As Mayor of Fort Wayne, I am proud to support the East Central Forward Neighborhood Plan, a vision that enhances the quality of life for all residents. Investing in our neighborhoods is a key priority for my administration because strong, vibrant neighborhoods are essential to the well-being and success of our city. East Central Forward represents a collaborative effort to create a safer, healthier, and more connected neighborhood while honoring the unique history and spirit that makes East Central a special place.

This plan embraces the neighborhood’s stated values: safety, heritage, walkability, housing stability, and wellness. By prioritizing safe streets, accessible sidewalks, and well-maintained public spaces, East Central Forward builds a foundation for community pride and connection. We aim to proactively address public safety through strategic planning, ensuring every resident feels secure in their neighborhood. At the same time, we recognize the importance of preserving East Central’s rich heritage, elevating the stories and places that define the community’s identity.

Walkable neighborhoods are livable, and the plan’s focus on improving pedestrian infrastructure will make it easier for residents to move safely throughout the community. Investing in housing stability is central to our vision, ensuring everyone has access to safe, affordable, and quality homes. Recreation and wellness are equally vital, and this plan envisions parks and community spaces that inspire activity, health, and connection.

Together, we are building a thriving neighborhood. I encourage all residents to take pride in our progress and continue working alongside us to achieve the vision for East Central. Thank you for your dedication and commitment to making Fort Wayne a safe, fun and family-friendly city.

As the Fort Wayne City Councilman for the 5th District, I am honored to support the East Central Forward Plan. Working with engaged and dedicated neighbors, this plan represents the next stage of commitment for investment of time and other resources by the City of Fort Wayne to the residents of the East Central Neighborhood. My sincere thanks goes out to the residents and neighborhood association leadership who selflessly gave of their time to help City staff in the Department of Neighborhoods and others create this plan that will shepherd attention and investment over the next decade.

Now the work of implementation begins.

Through the collaborative planning process, the groundwork has been laid for successful investment and exciting additions to the neighborhood. I look forward to continued engagement and effective implementation.

Many people throughout East Central and the City of Fort Wayne have given time and expertise to create this multi-phase neighborhood plan. We greatly appreciate the residents, businesses, community organizations, and other stakeholders who provided their insights, thoughts, and feedback throughout the planning process.

City of Fort Wayne Elected Officials East Central Forward Committee

Sharon Tucker Mayor

Paul Ensley

City Council District 1

Russ Jehl

City Council District 2

Nathan Hartman

City Council District 3

Dr. Scott Myers City Council District 4

Geoff Paddock

City Council District 5

Rohli Booker

City Council District 6

Martin Bender

City Council At Large

Michelle Chambers

City Council At Large

Thomas Freistroffer City Council At Large

City of Fort Wayne Staff

Zoe Auer Fort Wayne City Council

Karl Bandemer Deputy Mayor

Chris Carmichael Property Management

Andy Downs Office of the Mayor

Megan Flohr Fort Wayne City Council

Sherese Fortriede Planning & Policy

Shan Gunawardena Public Works Director

Micky Hall Planning and Policy

Nick Jarrell Public Works

East Central Additional Support

Prof. Suzanne Beyeler Indiana Tech

Cameron Chandler Natl. Society of Black Engineers

Karen Couture Department of Planning Services

Jeff Crane BFA Commercial Photography

Sheila Curry-Campbell Pilgram Baptist Church

Nancy Etro Engineering and Planning Resources

Bernadette Fellows Fmr. Neighborhood Planning Staff

Zach Benedict

Natalie Cryer

Allison Geradot Elise Jones

Maye Johnson

Judy Roy

Elecia Peggins Dan Stoker

Sarah Strimmenos

Kellie Turner

East Central Leadership

Elecia Peggins East Central Neighborhood President

Kellie Turner Fmr. East Central Neighborhood President

Dan Baisden Department Head

Kevin Cobb Engage Fort Wayne Coordinator

Holly Muñoz Resource and Engagement Coordinator

Michael Terronez Neighborhood Planner

Alec Johnson Redevelopment

Kerry Korpela Office of Sustainability

Phil LaBrash Public Works

Nathan Law Planning & Policy

Jodi Leamon Office of Sustainability

Nate Lefever Historic Preservation

Jonathan Leist Community Development Director

Brad Lewis Public Works

Kelly Lundberg Community Development

Chip Gurkin Environmental Protection Agency

Elise Jones Fmr. Greater Fort Wayne Inc.

J.T. King Royal Developments

Megan McConville Engineering and Planning Resources

Garry Morr Fmr. City of Fort Wayne Controller

Ben Roussel Department of Planning Services Director

Nathan Schall Department of Planning Services

Réna Bradley Neighborhood Planner

Megan Grable Neighborhood Planner

Lauren Shank Neighborhood Planner

Steve McDaniel Parks & Recreation Director

James Reitz Public Works

Chanell Ridley Jennings Center Recreation

Chad Shaw Parks & Recreation

Creager Smith

Historic Preservation

Michelle Rupright Public Works

Pat Roller City Controller

Derek Veit Forestry Operations

Patrick Zaharako Public Works Dr. Andrea Robinson Economic Development Director

Allison Vanderhost, EDAC MKM Architecture + Design

Michelle Wood Department of Planning Services

Dylan Wright Natl. Society of Black Engineers

Logan York Miami Tribe of Oklahoma

Connie Haas Zuber Historian

Absentee Landlord

A property owner who does not reside at or near the rental property and is often perceived as less engaged in its maintenance or neighborhood impact.

Adaptive Reuse

The process of reusing an existing building for a purpose other than what it was originally built or designed for.

Affordable Housing

Housing is considered affordable if a family pays no more than 30% of its household income on housing-related costs.

Age Cohort

A group of individuals of the same age or within a defined age range tracked over time for demographic analysis.

Beautification

The action or process of improving the appearance of a person or place.

Block Party

A neighborhood gathering, often held outdoors, designed to build community, celebrate local identity, and engage residents in informal ways.

Building Permits

A type of authorization granted by a government or regulatory body before construction or alteration of a building.

Census Tract

Geographic units used by the U.S. Census Bureau for statistical analysis. Census tracts typically contain 1,200 to 8,000 people and are subdivided into smaller block groups. They do not always align with neighborhood boundaries.

City Beautiful

A design movement from the 1890s to the early 1900s that used grand architecture and beautification to inspire civic pride, encourage moral behavior, and elevate the overall quality of urban life.

Code Violation

An infraction of local building or property maintenance codes, which include issues like unsafe structures, overgrown lots, or illegal occupancy.

Community-Based Organization

A nonprofit or grassroots organization rooted in a particular community, often providing services or advocacy on behalf of residents.

Community Engagement

The process of working with community members and stakeholders to inform, consult, involve, and empower them in the decision-making process.

Complete Street

A street designed and operated to enable safe use and support mobility for all users (cars, bikes, and pedestrians).

Cost Burdened

A household that spends 30% or more of its income on housing costs (including utilities).

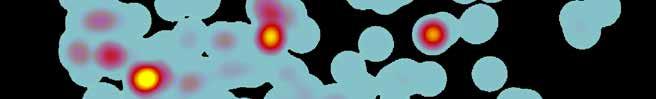

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED)

A multidisciplinary approach to reducing criminal behavior by using urban design, maintenance, and social dynamics.

Curb Cuts

A small ramp built into the curb of a sidewalk to make it easier for people using strollers or wheelchairs to pass from the sidewalk to the road.

Deed Restriction

A written agreement in a property’s deed that limits how a property can be used. Demographic Shift

Demographic Shift

A significant change in the composition of a population, such as changes in race, ethnicity, age, or household income over time.

Disinvestment

The process by which public or private sector funding and attention is withdrawn from a neighborhood, often resulting in physical, economic, and social decline.

Economic Leakage

Refers to the flow of money out of a local economy due to spending on goods and services that are produced outside of that economy.

Facade Improvements

Renovations to the exterior of buildings—especially storefronts— to enhance appearance, usability, and appeal to customers and residents.

Flag Stops

A type of public transportation system where buses stop only when requested or people are present at bus stops.

Focus Group

A facilitated discussion with a small, diverse group of people to gather in-depth insights on specific topics or issues.

Food Desert

A census tract that meets both low-income and low-access criteria for healthy and affordable foods.

Green Infrastructure

Natural or nature-based systems (e.g., parks, green roofs, permeable pavement) that improve air and water quality, manage stormwater, and provide habitat for local animals and insects.

Greenspace

An area of grass, trees, or vegetation set aside for recreational or aesthetic purposes.

Health Disparity

A difference in health outcomes between groups, often due to social or economic inequality in defined places.

Health Outcomes

Measures used to assess the health of individuals or populations, such as rates of disease, life expectancy, or mental health indicators.

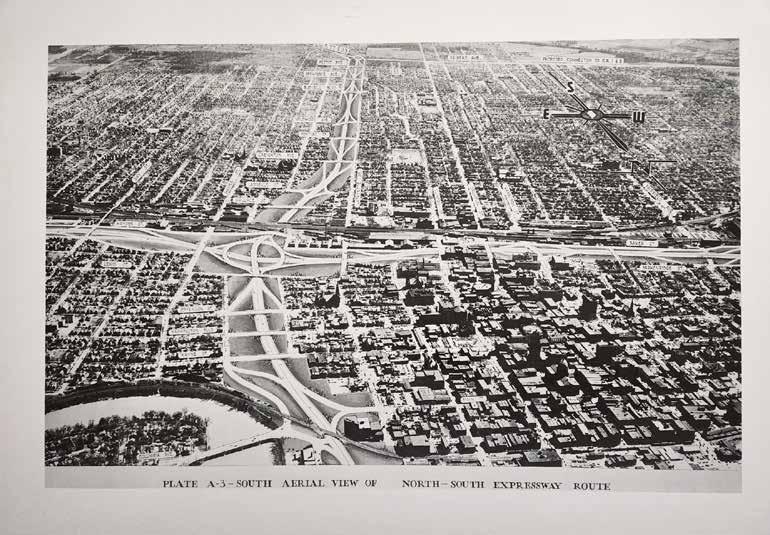

Highway Speculation

A period when proposed highways created uncertainty that discouraged investment in certain neighborhoods, even if the project was never completed.

Historic Preservation

Any activity that identifies, protects, rehabilitates, or enhances historic resources.

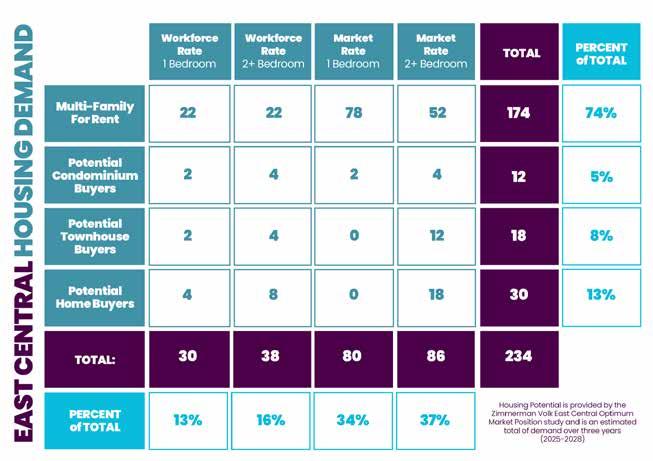

Housing Market Potential Study

A report that analyzes local housing trends and demand to guide future development decisions.

Impervious Surface

A surface (e.g., concrete, asphalt) that prevents water from absorbing into the ground.

Implementation Strategy

A detailed plan that outlines how a recommendation will be carried out, including timelines, responsible parties, and resource needs.

Infill

Adding new building(s) to underused or vacant lands in developed urban areas.

Interactive Mapping Tool

A digital platform that allows users to mark locations, provide input, or report concerns on a neighborhood map to help guide planning decisions.

Land Acknowledgement

A formal statement that recognizes and respects Indigenous Peoples as traditional stewards of the land.

Land Use

The current purpose of a property (e.g., residential, commercial, or agricultural).

Leisure Time Physical Activity

Any physical activity performed during free time that contributes to overall health and fitness (e.g., walking, sports, or recreational exercise).

Listening Tour

A structured engagement activity where officials or community leaders gather public input by visiting and speaking with residents directly, often door-to-door or at community events.

Median Household Income

The annual income earned by households that falls in the middle of a ranked list of all household incomes.

Mixed-Use

A lot or building that contains more than one use, for example, residential and commercial.

Mobile Health Clinic

A traveling healthcare service that provides basic medical care, screenings, or education to communities with limited access to permanent facilities.

Neighborhood Asset

Any feature—physical, social, or institutional—that contributes positively to the quality of life in a community (e.g., parks, community centers, schools).

Neighborhood Commercial Zoning

A zoning classification allowing small-scale commercial uses intended to serve local residential neighborhoods.

Neighborhood Planning Commitee

A group of residents and stakeholders organized to guide and inform the neighborhood planning process, helping ensure community-led decision-making.

Owner Occupied Housing

A home that is lived in by the person or household that owns the property.

Persistent Poverty

A U.S. Census designation for areas with poverty rates of 20% or higher for at least 30 consecutive years.

Place Based Health Improvement Plan

A coordinated strategy to improve health outcomes focused on the specific needs and conditions of a particular geographic area.

Planning Recommendation

A proposed strategy or action that addresses a specific challenge or opportunity identified through community input or data analysis

Plat

A plot of land divided to be owned or sold.

Population Density

The number of people living per unit of area (e.g., per square mile), often used to measure how urban or rural a neighborhood is.

Public Open House

An event where community members are invited to review and comment on plans, proposals, or updates in an informal setting.

Redlining

The discriminatory and now illegal practice of denying loans or insurance based on race or ethnicity.

Renter Occupied Housing

A home lived in by someone who pays a rental payment but does not own the property in which they are living.

Sanborn Insurance Maps

Historical maps used to determine risk associated with insuring properties, often used in practices like redlining.

Summit City Entrepreneur and Enterprise District (SEED)

A City of Fort Wayne program that promotes entrepreneurial initiatives focused on community, economic, and neighborhood development.

Snowball Sampling

A recruiting technique where participants refer other potential participants to a study or initiative.

Social Capital

The networks and relationships among people who live and work in a particular society and enable that society to function effectively.

Social Determinants of Health

The conditions in which people live, work, and age that influence health outcomes and quality of life.

Spot Zoning

The process of singling out a small parcel of land for a use classification different from the surrounding area.

Stakeholder

An individual, group, or organization that has an interest or concern in a particular issue, project, or outcome directly or indirectly impacted by neighborhood planning.

Streetcar Suburb

A residential community whose growth was strongly shaped by streetcar lines.

Survey Instrument

A formal tool used to collect data or feedback from community members, typically through structured questions.

Tax Increment Financing

A financial tool that uses additional property tax revenue generated by new development to fund public infrastructure or other community projects.

Traffic Calming

Tools and methods used to slow down traffic and make the street safer for all users.

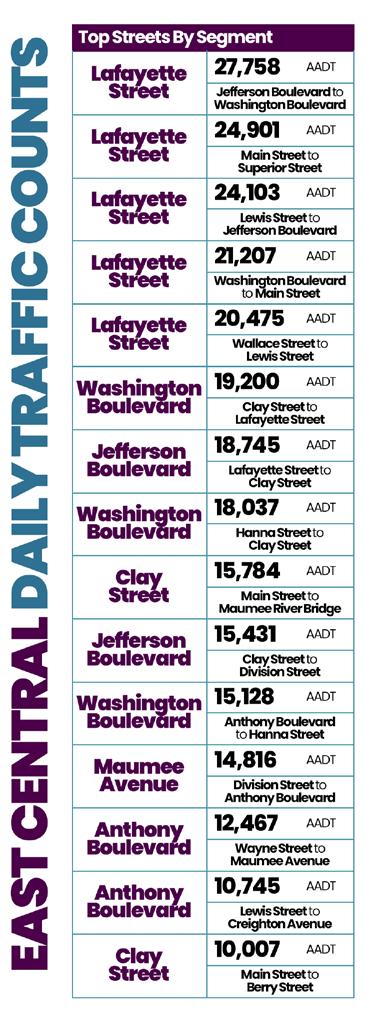

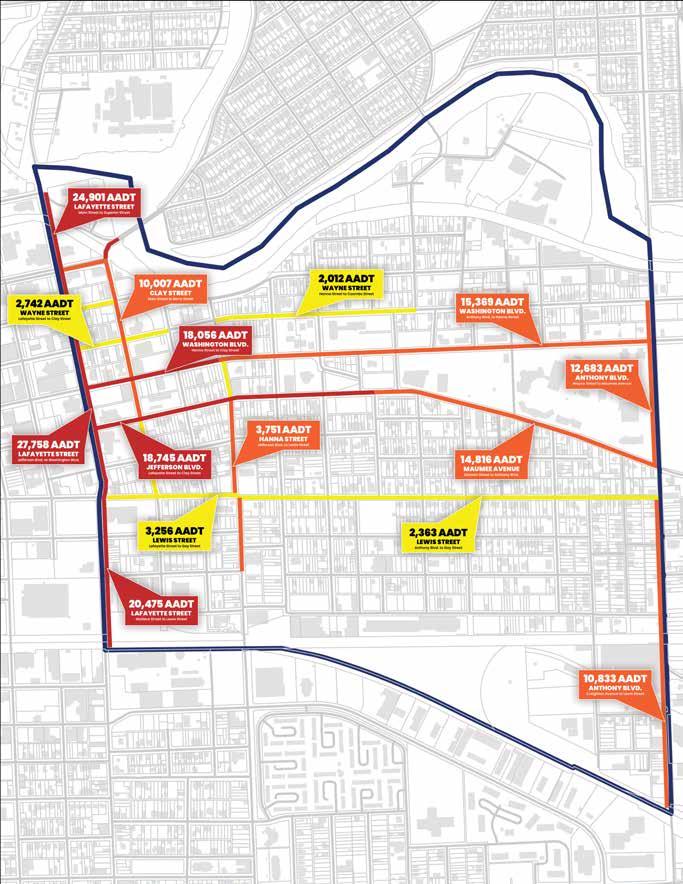

Traffic Study

A study used to evaluate a transportation system’s functioning and needs.

Tree Canopy

A measurement of how much area is covered by tree leaves, branches, and stems when viewed from above.

Urban Core

The central area of a city, typically more densely populated and often the economic and cultural hub.

Urban Corridor Zoning

A zoning designation that supports mixed-use, pedestrianoriented development along major urban streets.

Urban Heat Island

The overheating of urban spaces due to heat retention in buildings and paved surfaces.

Vacant Lot

A parcel of land with no existing structure, often resulting from previous demolition and awaiting redevelopment or reuse.

Walkability

The ability to walk to services and destinations within a reasonable distance—often considered a 30-minute or shorter walk.

Wayfinding

Informational signage placed in public areas to help people navigate and identify key locations within a neighborhood or city.

Zoning

Laws that regulate how land can be used (e.g., residential, commercial) and the standards associated with each use.

”East Central Neighborhood honors the lasting impact and influence of our rich history while focusing on the neighborhood’s bright future. The neighborhood is focused on promoting unity, education, advancement, and innovation while connecting residents for sustainable growth.

Elecia Peggins - East Central Neighborhood Association President

East Central Forward is a comprehensive neighborhood planning initiative that articulates a unified vision for the East Central neighborhood of Fort Wayne. Rooted in the community’s long legacy of resilience, diversity and civic pride, this plan establishes a framework to guide growth, investment and neighborhood transformation over the next decade. The East Central Forward plan reflects the aspirations of residents and stakeholders and provides actionable strategies to support a safe, inclusive, and thriving neighborhood.

This plan is designed to:

• Engage residents, stakeholders, and community partners in identifying priorities, challenges, and opportunities for the future of the East Central Neighborhood.

• Establish a shared, community-driven vision that promotes neighborhood revitalization, safety, housing stability, economic opportunity, and quality public spaces.

• Celebrate and elevate East Central’s rich heritage, historic identity, and community leadership as foundational assets.

• Define clear goals and implementation strategies that guide neighborhood, development, public investment, design enhancements, and programmatic initiatives.

• Provide guidance to the East Central Neighborhood, the City of Fort Wayne, decision-makers, public agencies, developers, investors, for-profit corporations and non-profit corporations

WHO DOES IT INCLUDE

• East Central Neighborhood Association

• Residents and community leaders in East Central

• City of Fort Wayne Staff and Departments

• Institutional partners (e.g., Indiana Tech)

• Faith-based organizations, non-profits and foundations in East Central

• Local businesses, investors, and developers

WHAT DOES IT INCLUDE

• Planning Framework (principles, organization, process and timeline)

• Context and Background

• Neighborhood Profile (demographics, health, statistics, traffic, crime and safety, economic development, etc.)

• Strengths and Challenges

• Strategic Recommendations

• Implementation Matrix

The following principles serve as the foundation of East Central Forward, guiding all strategies, actions, and recommendations within the plan. Rooted in the community’s values and priorities, these principles reflect a shared vision for a stronger, more connected, and resilient neighborhood. They respond to both present-day challenges and long-term opportunities, ensuring that East Central remains a place where residents feel safe, supported, and proud to call home.

We believe that all residents deserve to feel safe in their neighborhoods. East Central Forward prioritizes strategies that strengthen public safety, encourage community involvement, and create inviting public spaces. By fostering a greater sense of trust, connection, and visibility, we aim to enhance safety and peace of mind throughout East Central.

East Central’s past is a source of strength and identity. This plan supports efforts to celebrate the neighborhood’s cultural heritage, honor those who have shaped it, and preserve historic places and stories. By elevating community memory, we build pride and support connections to East Central for future generations.

A walkable neighborhood is a livable neighborhood. East Central Forward emphasizes the importance of safe, connected, and accessible pedestrian infrastructure. We prioritize sidewalk improvements near schools, parks, and activity centers to promote healthier lifestyles and improve mobility for people of all ages and abilities.

Stable, quality housing is the heart of a strong neighborhood. East Central Forward promotes housing that is safe, affordable, and well-maintained. Supporting reinvestment in existing homes, responsible infill development, and policies that help residents remain in their homes and build long-term stability.

Access to recreation and wellness resources is essential to community well-being. East Central Forward advocates for the enhancement of parks, trails, and community spaces as hubs for physical activity, connection, and health services. Ensuring that every resident has access to safe, vibrant places to play, gather, and thrive.

East Central Forward is a guiding document developed to support coordinated action and reinvestment in the East Central neighborhood just east of downtown Fort Wayne. This plan reflects a shared community vision informed by the neighborhood’s rich history and lived experience. It includes its role as the city’s first historically Black neighborhood and its journey through periods of growth, disinvestment, and resilience. It is intended to be used by the East Central Neighborhood Association, City of Fort Wayne departments, Allen County departments, nonprofit and for-profit partners, developers, residents, business owners, and other stakeholders whose decisions and efforts impact neighborhood outcomes. It also provides direction for projects and initiatives that can be led or supported to move East Central forward.

East Central Forward outlines a comprehensive yet adaptable framework for neighborhood improvement. The plan is organized around Goals, Strategies, and Action Steps that provide practical, communityinformed pathways to guide investments in safety, housing, connectivity, and well-being. While broad in scope, the plan is intentionally designed to evolve in response to the neighborhood’s changing needs and serve as a foundation for more detailed project planning, engagement, and implementation.

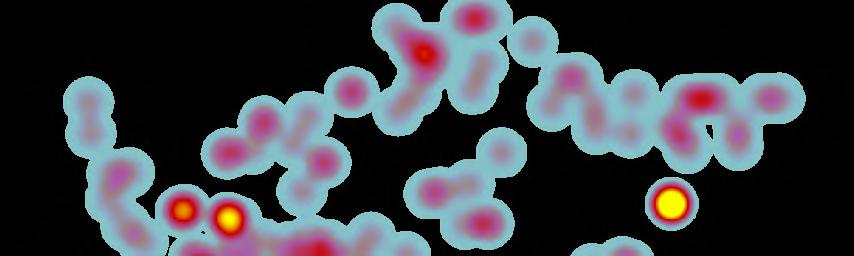

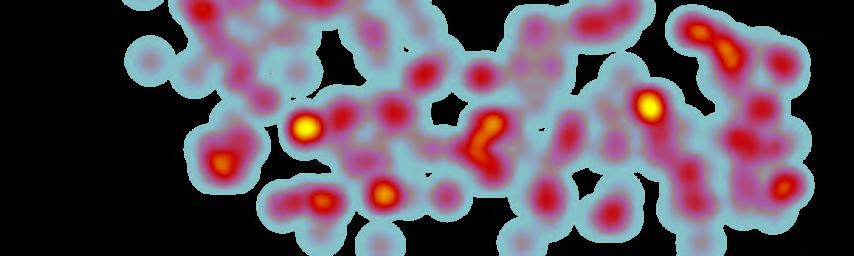

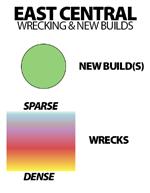

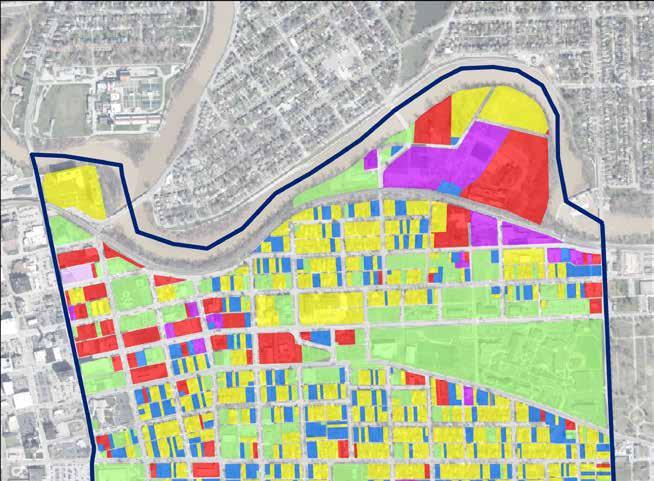

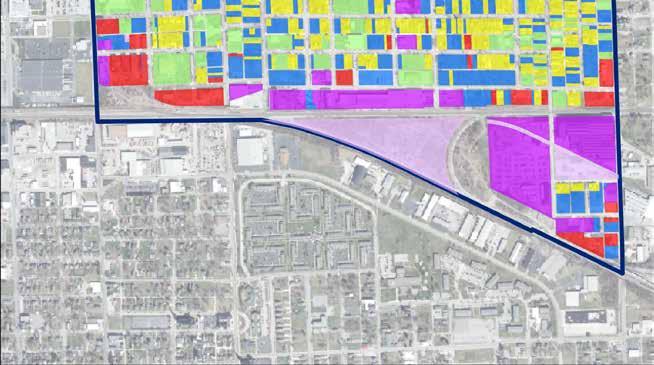

The maps, diagrams, illustrations, and photos included in East Central Forward are intended to communicate key themes and ideas that emerged throughout the planning process. These visual tools help translate complex information into accessible content and reflect the community’s voice during outreach efforts. While they do not guarantee specific outcomes, they represent shared aspirations and provide a visual guide for future planning. The success of this plan depends on continued collaboration, community priorities, available resources, and the sustained engagement of neighborhood partners.

A neighborhood plan is an essential tool that allows local stakeholders to come together to shape the future of their community. Residents, businesses, and institutions can identify a shared vision through the planning process and outline strategies to achieve it. Neighborhood plans help guide growth and development in ways that reflect community priorities. They provide detailed recommendations tailored to the area’s unique needs, something a citywide comprehensive plan cannot fully capture. The last neighborhood plan for East Central was developed in 2005 and much has changed over the past two decades. Updating the plan ensures that it reflects the current realities and aspirations of the community, laying the foundation for thoughtful, inclusive, and sustainable growth.

Portions of East Central Forward made responsible and transparent use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools to support specific aspects of the research and writing process. They were employed to assist with language refinement, summarization of data findings. At no point did AI replace the author’s own critical analysis, original ideas, or ethical reflections; rather, AI outputs were carefully reviewed, verified, and contextualized within the broader research conducted in the planning process. The limitations and potential biases inherit in AI-generated content were acknowledged, and extra measures were taken to cross-check accuracy against reliable sources.

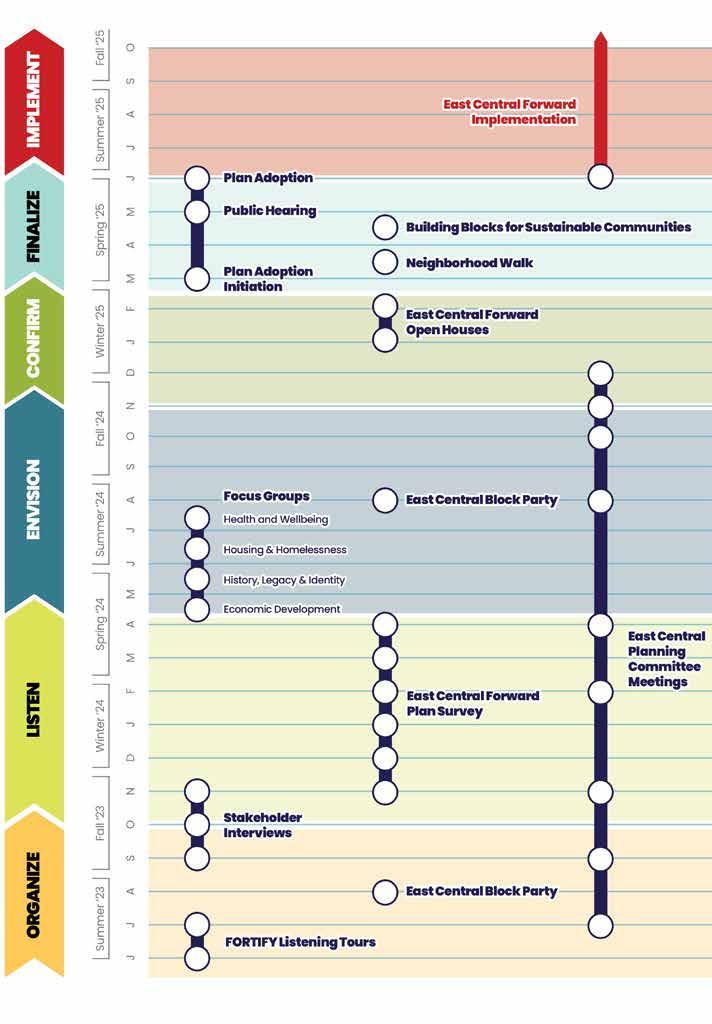

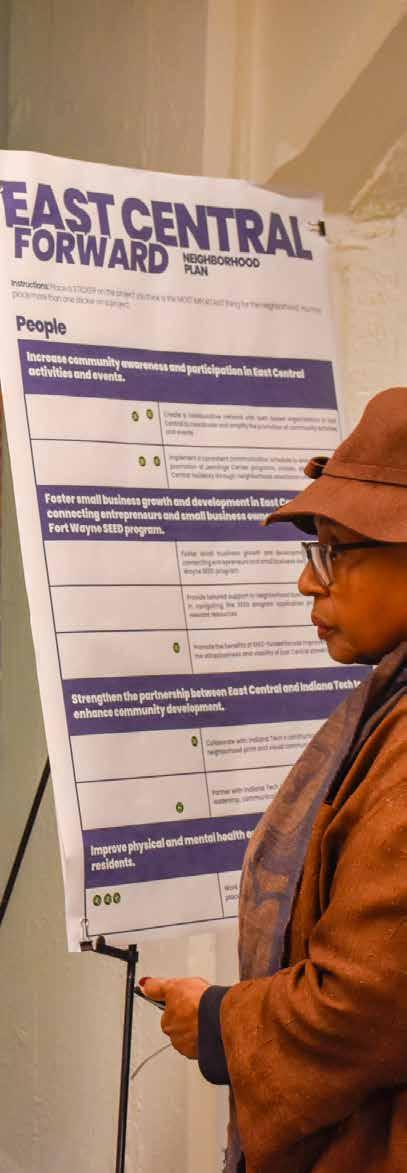

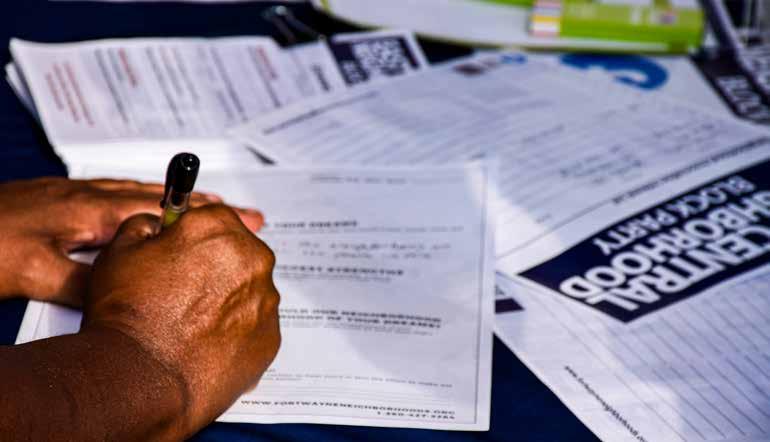

Effective neighborhood planning relies on genuine and widespread community participation. East Central Forward was developed through extensive engagement with diverse community stakeholders including residents, local businesses, faith-based and non-profit organizations, foundations, and other community institutions. The engagement strategy utilized a combination of in-person meetings, workshops, door-to-door outreach, and online participation opportunities conducted from 2023 to 2025. Additionally, a neighborhood planning committee composed of East Central residents and organizational representatives guided the overall process.,

Below is an overview of the primary engagement activities and summarized findings:

East Central participated in the first cohort of the City of Fort Wayne’s Department of Neighborhood’s FORTify Neighborhood Accelerator in 2023. The city-led initiative aimed to support neighborhood leaders by providing workshops, mentoring, and resources to strengthen neighborhood advocacy and organization skills.

Through the FORTify Listening Tour resident volunteers, City staff, and local partners conducted door-to-door outreach within the East Central neighborhood. This effort included personal interviews and surveys, resulting in input from over 90 individuals and completion of 43 detailed surveys.

Additional feedback was gathered during the 2023 East Central Block Party, where another 32 surveys and 84 points of community input were collected through interactive project boards. Youth input was specifically encouraged through youth-targeted engagement activities, with 15 children and teenagers contributing their perspectives.

The community feedback obtained from these activities directly informed the key priorities highlighted throughout the East Central Forward neighborhood plan.

Key Neighborhood Priorities: Based on community input, residents identified several key priorities to guide recommendations in the FORTify community engagement process:

Residents expressed a clear desire for cleaner streets, reduced litter, and enhanced greenery including more street trees and flowers.

Safety and Crime Reduction

Safety consistently emerged as a significant concern. Residents frequently emphasized the need for improved street and sidewalk lighting, regular and meaningful interactions with local police, and measures to reduce neighborhood violence.

After experiencing significant demolitions over several decades, residents stressed the importance of developing quality housing opportunities, promoting affordable homeownership, and addressing potential displacement due to rising housing costs from downtown Fort Wayne’s recent growth and expansion.

Neighborhood Infrastructure

Residents prioritized improvements to infrastructure, specifically highlighting the need for repaired sidewalks and alleys, street enhancements, and additional lighting to improve safety and connectivity. Although appreciative of recent improvements, residents felt more action is necessary to improve safety in the neighborhood, and how infrastructure supported could help support those concerns.

Recreation

Community members indicated a strong interest in improved recreational amenities, emphasizing the need for safe play spaces for children, wellmaintained basketball courts, and comfortable seating near playground areas.

FORTify Block Party and FWFD Department of Neighborhoods

In order to gather diverse and in-depth perspectives directly from those most familiar with the neighborhood, the City of Fort Wayne’s Department of Neighborhoods held over 40 one-hour one-on-one stakeholder interviews in 2024. Each interview began with a series of similar questions, such as (1) what is an important asset or identity about East Central, (2) what brought you to the neighborhood, (3) what do you believe are some opportunities in the neighborhood, and (4) what specific details do you think the East Central Forward neighborhood plan should address. East stakeholder was then given ample time to ask additional questions and provide input that may not have been asked during the sample questions portion of the interview. To ensure a wide variety of stakeholders were asked to participate in the effort, each person interviewed was asked to provide the name of another person who should be contacted within the neighborhood.

Much like the FORTify listening tour, the feedback obtained from these interviews directly informed the key priorities highlighted throughout the East Central Forward neighborhood plan.

Key Neighborhood Priorities: Based on stakeholder input, several key priorities, much of them overlapping with previous input were identified from stakeholder interviews:

Many residents expressed the need for increased street lighting, better sidewalk connectivity, and improved relationships with the Fort Wayne Police Department to address safety concerns consistently raised by stakeholders.

Stakeholders noted they would like to see new, quality housing construction in the neighborhood, and improved maintenance standards for the existing housing stock, particularly to address absentee landlords.

Several stakeholders noted during the interviews that they would like to see improved aesthetics in East Central, specifically well-maintained parks

and gathering spaces, landscaping, cleaner streets and sidewalks, and improved sidewalk conditions to make the neighborhood more accessible.

Many of the stakeholders interviewed noted they would like to see expanded access to recreational and youth-oriented facilities in the neighborhood, either through increased programming at the Jennings Center, or through strategic partnerships at Indiana Tech. An overwhelming emphasis was placed on ensuring the long-term sustainability and viability of the Jennings Center as residents find it the most important asset in the neighborhood and want to see its continued growth.

While most stakeholders noted that the neighborhood alone could not solve the issue of homelessness, many wanted increased collaboration with organizations and institutions to address root causes of homelessness, improved resource availability, and increased effective outreach to vulnerable members of the community.

To ensure that the East Central Forward neighborhood plan reflects the residents’ priorities, the City of Fort Wayne launched a resident survey.

Over 120 surveys were collected during the engagement period through both in-person outreach and online submissions. Residents completed a 25-question survey that explored a wide range of issues facing East Central. In addition to the survey, participants were encouraged to use an interactive online mapping tool to pinpoint specific locations where they would like improvements.

To support these efforts and broaden participation, the City launched EastCentralPlan.com, a dedicated project website. The site served as a central hub for engagement, offering residents access to project updates, meeting announcements, survey links, and interactive tools. Since its launch in Fall 2023, the website has had over 1,500 visitors, showing the strong community interest in shaping the future of the neighborhood.

Feedback gathered through both the survey and mapping tools revealed clear and consistent themes, which have helped shape the priorities of the plan.

Key Neighborhood Priorities: Based on survey responses, several key priorities were identified, many

of which are similar to results from other engagement efforts:

Residents expressed serious concerns about vacant and abandoned homes, poorly maintained properties, and abandoned trailers and vehicles, especially along key corridors like Anthony Boulevard and Washington Boulevard.

Pedestrian Safety, Sidewalks, and Street Lighting

There is a strong demand to improve pedestrian safety by repairing existing sidewalks throughout the neighborhood, upgrading crosswalks to meet ADA accessibility standards, enhancing street lighting, especially on Hanna, Lewis, and Monroe Streets, and connecting East Central to the existing trail network.

Residents raised concerns about poor health outcomes in the neighborhood. Access to healthcare services, including mobile clinics and preventative health education is seen as an essential opportunity to improve community wellness.

Housing affordability, property maintenance, and the need for new housing options are major concerns by residents. While supporting homeownership and holding landlords accountable for property conditions were a priority, an overwhelming number of survey responses wanted to ensure East Central remained affordable and accessible to the community.

Celebrating East Central’s diverse history and cultural legacy is a clear priority. Residents expressed a desire to honor Black and immigrant narratives through public art, signage, and community events. Notably, residents also wanted to celebrate gateway features in the neighborhood, clearly defining the boundaries of East Central, and install public art and historic markers to tell local stories.

Safety improvements throughout East Central are considered critical to the long-term health of the neighborhood. Residents emphasized the need for proactive crime prevention efforts, such as enhanced lighting, and improved environmental design efforts, would help improve safety and security for residents.

Focus groups were essential to the East Central Forward neighborhood planning process, as they offered structured, yet informal settings for residents, local business owners, non-profit representatives, and other stakeholders to openly discuss critical issues facing the East Central neighborhood. These sessions were crucial to deepen understanding of complex concerns and bring together diverse voices in an effort to collaborate between community members and local organizations serving the neighborhood.

The focus group topic areas were inspired by members of the planning committee, who had been reviewing the results of the surveys, listening tours, and stakeholder interviews. Each focus group was led by an outside facilitator, including three by Geoff King of Love Fort Wayne, and one by Zach Benedict of MKM Architecture + Design. This method was preferred to ensure that attendees did not feel dissuaded to share concerns in front of City of Fort Wayne staff or elected officials.

The first of four focus groups was held on May 20th, 2024, at the Community Foundation of Greater Fort Wayne. The key insights gathered from participants at this focus group help shape the recommendations found in this plan:

East Central’s strategic proximity to downtown Fort Wayne positions the neighborhood for significant economic growth, particularly given the abundance of vacant land – much of which is owned by local institutions and churches. Residents see this available land as a catalyst for new development opportunities that could bring needed vibrancy to the area.

A critical need identified by participants in the focus group is the expansion of local food retail and restaurant options. With Indiana Tech students and families seeking more neighborhood amenities, East Central has a prime opportunity to focus on growing these sectors, especially by creating family-friendly destinations and services.

The revitalization of both the Jennings Center and Hanna Homestead parks was another priority. Participants envision both of these spaces as vibrant community hubs that offer expanded programming, promote wellness, and create recreational and wellbeing opportunities for all ages.

However, safety and livability concerns must be addressed first to realize this vision. Residents expressed the importance of improving infrastructure to support walkability, enforcing safe housing standards, and maintaining public cleanliness. In addition, a proactive partnership with existing service organizations is necessary to address the rising homelessness issues, which residents and business owners alike noted are creating safety concerns that could deter future homeowners and businesses from investing in East Central.

East Central’s path forward is clear: strengthen core infrastructure, leverage existing neighborhood assets, build strategic partnerships, and activate available land to drive sustainable, community-centered economic development.

The second of four focus groups focused on preserving East Central’s diverse cultural and historical legacy was held on May 31st, 2024, at MKM Architecture + Design. The key insights gathered from participants at this particular focus group were critical to helping shape recommendations in the plan that are rooted in the core identity of the East Central neighborhood:

Residents who attended emphasized an outsized importance in honoring the East Central neighborhood’s rich history, including the significant contributions of Black, Jewish, Native American and immigrant communities that developed much of the community. Historic preservation was also recognized, not only as a matter of cultural pride but also as essential to strengthen the community’s identity, fostering cohesion and guiding future development.

Participants highlighted the urgent need to restore and protect historic sites in the East Central neighborhood, including the Brighton House, a documented part of the Underground Railroad, and the African American History Museum. These landmarks are seen as vital anchors for community storytelling and neighborhood revitalization.

Residents believe that leveraging East Central’s unique history can attract investment, promote tourism, and inspire a new generation of residents and entrepreneurs

to engage with the neighborhood. Participants in the focus group recommended several steps to advance this, which is outlined in the Recommendations segment of the plan.

East Central’s path forward is clear: Preserving and celebrating East Central’s deep history and unique identity is not just about honoring the past – it is a strategic investment in the neighborhood’s future vitality and long-term resilience.

With significant concerns in previous surveys, listening tours and stakeholder interviews surrounding housing and increased homelessness, the third of four focus groups was held on June 24, 2024, at Indiana Tech to discuss the topic. Several key insights gathered from focus group participants help influence recommendations in the plan:

As East Central continues to change, providing safe, stable, and affordable housing is essential to the longterm vitality of the neighborhood. Several residents identified the need to expand affordable and accessible housing options, particularly for the neighborhood’s aging population. As the neighborhood continues to attract older residents, especially because of its proximity to downtown and nearby service providers, both physical design of homes and supportive services such as independent living skills training

were considered critical for maintaining a strong and inclusive multi-generational neighborhood.

Participants also emphasized the importance of enabling diverse housing development options through proactive policies and zoning reforms, allowing a broad mix of housing types to meet the needs of residents while encouraging neighborhood stability and promoting growth. Most of the group also expressed ongoing concerns about absentee landlords and shared that poor property maintenance and high vacancy rates are holding the neighborhood back from its full potential. Most of those in attendance would like to see property owners held accountable and promote higher standards for rental housing in the neighborhood.

Finally, tackling the issue of homelessness in the neighborhood was discussed. Participants noted that housing insecurity requires a coordinated, comprehensive response. Residents stressed that expanded shelter options, day-centers, street outreach, and integrated social services must be prioritized through city-wide collaboration.

East Central’s path forward is clear: Ensuring accessible, high-quality housing and addressing the increasing concerns surrounding homelessness are fundamental to East Central’s vision for a resilient, inclusive, and thriving future.

The final of four focus groups was centered on addressing the urgent health and wellbeing challenges facing East Central, and was held on June 26th, 2024, at the Foellinger Foundation. Participants in the focus group were keenly aware of the existing challenges facing the 46803-zip code, and stressed that improving access to quality healthcare and an improved built environment must be a top priority in recommendations outlined in the plan:

Participants in the focus group discussed that the best way to address the health needs in the neighborhood is to establish potential partnerships with major healthcare providers, such as Parkview Health and Bowen Health. While constructing a critical access facility would be hard to justify, attendees discussed considering a mobile clinic service at accessible community locations like the Jennings Center. This approach was seen as a practical and immediate solution to reduce barriers to care, particularly for children and residents without reliable transportation.

In addition to clinical services, participants emphasized the critical importance of increasing community awareness around health issues such as diabetes, hypertension, and mental health conditions. Preventative education campaigns and outreach initiatives were recommended to empower residents with knowledge and resources to manage and improve their long-term health outcomes.

Recreational opportunities and mental health support were also highlighted as essential components of holistic wellbeing. Participants encouraged the creation of programs that promote physical activity, community engagement, and access to mental health resources to build a healthier East Central.

East Central’s path forward is clear: Strategic partnerships, expanded healthcare access, preventative education, and wellness programming are all vital to transforming East Central into a community where every resident has an opportunity to live their lives to the fullest.

On August 10th of 2024, the Department of Neighborhoods joined the East Central Block Party at Hanna Homestead Park to provide an opportunity for residents to share their voice. Residents were able to enjoy live music, public art, street dancing, free food, as well as a chance to meet neighbors and provide more guidance to the East Central Forward plan. The discussions were

Residents Prioritizing Plan Strategies

positive, with residents expressing the deep value they have for their community and Hanna Homestead Park. This event also showcased the multigenerational roots of residents, telling stories of the old baseball diamond, swing sets, and the longevity of their family ties to the park. The block party engagement helped to narrow the scope of priorities that the community had established in previous engagement, and ultimately shaped the strategy that focus on housing, parks, safety, and community.

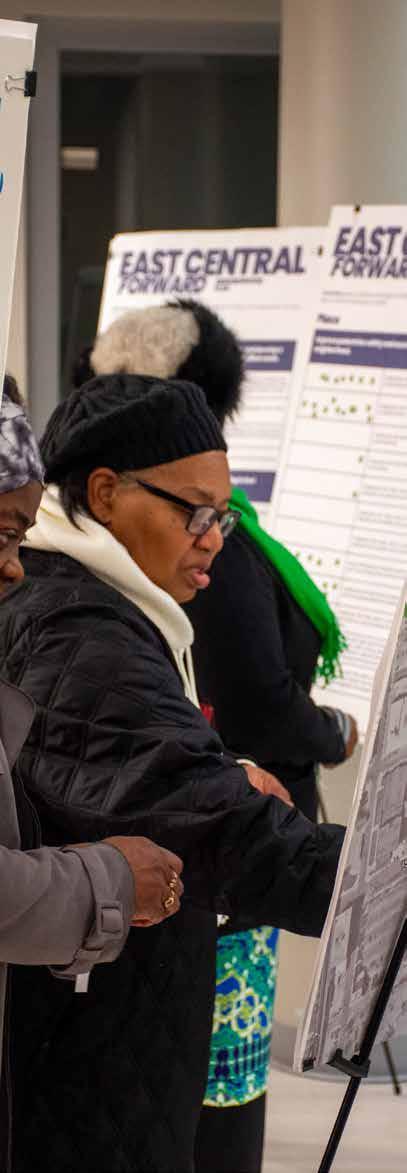

On February 19 and 20, 2025, two public open houses were held at MKM Architecture + Design located in the southern half of East Central, and the Foellinger Foundation located in the northern half of the neighborhood. The goal of these two events was to have members of the community review the recommendations outlined in the East Central Forward plan and provide additional community feedback. More than 75 residents attended the two events, engaging with staff from the City’s Department of Neighborhoods, in addition to members of the East Central planning committee. Overall, community members expressed strong support for the proposed recommendations, validating the direction of the plan.

Attendees also offered suggestions to strengthen specific action steps, ensuring that the implementation strategies outlined in the plan are both realistic and responsive to neighborhood priorities

Councilman Geoff Paddock and neighborhood leaders hosted a neighborhood walk on April 25, 2025. The walk hosted city division leaders, local religious congregation members, and other interested residents, and toured key points of interest. Common concerns included dilapidated alleys, high crime intersections, and houses with consistent code violations. Several homes were known concerns to the code enforcement officers in attendance, and the group discussed limitations of what could be done without beginning the process of demolition due to inheritance issues. The group agreed that demolition should be avoided, if possible, to preserve a viable home in a neighborhood with as many vacant lots as East Central. Several homes were also flagged as either currently or previously being occupied by upwards of a dozen squatters. The intersection of South Hanna Street & East Lewis Street was toured and concerns with persistent high crime were discussed with FWPD leadership present. Certain

alleys in poor condition were flagged for investigation into possible repairs.

In early spring 2025, the City of Fort Wayne Department of Neighborhoods was awarded the Environmental Protection Agency grant Building Blocks for Sustainable Communities. The grant focuses on a collaboration between a community and agency, in this case the City of Fort Wayne and the East Central Neighborhood, and engages the community to identify strategies for building environmental resilience. The grant in the 2025 cycle focused on extreme heat resilience, a natural continuation of the work of the City to map the urban heat island through a grant with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and this neighborhood plan.

Community engagement included a pilot youth engagement portion, in which Indiana Tech’s National Society of Black Engineers collaborated with the Department of Neighborhoods and Professor Beyeler, head of the Environmental Science & Sustainability Program at Indiana Tech. The students visited the Jennings Center, a community center located in the East Central Neighborhood, and taught the students about extreme heat, did site visits to two parks, and walked the neighborhood. The results of the students’ engagement will be featured in a larger community engagement event in July 2025, in which the East Central Neighborhood will be informed about the risks of extreme heat and asked to provide input on how best to address this climate resiliency issue in their own neighborhood.

The students identified the following primary concerns and opportunities:

Indiana Tech & Jennings Center students identified an increased tree canopy as a major opportunity to reduce heat islands in their community. In particular, they wanted increased tree canopy along major corridors, near and in neighborhood parks, and along streets surrounding the Jennings Center.

Students identified how cooling the pond at Lakeside Park is and identified a desire for a water feature or recreational water infrastructure in their own neighborhood.

“We Love Our Neighborhood”

”In East Central Fort Wayne, I see a vision of growth and responsibility for our youth. To re-create generational wealth while thriving within their own community.

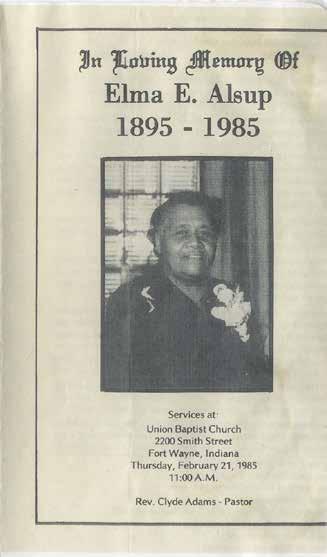

Written By: Connie Haas Zuber, Local Historian, Fort Wayne

Edited By: Logan York, kaakiihsitaakia/ Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, Miami Tribe of Oklahoma

The neighborhood we know as East Central is where the big events of the world have been happening — to the land itself and to the people who live on it — for a very long time.

From geological history, through human history, including precontact history and the years of European colonization, blooming into the ongoing great American experiment, as George Washington called it, what Fort Wayne now knows as East Central was and is a place where things happen, people’s lives are lived, and the world grew and changed into the one we know today.

Three dramatic and significant events frame how the years played out before there was a central Fort Wayne to provide a setting for an East Central Neighborhood.

The first happened as the Ice Age was ending and gives East Central a starring role in how Fort Wayne earned its nickname as The Summit City.

The East Central Neighborhood encompasses within its boundaries evidence of events from more than ten thousand years ago when the last glaciers were melting and receding northeast away from Northeast Indiana.

East Central includes land south of the Maumee River that was beneath Glacial Lake Maumee, the giant lake created 12,000 or so years ago as the last glacier to cover this area retreated and melted before forming Lake Erie. It also includes parts of the Fort Wayne Moraine, the ridge of soil and rocks the glacier pushed before it that formed the wall that held back the lake waters — until it couldn’t

Written By: Connie Haas Zuber | Edited By: Logan York

anymore. Around what is now the confluence of our three rivers, the moraine was overtopped and failed, releasing an unthinkably huge torrent of icy water west toward what is now Huntington. The resulting outflow channel was wide. Maps show the breach in the moraine stretching from a southern edge along what is now the East Wayne/East Berry corridor in East Central to its northern edge almost out to North Side High School. It’s long, too, stretching west past the Eagle Marsh area to Huntington and the Wabash River. The glaciers and outflow left a continental divide that canal surveyors measured, giving Fort Wayne its nickname of Summit City.

Animals and people came here to live as the ice retreated, as they followed the ice toward livable land everywhere on the continent. East Central was high ground, a good place to hunt and make shelter but still conveniently close to the river for water, finding food and transportation, so people would likely have camped or settled here. The archaeological evidence of precontact and European cities in the area of East Central is undiscovered, which is not surprising, given that the city of Fort Wayne was built up over any sites before archaeology became a scientific discipline. When Indiana’s founding scientific archaeologist Dr. Glenn A. Black did his Allen County Archaeological Survey in 1936, he identified sites mostly outside the city limits. His work confirmed that prehistoric and historically familiar native American peoples lived in the county.

Myaamia is the correct spelling of the “Miami,” although often referred to this way, including in our local middle school.

Kiihkayonki is often, even in the City seal, misspelled as Kekionga, and that it is often mistakenly attributed to mean “blackberry patch.” This is according to experts and language speakers at the Myaamia Center at Miami University.

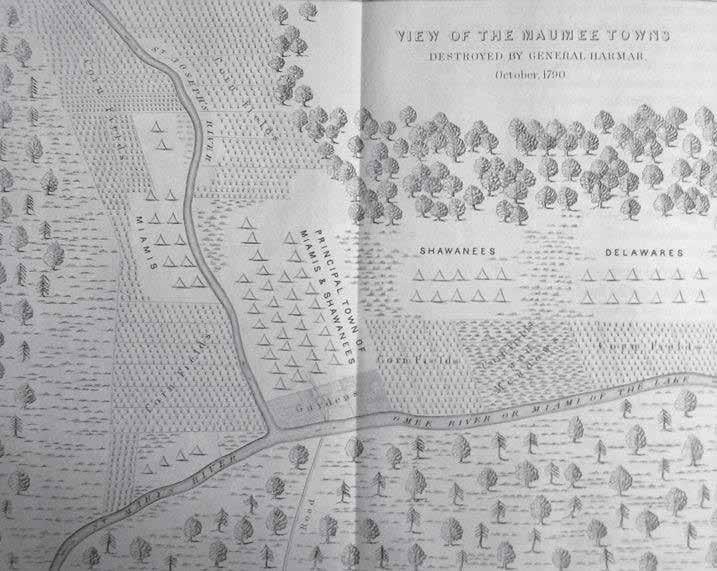

The Myaamia people had been in residence here since early in their history as a people with what became their largest and best-known settlement called Kiihkayonki. Kiihkayonki, on the opposite bank of the Maumee River from East Central, was the heart of a cluster of native settlements at the three rivers and in this area during historical times. Though none of the settlements were centered in East Central, people lived in the area. The area was the home of native peoples in agrarian permanent villages for 1,000 years before European contact.

The portage was owned by the Myaamia people, specifically one person named Tacumwah.

Northwest Confederacy is often incorrectly referred to as the “Miami Confederacy,” because these were Miami homelands, but other tribes were also in the area. The Confederacy was co-led by Little Turtle (Mihšihkinaahkwa), Blue Jacket, and Buckongehelas. It is referred to as “Taawaawa siipiiwi alliance” by the Myaamia today.

During the era of contact with Europeans, which began in the late 1600s, French missionaries, soldiers and fur trappers were the first Europeans to be active here. The portage between the Maumee River and the Little River in southwest Allen County (which leads to the Wabash and on to the Mississippi) created by the glacial torrent was a key link for the French between their North American footholds in Quebec and Louisiana. Once the French, who ceded their control of this area to

the British after a war, and then the British, who lost the Revolutionary War to the American colonists, ceded their control, the Americans invaded and claimed the lands previously occupied by the Northwest Confederacy. In 1790, when American troops invaded Kiihkayonki, it was a large and cosmopolitan native city with many hundreds if not thousands of residents, well supplied with crops from its fertile fields along the rivers and at the center of a network of communication links.

East Central became part of the site of the 1790 attack on Kiihkayonki by U.S. Gen. Josiah Harmar, who sent four companies into battle through East Central into Kiihkayonki only to be decisively beaten by the natives led by Little Turtle. The surviving Americans, who lost 183 soldiers that day, retreated as they had attacked, through the forest of East Central.

The outcome four years later was very different. Gen. Anthony Wayne had won the Battle of Fallen Timbers near Maumee, Ohio, and he marched his troops toward Kiihkayonki but chose the higher land of East Central to build a fort. Kiihkayonki still existed across the rivers. He dedicated the first Fort Wayne, which was built in East Central at what is now the corner of Clay and Berry Streets, purposely on the fourth anniversary of Harmar’s defeat, well aware of the symbolism of the date and its location across the river from Kiihkayonki. The battle of Fallen Timbers was waged, this one with roughly 500 Native troops and 2,000 American troops present. 84 men died, 44 of whom were Americans. The British troops, which had previously supported and promised to support the Native troops, locked the retreating Native troops out of the British fort. When the Northwest Confederacy (Taawaawa siipiiwi alliance) realized that they no longer had British support against the invading American troops, they concluded that they could not win the war and the confederacy broke. Later, the Myaamia surrendered at the Treaty of Greenville.

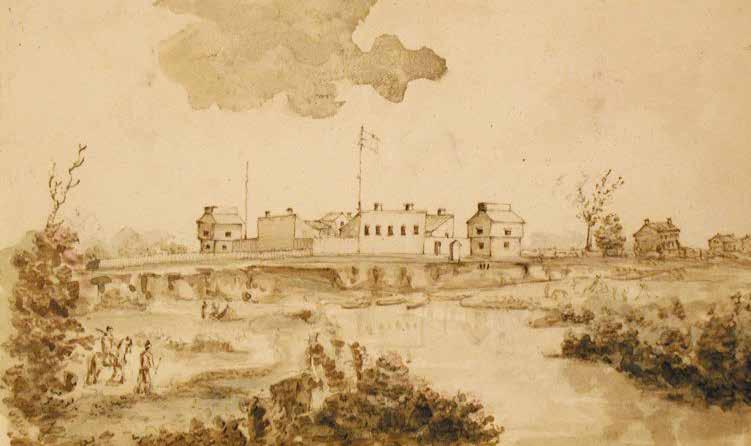

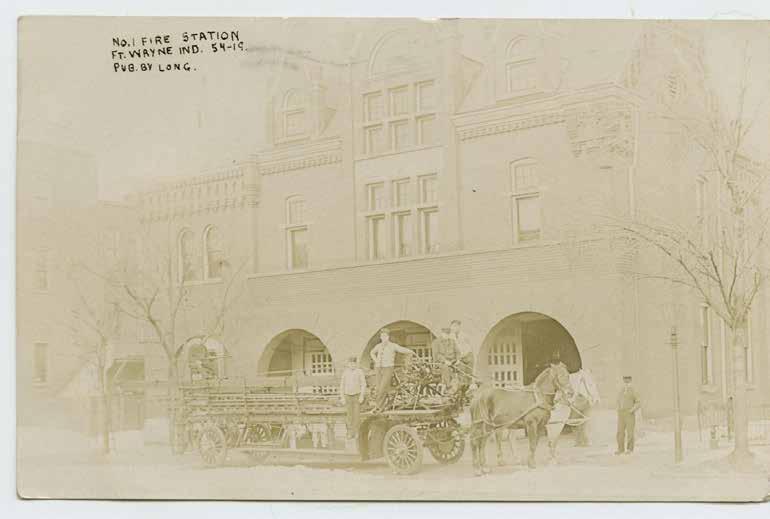

The second and third Forts Wayne, built to replace the hastily built and decaying original, were also built in East Central in the area of what is now Old Fort Park, directly next to current Fire Station 1, at the northwest corner of E Main Street and Clay Street. The final 1815 fort was decommissioned in 1819.

Current day Harmar Street is a reference back to the history of Harmar’s Defeat, and the Coombs Street bridge crosses the Maumee at Harmar’s Ford.

The forts changed the East Central landscape because the American military not only felled trees to build them, but it also cleared a large area around its forts for a clear view of approaching friends or foes and a good field of fire. About four square miles were cleared around the 1815 fort. The clearing provided a striking view of the beautiful and promising place the Americans had won control of after the Native peoples had fought for nearly 200 years to protect their homeland from the invasion and wars following the arrival of the French, the British, and finally the Americans.

The process of change from a Native village to a military outpost to a city began slowly, given the location’s isolation and distant connections

Written By: Connie Haas Zuber | Edited By: Logan York

to even the nearest European settlements. The wheels of change began to spin in the 1820s and accelerated in the 1830s when the roots of East Central were planted. Federal regulations that made land sales possible had been established, and Allen County was created in 1823, the same year land was bought and platted as the Original Plat of Fort Wayne. Plats define streets, alleys, and lots on undeveloped land as a necessary first step to selling and building on it.

By 1825, after being home to thousands of people when a Native settlement, Fort Wayne had not quite 200 permanent White residents. Their first

In 1780, French officer Augustin de La Balme led a raid on the Myaamia town of Kiihkayonki, seizing British supplies and briefly occupying the settlement under the French flag. La Balme left a small detachment to guard the captured supplies in Kiihkayonki, and marched his main force toward the Eel River. La Balme was ambushed on November 5, 1780, by Myaamia warriors led by Little Turtle. The Myaamia surrounded and overwhelmed the Frenchled troops, killing most of them—including La Balme—and dismantling the expedition in a swift and decisive defeat.

George Rogers Clark’s campaigns in the area referred to as the Northwest during the late 1770s and 1780s aimed to weaken British influence and secure American claims to the region, resulting in key victories for the Americans such as the capture of Fort Sackville. Though Clark achieved early victories, in 1786, Clark was ordered to lead an expedition to capture the Myaamia village of Kiihkayonki. As the troops faced severe supply shortages and a mutiny broke out, Clark abandoned the campaign and retreated.

In 1791, U.S. Governor Arthur St. Clair led a military campaign to assert control over Kiihkayonki, advancing from Fort Washington to the Wabash River near Myaamia villages. On November 4, Native forces led by Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, and Buckongahelas decisively defeated St. Clair’s army in what became the most devastating loss in U.S. military history to Native American forces.

Fort Wayne, 1816, by Major Francis

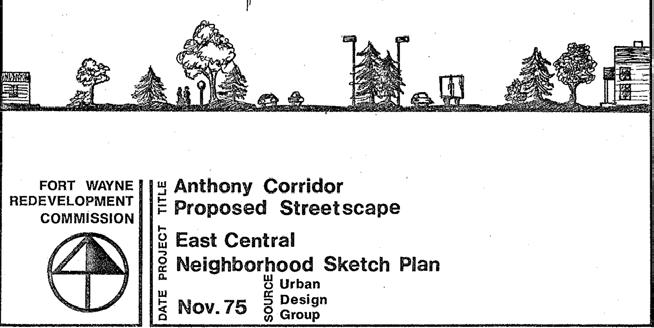

Historic Fort Wayne civic interest was the Wabash-Erie Canal, which ran through East Central along the south bank of the Maumee River. After several years of discussion, politicking and arranging of finances, construction began in 1832.

The Original Plat only went as far east as Barr Street, but the second and third plats added to the east side of the new town and are now part of East Central. Fort Wayne welcomed its second plat, the County Addition (two blocks either side of Lafayette from Superior to Berry Street) in 1830 and Taber’s Addition (along the canal where Main, Berry, Clay and Monroe Streets dead-ended into it), in 1835.

In 1837, Samuel Hanna, an East Central resident who was a part of every important development in the town’s formative years and who made a considerable part of his fortune as a land speculator and developer, began platting and developing the east side on a large scale. In a series of plats, he laid out lots, alleys, and streets stretching from Calhoun Street south of the existing plats all the way east to Harmar Street, north up to the Maumee River, and as far south as Lewis Street. His own estate was where Hanna Homestead Park is today. He also platted land he owned south of Lewis Street and in other parts of Fort Wayne, but nowhere is his footprint as large as in East Central.

Kentucky-born Hanna, who arrived here from Ohio in 1819, is recognized for his work as a civic leader, elected official and circuit court judge, as well as an active entrepreneur who saw to it that land was developed and plank roads, then the canal and then the railroads were built to connect Fort Wayne with the world. He should also be remembered for the start he gave to the East Central neighborhood. He died in 1866, leaving his heirs to plat even more of the neighborhood and city.

Hanna singlehandedly platted more lots in his first plat than there were people in Fort Wayne at the time, and that was after the County and Taber additions had added 100 other lots. None of the plats were misguided, though. By 1840, when the town of Fort Wayne upped its official status to city, the population had exploded to 2,000. Houses were lining the new streets of East Central as far east as Harmar Street and as far south as Lewis Street, and businesses were in place conveniently close to the canal.

The canal was driving the early growth of the city and the neighborhood, attracting both residents and businesses. Hanna wasn’t the only person of civic renown to live in East Central in its early years. Thomas Tigar, editor of the city’s first newspaper,

lived on Berry between Clay and Canal streets. F. Perry Randall’s handsome mansion with its impressive gardens was at the northeast corner of Wayne and Lafayette streets. Randall came to Fort Wayne in 1838 and served multiple terms as mayor.

The story of longtime Madison Street resident Henry C. Niemeyer is a good example of how East Central grew. Born in Germany in 1816, he emigrated to the US in 1836 and joined other German immigrants to help build the canal when the section from Fort Wayne to Huntington was under construction. His 1904 obituary in the Fort Wayne Weekly JournalGazette notes that he saved his earnings and bought a farm in Adams Township. An 1860 plat map shows 40 acres in the township’s southwest corner owned by him. By 1878, though, those 40 acres belonged to the adjoining farm. Henry had moved into town.

His obituary says he spent time as a canal boat captain and became a teamster when the canal business faded and railroads took over. The first city directory is dated 1858, and the earliest city directory listing that includes him is 1860, when he is listed as a teamster living at 157 Madison Street, which is probably the house to the east of what is now 705 after the addressing of city properties was changed in 1902. He and his wife Caroline (they married in 1849) stayed on Madison Street through years of his work as a teamster, with occasional listings showing him working for local lime, stone, and cement yards or lumber yards along the canal. His address changed in 1872 to 153 Madison Street (now 705 after the addressing change in 1902), which is likely when he and Caroline built the Italianate brick 705 Madison Street and moved their growing family into it. According to the 1880 Census, they had four sons and two daughters, the youngest of whom was 6 in 1880.

Caroline died in 1901, followed by Henry in 1904, after which their youngest son Ernest raised his family in the home. Ernest, a salesman for the George DeWald Company, and his wife Louise were still listed as living there in the 1950 city directory, though by 1952 their son Ernest Jr. was listed as living with them. Ernest died in 1953. In 1954, Ernest Jr. and Louise were still on Madison Street, but the 1956 city directory has them moved out of the neighborhood onto Lake Avenue. The stately brick Italianate house at 705 Madison Street was in the Niemeyer family for more than 80 years. Several other brick Italianate homes very similar to 705 are

Written By: Connie Haas Zuber | Edited By: Logan York

in the few blocks nearby. Any one of them could have an equally compelling story.

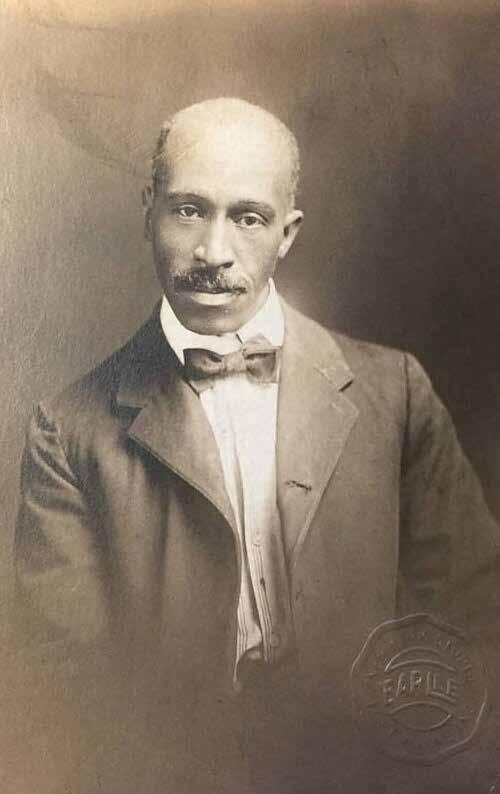

The story of the early years of Fort Wayne’s free black community, centered in the Hanna’s First Addition area of East Central, shows how Indiana’s ban on slavery and then the federal Fugitive Slave Act affected where free black people chose to live. Black people had lived in the Fort Wayne area since colonial times, with connections to other free black settlements in other counties and states. By 1850, the number of black or multi-racial residents in Wayne Township had increased from 14 in 1840 to 81. An 1831 state law required “colored persons” to post a bond of $500 as a guarantee against becoming public charge and as a pledge of good behavior, but it was rarely enforced. The free blacks who came to Fort Wayne ranged from illiterate, hard-working farmers to skilled tradesmen who ran successful businesses and owned property and whose whole families were educated and literate.

Several of the families were active in the Fort Wayne free black community in the 1840s and 1850s, contributing to the formation of the Turner Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1849, the first of more than 100 black congregations formed here. The Turner Chapel Church has always been in East Central. But the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and tensions that led to the Civil War were making a difference in Indiana, which saw an overall decline in its free black population through the Civil War. Allen County’s decline was among the most dramatic, with the population falling to 37 by 1870. Many of the families had moved on to more welcoming places. George Fisher lived out his life here, dying in 1884 as an “esteemed citizen,” according to a news story announcing his death in the October 23 Journal Gazette. He had moved to Fort Wayne in 1846 and attracted the notice of Judge Samuel Hanna, who appreciated his intellect and gave him a lot in East Central for his home and helped him establish his plastering business. Fisher’s obituary recounted his role in the establishment of Turner Chapel and praised his philanthropic work in the community.

The purchase of a large estate to establish Concordia College by St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, founded in 1837 and soon located on Barr Street at the west end of Madison Street, may have accelerated East Central’s eastward development. The church bought “Woodlawn,” the country estate of Col. Marshall S. Wines in 1848. In

1860, Chute’s Homestead Addition was platted south of Maumee Road along Division, Walnut, Ohio and Elm streets. In 1863, Comparet’s Addition was platted from Harmar to University Street west of the university grounds north of Maumee Road. The College Addition was platted in 1864 north of Maumee Road along College and Walton (now Anthony) to Wayne Street.

East Central also claims a series of firsts and important founding for the City of Fort Wayne:

1848: City’s first telegraph line between Toledo and Evansville follows the canal route through town.

1848: St. Mary’s Catholic Church founded on Lafayette Street south of Jefferson Street.

1852: The city’s first railroad locomotive is unloaded from a canal boat at the north end of Lafayette and placed on tracks laid down Lafayette to deliver it to the railroad being built on the south edge of East Central. Those tracks were in place until 1857.

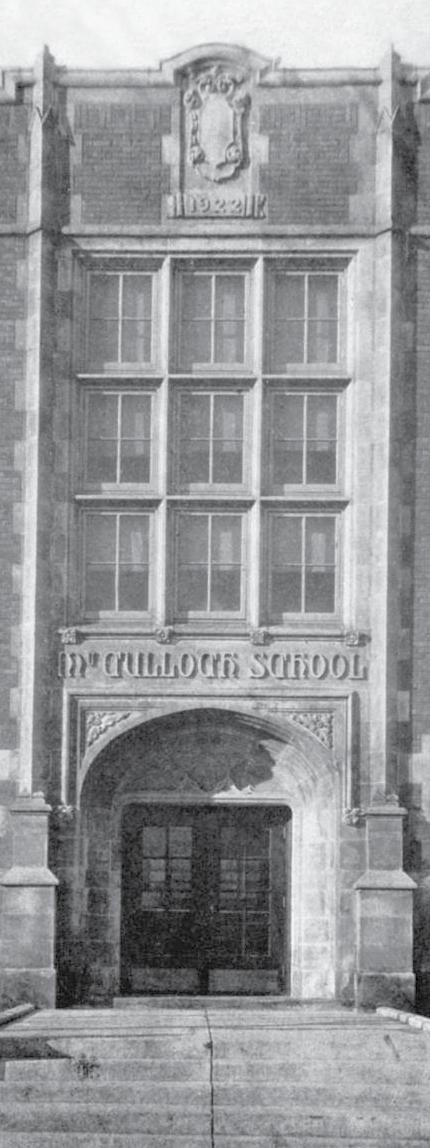

1853: The city’s first public school established on the east side of Lafayette between Main and Berry in the old McJunkin school building. A west-side school opened at the same time at Wayne and Ewing streets. The next school to open, Clay School at Clay and Washington, was in 1857.

1856: The Wabash Railway is completed through Fort Wayne — and East Central — to Lafayette.

1857: The beginnings of the famous Pennsylvania Railroad shops at Lafayette and the Pennsy tracks are dated to this year when the Fort Wayne firm of Jones, Bass & Co. sold its foundry and machine shops to the Pennsylvania Railroad.

1860: Maj. Samuel Lewis filed the first plat in Fort Wayne that has the north-south streets running true north and south instead at the angle of the original downtown streets, which were already established when the Original Plat was drawn. The Lewis Addition goes south from Lewis Street between Lafayette and Hanna to Lasselle Street.

1863: Old Fort Park, at the northwest corner of Clay Street and East Main Street becomes Fort Wayne’s first public park.

The Civil War dominated the nation, Indiana, and

Fort Wayne from April 1861 through April 1965, when the Union defeated the Confederacy. Fort Wayne entered the war years with many demonstrations of support for the Union cause, but the city and area had significant numbers of supporters for the Confederacy too, and the federal draft was very unpopular. However, the city’s transportation and manufacturing resources gave it a valued role in the war effort and brought money into the local economy.

Historians remember the Civil War as the turning point in Fort Wayne’s history from town, with the familiar “small town” hallmarks, to city, with the city-style bustle, hustle and more impersonal ways of getting things done. In East Central, those turning point changes matured the neighborhood from a place that was filling out with homes and related businesses to a magnet for commerce and industry. The neighborhood’s residential heart persisted and filled out, but along the railway lines on the north and south borders of East Central, large commercial and industrial concerns dominated the landscape. By the land-use logic of the day, the people who lived in the heart of the neighborhood then had an easy walk to work in any of the industries.

From the late 1860s until the 1910s, developers continued to file generally smaller plats for residential subdivisions, preparing the last available areas in East Central for building homes. The exception was the large Eliza Hanna Seniors Addition of 1873, which added 250 lots in an area bounded by Lewis Street on the north, both sides of Harmar and Ohio streets on the west and east, and a railroad track on the south. Neighborhood commercial development followed the plats all over the neighborhood, with grocery stores, bakeries, butcher shops, beauty salons, barber shops, churches, and public schools dotting the East Central streets. Harmar Elementary School opened at Harmar and East Jefferson in 1866. Maumee Road became a commercial strip, as did Lafayette Street. Hanna, Washington, Jefferson, Wayne and Lewis were the second tier of commercial streets, remaining mostly residential.

Four East Central properties protected as Local Historic Districts date from this period of neighborhood residential and commercial development.

Jesse and Ione White House, a gabled ell cottage built c. 1890 at 1223 Summit St. Protected for its

connection with the 20th Century life and work of the Rev. White, who was a significant local civil rights leader also known and respected more widely.

Bostick-Keim House, a Queen Anne home built 1888 at 429 E. Wayne St. Protected for its intact architecture and connection to Fort Wayne’s commercial history through builders John and Louisa Bostick. John had a successful business as a second-generation merchant tailor. After the Bosticks, the Keim family owned the house for more than 70 years.

Moellering Building, a Queen Anne/Neoclassical commercial warehouse built c. 1889 at 1301-1309 S. Lafayette St. Protected for how it embodies its architectural style and for how it represents the development of the city as an example of the Moellering Company’s brick and stone company’s expertise and quality products. It was built by Henry Wehrenberg’s company.

Doubleday Building, a Craftsman commercial building built 1916 at 437-441 E. Berry St. Protected for how it demonstrates the environment in an era of the city’s development characterized by builders’ and developers’ use of this architectural style. Its historical name is the Western Newspaper Union Building, and it is now known as the Hall Arts Center, owned by Arts United.

The dominant change, though, was the arrival of industries, which no longer were focused on the downtown canal landings. They were taking

Bostick-Keim House City Historic Preservation Office

Written By: Connie Haas Zuber | Edited By: Logan York

advantage of the miles of railroad access on the north and south boundaries of East Central. The change did not happen overnight, but it did proceed steadily. The Sanborn Fire Insurance Company maps provide a good guide to the changes.

In 1885, the maps show four big industries present along the tracks on the north side of East Central stretching from Clay to Schick streets. They include a furniture factory, a box factory, a cooperage manufacturer and the City Carriage Works. The 1890 maps show five in roughly the same area: the cooperage manufacturer, one designated simply “manufacturing,” a heavy hardware warehouse, a pipe and supply company, and a bottling works.

By 1902, the industrial development has spread out to the east and south in East Central. The north area has added a washing machine manufacturer, a shirtwaist factory, a box factory, a woodworking company, a mattress factory, Wayne Oil Tank Company, a large greenhouse, and a cigar factory. To the east but still along the northern band of tracks, the maps show a mattress factory, a sawmill and box factory, a foundry, a handle company, and a leather and heel company in the still-industrial area near the Coombs Street bridge. Along the neighborhood’s south band of railroad tracks are a coal and wood yard, a warehouse, a novelty company, a plaster company, an ice cream factory, a wholesale grocery warehouse, and a contractor in addition to the Pennsylvania Railroad shops. A blacksmith and wagon shop is listed on Maumee Road along with the more traditionally neighborhood commercial shops.

In 1918, the north area has added a broom factory, and the Coombs Street area has added a warehouse and the Maumee Valley Coal Company. Wayne Oil Tank and Pump Company, the major local company that was founded downtown in East Central in 1887, has moved to a larger property also in East Central. To the east along the northern tracks, Henry Franke’s wood products company, a junkyard, an ice company, a lumber yard, and a sawmill had joined the existing businesses. Along the south tracks in 1918 were a grocery warehouse, the machine shop for the Bowser pump company, an oil company distribution facility, a lumberyard and planing facility, Fort Wayne Building Supply, W.K. Noble Machine Co., and the fully built-out Pennsylvania Railroad shops, stretching from Lafayette to Francis streets along the tracks, which had been elevated over Lafayette and Hanna

streets in a project co-funded by the Pennsylvania and Wabash railroads and city beginning in 1910.

Wayne Oil Tank, later and better known as Wayne Pump, was part of a trio of Fort Wayne companies that made this city a center of pump manufacturing for the nation. The others were Bowser Pump, located further south on Creighton Avenue, and

Moellering Building

City Historic Preservation Office

Tokheim, the last to be incorporated, located east of Anthony Boulevard near its intersection with New Haven Avenue. Wayne Pump’s engineers invented the machinery that measured and displayed the cost of the fuel pumped as well as the quantity, but the company found it needed to convince the marketplace that this was a useful function. It hired local agency Bonsib Advertising who coined the catchphrase “Fill ’er up!” and developed a marketing plan that worked. The new pump was a success.

Doubleday Building

City Historic Preservation Office

The option to walk to work was both necessary and welcome at this time, even once two different trolley bus lines ran east-west through East Central on Main Street, Washington Boulevard and Lewis Street beginning in the 1870s. But not all industry is welcome as a neighbor. It was the noise, smoke, and dirtiness of industry that triggered the development of Fort Wayne’s first suburbs, northeast in Lakeside and south in Williams Woodland and South Wayne, after the Civil War and into the Gilded Age. The people who kept on living in the city neighborhoods had to deal not only with furniture and pump manufacturers but also foundries and, worst of all, stockyards, meat packers, and fertilizer plants. East Central had some of each. Stockyards were along both the north and south railroad lines. In 1922, East Central residents undoubtedly sided with their East Side neighbors further east and helped pack a City Council public hearing fighting the establishment of yet another stockyard on Roy Street. In 1906, East Central citizens were pressuring the city to close the Bash Fertilizer plant, part of the Bash Packing Co. facility just north of the Nickel Plate tracks at the north end of Hanover Street. The company had already been fined for creating a nuisance several times, according to newspaper reports, so the council formed a special committee of two council members, the mayor, and a board of health representative to go check for themselves.

“The stench drove us away,” one of the councilmen reported. The property is marked as “Vacant except for storage” 12 years later on the 1918 Sanborn map.

East Central underwent other changes after the Civil War also.

The changing number of stables indicates the neighborhood’s growth and then a different kind of neighborhood being built. Sanborn maps indicate stables on lots, so stables can be counted. In 1890, East Central had 312 stables, nearly all of them behind residences. The neighborhood had grown by 1902 and had 387 stables — and a livery. But in 1918 the number of stables had fallen to 212 as many former stables had become either garages for cars or residences along alleys. By 1918, new neighborhoods were not being built with stables.

The neighborhood’s black population also began to rebound as hard times in the South and the hope for manufacturing jobs in a city pushed black Southerners north. In the South, 80 percent of black people were sharecropper farmers. The economic depressions of the 1870s and 1890s forced tens of

thousands of farmers off the land, followed by years of crop failures in the 1910s. The South’s Jim Crow laws institutionalized discrimination, and the active Ku Klux Klan terrorized black people, with black men lynched in the South an average of two per week from 1880 to 1910. In addition, laborers were needed in the North, where black workers were used to break strikes and to meet the needs of World War I production. Fort Wayne’s black population doubled from 1900 to 1910, reaching 572, which was still less than 1 percent of the city’s total population.

The earliest arrivals found Fort Wayne offered an imperfect but real freedom to live wherever they could afford to and to take whatever job they could find, according to local people interviewed.