. (Janssen 2022)

Famous People and their cats

Yet despite this unfavourable record, cats have impacted people in a positive way in the domestic sphere. One figure that stands out is Abraham Lincoln. Whilst many know Lincoln to be the first president to be assassinated in office or his vital role in the American Civil War, few know about his

passion for animals. Before becoming President, Lincoln owned a dog, but due to complications was forced to leave his dog in Springfield. Once in office, his Secretary of State gifted Lincoln two cats which he named Tabby and Dixie. There are many sources that give us insight into how Lincoln operated with his cats. One of the sources claims that during a formal dinner party Lincoln started to feed Dixie much to the dismay of many onlookers one of which was his wife. (Presidential Pet Museum 2014). Another time out of pure frustration it is stated that Lincoln burst out claiming that 'Dixie is smarter than my whole cabinet. And furthermore, she does not talk back.' This showed that the cats helped the most influential people and gave them joy.

Conclusion

To conclude, like every animal, the cat adapted to survive, and by allowing itself to become domesticated, it cemented its fate with humans, sometimes for ill, but largely for good, and now the fully domesticated cat seems able to be resting upon the 9,000 years of effort its predecessors made for it. Now imagine this: you are in your home on a cold winter’s day sitting reading a book; you are engrossed. And then your cat jumps up onto your lap and starts settles down to sleep. And, more importantly, you know the history of cats.

References:

Admin (2020) 12 Amazing facts about cats in ancient Egypt [Online]. Available at: historicaleve.com/facts-about-cats-in-ancient-egypt/

Anon (2021) Neolithic Cat Burial in Cyprus; The oldest known evidence of taming of cats. The Archaeologist [Online]. Available at: www.thearchaeologist.org/blog/neolithic-cat-burial-in-cyprus-the-oldest-knownevidence-of-cat-taming

Clare, F. (2022) The Legend of Unsinkable Sam: Did This Death-Defying Cat Really Exist? [Online]. Available at: www.warhistoryonline.com/world-war-ii/unsinkable-sam.html Feeney-Hart A. (2013) The little-told story of the massive WWII pet cull [Online]. Available at: www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-24478532

Janssen M. (2022) When Pope Greggory IX Declared a War on Cats [Online]. Available at: historycolored.com/articles/7385/when-pope-gregory-ix-declared-a-war-on-cats/ Loss, S. Will, T. and Marra, P. (2013) The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nature Communications [Online] Issue 4, article 1396. Available at: doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2380

Mark, J. (2012) Cats in the Ancient World [Online]. Available at: www.worldhistory.org/article/466/cats-in-the-ancient-world/

McKie, R. (2023) First cat in space: how a Parisian stray called Félicette was blasted far from Earth. The Guardian [Online]. Available at: www.theguardian.com/science/2023/sep/09/first-cat-space-felicette-orbit-humansearth-atmosphere

Guilaine, J. and Haye, L. (2004) Oldest Known Evidence Of Cat Taming Found In Cyprus. Science Daily [Online]. Available at: www.sciencedaily.com/ releases/2004/04/040409092827.htm

Pierotti, R. and Fogg, B. R. (2017) 'The Beginnings', The First Domestication: How Wolves and Humans Coevolved. New Haven, CT, [Online]. Yale Scholarship Online, 2018. Available at:doi. org/10.12987/yale/9780300226164.003.0001

Presidential Pet Museum (2014) Abraham Lincoln's Cats [Online]. Available at: www. presidentialpetmuseum.com/pets/abraham-lincoln-cats/

Smith, C. (2017) Cats Domesticated Themselves, Ancient DNA shows. National Geographic [Online]. Available at: www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/ domesticated-cats-dna-genetics-pets-science

Syufy (2023) Myths and Superstition about black cats [Online]. Available at: www.thesprucepets.com/black-cat-superstitions-554444

Image:

Cedric Photography (2019) Looking at the sun. Unsplash.com.

Arts

Beyond the Pastoral: How Did the Greeks and Romans do Literary Criticism?

Finn Van Landeghem, Lower Sixth, Vanbrugh House. Supervised by Mr Waldron.

The way in which the Romans and Greeks viewed poetry and literature changed over time, however some aesthetic principles seem to permeate through most parts of Roman literature. These poetic practices were perfected by the Augustan and neoteric poets of ancient Rome but find their roots in the Greeks of Alexandria and Athens almost 300 years earlier. This essay is an exploration of said ideals and images and their origins in the works of the Augustans and their provenance in earlier Greek works.

The Augustan period was one of great change for the Romans, with the founding of one of the world’s greatest empires and the consecration of their culture. This golden age was defined and remembered by their ingenuity of adapting and creating their own culture, which was done through the aesthetic changes discussed below. These changes had such a large impact on the way in which poetry is perceived and written, that their values still permeate through the greatest poets of the modern age. One of the best Augustan poets is undoubtedly Virgil, best known for his epic The Aeneid, which transported the Greek epic tradition into the Roman culture. He also wrote epyllion. Epyllion is a new literary form, which was popularised by the Augustans. It is a smaller form of epic with the subject matter being much less heroic and much more imperfect and contrived. Within Eclogue 6 Virgil uses many metaphors to do literary criticism:

Cum canerem reges et proelia, Cynthius aurem vellit, et admonuit: 'Pastorem, Tityre, pinguis pascere oportet ovis, deductum dicere carmen.'

When I sang of kings and battles the Cynthian grasped my ear and warned me: ‘Tityrus, a shepherd should graze fat sheep, but sing a slender song.’ (Kline 2001)

The notion of ‘kings and battles’ is a reference to epic, with its heroic themes, and the image of the ‘Cynthian’, alluding to Apollo, god of the muses, grasping Virgil by the ear and telling him to ‘graze fat sheep but sing a slender song’, is a recurring image in the new sensibilities of poetry. The slenderness, both referring to the length of a poem and the subject matter of a poem, meaning a poet’s words should be light yet very detailed, rather than heavy and abstract. Furthermore, Virgil sets out to write:

agrestem tenui meditabor arundine Musam.

I’ll study the rustic Muse on a graceful flute. (Kline 2001)

It shows the self-aware nature of the new poet as he must choose carefully what to write. ‘The rustic muse’ implies that Virgil will take on pastoral themes in his poem yet sing it ‘with a graceful flute’, again reasserting his desire for a refined approach. Lastly, the Eclogue is a nested narrative, which adds to the complexity of the poem, which was another essential part of the poetics.

One form of the epyllion is done by neoteric poet Catullus, in which he explores the wedding of Thetis and Peleus, mother and father of famed hero Achilles. In Catullus 64 we see many of the same features reappear as in the Eclogue, but Catullus places a particular emphasis on the Alexandrian qualities within his writings, mainly extensive pastoral description and learned references. The reason for this is that epic started as an oral tradition, performed for the masses with familiar stories of heroes and legends. But these new aesthetic practices called for a less accessible poetry, steeped in obscure references, to make the reader think and force a sort of elitism onto poetry. Catullus in his opening lines sets the scene through peculiar geography alluding to the story of Jason and the Argonauts:

Peliaco quondam prognatae vertice pinus dicuntur liquidas Neptuni nasse per undas Phasidos ad fluctus et fines Aeeteos, cum lecti iuvenes, Argivae robora pubis, auratam optantes Colchis avertere pellem ausi sunt vada salsa cita decurrere puppi, caerula verrentes abiegnis aequora palmis.

The noble pine trees bred on Pelion's top Once swam, they say, through Neptune's sliding element

As far as the river Phasis and the realm Of King Aeetes; that was when the pick And pride of the young Argive chivalry Burning to loot the Golden Fleece from Colchis,

Dared the salt depths in their impetuous ship, Churning the blue to white with firwood blades. (Burton 1894)

The first two lines referring to the Argo, Jason’s ship, fashioned from the trees on Pelion by the gods, introducing the narrative of Jason and the Argonauts as they sail across Greece in search of the Golden fleece. Notice the fifth foot spondee, which is rare in most verse but for Catullus it is a neoteric signature, which places an emphasis on emotion and drama. However, the subject matter then completely shifts to Peleus, one of the Argonauts, who falls in love with Thetis a sea-nymph, and their wedding. Then the subject matter shifts again with an ecphrasis to an embroidery of Ariadne left, by Theseus, on the island of Naxos. Ariadne retells the story of what occurred on Crete and Theseus’ apparent betrayal. The poem proceeds to switch back to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis and the destiny of their son, Achilles is foretold (Higgins 2007).

Many Augustan ideals are propagated through imagery and metaphor, especially by writers such as Horace, Ovid, and Propertius. Horace uses the metaphor of a bee and a river to describe the differences in poetic disciplines of him and his Greek predecessor Pindar (Odes 4.2):

Monte decurrens velut amnis, imbres quem super notas aluere ripas fervet immensusque ruit profundo Pindarus ore.

The river burst its bank and rushes down a mountain with uncontrollable momentum rain-saturated, churning, chanting thunder there you have Pindar’s style.

(Hart-Davis 1964)

The metaphor of the river perfectly describes the aesthetic values of previous poets, weighty words, long and too powerful texts, yet dirty and common. While the metaphor of the bee describes Horace’s style:

… ego apis Matinae more modoque

grata carpentis thyma per laborem plurimum circa nemus uvidique Tiburis ripas operose parvus carmina fingo

I who resemble more the small laborious bee from mount Matinus gathering from Tibur’s rivery environs The thyme it loves, find it as hard to build up poems as honeycomb. (Hart-Davis 1964)

The bee’s fragility and sensitivity represent the poet’s precision, as do the learned references, while its size reflect the poet’s lyrical form, and the honeycomb represents the poem's inherent complexity. These same values are seen in Propertius 3.3:

Visus eram molli recubans Heliconis in umbra, Bellerophontei qua fluit umor equi, reges, Alba, tuos et regum facta tuorum, tantum operis, nervis hiscere posse meis; parvaque iam magnis admoram fontibus ora …

cum me Castalia speculans ex arbore Phoebus sic ait aurata nixus ad antra lyra: 'quid tibi cum tali, demens, est flumine? quis te carminis heroi tangere iussit opus? non hinc ulla tibi sperandast fama, Properti: mollia sunt parvis prata terenda rotis; ut tuus in scamno iactetur saepe libellus, quem legat exspectans sola puella virum. cur tua praescriptos evectast pagina gyros? non est ingenii cumba gravanda tui.

I dreamt I lay in Helicon’s soft shade, where the fountain of Pegasus flows, and owned the power, Alba, to speak of your kings, and the deeds of your kings, a mighty task. I’d already put my lips to those lofty streams.

Then Phoebus, spotting me, from his Castalian grove, leant on his golden lyre, by a cave-door, saying: ‘What’s your business with that stream, you madman?

Who asked you to meddle with epic song? There’s not a hope of fame for you from it, Propertius: soft are the meadows where your little wheels should roll, your little book often thrown on the bench, read by a girl waiting alone for a lover. Why is your verse wrenched from its destined track?

Your mind’s little boat’s not to be freighted. (Kline 2002)

The metaphor of the popular fountain echoes Horace’s wish to move away from the over-done epic about heroes and battle, and rather to write more quotidian and sometimes pastoral poetry. Furthermore, the emphasis on scale, the ostentatious epic as opposed to Propertius' neat elegies and the heroic subject matter, like the storm, versus Propertius’ small boat, destined to write lyrical poems. Finally, Ovid, who again revolutionised the epic form with the compartmentalisation of an epic into many different poems bound together by a theme:

metamorphosis, but in the introduction to his Amores he writes:

Arma gravi numero violentaque bella parabam edere, materia conveniente modis. par erat inferior versus: risisse Cupido dicitur atque unum surripuisse pedem.

For mighty wars I thought to tune my lute, And make my measures to my subject suit. Six feet for every verse the muse designed, But Cupid laughing, when he saw my mind, From every second verse a foot purloined.

(Hopkinson 2020)

The pun being that epic is written in dactylic hexameter comprising six feet and Cupid stole one turning the verse into the less prestigious elegiac couplets. These intertextual references to the new aesthetic pillars are what define these poets and the poetry of many years to come and allowed Latin poetry to become its own discipline rather than a weak imitation of Greek literature.

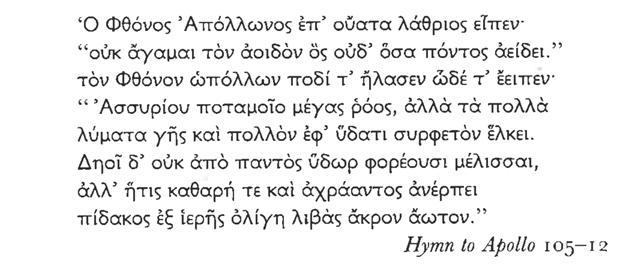

However, that does not mean that these poetics were completely new. In fact Alexandrian poet, Callimachus revolutionised the lyrical poem almost 200 years prior. Callimachus in his great works The Iambi, The Aetia and The Reply sets out his new aesthetic principles of brevity, refinement, erudition, and rarity, using imagery, much like the Augustan poets. He writes (Hopkinson):

I hate the cyclic poem, I do not like the path that carries many to and fro, I hate too the roaming lover,

I do not drink at the public fountain, I loathe all common things. Lysanias, yes fair you are, how fair – the words are scarcely out, says an echo ‘he’s another affair.

(Hopkinson 2020)

The images of the public road and the promiscuous lover represent the same ideals of the Augustan poets, with the image of the public fountain seeming to manifest itself almost exactly in Propertius. Furthermore, the image of the bees returns:

Envy spoke secretly in Apollo’s ear (I do not admire the poet who does not even sing as much as the sea.)

Apollo gave envy a kick with his foot and spoke as follows:

‘Great is the stream of the Assyrian River, but for much of its course it drags on its waters filth from the land and much refuse.

For Demeter, the bees do not bring water from any source, but from a trickle, which pure and unsullied comes up from a holy fountain. (Hopkinson 2020)

The contrast here between the images of the Euphrates: length, unity, magnitude, accessibility, and the individual droplets from the purest spring: polish, refinement, exclusivity, and self-consciousness, is almost exactly emulated by Ovid. Lastly, Callimachus’ bon mot ‘a big book is a big evil’ (Hopkinson):

is entirely reminiscent of the Propertius whose little boat is not made for the storm.

Clearly, the Augustan poets were profoundly affected by Callimacheanism, with Propertius even directly evoking him in his poems (Elegies 3.1), but not all of Callimachus’ writings survive. However, his more pastoral contemporaries were evidently influenced by him such as Theocritus:

shepherds then shifts from the cup to the story of Daphnis, a shepherd who sings to the muses about his unrequited love to Nais, a nymph:

And I will give you a deep, two-handled cup, newmade

Washed in fresh wax, still fragrant from the knife.

Beneath is a woman’s figure, delicately worked. (Wells 1988)

The hyper-fixation on the details on the cup, which becomes the narrative of Theocritus’ oeuvre, is very Callimachean, as well as the extensive use of imagery and crafted language. The story of the two

Muses, sing for a shepherd, sing me your song.

Jackals and wolves howled their lament for Daphnis

The lion wept in the forest-bound retreat.

Many the cattle that watched about him dying,

The bulls and cows and calves couched at his feet.

(Wells 1988)

The pastoral images are evident in this passage, which aren’t particularly Callimachean but do reoccur especially in the Eclogues. The invocation of the muses is a very familiar theme, as is the overall structure of the idylls.

In conclusion, these new aesthetic values changed the perception of good poetry and literature for many years for the Romans, and perhaps even to this day. And although the Augustan and neoteric poets are the first Romans to use these new practices, the Callimachean poets sketched out these new poetics, mainly that of brevity, learned references, exoticness, to some extent elitism, and self-deprecation, much earlier.

References:

Burton, R. F. (1894) Catullus – 69. Perseus [Online]. Available at: http://www.perseus. tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0006%3Apoem%3D64 Cheesman, M. (2015) Callimachian Poetics. London: King’s College.

Coleman, R. (1977) Eclogues – Virgil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Hart-Davis, R. (1964) Horace – Odes. London: Penguin Books.

Higgins, C. (2007). In Love’s Labyrinth. The Guardian [Online] 6 October 2007. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/oct/06/featuresreviews. guardianreview34

Hopkinson, N. (2020) A Hellenistic Anthology of Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics. Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

Kline. A S (2001) Eclogues – Virgil. Perseus [Online].

Available at:

https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/ VirgilEclogues.php

Kline, A. S. (2002) Propertius. Elegies. Poetry in translation [Online]. Available at: https://www.poetryintranslation.com/ PITBR/Latin/PropertiusBkThree.php

Wells, R. (1988) Theocritus – Hylas. Manchester: Carcanet Press Limited.

Image:

Hammer, V. (2019) Guardians of the Tibery. Rome: Unsplash.com.

Yeti, A. (2017) The Erechtheum. Athens: Unsplash.com.

What is a Genius?

Evie Walker, Fourth Form, Swift House. Supervised by Miss Hutchinson.

The world without genius would be stuck. Stuck in a line in which no new ideas would ever be formed.

When people picture a genius, they typically see Albert Einstein studying at his desk, or they see Isaac Newton dropping an apple. They do not open their minds to the world of possibility that is genius. The myriad of thought, the new ideas and wonderful creations, the journey of one single idea, changing the course of society forever. That’s what a genius can do. That’s the power that genius holds. Genius is subjective (Tracy V Wilson, 2006). There is no specific test for genius, there is really no exact definition for what the word entails. Everyone has a bit of genius in them, some much more than others. The word is a scale, and everyone is on that scale. Genius is thinking outside of the box. It’s an innate ability to ask questions few others have ever asked before, and in some cases, to answer them (Hannah Beresford, 2021).

One genius can shape society. It’s almost scary, that one single being has the power to literally change the way the world works, simply with their minds. It’s incredibly important, however, that this happens. Because if there were no geniuses, we’d be stuck in a world that had no new ideas, no creativity, no originality. A genius is a breath of fresh air. We would

be stuck in a stuffy room, with nothing new to live off, without these brilliant minds.

Intelligence and genius are often mixed up. The stereotype of being a genius is often linked with academic ability, but we know this isn’t always true. Intelligence is often about representing a high level of cognitive ability, about being curious to answer a question but perhaps never quite answering it (Michael Michalko, 2012). An intelligent person might be highly logical and think clearly. Genius represents a high level of creativity and innovation. They may also be highly logical and think clearly, but they simply go above and beyond; they use their intelligence; they use their talents and combine them to create something entirely new and different. It’s almost beautiful. An intelligent person follows the rules; a genius breaks them.

The dictionary defines ‘insane’ as a state of mind which prevents normal perception. Creative work involves out of the ordinary thinking and willingness to stand alone and take risks. So genius and madness are incredibly similar, perhaps even interlinked. Those

who are perhaps called ‘mad’ often see the world differently, perceive things in ways we could never even imagine. Whilst these ways of thinking are weird and wonderful, they are often not ways that society agree with (Arne Dietrich, 2023). The difference between these geniuses and these insane people is the way that society views them; the way in which we choose to value their opinions. The difference between insanity and genius could also be success. If Albert Einstein had not contributed to the physics world what he had, perhaps he would be regarded as some loopy old man who sat at his desk all day. This once again proves that genius is subjective, and the topic often revolves around the thoughts and views of what a genius is, rather than what the word actually means. There might be so many geniuses who could have added so much to this world, but haven’t, simply due to the judgement of society, due to the prejudice of people.

Neurodivergence is also something that is also interlinked with genius. The dictionary defines neurodivergence as ‘differing in mental function from what is normal or typical.’ Once again, these characteristics are incredibly similar to that of a genius. Both neurodivergence and genius are entirely about changing perspectives, seeing the world an entirely different way, putting a different lens on the camera. This isn’t to say that a genius is neurodivergent, nor that someone who is neurodivergent is a genius, but simply to point out the

‘Talent hits a target no one else can hit, genius hits a target no one else can see.’Arthur Schopenhaeur German Philosopher

Our understanding of genius has evolved and changed over time. In the 18th century, the concept of genius was thought to be someone who had special and amazing talents, for example, to see into the

the modern era, we recognise that genius is not solely limited to intellectual brilliance, but also originality and exceptional insight into something that surpasses expectations and sets new standards. We also know that genius can only be achieved when nurtured and developed through hard work.