In partnership with The City of Coffs Harbour and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service,

In partnership with The City of Coffs Harbour and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service,

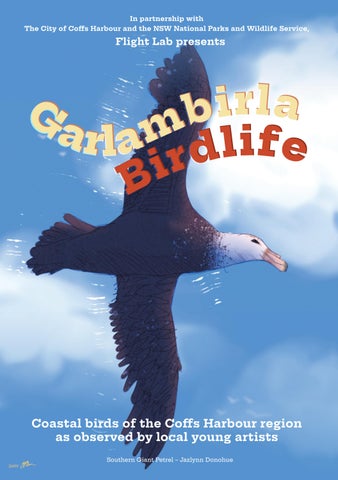

Flight Lab presents Coastal birds of the Coffs Harbour region as observed by local young artists

T he City ofCofsHarbour and NSW

lanoitidart htfosnaidotsuc e ldna , t h e Gumbaynggirrpeople, who have caredfor thi s l a n d s ecni

eW tcepserruoyap s t o t heir elders,past, present andemerging , a n d sevlesruotimmoc ot a erutuf htiw er c o nciliationand renewalatitsh ear

Globally recognised and certified as New South Wales’ first ECO Destination, people come from around the world to enjoy Cofs Coasts’ particular patch of nature’s beauty.

Nestled between the subtropical seas of the Pacific Ocean and the forested foothills of the Great Dividing Range, we have an abundance of natural treasures, including rainforests, coastal forests, wetlands, estuaries, and ocean sanctuaries.

The traditional custodians of the Cofs Harbour region are the Gumbaynggirr people, who have occupied this land for thousands of years.

The Gumbaynggirr Nation forms one of the largest coastal Aboriginal Nations in NSW, and stretches from the Nambucca Valley in the south to around the Clarence River in the north and the Great Dividing Range in the west.

‘Garlambirla’ is the Gumbaynggirr word for Cofs Harbour. It is also the name of one of the six clan groups on Gumbaynggirr country –Bagawa, Garby, Garlambirla, Yurrunga, Ngambaga and Gambalamam.

Whilst we flourish from the many visitors to our special shores, we must ensure that we also protect our most vulnerable inhabitants who cannot protect themselves.

Many wildlife species are threatened, particularly our unique coastal birds with whom we share our shores. We can work together to protect their future and ours, keeping the Coffs Coast a natural haven that allows us all to thrive.

Birds inspire us

Birds enchant us with their vibrant displays of movement, colour, and song. Birdsong at dawn gives hope to the day. An elegant spread of wings draws our minds to flight and far horizons. Songs beckon, cries warn, eggs delight, plumage wows, a feather floats.

They invite us to pause and appreciate life’s beauty as it irresistibly happens in vivid detail all around us

Birds support us

Birds are more than just beautiful creatures. They work tirelessly as pollinators, seed dispersers and pest controllers to keep nature humming along. Our feathered friends underpin the health of our ecosystems, agriculture, and environment, enriching the quality of our lives.

They remind us we work best when we work in harmony with our environment

Birds need us... almost as much as we need them!

Birds, like all creatures we share this planet with, are greatly affected by human activities such as climate change, fires, habitat disturbances and loss, and predation from introduced species like foxes, cats, and dogs.

Let’s give the most vulnerable of our feathered friends an extra helping hand to keep them safe from harm.

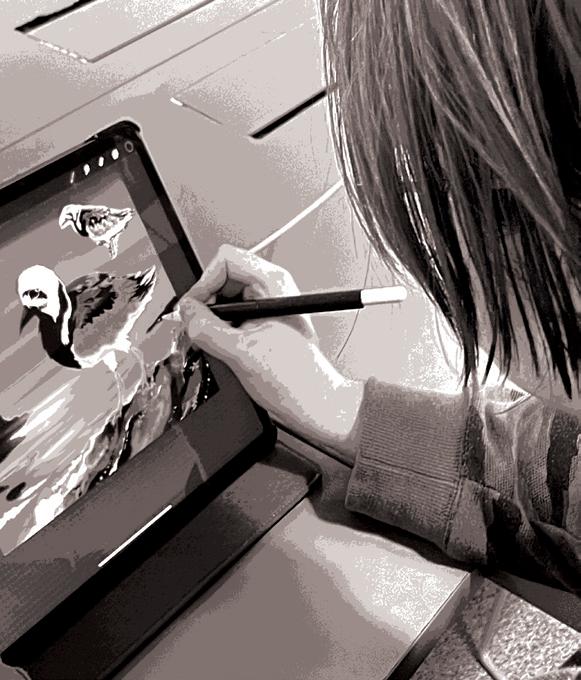

In 2024, 22 young local artists and budding scientists aged 12 to 23 came together for a Sustainable Living program developed by the City of Coffs Harbour (CHCC) and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). Flight Lab: Young Minds in Action combines citizen science and creative new media to raise awareness about protecting local bird species and their environment.

Young minds in action

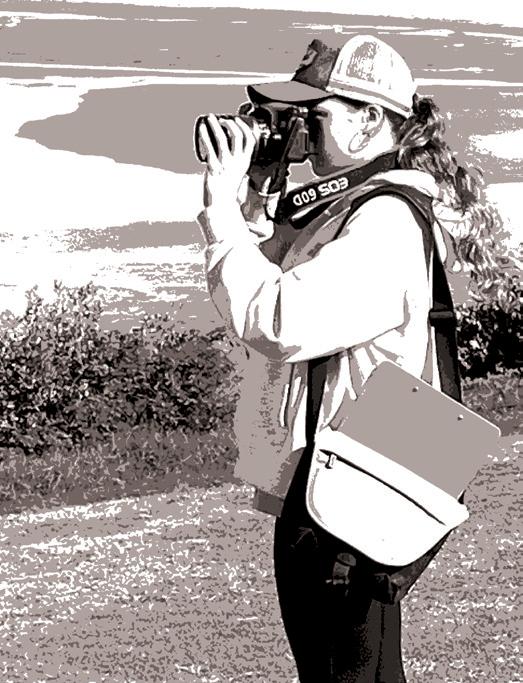

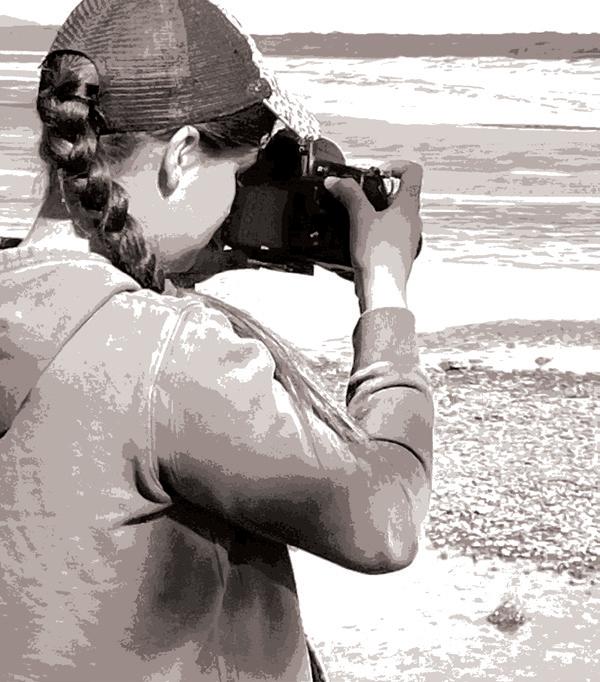

Flight Lab captured the everyday magic of coastal birdlife through field trips, expert guidance, research and creative expression through mixed media techniques.

Armed with binoculars, cameras, art materials and a passion for making a difference, crew members explored the world of local bird species, uncovering the intricate details of their lifecycles, habitats, and daily struggles.

Venturing into the field with an NPWS Discovery Ranger and local creatives, the crew explored significant coastal bird habitats in the local area, including Sawtell, Woolgoolga, and Coffs Harbour.

Garlambirla Birdlife, Vol. 1

The result of their efforts is this extraordinary volume full of vibrant artworks and the latest conservation facts. This youth-led creation is a heartfelt gift to the local community helping us all become more aware of the precious birds of the Coffs Coast and how we can help protect them for future generations.

Leave no bird behind!

Flight Lab crew

Alex Accadia

Alice McKeon

Amelie Anders

Amelie Ferreira

Annie McMahon

Asha Foran

Charlotte Maunder

Eden Bradley

Eleanor Frost

The birds in this book are special helpers for nature. When we take care of them, we’re also looking after many other animals, plants, and the wild places they call home –like sandy beaches, salty wetlands, and grassy dunes. It’s a bit like opening a big, colourful umbrella. When it opens, it doesn’t just cover one little bird – it keeps a crowd of creatures, great and small, safe and happy underneath. So when we help one special creature, we’re helping them all!

Together, we can treasure and protect our natural wonders.

Jasper Ruigrok

Jazlynn Donohue

Jessie-Rose Bennett

Kane O’Dell-Walder

Lacey Elliott

Lani Parsons

Maddy Gagnon

Maggie Browne

Miranda Mitchell

Paige Sutton

Portia Brazier

Rani Foran

Sabriya Harrison

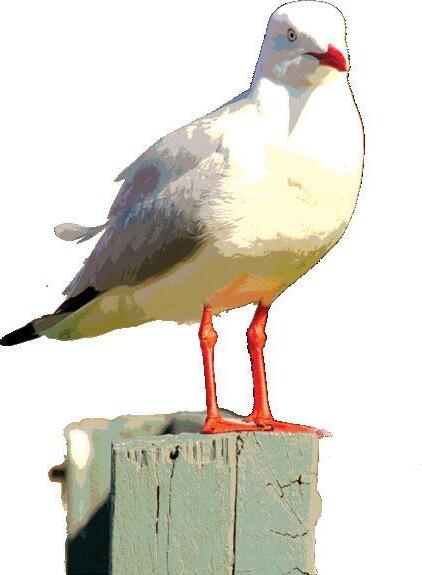

About 85% of Australians live on the coast, placing huge pressure on our shorelines.

Beach-nesting birds are some of the most threatened birds in Australia, as they struggle to find undisturbed spaces on our coastlines to nest. Breeding shorebirds often create shallow sand scrapes to lay their precious eggs. Unfortunately, this exposes them to egg and chick predation and accidental destruction from dogs, beachgoers and vehicles.

Help look after our coastal areas so native birds can thrive and be here for generations to come.

We can all enjoy the beach and support the well-being of our local sea and shorebirds to enhance the coastal experience for everyone.

Take the ‘Share the Shore’ pledge * to protect our threatened local shorebirds:

Sooty Oystercatcher

Local beach-nesting bird species listed as endangered or vulnerable to extinction in NSW or nationally include:

Threatened shorebirds nest on our beaches from August to March (late winter to early autumn) each year.

It’s vital that they have a safe space to lay eggs and raise their chicks. Please help them have successful breeding seasons by considering their wellbeing when you visit the beach.

; Read and respect signage and check for fenced-off nesting areas on the beach

; Ensure dogs are only walked on an approved dog beach and always kept on a leash

; Only drive on 4WD beaches and follow beach-driving rules, including staying out of nesting areas and driving on the wet sand (dry sand is where birds nest)

; Take fishing lines and rubbish with you

; Give the birds space – share the shore *

; Join a local community group or organisation that fosters conservation efforts in your area or be a part of a citizen science project like this one

; Spread the word about how to help our birds

* Scan the QR to learn more about the ‘Share the Shore’ pledge and how you can help our endangered beach-nesting birds have a successful breeding season.

AUS CONSERVATION STATUS CRITICALLY ENDANGERED

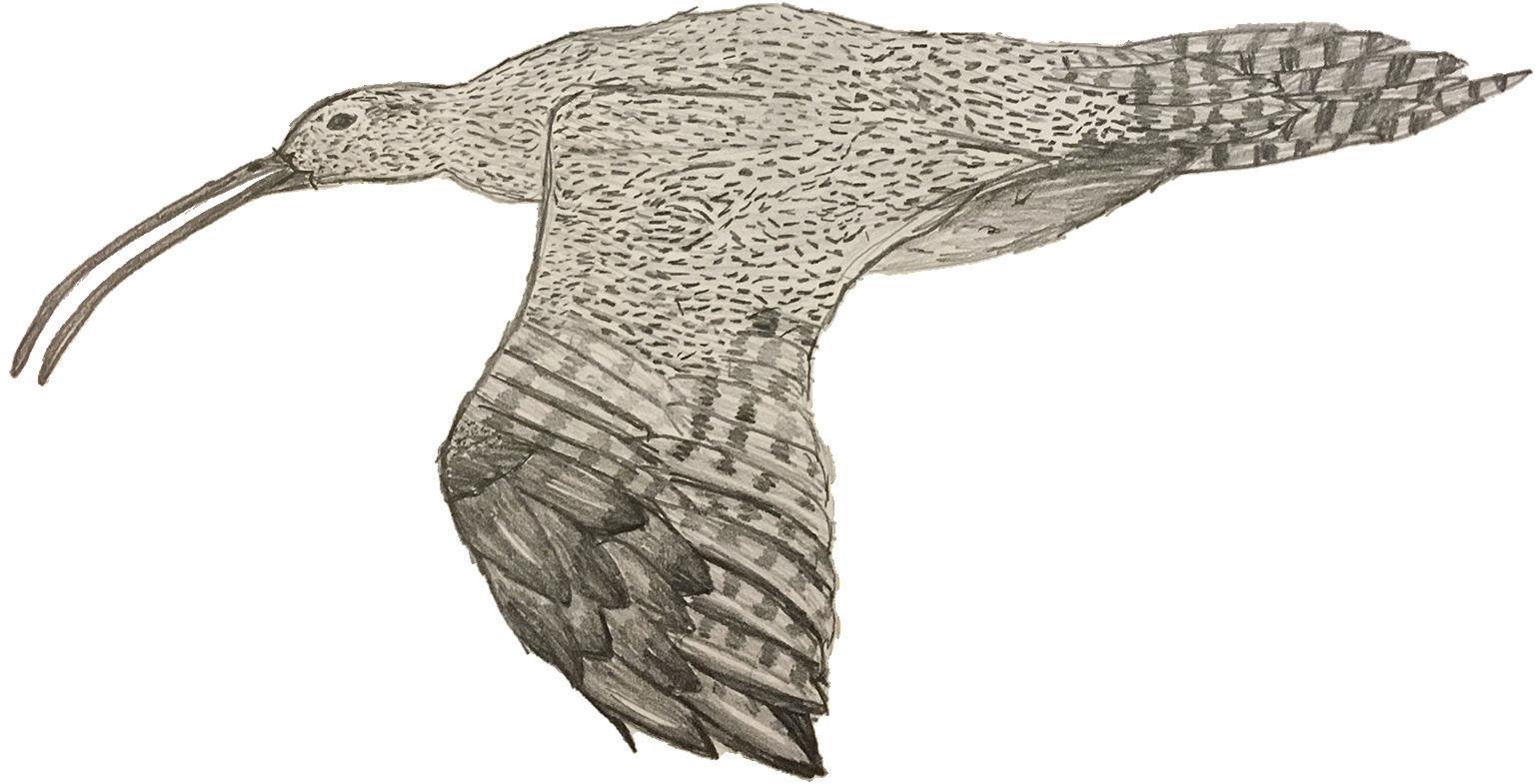

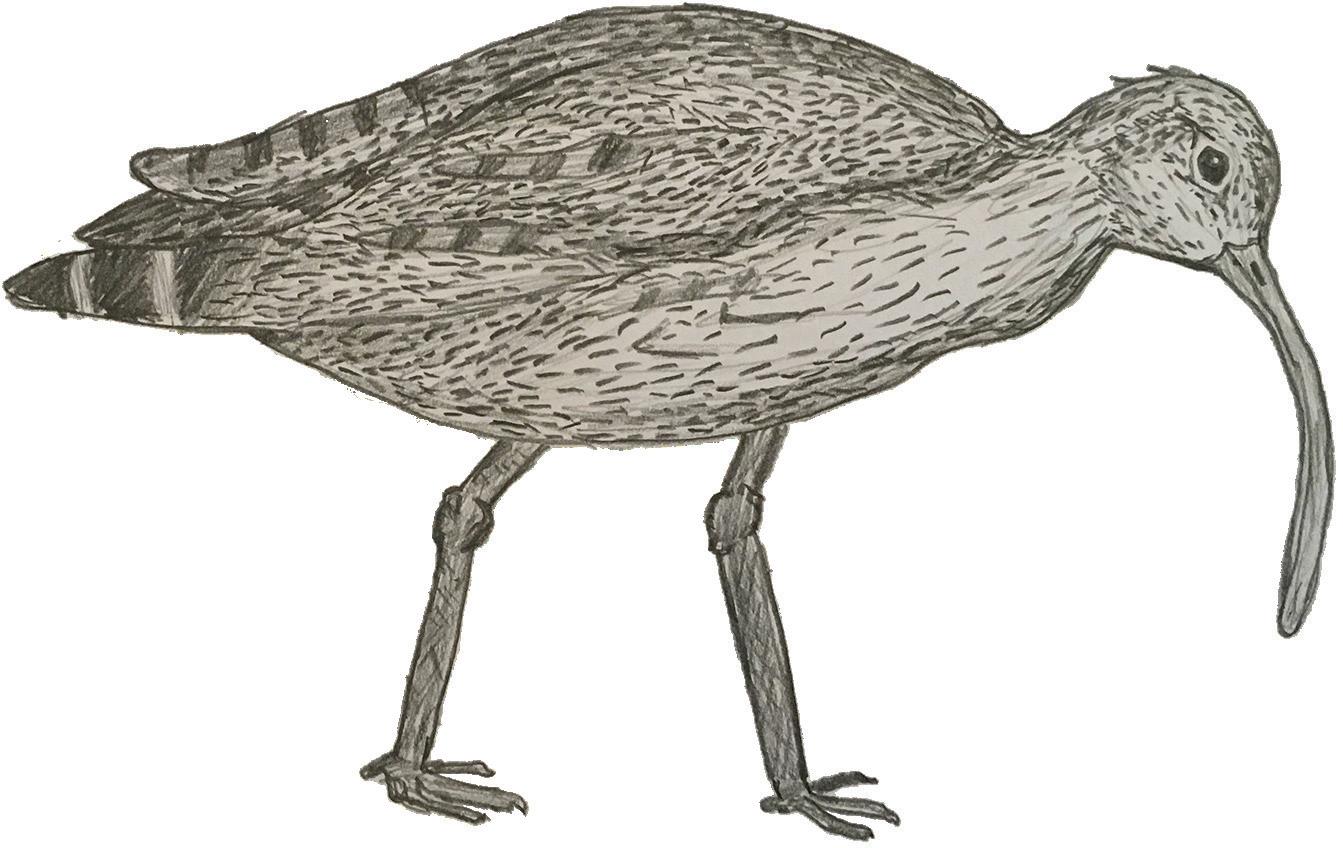

The remarkable Eastern Curlew, a large migratory wader, embarks on an epic journey of 12,000 km from the Australian coast to northern China and Russia to breed.

They can fly non-stop for up to 12 hours during this incredible feat of migration

Global populations have declined by about 80% in the last 30 years

During their long journey across continents, they face many threats, including habitat loss due to coastal development, human disturbance, illegal hunting, climate change and extreme weather, and predation by dogs, cats and foxes.

Residential and industrial development, beach-combing disturbances, and 4WD vehicles have significantly contributed to the decline of this species in NSW.

About 75% of the world’s population of Eastern Curlews stops over down under Imagine the relief an exhausted curlew must feel when, after flying half-way around the Earth, it finally touches down on a mudflat along the north coast to rest and feed.

Community conservation efforts are crucial for the survival of these remarkable migrants. Let’s make room for them, share the shore and thrive together this summer.

The Eastern Curlew’s unique and haunting call, often heard during its breeding season, is essential for communicating with mates and establishing territory.

Esacus magnirostris, aka Beach thick-knee

NSW CONSERVATION STATUS CRITICALLY ENDANGERED

These days, you’ll be lucky to catch a glimpse of this striking large shorebird, as it is in severe decline in NSW. At last count, only 15 breeding pairs remain.

Look out for them on our coastline

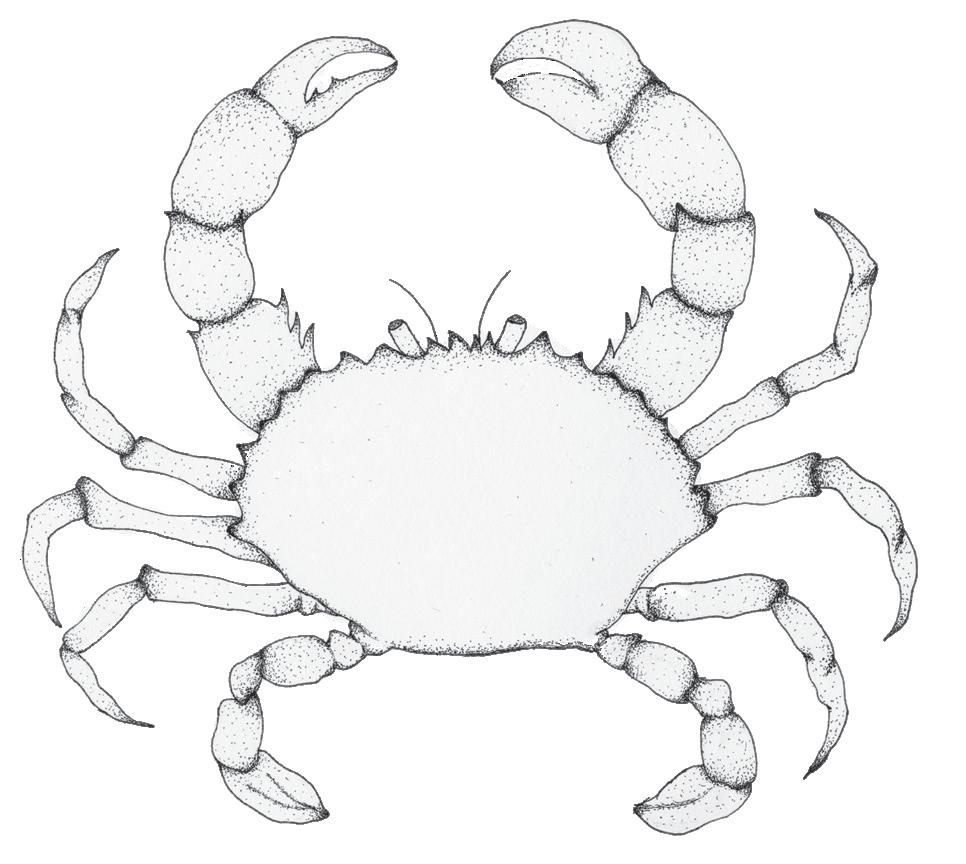

Beach Stone-curlews hammer crabs open with their bills and sometimes wash them before swallowing.

These rarely seen birds are mainly active at dawn, dusk and night. Breeding birds call at night with a harsh, wailing ‘weer-loo’. Scan the QR to listen.

Residential and industrial development,

This rare and iconic shorebird has distinctive patterned markings, a large bill and ‘thick knees’. Usually seen alone or in pairs, Beach Stone-curlews mate for life, returning to a handful of precious coastal nesting sites every year. Nests are typically found at the backs of beaches, on sandbanks and islands, or among open mangroves.

Only 4–6 pairs breed each summer in NSW

Breeding season runs from October to March. Each clutch contains only one chick, and both parents are responsible for defending the nest and caring for their chick until it is 7 to 12 months old. They rely on the camouflage of their nests and eggs, as well as cryptic behaviour, which helps them avoid being detected by other animals.

Artist: Name goes here

Will these special guests disappear forever from our coastline?

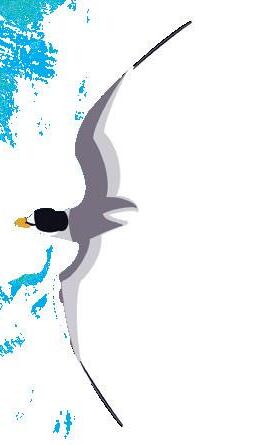

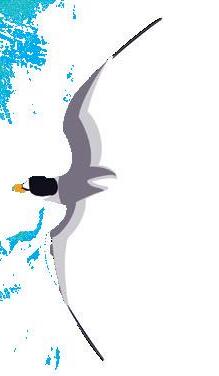

The Little Tern, Australia’s smallest tern, is at risk of extinction in NSW. Its nests are shallow scrapes in the sand, making their chicks easily exposed to danger.

Aerodynamic diving dynamos

Little Tern colonies are sensitive to a wide range of threats

After over 20 years in decline, with breeding colonies becoming rare, endangered Little Terns are experiencing a recent resurgence in numbers in NSW, with an almost 15 percent increase in breeding pairs from last season.

Despite the recent promising results, they are susceptible to a wide range of threats from native and introduced predators, including seagulls, foxes and dogs, crushing and disturbance from vehicles, extreme weather events intensified by climate change, and human interference near nesting sites.

Some populations migrate over 2,000 km non-stop across open water

Little Terns show remarkable endurance and navigational skills by migrating to the Coffs Coast from eastern Asia to breed annually between October and March.

Little Terns are usually seen in small flocks. They cooperate to noisily mob avian predators, like silver gulls, crows and ravens, who will happily eat unguarded tern eggs or defenceless chicks.

You will often see these elegant birds diving in the ocean and nearby waterways. They are expert fishers and skilled flyers, diving into the water at high speeds to catch small fish and invertebrates.

Little Tern chicks weigh less than a scoop of ice cream!

Little Tern chicks are tiny, and their speckled dusty yellow plumage makes them hard to spot on the open sand. Unfortunately, their protective camouflage makes them particularly vulnerable to accidental harm from humans, especially when walking, running, riding, or driving in nesting areas.

NPWS and local communities are taking measures to protect Little Tern colonies by fencing off nesting sites, enforcing pest control, and running communityfocused education programs.

One of the most significant threats to Southern Giant Petrels is becoming bycatch in fishing –when they get accidentally caught on longlines trailing behind fishing boats.

These opportunistic scavengers are a regular sight from fishing boats and cruise ships, where they love to tag along for an easy meal.

Onboard desalinators

Southern Giant Petrels have the ability to spend extended periods at sea due to their specialised nostrils, which allow them to excrete excess salt.

And now the good news

The population of Southern Giant Petrels in Australia was once critically endangered, with only a tiny breeding population limited to a few islands. However, thanks to conservation efforts and habitat protection, their numbers have shown signs of recovery in recent years.

Males are from Mars....

These birds exhibit a striking difference in diet based on sex: males typically stick to scavenging, while females are more likely to hunt live prey like fish and squid. A rare behaviour among bird species, this dietary divergence helps reduce competition between the sexes. Their feeding behaviour plays an essential role in the ecosystem as scavengers, helping to keep these coastal areas clean by feeding on animal remains.

Artist: Annie McMahon

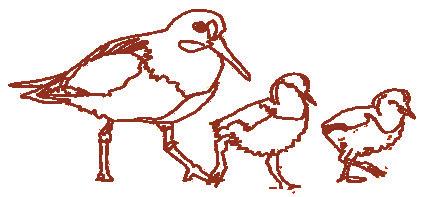

Despite their name, Pied Oystercatchers rarely eat oysters! Young Oystercatchers often watch and mimic adults to learn foraging skills, showing a remarkable example of social learning among shorebirds.

Pied Oystercatchers often mate for life and return yearly to the same nesting scrape. Breeding pairs nest mostly on coastal or estuarine beaches, making shallow scrapes in the sand above the high tide mark. Fewer than two hundred breeding pairs are estimated to remain in the state.

Pied parents are star performers, protecting their chicks with creative theatrical moves.

Some exit stage left and quietly walk away; bolder antagonists will cause a ruckus and loudly swoop, whilst some savvy dramatists nurse a ‘broken wing’ to lure predators away.

Taking up to six weeks to fledge, these fluffy chicks make for an anxious breeding season. This precarious period leaves them highly vulnerable to human disturbance and predation, particularly by dogs.

Pied Oystercatchers run down the beach behind a receding wave and drill into the sand for molluscs, crabs, marine worms and small fish. They open pippies and other molluscs with their strong chiselshaped beaks.

Pied Oystercatchers lay two to three well-camouflaged eggs between August and January.

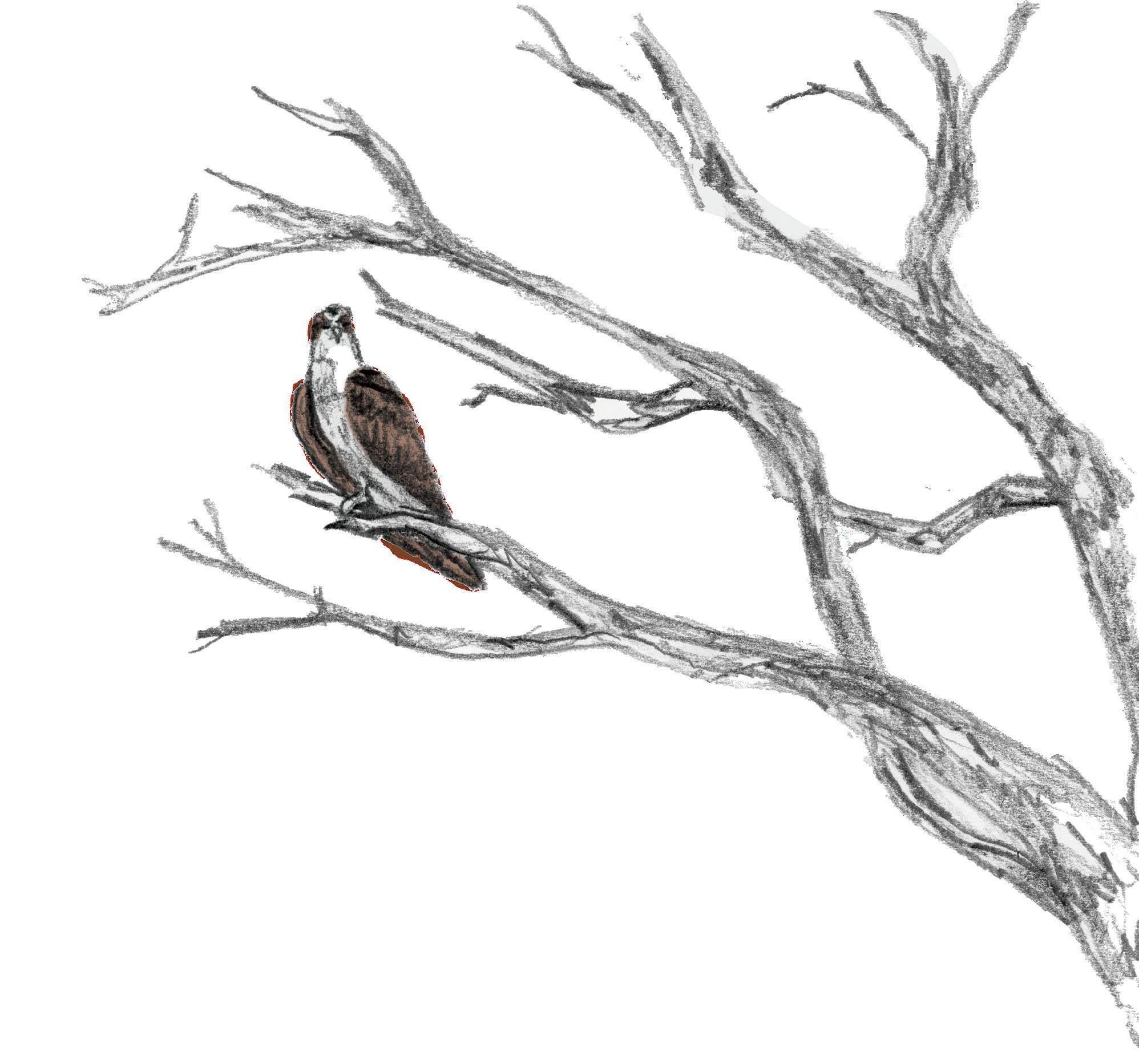

The Eastern Osprey is one of the smaller Australian raptors. This graceful and agile sea-hunter glides the air currents over coastal waters in search of slippery prey.

The Eastern Osprey has a renowned fishing success rate of 70 percent! Targeting fish swimming close to the surface, it dives feet forward with talons outstretched, wrenching its meal from the water. It then carries its writhing prey head-forward to reduce wind drag in flight.

Ospreys are one of the only hunters with reversible outer toes, allowing them to grip their prey with two toes in front and two behind. This adaptation is particularly useful for catching slippery meals.

Eastern ospreys have incredibly powerful eyesight. They have a third eyelid that functions like goggles, enabling them to see underwater when diving into the sea to catch fish. Additionally, their oily water-resistant feathers allow them to take off easily after diving.

Mating pairs build large nests using sticks, driftwood, and seaweed, often on cliffs, in dead trees, or even in man-made structures. They return to the same nest yearly to breed and maintain these impressive constructions.

railway bridges and artificially created structures underpin their ongoing successful recovery.

These cute little carnivores love setting up home near rotting seaweed!

They eat maggots and larvae found in the decomposing seaweed plus insects, worms and molluscs. They also chase small crabs, using their beak to probe crab holes.

These tough little birds are declining globally, as they rely on specific stopover sites during migration. Protecting important migratory sites and coastal habitats ensures their continued survival.

Endurance and speed

Ruddy Turnstones can fly non-stop for long periods, covering up to 10,000 kilometres each way. They must fly quickly to cover this vast distance, with average flight speeds ranging from 43 to 75 km/hr.

Adapt and get fat

Getting fat is critical to powering their longdistance journey, so these opportunistic carnivores readily adapt to different food sources.

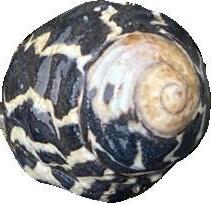

Made for rocky shores

Ruddy Turnstones have webbed feet with short, sharply curved toenails and a low centre of gravity due to their short legs, allowing them to maintain a secure grip on sharp, wet, and slippery rocks.

Young Ruddy Turnstones need to learn to fly quickly. They take their first flight when they are around 19 days old and set off for the other side of the world (without their parents) just two days later! AUS CONSERVATION STATUS VULNERABLE

Skilful stone-flippers

This short-legged, web-footed shorebird flips over stones, shells, and seaweed with its slightly upturned bill in search of food.

Tricolour camouflage

These stocky little birds are best known for their calico cat plumage, which helps them blend into rocky shoreline environments. During the breeding season, Ruddy Turnstones sport vibrant hues –bright orange legs, pied face, and rich chestnut and black feathers –making them one of the most strikingly coloured shorebirds and a particular delight for birdwatchers... ...around the world Ruddy Turnstones inhabit rocky shorelines and tundra in the high Arctic during the breeding season, migrating thousands of kilometres to their wintering grounds along the coastlines of Australia.

Sooty Oystercatchers forage on exposed rock or coral at low tide for limpets, mussels, crabs, starfish and sea urchins. They use their strong, pointed bills and specialised techniques to pry open or crack shells.

Before taking flight, the Sooty Oystercatcher gives a loud whistling or a sharp piercing call if intruders approach its nest.

The Sooty Oystercatcher is the only all-black shorebird species in Australia. They are a striking sight with their inkblack plumage, bright orange-red bill, eye-ring and iris, and pink legs and feet.

Known to form strong, monogamous, long-lasting bonds, with pairs often staying together for life, Sooty Oystercatchers return to the same nesting sites each breeding season.

Like their pied relatives, these bold parents defend their nests and chicks with shows of loud alarm-calls, aggressive swoops, and feigned injuries

After breeding, the Wedge-tailed Shearwater undertakes a vast migration across the Pacific Ocean, travelling to northern Asia and beyond. Adults return to the same breeding sites, including Muttonbird Island, annually.

Baby Muttonbirds often weigh more than their parents just before they fledge!

The extra weight gives them a head start, preparing them for their first migratory journey and life at sea. Fledglings leave two to three weeks after their parents. Guided solely by instinct, they follow the moon’s light out to sea and northward.

The Wedge-tailed Shearwater (Ardenna pacifica) is a key species on the Cofs Coast.

Many shearwater species are found along the coastal waters of NSW.

Local species include the Short-tailed Shearwater (Ardenna tenuirostris) and the Flesh-footed Shearwater (Ardenna carneipes)

Muttonbird Island Giidany Miirlarl (moon special place)

Muttonbird Island Nature Reserve is a critical breeding rookery for the Wedge-tailed Shearwater.

City lights can disorient fledglings

Plastic ocean pollution is a significant issue for shearwaters as they often mistake small plastic pieces for food.

feed on small

l

The White-bellied Sea Eagle is a skilled and powerful raptor with a 2m wingspan, powerful talons and a strong hooked beak. Their hunting prowess and dominance over other coastal birds make them apex predators of their habitat.

Territorial and monogamous

White-bellied Sea Eagles may be solitary, live in pairs, or small family groups made up of a pair of adults and dependent young. They form long-lasting pair bonds and maintain and defend large territories along coastal areas. They typically lay two eggs between June and September. After the fledglings have flown from the nest for the first time, they will remain in their parents’ territory for a few more months to gain the skills they need to hunt and survive on their own successfully.

Australia’s second-largest raptor

Protecting the White-bellied Sea Eagle is crucial; as an apex predator, it plays a vital role in maintaining the health of aquatic and coastal ecosystems.

White-bellied sea eagles hunt for fish, turtles, waterbirds, reptiles, small mammals and even prey up to the size of a swan. They will attack bats roosting in trees and chase aquatic birds until they are exhausted. Their dietary flexibility allows them to thrive in different habitats, taking advantage of available food sources.

Artist: Maddy Gagnon

Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoos are known for their unmistakable, eerie, mournful calls, which carry across the landscape. Their call often signifies rain or stormy weather, earning them a reputation as ‘storm birds’.

Streamlined formations of jet-black and gold

These iconic birds are one of Australia’s largest cockatoo species, known for their golden-yellow splashes on their tails and cheeks, graceful dancing movements, and stunning aerial acrobatics.

Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoos are a mesmerising sight as they soar in flocks across the landscape in search of seasonal food. According to mythological lore, these distinguished birds can symbolise auspicious change, luck and coming rain.

season of care and cooperation

Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoos have a long breeding season, where both parents build a nest in large tree hollows. The female

Curious and charismatic,

Powerful beaks for a special diet

Cockatoos have strong, hooked beaks that allow them to break into pine cones, banksia, and eucalyptus seeds, as well as extract insect larvae from tree trunks. Their strength and unique feeding technique enable them to tear through wood easily.

Hollows

These birds depend on mature trees with hollows for nesting, which can take centuries to form. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to deforestation, urban development, and agricultural land clearing destroy nesting hollows and limit their access to feeding grounds.

The average lifespan for a Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo is between 40 and 60 years, making them one of the longest-lived birds on earth.

Artist: Lacey Elliott

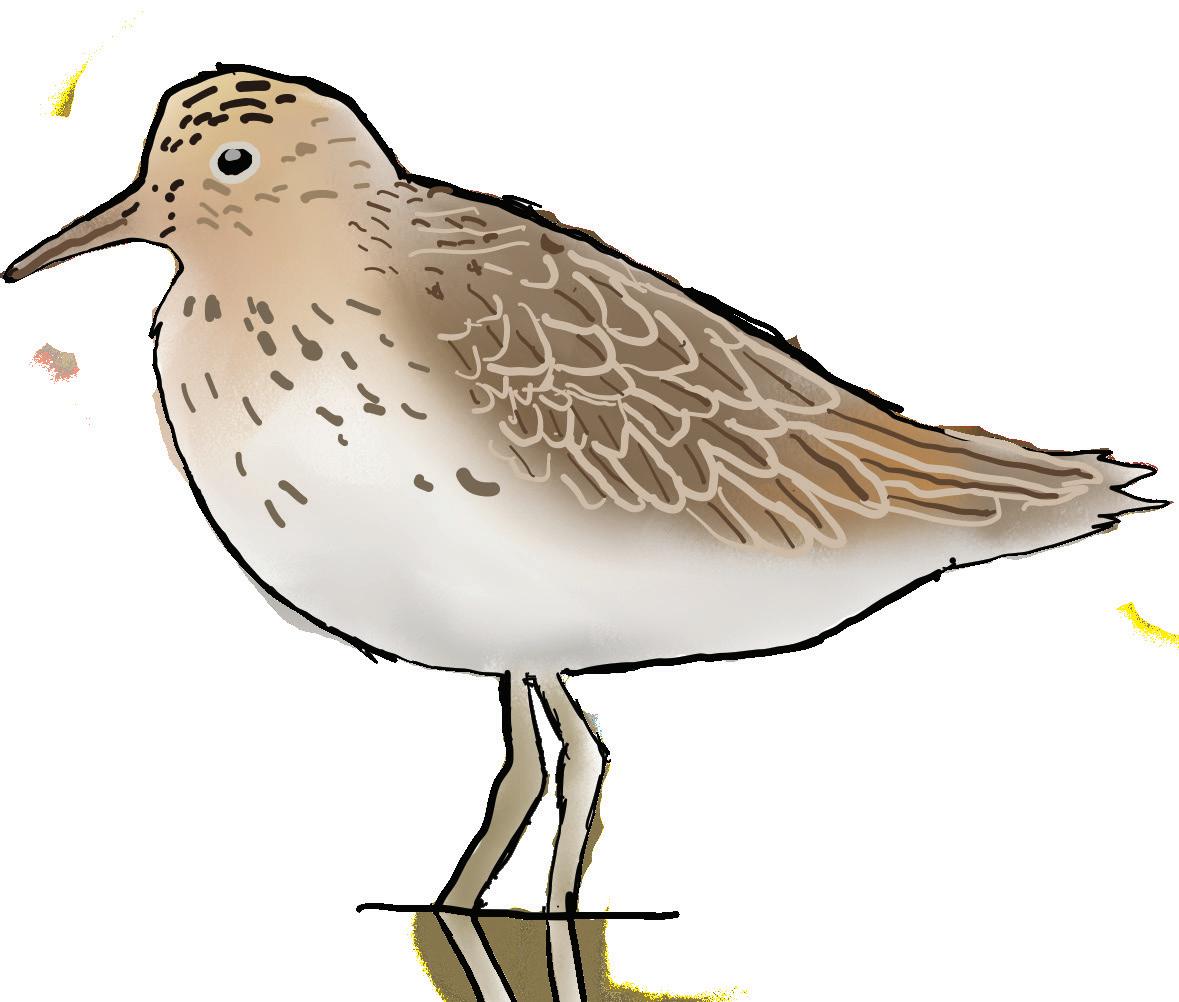

Sharp-tailed Sandpipers travel an extraordinary distance to reach our shores, migrating from their summer breeding grounds in far-off Siberia.

Sharp-tailed Sandpipers have incredible migratory endurance and are more flexible with habitat choice and diet than most shorebird species. They journey to the Coffs Coast each year, covering thousands of kilometres to escape the Arctic winter and enjoy Australia’s milder climate and abundant food.

To conserve this species, we need to protect important migratory and wetland habitats in the region and globally.

Artist: Amelie Ferreira

Many of the Sharp-tailed Sandpipers seen in NSW are young birds on their first migration. In a remarkable feat of endurance and orientation, juvenile birds journey south without adult guidance, relying on internal magnetic-field mapping and perhaps star orientation systems to navigate the long route to Australia.

Sharp-tailed Sandpipers quickly dart across mudflats, foraging for small invertebrates such as insects, mollusks, and crustaceans. They also use their bills to probe into the mud in search of buried food. While they mainly eat small invertebrates, they may switch to seeds and plant matter, showing extraordinary adaptability that helps them survive in changing conditions.

Eastern Reef Egrets play a crucial role in maintaining healthy coastal and marine habitats, supporting various other animals, and recycling nutrients within their environment.

These small herons represent adaptability and the ability to thrive in dynamic and challenging environments.

shores, coral reefs, mangroves, and tidal and other marine life. They are adapted to harsh coastal conditions, such as salt spray, strong winds, and fluctuating tides.

Eastern Reef Egrets exhibit two distinct variations can be found within the same population, and it’s not unusual to see

Eastern Reef Egrets have a variety of hunting techniques. They often crouch low, stealthily approaching prey, or use their wings to create shade, reducing glare on the water surface. This ‘canopy feeding’ method helps them see their prey better, especially in bright, reflective coastal waters.

The Eastern Reef Egret develops long plumes on its crest, foreneck and back in

This elegant heron, with its slender light-grey body and white face, is a common graceful presence in diverse landscapes across the country.

Adapt and flourish

White-faced Herons are highly adaptable birds that play a vital role in maintaining coastal and wetland ecosystems. They thrive in both freshwater and saline shallow-water habitats, such as estuaries, rivers, seagrass beds, mangroves, reefs, lagoons, and dams.

Whatever the conditions

They also inhabit drier areas, including paddocks, golf courses, gardens, and garbage dumps. These herons often live close to humans as long as they can access food and safe nesting sites.

These clever herons ‘foottremble’ in shallow water, vibrating one foot to stir up hidden prey. They also wait motionless for fish or crabs before striking quickly.

White-faced Herons help farmers by eating large quantities of crickets in pastures.

Rainy day partners

White-faced Herons can breed outside their usual season in response to rainfall. Both parents take part in building the untidy nest of sticks, usually located high in a tree, and in caring for their young. Typically, they raise only one brood each year.

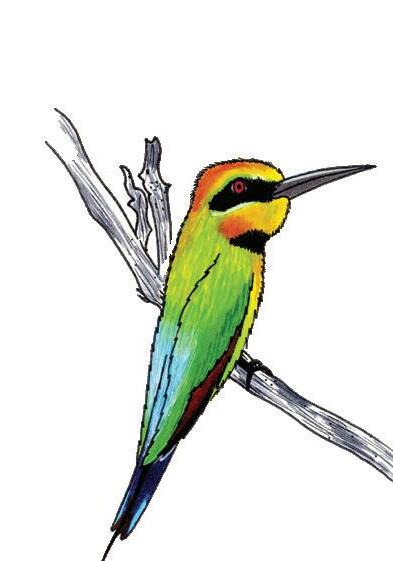

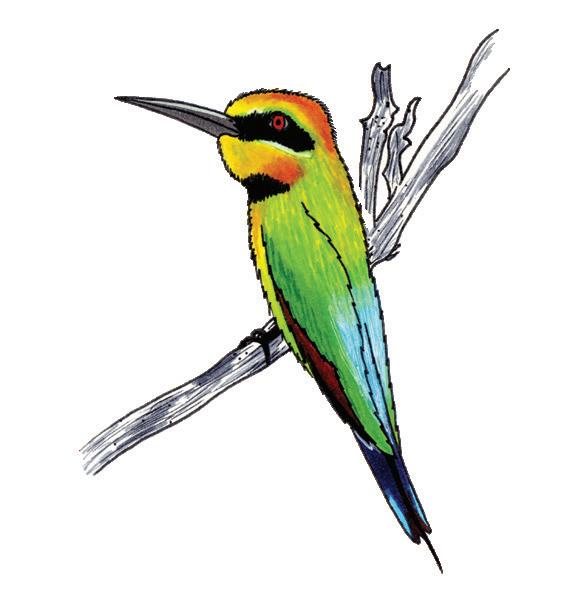

Merops ornatus aka Gold miners, Gold diggers

This brilliant bird lives up to its name with vibrant, iridescent colours of green, blue, orange, and yellow, a striking black eye stripe and long, pointed tail feathers.

Beloved aerial acrobats

The Rainbow Bee-eater is the only species of bee-eater found in Australia. These birds are highly skilled flyers known for their remarkable agility. When hunting, they display impressive aerial acrobatics, darting and twisting mid-air to catch insects. Their agile flight and vibrant colours make them a joy to watch in action.

Over-winter in the north

Introduced species like foxes, cats, and rats can prey on eggs and chicks in burrows.

Immune to bee stings

Bee-eaters feed on bees and other flying insects. They catch flying insects on the wing and carry them back to a perch to beat them against it before swallowing them. When catching stinging insects, they press and rub the insect’s body against the perch to remove the sting and venom sac.

Rainbow Bee-eaters help control insect populations, benefiting the ecosystem and indirectly supporting agriculture by reducing the need for chemical insecticides.

Rainbow Bee-eaters migrate north during the colder months to northern Australia, Papua New Guinea, and parts of Indonesia. They return in spring and summer to breed, bringing a vibrant splash of colour to the landscape as they arrive.

Social little diggers

Rainbow Bee-eaters come together in small flocks before migrating back to their summer breeding grounds. Both parents select the nesting site (sandy banks, cliffs, or flat ground), where they dig a long, horizontal burrow (up to 1m) leading to a nesting chamber lined with grasses. After laying their eggs, the parents take turns incubating them and feeding the young, occasionally with the help of other bee-eaters.

Help protect our birds by becoming a Coastal Guardian –a real-life hero for our feathered friends!

There are so many special birds that raise their chicks on our beaches and coastline, and they need YOUR help to survive. The good news is that it only takes a few small actions to make a big difference.

Here are seven easy ways you can help:

Take the pledge!

Scan the QR to take the official Share the Shore pledge.

Walk your dog on dog designated beaches. Be aware of restrictions around nesting seasons. Even well-behaved dogs can have a big impact on nesting birds.

Give birds plenty of space. If a bird looks nervous, walks away, or calls out, you’re too close! Step back and let them feel safe.

Respect signs and fences. Protect birds doing their best to raise their young. Take all fishing lines, hooks, and rubbish with you. These can injure or kill birds who mistake plastic for food.

Spread the word!

The more people who know, the more chicks we can save.

Become a citizen scientist.

Scan the QR to find out about BirdLife

You can also volunteer with amazing groups like NPWS, WIRES, Australian Seabird Rescue, Landcare or Coastcare.

Whether it’s snapping photos, planting dunes, or helping monitor nests, you’re giving our precious coastal birds a fighting chance to ensure future generations get to enjoy the magic of seeing them in the wild!

We can all thrive together – people, pets and wildlife.

– your creativity, courage, and commitment shone through every thoughtful word, stunning visual, and carefully crafted design element. Thank you for embracing the journey and

Program Facilitators – thank you for steering this program from beginning to end with care and vision. NPWS Discovery Rangers –enthusiasm, insight, and love for Country have truly inspired us.

Squires – your boundless creativity, passion, and dedication have woven this book together with magic. Bernard Kelly-Edwards – thank you for sharing your deep knowledge and cultural wisdom that helped shape this book.

Australia’s Birdata app and record bird sightings. Every entry helps protect birds and their habitat.

Jeremy Sheehan – your steady guidance and support on the ground kept the crew soaring in the right direction. Christiana Ferriera thank you for sharing your beautiful photos which have been lovingly intertwined throughout these pages.

Many thanks, The Sustainable Living Team, City of Coffs Harbour

With the support of City of Cofs Harbour’s Sustainable Living Program, in partnership with the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Flight Lab have fledged. A collective of local young artists and citizen-scientists in action, the Flight Lab crew created this book for you to discover the amazing birds of the Cofs Coast and to share simple ways we can help our threatened seabirds and shorebirds.

Together,we can all thrive!

Together,we can all thrive!

Scan the QR to learn about the ‘Share the Shore’ pledge and how you can help our endangered beachnesting birds have a successful breeding season.

Share the Shore is a NSW Government Environment and Heritage initiative – https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/animalsand-plants/threatened-species/saving-our-species-program/ resources/share-the-shore#pledge