THE RAMBLING ROSE

Clifton High School Pupil Newspaper

Foreword

Whenever I sit down to think of how to précis the most recent issue of our wonderful Rambling Rose, I always look at what is going on in nature. As I write this, the nights are drawing in; twinkly fairy lights are beginning to grace trees and doorways; and there is a definite smokiness to the winter chill. There is something undeniably irresistible about writings that invite us into shadowed corners and flickering lamplight. This issue of the Rambling Rose (our tenth!) embraces that spirit - none more so than Amba’s article on the Gothic: a genre that thrives on mystery, atmosphere, and the thrill of the unknown.

From haunted halls to ghost stories, our journalists explore what it means to confront fear and fascination. Esme’s visit to Shepton Mallet prison reminds us that real-life spaces can feel as chilling as any fictional castle; while Jason’s article on world-building transports us to Antarctica - a landscape as conflicted and sublime as any Gothic moor.

Yet the Gothic is not only darkness; it is also about searching for meaning in complexity. That same impulse runs through this issue’s articles on the joy of orchestras, the history of art, and even the cutting-edge questions of AI in medicine, gender bias in clinical trials, and how to be considered a valid citizen. Each asks: how do we make sense of emerging patterns, whether in art, technology, sound, society, or data?

Revolutions (French or otherwise) carry their own Gothic undertones: the clash of ideals, the shadows of uncertainty, and the human struggle to carve order from chaos. In times of upheaval, we turn to places of refuge and renewal, and what better sanctuary than a room full of books? Leah’s short story, The Library, offers that perfect retreat: a space where knowledge and imagination meet, waiting for you to turn the page.

So settle in, wrap up, and let our tenth Rambling Rose take you from the eerie to the enlightening: a winter’s journey through shadows and sparks of [individual] brilliance.

Stay warm, and season’s greetings to everyone in our community.

Mrs Pippa Lyons-White Head of English

Cover photo by Ethan Chau, Year 13

ART

History of Art

Art has always been humanity’s way of telling its stories, from cave walls to modern galleries. The history of art begins tens of thousands of years ago with cave paintings in places like Lasceax, France. This early work was completed out of raw materials depicting animals and hunting scenes for both ritual and storytelling purposes. As civilisations grew, art became linked to power and religion. Egyptian art focused on gods and the afterlife, producing monumental pyramids and tomb paintings symbolising kingship. In Greece and Rome, artists created marble sculptures and templates showcasing the beauty of gods and humans alike.

After the fall of Rome, art in Europe became deeply tied to Christianity. Mediaeval art filled churches with mosaics, stained glass, and manuscripts. Cathedrals were also designed with their iconic towering spires and colourful windows.

The Renaissance (14th to 17th century) was a turning point. Artists studied anatomy, mathematics and perspective to make their work more life-like. This was the age of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo, whose works were of a more realistic style, embracing creativity.

Modern and contemporary art is a dramatic shift from tradition, reflecting the change and innovation of the 19th century and onwards. Artists like Claude Monet and Pablo Picasso broke away from traditional art by capturing light and vibrancy in everyday life. The 20th century brought colour, with Georgia O’Keeffe’s modernistic paintings and abstract styles shown in Andy Warhol’s work. Art in the world today is very diverse and open to many forms of expression. People create paintings, sculptures, photography, street art, and even digital works using computers and virtual reality. Unlike in the past, where art often followed strict styles or served religious or political purposes, modern art can be personal, experimental, and global. Artists use it to share ideas about identity, culture, technology, and social issues. Museums, galleries, and online platforms make it easier than ever for people everywhere to see and enjoy art, showing that creativity is still a powerful way to connect us across various places and cultures.

Michelangelo

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born in Tuscany in 1475 and died in 1564. He was an Italian artist who had been skilful in sculpture, painting, architecture and poetry. He is best known for some of his major works like the statue of David, the Pietà, and the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. At 13, he went to Domenico Ghirlandaio in Florence, a leading painter, and studied classical sculpture in the gardens of Lorenzo de’ Medici, exposing himself to humanist ideas. Michelangelo was known for his intense dedication and perfectionism. He once said, “If people knew how hard I had to work to gain my mastery, it would not seem so wonderful at all.” His art combined technical skill, emotional depth, and classical inspiration, influencing many generations of artists. On the facing page are some images of Michelangelo’s work

Overall, art has always been a way through which people share their ideas, beliefs and stories. From the very first cave paintings to the digital works of today, it shows the development of human thought and time in the Earth’s history. Each era of history has left a different mark, whether it is the pyramids in Egypt, or famous paintings like the Mona Lisa. Whether in museums, as paintings, on city walls or online, art still has an impact on people worldwide.

Is AI Ruining the

Art World?

With the rise of AI, anyone can create works of art within seconds with a simple ‘ChatGPT, generate me a picture.’ How can we be sure that AI won’t forever change the art industry? How can we be sure that human creativity won’t be lost to ‘perfect’ AI generated images? To answer these questions, we must first dive into how AI image generation even works.

AI Image Generation

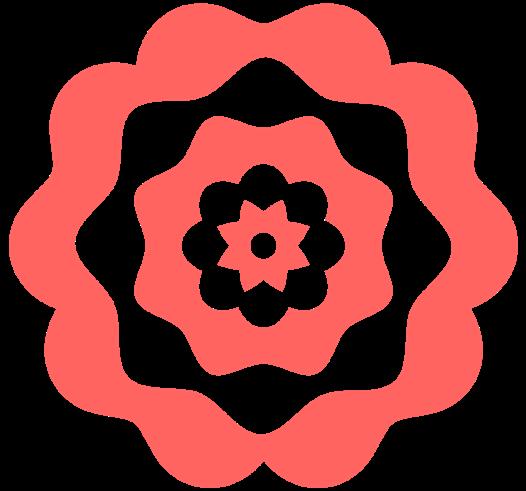

Now I am no computer scientist so when I began to research the topic, I was immediately overwhelmed with complex computing terms. To put it (relatively) simply, AI image generation works through a process called “diffusion”. This process begins with a set of images that slowly adds a pixelated effect (such as adding noise) to the original image.

This image shows the process of adding noise to make the artwork almost impossible to recognise. Once these images have been inputted, the AI software will learn to reverse this process, starting with an almost unrecognisable image and predicting what the original image would’ve looked like. Once it has learned this algorithm, it is able to generate images just from a prompt, predicting what the image will look like. In simple terms, AI software “steals” others’ art, inputs it into themselves and use them to generate images.

Dangers of AI

AI art is seen by some people as a form of expressionism for people who have either physical disabilities or struggles, or just don’t want to draw. However, it is important to recognise the dangers and problems of using such software. Firstly, AI generation is extremely tolling on the environment. This doesn’t just apply to image generation and instead, this applies to all AI usage. Interacting with ChatGPT produces approximately 2-5 grams of CO2 every single time. That’s 10 times the amount of CO2 emitted compared to a Google search. On average, ChatGPT processes over a billion prompts daily and over 20 interactions per person per day, summing up to 912,500,000,000 grams of CO2 emissions happen every year because of ChatGPT usage.

My experiment with AI

In order to test the efficiency and effectiveness of AI software, I decided to perform an experiment. I inputted basic prompts into an AI software to see if they could “beat” these famous paintings.

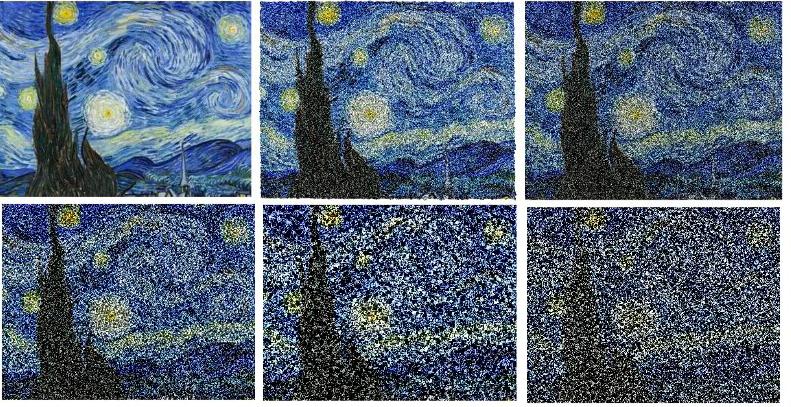

Prompt: “Night sky yellow and dark blue with dark shape in foreground swirly van Gogh style”

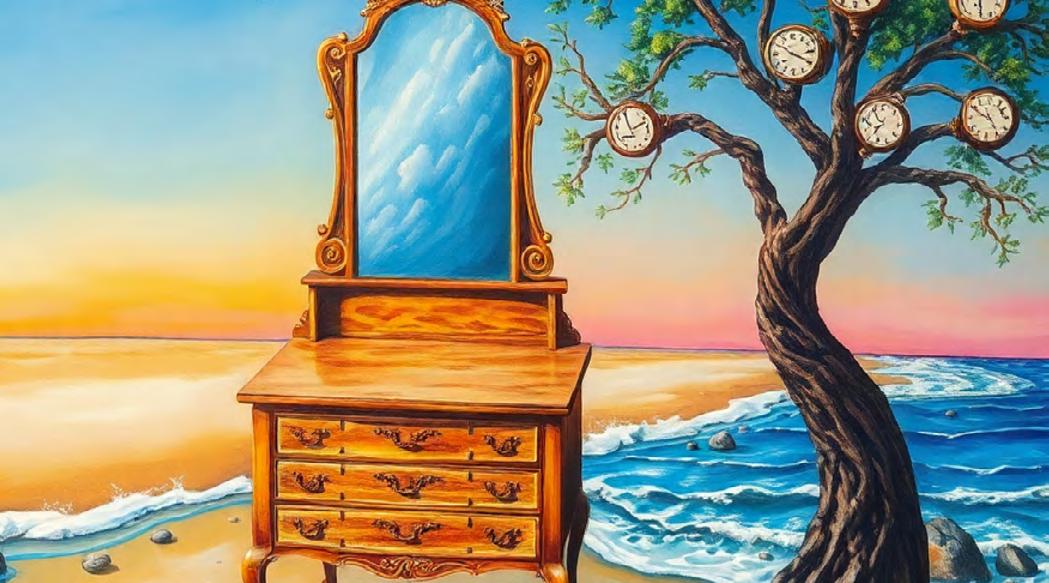

Prompt: “Beach with dressing table and tree on one side with clocks melting all around Salvador Dali style”

Conclusion

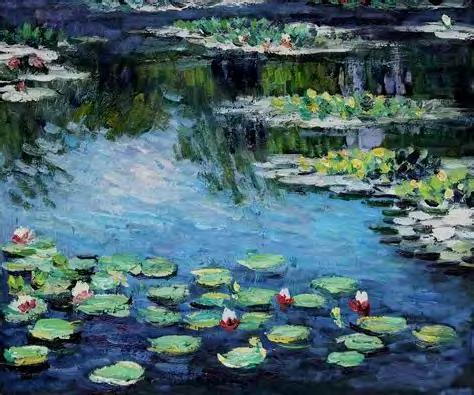

Obviously, the original paintings won by a landslide. However, with AI software improving so rapidly, who knows what the future of art holds. Who knows, maybe one day there will be AI software able to generate a

Prompt: “Lake with lilies Monet style”

better “night sky with yellow and dark blue swirls and dark shape in foreground” than Van Gogh’s iconic piece. However, one thing that AI software will never be able to learn is human emotion. While anyone can generate an image in two seconds and claim it as their own, only artists will know the true meaning behind their own art, the story behind it, mistakes they made and how these mistakes complement the final piece. Because of this, I believe that AI will not replace artists for a long time to come.

ENGINEERING

The Hidden Social Benefits of Civil Engineering

Introduction

The Merriam Webster dictionary lists multiple definitions for ‘infrastructure’; the first defines it as ‘the system of public works of a country, state, or region’1, and this is likely what most people imagine when they think of infrastructure: roads, pipes, power lines, any physical industrial constructions that keep society running. However, infrastructure is more than this, and here’s where the dictionary’s second definition comes in –infrastructure is also ‘the underlying foundation or basic framework (as of a system or organization)’2. As you can see, infrastructure in fact encompasses both physical assets and the non-physical sociopolitical systems through which the former is implemented; infrastructure is simultaneously the painting and the paintbrush used to paint it.

The artist holding the paintbrush would therefore be a civil engineer, responsible for the planning, design, construction, and maintenance of infrastructure projects. This means not only using maths and science to calculate the quantitative specifics of a project, but also commanding a knowledge of humanities like geography and sociology to determine how a project might positively or negatively impact communities socially, economically, and environmentally.

This article briefly covers some examples of the less obvious social benefits of civil engineering projects. Oftentimes, overlaps exist between the social benefits of infrastructure and their economic or environmental benefits. However, this article will primarily analyse infrastructure’s positive social impact, which a humanist would argue to be its most important facet.

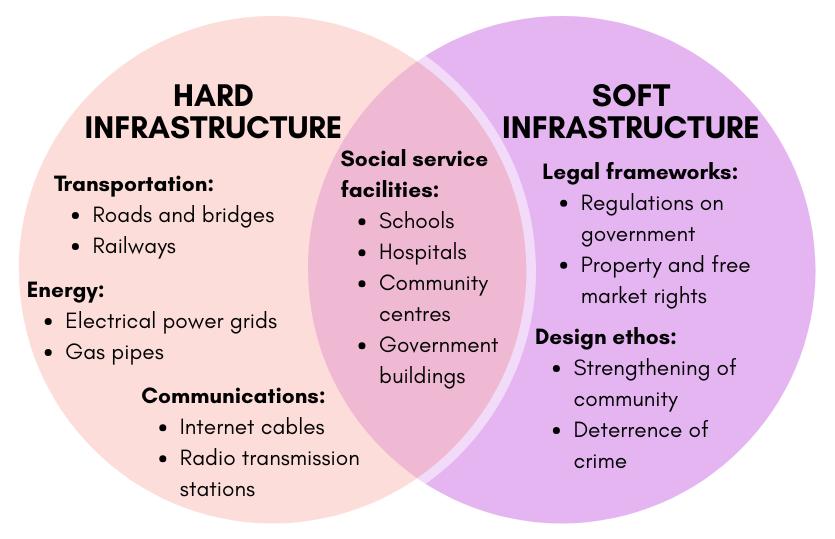

Hard vs Soft Infrastructure

It is first important to draw the distinction between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure. There exists multiple interpretations, but the difference typically boils down to hard infrastructure pertaining to industrial projects like transportation or energy networks3, and soft infrastructure pertaining to facilities providing social services like education4 as well as non-physical assets like legal frameworks5. In other words, hard infrastructure always exclusively relates to Merriam Webster’s first definition for infrastructure, whereas soft infrastructure can relate to both their first and second definitions. This article will use the interpretation that hard infrastructure relates to just industrial projects, while soft infrastructure relates to social service facilities and non-physical assets.

A Venn diagram showing the differences in interpretations of what hard and soft infrastructure involve

1Merriam-Webster (2019). Definition of INFRASTRUCTURE. [online] Merriam-webster.com. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ infrastructure [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025]. 2Ibid.

3Adejuwon, D. (2015). Workshop on Aid for Trade and Infrastructure: Bridging the Financing Gap. [online] Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/devel_e/a4t_e/wkshop_feb15_e/session-i_david_ademola_adejuwo_nigeria.pdf. 4Ibid.

5Yanamandra, S. (2020). Sustainable Infrastructure: An Overview Placing infrastructure in the context of sustainable development. [online] Available at: https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/sustainable-infrastructure-an-overview.pdf.

Hidden Social Benefits of Hard Infrastructure

Although the social benefits of hard infrastructure are typically more noticeable than those of soft infrastructure, it still boasts some lesser-known positive impacts. For example, the improvement of transport infrastructure can cause health benefits in unexpected ways – for example, reduced traffic congestion can benefit both physical health and mental health. Such improved physical health can come from the reduction of air pollution by reducing the number of idling vehicles in traffic6, the enhancement of pedestrian safety by decreasing the number of vehicles on the road7, and the improvement of civilian access to healthcare providers8. As for improving mental health, reduced congestion can remove stress from traffic congestion (i.e. road rage)9 and enhance social connections by reducing a phenomenon known as ‘community severance’, where excessive or poorly-designed traffic infrastructure can ironically restrict access between members of a community due to the presence of barriers like railway lines and motorways prohibiting pedestrian travel. 10

Some examples of methods to reduce congestion include designing roads to optimise traffic flow using intelligent traffic control and interconnected road networks11. It would also help to construct and expand dedicated public transport infrastructure like railways, tram tracks, and guided busways – road tracks for buses that are fully separated from general traffic, unlike bus lanes, and therefore less vulnerable to unauthorised obstructions.

Aside from transportation, effective hard infrastructure relating to water provision can also massively benefit a community – by reducing the destructive effects of widespread lead poisoning. Historically, lead had been extensively used in water pipes for its versatility12; the full magnitude of its toxicity was only made common knowledge in recent decades. Alongside physical effects such as reproductive and respiratory illnesses, lead is also proven to cause long-lasting impacts on individuals’ intelligence and emotional maturity. Studies consistently show that generations of children living in areas that exposed them to even minuscule amounts of lead in childhood are thought to lose an average of five IQ points compared to those who weren’t13. This also stunts emotional development, in turn leading to increased anti-social behaviour and criminal activity in adolescence regardless of socioeconomic status in childhood or adulthood14. Such increased crime is estimated to cost the US $1.2 trillion15, a testament to the large scale of the devastating impacts of lead poisoning. It is therefore important to mitigate its effects with relevant hard infrastructure solutions, such as large-scale government-funded lead pipe removal schemes and building new pipes with alternative materials like copper, iron, or plastic16

6Zorrilla, M. (2020). Better Transport Infrastructure Can Increase Well-Being in the West Midlands. [online] Available at: https://blog.bham.ac.uk/cityredi/ better-transport-infrastructure-can-increase-the-regions-well-being/ [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

7Ibid.

8Cambridge Ahead. (2025). The Benefits of Improvements in Public and Active Transport Infrastructure to Quality of Life. [online] Available at: https:// www.cambridgeahead.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/rapid-evidence-review-the-benefits-of-improvements-in-public-and-active-transport-infrastructure-to-quality-of-life.pdf.

9Zorrilla, M. (2020). Better Transport Infrastructure Can Increase Well-Being in the West Midlands. [online] Available at: https://blog.bham.ac.uk/cityredi/ better-transport-infrastructure-can-increase-the-regions-well-being/ [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

10Transport for the North (2024) Community severance across England. [online] Available at: https://www.transportforthenorth.com/wp-content/uploads/Community-severance-across-England.pdf

11Pinnacle IIT. (2025). How Traffic Engineering is important for Urban Congestion. [online] Available at: https://pinnacleiit.com/blogs/how-traffic-engineering-is-important-for-urban-congestion/ [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

12Wani AL, Ara A, Usmani JA. Lead toxicity: a review. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2015 Jun;8(2):55-64. doi: 10.1515/intox-2015-0009. PMID: 27486361; PMCID: PMC4961898.

13Hanna-Attisha M, Lanphear B, Landrigan P. Lead Poisoning in the 21st Century: The Silent Epidemic Continues. Am J Public Health. 2018 Nov;108(11):1430. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304725. PMID: 30303719; PMCID: PMC6187797.

14T. Schwaba, W. Bleidorn, C.J. Hopwood, J.E. Gebauer, P.J. Rentfrow, J. Potter, & S.D. Gosling, The impact of childhood lead exposure on adult personality: Evidence from the United States, Europe, and a large-scale natural experiment, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118 (29) e2020104118, https://doi.org/10.1073/ pnas.2020104118 (2021).

15Ibid.

16Drinking Water Inspectorate. (n.d.). Lead in Drinking Water. [online] Available at: https://www.dwi.gov.uk/lead-in-drinking-water/. [Accessed 30 Oct. 2025].

A guided busway in Australia

Hidden social benefits of soft infrastructure

Alongside the social benefits of hard infrastructure in maintaining the physical functioning of society, soft infrastructure can have more subtle effects, such as strengthening the resilience of a community. This means constructing community facilities like parks, community centres, places of worship, libraries, and health centres in conjunction with communal services like educational and sport programmes17. By introducing convenient meeting spaces, members of a community can more easily bond with one another – not only can this increase quality of life, but it can also bring more tangible benefits such as strengthening individuals’ physical and mental wellbeing, consolidating community resilience in times of hardship, and increasing employment opportunities for community members who have learnt new skills from community services like interest classes18. This is a concept known as ‘social capital’, which refers to how the value of a social network in bringing benefits to a community19.

However, attempts to develop social capital can backfire – the construction of communal facilities without proportional consideration of the accompanying provision of community services may make such facilities fall into neglect, possibly attracting crime and diverting resources into repairing the little-used facilities. In addition, if the method of excessively renovating residential infrastructure is used to regenerate neighbourhoods instead of building new communal facilities, “gentrification” may occur, a phenomenon where previous residents of a formerly low-income neighbourhood are displaced and forced to live elsewhere due to increased property prices and cost of living20. Therefore, the development of social capital using infrastructural solutions requires extensive research and planning from civil engineers to determine how a balance between the positive and negative social impacts of soft infrastructure can be struck.

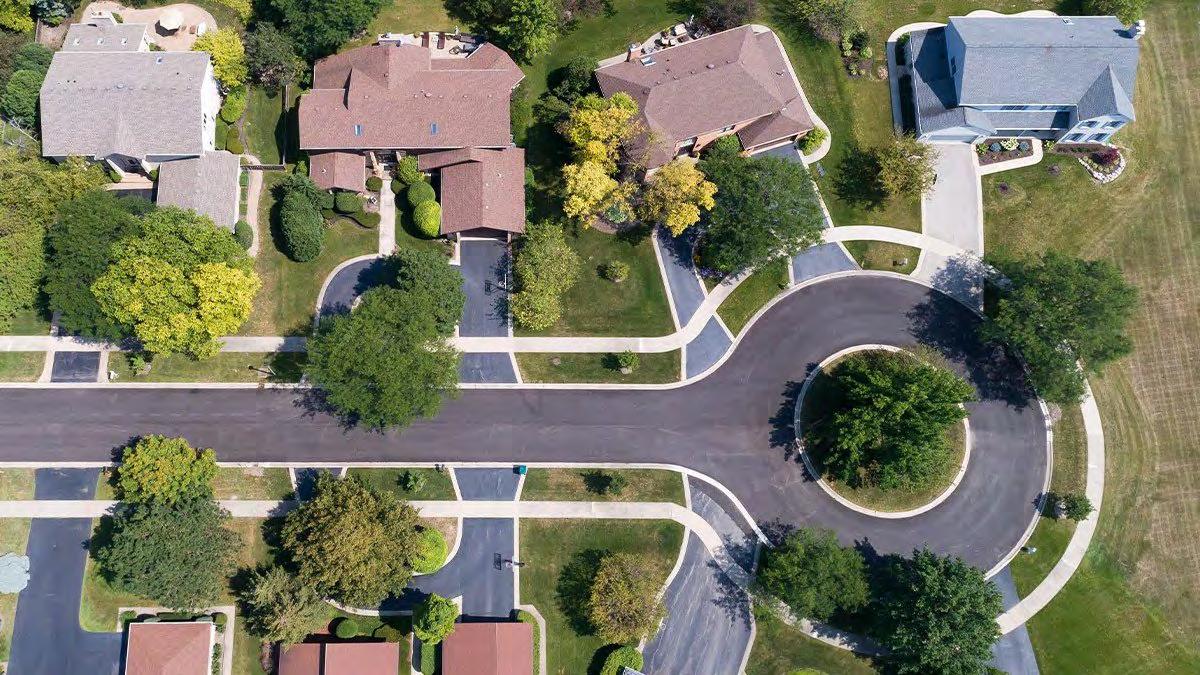

Similarly relating to the concept of balance, soft infrastructure intended to reduce crime in residential areas must also ensure it does not excessively hinder community cohesion. An example of crime-preventing residential infrastructure is cul-de-sacs, where houses are located on dead-end streets instead of interconnected grids. This means only residents have legitimate reasons to enter, residents can easily overlook the whole street, and any potential burglars only have one escape route21. Other solutions include illuminating junctions with public lighting and increasing climate-cooling green space to reduce stress that culminates in criminal activity22.

A cul-de-sac, where houses only have one route for access

However, certain infrastructural solutions have attracted criticism from some civil engineers for being excessive – the removal of public seating may indeed eliminate a source of attraction of antisocial behaviour but can also make neighbourhoods less accessible. Meanwhile, the overuse of culde-sacs in designing the layout of a neighbourhood can also complicate navigation on foot, discouraging active travel. As can be seen, security and community must be held in equal consideration when designing residential infrastructure. Alternatively, investment in supplementary communal infrastructure as described in the previous paragraph can also help deter crime by strengthening community resilience.

17Cambridge Ahead. (2025). The Benefits of Improvements in Public and Active Transport Infrastructure to Quality of Life. [online] Available at: https:// www.cambridgeahead.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/rapid-evidence-review-the-benefits-of-improvements-in-public-and-active-transport-infrastructure-to-quality-of-life.pdf.

18Local Trust. (2024). What is social infrastructure? [online] Available at: https://localtrust.org.uk/policy/what-is-social-infrastructure/. [Accessed 30 Oct. 2025].

19Claridge, T., 2004. Social Capital and Natural Resource Management: An important role for social capital? Unpublished Thesis, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia.

20Smith, R. (2023). Gentrification Pros and Cons: A Double-Edged Sword. [online] Available at: https://robertsmith.com/blog/gentrification-pros-and-cons/. [Accessed 30 Oct. 2025].

21Watson, S. (2023). Can we design away crime? [online] ww3.rics.org. Available at: https://ww3.rics.org/uk/en/modus/built-environment/ homes-and-communities/urban-design-prevents-crime.html. [Accessed 30 Oct. 2025].

22Washington, S., Love, H., and Sebastian, T. (2022). The infrastructure law’s untapped potential for promoting community safety. [online] Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-infrastructure-laws-untapped-potential-for-promoting-community-safety/. [Accessed 30 Oct. 2025].

Finally, the non-physical side of soft infrastructure also provides benefits to society. For example, an active government system enables continual improvements to society through democratic debate, whereas legal frameworks enshrine rights like property rights23. While this may seem as though it concerns law rather than civil engineering, such legal policies not only cannot function without specialised hard infrastructure like government buildings, but also impact the future implementation of infrastructure projects; they are intertwined with civil engineering in both cause and effect. Therefore, these non-physical frameworks can be considered an aspect of civil engineering.

The maintenance of government institutions can be facilitated by constructing geographically accessible physical government infrastructure to ensure constituents and elected representatives from varying locations all have equal access to facilities where they can effectively pursue their political desires; this thus facilitates democracy. In turn, by having an effective system of government in conjunction with a legal system, property rights can be empowered in physical parliamentary or court buildings, giving voices to those who may be, for example, affected by gentrification as described in previous paragraphs.

Conclusion

The maintenance of government institutions can be facilitated by constructing geographically accessible physical government infrastructure to ensure constituents and elected representatives from varying locations all have equal access to facilities where they can effectively pursue their political desires; this thus facilitates democracy. In turn, by having an effective system of government in conjunction with a legal system, property rights can be empowered in physical parliamentary or court buildings, giving voices to those who may be, for example, affected by gentrification as described As is evident, civil engineering is a broad discipline that requires engineers to consider both hard and soft infrastructure. It is therefore fitting that civil engineering solutions help solve a wide range of societal issues, albeit sometimes in less direct and visible ways. Hopefully, this article has brought light to some of these subtleties, and kindled interest in this fascinatingly multifaceted subject.

23Cambridge Ahead. (2025). The Benefits of Improvements in Public and Active Transport Infrastructure to Quality of Life. [online] Available at: https:// www.cambridgeahead.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/rapid-evidence-review-the-benefits-of-improvements-in-public-and-active-transport-infrastructure-to-quality-of-life.pdf.

FICTION

A Fictional History of Antarctica

Introduction

Worldbuilding is the art of creating a fictional, imaginary universe. Think creative writing, but without the restrictions of structure or prose. It is probably my favourite pastime, and I have spent countless hours penning history, developing politics, and designing culture.

Throughout my projects, I have definitely spent the most time on the universe my brother and I have named Krillsink Lore. In this world, multiple species besides humans also evolved sentience (intelligence and selfawareness), including penguins. What made penguins special was their isolation from the rest of the world, having established their society in the remote continent of Antarctica. Their seclusion from other civilisations lasted for most of history, with humans only finding the continent in the 1820s – this fact lent me plenty of freedom when developing a fictitious history for Antarctica.

Of course, no fiction is without its influences. Many events in Antarctic history draw parallels to other civilisations throughout the world; in this article, I have placed my real-world inspirations in the footnotes to demonstrate how stories are shaped by history.

This article is not a complete retelling of the lore I have developed, nor is my lore itself complete. There will always be finer details that are appended to this story, and even major facets of this history can be changed later on. Worldbuilding is a process which is never truly finished, and that is precisely what makes it so fun. The following is an abridged version of the mythos I have developed thus far, which I hope inspires you to embark on your own worldbuilding journey one day.

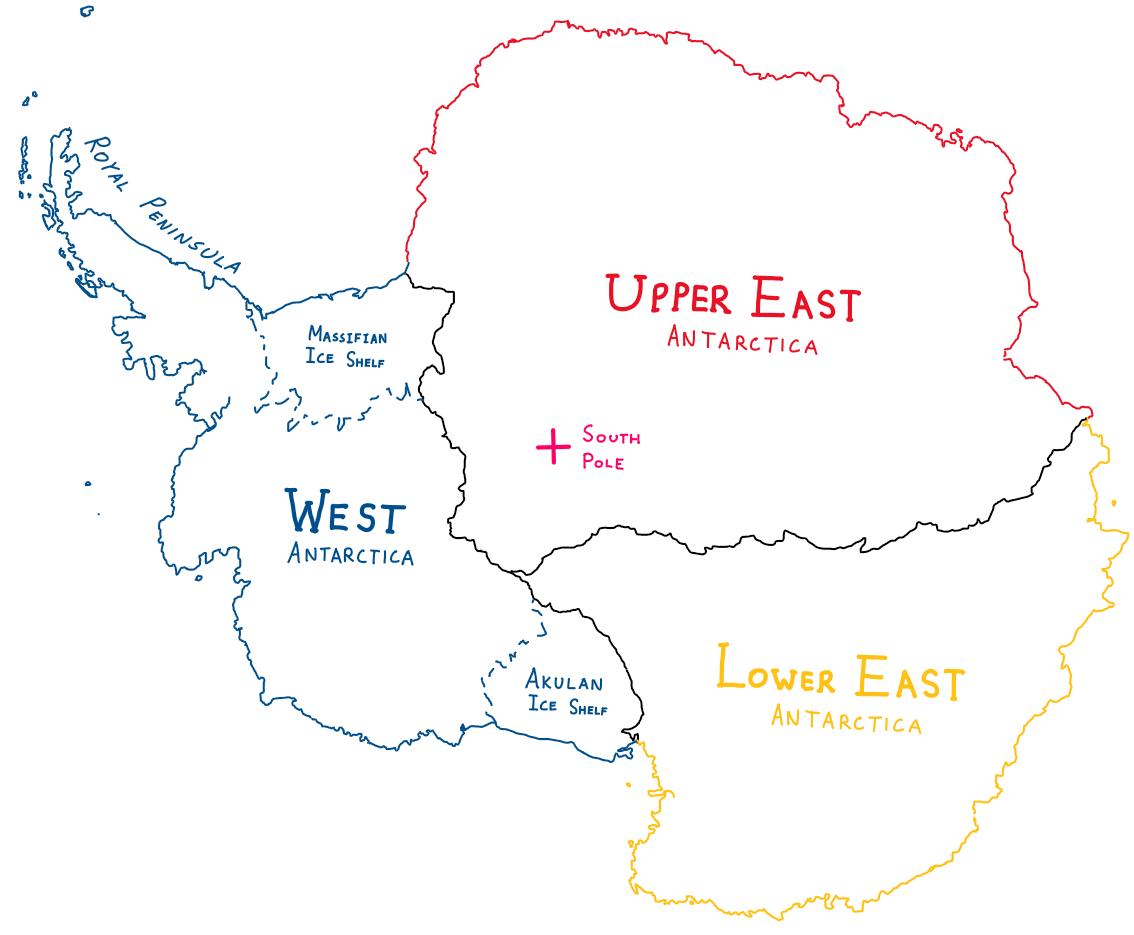

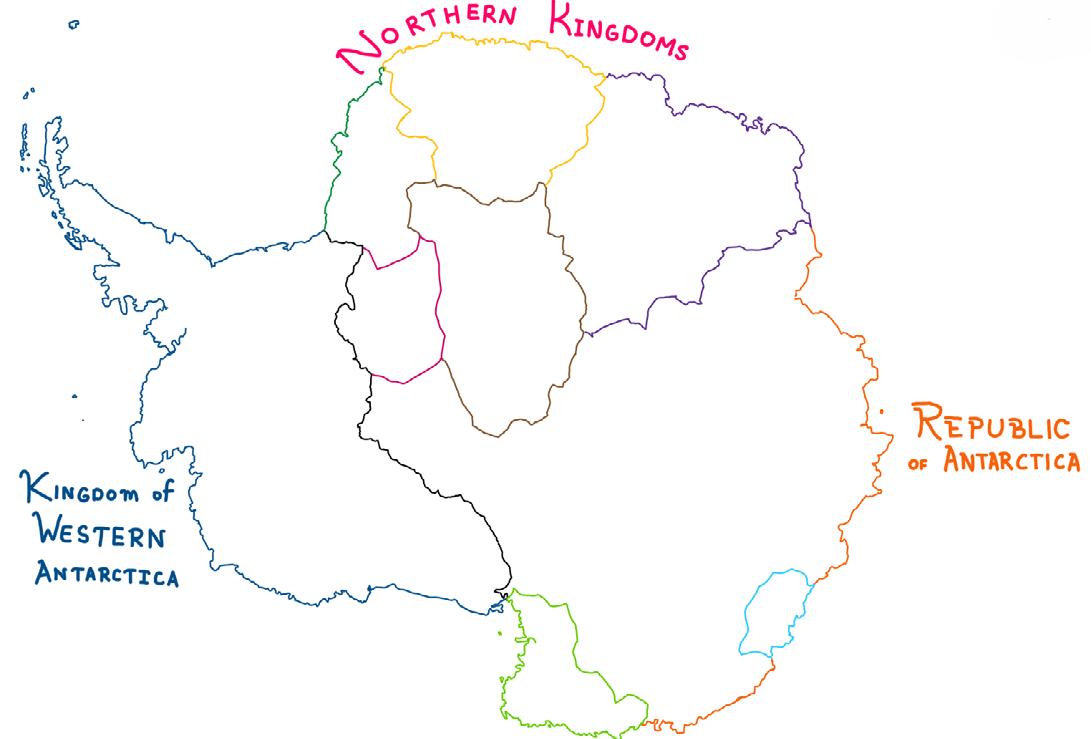

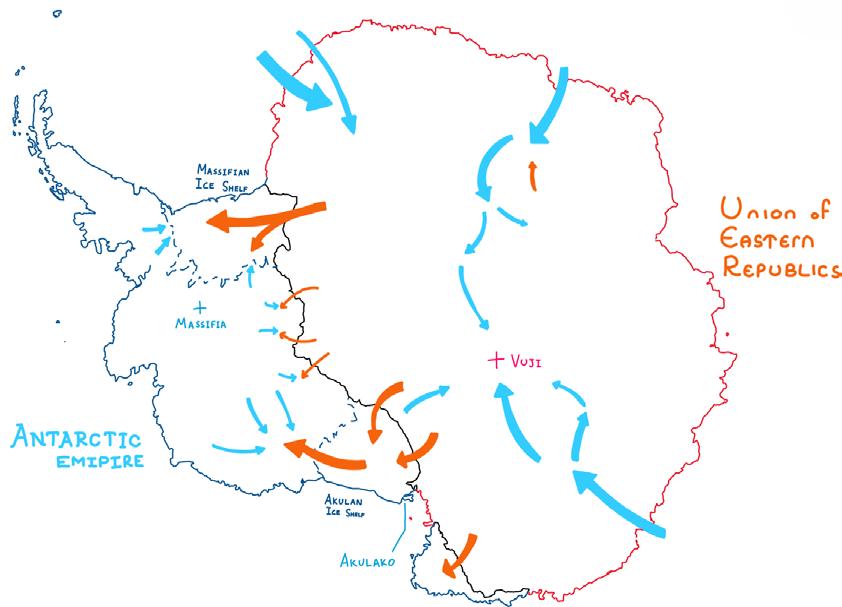

A basic geographic map of Antarctica, with the names of certain major regions included

Early Antarctic Civilisation (until 150 BCE)

Civilisation in Antarctica began as many small, fractured settlements around the continent’s coast. The evolution of intelligence was greatly advantageous for the penguin population, as tool use enabled easier hunts for Paleolithic colonies.

The rockiness of the Antarctic continent benefitted the penguins in a variety of ways. Spears were used in the hunting of seals and whales, which provided blubber as fuel for cooking and warmth. Most settlements constructed houses made of stone, the thickness of which granted some solace in the harsh winter climate. Villages in areas with volcanic activity also carved fishing boats out of light igneous rock.

As the population of these primitive settlements grew over the next few thousand years, so too did their technological advancements. Over the millennia, each of the hundreds of colonies harnessed the resource-rich Antarctic crust – the largest towns established quarries to extract materials such as iron, copper, and nickel. Coal

was an especially important discovery; blubber from the overhunted and dwindling whale population would not have been enough to satisfy the hungry forges of Iron Age Antarctica.

Eventually, the penguins would branch out and explore along the Antarctic coasts, reaching other villages and establishing trade relations. Certain regions along the coast soon became strongly bound by trade routes: both the Royal Peninsula and Akulan Ice Shelf had separately developed trade caravans connecting villages and towns.

By 2000 BCE, the largest few towns had developed into ancient cities. The most notable was Akulako, a sprawling conurbation formed from the merger of multiple towns around an active volcanic island on the Akulan Ice Shelf. Residents exploited the constant flow of lava for the city’s many forges, as well as mining the metal-abundant magma once it had cooled. Akulako’s material output was unrivalled; the city’s prosperity even helped it become the continent’s first shipyard.

It was soon clear that the coastal settlements were not sufficient to sustain growing populations. In search of more accessible metal ore, the first major attempts at inland expansion began. Facilitated by the increasingly important merchant caravans, towns could be established in the mountainous Antarctic interior; these inland settlements received vital supplies of food and in return exported vast amounts of iron and coal. As respite for the sub-zero interior climate, most of these towns were built directly into mountains and caves. Many settlements even took in live fish and krill to establish breeding grounds within expansive glacier caverns, so as to not rely on imports that could be easily disrupted by a week-long blizzard.

Regardless of this, trade caravans were still crucial to Antarctic civilisations. Merchants thus became highly important, with many across the continent establishing local and regional guilds. The most powerful of these was the Massifian Guild, whose merchant families ran a trade monopoly between peninsular settlements and Mount Maszi. Following multiple acquisitions and marriages between the largest of the Guild families, the House of Rau emerged as the dominant trade power across the region. Resultantly, the family soon came to rule the area and became the first emperors and empresses on the continent1

The onset of the Rau Dynasty triggered merchant nobility from the rest of the continent to pursue similar power grabs, as wealthy families competed to gain influence over their region or city. Monarchs drew borders to demarcate land they wished for, with territorial claims often overlapping with those of other nobles – these disputes would lead to many wars throughout the following centuries.

Kingdoms would rise and fall, and land would trade hands many times. The Rau Empire would collapse as incompetent sovereigns were overthrown and opportunistic army officers carved their own states from the kingdom. Throughout this fractured period, many regions also rejected monarchy, establishing republics to defend themselves from the expanding kingdoms and empires.

The Auroran Empire (150 BCE - 920 CE)

In the midst of this chaotic era, a religion began growing in the Far East of the continent. Around 150 BCE, a prophet posthumously named au-Vara began preaching a monotheistic faith. Supposedly in contact with the Architect of Heaven, they soon received a major following across the Eastern coast. Soon, au-Vara led their loyal devotees into a war of unification across Antarctica, claiming to have divine orders to bring harmony to the continent. The conquests were a major success, with the entirety of known Antarctica coming under their holy empire within 30 years2. The effects of this sprawling empire are still felt to this day; the term pertaining to penguins – Auroran – is an anglicised corruption of the prophet’s name.

The Auroran Empire preached a faith of peace and liberalism. Promoting personal freedoms and the uplifting of lower classes, the Empire proved popular among the vast majority of its civilians. The nation would last over a thousand years, becoming the longest lasting state in Antarctic history.

However, this millennium was not without its hurdles. In 700 CE, a major schism befell the au-Varan religion. Being the original birthplace of the faith, the Eastern half of Antarctica held more conservative views of the church – its clergy believed in the enforcement of the au-Varan faith on citizens. On the other hand, many in the West believed the church’s teachings of personal liberty meant there should be freedom of religion as well

1During the Middle Ages, many Italian city-states would be ruled by powerful noble families. These nobles often had mercantile roots, having gained economic and political influence through trade.

2The Prophet Muhammad united the many fractured tribes of the Arabian Peninsula, which was even welcomed by some Arab Jews and Christians due to their dissatisfaction with the constant wars that preceded the establishment of the Islamic State. Further Muslim conquests saw the religion spread throughout North Africa and Central Asia.

as a separation between church and state. This conflict ultimately resulted in the West’s breakaway from the Empire, splitting the continent in two upon the establishment of the Kingdom of Western Antarctica.

The independence of West Antarctica was hugely detrimental to the Auroran Empire, as the region was home to important trade routes and many major cities. Previously, the Empire’s success was engendered by its unification of the continent, as control over all of Antarctica’s resources meant there was no need for trade and diplomacy. By this era, the Empire was largely dependent on its transantarctic logistics – its overreliance on the West therefore hugely damaged it upon the region’s secession.

As the influence of the Auroran Empire waned, its peripheral provinces began dissenting against the au-Varan Church’s authority. These regions were home to many minority cultures, who resented the social and religious hegemony forced upon them by the central church. The successful independence of the West encouraged these provinces to seek their own autonomy, and eventually sovereignty.

The Auroran army failed to contain the independence movements, partially due to their inexperience following centuries of peace. As with the secession of the West, the withdrawal of more and more of its outer provinces brought the Empire into an ever-deepening logistical nightmare. In 920 CE, the Highest Council of the thousandyear-old nation voted to dissolve the Empire, granting independence to the rest of its rebellious provinces and establishing the Republic of Antarctica in place of the monarchy3.

New Imperial Era (920 - 1520s)

Since its independence, the Kingdom of Western Antarctica had grown prosperous from the infrastructure it inherited from the imperial era. It was a lot more self-sufficient than the other half of the Empire; the Royal Peninsula was rich with valuable metals while the Western coast had plentiful fish populations. In addition, its smaller size greatly reduced logistical challenges, as there were fewer inland cities for which constant trade was required.

After the disbandment of the Auroran Empire, expansionism became a hotly debated topic in the West. Some nobles believed the Kingdom held a claim to be the successor state of the Empire, and rallied for the annexation of the weaker kingdoms that had recently been granted independence. On the other hand, some argued that the self-sufficient Western autarky would have its resources strained if additional provinces were incorporated into it. The monarchy would hold onto the latter viewpoint until the 13th century, when the West’s population growth meant demand for resources exceeded the rate at which they could be extracted.

Despite trade agreements with the minor kingdoms and the Republic of Antarctica, the Kingdom of West Antarctica struggled to appease its populace. To boost the monarchy’s popularity and capture more resources, the West would establish the Second Empire and began several highly successful military campaigns against smaller kingdoms. Among the kingdoms subjugated into the new empire, some were allied with the Republic through defence pacts – heeding their calls for assistance, the Republic of Antarctica entered a long war with the West.

The Sixty Year War was a messy conflict with multiple sides, with each of the many kingdoms nominally supporting the Empire or Republic while pursuing their own political ambitions. In the end, Republican forces suffered several grave naval defeats after the shipbuilding city of Akulako defected towards the Imperialist cause. The conclusion of the war in 1310 saw the Second Empire once again unite the continent under a single banner.

Unlike its predecessor, the Second Empire was ruled by a single sovereign rather than a religious council. Ruling

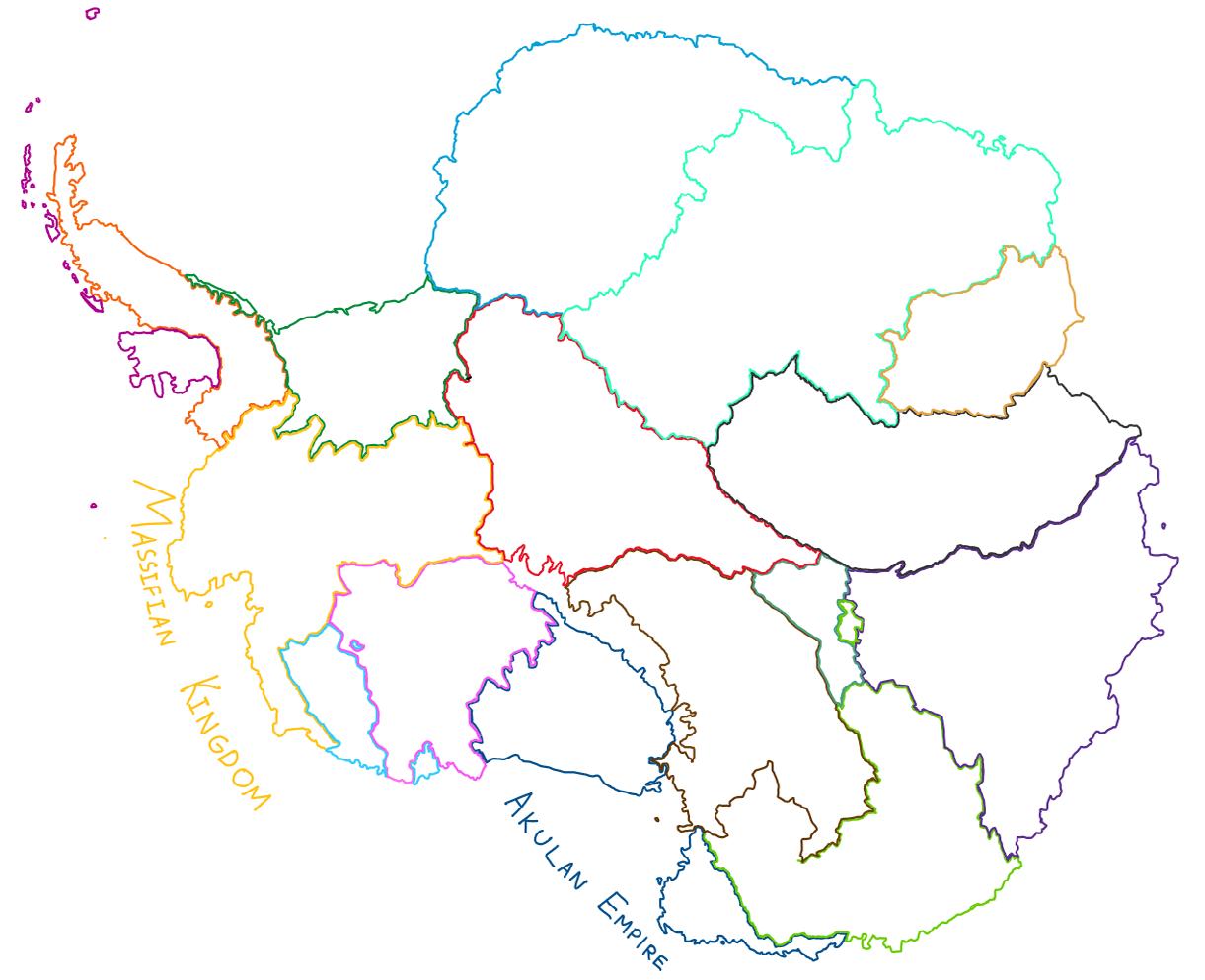

A map of the kingdoms and republics that succeeded the Auroran Empire

3The Holy Roman Empire lasted just over a thousand years before its dissolution. Right before the Empire was legally terminated, many of its Western states had seceded to form a Napoleonic client nation.

with absolute authority, each successive monarch was in full command of Antarctica’s industry and economy: the result was a vast but highly centralised network of mines, forges, and cities that fed into the Empire’s growing wealth.

The Second Empire’s prosperity was realised most clearly during the reign of Empress Twukwuq. Under her leadership, scientific discovery flourished and education became more widespread, with many universities being established across West Antarctica. In her later years, Twukwuq established Provincial Courts, giving important cities some extent of free rule. Nobles would gain more control over their land, and as such many important families grew massively in wealth and political power.

When the Empress died, the throne was passed to her only son, who was widely seen as incompetent by nobles and civilians alike. Indulging in lavish banquets and expensive vanity projects, he became hated by the Imperial Court he inherited from his mother. Many courtiers and nobles schemed against him, and planned to once again carve the continent up into kingdoms under their rule4.

The courtiers’ final straw came when the Emperor proposed the construction of a grand castle that would have occupied a sizable portion of the Empire’s annual budget. Soon after the project was unveiled, royal guards seized his palace at the behest of the Imperial Court and arrested him for a fabricated list of crimes.

The Emperor’s deposal swiftly descended Antarctica into civil war. Despite the nobles having previously made agreements as to what land each of them would inherit, many would crave more power when the time came. The continent became fractured into numerous kingdoms and alliances, all vying for increased control over their respective regions. Many landlocked cities were cut off from vital trade routes and were forced to sign treaties annexing them into a noble’s territory for survival.

Antarctic Industrial Revolution (1528-1677)

Plenty of these new kingdoms fell in under a year; a lack of trade contributed to their inability to sustain themselves and subsequent absorption into larger empires. By the end of the civil war in 1528, there were only sixteen kingdoms remaining, each of which occupied large areas of the Antarctic continent. The wealthiest of these was the western Kingdom of Massifia, which controlled important trade lanes and contained several significant cities.

The following century saw rapid industrialisation take place across the continent, exacerbated by the economic prosperity that resulted from the end of the war. In the mountains of East Antarctica, the discovery of a mineral named Valkyrine had a significant impact on industry – the versatile mineral could be ignited as fuel yet could also become a strong metal alloy when refined. The Valkyrine industry took off quickly, with mines, refineries, and factories dedicated to the mineral being built across the East.

A map of the kingdoms that remained from the civil war. These borders still exist today as provincial borders

Valkyrine power enabled mass manufacturing, contributing greatly to the Antarctic Industrial Revolution. This period is widely considered as Antarctica’s golden age: culture bloomed and increased manufacturing led to an improved quality of life among the middle class. Ice jazz, a genre still popular to this day, was born in this era. Trade between the kingdoms increased, with Eastern kingdoms exporting vast amounts of Valkyrine in return for machinery and luxury goods from the wealthier West.

The Akulan Kingdom even became a seafaring power, exploring beyond the inhospitable Southern Ocean and

4Many Chinese dynasties would undergo a similar cycle, where a benevolent Emperor would be followed by incompetent successors throughout multiple generations. They would then be overthrown and replaced with a new dynasty, which would often then follow the same cycle.

reaching the human Polynesian Empires in the Pacific. Although this contact between the empires was brief, the penguins soon became enshrined in Pacific folklore – a fact that would prove significant later.

To facilitate the massive rise in trade, the kingdoms would collaborate and create a multi-national organisation known as the Transantarctic Interregnum – a political alliance between every kingdom in Antarctica that would be used by monarchs to negotiate trade deals as well as control their citizens.

Regardless of the rapid increase in Antarctica’s wealth, the new prosperity was clearly unbalanced. While civilians in the West did benefit from improved standards of living under the Industrial Revolution, wealthy noble families would become exponentially richer. The wealth gap in the East was even more dramatic – labourers were afforded far fewer personal freedoms than their overlords. Worker rights and safety regulations were at a minimum; the Valkyrine industry was far too valuable for the nobles to justify otherwise. Labour movements would often fail to gain enough momentum before they were crushed, meaning these inequalities were left to grow for over a hundred years. For sweeping change to occur, the lower class needed a saviour with enough wealth and political power to lead them5.

The Eastern Spring (1677-1701)

In 1632, Pek Khimbu was born to a minor noble family in East Antarctica. His family owned a quarry, where a young Khimbu began sympathising with the poor treatment of workers across the Eastern kingdoms. While at university in the West, he crafted a political ideology in which the common people would be prioritised over monarchs or emperors. The ideology was named Tenetism, in reference to the Four Tenets which Khimbu described in his first manifesto:

1. All For One…

Khimbu stated that the citizens of a state should work together for a common goal that is considered a greater good for the nation.

2. ...And All For All

Khimbu argued that all of Antarctica should be united, as this would prevent clashing national interests. Tenetism called for amity, fraternity, and cohesion among all peoples and cultures.

3.

Not One For One…

This was the belief that the interest of the nation should always be prioritised. Khimbu declared that civilians should not strive towards goals that benefitted only themselves – society can only be improved through selflessness and total loyalty to the nation.

4.

...Nor One For All

Khimbu wrote that the reins of a nation should be held by workers, not by a single leader or group – whether they were a sovereign of an empire, a member of a noble family, or dictator of a republic.

A system where workers would be prioritised over a monarch became popular, especially among Upper Eastern Antarctica. The Antarctic Industrial Revolution had led to the region becoming industry-dominant; workers from mines, refineries, and factories toiled harder while the nobility became increasingly rich and dependent on the resources provided by the region. This wealth disparity angered many, with Khimbu’s teachings therefore becoming a favourable option.

5Karl Marx, the father of communism, was funded by his wealthy collaborator Friedrich Engels. Despite his wealthy family background and partial ownership of multiple textile mills, Engels was highly critical of capitalist mistreatment of workers, and dedicated his work towards revolutionary socialism.

Flag of the Transantarctic Interregnum

In 1677, Pek Khimbu formed the People’s Following of Labourers (PFL). Espousing Tenetism and promoting increased labour rights, the Following was massively popular. It amassed over several million followers by the end of the decade, presenting a formidable threat against both imperial rule and noble corporations6

When Khimbu died in 1692, many workers across the East – PFL members or otherwise – went on strike. The Tribute Movement was the largest labour protest in Antarctic history yet, and was successful in grinding the continent’s economy to a halt. Under pressure from the Transantarctic Interregnum, the monarchs across East Antarctica attempted a crackdown on the strikes and anti-nobility sentiment.

The militaries of each kingdom were deployed into cities, where PFL leaders were arrested and protests were violently suppressed. This ultimately culminated in the Bondoq Plaza Massacre, where hundreds of unarmed protestors were killed by infantry and cannon fire outside a royal residence. Despite attempts to contain news about the slaughter, information escaped and was met under intense outcry7. Particularly in the East, those who had considered themselves politically neutral grew antagonistic of the royalty, while those already opposed to nobility increasingly sought more forceful methods to bring about change.

A week following the massacre, a faction broke off from the Following, calling themselves the Devout PFL8.

The new splinter organisation was a paramilitary group, intent on using violent means to bring about Tenetist republicanism. On the summer solstice of 1693, the D-PFL organised a mass terror event across Upper East Antarctica, during which guerilla fighters stormed a dozen noble and royal palaces9. The solstice attacks marked the start of the Eastern Spring, a revolution that would grow to topple all five kingdoms in Upper East Antarctica.

In the wake of the attacks, the Upper Eastern Kingdoms dramatically increased their crackdown of any labour movements: any worker with suspicion of links to the PFL or D-PFL was imprisoned. The mass arrests resulted in a sharp decline in the workforce and a heavy strain on the economy – even business owners and the middleclass began to feel displeased by the continually incompetent monarchies.

6Although it was created within a dictatorship, Poland’s Solidarity trade union enjoyed similar levels of stratospheric growth. Gaining 10 million members within a year of its founding in 1980, its influence was in large part responsible for the country’s transition into democracy. The trade union went on to win the first free national election in a landslide victory and formed the first government of the Polish Republic.

7The 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre saw hundreds to several thousands of protestors killed by the Chinese military. Although widely criticised outside of China, it is a subject of heavy government censorship to this day, with information regarding the murders being expunged or thoroughly whitewashed as an event mainly featuring violent rioters attacking valiant servicemen

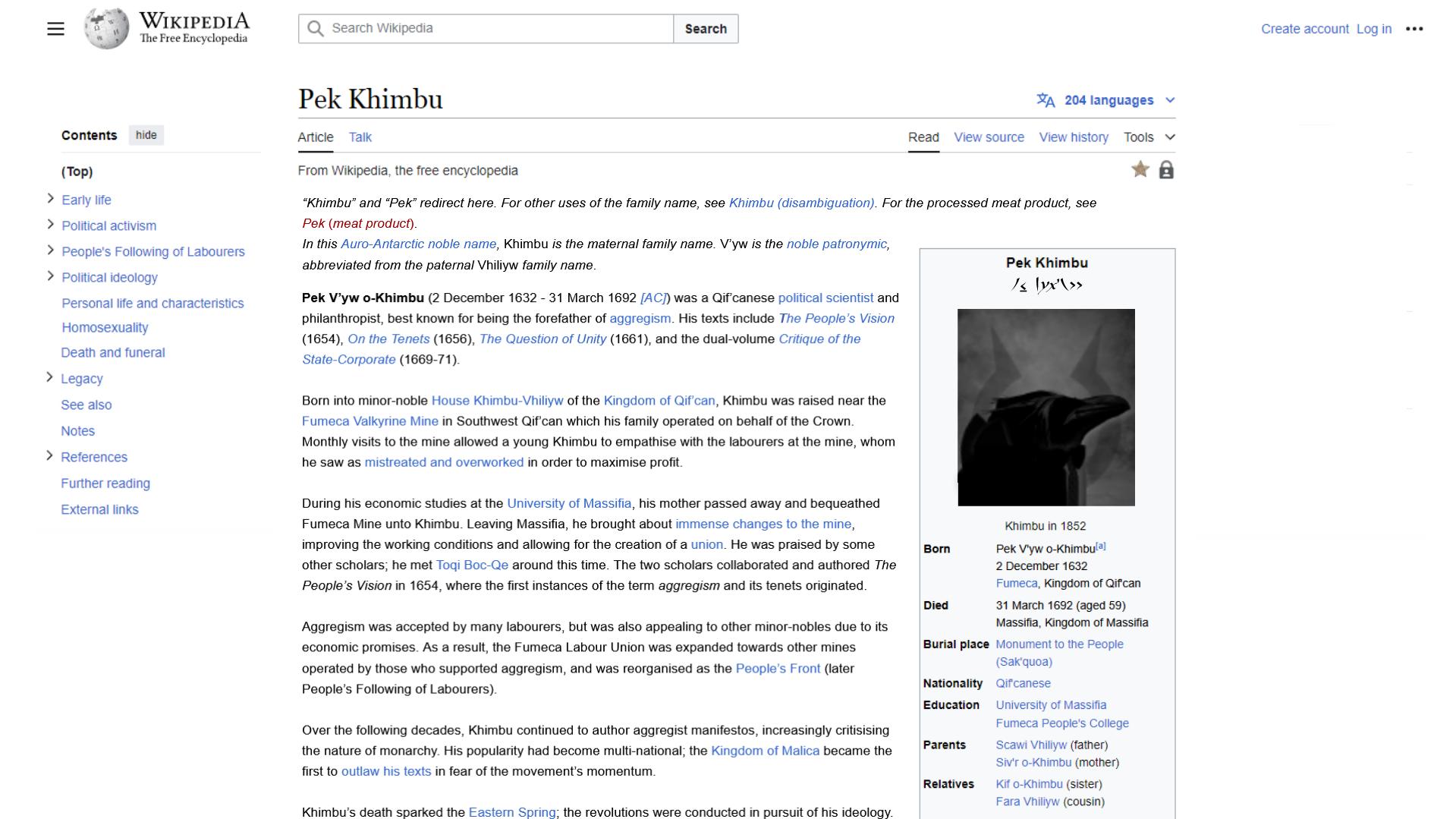

A screenshot of Pek Khimbu’s Wikipedia article

Despite having the same goals in mind, the PFL and D-PFL were locked in rivalry. Many PFL members rejected the violent nature of the paramilitary group, while the D-PFL was often undermined by the original Following’s smear campaigns against it. However, the increasingly authoritarian acts of the kingdoms saw the two organisations cooperate in opposition to nobility.

What came to be known as the Basalt Pact established a coalition between the groups, which would aim to replace each of the Upper East’s monarchies with a Tenetist republic. Both groups recognised the growing desperation of the nobles and resentment from the populace as opportunities for a regime change. Upon publishing their declaration of rebellion, the coalition ordered a number of uprisings across the region. Many civilians joined the cause to fight against the monarchies, which scrambled to deploy their soldiers to quell the resistance.

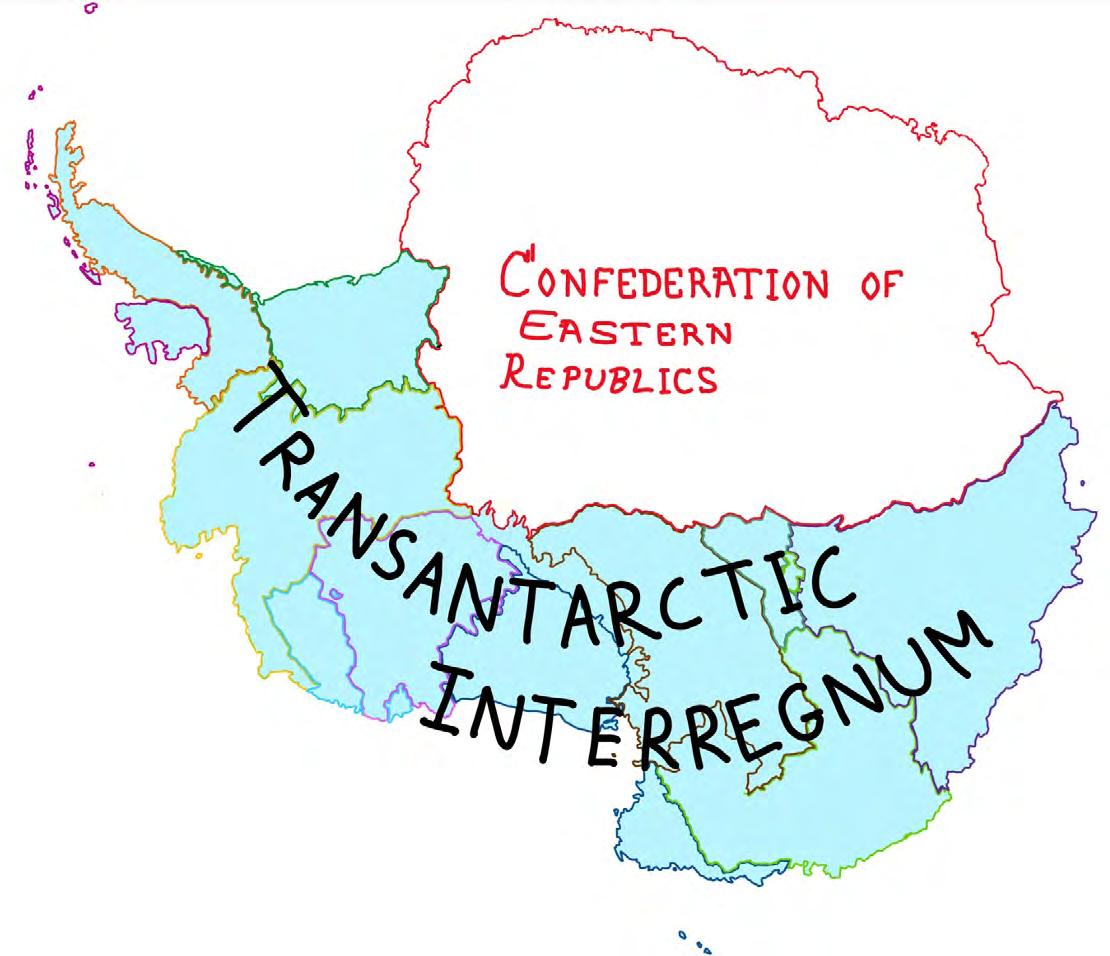

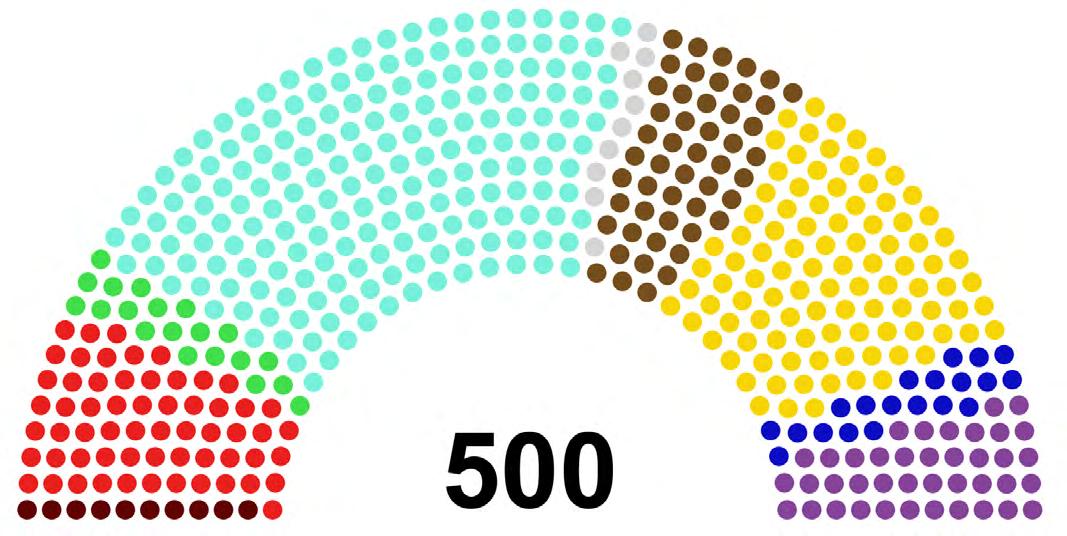

Map of Antarctica following the Eastern Spring. Note that the Transantarctic Interregnum is not a country, but an alliance of independent kingdoms

The revolutionary war lasted a mere three years. Despite receiving military aid from the Transantarctic Interregnum, the Upper East Kingdoms could not survive the popular uprising. One by one, the five monarchs were toppled and exiled, with a republic being established in their place. These five republics were united under the Confederation of Eastern Republics (CER), wherein power was shared between the republics in the Grand Council. This new nation spanned the entirety of the Upper Eastern Antarctica region (refer to the basic geographic map at the start of the article), therefore dwarfing each of the remaining kingdoms in size. As agreed to in the Basalt Pact, political affairs of the Confederation would be handled by the PFL, while the D-PFL would form part of their new military. This new nation would be independent from any monarch, and thus had no seat at the Interregnum.

The Confederation of Eastern Republics (1701 - 1775)

The establishment of the Confederation was of great worry to the other kingdoms. Many monarchs feared a similar uprising would befall themselves, and thus increased military funding for their kingdom. For 70 years, the Confederation coexisted with the other kingdoms – occasional border skirmishes took place, but for the most part tensions were allowed to simmer.

Within these seven decades, the Confederation was in constant turmoil. Tenetism soon proved itself unsustainable, as the economic stagnation that the ideology was designed to thrive in could only be achieved in a nation spanning the whole continent. Without sufficient resources or trade, the CER suffered blows to its industrial production.

To resuscitate its economic output, the PFL was forced to sign the Treaty of Sanquo’a, a trade deal with the Transantarctic Interregnum that came with the prerequisite that it would not be allowed to promote Tenetism beyond the Confederation’s borders. The CER also shifted from Tenetism to a new doctrine dubbed ‘aggregism’ (after the word aggregate), which scholars had designed to be a more economically successful ideology. Both of these decisions were unpopular among Khimbu’s loyalists, many of whom populated the D-PFL army.

Under their radically different political systems, relations between the kingdoms and the Confederation slowly worsened over the 18th century. Unbeknownst to regular civilians, multiple kingdoms had invested in military

8There is a frankly absurd number of splinter organisations of the Irish Republican Army, including the Provisional IRA, Official IRA, New IRA, Continuity IRA, and the Real IRA.

9The Tet Offensive was a large-scale assault by the Viet Cong on South Vietnamese towns and cities in 1968. Among the many targets of the attack were American buildings such as the US embassy in Saigon, which was occupied by guerilla fighters for multiple hours.

Flag of the Confederation of Eastern Republics

espionage against the CER, with some intentionally fuelling distrust between the PFL government and D-PFL military. Disagreements between the two organisations peaked in the 1770s, when the military accused the government of treason due to its soft stance on increasing imperial aggression.

The numerous clashes came to a head in the Dusk Revolt, wherein the military violently overthrew the PFL and declared itself the legitimate government of the Confederation. In the ensuing chaos, multiple kingdoms jointly marched their troops into the Eastern Republics under the guise of peacekeeping. The D-PFL found itself divided and in disarray: Khimbu loyalists struggled to take over the reins of governance while other soldiers disapproved of the group’s coup d’état and refused to arrest the deposed politicians. Unable to unify against Interregnum peacekeeper forces, the Confederation fell as quickly as it had risen.

With troops occupying the major cities of the former CER, the Transantarctic Interregnum restored the five Upper Eastern kingdoms that preceded the Confederation, appointing powerful aristocrats as each of their new monarchs. These kingdoms would be reincorporated into the Interregnum to protect them against potential revolutionaries, once again uniting the governments across the continent in a pro-monarchy alliance. Under the new monarchies, protests soon became uncommon as civilians grew fearful of the royal militaries’ modernised weaponry. All the while, the opportunity for resistance shrunk more with each piece of legislation that legitimised power within the new royal families – it was not until a century later that the spark of revolution would return.

Lantern Revolution (1860s)

Throughout these hundred years, humans finally reached Antarctica, with British hunting vessels having been shocked to find coastal ports in the otherwise barren whaling waters. Returning to Britain in 1822, the sailors would relay tales of the penguin civilisations to the public. However, they were met with scepticism, and demand for further expeditions would not arrive until decades later.

The call for Eastern Antarctic dissent would once again erupt in 1868, when a large explosion from a Valkyrine refinery razed large parts of the Lower Eastern factory city of Vuji. The incident, attributed to poor worker safety regulations, was met with anger by the few labour unions that were allowed to operate. Unfortunately for the monarchies, the event coincided with a period of general disdain for corruption among the Eastern nobility, and was therefore exploited by some labour groups to spread republican sentiment.

Over the following months, what began as an illegal strike within Vuji blossomed into a movement spanning the entire Eastern half of the continent. Despite the state media’s attempts to control the narrative, dissenters printed their own newspapers to distribute in every major Eastern city. The most significant of these was the Aggregist Voice, a paper espousing its titular ideology and published by the labour group Sunrise Order10

As the peaceful protests gained momentum, the East’s monarchs were placed in a dilemma. Uneager to repeat the events of the Eastern Spring, they acquiesced to certain aggregist demands, including the right to local elections. This proved disastrous for the nobility, as the first triennial election saw metropolitan and provincial councils become dominated by aggregists. Despite their limited power as local representatives, their arrival into office bolstered republican efforts by allowing law enforcement authorities to turn a blind eye to the increasingly rebellious populace.

On the third anniversary of the Vuji Incident, multiple cities across the East seceded from their respective kingdoms. The separatist movement was largely backed by the Sunrise Order, which by this time had developed a secret paramilitary wing – revolutionaries would clash with the royal militaries that were deployed into secessionist cities. Despite early losses, the revolution would be revived after a speech made by the Order’s Chairwoman Hu’aun Wyto was widely circulated in the Aggregist Voice. Following the publishing of the speech, many royal soldiers grew disillusioned with the anti-worker sentiment of the nobility and defected to the Order, providing the rebels with weapons stolen from their barracks.

After seizing total control of the rebellious cities, the Order turned to ‘liberating’ the rest of the kingdoms. Having been born from the Interregnum’s funding, the relatively young Upper Eastern Kingdoms had previously relied

10Many revolutionary groups propagated their ideas with newspapers. The Bolshevik newspaper Pravda published Lenin’s April Theses; its promise of ‘Peace, Land, and Bread’ secured much popular support for the communist revolutionaries. Meanwhile, the Nazi Party distributed ‘Der Stürmer’ throughout its early years, a virulently anti-Semitic propaganda newspaper which played a vital role in their popularity and rise to power.

11The Horseshoe Theory in politics argues that far-left and far-right policies contain some close resemblances rather than being polar opposites. Both Nazism and communism have resulted in autocratic dictatorships, where a one-party nation is supposedly necessitated by the evils of the elite and preexisting authorities. Extremist ideologies of either end of the political spectrum often hold onto oversimplified views of the world, with anyone opposing

on the West’s military aid to quell resistance. However, the Western kingdoms were embroiled in economic trouble at this time and thus were reluctant to finance the East. The five Upper Eastern Kingdoms swiftly fell to the now heavily armed Order, which was rapidly increasing in popularity.

Fearing violent upheaval from without and within, the Lower Eastern monarchs fled the region. The Sunrise Order was widely received as saviours, and were given popular permission to institute sweeping changes. The Order established the Union of Eastern Republics, with Hu’aun Wyto at the helm as Chairwoman. With her plenary executive authority, she outlawed support of nobility and seized corporations into the Union. Despite the totalitarian political climate engendered by Wyto, public sentiment in the East was far too anti-royalist at this time to notice the similar ensnarement of freedoms brought about by the increasingly power-hungry Sunrise Order11

Two-State Era (1870s - 1946)

Throughout this time of unrest, the rest of the world had begun to learn of Antarctica. As Britain stepped its imperial colossus into Oceania, they learnt of Polynesian tales regarding a civilisation of birds at the South Pole. Compounded with Norwegian and Russian sightings of the continent, the government finally ordered an expedition to Antarctica in 1875. Landing in the Western Kingdom of Massifia and looking to claim the continent for the British Crown, the expeditionaries were surprised to find a kingdom as industrialised as itself.

Rather than establishing a colony, the British left Antarctica with a trade deal with the Massifian Kingdom. The

Antarctic nobles, yet again in fear of an aggregist takeover, looked to remilitarise. Therefore a deal was made: Britain would receive a share of Antarctica’s mineral wealth, and in return it was promised that they would provide ships, machinery, and weapons for the kingdoms in their standoff against the East. As monarchists themselves, the British Crown did not want this new world to fall into the hands of what they perceived as a socialist threat.

Already the wealthiest of the Western kingdoms, Massifia soon grew into a military powerhouse as well, and it soon came to dominate the Transantarctic Interregnum. The Massifian king, eager for more power, proposed the establishment of the Antarctic Empire – a single nation across West Antarctica with himself as its emperor. This was not without resistance; the proposal was met with fury from the other kingdoms. Regardless, the Empire was established with the Kingdom of Massifia and some of its allied kingdoms in 1894. Slowly, the remaining kingdoms were pressured into accepting annexation. By the 1920s, the West was fully united under the imperial banner, and two nations remained on the continent: the Antarctic Empire and the Union of Eastern Republics.

Flag of the Union of Eastern Republics

Flag of the Antarctic Empire

An Encyclopaedia Britannica entry regarding the annexation of the Royal Peninsula into the Antarctic Empire

Tensions between the countries would rise substantially throughout the following decades, with the threat of war constantly looming over the continent. An intense arms race saw expansive developments in each nation’s army and navy, with Britain and later America funding the Empire and the Soviets bankrolling the Union after Stalin took power.

Under the regime of the Sunrise Order, colossal amounts of propaganda was produced to cultivate a sense of anti-Western resentment and fear. To advance their aims of mass radicalisation, the long-dead au-Varan religion was revived in a new form dubbed Neovaranism. The state religion had notable changes from the original faith; scriptures emphasising personal liberties were minimised and replaced with teachings about freedom from nobility and the importance of unity with other workers (under a central authority, of course). It was by no coincidence that the Archbishop of the Neovaran Church often served alongside Chairwoman Wyto herself – policies passed in the Union government often found themselves twisted into sermons supposedly from a divine messenger12.

Beyond the revival of au-Varanism, the Sunrise Order also saw other numerous references to the former Auroran Empire. Despite the Union’s republican nature, Chairwoman Wyto saw it as a successor to the Empire – Unionist architecture was deeply reminiscent of the ornate classical style used by the au-Varan Church13. Like the Auroran Empire, the Union was also ruled by the “Highest Council”, consisting of the most important people of the republics. Although some politicians within the Sunrise Order voiced anger at what they saw was a betrayal of the organisation’s ideals, they were quickly silenced and replaced with loyalists.

Before Hu’aun Wyto’s death in 1928, she instructed her title of Chairperson be handed down to her son. The hypocrisy of the role passing from parent to son in an anti-monarchic state was not lost on the populace, although most stayed quiet after those who protested were arrested and disappeared en masse14. Chairman Axaun Wyto’s rule was even more authoritarian than his mother’s, with the Sunrise Order, military, and even the Highest Council being purged of anyone who could resist his power15. As a result, the Council became populated by sycophants, which ironically would eventually contribute to Wyto’s downfall.

The opposing Antarctic Empire was also far from perfect16 Although it had a Parliament and (nominally) democratically elected Prime Minister, suffrage was not at all universal and elections were considered neither free nor fair. Regardless of the rigged democracy, the Emperor was still head of state, and held significant power over the nation. Surveillance was also rampant, with the Imperial Security Office imprisoning many over suspicions of supporting aggregism.

Antarctic Grand War (1946-1950)

An American political cartoon mocking the Antarctic Empire’s relentless arms race while claiming to have a moral high ground

The Antarctic continent remained out of both world wars, as both its nations were preoccupied in arming for an inevitable conflict against one another. The Grand War would finally come in 1946, when Union Chairman Wyto began a rapid invasion of both ice shelves under imperial rule. Although achieving quick advancements early in the war, the Republican war efforts were stalled when Imperial reinforcements held them back from the mainland. Led by ruthless War Minister Piki Caqan, the Imperial forces were determined to keep the Republicans on the ice shelves while they maintained control over the advantageous highlands.

the country away from Christianity to an explicitly pro-Nazi pagan religion. With most other churches banned, most remaining Protestant groups were annexed into the Reich Church to ensure they did not preach dissent against Nazi atrocities. 13Stalinist rule saw the rise of socialist classicism in architecture, where buildings were designed at a monumental scale and with abundant decorative elements.

14North Korea is probably the most egregious example of a communist nation being far from representative of the common people. Its position of Supreme Leader is dynastic, having passed down twice from father to son.

15Stalin and Hitler both instituted extensive internal purges. Stalin’s paranoia led to the Great Purge, in which suspected dissenters in the Communist Party and military were charged with treason and executed. An estimated one million were killed. In 1934, Hitler’s SS orchestrated the Night of the Long Knives, in which rival Nazis such as Ernst Röhm and Gregor Strasser were murdered.

16For most of the 20th century, both the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan) engaged in rampant human rights abuses. Until 1987, Taiwan was held under martial law, with those opposing the regime being subject to torture and execution. Regardless, it received US support due to its opposition to communism. The People’s Republic of China is still a dictatorship, with countless atrocities throughout its 76-year history.

17Hitler’s decision to invade the Soviet Union in 1941 was partially influenced by the slow progress made in the Western Front, where the Blitz had failed in gaining German air superiority over Britain. Although initially successful, Operation Barbarossa is widely seen to have contributed to the eventual downfall of Nazi Germany – opening a new front stretched German forces thin and resulted in major losses in Africa and Italy.

With the Imperial city of Akulako under siege and completely surrounded by Republican forces, Chairman Wyto ordered an extensive bombing campaign of the city, hoping to draw the Imperial forces out of their safe position to defend the Akulans. However, Caqan refused to compromise his army’s advantage, and allowed the bombing to continue. Only when the city was mostly destroyed did Wyto order a ground invasion of the city.

Wyto’s decision for such a large-scale bombing campaign was met with disapproval among some in the Highest Council of the Union. Akulako was the largest industrial region on the continent – none of the East’s own industrial cities could match its manufacturing output. By destroying vast swathes of Akulako’s factories rather than capturing them, the Republic had given up the opportunity to commandeer the city’s production of weapons, vehicles, and warships. The first cracks of the Highest Council’s loyalty had begun to show.

A map of the major troop movements throughout the Grand War. Blue represents the Antarctic Empire and orange represents the Union of Eastern Republics

Impatient for progress, Chairman Wyto ordered a third battlefront to be opened17. The mountain range dividing Antarctica was sparsely defended by Imperial forces; nevertheless, an invasion there would be highly risky as it would involve funnelling Republican soldiers through dangerous and narrow mountain passes. The mountain pass campaign was brief, with a combination of weather and quick Imperial defences driving the Union troops away. Furious, Wyto commanded the retreating Republicans to destroy any village or town they travelled through, murdering thousands in the process.

The atrocity drew international attention. Although the newly created United Nations attempted to pass legislation against the Union of Eastern Republics, all proposals were vetoed by the USSR. In response, the US Congress under President Truman ratified the Antarctic Alliance Aid Bill. Also known as the Triple-A Bill, the act promised to provide the Antarctic Empire with military and monetary support, beginning with a substantial grant for the Imperial Navy18. Combined with Imperial War Minister Caqan’s political manoeuvring, the Empire’s military began arming for a massive counter-invasion against the Union.

During the early years of the conflict, control over the Antarctic Empire’s war effort was largely split between the Imperial Military (led by War Minister Caqan) and the Imperial Parliament (led by Prime Minister Yao’ii Endanan). While most members of the Parliament were in support of the war, many were sceptical of the military’s mass spending, which was majorly straining the country’s economy. As such, the war budget was limited, much to Caqan’s infuriation.

Later in the war however, Prime Minister Endanan became terminally ill. Having been elected a decade prior, he was diagnosed with cancer in 1945. His condition quickly deteriorated and he became less and less active in Parliament. Despite calls for his resignation, Endanan refused to step down, leading to a decrease in support for his cabinet. By his death in 1947, Caqan had successfully rallied a majority in Parliament behind his cause, and massively increased funding for the war effort.

With Caqan’s new budget and American military aid, the Imperial Navy and Air Force grew immensely. By 1948, the Antarctic Empire was able to break the war’s stalemate with a series of successful attacks along the Eastern coastline. Caught by surprise and outnumbered massively, the Republic’s forces were soon forced into a hasty retreat from the border. This was exacerbated by Chairman Wyto’s poor war tactics, which deeply frustrated the Highest Council of the Union. Having been brought to power as sycophants and usurpers, the powerhungry Council members revolted against Wyto, establishing their own splinter governments from Republican territory19. Some of the rebellious Council members swiftly allied with the Empire to evade any punishment they would otherwise face, handing over valuable factory cities to the Imperial war effort in the process. By 1949, Imperial troops had surrounded the capital and the Union’s defeat looked inevitable. To escape the

18President Truman was deeply worried about the spread of communism – he was a strong proponent of the domino theory, believing that a nation that fell to communism would spread it to another. US foreign policy therefore followed the Truman Doctrine, which promised aid to countries under threat from “armed minorities or outside pressures”. The Doctrine was put into effect through the Greek and Turkish Assistance Act of 1947, which funded the countries’ wars against communist rebels.

19As Nazi Germany suffered increasing losses throughout the war, some within the military and government sought to betray Hitler’s authority. The July 20 plot saw members of the German Army attempt to assassinate and replace the Führer; the plan’s failure led to the purge of those suspected to have known of or participated in the plot. In 1945, the inevitability of Nazi defeat led SS leader Heinrich Himmler to attempt a peace deal with the Allies without Hitler’s knowledge in order to protect himself.

besieged city, Wyto arranged a short charter flight from his bunker to an aircraft carrier bound for the Soviet Union – however, his plane soon crashed into the Southern Ocean while navigating through a storm, killing the Chairman. A few days later, the remaining members of the Highest Council signed an unconditional surrender, effectively dissolving the Union of Eastern Republics and entirely uniting the continent under the Antarctic Empire.

Antarctica in the Cold War (19501970)

After the war, the Imperial government was reorganised under pressure from the United States. The reorganisation centralised power into the central government, reducing provincial autonomy as well as transferring most of the Emperor’s power to a democratically elected Prime Minister.

Following his successes in the Grand War, Piki Caqan received a surge in popularity among the West. His campaign for Prime Minister was successful; he led the right-wing Imperialist Party and was thus backed by the United States. A nationalist and militarist, Caqan was eager to show the nation’s allegiance with the US against communism. He proposed a Southern Hemisphere counterpart to NATO, with Antarctica as its foremost power.

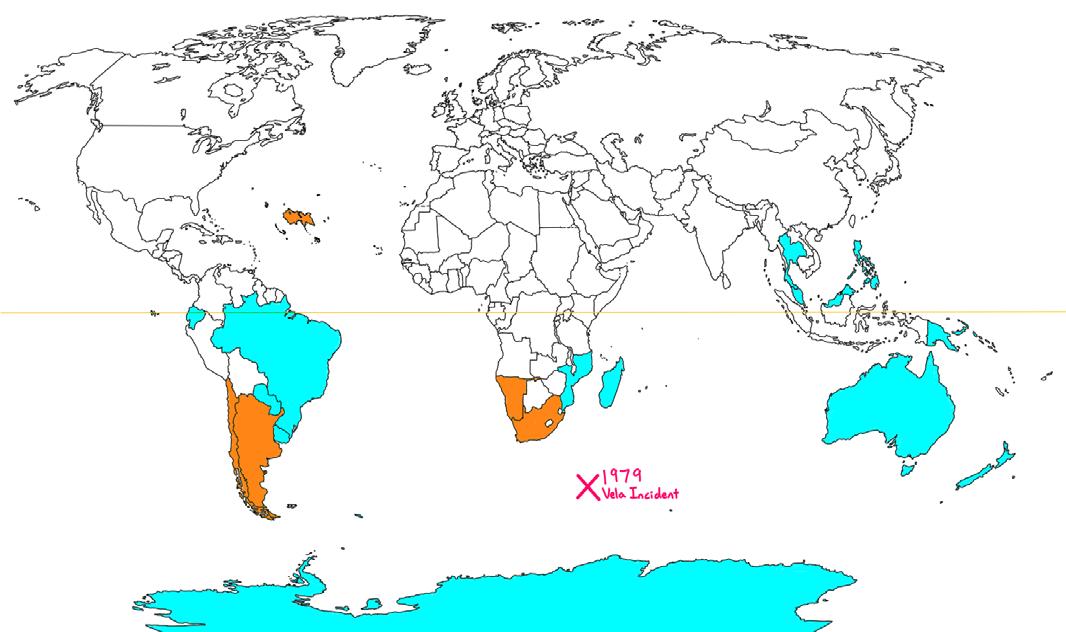

In 1952, the US voiced approval of the proposal, and Antarctica signed the Maputo Agreement with seventeen other countries to form the Southern Co-Protection Sphere (Scopros).

Scopros was founded primarily as a military organisation; each member was entitled to Antarctic protection if under communist threat. Antarctic troops saw small scale deployment in member states such as Mozambique and Malaya, but Caqan’s main goal was to spread Antarctic influence abroad through the establishment of overseas naval bases.

The largest test of Caqan’s ambition came in 1965. Following the Gulf of Tonkin Incident off the North Vietnamese coast, the US had approved the first deployment of ground troops to Vietnam20. America’s President Johnson sought support from Antarctica, which held a military presence in nearby Southeast Asian countries. Hoping to further improve trade relations with the US, Caqan obliged, sending troops and warships from bases in Thailand and the Philippines.

While most civilians supported the ideals of Scopros, Caqan’s involvement in Vietnam was controversial. The war soon proved costly, taking much more resources and troops than initially expected. Mounting casualties notwithstanding, the Antarctic government remained steadfast in their commitment in Vietnam – Caqan held an iron grip on the Imperialist Party, which

20The Gulf of Tonkin Incident occurred in international waters off the Vietnamese coast, where US naval ships alleged that they were attacked by communist North Vietnamese vessels. After the event, the US Congress granted President Lyndon B. Johnson the unprecedented authority to launch military action in Vietnam without a declaration of war.

21Many Americans thought US involvement in Vietnam would be a quick affair. Instead, the war lasted over ten years and led to the deaths of 58,000 US soldiers. Despite growing protests against the war, the US withdrawal would only begin after Richard Nixon was elected into office on a campaign of leaving Vietnam.

22See footnote 9. Before the attack, most Americans were hopeful that the war would soon end. However, after suffering great losses during the offensive, many began to doubt America’s place in the war.

A map of Scopros member states during the Cold War. Blue denotes current members and orange denotes countries that have since left or been expelled

The flag of Scopros

A propaganda poster protesting Antarctic involvement in Vietnam

had a majority in Parliament21.

The 1968 Tet Offensive further humiliated Caqan; the communist assault on Saigon demonstrated the US and Antarctica’s lack of control over the war22. Angered by the Viet Cong’s brazen attack on Antarctic troops, Caqan doubled down, pushing for the introduction of conscription into the Antarctic military. This proved highly unpopular, as support for the war was at an all-time low. Furthermore, despite Caqan’s previous success over the battlefields of the Grand War, his tactics in Asia proved disastrous. Antarctica suffered heavy losses against guerilla fighters, and many questioned the wisdom of sending penguins to fight in the humid jungles of Vietnam. Outrage against the war therefore led to the Imperialist Party’s catastrophic defeat in the 1970 general election. Victorious was the anti-war Antarctic Progressive Party, which campaigned upon reducing Antarctica’s military affairs and a focus on domestic reforms. Under the APP, Antarctica withdrew from Vietnam and banned conscription in its constitution. Furthermore, Scopros was reorganised into a diplomatic and economic assembly rather than a military body.

Auroran Renaissance (1970 onwards)

Diplomatic reforms would see Antarctica diverging from US foreign policies, instead choosing to seek a path of neutrality for the remainder of the Cold War. The APP massively decreased the Empire’s defence spending, reversing centuries of Antarctica’s seemingly unending cycles of military armament. Caqan’s centralisation of government powers would be overturned, with increased autonomy being granted to each province. Improved democratic standards would also be implemented through elevated press freedom and increased local elections. The APP also invested heavily in the East, which had suffered from economic neglect since its annexation into the Empire. Lastly, the worker protection rights and wage reforms introduced by the Party massively boosted its popularity, resulting in its domination in the following few elections.

During this time, Antarctica led the charge against the South African apartheid state. Following the regime’s brutal police crackdown on protestors in the Soweto township, Antarctica became one of the first countries pushing for an international embargo against South Africa. In 1979, a secret joint nuclear test between South Africa and Israel was detected in the Southern Indian Ocean, leading to international condemnation23 Due to the tests’ proximity to Antarctica, they began openly advocating for a regime change that would end apartheid.

Domestically, the APP also began implementing proenterprise policies to take advantage of the continent’s resources. Most significantly, funding for the state petroleum company was increased dramatically following research discovered Antarctica’s vast oil reserves24. The country also exported rare earth metals and Valkyrine, with many nobility-owned corporations contributing to Antarctica’s economic boom25.

Moreover, the Antarctic Empire was reorganised as the Federal State of Antarctica in 1982. Provincial autonomy was further increased, as the Empress surrendered all administrative powers and adopted a diplomatic role as the nation’s figurehead. This reformation has paved the way for the present day, where Antarctica has become one of the most progressive countries in the world. It scores highly in freedom and democracy indices,

23The event is known as the Vela Incident, after the satellite that detected the explosions. Under the apartheid regime, South Africa had developed extensive weapons of mass destruction, including biological and chemical warfare programmes. Following the end of the apartheid, South Africa would surrender its nuclear arsenal.

24Studies have estimated that Antarctica’s oil reserves hold 511 billion barrels worth of oil, almost double Saudi Arabia’s 268 billion barrels.

25China’s rare earth metal industry was vitally important for its economic boom. In the present day, Chinese rare earth metal mines produce 70% of the global supply, and 90% of all rare earth metal is processed and refined in China.

26Much of the South Korean economy is dominated by ‘chaebols’ – massive conglomerates run by wealthy families. 41% of the Korean GDP is composed of just four corporations; the companies’ economic importance grants the families immense political power and legal immunity.

Flag of the Federal State of Antarctica