FULLY SPECCED WITH HIGH-TECH EQUIPMENT FOR ALL YOUR ADVENTURES... NO MATTER WHERE IN THE WORLD! WITH 15,000KM

FULLY SPECCED WITH HIGH-TECH EQUIPMENT FOR ALL YOUR ADVENTURES... NO MATTER WHERE IN THE WORLD! WITH 15,000KM

MORE POWER - 150HP (110kw)

LONG SERVICE INTERVALS - 15,000kms

FULL ELECTRONICS ASSISTANCE PACKAGES (MSC, ABS AND MTC) AS STANDARD - SAVE THOUSANDS

MOTORCYCLE STABILITY CONTROL - MSC gives the rider a lean-sensitive traction control

MANAGED TRACTION CONTROL - MTC allows Sport, Street, Rain and Off-road modes

BOSCH 9ME C-ABS - Combined Anti-Lock Braking System

BREMBO BRAKES - Precise application, powerful and free from fading

MULTI-FUNCTION COCKPIT - State-of-the-art instrument cluster with adjustable features

MODE SWITCH - Simple and intuitive to use

ADJUSTABLE ERGONOMICS - to suit individuals

» Two handlebar clamping positions: horizontal +/- 10 mm

» Two rider seat heights 860 mm + 15 mm

» Two footrest positions: diagonal 10 mm high and back

ADJUSTABLE WINDSHIELD - To suit varied sizes of rider

WP STEERING DAMPER - Makes for a smooth ride

LED INDICATORS Brighter and better

By Tom Foster - Editor

Idon’t know whether I’m getting soft or smart.

Lately I’ve been riding a few bikes with anti-lock braking systems (ABS) and traction control, and I find more and more I’m expecting those rider aids to work, and work well.

I’m a little at sixes and sevens as to how I feel about that.

It seems like only a few years ago early ABS was a primitive hammering under the boot that caused so much distraction it just wasn’t worth having. It felt like riding over nasty corrugations. Traction control is newer in adventure bikes, and it seems as though it’s hit consumer bikes in a far more refined state than ABS did, but it can still be an unwanted limiting factor in certain situations.

Lately those situations seem

to occur less and less often. Rider aids have become so good I find myself riding in expectation of them saving my bacon. I ride harder into turns knowing the ABS will keep me from my usual monumental cockup-lockup, and I know I can crack open the throttle of a big-horsepower bike as early as I dare and the traction control will keep me from harm. Not only that, but these systems are getting so good that in a lot of situations I don’t know if I’d achieve anything extra relying on my own judgment.

So I trial them, work out which settings are best for me, and off I go.

Does that make me soft?

All those MotoGP guys are using that technology, and they wouldn’t do it if it didn’t make them faster. And I know from experience that good riders can perform much better with those things working for them. They have the talent to understand the potential and use the rider aids to add to their performance.

My problem is, I feel as though I’m cheating, or doing something sneaky, if I don’t judge the pressure on the brake or the twist of throttle to find the limit of traction myself.

So am I soft or smart?

I guess I’m a little of both.

I’m a huge fan of anything that keeps me from injury, and I’m not the stallion of man that I once wished I’d been (but never was), so I’m smart for using good equipment when it’s available. Not only that, everyone else is using it. I’d be a mug to let pride stand in the way of making it through the tough rides or covering the big distances, when in reality, a lot of other riders wouldn’t look that great either if they weren’t making use of what the bike had to offer. Or looking at it another way, those rider aids will mean I can do tougher rides, cover even longer distances, and when I need to, safely run at higher speeds.

I’m thinking I’m smart to embrace these new technologies, and the ones that are coming. If you’re smart, you will too.

Adventure Rider Magazine is published bi-monthly by Mayne Publications Pty Ltd

Publisher

Kurt M Quambusch

Editor/Advertising Sales

Tom Foster tom@advridermag.com.au (02) 8355 6842

Production Managers

Michelle Alder michelle@trademags.com.au

Arianna Lucini arianna@trademags.com.au

Design

Danny Bourke art@trademags.com.au

Subscriptions

W: www.advridermag.com.au/subscribe E: admin@advridermag.com.au P: (02) 8355 6841

Accounts

Jeewan Gnawali jeewan@trademags.com.au

ISSN 2201-1218

ACN 130 678 812

ABN 27 130 678 812

Postal address: PO Box 489, DEE WHY NSW 2099

Forum www.advridermag.com.au/forum

Website: www.advridermag.com.au

Enquiries:

Phone: 1300 76 4688

Int.ph: +612 9452 4517

Int.fax: +612 9452 5319

On the cover: TF fell in love with the mighty Triumph Explorer. Jeff Crow ventured out before breakfast on a crisp, clear Victorian morning to drop the shutter on this fabulous shot.

62 Suspension with Nick Dole

66 How To Ride with Miles Davis

70 Rules To Ride By with John Hudson

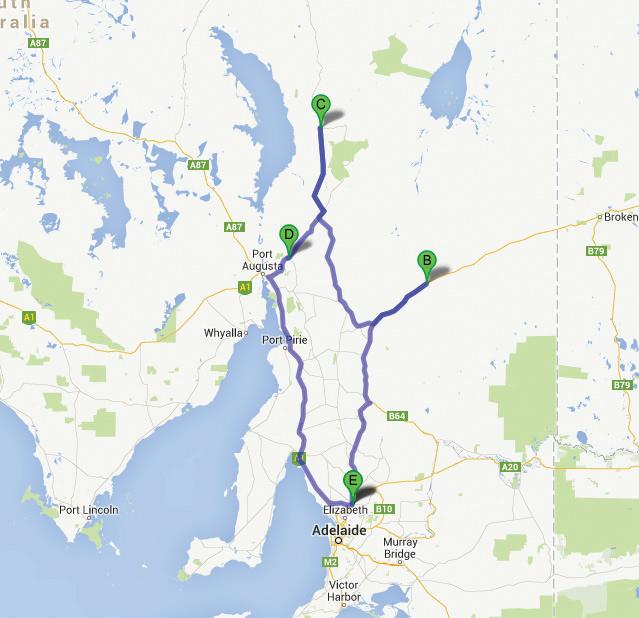

72 Reader’s Ride: The Flinders Ranges, SA

76 20 Things You Should Know About: KTM’s 950/990

80 10 Minutes With: Sam Sunderland

86 Reader’s Bike: Steve Evans’ HP2

88 Checkout 90 Next Issue

John Hudson

John thought adventure riders would love an event offering some of the thrill and challenge of The Dakar at a miniscule price, so in 2010 the real estate manager kicked off the APC Rally in 2010.

Karen’s in that growing group of females either returning to riding or taking it up. She’s worked in the Northern Territory as a governess/jillaroo, supervising kids and mustering on bikes, and bought her first bike from an undertaker.

Paul’s only been adventure riding for three years. He got his learners’ in 2010 and has vowed to complete the task of touching the four corners of Australia, plus hopefully do some adventures abroad, on a bike. If you’re travelling through Blackheath, NSW, pop into the Wattle Café for a chat about your adventures.

Ex-pat Denise and her daughter travelled to Mongolia to ride a Britton Adventures tour of the steppes. They went from being virtual novices to dead-set adventurers in just a couple of weeks.

Nick is an owner and director of Teknik Motorsport in Penrith, NSW. He runs a workshop specialising in a wide range of motorcycle suspension work, mechanical repairs and wholesale parts.

Craig has been riding motorcycles since he was five. He’s raced in Australia, South Africa, South America and Europe. In recent years he became obsessed with motorcycle rally racing, competing in several World Championship events.

A lifelong rider, Robin now rides, “whenever there’s a chance” on any bike available, on- or off-road. Between churning out Safari Tanks and importing high-quality Touratech gear, there’s not as much riding going on for this Victorianbased bloke as he’d like.

Craig has been riding for 40 years and has competed in enduros in Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. The purchase of Dalby Moto in 1984 was to feed his dirt-bike habit. Adventure riding came on the scene in 1995 and he’s ridden three Safaris and manages the largest trail ride series in the world.

Recently retired and only back on bikes for 10 years after a 30-year break, Trev, 61, loves riding the Flinders on his Tiger 800XC. The Flinders Ranges Classic is an annual highlight, and he reckons the retirement lark is a great opportunity to get out on the Tiger and explore.

Miles has been National Motorrad Marketing Manager for BMW Motorrad since 2006. He’s a very highly qualified motorcycling coach and an ex-professional mountain-bike racer. Miles is still riding every chance he gets, and has built an enviable reputation as both a world-class rider and a great riding companion.

All great adventure ideas start somewhere. Steve and Paul began theirs at the local, promising to reach all points of Australia eventually – north, south, east and west. The first destination was Australia’s most northern point, Cape York.

Just a week before we were due to leave everyone bailed, and Steve and I thought it’d be just the two of us.

But then good mate Dave said, “I have an idea. I’ll take both my Ténérés and bring my friend Mark.”

That balanced the numbers: two Suzukis and two Yamahas.

A DR650, DR250, Ténéré 600 and a Super Ténéré 750, and before we knew it we were bunked down in Cairns, ready to go.

We awoke to find the CREB Track closed, so our first day consisted of 80 per cent tar.

We didn’t hit the dirt until Cape Tribulation, 110km north, and we couldn’t wait to get to the Bloomfield Track. It’s a nice, flowing road with some knee-deep water crossings marked with warning signs for crocodiles. We were on one of few bridge crossings when we saw our first ‘snappy handbag’, a 2.5-metre salty. We pulled up and took photos for those who wouldn’t believe us.

The famous Lions Den Hotel, just short of Cooktown, was our first nights’ accom, offering a camp, pizza and a few celebration coldies. It was there at the pub we met Oliver, an English backpacker who’d

ridden from Victoria on an XR650, and invited him to tag along for the trip. After way too many coldies we made an executive decision to go to Cape Melville.

There was no plan in the itinerary to go to Cape Melville, and we had no research on the terrain, but what’s an adventure if you’re going to stick to a plan?

There and back

The next day we headed for Cooktown to stock up on tackle and fuel and venture up to the lighthouse for photos with 360-degree views.

After the complicated task

of getting an e-permit (a pre-booking for a campsite within a Queensland National Park) we had lunch and ended up at the police station to ask if there was a shortcut across to the Starke Track.

“Are you guys off to Cape Melville?” enquired the officer. “It took us five-and-ahalf-hours to get there on our last recovery”.

Nevertheless they were very helpful and told us of a trail that turned out to be a blast, twisting through banana plantations and making a change from all the cane fields further south.

Everything was fine as we continued up the Starke Track, and then, with panniers hitting the ruts, we regrouped about 10km into the bulldust and found it was already 4:30pm. A LandCruiser approached from the other direction, so we flagged it down and exchanged terrain stories. The driver told us there was another 50km of rutted bulldust to reach the Cape Melville turn off, then another 56km to our destination.

We made a decision right then to return to the Endeavour Falls Tourist Park and hightailed it south to get as much distance as we could before nightfall. It was 120km to the park, and 10km would be the bulldust we’d just ridden through.

The evening came rushing down as we went looking for our second night’s accommodation.

Now back to our itinerary. We headed for Battlecamp Road, through Lakefield National Park, stopped at the Old Laura homestead for a few photos and then Kalpowar for a bite to eat.

This day’s leg wasn’t that difficult, so we arrived at Musgrave in the early afternoon to fuel up and have a few coldies before calling it a night. Musgrave Roadhouse has a swamp behind it and if you look carefully there are ‘freshies’ in there.

Pfft. Freshies. They were still worth a photo.

Up the boring Peninsula Development Road to Weipa we went, saying goodbye to Oliver at Coen. He was starting to have a few issues with his bike…so he said. I think he’d just decided we were mad.

Archer River Roadhouse provided lunch, and the Ténéré boys were ahead for once when I got a flat 70km from Weipa. They were almost at Weipa when the Super Ténéré ran out of fuel and they waited for us. They were waiting a while!

The night’s stop was at Weipa Caravan Park, where we found Dave’s Super Ténéré was running really rough and the carbon-fibre exhaust on my DR650 had broken its rivets. Thankfully we’d planned the next day to be a rest day, and the exhaust was shortened with no problem. Unfortunately for Dave the Yamaha had sucked dust, and he decided to fly back to Cairns to pick up his LandCruiser and trailer and return to camp by the next morning. He flew out on a noon flight and, true to his word, was back in camp at 6.00am.

The plan for the following day was to complete the southern section of the Old Telegraph Track, then head east to Captain Billy’s Landing.

The bike and trailer was dumped

The Starke Track was a challenge.

at Moreton Telegraph Station and we headed for Bramwell Junction, the gateway to the Old Telegraph Track. This is where you choose between two options to arrive at the Jardine River Ferry. You either go up the Old Telegraph Track or the Bamaga Road, and our plan was to tackle the Old Telegraph Track. We were informed that this was the driest wet season for many years and the water levels at the creek crossings were well down, so we fuelled up and only four kilometres down the track found the first crossing at Palm Creek. The creek itself was only a trickle, but it was the entry and exit that were the fun bits.

After that, a couple of easy creek crossings had me a bit complacent and I entered a crossing to see the headlight go under and the bike cut out. Mark on the Ténéré 600 had the same problem. Steve made it through, and Mark and I got lucky with both bikes firing up after a little coughing and splattering.

The road to Captain Billy Landing, once off the Bamaga Road, is a sweet firetrail. As everyone says, Captain Billy Landing is windy, but bearable. We set up camp, set up a camp television and had a few well-deserved coldies.

Captain Billy Landing was like a fivestar hotel. With the crashing of the

ocean, we awoke early, keen to hit the northern section of the Old Telegraph Track, and our destination was Vrilya Point.

We arrived at Fruit Bat Falls, an oasis, there’s no other way to describe it. After days and days travelling on the corrugated Peninsula Road and then the sand of the Old Telegraph Track, it was like arriving at a day spa.

We had to eventually move onto the next oasis, Twin Falls, just 12km north. This place was just as good, but daylight was getting away from us and we reluctantly decided it was time to tackle the northern section of the Old Telegraph Track, and this is when we came across 15 or so fellas on their Massey Fergusons with their wives tagging along in the support 4WDs. It was a convoy of around 25 vehicles with an average speed of 30kph. Good on them I say.

Cypress Creek has a log bridge that would be eventful if a 4WD and a camper trailer were to come through this way. The LandCruiser only just fit!

Nolans Brook Crossing has the same reputation as Gunshot Creek, if not more infamous. It’s a deep crossing but there’s a three-log bridge about 20m to the left and we nursed our bikes across.

After consultation with the GPS we found the infamous bridge over Crystal Creek, and the following 30km road had sandy sections that would test the best. It seemed like every time we got into a great rhythm we arrived at a corner (and there aren’t that many on this road) where we had to suffer through 60cm-deep sections of fine sand for 100m and then back to great fire trail.

Eventually we got to Vrilya Point. What an amazing sight the Gulf Of Carpentaria presented. We found out we had to ride up the beach for 10km or so to get to the head for some great fishing. This was incredible. We set up camp and threw a few lines in. You wouldn’t want to be anywhere else!

u

We were planning to have a rest day, but despite the perfect location, we were all just too keen to get to the top the next day.

After a few hairy moments with wild pigs the next morning we got back to

the Bamaga Road and the Jardine River Ferry, and from there to the WWII plane wrecks near Bamaga Airport. In 1945 a DC3 came down not long after take-off, killing all five on board. Just near there are two other plane-crash sites to visit also. We started to head north again

and, after 40km or so, stopped off at the Croc Tent store for some souvenirs.

The last 15km to the tip was swampy, dark and eerie terrain, and once you reach the end you have to park and walk approximately 500m to the top, then wait in line for that photo of the little sign that says “You are standing at the northernmost point of the Australian continent”. With our task completed it felt a bit surreal.

We were happy to have completed our first of many missions and glad we’d made it all in one piece.

The lady at the Croc Tent had told us about a five-beach ride on the east coast of Cape York, over near Somerset Ruins. I’m glad she recommended this, as it was a great way to complete our day. It’s not very often you get to ride on a beach, but five adjoining beaches was fantastic.

We headed for Loyalty Beach on the west coast for celebration duties to finish off.

We headed south in the coming days, not seeing anything along the way as we did most of it on the way north. My rebuilt exhaust didn’t last long due to the 30cm-deep corrugations on the Bamaga Road and the remains of it now reside on the number-plate tree at Bramwell Junction, making for a long, noisy return trip.

We do have unfinished business at The Cape: Frenchman’s Track, Starke Track and the CREB Track. Dave has to complete the adventure on his now newly built 850 Super Ténéré and by the time we return, ‘corrugation concussion’ will have been totally forgotten.

Overall it was a great experience and I highly suggest you plan your own trip soon.

The Adventure Challenge is for reals. It’s here now, and it’ll be the biggest thing to happen to adventure riders since Preparation H. What’s it all about?

We’ll tell you.

Once a rider grabs a bike and gets kitted up, he – or she – is quite often left standing, looking vacantly out the shed door, wondering where the Fukuoka they can ride.

The road’s there to share, and that’s part of the problem. A big attraction of adventure riding is to get away from the overpopulated centres and overused roads, and to see those wide, open places that haunt the dreams of adventure riders everywhere – the mountain passes, river crossings, deserts and trails that even four-wheel drivers don’t know about.

But how does one – or two or three –find those places?

One way would be to grab a stack of maps and see what can be seen. Another way would be to ride to remote destinations and ask people –if you can find any.

But who has time for that?

Those who take the Adventure Challenge can log on to advridermag. com.au, decide how much time they have to spare, then choose from a plethora – yes, plethora – of possible destinations and trails. Having decided which one or two will suit the time available and the adventure the rider is looking for, it’s as easy as punching the location into the GPS, or marking it on a map, and heading on out there.

That’s all there is to it.

Once the destination is achieved, take a selfie, or have a mate shoot a pic, showing the landmark and the rider wearing the shirt, and upload it to the advridermag forum.

That’s all there is to it. That challenge is taken and conquered.

The smart riders will pick off some

weekend, and those with annual leave might get together to scratch a couple off the Bucket List.

And you’re not being spoon fed. It’s up to each Challenger to work out the route. If you find an especially fantastic road, trail or section, make sure you tell everyone on the website. The aim is for us all to share great locations and awesome riding.

The idea came from Your Local Shed Market kingpin Chris Laan, purveyor of high-quality adventure-bike shelters and maker of none-too-shabby coffee in his luxuriously appointed camper.

“It just seemed like a very good concept,” BMWed Chris, scowling at some nearby ducks in desperate need of a feed.

“Too often I’ve been on trips and I’ll pull up at a pub and talk to blokes. They’ll ask where I’ve been. I tell them, and they say, ‘Gee, 20km back, if you’d turned left and gone 300 metres, there’s a spectacular lookout or waterfall (or something).’ And I’d find myself wishing I’d known that.

“And we’d find a lot of fabulous places on our rides. We didn’t know they existed, and we’d tell others about them.

“So I was wondering how we could get started on a database of unique, interesting places or roads, and at the same time, raise some money for a good charity.”

The Adventure Challenge was the answer.

“Often one of the hardest things about planning a ride is where to go,” Chris GSed. “You know the roads you’ve been on, and I hate being on the same

road twice. If people not only put their pics on the forum, but outline the routes they used, other people are going to find new ways to get from one location to the next.”

And where does the charity come into it?

To sign up for the Challenge you… Hang on.

That’s the next bit!

Be part of it

So how do you get involved?

First up, log on to www.advridermag.com.au and go to the forum. Chances are you’re already a member there, but if you’re not, sign up and get your member on there.

After you’ve finished saying hello to all your mates – because they’ve all been spending their work days chatting to other Aussie adventure riders when they should’ve been earning a living – go to “The Adventure Challenge”, about halfway down the page.

Click on that bastard.

Straight away you’ll see a button that links to a T-shirt order, and another button that links to the Royal Flying Doctor Service.

To sign up, click on the RFDS link and make a donation. When that’s done, click on the link to buy the T-shirt.

From there you can work your way through the pages, reading how the idea developed and who’s doing what.

The next step is to have a look at the locations, pick one, and ride there. When you arrive, get a pic of yourself with the shirt in front of the landmark.

Then, when you’re next at your computer, upload the pic to the forum, tell everyone how you got there, and brag like anything about how great it all was.

You’re a Challenger. Done.

The fine print

Not so much fine print, but just to tie up a few little loose ends because we’re having to go to print a fair way in advance of the Challenge kicking off.

As we write this, we’re in high-level, top-secret negotiation with a very large and important player in the Australian motorcycle industry. This company is looking at the possibility of slinging a few prizes in the direction of some Challengers who achieve various

milestones, probably measured by the number of destinations they cross off. We can’t say any more until negotiations are concluded.

Everyone will no doubt want to know how many destinations there will be. We’re still not sure yet. Chris alone has 40 in NSW. Robin Box of Touratech Australia is running up a list of Victorian POIs, and John Hudson is covering Queensland. There’s likely to be a lot of possible destinations. Remember the idea isn’t for everyone to get to every destination. The idea is to offer a heap of possibilities in distance and terrain. Chris points out that all destinations can be reached in a Hyundai Getz with bald tyres. It’s up to the riders to decide how tough they want the route to be, but if they’re so inclined, it can be very easy indeed.

Also, there’s no requirement to actually be on a bike. If someone is on annual holidays with the family, and within cooee of a destination, grab the shirt and bang off a pic. That counts.

There’s no obligation on anyone to do anything except donate to the RFDS and buy a shirt. After that, riders can do a single destination for the whole year if they like. Or they might just choose the ones they’ve always dreamed of reaching. That’s up to each individual.

So there it is. Log on and start riding. Get those pics up there and let’s see this fabulous country.

HELMETLOK™

Designed to lock your helmet to your bike. Simply set your own 4 digit code, open the lock, slip the carabiner through your helmet’s D-shackle, attach it to your bike and lock it!

Ultra-compact, weighing in at only 570g, the MotoPressor™ can be used to inflate tyres, top off air shocks, air forks, inflate airbeds or anything else, anywhere, anytime, over and over

A puncture repair system for tubeless tyres. Simply remove the object that’s punctured your tyre, insert a plug into the puncture hole and pull the tool out of the tyre. Job’s done!

To order these and other products visit

Above: On the very first post there’s two buttons. Click on the first and make a donation to the Royal Flying Doctor Service. Click on the second and order a T-shirt.

Go through the thread and find the locations. Pick one that suits you. Click on it in Google Maps. Put the info into your GPS or

Have a ball riding to the destination/s with your mates. When you get there, get a pic of yourself with your T-shirt at the landmark. Post that pic on the The Adventure Challenge thread. Done. The more destinations you get, the bigger legend you are.

We built the Tiger 800XC to be just like the Tiger 800, but with a little bit more.

Using the rugged Tiger 800 as a starting point, we added a pack of special o -road equipment so you can keep on going when you run out of tarmac.

Top: The crew. Denise, the author, is third from the left.

Below: Mighty Mike Britton led the way. Those are yak in the background ignoring him.

You might think riding Mongolia would be all about temples, eagles, the Gobi and 2500km of off-road tracks uninterrupted by fences. You’d be right, except it’s all that and so much more. Ex-pat Aussie Denise Bentall joined a Britton Adventures tour to find out first-hand.

Relieved to survive the erratic traffic of Mongolia’s capital

Ulaan Baatar, local lead rider Munko shot off the four-metre

steppes of Mongolia. Instead of choosing a more sensible line I braced myself for the descent and remarkably stayed on. Rachael, my daughter, thought: ‘Mum made that look easy’ and followed.

That started the wonderful 17-day adventure.

Bikes used were 2010 WR450Fs and WR250Fs, with lowered KLX250s provided as requested for the ladies. Terrain was mostly off-road tracks, with speeds up to 90kph. Gravel, sand, river crossings and rocky roads full of potholes all offered plenty of fun, challenges and flat tyres. Auckland rider Murray set the record by getting

two flat tyres at once after “hitting a clay bank”. Whatever.

Trip leader, Mighty Mike Britton from NZ-based Britton Adventures rode as sweep, changing wheels or making repairs in a flash with assistance from the awesome Mongolian backup crew.

Munko, the human GPS, led the way and set the pace with the cornerman system in place to avoid anyone getting lost and having to beg to spend the night in a local ‘ger’ – felt-lined tents favoured by the Mongolian nomad tribes. Tradition has it the locals will take you in for the night if necessary, but they don’t speak a word of English. Riders were warned to be wary

of ger dogs as their role is to protect the stock from wolves, and they can be aggressive. None of the group was keen to risk a bite with rabies present in Mongolia, although Bogy, the local interpreter, was happy to let a wolf pup chew his hand.

Top right: The ger is a warm and comfortable shelter…even if the mattresses were sometimes a touch hard.

Above: Laying the smack down, Mongolian style.

Below: This could be any one of 100 places on the ride. The views were always spectacular.

Kitchen whizz

There were a few glitches getting used to the cornerman system. Mike chased a couple of mavericks who missed a turn, but eventually was forced to return without them. The pair were mopped up by the Mongolian crew down the track, turning up a little late for our gourmet lunch next to a Turkish monument dating back to the Ottoman rule.

Boldera, Mongolia’s answer to Nigella Lawson, had been talked into cooking for the trip and she served

up excellent lunches in the dining marquee set up especially each day. The marquee was transported to each location by UAZs, Russian 4WD vans, nicknamed ‘Ivan Delicas’ due to their heritage and resemblance to certain Mitsubishi vans.

The second day’s ride started with a blast in some sand dunes. Steve had his only off for the trip, and I discovered that ‘she who hesitates is lost’ on the lip of a steep dune.

That was followed by a two-hump camel ride. Rachael jumped on a pony for a quick gallop, and then it was some great off-road riding to the ancient capital and monastery of Chinggis Khaan and a photo shoot holding a hunting eagle. What a great way to start the trip!

In a ger camp that night we were treated to an amazing throat-singing concert and a 13-year-old u

Anywhere else in the world this would be an incredible, romantic scene. On the Britton Adventures tour of Mongolia, it was like this most nights. The marquee travelled with the group as a dining hut.

Top: None of a sheep is wasted. Boldera’s cooking up some sheep offal, but the Westerners were served more traditional cuts of mutton.

Above: Preparing food is a communal and very efficient process.

contortionist. Wow! These guys are talented musicians.

It turned out they weren’t such talented cooks...but as Angela said, you don’t come to Mongolia for the food. Vodka and Bordeaux wine proved to be able digestive assistants throughout the trip.

We were looked after amazingly well, riding through lovely valleys dotted with ger (the plural of ‘ger’ is ‘ger’) and

grazing herds of horses, sheep, yak, cattle and goats, usually tended by young boys without helmets or shoes riding bareback.

Arriving at the lunch marquee, we’d park our bikes, remove dust moustaches with wet wipes and tuck into restaurant-produced cream-ofmushroom soup, frozen and brought along in the Ivan Delica’s chest freezer. This was followed by burgers and a variety of chocolate bars guaranteed to foil any hope of losing a couple of kilos from all the extra exercise.

Crew

The backup team of Mongolians

There was plenty of animal life throughout the whole ride.

included: 60-year-old mechanic, triple Mongolian motocross champion and ex-policeman Buayan; Russian-military trained LandCruiser owner/driver Bold – who amazed us with his ability to look perfectly crisp and clean the entire trip despite sleeping in his car each night; and Tsegy, Ivan Jeep driver and next year’s lead rider.

The 4WDs used roads to keep up and be on hand in case of injury or mechanical problems, and to transport Angela Bruce, co-trip-organiser and first aider, and Bogy, trip interpreter.

Other locals drove the capable old two-wheel drive ZIL Russian truck with robust suspension and dual wheels which transported a spare bike, fuel and other supplies, and acted as a hanging post for the slaughtered sheep and goats purchased by the crew to take home on the last camping night of the trip. Kev, a Beijing-based, British oil-in dustry engineer, owns the bikes and wouldn’t miss the ride each year. He proved a fascinating source of information about life in Mongolia.

Most nights were spent in ger camps, traditional Mongolian nomadic round homes constructed of wooden roof poles and lattice held together with dried animal gut. The structure was covered in sheepskin wool felt and tensioned with horsehair rope. Beds were wooden with firm mattresses, and the pillows smelled of sheep and felt as though they were filled with rocks. Showers were usually hot, and mutton was served for most dinners. Some ger camps had hot pools and some had freezing lakes to take a dip. This isn’t a tour you’d recommend to girls who are into Club Med.

The camping nights were a breeze. Turning up after a

hard day’s riding to find your tent set up and dinner being cooked was magic. Angela informed us that camping nights were accompanied by a traditional Britton Adventures storm each year, and this trip was no exception. We expected to wake up toasted when gunshot thunder shook our tents as the sky came alive with lightning at 3.00am.

Mongolian nomads’ summer diet traditionally consists of a variety of dairy products made from sheep or mare’s milk, Lake Khovsgol near

Main: Another river crossing. Not too deep. No problem. Below: A Russian ZIL hauled all the clobber and the occasional sheep carcass.

including Airag, an eight-per-cent alcohol drink tasting like fizzy, fermented yoghurt, which is extremely popular.

Their winter diet consists almost exclusively of mutton, especially the fat and offal. No part of the sheep is wasted, as we saw when we watched a sheep killed for dinner. We were impressed with the communal cooperation, lack of fuss, efficient butchering and lack of waste. The whole procedure could be done inside a ger in the winter without a drop of blood being spilled.

Thankfully we Westerners scored chargrilled sheep meat for dinner. It was delicious.

Nadaam is an annual festival made up of three competitions designed to celebrate male prowess: horse racing, in which young boys race 30km cross-country with no saddle or helmet, archery, and wrestling. Trip drivers Bold and Tsegy drove us 20km to the nearest town while the bikes were being serviced, and we were fortunate enough to see the fun. The losing wrestler walked under the arm of the winner, who then slapped the loser on the bum and victory-danced around an altar waving his hands up and down –the kind of act no Western male would be found dead performing.

There was a fair variety of riding on the trip. Some tracks closely resembled the outback tracks of Australia, and the pothole-riddled roads were a blast.

The trip organisation was superb and riders didn’t have to worry about anything except staying on so we could

keep riding – and that was no mean feat at times.

At the end of the trip we counted 15 flat tyres, two fractures, two nasty bruises (one to Ulzy, the Mongolian backup rider), and a whole heap of fun. Everyone extended themselves, blasted away and had a ball. Nobody wanted the days to end.

There was some dispute as to what constituted a fall, it being generally accepted that one’s legs should be astride the bike at the time of falling to qualify, but everyone came off at least once, and the record of six offs went to…well, you know – what happens on tour stays on tour.

This ride was a favourite. Every single day was an adventure with great trail riding, no fences, beautiful scenery, herds of animals grazing freely, companionship, lots of laughs, fascinating cultural experiences and being looked after like royalty.

We wouldn’t have missed it for the world!

It wasn’t necessary to be particularly good at riding hills.

Touratech: $788

Wunderlich: $415

Motohansa: $309 Light Set

Touratec: $115

Wunderlich: $102

Motohansa: $79

Touratech: $496

Wunderlich: $454

Motohansa: $279

Touratech: $599

Wunderlich: $454 Motohansa: $309

There’d be very few Australian adventure riders, on- or off-road, who weren’t familiar with Andy Strapz gear. Starting with a high-tech strap back last century, Andy, the man who loves the letter ‘Z’, has built an enviable reputation for offering high-quality product that’s been thoroughly tested and proven. A big part of Andy’s well-deserved reputation stems from his insistence on personally testing every product he offers in real-life riding situations. If it doesn’t work for Andy, Andy Strapz won’t sell it. AdvRider Mag caught up with Andy himself, wringing out his merino socks, and making every rider’s adventure easier.

The Andy Strapz story starts back when Andy was an emergency nurse and needed to strap important stuff to his bike, but found the good ol’ ocky strap was a bit sub-par.

“They were the secondleading cause of permanent eye injury after playing squash,” Andy recalled. “Think about

the physics of the mass at the end of the elastic. Mass times acceleration equals force. And you pull it towards you. If they were trying to invent ocky straps now they’d never get them through Occupational Health And Safety.”

The inspiration for something as reliable, but less dangerous, came while working in

Everything Andy sells gets tested by Andy in the real, adventure-riding world.

Image: Jane Arnold

paediatric emergency in Western Australia. The hospital held patient charts together with binding of one-inch webbing and Velcro. Andy decided to put them to use attaching a pannier on his bike. They worked a treat, but there was room for improvement.

“I found 50mm-wide, flat, stretch webbing and it was just one of those ‘Eureka!’ moments,” he stretched.

Andy Strapz – the device, the shop, a logo and an entire product range – was off and running.

“It took seven or eight years, slowly building Andy Strapz to where it would support my family and staff,” Andy recalled.

“First I bought a sewing machine and taught myself to sew. That’s where we started.”

Interestingly, it came full circle about a year ago. “A hospital rang and ordered 200 straps to hold charts together,” Andy noted. “That’s about 17 years down the track.”

Andy is a keen rider and now a retailer of high-quality motorcycle equipment, especially adventure-riding gear, and he

Andy discovered off-road adventure riding on an old Elefant. These days he loves his Triumphs. Image: Jeff Crow

knows what riders in this segment of the market want, and don’t want, when they’re on a bike facing a challenge. Once he recognises a need for something that actually works, he has the courage and conviction to make it or find it and offer it to adventure riders through his store, website, and stalls at just about every motorcycle trade show in the nation.

“I don’t know whether it was stupidity, arrogance or inventiveness that made me decide things available on the shelf didn’t really suit what I had in mind for motorcycle travel,” Andy strapped. “Everything I’d come across seemed to be designed by committee, or by people too busy to spend time on the road testing their gear.” The equipment Andy makes from scratch does the job better.

“If they were trying to invent ocky straps now they’d never get them through Occupational Health And Safety.”

Like his seat bags. “I wanted a bag I could move from bike to bike, and if I sold the bike I could keep the bag,” luggaged Andy. So I developed my A and AA Bagz.”

“It’s all about paring down to key, necessary components.”

Consider his Pannierz – all Andy’z pluralz finish with a ‘z’ instead of an ‘s’ – designed for actual riding conditions.

“I wanted a set of panniers that, should I fall off and slide down the road, I could get up and not even worry about knocking the dust and mud off, and just keep going. Heavy-duty canvas was an obvious fabric choice because it’s designed to take abrasion.”

Andy’s hard-line attitude extends equally to items he doesn’t make himself. “If I haven’t tested it and don’t know exactly how it works, I don’t want to sell it to my customers,” he stitched.

u

The extent of testing depends on the product.

“Something obviously good, like a Sea To Summit liner bag, I’ll use once or twice to make sure it lasts. I’ll jump up and down on it. I’ll pull it and tug it. The Forma Adventure Boots I probably wore for six or eight months before I committed. Some things might take a year. Until I’m happy they work as they’re supposed to, I don’t take them on.”

It was a big break for off-road adventure riders when Andy got hold of his beloved Elefant 750. “Back then they were called ‘dualsporters’,” trumpeted Andy. From then on, specific off-road adventure products came in for the Andy Strapz treatment as well.

Thermals are a good example of Andy’s commitment. Most are clearly not designed with a motorcyclist in mind.

“Shirts were too short in the arm, too short in the back and had the wrong neck shape to work for a bike rider. Pants had no flies. After a long ride on a cold day you have to do the Urinal Dance to get the wedding tackle out. Neck warmers had non-stretch string,

making it difficult to move your head and do head checks.”

So the thermals Andy designed allow a rider to move around on a bike, urinate and move the head without recourse to Bikram Yoga.

Andy also stocks Back Country Cuisine tucker – freeze-dried roasts, curries, pastas and desserts – that become meals for two with the addition of boiling water. “It’s stuff I’ve used,” he said. “I have one in my kit in case I get stuck somewhere. All I need to do is boil water and I can hole up for the night.

“When we’re going into serious outback country and have to watch the load on the bike, quality food is really important. By freeze-drying it, they’ve removed all the water and the majority of the weight. It still maintains nutrition and taste, and it has a really long shelf

“Everything I’d come across seemed to be designed by committee, or by people

too busy to spend time on the road testing their gear.”

life. It’s easy, convenient, tastes good and it works.”

Understandably, Andy’s always on the lookout to adapt or develop items that work from outdoor, travel and camping markets; riding is clearly the best combination of all three.

Setting up and running a successful business has one fundamental flaw: it involves time. Lots of it. That can eat into your own riding time.

“Therein lies the problem,” Andy

acknowledged. “You get into something you love and you create a monster that starts taking over.”

Andy does make the time to get out and about. He has no choice. “My excuse is I need to get away and get some testing done. I went to the Alpine Rally last year. I took a week off, went into the high country and through the back of Braidwood. I saw a few people and did a few things.”

Having come from a road-bike background, Andy’s spent the last decade learning how to ride dirt and adventure bikes. “Rather than changing to a bigger bike, like the trailbike guys do, it’s all about skilling up for me,” he said. “Now I’ve got the skills to get myself into trouble, it’s time to learn how to get out of trouble.”

Andy’s bikes have grown over the years, but not by much, and there haven’t been many of them – mostly because he’s never really had “a lot of cash to splash around”. He still has the bike he got when he was 21 – a 750 Sport Ducati. “It’s glorious,” he twinned. “I just love it to bits.”

For a full selection of Andy Strapz products and stockists, visit www.andystrapz.com Desert. Coast. Whatever.

While the Andy Strapz shop is a factory and showroom in Frankston on Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay, Andy frequently hosts a stall at or near suitable motorcycle events, and trades online. He also has a ‘core dealership group’ of three shops in Sydney and a couple in Brisbane and Melbourne

Since then he’s had “a road-going Benz, one of the old model Tigers and a 1200GS”. His current – and favourite – is a Tiger XC.

“It’s pretty flash,” Andy roared. “It does everything. The road-bike part of me will never leave – I still love the corners, the winding mountain roads, and the Tiger does that beautifully. And when the road turns to dirt, it does that extremely well as well.” According to Andy, versatility is the key: “I love mountain roads and corners, and I love dirt roads and back roads as well. Much of the time the two are connected. There’s a bunch of nice corners and 20km of dirt that separate them. I think that’s heaven.”

that stock his gear. “They’re a select group,” he franchised. “My gear is a bit left-field and needs to be understood. There’s no point just sticking it on a shelf and hoping people find it. I want to work with people who understand it, take an interest and follow through.”

Touratech offer an extensive range of accessories, engineered to the highest quality, designed and made specifically to improve your adventure. Our accessories are tested not just in the lab, but throughout the world.

Order

With thousands of accessories available, the Touratech team have the knowledge, experience and the products to make your next adventure the trip of a lifetime.

Touratech - made for adventure!

It’s not a big step to take Suzuki’s DRZ400E from being a trailbike to an adventure bike. But when someone like Vince Strang, Australia’s foremost authority on Suzuki’s DR line, elected to start with the softer ‘S’ version, we had to find out why, and whether or not the result was a good one.

The 400cc trailbike has almost disappeared from the Australian landscape. There was a time when it seemed the 400 traillie was the people’s choice. It offered good, manageable horsepower, incredible versatility and light weight.

Those days are gone it seems, and Suzuki’s DRZ pretty much flies the flag for the once-popular class of bike, even though there have been innumerable occasions where the hardy little thumper has proved itself to be far more capable than the name ‘trailbike’ implies.

There’s two off-road versions of the DRZ, and it’s the E version that gets all the attention. The most noticeable difference between the E and S models is the plastic tank on the E. There are other variations, but that’s the giveaway. The S is a tad heavier, but it’s the steel tank that marks the S as the soft option.

‘E’ for enduro. ‘S’ for soft.

It’s strange people think that about the two versions, because neither is an enduro bike. The model run has covered 10 years so far, and even when the bike first appeared it couldn’t have been considered an enduro bike. Now there’s bikes like the WRF, EXC and KLX, and the DRZ looks slow and timid by comparison.

Of course, the durability and comfort of the Suzuki leaves those other bikes way behind over any kind of distance, and for the multitude of riders who never front a special test, the performance is actually pretty good. It’s not competitive-enduro good, but it’s well capable on single track and smooth as on the road. That sounds like a good start for an adventure bike.

The thing is, why would anyone choose the S model over the E as a starting platform? With anyone else we’d think it was a peculiarity, but we know from plenty of experience that Vince builds great adventure bikes, and he doesn’t miss much. So we asked him, “Why the S model?”

“My preference is generally for the S model for the majority of people,” insighted Vince. “It’s got a fan on it, so you can really ride it slow, whether it be mustering or poking along in traffic or stuck on a hill. The fan helps it keep calm in the heat department a lot better.

“Also, the S has a CV carb that’s

Top right: The DRZ’s steering will seem a little quick to those used to bigger adventure bikes. The RalleMoto steering damper helps keep things on the straight and narrow.

Below: A lowering link drops the rear of the bike, so the fork legs are slipped up through the triple clamps to maintain the bike’s correct attitude.

slightly smaller than the carburettor on the E model, so it’s better on fuel, and it has a brilliant, quiet exhaust.

To me it feels like it has a similar power output to the E, but the quietness is really nice.”

“I set this bike up for my daughter to come on her first outback ride,” Suzukied Vince. “We went out west through Bollon, Thargomindah, rode the properties there for a few days, then came back through Hungerford to Inverell.”

Crikey. That’s an adventure ride, for sure.

You can bet Vince won’t cut any corners when he’s setting up a bike for a family member, so let’s have a look at how he treats the DRZ.

Heavy-duty tubes are dropped inside a Michelin AC10 front and Dunlop 606 rear, and a Polisport front guard goes in place of the stocker. “It’s just a better-looking front guard,” explained Vince. A screen helps with protection from the wind and rain, and Renthal ’bars replace the low-bend Suzuki stockers, topped off with ProTaper grips, grip heaters and Acerbis handguards.

The Acerbis handguards fit the Suzuki very nicely, says Vince, and accommodate the longer levers, especially on the DR650, very well.

A Ralle-Moto under-’bar steering damper lifts the ’bars a tad and helps deal with tankslappers. The DRZ is a shortish bike by adventure standards, and the damper helps control weaving in the sand or at speed on loose terrain.

This bike also has a Talon lowering link on the rear, and the forks are raised a few millimetres in the triple clamp to keep the geometry level. That change is purely to suit Vince’s daughter, who’s not overly tall.

Right: The VSM heated grips are going to be a big bonus in the cold. u

Above right: Vince feels the Polisport front guard just looks better than the Suzuki unit. It’s a very neat fit and bolts straight on.

The fuel cell is a 17-litre Safari Tanks tank, which Vince says is really 20 litres.

“I guarantee they’re 20 litres, not 17,” laughed the Inverellian. “I think Robin (Box, owner of Safari Tanks) sells them as 17 litres so people don’t think they’re too big, but they fit this DRZ perfectly, and they’re made to accommodate the fan.”

The stock seat was replaced with a Sargent’s seat, and Vince says this was an important change.

“It’s still the same, narrow width at the front if you’re paddling or have your feet down,” he explained, “but where your bum sits most of the time it’s broader and kind of scalloped out. It tends to fit most smaller bums a lot better than the Suzuki seat.”

Suspension front and rear stays dead stock, as does the gearing (15/44), and a B&B bashplate and rack and Pivot Pegz, are bolted on.

A FunnelWeb airfilter rounds out the package.

A brand-new S model DRZ starts out at around $7900, and Vince reckons the bike we see here would cost about another $3000.

That makes for a very inexpensive adventure bike.

business

Inexpensive if it works, of course.

We clambered on board the DRZ ready to treat it gently and with our expectations suitably held in check.

It was a girl’s bike, after all.

The first thing to shatter our complacency was the height of the bike. After Vince saying the bike had been lowered to suit his daughter, we were a little nonplussed to feel as though we wouldn’t want the thing any taller. It’s not like a skinny, section-shredding enduro bike, but it’s not a Postie either. The height felt entirely comfortable to ‘regular’ Aussie

Left: Protection from the wind and the worst of the weather.

Bottom left: A Sargent seat offers a more comfortable perch for long-distance riding.

blokes. It’s easy to get the feet on the ground and there’s no danger of tearing a gusset while swinging a leg over, and that’s surely a big plus for a loaded adventurer.

Not only did the bike not feel short to mount and dismount, it didn’t feel as though it was short on ground clearance, either. We’d’ve been happy to steer this bike into the same ruts and rocks as we’d steer any other bike.

The next facet of the DRZ-S we’d badly underestimated was horsepower.

Because we’re so manly and really only ride ‘big’ bikes these days, we were ready for a 400cc traillee to be a bit soft in the rort department. The delivery was very smooth – as was everything about this bike – and for sure it won’t stretch anyone’s arms with its incredibly ferocious thrust, but without the rider making any effort at all the DRZ sung along at 100kph and 110kph on the tarmac. On the dirt it seemed to take less effort to go everywhere and do everything we were used to doing. The rider has to think a little more instead of just relying on a blast of throttle and wheelspin, but there’s enough grunt available to

take this lightweight package just about anywhere.

It finally dawned on us that the DRZ might have less horsepower than we’re used to, but it still has plenty for just about everything short of high-speed desert running. Because the bike’s so light, popping it over logs and ruts and steering it through tight going is a breeze.

As Vince pointed out, the mid-size Suzi is a little tighter in the steering geometry than some, and it’s noticeable when the bike is pushed toward the upper limit of its speed. It never gave a moment of trepidation or behaved unexpectedly, but the steering is undoubtedly light and fast. The payback, of course, is on any kind of tight going. The bike is like a hot knife through butter compared to, say, the DR650.

The ergos on the bike felt brilliant. Things like the ’pegs, seat, Ralle-Moto damper, screen and ’bars make for a very high-level of rider comfort, and the motor being so incredibly easy to use

means minimal fatigue. It’s light, so it’s a piece of cake to pick up, its reliability is unquestionable, and there’s a gazillion accessories and aftermarket parts available.

And buzzing along the bitumen it’s as much at home as any dualsporter we’ve ridden.

All this for around $11,000.

That’s pretty hard to beat.

We’ve overheard a lot of discussion lately from riders chewing over the idea of riding much smaller, lighter bikes and of the benefits they offer. They’re easier for the rider to handle, they’re far less expensive to run, they’ll do much greater distances on very much smaller fuel loads, and with the way

policing and regulation is going in This Great Country Of Ours, there’s not a lot of point in owning a bike capable of intergalactic velocities.

If you let your mind wander in that direction, and you begin feeling that a bike that’ll double as a trailbike and an adventurer would make a lot of sense, the DRZ would have to be a frontrunner. If you’ll take the advice of a seasoned campaigner who knows what he’s talking about, the S model is probably a better proposition than the more commonly fancied E model.

Think about that next time you’re trying to drag your 220kg longhauler from a creek or boghole, contemplating a 40-litre fuel load, or looking at a destroyed rear tyre you only fitted that morning.

Thanks to Vince and his entourage for roosting down from Inverell to let us ride this excellent little bike. Vince knows more about Suzuki off-roaders than just about anyone. For advice and a huge range of products give Vince Strang Motorcycles a call on (02) 6721 0610, or log on to www.vincestrangmotorcycles.com.au for more info.

A few old dogs let the cat out of the bag. Some of their equipment has a story of its own.

“Idon’t know how it happened,” thesaurused AdvRiderMag’s kneeguards in the mid-1990s sometime. I never liked them. They were never comfortable, they make me sweat like a rapist and most of the elastic straps busted and fell off maybe 15 years ago. I don’t know why, but I’m still wearing them. Any time I’m not wearing my CTi knee braces, I still wear these poxy things. They do offer great protection, and I’m at the point where I just wear them without thinking.”

“Ihave a Shoei helmet that near rips my ears off every time I take it off,” explained the Desert Dingo. That’s all Craig told us. He doesn’t say much.

he APC Rally’s head honcho has a camera that seems determined to stick around.

“The first time I lost it was on a Simpson crossing,” 1190ed Homer. “I photographed a mate riding up a dune and must’ve dropped the snapper in the dust. Some time later some four-wheel drivers found it and took it back to their home in Hervey Bay. They had a look at the pics and asked a policeman friend to see if he could find the owner of the bike in the images. The copper traced the rego number on my mate’s bike and contacted him in Darwin. The mate told the copper where to find me, and the camera arrived in the mail three months after I lost it.”

“All my life I’ve been really fussy about gloves,” says Australia’s ISDE veteran. “In the early days when there weren’t any good gloves I hardly wore them at all, and in fact used to ride most special tests without them.

“Nowadays they’re a lot better of course, and they come with pretty thin palm material on them that I

If that’s not amazing enough, on the recent Byron BaySteep Point crossing, John snapped a couple of pics of Craig Hartley fuelling up. John put the camera on his rear guard and, caught unawares when Craig roosted off, roosted off after him, once again dumping the Panasonic in the desert dust.

A few kilometres down the trail Hartley realised he’d lost a loose fuel cap and the pair went back looking for it. The cap was found, and lying within a few metres was the forgotten Panasonic.

really like, but I still go crazy with my old, worn-out favourites.

“Here’s my current adventure riding gloves and they’re just ‘ripe’ and in their prime! I just love ‘em!

“And bugger me if they don’t work fantastic when I pull up to check out what’s happening on my iPhone.”

What about the chills of winter, we wondered?

“With the double-up ‘softie specials’,” grinned GB, “I use heated grips as well as hand covers. I’m soft, but I can feel everything!”

“G’day,” e-gibbered Anton Seifert, a self-employed chippy from Adelaide.

“The storms were chasing us on the 13th day of the APC Rally. We were 60km west of Tilpa, NSW, and turning south to Ivanhoe.

“The locals said the night before, ‘Don’t turn west if it’s been raining overnight.’ Luckily for us the rain was a few hours behind. One of the guys running a day after us broke his leg on the wet, black clay that arvo.

“The rain finally caught us just before Narrandera that same day.”

Anton scores an exclusive Adventure Rider Magazine polo for this rip-snorter image. If you have an image you’d like to share, email it to tom@advridermag.com.au with your details and some brief info about the pic.

Building a serious long-distance tourer will drive most people to look at BMW first up. Rob Dunston at Sydney’s specialist BMW service centre Motohansa looked at the new R1200GS, looked at the gear on his shelves, got all excited and started building like a madman. The bolt-on Bavarian might sound like a big handful, but that’s because it is. A big handful of luxury and protection.

Before everyone starts e-mailling and going crazy on forums, we know this bike isn’t for everyone. No bike is. But even more than a straightup, long-distance tourer, the Motohansa R1200GS as you see it here would be a very specialist item. That’s not to say the individual protection and comfort features won’t have a place for the majority of R1200GS owners – or BMW owners in general in a lot of cases – but to have the whole lot set up on one bike is a big commitment. And that’s what this GS is all about. If you’re making the commitment to ride across a dozen European countries or around This Great Country Of Ours on an extended trip, living off the bike and heading to places where you don’t know who or what you’ll find, this is probably exactly what you’re looking for.

The bike itself is the R1200GS that Motohansa top banana Rob Dunston rode in both the GS Safari and GS Safari Enduro in 2013. It’s a hell of a bike with a superb, unbelievable motor, good suspension, and a bewildering array of electronic functions and readings. Watching all the menu pages and their variations flick over is like an extended scene from The Matrix 12: Morpheus eats

Main: For long-distance, hard-core adventure, this is the rig you want.

Right: Lots of luggage and lots of protection. Not much bling. Bottom right: The crash protection was excellent. We know. We put it to the test.

Moss. There are rider aids with varied settings up the wazoo and gauges, readings, and warning lights for everything including tyre pressure.

The stock, naked bike is a fabulous longdistance runner and a huge pleasure to ride, so it’s a great platform to build into a pukka tourer.

With a massive inventory of accessories and service options at Motohansa, we wondered how Rob knew where to start when he decided to build the bike. And when to stop.

“We looked at what we see as the functional items that improve the overall ‘usability’ of the bike,” chugged Rob. “Obviously the panniers are a no-brainer. This is a great, locking pannier system with top-loading boxes and a good quick-connect system.

“Luggage is prerequisite if you want to go touring, and protection is probably the next priority. Radiator guards are paramount, and along with the crash bars and a headlight protector are probably the three big protection items. A headlight for this bike is something like $2000. Are you going to run around without a headlight protector? Probably not.

“After that you go down to things like your sidestand enlarger.”

Not only is the protective gear functional, it looks good. We said so.

“SW Motech doesn’t tend to do much bling at all,” said Rob. “They tend to do only functional stuff. Probably the only thing Motohansa put on the bike that maybe could be put in the ‘bling’ box was the Arrow exhaust. I don’t think it provides a big improvement in performance, but it probably looks a bit better, it’s lighter than the stocker, and it gives the bike a bit of a growling note,

and a lot of riders like that,” muffled Rob.

“It’s a serious touring bike. If you want to cover serious distance around Australia, you clip the hard luggage on and off you go. If you want to go off-road for something like the GS Safari or Enduro, you clip the panniers off and you’re ready. The bike has all the protection gear it needs.”

Adventure Rider Magazine is always up for a challenge, and that sounded like a challenge to us. Would that protection gear be worthy of its name?

it

Mounting up on the Beemer is a serious proposition in itself. It’s a big hua. The panniers and top box give the impression of a large chunk of bike behind the rider, and the screen and tank don’t do anything to alter the overall impression of bigness.

Alongside that goes the wide, comfy seat, lots of leg room, an upright seating position and very nice spread of ’bars that has a rider feeling as though 500km between stops would

Above: The panniers and top box have great access and are surprisingly light. Just make sure your mates don’t all chuck their gear in there when you’re not looking.

A headlight with a price like that one deserves a guard.

be fine. Grip heaters were included, of course, but with the temperature nudging 30 degrees as the R1200GS nosed out on to the bitumen, we really didn’t give the grips too much thought.

It’s worth pointing out that the bike itself doesn’t feel wide or large on the road. The cylinders feel as though they might be a whisker higher and tighter to the bike than the air-cooled boxer-twin, but we’re not certain if that’s the case. It was just a feeling.

On the tarmac the bike just works. It sits solid and steady, the cruise control and screen leave the rider free of distraction and able to enjoy the scenery and the smooth running. The bitumen world is a very, very pleasant place. SWM auxiliary lights meant sunset at the other end of the day didn’t matter a damn, and thanks to the huge storage capacity there was no comfort stone left unturned when it came to jammies, clean socks and jocks, reading material and all the comforts of home.

It wasn’t long before the big girl was on the dirt, and with a motor as good as this one, every turn was a delight. Cracking the throttle open let the

rear come around a little –we were on the ‘Enduro’ setting with the ‘hard’ option –and blast the whole shooting match straight down the next section.

the rider, right down to the Pivotpegz and SWM gear shifter. There were quite a few guards scattered around the bike, but nothing got in the way and everything about riding the BMW was easy.

But Rob had talked about protection, so in the interests of credibility we decided to put that to the test as well.

As it turned out, the crash bars over the cylinders were gold. We thought the bike would fit through a gap, but it didn’t. As the rock chips flew, the motor roared and a sickening crunch shattered the mountain silence. The whole show ground to a halt in a fairly embarrassing position, crash bars and panniers wedged.

That was all very well, but the panniers and top box had a big pendulum effect that took some getting used to. In fact, the effect was just a little stronger than we expected, so at the first stop we had a look to see what we were carrying.

It seems all the riders thought the large luggage capacity shouldn’t be wasted. There were a couple of tool kits, a few first aid kits, a complete camera rig (the editor was shooting the story and had his camera in his bumbag, so the publisher decided there was no need for him to carry his as well), and sundry other items to which riders sullenly confessed to having stowed because “there seemed to be so much room”.

We were only trying to reset the tripmeter.

So there was a reasonable load on, even though there was still plenty of space for more. And from then on the panniers remained locked, thus showing the value of hard-pannier security. The thing about that is, the bike towed the load like it wasn’t there. It was only on change of direction it could be felt. Considering the clobber on board, we were impressed by that.

Testing. One. Two. The comfort was exceptional. This bike was really nice for

Now here’s the point: Of course we didn’t hit the gap hard, but even a fairly gentle nudge on a cylinder from a rock wall, boulder or tree stump can be a serious issue. In this case, the bars took the stress and the motor and vitals were completely untouched. After the AdvRider Mag crew sweated and strained to haul the bike over the boulder by main force, it was only a touch of the button – and a few harsh words to the editor who was riding the bike at the time – to have the bike back on the pace, charging hard and leaving the sweating, whinging princesses behind.

That’s what good crash protection can do for you. In fact the bars themselves still looked in good shape, we thought. We hoped Rob thought so too when he saw them.

We didn’t put any stress on the radiator guards or sump guard, but knowing SW Motech gear could cope with that kind of abuse let us relax and enjoy the challenges as they appeared.

One item on the list was a really good-looking enlarger for the foot of the sidestand. We’d like to rave about this feature, but to be honest we didn’t really put it to the test. The rocky terrain meant things were fairly stable most of the time. We did drop the bike

off the stand several times during clumsy panic attacks to get photos of fallen riders – for the benefit of you readers, of course – and once again were impressed with the way we couldn’t find any evidence of damage when the bike was back on its wheels.

We feel as though we gave this BMW a very fair run and treated it as would most owners who set up a bike this way, and not once during our test did the bike look as though it was threatened with any real damage. Features like the heel protector and gear shifter weren’t immediately obvious, and that’s probably an indicator of just how well they worked.

So we reckon it’s a great set-up for serious touring.

Here’s a rundown of the fittings:

SWM crash bars

Trax pannier system

v Trax top case

v SWM gear lever

v Pivotpegz

v SWM Fenda Extenda

v Brake guard

v Heel guard

v SWM auxiliary lights

v SWM headlight protector

Custom made sheds at “kit” prices-delivered Australia wide. We supply all plans and specifications for council approval

Today, you can see 100’s of the same model of bike but they will all be optioned and set-up differently to suit the owners individual style and preferences, the final design of your shed is no different.

We do not have any “standard” designed sheds, every shed can and is ordered individually to your design. Door and window locations and opening sizes can be tailored to suit your specific needs.

Radiator guards are another must-have for long-distance travellers, especially the off-roaders.

v SWM radiator guards

v SWM sump guard

v SWM slide protection

Arrow slip-on sports muffler

SWM sidestand foot enlarger

If you’re going to buy a premium item – and let’s face it, no-one can argue a BMW isn’t a premium item – and you’re going to hit the road or trail, you’ll want to organise some good protective gear, and you’ll want to tune it for comfort. With the rides already on the board for this specific bike, clearly the guys at Motohansa know how to do both.

Just check the luggage each morning and make sure your mates aren’t chucking all their heavy gear in there while you’re not looking.

Last but not least, if you’re heading for serious adventure, think about packing the GS 911 diagnostic tool and the Motohansa Pro Series tool kit. With these in your panniers you can do all but an engine rebuild on the side of the road. The GSs are very high-tech electronically –there’s no fuses and no way to diagnose the red warning light on the dash without the GS 911 – and they also have virtually no tool kit supplied stock. There’s nothing to change a wheel or remove a plug.

Thanks to Rob and the guys at Motohansa for letting us loose on their pride’n’joy. The shop these guys have in Sydney is an Aladdin’s cave for BMW owners. Give them a call on (02) 9638 4488, or log on to www.motohansa.com.au for more info.

One of the best things about our sport is the people it throws together. Here’s an AdvRider chosen at random from the thousands who read this magazine. Everyone, meet…

Q. Where’s home, Scott?

A. Born in Macksville, NSW. Now live in sunny Brisbane.

Q. What’s your age?

A. 45, I think.

Q. Are you registered on the AdvRiderMag forum? If so, what’s your handle?

A. I’m there as dirttrackbandit.

Q. What bike do you ride?

A. KTM 950SE Erzberg Special.

Q. What’s the best ride you’ve ever done?

A. Last year’s 14-day APC Rally was up there.

Q. What’s your favourite

place to ride?

A. Anywhere there’s a good pub.

Q. What do you like most about the mag?

A. Everything. I often sit at the front gate waiting for it to be delivered. It’s so awesome. I have anxiety issues waiting for it to arrive.

Q. What’s something that really peeves you on a ride?

A. Broken legs, collar bones, elbows or anything else that makes it a DNF. Other than that, nothing. Any ride is better than the best day of working.

Q. Have you ever raced or ridden competition?

A. Yes. I’m the current King

Of Mt Coree. No other results worth mentioning.

Q. Fuel-injection or carburettor?

A. Two of each, thanks.

Q. Foam or paper filters?

A. My bike has both.

Q. Goggles or visor?

A. Goggles, but I have a visored adventure helmet. I wear the goggles under the visor. I only put the visor down in really dusty conditions. When I’m hooking in it’s up so I have maximum vision.

Q. Did Steve McQueen really jump the fence in The Great Escape?

A. Yes. I think he may have jumped a few fences back in the day.

An excellent bike for getting to out-of-the-way places with minimum fuss.

What’s it all about? High-performance technology and a laptop? Or watching the sun set as you wind your way through a mountain pass, the dust thick on your visor and the thought of the day’s first cold beer making you grin with satisfaction at the distance you’ve covered and the things you’ve seen? If it’s all about the journey, the KLR650 is ready, willing and very able.

Kawasaki’s KLR is one of those bikes that’s been around, one way or the other, for a long time. It kicked off in the late 1980s and didn’t come in for any major updates until 2008. In a familiar story with bikes like this one, the long model run means costs are very low, and problems are very few.

Even the major redesign in 2008 kept the proven essentials of the bike. Upgrades included bigger diameter forks, a new swingarm and headlight,

a dual-piston rear brake, upgraded cooling system, heavier spokes and a fairing redesign. There were some other bits and pieces, but those are the main ones.

For 2014 there’s nothing major to talk about in the way of revolutionary changes, and after a couple of days on some wildly varying terrain, we’re not surprised. Why change something that’s so damn good.

Before some serious readers get their noses out of joint, the KLR isn’t a competitor for the high-end techno marvels leading the adventure-bike charge at the moment. It’s a very simple, single-cylinder, dual-overhead cam, 651cc, liquid-cooled four-stroke with (gasp) a carburettor, dual counterbalancers, a cable clutch and one of those trip meters where you push the button on the speedo and all the numbers roll around to zero. About the only thing it doesn’t have from the Old School of design is a kick start.

By today’s standards it’s a very simple motorcycle.

And that’s one of its greatest attractions.

The motor sounds simple because these days we all spend a lot of time looking at very involved electronics. The KLR doesn’t have things like fuel injection, selectable ignition maps, electronic suspension adjustment or even a digital clock. Or a clock at all. The forks are 41mm right-side uppers and the shock is a basic unit with adjustable preload and ‘stepless rebound clamping’ adjustment.

We don’t actually know what stepless rebound clamping adjustment is, and you know what? We don’t care. We climbed on that bike, touched the button, made sure it was running – it’s a smooth, quiet little puppy – then roosted off. That’s it. On other bikes we might’ve selected all kinds of technical variables, scrolled through menus on multi-function dashes and made sure we had every thing right to suit the weather or the trail surface. On the KLR we spent that

time cruising effortlessly up the Bells Line Of Road, dashing along rocky, mountain trails or even plunging knee-deep across crystal-clear creeks. And if the rear wheel started to spin we backed off the throttle a little bit. If the wheels locked, we eased up on the brakes. When we dropped it we just grabbed it and heaved it upright again without any special, ergonomically approved methods or intricate lifting systems.

Does it sound a little basic? You bet. It’s you, your bike and the world under your wheels. It’s what a huge number of riders go looking for when they think ‘adventure’.

First impressions of the KLR probably don’t happen any more. The bike’s been around so long that most people will already have a fair idea of what to expect. Even so, we couldn’t help but be struck by the quality of the paint and the finish in general. The shimmery green of our test bike was eye-catching as the sun played across it, and while we don’t think it looks all that great in photos, it’s quietly impressive in real life.

The screen provides good protection from windblast, and the simple instrumentation was very easy to read and understand.

The guys at Kawasaki fitted up our bike with a set of soft-shell luggage, and it covers up most of the tank. That was a shame from the point of view of looking sharp, but it also offered a lot of protection to that paintwork, so that was fair enough. The luggage itself was brilliant. It had the advantages of a soft luggage because it was a bit squashable, but the soft-plastic lids meant the panniers and top box held their shape, even when they were empty. Straps hold them on the bike, so it’s a little fiddley to get them on and off, but once we worked it out it was no big deal. The storage capacity was surprising, and in general, all the riders thought the luggage a big plus on this ride.

The tank bag wasn’t as well received as the panniers and top box. When empty it doesn’t hold its shape and flopped around a bit,

u

Above: The luggage was brilliant. There was good capacity, and the soft-shell manufacture meant it held its shape, but was light and malleable.

Left: A twin-pot rear calliper! Nice. Braking was good both ends.

Left below: By today’s standards the KLR is slim. Not only that, at under 200kg it’s light as well.

Bottom right: There’s lots of little modern fittings.

but with a few small bits and pieces chucked in it soon behaved itself. The clear map pocket in the top is always a bonus, and this one is a generous size.

We didn’t test the waterproofosity of this luggage – the editor went close during a squirmy creek run, but managed to stay upright – and as skies remained blue and temperatures punched into the mid-30s no-one gave it much thought.

In general, we liked the luggage.

To buy from a dealer the gear runs at the following prices: tail bag $184.80, saddlebags $330, and tank bag $116.40. But if you snap up a KLR before the end of February 2014, there’s a deal running where Kawasaki throws in an ‘Adventure Pack’ for free. All the luggage we have here is included, as well as a taller screen.

How frigging awesome is that!

With the bike off and running there are a couple of impressions that can’t be avoided.

The first is that the bike is really comfortable. It’s very smooth and very quiet. The dirt-bike style seat – with no step up to the pillion seat – is awesome for those who like to move around a little, and the fairing and screen mean the rider is well protected from annoying wind blast. Riders over about 180cm tall might want to look at some way of

raising the lip of the screen, but in general rider comfort is excellent. Even the handlebar/seat/footpeg relationship should have riders of average Aussie heights feeling pretty good about things.

The next thing most riders will notice is a very tame power output.

We think this has more to do with current trends toward marketing big-horsepower motors, because although we didn’t measure it, this motor felt very respectable for a carburetted, 650cc single. We didn’t once feel we were hampered by a lack of power delivery, and no doubt there’ll be plenty of tuners ready to give advice on how to wring more from the donk. We’d think very hard before doing any work of that kind. The reliability of the KLR is legendary, and we wouldn’t be keen to diminish that. The pipe isn’t very attractive to look at, but geez it’s quiet, and it’s mostly hidden anyway. The CV carb does its job.

Nah. We’d just ride it like it is, and enjoy the simple pleasure of it all.