REPORT 2023 – 2024

REPORT 2023 – 2024

In a year when the world was convulsed by conflict and the universities were sucked into the maelstrom, the Institute for Ideas and Imagination ser ved as a reminder of the power of ideas and the imagination to bring people together and open up new horizons of possibility. The 2023–24 class of Fellows revealed as perhaps never before the Institute’s essential value which is to make possible not merely conversations across fields and genres but new insights and new forms of thought that emerge from workshops, discussions, and casual encounters through the year. The Fellowship united scholars of everything (it seemed) from ancient history and medieval literature to postwar social science and Les Parapluies de Cherbourg with poets, photographers, filmmakers, and artists whose work defied classification. As disciplines and boundaries dissolved, key themes emerged across the year: the way memory inheres in things; the multiple forms of the archive; the indispensable elusiveness of translation in understanding the world.

The Fellows’ public talks in the SNF Rendez-Vous de l’Institut series were consistently attended by a large, robust, and curious audience, a testament to the quality and originality of their presentations. We pursued our partnership with the American Library in Paris and the Columbia Global Paris Center through our Entre-Nous series, welcoming a dozen speakers over six events, and including a memorable conversation between Yasmine Seale and the stage director Peter Sellars. Along with our Fellows, the Institute’s community welcomed twelve Faculty Visitors (also supported by the Paris Global Center) and former University Provost Mary Boyce. We also launched the Displaced Artists Initiative, a program jointly conducted by the Institute and the Paris Global Center, inspired by the success of the 2022–23 Harriman Residencies. Thanks to

the generosity of the EHA Foundation, several of our 2022–23 Fellows were able to bring the arts to a much wider public in Mozambique, the Philippines, and Philadelphia.

Our Fellows past and present continue to receive wide international recognition for their work. In an e xtraordinary sequence, Maria Stepanova and Eduardo Halfon won the Berman International Prize for Literature in 2023 and 2024, respectively: this is one of the most important literary prizes in the world. Pauchi Sasaki performed at Lincoln Center during the Latine Composers Showcase; and Hannah Reyes Morales was a 2024 Pulitzer Prize finalist for Feature Photography. The Financial Times singled out works by Deborah Levy, Isabella Hammad, and Clair Wills for their Best Books of 2023 list— all three books were written either partially or fully at the Institute. Lamia Joreige was nominated for a 2024 Daniel and Florence Guerlain Contemporary Ar t Foundation Drawing Prize and Dina Nayeri was a finalist for the 2024 National Book Critics Circle Award. Fabiola Ferrero was shortlisted for the Premio Gabo 2024. Karimah Ashadu was awarded the Silver Lion for promising young talent at the Venice Biennale. The poets Fiona Sze-Lorrain and Jay Bernard both appeared in “Poésie du Louvre,” a sound installation at the museum. Bernard was invited to the Providenza residency in Corsica, thus beginning a partnership between the Institute and this new ar tists’ program. Hammad will spend next year at the Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center at The New York Public Library, following in the footsteps of our 2022–23 Fellow, Yasmine Seale; Stepanova and Tash Aw won a DAAD fellowship in Berlin for 2024–25, and Aw and Tina Campt will also be residents at the American Academy in Berlin.

Our short-term visitorships support Columbia faculty who come to Paris for one to three weeks to meet Fellows, organize events, or work with colleagues in France. The number of applicants has significantly risen from one year to the next, indicating the popularity and need for such a scheme that was only confirmed by the visitors, who find their stays enriching and are able to make connections that couldn’t happen on campus. They included faculty from the Earth Institute and the Schools of Climate, Engineering, Journalism, and the Arts as well as from the Arts and Sciences. Taking advantage of their presence, the Institute recorded ten Library Chats and six podcasts (all of them available on the Cahiers section of our website), on subjects ranging from climate change, civic engagement, poetry, history and memory, war reporting, performance art, narrative medicine, screenwriting, Proust, and architecture. These programs have become a major form of public outreach over the past three years.

Opening applications to displaced artists and writers from all over the world, the Displaced Ar tists Initiative was able to support two residents: Anna Stavychenko and her newly launched 1991 Project to promote and preserve Ukrainian musicians and music, and Aliyeh Ataei, a writer from Afghanistan and Iran whose political engagement forced her and her family to flee Tehran. Both the 1991 Project and Aliyeh made gre at use of Reid Hall by organizing concerts, readings, and performances that were widely attended.

Our partnership with Columbia University Libraries provides resources, above all actual books, for the Fellows: what cannot be scanned is sent over from the US. The Institute’s partnerships with the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the American Library in Paris also continued, as did those enabled by the Columbia Alliance program with Sciences Po and the Sorbonne. Our close working relationship with the Columbia Paris Global Center was as indispensable as ever. On the Manhattan campus, the Maison Française continued to host our “Institute at the Maison” Fellows’ series and the School of the Arts provided a home for João Pina, former Abigail R. Cohen Fellow, who was a Visiting Professor for the second year in a row. Our new partnership with the Benaki Museum in Athens led to a second spring workshop in Kardamyli, which brought together Institute

Fellows and Stavros Niarchos Foundation Public Humanities Initiative (SNFPHI) project awardees and which will lead to a small annual workshop publication that they will distribute. The theme this year was "Home" and the workshop is described in more detail later on in this report.

O ver the course of the year, the Institute participated in no fewer than 58 public events. We want especially to acknowledge the memory of journalist Victoria Amelina, who was tragically killed by a Russian missile in Ukraine in June 2023 just weeks before she was going to join us in Paris as a Displaced Artist: a tribute to her was held at Reid Hall. From our Fellows, Maboula Soumahoro or ganized a series of events on transatlantic race relations and the legacy of French colonialism, and also hosted an homage to her mentor, the writer Maryse Condé, who died last April. And Maria Stepanova joined Georgi Gospodinov and several Eastern European writers, critics, and editors for a tribute to the late Dubravka Ugrešić.

We were lucky enough to have two notable poets in residence this past year: Maria Stepanova and Jay Bernard. On a magical evening in May, they invited fellow poets Sasha Dugdale, Eugene Ostashevsky, Yasmine Seale, and Alice Oswald for a private evening of poetry, sound, and music in the Institute lounge, accompanied by the jazz pianist Richard Sears and installations by the sound archeologist Pamela Jordan. It was an unforgettable night of performance, exploration, and celebration, that illustrated perfectly what the Institute means to its residents and visitors: a malleable space where writers, artists, and thinkers are free to experiment, work together, and benefit from the generous presence of their peers. The recording of this exceptional event is available online.

Reid Hall opened its doors for its second Nuit de l’Imagination—this year’s theme was boredom, though it was any thing but. A philosopher and an economist from Sciences Po joined a roundtable of ar tists, writers, composers, scientists, and a yoga instructor to discuss the value of slowing down and stepping away from one’s field of expertise. As last year, there were activities for children throughout the afternoon. The evening program featured a geneticist from the Institut Pasteur who also started the lab’s ro ck band, and two composers and sound artists who created an original interactive piece for the occasion.

Our flagship annual lecture is the Sidney N. Zubrow Memorial Lecture which is made possible thanks to the generosity of the Cohen family who have supported the Institute from the outset. We were fortunate this year to be able to welcome the architect Francis Kéré, winner of the 2022 Pritzker Prize. Never before had the Grande Salle GinsbergLeClerc held so many distinguished architects and architectural students, who mixed with a packed audience eager to hear Kéré’s remarkable presentation on his work in Africa and elsewhere, followed by an equally engaging conversation with Professor Barry Bergdoll, a former Fellow and architectural historian. Dinner saw no fewer than three former Pritzker Prizewinners deep in conversation with one another.

During its fifth year of operation, SNFPHI became fully integrated into the Institute for Ideas and Imagination to foster public engagement with the arts. This is just one of the many ways in which the Ins titute has flourished as a result of the support and generosity of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. SNFPHI Associate Director Dimitris Antoniou oversaw the deepening of the collaboration with Institute Fellows. Fellows Ana María Gómez López and Mohamed Elshahed each received a travel grant to pursue research and present their work in Athens. They also worked with Dimitris as he developed the Summer Research Internship in Public Humanities and Hellenic Studies for Columbia undergraduates. Meanwhile, Institute Fellow Paraskevi Martzavou worked with SNFPHI graduate student awardees pursuing independent public humanities projects on subjects ranging from sponge diving in the Aegean, and the his tory of the Black community of Avato

We received over 350 applications from more than fifty countries for the 2024–25 Fellowship class and have selected fourteen Fellows (listed at the end of this report). Once again, the short-term Faculty Visitor program attracted more applicants from Columbia faculty and researchers than ever before— over sixty. A grant from the university’s Center for Teaching and Learning has made podcasts a regular part of our outreach, facilitated by the creation of a dedicated new recording studio as part of the renovation of the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc. And the following artists were selected as the 2024–25 Displaced Writers in Residence: Maha Aldaya, a Palestinian visual artist, Doha Kalhout, a young poet and school te acher from Gaza, and Haman Mpadire, a dancer and choreographer from Uganda who has received many awards, including a Pina Bausch fellowship. Yasmine Seale will hold the 2024–25 II&I Visiting Professorship at Columbia University, an essential element in our projection of the Institute’s pedagogic work onto the Morningside campus.

We remain as ever grateful to our supporters for their generosity and heartened by the enthusiasm of those who continue to follow our work. We hope you will find in these pages a reflection of the spirit of experimentation and inquiry that animates the Institute.

—— MARK MAZOWER

STAVROS NIARCHOS FOUNDATION (SNF) DIRECTOR left

II&I Paris Director Marie d'Origny with Wafaa El-Sadr, Executive Vice President of Columbia Global, and Dimitris Antoniou, SNFPHI Associate Director.

intro page

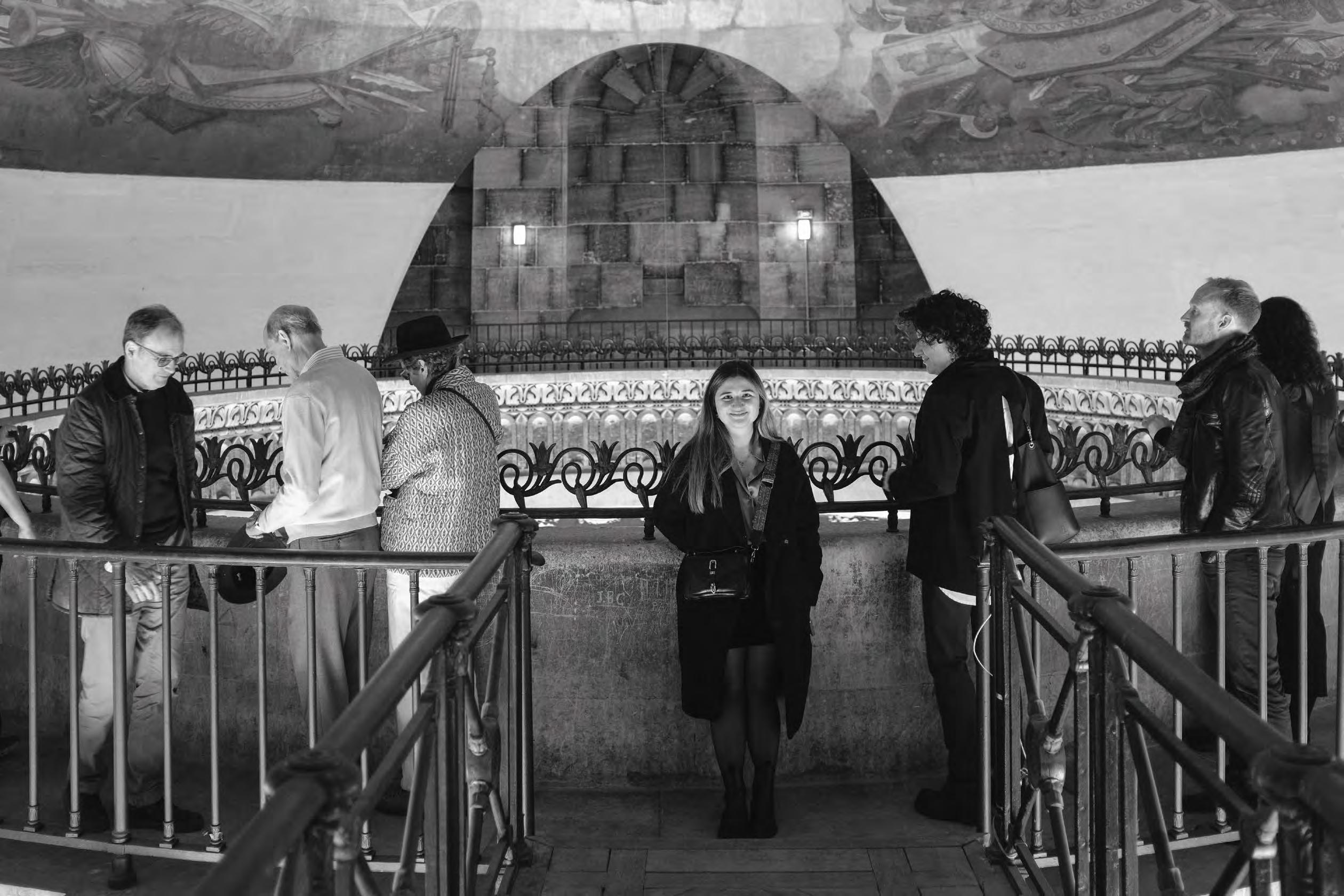

Mary Boyce and Mark Mazower leading the way to the top of the lantern on a tour of the Panthéon with Institute Fellows organized by Barry Bergdoll.

The last screenplay I wrote took 9 years to complete. The one I wrote at the Institute took 9 months. There is an alchemy to this place in large part owing to the quality of the people who work there... Probably one of the happiest years of my life.

—— Éric Baudelaire

Éric Baudelaire is an artist and filmmaker based in Paris, France. After training as a political scientist, Baudelaire established himself as a visual artist with a research-based practice in several media ranging from printmaking, photography, and the moving image to installation, performance, and letter writing. His feature films have circulated widely in film festivals. When shown in exhibition, his visual work is presented in the context of installations that include curated projects with works in other media and extensive discursive programs. He was awarded the 2019 Marcel Duchamp prize, and published a monograph titled Make, Do, With with Paraguay Press in 2023.

Éric’s fellowship at the Institute was devoted to researching and writing a feature film titled In Other Words, the fictional story of R, a Lebanese man who works as a prison visitor to Guantanamo. Several times a year, R visits the detainees, scrupulously listening to their stories, and then travels to the Middle East to give oral feedback to their families, and bring their stories back to the prisoners. In recent months, he has started to slip up and transgress, inserting himself into the stories rather than simply transmitting them. Some of his alterations (lies? fictions?) serve to enliven a session. Others seem gratuitous, random, even perverse. This unconscious shift runs parallel to a profound disruption in R’s own life.

above Éric and David Scott in the Seminar Room.

below

"The Day Before the Inauguration": a photo of the Abkazian Parliament from Éric's book Imagined States

Jay Bernard (FRSL, FRSA) is an interdisciplinary writer and artist from London whose work is rooted in social histories. Jay was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year 2020 and is the winner of the 2017 Ted Hughes Award for their first collection, Surge. Recent work includes My Name is My Own, a physical performance piece in response to June Jordan premiered at Southbank Centre’s Poetry International; Joint, a poetic-play about the history of joint enterprise; Crystals of this Social Substance, a sound installation at the Serpentine Pavilion; and Complicity, a pamphlet based on the collection at the Tate.

At the Institute, Jay worked with music, research, and poetry, based on their practice as both a sound artist and a writer. Their project looked at how the promise of the post-war period played out and how it is being rapidly dismantled today. Starting with the decline of the British empire and the rise of new forms of coloniality, this project begins on the ground circa 1960, with emergent ideas of class, race, sex, and gender via the consciousness-raising group, the shop floor, the sound system, the prison, the campaign group, the student union,

the night club, the social center, and the council estate. Set in a fictional part of South London, we hear from the people who lived under, within, and between the narratives that shaped, and changed British so ciety.

History

has rarely felt as vertiginous and ripe with possibility.

As Virginia

Woolf

could have put it, it now feels like a craft that might also be an art.

—— Thomas Dodman

Thomas Dodman is a Franco-British historian and an assistant professor of French at Columbia University. His research and teaching focus on forms and experiences of social transformation in the modern era, particularly in times of war and revolution, and as seen from the standpoint of affects and medicine. He is the author of What Nostalgia Was: War, Empire and the Time of a Deadly Emotion (Chicago, 2018) and a co-editor of Une histoire de la guerre, du XIXe siècle à nos jours (Seuil, 2018). He also co-edits the journal Sensibilités: histoire, critique & sciences sociales (Anamosa) and directs the Columbia University’s History and Literature MA at Reid Hall in Paris.

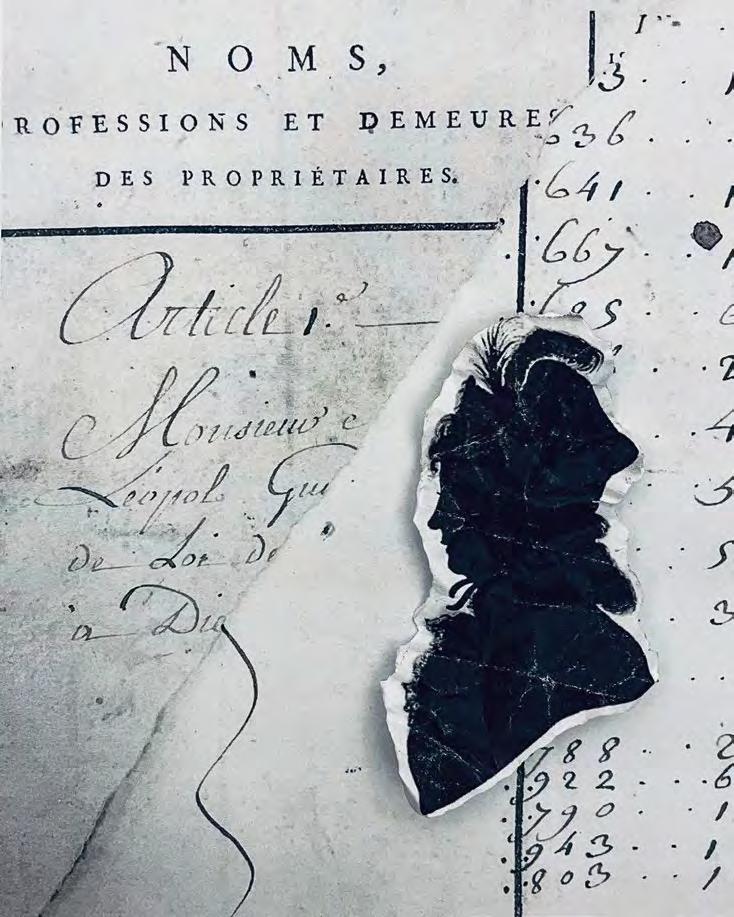

As a Fellow at the Institute, Thomas completed a book manuscript titled Les Volontaires: une romance familiale à l’âge de la Révolution française (for Éditions du Seuil). Part micro-history, part social biography, this book tells the extraordinary story of a young man raised to be Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Émile, and of his adoptive mother and his step-sister and future wife, in the ye ars of the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and the Restoration.

Mohamed Elshahed is a writer, curator, and critic of architecture. He is the author of Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide (AUC Press, 2020) and was the curator of Cairo Modern at New York’s Center for Architecture (October 2021–March 2022). He earned a Masters from MIT’s Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture and a PhD from NYU’s Department of Middle Eastern Studies. He is the curator of the British Museum’s Modern Egypt Project and of Modernist Indignation, Egypt’s winning pavilion at the 2018 London Design Biennale. In 2019 Apollo Magazine named him among the 40 most influential thinkers and artists in the Middle East. In 2011 he founded Cairobserver, a fluid project with six printed magazines distributed for free to stimulate public debates around issues of architecture, heritage, and urbanism. Mohamed is based in Mexico City.

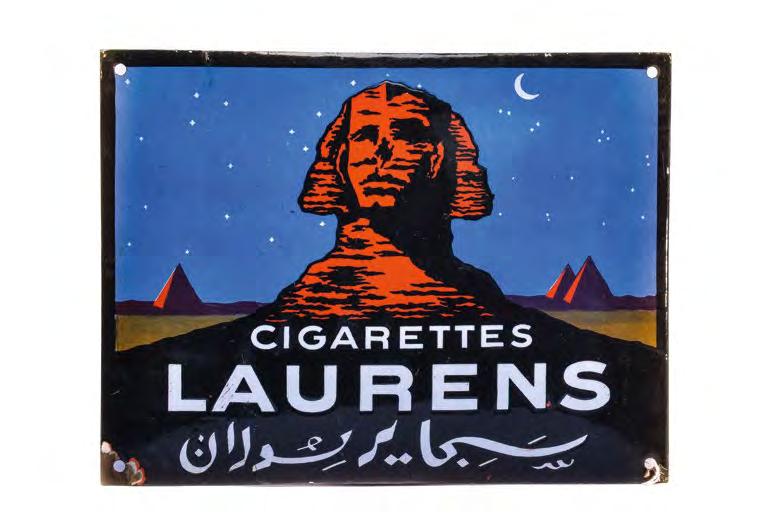

During his fellowship, Mohamed worked on a book about the British Museum’s Modern Egypt Project. Objects collected for the project ranged from ephemera and advertising material, to photographs, consumer items and packaging, clothing, and furniture. In addition to telling stories representing everyday life, the objects chronicle their time of making and their use, as well as the limits of the museum and its expectations, collecting and conservation challenges, issues of coloniality and nationalism, and the blurry line between history and nostalgia. The book presents individual items in detail along with a lengthy introduction. Envisioned as a companion to his previous book, Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide that focused on architecture, this book looks at the objects that populated and inhabited the modern Egyptian home, office, shop, and street.

above

Enameled metal sign advertising a cigarettes brand from early 20th century Egypt—one of the objects Mohamed added to the British Museum collection and included in his forthcoming book Rebellious Things, which he wrote during the fellowship.

previous page clockwise David Scott invited the poet Jason Allen-Paisant for a public conversation in the Salle de Conférence at Reid Hall; Hannah Weaver and Yea Jung Park during a visit of the Fondation Cartier; the 2023-24 class of Fellows and friends.

above

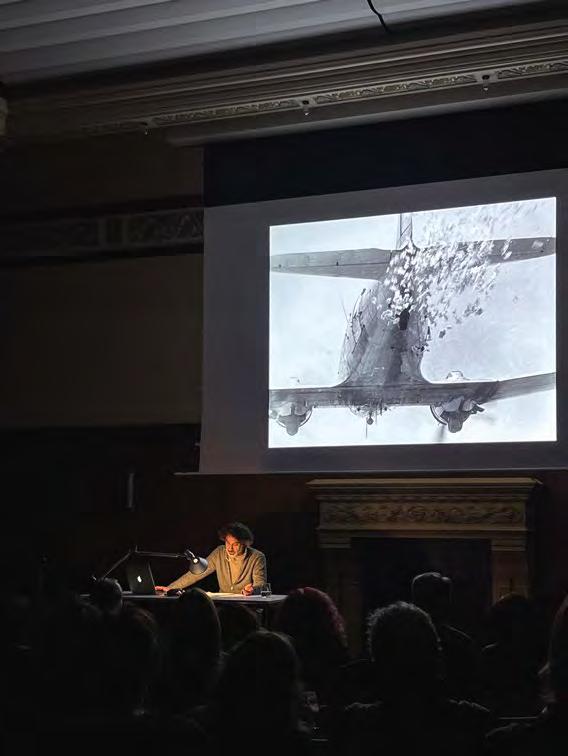

Film still from Éric Baudelaire's Also Known As Jihadi (2007). "Several people in the cohort were interested in questions of justice," noted Éric. "And so, oftentimes, I went with a handful of Fellows to see criminal court cases. We sat in trials of crimes against humanity in Rwanda, and at the trial of Rédoïne Faïd for his spectacular prison break in the north of France, which gave rise to conversations about differences between the judicial system in France and the United States."

below

While living in Paris, Fabiola Ferrero joined an interpretive theatre group. Here its members are pictured performing LUX: Sept tableaux le long de la mer in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc.

VENEZUELA ABIGAIL R. COHEN FELLOW

The environment you have built is really perfect for creation, and I think any artist would be incredibly grateful to be a part of it. I know I am.

—— Fabiola Ferrero

Fabiola Ferrero is a journalist and photographer born in Caracas. Her personal work results from the contrast between her childhood memories and contemporary Venezuela, her home country. Using her background in writing and investigative journalism, she develops long term visual projects about South America, and especially about Venezuela’s crisis. Interested in bringing opportunities to emerging photographers in the region, Fabiola founded Semillero Migrante, a photography mentorship program around migration. Among her recognitions are the Inge Morath Award, the Carmignac Award, 6Mois Photojournalism Award, and the Getty Images Editorial Grant.

“Over 7 million Venezuelans have left my country. My family. My friends. Myself. One by one, we all left. I saw my home become empty, and my memories blur, as if looking at my childhood through a foggy window. But I keep coming back, looking for the traces of the promise of prosperity we were given, of the countr y from my childhood memories and the future we never got to see. I found it, in the middle of solitude, s truggling to survive the general decay. Mixing archives from family albums, tes timonies of remembrance, documentary images, and multimedia elements, this project is a slow-paced dialogue between the past and present Venezuela. The illusion we built on oil seems to rapidly vanish, and it feels as if I’m trying to photograph a lake before it becomes a desert.”

—— Transcribed below is an excerpt of the conversation between Nina Alvarez and Fabiola Ferrero from their Library Chat "Stanley Greene: From Punk to War." You can find the full recording on the Cahiers page of our website.

NINA: It is great to be here in a place that relates so closely to the next film that I'm working on, which is about the American photographer Stanley Greene. He spent pretty much the most important years of his career based in Paris.

FABIOLA: And why do you think he chose to be based in Paris instead of New York?

NINA: I think it was a combination of things. He had an objective of being a fashion photographer. New York is also a fashion center, but it's not Paris. And I think that he really thought that this was going to be the place where he would establish himself as a fashion photographer.

FABIOLA: But he instead ended up doing war photography.

NINA: Yes, he started in fashion and through a series of odd twists, all having to do with women, he actually ended up becoming a war photographer by accident. He followed a woman to Africa. He spent some time in Mali, and then I think she dumped him. And he was at a loss, didn't know what to do. He was riding on a bus, and the way he told it, he was there and he had his camera and someone said, “Hey, you're a photographer, we need you to come and shoot our community.” And these, of course, were the Touaregs in Mali. He says it was not quite an invitation, but more akin to a kidnapping. He did his first photographs of some thing that was not really fashion or landscape oriented. I think that's where the bug got him. In photographing real life.

FABIOLA: That's interesting. I also have a friend, Tamara Merino from Chile, who has an amazing story about a documentary project. It reminds me of how serendipity plays a role in things. In Spanish, I would say, “se constelizan,” things magically fall into place in a way. She was driving in Australia and her van broke down. She tries to fix the van and notices that there are a bunch of holes in the ground around her. It turns out it was a whole town built underneath. And that's where she started Underland, a project about communities that live underground that really launched her career.

It reminds me of how these things can call you in instead of you looking for them. In the case of Stanley, it's interesting to me to see how somebody from fashion can go into a completely opposite direction. Did he leave fashion behind completely? Or did he do both at the same time?

NINA: I think he never stopped being a fashion photographer. You see it sometimes in his photography. You see that oddly beautiful portrayal of a devastating scene. There's a picture from Chechnya where everything is flattened except for this one woman walking through who could be on a runway. Or there's the picture during the fall of the Berlin Wall, where there's a woman in a motorcycle jacket and a tutu and she has put on a police officer's hat. It's totally a fashion photograph. So, I think he did keep that eye. He also photographed his friends, his girlfriends, in that way. You know, he wasn't just photographing war. He was photographing everything. Everything.

FABIOLA: Now that you mention Chechnya and his pictures of women in particular, there's one that we've talked about as well that I absolutely love: this portrait of a woman behind a window. It's kind of blurry. To me, that is such a beautiful portrait. But at the same time, it makes me wonder about conflict I also deal with a lot in my work: when you are photographing such hostile environments with such beauty, are you romanticizing this conflict? Or on the contrary, are we just really looking at this person beyond the stereotype that we're expecting? Because it's a conflict and we expect this person to be in a position of vulnerability. Instead, I'm highlighting other things, putting dignity in the frame as well. This picture in particular makes me think about that. I wonder, how did he deal with that? We must deal with the internal dilemma of chasing beauty in tragedy.

NINA: I know the picture you're talking about: that's Asya, who had also become a close friend of his. And she was a Chechen fighter. There were moments when it wasn't about the “bang bang,” it wasn't about the war, it was about people. He managed to capture something else. He managed to capture moments, almost stolen, right? People just accepted his presence.

He would photograph moments that no one ever got, like that one: she's just staring into the distance, there's rain on the window. And, you know, you're wondering, what is she dreaming about? There is also a sense of loss. She was, had been, a mother, but tragically lost her child. It's beautiful at first glance. But there's also a whole story behind that.

In the end, he blamed the industry for not appreciating what he could contribute. The industry had changed so much: because now it was digital, it was instant satisfaction. Editors could look over your shoulder while you were still in the field and you didn't have that trust anymore. Digital technology, I think he felt not only undermined photography as a whole, but also, he felt it undermined his career because he didn't want to beam back pictures. He wanted to sit with negatives and contact sheets and go through this beautiful process. Cameras were always on him. In Afghanistan I remember he looked like a Christmas tree. He had five cameras— film, digital, color, black and white, this lens, that lens— he had the instinct to reach for the right one.

FABIOLA: I think a lot of photographers nowadays would love to do that as well. It's just a matter of resources. It's not sustainable for an outlet to give you two months on an assignment and a bunch of film rolls. I've been thinking about how it's going to be different for me, as somebody who started this career when those years were already gone. Those days of shooting a bunch of film for three months and then figuring it out. Stanley died in 2017. That's the year when I started my career.

We’ve only talked about very positive things about Stanley’s work and his life, but how are you going to deal with problematic aspects that may arise while you dig into your friend's life?

NINA: Well, I think that's why I haven't made this film yet: because it's tough to make an honest film about someone you love. I've never done that, you know, and part of me dreads it.

FABIOLA: Well, you're doing what we were talking about before: giving a more complex portrait of a person and going beyond the stereotypes. That's pretty much what you're doing right now, looking for the shades and the hidden pieces that I, for one, knew nothing about when I was starting my career and saw him just once, and everybody was telling me, “you know that’s Stanley Greene. You know the one with the glasses.” I can’t wait to see the film because I want to see what was behind all of that.

Walter Frisch is H. Harold Gumm/Harry and Albert von Tilzer Professor of Music at Columbia University, where he has taught since 1982. Frisch is a specialist in the music of composers from the Austro-German sphere in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, ranging from Schubert to Schoenberg. He has written numerous articles and two books on Brahms, including Brahms and the Principle of Developing Variation (1984) and Brahms: The Four Symphonies (1996, 2003). Frisch’s publications on Schoenberg include the book The Early Works of Arnold Schoenberg, 1893-1908 (1993) and the edited volume Schoenberg and His World (1999). His volume in the series Music in the Nineteenth Century, was published in fall 2012. His book Arlen and Harburg’s Over the Rainbow appeared in 2017. His latest work, Harold Arlen and His Songs (Oxford University Press) was published in 2024.

above

Walter discussing Les Demoiselles de Rochefort with Stéphane Lerouge.

below

Catherine Deneuve in Jacques Demy's film Les Parapluies de Cherbourg.

“Un

Matisse

At the Institute, Walter researched and wrote a book on the 1964 French film musical, Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg). The film, written and directed by Jacques Demy, with a musical score by Michel Legrand, is a much beloved classic, especially in France. Les Parapluies was a pioneering endeavor. There is no spoken dialogue; the film is sung from beginning to end, in a variety of styles extending from heightened speech to lyrical song. Walter’s research, drawing in part on archival sources in Paris, seeks to place Les Parapluies in the context of film musicals, the Nouvelle Vague in French cinema, and the socio-cultural milieu of post-war France.

COLOMBIA ABIGAIL R. COHEN FELLOW

There’s no place that invests so rigorously in imagination.

—— Ana María Gómez López

Trained initially in forensic anthropology, Ana María Gómez López is an artist from Cali, Colombia who works with corporeal and durational media. Her practice centers on self-experimentation, definitions of biological life, and global legacies of utopian thought. First-hand engagement in archives, libraries, and scientific collections is a central component of all her projects. Previous and ongoing works include the germination of a plant seed in her eye, the external circulation of her blood through an extracorporeal web, and most recently the formation of an artificial pearl in her mouth, which was set in motion at the Institute for Ideas and Imagination.

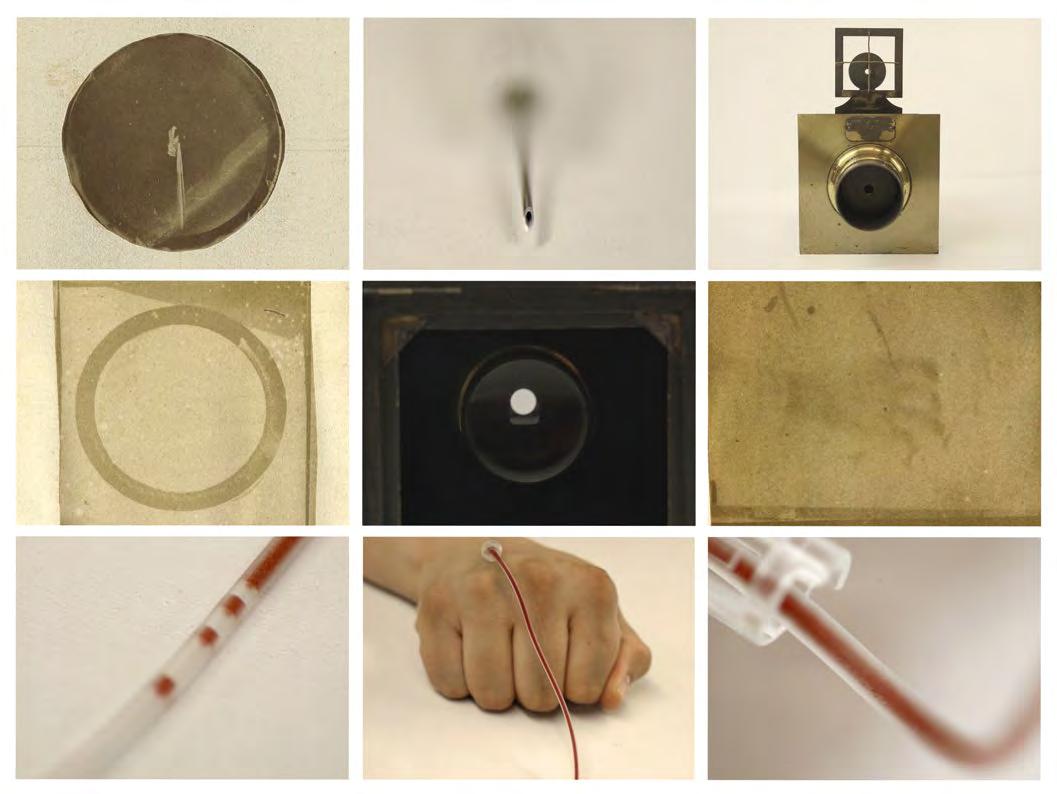

above

Stills from a film-in-progress featuring a 19th c. Bertsch pinhole camera, self-venipuncture images from the artists, and photographic prints from the Fonds Étienne-Jules Marey at the Collè ge de France, Paris.

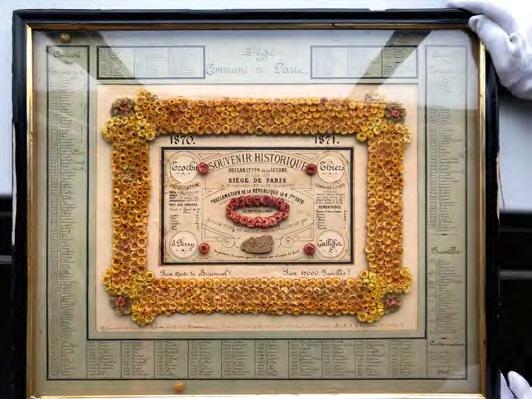

below A commemorative box with flowers and breadcrumbs from the 1871 Paris Commune.

Ana María’s fellowship project focused on a series of microphotographs taken by Auguste-Adolphe Bertsch (1813 – 1871), a French camera inventor whose images of mites, salt crystals, seed husks, and human blood cells revealed the minuscule structures of overlooked inanimate fragments. Taking the material traces in Bertsch’s pictures as a starting point, she developed an experimental short film and several durational works based on minutiae—smallscale and interdependent anatomies, ecologies, and living processes. These are set against the sweeping political, scientific, and technological changes of late 19th-century Paris, their detritus and debris enduring up to our present.

—— ANA MARÍA GÓMEZ LÓPEZ

Printmaking is as much about listening as it is about having image emerge on paper. At Idem Paris—a traditional lithography workshop just a few minutes walk from Reid Hall, around the corner from G are du Montparnasse—there may be interludes of stillness, but the mechanical cadence remains a constant. Here, running an edition means alternating one’s attention between the rhythmic clatter of the presses and the viscous hiss of ink spreading over the rollers, each rotation bringing the release of a fresh print. It is not unusual to have several of these enormous machines churning in tandem under Idem’s large glass roof. All have been there since 1881, when French lithographer and engraver Eugène Dufrenoy es tablished the print house to publish special edition maps. Back then the presses were powered through a steam boiler—one that most likely banged and whistled, adding to the overall clangor. The boiler is gone, yet several tons of limestones cut to multiple sizes still remain, stacked in shelves that rise all the way up to the ceiling. A veritable fossil library, produced by the fine accumulation of coral and shells through millions of years on the sea floor, continues to supply the supports for each print. Artists who have used these include Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Georges Braque, as well as more recently, Sophie Calle, William Kentridge, and David Lynch.

Throughout my tenure as an Abigail R. Cohen Fellow, I was fortunate to collaborate with master printer Martin Giffard and the exceptional team at Idem Paris to make La Perle (2024), the first in a series of lithographs about the creation of a pearl in my mouth. For this embodied artwork, my upper and lower jaws will act like a bivalve mollusk. In turn, my tongue will slowly convert a small grain of particulate matter into a tiny sphere. Similar to lithographs, pearls and limestone are formed layer by layer, both constituted primarily by minerals such as calcium carbonate. La Perle is based on a photograph where I am learning the lingual movements to configure this concentric miniature orb. Non-lexical vocalizations— oral repetitions in my organs of speech—are the basis for the pearl’s physical materialization. Much like the oyster that senses the breaking of the waves as it opens and closes its shells to the tide, I listen. With any luck, my utterances and their resonance will help compose this aquatic gem, if only in a poor human equivalent. Yet the lithograph with Idem Paris, like the entirety of my stay at the Institute for Ideas and Imagination, provided the initial grounds for making this possibility tangible: an artwork that, akin to a pearl, gives concrete shape to time and sound.

The making of the La Perle lithograph, picturing a double exposure of the artist's mouth, printed at

The close and frequent contact with open-minded and eager practitioners in many fields made me readier to incorporate “creative” elements into my predominantly formal academic work.

I learned about things I never dreamed of.

—— Jesse James

Jesse James is a classicist, historian, and lawyer whose research focuses on the social and psychological dimensions of law, especially in ancient Greece. He has written about legal socialization and Thucydides. He received his PhD in Classics from Columbia University as well as a JD from Berkeley School of Law, and he has held fellowships at the German Archaeological Institute, Harvard Law School, and the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. His dissertation explored how the Greeks understood international law and the role it played in relations between city-states.

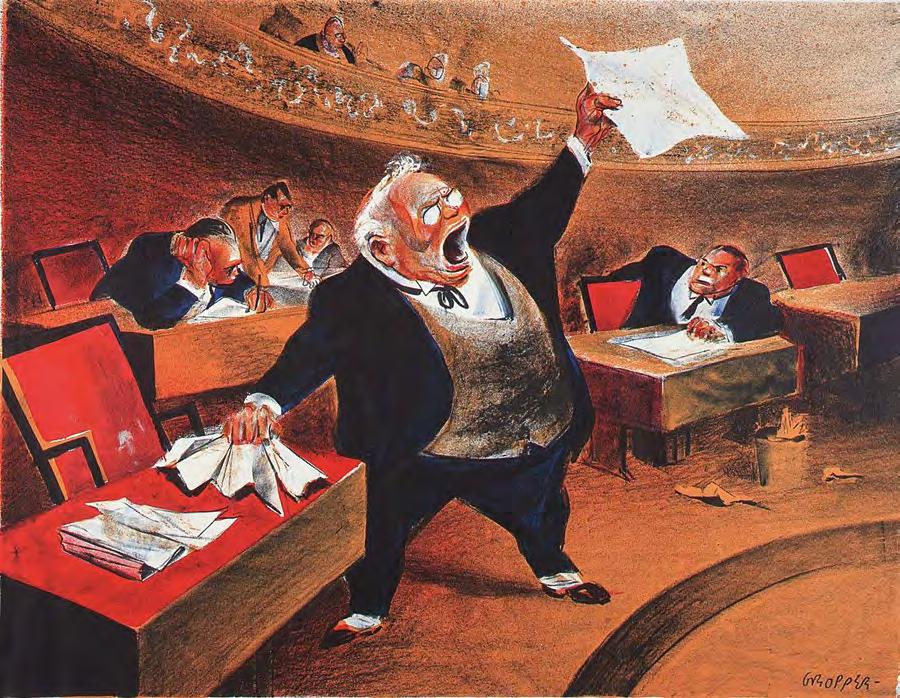

Rhetoric lay at the heart of ancient Greek and Roman education and forensic craft. But its role in recent legal practice and the larger relationship between ancient and modern legal behavior is less acknowledged. Jesse spent the year examining the role of psychology in the adversarial courtroom, the ways that court ruled and the law permitted litigants to use rhetoric and verbal art to persuade jurors and judges, even in an age of “scientific” evidence. During the fellowship, he explored how ancient Greek legal practice influenced the development of this relatively neglected aspect of modern Anglo-American and European legal systems.

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

Paraskevi Martzavou was born and raised in Thessaloniki, Greece, where she attended Aristotle University. She also studied in Hungary and worked as an archaeologist for the Greek Archaeological Service. She pursued her graduate studies in Paris and obtained her doctorate in epigraphy and ancient history at the École Pratique des Hautes Études. She was a post-doctoral fellow at Oxford University and since 2015 she has lectured in the Classics Department at Columbia University where she teaches Greek literature, history, and culture from Homer to the present. She has published on the post-classical Greek polis and is interested in the history of emotions in the ancient world.

The cult of the Egyptian gods (Isis, Osiris, Anubis, Sarapis) underwent a remarkable expansion in the Hellenistic and Roman periods in the Eastern and Western Mediterra nean. Through epigraphic and other forms of evidence, the world of Egyptian cult worship in the Greco-Roman world may be explored to shed light on the broader social, emotional, and institutional dimensions of religious prac tice and civic culture at that time, the subject of the monograph which Paraskevi completed during her fellowship.

above Paraskevi and Yea Jung Park in the Institute kitchen.

left A relief of Isis Pélagia in Delos.

below

Paraskevi presenting her SNF Rendez-Vous de l'Institut.

SOUTH KOREA

ABIGAIL R. COHEN FELLOW

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

The Institute gave me the blissful unstructured time for me to find my own rhythm for research and thinking, a luxury, and I used it to trawl through huge expanses of material, build my academic “archive,” and set up for years of scholarly production to come.

—— Yea Jung Park

Yea Jung Park is a medievalist and literary scholar from Seoul, South Korea. She received her PhD from Columbia University in 2022, specializing in Middle English literature, and will be starting as Assistant Professor of English at Saint Louis University following her fellowship. Her research interests include religion and literature, social epistemology, gesture studies, the history of medicine, and translation.

At the Institute, Yea Jung worked on her book project, which presents an account of medieval practices of mentalstate attribution, or "mind-reading," as they surface in literary narratives through the trope of “discernment.” The book provides a rationale for reading a variety of medieval literary genres, including works of religious instruction, epic and chivalric romances, and autobiography, as thought-experiments on the possibilities of mind-reading. The project tracks how narrative innovations arise in the pro cess of testing out methods of social cognition, and conversely, how new approaches to other minds are made possible through the affordances of literature and fiction.

—— YEA JUNG PARK

below

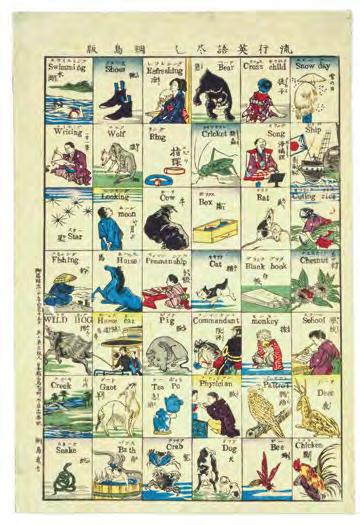

Multilingual and multimodal page from Ryūkō eigo zukushi (流行英語尽し; "Fashionable melange of English words"), woodcut by Utagawa Hiroshige Ⅲ, published by Tsunajima Kamekichi, 1887.

In March 2024, I cooked up a workshop titled “Translated and Back Again,” where Fellows and friends of the Institute gathered to try out some back-translation. Back- or retro-translation refers to the work of "returning" a translated text to its original language, moving once from Language A to Language B and then back into Language A. Though sent homeward, such texts never come quite full circle—or could they?

Like so many things at the Institute, the workshop was the result of a felicitous convergence of minds among Fellows. Hannah Weaver’s project highlighted how some medieval Latin texts were translated into European vernaculars and then back into Latin even when original Latin texts were still available, complicating received notions of medieval linguistic interaction between Latin and the vernacular. Meanwhile, I had been working on translating into English some modern Korean poetry that had epigraphs translated out of English or other European languages, and was fiercely debating whether to back-translate such passages myself or to draw on the “originals.” Inspired both by Hannah’s work and by recent full-blown publications of back-translated texts (e.g., an Icelandic Dracula and a Chinese Don Quixote), I decided to invite Institute folks to get our own hands messy in the work of “translating back.”

I asked workshop participants to bring a poem of their choice, originally written in English and translated into another language familiar to them, and gave everyone a half-hour to translate that text back into English on the spot. (I also brought in random selections for the empty-handed: French Eliot, Auden, and Hopkins; Spanish Anzaldúa; Latin Chaucer.) In a warm-up discussion, we shared what we thought back-translations would or should look like; after reading some of our own back-translations out loud to each other, we circled back to compare our findings. Many of us had guessed that back-translation would simplify details and smooth out idiosyncratic expressions, making for plainer texts; this was sometimes true, with results hewing closer to conventional rhetoric, metaphors, or turns of phrase spelled out literally, and so forth. However, we also discovered that back-translators could add extra verbal variety to avoid awkward repetitions, or make experimental moves to recreate vaguely remembered poetic effects. Marie d'Origny found herself working on a random excerpt so clunkily translated that she did not recognize the poem as a personal favorite; despite this mental block, Jay Bernard later managed to “hear” the original poem through the back-translation.

For some, back-translation was a creative language game with lots of room for poetic license. For others, it was truly a return trip, an exercise in guesswork, recognition, and excavation. As Jay put it, the beauty of the workshop was that “every single person hit on some unique facet of the translation process.” Back-translation as a practice still tends to crop up mainly in utilitarian contexts—as a double-check for accuracy in multilingual manuals, for example—but in our workshop, we were able to test out its potential both as an artistic opportunity and as metatextual work that helps to throw the very labor of translation into relief.

BACK - TRANSLATION WORKSHOP

CHARL OTTE FORCE, COMMUNICATIONS COORDINATOR AT COLUMBIA GLOBAL PARIS CENTER

TEXT: GOBLIN

MARKET BY CHRISTINA ROSSETTI

Matin et soir, Les jeunes filles entendaient le cri des lutins : « Venez acheter nos fruits du verger, Venez acheter, venez acheter : Pommes et coings, Citrons et oranges, Cerises dodues non becquetées, Melons et framboises, Pêches aux joues duveteuses, Mûres aux têtes cuivrées, Airelles nées en liberté,

Pommes sauvages, mûres des haies, Ananas, mûres des ronces, Abricots, fraises Tous bien mûrs

Dans une atmosphère d’été Matins qui passent Bonnes soirées qui s’envolent Venez acheter, venez acheter ; Nos raisins tout frais cueillis de la vigne Grenades pleines et goûteuses, Dattes et sirabelles piquantes, Reines-Claudes et poires remarquables, Quetsches et myrtilles, Goûtez-les, tâtez ; Raisins de Corinthe et groseilles à maquereaux, Épines-vinettes écarlates, Figues à vous en mettre plein la bouche, Citrons du Sud, Doux pour la langue, plaisants à l’œil, Venez acheter, venez acheter. »

Morning and evening

Maids heard the goblins cry: “Come buy our orchard fruits, Come buy, come buy:

Apples and quinces, Lemons and oranges, Plump unpeck’d cherries, Melons and raspberries, Bloom-down-cheek’d peaches, Swart-headed mulberries, Wild free-born cranberries, Crab-apples, dewberries, Pine-apples, blackberries, Apricots, strawberries;— All ripe together In summer weather,— Morns that pass by, Fair eves that fly; Come buy, come buy:

Our grapes fresh from the vine, Pomegranates full and fine, Dates and sharp bullaces, Rare pears and greengages, Damsons and bilberries, Taste them and try: Currants and gooseberries, Bright-fire-like barberries, Figs to fill your mouth, Citrons from the South, Sweet to tongue and sound to eye; Come buy, come buy.”

Dawn to dusk, Little girls heard the goblins call: “(Hither) come buy our orchard fruit Come by, come buy:*

Apples and quinces, Lemons and oranges, Whole juicy cherries,** Melons and raspberries, Fuzzy-cheeked peaches, Blushing red-topped blackberries, Lingonberries grown in liberty, Crabapples and brambleberries, Pineapples, hedge berries, Apricots, strawberries

All well ripened

In summer heat

Passing mornings

Good evenings that fly by, Come by, come buy,

Our freshly vine-cut grapes, Tasty, juicy pomegranates, Dates and spicy sirabelles, Royal plumps and remarkable pears, Damson plums and blueberries, Taste them, touch; Corinthian grapes and gooseberries, Scarlett barberries, Figs to fill your mouth, Citrus from the South, Lush to the tongue, sweet to the eye, Come by, come buy."

* I knew “ Come by, come buy” was poetic license, and that it’s really “come buy, come buy,” but I liked the ambiguity of the English homophone and wanted to make it explicit.

** In my translation notes, I considered alternate phrases: “fat cherries unpicked,” “juicy unpicked cherries,” and adjectives like “juicy,” “flawless,” and “chaste.” I chose “whole” because it suggests both the perfection of the fruit and the girls' reputations—the idea that once the fruit is eaten, or a girl “falls,” they are no longer whole. It’s intriguing that the fruit, as the instrument of the fall, also symbolizes the girls themselves.

David Scott teaches in the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University. He is the author of Formations of Ritual (1994), Refashioning Futures (1999), Conscripts of Modernity (2004), Omens of Adversity (2014), Stuart Hall’s Voice (2017), Irreparable Evil: An Essay in Moral and Reparatory History (2024), and (with Orlando Patterson) The Paradox of Freedom (2023). Scott is the founder and editor of the journal Small Axe and director of the Small Axe Project. He is interested in questions of friendship, moral theory, and biography.

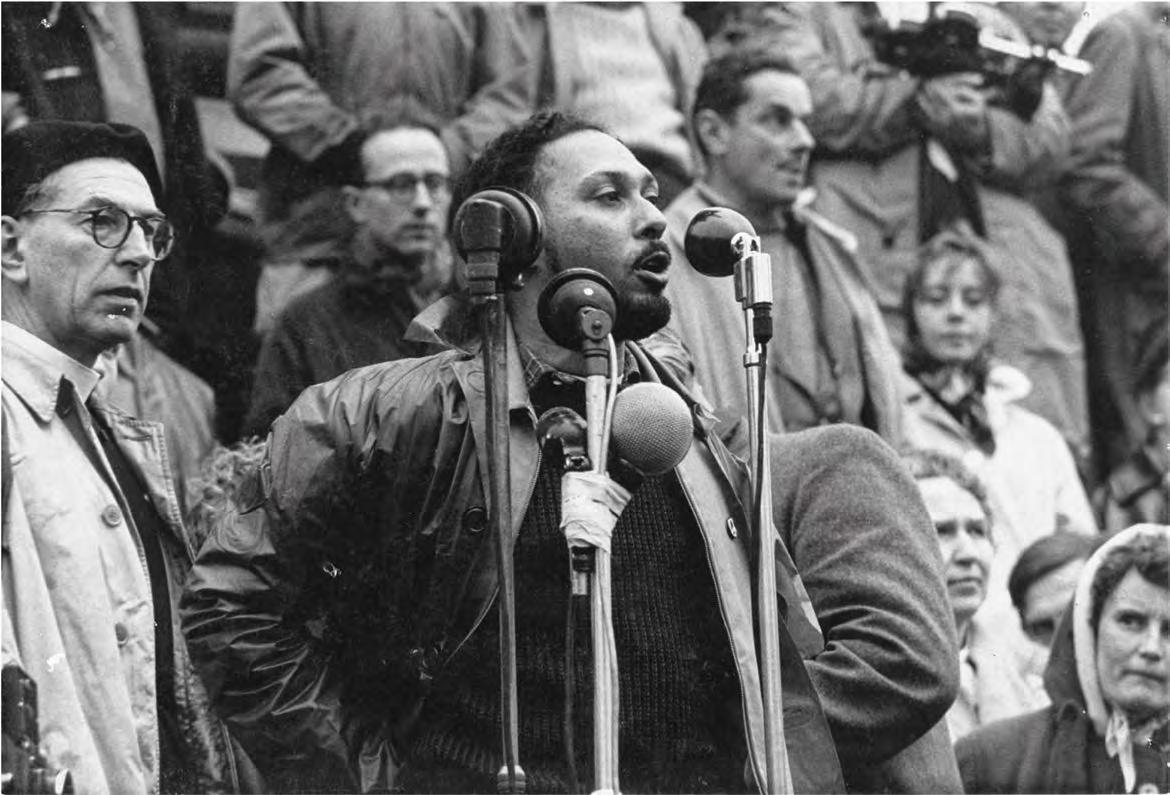

During the fellowship year, David worked on a biography of Stuart Hall (1932-2014), the Jamaican-British cultural theorist. Specifically, he focused on the “conjuncture” of 1956, the crisis (precipitated by the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian uprising, on the one hand, and the Anglo-French invasion of the Suez Canal Zone, on the other) that led to the formation of the British New Left. Hall, still a student at Oxford writing a dissertation on Henry James, was a central figure in its emergence. He was a founding editor of two of the defining journals of the moment—first the student-led Universities and Left Review, and subsequently the New Left Review.

above

below

Creating a cohort that brings together scholars and artists allows for the possibility to hear about, discuss, and reflect on other ways to think and do. It definitely expands possibilities as you have access to different modes of expression that can only fuel and enrich your own practice.

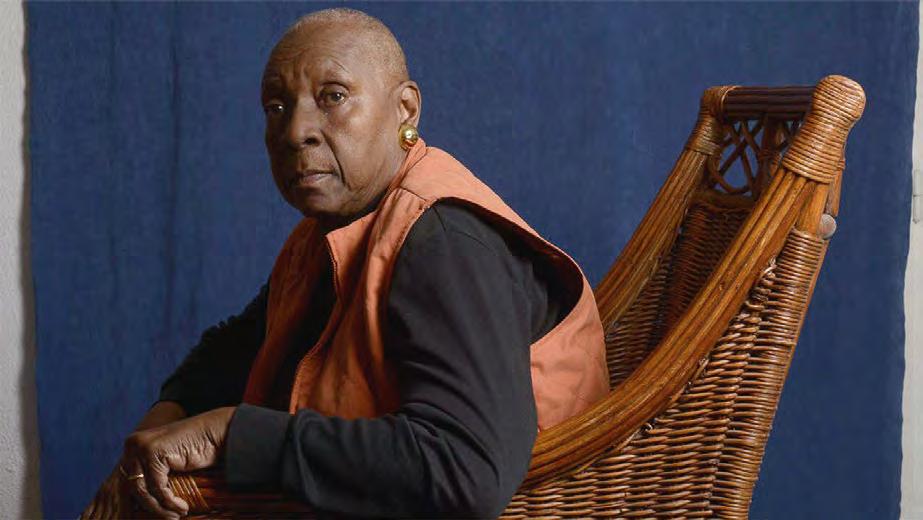

—— Maboula Soumahoro

Maboula Soumahoro is an associate professor in the English Department of the University of Tours. She was the 2022-2023 Mellon Arts Project International Visiting Professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University and Visiting Faculty at Bennington College. A specialist in the field of Africana Studies, Maboula has conducted research and taught in several universities and prisons in the United States and France. Widely published within and outside academia, she is the author of Le Triangle et l’Hexagone, réflexions sur une identité noire (La Découverte, 2021), translated into English by former Fellow Kaiama L. Glover as Black Is the Journey, Africana the Name (Polity, 2021). This book received the FetKann! Maryse Condé literary prize in 2020.

the

Maboula’s year as a Fellow was devoted to writing a series script based on French Guadeloupean writer Maryse Condé’s novel Segu (Robert Laffont, 1984; Penguin, 1987). In the hope of doing justice to the immensity of Condé’s magnum opus, this project of adaptation required finding a delicate combination of academic, artistic, and translation skills. Turning Condé’s seminal novel into a series script implied democratizing an invaluable piece of modern literature from the African diaspora.

—— MABOULA SOUMAHORO

In my scholarly navigations of Africana matters, I never thought that Charles Dickens would come in handy—even when the famed English author writes about Paris, my birthplace. Resorting to Dickens, however, appears to me as the only and most accurate way to describe my SNF Rendez-Vous de l’Institut, a talk scheduled months in advance for April 4, 2024. Mar yse Condé died on April 2, 2024. The following lines are fragments of what I managed to write and utter on that peculiar night.

I met Maryse Condé about 25 years ago in New York. I was a young graduate student at the time, away from Paris for an academic year, and she had lef t Guadeloupe and was now teaching in the United States. I randomly met Maryse. I more or less stumbled upon her as friends of mine had convinced me to attend a post-conference cocktail. The French department of the university where I was spending the year as an exchange student had organized a conference in honor of Maryse’s work. I had never he ard of her before, much less read her. I agreed to attend not the conference but the cocktail that followed, eager to eat and drink for free. I tell you, financially, these days were rough.

With my friends, we found Maryse in the departmental lounge, seated on a sofa, warm and smiling. She immediately asked us questions: who are you? Where are you from? What are you doing here? What do you study? When my turn came, she said “Soumahoro, your name is Soumahoro? Are you from Mali or Guinea?” I replied that my family was from the Ivory Coast. To which she added, quite assertively: “You’re Dioula, right? Well, you definitely have to read Segu.” In my mind I thought, “Woww, Lady! Hold your horses! I don’t know you! I don’t need any orders, recommendations, instructions from you, do I? I’m not even doing a PhD in literature, let alone French and francophone literature! I specialize in African American and Africana Studies, I do history, cultures, religion, black nationalisms, you know. I have no time for literature. I do serious things. The only reason you’re meeting me today is because I intend to shoot straight for the free food and drinks. Do you have any idea how expensive NYC is for a girl like me? Do you know how broke I am? Do you know what it took for me to even be able to enroll in this

e xchange program?? Do you know what it took for me to leave all this Dioula business behind? Far, far away, in Paris, in Abidjan, in Seguela. Now freely roaming the New World. Huh huh, tchip, do not send me back to the old worlds! Spare me Paris and France, and above all spare the Ivory Coast and all Dioula-related matters! I already reluctantly accepted to enroll in this weekly seminar given by some Martinican guy whom I don’t even know about, whom I have never read either, whose syllabus is so opaque with works by Deleuze, Guattari, and rhizomes. Césaire?? What?? Return to My Native Land?? Seriously?? Is that poetry?? Come on!!! What’s this professor’s name again? One Édouard… Glissant... or something like that.”

Back to real life, standing in front of Maryse for the first time, there and then in the lounge of this French department of this American university in New York, I politely and concisely replied: “Segu? Sure! Will do!” Silly young me. Wounded young me. Incomplete and lost, torn young me. Me in the making, not knowing at the time that you don’t just run away from anything, you don’t just reinvent yourself: your past, your genealogy, your roots—they will hunt and find you wherever and whenever. It took me three years to read the two-volume novel.

Condé’s magnum opus is an intellectual project of afrodiasporic historical narration. I have argued in an academic article that Condé’s resort to literature is a justifiable attempt to fill in the historical blanks of the African Diaspora. Faced with the scarcity of archival sources emanating from the enslaved themselves, how is the (hi)story of dispersal and dehumanization to be narrated? The historical fiction, resting on complete archival records and including the voices of all the parties involved, is impossible to write in the specific context of the African Diaspora. Invisibility and silence are part and parcel of the history written, told, and circulated. What literature seems to allow is the possibility to make use of informed imagination and creativity—both research-based—to tell history in a manner that leaves room for the voices and humanity of the Afrodiasporic subjects who have historically been muted. Literary fiction thus serves as a substitute for an unachievable historical narrative, and both are equally legitimate. Along those lines, literature is used as an imperative necessity central to the diasporic

historical narration. As such, this historical narration based on literary fiction can be understood as a project of re-humanization of the African-descended by way of rendering missing voices and stories audible. This process very much inspired, and was later theorized, as critical fabulation by Saidiya Hartman.

Such is my understanding and analysis of what Segu is. My intellectual and academic understanding and analysis of the novel, that is. Because there is another layer that I need to explore, now that I have embarked on this adaptation project. This layer is more personal, intimate even. Indeed, Segu is the first book I ever re ad that portrayed my family culture, when I had been born and raised in Hexagonal France, that is to say so far from our ancestral ways. For a long time, our ancestral ways were as foreign to me as the Hexagonal French ways. Only, the French ways, the Western ways, appeared more desirable. There is a history that accounts for the construction of this bias and hierarchy, I know that now. I did not know it when I firs t met Maryse in New York about 25 years ago. In Segu, I also learned about the character Nya, born Coulibali, who married into the Traore family that she co-rules as baramuso. This character strangely resembled my own mother, nicknamed Bamousso. One syllable separates the two terms: Baramuso and Bamousso. Each designates a woman and her status in a polygamous household or compound. I will forever mistake the one for the other. The baramuso is the favorite wife while the Bamousso is the dutilful wife, the head wife, the trustworthy wife. Forever a child,

I guess, I wonder to this day how one wife can be dutiful, trustworthy, reliable and a central pillar to the family without being the favorite. I will continue to misuse one term for the other until my last breath. I will never be able to get those meanings right, or perhaps I simply refuse to accept an injustice, something unfair that this mother of mine had to go through. All of that, I learned in this novel Segu

Much later, in 2022, when Maryse agreed to a screen adaptation of Segu in which I would be involved, she also gave me permission to betray her, saying: “That’s the rule, what else can you do? I’m ready.”

How am I approaching the task of adaptation as another form of translation, going from the written to the visual, paradoxically through the writing process? I have already been warned by the directors of the project: “Don’t be boring! Don’t be an academic! Have fun! Be passionate! Be your true self!” Interestingly, in one of the conversations I had with Maryse shortly af ter the publication of my book Black is the Journey/ Le Triangle et l’Hexagone back in 2020, she said: “ Your book is good, it’s excellent. So much better than Toni Morrison! Yet I miss your intimate voice. I want you to forget that you’re a professor, an academic demonstrating your great knowledge. Don’t hide behind academic jargon. I want you to remember that you are also a woman, in search of something that you still haven’t found. I want you to search and not find, make mistakes, be full of shit, be detestable, be pleasant, be yourself, be free. Be freer.”

Maria Stepanova is a poet, essayist, and editor, and the recipient of several Russian and international literary awards, including the Leipzig Book Prize for European Understanding and the Berman Literature Prize (both 2023). Her poems have been translated into a number of languages, including English, German, French, Italian, and Swedish. Her documentary novel Pamiati pamiati (In Memory of Memory) was published in November 2017 and received the Russian Big Book Prize in December 2018. The book was translated into 27 languages, shortlisted for the International Booker Prize and Prix Médicis, and longlisted for the National Book Award. It has also received the French Prix du meilleur livre étranger (2022). Since 2022, Stepanova has been based in Berlin.

A traveler, a respected landowner, an avid and sharp reader, a social climber, but mos t of all an ever-curious mind endlessly probing its surroundings for something new and worth exploring, Anne Lister (1791-1840) was meticulously putting to paper the minute details of her everyday life, including the weather, minor handiworks, hat prices, and bodily functions. Throughout her life Anne Lister was pursuing a certain goal that she never specified: her various studies, travels, and “unladylike” enterprises (mountain-hiking in the Pyrenees or dissecting with Cuvier in her Paris studio) were never meant to become an occupational activity. What kind of a sensibility shaped her obsessive writing— and what kind of a project do her diaries reflect? What is the story behind the story— and is there a right way of telling it?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez is the author of two collections of short stories, "Lovers on All Saints' Day" and "Songs for the Flames," and of six novels: The Informers, The Secret History of Costaguana, The Sound of Things Falling, Reputations, The Shape of the Ruins, and Retrospective. He has also published two books of literary essays. His books are currently published in 30 languages and have won, among others, the Premio Alfaguara, the Premio Gregor von Rezzori-Città di Firenze, the IMPAC International Dublin Literary Award, and the Prix du meilleur livre étranger. He has translated works by Joseph Conrad and Victor Hugo, among others. His opinion columns appear in the Spanish newspaper El País. In 2016 he was named Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters of the French Republic; in 2018 he was awarded the Order of Isabel la Católica by the King of Spain; in 2022 he was distinguished in the United Kingdom as International Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and in 2023 he was reported to have succeeded Javier Marias as King of Redonda.

The benefits I received from the fellowship were immeasurable. My work benefitted, obviously, from the luxury of time. But there were also unpredictable advantages, such as writing about a real character on the same street where she studied.

—— Juan Gabriel Vásquez

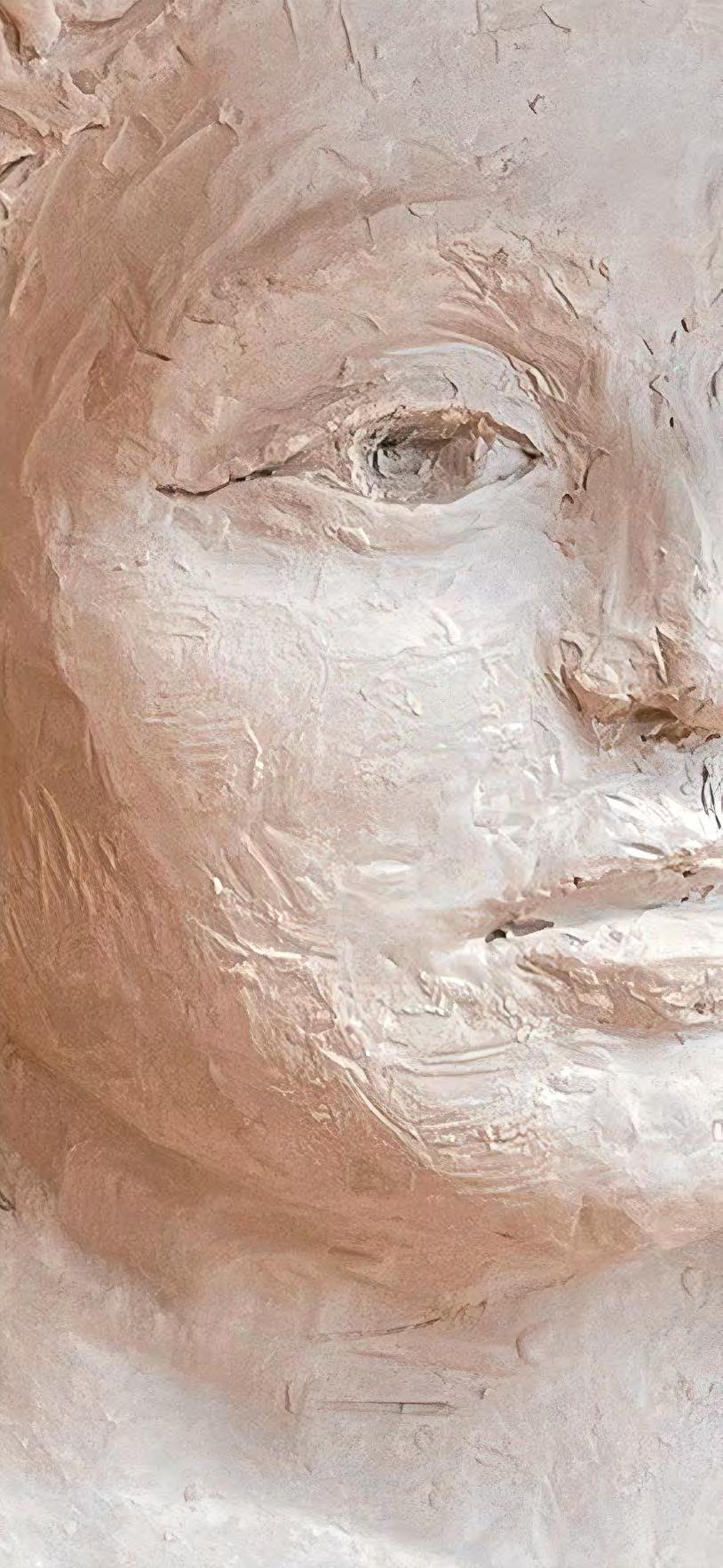

The project Juan developed while at the Institute is a novel. It is based on his reconstruction of the life of the Colombian artist Feliza Bursztyn (1933-1982) and of a series of real events, carried out through inter views and journalistic work, but interpreted through the lens (the language, the strategies) of fiction. Bursztyn was a sculptor born in Colombia to Polish Jewish immigrants. She studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière under Osip Zadkine among others and died in Paris in exile.

—— JUAN GABRIEL VÁSQUEZ

For nine months—yes, the duration of a pregnancy: how many times have you heard this?—you go to your room in Reid Hall to work on the novel. You try to get there early, because the early hours are always the best, but then you discover others have the same conviction. And this is a problem: because these people, your fellow Fellows, seem to be congenitally incapable of not being interesting. So you innocently leave your seclusion to get a cup of coffee, say, and you end up standing for ten minutes in the middle of the corridor talking with Hannah about the Latin etymology of the verb fingere, or planning to visit Julio Cortázar’s grave at Montparnasse cemetery because Ana María—artist, reader, forensic e xpert—wants to discuss her theory about his death. And the Protestant in you reluctantly comes to terms with the fact that very important things happen outside the workplace: namely, the strange spectacle of talented people being generous with what they have in their heads and genuinely curious about what you’re trying to do with what you have in yours.

Between conversations—about telekinesis and pasta with Éric, about Venezuelan poetry and beauty pageants with Fabiola—you try to do what you came here to do: write the novel. But the novel, for some reason, refuses to be written. You discuss your troubles with David, a biographer who is suspicious, and rightly so, of the way novelists deal with real human lives; you talk to Thomas about the difficulties of organizing the past—that thing we call History—on a page of fiction. But your novel is still a story in search of a shape. Which is appropriate: its main character is a Colombian sculptor, Feliza Bursztyn, who learned her trade in Paris in the 1950s and came back in the fall of 1981 to die a premature death in a Russian restaurant. You knew all this before you sat down at your desk for the first time; you will eventually realize that she died barely three hundred meters from Reid Hall, in a place that no longer exists. But nothing could have prepared you for the discovery you make within seconds of being here: that the street you see when you open your window, when you step out onto your little terrace, is the very same street where Feliza studied sculpture in the 1950s. There it is: the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, the legendary place where she learned to work with plaster and clay and bronze, still exists, virtually unchanged. What choice do you have? Three months into the writing, when nothing else seems to be working in the solitude of the room, you visit Marie in her office and pronounce those impossible words:

“I’d like to take sculpture lessons.”

Your own request surprises you; it doesn’t surprise her in the least (at the Institute, hardly anything does). Over the following weeks, as winter turns to spring, you learn to avoid pockets of air in the clay to keep the future figure from exploding, or how to use a kitchen knife to create a convincing eyelid. And things start to materialize: on the table, but also in your imagination. You finally see this young woman, the Colombian sculptor, walking these s treets seventy years ago, having fled a violent marriage and a hostile country, coming into the Académie at 8 in the morning and gulping down a glass of some Hungarian liquor because her ins tructor thinks this is the way to warm up; you see her leaving her class in the afternoons and sitting down in a nearby café just to watch Giacometti from a distance; and you see her trying to make a face or a hand or a small body that doesn’t topple, working and failing and trying again. And then you go back to your room at the Institute, maybe on a Friday morning, and find your fellow Fellows aesthetically arranging themselves around the totem-like brownies, talking about everything and nothing. And somebody asks how the book is coming along, and you find you’re not lying when you answer that it’s coming along rather well.

Being in conversation with [artists] encouraged me to think laterally, to write seriously, to collaborate, and to get out of my lane.

—— Hannah Weaver

A native Midwesterner, Hannah Weaver is now Assistant Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York, where she writes and teaches about the literature of medieval Europe, particularly the regions now known as England and France. She asks questions about how the physical forms that stories take can inform us about how medieval people thought. Her first monograph, Experimental Histories: Interpolation and the Medieval British Past was published by Cornell UP in 2024. She has written about time in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the treachery of incomprehensible English.

Hannah Weaver’s current book project, Latinizing the Vernacular: Retrotranslation in Medieval Europe, 1200-1500, uncovers an unexplored site of language contact and exchange. Around the time of the Black Death, a strange phenomenon kept happening across Europe: certain works would be translated from Latin to a European vernacular and then, surprisingly, back to Latin—even as the original Latin source remained available. These retrotranslations demonstrate vibrant interaction between languages that endured long past

the moment when the vernacular supposedly superseded Latin and began long before the humanist reclamation of Latin as an aesthetic choice. They bear witness to a desire to literalize the wide-ranging circulation of texts, people, and ideas in this period through the act of translation itself. This project offers a vision of linguistic cross-pollination and mutual influence that will revise our understanding of the role of the vernacular and the function of supralocal languages.

above

Hannah

previous page

Audience members experiencing a sound installation by Ursula Kwong-Brown and Danny Erdberg during the Nuit de l'Imagination: Bring Back Boredom.

this page clockwise

Kwong-Brown and Erdberg's installation was inspired by retreats at the Sea Ranch in California, a remote coastal communtity founded in the 1960's with utopian aspirations; Juan Gabriel Vásquez, Meredith Hunter-Mason, and Sari Castro celebrating the last SNF Rendez-Vous de l'Institut of the year with their bouquets given to them by the Fellows; Éric Baudelaire's tychoscope.

Aliyeh Ataei is an Iranian-Afghan author and screenwriter whose books have won major literary awards in Iran, including Mehregan-e-Adab for Best Novel. Born in 1981 in Iran, Aliyeh grew up in Darmian, a border region between the South Khorasan Province of Iran and the Farah province of Afghanistan. Part of her family lives in Iran, another in Afghanistan. A women’s rights activist, Ataei is deeply influenced by her observations and experiences growing up as a female member of a minority in Iran, and her writing is dedicated to themes of identity and immigration. She graduated from high-school in Birjand and went

next page clockwise

Lara Suyeux performing Aliyeh's play Danse de fumée in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc; Aliyeh and Lara Suyeux taking a bow after the performance of Danse de fumée; Anna with Yanzhyma Morozova, Antonina Krysa, Andrii Malakhov, and Nataliia Ivanovska of the Quartet Bleu et Or taking a bow after a concert at Reid Hall; Nikita Grigorov, 2022-23 Harriman Resident, and Luke Mogelson discuss war, journalism, and elections during a Library Chat.

1991 Project is led and inspired by Anna Stavychenko, a musicologist, music critic, and classical music producer. The 1991 Project is a nonprofit association whose purpose is to safeguard and promote Ukrainian music, by helping Ukrainian musicians preserve their artistic skills in France and in the Western world. The production of concerts, cultural, and educational events give visibility to the Ukrainian musical repertoire, in its tight connections to European cultural traditions. The 1991 Project, in collaboration with the Ukrainian Embassy in France, Columbia Global

left Aliyeh Ataei.

below Anna Stavychenko.

to Tehran to continue her studies in Tehran University of Art where she re and graduate degrees in screenplay writing. Her short stories have also been translated and published in several American and French magazines such as the Quarterly Review and Guernica personal essays, was published by Gallimard in April 2023 as

—— Marie d'Origny and the pianist and composer Richard Sears reminisce about Poetry Night over tea in the Institute Lounge.

MARIE: As most memorable Institute events, Poetry Night materialized from a casual conversation: Jay Bernard and I were chatting after their SNF Rendez-Vous de l’Institut, where Jay blended words, music, and sound in unexpected ways. It buttressed the content of their talk and made us listen differently. Jay mused that the Institute was becoming a den of poets and that several people here engaged with sound imaginatively. This made us think of Alice Oswald, and we said, “Let’s invite her.” She knew nothing about us or the Institute or what Poetry Night was about. But she said yes right away: Great poets, intimate evening, sound, experimentation, recitation —that made her curious. Yasmine Seale flew in from New York, Maria Stepanova invited from England her translator Sasha Dugdale, who is also a poet, and their friend Eugene Ostashevsky came from Berlin. We enlisted Pamela Jordan, Ana María Gómez López’s wife, who is a sound archeologist. How poetic is that for a job description? We realized the

lineup was missing music, and that’s when I thought of you, Richard.

When I asked if you would participate in our Poetry Night, you accepted in a heartbeat, as if this were a great gig at a prestigious venue that you couldn’t turn down. Yet you are a jazz pianist, classically trained, and you are at a point in your career where success and recognition mean you are in demand and you have a good sense of what you want and don’t want to do.

RICHARD: Being invited in the poets’ circle, I was excited by the opportunity of experimenting with words and sounds. In jazz there’s this ide a that playing with older musicians makes one better. Improvising on the piano alongside poets gave me that familiar feeling. Listening to others makes you value your own work. Specifically connecting with their rhythm. The way rhythm is felt and phrased is part of bridging the musical lineage.

MARIE: I admire the way you threaded the evening together. Each participant arrived with a clear idea of what they would do. Some had never set foot at the Institute and didn’t know anyone. You walked in and like a conductor you turned distinct pieces into a single performance, on the spot. Ten minutes before the guests arrived, you sat down and said: “Hi. I’m Richard. I’m a pianist, I’m here to serve you. If you prefer silence, that’s fine too.” You asked each one to say a word or two about what they would be doing. Slowly, most of them veered away from what they had planned to engage with the piano. You could see the thrill of possibilities lighten their faces. The result was artists in total command taking risks and experimenting, because suddenly that possibility was there.

RICHARD: You do that too in jazz: you use everything in the room. We had the conditions for that. Chance is a big part of it, and the willingness to take risks in public. I’m interested in this notion of listening differently, of what makes you pay attention. The poets have an awareness of this.

MARIE: By listening to your improvisations, I could hear the music in the poems. Suddenly it was all about sound. Jay, of course, who blends words, songs, and sound. Pam made us aware of architecture simply through the echo of footsteps in a cistern. Eugene writes very funny poetry, both in words and in diction. It’s all about the rhythm. Maria, speaking in Russian (I don’t speak Russian), became a musical experience. As Sasha read her translation, they both looked like singers in a choir. Yasmine’s ethereal delivery happened against an electric blue evening sky. Suddenly it was dusk, and Alice kept the lights off and recited in the dark.

RICHARD: Alice’s diction and concentration gave me this heavy feeling. And I mean heavy in a good way. Her phrasing taught me something. What she does is very kinetic, embedded in this performance tradition. She transferred that to me in the moment, as I played in response to her words.

MARIE: As they chose to either engage with you or not, you were the pivot that brought the room together. None of this was planned.

RICHARD: You don’t have to plan! Too much planning stresses the performers and stiffens the audience. Just put great players together. We were discovering all of this together.

I intended music as a palate cleanser, giving different charac ter to the performances, a pause to reflect. I went through pieces I had written as tiny interludes the day before, responding to the mood in the moment. Jazz practice is improvising within a form. These poems are composed, but the discrete improvisation happens in the way the poems are delivered. That night you could feel people listening. I think about Poetry Night ever y single day. That's not a hyperbole. Please don’t put this on paper but it felt like a romantic history of Paris, an evening that would show up in a novel or a memoir 20 or 30 years from now.

MARIE: It was like a celebratory laboratory, a halfway space in between experimentation and performance. Isn’t that the magic of jazz, in a way? I suppose the Institute is that liminal space. Poetry Night was a stirring illustration of its purpose.

above

Maria Stepanova recited her poems in Russian, while Sasha Dugdale read her English translations.

Jay Bernard reading one of their latest poems.

below left

Alice Oswald, Yasmine Seale, and Sasha Dugdale preparing for the evening of poetry.

The Visitorship program is a priceless offering for faculty like myself, who are unable to get away for a year, or even a semester. I feel very fortunate to be afforded this precious opportunity.

—— Magdalena Stern-Baczewska

Nina Alvarez is a journalist, documentarian, and video photographer. For over twenty-five years, she has reported breaking news and feature stories from around the world, on broadcast and web segments, radio reports and longform documentaries. An important theme in Alvarez's work has been the experience of migration, his torically and today.

Patricia Dailey is an Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. Her work spans medieval literature, contemporary philosophy, gender studies, psychedelic studies, and eco-criticism. She is the founder of the Colloquium for Early Medieval Studies, co-founder of the Affect Studies University Seminar, and Co-Chair of the Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies Council. She has t aught in France at the Université de Lille 3 and the Collè ge International de Philosophie.

Joshua DeVincenzo is the Assistant Director of Training and Education and Adjunct Lecturer at Columbia Climate School's National Center for Disaster Preparedness. Josh aims to provide accessible and quality educational programming on a large scale, focusing on climate change and equity. He has published his work on climate pedagogy and cognition in esteemed journals and outlets such as the Journal of International Affairs, Routledge, St ate of Planet, and the Hill.

Pierre Force is Professor of French and of History at Columbia University. He chaired the French Department from 1997 to 2007 and from 2011 to 2014 he served as the inaugural Dean of Humanities in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. He works at the interface between the humanities and the social sciences and has published in the fields of early modern French literature, intellectual history, and social history.

next page clockwise Film still from Naeem Mohaimen's Jole Dobe Na (Those Who Do Not Drown), 64’, 2020; Yannick Noah, the French tennis legend and the subject of Frank Guridy's forthcoming book; Nina Alvarez during a Library Chat about photographer Stanley Greene; Magdalena SternBaczewska playing the piano during a concert in the Grande Salle Ginsberg-LeClerc.

Frank Andre Guridy is the Dr. Kenneth and Kareitha Forde Professor of African American and African Diaspora Studies. He is also Professor of History and the Executive Director of the Eric H. Holder Initiative for Civil and Political Rights at Columbia. He is an award-winning historian whose recent research has focused on sport history, urban history, and the history of American social movements.

Irena Haiduk is Assistant Professor of Professional Practice in the Department of Art History at Barnard College. She directs Yugoexport, a blind and non-aligned oral corporation whose founding logic is equivalence, loyalty, and familial solidarity between people and things. Haiduk’s work is invested in relationships between aesthetics and economy, image ecology, and the way that economic infrastructures le ave clear aesthetic marks.

above

"Feather River Canyon" from Paradise, a book by photographer Maxime Riché that documents the aftermath of the 2021 Dixie Fire that devastated Paradise, California. Riché participated in a panel on "Invisible Consequences: Climate Disaster Recovery" co-organized by Faculty Visitor Joshua DeVincenzo at Reid Hall.

Dr. Radhika Iyengar is Director of Education and Research Scholar at the Center for Sustainable Development of Columbia University’s Earth Institute. She leads the Education for Sus tainable Development initiatives as a practitioner, researcher, teacher, and a manager. In addition to directing education initiatives at the Center and fieldwork in over 10 countries, she contributes to the scientific community focusing on international educational development with articles published in reputed journals and reports that are used by both domestic and international stakeholders.

Naeem Mohaiemen is a filmmaker and writer who combines photography, films, and essays to research the many forms of utopia-dystopia (families, borders, architecture, and uprisings) in the Muslim world after 1945. Despite underlining a historic tendency toward misrecognition of allies, the hope for a future international lef t, as an alternative to current silos of race and religion, is always a basis for his work.

I loved this re-defining of a fellowship. Makes my mind free to generate new ideas. World here I come…

—— Radhika Iyengar

Ngai Yin Yip is the Lavon Duddleson Krumb Assistant Professor of Earth and Environmental Engineering at Columbia University. He received his doctoral degree in Chemical and Environmental Engineering from Yale University. Yip is passionate about developing innovative solutions for critical separation challenges in water, energy, and the environment. Driven by his commitment to sustainability, his research focuses on recovery of valuable resources from waste streams, lithium harvesting from brines, and water purification, including high-salinity desalination and zero-liquid discharge.