Optimize your results

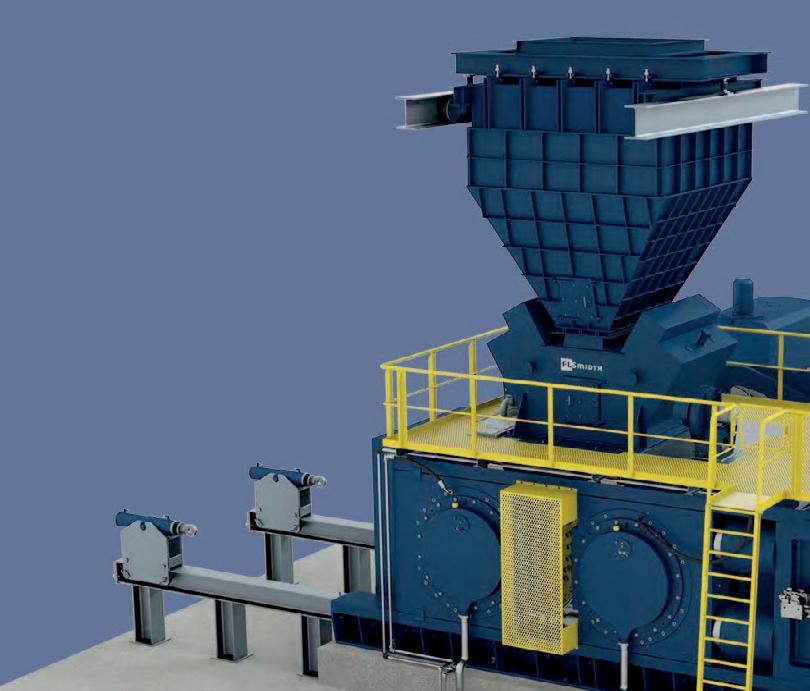

The HPGR Pro features are next-gen technology resulting in operational advantages versus conventional HPGR… features that are retrofittable!

Whether it’s a new machine or an upgrade for an existing unit, the HPGR Pro takes your grinding operations to the next level with the most efficient comminution product in grinding and milling!

Key benefits vs conventional HPGR

■ Increased throughput up to 20%

■ Reduce power demands by as much as 15%

■ Extend life of the rolls up to 30%

■ Maximize life of the bearings

■ On-line monitoring of roll surfaces

with the HPGR Pro the next evolutionary step in our market-leading HPGR technology

For more than 40 years, we’ve been providing the labor, expertise and products to keep you mining.

WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU NEED US!

SERVICES INCLUDE:

•CONTRACT MINING

•CONTRACT LABOR

•SHAFT WORK

•SHOTCRETE WORK

•BACK & RIB BOLTING

•MILL SITE MAINTENANCE

•CONCRETE WORK

•GLUE & GROUT INJECTION

•MINE SEALS

•MOBILE SERVICE

GROUND CONTROL

PRODUCTS INCLUDE:

•SPLIT SETS / FRICTION BOLTS

•EXPANDABLE BOLTS

•WIRE MESH

•QUICK INSTALL PROPS

•STEEL CAN SUPPORTS

42 Two industries at a crossroads

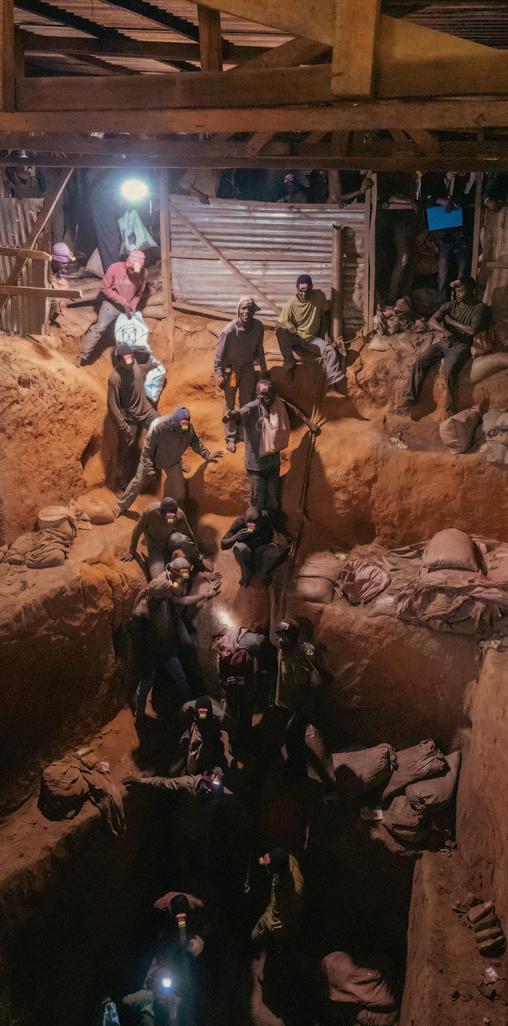

The formalization of artisanal and smallscale mining may be necessary to help meet global demand for critical minerals

By Kelsey Rolfe

By Kelsey Rolfe

Project Profile

48 Cluff Lake rebirth

Orano Canada spent 21 years decommissioning and reclaiming its Saskatchewan uranium project—almost as long as the 22 years the mine was in operation

By Alexandra Lopez-Pacheco

By Alexandra Lopez-Pacheco

51 Screen time

Efficiency, uptime and optimization is the focus of companies offering a wide range of screening technologies

By Tijana Mitrovic

By Tijana Mitrovic

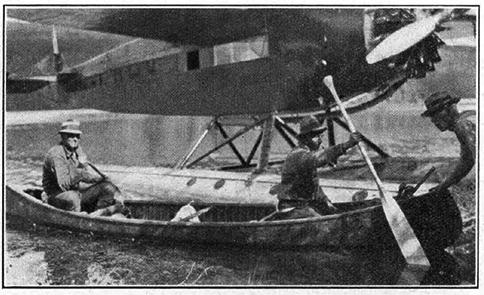

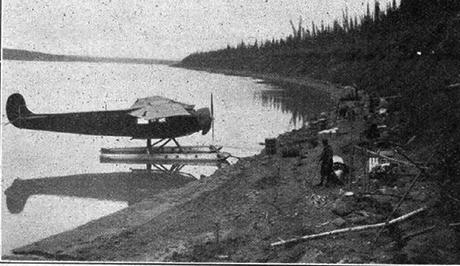

64 Aerial exploration

An excerpt of a 1929 paper by the staff of Northern Aerial Minerals Exploration, with an introduction by John E. Hammell, who became the company’s president, about the about the genesis of aerial exploration in Canada’s North

Compiled by Ailbhe Goodbody

In each issue

8 Editor’s letter

10 President’s notes

Tools of the trade

11 The best in new technology

Compiled by Alice Martin

Developments

12 Space sample could answer questions about asteroid mining

By Silvia Pikal13 The pursuit of United Nations sustainable development goals

By Tijana Mitrovic20 A protocol for diversity

By Alice MartinColumn

30 To restore confidence in mining projects, it is essential to return to the reporting standards upheld before the 2014 super cycle

By Manochehr Oliazadeh

By Manochehr Oliazadeh

Modern miner

32 In a traditionally maledominated industry, Mary-Jane Piggott creates opportunities for women to succeed

By Alice Martin

By Alice Martin

Pilot projects

34 Ammonia removal pilot projects seek to take on the challenges of biological wastewater treatment at mine sites

By Sarah St-Pierre

By Sarah St-Pierre

37 Following nearly two years of testing its autonomous haulage system at the Roy Hill iron ore mine, ASI Mining is ready to deploy its agnostic AHS technology to any mine fleet in the world

By Mehanaz Yakub40 Geoscientist Robert Horn says Canada has the tools needed to help develop Ukraine's metal and mineral resources

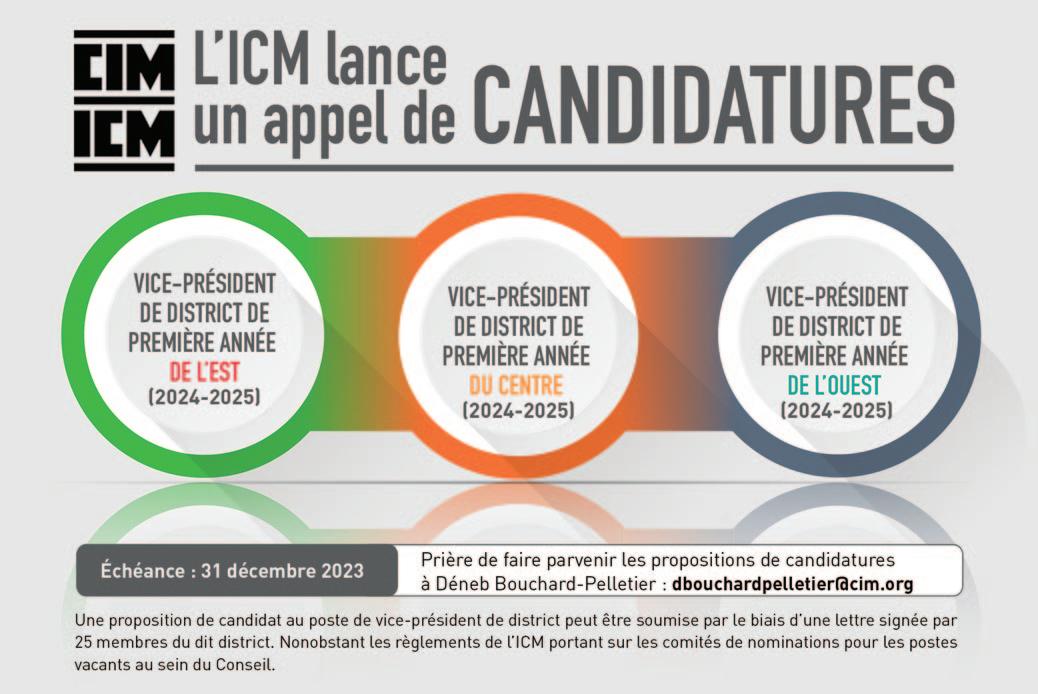

By Ailbhe GoodbodyCIM news

54 CIM launches new cloud-based mentorship program

By Sara King-AbadiContenu francophone

56 Table des matières

56 Lettre de l’éditeur

57 Mot du président

Article de fond

58 À la croisée de deux industries

L’officialisation de l’exploitation minière artisanale et à petite échelle : une étape nécessaire pour répondre à la demande mondiale en minéraux critiques

Par Kelsey Rolfe

Les actualités

63 Québec investit pour valoriser les résidus miniers amiantés

Par Alice Martin

The test of time

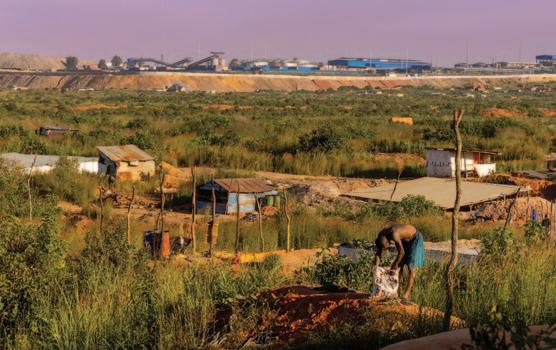

It has been almost exactly a decade since the last time we dug into the topic of artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) in CIM Magazine. In 2013, the run up in gold prices following the global financial crisis drew an enormous number of people in to the ASM sector. Despite its notoriety for poor safety, environmental practices and labour standards, the sector has been a key source of income for communities for generations and employs vastly more people than industrial-scale mining, often in areas where mining companies look to develop or grow their own operations.

The conflicts that resulted between small-scale miners and the industrial miners working the same deposits generated headlines and lawsuits. The unknown number of ASM miners who lost their lives in accidents and mine collapses did not.

At the time we explored this subject, we struggled to find mining companies that were prepared to talk about this thorny issue.

To its credit, Barrick Gold was willing to offer comment. The representative highlighted some of the work done to help lower the tension at its North Mara mine in Tanzania, but also conceded that finding a workable solution that improved safety, security and environmental practices, while reconciling the two sectors, was incredibly complex.

Ten years later, Barrick is still confronting these challenges and legal fallout from its unresolved conflict with artisanal miners in Tanzania.

In the feature for this issue, “Two industries at a crossroads” (p. 42), regular contributor Kelsey Rolfe provides a progress report of a kind.

Formalization, a framework for standards in the ASM sector that could begin to address the risks of the ASM sector, remains an elusive goal. A key advance has been the establishment of a diamond-buying program by De Beers. It is instructive both in how it works and for the enduring commitment required to make it work.

The role of cobalt in the energy transition, and the significant contribution the ASM sector makes to the overall output of the critical mineral, has reinvigorated the discussion of formalization. Manufacturers want to demonstrate their commitment to sustainable practices, yet at the same time, cutting out cobalt produced from small-scale miners could create a supply crunch soon.

A stamp of approval for artisanally sourced cobalt could be an important victory.

As the story details, such an outcome will only come from a sustained, multi-year effort. Up until now, the challenge has just been that there are few who have had the opportunity and persistence to commit that time and effort.

Ryan Bergen, Editor-in-chief editor@cim.org @Ryan_CIM_Mag

Editor-in-chief Ryan Bergen, rbergen@cim.org

Managing editor Michele Beacom, mbeacom@cim.org

Senior editor Ailbhe Goodbody, agoodbody@cim.org

Section editor Silvia Pikal, spikal@cim.org

Editorial intern Alice Martin, amartin@cim.org

Contributors Sara King-Abadi, Alexandra Lopez-Pacheco, Tijana Mitrovic, Manochehr Oliazadeh, Kelsey Rolfe, Sarah St-Pierre, Mehanaz Yakub

Editorial advisory board Mohammad Babaei Khorzhoughi, Vic Pakalnis, Steve Rusk, Nathan Stubina

Translations Karen Rolland, karen.g.rolland@gmail.com

Layout and design Clò Communications Inc., communications.clo@gmail.com

Published 8 times a year by:

Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum 1040 – 3500 de Maisonneuve Blvd. West Westmount, QC H3Z 3C1 Tel.: 514.939.2710; Fax: 514.939.2714 www.cim.org; magazine@cim.org

Advertising sales Dovetail Communications Inc.

Tel.: 905.886.6640; Fax: 905.886.6615; www.dvtail.com

Senior Account Executives

Leesa Nacht, lnacht@dvtail.com, 905.886.6640 ext 321

Dinah Quattrin, dquattrin@dvtail.com, 905.886.6640 ext 308

Neal Young, nyoung@dvtail.com, 905.886.6640 ext 306

Subscriptions

Online version included in CIM Membership ($197/yr). Print version for institutions or agencies – Canada: $275/yr (AB, BC, MB, NT, NU, SK, YT add 5% GST; ON add 13% HST; QC add 5% GST + 9.975% PST; NB, NL, NS, PE add 15% HST). Print version for institutions or agencies – USA/International: US$325/yr. Online access to single copy: $50.

Copyright©2023. All rights reserved.

ISSN 1718-4177. Publications Mail No. 09786. Postage paid at CPA Saint-Laurent, QC.

Dépôt légal: Bibliothèque nationale du Québec. The Institute, as a body, is not responsible for statements made or opinions advanced either in articles or in any discussion appearing in its publications

2020 2021 2022

DISTINGUISHED LECTURERS 2023-2024

THE PROGRAM

The Distinguished Lecturers program is offered to 31 CIM Branches, 11 Technical Societies and 8 Student Chapters. Universities can also request a lecture.

The CIM Distinguished Lecturers program started in 1968 and has continuously provided a lineup of individuals who have shared their knowledge with the mining community for over five decades.

Every year, the lecturers are elected by their peers through the CIM Awards program and hold the title for a complete season (September to June).

CIM is privileged to count more than 260 of the industry’s finest as its lecturers. Because the motto “once a lecturer, always a lecturer” defines our pride and dedication in ensuring that the learning curve is endless, a complete list of past lecturers is available at www.cim.org, where you can benefit from the ever-growing pool of expertise that the program has to offer.

LECTURERS ARE AVAILABLE FOR YOUR ONLINE OR IN-PERSON EVENTS.

A commitment to our shared future

News of climate-related events all around the world, including the recent tragic fires in Maui, remind us that we are all stakeholders when it comes to the effects of climate change. As we stand at the intersection of climate responsibility and the needs of our diverse stakeholders and land rights holders, the mining industry is presented with both a challenging journey and a remarkable opportunity. The year 2023 has thrust upon us an undeniable reality: the climate crisis is no longer a distant concern but an urgent call for collective action. The extreme heatwaves and forest fires that have swept across Canada this year serve as potent reminders that the impacts of climate change are no longer a future scenario, they are our present reality.

Our industry cannot remain insulated from these seismic shifts. As the chief financial officer at B2Gold Corp., a senior gold producer committed to responsible mining, I am acutely aware of the dual challenge we face: to drastically reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate our climate impacts while simultaneously nurturing the prosperity of our employees, local communities, host governments and the environment in which we operate.

At B2Gold, like many other mining companies, we are embracing this challenge by setting a target to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent by 2030. Yet, setting targets is only the first step in a long and complex journey. Our industry, by its very nature, is energy-intensive and often operates in remote corners of the world. The pursuit of renewable energy sources, the electrification of our operations and advancements in energy efficiency are at the forefront of our industry’s strategy. However, many technologies still require significant advancement or adequate market conditions before they can become technically or economically feasible for implementation. The road ahead is far from simple, and as such, our industry’s efforts to transition to low-carbon operations demand ambition, innovation and determination.

In our pursuit of emissions-reduction targets, we are not simply forging a path towards a more sustainable future, we are also honouring our commitment to our stakeholders and our communities. The mining industry, rightly so, is a beacon of economic progress, providing jobs, revenue and investments to countries and regions worldwide. Our obligation lies in ensuring that our emissions-reduction pathways are crafted with sensitivity to the needs of our employees, communities and governments. We recognize the right of nations to harness their resources for development, and it is our duty to facilitate this while maintaining our climate obligations.

The challenges our industry faces are formidable, but they are not insurmountable. The dynamic landscape of the climate transition compels us to adapt continuously and seek new avenues, technologies and partnerships. While the path may be uncertain, I am confident that the mining industry can, and will, respond effectively to the climate crisis. Our resilience is our strength, and our commitment to innovation and responsibility is unwavering.

As we navigate the climate transition, we are not just protecting our environment, we are also nurturing the livelihoods of our communities and the future of generations to come. Our commitment to climate responsibility is, at its core, a commitment to our shared future—one that is inclusive, resilient and sustainable.

Mike Cinnamond CIM President

“I am confident that the mining industry can, and will, respond effectively to the climate crisis.”

Versatile mapping tool

Quantum Systems’ Trinity Pro is an electric fixed-wing mapping drone for mines and large areas of up to 700 hectares. The drone has an optimal cruise speed of 17 metres per second and a maximum flight time of 90 minutes. The Trinity Pro comes with six fully integrated cameras, including RGB, oblique, multispectral and LiDAR cameras. Quantum Systems stated that the cameras help create 3D models of mine sites, which are used to monitor progress and identify potential hazards. The Trinity Pro can also be used for stockpile measurement using photogrammetry to calculate volume and weight.

High accuracy total station

Trimble Inc.’s SX12 scanning total station is an integrated system that combines surveying, imaging and 3D-scanning capabilities. With its high-power laser, users can stake out mine features, then scan to collect georeferenced point cloud data. The SX12’s eyesafe laser pointer has a diameter of three millimetres at 50 metres, which the company said is the smallest spot size in the industry. According to Trimble, the SX12 can boost accuracy and speed when performing volumetric surveys, including overbreak and underbreak comparisons. In April 2023, the SX12 was upgraded with Wi-Fi HaLow radio technology, providing up to 14 times higher bandwidth than long-range radio, which Trimble said allows for a more reliable and robust connection.

All-terrain robot for hazardous environments

Copperstone Technologies Ltd.’s HELIX Neptune is a 400kilogram amphibious robot that collects data and water samples from tailings storage facilities. Copperstone’s scroll-drive propulsion system allows the HELIX Neptune to move on many types of terrain, including mud, tailings, snow, ice and water. Since its release in September 2021, the HELIX Neptune has been upgraded from two to four cameras, which provide a 360-degree view on all aspects of the rover when in use. It was also upgraded with an increased battery capacity, a telemetry range of up to eight kilometres, a Wi-Fi range of 2.5 kilometres and now includes autopilot on all types of terrains.

Precise and reliable borehole surveying

Stockholm Precision Tools AB recently launched its GyroLogic Evo, a downhole directional survey tool intended for borehole surveying. The solid-state gyroscope’s continuous mode allows for rapid surveying with data points registered at centimetre intervals. The GyroLogic Evo is designed to work in magneticallydisturbed environments, reducing the risk of magnetic-induced errors while in operation. Bluetooth enables the tool to be operated remotely and it has a battery capacity of 12 hours.

Compiled by Alice MartinDevelopments

Space sample could answer questions about asteroid mining

On Sept. 8, 2016, the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft began its journey to Bennu, a dark and ancient asteroid thought to have formed over 4.5 billion years ago. The NASA mission is the Canadian Space Agency’s (CSA) first participation in an asteroid sample-return due to its contribution of the OSIRISREx Laser Altimeter (OLA), a laser system utilized by the spacecraft to create a 3D model of Bennu’s surface, which allowed (continued on page 13)

Recovery teams participate in helicopter training in July in preparation for the retrieval of the sample return capsule from NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission, at the U.S. Department of Defense’s Utah Test and Training Range.

of

scientists to pick the best sample site for the mission. A sample was successfully collected from Bennu in October 2020 and the spacecraft will return to earth on Sept. 24, 2023, when its sample capsule will parachute down into the Utah desert.

Moving the dial forward

Mining companies find appeal in the comprehensiveness of United Nations sustainability goals

By Tijana MitrovicWhen Barrick Gold Corporation published its 2022 Sustainability Report in April of this year, the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals (SDGs) were front and centre. It was another recent example of mining companies turning to the SDGs to go above and beyond environmental, social and governance (ESG) frameworks and disclosures.

“By using the SDGs as the skeleton for our reporting, we are better able to apply an integrated and holistic approach to sustainability management, and to avoid a siloed-thinking and mere box-ticking approach that can be a consequence of taking an ESG-compliance-driven approach,” explained the Barrick report.

Established in 2015, the SDGs are 17 interrelated goals that present a blueprint to achieve a more equitable and sustainable future by 2030 through addressing global challenges related to poverty, climate change, inequality and more.

In April 2023, the UN declared that “just 12 per cent of the SDG targets are on track” and urged decisive action to correct the course and meet the 2030 deadline. Due to its impact on the environment and local economies worldwide, the mining industry can contribute to the achievement of, and even lead the way on, many of the goals, according to the UN.

While there is no SDG that explicitly refers to mining, the industry can use

Due to the CSA’s contribution to OSIRISREx, Canada will receive a portion of the asteroid material. First discovered by scientists in 1999, Bennu is carbon-rich and will contain chemicals and rocks from the birth of the solar system

Developments

many of the goals to evolve its ESG reporting. According to Patrick Drouin, senior vice-president of investor relations and sustainability at Wheaton Precious Metals, which committed to supporting the SDGs in 2019, a significant benefit for mining companies of following the SDGs is that the goals help outline a holistic framework where companies can incorporate multiple SDGs and address multiple issues at once instead of using a one-by-one or piecemeal approach.

Agnico Eagle Mines is another company using the SDGs as part of its sustainability reporting. It first communicated its alignment with the goals in 2017. “We took the step to start aligning all of the work that we were doing that was contributing to the sustainability of communities and society with the framework set out by the UN SDGs,” said Melanie Plante, a sustainability performance and engagement manager at Agnico Eagle in an interview with CIM Magazine.

For Agnico Eagle, the goals provide a direction for its approach to sustainability and represent a common goal for

beneath its deeper-than-pitch-black surface. NASA is hopeful that the asteroid will also contain platinum and gold, and that studying it will determine if asteroid mining during deep-space exploration and travel is feasible. – Silvia

Pikalthe industry to work towards together. According to Plante, the SDGs are bigger than one company or the industry: they represent an opportunity for collective action to build a better future and provide concrete ways to contribute to that goal, as well as the inspiration to push further. “It requires us to look at how we tackle certain issues, and it pushes the boundaries of best practice,” Plante said. “It means every year we have to sort of level up what we do to go further.”

Agnico Eagle recently partnered with the Quebec government to use non-acidgenerating tailings from its Goldex gold mine to rehabilitate the abandoned Manitou site in northwestern Quebec. The rehabilitation directly connects to SDG 15, which respectively sets targets to ensure that water and sanitation are available and sustainably managed and to protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems. Plante described it as a “win-win partnership” in contributing to the SDGs.

More mining companies are following suit. Teck, for example, committed to

From the wire

Compiled by Alice MartinOsisko Gold Royalties has named Paul Martin as interim chief executive officer to replace Sandeep Singh, who left the position after three and a half years. Martin has held CEO and chief financial officer roles in the mining industry and currently serves as chair of the board at Red Pine Exploration. Osisko Gold Royalties stated it is still looking for a permanent CEO.

Lucara Diamond Corp. reappointed William Lamb as CEO, president and a director of the company, after Eira Thomas stepped down from the position, which she has held since 2018. Lamb previously held the position of CEO at Lucara Diamond from 2011 to 2018 and has more than 25 years of experience in mining project development and operations.

Taurus Gold Corp. appointed Frank Lagiglia as CEO and director, effective Sept. 1. Lagiglia has a background in corporate development and investor relations, as well as more than 20 years of experience in the capital markets and mining sector working with multiple mineral exploration and production companies.

The Mining Innovation Commercialization Accelerator (MICA) named Chamirai Charles Nyabeze as network director. Nyabeze is a co-founder of MICA and was previously MICA’s vice-president of business development and commercialization. For the past 11 years, he has also worked for the Centre for Excellence in Mining Innovation, where he is currently vice-president of business development.

Mich Resources Ltd. appointed Geoff Balderson as CFO. Balderson serves as the CFO and director of several publicly traded companies in various industries and is the founder and president of Harmony Corporate Services. He has been involved in the capital markets for 25 years and has a background in corporate compliance.

Samir Patel, general counsel and corporate secretary at First Mining Gold Corp., will leave his role to pursue another opportunity in the mining industry. Lisa Peterson, the company’s CFO, will assume corporate secretary duties on an interim basis.

aligning its sustainability strategy with the SDGs in 2022. One of its initiatives that contributes to the SDGs is its aim to become “nature positive by 2030” (an emerging framework focused on “[halting] and [reversing] the destruction of nature by 2030,” as described by the World Economic Forum). This framework will help Teck align with SDG 15, which is focused on sustainable land use. To meet this goal, Teck stated on its website that it plans to work with local partners, Indigenous peoples and communities to conserve ecologically and culturally significant lands. As an example of taking action, the company made a $10 million donation in June to Chile’s Protected Marine Areas Program with a focus on the Juan Fernández Archipelago, which is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and is “one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world.”

Mining companies not only have a responsibility to reduce environmental impacts and, according to the UN, ensure that when they “generate profits, employment and economic growth in low-income countries,” those benefits extend beyond the life of mine, but they may also find that existing organizational goals are already aligned with the SDGs. For example, mining for critical metals and minerals is needed for SDG 13 on climate action, which sets a target of achieving 40 to 45 per cent greenhouse gas emission (GHG) reductions below 2010 levels by 2030 and achieving netzero GHG emissions by 2050. “If you’re going to hit climate action, you’re not going to do that without copper, lithium, cobalt,” Drouin told CIM Magazine.

Another area where the industry is aligned with the SDGs, Drouin said, is goal 10, which aims to reduce income inequalities. “To me, mining is the best way to transfer wealth from the more affluent urban areas into the rural areas that don’t get resources,” he said. “That’s where mining shines. You’re not going to put a silicon chip plant in rural Mexico, but [you’re going to put a mine there] if there’s gold. And that will bring economic benefit to that region [through] job creation, economic growth, community infrastructure and funding for social programs. All that is crucial.”

However, there are challenges when following the SDGs, which include measuring the impact of policies and practices, Drouin explained. “[The impact] is not always quantifiable, but you want to

make sure that you’re getting the biggest benefit out of the efforts you’re putting in.” He said that the move towards an increased regulatory environment in some jurisdictions around the world may prevent miners from moving the dial forward on the goals.

There are also external challenges at play. Drouin said that while more permits and regulations that limit mining may give the illusion of protecting the environment, it comes at the trade-off of economic benefits that alleviate poverty and food insecurity and improve health and well-being and contribute more to the region. “Mining plays a crucial role, so it’s always concerning when you see increased regulatory permitting that causes roadblocks,” he said. “When done right, mining can tackle 16 of the 17 SDGs. And it does disturb the land. There’s no doubt. [But], you can do it responsibly and tackle everything else.”

While several mining companies are taking action, a 2020 report from the Responsible Mining Foundation, called “Mining and the SDGs: a 2020 status update,” stated that adoption across the mining industry needs to be higher to tackle the SDGs. The report, which reviewed 38 large-scale mining companies worldwide on their policies and practices, declared that systematic actions across the 17 SDGs were “largely lacking” and that “no one company is showing comprehensive actions to address all 17 SDGs.”

The report found four goals on which mining companies were taking the least action: SDG 3 on good health and wellbeing, SDG 5 on gender equality, SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation and SDG 14 on life below water. In addition, the report posited that while some companies strongly emphasize those goals as priorities, SDG 3 and 6 are “both among the most frequently prioritized SDGs, but show some of the weakest levels of action by mining companies.”

To reach the goals by 2030 and even beyond, the report stated that action must be the top priority. “[The goals] provide ambition, but if we don’t have action, it’s not going to make a difference,” Plante stated. “It’s great to say that we are aligned with the goals and we have targets in certain areas, but if we cannot demonstrate action, and if we’re not implementing initiatives on the ground, we’re never going to make steps towards those goals.” CIM

Health check

Formerly injured workers in sectors such as construction and mining in Ontario are more at risk of opioidrelated harms than workers in other sectors, according to findings emerging from the Opioid-related Harms Among Ontario Workers study.

The ongoing research project is being conducted by the Institute for Work & Health and the Occupational Cancer Research Centre at Ontario Health. The project was created to better understand which worker groups are most affected by Canada’s opioid crisis. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, more than 36,000 people in this country have died from apparent opioid toxicity deaths between January 2016 and December 2022.

The co-leads on the study, Dr. Jeavana Sritharan, scientist at the Occupational Cancer Research Centre, and Dr. Nancy Carnide, scientist at the Institute for Work & Health, described the findings to CIM Magazine

“When we’re looking at opioidrelated harms, what we see is that it tends to be men of working age that have been disproportionately affected by the opioid crisis,” Carnide said.

Sritharan explained that opioid-related harms include poisonings (when someone takes too much of an opioid drug) and

mental/behavioural disorders (this includes withdrawal or intoxication).

Carnide said that most of what is known about the role of occupation in opioid-related harms has come from studies in the U.S.

In Canada, empirical data on occupation among those affected by the opioid

crisis has been limited, Carnide said. To address this gap, the project is looking at data from 1.7 million Ontario workers who have been injured on the job and were recorded in the Occupational Disease Surveillance System (ODSS), which is designed to identify and monitor trends in work-related disease in the province. The study focuses on opioidrelated visits to the emergency department and hospitalizations.

“You can imagine that someone who has a workplace injury, depending on the nature of the injury, can experience quite a bit of pain; poor mental health; and pressures to return to work,” Carnide said. “It creates the environment and the risk factors for potentially developing a [substance] use disorder because they need pain management.”

She added that other factors could include working in a male-dominated environment, where there are gender norms present that encourage “toughing it out” and working through the pain; a stigma that prevents workers from disclosing they are struggling with pain from injury or substance use; and challenging aspects of the work environment, from stress to job insecurity.

July 12 webinar hosted by the CIM Management and Economics Society.

Consolidation

Pletcher stated in the presentation that since the gold industry is the most fractured of all the metal commodities, gold consolidation has emerged as a strong trend in the past four years.

He referenced Barrick Gold’s nopremium deal with Randgold in 2019, which was followed by Newmont’s acquisition of Goldcorp in the same year, as deals that established both companies as major players in the gold sector.

The researchers explained that they focused on two different comparisons among workers between 2006 and 2020: rates of opioid-related harms among workers in the ODSS compared to workers in the general Ontario population, and opioid-related harms compared between workers within the ODSS.

The study found that when compared to the general population of Ontario, the ODSS group has a risk of emergency department visits for opioid-related poisonings that is 2.41 times higher than the general population and a risk of hospitalization for opioid-related poisonings that is 1.54 times higher.

According to the ODSS data, the workers who are most at risk of opioid-related harms when compared to the general Ontario population included those who work in the construction and trades, materials handling, processing (minerals, metals, chemicals), machining, transport, mining, medicine and service industries.

“It tended to be traditionally blue collar, physically demanding jobs for the most part,” Carnide said. “It does seem to suggest that there are particular groups of workers in certain occupations that tend to be at a higher risk of developing opioid-related harms.”

The results were similar when comparing occupational groups within the ODSS. The researchers theorized that the role of workplace injuries is a significant factor in developing opioid-related harms.

When asked about the mining industry specifically, Carnide said mining jobs in Ontario typically occur in rural communities where workers may not have the same access to pain management programs found in more urban centres.

“We need to think about the role that the workplace can play in helping to address the opioid crisis,” Carnide said. “By bringing awareness to the fact that there are certain workplaces that should be aware of this, we can use the workplace as a point of intervention.”

“It is a much bigger public health crisis than I think most people understand right now,” Sritharan said. “The pandemic also exacerbated that. There’s a lot of work to do beyond what we’re doing right now—even just increasing worker awareness. That’s what we’re hoping to do with this project.”

The study’s key findings were presented at an Institute for Work & Health webinar on June 13 and can be viewed through iwh.on.ca/events.

– Silvia PikalThe mining industry’s top transactional and legal trends

Consolidation, environmental, social and governance (ESG)-driven transactions, Indigenous consultation and resource nationalism were four key trends that Fred R. Pletcher, chair of the Mining Group and a partner in the Securities and Capital Markets Group at Borden Ladner Gervais LLP, noted have defined the global mining industry recently. Pletcher was the featured presenter at a

Other significant deals in this arena identified by Pletcher included Newcrest’s acquisition of Pretium Resources— the Vancouver-based miner that operates the Brucejack mine in northwest B.C.—in 2021, the merger between Agnico Eagle and Kirkland Lake Gold in 2022 and earlier this year, Newmont’s acquisition of Newcrest.

“The top 10 producers in the gold industry only generate 28 per cent of the production, which is very different than more concentrated commodities, like iron ore, nickel or zinc,” he said. “Gold was an area crying out for consolidation.”

Copper

Copper deals outpaced gold mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in 2022 for the first time in four years with US$14.24 billion in total value. Big copper deals Pletcher noted included Rio Tinto’s acquisition of Turquoise Hill Resources in 2022, BHP’s takeover of OZ Minerals, which was finalized in May, and Glencore’s sale of its CSA copper mine in New South Wales, Australia, to Metals Acquisition Corp, which closed in June.

This year has seen its own copper rush, due to Glencore’s multiple unsolicited attempts to purchase Teck Resources and Hudbay Minerals’ acquisition of Copper Mountain Mining Corporation.

“That’s all been made easier by recent extremely strong copper prices, which has really given a lot of firepower to the copper players and allowed them to afford some of these acquisitions,” Pletcher said.

Due to U.S. President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, which was passed in August 2022, American automakers have also increasingly entered transactions with lithium producers to secure supply. This includes Canadian miner Nemaska Lithium’s recent deal with Ford, announced in

“We need to think about the role that the workplace can play in helping to address the opioid crisis.”

– Dr. Nancy Carnide, scientist at the Institute for Work & Health

May, to supply lithium products over an 11-year period.

A seller-friendly market

Pletcher described the current mining industry as a seller’s market, but due to the large number of parties interested in purchasing, pressure is being put on sellers when it comes to due diligence and exclusivity.

Pletcher also mentioned the recent increase in syndicated acquisitions in the mining industry, noting the joint acquisition of Yamana Gold by Pan American Silver and Agnico Eagle in March. He said syndicated acquisitions can be mutually beneficial for companies and help fund large transactions, but they also add closing risks and the risk of multiple negotiations.

Pletcher added that another impediment to transactions is M&A activism— or when shareholders use their ownership leverage to influence the structure of a transaction. He emphasized the importance of shareholder engagement in defending against M&A activism.

ESG-driven transactions

“In the last year, we’ve seen enormous ESG-driven transactions amongst some of the largest players in the industry,” Pletcher said.

He stated that the “poster child” for this trend is Teck Resources proposing to spin off its steelmaking coal business into a separate publicly traded company.

Pletcher added that companies may be forced into a transaction due to events that pose a threat to ESG principles.

“With the war between Russia and Ukraine, western companies [are forced to] exit Russia, and Kinross, unfortunately, had to sell its Russian assets at a deeply discounted price to [the Highland Gold Mining Group],” he explained. “Similarly, Tahoe Resources took a hit in [its] share price following a court-ordered shutdown at [its] Escobal mine in Guatemala to permit Indigenous consultation.” Pan American Silver seized the moment to buy Tahoe Resources shortly afterwards, completing the transaction in February 2019.

Indigenous consultation

The Tahoe Resources shutdown is a notorious example of the impact a failure to consult with local Indigenous communities could have on mining operations.

In 2021, Canada’s federal government incorporated the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) into law to support Indigenous rights to self-determination, as did the B.C. government in 2019.

UNDRIP includes a principle that stipulates Indigenous groups are entitled to “free, prior and informed consent” (FPIC) when a government is contemplating actions that might affect them negatively.

“Early statements from the federal government have been that FPIC doesn’t mean veto; what it means is meaningful

Developments

in-depth consultation,” Pletcher said. “Aboriginal consultation rates in Canada may change with the adoption of UNDRIP, but they’re only changing in one direction, in that they’ll be more robust.”

Increased mining nationalism

Countries are increasingly turning to state ownership for their natural resources. Pletcher stated that Mexico and Chile have been at the forefront of mining nationalism.

In April 2022, Mexico nationalized its lithium industry, despite having no producing mines. On May 8 of this year, Mexico also approved several mining reforms, including reserving most new mineral exploration activities to the Mexican state and requiring all new mining concessions to be granted pursuant to a public tendering process.

“So even if you held the exploration concessions, you may not be the company that ends up developing and operating those concessions,” Pletcher explained.

The reforms also introduced Indigenous consultation requirements, as well as environmental safeguards. Chile, the second-largest producer of lithium in the world, nationalized its lithium industry on April 20 of this year.

“The pendulum is swinging towards mining nationalism, away from mining investments,” added Pletcher. “Companies should be cautious when they’re operating outside of tier one established mining jurisdictions with a rule of law, and maybe even when they’re within those jurisdictions.” – Alice Martin

Battery X Metals Inc. named Alain Moreau as exploration manager of lithium properties and Brodie Gunning as senior manager of battery recycling. Moreau has more than 35 years of experience in exploration innovation, program management and corporate leadership, while Gunning has a background in battery storage, electric vehicle infrastructure and charging technologies across Asia and the Americas.

Powerstone Metals Corp. named Zachary Goldenberg, an existing board director and significant shareholder of the company, as CEO. Goldenberg is an executive, lawyer and corporate director with experience in public markets and corporate finance and also sits on the board of directors of several public and private companies.

Critical Minerals Market Review 2023 Highlights

The International Energy Agency (IEA) released its first annual “Critical Minerals Market Review 2023” in July, in which it noted unprecedented growth in the critical minerals market up and down the supply chain due to the energy transition. The report stated that global exploration spending rose by 20 per cent, exploration for nickel by 45 per cent and for lithium by 90 per cent in 2022. The search for new lithium and nickel deposits helped make Canada and Australia top jurisdictions for exploration spending—both saw a 40 per cent increase over the year before.

Compiled by Silvia PikalCANADA

In November 2022, General Motors Co. signed a long-term offtake agreement to receive 25,000 tonnes of batterygrade nickel sulfate annually from Vale’s proposed nickel sulfate facility in Bécancour, Quebec, with delivery starting in the second half of 2026.

UNITED STATES

Lithium-ion battery demand in the U.S. grew by about 80 per cent in 2022, due to SUVs still ruling the U.S. market, which require a larger battery.

In February 2023, Ford Motor Company announced it will build a US$3.5 billion electric-vehicle battery factory in Michigan.

Chile, the second-largest producer of lithium in the world, nationalized its lithium industry on April 20, 2023.

CANADA

In May 2023, General Motors Co. and South Korean company Posco Future M Co., Ltd. secured $300 million in funding from the provincial and federal governments to build a new electricvehicle battery component plant in Bécancour.

UNITED STATES

Critical mineral start-ups raised a record US$1.6 billion in 2022, bringing the critical minerals category to four per cent of all venture capital (VC) funding for clean energy. In 2023, battery recycling was the largest recipient of VC funding for clean energy, followed by lithium extraction and refining technologies. Companies based in the U.S. raised 45 per cent of the total funds between 2018 and 2022.

MEXICO

In April 2022, Mexico nationalized its lithium industry, despite having no producing mines. On May 8, 2023, Mexico also approved several mining reforms, including reserving most new mineral exploration activities to the Mexican state and requiring all new mining concessions to be granted pursuant to a public tendering process.

CHINA

Between 2018 and the first half of 2021, Chinese companies invested US$4.3 billion to acquire lithium assets outside of China, twice the amount invested by the U.S., Australia and Canada combined during the same period. While China is a global leader in lithium processing and refining, it still sources the bulk of its raw lithium products from beyond its borders, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence.

AUSTRALIA

In February 2022, Liontown Resources signed a five-year lithium supply deal with Tesla to provide 100,000 tonnes of lithium-spodumene concentrate in 2024 and to increase that annual amount to 150,000 tonnes in the following years.

China accounted for about 60 per cent of global electric car sales in 2022.

A protocol for diversity

New Towards Sustainable Mining protocol builds on industry commitment to attain high EDI standards

By Alice MartinIn December 2020, the Mining Association of Canada (MAC) and its members put out a statement that denounced all forms of discrimination, racism and sexism, as well as recommending actions for the Canadian mining industry to take in the hopes of eliminating them.

More than two years later, the original statement has been used as inspiration for MAC’s newest reporting protocol—the Equitable, Diverse, and Inclusive Workplaces protocol—in its Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) program, which requires participation from mining companies that are members of MAC, as well as members of other mining associations that have adopted the program. The TSM program is meant to assist mining companies in improving their environmental and social practices.

Katherine Gosselin, director of the TSM program at MAC, told CIM Magazine that it has received unanimous support from its members for the protocol, which was launched in June and sets out requirements for mining companies to improve equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) performance.

The protocol will measure mining companies’ performance on EDI using three indicators: 1) leadership and strategy; 2) advancing equity, diversity and inclusion; and 3) monitoring, performance and reporting.

“Then those indicators are themselves made up of detailed criteria [that assign] different levels of performance from Level C to Level AAA,” Gosselin said. “We consider [achieving a minimum of] Level A to be good practice.”

One of Level A’s criteria in the first indicator requires companies to have a corporate commitment and strategy on EDI that is communicated to workers, and they must update their board on progress towards implementation. Companies also need to have training or

awareness programs related to equity, diversity and inclusion available to all workers and management to attain Level A at the second indicator. For the third indicator, companies need to publicly report on their demographic diversity and have scope and methods for data collection and reporting.

Gosselin said that transforming these commitments into a protocol focused on EDI practices helps to ensure that the commitments made by the industry are implemented, and that performance within each company is tracked.

Putting the protocol into practice

MAC members will have to start publicly reporting on their performance on the EDI protocol in 2026.

“It’s to allow companies time to phase in the new requirements because it is a lot of work,” Gosselin said.

Companies will report confidentially to MAC in 2024 and 2025, and it will publish an initial industry-level picture of how companies are faring. At the time of print, MAC had 46 full members listed on its website and 59 associate members. While all members and associate members are required to sign onto the principles of the protocol, only companies with operating mines are required to report on their performance.

Industry engagement

MAC’s community of interest (COI) advisory panel was key in developing the program, Gosselin said. Both the COI

advisory panel and the TSM program were put into place in 2004. The panel includes individuals from Indigenous groups and communities where the industry is active, environmental and social NGOs and labour and financial organizations. Select MAC board members are also part of the panel to provide an industry perspective.

“We had multiple touchpoints with them over the last two years to get their views on what they felt were important criteria to set for the industry, making sure that the industry is setting sufficiently ambitious targets related to EDI,” Gosselin said. She added international industry partners like the Minerals Council of Australia also gave their input during the development of the protocol.

Gosselin said that capturing EDI as distinct yet interlinked concepts was an important part of the protocol development process.

EDI in mining companies

Georgina Blanco, vice-president of external affairs and social responsibility at Equinox Gold Corp., was part of the working group that developed the protocol.

“It was a very enriching experience because it was developed by us and our peers as an industry and not imposed by any external parties,” Blanco told CIM Magazine.

Blanco said one of Equinox Gold’s goals in the last year was to achieve a Level A rating for a minimum of 75 per

cent of all TSM protocol indicators, which it outlined in its 2022 ESG report. She added that Equinox Gold plans on scoring Level A on the EDI protocol, too.

ously want that to be more, but it already shows that women have their space in higher positions of decision-making,” Blanco said.

According to data compiled in April 2023 by S&P Global Commodity Insights, women in metals and mining companies globally held 14 per cent of executive positions, 12.3 per cent of board positions and 12.1 per cent of C-suite positions. According to Canada’s most recent census data, in 2021, women made up 16.4 per cent of the Canadian mining workforce.

Blanco stated that while Equinox wants to recruit more women, there have to be policies in place to retain women who are already in the workforce.

“We want to make sure that the women already working with us feel safe and respected at work and that their needs are covered by the company, in terms of family-work balance,” she said, adding that it could create a ripple effect to attract more women to the workforce.

ance is defined by BHP as “a minimum 40 per cent female and 40 per cent male in line with the definitions used by entities such as the International Labour Organisation and HESTA.” The Jansen project, located in Saskatchewan and expected to start production in late 2026, also has a leadership team comprised of 52 per cent women.

Simon Thomas, president of potash at BHP, told CIM Magazine it is also aiming to have Indigenous employees represent 20 per cent of the Jansen workforce by the end of the 2026 fiscal year, once operational. He said it would be representative of the community it operates in. Currently, the figure stands at 7.7 per cent.

“Workforces that are balanced and are inclusive are far more productive. The well-being of the individuals that work in those teams is much stronger and their connectivity to the organization, the outcomes they produce as a group, are stronger too,” he said.

In its report, Equinox Gold stated that women comprised 14 per cent of employees and held 20 per cent of executive and senior management positions. “We obvi-

On July 17, BHP Group Ltd. announced that the Jansen project’s workforce had achieved gender balance with 43.8 per cent female representation at the end of the 2023 fiscal year in June. Gender bal-

Across all of BHP’s operations, the company aims to achieve gender balance by June 30, 2025. As of June 30, 2023, the representation of women in BHP’s employee workforce stood at 35.2 per cent, according to its 2023 annual report.

“Workforces that are balanced and are inclusive are far more productive. The wellbeing of the individuals that work in those teams is much stronger and their connectivity to the organization, the outcomes they produce as a group, are stronger too.”

– Simon Thomas, president of potash at BHP

Eldorado Gold Corp. has also taken steps towards increasing the representation of women in its workforce. In 2018, the company joined the 30% Club Canada, an initiative that aims to achieve better gender balance at both the board and senior management levels. In its 2022 sustainability report, Eldorado Gold stated its board was composed of 56 per cent female directors, and that it set a goal for women to hold 30 per cent of senior management positions by 2023.

Shauna Goldenberg, director of inclusion and engagement at Eldorado Gold, told CIM Magazine that diversity is a strength for driving better quality business decisions. She noted the company undertakes a survey annually to better understand its employees and consequentially, better understand where to focus EDI practices.

She also pointed to a partnership between Eldorado and the School of Indigenous Studies at the University of Québec in Abitibi-Témiscamingue that aims to increase Indigenous participation in the mining industry. Through the expertise of teaching staff, the partners developed a project to retain members of the Anishinaabe community in the industry’s workforce.

Eldorado is currently using the new EDI protocol to assess where the company has gaps in its EDI performance, Goldenberg said.

“The TSM protocols have done a really great job outlining what organizations should be doing,” Goldenberg said. “Support from senior leaders combined with TSM protocols, like EDI, is the catalyst to see the change that we need and stimulate the mining industry for continued success.” CIM

Quebec University researches recovering minerals from asbestos tailings

The Quebec government has allocated $3 million over five years towards the creation of a new research chair at the Université de Sherbrooke that will focus on the recovery of critical minerals from asbestos mine tailings.

The funding from the provincial government will serve to establish and support the new research chair, which has

been operating since the start of June. The research chair aims to increase knowledge on the concentration of critical minerals in the tailings and to develop processing methods to extract them.

Asbestos mine waste is rich in magnesium and also contains nickel. Both critical minerals are crucial in the energy transition due to their use in solar panels and electric vehicle batteries.

Gervais Soucy, director of the department of chemical engineering and biotechnology engineering at the Université de Sherbrooke, and one of two chairholders of the research chair, told CIM Magazine the new funding will

#ICYMI

In case you missed it (ICYMI), here’s some notable news since the last issue of CIM Magazine, which is just a sample of the news you’ll find in our weekly recap emailed to our newsletter subscribers.

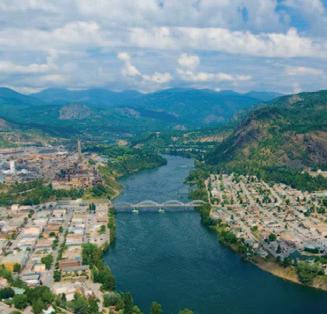

Teck’s Trail Operations (pictured) received $10 million in funding from the B.C. government’s CleanBC Industry Fund in July to support the progress of its Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage (CCUS) pilot project. Construction of the pilot plant is under way and once operational, which is expected to be later this year, it is expected to capture one tonne of CO2 per day from Teck’s Trail Operations.

India’s Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft landed on the moon’s south pole region on Aug. 23, which could be home to water ice deposits. According to Reuters, water ice could be key to a moon colony, lunar mining and potential missions to Mars. If water ice exists in sufficient quantities, it could be converted into fuel or drinking water to support missions to Mars and lunar mining.

The Mining Association of Canada (MAC)’s Towards Sustainable Mining standard has launched a new subscription service. MAC stated the service will help mining companies publicly report on sustainability data. Ioneer, an emerging lithium-boron producer, is the protocol’s first subscriber. Ioneer’s next ESG report will publicly report on its performance on the standards’ eight protocols.

An Aug. 8 report by the Conference Board of Canada said the rising demand for nickel will fuel investment in Sudbury, as reported by the CBC. The report stated that nickel demand is being driven by the war in Ukraine, along with an increased interest

in nickel exploration from the electric vehicle battery sector, which could help Sudbury’s local economy return it to prepandemic prosperity by 2026.

Canadian mining groups are asking for a one-year extension on the country’s planned January launch date of the Modern Slavery Act because of a lack of reporting and procedural guidelines in the law, as reported by Reuters Ben Chalmers, vice-president of the Mining Association of Canada, said that the organization is not disputing the law’s aim to fight forced and child labour in supply chains. Companies would first report under the law on or before May 31, 2024.

Sweden’s Climate Minister Romina Pourmokhtari has announced plans to lift the country’s ban on uranium mining to allow for greater nuclear energy capacity, as reported by Mining Technology According to the minister, the Swedish Parliament has shown majority support to lift the ban, and the government plans to build at least 10 large reactors in the next 20 years to meet the demand for lowcarbon energy. Several companies, including Canada’s District Metals, have already expressed interest in developing uranium sites in Sweden.

A consortium of Ford Motor Company and South Korean partners EcoProBM and SK On Co, Ltd. have chosen Bécancour, Quebec, as the location for a new $1.2 billion electric-vehicle battery materials plant, as reported by Reuters The facility is expected to produce 45,000 tonnes of cathode active materials per year for Ford electric vehicles. The facility is expected to be operational in the first half of 2026.

Sign up for our newsletter

Stay up to date on the latest mining developments with our weekly news recap, where we catch you up on the most relevant and topical mining news from CIM Magazine and elsewhere that you may have missed.

help the researchers undertake a variety of projects.

“Through this chair, we will train highly skilled people—masters and doctorate students and technicians—to support the [mining] industry,” Soucy said. “We are also aiming to create an overview of the science and research that has been made over the last 50 years on the topic of mineral recovery. Then, we want to make this [scientific literature review] available to the public.”

With the review, Soucy said the goal is to determine which technologies are most efficient and promising in the recovery of minerals from asbestos tailings.

“We want to avoid reinventing the wheel and instead use what has already been researched to build upon it,” he said. “For example, some mineral recovery technologies made a decade

Developments

ago were powered by combustible fuels; we want to see if we can use them with a more sustainable source of energy.”

The announcement was made in Valdes-Sources (formerly Asbestos and renamed in a 2020 referendum), where a large number of asbestos mines operated but are no longer active. However, around 800 million tonnes of asbestos mining waste are still present on these sites, according to the government. Valdes-Sources is situated 56 kilometres north of Sherbrooke, making the university a strategic location for research.

To avoid transporting the asbestos mine tailings, some of the larger research projects will take place directly at Valdes-Sources, while smaller-scale projects will take place at the university.

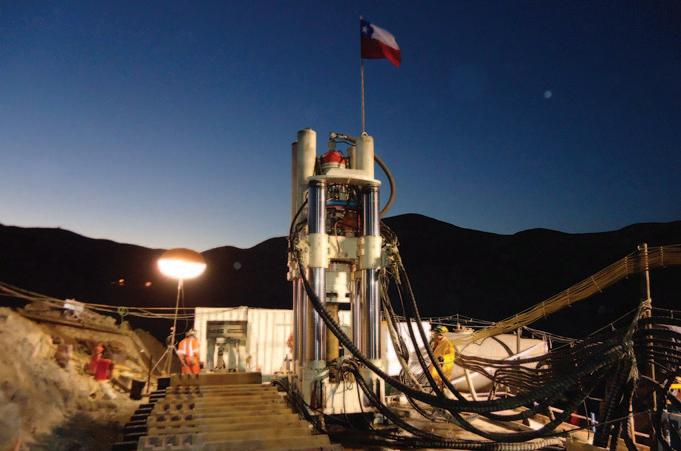

– Alice MartinLessons from the San José mine rescue

When the San José copper-gold mine in Chile collapsed on Aug. 5, 2010, it was a man-made and avoidable disaster, according to Cementation Americas director Roy Slack. He made these comments as part of his opening keynote at Hoist and Haul 2023, an international conference on hoisting and haulage that took place in Montreal on Aug. 14.

The rockfall at the San José mine blocked the ventilation shaft, which was its sole exit point. The mine was left

unstable, and 33 miners were trapped 700 metres underneath the surface for 69 days.

Slack told the audience that the San José mine rescue mission has valuable lessons to teach the mining industry, even more than a decade later.

“It was a great rescue success,” Slack said. “But we can’t forget it was a great mining failure.”

Slack added that the mine was notoriously dangerous. He noted that from 1998 to 2010, eight fatalities occurred at the mine. The mine operator had also been ordered to build a second means of egress

Number of operations simultaneously working to rescue the miners

33

Number of miners trapped underground

69

Number of days the miners spent trapped underground

in 2003, but when the mine collapsed in 2010, it still had not been constructed.

State-owned Chilean copper mining company Codelco was brought in by the government to coordinate the rescue mission. The government solicited rescue plans from around the world. Out of

more than 21 proposals submitted, the Cementation Group and its Chilean partner Terraservice were selected to carry out what became known as Plan A.

“One thing [the Chilean government] did was move quickly, as soon as the miners were found alive, to show that there was a plan in place,” Slack said. “I think that’s one of the reasons why we were picked—we could mobilize quickly and start Plan A while they began to look for other plans.”

Plan A involved drilling a first hole, then doing a second pass to widen it to a 28-inch hole, all with a Strata 950 raise drill. Soon thereafter, Plans B and C were also put into place. For Plan B, like Plan A, Chilean-American drilling company Geotec SA drilled two holes using a Schramm T130XD exploration drill.

Made-in-Canada technology gets a boost from MICA funding

Compiled by Silvia PikalThe Mining Innovation Commercialization Accelerator (MICA) Network, an initiative funded by the Government of Canada’s Strategic Innovation Fund to bridge gaps between innovation and commercialization in mining, announced in late June it will allocate more than $15 million in funding to 24 Canadian companies. The funding aims to accelerate the commercialization of mining technologies focused on increasing mine production capacity at a lower cost, reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, implementing autonomous systems and reducing environmental risk and long-term liabilities. CIM Magazine contacted five of the recipients to find out what they are planning to do with the funding.

$1.1 million

Prairie Clean Energy produces biomass fuel by utilizing flax straw, a byproduct of flax grown in Saskatchewan that is considered waste and usually burned, and processing it into pellets that can be used to heat potash mines in place of natural gas. The company said this biomass fuel has the potential to reduce the carbon intensity of heat energy consumed in potash production by up to 80 per cent. The MICA funding will support the annual production of 75,000 tonnes of flax straw pellets at a processing facility in Regina, in addition to the operation of a demonstration 250 kW modern biomass boiler at a training site in Moose Jaw in partnership with Saskatchewan Polytechnic.

Calgary-based Precision Drilling Corporation was responsible for Plan C, which consisted of a single hole drilled with a Rig 421 oil drill.

Plan B ended up rescuing the miners. On Oct. 13, 2010, the 33 miners were all successfully hoisted to the surface with the Phoenix 2, a rescue capsule.

Slack emphasized that the collaboration between the companies when one group’s plan was stuck was critical to the rescue’s success. When Plan B burned one of its drill bits and had difficulties fishing it out, Slack said the other groups were there to help. “There was interaction between all the groups working, there was collaboration and innovation,” he said. “Three plans made a difference.”

However, Slack said that while the urgency of the situation drove a successful

$850,005

Novamera Inc. creates surgical mining technologies that integrate into standard drilling equipment to pinpoint, map and extract ore from narrow vein deposits, which the company said is difficult to extract economically with conventional mining methods, and would typically be left unmined due to the deposits’ complex size and geometry. The company’s guidance tool gathers subsurface data and defines ore body geometry, which is then utilized to calculate optimal drill trajectory that maximizes ore extraction. The MICA funding will aid in the demonstration of its technology at a mine site in Newfoundland.

rescue mission, the accident could have been avoided, had the owner of the San José mine been mindful about safety.

“They didn’t spend money to make the mine a place where people wanted to work at, instead of a place where people had to work,” he said. “There were some things they could have done to make this mine safe and instead, they paid danger pay.”

Slack concluded by noting that the mining industry is facing big challenges to which it could apply the same sense of urgency that fuelled the innovation and collaboration at the San José mine rescue in 2010.

“I feel the largest challenge in our industry is tailings, and we’re still struggling with massive failures that [have] killed people,” he said. “I don’t have the answer, I just wish there was that sense

$579,696

Developments

Alice Martinof urgency we had at San José to solve that challenge.” –

Mining companies urged to boost cyber resilience

As the extractive sector becomes increasingly automated, companies have to be aware of cybersecurity threats and how they can negatively impact safety, reputation, operations and finances.

Rob Labbé was appointed chief information security officer (CISO)-in-residence on July 4 for the Mining and Metals Information Sharing and Analysis Centre (MM-ISAC), a non-profit, industryowned corporation established with the

RockMass Technologies Inc. builds data collection technology that allows geologists and geotechnical engineers to perform face mapping and assess tunnel stability. The MICA funding will help develop a product that uses LiDAR and computer vision to collect 3D georeferenced data, eliminating the need for data transcription and digitization, which the company said will save time and keep workers a safe distance away from hazardous ground conditions. Its software can identify and calculate geological features, enabling underground operations to rapidly make decisions using data collected from face mapping, structural mapping, ground support ID/audits, shotcrete thickness and more.

$500,000

aim of improving the cybersecurity of metals and mining companies. The organization currently has 20 members, six of which are based in Canada.

Labbé told CIM Magazine that the MM-ISAC tracked 11 cybersecurity incidents in July 2023 from a combined sample of the organization’s members and publicly reported incidents globally. This year, MM-ISAC noted an average of two to three cybersecurity incidents in the extractive sector each month. Last year, the number was around one to two cybersecurity incidents each month, which means the number of incidents since last year has doubled. Labbé said it is too early to tell if the July figures are the start of a new trend.

He said that the most common cybersecurity threat for companies in the

$292,333 Telescope Innovations, which is headquartered in Vancouver, is developing a carbonnegative technology to produce lithium carbonate from brines. The company stated it aims to address the lack of processing capacity in Canada, which it said is a net importer of lithium chemicals despite the country’s large lithium reserves. The funding will support the various technology phases, including brine sourcing and surveys, bench-scale proof-of-concept for its carbonation and crystallization process and bench-scale lithium carbonate production from a variety of brine compositions based on North American brines, including a scale-up of select processes.

Using abandoned chrysotile asbestos tailings in Baie Verte, Newfoundland, Baie Minerals Inc. has developed technology that extracts commercial grades of industrial and critical minerals, and destroys and eliminates chrysotile fibres from tailings, using a netzero carbon process. The company said its technology sequesters CO2 through the process of carbon mineralization. The MICA funding will be applied to the construction of a scalable CO2 capture and sequestration pilot plant.

View the full list of recipients online.

extractive sector is ransomware, which is a type of malware designed to lock a company out of its files or systems until a ransom is paid.

“A company that doesn’t rely on technology to perform their daily operations is not an attractive target to [hackers], because they don’t have the leverage to extort you for money,” Labbé explained.

Critical Elements Lithium Corporation appointed Nancy Duquet-Harvey as senior director of sustainable development and environment. Duquet-Harvey has more than 25 years of experience in environmental studies, environmental monitoring and permitting, as well as collaboration with local Indigenous groups.

NorZinc Ltd. named Jim Dainard as CFO and Robin Bienenstock as chair of its board of directors. Dainard is a chartered professional accountant with more than 22 years of experience, and most recently held the role of vice-president, finance at Victoria Gold Corp. Bienenstock is an investor and the Canadian representative of Resource Capital Funds, a mining-focused alternative investment firm.

Frontier Lithium Inc. appointed Erick Underwood as CFO. Underwood has more than 25 years of experience in the finance and project development sectors within the mining industry and held key positions at companies such as Chesapeake Gold Corp., Cia. Minera Zafranal (Teck Resources Ltd.), AQM Copper Inc. and BHP Billiton.

Premium Nickel Resources Ltd. appointed Peter Rawlins as senior vicepresident and CFO and Sean Whiteford as president of Premium Nickel Resources International Ltd., an indirect wholly owned subsidiary of the company. It also appointed CEO Keith Morrison as chair of the board and Mark Christensen to the board of directors.

“As we get more technology-driven and more complex, now we become a more attractive industry to those people.”

Labbé said that the extractive sector is seen as a lucrative target for hackers, but the threat may not be on the radar for most companies.

“Cyber risk hasn’t made it to a lot of the boards and executives in a significant way, so they’re unprepared to manage it as a company-wide event when an incident happens,” Labbé said. “Cybersecurity threats are very much seen as a technology problem in the industry, where really it needs to be looked at as a business risk.”

He added that while companies of all sizes face the risk of cybersecurity incidents, smaller companies are more at risk because of fewer resources.

In 2021, according to a Statistics Canada survey, 27.5 per cent of Canadian mining, quarrying and oil and gas extraction businesses were impacted by cybersecurity incidents, and 12.5 per cent of businesses in this sector were impacted by incidents to steal money or demand ransom payment.

Labbé pointed to a recent example of a significant cybersecurity incident in the mining industry: Copper Mountain Mining Corporation’s ransomware attack, which occurred on Dec. 27 of last year. The company preventively shut down its mill near Princeton, B.C., until Jan. 1 to address the attack and gradually returned to full production on Jan. 4, according to a Jan. 6 press release.

In a July 19 article, The Globe and Mail reported that Canadian miner Barrick Gold Corp. was one of at least 376 organizations impacted by a global data theft incident. Barrick Gold has yet to publicly confirm the attack took place.

The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (CCCS) counted about 305 reports of ransomware attacks last year, up from the 295 reported the year before. Sami Khoury, the head of the CCCS, told The Canadian Press in an article published on July 19 that the number could be 10 times higher as many organizations are too embarrassed to report that they have been impacted by cybercrimes.

Labbé said that it is often cybercrime groups that publicly announce the attack, instead of the company itself.

“When you communicate poorly, it becomes a massive distraction,” he said. “You’ve got employees, shareholders, investors and media asking you what’s

going on, which raises the pressure in the room. Good communication turns down the external volume so you can focus on the actual problems.”

Labbé said that to prevent a cybersecurity incident in the first place, all companies should plan for cybersecurity incidents and have action protocols in place for them. He compared the importance of planning to a fire drill. “Instead of hoping it doesn’t happen, companies need to realize this is something that has a high possibility of happening. Hope is not a security control,” he said.

As the new CISO-in-residence at MMISAC, Labbé’s role is to provide education and guidance to the industry. He also provides one-on-one counselling to MMISAC members on how to increase their cyber resilience. –

305

Alice MartinNumber of ransomware attacks in 2022 reported by the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security 11

Number of cybersecurity incidents tracked in the mining and metals industry in July 2023

27.5

Percentage of Canadian mining, quarrying and oil and gas extraction businesses impacted by cybersecurity incidents in 2021

“Cybersecurity threats are very much seen as a technology problem in the industry, where really it needs to be looked at as a business risk.”

Rob Labbé, CISO-in-residence for the MM-ISAC

Mining made fun

If you have ever browsed the app store for a mining game, you get a small window into how the public sees the industry: the images are usually of a man with a pickaxe or shovel digging and filling up a minecart with gold, which he rides all the way to the bank. That is not how it works and it is also an outdated picture of an industry that is rapidly changing in many aspects, from its technology to the people who make up its workforce.

A new strategy game called Mine Evolution has been designed to provide a more modern viewpoint of one of the world’s oldest industries.

Mine Evolution is a collaboration between The Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum, a number of its branches and societies and Science North, a science centre in Sudbury, Ontario, which hosts Dynamic Earth, an attraction with earth science and mining experiences. The game was developed by D&D Skunkworks.

Jennifer Beaudry, senior scientist at Dynamic Earth, told CIM Magazine that Science North had always wanted to develop a game and saw its chance after the pandemic hit and children were switching to online education.

“This was the opportunity for us to shed a different light on what modern

mining is about and where the future is heading,” she said.

As described on its website, the mission in the game is to “explore the ground beneath your feet and search for precious minerals that are critical to evolving your mine—from your building materials to Wi-Fi technologies.”

Users are involved in all aspects of mine development, some of which include picking a plot of land, extracting ore by blasting rocks, harnessing solar power and eventually closing the mine. Users run multiple mines across Canada to extract a short list of critical minerals including lithium, nickel and copper and earn financial, social and environmental credits to grow their operations.

Jacqueline Allison, chair of Canstar Resources Inc. and an executive on CIM’s Management and Economics Society, was one of the industry leaders who provided expertise into how to portray certain aspects of the mining industry. She told CIM Magazine that incorporating financial, social and environmental credits into the game is a way to demonstrate how many factors contribute to the success of a mining project.

“In addition to being technically sound, a mining project is expected to provide a financial return, which adequately compensates the operator for the risks being taken,” Allison said. “It is also important for the operator of a mining project to earn and maintain the social licence to operate while minimizing the environmental impact.”

The game intends to inspire younger generations to consider a career in the mining industry, by raising awareness of its innovation, technology and sustainability practices, and highlighting the importance of critical minerals to clean energy technologies.

“This is about introducing people to what mining is,” Beaudry said. “And first and foremost, it’s about having fun—we want people to have fun and play this game. But as you start digging into it, it’s about realizing that mining is high tech. Mining is socially and environmentally conscious. We need to be sustainable in order to continue mining and you see those aspects built throughout the entirety of the game.”

To showcase the people behind the industry, there are moments in the game that introduce actual workers, like Zara, a mining engineer nicknamed the “Rock Doctor” by her team.

Beaudry said the game takes care to showcase the leaps the mining industry has taken when it comes to everything from safety to environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards. For example, the game requires you to build a refuge station in your mine.

In addition to the game’s educational focus, Science North will release six les-

son plans in November geared for grades four to 12 across the country so that teachers have the option of incorporating the game into their curriculum.

At the time of print, Mine Evolution was in its beta stage and available for

Utility corridor could export potash from Prairies to Brazil

Fox Lake Cree Nation and FirstNation company NeeStaNan Projects Inc. announced in July they are partnering to spearhead the development of a utility corridor through the Prairie provinces to export natural resources like potash, natural gas, wheat, bitumen and other critical minerals landlocked in western Canada.

The proposed corridor would rely upon existing railway infrastructure and start in Fort McMurray, Alberta, and end in Port Nelson, on the Hudson Bay coast of Manitoba, where Fox Lake Cree Nation would construct and own a deep-sea port. A set route for the corridor has yet to be determined.

A memorandum of understanding has been signed between Fox Lake Cree Nation and NeeStaNan for the latter to conduct an environmental assessment and social impact study. The process is currently under way, according to Wil Jimmy, Fox Lake Cree Nation economic development officer, and is expected to take between eight and 12 months to complete.

download in English and French for PCs, Android and Apple devices, with an official launch date for the general public at Science North in Sudbury planned for November. It is downloadable and playable offline. – Silvia Pikal

The government of Manitoba announced on August 3 it would provide $6.7 million over the next two years to advance the utility corridor’s feasibility study, which the province said is contingent on funding participation from the governments of Alberta and Saskatchewan, as well as First Nations communities. The feasibility study is expected to cost $26.6 million.