Go with no compromises! No matter whether on asphalt or tough terrain: This bike is the ultimate all-rounder with an edge. Light, agile and with abundant power from the bottom up, thanks to a LC4 single cylinder engine with a full 690 cc. From hard enduro to drifting on dirt: This KTM 690 Enduro R masters every discipline, assuredly and with the greatest of ease. It’s time to GO and get ready...

By Tom Foster - Editor

Taking adventure riding as a pursuit in its own right – as opposed to considering it a type of trail riding – isn’t a totally new idea. There have been adventure riders pretty much as long as there have been motorcycles, and the issue of “what is adventure riding” has been thrashed out on a few web forums and even in a magazine or two, although I’ve never seen a definition everyone agreed on.

There’s no doubt we can all look at a ride and say, “Yep. That’s an adventure ride. Absolutely.” And we can look at others and say, “Pfft! All that support? And staying in four-star accom? There’s no adventure in that.”

But it’s difficult to put into a clear and concise definition. Obviously marketing and after-market suppliers think they know, because we’re at last being offered apparel and equipment designed and

manufactured specifically for the type of riding we do. For decades we’ve been making do with motocross gear. Call it enduro or trail if you like, but it’s been developed in motocross. Boots that offer the maximum protection with comfort a very distant consideration, jackets that don’t keep out the rain, tyres that are lucky to last a single day of mixed riding and a stack of other compromises. Now an adventure rider can walk into a dealer and expect to see suits made with Gore-tex, boots that are both waterproof and comfortable, heated gloves and vests, helmets designed to be worn for days at a time and all kinds of specific adventure-riding accessories. We even have our own magazine now.

Life is good, and the marketing guys have seemingly figured it out.

So where will a definition

come from?

There’s challenge and risk in an adventure ride for sure, but there’s challenge and risk in lots of riding. It’s nothing to do with the size of the bike, because some of the most amazing rides I’ve done have been on very small bikes. Honda CT110s, of course, but I’ve seen some awe-inspiring rides done on bikes I would’ve thought good choices as a commuter for a young girl with a learner’s permit. Should distance be a determining factor?

Nope. There’s plenty of adventure to be had in any given kilometre of just about anywhere.

I think the heart of the matter is that it’s the heart that matters.

If you get on your bike ready to look the world in the eye, and you’re backing yourself to deal with whatever fate throws at you, that’s adventure riding. It’s an attitude, not something you buy from a store.

Adventure Rider Magazine is published bi-monthly by Mayne Publications Pty Ltd

Publisher Kurt M Quambusch

Editor/Advertising Sales

Tom Foster tom@advridermag.com.au (02) 8355 6842

Production Managers

Michelle Alder michelle@trademags.com.au Arianna Lucini arianna@trademags.com.au

Design Danny Bourke art@trademags.com.au

Subscriptions admin@advridermag.com.au

Accounts Jeewan Gnawali jeewan@trademags.com.au

ISSN 2201-1218

ACN 130 678 812

ABN 27 130 678 812

Postal address: PO Box 489, DEE WHY NSW 2099

Website: www.advridermag.com.au

Enquiries: Phone: 1300 76 4688

Int.ph: +612 9452 4517

Int.fax: +612 9452 5319

90 Next Issue 84 16 80 72 30

54 How To Ride with Miles Davis

58 Simon Pavey

62 Group Therapy with John Hudson

66 Wish You Were Here

68 KTM700RR with Craig Hartley

72 Packing For Adventure with Robin Box

77 10 Minutes With: Cyril Despres

80 20 Things You Should Know About: The KLR650

82 Reader’s Bike: Kerrod Purcell’s R 1200 GS Adventure

84 Reader’s Ride: Cobbold Gorge, Queensland

86 Checkout. Christmas!

John thought adventure riders would love an event offering some of the thrill and challenge of The Dakar at a miniscule price, so in 2010 the real estate manager kicked off the APC Rally in 2010.

Karen’s in that growing group of females either returning to riding or taking it up. She’s worked in the Northern Territory as a governess/jillaroo, supervising kids and mustering on ’bikes, and bought her first bike from an undertaker.

Terry kicked off the Shock Treatment suspension tuning service back in 1996 after he found it difficult to get advice on setting up his own bike. Being a tad tall, Terry could see the need for a good suspension service that would take a rider’s personal needs into account.

Ken’s children and grandchildren keep trying to tell him he’s old and should slow down. His response is, “That’s rubbish. Just because I’m 70 doesn’t mean I can’t ride with the young blokes.” There’s never been a time where there wasn’t a dirtbike in the shed and he now uses the riding as a motivator to simply keep fit.

Nick is an owner and director of Teknik Motorsport in Penrith, NSW. He runs a workshop that specialises in a wide range of motorcycle suspension work, mechanical repairs and wholesale parts.

Craig has been riding for 40 years and has competed in enduros in Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. The purchase of Dalby Moto in 1984 was to feed his dirt-bike habit. Adventure riding came on the scene in 1995 and he’s ridden three Safaris and manages the largest trail ride series in the world.

Craig has been riding motorcycles since he was five, and he’s raced in Australia, South Africa, South America and Europe. In recent years become obsessed with motorcycle rally racing, competing in several World Championship events, with the best finish a third in the Open Production Class at the 2010 Sardinia Cross Country Rally.

A lifelong rider, Robin now rides, “whenever there’s a chance” on any bike available, on- or off-road. Between churning out Safari Tanks and importing high-quality Touratech gear, there’s not as much riding going on for this Victorian-based bloke as he’d like.

Ben contributed our reader ride for this issue. He started riding about 30 years ago on a YZ80 near Brisbane and has been riding on and off ever since. Ben got sensible and turned to adventure riding in 2008, and currently rides a 660 Ténéré. He’s the area coordinator for the Townsville region of the DSMRA.

Miles has been National Motorrad Marketing Manager for BMW Motorrad since 2006. He’s a very highly qualified motorcycling coach and an ex-professional mountain-bike racer. Miles is still riding every chance he gets, and has built an enviable reputation as both a world-class rider and a great riding companion.

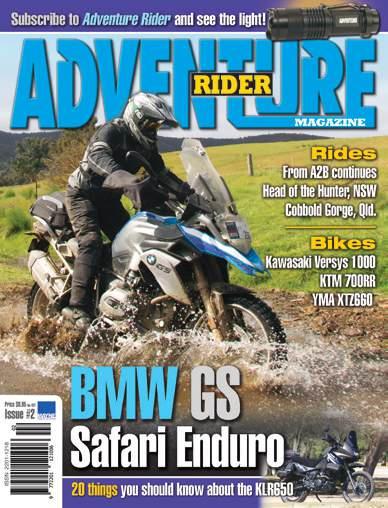

How much must BMW love adventure riders?

Building bikes is one thing, but organising and running rides like the GS Safari shows a huge commitment to our sport. And when it seems it just couldn’t get much better, the company stretches out and offers even more. The GS Safari Enduro.

The BMW Safaris kicked off in 1994, and the idea was to offer BMW owners a fiveday ride with the infrastructure to make the week-long exercise stress-free. There was lots of flexibility built in for a stack of variables, and the event was a success. It rocketed along, gaining momentum every year, until 2005 when numbers became a little too large, and the decision was taken to split the Safari into two events –the TS Safari and the GS Safari. The TS had panniers, top boxes, pillions and sensational roads. The GS had solo riders who were looking for more adventure and liked to get off-road. Splitting the two Safaris meant each group could have routes dedicated to the type of riding it enjoyed most.

The growth continued, and 2011 saw 220 riders sign up for the GS Safari in South Australia. BMW Motorrad, Australia’s branch of the Big Bavarian, sensibly thought that once again the numbers were becoming just a little too large for logistical comfort. When the 2013 ride was announced and sold out in just a few days, leaving 50 or so riders dangling on a waiting u

Ian Johnson,

and

enjoy the view over Bright on the third day. What an incredible experience to share with a few mates! Missing is Col Davis, who’d taken a biff to the ribs.

list, management decided it was time to take the next step. The GS Safari ran as usual, but a new event was offered, the GS Safari Enduro. The idea was simple enough: offer a tougher, more demanding, off-road course while remaining true to the original ideal of having all the logistics taken care of so BMW owners were free to enjoy it.

In the last few days of October 2013, 55 riders cruised, scrambled, sweated and laughed their way around the Victorian High Country, and we doubt there was a single rider who wasn’t blown away with the terrain, the scenery and the organisation.

Oh yeah. This was a really, really good one.

Service with a smile

With the weather approaching perfection it’s hard to imagine how

Rob Turton and the crew seemed to be everywhere. It made everyone’s maintenance a whole lot easier.

this ride could be improved. The accommodation was excellent, the support services absolutely first-class, and the Victorian High Country showed its best.

That doesn’t mean there weren’t a few mishaps along the way, of course. It was an adventure ride after all, so there were mechanical challenges

and a few bumps and bruises, including one case of suspected broken ribs, along the way. But having people like Geoff Ballard and Chris Cater tagging along to offer help when needed, and of course, BMW Motorrad National Marketing Manager Miles Davis keeping an eye on things, took most of the drama out of any challenging situations. A specially prepared medic bike was set up and on the course, and Rob Turton and his people were seemingly everywhere doing tyre repairs and changes, and even the occasional set of wheelbearings.

If it sounds like an adventure-rider’s paradise, we think it was probably as near to it as we’ll ever see.

The format for navigation was as well-sorted as everything else. Riders were given a route sheet at

Below: Rob Sellar’s bitsa was amazing. An R65 motor with 1000cc cylinders, enlarged exhaust valves, re-geared fivespeed box, CR500 forks, 1992 R10 frame and R1100GS rear suspension with a relocated suspension pivot. No electronic rider aids, and Rob and his bike smashed the whole route like it was a golf course. Legend!

Left: BMW Motorrad National Marketing Manager Miles Davis kept an eye on things and lent a helping hand here and there.

Above: Socialising and telling tall stories at briefing was a big part of every day.

briefing each night, and just to be doubly sure, the routes were arrowed each day by Huffy and Nick, two enormously cheerful and happy guys who seemed to enjoy their work. The little hi-viz arrows shone from tree trunks and road signs all over the High Country.

Aside from the route sheets and arrows, the courses where also available as GPS tracks, so there was nothing left to chance. It would’ve taken a pretty dim rider to lose the course with all that information available (AdvRider’s editor was one of the few who managed it).

As for the riding itself, there’s not much left we can say. It was superb. There was dust on some days and patchy rain on others, and there were hills and creek crossings that presented a challenge. But there was always help available and cut-outs for

anyone who didn’t want to tackle the more testing sections. There was no ridiculous, 450-only type single track, and even the bitumen sections were either lined with sensational scenery or twisted and wound their way along in such a way as to give the electronic rider aids on the newer bikes a good workout.

Mostly it was amazing dirt road connecting one sensational scene with another.

As the event progressed and the BMW guys could see the riders were capable and really did want an off-road challenge, a few tougher sections were allowed. The climb up Eskdale Spur Track on the fourth day held up a few riders for a while, but the view from the

hang-glider launch at the lookout was a fair reward for the effort it took to get there. The creek crossings were all shallow and passable, but creek crossings are funny things, and a few riders were caught out on slippery gibbers or by following the directions of evil photographers hoping for a good pic.

Fittingly, the fifth and final day was the most challenging and the most spectacular.

In a very late call it was decided the weather was good and the riders proficient enough, so the route included a run from Bright up to Lake Cobbler, which was pretty, then a

Beautiful scenery and smooth dirt roads made up a big part of the five days. It was a pleasure just to be there.

The climb up Eskdale Spur Track gave riders something to think about. Rod Marr looked like he was giving it plenty of thought.

run down the The Staircase of the Circuit Road, which, to be honest, could’ve been downright ugly. It had a heap of fallen branches scattered all over its 20km or so, and we have no idea why it was called The Staircase. Staircases are even and go from one level to another. This trail was a loose collection of stony rubble wandering up and down all over creation, and it was all first- and secondgear the whole way.

Still, when you get to the end of a section like that after five days on the throttle, you know you’ve taken a challenge and beaten it, and all the riders who attempted it came out the other end smiling. It doesn’t get much better than that.

From The Circuit Track it was a cruise up to the iconic Craig’s Hut, the setting for the movie The Man From Snowy River, and that was a real blast.

In a final gesture of farewell, the course left the Circuit Track and began the climb to Mt Buller resort, the final night’s accommodation.

But just as everyone began to relax the brightorange arrows suddenly speared off onto a rocky, crappy Corn Hill Road. That meant riders were on their toes – almost literally – for the final seven kilometres or so leading to the bitumen climb up to the resort itself.

That was a nice little kicker for anyone who thought the job was done, and capped off a sensational five days with an achievable challenge that will be talked about for some time.

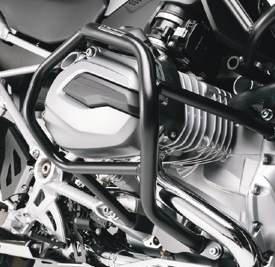

For this ride BMW Motorrad put us on an F800GS Adventure.

We loved the bike when we rode it last issue, but a real-world, bonegrinding ride like this one tells more about a bike than any amount of controlled testing ever could. There’s no trailer if things aren’t quite right and no trip to the dealership for advice. Every breakage and failure has to be carried to the end.

The 800 was amazing. In a strange way we almost feel as though we cheated because the bike was so damn good. When the hills got loose, rocky and gnarly, the torquey motor lugged us up using almost no revs and seemingly without trying. When we were tired and braked late into the loose, sandy corners the ABS gently let us lock the wheels, but kept everything turning over so the rider never lost control. And when we slammed into rocks and causeways at ridiculous speeds so both ends slammed on the bumpstops like a blacksmith’s hammer, it coped. No breakages and no spearing off at right angles with a mind of its own.

The creek crossings were gentle enough, but creek crossings can be tricky. A few riders ended up with wet bums.

In short, this bike was an absolute pleasure to ride. That’s recommendation enough, but the 800 Adventure made us look very good, and believe us, that’s not easy to do.

Above: Nick Selleck and Glen ‘Huffy’ Hough did a brilliant job arrowing the course, and seemed to have a ball doing it.

All over…for now Tall tales were told and drinks and good food were consumed that night. That meant it was the same as every night on this ride, though. A few awards were given out by the BMW folks, and in general the talk ebbed and flowed as the rider’s stories of their prowess became more and more exaggerated.

an adventure.

Right: The riders were told at briefing, “If you get a flat, get your wheel out while you’re waiting for the sweeps”. Juan Roncallo did exactly that. Except, Juan had a tubeless fitted. D’oh.

A huge farewell celebration dinner was enjoyed by everyone.

The accommodation at Mt Buller was truly amazing as the warm, sunny weather offered spectacular views and the Bogong moths camped in the boots and riding gear left out to dry.

We admit to choking back a little tear or two as we watched the riders

Thanks!

Right: The hill on the Eskdale Spur Track had Rod Marr running a little wide.

Below right: Rob McClurg learned the hard way not to trust photographers when they suggest a line through a tricky creek crossing. The bike started first touch of the button and Rob was straight back on the pipe after wringing out his socks.

Left: Stuart Woodberry found some loose, slippery clay. How did AdvRider Mag know to stop and shoot right there? The editor had face-planted there himself two minutes before and figured someone else was sure to have the same result.

retrieve their clobber from the support truck and head for their various homes. It was a great ride in every respect, and we can only hope the Enduro takes its place alongside the TS and GS Safaris as an annual event. If it does, we hope we get invited again. We’d hate to miss a ride as good as this one.

A massive thanks to BMW Motorrad and everyone involved for inviting us on this ride, and for making it such a trouble-free, fun, exhilarating event while we there. You guys rock.

Wunderlich: $415

Motohansa: $309

Touratec: $115

Wunderlich: $102

Motohansa: $79

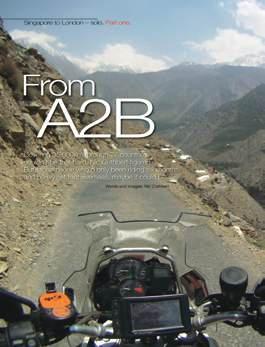

Singapore to London – solo.

Continuing his epic journey over 35,000km through 27 countries, raising funds for humanitarian cause ActionAid, Nic Cuthbert pushes on.

Irolled my BMW F800GS over the Iranian border as part of my overland adventure riding from Singapore to London. I was roughly halfway through the trip and Europe beckoned. The bulk of Asia had already passed under my wheels, and blood, sweat and tears had got me to where I was ready to tackle perhaps one of the most misunderstood of all nations.

As I poked my head out of my tent and stood to meet the breeze from across the Lut Desert, I felt the change in the air. I saddled up Snow, my BMW, keen to put the previous day’s ride under Military Police escort well behind me and allow the country’s smooth roads – built to the standard of perfection that only oil-money could afford –to carry me quickly onwards to Europe. I did 751km that day, and every kilometre was filled with exhilaration and enjoyment as I cruised along desert highways and glided past farming communities on my way to Esfahan in the nation’s south-east.

A couple of nights later I was riding at night on a brand new highway, yet to be lit, around the outskirts of Tabriz. It felt like a magic-carpet ride through the hot Persian night. It was stunning.

Although I did my first 600km in Iran under heavily armed guard and

Through Iran and into Europe on this second leg. u

got pulled over every time the police saw me, the country couldn’t be further from its widely portrayed stereotype. For me it turned out to be an exquisite place, immensely rich in culture with easily the friendliest citizens I encountered. It also included surprises like the ancient ruins of the Persepolis, 2500 years old, and the city of Esfahan, once described as the most beautiful city in the world. In Iran, the barren lands of the Far East gave way to broad-acre farms and John Deere machinery. Horses and carts hobbling along tattered roads in Pakistan gave way to four-lane, cross-country freeways traversed by Scania prime movers and Renault family cars. While many consider Turkey the transition from East to West, I saw most of that in Iran, not to mention the huge contrast in

landscapes, from stinking hot deserts to lakeside resorts and snow in the Alps just behind the conurbation of Tehran.

There’s a dark side to this stunning country of course, and I was privileged to an extraordinary insight into that when I couch-surfed with locals in Tehran. Segregated public spaces, strict control on the rights of women and highly visible propaganda are just some of the obvious signals of a population living at the mercy of a malevolent regime. Iranians are always willing to discuss politics though, and this I particularly enjoyed over red wine served from a mineral-water bottle. It was a recipe refined over many years and served in the homes of an ever-resilient population dealing with an alcohol prohibition.

I was in Turkey shortly after leaving Tehran, and with helicopters buzzing overhead and cruise ships pushing out to sea below, I rode over the Bosphorus Bridge, the main artery of Istanbul.

Turkey’s biggest city is widely considered not just the physical connection, but also the cultural confluence, of East and West, or Asia and Europe, if you prefer. Pushing into a stiff breeze and looking out across the Mediterranean I felt my knees weaken as I remembered and recaptured my love of the ocean. Later, walking through Taksim Square, having only recently stumbled out of the dusty plains of the Pakistani and Irani deserts, I must’ve looked slightly odd. I’m sure I resembled a life-size dashboard Elvis, my head bobbing around to take it all in like I’d never before seen a big city. Either that, or even more likely, I looked like a kid from The Land Downunder who had in fact never before seen a major European city. Three days later I camped out at a small cove 365km southwest of the hustle and bustle. It was there, after travelling over 19,000km by road across two continents, I took my first swim in the ocean. It was a monumental moment for me given my attachment with the sea and past as a surf life saver, but no less coincidental in it being the same beach that, 99 years before, Australian and New Zealand troops waded ashore for their fateful WW1

landing at Gallipoli. I was camped at ANZAC Cove.

Goosebumps.

Far outlasting a predicted 8000km, the Metzeler Enduros I’d fitted in Kuala Lumpur had rolled over more than 17,000km of bitumen, rock, sand and ice by the time I reached Turkey, and they were well due for replacement.

Fortunately Istanbul also represents the first place big-bike tyres became available on an East-West globetrot, and it was there I treated Snow to new shoes – Metzeler Tourances front and rear. The new tread allowed me to pick up the pace, lean into a turn or two and enjoy the incredible tarmac-based riding that Europe had to offer. And I was starting to realise that Europeans adore their bikes, particularly BMWs.

As I headed initially east into Greece and then north through the Balkans to the Dolomites I passed through toll gates, cruised along tram tracks, got waved into splitting lanes by cars

and was regularly motioned to park on footpaths directly outside major tourist landmarks like the Hagia Sophia (Istanbul), the Acropolis (Athens) and the Eiffel Tower (Paris). It seems that more than being welcomed, riding a ’bike is revered.

But with all the many reasons I can make for why touring on a ’bike is awesome, it must be said that for sightseeing the awesomeness can’t be overstated. Seeing a new city on a ’bike is a pleasurable treat. I quickly became accustomed to

punching in tourist hot spots as via points on my BMW Navigator, hitting the start button and letting the tour begin.

The countries of Europe seemed to fly by, and more than anything it felt like a holiday after the trials of earlier parts of the trip. Spectacular sections of coastline in Croatia, rolling countryside in France and Italy passed by, and before I knew it I was pushing through high winds and a torrential downpour as I tried to make Calais and the last ferry across the English Channel for the day. I’d ridden non-stop from Paris, hoping to surprise my partner Donna, making London two days earlier than planned.

After spending a few days relaxing and recuperating we departed two-up for the north of Great Britain where I officially ended my tour. The ride through Scotland, although incredibly scenic, turned out to be frustrating as it rained almost non-stop. However, late on the afternoon of Friday, July 27, the pouring rain at John O’Groats briefly parted and the sun shone down as we rode up to complete my overland adventure.

Riding any ’bike down the street is exhilarating; riding a ’bike down the road less travelled is an unforgettable experience, and following that road all the way across continents has changed me in a way I can’t accurately describe. More than my trip from Singapore to London being a huge adventure and personally rewarding, I was honoured to be riding for a cause. Throughout the journey I witnessed jaw-dropping and confronting poverty in many of the places I visited, but I was lucky enough to experience the heart-warming care and selflessness of an even wider population.

I want to take this opportunity to thank everyone who’s been involved in either making FromA2B happen, making it the epic adventure it was, or donating to ActionAid via www.froma2b.com.au.

As they say, this really is only the

beginning, and planning has already begun for the next adventure, FromA2B: Around The World. In 2015 I, together with my partner, will be shipping out to

There was plenty to see in Europe, but the actual riding was much less demanding than the Persian deserts.

London to ride from there to Tokyo where we plan to ship to Anchorage in Alaska before riding all the way to Cape Horn. Join the adventure!

Done. Singapore to London and on to John O’Groats in northern Scotland.

Order your FREE 1800 page catalogue, with thousands of Touratech parts, including the all-new BMW R 1200 GS.

l Touratech make the world’s best GPS mounting systems, allowing you to safetly protect your valuable navigation device in all conditions.

l Touratech mounts fit any bike, and are robust, durable and provide an anti-vibration system that is second to none. Lockable mounts are also available.

l Designed to fit Garmin, Tom Tom and Magellan GPS units, you have a choice of a cross-bar, handlebar or Ram mounting.

Priced from $187

l Touratech’s incredibly lightweight aluminium camp seat weighs just 470 grams.

l With a load rating of 110kg, size isn’t everything.

l You’ll sit a comfy 42cm above the ground.

l Folded, the seat is just 35 x 5.5 x 4cm in size and will fit easily into your panniers or your back pack.

Priced at just $74.95

Order at:

l Highly abrasionresistent kangaroo leather palm.

l Spandex leather detailed back.

l Colourfast and sweat proof.

l Velcro adjustment at cuffs.

l Air vents on fingers.

l Perforated finger side walls.

l Hard plastic knuckle protection

l Stylish grey-yellow design.

Priced at $180.40

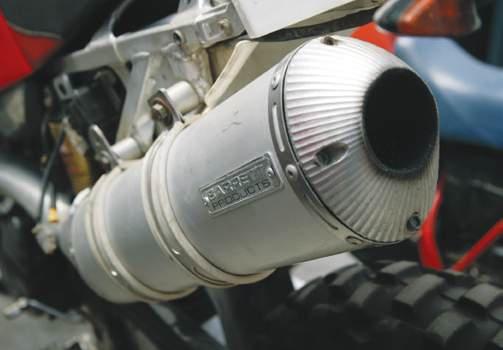

Aftermarket pipes are a favourite of nearly all bike owners. But are they a must-have or a marketing concept? Nick Dole, owner of Teknik Motorsport, is all about performance. Glossy photos, big-budget marketing campaigns and loud opinions on internet forums cut no ice at Teknik. Nick’s pay cheques are written on chequered flags and dyno charts. He shared a few thoughts on after-market pipes and adventure riding.

Main: Those running loud pipes are costing all the sensible riders access to riding areas. Stock pipes are not only usually quieter than aftermarket pipes, they often work better in an adventure application.

Adventure riding means different things to different people. For many, it’s an opportunity to get away from the routine of daily life, see new places, forge new friendships and explore. While we do all this, we leave a footprint on the places we ride. Not just tyres and the odd ploughing from a DR650 bashplate, but loud, echoing noise.

Like it or not, most adventure bikes get into some sensitive areas, and the pulses from a single-cylinder bike do travel in gullies and bounce off valley walls. Sometimes they’ll echo on for kilometres. We then have a question: do we care if the local inhabitants hear us riding in their little piece of Utopia?

While local residents don’t have the final say on what forest trails are left open, there’s been heavy petitioning at times to keep bikes (and 4WDs) out of certain areas. One of the first items on peoples’ shopping list with a new bike is a pipe. Why? General perception is that stock units are heavy, ugly and cost power. Is that true or false?

Above & below: Two Tiger XC800s. One has the stock pipe, one an aftermarket pipe. Is the stock pipe really that ugly?

The noisy-bike debate has been going on for as long as I can remember. It’s not just the risk of pissing off locals, but have you ever followed a bike with a noisy pipe for a few hours? It’s enough to make you want to pass them or drop back.

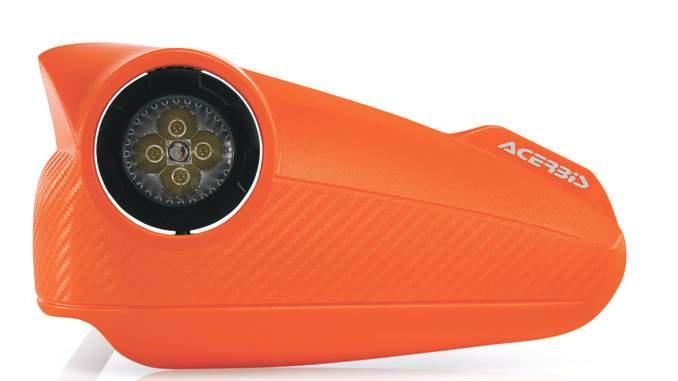

A few decades ago, when the two-stroke was king, Italian plastics giant Acerbis made a plastic muffler. I had one on my Six Day KTM 250. Coupled with the factory Slechin double-wall pipe it made great power and was very quiet. All the KTM Six Day bikes had that exhaust combo for the event. It was so quiet you often had to shout at people on single trail to get them to move over. Acerbis only made the mufflers for a few years. They weren’t the biggest sellers, and the public preferred noisy mufflers like the FMF and Pro Circuit shorties. Shaun Reed showed us all how much we were kidding ourselves at the 1994 A4DE. He dominated the entire event on a TTR250 with a stock muffler. From memory they were calling him “the whispering killer” or something like that.

So, what does an aftermarket pipe add in the horsepower department? It depends entirely on the bike. Taking the

DR650 as an example, about five horsepower is the gain. The bike isn’t overly powerful to start with, so you really feel the difference. A WR450F is a different story. The stock muffler is actually very good, especially with the GYTR insert. Can you really ride a 450 to the point where you need more power? Most top enduro guys are looking for ways to tame a 450 down. The aftermarket pipes for fourstrokes are performance orientated, and the power is made mostly higher up in the RPM range. That’s not great for long-distance work. What about the weight, then?

True, some stock, steel mufflers are pretty heavy and there’s often a few kilograms to be lost. I’m not sure of the relevance to this on an adventure bike where we tend to load them up with between 10kg and 30kg of gear, but everyone considers this another justification. I will say this about heavy, ugly stock pipes: they are durable! I’ve seen and welded up a lot of aftermarket pipes that have cracked, fallen apart and generally self-destructed. When was the last time you saw a stock pipe crack and fail?

Seeing as exhaust swaps seem unavoidable we can break them down into three main types to help you work out what u

noisemaker you should be more inclined to spend your hard-earned on.

The first is the mechanicalbaffle type.

Most stock pipes are mechanically baffled. The exhaust has to find its way through a labyrinth of plates, tubes and holes. While there may be some sound-absorbing material, it’s not replaceable and lasts forever anyway. From all these tubes and plates comes weight, and there’s usually a

Left: A well-used Barrett muffler. It’s several years old but still in great condition. They’re very durable, and that’s a big consideration if you’re planning to cover big distances.

double-skin too, which keeps the outside of the muffler cooler and is a consideration for soft bags that push sidecovers on to the exhaust. The manufacturers do a lot of durability testing, so while it’s heavy, power-sapping and ugly, at least it won’t fall apart. This is something you should consider if you plan on being away from home for a few weeks or months. Next up is the perforated-core style that needs packing.

A perforated (‘perf’) core is a steel tube with lots of holes in it surrounded by sound-absorbing material – usually fibreglass packing. All performance motocross bikes are perforated-core only. There’s some mechanical baffling used at times, but it’s fairly minimal.

Most aftermarket pipes are perforatedcore only, and that’s why they’re so damn loud. There are exceptions – like the FMF Q Core – that are a mix of mechanical and perforated. While these pipes are loud stock, the real issue is when the packing, usually glass fibre, gets loose and starts blowing out the end. You can watch it happen. Rev a bike with a motocross-type muffler and watch the little shards of glass packing flying out. Once the packing gets loose things go downhill very quickly. Not only does it lose power, it also makes more noise and the core is unsupported, leading to cracking. If you have a typical FMF/ Yoshi/Pro Circuit muffler on a single you’ll need to repack as soon as the bike shows any increase in volume at all. All manufacturers sell repack kits, and you can also purchase quiet end caps for most of these pipes. So you can have the lightweight look and power without annoying the guy riding behind you and buzzing koalas out of their trees.

Perforated core with lifetime packing

There are not a lot of pipes in this next category. Staintune and Barrett are the two most prominent. They don’t use a glass-fibre packing, they use stainless steel packing and it seems to last forever. Both have quiet inserts supplied with the pipes (not as optional extras). The Staintune gets the nod for durability too, with many units in service at well over 100,000km.

You can borrow a bit of technology to transfer into your glass-packed muffler by wrapping the perforated core in stainless-steel wool for a layer or two. This will protect the glass material from being blown out. Any industrial-supply company will be able to order the stainlesssteel wool in for you. The longstrand fibreglass packing is available free from yours truly. I hate unpacked mufflers so much I give the packing away free in some vain hope it’s helping the collective masses.

Right: Free muffler packing! Nick is so keen to keep bike noise levels acceptable that he makes quality packing available free to those smart enough to use it.

It should be noted multi-cylinder bikes don’t have as many problems with packing blowing out of mufflers as singles. The pressure-wave pulsing of a single seems to dislodge the packing pretty quickly.

If you just cannot have a stock muffler, my suggestion is to get one that either needs no repacking (Barrett and Staintune for instance, and run the ‘quiet’ inserts), or run cans with plenty of surface area to absorb noise, like the twin mufflers on the Ténéré 660s. They do a good job even in perforated, glass-pack form.

Buying a motocross-inspired muffler for an adventure bike is just asking for the world to hate you and, in turn, the rest of us.

So, what’s too loud?

Do you need to wear earplugs?

Do your mates hate following you?

Do you get a headache from your own noise? Do people give you a dirty look when you ride past?

If that’s you, do something about it before we alienate the general public even more.

If you just love the sound of a noisy motorcycle, go drag racing and stay the hell away from the rest of us.

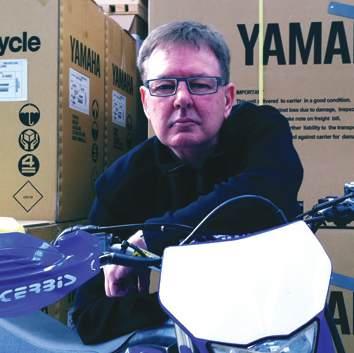

Adv: What’s your official title at Yamaha Motor Australia these days, and how did you start riding?

PP: I’m Brand Development Manager, which is principally about the behind-thescenes stuff.

I’ve been in the industry since 1972 and actually didn’t start riding until I was 17. A guy I went to school with in the outer

Those who’ve been around a while know Peter Payne as one of Australian motorcycling’s quietly spoken true gentleman. Having recently returned from a long stint with Yamaha in New Zealand, we caught up with the bloke who made our jaws drop by taking the Super Ténéré through terrain we thought was challenging on a WRF. Not only does he take the bike through that terrain, he does it in a very tidy, unflustered and commanding fashion. He’s so tidy his hair somehow stays neat when he takes off his helmet. Any wonder he’s called Mr Clean. We wanted to know how the man who’s now one of Yamaha Motor Australia’s management got his start.

Main: No photo-trickery here. That’s a frigging steep, rocky hill, and Mr Clean’s making it look easy on the big Yamaha.

Below: Peter Payne – Brand Development Manager for Yamaha Motor Australia, and a bloke with plenty of ’bike cred.

suburbs of Brisbane had an AT1 Yamaha that he’d received for his 17th birthday, and he used to ride it to school. I was intrigued to the max with it, and eventually one afternoon I got to ride it along the bank of the nearby river. I was just like, “How good is this!”

But it wasn’t until the next year after I’d left school that I got my first bike, a Suzuki TS185.

Carel Berendes (pronounced Carl) was the local motorcycle dealer. I used to walk past, and often look inside, when catching the train to and from school. He sold Suzukis. It wasn’t a big dealership and he did lawnmower and small-motor repairs,

but he was a true enthusiast. He was a keen road racer who also knew about the Six Days and all that sort of stuff that we’d never heard of.

I just wanted a trailbike, and at that time I thought a DT1 would be cool. I thought they were the neatest thing of all, but they were too expensive for me. Carel advised not to get something that big. He suggested I get something lighter as it’d be easier to learn on.

So I went, “Oh. Okay!” as he knew what he was talking about.

I eventually went trailriding with him, and he was also friends with Brian Foster, who was then a Sales Manager with Yamaha, and Vince Walker, who was also a former road racer. Those guys taught me a lot. Carel the Suzuki dealer also had a 185 Suzuki that he’d fitted with a 21-inch front wheel, alloy guards, a tank bag, a little headlight and a little tail light, steel footpegs, knobby tyres and so on…this was 1971. I was like, “What’s all that for? And what’s a Six Days?” They tried to tell me, but it wasn’t until I saw On Any Sunday that I knew what the ISDT was.

The first competitive event I rode was in 1972 at Beaudesert, and I think it was Queensland’s first enduro. Adv: What brought about the start with Yamaha?

PP: The 185 Suzuki was great and Carel was right, I did learn a lot, and then I moved up to a TS400.

Initially my parents didn’t want me to ride. They wanted me to learn to fly as that was a bit of a family thing, but I said, “Nah. I want to be around motorbikes.” I didn’t care if I had to sweep the floors, I just wanted to

be around bikes, and eventually I started working with a Yamaha dealer at Moorooka in 1972. Steven Cotterell, (now Director and General Manager of Yamaha Motor Australia) was just as fanatical about bikes and riding, and we became friends and riding buddies. Eventually I started working for Annand and Thompson, the Queensland Yamaha distributors at the time, in 1974, and in 1975 we officially started the Yamaha enduro team for Annand and Thompson. Steven used to work there as well on and off while juggling work, riding and Uni.

“Those round things? They’re wheels.”

Adv: Racing in the ’70s must’ve been very different to today.

PP: The QTRA (Qld Trail Riders Association) enduro events were running at the time, and usually they were a single 300km loop to be ridden in a day with a few special tests included on the trail. For a two-day the loop was usually a reverse of the first day. I was still learning, but I finished those first couple of events okay, and in 1974 I won the Queensland State Championship for my class, as did Steven. In 1975 we went to Oberon

for our first interstate event and that was an eye-opener. Again we went okay, and at the end of that year we went down to Victoria for the Newry Two-Day, run by Norm Watts. It was a great event, and we got gold medals. I still have the memory of the fresh smell of the eucalyptus forests that were so different to Queensland, and the looks from the Victorians wondering what we were doing so far from home.

We’d also started to really develop the bikes around this time, and the first real development project we built was based on the YZ125C alloy-tanked Monocross motocrosser that was converted to a 175cc enduro model. Another friend we rode with, Bob Esler, had the first one that was developed with input from him. It had a few teething issues, – like no power until very high revs – but they were eventually ironed out. We then built one for Steven, and he won a lot on that bike while I was on the 400cc models.

We’d do motocross as well, but I was never any good at it. Steven was an A-Grade motocrosser and did well, but I was an also-ran. I just wanted to ride single trails in the forests. The footage of Malcolm Smith in On Any Sunday on the tree-lined single track during the ISDT in Spain is indelibly imprinted on my mind, and that was my favourite type of riding. Motocross wasn’t.

There were some great events as enduro began to take shape in the ’70s – the Forest 300s at Dungog were great and I see that it’s been suggested to run one again in the future. The Lance Watsons, The A4DEs, Kenilworth in Queensland…

John Nic (left), founder of Kiwi Rider magazine and NZ legend, and Peter Payne show why he enjoyed his time there so much. That kind of terrain is everywhere in the Shakey Isles. u

Bathurst, Orange…they were all great events run by a lot of enthusiastic people.

The first Australian Four Day Enduro Championship at Cessnock in 1977 was a bit of a disaster for both Steven and myself. I had a head-on with one of the organiser’s cars on the second section. That was the end of event for me as the bike was damaged. Steven broke his wrist on a slippery wooden bridge not long after.

I won another championship in 1978, and the Yamaha team continued to go well. We had ITs by then, and the 1978 IT400 I had was a great bike. It was just one of those bikes that was a real gem. I had the chance to go to the Six Days in Sweden that year, but I really didn’t have the money to do it.

In 1980 I got another Queensland Championship and we won the Trophy Teams event at the Four Day, but I rode Husqvarna for a short time as we had sponsorship that allowed me to go to the ISDT in France. Adv: That must’ve been an experience.

PP: It was an awesome experience as well as a total eye-opener.

That was the year Geoff Ballard won his final moto at what was the last ISDT before the name changed. GB had been in Europe for the year living in his old green Kombi and he’d really matured. He was always fast, but by then he’d risen to a new level.

That led into the 1980s, and enduros had begun to change. In general they’d become smaller loops ridden several times, instead of one big, long loop, and had motocross-style special tests instead of the trail type. I was just getting bored with the repetition and I decided that was it.

I went to the Six Days in Italy in 1981 and did okay, finishing with a silver. It was an okay event, but I wanted to do other things as the trailriding had changed. I was still working for Yamaha and I continued on, but I wasn’t competing in Enduros. Adv: You moved to Honda. PP: I did. In 1982.

There was a lot of crossover of staff back then. The Yamaha distributor and

Honda distributor were owned by the same parent company, and when a pretty good job came up with Honda one of the managers there who used to work for Annand and Thompson Yamaha suggested I apply for it. I said, “Okay.”

I ended up staying there until 1997. Meanwhile, Steven had his own Yamaha dealership from 1980, but had come back to A&T Yamaha in 1984 as Sales Manager. When Yamaha Motor Australia had taken over A&Ts in 1989 the Director was Bill Vivien. Bill was my boss when I first started in spare parts with Yamaha. It was a bit of an in- joke between us with them asking repeatedly, “Why don’t you come home?”

I really enjoyed working with Stuart Strickland when I was at Honda, but in 1997 I went back (home) to Yamaha, and I still hadn’t really ridden any offroad bikes.

Adv: Was it the change back to Yamaha that started you riding again? PP: It was the YZ400F in 1997.

We had a pre-production model

arrive at work, and I looked at it and thought, “I just have to ride this thing.” I took it down to Steve Smith’s property at Beaudesert and wondered what it was going to be like! The handling and power were fine, but I couldn’t believe the brakes. Disc brakes front and back! You could go through water and you still had brakes. You could go down hills and you still had brakes. You could do anything and you still had brakes. It was the biggest single thing that hit me after almost 16 years off dirt bikes. The brakes were amazing.

I began doing some trailriding again, and together with Steven, we again started doing a bit of development work.

I’m a bit of a pain for neatness and having everything just right, but I’m okay with picking up things from bikes just by feel. I did some development on the early WR250F along with GB and Steven, and eventually went to Japan with some development work there. We took Ben Grabham along with us for the first electric-start WR. He was riding Yamaha then.

I was doing the riding with the development of the bikes, and that led to more trailriding.

Adv: You went to New Zealand for Yamaha.

PP: Yeah. When Yamaha took over from the previous distributor we had to change things, and it meant changing a generation of the culture about Yamaha in the marketplace. It was difficult at times, but I really enjoyed living there. I even got used to the cold and wet, and I especially loved the riding. I was initially to be there for two years and almost nine years later I was still there.

We had some success in New Zealand eventually.

Adv: Now you’re back in Australia and Yamaha is having a lot of success with the Ténérés. We’ve spotted you on trails here and there, and you’re as tidy and composed as ever, still riding the cleanest lines and making everything look easy. Will we ever get to see you with a Super T stuck on the upside of a sandy dune or drowned in some rocky, fast-flowing creek?

PP: (Laughs) Hope not!

The Dark side

Main: AdvRider Mag’s publisher deals with one of the 21 creek crossings on the afternoon run to home.

What started out as a two-man, one-day ride to redeem a rider’s fallen pride ended up as seven riders out to photograph the headwaters of the Hunter River in NSW.

Most of us don’t need an excuse to go for a ride, but we have to come up with some kind of believable justification for our Significant Other. These reasons can, at times, be quite spectacular.

In this case the need to complete a section which had got the better of me once before would’ve been perfectly obvious to any rider with even the tiniest

levels of testosterone, but I suspected the motivation might not have carried the same urgency with others in my household, so something a little more Bear Grylls was called for.

“We’ll search for the source of Hunter River,” I declared, “Like the African explorers of old searching for the source of The Nile!”

Whether or not this was credited as a “good reason to go riding” I elected not to find out. I packed my clobber and rode off into history.

This particular ride sprung out of the need to re-ride the first day of the 2013 APC Rally, hopefully without the dramas of our last attempt.

The contenders for this jaunt were four blokes from Sydney and three Hunter Valley locals. Three of the bikes trailered up from The Big Smoke for the 8:00am kick off. Laguna, our start point, was halfway between Bucketty and Wollombi, about 50km west of the NSW Central Coast region and on

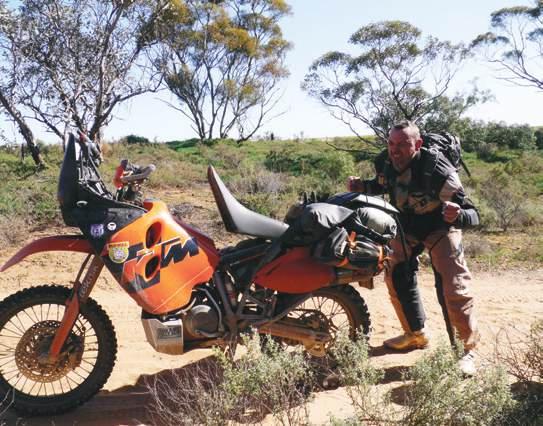

the edge of the much-loved Watagans. The aim of the two days was obviously to have fun, but also for the country bumpkins to show the city slickers a bit of their backyard. There was no consistency in bike brand or size. Weapons of choice for the boys from the bush were a KTM 950 Adventure, a nice, shiny, new Triumph 800XC Tiger and a KTM 690 Enduro R, while the city slickers fronted a Husqvarna TE630, another KTM 690, the bulletproof Suzuki DR650 and the mighty BMW R1200GS Adventure. Everyone was looking forward to watching the performance of the various steeds over the two days.

The only “real” (ride-it-fromhome) city slicker adventure rider was Curley on the big Beemer.

The group rolled straight into the bush on the Boree Valley Road west of the Watagans National Park. It was nice, easy going, but bloody dusty. Curley had just oiled his riding gear and within a couple of minutes he looked a bit like a bull who throws dust all over himself to show who’s top dog...or bull, I guess. Excellent

open, free-flowing trails led on to the Putty Road for a blast down the tar, and then the really interesting riding kicked off at the Putty Creek Road beginning the run through Wollemi National Park. For the smaller bikes the next few hours were an absolute blast filled with all the usual fare: rocks, hills and dozens of drainage humps –all quite fast and lots of opposite-lock and air time.

As lead rider, I had clean air and made good time, but waiting to drop off a corner man for 15 minutes or so seemed a bit long, so back down the track I went to see what was wrong. Leaving the corner men in place as I passed, I rode back about 20km before I came across the Triumph with a flat front tyre. That’s not usually a problem, except Triumph must be so confident of its machinery that the stock toolkit doesn’t include the gear needed to remove the front wheel.

Pete admitted he should’ve checked

Below: The tools needed to remove the front wheel of the Tiger aren’t in the standard kit, so the tube had to be patched in place. It meant something that should’ve taken four minutes took two hours.

that before launching off into the bush, but it’s not an unreasonable expectation for a new-bike owner to think the tools for basic maintenance would be on board. Tiger riders be aware.

So what do you do in this situation? Just patch the existing tube with the wheel in the bike of course.

All up this simple flat cost about two hours. After a bit of a powwow four riders went on to attempt our planned course for the day with the intention of a regroup at the pub at Moonan Flat that night.

The puncture boys, via the tar, got into the pub just one beer ahead of the hardcore group. One of the less-experienced riders became quite dizzy and ill during the latter part of the afternoon. He hadn’t carried a hydration pack and most likely suffered from dehydration. One would hope the lesson has been learned and from now on a drinker will be part of his essential kit.

The Victoria Hotel at Moonan Flat is a great place to stay. It’s a real country pub that boasts some history from the days of Thunderbolt the bushranger. On Monday nights the restaurant is usually closed, but they opened up for

us and provided a typical country pub meal. These rural boys sure know how to eat!

It was supposed to be an early start next morning, but a sore head or two and a photo shoot slowed things down a bit. The crew did finally get away and headed up to the snow country of the Barrington Tops.

Of course we really did have to try and find the elusive spring that is the real start of the mighty Hunter River. Questions were bound to be asked and we’d need proof. I’d been there before, so locating the source was no real problem, but it’d been a bit dry lately and the beautiful bubbling spring I’d seen on previous trips was now just a dried-up pond. Nevertheless, we took a shot or two next to the moss-covered seep which qualifies as the ‘Head of the Hunter’, and thus proved our explorational prowess and had some photographic evidence of our expedition’s success for when it was requested.

Another powwow was called when a broken throttle cable had to be dealt with and it was decided not to go too deep into the bush.

One of the good things about this part of the world is there’s always lots of choice. Instead of heading east into the wilds we headed to Nundle, via Glenrock and Barry Stations. If you haven’t done this run, then do yourself a favour sometime and give it a crack. The route takes you past Ellerston (the Packer property). You’ll be amazed as you gaze over the chain-wire fence

“Ommmm…” Curley considers moving the AirHawk from the Beemer to the fence post. He does look fairly happy there though, doesn’t he?

and take in the panorama of the small township and manicured polo grounds that are part of the Kerry Packer legacy.

Once you leave the splendour of Ellerston the real riding begins. If I counted correctly there were 21 creek crossings. What a ride!

It was a while since I’d last done this trip and I’d forgotten just how good it is. The big bikes especially just loved the sweeping uphill terrain as we climbed out of the valley to top out at Hanging Rock, 1300m up.

After a quick lunch at Nundle it was time to head south again, and the Crawney Pass offered a great run

before the slickers headed back down the tar while the hayseeds blasted off into the bush again for one last injection of creeks, rocks and roost.

With 945km on the clock we arrived home having not broken a bike, and the APC bogey man who whacked me with a tree last time through there had been well and truly put in his place.

So which bike was best? As one of the boys said, “The best bike is the one you’re on today”. Ain’t that the truth.

Do you remember your first Adventure ride?

I do. It was a trip to Barrington Tops

Above: Found it! That bit of damp ground in front of them isn’t where they just peed. That’s the true beginnings of the Hunter River…it was just a bit dry on this day.

in winter on a Honda 90. Did I have fun? You bet! Was the bike a challenge? You bet! Did I come back for more? You bet!

Who cares what bike you’re on. Get off the lounge, scrape the cow dung off the ag bike, borrow your grandma’s scooter, or hop on your brand-new, fully blinged, personalised machine – but just get out there and let the adventure begin.

In August a swag of riders got together to celebrate an Aussie bike-journo pioneer, Tony “TK” Kirby.

For those who’ve been adventure riding since before there was such a thing, TK has legendary status – the kind of status where a big group of riders from all over Australia gathers to ride in his honour each year.

That’s largely because in 1995, when Australia was embracing the Thumper Nats, Yamaha was messing about with a fourstroke motocrosser and some young Americans had just begun making the videos that were to give birth to freestyle motocross, TK walked out of his job as editor of Australia’s biggest dirt-bike magazine and kicked off his own venture, SideTrack Magazine.

He’d been a huge exponent of the KLR600, then the XR600, and most BMW adventure riders of today revere his name for his exploits on an 1150GS.

TK first came to most riders’ attention when he signed on as Features Editor at Australasian Dirt Bike in the early 1990s. He’d been working at the lab which developed the slide film for ADB, and during a visit by the magazine’s owner, TK showed him a few pics he’d taken himself on an outback ride.

One thing led to another, and before long TK had his start in publishing.

He would go on to become editor of that iconic journal in late 1993.

Carving his own rut

SideTrack was a bold move for a couple of reasons.

First of all, it was Australia’s first motorcycle magazine – one of Australia’s first magazines of any kind – to go “direct-to-plate”. What that meant, effectively, was the magazine was produced using digital technology, and in 1995, that was about as radical as things could be.

But there were very few people around, then or now, who could match TK for boldness or backbone. Not only was SideTrack direct-to-plate, its content was entirely adventure riding.

– dealer principal at Dalby Moto and hard-bitten adventure campaigner. When Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson first crossed the Blue Mountains, they probably did it by following Hartley’s knobby tracks. He’s been riding THAT long.

“I remember TK as a person who was so passionate about what he did with his SideTrack Magazine that he literally lived and breathed the adventure. No doubt there are abundant examples of this, but one personal example is when he turned up with his slide-on camper, bike trailer, bike, race quad and canoe and simply set up home/office in my garden beside

This was a shock to everyone. There was no “adventure” riding back then. There was trail riding, and some people rode big trailbikes into the desert sometimes, but the idea of adventure riding being a section of the sport on its own was science fiction.

TK made it a reality.

In the process he showed us rides that make the highlights of any rider’s list today. The Canning. Across Australia. Birdsville. Arkaroola. Cameron Corner. Lake Eyre. Poeppel Corner, The Gibb River Road… these and many others were names unknown to a fledgling adventureriding group in the mid-1990s. He wrote about things the mainstream dirt-bike mags considered ridiculous or irrelevant, like screens, large fuel tanks, dealing with dust, locked gates on public thoroughfares and how loud bikes would put an end to the sport. TK rode and wrote about all of those places and subjects. He opened a new world of possibility to riders across the country.

As a rider TK wasn’t exceptionally fast, but he was one seriously tough bugger.

When it came to manhandling bigbores through tough terrain, he was the master, all 70kg of him.

And if big-bores made something

the dam and continued to do work on the next edition of SideTrack

In the same week we then went to Manar Park near Gayndah and ran the subscriber’s ride for 2000, and I have no doubt he would have punched out a few more paragraphs in the few spare minutes he would’ve had over the weekend.

Tony often related stories of how he’d compiled magazines in National Parks, beside dams, overlooking oceans or from atop mountain ranges. He had all the equipment in his flash camper to build the whole magazine: stories, photographs, advertising…and all content was done by Tony in the camper and then sent on to the printers.

I guarantee no other super-successful magazine in Australia would’ve ever been put together in a mobile office/home.

Some of the places that SideTrack would have been put together would astound many, but the truth is Tony was living the dream and making some of the nicest places in Australia his own front yard and office.”

easy, he’d turn around and do it on a small-bore. And do it cheaper. Doing things cost-effectively was a hallmark of TK’s philosophy, and sharing his cost-cutting measures didn’t always earn him the high regard of advertisers.

How tough was he?

He won his class in the Australasian Safari on a DR250. He took his BMW GS1150 to places that left BMW owners reeling in shock, and when finances got tight he grabbed a camper and produced his magazine as he lived a nomad lifestyle.

And when it came to planning a ride, he was the master. Aside from all that, TK was instrumental in the founding of the DSMRA and had a laugh like a demented hyena.

Spare a thought

So there you have it. That was TK.

Our sport owes him a lot, and there are a huge number of died-in-the-wool adventure riders today who’ll say it was TK and SideTrack Magazine who inspired them to embrace adventure riding in the first place.

TK sold SideTrack in 2006 and finally succumbed to Motor Neuron Disease in 2010. He stayed belligerent and unbeaten right to the last, cutting special test times on his mobility scooter in the shed with his close friends when he couldn’t sit a bike upright any longer.

That’s who those riders are remembering when they ride each year, and a bloke we should all be saluting whenever we think about the glory of adventure riding as it is today.

Here’s the thoughts of a couple of riders who knew him well…

– owner of the Motorbikin’ franchise, instigator of the Hardcore Postie runs and genuine adventure rider. Burke and Wills probably asked Phil for directions he’s been riding outback for so long.

“A lot of people will remember Tony Kirby as a leading journalist, wordsmith and editor of the legendary SideTrack Magazine, but I remember him as a tough little bastard!

He had a penchant for small-bores and coined the phrase “250s thrive on revs!” when he took his DR250 to a class win in the Australian Safari. He launched the WR400 for Yamaha, setting a coast-to-coast record across Australia and dispelling the popular belief at the time that the WR was a “hand grenade”.

And he defied all odds when he rode a massive GS1150 down the Canning Stock Route, once again launching it for the manufacturers. Punters all over the country snapped up the big Bavarians and rode them out into the desert to their doom!

TK is gone now, but it turns out he had an awesome bunch of mates and while the TK Ride is about remembering him, it’s also about catching up with familiar faces.

Craig Hartley, Danny Wilkinson, Phil Gill, Yap Williams, Hedge and of course, the mighty Boulder Brothers to name a few.

So long as blokes like these are keen to saddle up and ride, TK’s memory will live on.”

www.motorbikin.com.au

One of the best things about our sport is the people it throws together. Here’s an AdvRider chosen at random from the thousands who read this magazine. Everyone, meet…

Q. Where are you from, Neil?

Q. What’s the best ride you’ve ever done?

A. The 2011 APC Rally would have to be the most eventful and varied.

A. Originally Birmingham, England, but for the last 20 years I’ve lived in Sydney.

Q. How old are you?

A. Too old – 43.

Q. Are you registered on the AdvRiderMag forum? If so, what’s your handle on there?

A. Registered as ‘nry’.

Q. What bike do you ride?

A. A KTM640 on the long trips, a CRF450X for single track and a CRF450R for motocross.

Q. Where would be your dream riding destination?

A. Finish line of The Dakar.

Q. What do you like most about the mag?

A. It’s Australian and has some great articles and contributors.

Q. What’s something that really peeves you on a ride?

A. Nothing, although I’d rather do without electrical problems.

Q. Have you ever raced or

ridden competition?

A. I road raced for 10 years. On dirt I’ve ridden a couple of enduros. Last year I rode the Condo 750 and will be back there again in 2014. If I go okay I’ll enter the Australasian Safari.

Q. Is Charley Boorman a hero or a twat?

A. I like his sense of humour and honesty, and I enjoyed Race To Dakar. I very rarely watch television, though. I’ll go with ‘hero’.

Q. Fuel-injection or carburettor?

A. Carburettor. It’s much easier to fix in the bush.

Want to introduce yourself to AdvRider Mag’s readers? Email tom@advridermag.com.au and we’ll punt you a few questions like these. You’ll need to be able to supply a head’n’shoulders pic, and maybe a pic with your bike.

Not every adventure ride has to cover trackless desert or teeter on the edge of a treacherous mountain ledge. There’s amazing destinations and routes that require covering long, long stretches of bitumen, forest thoroughfares the maps call “secondary roads” and stretches of dirt that are basically flat and in good shape. In that terrain the Versys is at home. And a very quick, comfortable and capable home it is, too.

Afuel-injected, liquid-cooled, 1043cc in-line four built from the white-knuckle Z1000 motor powering a dualsporter! What was Kawasaki thinking?

Mr K was probably thinking, “Hmm… there’s a lot of people with a roadbike background who’re moving into dualsporting and adventure riding, and they’d like a bike with a familiar feel.”

Mr K was right. As unlikely as the Versys may look to the hardcore single-cylinder, blood-and-guts guys, there’s a huge swag of mature road-riders who’ll climb on this bike and be surprised at how comfortable and non-surprising it is. They’ll head down the Great Ocean Road or out to Broken Hill on some of the lessthan-perfect backroads – especially if they’re two-up – and rightly feel they were on the perfect bike for the job.

Looking at the spec sheet the Versys can seem a little startling. As we said, this motor earned its stripes in the take-no-prisoners world of the streetfighter bikes, but in the Versys’ incarnation it’s been tamed to a mere 118 horsepower. In keeping with the current trend on some of the power monsters we’re seeing lately, there’s a thumb switch that allows a ‘Low’ or soft setting, reducing the horsepower output by around 25 per cent.

That’s still a big handful of mumbo for those not used to it.

Combined with the nifty power settings are three traction-control settings (plus ‘Off’) and ABS. There’s no option to switch off the ABS, but for once we’re pretty comfortable about that. If you had in mind to tackle the type of terrain where ABS was a problem, this isn’t the sort of bike we’d expect you to be considering.

Of course, horsepower needs to be considered alongside mass, and measured at the brochure this is a 239kg bike, fuelled up and ready to go. That’s actually very manageable, and

Left: A multi-function switch cycles through the functions on the various trip meters and gauges, as well as the different traction control and horsepower settings. It was a little fiddley to get it in the right selection mode, but it allowed settings to be changed on the fly.

with figures like that it’s a weapon.

Kawasaki also explains in the media kit that the tuning of the motor has been aimed at a strong low- and mid-range response, and that seems entirely sensible given the bike’s intended use. The bike pulls away well from idle and is very forgiving at low revs once the rider becomes accustomed to just how lively that motor is. Still, peak horsepower is at 9000rpm. That’s a lot of revs for those used to singles and loping V-twins.

The first impression of the bike revolves around what seem to be big, wide sweeping ’bars. It feels as though you’re sitting on a long-horn cow and steering it by the horns. That only lasts about a second, because then it becomes obvious that the ’bars are no wider than those we see on most dualsporters. They have a kind of sweep where they curve down

inside the fairing and that makes them seem long. By the time the rider’s mind has grasped that, it’s already spinning away on just how comfortable the riding position is. Riders around the 170cm to maybe two metres tall will sit on the that wide, comfortable seat with their

Forestry roads and bad bitumen are handled with ease. Tyres with more bite would make a huge difference on the dirt.

at both ends, even on loose surfaces. It was a very impressive feature of the bike.

The six-speed box was a smooth-shifting delight and the cable clutch was quite light. We kept thinking we wanted an extra top gear, but we realised we were riding the Versys like a twin, and thanks to the willingness of the motor we could coast along at very low revs and get done all we needed. It was only when we noticed the redline was all the way up at 10,000rpm that we thought, “Maybe we should give it a little squirt and see what happens”.

Snort and rort

Holy mother of Dog! That motor is a sweetheart, but it’s a snarling beastie too.

backs fairly straight and their arms in the sweetest, laziest position with their hands on the grips. The ’pegs allow a very open and easy seating position, and overall, the comfort of this bike is pretty damn amazing.The more we rode it, the more we felt that reinforced. Comfort is a very big factor on the Versys.

Before we get too carried away we should cover some of the other tech features.

Suspension is Kayaba front and rear, and both ends are adjustable for preload and rebound. The fork rebound is adjusted by a clicker on the right fork leg, while the shock has an easy-to-use winder on the side of the frame. We thought the winder was for

rebound, but as the Kawasaki guys patiently explained, “The tank at the end of the flexible hose is the preload adjuster hydraulic system. Wind the adjuster and it puts oil in to expand the adjusting mechanism and preload the spring. The shock is a sealed design and is gas pressurised without a separate reservoir.”

Oh.

Anyway, the winder is covered by the panniers, but they’re so easy to click on and off the bike it’s hardly worth mentioning. Shock preload is the adjustment that would be used most, so it makes sense it’s in such a convenient position.

Braking is superb. Twin Tokico four-spot calipers at the front are moderately sensational and, along with the single-pot rear, offer great feel. The braking isn’t incredibly strong at the first touch of the lever or pedal, but as we settled into the bike we realised it was a beautiful asset. Instead of a sudden snatch whenever the brakes were touched, the stoppers come on with an incredible linear application that inspired huge confidence in late-braking on the tarmac, and offered no intimidation whatsoever on the dirt. The ABS actually allowed some fairly aggressive application of the stoppers

When we finally let it have its head it’s as though it rewarded us for working out what it was made for, and the traction control suddenly went from being something we thought a bit interesting to something we found a genuine and welcome asset.

On the road at around 6,000rpm in top the Versys is sitting on about 160kph. From there you can twist the throttle and launch away with little or no effort.

On the dirt, 3,000rpm or 4,000rpm with the traction control off will be lively enough to test a rider’s competence in any gear. With the traction control on, and at the power setting which best suits the rider’s ability, the Versys once again settles down to being a very frigging exciting and fun bike to ride. The muted howling of the induction noise combines with the very quiet exhaust note and will pitch a tent in the pants of any red-blooded speed hound, but the electronic rider aids will make even a squid (like the AdvRider staffers) look good and in control.

We really enjoyed this bike, and a large part of it was down to the motor and how manageable and exciting it was.

We did take the Versys off-road, because that’s the type of riding we like. In general the bike did well, but the biggest limiting factor was the Pirelli Scorpion tyres. There’s nothing

Lots of information available, including a funny little cloverleaf sign every time we backed off the throttle. It turned out to be a symbol letting us know we were in the ‘ECO’ mode – being economical.

wrong with Scorpions, they’re a good tyre, but they’re a very smooth road pattern with no knobs or bite at all. The Versys did well to cope with the dirt as it did, but with a little bite from the rubber we think it’d be quite capable in the leaf litter and loose going of State Forests.

On the bitumen it’s a delight, and of course the Scorpions did really well, so that’s a fair observation.

The 17-inch wheels front and rear shouldn’t be too restrictive for tyres, especially the rears. There should be some good performers to choose from. Mitas has a couple of good options, so there’s a start.

Over all

A great motor and sensational comfort. The Versys 1000 is a brilliant getaway machine.

Web: www.kawasaki.com.au Rec retail: $15,999 plus ORC

Not to be too general about things, but we loved the Versys. The suspension was very capable, the motor amazing, and above all, it was extremely comfortable and a scream to ride.

The 21-litre fuel capacity gave a comfortable 300km range – and uncomfortable 50km or so with the fuel gauge flashing after that, with us having no idea how much further it’d go. That should be plenty for the riding this bike is designed for.

Our test bike also had a pair of Kawasaki hard panniers fitted. The pannier rack was incredibly sturdy, and the system for clipping the pannier boxes on and off was brilliant. We chucked all our tools and camera gear in there and forgot all about them. We couldn’t even get any water to make its way inside the panniers with the pressure washer, so we felt pretty comfortable leaving our clobber in there.

One last thing we want to give a thumbs up: the screen. It’s not huge, but it offered great protection, and the adjustment for height was the easiest and best we’ve seen. No tools needed. Just undo two thumbwheels, slide the screen to the position that suits, and tighten the thumbwheels again. Sweet!

It’s not a hard-core adventurer for tackling rocky, mountain single-track. It’s a bike made to cover long distances and crappy, second-rate bitumen and dirt road, and it does those things with incredible comfort for the rider. And of course, when you hit a road in good shape, especially if that road has a few curves and bends, the Versys will treat you to the kind of ride only a four-cylinder powerhouse with this kind of pedigree can offer.

Left: We’re not normally fans of hard panniers, but the more we used these, the more we liked them. They had the easiest-ever system for fitting and removal.

Engine type: Liquid-cooled, four-stroke, DOHC, 16-valve, in-line, four-cylinder

Displacement: 1043cc

Bore/stroke: 77mm X 56mm

Compression ratio: 10.3:1

Fuel management: Keihin electronic fuel injection

Ignition: Digital

Lubrication: Forced lubrication, wet sump

Starter: Electric

Fuel tank capacity: 21 litres

Final transmission: Sealed chain

Transmission: Six-speed

Length: 2235mm

Width: 900mm

Height: 1430mm (with windscreen raised)

Seat height: 845mm

Wheelbase: 1520mm

Brakes front: Dual semi-floating 300mm petal discs. Dual opposed four-piston caliper with ABS

Brakes rear: Single 250mm petal disc.

Single-piston caliper with ABS

Tyre front: 120/70 x 17

Tyre rear: 180/55 x 17

Ground clearance: 155mm

Kerb mass (with full fuel tank): 239kg

Maximum power: 86.8kW (118PS) @ 9000rpm

The current stock Ténéré is a good adventure bike. There’s a lot of things about it that are great. Still, there’s room for personalisation and improvement in every bike, and these days, more and more, owners are hungry for aftermarket equipment and technology. With so much available it’s hard to know where an average bloke should start. But what about someone who’s not average? What about someone who has access to leading-edge technology and first-class technical advice? When we heard Yamaha Motor Australia had built two XTZ660 Ténérés we were drooling to find out the details.

It doesn’t look radically different to standard, but it feels it.

The good ol’ Ténéré has been a favourite since Yamaha released a big-tanked trailbike in 1983, just as adventure riding was about to become fashionable.

That first Ténéré is now considered a classic, and rightly so, but the latest Ténérés are, predictably, a technological world away from the models which captured the hearts and imaginations of riders all over the world during the 1980s. Fuel injection, hi-tech plastics, and advances in metallurgy and technology in general have monumentally changed the bikes and the expectations of owners. Fortunately, the longing of riders for adventure has remained the same, and the Ténéré is still the ticket to freedom for a huge number of riders worldwide.

Finding ways to improve modern bikes is tricky. There’s any amount of conflicting toss offered on internet forums, and some things are just so frigging expensive most riders will never get the chance to try them.

We figured the guys at Yamaha Motor Australia (YMA) should have an inside line on what to look for and what’s worth having.

YMA’s Brand Manager is Peter Payne (see page 26) and one of the bikes we’re looking at here is his. Another was built for YMA Communications Manager Sean ‘Geeza’ Goldhawk. The two bikes are essentially the same, except for minor personal preferences.

Peter’s bike – the one we rode and feature here – is a 2012 model. There’s been no major change since its launch in 2008, so there’s no disadvantage in the bike not having ‘2013’ on the compliance plate. The motor, brakes and gearbox are all bog stock, except for the removal of the Air Induction System emissions-control gear on the front of the motor. The AIS is included to meet Euro and American emissions standards and isn’t required to meet ADR. Its removal not only helps save weight, but Geez says the engine has far less popping on overrun without it. A plate was machined to blank off the entry port in tight behind the header pipes.

The seat, wheels, tank and lighting are all stock as well.

That makes you wonder what’s been changed then, doesn’t it?

The aim of the game

“We wanted to go dirt-bike riding in Australia,” communicated Geez, corporately, “and we wanted to do it on a Ténéré.

But, basically, the Ténéré is built in Europe for Europeans, so the bikes aren’t as Australian-friendly as they might be. Payne and I wanted to join the Old Bull navigation rides, and even though the Ténéré is a great bike, we thought we could tune it to better suit that type of riding.

Most of the aftermarket equipment on the bike isn’t from Yamaha’s own comprehensive catalogue, but available from Adventuremoto.

“Yamaha Genuine parts are great, but they’re generic items designed for a global market,” the YMA guys serioused. “Having ridden with Steve Smith of Adventure Moto and Greg Yager, the Old Bull Trail Boss, we knew the parts they fit to their bikes get a thorough workout in Aussie conditions. So we were confident they were the right parts for the job.

“In addition we enlisted the help of skilled local technicians who understand the type of riding involved.”

Above: A Barrett muffler shaves off a big chunk of weight.

Left: The bashplate and crash bar are a beautiful fit.

Right: Good Aussie product, and a far more comfortable alternative to the standard