Tom Foster - Editor

This year got off to a shit start when Toby Price didn’t win Dakar and it’s been all downhill from there. Getting this issue over the line hasn’t been easy, and the next one looks like it’ll take some seriously fast footwork.

Sometimes when things get tough I can’t help myself. I look out the window next to my desk and I begin to daydream.

I imagine I’m on my bike – the bike I’ve had for years. The one I keep in tiptop condition although it hardly ever leaves the shed – and I’m riding with no time constraints.

It’s always sunny and warm in the dream. No-one’s phoning me and I don’t have to be anywhere at any particular time. Sometimes I’m scything through

dunes and struggling with the dust and sand. Sometimes I’m cruising along a back-country road and loving the smell of a freshly slashed paddock. Sometimes I’m sitting on a headland watching an incredible sunrise, and other times I’m at a single-pump servo in a town so far from civilization no-one’s ever heard of it. There’s me and another rider and we swap a couple of sentences on what’s ahead and what’s behind before enjoying a quiet cold drink and heading in opposite directions to whatever our futures may hold. Sometimes in the dream I’m not even riding anywhere. I’m camped on a beach I don’t even know the name of with a smouldering fire and some cooking gear, and I’m savouring the flavour of a freshly caught fish cooked over the flames. Nothing complex. Just the fish and perhaps a lemon and a sprinkle of herbs I carried with me for the occasion.

“ This year got off to a shit start when Toby Price didn’t win Dakar and it’s been all downhill from there. ”

forward. The wind and rain are hammering us, but we, the bike and I, meet it head-on, tough it out, and master it, arriving shattered at a deserted campsite where there’s dry wood and shelter. The sleeping bag has stayed dry, and with the fire crackling away there’s coffee and sugar in a cup and a lamb-with-mint-mashed-potatoes dehydrated meal waiting beside it. As the night closes in, I stretch out and think how life couldn’t be a whole lot better. Maybe I’ll run a spanner over the bike, more out of affection than need, then get some sleep before heading off in the morning.

On a different day the dream might be facing up to a really wild, tough storm. One so demented it’s difficult to keep the bike upright, let alone moving

Then the phone or an e-mail alert will shred the illusion and reality will sink its teeth deep into my day again. Deadlines loom, there’s always problems – with travel or injury or some stupid virus – and the real world keeps turning the screw.

Don’t ever let your dreams go. Dreams are the start of great adventures.

Adventure Rider Magazine is published bi-monthly by Mayne Media Group Pty Ltd

Publisher Kurt Quambusch

Editor Tom Foster tom@maynemedia.com.au

Group Sales Manager Mitch Newell mitch@maynemedia.com.au

Phone: (02) 9452 4517 Mobile: 0402 202 870

Production Arianna Lucini arianna@maynemedia.com.au

Design Danny Bourke art@maynemedia.com.au

Subscriptions (02) 9452 4517

ISSN 2201-1218

ACN 130 678 812

ABN 27 130 678 812

Postal address: PO Box 489, DEE WHY NSW 2099 Australia

Website: www.advridermag.com.au

Enquiries:

Phone: (02) 9452 4517

Int.ph: +61 2 9452 4517

Int.fax: +61 2 9452 5319

$24,750 RIDE AWAY*

$24,150 RIDE AWAY*

A QUANTUM LEAP FORWARD IN CAPABILITY, FOR MAXIMUM ADVENTURE IN EVERY RIDE.

TIGER 900 GT - Built specifically for road-going adventure, comfort and capability, the new Tiger 900 GT range has all the performance, rider-focused equipment and technology to approach every ride in confidence.

TIGER 900 RALLY - An exciting new Tiger range designed for maximum o -road adventure and all-day riding capability, control and comfort, courtesy of the greatest ever triple engine performance and specification.

Q Year one excuse: work commitments

Q Year two excuse: family holiday

R Year three…game on. Chris Bostelman tackled a big one.

Left: Not one, but two spare clutch plates. Both were needed.

Above: The planned route was Tibooburra to Cameron Corner, across the Merty Merty dunes to the Old Strzelecki Track and down into Arkaroola. Then The Oodnadatta Track to make Mount Dare and across The Simpson before heading back through Innamincka to Tibooburra.

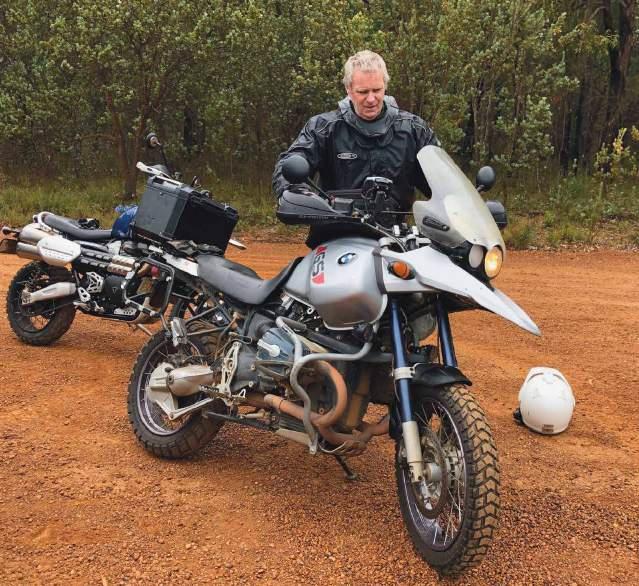

We started off seven riders strong – five from Port Macquarie and two from Sydney –for an unsupported crossing of the Simpson Desert.

The crew consisted of Allan on a DR650, Adam on a 500EXC, Scott with a Husky 701, and Mick, Greg, Dave and myself all on 690s. And yes, we had spares, including fuel pumps and an injector. The tyres of choice were from the Motoz range. We had Tractionator Deserts, Tractionator ITs and Tractionator Adventures.

The bikes were towed from various home locations through Broken Hill and into Tibooburra, with the first of several kangaroo strikes just outside Broken Hill.

At the Family Hotel in Tibooburra there were discussions with another group that had just crossed. They advised us we’d struggle unsupported. Half the bikes in their group came out of the desert on the back of utes. Some had mechanical issues, some crashes, and there were lots of tyre troubles every day.

I have to admit that unnerved us all a little.

The planned route for the first day was Tibooburra to Cameron Corner, across the Merty Merty dunes to the Old Strzelecki Track and down into Arkaroola.

The following few days were to be spent on The Oodnadatta Track to make Mount Dare before attacking The Simpson.

With all the last-minute items attended to we were off! Or so we thought…the DR wouldn’t start. We managed to tow start it, but a cough and a splutter later it would run no more. Battery voltage was good, but a jump starter was tried anyway. The DR wasn’t going anywhere.

Fuel check? Pass.

Spark check? Fail.

After a few tests we were down to either the stator or pick-up sensor. We tried the pub, shops and servo in Tibooburra for parts, but as expected, with no luck. We called Broken Hill for parts and received the reassuring news: “Sure, mate. We can have one

u

there in a week or so.” By then we were all due back at work.

Out of nowhere, Adam on the 500 said with euphoric glee, “I saw a DR650 in the shed at the top of the hill.”

That was amazing, and not just because there was a DR nearby, but because there was a hill out there.

So, with a new mission, the crew split up and started asking around town for the owner of the mystery bike.

One of the girls at the pub had the answer and offered to call the owner!

Only a few minutes later, Burt drove up to Al’s poor, stricken DR, rolled down the window and the quest to borrow parts began. We explained the situation and after chatting with Burt about our grand plans for adventure, we were given

permission to violate the left-hand crankcase and borrow the parts off Burt’s 17-year-old bike.

People sometimes pick on the trusty DR650. It’s old, heavy, underpowered and so forth, but on this day we were happy. The parts were identical. We completed the transplant, reassembled the donor DR and we were off.

Allan, the owner of the spritely three-yearold DR650, and I left five hours behind the rest of the crew. Leaving late meant, after we hit the Old Strzelecki Track, we had to shortcut across towards Lyndhurst to meet the Fantastic Five. We didn’t make it to town before the ’roos came out to play, so a bush camp it was for the Sydneysiders.

An early start was in order the next morning to try and beat the boys to where our paths were to cross 100km or so later. As it turned out, they had so much fun in the Flinders Ranges we beat them to breakfast. When we couldn’t get in contact we assumed, dangerously, they were in front of us. We rolled on after a lazy breakfast and left a message via Delorme Inreach with our new plan. We wouldn’t hear from them or see them until later that night at William Creek. Allan and I made it to William Creek in time for a late lunch and some leisure to do bike maintenance, laundry and some carefully considered rehydration at the pub before the others arrived.

From William Creek we bounced and rattled our way to the Pink Roadhouse the next morning, intending to make it to Mount Dare.

Discussion at the stop revolved around how far the lead rider would travel before checking everyone was together and moving forward. All options were considered, and it was agreed to use the cornerman system. Once in the desert this also meant stopping regularly to ensure the distance between the lead bike and sweep bike wasn’t too great. Simply stopping at the top of a dune and making sure the bike behind was still

Above: Together again: The seven dualsport delinquents on the Oodnadatta Track.

Far left: The white of the salt pan looked distinctly blue from the hill above.

Left: An Aussie icon.

Below: Cameron Corner on day one.

Right: Check your bike after you have a lie down. Even better, get a mate to check it while you catch your breath.

in view was thought to be safe enough and wouldn’t slow progress as much as stopping all the time to re-group. We also wanted to avoid the first bike having to cover big distance returning to help the last bike as that would use valuable fuel. We tried the system after topping up food, water and fuel and it all fell apart at the first turn. We ended up with an hour’s delay and five of the seven bikes using a lot of fuel in the process. That wasn’t critical at that stage as we still had a fuel stop in front of us, but it was a good lesson.

Later that day Allan hit a bulldust patch just in front of me and all I saw was the fat acrobat – the DR650 – get a serious wobble up. I lost sight of bike and rider and thought they’d separated from

each other. My avoidance of the fallen body and bike resulted in a couple of injured ribs, and while I don’t know the actual diagnosis, they bloody hurt over rough corrugated tracks. One helpful chap at Mount Dare pointed out there were 234,683,212 corrugations between William Creek and Mount Dare, and he only counted them if they were 10cm or higher.

The first day of the Simpson Desert crossing was just in front of us. Everyone had done their internet research and knew how much fuel it should take to cross and had added a few extra litres. In theory this should’ve been fine, as long as we didn’t make any navigational mistakes or have any fuel loss. Allan and I each had between six and eight litres more than we thought we would need and enough food for four full days.

Did anyone say ‘doomsday preppers’?

Late that afternoon our final preparations had been made. Bikes had been checked and fuel, food, water and courage had all been topped up. As far as fuel went,

Adam, Dave, Mick and Greg all had 36 litres, Scott had 38 litres, and Allan and myself had 50 litres.

The fourth day dawned and we left Mount Dare in the dark. I figured the corrugations wouldn’t be as bad if I couldn’t see them.

We pulled into Dalhousie Springs and decided a swim would take too much effort and time. If you haven’t been and you have the time, it really is a must. Watch out for the flies and mozzies though. They can be ferocious.

Onwards to Birdsville we went.

The scenery and colours of outback Australia are truly breathtaking. Making time to soak up the desert ambience should be on everyone’s bucket list.

It was around about Purnie Bore it hit us. It was harder than any of us had imagined.

Our bikes were loaded to the point where we might as well have had pillions. The going was slow and tough. Anyone with shorter legs struggled to stop without having a lie down in the sand, and the game of using fuel so as to reduce weight versus being conservative and maintaining fuel range was on.

I admit I wasn’t feeling good for the first part of the morning, but once in the groove and used to the weight, things got a little easier. By midmorning though, a few of the crew were starting to run out of energy. We had each emptied the first of our fuel bladders and already we had some fuel loss due to bladder leakage… fuel-bladder leakage that is.

After a few more lie downs the energy

levels and mood had dropped. The going was hard. The Stockton Beach sand practice, although useful, hadn’t prepared us for the level of challenge. We were late in the season, the days were getting hotter and finding a clean line to run at a moderate pace over a dune was almost unachievable carrying such big loads. By lunchtime talk had started about a Plan B. Turning around was an option, although not favoured by most. Research showed what we had experienced on the French Line so far was likely to continue for quite a while. Being late in the season, the traffic over the dunes had created huge sandy ruts and corrugations between 60cm and 90cm deep. Plan

Above: Adam on the ‘little’ 500cc single on the fourth day. The KTM was the best-sounding bike on tour.

Below left: A turning point.

Below: Celebration! The DR made it to Poeppel Corner. u

B further developed and became a run down the Colson Track to the Rigg Road and then across to Knolls Track in order to bypass some of the French Line. The idea was to cover some distance and get the confidence up on the southern dunes which weren’t as high or challenging. The distance was greater, but our fuel use should balance out as the going was to be far easier.

With confidence restored we were hoping the French Line would be conquered on the second day in the desert.

After much deliberation we turned south at the Colson Track and then on to the Rigg Road where we camped that night. After the final fuel top up for the day it soon became apparent fuel consumption, particularly that morning, had been a lot higher than anticipated. Those with less fuel on board started to get concerned about making it to Birdsville. On top of that was some only having one day and night’s worth of food left, and the discussion started again about turning back.

On the other hand, a few of us had overpacked food and fuel, and to be quite frank, beyond the weight penalty, we were comfortable we could make it across even if it took a few more days. We would probably have had enough for the seven of us to get across if we’d pooled provisions.

There were a few bottles of red and the odd chair came out to the fire that night, so we weren’t doing it too tough. That space would probably have been better used for additional fuel and food, though. Another lesson learned maybe.

We hunkered down by the fire and watched the magnificent desert sky. The Milky Way was spectacular out in the desert – another outback highlight.

It was decision time.

After rehydrating by the fire, rider’s choices were clear: Adam, Greg, Mick, Dave and Scott decided to err on the side of caution and planned to run back up to the intersection of the WAA Line and the Colson Track before heading west along the Rig Road to the Oodnadatta Track for some more corrugations; Allan and I decided to continue on as we felt we had sufficient supplies. We made sure each

group had suitable provisions and spares before we parted company.

Nights are generally cold in the desert so tents, bivvies, sleeping bags and thermals were unpacked. To give an idea of the drop in temperature after sundown, the water bladder on my bike had a sheet of ice on it in the morning.

Travelling in remote areas is dangerous. Having too much or not enough can be the difference between an amazing trip and a potential disaster. Too much gear and you’re too heavy. Not enough and you can get into trouble if the weather turns and you can’t move forward.

The mighty DR650 and the oldest KTM690 were packed and warmed up in time for first light: ‘Birdsville, here we come’ was our mental war cry.

Sand dunes, clay pans and salt pans were the order of the day. Wildflowers were starting to bloom and the trees were greenish in most areas.

Before we turned on to Knolls Track

Above: Once in the groove and used to the weight, things got a little easier.

Below left: Borrowing Burt’s DR650 bits.

Thanks again, Burt!

Below: The parts from the 17-year-old donor bike were identical.

we were greeted by an enormous lake. Whether or not it was dry was the question. The white of the salt pan looked distinctly blue from the hill above and we thought we may have to find a way around. But as we approached we realised it was a reflection from the magnificent blue sky. Phew. Tackling salt or clay pans with caution is advisable. There appeared to be a solid surface crust, but we kept a good distance between ourselves in case the bikes started to sink.

The sand dips on Knolls Track would’ve swallowed a 4WD. In the middle of a dip, while standing up on the ’pegs, we were literally at eye level with the grass on the side of the track.

Back on the French Line the dunes were soft, badly rutted and had metre-deep holes in the wheel tracks. If you didn’t make it up and over on the first attempt,

there was no hopping off and pushing to the top. You simply had to turn around and have another go. After hours of the dunes getting softer and deeper, we needed a revised dune-riding technique.

At the bottom of each dune this wise mantra would echo in our brains…

R Hold it wide open in third or fourth

R Pause at the top but don’t let the wheels stop turning

R Check the coast is clear and you have a good line

R Change down one gear and nail it again

R Rest in the gap between dunes. It was thoroughly addictive, and while the above worked, there were other things to consider. At the bottom of a dune we had to pick the clearest, straightest line from an existing wheel track to the desired wheel track at the top. We had to ignore any track conditions that wouldn’t make us crash into a tree, bike, person or car. The idea was to look

ahead at the destination and accelerate to a speed that helped the bike float over the top of the ruts. It was important to not ride down into, and back out of, every dip.

The afternoon saw us within range of Big Red. We’d kept a steady pace all day with food breaks every few hours to keep the energy up. We swapped the lead every 10km and checked on each other using a simple thumbs up while still moving.

We hit the Eyre Creek detour and enjoyed the sights and sounds of the trees, creek and the numerous bird species. We

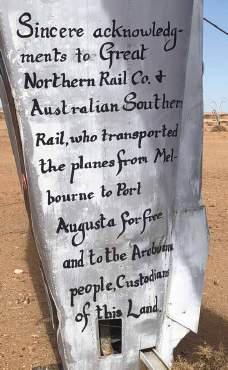

Above: ‘Planehenge’. A well-known landmark on the Oodnadatta Track.

Below left: Back at Tibooburra. ‘Hey! Let’s work on the DR again!’

Below: Broken weld? No problems. Just add cable ties.

Harder then any of us imagined

knew we weren’t far away from the edge of the desert and this gave us a much-needed boost. We were chasing our own shadows as we approached Big Red.

As we came across the final clay pan we were greeted by several tourist buses at the top of the big sand hill. They would be witnesses to our success…or failure. Time would tell.

We initially hit the base of the dune at between 70kph and 80kph, heading to the tracks on the steepest ascent. The tourist cameras caught us at the top… almost. We stopped with a just a few metres to go.

We dragged the bikes around and headed back down for a second attempt.

For round two we hit it slightly faster and used our own track. This tactic took us to the top of the steepest ascent and we sailed up and over. The DR had definitely left some of its clutch behind, and after it cooled down we thought it may have just been overheating that was causing the slip.

We watched the sunset over the desert, took a few happy snaps and headed off for the cold ride to town, arriving at the Birdsville Hotel in the dark and celebrating with a huge outback meal and plenty of carefully chosen rehydration fluid.

Plating up

The plan was to be back in Tibooburra

in two days, with an overnight at Innamincka on the way.

After a good rest and a leisurely start, we rolled on. But only minutes after leaving Birdsville the mighty DR halted forward progress. The poor Suzi needed a little lie down and some clutch-plate lovin’.

Allan rustled through his DR parts bag, which I must say was quite cavernous. He had a choice of two clutch plates, both new in genuine-Suzuki bags, and the rebuild began. There was one friction plate that was no more, so we changed it out. It was probably close to 30 minutes and we were off again. The second DR surgery had been a success.

After turning onto Walkers Crossing Track at the 44-gallon drum the ‘road’ went to wrack and ruin. The track’s wheel ruts snaked through the gibber plains, then the corrugations started and I thought, “F%^$! Not again.” This continued for about 20 minutes, but soon mercifully turned into an outback version of the Oxley Highway for adventure bikes.

Top: Camping on the Rigg Road.

Left top: Mick, winner of the ‘Sexiest Bike On Tour’ award.

Left: Scott prefers his KTM in blue-and-white.

It was like being on a Moto 3 bike with knobbies: head under the screen and elbows tucked in. The fun had begun.

Not far onto this awesome track the power of the Allan/Burt hybrid DR650 was too much for the clutch and the third DR open-heart surgery was scheduled. Allan had the spare clutch plate whipped out of his bag in a jiffy and we were into it. This one took a bit more time. We had to remove the friction plate material from the spring plate, rather painstakingly, with a hacksaw blade and a file from a Leatherperson multitool. It probably took us an hour before we were ride tested, luggage loaded and on the move again.

We used more fuel on the track to Innaminka than we did on the second day of the Simpson crossing and we covered a similar distance, and by the time we hit Innaminka we were grinning in our helmets as we topped up the desert sleds for our final ride day.

We pulled up at Tibooburra in the early afternoon of the next day and started to return the left-side crankcase to the rest of the mature DR in the shed. DR surgery number four was almost completed when Dave,

Greg, Adam, Scott and Mick arrived back at the trailers having finished their own adventure.

Burt, the saviour of our trip, thought the rest of his bike would be jealous with the left side of the motor doing a Simpson Desert crossing while the rest of the bike stayed home, probably destined for nothing more than future mustering duties. There you go, we did the old DR a favour.

Well parts of it anyway.

A massive shout out to Burt. Without his willingness to help and loaning us the parts we would never have left Tibooburra and had such an amazing outback adventure.

It turned out Burt owned the Family Hotel at Tibooburra. I’ve stayed there half a dozen times now and have always enjoyed the outback hospitality with great food and accommodation. If you pass through, drop in for a meal or, even better, stay the night and support a fellow rider and a top bloke.

With over 1200km to get home and very little afternoon light remaining, we loaded up and made tracks. Stopping at Broken Hill, we met up for dinner and shared the stories of adventures since we’d parted a few days earlier. The mood was sombre with our outback adventure done for another year.

Conversation soon turned to bike modifications and returning next year for a double unsupported crossing.

You have been warned. It is very addictive.

R Check your bike after you have a lie down. Even better, get a mate to check it while you catch your breath

R For heavy off-road riding use soft luggage and containers. A Rotopax-style container or hard luggage can hit your legs and can also pin you under the bike

R Choose water-bladder brands carefully. Running out of water can be life threatening. Some bladders don’t cope with heavy corrugations.

R Choose on-bike fuel containers carefully. Loss of fuel can be a real issue on an unsupported crossing

R Do your track research well. Have a Plan B. Know the conditions of all alternate routes

R Try not to travel late in the season. Tracks are softer and heavily damaged from all the traffic

R Allow plenty of extra food, fuel and water. Shit happens, and you need some contingency

R Have good communications to call for help if needed. Even better, have several comms options

R Make sure you have check-in points with someone not on the trip who knows your itinerary

R Cable ties can fix almost anything

R Use Motoz Tyres. We had no tyre issues on this trip. With seven bikes travelling over 3000km each that’s over 40,000km of trouble-free outback travel

R Watch out for bulldust. Riding too close leaves few options if things go wrong with the bike in front

R Have a good group riding plan. Include recovery options and hope you never need them

Will Fennell headed to South Australia’s Kangaroo Island and found a spectacular adventure riders’ paradise rising from the ashes of recent

fires.

During the summer of 2020 South Australia’s Kangaroo Island was severely affected by horrific bushfires. Thousands of hectares of national park, farmland and forestry, predominantly on the western end of the island, were decimated by the intense fires. Aside from the significant damage to the natural environment and catastrophic wildlife losses, tourists were down to about one-third of usual numbers. Consequently, many businesses on the island were suffering.

In January 2020, in response to the #bookthemout and #spendwiththem social-media campaigns, I put the call out for any riders interested in heading over to the island to explore its remarkably changed landscape, but moreover to spend money in the local cafés, pubs and petrol stations which were badly in need of tourist dollars.

My call was answered by a group of three fine lads on trailbikes who were up for the ride. Our team was comprised of Alex on his 450EXC, Huon on his WR450F, ‘Dr Zee’ on his DRZ and I’d be riding my well-travelled BMW G650GS Sertão. Generally I ride with 800cc and larger adventure bikes, so I was looking forward to for once being the guy with the largest fuel tank.

I pretty quickly worked out that, with no fuel available west of Vivonne Bay, we were going to need a support vehicle if we were to have any chance of covering the sort of distances I had in mind. Luckily my lovely fiancée Lucy and her bestie Ally were keen to join in on the adventure, bringing up the rear in a VW Amarok. Normally I’d have worried about there being no ’roo bar, but frankly, given recent events, we didn’t expect to see many ’roos.

The itinerary

We planned a weekend trip, arriving in Penneshaw late Friday night and departing Sunday afternoon. Our navigation plan was simple. On Saturday we would explore the south coast of the island and

Snellings Beach, one of the most picturesque parts of Kangaroo Island.

stay overnight at Parndana (a rural town almost dead centre of the island), and on Sunday we would explore the northern coastline. Huon was very familiar with the island and acted as our local guide.

With some late-night electrical work in the lead up to the trip we managed to get UHF comms between the Sertão and the Amarok, thanks mainly to a Sena SR10. Being able to talk on the go between at least one bike and a trailing 4WD meant less stops and more ground covered.

The trip commenced with a tarmac ride from Adelaide to Cape Jervis before a 45-minute ferry trip to Penneshaw. The ferry workers did a first-class job securing the bikes, and after a smooth crossing we were met with gently drizzling rain. We quickly setup camp before heading up to the Penneshaw Hotel to settle in for the evening.

It was clear by breakfast on Saturday morning no-one was going to weigh any less on the ferry on the way home. After a round of delicious bacon-and-egg rolls at the aptly named Fat Beagle Café in Penneshaw we headed for our first destination, D’Estrees Bay.

One of the great features of Kangaroo Island for adventure riders is beach access for motorcycles, and D’Estrees provided our first opportunity for a play in the sand. We also found some great sandy twin track running parallel to the beach. Luckily Alex noticed, before it flew off into the scrub, that the seat on his KTM wasn’t attached to the subframe due to a seat bolt having rattled loose on the corrugated Kangaroo Island roads. Fortunately for Alex a bolt out of my BMW spares pack was a perfect fit, and with the KTM reassembled we headed for a sightseeing stop at Seal Bay.

No prizes for guessing what we found there.

The next stop along the south coast that morning was Vivonne Bay. The general store is famous for its whiting burger, and with breakfast barely digested we tucked into lunch. Suffice to say the whiting burgers lived up to their legendary reputation.

After lunch we witnessed the first seriously fire-impacted area on the seafront at Vivonne Bay. The fires had burned right across the dunes down to the beach, leaving exposed a fragile dune system.

From there the extent of the fires became even more apparent as we made our way west along South Coast Road towards Flinders Chase National Park. Road signs had literally melted and once dense and impassable bushland was burned to the ground. The fires had raged for miles and miles, and seemingly always along the roadway. That must’ve made firefighting for the CFS precarious to say the least. The intense damage gave us a real appreciation for the

bravery of the men and women who had fought those fires.

We then made our way down to the recently reopened Hanson Bay. Although the beach had vehicle access, it was soft like quicksand. Even the wet sand offered little support. The boys enjoyed watching the Sertão plough slowly along the beach with rev limiter engaged as it struggled to gain momentum.

We then made our way northeast to our overnight stop in Parndana. There were several north-south roads to choose from, but we chose the Gosse Ritchie Road, a spectacular ride through both National Park and forestry areas. It was a surreal experience picking our way along that road with thousands of acres of burned-out National Park to our left and burned-out forestry to our right.

We’d arrived in Parndana by around 6:30pm and set up camp in the large and reasonably well-provisioned caravan park. The smell of bushfire smoke was

inescapable during the evening shower. I thought it must have been on me –from riding all day through these areas –but it turned out the local water supply at Middle River had been contaminated by ash.

“ The intense damage gave us a real appreciation for the bravery of the men and women who had fought those fires.”

The Parndana Hotel has excellent meals and as we reflected on the day we all said it had been some of the most interesting adventure riding we’d ever done. Despite the devastation, it really had felt like a once-in-a-lifetime experience to see the countryside stripped back to such an extent.

On Sunday morning we packed up camp and headed over to Davo’s Deli in Parndana.

We sat and drank a great coffee in the morning sun and watched some seriously impressive army trucks on their way to the Parndana oval which was being used as a base for the army and also as a campsite for displaced locals. We ended up going down for a look and what turned out to be a poignant experience. It was clear the army, many of whom were reservists, were playing a pivotal role in getting the Kangaroo Island community back on its feet.

We then headed north-west from Parndana along Johncock Road and out to Western River Road. Before we left on this trip I’d been warned about slippery ‘marble-like’ gravel on the western end of Kangaroo Island, and on Sunday we definitely came across it. Combined with bad corrugations, no-one wanted to be rolling too hot into corners.

Top: Melted road signs alongside hectares of burned scrub.

Left: Inspecting the Parndana town water supply, contaminated by ash.

Below: From left: Lucy Damin, Ally Newcombe and Will Fennell. Lucy and Ally were brilliant in the support vehicle.

We followed Western River Road east to join North Coast Road and head towards Snellings Beach. The views along those roads were truly spectacular. Snellings Beach is also vehicle-accessible and, unlike Hanson Bay, was firm to ride on. Naturally, we had a play.

Our Sunday lunch stop was in Stokes Bay at the Rockpool Café. There we caught up with husband-and-wife managers Lucy and Josh, and owner Matt, who all took a few minutes out of their busy day to meet us and have a photo taken. Lucy and Josh had recently lost their home to the fires but, like most islanders, they seemed to be getting on with life with typical Aussie resilience. The food at Rockpool was top notch and we would highly recommend a stop there. We also noticed a camping area out the back of the Rockpool Café and would’ve stayed there if we’d had more time.

After lunch we made our way from Stokes Bay back towards Penneshaw along Bark Hut Road. We found some open forestry roads and great 4WD tracks to explore, but ended up a touch lost in the forest. Burned-out forest looks very different to lush green forest and previous reference points were gone.

After a somewhat dicey crossing through a creek with steep and badly eroded banks – well…dicey on my 185kg Sertão. The smaller bikes just cruised through it – we made our way out of the forest and along a mixture of dirt and bitumen to arrive at the ferry terminal in good time for our journey home on the 4.00pm ferry.

Adventure riders sometimes seek out discomfort and misadventure in search of the ultimate adventure experience.

So, given we didn’t drop a bike and barely turned a spanner all weekend, did we still have fun?

Hell yes! We did!

I’d go even further and say this was one of the best adventure weekends I’ve enjoyed. Why? It was a real experience. We saw recently burned landscapes that many people never get to see in their lifetimes. Some of what we saw was confronting. But, most important, we helped make a difference, albeit a small one, to the towns and businesses we visited.

More broadly the fires had highlighted to us the remarkable strength and resilience of Australia and its people, from the incredibly brave CFS volunteers who had fought the fires to the everyday Australians like Lucy and Josh from the Rockpool Café who were stoically getting on with life in the face of adversity. What an amazingly courageous bunch we are. Lastly, the tourism promoters have suggested people should visit the eastern end of Kangaroo Island that was untouched by the fires, mainly because it’s business as usual over that side. But I reckon they’re wrong. The western end was absolutely spectacular and the businesses over that way need our help the most. The wildflowers in the burned-out areas this coming spring will no doubt present an amazing spectacle. Grab a ferry ticket and go #spendwiththem on Kangaroo Island. You won’t regret it.

Top: The dunes at Vivonne Bay left exposed and fragile.

Left: Snellings Beach is vehicle-accessible and firm to ride on.

KTM Group – that’s KTM Australia, Husqvarna Australia and GasGas – has a new marketing manager. New in the role she may be, but she’s a very familiar face to riders of those brands.

At 33, Canadian rider Rosie Lalonde has been around motorcycling in Australia for quite a while.

A serious showjumper –horses – at an international level in her younger years living in Canada, Rosie’s family were all keen motorcycle riders. Her parents met racing bikes and Rosie’s sister, Leigh, made the transition from horses to bikes in her teens. A trip to the 2002 Czech Republic ISDE resulted in meeting the Australian ISDE team and the Braico family, mainstays of the Australian enduro scene.

Showjumping for Rosie progressed to the point where a capable horse would ‘cost the same as a house’, and she had some tough decisions to make.

Meanwhile, Rosie’s sister had moved to Australia and was riding and racing enduros and off-road events. After several visits, in 2004 Rosie and her parents packed up and moved here as well. Rosie had finished secondary school and started racing bikes in good ol’ Aussie.

“Going through that transition, from the horse background and into the motorcycling community, was a tough one,” remembered the irrepressibly cheerful Brisbane girl. “On top of that, I was in a completely different country and making new friends. That was a challenge.”

Rosie’s father was a Canadian trials champion and a keen ice racer, and

racing enduro had always been part of life for Rosie alongside her showjumping. When the Australian Off Road Championship kicked off in 2005 she and her sister were on the start line. She stuck with the series for the next five years or so, and also competed in the NSW enduro series and fronted –finishing on the podium in her class –a couple of A4DEs.

“The enduro scene in Australia is like a big family,” explained Rosie. “We felt very welcome.”

While the racing took up a fair percentage of Rosie’s leisure time, studying for a Bachelor of Visual Communications, majoring in graphic design, at Newcastle Uni took some commitment as well.

“My goal, right from when I first started at university, was always to combine my passions of motorcycles and design,” she said. “Back in the day I really wanted to work in a graphics company and make motorcycle graphics. In my mind that would’ve been super cool.”

After an internship at a graphicdesign company and finishing her degree, travel beckoned and Rosie travelled the world. She found herself back in Australia in 2009 and looking for work. A hand injury while working with a horse led to a move back up to her family in Brisbane for rehab, and she was in an ideal place when a Queensland-based position became available.

Rosie knew the Oliver family – owners

“It was like my dream!” she swooned.

“They took a chance on me, a fresh face just out of university.”

Over the next six years Rosie moved from marketing assistant to marketing co-ordinator, and TeamMoto itself went through some massive growth, culminating in a takeover by Motorcycle Holdings Group, Australia’s biggest motorcycle dealership network.

“My time at TeamMoto, and then Motorcycle Holdings, taught me the ways of the industry. It gave me the opportunity to combine my love of motorcycles with my growing marketing career,” she mused.

It was also around the time Rosie moved into adventure riding.

“I really embraced the adventure-riding concept,” related Rosie.

“I’d gone away from racing enduro in around 2010 or 2011. It was just becoming too difficult with a full-time job, trying to get away for the weekends and travelling. It was just too much. I still had a passion for riding, and the adventure concept of more casual fun and low pressure really appealed to me.”

The first adventure outing was on a DR650, closely followed by a move to a

u of TeamMoto Motorcycles – from her racing. When TeamMoto was looking for a marketing assistant and offered Rosie the job, she couldn’t believe it.

Main: Four hugely successful KTM Adventure Rallyes in New Zealand, four in Australia, and one Husky 701 Enduro Trek have all been the result of Rosie’s personal planning and supervision.

Left: KTM Group’s new marketing manager, Rosie Lalonde.

Above: The CR250 that she learned to ride on back in Canada, sitting on the ice of their pond.

Triumph Tiger 800. Then came the first ride on a KTM.

“It was a 690 Enduro R,” smiled Rosie with a far-away look in her eye. “I instantly fell in love.

“I’d been riding enduro on a 250EXC-F, and the KTM brand had always appealed to me. I felt there were two companies that did marketing the absolute best: Harley-Davidson and KTM. I just felt the passion and the community each of those brands had built was leaps and bounds ahead of any others.

“In my time at TeamMoto I’d worked with 10 different brands, and it really gave me the chance to see the difference in the way each brand portrayed itself. For me it was always KTM and Harley that did it the best.”

As part of her day-to-day work, Rosie had kicked off a two-day ride, the TeamMoto Adventure Rally, and discovered

a great enjoyment in putting together an experience for TeamMoto’s customers.

By this time she’d made some good friends throughout the Australian motorcycling industry, one of whom was Ray Barnes, KTM’s brand manager for Queensland.

Answer the call

“Ray Barnes called me up one day in 2015,” she remembered.

“KTM was looking for someone to run a customer-experience event like the BMW Safari, and Ray asked if I knew anyone who might suit. I told Ray I’d put on my thinking cap and hung up. About half-an-hour later I ran outside and called him back and said, ‘Ray! That sounds like me! I want to do that. I want to work for KTM.’”

It was thanks to that conversation Rosie moved to KTM as event manager, where

so many Australian KTM and Husqvarna owners would have seen and met her.

“As it turned out, my very first day with KTM was in Fiji at a dealer conference,” laughed the effervescent Rosie. “It all stemmed from Jeff Leisk’s dream to start the KTM Rallyes. He wanted to offer something special to KTM customers, and that’s why they hired me.”

So far there have been four hugely successful KTM Adventure Rallyes in New Zealand, four in Australia, and one Husky 701 Enduro Trek, all the result of Rosie’s personal planning and supervision. She was also invited to Europe to assist at, and MC, the first European KTM Adventure Rallye in northern Italy and the second in Sardinia. Rosie has even spent holidays riding two of the American KTM Rallyes.

“It was fascinating for me to see how the KTM adventure customers from all over the world are so similar,” she said. “They want to push their bikes to the limit, they want to meet new people and have an awesome time, and they want to enjoy a cold beer at the end of the day.

“It’s been really special for me to see that.”

Top left: Rosie, her sister Leigh (left), and Dad Gord at a round of the 2007 AORC.

Above: Ray Barnes, Jeff Leisk and Rosie at the “finish” of the epic 2018 KTM Australia Adventure Rallye Outback Run.

Left: Participating in the Ice Cream Relay at the New Zealand all-ladies Queens Of Dirt in 2019.

Top right: Hanging out with the A team.

Right: “I need to study and see what will potentially work for us over the next six to 12 months.”

Far right: A true adventure rider.

What will a new hand at the marketing helm mean for KTM, Husqvarna Motorcycles and GasGas in the future?

“We’re in such uncharted times right now,” she offered. “I need to study and see what will potentially work for us over the next six to 12 months. We need to hold steady with our brand values and stay connected with our customers. The rides, whether they’re Rallyes or Treks, are good, and maybe, potentially, might grow into more adventure-experience events.”

Rosie’s also looking for opportunities to introduce new riders to the brands using entry points like KTM’s LAMSapproved 390 Adventure.

Whatever direction KTM Group and its brands go, with Rosie steering things along everyone can expect it be a fun, polished and thoroughly enjoyable experience. It’s what she’s all about.

It’s not an easy story to tell…a couple of blokes feeling the stress of isolation needed some release. A ride was the answer.

u

Let’s say this all happened a few months ago. Let’s say riding was being considered not in the best interests of society at the time, although it wasn’t illegal to leave home. And let’s say a couple of blokes, we’ll call ’em Craig and Marty – seeing as that’s their names – thought they were at serious risk of going postal if they didn’t get some time on their bikes.

The pair, always with the best interests of society in mind, planned a quiet day trip through some scarcely used, unpopulated subtropical rainforest. Are you jealous yet? You should be.

The pair set off on a humid and overcast morning with Marty offering to lead. He had a twinkle in his eye and his backpack made a curious clinking sound as he touched the button to fire up his DR650 and lead off into the moist, slippery forest which reached right up to his back door.

Craig followed at a safe and socially aware distance. His DR, like some kind of Swiss-army-knife bike, bristled with bush saws (two of them) and highspec equipment. Upside-down forks and the yellow gleam of an Öhlins shock reservoir gave a hint of what lay underneath.

Enquiries as to the destination had been met with a mystical stare.

“Just follow,” said Marty with a gleam in his eye. “I know a good place to visit.” So it began.

Through the slippery clay forest the boys hurtled, crossing ridges offering incredible scenery and along trails so

slimy no germ could adhere to their surface. The DRs shimmied and wobbled in the wet going and roared and swooped through the dry. The

“The boys revelled in the primordial setting. It seemed likely no human being had been there for many years.”

awesome subtropical forest at times closed in tight to the trails and at others fell back to allow the lush, long grasses to hold sway.

An interesting creek needed some

exploration and Marty threw himself in at the deep end to discover a glorious setting which deserved, and received, some minutes of quiet admiration. The water was crystal clear and the luscious trees, ferns and vines framed the creek in the distance.

Not a single human being had been sighted since departure, and as the boys revelled in the primordial setting it seemed likely no human being had been there for many years.

The stress, already greatly

Far left: Craig’s DR bristled with bush saws (two of them) and high-spec equipment.

Left: Sections had tree limbs and rocks scattered across their wet, grippy surfaces.

Bottom left: Some trails took a touch of skill to master.

Right: An interesting creek needed some exploration.

Below: In places the lush, long grasses held sway.

decreased in both riders, melted away as sunbeams struck down through the canopy to shed a golden light over the scene.

Although reluctant to leave such a place of serenity, the lads knew they had a task to fulfil. The destination was still a good way off.

The day continued. The trails, one after the other, could only have been put together in a dream. Some were open and fast, some needed a touch of skill to master, and some had tree limbs and rocks scattered across their wet, grippy surfaces.

Marty knew them all. So did Craig, but the destination and the promised revelation were still hidden.

A longish climb up a well-maintained and familiar fire road had the pair at an elevated ridge with awesome views in all directions. They stopped, unpacked a few snacks and a cold drink or two and lost themselves in the moment. Mist hung over the valleys, and the trees, blackened by fire a short time before, had green halos. Mother Nature showed, as she has for millennia, that no natural disaster of any kind was her equal.

The boys stayed an acceptable distance apart and thought long and hard about the state of the world and what they were seeing.

“Let’s go,” said Marty, packing his kit and ensuring nothing was left behind.

Winding down the mountainside and into the farmland below the pair increased their pace while maintaining their distance from each other. The paddocks, supporting fat, sleek cattle, flew by as the riders piloted their bikes along the hard-packed country dirt roads. A few villages came and went, but not a soul was seen.

Finally the pair rolled into Taylors Arm, and propping the bikes on the stands in front of one of Australia’s best-known landmarks, absorbed the sight before them.

“This is why we’re here,” said Marty, shrugging off his backpack and producing two distinctive, amber-coloured bottles.

The hotel in front of them was deserted.

“It’s a beer with no pub,” smiled Marty, well pleased with his quip.

The pair clinked the icy bottles together and enjoyed a quiet moment of shared solitude.

Their beer of choice?

Corona, of course.

The line of ancestry from the first Africa Twin in 1988 to the bike seen here is a little tenuous. Like a few others from the 1980s and 1990s, the current bike is a relaunch of the name on a totally new bike. It’s aimed at largely the same rider and terrain as the original, but there’s a considerable time and technology gap.

The Africa Twin kicked off in 1988 as a 650cc V-twin and, typically of Honda, was just a little in front of the other ‘Dakar-inspired’ soft-roaders on sale at around that time. The name

was dropped from Honda’s line-up in the early 2000s as riders’ tastes moved elsewhere, with the final model a 750cc V-twin labelled the XRV750T.

In 2016 the model name was resurrected on the CRF1000L, a bike which, at first glance, didn’t have a lot in common with previous Africa Twins. For starters the 2016 bike was a 998cc parallel twin. But thanks to some clever marketing from Honda and the high regard for previous Africa Twins, it was snapped up almost as soon as bikes hit dealer floors.

u

The CRF1000L was offered in three variations: a standard model, an ABS model and a DCT model.

The standard model was a fuel-injected parallel twin with a 270-degree firing order which kept the V-twin feeling in mind, and no electronic rider aids. The ABS model was the same bike with, predictably, ABS. The Dual Clutch Transmission (DCT) model was the eye-opener, offering what amounted to an automatic gearbox. A touch of a button engaged ‘drive’, and from there all the rider had to think about was staying upright. Gear selection could also be done manually via the left switchblock, and like an auto car, there was no manual clutch.

Some people loved the DCT and some didn’t, but Honda stuck with it, and individual rider preferences aside, there’s no doubt the DCT system works well.

The 2020 model lineup of Africa Twins no longer includes a non-ABS model, and Honda says there’s now two to choose from: the CRF1100L, and the CRF1100L Adventure Sports. We feel like the DCT bike makes for a third choice, but it’s considered an option on the Adventure Sports model.

Probably the biggest feature of note on the 2020 models is the motor. The 1084cc parallel twin is 86cc bigger than last

year’s and is Euro 5-compliant. Emissions controls always seem to be about to stifle motorcycles out of business, but Honda’s motor meets what are currently the toughest emissions standards on the planet in a package that’s slimmer, has a 10-per-cent improvement in power-toweight ratio from the previous CRF1000L and offers more torque.

The frame is lighter than the previous model as well, and there’s a suite of electronics that’ll sit the Honda right alongside the other big-money, big-bore adventure tourers. Six modes, including two rider modes, are there for fiddling with, and a six-axis inertial measurement unit (IMU) measures and shapes things like traction control, wheelie control, cornering ABS and rear-lift control. The rider makes selections via the left-hand switchblock and gets the state of play from a 16.5cm TFT display. Cruise control is standard on both models, cornering lights on the Adventure Sports arc up when the bike’s going around a turn, and for the up-spec model there’s electronic suspension available. Honda calls it Electronically Equipped Ride Adjustment (EERA).

We’ll just call it ‘electronic suspension’.

There are a couple of tech features we found interesting. They’re small in the scheme of things, but we thought they

were intriguing and the kind of detail Honda’s always done well.

The first is an exhaust control valve that essentially routes the exhaust gasses through a smaller outlet in the muffler at low revs, then opens to let the gasses escape through an additional larger outlet at higher revs. It’s a simple mechanical valve activated by the ECU, and the same set up as used on the arse-tearing new CBR1000RR. It’s a great concept. The bike sounds meek and mild at idle and horn with the throttle cracked open.

The other tech change which caught our eye was the throttle-body butterfly gears being moved to allow a straighter induction path into the combustion chambers. That seems like some good old-school thinking in a modern setting. The throttle bodies are two millimetres larger this year and the cylinder sleeves are now aluminium.

Standard suspension is fully adjustable Showa front and rear. The front sports 45mm USDs and the rear good ol’ ProLink. The shock on the conventionally suspended bikes has a decent-sized adjuster for preload which was easy to tweak.

The big news for most potential buyers will be the optional electronic suspension available on the Adventure Sports model. Like other electronic suspension units

Left: The Africa twin handles its weight really well, especially in technical and tricky situations. Above: Not as complex as it first appears, but still takes some getting used to. Backlighting the switches would’ve been good for night riding. Right: An LCD panel underneath the TFT screen shows speed, gear selection, an odometer and a handful of warning lights. Note the little ledge over the TFT display. It was brilliant.

we’ve tried, it does have a definite ‘feel’. Adjustments are made in near real time –15 milliseconds – and we’re not going to even try and explain the technology (we couldn’t if we wanted to). Once the rider

gets the thing set it’s just a matter of riding and letting the bike do the rest. There was some experimenting with shock preload selection and it was found to have a very noticeable effect on suspension performance overall, so don’t just accept the offered ‘rider only’ settings. Try out the pillion and other settings, even for a solo rider. It’s worth some trial and error to find what will work best. Another thing to keep in mind with

the electronic suspension is it adds some heft. The standard Africa Twin, measured at the brochure, comes in at 226kg. The electronic suspension model is 250kg.

It’s all very well for us to say, “Mess about with it and see what works,” but first the rider has to come to grips with the menu and what the TFT display is trying to say. Learning new menu systems and

display readings every time we ride a new bike is getting challenging, but has to be done.

The Honda system is mostly straightforward enough. The left switchblock is laid out with what looks to be an impossible array of buttons and switches, especially on the DCT model, but which actually is fairly sensible once it’s been explained six or seven times. The gearselection levers add a bit of initial extra confusion to the DCT model, and the Apple CarPlay buttons – standard on all the bikes – do a bit as well, but once they’re sorted things become mostly fairly clear.

The panel which matters most is the section with the up/down arrows and the enter button. That’s the section which gets the most attention for regular riding. It gives access to the six rider modes –Tour, Urban, Gravel, Off-road, User 1 and User 2 – and allows adjustment of various parameters within those modes…where parameters are adjustable. The graphics which accompany the settings need to be learned as well, and we’re still confused about whether a quarter of the circle in blue means maximum or minimum intervention. Traction control (HSTC) and wheelie control can be adjusted on the fly in all modes. There’s a rear-wheel lift control as well, so there’ll be no Jack Miller impersonations on this bike, thank you very much (it can be adjusted too, of course).

The little paddle in the middle also moves a display panel

across to show adjustable parameters for different performance facets.

We’re not going to spend pages trying to explain selection and tuning of the modes. If you’re keen, go to a dealer and get a demonstration. It’s a lot easier when you can watch it happen.

The DCT model also has a button to activate a sort of slipping-clutch arrangement. When the bike’s being urged forward on a loose surface, instead of the rear wheel instantly responding to the throttle it feels as though the clutch slips and allows a more gentle application of power.

We can’t remember which one of the buttons it was, though.

It was one of them. And it was good.

There’s quite a marked difference between the Standard and Adventure Sports models. To try and keep things moving along, we’ll aim for a summary.

The CRF1100L has:

R Plastic handguards

R An 18.8-litre tank

R Tubed tyres

R A low, fixed screen

R Lightweight bashplate, AND

R Weighs 226kg.

The Adventure Sports model has:

R Larger handguards

R A 24.8-litre tank

R Tubeless tyres

R Optional electronic suspension and/ or DCT

R Heated grips and 12-volt socket

R Five-position tall screen

R Three-stage cornering lights, AND

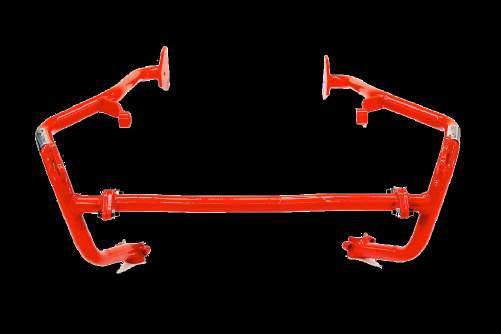

R Weighs 238kg (with manual transmission and mechanical suspension). Naturally there’s a stack of accessories available for both. Panniers, top boxes, tankbags, quickshifter, a footpedal gear selector for the DCT, handguards, crash bars…all kinds of stuff. An owner could do a very substantial fit out using the OEM accessories on offer.

Considering the new Africa Twin is near enough an 1100 it feels remarkably compact. It’s one of those bikes that carries its weight well, so although it’s a fair chunk to push around in the Northern Territory sand, it’s easy to forget the mass when the bike’s in motion. The motor’s quite narrow and the seating position is open and relaxed. The bike also didn’t feel tall, and we’re grateful every time we get on a big bike and can get our feet on the ground. Thanks, Honda!

The most daunting thing for a rider mounting the Africa Twin for the first time is the amount of switching on the ’bars, and then, once the key is turned, the sheer information overload from the

Left: We had such a good time on the standard bike we didn’t give much thought to tuning or adjusting anything.

Above: A bigger motor with more torque, Euro 5 compliant, yet still weighing less than the CRF1000L motor. Power delivery is smooth and very easy to use.

‘Multi Information Display’ – the TFT screen.

There’s also an LCD panel underneath the TFT screen which shows speed, gear selection, an odometer and a handful of warning lights.

Ye gods!

The LCD panel is very conventional and makes it easy for Honda newbies to get basic information fast and with no fuss.

As with all new bikes, once we’d settled in to the menu and display it mostly made sense, although this TFT display on its own does seem to offer a few too many options for someone who just wants to go for a ride. The information available, if you know where to look, is mind-boggling. But the display itself has different levels – gold, silver and bronze – which show different amounts of information. Gold displays heaps. All kinds of things we’d never even think of asking for are there, or are available, and it’s just a tad wild.

Silver, predictably, shows a little less info, and bronze, of course, shows just the basic stuff. We thought we were bronzies for sure, but once we’d been on the bike a while we kept thinking there were some things we wanted to see, so clearly it’s a matter of becoming familiar with what’s available and making the right selection. By the end of our ride we were hard’n’fast goldies in all modes.

And while we’re thinking about the switching, Honda went to some lengths to ensure we could experience the cornering lights. The lights worked well, but being out in the dark also showed up the switching being very difficult to use at night. The switches aren’t backlit, so black switches on black switchblocks at night, on a bike so heavily reliant on electronics… it was one of very few things we think Honda may have misjudged on the big CRF.

We started our riding on the Adventure Sports with mechanical suspension. It’s a gorgeous, tricolour beastie with a beautiful finish and a very high level of comfort. We plugged the phone into the USB port as instructed, but then became engrossed in the bike and the scenery – a lap around Uluru in the late afternoon –and ended up never actually activating Apple CarPlay.

Instead we grabbed a handful of the lightish clutch, snicked the big girl into gear and revelled in the restrained growl of the motor and the very comfortable, upright seating position. Honda claims 100hp from the new motor and the power comes on nicely. We hadn’t ridden an Africa Twin for a long time, but there were plenty of comments from other riders about how the motor was much torquier than the old 1000. It definitely pulled nicely from low revs, and it’s not a motor that particularly needs to be revved hard – although we were impressed with how it worked high in the rev range. It’s smooth, sounds tough and was a pleasure to use.

The tank on the Adventure Sports feels wide at the front, no doubt about it. It doesn’t interfere with riding the bike until it’s time to stand up and get forward, but it’s noticeable in the corner of each eye. Gear changes were very smooth and easy and, in general, the rider was well protected from windblast. We first thought that was courtesy of the tall screen which could be adjusted for height just by grabbing the clips on either side

and sliding it up or down.

The ’pegs have rubber inserts which came in for a lot of unkind comment over the few days of hammering along some rough roads, and quite a few were removed. We chucked ours early in case of river crossings, so we didn’t get the sore feet other riders complained about. River crossings? In the Red Centre?

After spending a day or so on the Adventure Sports we changed over to the ‘standard’ bike and were surprised at the difference.

The Adventure Sports is heavier than the standard bike, and we should’ve expected it, but when we hit rough going the standard bike was quite a bit livelier than its heavier sibling. It shook its head a little in fast going on rocky roads and kicked its heels up over sharp edges and corrugations. It was a lot of fun to ride fast. In the sand a rider’s body position had more influence, and in anything a little technical or gnarly, the standard bike was easier to move around. It was easier to change direction in deep sand or at speed, too.

Conversely, of course, the Adventure Sports was better at holding a line in deep sand and needed less attention from the rider at speed.

We didn’t do any suspension tuning, and that could’ve made a big difference, but that doesn’t change the feeling of the standard bike being lighter and narrower

around the front of the tank. We have to be honest, we were having such a good time on the standard bike we didn’t give much thought to tuning or adjusting anything. Most of our time was spent trying to walk the fine line between fanging about like lunatics and showing proper courtesy to our fellow riders.

Aside from that, there wasn’t much to talk about between the two. Performance from the drive trains seemed pretty much the same to us, although we felt the standard bike may have accelerated a little quicker. We’re perfectly prepared to accept that was a perception brought on by the lighter feel of the bike rather than a reality, but whether it was the case or not, we felt the standard bike was a touch more playful and fun to muscle around.

One very big difference between the two models, believe it or not, is the windscreen.

The Adventure Sports has a biggish screen which can be adjusted up and down. The standard bike has a short arrangement which finishes nearly level with the top of the TFT display. The big screen was a pain in backside when it got dusty and fairly substantially obscured the rider’s view of the terrain. The short

All the different model variations coped well. Photographer Damien Ashenhurst lined ’em up for more time in the rocks. u

Honda didn’t mollycoddle the bikes. They copped a hammering.

screen seemed to keep just as much wind off the rider, both on and off road, and didn’t get in the way at all.

So that was interesting.

Also, one of the bikes had a little ledge arrangement over the TFT screen which was brilliant for keeping the glare off it and making it super easy to read. We didn’t have any problem reading the TFT display even in direct sunlight, but that little overhang was a very nice touch.

We haven’t said any more about the

electronic suspension, but we’re still a little unsure how we feel about it. It worked fine, it added some weight to the bike, and it made adjustments for things like pillions and luggage really easy. The system even reads when the bike’s in the air and adjusts for a hard landing. It’s quite incredible.

But did we prefer it to properly set up mechanical suspension?

Probably not.

The thing we keep coming back to there is, so few riders make the effort to get their suspension sorted. If paying a

We’re being a little mischievous with the name of the panel. It’s actually the G switch we wanted to talk about. Apparently there’s something funny about a G spot and everyone in the office snickers when we say it, so we thought it would be a good way to introduce this section

In the copy we mentioned a ‘slipping-clutch arrangement’ on the DCT bike.

The correct name is the G switch. It’s activated from the touch screen on the TFT display and, to quote Honda’s tech material:

‘The G switch can change the engine characteristics of your vehicle to help improve traction and machine control for offroad riding by reducing the amount of clutch slip during throttle operation.

v Other than USER 1 and USER 2 MODE: Each time the ignition switch is turned to the ‘On’ position, the G switch will automatically be set to default setting.

USER 1 and USER 2 MODE: The G switch setting will be maintained even if the ignition switch is turned to the off position.

v The G switch may not compensate for rough road conditions. Always consider road and weather conditions, as well as your skills and condition, when applying the throttle.’

tuner, or learning to sort suspension yourself, isn’t going to happen, the electronic suspension is a gift. Just select the parameters from the menu that suit and she’ll be right. It might not be as good as it can possibly be, but it’ll be pretty damn good for most situations, and that’s more than most riders will get from any other kind of stock suspension unless they have it set up by someone who knows what they’re doing.

DCT will be a talking point for a long time to come. Performance of the auto gearbox on this ride was exceptional.

Recommended retail (including GST + on-roads):

Standard $19,990. Adventure Sports (manual transmission) $23,499. Adventure Sports (DCT) $24,499. Adventure Sports (EERA) $26,499

Web: motorcycles.honda.com.au

Engine type: Liquid cooled, SOHC, eight-valve, four-stroke, parallel-twin

Displacement: 1084cc

Bore x stroke: 92mm x 81.5mm

Compression ratio: 10:1

Maximum power: 75kW (100hp) @ 7500rpm

Maximum torque: 105Nm @ 6250rpm

Carburation: PGM-FI electronic fuel injection

Starter system: Electric

Transmission system: Standard/Adventure Sports – six-speed manual.

Adventure Sports DCT – six-speed auto DCT

Final drive: Chain

Front suspension system: Inverted fork

Front-axle travel: 204mm

Rear suspension system: ProLink

Rear-axle travel: 220mm

Front brake: 310mm dual wave floating discs with aluminium hub and radial-mounted four-piston Nissin calipers

Rear brake: 256mm wave hydraulic disc. Single piston Nissin caliper

Front tyre: 90/90-21

Rear tyre: 150/70-18

Length: 2330mm

Width: 960mm

Height: Standard 1395mm, Adventure Sports 1560mm (1620mm with high screen)

Seat height: Standard position 870mm. Low position 850mm

Wheelbase: 1575mm

Ground clearance: 250mm

Kerb weight: Standard 226kg. Adventure Sports 238kg. DCT 248kg. DCT EERA 250kg

Fuel capacity: Standard 18.8 litres. Adventure Sports 24.8 litres

Service intervals: After first service, engine oil every 8000km and valve clearances every 16,000km

Colours: Standard bike – Matte Ballistic Black Metallic and Grand Prix Red.

Adventure Sports – Pearl Glare White Tricolour

Warranty: 24 months

No matter how rough the terrain or deep the sand, the DCT worked in the rider’s favour. Every time.

It has a few settings of its own, and again, the right setting at the right time can make a good ride a great ride, but there’ll still be plenty who prefer a standard clutch and gearbox.

Don’t jump to conclusions, though. Give it a try before you make up your mind. You might be surprised.

Adventure Rider Magazine tips its hat to Honda Australia for not being protective of its bikes. This three-day ride from Uluru to Alice Springs in the Northern Territory covered some serious terrain, and lots of it. Over the three days the bikes were hammered through something approaching 2000km of bitumen, rock, sand, a couple of little creek crossings, and some long, rough, shitty sections that were all of the above. We even went for a short blast on the Finke Desert Race track. If anything was going to fail on any of those dozen or so bikes it would’ve failed under that kind of treatment from riders who weren’t all that concerned about looking after them.

Nothing failed. The bikes coped with all of it, and coped well. We were especially – and pleasantly – surprised at how well all the model variations coped with the dunes.

And while they proved themselves tough, the first day had over 800km of bitumen and the comfort level was amazing.

The CRF1100 Africa Twin is a first-class, big-bore adventurebike option.

Plan A started in October when I purchased a new KTM 690 Enduro R and had it fitted up with good gear from Barrett’s, B&B and so on. What could be a better test than a run through the dirt tracks of the Victorian and NSW high country in, say, January?

But first there was the small matter of a November Compass Expeditions ride down Chile’s Caraterra Austral to enjoy.

A fine ride it was too, until an oncoming truck and I decided we wanted to share the same piece of gravel on the apex of a blind corner. I’ve always believed in light adventure bikes, and the pain of an 800GSA using me to cushion its fall did nothing to change my opinion.

Hey, it was only a broken fibula. It was easy to deny because I could still walk and ride… at least until I got home to see my friendly orthopaedic surgeon.

At the time I thought Plan A was still a possibility, but it wasn’t to be.

Plan B was hatched after the summer heat had died down and my leg healed.

The plan consisted of a run up to Mungo, Menindee, Cameron Corner, Innaminka and home through the Flinders. I thought late March would be good.

But every story has a twist, hence Plan C emerged when a friend mentioned he was heading to Lake Gairdner to take in the drylake racing.

‘Easy,’ I reasoned. ‘If I head to Lake Gairdner first I can simply ride my original route in reverse and take in some great racing on the way’.

But a week before the event the organisers bravely but wisely pulled the pin when the early signs of the Covid 19 threat began to emerge.

Plan D evolved – and I use the term after consideration given the viral climate – out of a sense of stubbornness and naivety. It was the

In 1785 Robert Burns composed the poem To A Mouse in which he penned the words ‘the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry’. Don Bromfield is no poet, but his best-laid plans still went awry.

early days before the full reality of the effect Covid 19 was to have on all our futures. The plan was to head to Adelaide and then into the Flinders, Innaminka, Cameron Corner and home via Mungo if my nine-day window allowed. What could go wrong?

Riding a KTM on the Western Highway into South Australia was hardly riveting adventure, but I would be remiss not to recommend the free camping at the lake

at Bordertown. After a night in Adelaide where some idiot stole my el-cheapo wet-weather onesie – why would anyone bother? – it was off to Yunta for the start of the adventure ride.

Plan D had me riding the Tea Tree Road north to Arkaroola. Most of my adventure riding had taken place overseas on the bitumen, hard-pack gravel or loose pebbles of Europe and North and South America, so this was to be my introduction to outback adventure riding. At 66 I decided it was high time I started seeing my own backyard. And anyway, the bulldust couldn’t be that hard, could it?

All went well on the run to Waukaringa. A bullet-ridden truck body with a rusty engine block laying in the dirt, accompanied by the roofless, decaying, yellow clay walls of an early settlers,

cottage, held my interest as I wandered around looking for that special spot to frame my photo. Further on the ruts from mining trucks, filled with bulldust, may not have introduced me to my maker, but they certainly tested my resolve to keep the power on and the weight back as the Kato bucked and wobbled up the road. I was learning.

Outback travel is renowned for heat and flies, and this part of the trip certainly didn’t disappoint in that department. What surprised me was the lack of traffic. Two trucks in 300km was a harbinger of times to come as Covid 19 began to force people to stay home.

Road warnings towards Innaminka, solo travel, 35-degree heat and the lack of traffic had me considering if it was wise to head further north. I decided on a rest day at Arkaroola for the opportunity to

u

ride to some of the nearby sites and further contemplate Plan E.

A chance meeting with an Aboriginal ranger servicing the stone-and-iron Nudlamutana Hut led to a pleasant conversation about the history of the area and the bush tucker available. Bush banana flowers eaten straight off the tree resulted. The windmill with its spinning galvanised blades perched atop the spindly framework servicing the hut appeared a poignant reminder of past meeting present. That was until she pointed out that the two solar panels mounted at its base were really doing the work. WHS precluded climbing the tower for service work, but at least it looked the part.

The rest of my day was spent poking in and out of the remote, red, ironstone trails and sandy, dry creek crossings of the Gammon Range. The lack of tourists was evident both on the ride and back at Arkaroola Village, where only five people were camped in the unpowered area. The flies there were horrific and drank straight Aerogard with abandon. Apparently the prolonged drought and subsequent destocking of the grazing country meant they’d all come to hang out at the popular tourist spots. Plan E swept onto the scene that

evening when my daughter WhatsApped me that South Australia was to close its borders in two days’ time. While aware the situation was deteriorating, the remote location tended to cushion one from the harsh realities being faced in more-populous areas. Maps.me indicated the closest crossing into Victoria was at Renmark, so Plan E became a long day’s ride to Berri and then to see how the Victorian government was dealing with the border closures.

An 800km day on a Kato 690? No worries. It’s an adventure.

The early-morning start saw me catch the long shadows on the harsh, red, raw landscape in the drought-parched Gammon Range on the run to Copley. I shared the dusty road with one car as we leapfrogged, taking photos, on the 120km to the bitumen.

The Kato has a 13-litre tank, which was good for 300km at a leisurely pace, so I reasoned I could make it to Parachilna. Well…five kilometres was close.

After unpacking and a splash from the Rotopax it was into town where I discovered there was no servo.

After unpacking again and emptying the Roto into the tank it was off on the great gravel run through the Heysen Range to Blinman. There I was provided

my first experience of the takeaway Covid regime as the lady in the cafe explained the new protocols that had come in that morning. The potential of the harsh impact of the virus on the small businesses and towns of the outback was just beginning to emerge.

From Blinman I headed south on deserted roads through the Flinders on to Berri on the banks of the Murray for the night. It had been a long day, but the Kato seat proved either surprisingly liveable or my bum was fatter than I thought.

The following day I decided to head south to Naracoorte and over the border past Arapiles and into The Grampians. The curving, winding, climbing-andfalling track into Halls Gap and the town itself were surprisingly quiet. There were more kangaroos in the main street than tourists.

As dusk slowly fell I was left to share the peaceful solitude of Boreang campsite with only the kangaroos and possums. Adventure riding provided the ideal Covid isolation solution.

The Grampians were new territory for me, so I decided to meander via the back roads through the spectacular rocky mountain bluffs and forest scenery. Avoiding the occasional ’roo on the Glenelg River Road, Sera Road

and Jimmys Creek Road, I finally exited onto the farming country west of Mafeking for the run to Dunkeld via Yarram Gap.

It was all good fun and great adventure riding on well-maintained dirt roads.

That night, in an eerily quiet Warnambool, the next twist in Plan E emerged when I learned all campgrounds were about to be closed. There went my

plan to camp at Stevenson Falls in the Otways the next night.

So Plan-whatever-we-are-up-tonow saw me book into a motel in Lorne instead.

After Warrnambool I wasn’t surprised by the lack of traffic and tourists as I cruised past the now-closed scenic spots of the Great Ocean Road. One could only visit the toilet block at The Twelve Apostles because all else was enclosed by barricades.

Delaneys Road and Erskine Falls Road.

A very quiet night followed in Lorne before I finally headed home after another taste of Otway forests along Wye Road and Benwerrin-Mt Sabine Road.

Below