Prepared for:

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAURU

Department of Climate Change & National Resilience

The Honourable Rennier Gadabu M.P., Minister for Climate Change and National Resilience

Under the leadership & guidance of:

The Ministerial Troika:

The Honorable Martin Hunt M.P.,

The Honorable Rennier Gadabu M.P.,

The Honorable Reagan Aliklik M.P.,

The Higher Ground Initiative Committee:

Marlene Moses

Berilyn Jeremiah

Reagan Moses

Novena Itsimaera

Chitra Jeremiah

Gabrissa Hartman

Yvette Duburiya

Newman Rykers

Dexter Bretchefeld

With support from:

Benedict Joseph Abourke

Chelsa Buramen

Minister for Finance and Sustainable Development

Minister for Climate Change and National Resilience

Minister for Nauru Rehabilitation Corporation

Chair Secretary for Commerce Industry and Environment

Secretary for Climate Change and National Resilience

Secretary for Finance

Secretary for Foreign Affairs and Trade

Secretary for Infrastructure

Secretary for Lands Management

Chair for RONPHOS Corporation

Chair for Nauru Rehabilitation Corporation

Operations Manager, Nauru Rehabilitation Corporation

Operations Manager, RONPHOS Corporation

Prepared by:

Mallory Baches

Demetri Baches

and:

Project Director, Strategic Planning

Project Manager, Master Planning

MERRILL, PASTOR & COLGAN

Scott Merrill

David Colgan

Michael Dixey

Cecilia Hall

Lead Architect

Architecture & Design

Architectural Renderings

Formatting & Document Prep

Housing + Architecture

SECTION 1.0

SECTION 2.0

LAND PORTION #230

METROCOLOGY MERRILL, PASTOR & COLGAN

SECTION 3.0

SECTION 4.0

SITE PLANNING ON LAND PORTION 230

SECTION 5.0

SECTION 1.0: PRECEDENT STUDIES

A. Introduction: Summary Notes

B. Overview of the Process

1. The Four Phases of the work on Housing

2. General Comments on the Process

3. General Comments on the Sources

4. General Comments on First Phase Studies

5. A Comparison with Typical Precedent Studies

6. General Comments on the Second Phase Studies

C. Building Assemblies

1. Substrates, Footings and Ground Floor Slabs

2. Walls

3. Roofs

4. Prefabricated Houses versus Site Built Houses

5. Overall Conclusions

D. Questions for the Housing Committee

E. Appendix

1. 2011 Republic of Nauru Census Graphs

2. Historic Housing Photographs

SECTION 2.0: PROGRAMMING

A. Introduction

B. Programming

1. Three Ways to Think of Programming Houses

P.5

C. House Types

1. Proposed Single Family House Types

SECTION 3.0: AGGREGATION STUDIES

A. Three Aggregated Studies

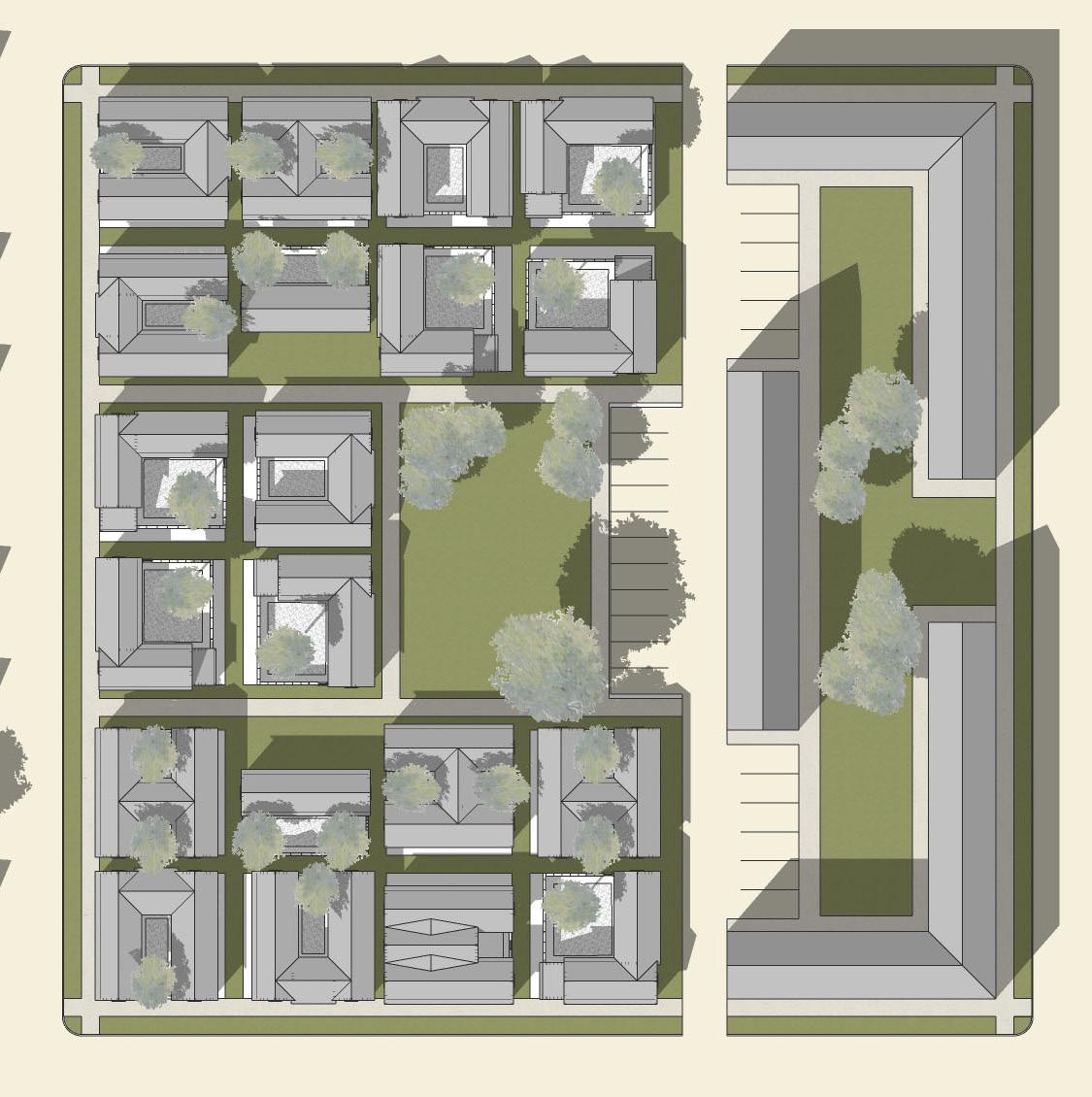

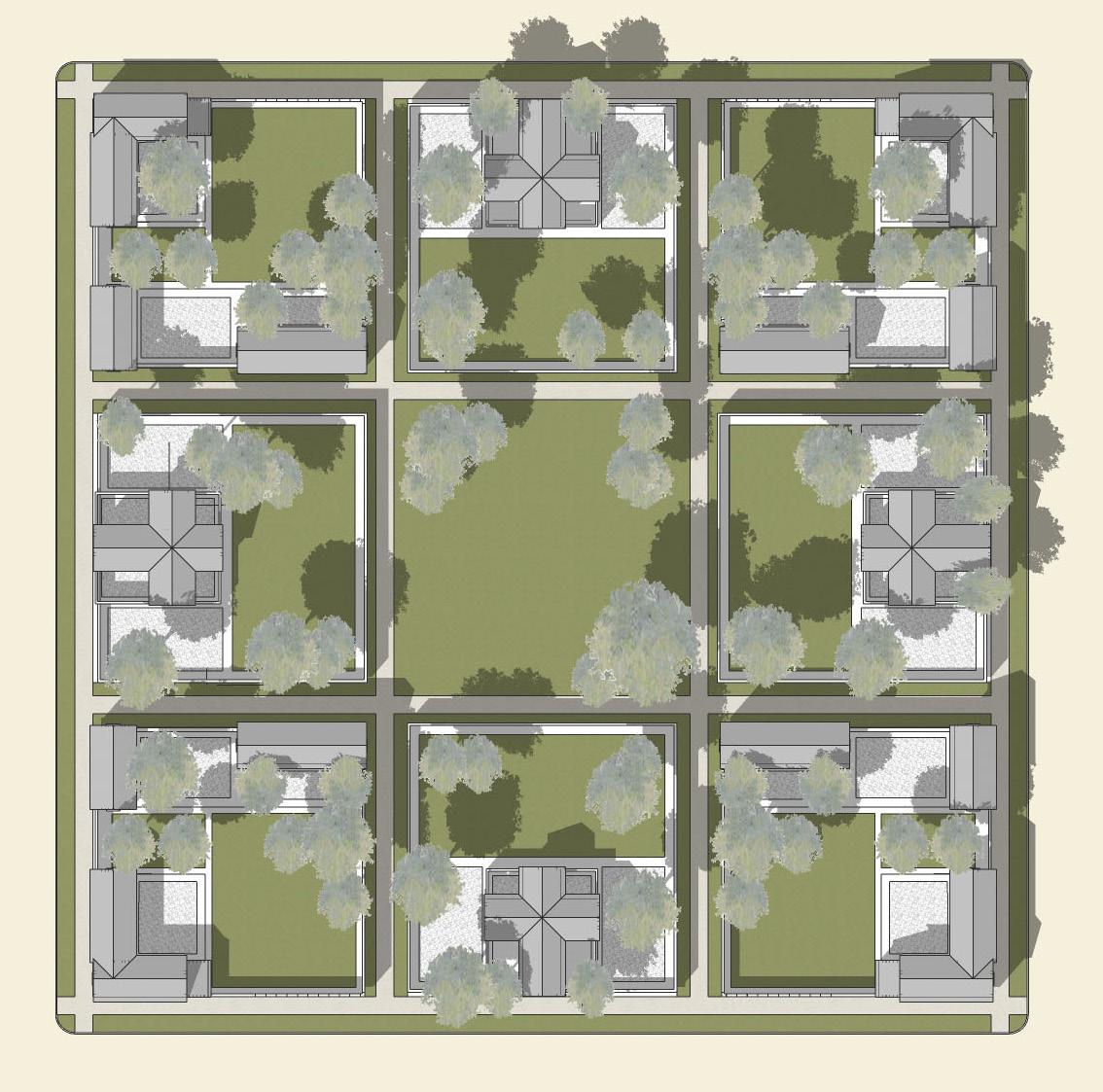

1. Large One Hectare Block Studies

2. Linear Site Plan with Single Family Courtyard Housing

3. Block Plan with Larger Multi-Family Buildings

SECTION 4.0: SITE PLANNING ON LAND PORTION 230

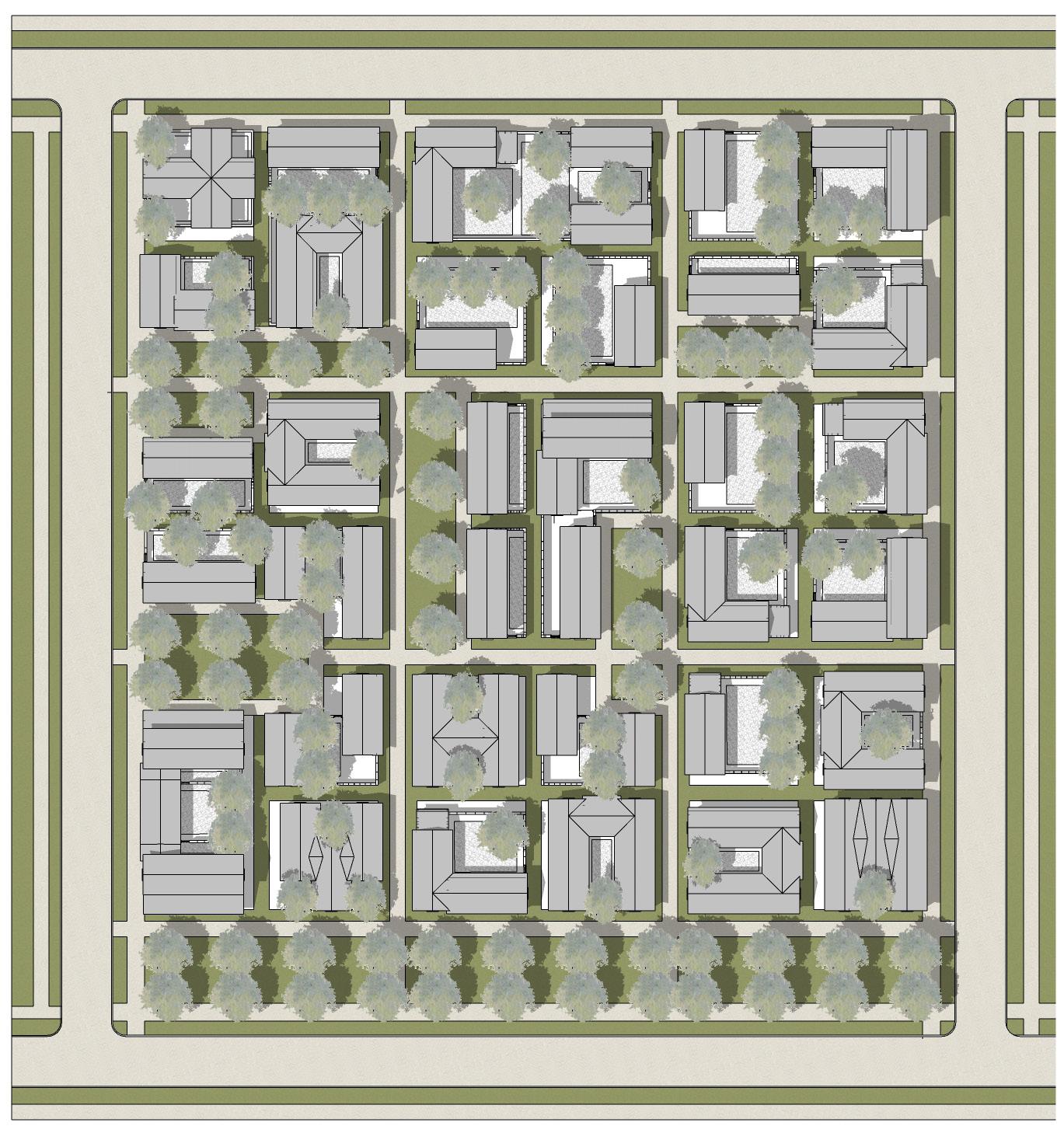

A. Aggregated Studies for the Master Plan of Land Portion 230

1. Higher Density Blocks North of the Rugby Field

2. Public Buildings on the East Side of the Rugby Field

3. Dispersed Housing in the East Neighbourhood

SECTION 5.0: PORT STUDIES

A. Port Housing

B. Conclusion: Summary Notes

P.35

2. Notes on the Presentation by Fadhel Kaboub and the Global Institute for Sustainable Prosperity

3. What the Census, The Poverty Report, Existing Housing, and the Smart House Tell us About Programming

P.57

P.85

P.94

November 12, 2021

Thank you all for your time. After the session two days ago and after hearing some of the comments, I changed the way I want to introduce this material. First of all, let me describe why we started work so early and how the precedent study fits in with the overall housing effort.

As outlined in the precedence study, our work on housing will include four phases of work- this precedence study, the programming studies which are going on right now, the integration of the housing studies into the master plan efforts, and finally a fourth phase of redirection for us to make any changes to earlier work.

It might seem a little strange that we have started such detailed work so soon, so please let me address that. The first two phases of our work require no work on the part of the other members of the team- no mapping, not even a site- and it was something we could get started on right away. If we are discussing it in the same time frame as master planning and tenure, I don’t mean to suggest it is as important as these things.

The precedent study basically tries to understand current building methods on the island so that we might establish some kind of means for evaluating current methods, and affordable alternatives.

We have been careful not to recommend specific ways of building a given assembly but to provide a list of considerations for choosing from among reasonable choices. We start at the foundations of a house and work our way up to the roof. So for example, there are probably half a dozen types of foundations we have discussed in terms of materials, labor, ease of construction and substrate, or the ground on which a house is to be built.

The housing report is tough to work through. And unless you love construction like I do, it is probably dull material. It is for people who build and who make difficult decisions about how construction money is spent. It is not glamorous stuff, but it is important because money is always scarce.

The entire housing report could be boiled down to a plea to spend money intelligently and to good effect and to the benefit of those who live in those homes. This is the first and last point of reference for the housing report. Who is served well? And while this session is on housing, I would apply this measure to everything and to every scale. Who is served? Is the money spent to good effect?

The thing that is so tough about a construction budget is that you seldom choose between a good thing and a bad thing. The difficulty of this material, I think, is that you have to choose constantly between two good things that everyone wants, and so there have to be criteria

established for how these difficult decisions are to be made. This is genuinely hard.

Honest people will disagree on the options presented in the study because the tradeoffs described are often subtle. We can lay these considerations out, but we can’t give the appropriate weight to them. Only Nauruans can, and I want to be clear that people involved in these decisions will give these decisions different weights and come to different conclusions. By all means, let us all air our concerns and our opinions. But as you continue to assess options for how to build, please keep in mind that everyone will bring good faith to this debate.

So for example, cross ventilation and natural cooling, which everyone wants, is better in thinner house plans, but thinner house plans have less efficient building envelopes and so much of the cost of construction is in exterior walls. The most expensive parts of an exterior wall are the openings, and so good cross ventilation simply costs more. I can point this out, but I can’t tell you if the extra money is worth it to you.

This precedent study is not as important at this stage as the other work that has been presented this week, but it is not trivial, either. As an example, consider the remediated land on which we are building. Everyone says, yeah, yeah yeah, it is not a problem. But in considering the question of foundations the study is very clear about concerns of settlement in the remediated areas.

No one can afford for this to be that pilot project in which foundations crack and telescope through the block because dirt between the pinnacles settled more than dirt directly over a pinnacle that is covered by only 200 mm of backfill.

Is the material in the report difficult to wade through? Yes. Is it tedious? Maybe. Are the graphics a little dry? Yes. I wish I could make it easier to engage. Does it seem early to talk about this stuff. Probably. But issues of building are serious, and we have tried to take these issues seriously. And this stuff comes first, I think, before more fun and gratifying studies that will follow.

Last evening two or three members of the steering committee mentioned a trip to Abu Dhabi. Please send photographs of the project you liked. When I ask for people to give us photographs, I also ask them to explain exactly what they liked about the project.

Was the project beautiful? Was it practical? Was it affordable? Can you see the Nauruan government subsidizing a similar project? Could it last in the Nauruan climate? Could it be built with Nauruan trades? Or does it just somehow convey, at an emotional level, a sense of a new start for Nauru housing?

The references stuck with me because, I have worked on two projects in Abu Dhabi province - one in the city of Abu Dhabi itself and one in the city of Al Ain, which is the fourth most populous city in the UAE. They represent an interesting contrast. Abu Dhabi has the confidence to import ideas from all over the world. Al Ain, an inland desert city, thinks of itself

as the upholder of traditions in the UAE, consciously in contrast to Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

Another way to characterize Abu Dhabi, is that it lacks confidence in the ability of its history and culture to solve modern problems, and I think this lack of confidence in their own traditions results in a vacuum that draws in ideas from everywhere. I would say this is neither good nor bad in itself, but it is worth thinking about.

I appreciated Al Ain more because it has pride in the country’s traditions, and while these traditions are sometimes not up to solving modern problems, sometimes they are, and this faith in their culture and traditions makes decision makers from Al Ain a little more skeptical about the ideas paraded in front of them.

I’m not sure that describing Abu Dhabi as an innovative city or Al Ain as a conservative city is very helpful. Ideally, you would not have to choose between the temperaments of these two great cities, and you would draw the best from both.

You want to have Abu Dhabi’s openness to new approaches, but I think Nauru also needs to bring some of Al Ain’s pride and worldly skepticism to bear on the matter of innovation that comes from other places. And it needs to ask whether something that looks different is really innovative, and whether something that looks familiar can be innovative.

Housing is unavoidably conservative. It is a family’s most expensive asset. You don’t take undue risks with that. The ministers want to create a block and concrete industry. We agree with that, but these are not glamorous trades or building methods.

Money is also always short in any country. We asked the housing committee about using plywood roof decks to help keep water out and strengthen the houses against wind and were told that plywood is unaffordable. I understand this and accept it. But if plywood would improve the quality of Nauru housing and it is unaffordable, what does innovative housing look like?

The pre-fab housing on Nauru, which I think everyone has concerns about, was likely the innovation of its day. How has it survived with its styrofoam sandwich panels? Were the houses easily repaired by people on the island or did it make Nauruans more dependent on foreign knowledge?

Did it save money through quicker construction time, or did it stunt the development of local concrete and block trades that the ministers now want? These are the kinds of questions I would ask when you are considering the idea of innovation now.

Regarding sustainability, I sense everyone wants to talk about it in the same terms it is discussed throughout the world- in terms of energy loss across an exterior wall. But I don’t think this is helpful in Nauru. There is little difference in temperature across a Nauru wall as there is across an Abu Dhabi wall, which exists primarily because of air-conditioning, so why talk about sustainability in terms of energy loss like every other country does?

If all this sounds too conservative, I’d like to close these opening remarks by telling you why I think this early report speaks to innovation in the right sense. In addressing sustainability, Nauru should

focus on the embodied energy of new construction and how to make buildings last as long as possible. Somehow we can’t manage this in the US. The competitive housing markets punish builders who want to build more durably. If Nauru could do this, it would be truly innovative.

Could Nauru housing focus on building in a way that would allow housing to be an asset after 20 or 30 years instead of having it fail and lose value? Durable construction costs a little more upfront and so it doesn’t happen naturally, and it requires you to look at longer horizons and this does not come naturally to any of us. But if you could do this, regardless of what the housing looked like, it would be innovative.

The other aspect of durability is adaptability. If housing is to be durable it has to have construction integrity, but it also needs to accommodate change over the life of its inhabitants- the growth of family size, or family income, children leaving and older parents coming back, income falling again, and renters maybe helping underwrite the cost of rent when necessary. This adaptability is a focus of the second phase of our work.

One of the words that kept coming up two days ago was ‘options’. You want options. The second phase of our work will lay out more types of housing than you can ever build. This allows us to be wide of the mark on a lot of things and still be on target enough of the time. This is the only way it seems to me that we can hope to address a range of aspirations that may not all move in concert.

The precedent report focused on building assemblies and on wall sections- on money and leaks and settlement. This is not glamorous stuff. It will not quicken your heartbeat. It will not stir your soul. But the wall section is not the scale at which innovation works best for Nauru.

In this next phase of studies we are working at the scale where responsible innovation is more appropriate- in the configurations of the houses, in natural cooling, in security, in the relationship of a house to a street or a block or a neighbourhood or a garden or a park; in a reduced number of car trips, in greater independence for people without cars. I know what is coming this winter and you will be presented with unimaginable options that don’t currently exist on Nauru. But I would like to get there through a responsible and methodical process.

I think I have told you this before, but I live at two meters above sea level, on a migrating barrier island. I am chased from my home periodically by hurricanes. Water starts to dissolve our buildings the day we take occupancy. Salt corrodes. Humidity causes mold. It is a beautiful place but a hostile environment, and it has probably made me a little wary of experimentation because I see new products and new assemblies come and go out of fashion all the time. Maybe this is why I identified more readily with Al Ain than Abu Dhabi.

But we build for some really wealthy people, and we build for them - with stolid, unglamorous materials and simple assemblies - the same way we are recommending you build.

Kindest Regards,

Scott Merrill

As you know, housing is a small part of a larger master planning effort led by Demetri Baches and Mallory Baches, of Metrocology LLC. We are glad to be started and look forward to a collaborative process that belies our physical separation from you. Our work with you will be part of a nearly year-long process but we hope we can finish the work on the houses in much less time. The master planners have a lot more work to do, and they will be able to use our work with you as they start to consider the size of lots, blocks and streets.

We have proposed a very specific way of working, but we wish to have reasonable flexibility as well as some structure to our efforts. We will have lots of questions for you and it is not yet clear how soliciting your advice will affect the process. Let’s start with a process that is easy enough to describe and easy enough to modify. SECTION

Dear Ms. Marlene Moses,

The following points will be developed in greater detail:

■ The first two phases of the work on housing can be done prior to having a site plan.

■ This first phase of work will look at how various efforts have approached building on the island in the recent past.

■ The recurring emphasis is on relative costs and on how money is distributed throughout the construction budget. A secondary emphasis will be on upfront costs and ongoing costs.

■ The report is organized by building assemblies, from the substrate and foundation to the roofs.

■ People have had, and will continue to have, honest differences of opinion about the best way to build because the considerations and the tradeoffs are often subtle.

■ This report is based on framing the considerations that bear on each decision and not how these considerations are weighted. The Steering Committee and the Housing Committee will need to help us with this, and they have been very helpful.

■ The second phase of work, starting in mid-October and running through December, focuses on programming - the size and number of rooms, the phasing and expansion of houses, and the sizes of lots.

■ A major goal of the phasing effort will be to address a range of needs, now and over time, with a limited number of house types. This work will affect master planning this winter.

■ Three primary sources will be used for the first phase of work: A 1994 NAC study by architect David Whitfield; the 2011 RON Census, and the 2020 Smart House drawings.

■ The success of the HGI program rests on the quality of the substrate left after remediation of the phosphate mining. Housing and infrastructure will require good bearing and drainage. Differential settlement will strain foundations.

■ Building configurations and the efficiency of building envelopes are the single most important determinants of costs. They should be given weight, but thinner houses also improve quality of life.

■ Nauru has used prefabricated housing in the past. The 1994 NAC report cites a number of problems experienced with prefabricated housing, and prefabricated housing goes against Nauru’s wishes to develop the building trades.

■ A range of foundation types, and their advantages and disadvantages, have been described in detail.

■ There is an island preference for concrete slabs and block walls, which coincides with island resources, with construction durability, and with the determination to further develop the building trades.

■ Wall openings are the most expensive part of the walls, and so to a degree, economy and cross ventilation are difficult to reconcile.

■ Insulation is rare, and sustainability may be better thought of in terms of durability than in terms of thermal loss across walls, roofs and floors.

■ There are alternative ways to frame and sheath roofs, giving them more lateral strength and helping them protect more against rain but the current way of building roofs likely won’t change because of the cost of materials.

■ There are strong incentives to reduce up-front costs as much as possible, even if it means incurring inordinate maintenance costs later, or if housing, as an asset drops in value over time.

■ The HGI could distinguish itself if policy could recalibrate some of these short-term decisions so that Nauruans could afford houses built to be an asset after 20 or 30 years.

There are to be four phases to our work. The first two are to be finished by the end of 2021, and the other two will unfold in the early months of 2022. These are the four proposed phases:

a) Precedent Studies

b) Program Diagrams

c) Aggregation Studies

d) Revisions and Final Presentation Drawings

These phases are in order, buwt they aren’t completely categorical, and they will overlap some on the schedule. We may start work on the next phase while we wait for feedback on the previous phase. Here is a further description of each phase.

We can start this work without waiting for mapping or planning studies. It is a phase that requires close communication with the members of the Steering Committee, and those who helped develop the Smart House.

A conventional precedent study will be difficult. There have been plenty of housing models since about 1949 but they are not well documented, they have not always held up well over time, and they don’t always reflect modern housing preferences.

There are precedents for different types of foundations, walls, windows, and roofs. There are arguments in favor of most any basic way of building because they each give slightly different weight to all the considerations. The precedent study will lay out these choices and the considerations for making decisions about each assembly. The Steering Committee will then have to make decisions based on how much weight to give each consideration.

Most everything will come down to how money is spent and moved from one part of the construction budget to another, and to finding the right balance between cost and effect. This does not preclude elective add on costs, which we will study in phase 2.

This phase will draw from several documents we have in hand, and from any additional information the Steering Committee can bring to our attention. We will start with the substrate - the remediated mines - and work up through basic assemblies, from foundations to roofs.

SECTION 1.B

Establishing the right number of rooms and the size of each room will be important early on. We are encouraged by the affinity between the valuable information in the 2011 RON Census and the plans of the Smart House from last year. The precedent phase should summarize these affinities and help establish a program.

The program diagram phase should demonstrate how variants and alternate configurations can help capture the full range of information from the census which shows that bedroom count, as an example, ranges fairly broadly by household.

Post-World War II housing types ranged from 67 square meters up to about 160 square meters. The Welcome Homes of 1987-1988 fell within a much narrower range of 111-121 square meters. The four bedroom variant of the Smart House is squarely in the middle of this range.

Apparently, a lot of Nauruans start with the overall size of the house they think they can afford and then back into the room count and room size. This is a reasonable way to program house prototypes. The ideal programming process will work from both ends - adding up room needs and deriving an overall size, and starting with an overall size and backing into a room count and room sizes. We will try to do both.

In this phase we should be gauging the need for variants, elective add-ons and phasing for household growth. There may be a need for a very small house, smaller than the two bedroom variant of the Smart House, that can be added onto as families grow and incomes increase. These studies can be undertaken before we have a site plan.

This phase requires some preliminary lot and block sizes and configurations, which we should have toward the end of 2021. In this phase we will populate the blocks and the streets of the first phase master plan with the variants we study in phase 2. This phase requires the closest collaboration with the planning and the sizing of lots. It is the phase in which the variety of the work of phase 2 will become evident.

It will also be more clear in this phase what the average lot size, and the range of lot sizes need to be. This is the phase in which we will consider the lot beyond the house itself- the private outdoor spaces - and the streets. The relationship of the rooms and the yards will be more important, as well. Privacy and security will become more important issues. We will want the houses to contribute to the streets as well, without compromising their security.

The drawings for this phase will include block plans, roof plans, aerials, elevations, and eye level perspectives, including street perspectives.

This is a period in which all work can be reviewed by the Steering Committee, with the benefit of a little more time. It is assumed that previous approvals will be revisited in detailed but not fundamental ways. It is a period in which we can do our final drawings.

The beginning of the process in the first phase, Section 1.0, will be very fine grained and methodical, and maybe a little tedious for people who are not responsible for building the houses. We will go from the foundation to the ridges of the house looking at different options. The houses need to be simple and durable. Additive options and elective assemblies will introduce more variety during the programming phase. A single configuration won’t address the full range of needs reflected in the census and so we will assess how flexibility might be introduced at reasonable costs. The Smart House is a great example of a plan that can accommodate two or four bedrooms.

Likely the needs of a given household might change over time and so phasing in changes or additions will be part of what we look at in the second phase. Generally, the promise of the work will start to show in this second phase, but it will only be fully apparent when we have a varied site we can drop houses into.

We need simple buildings that vary in a fairly narrow range in order to keep costs down. But everyone rightly wants variety and richness throughout a neighbourhood. It’s not that difficult to reconcile these two things. Simple individual houses can be laid out for a range of lots sizes, and lot configurations can vary, and block sizes can vary and streets can vary, all without additional cost. The richness and variety will come later in the third phase from the aggregation of simple house types.

We will start with the benefit of three documents. We will benefit from as much additional information as we can get and hope the committee will bring additional documents to our attention. We are especially interested in the range of post war housing, and the Welcome House of the late 1980’s. It would help to have plans and walls sections, if they exist, and it would help to know how various materials and assemblies weathered over time.

The documents on which we will rely most heavily at the beginning are:

a) A n NAC paper by an Australian architect named David Whitfield, from 1994

Whitfield co-wrote this paper with an economist named Bob Carstairs. We like this document for two reasons. Whitfield is methodical and detail oriented and very practical. Carstairs contributes extended considerations of costs. Their priorities generally conform with what we know about your preferences to source as many things on island as possible, to limit shipping costs, and to train trades locally. They contribute some skepticism about pre-fab assemblies shipped in and assembled by off island trades. The report has some valuable information on programming. We agree with most all their conclusions except for the proper lot and block sizes, which we think are excessive for the likely number of houses we need to accommodate on a fixed parcel in the first phase.

b) The 2011 Republic of Nauru Census

Whitfield and Carstairs obviously did not have the benefit of the 2011 Census, but they explicitly recommended that a survey be undertaken on family income, number of family units, persons per household, and existing housing conditions. The 2011 Census answers most all of this. Like their own study, the census is fine grained, and it contains a wealth of information.

The survey is unique in the attention it gives to the houses and households of Nauru. Along with the Smart House and post war precedents, the census will help give a basis for the programming of the houses- the list of rooms and their sizes. The census captures a broader range of household needs than any one design can, and addressing this range will be a major focus on the second and third phases of work.

The Whitfield document was a text. The census relied heavily on graphics. The Smart House initiative has incredibly detailed recommendations for how to build. If it did not draw directly from the Census of 2011, it is consistent with it. It is flexible and will be a model for our program and phasing alternates. It has an efficient building envelope - the ratio of envelope area to enclosed area - which is the most important determinant of cost.

We have received some historical photos from Mark Jariobka and from the housing committee. Whitfield describes a series of model homes since 1949. To this point we have no plans for these models, but the information we have on overall square footage from these prototypes is helpful.

SECTION 1.B

(Regarding additional sources for precedents: Note that Whitfield references modern housing types with great specificity. He references housing types 1 through 7, the size of the small type 1-67 square meters - and the subsequent growth in the size of the types; the type IV which is two stories and 163 square meters, and typically four bedroom but sometimes 5. It would help to find these types. There are no references to years but they are apparently just post-war programs.

There is a reference to a housing program of prefabricated kit houses started in 1987/8 and built in Australia and New Zealand. These houses were between 111 and 121 square meters, excluding porches. Porches were 1.8 to 2 meters wide. Whitfield cites lots of complaints about these houses, but we need to know more about both programs. The Smart House is closer to the size of the Welcome Houses of the late 80’s and early 90’s.)

Part of the method in this phase will be to collate comments from these different sources. So for example, historical photos show model house programs with a range of foundation types. Whitfield acknowledges a range of possible foundation types but recommends slabs on grade for government programs. The Smart House has a hybrid foundation of piers and crawlspaces under the front rooms of the houses, and a matt foundation and a raised slab under the bedroom wing. The precedent study should help foster a decision between these choices

This first phase of work will characterize the advantages and disadvantages of each type. The Committee will assign their own weight to the considerations. There is always a range of reasonable options.

Another example would be the percentage of openings in the walls. Whitfield recommends a very high percentage of openings - 50 to 80%. Most of the money in a house is in the exterior envelope and openings are the most expensive part of the envelope. But openings admit daylight and afford cross ventilation, which was Whitfield’s focus. The Smart House has a much lower percentage of openings, probably because costs were given more weight. Likely Whitfield’s recommendation is too high.

Ventilation, whether it is through the walls or under the floors, is highly desirable but it is costly and every increase in cost will make housing less affordable or require smaller or fewer rooms. So we will frame these kinds of issues, and in phase 2 we will provide examples of a range of percentage of openings, and let Nauruans find the right balance of two inarguably desirable things.

This will be different from most precedent studies. Most modern Nauru precedents will fall short by some important measure, and so historical and current examples will be helpful in thinking about the performance of materials in the climate over time, or the capability of the trades, or the relative advantages of prefabrication versus site built housing, but we will need to rethink building on the island from the substrate on up.

If there are not enough precedents in Nauru, we will consider how people build in similar climates. We are half a world away from you, but we live and work on a migrating barrier island of sand and we live and work at two meters above sea level. We have high humidity. Water starts to dissolve our buildings from the day we take occupancy.

The heat blisters dark painted surfaces. High rainfall will migrate through our masonry walls if they don’t have a vapor barrier on the outside. We have seasonal breezes that shift from season to season. We build defensively and will bring this same conservative attitude toward building in Nauru.

But there are unprecedented things about Nauru. We will inherent unusual, remediated mining sites. Environmental considerations are changing rapidly. There is a history of health issues in the 1930’s. Cesspools are still common. There will be modern security issues. Nauruans build with little or no insulation, and plywood is too expensive to use. And so there will have to be alternate ways to provide resistance to wind loads, and other ways to keep water from penetrating the roof.

There may be more reason to look forward to the planning process this winter than to look back on housing precedents. The first phase planning will provide opportunities that don’t currently exist on the island, and so it is important to anticipate the advantages of attractive public streets and secure private yards. And it will be important to create variety based on minor variants of limited housing types, and on variations in siting and orientation and entry. It will be important to provide for changes over time, and it will be important to accommodate a range of family sizes and numbers of generations served by a single house.

The 2011 Republic of Nauru Census has figures on household size by district; on head of household by gender; on the percentage of owners and renters, on single and multi-family

SECTION 1.B

housing; on the age of housing; on the number of rooms, and the number of bedrooms; on how many households do or don’t have a dining room, or a kitchen and on whether bathrooms or kitchens are shared with other households.

The census has statistics on construction; on the percentage of concrete block houses versus wood houses; on metal and asbestos roofs; on guttering and gutter materials; on how any houses have downspouts and what percentage are connected to water storage and even the capacity of water storage tanks and what they are made of and whether they are shared with otherhouseholds.

On those dependent on catchment water versus desalinized water; on those who can depend on freshwater; on the use of gas or electricity or wood for cooking; on the types of toilets and whether they are shared; on the percentage of households on a sewer system versus on septic or cesspool; on the percentage with internet; on those with phones or cell phones, or refrigerators or freezers or microwaves or air conditioners or ceiling fans.

This census information will help with programming and with assemblies. Whitfield’s report is full of interesting programming guidance. He cites housing programs for which we have no plans but lists sizes and conventions for square meters per person, which he thinks is twice as high on Nauru - at 13 square meters per person - than on other Pacific islands. He mentions the Welcome Houses at 111-121 square meters. He mentions an older series of seven house types ranging from 67 square meters (type 1) to 163 square meters (type 4 with 4-5 bedrooms).

For comparison the one story two bedroom Smart House is about 75 square meters, just barely larger than the postwar, type 1 houses, and the two story four bedroom version is about 115 square meters, or right at the size of the Welcome Houses of the 1980’ and 1990’s, but smaller than the older two story, four bedroom type 4.

The Smart House captures two different bedroom scenarios with admirable economy and efficiency. But the census shows household room and bedroom counts beyond these two scenarios. The programming phase will generate a flexible and phaseable range of programming options. These options would allow households to stay in the same house, should moving prove difficult, even as their income or household size may change.

Since kitchen and dining rooms are relatively fixed, according to the census, the principal programming variable will be bedroom count, but even for a given number of bedrooms, the configuration can vary. With identical bedroom counts, houses can be one story or two. They can be straight in line layouts, or L’s or U shapes. They can be one room deep or two rooms deep.

Their narrow end or their broad side can face the street. They can enter off courtyards or off streets. They could share a courtyard with households with whom they share toilets or kitchens or they could be the only units that face smaller courtyards. There can be very small starter houses for younger people or people with no credit. These houses could be expandable or, if a market for houses is in place, they can be sold over and over to similar households.

The census does not seem to address porches. Porches are a luxury, but they appear in a number of current and historic house types. Porches could be built with the house or added later. They could face courtyards so they are secure. Balconies on stacked plans could face the street. They could have wood posts or masonry piers. They could have their own roofs or be under a second floor with rooms.

The census cannot address things that don’t currently exist in Nauru and so house types might anticipate certain aggregations that could form courtyards, or line small mid-block streets, or have common end walls that can form rows of buildings. Densities could increase toward the centres of neighbourhoods and decrease toward the perimeters, so that lot sizes might vary naturally. Stacked house types could line squares or plazas and one stories spread over large areas.

The programming phase will be conducted before we have a site or a master plan and the programming and the configuration studies might help inform lot and block sizes. Whitfield suggested lots of 300 square meters and 10,000 square meter blocks. There will be a range of lot and block sizes that the programming phase has to anticipate but with the limited availability of land it seems likely that many lots and blocks will be smaller than this.

Since World War II housing programs have been developed without regard to a context. The programming and configurations studies of phase 2, will anticipate a context of varied lots, blocks, and streets.

(Note that we have heard more about the correlation of crime and density than about health and density. We need to know more about health concerns. Disease has devasted the island at times, including tuberculosis in the 1930’s. While Whitfield is clear that we do not know if housing conditions contributed to epidemics, he cites Australian studies that recommend against compounds housing extended families, and studies that recommend single family dwellings. This is probably why he suggests larger lots than we will likely deliver. The 2011 Census shows that there are still a number of people using cesspools and so we need to address concerns that correlate health and density as much as concerns about crime and density.)

SECTION 1.B

David Whitfield’s 1994 document recommended that a handbook for the guidance of self-help housing be produced. This should, he said, “simply illustrate the necessary elements of house construction technology and highlight important issues and options available so that informed decisions can be made.”

Our charge for a government sponsored program is a little different than a self-help guide, but this document lays out the basic choices for different assemblies so that the Steering Committee can make informed choices.

The recent documents described in Section 1.B differ in how they recommend Nauruans should build. The differences are relatively small differences, and honest differences; the differences of people all trying to arrive at the right conclusions. There is no reason to expect complete agreement about how to build.

The purpose of this document is not to recommend still another way to build, but to look at the choices, to consider the thinking that goes into the choices, and to help frame trade-offs. The reason there are honest differences about how to build is because the trade-offs are complex and subtle, and subject to change over time.

The Steering Committee alone can give relative weight to these trade-offs. And the building program may even start out with one set of assemblies and then switch to another as they are priced or fabricated.

Disagreement within a narrow range seems likely. Experimentation within a narrow range seems entirely reasonable. Responding to changing circumstances, to changing prices, to the progress of the port, to the development of the skills of the trades, or to the performance of materials over time, seems inevitable.

The description of building assemblies that follows provides good examples of why it is difficult and even undesirable to have complete agreement on how to build. You should try different approaches.

The substrate, the footings and the slabs will be considered together because the slope, drainage and bearing capacity of the substrate will affect the selection of a footing type, and sometimes the footing and the ground floor slab are poured separately and sometimes they are the same pour. It’s hard to consider these things separately.

The discussion of the substrate from remediated mines has been debated for a long time. Geoffrey Davey of the Nauru Lands Rehabilitation Committee wrote a report in 1966. He cites a 1954 study commissioned by the Australian government that confirmed the feasibility of knocking down the pinnacles and covering them with imported topsoil, but it cited the lack of water for growing anything. A study by the British Phosphate Commissioners in 1965 estimated a cost of $7300/acre, but over an enormous area of 3500 acres.

Housing is typically mentioned as one possible use for reclaimed land, but there are specific concerns for housing that would not apply to other uses. The NRC RONPHOS diagrams from 2021 show the pinnacles in a typical Nauru open pit phosphate mine. The secondary mining and remediation process requires that a very unbuildable landscape be made buildable. This is done by leveling the pinnacles and filling in the cavities. This kind of aggregate substrate should drain well and if properly prepared, it should have good bearing capacity. There will have to be soil borings done to test the capacity of the substrate before buildings are built.

The engineers undertaking the remediation are confident about providing a buildable pad for housing, but other than the Australian Detention facility, we are unaware of where there has been experience building over this kind of landscape, and we are unaware of any observation of similarly reclaimed areas over time, that might offer insight into settlement issues.

Typically an engineer will want a substrate consisting of fill brought in in shallow layers that are then individually compacted, one layer at a time and over a large open area. The fill from secondary mining process, by contrast, is in small isolated cavities that can’t be rolled and so the mechanics of this compaction are unclear, and we don’t know the size range of the aggregate.

The combined topping layers over the leveled pinnacles from secondary mining is 200 mm and so an additional consideration is differential settlement, which may be just as important as the compaction of the cavities. If fill is not properly compacted, or if there is insufficient fill over the pinnacles, the fill may settle where the pinnacles do not settle. This kind of condition could put stress on the footings that does not occur in conditions of minimal and reasonable settlement of continuous fill.

Because the remediation is being undertaken by one party in one time frame, and construction by another party in a different time frame, there may be an incentive to prepare a site in ways that do not ensure a decent substrate for a building’s foundation. Some consideration should be given in advance of remediation, to aligning everyone’s incentives or there will be a risk that site preparation costs will be minimized by those preparing the site and shifted to those constructing the houses. And the worst outcome would be differential settlement that was only noticeable over time. The structural integrity of the houses depends on the proper preparation of the substrate.

■ Secondary mining will occur in a couple of stages. The pinnacles will be knocked down and this will make secondary deposits accessible. The secondary removal will create pinnacles again, and the pinnacles will be cut down and used for filling the voids of the secondary removal. Then there will be several topping layers totaling 200 mm.

■ The text raises question about differential settlement and the effect on the selection of a foundation types. It also raises questions about the incentives of separate parties for mining and site prep. The depth of the topping is probably not sufficient to allay concerns about differential settlement. Engineers should be consulted, borings taken and bearing capacities determined. The crushed rock should drain well and have good bearing, but if differential settlement takes place it will be cause of the difficulty in compacting crushed rock fill in these small but deeper cavities.

■ To our knowledge there has only been one building built on a remediated phosphate mine - the Australian Detention Centre - and we don’t know if the settlement of the substrate has been observed over time. We would like to have any drawings of the facility and the foundations, that might be available.

Regardless of the foundation type, you want consistent bearing capacity through the building sites. This provides maximum flexibility in choosing a foundation type. Figure 4 describes several basic types of foundations that will be reviewed here - a monolithic slab, a single pour that acts as both slab and footing; a continuous spread footing with a stem wall and a raised slab on compacted fill; a pier foundation, a crawl space with a wood floor, a raised slab formed in place, and a thick matt slab in the event substrate quality varies.

Whitfield recommended a slab on grade. The Smart House has a crawlspace with a wood floor in one part and a matt slab and a raised poured in place slab in another part. Both portions are on poured concrete piers. So you have a range of choices and have to evaluate the tradeoffs of each one.

The housing committee, for example, advised us that the labor costs of the pier foundations of the Smart House came in relatively high. This, of course makes ventilation relatively more expensive and slabs on grade or raised slabs relatively more affordable. With this information the committee is better prepared to consider the tradeoffs of cost and ventilation. As you get more information on the costs of any assembly, you will make more informed decisions.

The bearing capacity of the site has to be considered. The fall of the site has to be considered. Runoff has to be considered. Humidity and rot have to be considered. The cost of the rough carpentry to form the concrete has to be considered. Sourcing and shipping costs have to be considered. Studies always cite the fact that there are sources of aggregate on the island, but concrete requires clean fresh water, clean sand free of salt, steel, and cement, and some of these components will be imported at great cost.

Whitfield didn’t clarify whether the slab he preferred was on existing grade or raised up on compacted fill. The least expensive option is usually a relatively thin slab on grade, where the slab thickens at the edges to act as a footing as well. This type of foundation combines two concrete pours into one pour. It requires a flat site, and it requires a comprehensive site drain age plan that will keep water away from a slab very close to adjacent grades.

If you don’t have a flat site or if runoff from upslope is a concern you may need to raise the floor. This can be done with piers, or with a continuous footing below several block courses. If you have a continuous footing and continuous stem wall you can fill inside it, compact the fill, and use the fill as formwork for a raised slab.

■ Diagram A describes the composite floor framing plan of the two room deep Smart House. The other diagrams are the same size but illustrated alternate floor assemblies. The Smart House has a front tier of rooms with a raised wood floor supported by piers, and over the water tanks. A perimeter beam catches joists between piers. The piers provide ventilation required of raised wood floors. The bedroom wing is over a raised poured in place slab on concrete piers at small intervals.

■ Diagram B s hows a wood floor system over the same entire area. Piers are more widely spaced and fewer in number. This requires slightly larger perimeter beams. A centre row of piers would support the wall between the living room and bedroom wings.

■ Diagram C shows the same area with perimeter stem walls, like those of diagram B in the foundation types. Stem wall systems require two pours. The walls are above a continuous footing. The foundation walls would be filled and the earth compacted and a raised floor slab poured over the compacted fill.

■ Diagram D shows a slab on grade - a single pour for the footings and the thin floor slab. This is the most economical floor type, but it requires flat sites and sites that drain away from the house.

■ This is a series of cross sections describing different foundations. The upper left foundation, A, is a single concrete pour that combines the thin floor slab and the footing. This is a very economical foundation, but it requires fairly flat sites. Diagram B requires two pours, a footing and a separate slab. Between these pours, masons build a stem wall, within which compacted fill provides earth formwork for the raised floor slab.

■ Diagram C is a matt, or raft slab. Matt slabs use a lot of concrete. The matt slab at the rear of the smart house is 0.6 meters thick. This type of foundation would typically be used where the bearing capacity of the substrate is inconsistent. See the description of remediated substrates.

■ Diagram D is a raised poured in place slab spanning a continuous block stem wall. It has the cost of two concrete pours, but the floor slab itself has the considerable cost of temporary wood formwork and reinforced steel. It does provide a less permeable barrier between the crawlspaces and the first floor and would not be prone to the rot of wood rafters in unventilated spaces.

■ Diagrams E and F both have wood floor joists over a crawlspace. E is built on block piers, and F is built on a continuous stem wall. Piers provide the ventilation required for wood framing, but they require a perimeter beam to catch joists between piers. Continuous stem walls require vent panels. Both assemblies would support wood walls above. Owing to the humidity of the climate and the prevalence of termites, a crawlspace could be lined by a thin floating slab on grade.

■ Diagram G describes the foundation under the bedroom wing of the Smart House. It is a composite foundation containing a matt slab, poured piers and a raised poured in place floor slab.

■ Without doing detailed take-offs, you can think of each option in terms of the amounts of labor and material, sometimes moving money from one to the other. Concrete is either formed by boards of ply wood, or earth. There are either one or two or even three pours in these options. Raised poured in place slabs are especially costly because of the formwork.

The main rooms of the Smart House have poured piers and wood floor joists elevated from grade. (There is a variant with a continuous concrete block stem wall) Piers require a beam parallel to the piers to pick up joists that fall between the pier spacing. Raised floors requires a crawlspace and good ventilation to prevent the rotting of the floor joists. It is difficult to inspect crawl spaces for deterioration. Crawlspaces have to be kept clear of vermin. Wood floor joists will be sourced off island, and so they come with transportation costs and require minimal rough carpentry skills. The housing committee has told us that the grading of lumber is unreliable.

Whitfield and Carstairs acknowledged the advantages of piers, crawlspaces and raised floors for cooling but in the end recommended slabs on grade for economy. The foundation labor costs of the Smart House, and the inability to rely on properly graded lumber for floor joists both argue for either slabs on grade or raised slabs.

There are two common ways to have a raised slab - with prefabricated concrete plank, and formed and poured in place steel reinforced concrete. While plank is cheaper if it can be sourced nearby, it is unrealistic in Nauru because of shipping costs and the setup costs of a plant are prohibitive.

The bedroom wings of the Smart House have a grid of poured piers at tight intervals that sup port a raised poured in place slab. A raised poured in place slab is still expensive compared to other options but some material can be sourced on island and if you have people skilled in placing reinforced steel, it will provide another trade for Nauruans.

Wood formwork for spanning poured in place slabs is more expensive than formwork for walls or piers. Whereas a continuous stem wall foundation with a slab on compacted fill uses dirt for form work, a raised slab will be formed in place with temporary wood form work. Likely this is why the costs of the Smart House foundations are high. Poured in place slabs, for all their costs, provide raise floors without the maintenance concerns associated with wood floor systems over crawl spaces.

A matt foundation, or raft foundation, is a thick continuous slab at or below grade. It is expensive because of the amount of concrete that is required but is usually used to address substrates that might have differential settlement, like a remediated mine. It appears that the Smart Houses uses a matt foundation under the stacked bedroom wing, but it uses concrete piers above the matte slab and then a raised poured in place slab.

If the substrate of the remediated mine sites is properly prepared matt slabs should not be necessary. However, if it proves difficult to avoid differential settlement of the substrate, they might be necessary. A structural engineer should be involved in this decision.

Whitfield recommended slabs on grades. The Smart House has two types of raised foundations. Raised foundation generally cost more for one reason or another. But if skills are to be developed slightly, more labor intensive foundation types might be acceptable.

And if slightly more labor intensive foundations allow for systems with materials that can be sourced on island then higher labor costs might be offset by reduced shipping costs. But with regard to concrete it is necessary to consider its components- aggregate, clean sand, clean water, cement, and steel.

The housing committee said that aggregate from ground up pinnacles can be used for concrete. They said sea sand used to be used in mixing concrete. This is not an acceptable source for concrete but the committee also said that the pinnacles of the mine can be pulverized for use as sand. The clay required for cement has to be imported and according to Whitfield, the costs of imported cement are quite high. Steel will be imported at great cost. The housing committee has built in the cost of these imported materials.

So while block and concrete is nominally sourced on island, some of its components will still be imported and so in considering matt slabs, especially, but also poured piers, tie beams, tie columns, rake beams, and filled block cells, care should be taken to monitor the volumes of concrete for various foundations.

If more durable systems cost more at the time of construction, a life cycle analysis might justify greater upfront costs. On the other hand, any increase in the cost of construction may reduce home ownership and make renting relatively more attractive.

Finally, in a competitive building market, there is a disincentive for any one builder to incur unnecessary up-front costs, even if more costly methods increase the life cycle of the house. This is the case in mature real estate markets in the United States. If durable methods of construction are to be encouraged there will have to be incentives to build houses that will be worth more after twenty or thirty years, rather than depreciated. This won’t happen naturally and in the markets where we work, this problem is unresolved. If this is a sustainable initiative, incentives have to be in place so that durability is encouraged and not naturally disincentivized as it is here in the States. Part of having this be a model project should be thinking about how durable systems and longer term horizons can be encouraged. If durable methods of construction can be incentivized, you will leap ahead of the U.S. housing market in some ways.

An inordinate amount of the construction budget is in the building envelope. Therefore, one of the best measures of efficiency and cost effectiveness of a house is envelope efficiency. Envelope efficiency is the ratio of the enclosing envelope to the enclosed area. It can be an area to area calculation. It can be a linear to area calculation. It needn’t be tracked obsessively, but it is a good idea to understand its broad implications.

The most efficient house is square. Envelopes become increasing inefficient as plans thin and elongate. Some modifications are more expensive than others. If you widen an elongated plan the cost increase will be less than directly proportional to the area added. If you lengthen an elongated plan the increase in cost will more nearly approach a proportional increase in costs.

For example, if you widen a 3.5 meter by 10 meter volume by half a meter you will increase the area by about 14% but you will only increase the linear feet of building envelope by one meter from 27 linear meters to 28 linear meters.

Flooring or roofing will increase roughly proportionally to the increase in floor area. Building shell trades will increase by much less. Roof framing will only increase marginally.

If there were no offsetting considerations, rational housing would converge on square plans. But elongated plans get more daylight and better cross ventilation. And they may be better at forming streets or courtyards. We work a lot with thinner plans. They are small luxuries, and we might be better off scrutinizing other forms of inefficiencies that don’t offer off setting improvements in the quality of habitation.

Whitfield recommended plans a single room deep if possible, which means he gave more weight to the benefits of better light and ventilation, and relatively less to the increased costs of a thin house. The Smart House is two rooms deep, which probably means that envelope efficiency was given slightly greater weight than cross ventilation. This is one of many examples of how people arrive at different conclusions about how to build on Nauru. But everyone makes these decisions in good faith.

It was a little surprising to see in the 2011 Census how common wood and even metal houses were. Whitfield cites surveys that reflect a Nauruan preference for masonry. The Steering Committee may have a preference for a particular wall material or may want to encourage a mix going forward. Preliminary feedback from the housing committee suggests a preference for concrete block walls.

■ Wall openings are the most expensive part of the building envelope, which is the most expensive assembly in a building. Whitfield recommended a percentage of openings of 50-80% because he placed a lot of weight on cross ventilation. The Smart House, on the upper left, has a much smaller percentage of openings because they placed relatively more weight on costs. Keeping costs down increases the accessibility of home ownership. The percentage of openings will vary from one exposure to the next.

■ It is almost impossible to hit the high end of Whitfield’s recommended range. 80% would be like an enclosed porch, and maybe this can be an additive option. The percentage of opening in the Smart House could be higher because the plan is two rooms wider and less conducive to cross ventilation that the single room plans Whitfield liked.

■ It mig ht be low for reasons of security but when we have real sites and configurations, secure exposures in courtyards might have better ventilation without compromising security. In the next phase we will probably start with about 30% openings and go a little either side of that, depending on the sun exposure and the street and block setting.

Wood and concrete block should both perform well against winds loads provided there is sheathing on wood frame walls, but plywood is expensive and is not used on roofs. Sourcing, labor skills, transportation costs, and climate will be bigger considerations in deciding between wood and block. If you can set up a block plant and a concrete batching plant on island it will eliminate sea transport costs. Reinforcing steel would still be shipped. Wood is lighter but would be shipped in. According to the housing committee, grading of lumber is unreliable.

Wood can be used in most climates, but wood species vary in rot resistance. New growth generally underperforms old growth woods. Old growth woods are increasingly rare. Wood is renewable and block and concrete and cement have high embodied energy. But Whitfield is clear on the danger posed by termites- both flying termites and nests in the ground.

Either material should have a vapor barrier on the outside. With block this is generally obtained with paint vapor barriers. Stucco over block is more forgiving of the masonry skills and it covers transitions between block and concrete It looks like it is uncommon on Nauru but the housing committee says it is the customary. It doesn’t appear to be used on the Smart House. The vapor barrier for wood framing is straightforward and light weight. There is cost in the siding over wood walls. The siding is painted and provides additional moisture barriers. Both stucco and siding require ongoing maintenance.

Wood walls are more readily insulated to higher R values, but the housing committee says that insulation is unusual. Block walls are generally insulated by furring the inside of the walls and is thinner with lower R values but again, the housing committee says that the interiors of block walls just have a stucco coat applied directly to the block

When all factors are considered, block walls appear to be the more likely choice.

If construction costs lie inordinately in the building envelope, envelope costs lie inordinately in openings in the envelope. Whitfield recommended 50 to 80 percent opening in the walls for cross ventilation. This seems very high. A low percentage of openings would reduce costs considerably and reduce heat gain. But the cross ventilation and natural light provided by a high percentage of openings is very desirable.

The jalousie windows used on the Smart House, and apparently common on the island, are distinct and attractive. We would be interested to know more about the performance of the openers in a salt environment, and about their water tightness. Also it would be important to have a supplier with the ability to service and repair any windows you use. For a given area of glass, windows are generally much less expensive than doors. The housing committee says that shutters are a common alternative to windows.

SECTION 1.C

■ This sheet shows the range of roof forms considered at greater length in the text. There are three basic types with different gable end eave conditions. Each roof form has construction assembly implications, which will also be developed at a larger scale. Hip roofs are easier to frame with trusses but possible to stick frame. They have the advantage of having continuous horizontal eaves and horizontal tie beams at the tops of the walls. Nauru has some examples of hips transitioning into gables. This would accommodate a porch, as an example, as a lower space and the main rooms under the higher open gable; the exposed gable providing ventilation.

■ The three middle diagrams show gables, which seem to be the most common roof form on the island. The variants are distinguished by that material of the gable end wall the relationship of the gable wall to the roof. Parapeted gables don’t seem to be used on the island. Raking eaves, which are hard to build, typically protect the upper wall from driven rain. There is an entire sheet dedicated to gable end eave construction.

■ Shed roofs, single pitches, are common and typically extend past both the end walls and the high side walls, like on the Smart House. Care has to be taken to keep water on the high side soffit from running back to the walls.

The housing committee says that insect screens are rare but that mosquitos and other insects are common. In considering window types, consideration needs to be given to allowable percentage of opening. Jalousies can open 100%. Whitfield cited complaints about the siding windows of the 1990’s kit houses for not being able to open more than 50%.

Windows and doors in wood walls are a little more expensive to flash and waterproof. Windows and doors in masonry walls are most prone to leaks where the frame meets the rough framing, and less likely where the frame meets the sash.

The Smart House building sections show both block and wood framed walls, just as they show both wood and concrete floor systems. We assumed that block would have an edge over wood but that will vary with the ability to produce block and concrete on the island, on transportation costs, the skills of the trades, the premium placed on relatively clean, renewable resources, the availability of durable faming species, and the ravages of the climate and environment.

The use of wood is appealing because it is a renewable resource, but fast growth woods are less rot resistant. When you add the cost of siding and flashing any price advantages may disappear. Whitfield cites surveys which say that the majority of Nauruans prefer block over wood. This may derive from the perception of greater durability. Life cycle costs will tilt cost advantages to block, and better maintain the value of initial investments.

Based on what we have heard from the housing committee, the energy performance of walls and windows is rarely considered. Wood isn’t reliably graded. Plywood is prohibitively expensive. If block is made on island and is preferred by Nauruan homeowners, the arguments for wood aren’t very strong.

Historical and current examples of Nauruan houses show gable roofs and shed roofs, and flat roofs, and hip roofs and hips going into gables. The Smart House has a lower shed leaning against an upper shed sloping in the opposite direction. This variety of basic roof forms is evidence that, even with the benefit of time, there is no right way to approach a basic building assembly.

■ Gable roofs, which are common on Nauru, have raking eaves on the gable ends. This is usually a complicated assembly and can be constructed in several ways. Diagram A shows a masonry parapet extending beyond the roof. The top of the wall would be flashed. There would be flashing where the roof meets the raking gable wall. This is not a common assembly on Nauru for two reasons. Masonry gable ends are not common, and the upper walls is not afforded shade or protection.

■ Diagrams A and B both show plywood roof sheathing, which is prohibitively expensive on Nauru. The plywood extends to a rafter bolted to the wall. The sheathing is edge nailed to this rafter providing continuity between the wall and roof assemblies.

■ Diagram B shows a masonry gable end, which eliminates wood there, but it requires forming a concrete rake beam at an angle. The eaves project to protect the upper wall. The rafters extend to the roof sheathing. A short ladder is formed over the rake beam, supporting the cantilevered eave.

■ Diagram C reflects framing more common to Nauru and reflected on the Smart House. The Smart House has shallower rafters and deeper purlins, and the purlins form the eaves. There is a deep raking fascia that is essentially hung from the extended purlins. There is no plywood roof sheathing. The gable end wall is framed with wood.

■ All gable roofs have raking eaves. Hip roofs do not. Diagram D shows a continuous horizontal eave that can be open or closed. It is shown closed here to protect the roof truss extensions. Hip roofs can be stick framed but are more commonly framed by trusses, and the lack of trusses on the island may make gables more common than hips.

■ The top row of diagrams show roof trusses, and diagrams D through H show different forms of framing with dimensional lumber. Diagrams vary in how the eaves are framed and how the outward thrust of the rafter is counteracted. Trusses all have bottom chords at the ceilings that counter thrust. Trusses require engineering and a modest plant and may not be an option on the island.

■ Diagram A shows the eaves formed by an extension of the top chords of the truss. The soffit framing member would be added in the field. These eaves are enclosed and protected from the elements. Diagram B also forms the eaves with an extension of the top chord, but the eaves are open and subject to the ravages of the environment. Diagram C address this by scabbing a separate rafter tail onto the trusses so that if an eave assembly need to be repaired, the structural members of the roof are separate and protected inside the wall.

■ Diagram D has open eaves formed by rafter tails scabbed onto the rafters. It has a collar ties at the ceiling. The width of the span would be limited by the length of this collar tie. The flat ceiling hides the scabbing of the rafter tails. The ridge is nonstructural because of the collar ties. Diagram E has a higher collar tie and the roof framing is open to the rooms below in order to let warm air rise. The ridge is non-structural. When framing is visible from below, it requires better workmanship.

■ Diagram F has no collar tie because the ridge is a structural ridge which renders the rafters a simple span with no outward thrust. Structural ridges have to post down at intervals and so this affects the flexibility of the plan.

■ Diagrams G and H show shed roofs which are common on Nauru and used on the Smart House. Shed roofs work best when their high end leans against a taller volume like in diagram G, as they do in the front room of the Smart House. When the upper end is open as it is on H, water is prone to flowing down the underside of the eaves back to the wall. The eaves are more prone to rot and the walls to leaking. The Smart House addresses this with a small return pitch.

There are some basic considerations for making a decision about the form of the roof. First, virtually all roofs slope because water must be diverted. Even what we describe as flat roofs slope behind a parapet wall and are either drained internally or through the parapet.

Shed roofs usually lean against a taller volume. If they don’t, they are subject to water intrusion on their high side. The Smart Houses addresses this with a short return roof on the upper shed that forms a ridge. Gable roofs, with two equal pitches are the most common roof form on the island but the construction challenge is in building the triangle above the end walls. Hip roofs are harder to stick frame and easier to build with trusses, which may not be an option on the island, but their eaves are easier to construct.

Because it is harder to build block walls on an angle (it requires a sloping concrete beam just under the raking eaves), block houses with gable roofs often frame this triangle in wood. Hip roofs have slightly more complicated framing than gables, but they have the same height walls all the way around the house and avoid this triangle. Occasionally there are hip roofs that lean, like sheds, against the end of a gable.

While pitches on gable roofs vary, lower pitches seem more common on current Nauru house types. Whitfield acknowledged the need for relatively low eaves but recommended higher pitches of at least thirty degrees, for cooling the interior. Standing seam metal roofs work at very low pitches.

Hip roofs perform better in very high winds because they are better braced on all four directions. Low pitch hips perform the best in high winds. Historically, this has not dissuaded Nauruans from using the more common gable roof form on modern era houses.

Water can be collected from any of these roof forms. Any roof form can be framed with trusses or stick framed with simple dimensional lumber. Trusses, which are made from very small stick members, are typically made in a modest plant. Trusses are engineered and the small members are held together with gang nails. Trusses can span greater lengths and their bottom chords act against the forces that spread a roof outward at the top of the walls and provide framing for a ceiling.

Stick framed roofs have to counteract the outward thrust of the roof by other means. There can be a structural ridge against which the rafters lean. This eliminates outward thrust, but ridges have to post at intervals where trusses do not. Posting a ridge affects the flexibility of the plan. The shed roofs of the Smart House have short spans supported at each shed by a structural wall running down the middle of the plan. If there is not a structural ridge, collar ties can counter the roof’s outward thrust.

In the U.S. even expensive houses can be built either with trusses of stick framed rafters. There is no common agreement about the right way to frame a roof. It still varies greatly by region. We build in a part of the country where carpentry skills are more limited but there is a thriving truss industry. If you stick frame in Nauru, you just need plans that allow for shorter spans, like those of the Smart House.

Eaves probably pose the most complicated considerations and if window openings are the most expensive sub-assembly of a wall, eaves are the most expensive sub-assembly of the roofs.

First of all, consider the differences between the framing inside the walls and the framing outside the walls that form the eaves. You can form the eaves with an extension of the roof framing or you can attach a separate framing system that forms the eaves. Forming the eaves with an extension of the roof framing - especially if it is stick framing - is less expensive.

The argument against it is that if the eave starts to deteriorate owing to its exposure it is rotting a structural member too, that is more difficult to replace. Separate external framing systems can be scabbed onto the structural roof framing and replaced separately but attached rafter tails are more expensive.

Second consider the difference between an eave over a wall with a flat top and the eaves along the raking wall at the end of a gable roof. Most Nauruan houses with gable roof, extend the roof over the end wall to protect it from rain. This is appropriate but these raking eaves are more complicated to build. Typically they are built like ladders, half over the inside of the building and half cantilevered beyond the wall. The Smart House appears to build the raking eaves with extensions of their purlins.

There is a variant for block houses where the gable end is built of masonry, and running above it- a parapeted gable. This eliminates the cost of the raking eave but requires flashing where the roof framing meets this wall, and it does not afford shade of protection from rain. If this eave type is to be considered, there has to be a concrete rake beam formed at the top of the wall.

A hip roof would have a gutter on all four sides of a house. A gable roof has gutters on two side. A shed is like half a gable and collects water on one side. Eaves help throw the roof runoff clear of the upper walls but they need to be detailed to keep water from running back along the underside of the assembly. This is done simply with a drip edge.

The high side of a shed roof, by contrast, is more prone to water running back to the upper wall, which is why the Smart House has a short return roof to prevent this. Alternatively, this is sometimes done with a parapet wall that goes above the roof. Generally sheds make more sense make more sense when they lean against a taller wall, like the lower shed roofs of the Smart House.

Eave assemblies need to be detailed to carry gutters. Gutters full of water tend to overturn and so an eave provides a supported vertical surface, a fascia, supported by rafters, from which gutters hang. The Smart House has a deep fascia than accommodates the minimal fall of the gutter required for the gravity flow of water

Gutters, downspouts and cisterns are elective costs, but the 2011 Republic of Nauru Census shows how common gutters are even now. The collection of rainwater will be an important means of decreasing dependence on desalinized water and so the upfront costs of gutters and downspouts will be recovered over a relatively short period of time.

David Whitfield noted the use of ridge vents in some Nauruan houses but also noted complaints about wind driven rain intruding. He expressed the hope that improved vent systems would allow for the release of warm air and the protection from rain and insects. The Smart House has a ridge vent but no plywood deck.

We build in a saline environment similar to Nauru’s and there had been a protracted debate on advisability of venting the eaves, which can be more protected than the ridge. But the recent consensus is that vented eaves allow corrosive salt air into the attics that rust gang nails and metal tie downs.

Roof insulation, like wall insulation, is uncommon on Nauru.

Typically a plywood substrate lends resistance to lateral wind loads and it provides a surface for a moisture barrier. The Smart House does not use plywood roof sheathing and it appears most Nauruan houses do not use a plywood deck. The housing committee says that plywood is rare because it is prohibitively expensive.