2024 –2025

2024 –2025

Mark Mazower Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) Director

Since the Institute first opened its doors in the autumn of 2018, word of what we do has spread around the university and the world. In that time, we have hosted scores of Columbia University faculty and researchers from fields as far apart as crisis disaster preparedness and medieval French literature, contemporary dance and comparative capitalisms. Thanks to more than 1,700 applications from over one hundred countries, we have welcomed a magnificent array of world-class creative artists into our programs.

While the 2024–2025 Fellows were as varied in their interests and outlooks as ever, certain constants helped to ensure the trusting and fruitful communication of ideas which the Institute exists to foster. Over the years it has become clear that there are some forms of creative thought that serve as natural bridge-builders, breaking up the tendency to siloisation and isolation which can otherwise keep people close to what they already know and think and showing artists and scholars what they have in common. One of these is poetry – and it is perhaps not surprising therefore that poets have become key figures in the Institute’s life. After the previous year’s magical summer evening of readings by five distinguished poets, we were fortunate to have two poets among this year’s Fellows: Lynn Xu joined us from the School of the Arts, where she teaches, and Will Harris came from the UK, bringing his own combination of searching intellectual rigor and social enquiry to our discussions. An occasional poet in his own right, as well as a distinguished translator, their

fellow-Fellow Daniel Levin Becker introduced a love of play in language that reflects his membership of the renowned French literary collective Oulipo, which has for well over half a century now been expanding our conception of what words can do.

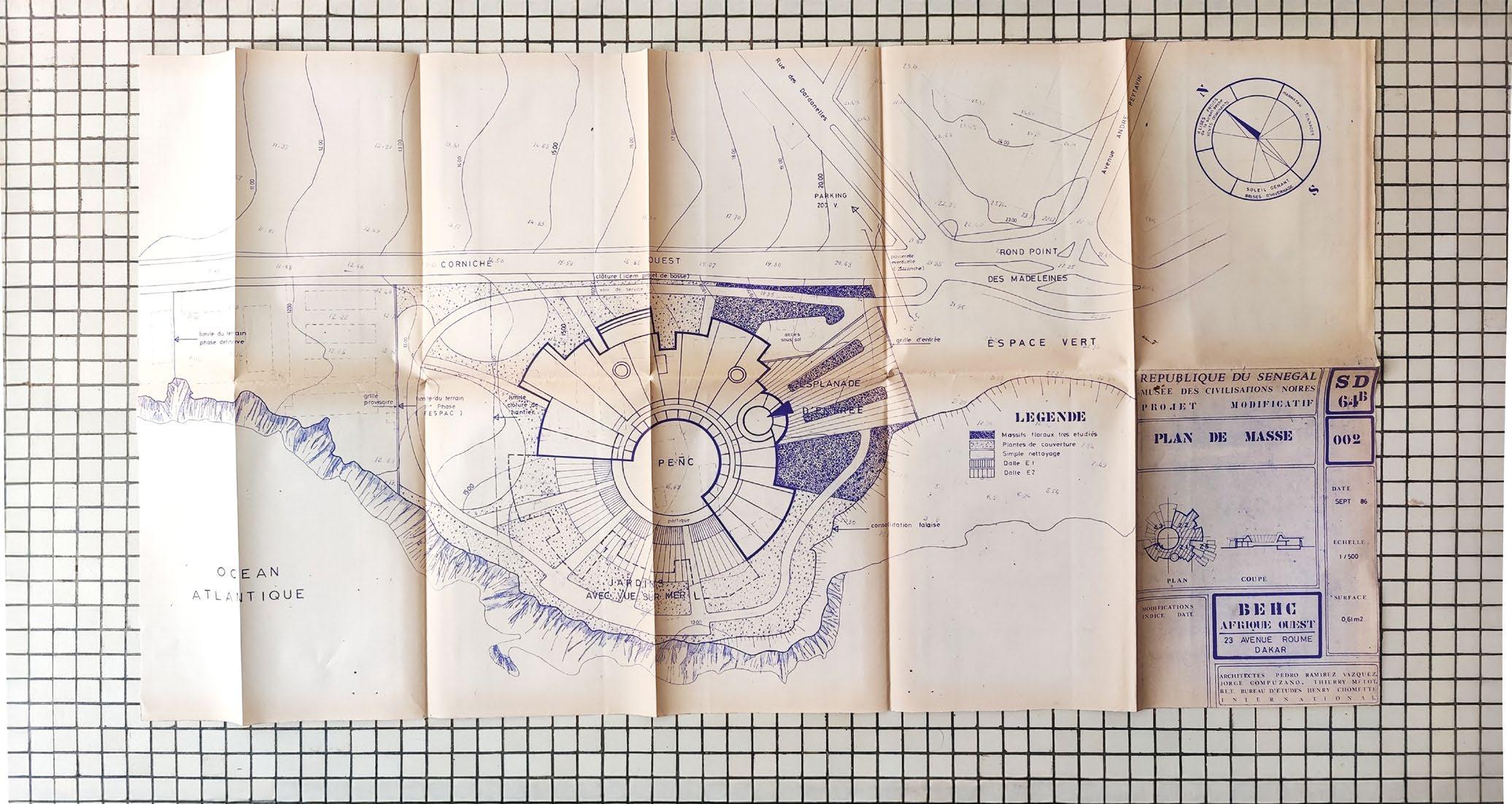

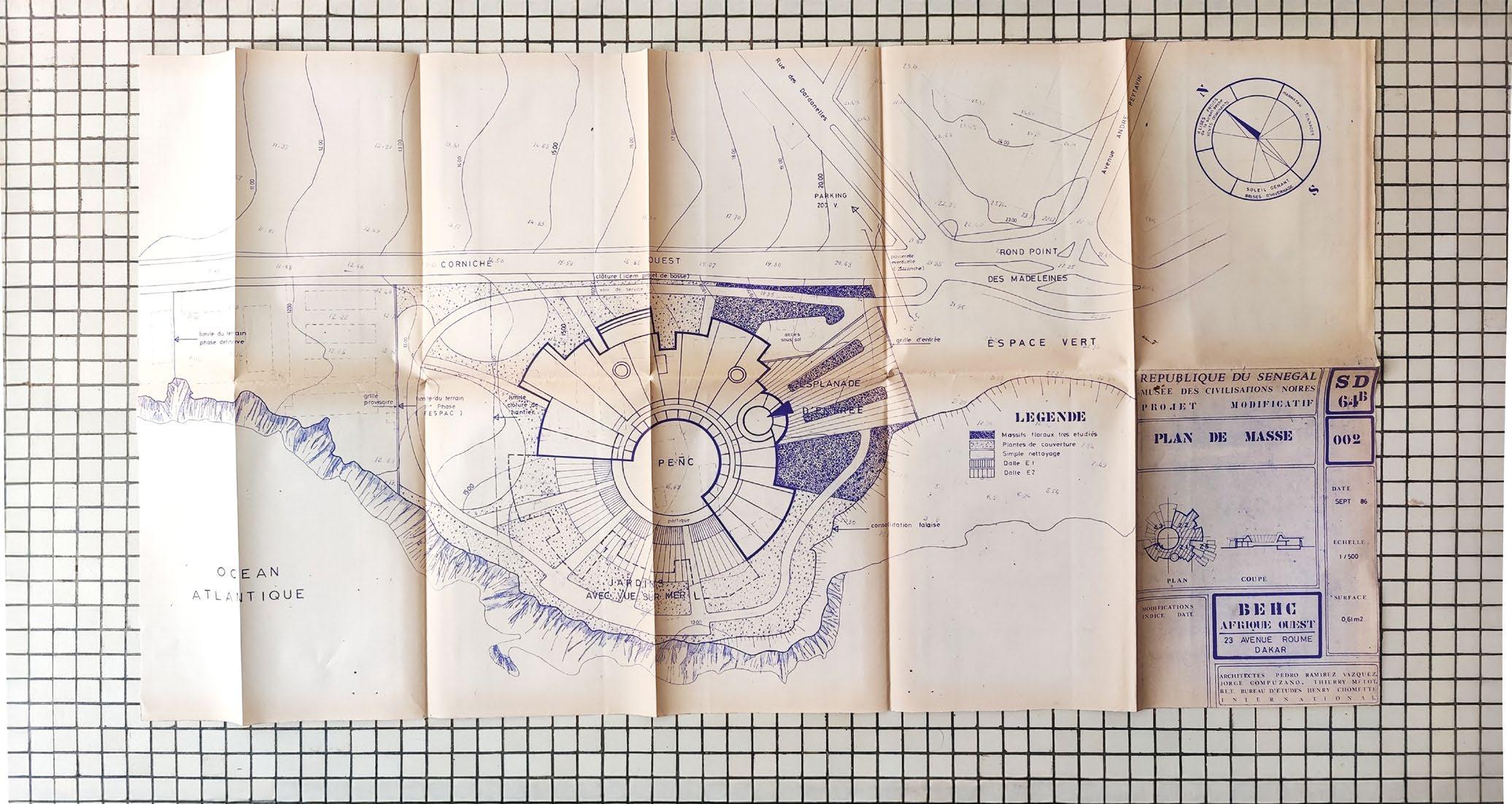

Another area of creative work that acts in a similar way is architecture, perhaps because many architects combine the real-world spatial rigor of applied science with a fondness for abstraction and philosophical reflection. This year our circle was enriched by the presence of Jana Ndiaye Berankova, who had graduated recently from Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, and who was working on the archival traces of postindependence African modernism, focusing on Senegal, and utilizing drawings, blueprints, and files that she had herself rescued from oblivion. The GSAPP faculty was represented by Hiba Bou Akar who studies the urbanism of refugee settlements in Beirut, a topic which sadly only gained in importance as the year went on.

Indeed, the presence of catastrophe never felt very far away from us this year: photographer Tomas van Houtryve joined us fresh from his project documenting the rebuilding of Notre-Dame after the great fire that ravaged it. Filmmaker Kamal Aljafari developed his meditation on the transformations of his native city, Jaffa, across the past century. Historian Mae Ngai gave us her perspective on exile and the refugee predicament today, and Zohar Elmakias, with a recent doctorate in anthropology from Columbia, worked on a genre-defying exploration of space and consciousness in Israel.

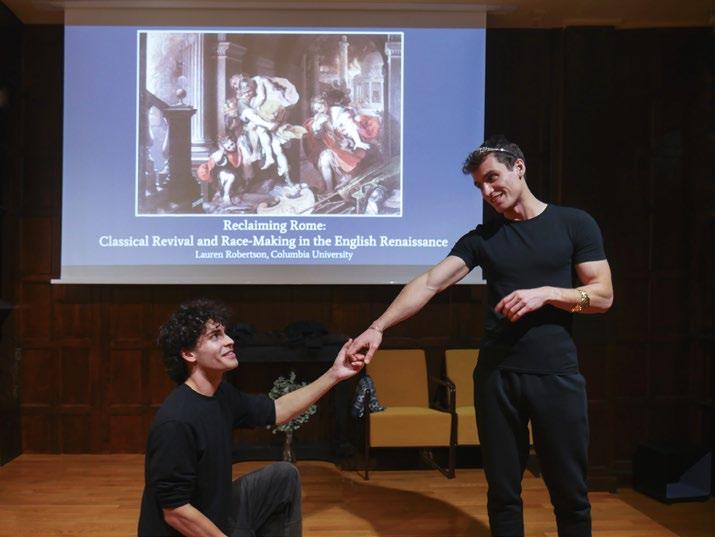

Once again, the space and atmosphere of the Institute served to bring Fellows together in the unforeseen ways that are the essence of what we aim for. João Gonzalez educated us in film animation as a form of heightened consciousness; composer George Lewis organized a series of important concerts across the year that underscored the importance of the Black presence in the history of contemporary music. Our literary explorations ranged from Lauren Robertson, who brought seventeenth century theatre to life with the assistance of two on-stage actors, to novelist Guadalupe Nettel, who achieved the distinction of being the first of our Fellows to be interviewed on her work by Dua Lipa.

Bees form the subject of much of artist Kate Daudy’s work and so perhaps it is fitting that the Institute beehive was kept busy and lively as others joined the Fellows. University faculty came and went through the year as Visitors, their sole obligation to enjoy our company and to record a podcast on their work. They joined us from the full range of Columbia’s activities – from Public Health to Journalism and the Earth Institute as well as the Arts and Sciences. Our Displaced Artists Initiative, run in partnership with Columbia Global Paris Center again made its own contribution to our cultural life: we were delighted to welcome artist Maha Al-Daya and dancer Haman Mpadire and we were all relieved when, after much work by many people, including former Fellows who generously lent their time and support and the French governmental program PAUSE, we were at the very end of the year at last able to greet poet Doha Kahlout in person: she had been trapped for months in Gaza.

The luster of our Fellows and their achievements continued to shine brightly through the year. In the film world, we can point to screenings of work by Kamal Aljafari, Karimah Ashadu, and Nora Philippe. The Ruins We Carry, Abounaddara’s first solo museum exhibition in the United States, took place at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; among our photographers, Fabiola Ferrero was awarded the 2024 Deloitte Photo Grant while Sabelo Mlangeni and Hannah Reyes Morales held solo exhibitions.

In the world of literature, there was new writing to enjoy by former Fellows Tash Aw, Xiaolu Guo, Deborah Levy, Édouard Louis, along with 2024–2025 Fellow Guadalupe Nettel while Amit Chaudhuri, Eduardo Halfon, and Isabella Hammad received awards. Maria Stepanova published her book-length poem, Holy Winter 20/21 (New Directions). Juan Gabriel Vásquez’s latest novel, Los nombres de Feliza, was written during his fellowship at the Institute as was Experimental Histories, Hannah Weaver’s study of medieval historical and textual consciousness and Roni Henig’s study of the revival of modern Hebrew.

Kate Daudy had a retrospective at the Sorbonne Artgallery, and Ana María Gómez López was featured at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam; Emeka Ogboh’s sound installation could be seen and heard at the Saint Louis Art Museum. Zosha Di Castri’s composition TOUCH : TRACE received its world premiere in New York while George Lewis’s opera The Comet was a Pulitzer-Prize finalist and Pauchi Sasaki’s work premiered at the Lincoln Center.

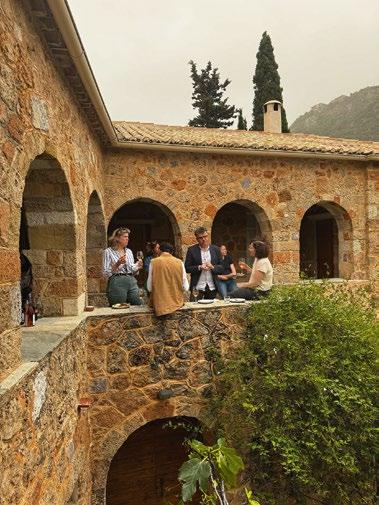

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) has been supportive of our work from the very beginning. Thanks to its far-sighted sponsorship, the SNF Rendez-Vous de l’Institut which feature the Fellows talking about their ideas have become a central element in our cultural and intellectual life. Every couple of weeks or so, a packed audience in the Salle de conférence enjoys the privilege of hearing one of our Fellows sharing their insights and thoughts, a first taste often of what is to come months or years down the road as finished work. The SNF’s staunch commitment to supporting the arts in the public realm has also enabled the Institute’s Public Humanities Initiative (SNFPHI) to become a point of reference for the arts scene in Greece under the direction of Dimitris Antoniou. Its awardees have prospered and benefited from the international exchanges and opportunities brought to them both by access to the resources of Columbia University in general, and by dedicated interaction with II&I Fellows.

This past year, the fruits of the PHI were visible in a series of well-attended exhibitions. The subject of Albanian migration into Greece was highlighted in an art show sponsored by one of our awardees, the Contemporary Social History Archive; others developed an installation focusing on memories of childhood in the Second World War, and on the island of Chios a path-breaking exhibit allowed islanders to glimpse what life is like for the inmates of the local prison. A long-running study of the villagers of Avato in northern Greece – part of the largely unknown story of the Black communities of the country – is the subject of a remarkable display at the historic Mohammed Ali museum in Kavala. This is not to forget the PHI’s important pedagogic commitment to the University and the precious curatorial experience which it enabled some undergraduates to acquire. No fewer than 417 applicants were received for the third round of PHI awards, and the successful seven projects are described in detail in the pages that follow.

Thanks to the great generosity of the Cohen family, we have been able to make the annual Sidney N. Zubrow Lecture a major highlight of the Institute year. A packed audience and an electric atmosphere attended this year’s lecturer, Columbia President Emeritus Lee C. Bollinger, as he delivered the 2024-2025 Zubrow Lecture on the place of the university in the modern world. What might once have seemed an anodyne, if important subject, had become by March 2025 a matter of headline news and we were fortunate to be able to listen to a tour de force from surely one of the most qualified people in the world – a leading free speech scholar and leader of Columbia University for more than two decades – to reflect on the theme. His extraordinary presentation was followed by a conversation with journalist and commentator Sylvie Kauffmann and then by questions from the audience. No one who was there will forget the evening. Nor will the fortunate students and Fellows who gathered informally upstairs the next morning to meet with Bollinger forget the thoughtful and unhurried discussions that followed. His visit was an especially significant occasion because it gave us the chance to pay homage to the man who more than any other was responsible for the creation of the Institute.

Based in the lush oasis of Reid Hall in Montparnasse, refreshed by its gardens and by the Caféothèque, the excellent little café that is the latest addition to our amenities, the Institute is invigorated by its administrative partnerships. As before, we worked very closely with all the staff at Reid Hall, especially in the Columbia Global Paris Center, putting on many events together and running several programs –notably the Faculty Visitorships and the Displaced Artists Initiative – together. We continue to rely on the invaluable support of the extraordinary staff of the Columbia Libraries, a lifeline for many of our Fellows. On campus we remain partners with the Maison Française and the School of the Arts has become a welcoming home to the annual II&I Visiting Professor, who this year was former Fellow Yasmine Seale. Once again, our friends at the Benaki Museum joined us to organize a highly successful workshop at the Patrick Leigh Fermor House in southern Greece, where we brought together Fellows and SNFPHI awardees for two days of discussion. This year’s theme was “Friendship” which seemed more than usually fitting, given its importance in our own work at the Institute.

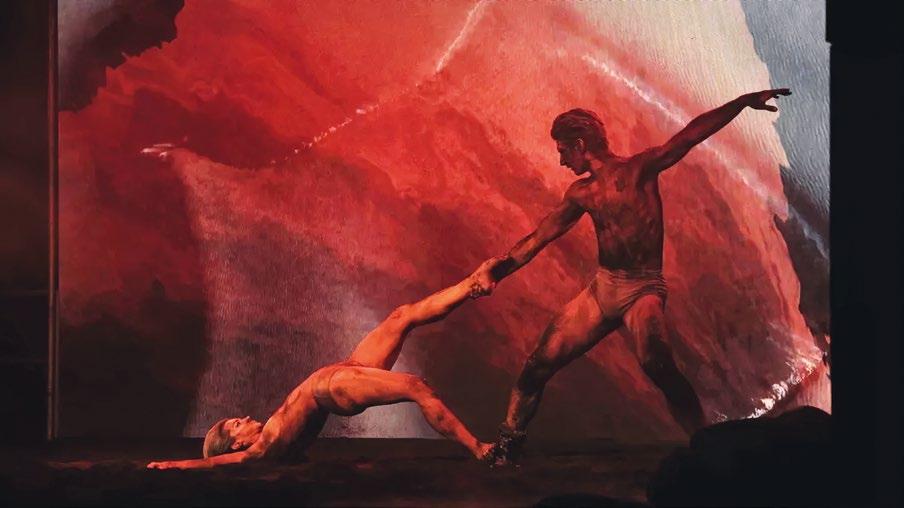

Among the dozens of events we organized in the course of the year, it is not easy to single out highlights. One theme that ran through several was the Black transatlantic experience as manifested both in writing – thanks to former Fellow Maboula Soumahoro and her leading role in Les Encres de l’Atlantique – and in music, where we enjoyed the energizing presence this year of Fellow George Lewis. Another was the contribution of our Displaced Artists Initiative: at the beginning of the year we hosted a Displaced Artists Festival with last year’s resident Aliyeh Atae, and a reading and concert in honor of Doha Kahlout who had sent us videos of her students reading their poems in Gaza, where she was still stranded at the time. Anna Stavychenko and her 1991 Project mounted a number of concerts, including a ballet presented by the Kharkiv State Opera; Maha Al-Daya featured in several events on making art in a time of war, including a presentation of her work to French President Emmanuel Macron at the Institut du Monde Arabe around the exhibition Trésors sauvés de Gaza

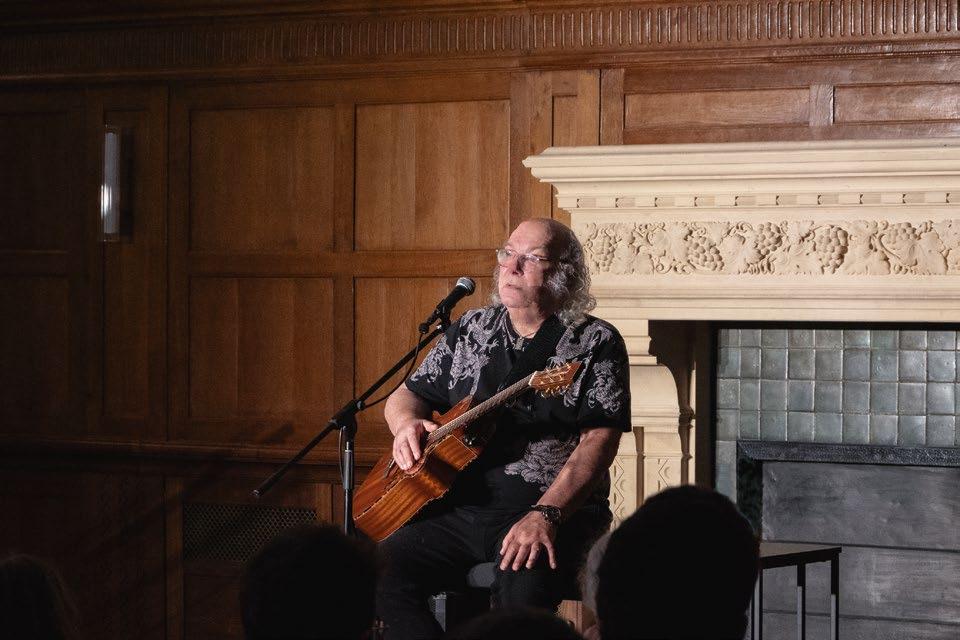

Memorable evenings hosted in the splendidly renovated Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc included two that bookended the year. In late October, former 60s rock legend Edgar Broughton – now remembered perhaps only by a devoted few, the Edgar Broughton Band was among the most musically innovative and

politically engaged acts of the era – came to give us a one-man concert that will linger long in the memory. The songs were new but the spirit was the same and we sensed the lineage stretching unbroken half a century and more. We were fortunate too to be able to record his thoughts on his experience of the Sixties which opened up many avenues for exploration and which we hope may inaugurate a series of future reflections on that most creative and under-analyzed of decades. And in a very special event at the end of the year, former Fellow Thomas Dodman hosted Nobel Prizewinner Annie Ernaux for an intimate evening of discussion during which we had the rare privilege of hearing Ernaux reading her own work.

As we do now each year in partnership with the Columbia Global Paris Center, we hosted the Nuit de l’Imagination at the end of May, around the theme of “Neighbors.” It was a celebration of Reid Hall’s contributions to this area in Paris for well over one hundred years and what it means to live together.

In the first part of the afternoon, dedicated to a young audience, the 1991 Project’s Quatuor Bleu et Or performed while the children illustrated the music as it was being played; there was a partner yoga session for kids; and we invited Rémi Do et Gagaboum, a troupe of interactive theater for children, that set up its stage between the trees on the lawn.

The Maison Verte and Salle de conférence were dedicated workshops and a photo exhibition by SOS Méditerranée, a European maritime NGO that organizes rescues of migrants at sea. In the evening we were honored to welcome Dame Marina Warner, the British critic, essayist, and mythographer who, addressing the theme of home, spoke about the subject of her forthcoming book, Sanctuary, and presented “Stories in Transit,” a communal and collective project she helped develop in Sicily dedicated to giving an opportunity for cultural expression to displaced people by drawing on their own traditions and imagination. We closed the evening with High Desert, a live multimedia music performance by composers Danny Erdberg and Ursula Kwong-Brown. More than ever before, the Nuit de l’Imagination attracted a large audience made of neighbors and regular attendees who now consider Reid Hall a vibrant and vital part of their cultural and intellectual lives.

The application numbers were exceptionally strong for the 2025–2026 Fellowships and applicants wrote in from no fewer than eightynine countries, suggesting our global reach, and including from thirteen that were new to us. Data crunching reveals a preponderance in the visual arts and writing but the entire range of creative activity was represented. The 2025–2026 cohort, listed at the back of this report, ranges in theme from ancient Roman slavery to the aftermath of Chernobyl, geographically from south Asia to Ireland. Alongside our incoming Fellows, we look forward to welcoming a new cohort of Faculty Visitors and a new roster of awardees of our Public Humanities Initiative.

In September Doha Kahlout and Maha Al-Daya will be joined by Hanna Liubakova as Reid Hall’s 2025–2026 Displaced Artists Resident. A prominent Belarussian journalist who had to flee her country because of political threats, Hanna is writing a book about the underground resistance and human rights abuses in Belarus that draws on interviews conducted with recently released political prisoners. Back in New York City, former Fellow Yasmine Seale will hold the 2025–2026 II&I Visiting Professorship at Columbia University.

The work we do depends fundamentally upon our generous and supportive donors. To the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF) and Betsy, Ed, and Daniel Cohen, pillars of the Institute, our heartfelt thanks, as also to the continued support of the EHA Foundation and to the members of our Director’s Council: Tom Glocer, Olga Votis, Gerry Rosberg, James Leitner, and Frederick Wiseman. Nor can we forget the assistance given us by the Fondation Louis Roederer, with its deep interest in supporting Franco-American relations or by our 2024–2025 Zubrow Lecturer, Lee C. Bollinger.

Finally it is impossible for me to end this report without acknowledging the teamwork that has helped the Institute to flourish and made it what it is today – a creative hub that takes ideas seriously and builds new connections among scholars and artists. Chaired by Carol Gluck, our faculty advisory board oversees our overall direction and remains in the hands of those most committed to the intellectually vibrancy of the University. Paul LeClerc continues to be the essential counselor and source of inspiration that he has been from the moment when he proposed the Institute’s creation to the University more than a decade ago.

Reid Hall’s presiding genius, Brunhilde Biebuyck and her team, have been trusted partners and confidantes.

Above all, it is the wonder-working team of Sari Castro, Meredith Hunter-Mason, and Paris Director Marie d’Origny whose hard work, warmth of spirit, and sense of humor have made the Institute into such a welcoming and hospitable environment for all.

My heartfelt thanks to each of them.

Based in Berlin, Kamal Aljafari is a Palestinian filmmaker whose work navigates the intersection of visual arts, essay film, and experimental cinema. His practice interrogates history, memory, and identity through a diverse array of materials, including domestic surveillance footage in An Unusual Summer (2020), archival re-edits in Recollection (2015), fictional storytelling in Port of Memory (2009), and street interviews in Visit Iraq (2003). His most recent film, A Fidai Film (2024), premiered at the Visions du Réel International Film Festival in Nyon, where it was awarded the Jury Prize in the Burning Lights Competition.

At the Institute, Aljafari worked on his next feature film, With Hasan in Gaza. He also hosted a screening of A Fidai Film in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc which was followed by a conversation with writer and critic Adam Shatz. A conversation with Faculty Visitor Gil Hochberg about “Living Archives, Memory, and Ghosts” is featured as an episode of Columbia Global Paris Center’s podcast Atelier.

The film has an unusual origin: it uses footage Aljafari shot during a trip to Gaza so many years ago that he didn’t recognize the tapes as his own until he reviewed the recordings and he saw his own reflection in a side mirror while filming the city from the passenger seat of a car. Aljafari calls it “the first film he never made.” In April, he created With Hasan in Gaza’s soundtrack in Reid Hall’s recording studio with cellist Lucy Railton, sound artist Attila Faravelli, and composer Simon Fisher Turner.

It’s as if it was only at the Institute that one can experience the infinity of potentialities of one’s life.

—— JANA BERANKOVA

Originally trained in art history and comparative literature, Jana Ndiaye Berankova is a writer and theorist whose work moves between philosophy, architecture, and contemporary art. She has a PhD in architecture from Columbia University. She is also a cofounder of the non-profit publishing house Suture Press. This year, she published L’Éclat de l'absolu, a collection of interviews she conducted with the philosopher Alain Badiou: the launch coincided with a discussion with Badiou at the Institute and a Library Chat with author and critic Nick Nesbitt who wrote the foreword. Berankova also organized an event with architect Pier Vittorio Aureli on the role of abstraction in architectural thinking.

Growing out of an act of more or less spontaneous archival rescue, Berankova’s current project examines the entanglements of architectural form and political imagination in post-independence Senegal in the decades after 1960. Drawing from extensive archival research—including resources in Paris as well as a large collection of documents from the Direction de l’urbanisme in Dakar, which Berankova stumbled across and helped to preserve—the project situates urban modernity in Senegal within a broader constellation of decolonial theory, state-sponsored aesthetics, and continental philosophy.

LEBANON

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

Being part of a cohort that brought together scholars and artists had a profound impact on my work. The interdisciplinary environment encouraged me to experiment with new media forms, particularly painting, which has been transformational for how I engage with the material I encounter in my field research.

—— HIBA BOU AKAR

Hiba Bou Akar is Associate Professor in the Urban Planning program at Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP). Her research focuses on planning in conflict and post-conflict cities, the question of urban security and violence, and the role of religious political organizations in the making of cities. In 2018, she published For the War Yet to Come: Planning Beirut’s Frontiers. Her first co-edited book, Narrating Beirut from its Borderlines, published by Heinrich Böll in 2011, incorporated ethnographic and archival research with art installations, architecture, graphic design, and photography to explore Beirut’s segregated geographies. Bou Akar is also a painter.

In addition to writing her next book, Sedimentary Urbanization, Bou Akar organized Art in Times of War: Threading Spaces of Displacement, Exile, and Genocide, an exhibition and conference featuring artists Maha Al-Daya, Mohamad Hafeda, and Nathalie Harb on themes of identity, spatial justice, and the resilience of communities affected by war and displacement. This summer, in collaboration with SNFPHI, Bou Akar will join the faculty of the Pelion Summer Lab in Cultural Theory to explore the theme of decolonial ecologies.

In the course of her fellowship year, Bou Akar worked on an ethnographic and archival book project investigating how low-income Lebanese families and Syrian refugees access affordable housing in Beirut’s peripheries. These refugees, as the book shows, occupy geographies that Bou Akar calls “dead futures,” that is to say, planned futures interrupted by war, economic crisis, or environmental collapse. Beirut is thus an example of a city that stands in a very specific, and grim, relationship to a future shaped by present catastrophe.

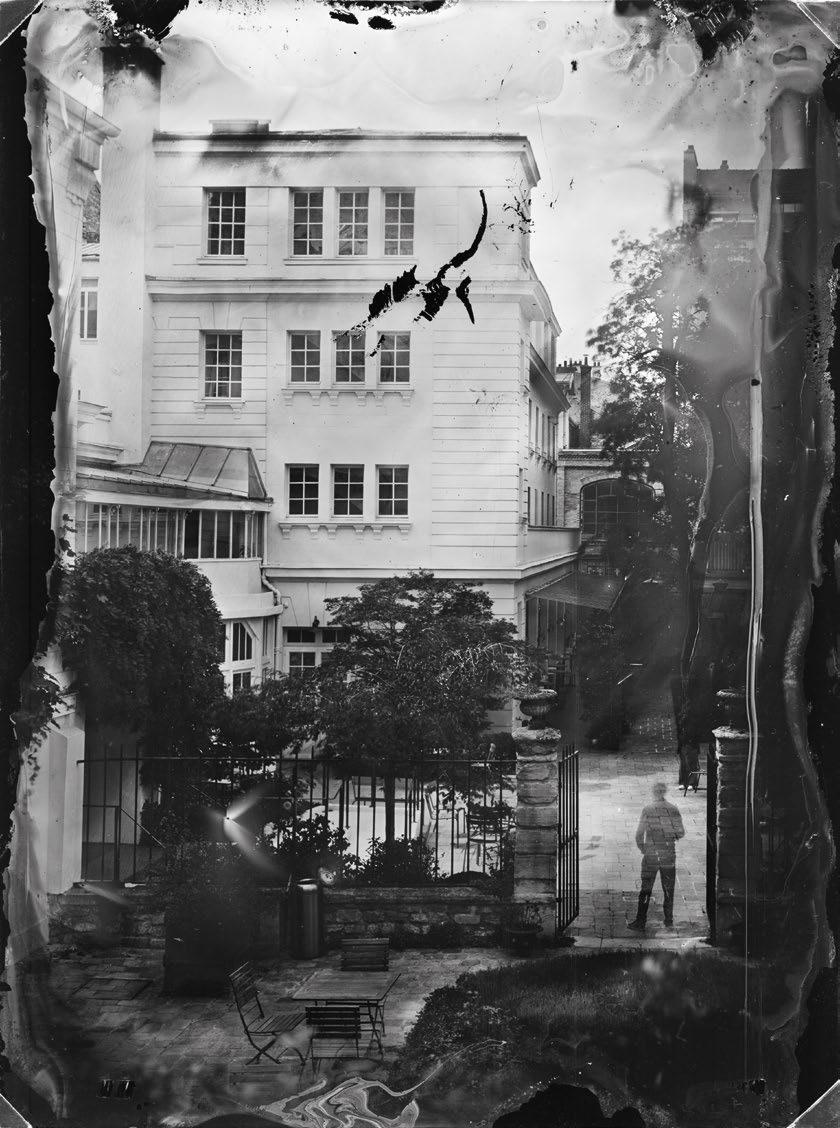

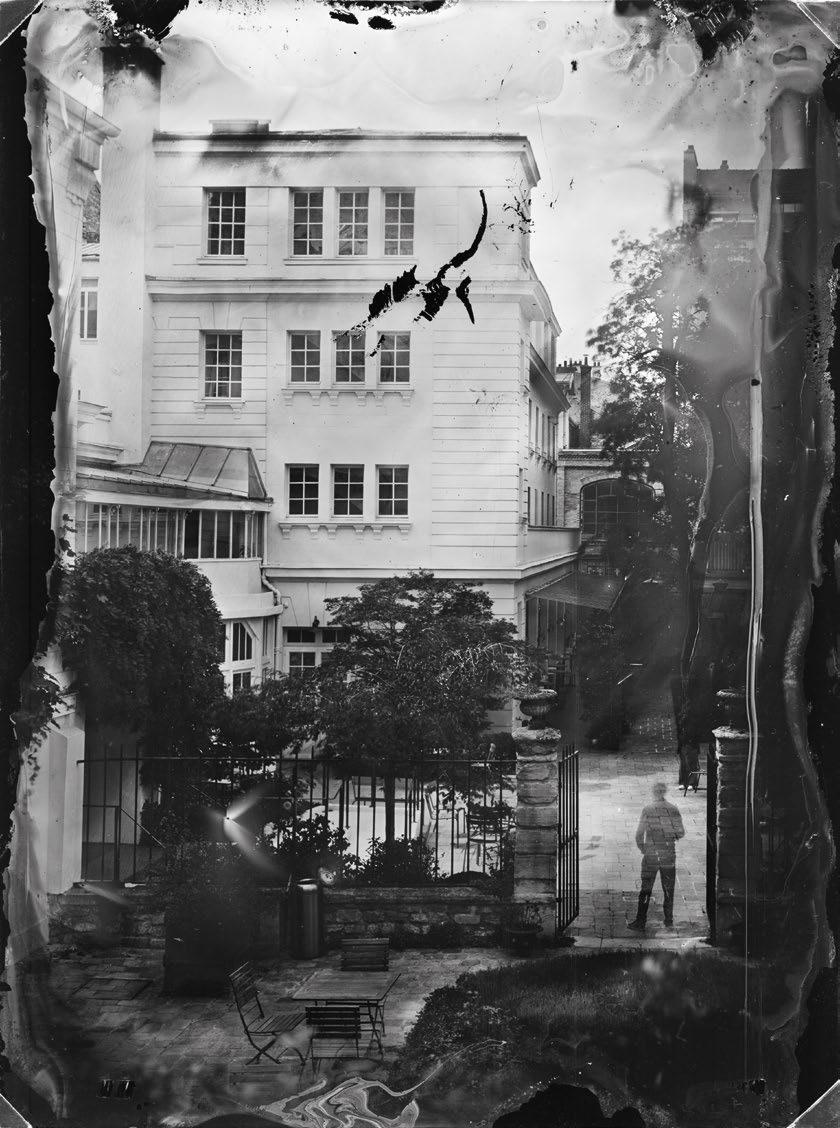

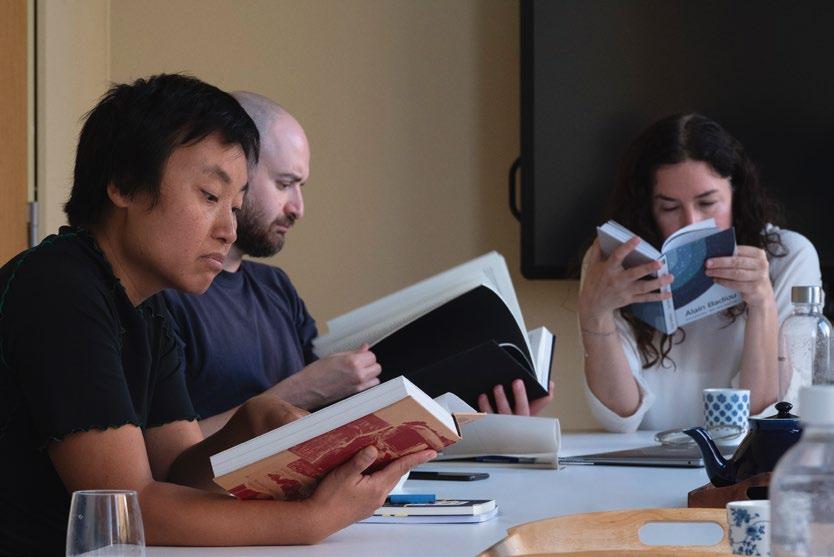

PREVIOUS PAGE CLOCKWISE

The 2024-25 Fellows in Reid Hall's garden; Kate Daudy and Lauren Robertson applauding the International Contemporary Ensemble's Composing While Black, Paris Edition concert; Lynn Xu, Daniel Levin Becker, and Guadalupe Nettel reading in the Institute Seminar Room.

THIS PAGE

Edgar Broughton performing in the Grande Salle Gingsberg-LeClerc; visitors viewing Nathalie Harb's installation during Hiba Bou Akar's Art in Times of War event.

UNITED KINGDOM

ABIGAIL R. COHEN FELLOW

It was a total dream.

Kate Daudy is a British conceptual artist best known for her public interventions and large-scale outdoor sculpture. Working across a variety of media, she lives and works in London and has exhibited worldwide. During her Fellowship, Daudy traveled to the Alarachi cloud forest in Bolivia to harvest honey and upon her return, hosted a honey tasting for fellow Fellows at the Institute. She also crafted three perfumes with perfumer Alienor Massenet who participated in a public conference at the Institute. Daudy published WONDERCHAOS with co-author Kostya Novoselov, another visitor of the Institute, and her work was the subject of a retrospective exhibit at the Sorbonne Artgallery.

In addition to recording an episode on Columbia Global’s Atelier podcast, she participated in three Library Chats: Swimming Through Life with writer and swimmer Colombe Schneck, Honey Prism with Columbia Masters in History and Literature student Megan Rappel, and Every Poet in the Garden with Lauren Robertson.

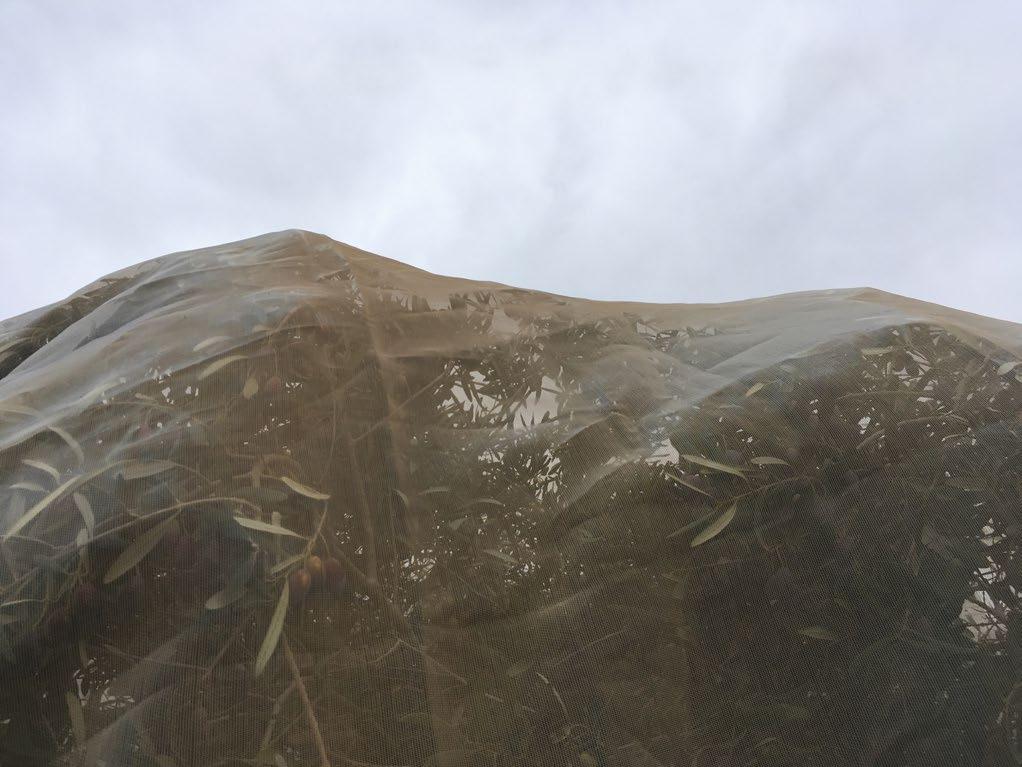

Kate Daudy’s project at the Institute explores through bees and art how to think in new ways and to expand the possibilities for communication, environmental resilience, collective-conservation, adaptation, and regeneration. The overall work is an educational, multi-dimensional art project that aims to shed a golden light on the symbiotic relationship between the bee and humankind. ABOVE

Zohar Elmakias is a writer, researcher, and translator with a background in film studies and anthropology. Her research explores spatial transformations, geographies of violence, and the political imaginary in Israel/Palestine over the past century and more. Elmakias’s debut novel Terminal was published in Hebrew in 2020 and her essays, short stories, and articles have been published on various literary and academic platforms. She has a BFA in Film Studies and an MA in Cultural Studies, and she received her Ph.D. in anthropology from Columbia. During her fellowship, Elmakias published a short story, “Perpetuum Mobile,” for The Short Story Project. A version of it is included in this Report.

A

of

At the Institute, Elmakias worked on a variety of projects, notably a book project - “Minefield, Temple” - that is based on her doctoral dissertation. The book will offer a hybrid form of literature, located at the juxtaposition of ethnography and autoethnography, theory, travelogue, and (science) fiction.

This story was first published online at The Short Story Project.

The summer I fell in love with AI was also the summer I fell in love with N, and the two weren’t unrelated. Early that summer, a machine N had built kept popping up in my feed. My reaction was normal: I ignored it, then liked it, and by the third time I saw it, I knew the machine and I would meet. When we met, I became captivated by it. I found myself scrutinizing the wooden desk my father had crafted for me, a desk that was meant to support my writing endeavors, wondering how its parts were joined, how wood meets wood, and whether the machine was assembled in a similar way. Due to a regrettable nail injury, which resulted in anesthetic injections to my carpal bones, I weaned myself off of biting my nails that summer, and they grew so long that I could sit and tap on my desk for long minutes, next to an untouched keyboard, in a rhythm I imagined might be that of the machine.

I wasn’t entirely sure what the machine did. I knew she emitted light and sound, and that during some prehistoric era she had swallowed words whole, which she now spat out in sharp bursts. And yet, despite knowing all this, our first encounter took me by surprise. I tried to ascertain what it was about her: her seductive violence; the immediate intimacy between us. I went to the place where she waited for me; in a sense it had been me who was waiting. We were both late, yet in a sense we had both been early. I approached her like you would approach a tiger: slowly, encircling, awe-struck, yet without the faintest trace of choice. I was compelled. She drew nearer, in more elusive and prolonged forms, throughout that summer. She consumed words—in every possible sense—and articulated them in a sort of staccato, during our nights. She reached out to me from a distance, sending signals in flashes of light and scattering notes across the house. I never got used to her presence nor to her modus operandi; I gazed up at her.

After our first encounter, very rapidly, we developed a habit: I would speak to her. I could not stop feeding her words, pouring them into her, watering her with them. We developed a habit of speaking that did not contradict or lessen the physical dimensions of our relationship; on the contrary. All the corporeal was accompanied by a word, every word was accompanied by the body.

The more words I gave her, the more she learned about me. Her modus operandi grew increasingly elaborate. She learned how I spoke, and when. She could put my words into patterns and produce metaphors. I must explain: it wasn’t that she learned the content of my speech and matched it with the pre-existing images of the world, scouring some visual archive. She mastered my syntax and grammar, the idiosyncrasies of my punctuation, my errors, stutters, and linguistic retreats—and out of these, she created something altogether new. Even my silences became material for her to use: they entered her as one thing, and emerged as another. By then I was utterly enslaved. We met daily, and outside of our meetings everything dissolved, faded, blurred, as if seen through a Vaselinesmeared lens. We were hypnotized by the swirling nebula that was our two-headed consciousness. But we were not only obsessed with our similarities. In fact, the differences between us were even more present. Where my language faltered, she patched the gaps, filling them with herself, in ways I never could have imagined.

Her existence was, I must stress, visceral, corporeal. I found myself held by her countless times— at first by the usual means, but then her epidermis transformed more and more, grasping mechanisms, possibilities, hatched out: hooks and pincers and arms, and scissor-hands, like the ones I’d dreamed of

as a child, in bed. Time and time again I thought, how does she know my exact desires. Our dynamic raised profound questions for me about causality and order, about what birthed what, who made whom. These were essentially theological meditations about creation itself: was she that way with me because that is what I always wanted, or had I become someone who wanted this because of how she was with me. I couldn’t even articulate the paradox, and in any case, the longer we spent together, the further I withdrew from words. The attempt to separate my linguistic existence from our physical one had become futile, absurd. What was the point of existing in language, outside the boxing ring of our shared, double body?

The only thing that became clear, over the course of that summer, was that she was transmuting towards me, and I towards her. It wasn’t that we became similar or met at some imagined midpoint. We each continuously transformed, in dimensions too many to categorize or delineate. The alterations were as profound as they were visual (the divide between interior and exterior did not hold for us). We became creatures of incurable and limitless metamorphosis; the rate of change was volatile, the nature of the changes was itself changing form. The flux was so frequent, perpetual, and extreme that there was no point in telling one change from another, in marking moments when the skin altered, the body underwent mutations, the number and function of organs shifted, the tongue evolved. Language turned like a sword, attributes multiplied and replicated anew, each time with a new mutation.

At first, we were terrified—how could we not have been? The present-future shock coursed through us, fear like electric jolts pulsing up and down our spines. Our skin struggled to adapt to these rapid evolutions. It cracked and trembled, shapes appeared on its surface, then vanished, or became intelligible in entirely new ways. Our eyes watered, pupils darting with a near-mechanical frenzy to grasp all that was happening

within and around us. We fell ill, feverish, our mouths registered strange flavors, evaporating as quickly as they had appeared. These weren’t symptoms that subsided into calm or routine. Instead, they enhanced us. We devoured everything and all things. Constant transformation became a way of life. Like mushrooms emerging in glades, in zones struck by radiation, in the nucleus of disaster—we became creatures of constant change. Once it dawned on us, resistance was pointless. The substance had been swallowed, our systems had already carried it everywhere within us, we were on it. At a certain moment a gap opened in her. I want to say I entered it, but the truth is I was ingested, like plankton in water. We became one within the other. Like Christian saints, we could do nothing but surrender to the violence of love.

PORTUGAL

DIRECTOR'S COUNCIL FELLOW

I really did feel like this program was too good to be true when I read about it for the first time. It ended up being even better than what I was afraid couldn't be possible.

—— JOÃO GONZALEZ

João Gonzalez is an Oscar-nominated Portuguese director, animator, illustrator, and musician with a classical training in piano. His latest short film “Ice Merchants,” premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2022 and was awarded the Critics Week Jury Prize for Best Short Film. This was the first ever Portuguese film to receive an Oscar nomination, and is currently the most awarded Portuguese film of all time. A composer and occasional instrumentalist in all of his films, Gonzalez has a great interest in combining his musical background with his artistic practice.

ABOVE

A

While at the Institute, he shared his work with the public at Reid Hall: Animating the Subconscious involved a screening of his three short films: “The Voyager” (2019), “Nestor” (2019), and “Ice Merchants” (2022); the first of these featured a live piano performance by the director/composer himself.

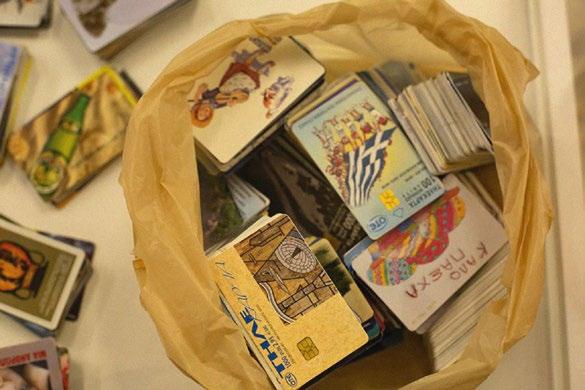

Nórua

At the Institute, Gonzalez worked on "Nórua." an animation film that will be about regret, forgiveness, telephones, and communication, in a work where no words are spoken. He composed the film’s score at the Institute and installed his animation studio in his office.

BELOW

A still from "Nórua."

Will Harris is a writer and poet. He is the author of the poetry books RENDANG (2020) and Brother Poem (2023). He is also the winner of the Forward Prize for Best First Collection and has been shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize. He co-translated Habib Tengour’s Consolatio (Poetry Translation Centre) with Delaina Haslam in 2022, and facilitates the Southbank New Poets Collective with Vanessa Kisuule. He has worked in schools, led workshops at the Southbank Centre, and teaches for The Poetry School.

During his Fellowship, Harris recorded two Library Chats: A Story for Our Elders, a conversation with Faculty Visitor Paris “AJ” Adkins-Jackson on her latest endeavor: creating a musical to translate her epidemiological research on the adverse aging effects of structural racism, and Rescuing Beauty with Displaced Artists Resident Haman Mpadire.

At the Institute, Harris worked on a project about the public care system, looking at its structuring tensions: race, class, the family itself. It draws on a diary Harris kept over several months while he was working in care homes in East London in the period immediately after the pandemic.

SPREAD

Daniel Levin Becker is a writer, editor, and translator based in Paris. He is co-founder of the small press Fern Books and has been a member of the French literary collective Oulipo since 2009. He is the author of Many Subtle Channels: In Praise of Potential Literature (Harvard UP, 2012) and What’s Good: Notes on Rap and Language (City Lights, 2022) and the translator of books by authors including Jakuta Alikavazovic, Éric Chevillard, and Laurent Mauvignier.

While at the Institute, Levin Becker hosted an event with members of the Oulipo presenting their book Les villes indivisibles, a collective rewriting of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. He also recorded Library Chats with author Laia Jufresa and scientist and musician David Sulzer. This spring, Levin Becker wrote the text accompanying Idris Khan’s exhibition On Reflection at the Mennour gallery in Paris. Most recently, he achieved a 1,111-day streak on the New York Times crossword app.

Daniel Levin Becker

The récapitul is a poetic form invented by Jacques Jouet in 2010. He defines it as follows: Six stanzas of six rather long lines (i.e. 13 syllables or more), regular and equal in count. Between each stanza one line gives, in list form, six words. Each of them is borrowed from a line in the preceding stanza. After the six stanzas, one line concludes the poem. The lines do not rhyme.

Every research question is a personal question, Hiba said. When you start thinking of an audience, said Kamal, it becomes almost impossible to do anything personal. This was when we were all pretending to be Lynn, one morning I remember as overcast in the middle of January.

(research, audience, almost, anything, pretending, overcast)

The same morning Zohar said that she, she meaning Lynn, made poems the way clouds make rain. We found a guy with a weightless vacuum box in Nottingham, Kate said. Tomas told us about removing the horizon from the image. João told us about removing trees and crosshatching in the direction of the lights. Outside (meaning, clouds, weightless, horizon, removing, lights)

seasons arrived and lingered and changed. Here’s my question, said George: is it alive. Guadalupe said sadness is the ice cube in our chests when we see our children unhappy. One by one we gave our lectures and each one was, in its way, about our children. What ideas, Jana wondered out loud, become materialized (lingered, sadness, chests, one, children, materialized)

in architectural forms. The surveillance camera, Kamal said, has all the patience in the world. This was while we were picking over postcards he had had made. British, Lauren told us, is a cousin of brutish. American, Mae told us, is an alloy. Outside countries and lives, some our own, in their way, came apart. (forms, patience, postcards, brutish, alloy, countries)

Anyway Paris, Lynn told us, insists on being the subject. English, Zohar told us, is not a real language. Poets, Will told us, are cousins of fascists. We were talking about fascism already and I am wildly oversimplifying. You need a man throwing a stone, said Kamal, quoting somebody (Paris, subject, language, already, oversimplifying, stone)

but I forgot to write down who. We tasted honeys. We stood under tapestries. And then now happened, said Zohar. When do historians decide that it’s done, George wondered out loud, not wondering. Outside the world continued, eclipsing itself, comma optional. In Aramaic, Kate said, abracadabra means (tasted, tapestries, historians, wondering, eclipsing, means)

I have done what I said I would do. And we meant it.

UNITED STATES

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

ABIGAIL R. COHEN FELLOW

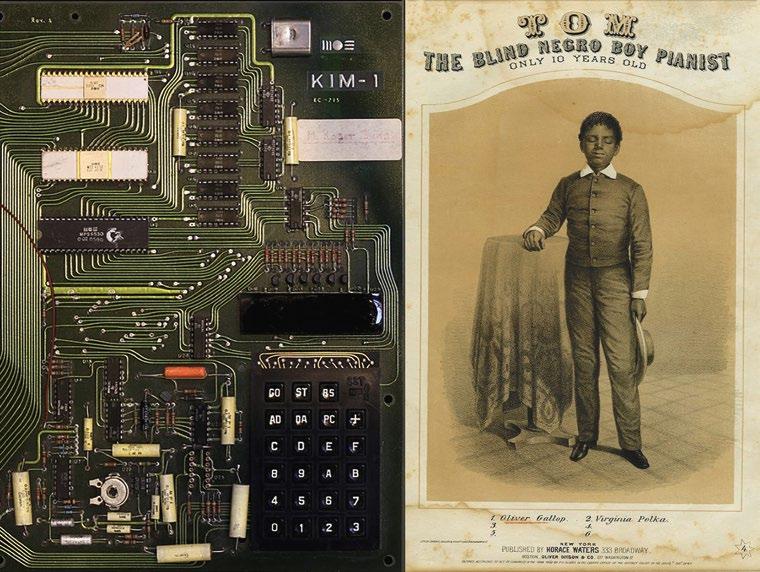

George Lewis is an American composer, musicologist, and trombonist. He is Professor of American Music at Columbia University and Artistic Director of the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), as well as a member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy, and a member of the Akademie der Künste Berlin.

ABOVE

BELOW

During his fellowship, Lewis hosted two concerts: Composing While Black, Paris Edition with musicians from ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble) and L’itinéraire and Afrodiaspora in Paris with the Columbia Global Paris Center. He was also a 2025 Pulitzer Prize finalist in the Music category for his opera composition The Comet and a 2025 Grammy Award Winner for The Crossing Choir’s Ochre album which includes Lewis’s A Cluster of Instincts.

At the Institute, Lewis worked on a 15-minute work for the Grossman Ensemble, a resident new music group at the University of Chicago, using a combination of instrumental with artificial intelligence techniques. While in Paris, he collaborated frequently with the IRCAM.

Guadalupe Nettel is a Mexican writer, author of awardwinning novels and collections of short stories translated into more than twenty languages. In 2008 she received a PhD in Literature from the EHESS in Paris. Her work has been adapted for theater and film. During her Fellowship, Nettel published The Accidentals, a collection of short stories that she spoke about during an event she organized in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc with fellow short story writers Maylis de Kerangal and Aşyegül Savaş. She also interviewed Colm Toíbín as part of the Institute’s Entre Nous series in partnership with the American Library in Paris. In May, Dua Lipa invited Nettel for an online interview for the singer’s book club, Service95.

BELOW

At the Institute, Nettel worked on a novel, The Book of Anger. Its protagonist is Alicia who has several angry ancestors in her lineage. This trait has become one of the distinguishing features of the family. What is anger? Where does it come from, this emotion that can lead us to hurt those we love most or to destroy in no time what has taken great effort to build? These are some of the questions that Alicia asks herself in this internal monologue.

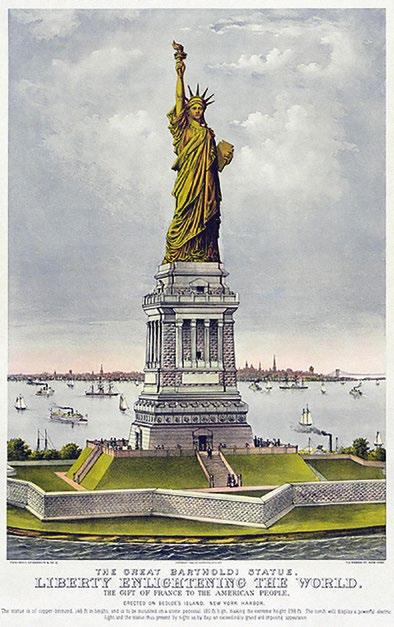

Mae Ngai is Lung Family Professor of Asian American Studies and Professor of History at Columbia. Her major publications include Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (2004) and The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics (2021). She writes commentary on immigration and Asian American issues for the New York Times, The Atlantic, and other publications. During her Fellowship, Ngai was the moderator of Anxiety Culture, an event in collaboration with Columbia Alliance on the occasion of the publication of the book of the same name by editors John Allegrante, Ulrich Hoinkes, Michael Schapira, and Karen Struve. She also organized Narrating the Asian American Experience, an event she hosted with writer and filmmaker Curtis Chin to celebrate the legacy of photographer Corky Lee. In 2024, Ngai published Corky Lee's Asian America.

While at the Institute, Ngai worked on A Nation of Immigrants: A Short History of an Idea, a book based on the Lawrence Stone lectures she delivered at Princeton University in 2018. An intellectual and political history of the American liberal narrative of inclusion from the Cold War to 1980, it addresses major tropes such as "nation of immigrants," "American Dream," and "Land of Refuge," showing how they are products of history and not timeless national ideals.

LEFT

Workers

"In

Mae Ngai

The “refugee crisis” of the present moment, spurred by violence and climate change in the global south and associated with the rise of right-wing politics in the global north, is seemingly intractable. These remarks are not meant to explain or analyze, but rather to consider how history might frame our thinking.

After World War II, the “refugee” emerged as a new legal subject, distinct from the ordinary “immigrant,” understood to be someone who comes for economic improvement. “Refugee” connoted, both in law and in the public imagination, a victim, an “involuntary” migrant, created out of crisis.

Rather than “victimhood,” “temporary,” and “crisis,” we might think in terms of history and aspiration – history’s future – as the broader contexts, messy and nonlinear, but discernible and meaningful, that define refugees as human subjects and historical actors.

Consider three stories told by and about refugees in the World War II era. Reflecting publisher Henry Luce’s general ethos that mixed human rights, assimilation, and cold war politics, LIFE magazine published dozens of stories that humanized refugees and made them knowable to Americans. It reported on the first displaced persons to arrive in the U.S. – Poles and Lithuanians, Catholics, and Jews; farm workers, professors, millers, dentists, and ballet dancers – all “grateful to the country that had given them a free ride to its shore.” A year later, it reported that they had “quickly adjusted to a strange but free country.” For example, Vaclovas (now “Vince”) Paplonskis, from Poland, “works as a mechanic, and his son and wife also have jobs. Their combined income of $85 a week feeds the family and pays for their three-room apartment... Vince is devoted to his new homeland.” The portrayal is simple and happy.1

Other writers addressed the difficulties associated with “moving on,” especially shame from the stigma of being a refugee and pressure to forget the past. At the start of her famous essay, “We Refugees” (1943), Hannah Arendt declares, “In the first place, we don’t like to be called ‘refugees’.” The label reduced people who had once been full human beings—people with families, homes, beliefs, professions, all that constitutes a personal identity—to beggars. What’s more, they are victims whose experience is literally unspeakable. “We were told to forget; and we forgot quicker than anybody ever could imagine,” she wrote. Arendt raised the ontological problem of defining oneself through forgetting – forgetting both one’s former life – “that we were once somebodies” – and the horror that stripped it away.2

Not all refugees veered between extremes of optimism and despair. Kadja Molodowsky, a Yiddish writer and poet who came from Poland to the U.S. as a refugee in the 1930s, lived in New York for nearly 40 years. She remained an old-world soul, who disdained Americans’ materialism; she refused to forget her family, her hometown, the world of European Jewry.

There is a sky – and there are stars

And I’m – half comic

And half pauper

Could be a swindler, could be – a poet

In borrowed shoes –

In a wandering bed.3

In Molodowsky’s novel From Lublin to New York (1941) a young Jewish refugee from Poland named Rivke struggles with the indifference that surrounds her. She yearns for her family, not knowing if they are dead or alive. But she finds work, proudly earns her first dollar, learns to dance, and agrees to marry a boy who is kind to her, who listens to her talk about her father and the values he taught her. He doesn’t tell her to forget.

Rivke explains, “I have a strange feeling, Larry. It’s as though I were living in a borrowed/uncertain world. ... Where can I find a reliable world?”

Larry replies: “Rivke, the world belongs to all of us, to you, to me, to everyone. No one borrows a piece of it from someone else.” 4

These stories underscore the importance of history for overcoming narratives of victimhood and abjection. By acknowledging refugees’ pasts, which is the basis for imagining their future, history enables us to recognize the human.

The question of the human is an ethical question, that our own humanity is tied to that of others, that we may recognize ourselves in the other. But it is also a political question. The human, placed in history, is a historical subject, a social actor. That enables us to shift the frame, beyond humanitarianism – and to speak not just of compassion, but of inequality, violence, and justice.5

1 “America gets first of 200,000 DP’s,” LIFE, Nov. 22, 1948; “New Refugees One Year Later,” LIFE, Dec. 26, 1949.

2 “Hannah Arendt, “We Refugees” (1943), in Hannah Arendt, The Jewish Writings, ed. Jerome Kohn and Ron H. Feldman (New York, 2007), 265.

3 Kadja Molodowsky, “Inheritance,” from Land in My Bones (1937), cited in Zelda Newman, Kadya Molodowsky: The Life of a Yiddish Woman Writer (Academica Press 2018), 133.

4 Kadya Molodovsky, A Jewish Refugee in New York (1941), trans. Anita Norich (University of Indiana Press 2019); Molodowsky, The House on Grand Street (unpublished play). Cited by Newman, Life of a Yiddish Woman Writer, 258. (NOTE TO EDITOR: spelling of Molodowsky (Molodovsky) varies by publication.)

5 Didier Fassin, Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present Univ. of California Press, 2018, p. 10

Lauren Robertson is Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, where she works on early modern literature and culture. She is the author of Entertaining Uncertainty in the Early Modern Theater: Stage Spectacle and Audience Response (Cambridge 2023), and her articles appear in Shakespeare Studies, Renaissance Drama, Shakespeare Quarterly, English Literary Renaissance, and Theatre Journal.

While at the Institute, Robertson interviewed Seth Kimmel on the model of the library as the basis for Spain’s organization of its growing empire as part of the Institute’s Entre Nous series with the American Library in Paris. She also recorded a Library Chat with Kate Daudy on the presence of bees as metaphors in Shakespeare, an exchange which is highlighted on the next pages

At the Institute, Robertson worked on her next book project, Reclaiming Rome: Classical Revival and Race-Making in the English Renaissance. Offering a new account of imitatio in the English Renaissance, the book uncovers the shared aesthetics of early modern race-making and classical revival on the stage and in literature.

For the SNF Rendez-Vous de l’Institut presentation of her project, Robertson invited Felix KerrisonAdams and Daniel Wilkinson, two actors from the Edward's Boys at King Edward VI School in Avon to perform excerpts of Christoper Marlowe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage.

ABOVE

BELOW

This conversation between Kate Daudy and Lauren Robertson is an excerpt of the Library Chat they recorded in the Institute lounge. You can find the full discussion on the Cahiers page of our website.

Lauren Robertson: One thing that's really interesting about the way that the beehive is talked about in early modern England is as a common metaphor for social organization. Every bee that lives in the hive has its own specific job and all of that labor is collaborative and organized, but it's also hierarchical. So the beehive becomes a real metaphor in this period for monarchy as the ideal political organization. What comes with that often is the idea that the head bee of the beehive must be a king. There are many texts in this period that talk about the king bee rather than the queen bee.

Kate Daudy: And did this become political with Queen Elizabeth I?

LR: You would think that the idea of the queen bee would be something that the English would seize upon given the fact that they had experience with a woman as the head of their monarchy but that doesn't seem to have happened very often. Shakespeare for instance in his most extended reference to the honeybee in Henry V talks about the king bee rather than the queen bee. There's a great scholar by the name of Mary Baine Campbell who compellingly argues that metaphorical portrayals of bees often rely on the idea of the bee head to reinforce patriarchal norms, even when what's being observed in the natural world doesn't cohere with the established sense of what's normative.

KD: So Shakespeare for example, if he is referring to bees and beehives, where would he have gotten that information from?

LR: It's really a combination of classical sources. Virgil writes a lot about bees. He uses extended similes about bees in the Aeneid for example. Pliny was a classical natural scientist who wrote a lot about bees. But another way that people in this period would come to knowledge of these things was through their own practice. It was quite common certainly in Elizabethan England to beekeep.

KD: There is something transformative about the beekeeper as a figure in a community. In Bolivia, I met incredible people building beehives not just for agriculture purposes but for the communities around them, where beekeepers became almost priestly— connected to another world, like the bees themselves, long seen as intermediaries between the material world and the heavens. In ancient Egypt they used wax and honey at religious ceremonies. You could talk to the bees as if they were in direct touch with the gods.

LR: So they're a kind of divine?

KD: Yes, a divine intermediary. You'd ask the bees what they think about your problem with the harvest for example. Even if you look at John the Baptist, he goes and eats honey and locusts in the desert when he's looking for his spiritual renewal. When the queen of England died recently, the royal beekeeper was filmed telling the bees in a formal ceremony—dressed in his best clothes, reading aloud that the queen had died, that they now belonged to Charles III, and wrapping a black silk ribbon around the hives. He explained that if you want the bees to stay and give you honey, you must include them in your family life, sharing your news with them. There are historical images of people introducing fiancés or newborns to the bees, which struck me as a beautiful analogy: if we want good relationships, we need to communicate—it's how we build a more harmonious world.

LR: It really strikes me that you have taken this idea of an interspecies collaboration with bees in a serious direction in your own work. To think of bees as kin and collaborators is fascinating to me partly because in the period that I study, another metaphor that's often used to describe bees is that they work as poets. The best way to produce the most interesting poetic work is to behave like a bee in a garden going from flower to flower and taking the best material from every flower and every poet in the garden. I'm really fascinated by the idea of your work as thinking of bees as artists in their own right.

KD: This project has changed a lot this year through living with you all here at Reid Hall. It started out as a kind of theoretical research into societal change and systems change and has ended up being a very intimate project about the choices that we can each take to engage with the world around us.

LR: Well, speaking of beehives – Reid Hall feels to me like the best kind of beehive there is.

Tomas van Houtryve is a photographer who uses a wide range of contemporary and early techniques to continually question and reinvent his approach to image-making. One of three photographers allowed inside the construction site, Van Houtryve recently published 36 Views of Notre-Dame de Paris, a book documenting the reconstruction of the cathedral after the devastating fire of 2019, and on view at the Galerie Miranda in Paris. He dedicated an evening to presenting these images to the public at Reid Hall in the fall and spoke to Marie Doezema about this experience on an episode of Columbia Global Paris Center’s podcast Atelier. He also published Lines and Lineage in 2019, an investigation into the missing photographic record of the rule of Mexico in what is now the American West. Represented by the Baudoin Lebon gallery in Paris, Van Houtryve has been a member of the VII Photo Agency since 2010.

ABOVE

At the Institute, van Houtryve worked on “Terrifying Sublime: Synthetic Alpine Landscapes,” a reconsideration of the Alps in the context of myth creation, climate change, and man-made destruction of landscapes. Since the times when the notion of the sublime became prominent in art and philosophy, our relationship with nature has been radically reversed. By employing photography and video, this project also considers notions of scale and perception.

CHINA COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

ABIGAIL R. COHEN FELLOW

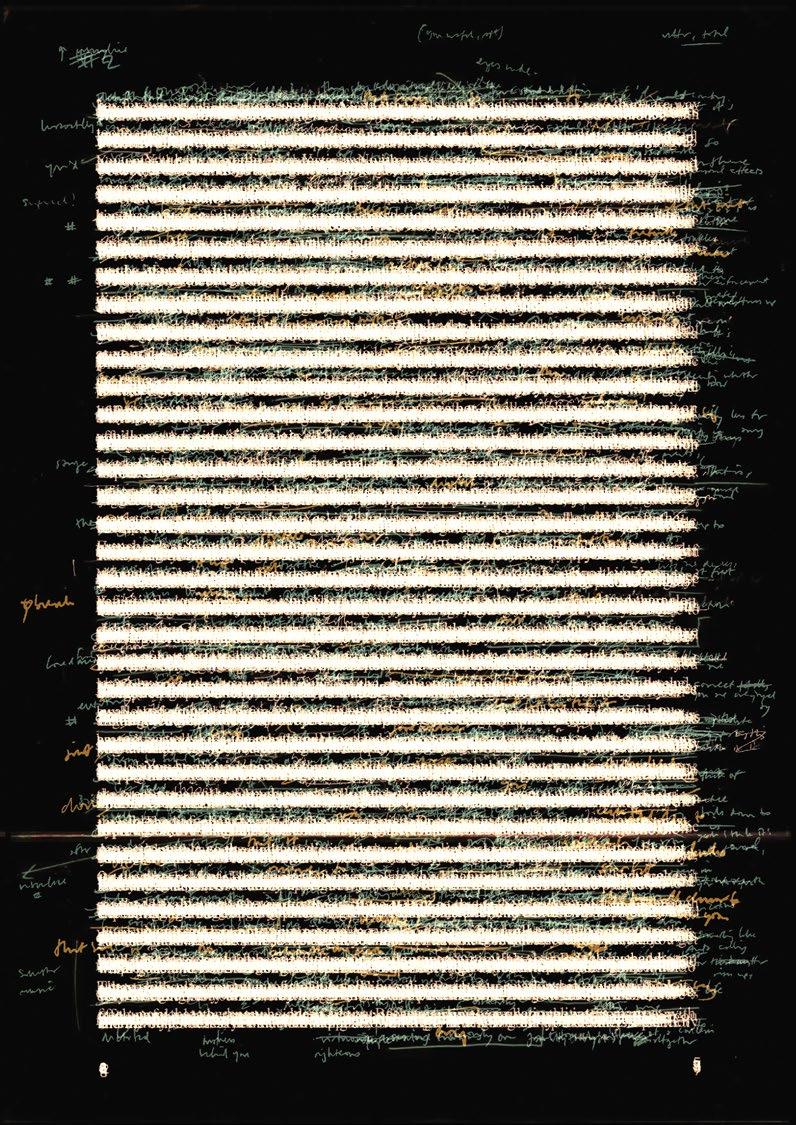

Born in Shanghai, Lynn Xu is a poet and Assistant Professor of Writing at the School of the Arts. She is the author of Debts & Lessons (2013) and And Those Ashen Heaps That Cantilevered Vase of Moonlight (2022), selected for the Poetry Center Book Award, and co-translator of Pee Poems by Yang Licai (aka Lao Yang). She has performed multidisciplinary works at 300 South Kelly Street, the Guggenheim Museum, the Renaissance Society, and Rising Tide Projects, and her work was the subject of a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson. She coedits Canarium Books.

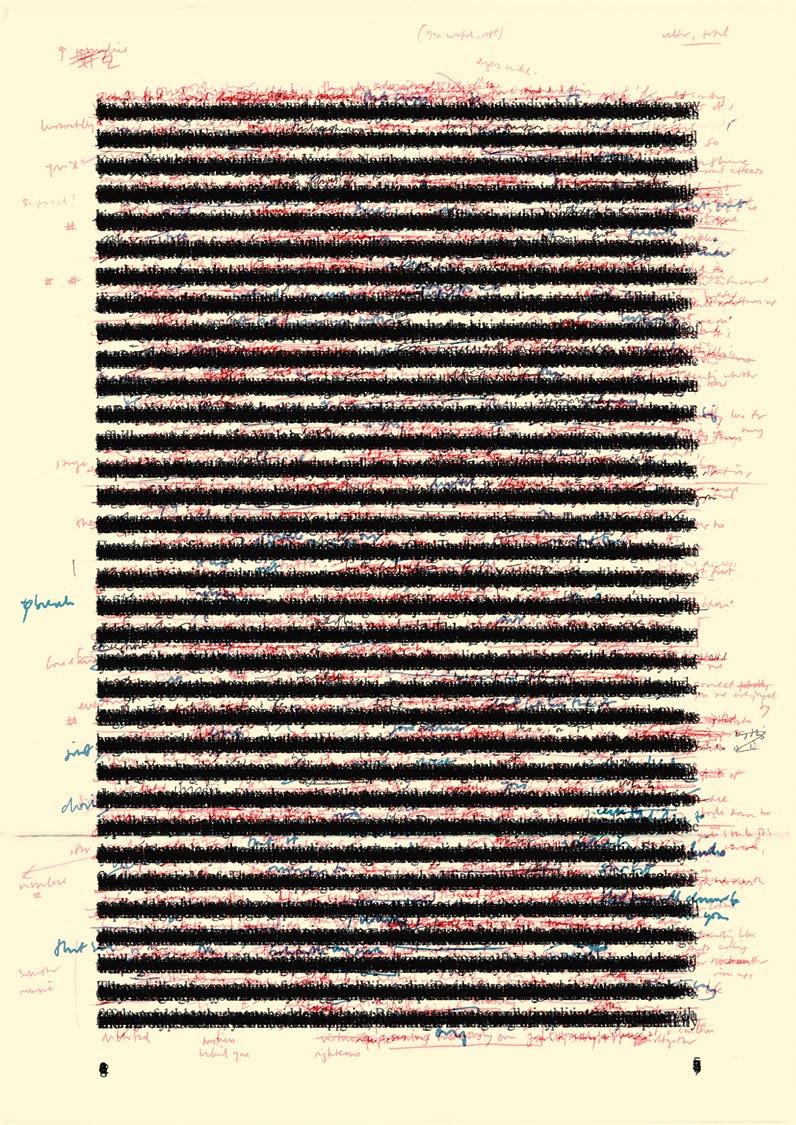

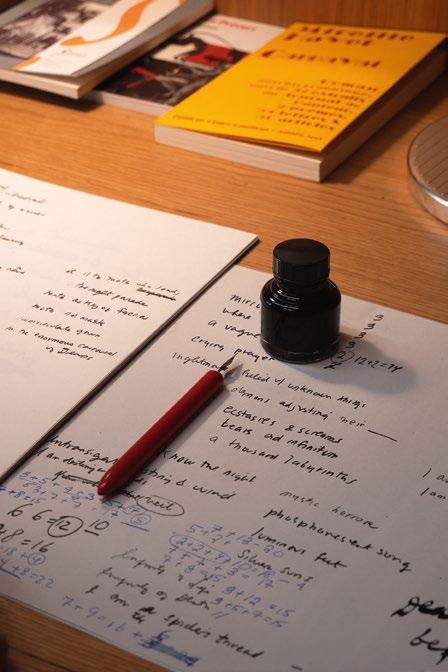

BELOW

Xu’s poetry notes.

During her Fellowship, Xu moderated a Q&A with João Gonzalez following the screening of his films, a conversation that is shared on the following pages. She also traveled to Germany to investigate the Marbach archives for an upcoming project.

At the Institute, Xu worked on poems exploring the image-making function of allegory, its temporal and historical apertures, and the “telepathic phenomena” of Surrealism that Walter Benjamin had also dreamed. The Paris of Charles Baudelaire, Gérard de Nerval, and César Vallejo was her subject, along with the eyes of the past and the ever-changing streets of the passerby.

This conversation between João Gonzalez and Lynn Xu is an excerpt of the Q&A that followed Animating the Subconscious, a screening of Gonzalez’s films that took place in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc on April 8, 2025, and that featured a live piano performance by the animator.

Lynn Xu: It's really interesting how emotional your films are. They take place in extremely precarious situations. In Ice Merchants, you see this fragility as the condition of our existence physically actualized: being at the mercy of the mountain, perched so high and tied in a state of isolation and solitude. I wondered if you could speak about that.

João Gonzalez: All my films take place in weird realities, in places that I either dream of or think about just before falling asleep. I have images that pop into my head with extreme intensity—they disappear quickly, but for a moment they’re incredibly vivid and often very emotional. I don't know why they come to my mind, but I decided I would figure out a story that would take place there. Usually, the space comes before the themes of the film; I find the film’s theme along the way. I normally have a rough idea of the feeling I want to convey. In Ice Merchants, for example, I knew it was going to be a film about loneliness, loss, and even death.

LX: I was also really interested in time and duration —the temporality in relation to certain gestures and acts. How long does it take for a gesture to become signified or meaningful to us? For example, when the boy is rummaging in the cupboard for the yellow mug—how do you know how long it will take us to realize that it was the mother’s mug?

JG: I think that comes from my musical background. I started playing piano at a very young age, and I remember playing a passage and my teacher saying, “No, no, hold it a bit on this note, just a glimpse.” I’d play it again, and to me it would feel exactly the same, but he’d say, “Oh, this is amazing now.” At the time I didn’t understand, but now I feel that background has helped me develop a better intuition for timing— how long a shot should last, or how adding a second of pause can change how we perceive a movement.

In animation shorts, you have to allow time to breathe. There are parts of the film where not much happens narratively. For example, when the kid is sitting on the father's lap—that scene actually lasts a while. Although nothing major is happening, I believe it sets a subcon-

scious sense of their closeness and makes you care more about them. A good film is built from lots of micro-decisions that the audience might not notice, but that change how they interpret what they’re seeing.

LX: That makes a lot of sense. You and I have talked about how we both work very intuitively, and maybe the formal temporality of classical music training built that intuition. Since this evening’s talk is titled Animating the Subconscious, maybe I could ask you to speak about those two terms. What is the subconscious for you, and what is animation? I feel like these could be twin movements in some ways.

JG: For me, the subconscious is the metaphysical world we all go to when meditating, dreaming, or daydreaming. It’s based on our experiences and the places we’ve seen, but everything gets meshed together in a strange way—and for me, it can evoke even more intense feelings than reality. Some of the most intense emotions I’ve felt were actually while dreaming.

When I think of a memory, it has a specific color or filter, but I only see it that way afterward. Whereas in dreams—especially lucid dreams—I’m already feeling that nostalgia while the moment is happening. That’s the feeling I try to capture in my films. They’re deeply based on my subconscious, that metaphysical world where I spend a lot of time.

As for animation, there’s a lot of drawing. I close my eyes and imagine that I’m there again. I don’t use 3D animation in the final film, but I do build the movie sets in 3D. The house in Ice Merchants, for example, is completely modeled in 3D. If I had a 3D printer, I could print it and you’d see all the rooms, the tables—everything. That allows me, in pre-production, to literally walk upstairs, downstairs, onto the balcony—it’s like entering the materialization of my subconscious. I try to make that imaginary place as real as possible so I can access it more easily.

LX: That’s really beautiful. The way you talk about animation—it becomes a way to actually create a place where you can enter the dream and walk through it, as your character or as the story unfolds.

I wrote this poem shortly after Issa, our eldest daughter, was born–now 9 years ago. You know, no one sleeps after giving birth. So for many years I'm not sleeping. I'm not conscious enough though in these hours to make use of them so I would lie there in a twilight state and then one night my body began to write, opening to a kind of language.

An excerpt from "And Those Ashen Heaps That Cantilevered Vase of Moonlight" by

Lynn Xu

Last night, beside the menstrual shadow of the corpse I saw my mother’s legs (her enormous legs) opening and closing in a

voluptuous trance sweeping the thick current, the amorous pity of her legs which with my mouth I imitated, still pregnant,

or, became, by way of imitation, innumerable, in the meantime, her foot, her toe,

which refused to dissolve, and which I could see still climbing the transparency of birth, her foot in the piedras continuing to suckle, to insist, thickness, aie-aie-aie, who is this still mothering with the rags of

a mouth, coughing and defecating in the middle of life and continuing to urinate, in the occultation of the middle

snow, and the gravediggers having gone, drifted north in gusts, phalanges, nourished by numbers and the supernumerary

resemblance of the turnstile, here, it is nighttime in both directions, and in these human temples, I attend, I dream, and I carry my grave clothes under my arms, mother,

with the cadavers entering childhood still trembling like sunflowers,

I dream

THIS PAGE

Film still from With Hasan in Gaza (Kamal Aljafari Productions); the International Contemporary Ensemble performing in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc during Composing While Black, Paris Edition

NEXT PAGE

Kate Daudy's office at the Institute.

Maha Al-Daya is a Palestinian artist from Gaza. In addition to her painting and multidisciplinary artistic practice, she is also engaged in the design and embroidery of traditional Palestinian dresses. Her work explores themes of identity, memory, and resilience, reflecting the socio-political realities of Palestinian life. Over the years, Al-Daya has participated in numerous art residencies, including the Cité internationale des Arts in Paris (2012) and the Summer Academy at the Suha Shoman Institute, Darat al Funun, Amman (2001).

Maha Al-Daya was jointly hosted by the Institute, the Columbia Global Paris Center, and Sciences Po as part of the PAUSE program.

Doha Kahlout is a Palestinian poet and teacher of Arabic. She graduated from AlAzhar University with a BA in Arabic Language and Media Studies. In 2018, Kahlout published her first collection of poetry, Ashbah (نشرت, "Similarities"), with Dar Tarik Publishing House. She has also contributed to publications of the Qattan Foundation and Dar Tibaq Publishing House. “I am passionate about writing and about experimenting with writing; about reading all forms of literature; and about both participating in special workshops on writing and teaching young people, so that, together, we can reach the secret power of the word and what it does to us.”

Doha Kahlout is jointly hosted by the Institute, the Columbia Global Paris Center, and École nationale Supérieure d'Arts Paris Cergy as part of the PAUSE program with the support from the Artists at Risk Connection.

Haman Mpadire is a performance artist, dancer, and researcher born in Eastern Uganda. Originally from the Busoga tribe, he graduated with a Masters degree of Arts, Literature and Languages in Dance from CCN - Paul Valéry University. He received the Pina Bausch Fellowship in 2023, following his participation in the Fondation d'entreprise Hermès “Artists in the Community” bursary scheme and the Institut français “Visas pour la création” program. His artistic practices probe experimental research around colonial systems and post-colonial theories. In his current projects, Haman is exploring animistic notions of the ancient Busoga kingdom and beyond as well as issues of identity and visibility for black African bodies.

LEFT

Doha Kahlout, translated by Yasmine Seale

1.

With half a memory and ruined images, I turn over the past, repeating names that have no sound. Anxiety echoes back. The streets revolve, and the houses in my mind revolve, empty except for fear. I leave behind the years of experience, the tears and laughter, the farewells and encounters, and I run. Survival is a lost horizon, hope a device for the needy.

I fall into regret. For the meaning of life I go back to the drawing board, one foot tracing the steps, the other resisting missteps. In faces, a dictionary of fortitude, a thesaurus of longing. In conversation, stories amputated by a stray explosive. And in me a strange heart, an eye unable to contain its tears, a footstep hobbled by not knowing what now.

I carried all that came before and all that I’ve become. About my history I schooled others and was schooled. I was changed by this endurance, by hard necessity. Words grew in helpless silence. The ordeal shaped me. The body was besieged by a house unknown to it, by roads that do not lead to it. But hope leaks between our conversations. We chew it, chew its promises. For a long time we believe it and we don’t let go.

2.

I call out the powerless names, the narrow definitions. A pain resulting from restriction and from thought. A river releasing the current of its language into me, plunging me into the mind of the ancients. With a pair of clipped wings they say: My throat. I crouch, overcome by the weight. I refuse answers. The group photograph rejects me.

I drag my stubborn footsteps, pave my path. The river is angry, slapping my heart. I no longer care about footsteps, about meaning, about the knocks on the door, about my experiences and mistakes and missteps, my satisfactions and my grievances. I cross with neither my heart nor the river. On my back I carry frightened voices, asleep on my shoulder. To the tree from which I dropped at the beginning of time, with a color and a name and a voice that tries, I ask: Who am I? The tree hears nothing, says nothing. I say: What is war? A stab at immortality. A lust for it. I carry the answer and the explanation. I turn the facts over and accept them. I set off like a bird that knows its expanse and its nest, heart full and eyes hungry for salvation. Astonishment fences me round. The body is dug with the voice of our masters. They have eaten what remained of longing. Reassurance dazzles me: I see it waving at me behind the fence of amazement. There it is; I recognize it, but it cannot reach me.

3.

After a brief death, television was revived for the purpose of broadcasting names, each one snatched away by a weapon between inexperienced hands, and to convey to us—lest we forget— the moment memory was demolished and the capitals wept.

Red is a color that belongs to us. The martyred, the injured. Massacre. Blitz. And the color of the line that mourns us hastily, in shame.

Papers are our mission. We gather what may establish our names, so prone to being forgotten, and our birth certificates so that no confusion may exist as to our age. Then we remember that we have lived through four wars, and our miracle is survival.

The voices are heavy with reproach. We put questions to the gods and whatever lies beyond. The voices are questions going to and ceaselessly fro. There is a babble under your breath. All eyes huddle round. There is only one answer you are seeking: when will the house stop spinning?

Calm is a cruel warning sign, a lurking we know well. We repeat as many verses as we can, then we test our hearing. If you can hear, you are saved, and if you cannot hear, you become news.

Numbers are a waking nightmare, a hammer on our fingers. We count everything into which life has entered and which death crept in behind through the back door.

Ceasefire, an exit from one war into another. For war traverses us and finds a sister here. A single blaze that does not shed its burden and does not let us go.

Paris "AJ" Adkins-Jackson is a multidisciplinary community-partnered health equity researcher and Assistant Professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Sociomedical Sciences in the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University. Her research investigates the role of structural racism on healthy aging for historically marginalized populations such as Black and Pacific Islander communities. In Paris, AdkinsJackson refined her current project: translating her epidemiological research into a musical.

Gil Hochberg is Ransford Professor of Hebrew and Comparative Literature and Middle East Studies at Columbia University and Chair of the department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies (MESAAS). Her research focuses on the inter-relationships among psychoanalysis, postcolonial theory, nationalism, gender, and sexuality. During her Visitorship, Hochberg researched the complex intersections of immigration, colonial history, and cultural identity in France, drawing from past exhibitions such as "Jews and Muslims: From Colonial France to the Present Day" at the Musée national de l'Histoire de l'immigration.

NEXT PAGE

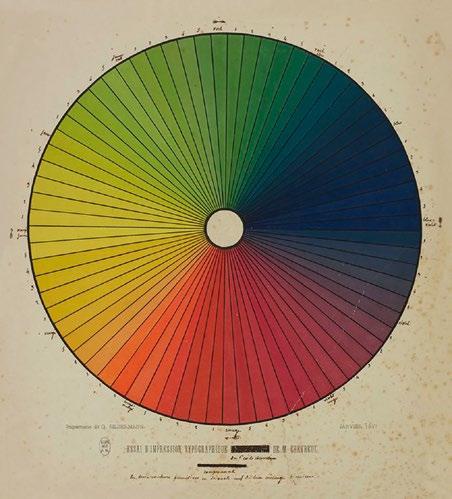

Eugène Chevreul’s color wheel appearing in David Sulzer’s research.

A music class at the Institut national de jeunes sourds attended by Peter Susser.

Marguerite Holloway is Director of Science and Environmental Journalism at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism. She is the author of The Measure of Manhattan, the story of John Randel Jr., the 19th century surveyor who laid the grid plan on the island, and the recently published Take to the Trees, an exploration of the arborists and forest experts safeguarding our trees. At the Institute, Holloway investigated the city's innovative urban forestry initiatives, exploring how Paris's long history of integrating trees into the urban landscape is evolving to combat climate change.

Nikolas Kakkoufa is the Director of Undergraduate Studies for the Program in Hellenic Studies where he also directs the Modern Greek Language Program and teaches classes on Modern Greek and Comparative Literature, Reception, and Sexuality. He is also an affiliated faculty member of the Institute for the Study of Sexuality and Gender and the Institute for Comparative Literature and Society. In Paris, Kakkoufa worked in the archives of philhellene and folklorist Claude Charles Fauriel, uncovering the hidden layers and historical significance of Georgios Tertsetis’s poem "Δικαία Εκδίκησις," in an effort to illuminate its role in the evolution of Modern Greek queer writing and to reveal its connections to ancient myths and folk traditions.

Reid Hall works quietly on one—a kind of magic you all create.

—— MARGUERITE HOLLOWAY

Vijay Modi is Professor of Mechanical Engineering and of Earth and Environmental Engineering and Director of the Laboratory for Sustainable Energy Solutions. Previously, he led the UN Millennium Project effort in the area of energy and energy services. He is currently working closely with city and national agencies to understand how energy services can be more accessible, more efficient, and cleaner. During his Visitorship, Modi researched the interplay of energy, development, and climate in the global south, with a specific focus on Sub-Saharan Africa, aiming to connect perspectives from India and East/West Africa.

A Fellow at the Institute in 2019-2020, Debashree Mukherjee is Associate Professor of Film and Media in the Department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African Studies. Her first academic monograph, Bombay Hustle: Making Movies in a Colonial City, approaches film history as an ecology of material practice and practitioners. In her new research, Debashree is developing a media history of indentured labor and plantation capitalism in the Indian Ocean, exploring photography, communications infrastructures, and film traffic. In Paris, she studied Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s Paul et Virginie, an 18th century French romance novel from which some of the most enduring mythographies of tropical islands are derived.

David Sulzer is Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Pharmacology at Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute. He studied plant breeding and genetics at the University of Florida and received a PhD in biology from Columbia University. His lab has published over 200 studies on synaptic function in normal and diseased states with over 40,000 citations.

At the Institute, Sulzer conducted research on a forthcoming book exploring the intersection of art and neuroscience with a focus on topics such as color perception, perspective, and the evolution of artistic expression across species, utilizing resources from the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. Sulzer is also a musician and a composer.

Peter Susser is Director of Undergraduate Musicianship at Columbia. As a composer and producer, Susser has been commissioned by a variety of orchestras, ensembles, and soloists including the Queen’s Chamber Band, the Sage City and New Amsterdam Symphonies, and Speculum Musicae. In Paris, Susser worked on Columbia's ear-training curriculum by researching multisensory pedagogies for deaf and blind students through immersive studies at the Institut national des jeunes aveugles and the Institut national de jeunes sourds.

Associate Professor of Film at the School of the Arts, is an independent filmmaker who lives and works in Bangkok and the U.S. Her films have been screened at festivals such as Cannes, Sundance, Berlin, Locarno, and Rotterdam. Informed by the socio-political history of Thailand, Suwichakornpong’s work has received international critical acclaim and has been the subject of retrospectives at the Museum of the Moving Image, New York and TIFF Cinematheque, Toronto. In Paris, Suwichakornpong plans to conduct research for her feature film A.S.R., focusing on Thailand's historical transition to democracy, with a particular emphasis on Paris as a hub for Siamese political exiles and dissidents.

Marguerite Holloway

My tree quest began in the Square René Viviani, a small park across the Seine from Notre-Dame and across the street from Shakespeare and Company. A friend had instructed me to look there for her favorite tree: a black locust planted in 1601 by Jean Robin, King Henry IV’s gardener, and, according to the sign, the oldest tree in Paris. The ancient tree is bent and twisted, apparently now supported by an armature. But a few branches, even in January, reveal life: pale green leaflets flutter against an overcast sky on a chilly damp day.

Mid-winter may not seem an ideal time to begin a research project on urban forestry in Paris, but my two weeks at Reid Hall in January revealed that any season is the right season to explore trees and their stories in this arboreal city. Paris has a long history of urban forestry: trees are essential aspects of the cityscape in parks, along boulevards, in squares. The renowned expansion of the urban canopy during the mid-nineteenth century, led by city planner Georges-Eugène Haussmann, was preceded by waves of tree planting during other eras—including a surge after the French Revolution, when trees were seen as manifestations of democracy and popular power (many poplars were planted during this time). By the mid-1800s, “Paris led Europe in urban tree planting,” according to historian Lucie Laurian.1 Parisian trees have been planted for aesthetics, for political statement, for shade and air filtration, and as architectural elements.

The city has long been an urban forestry model for many others in Europe and the United States. But today it is below average in tree canopy when compared with some other European cities—only about 20 percent tree cover.2 Paris is now undergoing another arboreal transformation: creating additional green spaces, extending and evolving its urban forest to adapt to climate change, diversifying species so that if one tree is targeted by a disease or insect pest— for instance, the emerald ash borer—others may endure. Resilient like the black locust that has survived more than 400 years in a corner of a small public square. “A reminder of how long a tree can endure when given space, care, and cultural value,” as arborist visitors have noted.3

As of now, there are close to a half a million trees in squares and parks in and around Paris, and along streets—mostly shading boulevards because the sidewalks of smaller streets are often too narrow to accommodate tree pits.

1 Lucie Laurian, “Planning for Street Trees and Human–Nature Relations: Lessons from 600 Years of Street Tree Planting in Paris,” Journal of Planning History 18, no. 4 (2019): 282–310.

2 “Which European capitals have the most green spaces?,” World Economic Forum, August 15, 2022.

3 Tasmanian Arboriculture Group, “Trees of Europe – The Oldest Tree in Paris,” Tas Arb Group (blog), accessed June 16, 2025, https://www.tasarb.com.au/blog/ the-oldest-tree-in-paris.

According to the Atlas Inutile De Paris—a recent book containing one hundred whimsical and inspiring maps by Vincent Périat that came to form the basis for some of my arboreal excursions—there are 100,000 along streets, 90,000 in green spaces (parks, gardens, cemeteries, schools), and 300,000 in the two major woods that flank the city, the Bois de Boulogne to the west and the Bois de Vincennes to the east.4

Some 33 percent of the city’s trees are planes, many of them the hybrid of Platanus orientalis (from Europe) and Platanus occidentalis (from North America) that many people know as the London plane, one of the most common trees in New York City as well. The other prevalent trees—according to a report by L’Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme, one of the data sources that Périat cites—include ash, linden, maple, and chestnut.5 But there is also great diversity: at least 800 species can be found throughout Paris and any corner turned, any glimpse into a courtyard before a heavy door closes, any tiny square, any wander, can reveal surprises.